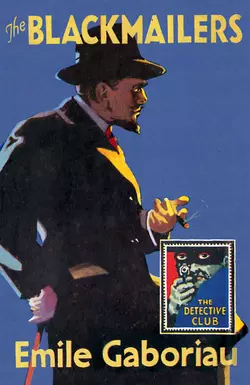

The Blackmailers: Dossier No. 113

Richard Dalby

Ernest Tristan

Gaboriau Émile

Monsieur Lecoq of the French Sûreté is called to investigate a Bank Robbery in one of the world’s first detective novels, widely credited as the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes.A sensational bank robbery of 350,000 francs is the talk of Paris, with suspicion falling immediately upon Prosper Bertomy, the young cashier whose extravagant living has been the subject of gossip among his friends. As a network of deceit, blackmail, murder and villainy closes around Prosper and his lover Madeleine, Monsieur Lecoq of the French Sûreté embarks on a daring investigation to prove the young man’s innocence in the face of damning evidence and discover the truth behind an otherwise impossible crime.Émile Gaboriau is widely regarded as France’s greatest detective writer and a true pioneer of the genre. He created the archetypal detective Monsieur Lecoq, who appeared as a supporting character in L’Affaire Lerouge in 1866 and took centre-stage the following year in Le Dossier No.113, published in English as The Blackmailers. A master of disguise and guile, the stylish Lecoq appeared in only five novels before Gaboriau’s death in 1873 aged 40, having created the template for his natural successor – Sherlock Holmes.This detective Story Club classic is introduced by detective fiction expert and researcher Richard Dalby, who examines the work of the Frenchman frequently credited as the creator of the modern detective story.

COPYRIGHT (#ua9a06465-e824-57cb-ba20-282742bb890e)

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in French as Dossier No.113 by E. Dentu 1867 Translated as The Blackmailers by Ernest Tristan 1907 Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd for Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1929 Introduction Richard Dalby 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2016

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137519

Ebook Edition © April 2016 ISBN: 9780008137526

Version: 2016-02-19

CONTENTS

COVER (#u0b39e897-838d-52a2-abed-2af602f88c07)

TITLE PAGE (#ud404571c-054f-5c8e-a522-c4c4424612bf)

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

CHAPTER XXII

CHAPTER XXIII

CHAPTER XXIV

CHAPTER XXV

ABOUT THE BOOK

THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION (#ua9a06465-e824-57cb-ba20-282742bb890e)

ÉMILE Gaboriau’s ingenious creation Monsieur Lecoq was the first important literary detective to be featured in a series of novels during the 1860s. Published midway between Edgar Allan Poe’s three celebrated stories featuring C. Auguste Dupin (including ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’) in the early 1840s and Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel in 1887, Monsieur Lecoq was also an exact contemporary of Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (1868), considered to be Britain’s first classic detective novel.

Gaboriau moved ahead of his contemporaries by focusing attention on the gathering and interpretation of evidence in the detection of crime. Historically he is second only to Poe in creating pure detective fiction, by writing the first novels in which the nature of the crime, the role of the detective, the misdirections, the reader participation and the solution are all carried through successfully in the contemporary manner, a great inspiration to all who followed in this genre.

Émile Gaboriau was born in the town of Saujon, France, on 9 November 1832, the son of a notary. He spent seven years in the cavalry before settling in Paris, where he wrote poetic mottoes for birthday cakes and songs for street singers.

He then became assistant, secretary and ghost-writer to Paul Féval, author of widely-read criminal romances for feuilletons (inserted as supplements in daily newspapers). Gaboriau gathered much of his material in police courts for Féval, and in 1858 broke away to begin work on his own serialised novels.

After writing seven popular romances, Gaboriau produced his first detective novel, L’Affaire Lerouge, which began its newspaper serialisation in September 1865, and was published in book form the following year. In this story, Gévrol, chief of the detective police in the Paris Sûreté, is in charge, but the major detection is provided by Père Tabaret, an amateur consultant who explains his methods to the young Lecoq. Tabaret has studied the literature of crime for a long time and worked by ratiocination, or precise thinking, to solve a very deceptive crime, said to have been based on a contemporary murder.

Lecoq began in L’Affaire Lerouge as a minor detective with a shady past who had previously contemplated illegal methods of gaining wealth before joining the Sûreté. His career was inspired and closely based on the life and memoirs of the real-life detective Eugène François Vidocq (1775–1857), who also joined the Sûreté after a life of crime.

After his début, Lecoq had much more important leading roles in Le Crime d’Orcival (1867), Le Dossier No.113 (1867), Les Esclaves de Paris (1868, initially in two volumes), and Monsieur Lecoq (1869, also in two volumes). These enthralling mysteries ensured that Lecoq gained countless admirers throughout Europe, including the statesmen Benjamin Disraeli and Otto von Bismarck. As Gaboriau’s reputation grew, so were his novels translated and published in the UK, but none were more successful than the bestselling Lecoq quintet, issued by Routledge in the summer of 1887 in cheap paperback and yellowback editions under the titles The Widow Lerouge, The Mystery of Orcival, File No.113, The Slaves of Paris and Monsieur Lecoq.

In addition to becoming a master of disguise, Lecoq developed valuable crime-fighting techniques, such as using plaster to make impressions of footprints and devising a test of when exactly a bed has been slept in. He was always a supreme master of excavating and analysing deeply-buried vital clues. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the first Sherlock Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet, followed shortly after the Routledge paperbacks, at Christmas in the same year.

Émile Gaboriau died suddenly on 28 September 1873, supposedly of ‘overwork’, aged only 40, having written 21 novels in thirteen years (fourteen of them in his last seven years of life). He described his works as romans judiciaires, a crime-mystery form much imitated by writers in the century to come.

The third Monsieur Lecoq novel, Le Dossier No.113, was first translated into English in 1875 and published by A. L. Burt in New York. The work was copyrighted to James R. Osgood & Co., but the identity of the translator was not given. Running to 145,000 words, the English translation was literal and rather cumbersome, although the book proved to be popular and was reissued by a number of publishers many times over the next four decades.

In 1907, a new translation by Ernest Tristan was published by Greening & Co. under the more evocative title The Blackmailers, a complete but more efficient interpretation of the book that halved its page count. It was this version that William Collins Sons & Co. of Glasgow later released in their rapidly expanding series of Pocket Classics. Also selected as the sixth book in Collins’ new Detective Story Club imprint, it was published in September 1929 with typical fanfare:

‘Émile Gaboriau is France’s greatest detective writer. The Blackmailers is one of his most thrilling novels, and is full of exciting surprises. The story opens with a sensational bank robbery in Paris, suspicion falling immediately upon Prosper Bertomy, the young cashier whose extravagant living has been the subject of talk among his friends. Further investigation, however, reveals a network of blackmail and villainy which seems as if it would inevitably close round Prosper and the beautiful Madeleine who is deeply in love with him. Can he prove his innocence in the face of such damning evidence?’

The story was filmed in Hollywood in 1932 under the older title File No.113, starring Lew Cody as the subtly renamed ‘Le Coq’.

Although Gaboriau’s fame and reputation were inevitably overshadowed by newer crime writers after his death, he was later championed by several discerning critics including the novelists Valentine Williams (in a 1923 landmark essay, ‘Gaboriau: Father of the Detective Novel’) and Arnold Bennett, who praised all the Lecoq novels in 1928, stating that they are ‘brilliantly presented and, besides the detection and crime-solving, Gaboriau was able to provide a really good, sound and emotional novel’.

After 150 years, Gaboriau’s novels will always deserve to be savoured, appreciated and rediscovered by connoisseurs of early detective fiction.

RICHARD DALBY

January 2016

CHAPTER I (#ua9a06465-e824-57cb-ba20-282742bb890e)

THERE appeared in all the evening papers of Tuesday, February 28, 1865 the following paragraphs:

‘An extensive robbery from a well-known banker of the city, M. André Fauvel, this morning caused great excitement in the neighbourhood of the Rue de Provence. The thieves with extraordinary skill and daring succeeded in entering his office, forcing a safe, which was believed to be burglar-proof, and carrying off the enormous sum of 350,000 francs in banknotes.

‘The police, who were at once informed of the robbery, displayed their usual zeal, and their efforts have been crowned with success. One of the employees, “P.B.”, has been arrested; it is to be hoped that his accomplices will soon be in the clutches of the law.’

