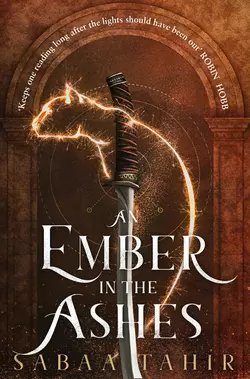

An Ember in the Ashes

Sabaa Tahir

‘Tahir spins a captivating, heart-pounding fantasy’ Us WeeklyRead the explosive New York Times bestselling debut that’s captivated readers worldwide. Set to be a major motion picture, An Ember in the Ashes is the book everyone is talking about.What if you were the spark that could ignite a revolution?For years Laia has lived in fear. Fear of the Empire, fear of the Martials, fear of truly living at all. Born as a Scholar, she’s never had much of a choice.For Elias it’s the opposite. He has seen too much on his path to becoming a Mask, one of the Empire’s elite soldiers. With the Masks’ help the Empire has conquered a continent and enslaved thousands of Scholars, all in the name of power.When Laia’s brother is taken she must force herself to help the Resistance, the only people who have a chance of saving him. She must spy on the Commandant, ruthless overseer of Blackcliff Academy. Blackcliff is the training ground for Masks and the very place that Elias is planning to escape. If he succeeds, he will be named deserter. If found, the punishment will be death.But once Laia and Elias meet, they find that their destinies are intertwined and that their choices will change the fate of the Empire.In the ashes of a broken world one person can make a difference. One voice in the dark can be heard. The price of freedom is always high and this time that price might demand everything, even life itself.

AN EMBER IN THE ASHES

SABAA TAHIR

Copyright (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Sabaa Tahir 2015

Published by arrangement with Razorbill, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC

Cover design and illustration by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover illustrations © Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com) (background, cat)

Maps by Jonathan Roberts

Sabaa Tahir asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007593262

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780008125073

Version: 2018-07-03

Praise for An Ember in the Ashes (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

‘Game of Thrones fans will relish Tahir’s debut set in a brutal Rome-inspired empire’ Independent

‘The writing is as smooth as silk and keeps one reading long after the lights should have been out’ Robin Hobb

‘Sabaa Tahir shows us light in darkness, hope in a world of despair, and the human spirit reaching for greatness in difficult times’ Brandon Sanderson

‘Blew me away … This book is dark, complex, vivid, and romantic – expect to be completely transported’ MTV.com (http://MTV.com)

‘Perfect for fans of … Sarah J. Maas’s Throne of Glass series … The book is already set to be a film, which will be EPIC!’ TeenVogue.com (http://TeenVogue.com)

‘A heart-pounding story of love and loss, with the most original worldbuilding I’ve read all year … I could not put it down’ Margaret Stohl

‘Tahir spins a captivating, heart-pounding fantasy’ Us Weekly

Dedication (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

For Kashi,

who taught me that my spiritis stronger than my fear

Contents

Cover (#u7bd5a8cf-6e1f-5f9d-8201-6dddcbecaa30)

Title Page (#u88ea4a59-559b-5d05-b731-c95d38c9ccd7)

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Maps (#uc608b48c-bac0-5c5d-9fcf-52176a81e239)

Part One: The Raid

Chapter One: Laia

Chapter Two: Elias

Chapter Three: Laia

Chapter Four: Elias

Chapter Five: Laia

Chapter Six: Elias

Chapter Seven: Laia

Chapter Eight: Elias

Chapter Nine: Laia

Chapter Ten: Elias

Chapter Eleven: Laia

Chapter Twelve: Elias

Chapter Thirteen: Laia

Part Two: The Trials

Chapter Fourteen: Elias

Chapter Fifteen: Laia

Chapter Sixteen: Elias

Chapter Seventeen: Laia

Chapter Eighteen: Elias

Chapter Nineteen: Laia

Chapter Twenty: Elias

Chapter Twenty-One: Laia

Chapter Twenty-Two: Elias

Chapter Twenty-Three: Laia

Chapter Twenty-Four: Elias

Chapter Twenty-Five: Laia

Chapter Twenty-Six: Elias

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Laia

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Elias

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Laia

Chapter Thirty: Elias

Chapter Thirty-One: Laia

Chapter Thirty-Two: Elias

Chapter Thirty-Three: Laia

Chapter Thirty-Four: Elias

Chapter Thirty-Five: Laia

Chapter Thirty-Six: Elias

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Laia

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Elias

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Laia

Chapter Forty: Elias

Chapter Forty-One: Laia

Chapter Forty-Two: Elias

Chapter Forty-Three: Laia

Chapter Forty-Four: Elias

Part Three: Body And Soul

Chapter Forty-Five: Laia

Chapter Forty-Six: Elias

Chapter Forty-Seven: Laia

Chapter Forty-Eight: Elias

Chapter Forty-Nine: Laia

Chapter Fifty: Elias

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

CHAPTER ONE (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

Laia (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

My big brother reaches home in the dark hours before dawn, when even ghosts take their rest. He smells of steel and coal and forge. He smells of the enemy.

He folds his scarecrow body through the window, bare feet silent on the rushes. A hot desert wind blows in after him, rustling the limp curtains. His sketchbook falls to the floor, and he nudges it under his bunk with a quick foot, as if it’s a snake.

Where have you been, Darin? In my head, I have the courage to ask the question, and Darin trusts me enough to answer. Why do you keep disappearing? Why, when Pop and Nan need you? When I need you?

Every night for almost two years, I’ve wanted to ask. Every night, I’ve lacked the courage. I have one sibling left. I don’t want him to shut me out like he has everyone else.

But tonight’s different. I know what’s in his sketchbook. I know what it means.

‘You shouldn’t be awake.’ Darin’s whisper jolts me from my thoughts. He has a cat’s sense for traps – he got it from our mother. I sit up on the bunk as he lights the lamp. No use pretending to be asleep.

‘It’s past curfew, and three patrols have gone by. I was worried.’

‘I can avoid the soldiers, Laia. Lots of practice.’ He rests his chin on my bunk and smiles Mother’s sweet, crooked smile. A familiar look – the one he gives me if I wake from a nightmare or we run out of grain. Everything will be fine, the look says.

He picks up the book on my bed. ‘Gather in the Night,’ he reads the title. ‘Spooky. What’s it about?’

‘I just started it. It’s about a jinn—’ I stop. Clever. Very clever. He likes hearing stories as much as I like telling them. ‘Forget that. Where were you? Pop had a dozen patients this morning.’

And I filled in for you because he can’t do so much alone. Which left Nan to bottle the trader’s jams by herself. Except she didn’t finish. Now the trader won’t pay us, and we’ll starve this winter, and why in the skies don’t you care?

I say these things in my head. The smile’s already dropped off Darin’s face.

‘I’m not cut out for healing,’ he says. ‘Pop knows that.’

I want to back down, but I think of Pop’s slumped shoulders this morning. I think of the sketchbook.

‘Pop and Nan depend on you. At least talk to them. It’s been months.’

I wait for him to tell me that I don’t understand. That I should leave him be. But he just shakes his head, drops down into his bunk, and closes his eyes like he can’t be bothered to reply.

‘I saw your drawings.’ The words tumble out in a rush, and Darin’s up in an instant, his face stony. ‘I wasn’t spying,’ I say. ‘One of the pages was loose. I found it when I changed the rushes this morning.’

‘Did you tell Nan and Pop? Did they see?’

‘No, but—’

‘Laia, listen.’ Ten hells, I don’t want to hear this. I don’t want to hear his excuses. ‘What you saw is dangerous,’ he says. ‘You can’t tell anyone about it. Not ever. It’s not just my life at risk. There are others—’

‘Are you working for the Empire, Darin? Are you working for the Martials?’

He is silent. I think I see the answer in his eyes, and I feel ill. My brother is a traitor to his own people? My brother is siding with the Empire?

If he hoarded grain, or sold books, or taught children to read, I’d understand. I’d be proud of him for doing the things I’m not brave enough to do. The Empire raids, jails, and kills for such ‘crimes’, but teaching a six-year-old her letters isn’t evil – not in the minds of my people, the Scholar people.

But what Darin has done is sick. It’s a betrayal.

‘The Empire killed our parents,’ I whisper. ‘Our sister.’

I want to shout at him, but I choke on the words. The Martials conquered Scholar lands five hundred years ago, and since then, they’ve done nothing but oppress and enslave us. Once, the Scholar Empire was home to the finest universities and libraries in the world. Now, most of our people can’t tell a school from an armoury.

‘How could you side with the Martials? How, Darin?’

‘It’s not what you think, Laia. I’ll explain everything, but—’

He pauses suddenly, his hand jerking up to silence me when I ask for the promised explanation. He cocks his head towards the window.

