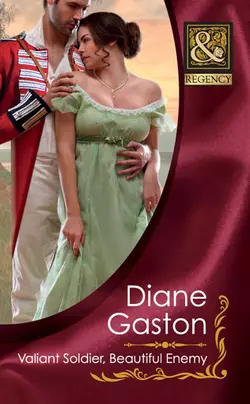

Valiant Soldier, Beautiful Enemy

Valiant Soldier, Beautiful Enemy

Diane Gaston

SOLDIER’S SECOND CHANCECaptain Gabriel Deane has known his fair share of pain, but he’d take a dagger to the chest rather than relive the torture of rejection from the woman he loves. Saying no to Gabriel broke Emmaline Mableau’s heart. She wears his ring around her neck: a reminder of the life – and the man – that can never be hers.Two years later, Emmaline’s hand trembles as she goes to knock on Gabriel’s door. Now she has a proposal for him, but will he say yes?

âBonjour,Gabriel.â

Emmaline.

She looked even more beautiful than the image of her that inhabited his dreams at night. Her lace-lined bonnet of natural straw perfectly framed her flawless face. The dark blue of her walking dress made her eyes even more vibrant.

Good God. After two years she still had the power to affect him.

âWhy did you come to see me?â

Her lips trembled before she spoke. âOh, Gabriel. I need you.â

The hard earth heâd packed around his emotions began to crack.

She swallowed and went on, âI need your help.â

He came to his senses. âHelp with what?â

She met his eyes. âI need you to find Claude.â

âClaude.â The son whoâd driven a wedge between them.

About the Author

As a psychiatric social worker, DIANE GASTON spent years helping others create real-life happy endings. Now Diane crafts fictional ones, writing the kind of historical romance sheâs always loved to read. The youngest of three daughters of a US Army Colonel, Diane moved frequently during her childhood, even living for a year in Japan. It continues to amaze her that her own son and daughter grew up in one house in Northern Virginia. Diane still lives in that house, with her husband and three very ordinary housecats. Visit Dianeâs website at http://dianegaston.com

Previous novels by the same author:

THE MYSTERIOUS MISS M

THE WAGERING WIDOW A REPUTABLE RAKE INNOCENCE AND IMPROPRIETY A TWELFTH NIGHT TALE (in A Regency Christmas anthology) THE VANISHING VISCOUNTESS SCANDALISING THE TON JUSTINE AND THE NOBLE VISCOUNT (in Regency Summer Scandals) * (#ulink_272efac7-c7ba-5e1a-9712-63c32a96865e)GALLANT OFFICER, FORBIDDEN LADY * (#ulink_272efac7-c7ba-5e1a-9712-63c32a96865e)CHIVALROUS CAPTAIN, REBEL MISTRESS

* (#ulink_3cd5b110-9b49-5470-84a2-8dc2e814dfe9)Three Soldiers mini-series

And in Mills & Boon

HistoricalUndone!eBooks:

THE UNLACING OF MISS LEIGH

Look for Claudeâs storyTHE LIBERATION OF MISS FINCHcoming soon inMills & Boon

HistoricalUndone!eBooks

Did you know that some of these novelsare also available as eBooks?Visit www.millsandboon.co.uk

AUTHOR NOTE

Here is the final book in my Three Soldiers series, Valiant Soldier, Beautiful Enemy, Gabriel Deaneâs story. Unlike the heroes of Gallant Officer, Forbidden Lady and Chivalrous Captain, Rebel Mistress, Gabriel Deane was a career soldier, a man who believed the army was where he belonged. Like so many other men and women, both in history and in todayâs world, Gabriel gave up a normal conventional life for service to his country. He went where his government sent him and valiantly did what he was ordered to do, no matter how difficult or dangerous.

While the Three Soldiers series has focused on the effect of war on the soldier, specifically the effect of one horrific event, the theme of this book is how war affects everyone, the soldier and civilian alike. The more important message of all the books is that, in spite of war, love can still flourish and lead to happy endings.

That is my wish for all the soldiers

and their families in todayâs world: Love and a happy ending.

Look for Claudeâs story THE LIBERATION OF MISS FINCH coming soon in Mills & Boon

HistoricalUndone!eBooks

Valiant Soldier, Beautiful Enemy

Diane Gaston

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Dedication

In memory of my cousin,

Lt. Commander James H. Getman, who lost his life at age 31 while on active duty with the U.S. Coast Guard. And to all who lost their lives while serving their country. We are grateful.

Prologue

Badajoz, Spainâ1812

A womanâs scream pierced the night.

Countless screams had reached Captain Gabriel Deaneâs ears this night, amidst shattering glass, roaring flames and shouts of soldiers run amok. The siege of Badajoz had ended and the pillaging had begun.

The marauding soldiers were not the French, not the enemy known to live off the bounty of the vanquished. These were British soldiers, Gabeâs compatriots, prowling through the city like savage beasts, plundering, killing, raping. A false rumour saying Wellington would permit the plundering had sparked the violence.

Gabe and his lieutenant, Allan Landon, had been ordered into this cauldron, but not to stop the rioting. Their task was to find one man.

Edwin Tranville.

Edwinâs father, General Tranville, had ordered them to find his son, whoâd foolishly joined the marauders. Once inside the city Gabe and Landon had enough to do to save their own skins from drunken men in the throes of a bloodlust that refused to be slaked.

The scream sounded again, not distant like the other helpless cries of innocent women and childrenâthis womanâs cry was near.

They ran in the direction of the sound. A shot rang out and two soldiers dashed from an alley, almost colliding with them. Gabe and Landon turned into the alley and emerged in a courtyard illuminated by flames shooting from a burning building nearby.

A woman stood over a cowering figure wearing the uniform of a British Officer. She raised a knife and prepared to plunge its blade into the British officerâs back.

Gabe seized her from behind and wrenched the knife from her grasp. âOh, no, you donât, señora.â She was not in need of rescue after all.

âShe tried to kill me!â The British officer, covering his face with bloody hands, attempted to stand, but collapsed in a heap on the cobblestones.

At that moment another man stepped into the light. Lieutenant Landon swung around, pistol ready to fire.

âWait.â The man raised his hands. âI am Ensign Vernon of the East Essex.â He gestured to the unconscious officer. âHe was trying to kill the boy. And he attempted to rape the woman. I saw the whole thing. He and two others. The others ran.â

The two men who passed them? If so, it was too late to pursue them.

âThe boy?â Gabe glanced around. What boy? He saw only the woman and the red-coated officer she was about to kill. And nearby the body of a French soldier, pooled in blood.

Gabe kept a grip on the woman and used his foot to roll over her intended victim. The manâs face was gashed from temple to chin, but Gabe immediately recognised him.

He glanced up. âGood God, Landon, do you see who this is?â

Ensign Vernon answered instead. âEdwin Tranville.â His voice filled with disgust. âGeneral Tranvilleâs son.â

âEdwin Tranville,â Gabriel agreed. Theyâd found him after all.

âThe bloody bastard,â Landon spat.

Vernon nodded in agreement. âHe is drunk.â

When was Edwin not drunk? Gabe thought.

Another figure suddenly sprang from the shadows and Landon almost fired his pistol at him.

The ensign stopped him. âDo not shoot. It is the boy.â

A boy, not more than twelve years of age, flung himself atop the body of the French soldier.

âPapa!â the boy cried.

âNon, non, non, Claude.â The woman strained against Gabeâs grip. He released her and she ran to her son.

âGood God, they are French.â Not Spanish citizens of Badajoz. A French family trying to escape. What the devil had the Frenchman been thinking, putting his family in such danger? Gabe had no patience for men who took wives and children to war.

He knelt next to the body and placed his fingers on the manâs throat. âHeâs dead.â

The woman looked up at him. âMon mari.â Her husband.

Gabe drew in a sharp breath.

She was lovely. Even filled with great anguish, she was lovely. Hair as dark as a Spaniardâs, but with skin as fair as the very finest linen. Her eyes, their colour obscured in the dim light, were large and wide with emotion.

Gabeâs insides twisted in an anger that radiated clear to his fingertips. Had Edwin killed this man in front of his family? Had he tried to kill the boy and rape the woman, as the ensign said? What had the two other men done to her before it had been Edwinâs turn?

The boy cried, âPapa! Papa! Réveillez!â

âIl est mort, Claude.â Her tone, so low and soft, evoked a memory of Gabeâs own mother soothing one of his brothers or sisters.

