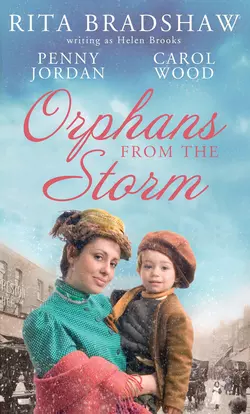

Orphans from the Storm: Bride at Bellfield Mill / A Family for Hawthorn Farm / Tilly of Tap House

PENNY JORDAN

HELEN BROOKS

Carol Wood

For the children’s sake…Lancashire, 1903Clutching her infant son, widowed Marianne Brown headed towards the chimneys of Bellfield Mill. She had to get work and luckily the dark and brooding Heywood Denshaw needed a housekeeper – but the Master soon begun to wish for more…Sunderland, 1899Wealthy farmer Luke Hudson gets more than he bargained for when he plucks a destitute young woman from the workhouse. He may have rescued Connie Summers from a life of penury, but her spirit and warmth give him a second chance at love.Isle of Dogs, 1928Doctor Harry Fleet and compassionate nurse Tilly Dainty can’t help but clash at the Tap House Surgery. But working together to help the sick turns out to be the healing balm both their hearts needed.

Orphans from the Storm

Rita Bradshaw

Writing as Helen Brooks

Penny Jordan

Carol Wood

* * *

Three amazing bestselling authors use their historical saga writing talents to create three unforgettable heroines!

Orphans from the Storm

Bride at Bellfield Mill

Penny Jordan

A Family for Hawthorn Farm

Rita Bradshaw

Writing as Helen Brooks

Tilly of Tap House

Carol Wood

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

To my wonderful editor, Bryony Green, for her encouragement and support.

Contents

Cover (#ud74b9094-0d44-502f-9e87-e93784782e89)

Title Page (#u30992846-ccd3-50b3-b574-75e340a2d51a)

Dedication (#u83620213-20e7-5c89-b410-49b25e796e3d)

Bride at Bellfield Mill

About the Author (#u82a1e6dc-df9e-503a-8647-7922afd87cac)

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

A Family for Hawthorn Farm

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

Tilly of Tap House

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Bride at Bellfield Mill (#u7b3ccc40-0b36-5e53-ba5e-4de9466f11bc)

PENNY JORDAN, one of Mills & Boon’s most popular authors, unfortunately passed away on 31st December 2011. She leaves an outstanding legacy, having sold over a hundred million books around the world. Penny wrote a total of one hundred and eighty-seven novels for Mills & Boon, including the phenomenally successful A Perfect Family, To Love, Honour & Betray, The Perfect Sinner and Power Play, which hit the New York Times and Sunday Times bestseller lists. Loved for her distinctive voice, she was successful in part because she continually broke boundaries and evolved her writing to keep up with readers’ changing tastes. Publishers Weekly said about Jordan, ‘Women everywhere will find pieces of themselves in Jordan’s characters.’ It is perhaps this gift for sympathetic characterisation that helps to explain her enduring appeal.

Penny Jordan also wrote World War II sagas as Annie Groves, published by HarperCollins.

CHAPTER ONE (#u7b3ccc40-0b36-5e53-ba5e-4de9466f11bc)

‘I CAN’T take you no further, lass, seein’ as I’m bound for Wicklethwaites Farm and you’re wantin’Rawlesden,’ the carter informed Marianne in his broad Lancashire accent, as he brought the cart to a halt at a fork in the rutted road. ‘You must take this turning ’ere and follow the road all the way down to the town. You’ll know it before you gets there on account of the smoke from Bellfield Mill’s chimneys, and then you keeps on walking when you gets to the Bellfield Hall.’

‘Why do you say that?’ Marianne asked the carter uncertainly.

She needed to find work—and quickly, she acknowledged as she looked down into the too-pale face of the baby in her arms. A lone woman with no work and a baby to care for could all too easily find herself in the workhouse—as she knew already to her cost.

The rich might be celebrating the Edwardian era, and a new king on the throne, but nothing had changed for the poor.

‘I says it on account of him wot owns it—aye, and t’mill an’ all. There’s plenty round here who says that he only come by them by foul means, and that the Master of Bellfield wouldn’t think twice about ridding himself of anyone wot was daft enough to stand in his way. There’s one little lass already disappeared from these parts with no one knowing where she’s gone. Happen that’s why he can’t get no one working up at the hall for him. No one half decent, that is…’

‘He doesn’t sound very pleasant,’ Marianne agreed as she clambered down from the cart, and then thanked the carter as he handed her the shabby bundle containing her few possessions.

‘I still dunno wot would bring a pretty lass like you looking for work in these parts.’

Marianne could tell that the carter was eager to know as much about her as he could—no doubt to add to his stock-in-trade of gossip. He had already regaled her with several tales of the doings of those who lived in the town and the small farms on the moors beyond it, with a great deal of relish. Marianne suspected it was an enclosed, shut-off life here in this dark mill town, buried deep in a small valley between the towering Pennine hills.

Her large brown eyes with their fringing of thick black eyelashes shadowed slightly in her small heart-shaped face. The carter had referred to her as a ‘pretty lass,’ but she suspected that he was flattering her. She certainly did not feel like one, with her hair damp and no doubt curling wildly all over the place, her clothes old and shabby and her skin pinched and blue-looking from the cold. She was also far too fine-boned for the modern fashion for curvaceous women—the kind of women King Edward favoured.

‘It’s just as I explained to you when you were kind enough to offer me a lift,’ she answered the carter politely. ‘My late husband’s dying wish was that I should bring his son here, to the place where he himself was born.’

‘So you’ve got family here, then, have you?’

‘I haven’t.’ Marianne forced herself to sound confident and relaxed. ‘My late husband did have, but alas they, like him, are dead now.’

‘Aye, well, it’s natural enough that a man should want to think of his child following in his own footsteps. Dead now, you said?’

‘Yes. He…he took a fever and died of it,’ Marianne told him. It would not do to claim too close an acquaintance on her late husband’s part with anything that might enable others to ask her too many questions.

‘Well, I hope you manage to find yourself a decent place soon, lass. Although it won’t be easy, wot with you having the babby, and you don’t want to find yourself taken up by the parish and put in t’workhouse,’ he warned her, echoing her own earlier thoughts.

‘They don’t suffer strangers easily hereabouts. Especially not when they’re poor and pretty. T’master, is a hard man, and it’s him wot lays down the law on account of him owning t’mill.’

Despite her best intentions Marianne shuddered—but then who would not do so at the thought of ending up in a parish workhouse?

Images, memories she wanted to banish for ever were trying to force themselves upon her. That sound she could hear inside her head was not the noise of women screaming in hunger and pain, but instead merely the howl of the winter wind, she assured herself firmly.

‘You’ve no folk of yer own, then, lass?’

‘I was orphaned young,’ she answered the carter truthfully, ‘and the aunt who brought me up is now dead.’

‘Well, think on about what I just said,’ the carter told her as he gathered up the reins and clicked his tongue to instruct the raw-boned horse between the shafts to move on. ‘Keep away from Bellfield and its master if you want to keep yourself safe.’

There it was again—the unmistakable admonition that the mill and its master were dangers to be avoided. But it was too late to ask the carter any more questions, as the rain-soaked darkness of the November evening was already swallowing him up.

Picking up her bundle, Marianne pulled her cloak as closely around the baby as she could before bracing herself against the howl of the wind and setting off down the steep rutted and muddy track the carter had told her led into the town.

Marianne grimaced as mud from the uneven road came up over the sides of her heavy clogs and the sleet-laden wind whipped cruelly at her too-thin body, soaking through her cheap cloak. The carter had talked of how winter came early to this part of the world, and how it wouldn’t be too long before it saw snow. She had only walked a mile or so since the carter had set her down at the fork in the road that led down off the Lancashire moors into the town below, but already she was exhausted, her teeth chattering and her hands blue with cold. What money she’d had to spare on the long journey here had gone on food and a good woollen blanket to wrap around the baby she was cradling so protectively.

