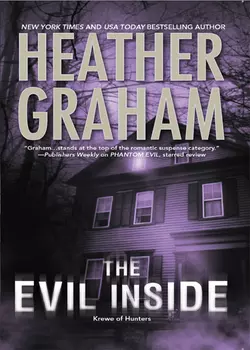

The Evil Inside

Heather Graham

SOME DEATHS LIVE ON FOREVERFor as long as it has stood overlooking New England’s jagged coastline, Lexington House has been the witness to madness… and murder. But in recent years the inexplicable malice that once tormented so many has lain as silent as its victims. Until now…A member of the nation’s foremost paranormal forensic team, Jenna Duffy has made a career out of investigating the inexplicable. Yet nothing could prepare her for the string of slayings once again plaguing Lexington House—or for the chief suspect, a boy barely old enough to drive, much less kill.With the young man’s life on the line, Jenna must team up with attorney Samuel Hall to pinpoint who—or what—is taking the lives of those who get too close to the past. But everything they learn brings them closer to the forces of evil stalking this tortured ground.

Praise for the novels of Heather Graham

“Graham expertly blends a chilling history of the mansion’s former residents with eerie phenomena, once again demonstrating why she stands at the top of the romantic suspense category.”

—Publishers Weekly on Phantom Evil, starred review

“An incredible storyteller.”

—Los Angeles Daily News

“A fast-paced and suspenseful read that will give readers chills while keeping them guessing until the end.”

—RT Book Reviews on Ghost Moon

“If you like mixing a bit of the creepy with a dash of sinister and spine-chilling reading with your romance, be sure to read Heather Graham’s latest… . Graham does a great job of blending just a bit of paranormal with real, human evil.”

—Miami Herald on Unhallowed Ground

“The paranormal elements are integral to the unrelentingly suspenseful plot, the characters are likable, the romance convincing, and, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Graham’s atmospheric depiction of a lost city is especially poignant.”

—Booklist on Ghost Walk

“Graham’s rich, balanced thriller sizzles with equal parts suspense, romance and the paranormal—all of it nail-biting.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Vision

“Mystery, sex, paranormal events. What’s not to love?”

—Kirkus Reviews on The Death Dealer

The

Evil Inside

Heather Graham

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For Lisa Manetti, Corinne De Winter, Brent Chapman, Juan Roca, Dennis Pozzessere, Jason Pozzessere, Dennis Cummins, and all our group, and the amazing scares and laughs we all shared at the Lizzie Borden House. (And thanks to the house’s beautiful current owner!)

In memory of my in-laws, Angelina Mero and Alphonso Pozzessere; I can’t think of Massachusetts without thinking about them, and smiling.

And in memory of Alice Pozzessere Crosbie and “Uncle Buppy,” and for the Crosbie clan, Steven, Ginger, Linda, Tommy, Billy, and Mary, and their families.

And for the great, diverse state of Massachusetts. Especially Gloucester, and Hammond Castle, where Derek and Zhenia had the most beautiful wedding ever.

Prologue

The boy stood naked in the middle of the road.

Sam Hall’s headlights caught him there, frozen in position, like a deer. He was covered in something slick, and it dripped down his flesh. It looked reddish, like blood, as if the kid had run off the set of a horror movie after being drenched in buckets of the stuff.

Sam slammed his foot on the brake pedal, grateful for once that his years with Mahon, Mero and Malone had given him the ability to afford the new Jaguar with the stop-on-a-dime brakes.

Even then, the car pulled to a halt just inches before the boy.

Swearing softly beneath his breath and puzzled beyond measure, Sam jumped out of the car. “Hey, what the hell are you doing there, son?”

The boy didn’t move, didn’t seem to realize that he’d nearly been roadkill. He just shook as he stood there. Summer had recently turned to fall, and the air had a sharp nip, typical for Massachusetts at this time of year. Tree-laden tracts lined the road; the old oaks seemed to bend and moan with the breeze, while multicolored leaves danced on the road and swept around the scene as if they, too, were deeply disturbed.

The boy didn’t acknowledge Sam or look at him.

Again Sam swore softly. There was obviously something really wrong, though this kid couldn’t have been injured severely and still be able to stand as he was.

He couldn’t have lost that amount of blood and still be conscious.

Was it really blood … couldn’t be.

Either way, Sam couldn’t leave him in the middle of the road.

He looked at the new Jag he really loved, with the leather seats he also loved, and walked around to his trunk and found the beach blanket he’d picked up on his recent drive to the Florida Keys. It was sandy, but it would warm the kid.

He returned quickly, but the kid hadn’t run off, much less moved. “Are you hurt?” he asked quietly.

He received no response.

“Here, here, you’re going to have to get into my car,” Sam said, approaching the boy with the blanket. “We’ll get you to a hospital.”

Sam wrapped the blanket around him. “Sorry about the sand,” he said.

The kid looked to be somewhere between fifteen and seventeen, but underdeveloped. He was painfully thin. His eyes were huge and brown in the lean contours of his face. His chest was devoid of hair, so most of the blood had slid down his chest.

The temperature seemed to be around forty degrees Fahrenheit. It wasn’t freezing, but the kid shouldn’t be exposed to this long.

Sam intended to get him into the car. And yet, as he stood there, trying to be compassionate while saving his wool coat from the sticky red substance that looked like blood, he suddenly froze.

It didn’t just look like blood—it was blood.

Denial rushed through his mind.

But it was blood, no denying it.

Pig’s blood, cow’s blood … hell, rabbit’s blood.

But something told Sam that it was not.

He drew the blanket off the boy and turned him around, seeking an injury that might have caused that amount of blood.

But he didn’t find any. If he had, the boy wouldn’t have been standing upright. He wouldn’t have been breathing. He’d have been dead from a wound like that.

He’d already wrapped the blanket around the kid. No undoing that.

And if he could, would he leave the kid there shivering with nothing?

Still standing in front of the boy, who didn’t even reach up to hold the blanket in place, he fumbled in his pocket for his cell phone and hit 911. An operator with a droning voice asked him what his emergency was.

“My name is Samuel Hall. I was driving into Salem when I nearly hit a young man in the road. He’s covered in blood. It doesn’t appear to be his blood, but I can’t be certain that he isn’t injured. He’s standing on his own, and doesn’t seem in any way to be too weak to do so, but he’s nonresponsive. He may be in shock. Can you get someone out here—fast?” He looked around and quickly gave his position as best he could. Hell, it was a quiet backwoods road. He’d opted to take IA north from Boston, but had turned off early. The dark, quiet road through the trees had seemed a soothing path for his first visit home in a long time.

“Stay calm now, Mr. Hall,” the operator told him. “I’ll have a car out to your position immediately. Patrolmen are in the vicinity. It won’t be long. You’re sure the young man isn’t bleeding? If so, you must stanch the flow of blood. Stay calm. Are you doing all right?”

He hesitated for the fraction of a second, staring at the phone, his mind racing. He thought of the horrors he had witnessed in the military, and he thought of the crime-scene photos he’d studied as a criminal attorney.

“Ma’am,” he said, his voice even and strong, “I’m about as calm as a dead Quaker. But you need to get someone out here fast. I’m going to suggest you send an investigator, because I have a feeling this might be human blood, and I don’t want to compromise any more evidence than I already have by putting my blanket around the boy.”

“Of course, sir. Please remain on the line. And do your best to remain calm.”

“If you tell me to remain calm one more time, I’m going to implode and become consumed by spontaneous combustion—”

“There’s already a car on the way. Sir, you just have to remain calm. This is Salem, Massachusetts, sir, and we are moving into the Halloween season now, you know. You may be the victim of prank. Now, stay on the line, and remain calm, Mr. Hall.” She gasped suddenly, her well-learned rhetoric failing her for a moment. “Oh, you’re the Sam Hall—”

He heard the sound of a siren then. “They’re here” is all he said. “Thanks.” He hit the end icon on his phone.

A patrol car pulled up on the road in front of him, and the glare of its lights met and mingled with the Jag’s headlights, almost blinding him for a minute. Two uniformed officers exited from either side of the car, guns in position.

“He’s not armed!” Sam called. “He’s—he’s in shock. He needs medical attention.”

“An ambulance is on the way,” the driver called out. “And Detective Alden. I radioed him on my way out.”

Alden? He wondered if it was his old friend John. Puritan names still abounded here, and John Alden and he had been on the football team together. John had always wanted to be a cop, a detective, actually. He must have worked his way up through the ranks.