Fists clenched, Gabe rose and strode back to Edwin, ready to kick him into a bloody pulp. He stopped himself.

Edwin rolled over again and curled into a ball, whimpering.

Gabe turned his gaze to Ensign Vernon and his voice trembled with anger. âDid Edwin kill him?â He pointed to the dead French soldier.

The ensign shook his head. âI did not see.â

âWhat will happen to her now?â Gabe spoke more to himself than to the others.

The woman pressed her son against her bosom, trying to comfort him, while shouts sounded nearby.

Gabe straightened. âWe must get them out of here.â He gestured to his lieutenant. âLandon, take Tranville back to camp. Ensign, Iâll need your help.â

âYou will not turn her in?â Landon looked aghast.

âOf course not,â he snapped. âIâm going to find her a safe place to stay. Maybe a church. Or somewhere.â He peered at Landon and at Ensign Vernon. âWe say nothing of this. Agreed?â

Landon glared at him and pointed to Edwin. âHe ought to hang for this.â

Gabe could not agree more, but over fifteen years in the army had taught him to be practical. He doubted any of the soldiers would face a hanging. Wellington needed them too much. General Tranville would certainly take no chances with his sonâs life and reputation. Gabe and Landon needed to protect themselves lest Tranville retaliate.

More importantly, Gabe needed to protect this woman.

âHe is the generalâs son.â His tone brooked no argument. âIf we report his crime, the general will have our necks, not Edwinâs.â He tilted his head towards the woman. âHe may even come after her and the boy.â The captain looked down at the now-insensible man who had caused all this grief. âThis bastard is so drunk he may not even know what he did. He wonât tell.â

âDrink is no excuseââ Landon began. He broke off and, after several seconds, nodded. âVery well. We say nothing.â

The captain turned to Vernon. âDo I have your word, Ensign?â

âYou do, sir,â the ensign readily agreed.

Glass shattered nearby and the roof of the burning building collapsed, sending sparks high into the air.

âWe must hurry.â Gabe paused only long enough to extend a handshake to the ensign. âI am Captain Deane. That is Lieutenant Landon.â He turned to the woman and her son. âIs there a church nearby?â His hand flew to his forehead. âDeuce. What is the French word for church?â He tapped his brow. âÃglise? Is that the word? Ãglise?â

âNon. No church, capitaine,â the woman replied. âMy ⦠my maisonâmy house. Come.â

âYou speak English, madame?â

âOui, un peuâa little.â

Landon threw Edwin over his shoulder.

âTake care,â Gabe said to him.

Landon gave a curt nod before trudging off in the direction they had come.

Gabe turned to the ensign. âI want you to come with me.â He looked over at the Frenchmanâs body. âWe will have to leave him here.â

âYes, sir.â

The woman gazed at her husband, her posture taut as if she felt pulled back to his side. Gabeâs heart bled for her. She put an arm around her son, who protested against leaving his father, and Gabe felt their struggle as if it were his own.

âCome,â she finally said, gesturing for them to follow her.

They made their way through the alley again and down a narrow street.

âMa maison,â she whispered, pointing to a wooden door that stood ajar.

Gabe signalled them to remain where they were. He entered the house.

Light from nearby fires illuminated the inside enough for him to see the contents of a home broken and strewn across the floor: legs from a chair, shards of crockery, scattered papers, items that had once formed the essence of everyday life. He searched the large room to be certain no one hid there. He continued into a small kitchen and a bedroom, both thoroughly ransacked.

He walked back to the front door. âNo one is here.â

The ensign escorted the mother and son through the doorway. The womanâs hand flew to cover her mouth as her eyes darted over the shambles of what had once been her life. Her son buried his face into her side. She held him close as she picked her way through the rubble towards the kitchen.

Determined to make her as comfortable as possible, Gabe strode into the bedroom and pulled the remains of the mattress into the large room, clearing a space for it in the corner. He found a blanket, half-shredded, and carried it to the mattress.

The woman emerged from the kitchen and handed him water in a chipped cup. The boy gripped her skirt, like a younger, frightened child.

He smiled his thanks. As he took the cup, his fingertips grazed her hand and his senses flared at the contact. He gulped down the water and handed her back the cup. âTheâthe Anglais, did they hurt you?â What was the French word? âViolate? Moleste?â

Her long graceful fingers gripped the cup. âNon. Ils mâont pas molester.â

He nodded, understanding her meaning. She had not been raped. Thank God.

âCan you keep watch?â he asked Ensign Vernon. âIâll sleep for an hour or so and relieve you.â Heâd not slept since the siege began, over twenty-four hours before.

âYes, sir,â the ensign replied.

They blocked the door with a barricade of broken furniture. The ensign found the remnants of a wooden chair with the seat and legs intact. He placed it at the window to keep watch.

The mother and child curled up together on the mattress. Gabe slid to the floor, his back against the wall. He glanced over at her and her gaze met his for one long moment as intense as an embrace.

Gabe was shaken by her effect on him. It did him no credit to be so attracted to her, not with the terror sheâd just been through.

Perhaps he was merely moved by her devotion to her child, how she held him, how she gazed upon him. Gabe had often watched his own mother tend as lovingly to his little sisters.

Or maybe her devotion to her son touched some deep yearning within him. The girls had come one after the other after Gabe was born, and he had often been left in the company of his older brothers, struggling to keep up.

What the devil was he musing about? He never needed to be the fussed over like his sisters. Much better to be toughened by the rough-housing of boys.

Gabe forced himself to close his eyes. He needed sleep. After sleeping an hour or two, heâd be thinking like a soldier again.

The sounds of looting and pillaging continued, but it was the womanâs voice, softly murmuring comfort to her son, that finally lulled Gabe to sleep.

The carnage lasted two more days. Gabe, Ensign Vernon and the mother and son remained in the relative safety of her ransacked home, even though the forced inactivity strained Gabeâs nerves. Heâd have preferred fighting his way through the town to this idleness.

His needs were inconsequential, however. The woman and child must be safeguarded.

What little food they could salvage went to the boy, who was hungry all the time. Ensign Vernon occupied the time by drawing. Some sketches he kept private. Some fanciful pictures of animals and such he gave to the boy in an attempt to amuse him. The boy merely stared at them blankly, spending most of his time at his motherâs side, watching Gabe and Vernon with eyes both angry and wary.

None of them spoke much. Gabe could count on his fingers how many words he and the woman spoke to each other. Still, she remained at the centre of his existence. There was no sound she made, no gesture or expression he did not notice, and the empty hours of waiting did not diminish his resolve to make certain she and her son reached safety.

On the third day it was clear order had been restored. Gabe led them out, and the woman only looked back once at what had been her home. Outside, the air smelled of smoke and burnt wood, but the only sound of soldiers was the rhythm of a disciplined march.

They walked to the cityâs centre where Gabe supposed the armyâs headquarters would be found. There Gabe was told to what building other French civilians had been taken. They found the correct building, but Gabe hesitated before taking the mother and son inside. It was difficult to leave her fate to strangers.

In an odd way he did not understand, she had become more important to him than anything else. Still, what choice did he have?

âWe should go in,â he told her.

Ensign Vernon said, âI will remain here, sir, if that is agreeable to you.â

âAs you wish,â Gabe replied.

âGoodbye, madame.â The ensign stepped away.

Looking frightened but resigned, she merely nodded.

Gabe escorted her and her son through the door to the end of a hallway where two soldiers stood guard. The room they guarded was bare of furniture except one table and a chair, on which a British officer sat. In the room were about twenty people, older men, once French officials perhaps, and other women and children whose families had been destroyed.

Gabe spoke to the British officer, explaining the womanâs circumstance to him.

âWhat happens to them?â he asked the man.

The officerâs answer was curt. âThe women and children will be sent back to France, if they have money for the passage.â

Gabe stepped away and fished in an inside pocket of his uniform, pulling out a purse full of coin, nearly all he possessed. Glancing around to make certain no one noticed, he pressed the purse into the womanâs hands. âYou will need this.â

Her eyes widened as her fingers closed around the small leather bag. âCapitaineââ

He pressed her hand. âNo argument. Noââ he pronounced it the French way ââargument.â

She closed her other hand around his and the power of her gaze tugged at something deep inside him. It was inexplicable, but saying goodbye felt like losing a part of himself.

He did not even know her name.

He pulled his hand from hers and pointed to himself. âGabriel Deane.â If she needed him, she would at least know his name.

