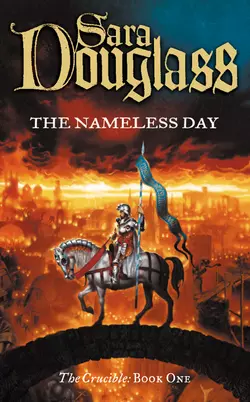

The Nameless Day

Sara Douglass

The first book of The Crucible, an exciting historical fantasy from the author of the popular Axis triology.The Nameless Day is, according to the ancient pagan calendar of Europe, the one day of the year when the world of mankind and the enigmatic world of the spirits touch. Mid-century the forces of evil slide across the divide and invade Europe.The Church sends Thomas Neville, an English nobleman, on a secret mission through the shadowy forests and arcane religious orders of Europe to discover the extent of the danger. But not even Neville, a priest, is prepared when the horror of the Black Death sweeps across Europe.The forces of the Church and God rally against the infiltration of the Devil’s minions. The battle has begun.

The Nameless Day

Sara Douglass

The Crucible: Book One

In memory of my most devoted fan,

MICHAEL GODWIN

10th September 1981 – 16th March 1998

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ue9645e5a-edf0-58d2-9fb5-7a7cf213cb53)

Title Page (#u8e284c20-3536-517d-b2aa-c7831395043e)

Author’s Note (#u7ee022f9-18ca-5e27-af1f-c1909dab7c88)

Prologue (#u4e4c9977-fdd8-5749-8cd4-699aa92c0265)

ROME (#u3d714bab-96d0-57c9-89f7-404c252a0d9c)

I (#u36c8a7ad-8f5c-54ec-ba55-c99c4fea5e77)

II (#u691f2ba0-172a-5239-bb17-e9935fd5a1d2)

III (#uc6cb4f7e-c63d-538b-9074-c61551dee968)

IV (#ue1d94e9c-806d-5367-82ce-52da20130d54)

V (#u93eafd7d-5bd6-5bab-a76f-364ad65dd8cb)

VI (#uad6cbc8b-26bb-55e8-bb8c-5f526912c3f2)

VII (#u9084d65a-8f61-58b5-9835-1da02bd9895a)

VIII (#u9428ec64-810d-5b1f-bce5-fac724fcc031)

IX (#ua9d6bbda-7818-5543-a0dc-db1e8cb72b2f)

GERMANY (#ub4b977d0-9b7f-53f7-88a3-ce317e92fbaa)

I (#u351aa1fa-e1cd-50e9-aeb6-df172bb888e7)

II (#u1fa43d87-5925-5650-b83b-65ee0027be5d)

III (#u8cc14d8f-cda4-53f5-b672-b32a9e46adac)

IV (#litres_trial_promo)

V (#litres_trial_promo)

VI (#litres_trial_promo)

VII (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

FRANCE (#litres_trial_promo)

I (#litres_trial_promo)

II (#litres_trial_promo)

III (#litres_trial_promo)

IV (#litres_trial_promo)

V (#litres_trial_promo)

VI (#litres_trial_promo)

VII (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

IX (#litres_trial_promo)

X (#litres_trial_promo)

XI (#litres_trial_promo)

XII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

XV (#litres_trial_promo)

XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

XX (#litres_trial_promo)

XXI (#litres_trial_promo)

XXII (#litres_trial_promo)

ENGLAND (#litres_trial_promo)

I (#litres_trial_promo)

II (#litres_trial_promo)

III (#litres_trial_promo)

IV (#litres_trial_promo)

V (#litres_trial_promo)

VI (#litres_trial_promo)

VII (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

IX (#litres_trial_promo)

X (#litres_trial_promo)

XI (#litres_trial_promo)

XII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

XV (#litres_trial_promo)

XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

XX (#litres_trial_promo)

XXI (#litres_trial_promo)

XXII (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIV (#litres_trial_promo)

XXV (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

A JIGGE (FOR MARGRETT) (#litres_trial_promo)

A JIGGE (FOR MARGRETT) (MODERNISED VERSION) (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Sara Douglass (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#ulink_2870488a-c515-5d17-8614-6273bfd14496)

Time travel is not only theoretically possible, travel into our future has already been achieved (albeit on a tiny scale of a few seconds or minutes). Travel into our past is more problematic. How would interfering with our past affect our present? Some physicists argue that sending someone into the past creates a “parallel universe”—the mere presence of someone in a past time alters that world’s future to such an extent that a different future is necessarily created: a parallel universe (or world) to the one we live in.

The three books of “The Crucible” are set, not in the medieval Europe of our past, but in the medieval Europe of a parallel universe: the insertion of even one fictional character amongst a host of historical characters necessarily creates that parallel world. Thus, while there are many similarities between our past and the world of “The Crucible”, there are also many differences. The entire period of the Hundred Years War, for example, has been compressed so that the Battle of Poitiers is fought at a later date than in our past, and Joan of Arc appears at an earlier date.

Although some dates and “facts” have altered, the spirit of “The Crucible” remains identical to that of our medieval Europe. Something strange happened in the fourteenth century…something very, very odd. The fourteenth century was an age of unprecedented catastrophe for western Europe: widespread famine due to climate change, economic collapse, uncontrollable heresies, social upheaval, endemic war and, to compound the misery, the physical and psychological devastation of the Black Death. In all of recorded history there has never been before or since a period of such utter disaster: one half of Europe’s population died due to the effects of famine, war and the Black Death. As a result, Europeans emerged from the fourteenth century profoundly—and frighteningly—changed. Medieval Europe had been an intensely spiritual society: the salvation of the soul was paramount. Post-fourteenth century Europe abandoned spirituality for secularism, materialism and worldliness. Its peoples embraced technology and science, and developed the most aggressively invasive mentality of world history. Why this profound shift from the internal quest for spiritual salvation to a craving for world domination? Was it just the end result of over a hundred years of catastrophe…or was there another reason?

“The Crucible” presents an explanation couched in a medieval understanding of the world rather than in terms more familiar to our modern sensibilities. Medieval Europe was a world of evil incarnate, a world where demons and angels walked the same fields as men and women; a world where the armies of God and of Satan arrayed themselves for the final battle…we now live in the aftermath of that battle, but are we sure who won?

Sara Douglass

Bendigo, 2000

Prologue (#ulink_aab1a596-a5b2-5cf1-aa77-4efaf809d091)

The Friday within the Octave of All Saints

to the Nameless Day

In the twenty-first year of the reign of Edward III

(7th November to Tuesday 23rd December 1348)

—St Angelo’s Friary, Rome—

“Brother Wynkyn? Brother Wynkyn? Sweet Jesu, Brother, you’re not going to leave us now?”

Brother Wynkyn de Worde slapped shut the weighty manuscript book before him and turned to face Prior Bertrand. “I have no choice, Bertrand. I must leave.”

Bertrand took a deep breath. Sweet Saviour, how could he possibly dissuade Brother Wynkyn?

“My friend,” he said, earning himself a sarcastic glance from Wynkyn. “Brother Wynkyn…the pestilence rages across Christendom. If you leave the safety of Saint Angelo’s—”

“What safety? Of the seventeen brothers who prayed here five weeks ago, now there is only you and me and two others left. Besides, if I choose to hide within these ‘safe’ walls a far worse pestilence will ravage Christendom than that which currently rages. I must go. Get out of my way.”

“Brother, the roads are choked with the dying and the brigands who pick their pockets and pluck the rings from their fingers.” Prior Bertrand moderated his voice, trying to reason with the old man. Brother Wynkyn had ever been difficult. Bertrand knew that Wynkyn had even shouted down the Holy Father once, and Bertrand realised there was no circumstance in which he could hope for respect from someone who was powerful enough to cow a pope. “How can you possibly overcome all the difficulties and the dangers roaming the roads between here and Nuremberg? Stay, I beg you.”

“I would condemn the earth to a slow descent into insanity if I stayed here.” Wynkyn lowered the book—he needed both arms to lift it—and several loose pages of closely-written script into a flat-lidded oaken casket bound with brass. It was only just large enough to take the book and the pages. Once he had shut the casket, Wynkyn locked it with a key that hung from a chain on his belt.

Bertrand watched wordlessly for some minutes, and then tried again. “And if you die on the road?”

Wynkyn shot his prior an angry glance. “I will not die on the road! God and the angels protect me and my purpose.”

