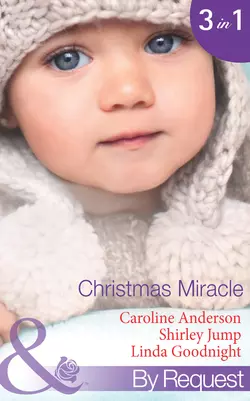

Christmas Miracle: Their Christmas Family Miracle

Shirley Jump

Caroline Anderson

Linda Goodnight

Their Christmas Family MiracleWhen suddenly homeless single mum Amelia Jones is offered the chance to stay in an empty country house for Christmas, she jumps at the chance. As snow falls, Millie starts to believe that Christmas wishes can come true. Until owner Jake Forrester steps through the door…A Princess for ChristmasBulldozing his way into Harbourside, property tycoon Jake Lattimore laughs in the face of opposition – until he’s stopped by fiery Italian Mariabella. As Jake begins to fall for the town, he has no idea that Mariabella carries a secret, in the form of a diamond tiara!Jingle-Bell BabyOn a dusty Texas roadside, rancher Dax Coleman delivered Jenna Garwood’s baby. As a single dad, Dax knows what it’s like to raise a newborn alone, so he offers her a job. But he’s not prepared for the fireworks between them, or Jenna’s secret, which could shatter his trust.

Christmas

Miracle

Their Christmas

Family Miracle

Caroline Anderson

A Princess for Christmas

Shirley Jump

Jingle-Bell Baby

Linda Goodnight

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#ufb2a3209-20cf-58b2-93bd-90cb05c93099)

Title Page (#ucd1e69aa-f6f3-5633-a030-4986eaa7a59d)

Their Christmas Family Miracle (#u6cef0ed6-e326-5fdf-8772-0b8a1abdee71)

About the Author (#uc47ec1f1-2aab-5ab4-8c1a-f961304e9f2f)

Chapter One (#uf12b313c-6b68-5c42-b39f-4bd9775911d5)

Chapter Two (#u2606269e-4da8-5d7e-b7ee-e571d74a38df)

Chapter Three (#ucbe5c690-25aa-52a2-bdbd-a4dddf4bb29d)

Chapter Four (#ue3d37517-a531-5e4e-aeb3-5f80509cf089)

Chapter Five (#u94c76896-3f2d-5104-b14a-c84b51702ba3)

Chapter Six (#u0df19d0a-3088-542f-844e-8aa1e9d320b2)

Chapter Seven (#u536cabf7-f688-5c95-ae1a-6f2bdcab4287)

Chapter Eight (#ucca6521b-779b-5ffa-b2e9-24e3e3572d51)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

A Princess for Christmas (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Jingle-Bell Baby (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Their Christmas Family Miracle (#ulink_977e8d07-9bfd-568d-bb41-13273f4d9637)

CAROLINE ANDERSON has the mind of a butterfly. She’s been a nurse, a secretary, a teacher, run her own soft-furnishing business and now she’s settled on writing. She says, “I was looking for that elusive something. I finally realized it was variety, and now I have it in abundance. Every book brings new horizons and new friends, and in between books I have learned to be a juggler. My teacher husband, John, and I have two beautiful and talented daughters, Sarah and Hannah, umpteen pets and several acres of Suffolk that nature tries to reclaim every time we turn our backs!”

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_2d6b1db4-48f7-5034-8f28-b28ee55da758)

‘WE NEED to talk.’

Amelia sat back on her heels and looked up at her sister with a sinking heart. She’d heard them arguing, heard her brother-in-law’s harsh, bitter tone, heard the slamming of the doors, then her sister’s approaching footsteps on the stairs. And she knew what was coming.

What she didn’t know was how to deal with it.

‘This isn’t working,’ she said calmly.

‘No.’ Laura looked awkward and acutely uncomfortable, but she also looked a little relieved that Amelia had made it easy for her. Again. Her hands clenched and unclenched nervously. ‘It’s not me—it’s Andy. Well, and me, really, I suppose. It’s the kids. They just—run around all the time, and the baby cries all night, and Andy’s tired. He’s supposed to be having a rest over Christmas, and instead—it’s not their fault, Millie, but having the children here is difficult, we’re just not used to it. And the dog, really, is the last straw. So—yes, I’m sorry, but—if you could find somewhere as soon as possible after Christmas—’

Amelia set aside the washing she was folding and got up, shaking her head, the thought of staying where she— no, where her children were not wanted, anathema to her. ‘It’s OK. Don’t apologise. It’s a terrible imposition. Don’t worry about it, we’ll go now. I’ll just pack their things and we’ll get out of your hair—’

‘I thought you didn’t have anywhere to go?’

She didn’t. Or money to pay for it, but that was hardly her sister’s fault, was it? ‘Don’t worry,’ she said again. ‘We’ll go to Kate’s.’

But crossing her fingers behind her back was pointless. Kate lived in a tiny cottage, one up one down, with hardly room for her and her own daughter. There was no way the four of them and the dog could squeeze in, too. But her sister didn’t know that, and her shoulders dropped in relief.

‘I’ll help you get their things together,’ she said quickly, and disappeared, presumably to comb the house for any trace of their presence while Amelia sagged against the wall, shutting her eyes hard against the bitter sting of tears and fighting down the sob of desperation that was rising in her throat. Two and a half days to Christmas.

Short, dark, chaotic days in which she had no hope of finding anywhere for them to go or another job to pay for it. And, just to make it worse, they were in the grip of an unseasonably cold snap, so even if they were driven to it, there was no way they could sleep in the car. Not without running the engine, and that wasn’t an option, since she probably only had just enough fuel to get away from her sister’s house with her pride intact.

And, as it was the only thing she had left, that was a priority.

Sucking in a good, deep breath, she gathered up the baby’s clothes and started packing them haphazardly, then stopped herself. She had to prioritise. Things for the next twenty-four hours in one little bag, then everything else she could sort out later once they’d arrived at wherever they were going. She sorted, shuffled, packed the baby’s clothes, then her own, then finally went into the bedroom Kitty and Edward were sharing and packed their clothes and toys, with her mind firmly shut down and her thoughts banished for now.

She could think later. There’d be time to think once they were out of here. In the meantime, she needed to gather up the children and any other bits and pieces she’d overlooked and get them out before she totally lost it. She went down with the bags hanging like bunches of grapes from her fingers, dumped them in the hall and went into the euphemistically entitled family room, where her children were lying on their tummies watching the TV with the dog between them.

Not on the sofa again, mercifully.

‘Kitty? Edward? Come and help me look for all your things, because we’re going to go and see Kate and Megan.’

‘What—now?’ Edward asked, twisting round, his face sceptical. ‘It’s nearly lunch time.’

‘Are we going to Kate’s for lunch?’ Kitty asked brightly.

‘Yes. It’s a surprise.’ A surprise for Kate, at least, she thought, hustling them through the house and gathering up the last few traces of their brief but eventful stay.

‘Why do we need all our things to go and see Kate and Megan for lunch?’ Kitty asked, but Edward got there first and shushed her. Bless his heart. Eight years old and she’d be lost without him.

They met up with Laura in the kitchen, her face strained, a bag in her hand.

‘I found these,’ she said, giving it to Amelia. ‘The baby’s bottles. There was one in the dishwasher, too.’

‘Thanks. Right, well, I just need to get the baby up and fold his cot, and we’ll be out of your hair.’

She retreated upstairs to get him. Poor Thomas. He whimpered and snuggled into her as she picked him up, and she collapsed his travel cot one-handed and bumped it down the stairs. Their stuff was piled by the door, and she wondered if Andy might come out of his study and give them a hand to load it into her car, but the door stayed resolutely shut throughout.

It was just as well. It would save her the bother of being civil.

She put the baby in his seat, the cold air bringing him wide awake and protesting, threw their things into the boot and buckled the other two in, with Rufus on the floor in the front, before turning to her sister with her last remnant of pride and meeting her eyes.

‘Thank you for having us. I’m sorry it was so difficult.’

Laura’s face creased in a mixture of distress and embarrassment. ‘Oh, don’t. I’m so sorry, Millie. I hope you get sorted out. Here, these are for the children.’ She handed over a bag of presents, all beautifully wrapped. Of course. They would be. Also expensive and impossible to compete with. And that wasn’t what it was supposed to be about, but she took them, her arm working on autopilot.

