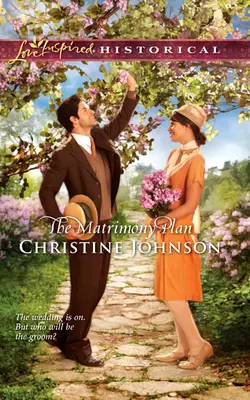

The Matrimony Plan

Christine Johnson

A Society Princess—and a Penniless Preacher? Felicity Kensington is preparing for the grandest wedding Pearlman, Michigan, has ever seen. True, her prospective husband is virtually a stranger. But the well-connected engineer her father hired fits all her marriage criteria. Except for one tiny flaw: it’s the town’s new pastor, not the wealthy engineer, who makes Felicity’s heart race….Gabriel Meeks left New York to avoid high society’s foolish rules. Instead, he’s immediately smitten with the high-andmighty Miss Kensington. Beneath Felicity’s misplaced pride is a woman of genuine worth, if he can only help her see it. And nothing could make him happier than ensuring that her matrimony plan takes an unexpected twist!

She involuntarily trembled, and her cheek burned where his finger had brushed it.

“Are you cold?” he breathed.

“No.” It wasn’t cold—it was much worse. That horrible hot-and-cold tingling ran through her again, but it couldn’t be. She needed to marry Robert. She couldn’t be attracted to Gabriel. That would lead nowhere and ruin everything. She stood abruptly. “I need to go.”

“Go?” He didn’t try to hold her. He let her back away, but his expression said it all. He liked her. A lot.

His intensity terrified her. She looked around wildly. The picket fence enclosed the yard, trapping her, stifling her. “I—I need to go,” she repeated, even less sure of herself. Stay another moment, and she’d never leave. “I’m sorry.”

“Felicity.”

She couldn’t look at him. The expression on his face would make her stay, and then what? She could have no future with him. She stumbled away, feet as unsure as her heart.

The Matrimony Plan

Christine Johnson

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Dear Reader,

I hope you enjoyed Gabriel and Felicity’s journey. They’re bound to have a full house in coming years, the perfect way for them to share the love they’ve found in each other.

What we now call orphan trains began in the mid-nineteenth century with the Children’s Aid Society train from New York to Dowagiac, Michigan. Other organizations joined the movement, sending children by train from what people believed to be the “squalor” of the cities to “healthy” small towns. The orphan trains ran into the late 1920s and early 1930s. Several books have been written on the topic, and many articles can be found on the internet. I’ve noted a few on my website.

I dearly love hearing from readers. If Gabriel and Felicity’s story touched your heart, please send me a note in care of Love Inspired Historical or through my website at http://www.christineelizabethjohnson.com.

Thank you for joining me, and may God bless you richly.

Christine Johnson

For my parents, who raised me

in the fertile soil of love

For every one that exalteth himself shall be abased;

and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.

—Luke 18:14b

Chapter One

Pearlman, Michigan June 15, 1920

Today, Felicity Kensington was going to meet her future husband. He didn’t know this yet, of course, but he had a full two months to come to that conclusion.

She pinched her cheeks for color and took a deep breath for courage. The vanity mirror revealed every imperfection. Her eyes were an odd hue of green, and she was a bit too tall for most men, but Daddy’s money could overcome those deficiencies. She pinned her chignon and checked that every pleat of her skirt fell in place. Crisp, conservative, and irresistibly efficient. Mr. Robert Blevins, civil engineer, had to fall in love with her.

A hand bell tinkled downstairs. “Felicity, you’re late.”

Mother. She was the only hitch in an otherwise flawless plan. She insisted Felicity attend this afternoon’s Ladies’ Aid Society meeting to greet the new pastor, but that meant she’d miss Mr. Blevins’s train. All the other eligible girls would see him before she did. Felicity had to reach the train first.

Hopefully Mother would accept a mere engineer as a son-in-law. He did hail from New York, and Mother always espoused the social superiority of Easterners. If society mattered to Mother, distance was the key for Felicity. Robert Blevins would take her far from Mother’s manipulations.

“Felicity.” The bell ran with greater urgency. “We’re waiting.”

Felicity shooed Ms. Priss, the neighbor’s sociable cat, out the window with parting advice. “Don’t let her see you.” The cat wisely scampered across the porch roof and onto the limb of an overhanging elm.

After brushing the bed free of cat hair, which then necessitated cleaning Grandmama’s sterling hairbrush, she took a deep breath, cast a quick prayer for courage and descended the sweeping staircase with its polished mahogany rail. Little rainbows danced off the crystals of the hall chandelier and flitted across her arm, but the beauty couldn’t calm Felicity’s nerves.

“Why did you take so long?” Mother primped in front of the mirror, poking her tight dark curls into place. She looked perfect in her fawn-colored suit. She always looked perfect. “You know we need to leave early so your father can pick up Reverend Meeks.”

Reverend Meeks…what a ghastly name. He’d surely be thin and pale with pox scars, a hawkish nose and a receding hairline. He’d never smile or grant the slightest leniency. He would conduct fire and brimstone sermons. Children would cower. Congregants would scurry away, chastened.

Thankfully, she’d be gone soon, married in the wedding of the century—at least for Pearlman. Pearlman, whose cultural center was the drugstore. Pearlman, with its gravel Main Street and single cinema. Pearlman, where everyone knew everything about everyone. She could not wait to arrive in New York City as Mrs. Robert Blevins.

Mother rang the servant’s bell, and Smithson, the butler, glided from the kitchen to the front door and opened it without a word. Now was the time to act, before Mother trapped her in the motorcar.

“I’d like to—”

“Don’t forget the letter.” Mother pressed the ivory vellum envelope from the National Academy of Design into Felicity’s hand. “You’ll want to show it to everyone.”

Felicity wanted to crumple that letter and throw it in the fireplace. The whole idea was Mother’s. She was the one who wanted to go to art school. She was the one with talent. Felicity couldn’t draw a straight line. Aside from the humiliation of being the only nonartist at the prestigious art school, Mother would never leave her alone. She’d visit for weeks at a time and fix every one of Felicity’s projects. Art school could not happen, and if all went as planned, she’d never set foot in the National Academy.

Mother, of course, never noticed her discomfort. She swooped down the granite steps to the Packard, and Felicity had no choice but to follow—as usual.

Daddy stood by a marble pillar, idly stroking his walrus mustache. He’d gained a little weight around the midsection and had to wear his spectacles all the time now, but he still saw her as his little girl.

“Good luck.” He winked at Felicity.

Mother clucked her tongue while she waited for Smithson to open the motorcar’s passenger door. “Branford, I thought you were in a hurry. Quit lollygagging.”

Daddy rolled his eyes behind his presidential spectacles and sauntered toward the Packard while Smithson opened the rear door for Felicity.

This was her last chance. Though her fingertips tingled and her pulse raced, she mustered the calm smile preached by the Highbury School for Girls, the New York boarding school she’d attended. “I believe I’ll walk.”

“Walk?” Mother glared through her open window. “In this heat? Your dress will wilt, and you’ll perspire.” She said the last word as if it was the most sinful thing in the world. “That’s not the image to project when you want to curry favor.”

“But I don’t want to curry favor.”

“Of course you do. It’s the only way to get elected chairwoman of the Beautification Committee. You’ll ride, and that’s that.”

Felicity didn’t want to chair the Beautification of the Sanctuary Committee, nor did she have the faintest idea how to go about Mother’s latest pet project, commissioning a new stained-glass window. The best solution was to avoid the meeting altogether.

“I prefer to walk.” She proceeded down the steps and away from the car.

“Now is not the time to show your independence, child.” Mother pressed a handkerchief to her forehead. “If only you could have inherited my good sense.”

“Eugenia,” Daddy warned.

Mother ignored him as always. “Felicity, come here. You are giving me a headache.”

Daddy paused at the driver’s door, walrus mustache bristling and linen jacket unbuttoned. “A walk’ll do her good, Eugenia. Get a little color in her cheeks. Want to make a good impression on the new pastor.”

Forget the pastor. Felicity had set her sights on the engineer.

Daddy started the car and put it into gear before Mother gathered wind for the next protest, but as the Packard lurched forward, she found her voice. “Don’t be late. Sophie Grattan will hold it over my head forever.”

Her plea trailed off as the car rolled down the driveway, leaving Felicity in wondrous calm. The birds chattered. Ms.

Priss crouched beneath a sugar maple, intent on a pair of cardinals who scolded and stayed well out of reach.

She had forty-five minutes until the train arrived, plenty of time to get to the depot before Sally Neidecker and the rest of the girls. The way they’d twittered about Mr. Blevins all week was sickening.