During four whole days Paris talked of nothing but this robbery.

Then other serious events happened, an acrobat broke his leg at the circus, a young actress made her début at a little theatre, and the paragraph of February 28 was forgotten.

But this time the newspapers, perhaps on purpose, had been badly or inaccurately informed.

A sum of 350,000 francs had, it was true, been stolen from M. André Fauvel, but not in the way indicated. An employee, in fact, had been detained for a time, but no real charge was made against him. The robbery, though of unusual importance, remained unexplained if not inexplicable.

Here are the facts as related in detail in the report of the inquiry.

CHAPTER II (#ua9a06465-e824-57cb-ba20-282742bb890e)

THE André Fauvel bank premises, No. 87 Rue de Provence, is an important building and with its large staff looks almost like a Government office.

The counting-house of the bank is on the ground floor, and the windows which look out into the street are fitted with bars, so thick and close together as to discourage all attempts at robbery.

A large glass door opens into an immense vestibule in which, from morning to night, three or four messengers are stationed.

To the right are the offices, into which the public are admitted, and a passage leading to the entrance to the strong room. The correspondence, ledger and accountant general’s departments are on the left.

At the rear there is a little courtyard covered in with glass, into which seven or eight doors open. At ordinary times they are not used, but at certain times they are indispensable.

M. André Fauvel’s private room is on the first floor in a fine suite of apartments.

This private room communicates directly with the counting-house by a little black staircase, very narrow and steep, which descends into the chief cashier’s room.

This room, which is called the strong room, is protected from a sudden attack, and from a siege almost, for it is armour plated like a battleship.

Thick plates of sheet-iron protect the doors and the partitions, and a strong grating obstructs the chimney.

Inside these, let into the wall with enormous cramps, is the safe; one of those fantastic and formidable objects which make a poor devil, who can easily carry his fortune in his purse, dream.

The safe, a fine specimen by Becquet, is two metres high and one and a half broad. Made entirely of wrought-iron it is built with three walls, and inside is divided into isolated compartments in case of fire.

One tiny key opens this safe. But the opening with the key is quite an unimportant business. Five movable steel buttons, upon which are engraved all the letters of the alphabet, constitute the secret of its strength. Before putting the key in the lock it is necessary to be able to replace the letters in that order in which they were when the safe was locked.

There, as elsewhere, the safe was closed with a word which was changed from time to time.

This word was only known to the head of the firm and the cashier. Each of them had a key.

With such a property, though possessed of more diamonds than the Duke of Brunswick, a person ought to be able to sleep soundly.

There appears to be only one risk, that of forgetting the ‘Open Sesame’ of the iron door.

On the morning of February 28 the staff arrived as usual.

At half past nine when they were all attending to their duties, a very dark man of uncertain age and military bearing, in deep mourning, entered the office nearest the strong room, in which five or six of the staff were at work. He asked to see the chief cashier.

He was told that the cashier had not yet arrived and that the strong room did not open till ten, a large notice to this effect being displayed in the vestibule.

This reply seemed to disconcert and annoy the newcomer.

‘I thought,’ he said in a dry almost impertinent tone, ‘that I should find someone here to see me, after arranging with M. Fauvel yesterday. I am Count Louis de Clameran, ironmaster at Oloron. I have come to withdraw 300,000 francs deposited here by my brother, whose heir I am. It is surprising that you have not received instructions.’

Neither the title of the noble ironmaster nor his business seemed to touch the staff.

‘The cashier has not yet come,’ they repeated, ‘we can do nothing.’

‘Then let me see M. Fauvel.’ After a certain amount of hesitation, a young member of the staff named Cavaillon, who worked near the window, said:

‘He always goes out about this time.’

‘I shall go then,’ said M. de Clameran.

He went out without saluting or raising his hat, as he had done when he came in.

‘Our client is not very polite,’ said Cavaillon, ‘but he has no luck, for here is Prosper.’

The chief cashier, Prosper Bertomy, was a fine fellow of thirty, he was fair with blue eyes and dressed in the latest style.

He would have been very good-looking but for an exaggerated English manner, making him cold and formal at will, and an air of conceit, which spoiled his naturally laughing face.

‘Ah, here you are,’ said Cavaillon. ‘Someone has been asking for you already!’

‘Who was it? An ironmaster, was it not?’

‘Precisely.’

‘Ah, well, he will came back. Knowing I should be late this morning, I made preparations yesterday.’ Prosper having opened the door of his room as he spoke went in and shut it after him.

‘He is a cashier who does not worry,’ one of the staff said. ‘The chief has had twenty scenes with him for being late, and he takes as much notice as he does of the year forty.’

‘He is quite right, too, for he gets all he wants out of the chief.’

‘Besides, how does he look in the morning? Like a fellow who leads a terrible life and enjoys himself every night. Did you notice his ghastly look this morning?’

‘He must have been playing again, like he did last month. I found out from Couturier that he lost 1,500 francs at a single sitting!’

‘Does he neglect business?’ asked Cavaillon. ‘If you were in his place—’

He stopped short. The strong room door opened, and the cashier came in tottering.

‘I have been robbed!’ he cried.

Prosper’s look, his raucous voice, his tremors, expressed such frightful anguish, that all the staff got up and rushed to him. He almost fell into their arms, he could not stand, he felt ill and had to sit down.

But his colleagues surrounded him, all asking questions at the same time and pressing him to explain.

‘Robbed,’ they said; ‘where, how, by whom?’

Prosper gradually recovered.

‘All I had in the safe,’ he replied, ‘has been taken.’

‘Everything?’

‘Yes, three packets of a hundred one thousand franc notes, and one of fifty. The four packets were wrapped round by a piece of paper and tied together.’ With the rapidity of a flash of lightning the news of the robbery spread through the bank, and the room was quickly filled with a curious crowd.

‘Has the safe been forced?’ Cavaillon asked Prosper.

‘No, it is intact.’

‘Well, then?’

‘It is none the less a fact that last evening I had 350,000 francs and this morning they are gone.’ Everybody was silent; one old servant did not share the general consternation.

‘Do not lose your head like this, M. Bertomy,’ he said. ‘Perhaps the chief has disposed of the money?’

The unfortunate cashier jumped at the idea.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘you are right; it must be the chief.’

Then, after reflection, he went on in a deeply discouraged tone:

‘No, it is not possible. Never during the five years I have been cashier has M. Fauvel opened the safe without me! Two or three times he has needed funds and has waited for me, or sent for me rather, than touch it in my absence.’

‘That does not matter,’ objected Cavaillon.

‘Before distressing ourselves, we must let him know.’ But M. André Fauvel knew already. A clerk had gone up to his private room and told him what had taken place.

Just as Cavaillon suggested going to tell him he appeared.

M. André Fauvel was a man of about fifty, of medium height, and hair turning grey, who walked with a slight slouch. He had an air of benevolence, a frank open face and red lips. He was born near Aix, and in times of excitement he spoke with a slight provincial accent.

The news he had heard had disturbed him, for he was very pale.

‘What is the matter?’ he asked the employees, who respectfully drew back as he approached. The cashier got up and advanced to meet him.

‘Sir,’ he began, ‘yesterday I sent for 350,000 francs from the bank to make the payment today of which you are

aware.’

‘Why yesterday?’ the banker interrupted ‘I have told you a hundred times to wait till the day.’

‘I know, sir, I was wrong, but the mischief is done. The money has disappeared, without the safe being forced.’

‘You must be mad or dreaming!’ cried M. Fauvel.

Prosper answered almost without trouble or rather with the indifference of one in a hopeless position.

‘I am not mad nor dreaming. I am telling you the truth.’

This calmness seemed to exasperate M. Fauvel. He seized Prosper by the arm and shook him, as he said:

‘Speak! Speak! Who opened the safe?’

‘I cannot say.’

‘Only you and I knew the word; only you and I had the key.’

After these words, which were almost an accusation, Prosper gently freed his arm and continued:

‘No one but I could have taken the money, or you.’

‘You rascal!’ the banker cried with a threatening gesture. Just then there was the noise of an argument outside. A client insisted upon coming in. It was M. de Clameran. He entered with his hat on and said:

‘It is after ten, gentlemen.’