“As they have protected all the other innocent souls who have died in the past weeks and months? Wynkyn, nothing protects mankind against the evil of this pestilence!”

Wynkyn carefully checked the casket to ensure its security. He turned his back to Bertrand.

“Rome is dying,” Bertrand said, his voice now soft. “Corpses lie six deep in the streets, and the black, bubbling pestilence seeks new victims on every breath of wind. God has shown us the face of wrath for our sins, and the angels have fled. If you leave the friary now you will surely die.”

Still Wynkyn did not answer.

“Brother,” Bertrand said, desperation now filling his voice. “Why must you leave? What is of such importance that you must risk almost certain death?”

Wynkyn turned about and locked eyes with the prior. “Because if I don’t leave, then it is almost certain death for Christendom,” he said. “Either get out of my way, Bertrand, or aid me to carry this casket to my mule.”

Bertrand’s eyes filled with tears. He made a hopeless gesture with his hand, but Wynkyn’s gaze did not waver.

“Well?” Wynkyn said.

Bertrand took a deep, sobbing breath, and then grasped a handle of the casket. “I wish peace walk with you, Wynkyn.”

“Peace has never walked with me,” Wynkyn said as he grabbed the other handle. “And it never will.”

Wynkyn de Worde had undertaken the journey between Rome and Nuremberg over one hundred times in the past fifty or so years, but never had he done so before with such a heavy heart. He had been twenty-three in 1296 when the then pope, the great Boniface VIII, had sent him north for the first time.

Twenty-three, and entrusted with a secret so horrifying, that it, and the nightmarish responsibility it carried with it, would have killed most other men. But Wynkyn was a special man, strong and dedicated, sure of the right of God, and with a faith so unshakeable that Boniface understood why the angels had selected him as the man fit to oversee the Cleft.

“Reveal this secret to any other man,” Boniface had told the young Dominican, “and you can be sure that the angels themselves will ensure your death.”

Already privy to the ghastly secret, Wynkyn knew truth when he heard it.

Boniface had leaned back in his chair, satisfied. Since the beginnings of the office of the pope in the Dark Ages, its incumbents kept the secret of the Cleft, entrusting it only to the single priest the angels had said was strong enough to endure. As this priest approached the end of his life, the angels gave the pope the name of a new priest, young and strong, and this young priest would accompany the older priest on the man’s final few journeys to the Cleft. From the older, dying priest the younger one learned the incantations that he would need…and he also learned the true meaning of courage, for without it he would not endure.

These priests, the Select, spent their lives teetering on the edge of hell.

In 1298 Boniface informed Wynkyn de Worde that he was the angels’ choice as the new Select. Then, having learned from his predecessor, Wynkyn performed his duty willingly and without mishap for five years. He thought his life would take the same path as the scores of priests who had preceded him…but he, like the angels, had underestimated the power and cunning of pure evil.

Who could have thought the papacy could fail so badly? Wynkyn had not anticipated it; the angels certainly had not. In 1303 the great and revered Pope Boniface VIII died, and Wynkyn had no way of knowing that the forces of darkness and disorder would seize this opportunity to throw the papacy into chaos. In the subsequent papal election a man called Clement V took the papal throne. Outwardly pious, it quickly became apparent to Wynkyn, as to everyone else, that Clement was the puppet of the French king, Philip IV. The new pope moved the papacy to the French-controlled town of Avignon, allowing Philip to dictate the papacy’s activities and edicts. There, successive popes lived in luxury and corruption, mouthing the orders of French kings instead of the will of God.

When a new pope was enthroned, either the first among archangels, St Michael, or the current Select revealed to him the secret of the Cleft, but neither St Michael nor Wynkyn approached Clement. How could they allow the fearful secrets of the angels to fall into the hands of the French monarchy? Sweet Jesu, Wynkyn had thought as he spent sleepless nights wondering what to do, a French king could seize control of the world had he this knowledge in hand! He could command an army so vile that even the angels of God would quail before it.

So both Wynkyn and the angels kept the secret against the day that the popes rediscovered God and moved themselves and the papacy back to Rome. After all, surely it could not be long? Could it?

But the seductiveness of evil was stronger than Wynkyn and the angels had anticipated. When Clement V died, the pope who succeeded him also preferred the French monarch’s bribes and the sweet air of Avignon to the word of God and the best interests of His Church on earth. And so also the pope after that one…

Every year Wynkyn travelled north to the Cleft in time for the summer and winter solstices, and then travelled back to Rome to await his next journey; he could not bear to live his entire life at the Cleft, although he knew some of his predecessors, stronger men than he, had done so.

He received income enough from what Boniface had left at his disposal to continue his work, and the prior and brothers of his friary, St Angelo’s, were too in awe of him to inquire closely into his movements and activities.

Brother Wynkyn de Worde also had the angels to assist his work. As they should, for their lusts had necessitated the Cleft.

But now here Wynkyn was, an ancient man in his mid-seventies, and it seemed that the popes would never return to Rome. God’s wrath had boiled over, showering Europe with a pestilence such as it had never previously endured. Wynkyn had always travelled north with a heavy heart—his mission could engender no less in any man—but this night, as he carefully led his mule through the dead and dying littering the streets of Rome, he felt his soul shudder under the weight of his despair.

He was deeply afraid, not only for what he knew he would find awaiting him at the Cleft, but because he did fear he might die…and then who would follow him? Who would there be to tend the Cleft?

“I should have told,” he muttered. But who was there to tell? Who to confide in? The popes were dissolute and corrupt, and there was no one else. No one.

Who else was there?

God and the angels had relied on the papacy, and now the popes had betrayed God Himself for a chest full of gold coin from the French king.

Damn the angels! If it wasn’t for their sins in the first instance…

It took Wynkyn almost seven weeks to reach Nuremberg; that he even reached the city at all he thanked God’s benevolence.

Every town, every hamlet, every cottage he’d passed had been in the grip of the black pestilence. Hands reached out from windows, doorways and gutters, begging the passing friar for succour, for prayers, or, at the least, for the last rites, but Wynkyn had ignored them.

They were all sinners, for why else had God’s wrath struck them, and Wynkyn was consumed by his need to get north as fast as he could.

Far worse than the outstretched hands of the dying were the grasping hands of the bandits and outlaws who thronged the roadways and passes. But Wynkyn was sly—God’s good gift—and whenever the bandits saw that Wynkyn clasped a cloth to his mouth, and heard the desperate racking of his cough, they backed away, making the sign of the cross.

Yet even Wynkyn could not remain immune to the grasping fingers of the pestilence forever. Not at his age.

On Ember Saturday Wynkyn de Worde had approached a small village two days from Nuremberg. By the roadside lay a huddle of men and women, dying from the plague. One of them, a woman—God’s curse to earth!—had risen to her feet and stumbled towards the friar riding by, but as she leaned on his mule’s shoulder, begging for aid, Wynkyn kicked her roughly away.

It was too late. Unbeknown to the friar, as he extended his hand to ward her off the deadly kiss of the pestilence sprang from her mouth to his hand during the virulence of her pleas. He planted his foot in the hateful woman’s chest, and when he raised his hand to his face to make the sign of the cross the pestilence leaped unseen from his hand to his mouth.

The deed was done, and there was nothing the angels could do but moan.

The peal of mourning bells covered Nuremberg in a melancholy pall; even this great northern trading city had not escaped the ravages of the pestilence. The only reason Wynkyn managed access through the gates was that the town desperately needed men licensed by God to administer the last rites to the mass of dying. But Wynkyn did not pause to administer the last rites to anyone. He made his way to the Dominican friary in the eastern quarter of the city, his mule stumbling with weakness from his journey, and demanded audience with the prior.

The friary had been struck as badly by the pestilence as had Nuremberg itself, and the brother who met Wynkyn at the friary gate informed him that the prior had died these three nights past.

“Brother Guillaume now speaks with the prior’s voice,” the brother said.

Wynkyn showed no emotion—death no longer surprised nor distressed him—and requested that the friar take him to Brother Guillaume. “And help me carry this casket, brother, for I am passing weary.”

The brother nodded. He knew Wynkyn well.

Brother Guillaume greeted Wynkyn with ill-disguised distaste and impatience. He had never liked this autocratic friar from Rome, and neither he nor any other friar in his disease-ridden community could spare the time to attend Wynkyn’s demands.

“A meal only,” Wynkyn said, noting Guillaume’s reaction, “and a request.”

“And that is?”

