The Fire Sermon

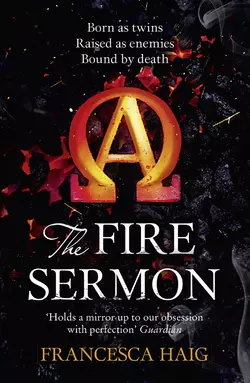

The Fire Sermon

Francesca Haig

BORN AS TWINSRAISED AS ENEMIESBOUND BY DEATHCass is born a few minutes after her brother, Zach. Both infants are perfect, but only one is a blessing; only one is an Alpha.The other child must be cast out. But with no discernible difference, other than their genders, their parents cannot tell which baby is tainted.Perfect twins. So rare, they are almost a myth. But sooner or later the Omega will slip up. It will eventually show its true self. The polluted cannot help themselves.Then its face can be branded. Then it can be sent away.

Copyright (#ulink_7803e6f6-927d-5386-9edf-2678c2325cc0)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © De Tores Ltd 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover illustration and title typography created by Alexandra Allden

Other cover images © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (additional figure and tree features)

Francesca Haig asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007563050

Ebook Edition © February 2015 ISBN: 9780007563074

Version: 2016-03-10

Praise for Francesca Haig (#ulink_1758d154-1ad8-5304-9764-1dd57c739c04)

‘This terrific set-up spools out into a high-tension tale of mistrust and dependency, injustice and optimism, told with poetic intensity’

Daily Mail

‘Haig’s post-apocalyptic world is colourfully fleshed out, and the conclusion asks us to consider who, really, is the Other’

Washington Post

‘It holds a mirror up to our obsession with perfection’

Guardian

‘Words like “masterpiece” and “instant classic” are cliché, but in the case of Francesca Haig’s astounding The Fire Sermon, they’re the only words to use. It’s a breath-taking, passionate, absolutely sensational work of imagination, perfectly structured, beautifully written, populated with fabulous characters and packed with intrigue, violence, compassion and underlined by a very important human message that is always present without ever becoming homily. The Fire Sermon is completely without equal – it leaves Hunger Games, Divergent, Twilight blah blah-yawn twitching in the dust’

Starburst Magazine

‘A hell of a ride. I would recommend it to anyone I can, regardless of age’

JAMES OSWALD

‘This book is a thought-provoking whirlwind of a story, with a fab lead character, grisly politics and brave adventure. I loved it!’

JESSIE BURTON

Dedication (#ulink_ef3b35af-9572-5eab-b4e2-7f277eb9e30c)

This book is dedicated, with love and admiration, to my brother, Peter, and my sister, Clara. Knowing how much they mean to me, it should come as no surprise that my first novel is about siblings.

Contents

Cover (#ufa3f2766-8a37-5fa7-8dea-9dff6598c34a)

Title Page (#u1ae988c2-340b-5df8-81af-d74597cc5b0f)

Copyright (#u34a61941-e9f6-505e-928e-b10f705ae6b3)

Praise (#ud352f81d-7b00-51c4-986a-7481487a9d99)

Dedication (#uc922ecd6-8439-5f8b-adeb-69f0852c4459)

Chapter 1 (#u7472a1d7-6583-5bcf-a5e3-d6d4e9d3aaf7)

Chapter 2 (#u56190231-442e-5921-b479-75ca612cdb33)

Chapter 3 (#uc1a991df-4a75-505a-b1b0-c7adbe05df30)

Chapter 4 (#uf2244046-8f44-5cfd-aabe-978087533640)

Chapter 5 (#u301adb32-47bf-5ec8-b18c-5f88e370c454)

Chapter 6 (#u4bf8ff28-acd1-5f94-bd8e-a1f9e38cba3b)

Chapter 7 (#ua8c7f2f5-6a6c-52fb-aa3a-9f6d63cac298)

Chapter 8 (#ub6b4ac34-b323-50d5-a6ae-67708f34bda9)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Read an Extract of The Map of Bones (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_9409b783-86fb-5c60-ae3e-8809702aafc6)

I’d always thought they would come for me at night, but it was the hottest part of the day when the six men rode onto the plain. It was harvest time; the whole settlement had been up early, and would be working late. Decent harvests were never guaranteed on the blighted land permitted to Omegas. Last season, heavy rains had released deeply buried blast-ash in the earth. The root vegetables had come up tiny, or not at all. A whole field of potatoes grew downwards - we found them, blind-eyed and shrunken, five feet under the mucky surface. A boy drowned digging for them. The pit was only a few yards deep but the clay wall gave way and he never came up. I’d thought of moving on, but all the valleys were rain-clogged, and no settlement welcomed strangers in a hungry season.

So I’d stayed through the bleak year. The others swapped stories about the drought, when the crops had failed three years in a row. I’d only been a child, then, but even I remembered seeing the carcasses of starved cattle, sailing the dust-fields on rafts of their own bones. But that was more than a decade ago. This won’t be as bad as the drought years, we said to one another, as if repetition would make it true. The next spring, we watched the stalks in the wheat fields carefully. The early crops came up strong, and the long, engorged carrots we dug that year were the source of much giggling amongst the younger teenagers. From my own small plot I harvested a fat sack of garlic which I carried to market in my arms like a baby. All spring I watched the wheat in the shared fields growing sturdy and tall. The lavender behind my cottage was giddy with bees and, inside, my shelves were loaded with food.

It was mid-harvest when they came. I felt it first. Had been feeling it, if I were honest with myself, for months. But now I sensed it clearly, a sudden alertness that I could never explain to anybody who wasn’t a seer. It was a feeling of something shifting: like a cloud moving across the sun, or the wind changing direction. I straightened, scythe in hand, and looked south. By the time the shouts came, from the far end of the settlement, I was already running. As the cry went up and the six mounted men galloped into sight, the others ran too – it wasn’t uncommon for Alphas to raid Omega settlements, stealing anything of value. But I knew what they were after. I knew, too, that there was little point in running. That I was six months too late to heed my mother’s warning. Even as I ducked the fence and sprinted toward the boulder-strewn edge of the settlement, I knew they would get me.

They barely slowed to grab me. One simply scooped me up as I ran, snatching the earth from under my feet. He knocked the scythe from my hand with a blow to my wrist and threw me face-down across the front of the saddle. When I kicked out, it only seemed to spur the horse to greater speed. The jarring, as I bounced on my ribs and guts, was more painful than the blow had been. A strong hand was on my back, and I could feel the man’s body over mine as he leaned forward, pressing the horse onwards. I opened my eyes, but shut them again swiftly when I was greeted by the upside-down view of the hoof-whipped ground bolting by.

Just when we seemed to be slowing and I dared to open my eyes again, I felt the insistent tip of a blade at my back.

‘We’re under orders not to kill you,’ he said. ‘Not even to knock you out, your twin said. But anything short of that, we won’t hesitate, if you give us any trouble. I’ll start by slicing a finger off, and you’d better believe I wouldn’t even stop riding to do it. Understand, Cassandra?’

I tried to say yes, managed a breathless grunt.

We rode on. From the endless jolting and the hanging upside down, I was sick twice – the second time on his leather boot, I noted with some satisfaction. Cursing, he stopped his mount and hauled me upright, looping a rope around my body so that my arms were bound at my sides. Sitting in front of him, the pressure in my head was eased as the blood flowed back down to my body. The rope cut into my arms but at least it held me steady, grasped firmly by the man at my back. We travelled that way for the rest of the day. At nightfall, when the dark was slipping over the horizon like a noose, we stopped briefly and dismounted to eat. Another of the men offered me bread but I could manage only a few sips from the water flask, the water warm and musty. Then I was again hoisted up, in front of a different man now, his black beard prickling the back of my neck. He pulled a sack over my head, but in the darkness it made little difference.

I sensed the city in the distance, long before the clang of hoofs beneath us indicated that we’d reached paved roads. Through the sacking covering my face, glints of light began to show. I could feel the presence of people all about me – more even than at Haven on market day. Thousands of them, I guessed. The road steepened as we rode on, slowly now, the hoofs noisy on cobbles. Then we halted, and I was passed, almost tossed, down to another man, who dragged me, stumbling, for several minutes, pausing often while doors were unlocked. Each time we moved on, I heard the doors being locked again behind us. Each scrape of a bolt sliding back was like another blow.