No one replied, but he espied the banker and went to him.

‘I am delighted to see you, sir,’ he said. ‘I called once before this morning, but the cashier had not arrived and you were out.’

‘You are mistaken, sir. I was in my private room.’

‘This young man,’ pointing to Cavaillon, ‘told me so; but on my return just now I was refused admittance. Will you be good enough to tell me whether I can withdraw my money or not.’

M. Fauvel listened to him, trembling with rage the while, and then replied:

‘I shall be glad of a little delay. I have just become aware of a theft of 350,000 francs.’ M. de Clameran bowed ironically. ‘Shall I have long to wait?’ he asked.

‘The time it will take to send to the bank,’ M. Fauvel said, as he turned to his cashier and instructed him to write a note and send a messenger as quickly as possible to the bank.

Prosper made no movement.

‘Don’t you hear me?’ the banker shouted.

The cashier shuddered, as if awakening out of a dream, and answered:

‘That is useless, there is not a hundred thousand francs to your credit.’

At that time Paris was in a state of financial panic. Many old and honourable firms had gone to the wall, ruined by the wave of speculation which had swept over the country.

M. Fauvel noticed the impression produced on the ironmaster and, turning to him, said:

‘Have a little patience, sir, I have plenty of other securities. I shall be back in a minute.’

He went upstairs to his private room and returned in a few minutes with a letter and a packet of securities in his hand.

‘Take this, he said to Couturier, one of the clerks, ‘and go to Rothschild’s with this gentleman. Give them the letter and they will hand you 300,000 francs, which you are to give to this gentleman.’

The ironmaster seemed anxious to excuse his impertinence, but the banker cut him short.

‘All I can do,’ he said, ‘is to offer you my apologies. In business a man has neither friends nor acquaintances. You are quite within your rights. Follow my clerk and you will receive your money.’

Turning to the clerks who had gathered round, he ordered them to get on with their work, and then found himself face to face with Prosper, who had remained standing quite still.

‘You must explain,’ he said; ‘go into your room.’

The cashier did so without a word, and was followed by his employer. The room showed no signs of the robbery having been committed by anyone not familiar with the place. Everything was in order, the safe was open, and upon the upper shelf was a little gold, which had been either forgotten or disdained by the thieves.

‘Now we are alone, Prosper,’ M. Fauvel, who had recovered his usual calm, began, ‘have you nothing to tell me?’

The cashier trembled but replied:

‘Nothing, sir; I have told you everything.’

‘What, nothing? You persist in this absurd story which no one will believe! Trust me, it is your only chance. I am your employer, but I am your friend as well. I cannot forget that you have been with me for fifteen years and done good and loyal service.’

Prosper had never before heard his employer speak so gently and in such a fatherly way, and an expression of surprise came into his face.

‘Have I not,’ continued M. Fauvel, ‘always been like a father to you? You were even a member of my family circle for a long time, till you wearied of that happy life.’

These souvenirs of the past made the unhappy cashier burst into tears, but the banker continued:

‘A son can tell his father everything. Am I not aware of the temptations which assail a young man in Paris? Speak, Prosper, speak!’

‘Ah, what would you have me say?’

‘Tell the truth. Even an honest man can make a mistake, but he always redeems his fault. Say to me: “Yes, the sight of the gold was too much for me, I am young and passionate.”’

‘I,’ Prosper murmured. ‘I—!’

‘Poor child,’ the banker said sadly, ‘do you think I am ignorant of the life you have been leading? Your fellow clerks are jealous of your salary of 12,000 francs a year. I have learned of every one of your follies by an anonymous letter. It is quite right, too, that I should know how the man lives who is entrusted with my life and honour.’

Prosper tried to make a gesture of protest.

‘Yes, my honour,’ M. Fauvel insisted; ‘my credit might have today been compromised by this man. Do you know the cost of the money I am giving to M. de Clameran?’

The banker stopped for a moment as if expecting a confession, which did not come, and then continued:

‘Come, Prosper, courage! I am going out, and by my return this evening I am sure you will be able to replace at least a large part of the money, and tomorrow we shall both have forgotten this false step.’

M. Fauvel got up and went to the door, but Prosper seized him by the arm.

‘Your generosity is useless, sir,’ he said in bitter tones; ‘having taken nothing, I can return nothing. I have searched high and low, and the banknotes have been stolen.’

‘By whom, poor fool, by whom?’

‘I swear by all I hold sacred that it is not by me.’

A flush spread over the banker’s face.

‘Rascal,’ he cried, ‘what do you mean? You mean by me!’

Prosper bent his head and made no answer.

‘In that case,’ M. Fauvel, who was unable to contain himself, said, ‘the law shall decide between us. I have done all I can to save you. A police officer is waiting in my private room, must I call him in?’

Prosper made a gesture of despair and said: ‘Do so.’

The banker turned to one of the boys and said: ‘Anselme, ask the superintendent of police to come down.’

CHAPTER III (#ua9a06465-e824-57cb-ba20-282742bb890e)

IF there is one man in the world whom no event ought to surprise or move, that man is a superintendent of police in Paris.

The one sent for by M. Fauvel came in at once, followed by a little man dressed in black.

The banker hardly troubled to greet him, but began:

‘I dare say you have heard what painful circumstances have compelled me to send for you?’

‘I was told it was robbery.’

‘Yes, an odious and inexplicable robbery, committed here from that safe you see open, of which only my cashier’—pointing to Prosper—‘has the word and the key.’

‘Excuse me, officer,’ the cashier said in a low voice, ‘my chief, too, has the word and the key.’

‘To be sure, of course I have.’

The officer could see that it was a case in which each accused the other, and though one was the banker and the other the cashier, he observed them both very closely to try and draw a profitable conclusion from their manner.

The cashier was pale and drooping in his chair with his arms inert, while the banker was standing red and animated, expressing himself with extraordinary violence.

‘The importance of the loss is enormous, 350,000 francs is a fortune. Such a loss might have serious consequences for the wealthiest of firms. Today, too, I had a large sum to pay away.’

There was no mistaking the tone in which the superintendent of police said: ‘Oh, really?’ The first suspicion had crossed his mind.

The banker noticed it and quickly continued: ‘I met my obligations, though at a disagreeable sacrifice. I ought to add that if my orders had been carried out the money would not have been in the safe. I do not care to keep large sums here, and my cashier has orders to wait till the last moment before obtaining money from the Bank of France.’

‘Do you hear?’ the superintendent said to Prosper.

‘Yes, sir,’ the cashier replied, ‘it is quite right.’ This explanation dispelled the police officer’s suspicion.

The officer continued: ‘A robbery has been committed. By whom? Did the thief come from outside?’

After a little hesitation the banker said: ‘I don’t think so.’

‘I am certain,’ Prosper declared, ‘he did not.’

Turning to the man who had accompanied him, the superintendent of police said:

‘See if you can discover, M. Fanferlot, any clue which has escaped these gentlemen.’

M. Fanferlot, nicknamed the squirrel on account of his agility, had a turned up nose, thin lips and little round eyes. He had been employed for five years by the police and was ambitious, as he had not yet made himself famous. He made a careful examination and said:

‘It appears to me very difficult for a stranger to get in here.’

He looked round.

‘Is that door,’ he asked, ‘shut at night?’

‘Always locked.’

‘Who keeps the key?’

‘The porter,’ Prosper replied. ‘I leave it with him every night when I go.’

‘Is he here?’ the superintendent asked.

‘Yes,’ the banker replied.

He opened the door and called:

‘Anselme.’

This young fellow had been for ten years in M. Fauvel’s service and was above suspicion, but he trembled like a leaf as he entered the room.

‘Did you sleep last night in the next room?’ the superintendent of police asked him.

‘Yes, sir, as usual.’

‘What time did you go to bed?’

‘About half past ten; I spent the evening at a restaurant with the valet.’

‘Did you hear any noise in the night?’

‘No! And yet I am a very light sleeper, and the master’s light footsteps, when he goes down to the strong room in the night, awaken me.’

‘Does M. Fauvel often come down in the night?’

‘No, sir, very rarely.’

‘Did he come down last night?’

‘No! I am quite sure he did not, for I hardly closed my eyes last night, as I had been drinking coffee.’

The superintendent dismissed him, and M. Fanferlot resumed his search.