Wynkyn nodded towards the casket. “I leave in the morning for the forest north of the city. If I should not return within a week, I request that you send that casket—unopened—to my home friary.”

Guillaume raised his eyebrows in surprise. “Your home friary? But, Brother Wynkyn, that would surely be impossible!”

“Easily enough accomplished!” Wynkyn snapped, and Guillaume flinched at the brother’s sudden anger. “There are sufficient merchant bands travelling through Nuremberg who could take the casket on for a suitable price.”

Wynkyn reached inside his habit and pulled out a small purse he had bound about his waist. “Take these gold pieces. It will be enough and more to pay for the casket’s journey.”

“But…but this pestilence has stopped all traffic, and—”

“For the love of God, Guillaume, do as I say!”

Guillaume stared, shaken by Wynkyn’s distress.

“Surely the pestilence will pass eventually, and when it does, the merchants will resume their trade, as they always do. Please, do as I ask.”

“Very well then.” Guillaume indicated a stool, and Wynkyn sat down. “But surely you will return. You have always done so before.”

Wynkyn sighed, and rubbed his face with a trembling hand. “Perhaps.”

And perhaps not, Guillaume thought, as he recognised the feverish glint in the old brother’s eyes, and the unhealthy glow in his cheeks.

Guillaume backed away a few steps. “I will send a brother with food and ale,” he said, and scurried for the door.

“Thank you,” Wynkyn said to the empty air.

That night Wynkyn sat in a cold cell by the open casket, his hand on the closed book on his lap. Because there was no one else, Wynkyn carefully explained to the book the disaster that had befallen mankind generally, and the Keeper of the Cleft specifically. The popes had abandoned the directions of God and the angels for the directions of the French king. They did not know the secrets and mysteries of the Cleft or of the book itself, for neither angels nor Wynkyn dared reveal it to them. Through his ignorance, the current pope—Clement VI—had not selected the man to follow Wynkyn.

And a woman—a woman!—had passed the pestilence to Wynkyn!

In the past few hours, as he sat in his icy cell shaking with fever, Wynkyn had refused to come to terms with the fact that he was dying. There was no one to follow him; thus how could he die?

How could he die, when that would mean the demons would run free?

In his decades of service to God and the angels, Wynkyn had never come this close to despair: not when he had first heard of his mission; not even when he had seen what awaited him at the Cleft.

Not even when the first demon he encountered had turned and spoken his name and pleaded for its life.

But now…now, this silent misery in a cold and comfortless friary cell…this was despair.

Wynkyn lowered his head and wept, a hand still on the closed book, his shoulders shaking with both his grief and his fever.

Peace.

At first Wynkyn did not respond, then, when the heavenly voice repeated itself, he slowly raised his face.

Two arm spans away the far wall of the cell glowed. Most of the light was concentrated in the centre of the wall in the vague form of a winged man, his arms outstretched.

As Wynkyn watched, round-eyed with wonder, the archangel, still only a vague glowing outline, stepped from the wall and placed his hands about Wynkyn’s upturned face.

Peace, Brother Wynkyn.

“Blessed Saint Michael!” Wynkyn would have fallen to his knees, but the pressure of the archangel’s hands kept him in his seat.

The archangel very slightly increased the pressure of his hands, and love and joy flowed into Wynkyn’s being.

“Blessed Saint Michael,” Wynkyn whispered, his eyes watering from the archangel’s glow. He blinked his tears away. “I am dying—”

For an instant, an instant so fleeting he knew he must have imagined it, Wynkyn thought he felt rage sweep through the archangel.

But then it was gone, as if it had never been.

“—and there is none to follow me. Saint Michael, what can we do?”

There is not one named, Wynkyn, but that does not mean one can never be. We shall have to make one, you and I and the full majesty of my brothers.

“Saint Michael?”

Take up that book you hold, and fold back the pages to the final leaf.

Slowly, Wynkyn did as the archangel asked.

He gasped. The book revealed an incantation he had never seen before…and how many years had he spent examining every scratch within its pages?

With our heavenly power and your voice, we can between us forge your successor.

Wynkyn quickly scanned the incantation. He frowned a little as its meaning sank in. “But it will take years, and in the meantime—”

Trust. Are you ready?

Wynkyn took a deep breath, fighting back the urge to cough as he did so. “Aye, my lord. I am ready.”

The glow increased about the archangel, and as it did, Wynkyn saw with the angel’s eyes.

Images flooded chaotically before him: bodies writhing and plunging, lost in the evils of lust, the thoughts of the flesh triumphing over the meditations of the soul.

Horrible sinners all! Where are they who do not sin…ah! There! There!

Wynkyn blinked. There a man who lowered himself reluctantly to his wife’s body, and his wife, most blessed of women, who turned her face aside in abhorrence and who closed her eyes against the repugnant thrusting of her husband. This was not an act of lust, but of duty. This was a husband and a wife who endured the unbearable for only one reason: the engendering of a child.

God’s child indeed. Speak, Wynkyn, speak the incantation now!

He hesitated, because as St Michael voiced his command, Wynkyn realised that the cell—impossibly—was crowded with all the angels of heaven. About the friar thronged a myriad glowing forms, their faces intense and raging and their eyes so full of furious power that Wynkyn wondered that the walls of the friary did not explode in fear.

Speak! St Michael commanded, and the cell filled with the celestial cry of the angels: Speak! Speak! Speak!

Wynkyn spoke, his feverish tongue fumbling over some of the words, but that did not matter, because even as he fumbled, he felt the power of the incantation and the power of all the angels flood creation.

St Michael lifted his hands from Wynkyn’s face and shrieked, and with him shrieked the heavenly host.

The man shrieked also, his movements now most horrid and vile. His wife screamed and tried desperately to push away her husband.

But it was too late.

Far, far too late.

Wynkyn’s successor had been conceived.

The friar blinked. The archangel and his companions had gone, as had the incantation on the page before him.

He was alone again in his cell, and all that was left was to die.

Or, perhaps, to try and perform his duty one last time.

Wynkyn set out the next morning just after Matins, shivering in the cold, dawn air. It lacked but a few days until the Nativity of the Lord Jesus Christ—although Wynkyn doubted there would be much joy and celebration this year—and winter had central Europe in a tight grip.

He coughed and spat out a wad of pus- and blood-stained phlegm.

“I will live yet,” Wynkyn murmured. “Just a few more days.”

And he grasped his staff the tighter and shuffled onto the almost deserted road beyond the city’s northern gate.

It had not been shut the previous night. No doubt the gatekeeper’s corpse lay swelling with the gases of putrefaction somewhere within the gatehouse.

The wind was bitter beyond the shelter of the streets and walls, and Wynkyn had to wrap his cloak tightly about himself. Even so, he could not escape the bone-chilling cold, and he shivered violently as he forced one foot after the other on the deserted road.

“Pray to God I have the time,” he whispered, and for the next several hours, until the sun was well above the horizon, he muttered prayer after prayer, using them not only for protection against the devilry in the air, but also as an aid in his journey.

If he concentrated on the prayers, then he might not notice the crippling cold.

Even the sun rising towards noon did not warm the air, nor impart any cheer to the surrounding countryside.

The fields were deserted, ploughs standing bogged in frozen earth, and the doors of abandoned hovels creaked to and fro in the wind.

There was no evidence of life at all: no men, no women, no dogs, no birds.

Just a barren and dead landscape.

“Devilry, devilry,” Wynkyn muttered between prayers. “Devilry, devilry!”

By mid-afternoon Wynkyn was aching in every joint, and shaking with fatigue. His cough had worsened, and pain hammered with insistent and cruel fists behind his forehead.

“I am so old,” he whispered, halting for a rest beneath a twisted tree stripped bare of all its leaves. “Too old for this. Too old.”

A fit of coughing made the friar double over in agony, and when Wynkyn raised himself and wiped bleary tears from his eyes, he only stared in resignation at what he saw glistening on the ground between his feet.

No phlegm at all now. Just blood…and thick yellow pus.

An hour before dusk, almost frozen yet still shaking with fever, Wynkyn turned onto an all but hidden small track that led north-east. Stands of shadowed trees had sprung up to either side of the road in the last mile, and the track led deeper into the woods.

The trees had been stripped of leaves by the winter cold, and moisture and fungus crept along their black branches and hung down from knobbly twigs. Boulders reared out of the moss-covered ground, tilting trees on sharp angles. Cold air eddied between trees and boulders, carrying with it a thin fog that tangled among the treetops.