The patrolmen walked forward, slowly holstering their guns as they saw that the shaking youth carried no weapon and that Sam seemed nonthreatening, as well.

“Patrolman Nathan Brewster,” one said, introducing himself. “And my partner, Robert Bishop.”

Sam nodded. “Samuel Hall,” he said, but the patrolmen were just staring at the boy. They glanced at each other uneasily.

“Yeah, yeah, Detective Alden is on his way. Any minute now,” Brewster said, almost as an afterthought.

“What’s going on?” Sam asked. The two were behaving curiously. They had holstered their weapons but appeared ready to spring for them again at any second.

Neither touched the boy. Neither spoke to him. The kid was shaking harder and harder, despite the blanket Sam had set around his shoulders. Neither did the boy make any attempt to hold the blanket to his bony frame.

Again, the two exchanged glances. “We’re not really at liberty to say, sir.”

“Fine, well, I think we have to get him into a heated car, or he’ll die of exposure pretty soon,” Sam said. True or not, he couldn’t bear watching the shocked youth stare wide-eyed at nothing and shake anymore.

But before the patrolmen were compelled to respond, the sound of sirens suddenly seemed to grow to an alarming pitch. First on the scene was an unmarked car. A grim, solid-looking man of about fifty in a worn woolen coat and plaid sweater exited the driver’s side of the car and strode quickly toward them.

Plainclothes cop. Detective, Sam thought. He hoped it was John.

And it was.

But unlike the others, he didn’t pull a weapon. He hurried forward, passing between the patrolmen and Sam and the youth. He didn’t look at Sam, but at the boy, and his expression wasn’t authoritarian or harsh, but sad.

“Malachi,” he said. “Good God, Malachi, you’ve done it now.”

“Excuse me. He’s shivering. He’s freezing. He’s in shock. John? It’s Sam—Sam Hall.”

John Alden turned and looked at Sam.

“Sam!”

“I was on my way to the folks’ place. I nearly hit the boy. He was just standing there, in the road. Covered in blood.”

“Sam,” Alden repeated.

He looked as if he was about to say good to see you or something to that effect, but in the road with a blood-splattered boy, it just wasn’t appropriate.

“John, this kid needs help. I think he’s in shock,” Sam repeated.

John Alden nodded and indicated, with the cast of his head, the ambulance that had arrived. “Yeah, he’ll get medical attention. And he’s in shock, you say? He should be. He just hacked his family to death.”

1

Lexington House.

There it stood, on a cliff by the water. It might have been a postcard or a movie poster, and it was as eerie as ever—a facade that graced the darkest horror movie. Its paint was chipping, the exterior was gray and it had been weathered through the centuries by icy winds ripping in off the Atlantic Ocean. The ground-floor windows seemed like black eyes; the second-floor windows might have been startled brows, half covered by the eaves of the roof.

Oddly enough, Lexington House had always remained in private hands. From its builder—the Puritan Eli Lexington—to its recent owner—the now deceased Abraham Smith—it had always found a new buyer after each and every one of its tragedies. People had once known its early history, of course, but that had been lost amid the witchcraft trials that scarred American history and continued to fascinate the social sciences. And when Mr. and Mrs. Braden had been brutally murdered two centuries later, in the 1890s, the world knew that their son had been guilty of the crime. But the legal system had worked for the killer this time, and he’d been acquitted. He and his sister had promptly sold the house to another private party. Eighty years later it had become a bed-and-breakfast, and then it had been purchased by Abraham Smith, who had longed for the property on its little cliff, segregated from all but a few neighbors.

One of whom had been murdered last week.

And now today …

Jenna Duffy had heard about nothing but the Lexington House on the radio since she’d started for Salem from Boston this morning. Uncle Jamie had called her days before, begging that she come to Salem and speak with him. Peculiar timing.

She’d pulled to the side of the road and parked to stare at the place.

A patrol car sat near the house; crime-scene tape cordoned off the entire house. There were no onlookers, though. The house was at a little distance from the historic section of town, where most visitors strolled through the Old Burial Ground, visited the House of the Seven Gables or sought out history at any one of the witch museums or the Peabody Essex Museum. And since it was October and Halloween was approaching, the real-life contemporary tragedy would fuel the ghost stories that were already being told around town.

She stared at the house awhile longer, wondering about its history. What happened at Lexington House would prove to be another horrible case of mental instability or greed, and as much as she longed to actually see the property that brought about such gruesome tragedy, she had a meeting with her uncle. She glanced at her watch and pulled back onto the road. With Halloween tourists clogging the city, it might take her time to get where she was going.

Somehow she was still early.

She parked her car at the Hawthorne Hotel’s parking lot, and wandered across the street to the common.

Autumn leaves, beautiful in their warm orange, magenta and yellow colorings, rustled beneath Jenna’s feet as she strolled. Before her and around her, the leaves swirled and lifted inches into the air as the breeze picked them up and whimsically tossed them about.

She heard the laughter of schoolchildren as they made their way through Salem Common, heading home but not too quickly. Autumn was certainly one of the most beautiful seasons in New England, and schoolchildren, raised with all the colors as they may have been, still loved to stop and lift the leaves, toss them about and roll in them.

Jenna had loved Salem since she’d first come to the States and her parents had chosen nearby Boston, Massachusetts, as the place to begin their new lives. They had come up here weekends, in the summers and for the Halloween festivity, and also for the fall leaves and to see Uncle Jamie.

But this was a difficult visit. She was about to meet Uncle Jamie at the Hawthorne Hotel, and she was worried about him. He’d been so anxious when he’d asked her to come. He was asking her in a professional capacity, but he didn’t want her bringing “your team” or “your unit” or “the official group” with which she worked, not yet.

As she walked across the common, her attention was drawn back to the children. A group of five- to seven-year-olds were holding hands, running in a circle and playing a game.

She froze as she heard them reciting the old rhyme repeated not just in this area, but around the country.

Oh, Lexington, he loved his wife,

So much he kept her near.

Close as his sons, dear as his life;

He chopped her up;

He axed them, too,

and then he kept them here.

Duck, duck, wife!

Duck, duck, life!

You’re it!

Jenna felt as if ice water had suddenly been injected in her veins—the old ditty now seemed to be words of mockery and cruelty. A young woman, who had been standing with another group of parents watching over small children and a group of older teens who had gathered in the park, rushed forward. She caught hold of the little boy’s arms, spun him around and shook a finger at him, reprimanding him.

Another of the mothers came hurrying over to her, her voice carrying in the cool air. “Cindy, don’t be so hard on them! They don’t … know. We used to say that rhyme all the time when we were kids.”

“Samantha, I know, it’s just that … now? Now, with what’s happened again? It’s that house! That horrible house, and that boy … He used to go to school with our kids.”

“But, it’s over now, Cindy. It’s over. They have the boy in custody.”

Other parents began calling out sharply to their children. The two women herded the children toward the group of parents. A tall man in the group said something sharply to the teens, words that Jenna couldn’t quite hear, and they disbanded, as well. The conversation they all exchanged became whispers. The families and the unattached teens began to drift away, as if none of them wanted the reality of the situation.

The great seafaring days of Salem were in the past. The city survived on tourism, and most of it wasn’t because of the autumn leaves. Salem had been the site of the infamous Salem Witch Trials—and it had also been the site of two horrendous and savage murdering sprees.

And, now, a third.

Tragic incidences of human ignorance and brutality in the past were one thing; bloodletting in the present was quite another, especially with the town anticipating the season’s mammoth number of visitors. The income generated by the holiday alone could sustain many a shopkeeper and inn through the brutal New England winter to follow.

Of course, for Uncle Jamie, the recent tragedy would not be in any way fiscal but personal. She knew Jamie and loved him dearly, because he was a man who took the troubles of others to heart. This was often to his own detriment, but that was Jamie.

From her vantage spot, she could see the Salem Witch Museum with its English Gothic facade across the street on North Washington Square—the point where she always told friends to begin their exploration of the city. In a comparatively short presentation, the museum did a fine job of explaining the climate of the city during the days of the infamous trials. The statue of Roger Conant, town founder, stood proud before her as well, larger than life, his heavy cape appearing to blow in the same breeze that tossed the leaves about.

