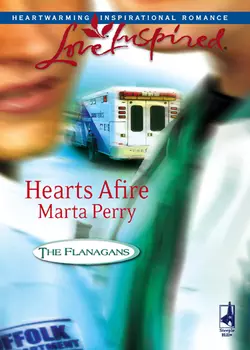

Hearts Afire

Hearts Afire

Marta Perry

Firefighter paramedic Terry Flanagan saw her clinic for migrant farm workers as the perfect way to make a difference.But when Dr. Jacob Landsdowne was assigned to oversee her project, she wondered if her dreams would go up in smoke. Two years ago a tragedy had touched both their lives and almost destroyed Jacob's career. Now he was intent on rebuilding his reputation, and Terry's clinic was an unwanted distraction.Yet, with the well-being of women and children hanging in the balance, maybe it was time Jacob put aside his trust in himself…and turn to God.

“We need a volunteer from our own medical staff to head up the clinic. I’m sure Dr. Landsdowne would be willing to volunteer.”

Silence, dead silence. Jake stared at the chief of staff, appalled. Jake had every reason in the world to say no, but he had no choice.

He straightened, trying to assume an expression of enthusiasm. “Of course I’d be happy to take this on. Assuming Ms. Flanagan is willing to work with me, naturally.”

Terry might be infuriated at being given a supervisor, but she had no more choice than he did. “Yes.”

Jake glanced at Terry, his gaze colliding with hers. She flushed, but she didn’t look away. Her mouth set in a stubborn line that told him he was in for a fight.

He didn’t mind a fight, but one thing he was sure of: Terry Flanagan and her clinic couldn’t be allowed to throw his career off course. No matter what he had to do to stop her.

MARTA PERRY

has written almost everything, including Sunday school curriculum, travel articles and magazine stories in twenty years of writing, but she feels she’s found her home in the stories she writes for the Love Inspired line.

Marta lives in rural Pennsylvania, but she and her husband spend part of each year at their second home in South Carolina. When she’s not writing, she’s probably visiting her children and her beautiful grandchildren, traveling or relaxing with a good book.

Marta loves hearing from readers and she’ll write back with a signed bookplate or bookmark. Write to her c/o Steeple Hill Books, 233 Broadway, Suite 1001, New York, NY 10279, e-mail her at marta@martaperry.com, or visit her on the Web at www.martaperry.com.

Hearts Afire

Marta Perry

Therefore we also, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us lay aside every weight, and the sin which so easily ensnares us, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us.

—Hebrews 12:1

This story is dedicated to my granddaughter,

Ameline Grace Stewart, with much love

from Grammy. And, as always, to Brian.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Questions for Discussion

Chapter One

Terry Flanagan flashed a penlight in the young boy’s eyes and then smiled reassuringly at the teenage sister who was riding with them in the rig on the trip to the hospital.

“You can hit the siren,” she called through the narrow doorway to her partner. Jeff Erhart was driving the unit this run. They had an unspoken agreement that she’d administer care when the patient was a small child. With three young kids of his own, Jeff found a hurt child tough to face.

The sister’s dark gaze focused on Terry. “Why did you tell him to start the siren? Is Juan worse? Tell me!”

“He’s going to be fine, Manuela.” She’d agreed to take the sister in the unit because she was the only family member who spoke English. “You have to stay calm, remember?” Naturally it was scary for Manuela to see her little brother immobilized on a backboard, an IV running into his arm.

The girl swallowed hard, nodding. With her dark hair pulled back in braids and her skin innocent of makeup, Manuela didn’t look the sixteen years she claimed to be. Possibly she was sixteen only because that was the minimum age for migrant farmworkers to be in the fields. The fertile farmlands and orchards that surrounded the small city of Suffolk in southern Pennsylvania were a magnet for busloads of migrant farmworkers, most from Mexico, who visited the area for weeks at a time. They rarely intersected with the local community except in an emergency, like this one.

“Juan will need stitches, yes?” Manuela clasped her little brother’s hand.

“Yes, he will.” Terry lifted the gauze pad slightly. The bleeding had slowed, but the edges of the cut gaped.

The child looked up at her with such simple trust that her stomach clenched. Lord, I haven’t forgotten anything, have I? Be with this child, and guide my hands and my decisions.

She ticked over the steps of care as the unit hit the busy streets of Suffolk and slowed. She’d been over them already, but somehow she couldn’t help doing it again. And again.

She knew why. It had been two years, but she still heard that accusing voice at moments like this, telling her that she was incompetent, that she—

No. She wouldn’t go there. She’d turn the self-doubt over to God, as she’d done so many times before, and she’d close the door on that cold voice. The wail of the siren, the well-equipped emergency unit, the trim khaki pants and navy shirt with the word Paramedic emblazoned on the back—all those things assured her of who she was.

She smiled at the girl again, seeing the strain in her young face. “How did your brother get hurt? Can you tell me that?”

“He shouldn’t have been there.” The words burst out. “He’s too little to—”

The child’s fingers closed over hers, as if he understood what she was saying. A look flashed between brother and sister, too quickly for Terry to be sure what it meant. A warning? Perhaps.

She could think of only one ending to what Manuela had started to say. “Was Juan working in the field?” It was illegal for a child so young to work in the fields—everyone knew that, even those who managed to ignore the migrant workers in their midst every summer and fall.

Alarm filled the girl’s eyes. “I didn’t say that. You can’t tell anyone I said that!”

The boy, catching his sister’s emotion, clutched her hand tightly and murmured something in Spanish. His eyes were huge in his pinched, pale face.

Compunction flooded Terry. She couldn’t let the child become upset. “It’s okay,” she said, patting him gently. “Manuela, tell your brother everything is okay. I misunderstood, that’s all.”

Manuela nodded, bending over her brother, saying something in a soft voice. Terry watched, frowning. Something was going on there—something the girl didn’t want her to pursue.

She glanced out the window. They were making the turn into the hospital driveway. This wasn’t over. Once they were inside, she’d find out how the child had been injured, one way or another.

Jeff cut the siren and pulled to a stop. By the time she’d opened the back doors, he was there to help her slide the stretcher smoothly out.

They rolled boy and stretcher quickly through the automatic doors and into the hands of the waiting E.R. team.

Terry flashed a grin at Harriet Conway. With her brown hair pulled back and her oversized glasses, Harriet might look severe, but Terry knew and respected her. The hospital had been afloat with rumors about the new head of emergency medicine, but no one seemed to know yet who it was. All they knew was that the new appointment probably meant change, and nobody liked change.

She reported quickly, in the shorthand that developed between people who liked and trusted each other. Harriet nodded, clipping orders as they wheeled the boy toward a treatment room. This was usually the paramedic’s cue to stay behind, unless the E.R. was shorthanded, but Terry was reluctant.

She bent over the child. “This is Dr. Conway, Juan. She’s going to take good care of you.”

She looked around for Manuela, and found the girl near the door, her arms around her mother. Two men stood awkwardly to the side, clearly uncomfortable with the woman’s tears. One, the father, turned a hat in work-worn hands, the knees of his work pants caked with mud from kneeling in the tomato field.

The other man was the crew chief, Mel Jordan. He’d driven Mr. and Mrs. Ortiz. He’d know if Juan had been working in the field when he was injured, but he wouldn’t want to admit it.

Manuela came back to the stretcher in a rush, repeating Terry’s words to her little brother. Taking in the situation, Harriet jerked her head toward the exam room.

“Looks like you’d both better come in.”

Good. Terry pushed the stretcher through the swinging door. Because she didn’t intend to leave until she knew what had happened to the child.

The next few minutes had to be as difficult for the sister as they were for the patient, but Manuela hung in there like a trouper, singing to Juan and teasing a smile out of him.

Finally the wound was cleaned, the stitches in, and Harriet straightened with a smile. “Okay, good job, young man. You’re going to be fine, but you be more careful next time.”

Manuela translated, and Juan managed another smile.

Harriet headed for the door. “I’ll send the parents in now. Thanks, Terry.”

This was probably her only chance to find out what had really happened at the camp. She leaned across the bed to clasp Manuela’s hand.

“How was your brother hurt? What happened to him?”

Manuela’s eyes widened. “I don’t understand.”

She bit back frustration. “I think you do. I want to know how your little brother cut his head. Was he working in the field?”

“What are you trying to pull?”