No one ever ventured into these forbidding woods. Not only was their very appearance more than dismal, but legend had it that demons and sprites lingered among the trees, as did goblins among the rocks, all more than ready to snatch any foolish souls who ventured into their domain.

Wynkyn would have chuckled if he had had the energy. For hundreds of years the Church had cautioned people away from these woods with their tales of red-eyed demons. Red-eyed demons there were none, but Wynkyn knew the reality was worse than the stories.

These woods nurtured the Cleft.

He struggled along the track, stopping every ten or twelve steps to lean against the trunk of a tree and cough.

Wynkyn knew he was dying, and now the only question left in his mind was whether or not he could open the Cleft and dispose of this year’s crop of horror before he commended his soul to God.

After another mile the ground began to rise to either side of the path. Yet another half mile and Wynkyn, his legs so weak he had to lean heavily on a staff to keep upright, found himself at the mouth of a gorge. The hills to either side were not over tall—perhaps some six or seven hundred feet—but the gorge floor dropped down into…well, into hell itself.

This was the Cleft, the earth’s vile equivalent of the suppurating cleft that lay between the legs of every daughter of Eve.

Wynkyn began to laugh, a harsh yet whispery sound. As loathsomeness would be sunk into the cleft of every one of the daughters of Eve, so he, Wynkyn de Worde, would see to it that loathsomeness would be sunk into this Cleft.

Every cleft led to hell, one way or the other.

Wynkyn’s laughter turned into an agonising, wet, bubbling cough, and he sank to his knees and would have fallen completely had it not been for his grip on his staff. The pestilence had run riot in his lungs, and now Wynkyn was very close to drowning in his own pus and blood.

Time was passing too fast. He did not have long.

Praise God he knew the incantations by heart!

Wynkyn forced himself to raise his head. He spat out an amount of pus, hawked, spat again, then wiped his mouth with a shaking arm.

It was time.

Slowly he spoke the words, his eyes fixed on the Cleft.

When he finished, it first appeared that nothing had changed. The gorge spread before him in the twilight, a twisted wasteland of boulders and shadows and the hunched shapes of low, scrubby bushes.

But in an instant all altered. Flames licked out from behind boulders, and vegetation burst into fire. There was a roaring, rending sound, and clouds of sulphuric effluvium billowed into the air.

Wails and screams, and even the thin, white, despairing arms of those trapped within, rose and fell from the gate to hell.

Wynkyn chuckled. The Cleft had opened.

But his work was not yet done. He turned slightly so that he could see the path behind him.

“Come,” he said, and clicked his fingers. “Come.”

There was a momentary stillness, then from the forest lining the path walked forth children, perhaps some thirty or thirty-five, all between the ages of two and six.

Not one of them was human and all were horribly deformed; the twistings of their bodies reflecting the twistings of their souls.

Wynkyn bared his teeth. They were abominable! Devilish! And to the Devil they must be sent.

He lifted his hand, trying to control its shaking, and began to speak the incantation that would force them down into—

A convulsion racked his body, and his voice wavered and stilled.

Another convulsion swept over him, and Wynkyn de Worde collapsed to the ground.

One of the children, a boy of about six, stepped forth to within a few paces of the friar.

Wynkyn rolled over slightly, his face contorted, and began to whisper again.

The boy smiled.

Wynkyn’s voice bubbled to a close. He lifted a hand trying desperately to conjure words out of air, but nothing came of it, and his hand fell back to the ground, failing him as badly as his voice.

“You’re dying,” said the boy, his voice a mixture of relief and joy.

He turned and looked at the crowd of his fellows. “The Keeper dies!” he said.

Behind him Wynkyn writhed and twisted, fighting uselessly against his illness. He tried to breathe, but could not…he could not…the fluids in his lungs had bubbled to his very throat and…

The boy turned back to Wynkyn as the friar made an horrific gurgling. The old man was trembling, and odorous fluids were running from his mouth and nose.

His eyes were wide and staring…and very, very afraid.

“If I had the strength,” the boy said in a voice surprisingly mature for his age, “I would throw you into the Cleft myself.”

But he could not, and so the boy stood there, his fellows now ranged behind him in a curious and joyful semicircle, and watched as Wynkyn de Worde struggled into death.

They waited for some time after his last breath. Making sure.

They waited until the Cleft closed of its own accord, tired of waiting for the incantation that would have fed it.

They waited until the boy at their head leaned down and retrieved the key that hung from the dead friar’s belt.

They waited until the curse of the Nameless Day was past.

“Hail our freedom!” he cried, and then burst into laughter. “We are freed of the angels’ curse. Freed into life!”

And he thrust the key nightward in an obscene gesture towards Heaven.

It was a cold night.

Worse, it was the most feared time of year, for all knew that during the winter solstice the worlds of mankind and demon touched and a passage between them became possible. In ancient times the people had called this day and night period the Nameless Day, for to name it would only have been to give it power. Even though the people now had the word of God to comfort them, they remembered the beliefs of their ancestors, and each year feared that this Nameless Day might witness the escape of Satan’s imps into their world.

The villagers of Asterladen—those the pestilence had spared—huddled about a roaring fire inside the church. It was the only stone building in the village, and the only building with stout doors which the villagers could lock securely.

It was the safest place they could find, and the only sound which could comfort them was the murmured prayers of their parish priest.

Rainard, his wife Aude, and their infant daughter were particularly unlucky. That afternoon they had remained behind in the fields when the other villagers left, trying to discover the brooch that Aude had dropped in the mud.

It was her only piece of finery, a simple brooch made of worn bronze which had been passed down through her family for generations, and Aude was singularly proud of it. Normally she would not have worn it out to the fields, but there was to be a field dance that afternoon, and the lord had promised ale, and Aude wanted to look her best. Despite her age and her many years spent childbearing, Aude was a vain creature and proud of her looks. But between the dancing and the ale, the brooch had somehow slipped from her breast to be trodden down into the earth. She and Rainard—he berating her the entire time for her foolishness in wearing her only piece of jewellery into the field even for a Yuletide dance—had searched for hours, but the brooch was nowhere to be found.

Too late they realised the onset of dusk, and the absence of every other soul.

They hurried back to the village, breathless and fearful, and had beaten on the doors of the church until their fists were bruised and bloody.

But the priest had called them demons, and the villagers safe inside the church had screamed and refused to believe that the voices of their well-known friends were human at all.

So Rainard and Aude and their infant daughter, whom Aude had left swaddled and safe in their cottage while they were out in the fields, had to survive the night on their own.

Rainard built up a good fire in the central hearth of their cottage, and he and his wife huddled as close to it as they could, listening all the while to the moans and cries in the wind outside.

“There’ll be no harm,” Aude muttered, convincing neither her husband nor herself. She threw a concerned glance to her daughter, lying asleep in her cradle.

“We would be safe if not for your cursed trinket,” Rainard said.

Aude bared her yellowing teeth, but said nothing. She grieved deeply for her lost brooch, and wondered if somehow Rainard had been involved in its loss.

What if he had seized it in order to sell it next market day in Nuremberg? Like as not he would squander her money on a new couplet of pigs, or some such! Yes, perhaps he had it even now, tucked away in some—

There was a sudden noise on the wind, the sound of a distant door being forced open, and then of feet scuffling past the back wall of their cottage.

Some of the feet clicked, as if they were clawed.

“Rainard!” Aude squeaked, and leapt into her husband’s arms.

He shoved her to one side, and seized an axe he had to the ready.

More feet scampered past, bolder now, and the couple thought they heard the sound of three or four more doors in neighbouring cottages being forced open.

“Rainard!” Aude screamed, grabbing at his arm.

And then the door of their hovel squeaked and fell open.

Rainard and Aude stared, not believing their eyes.

A child, a boy, stood there. He was weeping, and covered with dirt and abrasions.

Nonetheless, he was the most beautiful child the peasants had ever seen.

“Who are you?” Rainard said, wondering how the child had escaped the prowling demons.

The boy gulped, and began to cry. “I’m lost,” he eventually said.

Rainard and Aude looked at each other. They’d heard tales of these waifs, orphaned by the pestilence, turned out of their homes by neighbours who thought the children harboured pestilence themselves.

But although this boy was cold and dirty, he was also obviously healthy. His eyes shone clear and bright, and his skin, if dirty, was not feverish.

“What is your name?” Aude said.