âGabriel,â she whispered, speaking his name with the beauty of her French accent. âMerci. Que Dieu vous bénisse.â

His brows knit in confusion. Heâd forgotten most of the French heâd learned in school.

She struggled for words. âDieu ⦠God â¦â She crossed herself. âBénisse.â

âBless?â he guessed.

She nodded.

He forced himself to take a step back. âAu revoir, madame.â

Clenching his teeth, Gabe turned and started for the door before he did something foolish. Like kiss her. Or leave with her. She was a stranger, nothing more, important only in his fantasies. Not in reality.

âGabriel!â

He halted.

She ran to him.

She placed both hands on his cheeks and pulled his head down to kiss him on the lips. With her face still inches from his, she whispered, âMy name is Emmaline Mableau.â

He was afraid to speak for fear of betraying the swirling emotions inside him. An intense surge of longing enveloped him.

He desired her as a man desires a woman. It was foolish beyond everything. Dishonourable, as well, since sheâd just lost her husband to hands not unlike his own.

He met her gaze and held it a moment before fleeing out the door.

But his thoughts repeated, over and overâEmmaline Mableau.

Chapter One

Brussels, BelgiumâMay 1815

Emmaline Mableau!

Gabeâs heart pounded when he caught a glimpse of the woman from whom heâd parted three years before. Carrying a package, she walked briskly through the narrow Brussels streets. It was Emmaline Mableau, he was convinced.

Or very nearly convinced.

Heâd always imagined her back in France, living in some small village, with parents ⦠or a new husband.

But here she was, in Belgium.

Brussels had many French people, so it was certainly possible for her to reside here. Twenty years of French rule had only ended the year before when Napoleon was defeated.

Defeated for the first time, Gabe meant. LâEmpereur had escaped from his exile on Elba. Heâd raised an army and was now on the march to regain his empire. Gabeâs regiment, the Royal Scots, was part of Wellingtonâs Allied Army and would soon cross swords with Napoleonâs forces again.

Many of the English aristocracy had poured into Brussels after the treaty, fleeing the high prices in England, looking for elegant living at little cost. Even so, Brussels remained primed for French rule, as if the inhabitants expected Napoleon to walk its streets any day. Nearly everyone in the city spoke French. Shop signs were in French. The hotel where Gabe was billeted had a French name. Hôtel de Flandre.

Gabe had risen early to stretch his legs in the brisk morning air. He had few official duties at present, so spent his days exploring the city beyond the Parc de Brussels and the cathedral. Perhaps there was more of the cloth merchantâs son in him than heâd realised, because he liked best to walk the narrow streets lined with shops.

Heâd spied Emmaline Mableau as he descended the hill to reach that part of Brussels. Sheâd been rushing past shopkeepers who were just raising their shutters and opening their doors. Gabe bolted down the hill to follow her, getting only quick glimpses of her as he tried to catch up to her.

He might be mistaken about her being Emmaline Mableau. It might have been a mere trick of the eye and the fact that he often thought of her that made him believe the Belgian woman was she.

But he was determined to know for certain.

She turned a corner and he picked up his pace, fearing heâd lose sight of her. Near the end of the row of shops he glimpsed a flutter of skirts, a woman entering a doorway. His heart beat faster. That had to have been her. No one left on the street looked like her.

He slowed his pace as he approached where she had disappeared, carefully determining which store sheâd entered. The sign above the door read Magasin de Lacet. The shutters were open and pieces of lace draped over tables could be seen though the windows.

A lace shop.

He opened the door and crossed the threshold, removing his shako as he entered the shop.

He was surrounded by white. White lace ribbons of various widths and patterns draped over lines strung across the length of the shop. Tables stacked with white lace cloth, lace-edged handkerchiefs and lace caps. White lace curtains covering the walls. The distinct scent of lavender mixed with the scent of linen, a scent that took him back in time to hefting huge bolts of cloth in his fatherâs warehouse.

Through the gently fluttering lace ribbons, he spied the woman emerging from a room at the back of the shop, her face still obscured. With her back to him, she folded squares of intricate lace that must have taken some woman countless hours to tat.

Taking a deep breath, he walked slowly towards her. âMadame Mableau?â

Still holding the lace in her fingers and startled at the sound of a manâs voice, Emmaline turned. And gasped.

âMon Dieu!â

She recognised him instantly, the capitaine whose presence in Badajoz had kept her sane when all seemed lost. Sheâd tried to forget those desolate days in the Spanish city, although sheâd never entirely banished the memory of Gabriel Deane. His brown eyes, watchful then, were now reticent, but his jaw remained as strong, his lips expressive, his hair as dark and unruly.

âMadame.â He bowed. âDo you remember me? I saw you from afar. I was not certain it was you.â

She could only stare. He seemed to fill the space, his scarlet coat a splash of vibrancy in the white lace-filled room. It seemed as if no mere shop could be large enough to contain his presence. Heâd likewise commanded space in Badajoz, just as he commanded everything else. Tall and powerfully built, he had filled those terrible, despairing days, keeping them safe. Giving them hope.

âPardon,â he said. âI forgot. You speak only a little English. Un peu Anglais.â

She smiled. Sheâd spoken those words to him in Badajoz.

She held up a hand. âI do remember you, naturellement.â She had never dreamed she would see him again, however. âIâI speak a little more English now. It is necessary. So many English people in Brussels.â She snapped her mouth closed. Sheâd been babbling.

âYou are well, I hope?â His thick, dark brows knit and his gaze swept over her.

âI am very well.â Except she could not breathe at the moment and her legs seemed too weak to hold her upright, but that was his effect on her, not malaise.

His features relaxed. âAnd your son?â

She lowered her eyes. âClaude was well last I saw him.â

He fell silent, as if he realised her answer hid some- thing she did not wish to disclose. Finally he spoke again. âI thought you would be in France.â

She shrugged. âMy aunt lives here. This is her shop. She needed help and we needed a home. Vraiment, Belgium is a better place toâhow do you say?âto rear Claude.â

Sheâd believed living in Belgium would insulate Claude from the patriotic fervour Napoleon had generated, especially in her own family.

Sheâd been wrong.

Gabriel gazed into her eyes. âI see.â A concerned look came over his face. âI hope your journey from Spain was not too difficult.â

It was all so long ago and fraught with fear at every step, but there had been no more attacks on her person, no need for Claude to risk his life for her.

She shivered. âWe were taken to Lisbon. From there we gained passage on a ship to San Sebastian and then another to France.â

Sheâd had money stitched into her clothing, but without the capitaineâs purse she would not have had enough for both the passage and the bribes required to secure the passage. What would have been their fate without his money?

The money.

Emmaline suddenly understood why the captain had come to her shop. âI will pay you back the money. If you return tomorrow, I will give it to you.â It would take all her savings, but she owed him more than that.

âThe money means nothing to me.â His eyes flashed with pain. Sheâd offended him. Her cheeks burned. âI beg your pardon, Gabriel.â

He almost smiled. âYou remembered my name.â

She could not help but smile back at him. âYou remembered mine.â

âI could not forget you, Emmaline Mableau.â His voice turned low and seemed to reach inside her and wrap itself around her heart.

Everything blurred except him. His visage was so clear to her she fancied she could see every whisker on his face, although he must have shaved that morning. Her mind flashed back to those three days in Badajoz, his unshaven skin giving him the appearance of a rogue, a pirate, a libertine. Even in her despair sheâd wondered how his beard would feel against her fingertips. Against her cheek.

But in those few days sheâd welcomed any thought that strayed from the horror of seeing her husband killed and hearing her sonâs anguished cry as his father fell on to the hard stones of the cobbled street.

He blinked and averted his gaze. âPerhaps I should not have come here.â

Impulsively she touched his arm. âNon, non, Gabriel. I am happy to see you. It is a surprise, no?â

The shop door opened and two ladies entered. One loudly declared in English, âOh, what a lovely shop. Iâve never seen so much lace!â

These were precisely the sort of customers for whom Emmaline had improved her English. The numbers of English ladies coming to Brussels to spend their money kept increasing since the war had ended.

If it had ended.

The English soldiers were in Brussels because it was said there would be a big battle with Napoleon. No doubt Gabriel had come to fight in it.

The English ladies cast curious glances towards the tall, handsome officer who must have been an incongruous sight amidst all the delicate lace.

âI should leave,â he murmured to Emmaline.

His voice made her knees weaken again. She did not wish to lose him again so soon.