Terry swung around. The crew chief stood in the door, Dr. Conway and the anxious parents behind him.

“No kid works in the field. It’s against the law. You think I don’t know that?” Inimical eyes in a puffy, flushed face glared at her. Jordan had the look of a man who drank too much, ate unwisely and would clog his arteries by fifty if he had his way.

Dr. Conway pushed past him, letting the parents sidle into the room with her. “What’s up, Terry? Is there some question about how the boy was hurt?”

“I’d like to be sure.” Ignoring the crew chief, she focused on Manuela, who was talking to her parents. “Manuela, what was your little brother doing when he was hurt?”

Manuela’s father said something short and staccato in Spanish, his dark eyes opaque, giving away nothing. How much of this had he understood? Why hadn’t she taken Spanish in high school, instead of the German for which she’d never found a use?

There was a flash of rebellion in Manuela’s face. Then she looked down, eyes masked by long, dark lashes.

“He was playing. He fell and hit his head on a rock. That’s all.”

She was lying, Terry was sure of it. “When we were in the ambulance, you said—”

“The girl answered you.” The crew chief shoved his bulky figure between Terry and the girl. “Let’s get going.” He added something in Spanish, and the father bent to pick up the boy.

“Wait a minute. You can’t leave yet.” They were going to walk out, and once that happened, she’d have no chance to get to the truth, no chance to fix things for that hurt child.

“We’re going, and you can’t keep the kid here.”

The mother, frightened, burst into speech. Her husband and Manuela tried to soothe her. The boy began to cry.

Terry glanced to Dr. Conway in a silent plea for backup. But Harriet was looking past her, toward the open door of the exam room.

“What’s the problem here?” An incisive voice cut through the babble of voices. “This is a hospital, people.”

“The new E.R. chief,” Harriet murmured to Terry, the faintest flicker of an eyelid conveying a warning.

Terry didn’t need the warning. She knew who was there even before her mind had processed the information, probably because that voice had already seared her soul. Slowly she turned.

She hadn’t imagined it. Dr. Jacob Landsdowne stood glaring at her. Six feet of frost with icicle eyes, some wit at Philadelphia General had once called him. It still fit.

He gave no sign that he recognized her, though he must. She hadn’t changed in two years, except to gain about ten years of experience. Those icy blue eyes touched her and dismissed her as he focused on Harriet.

Harriet took her time consulting the chart in her hand before answering him. Terry knew her friend well enough to know that was deliberate—Harriet letting him know this was her turf.

Well, good. Harriet would need every ounce of confidence she possessed to hold her own against Jake Landsdowne.

Harriet gave him a quick précis of Juan’s condition and treatment, giving Terry the chance to take a breath.

Steady. Don’t panic. You haven’t done anything wrong.

“The paramedic questions how the child was injured,” Harriet concluded. “I was about to pursue that when you came in.” She nodded toward Terry. “Terry Flanagan, Suffolk Fire Department.”

She couldn’t have extended her hand if her life depended on it. It didn’t matter, since the great Dr. Landsdowne wouldn’t shake hands with a mere paramedic. He gave a curt nod and turned to the group clustered around the child.

“The kiddo’s folks don’t speak English, Doc.” The crew chief was all smiles now, apparently smart enough to realize his bluster wouldn’t work with Landsdowne. “Manuela here was saying that the little one fell and cut his head. Shame, but just an accident.”

She wouldn’t believe the man any farther than she could throw him, but Landsdowne’s face registered only polite attention. He looked at Manuela. “Is that correct?”

Manuela’s gaze slid away from his. “Yes, sir.”

“Then I think we’re done here. Dr. Conway, I’ll leave you to sign the patient out.” He turned and was gone before Terry found wits to speak.

Quickly, before she could lose the courage, she followed him to the hall. “Dr. Landsdowne—”

He stopped, frowning at her as if she were some lower species of life that had unaccountably found its way into his Emergency Room. “Well?”

She tried to blot out the memory of their last encounter. “While we were en route, I got the impression there might be more to this. If the child was injured while working in the field—”

“Did anyone say that?”

“Not in so many words.”

“Then the hospital has no right to interfere. And neither do you.”

He couldn’t turn his back on her fast enough. He swept off with that long lope that seemed to cover miles of hospital corridor.

That settled that, apparently. She looked after the retreating figure.

Jake Landsdowne had changed more than she’d have expected in the past two years. He still had those steely blue eyes and the black hair brushed back from an angled, intelligent face, that faintly supercilious air that went along with a background of wealth and standing in the medical community.

But his broad shoulders appeared to carry a heavy burden, and those lines of strain around his eyes and mouth hadn’t been there when she’d known him.

What was he doing here, anyway? She could only be surprised that she hadn’t thought of that question sooner.

Jacob Landsdowne III had been a neurosurgery resident in Philadelphia two years ago, known to the E.R. staff and a lowly paramedic only because he’d been the neurosurgery consult called to the E.R. He’d been on the fast track, everyone said, the son of a noted neurosurgeon, being groomed to take over his father’s practice, top ten percent of his med school class, dating a Main Line socialite who could only add to his prestige.

Now he was a temporary Chief of Emergency Services at a small hospital in a small city in rural Pennsylvania. She knew, only too well, what had happened to the socialite. But what had happened to Jake?

He’d changed. But one thing hadn’t changed. He still stared at Terry Flanagan with contempt in his face.

“Glad you could join us, Dr. Landsdowne.” Sam Getz, Providence Hospital’s Chief of Staff, didn’t look glad. Let’s see how you measure up, that’s what his expression always said when he looked at Jake.

“I appreciate the opportunity to meet with the board.” He nodded to the three people seated around the polished mahogany table in the conference room high above the patient care areas of the hospital.

A summons to the boardroom was enough to make any physician examine his conduct, but Getz had merely said the board’s committee for community outreach was considering a project he might be interested in. Given the fact that Jake’s contract was for a six-month trial period, he was bound to be interested in anything the board wanted him to do.

Last chance, a voice whispered in his head. Last chance to make it as a physician. They all know that.

Did they? He might be overreacting. He helped himself to a mug of coffee, gaining a moment to get his game face on.

Getz knew his history, but the elderly doctor didn’t seem the sort to gossip. In fact, Sam Getz looked like nothing so much as one of the Pennsylvania Dutch farmers Jake had seen at the local farmer’s market, with his square, ruddy face and those bright blue eyes.

Dr. Getz tapped on the table, and Jake slid into the nearest chair like a tardy student arriving after the lecture had begun. “Time to get started, folks.” He nodded toward the door, where two more people were entering. “You all know Pastor Flanagan, our fellow board member. And this is his cousin, Paramedic Terry Flanagan. They have something to say to the board.”

Good thing his coffee was in a heavy mug. If he’d held a foam cup, it would have been all over the table. Terry Flanagan. Was she here to lodge a complaint against him?

Common sense won out. Terry would hardly bring up that painful incident, especially not to the community outreach committee. This had to be about something else.

The other people seated around the table were flipping open the folders that had been put at each place. He opened his gingerly, to find a proposal for Providence Hospital to establish a clinic to serve migrant farmworkers.

He pictured Terry, bending over the migrant child in the E.R., protectiveness in every line of her body. Was that what this was about?

He’d been so shocked to see her that he’d handled the situation on autopilot. He’d read equal measure of shock in her face at the sight of him. What were the chances that they’d bump up against one another again?

He yanked his thoughts from that, focusing on the minister. Pastor Flanagan spoke quickly, outlining the needs of the migrant workers and the efforts his church was making. So he was both Terry’s cousin and a member of the board—that was an unpleasant shock.

This was what she’d done then, after the tragedy. She’d run home. At the time, he’d neither known nor cared what had become of her. He’d simply wanted her away from his hospital. Not that it had stayed his hospital for long.

The minister ended with a plea for the board to consider their proposal, and Terry stood to speak. Her square, capable hands trembled slightly on the folder until she pressed them against the tabletop.

Had she changed, in the past two years? He couldn’t decide. Probably he’d never have noticed her, in that busy city E.R., if it hadn’t been for her mop of red curls, those fierce green eyes, and the air of determination warring with the naiveté in her heart-shaped face.

That was what had changed, he realized. The naiveté was gone. Grim experience had rubbed the innocence off the young paramedic.