Through the thin walls, I hear Pop’s snores, Nan shifting in her sleep, a mourning dove’s croon. Familiar sounds. Home sounds.

Darin hears something else. The blood drains from his face, and dread flashes in his eyes. ‘Laia,’ he says. ‘Raid.’

‘But if you work for the Empire—’ Then why are the soldiers raiding us?

‘I’m not working for them.’ He sounds calm. Calmer than I feel. ‘Hide the sketchbook. That’s what they want. That’s what they’re here for.’

Then he’s out the door, and I’m alone. My bare legs move like cold molasses, my hands like wooden blocks. Hurry, Laia!

Usually, the Empire raids in the heat of the day. The soldiers want Scholar mothers and children to watch. They want fathers and brothers to see another man’s family enslaved. As bad as those raids are, the night raids are worse. The night raids are for when the Empire doesn’t want witnesses.

I wonder if this is real. If it’s a nightmare. It’s real, Laia. Move.

I drop the sketchbook out the window into a hedge. It’s a poor hiding place, but I have no time. Nan hobbles into my room. Her hands, so steady when she stirs vats of jam or braids my hair, flutter like frantic birds, desperate for me to move faster.

She pulls me into the hallway. Darin stands with Pop at the back door. My grandfather’s white hair is scattered as a haystack and his clothes are wrinkled, but there’s no sleep in the deep grooves of his face. He murmurs something to my brother, then hands him Nan’s largest kitchen knife. I don’t know why he bothers. Against the Serric steel of a Martial blade, the knife will only shatter.

‘You and Darin leave through the backyard,’ Nan says, her eyes darting from window to window. ‘They haven’t surrounded the house yet.’

No. No. No. ‘Nan,’ I breathe her name, stumbling when she pushes me towards Pop.

‘Hide in the east end of the Quarter—’ Her sentence ends in a choke, her eyes on the front window. Through the ragged curtains, I catch a flash of a liquid silver face. My stomach clenches.

‘A Mask,’ Nan says. ‘They’ve brought a Mask. Go, Laia. Before he gets inside.’

‘What about you? What about Pop?’

‘We’ll hold them off.’ Pop shoves me gently out the door. ‘Keep your secrets close, love. Listen to Darin. He’ll take care of you. Go.’

Darin’s lean shadow falls over me, and he grabs my hand as the door closes behind us. He slouches to blend into the warm night, moving silently across the loose sand of the backyard with a confidence I wish I felt. Although I am seventeen and old enough to control my fear, I grip his hand like it’s the only solid thing in this world.

I’m not working for them, Darin said. Then whom is he working for? Somehow, he got close enough to the forges of Serra to draw, in detail, the creation process of the Empire’s most precious asset: the unbreakable, curved scims that can cut through three men at once.

Half a millennium ago, the Scholars crumbled beneath the Martial invasion because our blades broke against their superior steel. Since then, we have learned nothing of steelcraft. The Martials hoard their secrets the way a miser hoards gold. Anyone caught near our city’s forges without good reason – Scholar or Martial – risks execution.

If Darin isn’t with the Empire, how did he get near Serra’s forges? How did the Martials find out about his sketchbook?

On the other side of the house, a fist pounds on the front door. Boots shuffle, steel clinks. I look around wildly, expecting to see the silver armour and red capes of Empire legionnaires, but the backyard is still. The fresh night air does nothing to stop the sweat rolling down my neck. Distantly, I hear the thud of drums from Blackcliff, the Mask training school. The sound sharpens my fear into a hard point stabbing at my centre. The Empire doesn’t send those silver-faced monsters on just any raid.

The pounding on the door sounds again.

‘In the name of the Empire,’ an irritated voice says, ‘I demand you open this door.’

As one, Darin and I freeze.

‘Doesn’t sound like a Mask,’ Darin whispers. Masks speak softly with words that cut through you like a scim. In the time it would take a legionnaire to knock and issue an order, a Mask would already be in the house, weapons slicing through anyone in his way.

Darin meets my eyes, and I know we’re both thinking the same thing. If the Mask isn’t with the rest of the soldiers at the front door, then where is he?

‘Don’t be afraid, Laia,’ Darin says. ‘I won’t let anything happen to you.’

I want to believe him, but my fear is a tide tugging at my ankles, pulling me under. I think of the couple that lived next door: raided, imprisoned, and sold into slavery three weeks ago. Book smugglers, the Martials said. Five days after that, one of Pop’s oldest patients, a ninety-three-year-old man who could barely walk, was executed in his own home, his throat slit from ear to ear. Resistance collaborator.

What will the soldiers do to Nan and Pop? Jail them? Enslave them?

Kill them?

We reach the back gate. Darin stands on his toes to unhook the latch when a scrape in the alley beyond stops him short. A breeze sighs past, sending a cloud of dust into the air.

Darin pushes me behind him. His knuckles are white around the knife handle as the gate swings open with a moan. A finger of terror draws a trail up my spine. I peer over my brother’s shoulder into the alley.

There is nothing out there but the quiet shifting of sand. Nothing but the occasional gust of wind and the shuttered windows of our sleeping neighbours.

I sigh in relief and step around Darin.

That’s when the Mask emerges from the darkness and walks through the gate.

CHAPTER TWO (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

Elias (#u1e49439b-f574-5054-a796-722157f0530d)

The deserter will be dead before dawn.

His tracks zigzag like a struck deer’s in the dust of Serra’s catacombs. The tunnels have done him in. The hot air is too heavy down here, the smells of death and rot too close.

The tracks are more than an hour old by the time I see them. The guards have his scent now, poor bastard. If he’s lucky, he’ll die in the chase. If not …

Don’t think about it. Hide the backpack. Get out of here.

Skulls crunch as I shove a pack loaded with food and water into a wall crypt. Helene would give me hell if she could see how I’m treating the dead. But then, if Helene finds out why I’m down here in the first place, desecration will be the least of her complaints.

She won’t find out. Not until it’s too late. Guilt pricks at me, but I shove it away. Helene’s the strongest person I know. She’ll be fine without me.

For what feels like the hundredth time, I look over my shoulder. The tunnel is quiet. The deserter led the soldiers in the opposite direction. But safety’s an illusion I know never to trust. I work quickly, piling bones back in front of the crypt to cover my trail, my senses primed for anything out of the ordinary.

One more day of this. One more day of paranoia and hiding and lying. One day until graduation. Then I’ll be free.

As I rearrange the crypt’s skulls, the hot air shifts like a bear waking from hibernation. The smells of grass and snow cut through the fetid breath of the tunnel. Two seconds is all I have to step away from the crypt and kneel, examining the ground as if there might be tracks here. Then she is at my back.

‘Elias? What are you doing down here?’

‘Didn’t you hear? There’s a deserter loose.’ I keep my attention fixed on the dusty floor. Beneath the silver mask that covers me from forehead to jaw, my face should be unreadable. But Helene Aquilla and I have been together nearly every day of the fourteen years we’ve been training at Blackcliff Military Academy; she can probably hear me thinking.

She comes around me silently, and I look up into her eyes, as blue and pale as the warm waters of the southern islands. My mask sits atop my face, separate and foreign, hiding my features as well as my emotions. But Hel’s mask clings to her like a silvery second skin, and I can see the slight furrow in her brow as she looks down at me. Relax, Elias, I tell myself. You’re just looking for a deserter.

‘He didn’t come this way,’ Hel says. She runs a hand over her hair, braided, as always, into a tight, silver-blonde crown. ‘Dex took an auxiliary company off the north watchtower and into the East Branch tunnel. You think they’ll catch him?’

Aux soldiers, though not as highly trained as legionnaires and nothing compared to Masks, are still merciless hunters. ‘Of course they’ll catch him.’ I fail to keep the bitterness out of my voice, and Helene gives me a hard look. ‘The cowardly scum,’ I add. ‘Anyway, why are you awake? You weren’t on watch this morning.’ I made sure of it.

‘Those bleeding drums.’ Helene looks around the tunnel. ‘Woke everyone up.’

The drums. Of course. Deserter, they’d thundered in the middle of the graveyard watch. All active units to the walls. Helene must have decided to join the hunt. Dex, my lieutenant, would have told her which direction I’d gone. He’d have thought nothing of it.

‘I thought the deserter might have come this way.’ I turn from my hidden pack to look down another tunnel. ‘Guess I was wrong. I should catch up to Dex.’

‘Much as I hate to admit it, you’re not usually wrong.’ Helene cocks her head and smiles at me. I feel that guilt again, wrenching as a fist to the gut. She’ll be furious when she learns what I’ve done. She’ll never forgive me. Doesn’t matter. You’ve decided. Can’t turn back now.

Hel traces the dust on the ground with a fair, practised hand. ‘I’ve never even seen this tunnel before.’

A drop of sweat crawls down my neck. I ignore it.

