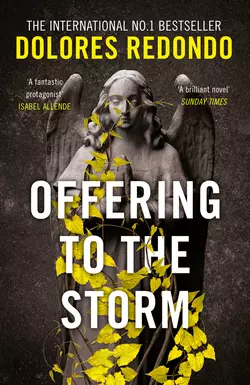

Offering to the Storm

Dolores Redondo

It begins with a murdered child. It ends in a valley where nightmares are born.

When Detective Inspector Amaia Salazar is called in to investigate the death of a baby girl, she finds a suspicious mark across the child’s face – an ominous sign that points to murder.The baby’s father was caught trying to run away with the body, whether from guilt or grief nobody can be sure. And when the girl’s grandmother tells the police that the ‘Inguma’ was responsible – an evil demon of Basque mythology that kills people in their sleep – Amaia is forced to return to the Baztán valley for answers.Back where it all began, in the depths of a blizzard, she comes face to face with a ghost from her past. And finally uncovers a devastating truth that has ravaged the valley for years.Copyright (#ua3e92a81-94f0-5908-bd3c-8a54345460b6)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Dolores Redondo 2014

Translation copyright © Nick Caistor and Lorenza García 2017

Dolores Redondo asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Originally published in 2014 by Ediciones Destino,

Spain, as Ofrenda a la tormenta

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Wojciech Zwolinski/Arcangel Images (statue), Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com) (other images)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2017 ISBN: 9780008165550

Source ISBN: 9780008165543

Version: 2018-04-20

Dedication (#ua3e92a81-94f0-5908-bd3c-8a54345460b6)

For Eduardo, as with everything I do.

For my aunt Angela and all the proud women in my family, who have always done what had to be done.

And above all, for Ainara.

I cannot bring you justice, but at least I shall remember your name.

‘It is never too late, Dorian. Let us kneel down, and try if we cannot remember a prayer.’

‘Those words mean nothing to me now.’

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde

‘All things that have a name exist.’

A popular Baztan belief, recorded by José Miguel de Barandiarán in Brujería y brujas

Table of Contents

Cover (#u453d534a-90ac-5caa-9849-76dba3e4b5a9)

Title Page (#u3c06d27c-0971-5a92-bd08-2890cbc63f57)

Copyright (#u2a76a274-9a3c-56de-87de-ac5f68b02f36)

Dedication (#u81e7945d-45a5-5d6f-86f3-bf20c3b89a87)

Epigraph (#u6c1f7bc5-88c8-5ead-a357-4b8ceb5d5711)

Chapter 1 (#ua65933ae-905a-558e-a22d-183879412461)

Chapter 2 (#uf346d3b1-db6e-5355-992f-1f2ddeb9e130)

Chapter 3 (#ud519dc77-8c1d-523c-803f-c3f46c7bceca)

Chapter 4 (#u849d1bf3-d384-52a8-a3ff-0b5fecce788f)

Chapter 5 (#ud550445f-2795-5824-8b0d-a96852286b80)

Chapter 6 (#ub2fdcc4d-d5fb-54cd-bf21-fe2077e71e7e)

Chapter 7 (#u6526641d-e26e-59d5-8d57-04d8671ded36)

Chapter 8 (#ue4e45841-203e-5d23-9adc-da7cff01f3dd)

Chapter 9 (#ub7be1556-df30-5bcd-90f3-83389ef23438)

Chapter 10 (#u4c445990-423f-580e-87b7-0fa376b1b443)

Chapter 11 (#u50845a2b-b8a7-518e-a3e5-6f7fb1ed182d)

Chapter 12 (#ue7bebc26-f9be-5021-ac5a-b215d4b56b5c)

Chapter 13 (#ufc2b19a0-95e7-5766-b19c-5ec7a5c720e3)

Chapter 14 (#u2cd67bc3-b0bb-5fa0-a3f2-b9af135f84aa)

Chapter 15 (#u620b77d8-1812-56e4-b9f2-aa597eb47cdd)

Chapter 16 (#ufa7885e5-4a9c-51bc-8be9-1fe2e3e9b574)

Chapter 17 (#u05f5b9f4-320d-5d73-bff1-9e399b2fe7f3)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Dolores Redondo (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ua3e92a81-94f0-5908-bd3c-8a54345460b6)

The lamp on the bedside table cast a warm, pink glow over the room, taking on different tones as it shone through the fairy patterns on its glass shade. From the shelf, a collection of stuffed toys gazed with beady eyes at the intruder silently gazing at the sleeping child. The intruder could hear the murmur of the television in the adjacent room, and the heavy breathing of the woman asleep on the sofa, lit by the screen’s cold light. The intruder’s eyes slid over the room, captivated by the moment, drinking in every detail, as though wanting to preserve that instant, transform it into a memento to be cherished forever. Eager but calm, the figure memorised the gentle pattern of the wallpaper, the framed photographs, the travel bag containing the little girl’s nappies and clothes, and then focused on the cot. A feeling akin to intoxication overcame the intruder, accompanied by nausea in the pit of the stomach. The baby was lying on her back, dressed in a pair of flannel pyjamas, a flowered bedspread drawn up to her waist. The intruder pulled the bedspread back, wanting to see all of her. The baby sighed in her sleep; a tiny thread of saliva trickled from her pink lips, leaving a damp patch on her cheek. The chubby hands, splayed out either side of her head, quivered a few times then relaxed once again. Reacting to the sight, the intruder sighed, overcome by a fleeting wave of tenderness. Picking up the soft toy sitting at the foot of the cot like a silent guardian, the intruder was vaguely aware of the care someone had taken to place it there. It was a polar bear, with small black eyes and a bulging stomach. An incongruous red ribbon fastened about its neck hung down to its hind legs. The intruder stroked the polar bear’s head, enjoying its softness, then, nose pressed into the furry belly, inhaled the sweet aroma of the expensive new toy.

