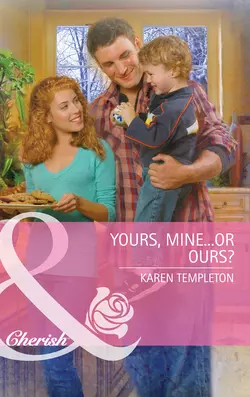

Yours, Mine...or Ours?

Yours, Mine...or Ours?

Karen Templeton

He took one look and fell in loveFrom the moment Rudy Vaccaro saw her, he was a goner. Never mind that his twelve-year-old daughter hated the house on sight. Rudy could see the place’s potential. So could Violet Kildare… The house was supposed to be hers! Now Violet would have to find another place for her and her two sons to live.Then Rudy made an offer the struggling single mother couldn’t refuse. Rudy needed Violet’s help – actually, he needed Violet, period. Somehow he had to show the once-burned mum that what was his was hers – and vice versa!

“Rudy?”

He blinked, then looked down into Violet’s flushed face, framed by a zillion coppery coils that slid across her shoulders. In the sunshine, she was…incredible. He had to literally order his hand not to lift to her face.

“I’ve been calling and calling you,” she said, a small voice in a big pink coat. She looked over her shoulder at a mud-and-salt-splattered sedan that had seen its share of New England winters. Her son’s grinning face popped up in one of the back windows. She waved, then turned back. “You get your girl all settled in?”

“She’s twelve. Settling’s not exactly her strong suit.”

“She’ll make friends,” Violet said. “She’ll be fine. Anyway, I was going to call you, but since you’re here, the answer’s yes. Cooking, fixing the place up…whatever you need, I’m your girl.”

Maybe you shouldn’t put it like that, Rudy thought, eyeing a stray curl that was toying provocatively with her mouth.

KAREN TEMPLETON,

a bestselling author and RITA

Award nominee, is the mother of five sons and living proof that romance and dirty nappies are not mutually exclusive terms. An Easterner transplanted to Albuquerque, New Mexico, she spends far too much time trying to coax her garden to yield roses and produce something resembling a lawn, all the while fantasising about a weekend alone with her husband. Or at least an uninterrupted conversation.

She loves to hear from readers, who may reach her online at www.karentempleton.com.

Yours, Mine…or Ours?

Karen Templeton

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

To Shannon Stacey,

whose answers to all my dumb New England

questions made me more grateful than ever

for New Mexico winters.

And to Gail C and Charles G,

the best editorial team evah,

for keeping me sane.

I love you guys.

Chapter One

Rudy Vaccaro took one look at her and fell in love.

Hopelessly, impossibly, insanely in love.

Even though she wasn’t perfect. Hell, she wasn’t even all that good-looking, not in the shape she was in. And high maintenance? Hoo-boy. Yeah, he’d gotten himself in deep with this one.

But then, maybe that’s what he loved about her, Rudy thought, standing there grinning like a loon, that she needed him. Needed him bad—

“Ohmigod, Dad—I cannot believe you ruined my life for this!” said his twelve-year-old daughter, Stacey.

That was followed by his younger brother Kevin’s, “Exactly how closely did you look at the place before you bought it?”

Refusing to let either his daughter’s horror or his brother’s skepticism deflate him, Rudy lifted his grin to the (peeling) ceiling in the inn’s front room/lobby/whatever and let out a whoop of sheer, unadulterated joy.

For twelve years he’d anticipated this moment, squirreling away as much of his cop’s salary as he could, even before he fully understood what he was squirreling it away for. Twelve years of nudging a vague dissatisfaction into a dream, then a goal, and now—thanks to a confluence of events he could have never foreseen—reality.

A hundred-fifty-year-old, six-bedroom reality with curling wallpaper, carpeting in assorted shades of barf and cobwebs thick enough to snag Cessnas.

Rudy’s breath frosted the unheated air as he clapped his hands together, eager to get on with the new year, his new life, both barely two days old.

Mine. All mine, he thought as he tromped across the threadbare carpeting, his size thirteen workboots making the joists squawk underneath. After six months’ vacancy, the ancient studs were rheumatic with New England winter damp. Silence met his tap on the thermostat by the dining room archway. Huh. Probably no oil in the furnace.

If he was lucky.

But oh, he was. The luckiest bastard on the face of the earth. Finally, a home, a life of his own—

“Like, eww,” his smart, scowling daughter said to a sagging, suspiciously stained wing chair that might have been yellow in another life. Or pale green. Horrified, gorgeous brown eyes lifted to his. Okay, so this part of things needed work. Already pissed at him for jerking her away from all her friends, not to mention an extended family with ties to half of Massachusetts, clearly the idea of spending her formative years in the Lemony Snicket house wasn’t exactly racking up points. “People actually sat in that?”

“Thousands, from the looks of it,” Kevin said.

Stacey backed away, shuddering.

Rudy yanked off his knitted cap, ruffling his short, prickly hair. “There’s a reason I got it so cheap,” he said, proudly. Almost smug. He turned to his spiky-haired brother, six years his junior, not quite as tall, a good fifty pounds lighter. Not counting the five layers of denim, flannel, cotton jersey. Kev was still trying to get a handle on what—and who—he wanted to be when he grew up. However, with all the restoration skills he’d picked up over the past few years, he’d decided for the next cuppla months he could figure that out here as well as anywhere. “You got any idea what prices are like up here, normally?”

Arms crossed, Kev frowned at a dark streak meandering from ceiling to floor, through endless, drab green marshes populated with faded ducks. “That looks like a leak. If you’re lucky, maybe only from a bad radiator or something—”

“I gotta go to the bathroom,” Stacey said, hands stuffed in the pockets of her puffy vest, her long, dark hair alive with static. Coffee bean eyes still flashed you-will-so-pay-for-this messages. Rudy’s smile never wavered. You’ll come around. You’ll see how right this is. For both of us.

“There’s six,” he said. “Four upstairs, two down here. Take your pick.”

Her mouth dropped. She was tall for twelve, although still stick straight, thank God. Another year, maybe, before he’d have to unpack the stick. “Six?”

“Yep.” Rudy grinned at Kevin, willing him to stop frowning. See? his grin said. Not as dumb as I look. He’d save a bundle, not having to add bathrooms. Although what condition the plumbing was in…

He’d think about that tomorrow. Now he pointed down the hall. “Closest one’s down there.” As Stacey tramped off, Rudy met Kevin’s still-not-gone frown. “The Realtor sent me a floor plan,” he said, shrugging.

“A floor plan.”

“Yep.”

“So what you’re sayin’ is, you invested your life’s savings sight unseen.”

For the first time since they’d walked into the house, Rudy’s grin wavered. But only for a second. He even clapped his brother’s shoulder. “At least give me some credit. The agent also sent me dozens of photos from her camera phone.”

“Oh, well, then.”

“Look, I had to move fast. The price had just dropped—a lot—and there were two other interested parties. I made an offer and the seller pounced. It did pass the basic inspection, Kev, so you can stop looking at me like that. The roof’s not gonna cave in—probably—and no termites. It’s more run-down and neglected than anything. And anyway, with your lousy track record in the responsibility department, you’ve got one hell of a nerve looking at me like that.”

The creep actually laughed. “That’s just it—this is the kind of stunt I would pull, not you. You’re supposed to be…I dunno.” He frowned up at the stain again. “Not somebody who’d blow his entire wad on a piece-of-crap inn in the middle of freaking nowhere.”

“It’s not nowhere. It’s New Hampshire. You go forty-five minutes, an hour at the most, in any direction, you run into something. Lake Winnipesaukee, the mountains, even a speedway. What more could anybody want?”

“Civilization?”

“Now you sound like Stacey.”

“With good reason. What were you thinking, man?”

“What I was thinking,” Rudy said, caressing the wood fireplace mantel that probably hadn’t been refinished, or even polished, since Elvis’s heyday, “was that for thirteen years I’ve devoted every waking moment to my kid.” He turned his gaze on his brother. “Thirteen years of ignoring my own needs, my own life. All just so I could scrub this—” he made the L for Loser sign “—from my forehead.”

“Yeah,” Kevin said, his mouth twitching, “I can see where buying the Bates Motel—sight unseen—would do that—”

Stacey screamed. Rudy streaked from the room, Kevin on his heels, only to nearly collide with his hysterical daughter shooting from the opposite direction.

“It went in there!” she shrieked, the friendship-bracelet-choked hand pointing toward the kitchen a blur. “Get it out, Daddy! Get it out!”

“Get what out, honey?” he said as both he and Kevin crept toward the kitchen, unarmed except for their cell phones and the keys to the SUV.