‘Thank you. I’m afraid I haven’t got round to getting yours yet—’

‘It doesn’t matter. I hope you find somewhere nice soon. And—take this, please. I know money’s tight for you at the moment, but it might give you the first month’s rent or deposit—’

She stared at the cheque. ‘Laura, I can’t—’

‘Yes, you can. Please. Owe me, if you have to, but take it. It’s the least I can do.’

So she took it, stuffing it into her pocket without looking at it. ‘I’ll pay you back as soon as I can.’

‘Whenever. Have a good Christmas.’

How she found that smile she’d never know. ‘And you,’ she said, unable to bring herself to say the actual words, and getting behind the wheel and dropping the presents into the passenger footwell next to Rufus, she shut the door before her sister could lean in and hug her, started the engine and drove away.

‘Mummy, why are we taking all our Christmas presents and Rufus and the cot and everything to Kate and Megan’s for lunch?’ Kitty asked, still obviously troubled and confused, as well she might be.

Damn Laura. Damn Andy. And especially damn David. She schooled her expression and threw a smile over her shoulder at her little daughter. ‘Well, we aren’t going to stay with Auntie Laura and Uncle Andy any more, so after we’ve had lunch we’re going to go somewhere else to stay,’ she said.

‘Why? Don’t they like us?’

Ouch. ‘Of course they do,’ she lied, ‘but they just need a bit of space.’

‘So where are we going?’

It was a very good question, but one Millie didn’t have a hope of answering right now …

It was an ominous sound.

He’d heard it before, knew instantly what it was, and Jake felt his mouth dry and his heart begin to pound. He glanced up over his shoulder, swore softly and turned, skiing sideways straight across and down the mountain, pushing off on his sticks and plunging down and away from the path of the avalanche that was threatening to wipe him out, his legs driving him forward out of its reach.

The choking powder cloud it threw up engulfed him, blinding him as the raging, roaring monster shot past behind him. The snow was shaking under his skis, the air almost solid with the fine snow thrown up as the snowfield covering the side of the ridge collapsed and thundered down towards the valley floor below.

He was skiing blind, praying that he was still heading in the right direction, hoping that the little stand of trees down to his left was now above him and not still in front of him, because at the speed he was travelling to hit one could be fatal.

It wasn’t fatal, he discovered. It was just unbelievably, immensely painful. He bounced off a tree, then felt himself lifted up and carried on by the snow—down towards the scattered tumble of rocks at the bottom of the snowfield.

Hell.

With his last vestige of self-preservation, he triggered the airbags of his avalanche pack, and then he hit the rocks …

‘Can you squeeze in a few more for lunch?’

Kate took one look at them all, opened the door wide and ushered them inside. ‘What on earth is going on?’ she asked, her concerned eyes seeking out the truth from Millie’s face.

‘We’ve come for lunch,’ Kitty said, still sounding puzzled. ‘And then we’re going to find somewhere to live. Auntie Laura and Uncle Andy don’t want us. Mummy says they need space, but I don’t think they like us.’

‘Of course they do, darling. They’re just very busy, that’s all.’

Kate’s eyes flicked down to Kitty with the dog at her side, to Edward, standing silently and saying nothing, and back to Millie. ‘Nice timing,’ she said flatly, reading between the lines.

‘Tell me about it,’ she muttered. ‘Got any good ideas?’

Kate laughed slightly hysterically and handed the three older children a bag of chocolate coins off the tree. ‘Here, guys, go and get stuck into these while Mummy and I have a chat. Megan, share nicely and don’t give any chocolate to Rufus.’

‘I always share nicely! Come on, we can share them out—and Rufus, you’re not having any!’

Rolling her eyes, Kate towed Amelia down to the other end of the narrow room that was the entire living space in her little cottage, put the kettle on and raised an eyebrow. ‘Well?’

She shifted Thomas into a more comfortable position in her arms. ‘They aren’t really child-orientated. They don’t have any, and I’m not sure if it’s because they haven’t got round to it or because they really don’t like them,’ Millie said softly.

‘And your lot were too much of a dose of reality?’

She smiled a little tightly. ‘The dog got on the sofa, and Thomas is teething.’

‘Ah.’ Kate looked down at the tired, grizzling baby in his mother’s arms and her kind face crumpled. ‘Oh, Amelia, I’m so sorry,’ she murmured under her breath. ‘I can’t believe they kicked you out just before Christmas!’

‘They didn’t. They wanted me to look for somewhere afterwards, but …’

‘But—?’

She shrugged. ‘My pride got in the way,’ she said, hating the little catch in her voice. ‘And now my kids have nowhere to go for Christmas. And convincing a landlord to give me a house before I can get another job is going to be tricky, and that’s not going to happen any time soon if the response to my CV continues to be as resoundingly successful as it’s being at the moment, and anyway the letting agents aren’t going to be able to find us anything this close to Christmas. I could kill David for cutting off the maintenance,’ she added under her breath, a little catch in her voice.

‘Go ahead—I’ll be a character witness for you in court,’ Kate growled, then she leant back, folded her arms and chewed her lip thoughtfully. ‘I wonder …?’

‘What?’

‘You could have Jake’s house,’ she said softly. ‘My boss. I would say stay here, but I’ve got my parents and my sister coming for Christmas Day and I can hardly fit us all in as it is, but there’s tons of room at Jake’s. He’s away until the middle of January. He always goes away at Christmas for a month—he shuts the office, gives everyone three weeks off on full pay and leaves the country before the office party, and I have the keys to keep an eye on it. And it’s just sitting there, the most fabulous house, and it’s just made for Christmas.’

‘Won’t he mind?’

‘What, Jake? No. He wouldn’t give a damn. You won’t do it any harm, after all, will you? It’s hundreds of years old and it’s survived. What harm can you do it?’

What harm? She felt rising panic just thinking about it. ‘I couldn’t—’

‘Don’t be daft. Where else are you going to go? Besides, with the weather so cold it’ll be much better for the house to have the heating on full and the fire lit. He’ll be grateful when he finds out, and besides, Jake’s generous to a fault. He’d want you to have it. Truly.’

Amelia hesitated. Kate seemed so convinced he wouldn’t mind. ‘You’d better ring him, then,’ she said in the end. ‘But tell him I’ll give him money for rent just as soon as I can—’

Kate shook her head. ‘No. I can’t. I don’t have the number, but I know he’d say yes,’ she said, and Amelia’s heart sank.

‘Well, then, we can’t stay there. Not without asking—’

‘Millie, really. It’ll be all right. He’d die before he’d let you be homeless over Christmas and there’s no way he’d take money off you. Believe me, he’d want you to have the house.’

Still she hesitated, searching Kate’s face for any sign of uncertainty, but if she felt any, Kate was keeping it to herself, and besides, Amelia was so out of options she couldn’t afford the luxury of scruples, and in the end she gave in.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Absolutely. There won’t be any food there, his housekeeper will have emptied the fridge, but I’ve got some basics I can let you have and bread and stuff, and there’s bound to be something in the freezer and the cupboards to tide you over until you can replace it. We’ll go over there the minute we’ve had lunch and settle you in. It’ll be great—fantastic! You’ll love it.’

‘Love what?’ Kitty asked, sidling up with chocolate all round her mouth and a doubtful expression on her face.

‘My boss’s house. He’s gone away, and he’s going to let you borrow it.’

‘Let?’ Millie said softly under her breath, but Kate just flashed her a smile and shrugged.

‘Well, he would if he knew … OK, lunch first, and then let’s go!’

It was, as Kate had said, the most fabulous house.

A beautiful old Tudor manor house, it had been in its time a farm and then a small hotel and country club, she explained, and then Jake had bought it and moved his offices out here into the Berkshire countryside. He lived in the house, and there was an office suite housing Jake’s centre of operations in the former country club buildings on the far side of the old walled kitchen garden. There was a swimming pool, a sauna and steam room and a squash court over there, Kate told her as they pulled up outside on the broad gravel sweep, and all the facilities were available to the staff and their families.

Further evidence of his apparent generosity.

But it was the house which drew Amelia—old mellow red brick, with a beautiful Dutch gabled porch set in the centre, and as Kate opened the huge, heavy oak door that bore the scars of countless generations and ushered them into the great entrance hall, even the children fell silent.

‘Wow,’ Edward said after a long, breathless moment.

Wow, indeed. Amelia stared around her, dumbstruck. There was a beautiful, ancient oak staircase on her left, and across the wide hall which ran from side to side were several lovely old doors which must lead to the principal rooms.