He opened a door and said:

‘Where does this staircase lead to?’

‘To my private room,’ M. Fauvel replied, ‘the room into which you were shown on your arrival.’

‘I should like to have a look round it,’ M. Fanferlot declared.

‘Nothing can be easier,’ M. Fauvel replied. ‘Come along, gentlemen, and you too, Prosper.’

M. Fauvel’s private office was divided into two parts: a sumptuously furnished waiting room, and plainly furnished room for his own use. These two rooms had only three doors: one opened on to the staircase they had ascended, another opened into the banker’s bedroom, and the third opened on to the vestibule of the grand staircase; by this door his clients entered.

After M. Fanferlot had glanced round the inner room, he went into the waiting room, followed by all but Prosper.

Prosper was in a state of utter bewilderment, but he was beginning to realize that the affair had resolved itself into a struggle between his employer and himself. At first he had not believed his master would carry out his threats, for though he realized how poor his chances of success were, on the other hand, in a case of the sort, the employer had much more at stake than his cashier.

At that moment the door of the banker’s bedroom opened and a beautiful young girl entered. She was tall and slender and her morning wrapper showed off her beautiful figure. She was a brunette with large soft eyes and beautiful black hair. She was M. André Fauvel’s niece, and her name was Madeleine.

Expecting to see her uncle alone, she uttered an exclamation of surprise at the sight of Prosper Bertomy.

Prosper, who was as surprised as she was, could do nothing but murmur her name. After they had stood for a few moments with bent heads in silence, Madeleine murmured:

‘Is that you, Prosper?’

These few words seemed to break the charm and Prosper replied in a bitter tone:

‘Yes, it is your old playfellow, Prosper, and he is accused of a cowardly and shameful theft; and before the day is over he will be in prison.

‘Good God!’ she cried with a gesture of affright. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Have not your aunt and cousins told you, mademoiselle?’

‘No, I have hardly seen them this morning. Tell me what has happened?’

The cashier hesitated and sadly shook his head.

‘Thank you, mademoiselle,’ he said, ‘for this proof of your interest; but allow me to spare you a sorrow by keeping silent.’

Madeleine interrupted him with an imperious gesture.

‘I want to know,’ she said.

‘Alas, mademoiselle,’ the cashier replied, ‘you will learn soon enough my shame and misfortune.’

She tried to insist, to command, and then pleaded, but he had made up his mind.

‘Your uncle is in the next room with the superintendent of police,’ he resumed, ‘and they will return in a minute. Please withdraw, so that they do not see you.’

As he gently pushed her through the door the others returned from their search.

But Fanferlot had kept observation on the cashier with the idea of finding out something from the expression of his face when he believed himself to be alone, and so had witnessed the interview. He at once formed a theory from it, which he decided to keep to himself for the present. He thought that they were lovers against the banker’s wish, and that the latter had himself committed the robbery in order to accuse this undesirable suitor of it and so get rid of him.

The search of the upper part of the premises completed, the party descended to the cashier’s office, where the superintendent remarked that their search had simply confirmed the opinions they had first formed.

The detective who was making a minute examination of the safe gave the most manifest signs of surprise, as if he had made a discovery of the utmost importance. The others at once gathered round and asked what he had discovered. After some hesitation he replied:

‘I have found out that the safe has been quite recently opened or shut in a hurry, and with some violence.’

‘How do you know that?’ the superintendent asked.

The detective, as he handed him the magnifying-glass, pointed out a slight chafing which had marked the varnish for a distance of twelve or fifteen centimetres.

‘Yes, I can see it,’ the superintendent said, ‘but what does it prove?’

‘Nothing at all,’ Fanferlot replied, though he did not think so.

This scratch seemed to him to confirm his theory, for the cashier could have taken millions without any need for haste. The banker, however, if he came downstairs quietly at night to rob his own safe, had a thousand reasons for haste and might easily have made the scratch with the key.

The detective, who had quite made up his mind to solve the mystery, was now more determined than ever to keep his theories to himself, as well as the interview he had witnessed.

‘In conclusion,’ he said to the superintendent, ‘I declare that the robbery was not committed by an outsider. The safe has not been forced, nor has any attempt been made to force it. It was opened by someone who knew the word and had the key.’

This formal declaration convinced the superintendent, who at once said:

‘I shall be glad of a minute’s private talk with M. Fauvel.’

Prosper and the detective went into the next room, and the latter, in spite of his theories, was quite determined to keep his eye upon the cashier, who had taken a vacant chair.

The other clerks were burning to know the result of the inquiry and at last Cavaillon ventured to ask Prosper, who replied with a shrug of the shoulders:

‘It is not decided.’

His fellow clerks were surprised to see that he had lost all trace of emotion and had recovered his usual attitude, one of icy hauteur, which kept people at a distance and had made him many enemies.

After a few minutes Prosper took a sheet of paper and wrote a few lines upon it.

The detective seemed to suddenly awaken out of a deep sleep, and the thought came to him that now he would find out something positive.

After finishing his short letter, Prosper folded it up as small as possible and threw it to Cavaillon, saying, as he did so, one word only:

‘Gypsy!’

This was effected with such skill and sangfroid that even the detective was surprised.

Before taking action the superintendent, either out of deference or from the hope of obtaining more information from a private conversation, decided to warn the banker.

‘There can be no doubt, sir,’ he said as soon as they were alone, ‘that this young man has robbed you. I should be neglecting my duty if I did not arrest him; afterwards the magistrate will either confirm his arrest or set him at liberty.’

This statement appeared to touch the banker, for he murmured:

‘Poor Prosper!’

Seeing the superintendent’s astonishment at this, he added:

‘Till today I had the utmost faith in his probity and would have trusted him with my fortune. I almost went down upon my knees to get him to admit his fault and promised him pardon, but I could not touch him. I loved him and do so still, in spite of the humiliation I foresee!’

‘What humiliation?’ asked the superintendent.

‘I shall be questioned.’ M. Fauvel quickly resumed. ‘I shall be obliged to lay bare to a judge my exact business position and operations.’

‘Certainly, sir, you will be asked a few questions, but your well-known integrity—’

‘But he was honest also. Who would have been suspected this morning if I had been unable to find 300,000 francs at once?’

To a man with a heart, the thought, the possibility even of suspicion, is a cruel suffering. The superintendent could see that the banker was suffering.

‘Compose yourself, sir,’ he said; ‘in less than a week we shall have evidence enough to convict the criminal, whom we can now recall.’

Prosper received the news of his arrest with the utmost calm. His only remark was:

‘I swear that I am innocent!’

M. Fauvel, who seemed much more disturbed than his cashier, made one last effort:

‘There is still time,’ he said, ‘reflect—’

Prosper took no notice of him, but drew a key from his pocket and put it on the shelf, saying:

‘There is the key of your safe; I hope you will recognize before it is too late that I have not stolen anything from you. There are the books and papers my successor will need. I must tell you, also, that without reckoning the 350,000 francs you will find a deficit in my cash.’

At the word deficit his hearers became all the more certain of his guilt; even the detective became doubtful of his innocence. The explanation, however, which Prosper gave soon diminished the gravity and significance of this deficit.

‘My cash is 3,500 francs short,’ he said. ‘I have drawn 2,000 francs of my salary in advance, and advanced 1,500 francs to several of my colleagues. Today is the last day of the month, and tomorrow we receive our salaries.’

‘Were you authorized to do this?’ asked the superintendent.

‘No,’ he replied, ‘but in doing so I have merely followed the example of my predecessor, and I am sure M. Fauvel would not have refused me permission to oblige my colleagues.’

‘Quite right,’ was M. Fauvel’s comment on the cashier’s remarks.

This completed the superintendent’s inquiry, and announcing that he was about to depart, he ordered the cashier to follow him.

Even at this fatal order, Prosper did not lose his studied indifference. He took his hat and umbrella and said:

‘I am ready to accompany you, sir!’

The superintendent shut up his portfolio and saluted M. Fauvel, who watched them depart with tears in his eyes and murmured to himself:

‘Would that he had stolen twice as much and I could esteem him and keep him as before.’

Fanferlot, the man with the open ears, overheard the expression. He had remained behind looking for an imaginary umbrella, with the intention of obtaining possession of the note Prosper had written, which was now in Cavaillon’s pocket. He could easily have arrested the latter and taken it by force. But after reflection the detective decided that it would be better to watch Cavaillon, follow him and surprise him in the act of delivering it.