‘It’s hot, and it reeks,’ I say. ‘Like everything else down here.’ Come on, I want to add. But doing so would be like tattooing ‘I am up to no good’ on my forehead. I keep quiet and lean against the catacomb wall, arms crossed.

The field of battle is my temple. I mentally chant a saying my grandfather taught me the day he met me, when I was six. He insists it sharpens the mind the way a whetstone sharpens a blade. The swordpoint is my priest. The dance of death is my prayer. The killing blow is my release.

Helene peers at my blurred tracks, following them, somehow, to the crypt where I stowed my pack, to the skulls piled there. She’s suspicious, and the air between us is suddenly tense.

Damn it.

I need to distract her. As she looks between me and the crypt, I run my gaze lazily down her body. She stands two inches shy of six feet – a half-foot shorter than me. She’s the only female student at Blackcliff; in the black, close-fitting fatigues all students wear, her strong, slender form has always drawn admiring glances. Just not mine. We’ve been friends too long for that.

Come on, notice. Notice me leering and get mad about it.

When I meet her eyes, brazen as a sailor fresh into port, she opens her mouth, as if to rip into me. Then she looks back at the crypt.

If she sees the pack and guesses what I’m up to, I’m done for. She might hate doing it, but Empire law would demand she report me, and Helene’s never broken a law in her life.

‘Elias—’

I prepare my lie. Just wanted to get away for a couple of days, Hel. Needed some time to think. Didn’t want to worry you.

BOOM-BOOM-boom-BOOM.

The drums.

Without thought, I translate the disparate beats into the message they are meant to convey. Deserter caught. All students report to central courtyard immediately.

My stomach sinks. Some naïve part of me hoped the deserter would at least make it out of the city. ‘That didn’t take long,’ I say. ‘We should go.’

I make for the main tunnel. Helene follows, as I knew she would. She would stab herself in the eye before she disobeyed a direct order. Helene is a true Martial, more loyal to the Empire than to her own mother. Like any good Mask-in-training, she takes Blackcliff’s motto to heart: Duty first, unto death.

I wonder what she would say if she knew what I’d really been doing in the tunnels.

I wonder how she’d feel about my hatred for the Empire.

I wonder what she would do if she found out her best friend is planning to desert.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_32a0edd7-5b17-5e72-8077-c4e2516a0c64)

Laia (#ulink_32a0edd7-5b17-5e72-8077-c4e2516a0c64)

The Mask saunters through the gate, big hands loose at his sides. The strange metal of his namesake clings to him from forehead to jaw like silver paint, revealing every feature of his face, from the thin eyebrows to the hard angles of his cheekbones. His copper-plated armour moulds to his muscles, emphasizing the power in his body.

A passing wind billows his black cape, and he looks around the backyard like he’s arrived at a garden party. His pale eyes find me, slide up my form, and settle on my face with a reptile’s flat regard.

‘Aren’t you a pretty one,’ he says.

I yank at the ragged hem of my shift, wishing desperately for the shapeless, ankle-length skirt I wear during the day. The Mask doesn’t even twitch. Nothing in his face tells me what he’s thinking. But I can guess.

Darin steps in front of me and glances at the fence, as if gauging the time it will take to reach it.

‘I’m alone, boy.’ The Mask addresses Darin with all the emotion of a corpse. ‘The rest of the men are in your house. You can run if you like.’ He moves away from the gate. ‘But I insist you leave the girl.’

Darin raises the knife.

‘Chivalrous of you,’ the Mask says.

Then he strikes, a flash of copper and silver lightning out of an empty sky. In the time it takes me to gasp, the Mask has shoved my brother’s face into the sandy ground and pinned his writhing body with a knee. Nan’s knife falls to the dirt.

A scream erupts from me, lonely in the still summer night. Seconds later, a scimpoint pricks my throat. I didn’t even see the Mask draw the weapon.

‘Quiet,’ he says. ‘Arms up. Now get inside.’

The Mask uses one hand to yank Darin up by the neck and the other to prod me on with his scim. My brother limps, face bloodied, eyes dazed. When he struggles, a fish on a hook, the Mask tightens his grip.

The back door of the house opens, and a red-caped legionnaire comes out.

‘The house is secure, Commander.’

The Mask shoves Darin at the soldier. ‘Bind him up. He’s strong.’

Then he grabs me by the hair, twisting until I cry out.

‘Mmm.’ He bends his head to my ear, and I cringe, my terror caught in my throat. ‘I’ve always loved dark-haired girls.’

I wonder if he has a sister, a wife, a woman. But it wouldn’t matter if he did. To him, I’m not someone’s family. I’m just a thing to be subdued, used, and discarded. The Mask drags me down the hallway to the front room as casually as a hunter drags his kill. Fight, I tell myself. Fight. But as if he senses my pathetic attempts at bravery, his hand squeezes, and pain lances through my skull. I sag and let him pull me along.

Legionnaires stand shoulder-to-shoulder in the front room amid upturned furniture and broken bottles of jam. Trader won’t get anything now. So many days spent over steaming kettles, my hair and skin smelling of apricot and cinnamon. So many jars, steamed and dried, filled and sealed. Useless. All useless.

The lamps are lit, and Nan and Pop kneel in the middle of the floor, their hands bound behind their backs. The soldier holding Darin shoves him to the ground beside them.

‘Shall I tie up the girl, sir?’ Another soldier fingers the rope at his belt, but the Mask leaves me between two burly legionnaires.

‘She’s not going to cause any trouble.’ He stabs at me with those eyes. ‘Are you?’ I shake my head and shrink back, hating myself for being such a coward. I reach for my mother’s tarnished armlet, wrapped around my bicep, and touch the familiar pattern for strength. I find none. Mother would have fought. She’d have died rather than face this humiliation. But I can’t make myself move. My fear has ensnared me.

A legionnaire enters the room, his face more than a little nervous. ‘It’s not here, Commander.’

The Mask looks down at my brother. ‘Where’s the sketchbook?’

Darin stares straight ahead, silent. His breath is low and steady, and he doesn’t seem dazed anymore. In fact, he’s almost composed.

The Mask gestures, a small movement. One of the legionnaires lifts Nan by her neck and slams her frail body against a wall. Nan bites her lip, her eyes sparking blue. Darin tries to rise, but another soldier forces him down.

The Mask scoops up a shard of glass from one of the broken jars. His tongue flickers out like a snake’s as he tastes the jam.

‘Shame it’s all gone to waste.’ He caresses Nan’s face with the edge of the shard. ‘You must have been beautiful once. Such eyes.’ He turns to Darin. ‘Shall I carve them out of her?’

‘It’s outside the small bedroom window. In the hedge.’ I can’t manage more than a whisper, but the soldiers hear. The Mask nods, and one of the legionnaires disappears into the hallway. Darin doesn’t look at me, but I feel his dismay. Why did you tell me to hide it, I want to cry out. Why did you bring the cursed thing home?

The legionnaire returns with the book. For unending seconds, the only sound in the room is the rustling of pages as the Mask flips through the sketches. If the rest of the book is anything like the page I found, I know what the Mask will see: Martial knives, swords, scabbards, forges, formulas, instructions – things no Scholar should know of, let alone re-create on paper.

‘How did you get into the Weapons Quarter, boy?’ The Mask looks up from the book. ‘Has the Resistance been bribing some Plebeian drudge to sneak you in?’

I stifle a sob. Half of me is relieved Darin’s no traitor. The other half wants to rage at him for being such a fool. Association with the Scholars’ Resistance carries a death sentence.

‘I got myself in,’ my brother says. ‘The Resistance had nothing to do with it.’

‘You were seen entering the catacombs last night after curfew’ – the Mask almost sounds bored – ‘in the company of known Scholar rebels.’

‘Last night, he was home well before curfew,’ Pop speaks up, and it is strange to hear my grandfather lie. But it makes no difference. The Mask’s eyes are for my brother alone. The man doesn’t blink as he reads Darin’s face the way I’d read a book.

‘Those rebels were taken into custody today,’ the Mask says. ‘One of them gave up your name before he died. What were you doing with them?’

‘They followed me.’ Darin sounds so calm. Like he’s done this before. Like he’s not afraid at all. ‘I’d never met them before.’

‘And yet they knew of your book here. Told me all about it. How did they learn of it? What did they want from you?’

‘I don’t know.’

The Mask presses the shard of glass deep into the soft skin below Nan’s eye, and her nostrils flare. A trickle of blood traces a wrinkle down her face.

Darin draws a sharp breath, the only sign of strain. ‘They asked for my sketchbook,’ he says. ‘I said no. I swear it.’

‘And their hideout?’

‘I didn’t see. They blindfolded me. We were in the catacombs.’

‘Where in the catacombs?’

‘I didn’t see. They blindfolded me.’

The Mask eyes my brother for a long moment. I don’t know how Darin can remain unruffled beneath that gaze.