She ran her hand over the top of the newel post, once heavily carved, the carving now almost worn away by the passage of generations of hands. She could feel them all, stretching back four hundred years, the young, the old, the children who’d been born and grown old and died here, sheltered and protected by this beautiful, magnificent old house, and ridiculous though it was, as the front door closed behind them, she felt as if the house was gathering them up into its heart.

‘Come on, I’ll give you a quick tour,’ Kate said, going down the corridor to the left, and they all trooped after her, the children still in a state of awe. The carpet under her feet must be a good inch thick, she thought numbly. Just how rich was this guy?

As Kate opened the door in front of her and they went into a vast and beautifully furnished sitting room with a huge bay window at the side overlooking what must surely be acres of parkland, she got her answer, and she felt her jaw drop.

Very rich. Fabulously, spectacularly rich, without a shadow of a doubt.

And yet he was gone, abandoning this beautiful house in which he lived alone to spend Christmas on a ski slope.

She felt tears prick her eyes, strangely sorry for a man she’d never met, who’d furnished his house with such love and attention to detail, and yet didn’t apparently want to stay in it at the time of year when it must surely be at its most welcoming.

‘Why?’ she asked, turning to Kate in confusion. ‘Why does he go?’

Kate shrugged. ‘Nobody really knows. Or nobody talks about it. There aren’t very many people who’ve worked for him that long. I’ve been his PA for a little over three years, since he moved the business here from London, and he doesn’t talk about himself.’

‘How sad.’

‘Sad? No. Not Jake. He’s not sad. He’s crazy, he has some pretty wacky ideas and they nearly always work, and he’s an amazingly thoughtful boss, but he’s intensely private. Nobody knows anything about him, really, although he always makes a point of asking about Megan, for instance. But I don’t think he’s sad. I think he’s just a loner and he likes to ski. Come and see the rest.’

They went back down the hall, along the squishy pile carpet that absorbed all the sound of their feet, past all the lovely old doors while Kate opened them one by one and showed them the rooms in turn.

A dining room with a huge table and oak-panelled walls; another sitting room, much smaller than the first, with a plasma TV in the corner, book-lined walls, battered leather sofas and all the evidence that this was his very personal retreat. There was a study at the front of the house which they didn’t enter; and then finally the room Kate called the breakfast room—huge again, but with the same informality as the little sitting room, with foot-wide oak boards on the floor and a great big old refectory table covered in the scars of generations and just made for family living.

And the kitchen off it was, as she might have expected, also designed for a family—or entertaining on an epic scale. Vast, with duck-egg blue painted cabinets under thick, oiled wood worktops, a gleaming white four-oven Aga in the inglenook, and in the middle a granite-topped island with stools pulled up to it. It was a kitchen to die for, the kitchen of her dreams and fantasies, and it took her breath away. It took all their breaths away.

The children stared round it in stunned silence, Edward motionless, Kitty running her fingers reverently over the highly polished black granite, lingering over the tiny gold sparkles trapped deep inside the stone. Edward was the first to recover.

‘Are we really going to stay here?’ he asked, finally finding his voice, and she shook her head in disbelief.

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Of course you are!’

‘Kate, we can’t—’

‘Rubbish! Of course you can. It’s only for a week or two. Come and see the bedrooms.’

Amelia shifted Thomas to her other hip and followed Kate up the gently creaking stairs, the children trailing awestruck in her wake, listening to Megan chattering about when they’d stayed there earlier in the year.

‘That’s Jake’s room,’ Kate said, turning away from it, and Amelia felt a prickle of curiosity. What would his room be like? Opulent? Austere? Monastic?

No, not monastic. This man was a sensualist, she realised, fingering the curtains in the bedroom Kate led them into. Pure silk, lined with padding for warmth and that feeling of luxury that pervaded the entire house. Definitely not monastic.

‘All the rooms are like this—except for some in the attic, which are a bit simpler,’ Kate told her. ‘You could take your pick but I’d have the ones upstairs. They’re nicer.’

‘How many are there?’ she asked, amazed.

‘Ten. Seven en suite, five on this floor and two above, and three more in the attic which share a bathroom. Those are the simpler ones. He entertains business clients here quite often, and they love it. So many people have offered to buy it, but he just laughs and says no.’

‘I should think so. Oh, Kate—what if we ruin something?’

‘You won’t ruin it. The last person to stay here knocked a pot of coffee over on the bedroom carpet. He just had it cleaned.’

Millie didn’t bother to point out that the last person to stay here had been invited—not to mention an adult who presumably was either a friend or of some commercial interest to their unknowing host.

‘Can we see the attic? The simple rooms? It sounds more like our thing.’

‘Sure. Megan, why don’t you show Kitty and Edward your favourite room?’

The children ran upstairs after Megan, freed from their trance now and getting excited as the reality of it began to sink in, and she turned to Kate and took her arm. ‘Kate, we can’t possibly stay here without asking him,’ she said urgently, her voice low. ‘It would be so rude—and I just know something’ll get damaged.’

‘Don’t be silly. Come on, I’ll show you my favourite room. It’s lovely, you’ll adore it. Megan and I stayed here when my pipes froze last February, and it was bliss. It’s got a gorgeous bed.’

‘They’ve all got gorgeous beds.’

They had. Four-posters, with great heavy carved posts and silk canopies, or half testers with just the head end of the bed clothed in sumptuous drapes.

Except for the three Kate showed her now. In the first one, instead of a four-poster there was a great big old brass and iron bedstead, the whole style of the room much simpler and somehow less terrifying, even though the quality of the furnishings was every bit as good, and in the adjoining room was an antique child-sized sleigh bed that looked safe and inviting.

It was clearly intended to be a nursery, and would be perfect for Thomas, she thought wistfully, and beside it was a twin room with two black iron beds, again decorated more simply, and Megan and Kitty were sitting on the beds and bouncing, while giggles rose from their throats and Edward pretended to be too old for such nonsense and looked on longingly.

‘We could sleep up here,’ she agreed at last. ‘And we could spend the days in the breakfast room.’ Even the children couldn’t hurt that old table …

‘There’s a playroom—come and see,’ Megan said, pelting out of the room with the other children in hot pursuit, and Amelia followed them to where the landing widened and there were big sofas and another TV and lots and lots of books and toys.

‘He said he had this area done for people who came with children, so they’d have somewhere to go where they could let their hair down a bit,’ Kate explained, and then smiled. ‘You see—he doesn’t mind children being in the house. If he did, why would he have done this?’

Why, indeed? There was even a stair gate, she noticed, made of oak and folded back against the banisters. And somehow she didn’t mind the idea of tucking them away in what amounted to the servants’ quarters nearly as much.

‘I’ll help you bring everything up,’ Kate said. ‘Kids, come and help. You can carry some of your stuff.’

It only took one journey because most of their possessions were in storage, packed away in a unit on the edge of town, waiting for the time when she could find a way to house them in a place of their own again. Hopefully, this time with a landlord who wouldn’t take the first opportunity to get them out.

And then, with everything installed, she let Rufus out of the car and took him for a little run on the grass at the side of the drive. Poor little dog. He was so confused but, so long as he was with her and the children, he was as good as gold, and she felt her eyes fill with tears.

If David had had his way, the dog would have been put down because of his health problems, but she’d struggled to keep up the insurance premiums to maintain his veterinary cover, knowing that the moment they lapsed, her funding for the dog’s health and well-being would come to a grinding halt.

And that would be the end of Rufus.

She couldn’t allow that to happen. The little Cavalier King Charles spaniel that she’d rescued as a puppy had been a lifeline for the children in the last few dreadful years, and she owed him more than she could ever say. So his premiums were paid, even if it meant she couldn’t eat.

‘Mummy, it’s lovely here,’ Kitty said, coming up to her and snuggling her tiny, chilly hand into Millie’s. ‘Can we stay for ever?’

Oh, I wish, she thought, but she ruffled Kitty’s hair and smiled. ‘No, darling—but we can stay until after Christmas, and then we’ll find another house.’

‘Promise?’

She crossed her fingers behind her back. ‘Promise,’ she said, and hoped that fate wouldn’t make her a liar.

He couldn’t breathe.

For a moment he thought he was buried despite his avalanche pack, and for that fleeting moment in time he felt fear swamp him, but then he realised he was lying face down in the snow.

His legs were buried in the solidified aftermath of the avalanche, but near the surface, and his body was mostly on the top. He tipped his head awkwardly, and a searing pain shot through his shoulder and down his left arm. Damn. He tried again, more cautiously this time, and the snow on his goggles slid off, showering his face with ice crystals that stung his skin in the cold, sharp air. He breathed deeply and opened his eyes and saw daylight. The last traces of it, the shadows long as night approached.