He nodded curtly. âI am pleased to know you are well.â He stepped back.

He was going to leave!

âUn moment, Gabriel,â she said hurriedly. âIâI would ask you to eat dinner with me, but I have nothing to serve you. Only bread and cheese.â

His eyes captured hers and her chest ached as if all the breath was squeezed out of her. âI am fond of bread and cheese.â

She felt almost giddy. âI will close the shop at seven. Will you come back and eat bread and cheese with me?â

Her aunt would have the apoplexie if she knew Emmaline intended to entertain a British officer. But with any luck Tante Voletta would never know.

âWill you come, Gabriel?â she breathed.

His expression remained solemn. âI will return at seven.â He bowed and quickly strode out of the shop, the English ladies following him with their eyes.

When the door closed behind him, both ladies turned to stare at Emmaline.

She forced herself to smile at them and behave as though nothing of great importance had happened.

âGood morning, mesdames.â She curtsied. âPlease tell me if I may offer assistance.â

They nodded, still gaping, before they turned their backs and whispered to each other while they pretended to examine the lace caps on a nearby table.

Emmaline returned to folding the square of lace sheâd held since Gabriel first spoke to her.

It was absurd to experience a frisson of excitement at merely speaking to a man. It certainly had not happened with any other. In fact, since her husbandâs death sheâd made it a point to avoid such attention.

She buried her face in the piece of lace and remembered that terrible night. The shouts and screams and roar of buildings afire sounded in her ears again. Her body trembled as once again she smelled the blood and smoke and the sweat of men.

She lifted her head from that dark place to the bright, clean white of the shop. She ought to have forgiven her husband for taking her and their son to Spain, but such generosity of spirit eluded her. Remyâs selfishness had led them into the trauma and horror that was Badajoz.

Emmaline shook her head. No, it was not Remy she could not forgive, but herself. She should have defied him. She should have refused when he insisted, I will not be separated from my son.

She should have taken his yelling, raging and threatening. She should have risked the back of his hand and defied him. If she had refused to accompany him, Remy might still be alive and Claude would have no reason to be consumed with hatred.

How would Claude feel about his mother inviting a British officer to sup with her? To even speak to Gabriel Deane would be a betrayal in Claudeâs eyes. Claudeâs hatred encompassed everything Anglais, and would even include the man whoâd protected them and brought them to safety.

But neither her aunt nor Claude would know of her sharing dinner with Gabriel Deane, so she was determined not to worry over it.

She was merely paying him back for his kindness to them, Emmaline told herself. That was the reason sheâd invited him to dinner.

The only reason.

The evening was fine, warm and clear as befitted late May. Gabe breathed in the fresh air and walked at a pace as rapid as when heâd followed Emmaline that morning. He was too excited, too full of an anticipation he had no right to feel.

Heâd had his share of women, as a soldier might, short-lived trysts, pleasant, but meaning very little to him. For any of those women, he could not remember feeling this acute sense of expectancy.

He forced himself to slow down, to calm himself and become more reasonable. It was curiosity about how sheâd fared since Badajoz that had led him to accept her invitation. The time theyâd shared made him feel attached to her and to her son. He merely wanted to ensure that Emmaline was happy.

Gabriel groaned. He ought not think of her as Emmaline. It conveyed an intimacy he had no right to assume.

Except she had called him by his given name, he remembered. To hear her say Gabriel was like listening to music.

He increased his pace again.

As he approached the shop door, he halted, damping down his emotions one more time. When his head was as steady as his hand he turned the knob and opened the shop door.

Emmaline stood with a customer where the ribbons of lace hung on a line. She glanced over at him when he entered.

The customer was another English lady, like the two who had come to the shop that morning. This lady, very prosperously dressed, loudly haggled over the price of a piece of lace. The difference between Emmalineâs price and what the woman wanted to pay was a mere pittance.

Give her the full price, Gabe wanted to say to the customer. He suspected Emmaline needed the money more than the lady did.

âTrès bien, madame,â Emmaline said with a resigned air. She accepted the lower price.

Gabe moved to a corner to wait while Emmaline wrapped the lace in paper and tied it with string. As the lady bustled out she gave him a quick assessing glance, pursing her lips at him.

Had that been a look of disapproval? She knew nothing of his reasons for being in the shop. Could a soldier not be in a womanâs shop without censure? This ladyâs London notions had no place here.

Gabe stepped forwards.

Emmaline smiled, but averted her gaze. âI will be ready in a minute. I need to close up the shop.â

âTell me what to do and Iâll assist you.â Better for him to be occupied than merely watching her every move.

âClose the shutters on the windows, if you please?â She straightened the items on the tables.

When Gabe secured the shutters, the light in the shop turned dim, lit only by a small lamp in the back of the store. The white lace, so bright in the morning sun, now took on soft shades of lavender and grey. He watched Emmaline glide from table to table, refolding the items, and felt as if they were in a dream.

She worked her way to the shop door, taking a key from her pocket and turning it in the lock. âCâest fait!â she said. âI am finished. Come with me.â

She led him to the back of the shop, picking up her cash box and tucking it under her arm. She lit a candle from the lamp before extinguishing it. âWe go out the back door.â

Gabe took the cash box from her. âI will carry it for you.â

He followed her through the curtain to an area just as neat and orderly as the front of the shop.

Lifting the candle higher, she showed him a stairway. âMa tanteâmy auntâlives above the shop, but she is visiting. Some of the women who make the lace live in the country; my aunt visits them sometimes to buy the lace.â

Gabe hoped her aunt would not become caught in the armyâs march into France. Any day now he expected the Allied Army to be given the order to march against Napoleon.

âWhere is your son?â Gabe asked her. âIs he at school?â The boy could not be more than fifteen, if Gabe was recalling correctly, the proper age to still be away at school.

She bowed her head. âNon.â

Whenever he mentioned her son her expression turned bleak.

Behind the shop was a small yard shared by the other shops and, within a few yards, another stone building, two storeys, with window boxes full of colourful flowers.

She unlocked the door. âMa maison.â

The contrast between this place and her home in Badajoz could not have been more extreme. The home in Badajoz had been marred by chaos and destruction. This home was pleasant and orderly and welcoming. As in Badajoz, Gabe stepped into one open room, but this one was neatly organised into an area for sitting and one for dining, with what appeared to be a small galley kitchen through a door at the far end.

Emmaline lit one lamp, then another, and the room seemed to come to life. A colourful carpet covered a polished wooden floor. A red upholstered sofa, flanked by two small tables and two adjacent chairs, faced a fireplace with a mantel painted white. All the tables were covered with white lace tablecloths and held vases of brightly hued flowers.

âCome in, Gabriel,â she said. âI will open the windows.â

Gabe closed the door behind him and took a few steps into the room.

It was even smaller than the tiny cottage his uncle lived in, but had the same warm, inviting feel. Uncle Will managed a hill farm in Lancashire and some of Gabeâs happiest moments had been spent working beside his uncle, the least prosperous of the Deane family. Gabe was overcome with nostalgia for those days. And guilt. Heâd not written to his uncle in years.

Emmaline turned away from the window to see him still glancing around the room. âIt is small, but we did not need more.â

It seemed ⦠safe. After Badajoz, she deserved a safe place. âIt is pleasant.â

She lifted her shoulder as if taking his words as disapproval.

He wanted to explain that he liked the place too much, but that would be even more difficult to put into words.

She took the cash box from his hands and put it in a locking cabinet. âI regret so much that I do not have a meal sufficient for you. I do not cook much. It is only for me.â

Meaning her son was not with her, he imagined. âNo pardon necessary, madame.â Besides, he had not accepted her invitation because of what food would be served.

âThen please sit and I will make it ready.â

Gabe sat at the table, facing the kitchen so he could watch her.

She placed some glasses and a wine bottle on the table. âIt is French wine. I hope you do not mind.â

He glanced up at her. âThe British pay smugglers a great deal for French wine. I dare say it is a luxury.â

Her eyes widened. âCâest vrai? I did not know that. I think my wine may not be so fine.â

She poured wine into the two glasses and went back to the kitchen to bring two plates, lace-edged linen napkins and cutlery. A moment later she brought a variety of cheeses on a wooden cutting board, a bowl of strawberries and another board with a loaf of bread.

âWe may each cut our own, no?â She gestured for him to select his cheese while she cut herself a piece of bread.