She strolled down the hill through Kensington Estates, passing the Neidecker home with its quaint Victorian gingerbread and the Williams’s squat prairie-style house. At the junction of Elm and Main, motorcars mixed with the occasional horse and buggy, and the wood sidewalks were crowded with pedestrians. If Daddy had his way with the city council, the street would be paved by autumn.

Mr. Neidecker’s Pierce-Arrow glided past, and she realized Daddy might drive by and catch her before she reached the train station. She quickened her step and passed the drugstore with scarcely a glance in the windows. The early summer heat dampened her brow and made her feel a bit light-headed, but she had to hurry.

She checked the clock on city hall. Three-ten. Daddy would have left Mother at the church by now and headed for the station. If he spotted her, he’d cart her back to the church, but if he didn’t see her until after the train arrived, it would be too late, and she would have her Mr. Blevins.

“Good aft’noon.” Dennis Allington, the depot manager, crossed the street in front of her.

She nodded slightly and hurried on. She should have taken State Road instead. It was longer and dustier, but Daddy would never have driven the Packard through those potholes.

“Felicity? I’m surprised to see you here.” Mrs. Grattan stepped out of Kensington Mercantile and stopped directly in front of her. Ruddy and heavy-jowled, she epitomized the farm wife. Her thick arms could strangle a goose or birth a calf. “Aren’t you going to the meeting?”

Felicity stalled. She’d never considered what to say if she met a society member, and Mrs. Grattan always managed to terrify her. Lowering her eyelids, she shrank behind the polite facade preached at Highbury.

“Please inform my mother that I may be a little late.”

“Late?” Mrs. Grattan clucked her tongue. “With the new minister coming?”

Felicity gritted her teeth behind an artificial smile. Mrs. Grattan and her husband acted like they held the patent on righteousness, as if owning a dairy farm and a half-dozen delivery trucks made them moral authorities.

“My Eloise can hardly wait to meet him,” Mrs. Grattan stated.

Felicity’s smile faded. “Eloise is attending?” The eldest Grattan girl never went to society meetings.

“Of course.” Mrs. Grattan acted like it was obvious that Eloise, still unwed at twenty-four, would be there.

With a start, Felicity remembered one key fact about the new pastor. Pearlman wasn’t welcoming just one bachelor into town today; it was welcoming two. Well, as far as she was concerned, Eloise Grattan could have weaselly, pock-faced Reverend Meeks.

“Wish her luck.” She giggled at the thought of the bovine Eloise standing beside a miserly Reverend Meeks.

Mrs. Grattan’s eyes narrowed to dots. “No woman can do better than a man of God, Felicity Kensington.”

Felicity cringed. “I didn’t mean…” she began, but Mrs. Grattan turned away with a harrumph and stalked toward the church.

Discombobulated, Felicity took a few steps in the wrong direction. Then to her horror, she spied Daddy’s Packard coming down Main Street. Oh, no. He couldn’t see her. Not yet. She looked for an escape and, seeing as she was nearly out of time, slipped into Kensington Mercantile.

The little bell above the door tinkled as she entered, and the clerk, one of the younger Billingsley brothers, nodded at her before returning his attention to Mrs. Evans. Felicity walked just far enough inside so Daddy wouldn’t spy her and pretended to examine the contents of the display case.

Since her brother, Blake, had taken over managing Daddy’s store, they stocked plain, useful goods that anyone in Pearlman could afford. The few luxuries on hand were displayed in the locked glass display case atop the long oaken counter. A cloisonné jewelry box, scrimshaw ivory pipe, sterling vanity box, pocket watches, assorted pendants and rings and a red leather satchel nestled on royal blue satin. A small sign noted that the satchel was perfect for the university student.

“May I help you decide?” The warm, masculine voice flowed over her like melted chocolate.

Felicity sought the source of that rich baritone and was surprised to find a man perhaps three years older than her, certainly no more than twenty-five. She’d never seen him in town before. Unruly brown curls went unchecked by comb or hat, and his shirtsleeves had been rolled up like a common worker’s. His eyes sparkled in a most unnerving way, and his smile suggested mischief.

That smile could disarm the most hardened woman, and Felicity was no exception. She stared at the merchandise as she struggled to regain her composure. “Do you work here?” She didn’t recall Blake saying he’d hired anyone new.

“No, but I thought I might help.” His reflection in the mirrored back of the case proved just as potent as the real thing, and she prayed he didn’t notice the pink hue creeping up her cheeks.

“I don’t require any assistance.”

He took the hint and stepped away, but she couldn’t help watching him in the mirror. First he scanned the nearby bookshelf and then perused the dress goods. A man buying fabric? She couldn’t resist a peek. The man strolled back to the books and picked up the volume of Coleridge that had been on the shelf for years. What common worker read poetry?

He looked up, and his eyes met hers. “Are you sure I can’t help?”

“No.” She jerked her gaze back to the display case. “No, thank you.” If she stood in just the right place, she could see him in the mirror. One curl fell across his forehead as he studied the volume. She caught her breath. He was handsome.

Oh, dear. He closed the book and headed her way.

“I don’t think anything here will do.” She darted a panicked glance out the window. Daddy must have driven past by now.

“There are a lot of fine things here.” The man stood so close that her skin tingled.

“Are you certain you don’t work here?” Her voice squeaked like a schoolgirl asked to her first dance. She swallowed and tried again. “You sound like a salesman.”

“I suppose I am, in a manner of speaking.” His lips quirked into a semi-smile, and a tremor shook her. What was wrong with her?

“I—I should be going.” She stepped into the welcome breeze from an electric fan. The train would be arriving at any moment. “I need to leave.”

“But we haven’t even met.” He extended a hand.

She stared. If she shook his hand, she’d lose all control. Leave, and everyone would know he’d affected her. She chose the lesser of the two evils and dashed for the door. Unfortunately, her hip caught the corner of a table and jostled the display of canned rhubarb.

“Excuse me,” she said too loudly as she stilled the wobbling jars.

Mrs. Evans stared. Josh Billingsley snickered. She didn’t even want to know what the stranger thought.

Without a glance back, she yanked open the door and rushed out into the heat of the afternoon, glad to hear the soft shwooft of the door settling shut behind her. After looking up and down Main Street, she spotted Daddy’s Packard parked in front of the bank. She’d never had to go into the mercantile at all. If only she’d walked on. If only she’d kept her composure.

A lady always remembers her station and acts accordingly. Mother had drilled the rules for ladylike behavior into her from childhood. Yet she’d forgotten every single one when she needed them most. She should have politely excused herself. She should never have engaged in such personal conversation, but he flustered her so that she couldn’t think straight.

Oh, dear. What had she done? And Robert Blevins was due at any moment. She fanned her face with her handbag. He couldn’t see her blushing over another man.

The clock on city hall read nearly three-thirty. The train would arrive at any moment. Felicity hurried toward the depot, perspiration trickling between her shoulder blades and her head buzzing.

Soon the businesses gave way to bungalows with bare yards and unpainted fences. This was the poor part of town where people like the Simmonses lived.

“Ms.?”

She yelped as the stranger from the mercantile planted himself before her. “Why are you following me?” She ducked around him. “I don’t want to buy anything.” She hurried on, hoping he’d leave her alone.

He didn’t. “I’m sorry I startled you. I thought you heard me.” He matched her pace. “I’ve been calling out for you since you left the store.”

“Well, I’m not interested in whatever you have to sell. Good day, sir.” She strode as fast as she could, but he easily kept up.

“I’m not selling anything. I wondered if this might be yours.” He held up an envelope—an ivory vellum envelope.

She halted. The National Academy letter. She must have dropped it in the store. The man wasn’t harassing her; he was trying to return her letter.

“The National Academy has one of the finest art schools in the country,” he said. “Congratulations.”

Until that moment, she was going to apologize, but not now. He’d read the letter. The man had opened her mail and read it. She snatched the envelope from his hand. “That is private.”

“Of course it is.”

She hurried on, but he still followed her.

“You don’t think…” he said. “Believe me, I would never read a personal letter. I simply assumed, given the time of year and where it was from, that it was an acceptance letter. My apologies if I was wrong.”

She silently plodded on, eyes fixed dead ahead.

“What’s more, your father—at least I assume he’s your father—did happen to mention that his daughter would be attending the academy.”

Felicity froze in her tracks. “You know Daddy?”

“We met in New York when he offered me the position.”

Felicity gasped as she realized her horrible blunder. This man wasn’t a farm laborer; he was Robert Blevins. Of course an engineer would be dressed for the field. Daddy had hired him to construct the new airfield and flight school. Mr. Blevins would want to walk the property and take measurements. That’s why he was dressed so casually.

She’d been a fool, a complete fool.