He managed to clear the snow from around his arms, and shook his head to clear his goggles better and regretted it instantly. He gave the pain a moment, and then began to yell into the silence of the fading light.

He yelled for what seemed like hours, and then, like a miracle, he heard voices.

‘Help!’ he bellowed again, and waved, blanking out the pain.

And help came, in the form of big, burly lads who broke away the snow surrounding him, dug his legs out and helped him struggle free. Dear God, he hurt. Everywhere, but most particularly his left arm and his left knee, he realised. Where he’d hit the tree. Or the rocks. No, he’d hurt them on the tree, he remembered, but the rocks certainly hadn’t helped and he was going to have a million bruises.

‘Can you ski back down?’ they asked, and he realised he was still wearing his skis. The bindings had held, even through that. He got up and tested his left leg and winced, but it was holding his weight, and the right one was fine. He nodded and, cradling his left arm against his chest, he picked his way off the rock field to the edge, then followed them slowly down the mountain to the village.

He was shipped off to hospital the moment they arrived back, and he was prodded and poked and tutted over for what seemed like an age. And then, finally, they put his arm in a temporary cast, gave him a nice fat shot of something blissful and he escaped into the blessed oblivion of sleep …

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_4a074a6c-b1ea-58af-8a35-5c6c3f67181d)

SHE refused to let Kate turn up the heating.

‘We’ll be fine,’ she protested. ‘Believe me, this isn’t cold.’

‘It’s only on frost protection!’

‘It’s fine. We’re used to it. Please, I really don’t want to argue about this. We have jumpers.’

‘Well, at least light the woodburner,’ Kate said, relenting with a sigh. ‘There’s a huge stack of logs outside the back door.’

‘I can’t use his logs! Logs are expensive!’

Kate just laughed. ‘Not if you own several acres of woodland. He has more logs than he knows what to do with. We all use them. I throw some into the boot of my car every day and take them home to burn overnight, and so does everyone else. Really, you can’t let the kids be cold, Millie. Just use the wood.’

So she did. She lit the fire, stood the heavy black mesh guard in front of it and the children settled down on the rug with Rufus and watched the television while she made them something quick and simple for supper. Even Thomas was good, managing to eat his supper without spitting it out all over the room or screaming the place down, and Amelia felt herself start to relax.

And when the wind picked up in the night and the old house creaked and groaned, it was just as if it was settling down, turning up its collar against the wind and wrapping its arms around them all to keep them warm.

Fanciful nonsense.

But it felt real, and when she got up in the morning and tiptoed downstairs to check the fire before the children woke, she found Rufus fast asleep on the rug in front of the woodburner, and he lifted his head and wagged his tail. She picked him up and hugged him, tears of relief prickling her eyes because finally, for the first time in months, she felt—even if it would only be for a few days—as if they were safe.

She filled up the fire, amazed that it had stayed alight, and made herself a cup of tea while Rufus went out in the garden for a moment. Then she took advantage of the quiet time and sat with him by the fire to drink her tea and contemplate her next move.

Rattling the cage of the job agencies, of course. What choice was there? Without a job, she couldn’t hope to get a house. And she needed to get some food in. Maybe a small chicken? She could roast it, and put a few sausages round it, and it would be much cheaper than a turkey. Just as well, as she was trying to stretch the small amount of money she had left for as long as possible.

She thought of the extravagant Christmases she’d had with David in the past, the lavish presents, the wasted food, and wondered if the children felt cheated. Probably, but Christmas was just one of the many ways in which he’d let them down on a regular basis, so she was sure they’d just take it all in their stride.

Unlike being homeless, she thought, getting to her feet and washing out her mug before going upstairs to start the day. They were finding that really difficult and confusing, and all the chopping and changing was making them feel insecure. And she hated that. But there was Laura’s cheque, which meant she might be able to find somewhere sooner—even if she would have to pay her back, just for the sake of her pride.

So, bearing the cheque in mind, she spent part of the morning on the phone trying to find somewhere to live, but the next day would be Christmas Eve and realistically nobody wanted to show her anything until after the Christmas period was over, and the job agencies were no more helpful. Nobody, apparently, was looking for a translator at the moment, so abandoning her search until after Christmas, she took the kids out for a long walk around the grounds, with Thomas in his stroller and Rufus sniffing the ground and having a wonderful time while Kitty and Edward ran around shrieking and giggling.

And there was nobody to hear, nobody to complain, nobody to stifle the sound of their childish laughter, and gradually she relaxed and let herself enjoy the day.

‘Mummy, can we have a Christmas tree?’ Edward asked as they trudged back for lunch.

More money—not only for the tree, but also for decorations. And she couldn’t let herself touch Laura’s money except for a house. ‘I don’t know if we should,’ she said, blaming it on the unknown Jake and burying her guilt because she was sick of telling her children that they couldn’t have things when it was all because their unprincipled and disinterested father refused to pay up. ‘It’s not our house, and you know how they drop needles. He might mind.’

‘He won’t mind! Of course he won’t! Everyone has a Christmas tree!’ Kitty explained patiently to her obviously dense mother.

‘But we haven’t got the decorations, and anyway, I don’t know where we could get one this late,’ she said, wondering if she’d get away with it and hating the fact that she had to disappoint them yet again.

They walked on in silence for a moment, then Edward stopped. ‘We could make one!’ he said, his eyes lighting up at the challenge and finding a solution, as he always did. ‘And we could put fir cones on it! There were lots in the wood—and there were some branches there that looked like Christmas tree branches, a bit. Can we get them after lunch and tie them together and pretend they’re a tree, and then we can put fir cones on it, and berries—I saw some berries, and I’m sure he won’t mind if we only pick a few—’

‘Well, he might—’

‘No, he won’t! Mummy, he’s lent us his house!’ Kitty said earnestly and, not for the first time, Millie felt a stab of unease.

But the children were right, everybody had a tree, and what harm could a few cut branches and some fir cones do? And maybe even the odd sprig of berries …

‘All right,’ she agreed, ‘just a little tree.’ So after lunch they trooped back, leaving the exhausted little Rufus snoozing by the fire, and Amelia and Edward loaded themselves up with branches and they set off, Kitty dragging Thomas in the stroller backwards all the way from the woods to the house.

‘There!’ Edward said in satisfaction, dropping his pile of branches by the back door. ‘Now we can make our tree!’

The only thing that kept him going on that hellish journey was the thought of home.

The blissful comfort of his favourite old leather sofa, a bottle of fifteen-year-old single malt and—equally importantly—the painkillers in his flight bag.

Getting upstairs to bed would be beyond him at this point. His knee was killing him—not like last time, when he’d done the ligaments in his other leg, but badly enough to mean that staying would have been pointless, even if he hadn’t broken his wrist. And now all he could think about was lying down, and the sooner the better. He’d been stupid to travel so soon; his body was black and blue from end to end, but somehow, with Christmas what felt like seconds away and everyone down in the village getting so damned excited about it, leaving had become imperative now that he could no longer ski to outrun his demons.

Not that he ever really managed to outrun them, although he always gave it a damn good try, but this time he’d come too close to losing everything, and deep down he’d realised that maybe it was time to stop running, time to go home and just get on with life—and at least here he could find plenty to occupy himself.

He heard the car tyres crunch on gravel and cracked open his eyes. Home. Thank God for that. Lights blazed in the dusk, triggered by the taxi pulling up at the door, and handing over what was probably an excessive amount of money, he got out of the car with a grunt of pain and walked slowly to the door.

And stopped.

There was a car on the drive, not one he recognised, and there were lights on inside.

One in the attic, and one on the landing.

‘Where d’you want these, guv?’ the taxi driver asked, and he glanced down at the cases.

‘Just in here would be good,’ he said, opening the door and sniffing. Woodsmoke. And there was light coming from the breakfast room, and the sound of—laughter? A child’s laughter?

Pain squeezed his chest. Dear God, no. Not today, of all days, when he just needed to crawl into a corner and forget—

‘There you go then, guv. Have a good Christmas.’

‘And you,’ he said, closing the door quietly behind the man and staring numbly towards the breakfast room. What the hell was going on? It must be Kate—no one else had a key, and the place was like Fort Knox. She must have dropped in with Megan and a friend to check on the house—but it didn’t sound as if they were checking anything. It sounded as if they were having fun.

Oh, Lord, please, not today …

He limped over to the door and pushed it gently open, and then stood transfixed.

Chaos. Complete, utter chaos.