“I don’t k-know!” Stacey whimpered behind them, so close Rudy could smell her girly shampoo. “Something big and fat and furry, with disgusting beady eyes!” She grabbed the back of Rudy’s plaid jacket; he could barely make out her muffled, “I hate it here, I hate it! I want to go home!”

It’s okay, these days she hates everything, Rudy reminded himself as the three of them shuffled like some giant, six-footed, whimpering (from Stacey) bug into the kitchen. Big, Rudy thought, his mood lifting even more. Lots of light.

Ugly as sin, he thought, chasing the thought with, Ugly can be fixed.

The Nixonian-era palette of avocado and burnt-orange reminded him of his childhood, when his parents had been too busy trying to keep six children alive to worry about things like color schemes and such. Even the boxy refrigerator and standard four-burner gas range were planted in their spots like a pair of alien geezers at the Home, waiting for Jeopardy! Extraterrestrial Edition to come on.

Fake-brick-patterned vinyl flooring covered God knew how many previous incarnations; blistering, dingy gold enamel choked the paned cabinets. But one large window faced east (morning sun!), another the woods behind the woefully neglected gardens. And wallpaper could be stripped. And maybe there were wood floors—

“Whatever it was apparently escaped,” Kevin said. “There’s a big hole in the plasterboard by the back door, probably leading outside.”

Right. The wildlife issue.

Kevin was bent at the waist, hands on knees, peering inside the hole. “Could’ve been a raccoon, maybe. Or a skunk.”

“A skunk!” Stacey shrieked again in the vicinity of Rudy’s kidneys. “Gross!” Except then she said, with great authority, “No, it definitely wasn’t a skunk—it wasn’t black and white.” As though suddenly realizing how uncool it was to be clinging to her father, she let go of Rudy’s jacket. Only to immediately say, “Do we have to stay here tonight?”

“Of course we’re stayin’ here tonight—”

“There’s no heat, bro,” Kevin quietly reminded him. “Or,” he said, flicking the lifeless light switch, “electricity.”

Damn. The Realtor had promised him the utilities would be back on. But they had candles. And he’d seen stacks of firewood on the back porch. And the nearest motel was clear on the other side of town.

“So we’ll fire up the woodstoves,” Rudy said heartily, “light some candles. And we brought a sh—uh, boatload of camping equipment, we’ll be fine. And tomorrow I’ll call the utility people, get the juice turned back on.” At Stacey’s skeptical look, he gave her shoulders a squeeze. “Oh, come on—where’s your spirit of adventure?”

“In the Bahamas,” she said drily.

Behind him, Kevin choked on his laugh.

At the height of the dinner rush, Violet Kildare grabbed one, two, three, four specials for table six from underneath the warming lights and thought, Whatever doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.

“Mom!” George, her nine-year-old son, yelled as she whizzed past the booth where he and his younger brother Zeke sat surrounded by backpacks, Game Boys, assorted school papers and the remnants of the burgers and fries she’d tossed at them an hour ago. “What’s five plus four?”

“Use your fingers!” she called back as she set the plates down in front of Olive, Pesha, and the Millies, who trooped down to the diner from the retirement community every night, unless it was raining or the snow was over six inches deep, smiling for them even though they never tipped and at least one of them was guaranteed to find something wrong with her food.

“You shouldn’t tell him that, dear,” Old Millie (eighty-six as opposed to “Young” Millie’s eighty-two) said. “How’s he ever going to learn his sums if he keeps using his fingers?”

The other ladies all murmured their assent, interrupted only when Pesha—bony, blond and half-blind—poked Violet in the hip with one sharp fingernail.

“This isn’t what I ordered.”

“Yes, it is, Pesha. You ordered the special. Hot roast beef.”

“No, the special’s Salisbury steak.”

“That was yesterday. Today’s hot roast beef.”

Pesha squinted at Young Millie’s plate, directly across from her. “Is that what she’s having?”

“Yes, ma’am, that’s what they’re all having.”

“Well, I don’t want hot roast beef, I want Salisbury steak. Mushrooms on the side.” She shooed at the plate. “Take it away.”

With a heavy sigh, Violet snatched up the plate and headed back toward the kitchen. “Nine?” George called out. “Is five plus four nine?”

“That’s right, baby,” Violet said, shoving an orange—not auburn, not chestnut, not ginger—corkscrew curl out of her eyes as she swallowed back hot, pissed tears. She hadn’t signed on for this, night after night of chronically sore feet and aching back muscles, of dealing with cranky, cheapskate old ladies and old farts who clearly thought she should feel flattered by their very unwelcome attention. Night after night of tossing her babies scraps of attention, instead of being able to sit down with George like a good mother and help him navigate the minefield of letters and numbers he brought home from school every day.

“What the hell’s this?” came the stringy, snarly voice from the other side of the warming counter when Violet shoved the uneaten roast beef back across it.

“Sorry, Maude, Pesha wants Salisbury steak instead,” Violet said tiredly to the dull brown eyes peering out at her from underneath black bangs with more staying power than the Berlin wall. “Mushrooms on the side.”

The sixty-something owner of Mulligan Falls’s only independently-owned-and-operated-since-1948 eating establishment grabbed the plate, muttering, as “Mo-om! What’s six plus two?” sailed across the crowded restaurant, piercing her skull like a nail gun, and she thought, Buck up, chickie,’ cause going under’s not an option, even if she had been left on her own to deal with their smart-as-a-whip son who still couldn’t remember that five plus four made nine, who had to have all the directions on his assignments explained three times because he couldn’t remember them on his own. With their younger son who barely spoke, even at four, but whose smile could melt the hardest heart.

Not that she’d ever expected life to be easy—she wouldn’t even know what to do with easy—but she wasn’t asking for easy, just a chance—

“Here you go,” Maude said, clunking Pesha’s Salisbury steak on the serving counter. Pesha’s mushroom-smothered Salisbury steak. Not even taking the time to sigh, Violet grabbed a fork and scraped the fungus into a little glob beside the meat.

Then, hoping for the best, she strode back toward the old ladies’ booth, yelling out, “Use your fingers!” to George.

The bell over the front door tinkled. More customers. Yippy skippy. The diner went eerily silent, as though somebody’d pressed the mute button. Violet glanced up, skidding smack into a pair of smoky-blue eyes in a male face that didn’t have a single soft anything, anywhere. At least, what she could see underneath the beard haze.

He was big, bodyguard big, his head stubbled with little more hair than his face, big enough to nearly blot out the younger man behind him, to dwarf the pretty, long-haired girl in front, her slender shoulders swallowed by a pair of huge, hard hands.

“Three?” Darla, the other waitress, finally got out, gawking at the taller man as though she wouldn’t mind clutching him to her flat little bosom like one of the front-door-size laminated menus in her arms.

“Yeah, three,” he said, and Violet more felt than heard his voice, deep, not from around here, felt it seep into her skin, through her pores…

No more romance novels for you, she thought, shrugging off two years’ worth of unused hormones, about the same time she realized Darla had seated the trio in Violet’s station because hers was all filled.

Great. Just great, she thought as Darla passed around the menus, her long face sagging with disappointment.

But a gal’s gotta do what a gal’s gotta do. So, jerking her pencil out of her hair, Violet marched over to take their orders.

“Smile,” Darla hissed at her as she passed, and Violet reminded herself that her sore feet and bitching back were not these peoples’ fault. And that the grumpy approach was probably not the best way to get a tip.

Both men were slouched heavily against the padded booth backs, the girl’s face folded into the standard issue adolescent glower. Without even knowing the particulars, Violet felt a tremor of sympathy for her. Orders taken, she called them out to Maude—burgers and fries, the special, spaghetti for the girl—then asked, “So what brings you to Mulligan Falls?”

Those sharp blue eyes swung to hers, and assorted body parts quivered, remembering. Then he said, “I just bought the old Hicks Inn, up on the hill.”

And presto-chango, Mitch fell to second place on Violet’s Men Who Screwed Me Over list.

“Your food’ll be here in a sec,” the redheaded waitress said, her voice like needles as she snatched up the menus, and Rudy thought, Huh? But the needles had pricked him awake, at least enough to notice her as something other than the means by which food would eventually reach his stomach. Enough to catch the sparks of anger, of hurt, in her big, silvery-green eyes, before she wheeled around and tromped off, the diner’s overhead lights tangling in a thousand tiny ringlets the same color orange as in the wallpaper in his “new” kitchen.

Then the haze of exhaustion cleared enough for him to notice the body underneath the curls, short and curvy and compact in the pale green uniform, like one of those VW Bugs, he thought, stronger and far more crash-resistant than one might think.

