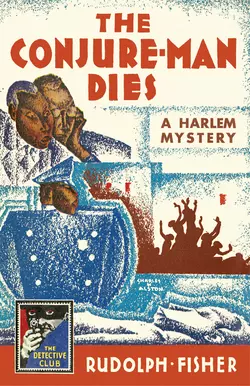

The Conjure-Man Dies: A Harlem Mystery

Stanley Ellin

Rudolph Fisher

The first known mystery novel written by an African-American, originally published in 1932.When the body of N’Gana Frimbo, the African conjure-man, is discovered in his consultation room, Perry Dart, one of Harlem’s ten black police detectives, is called in to investigate. Together with Dr Archer, a physician from across the street, Dart is determined to solve the baffling mystery, helped and hindered by Bubber Brown and Jinx Jenkins, local boys keen to clear themselves of suspicion of murder and undertake their own investigations.The Conjure-Man Dies (1932) was the very first detective novel written by an African-American. A distinguished doctor and accomplished musician and dramatist, Rudolph Fisher was one of the principal writers of the Harlem Renaissance, but died in 1934 aged only 37. With a complex and gripping plot, vividly drawn characters and unique cultural elements, Fisher’s witty novel is a genuine crime classic from one of the most exciting eras in the history of black fiction.THIS DETECTIVE STORY CLUB CLASSIC includes an archival introduction by New York crime writer Stanley Ellin, plus Fisher’s last published story, ‘John Archer’s Nose’, in which Perry Dart and Dr Archer return to solve the case of a young man murdered in his own bed.

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of Collins Crime Club reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright (#ulink_73908e30-57ff-5599-9309-686eabaae50e)

Collins Crime Club

an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by Covici-Friede, New York 1932

‘John Archer’s Nose’ first published in The Metropolitan by Meeks Publishing Co. 1935 Introduction first published by Arno Press Inc. 1971

First edition cover art by Charles H. Alston 1932

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216450

Ebook Edition © February 2017 ISBN: 9780008216467

Version: 2016-11-18

Contents

Cover (#u98654cc4-4a06-55fd-b5c4-acad2688f06c)

Title Page (#u00b5c280-cddd-5e24-8eec-30e1261c2a8d)

Copyright (#u8b26d9ff-6242-54f0-b507-dde9207e594b)

Introduction (#u539bc71e-6588-5a05-908e-c9f6b98b51bd)

Chapter I (#u858c286e-71c1-515b-9f32-1b4575456f23)

Chapter II (#uf03a4483-1312-5fac-a45f-bfbdd66a009b)

Chapter III (#u85b7ad6c-5cef-56c3-8865-3b00f64530be)

Chapter IV (#u782ac574-ef1c-56d7-940b-6cf000323e30)

Chapter V (#u689b5f74-86ba-5241-bd8a-2c4b349511cc)

Chapter VI (#u5161f0b6-9d58-5bd2-a36a-10216948a60c)

Chapter VII (#u2ae2903f-1bd9-5c14-be04-a73868cb1c5d)

Chapter VIII (#u2c6935a9-76e4-56a9-b390-157bce51a02a)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIV (#litres_trial_promo)

John Archer’s Nose

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_f476684f-ca8c-5b55-9dcd-5ff3bdb4d2e7)

THE CONJURE-MAN DIES is, first and foremost, highly readable, wholly entertaining.

This should go without saying, since the book is a mystery novel of merit, and the sole function of any mystery story is to entertain. Of all types of fiction, it is probably the least pretentious, which is all in its favour at a time when the novel is so often used by authors as sugar coating for indigestible messes of philosophy or polemics calculated to make the reading of fiction a duty rather than a pleasure. Or for self-indulgent exercises in Beautiful Writing by poets manqués which make it neither a duty nor a pleasure.

This is not to deny that the formal mystery story does have its limitations, nor that too many of its practitioners, adopting these limitations as a rule book, tend to turn out a sort of mechanically contrived product, one cheapjack job after another rolling off the production line, each similar to the other beneath its coat of paint.

But it is a fact that a writer of authentic talent can and will create within the genre a novel which, while staying in bounds, offers a good example of that talent. Rudolph Fisher was such a writer, and the one mystery novel he wrote, The Conjure-Man Dies, originally published in 1932, offers striking evidence of it, especially when viewed in the light of its times. Its success on publication was great enough to carry it into production as a play by the Federal Theater Project in 1936. Its rediscovery, and appearance in this edition, are no more than proper tributes to both its readability and its merits as a record of its period.

Fisher himself was an extraordinary man. A Negro, born on 9 May 1897 in Washington, D.C., he graduated from Brown University with honours and went on to become a distinguished doctor of medicine, specializing in Roentgenology. At the height of his medical career, he turned to writing as an avocation and was soon being published by such magazines as Atlantic Monthly, Crisis, McClures, American Mercury and Story. A novel, The Walls of Jericho, published in 1928, received high critical praise, and when one adds the success of The Conjure-Man Dies to the list of Fisher’s literary achievements, it is plain that he was at least as talented in writing as he was in the practice of medicine. He died, however, on 26 December 1934, tragically young, and with a brilliantly promising career in letters unfulfilled.

His authorship of The Conjure-Man Dies gave Fisher a lonely distinction. Since the 1860s, when Metta Victor in America and Wilkie Collins in England produced the first formal mystery novels, there had been no Negro writer who utilized this technique as a means of literary expression until Fisher came along. After his death there was again a hiatus until the 1960s, when Chester Himes appeared on the scene with his detective stories of Harlem. The time now ripe for it, Himes, an enormously talented writer himself, came to achieve a prestige and financial success from his mystery stories which Fisher could never have conceived.

What adds a special dimension to Fisher’s novel from the present reader’s point of view is the date of its publication, 1932. The Negro experience that year was still basically unchanged from the era of the Reconstruction. The vaunted Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s had not gone below the surface; excellent as some of the literature emerging from it was, there was a strong smell of the dilettante about the movement, largely emanating from the whites who were part of it. And the Great Depression had stopped even the meagre economic life blood that was left in black communities from flowing. If life everywhere was hard, life in Harlem came down to a desperate day by day struggle for mere survival in a world where the most minimal public works and inadequate welfare payments were only glimmerings on the Rooseveltian horizon, and where the word ‘militant’ was the exclusive property of white-dominated radical organizations.

Under these life and death conditions, the Negro role, as prescribed by the white world, remained consistent. It was a role, familiar as ever, presented to the black by, among other things, the mystery stories of Octavus Roy Cohen in The Saturday Evening Post where the antics of the comically uppity Florian Slappey and his dull-witted, head-scratching cohorts illustrated it so vividly, and by mystery movies where the trusty but terrified and goggle-eyed black servant could perform it larger than life on the screen.

On the other hand, the Negro could take what comfort he might from the solicitous white intellectual and dilettante who, heading in the opposite directon from the arrant racist, sentimentalized the black, romanticized his bitter life style into something delightfully exciting, and, in effect, patted him on the head as one would a pet spaniel. It was ironic and inevitable that neither the racist nor the sentimentalist knew how nicely they were cooperating in the destruction of a people’s identity and individuality by barring the way to the honest exploration and discovery of them. This, of course, is the function of the stereotype, and it matters very little whether the stereotype is that of vicious hound or pet poodle.

The mystery novel of that day, where it dealt with the Negro at all, played both angles. The Negro was either servitor or hardboiled crap shooter, take it or leave it. Hardly surprising when one considers that, first, the mystery novel is popular fiction, and popular fiction always tends to cater to popular prejudices, and, second, that the genre itself had, by and large, used as its subjects the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant middle and upper classes, always acknowledging their superiority to the non-WASP world without question.

The classical mysteries written under these conditions were essentially puzzles where the reader was invited to unearth the murderer before the author did so. Their structures were as rigid as those of a Japanese no play, their characters one-dimensional, their styles generally florid, representative of the snob’s idea of Good Writing. A rereading of S. S. Van Dine, most successful mystery writer of that time, will be enlightening to anyone questioning what might seem excessively harsh judgments in the foregoing.

Luckily, in 1930, there crept into this WASP paradise of genteel murder a serpent named Dashiell Hammett. With a background as Pinkerton investigator and pulp writer, with a superb talent for fiction and a highly-developed social conscience, he plucked the apple right out of the tree that year with his his publication of The Maltese Falcon. Suddenly, murder in the mystery novel showed some of the forms it had already demonstrated in such outstanding pulp magazines as Black Mask and Flynn’s. Suddenly it was booted right out of the vicar’s garden and into the gutter, a much more likely setting for it. There was a hard-edged realism to Hammett’s characters and events, a comprehension of the meanness and viciousness of the urban world they inhabited. And his prose, clipped, economical, earthy, broke completely with the sort of overblown style favoured by S. S. Van Dine and his confreres.