The residences and businesses surrounding the common were decked out for fall. Pumpkins and black cats adorned windows and lawns, while skeletons and, naturally, witches dangled from branches. Some people were more into the traditional concept of fall itself, and they had decorated with scarecrows, feathered turkeys and cornucopias. The image of the city of Salem she saw as she stood in the common was that of old New England, family and festivity, tinged with the strange pleasant warmth of the coming of fall.

She glanced at her watch again. It was time to go and meet Uncle Jamie; she suddenly realized she had been dreading the meeting, and she didn’t even know why.

Sam poured himself a second cup of coffee and looked around the house, trying to concentrate on its details and trying to make up his mind. He didn’t like wondering what the hell he was going to do about the house, but it was better than thinking about the bizarre and tragic circumstances under which he had finally made it home.

He didn’t need to get involved—he wasn’t staying here. He’d already taken a nice long leave of absence, and it was time to go back to work. But, then, he mused, maybe he shouldn’t. He’d not only saved his client from prison, but he’d proved beyond a doubt that the man not only deserved to be declared innocent, but was, in fact, innocent. And he was still a bit worn down from all the effort.

Sam had really stepped on every rung of the ladder on his way to becoming a renowned attorney. He’d worked in the D.A.’s office following college and the military. He’d worked as an investigator as well before joining his first small firm, because his boss had needed an investigator more than another attorney in the office. He’d learned the ropes from Colin Blake, Esquire, and he’d come to terms with a sad truth: a defense attorney was still required to give his best effort in a legal defense, even if he thought his client was guilty as all hell. He’d learned to make the cops and the prosecutors suffer, but discovered he didn’t much like that side of the business. Still, despite that, he wasn’t sure he could ever go back to being a prosecutor. It wasn’t the money. Well, it was about money. Often. It was sometimes about the money it took to put together a great team of defense attorneys. He’d seen a young woman sent to prison for years, convicted of the murder of her newborn. He’d seen a rich young man walk on drug charges, and a poor one sent up fifteen years for the same offense. He understood the law; he didn’t understand why the slow wheels of Congress took so long to correct the inequities that were to be found in so many instances. He was violently opposed to the death penalty, always afraid that somewhere, sometime, it would send an innocent person to his or her death, and yet he understood the desire others felt to see it utilized. Too many drug lords, murderers and rapists made it back onto the street. But last night …

Something about the kid he’d come upon in the street was still tugging at his heartstrings.

The kid, according to police, had axed his family to death.

There was no doubt that Malachi Smith’s father, mother, grandmother and great-uncle had been murdered, and horribly so. Jumping on the internet that morning, he’d seen that the news regarding the killings had gone global. Abraham Smith, sixty-two, Beth Smith, fifty-nine, Abigail Smith, eighty-three, and Thomas Smith, eighty-seven, had all died from exsanguination—Beth, Abigail and Thomas all receiving at least eight blows from a honed ax, Abraham over twenty. The previous week, a neighbor, Mr. Earnest Covington, had been found hacked to death on his parlor floor. Six months earlier, a Salem native living in nearby Andover had been found murdered in his barn. Police had been following leads and now suspected that the cases were related.

Indisputable evidence indicated that the youngest son of the Smith family, Malachi, was the killer. The police had the young man in custody, and he remained under guard in isolation at a correctional facility hospital.

The Smiths were the current owners of Lexington House, famed for its bloody reputation. The family had adhered to strict fundamentalist teachings, being members of the Old Meeting House in Beverly, Massachusetts. This was a strange connection of sorts with the original murders in the place. In the midst of the witchcraft trials, Eli Lexington had murdered his family with an ax. He’d been imprisoned with the nearly two hundred arrested for witchcraft at the time. Then he disappeared. There were no records of his fate after prison.

Then, in the late eighteen hundreds, Mr. and Mrs. Braden had been killed in the house, as well. A historical parallel of the Menendez case? From the books, movies and court records that had come down through time, it appeared that a disgruntled son had killed his parents for the money. And, of course, similar cases had been suspected elsewhere. The Braden case was similar, too, to the Lizzie Borden murders. Both Lizzie and the Braden boy had been acquitted, but nobody doubted that each of them had murdered their families.

Just like today’s case.

Sam told himself over and over to get the hell away from his computer. He was not involved. But he was.

He’d found the kid in the road.

And, he’d grown up in Salem. He could still remember being a school kid, and the rhyme every school kid in the area had learned. Oh, Lexington, he loved his wife …

A good attorney, of course—even a hack—would go for an insanity plea. The kid had grown up in what everyone in the area termed a haunted house—a really haunted house—which, in a city like Salem, was saying something.

Any attorney could defend the boy. It was too easy. He forced himself to leave the computer screen and walk around the house.

His parents had been dead for nearly two years; he’d returned for the funeral, and he hadn’t been back since. The house, however, was in excellent shape. His father, until his death, had seen to it that no electrical wires frayed, that the heating system was state-of-the-art and that every board that even seemed slightly damaged was replaced. His father’s friend and contractor, Jimmy Chu, had kept the house in good repair during the two years. His dad had come from old Puritan stock, and he’d considered it an honor to care for the home that his parents had owned, just as his grandparents before them did. It wasn’t one of the oldest houses in the area, but it ranked right in there with many of the homes surviving from the turn of the eighteenth century all the way into the twenty-first.

He smiled suddenly, shaking his head and taking a sip of the coffee he still held, untouched. “Darn you, Dad. You knew that I won’t be able to sell the damned thing!”

A house—in a city in which he no longer lived—was a pain in the ass, no matter what. He guessed that his father had always figured he’d come home one day.

Well, he’d managed to, but on the wrong damned day. He dropped his head. He didn’t want to be involved with a legal situation here.

But he couldn’t blink without seeing in his mind’s eye the blank brown eyes of the naked boy covered in blood and shaking on the road.

“Jenna!” Uncle Jamie drew her to him, giving her a warm and emphatic hug.

She hugged him in turn. She loved Jamie. She loved her family in general. Despite their long history of warfare, the Irish were an exceptionally warm, passionate and profuse people. They were full of magical tales, and they seldom felt obliged to refrain from speaking their minds.

“Uncle Jamie!” she said.

He pulled her away for a moment, holding her at arm’s length to study her. Jamie had brilliant green eyes and graying auburn hair. He was her mother’s younger brother, and had always had a mischievous side to him, making him very popular among children. He was so devout that he’d nearly gone into the priesthood, but had decided at the last minute that he didn’t really have the calling. He’d attended medical school and become a psychiatrist instead.

“You look good, my girl, aye, that you do! Pretty thing, you always were. Beautiful eyes, green like Eire, and hair like fire—you got my sister’s temper to go with it, eh?” Her own accent had become little more than a hint of a different place, but she had come to the States when she’d been a young teen. Jamie had been a grown man.

“Mum’s temper isn’t that bad, Uncle Jamie. She’s a lot like you—opinionated.”

He grinned. “Come over here, I’ve a booth for us,” he told her. He slipped an arm through hers, leading her toward a corner booth. “Lovely, lovely, isn’t it? I’ve always loved this city. You have the Wiccans with their wonderful shops—and their Wiccan gossip and squabbles, of course! You’ve got the immigrants and the old Puritan families, and all of them getting along—and not. But fall here is the most wonderful season in the world—everyone loving life and creating cornucopias and carving out pumpkins.”

“Yes, I love it here, too, Uncle Jamie.”

He looked around and motioned to the waitress. “What will you have, niece?”

She was surprised to feel a sudden chill. Jamie was hedging, and he usually just spoke plainly. It was unusual that he’d dawdle by ordering like this, but she decided she’d let him talk at his own speed. “Something warm,” she replied.

“An Irish coffee?” he suggested.

“Why not?” she said.

Their waitress was wearing a cute, short-skirted pirate costume. Jamie asked to make sure that the bartender used Jameson Irish whiskey, and that they didn’t go putting a wallop of “white stuff”—whipped cream—on either drink. The waitress smiled. “Jamie, you order the same thing every time you come in.”

“So I do,” Jamie told her, grinning. “But, still, a man’s got to be careful when he orders his drink.”

Laughing and shaking her head, the waitress moved on with a swish of her short skirt.

“They do get into Halloween early, don’t they,” Jenna murmured.

“Well, you know the whole pumpkin-carving thing is Irish, of course,” Jamie said.

“I know, Uncle Jamie …” she said to the familiar information, knowing it wouldn’t stop him. She thanked the waitress as she delivered their drinks. Jamie didn’t seem to notice.