The carter, with blackened stumps where his teeth had been, and his habit of spitting out the tobacco he was chewing, might not have been her preferred choice of companion, but his kindness in taking her up with him had brought tears of relief to her eyes. His offer had come after he had heard her begging the station master at Rochdale, who had turned her off the train, to let her continue her journey—a journey for which she had told him she had a ticket, even if now she couldn’t find it. She certainly couldn’t have walked all those extra miles that had lain between Rochdale and the small mill town that was her destination.

Now, as she struggled to stand upright against the battering wind, the moon emerged from behind a cloud to shine down on the canal in the valley below her. Alongside the canal ran the railway—the same railway on which she should have travelled to Rawlesden. She could see smoke emerging from the tall chimneys of the mills. Mills that made fortunes for their owners whilst becoming a grim prison for those who worked in them. She had never so much as visited a mill town before, never mind been inside a mill. The aunt who had brought her up had owned a small estate in Cheshire, but it was no mere chance that brought her here to this town now.

The baby gave a small weak whimper, causing her heart to turn over with sick fear. He was so hungry and so weak. Her fear for him drove her to walk faster, slipping and sliding on the muddy road as she made herself ignore the misery of her cold, wet body.

She was halfway down the hillside now, and as she turned a sharp bend in the road the large bulk of an imposing mansion rose up out of the darkness in front of her, its presence shocking her even though she had been looking for it. Its façade, revealed by the moonlight, was grim and threatening, as though daring anyone to approach it, and was more that of a fortress than a home. A pair of heavy iron gates set into a stone wall barred the way to it, and the moon shone on dark unlit windows whilst the wind whipped ferociously through the trees lining the carriageway leading to the house. She had known what it was even before she had seen the name Bellfield Hall carved into the stone columns supporting the huge gates.

A thin curl of smoke from one of its chimneys was the only evidence that it was inhabited. No wonder the carter had urged her to avoid such an inhospitable-looking place. Marianne shivered as she looked at it, before turning away to comfort the baby who had started to cry.

It was then that it happened—that somehow she took a careless step in the muddy darkness of the cart track, causing her ankle to turn so awkwardly that she stumbled heavily against the gate, pain spearing her even whilst she hugged the baby tightly to her to protect him.

As she struggled to stand upright she found that just trying to bear her own slender weight on her injured ankle brought her close to fainting with the pain. But she could not fail now. She must not. She had given her promise, after all. She looked down into the town. It was still a good long walk away, whilst the hall…This was not how she had planned for things to be, but what choice did she have? She reached for the heavy gate handle and turned it.

CHAPTER TWO (#u7b3ccc40-0b36-5e53-ba5e-4de9466f11bc)

IT HAD taken her longer to walk up the carriageway to the house than Marianne had expected, and then she’d had to find her way round to the servants’ entrance at the rear. The smell from the mill chimneys was stinging her throat and eyes, and the baby’s thin wail warned her that he too was affected by the smoke. A stabbing pain shot through her ankle with every step she took.

Relief filled her when she saw the light shining from a window to one side of the door. Here, surely, despite what the carter had told her, she would find some respite from the harsh weather, and a fire to sit before—if only for long enough to feed the baby. She was certain no one could be so hard-hearted as to send her out into a night like this one. Milo had often talked with admiration and pride of the people of this valley and their generosity of spirit. A poor, hard-working people whom he had been proud to call his own. He had shown her the sign language used by the mill workers to communicate with one another above the sound of the looms, and he had told her of the sunny summer days he had spent roaming free on the moors above the valley as a young boy. He had desperately wanted to come back here, but in the end death had come and snatched him away more speedily than either of them had anticipated.

She raised her hand toward the door knocker, but before she could reach it the door was suddenly pulled open, to reveal the interior of a large and very untidy kitchen. A woman emerged—the housekeeper, Marianne assumed. For surely someone so richly dressed, in a bonnet lavishly trimmed with fur and feathers and a cloak lined with what looked like silk, could not possibly be anything else. Certainly not a mere housemaid, or even a cook, and no lady of the house would ever exit via the servants’ door.

The woman was carrying a leather portmanteau, and her high colour and angry expression told Marianne immediately that this was no ordinary leave-taking.

The man who had pulled open the door looked equally furious. He was tall and broad-shouldered, with thick dark hair and a proudly arrogant profile, and both his appearance and his demeanour made it plain that he was the master of the house and in no very good humour.

‘If you think you can turn me off with nothing but a few pennies and no reference, Master Denshaw, then you’ll have to think again—that you will. An honest woman, I am, and I’m not having no one say no different…’

‘An honest woman? So tell me then, Mrs Micklehead, how does such an honest woman, paid no more than ten guineas a year, manage to afford to clothe herself in a bonnet and a cloak that even to my untrained male eye would have cost in the region of ten times that amount?’

The woman’s face took on an even more crimson hue.

‘Given to me, they was, by Mr Awkwright what I worked for before I come here. Said how I could have them, he did, after poor Mrs Awkwright passed away on account of how well I looked after her.’

‘So well, in fact, that she died of starvation and neglect, you mean? Well, you might have hoped to starve me into submission—or worse—Mrs Micklehead, with your inability to perform any of the tasks for which you were employed—’

‘An’ ousekeeper were what I were taken on as—not a skivvy nor a cook. I come here out of the goodness of me heart.’

‘You came here, Mrs Micklehead, for one reason and one reason only, and that was so that you could line your own pockets at my expense.’

‘If you was real quality, and not just some poor brat what managed to marry up into a class what was too good for him, you’d know how the real quality and them that works for them goes about things. Call yourself the Master of Bellfield? The whole town knows there was another what should have had that right, even if they’re too feared of you to say so.’

‘Hold your tongue, woman.’

The order thundered round the chaotic room.

‘You’re no housekeeper,’ he continued grimly into the silence he had commanded. ‘You’re a lazy good-for-nothing, a thief and a liar, and I’m well rid of you.’

‘You may well be, but I’ll tell you this—you won’t find no one daft enough to come looking to take me place, that you won’t,’ she told him vigorously. ‘Not when I’ve had me say—’

‘Excuse me…’

At the sound of her faltering interruption they both turned to look at Marianne.

‘Oh, I see—got someone to take me place already, have you?’ The housekeeper gave Marianne an angrily contemptuous look, and then, without giving either Marianne or her late master time to correct her, she continued challengingly, ‘So where’s he had you from, then? One of them fancy domestic agencies down in Manchester, I’ll be bound, with that posh way you talk. Well, you won’t last a full day here, you won’t. You’ll have come here expecting to be in charge of a proper gentleman’s household, with a cook and parlour maids, and even one of them butlers. There ain’t nowt like that here. Take my advice, love, and get yourself back where you’ve come from whilst you still can. This ain’t no place for the likes of you, this ain’t.’

Turning away from Marianne, she addressed the man watching them both. ‘She won’t last five minutes, by the looks of her. She don’t look like no housekeeper I’ve ever seen.’

‘I know enough to recognise a house with a kitchen that isn’t being run properly,’ Marianne told her pointedly. On any other occasion it might almost have made her smile to see the look on the other woman’s face as she realised that Marianne wasn’t going to be manipulated, as she’d hoped, or used as a bullet she could fire at her employer.

‘Well, some folks don’t know when they’re being done a favour, and that’s plain to see,’ she told Marianne, bridling angrily. ‘But don’t expect no sympathy when you find out what’s what.’ With a final angry glower she stormed past Marianne and out into the darkness.

‘I don’t know what brings you here,’ the Master of Bellfield said to Marianne coldly once the housekeeper had gone, ‘But we both know that it wasn’t an interview for the post of housekeeper via an employment agency in Manchester.’

‘I am looking for work,’ Marianne informed him swiftly.

‘Oh, you are, are you? And you thought to find some here? Well, you must be desperate, then. Didn’t you hear what Mrs Micklehead had to say about me?’

‘She is entitled to her opinion, but I prefer to form my own.’

Marianne could see from the look of astonishment on his face that he hadn’t expected her to speak up in such a way.

‘Is that wise in a servant?’

‘There is nothing, so far as I know, that says a servant cannot have a mind of her own.’

‘If you really think that you are a fool. There’s no work for you here.’

Marianne stood her ground.

‘Forgive me, sir, but it looks to me as though there is a great deal of work to be done.’

