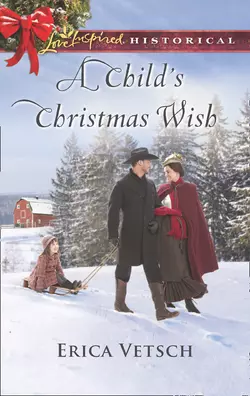

A Child′s Christmas Wish

Erica Vetsch

A Baby for ChristmasThe only Christmas gift Oscar Rabb’s four-year-old daughter prays for is one the widower can’t provide: a baby sibling. And when his neighbor’s house burns down, he’s willing to open his home to pregnant and widowed Kate Amaker and her in-laws—but not his heart. Even if his little girl’s convinced Kate’s unborn child is the answer to her wish.Kate quickly sees the generous but aloof Oscar has little interest in growing closer to his houseguests. Still, she intends to make the coming Christmas a season to remember for his daughter. And as Oscar starts to open up to her, Kate can’t help picturing just how wonderful the holidays—and a future together—might be.

A Baby for Christmas

The only Christmas gift Oscar Rabb’s four-year-old daughter prays for is one the widower can’t provide: a baby sibling. And when his neighbor’s house burns down, he’s willing to open his home to pregnant and widowed Kate Amaker and her in-laws—but not his heart. Even if his little girl’s convinced Kate’s unborn child is the answer to her wish.

Kate quickly sees the generous but aloof Oscar has little interest in growing closer to his houseguests. Still, she intends to make the coming Christmas a season to remember for his daughter. And as Oscar starts to open up to her, Kate can’t help picturing just how wonderful the holidays—and a future together—might be.

Oscar found himself wanting to put his arm around Kate, to shield her from the life blows she’d been taking.

Which brought him up short. What was he doing thinking about a woman that way? He had no business having tender feelings for anyone. What was wrong with him?

“I’ve got chores to do and then I need to get into the workroom. Orders are backing up with all the time I’ve been spending on other things.” He let his daughter Liesl slide to the ground, but in spite of cautioning himself, his thoughts were still on Kate and his reaction to her.

He’d done more than he’d intended already, housing her, feeding her, even clothing her. That was neighborly, and that was also where he drew the line. He’d share his material possessions up to a point, but he would not share his heart. That belonged entirely to his dead wife.

He needed to be by himself to get his head on straight. Too much time spent with the widow Amaker was making him forget himself.

+

Dear Reader (#u8ab8a38d-5811-5016-99a5-6382617e2454),

I love Christmas, don’t you? I especially love Christmas traditions, those special things we do once a year, those things we anticipate all year long. For the Vetsch family it is making peanut brittle, watching the 1951 Alastair Sim version of Scrooge, waffles on Christmas Day and reading the Christmas story from Luke 2 before we open gifts.

In A Child’s Christmas Wish, the Christmas activities center around Swiss traditions—especially dear to me, as my husband’s family is Swiss. In Switzerland, Advent calendars are a big part of the festivities. Parents desire to instill both patience and anticipation in their children through the countdown to Christmas Day. I love this practice, because isn’t anticipation of Christmas a huge part of the holiday season?

I hope you enjoy A Child’s Christmas Wish, and that you will celebrate this season with a few traditions of your own!

Merry Christmas!

Erica Vetsch

ERICA VETSCH is a transplanted Kansan now residing in Minnesota. She loves history and romance and is blessed to be able to combine the two by writing historical romances. Whenever she’s not immersed in fictional worlds, she’s the company bookkeeper for the family lumber business, mother of two, wife to a man who is her total opposite and soul mate, and an avid museum patron.

A Child’s Christmas Wish

Erica Vetsch

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Glory to God in the highest,

and on earth peace, good will toward men.

—Luke 2:14

For Heather Vetsch, whose love language is gift giving, and who anticipates Christmas better than anyone I know. Love you, dolly! —Mom

Acknowledgments: (#u8ab8a38d-5811-5016-99a5-6382617e2454)

My thanks to Adriana Gwyn for her help with the German translations, and to the Dodge County Historical Society for help with the history of Berne and Mantorville, Minnesota.

Contents

Cover (#u71e95095-415e-50a4-ac8e-78edcda496d1)

Back Cover Text (#u666762fc-9eb6-58d5-a733-03a2eed437a1)

Introduction (#u56065280-3a52-5d67-a563-d0fdd76639b7)

Dear Reader (#u23d4da93-4920-5203-81ed-12c6ffe55be2)

About the Author (#u8c70bbc2-1780-54b9-aa43-f99e59cbe9c4)

Title Page (#u341171f5-c992-55bc-9f92-d41015a29805)

Bible Verse (#ub4394a5f-4aad-57a0-9bf2-d36f6dc57c0d)

Dedication (#u676c1d3e-c204-5bbd-a3a8-496e4130e070)

Acknowledgments (#u3b0fcd82-9702-5795-81c8-29feebd2537c)

Chapter One (#u11e381c8-09f1-5719-840c-2530f1d9ef84)

Chapter Two (#uebcdadab-7660-5a14-99ca-13fc96a53fb4)

Chapter Three (#ufbe7bc09-1f41-537e-b3c8-1f857a6874ce)

Chapter Four (#u13eed904-4a62-5f02-ae38-967fde1d7c57)

Chapter Five (#u80f09d17-d948-589e-a6d3-6626dbaa8422)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#u8ab8a38d-5811-5016-99a5-6382617e2454)

Berne, Minnesota

November 1, 1875

“Lord, haven’t we suffered enough?” Kate Amaker didn’t say the words aloud, but they echoed in her head as Grossvater Martin urged the horses to hurry over the wooden bridge and up the slight rise to their farm drive. “How much more can we take?”

Ahead, a dull orange colored the night sky, illuminating the undersides of billowing gray clouds of smoke. Something on their farm was burning. Something big. What building was it? The barn? Thankfully, all the cows were out in the pasture tonight. The cheese house? An entire summer’s worth of cheeses gone up in smoke? All their equipment...their livelihood?

Rattling over the bridge, they drew near, and Kate’s heart sank. It was neither the barn nor the cheese house.

It was their home.

Kate put her arm around Grossmutter Inge and gripped the edge of the wagon seat with her other hand. The horses responded to Grossvater’s shouts by galloping up the hill, the wagon jouncing and slewing.

Johann and Grossvater had built the farmhouse together, replacing the three-roomed log cabin the family had lived in when they first arrived from Switzerland more than twenty years before. It was the house Johann had been so proud to bring his bride home to after their wedding almost two years before. The farmhouse was to shelter them through the coming Minnesota winter and welcome her baby in a few weeks. An ache started behind Kate’s ribs, so heavy she couldn’t take a deep breath.

Flames shot from every window and licked out under the eaves. Smoke bellied out in puffs and twists and tendrils, drawn up against the stars.

Grossvater brought the wagon to a halt well back from the fire. The horses snorted and stamped, and Kate sat in frozen horror on the wagon seat as the merciless flames engulfed the house.

Grossmutter clutched Kate’s arm, her mouth open but not making a sound. Tears tracked down her cheeks, catching the light of the fire and glittering as they followed the wrinkles and seams of her lined face.

Kate turned back to the fire, knowing it was far too advanced to stop. Already the shingles were beginning to smoke. Soon, the flames would engulf the roof. Nothing could be saved. She huddled in her late husband’s woolen coat, too shocked to grieve.

Shouts caught her attention, and the sounds of horses and wagon wheels on the road. Neighbors, coming home from the same church service where the Amakers had been worshipping and giving thanks to God for this year’s harvest, drawn by the flames.

They drove into the farmyard in their wagons and buggies, but once they spied the three Amakers, no one dashed about trying to rescue anyone or save anything. No one tried to put out the fire. It was too late, and everyone knew it. Instead, they sat, faces illuminated by the angry blaze, silent, like Kate and Grossmutter and Grossvater.

What was there to say?

After a time, someone reached up to assist Grossmutter to the ground, and then reached up again for Kate, putting his hands under her arms. Numbly, she braced herself on the man’s shoulders and found herself looking into the eyes of their closest neighbor, Oscar Rabb.

He took great care swinging her to the ground, and she felt the solidness of his muscles under his thick, black coat, steady and strong. The moment she was on her feet, he let go, stepping back. His broad-brimmed hat shaded his eyes, but the glow from the fire touched his cheeks and beard. He watched her, as if he thought he might need to catch her if she fainted.

She hadn’t realized how big he was. Not just tall, but solid. She’d only seen him before from a distance as he worked in his fields, never this near. He had been an acquaintance of Johann’s, but not a close friend. He was something of a recluse, a widower with a little girl, she believed.

