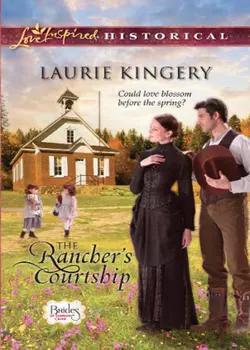

The Rancher′s Courtship

Laurie Kingery

Though Caroline Wallace can’t have a family, she can still have a purpose.Becoming Simpson Creek’s new schoolmarm helps heal the heartache of losing Pete, her fiancé, to influenza. Then Pete’s brother arrives, trailing a herd of cattle and twin six-year-old girls. Jack Collier expected Pete and his bride to care for his daughters until he was settled in Montana.But bad weather and worse news strand Jack in Texas until spring. It’s little wonder Caroline grows fond of Abby and Amelia. But could such a refined, warmhearted woman fall for a gruff rancher…before the time comes for him to leave again?

Small-town Texas spinsters find love with mail-order grooms!

Though Caroline Wallace can’t have a family, she can still have a purpose. Becoming Simpson Creek’s new schoolmarm helps heal the heartache of losing Pete, her fiancé, to influenza. Then Pete’s brother arrives, trailing a herd of cattle and twin six-year-old girls.

Jack Collier expected Pete and his bride to care for his daughters until he was settled in Montana. But bad weather and worse news strand Jack in Texas until spring. It’s little wonder Caroline grows fond of Abby and Amelia. But could such a refined, warmhearted woman fall for a gruff rancher…before the time comes for him to leave again?

“Where’s my brother?” Jack Collier demanded again. “Why are you wearing black?”

Lord, help me to tell him with compassion, Caroline prayed.

“I’m sorry to tell you this, Mr. Collier, but your brother Peter passed away this last winter—” she paused when she heard his sharp intake of breath “—during an influenza epidemic.”

“Pete’s…dead?” he murmured. “Why didn’t you let me know?”

The last question was flung at her like a fist, but she heard the piercing loss contained in it.

“I did try. But I wasn’t able to get your address from Pete before…before he d-died.”

She grabbed her black-edged handkerchief and dabbed at her eyes.

“What am I going to do now?” Jack Collier wondered aloud.

“I’m sorry you’ve come all this way, only to hear such awful news…. I’m sure Mama and Papa would be glad to put you up until you feel able to return home.”

“You don’t understand,” Jack Collier told her. “I can’t go back.”

Laurie Kingery

makes her home in central Ohio, where she is a “Texan-in-exile.” Formerly writing as Laurie Grant for the Harlequin Historical line and other publishers, she is the author of eighteen previous books and the 1994 winner of a Readers’ Choice Award in the Short Historical category. She has also been nominated for Best First Medieval and Career Achievement in Western Historical Romance by RT Book Reviews. When not writing her historicals, she loves to travel, read, participate on Facebook and Shoutlife and write her blog on www.lauriekingery.com.

The Rancher’s Courtship

Laurie Kingery

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

And they said, let us rise up and build. So they strengthened their hands for this good work.

—Nehemiah 2:18

To Stephanie, the teacher in our family, in honor of the teachers who only had one-room schoolhouses to teach in.

To Susan Alverson, who helped me through the rough patches and was always there to listen.

And always, to Tom.

Contents

Chapter One (#u60d5e5fd-10f3-5582-a528-32246be886c3)

Chapter Two (#u26a5e6b7-bd59-5977-9fd9-3690c721eb9e)

Chapter Three (#u5b84ed8c-b9ae-5a31-bb89-4b93ae95fae8)

Chapter Four (#u062bcc1f-be10-5668-a7b0-2e71ac466ddc)

Chapter Five (#u5845f1db-6cb6-5904-9132-ec99893844d6)

Chapter Six (#u3359ca8f-e371-502a-9c02-beac426c2d16)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Questions for Discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One

Simpson Creek, Texas

October 1868

Jack Collier looked up and down the main street of the little town of Simpson Creek, but try as he might, he didn’t see a druggist’s store. A hotel, a mercantile, a post office, a combined barbershop-bathhouse, a jail, a bank, a doctor’s office and a church, yes, but no druggist’s shop. A search of the side streets and Travis Street, which ran parallel to Main Street, netted the same lack of results.

He’d been the recipient of several second looks by the townspeople, as he rode down the streets, his own horse flanked by the dependable old cow pony that didn’t mind his twin daughters riding double on it. People tended to stare at twins, and yet it seemed to be his own face they focused on, not Abigail’s and Amelia’s.

Well, he’d always been told he looked a lot like Pete, so that must be the reason for the stares. He started to ask one or two of them if they knew where to find his brother, but he had wanted his arrival to be a surprise for Pete. He didn’t want anyone running ahead of him with the news.

But where was Pete? Had he gone into some other line of work since he’d last written Jack? It was possible, Jack supposed, but it wasn’t like Pete to change his mind on such a matter. Pete had always set a course, then held to it. He’d traveled up to the Hill Country town in San Saba County last year with the announced goals of meeting the lady he’d been corresponding with and opening up his own druggist’s shop. Around Christmas, Pete had written that he and Miss Caroline Wallace were in love and would be married in early spring. He wanted Jack to be there.

That was the last time he’d heard from Pete—no letter, no wedding invite had followed.

Mail went astray all the time, though. He and his daughters had probably missed the wedding, but Jack had assumed he’d find Collier’s Drugs and Patent Medicines prospering, with his happily married brother as the proprietor. Pete and his bride would have a little house on one of these side streets, no doubt with a picket fence around it and the smell of freshly baked bread wafting from the kitchen.

“When are we gonna find Uncle Pete, Papa?” queried his daughter Amelia, clutching a china-headed doll to her chest.

“Yeah, and Aunt Caroline?” her twin sister, Abigail, piped up from behind her. “Did they go someplace else?”

Jack rubbed his chin and considered the matter. “I don’t know, girls, but I’m sure enough going to find out.”

After riding up Travis Street, they’d passed the churchyard and headed back onto Main Street, but now he paused by the jail to look around him, wondering where the best place to make inquiries would be.

“Can I help you, mister?”

Jack looked down to see a lanky Mexican youth with black hair and dark eyes looking up at him from beside the open door of the jail. He wore a five-pointed star that had “Deputy” inscribed across its middle.

The sheriff ought to know where to find any of the small town’s inhabitants, Jack reckoned. “Is the sheriff in, Deputy?”

“Sheriff Bishop is away for a few days, sir. I’m Deputy Luis Menendez—perhaps I may help you?” The last part was said with courteous pride.

“I hope so. We’re looking for Peter Collier and his wife, Caroline. He’s my brother. He was supposed to have started a druggist’s shop here in Simpson Creek, but I don’t see one, so maybe his plans changed. Would you know where they live?”

The young man’s brow furrowed, and something troubled shone in the obsidian depths of his eyes. “Miss Caroline is the schoolteacher. Perhaps it is best you speak to her.”

“Miss Caroline?” What in thunder? Had Caroline and Pete had a falling-out and never married? Had Pete left Simpson Creek? Why hadn’t he written Jack about it? Jack had made plans based on what Pete had told him, and if the marriage was off and Pete had gone elsewhere, Jack was going to find himself in a right pickle.

He was conscious of the youth still studying him, a hand shading his eyes from the bright sun. “May I direct you to the schoolhouse, Mr. Collier?”

Jack shook his head, “No, we passed it a while back, while we were looking for his shop, so I know where it is. Thanks.”

The rapping at the door startled Caroline. Who could it be? Her pupils were all present and accounted for—two dozen in number and ranging from first to sixth-graders. Now they all raised their heads from the slates on which they were working sums and looked behind them. No one in Simpson Creek would think of knocking on the door of the one-room schoolhouse. If they had to interrupt the schoolmarm during class, they’d likely just barge right in and explain their business.

When the knock quickly sounded again, as if whoever stood outside had grown impatient, Lizzie raised her hand. “Miss Wallace, do you want me to see who’s there?”

“No, thank you, Lizzie. I’ll do it. Please continue your work.” Rising, Caroline left her desk, walked down the aisle that separated the girls from the boys and went to the door. She hoped whoever it was wouldn’t stay long. It was hard enough to keep her students working on arithmetic in the last hour of the school day, even without interruptions. Most of them were fidgeting, staring longingly out the one-room schoolhouse’s open window to where fall sunshine beckoned. When would she learn to drill them in mathematics in the morning, when they were still fresh? But she’d only been the schoolteacher for a month, having taken on the job when Miss Phelps left.

