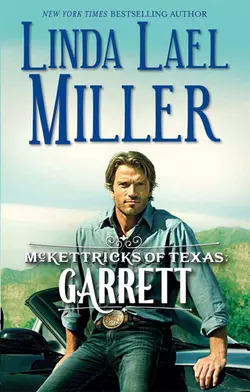

McKettricks of Texas: Garrett

Linda Lael Miller

Let New York Times bestselling sensation Linda Lael Miller take you away to the dusky Texas plains as the gorgeous McKettrick brothers find love and home Fast track up the political ladder, fast cars, fast women – that’s Garrett McKettrick. Or it was, until a scandal brought him home to Blue River, Texas, to plan his next move. Which doesn’t include staying at the family ranch with his brothers.A city boy, Garrett doesn’t think he has the land in his blood. But Blue River has other attractions, like former nemesis Julie Remington. Now a striking woman, Julie comes complete with a four-year-old son and deep ties to the community. Good thing they have nothing in common… except their undeniable attraction that burns as bright as the Texas sun.

Praise for the novels of

LINDA LAEL

MILLER

‘Linda Lael Miller creates vibrant characters and stories

I defy you to forget.’

Debbie Macomber

‘As hot as the noontime desert.’

Publishers WeeklyonThe Rustler

‘This story creates lasting memories of soul-searing redemption and the belief in goodness and hope.’

RT Book ReviewsonThe Rustler

‘Miller’s prose is smart, and her tough Eastwoodian cowboy cuts a sharp, unexpectedly funny figure in a classroom full of rambunctious frontier kids.’

Publishers WeeklyonThe Man from Stone Creek

‘[Miller] paints a brilliant portrait of the good, the bad and the ugly, the lost and the lonely, and the power of love to bring light into the darkest of souls. This is western romance at its finest.’

RT Book ReviewsonThe Man from Stone Creek

‘Sweet, homespun, and touched with angelic Christmas magic, this holiday romance reprises characters from Miller’s popular McKettrick series and is a perfect stocking-stuffer for her fans.’

Library JournalonA McKettrick Christmas

‘An engrossing, contemporary western romance …’

Publishers WeeklyonMcKettrick’s Pride(starred review)

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the second of three books starring a brand-new group of modern-day McKettrick men. Readers who have embraced the irrepressible, larger-than-life McKettrick clan as their own won’t want to miss the stories of Tate, Garrett and Austin—three Texas-bred brothers who meet their matches in the Remington sisters. Political troubleshooter Garrett McKettrick and drama teacher Julie Remington are as different as two people can be … but opposites have a way of attracting in Blue River, Texas, and when fate brings their families together, the sparks begin to fly.

I also wanted to write today to tell you about a special group of people with whom I’ve become involved in the past couple years. It is the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), specifically their Pets for Life programme.

The Pets for Life programme is one of the best ways to help your local shelter: that is, to help keep animals out of shelters in the first place. Something as basic as keeping a collar and tag on your pet all the time, so if he gets out and gets lost, he can be returned home. Be a responsible pet owner. Spay or neuter your pet. And don’t give up when things don’t go perfectly. If your dog digs in the yard, or your cat scratches the furniture, know that these are problems that can be addressed. You can find all the information about these—and many other common problems—at www.petsforlife.org.

This campaign is focused on keeping pets and their people together for a lifetime.

As many of you know, my own household includes two dogs, two cats and six horses, so this is a cause that is near and dear to my heart. I hope you’ll get involved along with me.

With love,

McKettricks of Texas:

Garrett

Linda Lael Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Also available from

Linda Lael Miller and Mills & Boon

McKettricks of Texas: Tate (in the Untameable collection with Diana Palmer)

Don’t miss the further adventures of

THE McKETTRICKS OF TEXAS

McKettricks of Texas: Austin August 2012

For Jeremy Hargis, with love.

CHAPTER ONE

GARRETT MCKETTRICK WANTED A HORSE under him—a fleet cow-pony like the ones bred to work the herds on the Silver Spur Ranch. But for now, anyway, the Porsche would have to do.

Because of the hour—it was a little after 3:00 a.m.—Garrett had that particular stretch of Texas highway all to himself. The moon and stars cast silvery shadows through the open sunroof and shimmered on the rolled-up sleeves of his white dress shirt, while a country oldie, with lots of twang, pounded from the sound system. Everything in him—from the nuclei of his cells outward—vibrated to the beat.

He’d left the tuxedo jacket, the cummerbund, the tie, the fancy cuff links, back in Austin—right along with one or two of his most cherished illusions.

The party was definitely over—for him, anyhow.

He should have seen it coming—or at least listened to people who did see it coming, specifically his brothers, Tate and Austin. They’d done their best to warn him.

Senator Morgan Cox, they’d said, in so many words and in their different ways, wasn’t what he seemed.

Against his will, Garrett’s mind looped back a few hours, and even as he sped along that straight, dark ribbon of road, another part of him relived the shock in excruciating detail.

Cox had always presented himself as a family man, in public and private. A corner of each of his hand-carved antique desks in both the Austin and Washington offices supported a small forest of framed photos—himself and Nan on their wedding day, himself and Nan and the first crop of kids, himself and Nan and more kids, some of whom were adopted and had special needs. Altogether, there were nine Cox offspring.

The dogs—several generations of golden retrievers, all rescued, of course—were pictured as well.

That night, with no warning at all, Garrett’s longtime boss and mentor had arrived at an important fundraiser, held in a glittering hotel ballroom, but not with Nan on his arm—elegant, articulate, wholesome Nan, with her own pedigree as a former Texas governor’s daughter. Oh, no. This powerful U.S. senator, a war hero, a man with what many people considered a straight shot at the White House, had instead escorted a classic bimbo, later identified as a twenty-two-year-old pole dancer who went by the unlikely name of Mandy Chante.

Before God, his amazed supporters, the press and, worst of all, Nan, the senator proceeded to announce that he and Mandy were soul mates. Kindred spirits. They’d been lovers in a dozen other lifetimes, he rhapsodized. In short, Cox explained from the microphone on the dais—his lover hovering earnestly beside him in a long, form-fitting dress rippling with ice-blue sequins, which gave her the look of a mermaid with feet—he hoped everyone would understand.

He had to follow his heart.

If only the senator’s heart were the organ he was following, Garrett lamented silently.

One of those freeze-frame silences followed, vast and uncomfortable, turning the whole assembly into a garden of stone statues while several hundred people tried to process what they’d just heard Cox say.

Who was this guy, they were probably asking themselves, and what had he done with the Morgan Cox they all knew? Where, Garrett himself wondered, was the man who had given that stirring eulogy at the double funeral after Jim and Sally McKettrick, his folks, were killed a decade before?

The mass paralysis following Morgan’s proclamation lasted only a few seconds, and Garrett was quick to shake it off. Automatically, he scanned the room for Nan Cox—his late mother’s college roommate—and found her standing near the grand piano, alone.

Most likely, Nan, a veteran political wife, had been in transit between one conversational cluster and another when her husband dropped the bombshell. She was still smiling, in fact, and the effect was eerie, even surreal.

Like the true lady she was, however, Nan immediately drew herself up, made her way through friends and strangers, enemies and intimate confidants to step up to Garrett’s side, link her arm with his and whisper, “Get him out of here, Garrett. Get Morgan out of here now, before this gets any worse.”

Garrett glanced at the senator, who ignored his wife of more than three decades, the mother of his children, the flesh-and-blood, hurting woman he had just humiliated in a very public way, to gaze lovingly into the upturned face of his mistress. The mermaid’s plump, glistening lower lip jutted out in a pout.

Cox patted the young woman’s hand reassuringly then, acting as though she, not Nan, might have been traumatized.

The cameras came out, amateur and professional; a blinding dazzle surrounded the happy couple. Within a couple of minutes, some of that attention would surely shift to Nan.

“I’m getting you away first,” Garrett told Nan, using his right arm to lock her against his side and starting for the nearest way out. As the senator’s aide, Garrett had a lot of experience at running interference, and he always scoped out every exit in every venue in advance, just in case. Even the familiar ones, like that hotel, which happened to be the senator’s favorite.

Nan didn’t argue—not then, anyway. She kept up with Garrett, offered no protest when he hustled her through a corridor crowded with carts and wait-staff, then into a service elevator.

Garrett flipped open his cell phone and speed-dialed a number as they descended, Nan leaning against the elevator wall now, looking down at her feet, stricken to silence. Her beautifully coiffed silver hair gleamed in the fluorescent light.