“What was that all about?” Kevin asked, and Rudy shook his head, half-annoyed, half-relieved that he hadn’t imagined it.

“No idea,” he said. But after a flurry of murmurings and gasps, Rudy noticed several heads had turned in their direction.

“Dad?” Stacey whispered. “Why’s everybody looking at us?”

“Beats me, honey.”

Kevin leaned forward. “Why do I feel like we just landed in the middle of a Stephen King novel?”

Stacey sidled closer as Rudy kicked Kevin under the table.

Until three minutes ago, Rudy hadn’t had too much trouble keeping his good mood aloft. Much to their surprise—and Rudy’s profound relief—three of the upstairs bedrooms were in fairly good shape, as were the bathrooms. Yeah, the downstairs needed a lot of work, but no huge surprises. So he’d decided—especially after four hours of nonstop cleaning and inspection and plugging up unplanned critter doors—that nobody, including him, was up to canned Dinty Moore stew warmed up over a camp stove. And besides, promising Stacey any dessert she wanted might earn him enough points to see them through at least the next twenty-four hours.

So, with the U-Haul trailer unhitched, they’d piled into his edging-toward-classic-status Bronco and headed to town, “town” being Main Street, basically, five blocks long and anchored by an old-fashioned square, across from which sat Maude’s. Applebee’s, it wasn’t, but—as he explained to his sneering daughter—the sooner they started mixing with the locals, the sooner they’d stop feeling like outsiders.

“Never happen,” she’d muttered as they’d walked in. Although he already knew she had her eye on a piece of chocolate cream pie in the old-fashioned display tower on the counter.

He hadn’t counted, however, on being regarded like their ship had just cut swathes in the crop fields. Unnerving, to say the least. And frankly annoying. For God’s sake, the minute he or Kev opened their mouths it was pretty clear the Vaccaros hailed from the same good, solid working-class stock as the majority of Mulligan Falls’s residents. So what the hell?

Their waitress returned with their drinks, which she clunked in front of them, her mouth pressed tight, and Rudy saw the pinch of frustration and exhaustion in those squeezed lips. Although what that had to do with him, he had no idea. His cop senses sprang to attention, that this was someone about to blow, and he thought, I could fix, you, too.

What the freaking hell?

“Oh, and, miss?” he said, gently, “my daughter would love a piece of that chocolate pie, if you could add it to our order?”

“Sure thing,” she said, not meeting his eyes but smiling just enough at Stacey for Rudy to see through at least some of those suffocating layers of resentment.

Then one of the old biddies at the booth across the way called her over, in that imperious way people have when they think you exist solely for their comfort, complaining about her food being cold or something, and at the back of the restaurant a little boy yelled, “Mom! What’s twelve take away seven?” as the woman behind the serving counter dinged an obnoxiously loud bell and hollered, “Violet! Order up!”

He saw her—Violet—stop for a second, her back expanding with the force of her breath, before yelling, “Use your fingers!” to the boy (there were two of them, Rudy now saw, practically buried by books and things in the booth), grabbing the old lady’s plate and carrying it back to the kitchen, where she exchanged it for the three plates waiting for her.

The plates precariously balanced, she spun around again at the precise moment the youngest boy darted out of the booth and into her path. On a yelp, the waitress—Violet—stumbled, the plates leaping, flying, crashing magnificently onto the tile floor as, catching her son in her arms, she went down, too.

Rudy and Kevin were instantly out of their seats, Kevin snatching the child out of the pile of shattered plates and splattered spaghetti and scattered fries and roast beef and gravy as Rudy grabbed for the crumpled waitress.

“Leave me alone!” she cried, close to meltdown, slapping at his hands as she struggled to her knees and grabbed her chick. “Zeke! You okay? Does anything hurt?” Heedless of the spaghetti sauce and gravy clinging to her breasts, dribbled down her skirt, she frantically checked for blood and bruises. A noodle dangled from her hair; she yanked it out and tossed it on the floor, then clamped one tiny shoulder with a short-nailed hand, holding the other one three inches from the kid’s nose. “How many fingers?”

“Th-three,” the kid said, small-voiced, trembling. “I’m sorry, Mama, I had to pee! I didn’t see you!”

“It’s okay, baby, it’s okay.” The boy momentarily vanished into her bosom to have a dozen kisses rained upon a crop of short blond curls. “It’s okay,” she said again. “Accidents happen, it wasn’t your fault.”

Out of the corner of his eye, Rudy saw Stacey pick her way through the carnage. “If you want, I could take your little boy to the restroom and get him cleaned up,” she said, and Rudy gawked at her.

“Thank you,” Violet said, nodding, only now seeming to notice the extent of the mess, which verged on epic proportions. As Stacey led Zeke away, Violet sat back on her haunches and moaned. A tall, shapeless, hairnetted brunette in a grease-splotched apron appeared out of nowhere, bringing with her a deathly silence. Rudy glanced over his shoulder: Every eye was trained on the scene.

“This makes what, Violet?” she said. “The third time this month?”

“I know,” she said, flushing red as she began gathering the jagged pieces of earthenware, their soft clanking like screams in the deep hush. Rudy squatted to help her; she glared at him, then shrugged. “Zeke ran out in front of me—”

“And didn’t I say you could only bring the kids here while you worked as long as they weren’t a nuisance?”

“It was an accident, Maude.” The waitress kept her eyes on the floor, tense fingers clutching two neat halves of a broken plate, weariness and embarrassment stiffening her back. Kevin appeared with a gray plastic tub, started tossing the mess into it; Rudy tried to pry the broken plate from Violet’s hands, which earned him another glare. She tossed the destroyed crockery into the bin, saying, “I’ll pay for the loss. Like always.”

“I’m sorry, Violet, I really am,” the older woman said, not sorry at all. “This isn’t working out—”

“No! Maude, please!” Tears bulged in Violet’s eyes when she looked up. “I promise it won’t happen again—”

Rudy was on his feet, staring down whoever the hell this Maude was, his steady, now-we-don’t-want-any-trouble cop’s voice barely masking his irritation. “Like she said, it was an accident. So how about cutting the lady a break?”

“You stay out of this,” Violet said, now standing as well, the eyes inches away, as were the breasts, like double-dip mounds of pistachio ice cream, or maybe mint, the image almost enough to neutralize a tone meant to shrink gonads in a hundred-yard radius. Too bad for her Rudy’s were the nonshrinkable variety. He may have turned in his badge and gun, but not those. “I don’t need some stranger fighting my battles for me!”

“Then let me introduce myself,” he said, extending his hand. “Rudy Vaccaro.”

For a second, he thought she might spit at him.

“Who?” Maude said.

“He bought Doris’s place,” Violet said, and something in her voice brought his head around. Then, to add to the bizarreness, Maude laughed. Rudy’s head swung back to Maude. Who was smirking.

“No, mister, I sincerely doubt she wants your help,” she said, as Stacey returned with the younger boy, who immediately plastered himself to his mother’s side. As Violet cupped the boy’s head, her boss said, “So what’s it gonna be? You gonna find somebody to babysit your brats or what?”

The waitress flushed again, the deep pink a weird contrast to the orange hair, then turned, wagging her hand at the older boy. “Get your stuff together. We’re leaving,” she said softly.

Kevin tugged Rudy’s sleeve and whispered, “Not your problem, bro, let’s get back to the table, okay? Rudy!”

Torn, Rudy frowned into his brother’s eyes. “Obviously, you hanging around is only making this harder for her,” Kevin said under his breath. “Come on.”

After a final glance at Violet as she herded her sons through the restaurant and out the back door, Rudy followed his brother and daughter back to the booth. But everyone was still staring, and he knew damn well they were the subject of at least a half-dozen whispered conversations, too.

So when the other waitress brought them their redone dinners, Rudy asked, “Okay, clearly I’m missing something. What’s my buying the Hicks place got to do with Violet?”

Her eyes banged into his. “You don’t know?”

When Rudy shook his head, the waitress said, “Then let me be the first to break it to ya…”

Chapter Two

“Let me guess,” Kevin said as they made their way back to the car. “You’re about to bust something trying to figure out what to do about this new wrinkle.”

Rudy waited until Stacey, who’d run ahead, was out of earshot before he replied, “Yeah. Nothin’ worse than being the bad guy when it’s not even your fault. I mean, if there wasn’t a will—”

“Then I would think legally you’re in the clear,” his brother said, halting in front of a gated sports equipment store. “Not that I’m any expert, but like you said, you didn’t do anything wrong. Now, what I’m wondering is, what you’re gonna do about Violet?”

Rudy frowned at him, tempted to think he’d liked his brother better when he’d been a stoner and too out of it to stick his nose in. “What makes you think I should do anything about Violet?”

