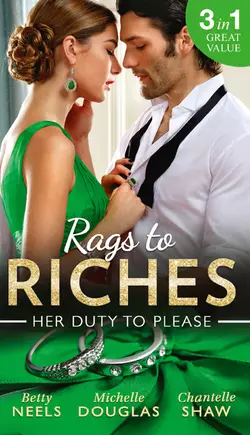

Rags To Riches: Her Duty To Please: Nanny by Chance / The Nanny Who Saved Christmas / Behind the Castello Doors

Betty Neels

Chantelle Shaw

Michelle Douglas

NANNY BY CHANCEJust as Araminta Pomfrey was to begin her nurse’s training, her parents volunteered her as a nanny to Dr. Marcus van der Breugh’s twin nephews. Outraged, Araminta decided to personally inform Marcus she would not do it. But after meeting him—and learning that she could help and be a student at his hospital—she changed her mind. Perhaps nursing wasn’t really what she wanted to do…THE NANNY WHO SAVED CHRISTMASThis Christmas, Nicola McGillroy will:1. Be a great nanny to Cade Hindmarsh’s two adorable little girls, and give them the best Christmas they've had since their mother left.2. Enter into the Christmas spirit and forget the fact she should have been planning her own wedding right now.3. Keep a straight head in her attraction to her gorgeous off-limits boss… Surely this is just a rebound thing and not true love—for both of them?BEHIND THE CASTELLO DOORSCesario Piras, brooding master of the Castello del Falco wasn’t prepared for the visitor that turned up on his doorstep during a raging storm – or with a little bundle bearing the Piras name she has in tow. Cesario’s head screamed run, but his damaged heart began to betray him.Beth Granger knew that the moment she knocked on the castle door that there was no going back. She had a job to do, but the moment Cesario looked deep into her pleading eyes her faultless plan crumbled around her…

Rags to Riches: Her Duty to Please

Nanny by Chance

Betty Neels

The Nanny Who Saved Christmas

Michelle Douglas

Behind the Castello Doors

Chantelle Shaw

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#uc5b492b0-574a-5b1a-b96a-93051284ce71)

Title Page (#uc60bfc5b-446e-54eb-bcb0-ef66c3c8152b)

Nanny by Chance (#u10ea0ef0-28ef-5695-ad6d-e9a3bad7b126)

About the Author (#u8f7bdf0b-addb-5b7d-b68a-7172ce163282)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_e77df400-3cbd-5fd4-8958-70efa7ae8c4f)

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_4e915af6-6497-5241-8b20-a24ed5dc8440)

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_bc5ac731-a7cd-55fe-a571-eaabeae23ea0)

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_2ba276a8-4a44-5258-8e66-ff39590d42c1)

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_5dedb860-2f0a-5c72-b55e-c578e2ee0498)

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_d56dcf3d-6e88-56f5-b4af-93529bc30158)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_6f20ef8d-b2fb-56f5-a8cd-79bcc6299535)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

The Nanny Who Saved Christmas (#litres_trial_promo)

Back Cover Text (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Behind the Castello Doors (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Nanny by Chance (#u2147d37a-02d5-5e60-8e30-52c0ddd5f88f)

Betty Neels

Romance readers around the world were sad to note the passing of BETTY NEELS in June 2001. Her career spanned thirty years, and she continued to write into her ninetieth year. To her millions of fans, Betty epitomised the romance writer, and yet she began writing almost by accident. She had retired from nursing, but her inquiring mind still sought stimulation. Her new career was born when she heard a lady in her local library bemoaning the lack of good romance novels. Betty’s first book, Sister Peters in Amsterdam, was published in 1969, and she eventually completed 134 books. Her novels offer a reassuring warmth that was very much a part of her own personality, and her spirit and genuine talent live on in all her stories.

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_334f5ceb-f272-58e5-bb81-7d252776377b)

ARAMINTA POMFREY, a basket of groceries over one arm, walked unhurriedly along the brick path to the back door, humming as she went. She was, after all, on holiday, and the morning was fine, the autumn haze slowly lifting to promise a pleasant September day—the first of the days ahead of doing nothing much until she took up her new job.

She paused at the door to scratch the head of the elderly, rather battered cat sitting there. An old warrior if ever there was one, with the inappropriate name of Cherub. He went in with her, following her down the short passage and into the kitchen, where she put her basket on the table, offered him milk and then, still humming, went across the narrow hall to the sitting room.

Her mother and father would be there, waiting for her to return from the village shop so that they might have coffee together. The only child of elderly parents, she had known from an early age that although they loved her dearly, her unexpected late arrival had upset their established way of life. They were clever, both authorities on ancient Celtic history, and had published books on the subject—triumphs of knowledge even if they didn’t do much to boost their finances.

Not that either of them cared about that. Her father had a small private income, which allowed them to live precariously in the small house his father had left him, and they had sent Araminta to a good school, confident that she would follow in their footsteps and become a literary genius of some sort. She had done her best, but the handful of qualifications she had managed to get had been a disappointment to them, so that when she had told them that she would like to take up some form of nursing, they had agreed with relief.

There had been no question of her leaving home and training at some big hospital; her parents, their heads in Celtic clouds, had no time for household chores or cooking. The elderly woman who had coped while Araminta was at school had been given her notice and Araminta took over the housekeeping while going each day to a children’s convalescent home at the other end of the village. It hadn’t been quite what she had hoped for, but it had been a start.

And now, five years later, fate had smiled kindly upon her. An elderly cousin, recently widowed, was coming to run the house for her mother and father and Araminta was free to start a proper training. And about time too, she had reflected, though probably she would be considered too old to start training at twenty-three. But her luck had held; in two weeks’ time she was to start as a student nurse at a London teaching hospital.

Someone was with her parents. She opened the door and took a look. Dr Jenkell, a family friend as well as their doctor for many years.

She bade him good morning and added, ‘I’ll fetch the coffee.’ She smiled at her mother and went back to the kitchen, to return presently with a tray laden with cups and saucers, the coffeepot and a plate of biscuits.

‘Dr Jenkell has some splendid news for you, Araminta,’ said her mother. ‘Not too much milk, dear.’ She took the cup Araminta offered her and sat back, looking pleased about something.

Araminta handed out coffee and biscuits. She said, ‘Oh?’ in a polite voice, drank some coffee and then, since the doctor was looking at her, added, ‘Is it something very exciting?’

Dr Jenkell wiped some coffee from his drooping moustache. ‘I have a job for you, my dear. A splendid opportunity. Two small boys who are to go and live for a short time with their uncle in Holland while their parents are abroad. You have had a good deal of experience dealing with the young and I hear glowing accounts of you at the children’s home. I was able to recommend you with complete sincerity.’

Araminta drew a steadying breath. ‘I’ve been taken as a student nurse at St Jules’. I start in two weeks’ time.’ She added, ‘I told you and you gave me a reference.’

Dr Jenkell waved a dismissive hand. ‘That’s easily arranged. All you need to do is to write and say that you are unable to start training for the time being. A month or so makes no difference.’

‘It does to me,’ said Araminta. ‘I’m twenty-three, and if I don’t start my training now I’ll be too old.’ She refilled his coffee cup with a steady hand. ‘It’s very kind of you, and I do appreciate it, but it means a lot to me—training for something I really want to do.’

She glanced at her mother and father and the euphoria of the morning ebbed way; they so obviously sided with Dr Jenkell.

‘Of course you must take this post Dr Jenkell has so kindly arranged for you,’ said her mother. ‘Indeed, you cannot refuse, for I understand that he has already promised that you will do so. As for your training, a few months here or there will make no difference at all. You have all your life before you.’

‘You accepted this job for me without telling me?’ asked Araminta of the doctor.

Her father spoke then. ‘You were not here when the offer was made. Your mother and I agreed that it was a splendid opportunity for you to see something of the world and agreed on your behalf. We acted in your best interests, my dear.’

I’m a grown woman, thought Araminta wildly, and I’m being treated like a child, a mid-Victorian child at that, meekly accepting what her elders and betters have decided was best for her. Well, I won’t, she reflected, looking at the three elderly faces in turn.

‘I think that, if you don’t mind, Dr Jenkell, I’ll go and see this uncle.’