The glass broke in the upstairs windows and fire shot out, voracious, consuming everything in its path. A hard lump formed in Kate’s throat. All their things, all their memories.

“There was no one in the house?” Oscar asked. He stood facing the fire, his hands in his coat pockets, his breath making frosty puffs in the night air.

Kate shook her head. “No. We were in town. At church.”

She turned away and put her arm around Grossmutter, who wept softly. When the fire began to encroach on the grass, neighbors brought buckets from the trough, dousing the flames lest they race toward the barn.

The heat was intense, smoke billowed toward them, stinging eyes and lungs. Grossvater led the team farther from the fire, and Kate guided Grossmutter back to stand beside the wagon.

“Oh, Katie, dear.” Mrs. Hale bustled over. The proprietress of the only mercantile in town, along with her soft-spoken husband, Mrs. Hale had her finger in every possible piece of gossip pie. “So terrible.” She fluttered and patted Kate’s arm, an “isn’t it awful” delight in her eyes. No doubt she’d be giving firsthand accounts to everyone who came into the store for the next week.

Kate nodded, unable to speak.

“We saw the flames clear from town and just had to come to see if we could help. Your poor house. God’s blessing no one was inside.” Mrs. Hale’s hat, festooned with flowers and feathers, bobbed in the orange glow. “Did you leave a candle lit? Or a fire in the fireplace? That’s how these things start, you know. I’m always so careful. I never leave the house without checking that I’ve put out all the lamps. Imagine how difficult it would be for us, and for the whole town, really, if we lost our house and the store. Hale’s Mercantile is so vital to the town, after all. Why, folks would have to go clear to Mantorville for their purchases.” She leaned in. “Are you sure you put out all the lamps?” Casting a glance Grossmutter’s way, she whispered, “Old folks can be so forgetful, can’t they?”

Anger burned in Kate’s chest, hot as the house fire. Mrs. Hale was such a busybody that by tomorrow she would have it spread around that the Amakers had no one to blame but themselves for the fire, since they were so careless. “How it started isn’t important, and I’m sure it had nothing to do with my family’s age. Accidents happen, fires happen, and assigning blame or starting rumors won’t help.”

Mrs. Hale’s brows, carefully plucked and arched, rose. Her lips puckered, and she put on her most long-suffering look. “You’re distraught, Katie, dear. No doubt that’s the reason for your harsh tone.”

“Kate.”

“Excuse me?”

“My name is Kate, not Katie. Kate or Mrs. Amaker.” She eased Mrs. Hale’s hand off her arm.

“Well.” Mrs. Hale straightened, her chin going up. “I see Mrs. Quilling over there. I’ll just go ask about her lumbago. She appreciates my concern.” She lifted her hem and strode away, and Kate’s heart fell. Why had she risen to Mrs. Hale’s bait when she knew from experience that it did no good?

She tucked her hands into her coat pockets, pressing her palms against her stomach, feeling the hard roundness and the reassuring kick of her unborn baby.

The baby that now had no place to lay its head when it arrived.

It was all gone. Their clothes and food stores, books, blankets, furniture. All gone.

What were they going to do now?

* * *

The Amaker place was a total loss.

Oscar Rabb turned away from the blaze and went to his wagon to check on his daughter, Liesl. The four-year-old lay wrapped in a quilt, sleeping in the wagon box on a mound of straw. Rolf, his Bernese mountain dog, lay beside her. When Oscar drew near the wagon, the big animal raised his black-and-white head, his tail swishing the straw. Seeing that his daughter was safe, Oscar leaned against the wagon box to watch the fire. Rolf rose, shook himself and sidled over to put his head on Oscar’s arm, begging to be petted.

The poor Amakers. The old couple and the young woman. He hadn’t had much to do with them for a while. Then again, he hadn’t had much to do with anyone but Liesl for the past two years. To his knowledge, he’d never met the younger woman, though he’d seen her from time to time. Pretty enough, he supposed, in a wholesome way. He remembered hearing that Johann Amaker had gotten hitched, but at the time Oscar had been too deep in his own grief to want to celebrate someone else’s marriage.

But tonight, when he’d looked out his front window and seen the orange glow, he had scooped Liesl out of her bed, wrapped her in a blanket and raced out to hitch up his team. All the way to the neighboring farm, he’d feared that the Amakers were trapped by the fire. When he’d arrived at the blazing house at almost the same time as Martin’s wagon had raced into the farmyard, he’d been weakened with relief. A house could be rebuilt, but a life lost was gone forever. Seeing them safe, he’d almost turned around and gone home, but something had made him stay.

“Tough time of year for this to happen,” George Frankel said, stuffing his hands in his pockets and rocking on his boots. George had a farm a quarter mile to the south and a houseful of children, twelve at the last count. He was an easygoing—some said lazy—fellow who always had big plans but never seemed to accomplish any of them. He liked to chew the fat, and Oscar avoided him whenever possible.

“Any time of year is a tough time for this to happen.” Oscar stroked his dog’s broad black-and-white head. “It’s good they weren’t home.” The flames were no longer roaring. Instead, they crackled and popped like a campfire. The wind carried most of the smoke to the north, away from where the handful of people milled and shuffled, but occasionally a gust would drift toward them, stinging eyes and clogging throats.

“Course, if they were home, it probably wouldn’t have happened. They could’ve put it out before it spread.” George shrugged, sneezed and dug in his pocket for a huge, wrinkled handkerchief.

Or they might have been in bed and trapped by the fire or overcome with smoke. George had a way of speaking his thoughts that assumed there was no other way of looking at things than his, and he loved to argue. Oscar wondered how soon he could get away. If he had known there was no danger to the family and that so many people would come, he would’ve stayed home.

Neighbors drifted by the Amakers, shaking Martin’s hand, hugging the old woman and the younger one...what was her name? Kathy? No, that wasn’t it. But something like that.

She was small—shorter than his wife had been—with dark brown hair. What had surprised him as he’d lifted her down from the wagon was that her eyes were blue. The clear blue of a summer sky. He wasn’t used to looking into blue eyes. Gaelle’s eyes had been brown, brown like Liesl’s, brown like his.

Mrs. Hale, the shopkeeper’s wife, bustled around, talking nineteen to the dozen. Another person Oscar avoided if he could. She was a do-gooder, but she never seemed to act out of true kindness. More like she wanted everyone to know she was doing good, as if someone was keeping a scorecard and she wanted to make sure she got full credit for her charity. Whatever she was saying to the younger Mrs. Amaker wasn’t going down too well.

Good for young Mrs. Amaker. Someone should stand up to the old biddy’s interfering ways.

“The question is, what are they going to do now?” George blew his nose, honking like a southbound goose. “I’d have them to my place, but we’re cheek-by-jowl now.”

And you have never gotten around to adding onto your house, though you’ve talked about it for ages...half a dozen kids ago.

Per Schmidt edged over, his whitish-blond hair bright in the glow of the fire. “I vish I could take zem in, but zere is no room at my house. My brother und his family haf come from de Old Country to live vid me und Gretel.” His accent was so thick Oscar wished he’d just go ahead and speak German, which was as commonly heard in Berne, Minnesota, as English. But Per was proud of his English, proud to be an American now.

Martin Amaker, a tall, spare man, looked stooped and sort of caved in upon himself. He drew off his hat and ran his gnarled hand through his thin, white hair, staring at the destruction where his home used to be.

Oscar felt for the old man. With winter coming, two women dependent upon him and his house gone up in a shower of sparks, he had to be feeling bludgeoned. Oscar patted his hip pocket, feeling the small lump of his wallet. Hopefully the community would take up a collection so Oscar could contribute. He didn’t want to just walk up and offer Martin money. That would be unbearable for both of them. No, a collection would be best. Oscar didn’t mind giving money toward a good cause, mostly because it was anonymous and simple.

Another buggy rolled into the yard, the snazzy chestnut pulling it stomping and blowing, tossing her head. Ah, here was just the man to start passing the hat. The preacher levered his bulk out of the buggy, setting the conveyance to rocking. His tiny wife took his hand, looking like a child next to her giant of a husband. They both went right to the Amakers, heads bent in empathy.

They spoke, and Mr. Amaker shook his head, shrugging. Pastor Tipford scanned the crowd of neighbors who were already filtering toward their wagons, and his eyes came to rest on Oscar. An uncomfortable feeling skittered across Oscar’s chest. Pastor Tipford visited Oscar regularly, trying to get him to come back to church, trying to get him involved in the community again. But Oscar wasn’t ready for that. He still felt too raw inside to endure the company of well-meaning church folk.

He motioned for Oscar to come over.