The senator’s personal driver, Troy, answered on the first ring, his tone cheerful. “Garrett? What’s up, man?”

“Bring the car around to the back of the hotel,” Garrett said. “And hurry.”

Nan looked up, met Garrett’s gaze. She was pale, and her eyes looked haunted, but the smile resting on her mouth was real, if slight. “You’re probably scaring poor Troy to death,” she scolded, putting a hand out for the cell phone.

Garrett handed it over just as they reached the ground floor, and Nan spoke efficiently into the mouthpiece.

“Troy? This is Mrs. Cox. Just so you know, there’s no fire, and nobody’s been shot or had a heart attack. But it probably is a good idea for me to leave the building, so be a dear and pick me up behind the hotel.” A pause. “Oh, you are? Perfect. I’ll explain in the car. Meanwhile, here’s Garrett again.”

With that, she handed the phone back to Garrett.

When he put it to his ear, he heard Troy suck in a nervous breath. “I’m outside the kitchen door, buddy,” he said. “I’ll take Mrs. Cox home and come straight back, in case you need some help.”

“Excellent idea,” Garrett said, as the elevator doors opened into the institution-sized kitchen.

The senator’s wife smiled and nodded to a bevy of surprised kitchen workers as she and Garrett headed for the outside door.

True to his word, Troy was waiting in back, the rear passenger-side door of the sedan already open for Mrs. Cox.

He and Garrett exchanged glances as Nan slipped into the back seat, but neither of them spoke.

Troy closed her door, but she immediately lowered the window.

“My husband needs your help,” she told Garrett quietly but firmly. “This is no time to judge him—there will be enough of that in the media.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Garrett answered.

Troy climbed behind the wheel again, and Garrett was already heading back through the kitchen door when they pulled away.

He strode to the service elevator, pushed the button and waited until it lumbered down from some upper floor.

When the doors slid open, there were the senator and the bimbo.

The senator blinked when he saw Garrett. He looked older somehow, and he was wearing his glasses. “There you are,” he said. “I was wondering where you’d gotten to, young McKettrick. Nan, too. Have you seen my wife?”

Nan’s remark, spoken only a minute or two before, echoed in Garrett’s mind.

My husband needs your help.

And juxtaposed to that, the senator’s oddly solicitous, Have you seen my wife?

Garrett made an attempt at a smile, but it felt like a grimace instead. He narrowed his eyes slightly, shot a glance at the mermaid and then faced the senator again. “Mrs. Cox is on her way home, sir,” he said.

“I imagine she was upset,” Cox replied, looking both regretful and detached.

“She’s a lady, sir,” Garrett answered evenly. “And she’s behaving like one.”

Cox gave a fond chuckle and nodded. “First, last and always, Nan is a lady,” he agreed.

Beside him, the mermaid seethed, clinging a little more tightly to the senator’s arm and glaring at Garrett.

Garrett glared right back. This woman, he decided, was no mermaid, and no lady, either. She was a barracuda.

“It would seem I haven’t chosen the best time to break our news to the world, my dear,” the senator said, patting his beloved’s bejeweled and manicured hand in the same devoted way he’d done upstairs. “I probably should have told Nan in private.”

Ya think? Garrett asked silently.

“You work for Senator Cox,” said the barracuda, turning to Garrett, “not his wife. Why did you just go off and leave us—him—stranded like that? The reporters—”

Garrett folded his arms and waited.

“It was awful!” blurted the barracuda.

What had the woman expected? Champagne all around? Congratulatory kisses and handshakes? A romantic waltz with the senator while the orchestra played “Moon River”?

“Luckily,” the senator told Garrett affably, as though there had been no outburst from the sequined contingent, “I remembered how often you and I had discussed security measures, and Mandy and I were able to slip away and find the nearest service elevator.”

The corridor seemed to be closing in on Garrett. He undid his string tie and opened the top three buttons of his shirt. “Mandy?” he asked.

The senator laughed warmly. “Mandy Chante,” he said, “meet Garrett McKettrick, my right-hand man.”

“Mandy Chante,” Garrett repeated, with no inflection at all.

Mandy’s eyes blazed. “What are we supposed to do now?” she demanded.

“I guess that depends on the senator’s wishes,” Garrett said mildly. “Will you be going home to the ranch tonight, sir, or staying in town?”

Or maybe I could just drop you off at the nearest E.R. for psychiatric evaluation.

“I’m sure Nan will be at the condo,” the senator mused. “Our showing up there could be awkward.”

Awkward. Yes, indeed, Senator, that would be awkward.

Garrett cleared his throat. “Could I speak to you alone for a moment, sir?” he asked.

Mandy, with one arm already resting in the crook of the senator’s elbow, intertwined the fingers of both hands to get a double grip. “Pooky and I have no secrets from each other,” she said.

Pooky?

Garrett’s stomach did a slow roll.

“Now, now, dear,” Cox told Mandy, gently freeing himself from her physical hold, at least. “Garrett means well, and you mustn’t feel threatened.” Addressing Garrett next, the older man added, “This is not a good time for a discussion. I’d rather not leave Mandy standing alone in this corridor.”

“Sir—”

“Tomorrow, Garrett,” the senator said. “You and I will discuss this tomorrow, in my office.”

Garrett merely nodded, clamping his back teeth together.

“It’s weird down here,” Mandy complained, looking around. “Weird and spooky. Couldn’t we get a suite or something?”

“That’s a fine idea,” Cox replied ebulliently. There was more hand-patting, and then the senator turned to face Garrett again. “You’ll take care of that for us, won’t you, Garrett? Book a suite upstairs, I mean? Under your own name, of course, and not mine.”

“Sure,” Garrett answered wearily, thinking of Nan and the many kids and the faithful golden retrievers. Pointing out to his employer that nobody would be fooled by the suite-booking gambit would probably be futile.

“Good,” the senator said, satisfied.

“Do we have to wait here while he gets us a room, Pooky?” Mandy whined. “I don’t like this place. It’s like a cellar or something.”

Cox smiled at her, and his tone was soothing. “The press will be watching the lobby for us,” he said reasonably. “And we won’t have to wait long, because Garrett will be quick. Won’t you, Garrett?”

Bile scalded the back of Garrett’s throat. “I’ll be quick,” he answered.

That was when he started wanting the horse under him. He wanted to hear hooves pounding over hard ground and breathe the clean, uncomplicated air of home.

Duty first.

He went upstairs, arranged for comfortable quarters at the reception desk, and called the senator’s personal cell phone when he had a room number to give him.

“Here’s Troy, back again,” the senator said on the other end of the call, sounding pleased. “I’m sure he wouldn’t mind escorting us up there. If you’d just get us some ice before you leave, Garrett—”

Garrett closed his eyes, refrained from pointing out that he wasn’t a bellman, or a room service waiter. “Yes, sir,” he said.

Fifteen minutes later, he and Troy descended together, in yet another service elevator. For a black man, Troy looked pale.

“Is he serious?” Troy asked.

Garrett sighed deeply, looking up and watching the digital numbers over the doors as they plunged. His tie was dangling; he tugged it loose from his shirt collar and stuffed it into the pocket of his tuxedo jacket. “It would seem so,” he said.

“Mrs. Cox says the senator is having a mental breakdown, and we all have to stick by him,” Troy said glumly, shaking his head. “She’s sure he’ll come to his senses and everything will be fine.”

“Right,” Garrett said, grimly distracted. He’d sprint around to the side parking lot once he and Troy were outside, climb into his Porsche, and head for home. In two hours, he could be back on the Silver Spur.

They were standing in the alley again when Troy asked, “Why do I get the feeling that this comes as a surprise to you?”

The question threw Garrett, at least momentarily, and he didn’t answer.

Troy thumbed the fob on his key ring, and the sedan started up. “Get in, and I’ll give you a lift to your car,” he told Garrett, with a sigh.

Garrett got into the sedan. “You knew about Mandy and the senator?” he asked.

Troy shook his head again and gave a raspy chuckle. “Hell, Garrett,” he said, “I drive the man’s car. He’s been seeing her for months.”

Garrett closed his eyes. Tate had accused him once of having his head up his ass, as far as the senator’s true nature was concerned. And he’d defended Morgan Cox, been ready to fight his own brother to defend the bastard’s honor.

“What about Nan? Did she know, too?” Remembering the expression on her face earlier, in the ballroom, Garrett didn’t think so.

“Maybe,” Troy said. “She didn’t hear it from me, though.”