The determination was still there. Even though her audience didn’t give her much encouragement, her voice grew impassioned, and the force of her desire to help wrung a bit of unwilling admiration from him. She knew her stuff, too—knew how many migrant workers came through in a season, how many children, what government programs were in place to help.

William Morley, the hospital administrator, shifted uneasily in his chair as her presentation came to a close. His fingers twitched as if he added up costs.

“What you say may be true,” he said. “But why can’t those people simply come to the emergency room? Or call the paramedics?”

“They’ll only call the paramedics in case of dire emergency.” Terry leaned forward, her nervousness obviously forgotten in her passion. “Too many migrants are afraid of having contact—afraid their papers aren’t in order or they’re simply afraid of authority. As for the E.R., no one from the migrant camps comes in unless it’s a case where the police or the paramedics become involved. They’re afraid, and they’re also dependent on the crew chief for transportation.”

Jake heard what she didn’t say. He hadn’t thought too highly of the unctuous crew chief, either. But would he really refuse to transport someone who needed care? And did Terry, in spite of her enthusiasm, have the skills necessary to manage a job like this? He doubted it.

Morley was already shaking his head, the overhead light reflecting from it. If he’d grown that pencil-thin moustache to compensate for his baldness, it wasn’t working. “Starting a clinic isn’t the answer. Let the government handle the situation. We do our part by accepting the cases in the E.R. And, might I add, we are rarely paid anything.”

“That’s a point.” A board member whose name escaped Jake leaned forward, tapping his pen on the table for emphasis. “We’d put ourselves at risk with a clinic. What about insurance coverage? When they come to the E.R., we have backups and safeguards. If Ms. Flanagan or one of her volunteers made a mistake, we’d be liable.”

He thought Terry’s cheeks paled a little at that comment, but she didn’t back down. “The hospital can establish any protocol it wishes for treatment. And I plan to recruit staff from among the medical professionals right in our community.”

“How many people do you think have the time to do that?” Morley’s head went back and forth in what seemed his characteristic response to any risk. “Really, Ms. Flanagan, I don’t see how you can make this work in such a short time. Perhaps in another year—”

The mood of the board was going against her, Jake sensed. Well, he couldn’t blame them. They didn’t want to take a chance. He understood that.

“I have several volunteers signed up from my congregation,” Pastor Flanagan said. “And I’ve spoken with the owner of Dixon Farms, the largest employer of migrant workers in the county.”

“You’re not going to tell me old Matthew Dixon agreed to help.” Dr. Getz spoke for the first time, and Jake realized he’d been waiting—for what, Jake couldn’t guess. “The man still has the first dollar he ever made.”

If the minister agreed, he didn’t show it. “He’ll allow us to establish the clinic on his property. There’s even a building we can use.”

“If you can sell this idea to Matt Dixon, Pastor, you’re wasted in the ministry. You should be in sales.” Getz chuckled at his own joke, and Pastor Flanagan smiled weakly.

“That hardly solves the problem of liability,” Morley said. “No, no, I’m afraid this just won’t do. We can’t—”

Getz interrupted with a gesture. “I have a solution that will satisfy everyone.” The fact that Morley fell silent and sat back in his chair told Jake volumes about the balance of power in this particular hospital. “We need a volunteer from our own medical staff to head up the clinic. That’s all.” He turned toward Jake, still smiling. “I’m sure Dr. Landsdowne would be willing to volunteer.”

Silence, dead silence. Jake stared at him, appalled. He could think of a hundred things that could go wrong in an operation like this, and any one of them could backfire on him, ending his last hope for a decent career. He had every reason in the world to say no, but one overriding reason to say yes. He had no choice. This wasn’t voluntary, and he and Getz both knew it.

He straightened, trying to assume an expression of enthusiasm. “Of course, I’d be happy to take this on. Assuming Ms. Flanagan is willing to work with me, naturally.”

Terry looked as appalled as he felt, but she had no more choice than he did. “Yes.” She clipped off the word. “Fine.”

“That’s settled, then.” Getz rubbed his palms. “Good. I like it when everything comes together this way. Well, ladies and gentlemen, I think we’re adjourned.”

Chairs scraped as people rose. Jake glanced at Terry, his gaze colliding with hers. She flushed, but she didn’t look away. Her mouth set in a stubborn line that told him he was in for a fight.

He didn’t mind a fight, but one thing he was sure of. Terry Flanagan and her clinic couldn’t be allowed to throw him off course toward his goal. No matter what he had to do to stop her.

Chapter Two

“It’s not the best thing that ever happened to me, that’s for sure.” Terry slumped into the chair across from Harriet in the E.R. lounge a few days later, responding to her friend’s question about working with Jake Landsdowne. “It looks as if he’s not any more eager to supervise the clinic than I am to have him. He hasn’t been in touch with me at all.”

Actually, she was relieved at that, although she could hardly say so. She’d tensed every time the phone had rung, sure it would be him.

“That’s too bad. How are you going to make any progress if Dr. Landsdowne won’t cooperate?”

Terry shrugged. “I’ve gone ahead without him.”

“I’m not sure that’s such a good idea.” Harriet frowned down at her coffee mug. “He’s very much a hands-on chief. He’s been shaking up the E.R., let me tell you.”

“I’m sorry.” But not surprised. Jake Landsdowne had always been supremely confident that his way was the best way. The only way, in fact.

Harriet shrugged. “I expected it. Just be careful with him. I know how much this clinic means to you. You don’t want to put the project in jeopardy by antagonizing the man.”

Terry thought of Juan’s frightened face, of the suppressed anger she’d sensed in Manuela. Of the other children she’d glimpsed on her trip to the migrant camp.

“I’ll be careful.” She had more reason than most to know she had to tread carefully. For a moment the need to confide in Harriet about her past experience with Jake almost overwhelmed her caution.

Almost, but not quite. She had to watch her step.

Please, Father, help me to guard my tongue. Telling Harriet would put her in an impossible position, and it wouldn’t be fair to Jake, either. I just wish You’d show me a clear path through this situation.

“Did you know Dr. Landsdowne when you worked in Philadelphia? You must have been there at about the same time.”

Harriet’s question shook her. She hadn’t realized that anyone would put the two things together, but naturally Harriet would be interested in her new boss’s record.

“I knew him slightly,” she said carefully. She wouldn’t lie, but she didn’t have to spell out all the details, either. “Mostly by reputation.”

Anybody’s life could be fodder for hospital gossip, and the handsome, talented neurosurgery resident had been a magnet for it. Still—

“Excuse me.”

Terry spun, nerves tensing. How long had Jake been standing in the doorway? How much had he heard?

“Dr. Landsdowne.” Harriet’s tone was cool. Clearly Jake hadn’t convinced her yet that he deserved to be her superior.

“I heard Ms. Flanagan was here.” The ice in his voice probably meant that he knew she’d been talking about him. “I’m surprised you haven’t been here before this. We need to talk about this clinic proposal.”

Not a proposal, she wanted to say. It’s been approved, remember?

Still, that hardly seemed the way to earn his cooperation. “Do you have time to discuss it now?”

He nodded. “Come back to my office.” He turned and walked away, clearly expecting her to follow.

She’d rather talk on neutral ground in the lounge, but she wasn’t given a choice. She shrugged in response to Harriet’s sympathetic smile and followed him down the corridor. All she wanted was to get this interview over as quickly as possible.

The office consisted of four hospital-green walls and a beige desk. Nothing had been done to make it Jake’s except for the nameplate on the desk. Maybe that was what he wanted.

He stalked to the desk, picked up a file folder, and thrust it at her. “Here are the regulations we’ve come up with for the clinic. You’ll want to familiarize yourself with them.”

She held the folder, not opening it. “We?”

His frown deepened. “Mr. Morley, the hospital administrator, wanted to have some input.”

She could imagine the sort of input Morley would provide, with his fear of doing anything that might result in a lawsuit. Well, that was his job, she supposed. She flipped open the folder, wondering just how bad it was going to be.

In a moment she knew. She snapped the folder shut. “This makes it practically impossible for my volunteers to do anything without an explicit order from a doctor.”

“Both Mr. Morley and I feel that we can’t risk letting volunteers, trained or not, treat patients without the approval of the physician in charge.”

“You, in other words.”

“That’s correct.” His eyebrows lifted. “You agreed to the terms, as I recall.”

“I didn’t expect them to be so stringent. My people are all medical professionals—I don’t have anyone with less than an EMT-3 certification. You’re saying you don’t trust them to do anything without your express direction.”

