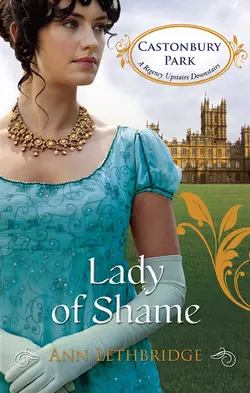

Lady of Shame

Ann Lethbridge

‘You’re in danger of dishonouring the family name for good!’ Lady Claire must put pride above prattle if she is to shake off the not-so-respectable reputation of her youth. Swapping rebellion for reserve, she returns to her imposing childhood home, Castonbury Park, seeking her family’s help. Penniless Claire needs a sensible husband…and fast!But when the dark gaze of head chef Monsieur André catches her eye, he’s as deliciously tempting as the food he prepares. Claire knows he’s most unsuitable… even if the chemistry between them is magnetic.Risking her reputation for André would be shameful – but losing him could be even worse!

This Christmas, we’ve got some fabulous treats to give away! ENTER NOW for a chance to win £5000 by clicking the link below.

www.millsandboon.co.uk/ebookxmas (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk/ebookxmas)

Duke of Rothermere

Castonbury Park

Claire,

Sister, you are normally so sensible and the one I have come to rely on. But I must be honest with you. With the family shrouded in disgrace and scandal, and the news of Jamie still uncertain, any more unwanted attention may prove to be harmful. I had hoped better of you, but I will put what has happened down to an unfortunate phase. I trust you will use your time wisely in the future, to build up the respect you once had and at all costs avoid any more gossip. It is only because I love you that I feel the need to be so candid.

Your brother

About the Author

ANN LETHBRIDGE has been reading Regency novels for as long as she can remember. She always imagined herself as Lizzie Bennet, or one of Georgette Heyer’s heroines, and would often recreate the stories in her head with different outcomes or scenes. When she sat down to write her own novel it was no wonder that she returned to her first love: the Regency.

Ann grew up roaming Britain with her military father. Her family lived in many towns and villages across the country, from the Outer Hebrides to Hampshire. She spent memorable family holidays in the West Country and in Dover, where her father was born. She now lives in Canada, with her husband, two beautiful daughters and a Maltese terrier named Teaser, who spends his days on a chair beside the computer, making sure she doesn’t slack off.

Ann visits Britain every year, to undertake research and also to visit family members who are very understanding about her need to poke around old buildings and visit every antiquity within a hundred miles. If you would like to know more about Ann and her research, or to contact her, visit her website at www.annlethbridge.com. She loves to hear from readers.

Previous novels by the same author:

THE RAKE’S INHERITED COURTESAN ^ (#ulink_9ca9df2c-b90a-50b4-8b98-21d0355ff343)

WICKED RAKE, DEFIANT MISTRESS

CAPTURED FOR THE CAPTAIN’S PLEASURE

THE GOVERNESS AND THE EARL

THE GAMEKEEPER’S LADY * (#ulink_598a12d5-2078-505b-9a02-14e1a9123536)

MORE THAN A MISTRESS * (#ulink_598a12d5-2078-505b-9a02-14e1a9123536)

LADY ROSABELLA’S RUSE ^ (#ulink_9ca9df2c-b90a-50b4-8b98-21d0355ff343)

And in Mills & Boon

HistoricalUndone!eBooks:

THE RAKE’S INTIMATE ENCOUNTER

THE LAIRD AND THE WANTON WIDOW

ONE NIGHT AS A COURTESAN

UNMASKING LADY INNOCENT

DELICIOUSLY DEBAUCHED BY THE RAKE

And in Mills & Boon Historical eBooks:

PRINCESS CHARLOTTE’S CHOICE

* (#litres_trial_promo) linked by character

^ (#litres_trial_promo) linked by character

Lady

of Shame

Ann Lethbridge

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

I would like to dedicate this book to my critique group, Mary, Maureen, Molly and Sinead. We had so much fun brainstorming ideas around this book and I really think they deserve a great deal of credit. I also want to thank the Beau Monde chapter of RWA for providing such a fabulous course on cooking and kitchens in the Regency, in particular Delilah Marvelle, our wonderful and saucy — in both senses of the words —teacher, as well as all the fabulous people at Mills & Boon who allowed this project to come to fruition.

Chapter One

When at Castonbury Park had seemed as cold as the stones in its walls. Today, as she paused halfway down the combed gravel drive, the stairs sweeping around each side of the columned portico welcomed her like open arms. The facade, with its swagged decorations and artistically placed statues, gleamed pale yellow in the weak January sunlight and promised sanctuary within its solemn splendour.

Home.

It looked so solid. So impregnable. So safe. Shivering against the north wind gusting down from the Peaks, Claire allowed herself to believe she had made the right choice. If not, she didn’t know what she would do. Where she would go next.

At her side, gripping her hand, her daughter, Jane, stared at the house. Seven years old and already her grey eyes were wise and world-weary. ‘This is where you grew up? It is huge.’

‘Yes,’ Claire said, resuming the long trudge to the front door. ‘This is where I lived when I was your age. Do not wander off, while you are here. It is a large place and it is easy to get lost.’

‘I won’t, Mama.’

Gravel crunched under their feet and the clean sharp smell of incipient snow filled Claire’s nostrils. She trod firmly. Confidently. Or at least she hoped her inner fears did not show.

It would have been so much better if they could have driven up to the door in a post chaise. More appropriate to her station. But they had no coin for such luxuries and, as Claire had learned these past eight years, what could not be cured must be endured. Instead they had taken the stage from London to Buxton and then accepted a ride in a farmer’s cart to Castonbury village. They had walked the rest of the way. To her surprise, the gatekeeper had let them pass on foot without question.

Were they always so lax about visitors? Did they let just anyone pass? She glanced over her shoulder. No one following. Nor would there be. Ernie Pratt knew only the assumed name George had invented after his brush with the law. She hoped.

Footsteps rustled behind them. Her heart leapt to her throat. She spun around, pushing Jane behind her.

No one. There was no one there. Just leaves blowing across the park, tumbling across the gravel.

‘What is it?’ Jane asked.

‘Nothing,’ Claire said, relief filling her. ‘Nothing at all.’

Yet still she picked up her pace. Hurrying towards the front door and safety.

A quick swallow did nothing to ease the dryness in her throat as she looked up at stone Corinthian columns towering three stories above. A declaration of the Duke of Rothermere’s wealth and status. And his power.

Once she had resented that power, now it felt like a lifeline.

They passed beneath the arches hiding the ground floor rustic stonework and marched up to the black painted front door gleaming with brass fittings. The everyday door. Only for very special events did visitors climb the stairs to the grand entrance above.

The lion’s head door knocker glared at her in disapproval. Her heart thundered. No. She was not fearful. Definitely not. Just filled with the anticipation of seeing her brother after so many years. She lifted the ring in the great jaws and let the knocker fall with a bang that echoed in the entrance hall beyond.

No going back now. She was committed. For Jane’s sake. She smiled down at her daughter, who pressed tight up against her hip.

The door opened. A young footman in red-and-gold livery looked down his nose at them. ‘’Tis at the wrong door, you are. Don’t you people know nothing? Servants’ entrance is round the back of the west pavilion.’ He pointed to the left. ‘That there large block at the end.’

He slammed the door in their faces.

Shocked speechless, she recoiled. Her heart gave a horrid little dip. The footman thought her a servant. She glanced down at herself and Jane. They were respectably, if shabbily, dressed; her widow’s weeds had seen better days, and her skirts were dusty, wrinkled from their travels.

The doubts about their welcome attacked her anew. The seed of hope nurtured in her chest all the way from London shrivelled, sapping the strength that had sustained her once she had made up her mind to bury her pride and ask for help.

Should she knock again and risk a more violent rejection? What if none of the family were home? No one to endorse her claim?

‘Why did he close the door?’ Jane asked, her voice weary.

Why indeed. Might Crispin have left word she wasn’t to be admitted? She shivered. ‘I think he thought we were someone else.’

Jane tugged at her skirt. ‘What shall we do?’

She forced a confident smile. ‘Why, we will go around the back just as the nice man suggested.’ Perhaps there she would find a servant she knew. She retraced her steps back to the drive.

‘He wasn’t nice,’ Jane grumbled as they trudged along the walkway leading to the servants’ wing. ‘The farmer with the cart was nice. Why couldn’t we stay with him?’

‘Because he isn’t family.’

Jane looked up at the house, her face full of doubt. ‘I want to go home.’