She pressed a gloved hand to her hot cheeks. “Th-then the train already arrived.” Please say no. Please let her be wrong.

“It was early.”

Oh, no. She should have known. Dennis Allington wouldn’t be walking through town unless the train had already left.

“I—I,” she stammered, backing away, but there wasn’t any way to get past the truth. Nothing could erase such an enormous gaffe. The only thing to do was walk away with as much dignity as possible. Less than two hours into the execution of her plan, she’d failed.

“Excuse me,” she murmured and took off, not caring where she went as long as it was away from him.

Naturally he followed. “Where are you going? What did I say?”

“Nothing,” she cried out, exasperated. Why couldn’t he leave her alone?

“Whatever it was, I’m sorry.” He drew near.

She walked more briskly.

He reached her side. “Please stop. Let’s talk. I’d like to be friends.”

“Friends?” She turned from him. “But I’ve made such a fool of myself. I—I thought you were a farm worker.”

“Is that how you normally treat farm workers?”

Shame washed over her as she stilled her steps. She owed him an apology. “No, that is, I’m sorry. It’s just that I’m overwrought. The letter…” How could she explain to a mere stranger that her mother had lied and cheated to get her into art school? He wouldn’t think any better of her for having such a family. “There’s no excuse,” she said ruefully.

“Perhaps.” He surveyed her for intolerable seconds. “But it takes character to admit fault.”

Warmth rose from deep inside, sweeping through her with shocking speed. They’d barely met. She’d insulted him, and yet he forgave her. “Thank you,” she whispered.

He laughed and held out an arm. “We all make mistakes. May I escort you to wherever you’re going?”

Where was she going? Now that she’d met Mr. Blevins and had even been forgiven by him, she had no destination. Think of his needs.

She smiled at him. “You must want to look over the site. Baker’s Field is south and east of here. We could walk, but my brother, Blake, should be here with the car soon.”

“Your brother? I thought—” His brow furrowed. “I expected your father.”

“Daddy? Why?”

Instead of answering, he dropped her hand and took off at a run. What on earth? Felicity spun about and instantly saw what had caught his attention. An envelope—her envelope—bounced along the ground. She must have dropped it in her confusion.

“Oh, no,” she cried, running after both the envelope and Mr. Blevins.

Suddenly, a black dog streaked across both their paths, snatched the envelope and took off toward the depot.

“Slinky, no.” The town stray would chew the letter. He’d ruin it, and Mother would be furious. Felicity abandoned propriety and hobbled after the dog as fast as she could. “Give it back. Slinky, bring it here.”

As if he heard her, the mutt paused, head cocked and one ear flopped over, but as soon as she drew near, he took off again.

“No,” she cried in exasperation. Her head spun, and she could barely catch her breath. She’d never get the letter back.

Worse, Mr. Blevins was laughing.

“Stop it,” she cried. “It’s not funny.”

He wiped his eyes and tried his best to keep a straight face. “I’m sorry, Ms. Kensington, but that’s no way to get something from a dog. He thinks you’re playing a game.” He whistled. “Here, boy. What did you call him? Slinky? Here, Slinky.” He held out a hand, palm up, and after a little more cajoling, the dog came to him.

He patted Slinky’s head and pried the letter from his jaws. He then held it out to her.

The envelope had been chewed, bit through and was soaked in dog saliva. Gingerly, she took hold of one corner. “It’s ruined.”

“Allow me to wipe it off.” He offered his handkerchief.

She sniffled. “That won’t help the holes or the dirt.”

“The words are still the same. I’m sure we can piece it together.”

She shook her head. “It doesn’t matter anymore.” Indeed it didn’t. She’d found her Mr. Blevins, and he was smiling at her. He might be a little less than elegantly attired, but he liked her. Surely he could love her. And she could clean him up. With a little effort, a decent suit and a haircut, he might pass as quite stylish. Yes, she could do this. In two months, maybe less, she’d be Mrs. Robert Blevins.

“Thank you,” she breathed, holding his gaze a bit longer than respectable.

His smile curled around her heart. “I’ll see you again?”

She nodded, and for a moment she thought he would take her hand, but then a motorcar horn honked. Not just any motorcar. Daddy’s Packard. After a backfire and a cloud of blue smoke, the car stopped and Daddy sprang out.

“Sorry I’m late, Pastor Gabriel.”

Pastor? Felicity reeled. This man she’d let take her hand, the one she’d promised to see again, was Reverend Meeks? He was supposed to be old and gaunt and ugly, not handsome and charming.

Her head whirled. She gulped the tepid air. Her ears rang. A minister. She’d agreed to see the new minister, her new minister, but her plan was to attract Mr. Blevins. Pastor Gabriel wouldn’t get her out of Pearlman; he’d tie her to the town—and Mother—forever. Her plan was ruined before it had even begun.

She stifled a sob, and then, as the world around her blurred, she did what any woman in such circumstances would do.

She fainted.

Chapter Two

Gabriel Meeks caught Ms. Kensington a moment after her eyes fluttered shut. She’d paled, and he rushed to her side, knowing she was about to faint.

Time paused the instant he touched her. Such beauty. Delicate veins laced her eyelids. Her ebony hair glistened, its tendrils like spring vines. The artist Alphonse Mucha could not have drawn a more beautiful woman.

The heady scent of roses overwhelmed his ordinarily good sense, leaving him gaping at her as seconds ticked away. From the moment he first saw her in the general store, he longed to know her better. Never did he imagine he’d hold this beauty in his arms. How perfectly she fit the cup of his shoulder and crook of his arm, as if God had made them two halves of the one whole.

“Lay her down,” barked her father, head of the Church Council, as he stripped off his jacket. “Get the blood flowing to her head.”

Though Gabriel wished he could hold her forever, he did as instructed, placing her head on the folded jacket. Spying the chewed envelope, he snatched it up and began fanning her face.

Still, she showed no sign of coming to.

“Do you have smelling salts?” he inquired.

Mr. Kensington shook his head and squatted beside him.

Gabriel fanned harder. Ms. Kensington hadn’t moved, and her color hadn’t improved.

“What if she doesn’t wake?”

“Don’t worry, son. She’ll come around in a moment. They always do. I’ve seen my share of ladies dropping off. Why I remember one dance where…”

Mr. Kensington’s story brought back a painful memory. Years ago, a girl who Gabriel had escorted to a dance claimed to feel faint. He left her on a sofa and went to fetch water. Upon his return, he spied her escaping to the garden with another man. His older brothers laughingly informed him that he’d just been initiated into high society. According to them, girls used this trick all the time, and he’d fallen for it. The humiliation still stung.

He hoped Ms. Kensington wasn’t that type of woman, but her expensive clothing and snobbish attitude put her squarely with the rest of the upper class. He’d been hoodwinked once. Never again.

“Perhaps we should fetch a doctor,” he said brusquely.

“Nonsense.” Kensington grabbed her handbag. “Let’s see if Felicity has some smelling salts with her.”

So her name was Felicity, meaning great happiness or bliss. Never had a name flowed so beautifully nor fit so poorly. This Felicity looked anything but happy. The only time she’d shown a glimpse of joy was when she chased the dog. Too bad it had vanished so quickly. Beautiful yet unhappy—how often Gabriel had seen that painful combination. He brushed a strand of silken hair from her eyes.

Kensington cleared his throat. “Pastor?”

He shouldn’t have done that. “I, uh, did you find any smelling salts?”

Kensington grinned beneath his mustache. “No, but she’s coming to, just like I said she would.”

The man was right. Felicity’s face had regained some color, and her eyelids opened, revealing splendid green eyes.

She flinched as if alarmed to see him and looked around. “Daddy? Wh-what happened?”

Disappointment knifed through Gabriel.

“You fainted, little one.” Kensington knelt beside his daughter, gently helping her to a sitting position.

His love for her was evident. She was cherished, the prize of his life, and completely spoiled. Such women brought nothing but trouble. Gabriel was better off without her.

“Can you stand?” Kensington asked her. “We need to get the pastor to the Ladies’ Aid Society meeting.”

Gabriel gulped. The Ladies’ Aid Society? He’d never been privy to that sacred enclave, but he’d heard tales. If the stories were correct, the ladies would have his entire life laid out for public display before the end of the afternoon. With any luck, that dissection would not include Felicity Kensington.

Felicity convinced Daddy to take her home. She couldn’t face Mother and the Ladies’ Aid Society, not in front of Gabriel.

Gabriel. Why did he have to be so handsome? She pressed into the dark corner of the Packard’s rear seat and watched him talk to Daddy. If he was nervous, he didn’t show it. She could grudgingly admire that quality. Most men cowered before her father.

But why had she agreed to see him again? She’d never be able to explain that to Mother, and it would ruin everything with Mr. Blevins.