Dr Jenkell beamed at her. ‘That’s right, my dear—get some idea of what is expected of you. You’ll find him very sympathetic to any adjustments you may have in mind.’

Araminta thought this unlikely, but she wasn’t going to say so. She loved her parents and they loved her, although she suspected that they had never quite got over the surprise of her arrival in their early middle age. She wasn’t going to upset them now; she would see this man, explain why she couldn’t accept the job and then think of some way of telling her parents which wouldn’t worry them. Dr Jenkell might be annoyed; she would think about that later.

Presently the doctor left and she collected the coffee cups and went along to the kitchen to unpack her shopping and prepare the lunch, leaving her mother and father deep in a discussion of the book of Celtic history they were writing together. They hadn’t exactly forgotten her. The small matter of her future having been comfortably settled, they felt free to return to their abiding interest…

As she prepared the lunch, Araminta laid her plans. Dr Jenkell had given her the uncle’s address, and unless he’d seen fit to tell the man that she intended visiting him she would take him by surprise, explain that she wasn’t free to take the job and that would be that. There was nothing like striking while the iron was hot. It would be an easy enough journey; Hambledon was barely three miles from Henley-on-Thames and she could be in London in no time at all. She would go the very next day…

Her mother, apprised of her intention, made no objection. Indeed, she was approving. ‘As long as you leave something ready for our lunch, Araminta. You know how impatient your father is if he has to wait for a meal, and if I’m occupied…’

Araminta promised cold meat and a salad and went to her room to brood over her wardrobe. It was early autumn. Too late in the year for a summer outfit and too warm still for her good jacket and skirt. It would have to be the jersey two-piece with the corn silk tee shirt.

Her mother, an old-fashioned woman in many respects, considered it ladylike, which it was. It also did nothing for Araminta, who was a girl with no looks worth glancing at twice. She had mousy hair, long and fine, worn in an untidy pile on top of her head, an unremarkable face—except for large, thickly fringed hazel eyes—and a nicely rounded person, largely unnoticed since her clothes had always been chosen with an eye to their suitability.

They were always in sensible colours, in fabrics not easily spoilt by small sticky fingers which would go to the cleaners or the washing machine time and time again. She studied her reflection in the looking glass and sighed over her small sharp nose and wide mouth. She had a lovely smile, but since she had no reason to smile at her own face she was unaware of that.

Not that that mattered; this uncle would probably be a prosey old bachelor, and, since he was a friend of Dr Jenkell, of a similar age.

She was up early the following morning to take tea to her parents, give Cherub his breakfast and tidy the house, put lunch ready and then catch the bus to Henley.

A little over two hours later she was walking along a narrow street close to Cavendish Square. It was very quiet, with tall Regency houses on either side of it, their paintwork pristine, brass doorknockers gleaming. Whoever uncle was, reflected Araminta, he had done well for himself.

The house she was looking for was at the end of the terrace, with an alley beside it leading to mews behind the houses. Delightful, reflected Araminta, and she banged the knocker.

The man who answered the door was short and thin with sandy hair, small dark eyes and a very sharp nose. Just like a rat, thought Araminta, and added, a nice rat, for he had a friendly smile and the little eyes twinkled.

It was only then that she perceived that she should have made an appointment; uncle was probably out on his rounds—did doctors who lived in grand houses have rounds? She didn’t allow herself to be discouraged by the thought.

‘I would like to see Dr van der Breugh. I should have made an appointment but it’s really rather urgent. It concerns his two nephews…’

‘Ah, yes, miss. If you would wait while I see if the doctor is free.’

He led the way down a narrow hall and opened a door. His smile was friendly. ‘I won’t be two ticks,’ he assured her. ‘Make yourself comfortable.’

The moment he had closed the door behind him, she got up from her chair and began a tour of the room. It was at the back of the house and the windows, tall and narrow, overlooked a small walled garden with the mews beyond. It was furnished with a pleasant mixture of antique cabinets, tables and two magnificent sofas on either side of an Adam fireplace. There were easy chairs, too, and a vast mirror over the fireplace. A comfortable room, even if rather grand, and obviously used, for there was a dog basket by one of the windows and a newspaper thrown down on one of the tables.

She studied her person in the mirror, something which brought her no satisfaction. The jersey two-piece, in a sensible brown, did nothing for her, and her hair had become a little ruffled. She poked at it impatiently and then looked round guiltily as the door opened.

‘If you will come this way, miss,’ said the rat-faced man. ‘The boss has got ten minutes to spare.’

Was he the butler? she wondered, following him out of the room. If so, he wasn’t very respectful. Perhaps modern butlers had freedom of speech…

They went back down the hall and he opened a door on the other side of it.

‘Miss Pomfrey,’ he announced, and gave her a friendly shove before shutting the door on her.

It was a fair-sized room, lined with bookshelves, one corner of it taken up by a large desk. The man sitting at it got to his feet as Araminta hesitated, staring at him. This surely couldn’t be uncle. He was a giant of a man with fair hair touched with silver, a handsome man with a high-bridged nose, a thin, firm mouth and a determined chin. He took off the glasses he was wearing and smiled as he came to her and shook hands.

‘Miss Pomfrey? Dr Jenkell told me that you might come and see me. No doubt you would like some details—’

‘Look,’ said Araminta urgently, ‘before you say any more, I’ve come to tell you that I can’t look after your nephews. I’m starting as a student nurse in two weeks’ time. I didn’t know about this job until Dr Jenkell told me. I’m sure he meant it kindly, and my parents thought it was a splendid idea, but they arranged it all while I wasn’t there.’

The doctor pulled up a chair. ‘Do sit down and tell me about it,’ he invited. He had a quiet, rather slow way of speaking, and she felt soothed by it, as was intended.

‘Briskett is bringing us coffee…’

Araminta forgot for the moment why she was there. She felt surprisingly comfortable with the doctor, as though she had known him for years. She said now, ‘Briskett? The little man who answered the door? Is he your butler? He called you “the boss”—I mean, he doesn’t talk like a butler…’

‘He runs the house for me, most efficiently. His rather unusual way of talking is, I fancy, due to his addiction to American films; they represent democracy to him. Every man is an equal. Nevertheless, he is a most trustworthy and hard-working man; I’ve had him for years. He didn’t upset you?’

‘Heavens, no. I liked him. He looks like a friendly rat,’ she explained. ‘Beady eyes, you know, and a sharp nose. He has a lovely smile.’

Briskett came in then, with the coffee tray, which he set down on a small table near Araminta’s chair. ‘You be mother,’ he said, and added, ‘Don’t you forget you’ve to be at the hospital, sir.’

‘Thank you, Briskett, I’ll be leaving very shortly.’

Asked to do so, Araminta poured their coffee. ‘I’m sorry if I’m being inconvenient,’ she said. ‘You see, I thought if you didn’t expect me it would be easier for me to explain and you wouldn’t have time to argue.’

The doctor managed not to smile. He agreed gravely. ‘I quite see that the whole thing is a misunderstanding and I’m sorry you have been vexed.’ He added smoothly, with just a touch of regret allowed to show, ‘You would have done splendidly, I feel sure. They are six years old, the boys, twins and a handful. I must find someone young and patient to cope with them. Their parents—their mother is my sister—are archaeologists and are going to the Middle East for a month or so. It seemed a good idea if the children were to make their home with me while they are away. I leave for Holland in a week’s time, and if I can’t find someone suitable, I’m afraid their mother will have to stay here in England. A pity, but it can’t be helped.’

‘If they went to Holland with you, would they live with you? I mean, don’t you have a wife?’

‘My dear Miss Pomfrey, I am a very busy man. I’ve no time to look for a wife and certainly no time to marry. I have a housekeeper and her husband, both too elderly to cope with small boys. I intend sending them to morning school and shall spend as much time with them as I can, but they will need someone to look after them.’

He put down his coffee cup. ‘I’m sorry you had to come and see me, but I quite understand that you are committed. Though I feel that we should all have got on splendidly together.’

She was being dismissed very nicely. She got up. ‘Yes, I think we would too. I’m sorry. I’ll go—or you’ll be late at the hospital.’

She held out a hand and had it taken in his large, firm clasp. To her utter surprise she heard herself say, ‘If I cancelled my place at the hospital, do you suppose they’d let me apply again? It’s St Jules’…’

‘I have a clinic there. I have no doubt that they would allow that. There is always a shortage of student nurses.’