She opened the door to see two little girls standing on the uppermost step. They were as alike as two peas in a pod, both dark-haired and blue-eyed, each one’s hair done in two thick braids with red bows at the end, their dresses blue gingham with white pinafores. Each clutched a doll with a dress that matched what its owner wore.

Beyond them she could see a man with his back to her, securing the second of two horses to the hitching rail next to the mule a pair of her students rode to school.

“Them girls is exactly the same,” breathed Lizzie, peeking around her teacher from behind.

“Those girls are exactly the same,” Caroline corrected automatically. “Please go back to your seat, Lizzie.”

“Ain’t you ever seen twins before, Lizzie Halliday?” one of the boys hooted scornfully.

“Haven’t you,” Caroline corrected again. “Class, be quiet while I speak to their father.” She could only guess the man was here to register his daughters, though why he’d come in the afternoon, rather than first thing in the morning, she couldn’t imagine—nor why a father would be bringing the children, rather than their mother. A closer look at the girls’ dresses revealed a smudge on the hem of one, a rip in the sleeve of the other. Maybe their mother was ill? Or…well. Perhaps there was no mother anymore.

The two girls smiled in unison at her, and Caroline felt an instant liking for them. Already mentally rearranging the seating chart to accommodate two more students while the man was turning from the hitching rail, she now focused on his face.

And blinked. And stared, as he climbed the steps and came closer.

Like his daughters, the man had blue eyes and black hair, but the eyes that studied her were so like Pete’s eyes—Peter Collier, her fiancé, who had died in the influenza epidemic last winter, and for whom she still wore mourning black. The mouth that now narrowed reminded her of Pete’s mouth, a mouth that had kissed her many times, and would never do so again.

Oh, no, she was doing it again. Right after Pete had died, she had frequently seen his face in that of strangers passing through town, and her heart would give a little happy leap before her brain realized it was not Pete. Yes, that must be the case. I only think the man looks like Pete. The resemblance will fade in a moment, as it always has before. It isn’t real. Pete’s brother would have come long ago, if he was going to.

“You’re Miss Caroline Wallace? I was told I would find her here,” the man said. Absently she noted that while his voice was similar, it didn’t have Pete’s exact cadence. Pete always said what he meant right out. This man’s voice was deeper and had more of a considering drawl to it.

He continued to study her as if he found her black dress mystifying—had he never seen mourning clothes before?

“Please, come in,” she said, gesturing. “You have children to enroll, sir?” she asked, with a meaningful look at them.

They did as she had bidden, stepping into the back of the classroom. The man opened his mouth to say something, but before he could reply to her question, one of his twins asked, “Are you our Aunt Caroline? And where’s Uncle Pete?”

Caroline felt her jaw drop and her heart begin to pound as she raised her gaze from the little girl to her father.

“I’m Caroline Wallace,” she said slowly, realizing that she had guessed correctly to begin with. “And you are—?”

The man’s gaze narrowed. “Jack Collier, Pete’s brother. These are my daughters, Amelia and Abigail. Aren’t you supposed to be ‘Mrs. Collier’ by now? Where’s Pete?”

She felt the color drain from her face and leave a coating of ice behind. It couldn’t really be happening. Pete’s brother couldn’t have shown up now, unaware his brother was dead, some seven months after Pete’s funeral.

But thinking it could not be so didn’t make it any the less true, and she realized with panic she would have to be the one to break the news to him. She wondered who had told him how to find her, yet had not mentioned his brother was dead.

Determined not to tell him about Pete in front of the two bright-eyed children staring curiously at her—not to mention all the other children eyeing them with avid interest—she forced herself to speak normally.

“Why don’t we let your daughters play outside with the other children for a few minutes?” she suggested.

He gave a curt nod by way of permission, his eyes still narrowed, and she bent to speak to Lizzie, whose desk was nearby. “Lizzie, will you take Amelia and Abigail with you and introduce them to the other girls? Let them play with you?”

“Yes, Miss Wallace. Are they gonna come t’ school with us?”

“We’ll see.” In a louder voice she said, “Class, we’ll take a fifteen-minute recess.” The boys didn’t hesitate, scrambling out of their seats and out the door almost before she finished speaking, as if fearing their new schoolmarm would change her mind. The girls were a bit slower but, clustering around the twins, made their way out the door just as happily.

Caroline turned back to the suspicious-eyed man waiting by her desk and took a deep breath.

“Please, Mr. Collier, won’t you sit down?” she said and took her place behind the shelter of her desk.

Jack Collier stared at the small desks that sat in neat rows behind him. There were larger desks for the older students, but these were at the back of the room, and his long legs still wouldn’t have fit under them. But at last he settled for sitting on top of one of the front desks, though he dwarfed it.

“Where’s my brother?” Jack Collier demanded again. “Why are you wearing black?” His questions came like rapidly fired bullets, but his eyes, those eyes so like Pete’s, gave away his fear of her answer.

Lord, help me to tell him with compassion, she prayed.

“I’m sorry to tell you this, Mr. Collier, but your brother Peter passed away this last winter—” she paused when she heard his sharp intake of breath “—during an influenza epidemic.”

She didn’t dare look at him as he absorbed this news and sensed rather than saw him rock back on the small desktop as if he’d been struck a physical blow.

“Pete’s…dead?” he murmured, his hoarse voice hardly above a whisper. “But…that’s impossible. I got his letter…saying he was going to be married to the woman he met from…‘the Spinsters’ Club,’ he called it, this spring. In March. That was you he was marrying, wasn’t it? When I didn’t hear anything more, the girls and I just came ahead, figuring the invite got lost in the mail or something…I figured we missed the wedding, but we’d find you and Pete all settled in together… . Why didn’t you let me know?”

The last question was flung at her like a fist, but she heard the piercing loss contained in it.

Caroline had left her hands in her lap below the level of the desk, and now they clutched at one another so he wouldn’t see them shake. She let her gaze drop, unable to face the raw grief she’d glimpsed in his face, the mingled astonishment and fury stabbing at her from those too-familiar blue eyes. She felt a tear escape down her cheek, and she swept it away with a trembling hand.

“I—I’m sorry, Mr. Collier. I did try. When it…became apparent that Pete was sinking, I tried to ask him your address… He had it memorized, you see, not written down anywhere. But he was delirious, and…I—I’m afraid I wasn’t able to get it from him before…before he d-died.” She grabbed the black-edged handkerchief she kept always within reach in her pocket and, after dabbing at her eyes, took a deep breath. “I…tried to write you,” she said. “I couldn’t remember the name of your ranch, only that it was in Goliad County, so I addressed it General Delivery to Goliad. I…I guess it didn’t find you. I’m very sorry about that, but…I didn’t know what else to do. Pete said you were his only living relative—relatives,” she amended, to include his daughters. Pete had mentioned that his brother was a widower and had a couple of daughters, but after her only attempt to contact them had borne no fruit, she had been too weighed down with sorrow to spare them another thought.

“What am I going to do now?” Jack Collier wondered aloud as if talking to himself, his voice raspy.

She lifted her eyes to his again. “I…I’m sorry you’ve come all this way, only to hear such awful news…I’m sure Mama and Papa would be glad to put you up until you feel able to return home.” Her mind raced ahead. She could dismiss school early and have him follow her to the little house behind the post office where she, her brother and her parents lived. She would explain to them what had happened. Mr. Collier could sleep on the summer porch with his daughters.

“No,” he muttered.

She thought he was being polite, not wanting to put them to any inconvenience since his visit had been unexpected. “Oh, it’s no trouble,” she assured him kindly, “and it’s the least we can do for Pete’s only family…”

“No, you don’t understand,” Jack Collier told her, his face haggard. “I can’t go back. I—I sold my ranch. I’m on the way to Montana Territory with a herd of cattle, and I thought I could leave the girls here with you and Pete until I got settled up there… .” His voice trailed off, and he looked away, but not before she saw the utter misery in his eyes.

She was distracted by it for only a moment until she was able to process what he had said.

“You thought… You were planning…to leave your daughters with us, with Pete and me? While you went on to Montana with your herd?” She repeated his words, as if merely asking for clarification, while inside, the effrontery of it took her breath away. He’d thought he could leave two children with his newly wed brother without so much as a word of warning, without writing to ask if it would be all right with Pete and, more importantly, with Pete’s bride?