‘This is our home.’ Claire hoped the anxiety fluttering in her stomach wasn’t apparent in her voice. She quickened her pace, heading away from the block for family and guests, feeling very much like a stranger who didn’t belong.

Another set of arches hid the kitchens and cellars and quarters for the staff. They stopped at a plain brown door. She squared her shoulders and rapped hard. This time she would not be turned away.

It opened. A waft of warmth hit her face along with a delicious scent of cooking. She swayed as it washed over her and she heard Jane sniff with appreciation.

A tall man in his mid-thirties wearing a chef’s white toque and a pristine white apron gazed at them down an aristocratic nose. At some point that haughty nose had been broken and badly set, resulting in a bump that only slightly ruined the elegant male beauty of hard angles and planes. Not English, she thought, taking in the olive cast to his complexion and jet hair.

Onyx eyes fringed with black lashes too thick and long for a man swiftly roved her person. They took in her undecorated bonnet, her black bombazine skirts and her scuffed half-boots. She had the feeling he could see all the way to her plain worn shift with that piercing dark glance.

Sympathy softened his harsh features. ‘Step inside, madame.’ His voice was deep and obviously foreign.

Giddy with relief, she almost fell over the threshold.

‘Careful, madame.’ A muscular arm, hard beneath the fabric of his coat, caught her up.

A thrill rippled through her body. A recognition of his male physical strength. Shocked, she pulled away.

He released her and stepped back as if he, too, had felt something at the contact. He gestured her forward into what must be the scullery with its dingy whitewashed walls and a large lead-lined sink.

‘Sit,’ he said. ‘At the table.’ He pulled back a bench.

Claire sank down, glad of the respite, while she gathered her wits. Jane hopped up beside her.

‘Mademoiselle Agnes,’ he called out. ‘Vite, allez.’

A young woman in a mob cap ran in from the larger room beyond. The kitchen proper, no doubt.

‘Bring soup and bread,’ he ordered.

The girl ducked her head and disappeared.

‘No, really,’ Claire managed, gathering her scattered wits. ‘I need to—’

‘It is fine, madame. No need to be anxious,’ he said. ‘You are hungry, non?’ he said, smiling at Jane.

‘Starving,’ the child replied with the honesty of youth.

‘You don’t understand,’ Claire said. ‘I need to speak to Mrs Stratton.’ She held her breath, hoping beyond hope that the housekeeper she’d known as a girl was still employed here.

‘She has no work. I am sorry, madame, all I am permitted is to offer you soup and send you on your way.’

Permitted? On whose orders? Heat rushed through her. So much heat, after coming in from outside. Her head spun. She tugged at the button of her coat, tried to undo the scarf around her neck. It tangled with her anxious fingers.

‘Are you ill?’ He crouched down and with strong competent hands worked at the knot. She could not help but stare at the handsome face so close to hers, so serious as he focused on the task at hand. Such a face might have modelled for an artist’s rendition of a Roman god of war. His fingers brushed the underside of her chin. Liquid fire ran through her veins. He glanced up, his eyes showing shock and awareness. His lips parted in a breathless sigh.

For one long moment it was as if nothing else existed in the world but the two of them.

Her skin tingled. Her body lit up from within.

He jerked back, his hands falling away. He swallowed. ‘It is free now.’ He rose to his feet and backed up a few steps, gesturing to the table. ‘You will feel better after you eat.’

Still shocked, she could only stare at him. How could she have responded to him in such a wanton way? Because he was handsome? Or because it was a long time since a man had shown her and Jane such kindness? In either case, it was not appropriate.

‘Soup sounds awfully good,’ Jane said wistfully.

‘No,’ Claire said, fighting to catch her breath. ‘I did not come here for food. Or work. I must speak with Mrs Stratton. Please tell her Lady Claire wishes to speak with her.’

Confusion entered his dark eyes. Followed swiftly by comprehension.

‘Mademoiselle Agnes,’ he called out. ‘At once.’

The girl popped her head back through the door. ‘I’m pouring the soup,’ she said. ‘Give a girl a minute.’

‘Never mind that. Fetch Mrs Stratton. Immédiatement.’

‘What? To see some vagabond?’ the girl said.

Claire stiffened.

The chef glowered. ‘Now.’

The maid tossed her head. ‘First you want soup. Now you want the housekeeper. Make up your mind, can’t you?’ She scampered off.

‘Can’t we have soup?’ Jane asked.

‘Later,’ Claire said. She wasn’t going to let anyone see them begging for food as if they really were vagabonds. They would eat in the dining room, like Montagues.

‘I apologise for the mistake.’ He grimaced. ‘We were not expecting you, I think?’

The apology gave her renewed hope. She offered him a smile. ‘It is my fault for coming to the scullery door.’

As he gazed at her face, his eyes darkened, his lips formed a straight line. ‘Madame is generous.’ He had transformed from a man who seemed warm and caring to one whose back was rigid and whose attitude was formal and distant. A huge gap opened up between them and they were now in their proper places. Or perhaps he would not think so, once he knew her story.

‘Madame Stratton will be with you shortly,’ he murmured. ‘You will excuse me, I think?’

Claire smiled her gratitude. ‘Thank you so much for your help.’

‘De rien. My pleasure.’ He bowed and left.

Pro forma, of course, but her thanks had been heartfelt even if her responses to his touch had been distinctly strange.

He had disappeared into the kitchen.

A strategic retreat.

Jane pressed a hand to her tummy. ‘I’m so hungry. Why did you say no to the soup? I can smell it.’

So could Claire. The scent was aromatic and utterly tempting. She was hungry too. It had been a permanent state of affairs these past few months. Recalling the very formal arrangements for family dining at Castonbury Park, she anticipated it would be hours before dinner was served. ‘We will ask for some tea and biscuits,’ she said. ‘As soon as we are invited in.’ If they were invited in.

Jane heaved a sigh, but folded her mittened hands in her lap and swung her legs back and forth.

Claire reached out and squeezed the small hands in hers. ‘It won’t be long.’ She prayed she was right.

At the sound of the tap of quick footsteps on the flags and the rustle of stiff skirts, Claire came to her feet, half fearful, half hopeful. Now she would know if she was welcome here or not.

Despite the grey now mingled with the blonde hair neatly confined within her cap and the new wrinkles raying out from the corners of her friendly blue eyes, Claire recognised the housekeeper at once.

The footman who had closed the front door in their faces only moments before peered over the housekeeper’s shoulder. ‘Saints, another one crawling out of the woodwork claiming to be a relative.’

‘Be quiet, Joe,’ Mrs Stratton said sharply. ‘Go back to your post at once.’

The footman glowered, but stomped off.

The housekeeper turned back to Claire, her kindly face showing surprise mingled with shock. No doubt she saw changes in Claire, too, but it was the shock of recognition and Claire felt a rush of relief.

‘Lady Claire. It is you.’ Genuine pleasure warmed the housekeeper’s voice as she dipped a curtsey. ‘And sent to the servants’ door too. I am so sorry about Joe. It is almost impossible to get good staff these days.’ This welcome was far warmer than she had ever dared hope.

‘It is Mrs Holte now,’ she said with a smile that felt stiff and awkward as her voice scraped against the hot hard lump that had formed in her throat. ‘I wasn’t sure you would remember my married name after all these years.’ If Mrs Stratton had heard it at all. The Montagues had cast her off the moment she had married. ‘It is good to see you again.’

Jane tugged on her arm.

She indicated the child. ‘Jane, this is Mrs Stratton.’ She smiled at the woman. ‘Jane is my daughter.’

Mrs Stratton dipped her head. ‘Welcome, Miss Jane. Are you hungry after your journey?’

‘Yes, if you please,’ Jane said. She glowered at Claire. ‘We almost had soup.’

Claire took her hand. ‘I would like to speak with my brother.’

‘I don’t believe His Grace is receiving today, but I will check. In the meantime, I will ask that tea be sent up to the small parlour.’ Her voice sounded a little strained. ‘I am sorry, but none of the other family members are in residence at the moment.’

Not receiving? Would this visit of hers be for nothing, after all? ‘Is His Grace unwell?’

‘He has been not been himself for a while. Worse since Lord Edward’s death, I’m afraid. He rarely sees anyone.’ She pressed her lips together as if she wanted to say more, but thought it unwise. Claire knew the feeling. How often had she stifled her words in George’s presence for fear of saying the wrong thing?

‘I read of Lord Edward’s demise in the papers after Waterloo. It must have been a dreadful blow after poor Lord Jamie such a short time before.’ She shook her head knowing how she would feel if anything happened to Jane. ‘Perhaps I should not have come unannounced.’ How could she have thought to impose when he was suffering such sorrow? ‘I will go.’