‘And how long would I be in Holland?’

‘Oh, a month, six weeks—perhaps a little longer. But you mustn’t think of altering your plans just to oblige me, Miss Pomfrey.’

‘I’m not obliging you,’ said Araminta, not beating about the bush. ‘I would like to look after the boys, if you think I’d do.’ She studied his face; he looked grave but friendly. ‘I’ve no idea why I’ve changed my mind,’ she told him, ‘but I’ve waited so long to start my training as a nurse, another month or two really won’t matter.’ She added anxiously, ‘I won’t be too old, will I? To start training…?’

‘I should imagine not. How old are you?’

‘Twenty-three.’

‘You aren’t too old,’ he assured her in a kind voice, ‘and if it will help you at all, I’ll see if I can get you on to the next take-in once you are back in England.’

‘Now that would be kind of you. Will you let me know when you want me and how I’m to get to Holland? I’m going now; you’ll be late and Briskett will hate me.’

He laughed then. ‘Somehow I think not. I’ll be in touch.’

He went into the hall with her and Briskett was there, too.

‘Cutting it fine,’ he observed severely. He opened the door for Araminta. ‘Go carefully,’ he begged her.

Araminta got on a bus for Oxford Street, found a café and over a cup of coffee sorted out her thoughts. That she was doing something exactly opposite to her intentions was a fact which she bypassed for the moment. She had, with a few impulsive words, rearranged her future. A future about which she knew almost nothing, too.

Where exactly was she to go? How much would she be paid? What about free time? The language question? The doctor had mentioned none of these. Moreover, he had accepted her decision without surprise and in a casual manner which, when she thought about it, annoyed her. He should be suitably grateful that she had delayed her plans to accommodate his. She had another cup of coffee and a bun and thought about clothes.

She had a little money of her own. In theory she kept the small salary she had been getting at the convalescent home to spend as she wished, but in practice she used it to bolster up the housekeeping money her father gave her each month.

Neither he nor her mother were interested in how it was spent. The mundane things of life—gas bills, the plumber, the most economical cuts of meat—meant nothing to them; they lived in their own world of the Celts, who, to them at least, were far more important and interesting.

Now she must spend some of her savings on clothes. She wouldn’t need much: a jacket, which would stand up to rain, a skirt and one or two woollies, and shoes—the sensible pair she wore to the convalescent home were shabby. No need for a new dress; she wasn’t likely to go anywhere.

And her parents; someone would have to keep an eye on them if she were to go to Holland in a week’s time and if Aunt Millicent, the elderly cousin, was unable to come earlier than they had arranged. Mrs Snow in the village might oblige for a few days, with basic cooking and cleaning. Really, she thought vexedly, she could make no plans until she heard from Dr van der Breugh.

Her parents received her news with mild interest. Her mother nodded her head in a knowledgeable way and observed that both she and Araminta’s father knew what was best for her and she was bound to enjoy herself, as well as learn something of a foreign land, even if it was only a very small one like Holland. She added that she was sure that Araminta would arrange everything satisfactorily before she went. ‘You’ll like looking after the dear little boys.’

Araminta said that, yes, she expected she would. Probably they were as tiresome and grubby as all small boys, but she was fond of children and had no qualms about the job. She would have even less when she knew more about it.

A state of affairs which was put right the next morning, when she received a letter from Dr van der Breugh. It was a long letter, typed, and couched in businesslike language. She would be called for at her home on the following Sunday at eleven o’clock and would spend a few hours with her charges before travelling to Holland on the night ferry from Harwich. She would be good enough to carry a valid passport and anything she might require overnight. It was hoped that her luggage might be confined to no more than two suitcases.

She would have a day off each week, and every evening after eight o’clock, and such free time during the day as could be arranged. Her salary would be paid to her weekly in Dutch guldens… She paused here to do some arithmetic—she considered it a princely sum, which certainly sweetened the somewhat arbitrary tone of the letter. Although there was no reason why it should have been couched in friendlier terms; she scarcely knew the doctor and didn’t expect to see much of him while she was in Holland.

She told her mother that the arrangements for her new job seemed quite satisfactory, persuaded Mrs Snow to undertake the housekeeping until Aunt Millicent could come, and then sifted through her wardrobe. The jersey two-piece and the corn silk blouse, an equally sober skirt and an assortment of tops and a warmer woolly or two, a short wool jacket to go over everything and a perfectly plain dress in a soft blue crêpe; an adequate choice of clothes, she considered, adding a raincoat, plain slippers and undies.

She had good shoes and a leather handbag; gloves and stockings and a headscarf or two would fill the odd corners in the one case she intended taking. Her overnight bag would take the rest. She liked clothes, but working in the children’s convalescent home had called for sensible skirts and tops in sensible colours, and she had seldom had much of a social life. She was uneasily aware that her clothes were dull, but there was no time to change that, and anyway, she hadn’t much money. Perhaps she would get a new outfit in Holland…

The week went quickly. She cleaned and polished, washed and ironed, laid in a stock of food and got a room ready for Aunt Millicent. And she went into Henley and bought new shoes, low-heeled brown leather and expensive, and when she saw a pink angora sweater in a shop window she bought that too. She was in two minds about buying a new jacket, but caution took over then. She had already spent more money than she’d intended. Though caution wasn’t quite strong enough to prevent her buying a pretty silk blouse which would render the sober skirt less sober.

On Sunday morning she was ready and waiting by eleven o’clock—waiting with her parents who, despite their wish to get back to researching the Ancient Celts, had come into the hall to see her off. Cherub was there too, looking morose, and she stooped to give him a final hug; they would miss each other.

Exactly on the hour a car drew up outside and Briskett got out, wished them all good morning, stowed her case in the boot and held the rear car door open for her.

‘Oh, I’d rather sit in front with you,’ said Araminta, and she gave her parents a final kiss before getting into the car, waved them a cheerful goodbye and sat back beside Briskett. It was a comfortable car, a Jaguar, and she could see from the moment Briskett took the wheel that despite his unlikely looks they hid the soul of a born driver.

There wasn’t much traffic until they reached Henley and here Briskett took the road to Oxford.

‘Aren’t I to go to the London address?’ asked Araminta.

‘No, miss. The doctor thought it wise if you were to make the acquaintance of the boys at their home. They live with their parents at Oxford. The doctor will come for you and them later today and drive to Harwich for the night ferry.’

‘Oh, well, I expect that’s a good idea. Are you coming to Holland too?’

‘No, miss. I’ll stay to keep an eye on things here; the boss has adequate help in Holland. He’s for ever to-ing and fro-ing—having two homes, as it were.’

‘Then why can’t the two boys stay here in England?’

‘He’ll be in Holland for a few weeks, popping over here when he is needed. Much in demand, he is.’

‘We won’t be expected to pop over, too? Very unsettling for the little boys…’

‘Oh, no, miss. That’s why you’ve been engaged; he can come and go without being hampered, as you might say.’

The house he stopped before in Oxford was in a terrace of similar comfortably large houses, standing well back from the road. Araminta got out and stood beside Briskett in the massive porch waiting for someone to answer the bell. She was a self-contained girl, not given to sudden bursts of excitement, but she was feeling nervous now.

Supposing the boys disliked her on sight? It was possible. Or their parents might not like the look of her. After all, they knew nothing about her, and now that she came to think about it, nor did Dr van der Breugh. But she didn’t allow these uncertain feelings to show; the door was opened by a girl in a pinafore, looking harassed, and she and Briskett went into the hall.

‘Miss Pomfrey,’ said Briskett. ‘She’s expected.’

The girl nodded and led them across the hall and into a large room overlooking a garden at the back of the house. It was comfortably furnished, extremely untidy, and there were four people in it. The man and woman sitting in easy chairs with the Sunday papers strewn around them got up.

The woman was young and pretty, tall and slim, and well dressed in casual clothes. She came to meet Araminta as she hesitated by the door.

‘Miss Pomfrey, how nice of you to come all this way. We’re so grateful. I’m Lucy Ingram, Marcus’s sister—but of course you know that—and this is my husband, Jack.’

Araminta shook hands with her and then with Mr Ingram, a rather short stout man with a pleasant rugged face, while his wife spoke to Briskett, who left the room with a cheerful, ‘So long, miss, I’ll see you later.’