Finally, I was pushed down onto a soft surface. I heard a rasp of metal behind me, a knife sliding from a sheath. Before I had time to cry out, the rope around my body fell away, slit. Hands fumbled at my neck, and the sack was ripped from my head, the rough hessian grazing my nose. I was on a low bed, in a small room. A cell. There was no window. The man who’d untied me was already locking the metal door behind him.

Slumped on the bed, the taste of mud and vomit in my mouth, I finally allowed myself to cry. Partly for myself, and partly for my twin; for what he’d become.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_d208167a-8947-5530-9d64-bc8f9969597e)

The next morning, as usual, I woke from dreams of fire.

As the months passed, the moments after such dreams were the only times I was grateful to wake to the confines of the cell. The room’s greyness, the familiarity of its implacable walls, were the opposite of the vast and savage excess of the blast I dreamed of nightly.

There were no written tales or pictures of the blast. What was the point of writing it, or drawing it, when it was etched on every surface? Even now, more than four hundred years after it had destroyed everything, it was still visible in every tumbled cliff, scorched plain, and ash-clogged river. Every face. It had become the only story the earth could tell, so who else would record it? A history written in ashes, in bones. Before the blast, they say there’d been sermons about fire, about the end of the world. The fire itself gave the last sermon; after that there were no more.

Most who survived were deafened and blinded. Many others found themselves alone – if they told their stories, it was only to the wind. And even if they had companions, no survivor could ever properly describe the moment it happened: the new colour of the sky, the roar of sound that ended everything. Struggling to describe it, the survivors would have found themselves, like me, stranded in that space where words ran out and sound began.

The blast shattered time. In an instant, it cleaved time irrevocably into Before and After. Now, hundreds of years later, in the After, no survivors remained, no testimonies. Only seers like me could glimpse it, momentarily, in the instant before waking, or when it ambushed us in the half-second of a blink: the flash, the horizon burning up like paper.

The only tales of the blast were sung by the bards. When I was a child, the bard who passed through the village each autumn sang of other nations, across the sea, sending the flame down from the sky, and of the radiation and the Long Winter that had followed. I must have been eight or nine when, at Haven market, Zach and I heard an older bard with frost-grey hair singing the same tune but with different words. The chorus about the Long Winter was the same, but she made no mention of other nations. Each verse she sang just described the fire, and how it had consumed everything.

When I’d pulled our father’s hand and asked him, he’d shrugged. There were lots of versions of the song, he said. What difference did it make? If there’d once been other lands, across the sea, there were no longer, as far as any sailor had lived to tell. The occasional rumours of Elsewhere, countries over the sea, were only rumours – no more to be believed than the rumours about an island where Omegas lived free of Alpha oppression. To be overheard speculating about such things was to invite public flogging, or to end up in the stocks, like the Omega we’d once seen outside Haven, pinned under the scathing sun until his tongue was a scaled blue lizard protruding from his mouth, while two bored Council soldiers kept watch, kicking him from time to time to ensure he was still alive.

Don’t ask questions, our father said; not about the Before, not about Elsewhere, not about the island. People in the Before asked too many questions, probed too far, and look what that got them. This is the world now, or all we’ll ever know of it: bounded by the sea to the north, west, and south; the deadlands to the east. And it made no difference where the blast came from. All that mattered was that it came. It was all so long ago, as unknowable as the Before that it had destroyed, and from which only rumours and ruins remained.

*

In my first months in the cell, I was granted the occasional gift of sky. Every few weeks, in the company of other imprisoned Omegas, I was escorted on to the ramparts for some exercise and a few moments of fresh air. We were taken in groups of three, with at least as many guards. They watched us carefully, keeping us not only apart but also well away from the crenellations that overlooked the city below. The first outing, I’d learned not to try to approach the other prisoners, let alone to speak. As the guards escorted us up from the cells, one of them had grumbled about the slow pace of the pale-haired prisoner, hopping on one leg. ‘I’d be quicker if you hadn’t taken away my cane,’ she’d pointed out. They didn’t respond, and she’d rolled her eyes at me. It wasn’t even a smile, but it was the first hint of warmth I’d seen since entering the Keeping Rooms. When we reached the ramparts, I’d tried to sidle close enough to her to attempt a whisper. I was still ten feet from her when the guards tackled me against the wall so hard that my shoulder-blades were bruised against the stone. As they hustled me back down to the cell one of them spat at me. ‘Don’t talk to the others,’ he said. ‘Don’t even look at them, do you hear?’ With my arms held behind my back, I couldn’t wipe his spittle from my cheek. Its warmth was a foul intimacy. I never saw the woman again.

A month or more later was my third outing to the ramparts, and the last for any of us. I was standing by the door, letting my eyes accustom to the glint of sun on polished stone. Two guards stood to my right, chatting quietly. Twenty feet to my left, another guard leaned against the wall, watching a male Omega. He’d been in the Keeping Rooms longer than me, I guessed. His skin, which must once have been dark, was now a dirty grey. More telling were the twitchy motions of his hands, and the way he kept moving his lips, as if they didn’t fit over his gums. The whole time we’d been up there, he had walked backwards and forth on the same small patch of stones, dragging his twisted right leg. Despite the interdiction on speaking to one another, I could periodically hear his muttered counting: Two hundred and forty-seven. Two hundred and forty-eight.

Everyone knew that many seers went mad – that over years the visions burned our minds away. The visions were flame, and we were the wick. This man wasn’t a seer, but it didn’t surprise me that anyone held for long enough in the Keeping Rooms would go mad. What chance, then, for me, contending with the visions at the same time as the unrelenting walls of my cell? In a year or two, I thought, that might be me, counting out my footsteps as if the neatness of numbers could impose some order on a broken mind.

Between me and the pacing man was another prisoner, perhaps a few years older than me, a one-armed woman with dark hair and a cheerful face. It was the second time we’d been taken to the ramparts together. I walked as close to the edge of the ramparts as the guards would allow, and stared beyond the sandstone crenellations as I tried to contrive some way that I might speak or signal to her. I couldn’t get close enough to the edge to get a proper look at the city that unfolded beneath the mountainside fort. The horizon was curtailed by the ramparts, beyond which I could see only the hills, painted grey with distance.

I realised the counting had stopped. By the time I’d turned around to see what had changed, the older Omega had already rushed at the woman and gripped her neck between his hands. With only one arm she couldn’t fight hard enough or cry out quickly enough. The guards reached them while I was still yards away, and in seconds they’d pulled him off her, but it was too late.

I’d closed my eyes to block the sight of her body, face down on the flagstones, head turned sideways at an impossible angle. But for a seer there’s no refuge behind closed eyelids. In my shuddering mind I saw what else happened at precisely the moment that she died: a hundred feet above us, inside the fort, a glass of wine dropped, sharding red over a marble floor. A man in a velvet jacket fell backwards, scrambled for a second to his knees, and died, his hands to his neck.

After that, there were no more trips to the ramparts. Sometimes I thought I could hear the mad Omega shouting and thrashing the walls, but it was only a dull thud, a throb in the night. I never knew whether I was really hearing it, or just sensing it.

Inside my cell, it was almost never dark. A glass ball suspended in the ceiling gave off a pale light. It was lit constantly, and emitted off a slight buzz, so low that I sometimes wondered whether it was just a ringing in my own ears. For the first few days I watched it nervously, waiting for it to burn out and leave me in total darkness. But this was no candle, not even an oil lamp. The light it gave off was different: cooler, and unwavering. Its sterile light only faltered every few weeks, when it would flicker for several seconds and disappear, leaving me in a formless black world. But it never lasted more than one or two minutes. Each time the light would return, blinking a couple of times, like somebody waking from sleep, before resuming its vigil. I came to welcome these intermittent breakdowns. They were the only interruptions from the light’s ceaseless glare.