There was a small silence whilst they both contemplated the grim state of the kitchen, and then he demanded, ‘And you reckon you can do it, do you? Well, you’ve got more faith in yourself than I have. Because I don’t. Not from the looks of you.’

‘A fair man would give me the chance to prove myself and not dismiss me out of hand,’ Marianne told him bravely.

‘A fair man?’ He gave a harsh shout of laughter. ‘Didn’t you hear what Mrs Micklehead had to say? I am not a fair man. I never have been and I never will be. No. I am a monster—a cruel tyrant who is loathed and hated by those who are forced to work for me.’

‘As I’ve said, I prefer to make my own judgements, sir.’

‘Well, I must say you have a great deal to say for yourself for a person who arrives at my door looking like a half-starved cat. You are not from ’round here.’

‘No, sir.’

‘So what brings you here, then?’

‘I need work. I saw that this is a big house, and I thought that maybe…’

‘I’d be mad to take on another housekeeper to pick my pockets and attempt to either starve or poison me. And why should I when I can rack up at a hotel and oversee my mills from there?’

‘A man needs his own roof over his head,’ Marianne told him daringly, drawing courage from the fact that he had not thrown her out immediately. She was pretty certain that this man would want to stay in his own house, and would not easily tolerate living under the rule of anyone else.

‘And a woman needs a clever silken tongue if she is to persuade a man to provide a roof over hers, eh, little cat?’

Marianne looked down at the floor, sensing that his mood had changed and that he was turning against her.

‘It is work I am looking for, sir—honest, decent work. That is all,’ she told him quietly. She could feel him weighing her up and judging her, and then putting that judgement into the scales to be weighed against his past experience and his cynicism.

‘And you reckon you can set this place to order, do you, with this honest, decent work of yours?’

Why was she hesitating? she thought. Wasn’t this what she wanted—why she had come here? The kitchen might be untidy and chaotic, but at least it was warm and dry. Where was she to go if she was turned away now? Back to where she had come from? Hardly. Yet still she hesitated, warned by something she could see in the arrogant male face with its winter-sky-grey eyes. His gaze held a hint of latent cruelty, making her feel that if she stepped over the threshold of this house and into his domain she would be stepping into danger. She could turn back. She could walk on into the town and find work there. She could…

A gust of wind rattled the windows and the door slammed shut—closed, Marianne was sure, not by the force of the wind but by a human hand.

‘Yes.’ Why did she feel as though she had taken a very reckless step into some dark unknown?

She could still feel him looking at her, assessing her, and it was a relief when he finally spoke.

‘So, tell me something of the cause of such an urgent need for work that it has brought you out on such a night and to such a place. Got turned off by your mistress, did you?’

Although his voice had a rich northern burr, it was not as strong as that of the departing housekeeper. She could hear the hostility and the suspicion in it, though.

‘No!’

‘Then what?’

‘Beggars can’t be choosers, sir,’ she replied quietly, looking not at him but down at the floor. It had taken more than one whipping before she had known that it was not her right to look her betters in the eye.

‘Beggars? You class yourself as such, and yet you are aspiring to the post of a housekeeper?’

‘I know the duties of a housekeeper, sir, and have carried them out in the past. On this occasion, though, I was not in any expectation of such an elevated post.’

‘Elevated? So you think that working for me as my housekeeper would be a rare and juicy plum of a post, do you?’

‘I had not thought of it in such terms, sir. Indeed, I had not thought of taking that position at all—you are the one who has done that. All I was looking for was the chance of work and a roof over my head.’

‘But you have worked as a housekeeper, you say?’

‘Yes, sir.’ It was, after all, the truth.

‘Where was your last post?’

‘In Cheshire, sir. The home of an elderly lady.’

‘Cheshire! So what brings you to Lancashire?’

The baby, who had fallen asleep, suddenly woke up and started to cry.

‘What the devil?’ He snatched up a lantern from the table and held it aloft, anger pinching in his nostrils and drawing down the corners of his mouth into a scimitar curve as he stared at them both. ‘What kind of deceit is this that you try to pass yourself off as a servant when you have a child?’

‘No deceit, sir. I am a respectable widow, forced to earn a living for myself and my child as best I can.’

‘No one employs a woman with a child as a servant.’

It was true enough. Live-in domestic staff were supposed to remain single. Housekeepers might be given the courtesy title of ‘Mrs,’ but they were certainly not supposed to have a husband, and most definitely not a child.

‘I was in service before my marriage,’ she answered his charge, speaking the truth once again.

‘So you’re a widow, are you? What happened to your husband?’

‘He died, sir.’

‘Don’t bandy words with me. I don’t have the temperament for such women’s ways. There’s no work here for the likes of you. You might have more luck in one of the bawdy houses of Manchester—or was that how you came by your brat in the first place?’

‘I am a respectably married woman.’ Marianne told him angrily. ‘And this child, my late husband’s child, was born in wedlock.’

‘I’m surprised you haven’t had the gall to farm it out to someone else, or left it outside a chapel door to add to the problems of some already overburdened parish. Without it you might have convinced me to give you some work.’ He was walking towards the door, obviously intending to force her to leave.

It was too late now for her to wish that she had not allowed her pride to overrule her caution.

‘Please…’ She hated having to beg for anything from anyone, but to have to beg from a man like this one was galling indeed. However, she had given her promise. A deathbed promise what was more. ‘Please let me stay—at least for tonight. If nothing else I could clean up this kitchen. Please…’

She hated the way he was looking at her, stripping her of her dignity and her pride, reducing her to nothing other than the miserable creature he perceived her to be.

He gave a mirthless bark of derisory laughter.

‘Clean this place—in one night? Impossible! What is your name?’

‘Marianne—I mean Mrs…Mrs Brown.’

Something too sharp and knowing gleamed in his eyes.

‘You don’t seem too sure of your surname, Mrs Brown. Could it be that you have forgotten it and that it could just as readily be Smith or Jones? Where were you wed?’

‘I was married in Cheshire, in the town of Middlewich, and my name is Brown,’ Marianne told him fiercely.

‘Aye, well, anyone can buy a cheap brass ring and lay claim to a dead husband.’

‘I am married. It is the truth.’

‘You have your marriage lines?’

Marianne could feel her face starting to burn. ‘Not with me…’

He was going to make her leave…

‘If I turn you out, you and the brat will no doubt end up on the parish, and the workhouse governors will have something to say about that. Very well, you may stay the night. But first thing in the morning you are to leave—not just this house, but the town as well. Is that understood?’

He had gone without giving her the opportunity to answer him. Which was just as well, given the circumstances that had brought her here.

For tonight at least she and the baby would have the warmth of this kitchen. A kitchen she had promised to clean in return for its shelter, she reminded herself, as she rocked the baby back to sleep and prayed she would be able to find some milk for him somewhere in the chaos.

Her arms ached from carrying both the child and their few possessions, and her ankle was still throbbing. She limped over to an empty chair and placed the silent swaddled bundle down on it. Her heart missed a beat as she studied the small waxen face. She turned towards the fire glowering sullenly in the range. Ash spilled from beneath it, suggesting that it was some time since it had been cleaned out properly, and she would need a good fire burning if she was to heat enough water to get this place properly clean.

Picking up the lantern, she walked slowly round the kitchen. Half a loaf of bread had been left uncovered and drying out on the table, along with some butter, and a jar of jam with the lid left off, causing her mouth to water at the sight of it. But she made herself resist the temptation to fall on it and silence the ache of hunger that tore at her insides. Everywhere she looked she could see filthy crockery, and the floor was sticky with dirt.

A door opened off the kitchen into a large pantry, in which Marianne was relieved to find a large pitcher of milk standing on a marble slab. Before she did anything else she would feed the baby. Another door opened down to the cellars, but Marianne decided not to bother exploring them. A good housekeeper would keep a domain like this well stocked and spotlessly clean, and it would be run meticulously in an ordered routine, to provide for the comfort of its master and mistress and their family. If the kitchen was anything to judge from, this house did not provide comfort for anyone.

In the back scullery Marianne found a sink piled high with dirty pots. The pain in her ankle had turned into a dull ache, so she found a small pan, unused and clean enough to need only rinsing under a tap before she put some milk in it to heat up for the baby. He was so very, very frail. Tears filled her eyes.