He drew the sedan to a stop behind Garrett’s Porsche. News vans were pulling out on the other end of the lot, along with a stream of ordinary cars.

Film clips and sound bites were probably already running on the local channels.

Turn out the lights, Garrett thought dismally. The party’s over.

The senator not only wouldn’t be getting the presidential nomination, he’d be lucky if he wasn’t forced to resign before he’d finished his current term in office.

All of which left Garrett himself up Shit’s Creek, without a paddle.

He got out of the sedan and said goodnight to Troy.

After his friend had driven away, Garrett climbed into the Porsche.

He made a brief stop at his town house, swapping the formal duds for jeans, a Western shirt and old boots. Once he’d changed, he could breathe a little better.

Returning to the kitchen, he turned on the countertop TV, flipping between the networks, watching in despair as one station after another showed Senator Cox and Mandy slipping out of the ballroom, arm in arm.

Deciding he’d seen enough, Garrett turned off the set.

NOW, NEARLY TWO HOURS LATER, only about a mile outside of Blue River, Garrett sped on toward home, the word fool drumming in his brain. He was stone sober, though a part of him wished he were otherwise, when the dazzle of red and blue lights splashed across his rearview mirror.

Garrett swore under his breath, downshifted—Fifth to Fourth to Third to Second, finally rolling to a stop at the side of the road. There, without shutting off the ignition, he waited.

He buzzed down the passenger-side window just as Brent Brogan, chief of police, was about to rap on the glass with his knuckles.

“Are out of your freakin’ mind?” his brother’s best friend demanded, bending to peer through the opening. Brogan’s badge caught a flash of moonlight. “I clocked you at almost one-twenty back there!”

Garrett tensed his hands on the steering wheel, relaxed them without releasing his hold. “Sorry,” he said, gazing straight ahead, through the bug-splattered windshield, instead of meeting Brogan’s gaze. Tate had dubbed the chief “Denzel,” since he resembled the actor’s younger self, and used the nickname freely, especially when the moment called for a little lightening up—but Garrett wasn’t on such easy terms with Brent Brogan as his brother was.

“You’re sorry?” Brogan asked, in a mocking drawl. “Well, that’s another matter, then. Garrett McKettrick is sorry. That just makes all the difference in the world, and pardon me for pulling you over before you killed yourself or somebody else.”

Garrett thrust out a sigh. “Write the ticket,” he said.

“I ought to arrest you,” Brogan said, and he sounded like he was musing on the possibility, giving it real consideration. “That’s what I ought to do. Throw your ass in jail.”

“Fine,” Garrett said, resigned. “Throw me in jail.”

Brent opened the passenger door and folded himself into the seat, keeping his right leg outside the car. He was a big man, taller than Garrett and broader through the shoulders, and that made the quarters feel a mite too close. “There’s no elbow room in this rig,” Brogan remarked. “Why don’t you get yourself a truck?”

Garrett gave a harsh guffaw, with no humor in it. Shoved his right hand through his hair and waited, too stubborn to answer.

It was the chief’s turn to sigh. “Look, Garrett,” he said, “I know you—you’re not drinking and you’re not high. Of all the people I might have pulled over tonight, shooting along this road like a bullet headed for the bull’s-eye, you’ve got more reason to know better than most.”

The old ache rose inside Garrett, lodged in his throat.

He closed his eyes, trying to block the images, but he couldn’t. He heard the screech of tires grabbing at asphalt, the grinding crash of metal careening into metal, even the ludicrously musical splintering of glass. He hadn’t been there the night his mom and dad were killed in a horrendous collision with an out-of-control semi, but the sounds and the pictures in his mind were so vivid, he might as well have been.

For the millionth time since the accident, a full decade in the past now, Garrett tried to come to terms with the loss of his parents. For the millionth time, it didn’t happen.

What would he have given to have them both waiting at the ranch house, just like in the old days?

Just about anything.

“You fixing to tell me what’s the matter?” Brogan asked, when a long time had passed. “I’m on duty until eight o’clock tomorrow morning, when Deputy Osburt relieves me. I can sit here and wait till hell freezes over and till the cows come home, if that’s what I have to do.”

Garrett assessed the situation. Dawn was hours away. The September darkness was weighted with heat, and with Brogan holding the Porsche’s door open like that, the air-conditioning system was of negligible value. He tightened his fingers around the steering wheel again, hard enough to make his knuckles ache.

“I had a bad day, that’s all,” he said. And a worse night.

Brogan laid a hand on his shoulder. “You headed for the Silver Spur?”

Garrett nodded, swallowed. He could feel the pull of home, deep inside; he was drawn to it.

“I’m going to follow you as far as the main gate,” Brogan said, after more pondering. “Make sure you get home in one piece.”

Garrett looked at him. “Thanks,” he said, without much inflection.

Brogan got out of the Porsche, shut the door, bent to look through the open window again. “Meantime, keep your foot light on the pedal,” he warned. “About the last thing on this earth I want to do right now is roust your big brother from his bed and break the news that you just wrapped yourself around a telephone pole.”

Tate was only a year older than he was, Garrett reflected, and they were about the same height and weight. So why did “big” have to preface “brother”? He was pretty sure nobody referred to him as Austin’s “big brother,” though he had a year on the youngest member of the family, along with a couple of inches and a good twenty pounds.

Garrett waited until Brogan was back in his cruiser before pulling back out onto the highway. The town of Blue River slept just up ahead; the streetlights tripped on, one by one, as he passed beneath them.

At this time of night, even the bars were closed.

As Garrett drove, with his one-man police escort trailing behind him, he thought about Tate, probably spooned up with his pretty fiancée, Libby Remington, in the modest house by the bend in the creek, and felt a brief but bitter stab of envy.

They were happy, those two. So crazy in love that the air around them seemed to buzz with pheromones. Tate and Libby were planning the mother of all weddings for New Year’s Eve, following that up with a honeymoon cruise in the Greek Islands. The sooner they could give Tate’s six-year-old twin daughters, Audrey and Ava, a baby brother or sister, they figured, the better.

Garrett calculated he’d be an uncle again about nine months and five minutes after the wedding ceremony was over.

The thought made him smile, in spite of everything.

The countryside slipped by.

At the main gates opening onto the Silver Spur, Brogan flashed his headlights once, turned the cruiser back toward town and drove off.

Pushing a button on his dashboard, Garrett watched as the tall iron gates, emblazoned with the name McKettrick, swung open to admit him.

Home, he reflected, as he drove through and up the long driveway leading toward the house. The place where they have to take you in.

HOW DID ANYBODY MANAGE to sleep in this huge place? Julie Remington wondered, as she flipped on the lights in the daunting kitchen of the main ranch house on the Silver Spur Ranch. She and her four-going-on-five-year-old son, Calvin, along with their beagle, Harry, had been staying in the first-floor guest suite for nearly a week because there were termites at their rented cottage in town and the whole structure was under a tent.

Taking her private stash of herbal tea bags from a cupboard, along with a mug one of her high school drama students had given her for Christmas the year before, Julie set about brewing herself a cup of chamomile tea.

Coffee would probably have made more sense, she thought, pumping hot water from the special spigot by the largest of several sinks, since it would be morning soon, but she still had hopes of catching a few winks before the day began in earnest.

She had just turned, cup in hand, planning to head back to bed, when the door leading into the garage suddenly opened.

Julie nearly spilled the tea down the front of her ratty purple quilted bathrobe, she was so startled.

Garrett McKettrick paused just over the threshold, and she knew by the pensive look in his eyes that he was wondering what she was doing in his kitchen.

She was unprepared for the grin breaking over his handsome face, dispelling the strain she’d glimpsed there only a moment before.

“Hey,” he said, shutting the door behind him, tossing a set of keys onto a granite countertop.

“Hey,” Julie said back, wondering if he’d remembered her yet. She crossed the room, put out her free hand for him to shake. “Julie Remington,” she reminded him.

He laughed. “I know who you are,” he replied. “We grew up together, remember? Not to mention a more recent encounter at Pablo Ruiz’s funeral.”

A trained actress, Julie was playing the part of a woman who didn’t feel self-conscious standing in someone else’s kitchen in the middle of the night, drinking tea and wearing an old bathrobe. Or trying to play the part, anyhow.

It was proving difficult to carry off. Especially after she blew her next line. “I just thought—with all the people you must know—”

All the women you must know …

Garrett’s eyes were that legendary shade of McKettrick blue, a combination of summer sky, new denim and cornflower, and solemn as they regarded her.