In that moment, she felt like a traveller who had walked miles only to be faced with a cliff she couldn’t possibly climb and had to retrace her steps and start all over again. Yet there had been no other path to take that she had been able to see. If she left now, she would never find the courage to come back. And she had so hoped she and Jane could stay, that they could finally have somewhere they could really call home after so many years of moving from place to place.

Mrs Stratton glanced down at the small valise and back at Claire.

What must the housekeeper think of her turning up here after all these years without any notice? Pride forced her spine straight. ‘I thought to seek my brother’s advice on a matter of importance while I was visiting in the district. I would have written requesting an audience had I realised he was indisposed.’

‘I know His Grace will wish to be informed of your arrival,’ Mrs Stratton said gently. ‘Later. I will ask Smithins to let him know you are here. In the meantime, may I show you to the parlour?’

Confused, Claire could do no more than smile and nod. She followed the housekeeper through the kitchen, with its gleaming pots and huge open fire. The chef looked up from a pot over the stove, his dark gaze meeting hers with an intensity that sent trickles of heat through her blood.

Unnerved by her strange reaction, she looked away and hurried after the housekeeper, along the servants’ corridor to the columned entrance hall and up the stairs into the family wing.

As they walked, Claire’s heartbeat returned to a more moderate rate and she was able to take in the familiar sights of her old home. Hope once more began to build. She ruthlessly tamped it down. The duke might yet toss her out of his house.

And if he did, somehow she would manage.

The small parlour was light and airy and faced south to get the afternoon sun. The blue paint on the walls contrasted delightfully with the heavy white and gilt ceiling mouldings. Landscapes and the occasional portrait decorated the walls, and tables were littered with Greek and Roman artefacts collected by her father as a young man on his grand tour.

She sat down on the gold-and-blue-striped sofa beside the hearth and Jane wriggled up beside her. ‘Do you think they will bring us something to eat soon?’

‘We can hope.’ She cupped her daughter’s face in her palm and gave her cheek a pat. The child was worth any amount of humiliation, if humiliation was what she had in store. For all she knew, Rothermere might still hold a grudge for her disobedience. Their ages were too far apart for closeness and he had always seemed more like an uncle than a brother.

The door opened. The butler, old Mr Lumsden Claire was pleased to see, ushered in Joe the footman carrying a silver tray. Lumsden proceeded to set a small table in front of her and the footman placed the tray on it.

The tray held the ducal silver service and crested china plates displaying the daintiest sandwiches and most artistically prepared sweetmeats Claire could ever remember seeing.

Her stomach clenched with visceral pleasure at the sight of the food. Jane eyed the plates like a starving wolf, or rather a starving child. Which she was.

‘Will that be all, madam?’ Lumsden asked. His voice was carefully blank. In that blankness was a wealth of disapproval.

Her appetite fled. The butler would remember her fall from favour, of course, as no doubt Mrs Stratton had. He would know she was returning cap in hand and that left a bitter taste in her mouth that did not go with dainty sandwiches and spun sugar arrayed in a fountain of colour.

‘Thank you, that is quite sufficient,’ she said calmly.

The butler bowed and left.

A coiled spring could not have been tenser than her daughter as she stared at the food on the tray. ‘Are we really allowed to eat those?’ She pointed at the sweetmeats. ‘They look too pretty.’

Claire wanted to cry. ‘Yes. They are for us. Take what you want.’ She handed her one of the small frilly edged plates. ‘Would you like tea or milk?’

‘Milk, please.’ Jane’s hand hovered over the sweetmeats.

‘Try some sandwiches first.’

Disappointment filled the child’s face. Claire couldn’t bear it. ‘Take whatever you want.’

The little girl filled her plate with sugarplums and sugared almonds and comfits. She popped something dusted with sugar in her mouth. She closed her eyes. ‘Oh, good,’ she said after a couple of chews and a swallow.

Claire poured tea for herself and milk for her daughter.

Her teacup rattled in its saucer as she picked it up. Nerves. Weariness. She sipped at the scalding brew. It was perfect. Brewed only once too. What was she thinking? Dukes didn’t need to reuse their tea leaves.

‘Aren’t you going to try them?’ Jane asked, pointing at the tray.

The thought of putting food in her mouth made Claire feel ill. How could she eat when their fate hung in the balance?

Hopefully the duke would see her today and she could have their interview over and done and know where she stood.

A moment later the door opened. Her heart seemed to still in her chest as she steeled herself to meet the duke. But it was only the kindly Mrs Stratton, her blue eyes a bit misty, the smile on her face still tense.

‘His Grace cannot see you today, Mrs Holte.’

‘Cannot?’ Her heart felt as heavy as lead. ‘Or will not?’

‘Smithins says his melancholy is bad today. He rarely sees anyone at all. The vicar sometimes. Lord Giles when he must.’

Numbness enveloped her. That was that, then. No help here. She looked at the plate of food and wondered if she could somehow slip some of the sandwiches into her reticule for later. She had enough money for one night at an inn, but not for supper.

She’d have to find work again. Somewhere else. Not nearby. The duke’s pride would never allow that. Nor would her own. She would never let her family see the depths to which she had fallen. ‘Please present my good wishes to the duke.’ Claire rose to her feet.

‘Smithins said he is sure the duke would be pleased to see you on a better day.’

Smithins, the duke’s valet, had been with her brother since before Claire was born and it was kind of him to offer hope, but there would be no coming back.

‘I will have your old room prepared for you,’ Mrs Stratton said. ‘And the adjoining one for Miss Jane.’

Her heart stilled. Her spine stiffened. ‘Is this on the duke’s instruction?’

Mrs Stratton cheekbones stained pink. ‘I can only guess at what His Grace might instruct us, Mrs Holte, but I know Lord Giles would insist.’ The woman tilted her head. ‘That is unless you have other plans?’

They could stay. She felt suddenly weak. ‘No. No other plans. Not today.’

‘Dinner is at five,’ Mrs Stratton said. ‘His Grace keeps country hours.’

A roof over her head for the night and a dinner promised. It seemed too good to be true. She just wished she could be certain of Crispin’s eventual forgiveness. That he would agree to give them a home. Only then could she feel easy in her mind. Or at least as easy as she could be until she had settled matters with Ernie Pratt.

Chapter Two

Two more finicky appetites to tempt. Andre’s hands fisted at his sides as he looked at the tray returned from the drawing room. The sandwiches were untouched and only one plate had been used even though the gaunt woman and child he’d seen in the kitchen had looked half starved. Madame Holte had eaten nothing and the child had eaten sweetmeats. The more he knew of them, the more he thought the English aristocracy were completely mad.

Ire rose in his chest. He was tired of preparing meals for people who cared little about what appeared on their plates. Food he’d prepared with his heart and soul.

Becoming the personal chef to a duke had not been the hoped-for triumph. No grand entertainments for members of the ton. No culinary feasts.

But there had been something else. A realisation of the subtle role food played in a life. The duke preferred the comfort of familiar dishes. Almost as if they offered a haven from the devastating changes in his life. André had sought out those dishes and prepared them in the manner of the duke’s youth. And the duke had regained his appetite, somewhat, and Lord Giles had been pleased.

Based on that success, he would return to London at the end of the month with the promised letter of endorsement.

In the meantime, he had a dinner to prepare and he needed to think of something to tempt a woman who looked like a small brown mouse and had turned out to be the sister of a duke. And a child. A little girl with the same sad grey eyes as her mother. What did he know of what children liked? Thoughts of his own boyhood only made him angry, so he’d locked those memories away. Still, he would like to see the child eat something to put a bit of flesh on her bones, and her mother too.

He did remember starving on the streets of Paris for months until he was taken up in the army. He knew what it was to be hungry. It was the reason he’d convinced His Grace to permit a pot of soup on the stove for those wandering the dales in search of work.

He strode to the larder and looked at his plentiful supplies. The pantry always made him feel good. Nothing but the best for the duke and no expense spared. And still the old man preferred a haunch of venison and suet puddings to the delicate sauces and fricassées André longed to prepare. Puddings. Pah. If the great Carême could see him now, he would be horrified.

He brought an armful of ingredients into the kitchen and laid them on the long plank table. As usual, he gave a swift glance around his domain. What he saw made his gut clench. Fear grabbed him by the throat. The swaying skirts of the scullery maid were inches from the flames leaping hungrily at the fat dripping from the meat.

‘Mademoiselle Becca,’ he barked. ‘Step back from the fire, s’il vous plaît.’

The scullery maid squeaked and leapt back, her lank hair slipping loose from her cap.