Two children were sitting on the floor by the fire in a welter of greenery, carefully tying berries to some rather battered branches that looked as if they had come off the conifer hedge at the back of the country club, but it was the woman standing on the table who held his attention.

Tall, slender, with rather wild fair hair escaping from a ponytail and jeans that had definitely seen better days, she was reaching up and twisting another of the branches into the heavy iron hoop over the refectory table, festooning the light fitting with a makeshift attempt at a Christmas decoration which did nothing to improve it.

He’d never seen her before. He would have recognised her, he was sure, if he had. So who the hell—?

His mouth tightened, but then she bent over, giving him an unrestricted view of her neat, shapely bottom as the old jeans pulled across it, and he felt a sudden, unwelcome and utterly unexpected tug of need.

‘It’s such a shame Jake isn’t going to be here, because we’re making it so pretty,’ the little girl was saying.

‘Why does he go away?’ the boy asked.

‘I don’t know,’ the woman replied, her voice soft and melodious. ‘I can’t imagine.’

‘Didn’t Kate say?’

Kate. Of course, she’d be at the bottom of this, he thought, and he could have wrung her neck for her abysmal timing.

Well, if he had two good hands … which at the moment, of course, he didn’t.

‘He goes skiing.’

‘I hate skiing,’ the boy said. ‘That woman in the kindergarten was horrible. She smelt funny. Here, I’ve finished this one.’

And he scrambled to his feet and turned round, then caught sight of Jake and froze.

‘Well, come on then, give it to me,’ the woman said, waving her hand behind her to try and locate it.

‘Um … Mum …’

‘Darling, give me the branch, I can’t stand here for ever—’

She turned towards her son, followed the direction of his gaze and her eyes flew wide. ‘Oh—!’

‘Mummy, do I need more berries or is that enough?’ the little girl asked, but Jake hardly heard her because the woman’s eyes were locked on his and the shock and desperation in them blinded his senses to anything else.

‘Kitty, hush, darling,’ she said softly and, dropping down, she slid off the edge of the table and came towards him with a haphazard attempt at a smile. ‘Um … I imagine you’re Jake Forrester?’ she asked, her voice a little uneven, and he hardened himself against her undoubted appeal and the desperate eyes.

‘Well, there you have the advantage over me,’ he murmured drily, ‘because I have no idea who you are, or why I should come home and find you smothering my house in bits of dead vegetation in my absence—’

Her eyes fluttered briefly closed and colour flooded her cheeks. ‘I can explain—’

‘Don’t bother. I’m not interested. Just get all that—tat out of here, clear the place up and then leave.’

He turned on his heel—not a good idea, with his knee screaming in protest, but the pain just fuelled the fire of his anger and he stalked into the study, picked up the phone and rang Kate.

‘Millie?’

‘So that’s her name.’

‘Jake?’ Kate shrieked, and he could hear her collecting herself at the other end of the line. ‘What are you doing home?’

‘There was an avalanche. I got in the way. And I seem to have guests. Would you care to elaborate?’

‘Oh, Jake, I’m so sorry, I can explain—’

‘Excellent. Feel free. You’ve got ten seconds, so make it good.’ He settled back in the chair with a wince, listening as Kate sucked in her breath and gave her pitch her best shot.

‘She’s a friend. Her ex has gone to Thailand, he won’t pay the maintenance and she lost her job so she lost her house and her sister kicked her out yesterday.’

‘Tough. She’s packing now, so I suggest you find some other sucker to put her and her kids up so I can lie and be sore in peace. And don’t imagine for a moment that you’ve heard the end of this.’

He stabbed the off button and threw the phone down on his desk, then glanced up to see the woman—Millie, apparently—transfixed in the doorway, her face still flaming.

‘Please don’t take it out on Kate. She was only trying to help us.’

He stifled a contemptuous snort and met her eyes challengingly, too sore in every way to moderate his sarcasm. ‘You’re not doing so well, are you? You don’t seem to be able to keep anything. Your husband, your job, your house—even your sister doesn’t want you. I wonder why? I wonder what it is about you that makes everyone want to get rid of you?’

She stepped back as if she’d been struck, the colour draining from her face, and he felt a twinge of guilt but suppressed it ruthlessly.

‘We’ll be out of here in half an hour. I just need to pack our things. What do you want me to do with the sheets?’

Sheets? He was throwing her out and she was worrying about the sheets?

‘Just leave them. I wouldn’t want to hold you up.’

She straightened her spine and took another step back, and he could see her legs shaking. ‘Right. Um … fine.’

And she spun round and walked briskly away in the direction of the breakfast room, leaving him to his guilt. He sighed and sagged back against the chair, a wave of pain swamping him for a moment. When he opened his eyes, the boy was there.

‘I’m really sorry,’ he said, his little chin up, just like his mother’s, his eyes huge in a thin, pale face. ‘Please don’t be angry with Mummy. She was just trying to make a nice Christmas for us. She thought we were going to stay with Auntie Laura, but Uncle Andy didn’t want us there because he said the baby kept him awake—’

There was a baby, too? Dear God, it went from bad to worse, but that wasn’t the end of it.

‘—and the dog smells and he got on the sofa, and that made him really mad. I heard them fighting. And then Mummy said we were going to see Kate, and she said we ought to come here because you were a nice man and you wouldn’t mind and what harm could we do because the house was hundreds of years old and had survived and anyway you liked children or you wouldn’t have done the playroom in the attic.’

He finally ran out of breath and Jake stared at him.

Kate thought he was that nice? Kate was dreaming.

But the boy’s wounded eyes called to something deep inside him, and Jake couldn’t ignore it. Couldn’t kick them all out into the cold just before Christmas. Even he wasn’t that much of a bastard.

But it wasn’t just old Ebenezer Scrooge who had ghosts, and the last thing he needed was a houseful of children over Christmas, Jake thought with a touch of panic. And a baby, of all things, and—a dog?

Not much of a dog. It hadn’t barked, and there was no sign of it, so it was obviously a very odd breed of dog. Or old and deaf?

No. Not old and deaf, and not much of a dog at all, he realised, his eyes flicking to the dimly lit hallway behind the boy and focusing on a small red and white bundle of fluff with an anxiously wriggling tail and big soulful eyes that were watching him hopefully.

A little spaniel, like the one his grandmother had had. He’d always liked it—and he wasn’t going to be suckered because of the damn dog!

But the boy was still there, one sock-clad foot on top of the other, squirming slightly but holding his ground, and if his ribs hadn’t hurt so much he would have screamed with frustration.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Edward. Edward Jones.’

Nice, honest name. Like the child, he thought inconsequentially. Oh, damn. He gave an inward sigh as he felt his defences crumble. After all, it was hardly the boy’s fault that he couldn’t cope with the memories … ‘Where’s your mother, Edward?’

‘Um … packing. I’m supposed to be clearing up the branches, but I can’t reach the ones in the light so I’ve got to wait for her to come down.’

‘Could you go and get her for me, and then look after the others while we have a chat?’

He nodded, but stood there another moment, chewing his lip.

Jake sighed softly. ‘What is it?’

‘You won’t be mean to her, will you? She was only trying to look after us, and she feels so guilty because Dad won’t give us any money so we can’t have anything nice ever, but it’s really not her fault—’

‘Just get her, Edward,’ he said gently. ‘I won’t be mean to her.’

‘Promise?’

Oh, what was he doing? He needed to get rid of them before he lost his mind! ‘I promise.’

The boy vanished, but the dog stayed there, whining softly and wagging his tail, and Jake held out his hand and called the dog over. He came, a little warily, and sat down just a few feet away, tail waving but not yet really ready to trust.

Very wise, Jake thought. He really, really wasn’t in a very nice mood, but it was hardly the dog’s fault. And he’d promised the boy he wouldn’t be mean to his mother.

Well, any more mean than he already had been. He pressed his lips together and sighed. He was going to have to apologise to her, he realised—to the woman who’d moved into his house without a by-your-leave and completely trashed his plans for crawling back into his cave to lick his wounds.

Oh, damn.

‘Mummy, he wants to talk to you.’

Millie lifted her head from the bag she was stuffing clothes into and stared at her son. ‘I think he’s said everything he has to say,’ she said crisply. ‘Have you finished clearing up downstairs?’

‘I couldn’t reach the light, but I’ve put everything else outside and picked up all the bits off the floor. Well, most of them. Mummy, he really does want to talk to you. He asked me to tell you and to look after the others while you have a chat.’