“It all came from Stingy Jack,” Jamie said, studying his cup, and speaking to himself more than her.

“A myth about a man named Stingy Jack,” Jenna reminded him.

He waved a hand in the air.

“The devil invited old Jack to have a drink with him, and Jack, he wasn’t about to pay for the drinks, but then neither was he about to turn one down. So, our Jack, he tells the devil that he must turn himself into a handful of coins to pay for the drink. But, thirsty though he was, Jack was a clever boy, and put the coins in his pocket, around his silver cross, and the devil, next to that cross, couldn’t turn himself back into the devil, not next to the holy relic! Finally, though, Jack let the devil return to his old self—long as he didn’t bother Jack for a year and a day—and would not claim his soul if he should die. There are stories of Jack playing a few other tricks on the devil over his lifetime. Eventually, of course, he did die. And when he did, the Good Lord would not let him into Heaven, and the devil could not claim his soul, and so he was sent into the dark of the night with only a burning lump of coal to light his way. Well, Jack found a pumpkin, carved it out, and carried it about endlessly through the darkness of the night. And so he was called Jack of the Lantern, and finally, Jack-o’-Lantern.” He paused to take a gulp.

“It’s not a bad tradition—especially for those who scoop out the pumpkin and make pie and then carve the pumpkin to burn with an eerie—or happy!—face throughout the night,” he finished.

“Pumpkin pie is delightful,” Jenna said, leaning toward him and touching his hand. “But I’m pretty sure this story isn’t why I’m here, Uncle Jamie. Talk to me. Why did you want me here? I’m delighted to see you, you know that. But you called me and said that you needed me.”

Jamie nodded, running his fingers over the varnished wood of the table. “It may be too late,” he said softly. Then he looked up at her. “They think they have him dead to rights. They say that the blood of those he murdered was all over him, and that his fingerprints were on the ax. But he didn’t do it, Jenna. He didn’t do it.”

She frowned. He was talking now, but he was beginning in the middle.

“You asked me here … about the murders that occurred? But … the family was just killed last night. You called me two days ago.”

Jamie shook his head. “I called you about two murders that had happened earlier—and then last night occurred … and now they have the boy … and I just don’t believe he did it. He’ll be railroaded into a mental hospital for the rest of his life—but he’s not crazy! People started saying that it was the house—that it’s Lexington House, and that he lived there and started killing because he was listening to ghosts. Thing is, I know that by what seems like obvious evidence he looks guilty as all hell, but that’s only what it looks like. He didn’t do it.”

She shook her head. “All right, back up. You called me because of the two previous murders. The radio mentioned those on the way up here, too, but only bits and pieces and suppositions. I don’t really know details. Tell me about them.”

“Six months ago, a farmer in Andover, Peter Andres, was killed in his barn—with a scythe. The police had no suspects—the scythe was in the barn, but there were no fingerprints other than those of Andres. Everyone was baffled. Andres was known as an affable man. But the rumor mill got started—the rhyme about Lexington House doesn’t tell it all. In the nineteenth century, a scythe was supposedly used on the Braden father before he was given the final blows by the ax. So, the police started looking at people with an interest in Lexington House, and then at Lexington House itself. Malachi was always the subject of some rumor or other—he’s a strange lad. But he tells me that he prays, and he believes deeply in God and in Heaven.”

“Many killers find Jesus,” Jenna said softly. “How did you know all this about him?”

Jamie shook his head. “They find Jesus in prison—Malachi has always had him.” He sighed. “The boy came to me three years ago. His parents brought him to me—they were forced to, by children’s services, after a few incidents at school.”

“Like what—he attacked other children? Threw rocks at birds … set cats on fire?”

“No, no. Nothing of the like. He was teased, beaten and bullied by other boys. He just sat there when they hurt him and said that God was his protector and that Jesus would turn the other cheek.”

“And then?”

“Soon after, the parents decided to take him out of school, but because of another incident, a really strange incident. And that’s when children’s services ordered that he see a psychiatrist—me.”

“So how long have you been seeing him?” she asked.

“If you’d asked the parents? He was my patient for a year. Social services paid me for a year. But I’ve seen him ever since—more as a friend than a patient. It all began about three years ago, when his parents pulled him out of school. Thing was, in his own way, he was happy to come see me. Musical instruments, other than the voice, were a sin in his house. But he’s something of a genius with the piano. At my house, he could play.”

“What was the incident that caused social services to step in?” Jenna asked.

“He looked at a boy,” Jamie said.

“Looked at him?” Jenna repeated, puzzled.

Jamie nodded. “The boy was throwing food from his lunch tray at Malachi. Malachi looked at him, and this other boy froze—and then he picked up his tray and beat himself over the head with it so hard that he had a concussion. He was hysterical and told the doctors that Malachi had forced him to do it—with his eyes.”

Jenna leaned back, staring at Jamie, frowning. “Wait—this other kid said that Malachi looked at him, and made him beat himself silly?”

Jamie nodded.

Jenna shook her head. “Why—that’s preposterous. Especially here. It’s like the girls crying Witch! Witch! Witch! and causing the unjust deaths of twenty people and the incarceration of nearly two hundred more. I’d thought we’d learned some lessons …”

Jamie sighed. “He was better off out of school. The thing is, I think that Malachi desperately wanted to be normal. He was malnourished, and he was raised to think that just about everything in the world was evil, an idea browbeaten into him by a fanatical father. He never lost his temper—the other kids couldn’t goad him to act. And that made them mad. He’s the most peace-loving individual I’ve ever met. When the neighbor, Earnest Covington, was killed, one of the boys who he’d been with at school went to the police and told them that Malachi had come running out of the house. They brought Malachi in for questioning, but Mrs. Sedge at the grocery store, said that Malachi had been in the meat section at the time, choosing dinner cuts for his mother—she never left the house—so he was off the hook. But, then, last night … well, Malachi was found drenched in his family’s blood, standing naked in the road.”

Jenna put her hand on her uncle’s. “Uncle Jamie, you have a friendship with this boy … but, if he was found covered in his family’s blood …?”

“Jenna, I need you to find out the truth about that house,” he said with resolution.

“Uncle Jamie—”

“We can’t let the system take this boy. We have to somehow make it work for him now—now that he has a chance.”

“A chance?”

“His parents are gone now,” Jamie said quietly. He looked toward the ceiling. “God forgive me!” he murmured and crossed himself. He looked at Jenna solemnly. “You know I’m a religious man, right, Jenna?”

Surprised by the sudden question, she arched a brow to him. “Well, you were almost a priest… . I didn’t figure that meant you’d turned away completely but—sorry! No, I know that you still love the church.”

He nodded. “I’m disappointed in the way human beings interpret religion at times, and God knows I loathe the horrible things done daily in the name of God and religion. But you don’t go throwing the baby out with the bathwater, you know?”

“Jamie, you’re losing me again.”

“They were—fanatics,” Jamie said. “I don’t even know exactly what belief they adhered to, but it was with a vengeance. There was hell to pay when that boy didn’t learn his Bible verses or when he couldn’t recite huge tracts of the Bible.”

“He was abused?”

“Not physically—they weren’t beatings, or even severe spankings. Parents often tap the hands of little ones—to stop them touching a stove top, a light socket … No, the abuse was mental and, well, I do suppose physical in a way. No food could be eaten without the father’s blessing… .”

Jamie stopped speaking for a minute.

“You can’t imagine the peace in that boy’s eyes at times. He doesn’t do evil things because of the ghosts in a house, and he doesn’t do evil things because his father was a religious zealot who turned everything to sin. I don’t believe he does evil things at all—especially not murder. If ever anyone has been touched by the hand of God, I think it’s that boy. And you have to help me save him. Maybe it’s my mission in life, I don’t really know. But I’m begging you. You have to get into that house, and you have to speak with Malachi.”

“And how am I going to interfere when he’s now in the hands of the police?”

Jamie looked past her and lowered his voice. “Well, with a wee bit of help from the Lord, I think I can convince his defense attorney that he needs your assistance.”

She turned to see what had drawn Jamie’s attention. It was a man, tall and broad shouldered. The coat he had worn into the bar was excellently cut, and he moved like someone accustomed to custom-tailored clothing. His face was strongly molded with a classic masculine line. His hair was neatly cut and combed, just slightly awry from the breeze. She thought that she recognized him, but she didn’t know why she should have.

“Who is he?” she whispered.

“Samuel Anthony Hall, attorney-at-law.”