For such simple fare, it tasted better than any meal heâd eaten in months. He asked her about her travel from Badajoz and was pleased that the trip seemed free of the terrible trauma she and her son had previously endured. She asked him about the battles heâd fought since Badajoz and what heâd done in the very brief peace.

The conversation flowed easily, adding to the comfortable feel of the surroundings. Gabe kept their wine glasses filled and soon felt as relaxed as if heâd always sat across the table from her for his evening meal.

When theyâd eaten their fill, she took their plates to the kitchen area. Gabe rose to carry the other dishes, reaching around her to place them in the sink.

She turned and brushed against his arm. âThank you, Gabriel.â

Her accidental touch fired his senses. The scent of her hair filled his nostrils, the same lavender scent as in her shop. Her head tilted back to look into his face. She drew in a breath and her cheeks tinged pink.

Had she experienced the same awareness? That they were a man and a woman alone together?

Blood throbbed through his veins and he wanted to bend lower, closer, to taste those slightly parted lips.

She turned back to the sink and worked the pump to fill a kettle with water. âI will make coffee,â she said in a determined tone, then immediately apologised. âI am sorry I do not have tea.â

âCoffee will do nicely.â Gabe stepped away, still pulsating with arousal. He watched her light a fire in a tiny stove and fill a coffee pot with water and coffee. She placed the pot on top of the stove.

âShall we sit?â She gestured to the red sofa.

Would she sit with him on the sofa? He might not be able to resist taking her in his arms if she did.

The coffee eventually boiled. She poured it into cups and carried the tray to a table placed in front of the sofa. Instead of sitting beside him, she chose a small adjacent chair and asked him how he liked his coffee.

He could barely remember. âMilk and a little sugar.â

While she stirred his coffee, he absently rubbed his finger on the lace cloth atop the table next to him. His fingers touched a miniature lying face down on the table. He turned it over. It was a portrait of a youth with her dark hair and blue eyes.

âIs this your son?â If so, heâd turned into a fine-looking young fellow, strong and defiant.

She handed him his cup. âYes. It is Claude.â Her eyes glistened and she blinked rapidly.

He felt her distress and lowered his voice to almost a whisper. âWhat happened to him, Emmaline? Where is he?â

She looked away and wiped her eyes with her fingers. âNothing happened, you see, but everything â¦â Her voice trailed off.

He merely watched her.

She finally faced him again with a wan smile.

âClaude was so young. He did notâdoes notâunder-stand war, how men do bad things merely because it is war. Soldiers die in war, but Claude did not comprehend that his father died because he was a soldierââ

Gabe interrupted her. âYour husband died because our men were lost to all decency.â

She held up a hand. âBecause of the battle, no? It was a hard siege for the British, my husband said. Remy was killed because of the siege, because of the war.â

He leaned forwards. âI must ask you. The man who tried to molest youâdid he kill your husband?â

She lowered her head. âNon. The others killed my husband. That one stood aside, but his companions told him to violate me.â

His gut twisted. âI am sorry, Emmaline. I am so sorry.â He wanted even more than before to take her in his arms, this time to comfort her.

He reached out and touched her hand, but quickly withdrew.

âYou rescued us, Gabriel,â she said. âYou gave us money. You must not be sorry. I do not think of it very much any more. And the dreams do not come as often.â

He shook his head.

She picked up the miniature portrait of her son and gazed at it. âI told Claude it happened because of war and to try to forget it, but he will not. He blames the Anglais, the British. He hates the British. All of them. If he knew you were here, he would want to kill you.â

Gabe could not blame Claude. Heâd feel the same if heâd watched his family violently destroyed.

âWhere is Claude?â he asked again.

A tear slid down her cheek. âHe ran away. To join Napoleon. He is not yet sixteen.â She looked Gabe directly in the face. âThere is to be a big battle, is there not? You will fight in it.â Her expression turned anguished. âYou will be fighting my son.â

Chapter Two

Emmalineâs fingers clutched Claudeâs miniature as she fought tears.

âI did not mean to say that to you.â The pain about her son was too sharp, too personal.

âEmmaline.â Gabrielâs voice turned caring.

She tried to ward off his concern. âI am merely afraid for him. It is a motherâs place to worry, no?â She placed the small portrait on the table and picked up her cup. âPlease, drink your coffee.â

He lifted his cup, but she was aware of him watching her. She hoped she could fool him into thinking she was not distressed, that she would be able to pretend she was not shaken.

He put down his cup. âMost soldiers survive a battle,â he told her in a reassuring voice. âAnd many are not even called to fight. In Badajoz your son showed himself to be an intelligent and brave boy. There is a good chance he will avoid harm.â

She flinched with the memory. âIn Badajoz he was foolish. He should have hidden himself. Instead, he was almost killed.â Her anguish rose. âThe soldiers will place him in the front ranks. When my husband was alive the men used to talk of it. They put the young ones, the ones with no experience, in the front.â

He cast his eyes down. âThen I do not know what to say to comfort you.â

That he even wished to comfort her brought back her tears. She blinked them away. âThere is no comfort. I wait and worry and pray.â

He rubbed his face and stood. âIt is late and I should leave.â

âDo not leave yet,â she cried, then covered her mouth, shocked at herself for blurting this out.

He walked to the door. âI may be facing your son in battle, Emmaline. How can you bear my company?â

She rose and hurried to block his way. âI am sorry I spoke about Claude. I did not have theâthe intention to tell you. Please do not leave me.â

He gazed down at her. âWhy do you wish me to stay?â

She covered her face with her hands, ashamed, but unable to stop. âI do not want to be alone!â

Strong arms engulfed her and she was pressed against him, enveloped in his warmth, comforted by the beating of his heart. Her tears flowed.

Claude had run off months ago and, as Brussels filled with British soldiers, the reality of his possible fate had eaten away at her. Her aunt and their small circle of friends cheered Claudeâs patriotism, but Emmaline knew it was revenge, not patriotism, that drove Claude. Sheâd kept her fears hidden until this moment.

How foolish it was to burden Gabriel with her woes. But his arms were so comforting. He demanded nothing, merely held her close while she wept for this terrible twist of fate.

Finally the tears slowed and she mustered the strength to pull away. He handed her a clean handkerchief from his pocket, warmed by his body.

She wiped her eyes. âI will launder this for you.â

âIt does not matter,â he murmured.

She dared to glance up into his kind eyes and saw only concern shining in them.

âI am recovered,â she assured him. New tears formed and she wiped them with his handkerchief. âDo not worry over me.â

He stood very still and solid, as if she indeed could lean on him.

âI will stay if you wish me to,â he said.

She took in a breath.

She ought to say no. She ought to brush him away and tell him she needed no one to be with her.

Instead, she whispered, âPlease stay, Gabriel.â

Something softened in his face and he reached out his hand to her. âI will help you with the dishes.â

Her tension eased. He offered what she needed most at the moment: ordinary companionship.

They gathered the cups and coffee pot and carried them to the little sink. She filled the kettle with water and put it on the stove again. While it heated he took the tablecloth to the door to shake out. She dampened a cloth and wiped the table and the kitchen. When the water was hot, Gabriel removed his coat and pushed up his shirt sleeves. He washed and rinsed. She dried and put the dishes away.

What man had ever helped her do dishes? Not her husband, for certain. Sheâd not even required it of Claude. But it somehow seemed fitting that Gabriel should help her.

When they finished, he wiped his hands on the towel and reached for his coat.

Her anxieties returned. âYou will stay longer?â

He gazed at her. âLonger? Are you certain?â

Suddenly she knew precisely what she was asking of him and it was not merely to keep her from being alone. âI am certain.â

She picked up a candle and took his hand in hers, leading him towards the stairway. There were two small rooms above stairs. She kept the door to Claudeâs bedroom closed so she would not feel its emptiness. She led Gabriel into the other room, her bedroom, her excitement building. She kicked off her shoes and climbed atop the bed.

He held back, gazing at her.

How much more permission did she need to give?

Sheâd vowed to have no more of men since her husbandâs death. Claude could be her only concern. He needed to release the past and see that he had his whole life ahead of him.

If Napoleon did not get him killed in the battle, that is.

Until Claude returned to her, she could do nothing, but if God saw fit to spare him in the battle, Emmaline had vowed to devote her life to restoring her sonâs happiness.

But Claude was not here now and Gabriel would not remain in Brussels for long. The British army would march away to face Napoleon; both Claude and Gabriel would be gone. What harm could there be in enjoying this manâs company? In making love with him? Many widows had affairs. Why not enjoy the passion Gabrielâs heated looks promised?