A few judicious inquiries as he was leaving informed the detective that there was only one entrance and exit to the premises of M. Fauvel, the main entrance in the Rue de Provence.

The detective on leaving the bank premises took up a position in a doorway opposite, which not only commanded a view of the entrance, but by standing on tiptoe he could see Cavaillon at his desk.

After a long wait, which he spent in considering the facts of the robbery, he saw Cavaillon get up and change his office coat. A minute afterwards he appeared at the door, and glanced to right and left before starting off in the direction of the Faubourg Montmartre.

‘He is suspicious,’ thought the detective, but it was simply a desire to take the shortest cut, so that he might be back as quickly as possible, which caused him to hesitate.

He walked so quickly that the detective had some difficulty in keeping pace with him, till he reached number 39, Rue Chaptal, where he entered.

Before he had gone more than a step or two along the corridor the detective tapped him on the shoulder. Cavaillon recognized the detective, turned pale, and looked round for a way of escape, but his progress was barred.

‘What do you want?’ he asked in a frightened voice.

With the civility for which he was famous, M. Fanferlot, nicknamed the squirrel, replied:

‘Excuse the liberty I have taken, but I shall be glad if you will give me a little information.’

‘But I don’t know you.’

‘You saw me this morning. Be good enough to take my arm and come into the street with me for a minute.’

There was no help for it, so Cavaillon took his arm and went out. The Rue Chaptal is a quiet street, well adapted for a talk.

‘Is it not, sir, a fact,’ began the detective, ‘that M. Prosper Bertomy threw you a note this morning?’

‘You are mistaken,’ he replied, blushing.

‘I should be sorry to say you were not telling the truth, unless I were sure.’

‘I assure you Prosper gave me nothing.’

‘Pardon me, sir, but do not deny it,’ Fanferlot said, ‘or you will force me to prove that four of your fellow-clerks saw him throw you a note.’

Seeing that denial was useless, the young man changed his method.

‘Yes, that is quite right; I received a note from Prosper, but it was private, and after reading it I tore it up and threw the pieces in the fire.’

It was very likely that this was true, but Fanferlot decided to take his chance.

‘Allow me, sir, to remark that is not correct; the note was to be delivered to Gypsy.’

Cavaillon made a despairing gesture which told the detective that he was right, and began:

‘I swear to you, sir—’

‘Do not swear at all, sir,’ Fanferlot interrupted; ‘all the oaths in the world are useless. You have the note in your pocket and entered that house to deliver it.’

‘No, sir; no.’ The detective took no notice of the denial and went on:

‘You will be good enough to let me read the note.’

‘Never,’ Cavaillon replied.

Thinking this was a favourable opportunity, the young man tried to free his arm, but the detective was as strong as he was polite.

‘Take care not to injure yourself, young man,’ the detective said, ‘and give me the note.’

‘I have not got it.’

‘Come; you will force me to adopt unpleasant measures. Do you know what will happen? I shall call two policemen and have you arrested and searched.’

It seemed to Cavaillon, devoted to Prosper though he was, that the struggle was now useless, and he did not even have the opportunity to destroy the note. To deliver up the note under these circumstances was not betraying a trust.

‘You are the stronger,’ he said; ‘I obey.’ He took the note from his case, cursing his own powerlessness as he did so, and handed it to the detective, whose hands trembled with pleasure as he opened it and read:

‘DEAR NINA,

‘If you love me, obey me quickly without a moment’s hesitation. When you receive this, take everything belonging to you—everything, and go and live in a furnished house at the other end of Paris. Do not show yourself; disappear as much as possible. On your obedience my life perhaps depends. I am accused of a large robbery and I am going to be arrested. There should be 500 francs in the drawer; take it. Give your address to Cavaillon and he will explain to you what I cannot tell you.

‘PROSPER.’

Had Cavaillon been less occupied with his own thoughts, he would have noticed a look of disappointment on the detective’s face. Fanferlot had hoped that this note was of importance, but it seemed to be merely a love-letter. The word ‘everything’ was, it was true, underlined, but that might mean anything.

‘Is Madame Nina Gypsy,’ the detective asked Cavaillon, ‘a friend of M. Prosper Bertomy?’

‘She is his mistress.’

‘She lives at No. 39, does she not?’

‘You know very well she does, for you saw me go in.’

‘Does she occupy rooms in her own name?’

‘No, she lives with Prosper.’

‘On what floor?’

‘The first.’

M. Fanferlot carefully refolded the note and put it in his pocket.

‘I am much obliged,’ he said, ‘for your information, and in return I will deliver the letter for you.’

Cavaillon offered some resistance to this, but M. Fanferlot cut him short with these words:

‘I will give you some good advice. If I were in your place, I would go back to the office and have no more to do with this affair.

‘But he is my friend and protector.’

‘All the more reason you should keep quiet. How can you help him? You are more likely to do him harm.’

‘But, sir, I am sure Prosper is innocent.’

That was, too, Fanferlot’s opinion; but he did not consider it wise to tell the young man this, so he said:

‘It is quite possible, and I hope it is so for M. Bertomy’s sake, and also for your sake, for if he is found guilty, you may be suspected too. So, go back to your work.’

The poor fellow obeyed with a heavy heart, wondering how he could help Prosper and warn Madame Gypsy.

As soon as he had disappeared, Fanferlot went over to the house and rang the first-floor bell. It was answered by a page to whom he showed the note when he asked to see the lady. He was shown into a beautifully-furnished drawing-room, and Madame Nina Gypsy came in at once.

She was a frail, delicate little woman, a brunette or rather golden, like a Havanna quadroon, with the feet and hands of a child. She had long silky lashes and large black eyes, and her lips, which were a little thick, displayed when she smiled the most beautiful white teeth.

She was not yet dressed, but appeared very charming in a velvet wrapper, and the detective was at first quite dazzled. She seemed surprised to see this shabby looking person in her drawing-room and at once assumed her most disdainful manner.

‘What do you want?’ she asked.

‘I have a note to give you,’ said the detective in his most humble voice, ‘from M. Bertomy.’

‘From Prosper! Do you know him?’

‘I have the honour, and if I dare use the expression, I am one of his friends, one of the few who now have the courage to admit their friendship.’

The detective looked so serious that Madame Gypsy was impressed.

‘I am not clever at riddles,’ she said dryly; ‘what do you mean to insinuate?’

He took the letter from his pocket and handed it to the lady, saying as he did so:

‘Read this.’

Adjusting an eye-glass to her charming eyes she read the note at one glance. First she turned pale, then she became flushed and trembled as if she were about to faint. But in an instant she pulled herself together, and seizing the detective’s wrists in a grip which made him cry out:

‘Explain,’ she said; ‘what does it mean? You know what this letter says?’

Brave as he was, Fanferlot was almost afraid of Madame Nina’s anger.

‘Prosper is accused of taking 350,000 francs from his safe,’ he murmured.

‘Prosper a thief!’ she said; ‘how foolish. Why should he be a thief? He is well off, isn’t he?’

‘No; people say he is not rich, but has to live upon his salary.’

This reply seemed to confuse Madame Gypsy’s ideas.

‘But,’ she insisted, ‘he always has plenty of money—’

She dared not finish her sentence, for it suddenly occurred to her that if he were a thief it would be for her. But after a few seconds’ reflection her doubts disappeared.

‘No,’ she cried, ‘Prosper has never stolen a half-penny for me. A cashier might steal for the woman he loved, but Prosper does not love me and has never done so.’

‘Beautiful lady,’ protested the polite Fanferlot, ‘you don’t mean that.’

‘I do,’ she replied with tears in her eyes, ‘and it is true. He humours my fancies, but that proves nothing. I am nothing in his life—hardly an accident.’

‘But why—?’

‘Yes,’ Madame Gypsy interrupted, ‘why? You will be clever if you can tell me. I have tried to find out for a year. It is impossible to read the heart of a man who is so far master of himself that what is passing in his heart never mounts to his eyes. People think he is weak, but they are mistaken. This man with blonde hair is like a bar of steel painted like a reed.’

Carried away by the violence of her sentiments, Madame Nina was laying bare her heart to this man whom she believed was a friend of Prosper’s, while the detective was complimenting himself upon his skill in obtaining all this valuable information.