It is highly probable that Rudolph Fisher, intrigued by the idea of presenting Harlem, from top to bottom, in a mystery novel that could reach a larger audience than a straight novel, devoted himself to some serious study of what made the books of both Hammett and S. S. Van Dine tick, since both their approaches are clearly evident in The Conjure-Man Dies. Fisher’s extremely complex plotting and his occasionally too-pedantic writing of descriptive and expository passages is in the classical mode. But the characters, their broad range of background, and the handling of dialogue are wholly of Hammett’s realistic school.

Overall, it is clear that Fisher’s own sympathies and interests lie with Hammett, much as he deferred to traditional techniques. Stylistically, if one judges by the descriptive and expository writing in his novel, The Walls of Jericho, it is possible that he was not so much deferring to what he thought the mystery reader demanded as reflecting a background of pre-World War I reading. Every writer is strongly influenced by the reading he most enjoyed in his teens. It is the exceptional writer who, like Fisher, can dispense with its influence even in part.

In either case, there is no question that it is Fisher’s adherence to the new realism which, as in Hammett’s works, invests The Conjure-Man Dies with the qualities of a social document recording a time and a place without seeming to. One is drawn through the book by its story, but emerges at last with much more than that story in mind.

In the end, of course, it is the book itself that must speak for its author. And what one can best do in introducing a book so happily rediscovered after decades of obscurity is only to mark its place in history, and then step aside.

STANLEY ELLIN

New York, 1971

CHAPTER I (#ulink_7e36ea00-0370-53b5-aad1-79c2ac0a3e08)

ENCOUNTERING the bright-lighted gaiety of Harlem’s Seventh Avenue, the frigid midwinter night seemed to relent a little. She had given Battery Park a chill stare and she would undoubtedly freeze the Bronx. But here in this mid-realm of rhythm and laughter she seemed to grow warmer and friendlier, observing, perhaps, that those who dwelt here were mysteriously dark like herself.

Of this favour the Avenue promptly took advantage. Sidewalks barren throughout the cold white day now sprouted life like fields in spring. Along swung boys in camels’ hair beside girls in bunny and muskrat; broad, flat heels clacked, high narrow ones clicked, reluctantly leaving the disgorging theatres or eagerly seeking the voracious dance halls. There was loud jest and louder laughter and the frequent uplifting of merry voices in the moment’s most popular song:

‘I’ll be glad when you’re dead, you rascal you,

I’ll be glad when you’re dead, you rascal you.

What is it that you’ve got

Makes my wife think you so hot?

Oh you dog—I’ll be glad when you’re gone!’

But all of black Harlem was not thus gay and bright. Any number of dark, chill, silent side streets declined the relenting night’s favour. 130th Street, for example, east of Lenox Avenue, was at this moment cold, still, and narrowly forbidding; one glanced down this block and was glad one’s destination lay elsewhere. Its concentrated gloom was only intensified by an occasional spangle of electric light, splashed ineffectually against the blackness, or by the unearthly pallor of the sky, into which a wall of dwellings rose to hide the moon.

Among the houses in this looming row, one reared a little taller and gaunter than its fellows, so that the others appeared to shrink from it and huddle together in the shadow on either side. The basement of this house was quite black; its first floor, high above the sidewalk and approached by a long greystone stoop, was only dimly lighted; its second floor was lighted more dimly still, while the third, which was the top, was vacantly dark again like the basement. About the place hovered an oppressive silence, as if those who entered here were warned beforehand not to speak above a whisper. There was, like a footnote, in one of the two first-floor windows to the left of the entrance a black-on-white sign reading:

SAMUEL CROUCH, UNDERTAKER.

On the narrow panel to the right of the doorway the silver letters of another sign obscurely glittered on an onyx background:

N. FRIMBO, PSYCHIST.

Between the two signs receded the high, narrow vestibule, terminating in a pair of tall glass-panelled doors. Glass curtains, tightly stretched in vertical folds, dimmed the already too-subdued illumination beyond.

It was about an hour before midnight that one of the doors rattled and flew open, revealing the bareheaded, short, round figure of a young man who manifestly was profoundly agitated and in a great hurry. Without closing the door behind him, he rushed down the stairs, sped straight across the street, and in a moment was frantically pushing the bell of the dwelling directly opposite. A tall, slender, light-skinned man of obviously habitual composure answered the excited summons.

‘Is—is you him?’ stammered the agitated one, pointing to a sign labelled ‘John Archer, M.D.’

‘Yes—I’m Dr Archer.’

‘Well, arch on over here, will you, doc?’ urged the caller. ‘Sump’m done happened to Frimbo.’

‘Frimbo? The fortune teller?’

‘Step on it, will you, doc?’

Shortly, the physician, bag in hand, was hurrying up the greystone stoop behind his guide. They passed through the still open door into a hallway and mounted a flight of thickly carpeted stairs.

At the head of the staircase a tall, lank, angular figure awaited them. To this person the short, round, black, and by now quite breathless guide panted, ‘I got one, boy! This here’s the doc from ’cross the street. Come on, doc. Right in here.’

Dr Archer, in passing, had an impression of a young man as long and lean as himself, of a similarly light complexion except for a profusion of dark brown freckles, and of a curiously scowling countenance that glowered from either ill humour or apprehension. The doctor rounded the banister head and strode behind his pilot toward the front of the house along the upper hallway, midway of which, still following the excited short one, he turned and swung into a room that opened into the hall at that point. The tall fellow brought up the rear.

Within the room the physician stopped, looking about in surprise. The chamber was almost entirely in darkness. The walls appeared to be hung from ceiling to floor with black velvet drapes. Even the ceiling was covered, the heavy folds of cloth converging from the four corners to gather at a central point above, from which dropped a chain suspending the single strange source of light, a device which hung low over a chair behind a large desk-like table, yet left these things and indeed most of the room unlighted. This was because, instead of shedding its radiance downward and outward as would an ordinary shaded droplight, this mechanism focused a horizontal beam upon a second chair on the opposite side of the table. Clearly the person who used the chair beneath the odd spotlight could remain in relative darkness while the occupant of the other chair was brightly illuminated.

‘There he is—jes’ like Jinx found him.’

And now in the dark chair beneath the odd lamp the doctor made out a huddled, shadowy form. Quickly he stepped forward.

‘Is this the only light?’

‘Only one I’ve seen.’

Dr Archer procured a flashlight from his bag and swept its faint beam over the walls and ceiling. Finding no sign of another lighting fixture, he directed the instrument in his hand toward the figure in the chair and saw a bare black head inclined limply sidewise, a flaccid countenance with open mouth and fixed eyes staring from under drooping lids.

‘Can’t do much in here. Anybody up front?’

‘Yes, suh. Two ladies.’

‘Have to get him outside. Let’s see. I know. Downstairs. Down in Crouch’s. There’s a sofa. You men take hold and get him down there. This way.’

There was some hesitancy. ‘Mean us, doc?’

‘Of course. Hurry. He doesn’t look so hot now.’

‘I ain’t none too warm, myself,’ murmured the short one. But he and his friend obeyed, carrying out their task with a dispatch born of distaste. Down the stairs they followed Dr Archer, and into the undertaker’s dimly lighted front room.

‘Oh, Crouch!’ called the doctor. ‘Mr Crouch!’

‘That “mister” ought to get him.’

But there was no answer. ‘Guess he’s out. That’s right—put him on the sofa. Push that other switch by the door. Good.’

Dr Archer inspected the supine figure as he reached into his bag. ‘Not so good,’ he commented. Beneath his black satin robe the patient wore ordinary clothing—trousers, vest, shirt, collar and tie. Deftly the physician bared the chest; with one hand he palpated the heart area while with the other he adjusted the ear-pieces of his stethoscope. He bent over, placed the bell of his instrument on the motionless dark chest, and listened a long time. He removed the instrument, disconnected first one, then the other, rubber tube at their junction with the bell, blew vigorously through them in turn, replaced them, and repeated the operation of listening. At last he stood erect.

‘Not a twitch,’ he said.

‘Long gone, huh?’

‘Not so long. Still warm. But gone.’

The short young man looked at his scowling freckled companion.

‘What’d I tell you?’ he whispered. ‘Was I right or wasn’t I?’

The tall one did not answer but watched the doctor. The doctor put aside his stethoscope and inspected the patient’s head more closely, the parted lips and half-open eyes. He extended a hand and with his extremely long fingers gently palpated the scalp. ‘Hello,’ he said. He turned the far side of the head toward him and looked first at that side, then at his fingers.