Well, that sounded like a quote, she thought, and her heart sank. It was bad enough enduring the humiliation of one verbal battering. The last thing she needed was to go back down there now he’d drawn breath and had time to think about it and give him the opportunity to have a more concerted attack.

‘Please, Mummy. He asked—and he promised he wouldn’t be mean to you.’

Her eyes widened, then she shut them fast and counted to ten. What on earth had Edward been saying to him? She got to her feet and held out her arms to him, and he ran into them and hugged her hard.

‘It’ll be all right, Mummy,’ he said into her side. ‘It will.’

If only she could be so sure.

She let him go and made her way downstairs, down the beautiful old oak staircase she’d fallen so in love with, along the hall on the inches-thick carpet, and tapped on the open study door, her heart pounding out a tattoo against her ribs.

He was sitting with his back to her, and at her knock he swivelled the chair round and met her eyes. He’d taken off the coat that had been slung round his shoulders, and she could see now that he was wearing a cast on his left wrist. And, with the light now shining on his face, she could see the livid bruise on his left cheekbone, and the purple stain around his eye.

His hair was dark, soft and glossy, cut short round the sides but flopping forwards over his eyes. It looked rumpled, as if he’d run his fingers through it over and over again, and his jaw was deeply shadowed. He looks awful, she thought, and she wondered briefly what he’d done.

Not that it mattered. It was enough to have brought him home, and that was the only thing that affected her. His injuries were none of her business.

‘You wanted to see me,’ she said, and waited for the stinging insults to start again.

‘I owe you an apology,’ he said gruffly, and she felt her jaw drop and yanked it up again. ‘I was unforgivably rude to you, and I had no justification for it.’

‘I disagree. I’m in your house without your permission,’ she said, fairness overcoming her shock. ‘I would have been just as rude, I’m sure.’

‘I doubt it, somehow. The manners you’ve drilled into your son would blow that theory out of the water. He’s a credit to you.’

She swallowed hard and nodded. ‘Thank you. He’s a great kid, and he’s been through a lot.’

‘I’m sure. However, it’s not him I want to talk to you about, it’s you. You have nowhere to go, is this right?’

Her chin went up. ‘We’ll find somewhere,’ she lied, her pride rescuing her in the nick of time, and she thought she saw a smile flicker on that strong, sculpted mouth before he firmed it.

‘Do you or do you not have anywhere else suitable to go with your children for Christmas?’ he asked, a thread of steel underlying the softness of his voice, and she swallowed again and shook her head.

‘No,’ she admitted. ‘But that’s not your problem.’

He inclined his head, accepting that, but went on, ‘Nevertheless, I do have a problem, and one you might be able to fix. As you can see, I’ve been stupid enough to get mixed up with an avalanche, and I’ve broken my wrist. Now, I can’t cook at the best of times, and I’m not getting my housekeeper back from her well-earned holiday to wait on me, but you, on the other hand, are here, have nowhere else to go and might therefore be interested in a proposition.’

For the first time, she felt a flicker of hope. ‘A proposition?’ she asked warily, not quite sure she liked the sound of that but prepared to listen because her options were somewhat limited. He nodded.

‘I have no intention of paying you—under the circumstances, I don’t think that’s unreasonable, considering you moved into my house without my knowledge or consent and made yourselves at home, but I am prepared to let you stay until such time as you find somewhere to go after the New Year, in exchange for certain duties. Can you cook?’

She felt the weight of fear lift from her shoulders, and nodded. ‘Yes, I can cook,’ she assured him, hoping she could still remember how. It was a while since she’d had anything lavish on her table, but cooking had once been her love and her forte.

‘Good. You can cook for me, and keep the housework under control, and help me do anything I can’t manage—can you drive?’

She nodded again. ‘Yes—but it will have to be my car, unless you’ve got a big one. I can’t go anywhere without the children, so if it’s some sexy little sports car it will have to be my hatchback.’

‘I’ve got an Audi A6 estate. It’s automatic. Is that a problem?’

‘No problem,’ she said confidently. ‘David had one.’ On a finance agreement that, like everything else, had gone belly-up in the last few years. ‘Anything else? Any rules?’

‘Yes. The children can use the playroom upstairs on the landing, and you can keep the attic bedrooms—I assume you’re in the three with the patchwork quilts?’

She felt her jaw sag. ‘How did you guess?’

His mouth twisted into a wry smile. ‘Let’s just say I’m usually a good judge of character, and you’re pretty easy to read,’ he told her drily. ‘So—you can have the top floor, and when you’re cooking the children can be down here in the breakfast room with you.’

‘Um … there’s the dog,’ she said, a little unnecessarily as Rufus was now sitting on her foot, and to her surprise Jake’s mouth softened into a genuine smile.

‘Yes,’ he said quietly. ‘The dog. My grandmother had one like him. What’s his name?’

‘Rufus,’ she said, and the little dog’s tail wagged hopefully. ‘Please don’t say he has to be outside in a kennel or anything awful, because he’s old and not very well and it’s so cold at the moment and he’s no trouble—’

‘Millie—what does that stand for, by the way?’

‘Amelia.’

He studied her for a second, then nodded. ‘Amelia,’ he said, his voice turning it into something that sounded almost like a caress. ‘Of course the dog doesn’t have to be outside—not if he’s housetrained.’

‘Oh, he is. Well, mostly. Sometimes he has the odd accident, but that’s only if he’s ill.’

‘Fine. Just don’t let him on the beds. Right, I’m done. If you could find me a glass, the malt whisky and my flight bag, I’d be very grateful. And then I’m going to lie down on my sofa and go to sleep.’

And, getting to his feet with a grunt of pain, he limped slowly towards her.

‘You really did mess yourself up, didn’t you?’ she said softly, and he paused just a foot away from her and stared down into her eyes for the longest moment.

‘Yes, Amelia. I really did—and I could do with those painkillers, so if you wouldn’t mind—?’

‘Right away,’ she said, trying to remember how to breathe. Slipping past him into the kitchen, she found a glass, filled it with water, put the kettle on, made a sandwich with the last of the cheese and two precious slices of bread, smeared some chutney she found in the fridge onto the cheese and took it through to him.

‘I thought you might be hungry,’ she said, ‘and there’s nothing much else in the house at the moment, but you shouldn’t take painkillers on an empty stomach.’

He sighed and looked up at her from the sofa where he was lying stretched out full length and looking not the slightest bit vulnerable despite the cast, the bruises and the swelling under his eye. ‘Is that right?’ he said drily. ‘Where’s the malt whisky?’

‘You shouldn’t have alcohol—’

‘—with painkillers,’ he finished for her, and gave a frustrated growl that probably should have frightened her but just gave her the urge to smile. ‘Well, give me the damned painkillers, then. They’re in my flight bag, in the outside pocket. I’ll take them with the water.’

She rummaged, found them and handed them to him. ‘When did you take the last lot? It says no more than six in twenty-four hours—’

‘Did I ask you for your medical advice?’ he snarled, taking the strip of tablets from her and popping two out awkwardly with his good hand.

Definitely not vulnerable. Just crabby as hell. She stood her ground. ‘I just don’t want your family suing me for killing you with an overdose,’ she said, and his mouth tightened.

‘No danger of that,’ he said flatly. ‘I don’t have a family. Now, go away and leave me alone. I haven’t got the energy to argue with a mouthy, opinionated woman and I can’t stand being fussed over. And find me the whisky!’

‘I’ve put the kettle on to make you tea or coffee—’

‘Well, don’t bother. I’ve had enough caffeine in the last twenty-four hours to last me a lifetime. I just want the malt—’

‘Eat the sandwich and I’ll think about it,’ she said, and then went out and closed the door, quickly, before he changed his mind and threw them all out anyway …

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_5fa302d4-4e2c-541d-aebd-dade5198fff8)

EDWARD was waiting for her.

He was sitting on the top step, and his eyes were full of trepidation. ‘Well?’

‘We’re staying,’ she said with a smile, still not really believing it but so out of options that she had to make it work. ‘But he’d like us to spend the time up here unless we’re down in the breakfast room or kitchen cooking for him, so we don’t disturb him, because he had an accident skiing and he’s a bit sore. He needs to sleep.’

‘So can I unpack my things again?’ Kitty asked, appearing on the landing, her little face puzzled and a bulging carrier bag dangling from her fingers.

‘Yes, darling. We can all unpack, and then we need to go downstairs very quietly and tidy up the kitchen and see what I can find to cook us for supper.’

Not that there was much, but she’d have to make something proper for Jake, and she had no idea how she’d achieve that with no ingredients and no money to buy any. Maybe there was something in his freezer?