Kevin chuckled. Rudy sighed. Okay, so those damn pale green eyes were burned into his brain, along with all that Icould fix you crap. Which was really stupid because maybe—maybe—Rudy could fix a house, but fixing women wasn’t part of his job description. Especially since, if memory served, women didn’t generally take kindly to being fixed.

But the more Darla, the other waitress, had yakked away about Violet’s situation, the more Rudy realized he had to do something. He’d had no idea, obviously, when he’d bought the place that the old lady had promised to leave it to Violet—

“Da-ad!” Stacey called, hopping up and down beside the car, her hands jammed inside her vest pockets. “Hello? Open the door?”

“Oh, sorry,” he mumbled, hitting the remote on his key chain. The car be-booped itself unlocked. Stacey yanked open the door and scrambled inside, slamming it shut again.

Somehow, he doubted Darla had exaggerated about Violet’s situation, even if she did have that gleam in her eye common to people taking comfort in other people’s troubles. She’d told him all about how Doris Hicks’s daughter had thrown Violet and her sons out of the house she’d believed would be hers in exchange for the eighteen months Violet had spent helping Doris to keep the inn open—an arrangement mutually beneficial for both an old woman determined to stay in her own home and a struggling young mother whose husband had taken a hike.

He could only imagine how blindsided she must’ve felt. Just like he’d been when Stacey’s mother had said, “Forget this,” leaving a rookie cop with a colicky six-month-old and a hole in his heart the size of the Grand Canyon. But at least Rudy’d had a safety net, in that huge extended family. There’d always been a home for his daughter, even if not one he’d envisioned.

He pulled up in front of the inn, shrouded in darkness save for the moonlight and the anemic ghosts of a half-dozen or so wussy, solar-powered yard lights standing lethargic sentry along the disintegrating walk. Armed with a flashlight, Stacey shot out of the car—bathroom call, Rudy was guessing. Kevin, however, stayed put, staring at Rudy’s profile. Noting, no doubt, that Rudy hadn’t killed the engine. Then he chuckled.

“I’ll start a fire, how’s that?”

Slamming the door shut behind him, Kevin started up the walk, warbling some country song Rudy didn’t recognize.

And Rudy drove back into the winter night, hoping maybe to put a fire or two out.

Rubbing her bottom—still tingling from the ice-cold toilet seat—Stacey crept back to the even colder, totally dark front room, where she found her uncle kneeling in front of the woodstove wedged into the fireplace. By the puny beam of his flashlight, he was trying to coax some kindling to catch fire. Stacey shuddered. Like it wasn’t creepy enough in here in the daylight. Sure, she’d gone camping and stuff, but this was different. Maybe because she’d wanted to go camping and she so didn’t want to be here.

“Wh-where’s Dad?” she said through chattering teeth.

“He had something he needed to do,” Uncle Kev said between puffs to the kindling. “He’ll be back soon.”

Stacey rolled her eyes, even though that was so juvenile. But honestly, why was it so hard for grown-ups to just be up-front with you?

“It’s so cold in here,” she said, rubbing her arms. She’d ripped off her coat when she’d run inside earlier, but now she found it again in the weak, fluttering light and shrugged back into it. Yeah, freezing to death was real high on her list. And without electricity or phone service or broadband or anything she couldn’t even log on and check her e-mail and stuff. What was the point of giving her a new laptop for Christmas—a bribe, she knew, for destroying her life—if she couldn’t even use it?

Tears pricked at her eyes, but she blinked them back. No way was she going to let her dad and Uncle Kev think she was some dumb little crybaby. Not that she had any idea yet how to convince Dad that moving here had been, like, the lamest move ever, but acting like a whiny brat—tempting though it was—wasn’t going to do it. Probably.

“It’ll warm up pretty quick now,” Uncle Kev said, sitting back to admire his handiwork through the open stove doors. Stacey glanced around, shuddering again. Nothing like dancing shadows to up the creep factor. She inched closer to her uncle, now sitting on a superthick, unrolled sleeping bag in front of the fire. Grinning up at her, he patted the space beside him.

She sighed and joined him, cross-legged, elbows on her knees, chin sunk in her palms. One of those heavy silences fell between them, the kind right before the adult says something Really Important.

What now? Stacey thought as her eyes slid to the side of his face. The flames made him look older, she decided. More serious, maybe. Not like the goofball who usually hung out in her youngest uncle’s body. Objectively speaking—a phrase she’d picked up from a book or something—she’d have to say that Uncle Kev was the best-looking of the five brothers. Her grandparents had only had one girl, her aunt Mia, who was marrying this superrich dude in Connecticut the following summer and had asked Stacey to be her junior bridesmaid—

“I know you’re pretty unhappy about this move,” Uncle Kev finally said, interrupting Stacey’s daydream about dresses and shoes and stuff.

“Let’s see,” she said, her chin still propped in her hands as she again stared into the hissing, sputtering fire. “I had to leave all my friends, start in a new school in the middle of the year, I’m guessing there’s no mall within five hundred miles, and this house is like, totally disgusting.”

“Okay, the leaving your friends and new school in the middle of the year—yeah, those really blow. But I happen to know there’s something even better than a regular mall, not ten miles away.”

“Like what?”

“A two-hundred-store outlet mall.”

“Yeah, right. Dad taking me to an outlet mall? Get real.”

“So you’ll make new friends, Stace. Friends with moms who love nothing better than goin’ to outlet malls. And the house isn’t gonna be disgusting forever, because your dad and I are gonna get it all fixed up, get rid of the sucky carpet and wallpaper… You’ll see,” he said, nudging her with his shoulder. “It’ll be great. So you think you could just, you know…give it a chance? Because this is really important to your dad.”

Stacey sighed, wishing the fire was one of those Harry Potter things that sent you someplace else. In her case, back to her grandparents’ nice, warm house in Springfield. Of course, they weren’t gonna be around all the time anymore, she knew that. That’s one of the reasons she couldn’t stay behind, because they were gonna do some traveling and wouldn’t be there to take care of her. And her aunts’ and uncles’ houses were too full of their own kids, and maybe she could’ve gone to live with Aunt Mia, but then she would’ve still had to go to a different school….

“I just don’t get why things couldn’t stay the way they were,” she said, still staring. “Why we couldn’t stay where we were.”

“Because your dad was unhappy, Stace,” Kev said softly, and Stacey’s eyes shot to his. Yeah, okay, her uncle was definitely a hottie. Objectively speaking. Her dad was okay-looking, she supposed, but nothing like Kevin. Women went stupid when they saw Kevin. Okay, so sometimes women went all zombie around her dad, too, but that’s probably because he was so freaking big he scared ’em.

She looked back at the fire. “He never said anything to me about being unhappy.”

“No. He wouldn’t. And he’d kill me if he knew I was saying any of this to you, so you gotta promise to keep your yap shut, okay?” When she nodded, secretly thrilled to be part of a conspiracy, Kev said, “The thing is, from the minute you were born, everybody’s been hot to give your dad advice on how to raise you, what he should and shouldn’t do, stuff like that. He finally got tired of all the interference. Well, actually, he’s been tired of it for a long time. He just couldn’t do anything about it before now.”

Stacey felt her brow knot. “Interference?”

“You know, not being able to make his own decisions. About you. If you want my take on it, I think he was afraid of losing you. That it was getting harder and harder for the two of you to have your own thing, you know?”

“That’s nuts,” she said, her jaw crunching from her holding it in her hands. “Nothing’s ever gonna come between Dad and me.” This was one of those things she simply knew, the way she knew she’d never, ever like Brussels sprouts. “And anyway,” she added, still crunching, “so why couldn’t he just, I don’t know, get us our own apartment or something in Springfield?”

“Because sometimes a person can’t figure out who they really are until they break free of everything they’ve known before. Am I making any sense?”

Not really. But another thrill made her shiver, that Kev thought she was mature enough to handle what he was telling her. Not that she liked it, necessarily, but you can’t have everything.

She sat up straight to look at him. “Is that why you left home?”

“Basically, yeah. But some of the stuff I was into… Trust me, Stace, you don’t wanna know. I was a mess. Your dad, though—he’s always been solid as a rock. Dependable. Selfless. Always puttin’ everybody else first. Like you. No matter what, it’s always been about you. You first, then everybody else, then—maybe—him.”

He got up to stoke the fire, setting off a miniature fireworks display before he shut the doors with a screechy clang. Then he straightened, his hands in his pockets. It was finally beginning to warm up a little, enough for Stacey to open her coat. She wondered where her uncle was going with this.