âCome, Gabriel,â she whispered.

He walked to the edge of the bed and she met him on her knees, her face nearly level with his. He stroked her face with a gentle hand, his touch so tender it made her want to weep again.

âI did not expect this,â he murmured.

âI did not, as well,â she added. âBut itâit feels inévitable, no?â

âInevitable.â His fingers moved to the sensitive skin of her neck, still as gentle as if she were as delicate as the finest lace.

She undid the buttons on his waistcoat and flattened her palms against his chest, sliding them up to his neck.

She pressed her fingers against his smooth cheek. âYou shaved for dinner, nâest-ce pas?â Her hands moved to the back of his neck where his hair curled against her fingers.

He leaned closer to her and touched his lips to hers.

Her husbandâs kisses had been demanding and possessive. Gabriel offered his lips like a gift for her to open or refuse, as she wished.

She parted her lips and tasted him with her tongue.

He responded, giving her all that she could wish. She felt giddy with delight and pressed herself against him, feeling the bulge of his manhood through his trousers.

âMon Dieu,â she sighed when his lips left hers.

He stepped away. âDo you wish me to stop?â

âNo!â she cried. âI wish you to commence.â

He smiled. âTrès bien, madame.â

She peered at him. âYou speak French now?â

âUn peu,â he replied.

She laughed and it felt good. It had been so long since she had laughed. âWe shall make love together, Gabriel.â

He grinned. âTrès bien.â

She unhooked the bodice of her dress and pulled the garment over her head. While Gabriel removed his boots and stockings, she made quick work of removing her corset, easily done because it fastened in the front. She tossed it aside. Now wearing only her chemise, she started removing the pins from her hair. As it tumbled down her back, she looked up.

He stood before her naked and aroused. His was a soldierâs body, muscles hardened by campaign, skin scarred from battle.

Still kneeling on the bed, she reached out and touched a scar across his abdomen, caused by the slash of a sword, perhaps.

He held her hand against his skin. âIt looks worse than it was.â

âYou have so many.â Some were faint, others distinct.

He shrugged. âI have been in the army for over eighteen years.â

Her husband would have been in longer, had he lived.

Heâd been rising steadily in rank; perhaps he would have been one of Napoleonâs generals, preparing for this battle, had he lived.

She gave herself a mental shake for thinking of Remy, even though heâd been the only man with whom sheâd ever shared her bed.

Until now.

A flush swept over her, as unexpected as it was intense. âCome to me, Gabriel,â she rasped.

He joined her on the bed, kneeling in front of her and wrapping his arms around her, holding her close. His lips found hers once more.

He swept his hand through her hair. âSo lovely.â She felt the warmth of his breath against her lips.

His hand moved down, caressing her neck, her shoulders. Her breasts. She writhed with the pleasure of it and was impatient to be rid of her chemise. She pulled it up to her waist, but he took the fabric from her and lifted it the rest of the way over her head. With her chemise still bunched in his hands he stared at her, his gaze so intense that she sensed it as tangibly as his touch.

âYou are beautiful,â he said finally.

She smiled, pleased at his words, and lay against the pillows, eager for what would come next.

But if she expected him to take his pleasure quickly, she was mistaken. He knelt over her, looking as if he were memorising every part of her. His hands, still gentle and reverent, caressed her skin. When his palms grazed her nipples, the sensation shot straight to her most feminine place.

Slowly his hand travelled the same path, but stopped short of where her body now throbbed for him. Instead, he stroked the inside of her thighs, so teasingly near.

A sound, half-pleasure, half-frustration, escaped her lips.

Finally he touched her. His fingers explored her flesh, now moist for him. The miracle of sensation his fingers created built her need to an intensity she thought she could not bear a moment longer.

He bent down and kissed her lips again, his tongue freely tasting her now. Her legs parted, ready for him.

She braced for his thrust, a part of lovemaking always painful for her, but he did not force himself inside her. Wonder of wonders, he eased himself inside, a sweet torture of rhythmic stroking until gradually he filled her completely. The need inside her grew even stronger and she moved with him, trying to ease the torment.

More wonders, he seemed to be in complete unison with her, as if he sensed her growing need so he could meet it each step of the way. The sensation created by him was more intense than she had ever experienced. Soon nothing existed for her but her need and the man who would satisfy it.

The intensity still built, speeding her forwards, faster and faster, until suddenly she exploded with sensation inside. Pleasure washed through her, like waves on the shore. His grip on her tightened and he thrust with more force, convulsing as he spilled his seed inside her. For that intense moment, their bodies pressed together, shaking with the shared climax.

Gabe felt the pleasure ebb, making his body suddenly heavy, his mind again able to form coherent thought.

He forced himself not to merely collapse on top of her and crush her with his weight. Instead, he eased himself off her to lie at her side.

As soon as he did so she flung her arms across her face. He gently lowered them.

She was weeping.

He felt panicked. âEmmaline, did I injure you?â He could not precisely recall how he might have done so, but during those last moments heâd been consumed by his own drive to completion.

She shook her head. âNon. I cannot speakââ

âForgive me. I did not mean to distress you.â He ought not to have made love to her. Heâd taken advantage of her grief and worry. âI did not realise â¦â

She swiped at her eyes and turned on her side to face him. âYou did not distress me. How do I say it?â He could feel her search for words. âI never felt le plaisir in this way before.â

His spirits darkened. âIt did not please you.â

Tears filled her eyes again, making them sparkle in the candlelight. She cupped her palm against his cheek. âTu ne comprends pas. You do not comprehend. It pleased me more than I can say to you.â

Relief washed through him. âI thought I had hurt you.â He wrapped his arms around her and held her against him, resting her head against his heart.

Gabe allowed himself to enjoy the comfort of her silky skin against his, their bodies warming each other as cool night air seeped through the window jamb.

She spoke and he felt her voice through his chest as well as hearing it with his ears. âIt was not so with my husband. Not so ⦠long. So ⦠much plaisir.â

The image of a body in a French uniform flashed into Gabeâs mind, the body they had been forced to abandon in Badajoz. Now heâd made love to that manâs wife. It seemed unconscionable. âHas there been no other man since your husband?â

âNo, Gabriel. Only you.â

He drew in a breath, forcing himself to be reasonable. Heâd had nothing to do with the Frenchmanâs death. And three years had passed.

He felt her muscles tense. âDo you have a wife?â

âNo.â Of that he could easily assure her. Heâd never even considered it.

She relaxed again. âCâest très bien. I would not like it if you had a wife. I would feel culpabilité.â

He laughed inwardly. They were both concerned about feeling the culpabilité, the guilt.

They lay quiet again and he twirled a lock of her hair around his fingers.

âIt feels agreeable to lie here with you,â she said after a time.

Very agreeable, he thought, almost as if he belonged in her bed.

After a moment a thought occurred to him. âDo you need to take care of yourself?â

âPardon?â She turned her face to him.

âTo prevent a baby?â He had no wish to inflict an unwanted baby upon her.

Her expression turned pained. âI do not think I can have more babies. I was only enceinte one time. With Claude. Never again.â

He held her closer, regretting heâd asked. âDid you wish for more children?â

She took a deep breath and lay her head against his chest again. âMore babies would have been very difficult. To accompany my husband, you know.â

What kind of fool had her husband been to bring his family to war? Gabe knew how rough it was for soldiersâ wives to march long distances heavy with child, or to care for tiny children while a battle raged.

âDid you always follow the drum?â he asked.

She glanced at him. âThe drum? I do not comprehend.â

âAccompany your husband on campaign,â he explained.

âAh!â Her eyes brightened in understanding. âNot always did I go with him. Not until Claude was walking and talking. My husband did not wish to be parted from his son.â

âFrom Claude?â Not from her?

Had her marriage not been a love match? Gabe could never see the point of marrying unless there was strong devotion between the man and woman, a devotion such as his parents possessed.

Emmaline continued. âMy husband was very close to Claude. I think it is why Claude feels so hurt and angry that he died.â

âClaude has a right to feel hurt and angry,â Gabe insisted.

âBut it does not help him, eh?â She trembled.