“Looks like the pastor wants you.” George sniffed again. “Rotten cold I’ve got. Passed it around the house like candy, we did. Every last kid sneezing and coughing and dripping. Not even the baby escaped.”

Oscar stepped back. The last thing he wanted was to pick up George’s cold and risk passing it on to Liesl.

Pastor Tipford motioned again.

“You better see vat he vants.” Per hitched up his pants. “I vill be going now. Nothing to do here anyway. The house is gone.” He went to his wagon, and climbed aboard. “Gute Nacht... I mean, good night.”

Oscar checked on Liesl once more, told the dog to stay and waited for Per’s wagon to roll past him and down the drive before heading toward Pastor Tipford and the Amakers. He braced himself for the sorrow in their eyes, tucking his hands into his coat pockets, taking a deep breath. Other people’s grief always made his own more acute.

“Ah, just the man we need.” Pastor Tipford clapped him on the shoulder, a hefty blow.

“Pastor.” He nodded. “Mr. Amaker, I’m sorry about your house. I wish we could have saved it.”

Martin Amaker looked at him, but he didn’t really seem to see. His eyes behind his spectacles were unfocused and blank.

Shock.

The elder Mrs. Amaker trembled, twisting her fingers in the fringe of her shawl. The knot on the kerchief under her chin wobbled. The pastor’s wife hugged her again, rubbing her arms as if trying to restore warmth.

But it was the younger Mrs. Amaker that drew Oscar’s attention. She stood a little apart, her face golden in the reflection of the lowering flames. Her eyes were wide, and she huddled into the coat that was too large for her. It looked like a man’s garment. Her dead husband’s perhaps?

They had that in common, he realized. The loss of a spouse. He could understand her desire to keep her husband’s memory close. She must really be missing him now.

God, you exact too high a price. What did she do to deserve this? First her husband and now her home? For that matter, what did I do to deserve to lose Gaelle? Or Liesl her mother?

“Oscar, the Amakers need a place to stay for the night.” Pastor Tipford spoke in his most “let’s all be reasonable” tone. “Your place would be perfect. You have the room, and you’re right next door, so tending to the chores tomorrow would be simpler for everyone.”

His place?

No.

He hadn’t offered hospitality in years. Not since...

Everyone looked at the pastor. “The Frankels are too crowded, and anyway, there’s been sickness there. And the parsonage is tiny,” he pointed out. “You can help out, can’t you, Oscar?”

Mrs. Tipford spoke up. “Of course he will. And I’m sure Liesl will love having some company.” She gave Mrs. Amaker another reassuring squeeze. “It’s all going to be all right, my dear. You can rebuild a house. We’re just thankful that no lives were lost. Now, it’s late, and it’s chilly, and there’s nothing more we can do here. Everything will look better in the morning.” She turned Mrs. Amaker toward the wagon, still whispering in her ear.

Without so much as a nod from him that it was all right. Women could be like that...tornadoes in petticoats, pushing the world around to suit themselves, and in such a nice way that men hardly protested.

But Oscar was going to protest. His home wasn’t open for visitors, even for a night. There had to be another option, something that didn’t involve strangers invading his peace.

“Come along, Kate,” Mrs. Tipford called over her shoulder. “You shouldn’t be out in this night air any longer.”

Kate. So that was young Mrs. Amaker’s name. Pretty name.

She reached up with both hands to tuck stray tendrils of hair off her face and her coat fell open.

Oscar felt as if he’d been punched in the gut.

She was pregnant.

He turned away, but the image was seared on his brain, and he was jerked right back to the center of his own grief. He’d lost his wife in childbirth two years ago come this Christmas. Having a woman in the family way around his house, even for one night, was going to rip open all the old wounds.

He couldn’t do it. He wouldn’t do it. Pastor Tipford would have to find someone else.

A hand touched his arm. He looked down into Kate Amaker’s face. Her cheeks were gently rounded and looked so soft. How long had it been since he’d stood this close to a woman? Oscar sucked in a breath and smelled lavender mixed with wood smoke.

“Thank you.” She bit her lip for a moment, her eyes looking suspiciously moist.

His muscles tensed. He hated to see any woman cry, even Liesl. It made him feel so helpless.

“It’s kind of you to put us up. I don’t know what we would do, where else we would go.” She blinked hard, lifting her chin, her shoulders rising and falling as she breathed rapidly, staring at the glowing embers. “I...it’s just...gone.” Her pretty eyes met his once more.

And just like that, Oscar had houseguests.

Chapter Two (#u8ab8a38d-5811-5016-99a5-6382617e2454)

Everything...gone. Kate could hardly wrap her mind around the fact. Her clothes reeked of smoke, and if she closed her eyes, she could still see the merciless flames, the showers of skyward-rushing sparks, hear the crackle and roar. It was so hard to believe.

Away from the fire, the night was black and cold, the moon barely a sliver and the stars remote. The wagon rattled up the drive toward Oscar Rabb’s house, and Kate kept her arm around Grossmutter. Neither had said a word since climbing onto the high seat. What was there to say? Words weren’t enough to describe her sense of loss.

Oscar’s house sat atop a small hill, facing south. Two-storied, white clapboard, with lots of windows. A porch stretched along the front. The overall design was more compact and less flamboyant than the house Johann had built, but the porch was similar. How many evenings had Kate and Grossmutter sat on the porch shelling peas, snapping beans, while Grossvater and Johann had sat on the steps, talking over the day’s work, planning for the future? A hard lump formed in Kate’s throat.

Oscar Rabb’s house, porch notwithstanding, looked dark and forbidding with not a single light shining from any of the windows.

Ahead of them, Oscar drove his wagon down the slope behind the house toward his barn. Kate knew Oscar hadn’t wanted to offer hospitality, that he’d been on the verge of refusing, but he had been too well-mannered. And Mrs. Tipford had practically coerced him into it. Well, they didn’t want to have to accept hospitality, either, but what else was there? Pastor Tipford had been right. Oscar’s place was the logical, if reluctantly given, choice.

Grossvater directed the horses, Schwarz und Grau—Black and Gray—after Oscar’s wagon, drawing up in front of the immense red barn with its gambrel roof and sliding doors.

A large dog leaped from the bed of Oscar’s wagon, his tail a bushy plume and his breast glowing white in the darkness. Every bone ached as Kate forced herself to stand and climb down over the wagon wheel. The dog came over, friendly and sniffing, nudging her hand with his broad head for a pat.

“Rolf, come.” Oscar snapped his fingers, and the big dog bounded to his side. “He can be a nuisance sometimes.”

Kate and Grossmutter stood out of the way as the horses were unhitched and turned out into a small pen. Oscar forked some hay over the fence and then went to his wagon. He scooped up a blanket-wrapped bundle, holding it to his shoulder. Kate spied small, stocking-clad feet peeping from under the hem of the blanket.

This must be Oscar’s daughter. Liesl, wasn’t it? Kate’s mind was so muddled she hadn’t even thought to wonder where the child had been during the fire.

“This way.” Oscar led the way up the curved path to the back of the house. “Watch your step.”

“You go ahead. I’ll follow.” Kate let Grossvater take Grossmutter’s arm and fell in behind them, lifting her skirt and the hem of Johann’s heavy coat, weary beyond words. All she wanted was a quiet, warm bed, some place to curl up and sleep...to forget what had happened for a while.

They gained the porch, and Oscar held the door open. “I’ll light a lamp.”

He laid his daughter down on a bench beside the door and rattled the matchbox on the wall. A scritch, and light flared, illuminating his face. He touched the match to the wick of a glass kerosene lamp on the table and replaced the chimney. Light hovered around the table and picked out objects around the edges of the large room.

He’d brought them into the kitchen rather than through the front door, but the room seemed to have a dual purpose, one end for cooking and eating, while the other, through open pocket doors, appeared to be the sitting room. Chairs and a settee grouped around a massive fireplace. In the kitchen, beautiful wooden furniture filled the room—a sideboard, a bench, a table and chairs, all decorated with intricate carving. Oscar Rabb must be better off than most of the farmers around Berne if he could afford such fine furnishings.

The dog’s nails clicked on the hardwood floor as he went to his water dish, lapping noisily and scattering droplets when he raised his head.

Upon closer inspection, the large room was...rather untidy. Not filthy, but definitely cluttered. Boots and shoes were piled by the door, and it appeared someone had taken apart some harness on the table. Straps and buckles and bits lay everywhere. At least there weren’t dirty dishes, but Kate could tell it had been a long time since the room had received a thorough scrubbing.

Battered children’s books and blocks lay on the rug in front of the settee, a rocking horse stood in one corner and what looked like a pinafore hung from his ear. A stack of newspapers stood beside a large wooden rocker. Was that where Oscar sat each night, reading while Liesl played? She categorized what she saw without really caring, observing only, too tired to do much else.