Julie’s heart took up a thrumming rhythm. “I suppose you’re wondering what I’m doing here,” she prattled on.

What was wrong with her? It wasn’t as if she’d been caught breaking and entering, after all. Tate had practically insisted that she and Calvin move into the mansion, instead of taking a motel room or making some other arrangement, while the cottage was being pumped full of noxious chemicals.

One corner of Garrett’s mouth tilted up in a grin, and he walked over to the first of a row of built-in refrigerators, pulled open the door and assessed the contents.

“Actually,” he said, without turning around, “I wasn’t wondering that at all.”

Julie, who was not easily rattled, blushed. “Oh.”

He plundered the refrigerator for a while.

“Well,” Julie said, too brightly, “good night, then.”

Holding a storage container full of Julie’s special chicken lasagna, left over from supper, Garrett faced her, shouldering the refrigerator door shut in the same motion. “Or good morning,” he said, “depending on your viewpoint.”

“It’s barely four,” Julie remarked.

Garrett stuck the container into the microwave, pushed a few buttons.

“Don’t!” Julie cried, rushing past him to rescue the dish. “This kind of plastic melts if you nuke it—”

He arched an eyebrow. “I’ll be damned,” he said. Then, while Julie busied herself transferring the contents of the container onto a microwave-safe plate, he added, “Are your eyes really lavender, or am I seeing things?”

The question flustered Julie. “It’s the bathrobe,” she said, as the microwave whirred away, heating up the lasagna.

“The bathrobe?” Garrett asked, sounding confused. He was standing in Julie’s space; she knew that even though she couldn’t bring herself to look directly at him again, which was stupid, because just as he’d said, Blue River was home to both of them. They’d gone to the same schools and the same church growing up. And with their siblings engaged, they were practically family.

Julie, who never blushed, blushed again, and so hard that her cheeks burned. She was really losing it, she decided.

“My—my eyes are actually hazel,” she said, “and they take on the color of whatever I’m wearing. And since the bathrobe is purple—”

As soon as the words were out of her mouth, Julie bit down on her lower lip. Why couldn’t she just shut up?

Mercifully, Garrett didn’t comment. He just stood there at the counter, waiting for the microwave to finish warming up the leftover lasagna.

“Mom?” Calvin padded into the kitchen, blinking owlishly behind the lenses of his glasses. He wore cotton pajamas and his feet were bare. “Is it time to get up? It’s still dark outside, isn’t it?”

Julie felt the usual rush of motherly love, and an undercurrent of fear as well. Recently, Calvin’s biological father had been making overtures about “reconnecting” with their son and, although he’d paid child support all along, Gordon Pruett was a total stranger to the boy.

“Go back to bed, sweetheart,” she said gently. “You don’t have to get up yet.”

The dog, Harry, appeared at Calvin’s side. The adopted beagle was surprisingly nimble, although he’d been born one leg short of the requisite four.

Calvin’s attention shifted to Garrett, who was just sitting down at the table, the plate of lasagna in front of him.

“Hello,” Calvin said.

Harry began to wag his tail, though Julie figured the dog was at least as interested in the Italian casserole as he was in Garrett, if not more so.

“Hey,” Garrett responded.

“You’re Audrey and Ava’s uncle, aren’t you?” Calvin asked. “The one who gave them a real castle for their birthday?”

Garrett chuckled. Jabbed a fork into the food. “Yep, that’s me.”

“It’s at the community center now,” Calvin said, drawing a little closer, not to his mother, but to Garrett. “The castle, I mean.”

“Probably a good place for it,” Garrett said. “You want some of this pasta stuff? It’s pretty good.”

Unaccountably, Julie bristled. Pasta stuff? Pretty good? It was an original recipe, and she’d won a prize for it at the state fair the year before.

Calvin reached the table, hauled back a chair and scrambled into it. With a jab of his right index finger, he pushed his glasses back up his nose. His blond hair stuck out in myriad directions, and his expression was so earnest as he studied Garrett that Julie’s heart ached a little. “No, thanks,” the little boy said solemnly. “We had it for supper and, anyway, Mom makes it all the time.”

Garrett looked up at Julie, smiled slightly and turned his full attention back to Calvin. “Your mom’s a good cook,” he said.

Harry advanced and brushed up against Garrett, leaving white beagle hairs all over the leg of his jeans. Garrett chuckled and greeted Harry with a pat on the head and a quiet “Hey, dog.”

“Calvin,” Julie interceded, “we should get back to bed and leave Mr. McKettrick to enjoy his … breakfast.”

Garrett’s eyes, though weary, seemed to dance when he looked up at Julie. “‘Mr. McKettrick’?” he echoed. His gaze swung back to Calvin. “Do you call my brother Tate ‘Mr. McKettrick’?” he asked.

Calvin shook his head. “I call him Tate. He’s going to marry my aunt Libby on New Year’s Eve, and he’ll be my uncle after that.”

A nod from Garrett. “I guess he will. I will be, too, sort of. So maybe you ought to call me Garrett.”

The child beamed. “I’m Calvin,” he said, “and this is my dog, Harry.”

And he put out his little hand, much as Julie had done earlier.

They shook on the introduction, man and boy.

“Mighty glad to meet the both of you,” Garrett said.

CHAPTER TWO

THE COMBINATION OF A FIERCELY BLUE autumn sky, oak leaves turning to bright yellow in the trees edging the sundappled creek and the heart-piercing love she felt for her little boy made Julie ache over the bittersweet perfection of the present moment.

She turned the pink Cadillac onto the winding dirt road leading to the old Ruiz house, where Tate and Libby and Tate’s twin daughters were living, and glanced into the rearview mirror.

Calvin sat stoically in his car seat in back, staring out the window.

Since Julie had to be at work at Blue River High School a full hour before Calvin’s kindergarten class began, she’d been dropping him off at Libby’s on her way to town over the week they’d been staying on the Silver Spur. He adored his aunt, and Tate, and Tate’s girls, Audrey and Ava, who were two years older than Calvin and thus, in his opinion, sophisticated women of the world. Today, though, he was just too quiet.

“Everything okay, buddy?” Julie asked, tooting the Caddie’s horn in greeting as her sister Libby appeared on the front porch of the house she and Tate were renovating and started down the steps.

“I guess we’ll have to move back to town when the bugs are gone from our cottage and they take down the tent,” he said. “We won’t get to live in the country anymore.”

“That was always the plan,” Julie reminded her son gently. “That we’d go back to the cottage when it’s safe.” Recently, she’d considered offering to buy the small but charming house she’d been renting from month to month since Calvin was a baby and making it their permanent home. Thanks to a windfall, she had the means, but this morning the idea lacked its usual appeal.

Calvin suffered from intermittent asthma attacks, though he hadn’t had an incident for a long time. Suppose some vestige of the toxins used to eliminate termites lingered after the tenting process was finished, and damaged his health—or her own—in some insidious way?

While Julie was trying to shake off that semiparanoid idea, Libby started across the grassy lawn toward the car, grinning and waving one hand in welcome. She wore jeans and a navy blue sweatshirt and white sneakers, and she’d clipped her shiny light-brown hair up on top of her head.

A year older than Julie, Libby had always been strikingly pretty, but since she and Tate McKettrick, her onetime high school sweetheart, had rediscovered each other just that summer, she’d been downright beautiful. Libby glowed, incandescent with love and from being thoroughly loved in return.

Julie pushed the button to lower the back window on the other side of the car, smiling with genuine affection for her sister even as she felt a brief but poignant stab of stark jealousy.

What would it be like to be loved—no, cherished—by a full-grown, committed man like Tate? It was an experience Julie had long-since given up on, for herself, anyway. She was independent and capable, and of course she had no desire to be otherwise, but it would have been nice, once in a while, not to have to be strong every minute of every day and night, not to blaze all the trails and fight all the dragons.

Libby gave Julie a glance before she leaned through the back window to plant a smacking welcome kiss on Calvin’s forehead.

“‘Good morning, Aunt Libby,’” she coached cheerfully, when Calvin didn’t speak to her to right away.

“Good morning, Aunt Libby,” Calvin repeated, with a reluctant giggle.

“He’s a little moody this morning,” Julie said.

“I’m not moody,” Calvin argued, climbing out of the car to stand beside Libby on the gravel driveway, then reaching inside for his backpack. “I just want to live on a ranch, that’s all. I want to have my very own horse, like Audrey and Ava do. Is that too much to ask?”