‘How many times must I tell you, mademoiselle?’ André uttered fiercely, visions of other accidents raw and fresh. ‘Stand to one side of the spit or you will roast along with the pig.’ This kitchen needed modernising. He would speak to the steward again about installing a winding clock beside the hearth, then no one would risk themselves so close to the fire. It just wasn’t safe.

‘Sorry,’ the girl mumbled, wringing her hands. She positioned herself properly and once more turned the handle.

He frowned. ‘Where is Charles? I assigned him this duty.’

‘Mr Smithins sent Charlie on an errand, chef,’ the girl said.

Smithins, the duke’s valet, was a blasted nuisance. He seemed to think he ran the household, and had even tried throwing his weight around in André’s kitchen. Once. But young Charlie, the boot black, hated turning the spit.

Knowing he was watching, Becca turned the spit slowly, just the way he liked and he gave her a nod of approval. She returned a shy smile. Pauvre Becca, she thirsted for approval. He gave it as often as she deserved.

The kitchen maid, Agnes, stuck her head through the scullery door. ‘Shall I throw out this soup, then, monsewer?’

He hated the way these English servants said monsieur. It sounded as if he had crawled from the privy. But it did no good to correct them.

‘How much soup is left?’

‘A quarter of the pot. Not so many came today.’

‘Then the remainder will go to the servants’ hall for dinner.’

‘I don’t see why we should eat the leftovers from a bunch of dirty Gypsies,’ she muttered.

André swallowed a surge of anger at the scorn in her voice. This girl had never known what it was to go without. He kept his voice calm, but instructive. ‘The only difference between you and the Gypsies, as you call them, is you have work and they do not. N’est-ce pas?’

‘Nesper?’

Becca giggled behind her hand.

André frowned. Agnes scuttled back into the scullery and André returned to shucking the oysters.

‘I thought we’d prepared everything for dinner,’ Becca said, watching him, her arm turning the spit by rote.

‘The duke has a guest.’

‘His sister,’ Becca said, nodding. ‘Eloped she did. Years ago.’

That might account for the fear he’d seen in her eyes. A prodigal sister unsure of her welcome. Fear would account for the lack of appetite too. It did not, however, account for the lifeless pallid skin or the eyes huge in her face. She clearly had not eaten well for a long time.

If she had no appetite, she needed something to seduce her into putting food in her mouth. Not that he cared about Mrs Holte. Spoiled noblewomen didn’t interest him in the least, except as they could advance his prospects. If this one refused to eat his food, his reputation would suffer. He bit back his irritation. He would use it as a chance to put his theories about food to yet another test. No woman, noble or otherwise, would resist his food. He left the oysters to simmer and set to work braising fresh vegetables. This time the plates would not return untouched.

Normally, once dinner preparation was finished and the food taken up to the drawing room, André would have retired to the parlour set aside for the use of the upper servants—the butler and the housekeeper and any ladies’ maids present. Or he’d go to his own room and work on his menus for the hotel he planned to open in London. Tonight he found himself inspecting cuts of meat, counting jars of marmalade and generally annoying Becca, who was up to her elbows in hot soapy water washing the pots and pans in the scullery.

And while he counted and checked, he had one eye on the door.

He barely noticed when Joe returned with the duke’s tray. ‘Smithins said to tell you that His Grace said the beef could have used a bit more cooking,’ Joe announced with a cheeky grin, keeping well out of André’s reach.

‘M’sieur Smithins can go to hell,’ André replied, as he always did.

‘Bloody Frenchman,’ Joe muttered under his breath, and ran off.

The next set of dishes brought back to the kitchen were from the dining room where the mouse had sat in splendid isolation with her child.

The tureen of soup had been broached, the soup tasted. A spoonful or two from one bowl, more from the other. But neither was drained.

His jaw clenched hard when he saw nothing else had been touched, not the poached chicken or the pheasant pie or even the vegetables. There was something wrong with the woman. There had to be.

Joe leaned close and inhaled. ‘Smells lovely,’ he muttered. ‘We’ll be done right proud in the servants’ hall tonight.’

André bared his teeth. ‘You will touch none of it without my permission.’ He glanced at the dishes set ready to go up. ‘Take the last course.’

‘No point,’ Joe said cheerily. ‘The little one is sick. They went up to their rooms.’

‘Sick?’

‘Too many sweetmeats, my lady said.’

Not the food. Of course not the food. His food was delicious. He stared at the untouched meal and remembered the thin face and the grey eyes filled with worry. He recalled the child whose bones looked ready to burst from her skin and wanted to hit something. The child had eaten only sugarplums and made herself ill.

Faced with such a treat a hungry child would fill its belly to bursting. He should have sent only the plainest of food. The most easily digested morsels this afternoon. He should have known. He was an idiot.

‘Leave the pie,’ he instructed. ‘Take the rest to the hall with my compliments.’

Joe glowered. ‘Too high and mighty to share that pie with the rest of us, are you?’

André gave him a hard smile.

The lad picked up the tray and scurried off. ‘Be back with the rest of the dishes in a minute or two, Becca,’ he called over his shoulder.

Becca kept her gaze firmly fixed on her dirty pots in the sink.

The pie was a work of art. Pastry so flaky it melted in the mouth. The contents were cooked to perfection. His fists clenched and unclenched as he stared at it. Not because he was insulted. He knew his cooking was exceptional, but because the woman still had an empty belly after he’d sent up food fit for a queen.

It was nothing to do with the tingle of sparks he’d felt when he’d touched the delicate skin of her throat, or the pang of disappointment when he’d learned who she was. A woman above his touch. Not at all. It was simply a desire to see his patron’s family satisfied.

Mentally he shrugged. He’d provided the meal, what they ate was none of his business.

Automatically, he set a tray. The knife and fork just so. A napkin. A slice of pie on a plate and a selection of vegetables. Beautiful.

He glanced over at Becca. ‘Take the rest of the pie to Madame Stratton and M’sieur Lumsden.

La pauvre, as he thought of her, bobbed a curtsey. For some reason the sad little creature treated him like royalty no matter how often he explained that kitchen maids didn’t curtsey to chefs. There was a time when maids and footmen had curtseyed and bowed before running to do his bidding. Before the revolution that had ripped France apart and put it back together differently. He never looked back to that time. The looking back no longer hurt, but those times had become foggy, like a dream. Or a nightmare.

So why was he thinking about it now? Because of her. Mrs Holte. Curiosity and desire mingled with a longing he did not understand. Should not try to understand.

He picked up the tray. No one would remark on his absence. It wouldn’t be the first time he’d taken his food to his own rooms to eat.

He strode up the servants’ staircase.

Claire left Jane finally sleeping and returned to her own room, leaving the door between their chambers ajar. She sat in the chair by the window and stared out into the darkness. What if Rothermere refused to see her? Nausea rolled in her stomach. To have come so close to rescue would be too cruel.

Would remaining here when the man was so ill be similar to her husband preying on young green youths new to gambling? Except Crispin was family. And while he hadn’t despised her mother, who had been the old duke’s nurse, as some of his younger siblings had, he had not held her mother in any great affection either. The birth of yet another daughter so late in the duke’s life had come as a shock to all, but Crispin had always been kind to Claire. Until she had rejected his ducal decision and had more or less forced him to wash his hands of her.

While she had admitted her mistake to herself a long time ago, it would crush what little remained of her pride to beg his indulgence.

Perhaps if the Montagues had treated her more like family and less like an interloper in the years after her father died, she might not have been so vulnerable to the practiced seduction mounted by a fortune hunter like George Holte. Which ultimately left her forced to beg for her brother’s help.

And she would not be here, she reminded herself fiercely, if not for her daughter. Jane was the real victim of Claire’s mistake.

A light tap on the door brought her head up. Was this the summons to meet with her brother?

‘Come,’ she said, gripping her hands tightly in her lap.

The door opened to reveal a tall man in a dark coat. The chef from the kitchen, minus his white hat. The handsome man for whom she had warmed from the inside out at the slightest touch. Unless that was all in her imagination. Everything about him was dark. His eyes brooded. Lips finely moulded for kissing looked as if they rarely smiled.

He pushed the door wider, revealing the tray balanced on one large hand. She recognised the pie as part of the meal she’d been forced to leave behind. The delicious smell made her stomach growl so loudly she was sure he must hear.

‘You did not eat your supper, madame,’ he murmured.

His voice was deep and the trace of his French accent as attractive as the man himself. Her insides clenched with the pleasure of just looking at him. Madness.