‘Wh-what?’

‘Blood in his hair,’ announced the physician. He procured a gauze dressing from his bag, wiped his moist fingers, thoroughly sponged and reinspected the wound. Abruptly he turned to the two men, whom until now he had treated quite impersonally. Still imperturbably, but incisively, in the manner of lancing an abscess, he asked, ‘Who are you two gentlemen?’

‘Why—uh—this here’s Jinx Jenkins, doc. He’s my buddy, see? Him and me—’

‘And you—if I don’t presume?’

‘Me? I’m Bubber Brown—’

‘Well, how did this happen, Mr Brown?’

‘’Deed I don’ know, doc. What you mean—is somebody killed him?’

‘You don’t know?’ Dr Archer regarded the pair curiously a moment, then turned back to examine further. From an instrument case he took a probe and proceeded to explore the wound in the dead man’s scalp. ‘Well—what do you know about it, then?’ he asked, still probing. ‘Who found him?’

‘Jinx,’ answered the one who called himself Bubber. ‘We jes’ come here to get this Frimbo’s advice ’bout a little business project we thought up. Jinx went in to see him. I waited in the waitin’ room. Presently Jinx come bustin’ out pop-eyed and beckoned to me. I went back with him—and there was Frimbo, jes’ like you found him. We didn’t even know he was over the river.’

‘Did he fall against anything and strike his head?’

‘No, suh, doc.’ Jinx became articulate. ‘He didn’t do nothin’ the whole time I was in there. Nothin’ but talk. He tol’ me who I was and what I wanted befo’ I could open my mouth. Well, I said that I knowed that much already and that I come to find out sump’m I didn’t know. Then he went on talkin’, tellin’ me plenty. He knowed his stuff all right. But all of a sudden he stopped talkin’ and mumbled sump’m ’bout not bein’ able to see. Seem like he got scared, and he say, “Frimbo, why don’t you see?” Then he didn’t say no more. He sound’ so funny I got scared myself and jumped up and grabbed that light and turned it on him—and there he was.’

‘M-m.’

Dr Archer, pursuing his examination, now indulged in what appeared to be a characteristic habit: he began to talk as he worked, to talk rather absently and wordily on a matter which at first seemed inapropos.

‘I,’ said he, ‘am an exceedingly curious fellow.’ Deftly, delicately, with half-closed eyes, he was manipulating his probe. ‘Questions are forever popping into my head. For example, which of you two gentlemen, if either, stands responsible for the expenses of medical attention in this unfortunate instance?’

‘Mean who go’n’ pay you?’

‘That,’ smiled the doctor, ‘makes it rather a bald question.’

Bubber grinned understandingly.

‘Well here’s one with hair on it, doc,’ he said. ‘Who got the medical attention?’

‘M-m,’ murmured the doctor. ‘I was afraid of that. Not,’ he added, ‘that I am moved by mercenary motives. Oh, not at all. But if I am not to be paid in the usual way, in coin of the realm, then of course I must derive my compensation in some other form of satisfaction. Which, after all, is the end of all our getting and spending, is it not?’

‘Oh, sho’,’ agreed Bubber.

‘Now this case’—the doctor dropped the gauze dressing into his bag—‘even robbed of its material promise, still bids well to feed my native curiosity—if not my cellular protoplasm. You follow me, of course?’

‘With my tongue hangin’ out,’ said Bubber.

But that part of his mind which was directing this discourse did not give rise to the puzzled expression on the physician’s lean, light-skinned countenance as he absently moistened another dressing with alcohol, wiped off his fingers and his probe, and stood up again.

‘We’d better notify the police,’ he said. ‘You men’—he looked at them again—‘you men call up the precinct.’

They promptly started for the door.

‘No—you don’t have to go out. The cops, you see’—he was almost confidential—‘the cops will want to question all of us. Mr Crouch has a phone back there. Use that.’

They exchanged glances but obeyed.

‘I’ll be thinking over my findings.’

Through the next room they scuffled and into the back of the long first-floor suite. There they abruptly came to a halt and again looked at each other, but now for an entirely different reason. Along one side of this room, hidden from view until their entrance, stretched a long narrow table draped with a white sheet that covered an unmistakably human form. There was not much light. The two young men stood quite still.

‘Seem like it’s—occupied,’ murmured Bubber.

‘Another one,’ mumbled Jinx.

‘Where’s the phone?’

‘Don’t ask me. I got both eyes full.’

‘There ’tis—on that desk. Go on—use it.’

‘Use it yo’ own black self,’ suggested Jinx. ‘I’m goin’ back.’

‘No you ain’t. Come on. We use it together.’

‘All right. But if that whosis says “Howdy” tell it I said “Goo’by.”’

‘And where the hell you think I’ll be if it says “Howdy”?’

‘What a place to have a telephone!’

‘Step on it, slow motion.’

‘Hello!—Hello!’ Bubber rattled the hook. ‘Hey operator! Operator!’

‘My Gawd,’ said Jinx, ‘is the phone dead too?’

‘Operator—gimme the station—quick … Pennsylvania? No ma’am—New York—Harlem—listen, lady, not railroad. Police. Please, ma’am … Hello—hey—send a flock o’ cops around here—Frimbo’s—the fortune teller’s—yea—Thirteen West 130th—yea—somebody done put that thing on him! … Yea—O.K.’

Hurriedly they returned to the front room where Dr Archer was pacing back and forth, his hands thrust into his pockets, his brow pleated into troubled furrows.

‘They say hold everything, doc. Be right over.’

‘Good.’ The doctor went on pacing.

Jinx and Bubber surveyed the recumbent form. Said Bubber, ‘If he could keep folks from dyin’, how come he didn’t keep hisself from it?’

‘Reckon he didn’t have time to put no spell on hisself,’ Jinx surmised.

‘No,’ returned Bubber grimly. ‘But somebody else had time to put one on him. I knowed sump’m was comin’. I told you. First time I seen death on the moon since I been grown. And they’s two mo’ yet.’

‘How you reckon it happened?’

‘You askin’ me?’ Bubber said. ‘You was closer to him than I was.’

‘It was plumb dark all around. Somebody could’a’ snook up behind him and crowned him while he was talkin’ to me. But I didn’t hear a sound. Say—I better catch air. This thing’s puttin’ me on the well-known spot, ain’t it?’

‘All right, dumbo. Run away and prove you done it. Wouldn’t that be a bright move?’

Dr Archer said, ‘The wisest thing for you men to do is stay here and help solve this puzzle. You’d be called in anyway—you found the body, you see. Running away looks as if you were—well—running away.’

‘What’d I tell you?’ said Bubber.

‘All right,’ growled Jinx. ‘But I can’t see how they could blame anybody for runnin’ away from this place. Graveyard’s a playground side o’ this.’

CHAPTER II (#ulink_2d24507c-c9fd-560d-8756-b5a7654bd67b)

OF the ten Negro members of Harlem’s police force to be promoted from the rank of patrolman to that of detective, Perry Dart was one of the first. As if the city administration had wished to leave no doubt in the public mind as to its intention in the matter, they had chosen, in him, a man who could not have been under any circumstances mistaken for aught but a Negro; or perhaps, as Dart’s intimates insisted, they had chosen him because his generously pigmented skin rendered him invisible in the dark, a conceivably great advantage to a detective who did most of his work at night. In any case, the somber hue of his integument in no wise reflected the complexion of his brain, which was bright, alert, and practical within such territory as it embraced. He was a Manhattanite by birth, had come up through the public schools, distinguished himself in athletics at the high school he attended, and, having himself grown up with the black colony, knew Harlem from lowest dive to loftiest temple. He was rather small of stature, with unusually thin, fine features, which falsely accentuated the slightness of his slender but wiry body.

It was Perry Dart’s turn for a case when Bubber Brown’s call came in to the station, and to it Dart, with four uniformed men, was assigned.

Five minutes later he was in the entrance of Thirteen West 130th Street, greeting Dr Archer, whom he knew. His men, one black, two brown, and one yellow, loomed in the hallway about him large and ominous, but there was no doubt as to who was in command.

‘Hello, Dart,’ the physician responded to his greeting. ‘I’m glad you’re on this one. It’ll take a little active cerebration.’

‘Come on down, doc,’ the little detective grinned with a flash of white teeth. ‘You’re talking to a cop now, not a college professor. What’ve you got?’

‘A man that’ll tell no tales.’ The physician motioned to the undertaker’s front room. ‘He’s in there.’