Oscar shifted his weight, shoving his hands into his pockets. “Bedrooms are upstairs. I can carry some water up for you as soon as I get Liesl settled. I imagine you want to wash some of the smoke off.”

Kate wrinkled her nose. Her coat—Johann’s coat—reeked of the fire, and she knew her hair did, too. She’d love a hot bath, but she’d settle for a cold basin of water and a bit of soap.

Their host shucked his black, wool coat and tossed it over the back of a chair. He lifted his daughter into his arms, cradling her head against his chest. Kate spied glossy, dark hair, and rounded, sleep-flushed cheeks. Long lashes, limp hands, a pale nightgown. Her heart constricted. There was something so sweet about a sleeping child, especially one held in a parent’s embrace. Her hand went to her own baby, sleeping there under her heart.

“If you’ll get the lamp?” Oscar looked at Kate and inclined his head.

She lifted the glass lamp and followed him toward the staircase. Grossmutter and Grossvater followed behind. At the top of the stairs, a hallway bisected the house. Four doors, evenly spaced, two on each side of the carpeted runner, and a window let a small amount of light in at the far end.

“You can sleep in here. And the older folks across the hall. Liesl’s room is next to yours, and mine’s across from hers.” Oscar opened the first door on the right. A stale, closed-up smell rolled out. Starlight hovered near the windows, and the lamp lit only half the room as she stepped inside. The bare mattress on the bedstead had been rolled up and tied, and a sheet draped over what looked to be a chair. “There’s sheets in the bureau. Sorry the bed isn’t made.”

He really hadn’t been expecting company. Kate pushed a stray lock of hair off her forehead, forcing down a weary sigh. “It’s fine. We’ll take care of things.” She set the lamp on the bureau, found another lamp there and lit it for her in-laws. “Get your daughter settled back into bed. We’re sorry to inconvenience you like this.” She was barely hanging on, willing herself not to cry. How soon could she be alone?

Grossvater took the second lamp. “Come, Inge. We will get some rest. As Mrs. Tipford said, perhaps things will look better in the morning. Thank you, Oscar, for a place to stay tonight.” He put his arm around his wife and led her across the hall.

Oscar stood in the doorway, frowning. He lifted Liesl a bit higher in his arms, appeared about to say something and then shrugged. Finally, he turned away. “I’ll be back with that water.”

Kate left her coat on. She was chilly, though she wasn’t sure if it was because the house was cold or from shock.

The rope binding the mattress roll was rough on her hands, but the knots came loose easily enough. With a couple of tugs, the feather-tick flopped open. She nudged it square on the bed frame. Searching the bureau—another hand-carved beauty—she found a set of sheets and a pair of pillows in the deep drawers.

Across the hall, she heard some rustling and bumping. Peeking through her door, she saw Grossvater spreading a sheet across a wide bed while Grossmutter slid a pillow into a case. They were speaking to each other in German, soft, gentle tones. Kate smiled as Grossvater called his wife “liebchen.” There was so much love and affection in his tone it made Kate’s heart hurt. In spite of all they had lost, they still had each other.

Boots sounded in the hall, and Kate returned to making up her bed. She had just finished spreading the top sheet smooth when there was a tap at her open door.

“I brought you some blankets.” Oscar stood in the doorway, a bucket dangling from one arm, the other full of quilts.

“Thank you.” She came to take them, careful not to touch him. The sharp tang of cedar drifted up. The blankets had been in a chest somewhere. “I’ll share them across the hall.”

Coming back from leaving more than half the blankets with her in-laws, she found Oscar flinging open a patchwork quilt over the bed. He’d poured water into the pitcher on the washstand, and he’d raised the wick on the lamp.

He drew the covering sheet off the chair, setting the rocker in motion as he wadded the muslin up. Standing there in the glow of the lamp, he waited, watching her.

What did he want? She drew her coat around herself. “Thank you. I hope we won’t be too much of a bother. I’m sure we’ll get something sorted out tomorrow.” Though what, she couldn’t imagine right now. “We’ll need to be up early to tend the cows. If you wouldn’t mind knocking on my door when you wake up?”

He nodded. “I’ll say good night, then.” He crossed the room and closed the door behind himself.

Kate opened her coat and let the heavy garment slip down her arms. Laying it over the rocker, she reached up and began unpinning her long, brown hair. It tumbled in waves about her shoulders. She had no brush, so she finger-combed the locks, separating them into strands and forming them into a less-than-elegant braid. Pouring water from the pitcher into the basin, her lips trembled. The water was warm. He must’ve drawn it from the reservoir on the stove. That was thoughtful of him.

Looking into the mirror, she grimaced. Soot streaked her cheeks, and her eyes were red from smoke and unshed tears. She looked as if she’d been dragged through a knothole backward. What a sight.

Dipping the corner of a towel into the water, she scrubbed at her hands and face and neck. Patting herself dry, she considered her options for the night. No nightgown. Only a smoky dress with a let-out waist. Wrinkling her nose, she shed her dress and decided to sleep in her chemise and petticoat. She hurried to spread her clothing out over the footboard of the bed, hoping they would air overnight.

After all, they were the only clothing items she owned now.

Sliding under the covers, she curled up, wrapping her arms around her unborn baby. Loneliness swept over her, loss and sorrow crashing into her chest. She reached for the second pillow, burying her face in the feathery softness, letting the tears she’d been holding back flow.

The baby rolled and kicked, bumping against her hand, warm and safe in her belly. Which was just as well, since she had no home for him or her at the moment.

* * *

Oscar closed the damper on the stove, checking that the fire was well-banked and letting Rolf out for one last run before he climbed the stairs to his bedroom. The clock on the mantel said it was already tomorrow, and he needed to be up early. Familiar with his house in the dark, he didn’t bother with a lamp.

His boots sounded loud on the stairs, and he wished he had remembered to take them off in the kitchen. Liesl, once asleep, could slumber through a brass band marching through her bedroom, but his houseguests probably didn’t sleep that soundly.

Light snoring came from the old couple’s room. He was glad someone was getting some rest. They were in the room his wife had reserved for her parents when they came down to visit from Saint Paul. Those infrequent visits had always made Oscar uncomfortable. His in-laws had wanted their daughter to marry someone from town, a doctor or banker or lawyer, someone who could provide an easy life for her in the city in which she was born. But she had married him instead, a farmer and woodworker. It had been on one of his trips to the city to deliver his hand-carved furniture that he’d met Gaelle. One look and he’d been a goner. Three happy years of marriage, one daughter and a baby on the way...and now nearly two years of emptiness...except for Liesl. If he hadn’t had that little girl to look after, he didn’t know what he would’ve done.

He shook his head, letting go of the banister to start toward his own room. A sound to his right made him pause. The muffled sound of a woman crying. It seeped under the door and into his chest.

The widow.

Helplessness wrapped around him, and his own grief, never far below the surface, rose up to engulf him. He shifted his weight and a floorboard creaked.

The crying stopped, and he walked down the hall, feeling guilty at intruding upon her sorrow. Grief was a private thing, and it must be wrestled one-on-one. He knew from experience. Well-meaning outsiders weren’t welcome.

He peeked into Liesl’s room one last time to make sure she was still under the covers. His daughter often slept like a windmill, throwing aside blankets and pillows and apt to be sideways in the bed before dawn. A sound sleeper, but an active one.

For once, her head lay on the pillow, the blankets tucked to her chin where he’d placed them upon their return to the farmhouse. Her journey out into the night air didn’t seem to have done her any harm. Of course, she’d been well wrapped up and had Rolf curled up beside her, sharing his warmth. The dog followed him into the room and flopped onto the rug beside her bed, his tail softly thumping the floor. Oscar smiled and smoothed Liesl’s nut-brown hair, his hand engulfing her little head. She looked just like her mother and chattered like a chickadee from dawn till dusk. He’d do just about anything for her.

He shut her door and entered his own room. The weak moon had long set, and faint starlight was the only illumination, but there wasn’t much to worry about knocking into in here. A single bed, washstand, and armoire, all made by him, were the only furnishings.

He eased his suspenders off his shoulders, loosening his shirt where it had been pinned by his braces. Letting the suspenders fall against his thighs, he poured water into his washbasin. Washing quickly, Oscar got ready for bed.

Once in bed, he couldn’t sleep. Stacking his hands under his head, he looked up at the ceiling and thought about the Amakers. He’d known Johann for years. They’d gone to school together, loaned one another horses and equipment when in need, been members of the same congregation, but they weren’t close friends. Oscar wasn’t particularly social, and since his wife’s death, he’d stayed to himself even more.