“Yes, I’m going up there to join a couple of partners of mine who bought ranch land. I figured I’d find a nice lady there to marry so the girls could have a new mama, and then I’d send for them…or come back and fetch them.” He looked away, focusing on a portrait of Washington that hung on the wall as if George might have the answers.

“But…from what I understand, at least…the snow will be flying before you get halfway there, won’t it?” She wasn’t a cattleman’s daughter, but anyone knew moving a herd of the stubborn, cantankerous critters was no quick proposition—and a potentially dangerous one, at this time of year.

He shrugged, looking uncomfortable—as well he might, she thought, at announcing such a foolhardy notion.

“We got a late start, and that’s a fact,” he admitted. “I was going to wait to sell the ranch early next year, but…well, let’s just say I got an offer that was too good to pass up, so we rounded up the herd and left. Then halfway here my ramrod—my second-in-command, that is—got himself all into some uh…legal trouble, and there was no way I was just going to abandon him and move on. We had to wait till his name was cleared…so we figured we’d winter in Nebraska, then travel on in the spring.”

Caroline felt her jaw tightening and the beginnings of a headache throb at her temples. The muddle-headed, half-baked plans men came up with! Now she was angry, and though she was normally a circumspect and thoughtful woman, she was so upset and overwrought over meeting Jack and talking about Pete that her bitter feelings came tumbling out of her mouth.

“You assumed you could dump your children with Pete and me like a couple of sacks of flour, without even writing to ask first? If you had, you would have found out then that Pete had died!”

Chapter Two

His jaw dropped open, and she knew she should have stopped right there, but her emotions were out of control. She’d endured months of well-meaning people saying she had to go on living. “Pete would have wanted you to. After all, you weren’t married, only engaged,” they’d said. It had stoppered the grief inside her, and now grief, combined with anger and aggravation flooded out like a suddenly unbottled explosive mixture. Tears stung her eyes, but she refused to cry in front of this man.

Instead, she stabbed a finger at him in accusation. “And you assume decent women grow on trees up in that wild country, just waiting for handsome cowboys like yourself to come along and pluck them off the branches?” He was handsome, she had to admit, even more so than Pete had been. If she’d never met Pete, she would have found him very attractive indeed. But that didn’t mean she wasn’t furious at him.

And he with her, apparently. She saw the fire kindle in those blue eyes, those eyes so like Pete’s, though she’d never seen Pete’s eyes look quite like that. She and Pete had never exchanged so much as a cross word.

In fact, she couldn’t remember ever yelling at anyone like that in all her life. In her heart, she knew she wasn’t being fair to the man who had only learned of his brother’s death moments ago, but how good it felt to finally say what she was thinking after months of biting her tongue and forcing herself to smile and thank people for their kind words of condolence when all she’d wanted to do was scream that it wasn’t fair. It would never be fair that she’d had to lose the man she loved. She couldn’t yell at Pete for leaving her—he wasn’t there to be yelled at. But his brother was. His brother who wasn’t even listening to her. Instead he stared fixedly at her left hand.

“What—what’s wrong?” she asked, mystified.

“Mama’s pearl ring,” he rasped, pointing at the ring Pete had given her when they’d become engaged, still on her left ring finger.

She followed his gaze, and her anger was doused in shock. “Pete gave it to me when he asked me to marry him.” She raised her eyes to his, wondering what he was thinking. Did he believe she had no right to it anymore because Pete was dead? That must be it.

“Please…it’s all I have left, now that he’s gone…”

He said nothing, just stared at her as if trying to think what to say, and she became even more sure she had guessed right. He just didn’t know a polite way to ask for it back.

She wrenched it off her finger and held it out to him, feeling the tears escape down her cheeks, but powerless to stop them. “Here…take it. It properly belongs to you now, to keep for your girls…”

He stared at the gold band with its beautiful pearl while her last words echoed in his ears—to keep for your girls.

He was not now and hoped he never would be so low as to take such a thing from a bereaved woman. And Caroline Wallace was bereaved, he realized, just as he was. The fact that she was still wearing black and the haunted look in her pretty brown eyes told him this beautiful woman was still grieving for his brother.

He forgot that he was still stinging from her scorn and started to say something, but the realization that they were both sorrowing over Pete tangled the words in his throat. So he shook his head and took a step back.

His tacit refusal, however, seemed to make things worse.

“Take it, I said!” She held out the ring again. “You can keep it for some woman you haven’t even met yet!” And then she hurled it at him.

The ring bounced off Jack’s chest and fell to the floor with a clink. He bent and retrieved it, hesitated for a moment, then pocketed it as he straightened to face her. He’d give it back to her later, when she’d calmed down. Even though the disdainful things she had said to him moments ago still hurt, he should have been quicker to say that she could keep the ring with his blessing. That he understood why she’d want to have this symbol of the love his brother had felt for her.

Shocked by the unexpected news of Pete’s death, he had just blurted out his plans, and she had shown him with a few contemptuous words just how ill-considered they appeared. Caroline Wallace’s derision made him feel like a silly boy still wet behind the ears. She’d looked at him as if he’d tracked cow manure into her schoolroom.

It was a cinch she’d never looked at Pete that way. Pete had always been the polished one, the one who’d excelled at book learning. No doubt a lady like Caroline Wallace had valued those qualities.

“We’ll be going, ma’am, me and the girls,” he said, determined not to say anything else he’d be sorry for later.

“Going? Where?” Caroline asked, sounding dazed.

“On to Montana.”

“But…but you can’t take those two little girls to that unsettled country up there! Why, there are Indians in Montana, I’ve heard! And bears, and mountain lions.”

“Last I heard, you had Comanches around here, too,” he retorted. “And cougars. And rattlesnakes.”

“And blizzards, and wolves,” she went on, as if he hadn’t spoken. “You can’t possibly be thinking of taking two helpless children into such a situation.”

“The girls and I will do just fine, but thanks for your concern, Miss Wallace.” He bit out the words. “Sorry to have troubled you.” He turned on his heel, hoping he could postpone any explanation to Abigail and Amelia until they were away from her.

He reached the door before she caught up and tugged on his sleeve.

“Please, Mr. Collier, wait a moment.”

He turned around and beheld her whitened face, the tears still shining on her cheeks.

“I—I’m sorry. I was unforgivably rude, but I hope you’ll reconsider leaving just now. It’s already mid-afternoon, and—”

He took out the pocket watch that had been a gift to him from his mother, who, unlike their father, hadn’t played favorites between the two boys. “It’s only two o’clock. Plenty of time to make tracks up the road and rid you of our troublesome presence.” Then he realized how sarcastic he had been, for he saw pain flash across her face.

“Yes, it’s only two o’clock, but if you’re heading north, the next town is quite a piece up the road on the other side of the Colorado River.”

“Who needs a town? We’ve been camping out with the herd since we left south Texas. I left the cattle south of town, grazing by the creek. My drovers are there, but we should get back to them.” In actuality, his men were not expecting him to return before morning, but Caroline Wallace didn’t need to know that.

He could leave the ring at the post office. He remembered Pete telling him her father was postmaster.

“I—I’ve given you the worst of news. You can’t just leave, after that. Please, allow me to apologize, and again, offer you a place for the night at our house. Mama and Papa would want to meet you and your daughters—they would have been their grandnieces…”

If Pete had lived to marry her. “No, thanks,” he said and strode out the door. He spotted the twins not far away, each holding one end of a jump rope while a third girl jumped it. It looked as if they’d been readily accepted by the other girls and were having a great time.

He beckoned to them. “Abby, Amelia, come with me.” He watched as they bid quick farewells to their new playmates, snatched up their dolls and ran to him. “We’ll leave the horses here for now.” With any luck, Miss Wallace would be gone by the time they returned for them.

“Are we going to Uncle Pete’s house now?” Abby asked.

“Where does he live?” Amelia chimed in, as they fell into step with him.

In Heaven, he thought, but aloud he said, “There’s been a change of plans, girls. Let’s walk along the creek and I’ll tell you about it.” He wanted to get away from the schoolyard, in case Caroline Wallace was watching from the schoolhouse window. The girls walked along with him quietly, taking their cue from his solemn demeanor.

The creek for which the town had been named was lined with cottonwood and live oak trees. It wasn’t wide—a man on horseback could splash or swim across it in a moment, depending on the time of year, but it was pretty, flowing lazily past them. He saw a fish jump after a dragonfly and regretted for a moment that he wouldn’t be here long enough to bring a cane pole and try his luck.