Daddy stopped the car at the front door, and she scurried into the house before Gabriel could set a date. She slammed the solid oak door shut and leaned against its cool surface, but mere wood couldn’t quench the fire inside. Before Smithson or the cook or one of the other servants appeared, she retreated to the sanctity of her room and prepared a cold compress. She pressed it to her blazing cheeks, but even icy water couldn’t suppress the wild emotions.

A minister—she had been attracted to a minister. Not to say that there was anything wrong with the ministry but it just wasn’t for her. She had to marry wealth and privilege. She had to find a man who lived far from Pearlman if she ever hoped to escape Mother.

She unpinned the useless chignon and let her hair fall free. How could she have been so mistaken? He clearly wasn’t socially prominent—the dusty shoes, the rolled-up sleeves. But what pastor walked around so informally dressed? And with a Ladies’ Aid Society meeting to attend? Mother would tear him to pieces.

For a minute, she felt sorry for him. The ladies would gasp when he walked in, and Mother…well, no one should have to face that icy stare. Oh, Mother would speak with artificial politeness, but behind every word would be a barb, and at the next Church Council meeting, she’d petition for his removal. Poor Gabriel.

Poor Gabriel? What was she thinking? She’d promised to see him. Mother would have a conniption when she found out.

Felicity gnawed on her nails. Why had the church council hired a minister just out of school? There must have been older, better qualified pastors available, but no, they’d hired someone young and inexperienced and, well, handsome. Those curls, the twinkle in his eye, the hint of mischief… just thinking about him made her cheeks heat.

She dipped the compress in cold water, squeezed and re-applied.

His face had been the first thing she saw when she opened her eyes, and his concern had nearly melted her to the spot. She had to look away.

At first she’d been confused. How had she gotten on the ground? She didn’t feel any bruises or bumps, so someone must have caught her when she fainted. She prayed it was Daddy. Just the thought of Gabriel holding her sent hot shivers from her head to her toes.

There’d be no escaping the man or the rumors that would connect them. Practically the whole town had seen them together today including the Billingsley boy who clerked at the mercantile and Mrs. Evans. Felicity sucked in her breath. Mrs. Evans would tell everyone. All of Pearlman would know by tomorrow.

The trail of witnesses didn’t stop at the mercantile. Anyone at the businesses between the store and the train depot could have spotted them together, not to mention people on the street. And then there was the depot.

Her stomach flip-flopped. Maybe she was ill. Typhoid, influenza or scarlet fever would be better than facing the ridicule. Even Eloise Grattan, whose parents couldn’t buy her a beau, would snicker. And Sally Neidecker would lord it over her.

She groaned and sandwiched her head between two pillows. She could hear her childhood schoolmates now. Felicity and Gabriel, sweet as can be. Every childhood rhyme taunted her, each worse than the other. She needed to marry but not someone who would keep her in Pearlman the rest of her life.

What would Mother do when she found out? Felicity tossed the compress in her sink and paced back and forth across the room. Her mother would lecture and impose restrictions: no unsupervised walks, no unsupervised anything. How could Felicity meet the real Robert Blevins with Mother hounding her every move? It was terrible, horrible, the worst possible thing that could have happened.

She wrung out the compress, plopped on the bed again and pressed the cloth tight to her eyes. She needed a plan. A new plan, a better plan, one that could not fail.

The front door slammed. Mother. When that was followed by the strident ringing of the bell, she popped out of bed and re-pinned her chignon. A lady never has a hair out of place.

“Felicity,” Mother called out. “We need to talk.”

She knew. Daddy must have told her what had happened at the train station. Maybe Gabriel had spilled the whole story at the meeting. They’d doubtless had a jolly laugh over her while they sipped tea and downed Mrs. Simmons’s shortbread cookies.

Felicity tucked the last loose strand in place as Mother climbed the stairs. Thump. Thump. For such a small woman, Mother had a heavy step.

How could Felicity explain her reaction to Gabriel?

Thump. Thump. Mother’s steps matched Felicity’s heartbeat.

Heels clattered down the hallway.

Think.

“Felicity?” Mother threw open the door, her expression grim.

Too late. Felicity tried to swallow but her throat was dry. “What?” The word was barely audible.

“I told you not to walk to the meeting. I told you it would make you light-headed, and look what happened. You missed the most important meeting of the year. You left me alone. Why, if I hadn’t had Mrs. Williams’s support, you wouldn’t be chairwoman of the Beautification Committee. There wouldn’t even be a Beautification Committee. And the new minister. Felicity Anne Kensington. A lady always keeps her commitments.”

Felicity bore the lecture with bated breath, waiting for the worst to fall, but when Mother failed to mention anything about the train station or Daddy finding her with Gabriel Meeks, she relaxed.

“Thank goodness you have me to look out for your best interests,” Mother sniffed. “Change out of that filthy gown and try to make yourself presentable. We’re having a guest for dinner.”

A little knot formed in Felicity’s stomach. “A guest?” It had to be the new minister. Oh, how could she endure an evening with Gabriel Meeks? Daddy was bound to make a joke about finding them together. Mother would be horrified when she found out. Somehow she had to stop this dinner party. “Who’s coming?”

Mother ignored her question. “I wonder if he has Newport connections.”

“Newport?” Felicity gasped. “That’s not possible.” He was dressed too plainly to come from money, especially that kind of money. If only he didn’t have such a welcoming smile and warm brown eyes. The mere thought of him sent that peculiar hot and cold shiver through her again.

“Of course it’s possible. A man with his status could easily summer amongst the social elite. Hmm.” Mother surveyed her closet. “Nothing too fine in case he isn’t from proper society yet expensive enough to impress him if he is. Wear the pale green organdy.” She tossed the gown on the bed. “Traditional. You can’t go wrong with that.”

“Yes Mother.” It was always best to agree with Mother, especially when a greater concession was needed. “In fact, let’s put off the dinner until we know for certain.”

“Put it off?” Eugenia Kensington glared at her. “You can’t withdraw an invitation.” She pulled a pearl necklace from Felicity’s jewelry box and draped it around the neck of the dress. “Pearls will do quite nicely. I expect you downstairs by six o’clock. Try to display some of the social graces we paid for so dearly. Mr. Blevins might prove worth the effort.”

“M-Mr. Blevins?” Felicity stammered.

“Of course, Mr. Blevins. Who did you think I was talking about?”

Felicity averted her gaze, not wanting her mother to see that she’d been thinking about Gabriel.

Robert Blevins was coming to dinner. After such a disastrous day, she just might be able to salvage her plan. With any luck, she’d capture his affection before he learned about this afternoon’s fiasco.

Nothing about this first day had gone the way Gabriel anticipated. He came to Pearlman expecting a country church filled with salt of the earth, hardworking folk who would appreciate a down-to-earth sermon and a pastor who worked alongside them. The inequities and misery of the city wouldn’t exist here—no divide between rich and poor, colored and white, immigrant and citizen, and no stifling poverty or raging crime. The stains of abuse, liquor and hunger wouldn’t exist. In Pearlman, he could lead a church that would reach out to the sick and poor, taking them in and nurturing them into strong God-fearing people. It was the mission of his friend Mr. Isaacs’s Orphaned Children’s Society, and Gabriel planned to make it his own.

Today that idyllic image went right out the window.

The ladies at the meeting had pushed daughter after hapless daughter before him, but the only woman who’d touched his heart was proud and rich.

Then there was the parsonage. Instead of simplicity, he stood in a huge, two-story house large enough for a family of eight. The gleaming cherry Chippendale-style dining set and electric lighting looked to be recent installments, whereas the indoor plumbing had been in place for years judging by the mineral stains on the porcelain. The marble-topped sideboard and brocade-upholstered wingback chairs reeked of money. This was not a parsonage; it was a palace.

“Had my man put your trunk upstairs,” Branford Kensington said as he opened yet another door. This one led to a handsome library and study. “Encyclopedia, concordance and the Bible in the proper translation.” The man blustered around the room like a bull moose. “Of course there’s room for your books—” he patted the one empty shelf “—though judging by the size of your trunk, you won’t need all this space.” He laughed at his own joke.

Gabriel swallowed his irritation. “I guess you’re correct there.” He’d only brought the necessities, not wanting to put off any of the congregation with his upper-class background.

“I’ll give you until six o’clock and then send Smithson down. Come on up to the big house for dinner. Consider it a standing invitation until your housekeeper arrives.”

“Housekeeper? I don’t—” Gabriel started to correct him, but Kensington had already moved on.

“Fenced yard was installed some years back for Reverend Johanneson. He had four children and thought it would keep them out of mischief.” He chuckled at the memory. “Land goes clear to the river.”

Gabriel peered through the crystal-clear kitchen window. “It’s a fine piece of land.”