‘It has been said,’ he suggested, ‘that M. Bertomy is a great gambler.’

Madame Gypsy shrugged her shoulders.

‘Yes, that is true,’ she replied. ‘I have seen him win or lose considerable sums without a tremor, but he is not a gambler. He gambles in the same way that he sups and gets drunk—without passion and pleasure, but with a profound indifference which sometimes seems to me almost like despair. Nothing will ever remove the idea from my mind that he has a terrible secret in his life.’

‘Has he never spoken to you of the past?’

‘Did you not hear me tell you that he did not love me?’

Madame Nina began to weep, but after a few minutes her generous impulses told her that it was no time for despair.

‘But I love him,’ she cried, ‘and I must save him. I will speak to his employer and the judges, and before the day is over he will be free, or I shall be prisoner with him.’

This plan, though dictated by the most noble motives, did not meet with the detective’s approval, for he did not propose that the lady should appear till what he considered to be the proper moment. He therefore set to work to calm her and show the weakness of her plan.

‘What will you gain, dear lady?’ he said; ‘you have no chance of success and may be seriously compromised and treated as an accomplice.’

‘What does the danger matter?’ she cried. ‘I don’t think there is any; but if it exists, so much the better: it will give a little merit to a natural effort. I am sure Prosper is innocent, but if by any possible chance he is guilty, I wish to share his punishment.’

Madame Gypsy put on her hat and called upon Fanferlot to accompany her. But he had still several strings to his bow. As personal considerations had no weight with this lady he decided to introduce as an argument Prosper’s own interests.

‘I am ready, lady,’ he replied; ‘let us go. Only, while there is still time, let me tell you we shall probably do M. Bertomy more harm than good by taking a step he did not anticipate when he wrote to you.’

‘Some people,’ the young woman answered, ‘have to be rescued against their will. I know Prosper; he is the man to allow himself to be killed without a struggle—’

‘Excuse me, dear madame,’ the detective interrupted, ‘M. Bertomy does not seem to me that kind of man. I believe he has already fixed upon his line of defence, and perhaps by showing yourself at the wrong time you will destroy his most certain way of justifying himself.’

Madame Gypsy delayed her answer to consider Fanferlot’s objections.

‘But I cannot,’ she said, ‘remain inactive without trying to contribute to his safety.’

The detective, feeling that he had gained his point, said:

‘You have a simple way to serve the man you love, and that is to obey him; that is your sacred duty.’

She hesitated, so he picked up Prosper’s letter from the table and continued:

‘M. Bertomy when he is just about to be arrested writes to you and tells you to go away and hide, if you love him, and yet you hesitate. He has reasons for saying so you may be sure.’

M. Fanferlot had himself guessed the reason as soon as he entered the room, but he was keeping that in reserve.

Madame Gypsy was intelligent enough also to divine the reason.

‘Reasons!’ she began; ‘perhaps Prosper wished our liaison to remain a secret! No. I understand now. My presence here would be a serious charge against him. They would ask how he could give me all these things, and where he obtained the money to do so.’

The detective bowed his head in assent.

‘Then I must fly at once! Perhaps the police know already and will be here directly.’

‘Oh,’ Fanferlot said, ‘there is plenty of time.’

She rushed out of the room, calling her servants, and told them to put everything into her boxes as quickly as possible. She herself set the example. Suddenly an idea struck her and she went back to Fanferlot.

‘Everything is ready,’ she said, ‘but where am I to go?’

‘M. Bertomy said furnished rooms at the other end of Paris.’

‘But I do not know any.’

The detective seemed to reflect for a moment, and then, making every effort to conceal his joy at the idea, said:

‘I know a hotel where with an introduction from me you would be treated like a little queen, though it is not so luxurious as here.’

‘Where is it?’

‘On the other side of the water, the Hôtel du Grand-Archange, Quai Saint-Michel, kept by Madame Alexandré.

Nina never took long to make up her mind.

‘Here is the ink,’ she said, ‘write the introduction.’

He had finished in a moment.

‘With these three lines, lady,’ he said, ‘you will be well looked after.’

‘Very well! Now I must let Cavaillon know my address. He should have brought the letter—’

‘He could not come,’ the detective interrupted, ‘but I am going to see him and will let him know your address.

Madame Gypsy was about to send for a carriage, when Fanferlot volunteered to procure one for her. He stopped one as it was passing and instructed the driver to wait for a little dark lady, and if she ordered him to drive to the Quai Saint-Michel he was to crack his whip; but if she gave him any other address he was to get down from his box as if to put one of the traces right.

The detective crossed the road, entered a wine-shop opposite, and a minute afterwards the loud cracking of a whip disturbed the quiet street. Madame Nina had gone to the Grand-Archange.

The detective rubbed his hands with glee.

CHAPTER IV (#ua9a06465-e824-57cb-ba20-282742bb890e)

WHILE Madame Nina Gypsy was on her way to the Grand-Archange, Prosper Bertomy was at the police station.

He was kept waiting there for two hours, during which time he talked to the two policemen in whose charge he was. His expression never varied, his face was like marble. At midday he sent for lunch from a neighbouring restaurant, ate it with a good appetite, and drank almost a whole bottle of wine.

During this time ten other officers at least came to look at him, and they all expressed their views in similar terms. They said:

‘He is a stubborn fellow.’

When he was told that a carriage was waiting, he got up quickly, asked permission to light a cigar, and went downstairs. At the door he bought a buttonhole from a flower girl who wished him good luck.

He thanked her and got into the carriage which drove along the Rue Montmartre.

It was a lovely day, and he remarked to his guardians:

‘It is very strange, but I never felt so much like a walk before.’

One of them replied, ‘I can quite believe that.’

At the clerk’s office, while the entries were being made in the gaol book, Prosper answered the questions with disdainful hauteur. But when he was told to empty his pockets, a gleam of indignation shot from his eyes. He would perhaps have been subjected to further indignities but for the intervention of an oldish man of distinguished appearance, wearing a white necktie and gold-rimmed spectacles, who was warming himself at a stove and appeared quite at home. This was a noted member of the detective force, M. Lecoq, whose eyes had been intently fixed upon the cashier, and who had displayed considerable surprise at his entrance.

After the usual formalities had been completed the cashier was removed to a cell, where as soon as he was alone he burst into tears. His pent-up anger got beyond control; he shouted, cursed, blasphemed and beat the walls with his fists.

Prosper Bertomy was not what he appeared to be, he had ardent passions and a fiery temperament. One day at the age of twenty-four he was seized with ambition and a desire to be like the rich men he saw around him. He studied the careers of these financiers and discovered that at first they were worse off than he was, but that by energy, intelligence and audacity they had succeeded.

He swore to imitate them, and from that time he silenced his instincts and reformed not his character, but its outward appearance.

His efforts had not been wasted. Those who knew him said he was a coming man. But here he was in prison, and even if he were not guilty he would be marked as a suspected man.

The following morning—he had just gone to sleep after a sleepless night—he was awakened for his examination.

As the warder conducted him, he said:

‘You are fortunate; you have to deal with a good brave man.’

He was right. M. Patrigent possessed in a remarkable degree all the qualities necessary for a magistrate. He was keen, firm, unbiased, neither too lenient nor too severe, but a man of inexhaustible patience. This was the man before whom Prosper had to appear.

After walking a considerable distance the warder and his charge entered a long narrow gallery in which were several numbered doors, each of which admitted to the presence of a magistrate.

‘Here,’ the warder said, ‘your fate will be decided.’

The cashier and his guardian sat down upon an oak bench in the gallery which had already numerous occupants, to wait their turn. Groups of witnesses and gendarmes stood talking in low tones in the gallery, and at short intervals a door opened and an usher called out a name or number.

At last the usher called ‘Prosper Bertomy!’

The cashier on leaving the dark gallery suddenly found himself almost blinded by the light from the window of the courtroom.

The courtroom had nothing striking about it. It contained a large desk at which the magistrate sat with his face in shadow and with the light shining full in the faces of the accused and the witness. On his right was his clerk.

Prosper’s attention was, however, fixed upon the magistrate’s face, and he soon realized that the warder was right, for he had an attractive and reassuring face.

‘Take a chair,’ he said to Prosper, who was favourably impressed by this attention and took it as a good omen.