Pulse racing, skin beading with sweat, the intruder began to perspire. Suddenly infuriated, the intruder held the toy at arm’s length, then thrust it down over the baby’s nose and mouth. After that, it was simply a matter of pressing it.

The tiny hands flailed in the air, one of her little fingers brushing the intruder’s wrist. An instant later, she fell into what seemed like a deep, restorative sleep. Her muscles relaxed, and her starfish hands lay on the sheets once more.

The intruder pulled the toy away and looked at the little girl’s face. There was no sign that she had suffered, apart from a red mark between the eyebrows, caused by the polar bear’s nose. The light in her face was snuffed out, and the sensation of gazing upon an empty receptacle intensified as the intruder raised the toy, and inhaled once again the little girl’s aroma, now enriched by her escaping soul. The scent was so powerful and sweet that the intruder’s eyes filled with tears. With a sigh of gratitude, the killer straightened the polar bear’s ribbon before replacing it at the foot of the cot.

Seized by a sense of urgency, as though suddenly aware of lingering too long, the intruder fled, turning only once to look back. The glow from the lamp seemed to gleam in the eyes of the other eleven furry animals as they peered down in horror from the shelf.

2 (#ua3e92a81-94f0-5908-bd3c-8a54345460b6)

Amaia had been watching the house for twenty minutes from her car. With the engine switched off and the windows closed against the steady drizzle, condensation had formed on the windows, blurring the contours of the building with the dark shutters.

Presently, a small car pulled up outside the front door. A young man stepped out, opened his umbrella, and leaned over the dashboard to pick up a notebook, which he glanced at before tossing it back in the car. Then he went to the boot, retrieved a flat package and walked up to the house.

Amaia drew level with him just as he rang the doorbell.

‘Excuse me, who are you?’

‘Social services, we deliver this gentleman’s meals every day,’ he replied, indicating the plastic tray in his hand. ‘He’s housebound, and has no one else to take care of him. Are you a relative?’ he enquired hopefully.

‘No,’ she replied. ‘Navarre police.’

‘Ah,’ he said, losing interest.

He rang the bell again, then, leaning close to the door, shouted:

‘Señor Yáñez. It’s Mikel. From social services. Remember me? I’ve brought your lun—’

Before he could finish his sentence, the door swung open, and Yáñez’s wrinkled, grey face appeared.

‘I remember you, I’m not senile, you know … Or deaf,’ he replied, irritated.

‘Of course not, Señor Yáñez,’ said Mikel, smiling as he brushed past him into the house.

Amaia fumbled for her badge to show Yáñez.

‘There’s no need,’ he said, recognising her and moving aside to let her pass.

Over his corduroy trousers and woollen sweater, Yáñez wore a thick dressing gown, the colour of which Amaia couldn’t make out in the gloomy house. She followed Yáñez down the corridor to the kitchen, where a fluorescent light bulb flickered before coming on.

‘Señor Yáñez!’ the young man exclaimed in an over-loud voice. ‘You didn’t eat your supper last night!’ He was standing by the open fridge, exchanging food trays wrapped in cling film. ‘I’ll have to log that in my report, you know. Don’t go blaming me if the doctor tells you off,’ he added, as if speaking to a child.

‘Log it wherever you want,’ muttered Yáñez.

‘Didn’t you like the fish in tomato sauce?’ Mikel went on, ignoring his reply. ‘Today you’ve got stewed meat and chickpeas, with yoghurt for pudding, and soup, omelette and sponge cake for supper.’ He spun round holding the untouched supper tray, then crouched under the sink, tied a knot in a small rubbish bag containing only a few discarded wrappings, and started towards the door. Pausing next to Yáñez, he addressed him once more in an over-loud voice: ‘All done, Señor Yáñez, bon appetit, until tomorrow.’ Then he turned to leave, nodding to Amaia on the way out.

Yáñez waited until he heard the front door close before speaking.

‘What do you make of that? And today he stayed longer than usual. Normally he can’t get away quick enough,’ he added, turning out the kitchen light, and leaving Amaia to make her way to the sitting room in semi-darkness. ‘This house gives him the creeps. And I don’t blame him, it’s like visiting a cemetery.’

A sheet, two thick blankets and a pillow lay partially draped over the brown velvet sofa. Amaia assumed that Yáñez not only slept, but lived in this one room. Amid the gloom, she could see what looked like crumbs on the blankets and an orangish stain, possibly egg yolk. Amaia studied Yáñez as he sat down and leaned back against the pillow. A month had gone by since she’d interviewed him at the police station. He was awaiting trial under house arrest because of his age. He had lost weight, and his hard, suspicious expression had sharpened, giving him the air of an eccentric hermit. His hair was well kept, and he was clean-shaven, but Amaia wondered how long he’d been wearing the pyjama top showing beneath his sweater. The house was freezing, and clearly hadn’t been heated for days. Opposite the sofa, in front of the empty hearth, a flat-screen TV cast a cold, blue light over the room.