He paused when he found an inviting grassy bank and invited them to sit down with him.

“Miss Wallace told me some bad news, girls,” he began, when they were settled on either side of him.

They looked up at him, their faces serious, wary. “You mean Aunt Caroline?” Amelia asked.

He didn’t correct her, just nodded. They’d realize Miss Caroline Wallace was never going to be their aunt quickly enough. Best to get it over with—there was no way to soften the blow. “Miss Wallace told me that Uncle Pete became very sick this winter, and they couldn’t make him well again. He…he passed away, girls. He went to Heaven.”

Two identical shocked faces stared up at him, open-mouthed.

“He—he died, Papa? Uncle Pete died? Like Mama?” Abby asked, her voice breaking as a tear began to slide down her cheek. Beside her, Amelia had closed her eyes and sagged against her twin, whimpering.

He nodded, pulling them both against him, and for a few minutes he just held them while they sobbed. He let a few of his own tears trickle into their soft hair, knowing they would never notice in the midst of their crying, but he was careful not to lose control for fear of frightening them. They had only seen him weep when their mother died, but that had been almost three years ago and he thought they had probably been too young then to remember it.

A man couldn’t have asked for a better brother than Pete, Jack thought. He’d been Jack’s best friend, his playmate, his confidant—and his defender when Pa had taken out his frustrations on Jack. It hadn’t been Pete’s fault he was smarter, and he’d never rubbed Jack’s nose in it, never flaunted it. He’d thought it only fitting when Jack had inherited the ranch.

“So now where are we going to stay while you go to Montana to find us a new mama?” Amelia asked, knuckling the remains of her tears away. She was always the more direct one of the two.

“I think we should still stay with Aunt Caroline,” Abby said. She was the twin who made decisions quickly. Amelia was more wary and liked to consider all sides of a question.

Did her reply mean she’d liked Miss Wallace instantly or only that Abby had gotten used to the idea of staying with her uncle and his bride during the journey from south Texas? When he’d first told them of his plan to move to Montana, and they’d been ignorant of the rigors of a trail drive, they’d been upset that they wouldn’t be coming along, but joining him in Montana later. He’d talked up how happy they’d be with their uncle and aunt until the girls had started to sound excited about Simpson Creek and the family they’d find there.

He’d have to tread carefully now so as not to let on that he and Miss Caroline had had sharp words.

“What would you say, Abby, if I told you I’ve decided to take you two with me after all?” He’d keep them safe, he told himself. Other settlers had taken families with them to Montana Territory. It was a tough, dangerous journey, and even more so with a thousand head of unpredictable longhorns, but what choice did he have now that he couldn’t leave them with Pete and his bride? He’d be there to protect them. Surely they’d be all right if they rode in the chuck wagon, even though Cookie was a cranky, irascible old coot given to colorful language.

Identical faces turned identically stormy.

“Do we have to go with those nasty ol’ cows?” Abby asked, her voice dangerously close to a whine.

“Well, yes, we—I—have to stay with the herd,” he said, dismayed at their reaction, but knowing his daughters couldn’t appreciate the profit he’d make by driving cattle to hungry miners yearning for beef.

Abby and Amelia hadn’t complained much before this, once they’d gotten used to the ever-present dust and the brutally long days of slow progress northward. But apparently they’d been holding it in since they’d only had to put up with it till they reached Uncle Pete’s house.

“I don’t like sleeping on the hard ground, Papa,” Amelia said, lower lip jutting out.

What kind of father subjected little girls to sleeping outside in all kinds of weather? He could practically hear Caroline—or his father—asking the scornful question.

“But we’ll be together—you won’t have to wait till I send for you,” he said, hoping that would mollify them. After the shock of hearing Pete was dead, Jack didn’t have the heart to say he was their papa and they’d do as they were told. Then he remembered he wasn’t expected back to the herd till morning. “How about a special treat tonight, girls? We’ll stay at the hotel here, then rejoin the herd tomorrow.”

Amelia and Abby’s faces brightened somewhat. “With real beds and real food, Papa?” Amelia asked.

“Well, don’t let Cookie hear you saying that he hasn’t been serving you real food, Punkin. But yes, real food—maybe even fried chicken.” A diet of beans and corn bread and beef got old fast, especially to a child.

Something like a real grin spread across Abby’s face. “I love fried chicken, Papa.”

“All right then, let’s go.” He rose and gestured for them to follow.

“But…but what about Aunt Caroline, Papa? She’s sad, isn’t she? And she’ll be sadder if we leave,” Amelia said as she got to her feet.

She’s sad, isn’t she? An image of Caroline Wallace’s tearful face rose unbidden in his mind. She had wept because she’d thought she had been rude—and her tears had moved him a lot more than he was comfortable with. He had been surprised by his urge to comfort her, in spite of the harsh words they’d just exchanged. He’d wanted to comfort his brother’s—what?—almost-widow?

Amelia’s question was an awkward one. It would be heartless to tell them she wasn’t really their aunt, so they had no reason to ever see her again.

“Yes, she’s been sad for a while now, since Uncle Pete died last winter, but she understands why we have to go on to Montana.”

A few paces later, Abby said, “The fellows’ll be surprised to see us when we go back in the morning.”

Jack tried to suppress a flinch. His drovers wouldn’t be surprised in a good way. They’d endured the presence of his girls with good grace, knowing it was temporary, but it had meant they’d had to be ultracareful about their language and their actions. Children had no place on a cattle drive. The men would think their boss had gone loco when he returned with them, but it was his herd, and they were his employees. Knowing he had no choice, they’d have to respect his decision, even though they wouldn’t like it—or leave his employ.

“Come on, girls,” he said, rising and heading down Main Street toward the hotel.

But the hotel had no rooms available, having rented them out to folks in town for a funeral. The clerk referred him to the boardinghouse behind it.

When they arrived at Mrs. Meyer’s establishment, though, the tall, bony proprietress informed him she only had one cot to spare, and it would mean sharing a room with her aged father. Obviously that wouldn’t work for the three of them.

It was starting to look as if returning to the herd tonight was their only option. But the day had been overcast, and now the clouds were looking distinctly threatening. Rain was coming. The girls hadn’t noticed yet, but they would soon, and Abby was frightened by storms.

“I still think we should stay at Miss Caroline’s house,” Abby announced.

“Yeah, Papa. After all, we were going to stay with her and Uncle Pete while you were gone, anyway. I’m sure she wouldn’t mind if you stayed there, too.”

When pigs fly, he thought. She’d apologized for her heated reaction and politely offered them lodging, but he was sure she was relieved he hadn’t taken her up on it. He’d be about as welcome under that woman’s roof as fire ants at a picnic.

“Girls, Miss Caroline doesn’t have a house of her own, since Uncle Pete died. She lives with her parents. I—I’m not sure there’d be room,” he said, feeling guilty because Caroline had invited them, so there must be room enough.

Amelia shrugged, as if to say, So?

Then thunder rumbled overhead, and Abby cast a fearful eye upward. “Papa, it’s going to rain,” she said uneasily. “Can we ask her, please?”

It was the last word, desperately uttered, as if she was fighting tears again, that did in his resolve. Lucinda, their mother, had died during a thunderstorm, and though his daughter didn’t realize that was the source of her fear, Jack knew it, and he knew he was going to have to do the very thing he least wanted to do—swallow his pride, go back and take Caroline up on her offer.

He sighed. “All right, I suppose it wouldn’t hurt to ask,” he said, and they walked down Simpson Creek’s Main Street back toward the school again.

Caroline had just seen her last pupil, Billy Joe Henderson, out the door. She’d had to keep him after class long enough for him to write a list of ten reasons “Why I Should Not Throw Spitballs in Class.” After erasing his hurriedly scrawled list on the chalkboard, she was clapping the erasers together outside the window and wishing she’d assigned Billy Joe this chore too when she heard footfalls on the steps outside.

Billy Joe must have returned for his slingshot, which he’d left on top of his desk.

“I thought you might be back,” she murmured as she turned around, only to see it wasn’t Billy Joe at all.

Jack Collier stood there, and once again, he had a hand on each of his daughters’ shoulders. His face was drawn and his blue eyes red-rimmed, and the twins’ faces were puffy from recent crying. The girls stared at her, eyes huge in their pale faces.