Were they talking about her volunteers? Or her?

“You can give all the sanitation and nutrition advice you want. I’m sure that will be appreciated. Anything else, and—”

His condescending tone finally broke through her determination to play it safe with him. “Are you taking it out on the program because you blame me for Meredith Stanley’s death?”

She’d thought the name often enough since Jake’s arrival. She just hadn’t expected to say it aloud. Or to feel the icy silence that greeted it.

For a long moment he stared at her—long enough for her to regret her hasty words, long enough to form a frantic prayer for wisdom. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have said that.”

“No. You shouldn’t.” His face tightened with what might have been either grief or bitterness. He turned away, seeming to buy a moment’s respite by walking to the window that looked out over the hospital parking lot. Then he swung back to face her. “What happened two years ago has nothing to do with the clinic.” The words were clipped, cutting. “I think it best if we both try to forget the past.”

Could he really do that? Forget the suicide of a woman who’d said she loved him? Forget blaming the paramedics who’d tried to save her? Forget the gossip that said he was the one at fault?

Maybe he could. But she never would.

He seemed to take her assent for granted. He nodded toward the folder in her hands. “Read through that, discuss it with your volunteers. Possibly we can arrange for the clinic to be in phone or radio contact with the E.R. when it’s open. We’ll discuss that later.”

“Yes.” Her fingers clenched the manila folder so tightly someone would probably have to pry it loose. All she wanted now was to get away from him—as far away as possible.

He picked up a ring of keys from the desk. “Suppose we go out and look at this clinic of yours.”

“Not now.” The words came out instinctively. “I mean…we can schedule that at your convenience.”

His eyebrows lifted again. “Now is convenient. Would you like to ride with me?”

She didn’t even want to be in the same state with him. “No. Thank you, but I’ll need my car. Why don’t you follow me out? The camp is a little tricky to find.”

If she were fortunate, maybe he’d get lost on the maze of narrow country roads that led to the migrant compound. But somehow, she didn’t think that was likely to happen.

Jake kept Terry’s elderly sedan in sight as they left the outskirts of Suffolk and started down a winding country road. He hadn’t gotten used to the fact that the area went so quickly from suburbs to true country, with fields of corn and soybeans stretching along either side of the road.

He frowned at the back of her head, red curls visible as she leaned forward to adjust something—the radio, probably. He shouldn’t have been so harsh with her. It wasn’t Terry’s fault that he couldn’t see her now without picturing her racing the stretcher into the E.R., without seeing Meredith’s blank, lifeless face, without being overwhelmed with guilt.

Just let me be a doctor again. That’s all I ask. I’ll save other lives. Isn’t that worth something?

And did he really believe saving others would make up for failing Meredith? His jaw tightened. Nothing would make up for that. Maybe that was why God stayed so silent when he tried to pray.

Meredith’s death wasn’t Terry’s fault. But if someone more experienced had taken the call—if he had checked his messages earlier—if, if, if. No amount of what-ifs could change the past. Could change his culpability.

He pushed it from his mind. Concentrate on now. That means making sure Terry and her clinic don’t derail your future.

It was farther than he’d expected to the Dixon Farms. The route wound past rounded ridges dense with forest and lower hills crowned by orchards, their trees heavy with fruit. Finally Terry turned onto a gravel road. An abundant supply of No Trespassing signs informed him that they were on Dixon Farms property. Apparently, Matthew Dixon had strong feelings about outsiders.

He gritted his teeth as the car bottomed out in a rut. Surely there was a better way to provide health care for the migrant workers. Wouldn’t it make more sense to bring the workers to health care, instead of trying to bring health care to them? If Dr. Getz had given him any idea of what he’d been walking into that day at the board meeting, he’d have been prepared with alternatives.

Terry bounced to a stop next to several other vehicles in a rutted field. He drove up more slowly, trying to spare his car the worst of the ruts. Not waiting for him, she walked toward a cement block building that must be the site for the clinic. It was plopped down at the edge of a field. Beyond it, a strip of woods stretched up the shoulder of the ridge.

He parked and slid out. If he could find some good reason why this facility wasn’t suitable, maybe they could still go back and revisit the whole idea. Find a way of dealing with the problem that wouldn’t put the hospital at so much risk. To say nothing of the risk to what was left of his career.

Several people moved in and around the long, low, one-story building. Terry had obviously recruited volunteers already. The more people involved, the harder it would be to change.

Pastor Brendan Flanagan straightened at his approach, turning off the hose he was running. “Welcome. I’d offer to shake hands, but I’m way too dirty. I’m glad you’re here, Dr. Landsdowne.”

“Jake, please, Pastor.”

“And I’m Brendan to all but the most old-fashioned of my parishioners.” The minister, in cutoff jeans, sneakers and a Phillies T-shirt, didn’t look much like he had at the board meeting.

“Brendan.” Jake glanced around, spotting five or six people working. “What are you up to?”

“We recruited a few people to get the place in shape. Dixon hasn’t used it for anything but storage in a couple of decades.” He nodded toward what appeared to be a pile of broken farm implements. “It’ll be ready soon. Don’t worry about that.”

That wasn’t what he was worried about, but he wasn’t going to confide in the minister. “I’ll have a look inside.”

He stooped a little, stepping through the door. The farmer certainly hadn’t parted with anything of value when he’d donated this space.

“You must be Dr. Landsdowne.” The woman who had been brushing the walls down with a broom stopped, extending her hand to him. “I’m Siobhan Flanagan.”

“Another Flanagan?” He couldn’t help but ask. The woman had dark hair, slightly touched with gray, and deep blue eyes that seemed to contain a smile.

“Another one, I’m afraid. I’m Terry’s mother. Brendan recruited me to lend a hand today.” She gestured around the large, rectangular room, its floors pockmarked and dirty, its few windows grimy. “I know it doesn’t look like much yet, but just wait until we’re done. You won’t know the place.”

He might be able to tell Terry the place was a hovel, but he could hardly say that to the woman who smiled with such enthusiasm. “You must look at the world through rose-colored glasses, Mrs. Flanagan.”

“Isn’t that better than seeing nothing but the thorns, Dr. Landsdowne?”

He held up his hands in surrender. “I’ll take your word for it.” She’d made him smile, and he realized how seldom that happened recently.

Somehow the place didn’t seem quite as dismal as it had a moment ago. It reminded him of the clinic in Somalia. For an instant he heard the wails of malnourished children, felt the oppressive heat smothering him, sensed the comradeship that blossomed among people fighting impossible odds.

He shook off the memories. That was yet another place he’d failed.

Through the open doorway, he spotted the red blaze of Terry’s hair. She was in the process of confronting an elderly man whose fierce glare should have wilted her. It didn’t seem to be having that effect.

He went toward them quickly, in time to catch a few words.

“…now, Mr. Dixon, you can see perfectly well that we’re not harming your shed in any way.”

“Is there a problem?” Jake stopped beside her.

The glare turned on him. “I suppose you’re that new doctor—the one that’s in charge around here. Taking a man’s property and making a mess of it.”

This was Matthew Dixon, obviously. “I’m Dr. Landsdowne, yes. I understood from Pastor Flanagan that you agreed to the use of your building as a clinic. Isn’t that right?” If the old man objected, that would be a perfect reason to close down the project.

“Oh, agree. Well, I suppose I did. When a man’s minister calls on him and starts talking about what the Lord expects of him, he doesn’t have much choice, does he?”

“If you’ve changed your mind—”

“Who says I’ve changed my mind? I just want to be sure things are done right and proper, that’s all. I want to hear that from the man in charge, not from this chit of a girl.”

He glimpsed the color come up in Terry’s cheeks at that, and he had an absurd desire to defend her.

“Ms. Flanagan is a fully certified paramedic, but if you want to hear it from me, you certainly will. I assure you there won’t be any problems here.”

A car pulled up in a swirl of dust. The man who slid out seemed to take the situation in at a glance, and he sent Jake a look of apology. He was lean and rangy like the elder Dixon, with the same craggy features, but a good forty years younger.

“Dad, you’re not supposed to be out here.” He took Dixon’s arm and tried to turn him toward the car. “Terry and the others have work to do.” He winked at Terry, apparently an old friend. “Let’s get you back to the house.”

Dixon shook off his hand. “I’ll get myself to the house when I’m good and ready. A man’s got a right to see what’s happening on his own property.”