Still, it bothered him that Johann’s widow was crying down the hall, alone and grieving.

And pregnant.

Every time he thought about that, it was like a fist to his gut. He didn’t want to be responsible, even in a small way, for an expectant mother. Too much could go wrong. He’d have to find another place for the Amakers soon. Maybe even tomorrow. By tomorrow afternoon, he was sure a collection would’ve been taken up, and maybe they could rent a place in town until a new house could be built.

He rolled to his side and willed his eyes to shut and his mind to stop thinking about the woman across the hall.

It seemed he’d only been asleep for a minute when something patted his face. He squinted through his lashes, pretending to still be asleep as the light of a new dawn peeped through the window. Liesl stood beside his bed, her hair tousled, cheeks still flushed from sleep.

“Daddy, the sun is waking up.”

She said the same thing every morning. She’d always been an early riser, and he’d been forced to teach her that she couldn’t get out of her bed until the sun was up. So she waited, every morning, and at the first sign of dawn, she was in here urging him to get up and start his day. He lay still, eyes closed, playing the game.

“Da-a-a-dddyyy!” She patted his whiskers again. “You’re playing ‘possum.’”

He grinned, reached for her with a growl and grabbed her, wrapping a knitted afghan around her. “Brr, it’s too chilly to be standing there in your nightdress. Is it time to milk the chickens?” He rubbed his beard against her neck, careful not to scratch too hard.

She giggled and squirmed, kneeing him in the belly as she twisted in his grasp. “Silly Daddy, you don’t milk chickens.” Liesl took his face between her little hands, something she did when she wanted him to pay particular attention to her. “Daddy, I had a dream last night.”

Which was nothing new. Liesl was an imaginative child who had dreams, both night and daydreams, that were vivid in color and detail.

“What did you dream this time, punkin? That you were a princess?”

Her brown eyes grew round. “How did you know?”

He gave her a squeeze, tucking her head under his chin for a moment. “It might be because we read the princess story again before bedtime last night.”

Liesl giggled and shoved herself upright. Her hair wisped around her face, and she smeared it back with both hands. “I did dream I was a princess, and you were there, and we had a picnic, and I had a pink dress, and there were beautiful white horses and sunshine and cake.”

“So, it’s a pink dress now, is it? Yesterday it was blue. I thought blue was your favorite color.” He sat up and wrapped the blanket around her again, scooting up to rest his back against the headboard.

“I like all the colors, but today I like pink best.” She fingered the stitches edging the blanket. “Pink, with blue flowers? For Christmas?”

He laughed. “Pink with blue flowers. Got it.” Somewhere along the way, she’d latched on to the idea of presents for Christmas. He must’ve mentioned it to her once. That’s all it took with Liesl. Say something that interested her, and she grabbed it with both hands and ran with it. But he’d told her she could only expect one thing for Christmas, so she must be very sure what she decided upon. As a result, the wish changed every day.

He chucked her under the chin. “There’s something I need to tell you. We have visitors.”

Her little brows arched. “Where?” She looked around the room as if expecting them to pop out from behind the door.

Laughing, he dropped a kiss on her head. “They’re sleeping down the hall. Last night their house caught on fire, and they didn’t have anywhere else to sleep, so they came home with us.”

“A fire in a house?” Worry clouded her brown eyes. “What house?”

Pressing his forehead to hers, he wished he didn’t have to expose her to such harsh realities as house fires. “They are the Amakers, who live next door.”

“With the brown cows?” she asked.

“Yes, with the brown cows.” The Amaker pastures bordered Oscar’s land, and from the top of the hill, he and Liesl could look down and see the herd of Brown Swiss as they wended their way to the milking barn each evening. Speaking of which, he needed to get up and wake his guests as Kate had asked last night. There were chores to do, cows to milk and decisions to be made.

“Scamper back to your bed, Poppet, and I’ll be in to help you get dressed in a minute.”

“I can do it myself, Daddy.” She gave him a look that reminded him of her mother. Bossy, but sweet about it.

“I know, but I like to help.” And she still needed him, even if she didn’t think so, if only to fasten her dress up the back and button her little high-topped shoes.

He dressed quickly, ran his fingers through his unruly hair and went to Liesl’s room. She sat in the middle of her bed, leafing through one of the storybooks they read each night. She stopped on the picture of the princess. “See, pink.”

“I see.” He gathered her clothing. It was time to do laundry...again. It seemed he barely had the last washing put away before it was time to get out the tubs again. He would be the first to admit he wasn’t much of a housekeeper. The farm took so much of his time, the housework usually got a lick and a promise until he couldn’t ignore it any longer. “Well, it’s going to be a green dress today because that’s what’s clean.”

“I can do it, Daddy.” Liesl was growing more independent by the day, always wanting to be a bigger girl than she was. Oscar would do anything to hold back time, because he had firsthand knowledge of how fleeting it was, but that was something you couldn’t explain to a four-year-old.

He handed her the items one by one and she put them on. When it was time for her stockings, he got them started around her toes and heel and she pulled them up. Then the dress. She turned and showed him her back to do up the buttons. He laid her long, straight hair over her shoulder and fitted buttons to holes. Then her pinafore over the top, with a bow in the back.

“Time to do hair.” Oscar reached for her hairbrush on the bedside table.

“I don’t like doing hair. It tugs.” Liesl handed him the hairbrush, a scowl on her face.

“Can I help?”

The question had both Oscar and Liesl turning to the door.

Kate Amaker, dressed and ready for the day.

Oscar sucked in a breath, his heart knocking against his ribs, staring at her rounded middle that the voluminous coat had covered last night. He was no judge, but was she ready to deliver soon?

Liesl looked their guest over, and Oscar waited. The little girl could be quite definite in her likes and dislikes.

Evidently, Mrs. Amaker fell into the “likes” category, for Liesl smiled and handed her the hairbrush.

“What happened to your tummy?” She pointed at Mrs. Amaker’s middle.

A flush crept up her cheeks, and Oscar cleared his throat. “Liesl, that’s not polite.”

His daughter looked up at him with puzzled brown eyes. “Why, Daddy?”

“It’s all right.” Mrs. Amaker smiled, her face kind. “I’m going to have a baby. He’s growing in my tummy right now, and when the time is right, he’ll be born.”

Liesl’s face lit up. “A baby. In your tummy? When will the time be right? Today?”

Mrs. Amaker laughed. “No, sweetling. Not for a couple of months. Around Christmas.”

Oscar’s gut clenched. He’d lost his wife and second child around Christmas.

Liesl had a different reaction. She clapped her hands, bouncing on her toes. “That’s it, Daddy. That’s what I wish for this Christmas. A baby. Can I have a baby for Christmas?”

Chapter Three (#u8ab8a38d-5811-5016-99a5-6382617e2454)

Kate took the hairbrush from Oscar and sat on the side of the bed, not meeting his eyes. The poor man looked stricken. She should change the subject. “You have lovely hair.” She smiled at Liesl. “I love to brush and braid hair. Is it all right if I help you?”

Liesl, eyes round, nodded and turned, backing up until she rested against Kate’s knees. Oscar stood, jamming his hands into his pants’ pockets, looming, a frown on his bearded face. Kate wondered if she’d overstepped by offering to brush and braid Liesl’s hair, but it was too late to recall her offer.

“Are you a princess?” Liesl asked, breathless.

Kate laughed. “No, darlin’, but bless you for asking.” She wanted to hug the little sprite. “You’re Liesl, right? My name is Kate.”

Drawing the brush through Liesl’s hair, Kate remembered her mama doing the same thing for her. “Do you have ribbons for your braids, or do you use thread? My mama used to use thread for every day, and ribbons on Sunday for church.” Liesl’s hair fell almost to her waist, thick and glossy brown. It would be easy to braid.

“Daddy uses these.” She held up two strips of soft leather. “He calls it whang leather. He made it from a deer.”

Leather to tie up a little girl’s hair. Still, it probably worked well. She parted Liesl’s hair and quickly fashioned two braids, wrapping the leather around the ends and tying it. “There you go. You look sweet.”

“Thank you. Daddy says I am pretty like my mama, but it’s how I act that is important.”

“Your daddy is right.” She caught “Daddy’s” eye and smiled.

“Can we go eat breakfast now?” Liesl hopped on her toes.

“Absolutely. Right after we turn down your covers to air the bed. Shall we do it together?” Kate pushed herself up awkwardly, and before she got upright, Oscar was there at her elbow, helping her. His hand was warm on her arm, and she was grateful for his assistance. “Thank you. It’s getting harder to maneuver these days.”