This must be the Electric, I supposed. I’d heard the stories: it was like a kind of magic, the key to most of the technology from the Before. Whatever it had been, though, it was supposed to be gone now. Any machines not already destroyed in the blast had been done away with in the purges that followed, when the survivors had destroyed all traces of the technology that had brought the world to ash. All remnants of the Before were taboo, but none more than the machines. And while the penalties for breaking the taboo were brutal, the law was mainly policed by fear alone. The danger was inscribed on the surface of our scorched world, and on the twisted bodies of the Omegas. We needed no reminders.

But here was a machine, a piece of the Electric, hanging from the ceiling of my cell. Not anything terrifying or powerful, like the things people whispered about. Not a weapon, or a bomb, or even a carriage that could move without a horse. Just this glass bulb, the size of my fist, blaring light at the top of my cell. I couldn’t stop staring at it, the knot of extreme brightness at its core, sharply white, as though a spark from the blast itself were captured there. I stared at it for so long that when I closed my eyes the bright shape of it was etched on my eyelids’ darkness. I was fascinated, and appalled, wincing beneath the light in those first days as though it might explode.

When I watched the light, it wasn’t only the taboo that scared me – it was what this act of witness meant for me. If word got out that the Council was breaking the taboo, there’d be another purge. The terror of the blast, and the machines that had wrought it, was still too real, too visceral, for people to tolerate. I knew the light was a life sentence: now I’d seen it, I’d never be allowed out.

More than anything else, I missed the sky. A narrow vent, just below the ceiling, let in fresh air from somewhere, but never even a glimpse of sunlight. I calculated time’s passage by the arrival of food trays twice a day through the slot in the base of the door. As the months since that last visit to the ramparts receded, I found I could recall the sky in the abstract, but couldn’t properly picture it. I thought of the stories of the Long Winter, after the blast, when the air had been so thick with ash that nobody saw the sky for years and years. They say there were children born in that time who never saw the sky at all. I wondered whether they’d believed in it; whether imagining the sky had become an act of faith for them, as it now was for me.

Counting days was the only way I could cling to any sense of time, but as the tally grew it became its own torture. I wasn’t counting down towards any prospect of release: the numbers only climbed, and with them the sense of suspension, of floating in an indefinite world of darkness and isolation. After the visits to the ramparts were stopped, the only regular milestone was The Confessor coming each fortnight to interrogate me about my visions. She told me that the other Omegas saw no one. Thinking of The Confessor, I didn’t know if I should envy or pity them.

*

They say the twins started to appear in the second and third generations of the After. In the Long Winter there were no twins – barely any births at all, and fewer who survived. They were the years of melted bodies and failed, unrecognisable infants. So few lived, and fewer still could breed, so that it seemed unlikely humans would carry on at all.

At first, in the struggle to repopulate, the onslaught of twins must have been greeted with joy. So many babies, and so many of them normal. There was always one boy and one girl, with one from each pair perfect. Not just well formed, but strong, robust. But soon the fatal symmetry became evident; the price to be paid for each perfect baby was its twin. They came in many different forms: limbs missing, or atrophied, or occasionally multiplied. Absent eyes, extra eyes, or eyes sealed shut. These were the Omegas, the shadow counterparts to the Alphas. The Alphas called them mutants, said they were the poison that Alphas cast out, even in the womb. The stain of the blast that, while it couldn’t be removed, had at least been displaced onto the lesser twin. The Omegas carried the burden of the mutations, leaving the Alphas unencumbered.

Not entirely unencumbered, though. While the difference between twins was visible, the link between them was not. But it nonetheless asserted itself, every time, in the most unanswerable way. It made no difference that nobody could understand how it worked. At first, they might have dismissed it as coincidence. But gradually, disbelief was overruled by fact, by the evidence of bodies. The twins came in pairs, and they died in pairs. Wherever they were, and no matter how far apart, whenever someone died, their twin died too.

Extreme pain, too, or serious illness, would affect both twins. A high fever in one twin would soon peak in the other; if one twin was knocked out, the other would lose consciousness as well, wherever he or she was. Minor injur-ies or sickness didn’t seem to bridge the divide, but severe pain would see one twin wake, screaming, from the other twin’s wound.

When it became clear that Omegas were infertile, it was assumed for a while that they would die out. That they were only a temporary blight, a readjustment after the blast. But each generation since then was the same: all twins, always one Alpha and one Omega. Only Alphas could produce children, but each child they produced came with its Omega twin.

When Zach and I were born, a perfect match, our parents must have counted and recounted: limbs, fingers, toes. The complete set. They would have been disbelieving, though; nobody dodged the split between Alpha and Omega. Nobody. It wasn’t unheard of for an Omega to have a deformation that only became apparent later: one leg that refused to grow in tandem with the other; deafness that passed unnoticed in infancy; an arm that turned out to be stunted or weak. But there were also rumours, all over, about those few whose difference never showed itself physically: the boy who seemed normal until he screamed and ran from the cottage minutes before the roof-beam’s sudden collapse; the girl who wept over the shepherd’s dog a week before the cart from the next village ran it down. These were the Omegas whose mutation was invisible: the seers. They were rare – only one in every few thousand, if that. Everybody knew of the seer who came to the market each month at Haven, the big town downstream. Although Omegas weren’t permitted at the Alpha market, he’d been tolerated for years, lurking at the back of the stalls, behind the stacked crates and the mounds of spoiled vegetables. By the time I first went to the market he was old, but still plying his trade, charging a bronze coin in exchange for predicting next season’s weather to farmers, or telling a merchant’s daughter whom she’d end up marrying. But he was always odd: he muttered to himself steadily, an unending incantation. Once, when Zach and I walked past with Dad, the seer shouted, ‘Fire. Forever fire.’ The stallholders nearby didn’t even flinch – evidently such outbursts were common. That was the fate of most seers: the blast burned its way through their minds, as they were forced to relive it.

I don’t know when I first realised my own difference, but I was old enough to know that it had to be hidden. In the early years, I was as oblivious as my parents. What child doesn’t wake, screaming, from a bad dream? It took a long time for me to understand that there was something different about my dreams. The consistency of my dreams of the blast. The way that I’d dream of a storm that wouldn’t arrive until the following night. How the details and scenes in my dreams extended far beyond my own experience of the village, its forty or so stone houses clustered around the central green with its stone-rimmed well. All I had ever known was this shallow valley, the houses and the wooden barns grouped a hundred feet from the river, high enough up to avoid the floods that drenched the fields with rich silt each winter. But my dreams thronged with unfamiliar landscapes and strange faces. Forts that loomed ten times the height of our own small house with its rough-sanded floors and low, beamed ceilings. Cities with streets wider than the river itself, and swollen with crowds.

By the time I was old enough to wonder at this, I was old enough to know that Zach was sleeping through each night, undisturbed. In the cot that we shared, I taught myself to lie in silence, to calm my frenzied breathing. When the visions came in the daytime, especially the roaring flash of the blast, I learned not to cry out. The first time Dad took us downstream to Haven, I recognised the jostling market square from my dreams, but when I saw Zach hang back and grip Dad’s hand, I imitated my brother’s dumbfounded stare.

So our parents waited. Like all parents, they’d made only a single cot for us, expecting to send one child away as soon as we’d been split and weaned. When, at three, we remained stubbornly unsplit, our father built a pair of larger beds. Although our neighbour, Mick, was known throughout the valley for his skill at carpentry, this time Dad didn’t ask for his help. He built the beds himself, almost furtively, in the small walled yard outside the kitchen window. In the years that followed, whenever my lopsided, ill-made bed creaked I remembered the expression on Dad’s face when he’d dragged the beds into the room, setting them as far apart as the narrow walls would allow.

Mum and Dad hardly spoke to us, anymore. Those were the drought years, when everything was rationed, and it seemed to me that even words had become scarce. In our valley, where the low-lying fields were usually flooded every winter, the river thinned to an apathetic trickle, the exposed riverbed on each side cracked like old pottery. Even in our well-off village, there was nothing to spare. Our harvests were poor the first two years, and in the third year without rain the crops failed altogether, and we lived off hoarded coins. The dried-up fields were scoured by dust. Some of the livestock died – there was no animal feed to buy, even for those with coins. There were stories of people starving, further east. The Council sent patrols through all the villages, to protect against Omega raids. That was the summer they erected the wall around Haven, and most of the larger Alpha towns. But the only Omegas I glimpsed in those years, passing our village on the way to the refuges, looked too thin and weary to threaten anyone.