“Yes, but I promised you I’d take care of it, remember? You should be resting.” The son eased the older man to the car and helped him get in, talking softly. Once Dixon was settled, he turned to them.

“Sorry about that. I’m afraid once Dad gets an idea in his head, it’s tough to get it out. I’m Andrew Dixon, by the way. You’d be Dr. Landsdowne. And I know Terry, of course.” He put his arm around her shoulders. “She used to be my best girl.”

Terry wiggled free, but the look she turned on the man was open and friendly—a far cry from the way she looked at him. “Back in kindergarten, I think that was. Good to see you, Andy.”

“Listen, if you have any problems, come to me, not the old man. No point in worrying him.”

“There won’t be any problems.” He hoped.

Andrew smiled and walked quickly toward the driver’s side of the car, as if afraid his father would hop back out if he didn’t hurry.

The elder Dixon rolled down his window. “You make sure everything’s done right,” he bellowed. “Anything else, and I’ll shut you down, that’s what I’ll do.”

Shaking his head, Andrew put the car in gear and pulled out, disappearing quickly down the lane, the dust settling behind the car.

Jake looked down at Terry. There were several things he’d like to say to her. He raised an eyebrow. “So, are you still his best girl?”

Her face crinkled with laughter. “Not since he took my yellow crayon.”

He found himself smiling back, just as involuntarily as he had smiled at her mother. Her green eyes softened, the pink in her cheeks seeming to deepen. She had a dimple at the corner of her mouth that only appeared when her face relaxed in a smile.

These Flanagan women had a way of getting under his guard. Without thinking, he took a step closer to her.

And stopped.

I always told you your emotions would get the best of you. His father’s voice seemed to echo in his ears. Now it’s cost you your career.

Not entirely. He still had a chance. But that chance didn’t include anything as foolish as feeling attraction for anyone, especially not Terry Flanagan.

Terry took an instinctive step back—away from Jake, away from that surge of attraction. Don’t be stupid. Jake doesn’t feel anything. It’s just you, and a remnants of what you once thought you saw in him.

She turned away to hide her confusion, her gaze falling on the trailer Brendan had managed to borrow from one of his parishioners. Bren never hesitated to approach anyone he thought had something to offer for good works.

“Would you like to see the equipment we have so far?” She was relieved to find her voice sounded normal. “It’s stored in the trailer until we can get the building ready.” She started toward the trailer, and he followed without comment.

She was fine. Just because she’d had a juvenile crush on him two years ago, didn’t mean they couldn’t relate as professionals now. After all, half the female staff at the hospital had had a crush on Jake. He’d never noticed any of them, as far as she could tell.

“It’s locked, I hope?”

The question brought her back to the present in a hurry. She pulled the key from her pocket, showing him, and then unlocked the door. “We’ll be very conscious of security, since the building is so isolated.”

He nodded, grasping the door and pulling it open. “About meds, especially. All medications are to be kept in a locked box and picked up at the E.R. when clinic hours start and then returned with a complete drug list at the end of the day.”

Naturally it was a sensible precaution, but didn’t he think she’d figure that out without his telling her? Apparently not.

“This is what I’ve been able to beg or borrow so far. There are a few larger pieces, like desks and a filing cabinet, that we’ll pick up when we’re ready for them.” She pulled the crumpled list from her jeans pocket and handed it to him.

He looked it over, frowning. What was he thinking? His silence made her nervous. Was he about to shut them down because they didn’t have a fully equipped E.R. out here?

“I’m sure it looks primitive in comparison to what you’re used to, but anything is better than what the workers have now.”

“It looks fine,” he said, handing the sheet back to her. “I’ve worked in worse.”

She blinked. “You have?”

He leaned against the back of the trailer, looking down at her with a faint smile. “You sound surprised.”

“Well, I thought—” She blundered to a stop. She could hardly ask him outright what had happened to his promising neurosurgery career.

“I didn’t stay on in Philadelphia.” Emotion clouded the deep blue of his eyes and then was gone. “I spent some time at a medical mission in Somalia.”

She could only gape at him. Jacob Landsdowne III, the golden boy who’d seemed to have the world of medicine at his feet, working at an African mission? None of that fit what she remembered.

“That sounds fascinating.” She managed to keep the surprise out of her voice, but he probably sensed it. “You must have seen a whole different world there—medically, I mean.”

“In every way.” The lines in his face deepened. “The challenges were incredible—heat, disease, sanitation, unstable political situation. And yet people did amazing work there.”

She understood. That was the challenge that made her a paramedic, the challenge of caring for the sick and injured at the moment of crisis.

The emergency is over when you walk on the scene. That was what one of her instructors had drummed into them. No matter how bad it is, you have to make them believe that.

“You did good work there,” she said softly, knowing it had to be true.

“A drop in the bucket, I’m afraid. There’s so much need.” He glanced at her, his eyebrows lifting. “Hardly the sort of job where you’d expect to find me, is it?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“You were thinking it.”

“Yes, well—” They were getting dangerously close to the subject he’d already said he wouldn’t talk about. “Everyone said you were headed straight toward a partnership with your father in neurosurgery.”

“Everyone was wrong.” Tense lines bracketed his mouth. “I found the challenges in Africa far more interesting.”

There was more to it than that. There had to be, but he wouldn’t tell her. How much of his change in direction had been caused by Meredith’s death?

It had changed Terry’s life. She’d given up her bid for independence and come running home to the safety of her family. Had he run, too?

Jake closed the doors and watched while she locked them, then reached out and double-checked.

She bit back a sigh. He couldn’t even trust her to do something as simple as locking a door. How on earth were they going to run this clinic together?

Chapter Three

“Not a bad day, was it?” Terry glanced at her mother as they cleaned up after the clinic’s opening day.

She probably should get over that need for Mom’s approval. Most of her friends either called their mother by her first name and treated her like a girlfriend or else feigned complete contempt for anything a parent might think. She’d never been able to buy into either of those attitudes, maybe because Siobhan Flanagan never seemed to change.

Her mother turned from the cabinet where she was stacking clean linens. “No one would recognize this place from the way it looked a few short days ago. You can be proud of what you’ve accomplished.”

Terry stared down at the meds she’d just finished counting and locked the drug box. She should be proud. But…“Three clients wasn’t much for our first day, was it?”

“It will grow.” Her mother’s voice warmed. “Don’t worry. People just have to learn to trust what’s happening here. And they will.”

“I hope so.” It was one thing to charge into battle to help people and quite another to fear they didn’t want your help at all. “Maybe I’ve leaped before I looked again.” Her brothers had teased her mercilessly about that when she was growing up, especially when she’d tried to rope them into one of her campaigns to help a stray—animal or human.

“Don’t you think that at all, Theresa Anne Flanagan. You’ve got a warm heart, and if that sometimes leads you into trouble, it’s far better than armoring yourself like a—like an armadillo.”

Terry grinned. “Do you have any particular armadillo in mind?”

Siobhan gave a rueful chuckle. “That was a mite unchristian, I guess. I’m trying to make up for it, though. I’ve invited Dr. Landsdowne to your brother’s for the picnic on Sunday.”

“You’ve what?” She could only hope her face didn’t express the horror she felt. The Flanagan clan gathered for dinner most Sunday afternoons, and it wasn’t unusual for someone to invite a friend. But Jake wasn’t a friend—he was her boss, in a way, and also an antagonist. She wouldn’t go so far as to think of him as an enemy, and she certainly didn’t want to think of those moments when she’d felt, or imagined she’d felt, something completely inappropriate.

“What’s wrong?” Her mother crossed to Terry, her face concerned. “I know you think he’s a bit officious about the clinic, but if we get to know him better—”

“I already know him. From Philadelphia.” Her throat tightened, and she had to force the words out. “He’s the one I told you about. The one who blamed my team for the death of the woman he’d been seeing.”

The words brought that time surging back, carrying a load of guilt, anxiety and the overwhelming fear that perhaps he’d been right. Perhaps she had been responsible.

“Oh, Terry, I didn’t realize.” Her mother gave her a quick, fierce hug. “I’m sorry.”

She shook her head. “It’s all right. I didn’t tell anyone because—well, it didn’t seem fair to me or to him.”

Mom sat next to her on the desk. “Has he talked to you about it, since he’s been here?”

“Only to say he thinks we should leave the past alone.”