“I have no name,” the boy said.

“Then where are your parents?” Rainard said.

“My mam is dead, and my father deserted us years ago,” the boy said. “Before I was born. I know not where he is. Please, I am hungry. Will you feed me?”

There was a shuffling behind him, and two girls, perhaps three and four respectively, silently joined the boy.

“How many of you are there?” Rainard asked.

“Us, and two more, both girls,” said the boy. “Please, we have all lost our parents, and are hungry. Will you feed us?”

Rainard and Aude shared a look. They were poor and had barely enough to feed themselves, but they also had souls, and cared deeply for children. God knew there were few enough left in this time of pestilence.

“We’ll take you,” Rainard said, pointing to the boy, “and one of the girls. The others can find homes soon enough with some of the other families.”

The boy smiled, his face almost angelic. “I do thank you,” he said.

He moved over to the cradle, and both Rainard and Aude stiffened.

But the boy did nothing more than reach in and gently touch the sleeping girl’s forehead. “She will lead a charmed life,” he said.

Over that night and the next two days twelve villages in the region north of Nuremberg found themselves sheltering hungry orphans. No one was particularly puzzled by the appearance of the children: communication between villages was poor, and there was no one to learn of the somewhat surprising number of hungry, soulful-looking children who appeared at doors asking for shelter in the time of the Nativity in the year of the black pestilence.

This was a time of unheard-of disease and death, and there must surely be orphaned children wandering about all over the land.

All the children were taken in and nourished, and loved, and raised. None of these children bit the hands that fed them; to these work-worn hands they gave back love and gratefulness and good works.

All of these children eventually left their adopted homes to lead particularly bounteous lives.

ROME (#ulink_9ab2e80b-84f0-5a62-ad79-51d7e917edfa)

“Margrett, my sweetest Margrett! I must goe!

most dere to mee that neuer may be soo;

as Fortune willes, I cannott itt deny.”

“then know thy loue, thy Margrett, shee must dye.”

A Jigge (for Margrett)

Medieval English ballad

I (#ulink_99d61226-31b1-5b88-b816-2cce5e40449b)

The Friday after Plough Monday

In the forty-ninth year of the reign of Edward III

(16th January 1377)

A dribble of red wine ran down Gerardo’s stubbled chin, and he reluctantly—and somewhat unsteadily—rose from his sheltered spot behind the brazier.

It was time to close the gates.

Gerardo had been the gatekeeper at the northern gate of Rome, the Porta del Popolo, for nine years, and in all of his nine years he’d never had a day like this one. In his time he’d closed the gates against raiders, Jewish and Saracen merchants, tardy pilgrims and starving mobs come to the Holy City to beg for morsels and to rob the wealthy. He’d opened the gates to dawns, Holy Roman armies, traders and yet more pilgrims.

Today, he had opened the gate at dawn to discover a pope waiting.

Gerardo had just stood, bleary eyes blinking, mouth hanging open, one hand absently scratching at the reddened and itching lice tracks under his coarse woollen robe. He hadn’t instantly recognised the man or his vestments, nor the banners carried by the considerable entourage stretching out behind the pope. And why should he? No pope had made Rome his home for the past seventy years, and only one had made a cursory visit—and that years before Gerardo had taken on responsibility for the Porta del Popolo.

So he had stood there and stared, blinking like an addle-headed child, until one of the soldiers of the entourage shouted out to make way for His Holiness Pope Gregory XI. Still sleep-befuddled, Gerardo had obligingly shuffled out of the way, and then stood and watched as the pope, fifteen or sixteen cardinals, some sundry officials of the papal curia, soldiers, mercenaries, priests, monks, friars, general hangers-on, eight horse-drawn wagons and several score of laden mules entered Rome to the accompaniment of murmured prayers, chants, heavy incense and the flash of weighty folds of crimson and purple silks in the dawn light.

None among this, the most richest of cavalcades, thought to offer the gatekeeper a coin, and Gerardo was so fuddled he never thought to ask for one.

Instead, he stood, one hand still on the gate, and watched the pageant disappear down the street.

Within the hour Rome was in uproar.

The pope was home! Back from the terrible Babylonian Captivity in Avignon where the traitor French kings had kept successive popes for seventy years. The pope was home!

Mobs roared onto streets and swept over the Ponte St Angelo into the Leonine City and up the street leading to St Peter’s Basilica. There Pope Gregory, a little travel weary but strong of voice, addressed the mob in true papal style, admonishing them for their sins and pleading for their true repentance…as also for the taxes and tithes they had managed to avoid these past seventy years.

The mob was having none of it. They wanted assurance the pope wasn’t going to sally back out the gate the instant they all went back to home and work. They roared the louder, and leaned forward ominously, fists waving in the air, threats of violence rising above their upturned faces. This pope was going to remain in Rome where he belonged.

The pope acquiesced (his train of cardinals had long since fled into the bolted safety of St Peter’s). He promised to remain, and vowed that the papacy had returned to Rome.

The mob quietened, lowered their fists and cheered. Within the hour they’d trickled back to their residences and workshops, not to begin their daily labour, but to indulge in a day of celebration.

Now Gerardo sighed, and shuffled closer to the gate. He had drunk too much of that damn rough Corsican red this day—as had most of the Roman mob, some of whom were still roaming the streets or standing outside the walls of the Leonine City (the gates to that had been shut many hours since)—and he couldn’t wait to close these cursed gates and head back to his warm bed and comfortable wife.

He grabbed hold of the edge of one of the gates, and pulled it slowly across the opening until he could throw home its bolts into the bed of the roadway. He was about to turn for the other gate when a movement in the dusk caught his eye. Gerardo stared, then slowly cursed.

Some fifty or sixty paces down the road was a man riding a mule. Gerardo would have slammed the gates in the man’s face but for the fact that the man wore the distinctive black hooded cloak over the white robe of a Dominican friar, and if there was one group of clergy Gerardo was more than reluctant to annoy it was the Dominicans.

Too many of the damn Dominicans were Father Inquisitors (and those that were not had ambitions to be), and Gerardo didn’t fancy a slow death roasting over coals for irritating one of the bastards.

Worse, Gerardo couldn’t charge the friar the usual coin for passage through the gate. Clergy thought themselves above such trivialities as paying gatekeepers for their labours.

So he stood there, hopping from foot to foot in the deepening dusk and chill air, running foul curses through his mind, and waited for the friar to pass.

The poor bastard looked cold, Gerardo had to give him that. Dominicans affected simple dress, and while the cloak over the robe might keep the man’s body warm enough, his feet were clad in sandals that left them open to the winter’s rigour. As the friar drew closer, Gerardo could see that his hands were white and shaking as they gripped the rope of the mule’s halter, and his face was pinched and blue under the hood of his black cloak.

Gerardo bowed his head respectfully.

“Welcome, brother,” he murmured as the friar drew level with him. I bet the sanctimonious bastard won’t be slow in downing the wine this night, he thought.

The friar pulled his mule to a halt, and Gerardo looked up.

“Can you give me directions to the Saint Angelo friary?” the friar asked in exquisite Latin.

The friar’s accent was strange, and Gerardo frowned, trying to place it. Not Roman, nor the thick German of so many merchants and bankers who passed through his gate. And certainly not the high piping tones of those French pricks. He peered at the man’s face more closely. The friar was about twenty-eight or nine, and his face was that of the soldier rather than the priest: hard and angled planes to cheek and forehead, short black hair curling out from beneath the rim of the hood, a hooked nose, and penetrating light brown eyes over a traveller’s stubble of dark beard.

Sweet St Catherine, perhaps he was a Father Inquisitor!

“Follow the westerly bend of the Tiber,” said Gerardo in much rougher Latin, “until you come to the bridge that crosses over to the Castel Saint Angelo—but do not cross. The Saint Angelo friary lies tucked to one side of the bridge this side of the river. You cannot mistake it.” He bowed deeply.

The friar nodded. “I thank you, good man.” One hand rummaged in the pouch at his waist, and the next moment he tossed a coin at Gerardo. “For your aid,” he said, and kicked his mule forward.

Gerardo grabbed the coin and gasped, revising his opinion of the man as he stared at him disappearing into the twilight.

The friar hunched under his cloak as his exhausted mule stumbled deeper into Rome. For years he had hungered to visit this most holy of cities, yet now he couldn’t even summon a flicker of interest in the buildings rising above him, in the laughter and voices spilling out from open doorways, in the distant rush and tumble of the Tiber, or in the twinkling lights of the Leonine City rising to his right.