‘You’re prepared for this.’ The smallest bit of surprise creeps into the Mask’s voice. ‘Straight back. Deep breathing. Same answers to different questions. Who trained you, boy?’

When Darin doesn’t answer, the Mask shrugs. ‘A few weeks in prison will loosen your tongue.’ Nan and I exchange a frightened glance. If Darin ends up in a Martial prison, we’ll never see him again. He’ll spend weeks in interrogation, and after that they’ll either sell him as a slave or kill him.

‘He’s just a boy,’ Pop speaks slowly, as if to an angry patient. ‘Please—’

Steel flashes, and Pop drops like a stone. The Mask moves so swiftly that I don’t understand what he has done. Not until Nan rushes forward. Not until she lets out a shrill keen, a shaft of pure pain that brings me to my knees.

Pop. Skies, not Pop. A dozen vows sear themselves into my mind. I’ll never disobey again, I’ll never do anything wrong, I’ll never complain about my work, if only Pop lives.

But Nan tears her hair and screams, and if Pop was alive, he’d never let her go on like that. He wouldn’t have been able to bear it. Darin’s calm is sheared away as if by a scythe, his face blanched with a horror I feel down to my bones.

Nan stumbles to her feet and takes one tottering step towards the Mask. He reaches out to her, as if to put his hand on her shoulder. The last thing I see in my grandmother’s eyes is terror. Then the Mask’s gauntleted wrist flashes once, leaving a thin red line across Nan’s throat, a line that grows wider and redder as she falls.

Her body hits the floor with a thud, her eyes still open and shining with tears as blood pours from her neck and into the rug we knotted together last winter.

‘Sir,’ one of the legionnaires says. ‘An hour until dawn.’

‘Get the boy out of here.’ The Mask doesn’t give Nan a second glance. ‘And burn this place down.’

He turns to me then, and I wish I could fade like a shadow into the wall behind me. I wish for it harder than I’ve ever wished for anything, knowing all the while how foolish it is. The soldiers flanking me grin at each other as the Mask takes a slow step in my direction. He holds my gaze as if he can smell my fear, a cobra enthralling its prey.

No, please, no. Disappear, I want to disappear.

The Mask blinks, some foreign emotion flickering across his eyes – surprise or shock, I can’t tell. It doesn’t matter. Because in that moment, Darin leaps up from the floor. While I cowered, he loosened his bindings. His hands stretch out like claws as he lunges for the Mask’s throat. His rage lends him a lion’s strength, and for a second he is every inch our mother, honey hair glowing, eyes blazing, mouth twisted in a feral snarl.

The Mask backs into the blood pooled near Nan’s head, and Darin is on him, knocking him to the ground, raining down blows. The legionnaires stand frozen in disbelief and then come to their senses, surging forward, shouting and swearing. Darin pulls a dagger free from the Mask’s belt before the legionnaires tackle him.

‘Laia!’ my brother shouts. ‘Run—’

Don’t run, Laia. Help him. Fight.

But I think of the Mask’s cold regard, of the violence in his eyes. I’ve always loved dark-haired girls. He will rape me. Then he will kill me.

I shudder and back into the hallway. No one stops me. No one notices.

‘Laia!’ Darin cries out, sounding like I’ve never heard him. Frantic. Trapped. He told me to run, but if I screamed like that, he would come. He would never leave me. I stop.

Help him, Laia, a voice orders in my head. Move.

And another voice, more insistent, more powerful.

You can’t save him. Do what he says. Run.

Flame flickers at the edge of my vision, and I smell smoke. One of the legionnaires has started torching the house. In minutes, fire will consume it.

‘Bind him properly this time and get him into an interrogation cell.’ The Mask removes himself from the fray, rubbing his jaw. When he sees me backing down the hallway, he goes strangely still. Reluctantly, I meet his eyes, and he tilts his head.

‘Run, little girl,’ he says.

My brother is still fighting, and his screams slice right through me. I know then that I will hear them over and over again, echoing in every hour of every day until I am dead or I make it right. I know it.

And still, I run.

* * *

The cramped streets and dusty markets of the Scholars’ Quarter blur past me like the landscape of a nightmare. With each step, part of my brain shouts at me to turn around, to go back, to help Darin. With each step, it becomes less likely, until it isn’t a possibility at all, until the only word I can think is run.

The soldiers come after me, but I’ve grown up among the squat, mud-brick houses of the Quarter, and I lose my pursuers quickly.

Dawn breaks, and my panicked run turns to a stumble as I wander from alley to alley. Where do I go? What do I do? I need a plan, but I don’t know where to start. Who can offer me help or comfort? My neighbours will turn me away, fearing for their own lives. My family is dead or imprisoned. My best friend, Zara, disappeared in a raid last year, and my other friends have their own troubles.

I’m alone.

As the sun rises, I find myself in an empty building deep in the oldest part of the Quarter. The gutted structure crouches like a wounded animal amid a labyrinth of crumbling dwellings. The stench of refuse taints the air.

I huddle in the corner of the room. My hair has slipped free of its braid and lays in hopeless tangles. The red stitches along the hem of my shift are ripped, the bright yarn limp. Nan sewed those hems for my seventeenth year-fall, to brighten up my otherwise drab clothing. It was one of the few gifts she could afford.

Now she’s dead. Like Pop. Like my parents and sister, long ago.

And Darin. Taken. Dragged to an interrogation cell where the Martials will do who-knows-what to him.

Life is made of so many moments that mean nothing. Then one day, a single moment comes along to define every second that comes after. The moment Darin called out – that was such a moment. It was a test of courage, of strength. And I failed it.

Laia! Run!

Why did I listen to him? I should have stayed. I should have done something. I moan and grasp my head. I keep hearing him. Where is he now? Have they begun the interrogation? He’ll wonder what happened to me. He’ll wonder how his sister could have left him.

A flicker of furtive movement in the shadows catches my attention, and the hair on my nape rises. A rat? A crow? The shadows shift, and within them, two malevolent eyes flash. More sets of eyes join the first, baleful and slitted.

Hallucinations, I hear Pop in my head, making a diagnosis. A symptom of shock.

Hallucinations or not, the shadows look real. Their eyes glow with the fire of miniature suns, and they circle me like hyenas, growing bolder with each pass.

‘We saw,’ they hiss. ‘We know your weakness. He’ll die because of you.’

‘No,’ I whisper. But they are right, these shadows. I left Darin. I abandoned him. The fact that he told me to go doesn’t matter. How could I have been so cowardly?

I grasp my mother’s armlet, but touching it makes me feel worse. Mother would have outfoxed the Mask. Somehow, she’d have saved Darin and Nan and Pop.

Even Nan was braver than me. Nan, with her frail body and burning eyes. Her backbone of steel. Mother inherited Nan’s fire, and after her, Darin.

But not me.

Run, little girl.

The shadows inch closer, and I close my eyes against them, hoping they’ll disappear. I grasp at the thoughts ricocheting through my mind, trying to corral them.

Distantly, I hear shouts and the thud of boots. If the soldiers are still looking for me, I’m not safe here.

Maybe I should let them find me and do what they will. I abandoned my blood. I deserve punishment.

But the same instinct that urged me to escape the Mask in the first place drives me to my feet. I head into the streets, losing myself in the thickening morning crowds. A few of my fellow Scholars look twice at me, some with wariness, others with sympathy. But most don’t look at all. It makes me wonder how many times I walked right past someone in these streets who was running, someone who had just had their whole world ripped from them.

I stop to rest in an alley slick with sewage. Thick black smoke curls up from the other side of the Quarter, paling as it rises into the hot sky. My home, burning. Nan’s jams, Pop’s medicines, Darin’s drawings, my books, gone. Everything I am. Gone.

Not everything, Laia. Not Darin.

A grate squats in the centre of the alley, just a few feet away from me. Like all grates in the Quarter, it leads down into the Serra’s catacombs: home to skeletons, ghosts, rats, thieves … and possibly the Scholars’ Resistance.

Had Darin been spying for them? Had the Resistance got him into the Weapons Quarter? Despite what my brother told the Mask, it’s the only answer that makes sense. Rumour has it that the Resistance fighters have been getting bolder, recruiting not just Scholars, but Mariners, from the free country of Marinn, to the north, and Tribesmen, whose desert-territory is an Empire protectorate.

Pop and Nan never spoke of the Resistance in front of me. But late at night, I heard them murmuring of how the rebels freed Scholar prisoners while striking out at the Martials. Of how fighters raided the caravans of the Martial merchant class, the Mercators, and assassinated members of their upper class, the Illustrians. Only the rebels stand up to the Martials. Elusive as they are, they are the only weapon the Scholars have. If anyone can get near the forges, it’s them.