Even when the drought had broken, the Council patrols continued. Mum and Dad’s vigilance didn’t change, either. The slightest difference between me and Zach was anticipated, seized on, and dissected. When we both came down with the winter fever, I overheard my parents’ long discussion about who had sickened first. I must have been six or seven. Through the floor of our bedroom I could hear, from the kitchen below, my father’s loud insistence that I’d looked flushed the night before, a good ten hours before both Zach and I had woken with our fevers peaking in perfect unison.

That was when I realised that Dad’s wariness around us was distrust, not habitual gruffness; that Mum’s constant watchfulness was something other than maternal devotion. Zach used to follow Dad around all day, from the well to the field to the barn. As we grew older, and Dad became prickly and wary with us, he began to shoo Zach away, shouting at him to get back to the house. Still Zach would find excuses to tail him when he could. If Dad was gathering fallen wood from the copse upstream, Zach would drag me there too, to search for mushrooms. If Dad was harvesting in the maize field, Zach would find a sudden enthusiasm for fixing the broken gate to the next paddock. He kept a safe distance, but trailed our father like an oddly misplaced shadow.

At night I clenched my eyes shut when Mum and Dad would talk about us, as if that would block out the voices that seeped through the floorboards. In the bed against the opposite wall I could hear Zach shift slightly, and the unhurried rhythm of his breathing. I didn’t know if he was asleep, or just pretending.

*

‘You’ve seen something new.’

I scanned the cell’s grey ceiling to avoid The Confessor’s eyes. Her questions were always like this: phrased blankly, as statements, as if she already knew everything. Of course, I could never be sure that she didn’t. I knew, myself, what it was to catch glimpses of other people’s thoughts, or to be woken by memories that weren’t my own. But The Confessor wasn’t just a seer; she used her power knowingly. Each time she came to the cell, I could feel her mind circling mine. I’d always refused to talk to her, but I was never sure how much I succeeded in concealing.

‘Just the blast. The same.’

She unclasped and reclasped her hands. ‘Tell me something you haven’t told me twenty times before.’

‘There’s nothing. Just the blast.’

I searched her face, but it revealed nothing of what she knew. I’m out of practice, I thought. Too long in the cell, cut off from people. And anyway, The Confessor was inscrutable. I tried to concentrate. Her face was nearly as pale as mine had become over the long months in the cell. The brand was somehow more conspicuous on her face than on others’, because the rest of her features were so imperturbable. Her skin as smooth as a polished river pebble, except for the tight redness of the brand, puckering at the centre of her forehead. It was hard to tell her age. If you just glanced at her, you might think her the same age as me and Zach. To me, however, she seemed decades older: it was the intensity of her stare, the powers that it barely concealed.

‘Zach wants you to help me.’

‘Then tell him to come himself. Tell him to see me.’

The Confessor laughed. ‘The guards told me you screamed his name for the first few weeks. Even now, after three months in here, you really think he’s going to come?’

‘He’ll come,’ I said. ‘He’ll come eventually.’

‘You seem certain of that,’ she said. She cocked her head slightly. ‘Are you certain that you want him to?’

I would never explain to her that it wasn’t a matter of wanting, any more than a river wants to move downstream. How could I explain to her that he needed me, even though I was the one in the cell?

I tried to change the subject.

‘I don’t even know what you want,’ I said. ‘What you think I can do.’

She rolled her eyes. ‘You’re like me, Cass. Which means I know what you’re capable of, even if you won’t admit it.’

I tried a strategic concession. ‘It’s been more frequent. The blast.’

‘Unfortunately I doubt that you can have much valuable information to give us about something that happened four hundred years ago.’

I could feel her mind probing at the edges of mine. It was like unfamiliar hands on my body. I tried to emulate her inscrutability, to close my mind.

The Confessor sat back. ‘Tell me about the island.’

She’d spoken quietly, but I had to hide my shock that I had been infiltrated so easily. I’d only begun to see the island in the last few weeks, since the final trip to the ramparts. The first few times I dreamed of it, I’d doubted myself, wondered if those glimpses of sea and sky were a fantasy rather than a vision. Just a daydream of open space, to counteract the contraction of my daily reality into those four grey walls, the narrow bed, the single chair. But the visions came too regularly, and were too detailed and consistent. I knew that what I had seen was real, just as I knew that I could never speak of it. Now, in the overbearing silence of the room, my own breathing sounded loud.

‘I’ve seen it too, you know,’ she said. ‘You will tell me.’

When her mind probed mine, I was laid bare. It was like watching Dad skin a rabbit: the moment when he’d peel back the skin, leaving all the inner workings exposed.

I tried to seal my mind around images of the island: the city concealed in its caldera, houses clambering on one another up the steep sides. The water, merciless grey, stretching in all directions, pocked by outcrops of sharp stone. I could see it all, as I’d seen it many nights in dreams. I tried to think of myself as holding its secret inside my mouth, the same way the island nursed the secret city, nestled in the crater.

Standing, I said, ‘There is no island.’

The Confessor stood too. ‘You’d better hope not.’

*

As we grew older the scrutiny of our parents was matched only by that of Zach himself. To him, every day we weren’t split was another day he was branded by the suspicion of being an Omega, another day he was prevented from assuming his rightful place in Alpha society. So, unsplit, the two of us lingered at the margins of village life. When other children went to school, we studied together at the kitchen table. When other children played together by the river, we played only with each other, or followed the others at a distance, copying their games. Keeping far enough away to avoid the other children shouting or throwing stones at us, Zach and I could only hear fragments of the rhymes they sang. Later, at home, we would try to echo them, filling in the gaps with our own invented words and lines. We existed in our own small orbit of suspicion. To the rest of the village, we were objects of curiosity and, later, outright hostility. After a while, the whispers of the neighbours ceased being whispers, and became shouts: ‘Poison.Freak.Imposter.’ They didn’t know which one of us was dangerous, so they despised us equally. Each time another set of twins was born in the village, and then split, our unsplit state became more conspicuous. Our neighbours’ Omega son, Oscar, whose left leg ended at the knee, was sent away at nine months old to be cared for by Omega relatives. We often passed the remaining twin, little Meg, playing alone in the fenced yard of their house.

‘She must miss her twin,’ I said to Zach as we walked by, watching Meg chewing listlessly on the head of a small wooden horse.

‘Sure,’ he said. ‘I bet she’s devastated that she doesn’t have to share her life with a freak anymore.’

‘He must miss his family too.’

‘Omegas don’t have family,’ he said, repeating the familiar line from one of the Council posters. ‘Anyway, you know what happens to parents who try to hang on to their Omega kids.’

I’d heard the stories. The Council showed no mercy to the occasional parent who resisted the split and tried to keep both twins. It was the same for those rare Alphas who were found to be in a relationship with an Omega. There were rumours of public floggings, and worse. But most parents relinquished their Omega babies readily, eager to be rid of their deformed offspring. The Council taught that prolonged proximity to Omegas was dangerous. The neighbours’ hisses of poison revealed both disdain and fear. Omegas needed to be cast out of Alpha society, just as the poison was cast out of the Alpha twin in the womb. Was that the one thing Omegas are spared, I wondered? Since we can’t have children, at least we’d never have to experience sending a child away.

I knew my time to be sent away was coming, and that my secrecy was only deferring the inevitable. I’d even begun to wonder whether my current existence – the perpetual scrutiny of my parents and the rest of the village – was any better than the exile that was bound to follow. Zach was the one person who understood my odd, liminal life, because he shared it. But I felt his dark, calm eyes on me all the time.

In search of less watchful company, I’d caught three of the red beetles that always flocked by the well. I kept them in a jar on the windowsill, had enjoyed seeing them crawl about, and hearing the muted clatter of their wings against the glass. A week later I found the largest one pinned to the wooden sill, one wing gone, making an endless circle on the pivot of its guts.

‘It was an experiment,’ said Zach. ‘I wanted to test how long it could live like that.’

I told our parents. ‘He’s just bored,’ my mother said. ‘It’s driving him crazy, the two of you not being in school like you should be.’ But the unspoken truth continued to circle, like the beetle stuck on the pin: only one of us would ever be allowed to go to school.