“That’s kinda the point I’m trying to make,” he said, “in my own convoluted way—that on the surface, this might seem to be all about him. Except…” He sort of laughed. “Except your dad’s not capable of making anything all about him. So this whole crazy scheme—it’s about you, kid. You and him. See?”

But before she could say anything, her uncle’s cell rang—thank God they at least could get a signal out here—and he excused himself to answer it. Stacey wondered if it was a girlfriend. As cute as he was? He probably had girls up the wazoo. As opposed to Dad, who never had any. At least, not that Stacey was aware of. Thank God. She used to watch these movies or read books where the kids were all about trying to get their single father or mother hooked up with somebody, and Stacey had always thought, Why? Because she and Dad were fine, just the two of them. There was no way anybody else would ever fit in.

And, ohmigod—stepbrothers or stepsisters? Lots of her friends were part of these blended families, and they all totally hated it. So, yeah, she was cool with things, just the way they were.

But then, as she sat there, combing her fingers through her long hair, trying to look for split ends in the firelight, some of what Kevin said sank in. About how Dad always put her first.

For the first time since they’d arrived, she felt her lips curve into a smile.

Finally, she thought. Something to work with.

“It’s not fair!” George said, all elbows and indignation as he stood, arms crossed over his new SpongeBob jammies, in the Texas Hold ’Em–themed bathroom that made Violet’s eyes roll in their sockets. “Why do I hafta go to bed the same time as Zeke? He’s five years younger’n me!”

“Hey!” Violet said over the giggling, wriggling, terrycloth-covered mound that was her younger son, her mood perking up at the small miracle that had just taken place in this hideous bathroom that was not, thank God, hers. A small miracle that was somehow enough to momentarily blot out the cloud that was losing her job and having no home of her own and Rudy Vaccaro, with his damn strong jaw and kind blue eyes and his obvious penchant for helping the helpless.

And the letter, waiting for her on the entry table downstairs.

“What?” George said, damp red hair standing in spikes all over his head.

Violet grinned, heartened, and Rudy’s strong jaw and blue eyes faded a little more, even if the letter didn’t. “You just subtracted!”

“I did not,” he said, skeptical.

“You certainly did. You said Zeke was five years younger than you. Which means you subtracted his age—four—from yours—nine—to figure that out.”

“I did?”

“Uh-huh. Without even thinking about it.” She gave him a thumbs-up. Unfortunately her son was no fool.

Unlike his mother.

No. No, she was not going to believe that the occasional foolish choice made her a fool, kind blue eyes and strong jaws be damned.

“You didn’t answer my question,” George said.

“Since the answer’s no different than it was last night, or the night before that, or the night before that,” Violet said, yanking a Thomas the Tank-Engine top over Zeke’s damp, honey-gold curls, then kissing a soft pink cheek, just because she could, “there didn’t seem to be much point. Get your teeth brushed.”

Skinny bare feet stomped across the damp, slightly musty-smelling carpeting to the sink. Wall-to-wall in a bathroom? Let alone one used by small boys with delusions of Olympic glory in the hundred-meter freestyle? Not to mention lousy aim? Insane. But that was Betsy for you, Violet thought as, on the floor below, two of her best friend’s little boys launched into yet another brawl—

Her stomach clenched as It’s over, somebody else bought the house, nothing you can do about it now sailed through her head, along with the blue eyes. And the smile. One of those kick-to-the-nether-regions smiles, deep creases carved into slightly bearded cheeks…

Violet plopped her butt on the closed toilet lid with Zeke on her lap, tugging down the back of George’s pj top where it had stuck to his damp skin. “Have I told you recently how crazy I am about you guys?” she said, suddenly overcome with love and gratitude, despite the sensation of trying to dig out of a hundred-foot-deep sandpit with a teaspoon.

His mouth full of toothpaste suds, George looked at her, eyes bright with worry, and she thought, So much for falling back on maudlin sentimentality as an antidote to stress.

But she smiled anyway, inhaling her four-year-old’s berry-scented shampoo and innocence, and she cocooned him more tightly, cursing Mitch. Cursing herself, for finding herself attracted to another blue-eyed man, one who’d bought her inheritance out from under her. By rights she should have been heaping Irish curses upon his head. Not that she knew any, but she could probably find one or two on eBay, if she tried.

Her eldest eyed her for a moment, thankfully derailing thoughts of curses and sexual longing and such, then spit out his toothpaste. His front teeth were beaver teeth, enormous, one of them crooked. Braces, she thought, almost drowning in panic.

“You lost your job, huh?” George said, eyes huge in the mirror, beaver teeth glinting against a toothpaste-slicked lower lip. “Because of us?”

Swear to God, she would kill Maude Jenkins with her bare hands.

“Yes, I lost my job,” Violet said, being brave. “But no, not because of you.”

“But Maude said—”

“Maude’s a big fat poopyhead,” Zeke piped from Violet’s lap, and she bit her bottom lip to keep from laughing.

“We don’t call people poopyheads,” she said, kissing damp curls.

Zeke twisted around to look up at her, a single tiny crease marring that wonderful, perfect forehead. Mitch’s forehead, she thought, barely dodging the stab of regret in time. “What do we call ’em, then?”

Bitches, Violet thought with a sigh, getting to her feet, Zeke molded to her hip like a baby monkey. “Come on, you two—let’s get to bed.”

“Aw, Mom…”

She took George’s chin in her hand, which, she realized with a start, wasn’t nearly as low as it used to be. “Tomorrow, you can stay up later. Tonight, I need you to go to bed at eight-thirty.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m about to keel over.”

“That doesn’t make any sense.”

“Sometimes life doesn’t make any sense,” Violet muttered, steering him out of the steamy bathroom into the chilly, wallpapered hallway lined with photographs of somebody else’s children. “Suck it up.”

George griping and moaning the whole time, they made their way down the stairs of the tiny two-bedroom house, to the half-finished basement they’d called home for the past six months. Betsy’s husband, Joey, had originally fixed it up as a place where he and his buddies could watch games and not get in Betsy’s hair, which Betsy finally figured out was Joey-speak for hiding out so his sons wouldn’t get into his. It was what it was. Stained carpeting over the cement floor. Fake knotty pine paneling on two walls. A pair of small, grimy, shrub-choked windows hugging the ceiling that let in neither air nor light. An ancient, slightly musty pull-out couch on which all three of them slept.

True, Joey had grumbled a bit at first when his wife so generously offered his refuge to Violet when her life took yet another in a very long, very boring series of tumbles. But he was a good man, that Joey, the best in his price range, so he’d come around. Sometimes he even took Violet’s two with his three to McDonald’s or someplace, just so both women could catch their breaths for an hour or so.

Mitch had been like that, too, once upon a time.

Ignoring the temptation to wallow, Violet tucked both boys into bed like a normal mother, blinking away the tears pooling in the corners of her eyes. At times like this, all she wanted was to reverse the clock, to return to that brief period of her life when things actually made sense, when she knew she was loved.

Or at least believed she was.

Especially the weeks leading up to Mitch’s vanishing act, so she could study them, dissect them, figure out what had gone wrong. Because that’s what bugged her the most, that unanswered “Why?” The letters, filled with apologies without explanations (what the hell was she supposed to do with those?), weren’t helping, either.

Upstairs, Betsy’s boys went for each others’ throats, as usual. Joey worked second shift at a nearby machine factory—he wouldn’t be home before midnight. Violet’s kids, however, were nearly out before she doused the light, leaving only the night-light on so a sleepy boy wouldn’t break his neck tripping over forsaken skateboards and soccer shoes and badminton sets if he needed to go potty. They could sleep through anything, thank God. Unlike her, Violet thought wearily as she glanced up at the vibrating ceiling, thinking, For cripes’ sake, Betsy, put your kids to bed.

Overhead, something crashed; Betsy started yelling; somebody burst into loud tears.

That’s it, I’m outta here, Violet thought, dragging her old down coat on over her bathwater-splotched sweats. Not that she could actually leave, but even standing outside in twenty-degree weather was preferable to grinding her teeth for the next two hours until, one by one, her friend’s children passed out.

From the closet-size living room, she could see Betsy’s short, gelled, multitoned hair poking out over the top of the sofa, like a spooked tortoiseshell cat. “CSI’s on,” she yelled as Violet passed, cramming her own insane hair into the first hat she could find, a SpongeBob deal she’d given George for Christmas. Under normal circumstances, Violet loved CSI, in all its permutations. Tonight, however, she was feeling anything but normal.

“Thanks, I think I need to get some air,” she said, yanking open the door.

“You’re not leaving the kids with me?” Betsy called out over the shrieks of her youngest, a two-year-old who communicated mostly through punching and screaming.