The Resistance, I realize, might help me. My home was raided and burned to the ground, my family killed because two of the rebels gave Darin’s name to the Empire. If I can find the Resistance and explain what happened, maybe they can help me break Darin free from prison – not just because they owe me, but because they live by Izzat, a code of honour as old as the Scholar people. The rebel leaders are the best of the Scholars, the bravest. My parents taught me that before the Empire killed them. If I ask for aid, the Resistance won’t turn me away.

I step towards the grate.

I’ve never been in Serra’s catacombs. They snake beneath the entire city, hundreds of miles of tunnels and caverns, some packed with centuries’ worth of bones. No one uses the crypts for burial anymore, and even the Empire hasn’t mapped out the catacombs entirely. If the Empire, with all its might, can’t hunt out the rebels, then how will I find them?

You won’t stop until you do. I lift the grate and stare into the black hole below. I have to go down there. I have to find the Resistance. Because if I don’t, my brother doesn’t stand a chance. If I don’t find the fighters and get them to help, I’ll never see Darin again.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_870557ce-8c25-5146-b84e-58d70d8e878f)

Elias (#ulink_870557ce-8c25-5146-b84e-58d70d8e878f)

By the time Helene and I reach Blackcliff’s belltower, nearly all of the school’s three thousand students have formed up. Dawn’s an hour away, but I don’t see a single sleepy eye. Instead, an eager buzz runs through the crowd. The last time someone deserted, the courtyard was covered in frost.

Every student knows what’s coming. I clench and unclench my fists. I don’t want to watch this. Like all Blackcliff students, I came to the school at the age of six, and in the fourteen years since, I’ve witnessed punishments thousands of times. My own back is a map of the school’s brutality. But deserters are always the worst.

My body is tight as a spring, but I flatten my gaze and keep my expression emotionless. Blackcliff’s subject masters, the Centurions, will be watching. Drawing their ire when I’m so close to escaping would be unforgivably stupid.

Helene and I walk past the youngest students, four classes of maskless Yearlings, who will have the clearest view of the carnage. The smallest are barely seven. The biggest, nearly eleven.

The Yearlings look down as we pass; we are upperclassmen, and they are forbidden from even addressing us. They stand poker-straight, scims hanging at precise 45-degree angles on their backs, boots spit-shined, faces blank as stone. By now, even the youngest Yearlings have learned Blackcliff’s most essential lessons: Obey, conform, and keep your mouth shut.

Behind the Yearlings sits an empty space in honour of Blackcliff’s second tier of students, called Fivers because so many die in their fifth year. At age eleven, the Centurions throw us out of Blackcliff and into the wilds of the Empire without clothes, food, or weaponry, to survive as best as we can for four years. The remaining Fivers return to Blackcliff, receive their masks, and spend another four years as Cadets and then two more years as Skulls. Hel and I are Senior Skulls – just completing our last year of training.

The Centurions monitor us from beneath the arches that line the courtyard, hands on their whips as they await the arrival of Blackcliff’s commandant. They stand as still as statues, their masks long since melded to their features, any semblance of emotion a distant memory.

I put a hand to my own mask, wishing I could rip it off, even for a minute. Like my classmates, I received the mask on my first day as a Cadet, when I was fourteen. Unlike the rest of the students – and much to Helene’s dismay – the smooth liquid silver hasn’t dissolved into my skin like it’s supposed to. Probably because I take the damned thing off whenever I’m alone.

I’ve hated the mask since the day an Augur – an Empire holy man – handed it to me in a velvet-lined box. I hate the way it gloms on to me like some kind of parasite. I hate the way it presses into my face, moulding itself to my skin.

I’m the only student whose mask hasn’t melded to him yet – something my enemies enjoy pointing out. But lately, the mask has started fighting back, forcing the melding process by digging tiny filaments into the back of my neck. It makes my skin crawl, makes me feel like I’m not myself anymore. Like I’ll never be myself again.

‘Veturius.’ Hel’s lanky, sandy-haired platoon lieutenant, Demetrius, calls out to me as we take our spots with the other Senior Skulls. ‘Who is it? Who’s the deserter?’

‘I don’t know. Dex and the auxes brought him in.’ I look around for my lieutenant, but he hasn’t arrived yet.

‘I hear it’s a Yearling.’ Demetrius stares at a hunk of wood poking out of the blood-browned cobbles at the base of the belltower. The whipping post. ‘An older one. A fourth-year.’

Helene and I exchange a look. Demetrius’s little brother also tried to desert in his fourth year at Blackcliff, when he was only ten. He lasted three hours outside the gates before the legionnaires brought him in to face the Commandant – longer than most.

‘Maybe it was a Skull.’ Helene scans the ranks of older students, trying to see if anyone is missing.

‘Maybe it was Marcus,’ Faris, a member of my battle platoon who towers over the rest of us, says, grinning, his blond hair popping up in an unruly cowlick. ‘Or Zak.’

No such luck. Marcus, dark-skinned and yellow-eyed, stands at the front of our ranks with his twin, Zak: second-born, shorter and lighter, but just as evil. The Snake and the Toad, Hel calls them.

Zak’s mask has yet to attach fully around his eyes, but Marcus’s clings tightly, having joined with him so completely that all of his features – even the thick slant of his eyebrows – are clearly visible beneath it. If Marcus tried to remove his mask now, he’d take off half his face with it. Which would be an improvement.

As if he senses her glance, Marcus turns and looks Helene over with a predatory gaze of ownership that makes my hands itch to strangle him.

Nothing out of the ordinary, I remind myself. Nothing to make you stand out.

I force myself to look away. Attacking Marcus in front of the entire school would definitely qualify as out of the ordinary.

Helene notices Marcus’s leer. Her hands ball into fists at her sides, but before she can teach the Snake a lesson, the sergeant-at-arms marches into the courtyard.

‘ATTENTION.’

Three thousand bodies swing forward, three thousand pairs of boots snap together, three thousand backs jerk as if yanked straight by a puppeteer’s hand. In the ensuing silence, you could hear a tear drop.

But we don’t hear the Commandant of Blackcliff Military Academy approach; we feel her, the way you feel a storm coming. She moves silently, emerging from the arches like a fair-haired jungle cat from the underbrush. She wears all black, from her tight-fitting uniform jacket to her steel-toed boots. Her blonde hair is pulled, as always, into a stiff knot at her neck.

She’s the only living female Mask – or will be until Helene graduates tomorrow. But unlike Helene, the Commandant exudes a deathly chill, as if her grey eyes and cut-glass features were carved from the underbelly of a glacier.

‘Bring the accused,’ she says.

A pair of legionnaires march out from behind the belltower, dragging a small, limp form. Beside me, Demetrius tenses. The rumours were right – the deserter’s a Fourth-Yearling, no older than ten. Blood drips down his face, blending into the collar of his black fatigues. When the soldiers dump him before the Commandant, he doesn’t move.

The Commandant’s silver face reveals nothing as she looks down at the Yearling. But her hand strays towards the spiked riding crop at her belt, fashioned out of bruise-black ironwood. She doesn’t remove it. Not yet.

‘Fourth-Yearling Falconius Barrius.’ Her voice carries, though it’s soft, almost gentle. ‘You abandoned your post at Blackcliff with no intention of returning. Explain yourself.’

‘No explanation, Commandant, sir.’ He mouths the words we’ve all said to the Commandant a hundred times, the only words you can say at Blackcliff when you’ve screwed up utterly.

It’s a trial to keep my face blank, to drive emotion from my eyes. Barrius is about to be punished for the crime I’ll be committing in less than thirty-six hours. It could be me up there in two days. Bloodied. Broken.

‘Let us ask your peers their opinion.’ The Commandant turns her gaze on us, and it’s like being blasted by a frigid mountain wind. ‘Is Yearling Barrius guilty of treason?’

‘Yes, sir!’ The shout shakes the flagstones, rabid in its ferocity.

‘Legionnaires,’ the Commandant says. ‘Take him to the post.’

The resulting roar from the students jerks Barrius out of his stupor, and as the legionnaires tie him to the whipping post, he writhes and bucks.

His fellow Fourth-Yearlings, the same boys he fought and sweated and suffered with for years, thump the flagstones with their boots and pump their fists in the air. In the row of Senior Skulls in front of me, Marcus shouts his approval, his eyes lit with unholy joy. He stares at the Commandant with a reverence reserved for deities.

I feel eyes on me. To my left, one of the Centurions is watching. Nothing out of the ordinary. I lift my fist and cheer with the rest of them, hating myself.

The Commandant draws her crop, caressing it like a lover. Then she brings it whistling down onto Barrius’s back. His gasp echoes through the courtyard, and every student falls silent, united in a shared, if brief, moment of pity. Blackcliff’s rules are so numerous that it’s impossible not to break them at least a few times. We’ve all been tied to that post before. We’ve all felt the bite of the Commandant’s crop.