‘Such a reliable man, and so devoted to Marcus,’ said his sister. ‘Come and meet the boys.’

They were at the other end of the room, sitting at a small table doing a jigsaw puzzle, unnaturally and suspiciously quiet. They were identical twins which, reflected Araminta, wasn’t going to make things any easier, and they looked too good to be true.

‘Peter and Paul,’ said their mother. ‘If you look carefully you’ll see that Peter has a small scar over his right eye. He fell out of a tree years ago—it makes it easy to tell them apart.’

She beckoned them over and they came at once, two seemingly angelic children. Araminta wondered what kind of a bribe they had been offered to behave so beautifully. She shook their small hands in turn and smiled.

‘Hello,’ she said. ‘You’ll have to help me to tell you apart, and you mustn’t mind if I muddle you up at first.’

‘I’m Peter. What’s your name—not Miss Pomfrey, your real name?’

‘Araminta.’

The boys looked at each other. ‘That’s a long name.’

They cast their mother a quick look. ‘We’ll call you Mintie.’

‘That’s not very polite,’ began Mrs Ingram.

‘If you’ve no objection, I think it’s a nice idea. I don’t feel a bit like Miss Pomfrey…’

‘Well, if you don’t mind—go and have your milk, boys, while we have our coffee and then you can show Miss…Mintie your room and get to know each other a bit.’

They went away obediently, eyeing her as they went, and Araminta was led to a sofa and given coffee while she listened to Mrs Ingram’s friendly chatter. From time to time her husband spoke, asking her quietly about her work at the children’s home and if she had ever been to Holland before.

‘The boys,’ he told her forthrightly, ‘can be little demons, but I dare say you are quite used to that. On the whole they’re decent kids, and they dote on their uncle.’

Araminta, considering this remark, thought that probably it would be quite easy to dote on him, although, considering the terseness of his letter to her, not very rewarding. She would have liked to get to know him, but common sense told her that that was unlikely. Besides, once she was back in England again, he would be consigned to an easily forgotten past and she would have embarked on her nursing career…

She dismissed her thoughts and listened carefully to Mrs Ingram’s instructions about the boys’ clothing and meals.

‘I’m telling you all these silly little details,’ explained Mrs Ingram, ‘because Marcus won’t want to be bothered with them.’ She looked anxious. ‘I hope you won’t find it too much…’

Araminta made haste to assure her that that was unlikely. ‘At the children’s home we had about forty children, and I’m used to them—two little boys will be delightful. They don’t mind going to Holland?’

‘No. I expect they’ll miss us for a few days, but they’ve been to their uncle’s home before, so they won’t feel strange.’

Mrs Ingram began to ask carefully polite questions about Araminta and she answered them readily. If she had been Mrs Ingram she would have done the same, however well recommended she might be. Dr van der Breugh had engaged her on Dr Jenkell’s advice, which was very trusting of him. Certainly he hadn’t bothered with delving into her personal background.

They had lunch presently and she was pleased to see that the boys behaved nicely at the table and weren’t finicky about their food. All the same, she wondered if these angelic manners would last. If they were normal little boys they wouldn’t…

The rest of the day she spent with them, being shown their toys and taken into the garden to look at the goldfish in the small pond there, and their behaviour was almost too good to be true. There would be a reason for it, she felt sure; time enough to discover that during the new few weeks.

They answered her questions politely but she took care not to ask too many. To them she was a stranger, and she would have to earn their trust and friendship.

They went indoors presently and found Dr van der Breugh in the drawing room with their father and mother. There was no doubt that they were fond of him and that he returned the affection. Emerging from their boisterous greeting, he looked across at Araminta and bade her good afternoon.

‘We shall be leaving directly after tea, Miss Pomfrey. My sister won’t mind if you wish to phone your mother.’

‘Thank you, I should like to do that…’

‘She’s not Miss Pomfrey,’ said Peter. ‘She’s Mintie.’

‘Indeed?’ He looked amused. ‘You have rechristened her?’

‘Well, of course we have, Uncle. Miss Pomfrey isn’t her, is it? Miss Pomfrey would be tall and thin, with a sharp nose and a wart and tell us not to get dirty. Mintie’s nice; she’s not pretty, but she smiles…’

Araminta had gone a bright pink and his mother said hastily, ‘Hush, dear. Miss Pomfrey, come with me and I’ll show you where you can phone.’

Leading Araminta across the hall, she said apologetically, ‘I do apologise. Peter didn’t mean to be rude—indeed, I believe he was paying you a compliment.’

Araminta laughed. ‘Well, I’m glad they think of me as Mintie, and not some tiresome woman with a wart. I hope we’re going to like each other.’

The boys had been taken upstairs to have their hands washed and the two men were alone.

‘Good of you to have the boys,’ said Mr Ingram. ‘Lucy was getting in a bit of a fret. And this treasure you’ve found for them seems just like an answer to a prayer. Quiet little thing and, as Peter observed, not pretty, but a nice calm voice. I fancy she’ll do. Know much about her?’

‘Almost nothing. Old Jenkell told me of her; he’s known her almost all her life. He told me that she was entirely trustworthy, patient and kind. They loved her at the children’s home. She didn’t want to come—she was to start her training as a nurse in a week or so—but she changed her mind after refusing the job. I don’t know why. I’ve said I’ll help her to get into the next batch of students when we get back.’

The doctor wandered over to the windows. ‘You’ll miss your garden.’ He glanced over his shoulder. ‘I’ll keep an eye on the boys, Jack. As you say, I think we have found a treasure in Miss Pomfrey. A nice, unassuming girl who won’t intrude. Which suits me very well.’

Tea was a proper meal, taken at the table since the boys ate with them, but no time was wasted on it. Farewells were said, the boys were settled by their uncle in the back seat of his Bentley, and Araminta got into the front of the car, composed and very neat. The doctor, turning to ask her if she was comfortable, allowed himself a feeling of satisfaction. She was indeed unassuming, both in manner and appearance.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_bf65c10a-3acb-585c-8bce-4e9de8dcc7d1)

ARAMINTA, happily unaware of the doctor’s opinion of her, settled back in the comfort of the big car, but she was aware of his voice keeping up a steady flow of talk with his little nephews. He sounded cheerful, and from the occasional words she could hear he was talking about sailing. Would she be expected to take part in this sport? she wondered. She hoped not, but, being a sensible girl, she didn’t allow the prospect to worry her. Whatever hazards lay ahead they would be for a mere six weeks or so. The salary was generous and she was enjoying her freedom. She felt guilty about that, although she knew that her parents would be perfectly happy with Aunt Millicent.

The doctor drove through Maidenhead and on to Slough and then, to her surprise, instead of taking the ring road to the north of London, he drove to his house.

Araminta, who hadn’t seen Briskett leave the Ingrams’, was surprised to see him open the door to them.

‘Right on time,’ he observed. ‘Not been travelling over the limit, I hope, sir. You lads wait there while I see to Miss Pomfrey. There’s a couple of phone calls for you, Doc.’

He led Araminta to the cloakroom at the back of the hall. ‘You tidy yourself, miss; I’ll see to the boys. There’s coffee ready in the drawing room.’

Araminta, not in the least untidy, nonetheless did as she was bid. Briskett, for all his free and easy ways, was a gem. He would be a handy man in a crisis.

When she went back into the hall he was there, waiting to usher her into the drawing room. The doctor was already there, leaning over a sofa table with the boys, studying a map. He straightened up as she went in and offered her a chair and asked her to pour their coffee. There was milk for the boys as well as a plate of biscuits and a dish of sausage rolls, which Peter and Paul demolished.

They were excited now, their sadness at leaving their mother and father already fading before the prospect of going to bed on board the ferry. Presently the doctor excused himself with the plea that there were phone calls he must make and Araminta set to work to calm them down, something at which she was adept. By the time their uncle came back they were sitting quietly beside her, listening to her telling them a story.

He paused in the doorway. ‘I think it might be a good idea if you sat in the back with the boys in the car, Miss Pomfrey…’

‘Mintie,’ said Peter. ‘Uncle Marcus, she’s Mintie.’

‘Mintie,’ said the doctor gravely. ‘If Miss Pomfrey does not object?’

‘Not a bit,’ said Araminta cheerfully.