He stepped back, his eyes wary, and she laughed. “Don’t look so worried. I told Liesl the truth. I have a couple of months yet. Until Christmas.”

He didn’t laugh with her.

* * *

Breakfast was an ordeal. Kate had little appetite in the mornings these days, and especially not for oatmeal so sticky it clung to the roof of her mouth and tasted of damp newspaper. Grossmutter would have made a coffee cake for breakfast today, using her sourdough starter from the crock that always sat on the shelf behind the stove. Now the shelf, the crock and the stove were gone.

Their host and the maker of the meal shoveled the gooey mass into his mouth as if stoking a furnace. His daughter sat on a high chair, her little boots kicking a rung as she poked and stirred her oatmeal, taking little bites and watching the strangers at her table. Uncertain, but clearly curious.

As for Oscar Rabb... Someone had put a burr on his shirttail. He must have morning moods, because from the moment she’d offered to help with his daughter’s hair, he’d been wary and gruff, as if having them there put him out considerably and he couldn’t wait for them to leave.

Inge and Martin ate quietly, still looking exhausted and facing a difficult day. How could Kate help them through it when she felt as if she was barely hanging on herself? And yet, she must. Johann would expect it, and they needed her. And she loved them as if they were her own grandparents. Having lost her family soon after her wedding, Johann’s grandparents were all the family she had left now.

“I am finished.” She put her spoon down, her bowl still more than half full. “We had better get going soon. The cows will be waiting at the barn door.”

“Oscar,” Grossvater said. “I would like to leave Inge here, if that is all right? Kate and I can tend the cows and the cheeses. Perhaps Inge can help with the little one.” He nodded toward Liesl.

The little girl’s eyes grew rounder, and she looked to her father. “Actually...” He let his spoon clatter into his empty bowl. “I was thinking that you should all stay here. I can milk your cows for you today.”

Kate blinked. He’d been grouchy all morning, and now he was volunteering to milk ten cows all by himself? Cows that weren’t even his? He’d been reluctant from the first to have them in his house, and now he was offering to give them even more help?

“That’s very kind of you, Mr. Rabb.” Kate scooted her chair back and went to stand behind her family, putting her hands on their shoulders. “But we don’t want to be any more of a burden to you than we already have been. We must see to our own chores, and we must decide where we are to go.”

Inge stood and began clearing the table. “Nonsense, Martin. We will all go. We need to see what can be salvaged of the house, if anything, and there is plenty of work to do this morning. I am old, but I am not useless.” She gave her husband a determined look, and he shook his head, smiling and patting her hand.

“I only wanted to spare you the unpleasantness for a while. If you are sure, we will all go.”

Liesl hopped off her chair and scampered toward the door, lifting a contraption of wood and straps and toting it to her father. “Me, too, Daddy?”

He took the odd item and rubbed her head with his large hand. “You, too, Poppet, but we’ll take the wagon over and use this later.”

“Can she ride in our wagon with us?” Liesl pointed to Kate.

Kate stopped buttoning her coat—still smelling of smoke—in surprise. “Me?”

Liesl nodded. “I like you. You’re pretty. Are you sure you aren’t a princess? You look like the princess in my book.” She turned to Grossmutter. “Did you know she has a baby in her tummy? Daddy’s going to get me a baby for Christmas. He said I should ask for the one thing that I want most, and he would get it for me.”

Grossmutter smiled. “Do you mean a doll baby?”

Liesl shook her head, her braids sliding on her shoulders. “No, I have a doll baby. I want a real baby. Like Miss Kate’s.” She crossed her arms, a determined look in her little brown eyes. “I like Miss Kate.”

Kate laughed, smoothing her unruly hair and glancing down at her masculine coat, ordinary farm dress and burgeoning middle. “Bless you, child. I like you, too.” Her father had his hands full with this one. Just how was he going to dissuade her from her wish of a real baby for Christmas?

Oscar’s frown took some of the pleasure out of the little girl’s compliment. “Mrs. Amaker probably wants to ride with her family. Don’t pester her.”

Which Kate took to mean he didn’t want her riding with him and his daughter. Liesl’s mouth set in a stubborn line, but she didn’t argue with her father.

So they arrived at the Amaker farm in two wagons. Kate took one look at the burned-out shell of a house, the half-toppled chimney and the wisps of smoke still drifting from the piles of ashes, and covered her mouth with trembling fingers.

It definitely did not look better in the morning light.

Grossvater pulled the wagon to a stop and sat with the reins loose in his hands, resting his forearms on his thighs. “We must thank God that we were not at home when this happened, that none of us was lost in this fire.”

He wrapped the lines around the brake handle and climbed down, reaching up to help Grossmutter. Kate began to descend the other side of the wagon, but before she could step on the high wheel, Oscar was there, reaching up for her and lifting her gently to the ground. He looked sober and wary.

“You should be careful. You wouldn’t want to fall.” He stepped back. Liesl waited in his wagon, but the dog had jumped down, already nosing around the edges of the devastation.

“Come, Kate,” Grossvater said, holding out his hand. “We need to pray.”

She rounded the wagon and joined the old couple. She needed to hear Grossvater pray, to lean on the strength of his faith, because hers was feeling mighty small this morning. Tucking her hand into his work-worn, age-spotted clasp, she sucked in a deep breath and bowed her head. A smile touched her lips as Liesl’s hand slipped into hers.

“Our Father, we give You thanks for this day and that we are here to praise You. We thank You that we still have our cows and our barns and our land. Our hearts are heavy, but we are trusting in You. You are sovereign. You are good. You have a plan to bring good out of something we see as a tragedy today. We are weak, and we need Your strength.

“We give You thanks for Oscar Rabb and Liesl, and for their hospitality. We ask that You bless them and help us to be a blessing to them as they have been to us.

“Please give us the peace that is beyond our earthly understanding. Make Your will plain to us. We are trusting You to provide. Dein Wille geschehe.”

Liesl tugged on Kate’s hand and whispered loudly, “What does that mean?”

Kate bent as far as her rounded belly would allow. “It means ‘Your will be done.’ Sort of like ‘Amen.’”

“Oh, amen, then.” She grinned, then sobered. “It’s sad about your house. Are you going to live with us now?”

Oscar made a noise that wasn’t really a word but wasn’t exactly a grunt, either. Kate shook her head. “No, sweetling. We aren’t going to live with you. Your father was kind enough to offer us a place for the night until we could decide what to do.”

Inge put her arm through Martin’s. “This is our home. We will rebuild.”

Kate looked at Grossvater over the old woman’s head, noting the strain in his eyes. Where would the money to rebuild come from?

Martin patted his wife’s hand. “For now, we need to milk the cows. They are setting up their chorus.”

Down by the barn, the herd of ten Brown Swiss bovines stood near the door, and from time to time a plaintive moo sounded. At the gate on the other side of the barn, four crossbred heifer calves nosed one another, tails swishing, ready for breakfast.

“Climb aboard, Poppet.” Oscar shouldered his way into the contraption Liesl had brought to him in the house, and it arranged itself into a sort of pack. He crouched, and the little girl grasped the straps and threaded her legs into the correct places, facing backward and sitting in a little webbed seat on her father’s back. Oscar stood carefully and looked over his shoulder. “All set?”

“Yep.” Her small boots swung, and she grinned.

Kate stared.

Oscar shrugged, gently, so as not to unseat Liesl. “She’s been riding in this since she was two. I couldn’t leave her alone in the house while I worked, so I made this.”

Grossvater let the cows into the barn, and creatures of habit that they were, they each went to their own stall. Kate took her milking stool from its peg on the wall, and Grossmutter gathered the buckets they had cleaned and put away before going to church last night. While Grossvater fed the cows, Kate started at the far end with the milking.

All the cows were named after Swiss cantons and towns—Grossvater’s choice. Saint Gallens, Zug, Geneva, Lucerne, Berne... Kate knew each one well. The barn smelled of hay and cows and milk and dust. Light came in the high windows and the open door at the end, and she rested her cheek against Jura’s warm side, falling into the steady milking rhythm, hearing the milk zing into the bucket, the tone changing as the level rose. Soon, Grossvater began milking the cows on the other side of the aisle, and farther down, she heard Liesl’s voice, chatting with her father as he, too, milked cows.

Grossmutter patted Kate on the shoulder. “I will go to the cheese house and brush and turn the cheeses.”

“We won’t be long here. We’ll put the milk in the springhouse. I won’t worry about cooking another batch of cheese today.” Kate finished with Jura and picked up the heavy bucket of warm, foamy milk.