Dart turned to his men. ‘Day, you cover the front of the place. Green, take the roof and cover the back yard. Johnson, search the house and get everybody you find into one room. Leave a light everywhere you go if possible—I’ll want to check up. Brady, you stay with me.’ Then he turned back and followed the doctor into the undertaker’s parlour. They stepped over to the sofa, which was in a shallow alcove formed by the front bay windows of the room.

‘How’d he get it, doc?’ he asked.

‘To tell you the truth, I haven’t the slightest idea.’

‘Somebody crowned him,’ Bubber helpfully volunteered.

‘Has anybody ast you anything?’ Jinx inquired gruffly.

Dart bent over the victim.

The physician said:

‘There is a scalp wound all right. See it?’

‘Yea—now that you mentioned it.’

‘But that didn’t kill him.’

‘No? How do you know it didn’t, doc?’

‘That wound is too slight. It’s not in a spot that would upset any vital centre. And there isn’t any fracture under it.’

‘Couldn’t a man be killed by a blow on the head that didn’t fracture his skull?’

‘Well—yes. If it fell just so that its force was concentrated on certain parts of the brain. I’ve never heard of such a case, but it’s conceivable. But this blow didn’t land in the right place for that. A blow at this point would cause death only by producing intracranial haemorrhage—’

‘Couldn’t you manage to say it in English, doc?’

‘Sure. He’d have to bleed inside his head.’

‘That’s more like it.’

‘The resulting accumulation of blood would raise the intra—the pressure inside his head to such a point that vital centres would be paralysed. The power would be shut down. His heart and lungs would quit cold. See? Just like turning off a light.’

‘O.K. if you say so. But how do you know he didn’t bleed inside his head?’

‘Well, there aren’t but two things that would cause him to.’

‘I’m learning, doc. Go on.’

‘Brittle arteries with no give in them—no elasticity. If he had them, he wouldn’t even have to be hit—just excitement might shoot up the blood pressure and pop an artery. See what I mean?’

‘That’s apoplexy, isn’t it?’

‘Right. And the other thing would be a blow heavy enough to fracture the skull and so rupture the blood vessels beneath. Now this man is about your age or mine—somewhere in his middle thirties. His arteries are soft—feel his wrists. For a blow to kill this man outright, it would have had to fracture his skull.’

‘Hot damn!’ whispered Bubber admiringly. ‘Listen to the doc do his stuff!’

‘And his skull isn’t fractured?’ said Dart.

‘Not if probing means anything.’

‘Don’t tell me you’ve X-rayed him too?’ grinned the detective.

‘Any fracture that would kill this man outright wouldn’t have to be X-rayed.’

‘Then you’re sure the blow didn’t kill him?’

‘Not by itself, it didn’t.’

‘Do you mean that maybe he was killed first and hit afterwards?’

‘Why would anybody do that?’ Dr Archer asked.

‘To make it seem like violence when it was really something else.’

‘I see. But no. If this man had been dead when the blow was struck, he wouldn’t have bled at all. Circulation would already have stopped.’

‘That’s right.’

‘But of one thing I’m sure: that wound is evidence of too slight a blow to kill.’

‘Specially,’ interpolated Bubber, ‘a hard-headed cullud man—’

‘There you go ag’in,’ growled his lanky companion.

‘He’s right,’ the doctor said. ‘It takes a pretty hefty impact to bash in a skull. With a padded weapon,’ he went on, ‘a fatal blow would have had to be crushing to make even so slight a scalp wound as this. That’s out. And a hard, unpadded weapon that would break the scalp just slightly like this, with only a little bleeding and without even cracking the skull, could at most have delivered only a stunning blow, not a fatal one. Do you see what I mean?’

‘Sure. You mean this man was just stunned by the blow and actually died from something else.’

‘That’s the way it looks to me.’

‘Well—anyhow he’s dead and the circumstances indicate at least a possibility of death by violence. That justifies notifying us, all right. And it makes it a case for the medical examiner. But we really don’t know that he’s been killed, do we?’

‘No. Not yet.’

‘All the more a case for the medical examiner, then. Is there a phone here, doc? Good. Brady, go back there and call the precinct. Tell ’em to get the medical examiner here double time and to send me four more men—doesn’t matter who. Now tell me, doc. What time did this man go out of the picture?’

The physician smiled.

‘Call Meridian 7-1212.’

‘O.K., doc. But approximately?’

‘Well, he was certainly alive an hour ago. Perhaps even half an hour ago. Hardly less.’

‘How long have you been here?’

‘About fifteen minutes.’

‘Then he must have been killed—if he was killed—say anywhere from five to thirty-five minutes before you got here?’

‘Yes.’

Bubber, the insuppressible, commented to Jinx, ‘Damn! That’s trimming it down to a gnat’s heel, ain’t it?’ But Jinx only responded, ‘Fool, will you hush?’

‘Who discovered him—do you know?’

‘These two men.’

‘Both of you?’ Dart asked the pair.

‘No, suh,’ Bubber answered. ‘Jinx here discovered the man. I discovered the doctor.’

Dart started to question them further, but just then Johnson, the officer who had been directed to search the house, reappeared.

‘Been all over,’ he reported. ‘Only two people in the place. Women—both scared green.’

‘All right,’ the detective said. ‘Take these two men up to the same room. I’ll be up presently.’

Officer Brady returned. ‘Medical examiner’s comin’ right up.’

The detective said, ‘Was he on this sofa when you got here, doc?’

‘No. He was upstairs in his—his consultation room, I guess you’d call it. Queer place. Dark as sin. Sitting slumped down in a chair. The light was impossible. You see, I thought I’d been called to a patient, not a corpse. So I had him brought where I knew I could examine him. Of course, if I had thought of murder—’

‘Never mind. There’s no law against your moving him or examining him, even if you had suspected murder—as long as you weren’t trying to hide anything. People think there’s some such law, but there isn’t.’

‘The medical examiner’ll probably be sore, though.’

‘Let him. We’ve got more than the medical examiner to worry about.’

‘Yes. You’ve got a few questions to ask.’

‘And answer. How, when, where, why, and who? Oh, I’m great at questions. But the answers—’

‘Well, we’ve the “when” narrowed down to a half-hour period.’ Dr Archer glanced at his watch. ‘That would be between ten-thirty and eleven. And “where” shouldn’t be hard to verify—right here in his own chair, if those two fellows are telling it straight. “Why” and “who”—those’ll be your little red wagon. “How” right now is mine. I can’t imagine—’

Again he turned to the supine figure, staring. Suddenly his lean countenance grew blanker than usual. Still staring, he took the detective by the arm. ‘Dart,’ he said reflectively, ‘we smart people are often amazingly—dumb.’

‘You’re telling me?’

‘We waste precious moments in useless speculation. We indulge ourselves in the extravagance of reason when a frugal bit of observation would suffice.’

‘Does prescription liquor affect you like that, doc?’

‘Look at that face.’

‘Well—if you insist—’

‘Just the general appearance of that face—the eyes—the open mouth. What does it look like?’

‘Looks like he’s gasping for breath.’

‘Exactly. Dart, this man might—might, you understand—have been choked.’

‘Ch—’

‘Stunned by a blow over the ear—’

‘To prevent a struggle!’

‘—and choked to death. As simple as that.’

‘Choked! But just how?’

Eagerly, Dr Archer once more bent over the lifeless countenance. ‘There are two ways,’ he dissertated in his roundabout fashion, ‘of interrupting respiration.’ He was peering into the mouth. ‘What we shall call, for simplicity, the external and the internal. In this case the external would be rather indeterminate, since we could hardly make out the usual bluish discolourations on a neck of this complexion.’ He procured two tongue depressors and, one in each hand, examined as far back into the throat as he could. He stopped talking as some discovery further elevated his already high interest. He discarded one depressor, reached for his flashlight with the hand thus freed, and, still holding the first depressor in place, directed his light into the mouth as if he were examining tonsils. With a little grunt of discovery, he now discarded the flashlight also, took a pair of long steel thumb-forceps from a flap in the side of his bag, and inserted the instrument into the victim’s mouth alongside the guiding tongue-depressor. Dart and the uniformed officer watched silently as the doctor apparently tried to remove something from the throat of the corpse. Once, twice, the prongs snapped together, and he withdrew the instrument empty. But the next time the forceps caught hold of the physician’s discovery and drew it forth.

It was a large, blue-bordered, white handkerchief.

CHAPTER III (#ulink_67f5abc4-5e27-5544-bc86-50d72c16b5fa)

‘DOC,’ said Dart, ‘you don’t mind hanging around with us a while?’

‘Try and shake me loose,’ grinned Dr Archer. ‘This promises to be worth seeing.’