So he’s told them about Pete’s death, she thought with a pang, remembering how awful those first few hours of grief had been for her. Their mourning was just beginning.

Caroline’s eyes were a bit swollen, Jack noted, and he wondered how hard it had been to carry on with class as if nothing had happened after their emotional confrontation.

“Miss Wallace, I—I wonder if it’s too late for me to take you up on your offer of a bed for the night? The hotel doesn’t have any rooms available, and the boardinghouse couldn’t accommodate all three of us.”

She looked at him, then at the girls, then back at him again. “All right. I was just about to go home, so it’s good that you came just now.” As he watched, she gathered up a handful of slates, tucking them into a poke bag, and took her bonnet and shawl down from hooks by the door.

“I’ll take that,” he said, indicating her poke, and held the door for her.

She gave him an inscrutable, measuring look. “Thank you, Mr. Collier.”

He untied the horses from the hitching post. “Is there a livery where I can board the horses overnight?”

She nodded. “Calhoun’s, on Travis Street, near where I live.” Then she turned to the girls. “My father is the postmaster,” she said as they all walked out of the schoolyard and onto the street that led back into town, “so we live right behind the post office. Papa and Mama will sure be happy to have some children to spoil tonight,” she told them. “My brother Dan’s still at home, but he finished his schooling last year and works at the livery, so he fancies himself a young man now, too old to be cosseted.” Jack thought there was something in her gaze that hinted she’d be happy to have the children around, too, if only for one night.

“How old is he?” Abby asked.

“Thirteen,” Caroline said. “And how old are you two? I’m guessing six?”

“Right!” Amelia crowed, taking her hand impulsively. “How did you know, Aunt Caroline?”

“I’m the oldest,” Abby informed Caroline proudly, taking her other hand. “By ten minutes.”

“Is that a fact?” Caroline looked suitably impressed.

He was touched by the way she’d taken to his children, even if she’d decided he had about as much sense as last year’s bird nest, Jack thought as he followed behind them leading the horses.

He was dreading the meeting with her parents, knowing he’d be unfavorably compared with Pete, who had always been so wise in everything he’d done. Pete would have never been so foolish as to set out for Montana so late in the year with a herd of half-wild cattle. The only remotely impulsive thing Pete had ever done was moving to Simpson Creek to court the very woman Jack now followed.

And yet Jack also looked forward meeting the Wallaces, hoping they would tell him about Pete’s life during the months he’d spent in this little town before his death. He’d probably hear more about it from them than he would from Caroline, for she was still a little stiff with him.

He was acutely conscious of the ring that she’d flung at him riding in his pocket. Though it weighed almost nothing, it seemed to burn him like a hot coal—as if he’d stolen it from her.

After leaving the horses at Calhoun’s, they reached the Wallaces’ small tin-roofed frame house, which was attached to the post office.

“Perhaps I should go ahead into the kitchen and explain,” she began, letting go of the twins’ hands to open the door. They stepped into a simple room with a stone fireplace, two rocking chairs and a horsehair sofa.

“Papa, Mama—” she began to call and then was clearly startled when an older man rose from one of the rocking chairs, laying aside a book he’d been reading. She apparently hadn’t expected him to be there.

“Hello, Caroline,” he said. “And who do you have here?”

Before she could answer, however, a woman who had to be Caroline’s mother bustled in. She must have come from the kitchen, for she still wore an apron and held a big stirring spoon in one hand. Both of them looked at the girls with obvious delight, but when Mrs. Wallace shifted her eyes from the twins to Jack, she stared at him before her gaze darted uncertainly back to Caroline.

Caroline knew her mother had noticed Jack’s striking resemblance to Pete.

Chapter Three

“Mama, Papa, this is Jack, Pete’s brother, and his daughters, Amelia and Abigail.” Caroline could understand her mother’s reaction, for she’d had a similar one herself. Her mother blinked and tried to smile a welcome at Jack and the two girls.

“Jack, h-how nice to meet you,” she began in a quavery voice. “And your girls. I…”

“It’s all right, Mrs. Wallace. I know I look like my brother,” he said, taking the trembling hand the older woman extended to him, before taking Caroline’s father’s in turn.

“That you do, Jack,” her father said, shaking Jack’s hand. “Pete told us about you, of course, but you understand that it’s still a surprise to…” His voice trailed off and his gaze fell. Then he looked up at Jack again. “We set great store by your brother Pete. He was a good man, and we miss him.”

“Yes, he was mighty good to our Caroline,” Mama said, her gaze caressing her daughter for a moment. “We were so proud he chose our daughter.”

Jack’s throat felt tight, but he managed to say, “Thank you, Mr. and Mrs. Wallace.”

“Your coming is such a nice surprise,” Mrs. Wallace went on, with an attempt at a sociable smile. “Please, won’t you sit down?” She gestured to the horsehair couch. “Caroline, why don’t you bring in a chair from the kitchen?”

Caroline went to fetch it, wishing as she walked down the hallway that her brother would show up so he could take the twins out of the room to see the kittens in the shed while she explained what had happened—some of it, anyway. She wasn’t about to tell her parents about the angry conversation she’d had with Jack before he’d left the schoolhouse the first time. But she did want to tell them about Jack’s traveling plans, to see if they could help her to change his mind. She didn’t want to bring it up with the girls there, yet! Even though it was nearly time for supper, and Dan was always “starving,” he hadn’t put in an appearance. She hadn’t seen him at the livery stable when they’d dropped off Jack’s horses, so maybe he was lounging by the creek with the trio of boys he ran around with.

She couldn’t send Jack’s daughters out to find the kittens by themselves, so she’d have to explain the situation in front of them. By the time she’d brought in the chair for herself, Jack and the girls were settled on the sofa and her parents in their rocking chairs. Caroline took a deep breath and said, “Mama, Papa, Mr. Collier didn’t know about his brother’s death. He apparently didn’t get the letter I sent after Pete passed away.”

Her mother gasped and clapped two hands to her cheeks. “Oh, Mr. Collier, I’m so sorry! What a shock that must have been, to come all this way, and…Amos Wallace, I told you we should have sent someone down there to find him,” she added with a touch of asperity.

“No sense worryin’ about that now, dear,” her father said, patting his wife’s hand soothingly. “What’s done is done. Yes, I’m sorry that you got the bad news that way, Mr. Collier—may I call you Jack? Pete was already like a son to us, so I don’t feel like we need to stand on ceremony with you.”

“Jack is fine,” Jack assured them. “Yes, it was a shock, all right. But I reckon I should have suspected something when I never got the wedding invitation. I was busy getting ready to sell the ranch, and—”

Her father interrupted. “You’re selling your ranch? Why’s that?”

Jack flashed a glance at her. Caroline couldn’t tell if he wanted her to tell the rest or if he was merely pleading that she not reveal how little she thought of his scheme. She kept her silence, thinking Jack Collier richly deserved to explain his half-baked plan without her assistance.

“I’ve sold it, actually,” Jack said. “I—we—are on the way to Montana with my herd to join my partners. They bought a big ranch up there, and they asked me to throw in with them.”

Caroline saw her mother blink as she came to the same conclusion she had. “But your girls, Mr. Collier—Jack,” her mother began. “What were you going to do with them?”

“We’re goin’ to Montana, too,” one of the twins—Abby?—announced. “But I don’t like cows and sleeping on the ground.”

“And eatin’ beans and corn bread,” added the other girl—Amelia? “We were gonna stay with Uncle Pete and Aunt Caroline till Papa found a nice lady to marry and sent for us,” she began, “but now we’re going with Papa instead of waiting. Right, Papa?”

Caroline was human enough to feel a jolt of satisfaction as her mother’s jaw dropped, and her father’s jaw set in a hard line.

“Caroline,” her father said, “I’ll bet those young ladies would like to see the kittens out in the shed, wouldn’t you, girls? Why don’t you take them out to see them, dear?”

“Sure, Papa, that’s a great idea,” she said. “And when we come back in, I think Mama’s got some lemonade, if Dan hasn’t drunk it already.” She rose and gestured for Amelia and Abigail to join her, and they seemed happy enough to do so, excitedly asking what color the kittens were, and how many, as they left the room.

She wished she could be a fly on the wall, so she could hear the dressing-down Jack Collier was about to get. Her father wasn’t one to suffer fools gladly.

Caroline stayed out in the shed with the girls and played with the kittens as long as she dared, purposely staying away from the parlor. Then they came inside via the kitchen door and found her mother working on supper.