An intense dark gaze riveted on her face. She had the feeling he could see right into her mind. As if he could see her lustful reactions. An answering spark flared in his eyes. Her cheeks warmed. This was not behaviour befitting a duke’s daughter.

‘My daughter felt unwell.’

‘Too much rich food before dinner.’ His face remained impassive, but she was sure she heard condemnation in his voice. He thought her an unfit mother.

‘It has been a long time since Jane had such delicious treats.’ Oh, why was she offering up an excuse? Servants always gossiped and they had enough to scorn without her giving them more ammunition.

Why should she care what a chef thought? Was it the delicious smell of the food on the tray undermining her reserve?

‘Now the child is settled,’ he said briskly, ‘there is time for you to eat.’ He set the tray on the small table at her elbow, then lifted the table and set it before her.

Her mouth watered. ‘This is very kind of you, Mr …?’

‘André. Monsieur André.’

She smiled. ‘My thanks, Monsieur André.’

He acknowledged her gratitude with an incline of his head and folded his arms over his wide chest. ‘Eat.’

‘Yes, thank you.’ She looked at him, expecting him to leave. He didn’t move. ‘Is there something more?’

His eyes widened a fraction. Chagrin flickered across his face. Or was it anger? His expression was now so impassive, so carefully blank, she couldn’t be sure. ‘I wish your opinion on the pie, madame,’ he finally said. ‘Is it good enough to send up to the duke?’

‘Oh.’ Her chest tightened at the idea that he would think she had such authority. ‘It is not my place to say, I am sure.’ She looked down at the plate, at the pastry, golden and flaking at the edges, the thick creamy sauce coating the vegetables and meat. ‘It looks and smells delicious. I am not sure—’

‘You will taste it, madame.’

That was an order if ever she’d heard one. French chefs. She’d heard they were difficult. She had no wish to upset him. No wish to anger her brother. Not before they had a chance to talk. She picked up the cutlery.

Monsieur André leaned forward and shook out the napkin and spread it over her skirts. He moved so close, she could see the individual black lashes so thick and long around his dark eyes, and the way his hair grazed the pristine white collar showing above the black of his coat. Her breath seemed to lodge in her throat at the beauty of his angular face so close to hers and the warmth of him washing up against her skin. The scent of him, lemon and some darker spice, filled her nostrils. Her head swam a little.

Only when he stepped back could she take in a deep enough breath to dispel the dizziness. It must be hunger.

What else could it be?

A flush lit her face and neck. She lowered her gaze to her plate and cut into the pastry. She stabbed a fragment of partridge coated with sauce with her fork and put the whole in her mouth. The flavours were sensational. Creamy. Seasoned to perfection. Tender. She closed her eyes. Never had she tasted food this good. She finished the mouthful and glanced up at the chef who was watching her closely.

Once more she had the feeling he could read her thoughts. The man’s intensity was positively unnerving.

‘It is delicious. Thank you. I am quite sure His Grace will be pleased.’

She set down the knife and fork, expecting him to depart. Would he take the tray with him? She hoped not.

‘You need to eat more to be certain,’ he said.

She blinked. ‘I really don’t think—’

‘It might be too rich,’ he said. ‘You cannot tell from one mouthful. Did you not find the oyster soup too rich?’

‘Oh, no, it was delicious. Really.’

He raised a brow. ‘You ate so little, how could you tell?’

Goodness, the man was as autocratic as he looked and that bump on his nose reinforced the fierceness in his eyes. A warrior chef? ‘Very well.’ She picked up her knife and fork and ate two more mouthfuls and found herself wanting to shovel the rest into her mouth. The more she ate, the more she wanted. Before she knew it, the plate was empty and she felt full to the brim. She sighed.

When she looked up, the chef’s full sensual lips had the faintest curve. A smile?

Her stomach flipped over in the most decadent way.

What was wrong with her? Hadn’t she learned her lesson with regard to attractive men? They didn’t want her at all; they wanted her family connections. Mortifying it might be, but it was the truth.

She straightened her spine, picked up the napkin and flung it over the empty plate as if it would hide just how hungry she’d been. Too hungry to leave a morsel. No doubt they would be talking about that in the kitchen tomorrow while they dredged up the old scandal. ‘That was delicious, Monsieur André.’ She waved permission for him to take away the tray.

His posture stiffened. ‘Madame would like some dessert? There is a vanilla blancmange in the kitchen.’

It sounded heavenly. And he offered it in such velvety tones she could almost taste the vanilla on her tongue as his voice wrapped around her body. Charm. She fell for it so easily. She clenched her hands in her lap. ‘No. Thank you.’

A muscle in his axe blade of a jaw flickered as if he would argue. A mere twitch, but it broke the spell. What was she doing, letting this man order her about? Never again would she be any man’s doormat. Her spine stiffened in outrage, at him, at herself. ‘That will be all, Monsieur André.’

He recoiled, his eyes widening. ‘I simply saw that you did not eat and thought—’

‘What I eat, when I eat, is my concern alone, monsieur.’

‘I beg your pardon, madame,’ he said stiffly. There was anger in his tone, but something else gleamed in his dark gaze. Hurt? Gone too quickly to be sure, he was once more all arrogant male as he bowed. ‘I will relieve you of my unwelcome presence.’ He swept up the tray and strode from the room.

Blast. Now she’d upset Crispin’s chef. Montague pride, when she had nothing to be proud about. Hopefully the man would not vent to her brother, or take his anger out on the kitchen staff. She would probably have to apologise, even though the chef was in the wrong.

Chapter Three

The breakfast room overlooked the lawn at the side of the house. If one stood close to the window, one could just get a glimpse of the lake, with its decorative bridge and the island in the middle. Now it was frozen and dusted with a fresh fall of snow. She would take Jane outside later to look at it. Tell her about rowing over to the island in summer. Right now the child was tucking into coddled eggs and ham and had ceased to chatter for once.

‘Don’t eat too quickly, dearest, or you will be ill again,’ she cautioned.

She glanced at a sideboard weighed down with platters of food—eggs scrambled and coddled, bacon with curly brown edges and a hint of a sear, assorted breads and pastries and a juicy steak. The footman had delivered the food under Lumsden’s eagle eye from the moment she arrived.

‘Will His Grace be coming to breakfast soon?’ she asked Lumsden as she added cream to her coffee.

‘His Grace breaks his fast in his chambers, madam.’

She stared at the array of food on the sideboard and down at her plate of ham and poached egg and the bowl which had contained deliciously stewed plums and prunes. She and Jane had scarcely made a dint in the feast. At most she might manage a piece of toast and marmalade when she was finished with this.

‘Then who else is coming for breakfast?’

Jane looked up with interest.

‘No one else, madam,’ the butler said.

Claire frowned. Such extravagance. All this food would be wasted.

Lumsden must have guessed the direction of her thoughts because a fleeting smile crossed his face. ‘The food will end up in the servants’ hall, madam. The staff had a small piece first thing this morning, bread and cheese, before the fires were alight, but they will have breakfast proper when early-morning chores are done.’

Heat travelled up her cheeks. She had forgotten how it went in a house full of servants; she had never had more than a couple of live-out maids during all of her marriage and sometimes none at all. These past months she’d been her own cook and housemaid. How would she ever fit back into this world of privilege and idleness if she kept thinking like a poverty-stricken widow?

‘Will there be anything else, madam?’ the butler asked.

Claire looked at her plate and at the piles of food on the sideboard and couldn’t eat another bite. No matter that she’d felt hungry when she first walked into the room, it was all just too much.

‘No, thank you. Jane, are you finished?’

Her daughter, who now had nothing but a few smears of egg on her plate and crumbs on the tablecloth, nodded.

‘Then that will be all, thank you, Lumsden. You may clear away.’

Lumsden frowned, looked as if he was about to speak, then pressed his lips together. No doubt he wanted to tell her the chef would not be pleased she’d eaten so little. Next the man would be bringing her another plate of food. Surely not after her unfriendly dismissal the previous evening. He wouldn’t dare to visit her room again. And a good thing too, even if she did admire his dedication to his work.

As she’d come to admire the hard-working shopkeepers, merchants and other businessmen with whom she’d come into contact while living on her own. Unlike George, who had dedicated his life to doing as little as possible, they were dedicated to the improvement of their families.

Perhaps that was what made the chef seem so attractive. He cared about his work.

Lumsden took her plate back to the sideboard and clicked his fingers, signalling the waiting footman to clear the platters.

‘I would like to see His Grace at the earliest opportunity, preferably this morning,’ Claire said, rising from her seat.

‘Indeed, madam. Smithins will collect you from the blue drawing room.’