I squashed the beetle myself, with the heel of my shoe, to put an end to its circular torment. That night, I took the jar and the two remaining beetles with me to the well. When I removed the lid and tipped the jar on its side, they were reluctant to venture out. I coaxed them out with a blade of grass, transferring them carefully to the stone rim on which I sat. One attempted a short flight, landing on my bare leg. I let it sit there for a while before blowing it gently back into flight.

Zach saw the empty jar that night, beside my bed. Neither of us said anything.

*

About a year later, gathering firewood by the river on a still afternoon, I made my mistake. I was walking just behind Zach when I sensed something: a part-glimpse of a vision, intruding between the real world and my sight. I dashed to catch up with him, knocked him out of the way before the branch had even begun to fall. It was an instinctive response, the kind I’d grown used to repressing. Later I would wonder whether it was fear for his safety that led to my lapse, or just exhaustion under the constant scrutiny. Either way, he was safe, sprawled beneath me on the path, by the time the massive bough creaked and fell, snagging and tearing off other branches on the way down, to land finally where Zach had stood earlier.

When his eyes met mine I was amazed at the relief in them.

‘It wouldn’t have done much damage,’ I said.

‘I know.’ He helped me up, brushed some leaves off the side of my dress.

‘I saw it.’ I was speaking too quickly. ‘Saw it starting to fall, I mean.’

‘You don’t need to explain,’ he said. ‘And I should thank you, for getting me out of the way.’ For the first time in years, he was smiling at me in the unguarded, wide-mouthed way that I remembered from our early childhood. I knew him too well to be glad.

He insisted on adding my own bundle of firewood to his, carrying the whole load all the way back to the village. ‘I owe you,’ he said.

In the weeks that followed we passed most of the time together, the same as always, but he was less rough in our games. He waited for me on the walk to the well. When we took the shortcut across the field, he called behind to warn me when he came across a patch of stinging nettles. My hair went unpulled, my possessions undisturbed.

Zach’s new knowledge allowed me some respite from his daily cruelties, but it wasn’t enough to declare us split. For that, he needed proof – years of impassioned but futile assertions on his part had taught him that. He waited a while for me to slip up again and reveal myself, but for nearly a whole year more I managed to hold my secret. The visions had grown stronger, but I’d trained myself not to react, not to cry out at the flashes of flame that punctuated my nights, or at the images of distant places that drifted into my waking thoughts. I spent more time alone, venturing far upstream, even as far as the deep gorge leading away from the river, where the abandoned silos were hidden. Zach no longer followed me when I went off by myself.

I never entered the silos, of course. All such remnants were taboo. Our broken world was scattered with these ruins, but it was against the law to enter them, just as it was forbidden to own any relics. I’d heard rumours that some desperate Omegas had been known to raid the wreckage, searching out usable fragments. But what would be left to salvage after all these centuries? The blast had levelled most cities. And even if there were anything salvageable in the taboo towns now, centuries later, who would dare to take it, knowing the penalty? More frightening than the law were the rumours of what those remnants could hold. The radiation, said to shelter like a nest of wasps in such relics. The contaminating presence of the past. If the Before was mentioned at all, it was in hushed voices, with a mixture of awe and disgust.

Zach and I used to dare each other to get close to the silos. Always braver than me, once he ran right up to the closest one and placed a hand on the curved concrete wall before running back to me, giddy with pride and fear. But these days I was always alone, and would sit for hours under a tree that overlooked the silos. The three huge, tubular buildings were more intact than many such ruins – they’d been shielded by the gorge that surrounded them, and by the fourth silo, which must have taken the brunt of the blast. It had collapsed entirely, leaving only its circular base. Twisted metal spars rose out of the dust like the grasping fingers of a world buried alive. But I was grateful for the silos, despite their ugliness – they guaranteed that nobody else would go near the place, so I could at least count on solitude. And unlike the walls of Haven, or the larger of the villages nearby, there were no Council posters flapping at the wind: Vigilance against Contamination from Omegas. Alpha Unity: Support Increased Tithes for Omegas. Since the drought years, everything seemed scarcer except for new Council posters.

I wondered, sometimes, whether I was drawn to the ruins because I recognised myself in them. We Omegas, in our brokenness, were like those taboo ruins: dangerous. Contaminating. Reminders of the blast and what it had wrought.

Although Zach no longer came with me to the silos, or on my other wanderings, I knew he was still observing me more intently than ever. When I came back from the silos, tired from the long walk, he’d smile at me in his watchful way, ask politely about my day. He knew where I’d been, but never told our parents, although they would have been furious. But he left me alone. He was like a snake, drawing back before the strike.

The first time he tried to expose me, he took my favourite doll, Scarlett, the one in the red dress that Mum had sewn. When Zach and I had first been given separate beds, I’d hung on to that doll for comfort at night. Even at twelve, I always slept with Scarlett under one arm, the coarse, plaited wool of her hair reassuringly scratchy against my skin. Then one morning she was gone.

When I asked about Scarlett at breakfast, Zach was buoyant with triumph. ‘It’s hidden, outside the village. I took it while Cass was asleep.’ He turned to our parents. ‘If she finds where I buried it, she has to be a seer. It’ll be proof.’ Our mother chided him, and put a hand on my shoulder, but all day I saw how my parents watched me even more carefully than usual.

I cried, as I had planned. Seeing the hopeful alertness of my parents made it easy. How keen they were to solve the riddle that Zach and I had become, even if it meant being rid of me. In the evening, I pulled from the small toybox an unfamiliar-looking doll with awkwardly chopped short hair and a simple white smock. That night, tucked under my left arm, Scarlett was returned from the toybox exile that I’d imposed on her a week before, when I’d swapped her red dress onto an unfavoured doll, and hacked off her long hair.

From then on Scarlett remained secret, in full view, on my bed. I never bothered to go to the lightning-charred willow downstream and dig up the doll in the red dress that Zach had buried there.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_e39a08c5-134c-51e1-8e4c-ed951b76ac0a)

Downstairs, Mum and Dad were fighting again, the sound of their argument drifting up through the floorboards, insidious as smoke.

‘It’s more of a problem every day,’ Dad said.

Mum’s voice was quieter. ‘They’re not “a problem” – they’re our children.’

‘One of them is,’ he replied. A pot clattered loudly on the table. ‘The other one’s dangerous. Poison. We just don’t know which one.’

Zach hated to let me see him cry, but the dregs of the candle threw out enough light for me to see the slight shuddering of his back under the blanket. I slipped out from under my quilt. The floorboards creaked slightly as I took the two steps to the edge of Zach’s bed.

‘He doesn’t mean it,’ I whispered, putting a hand on his back. ‘He doesn’t mean to hurt you when he says things like that.’

He sat up, shrugging off my hand. I was surprised to see he didn’t even try to wipe away the tears. ‘I’m not hurt by him,’ he said. ‘What he says, it’s all true. You want to pat me on the back, comfort me, act like you’re the caring one? It’s not them hurting me. Not even the other kids, the ones who throw stones. See all of this?’ The sweep of his hand took in the sounds from the kitchen below, as well as his own tear-streaked face. ‘It’s all your fault. You’re the problem, Cass, not them. You’re the reason we’re stuck in this limbo.’

I was suddenly aware of the cold boards underfoot, and the night air on my bare arms.

‘You want to show you really care about me?’ he said. ‘Then tell them the truth. You could end it right away.’

‘Do you really want me sent away? It’s me. I’m not some strange creature. Forget what the Council says about contamination. It’s just me. You know me.’

‘You keep saying that. Why should I think I know you? You’ve never been honest with me. You never told me the truth. You made me figure it out for myself.’

‘I couldn’t tell you,’ I said. Even admitting as much to him, alone in our room, was risky.

‘Because you didn’t trust me. You want to make out that we’re so close. But you’re the one who’s lied this whole time. You never trusted me enough to tell me the truth. All these years, you left me to wonder. To fear that it might be me who was the freak. And now you think I should trust you?’

I retreated to my bed. He was still staring at me. Could things ever have been different, if I’d trusted him with the truth? Could we have found a way to share the secret, to make our way together? Had he caught his distrust from me? Maybe that was the poison I’d been carrying – not the contamination of the blast that all Omegas bore, but the secret.