“Jack’s agreed to spend the night with us, him and his girls,” her mother announced happily and beamed when the girls cheered.

Caroline stifled a snort. He’d “agreed,” as if he was bestowing a favor on them? Her mother didn’t know she had already invited them. But who was she to complain about something that obviously made her mother so happy? Mama had enjoyed helping Caroline cook special meals for Pete, and now she was clearly overjoyed at the prospect of having girls to spoil, at least for one night.

Caroline had found she was enjoying Abby and Amelia’s company, too. Was it because they looked so much like Pete? It was like seeing the children she and Pete might have had together, which made her confusingly happy and sad at the same time.

So she snapped beans and made corn bread while her mother plied the girls with lemonade and got them to talk about themselves.

The rain came at last, pounding on the tin roof with an intensity of a marching army, but neither girl seemed to notice.

Caroline didn’t hear any raised voices coming from the parlor, which she thought was a good sign. Of course, it could mean the two men had reached a stalemate, with Jack refusing to admit his idea of taking the girls on a trail drive was foolish beyond words, and her father glowering in silent disapproval.

The kitchen door was flung open and Dan burst in, dripping rainwater. “It’s comin’ a gully washer out there,” he announced. “What’s for supper? I’m hungry enough to eat an iron skillet.” Then he spotted the girls, who smiled at him from over their lemonade, and he headed for the table to meet the newcomers.

Caroline stepped between him and the twins. “A skillet is all you may have to eat unless you take those muddy, smelly boots off, Dan,” she told him tartly, pointing at the offending articles. “You can meet our guests after you go take them off outside.”

For once, he did as he was bid, without grousing at the sisterly reprimand, and was introduced when he returned. But the twins didn’t get much time to talk to him, for as soon as he learned the girls’ father planned to drive a herd to Montana, he dashed toward the parlor.

“Montana? Great stars an’ garters! Can I go, Ma?”

Caroline caught her brother by his collar. “Dan, you stay out here—Papa and Mr. Collier are talking.”

“Oh, let him go, Caroline. They’re probably done by now,” her mother said calmly, but as Dan wrenched free, she added, “And no, son, you may not go on a trail drive. You’re too young yet.”

An hour later, when they all sat down to supper together, her father and Jack seemed to be in perfect amity, much to Caroline’s mystification. If Jack had received a dressing-down, she couldn’t discern it from his relaxed, amiable manner as Dan pestered him with questions about cattle drives. And yet her father had looked so upset when he’d heard Jack’s plan…

As it turned out, her father had been biding his time. The twins and Dan ate quickly, then proclaimed themselves full. Once they’d been excused, so Dan could show the girls his collection of arrowheads, Caroline saw her father turn to Jack.

“You know, Jack, late in the year as it is, you won’t no more than get to the Panhandle with them beeves before the snow’s apt t’ start fallin’. And that’ll leave you in the Llano Estacado—the Staked Plains—right where the Antelope Comanches set up winter camp, so you don’t want to be lingerin’ around there, no sirree.”

He bit off a large chunk of his corn bread, buttered it and sat chewing while he waited for Jack’s response.

Jack took a sip of lemonade before he replied, his tone considering. “Oh, I was thinking we could get to Colorado or at least Kansas, depending on the trail we took.”

“It’s my opinion you wouldn’t,” her father said. “And you ought not to gamble with those girls of yours along.”

Caroline realized Papa and Jack Collier must not have even spoken about Jack’s plan when they’d been left alone. Her wily father must have spent the time speaking of some related topic like ranching in general, drawing Jack out, creating a relationship—“softening him up,” he’d call it—before broaching this difficult topic now, after Jack and his daughters had been treated to a delicious supper and were about to spend the night.

“Please, won’t you leave the girls with us?” her mother pleaded. “You could always send for them once you were settled, as you originally intended.”

To Caroline’s surprise, Jack’s only response was to look at her.

Was he waiting for Caroline to give permission before he agreed, since they’d had a confrontation? She was willing to bend, if it meant the girls would be left in safety with them. She said, “Please, Mr. Collier. We’d be happy to have them for as long as you need them to stay. Let them stay with us.”

Jack’s eyes were unreadable as he finished chewing before answering, but before he could do so, Caroline’s father spoke again.

“I’ve got a better idea than that. You don’t want to lose half your cattle to a pack of hungry Indians, even assuming they’d let you pass safely. Why not spend the winter here in Simpson Creek? You could stay with your girls that way, and set out in the spring, when you’d have the best chance of actually getting to Montana with your herd intact.”

That was obviously the last thing Jack Collier expected to hear, for he blinked and set down his fork. “And where would I keep a thousand head of ornery longhorns around here, Mr. Wallace?”

The fact that Jack hadn’t refused to consider her father’s suggestion surprised Caroline. Maybe he was beginning to see reason.

“There’s a ranch south a’ town that’s come vacant recently,” her father said. “The owner died.”

Caroline knew he was referring to the Waters place, next to her friends Nick and Milly Brookfield’s ranch. Old Mr. Waters had died in a Comanche attack two years back, while his nephew from the east, who had inherited it, had fallen victim to a murderous bunch of men bent on taking over the area this summer. The Comanches had damaged the ranch house badly, but the conspirators had finished the job, burning it to the ground, along with the Simpson Creek church.

“No buildings on it just now, but you and your men had reckoned on camping out anyway. Seems to me it’d be a perfect place for you to stay the winter, then make a fresh start in the spring,” Mr. Wallace went on. “The bank is trustee for the property, since the heir back east wants no part of it.”

“And they’d be willing for us to keep the herd there for the winter? How much would they want as rent?”

“Probably not much—maybe even nothing. If you and your cowboys built a cabin there, you’d have a dry, warm roof over your heads, and your cattle would have a place to stay.” Her father spread his hands. “Sounds like a perfect solution to me.”

Well, it didn’t sound perfect to Caroline. She’d liked the idea of keeping Jack’s appealing children till he sent for them, but the prospect of having the man himself anywhere near, a man who looked like Pete but could never be Pete, rankled. Besides, she hadn’t forgotten that Jack had taken back the ring Pete had given her. And there was a disturbing feeling of attraction she’d felt instantly for him, the same attraction that had led her to blurt out during their confrontation at the schoolhouse that he was handsome.

Now as she felt his gaze swing toward her, she turned to stare out the window, lowering her hand below the table so he wouldn’t see her touching the empty space on her finger where the ring had been.

Out of the corner of her eye she saw Jack scratch his chin. “I dunno… .”

“It wouldn’t hurt for you to talk to the bank president, see what the terms would be,” her father said reasonably.

None of them had heard the twins creep back into the room until they exploded around their father, jumping and shrieking.

“Papa, do it! Stay on that ranch!”

“Yeah, Papa, then you wouldn’t have to travel in cold weather!”

“I don’t know, girls… .”

It was the most reasonable plan, Caroline thought with irritation. Was Jack too proud, or pigheaded, to see it? Why was he hesitating?

“I’ll have to think on it, Punkins,” he said, gathering them into his arms and kissing each on the tops of their heads.

Her throat tightened. He was obviously an affectionate father who cared for his children. How could he love them yet be willing to either expose them to danger on the trail or leave them for months on end? They were excited to have him stay nearby now, but wasn’t that postponing what would be a painful separation in the spring? Why had he sold the ranch in south Texas?

She burned with questions, but held her tongue. As a result, the evening passed pleasantly enough, with Dan agreeably playing games with the twins while Jack and her father sat reminiscing about the war years, her mother knitting and Caroline sitting silently, listening. As an older man, her father had joined the home guard, rather than the regular army, and had spent the war protecting Texans against the depredations of the Indians. Jack had served with General Hood, rising to the rank of major before the war was over.

When the clock struck nine, her mother rose. “Girls, let’s arrange your beds on the summer porch. We can make up your father’s bed there, too. I’ll put out some quilts, but it’s still plenty warm at night, so you’ll be comfortable.”

Abigail and Amelia followed her eagerly, and Caroline guessed they found it a treat not to be sleeping out in the open for a change. The rain had stopped, but the ground would surely have been muddy.

“I’m tired. Reckon I’ll turn in,” her father said, yawning as he stood up. “You, too, Dan, since you have to be at the livery at sunrise.”