She almost laughed aloud. She knew why she recognized him—she’d recently seen his name and picture all over the internet. The world had wanted his last client to fry for the heinous murder of his pregnant fiancée. The prosecution had DNA evidence that the two had engaged in intercourse the day of the murder, but Hall had proved that one of his client’s enemies had killed the woman—a revenge killing. She couldn’t remember the details, but the client had loose mob ties and the case had received major press attention.

“Actually, you’ve met him before, you know,” Jamie said.

“I have?” Jenna looked at her uncle.

“You knew his parents, Betty and Connor. They were friends of mine, and they were friends of your folks, as well. You’ve been in his home. Maybe only once or twice—you were here when you were a young teenager and he was home from law school. He was supposed to be watching over you and a few of your friends. Silly, giggling girls. He thought you all were torture.”

“Wow. Can’t wait to meet him again, though I think I do remember his folks. They were very nice people.”

“They were.”

She studied Sam. He had the bearing of a man in charge—and a fighter. Or a bulldog.

“Samuel Hall,” she mused, turning back to her uncle, slightly amused. “That’s not the kind of attorney the state acquires when you haven’t the resources to hire your own. And I’m assuming all the money Malachi might have will be in probate. And unless you’ve changed your ways—working for the state most of the time for almost nothing—you can’t afford him. And even if our entire family was to put in our life savings, we still couldn’t afford him. He was said to have made several hundred thousand—just off his last case.”

“Yes, he can command a high fee,” Jamie murmured.

“Too high,” Jenna told him softly.

“He’s going to do it pro bono,” Jamie said.

She stared at him with surprise.

He grinned. “All right, so he doesn’t know it yet.” He leaned forward. “And, dear niece, if you don’t mind, please give him one of your best smiles and your sweetest Irish charm.”

2

“Sam!”

Sam Hall turned to see that Jamie O’Neill was hailing him from one of the booths. O’Neill wasn’t alone. He was with a stunning young redheaded woman who had craned her neck to look at him. She was studying him intently, her forehead furrowed with a frown.

He thought at first that she was vaguely familiar, and then he remembered her.

She had changed.

He couldn’t quite recall her name, but he remembered her being a guest at his house once, and that she—and half a dozen other giggling girls—had turned his house upside down right when he’d been studying. But his mother had loved to host the neighborhood girls, not having had a daughter of her own.

Before, she had been an adolescent. Now, she had a lean, perfectly sculpted face and large, beautiful eyes. Her hair was the red of a sunset, deep and shimmering and—with its swaying, long cut—sensual. She appeared grave as she looked at him and, again, something stirred in his memory; maybe he’d seen her somewhere—or a likeness of her—since she’d become an adult. She was O’Neill’s niece, of course. And her parents, Irish-turned-Bostonian, had been friends with his folks.

“Sam, please! Come and join us,” Jamie called.

He’d ordered a scotch and soda. Drink in hand, he walked to the booth. He liked the old-timer. O’Neill was a rare man. He possessed complete integrity at all costs. An immigrant, he’d put himself through eight years of school to achieve his degree in psychiatry. He lived modestly in an old wooden house, and he still probably took on more patients through the pittance granted him by the state than any other person imaginable. Sam had heard a rumor that Jamie had gone through a seminary but then opted to live a life outside the Catholic church.

But when he really looked at the grave look on Jamie’s face, he felt a strange tension shoot through his muscles.

Jamie wasn’t calling him over just to say hello. He wanted something from him.

Sam wished he’d never come into the bar.

“Sam, do you remember my niece, Jenna Duffy? Jenna, Sam, Sam Hall.”

Jenna Duffy offered him a long, elegant hand. He was surprised that, when he took it, her handshake was strong.

“We’ve met, so I’ve been told,” she said. He found himself fascinated with her eyes. They were so green. Deep viridian, like a forest.

“I have a vague memory myself,” he said.

“Sam, sit, please—if you have the time?” Jamie asked.

He was tempted to say that he had a pressing engagement.

Hell, he’d gone to law school and, sometimes, in a courtroom, he realized that it had almost been an education in lying like wildfire while never quite telling an untruth. It was all a complete oxymoron, really.

“You’re on a leave, aren’t you? Kind of an extended leave?” Jamie asked him, before he could compose some kind of half truth.

“It’s not exactly a leave, since I choose my own cases, but, yeah, I’ve basically taken some time. I’m just deciding what to do with my parents’ home,” he replied.

He slid into the seat next to Jenna Duffy. He noted her perfume—it was nice, light, underlying. Subtle. It didn’t bang him on the head. No, this was the kind of scent that slipped beneath your skin, and you wondered later why it was still hauntingly in the air.

“You’re not going to sell your parents’ house, are you?” Jamie sounded shocked.

“I’ve considered it.”

“They loved that place,” Jamie reminded him.

Jenna was just listening to their conversation, offering no opinion.

“They’re gone,” Sam said. He shook his head. “I just don’t really have a chance to get up here all that often anymore.”

“It’s a thirty-minute ride,” Jamie said. “And it’s—it’s so wonderful and historic.” “So is Boston,” Sam said.

“Ah, but nothing holds a place in the annals of American—and human!—history as does Salem,” Jamie said.

“You’re trying to shame me, Jamie O’Neill,” Sam said. He smiled slowly.

Jamie waved a hand in the air. “It’s not as if you need the money.”

Ouch. That one hurt, just a little bit.

“Jamie, you didn’t call me over here to give me a guilt complex about my parents’ house …” Sam said.

Jamie looked hurt. “Young man—”

“Yes, you would have said hello—you would have asked about my life. But what’s going on? I know you. And that Irish charm. You’re a devious bastard, really.” Then he looked at Jenna and murmured, “Sorry.”

“Oh, I don’t disagree,” she told him.

“So?”

“You found Malachi Smith in the road last night,” Jamie said quietly.

Sam tensed immediately. The incident had been disturbing on so many levels. He couldn’t forget the way that the boy had been shaking.

He stared back at Jamie. “I did.”

“I don’t believe that he did it,” Jamie said.

Sam winced, staring down at his drink. He rubbed his thumb over the sweat on his glass. “Look, Jamie, I feel sorry for that kid. Really sorry for him. I’ve been watching the news all morning. His life must have been hell. But I saw him. He was covered in blood. How else did he become covered in blood if he wasn’t the one who did it?”

“Ah, come on, you’re a defense attorney!” Jamie said.

“It’s obvious.”

“I’m missing obvious,” Sam said drily. No, not really. There was just this odd feeling. Why get involved any more than he already was? The horror he’d felt whenhe’d come upon the boy bathed in blood, in the middle of the road …

“I think,” Jenna said, “that it’s possible that Malachi Smith came home to find his family butchered, and that he tried to wake them up, or perhaps wrap them in his arms, and therefore became covered in the blood.”

“He was naked,” Sam said flatly.

“Right. He became horrified by the amount of blood all around him, all over his clothing, and tried to strip it off—but there was so much of it, it was impossible,” Jenna said.

He looked at her. “And you believe this?” he asked pointedly.

“I didn’t grow up here—I was always a visitor—I never knew Malachi Smith or his family. I heard the rumors about them, and, naturally, everyone in the area knows about Lexington House. Well, it’s the kind of legend that gets around everywhere, I suppose. I can’t tell you about Malachi Smith—not the way that Uncle Jamie can. Jamie treated the boy. But I think that’s the kind of possibility my uncle might have in mind. And I myself suppose it’s possible. We’d have to know what Malachi has to say.”

Sam stared at her for a long moment. Her eyes were enigmatic, so deep and mesmerizing a green. If he remembered correctly, she’d been something of a wiseass kid.

“Sam, they are your roots,” Jamie said.

He laughed. “My roots? Lexington House is not part of my roots—I barely knew the Smiths. Again, and please, listen to me, Jamie, I understand how you feel. I’m sorry for the boy. But, I don’t like staying here too long—you wind up tangled in the history of the place, shopping for incense, herbs and tarot cards—and hating the Puritans. Religious freedom? Hell, they kicked everyone else out. Witchcraft? Spectral evidence … it’s no wonder we have religious nuts like the Smiths moving in. And I like our modern Wiccans—do no harm and all that. But I’m not into chanting and worshipping mother earth, either. I seem to get too wrapped up when I’m here—I’m like you. I want to argue the ridiculous legal system of the past, and I find myself wondering sometimes if it does affect any insanity that goes on in the present. Maybe it’s in the air, maybe it’s in the grass and maybe people just really want to hurt one another. Maybe they can’t not buy into all the hype of this place.”