The quiet doesn’t last. Barrius screams, and the students howl in response, flinging jeers at him. Marcus is loudest of all, leaning forward, practically spitting in excitement. Faris rumbles his approval. Even Demetrius manages a shout or two, his green eyes flat and distant as if he is somewhere else entirely. Beside me, Helene cheers, but there’s no joy in her expression, only a stern sadness. The rules of Blackcliff demand that she voice her anger at the deserter’s betrayal. So she does.

The Commandant seems indifferent to the clamour, fixated as she is on her work. Her arm rises and falls with a dancer’s grace. She circles Barrius as his skinny limbs begin to seize, pausing between each lash, no doubt pondering how she can make the next one more painful than the last.

After twenty-five lashes, she takes him by his limp stalk of a neck and turns him around. ‘Face them,’ she says. ‘Face the men you’ve betrayed.’

Barrius’s eyes beseech the courtyard, seeking out anyone willing to offer him a shred of pity. He should have known better. His gaze collapses to the flagstones.

The cheers continue, and the crop comes down again. And again. Barrius falls to the white stones, the pool of blood around him spreading rapidly. His eyes flutter. I hope his mind is gone. I hope he can’t feel it anymore.

I make myself watch. This is why you’re leaving, Elias. So you’re never a part of this again.

A gurgling moan trickles from Barrius’s mouth. The Commandant drops her arm, and the courtyard is silent. I see the deserter breathing. In once. Out. And then nothing. No one cheers. Dawn breaks, the sun’s rays tracing the sky above Blackcliff’s ebony belltower like bloodied fingers, tingeing everyone in the courtyard a lurid red.

The Commandant wipes her crop on Barrius’s fatigues before returning it to her belt. ‘Take him to the dunes,’ she orders the legionnaires. ‘For the scavengers.’ Then she surveys the rest of us.

‘Duty first, unto death. If you betray the Empire, you will be caught, and you will pay. Dismissed.’

The lines of students dissolve. Dex, who brought the deserter in, slips away quietly, his darkly handsome face slightly sick. Faris lumbers after, no doubt to clap Dex on the back and suggest he forget his troubles at a brothel. Demetrius stalks off alone, and I know he’s remembering that day two years ago when he was forced to watch his little brother die just like Barrius. He won’t be fit to speak with for hours. The other students drain out of the courtyard quickly, still discussing the whipping.

‘—only thirty lashes, what a weakling—’

‘—did you hear him gasping, like a scared girl—’

‘Elias.’ Helene’s voice is soft, as is the touch of her hand on my arm. ‘Come on. The Commandant will see you.’

She’s right. Everyone is walking away. I should too.

I can’t do it.

No one looks at Barrius’s bloody remains. He is a traitor. He is nothing. But someone should stay. Someone should mourn him, even if for a moment.

‘Elias,’ Helene says, urgent now. ‘Move. She’ll see you.’

‘I need a minute,’ I reply. ‘You go on.’

She wants to argue with me, but her presence is conspicuous, and I’m not budging. She leaves with a last backward glance. When she’s gone, I look up to see the Commandant watching me.

We lock eyes across the long courtyard, and I am struck for the hundredth time at how different we are. I have black hair, she has blonde. My skin glows golden brown, and hers is chalk-white. Her mouth is ever disapproving, while I look amused even when I’m not. I am broad-shouldered and well over six feet, while she is smaller than a Scholar woman, even, with a deceptively willowy form.

But anyone who sees us standing side by side can tell what she is to me. My mother gave me her high cheekbones and pale grey eyes. She gave me the ruthless instinct and speed that make me the best student Blackcliff has seen in two decades.

Mother. It’s not the right word. Mother evokes warmth and love and sweetness. Not abandonment in the Tribal desert hours after birth. Not years of silence and implacable hatred.

She’s taught me many things, this woman who bore me. Control is one of them. I tamp down my fury and disgust, emptying myself of all feeling. She frowns, a slight twist of her mouth, and raises a hand to her neck, her fingers following the whorls of a strange blue tattoo poking out of her collar.

I expect her to approach and demand to know why I’m still here, why I challenge her with my stare. She doesn’t. Instead, she watches me for a moment longer before turning and disappearing beneath the arches.

The belltower tolls six, and the drums thud. All students report to mess. At the foot of the tower, the legionnaires heave up what’s left of Barrius and carry him away.

The courtyard stands silent, empty except for me staring at a puddle of blood where a boy once stood, chilled by the knowledge that if I’m not careful, I’ll end up just like him.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_d025f260-84da-5503-b0c5-d86cd163217b)

Laia (#ulink_d025f260-84da-5503-b0c5-d86cd163217b)

The silence of the catacombs is as vast as a moonless night, and as eerie. Which isn’t to say that the tunnels are empty; as soon as I drop through the grate, a rat skitters across my bare feet, and a clear, fist-sized spider descends on a thread inches from my face. I bite my hand so I don’t scream.

Save Darin. Find the Resistance. Save Darin. Find the Resistance.

Sometimes I whisper the words. Mostly I chant them in my head. They keep me moving, a charm to ward off the fear nipping at my mind.

I’m not sure, really, what I should be looking for. A camp? A hideout? Any sign of life that isn’t rodent in nature?

Since most of the Empire’s garrisons are located east of the Scholars’ Quarter, I head west. Even in this skies-forsaken place, I can point unfailingly to where the sun rises and where it sets, to the Empire’s capital in the north, Antium, and to Navium, its main port due south. It’s a sense I’ve had for as long as I can remember. When I was a child and Serra should have seemed vast to me, I was always able to find my way.

I take heart from it – at least I won’t be wandering in circles.

For a time, sunshine trickles into the tunnels through the catacomb grates, weakly lighting the floor. I hug the crypt-pocked walls, swallowing my revulsion at the reek of rotting bones. A crypt is a good place to hide if a Martial patrol gets too close. Bones are just bones, I tell myself. A patrol will kill you.

In the daylight, it’s easier to push away my doubts and convince myself that I’ll find the Resistance. But I wander for hours, and eventually, the light fades and night falls, dropping like a curtain over my eyes. With it, fear comes rushing into my mind, a river that’s broken a dam. Every thump is a murderous aux soldier, every scritch a horde of rats. The catacombs have swallowed me as a python swallows a mouse. I shudder, knowing that I have a mouse’s chance of survival down here.

Save Darin. Find the Resistance.

Hunger gathers into a knot in my stomach, and thirst burns my throat. I spot a torch flickering in the distance, and feel a mothlike urge to head towards it. But the torches mark Empire territory, and the aux soldiers who get tunnel duty are probably Plebeians, the most lowborn of the Martials. If a group of Plebes catches me down here, I don’t want to think of what they’ll do.

I feel like a hunted, craven animal, which is exactly how the Empire sees me – how it sees all Scholars. The Emperor says that we are a free people who live under his benevolence. But that’s a joke. We can’t own property or attend schools, and even the mildest transgression results in enslavement.

No one else suffers such harshness. Tribesmen are protected under a treaty; during the invasion, they accepted Martial rule in exchange for free movement for their people. Mariners are protected by geography and the vast amounts of spices, meat, and iron they trade.

In the Empire, only Scholars are treated like trash.

Then defy the Empire, Laia, I hear Darin’s voice. Save me. Find the Resistance.

The darkness slows my footsteps until I’m practically crawling. The tunnel I’m in narrows, the walls crowding closer. Sweat pours down my back, and my whole body quakes – I hate small spaces. My breath echoes raggedly. Somewhere ahead, water falls in a lonely drip. How many ghosts haunt this place? How many vengeful spirits roam these tunnels?

Stop, Laia. No such things as ghosts. As a child, I spent hours listening to Tribal tale-spinners weave their legends of the mythical fey: the Nightbringer and his fellow jinn; ghosts, efrits, wraiths, and wights.

Sometimes the tales spilled into my nightmares. When they did, it was Darin who calmed my fears. Unlike Tribesmen, Scholars are not superstitious, and Darin has always had a Scholar’s healthy scepticism. No ghosts here, Laia. I hear his voice in my mind and close my eyes, pretending he’s beside me, allowing myself to be reassured by his steady presence. No wraiths either. There’s no such thing.

My hand goes to my armlet, as it always does when I need strength. It’s nearly black with tarnish, but I prefer it that way; it draws less attention. I trace the pattern in the silver, a series of connecting lines that I know so well I see it in my dreams.

Mother gave me the armlet the last time I saw her, when I was five. It’s one of the few clear memories I have of her – the cinnamon scent of her hair, the sparkle in her storm-sea eyes.

‘Keep it safe for me, little cricket. Just for a week. Just until I come back.’

What would she say now, if she knew I’d kept the armlet safe but lost her only son? That I’d saved my own neck and sacrificed my brother’s?