They left shortly after that, crossing London in the comparative calm of a Sunday evening, onto the A12, through Brentford, Chelmsford, Colchester and finally to Harwich. Long before they had reached the port the two boys were asleep, curled up against Araminta. She sat, rather warm and cramped, with an arm around each of them, watching the doctor driving. He was a good driver.

She reflected that he would be an interesting man to know. It was a pity that the opportunity to do that was improbable. She wondered why he wasn’t married and allowed her imagination to roam. A widower? A love affair which had gone wrong and left him with a broken heart and dedicated to his work? Engaged? The last was the most likely. She had a sudden urge to find out.

They were amongst the last to go on board, and the doctor with one small sleeping boy and a porter with the other led the way to their cabins.

Araminta was to share a cabin with the boys; it was roomy and comfortable and well furnished, with a shower room, and once her overnight bag and the boys’ luggage had been brought to her she lost no time in undressing them and popping them into their narrow beds. They roused a little, but once tucked up slept again. She unpacked her night things and wondered what she should do. Would the doctor mind if she rang for a pot of tea and a sandwich? It was almost midnight and she was hungry.

A tap on the door sent her to open it and find him outside.

‘A stewardess will keep an eye on the boys. Come and have a meal; it will give me the opportunity to outline your day’s work.’

She was only too glad to agree to that; she went with him to the restaurant and made a splendid supper while she listened to him quietly describing the days ahead.

‘I live in Utrecht. The house is in the centre of the city, but there are several parks close by and I have arranged for the boys to attend school in the mornings. You will be free then, but I must ask you to be with them during the rest of the day. You will know best how to keep them happy and entertained.

‘I have a housekeeper and a houseman who will do all they can to make life easy for you and them. When I am free I will have the boys with me. I am sure that you will want to do some sightseeing. I expect my sister has told you her wishes concerning their clothes and daily routine. I must warn you that they are as naughty as the average small boy…they are also devoted to each other.’

Araminta speared a morsel of grilled sole. ‘I’ll do the best I can to keep them happy and content, Dr van der Breugh. And I shall come to you if I have any problems. You will be away during the day? Working? Will I know where you are?’

‘Yes, I will always leave a phone number for you or a message with Bas. He speaks English of a sort, and is very efficient.’ He smiled at her kindly. ‘I’m sure everything will be most satisfactory, Miss Pomfrey. And now I expect you would like to go to your bed. You will be called in good time in the morning. We will see how the boys are then. If they’re too excited to eat breakfast we will stop on the way and have something, but there should be time for a meal before we go ashore. You can manage them and have them up and ready?’

Araminta assured him that she could. Several years in the convalescent home had made her quite sure about that. She thanked him for her dinner, wished him goodnight, and was surprised when he went back to her cabin with her and saw her into it.

Nice manners, thought Araminta, getting undressed as fast as she could, having a quick shower and jumping into her bed after a last look at the boys—deeply asleep.

The boys woke when the stewardess brought morning tea. They drank the milk in the milk jug and ate all the biscuits. Talking non-stop, they washed and cleaned their teeth and dressed after a fashion. Araminta was tying shoelaces and inspecting fingernails when there was a knock on the door and the doctor came in.

‘If anyone is hungry there’s plenty of time for breakfast,’ he observed. He looked at Araminta. ‘You all slept well?’

‘Like logs,’ she told him, ‘and we’re quite ready, with everything packed.’

‘Splendid. Come along, then.’ He sounded briskly cheerful and she wondered if he found this disruption in his ordered life irksome. If he did, he didn’t allow it to show. Breakfast was a cheerful meal, eaten without waste of time since they were nearing the Hoek of Holland and the boys wanted to see the ferry dock.

Disembarking took time, but finally they were away from the customs shed, threading their way through the town.

‘We’ll go straight home,’ said the doctor. He had the two boys with him again and spoke to Araminta over his shoulder. ‘Less than an hour’s drive.’ He picked up the car phone and spoke into it. ‘I’ve told them we are on our way.’

There was a great deal of traffic as they neared Rotterdam, where they drove through the long tunnel under the Maas. Once through it, the traffic was even heavier. But presently, as they reached the outskirts of the city and were once more on the motorway, it thinned, and Araminta was able to look about her.

The country was flat, and she had expected that, but it was charming all the same, with farms well away from the highway, small copses of trees already turning to autumn tints, green meadows separated by narrow canals, and cows and horses roaming freely. The motorway bypassed the villages and towns, but she caught tantalising glimpses of them from time to time and promised herself that if she should get any free time, she would explore away from the main roads.

As though he had read her thoughts, the doctor said over his shoulder, ‘This is dull, isn’t it? But it’s the quickest way home. Before you go back we must try and show you some of rural Holland. I think you might like it.’

She murmured her thanks. ‘It’s a very good road,’ she said politely, anxious not to sound disparaging.

‘All the motorways are good. Away from them it’s a different matter. But you will see for yourself.’

Presently he turned off into a narrow country road between water meadows. ‘We’re going to drive along the River Vecht. It is the long way round to Utrecht, but well worth it. It will give you a taste of rural Holland.’

He drove north, away from Utrecht, and then turned into another country road running beside a river lined with lovely old houses set in well-kept grounds.

‘The East Indies merchants built their houses here—there’s rather a splendid castle you’ll see presently on your right. There are a number in Utrecht province—most of them privately owned. You must find time to visit one of those open to the public before you go back to England.’

Apparently satisfied that he had given her enough to go on with, he began a lively conversation with the boys, leaving her to study her surroundings. They were certainly charming, but she had the feeling that he had offered the information in much the same manner as a dutiful and well mannered host would offer a drink to an unexpected and tiresome guest.

They were on the outskirts of Utrecht by now, and soon at its heart. Some magnificent buildings, she conceded, and a bewildering number of canals. She glimpsed several streets of shops, squares lined by tall, narrow houses with gabled roofs and brief views of what she supposed were parks.

The boys were talking now, nineteen to the dozen, and in Dutch. Well, of course, they would, reflected Araminta. They had a Dutch mother and uncle. They were both talking at once, interrupted from time to time by the doctor’s measured tones, but presently Paul shouted over his shoulder, ‘We’re here, Mintie. Do look, isn’t it splendid?’

She looked. They were in a narrow gracht, tree-lined, with houses on either side of the canal in all shapes and sizes: some of them crooked with age, all with a variety of gabled roofs. The car had stopped at the end of the gracht before a narrow red-brick house with double steps leading up to its solid door. She craned her neck to see its height—four storeys, each with three windows. The ground floor ones were large, but they got progressively smaller at each storey so that the top ones of all were tucked in between the curve of the gable.

The doctor got out, went around to allow the boys to join him and then opened her door. He said kindly, ‘I hope you haven’t found the journey too tiring?’

Araminta said, ‘Not in the least,’ and felt as elderly as his glance indicated. Probably she looked twice her age; her toilet on board had been sketchy…

The boys had run up the steps, talking excitedly to the man who had opened the door, and the doctor, gently urging her up the steps said, ‘This is Bas, who runs my home with his wife. As I said, he speaks English, and will do all he can to help you.’

She offered a hand and smiled at the elderly lined face with its thatch of grey hair. Bas shook hands and said gravely, ‘We welcome you, miss, and shall do our best to make you happy.’

Which was nice, she thought, and wished that the doctor had said something like that.

What he did say was rather absent-minded. ‘Yes, yes, Miss Pomfrey. Make yourself at home and ask Bas for anything you may need.’

Which she supposed was the next best thing to a welcome.

The hall they entered was long and narrow, with a great many doors on either side of it, and halfway along it there was a staircase, curving upwards between the panelled walls. As they reached a pair of magnificent mahogany doors someone came to meet them from the back of the house. It was a short, stout woman in a black dress and wearing a printed pinny over it. She had a round rosy face and grey hair screwed into a bun. Her eyes were very dark and as she reached them she gave Araminta a quick look.

‘Jet…’ Dr van der Breugh sounded pleased to see her and indeed kissed her cheek and spoke at some length in his own language. His housekeeper smiled then, shook Araminta’s hand and bent to hug the boys, talking all the time.

The doctor said in English, ‘Go with Jet to the kitchen, both of you, and have milk and biscuits. Miss Pomfrey shall fetch you as soon as she has had a cup of coffee.’