‘Very well. Come, Jane.’ She swept from the room with Jane’s hand in hers. At least she hadn’t made a complete cake of herself, playing the duke’s daughter. As she and Jane wandered along the corridor lined with pictures of her ancestors, she regretted not finishing her breakfast. It seemed that standing up for herself had restored her appetite.

Then she remembered a thought that had occurred in the deep reaches of the night. It hadn’t woken her. No, her rest had been disturbed by a low seductive voice in her dreams and images of an arrogant chef running long tanned fingers down her arm, then moving on to the rise of her breast.

Panting and hot she’d sat up in bed, not terrified but full of longing. For passion.

She squeezed her eyes closed against the memory of the heat and the flutters low in her belly. She would not think of that. But as she had lain there in the dark regaining her composure with the ticking of the clock and the howl of the wind among the chimneys for company, she had remembered the words spoken yesterday. Another one crawling out of the woodwork claiming to be a relative.

What had the cheeky Irish footman meant by ‘another one’? It was a question she intended to ask Mrs Stratton.

Jane skipped into the drawing room with its heavy gilded and scrolled furniture adorned by, Claire blinked, half-naked females. Mermaids. She had better not linger in this room for too long or Jane would be asking her about them.

‘Can we go outside now, Mama?’ the child asked, looking around her with obvious disappointment. ‘To see the lake?’

‘Perhaps. After we see the duke.’

Jane slumped back against the chair cushions and folded her hands in her lap. Her daughter was much too obedient, Claire thought with a pang. Too still. Too careful. George’s fault. He’d had a temper in his cups. They’d both learned to walk quietly around him.

The child needed laughter and joy.

And she would find it at Castonbury if they were permitted to stay. There would be no more moving. No more running from debtors.

A scratch at the door before it swung back brought her upright. An elegantly garbed gentleman of some sixty years entered the room. He was no more than five feet tall and his person was slim. He had thick white hair carefully coifed à la brutus.

He held out both hands in a gesture that seemed almost feminine. ‘Lady Claire. How wonderful to see you home after all these years. And your daughter.’ He executed a flourishing bow.

‘Smithins,’ she said, smiling at his effusive greeting and obvious warmth. ‘It has been a long time.’

‘Seven years at least, Mrs Holte.’

‘Are you here to escort me to His Grace?’

‘Madam, I am. His Grace is quite chipper this morning.’ He beamed at her, then his smile dimmed. ‘Of a surety you will find him much changed. It is the doctor’s opinion that too much excitement is bad for him, but knowing you are here, he has made a great effort to be up and about this morning.’ He smiled triumphantly as if bestowing a gift.

The nerves in Claire’s stomach leapt around like butterflies in boots. ‘So he has agreed to see me.’

‘He looks forward to it.’ He glanced at Jane. ‘And to meeting the little lady.’ He spun around and headed out of the door.

She took Jane’s hand and followed.

‘His Grace uses the old state apartments these days,’ Smithins said as he directed her along the corridor to the central block. ‘Fewer stairs to climb. I am sure you remember the way.’

‘Smithins?’ she asked as they travelled through the antechamber towards the great double doors, ‘who else has come to claim relationship to the duke?’

Smithins stopped and pivoted a hand to his lips. ‘You have heard already?’

‘I heard a chance remark. It is not one of his … his …’

The duke had been a bit of a rake before his marriage. And after, if some of the tales were true.

‘No, no.’ The man waved an elegant hand like a lady batting away a fly. ‘It is Lord Jamie’s wife.’

‘I hadn’t heard that Lord James had married.’ She’d always watched the newspapers for news of her family. Births, deaths and the occasional mention in court reports.

‘Nor had anyone else,’ Smithins said with a sly smile. ‘Married her on the continent. She arrived just a few months ago with her son, Lord Jamie’s heir.’ He lowered his voice. ‘And very little proof, I’m told. But His Grace is happy to be convinced.’

‘She’s here at Castonbury?’ It was strange she hadn’t taken dinner with Claire or that Mrs Stratton hadn’t mentioned her.

‘She lives in the Dower House.’ He flung back the door and ushered her and Jane into a vast room where the curtains covered the windows and only one branch of candles shed any light apart from that given off by the hearth.

A smell of illness pervaded the room. Sickly smells. And the smell of elderly man. Someone should open a window and let the fresh air in. It reminded her of visits to her aged father, the previous duke.

It took a moment for her eyes to adjust to the gloom. When they did, she made out a male figure sitting close to the flames in a scarlet banyan and slippers with a matching embroidered cap perched on a balding pate.

He looked like a man of eighty instead of the sixty summers she knew he owned. The gaze fixed on her seemed bright enough though. She approached his chair. ‘Your Grace.’ She dipped a curtsey. ‘It is Claire. Your sister. I am come home. This is my daughter, Jane.’ She drew the child closer.

Jane bent her knees and wobbled only a little. Claire felt very proud. Jane might carry the name Holte, but she was also a Montague through and through.

‘Claire,’ His Grace said with a vague wave of a trembling hand. ‘Welcome. Forgive me for not rising. Knees aren’t what they used to be. Pull up that stool and sit in the light where I can see you. I don’t see as well these days.’ He shook his head.

Claire did as she was bid and once seated she gazed long at her half-brother, looking for the man he had been, proud, tall, full of authority. She found only a face etched in lines of grief and a body bowed over with sorrow.

‘What brings you home, Claire?’ A shade of his old smile kicked up one corner of his mouth. ‘I thought you’d brushed off all signs of Castonbury dust. How can I be of help?’

Her angry words coming back to haunt her. It saddened her that he realised she had not simply come to visit. He must be used to receiving petitioners, people who came because of his power, not for the man himself. She regretted it could not be otherwise with her.

‘My husband is dead.’

‘I am sorry, my dear.’ The regret sounded genuine.

‘I am not. You were right. He was not a kind man. Or a good one. But I made the best of it until he left us destitute.’

Worse than that, in truth. But she would hold that information until she had a sense of his reaction.

Rothermere sat silent for a moment staring at the fire and Claire wondered if he had slipped away into his own melancholy and forgotten her. She glanced at Jane, who was staring at her uncle intently.

‘Why is he wearing his night clothes?’ the child whispered. Jane’s whispers were piercing.

‘Hush,’ Claire said, thinking she would have to leave and try another day. ‘Your uncle is not well.’

The duke raised his head and looked at her. ‘I followed, you know. I almost had you just before the border. Hit a rut and broke a wheel.’

‘You came after me?’

He nodded.

So a wheel had altered the path of her life. ‘I had no idea.’

Jane slipped off her stool and wandered across the room to look at a portrait of a man in a full Elizabethan ruff, then moved on to peer into a glass cabinet full of snuff boxes.

‘When he came later, for his money,’ Crispin said, drawing Claire’s attention back to his face which looked quite sad, ‘he said you never wanted anything to do with us, but he wanted the dowry I owed.’

Claire gasped. ‘You didn’t pay it?’

The bushy brows drew down. ‘I did. Not that he was all that grateful. I think he thought it would be more.’

She gasped. The money was gone? Her heart twisted, her mind reeled. She’d been relying on her dowry to resolve her troubles. ‘George said you refused to part with a penny.’ George had cursed the name of Montague. Blamed his failures on not receiving his proper due. This was worse than anything she could have imagined. ‘He told me you threatened to horsewhip him for his audacity.’

The gnarled hand tightened on his stick. ‘I should have.’

Jane moved on to look at a suite of armour. ‘Don’t touch it, please, darling,’ Claire said.

‘I’m glad you came home, Claire.’ Crispin’s eyes glistened. Tears? For her? ‘I made a mess of things, Claire. Cocked it up.’ He shook his head. ‘No. Wrong words in front of a female. I sold when I should have bought.’ He lowered his head as if to hide his anguish.

‘I don’t understand, Crispin,’ she said softly.

‘The funds. I sold them. Jamie would have known better. And now, finally when you come to me for help, I’m of no use to you or anyone. Not any more. Not any more.’ His lifted his head, his eyes focusing sharply. ‘I was right about Holte though. You wouldn’t listen to me. But I was right. I told you he was a dashed loosed screw.’

‘Yes.’ She swallowed. ‘You were right.’

He glanced over at Jane, who was now inspecting a statue of a Roman soldier. ‘Your daughter looks like you.’

He meant Jane was not pretty. Was not a true Montague. All the Montague women were lovely. And the men handsome as sin. It hadn’t carried through to the child of the duke’s second marriage or to her daughter. But to Claire, Jane was the most beautiful child ever born. ‘She has some of me and some of her father.’