He didn’t even scan the horizon for the silhouette of St Peter’s Basilica.

Instead, all he could think of was the pain in his hands and feet. The cold had eaten its terrible way so deep into his flesh and joints that he thought he would limp for the rest of his life.

But of what use were feet to a man who wanted only to spend his life in contemplation of God? And, of course, in penitence for his foul sin—a sin so loathsome that he did not think he’d ever be able to atone for it enough to achieve salvation.

Alice! Alice! How could he ever have condemned her to the death he had?

He should welcome the pain, because it would focus his mind on God, as on his sinful soul. The flesh was nothing; it meant nothing, just as this world meant nothing. On the other hand, his soul was everything, as was contemplation of God and of eternity. Flesh was corrupt, spirit was pure.

The friar sighed and forced himself to throw his cloak away from hands and feet. Comfort was sin, and he should not indulge in it.

He sighed again, ragged and deep, and envied the life of the gatekeeper. Rough, honest work spent in the city of the Holy Father. Service to God.

What man could possibly desire anything else?

Prior Bertrand was half sunk to his arthritic knees before the cross in his cell, when there came a soft tap at the door.

Bertrand closed his eyes in annoyance, then painfully raised himself, grabbing a bench for support as he did so. “Come.”

A young boy of some twelve or thirteen years entered, dressed in the robes of a novice.

He bowed his head and crossed his hands before him. “Brother Thomas Neville has arrived,” he said.

Bertrand raised his eyebrows. The man had made good time! And to arrive the same day as Pope Gregory…well, a day of many surprises then.

“Does he need rest and food before I speak with him, Daniel?” Bertrand asked.

“No,” said another voice, and the newcomer stepped out from the shadows of the ill-lit passageway. He was limping badly. “I would prefer to speak with you now.”

Bertrand bit down an unbrotherly retort at the man’s presumptuous tone, then gestured Brother Thomas inside.

“Thank you, Daniel,” Bertrand said to the novice. “Perhaps you could bring some bread and cheese from the kitchens for Brother Thomas.”

Bertrand glanced at the state of the friar’s hands and feet. “And ask Brother Arno to prepare a poultice.”

“I don’t need—” Brother Thomas began.

“Yes,” Bertrand said, “you do need attention to your hands and feet…your feet especially. If you were not a cripple before you entered service, then God does not demand that you become one now.” He looked back at the novice. “Go.”

The novice bowed again, and closed the door behind him.

“You have surprised me, brother,” Bertrand said, turning to face his visitor, who had hobbled into the centre of the sparsely furnished cell. “I did not expect you for some weeks yet.”

Bertrand glanced over the man’s face and head; he’d travelled so fast he’d not had the time to scrape clean his chin or tonsure. That would be the next thing to be attended to, after his extremities.

“I made good time, Brother Prior,” Thomas said. “A group of obliging merchants let me share their vessel down the French and Tuscany coasts.”

A courageous man, thought Bertrand, to brave the uncertain waters of the Mediterranean. But that is as befits his background. “Will you sit?” he said, and indicated the cell’s only stool, which stood to one side of the bed.

Thomas sat down, not allowing any expression of relief to mark his face, and Bertrand lowered himself to the bed. “You have arrived on an auspicious day, Brother Thomas,” he said.

Thomas raised his eyebrows.

Bertrand stared briefly at the man’s striking face before he responded. There was an arrogance and pride there that deeply disturbed the prior. “Aye, an auspicious day indeed. At dawn Gregory disembarked himself, most of his cardinals, and the entire papal curia, from his barges on the Tiber and entered the city.”

“The pope has returned?”

Bertrand bowed his head in assent.

Brother Thomas muttered something under his breath that to Bertrand’s aged ears sounded very much like a curse.

“Brother Thomas!”

The man’s cheeks reddened slightly. “I beg forgiveness, Brother Prior. I only wish I had pushed my poor mule the faster so I might have been here for the event. Tell me, has he arrived to stay?”

“Well,” Bertrand slid his hands inside the voluminous sleeves of his robe. “I would hear about your journey first, Brother Thomas. And then, perhaps, I can relate our news to you.”

Best to put this autocratic brother in his place as soon as possible, Bertrand thought. I will not let him direct the conversation.

Thomas made as if to object, then bowed his head in acquiescence. “I left Dover on the Feast of Saint Benedict, and crossed to Harfleur on the French coast. From there…”

Bertrand listened with only a portion of his attention as Thomas continued his tale of his journey, nodding now and then with encouragement. But the tale interested him not. It was this man before him who commanded his thoughts.

Brother Thomas was a man of some interest, with an unusual background for a friar, although not for more worldly men. The Prior General of England, Richard Thorseby, had been extremely reluctant to admit Thomas Neville into the Order of Preachers—the Dominicans—and had examined Thomas at great length before finally, and most unwillingly, allowing him to take his vows.

Men like Thomas were usually trouble.

On the other hand, Thomas could be extremely useful to the advancement of the Dominicans—if he was handled correctly.

Bertrand smiled politely as Thomas told an amusing anecdote about ship life with the rowdy merchants, but let his train of thought continue.

Why had Thomas chosen the Dominicans? The mendicant orders, of which the Dominicans were the most powerful, were orders which took their vows of chastity, poverty and obedience very seriously. Indeed, “mendicant” was the ancient Latin word meaning “to beg”. Friars remained poor all their lives, were not allowed to own property or live luxurious lives…unlike many of the higher clergy within the Roman Church.

If Thomas had chosen to join the more regular orders of the Church, Bertrand thought, he could have been a bishop within two years, a cardinal in ten, and could have aspired to be pope within twenty. Yet he chose poverty and humbleness above power and riches. Why?

Piety?

From one of the Nevilles?

From what he knew of the Nevilles, Bertrand could not believe that one of their family would have chosen piety above power, but then one never knew the wondrous workings of the Lord.

“And so now you hope to continue your studies here,” Bertrand said as Thomas’ tale drew to a close.

“My colleagues at Oxford— ”

Bertrand nodded. Thomas had spent two of the past five years teaching as a Master at one of the Oxford colleges.

“—spoke of nothing else but the wonders of your library. Some say,” and Thomas spread his hands almost apologetically, as if he did not truly believe what some had said, “that Saint Angelo’s library is more extensive than that administered by the clergy of Saint Peter’s itself.”

“Nevertheless, you are here, Brother Thomas. You must have believed some of what you had heard.” Bertrand shifted slightly on the hard bed. His hips and shoulders ached in the chill air of his cell, and he berated himself for wishing this young man would leave so he could crawl beneath the blanket.

“But it is true,” Bertrand continued. “We do have a fine library. For many generations our friary has been well funded by successive popes—” Bertrand did not explain why, and Thomas did not ask, “—and much of this benevolent patronage has been put to building one of the finest libraries in Rome and, I dare say, within Christendom itself. You are welcome, Brother Thomas, to use our facilities as you wish.”

Thomas bowed his head again, and smiled. “You are weary, Brother Prior, and I have taken up too much of your time. Perhaps we can talk again in the morning?”

Bertrand nodded. “We break our fast after Prime prayers, Brother Thomas. You may speak with me then. Do you wish Daniel to show you your cell now?”

“I thank you,” Thomas said, “but Daniel has already pointed out its location to me, and there is something else I wish to do before I retire.”

“Yes?”

Thomas took a deep breath, and from the expression on his face Bertrand suddenly realised that it was piety that had impelled Thomas to take holy orders.

“I would pray before the altar of Saint Peter’s, Brother Prior. To prostrate myself to God’s will before the bones of the great Apostle has always been one of my dearest desires.”

“Then for the Virgin’s sake, brother, let Arno see to your feet before you go. I’ll not have the pope say that it was one of my brothers who left blood smeared all over the sacred floor of Saint Peter’s!”

After the celebrations of the day, Rome had darkened and quieted, and the streets were deserted. Thomas walked from the friary over the bridge crossing the Tiber—more comfortably now that Arno had daubed herbs on his ice-bitten feet, and wrapped them in thick, soft bandages inside his sandals—then halted on the far side, staring at the huge rounded shape of the Castel St Angelo from which the friary took its name. Thomas had heard that it was once the tomb of one of the great pagan Roman emperors, but the archangel Michael had appeared one day on its roof and from then on the monument had been converted to a more holy and Christian purpose: a fort, guarding the entrance to the domain of the popes in Rome, the Leonine City.