“Yes, it is.” Kensington stuck out his hand. “Well son, I’ll leave you to settle in. Smithson’ll be here with the car at six sharp.”

Gabriel blanched at being driven by a chauffeur. People would talk. “No, that won’t be necessary. I’d rather spend a quiet night.”

“Nonsense. My wife will have my head if you don’t come.”

Gabriel hesitated. An evening with Branford and Eugenia Kensington promised to try the patience of a saint. He’d barely made it through the Ladies’ Aid Society meeting.

“You’ll want to check on Felicity,” Kensington noted with a wink, “to see if she’s recovered.”

Memories of her flooded back: eyes the color of watercress and an elegance seldom seen in small towns. If Gabriel was honest with himself, he did want to see her. “Six o’clock?”

“I’ll send the car.”

Gabriel shook his head. “I prefer to walk. Just give me the address and point the way.”

“Walk, eh?” Kensington eyed him with what seemed to be new respect. “Physical exertion builds a man’s character. I recall my trek up Kilimanjaro in 1898—”

“Thank you, sir.” Gabriel was too tired for a lengthy story. “The address?”

“Oh, ahem.” Kensington cleared his throat. “Naturally you’ll want to freshen up first. It’s the big Federal on top of the hill. Can’t miss it. Twin lions at the head of the drive.” He nodded slightly and took his leave.

The house quieted after Kensington left. Gabriel drank in the solitude, spending time in prayer while he unpacked. As he half filled two of the bureau’s four large drawers, he wondered if he had made a mistake coming to Pearlman. Mr. Isaacs had asked Gabriel to join him at the Orphaned Children’s Society back in New York City.

“We could use a man like you,” Isaacs had said. “You’ve volunteered here for years, and your seminary experience would be a plus. There are other places besides the ministry where you can do God’s work. You’d be a splendid agent for the children.”

As much as the offer tempted Gabriel, he had to decline. “I need to go to Pearlman. God has called me to pastor there. I don’t know why, just that I must go.”

Isaacs had understood, as always. “Go then, with my blessing, but if you ever feel your task there is complete, the offer stands.”

After today, Gabriel wondered if he misunderstood God’s call and should have accepted Mr. Isaacs’s offer.

“Why did you bring me here, Lord?” Gabriel asked as he shut the drawer. Today had given him no clue, and the silence of the huge house didn’t either. He thought Pearlman might bring him the good, honest wife he’d longed to meet, but instead he’d found Felicity Kensington. For all her beauty, she would never make a good minister’s wife. She was too concerned about appearances.

He sighed and walked to the parlor. From the front windows, he could see Main Street and the church’s steeple above the rooftops. To the right sat a pretty little park, wooded along its edges and studded with lilac bushes and iris in bloom. He envisioned picnics and revivals, music, laughter and children playing.

Strange to place the parsonage so far from the church. It must be a good two blocks away. From what he’d seen, the parsonage was one of the last homes before farmland. And the property stretched back into the trees. What had Kensington said about a river?

For as long as he could remember, his parents had taken the family to the Catskills in the summer. The cabin emptied onto a lake filled with trout and bass. Gabriel had spent long hours swimming and fishing in that lake. Maybe this river had good fishing. He’d take a look.

The kitchen door opened easily, but the screen door stuck and squeaked. He’d mention it to the church trustees. Two concrete steps led down to the fenced yard. He stretched his back and surveyed the grounds. Other than an overgrown lilac and four-strand clothesline, the yard was bare. The whitewashed picket fence looked solid enough, probably recently painted. Gates pierced both sides and the end.

Beyond the far gate stood the forest, sparse at first but thickening to dense woods. He headed that way, passed through the gate and stepped into the wildness beyond. He clambered over fallen logs and crashed through the undergrowth. When he reached the edge of the river, he dropped to a lichen-covered log to watch the water flow past. He didn’t see any fish, but they’d be there in the deep pools.

The river ran dark green over a stony bottom. In the shallows, the color turned to brown, though in a few places it glistened light green over a patch of sand. The same green as Felicity Kensington’s eyes.

The thought sent an unwelcome ripple of pleasure through him. He tried to shake some sense into his head. Felicity was precisely the wrong type of woman: rich, controlling parents; a highly cultivated sense of superiority; a society girl. No matter how lovely, Felicity Kensington was one temptation he should avoid. If only he hadn’t agreed to dine at the Kensingtons’ house tonight.

Lord, lead me not into temptation. But how?

He watched the rustling treetops. They gave no answer. Neither could he hear God’s still, small voice. With a sigh, he roused himself. He’d accepted and must attend. Until then, he could take solace in the river. He followed the riverbank away from the park, occasionally peering into the depths to look for fish.

Within minutes, he reached the edge of the wood and the end of the path. A half-fallen barbed-wire fence blocked the way. Since the post had rotted away and the path clearly continued on the other side, Gabriel figured the owner must not have gotten around to removing it.

Two steps into the field, he heard a gun being loaded. Every hair rose on back of his neck.

“Hello?” He slowly lifted his palms to show he was unarmed and looked for the source of the threat. “I’m Reverend Meeks, the new pastor.” Never had he been so glad to use the title.

“I dun’t care who y’are. This here land’s private. Coughlin land, and dun’t ye forget it.” A narrow-eyed, dungaree-clad man climbed up from the riverbank, shotgun pointed directly at Gabriel.

“Sorry. It looked like the path continued.”

“You city folk don’t know what a fence is?” He waved Gabriel back with the tip of his gun.

“Uh, I guess not.”

“Well, lemme learn you up. This here fence marks my property, Mister Reverend. You stay on your side, and I stay on mine. Understand?”

Gabriel stepped back over the fallen fence, but he didn’t dare bring his hands down yet. “I thought the fence was abandoned.”

The man’s bulbous nose shone red in the sun. “It’s them criminals. As soon as I put it up, they take it right back down.”

“Criminals? Here?” Though Gabriel had only been in town a few hours, he had a hard time believing it supported a large criminal population.

“City folk.” The man spat and aimed his shotgun at Gabriel’s head.

“Don’t shoot!” Gabriel jumped back, nearly tripping on an exposed root.

The man lifted the gun higher and fired. With a derisive cackle, he said, “I was jess going for a squirrel.”

Gabriel’s heart pounded so hard that he could barely speak. “Did you get it?” The question barely fit through his constricted throat.

“Naw. Too devilish fast for this old gun.” He shook the discharged shotgun. “R’member. You stay on your side, and I stay on mine.” With that declaration, he headed across the field to the distant ramshackle farmhouse.

“Pleased to meet you, Mr. Coughlin,” Gabriel called out.

The man either didn’t hear or didn’t want to. Peculiar man. Peculiar town.

Chapter Three

“You did what?” Mother’s screech carried all the way upstairs.

Felicity checked the clock. It was not yet five forty-five. Mother’s conniption fit couldn’t be about her. She eased the emerald-colored taffeta jacket over her shoulders. Conservative would no longer do. She had to dazzle Robert Blevins tonight, before he heard any malicious gossip connecting her to Gabriel Meeks.

She pulled a matching ribbon from her vanity drawer and wove it into her hair. A diamond-headed hairpin secured it and added the necessary bit of sparkle. Robert had to fall for her. He just had to.

“How could you?” Mother wailed downstairs.

Felicity inched noiselessly to the stairway landing and from that perch saw that Mother had pinned Daddy and Blake at the front door. Blake’s wife, Beatrice, a pretty blonde, hovered near the parlor entrance, anxiously waiting for Mother to vent the rest of her anger.

“That makes an odd number of guests,” Mother cried.

“What’s one more?” Daddy waved off her concern. “The more the merrier, eh, Blake?” He gave a little laugh, meant to calm her.

Felicity’s brother shrugged. “Fine with me. We’ll have plenty to discuss.”

Apparently Daddy had invited someone else, probably Jack Hunter, since the airfield project most directly involved him. Ever since Jack and Darcy Hunter had attempted the transatlantic crossing last year, Blake and Daddy wanted to bring aviation to Pearlman. Blake had come up with the idea of the airfield and flight school, and Daddy had supplied the funds. Jack Hunter would do the training. Most importantly, Daddy had hired Mr. Robert Blevins to engineer the project, and now Felicity would engineer a marriage.

Mother threw up her hands. “But an odd number means one person won’t be paired.”

That was strange. If Jack Hunter were coming, wouldn’t he bring his wife? Perhaps Daddy hadn’t invited Mr. Hunter. A horrible thought raced through Felicity’s mind. What if Daddy had invited a lady? And what if that lady was unmarried? Felicity did not need more competition for Mr. Blevins’s attention.