He held her closer. âEveryone has hardship in their lives to overcome. It will make him stronger.â

She looked into his eyes. âWhat hardship have you had in your life?â She rubbed her hand over the scar on his abdomen. âBesides war?â

âNone,â he declared. âMy father was prosperous, my family healthy.â

She nestled against him again. âTell me about your family.â

There was not much to tell. âMy father is a cloth merchant, prosperous enough to rear eight children.â

âEight? So many.â She looked up at him again. âAnd are you the oldest? The youngest?â

âI am in the middle,â he replied. âFirst there were four boys and then four girls. I am the last of the boys, but the only one to leave Manchester.â

Her brow knitted. âI was like Claude, the only one. I do not know what it would be like to have so many brothers and sisters.â

He could hardly remember. âIt was noisy, actually. I used to escape whenever I could. I liked most to stay with my uncle. He managed a hill farm. I liked that better than my fatherâs warehouse.â His father had never needed him there, not with his older brothers to help out.

âA hill farm?â She looked puzzled.

âA farm with sheep and a few other animals,â he explained.

She smiled at him. âYou like sheep farming?â

âI did.â He thought back to those days, out of doors in the fresh country air, long hours to daydream while watching the flocks graze, or, even better, days filled with hard work during shearing time or when the sheep were lambing.

âWhy did you not become a farmer, then?â she asked.

At the time even the open spaces where the sheep grazed seemed too confining to him. âNelson had just defeated Napoleonâs fleet in Egypt. Lancashire seemed too tame a place compared to the likes of Egypt. I asked my father to purchase a commission for me and he did.â

âAnd did you go to Egypt with the army?â Her head rested against his heart.

He shook his head. âNo. I was sent to the West Indies.â

He remembered the shock of that hellish place, where men died from fevers in great numbers, where he also had become ill and nearly did not recover. When not ill, all his regiment ever did was keep the slaves from revolting. Poor devils. All theyâd wanted was to be free men.

He went on. âAfter that we came to Spain to fight Napoleonâs army.â

Her muscles tensed. âNapoleon. Bah!â

He moved so they were lying face to face. âYou do not revere LâEmpereur?â

âNo.â Her eyes narrowed. âHe took the men and boys and too many were killed. Too many.â

Her distress returned. Gabe changed the subject. âNow I have told you about my life. What of yours?â

She became very still, but held his gaze. âI grew up in the Revolution. Everyone was afraid all the time, afraid to be on the wrong side, you know? Because you would go to la guillotine.â She shuddered. âI saw a pretty lady go to the guillotine.â

âYou witnessed the guillotine?â He was aghast. âYou must have been very young.â

âOui. My mother hated the Royals, but the pretty lady did not seem so bad to me. She cried for her children at the end.â

âMy God,â he said.

Her gaze drifted and he knew she was seeing it all again.

Gabe felt angry on Emmalineâs behalf, angry she should have to endure such a horror.

He lifted her chin with his finger. âYou have seen too much.â

Her lips trembled and his senses fired with arousal again. He moved closer.

Her breathing accelerated. âI am glad I am here with you.â

He looked into her eyes, marvelling at the depth of emotion they conveyed, marvelling that she could remain open and loving in spite of all sheâd experienced. A surge of protectiveness flashed through him. He wanted to wipe away all the pain sheâd endured. He wanted her to never hurt again.

He placed his lips on hers, thinking heâd never tasted such sweetness. He ran his hand down her back, savouring the feel of her, the outline of her spine, the soft flesh of her buttocks. Parting from her kiss, he gazed upon her, drinking in her beauty with his eyes. The fullness of her breasts, the dusky pink of her nipples, the triangle of dark hair at her genitals.

He touched her neck, so long and slim, and slid his hand to her breasts. She moaned. Placing her hands on the sides of his head, she guided his lips to where his fingers had been. He took her breast into his mouth and explored her nipple with his tongue, feeling it peak and harden.

Her fingernails scraped his back as he tasted one, then the other breast. She writhed beneath him. Soon he was unable to think of anything but Emmaline and how wonderful it felt to make love to her, how he wished the time would never end. Even if he had only this one night with her, he would be grateful. It was far more than heâd expected.

The need for her intensified and he positioned himself over her. She opened her legs and arched her back to him. His chest swelled with masculine pride that she wanted him, wanted him to fill her and bring her to climax.

He entered her easily and what had before been a slow, sublime climb to pleasure this time became a frenzied rush. She rose to meet him and clung to him as if to urge him not to slow down, not to stop.

As if he could. As if he ever wanted this to end, even knowing the ecstasy promised.

The air filled with their rapturous breathing as their exhilaration grew more fevered, more consuming. Gabe heard her cry, felt her convulse around him and then he was lost in his own shattering pleasure.

Afterwards they did not speak. He slid to her side and Emmaline fell asleep in his arms as the candle burned down to a sputtering nub. While it still cast enough light, he gazed upon her as she slept.

He did not know what the morning would bring. For all he knew she might send him away in regret for this night together. Or he might be called away to the regiment. Would the regiment be ordered to march, to meet Napoleonâs forces?

Would he face her son in battle and take from her what she held most dear?

Chapter Three

Emmaline woke the next morning with joy in her heart. The man in her bed rolled over and smiled at her as if he, too, shared the happy mood that made her want to laugh and sing and dance about the room.

Instead he led her into a dance of a different sort, one that left her senses humming and her body a delicious mix of satiation and energy. She felt as if she could fly.

His brown eyes, warm as a cup of chocolate, rested on her as he again lay next to her. She held her breath as she gazed back at him, his hair rumpled, his face shadowed with beard.

This time she indulged her curiosity and ran her finger along his cheek, which felt like the coarsest sackcloth. âI do not have the razor for you, Gabriel.â

He rubbed his chin. âI will shave later.â

From the church seven bells rang.

âIt is seven of the clock. I have slept late.â She slipped out of the tangled covers and his warm arms, and searched for her shift. âI will bring you some water for washing tout de suite.â

His brows creased. âDo not delay yourself further. I will fetch the water and take care of myself.â

She blinked, uncertain he meant what he said. âThen I will dress and begin breakfast.â

He sat up and ran his hands roughly through his hair. She stole a glance at his muscled chest gleaming in the light from the window. He also watched her as she dressed. How different this morning felt than when sheâd awoken next to her husband. Remy would have scolded her for oversleeping and told her to hurry so he could have fresh water with which to wash and shave.

As she walked out of the room, she laughed to herself. Remy would also have boasted about how more skilled at lovemaking a Frenchman was over an Englishman. Well, this Englishmanâs skills at lovemaking far exceeded one Frenchmanâs.

She paused at the top of the stairs, somewhat ashamed at disparaging her husband. Remy had been no worse than many husbands. Certainly he had loved Claude.

Early in her marriage sheâd thought herself lacking as a wife, harbouring a rebellious spirit even while trying to do as her much older husband wished. Sheâd believed her defiance meant she had remained more child than grown woman. When Remy dictated she and Claude would accompany him to war, sheâd known it would not be good for their son. She had raged against the idea.

But only silently.

Perhaps her love for Remy would not have withered like a flower deprived of sun and water, if sheâd done what she knew had been right and kept Claude in France.

Emmaline shook off the thoughts and hurried down the stairs to the kitchen to begin breakfast, firing up her little stove to heat a pot of chocolate and to use the bits of cheese left over from the night before to make an omelette with the three eggs still in her larder. Gabriel came down in his shirtsleeves to fetch his fresh water and soon they were both seated at the table, eating what sheâd prepared.

âYou are feeding me well, Emmaline,â he remarked, his words warming her.

She smiled at the compliment. âIt is enjoyable to cook for someone else.â

His eyes gazed at her with concern. âYou have been lonely?â

She lowered her voice. âOui, since Claude left.â But she did not want the sadness to return, not when she had woken to such joy. âBut I am not lonely today.â

It suddenly occurred to her that he could walk out and she would never see him again. Her throat grew tight with anxiety.

She reached across the table and clasped his hand. âMy night with you made me happy.â

His expression turned wistful. âIt made me happy, too.â He glanced away and back, his brow now furrowed. âI have duties with the regiment today, but if you will allow me to return, I will come back when you close the shop.â

âOui! Yes.â She covered her mouth with her hand. âOh, I cannot, Gabriel. I have no food to cook and I have slept too late to go to the market.â She flushed, remembering why sheâd risen so late.

His eyes met hers. âI will bring the food.â

Her heart pounded. âAnd will you stay with me again?â

Only his eyes conveyed emotion, reflecting the passion theyâd both shared. âI will stay.â

The joy burst forth again.

Gabe returned that evening and the next and the next. Each morning he left her bed and returned in the evening, bringing her food and wine and flowers. While she worked at the shop, he performed whatever regimental duties were required of him. It felt like he was merely marking time until he could see her again.