Ten minutes later she was seated in the rocking chair she had drawn up to the range, feeding the baby small pieces of bread soaked in the warm milk into which she had melted a teaspoon of honey and beaten a large fresh egg. He was so weak that he didn’t even have the energy to suck on the food, and Marianne’s hand shook as she gently squeezed so that the egg and milk mixture ran into his mouth.

It was over an hour before she was satisfied with the amount of nourishment he had been able to take, and then she removed the swaddling bands to wash him gently in a bowl of warm water in front of the range. After she had dried him, she used a clean cloth she had found to make a fresh clout for him. He was asleep before she had finished, and Marianne put him down in a wicker basket she had found in the larder, which she had lined with soft clothes she had warmed on the range.

Was it her imagination, or was there actually a hint of warm pink colour in his cheeks, as though finally he might begin to thrive?

Marianne turned her attention to the range, ignoring the aching misery of her ankle as she poked and raked at the old ashes until she had got the fire blazing brightly and the discarded ash swept into a bucket ready to be disposed of. An empty hod containing only a couple of pieces of coke told her what the range burned, but whilst in a properly organised household such a hod—and indeed more than one—would have been ready filled with coke, so that the range could be stoked up for the night, in this household no such preparation had been made.

There was no help for it. Marianne recognised that she was going to have to go out into the yard and find the coke store, otherwise the range would go out.

The wind had picked up during the time she had been inside, and it tore at her cloak, whipping it round her as she held a lantern aloft, the better to see where the coke supply might be. To her relief she found it on her third search of the yard. But again, just like the kitchen, the store was neglected, and without a cover to keep the rain from the coke. The handle of the shovel she had to use to fill the hob was gritty, but she set her jaw and ignored the discomfort.

She had just finished filling the hod when she felt something cold and wet slither against her ankles. She had lived in poverty long enough to know the creatures that haunted its darkness, nor did it surprise her that there should be rats so close to the house. Instead of screaming and running away, she gripped the shovel more firmly and then raised it, ready to despatch the too-bold vermin.

‘Miaouww.’

It was a cat, not a rat. Half wild, starving, and probably infested with fleas. Marianne tried to shoo it away, but as though it sensed her instinctive sympathy for it the cat refused to go.

Perhaps she would put out a saucer of milk for it if it was still there in the morning, Marianne decided, as she shooed it away a second time. She started pulling the hod back across the yard, but its weight forced her to rest several times before she finally reached the back door. She leaned against it, then pushed it open and dragged the hod into the kitchen. Her ankle was still swollen and aching, but at least she had not twisted it so severely that she could not walk, she reflected gratefully.

First thing in the morning she intended to find out if the Master of Bellfield employed an outside man to do such things as bring in the kindling and fuel to keep the fires burning. If he didn’t, then she was going to insist that he provided her with a wheelbarrow, she decided breathlessly as she opened the range doors and stoked up the fire. Properly banked down it should stay in until the morning.

She stood up and stepped back from the fire to check on the baby, who thankfully was still sleeping peacefully. When she looked back towards the fire she saw to her bemusement that the cat was sitting in front of it, basking in its warmth. It must have slipped in without her noticing when she had brought in the hod. Its fur was a silky soft grey, thick and long, and beautifully marked. Marianne stared at it in astonishment as it looked back at her with an unblinking gaze. She frowned, remembering how long ago, as a child, her aunt had taken her to visit a friend of hers. She had been entranced by the cat that lived there because of its beautiful long coat. It had been a special and very expensive, very aristocratic breed, she remembered her aunt’s friend informing them.

But, no matter how aristocratic its coat, the cat couldn’t possibly stay inside. Marianne went briskly towards it, scooping it up. Beneath its thick coat she could feel its bones and its thinness. Surely that wasn’t silent reproach she could see in those eyes? Marianne hesitated. It wouldn’t hurt to give it a saucer of milk and let it stay inside for a while. It would be company for her whilst she set to work cleaning the kitchen.

Telling herself that she was far too soft-hearted, Marianne returned the cat to the hearth and poured it some milk.

Even the way it lapped from the saucer was delicate and dainty, and when it had finished it set to immediately cleaning its face, before curling up into a tight ball and going straight off to sleep.

Lucky cat, Marianne reflected, as she covered the baby’s basket with some muslin netting, just in case the cat should be tempted to climb into the basket whilst her back was turned. Marianne had never forgotten hearing her aunt’s cook telling the most dreadful story of how in one place she had worked the mistress of the house had gone mad with grief after her pet cat had got into the nursery and lain on top of the baby, smothering it to death.

The pans of water she had set to boil whilst she had been out filling the hod were now bubbling and spitting with the hot water she needed to start washing the dirty crockery that seemed to have been left where it had been used. Marianne had no idea how anyone could tolerate so much disorder.

It took her the best part of another hour, but at length the crockery was washed and dried and put back on dresser shelves that she’d had to wipe down first to remove the dust and grease.

She was so tired—too tired now to want to eat the bread and jam that had made her mouth water so much earlier. But she could not sleep yet. There was still the table to scrub down and bleach, and the floor to be cleaned, the range to be stoked up again for the morning, and the baby to be fed again—if he could be coaxed into taking a little more bread. Refusing to give in to her own exhaustion, Marianne set to work on the table.

The mixture of strong carbolic soap and bleach stung her eyes as she scrubbed, and turned her hands red and raw, but there was still a sense of accomplishment and pleasure in being able to stand back from the table to survey her finished handiwork.

The glow from the oil lamps was now reflecting off a row of clean shiny pans above the range, and the air in the kitchen smelled fresh instead of stuffy. The baby gave a small thin cry, signalling that he was waking up, and the cat, no doubt disturbed by the sound, uncurled itself and stretched.

Washing her hands carefully, Marianne headed for the pantry—and gave a small shriek as she opened the door to see three or four mice scattering in the lantern light, a tell-tale trail of flour trickling from one of the many bags of foodstuffs stacked on the larder floor.

A streak of grey flashed past her to pounce on a laggard mouse, before despatching it with swift efficiency and then padding towards Marianne to drop the small body at her feet.

‘So, you’re a good mouser, are you? Well, then, between us we should be able to get this kitchen into a proper state. That’s if the Master of Bellfield will allow us to stay,’ she warned the cat, which, having accepted its due praise, retrieved its trophy—much to Marianne’s relief.

The baby’s basket would be safer tonight placed up on the table, she decided a few minutes later, watching in relief as the baby fed sleepily on his milk and egg bread. Marianne thought he was already a little bit heavier and stronger, and she prayed that it might be so. There had been so many times during the dark days since his father’s death when she had feared that he too might slip away from her.

Fed and changed, the baby was restored to his cosy bed, now safely elevated away from any wandering mice daring enough to creep past the cat. Marianne ignored her own tiredness to set to work on the kitchen floor, which she could see needed not only rushing but a good scrubbing as well…

Marianne had no idea what time it was when she finally emptied away the last bucket of water and squeezed out the mop. All she did know was that the kitchen floor was now clean enough for even its master to eat his dinner off, and that she herself was exhausted.

The baby was still fast sleep, and so it seemed was the little cat—who for a while had sat up to watch her whilst she worked, as though wanting to oversee what she was doing. She felt so very tired, and so very dirty. Marianne stretched out in front of the fire, her too-thin body greedy for its heat. In the hallway, beyond the green-baize-covered door that separated it from the kitchen, a clock chimed the hour—but Marianne was already fast asleep and unable to hear it.

Not so the Master of Bellfield, to whom the striking of the hour heralded the start of a new working day. Like those who worked for him, the Master of Bellfield rose early, where others might have lain in their beds, enjoying the comfort and luxury paid for by the success of their mills.

There was no immaculately dressed maid to bring up the morning tea and a freshly ironed newspaper, no manservant to wake his master and announce that his bath had been drawn and his clothes laid out. How, after all, could a man reared on the cold charity of the workhouse, following the failure of his father’s business, appreciate such refinements?