‘I’ll be very, very quiet,’ Kitty whispered, her grey eyes serious, and tiptoed off to her room with bag in hand and her finger pressed over her lips.

It worked until she bumped into the door frame and the bag fell out of her hand and landed on the floor, the book in the top falling out with a little thud. Her eyes widened like saucers, and for one awful minute Millie thought she was going to cry.

‘It’s all right, darling, you don’t have to be that quiet,’ she said with an encouraging smile, and Edward, ever his little sister’s protector, picked up his own bag and went back into the bedroom and hugged her, then helped her put her things away while Millie unpacked all the baby’s things again.

He was still sleeping. Innocence was such a precious gift, she thought, her eyes filling, and blinking hard, she turned away and went to the window, drawn by the sound of a car. Looking down on the drive as the floodlights came on, she realised it was Kate.

Of course. Dear Kate, rushing to her rescue, coming to smooth things over with Jake.

Who was sleeping.

‘Keep an eye on Thomas, I’m going to let Kate in,’ she said to Edward and ran lightly down the stairs, arriving in the hall just as Kate turned the heavy handle and opened the door.

‘Oh, Millie, I’m so sorry I’ve been so long, but Megan was in the bath and I had to dry her hair before I brought her out in the cold,’ she said in a rush. ‘Where are the children?’

‘Upstairs. It’s all right, we’re staying. Megan, do you want to go up and see them while I make Mummy a coffee?’

‘I don’t have time for a coffee, I need to see Jake. I’ve got to try and reason with him—what do you mean, you’re staying?’ she added, her eyes widening.

‘Shh. He’s asleep. Go on, Megan, it’s all right, but please be quiet because Jake’s not well.’

Megan nodded seriously. ‘I’ll be very quiet,’ she whispered and ran upstairs, her little feet soundless on the thick carpet. Kate took Millie by the arm and towed her into the breakfast room and closed the door.

‘So what’s going on?’ she asked in a desperate undertone. ‘I thought you’d be packed and leaving?’

Amelia shook her head. ‘No. He’s broken his wrist and he’s battered from end to end, and I think he’s probably messed his knee up, too, so he needs someone to cook for him and run round after him.’

Kate’s jaw dropped. ‘So he’s employing you?’

Millie felt her mouth twist into a wry smile. ‘Not exactly employing,’ she admitted, remembering his blunt words with an inward wince. ‘But we can stay in exchange for helping him, so long as I keep the children out of his way.’

‘And the dog? Does he even know about the dog?’

She smiled. ‘Ah, well, now. Apparently he likes the dog, doesn’t he, Rufus?’ she murmured, looking down at him. He was stuck on her leg, sensing the need to behave, his eyes anxious, and she felt him quiver.

When she glanced back up, Kate was staring at her openmouthed. ‘He likes the dog?’ she hissed.

‘His grandmother had one. He doesn’t go a bundle on the Christmas decorations, though,’ she added ruefully with a pointed glance at the light fitting. ‘Come on, let’s make a drink and take it upstairs to the kids.’

‘He was going to put a kitchen up there,’ Kate told her as she boiled the kettle. ‘Just a little one, enough to make drinks and snacks, but he hasn’t got round to it yet. Pity. It would have been handy for you.’

‘It would. Still, I only need to bring the children down if I’m actually cooking. We’re quite all right up in the playroom, and at least it’ll give us a little breathing space before we have to find somewhere to go.’

‘And, actually, it’s a huge relief,’ Kate said, sagging back against the worktop and folding her arms. ‘I was wondering what to do about Jake—I mean, I couldn’t leave him here on his own over Christmas when he’s injured, but my house is going to be heaving and noisy and chaotic, and I would have had to run backwards and forwards—so you’ve done me a massive favour. And, you never know, maybe you’ll all have a good time together! In fact—’

Amelia cut her off with a laugh and a raised hand. ‘I don’t think so,’ she said firmly, remembering his bitterly sarcastic opening remarks. ‘But if we can just keep out of his way, maybe we’ll all survive.’

She handed Kate her drink, picked up her own mug and then hesitated. No matter how rude and sarcastic he’d been, he was still a human being and for that alone he deserved her consideration, and he was injured and exhausted and probably not thinking straight. ‘I ought to check on him,’ she said, putting her mug back down. ‘He was talking about malt whisky.’

‘So? Don’t worry, he’s not a drinker. He won’t have had much.’

‘On top of painkillers?’

‘Ah. What were they?’

‘Goodness knows—something pretty heavy-duty. Nothing I recognised. Not paracetamol, that’s for sure!’

‘Oh, hell. Where is he?’

‘Just next door in the little sitting room.’

‘I’ll go—’

‘No. Let me. He was pretty cross.’

Kate laughed softly. ‘You think I’ve never seen him cross?’

So they went together, opening the door silently and pushing it in until they could see him sprawled full length on the sofa, one leg dangling off the edge, his cast resting across his chest, his head lolling against the arm.

Kate frowned. ‘He doesn’t look very comfortable.’

He didn’t, but at least there was no sign of the whisky. Amelia went into the room and picked up a soft velvety cushion and tucked it under his bruised cheek to support his head better. He grunted and shifted slightly and she froze, waiting for those piercing slate grey eyes to open and stab her with a hard, angry glare, but then he relaxed, settling his face down against the pillow with a little sigh, and she let herself breathe again.

It was chilly in there, though, and she had refused to let Kate turn the heating up. She could do it now but, in the meantime, he ought to have something over him. She spotted a throw over the back of the other sofa and lowered it carefully over him, tucking it in to keep the draughts off until the heat kicked in.

Then she tiptoed out, glancing back over her shoulder as she reached the door.

Did she imagine it or had his eyelids fluttered? She wasn’t sure, but she didn’t want to hang around and provoke him if she’d disturbed him, so she pushed Kate out and closed the door softly behind them.

‘Can you turn the heating up?’ she murmured to Kate, and she nodded and went into his study and fiddled with a keypad on the wall.

‘He looks awful,’ Kate said, sparing the door of the room another glance as she tapped keys and reprogrammed the heating. ‘He’s got bruises all over his face and neck. It must have been a hell of an avalanche.’

‘He didn’t say, but he’s very sore and stiff. I expect he’s got bruises all over his body,’ Millie said, trying not to think about his body in too much detail but failing dismally. She stifled the little whimper that rose in her throat.

Why?

Why, of all the men to bring her body out of the freezer, did it have to be Jake? There was no way he’d be interested in her—even if she hadn’t upset and alienated him by taking such a massive liberty with his house, to all intents and purposes moving into his house as a squatter, she’d then compounded her sins by telling him what to do!

And he most particularly wouldn’t be interested in her children. In fact it was probably the dog who was responsible for his change of heart.

Oh, well, it was just as well he wouldn’t be interested in her, because there was no way her life was even remotely stable or coherent enough at the moment for her to contemplate a relationship. Frankly, she wasn’t sure it ever would be again and, if it was, it certainly wouldn’t be with another empire builder. She’d had it with the entrepreneurial type, big time.

But there was just something about Jake Forrester that called to something deep inside her, something that had lain undisturbed for years, and she was going to have to ignore it and get through these next few days and weeks until they could find somewhere else. And maybe then she’d get her sanity back.

‘Come on, let’s go back up and leave him to sleep,’ she said, crossing her fingers and hoping that he slept for a good long while and woke in a rather better mood …

He was hot.

He’d been cold, but he’d been too tired and sore to bother to get the throw, but someone must have been in and covered him, because it was snuggled round him, and there was a pillow under his face and the lingering scent of a familiar fragrance.

Kate. She must have come over and covered him up. Hell. He hadn’t meant her to turn out on such a freezing night with little Megan. He should have rung her back, he realised, after he’d spoken to Amelia, but he’d been high as a kite on the rather nice drugs the French doctor had given him and he hadn’t even thought about it.

Damn.

He rolled onto his back and his breath caught. Ouch. That was quite a bruise on his left hip. And his knee desperately needed some ice, and his arm hurt. Even through the painkillers.

He struggled off the sofa, eventually escaping from the confines of the throw with an impatient tug and straightening up with a wince. The gel pack was in the freezer in the kitchen. It wasn’t far.

Further than he thought, he realised, swaying slightly and pausing while the world steadied. He took a step, then another, and blinked hard to clear his head.

Amelia was right, he shouldn’t have too many of those damn painkillers. They were turning his brain to mush. And it was probably just as well he hadn’t taken them with whisky either, he thought with regret. Not that she’d been about to give him any, the bossy witch.