He stopped speaking. He was surprised at his own bitterness. He had never hated Salem. It was his home. The Peabody Essex Museum was an amazing place. People still tried hard to figure out just what had gone on, and how to improve the world in the future, to learn how to stop the ugliness of prejudice and hatred. Actually, he loved Salem itself. He loved many of the people. Maybe it was just him; maybe he still wanted to understand what could never be truly comprehended in the world they lived in now. But people tried. Tried to preserve the past to improve the present and the future.

And yet a whacked-out son of a bitch like Abraham Smith had moved in, tortured his son in a like manner to the rigid principles practiced long ago, and he’d never forget the way the kid had looked in the middle of the road, shaking, his eyes huge and terrified, blood drippingoff his naked body … and he couldn’t help but feel that the father’s method of raising the son had something to do with all that death.

Jamie was nonplussed by his speech. Jenna just looked at him with those beautiful green eyes that seemed to rip into the soul.

He sighed deeply. “You want me to defend the boy. It should be an open-and-shut case. There’s just no way that a prosecutor would ever get a jury to believe that the boy was mentally competent when he committed the act.”

“No!” Jamie said firmly. “I want you to prove that the boy didn’t do it.” Sam groaned softly.

“Isn’t that your specialty?” Jamie asked him. “Proving your client’s innocence—and in so doing, finding the real killer?”

“Jamie, I’d like to help, but in this case—” “I know we don’t pay as well as the mob …” Jamie cut in.

“Oh, low blow, Jamie. Not fair. I’ve worked pro bono many times.” He sighed deeply. “You don’t just want me to defend Malachi Smith—you want me to find a killer. I haven’t lived here in years—I wouldn’t even begin to know where to look. And I’m an attorney—”

“You keep up with your private investigator’s license,” Jamie pointed out.

“We could be talking a conflict of interest in this situation,” Sam said, “if I’m defending him and investigating the case.”

Jamie smiled serenely. “Nope. It’s perfectly legal for you to hold and use your P.I. license while you practice law. And you know it. That’s not an excuse—you’ve just come off a case in which you managed to do both. Any time whatsoever you’re afraid of a conflict of interest, you send someone else out. You use your mind and your license when you need them. Send others out to do the work you’ve decided needs to be done.”

“What others?” Sam asked, aggravated.

“Jenna,” Jamie said, smiling then like the Cheshire cat.

“Your niece?”

“Jenna,” Jamie repeated. “My niece is part of a special unit of the FBI.”

Sam stared at the redheaded woman at his side. FBI? Special Unit?

“I’m not here officially,” she said quickly.

“Of course not, you’d have to be invited in, and Detective John Alden is certain that he doesn’t need help, that he has his murderer,” Sam said, looking at her. “What kind of a special unit?”

“Jenna’s team was instrumental in solving some of the most high-profile cases in the country,” Jamie said proudly. “The recent Ripper murders in New York? That was her team. And all that trouble down in Louisiana with the death of a senator’s wife—them again.”

Sam stared at her, memories stirring in his mind. He remembered now. In the news they’d been called the Krewe of Hunters, and they had a phenomenal success rate. But they were known to be … special, all right. They looked for paranormal occurrences. And what better place than Salem?

He didn’t mean to be so rude; he took his eyes off Jenna when he spoke. “The ghost of old Eli Lexington caused Malachi Smith to murder his family? No, wait, he wouldn’t be innocent then. The ghost killed the family himself!”

“In my experience,” she said evenly, “a ghost has never killed anyone.”

“Kill someone? Ghosts don’t even—” But he cut himself short.

Ass, he told himself. She was being even-keeled. He was looking like a superior fool.

“I’m sorry, Jamie, I’m not sure how we can possibly solve this thing, really. The kid was covered in blood. John Alden has arrested him.”

“So,” Jamie said, smiling, “that should get you going! It’s too easy—way too easy—to take that line of defense. You should step up to the plate quickly. Please, Sam! Come on—they’ll give him some kid fresh out of school as his public defender. Doesn’t this interest you?”

“It is quite a challenge,” Jenna said.

Sam groaned. “How about I sleep on it?”

“Evidence is growing cold,” Jamie told him.

Jenna smiled suddenly, looking at him. “You’re going to do it, and you know you’re going to do it.”

“Oh? Out of the kindness of my heart?” Sam asked.

“Maybe,” she said. “More likely, because it is such a challenge. If you pull this off, you’ll be known not just as an incredible attorney, but as a miracle worker.”

Sam stood, not sure why the meeting with Jamie O’Neill and his niece had seemed to set him so off balance.

Could he do it? Yes. He didn’t need money. Was it an intriguing challenge? Maybe—and maybe it was more likely that the kid had done it.

“I’ll let you know in the morning,” he said, and walked away from the table. Then he headed back. “Look, I don’t think you know how much is involved here. Besides the filing, the briefs … paperwork you can’t even begin to imagine. And then, yes, investigating this? When the police think that they have their man? Not to mention the fact that you don’t have a plausible alternate suspect. In fact, none of us has a clue.”

For a moment he saw something in Jenna’s eyes that agreed with him, and he wondered if Jamie hadn’t managed to challenge his niece into this, as well. But just as quickly as the glint appeared, it vanished. Now, when she stared up at him, her eyes seemed as sharp as her tone. “Two other people were murdered and no arrests were made. With no real evidence, it’s being quietly assumed that Malachi Smith murdered those other men, as well. He hasn’t been charged with those murders, and I don’t believe that they have a plan to charge him with them because they do have conflicting evidence where Peter Andres and Earnest Covington are concerned. So, in fact, you won’t be going against the police if you are to claim to primarily be looking at those two incidents. There are plenty of places to start, Mr. Hall. Who were the other victims? What enemies might they have had? And what about the church Malachi Smith was involved with? It certainly had to be out of the ordinary.”

“And you’re going to investigate all this?” he asked her.

She smiled serenely. “I do have friends, Mr. Hall.” “Ah, yes, team members.”

“I’ll remind you that most of the cases we solve are at first thought to be almost impossible,” Jenna said.

He couldn’t decide what was really going on in her mind, her voice remained so even, and she maintained such an unruffled calm. He couldn’t help but goad her on.

“Funny—I thought the NYPD had something to do with that last one!”

“The point is, Mr. Hall, no one is asking you to do all the work. I’m not a lawyer, but I do know how to work my way around legend and superstition, and the head of my team is one of the foremost behavioral scientists in the country. We can help you.”

“And the police are just going to let you snoop around?” he asked.

“You, as the defense attorney, will demand that leeway be given in your investigation—for the benefit of your client, of course,” Jenna said impatiently.

He didn’t know why he was feeling such a hot tension, or why his muscles seemed to be bunching and his temper flaring.

Because he didn’t think that they could do it? As much as he didn’t want to think of the boy as a murderer, it seemed the most logical scenario.

He looked back at Jamie. “I’ll let you know in the morning,” he said, and strode out of the room.

Jenna looked at her uncle long and hard after Sam had left, then finally spoke. “I’m not so sure that telling Sam Hall who I am and what I do was the best move you might have made.”

“And why not?” Jamie asked indignantly.

“Some people accept that the team gets the job done. And some people think that it’s a joke. Even among the Feds,” she told him.

“You can find the truth. I know that you can find who did this—you always had the knack.”

“Oh, Jamie! Please, I’m not a miracle worker, either… . And, you have to be ready for whatever we do find. We don’t know that Malachi didn’t commit the murders yet.”

“I know,” he said quietly. “But, never mind that now—what would you like for dinner?”

She laughed. “Nice change of pace! Scrod, of course. Only in New England can you have really wonderful scrod!”

Jamie veered the conversation away from Malachi while they ate. He talked about “Haunted Happenings,” an October event that brought tourism to Salem. He was a man who had his own deep and binding beliefs, but he was also fascinated by the faiths that others believed in. There were Wiccans in the city who were really Wiccans, believing in the gods and goddesses of the earth and in doing no harm to others, lest it come back threefold. And, he advised her, there were Wiccans in the city who were Wiccans because it was a very nice commercial venture in “Witch City.” There were parades and balls, special events for children, theatrical programs on the tall ships at Derby Wharf and so much more.