M. Patrigent made a sign to the clerk and said:

‘We are ready to begin, Sigault.’

Turning to Prosper, he asked:

‘What is your name?’

‘Auguste Prosper Bertomy, sir.’

‘How old are you?’

‘I shall be thirty-five on the fifth of May.’

‘What is your occupation?’

‘I am, or rather I was the cashier at the André Fauvel Bank.’

The magistrate stopped to consult his papers and then asked:

‘Where do you live?’

‘At 39, Rue Chaptal for the last four years. Before that I lived at No. 7, Boulevard des Bategnolles.’

‘Where were you born?’

‘At Beaucaire, in the Department du Gard.’

‘Are your parents alive?’

‘I lost my mother two years ago, but my father is still alive.’

‘Does he live in Paris?’

‘No, sir, he lives at Beaucaire with my sister, who married an engineer of the Midi Canal.’

Prosper replied to the last question in a troubled voice. There are times in a man’s life when the remembrance of his relations consoles him, but there are also times when he wishes to be alone in the world.

M. Patrigent noted his emotion and continued:

‘What is your father’s profession?’

‘He was, sir, employed on the Midi Canal; now he has retired.’

‘You are accused of stealing 350,000 francs from your employer. What have you to say?’

‘I am innocent, sir; I swear I am innocent!’

‘I hope so,’ M. Patrigent said, ‘and you can count on my assistance in proving your innocence. Have you any facts to mention in your defence?’

‘Sir, what can I say? I can only invoke my whole life.’

The magistrate interrupted. ‘Let us be precise; the robbery was committed in such a way that suspicion can only rest upon M. Fauvel and you. Can you throw suspicion on anyone else?’

‘No, sir.’

‘You say you are innocent, so M. Fauvel must be the criminal.’

Prosper made no answer.

‘Have you,’ M. Patrigent insisted, ‘any reason to think your employer robbed himself? Tell me it, however trifling it may be.’

As he made no reply the magistrate said:

‘I see you still need time for reflection. Listen to the reading of your evidence, and after you have signed it you will return to prison.’

The cashier was overwhelmed by these words. He signed the statement without hearing a word of the reading and staggered so on leaving the courtroom that the warder told him to lean upon him and take courage.

His examination was a formality carried out in obedience to the law, which ordered that a prisoner was to be examined within twenty-four hours of his arrest.

Had Prosper remained an hour longer in the gallery, he would have heard the same usher call out ‘number three’.

The witness who was number three was sitting on the bench in the person of M. Fauvel. He was a changed man. His ordinary benevolence had disappeared and he was full of resentment against his cashier.

He had hardly answered the usual questions before he launched out into such recriminations and invectives against Prosper that the magistrate had to silence him.

‘Let us take things in their proper order,’ he said to M. Fauvel, ‘and please confine yourself to answering my questions.

‘Did you doubt your cashier’s honesty?’

‘Certainly not; and yet a thousand reasons might have led me to do so.’

‘What reasons were they?’

‘M. Bertomy, my cashier, gambled and sometimes lost large sums. On one occasion, with one of my clients, he was mixed up in a scandalous gaming affair, which began with a woman and ended with the police.’

‘You must admit, sir,’ the magistrate said, ‘you were imprudent, if not culpable, to entrust your cash to such a man.’

‘But, sir,’ M. Fauvel replied, ‘he was not always like it. Till a year ago he was a model. He resided in my house and I believed him to be in love with my niece Madeleine.’

M. Patrigent had a way of knitting his brows when he thought he had made a discovery.

‘Perhaps that was the reason of his departure?’ the magistrate asked.

‘Why,’ the banker replied with a surprised look, ‘I would have willingly given him my niece’s hand, and she is a pretty girl with money.’

‘Then you can see no motive in your cashier’s conduct?’

‘Absolutely none,’ the banker replied, after a little thought. ‘I always thought he was led astray by a young man he knew at that time, M. Raoul de Lagors.’

‘Who is he?’

‘A relative of my wife’s, a charming fellow, but rich enough to pay for his amusement.’

The magistrate did not seem to be listening, he was adding Lagors to his long list of names.

‘Now,’ he resumed, ‘you are sure the robbery was not committed by anyone in your house?’

‘Quite sure, sir.’

‘Your key was never out of your possession?’

‘Very rarely; and when I did not carry it, it was in one of the drawers in my desk.’

‘Where was it on the evening of the robbery?’

‘In my desk.’

‘But then—’

‘Excuse me, sir,’ M. Fauvel interrupted, ‘but may I mention that with a safe like mine the key counts for little. One must know the word at which to set the five movable buttons.’

‘Did you tell anyone the word?’

‘No, sir. Besides, Prosper changed the word when he felt so disposed. He used to tell me and I often forgot.’

‘Had you forgotten it on the day of the robbery?’

‘No; the word was changed the previous evening, and its strangeness struck me.’

‘What was it?’

‘Gypsy. G-y-p-s-y.’ (The banker spelt it.)

This word M. Patrigent also wrote down.

‘One more question, sir,’ he said. ‘Were you at home the evening of the robbery?’

‘No, sir; I dined and spent the evening with a friend. When I returned, about one o’clock, my wife was in bed and I retired at once.’

‘You are not aware of the sum of money in the safe?’

‘No. My orders were that only a small sum should be kept there.’

M. Patrigent was silent. The important fact to him seemed to be that the banker was not aware there was 350,000 francs in the safe, and Prosper exceeded his duty in withdrawing it from the bank. The conclusion seemed obvious.

Seeing that he was not to be asked any more questions, the banker considered it a good opportunity to say what he had on his mind.

‘I consider myself above suspicion,’ he began, ‘but I shall not sleep in peace till the robbery is brought home to my cashier. The sum is quite a fortune, and I shall be glad if you will examine my business affairs and see that I have no object in robbing myself.’

‘That will do, sir,’ the magistrate interposed; ‘sign your statement, please!’

After the banker had gone, the clerk remarked:

‘It is a very obscure affair; if the cashier is firm and clever it will be difficult to convict him, I think.’

‘Perhaps,’ the magistrate replied, ‘but I will examine the other witness.’

Number four witness was Lucien, M. Fauvel’s eldest son. He was a fine fellow of twenty-two, who said he was very fond of Prosper and looked upon him as an honest man.

He said he could offer no explanation as to why Prosper should commit the theft. He was sure he did not gamble as much as people made out and did not live beyond his means.

With regard to his cousin Madeleine he said:

‘I always thought Prosper loved Madeleine and would marry her. I always attributed Prosper’s departure to a quarrel with her, but I felt sure they would make it up.’

Lucien signed his statement and withdrew.

Cavaillon was the next to be examined. He was in a pitiful state, but determined to repair the mistake he made the previous day if possible.

He did not exactly accuse M. Fauvel, but he said he was a friend of the cashier, and as sure of his innocence as of his own. But unfortunately he had no evidence to support his statement.

Six or eight of the bank staff also made statements, but they were not important.

One of them gave a detail which the magistrate noted. He made out that he knew that Prosper had made a good deal of money on the Stock Exchange through M. Raoul de Lagors.

After the witnesses had concluded M. Patrigent sent the usher to find Fanferlot, which he did after some delay. The detective gave an account of the incident of the letter, which he was able to produce, having stolen it from Madame Gypsy, and furnished a number of biographical details he had gathered concerning Prosper and Madame Gypsy.

At the conclusion of the detective’s story M. Patrigent murmured:

‘Evidently the young man is guilty.’

This was not Fanferlot’s opinion, and he was pleased to think the magistrate was upon the wrong track.

After he had furnished all the information possible, the detective was dismissed, the magistrate telling him to keep a careful eye upon Madame Gypsy as she probably knew something about the money.

The next day the magistrate took the evidence of Madame Gypsy and recalled M. Fauvel and Cavaillon. Only two of the witnesses who had been summoned failed to appear; the first was the messenger Prosper sent to the bank, who was ill, and M. Raoul de Lagors.

CHAPTER V (#ua9a06465-e824-57cb-ba20-282742bb890e)

THE first two days of his imprisonment had not seemed very long to Prosper. He had been provided with writing materials and drawn up his defence. After that he became impatient at not being re-examined.

On Monday morning the door of his cell opened and his father, an old man with white hair, entered.