Bas opened the doors and Araminta, invited to enter the room, did so. It was large and lofty, with two windows overlooking the gracht, a massive fireplace along one wall and glass doors opening into a room beyond. It was furnished with two vast sofas on either side of the fireplace and a number of comfortable chairs. There was a Pembroke table between the windows and a rosewood sofa table on which a china bowl of late roses glowed.

A walnut and marquetry display cabinet took up most of the wall beside the fireplace on one side, and on the other there was a black and gold laquer cabinet on a gilt stand. Above it was a great stoel clock, its quiet tick-tock somehow enhancing the peace of the room. And the furnishings were restful: dull mulberry-red and dark green, the heavy curtains at the windows matching the upholstery of the sofas and chairs. The floor was highly polished oak with Kasham silk rugs, faded with age, scattered on it.

A magnificent room, reflected Araminta, and if it had been anyone other than the doctor she would have said so. She held her tongue, however, sensing that he would give her a polite and chilly stare at her unasked-for praise.

He said, ‘Do sit down, Miss Pomfrey. Jet shall take you to your room when you have had coffee and then perhaps you would see to the boys’ things and arrange some kind of schedule for their day? We could discuss that later today.’

Bas brought the coffee then, and she poured it for them both and sat drinking it silently as the doctor excused himself while he glanced through the piles of letters laid beside his chair, his spectacles on his handsome nose, oblivious of her presence.

He had indeed forgotten her for the moment, but presently he looked up and said briskly, ‘I expect you would like to go to your room. Take the boys with you, will you? I shall be out to lunch and I suggest that you take the boys for a walk this afternoon. They know where the park is and Bas will tell you anything you may wish to know.’

He went to open the door for her and she went past him into the hall. She would have liked a second cup of coffee…

Bas was waiting for her and took her to the kitchen, a semi-basement room at the back of the house. It was nice to be greeted by cheerful shouts from the boys and Jet’s kind smile and the offer of another cup of coffee. She sat down at the old-fashioned scrubbed table while Bas told her that he would serve their lunch at midday and that when they came back from their walk he would have an English afternoon tea waiting for her.

His kind old face crinkled into a smile as he told her, ‘And if you should wish to telephone your family, you are to do so—mijnheer’s orders.’

‘Oh, may I? I’ll do that now, before I go to my room…’

Her mother answered the phone, expressed relief that Araminta had arrived safely and observed that there were some interesting burial mounds in the north of Holland if she should have the opportunity to see them. ‘And enjoy yourself, dear,’ said her parent.

Araminta, not sure whether it was the burial mounds or her job which was to give her enjoyment, assured her mother that she would do so and went in search of the boys.

Led upstairs by Jet, with the boys running ahead, she found herself in a charming room on the second floor. It overlooked the street below and was charmingly furnished, with a narrow canopied bed, a dressing table under its window and two small easy chairs flanking a small round table. The colour scheme was a mixture of pastel colours and the furniture was of some pale wood she didn’t recognise. There was a large cupboard and a little door led to a bathroom. The house might be old, she thought, but the plumbing was ultra-modern. It had everything one could wish for…

The boys’ room was across the narrow passage, with another bathroom, and at the end of the passage was a room which she supposed had been a nursery, for it had a low table and small chairs round it and shelves full of toys.

She was right. The boys, both talking at once, eager to show her everything, told her that some of the toys had belonged to their uncle and his father; even his grandfather.

‘We have to be careful of them,’ said Paul, ‘but Uncle Marcus lets us play with them when we’re here.’

‘Do you come here often?’ asked Araminta.

‘Every year with Mummy and Daddy.’

Bas came to tell them that lunch was ready, so they all trooped downstairs and, since breakfast seemed a long time ago, made an excellent meal.

The boys were still excited, and Araminta judged it a good idea to take them for the walk. She could unpack later, when they had tired themselves out.

Advised by Bas and urged on by them, she got her own jacket, buttoned them into light jackets and went out into the street. The park was five minutes’ walk away, small and beautifully kept, a green haven in the centre of the city. There was a small pond, with goldfish and seats under the trees, but the boys had no intention of sitting down. When they had tired of the goldfish they insisted on showing her some of the surrounding streets.

‘And we’ll go to the Dom Tower,’ they assured her. ‘It’s ever so high, and the Domkerk—that’s a cathedral—and perhaps Uncle will take us to the university.’

They were all quite tired by the time they got back to the house, and Araminta was glad of the tea Bas brought to them in a small room behind the drawing room.

‘Mijnheer will be home very shortly,’ he told her, ‘and will be free to have the boys with him for a while whilst you unpack. They are to have their supper at half past six.’

Which reminded her that she should have some kind of plan ready for him to approve that evening.

‘It’s all go,’ said Araminta crossly, alone for a few moments while the boys were in the kitchen, admiring Miep—the kitchen cat—and her kittens.

She had gone to the window to look out onto the narrow garden behind the house. It was a pretty place, with narrow brick paths and small flowerbeds and a high brick wall surrounding it.

‘I trust you do not find the job too tiresome for you?’ asked the doctor gently.

She spun round. He was standing quite close to her, looking amused.

She said tartly, ‘I was talking to myself, doctor, unaware that anyone was listening. And I do not find the boys tiresome but it has been a long day.

‘Indeed it has.’ He didn’t offer sympathy, merely agreed with her in a civil voice which still held the thread of amusement.

He glanced at his watch. ‘I dare say you wish to unpack for the boys and yourself. I’ll have them with me until half past six.’

He gave her a little nod and held the door open for her.

In her room, she put away her clothes, reflecting that she must remember not to voice her thoughts out loud. He could have been nasty about it—he could also have offered a modicum of sympathy…

She still wasn’t sure why she had accepted this job. True, she was to be paid a generous salary, and she supposed that she had felt sorry for him.

Upon reflection she thought that being sorry for him was a waste of time; it was apparent that he lived in some comfort, surrounded by people devoted to him. She supposed, too, that he was a busy man, although she had no idea what he did. A GP, perhaps? But his lifestyle was a bit grand for that. A consultant in one of the hospitals? Or one of those unseen men who specialised in obscure illnesses? She would find out.

She went to the boys’ room and unpacked, put everything ready for bedtime and then got out pen and paper and wrote out the rough outline of a routine for the boys’ day. Probably the doctor wouldn’t approve of it, in which case he could make his own suggestions.

At half past six she went downstairs and found the boys in the small room where they had their tea earlier. The doctor was there, too, and they were all on the floor playing a noisy game of cards. There was a dog there too, a black Labrador, sitting beside his master, watching the cards being flung down and picked up.

They all looked up as she went in and the doctor said, ‘Five minutes, Miss Pomfrey.’ When the dog got to its feet and came towards her, he added, ‘This is Humphrey. You like dogs?’

‘Yes.’ She offered a fist and then stroked the great head. ‘He’s lovely.’

She sat down until the game came to an end, with Peter declared the winner.

‘Supper?’ asked Araminta mildly.

The doctor got on to his feet, towering over them. ‘Come and say goodnight when you’re ready for bed. Off you go, there’s good fellows.’

Bas was waiting in the hall. ‘Supper is to be in the day nursery on the first floor,’ he explained. ‘You know the way, miss.’ And they all went upstairs and into the large room, so comfortably furnished with an eye to a child’s comfort.

‘Uncle Marcus used to have his supper here,’ Paul told her, ‘and he says one day, when he’s got some boys of his own, they’ll have their supper here, too.’

Was the doctor about to marry? Araminta wondered. He wasn’t all that young—well into his thirties, she supposed. It was high time he settled down. It would be a pity to waste this lovely old house and this cosy nursery…

Bas came in with a tray followed by a strapping girl with a round face and fair hair who grinned at them and set the table. Supper was quickly eaten, milk was drunk and Araminta whisked the boys upstairs, for they were tired now and suddenly a little unhappy.

‘Are Mummy and Daddy going a long way away?’ asked Peter as she bathed them.

‘Well, it would be a long way if you had to walk there,’ said Araminta, ‘but in an aeroplane it takes no time at all to get there and get back again. Shall we buy postcards tomorrow and write to them?’

She talked cheerfully as she popped them into their pyjamas and dressing gowns and they all went back downstairs, this time to the drawing room, where their uncle was sitting with a pile of papers on the table beside him.