The Master of Bellfield knew well what people thought of him—and what they said of him behind his back. That gossip would be fuelled afresh now, following the departure of his housekeeper, he acknowledged as he shaved with cold water, ignoring the sting of the razor. His dark hair, untamed and thick, was in need of a barber, and he knew that at the next Mill Owners’ Meeting at the fancy hotel in Manchester, where his peers met ostensibly to discuss business, he would be looked down upon by those who liked to pretend to some kind of superiority. Those who had lost their northern accents, smothered their hair in sickly smelling pomades and generally acted more like members of the landed gentry than mill owners.

That kind of foolishness wasn’t for him. It had, after all, been the cause of his own father’s downfall—too many nights spent playing cards with his newfound fancy friends, and too few days keeping an eye on how his mills were working and their profit and loss accounts.

His sister could screech all she liked to who she liked that their father had been cheated out of what was rightfully his when the bank had foreclosed on him, but the Master of Bellfield knew better.

He also knew how people had mocked and despised him for the steps he had taken to turn round his own fortunes—until they had learned to fear him and talk about their suspicions in hushed whispers. Well, let them say what they wished. Let the other mill owners’ stupid wives, with their airs and graces and their falsely genteel accents, ignore him and exclude him from the fancy parties they gave to catch a husband for their virginal daughters. He didn’t care.

He pulled on a cold and unironed shirt, and then stepped into a pair of sturdy trousers made from his own cloth. Only then did he pull back the shabby curtain from the windows and stare out into the darkness, illuminated by pinpoints of light coming from the various mills. He picked up his pocket watch.

One minute to five o’clock. He waited in silent impatience, only moving when, dead on the hour, he saw smoke billowing from the chimneys of his mills.

In the kitchen, two of its three occupants remained fast asleep when the Master of Bellfield entered the room, the third having padded silently over to the settle against the wall and crawled out of sight beneath it.

The first thing the master noticed was the young woman, lying in front of the fire. The second was the unfamiliar clean smell. His eyes narrowed as he strode against the scrubbed stone floor. The woman was lying on her side, one frail wrist sticking out from the thin shawl she had pulled about herself. He frowned as he looked down at her. He had not expected for one minute that she would be able to make good her claim to clean the kitchen. He had no doubt that she must have worked virtually throughout the night in order to do so. Why? Because she hoped to prevail on him to let her stay?

His mouth compressed as he looked at the basket on the table. If that was the case she was soon going to realise her mistake. Soon, but not now. It was half past five. Time for him to leave if he wanted to be at the mill for six, which he most assuredly did. Those who worked at Bellfield knew better than to try to sneak in later when its master was there to watch them clock in.

No foreman could instil the respect in his workforce that a watchful mill master could, nor ensure that the cloth woven in his mills was of such excellent quality that it was highly sought after. Let the other masters and their wives give themselves what airs and graces they pleased. It was Bellfield wool that was the true aristocrat of the northern valleys.

He made to step past the sleeping woman, but then turned to go back to the hall. He opened one of several pairs of heavy double mahogany doors that lined it and strode into the room beyond to remove from a fading red-velvet-covered sofa a dark-coloured square of cleanly woven wool.

Returning to the kitchen, he dropped the wool over her, and then headed for the back door. Other mill owners might choose to ride, or be driven in a carriage down to their mills. He preferred to walk. His head bare, ignoring the cold wind and the fraying cuffs of his shirt and jacket, he strode out across the yard, whilst behind him in the kitchen Marianne opened her eyes, wondering for a few seconds where she was, whilst the cat emerged from its hiding place to rub itself around her feet and mew demandingly.

Ignoring it Marianne fingered the fine wool cover that was now warming her. Someone had put it there, and there was only one person who could have done that. A faint blush of pink colour washed up over her skin.

An act of kindness from the Master of Bellfield? She shook her head in disbelief.

CHAPTER THREE (#u7b3ccc40-0b36-5e53-ba5e-4de9466f11bc)

UNEXPECTEDLY—at least so far as Marianne was concerned—after the biting sleet-laden wind of the previous day, the morning had brought a sky washed clear of clouds and sharp cold sunlight, making her grimace as it revealed the grimy state of the kitchen windows.

A commanding cry from the cat had her obediently opening the kitchen door for it. The yard looked a bit more hospitable this morning, and there were even a few hens scratching around it. As she studied them, wondering if and where they might be laying, an errand boy riding a bicycle that looked too big for him came cycling into the yard, grinning cheerfully at her as he brought his bike to a halt and slid off it.

‘Charlie Postlethwaite of Postlethwaite’s Provisions,’ he introduced himself, whilst pointing to the lettering on the bicycle. ‘That’s me dad,’ he told her proudly, ‘and he told me to get myself up here,’ he announced, opening the basket on the back of the bicycle. ‘He said how he’d heard about that old besom that called herself an ’ousekeeper had done a flit, and that like as not she’d have emptied the larder afore she went. He said that he’d heard that the t’master had taken on someone new and all.’

Having removed a small flitch of bacon from his basket, he was eyeing Marianne speculatively.

‘Going’ to be stayin’, are you?’

‘That depends on Mr Denshaw,’ Marianne told him circumspectly folding her hands in front of her and trying to look like a proper housekeeper.

‘Ooh, Mr Denshaw, is it? We call him t’master round here, we do, ’cos that’s what he is. Down at t’mill he’ll be now, aye, and ready for his breakfast when he gets back. Me dad said to say how he’ll be happy to sort out an order for you if you were wishing to send one back with me.’

‘Mr Denshaw hasn’t had time to acquaint me with the names of the tradespeople he favours as yet,’ Marianne responded repressively, but her attempt at formality was rather spoilt when the baby gave a shrill wail and the boy looked past her into the kitchen and gave a low whistle.

‘You’ve never brought a babby with you, have you?’ he exclaimed. ‘Hates them, t’master does, on account of him losing his own—and his wife and all. Went into labour early, she did, when t’master were away, and died. Oh, and my cousin Jem said to tell you that if you was wantin’ someone to do a bit of outdoor work, he’d be willin’.’

Marianne had never known a boy so loquacious, nor so full of information. Just listening to him was making her feel slightly breathless. The cat, having finished its business outside, ran back across the yard, pausing to stand in front of her, very much in the manner of a small guard.

‘Here, that’s one of Miss Amelia’s fancy cat’s kittens, ain’t it?’ the boy exclaimed in some astonishment as he stared at the cat. ‘I’d heard how t’master had given orders that they was all to be drowned. Took it real bad, he did, when she left. There was some that said he’d brought her home from that posh school of hers so as he could make her his wife, and that it were on account of that she upped and ran off. Took her cat with her and all, she did, and when it come back, months after she’d gone, t’master had it killed. Some round these parts said that the cat weren’t the only thing he’d done away with, and that he’d killed Miss Amelia an all. Aye—and her cousin, that were t’master’s stepson.’

Such a garbled and gothic tale was bound to be overexaggerated, Marianne knew. Nevertheless she found that she was shivering, and that her stomach was cramping hollowly as small tendrils of fear uncurled inside it to grip hold of her.

‘Thank you, Charlie.’ She stemmed the tide of information, determinedly starting to turn away, hoping that the boy would take the hint.

‘Aye, you’d better go and get some of that bacon on. He’s got a mean temper on him, t’master has, and he won’t be too pleased if he comes back to find his breakfast ain’t ready for him.’

‘You’re right. I shall go inside and cook it now,’ Marianne told him swiftly, exhaling with relief when this time the boy finally swung his leg up and over his bicycle.

‘So,’ she told the cat sitting watchfully at her feet a few minutes later, as she nursed the baby now sucking eagerly at his milky bread, ‘We have two good reasons why Mr Denshaw won’t want to keep me on. The baby, and you.’

She gave a small sigh. If the Master of Bellfield did but know it, she was as reluctant to be here as he was to have her here. But she had given her promise—a deathbed promise that could not be broken.

The baby had finished his milk. Marianne lifted him to her shoulder and rubbed his back to bring up his wind.

Within half an hour of Charlie Postlethwaite leaving, the baby had been fed and changed, and was back in his makeshift crib, now returned to the floor, whilst Marianne was carefully turning the bacon she was frying ready for the master’s return. All the while she kept a cautious eye on the cat, who had forsaken the hearth to go and sit beside the basket, where it was watching the sleeping infant.

‘Don’t you dare get in that basket,’ she warned it.