‘Hmmph. Well, why did you come back?’ His mind seemed to dart hither and yon and there would be no point in beating about the bush if she was to get an answer.

‘Holte left debts. I thought to ask for my dowry to pay them off, but it seems he was before me.’

‘Money,’ he said gloomily. ‘You’ll need to speak to Giles about financial matters. There’s little to be had.’

She knew a refusal when she heard one. She’d humbled her pride for nothing, but in truth she was glad to know her brother didn’t hate her. Glad to know he was happy to see her again, even if he couldn’t be of assistance. ‘I am so sorry to have troubled you,’ she said. ‘You clearly have more important things on your mind. Jane and I will leave in the morning.’

‘You need a husband.’

She gasped. The beautiful face of the chef flashed into her mind, leaving her aghast at the wayward turn of her thoughts. ‘It is the last thing I need.’

He shook his head. ‘Every gel needs a husband. You are young. You are still in your child-bearing years. A duke’s sister is quite a catch, you should do very nicely on the marriage mart.’

She didn’t want another husband. She did not want to be at another man’s beck and call, subject to his temper and foibles. She’d wanted to come home to Castonbury and hide. ‘Who would want to marry me, after all the scandal I caused?’

‘There are still plenty willing to ally themselves with this family, aye and pay for the privilege. If you want my help with these debts, you will be guided by me.’

The snare pulled tighter around her. ‘Crispin, please, I have my daughter to think of.’

‘Then think of her, not yourself. There are a few good men in this county who would see marrying my sister as a step up, and who are deep in the pockets too.’

She hesitated, panicked, not sure how to answer. She had not expected this.

‘I can’t force you to marry anyone, Claire.’ He cracked a laugh and put a hand to his chest as if it hurt. ‘I learned that lesson, but perhaps you would trust my judgement this time? You would be helping the family.’

The anxiety in his voice made her nervous. ‘How?’

‘As I said, there are some who would pay handsomely to claim kinship to a duke. And for the influence they’d gain. The estate could use an infusion of money.’

Money for the dukedom. He wanted to sell her to the highest bidder in return for welcoming her back into the family. Heart pounding, her gaze sought her child, now seated on the floor with the statue, making him march along the patterned edge of the carpet. Jane needed security and safety. This would provide it.

And this time Crispin would choose. Wisely. A choice made of reason and logic. ‘Do you have someone in mind?’

He looked pleased. ‘I’ll make up a list of possibilities. Then I advise you talk to Seagrove. Get a sense of the men. He knows people’s hearts.’

‘Seagrove?’

‘Bloody parson. You remember him. Plays chess.’

So she was to consult with the vicar about a suitable husband. It seemed a little embarrassing to say the least. ‘How is Lily Seagrove? Does she still live at home?’

The duke raised his head. ‘Aye. For the nonce. She’s to marry Giles in the summer.’

Now that was a surprise. ‘I didn’t think they liked each other.’

The duke’s eyes began to glaze as if the topic wearied him. Dash it, she had one more thing to ask. ‘I was wondering if Jane and I could stay here at Castonbury.’

‘Stay? Yes, stay. What else did you think? No females here at the moment, I’m afraid. No one to act as chaperone. Phaedra is off somewhere with her aunt Wilhelmina. Ask Smithins where they went. He’ll know.’ He lowered his voice. ‘Kate married, you know.’ He leaned closer. ‘An American.’

He made it sound as if she’d married a criminal. She’d seen the notice in the papers and had dithered about sending congratulations. She wasn’t even sure Kate would remember her. And Phaedra had been so young when she left.

The lost years saddened her. ‘I’m a widow. I don’t need a chaperone, but if I am to meet these men, I will need to entertain a little.’

‘That’s the ticket. Catch yourself a husband.’ He nodded as if they hadn’t just discussed the matter in detail. ‘I’ll have that steward of mine give you some pin money. We can’t have you looking like a crow. You are a Montague.’

Tears scalded the back of her throat. ‘You really are too kind, Crispin.’

‘Should have run the bugger through. That would have been kind. I was as hotheaded as you, I suppose. I wanted you to learn your lesson.’

She bowed her head. ‘I did. You don’t know how often I regretted what I did.’

He glared at Jane, who had wandered back to stand at Claire’s side. ‘Learn from your mother, girl. Do what your family expects.’

Jane visibly wilted.

Crispin turned his head to stare into the fire. ‘We need Jamie. That’s who we need. He would have known what to do.’

Smithins appeared as silent as a wraith at Claire’s elbow. ‘Best leave now, Mrs Holte. I will issue his instructions.’ He gestured to the door.

Claire rose and took Jane’s hand.

‘Why, he has fallen asleep,’ Jane said, looking at her uncle, bending over to peer right up into his face. ‘Uncle Duke?’

Smithins smothered a giggle. ‘He’ll rest now until lunch. It’s the laudanum, you know. It keeps the pain at bay.’

‘Come, Jane,’ Claire said. ‘Let us leave your uncle Rothermere to his nap.’ She led the child outside.

The smell of illness lingered in her nostrils.

‘Why don’t we go for a walk?’ she said to Jane.

The little girl gave a skip. ‘Can we make a snowman?’

‘I don’t see why not.’ Fresh air would help her come to grips with this new development. Find a husband? She almost laughed hysterically. Seemingly she had stepped from the frying pan into the fire.

Her stomach gave a sickening lurch.

Chapter Four

‘No eggs?’ André growled.

Becca shrugged.

‘Sacrebleu. How am I supposed to provide dinner without eggs?’

The girl looked at him with a considering gaze. André half expected her to tell him. The girl was as nervous as a cat most of the time, but when they were alone in the kitchen, she sometimes displayed a hidden courage. He tried to encourage it.

‘What flea’s biting you this morning, monsieur?’ she asked instead.

‘I beg your pardon? I do not have fleas.’

‘You’ve been as bad tempered as a dog with fleas since you got in here this morning. Which one bit you?’

Ah, the English vernacular. It always caught him out.

Yes, he had been out of temper. Not screaming and yelling as some chefs did when angry, but edgy and perhaps a little too sharp. It was his unexpected response to the Englishwoman that had unsettled him. His urge to help, when she had been quite clear she needed nothing from him. Such concern for a highborn woman wasn’t like him. And it certainly wasn’t Becca’s fault that there were no eggs in the pantry. ‘I beg your pardon, mademoiselle.’

She stifled a giggle behind a red work-roughened hand. She always did that when he called her mademoiselle. It made him smile back.

‘The boy didn’t bring no eggs yesterday afternoon,’ she said, bending to grab another potato. ‘I wondered why you didn’t ask him.’

She could have said something. He was lucky they’d had enough for breakfast. Merde, he’d been so incensed about Mrs Holte eating none of his sandwiches, so keen on making something to tempt her at dinner, he hadn’t noticed.

She’d made him forget what he was about, with her pale face and the crescents of lavender beneath sad grey eyes. And led him to go where he was not welcome. Her dismissal still irked.

He let go a sigh. There was no one to blame but himself and therefore he must solve the problem. He would go to the Dower House and see if the cook there had any eggs to spare. If not he would be walking to the village. In either case a walk would do him good. Clear his head of visions of the mousy Englishwoman who intruded upon his thoughts when he least expected.

He didn’t like skinny women. He liked them plump and curvaceous, with hearty appetites at the table and in bed. Women who did not cling or need cosseting. Women who enjoyed and moved on as he did. It was better that way.

Mrs Holte looked as if she needed a strong arm at her waist, or she would blow away in one of the infernal winds that swept down from the foothills they called Peaks. No, Mrs Holte was not his style at all.

So why could he not get her out of his mind?

He tossed his hat on the desk in his tiny office where he kept his papers and accounts and hung up his apron. He grabbed his coat from the hook behind the door. ‘I will not be more than an hour or two. Finish the potatoes and the root vegetables. They should keep you employed until I return. Agnes can help you when Madame Stratton has finished with them. Tell Charlie to bring in more wood, and coal too.’

Tonight there would be no untried dishes.

He stepped out into a grey day. Clouds obscured the hills he scorned and had left a fresh layer of white over the ground. Barely enough to cover the toes of his boots. He turned up his coat collar and headed for the path that wandered across the grounds to the small house set aside for the widow of the heir.

As he left the courtyard the wind hit him full force, tugging at his coat and making him grab for his hat. But it wasn’t the wind that took his breath away; it was the sight of the woman and the child in the middle of the lawn scooping snow into a pile.