‘May I open the shutters?’ asked Amaia.

‘If you insist, but leave them as they were before you go.’

She nodded, pushing open the wooden panels to allow the gloomy Baztán light to seep through. When she turned around, Yáñez was staring at the television.

‘Señor Yáñez.’

The man continued gazing at the screen as if she wasn’t there.

‘Señor Yáñez …’

He glanced at her, irritated.

‘I’d like to …’ she began, motioning towards the corridor. ‘I’d like to have a look round.’

‘Go ahead,’ he said, with a wave of his hand. ‘Look all you like, just don’t touch anything. After the police were here, the place was a mess. It took me ages to put everything back the way it was.’

‘Of course.’

‘I trust you’ll be as considerate as the officer who called yesterday.’

‘A police officer came here yesterday?’ she said, surprised.

‘Yes, a nice lad. He even made me a cup of coffee.’

Besides the kitchen and sitting room, Yáñez’s bungalow boasted three bedrooms and a largish bathroom. Amaia opened the cupboards, checking the shelves, which were crowded with shaving things, toilet rolls and a few bottles of medicine. The double bed in the main bedroom looked as if it hadn’t been slept in recently. Draped over it was a floral bedspread that matched the curtains, bleached by years of sunlight. Judging by the vases of garish plastic flowers and the crocheted doilies adorning the chest of drawers and bedside tables, the room had been lovingly decorated in the seventies by Señora Yáñez, and preserved intact by her husband. It was like looking at a display in an ethnographic museum.

The second bedroom was empty, save for an old sewing machine standing next to a wicker basket beneath the window. She remembered it from the inventory in the report. Even so, she removed the cover to examine the spools of cotton, recognising a less faded version of the curtain colour in the main bedroom. The third bedroom had been referred to in the inventory as ‘the boy’s room’, and it was exactly that: the bedroom of a ten- or eleven-year-old boy. The single bed with its pristine white bedspread; the shelves lined with children’s books, a series she recalled having read herself; toys, mostly model ships and aeroplanes, as well as a collection of toy cars, all carefully aligned, and without a speck of dust on them. On the back of the door was a poster of a classic vintage Ferrari, and on the desk some old school textbooks, and a bundle of football cards tied with a rubber band. As she picked them up, she saw that the degraded rubber had stuck to the faded cards. She put them back, mentally comparing the cold bedroom to Berasategui’s flat in Pamplona.

There were two other rooms in the house, plus a small utility area and a well-stocked woodshed where Yáñez kept his gardening tools and some boxes of potatoes and onions. Over in a corner, Amaia noticed an unlit boiler.

She picked up one of the dining chairs, and placed it between Yáñez and the television.

‘I’d like to ask you a few questions.’

He used the remote beside him to switch off the TV. Then he stared at her in silence, waiting with that same look of anger and resentment he’d directed at Amaia the first time they met.

‘Tell me about your son.’

The man shrugged.

‘What sort of relationship did you have?’

‘He’s a good son,’ Yáñez replied, too quickly. ‘He did everything you’d expect a good son to do.’

‘Such as?’

This time Yáñez had to give it some thought.

‘Well, he gave me money … sometimes he did the shopping, bought me food – that sort of thing.’

‘That’s not what I’ve been hearing. People in the village say that after your wife died, you packed your son off to school abroad, and that he didn’t show his face around here for years.’

‘He was studying. He was a good student, he did two degrees, and a masters, he’s one of the top psychiatrists at his clinic …’

‘When did he start visiting you more frequently?’

‘I don’t know, about a year ago.’

‘Did he ever bring anything other than food? Something he kept here, or that he asked you to keep for him somewhere else?’

‘No.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ve looked over the house,’ she said, glancing about. ‘It’s spotless.’

‘I have to keep it clean.’

I understand. You keep it clean for your son.’

‘No, for my wife. Everything is exactly the way it was when she left …’ Yáñez’s face twisted into a grimace of pain and grief. He remained that way for a few seconds, not making a sound. Amaia realised he was crying when she saw the tears roll down his cheeks.

‘That’s the least I could do; everything else I did was wrong.’

Yáñez’s eyes danced from one object to another, as if he were searching for an answer hidden among the faded ornaments standing on doilies and side tables, until he met Amaia’s gaze. He grasped the edge of the blanket, lifting it in front of his face for a few seconds, then flinging it aside, as though disgusted with himself for having cried in front of her. Amaia felt certain the conversation would end there, but then Yáñez reached behind the pillow he was leaning against and pulled out a framed photograph. He gazed at the image as if spellbound, then passed it to her. Yáñez’s gesture took Amaia back to the previous year, when, in a different sitting room, a grieving father had handed her the portrait of his murdered daughter, which he also kept hidden under a cushion. She hadn’t seen Anne Arbizu’s father since, but the memory of his pain had stayed with her.

A woman no older than twenty-five smiled at her from the picture. Amaia glanced at her, then handed the photograph back to Yáñez.