He hugged them, teased them gently, told them he would see them at breakfast in the morning and bade them goodnight. As they went, he reminded Araminta that dinner would be in half an hour.

The boys were asleep within minutes. Araminta had a quick shower and got into another skirt and a pretty blouse, spent the shortest possible time over her face and hair and nipped downstairs again with a few minutes to spare. She suspected that the doctor was a man who invited punctuality.

He was in the drawing room still, but he got up as she went in, offered her a glass of sherry, enquired if the boys were asleep and made small talk until Bas came to tell them that dinner was ready.

Araminta was hungry and Jet was a splendid cook. She made her way through mushrooms in a garlic and cream sauce, roast guinea fowl, and apple tart with whipped cream. Mindful of good manners, she sustained a polite conversation the while.

The doctor, making suitable replies to her painstaking efforts allowed his thoughts to wander.

After this evening he would feel free to spend his evenings with friends or at the hospital; breakfast wasn’t a problem, for the boys would be there, and he was almost always out for lunch. Miss Pomfrey was a nice enough girl, but there was nothing about her to arouse his interest. He had no doubt that she would be excellent with the boys, and she was a sensible girl who would know how to amuse herself on her days off.

Dinner over, he suggested that they had their coffee in the drawing room.

‘If you don’t mind,’ said Araminta, ‘I’d like to go to bed. I’ve written down the outlines of a day’s schedule, if you would look at it and let me know in the morning if it suits you. Do we have breakfast with you or on our own?’

‘With me. At half past seven, since I leave for the hospital soon after eight o’clock.’

Araminta nodded. ‘Oh, I wondered where you worked,’ she observed, and wished him goodnight.

The doctor, politely opening the door for her, had the distinct feeling that he had been dismissed.

He could find no fault with her schedule for the boys. He could see that if she intended to carry it out to the letter she would be tired by the end of the day, but that, he felt, was no concern of his. She would have an hour or so each morning while the boys were at school and he would tell her that she could have her day off during the week as long as it didn’t interfere with his work.

He went back to his chair and began to read the patients’ notes that he had brought with him from the hospital. There was a good deal of work waiting for him both at Utrecht and Leiden. He was an acknowledged authority on endocrinology, and there were a number of patients about which he was to be consulted. He didn’t give Araminta another thought.

Araminta took her time getting ready for bed. She took a leisurely bath, and spent time searching for lines and wrinkles in her face; someone had told her that once one had turned twenty, one’s skin would start to age. But since she had a clear skin, as soft as a peach, she found nothing to worry her. She got into bed, glanced at the book and magazines someone had thoughtfully put on her bedside table and decided that instead of reading she would lie quietly and sort out her thoughts. She was asleep within minutes.

A small, tearful voice woke her an hour later. Paul was standing by her bed, in tears, and a moment later Peter joined him.

Araminta jumped out of bed. ‘My dears, have you had a nasty dream? Look, I’ll come to your room and sit with you and you can tell me all about it. Bad dreams go away if you talk about them, you know.’

It wasn’t bad dreams; they wanted their mother and father, their own home, the cat and her kittens, the goldfish… She sat down on one of the beds and settled the pair of them, one on each side of her, cuddling them close.

‘Well, of course you miss them, my dears, but you’ll be home again in a few weeks. Think of seeing them all again and telling them about Holland. And you’ve got your uncle…’

‘And you, Mintie, you won’t go away?’

‘Gracious me, no. I’m in a foreign country, aren’t I? Where would I go? I’m depending on both of you to take me round Utrecht so that I can tell everyone at home all about it.’

‘Have you got little boys?’ asked Peter.

‘No, love, just a mother and father and a few aunts and uncles. I haven’t any brothers and sisters, you see.’

Paul said in a watery voice, ‘Shall we be your brothers? Just while you’re living with us?’

‘Oh, yes, please. What a lovely idea…’

‘I heard voices,’ said the doctor from the doorway. ‘Bad dreams?’

Peter piped up, ‘We woke up and we wanted to go home, but Mintie has explained so it’s all right, Uncle, because she’ll be here with you, and she says we can be her little brothers. She hasn’t got a brother or a sister.’

The doctor came into the room and sat down on the other bed. ‘What a splendid idea. We must think of so many things to do that we shan’t have enough days in which to do them.’

He began a soothing monologue, encompassing a visit to some old friends in Friesland, another to the lakes north of Utrecht, where he had a yacht, and a shopping expedition so that they might buy presents to take home…

The boys listened, happy once more and getting sleepy. Araminta listened too, quite forgetting that she was barefoot, somewhere scantily clad in her nightie and that her hair hung round her shoulders and tumbled untidily down her back.

The doctor had given her an all-seeing look and hadn’t looked again. He was a kind man, and he knew that the prim Miss Pomfrey, caught unawares in her nightie, would be upset and probably hate him just because he was there to see her looking like a normal girl. She had pretty hair, he reflected.

‘Now, how about bed?’ he wanted to know. ‘I’m going downstairs again but I’ll come up in ten minutes, so mind you’re asleep by then.’

He ruffled their hair and took himself off without a word or a look for Araminta. It was only as she was tucking the boys up once more that she realised that she hadn’t stopped to put on her dressing gown. She kissed the boys goodnight and went away to swathe herself in that garment now, and tie her hair back with a ribbon. She would have to see that man again, she thought vexedly, because the boys had said they wouldn’t go to sleep unless she was there, but this time she would be decently covered.

He came presently, to find the boys asleep already and Araminta sitting very upright in a chair by the window.

‘They wanted me to stay,’ she told him, and he nodded carelessly, barely glancing at her. Perhaps he hadn’t noticed, she thought, for he looked at her as though he hadn’t really seen her. She gave a relieved sigh. Her, ‘Goodnight, doctor,’ was uttered in Miss Pomfrey’s voice, and he wished her a quiet goodnight in return, amused at the sight of her swathed in her sensible, shapeless dressing gown. Old Jenkell had told him that she was the child of elderly and self-absorbed parents, who hadn’t moved with the times. It seemed likely that they had not allowed her to move with them either.

Nonetheless, she was good with the boys, and so far had made no demands concerning herself. Give her a day or two, he reflected, and she would have settled down and become nothing but a vague figure in the background of his busy life.

His hopes were borne out in the morning; at breakfast she sat between the boys, and after the exchange of good mornings, neither she nor they tried to distract him from the perusal of his post.

Presently he said, ‘Your schedule seems very satisfactory, Miss Pomfrey. I shall be home around teatime. I’ll take the boys with me when I take Humphrey for his evening walk. The boys start school today. You will take them, please, and fetch them at noon each day. I dare say you will enjoy an hour or so to go shopping or sightseeing.’

‘Yes, thank you,’ said Araminta.

Peter said, ‘Uncle, why do you call Mintie Miss Pomfrey? She’s Mintie.’

‘My apologies. It shall be Mintie from now on.’ He smiled, and she thought how it changed his whole handsome face. ‘That is, if Mintie has no objection?’

She answered the smile. ‘Not in the least.’

That was the second time he had asked her that. She had the lowering feeling that she had made so little impression upon him that nothing which they had said to each other had been interesting enough to be remembered.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_58b3b166-b8e7-552b-b41c-38fa50e4273a)

THE boys had no objection to going to school. It was five minutes’ walk from the doctor’s house and in a small quiet street which they reached by crossing a bridge over the canal. Araminta handed them over to one of the teachers. Submitting to their hugs, she promised that she would be there at the end of the morning, and walked back to the house, where she told Bas that she would go for a walk and look around.

She found the Domkerk easily enough, but she didn’t go inside; the boys had told her that they would take her there. Instead she went into a church close by, St Pieterskerk, which was Gothic with a crypt and frescoes. By the time she had wandered around, looking her fill, it was time to fetch the boys. Tomorrow she promised herself that she would go into one of the museums and remember to have coffee somewhere…

The boys had enjoyed their morning. They told her all about it as they walked back, and then demanded to know what they were going to do that afternoon.

‘Well, what about buying postcards and stamps and writing to your mother and father? If you know the way, you can show me where the post office is. If you show me a different bit of Utrecht each day I’ll know my way around, so that if ever I should come again…’

‘Oh, I ’spect you will, Mintie,’ said Paul. ‘Uncle Marcus will invite you.’