‘If you’d said no,’ Dart grinned back, ‘I’d have held you anyhow as a suspect. I’m going to need some of your brains. I’m not one of these bright ones that can do all the answers in my head. I’m just a poor boy trying to make a living, and this kind of a riddle hasn’t been popped often enough in my life to be easy yet. I’ve seen some funny ones, but this is funnier. One thing I can see—that this guy wasn’t put out by any beginner.’

‘The man that did this,’ agreed the physician, ‘thought about it first. I’ve seen autopsies that could have missed that handkerchief. It was pushed back almost out of sight.’

‘That makes you a smart boy.’

‘I admit it. Wonder whose handkerchief?’

‘Stick it in your bag and hang on to it. And let’s get going.’

‘Whither?’

‘To get acquainted with this layout first. Whoever’s here will keep a while. The bird that pulled the job is probably in Egypt by now.’

‘That wouldn’t be my guess.’

‘You think he’d hang around?’

‘He wouldn’t do the expected thing—not if he was bright enough to think up a gag like this.’

‘Gag is good. Let’s start with the roof. Brady, you come with me and the doc—and be ready for surprises. Where’s Day?’

The doctor closed and picked up his bag. They passed into the hallway. Officer Day was on guard in the front vestibule according to his orders.

‘There are four more men and the medical examiner coming,’ the detective told him. ‘The four will be right over. Put one on the rear of the house and send the others upstairs. Come on, doc.’

The three men ascended two flights of stairs to the top floor. The slim Dart led, the tall doctor followed, the stalwart Brady brought up the rear. Along the uppermost hallway they made their way to the front of the third story of the house, moving with purposeful resoluteness, yet with a sharp-eyed caution that anticipated almost any eventuality. The physician and the detective carried their flashlights, the policeman his revolver.

At the front end of the hallway they found a closed door. It was unlocked. Dart flung it open, to find the ceiling light on, probably left by Officer Johnson in obedience to instructions.

This room was a large bedchamber, reaching, except for the width of the hallway, across the breadth of the house. It was luxuriously appointed. The bed was a massive four-poster of mahogany, intricately carved and set off by a counterpane of gold satin. It occupied the mid-portion of a large black-and-yellow Chinese rug which covered almost the entire floor. Two upholstered chairs, done also in gold satin, flanked the bed, and a settee of similar design guarded its foot. An elaborate smoking stand sat beside the head of the bed. A mahogany chest and bureau, each as substantial as the four-poster, completed the furniture.

‘No question as to whose room this is,’ said Dart.

‘A man’s,’ diagnosed Archer. ‘A man of means and definite ideas, good or bad—but definite. Too bare to be a woman’s room—look—the walls are stark naked. There aren’t any frills’—he sniffed—‘and there isn’t any perfume.’

‘I guess you’ve been in enough women’s rooms to know.’

‘Men’s too. But this is odd. Notice anything conspicuous by its absence?’

‘I’ll bite.’

‘Photographs of women.’

The detective’s eyes swept the room in verification.

‘Woman hater?’

‘Maybe,’ said the doctor, ‘but—’

‘Wait a minute,’ said the detective. There was a clothes closet to the left of the entrance. He turned, opened its door, and played his flashlight upon its contents. An array of masculine attire extended in orderly suspension—several suits of various patterns hanging from individual racks. On the back of the open door hung a suit of black pyjamas. On the floor a half-dozen pairs of shoes were set in an orderly row. There was no suggestion of any feminine contact or influence; there was simply the atmosphere of an exceptionally well ordered, decided masculinity.

‘What do you think?’ asked Dr Archer.

‘Woman hater,’ repeated Dart conclusively.

‘Or a Lothario of the deepest dye.’

The detective looked at the doctor. ‘I get the deep dye—he was blacker’n me. But the Lothario—’

‘Isn’t it barely possible that this so very complete—er—repudiation of woman is too complete to be accidental? May it not be deliberate—a wary suppression of evidence—the recourse of a lover of great experience and wisdom, who lets not his right hand know whom his left embraceth?’

‘Not good—just careful?’

‘He couldn’t be married—actively. His wife’s influence would be—smelt. And if he isn’t married, this over-absence of the feminine—well—it means something.’

‘I still think it could mean woman-hating. This other guess-work of yours sounds all bass-ackwards to me.’

‘Heaven forfend, good friend, that you should lose faith in my judgment. Woman-hater you call him and woman-hater he is. Carry on.’

A narrow little room the width of the hallway occupied that extent of the front not taken up by the master bedroom. In this they found a single bed, a small table, and a chair, but nothing of apparent significance.

Along the hallway they now retraced their steps, trying each of three successive doors that led off from this passage. The first was an empty store-room, the second a white tiled bathroom, and the third a bare closet. These yielded no suggestion of the sort of character or circumstances with which they might be dealing. Nor did the smaller of the two rooms terminating the hallway at its back end, for this was merely a narrow kitchen, with a tiny range, a table, icebox, and cabinet. In these they found no inspiration.

But the larger of the two rear rooms was arresting enough. This was a study, fitted out in a fashion that would have warmed the heart and stirred the ambition of any student. There were two large brown-leather club chairs, each with its end table and reading lamp; a similarly upholstered divan in front of a fireplace that occupied the far wall, and over toward the windows at the rear, a flat-topped desk, upon which sat a bronze desk-lamp, and behind which sat a large swivel armchair. Those parts of the walls not taken up by the fireplace and windows were solid masses of books, being fitted from the floor to the level of a tall man’s head with crowded shelves.

Dr Archer was at once absorbed. ‘This man was no ordinary fakir,’ he observed. ‘Look.’ He pointed out several framed documents on the upper parts of the walls. ‘Here—’ He approached the largest and peered long upon it. Dart came near, looked at it once, and grinned:

‘Does it make sense, doc?’

‘Bachelor’s degree from Harvard. N’Gana Frimbo. N’Gana—’

‘Not West Indian?’

‘No. This sounds definitely African to me. Lots of them have that N’. The “Frimbo” suggests it, too—mumbo—jumbo—sambo—’

‘Limbo—’

‘Wonder why he chose an American college? Most of the chiefs’ sons’ll go to Oxford or bust. I know—this fellow is probably from Liberia or thereabouts. American influence—see?’

‘How’d he get into a racket like fortune telling?’

‘Ask me another. Probably a better racket than medicine in this community. A really clever chap could do wonders.’

The doctor was glancing along the rows of books. He noted such titles as Tankard’s Determinism and Fatalism, a Critical Contrast, Bostwick’s The Concept of Inevitability, Preem’s Cause and Effect, Dessault’s The Science of History, and Fairclough’s The Philosophical Basis of Destiny. He took this last from its place, opened to a flyleaf, and read in script, ‘N’Gana Frimbo’ and a date. Riffling the pages, he saw in the same script pencilled marginal notes at frequent intervals. At the end of the chapter entitled ‘Unit Stimulus and Reaction,’ the pencilled notation read: ‘Fairclough too has missed the great secret.’

‘This is queer.’

‘What?’

‘A native African, a Harvard graduate, a student of philosophy—and a sorcerer. There’s something wrong with that picture.’

‘Does it throw any light on who killed him?’

‘Anything that throws light on the man’s character might help.’

‘Well, let’s get going. I want to go through the rest of the house and get down to the real job. You worry about his character. I’ll worry about the character of the suspects.’

‘Right-o. Your move, professor.’

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_e1ee34c4-8a52-50b2-ae71-6fd54d4276bf)

MEANWHILE Jinx and Bubber, in Frimbo’s waiting-room on the second floor, were indulging in one of their characteristic arguments. This one had started with Bubber’s chivalrous endeavours to ease the disturbing situation for the two women, both of whom were bewildered and distraught and one of whom was young and pretty. Bubber had not only announced and described in detail just what he had seen, but, heedless of the fact that the younger woman had almost fainted, had proceeded to explain how he had known, long before it occurred, that he had been about to ‘see death.’ To dispel any remaining vestiges of tranquillity, he had added that the death of Frimbo was but one of three. Two more were at hand.

‘Soon as Jinx here called me,’ he said, ‘I knowed somebody’s time had come. I busted on in that room yonder with him—y’all seen me go—and sho’ ’nough, there was the man, limp as a rag and stiff as a board. Y’ see, the moon don’t lie. ’Cose most signs ain’t no ’count. As for me, you won’t find nobody black as me that’s less suprastitious.’

‘Jes’ say we won’t find nobody black as you and stop. That’ll be the truth,’ growled Jinx.

‘But a moonsign is different. Moonsign is the one sign you can take for sho’. Moonsign—’

‘Moonshine is what you took for sho’ tonight,’ Jinx said.