‘I thought we’d live happily ever after, you know? She was a young, pretty, kind woman … But after the boy was born she started acting strangely. She grew sad, she never smiled, she wouldn’t even hold him, she said she wasn’t ready to love the boy, and that he rejected her. Nothing I said did any good. I told her she was talking nonsense – of course the boy loved her – but she only grew sadder. She was sad all the time. She kept the house tidy, she did the cooking, but she never smiled; she even stopped sewing, and the rest of the time she slept. She kept the shutters closed, the way I do now, and she slept … I’ll never forget how proud we were when we first bought this place. She made it look so pretty: we painted the walls, planted window boxes … Life was good. I thought nothing would ever change. But a house isn’t the same as a home, and this became her tomb … Now it’s my turn, although they call it house arrest, and the lawyer says they’ll let me serve out my sentence here. I lie here every night, unable to sleep, smelling my wife’s blood below my head.’

Amaia looked intently at the sofa. The cover didn’t go with the rest of the décor.

‘I had it recovered because of the bloodstains, but they’d stopped making the original fabric so they used this one instead. Otherwise everything’s the same. When I lie here, I can smell her blood beneath the upholstery.’

‘The house is cold,’ said Amaia, disguising the shiver that ran up her spine.

He shrugged.

‘Why don’t you light the boiler?’

‘It hasn’t worked since the night of the storm, when the power went.’

‘That was over a month ago. You mean to say you’ve been without heating all this time?’

Yáñez didn’t reply.

‘What about the people from social services?’

‘I only open the door to the fellow who brings the trays. I told them on day one that if they come round here, I’ll be waiting for them with an axe.’

‘You have plenty of wood. Why not make a fire? There’s no virtue in being cold.’

‘It’s what I deserve.’

Amaia got up and went out to the shed, returning with a basket of logs and some old newspapers. Kneeling in front of the hearth, she stirred the cold ashes to make space for the wood. She took a box of matches from the mantelpiece and lit the fire. Then she sat down again. Yáñez stared into the flames.

‘You’ve also kept your son’s room just as it was. I find it hard to imagine a man like him sleeping there.’

‘He didn’t. Occasionally he stopped for lunch, and sometimes supper, but he never spent the night. He would leave, then come back early the next day. He told me he preferred a hotel.’

Amaia didn’t believe it; they had found no evidence of Berasategui staying at any of the hotels, hostels or bed and breakfast places in the valley.

‘Are you sure?’

‘I think so, but I can’t be a hundred per cent sure – as I told the police, my memory is worse than I let on to social services. I forget things.’

Amaia plucked her buzzing phone from her pocket. The display showed several missed calls but she ignored them, scanning through her photos until she found the right image, then touching the screen to enlarge it. Averting her eyes from the photo, she showed it to Yáñez.

‘Did your son ever come here with this woman?’

‘Your mother.’

‘You know her? Did you see her that night?’

‘No, but I’ve known your mother for years. She’s aged, but I recognise her.’

‘Think again, you just told me your memory isn’t so good.’

‘Sometimes I forget to have supper, or I have supper twice because I forget I’ve already had it, but I remember who comes to my house. Your mother has never set foot in here.’

She slipped the phone back into her coat pocket, replaced the dining chair, pulled the shutters to and left. As soon as she was in the car, she reached for her phone and, ignoring the insistent buzzing, dialled a number from her contacts list. After a couple of rings, a man answered.

‘Could you please send someone to fix a boiler that broke down on the night of the storm,’ she said, and gave him Yáñez’s address.

3 (#ua3e92a81-94f0-5908-bd3c-8a54345460b6)

By the time Amaia parked in the square next to the Lamia fountain, the drizzle had turned to a downpour. She pulled up the hood of her coat and hurried through the arch into Calle Pedro Axular, following the sound of raised voices. The anguish and urgency of those missed calls was reflected in Inspector Iriarte’s face as he struggled to contain a group of people intent upon approaching the patrol car. In the rear passenger seat, a weary-looking individual was sitting with his head propped against the rain-beaded window. Two uniformed officers were unsuccessfully attempting to cordon off the area surrounding a rucksack, which lay on the ground in the middle of a puddle. Amaia took out her phone and called for back-up as she hurried over to assist them. Just then, two more patrol cars advanced across the Giltxaurdi Bridge, distracting the angry mob, whose shouts were momentarily drowned out by the wailing sirens.

Iriarte was soaked to the bone, and as he spoke to Amaia, he kept wiping his brow to stop the water going in his eyes. Deputy Inspector Etxaide appeared out of nowhere with a large umbrella, which he handed to them, then went to help the other officers pacify the crowd.

‘Well, Inspector?’