Mother pouted. “Fine. Don’t consider me. Don’t ever consider me. How am I supposed to arrange the table? One gentleman will inevitably be left out.”

Thank goodness…another man. It must be Jack Hunter after all. With a smile of satisfaction, Felicity glided down the staircase. “Has our guest arrived?”

“Branford,” Mother scolded, “what will people say when they hear we invited an extra guest?”

“They’ll think we’re generous.” Daddy downed his lemonade in one swallow and patted Mother’s arm. “It’ll be fine, Eugenia.” He slipped into the parlor to refill his glass.

Mother’s lips had set into a grim line that only grew thinner the moment she saw Felicity. “That jacket doesn’t match your gown.”

Beatrice shot Felicity a sympathetic look. Everyone in the family knew how unbearable Mother could be when she was nervous.

“Take it off.” Mother waved Felicity upstairs and then glanced at the clock. “Stop. There’s not enough time. We’ll have to make do. But take that ridiculous ribbon out of your hair. You look like a floozy.”

“I think it’s lovely,” Beatrice said softly, but of course Mother ignored her opinion. She ignored everything about Beatrice except the children.

Before Felicity could remove the offensive ribbon, Daddy returned with his drink and whistled. “Don’t you look pretty, little one.”

Felicity could always count on him to lift her spirits. “It’s just an old gown.”

“It looks beautiful to me.” He pecked her cheek and escorted her into the parlor with the pomp of a princess to a ball.

“It might be acceptable for a masquerade,” Mother sniffed on their heels. “This is merely dinner.”

Felicity tried to let the slight bounce off her, but Mother’s comments had a way of sticking to her like a burr. No matter how quickly she pulled them away, some of the barbs stuck tight.

“I think I’m past the morning sickness,” Beatrice said in an obvious attempt to change the topic. She was expecting her second baby in December.

“I was never sick,” said Mother. “Not a single day.”

Felicity felt sorry for her sister-in-law, who bravely bore Mother’s snubs. Beatrice didn’t come from a good enough family to suit Mother. The Foxes ran a dress shop—respectable but not the upper-class connections Mother wanted for her only son.

“How is little Tillie?” Felicity asked. Beatrice had named her first child Matilda after her grandmother, again irritating Mother.

Beatrice brightened. “She’s such a dear, cooing away in her own special language. My mother loves watching her, but I do miss her, even for a few hours.”

Blake laughed. “I don’t think we’ll ever untie Tillie from her mother’s apron strings. It was hard enough getting Beattie to turn her over to Grandma so we could come to dinner tonight.”

Beatrice blushed. “She’s just a baby, dearest.”

“Speaking of dinner,” Mother said, cutting off the line of conversation, “apparently my wishes are to be ignored. Felicity, set another place at the table.”

Despite having a cook, housekeeper, gardener and butler on staff, Mother always expected Felicity to take care of any last-minute changes. Felicity chafed at the directive, but getting upset would not change Mother or charm Robert. She stifled her resentment and obeyed.

Once in the dining room, she discovered the housekeeper had heard Mother’s fit and already added a place setting between Felicity and Robert. All Felicity had to do was rearrange the sterling place card holders to put Robert on her right.

Within two minutes, she returned to the foyer to find that Mr. Robert Blevins had arrived. Tall with strawberry blond hair, Mr. Blevins lacked the ideal figure extolled in the ladies’ magazines. He was a bit too broad across the midsection and narrow in the shoulders. A little too much brilliantine for her taste, but elegantly coiffed, his wavy hair was parted down the center. He sported a mustache with the tips curled and waxed. The red-and-white-striped silk waistcoat and white linen suit weren’t quite appropriate for dinner, which Mother thankfully did not point out.

He tapped his gold-knobbed cane on the slate floor, and with a flick of the wrist, he caught it midlength before depositing it into the umbrella stand.

Mother batted her eyelashes like a debutante. “Call me Eugenia. Everyone does.”

He gave her his full attention. “Very well, Eugenia. And if I may say so, your gown would disgrace every lady at Carnegie Hall.”

Mother fairly warbled. “And you are quite handsomely dressed yourself. Blevins, you said? Any relation to the Blevinses of Newport?”

Felicity blushed at her mother’s lack of tact, but he didn’t seem to notice.

“The very ones,” he beamed, chest thrust out.

“You don’t say. Felicity!” The screech was a call to battle. “You must meet my daughter.”

Felicity glided near. “You called, Mother?”

“Ah, Felicity, there you are. I’d like you to meet the engineer for the airfield project, Mr. Robert Blevins. Do you go by Robert or Bob?”

“Whatever suits you, ma’am.” He bent elegantly over Felicity’s hand, kissing it lightly. His mustache scratched like Daddy’s, and she resisted the urge to giggle. “Or you, Ms. Felicity.”

“Ah, such manners,” Eugenia crowed. “Few young people today have good manners.”

“I can see your daughter does.” He gave Felicity a wide smile. “It is a pleasure to make your acquaintance.”

Felicity returned his pleasantries, eager to remove Mother from the conversation. “You’ll be here long?”

“Some months, I imagine.”

Perfect. “Then we’ll have a lot of time to get better acquainted.”

“Come, Blevins, we’re all in the parlor,” said Daddy, clapping the man on the back. “You’ve had a look around the site, I hear. Can the project be done?”

“Of course.”

Blake added, “We’ll have the airfield completed by August.”

“Under budget?” Daddy asked.

Robert nodded. “If Mr. Hunter agrees to the smaller hangar and your figures on the cement are correct, it can be done for two thousand less than projected.”

“Two thousand, eh?” In the blink of an eye, Daddy had ripped the man from Felicity’s grasp. The three men huddled like schoolboys on a ball diamond plotting the next pitch. How on earth was she to get Robert interested in her with Daddy and Blake monopolizing his attention?

Another knock on the door meant the unwelcome guest had arrived. Felicity edged toward the parlor, looking for a means to recapture Robert’s attention. Let Mother greet Jack Hunter. The man was married and of no interest whatsoever.

Smithson opened the front door, and Mother greeted the guest with decided coolness.

“Good evening, Mrs. Kensington. Ms. Kensington.” The warm, familiar voice flowed over her like honey. That voice. His. Her heart fluttered in a most unwelcome way. It couldn’t be. “I’m glad you’ve recovered.”

“Recovered from what?” asked Mother.

Felicity tried without success to fan away the heat that rushed into her cheeks. Everyone was staring at her, expecting an answer, but what could she say? How could she explain away his comment? The only solution was to give a vague answer. She forced a slight smile, the kind used by the elite girls at Highbury. “Yes, I have. Thank you for asking.”

He smiled back with such evident pleasure that Felicity half regretted treating him so coldly. He couldn’t help his birth. In fact, he’d done well to overcome it. Why tonight Gabriel looked nothing like he had earlier in the day. His hair had been combed into submission, and he wore a perfectly cut dark gray suit. By all appearances, it had been crafted by an exceptional tailor.

“I’m so glad.” His rich baritone embraced her a little too much.

That horrible warm and tingly feeling returned with tidal force. She opened her mouth, but nothing came out. Mother stared at her. Who had invited him, and why had he accepted? Surely he’d known how awkward this would be. Thoughts shot through her head quicker than swallows into a barn.

She must look like a fool, but she couldn’t get past the difference in Gabriel. He didn’t look like a laborer, a poor man or even a minister.

He looked like a suitor.

Gabriel had never seen such beauty in the parlors and theaters of New York, and he’d been to plenty. Though his parents followed solid Christian values and didn’t flaunt their hard-earned income, others of their acquaintance didn’t feel the same way. He’d seen more than his share of exquisite gowns and lavish jewels, all of which, his parents pointed out, did nothing to save a person’s soul. But on Felicity, the deep green taffeta shone. Her eyes sparkled brighter than the finest jewels. Her hair, drawn exquisitely to the side, gleamed like polished ebony.

He wanted to kiss her hand, a gesture he ordinarily found absurdly elitist, not to mention outdated. Yet such perfection demanded the highest manners. He bowed slightly and held out his hand, expecting to receive her finely tapered fingers.

She didn’t move.

He smiled, trying to warm away her fears.

Her mother practically glared at him. “Felicity, have you already met Reverend Meeks?”

Felicity stood as unmoving as a porcelain doll.

“Reverend Meeks?” A foppish redheaded man extended his hand.

Gabriel had seen him on the train. Though they’d shared the last leg of the journey, each man had kept to himself. Gabriel worked on his sermon while this man jotted in a little notebook like those used by reporters. Gabriel had been surprised when he got off the train in Pearlman. Why would a city newsman travel from Detroit to an ordinary small town? Gabriel certainly didn’t expect to see him here tonight.

He shook the man’s hand. “Pleased to meet you Mr….”