She took it down the barn to where clean, empty milk cans sat on the handcart Grossvater used to take milk down to the springhouse. The cows were giving less milk now. In high summer, each cow gave several gallons of milk every day, and Kate made a new batch of cheese every couple of days throughout the summer. But now they gave less than half the summer amount, and she could store the milk for a few days before making a batch of cheese.

“Let me do that. You shouldn’t be toting such heavy things.” Oscar took the bucket, lifting it easily and pouring it into the open can.

Liesl twisted over his shoulder and waved. “Daddy, can I get down?”

“Not just yet, Poppet. Wait until we’re done in the barn.”

“Mr. Rabb, I appreciate your help, but I’m not helpless.” Kate took the bucket to go to the next cow.

“No, you’re not helpless, but you are in a delicate way.” His face reddened a bit, and Kate’s warmed.

“The work must be done.” Not that she had always been the milkmaid. Making cheese was one thing, but barn work another. Johann hadn’t liked her in the barn doing what he considered a man’s chores. He had always been the herdsman, but after his death, Kate had needed to do more work about the farm. Grossvater couldn’t do it alone.

She’d been feeling overwhelmed with the farm work already. In a couple of months, after the baby was born, how would she be able to get everything done? At least the baby was coming in the winter, when farm work slowed down, but Martin and Inge weren’t getting any younger, and there would be another mouth to feed. Would they be able to keep up with all that the farm required? And how could they get the money together to rebuild the house? Everything was so costly, and their savings were meager. Last spring, Johann had spent a fair amount of their savings buying a Brown Swiss bull to improve his herd.

It was that bull that had caused the accident that had cost Johann his life.

Now the bull was gone and so was the money.

Kate’s shoulders bowed under the burden, and she tried hard to hold on to Grossvater’s faith-filled prayer.

God, help me find a way.

* * *

Oscar let Liesl climb out of the carrier. “Stay where I can see you, and don’t go near where the fire was.”

“Yes, Daddy.” She went to the gate where the calves had their heads down munching the hay Martin Amaker had forked over the fence. Rolf, her shadow, went with her, tail wagging gently, eyes alert.

A wagon rolled into the yard, and Per Schmidt climbed down from the high seat. “Guten Morgen.” He surveyed the charred remains of the house, sweeping his hat off his head when the Amaker ladies came out of the barn toward him.

“Morning.” Oscar began a slow circuit of the burned-out area, but he could see nothing in the ashes to salvage. Bits of bent metal, puddles of melted glass, bricks fallen from the chimney, but nothing worth saving.

“Dere is not much left.” Per followed him. “Vat are dey going to do? Do dey haff family to help?”

He didn’t know. Oscar glanced over to check on Liesl and found that Kate had helped her climb the gate to look over at the calves. Kate stood behind the little girl, holding her safely, their heads together.

Which reminded him of how easily she’d brushed and braided Liesl’s hair this morning—a task he usually struggled with—and how seeing the two of them together like that had been a kick to his middle. He’d been surprised at how quickly Liesl had warmed to having strangers in the house and to Kate in particular.

And now Liesl wanted a baby for a Christmas present. He wasn’t really worried about this, because she changed her mind every day. Tomorrow she would want a doll pram or a kitten or new hair ribbons.

“I saw Prediger Tipford coming down the road. He vill be here soon.”

Oscar hoped so. Surely by now Pastor Tipford had come up with a plan for the Amakers, a better place for them to stay until they could rebuild.

Martin Amaker came out of the barn slowly pulling the milk cart. Oscar nodded to Per and went down the path.

“Let me help.” He took the handle of the cart. “To the springhouse?”

“Yes. Thank you, son. Milking is heavy work, is it not?” Martin tugged a handkerchief out of his pocket and wiped his brow. “Though I must confess, everything seems heavier today.”

Oscar made short work of storing the milk. The springhouse, built over a diverted part of Millikan Creek, was damp and cold. A row of milk cans stood along the back wall, and Oscar added the two from the cart.

He tried to imagine Martin and Kate doing the heavy work of the farm all alone for the past six months. Guilt hit him. Johann had been gone for half a year now, and what had Oscar done to help his neighbors? Nothing. But he had his own farm to look after, and a child, and a house. He was nearly overwhelmed at times himself.

At least he could salve his conscience that he had offered them hospitality last night. A paltry bit of comfort, but it was something.

Pastor Tipford and his wife drove into the farmyard as Oscar returned the cart to the barn. Kate helped Liesl down from the fence, holding her hand as they walked up the slight slope to greet the newcomers.

Her other hand rested on the swell of her unborn child, and Oscar swallowed. Losing his wife in childbed had been a double blow. God had taken Gaelle and their second daughter on Christmas Eve almost two years ago. Even now, the grief could steal his breath.

“Ah, Oscar, I trust you got the Amakers settled last night, and you were all able to get some rest?” Pastor Tipford’s voice filled the farmyard. He always spoke as if he were talking to someone in the back pew.

Mrs. Amaker nodded. “He was most kind.”

The preacher’s wife smiled at him. “Of course he was.”

Oscar shoved his hands into his pockets. He wished they’d get on with the discussion. His own chores were waiting.

“Martin, Inge, we were able to spread the word of your situation last night when we returned to town, and a small collection was gathered.” Pastor Tipford handed Martin a small sack. “Everyone wishes it were more.” He shuffled his large feet.

Oscar frowned. He hadn’t been asked to contribute yet. Not that he had much hard cash. Most of his money was tied up in the farm, the implements and the livestock. With the harvest, he had enough to pay his account at Hale’s Mercantile and purchase basic supplies for the winter. He wouldn’t have any more cash coming in until he could finish and sell the furniture he made during the winter months. Several orders had come in, but they weren’t even started yet. But still, he would give a little something to the Amaker collection.

Martin Amaker took the purse from Pastor Tipford, his eyes suspiciously bright. Inge’s lips trembled, and Kate stood with her hand cupping Liesl’s head. “How can we thank everyone?” she asked.

“Don’t you worry, child,” Mrs. Tipford said. “Pastor has already thanked folks for you. Now, we need to get down to brass tacks. What are your plans?”

Martin shook his head. “We have had little time to discuss anything.”

“Well, the Bakers have said that Kate can come stay with them, and the Freidmans have a guest room for the two of you.”

Kate’s eyebrows rose. “Be separated? And away from the farm?”

Oscar frowned. The Bakers lived in town, but the Freidmans lived on a farm at least five miles north of Berne. He didn’t like the notion of the old couple that far from Kate, nor of Kate being on her own. And what about their livestock? Who would take care of the milking cows and calves?

“Child, no one we asked had room for all of you.” Mrs. Tipford shook her head. “I wish the parsonage had an extra bedroom or two, but it’s so small we almost have to go outside to change our minds.” She laughed at her little joke. “As for the farm, Gregor Freidman has said he will drive Martin out to do the chores twice a day. He’s retired now, so he has the time.”

From what Oscar remembered about Gregor Freidman, he was even older than Martin Amaker and twice as frail. If they got an early snowfall, all too likely here in Minnesota, two old men shouldn’t be on the road between here and town. It would be a twenty-mile round trip from one farm to the other.

Pastor Tipford rubbed his hands together. “Anyway, it is only for a few weeks, until you get another house built. Lots of folks will be willing to help with the work. It will be a community effort. I can drive you down to Mantorville to the sawmill to order the lumber today. They could probably have a couple wagonloads delivered tomorrow afternoon.”

Martin and Inge shared a look, and Kate bit her lip.

“That’s very kind of you, Pastor.” Martin straightened his age-bent back. “But we...” He stopped, staring at the horizon for a moment. “We are not in a position to rebuild right now.”

Rolf came to lean against Oscar’s leg, and he reached down to pat the dog’s head. He could sympathize with Martin. If he had lost his house, he wouldn’t have had enough laid by to rebuild. Of course, he could get a loan at the bank to pay for lumber and hardware. He hated to buy on time, but sometimes you had to.

“Not rebuild?” Pastor’s voice boomed.

Martin’s voice seemed thin and frail. “Not right now.”

They must be even harder up than Oscar thought. And now they were going to be separated from each other, living with different families in town?

Liesl reached up and took Kate’s hand, her face scrunched, looking from one adult to another, not understanding what was happening. She was a sensitive little thing, quick to perceive moods, even ones she didn’t understand.

Kate’s other hand rested on the gentle mound of her unborn baby, and her face was as pale as the milk he’d just put in the springhouse. Oscar had the ridiculous urge to go to her, to put his arms around her and offer her some of his strength. He shook his head. Their problems weren’t really his concern, were they? He had enough trouble of his own, which he took care of on his own.

“You don’t have to decide anything right now. You are welcome to stay at my place until you can make other arrangements.” Oscar almost bit his tongue, so surprised was he. Where had that come from? He’d just issued an invitation of indefinite duration? And not just to an old couple, but to an expectant widow?