‘Red moon mean bloodshed, new moon over your right shoulder mean good luck, new moon over your left shoulder mean bad luck, and so on. Well, they’s one moonsign my grandmammy taught me befo’ I was knee high and that’s the worst sign of ’em all. And that’s the sign I seen tonight. I was walkin’ down the Avenue feelin’ fine and breathin’ the air—’

‘What do you breathe when you don’t feel so good?’

‘—smokin’ the gals over, watchin’ the cars roll by—feelin’ good, you know what I mean. And then all of a sudden I stopped. I store.’

‘You whiched?’

‘Store. I stopped and I store.’

‘What language you talkin’?’

‘I store at the sky. And as I stood there starin’, sump’m didn’t seem right. Then I seen what it was. Y’ see, they was a full moon in the sky—’

‘Funny place for a full moon, wasn’t it?’

‘—and as I store at it, they come up a cloud—wasn’t but one cloud in the whole sky—and that cloud come up and crossed over the face o’ the moon and blotted it out—jes’ like that.’

‘You sho’ ’twasn’t yo’ shadow?’

‘Well there was the black cloud in front o’ the moon and the white moonlight all around it and behind it. All of a sudden I seen what was wrong. That cloud had done took the shape of a human skull!’

‘Sweet Jesus!’ The older woman’s whisper betokened the proper awe. She was an elongated, incredibly thin creature, ill-favoured in countenance and apparel; her loose, limp, angular figure was grotesquely disposed over a stiff-backed arm-chair, and dark, nondescript clothing draped her too long limbs. Her squarish, fashionless hat was a little awry, her scrawny visage, already disquieted, was now inordinately startled, the eyes almost comically wide above the high cheek bones, the mouth closed tight over her teeth whose forward slant made the lips protrude as if they were puckering to whistle.

The younger woman, however, seemed not to hear. Those dark eyes surely could sparkle brightly, those small lips smile, that clear honey skin glow with animation; but just now the eyes stared unseeingly, the lips were a short, hard, straight line, the skin of her round pretty face almost colourless. She was obviously dazed by the suddenness of this unexpected tragedy. Unlike the other woman, however, she had not lost her poise, though it was costing her something to retain it. The trim, black, high-heeled shoes, the light sheer stockings, the black seal coat which fell open to reveal a white-bordered pimiento dress, even the small close-fitting black hat, all were quite as they should be. Only her isolating detachment betrayed the effect upon her of the presence of death and the law.

‘A human skull!’ repeated Bubber. ‘Yes, ma’am. Blottin’ out the moon. You know what that is?’

‘What?’ said the older woman.

‘That’s death on the moon. It’s a moonsign and it’s never been known to fail.’

‘And it means death?’

‘Worse ’n that, ma’am. It means three deaths. Whoever see death on the moon’—he paused, drew breath, and went on in an impressive lower tone—‘gonna see death three times!’

‘My soul and body!’ said the lady.

But Jinx saw fit to summon logic. ‘Mean you go’n’ see two more folks dead?’

‘Gonna stare ’em in the face.’

‘Then somebody ought to poke yo’ eyes out in self-defence.’

Having with characteristic singleness of purpose discharged his duty as a gentleman and done all within his power to set the ladies’ minds at rest, Bubber could now turn his attention to the due and proper quashing of his unappreciative commentator.

‘Whyn’t you try it?’ he suggested.

‘Try what?’

‘Pokin’ my eyes out.’

‘Huh. If I thought that was the onliest way to keep from dyin’, you could get yo’self a tin cup and a cane tonight.’

‘Try it then.’

‘’Tain’t necessary. That moonshine you had’ll take care o’ everything. Jes’ give it another hour to work and you’ll be blind as a Baltimo’ alley.’

‘Trouble with you,’ said Bubber, ‘is, you’ ignorant. You’ dumb. The inside o’ yo’ head is all black.’

‘Like the outside o’ yourn.’

‘Is you by any chance alludin’ to me?’

‘I ain’t alludin’ to that policeman over yonder.’

‘Lucky for you he is over yonder, else you wouldn’t be alludin’ at all.’

‘Now you gettin’ bad, ain’t you? Jus’ ’cause you know you got the advantage over me.’

‘What advantage?’

‘How could I hit you when I can’t even see you?’

‘Well if I was ugly as you is, I wouldn’t want nobody to see me.’

‘Don’t worry, son. Nobody’ll ever know how ugly you is. Yo’ ugliness is shrouded in mystery.’

‘Well yo’ dumbness ain’t. It’s right there for all the world to see. You ought to be back in Africa with the other dumb boogies.’

‘African boogies ain’t dumb,’ explained Jinx. ‘They’ jes’ dark. You ain’t been away from there long, is you?’

‘My folks,’ returned Bubber crushingly, ‘left Africa ten generations ago.’

‘Yo’ folks? Shuh. Ten generations ago, you-all wasn’t folks. You-all hadn’t qualified as apes.’

Thus as always, their exchange of compliments flowed toward the level of family history, among other Harlemites a dangerous explosive which a single word might strike into instantaneous violence. It was only because the hostility of these two was actually an elaborate masquerade, whereunder they concealed the most genuine affection for each other, that they could come so close to blows that were never offered.

Yet to the observer this mock antagonism would have appeared alarmingly real. Bubber’s squat figure sidled belligerently up to the long and lanky Jinx; solid as a fire-plug he stood, set to grapple; and he said with unusual distinctness:

‘Yea? Well—yo’ granddaddy was a hair on a baboon’s tail. What does that make you?’

The policeman’s grin of amusement faded. The older woman stifled a cry of apprehension.

The younger woman still sat motionless and staring, wholly unaware of what was going on.

CHAPTER V (#ulink_30a5b77f-ff40-535d-bf53-2b896f60aa83)

DETECTIVE Dart, Dr Archer, and Officer Brady made a rapid survey of the basement and cellar. The basement, a few feet below sidewalk level, proved to be one long, low-ceilinged room, fitted out, evidently by the undertaker, as a simple meeting-room for those clients who required the use of a chapel. There were many rows of folding wooden chairs facing a low platform at the far end of the room. In the middle of this platform rose a pulpit stand, and on one side against the wall stood a small reed organ. A heavy dark curtain across the rear of the platform separated it and the meeting-place from a brief unimproved space behind that led through a back door into the back yard. The basement hallway, in the same relative position as those above, ran alongside the meeting-room and ended in this little hinder space. In one corner of this, which must originally have been the kitchen, was the small door of a dumbwaiter shaft which led to the floor above. The shaft contained no sign of a dumbwaiter now, as Dart’s flashlight disclosed: above were the dangling gears and broken ropes of a mechanism long since discarded, and below, an empty pit.

They discovered nearby the doorway to the cellar stairs, which proved to be the usual precipitate series of narrow planks. In the cellar, which was poorly lighted by a single central droplight, they found a large furnace, a coal bin, and, up forward, a nondescript heap of shadowy junk such as cellars everywhere seem to breed.

All this appeared for the time being unimportant, and so they returned to the second floor, where the victim had originally been found. Dart had purposely left this floor till the last. It was divided into three rooms, front, middle and back, and these they methodically visited in order.

They entered the front room, Frimbo’s reception room, just as Bubber sidled belligerently up to Jinx. Apparently their entrance discouraged further hostilities, for with one or two upward, sidelong glares from Bubber, neutralized by an inarticulate growl or two from Jinx, the imminent combat faded mysteriously away and the atmosphere cleared.

But now the younger woman’s eyes lifted to recognize Dr John Archer. She jumped up and went to him.

‘Hello, Martha,’ he said.

‘What does it mean, John?’

‘Don’t let it upset you. Looks like the conjure-man had an enemy, that’s all.’

‘It’s true—he really is—?’

‘I’m afraid so. This is Detective Dart. Mrs Crouch, Mr Dart.’

‘Good-evening,’ Mrs Crouch said mechanically and turned back to her chair.

‘Dart’s a friend of mine, Martha,’ said the physician. ‘He’ll take my word for your innocence, never fear.’

The older woman, refusing to be ignored, said impatiently, ‘How long you ’spect us to sit here? What we waitin’ for? We didn’ kill him.’

‘Of course not,’ Dart smiled. ‘But you may be able to help us find out who did. As soon as I’ve finished looking around I’ll want to ask you a few questions. That’s all.’

‘Well,’ she grumbled, ‘you don’t have to stand a seven-foot cop over us to ask a few questions, do you?’