Caroline stared after her father, wishing she could call him back. What could he be thinking, leaving me alone with this man? Can’t he sense the distrust between Jack and me? She didn’t want to admit, even to herself, the feeling of attraction that lay between them, too. She should have gone with her mother and the girls to help make up the beds on the porch, but it was too late. If she left to do that now, she’d obviously be fleeing Jack’s presence, and Caroline wasn’t about to let it look that way.

Jack watched her father and brother go. Then, when the sound of their doors closing echoed in the parlor, he turned to Caroline.

“Can we call a truce, Miss Caroline?” he asked, the lamplight flickering on his face.

“I…I wasn’t aware we were at war,” she said stiffly, unable to meet those blue eyes that reminded her so achingly of Pete’s.

He uttered a soft sound that might have been a barely stifled snort of disbelief, but he didn’t call her a liar, at least. “Please, Miss Caroline, for the sake of the man we both loved?”

Oh, unfair, she thought, to invoke your brother. But since he had, how could she disagree?

“Very well, Mr. Collier, in memory of Pete.”

“Please call me Jack. Mr. Collier was our father,” he said, as if that wasn’t a complimentary comparison. “And I have an olive branch of sorts to extend to you.” He reached into his shirt pocket, brought out the pearl ring and held it out to her. “Please, take this back and keep it with my blessing. It was wrong of me to take it. Pete would have wanted you to keep it, so…so that’s what I want, too.”

“But…shouldn’t it stay in the family?” she asked, wanting to do the right thing, the self-sacrificing thing. “For your girls?” For you to give the woman you will marry?

“I want you to have it.”

Something flickered in the depths of those blue eyes, and she wondered what he was thinking. She reached out and took the ring, finding it still warm from his body. Her hand shook a little as she slipped it back on her finger. “Thank you, M— Jack.”

“You’re welcome,” he said, smiling in approval.

She decided to test this moment of amity. “So…what are you going to do, Jack? About your daughters, and the cattle drive?” she asked, hoping the question wasn’t pushing him too hard.

“Said I was going to think about it, didn’t I?” he said, but his tone indicated he was amused rather than offended by her persistence.

She refused to be buffaloed by him. “You’ve already decided, I think.”

He rubbed his chin again. “I’m going to leave the girls here, for sure. I reckon it only makes good sense,” he admitted. “And I thought I’d talk to the bank president in the morning, and see what the terms would be, if we wintered on that ranch your pa spoke of.”

Even though they’d achieved a sort of peace, Caroline knew it wouldn’t be easy being around him. But aloud she said, “You’re making a wise decision, Jack. Papa wouldn’t steer you wrong.”

He held up a hand. “Now, hold your horses, Teacher. It’s all going to depend on what the banker says. And if I like his terms, I’ve still got to ride out to where the herd’s bedded down and talk that bunch of misfits that call themselves drovers into helping me build a bunkhouse where we can spend the winter. Cowboys are an independent lot, you know. They might not at all be willing to stay, especially if it means doing some hard work between now and cold weather.”

She fought to stifle a smile. There was something about the way he called his men misfits that told Caroline the bond between them went deep. And she didn’t want to admit, even to herself, how much she’d liked the way he called her “Teacher.” Her pupils called her that sometimes, but it felt different, somehow, when this man said it.

As soon as she thought it, she felt guilty, as if she were cheating on Pete. No. She’d lost the love of her life, and she was done with romance and marriage. And even if she wasn’t, she wouldn’t give the time of day to a man who would leave for Montana. She wouldn’t be left behind again.

Her mother returned just then, with the twins skipping ahead of her.

“Come see our beds, Papa! They’re oh-so-cozy!” one of them—Abby?—called.

“Yeah, we’ll be snug as bugs in a rug, Aunt Mary says,” the other one added, pulling on her father’s hand. “Come see.”

Aunt Mary? Caroline darted a glance at Jack, wondering if he would object to the name. After all, there was no real relationship between her mother and these two girls, any more than there was between them and herself.

“I hope you don’t mind if they call me that, Jack,” her mother said. “Mrs. Wallace just seems so formal.”

Jack shook his head. “Not a bit, ma’am. Good night, ladies.” His gaze lingered on Caroline, leaving her feeling decidedly unsettled.

Chapter Four

The scent of frying bacon led Jack to the kitchen the next morning where he was surprised to see the twins already freshly scrubbed and sitting at the table, digging into bacon and biscuits.

Caroline sat at the table, too, and raised her head as he entered. She looked clear-eyed and neat as a pin but once again was dressed in black. The hue looked impossibly severe on her, he thought. In spite of the unflattering dress, she was a lovely woman, with her glossy brown hair and large expressive eyes. He had no trouble understanding why his brother had fallen in love with her.

He wondered when she planned to give up wearing mourning. Surely she didn’t expect to wear black for Pete forever, even if she grieved inwardly for him? He couldn’t help imagining what she’d look like wearing some hue like deep green or gold. But some other man would have the pleasure of seeing her wearing colors again, and that man wouldn’t be a rancher with a weathered face and mud, or worse, on his boots. A woman of her education and refinement would pick another safe sort of husband who worked in the town, as Pete had. A shopkeeper or a preacher, perhaps.

“Good morning, Papa,” the twins chorused, catching sight of him.

“Morning, girls.” They looked neat and tidy, too, he noted. Amelia’s hem now was free of stains, and Abigail’s sleeve had been mended. Their hair was neatly braided.

He hadn’t even heard his daughters get up—which was natural, he supposed, considering how long he’d lain awake last night thinking about Pete. He’d shed some tears, too, but quietly, letting them leak soundlessly out of his eyes and soak into the pillow, lest he wake the girls.

They’d talked about Pete, before falling asleep, and though the girls were sad about the loss of their uncle, they hadn’t grown up with Pete as he had. Pete had been working in Houston in a druggist’s store by the time they were old enough to remember. He’d made it home to the ranch in Goliad County only a few times a year. In time their uncle would become a distant memory to his daughters, Jack knew. But he would always remember the older brother he’d idolized, the one with all the “book learnin’” their father seemed to prize so much. Jack had always disappointed the old man, even though he, not Pete, had been the one to follow in his father’s rancher footsteps.

“Good morning, Jack,” Mrs. Wallace said from the stove, where she was turning flapjacks. “I hope you slept well.”

“Sure was nicer than sleeping on the hard ground, ma’am,” he admitted, not about to let on how long into the night he had lain awake.

Caroline took a sip of coffee, then cleared her throat. “Why don’t you let Abby and Amelia go to school with me today, since you’re going to be busy going to the bank and out to talk to your men?”

Abby looked excited at the prospect. “Please, Papa, can we?”

“Yes, please? I love school,” Amelia added.

“How do you know, Punkin? So far you’ve only seen recess,” Jack teased. But he felt a surge of guilt, thinking of how slapdash their rearing had been thus far. They were only six, true, but with their mother gone, he’d been too busy around the ranch to teach them the things that children properly learned at their mothers’ knees. Things that prepared them to learn in school. He didn’t want them growing up ignorant of their letters and sums and history and such. Even wives and mothers needed to know these things. Would there be a school in Montana, when he got there?

“Yes, you can go with Miss Caroline,” he told them, and they clapped. “But you mind what she says,” he added quickly. “Make me proud.”

“We will, Papa,” Amelia promised, and Abby nodded. Both girls bounced happily in their chairs. “Hooray! We’re goin’ to school!”

“Then you’d better finish up,” Caroline told them. “The teacher has to be there earlier than anyone to ring the school bell. If you’re done with your breakfast in five minutes, you may take turns ringing it.”

Immediately they attacked what was left of their meal with enthusiasm.

Evidently done eating, Caroline brought a plate of flapjacks, bacon and biscuits to the table and set it in front of him, then refilled his coffee cup.

“Thank you, Miss Caroline,” Jack said. Silence reigned, broken only by the clink of forks on crockery plates, and he fell to musing about his situation. What would Pete have done, if their situations had been reversed?

Then he realized Mr. Wallace had said something to him while his thoughts wandered. “Pardon me, sir? Guess I’m not fully awake yet.”

Mr. Wallace looked faintly amused. “That’s all right, Jack. Drink some more of that strong coffee. Caroline makes it so strong a horseshoe will float in it. I was just saying that Caroline tells us you’ve decided to take my advice and talk to the bank president about the Waters ranch,” Mr. Wallace said.

Jack glanced at Caroline, who was smart enough to look down just then—so he couldn’t see the satisfaction shining in her eyes, he guessed. “I’ll see what the man has to say,” Jack said noncommittally. “And whether my men are willing to stay on here.”