“Of course not, Bets, I’m just right here in the yard.”

“You get the letter?”

Violet turned, eyeing the plain white envelope on the entryway table, addressed in Mitch’s microscopic print. She picked it up, shoved it into her coat pocket. “Yeah, got it.”

The front door shut on the chaos inside, Violet inhaled deeply, savoring the cold, sweet air against her skin, the relative silence soothing both her eardrums and her tender, shattered soul. She wavered for a moment, then dug the letter out of her coat pocket, yanking off her mitten with her teeth to rip open the envelope. Like all the others, it only took a second to read, the usual warp and weft of apologies and vague promises, fringed with a plea for forgiveness.

Eyes burning, she crumpled it up, the sharp edges pricking her lips when she pressed it to her mouth.

He’d sent money for the boys from the beginning, not regularly, but when he could. If he said anything at all, it rarely went beyond, “I’m okay, hope you and the boys are okay, too.” The actual letters, though, hadn’t started until after the divorce a year ago, when Betsy had finally convinced Violet she’d be better off financially as an official single mom. As much as it hurt, she’d taken Mitch’s not contesting the divorce as a sign that that chapter of her life was indeed over and done with. That there wasn’t enough love and patience in the world to fix whatever had gone wrong between them.

Except no sooner had the hole in her heart begun to close up than the letters started coming, from a P.O. Box in Buffalo. At first, only with the monthly money order for the boys. Then every other week. Now almost weekly, even though he never called, not even to talk to the boys, even though he swore he loved them—that he still loved her—in every letter.

The hardest part was writing back. Not knowing what to say, other than to thank him for the money, his concern, letting him know what the boys were up to. Not knowing what she was supposed to feel, other than hugely conflicted. What do you say to a man who saved you from a living hell, only to ten years later plunge you right back into another one?

A hot tear streaked down Violet’s cheek as she planted her butt on Betsy’s front porch steps to glower at the front yard, nearly bald save for the occasional patch of leftover, dully glistening snow. The tear track instantly froze; Violet wiped it away with the mitten, then stuffed her freezing hand back into it, giving in to a wave of self-pity she’d kept barely contained for months.

At the lowest point of her life, Mitch had been as close to a knight in shining armor as someone like her was ever going to get. But white knights aren’t supposed to bail when things get tough, when kids get sick and cry all night, or a half-dozen things break at once and have to be fixed.

Nor were they supposed to dangle half promises in front of you, making you want to believe in second chances, that the past two years had only been another in series of bad dreams.

I know I screwed up, Vi. And I’m working on fixing that…

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Violet muttered, cramming the letter back into her coat pocket. She shivered, her breath clouding her vision the same way this newest setback was clearly clouding her good sense. She didn’t need no steenkin’ white knight, from the past or otherwise, she needed a plan. Something to keep her moving forward instead of constantly glancing over her shoulder at the what-might-have-beens. Elbows planted on her knees, she breathed into her mittened palms, warming her face, rallying the weary, mutinous tatters of her resolve.

Because, dammit, was she simply going to curl up in defeat, or take charge of her own destiny? Was she going to sit on her fanny for the next thirty years boo-hooing into her Diet Pepsi about the dearth of white knights in the area, or was she going to get up off that fanny and go make her own opportunity?

The possible solution poked at her, carefully, cringing in anticipated rejection. And indeed, No way was Violet’s first, immediate reaction to the absurd suggestion. Except the idea poked again, more insistently this time, demanding she look it full in the face instead of automatically dismissing it out of hand.

So she did, partly to shut it up, partly because it wasn’t like there were any other ideas around, begging for an audience. And after she’d listened with an open mind, and considered the pros and cons, she finally conceded that—as a temporary measure only, just until she figured out her next step—it might work.

The issue barely settled in her mind, a white Bronco, ghostlike in the halogen glow of the streetlamp, turned the corner and rumbled down the street, pulling up in front of Betsy’s house.

And when Rudy Vaccaro got out, he of the square jaw and solid everything and searing blue eyes that saw far more than Violet probably wanted him to, she glanced up at the sin-black sky, studded with a million trillion suns, and thought, This is a joke, right?

If it hadn’t been for the streetlamp setting on fire the wisps of orange sticking out from underneath that silly hat, Rudy would have never recognized her. As Violet, as a woman, even—sad to say—as a human being. Since, unfortunately, in that puffy pink coat she looked like one of those awful coconut-covered marshmallow things his mother used to occasionally stick in their lunch boxes when she hadn’t had time to bake.

She stood as he approached, her expression uncertain. But only for a moment. Because almost instantly her gaze turned direct, purposeful, as though she’d tracked him down, not the other way around. Interesting.

“I asked Darla where you lived,” Rudy said, preempting.

“Because…?”

“Because you left before you got your tip.”

“I never actually served you, as I recall.”

“Technicality,” he said.

“I see. Well, then…” Unsmiling, she stuck out her hand.

Half amused, half unnerved, Rudy dug his wallet out of his back pocket, concentrating on fishing out a bill as he closed the gap between them. When he laid the bill in her mittened hand, however, he caught the smudged streaks on her cheeks. Despite the bitter cold, everything inside him melted.

She glanced up, surprised. Pleased. Clearly not in a position to protest his generosity. “Thanks,” she said, pocketing the twenty. “So. Was that it?”

Rudy crammed his own hands in his pockets, his ears fast-freezing by the second, even as he had this weird thought about how she was somehow like the house, neglected and closed up for far too long, her true potential hidden under umpteen layers of bad history. “Actually, no. I…we need to talk. About the inn.”

An odd mix of hurt, despair and determination flickered in her eyes. “Oh?”

“Yeah. Look, Darla told me you’d expected to get it, and…” A breeze nudged inside his jacket, salsa’d down his spine. “Is there someplace we can go? To talk? Someplace warm?”

“I can’t leave the boys,” Violet said, glancing back at the house. From inside, he heard a woman yell. Her gaze returned to his, eerily silver in the half-light. “They’re asleep.” Don’t ask, her eyes said.

“Can we at least go inside?” She shook her head. “My car, then.”

“Oh, right. Like I’m gonna get into a car with a complete stranger?”

“Dammit, Violet—I feel like crap about what happened, okay? All I want is a chance to at least try to make amends. But I’d rather not freeze my nuts off while I’m doing that, if it’s all the same to you.”

“Amends?” A wary curiosity flickered in her eyes. “Like how?”

“Like a job offer. Sort of. And a place to live.”

At her intake of breath, he moved in for the kill. “The car’s at least got a heater. And hot chocolate.”

“Hot chocolate?”

“I passed a Dunkin’ Donuts on the way over.” He shrugged. “I took a chance.” When her gaze drifted over to the car, he said, gently, “I was a cop. A good cop. I swear, you’re safe with me.”

He thought he might have seen one corner of her mouth twitch. “I only have your word on that, you know.”

Rudy flipped up his collar. His thighs were stinging, his butt was going numb and he didn’t even want to think about what was happening to other parts of his anatomy. “Okay, so yeah, for all you know I could be some raving weirdo. Actually my kid probably thinks I am, dragging her up here to live and everything. But that’s beside the point.”

He bent slightly to see her face, pretty and soft and round and pinked with the cold. Like one of those old porcelain-headed dolls his mother liked to collect. “So why don’t you go tell your friend inside to keep an eye out, and we’ll stay right where you can see the house.”

“I don’t know…”

“Violet. Please. Let me at least try to make this right, okay?”

She wavered for another several seconds before, with a sharp nod, she skipped up the porch stairs, opened the door and spoke to whoever was inside, then marched back down the walk, her coat swishing slightly in the still night air.

“This had better be some damn good hot chocolate,” she muttered as he opened the door for her.

Chapter Three

In the grand scheme of things, Violet mused as she sipped the hot chocolate, did it really matter who came up with the idea first? Because sometimes there was a fine line between forging your own destiny and begging. Between determination and desperation.

So all in all, she decided, sitting in Rudy’s nice warm car, the cozy throw he’d had dug out of the backseat snuggled around her thighs, the scent of big strong man mingling with the sweet, warm breath of the chocolate, things were probably working out better than she could have hoped.

“Better” definitely being a relative term. Because she felt a little how Moses’s mother must’ve felt after she’d hidden her baby in the rushes so Pharoah’s daughter would find him, then going and offering herself as a wet nurse. Yeah, she’d been able to stay with her baby, which was some consolation, but he was no longer really hers, was he? A temporary arrangement was all it had been.

Not that the house had ever been hers, Violet reminded herself. But in her heart, it was the same thing. She pressed her lips together, staring into the dark, jittery liquid. “Let me get this straight—you want me and the boys to come live in the house—”

“Well, in the apartment over the garage, if that’s okay. But yes.”