“I’m sure it would only be for a couple of weeks at the most, right? Just until you sort things out.”

Had he lost his mind?

And yet, he didn’t find himself wanting to renege.

What was wrong with him?

Chapter Four (#u8ab8a38d-5811-5016-99a5-6382617e2454)

When they returned to Oscar’s house, Grossvater went with him to the barn, but Oscar shook his head at Kate’s offer to help. “I don’t need you to muck out stalls. If you stay in the house and mind Liesl, that will be enough.”

He squatted beside his daughter. “You can show the ladies around the house, right?”

Liesl nodded, uncertainty wrinkling her brow. No doubt she went to the barn with him every morning.

“We’ll be back soon.” He brushed his knuckle down her cheek.

Kate watched the two men walking side by side down the slope to the barn, one white-haired and lean, the other strong and tall. How many times had she watched Johann and Grossvater like this, heading out for a day of farming together?

“What should we do now?” Liesl took Kate’s hand.

“What do you usually do in the mornings?” Kate asked.

“Go to the barn with Daddy.” Liesl shrugged. “That’s a funny coat.”

Kate smiled at the quick swap of topics. “It is, isn’t it? That’s because it belonged to my husband. It’s kind of big, but when I wear it, it helps me remember him.” She headed for the kitchen door, her stomach rumbling. “All that work made me hungry. How about we get a snack?”

Grossmutter was already in the kitchen, surveying the room, hands on hips. Kate knew that look.

“Liesl,” Kate said, bending to the little girl. “I don’t think we properly introduced you two. This is my Grossmutter. That means ‘grandmother.’ I am sure she won’t mind if you call her that, since it seems like we will be staying with you for a few more days.”

Grossmutter smiled, her lined face gentle as she put a work-worn hand on Liesl’s head. “Schätzchen.”

Liesl looked to Kate.

“That means ‘sweetheart.’”

The child beamed. “She’s nice. And so are you.”

“I think we should have our snack, and then we can see about helping out around here. We might not be welcome in the barn, but we can make a difference in the house.” Kate went to the cupboard. She felt the need to keep busy, to keep her thoughts at bay for a while. And to somehow repay a bit of Oscar Rabb’s kindness.

She sliced a rather misshapen loaf of bread and spread it with butter.

“There’s honey in the pot on the shelf.” Liesl pointed. “I like honey on my bread.”

So they had honey, too. Afterward, Grossmutter found a broom, and Kate wiped Liesl’s chin and hands with a damp cloth.

“You and I can do the dishes, and you can tell me where everything goes.” Kate drew a chair up to the counter for the child and filled the washtub with warm water from the stove reservoir. Shaving a few soap chips off the cake beside the pump, she stirred them until suds formed and placed the breakfast dishes and snack plates into the water.

Liesl talked the entire time they washed and wiped dishes. “Daddy doesn’t like doing dishes, so he waits until night time to clear up. He says he’d rather do a lot at once than have to do them a lot of times during the day.”

Kate smiled, handing her a tin cup to dry. She wasn’t overly fond of dishes herself.

“Daddy lets me help, but I can only dry the cups and spoons and forks. He does the plates himself. When I’m big enough, I’ll do all the dishes all by myself. Daddy says he will be glad when that day comes.”

Grossmutter opened the kitchen door and swept the dirt outside and off the porch. When she came in, she began sorting the boots and shoes beside the door into neat rows.

By the time the men had finished the barn chores and returned to the house, Kate had washed the kitchen windows with vinegar and water, scrubbing them with crumpled newspaper that Liesl had found for her, and Grossmutter had taken her broom to the cobwebs in the corners and along the crown moldings. Liesl had been given a damp cloth and the task of wiping down all the kitchen chairs, which had been moved into a row at the far end of the room. Kate had tied an empty flour sack around the little girl’s waist to spare her pinafore. She looked adorable, concentrating on each rung and chair leg, chattering the whole while, surprisingly at ease with the women when it was clear she spent almost all her time with just her father.

“What are you doing?” Oscar filled the doorway.

“Daddy. I’m cleaning. Aren’t I doing a good job?” Liesl held up the rag, her face alight. “Kate and Grossmutter are cleaning, too.”

Kate looked up from her hands and knees where she was scrubbing the floor around the stove, and Grossmutter put a row of glasses back in the cupboard, having just wiped down the shelves.

“You are doing a beautiful job.” He nodded to his daughter, but he didn’t take his eyes off Kate as he came in and put his hand under her elbow, helping her to stand. “Could you come outside for a moment?”

His eyes were stern, his expression fierce. Though his grip on her arm was firm, it wasn’t tight as he directed her to the porch.

“Where are you going, Daddy?”

“We’ll be back soon, Poppet. Just keep on with what you’re doing.” He closed the door behind him.

Kate clasped her elbows, turning to face the sunshine. Overhead, a V of Canada geese honked and flapped, heading for warmer temperatures.

“What are you doing?” Oscar asked. “Scrubbing my floors?”

She looked up at him. He stood with one hand braced on a porch post, the other on the railing, looking out over his fields dormant now that the harvest was over. He wore a patched flannel shirt, the plaid faded from many washings, the sleeves rolled up to reveal strong forearms dusted with brown hair. Everything about him exuded masculinity and strength. And his jaw had a hint of stubbornness.

He also clearly had a bee in his bonnet about expectant mothers doing basic chores. What was she supposed to do? Wrap herself in a quilt and huddle in a rocking chair until her time came?

“You don’t have to scrub my house. I know I’m no housekeeper, but my house isn’t exactly a pigsty.” He frowned, and she realized he wasn’t upset about her working while in what he called “a delicate condition.” Rather, they had offended him.

“Of course your home isn’t a pigsty.” She went to stand beside him. “I’m so sorry if we’ve overstepped. Grossmutter and I are keeping busy and, in a small way, trying to repay you for some of your kind hospitality.”

Some of the tightness went out of his shoulders. “I’m not looking to get repaid. Anyway, you shouldn’t be scrubbing floors. You should be sitting at that table with your family figuring out what you’re going to do next, where you’re going to go.”

Because the sooner they were out of his house, the better. He hadn’t wanted them to begin with, and he wanted them gone at the earliest possible moment. Her eyes stung, but she blinked hard, unwilling to cry.

“We’ll do that now.” She went back into the house, picked up the sudsy bucket and went outside, pitching the contents in a silvery arc onto the grass beside the steps. When she returned to the kitchen, she began placing the chairs around the table once more. Grossmutter and Grossvater stood at the dry sink, watching her with troubled eyes.

“Are we done?” Liesl asked, still holding her rag.

“For now. Why don’t you go see your daddy? He’s out on the porch.”

“I want to stay with you and clean. I like cleaning.” The child swiped the seat of the last chair with a flourish.

“I know you do, sweetling, but there are things we grown-ups have to talk about.” Kate motioned to her family.

Liesl’s eyes narrowed. “Things that little girls aren’t supposed to hear?”

Kate had to smile at the child’s perspicacity. “That’s right, little miss. You go outside, and take Rolf with you. I’m sure he’s ready for a run.”

Liesl took her sweet time going out, letting Kate know she wasn’t pleased with the end of the morning’s activities, and Kate smothered a smile. Such a saucy little minx.

Lowering herself carefully into a chair, Kate clasped her hands on the shiny tabletop and looked at Grossvater. “What are we going to do? Can we rebuild the house? Even a smaller one?”

Grossvater took his wife’s hand in his and shook his head. “There is not much money. Johann didn’t tell you both because he didn’t want you to worry, but he mortgaged the farm to build the new house. And the bull cost a great deal of money, I know. If we still had the bull, we could sell it to get some of the purchase price back, but...” His faded blue eyes were sad, remembering how he had needed to put down the expensive bull who had proven too mean to have on the farm. “We can pay off the loan as soon as we sell the cheeses, but there will not be anything left over. I will go to town tomorrow and talk to the banker, see if he will extend the mortgage and loan us enough to build at least a small house. And if I need to, I will look for a job.”

Patting his hand, Grossmutter nodded. “We need to find a place to stay where we can be together. We cannot stay here forever. Herr Rabb has been generous, but it is clear he would prefer us to be gone from his house. We will need to find a place to rent, and that will cost money.”

Kate twirled a strand of loose hair around her fingertip. “I’ll go to town with you and see if I can get a job, perhaps at the mercantile.” Though she would loathe working for Mrs. Hale, she would do it for these dear people. “Or perhaps at the bank or the café or the hotel. I’m good with figures, or I can cook or clean. At least for a couple of months.”