Julie sighed. “Well, yeah, Calvin, it kind of is too much to ask.”

Calvin didn’t say anything more; he merely shook his head and, lugging his backpack, headed off toward the house, his small shoulders stooped.

“What was that all about?” Libby asked, moving around to Julie’s side of the car and bending to look in at her.

Julie genuinely didn’t have time for a long discussion, but she had always confided in Libby, and now it was virtually automatic, especially when she was upset.

“Maybe I shouldn’t have let you and Tate talk me into staying on the Silver Spur,” she fretted. “It’s only been a week, but Calvin’s already too used to living like a McKettrick—riding horses, swimming in that indoor pool, watching movies in a media room, for heaven’s sake. I can’t give him that kind of life, Libby. I’m not even sure I’d want to if I could. What if he’s getting spoiled?”

Libby raised an eyebrow. “Take a breath, Jules,” she said. “You’re dramatizing a little, don’t you think? Calvin is a good kid, and it would take a lot more than a week or two of high living at the ranch to spoil him. Both of you are under extra stress—Calvin just started kindergarten, and you’re back to teaching full-time, with your house under a tent because of termites—and then there’s the whole Gordon thing….” Libby stopped talking, reached through the window to squeeze Julie’s shoulder. “The point is—things will even out pretty soon. Just give it time.”

Julie worked up a smile, tapped at the face of her watch with one index finger. Easy for you to say, she thought, but what she said out loud was, “Gotta go.”

Libby nodded and stepped away from the car, raised a hand in farewell. She seemed reluctant to let Julie go, and a worried expression flickered in her blue eyes as she watched her back up, turn around and drive off.

Libby had done her little-girl best to stand in after their mother had abandoned the family years before. She’d given up finishing college and arguably a lot more besides when their dad, Will Remington, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Libby had moved back to Blue River, started the Perk Up Coffee Shop—now reduced to a vacant lot across the alley from the house they’d all grown up in—and looked after their father as his illness progressed.

Of course, Julie had helped with his care as much as possible and so had Paige, but just the same, most of the hard stuff had fallen to Libby. Sure, she was the eldest, but the age difference was minor—they’d been born one right after the other, three children in three years. The truth was, Libby had been willing to make sacrifices Julie and Paige couldn’t have managed at the time.

Julie bit down on her lower lip as the town limits came into view, and she began reducing her speed. Their mother, Marva, had reappeared in Blue River months ago, moved into an apartment, and tried, in her own way, to establish some kind of relationship with her daughters. The results had been less than fabulous.

At first, Libby, Julie and Paige had resisted the woman’s every overture, but even after deserting them when they were small, breaking their hearts and their father’s as well, Marva was blithely convinced that a fresh start was just a matter of letting bygones be bygones.

In time, Julie and Paige had both warmed up to Marva somewhat, Libby less so.

The Cadillac bumped over potholes in the gravel parking lot behind Blue River High. The long, low-slung stucco building had grown up on the site of an old Spanish mission, though only a small part of the original structure remained, serving as a center courtyard. Classrooms, a small cafeteria and a gymnasium had been added over the decades, and during an oil boom in the mid-1930s, Clay McKettrick II, known as JR in that time-honored Southern way of denoting “juniors,” had financed the construction of the auditorium, with its two hundred plush theater seats, fine stage and rococo molding around the painted ceiling.

Erected on school property, the auditorium belonged to the entire community. Various civic organizations held their meetings and other events there, and several different denominations had used it as a church on Sunday mornings, while their own buildings were under construction or being renovated.

The auditorium, cool and shadowy and smelling faintly of mildew, had always been a place of almost magical solace for Julie, especially in high school, when she’d had leading roles in so many plays.

Although she’d performed with several professional road companies later on, Julie had never wanted to be an actress and live in glamorous places like New York or Los Angeles. All along, she’d planned on—and worked at—getting her teaching certificate, returning to Blue River and keeping the theater going.

There was no room in the budget for a drama department—the high school theater group supported itself by putting on two productions a year, one of them a musical, and charging modest admission. Like her now-retired predecessor, Miss Idetta Scrobbins, Julie earned her paycheck by teaching English classes—the drama club and the plays they put on were a labor of love.

Julie was thinking about the next project—three one-act plays written by some of her best students—as she hurried down the center aisle and through the doorway to the left of the stage, where she’d transformed an unused supply closet into a sort of hideaway. Officially, her office was her classroom, but it was here that she met with students and came up with some of her best ideas.

Hastily, she tossed her brown-bag lunch into the small refrigerator sitting on top of a file cabinet, kicked off her flat shoes and pulled on the low-heeled pumps she kept stashed in a desk drawer. She flipped on her computer—it was old and took forever to boot up—locked up her purse and raced out of the hideout, back up the aisle and out into the September sunshine.

She was five minutes late for the staff meeting, and Principal Dulles would not be pleased.

Everyone else was already there when Julie dashed into the school library and dropped into a utilitarian folding chair at one of the three long tables where students read and did homework. The library doubled as a study hall throughout the school day.

Up front, the red-faced principal puffed out his cheeks, turning a stub of chalk end over end in one hand, and cleared his throat. Julie’s best friend at work, Helen Marcus, gave her a light poke with her elbow and whispered, “Don’t worry, you didn’t miss anything.”

Julie smiled at that, looked around at the half-dozen other teachers who were her colleagues. She knew that Dulles, a middle-aged man from far away, made no secret of his opinion that Blue River, Texas, hardly offered more in the way of cultural stimulation than a prairie-dog town would have. He considered her a flake because of her colorful clothing and her penchant for putting on and directing plays.

For all of that, Arthur was a good person.

Like Julie, most of the other members of the staff had been born and raised there. They’d come home to teach after college because they knew Blue River needed them; high pay and job perks weren’t a factor, of course. To them, odd breed that they were, the community’s kids mattered most.

Dulles cleared his throat, glaring at Julie, who smiled placidly back at him.

“As some of you already know,” he began, “the McKettrick Foundation has generously agreed to match whatever funds we can raise on our own to buy new computers and special software for our library. Our share, however, amounts to a considerable sum.”

The McKettricks were community-minded; they’d always been quick to lend a hand wherever one was needed, but the foundation’s longstanding policy, except in emergencies, was to involve the whole town in raising funds as well. At the name McKettrick, Julie felt an odd quickening of some kind, at once disturbing and delicious, thinking back to her encounter with Garrett in the ranch-house kitchen.

The others shifted in their seats, checked their watches and glanced up at the wall clock. Students were beginning to arrive; the ringing slam of locker doors and the lilting hum of their conversation sounded from the wide hallway just outside the library.

Julie waited attentively, sensing that Arthur’s speech was mainly directed at her, but unable to imagine why that should be so.

No one spoke.

Arthur seemed reluctant, but he finally went on. He looked straight at Julie, confirming her suspicions. “It’s a pity the drama club is staging those three one-act plays for the fall production, instead of doing a musical.”

The light went on in Julie’s mind. Since the plays were original, and written by high school seniors, turnout at the showcase would probably be limited to proud parents and close friends. The box-office proceeds would therefore be minimal. But the musicals, for which Blue River High was well known, drew audiences from as far away as Austin and San Antonio, and brought in thousands of dollars.

The take from last spring’s production of South Pacific had been plenty to provide new uniforms for the marching band and the football team, with enough left over to fund two hefty scholarships when graduation rolled around.

Arthur continued to stare at Julie, most likely hoping she would save him the embarrassment of strong-arming her by offering to postpone or cancel the student showcase to produce a musical instead. Although her first instinct was always to jump right in like some female superhero and offer to take care of everything, today she didn’t.

They’d committed, she and Arthur and the school board, to staging Kiss Me Kate for this year’s spring production—casting and rehearsals would begin after Christmas vacation, with the usual three performances slated for mid-May.

She had enough on her plate already, between Calvin and her job.

The silence grew uncomfortable.

Arthur Dulles finally cleared his throat eloquently. “I’m sure I don’t need to remind any of you how important it is, in this day and age, for our students to be computer-savvy.”

Still, no one spoke.

“Julie?” Arthur prodded, at last.

“We’re doing Kiss Me Kate next spring,” Julie reminded him.

“Yes,” Arthur agreed, sounding weary, “but perhaps we could produce the musical now, instead of next spring. That way it would be easy to match the McKettricks’ contribution, since our musicals are always so popular.”