A tear had settled on the top of his upper lip. It glinted gold in the candlelight.

I didn’t want him to see the matching tear on my face. I reached out to the table and snuffed the flame.

‘It’s got to end,’ he whispered into the darkness. It was half a plea, half a threat.

*

His impatience to expose me grew with our father’s illness. Dad fell sick when we’d just turned thirteen. As with the previous year, there was no mention of our birthday – our age had become an increasingly shameful reminder of our unsplit state. That night, Zach had whispered across the bedroom: ‘You know what day it was today?’

‘Of course,’ I said.

‘Happy birthday,’ he said. It was only a whisper, so it was hard to tell whether he was being sarcastic.

Two days later, Dad collapsed. Dad, who had always seemed as robust and solid as the huge oak cross-beam that ran the length of the kitchen ceiling. He hauled buckets of water up the well faster than anyone else in the village, and when Zach and I were smaller he could carry us both at once. He still could, I thought, except that he rarely touched us now. Then, in the middle of the paddock on a hot day, he stumbled to his knees. From where I sat, shelling peas on the stone wall at the front of our yard, I heard the shouts of the others working near him in the field.

That night, after the neighbours had carried him back to the cottage, our mother sent for Dad’s twin, Alice, from the Omega settlement up on the plain. Zach himself went with Mick in the bullock cart to fetch her, returning the next day with our aunt lying in the hay on the back of the cart. We’d never met her before, and looking at her, the only similarity I could see between her and Dad was the fever that currently slickened their flesh. She was thin, with long hair, darker than Dad’s. The coarse, brown fabric of her dress had been mended many times and was now flecked with hay. Beneath the strands of hair that stuck to her sweaty forehead we could make out the brand: Omega.

We cared for her as much as we could, but it was clear from the start that she hadn’t long. We couldn’t allow her in the house, of course, but even her presence in the shed was enough to enrage Zach. On the second day his fury climaxed. ‘It’s disgusting,’ he shouted. ‘She’s disgusting. How can she be here, with us running around after her like servants? She’s killing him. And it’s dangerous for all of us, having her so close.’

Mum didn’t bother to hush him, but said calmly, ‘She’d be killing him more quickly if we’d left her in her own filthy hut.’

This silenced Zach. He wanted Alice gone, but not at the expense of admitting to Mum what he had told me in bed the night before: what he’d seen at the settlement when he collected Alice. Her small, tidy cottage; the whitewashed walls; the posies of dried herbs hanging above the hearth, just as they hung above ours.

Mum continued, ‘If we save her, we save him.’

It was only at night, when the candle was out and no voices could be heard from Mum and Dad’s room, that Zach would tell me about what he’d seen at the settlement. He told me that other Omegas at the settlement had tried to stop them from taking Alice away – that they’d wanted to keep caring for her there. But no Omega would dare to argue with an Alpha, and Mick had brandished his whip until they backed away.

‘Isn’t it cruel, though, to take her from her family?’ I whispered.

‘Omegas don’t have family,’ Zach recited.

‘Not children, obviously, but people she loves. Friends, or maybe a husband.’

‘A husband?’ He let the word hang. Officially Omegas weren’t allowed to marry, but everyone knew that they still did, although the Council wouldn’t recognise any such unions.

‘You know what I mean.’

‘She didn’t live with anyone,’ he said. ‘It was just a few other freaks from her settlement, claiming they knew what was best for her.’

We’d barely seen Omegas before, let alone spent time in close quarters with one. Little Oscar next door had been sent away as soon as he was branded and weaned. The few Omegas who passed through the area rarely stayed more than a night, camping just downstream of the village. They were itinerants, on the way to try their luck at one of the larger Omega settlements in the south. Or, in years when the harvest had been poor, there’d be Omegas who’d given up on farming the half-blighted land they were permitted to settle on, and were heading to one of the refuges near Wyndham. The refuges were the Council’s concession to the fatal bond between twins. Omegas couldn’t be allowed to starve to death and take their twins with them, so there were refuges near all large towns, where Omegas would be taken in, and fed and housed by the Council. Few Omegas went willingly, though – it was a place of last resort, for the starving or sick. The refuges were workhouses, and those who sought their help had to repay the Council’s generosity with labour, working on the farms within the refuge complex until the Council judged the debt repaid. Few Omegas were willing to trade their freedom for the safety of three meals a day.

I’d gone out with Mum, once, to give some food-scraps to one group on their way to the refuge near Wyndham. It was dark, and the man who stepped away from the fire and accepted the bundle from Mum had done so in silence, gesturing at his throat to indicate that he was mute. I tried not to stare at the brand on his forehead. He was so thin that the knuckles were the widest part of each finger, his knees the widest part of each leg. His very skin seemed insufficient, stretched miserly over his bones. I thought perhaps that we might join the travellers at the fire for a few minutes, but the guardedness in Mum’s eyes was more than matched by that in the Omega man’s. Behind him, I could see the group gathered around a thriving blaze. It was hard to distinguish between the strange shapes thrown by the firelight and the actual deformities of the Omegas. I could make out one man who leaned forward and poked at the fire with a stick, held between the two stumps of his arms.

Looking at the group, their huddled stance, their thin and cowed bodies, it was hard to believe the occasional whispers of an Omega resistance, or of the island where it was supposed to be brewing. How could they dream of challenging the Council, with its thousands of soldiers? The Omegas I’d seen were all too poor, too crippled. And, like the rest of us, they must know the stories of what had happened, a century ago or more, when there’d been an Omega uprising in the east. Of course, the Council couldn’t kill them without killing their Alpha counterparts, but what they did to the rebels, they say, was worse. Torture so terrible that their Alpha twins, even those hundreds of miles away, fell screaming to the ground. As for the rebel Omegas, they were never seen again, but apparently their Alpha twins continued to suffer unexplained pain for years.

After they’d crushed the uprising, the Council set the east ablaze. They burned all the settlements out there, even those that had never been involved in the uprising. The soldiers torched all the crops and houses, even though the east was already a bleak zone on the brink of the deadlands, a place so dire no Alphas would live there. They left nothing standing, until it was as if the deadlands themselves had crept further west.

I thought of those stories as I watched the group of Omegas, their unfamiliar bodies bending over the bundle of scraps my mother had given them. When she took my hand and led me quickly back to the village, I was ashamed at my own relief. The image of the mute Omega, his eyes avoiding ours as he took the food, stayed with me for weeks.

My father’s twin was not mute. For three days Alice groaned, shouted and cursed. The sweet, milky stench of her breath pervaded the shed first, and then the house as Dad grew sicker. All the herbs Mum threw on the fire could not quell it. While our mother took care of Dad inside, Zach and I were to take turns sitting with Alice. By unspoken contract we sat together most of the time, rather than taking turns alone.

One morning, when Alice’s cursing had subsided into coughs, Zach asked her quietly, ‘What’s wrong with you?’

She met his eyes clearly. ‘It’s the fever. I have the fever – your father too, now.’

He scowled. ‘But before that – what’s wrong with you?’

Alice burst out laughing, then coughing, then laughing again. Beckoning us closer, she drew aside the sweaty sheet that covered her. Her nightgown reached just below her knees. We looked at her legs, our distaste battling with our curiosity. At first I could see no difference at all: her legs were thin but strong. Her feet were just feet. I’d heard a story once about an Omega with nails grown like scales, all over his flesh, but Alice’s toenails were not only in place, but neatly clipped and clean.

Zach was impatient. ‘What? What is it?’

‘Don’t they teach you to count at your school?’

I said what Zach would not. ‘We don’t go to school. We can’t – we’ve not been split.’

He interrupted quickly: ‘But we can count. We learn at home – numbers, writing, all sorts of things.’ His eyes, like mine, went quickly back to her feet. On the left foot: five toes; on the right foot: seven.