“Now, you don’t mind staying awhile, really, do you? I rather threw you into that—I mean, saying that you’d investigate,” Jamie said. “And I know, too, that you’re employed by the government, that you have responsibilities—”

“It’s all right. A few team members are still in New York tying up some loose ends from our last case, and a few are in Virginia, outside of D.C., setting up our new offices.”

He let out a contented sigh. “So you can stay.”

She smiled. “Jamie, I knew from the beginning that you invited me up here for a reason. I didn’t realize I’d arrive in time for it to really … begin in earnest.”

He watched her oddly.

“What?”

“You always had it, you know,” he said.

“Had what?” “The sight.”

Jenna was quiet at that. Her grandmother had entertained her when she had been a child with the myths and legends of Eire. She would tell a fantastic story about banshees—and then remind her that, now and again, many a tale had started at a pub. There were spirits—and then again, there were spirits.

It was true. Her cousin, Liam, who had become a writer, had done so discovering that the fantastic tales he could tell after a night at the pub could be put down on paper—and pay.

It was equally true that a number of people in her family had seemed to have some kind of a special sense. They could often feel a place, and know that violence had been committed there. They were prone to hearing the footsteps of the ghosties as they moved about in a place, and they could sense the presence of something that remained, even after years had gone by.

But the first time she’d known she had some kind of sight was when she’d been working as an R.N., and had been down in the morgue on some business.

A corpse had spoken to her. He insisted he hadn’t died of natural causes, as would be assumed. He’d been helped into the great hereafter by a greedy family member.

Of course, that first time, she’d felt the speed of her heart escalate to dangerous levels. She wondered if, frequently, ghosts did not speak to their loved ones because they were afraid of giving them heart attacks—thus prematurely making ghosts of them, as well.

And, certainly, not every soul chose to walk the earth. Some remained because they felt they had unfinished business. Some remained because of the violence of their demise. Some had something that needed to be said, and some felt that their antecedents needed protecting.

“Uncle Jamie,” she said, moving her fish around on the plate, “you’re thinking that this is going to be a far easier thing than it is.” She spoke softly, looking around. “Perhaps I do have what you call ‘the sight.’ It doesn’t mean that I can go and see the corpse of Abraham Smith and he’ll tell me who did him in. He may not have remained behind, and if he did, he may not be able to communicate. We’ve never had an instance where it was easy and cut-and-dried—where we just walked into a morgue and said, Hey! Who’s the guilty one? Ghosts can help, but in many different ways.”

He was watching her, listening intently. At least, with Jamie, she never had to try to pretend. Jamie told her once that he believed in the “holy ghost,” and if he said so in a creed he spoke at religious services, he’d be an idiot not to believe that there was more beyond the average range of sight. Faith, he told her, was belief in what couldn’t be seen. If a man had faith, he couldn’t always doubt what he couldn’t see. Most people had faith—even if their faith was different. A lot of different roads climbed the same hill.

He folded his napkin and set it on the table. “Jenna, I know that your team deals with what is real and tangible and out there for all to see and know. I never thought that you could come here and solve all my problems with a simple chat with the dead. It’s never a simple ‘How do you do, and can you answer a question for me?’ But we are dealing with old stories and legends around here, true and enhanced.”

“These murders aren’t legends,” she said.

“No. But, but the natural ‘storytelling’ desire is to automatically say that the kid did it, neat and tidy and a juicy, repeatable story. That he freaked out because his father was a browbeating fanatic and he figured he could say that the house was filled with devils. People want to say this, for the newspapers at least. See what other stories are out there, from dead men or the living. I know that you can sort it all out.”

“You do have faith in me,” she murmured.

“Of course!” he said cheerfully. “Well, we’d best get on home, huh? I have a feeling it’s going to be an early morning.”

“And why is that?”

“Sam Hall is going to want me to visit his client with him,” Jamie said.

“He hasn’t agreed to defend Malachi Smith yet,” she said.

Jamie grinned. “Faith, lass. I live by it!” he said cheerfully.

It was good to be back at Uncle Jamie’s house. She’d spent a lot of time coming up here as a teenager. She smiled, thinking of the past. She’d had local friends—girls who had been glad to see her—and she brought the excitement of the big city, Boston, along with her.

They’d shopped at the wonderful stores; they’d played at being Wiccan, and it had surprised her at first that her Catholic parents hadn’t minded. They had been amused. But they had seen the wars fought in their own country over religion and economics and were tolerant.

Jamie’s house was old, but the family had always seemed to agree that it was a benign house. Whatever ghosts remained, they were tolerant, as well.

Jenna went to sleep in the familiar old bedroom her uncle had always referred to as “hers.” Jamie had allowed her to have her whims: there were posters of Gwen Stefani and No Doubt and other groups on the walls. They were a little incongruous there, since the bedroom was furnished entirely in period furniture, not from the seventeenth century, but the eighteenth century. Her bed was a four-poster; an old seafaring trunk sat at the foot of it, and a washstand with an antique ewer stood against the wall, along with an old wardrobe. To walk into the room—other than the posters and the stuffed Disney creatures on the shelves—was to walk into another time.

She lay awake a long time, what she had learned from Jamie rushing through her head. She admired her uncle and his steadfast faith; all the evidence in the world might stand against Malachi Smith, but Jamie believed in him.

When she fell asleep at last, she wasn’t sure that she had done so. The room still seemed to be bathed in a gray, half light. There seemed to be movement in her room, a movement of shadows, and then they stood still at the foot of her bed, staring at her.

It was a group of women, and they were in the rather stern and drab shades of the late sixteen hundreds. Only one seemed to be in a slightly different color, and in the shadows Jenna thought it might be a dark crimson. They just stared at her, and even she, who was accustomed to meeting the dead, felt a deep unease. And then an old woman in the front lifted a hand toward her. She whispered something, and at first, Jenna couldn’t make out the words. She wanted to wake up; she wanted to reach over and turn on the bedside light or just let out a scream and run into the hallway.

But then she comprehended the words the woman was trying to speak.

“Don’t let the dead have died in vain.”

Her throat was still tight; she was still so afraid. And, yet, she was the one who sought out those who had died.

Words came at her again.

“Don’t let the blood run, don’t let more blood run. Don’t let your blood run.”

Sam Hall arrived at Jamie’s door at precisely eight in the morning. He was going to defend Malachi Smith, and he was going to do it pro bono.

Jenna decided that her uncle really did know how to read people.

By the time he arrived, Jenna had mused over her dream, her waking dream or her nightmare—whatever it might have been. It had been natural, certainly. The conversation all day had been about blood and murder, and her thoughts had long lingered on Salem and the city’s past.

When she opened the door, dressed and ready to go as Jamie had suggested she be, Sam didn’t seem surprised, though he might have been a bit irritated that they both were confident he wouldn’t back away from the case.

“I’m not sure why you’re coming—I have to spend time at court. I have to become the attorney of record, see what the public defender has done, see where custody lies, file motions … it could be a long day,” he said. “I’m sure the public defender he hired has already made arrangements for Malachi to be seen by a court-appointed psychiatrist, and if we’re going for a not-guilty plea, I have to make sure that we stall the court date as long as possible.”

“I’m absolutely excellent at sitting around and waiting,” Jenna assured him.

Jamie came to the door. “Let’s go,” he said. “Sam, thank you.”

Sam grunted. “I’ll drive. You two do what I say, sit when I say sit and wait as long as you have to wait.”

Jamie was cheerfully agreeable.

It was a long morning, and there was a lot of paperwork to file. Since Malachi Smith was a minor with no family and still under the age of eighteen, he had become a ward of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and there were filings to be made with the state. None of that was difficult, not, apparently, when you were a hotshot attorney. Jamie was given a hearing and appointed Malachi’s guardian. Malachi had to fire the public defender he’d been assigned and accept Sam Hall as his attorney. That was easily accomplished—Jenna waited in the car while Jamie spoke to Malachi with Sam—but then time was needed for filing all the documents Sam had prepared.

When arraigned, Malachi had not been granted bail; the crime was far too heinous. They met Evan Richardson, Sam’s assistant, who had come to Salem as soon as Sam had called him and had already worked on the motions that had set the ball rolling. He would deal with more motions and more paperwork and the courts while Sam was engaged elsewhere. Jenna liked him. Just about her age, he was a pragmatic fellow from Syracuse, New York, not embroiled in the burden of history that often came with being a New Englander.