Our musicals, Julie thought. As if it would be Arthur who held tryouts every night for a week, and then two months of rehearsals, weekends included. Arthur who dealt with heartbroken teenage girls who hadn’t landed the part of their dreams—not to mention their mothers. Arthur who struggled to round up enough teenage boys to balance out the chorus and play the leads.

No, it would be Julie who did all those things.

Julie alone.

“Gosh, Arthur,” she said, smiling her team-player smile, “that would be hard to pull off. The showcase will be ready to stage within a month. We’d be lucky to get the musical going by Christmas.”

Bob Riza, who coached football, basketball and baseball in their respective seasons, in addition to teaching math, flung a sympathetic glance in Julie’s direction and finally spoke up. “Maybe the foundation would be willing to cut us a check for the full amount,” he said. “Forget the matching requirement, just this once.”

“I don’t think that’s fair,” Julie said.

Arthur folded his arms, still watching her. “I agree,” he said. “The McKettricks have been more than generous. Three years ago, you’ll all remember, when the creeks overflowed and we had all that flood damage and our insurance only covered the basics, the foundation underwrote a new floor for the gymnasium, in full, and replaced the hundreds of books ruined here and in the public library.”

Julie nodded. “Here’s the thing, Arthur,” she said. “The showcase won’t bring in a lot of money, that’s true. But it’s important—the kids involved are trying to get into very good colleges, and there’s a lot of competition. Having their plays produced will make them stand out a little.”

Arthur nodded, listening sympathetically, but Julie knew he’d already made up his mind.

“I’m afraid the showcase will have to be moved to spring,” he said. “The sooner the musical is under way, the better.”

Julie knew she’d lost. So why did she keep fighting? “Spring will be too late for these kids,” she said, straightening her spine, hiking up her chin. “The application deadlines are—”

Arthur shook his head, cutting her off. “I’m sorry, Julie,” he said.

Julie swallowed. Lowered her eyes.

It wasn’t that she didn’t appreciate Arthur’s position. She knew how important those new computers were—while most of the students had ready access to the Internet at home, a significant number of kids depended on the computers at the public library and here at the high school. Technology was changing the world at an almost frightening pace, and Blue River High had to keep up.

Still, she was already spending more time at school than was probably good for Calvin. Launching this project would mean her little boy practically lived with Libby and Paige, and while Calvin adored his aunts, she was his mother. Her son’s happiness and well-being were her responsibility; she couldn’t and wouldn’t foist him off and farm him out any more than she was doing now.

The first period bell shrilled then, earsplittingly loud, it seemed to Julie. She was due in her tenth-grade English class.

Riza and the others rose from their chairs, clearly anxious to head for their own classrooms.

Julie remained where she was, facing Arthur Dulles. She felt a little like an animal caught in the headlight beams of an oncoming truck, unable to move in any direction.

He smiled. Arthur was not unkind, merely beleaguered. He served as principal of the town’s elementary and middle schools as well as Blue River High, and his wife, Dot, was just finishing up a round of chemotherapy.

“It would be a shame if we had to turn down the funding for all that state-of-the-art equipment,” Arthur said forthrightly, standing directly in front of Julie now, “wouldn’t it?”

Julie suppressed a deep sigh. Her sister was engaged to Tate McKettrick; in his view, that meant Julie was practically a McKettrick herself. Maybe Arthur expected her to hit up the town’s most important family for an even fatter check.

“Couldn’t we try some other kind of fundraiser?” she asked. “Get the parents to help out, maybe put on some bake sales and a few car washes?”

“You know,” Arthur said quietly, walking her to the door, pulling it open so she could precede him into the hallway, “our most dedicated parents are already doing all they can, volunteering as crossing guards and lunchroom helpers and the like. I know you depend on several women to sew costumes for the musical every year. The vast majority, I needn’t tell you, only seem to show up when they want to complain about Susie’s math grades or Johnny playing second string on the football team.” He straightened his tie. “It isn’t like it used to be.”

“How’s Dot feeling?” she asked gently. Arthur’s wife was a hometown girl, and everybody liked her.

Arthur’s worries showed in his eyes. “She has good days and bad days,” he said.

Julie bit her lower lip. Nodded. So this was it, she thought. The showcase was out, the musical was in. And somehow she would have to make it all work.

“Thank you,” Arthur replied, distracted again. Once more, he sighed. “I’ll need dates for the production as soon as possible,” he said. “Nelva Jean can make up fliers stressing that we’re going to need more parental help than usual.”

Nelva Jean was the school secretary, a force of nature in her own right, and she’d been eligible for retirement even when Julie and her sisters attended Blue River High. But aged miracle though she was, Nelva Jean couldn’t work magic.

Julie and Arthur went their separate ways then, Julie’s mind tumbling through various unworkable options as she hurried toward her classroom, her thoughts partly on the three playwrights and their own hopes for the showcase.

She’d met with the trio of young authors all summer long, reading and rereading the scripts for their one-act plays, suggesting revisions, helping to polish the pieces until they shone. They’d worked hard, and were counting on the production to buttress their college credentials.

Julie entered her classroom, took her place up front. She had no choice but to put the dilemma out of her mind for the time being.

Class flew by.

“Ms. Remington?” a shy voice asked, when first period was over and most of the students had left.

Julie, who’d been erasing the blackboard, turned to see Rachel Strivens, one of her three young playwrights, standing nearby. Rachel’s dad was often out of work, though he did odd jobs wherever he could find them to put food on the table, and her mother had died in some sort of accident before the teenager and her father and her two younger brothers rolled into Blue River in a beat-up old truck in the middle of the last school year. They’d taken up residence in a rickety trailer, adjoining the junkyard run by Chudley Wilkes and his wife, Minnie, and had kept mostly to themselves ever since.

Rachel’s intelligence, not to mention her affinity for the written word, had been apparent to Julie almost immediately. Over the summer, Rachel had spent her days at the Blue River Public Library, little brothers in tow, or at the community center, composing her play on one of the computers available there.

The other kids seemed to like Rachel, though she didn’t have a lot of time for friends. She was definitely not like the others, buying her clothes at the thrift store and doing without things many of her contemporaries took for granted, like designer jeans, fancy cell phones and MP3 players, but at least she was spared the bullying that sometimes plagued the poor and the different. Julie knew that because she’d taken the time to make sure.

“Yes, Rachel?” she finally replied.

Rachel, though too thin, had elegant bone structure, wide-set brown eyes and a generous mouth. Her waist-length hair, braided into a single plait, was as black as a country night before the new moon, and always clean. “Could—could I talk with you later?”

Julie felt a tingle of alarm. “Is something wrong?”

Rachel tried hard to smile. Second period would begin soon, and students were beginning to drift into the room. “Later?” the girl said. “Please?”

Julie nodded, still thinking about Rachel as she prepared to teach another English class. Probably because she’d had to move around a lot with her dad, rambling from town to town and school to school, Rachel’s grades had been a little on the sketchy side when she’d started at Blue River High. The one-act play she’d written—tellingly titled Trailer Park—was brilliant.

Rachel was brilliant.

But she was also the kind of kid who tended to fall through the cracks unless someone actively championed her and stood up for her.

And Julie was determined to be that someone. Somehow.

APHONE WAS RINGING. Insistent, jarring him awake.

With a groan, Garrett dragged the comforter up over his head, but the sound continued.

Cell phone?

Landline?

He couldn’t tell. Didn’t give a damn.

“Shut up,” he pleaded, burrowing down deeper in bed, his voice muffled by the covers.

The phone stopped after twelve rings, then immediately started up again.

Real Life coalesced in Garrett’s sleep-fuddled brain. Memories of the night before began to surface.

He recalled the senator’s announcement.

Saw Nan Cox in his mind’s eye, slipping out by way of the hotel kitchen.

He recollected Brent Brogan providing him with a police escort as far as the ranch gate.

And after all that, Julie Remington, a little boy and a three-legged beagle appearing in the kitchen.

Knowing he wouldn’t be able to sleep after Julie had taken her young son and their dog back to bed in the first-floor guest suite—the spacious accommodations next to the maid’s rooms, where the housekeeper, Esperanza, stayed—Garrett had gone to the barn, saddled a horse, and spent what remained of the night and the first part of the morning riding.

Finally, when smoke curled from the bunkhouse chimney and lights came on in the trailers along the creek-side, Garrett had returned home, put up his horse, retired to his private quarters to strip, shower and fall facedown into bed.

The ringing reminded him that he still had a job.

“Shit,” he murmured, sitting up and scrambling for the bedside phone. “Hello?”

A dial tone buzzed in his ear, and the ringing went on.