‘That’s my problem, sweetheart,’ said Alice. ‘My toes don’t add up.’ She looked at Zach’s deflated face, and stopped her grinning. ‘I suppose there’s more,’ she said, almost kindly. ‘You’ve not seen me walk, only stagger to and from your cart, but I’ve always limped – my right leg’s shorter than the other, and weaker. And you know I can’t have children: a dead-end, as the Alphas like to call us. But the toes are the main problem: I never had a nice round number.’ She went back to laughing, then looked straight at Zach, raised an eyebrow. ‘If we were all so drastically different from Alphas, darling, why would they need to brand us?’ He didn’t answer. She went on: ‘And if Omegas are all so helpless, why do you think the Council’s so afraid of the island?’

Zach threw a glance over his shoulder, hushed her so urgently that I felt his spittle on my arm. ‘There is no island. Everyone knows. It’s just a rumour, a lie.’

‘Then why do you look so scared?’

I answered this time. ‘On the road to Haven, last time we went, there was a burnt-down hut. Dad said it belonged to a couple of Omegas who spread rumours of the island.’

‘He said Council soldiers took them away in the night,’ Zach added, looking at the door again.

‘And people say there’s a square in Wyndham,’ I said, ‘where they whip Omegas who’ve been heard just talking about the island. They whip them in public, for everyone to see.’

Alice shrugged. ‘Seems like a lot of trouble for the Council to go to, if it’s just a rumour. Just a lie.’

‘It is – is a lie, I mean,’ hissed Zach. ‘You need to shut up – you’re mad, and you’ll get us in trouble. There could never be a place like that, just for Omegas. They’d never manage it. And the Council would find it.’

‘They haven’t found it yet.’

‘Because it doesn’t exist,’ he said. ‘It’s just an idea.’

‘Maybe that’s enough,’ she said, grinning. She was still grinning several minutes later when the fever tipped her back into unconsciousness.

He stood. ‘I’m going to check on Dad.’

I nodded, pressed the cool flannel again to my aunt’s head. ‘Dad’ll be just the same – unconscious, I mean,’ I said. Zach left anyway, letting the shed door bang loudly behind him.

With the cloth resting there, over the brand in the centre of Alice’s forehead, I thought I could begin to recognise some of my father’s features in her face. I pictured Dad, thirty feet away in the cottage. Each time I passed the cloth across her forehead, grimacing with every gust of the sickened breath, I imagined that I was soothing him. After a minute I reached out and placed my own small hand over Alice’s, a gesture of closeness my father had not allowed for years. I wondered if it was wrong, to feel this closeness to this stranger who had brought my father’s illness to the house like an unwelcome gift.

*

Alice had fallen asleep, her breath gurgling slightly in the back of her throat. When I stepped out of the shed, Zach was sitting cross-legged on the ground, in the slant of afternoon sun.

I joined him. He was fiddling with a piece of hay, exploring the spaces between his teeth.

After a while, he said, ‘I saw him fall, you know.’

I should have realised, knowing how Zach still followed Dad around whenever he could.

‘I was looking for birds’ eggs in the trees by the top paddock,’ he went on. ‘I saw it. One moment he was standing. Then, just like that: he fell.’ Zach spat out a splinter of hay. ‘He staggered a bit, like he’d drunk too much, and sort of propped himself up with his pitchfork. Then he fell again, face first, so I couldn’t see him for the wheat.’

‘I’m sorry. It must have been scary.’

‘Why are you sorry? It’s her that should be sorry.’ He gestured at the shed behind us, from where we could hear Alice, her sodden lungs doing battle with the air.

‘He’s going to die, isn’t he?’

There was no point lying to him, so I just nodded.

‘Can’t you do anything?’ he said. He grabbed my hand. Amongst everything that had happened over those last few days – Dad’s collapse, and Alice’s arrival – the strangest of all was Zach reaching out for my hand, something he’d not done since we were tiny.

When we were younger, Zach had found a fossil in the riverbed: a small black stone imprinted with the curlicue of an ancient snail. The snail had become stone, and the stone had become snail. Zach and I were like that, I often thought. We were embedded in each other. First by twinship, then by the years spent together. It wasn’t a matter of choice, any more than the stone or the snail had chosen.

I squeezed his hand. ‘What could I do?’

‘Anything. I don’t know. Something. It’s not fair – she’s killing him.’

‘It’s not like that. She’s not doing it to spite him. It’d be the same for her if he’d fallen sick first.’

‘It’s not fair,’ he said again.

‘Sickness isn’t fair, not to anyone. It just happens.’

‘It doesn’t, though. Not to Alphas – we hardly ever get sick. It’s always Omegas. They’re weak, sickly. It’s the poison in them, from the blast. She’s the weak one, the contaminated one. And she’s going to drag Dad down with her.’

I couldn’t argue with him about the illness – it was true that Omegas were more susceptible. ‘It’s not her fault,’ I offered. ‘And if he fell down a well, or got gored by a bullock, he’d take her with him.’

He dropped my hand. ‘You don’t care about him, because you’re not one of us.’

‘Of course I care.’

‘Then do something,’ he said. He wiped angrily at a tear that emerged from the corner of his eye.

‘There’s nothing I can do,’ I said. I knew that seers were rumoured to have different strengths: a knack for predicting weather, or finding springs in arid land, or telling if somebody spoke the truth. But I’d never heard of any with a talent for healing. We couldn’t change the world – only perceive it in crooked ways.

‘I wouldn’t tell anyone,’ he whispered. ‘If you could do something to help him, I’d not say a word. Not to anyone.’

It made no difference whether I believed him. ‘There’s nothing I can do,’ I repeated.

‘What’s the point of you being a freak if you can’t even do anything useful with it?’

I reached once more for his hand. ‘He’s my dad too.’

‘Omegas don’t have family,’ he said, snatching his hand away.

*

Alice and Dad lasted two more days. It must have been well past midnight, and Zach and I were in the shed, asleep, Alice’s jagged breath grating on our dreams. I woke suddenly. I shook Zach and said, without thinking of hiding my vision, ‘Go to Dad. Go now.’ He was gone before he could even accuse me of anything, his footsteps racing on the gravel path to the cottage. I stood to go too: nearby, my father was dying. But Alice opened her eyes, briefly at first, and then for longer. I didn’t want her to be alone, in the cramped darkness of an unfamiliar shed. So I stayed.

They were buried together the next day, though the gravestone bore only his name. Mum had burned Alice’s nightdress, along with the sheets from both fever-sweated beds. The sole tangible proof that Alice had existed was hanging on a piece of twine around my neck, under my dress: a large brass key. The night she died, when Alice had woken briefly and seen that she was alone with me, she’d taken the key from her neck and passed it to me.

‘Behind my cottage, buried under the lavender, there’s a chest. Things that will help you when you go there.’ She entered another coughing fit.

I handed it back, loath to receive another uninvited gift from this woman. ‘How do you know it will be me?’

She coughed again. ‘I don’t, Cass. I just hope it is.’

‘Why?’ I, more than Zach, had cared for this woman, this reeking stranger. Why would she now wish this upon me?

She pressed the key again into my resisting hand. ‘Because your brother, he’s so full of fear – he’ll never cope if it’s him.’

‘He’s not afraid of things – and he’s strong.’ I wasn’t sure if I was coming to his defence, or my own. ‘He’s just angry, I suppose.’

Alice laughed, a rasp that differed only slightly from her usual coughing. ‘Oh, he’s angry all right. But it’s all the same thing.’ She waved my hand away impatiently as I tried to pass back the key.

In the end, I took it. I kept the key hidden, but it still felt like an admission, if only to myself. Looking at Zach’s face as we stood in the graveyard, squinting in the relentless sun, I knew it wouldn’t be long. Since Dad’s death, I’d felt something shift in Zach’s mind. The change in his thoughts felt like a rusted lock that finally gives way: the same decisiveness, the same satisfaction.

With Dad gone, our house was filled with waiting. I began to dream about the brand. In my dream that first night, I placed my hand again on Alice’s head, and felt her scar burning into the flesh of my own palm.

*

Only a month after the burial, I came home to find the local Councilman there. It was late summer, the hay freshly cut and sharp underfoot as I walked across the fields. On the path up from the river I saw the blurring of the sky above our cottage, and wondered why the fire was lit on such a hot day.

They were waiting for me inside. The moment I saw the black iron handle sticking out of the fire, I heard again the hiss of branded flesh that had sounded in my recent dreams, and I turned to run. It was my mother who grabbed me, hard, by the arm.