When they finished with the legal paperwork and headed back to see Malachi with all the papers properly filed, Jamie argued the point of Malachi’s incarceration with Sam.

“I can watch the young man day and night!” he told Sam.

Sam gave him a long sideways glance. “Jamie, you’re forgetting something,” he said.

“What’s that?” Jamie demanded.

“If Malachi Smith didn’t kill his family, a vicious killer remains at large.”

Jenna felt a streak of cold zip up her spine.

“Someone who has now killed six people,” Sam said.

Jamie was silent. She remembered her dream. Blood would flow… .

“All right,” Jamie said gruffly.

“And you do realize that the majority of the world will believe in Malachi’s guilt. The facts point to his guilt—until we can offer more facts,” Sam said.

Jamie nodded. “Yes, I see. If the killer strikes again, that will prove that Malachi is innocent, because he’ll have in indisputable alibi.”

“Yes. That and, if we’re going to do this, no one will really have the time to babysit Malachi every moment and make sure he’s safe. He’s better in the psych ward for now.” Sam stopped in the street, staring at Jamie. “And I have to tell you right now that if we don’t discover something, and it comes to the line, I’ve now taken Malachi on as my client, and under any circumstance, I will defend him to the best of my ability—including changing the plea to one of insanity if I don’t believe we can get reasonable doubt into the heads of the jury. You understand?”

“Of course,” Jamie assured him.

Jenna did her best to stay out of the finer points of argument. She wasn’t an attorney, and she knew full well that despite what she did know about federal law, she had no courtroom experience whatsoever.

“Let’s see our client again,” Sam said gruffly. He looked at Jenna and frowned as if he was still wondering just what she was doing there. But he didn’t argue her presence.

Jenna didn’t think that Sam was wrong to see to it that Malachi was kept in custody while they awaited trial. Jenna had expected something far worse—a long hall with bars and cells, the stench of fear and evil, and beady-eyed reprobates staring out with a desire to slit their throats, perhaps. But though Malachi was kept in isolation in a locked room with a small window box, the room was decent enough, if sparse.

It was almost like any other hospital unit. Almost. Malachi Smith was being incarcerated pending trial on murder charges. It wasn’t a pleasantly painted place, nor were there any concessions to creature comforts. Jenna was grateful for her status as an R.N.; Sam Hall used her qualifications in explaining the reason for the three-person visit when he was the attorney of note.

There was a nurses’ station. There was also a guard station. The guards were armed, and there was a series of doors to enter before arriving at Malachi’s “decent”

room. Jenna realized that the difference between his “room” and a cell was essentially that he had walls around him rather than bars.

The guards were professional and courteous. They seemed to be treating Malachi well. Extra chairs were brought; Malachi’s space included a simple cot and one chair.

Jenna’s heart immediately went out to the boy. He was pathetically slim and small for his age; she was certain that malnutrition had stunted his growth. He was a couple of inches shorter than herself, while Sam Hall and even Jamie seemed to dwarf the youth. His eyes were huge and brown, his face as lean as his frame. When he saw Jamie, he smiled. It was a smile filled with hope, but it faltered quickly and he looked at the three of them like he would begin crying in a matter of seconds.

And he did. No sooner had Malachi walked over to Jamie and leaned against him than great sobs started to rack his body. Sam stood back with Jenna, waiting for the torrent to subside.

“There, there,” her uncle said, patting the boy’s back. “We’re here to help you, Malachi.”

Sam glanced at Jenna. For the first time, it seemed that he was looking at her as if she could say something that might be helpful. Well, maybe the fact that she was a nurse and a special investigator led him to believe that she must have empathy with others.

“I believe that the tears are for his family, honest tears,” she whispered.

“And not because he was caught?” Sam asked.

“No.” She hesitated. “Though, even if he had committed the murders, the realization of his family’s deaths would be wrenchingly painful.”

Sam nodded, and seemed to accept her reply, especially with the caveat. She knew that he wasn’t convinced yet—no matter Jamie’s passion. To press forward as if she were positive as well might alienate him, and she wanted them all playing on the same side. She wasn’t Jamie. She hadn’t treated Malachi, and she didn’t know him.

But she did step forward and put a hand on Malachi’s trembling shoulder. “My uncle is right, Malachi. We’re here to help you. But we need you to try very hard and tell us exactly what happened.”

The boy’s thin frame still clung to her uncle.

“Malachi, we need you to help us,” Jenna persisted.

Finally he nodded against Jamie’s shoulder and turned to look at her. He seemed like such a little kid. She tried a gentle smile and eased his hair from his forehead. He smelled of antiseptic soap and was dressed in an orange-beige pajamalike suit that resembled scrubs.

Jail attire, of course. This was a hospital division, but it was jail, nonetheless.

“Can it help?” Malachi asked quietly. “You know that, in the eyes of others, I am already condemned.”

“Please, come, sit down on the bed, and we’ll go through it all,” Sam said. “You know that I’m going to defend you. And, remember, I’m your lawyer, so anything you say to me is confidential. If there is something that you want to say to me that should be kept confidential, I must speak with you alone. Now, Jamie doesn’t believe that you killed your family, Malachi. And if that’s true, and you want to tell us what happened, you can feel free to speak with us all here. Just remember, and this is important—I can’t repeat anything. Since Jamie isn’t officially your doctor right now, he could be compelled to repeat what you’ve said, and Jenna is Jamie’s niece, and an … investigator. So if you don’t wish to speak in front of them—”

“I didn’t do it,” Malachi blurted, drawing away from Jamie at last. His face was still tearstained, but he continued to speak earnestly and passionately. “I would never hurt them, never! I would never hurt anyone. I believe in God, and his only son, Jesus Christ—and He taught that all men should be peaceful, and seek to help their brothers. So help me, before God! I didn’t do it.”

As he spoke, his words so desperate and earnest, it seemed that a ray of sun burst through the barred windows.

The room was cast into an almost unearthly glow.

Then the glow faded, and Jenna wondered if it had just been the sun passing in front of an autumn cloud.

Malachi hung his head and repeated, “I didn’t do it.” He looked up, straight into Jenna’s eyes, and said, “Thou shalt not kill. Thou shalt not kill.”

3

“Malachi, do you remember me as the man who found you in the road?” Sam asked.

The boy reddened and shook his head.

“Let’s sit down now and relax,” Jamie said, leading Malachi to the bed. He sat the youth and smiled, then took the first chair, leaving the second and closest chair, for Sam. Jenna sat on the third.

“First, are you doing all right in here?” Sam asked pleasantly.

Malachi nodded and shrugged. “I know how to be alone,” he said softly.

Compassion filled Jenna at these words. She saw a child who lived such a strict and unusual life that he saw visions of Dante’s hell at home and was shunned by other children wherever he went.

“Good, good, I think this is the best place for you right now,” Sam told him. “Now, Malachi, what I need you to do is really try to relax—and I know how ridiculous that sounds. But I need you to go back and try very hard to remember everything that happened the evening when I found you on the road.”

“I found them,” he said. “I found them.” He started to tremble again; tears welled into his eyes. “My mother …”

Jenna didn’t remember getting up but she found herself crouching next to him and placing an arm around his shoulders. “It’s all right,” she said. “Malachi, it’s all right to cry. You loved them. You loved your mother very much, and she’s gone. It’s natural that you’d cry.”

He nodded and leaned against her shoulder.

Sam waited patiently for a few minutes, and then pressed on.

“Malachi, it’s important that we know where you were when it all happened. You weren’t home—or were you? Were you hiding somewhere in the house?”

Malachi stared across the room, his slender face crinkling into a frown of concentration. He shook his head thoughtfully, and was silent so long that Jenna thought he wouldn’t answer.

“I went to the cliff—the little cliff at the end of the road. It isn’t a real park, but the kids go there all the time. It’s like a park. Some of the kids just run around with Frisbees or soccer balls, and some of them go there to …” He broke off, embarrassed, and glanced at Jenna awkwardly. “You know. They go there to fool around.”

She smiled at him and patted his hand. “Why do you go there, Malachi?”

“I like the sea,” he said. “It’s up from the wharf, and you can be alone with the wind and sea and the waves crash against the rocks there. Right at the peak, you can always feel the breeze, and it feels so good. It’s like it whips through you, and it makes you all clean. Sometimes, I just sit and look out on the water. And I try to imagine what it would have been like, years ago, when the great sailing ships went to sea, and the whalers and the fishermen went out.”