Violet chewed the inside of her cheek to keep the flutter of excitement leashed. It was Violet herself who’d convinced Doris to renovate the space a few years ago, for families who might prefer a self-contained area with its own kitchen to staying in the bed-and-breakfast proper. The apartment wasn’t big, only one bedroom, but flooded with light in the winter, tenderly shaded by a dozen trees in the summer. And the sofa bed didn’t smell like old gym socks.

A dream she’d given up, twice, now hovered again in front of her, a firefly begging for capture—

Stop it, she told herself. Don’t you dare let yourself get caught up again in something that never existed except in your own head.

“And in exchange,” she said, not looking at him, not showing her hand, “you want me to help you put the inn back in order?”

“And then stay on as breakfast cook after we’re up and running again. Like you did for Doris.” She could feel his gaze on the side of her face, earnest and warm. Another man hell-bent on rescuing her. “I can’t pay you much to start, but at least all your living expenses would be covered.” He paused. “And if you wanted to work part-time somewhere else and needed to leave the boys…I suppose we could work something out about that, too.”

Violet’s eyes shot to his. Having no idea about his renovation plans, she’d only planned on asking for the cook’s job. Funny, she mused, doing her best to keep from slipping into that open, steady gaze, how guilt so often motivated the innocent far more than it ever did the guilty.

“Wow,” she said, looking away again. “That’s really generous.”

“Not a bit of it. You’d be doing me a huge favor. Because I’d have to hire someone eventually, anyway,” he said to her slight frown. “So who better than someone who already knew the drill?”

Another sip of hot chocolate was in order while she pretended to think. Rudy apparently took her hesitation for bitterness. With good reason.

“Violet,” he said in that gruff-soft way of his that would be her undoing if she wasn’t careful. If he wasn’t. Two years without a man’s touch is a long time. Becoming a nun, she thought ruefully, had never been on the short list. Yet another reason why she hadn’t exactly immediately embraced the idea. Because hanging around Rudy Vaccaro…

Yeah, she needed that aggravation like a hole in the head.

“I know this isn’t what you’d hoped for,” he was saying, “but I can’t undo what’s done. Or give you the place just because—”

“Of course you can’t give me the house!” she said, startled that he’d even think such a thing. “Yes, I’m disappointed, but I’m not delusional!” She already knew he’d bought the house outright. Which made him borderline insane as well as impossibly generous. Another strike against him. “The house is yours, fair and square. I mean, if there’s no will, there’s no will, right?”

He looked at her again, oozing concern and macho protectiveness, and she wanted to say, Quit it, will ya? because her body and her emotions and her head were on three different pages, which was not good.

“So Doris did tell you she was leaving it to you?”

Violet nodded. “A month before she died, maybe, she swore she was going to put it in writing, so there’d be no question. I knew Doris ever since I was little, I usedta work there during the summers when I was a teenager. I’d—” Her words caught in her throat. “I’d never known her to break a promise before.”

But then, her life was a junkyard of broken promises, wasn’t it?

“And you never had a chance to search the house?”

Violet looked right into those night-darkened eyes and half wanted to smack him one. “Jeez, what is it with you? I would think finding that will would be the last thing you’d want.”

“So maybe I’m just making sure I’ve got nothing to worry about.”

After a moment, she averted her gaze. “Not too long before Doris passed, her daughter Patty came up here from Boston and strong-armed the old girl into a nursing home. And of course, the minute Doris was out, so were the boys and me. A week later, the house went up for sale. I’m guessing Patty got power of attorney or whatever.”

“So when the old lady died, everything went to Patty.”

“Exactly. And obviously she wasn’t about to let me in to go looking for a will she’d hardly want me to find.”

“If there was one.”

Violet hesitated, then lifted the cup to her lips again. “If there was one,” she echoed over the stab of betrayal.

One wrist propped on the steering wheel, Rudy leaned back in his seat, momentarily unable to look at the tough little cookie sitting beside him. He suspected, though, that it wouldn’t take much to rip away the calluses buffering her flat, resigned words. He didn’t doubt her story for a minute—this was no con artist sitting beside him. But realizing his dream at the expense of somebody else’s had never been part of the plan.

He looked at her profile, all those crazy curls now free of the hat, and felt pulled apart by a weird combination of protectiveness and frustration. “I know I’m a stranger to you, but trust me, Violet—I don’t get my kicks from putting women and children out on the street.”

She stared straight ahead for several seconds before she said, “First off, I’m not out on the street. And anyway, it wasn’t your fault. You didn’t know.”

“No consolation to you, I’m sure.”

“No, but…” Her lips pursed, she swished the hot chocolate around in the cup. “Look, I’m sorry for reacting the way I did tonight. At the diner. You’re right, none of this is your fault, and it was pretty poor of me to take out my frustrations on you.”

“Forget it, no apology necessary.” He fisted his free hand to keep from touching her—taking her hand, squeezing her shoulder. Something. Anything. “I understand your husband left you and the boys?”

“Yeah,” she said after a moment. “He did. We’ve been divorced for a year. But since I’m not a big fan of being pitied—”

“Then there’s nothing to worry about here. Pity’s for the pathetic, Violet. People who make poor choices because they’re too dumb to see the pitfalls.”

“And how do you know that’s not the case here?”

One side of his mouth lifted. “Okay, so how about we agree that any decision made before we’re twenty-one doesn’t count?”

Her soft, half laugh died a quick death. “Oh. I take it—”

“Yep. Me, too.” Rudy let out a long, weighty sigh. “That bundle of attitude you saw me with tonight? It’s just been her and me since she was six months old. I only know her mother’s still alive because I run a periodic check to find out. Whether she knows—or even cares—if Stace and I are, I have no idea. So…what I’m seeing on your face right now? Is that pity? Or simpatico?”

“It’s amazement. That any woman could be that stupid.”

“You don’t know me, Violet.”

“I know enough. In the space of a cuppla hours, you stood up for a stranger in public, gave that stranger a twenty-dollar tip, brought her hot chocolate and offered her a job and place to live. Any woman who tosses out somebody like that…” She shook her head. “Stoo-pid.”

“Yeah, except she wasn’t a woman, she was a kid. We both were. I was twenty, she was eighteen. Too young.”

“Says who?” Violet said, a dark flush tingeing her cheeks. “I was eighteen when George came along, and I sure as hell didn’t bail on him. Unlike Mitch, who after eight years and two kids decided…whatever it was he decided. That he wasn’t cut out for family life, I suppose. Unfortunately he came to that conclusion the week before Christmas. Two years ago.” She smirked. “There was a fun holiday, let me tell you. Nothing says lovin’ like a note and a couple hundred bucks left on the kitchen table. Although we—or at least, I—still hear from him.”

Something in her voice—like a faint, bitter aftertaste you can’t quite identify—put Rudy on alert. He also decided he liked her much better mad than sad. Or, worse, in that dead zone where you try to make everybody think you’re okay. Mad, though…he could work with that. Because where there was anger, there was hope.

“He sees the boys?”

Curls quivered when she shook her head. “Although he says…he’s working up to it.”

“What on earth—”

“He says he’s figuring things out,” she said wearily. “In his head.”

“As in, a possible reconciliation?”

“Who the hell knows?” She rubbed her forehead. “Although, believe me, I’m not holding my breath. Promises…” Her mouth flattened. “Anybody can make a promise. Keeping it is something else entirely.”

As Rudy fought the temptation to ask her if she wanted a reconciliation, he realized, too late, that he’d inadvertently stripped away those calluses, leaving her tender and vulnerable and probably mad as hell at him. Feeling like an idiot, he touched her arm, making her jump.

“Hey,” he said, his voice thick. “You okay?”

“Yeah. Yeah, I’m…” She sucked in a breath, shaking her head. “Here’s the thing—you can chug along for years, getting by, making do, on whatever scraps you can piece together. You learn to find contentment, even joy, in the small stuff, like your baby’s smile or a new lipstick. Hanging out with friends on the first really warm spring night. And little by little, you start to inch forward. Or at least, you think you are. Sure, life slings mud at you, but you either wipe it off or you get real good at ducking. Only then…”

One hand waved, like she was struggling for the words. “Only then, out of the blue, some totally unexpected opportunity comes along, and suddenly you’re thinking in terms of bigger. Better. More.”

She looked away, but not before he saw her eyes fill. “I know,” he said softly, and she blew up on him.

“You don’t know! You don’t know anything about it, or me, or what that sorry, run-down place represented! Not just to me, but to Doris, who loved that house like it was her child. Who thought of her guests like family, because they made her feel needed. Important. Like she mattered.”