“But the inquiry cleared you of any wrongdoing. He should apologize, at least.”

Terry’s lips quirked at the thought of Jake apologizing. “He probably doesn’t see it that way. Anyway, if anyone’s guilty—” She stopped, regretting the words already.

Her mother just looked at her. Better people than she had crumbled at the force of that look.

“We’d been called to the woman’s apartment before. Two or three times. Always the same thing—she’d taken an overdose of sleeping pills or tranquilizers. We figured out finally that she was being careful. Never taking enough to harm herself. Just enough to make people around her feel guilty.”

“And Dr. Landsdowne was the person she wanted to feel guilty?”

She nodded, remembering the gossip that had flown around the hospital. “They’d been dating, but I guess when he wanted to break it off, she didn’t take it very well.” A brief image of Meredith flashed through her mind—tall, blond, elegant, the epitome of the Main Line socialite. “I don’t suppose anyone had ever turned her down before.”

“Poor creature.” Her mother’s voice was warm with quick sympathy. “And him, too. What a terrible thing, to feel responsible for someone committing suicide. But what happened? You said she was careful.”

“She took something she was allergic to.” Terry’s throat tightened with the memory. “We couldn’t save her.”

Her mother stroked Terry’s hair the way she had when Terry had been a child, crying over a scraped knee. “That’s probably why he blamed you. He couldn’t face it.”

Or because he did believe she was inept and incompetent. “I don’t know, Mom.” She pushed her hair back, suddenly tired. “I just know I’ve got to figure out how to deal with him now.”

“Do you want me to cancel the invitation?” It was a testament to her mother’s concern that she’d be willing to violate her sense of hospitality.

“No.” She managed a smile. “I’ve got to get used to his presence. At least I’ll be on my own turf there.”

Her mother laughed. “And surrounded by Flanagans, all prepared to defend you.”

“I don’t need defending.” The quick response was automatic. Her brothers had been trying to shelter her all her life. They’d never accept that she didn’t need their protection.

“I know.” Her mother gave her another hug and slid off the desk. “They mean well, sweetheart.”

The sound of a horn turned Siobhan toward the door. “There’s Mary Kate, coming for me. Are you heading for home now?”

“I just want to make one last check, okay?” And take a few minutes to clear her head. “I’ll be right behind you.”

“Walk out with me to say hi to your sister.” Her mother linked her arm with Terry’s.

Together they walked to where Mary Kate sat waiting. The back of her SUV was filled with grocery bags.

“Hi, Terry. Come on, Mom. I’ve got to get home before the frozen stuff melts.”

“I’m ready.” Siobhan slid into the car, while Terry leaned against the driver’s side, scanning her big sister’s face for signs of strain.

It had been ten months since Mary Kate lost her husband to a fast-moving cancer—ten months during which she kept up a brave face to the world, even to her own family.

“How’re you doing? How are the kids?”

“Fine.” Mary Kate’s smile was a little too bright. “They’re looking forward to seeing you on Sunday.”

“Me, too.” She wanted to say something—something meaningful, something that would help. But, as always, words faltered against Mary Kate’s brittle facade. She’d never relax it, certainly not in front of her baby sister.

Terry stepped back, waving as the car disappeared in a cloud of dust down the lane. Then she walked back into the clinic, mind circling the question she knew her mother had wanted to ask. Why hadn’t she told them the whole story about what happened in Philadelphia?

Because I was trying to prove I could accomplish something independent of my family. Because I failed.

Pointless, going over it and over it. She pushed herself into action, cleaning up the last few items that were out of place, locking the drug box, putting Jake’s list of rules in the desk drawer. The cases that had come in today were so minor she hadn’t even been tempted to bend any of the rules. Not that she would.

The door banged open. Manuela raced in. Terry’s heart clutched at the look on her face.

“Manuela, what is it?”

The girl leaned against the desk, breathing hard. “Juan. He’s sick. He’s so hot. Please, you have to come.” She grabbed Terry’s arm in a desperate grasp. “Now. You have to come!”

Jake’s rule flashed through her mind. Staff will not go to the migrant housing facility alone.

“I have to,” she said aloud. “I have to.” She grabbed her emergency kit and ran.

Manuela fled across the rutted field toward the back of the string of cement block buildings that served as dormitories for the workers. Terry struggled to keep up, mind churning. Juan’s cut could have become infected. That seemed the most likely cause for a fever, but there were endless possibilities. If she had to take him to the hospital, she’d also have to explain how she’d come to break Jake’s rules in her first day of operation.

The sun had already slid behind the ridge that overshadowed the camp. It would be nearly dark by the time she finished. She should have thought to bring a flashlight. She should have thought of a number of things, but it was too late now.

Please, Lord. Guide me and show me what must be done.

A snatch of guitar music, a burst of laughter, the blare of a radio sounded from the far end of the camp. Words that she couldn’t understand, cooking aromas that she couldn’t identify—it was like being transported to a different country.

Manuela stopped to peer around the corner of the building, her finger to her lips to ensure Terry’s silence. She didn’t need to worry. Terry had no desire to draw attention to her presence.

But why was the girl so concerned with secrecy? If she’d fetched Terry without her parents’ permission, that could be yet another complication to the rule she was already transgressing.

Manuela beckoned, and together they slipped around the corner and through the door. The room was a combination kitchen and living room, with a card table, a few straight chairs and a set of shelves against the wall holding plastic dishes and dented metal pots. An elderly woman, stirring something on a battered camp stove in the corner, stared at them incuriously and went back to her cooking.

Terry followed Manuela through a curtained door. At a guess, the whole family slept here on a motley collection of beds and cots jammed together. Juan lay on one of the cots, and to her relief, his mother sat next to him. Manuela grabbed an armful of clothes from the floor.

“Sorry.” In the dim light, it seemed her cheeks were flushed. “Mama and I try to keep it neat, but it’s hard.”

“I understand.” Six people were living in a room the size of the laundry room at the Flanagan house. No wonder it seemed cluttered. “Let’s have a look at Juan.”

Nodding to the mother, she bent over the cot. “Hi, there, Juan. Remember me?” She smiled reassuringly, trying to hide her dismay. His skin was hot and dry, his eyes sunken in his small face. She glanced at Manuela. “Any chance we can get more light in here?”

Nodding, she switched on a battery-powered lantern.

No electricity, overcrowded conditions, inadequate cooking facilities—surely someone like Matthew Dixon could do better than this for his employees, even if they were here for only a short period of time.

She checked the boy’s vital signs and cautiously removed the bandage on his head, relieved to find no sign of infection. “It doesn’t look as if his injury is causing this, Manuela. Has anyone else been sick?”

Manuela translated quickly for her mother and then nodded. “Some of the other children have had fever and stomach upsets.”

“Why didn’t their parents bring them to the clinic?”

Manuela shrugged, face impassive. If she knew the answer, she wasn’t going to tell.

“Tell your mother I’d like to have Juan checked out by the doctor.” She glanced at her watch. “Since it’s so late, maybe the best thing is to take him to the E.R.”

The mother seemed to understand that phrase. Nodding, she scooped Juan up, wrapping him in a frayed cotton blanket.

Terry followed them out, hoping she was making the right choice. Harriet would come to the camp if she called her, but by the time she’d tracked her down, they could be at the E.R. Jake wasn’t on duty tonight, so…

That train of thought sputtered out. Why exactly did she have his schedule down pat in her mind?

Mrs. Ortiz hurried outside. She stopped so suddenly that Terry nearly bumped into her. Mel Jordan, the crew chief, stood a few feet away, glaring at them.

“Where do you think you’re going?” He planted beefy hands on his hips.

Terry stepped around the woman. “Juan is running a fever. We’re taking him in to have the doctor look at him.”

“You people aren’t supposed to be here.” He jerked his head toward the building. “Take the kid back inside. You don’t want to go running around this time of night.”

Mrs. Ortiz started to turn, but Terry caught her arm. Manuela moved to her mother’s other side, so that the three of them faced the man.

“My car is at the clinic.” She tried to keep her voice pleasant, suppressing the urge to rage at the man. “I’ll run them to the hospital and bring them back. It’s not necessary for you to come.”

His face darkened. “I told you you’re not supposed to be here, interfering in what doesn’t concern you.” He took a step toward her, the movement threatening. “Just get out and take your do-good notions with you. We don’t need outsiders around here stirring up trouble.”