‘You know the Councilman, Cass, from downstream.’

I didn’t struggle, but kept my eyes fixed on the brand in the fire. The shape at its end, glowing in the coals, was smaller than I’d pictured it in my dreams. It occurred to me that it was made for use on infants.

‘Thirteen years now, Cassandra, we’ve waited for you and your brother to be split,’ said the Councilman. He reminded me of my father; his big hands. ‘It’s too long. One of you where you shouldn’t be, and one missing out on school. We can’t have an Omega here, contaminating the village. It’s dangerous, especially for the other twin. You each need to take your proper place.’

‘This is our proper place: here. This is our home.’ I was shouting, but Mum interrupted me quickly.

‘Zach told us, Cass.’

The Councilman took over. ‘Your twin came to see me.’

Zach had been standing behind the Councilman, head slightly bowed. Now he looked up at me. I don’t know what I’d expected to see in his eyes: triumph, I suppose. Perhaps contrition. Instead he looked as he so often did: wary, watchful. Afraid, even, but my own fear dragged my eyes back to the brand, from its long black handle down to the shape at the end, a serpentine curve in the coals.

‘How do you know he’s not lying?’ I asked the Councilman.

He laughed. ‘Why would he lie about this? Zach’s shown courage.’ He stepped up to the fireplace and lifted the brand. Methodically, he knocked it twice against the iron grill to shake loose the ash that clung to it.

‘Courage?’ I threw off my mother’s grasp.

The Councilman stepped back from the fire, the brand held high. To my surprise, Mum didn’t grab me again, or make any move to stop me as I backed away. It was the Councilman who moved, quicker than I would have imagined, given his size. He grabbed Zach by the neck and pressed him against the wall beside the hearth. In the Councilman’s other hand, raised above Zach’s face, the brand was smoking slightly.

I shook my head, as if trying to shake the world into some sort of sense. My eyes met Zach’s. Even with the brand so close to his face that its shadow fell across his eyes, I could now see the smirk of triumph. And I admired him, as I always had: my twin; my brave, clever twin. He’d managed to surprise me after all. Could I bring myself to surprise him? Call his bluff and play along, let him be branded and exiled?

I almost could have brought myself to do it, if I hadn’t detected, beneath his triumph, that splinter of terror, insistent as the brand itself. My own face was screwed up against the sizzling heat that I could sense in front of his.

‘He lied. It’s me. I’m the seer.’ I forced my voice into calmness. ‘He knew I’d tell you the truth.’

The Councilman pulled back the brand, but didn’t release Zach.

‘Why not tell us, if you knew it was her?’

‘I tried, for years. Nobody believed me,’ Zach said, his voice half-crushed by the Councilman’s hand at his throat. ‘I couldn’t prove it. I could never catch her out.’

‘And how do we know we can believe her now?’

In the end it was a relief for me to tell it all: how the flashes of vision came to me at night, at first, and later even when I was awake. How the blast tore open my sleep with its roar of light. How I sometimes knew things before they happened: the falling branch, the doll, the brand itself. My mother and the Councilman listened carefully. Only Zach, knowing it already, was impatient.

Finally the Councilman spoke. ‘You’ve given us all quite the runaround, girl. If it wasn’t for your brother, you might have kept on playing us for fools.’ He plunged the brand back into the coals with such force that it sparked against the metal grating. ‘Did you think you were different from the rest of the filthy Omegas?’ He hadn’t let go of the handle of the brand. ‘Better than them, just because you’re a seer?’ He pulled the brand again from the fire. ‘See this?’ He had me now by the throat. The brand, only inches away, singed a few strands of my hair. The smell and the heat forced my eyes shut. ‘See this?’ he said again, waving the brand before my clenched eyes. ‘This is what you are.’

I didn’t cry out when he pressed it to my forehead, though I heard Zach give a grunt of pain. My hand was at my chest, clutching the key that hung there. I squeezed it so tightly that later, upstairs, I saw that it had left its imprint on my flesh.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_98b046c0-3242-58fa-9f8a-8876750f874e)

They let me stay for four days, until the burn had begun to heal. It was Zach who rubbed balm on my forehead. He winced as he did it, whether from pain or disgust I didn’t know.

‘Hold still.’ His tongue emerged from the corner of his mouth as he peered close to clean the wound. He’d always done that when he concentrated. I was extra aware of these small things, now, knowing that I wouldn’t see them anymore.

He dabbed again. He was very gentle, but I couldn’t help but flinch as he touched the raw skin.

‘Sorry,’ he said.

Not sorry for exposing me – sorry only for the blistered flesh.

‘It’ll get better in a few weeks. But I’ll be gone by then. You’re not sorry about that.’

He put down the cloth and looked out the window. ‘It couldn’t stay the same. It couldn’t be the two of us, any longer. It’s not right.’

‘You realise you’re going to be by yourself, now.’

He shook his head. ‘You kept me by myself. I can go to school now. I’ll have the others.’

‘The ones who throw rocks at us when we pass by the school? It was me who cleaned up the wound when Nick landed that rock right above your eye. Who’s going to mop up your blood once they’ve sent me away?’

‘You don’t get it, do you?’ He smiled at me. For the first time I could remember, he was perfectly serene. ‘They only threw rocks because of you. Because you made us both into a freak show. Nobody’s going to be throwing rocks at me now. Not ever again.’

It was refreshing, in a way, to be able to speak openly after all the subterfuge. For those few days before I left, we were more comfortable together than we had been for years.

‘You didn’t see it coming?’ he asked, on my last night, when he’d blown out the candle on the table between our beds.

‘I saw the brand. I felt it burning.’

‘But you didn’t know how I’d do it? That I’d declare myself the Omega?’

‘I guess I only got a glimpse of what would happen in the end. That it would be me.’

‘But it might have been me. If you hadn’t said.’

‘Maybe.’ I shifted again. The only bearable way to lie was on my back, so that the burn didn’t touch the pillow. ‘In my dreams, it was always me branded.’ Did that mean that staying silent had never been an option? Had he known so surely that I would speak up? And what if I hadn’t?

I left at dawn the next day. Zach’s happiness was barely disguised, and didn’t surprise me, though I was saddened to see how my mother rushed the farewell. She avoided looking at my face, as she had ever since the branding. I’d seen it only once myself, sneaking into Mum’s room to meet my new face in the small mirror there. The burn was still raised and blistered, but despite the inflammation surrounding it, the mark was clear. I remembered the Councilman’s words, and repeated them to myself: ‘This is what I am.’ Holding my finger just above the scorched flesh I traced the shape: the incomplete circle, like an inverted horseshoe, with a short horizontal line spreading out at each end. ‘This is what I am,’ I said again.

What surprised me, when I left, was my own relief. Although the pain of my brand was still sharp, and although Mum pushed a parcel of food into my arms when I tried to embrace her, there was something liberating about leaving behind those years of hiding. When Zach said, ‘Take care of yourself,’ I nearly laughed out loud.

‘You mean: take care of you.’

He looked straight at me, not averting his eyes from my brand the way our mother did. ‘Yes.’

I thought that maybe, for the first time in years, we were being honest with each other.

Of course, I cried. I was thirteen years old and I had never been parted from my family before. The furthest I’d ever been from Zach was the day he journeyed to collect Alice. I wondered if it would have been easier if I’d been branded as a child. I would have been raised in an Omega settlement, never known what it was to be with my family, with my twin. I might even have had friends, though never having experienced any closeness apart from with Zach, I didn’t really know what that might mean. At least, I thought, I don’t have to hide who I am anymore.

I was wrong. I was hardly even out of the village when I passed a group of children my own age. Although Zach and I had not been able to attend the school, we knew all the local children, had even played with them in the early years, before our strange togetherness became a public problem. Zach had always carried himself with confidence, and insisted he would fight anyone who said he wasn’t an Alpha. But as the years passed, parents began to warn their children away from the unsplit twins, so we’d relied more and more on each other for company, even as Zach’s resentment at our isolation grew. During the last few years the other children had not just avoided us, but had openly taunted us, hurling rocks and insults if our parents were out of sight.