“Blevins. Robert Blevins.” The man’s idiotic grin betrayed him as a fool, more concerned with appearance than substance.

“He’s one of the Newport Blevinses,” said Mrs. Kensington.

“He’s an engineer here to design my new airfield and flight school,” Mr. Kensington explained.

An engineer? Gabriel looked again. In his experience, professionals dressed modestly, but perhaps that was only in his circles. It would explain the notepad. He must have been making notes on the project.

Kensington then quickly introduced his son, Blake, and daughter-in-law, Beatrice, a blue-eyed blonde that most men would find attractive but who paled beside Felicity. Both greeted him warmly, and he hoped they could become friends.

Mrs. Kensington maintained an artificially bright smile throughout the introductions but did not echo the warmth of Beatrice’s greeting. “We will be a bit crowded at the table tonight,” she sniffed, darting a glance at him, as if he was somehow the cause.

Kensington laughed, a deep guttural chortle meant to put everyone at ease while simultaneously exerting control. “The better to get to know each other, eh? I told Eugenia that you’re an easygoing fellow, Pastor, and won’t mind sharing a full table.”

That wasn’t all Gabriel had to share, judging by the glances Felicity cast at Blevins. The engineer rewarded her with an extended arm. “May I escort you to the parlor, Ms. Kensington?”

She eagerly accepted, and Blevins cast a look of triumph at Gabriel. “After you, Reverend.”

“No, no.” Mrs. Kensington brought the procession to a halt. “Dinner is ready.” She took her husband’s arm and headed in the opposite direction, drawing her daughter and Blevins with her. “Mr. Blevins, you will sit in the place of honor.”

The change in direction put all the couples in front of Gabriel. Eugenia and Branford Kensington led the way, followed by Felicity and Blevins and then Blake and Beatrice. Gabriel trailed behind, the only one without a partner.

At the entrance to the dining salon, ostentatiously outfitted with Irish linen, gold table service and English porcelain warmed by gold chargers, Eugenia Kensington turned to Gabriel, almost as an afterthought. “You may say grace, Reverend.”

At that moment, Gabriel saw the future stretching before him in one long, straight road through a barren desert. Gone were the camaraderie and familiar joking he’d enjoyed at dinners in the past. Gone were friendships and openness. Now he was Reverend Meeks, the pitiable wallflower, never truly welcome except in crisis. These people didn’t want a leader. They wanted to put him in a cupboard and take him out for Sunday worship and weddings, none of which would be his. Mrs. Kensington’s excessive attention to Blevins made it perfectly clear that Felicity was off-limits.

His place setting was the only one without a hand-scripted place card perched on the back of a sterling swan. He was the unanticipated guest, the outsider. Mr. Kensington’s invitation must have been made on the spur of the moment, a gaffe that his wife could not forgive. Everything was meant to demean Gabriel, yet as he stepped to the table, he couldn’t help but be pleased.

Eugenia Kensington’s stained red lips pursed so tightly that they looked like the tied-off end of a balloon. Felicity blushed madly. Gabriel folded his hands and closed his eyes in grateful prayer.

He was seated beside Felicity.

If Felicity had known Gabriel Meeks was the extra guest, she would have placed him as far away as possible, certainly not in the chair beside her. Every step toward the table was torture. Robert was on her right, and Gabriel was on her left. How could she bear it?

Robert pulled out her chair, and though she glued her attention on him, she felt Gabriel’s presence. His clean cotton scent rivaled Robert’s perfumed hair treatment. She sensed when Gabriel lifted the water glass to his lips, when he put the napkin on his lap, when he picked up his fork. She felt it all with the combined excitement and dread of waiting for her first dance. Would he try to talk to her? Did he feel anything for her? Would he tell Mother that she’d swooned? Worst of all, was he here to press his suit?

The cook placed steaming Chesapeake clams on the table, and Felicity’s stomach turned.

“Let me serve you, Ms. Felicity.” Robert proceeded to fill her plate with shells.

She stared at the clams, not daring to touch them lest she lose the contents of her stomach.

“Had them shipped fresh from the Bay,” Daddy bragged.

“I prefer Littlenecks myself.” Robert grinned round at the whole table. “We dig’em up on the Island every summer.” He smiled directly at her, the wrinkles at the corners of his eyes betraying his age. He had to be at least thirty-five. “You’d like it there.”

The hint should have made her heart dance, but Gabriel ruined that opportunity with a volley from her left. “I thought you summered in Newport, Mr. Blevins.”

Felicity picked at the clams. Gabriel was trying to trip up Robert. She could guess why, but it didn’t make her any more comfortable.

Robert laughed. “True, true, but we visit friends on Long Island from time to time. Need to keep in touch and all.”

Daddy seconded that, defusing the crisis. Felicity took a deep breath, but she still couldn’t stomach the clams. She pushed her plate away.

“Not hungry?” Robert asked.

She nodded, and he scooped her clams onto his plate.

“Clams don’t settle well for me either,” Beatrice said.

Felicity could have blessed her for that but not the next comment that came out of her mouth.

“Do you have a beau, Pastor?”

Felicity choked and coughed into her napkin.

Gabriel handed her a glass of water. “Are you all right?”

She was definitely not, but she nodded and sipped the water to calm her throat.

Then to her dismay, he proceeded to answer Beatrice. “No, Mrs. Kensington. Not yet, that is.”

Beatrice smiled. “If I can do anything to help.”

Help? Felicity glared at her sister-in-law.

“No, thank you,” Gabriel said hastily. “If you don’t mind, this is something I’d rather do on my own.”

“Ah,” murmured Beatrice, prolonging the conversation unnecessarily. “Then you have someone in mind?”

Felicity intensified her glare, and Beatrice smiled. Gabriel had paused, but Felicity didn’t dare look at him. She held her breath and waited excruciating seconds until he answered.

“Not yet.”

She breathed out with a whoosh. Thank goodness. He didn’t feel the same way she did. Her peculiar attraction was nothing more than a physical reaction based on the chance occurrence of thinking he was someone else. Once she got to know Robert, this unnatural feeling for Gabriel would vanish.

“But I do have an idea what I want in a wife,” Gabriel added, sending Felicity back to her napkin.

Mother’s eyebrows rose, and Daddy roared. “That’s the way to do it, son. Know what you want and go after it.”

“This is hardly a hunt, Branford,” Mother chided. “We’re talking about marriage.”

“And romance.” Beatrice smiled at Felicity. “Every woman longs for romance.”

Perhaps, but Felicity couldn’t afford it. She had to marry this summer before that horrid art school begins. “I’ve always believed a match is best made between two social equals with like minds.” She glanced at Robert to make her point perfectly clear. “Love can grow from there.”

“I suppose you’re right,” Beatrice conceded. “I didn’t always love Blake the way I do now. When we were young, I found him a bit of a rascal.”

“I was.” Blake laughed.

“Most boys are,” Gabriel said. “From what my sister says, I was, too. You ladies are right that love can grow over time.

It’s gentle and kind, two things we men are not too good at in our youth.”

“Gentle?” Robert snickered. “Very pastorly of you, Reverend, but in my experience, love is passionate and wild.” He gazed at Felicity. “It throws caution to the wind.”

Her pulse raced but not in an entirely pleasant way. His words should have thrilled, but a shiver of unease made her look away. She shook it off. He was merely telling her that he was interested—exactly what she wanted.

“Speaking of the wind,” Daddy said, “Blake tells me Hunter has some ideas on runway direction that contradict what you have on the blueprints.”

As the beef Wellington was served, Daddy, Blake and Mr. Blevins descended into talk about the airfield project. Felicity swallowed her disappointment. If only Daddy hadn’t changed the subject, Robert would have asked to see her again. She pulled the pastry off the beef and absently swirled it in gravy.

“I hear you’ve been accepted at a prestigious art college,” Beatrice suddenly said.

Felicity started. Why was Beatrice stirring up trouble tonight? On most occasions, she barely said a word.

Gabriel set down his fork. Was he going to tell everyone about their encounter this afternoon? She felt that awful heat wash over her again.

“Yes,” she said hastily, “an art academy.”

“The National Academy of Design to be precise,” Mother said haughtily. She leaned ever so slightly toward Gabriel. “That’s the finest art school in New York.”

Felicity blushed wildly. Gabriel knew that. “Mother,” she hissed.

“Well, it is.”

“And one of the finest in the country,” Gabriel said.

Once Mother got over the initial shock that he knew about art academies, she looked pleased. “See, Felicity. I told you that everyone has heard of the National Academy.”

Felicity squirmed. How could Mother slight Gabriel like that? He might be poor, but he wasn’t ignorant.