‘The suspect in the car is Valentín Esparza. His four-month-old daughter died last night while sleeping over at her maternal grandmother’s house. The doctor registered the cause as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. So far, a tragedy. Except that yesterday, the grandmother, Inés Ballarena, paid a visit to the police station. Apparently, the baby was staying the night with her for the first time because it was the parents’ wedding anniversary, and they were going out to dinner. She was looking forward to it, and had even prepared a room for her. She fed the baby and put her down for the night, then fell asleep in front of the television in the sitting room next door, although she swears the baby monitor was on. She was woken by a noise, and went to look in on the baby – who from the doorway appeared sound asleep. Then she heard the crunch of tyres on gravel outside. She looked through the window in time to see a large, grey car driving away. Although she didn’t see the number plate, she assumed it was her son-in-law, as he has one just like it,’ said Iriarte, with a shrug. ‘She claims she checked the time and it was just gone two in the morning. She thought the couple must have driven by on their way home to see if any lights were on. This didn’t strike her as odd because they live nearby. She thought no more about it, and went back to sleep on the sofa. When she woke up, she was surprised not to hear the baby crying to be fed, so she went into the bedroom where she found the child dead. She was upset, she blamed herself, but when the doctor gave the estimated time of death as between two and three in the morning, she remembered waking up and seeing the car in the driveway. She now believes she was woken by an earlier noise inside the house. When Inés asked her daughter about this, she told her they had arrived home at around one thirty; she doesn’t drink usually, so a glass of wine and a liqueur after the meal had knocked her out. However, when Inés questioned the son-in-law, he became agitated, refused to answer, flew into a rage. He told her it was probably a couple of lovebirds looking for a secluded spot; it wouldn’t have been the first time. But then Inés remembered something else: she keeps her two dogs outside and they bark like crazy whenever a stranger comes near the house, but they didn’t make a sound last night.’

‘What did you do next?’ asked Amaia.

Whether it was because they were intimidated by the police presence or simply wanted to get out of the rain, the crowd had retreated to the covered entrance of the funeral parlour. A woman at the centre of the huddle was embracing another, who was screaming and sobbing hysterically. It was impossible to make out what she was saying.

‘The woman screaming is the mother, the one with her arms around her is the little girl’s grandmother,’ Iriarte explained, following Amaia’s gaze. ‘Anyway, as I was saying, the grandmother was in a terrible state. She couldn’t stop crying while she was telling me her story. To begin with, I thought she was probably just trying to find an explanation for something that was difficult to accept. This was the first time they let her babysit, her first grandchild, she was distraught …’

‘But?’

‘But, even so, I called the paediatrician. He was adamant: Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The baby was premature, her lungs weren’t properly formed, and she’d spent half of her short life in the hospital. Although they’d discharged her, this past week the mother had brought her to the surgery with a cold – only a sniffle, but in a premature, underweight baby, the doctor had no doubt about the cause of death. An hour ago, Inés turned up at the station again, insisting the girl had a mark on her forehead – round, like a button – which wasn’t there earlier. She said that when she pointed it out to her son-in-law, he snapped at her and insisted they close the coffin. So I decided to take a look for myself. As we entered the funeral parlour, we bumped into the father, Valentín Esparza, on his way out. He was carrying that rucksack’ – Iriarte pointed to the wet bundle sitting in a puddle – ‘and something about the way he was holding it struck me as odd. Not that I carry a rucksack myself, but it didn’t seem right.’ He clasped his hands to his chest to imitate the posture. ‘The minute he saw me, he turned pale and started to run. I caught up with him next to his car, and that was when he started to yell, telling us to leave him alone, saying he had to finish this.’

‘To take his own life?’

‘That’s what I thought. It occurred to me he might have a weapon in there …’

Iriarte crouched down beside the rucksack, giving up the shelter of the umbrella, which he placed on the ground as a screen. He opened the flap, pulling the toggle to loosen the drawstring. The little girl’s dark, wispy hair revealed the soft spot on her head; her skin had that tell-tale pallor, although her mouth, slightly open, retained a hint of colour, giving a false impression of life, which held them transfixed until Dr San Martín leaned in, breaking the spell.

While the pathologist removed the sterile wrapping from a swab, Iriarte gave him a summary of what he had told Amaia. Then San Martín crouched next to the child’s body and gently used the swab to remove the make-up that had been hastily applied to the bridge of the baby’s nose.

‘She’s so tiny.’ The sorrow in the usually imperturbable pathologist’s voice made Iriarte and Amaia look at him in surprise. Conscious of their eyes on him, he immediately busied himself examining the mark on the child’s skin. ‘An extremely crude attempt to cover up a pressure mark. It probably occurred at the precise moment when she stopped breathing, and is only visible to the naked eye now that lividity has set in. Give me a hand, will you?’ he said.

‘What are you going to do?’

‘I have to see all of her,’ he replied, with an impatient gesture.

‘Not here, please,’ said Iriarte. He indicated the crowd outside the funeral parlour. ‘You see those people? They’re the baby’s relatives, including her mother and grandmother. We’ve had enough difficulty controlling them as it is. If they see her dead body lying on the ground, they’ll go crazy.’

‘Inspector Iriarte is right,’ said Amaia, glancing towards the crowd then looking back at San Martín.

‘Very well, but until I have her on my slab I can’t tell you if there are any other signs of violence. Make sure you are thorough when you process the crime scene; I remember working on a similar case, where a mark on a baby’s cheek turned out to be made by a button on a pillowcase. Although I can give you one piece of information that might help.’ San Martín produced a small digital device from his Gladstone bag, holding it up proudly. ‘A digital calliper,’ he explained, pulling apart the two metal prongs, and adjusting them to measure the diameter of the mark on the baby’s forehead. ‘There you are,’ he said, showing them the screen. ‘The object you’re looking for is 13.85 millimetres in diameter.’