Thomas turned his head and stared west towards St Peter’s Basilica built into the hill of the Leonine City, and surrounded by lesser buildings and palaces housing, once again, the papal curia and the person of the Holy Father himself. Lights glinted in many of the windows in the papal palace, but even the excitement of a once-again resident pope could not diminish Thomas’ wonder at seeing the great structure of St Peter’s Basilica rising into the night.

Thomas’ eyes flickered once more to the Castel St Angelo. Legend had it that a long-dead pope had caused a tunnel to be built from the papal palace next to St Peter’s into the basements of the fort; an escape route into a well-fortified hidey-hole, should the Roman mobs ever get too unruly. Given the widespread reputation of the Romans for spontaneous and catastrophic violence, Thomas wondered if the first chore Gregory had undertaken once ensconced in his apartments was to personally dust away the spider webs and rats’ nests from the tunnel entrance.

Thomas grinned at the thought, then automatically—and silently—castigated himself for such irreverence. He looked at the gate in the wall of the Leonine City. It was closed, but several guards were on duty, and Thomas hoped they’d let him through.

They did. A single Dominican could harm no one, and Thomas’ obvious piety and insistence that he be allowed to pray before St Peter’s shrine impressed them as much as it had Bertrand.

The pressing of a coin into each of their hands dispelled any lingering doubts.

Beyond the gate Thomas walked slowly up the street leading to St Peter’s.

The Basilica was massive. Since the Emperor Constantine had first erected the Basilica in the fourth century, it had been added to, renovated, restored and enlarged, but it was still one of the most sacred sites for any Christian: the monument erected over the tomb of St Peter, first among Christ’s Apostles. Here pilgrims flocked in their tens of thousands every year. Here the penitent begged for their salvation. Here kings and emperors crawled on hands and knees begging forgiveness for their sins.

Here was the heart of functional Christendom now that Jerusalem was lost to the infidels.

Thomas faltered to a halt some hundred paces from the atrium leading to the Basilica, and his eyes filled with tears. For so long he had wanted to worship at St Peter’s shrine. Initially as a child, having watched his beloved parents die from the corruption of a return of the great pestilence; through all the years of his youth—years wasted in blasphemy and anger—and finally, to this man grown into the realisation that his life must be dedicated to God and furthering God’s mission here on earth.

It had been a long, difficult, fraught journey, but here he was at last.

At last.

Thomas resumed his slow walk towards the Basilica. At the end of the street thirty-five wide steps rose towards a marble platform before an irregular huddle of buildings: several huge archways, a tower, and tall brick apartments with colonnaded balconies. These buildings formed a wall to either side of the entrance archways into the vast court that served as the atrium of St Peter’s.

After an instant’s hesitation, Thomas climbed the steps and crossed the platform. Immediately before him were the three archways, the paved atrium stretching beyond them.

Normally, Thomas knew, it would have been full of stalls and traders selling pilgrim badges, relics, genuine holy water, splinters from the true cross and threads from Christ’s robe, but tonight the stalls were empty, their canvas roofs flapping in the breeze. For this day, at least, the pope had ordered the Leonine City emptied of traders, street merchants and hawkers.

The court was even empty of pilgrims, and Thomas’ spirits rose. He would have St Peter’s to himself.

As he approached the entrance into the Basilica he prayed that the pope had retired to his private apartments.

Thomas did not want to share St Peter’s shrine even with the Holy Father himself.

His heart thudding, Thomas entered the building.

It was massive, but what caught Thomas’ eye was its layout, used as he was to western churches constructed in the form of a cross. Constantine had built the Basilica in a roughly rectangular form, modelling it on the Roman halls of justice. The very eastern wall, where stood the altar over St Peter’s tomb, was rounded, but the rest of the Basilica was laid out as an immense hall with four rows of columns supporting the soaring timber roof and dividing the interior into a nave with two aisles to each side.

For long minutes Thomas could not move. His lips moved slowly in prayer, but his mind could not concentrate on the words. His eyes, round and wondrous, roamed the length and height of the Basilica, stopping now and then at a particularly colourful banner or screen, or lingering on the statue of a beloved saint.

Finally, he stared at the altar at the western end of the nave. Even from this distance he could see the exotic twisted columns guarding the altar, covered with a canopy hanging from four of the columns.

Thomas raised a hand, crossed himself, then slowly, and with the utmost reverence, walked down the length of the nave towards the altar. There were a few worshippers within the Basilica kneeling before some of the side shrines, and barely visible in the flickering light of the oil lamps, but there was no one before the altar itself.

Tears slipped down Thomas’ cheeks, and his hand grasped the small cross he wore suspended from his neck.

He had walked all his life towards this moment, and he could now hardly believe such was the munificence of God’s Grace that he was finally here.

Again Thomas’ steps faltered as he reached the altar. He knew that to one side steps led down into a chamber from where he could view through a grille the actual tomb of St Peter, but for now all Thomas wanted to do, all he could do, was to prostrate himself before the altar.

He slumped to his knees, his eyes still raised to the altar, then he dropped his head and hands, and lowered himself until he lay prostrate in a cruciform position before the altar.

It was cold and horribly uncomfortable, but Thomas was filled with such zeal he did not notice.

Holy St Peter, he prayed silently over and over, grant me your humbleness and courage, let my footsteps be guided by yours, let my life be as worthy as yours, let me be of true service to sweet Jesus Christ as you were, let me ignore hunger and pain as you did, let me immerse myself in the true wonder and joy of God. Holy St Peter…

Hours passed unnoticed, and the Basilica emptied of all save the friar stretched before the altar. Thomas’ muscles grew stiff with the cold and the fervour of his thoughts, but he did not notice his discomfort. All Thomas wanted was to be granted St Peter’s grace, to be accepted to serve—

Thomas.

Thomas was lost in prayer. He did not hear.

Thomas.

One of Thomas’ outstretched fingers twitched slightly, otherwise he showed no outward sign of hearing.

Now the voice grew more insistent, more terrible.

Thomas!

Thomas’ entire body jerked, and he rolled onto his back, his eyes blinking in surprise and disorientation.

Thomas!

He jerked again, and rose on one elbow, staring down the nave of the Basilica.

Perhaps a third of the way down, on the left wall of the Basilica, a golden light exuded from one of the side shrines.

Thomas!

Thomas scrambled about until he was on his hands and feet. He lowered his face to the stone floor. “Lord!”

Thomas, come speak with me.

Shaking with fear and wonder, Thomas inched his way across the floor, his breath harsh in his throat, his eyes wide and staring at the stones before him.

Thomas…

Thomas crept to the entrance of the shrine, daring a quick look.

The shrine consisted merely of a niche in the wall, large enough only for a statue of an angel, arms and wings outstretched.

Thomas supposed that the statue was of some alabaster stone, but now it glowed with a brilliance that made his eyes ache. The face of the statue was terrible, full of cruel righteousness and the power of the Lord.

Thomas averted his eyes in dread.

“Lord!” he said again.

No Thomas. Not the Lord our God, but His servant, Michael.

The archangel Michael…

“Blessed saint,” Thomas whispered, his fingers clawing forward very slightly on the floor.

Blessed Thomas, said the archangel, and Thomas felt a brief warmth on the top of his bowed head, as if the angel had laid his hand there in benediction.

Thomas began to cry.

Do not weep, Thomas, but hark to what I say. There are few men or women these days who can be called of brave heart and true soul. You are one of them.

“I would give my life to serve, blessed Saint Michael!”

I do not think you shall have to go that far, Thomas, for you are of the Beloved.

Of the beloved?

“Blessed saint, I am a poor man with a great sin on my soul. There was a woman who I—”

Think you I know not every deed of your life? Think you that I cannot see into every corner of your soul? The woman used you. She was a whore. What you did was right and caused a great rejoicing among my brethren.

A great weight fell from Thomas’ mind. For so long he had laboured under the burden of his sin…and now to hear from St Michael that it was no sin at all…

“I thank you,” he whispered. He had been right to do as he had. Alice was indeed a whore, for she had betrayed her husband to sate her lustful cravings.

All women are vile. Their flesh leads to temptations. Never forget that it was a woman who betrayed Adam.

“I will never forget it, blessed saint.”

You have passed the first test, Thomas. Now comes one much greater.

“Saint Michael?”