The cat gave her an obliquely haughty look, that immediately changed to a wary twitch of its ears as it stared at the door, as though it had heard something that Marianne could not.

Sure enough, within seconds, just after the cat had retreated to its hiding place beneath the settle, Marianne could hear the sound of men’s voices in the yard.

Hurrying to the window, she saw a group of men surrounding and supporting the Master of Bellfield. His arms were about their shoulders and a bloodstained bandage was wrapped around his thigh.

Marianne rushed to the door and opened it.

‘What’s happened?’ she asked the nearest man.

‘It’s t’master,’ one of them told her unnecessarily. ‘There were an accident at t’mill with one of t’machines.’

‘Told us to get him back here he did,’ another man supplied.

As the two men now supporting their employer struggled to get him through the doorway they accidentally banged his injured leg, causing him to let out a small moan through clenched teeth.

His face was pale, waxen with sweat, and his eyes were half closed, as though he was not really fully conscious. Marianne could see the bloodstain on the makeshift bandage spreading as she watched.

‘He needs to see a doctor,’ she told the men worriedly.

‘Aye, the foreman told him that. But he weren’t having none of it. Threatened to turn him off if he dared to send for him. Said as how it were just a bit of a scratch, even though them of us who’d seen what happened saw the pin go deep into his leg. Sheered off, it did, looked like someone had cut right through it to me…’

Marianne saw the way the other man kicked the one who was speaking, and muttered something to him too low for her to hear before raising his voice to ask her a question.

‘What do you want us to do with him now that we’ve brought him back? Only he’ll dock us wages, for sure, if we don’t get back t’mill.’

Marianne tried not to panic. They were treating her as though she really were the housekeeper, when of course she was no such thing.

‘Perhaps you should consult your master—’ she began, and then realised the uselessness of her suggestion even before one of the men holding him spoke to her bluntly.

‘Out for the count t’master is, missus, and in a bad way an all, I reckon. Mind you, there’s plenty living round here that wouldn’t mind seein’ him go into his coffin, and that’s no lie.’

Instinctively Marianne recoiled from his words, even though she could well understand how a hard and cruel employer could drive those dependent on him to wish him dead. It was no wonder that some workforces went on strike against their employers.

‘You’d better take him upstairs,’ she told the waiting men. ‘And one of you needs to run and summon the doctor.’

‘You’d best do that, Jim,’ the oldest of the men announced, ‘seein’ as you’re the fastest on your legs. We’ll take him up then shall we, missus?’ he asked Marianne.

Nodding her head, Marianne hurried to open the door into the hall, trying to look as though she were as familiar with the layout of the house as a true housekeeper would have been, although in reality all she knew of it was its kitchen.

She had time to recognise how badly served both the house and its master had been by Mrs Micklehead as she saw the neglect and the dull bloom on the mahogany doors which should have been gleaming with polish. The hallway was square, with imposing doors which she assumed belonged to the main entrance, whilst the stairs curved upwards to a galleried landing, the balustrade wonderfully carved with fruit and flowers whilst the banister rail itself felt smooth beneath her hand.

Two corridors ran off the handsome landing and Marianne hesitated, not knowing which might lead to the master bedroom, but to her relief the Master of Bellfield had regained consciousness, and was trying to take a step towards the right-hand corridor.

Trying to assume a confidence she did not feel, Marianne hurried ahead of the men, who were now almost dragging the weight of their master. Halfway along the corridor a pair of doors stood slightly open. Taking a chance, Marianne pushed them back further, exhaling shakily as she saw from the unmade-up state of the bed that this must indeed be the master bedroom.

‘We can’t lay him down in that, lass,’ one of the men supporting the master told her, nodding in the direction of the large bed. He added trenchantly, ‘That looks like best quality sheeting, that does, and I reckon with the way he’s bleedin’ it’ll be ruined if we lie him on it.’

He was right, of course, but since she had no idea where the linen cupboards were Marianne shook her head and said firmly, ‘Then they will just have to be ruined. How long do you think it will be before the doctor gets here?’

‘Depends on how long it takes Jim to find him. If I know Dr Hollingshead, he won’t take too kindly to being disturbed before he’s finished his breakfast.’

The two men had managed to lay their master on the bed now, and Marianne’s heart missed a beat as she saw how much the bloodstain on his bandage had spread.

‘Come on, lads,’ the man who seemed to be the one in charge told the others.

‘There’s nowt we can do here now. We’d best get back t’mill.’

Marianne hurried after them as she heard them clattering down the stairs.

‘The doctor will want to know exactly what happened,’ she told them ‘Perhaps one of you should stay—’

‘There’s nowt we can tell him except that a metal pin shot off one of the machines and flew straight into his leg. Pulled it out himself, he did, and all,’ he informed Marianne admiringly, leaving Marianne to suppress a shudder of horror at the thought of the pain such an action must have caused.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_89ceeb80-b817-5b27-b505-5293c39bc978)

THE men had gone, but the doctor had still not arrived. Marianne, who had seen all manner of injuries during her time at the workhouse, and knew the dangers of uncleaned wounds, had set water to boil and gone in search of clean linen, having first checked that the baby was still sleeping.

When she eventually found the linen cupboards on the attic floor, she grimaced in distaste to see that much of the linen was mired in cobwebs and mouse droppings, whilst the sheets that were clean were unironed and felt damp.

Her aunt would certainly never have tolerated such slovenliness and bad housekeeping. This was what happened when a man was at the mercy of someone like Mrs Micklehead. Against her will Marianne found that she almost felt slightly sorry for the Master of Bellfield—or at least for his house, which must once have been a truly elegant and comfortable home, and was now an empty, shabby place with no comfort of any kind.

She made her way back down the servants’ staircase to the attic floor and along the corridor to the landing. The departing men had left the door to the master bedroom open, and she could hear a low groan coming from it.

Quickly she hurried down the corridor, pausing in the doorway to the room.

The Master of Bellfield was still lying where the men had left him. His eyes were closed, but his right hand lay against his thigh, bright red with the blood that was now soaking through his fingers.

Panic filled Marianne. He was bleeding so much. Too much, she was sure.

Whilst she hesitated, wondering what to do, someone started knocking on the front door.

Picking up her skirts, Marianne ran down the stairs and across the hallway, turning the key in the lock and tugging back the heavy bolts so that she could open the door.

‘Doctor’s here, missus,’ the man who had been knocking informed her, before turning his head to spit out the wad of tobacco he had been chewing.

Marianne could see a small rotund bearded man, in a black frock coat and a tall stovepipe hat, emerging from a carriage, carrying a large Gladstone bag.

‘I understand there’s been an accident, and that the Master of Bellfield has been injured,’ he announced, without removing his hat. A sure sign that he considered a mere housekeeper to be far too much beneath him socially to merit the normal civilities, Marianne recognised, as she dipped him a small curtsey and nodded her head, before taking the bag he was holding out to her.

‘Yes, that’s right. If you’d like to come this way, Doctor. He’s in his room.’

The bag was heavy, and she could see the contempt the doctor gave the dusty hallway. She vowed to herself that on his next visit she would have it gleaming with polish.

‘You’re new here,’ he said curtly as Marianne led the way up the stairs.

‘Yes,’ she agreed. Taking a deep breath, she added untruthfully, ‘Mr Denshaw sent word to an employment agency in Manchester that he was in need of a new housekeeper. I only arrived last night.’ She hoped that the sudden scald of guilty colour heating her face would not betray her.

She paused as they reached the landing to tell him, ‘The master’s bedroom is this way, sir.’

‘Yes, I know where it is. You will attend me whilst I examine him, if you please.’

Marianne inclined her head obediently.

The sheet was red with blood now, and the man lying on the bed was unconscious and breathing shallowly.

‘How long has he been bleeding like this?’ the doctor demanded sharply.

‘Since he was brought here, sir,’ Marianne told him, as she placed the doctor’s bag on a mahogany tallboy.

‘I shall need hot water and carbolic soap with which to wash my hands,’ he told her disdainfully, as he went to open it. ‘And tell my man that I shall need him up here. Quickly, now—there is no time to waste. Unless you wish to se your master bleed to death.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Marianne almost flew back down the stairs, thankful that her ankle, whilst swollen, was no longer bothering her. Opening the front door, she passed on the doctor’s instructions to his servant.