Blinking, she faced front. “I never expected Doris to offer me the house. I always assumed it would go to her daughter. So when she said she wanted to leave it to me, you have no idea how…honored that made me feel. That she trusted me to make the most of her gift. I had such plans, Rudy,” she said softly. “Such wonderful plans.”

Frowning, Rudy tucked his sleeve into his palm and brushed her cheek, blotting a tear that had spilled over, her frustration mingling with his. “But even if Doris had left you the house, how would you have managed? You couldn’t really open it again, not yet. It needs too much work.”

She frowned at that last little bit of hot—now cold, probably—chocolate in the bottom of her cup, then swirled it around and drank it anyway, grimacing. “I was going to sell it, Rudy,” she said flatly, not looking at him. “Sell it and get the hell out of here, finish my education. Set aside a college fund for the boys. Buy a car with less than 150,000 miles on it. Doris and I used to talk about it all the time. That’s why I know she’d wanted me to have the house, to give me a shot at my dream, the same way the house had allowed her to live hers.”

If nothing else, all those years of being a cop had taught Rudy a thing or two about reading people, about picking up clues from their body language, how most people’s voices change when they’re not being straight with you. And right now, Violet Kildare was setting off alarms loud enough to hear in China.

“So,” he said, casually, “you never actually wanted to run the inn?”

“Run the inn?” She burst out laughing. “Heavens no! Believe me, my aspirations, such as they were, never included turning into Doris Hicks’s clone.”

“Oh. Well. I guess I must’ve misunderstood, then.” He squinted over at her. “Darla seemed to think you had a real thing for the house itself.”

Even in the darkened car, he saw her blush. “The house was only a means to an end,” she said into her empty cup, then slid her eyes to his, her lips barely curved. “It’s getting late. I need to get back before Betsy freaks.”

Rudy let their gazes mingle. “That mean you’re not accepting my offer?”

She tapped the cup’s rim once, twice, then leaned over to screw it into the cup holder under the radio. “Can I think about it for a couple of days? Until school starts again, day after tomorrow?”

Rudy started. “Day after tomorrow…? I thought school started on Monday?”

“Uh, no, since yesterday was New Year’s? As it is the only reason they don’t start back tomorrow is because of some in-service day or something.”

Oh, crap. That should go over big with a certain party. Why had he assumed he’d have at least a week before they had to deal with that particular trauma? “Yeah, sure,” he said over the Good going, Dad reverberating through his brain. “Since I imagine it’ll be a day or so before we have heat and utilities, anyway. Here.” He reached for his wallet again, extracting one of his old cards. For a second, he stared at the tiny, grainy photo of him in uniform, then handed her the card. “My cell number’s on there, in case you need it.”

Nodding, she took the card. “I’ll let you know, then.” She pushed open the door and climbed out, then looked back, obviously relieved that that was over. “Thanks again for the tip,” she said, her breath a cloud around her face, then disappeared.

“So what was that all about?” Bets asked the minute Violet walked back inside. The noise level had dropped dramatically in the past half hour, thanks to two-thirds of Betsy’s spawn being down for the count. Only little Trey was still awake, cuddled next to his mother in a new-two-brothers-ago blanket sleeper, thumb plugged in mouth as they finished up CSI. Quiet and immobile, the kid was actually cute.

Like most of Mulligan Falls’s residents, Bets already knew about Rudy being the inn’s new owner. If you wanted to keep your business private, hiring Linda Fairweather as your Realtor was a bad idea. That’s how Violet knew about Rudy’s paying cash for the inn. And that he’d bought it sight unseen. Nice guy, but definitely certifiable.

Wriggling out of her coat, Violet sat on the edge of Joey’s recliner, trying not to touch the upholstery with actual skin. Betsy wasn’t a horrible housekeeper, but the chair had weathered the five kids in Betsy’s family as well as her three. Not that Violet’s were neat freaks, God knew, but her friend’s boys truly saw the world as their canvas.

“Rudy offered me my old job,” she said, trying to finger comb her tangled curls. “When the inn’s ready to open again, I mean. Apparently he’s going to completely refurbish it. Until then, if I want, I could help with the rehab.” Intent on catching the end of her program, Betsy was only half listening. “He also said the apartment over the garage is ours, if I want it.”

At that, her friend’s head whipped around, plucked eyebrows arching up underneath spidery bangs. “You gonna take it?”

“I told him I’d think about it.” After several seconds of the Golden-Eyed Stare for which her friend was famous, Violet said, “You’ll have your house back in a couple of days.”

“Did I say anything?” Betsy said, one hand pressed to a chest that had once provoked envy in every girl in junior high and wistful lust in every boy. “Have I ever complained about you guys being here, even once? And if this doesn’t work out, you know you’re welcome to come back, anytime. For as long as you need.”

Translation: Betsy was going to miss the hundred fifty bucks a month Violet had been giving her toward the utilities and “wear-and-tear,” as she put it.

But Violet only reached over and squeezed her friend’s hand. “Really, I don’t know how I would have made it through these last six months without you.” Because, if nothing else, Bets had given them a roof over their heads and something at least remotely resembling stability. Nothing to be sneezed at.

The credits came on, scrolling lickety-split over the promo for the next program. Noting that Trey had at last conked out, too, Betsy stabbed the remote, then shifted on the sofa, the baby’s head on her lap. A wicked grin stole across a living advertisement for twelve-hour lip gloss. Really, you could shellac floors with that stuff.

“I got a glimpse of that Rudy fella out the window,” Betsy said in a low voice. “He as good-looking up close as he is from a distance?”

Yeah, she’d known this was coming. Joey, God bless him, was more the teddy bear type—long armed, pudgy and slightly shaggy. Violet shrugged, thoughts of Rudy’s distinct lack of pudge setting off a few all-too-familiar tingles in several far-too-neglected places. “I s’pose. He’s no pretty boy, though. Everything’s where it should be, but nothing out of the ordinary.” Except the eyes, she thought, their laser brilliance burned into her brain. Betcha those eyes could get some women to do just about anything. “A big guy. Useta be a cop. In Springfield.”

“Mass?”

“Yeah.”

“A flatlander, huh?” Bets said, head propped in palm, still grinning, her other hand absently stroking little Trey’s damp hair back from his forehead as he slept. “So what made him chuck it all to move up here to Boonieville?”

“I have no idea,” Violet said, wobbling a little when she got to her feet. “But I’ll betcha dollars to doughnuts, he doesn’t stay.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Because they never do,” Violet said simply.

“You did what?” Stacey shrilled a scant yard from Rudy’s ear two days later, on their first drive to her new school. And yeah, she’d definitely been pissed when she’d found out it started today, until Rudy pointed out that at least going to school got her out of wallpaper stripping detail.

Although bitterly cold, the morning was nothing short of spectacular. Cloudless, picture-puzzle blue sky. Sun streaming through bare-branched trees. Glittering patches of snow. Perfect. The juice was back on, heating oil was being delivered that afternoon, the phone people were promising tomorrow between one and five, and the Dumpster—delivered yesterday—was rapidly filling up with shreds of linoleum and dreary carpet and basically anything receiving at least two “Gross!” votes.

Violet hadn’t contacted him—yet—but she’d said not before today, anyway, so he was hopeful on that front.

Okay, maybe hopeful wasn’t exactly the right word. Anxious, maybe.

What the hell, he wasn’t some freaking dictionary. All he knew was, those big gray-green eyes and that pale skin and the way she smelled and her obviously bruised emotions were doing a real number on his head. If she said “yes” things were liable to get a lot more complicated than he needed right now.

Because, frankly, after sitting with her in his car the other night…well, Rudy wasn’t sure how much longer he was going to be able to forgo female companionship. The kind of female companionship that some people—his eyes cut to his glowering daughter—might take exception to. But you know what? He’d cross that bridge when—and if—he came to it. For the first time since he could remember, more things were going his way than not, leaving him pretty much in a “bring it on” kind of mood.

Which is why, since he figured his daughter would appreciate a heads-up, he’d finally told Stace about his offering Violet the job. And the apartment. If she didn’t accept, it was no big deal. Right?

“Unknot your panties, Stace,” Rudy said mildly, his breath catching at the flash of red out of the corner of his eye, a cardinal and his wife out for breakfast. “This has nothing to do with your life.”

“How can you say that?” she said, appalled, and Rudy belatedly remembered that the life-impact Richter scale for teenagers (which his daughter was, in spirit if not yet in years) was a hundred times more sensitive than it was for other humans. “I mean, it’s bad enough we had to move here in the middle of the freaking winter—”