Ignoring this inquiry, the investigators continued with their observations. This was a spacious room whose soft light came altogether from three or four floor lamps; odd heavy silken shades bore curious designs in profile, and the effect of the obliquely downcast light was to reveal legs and bodies, while countenances above were bedimmed by comparative shadow. Beside the narrow hall door was a wide doorway hung with portières of black velvet, occupying most of that wall. The lateral walls, which seemed to withdraw into the surrounding dusk, were adorned with innumerable strange and awful shapes: gruesome black masks with hollow orbits, some smooth and bald, some horned and bearded; small misshapen statuettes of near-human creatures, resembling embryos dried and blackened in the sun, with closed bulbous eyes and great protruding lips; broad-bladed swords, slim arrows and jagged spear-heads of forbidding designs. On the farther of the lateral walls was a mantelpiece upon which lay additional African emblems. Dr Archer pointed out a murderous-looking club, resting diagonally across one end of the mantel; it consisted of the lower half of a human femur, one extremity bulging into wicked-looking condyles, the other, where the original bone had been severed, covered with a silver knob representing a human skull.

‘That would deliver a nasty crack.’

‘Wonder if it did?’ said the detective.

They passed now through the velvet portières and a little isthmus-like antechamber into the middle room where the doctor had first seen the victim. Dr Archer pointed out those peculiarities of this chamber which he had already noted: the odd droplight with its horizontally focused beam, which was the only means of illumination; the surrounding black velvet draping, its long folds extending vertically from the bottom of the walls to the top, then converging to the centre of the ceiling above, giving the room somewhat the shape of an Arab tent; the one apparent opening in this drapery, at the side door leading to the hallway; the desk-like table in the middle of the room, the visitors’ chair on one side of it, Frimbo’s on the other, directly beneath the curious droplight.

‘Let’s examine the walls,’ said Dart. He and the doctor brought their flashlights into play. Like two off-shoots of the parent beam, the smaller shafts of light travelled inquisitively over the long vertical folds of black velvet, which swayed this way and that as the two men pulled and palpated, seeking openings. The projected spots of illumination moved like two strange, twisting, luminous moths, constantly changing in size and shape, fluttering here and there from point to point, pausing, inquiring, abandoning. The detective and the physician began at the entrance from the reception room and circuited the black chamber in opposite directions. Presently they met at the far back wall, in whose midline the doctor located an opening. Pulling the hangings aside at this point, they discovered another door but found it locked.

‘Leads into the back room, I guess. We’ll get in from the hallway. What’s this?’

‘This’ proved to be a switch-box on the wall beside the closed door. The physician read the lettering on its front. ‘Sixty amperes—two hundred and twenty volts. That’s enough for an X-ray machine. What does he need special current for?’

‘Search me. Come on. Brady, run downstairs and get that extension-light out of the back of my car. Then come back here and search the floor for whatever you can find. Specially around the table and chairs. We’ll be right back.’

They left the death chamber by its side door and approached the rearmost room from the hallway. Its hall door was unlocked, but blackness greeted them as they flung it open, a strangely sinister blackness in which eyes seemed to gleam. When they cast their flashlights into that blackness they saw whence the gleaming emanated, and Dart, stepping in, found a switch and produced a light.

‘Damn!’ said he as his eyes took in a wholly unexpected scene. Along the rear wall under the windows stretched a long flat chemical work-bench, topped with black slate. On its dull dark surface gleamed bright laboratory devices of glass or metal, flasks, beakers, retorts, graduates, pipettes, a copper water-bath, a shining instrument-sterilizer, and at one end, a gleaming black electric motor. The space beneath this bench was occupied by a long floor cabinet with a number of small oaken doors. On the wall at the nearer end was a glass-doored steel cabinet containing a few small surgical instruments, while the far wall, at the other end of the bench, supported a series of shelves, the lower ones bearing specimen-jars of various sizes, and the upper, bottles of different colours and shapes. Dart stooped and opened one of the cabinet doors and discovered more glassware, while Dr Archer went over and investigated the shelves, removed one of the specimen-jars, and with a puzzled expression, peered at its contents, floating in some preserving fluid.

‘What’s that?’ the detective asked, approaching.

‘Can’t be,’ muttered the physician.

‘Can’t be what?’

‘What they look like.’

‘Namely?’

Ordinarily Dr Archer would probably have indulged in a leisurely circumlocution and reached his decision by a flank attack. In the present instance he was too suddenly and wholly absorbed in what he saw to entertain even the slightest or most innocent pretence.

‘Sex glands,’ he said.

‘What?’

‘Male sex glands, apparently.’

‘Are you serious?’

The physician inspected the rows of jars, none of which was labelled. There were other preserved biological specimens, but none of the same appearance as those in the jar which he still held in his hand.

‘I’m serious enough,’ he said. ‘Does it stimulate your imagination?’

‘Plenty,’ said Dart, his thin lips tightening. ‘Come on—let’s ask some questions.’

CHAPTER VI (#ulink_801f6399-3cb6-57ad-a1be-eb29b90516b0)

THEY returned to the middle chamber. Officer Brady had plugged the extension into a hall socket and twisted its cord about the chain which suspended Frimbo’s light. The strong white lamp’s sharp radiance did not dispel the far shadows, but at least it brightened the room centrally.

Brady said, ‘There’s three things I found—all on the floor by the chair.’

‘This chair?’ Dart indicated the one in which the victim had been first seen by Dr Archer.

‘Yes.’

The three objects were on the table, as dissimilar as three objects could be.

‘What do you think of this, doc?’ Dart picked up a small irregular shining metallic article and turned to show it to the physician. But the physician was already reaching for one of the other two discoveries.

‘Hey—wait a minute!’ protested the detective. ‘That’s big enough to have finger prints on it.’

‘My error. What’s that you have?’

‘Teeth. Somebody’s removable bridge.’

He handed over the small shining object. The physician examined it. ‘First and second left upper bicuspids,’ he announced.

‘You don’t say?’ grinned Dart.

‘What do you mean, somebody’s?’

‘Well, if you know whose just by looking at it, speak up. Don’t hold out on me.’

‘Frimbo’s.’

‘Or the guy’s that put him out.’

‘Hm—no. My money says Frimbo’s. These things slip on and off easily enough.’

‘I see what you mean. In manipulating that handkerchief the murderer dislodged this thing.’

‘Yes. Too bad. If it was the murderer’s it might help identify him.’

‘Why? There must be plenty of folks with those same teeth missing.’

‘True. But this bridge wouldn’t fit—really fit—anybody but the person it was made for. The models have to be cast in plaster. Not two in ten thousand would be identical in every respect. This thing’s practically as individual as a finger print.’

‘Yea? Well, we may be able to use it anyhow. I’ll hang on to it. But wait. You looked down Frimbo’s throat. Didn’t you notice his teeth?’

‘Not especially. I didn’t care anything about his teeth then. I was looking for the cause of death. But we can easily check this when the medical examiner comes.’

‘O.K. Now—what’s this?’ He picked up what seemed to be a wad of black silk ribbon.

‘That was his head cloth, I suppose. Very impressive with that flowing robe and all.’

‘Who could see it in the dark?’

‘Oh, he might have occasion to come out into the light sometime.’

The detective’s attention was already on the third object.

‘Say—!’

‘I’m way ahead of you.’

‘That’s the mate to the club on the mantel in the front room!’

‘Right. That’s made from a left femur, this from a right.’

‘That must be what crowned him. Boy, if that’s got finger prints on it—’

‘Ought to have. Look—it’s not fully bleached out like the specimens ordinarily sold to students. Notice the surface—greasy-looking. It would take an excellent print.’

‘Did you touch it, Brady?’

‘I picked it up by the big end. I didn’t touch the rest of it.’

‘Good. Have the other guys shown up yet? All right. Wrap it—here’—he took a newspaper from his pocket, surrounded the thigh bone with it, stepped to the door and summoned one of the officers who had arrived meanwhile. ‘Take this over to the precinct, tell Mac to get it examined for finger prints pronto—anybody he can get hold of—wait for the result and bring it back here—wet. And bring back a set—if Tynie’s around, let him bring it. Double time—it’s a rush order.’

‘What’s the use?’ smiled the doctor. ‘You yourself said the offender’s probably in Egypt by now.’

‘And you said different. Hey—look!’

He had been playing his flashlight over the carpet. Its rays passed obliquely under the table, revealing a greyish discolouration of the carpet. Closer inspection proved this to be due to a deposit of ash-coloured powder. The doctor took a prescription blank and one of his professional cards and scraped up some of the powder onto the blank.

‘Know what it is?’ asked Dart.

‘No.’

‘Save it. We’ll have it examined.’

‘Meanwhile?’

‘Meanwhile let’s indulge in a few personalities. Let’s see—I’ve got an idea.’