Her heart thudded, but she wouldn’t let him see fear. “You’ve got trouble already. The child is sick. You can’t keep him from medical care. Or any of the other children.”

It was obvious why none of the parents had brought their children to the clinic. Mrs. Ortiz trembled. Surely she didn’t think the man would dare become violent….

And if he does, what will you do, Terry? Once again you’ve leaped into a situation without thinking.

Well, she didn’t need to think about it to know these people needed help. What kind of a paramedic would she be if she walked away? One way or another, she was getting this child to a physician.

A pair of headlights slashed through the dusk as a car bucketed down the lane. Distracted, the crew chief spun to stare as the car pulled to a stop a few feet away, the beams outlining their figures.

She was caught in the act. She wouldn’t have to take Juan to a doctor. Jake had come to him.

Jake took his time turning off the ignition and getting out of the car. He needed the extra minutes to get his anger under control. One day into the program, and Terry had broken his rules already.

She’d also, from the tension in their stances when his headlights had picked them out, put herself in a bad situation. There had been something menacing about the way the crew chief confronted her, moderating Jake’s anger with fear for her.

The man—Jordan, he remembered—swung toward him. “What is this? A convention? Don’t you people have enough to do without bothering us?”

Jake let his gaze rest on the man until Jordan shifted his weight nervously. Then he turned toward Terry.

Her shoulders tensed, as if expecting an assault. But no matter how tempted he might be, he owed Terry a certain amount of professional courtesy.

“What do we have, Ms. Flanagan?”

Her breath caught a little. “Juan Ortiz, age six. You’ll recall he was treated in the E.R. Temp 103, upset stomach, dehydrated. I was about to bring him to the E.R. when Mr. Jordan intervened.”

He knew enough about Terry to know she couldn’t turn away from a sick child. His gaze sliced to Jordan. “Why were you trying to keep them from taking the child to the hospital?”

Jordan’s face twisted into a conciliatory smile. “Look, it was just a misunderstanding. I’d never do a thing like that.”

He felt Terry’s rejection of the words as if they were touching. Well, they’d deal with Jordan later. The important thing now was the child.

“Let’s go inside and examine Juan. Then we can see what else is necessary.”

The girl, Manuela, explained to her mother in a flood of Spanish, and they all trooped into the cement block building that appeared to be home.

A few minutes later he tousled Juan’s hair. “You’re going to be fine, young man.” He glanced at Terry, naming the medications he wanted. “You have all that at the clinic?”

She nodded. “I’ll run over and get them.”

“Wait. I’ll drive you.” And we’ll talk. He turned back to Manuela. “I’m writing down all the instructions for you. It’s very important to give him liquids, but just a little at a time. A couple of sips every ten or fifteen minutes. You’ll make sure your mother understands?”

“Yes, doctor.” She straightened, as if with pride. “I will take care of Juan myself. Everything will be done exactly as you say.”

“Good girl. You sound as if you’d make a good doctor or nurse one day.”

He saw something in her face then—an instant of longing, dashed quickly by hopelessness. He’d seen that look before. It shouldn’t be found on children’s faces.

“I would like, yes. But it’s not possible. This is my life.” Her gesture seemed to take in the fields, the building, the people.

“But, Manuela—” Terry began.

He shook his head at her and she fell silent. Now was not the time. But her expression made him fear Terry was taking off on another crusade.

“Well, you can practice your skills with your little brother.” He handed her the instructions. “Do you understand all that?”

She read through it quickly and nodded.

“Good girl. He’ll be a lot more comfortable once we get his fever down. We’ll be back in a few minutes with the medication, okay?”

“Okay.” Her smile blossomed, seeming to light the drab room.

He glanced at Terry. “Shall we go?”

She picked up her kit. “I’m ready.”

They walked to the car in silence. He’d intended to read the riot act to Terry once they were alone, but by the time they were bouncing down the lane, his anger had dissipated.

She was the one to break the silence. “Why did you come?”

He shrugged. “I wanted to check on how the first day went. Instead I found your car there, you gone. This seemed the likely place.”

“You mean you expected me to break the rules.” She sounded ready for battle.

“Let’s say I wasn’t entirely surprised.”

“The child was sick. What did you expect me to do?”

“You should have called me. Look, Terry, I understand why you went, but that’s not acceptable. If it happens again, I’ll pull the plug on the clinic.”

Her hands clenched into fists on her knees. “You’re pretty good at that, aren’t you? Cutting your losses.”

The jab went right under his defenses, leaving him breathless for an instant. He yanked the wheel, pulling to a stop in front of the clinic. Before she could get out, he grabbed the door handle, preventing her from moving. They were very close in the dark confines of the car.

“I thought we were going to leave the past behind.” He grated the words through the pain.

“I’m sorry.” It was a bare whisper, and the grief arced between them. “I shouldn’t have said anything.”

“No. You shouldn’t have.”

This was no good. They were both trapped by what had happened, and he didn’t see that ever changing.

Chapter Four

Terry walked back into the clinic, aware of Jake pacing behind her. Why didn’t he just leave and let her take care of getting the meds to Manuela? The last thing she needed was to have him trailing along behind her as if she couldn’t be trusted to do a simple thing like this.

And does he know that he can trust you, Theresa? The voice of her conscience sounded remarkably like her mother. You certainly haven’t shown him that you’ll follow his rules so far.

Even worse, she’d brought up the past that both of them knew they’d have to ignore if they were to have any sort of working relationship. She had to do better—had to find a way to curb her tongue, along with that Flanagan temper that flared too easily.

She took a small cooler from the shelf and began filling it with ice.

“The antibiotic doesn’t have to be refrigerated.”

He was second-guessing her already. She would not reply in kind, but her lip was going to get sore from biting it if she had to be around Jake too much.

“I know. I thought Manuela could give Juan some ice chips to suck on.”

He gave a short nod and took the cooler from her, holding it while she scooped the rest of the ice in. “Where is the drug box?” His voice sharpened. “Surely you didn’t leave it here with the clinic unattended.”

She held back a sarcastic reply with more control than she’d thought she possessed. She met his gaze. “It’s locked in the trunk of my car.”

“Good.” He snapped the word, but then he shook his head. “Sorry. That wasn’t an accusation.”

She supposed that was an olive branch. A good working relationship, she reminded herself. You don’t have to like the man, just get along with him professionally.

“I know. Believe me, being responsible for that drug box is at the top of my list.” She hesitated. How much more should she say about what had happened tonight? “My family always accuses me of leaping before I look. I guess I proved them right tonight, didn’t I? I reacted on instinct.”

That was an apology, if he’d take it that way.

“Fast reactions are important for first responders like paramedics—”

She had a feeling there was a but coming at the end of that sentence. “Don’t forget I’m a firefighter, too. Sometimes it’s tough to keep the jobs sorted out.”

He blinked. “I didn’t realize that. In the city, being a paramedic is a full-time job.”

“It’s what I’m doing most of the time, but our department isn’t all that big. When an alarm comes, I do whatever I have to.” She smiled. “Can’t let the rest of the family down.”

Now she’d confused him. “The rest of the family?”

“All of the Flanagans are associated with the fire department in one way or another. My father and one of his brothers started the tradition, and our generation just carried it on. Even my cousin, Brendan, the one you met at the board meeting—”

He nodded, frowning a little, as if that board meeting wasn’t the happiest of memories.

“Brendan’s the pastor of Grace Church, but he’s also the fire department chaplain. He manages to put himself in harm’s way a little too often to suit his wife. The others—well, you’ll meet them all at the picnic on Sunday.”

This was the point at which he could make some excuse to get out of Mom’s impulsive invitation. He probably wanted to.

“I’ll look forward to that.” He paused, his arm brushing hers as he reached for the lid of the cooler. “Unless that’s going to be uncomfortable for you. If you’d prefer I not come, I’ll respect that.”

He was too close, and she was too aware of him. Instead of looking up at his face, she focused on his capable fingers, snapping the cooler lid in place as efficiently as he’d stitch a cut.

An armistice between them—that was what she needed. Maybe letting him see the Flanagans in full force would help that along. Besides, as Mom had said, they’d all be on her side, whether she wanted their help or not.

The silence had stretched too long between them. He’d think she was making too much of this.

“Of course I want you to come.” She met his gaze, managing a smile. “You’re new in town. We all want to make you feel welcome.” Even though she’d rather he’d found any hospital in the country other than Suffolk’s Providence Hospital to work in.