‘Probably wants me to hold him down,’ he informed her. ‘You wouldn’t credit the yellin’ and cursin’ some of them do. Shouldn’t be surprised if he has to have his leg off. That’s what happens to a lot of them.’

Marianne shuddered.

By the time she got back upstairs, with a large jug of hot water, some clean basins and the carbolic, the doctor was instructing his servant to remove the scissors from his bag and cut through the fabric of his patient’s trousers so that he could inspect the wound.

One look at the servant’s grimy hands and nails had Marianne’s eyes rounding with shock. What kind of doctor insisted on cleanliness for his own hands but seemed not to care about applying the same safeguard to others? Marianne’s aunt had been a friend of Florence Nightingale’s family, and she had been meticulous about adopting the rules of cleanliness laid down by Miss Nightingale when doctoring her own household and estate workers. She had also been most insistent that Marianne learn these procedures, telling her many times, ‘According to Florence Nightingale it is the infection that so often kills the patient and not the wound, and thus it is our duty to ensure that everything about and around a sick person is kept clean.’

Impulsively Marianne reached for the scissors, remembering those words now. ‘Maybe I could do it more easily, sir. My hands being smaller,’ she said quickly.

Before the doctor could stop her she placed the scissors in one of the bowls she had brought up with her and poured some of the hot water over them, before using them to cut through the blood-soaked fabric.

The air in the room smelled of blood, taking Marianne back to scenes and memories she didn’t want to have. The poor house, with its victims of that poverty. A young woman left to give birth on her own, her life bleeding from her body whilst Marianne’s cries for help for her were ignored.

Her hands, washed with carbolic soap whilst she had been downstairs, shook, the scissors slippery now with blood. How shocked her aunt would have been at the thought of Marianne being exposed to the sight of a man’s naked flesh. But of course she was not the young innocent and protected girl she had been in her aunt’s household any more.

Soon she had slit the fabric far enough up the Master of Bellfield’s leg to reveal the wound from which his blood was flowing. Not as fast as it had been; welling rather than pumping now.

‘Come along, girl—can’t you see that there’s blood on my shoes? Clean it up, will you?’ the doctor was ordering her.

Marianne stared at him. He wanted her to clean his shoes? What about his patient’s wound? But she could sense the warning look his servant was giving her, and removing from her pocket the small piece of rag she had picked up earlier, intending to use it to clean the top of the range, she kneeled down and rubbed it over the doctor’s shoes.

‘Good. Now, wipe some of that blood off his leg, will you, so that I can take a closer look?’

Marianne could hardly believe her ears. Surely he wasn’t expecting her to wipe the blood from her employer’s leg with the rag she had just used to clean his shoes? Indignation sparkled in the normally quiet depths of her dark brown eyes. She turned to the pitcher of water she had brought upstairs and poured some into a clean bowl.

‘Of course, sir,’ she told him. ‘I’ll just wash my hands first, shall I?’ she suggested quietly, not waiting for his permission but instead rubbing her hands fiercely with the carbolic soap. She poured some water over them, before putting some fresh water in a clean bowl and then dipping a new piece of sheeting into it.

The only wounds she had cleaned before had been small domestic injuries to her aunt’s servants, and none of them had involved her touching a strongly muscled naked male thigh. But Marianne forced herself to ignore that and to work quickly to clean the blood away from the wound, as gently as she could. She could see that the pin had punctured the master’s flesh to some depth, and a width of a good half an inch, leaving ragged edges of skin and an ominously dark welling of blood. Even though he was still semi-conscious he flinched beneath her touch and tried to roll away.

‘Looks like we’ll have to tie him down, Jenks,’ the doctor told his servant. ‘Brought up the ropes with you, have you?’

‘I’ll go down and get them, sir,’ the servant answered him.

Marianne winced once again, moved to unwilling pity for her ‘new employer.’

‘Perhaps a glass of spirits might dull the pain and quieten him whilst you examine him, sir?’ she suggested quietly.

‘I dare say it would,’ the doctor agreed, much to her relief. ‘But I doubt you’ll find any spirits in this household.’

‘Surely as a doctor you carry a little medicinal brandy?’ Marianne ventured to ask.

The doctor was frowning now.

‘Brandy’s expensive. Folk round here don’t believe in wasting their brass on doctor’s bills for brandy. Hmm, looks like the bleeding’s stopped, and it’s a clean enough wound. Knowing Denshaw as I do, I’m surprised that it was his own machinery that did this. Cares more about his factory and everything in it than he does himself. Your master is a foolish man at times. He’s certainly not made himself popular amongst the other mill owners—paying his workers top rate, giving them milk to drink and special clothes to wear in the factory. That sort of thing is bound to lead to trouble one way or other. No need for those now, Jenks,’ he announced to his servant, who had come into the room panting from carrying the heavily soiled and bloodstained coils of rope he held in his arms.

‘Best thing you can do is bandage him up and let nature take its course. Like as not he’ll take a fever, so I’ll send a nurse up to sit with him. She’ll bring a draught with her that will keep him quiet until the fever runs its course.’

‘Bandage him up? But surely, Doctor—’ Marianne began to protest, thinking that she must have misheard him. Surely the doctor couldn’t mean that she was to bandage the Master of Bellfield’s leg?

‘Those are my instructions. And make sure that you pull the bandage tightly enough to stem the bleeding, but not too tightly. I’ll bid you good day now. My bill will be five guineas. You can tell your master when he returns to himself. You may feed him on a little weak tea—but nothing more, mind, in case it gives rise to a fever.’

Five guineas! That was a fortune for someone like her. But it was the information the doctor had given her about the Master of Bellfield’s astonishing treatment of his workers that occupied Marianne’s thoughts as she escorted the doctor back down the stairs, and not the extortionate cost of his visit. Her heart started to beat faster. Did this news mean that the task she had set herself before she arrived at Bellfield could be nearer to completion? If only that might be so. Sometimes the weight of the responsibility she had been given felt so very heavy, and she longed to have another to share it with. But for now she must keep her own counsel, and with it her secret.

As soon as she had closed the heavy front door behind the doctor she headed for the kitchen, where to her relief the cat was curled up in front of the fire whilst the baby was lying gurgling happily in his basket.

He really was the sweetest-looking baby, Marianne acknowledged, smiling tenderly at him. He was going to have his father’s cowlick of hair, even though as yet that cowlick was just a small curl. His colour was definitely much better, and he was actually watching her with interest instead of lying in that apathetic stillness that had so worried her. She was tempted to lift him out of the basket and cuddle him, but her first duty had to be to the man lying upstairs, she reminded herself sternly. After all, without him there would be no warm kitchen to shelter them, and no good rich milk to fill the baby’s empty stomach.

Bandage him up, the doctor had said. He hadn’t even offered to leave her any bandaging either, Marianne reflected, her sense of what was ethically right in a doctor outraged by his lack of proper care for his patient.

She would just have to do the best she could. And she would do her best—just as her aunt would have expected her to do. Now, what was it that boy on the bicycle had said his name was? Postlethwaite—that was it.

Marianne had seen the telephone in the hallway, and now she went to it and picked up the receiver, unable to stop herself from looking over her shoulder up the stairs. Not that it was likely that the Master of Bellfield was likely to come down to chastise her for the liberty she was taking.

A brisk female voice on the other end of the line was asking her what number she required.

‘I should like to be put through to Postlethwaite’s Provisions,’ she answered, her stomach cramping with a mixture of guilt and anxiety as she waited for the exchange operator to do as she had requested. She had no real right to be doing this, and certainly no real authority. She wasn’t really the housekeeper of Bellfield House after all.

‘How do, lass, how’s t’master going on?’

‘Mr Postlethwaite?’ Marianne asked uncertainly.

‘Aye, that’s me. My lad said as how he’d heard about t’master’s accident. You’ll be wanting me to send up some provisions for him, I reckon. I’ve got a nice tin of turtle soup here that he might fancy, or how about…?’

Tinned turtle soup? For a sick man? Marianne rather fancied that some good, nurturing homemade chicken soup would suit him far better, but of course she didn’t want to offend the shopkeeper.