‘Shouldn’t be at all surprised. What now?’

‘This guy Frimbo was smart. He put his people in that spotlight and he stayed in the dark. All right—I’m going to do the same thing.’

‘You might win the same reward.’

‘I’ll take precautions against that. Brady!’

Brady brought in the two officers who had not yet been assigned to a post. They were stationed now, one on either side of the black room toward its rear wall.

‘Now,’ said Dart briskly. ‘Let’s get started. Brady call in that little short fat guy. You in the hall there—turn off this extension at that socket and be ready to turn it on again when I holler. I intend to sit pat as long as possible.’

Thereupon he snapped off his flashlight and seated himself in Frimbo’s chair behind the table, becoming now merely a deeper shadow in the surrounding dimness. The doctor put out his flashlight also and stood beside the chair. The bright shaft of light from the device overhead, directed away from them, shone full upon the back of the empty visitors’ chair opposite, and on beyond toward the passageway traversed by those who entered from the reception room. They waited for Bubber Brown to come in.

Whatever he might have expected, Bubber Brown certainly was unprepared for this. With a hesitancy that was not in the least feigned, his figure came into view; first his extremely bowed legs, about which flapped the bottom of his imitation camels’ hair overcoat, then the middle of his broad person, with his hat nervously fingered by both hands, then his chest and neck, jointly adorned by a bright green tie, and finally his round black face, blank as a door knob, loose-lipped, wide-eyed. Brady was prodding him from behind.

‘Sit down, Mr Brown,’ said a voice out of the dark.

The unaccustomed ‘Mr’ did not dispel the unreality of the situation for Bubber, who had not been so addressed six times in his twenty-six years. Nor was he reassured to find that he could not make out the one who had spoken, so blinding was the beam of light in his eyes. What he did realize was that the voice issued from the place where he had a short while ago looked with a wild surmise upon a corpse. For a moment his eyes grew whiter; then, with decision, he spun about and started away from the sound of that voice.

He bumped full into Brady. ‘Sit down!’ growled Brady.

Said Dart, ‘It’s me, Brown—the detective. Take that chair and answer what I ask you.’

‘Yes, suh,’ said Bubber weakly, and turned back and slowly edged into the space between the table and the visitors’ chair. Perspiration glistened on his too illuminated brow. By the least possible bending of his body he managed to achieve the mere rim of the seat, where, with both hands gripping the chair arms, he crouched as if poised on some gigantic spring which any sudden sound might release to send him soaring into the shadows above.

‘Brady, you’re in the light. Take notes. All right, Mr Brown. What’s your full name?’

‘Bubber Brown,’ stuttered that young man uncomfortably.

‘Address?’

‘2100 Fifth Avenue.’

‘Age?’

‘Twenty-six.’

‘Occupation?’

‘Suh?’

‘Occupation?’

‘Oh. Detective.’

‘De—what!’

‘Detective. Yes, suh.’

‘Let’s see your shield.’

‘My which?’

‘Your badge.’

‘Oh. Well—y’see I ain’t the kind o’ detective what has to have a badge. No, suh.’

‘What kind are you?’

‘I’m a family detective.’

Somewhat more composed by the questioning, Bubber quickly reached into his pocket and produced a business card. Dart took it and snapped his light on it, to read:

BUBBER BROWN, INC., Detective

(formerly with the City of New York)

2100 Fifth Avenue

Evidence obtained in affairs of the heart, etc.

Special attention to cheaters and backbiters.

Dart considered this a moment, then said:

‘How long have you been breaking the law like this?’

‘Breaking the law? Who, me? What old law, mistuh?’

‘What about this “Incorporated”? You’re not incorporated.’

‘Oh, that? Oh, that’s “ink”—that means black.’

‘Don’t play dumb. You know what it means, you know that you’re not incorporated, and you know that you’ve never been a detective with the City. Now what’s the idea? Who are you?’

Bubber had, as a matter of fact, proffered the card thoughtlessly in the strain of his discomfiture. Now he chose, wisely, to throw himself on Dart’s good graces.

‘Well, y’see times is been awful hard, everybody knows that. And I did have a job with the City—I was in the Distinguished Service Company—’

‘The what?’

‘The D.S.C.—Department of Street Cleaning—but we never called it that, no, suh. Coupla weeks ago I lost that job and couldn’t find me nothin’ else. Then I said to myself, “They’s only one chance, boy—you got to use your head instead o’ your hands.” Well, I figured out the situation like this: The only business what was flourishin’ was monkey-business—’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Monkey-business. Cheatin’—backbitin’, and all like that. Don’t matter how bad business gets, lovin’ still goes on; and long as lovin’ is goin’ on, cheatin’ is goin’ on too. Now folks’ll pay to catch cheaters when they won’t pay for other things, see? So I figure I can hire myself out to catch cheaters as well as anybody—all I got to do is bust in on ’em and tell the judge what I see. See? So I had me them cards printed and I’m r’arin’ to go. But I didn’t know ’twas against the law sho’ ’nough.’

‘Well it is and I may have to arrest you for it.’

Bubber’s dismay was great.

‘Couldn’t you jes’—jes’ tear up the card and let it go at that?’

‘What was your business here tonight?’

‘Me and Jinx come together. We was figurin’ on askin’ the man’s advice about this detective business.’

‘You and who?’

‘Jinx Jenkins—you know—the long boy look like a giraffe you seen downstairs.’

‘What time did you get here?’

‘’Bout half-past ten I guess.’

‘How do you know it was half-past ten?’

‘I didn’t say I knowed it, mistuh. I said I guess. But I know it wasn’t no later’n that.’

‘How do you know?’

Thereupon, Bubber told how he knew.

At eight o’clock sharp, as indicated by his new dollar watch, purchased as a necessary tool of his new profession, he had been walking up and down in front of the Lafayette Theatre, apparently idling away his time, but actually taking this opportunity to hand out his new business cards to numerous theatre-goers. It was his first attempt to get a case and he was not surprised to find that it promptly bore fruit in that happy-go-lucky, care-free, irresponsible atmosphere. A woman to whom he had handed one of his announcements returned to him for further information.

‘I should ’a’ known better,’ he admitted, ‘than to bother with her, because she was bad luck jes’ to look at. She was cross-eyed. But I figure a cross-eyed dollar’ll buy as much as a straight-eyed one and she talked like she meant business. She told me if I would get some good first-class low-down on her big boy, I wouldn’t have no trouble collectin’ my ten dollars. I say “O.K., sister. Show me two bucks in front and his Cleo from behind, and I’ll track ’em down like a bloodhound.” She reached down in her stockin’, I held out my hand and the deal was on. I took her name an’ address an’ she showed me the Cleo and left. That is, I thought she left.

‘The Cleo was the gal in the ticket-box. Oh, mistuh, what a Sheba! Keepin’ my eyes on her was the easiest work I ever did in my life. I asked the flunky out front what this honey’s name was and he tole me Jessie James. That was all I wanted to know. When I looked at her I felt like givin’ the cross-eyed woman back her two bucks.

‘A little before ten o’clock Miss Jessie James turned the ticket-box over to the flunky and disappeared inside. It was too late for me to spend money to go in then, and knowin’ I prob’ly couldn’t follow her everywhere she was goin’ anyhow, I figured I might as well wait for her outside one door as another. So I waited out front, and in three or four minutes out she come. I followed her up the Avenue a piece and round a corner to a private house on 134th Street. After she’d been in a couple o’ minutes I rung the bell. A fat lady come to the door and I asked for Miss Jessie James.

‘“Oh,” she say. “Is you the gentleman she was expectin’?” I say, “Yes ma’am. I’m one of ’em. They’s another one comin’.” She say, “Come right in. You can go up—her room is the top floor back. She jes’ got here herself.” Boy, what a break. I didn’ know for a minute whether this was business or pleasure.

‘When I got to the head o’ the stairs I walked easy. I snook up to the front-room door and found it cracked open ’bout half an inch. Naturally I looked in—that was business. But, friend, what I saw was nobody’s business. Miss Jessie wasn’t gettin’ ready for no ordinary caller. She look like she was gettin’ ready to try on a bathin’ suit and meant to have a perfect fit. Nearly had a fit myself tryin’ to get my breath back. Then I had to grab a armful o’ hall closet, ’cause she reached for a kimono and started for the door. She passed by and I see I’ve got another break. So I seized opportunity by the horns and slipped into her room. Over across one corner was—’

‘Wait a minute,’ interrupted Dart. ‘I didn’t ask for your life history. I only asked—’

‘You ast how I knowed it wasn’t after half-past ten o’clock.’

‘Exactly.’