“You’ll find Henry Avery a reasonable soul,” Mr. Wallace said. “But it probably wouldn’t hurt to tell him I suggested it.”

“I will, sir, much obliged.” It could only add to his respectability to have the postmaster, a longtime resident, vouch for him. Mr. Wallace had told him yesterday afternoon that the town had held Pete in great esteem, but Jack knew drovers had a reputation everywhere for being wild and irresponsible.

Jack was thankful Mr. Avery wouldn’t be aware he’d considered pressing north with his herd and his children even with winter coming soon. The more he thought about it now, the more harebrained the idea seemed. What had he been thinking? It was a good thing Caroline and her parents had talked him out of it.

“Time to go,” Caroline announced to the twins. They jumped up, and she scooped up her poke. The slates rattled inside as she did so, and Jack wondered when she’d had time to look at them. Had she sat up, reading her students’ work by lamplight, after he and the girls had gone off to bed?

The twins jumped to their feet and dashed over to kiss him. “Bye, Papa,” they chorused.

“We’ll see you later, Jack,” Caroline said. “Good luck with your trip to the bank.”

“Bank doesn’t open till nine, young man,” Mrs. Wallace told him. “You might as well have another round of flapjacks.”

“Don’t mind if I do, thank you,” he said, sure these were better than any flapjacks Cookie had ever made. He thought about asking for the recipe, then realized there’d be no forgiveness from his cook if Jack suggested his pancakes were less than perfect already. Then, to fill the silence, he asked, “Does your daughter like teaching?”

“Seems to,” Mr. Wallace said.

“Yes, she needed something to occupy herself,” Mrs. Wallace said, as she plunked the coffeepot back on top of the stove. “She was devastated when your brother died during the influenza outbreak, Jack. We were worried she’d—well, we used to call it ‘going into a decline,’ back before the war. For a while we thought she was going to die of a broken heart.”

Jack’s own heart ached at the thought of Caroline’s grief hitting her so hard that she’d almost died of it. He remembered how he’d felt when his own wife had passed away—bewildered, helpless, but so busy keeping the chores done while trying to console his very young children who had lost their mother that he’d had little time to cry.

It had only been at night, when the ranch house was quiet, that he’d had time to lie awake and mourn for his young wife. He remembered he hadn’t slept much for about half a year, until his body eventually tired from sleep deprivation and his sleep became heavy and dreamless.

Was love really worth it if the loss of a mate could wreck a body like that? Yet he missed being married, missed the softness and tenderness of a woman.

Mr. Wallace rose, muttering that it was time to open the post office, and went through the door in the kitchen that connected their house to it. Mrs. Wallace came to the table with a small helping of bacon and eggs, finally sitting down to break her own fast now that everyone else was fed. He hated to leave her at the table by herself, and since his pocket watch indicated it was still only half-past eight, he decided to keep her company.

“When Pete left Houston, he wrote me that he was coming to Simpson Creek to meet the ladies of ‘the Spinsters’ Club,’” Jack began, thinking he’d satisfy his curiosity and make conversation at the same time.

Mrs. Wallace smiled. “Yes, they started out calling it ‘the Simpson Creek Society for the Promotion of Marriage,’ but that didn’t last too long. They’re really something, those girls. When the war ended, and the only men who managed to return home to Simpson Creek were the married men, Milly Matthews decided she didn’t want to be an old maid and organized the others who felt likewise into a club. Well, sir, they put an advertisement in the Houston newspaper inviting marriage-minded bachelors to come meet them, and the men began coming, singly and in groups. First one to get married was Milly herself, to a British fellow, Nick Brookfield. In fact, if you do spend the winter on the ranch, they’ll be your neighbors. Then her sister Sarah met her match, the new doctor, and Caroline would have been the third, except for the influenza…” Her face sobered, and she looked down.

“I understand quite a few folks died then, not just Pete,” Jack put in.

“Yes, too many. People on ranches, people in town. I reckon we might’ve lost more if Dr. Walker hadn’t been here. The mayor’s wife died, and her sister, and the livery stable owner, and the proprietor of the mercantile… It was awful, Jack. I don’t know why Mr. Wallace and I were spared, but we’re thankful.”

Jack deliberately changed the subject. “Did your daughter always want to be a teacher?”

Mrs. Wallace wiped her lips with a napkin, then shook her head. “No, she never said anything about it before, though she was always quick to learn. But when the old teacher announced she was leaving to be a missionary this summer, suddenly Caroline decided she was going to take her place and devote herself to the children of the town. Oh, she still helps out with the Spinsters’ Club, just because she’s friends with those ladies, but she’s made it clear she’s given up on the idea of marriage.”

“Well, hello there, Caroline!” a voice called, and Caroline looked up to see her friend Milly Brookfield just pulling up in her buckboard in front of the doctor’s office. No doubt she was here to visit her sister Sarah in the house attached to the back of the clinic. As Caroline approached with the curious girls at her side, the old cowboy who had been holding the reins took the baby Milly had been holding so Milly could descend, then handed him to her on the ground.

“Mornin’, Miss Caroline,” he called, fingering the brim of his cap. “You got some new students, eh?”

“Morning yourself, Josh. Yes, these are Amelia and Abigail Collier. They’re going to be staying with us for a while.”

“Nice to meet you, young ladies. Miz Milly, reckon I’ll jest mosey over to the mercantile and pick up those things you were wantin’,” Josh said. He set the brake, clambered down and walked stiffly down the street. Caroline guessed the old cowboy’s rheumatism had gotten worse, along with his hearing.

Milly hadn’t missed the significance of the girls’ surname, however, and raised her eyebrows, her eyes flashing a question to Caroline.

“Yes, these are Pete’s brother Jack’s daughters. He arrived yesterday.” Caroline stared straight into her old friend’s eyes, willing her to understand that there was more to the story that she didn’t want to discuss in front of the children. She knew Milly was aware that Caroline had never gotten an answer to the letter she’d sent to Pete’s brother informing him of Pete’s death.

Milly, God bless her, didn’t miss a beat. “Well, isn’t that wonderful that you could come for a visit!” she said, bending down to the girls. As she did so, baby Nicholas woke up and cooed, sending the girls into delighted giggles.

“He’s darling!” cried Amelia, while Abby asked, “What’s his name? How old is he? Can I hold him?”

“Another time, perhaps,” Caroline told them. “We have to get to school, remember?”

“I’m sure your mother’s thrilled to have two little girls to spoil,” Milly said, and then to the girls, she added, “I’m sure you’ll have a chance to hold little Nicholas. He’s just getting to the age where he likes to flirt with older women.”

The girls giggled again.

Milly turned back to Caroline. “I thought I’d drop in on Sarah for coffee, since we came to town to get supplies, but why don’t I stop over at the school at morning recess and we can catch up?”

Caroline could see from the avid interest in her friend’s eyes that she wanted to hear the full story of Jack Collier’s arrival. Which was fine, for Caroline needed to tell someone about it, someone who would understand the feelings that had overwhelmed her yesterday at seeing the man who looked so like his brother. Someone full of common sense, as Milly was, who would understand the contradictory feelings that had warred within Caroline after he had first exasperated her with his foolish plans, then confused her later with his kindness. Suddenly she could hardly wait till recess, when the children would be outside and she and Milly could have a frank talk. It had been too long since Caroline had shared her feelings with her friend.

“That would be wonderful,” she said. “I usually have recess at ten. Come on, girls, we’d better hurry, or Billy Joe Henderson will ring that bell before we get there.”

Henry Avery studied Jack with a skeptical gaze that told Jack he was drawing conclusions from his bedraggled appearance—Jack’s worn denims, down-at-the-heel boots, the shirt and vest he hadn’t managed to brush entirely free of trail dust, his battered, broad-brimmed hat. But once Jack told the bank president what he was there for and that Mr. Wallace had sent him, Mr. Avery showed him into his back office with encouraging eagerness.

“That’s a capital idea, capital!” he enthused about Jack’s proposal to winter at the Waters ranch. “I don’t mind telling you it’s been difficult to raise any interest in the place after the last two owners were murdered—”

“Yes, Mr. Wallace told me about their deaths,” Jack put in quickly, not wanting to hear another long recital of the tale. He didn’t want the sun to get too high by the time he made it out to the herd, for he knew his drovers would be wondering about him.