‘Yes, thank you, Mr. Postlethwaite,’ she answered him politely. ‘I shall be needing some provisions, but first and most important I wondered if you could give me the direction of a reliable chemist. One who can supply me with bandages and ointments, and quickly. The doctor is to send up a nurse, but in the meantime I am to bandage the wound.’

‘Aye, you’ll be wanting Harper’s. If you want to tell me what you’re wanting, I’ll send young Charlie round there now and he can bring it up.’

His kindness brought a lump to Marianne’s throat and filled her with relief. Quickly she told him what she thought she would need, before adding, ‘Oh, and I was wondering—would you know of anyone local who might have bee hives, Mr Postlethwaite. Only I could do with some honey.’

‘Well, I dunno about that,’ he answered doubtfully, ‘it not being the season to take the combs out of the hives. But I’ll ask around for you.’

‘It must be pure honey, Mr Postlethwaite, and not any other kind.’ Marianne stressed.

Her aunt had sworn by the old-fashioned remedy of applying fresh honey to open wounds in order to heal and cleanse them.

‘A word to the wise, if you don’t mind me offering it, Mrs Brown,’ Mr Postlethwaite was saying, his voice dropping to a confidential whisper. ‘If the doctor sends up Betty Chadwick to do the nursing you’d best make sure that she isn’t on the drink.’

‘Oh, yes…thank you.’

At least now she would have the wherewithal to follow the doctor’s instructions, and the larder would have some food in it, Marianne acknowledged as she carefully replaced the telephone receiver, even if the shopkeeper’s warning about the nurse had been worrying.

Mentally she started to list everything she would need to do. As soon as she had bandaged the master’s wound she would have to fill the copper and boil-wash a good supply of clothes with which to cleanse his wound when it needed redressing. She would also have to try to find some decent clean sheets, and get them aired—although she wouldn’t be able to change his bed until the nurse arrived to lift him.

Armed with a fresh supply of hot water, and a piece of clean wet sheeting she had washed in boiling water and carbolic soap, Marianne made her way back upstairs to the master bedroom.

Her patient was lying motionless, with his face turned towards the window and his eyes closed, and for a second Marianne thought that he might actually have died he was so still. Her heart in her mouth, she stared at his chest, willing it to rise and fall, and realised when it did that she was shaking with relief. Relief? For this man? A man who…But, no, she must not think of that now.

Quietly and carefully Marianne made her way to the side of the bed opposite the window, closest to his injured leg.

Congealed blood lay thickly on top of the wound, which would have to be cleaned before she could bandage it. Marianne raised her hand to place it against the exposed flesh, to test it for heat that would indicate whether the wound was already turning putrid, and then hesitated with her hand hovering above the master’s naked thigh. Eventually she let her hand rest over the flesh of the wound. A foolish woman, very foolish indeed, might almost be tempted to explore that maleness, so very different in construction and intent from her own slender and delicate limbs.

Marianne stiffened as though stung. There was no reason for the way she was feeling at the moment, with her heart beating like a trapped bird and her face starting to burn. In the workhouse she had become accustomed to any number of sights and sounds not normally deemed suitable for the eyes and ears of a delicately reared female. Naked male limbs were not, after all, something she had never seen before. But she had not seen any that were quite as strongly and sensually male as this one, with its powerful muscles and sprinkling of thick dark hair. And, shockingly, the flesh was not pale like her own, but instead had been darkened as though by the sun.

An image flashed through her head—a hot summer’s evening when, as a girl, she had chanced to walk past a local millpond where the young men of the village had stripped off to swim in its cooling waters. Over it her senses imposed the image of another man—older, adult, and fully formed in his manhood. This man. A fierce shockwave of abhorrence for her own reckless thoughts seized her. What manner of foolishness was this?

Deliberately Marianne cleared her head of such dangerous thoughts and forced herself to concentrate on the feel of the flesh beneath her hand as though she were her aunt. Was there heat coming up from the torn flesh, or was the heat only there in her own guilty thoughts? There was no flushing of the skin, but her aunt had always said that a wound should be properly cleaned before it be allowed to seal.

Marianne wished that the nurse might arrive and take from her the responsibility of judging what should be done. She had seen what could happen if a wound turned putrid when a young gypsy had been brought to her aunt’s back door, having been found on neighbouring land caught in a man trap. His leg had swelled terribly with the poison that even her aunt had not been able to stem, and he had died terribly, in agony, his face blackened and swollen.

Gripped by the horror of her memories, Marianne’s hand tightened on the Master’s thigh.

When he let out a roar and sat up in the bed, Marianne didn’t know which of them looked the more shocked as she snatched her hand away from his flesh and he stared in disbelief.

‘You! What the devil? What are you about, woman? Is this how you repay my charity? By trying to kill me?’

‘Dr Hollingshead said that I was to bandage your leg.’

‘Hollingshead? That fraudulent leech. If he has let that filthy man of his anywhere near me then I am as good as dead.’

Instantly Marianne tried to reassure him. ‘I took the liberty of suggesting that I should be the one…That is…since he had—wrongly, of course—assumed I was your new housekeeper…’

‘What?’

‘It was a natural enough mistake.’

‘Was it, by God, or did you help him on his way to making it?’

For a man who had lost as much blood as he had, and who must be in considerable pain, the swiftness of his comprehension was daunting, Marianne acknowledged.

‘I…I have a little nursing experience through my aunt, and if you will allow me, sir, I will bathe your wound and place a bandage around it until the nurse arrives. She is to bring a draught with her that will assist you to sleep.’

‘Assist me to sleep—finish me, off you mean, with an unhealthy dose of laudanum.’ He moved on the bed and then blenched, and Marianne guessed that his wound was causing him more pain than he was ready to admit.

‘The bed will need to be changed when the nurse arrives, and that will, I’m afraid, cause you some discomfort,’ she told him tactfully. ‘I suggested to the doctor that maybe a medicinal tot of brandy would help. However, he said that it was unlikely that I would find any, so I have taken the liberty of ordering some from Mr Postlethwaite, to be brought up with some other necessary provisions.’

He stared at her. ‘The devil you have! Well, Hollingshead was wrong! You’ll find a bottle in the library. Bottom cupboard on the left of the fireplace. Keys are in my coat pocket, and mind you bring them back. Oh, and when young Charlie gets here, tell him he’s to go to the mill and tell Archie Gledhill to get himself up here. I want to talk to him.’

‘You should be resting. The sickroom is not a place from which to conduct business,’ Marianne reproved him, earning herself another biting look of wonder.

‘For a charity case who only last night was begging at my door, you’re taking one hell of a lot of liberties.’ His eyes narrowed. ‘And if you’re thinking to take advantage of a sick man, then let me tell you—’ He winced and fell back against the pillows his face suddenly tense with pain. ‘Go and get that brandy.’

‘I really don’t think—’ Marianne began, but he didn’t let her continue, struggling to get up out of the bed instead.

Worried that he might cause his wound to bleed again, Marianne told him hurriedly, ‘Very well—I will fetch it. But only if you promise me that you will lie still whilst I am gone.’

‘Take the keys,’ he told her, ‘and look sharp.’

Marianne had to try two sets of doors before she found those that opened into the library—a dull, cold room that smelled of damp, with heavy velvet curtains at the window that shut out the light. There was a darker rectangle of wallpaper above the fireplace, as though a portrait had hung there at some time.

She found the brandy where she had been told it would be. The bottle was unopened, suggesting that the Master of Bellfield was normally an abstemious man. Marianne knew that here in the mill valleys the Methodist religion, with its abhorrence of alcohol and the decadent ways of the rich, held sway.

There were some dusty glasses in the cupboard with the brandy so she snatched one up to take back to the master bedroom with her.

When she reached the landing she hesitated, suddenly unwilling to return to the master bedroom now that the master had come to himself, wishing heartily that the nurse might have arrived, and that she could leave the master in her hands.

She heard a sudden sound from the room—a heavy thud followed by a ripe curse. Forgetting her qualms, she rushed to the room, staring in disbelief at the man now standing beside the bed, swaying as he clung to the bedstead, his face drained of colour and his muscles corded with pain.

‘What are you doing?’ she protested. ‘You should not have left the bed.’