Araminta thought this highly unlikely, but she didn’t say so. ‘That would be nice,’ she said cheerfully. ‘Let’s have lunch while you tell me some more about school.’

The afternoon was nicely filled in by their walk to the post office and a further exploration of the neighbouring streets while the boys, puffed up with self-importance, explained about the grachten and the variety of gables, only too pleased to air their knowledge. They were back in good time for tea, and when Bas opened the door to them they were making a considerable noise, since Araminta had attempted to imitate the Dutch words they were intent on teaching her.

A door in the hall opened and the doctor came out. He had his spectacles on and a book in his hand and he looked coldly annoyed.

Araminta hushed the boys. ‘Oh, dear, we didn’t know you were home. If we had we would have been as quiet as mice.’

‘I am relieved to hear that, Miss Pomfrey. I hesitate to curtail your enjoyment, but I must ask you to be as quiet as possible in the house. You can, of course, let yourself go once you are in the nursery.’

She gave him a pitying look. He should marry and have a houseful of children and become human again. He was fast becoming a dry-as-dust old bachelor. She said kindly, ‘We are really sorry, aren’t we, boys? We’ll creep around the house and be ourselves in the nursery.’ She added, ‘Little boys will be little boys, you know, but I dare say you’ve forgotten over the years.’

She gave him a sweet smile and shooed the boys ahead of her up the stairs.

‘Is Uncle Marcus cross?’ asked Paul.

‘No, no, of course not. You heard what he said—we may make as much noise as we like in the nursery. There’s a piano there, isn’t there? We’ll have a concert after tea…’

The boys liked the sound of that, only Peter said slowly, ‘He must have been a bit cross because he called you Miss Pomfrey.’

‘Oh, he just forgot, I expect. Now, let’s wash hands for tea and go down to the nursery. I dare say we shall have it there if your uncle is working.’

The doctor had indeed gone back to his study, but he didn’t immediately return to his reading. He was remembering Araminta’s words with a feeing of annoyance. She had implied that he was elderly, or at least middle-aged. Thirty-six wasn’t old, not even middle-aged, and her remark had rankled. True, he was fair enough to concede, he hadn’t the lifestyle of other men of his age, and since he wasn’t married he was free to spend as much time doing his work as he wished.

As a professor of endocrinology he had an enviable reputation in his profession already, and he was perfectly content with his life. He had friends and acquaintances, his sister, of whom he was fond, and his nephews; his social life was pleasant, and from time to time he thought of marriage, but he had never met a woman with whom he wanted to share the rest of his life.

Sooner or later, he supposed, he would have to settle for second best and marry; he had choice enough. A man of no conceit, he was still aware that there were several women of his acquaintance who would be only too delighted to marry him.

He read for a time and then got up and walked through the house to the kitchen, where he told Bas to put the tea things in the small sitting room. ‘And please tell Miss Pomfrey and the boys that I expect them there for tea in ten minutes.’

After tea, he reflected, they would play the noisiest game he could think of!

He smiled then, amused that the tiresome girl should have annoyed him. She hadn’t meant to annoy him; he was aware of that. He had seen enough of her to know that she was a kind girl, though perhaps given to uttering thoughts best kept to herself.

Araminta, rather surprised at his message, went downstairs with the boys to find him already sitting in the chair by the open window, Humphrey at his feet. He got up as they went in and said easily, ‘I thought we might as well have tea together round the table. I believe Jet has been making cakes and some of those pofferjes which really have to be eaten from a plate, don’t they?’

He drew out a chair and said pleasantly. ‘Do sit down, Miss Pomfrey.’

‘Mintie,’ Peter reminded him.

‘Mintie,’ said his uncle meekly, and Araminta gave him a wide smile, relieved that he wasn’t annoyed.

Tea poured and Jet’s botorkeok cut and served, he asked, ‘Well, what have you done all day? Was school all right?’

The boys were never at a loss for words, so there was little need for Araminta to say anything, merely to agree to something when appealed to. Doubtless over dinner he would question her more closely. She would be careful to be extra polite, she thought; he was a good-natured man, and his manners were beautiful, but she suspected that he expected life to be as he arranged it and wouldn’t tolerate interference. She really must remember that she was merely the governess in his employ—and in a temporary capacity. She would have to remember that, too.

They played Monopoly after tea, sitting at the table after Bas had taken the tea things away. The boys were surprisingly good at it, and with a little help and a lot of hints Peter won with Paul a close second. The doctor had taken care to make mistakes and had even cheated, although Araminta had been the only one to see that. As for her, she would never, as he had mildly pointed out, be a financial wizard.

She began to tidy up while the boys said a protracted goodnight to their uncle. ‘You’ll come up and say goodnight again?’ they begged.

When he agreed they went willingly enough to their baths, their warm milk drinks with the little sugar biscuits, and bed. Araminta, rather flushed and untidy, was tucking them in when the doctor came upstairs. He had changed for the evening and she silently admired him. Black tie suited him and his clothes had been cut by a masterly hand. The blue crêpe would be quite inadequate…

He bade the boys goodnight and then turned to her. ‘I shall be out for dinner, Miss Pomfrey,’ he told her with a formal politeness which she found chilling. ‘Bas will look after you. Dinner will be at the usual time, otherwise do feel free to do whatever you wish.’

She suppressed an instant wish to go with him. To some grand house where there would be guests? More likely he was taking some exquisitely gowned girl to one of those restaurants where there were little pink-shaded table lamps and the menus were the size of a ground map…

And she was right, for Paul asked sleepily, ‘Are you going out with a pretty lady, Uncle Marcus?’

The doctor smiled. ‘Indeed I am, Paul. Tomorrow I’ll tell you what we had for dinner.’

He nodded to Araminta and went away, and she waited, sitting quietly by the window, until she judged that he had left the house. Of course, there was no reason for him to stay at home to dine with her; she had been a fool to imagine that he would do so. Good manners had obliged him to do so yesterday, since it had been her first evening there, but it wasn’t as if she was an interesting person to be with. Her mother had pointed out kindly and rather too frequently that she lacked wit and sparkle, and that since she wasn’t a clever girl, able to converse upon interesting subjects, then she must be content to be a good listener.

Araminta had taken this advice in good part, knowing that her mother was unaware that she was trampling on her daughter’s feelings. Araminta made allowances for her, though; people with brilliant brains were quite often careless of other people’s feelings. And it was all quite true. She knew herself to be just what her mother had so succinctly described. And she had taught herself to be a good listener…

She might have had to dine alone, but Bas treated her as though she was an honoured guest and the food was delicious.

‘I will put coffee in the drawing room, miss,’ said Bas, so she went and sat there, with Humphrey for comfort and companionship, and presently wandered about the room, looking at the portraits on its walls and the silver and china displayed in the cabinet. It was still early—too early to go to bed. She slipped upstairs to make sure that the boys were sleeping and then went back to the drawing room and leafed through the magazines on the sofa table. But she put those down after a few minutes and curled up on one of the sofas and allowed her thoughts to wander.

The day had, on the whole, gone well. The boys liked her and she liked them, the house was beautiful and her room lacked nothing in the way of comfort. Bas and Jet were kindness itself, and Utrecht was undoubtedly a most interesting city. There was one niggling doubt: despite his concern for her comfort and civil manner towards her, she had the uneasy feeling that the doctor didn’t like her. And, of course, she had made it worse, answering him back. She must keep a civil tongue in her head and remember that she was there to look after the boys. He was paying her for that, wasn’t he?

‘And don’t forget that, my girl,’ said Araminta in a voice loud enough to rouse Humphrey from his snooze.

She went off to bed then, after going to the kitchen to wish Bas and Jet goodnight, suddenly anxious not to be downstairs when the doctor came home.

He wasn’t at breakfast the next morning; Bas told them that he had gone early to Amsterdam but hoped to be back in the late afternoon. The boys were disappointed and so, to her surprise, was Araminta.

He was home when they got back from their afternoon walk. The day had gone well and the boys were bursting to tell him about it, so Araminta took their caps and coats from them in the hall, made sure that they had wiped their shoes, washed their hands and combed their hair, and told them to go and find their uncle.

‘You’ll come, too? It’s almost time for tea, Mintie.’ Paul sounded anxious.