Building un bonhomme de neige. How many years was it since he had entered into such a childish game? A long time. If ever. He shook his head. Once, he recalled, the soldiers in his company had flung snowballs around. Then they’d created a man of snow and topped it with a shako, calling it their captain’s name and telling him what they thought of him. They’d all been very drunk, but they had laughed until they fell down. They were lucky not to have been flogged for such foolishness.

He’d been fifteen.

He stood watching them, mother and daughter. He heard their laughter carried on the wind. It made him want to smile. He liked children. He liked their innocence. Their lack of guile. He especially liked that Madame Claire would spend time with her child, instead of leaving her to a nursemaid. She was a woman to be admired.

He narrowed his eyes. They were making a very poor job of the man of snow.

He found himself walking closer. The child saw him first. ‘Have you come to help?’ she asked in a high piping voice. Her cheeks were rosy from the wind, her eyes bright, her smile welcoming.

‘Good morning, madame, mademoiselle.’ André looked at her mother, who regarded him warily. Her grey eyes reminded him of clouds full of rain. Her smiles for her child hid fear and sadness. He had a terrible urge to offer his help, not with the snowman, but with the deeper troubles reflected in her gaze. It wasn’t his place to offer anything.

He glanced down at the heap of snow at his feet and back at the child. ‘I do not wish to intrude, but if you take a handful of snow like this—’ he bent, picked up a handful of snow and formed a ball in his gloved palms, squeezing it until it was round ‘—and then you roll it like so …’ He rolled the ball and it gathered all the snow in its path until it grew three times its size. He looked up at the child. ‘Then you will soon have his body.’

He stood up.

‘Mama, look, isn’t he clever?’

‘Very,’ the woman said, but she did not smile. She no doubt found him impertinent. And he was. It was in his nature. Dictated by his heritage, he presumed. It had got him into all sorts of trouble in his youth. But he did not need trouble now, not when he was so close to achieving his dream.

He bowed. ‘I wish you both a good day.’ He headed for the path.

‘Don’t go,’ the child called. ‘Stay and help.’

He hesitated, then turned back.

‘I am sure Monsieur André has better things to do than play at making snowmen with us,’ her mother said. She had a nice voice. Light yet musical. She spoke his name beautifully, like a Frenchwoman.

‘I have time to build un bonhomme.’ The words were out of his mouth before he thought about them and the little girl was looking at her mother for agreement.

The woman raised her hands from her sides in defeat. ‘Then I am sure Jane and I will appreciate the help.’

In short order the three of them were pushing a very large and very heavy ball of snow around the lawn. Twice his hand touched that of the English madame. He felt the shock of it all the way from his fingers to his chest. And then lower down. Deep in the pit of his belly. The rise of desire.

She moved her hand away so quickly he had the sense she had felt the tingles too. After the second time it happened, she was careful to keep the child between them.

Finally they could barely push the uneven-shaped ball it was so heavy.

‘I think it is quite big enough,’ Mrs Holte said, laughing and panting.

‘I want him to be the biggest snowman ever,’ Jane said.

‘He is,’ André said. ‘Now we need a head. Make a ball the way I did and we will start again.’

Jane pressed snow together in her hands, then raced around in larger and larger circles gathering snow on her ball, the green grass being revealed in an increasingly wide track behind her.

Breathing hard, Madame Holte watched her daughter with a smile on her lips. She was really pretty when she smiled. Not pretty. Striking. Because it was so unexpected, and so full of joy.

A joy he’d made possible.

Insanity. He’d simply stopped to help the child. He’d wanted to see the little girl happy, that was all. Children deserved to be happy.

Did they not? His childhood, the parts he allowed himself to remember, must have had some happy moments. He tried to recapture the feeling he saw in Jane’s bright eyes and flushed cheeks. The delight and the innocence ringing in her laughter. He couldn’t do it. Yet he had the sense of memories buried deep inside.

What would it be like, having his own child? A family. During the war, he had always avoided thoughts of family, children, ties. Life was too dangerous. And since then he had been working too hard to establish himself.

Watching this child at play today had created a longing that had nothing to do with lust for the mother. It was far too much like a need of the soul. It cut the ground from under his feet in a way he did not like, yet could not seem to resist.

For some reason he felt as if he stood at the brink of an abyss.

He turned away from the sight, turned to speak to the mother. ‘She is having a good time, non?’ He was shocked at how husky his voice sounded. How unsure.

Her face tipped up to meet his gaze. The love in her smile held him entranced. ‘She is. Thank you for your help.’

The smile was not for him. It was for the child. And still it burned a path through his chest. Not all smiles were honest. Bitter experience had taught him not to believe them. He waved a dismissive hand. ‘De rien. We will build the head and then I must go.’

‘Of course. Thank you.’ She gazed at him, at his face, as if seeing the man, him, André, not the servant. His breath caught as warmth changed her eyes to silver, sparkling with female interest, disguised, but there nonetheless. It fired his blood and stirred his body to life.

Breaking contact with that considering gaze and the promise it held cost him a good deal of effort.

Bad idea, André, mon ami. Très mal.

He strode to the child, helped her finish the head and carried it back to the body all the while refusing to think about the watching woman. Refusing to think about his body’s urges.

He was a man, not a beast, after all. He’d become used to denying those urges when the only women available were those who wanted more than he had to offer, more than mere dalliance with no strings attached.

Because he’d learned early, there were no guarantees. Women were as frail in their promises as men. It was far better to trust only in oneself.

So why did this woman stir his blood to the point he could not keep these important lessons at the forefront of his mind? Was it her vulnerability feeding an urge to protect those weaker than himself? After all, he’d been fed a diet of chivalry as a very small child. Until he’d learned better. Had learned if he didn’t take care of himself, no one else would. Bitter experience had made it second nature.

And yet here he was playing in the snow with a child, to please this woman.

Whatever it was that drew him to her, it was not something he could or would do anything about.

Tomorrow was his day off. He would go to town and be rid of his excess energy in the boxing ring. And afterwards, if he still felt the need, he would find a willing woman. Then this little brown mouse would have no more effect on him after that. None at all. He wished he believed it.

‘There,’ he said to Jane, forming the shoulders. ‘Scoop some grooves to make his arms and then go to the kitchen and tell Mademoiselle Becca you are to have some coal for eyes and a carrot for a nose.’ He glanced at her mother, who was smiling admiringly. ‘Perhaps one of the other servants has an old hat he would be willing to donate.’

Mrs Holte nodded. ‘I expect we can find something.’

‘Then I bid you good day, madame, mademoiselle.’ His bow was jerky, as if his body wanted to refuse the instruction from his mind.

He strode away, angry at himself for wanting more than life permitted.

A man’s prick could land him in all sorts of trouble. He’d seen it time and again. He had no intention of losing everything he’d worked for in the hope of making a quiet woman smile.

He groaned out loud as he felt a surge of warmth in his veins at the memory of her smile. A soft tender warmth that made no sense. The woman was of the nobility. Not for him, a servant, even if he could ever be interested. Which he could not. He knew that kind of woman and did not like them at all.

He smiled ruefully. He had his life. His passion. He didn’t need a woman to complete him. He didn’t need anyone.

What he needed was eggs.

Buxton was the same thriving market town Claire remembered from her youth. It had not taken her long, after descending from the duke’s carriage, to remember her way around. Now Joe had an armful of parcels and she had depleted most of the money Mr Everett, the Castonbury steward, had given her from the duke’s strongbox.

She’d done well with her money. A couple of ready-made gowns for her and Jane to be going on with until the seamstress came by to measure her for gowns in the lovely material she’d picked up from Ripley and Hall in Castonbury village. She’d bargained well for her items as she’d learned to do over the past years and now she was exhausted. And cold. Her toes were numb in her worn boots where the slush on the pavement had seeped in, dampening her stockings.

Opposite her was the Bricklayer’s Arms. A coaching house boasting a coffee room, a taproom and private parlours for gentry, but it would not do for her to be seen there. Hard up against the inn was a gymnasium through whose portals men were to be seen coming and going singly and in groups.

But there was one place she could go to warm up without embarrassment. She turned back to Joe. ‘Take those to the carriage and wait for me there. I am going into the lending library.’

She pointed to the building opposite the market cross. She couldn’t remember the last time she had borrowed a book. Goodness, she couldn’t remember the last time she had read one.

A bell jingled as she walked through the library door and a clerk at the counter looked up with a smile. She nodded as only the daughter of a duke could do.

‘Can I help you, madam?’ the clerk asked.

‘What do you have that is new?’

The clerk handed her a sheet. She could have asked for every one of the titles listed. ‘Waverly, please. Oh, and these two, if you have them.’ She pointed to a couple of names she thought she knew.