Prosper went forward to embrace him, but his father repulsed him.

‘Keep away,’ he said.

‘You, too,’ Prosper cried. ‘You believe me to be guilty.’

‘Spare me this shameful comedy,’ his father interrupted, ‘I know everything.’

‘But, father, I am innocent, I swear it by my mother’s sacred memory.’

‘Wretch,’ M. Bertomy cried, ‘do not blaspheme! I am glad your mother is dead, Prosper, for your crime would have killed her.’

There was a long silence and then Prosper said:

‘You overwhelm me, father, when I need all my courage and am the victim of an odious plot.’

‘The victim!’ said M. Bertomy. ‘Are you making insinuations against your employer, the man who has done so much for you? It is bad enough to rob him; do not slander him. Was it a lie, too, when you wrote and told me to prepare to come to Paris, and ask M. Fauvel for his niece’s hand for you?’

‘No,’ Prosper said in a faint voice.

‘That is a year ago,’ his father continued, ‘and yet the thought of her could not keep you from bad companions and crime.’

‘But, father, I love her still; let me explain—’

‘That is enough, sir. I have seen your employer and know all about it. I have also seen the magistrate, and he gave me permission to visit you. I have seen your rooms and their luxury, and I can understand the reason of your crime; you are the first thief in the family.’

M. Bertomy, seeing his son was no longer listening to him, stopped.

‘But,’ he continued, ‘I am not come to reproach you. Listen to me. How much have you left of the 350,000 francs you have stolen?’

‘Once more, father, I am innocent.’

‘I expected that reply. Now it rests with your relatives to repair your fault. The day I learned of your crime, your brother-in-law brought me your sister’s dowry, 70,000 francs. I have 140,000 francs besides, making 210,000 francs in all. This I am going to hand to M. Fauvel.’

This statement roused Prosper.

‘Don’t do that!’ he cried.

‘I shall do so before night. M. Fauvel will give me time in which to pay the balance. My pension is 1,500 francs and I can live on 500. I am still strong enough to obtain employment.’

M. Bertomy said no more, stopped by his son’s expression of anger.

‘You have no right, father,’ he cried, ‘to do this. You can refuse to believe me if you like; but an action like that would ruin me. I am upon the edge of a precipice and you want to push me over. While justice hesitates, father, you condemn me without a hearing.’

Prosper’s tones at last made an impression upon his father, who murmured:

‘But the evidence against you is very strong.’

‘That does not matter,’ Prosper replied; ‘I will prove myself innocent or perish in the attempt, whether I am convicted or not. The author of my misfortune is in the house of M. Fauvel and I will find him. Why did Madeleine tell me one day to think no more of her? Why did she exile me, when she loves me as much as I do her?’

The hour granted for the interview had expired. M. Bertomy left his son almost convinced of his innocence. Father and son embraced with tears in their eyes.

The door of Prosper’s cell reopened almost immediately after his father’s departure and the warder entered to conduct him to his examination. This time he went with his head high and a firm step.

As he passed through the room where the detectives and police were, the man with the gold spectacles said:

‘Be brave, M. Bertomy, if you are innocent we will help you.’

Prosper, in surprise, asked the warder who the gentleman was.

The warder replied:

‘Surely you know the great Lecoq! If your case had been in his hands instead of Fanferlot’s it would have been settled long ago. But he seems to know you.’

‘I never saw him till I saw him here.’

‘Don’t be too sure of that, for he is a master of disguises.’

This time Prosper did not have to wait upon the wooden bench. M. Patrigent had arranged for his examination to immediately follow his interview with his father, with the object of getting the truth from him while his nerves were still vibrating with emotion.

The magistrate was, therefore, very surprised at the cashier’s proud and resolute attitude.

The first question was:

‘Have you reflected?’

‘Being innocent,’ Prosper replied, ‘I have nothing on which to reflect.’

‘Ah,’ the magistrate said, ‘you forget that sincerity and repentance are necessary to obtain lenient treatment.’

‘I have need, sir, neither of pardon or leniency.’

‘How would you answer,’ the magistrate resumed, ‘if I told you what had become of the money?’

Prosper shook his head sadly. ‘In that case,’ he said, ‘I should not be here.’

The ordinary method of examination employed by the magistrate often succeeds, but it did not do so in this case.

‘Then you persist in accusing your employer?’

‘Either him or someone else.’

‘Excuse me, it could only be he. No one else knew the word. Had he any reason to rob himself?’

‘I know of none, sir.’

‘Ah, well,’ the magistrate said, ‘I will tell you the reason you had to rob him.’

This was the magistrate’s last effort to break through the cashier’s calm and determined resistance.

‘Will you tell me,’ the magistrate began, ‘how much you spent last year?’

Prosper answered promptly: ‘About 50,000 francs.’

‘Where did you get the money?’

‘I inherited 12,000 francs from my mother. My salary and commission came to 14,000. I made about 8,000 on the Stock Exchange, and the rest I borrowed. I can repay the latter item as I have 15,000 francs to my credit with M. Fauvel.’

‘Who lent you the money?’

‘M. Raoul de Lagors.’

This gentleman had gone away on the day of the robbery, so he could not be examined.

‘Now, tell me,’ the magistrate said, ‘what made you withdraw the money from the bank the day before it was required?’

‘Because M. de Clameran gave me to understand, sir, that he required the money early in the morning.’

‘Was he a friend of yours, then?’

‘No, I did not like him, but he was a friend of M. de Lagors.’

‘How did you spend the evening of the robbery?’ the magistrate asked.

‘After leaving the office at five, I went by train to Saint Germain and to M. Raoul de Lagors’ country house with 1,500 francs he required. As he was not at home I left the money with the servant.’

‘Did you know M. de Lagors was going to travel?’

‘No, I do not know whether he is in Paris or not.’

‘What did you do when you left your friend’s house?’

‘I returned to Paris and dined with a friend at a Boulevard restaurant.’

‘After that?’

Prosper hesitated.

‘As you won’t say,’ M. Patrigent went on, ‘I will tell you how you spent your time. You went to the Rue Chaptal, dressed and went to a party given by a woman named Wilson, one of those women who disgrace the theatres by calling themselves dramatic artistes.’

‘That is quite right, sir.’

‘There is a good deal of play there, is there not?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘You frequent those kind of places, do you not? Were you not mixed up in a scandalous adventure with a woman of that class named Crescenzi?’

‘I thought I was giving evidence concerning a robbery.’

‘Yes, gambling leads to robbery. Did you not lose 1,800 francs at the woman Wilson’s?’

‘Excuse me, sir, only 1,100 francs.’

‘Very well. In the morning you paid a bill of 1,000 francs.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Besides, there was 500 francs in your desk and 400 francs in your purse when you were arrested. In all that was 4,500 francs in twenty-four hours.’

Prosper was stupefied at this exact information which had been obtained in so short a time. At last he said:

‘Your information is accurate, sir.’

‘Where did this money come from, seeing that the previous evening you were so short you put off paying a small

bill?’

‘Sir, on the day you mention, I sold through an agent some securities for 3,000 francs and drew 2,000 francs salary in advance. I have nothing to hide.’

M. Patrigent renewed the attack from another point.

‘If you have nothing to hide,’ he said, ‘why did you mysteriously pass this note to a colleague?’

The blow struck home. Prosper’s eyes dropped before the magistrate’s searching gaze.

‘I thought, I wished—’ he muttered.

‘You wanted to conceal your mistress.’

‘Yes, sir, that is true. I knew that when a man is accused of a crime, all the weaknesses of his life become evidence against him.’

‘You mean the presence of a woman would give weight to the charge. You live with a woman?’

‘I am young, sir.’

‘Justice can pardon passing indiscretions, but cannot excuse the scandal of these unions. The man who respects himself so little as to live with a fallen woman does not raise the woman up to him, but he descends to her.’

‘Sir.’

‘I suppose you know who this woman is to whom you have loaned your mother’s honourable name?’

‘Madame Gypsy was a governess when I met her; she was born at Oporto and came to France with a Portuguese family.’

The magistrate shrugged his shoulders.

‘Her name is not Gypsy,’ he said, ‘she has never been a governess, and she is not Portuguese.’

Prosper tried to protest, but M. Patrigent silenced him, and began searching through a number of documents.