They stood up, leaving the forensic technicians to place the rucksack inside a body bag. Amaia turned to see Judge Markina standing a few metres away, watching in silence. No doubt San Martín had notified him. Beneath his black umbrella, and in the dim light seeping through the leaden clouds, his face looked sombre; even so, she registered the sparkle in his eye, the intensity of his gaze when he greeted her. Although the gesture was fleeting, she looked nervously at San Martín then at Iriarte to see if they had noticed. San Martín was busy giving orders to his technicians and outlining the facts to the legal secretary beside him, while Iriarte was keeping a close watch on the relatives. The rumour had spread among them, and they began angrily to demand answers even as the mother’s howls of grief grew louder and louder.

‘We need to get this guy out of here now,’ declared Iriarte, motioning to one of the officers.

‘Take him directly to Pamplona,’ ordered Markina.

‘I’ll get a police van to move him there by this afternoon at the very latest, your honour. In the meantime, we’ll take him to the local police station. We’ll meet there,’ Iriarte said to Amaia.

She nodded at Markina by way of a goodbye, then started towards her car.

‘Inspector … Do you have a moment?’

She stopped in her tracks, wheeling round only to find him standing beside her, sheltering her with his umbrella.

‘Why didn’t you call me?’ This wasn’t exactly a reproach, or even a question; it had the seductive tone of an invitation, the playfulness of flirtation. The grey coat he wore over a matching grey suit, his impeccable white shirt and dark tie – unusual for him – gave him a solemn, graceful air, moderated by the lock of hair tumbling over his brow and the light covering of designer stubble. Beneath the canopy of the umbrella she felt herself being drawn into a moment of intimacy, conscious of the expensive cologne emanating from his warm skin, his intense gaze, the warmth of his smile …

Suddenly, Jonan Etxaide appeared out of nowhere.

‘Boss, the cars are all full. Could you give me a lift to the police station?’

‘Of course, Jonan,’ she replied, startled back to reality. ‘If you’ll excuse us, your honour.’

Having taken her leave, she made her way towards the car without a backward glance. Etxaide, however, turned once to contemplate Markina, who was standing where they had left him. The magistrate responded with a wave.

4 (#ua3e92a81-94f0-5908-bd3c-8a54345460b6)

The warmth of the police station hadn’t succeeded in bringing the colour back to Iriarte’s cheeks, but at least he’d managed to change out of his wet clothes by the time Amaia arrived.

‘What did he say?’ she asked. ‘Why was he taking her body?’

‘He hasn’t said a word. He’s sitting curled up in a ball in the corner of his cell, refusing to move or speak.’

She made to leave, but when she got to the door she turned to face the inspector.

‘Do you think Esparza’s behaviour was motivated by grief, or do you believe he is involved in his daughter’s death?’

‘I honestly don’t know,’ said Iriarte. ‘This could be a reaction to losing his daughter, but I can’t rule out the possibility he was trying to prevent a second autopsy, fearing it would confirm his mother-in-law’s suspicions.’ He fell silent, then sighed. ‘I can’t imagine anything more monstrous than harming your own child.’

The clear image of her mother’s face suddenly flashed into Amaia’s mind. She managed to thrust it aside only for it to be replaced by another, that of the midwife, Fina Hidalgo, breaking off newly sprouted shoots with a dirty fingernail, stained green: ‘The families mostly did it themselves; I only helped occasionally when they couldn’t bring themselves to destroy the fruit of their womb, or some such nonsense.’

‘Was the girl normal, Inspector? I mean, did she suffer from brain damage or any other disabilities.’

Iriarte shook his head. ‘Besides being premature, the doctor assured me she was a normal, healthy child.’

The holding cells at the new police station in Elizondo had no bars; instead, a wall of toughened glass separated them from the reception area, allowing each compartment to be viewed from outside, and making it possible for the occupants to be filmed round the clock. Amaia and Iriarte walked along the corridor outside the cells, all of them empty save for one. As they approached the glass, they could see a man crouched on the floor at the back of the cell between the sink and the toilet. His arms were looped around his knees, his head lowered. Iriarte switched on the intercom.

‘Valentín Esparza.’

The man looked up.

‘Inspector Salazar would like to ask you a few questions.’

He lowered his face again.

‘Valentín,’ Iriarte called out, more firmly this time, ‘we’re coming in. No need to get agitated, just stay calm.’

Amaia leaned towards Iriarte. ‘I’ll go in alone, I’m in plain clothes, I’m a woman, it’s less intimidating …’

Iriarte withdrew to the adjacent room, which was set up so that he could see and hear everything that went on.

Amaia entered the cell and stood facing Esparza. After a few seconds, she asked: ‘May I sit down?’

He looked at her, thrown by the question.

‘What?’

‘Do you mind if I sit down?’ she repeated, pointing to a wooden bench along the wall that doubled as a bed. Asking permission was a sign of respect; she wasn’t treating him as a prisoner, or a suspect.

He waved a hand.

‘Thank you,’ she said, sitting down. ‘At this time of day, I’m already exhausted. I have a baby too – a little boy. He’s five months old. I know that you lost your baby girl yesterday.’ The man raised his pale face and looked straight at her. ‘How old was she?’

‘Four months,’ he said in a hoarse voice.

‘I’m sorry for your loss.’

He swallowed hard, eyes downcast.

‘Today was supposed to be my day off, you know. And when I arrived I found this mess. Why don’t you tell me what happened?’