Set it right. Save Darin. Find the Resistance. I release the armlet and stumble on.

Soon after, I hear the first sounds behind me.

A whisper. The scrape of a boot on stone. If the crypts weren’t silent, I doubt I’d have noticed, the sounds are so quiet. Too quiet for an aux soldier. Too furtive for the Resistance. A Mask?

My heart thumps, and I whirl, searching the tarry blackness. Masks can prowl through darkness like this as easily as if they are part wraith. I wait, frozen, but the catacombs fall silent again. I don’t move. I don’t breathe. I hear nothing.

Rat. It’s just a rat. A really big one, maybe …

When I dare to take another step, I catch a whiff of leather and woodsmoke – human smells. I drop and search the floor with my hands for a weapon – a rock, a stick, a bone – anything to fight off whoever is stalking me. Then tinder hits flint, a hiss splits the air, and a moment later, a torch catches fire with a whoosh.

I stand, shielding my face with my hands, the impression of the flame pulsing behind my lids. When I force my eyes open, I make out a half-dozen hooded figures in a circle around me, all with loaded bows pointed at my heart.

‘Who are you?’ one of the figures says, stepping forward. Though his voice is cool and flat as a legionnaire’s, he doesn’t have the breadth and height of a Martial. His bare arms are hard with muscle, and he moves with fluid grace. A knife rests in one hand like it’s an extension of his body, and he holds the torch in his other. I try to find his eyes, but they’re hidden beneath the hood. ‘Speak.’

‘I—’ After hours of silence, I can barely manage a croak. ‘I’m looking for …’

Why didn’t I think this through? I can’t tell them I’m looking for the Resistance. No one with half a brain would admit to seeking out the rebels.

‘Check her,’ the man says when I don’t go on.

Another of the figures, slight and womanly, slings her bow on her back. The torch sputters behind her, casting her face into deep shadow. She looks too small to be a Martial, and the skin of her hands doesn’t have the dark hue of a Mariner’s. She’s probably either a Scholar or a Tribeswoman. Maybe I can reason with her.

‘Please,’ I say. ‘Let me—’

‘Shut it,’ the man who’d spoken before says. ‘Sana, anything?’

Sana. A Scholar name, short and simple. If she were Martial, her name would have been Agrippina Cassius or Chrysilla Aroman or something equally long and pompous.

But just because she’s a Scholar doesn’t mean I’m safe. I’ve heard rumours of Scholar thieves lurking in the catacombs, popping through grates to grab, raid, and usually kill whoever is nearby before dropping back into their lair.

Sana runs her hands over my legs and arms. ‘An armlet,’ she says. ‘Might be silver. I can’t tell.’

‘You’re not taking that!’ I jerk away from her, and the thieves’ bows, which had dropped a notch, come back up. ‘Please, let me go. I’m a Scholar. I’m one of you.’

‘Get it done,’ the man says. Then he signals to the rest of his band, and they begin to slip back into the tunnels.

‘Sorry about this.’ Sana sighs, but she has a dagger in her hand now. I retreat a step.

‘Don’t. Please.’ I knot my fingers together to hide their tremor. ‘It was my mother’s. It’s the only thing I have left of my family.’

Sana lowers the knife, but then the leader of the thieves calls to her and, seeing her hesitation, stalks towards us. As he does, one of his men signals to him. ‘Keenan, heads up. Aux patrol.’

‘Pair and scatter.’ Keenan lowers his torch. ‘If they follow, lead them away from base, or you’ll answer for it. Sana, get the girl’s silver and let’s go.’

‘We can’t leave her,’ Sana says. ‘They’ll find her. You know what they’ll do.’

‘Not our problem.’

Sana doesn’t move, and Keenan shoves the torch into her hands. When he takes me by the arm, Sana gets between us. ‘We need silver, yes,’ she says. ‘But not from our own people. Leave her.’

The unmistakable, clipped cadence of Martial voices carries down the tunnel. They haven’t seen the torchlight yet, but they will in just a few seconds.

‘Damn it, Sana.’ Keenan tries to go around the woman, but she shoves him away with surprising force, and her hood falls back. As the torchlight illuminates her face, I gasp. Not because she’s older than I thought or because of her fierce animosity, but because on her neck, I see a tattoo of a closed fist raised high with a flame behind it. Beneath it, the word Izzat.

‘You – you’re—’ I can’t get the words out. Keenan’s eyes fall on the tattoo, and he swears.

‘Now you’ve done it,’ he says to Sana. ‘We can’t leave her. If she tells them she saw us, they’ll flood these tunnels until they find us.’

He puts out the torch with brute swiftness and grabs my arm, pulling me after him. When I stumble into his hard back, he jerks his head around, and for a second, I catch the angry shine of his eyes. His scent, sharp and smoky, wafts over me.

‘I’m sorr—’

‘Keep quiet and watch your step.’ He’s closer than I realized, his breath warm against my ear. ‘Or I’ll knock you senseless and leave you in one of the crypts. Now move.’ I bite my lip and follow, trying to ignore his threat and instead focus on Sana’s tattoo.

Izzat. It’s Old Rei, the language spoken by Scholars before the Martials invaded and forced everyone to speak Serran. Izzat means many things. Strength, honour, pride. But in the past century, it’s come to mean something specific: freedom.

This is no band of thieves. It’s the Resistance.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_1a1b8efe-37c8-52ed-841f-c1ffabf39498)

Elias (#ulink_1a1b8efe-37c8-52ed-841f-c1ffabf39498)

Barrius’s screams blister my brain for hours. I see his body fall, hear the rasp of his last breath, smell the taint of his blood on the flagstones.

Student deaths don’t usually hit me this way. They shouldn’t – the Reaper’s an old friend. He’s walked with all of us at Blackcliff at some point. But watching Barrius die was different. For the rest of the day, I’m short-tempered and distracted.

My odd mood doesn’t go unnoticed. As I trudge to combat training with a group of other Senior Skulls, I realize Faris has just asked me a question for a third time.

‘You look like your favourite whore’s caught the pox,’ he says when I mutter an apology. ‘What the hell is wrong with you?’

‘Nothing.’ I realize too late how angry I sound, how unlike a Skull on the verge of Maskhood. I should be excited – bursting with anticipation.

Faris and Dex trade a sceptical glance, and I stifle a curse.

‘You sure?’ Dex asks. He’s a rule-follower, Dex. Always has been. Every time he looks at me, I know he’s wondering why my mask hasn’t joined with me yet. Piss off, I want to say to him. Then I remind myself that he’s not prying. He’s my friend, and he’s genuinely worried. ‘This morning,’ he says, ‘at the whipping, you were—’

‘Hey, leave the poor man be.’ Helene strolls up behind us, flashing a smile at Dex and Faris and throwing a careless arm around my shoulders as we enter the armoury. She nods at a rack of scims. ‘Go on, Elias, pick your weapon. I challenge you, best of three.’

She turns to the others and murmurs something as I walk away. I lift a blunted practice scim, checking its balance. A moment later, I feel her cool presence beside me.

‘What did you tell them?’ I ask her.

‘That your grandfather’s been hounding you.’

I nod. The best lies come from the truth. Grandfather is a Mask, and like most Masks, he’s never satisfied with anything less than perfection.

‘Thanks, Hel.’

‘You’re welcome. Repay me by pulling yourself together.’ She crosses her arms at my frown. ‘Dex is your platoon lieutenant, and you didn’t commend him after he caught a deserter. He noticed. Your entire platoon noticed. And at the whipping, you weren’t … with us.’

‘If you’re saying that I wasn’t baying for the blood of a ten-year-old, you’d be right.’

Her eyes tighten, enough for me to know that some part of her sympathizes with me, even if she’ll never admit it.

‘Marcus saw you stay behind after the whipping. He and Zak are telling everyone that you thought the punishment was too harsh.’

I shrug. As if I care what the Snake and Toad say about me.

‘Don’t be an idiot. Marcus would love to sabotage the heir to Gens Veturia a day before graduation.’ She refers to my familial house, one of the oldest and most respected in the Empire, by its formal title. ‘He’s all but accusing you of sedition.’

‘He accuses me of sedition every other week.’

‘But this time, you did something to earn it.’

My eyes jerk to hers, and for one tense moment, I think she knows everything. But there’s no anger or judgment in her expression. Only concern.

She counts off my sins on her fingers. ‘You’re squad leader of the platoon on watch, yet you don’t bring Barrius in yourself. Your lieutenant does it for you, and you don’t commend him. You barely contain your disapproval when the deserter’s punished. Not to mention the fact that it’s the day before graduation, and your mask has only just begun to meld with you.’

She waits for a response, and when I give none, she sighs.

‘Unless you’re stupider than you look, even you can see how this appears, Elias. If Marcus reports you to the Black Guard, they might have enough evidence to pay you a visit.’