To his credit, Gabriel fielded the derogatory comment with grace. “You’re probably right, Mrs. Kensington.” Then he ruined everything. “Ms. Kensington, your sketches are very well done. That still life of the rose is particularly good.”

Felicity didn’t have to follow his gaze to know he meant Mother’s sketch hanging on the opposite wall. “It’s not mine,” she said stiffly.

“It might as well be,” Mother said with a wave of the hand. “Felicity’s work is charming.”

She would lie to a minister? That was practically like lying to God. “No it’s not,” Felicity said in a moment of contrariness. “I can’t draw a thing.”

“Felicity,” Mother hissed.

“I’m sure that’s not true,” Beatrice graciously said. “You did a lovely sketch of a horse when we were in school.”

Mother did it. Mother always did Felicity’s sketches. Either the teachers didn’t know or they looked the other way.

“That’s why my Felicity is the perfect chairwoman of the Beautification Committee,” Mother stated, deftly turning the conversation in a new direction.

“Beautification Committee?” Gabriel asked.

Beatrice raised guileless blue eyes. “The Beautification of the Sanctuary Committee.”

Mother explained, “We’ve decided to replace the plate glass window inside the entry with stained glass.”

“We?” Gabriel looked around the table. “Why haven’t I heard about this?”

Felicity wanted to hide. Mother should have told him at the Ladies’ Aid Society meeting. She should have laid out all her plans to the new minister. It was just like her to settle the matter before he arrived to avoid any opposition.

Mother waved off the question. “Don’t fret. You’ll hear all about it at our next meeting.”

Gabriel gulped. “Are you telling me this is a Ladies’ Aid Society project?”

“Of course, and my Felicity is chairing the committee.”

Gabriel’s expression hardened. “I thought the Ladies’ Aid Society raised funds to help the poor.”

Mother’s artificial smile tightened in preparation for a fight. “That is one of our missions. Helping our church is another.”

“But the poor—”

“Pardon me, Reverend, but you’ve been in Pearlman less than a day. I believe we know a bit more about our town than you do.” Though Mother spoke in a singsong tone, her words cut with the efficiency of a scalpel.

Gabriel’s jaw dropped, and for a moment Felicity wanted to encourage him, but then she heard Robert snicker and realized what a fool Gabriel was making of himself. Mortified for him, she tried to think of another topic of conversation, but her mind had gone blank.

Looking stricken, Beatrice took the lead. “Felicity, when is the first meeting? We can discuss this all then, not at dinner.”

How could she answer? She didn’t know a thing about the project or the committee, not even who was on it, but she couldn’t admit ignorance. She lifted her jaw and squared her shoulders. “I will contact you when a date is set.”

“But shouldn’t we begin soon?” Beatrice asked. “I understand it can take some time for a window to be constructed. Bad weather will be here before we realize it.”

A lady always maintains her composure. Felicity kept her head high. “Everything is under control.” It clearly was not.

Gabriel was upset with Mother’s project, and Robert had resumed talking about the airfield. If she didn’t do something quickly, she’d lose her chance to claim his attention.

“I’m terribly hot,” she exclaimed, setting her napkin on the table. “May I be excused, Daddy? I’d like to take some air.” She didn’t wait for his approval to push her chair back.

“May I escort you, Ms. Kensington?” Robert asked, setting aside his napkin. He held out a hand.

Perfect. She beamed as she placed her hand on his. At last, her plan was underway.

Gabriel itched to follow Felicity, but she could never care for a man who chased after her. So he waited anxiously for the meal to end.

The Wellington lost its flavor, and he couldn’t ignore the empty places beside him. What would they say to each other? What would they do? No small part of him wanted to run out and protect her, for what kind of man spoke so carelessly of passion, equating it with lasting love? He knew the answer: a man who wanted to use a woman for his own pleasure.

“It is hot in here,” Kensington said, interrupting Gabriel’s thoughts. “Let’s all take our dessert in the garden.”

Though Gabriel eagerly assented, judging by the grim set of Eugenia Kensington’s lips, she supported her daughter’s withdrawal with Blevins. Thankfully her father had better sense.

They caught up with the pair on the porch. A waning moon couldn’t compete with the bright gas lanterns lining the driveway. Moths fluttered against the globes, hopelessly attracted to what would kill them.

Felicity still hung on Blevins’s arm, gazing into his ridiculous face with adoration.

Peeved, Gabriel asked if she felt cooler now.

Felicity ignored his question. “Founder’s Day,” she whispered to Blevins. “Remember, green satin ribbon.”

Judging by Blevins’s grin, he understood what she meant, but instead of answering, he kissed her hand and broke away just as Kensington approached.

“Mr. Blevins, join Blake and me in the study,” the patriarch said. “I have a question about your blueprints.”

Blevins of course obeyed. He had little choice, since Kensington employed him, but that left Gabriel to reap the rewards of being alone with the ladies. He snared a crystal bowl of strawberries with cream and offered it to Felicity.

“Would you care for dessert?”

She hugged her arms and shivered. “No, thank you. I’m still a bit fatigued.” Without asking his pardon, she departed, leaving a faint scent of roses lingering in the air.

Gabriel knew a brush-off when he saw one. Felicity Kensington not only preferred Blevins but she disliked him intensely. The feelings he had for her were not mutual.

He gathered the remnants of his battered pride and faced the remaining women. Eugenia and Beatrice Kensington had watched the entire exchange. Felicity’s mother smirked, while Beatrice looked dismayed. Gabriel forced a smile. “Nice evening.”

They exchanged small talk, but he could barely keep his mind on the conversation. He wondered what Felicity meant by those furtive instructions to Blevins. Clearly they’d planned to do something on Founder’s Day, whenever that was, but what did the green satin ribbon mean? Was it to indicate where they could meet in secret? Surely there was no need. Eugenia Kensington clearly supported a match between her daughter and Blevins. Clandestine meetings always led to no good. Gabriel had seen his share of unwed mothers, abandoned by their lovers as soon as they were with child. He shuddered to think that might happen to Felicity, but he didn’t trust Blevins. Something wasn’t right about the man.

“Pastor, glad to see you’re still here.” The hearty greeting came from Branford Kensington, flanked by his son and Blevins. He shook Blevins’s hand. “Shall we call it a night? You’ll want to start first thing in the morning.”

Blevins apparently understood a dismissal when he heard one, for he gathered his hat and cane and thanked Mrs. Kensington for a fine dinner. As the man passed, Gabriel smelled whiskey. That shouldn’t be—not with prohibition. Yet somehow he’d gotten liquor.

Kensington’s intense gaze honed in on Gabriel. “You and I have a little unfinished business, Pastor. Let’s go to my study.”

That was not a suggestion; it was a command. Gabriel swallowed a nut of worry. What had he done to upset Kensington? Had he been too forward with Felicity? Did Kensington suspect his interest in her? Every step down the long hall intensified his dread.

The study was paneled in mahogany and filled with heavy furniture. A gun rack with nine hunting rifles spanned the wall behind him. A Cape buffalo head stared blankly with dark, glassy eyes while gazelle, moose and antelope mounts graced the other walls.

Rather than sit in the low chair across the massive desk from Kensington, Gabriel remained standing. He’d been forced low enough for one night.

“Care for a drink?” Kensington pulled the stopper off a crystal decanter filled with a dark liquid.

Whiskey. Fingers of dread danced along Gabriel’s spine. That’s where Blevins got it. Kensington might have stockpiled a legal supply before the law took effect. Even if he hadn’t, like most rich men he would think he was above the law.

“I don’t drink,” he said with quiet condemnation.

Kensington held the stopper in midair and laughed. “It’s sarsaparilla, son, not alcohol.”

But Gabriel had smelled whiskey on Blevins. Perhaps Blevins carried a flask, or maybe Kensington put the liquor away for the minister.

“I’m not thirsty.”

“Suit yourself.” The man rapped his knuckles on the desktop before taking his seat. “I’m a man who likes to get straight to business.” He leaned back in his chair, at ease with the world and whatever he had to tell Gabriel. “You’ve seen the town, inspected the church, met a good portion of our congregation. You’re a man of education, correct?”

Gabriel nodded, though the question was rhetorical.

“Then you see how things add up around here.”

Gabriel saw nothing of the sort. “What adds up?”

Kensington smiled paternally. “You’re a bright young man and can see how things run in this town.” He steepled his fingers. “There’s one thing I’d like you to keep in mind.”

Gabriel’s mind raced through the hundred things Kensington could demand: silence about illicit alcohol, blinders for every indiscretion. He could even dictate the sermon topics.

Kensington leaned forward, gaze intent. “Remember who’s in charge.”

“What?” Gabriel backed up, not believing what he’d just heard. The man was threatening him, telling him that he had to get approval for every idea.

“I think you know what I mean.”