He sat up, motioning with his chin towards the camera behind the glass, and the spotlight illuminating the cell. His face looked serious, in pain, but not mistrustful.

‘Haven’t your colleagues told you?’

‘I’d like to hear it from you. I’m more interested in your version.’

He took his time. A less experienced interrogator might have assumed he had clammed up, but Amaia simply waited.

‘I was taking my daughter’s body away.’

Amaia noted the use of the word body; he was acknowledging that he had been carrying a corpse, not a child.

‘Where to?’

‘Where to?’ he asked, bewildered. ‘Nowhere, I just … I just wanted to have her a bit longer.’

‘You said you were taking her away, that you were taking her body away, and they arrested you next to your car. Where were you going?’

He remained silent.

She tried a different tack.

‘It’s amazing how much having a baby changes your life. There’s so much to do, so many demands on you. My boy gets colic every night after his last feed; sometimes he cries for as long as two or three hours. All I can do is walk round the house trying to calm him. I understand how that can drive some people crazy.’

Esparza appeared to nod sympathetically.

‘Is that what happened?’

‘What?’

‘Your mother-in-law claims you went to her house early in the morning.’

He started to shake his head.

‘And that she saw your car drive away …’

‘My mother-in-law is mistaken.’ His hostility was palpable. ‘She can’t tell one car from another. It was probably a couple of kids who pulled into the driveway hoping to find a quiet place to … you know.’

‘Yes, except that her dogs didn’t bark, so it must have been someone they knew. What’s more, your mother-in-law told my colleague about a mark on the girl’s forehead, which wasn’t there when she put her to bed. She also said she was woken up by a noise, and when she looked out of the window she saw your car driving off.’

‘That bitch would say anything to get me into trouble. She’s never liked me. You can ask my wife, she’ll tell you: we went out to dinner and afterwards we went straight home.’

‘My colleagues have spoken to her, but she couldn’t help much. She didn’t contradict your story, she simply doesn’t remember anything.’

‘I know, she had too much to drink. She isn’t used to it, what with the pregnancy …’

‘It must have been difficult for you this last year.’ He looked at her, puzzled. ‘I mean, the risky pregnancy, forced rest, no sex; then the baby is born premature, two months in hospital, no sex; at last she comes home, more worries, caring for the baby, and still no sex …’

He gave a faint smile.

‘I know from experience,’ she went on. ‘And on the day of your anniversary, you leave the baby with your mother-in-law, you go out to a nice restaurant, and after a few glasses of wine your wife is legless. You take her home, put her to bed, and … no sex. The night is young. You drive over to your mother-in-law’s house to check that everything’s all right. You arrive to find her asleep on the sofa, and that irritates you. Entering the girl’s room, you suddenly realise the child is a burden, she is ruining your life, things were much better before she came along … and you make a decision.’

He sat perfectly still, hanging on her every word.

‘So, you do what you have to do, only your mother-in-law wakes up and sees you driving away.’

‘Like I told you: my mother-in-law is a fucking bitch.’

‘I know how you feel – mine is too. But yours is also very astute. She noticed the mark on the girl’s forehead. Yesterday, it was barely visible, but today the pathologist is in no doubt that the mark was made by an object having been pressed into her skin.’

He heaved a deep sigh.

‘You noticed it too, that’s why you tried to cover it with make-up. And to ensure no one else would see it, you ordered the coffin to be sealed. But your bitch of a mother-in-law is like a dog with a bone, isn’t she? So you decided to take the body to prevent anyone asking questions. Your wife, perhaps? Someone saw you two quarrelling in the funeral parlour.’

‘You’ve got it all wrong. That was because she insisted on cremating the girl.’

‘And you were against it? You wanted a burial? Is that why you took her?’

Something appeared to dawn on him.

‘What will happen to the body now?’

Amaia was intrigued by Esparza’s choice of words; relatives didn’t usually refer to their loved one as a body or corpse, but rather as the girl, the baby, or … She realised she didn’t know his child’s name.

‘The pathologist will perform a second autopsy, after which the body will be released to the family.’

‘They mustn’t cremate her.’

‘That’s something you need to decide among yourselves.’

‘They mustn’t cremate her. I haven’t finished.’

Amaia recalled what Iriarte had told her.

‘What haven’t you finished?’

‘If I don’t finish, this will all have been in vain.’

Amaia’s curiosity deepened:

‘What exactly do you mean?’

Suddenly, Esparza seemed to realise where he was, and that he’d said too much. He immediately clammed up.

‘Did you kill your daughter?’

‘No,’ he replied.

‘Do you know who did?’

Silence.

‘Perhaps your wife killed her …’

Esparza smiled, shaking his head, as if he found the mere thought laughable.

‘Not her.’

‘Who, then? Who did you take to your mother-in-law’s house?’

‘No one.’

‘No, I don’t believe you did, because it was you. You killed your daughter.’

‘No!’ he yelled suddenly. ‘… I gave her up.’

‘Gave her up? Who to? What for?’

He grinned smugly.

‘I gave her up to …’ He lowered his voice to a muffled whisper: ‘… like all the others …’ he said. He murmured a few more words, then buried his head in his arms.