Amelia. Millie.

No, Amelia. Millie didn’t suit her. It was a little girl’s name and, whatever else she was, she was all woman. And damn her for making him notice the fact.

He limped into the breakfast room and saw that Edward had done a pretty good job of removing the branches and berries from the floor in front of the fire. He felt his brow pleat into a frown, and stifled the pang of guilt. It was his house. If he didn’t want decorations in it, it was perfectly reasonable to say so.

But had he had to be so harsh?

No, was the simple answer. Especially to the kids. Oh, rats. He made his way carefully through to the kitchen, took the pack out of the freezer and wrapped it in a tea towel, then went back to the breakfast room and sat down in the chair near the fire and propped the ice pack over his knee. Better.

Or it would be, in about a week. It was only a bruise, not a ligament rupture, thankfully. He’d done that before on the other knee, and he didn’t need to do it again, but he realised he’d been lucky not to be smashed to bits on the tree or the rock field.

Very lucky.

He eased back in the chair cautiously and thought with longing of the whisky. It was a particularly smooth old single malt, smoky and peaty, with a lovely complex aftertaste. Or was that afterburn?

Whatever, it was in the drinks cupboard in the drawing room, and he wasn’t convinced he could summon up the energy to walk all the way to the far end of the house and back again, so he closed his eyes and fantasised that he was on Islay, sitting in an old croft house with a peat fire at his feet, a collie instead of a little spaniel leaning on his leg and a glass of liquid gold in his hand.

He could all but taste it. Pity he couldn’t. Pity it was only in his imagination, because then he’d be able to put Amelia and her children out of his mind.

Or he would have been able to, if it hadn’t been for the baby crying.

‘Oh, Thomas, sweetheart, what’s the matter, little one?’

She couldn’t believe he was doing this. She’d fed him just before Jake had arrived home, but now he was awake and he wouldn’t settle again and he was starting to sob into her chest, letting fly with a scream that she was sure would travel all the way down to Jake.

He couldn’t be hungry, not really, but he obviously wanted a bottle of milk, and that meant going back down to the kitchen and heating it, taking the screaming baby with her, and by the time she’d done that, he would certainly have disturbed her reluctant host. Unless she left him with Edward?

‘Darling, could you please look after him for a moment while I get him his bottle?’ she asked, and Edward, being Edward, just nodded and held his arms out, and carried Thomas off towards the bedroom and closed the door.

She ran lightly downstairs to the sound of his escalating wails. As she hurried into the breakfast room, she came face to face with Jake sitting by the fire, an ice pack on his knee and the dog at his side.

She skidded to a halt and his eyes searched her face. ‘Is the baby all right?’

She nodded. ‘Yes—I’m sorry. I just need to make him a bottle. He’ll settle then. I’m really sorry—’

‘Why didn’t you bring him down?’

‘I didn’t want to wake you.’ She chewed her lip, only too conscious of the fact that he was very much awake. Awake and up and about and looking rumpled and disturbingly attractive, with the dark shadow of stubble on his firm jaw and the subtle drift of a warm, slightly spicy cologne reaching her nostrils.

‘I was awake,’ he told her, his voice a little gruff. ‘I put a gel pack on my knee, and I was about to make some tea. Want to join me?’

‘Oh—I can’t, I’ve left the baby with Edward.’

‘Bring them all down. Maybe I should meet them—since they’re staying in my house.’

Oh, Lord. ‘Let me just make the bottle so it can be cooling, and then we’ll get a little peace and I can introduce you properly.’

He nodded, his mouth twitching into a slight smile, and she felt relief flood through her at this tiny evidence of his humanity. She went into the kitchen and spooned formula into a bottle, then poured hot water from the kettle on it, shook it and plonked it into a bowl of cold water. Thankfully there had been some water in the kettle so it didn’t have to cool from boiling, she thought as she ran back upstairs and collected the children, suddenly ludicrously conscious of how scruffy they looked after foraging in the woods, and how apprehensive.

‘Hey, it’s all right, he wants to meet you,’ she murmured reassuringly to Kitty, who was clinging to her, and then pushed the breakfast room door open and ushered them in.

He was putting wood on the fire, and as he closed the door and straightened up, he caught sight of them and turned. The smile was gone, his face oddly taut, and her own smile faltered for a moment.

‘Kids, this is Mr Forrester—’

‘Jake,’ he said, cutting her off and taking a step forward. His mouth twisted into a smile. ‘I’ve already met Edward. And you must be Kitty. And this, I take it, is Thomas?’

‘Yes.’

Thomas, sensing the change of atmosphere, had gone obligingly silent, but after a moment he lost interest in Jake and anything except his stomach and, burrowing into her shoulder, he began to wail again.

‘I’m sorry. I—’

‘Go on, feed him. I gave the bottle a shake to help cool it.’

‘Thanks.’ She went into the kitchen, wondering how he knew to do that. Nieces and nephews, probably—although he’d said he didn’t have any family. How odd, she thought briefly, but then Thomas tried to lunge out of her arms and she fielded him with the ease of practice and tested the bottle on her wrist.

Cool enough. She shook it again, tested it once more to be on the safe side and offered it to her son.

Silence. Utter, blissful silence, broken only by a strained chuckle.

‘Oh, for such simple needs,’ he said softly, and she turned and met his eyes. They were darker than before, and his mouth was set in a grim line despite the laugh. But then his expression went carefully blank and he limped across to the kettle. ‘So—who has tea, and who wants juice or whatever else?’

‘We haven’t got any juice. The children will have water.’

‘Sounds dull.’

‘They’re fine with it. It’s good for them.’

‘I don’t doubt it. It’s good for me, too, but that doesn’t mean I drink it. Except in meetings. I get through gallons of it in meetings. So—is that just me, or are you going to join me?’

‘Oh.’ Join him? That sounded curiously—intimate. ‘Yes, please,’ she said, and hoped she didn’t sound absurdly breathless. It’s a cup of tea, she told herself crossly. Just a cup of tea. Nothing else. She didn’t want anything else. Ever.

And if she told herself that enough times, maybe she’d start to believe it.

‘Have the children eaten?’

‘Thomas has. Edward and Kitty haven’t. I was going to wait until you woke up and ask you what you wanted.’

‘Anything. I’m not really hungry after that sandwich. What is there?’

‘I have no idea. I’ll give the children eggs on toast—’

‘Again?’ Kitty said plaintively. ‘We had eggs on toast for supper last night.’

‘I’m sure we can find something else,’ their host was saying, rummaging in a tall cupboard with pull-out racking that was crammed with tins and jars and packets. ‘What did you all have for lunch?’

‘Jam sandwiches and an apple.’

He turned and studied Kitty thoughtfully, then his gaze flicked up to Amelia’s and speared her. ‘Jam sandwiches?’ he said softly. ‘Eggs on toast?’

She felt her chin lift, but he just frowned and turned back to the cupboard, staring into its depths blankly for a moment before shutting it and opening the big door beside it and going systematically through the drawers of the freezer.

‘How about fish?’

‘What sort? They don’t eat smoked fish or fish fingers.’

‘Salmon—and mixed shellfish. A lobster,’ he added, rummaging. ‘Raw king prawns—there’s some Thai curry paste somewhere I just saw. Or there’s probably a casserole if you don’t fancy fish.’

‘Whatever. Choose what you want. We’ll have eggs.’

He frowned again, shut the freezer and studied her searchingly.

She wished he wouldn’t do that. Her arm was aching, Thomas was starting to loll against her shoulder and if she was sitting down, she could probably settle him and get him off to sleep so she could concentrate on feeding the others—most particularly their reluctant host.

After all, she’d told him she could cook—

‘Go and sit down. I’ll order a takeaway,’ he said softly, and she looked back up into his eyes and surprised a gentle, almost puzzled expression in them for a fleeting moment before he turned away and limped out. ‘What do they like?’ he asked over his shoulder, then turned to the children. ‘What’s it to be, kids? Pizza? Chinese? Curry? Kebabs? Burgers?’

‘What’s a kebab?’

‘Disgusting. Anyway, you’re having eggs, Kitty, we’ve already decided that.’

Over their heads she met his eyes defiantly, and saw a reluctant grin blossom on his firm, sculpted lips. ‘OK, we’ll have eggs. Do we have enough?’

We? Her eyes widened. ‘For all of us?’

‘Am I excluded?’

She ran a mental eye over the meagre contents of the fridge and relaxed. ‘Of course not.’