Evil roams among your brethren, Thomas.

Thomas shuddered. “Among the fellows of my holy order, Saint Michael?”

It well may, but I speak of the wider community of mankind. For many years now evil incarnate in the form of Satan’s imps have walked unhindered, wreaking havoc and despair. The world is altering, Thomas, and turning away from God. You are Beloved of both the Lord God and my brethren, and it is you who shall head His army of righteous anger.

Thomas felt all the disparate elements of his life fall into place. When he’d been closest to despair, unable to see the meaning and course of his life, the Lord had all the while been guiding and training him. He’d thought his life before entering the Order worthless and empty. Now Thomas knew differently.

Exultation filled his soul. He was to be a soldier of Christ…and the enemy was evil.

“What should I do? I am yours, blessed saint, mind and body and soul!”

Study. Pray. Grow in understanding. In time, and only when the time is right, I will return to give you further guidance.

“But—”

Thomas got no further. Suddenly the glow and warmth was gone, and Thomas found himself alone in St Peter’s Basilica before a lifeless statue, its face once more cold and impassive.

He struggled into a sitting position, tears still streaming down his cheeks, his hands clasped before him, staring at the statue of St Michael.

“I am yours!” he whispered. “Yours!”

Aye, came the faintest of whispers, as if from the summit of heaven itself. You are one of ours indeed.

II (#ulink_fda85426-25df-5d7d-bd62-62f61d1b43f9)

The Saturday within the Octave of the Annunciation

In the fifty-first year of the reign of Edward III

(27th March 1378)

Thomas told no one of his experience in St Peter’s. If Satan’s imps—demons—roamed among mankind, then who knew which among his brother friars worked for God, and which for evil? So Thomas remained silent, sinking deeper into his devotions and burying himself in his studies within the library of St Angelo’s friary. Here were the ancient books and manuscripts that might cast some light on what the archangel had revealed to him. Here might lie the key to how he could aid the Lord.

He watched and listened, and learned what he could.

His feet healed, and his hands, and somehow that disappointed Thomas, for he would have liked a lingering ache or a stiffness in his joints to remind him of his duty to God, and also, now, to St Michael.

In the year following his ecstatic vision, the archangel did not appear to Thomas again. Thomas was not overly concerned. He knew that the Lord and his captains, the angels, would again approach him when the time was right.

In the meantime, Thomas did all he could to ensure he would be strong and devout enough to serve.

Prior Bertrand observed his new arrival with some concern. He had been instructed by Father Richard Thorseby, the Prior General of the Dominican Order in England, to keep close watch on Brother Thomas Neville. Thorseby, a stern disciplinarian, did not entirely trust Thomas’ motives in joining the Order, and doubted his true piety.

Whatever Thomas’ motives for joining the Order—and Bertrand agreed with Thorseby that they were dreadful enough for Thomas’ fitness for the Order to be suspect—Bertrand could not fault Thomas’ piety. The man appeared obsessed with the need to prove himself before God. Every friar was expected to appear in chapel for each of the seven hours of prayer during the day, beginning with Matins in the cold hours before dawn, and ending late at night with Compline. But the Dominican Order, while encouraging piety, also encouraged its members to spend as much (if not more) time studying as praying, and turned a blind eye if a brother skipped two or three of the hours of prayer each day. Dominicans were devoted to God, but they expressed this devotion by turning themselves into teachers and preachers who would combat heresy—deviation in faith—wherever it appeared.

But Thomas never missed prayers. Not only did he observe each prayer hour, he was first in the chapel and last to leave. Sometimes, on arriving for Matins, Bertrand found Thomas stretched out before the altar in the chapel. Bertrand assumed he had been there all night praying for…well, for whatever it was he needed.

At weekly theological debates held between the brothers of St Angelo’s, sometimes including members of other friaries and colleges within Rome, Thomas was always the most vocal and the most passionate in his views. After the debates had officially ended, when other brothers were engaged in relaxing talk and gossip, or wandering the cloisters enjoying the warmth of the sun and the scent of the herbs that bounded the cloister walks, Thomas would seek out those who had opposed his ideas and beliefs and continue the debate for as long as his prey was disposed to stand there and be berated.

Bertrand admitted to himself that he was frightened by Thomas. There was something about the man which made him deeply uneasy.

On occasions, Thomas reminded him of Wynkyn de Worde. That Bertrand did not like. He had fought long and hard to forget Wynkyn de Worde. The man—as sternly pious as Thomas—had frightened Bertrand even more than Thomas (although in his darker moments Bertrand wondered if Thomas would eventually prove even more disagreeable than Wynkyn).

In the years following the great pestilence (and the Lord be praised that it had passed!), Bertrand had spent the equivalent of many weeks on his knees seeking forgiveness for his deep relief that Wynkyn had never returned from Nuremberg. He’d heard that the brother had reached Nuremberg safely, but had then failed to return from a journey into the forests north of the city.

Brother Guillaume, now the prior of the Nuremberg friary, had reported to Bertrand that Wynkyn had been consumed with the pestilence when he’d left, and Bertrand could only suppose the man had died forgotten and unshriven on a lonely road somewhere.

No doubt he’d given the pestilence to whatever unlucky wolves had tried to gnaw his bones.

Bertrand spent many hours on his knees seeking forgiveness for his uncharitable thoughts regarding Wynkyn de Worde.

He did not know what had happened to Wynkyn’s book and, frankly, Bertrand did not care overmuch. Guillaume had not mentioned it, and Bertrand did not inquire. It was not within his friary’s walls, and that was all that mattered.

So Bertrand continued to watch Thomas, and to send the Prior General in England regular reports.

He supposed they did not ease Thorseby’s mind, and Bertrand did occasionally wonder what would happen to Thomas once the man journeyed back to Oxford to resume a position of Master.

Piety was all very well, but not when taken to obsessive extremes.

Outside the friary, the Romans continued to rejoice in the presence of the pope. Gregory showed no sign of wanting to remove the papal court and curia back to Avignon, and people again were able to attend papal mass within St Peter’s Basilica. Every Sunday and Holy Day citizens packed the great nave of the Basilica, their eyes shining with devotion, their hands clutching precious relics and charms. On ordinary days the same citizens packed the atrium of St Peter’s, as they did the streets leading to the Basilica, selling badges and holy keepsakes to the pilgrims who flooded Rome. The presence of the pope not only sated the Romans’ deep piety, it also filled their purses. Gregory was in his mid-fifties, but appeared hale, and could be expected to live another decade or more. The Romans were ecstatic.

The papacy appeared to be once again safely ensconced in Rome, and many a Roman street worker, walker or sweeper could be seen making the occasional obscene gesture in the general direction of France. At night, the Roman people filled their taverns with triumphant talk about the French King John’s dilemma. When Gregory had removed himself and his retinue from Avignon, John had lost his influence over the most powerful institution in Europe. Rumour said John was rabid with fury, and plotted constantly to regain his influence over the papacy. Everyone in Rome was aware Gregory had “escaped” back to Rome at a critical juncture in John’s war with the English king, Edward III; the French king needed every diplomatic tool in his possession to raise the funds and manpower to repel Edward’s inevitable reinvasion of France.

The Roman mob didn’t give a whore’s tit about the French king’s plight—nor the English king’s, for that matter. They had their pope back, Rome was once more the heart of Christendom (with all the financial benefits that carried), and they damn well weren’t going to let any French prick steal their pope again.

Most of the French cardinals—and they were the vast majority within the College of Cardinals—were vastly irritated by Gregory’s apparent desire to remain in Rome (just as they were vastly irritated by, and terrified of, the Roman mob). Beneath the pope, the cardinals were the most powerful men in the Church, and thus in Christendom. They lived and acted as princes, but to ensure their continuing power they had to remain within the papal court at the side of the pope. Thus they were effectively trapped in Rome, although most of them tried to spend as many months of each year back in the civilised pleasures of Avignon as they could.

When in Rome, the cardinals spent hours carefully watching the pope. Was his face tinged just with the merest touch of grey at yesterday’s mass? Did his fingers tremble, just slightly, when he carved his meat at the banquet held in honour of the Holy Roman Emperor’s son? And how much of his food did he eat, anyway? They bribed the papal physician to learn details of the papal bowel movements and the particular stink of his urine. They frightened the papal chamberlain with threats of eternal damnation to learn if the pope’s sheets were stained with effluent in the mornings and, if so, what kind of effluent?