His cell phone, then.

He grabbed for his jeans, abandoned earlier on the floor next to the bed, and rummaged through a couple of pockets before he found the cell.

“Garrett McKettrick,” he mumbled, after snapping it open.

“It’s about time you picked up the phone,” Nan Cox answered. She sounded pretty chipper, considering that her husband had stood up at the previous evening’s fundraiser and essentially told the world that he and Mandy Chante were meant to be together. “I’m at the office, and you’re not. You’re not at your condo, either, because I sent Troy over to check. Where are you, Garrett?”

He sat up in bed, self-conscious because he was talking to his employer’s wife, one of his late mother’s closest friends, naked. Of course, Nan couldn’t see him, but still.

“I’m on the Silver Spur,” he said, grabbing his watch off the bedside table and squinting at it.

Seeing the time—past noon—he swore again.

“The senator needs you. The press has him and the little pole dancer cornered in their hotel suite.”

Garrett tossed the comforter aside, sat up, retrieved his jeans from the floor and pulled them on, standing up to work the zipper and the snap. “I can understand why you think this might be my problem,” he replied, imagining Morgan and Mandy hiding out from reporters in the spacious room he’d rented for them the night before, “but I’m not sure I get why it would be yours. Some women would be angry. They’d be talking to divorce lawyers.”

“Morgan,” Nan said quietly, and with conviction, “is not himself. He’s ill. We still have five children at home. I’m not about to turn my back on him now.”

“Mrs. Cox—”

“Nan,” she broke in. “Your mother and I were like sisters.”

“Nan,” Garrett corrected himself, his tone grave. “Surely you understand that your husband’s career can’t be saved. He won’t get the presidential nomination. In fact, he will probably be asked to relinquish his seat in the Senate.”

“I don’t give a damn about his career,” Nan said fiercely, and Garrett knew she was fighting back tears. “I just want Morgan back. I want him examined by his doctor. He’s not in his right mind, Garrett. He needs my help. He needs our help.”

Although the senator was probably going through some kind of delayed midlife crisis, Garrett wasn’t convinced that his boss was out of his mind. Morgan Cox wouldn’t be the first politician to throw over his wife, family and career in some fit of eroticized egotism, nor, unfortunately, would he be the last.

“Look,” Garrett said quietly, “I’ve given this whole situation some thought, and from where I stand, resignation is looking pretty good.”

“Morgan’s?”

“Mine,” Garrett replied, after unclamping his jaw.

“You would resign?” Nan asked, sounding only slightly more horrified than stunned. “Morgan has been your mentor, Garrett. He’s shown you the ropes, introduced you to all the right people in Washington, prepared the way for you to run for office when the time comes….”

Her voice fell away.

Garrett thrust out a sigh. Would he resign?

He wasn’t sure. All he knew for certain right then was that he needed more of what his dad would have called range time—hours and hours on the back of a horse—in order to figure out what to do next.

In the meanwhile, though, Morgan and the barracuda were pinned down in a hotel suite in Austin, two hours away. The senator was obviously a loose cannon, and if he got desperate enough, he might make things even worse with some off-the-wall statement meant to appease the reporters lying in wait for him in the corridor.

“Garrett?” Nan prompted, when he didn’t speak.

“I’m here,” he said.

“You’ve got to do something.”

Like what? Garrett wondered. But it wasn’t the sort of thing you said to Nan Cox, especially not when she was in her take-on-the-world mode. “I’ll call his cell,” he told her.

“Good,” Nan said, and hung up hard.

Garrett winced slightly, then speed-dialed his boss.

“McKettrick?” Cox snapped. “Is that you?”

“Yes,” Garrett said.

“Where the hell are you?”

Garrett let the question pass. The senator wasn’t asking for his actual whereabouts, after all. He was letting Garrett know he was pissed.

“You haven’t spoken to the press, have you?” Garrett asked.

“No,” Cox said. “But they’re all over the hotel—in the hallway outside our suite, and probably downstairs in the lobby—”

“Probably,” Garrett agreed quietly. “First thing, Senator. It is very important that you don’t issue any statements or answer any questions before we have a chance to make plans. None at all. I’ll get back to Austin as soon as I can, but in the meantime, you’ve got to stay put and speak to no one.” A pause. “Do you understand me, Senator?”

Cox’s temper flared. “What do you mean, you’ll get back to Austin as soon as you can? Dammit, Garrett, where are you?”

This time, Garrett figured, the man really wanted to know. Of course, that didn’t mean he had to be told.

“That doesn’t matter,” Garrett replied, his tone measured.

“If I didn’t need your help so badly,” the senator shot back, “I’d fire you right now!”

If it hadn’t been for Nan and the kids and the golden retrievers—hell, if it hadn’t been for the people of Texas, who’d elected this man to the U.S. Senate three times—Garrett would have told Morgan Cox what he could do with the job.

“Sit tight,” he replied instead. “I’ll call off the dogs and send Troy to pick you up. You’re still going to need to lie low for a while, though.”

“I want you here, Garrett,” Cox all but exploded. “You’re my right-hand man—Troy is just a driver.” Another pause followed, and then, “You’re on that damn ranch, aren’t you? You’re two hours from Austin!”

Garrett had recently bought a small airplane, a Cessna he kept in the ramshackle hangar out on the ranch’s private airstrip. He’d fire it up and fly back to the city.

“I’ll be there right away,” Garrett said.

“Is there a next step?” Cox asked, mellowing out a little.

“Yes. I’m calling a press conference for this afternoon, Senator. You might want to be thinking about what you’re going to tell your constituents.”

“I’ll tell them the same thing I told the group last night,” Cox blustered, “that I’ve fallen in love.”

Garrett couldn’t make himself answer that time.

“Are you still there?” Cox asked.

“Yes, sir,” Garrett replied, his voice gruff with the effort. “I’m still here.”

But damned if I know why.

HELEN MARCUS DUCKED INTO JULIE’S OFFICE just as she was pulling a sandwich from her uneaten brown-bag lunch. Having spent her lunch hour grading compositions, she was ravenous.

At last, a chance to eat.

“Big news,” Helen chimed, rolling the TV set Julie used to play videos and DVDs for the drama club into the tiny office and switching it on. Helen was Julie’s age, dark-haired, plump and happily married, and the two of them had grown up together. “There is a God!”

Puzzled, and with a headache beginning at the base of her skull, Julie frowned. “What are you talking—?”

Before she could finish the question, though, Garrett McKettrick’s handsome face filled the screen. Commanding in a blue cotton shirt, without a coat or a tie, he sat behind a cluster of padded microphones, earnestly addressing a room full of reporters.

“That sum-bitch Morgan Cox is finally going to resign,” Helen crowed. “I feel it in my bones!”

While Julie shared Helen’s low opinion of the senator—she actually mistrusted all politicians—she couldn’t help being struck by the expression in Garrett’s eyes. The one he probably thought he was hiding.

Whatever the front he was putting on for the press, Garrett was stunned. Maybe even demoralized.

Julie watched and listened as the man she’d encountered in the ranch-house kitchen early that morning fielded questions—the senator, apparently, had elected to remain in the background.

Helen had been wrong about the resignation. Senator Cox was not prepared to step down, but he needed some “personal time” with his family, according to Garrett. Colleagues would cover for him in the meantime.

“So where’s the pole dancer?” Helen demanded.

“Pole dancer?” Julie echoed.

Garrett, the senator and the reporters faded to black, and Helen switched off the TV. “The pole dancer,” she repeated. “Some blonde the senator picked up in a seedy girlie club. He wants to marry her—I saw it on the eleven o’clock news last night and again this morning.” The math teacher rolled her eyes. “It’s true love. He and the bimbette have been together in other lives. And there’s our own Garrett McKettrick, defending the man.” A sad shake of the head. “Jim and Sally raised those three boys of theirs right. Garrett ought to know better than to throw in with a crook like that.”

Just then, Rachel Strivens appeared in the doorway of Julie’s office. “I’m sorry,” she said quickly, seeing that Julie wasn’t alone, and started to leave.

“Wait,” Julie said.

Helen was already turning off the TV set, unplugging it, rolling it back out into the hallway on its noisy cart. If Helen had planned on staying to talk, she’d clearly changed her mind.

Blushing a little, Rachel slipped reluctantly into the room.

“Rachel,” Julie said quietly, “sit down, please.”

Rachel sat.

“What is it?” Julie finally asked, though of course she knew. She’d announced the suspension of plans to produce the showcase—it was only temporary, she’d insisted, she’d think of something—in all her English classes that day.