A prickle of unease creeps down my neck. The Black Guard is tasked with ensuring the loyalty of the military. They wear the emblem of a bird, and their leader, once picked, gives up his name and is known simply as the Blood Shrike. He’s the right hand of the Emperor and the second most powerful man in the Empire. The current Blood Shrike has a habit of torturing first and asking questions later. A midnight visit from those black-armoured bastards will land me in the infirmary for weeks. My entire plan will be ruined.

I try not to glare at Helene. Must be nice to believe so fervently in what the Empire spoon-feeds us. Why can’t I just be like her – like everyone else? Because my mother abandoned me? Because I spent the first six years of my life with Tribesmen who taught me mercy and compassion instead of brutality and hatred? Because my playfellows were Tribeschildren, Mariners, and Scholars instead of other Illustrians?

Hel hands me a scim. ‘Fall in,’ she says. ‘Please, Elias. Just for a day. Then we’re free.’

Right. Free to report for duty as full-fledged servants of the Empire, after which we’ll lead men to their deaths in the never-ending border wars with Wildmen and Barbarians. Those of us not ordered to the border will be given city commands, where we’ll hunt down Resistance fighters or Mariner spies. We’ll be free, all right. Free to laud the Emperor. Free to rape and kill.

Funny how that doesn’t seem like freedom.

I keep quiet. Helene’s right. I’m drawing too much attention to myself, and Blackcliff is the worst place to do so. Students here are like starving sharks when it comes to sedition. One whiff of it, and they swarm.

For the rest of the day, I do my best to act like a Mask on the verge of graduation – smug, brutish, violent. It’s like covering myself in filth.

When I return to my cell-like quarters in the evening for a precious few minutes of free time, I tear off my mask and toss it on my cot, sighing when the liquid metal releases its hold.

At the sight of my reflection in the mask’s polished surface, I grimace. Even with the thick black lashes that Faris and Dex love to mock, my eyes are so much my mother’s that I hate seeing them. I don’t know who my father is, and I no longer care, but for the hundredth time, I wish that he’d at least given me his eyes.

Once I escape the Empire, it won’t matter. People will see my eyes and think Martial instead of Commandant. Plenty of Martials roam the south as merchants, mercenaries, and craftsmen. I’ll be one among hundreds.

Outside, the belltower tolls eight. Twelve hours until graduation. Thirteen until the ceremony is done. Another hour for pleasantries. Gens Veturia is a distinguished house, and Grandfather will want me to shake dozens of hands. But eventually, I’ll beg off and then …

Freedom. At last.

No student has ever deserted after graduating. Why would they? It’s the hell of Blackcliff that drives its students to run. But after we’re out, we get our own commands, our own missions. We get money, status, respect. Even the lowest-born Plebeian can marry high, if he becomes a Mask. No one with any sense would turn his back on that, especially after nearly a decade and a half of training.

Which is what makes tomorrow the perfect time to run. The two days after graduation are madness – parties, dinners, balls, banquets. If I disappear, no one will think to look for me for at least a day. They’ll assume I’ve drunk myself into a stupor at a friend’s house.

The passageway that leads from below my hearth into Serra’s catacombs pulses at the edge of my vision. It took me three months to dig out that damn tunnel. Another two months to fortify and hide it from the prying eyes of aux patrols. And two more months to map out the route through the catacombs and out of the city.

Seven months of sleepless nights and peering over my shoulder and trying to act normal. If I escape, it will all have been worth it.

The drums beat, signalling the start of the graduation banquet. Seconds later, a knock comes at my door. Ten hells. I was supposed to meet Helene outside the barracks, and I’m not even dressed yet.

Helene knocks again. ‘Elias, stop curling your eyelashes and get out here. We’re late.’

‘Hang on,’ I say. As I pull off my fatigues, the door opens and Helene marches in. A blush blooms up her neck at my undressed state, and she looks away. I raise an eyebrow. Helene has seen me naked dozens of times – when wounded, or ill, or suffering through one of the Commandant’s cruel strength-training exercises. By now, seeing me stripped shouldn’t cause her to do anything more than roll her eyes and throw me a shirt.

‘Hurry up, would you?’ She fumbles to break the silence that’s descended. I grab my dress uniform off a hook and button it on quickly, edgy at her awkwardness. ‘The guys already went ahead. Said they’d save us seats.’

Helene rubs the Blackcliff tattoo on the back of her neck – a four-sided black diamond with curved sides that is inked into every student upon arrival at the school. Helene took it better than most of our class fellows, stoic and tearless while the rest of us whimpered.

The Augurs have never explained why they only choose one girl per generation for Blackcliff. Not even to Helene. Whatever the reason, it’s clear they don’t select at random. Helene might be the only girl here, but there’s a reason she’s ranked third in our class. It’s the same reason that bullies learned early on to leave her alone. She’s clever, swift, and ruthless.

Now, in her black uniform, with her shining braid encircling her head like a crown, she’s as beautiful as winter’s first snow. I watch her long fingers at her nape, watch her lick her lips. I wonder what it would be like to kiss that mouth, to push her to the window and press my body against hers, to pull out the pins in her hair, to feel its softness between my fingers.

‘Uh … Elias?’

‘Hmm …’ I realize I’ve been staring and snap out of it. Fantasizing about your best friend, Elias. Pathetic. ‘Sorry. Just … tired. Let’s go.’

Hel gives me a strange look and nods at my mask, still sitting on the bed. ‘You might need that.’

‘Right.’ Appearing without one’s mask is a whipping offence. I haven’t seen any Skull maskless since we were fourteen. Other than Hel, none of them have seen my face, either.

I put the mask on, trying not to shudder at the eagerness with which it attaches to me. One day left. Then I’ll take it off forever.

The sunset drums thunder as we emerge from the barracks. The blue sky deepens to violet, and the searing desert air cools. Evening’s shadows blend with the dark stones of Blackcliff, making the blockish buildings appear unnaturally large. My eyes rove the shadows, seeking out threats, a habit from my years as a Fiver. I feel, for an instant, as if the shadows are looking back at me. But then the sensation fades.

‘Do you think the Augurs will attend graduation?’ Hel asks.

No, I want to say. Our holy men have better things to do, like locking themselves up in caves and reading sheep entrails.

‘Doubt it,’ is all I say.

‘I guess it would get tedious after five hundred years.’ Helene says this without a trace of irony, and I wince at the sheer idiocy of the idea. How can someone as intelligent as Helene actually think the Augurs are immortal?

But then, she’s not the only one. Martials believe that the Augurs’ ‘power’ comes from being possessed by the spirits of the dead. Masks, in particular, revere the Augurs, for it is the Augurs who decide which Martial children will attend Blackcliff. It is the Augurs who give us our masks. And we’re taught that it was the Augurs who raised Blackcliff in a single day, five centuries ago.

There are only fourteen of the red-eyed bastards, but on the rare occasions that they appear, everyone defers to them. Many of the Empire’s leaders – generals, the Blood Shrike, even the Emperor – make a yearly pilgrimage to the Augurs’ mountain lair, seeking counsel on matters of state. And though it’s clear to anyone with an ounce of logic that they are a pack of charlatans, they’re lionized throughout the Empire not just as immortal, but as oracles and mind-readers.

Most Blackcliff students only see the Augurs twice in our lives: when we’re chosen for Blackcliff and when we’re given our masks. But Helene has always had a particular fascination with the holy men – it’s no surprise that she hoped they’d come to graduation.

I respect Helene, but on this, we don’t agree. Martial myths are as believable as Tribal fables of jinn and the Nightbringer.

Grandfather is one of the few Masks who doesn’t believe in Augur rubbish, and I repeat his mantra in my head. The field of battle is my temple. The swordpoint is my priest. The dance of death is my prayer. The killing blow is my release. The mantra is all I’ve ever needed.

It takes all my control to hold my tongue. Helene notices.

‘Elias,’ she says. ‘I’m proud of you.’ Her tone is strangely formal. ‘I know you’ve struggled. Your mother …’ She glances around and drops her voice. The Commandant has spies everywhere. ‘Your mother’s been harder on you than on any of the rest of us. But you showed her. You worked hard. You did everything right.’

Her voice is so sincere that for a moment, I waver. In two days, she won’t think such things. In two days, she will hate me.

Remember Barrius. Remember what you’ll be expected to do after graduation.

I jostle her shoulder. ‘Are you turning sappy and girly on me?’

‘Forget it, swine.’ She punches me on the arm. ‘I was just trying to be nice.’

My laugh is falsely hearty. They’ll send you to hunt me down when I run. You and the others, the men I call brothers.

We reach the mess hall, and the cacophony within hits us like a wave – laughter and boasts and the raucous talk of three thousand young men on the verge of leave or graduation. It’s never this loud when the Commandant is in attendance, and I relax marginally, glad to avoid her.