“I’ll look forward to it, then.”

“Fine. I’ll write up the directions to my brother’s farm for you.” A truce, she reminded herself.

She began sorting the intake forms that had been left on the desk. “I’ll just put these away and then run the meds over to the camp on my way out. If you’d like to leave, please don’t feel you have to stay around.”

“I’ll take the meds over.” He shook his head before she could get a protest out. “It’s not a reflection on you, Terry. I just think it’s safer if you don’t go over there tonight. In fact, no one should be at the clinic alone.”

“Shall I add that to the rules?” She couldn’t keep the sarcasm out of her voice, and his mouth tightened.

“The rules are designed to keep everyone safe. Including you. But you have to follow them.”

“I know.” Stop making him angry, you idiot. “Next time anything comes up, I’ll call the hospital first.”

“No, call me. You have my cell number, don’t you?”

She nodded. “But you weren’t on duty tonight. Wouldn’t you rather we call the E.R.?” And now she’d let him know that she was keeping tabs on his schedule.

“That doesn’t matter. I’d prefer to be called, so I know firsthand what’s happening here. The welfare of the patients and the staff are my responsibility.”

That almost sounded as if he cared about the clinic, instead of finding it an unwelcome burden foisted on him by the hospital administration.

“I’m glad you feel that way. It’s good to know we can count on you.”

She glanced at him, but he wasn’t looking at her. Instead he was frowning at the cement block wall, as if he saw something unpleasant written there.

“My responsibility,” he repeated. Then he focused on her, the frown deepening. “Look, it’s just as well you understand this. Anything that goes wrong at the clinic is going to reflect on me in the long run. And I don’t intend to have my position jeopardized by other people’s mistakes. Is that clear?”

Crystal clear. She nodded.

It really was a shame. Just when she began to think Jake was actually human, he had to turn around and prove he wasn’t.

“Dr. Landsdowne, may I have a word, please?”

The voice of the hospital administrator stopped Jake in his tracks. It felt as if William Morley had been dogging his steps ever since the migrant clinic program got off the ground. He turned, pinning a pleasant look on his face, and stepped out of the way of a linen cart being pushed down the hospital hallway.

“I’m on my way down to the E.R., Mr. Morley. Can it wait until later?”

Morley’s smile thinned. “I won’t take much of your time, Doctor. Have you read the memorandum I sent you regarding cutting costs in emergency services?”

Every department in any hospital got periodic memos regarding cutting costs from the administrator—it was part of the administrator’s job. Morley did seem to be keeping an eagle eye on the E.R., though.

“Yes, I’ve been giving it all due attention.” How did the man expect him to assess cutting costs when he’d only been in the department for a couple of weeks?

Morley frowned. “In that case, I’d expected an answer from you by this time, detailing the ways in which you expect to save the hospital money in your department.”

Jake held on to his temper with an effort. He couldn’t afford to antagonize the man. “It’s important to take the time to do the job right, don’t you agree? I’m still assessing the needs and the current staffing.”

“Perhaps if that were your first priority, you’d be able to get to it more quickly.”

He stiffened. “The first priority of the chief of emergency services is to provide proper care for the patients who come through our doors.”

“Well, of course, I understand that.” Morley said the words mechanically and leaned a bit closer, as if what he had to say was a secret between the two of them. “However, the hospital has to make cuts if it’s going to remain solvent. We can’t afford to have money bleeding out of the E.R. every month. We need an E.R. chief who can make it run efficiently. I hope that’s you.”

Money wasn’t the only thing bleeding in the E.R., but it seemed unlikely Morley was ever going to understand that. The threat was clear enough, though.

“I’ll work on it. Now, if you’ll excuse me—”

Morley caught his arm. “Another thing—I’m sure you’re spending more time than you’d like dealing with this migrant clinic.”

Jake nodded. The need to approve every step taken by trained nurses and paramedics was tedious, but he couldn’t see any other way of dealing with the situation.

“It occurs to me that something might come up—perhaps has already come up—that the board would find a logical reason to postpone this effort until another time.”

The man was obviously fishing for any excuse to shut down the clinic. Jake’s mind flashed to the incident two nights earlier when Terry had gone to the migrant housing, clearly breaking his rules. If he told Morley about it, the daily hassle of supervising the clinic might be over.

But he couldn’t do it, no matter how much the clinic worried him. He’d promised Terry another chance. His mind presented him with an image of Terry’s face, stricken and pale when he’d lit into her team, accusing them of negligence in failing to save Meredith.

No. He owed her something for that.

The wail of a siren was a welcome interruption. He gave Morley a perfunctory smile. “There haven’t been any problems there yet. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m on duty.”

This time he escaped, pushing through the swinging door into the E.R.

The paramedics wheeled the patient in just as he arrived. Terry and her partner. He’d just been thinking of her, and here she was.

Terry gave him a cool nod as her partner reeled off the vital statistics—an elderly woman complaining of chest pain and difficulty breathing. He focused on the patient, who looked remarkably composed for someone brought in by paramedics.

He nodded to the nurse. “We’ll take it from here.”

Terry patted the elderly woman. “You listen to the doc now, Mrs. Jefferson. Everything will be fine.”

“Thank you, dear. I don’t know what I’d do if I couldn’t count on you.” The woman beamed at the paramedics.

He flashed a glance at Terry, who was fanning her flushed face. Her red curls were damp with perspiration and her neat navy shirt was wrinkled. “Stick around for a few minutes. I’d like to speak to you.”

She nodded, and he helped push the stretcher back to an exam room.

It didn’t take more than a few minutes to determine what he’d already suspected—there was nothing wrong with the woman that merited a trip to the emergency room. The fact that the nurse also knew Mrs. Jefferson well enough to know she’d like grape juice just confirmed it. He left the woman happily drinking her grape juice and went in search of the paramedics team.

He caught up with Terry in the hallway. “Where’s your partner?”

She swung toward him, resting a frosty water bottle against her temple. “Jeff’s restocking the unit. Do you want me to get him?”

“Not necessary. I can say what I need to say to you.” And he shouldn’t be noticing how those damp red curls clung to her skin. Terry didn’t mean anything to him except an obstacle to be overcome. “That woman shouldn’t have been brought to the E.R. There’s nothing wrong with her.”

“That decision isn’t really up to the paramedics, is it? We don’t practice medicine.”

He glanced around, but no one was in earshot. “Are you throwing my words back at me?”

Terry’s face crinkled into a sudden smile. “Sorry. It’s just that we all know Mrs. Jefferson is a frequent flyer.”

“Frequent flyer?” He understood, all right, although he hadn’t heard them called that—those people who called the paramedics when they got lonely or needed attention.

“Look, she lives alone in a third-floor walk-up and her air conditioner just broke. I suppose she got a little scared. Anybody might in this heat. It happens.”

“I know it happens, but it shouldn’t.” This was exactly the sort of thing Morley had been talking about. “It wastes the hospital’s resources.”

Terry looked unimpressed. “I don’t work for the hospital, I work for the city.”

He planted his hands on his hips. It was probably a good thing, for Terry’s sake, that she didn’t work for the hospital.

“That’s not the point. We have to cut costs in the E.R., and every patient that’s brought in here for no reason eats into our budget.”

“She probably doesn’t need a thing except to rest in a cool place for a while. That’s not going to take any of your budget.”

“She can find a cool place in a movie theater.” He stopped short, realizing he was letting himself get into an argument with a paramedic. “Take her home. Now.”

Terry looked at him as if she could hardly believe her ears. “You can’t expect us to haul her back to that hot apartment now. Give me a few hours. I’ll call Brendan and see if he can’t get someone to donate a new air conditioner.”

Brendan Flanagan, her minister cousin. The board member. Being caught between a board member and the hospital administrator was not a good place to be. For a moment longer he glared at Terry, annoyed at her ability to put him on the spot.

But this was a no-win situation. “All right. But she’s not staying for supper. You and your partner get back here for her before five, or I’ll call her a cab.”

“Right. We’ll do that.” She spun, obviously not eager to spend any more time in his company.

He stood for a moment, watching the trim, uniformed figure making for the door. At the last moment she stopped, turned and pulled something from her pocket.

She came back to him and held out a folded slip of paper. “I nearly forgot to give you this.” She stuffed it in his hand and hurried out the door.