They never spoke of the future, even though his orders to march could come at any time and they would be forced to part. They talked only of present and past, Gabe sharing more with Emmaline than with anyone heâd ever known. He was never bored with her. He could listen for ever to her musical French accent, could watch for ever her face animated by her words.

May ended and June arrived, each day bringing longer hours of sunlight and warmth. The time passed in tranquillity, an illusion all Brussels seemed to share, even though everyone knew war was imminent. The Prussians were marching to join forces with the Allied Army under Wellingtonâs command. The Russians were marching to join the effort as well, but no one expected they could reach France in time for the first clash with Napoleon.

In Brussels, however, leisure seemed the primary activity. The Parc de Brussels teemed with red-coated gentlemen walking with elegant ladies among the statues and fountains and flowers. A never-ending round of social events preoccupied the more well-connected officers and the aristocracy in residence. Gabeâs very middle-class birth kept him off the invitation lists, but he was glad. It meant he could spend his time with Emmaline.

On Sundays when she closed the shop, Gabe walked with Emmaline in the Parc, or, even better, rode with her into the country with its farms thick with planting and hills dotted with sheep.

This day several of the officers were chatting about the Duchess of Richmondâs ball to be held the following night, invitations to which were much coveted. Gabe was glad not to be included. It would have meant a night away from Emmaline.

His duties over for the day, Gabe made his way through Brussels to the food market. He shopped every day for the meals he shared with Emmaline and had become quite knowledgeable about Belgian food. His favourites were the frites that were to be found everywhere, thick slices of potato, fried to a crisp on the outside, soft and flavourful on the inside.

Heâd even become proficient in bargaining in French. He haggled with the woman selling mussels, a food Emmaline especially liked. Mussels for dinner tonight and some of the tiny cabbages that were a Brussels staple. And, of course, the frites. He wandered through the market, filling his basket with other items that would please Emmaline: bread, eggs, cheese, cream, a bouquet of flowers. Before leaving the market, he quenched his thirst with a large mug of beer, another Belgian specialty.

Next stop was the wine shop, because Emmaline, true to her French birth, preferred wine over beer. After leaving there, he paused by a jewellery shop, its door open to the cooling breezes. Inside he glimpsed a red-coated officer holding up a glittering bracelet. âThis is a perfect betrothal gift,â the man said. He recognised the fellow, one of the Royal Scots. Buying a betrothal gift?

Gabe walked on, but the words repeated in his brain.

Betrothal gift.

Who was the man planning to marry? One of the English ladies in Brussels? A sweetheart back home? It made no sense to make such plans on the eve of a battle. No one knew what would happen. Even if the man survived, the regiment might battle Napoleon for ten more years. What kind of life would that be for a wife?

No, if this fellow wanted to marry, he ought to sell his commission and leave the army. If he had any intelligence at all heâd have taken some plunder at Vittoria, like most of the soldiers had done. Then heâd have enough money to live well.

Gabe halted as if striking a stone wall.

He might be talking about himself.

He could sell his commission. He had enough money.

He could marry.

He started walking again with the idea forming in his mind and taking over all other thought. He could marry Emmaline. His time with her need not end. He might share all his evenings with her. All his nights.

If she wished to stay in Brussels, that would be no hardship for him. He liked Brussels. He liked the countryside outside the city even better. Perhaps he could buy a farm, a hill farm like Stapleton Farm where his uncle worked. When Gabe had been a boy all heâd thought of was the excitement of being a soldier. Suddenly life on a hill farm beckoned like a paradise. Hard work. Loving nights. Peace.

With Emmaline.

He turned around and strode back to the jewellery shop.

The shop was now empty of customers. A tiny, white-haired man behind the counter greeted him with expectation, âMonsieur?â

âA betrothal gift,â Gabe told him. âFor a lady.â

The manâs pale blue eyes lit up. âLes fiançailles?â He held up two fingers. âVous êtes le deuxième homme dâaujourdâhui.â Gabe understood. He was the second man that day purchasing a betrothal gift.

The jeweller showed him a bracelet, sparkling with diamonds, similar to the one his fellow officer had held. Such a piece did not suit Emmaline at all. Gabe wanted something she would wear every day.

âNo bracelet,â Gabe told the shopkeeper. He pointed to his finger. âA ring.â

The man nodded vigorously. âOui! Lâanneau.â

Gabe selected a wide gold band engraved with flowers. It had one gem the width of the band, a blue sapphire that matched the colour of her eyes.

He smiled and pictured her wearing it as an acknowledgement of his promise to her. He thought of the day he could place the ring on the third finger of her left hand, speaking the words, âWith this ring, I thee wed, with my body I thee worship â¦.â

Gabe paid for the ring, and the shopkeeper placed it in a black-velvet box. Gabe stashed the box safely in a pocket inside his coat, next to his heart. When he walked out of the jewellery shop he felt even more certain that what he wanted in life was Emmaline.

He laughed as he hurried to her. These plans he was formulating would never have entered his mind a few weeks ago. He felt a sudden kinship with his brothers and sisters, unlike anything heâd ever felt before. With Emmaline, Gabe would have a family, like his brothers and sisters had families. No matter she could not have children. She had Claude and Gabe would more than welcome Claude as a son.

As he turned the corner on to the street where her lace shop was located, he slowed his pace.

He still had a battle to fight, a life-and-death affair for both their countries. For Gabe and for Claude, as well. He could not be so dishonourable as to sell out when the battle was imminent, when Wellington needed every experienced soldier he could get.

If, God forbid, he should die in the battle, his widow would inherit his modest fortune.

No, he would not think of dying. If Emmaline would marry him before the battle, he would have the best reason to survive it.

With his future set in his mind, he opened the lace-shop door. Immediately he felt a tension that had not been present before. Emmaline stood at the far end of the store, conversing with an older lady who glanced over at his entrance and frowned. They continued to speak in rapid French as he crossed the shop.

âEmmaline?â

Her eyes were pained. âGabriel, I must present you to my aunt.â She turned to the woman. âTante Voletta, puis-je vous présenter le Capitaine Deane?â She glanced back at Gabe and gestured towards her aunt. âMadame Laval.â

Gabe bowed. âMadame.â

Her auntâs eyes were the same shade of blue as Emmalineâs, but shot daggers at him. She wore a cap over hair that had only a few streaks of grey through it. Slim but sturdy, her alert manner made Gabe suppose she missed nothing. She certainly examined him carefully before facing Emmaline again and rattling off more in French, too fast for him to catch.

Emmaline spoke back and the two women had another energetic exchange.

Emmaline turned to him. âMy aunt is unhappy about our ⦠friendship. I have tried to explain how you helped us in Badajoz. That you are a good man. But you are English, you see.â She gave a very Gallic shrug.

He placed the basket on the counter and felt the impression of the velvet box in his pocket. âWould you prefer me to leave?â

âNon, non.â She clasped his arm. âI want you to stay.â

Her aunt huffed and crossed her arms over her chest. How was Gabe to stay when he knew his presence was so resented?

He made an attempt to engage the woman. âMadame arrived today?â

Emmaline translated.

The aunt flashed a dismissive hand. âPfft. Oui.â

âYou must dine with us.â He looked at Emmaline. âDo you agree? She will likely have nothing in her house for a meal.â

Emmaline nodded and translated what he said.

Madame Laval gave an expression of displeasure. She responded in French.

Emmaline explained, âShe says she is too tired for company.â

He lifted the basket again. âThen she must select some food to eat. I purchased plenty.â He showed her the contents. âPour vous, madame.â

Her eyes kindled with interest, even though her lips were pursed.

âTake what you like,â he said.

âI will close the shop.â Emmaline walked to the door.

Madame Laval found a smaller basket in the back of the store. Into it she placed a bottle of wine, the cream, some eggs, bread, cheese, four mussels and all of the frites.

âCâest assez,â she muttered. She called to Emmaline. âBonne nuit, Emmaline. Demain, nous parlerons plus.â

Gabe understood that. Emmalineâs aunt would have more to say to her tomorrow.

âBonne nuit, madame.â Gabe took the bouquet of flowers and handed them to her, bowing again.

âHmmph!â She snatched the flowers from his hand and marched away with half their food and all his frites.

Emmaline walked over to him and leaned against him.

He put his arms around her. âI am sorry to cause you this trouble.â

She sighed. âI wish her visit in the country had lasted longer.â