Rachel looked up, her brown eyes glistening with tears. “I just wanted to let you know that it’s okay, about the showcase probably not happening and everything,” she said. The girl made a visible effort to gather herself up, straightening her shoulders, raising her chin. “I can’t do any extracurricular activities anyway—Dad says I need to start working after school, so I can help out with the bills. His friend Dennis manages the bowling alley, and with the fall leagues starting up, they can use some extra people.”

Julie took a moment to absorb all the implications of that.

Rachel hadn’t said she wanted to save for college, or buy clothes or a car or a laptop, like most teenagers in search of employment. She’d said she had to “help out with the bills.”

She wasn’t planning to go to college.

“I understand,” Julie said, at some length, wishing she didn’t.

Rachel bit her lower lip, threw her long braid back over one shoulder. “Dad tries,” she said, her voice barely audible. “Everything is so hard, without my mom around anymore.”

Julie nodded, holding back tears. In five years, in ten years, in twenty, Rachel might still be working at the bowling alley—if she had a job at all. Julie had seen the phenomenon half a dozen times. “I’m sure that’s true,” she said.

Rachel was on her feet. Ready to go.

Julie leaned forward in her chair. “Have you actually been hired, Rachel, or is the job at the bowling alley just a possibility?”

Rachel stood on the threshold, poised to flee, but clearly wanting to stay. “It’s pretty definite,” she answered. “I just have to say yes, and it’s mine.”

Things like this happened, Julie reminded herself. The world was an imperfect place.

Kids tabled their dreams, thinking they’d get back to them later.

Except that they so rarely did, in Julie’s experience. One thing led to another. They met somebody and got married. Then there were children and rent to pay and car loans.

Rachel was so bright and talented, and she was standing at an important crossroads. In one direction lay a fine education and every hope of success. In the other …

The prospects made Julie want to cover her face with her hands.

After Rachel had gone, she sat very still for a long time, wondering what she could do to help.

Only one course of action came to mind, and that was probably a long shot.

She would speak to Rachel’s father.

CHAPTER THREE

TATE WAS WAITING AT THE AIRSTRIP in his truck when Garrett landed the Cessna around five that afternoon.

Garrett taxied to a stop outside the ramshackle hangar that had once housed his dad’s plane and shut off the engines. The blur of the props slowed until the paddles were visible.

He climbed down, shut the door behind him and walked toward his brother.

They met midway between the Cessna and Tate’s truck.

Obviously, Tate had heard about the scandal in Austin by then, and Garrett figured he was there to say, “I told you so.”

Instead, Tate reached out, rested a hand on Garrett’s shoulder. “You okay?”

Garrett didn’t know what to say then. Flying back from the capital, he’d rehearsed another scenario entirely—and that one hadn’t involved the sympathy and concern he saw in his brother’s eyes.

He nodded, though he couldn’t resist qualifying that with “I’ve been better.”

Tate let his hand fall back to his side. Folded his arms. “I caught the press conference on TV,” he said. “Cox isn’t planning to resign?”

Garrett sighed, shoved a hand through his hair. “He will,” he said sadly. “Right now, he’s still trying to convince himself that the hullabaloo will blow over and everything will get back to normal.”

“How’s Nan taking all this?”

“She’s holding up okay,” Garrett said. “As far as I can tell, anyway.”

Tate took that in. His expression was thoughtful. “Now what?” he asked, after a few moments had passed. “For you, I mean?”

“I catch my breath and look for another job,” Garrett replied.

“You quit?” Tate asked, sounding surprised. If there was one thing a McKettrick didn’t do, it was desert a sinking ship. Unless, of course, that ship had been commandeered by one of the rats.

Garrett grinned wanly. Spread his hands at his side. “I was fired,” he said.

Now there, he thought, was a first. In living memory, he knew of no McKettrick who had ever been fired from a job. On the other hand, most of them worked for themselves, and that had been the case for generations.

The look on Tate’s face would have been satisfying, under any other circumstances. “What?”

Garrett chuckled. Okay, so his brother’s surprise was sort of satisfying, circumstances notwithstanding. It made up for Garrett’s skinned pride, at least a little. “The senator and I had words,” he said. “He wanted to go on as if nothing had happened. I told him that wouldn’t work—he needed to fess up, stand by his wife and his kids, if he wanted to come out of this with any credibility at all, never mind holding on to his seat in the Senate. I agreed to handle the press conference because Nan practically begged me, but when it was over, the senator informed me that my services were no longer needed.” Still enjoying Tate’s bewilderment, Garrett started toward the Cessna he’d just climbed out of, intending to roll it into the hangar. He stopped, looked back over one shoulder. “You wouldn’t be in the market for a ranch hand, would you?”

Tate smiled, but there was a tinge of sadness to it. “Permanent or temporary?”

“Temporary,” Garrett said, after a moment of recovery. “I still want to work in government. And I’ve already had a couple of offers.”

Tate’s disappointment was visible in his face, though he was a good sport about it. “Okay,” he said. “How long is ‘temporary’?”

Garrett wasn’t sure how to answer that. He needed time—thinking time. Horse time. “As long as it takes,” he offered.

Tate put out a hand so they could shake on the agreement, nebulous as it was. “Fair enough,” he said.

Garrett nodded, watched as Tate turned to walk away, open the door of his truck and step up on the running board to climb behind the wheel.

“See you in the morning,” Tate called.

Garrett grinned, feeling strangely hopeful, as if he were on the brink of something he’d been born to do.

But that was crazy, of course.

He was a born politician. He belonged in Austin, if not Washington. He wanted to be a mover and a shaker, part of the solution. Working on the Silver Spur was only a stopgap measure, just as he’d told Tate.

“What time?” he called back, standing next to the Cessna.

Tate’s grin flashed. “We’ve got five hundred head of cattle to move tomorrow,” he said. “We’re starting at dawn, so be saddled up and ready to ride.”

Garrett didn’t let his own grin falter, though on the inside he groaned. He nodded, waved and turned away.

IF RON STRIVENS, RACHEL’S FATHER, carried a cell phone, the number wasn’t on record in the school office, and since Strivens did odd jobs, he didn’t work in the same place every day, like most of her students’ parents. In the end, Julie drove to the trailer he rented just across the dirt road from Chudley and Minnie Wilkes’s junkyard, and found him there, chopping firewood in the twilight.

Seeing Julie, the tall, rangy man lodged the blade of his ax in the chopping block and started toward her.

Julie sized him up as he approached. He wore old jeans, beat-up work boots and a plaid flannel shirt, unbuttoned to reveal a faded T-shirt beneath. His reddish-brown hair was too long and thinning above his forehead, and the expression in his eyes was one of weary resignation.

“I’m Julie Remington,” Julie told him, after rolling down the car window. “Rachel is in my English class.”

Strivens nodded, keeping his distance. Behind him loomed the battered trailer. Smoke curled from a rusty stovepipe, gray against a darkening sky, and Julie thought she saw Rachel’s face appear briefly at one of the windows.

“What can I do for you, Ms. Remington?” he asked, shyly polite.

Julie felt her throat tighten. Money had certainly been in short supply while she was growing up, and the family home was nothing fancy, but she and her sisters had never done without anything they really needed.

“I was hoping we could talk about Rachel,” she said.

Strivens glanced back toward the trailer. The metal was rusting, and even curling away from the frame in places, and the chimney rose from the roof of a ramshackle add-on, more like a lean-to than a room. “I’d ask you in,” he told her, “but the kids are about to have their supper, and I don’t think the soup will stretch far enough to feed another person.”

Julie ached for Rachel, for her brothers, for all of them. “I’m in sort of a hurry anyway,” she said, and that was true. She still had to pick Calvin up at Libby and Tate’s place, and then there would be supper and his bath and a bedtime story. “Rachel tells me she’s taking on an after-school job.”

Strivens reddened a little, nodded once, abruptly. He’d been stooping to look in at Julie through the window, but now he took a couple of steps back and straightened. “I’m right sorry she has to do that,” he said, “but the fact is, we’re having a hard time making ends meet around here. The boys are always needing something, and there’s rent and food and all the rest.”

Julie’s heart sank. What had she expected—that Rachel’s father would say it was all a big misunderstanding and what had he been thinking, asking a mere child to help support the family?

“Rachel is a very special young woman, Mr. Strivens. She’s definitely college material. Her grades aren’t terrific, though, and she’s going to have even less time to study once she’s working.”