Amaia remained in the cell for a while, even though she realised that the interview was over, that she would get no more out of him. She buzzed for them to open the door from outside. As she was leaving, he spoke again:

‘Can you do something for me?’

‘That depends.’

‘Tell them not to cremate her.’

Deputy Inspectors Etxaide and Zabalza were waiting with Iriarte in the adjoining room.

‘Could you hear what he was saying?’

‘Only the part about giving her up to someone, but I didn’t hear a name. It’s on tape; you can see his lips move, but it’s inaudible. He was probably talking gibberish.’

‘Zabalza, see if you can do anything with the audio and video, jack up the volume as high as it’ll go. I expect you’re right, he’s messing with us, but let’s be on the safe side. Jonan, Montes and Iriarte, you come with me. By the way, where is Montes?’

‘He’s just finished taking the relatives’ statements.’

Amaia opened her field kit on the table to make sure she had everything she needed.

‘We’ll need to stop somewhere to buy a digital calliper.’ She smiled, as she noticed Iriarte frown. ‘Is something wrong?’

‘Today is your day off …’

‘Not any more, right?’ she grinned, picking up the case and following Jonan outside to where Montes was waiting for them in the car with the engine running.

5 (#ua3e92a81-94f0-5908-bd3c-8a54345460b6)

She felt a kind of sympathy bordering on pity for Valentín Esparza when she entered the room his mother-in-law had decorated for the little girl. Confronted with the profusion of pink ribbons, lace and embroidery, the sensation of déjà vu was overwhelming. This little girl’s amatxi had chosen nymphs and fairies instead of the ridiculous pink lambs her own mother-in-law had chosen for Ibai, but other than that, the room might have been decorated by the same woman. Hanging on the walls were half a dozen or so framed photographs of the girl being cradled by her mother, grandmother and an older woman, possibly an aunt. Valentín Esparza didn’t appear in any of them.

The radiators upstairs were on full, doubtless for the baby’s benefit. Muffled voices reached them from the kitchen below, friends and neighbours who had come round to comfort the two women. The mother seemed to have stopped crying now; even so, Amaia closed the door at the top of the stairs. She stood watching as Montes and Etxaide processed the scene, cursing her phone, which had been vibrating in her pocket since they left the station. The number of missed calls was piling up. She checked her coverage: as she had suspected, because of the thick walls it was much weaker inside the farmhouse. Descending the stairs, she tiptoed past the kitchen, registering the sound of hushed voices typical at wakes. She felt a sense of relief as she stepped outside. The rain had stopped briefly, as the wind swept away the black storm clouds, but the absence of any clear patches of sky meant that once the wind fell the rain would start again. She moved a few metres away from the house and checked her log of missed calls. One from Dr San Martín, one from Lieutenant Padua of the Guardia Civil, one from James, and six from Ros. First she rang James, who was upset to hear that she wouldn’t be home for lunch.

‘But, Amaia, it’s your day off—’

‘I’ll be home as soon as I can, I promise, and I’ll make it up to you.’

He seemed unconvinced.

‘But we have a dinner reservation …’

‘I’ll be home in an hour at the most.’

Padua picked up straight away.

‘Inspector, how are you?’

‘I’m fine. I saw your call, and—’ She could barely contain her anxiety.

‘No news, Inspector. I just rang to say I’ve spoken to Naval Command in San Sebastián and La Rochelle. All the patrol boats in the Bay of Biscay are on the alert and they know what to look for.’

Padua must have heard her sigh. He added in a reassuring tone:

‘Inspector, the coastguards are of the opinion, and I agree, that one month is long enough for your mother’s body to have washed up somewhere along the shore. It could have been swept up the Cantabrian coast, though the ascending current is more likely to have carried it to France. Alternatively, it could have become snagged on the riverbed, or the torrential rains could have taken it miles out to sea, into one of the deep trenches in the Bay of Biscay. Bodies washed out to sea are rarely found, and given how long it’s been since your mother disappeared, I think we have to consider that possibility. A month is a long time.’

‘Thank you, Lieutenant,’ she said, trying hard not to show her disappointment. ‘If you hear anything …’

‘Rest assured, I’ll let you know.’

She hung up, thrusting her phone deep into her pocket, as she digested what Padua had said. A month in the sea is a long time for a dead body. But didn’t the sea always give up its dead?

While talking to Padua, she had started to circle the house to escape the tiresome crunch of gravel outside the entrance. As she followed the line in the ground traced by rainwater dripping from the roof, she reached the corner at the back of the building where the eaves met. Sensing a movement behind her, she turned. The older woman from the photographs in the little girl’s bedroom was standing beside a tree in the garden, apparently talking to herself. As she gently tapped the tree trunk, she chanted a series of barely audible words that seemed to be addressed to some invisible presence. Amaia watched the old woman for a few seconds, until she looked up and saw her.

‘In the old days, we’d have buried her here,’ she said.

Amaia lowered her gaze to the trodden earth and the clear line traced by water falling from the eaves. She was unable to speak, assailed by images of her own family graveyard, the remains of a cot blanket poking out from the dark soil.

‘Kinder than leaving her all alone in a cemetery, or cremating her, which is what my granddaughter wants to do … The modern ways aren’t always the best. In the old days, we women weren’t told how we should do things; we may have done some things wrong, but we did others much better.’ The woman spoke to her in Spanish, although from the way she pronounced her ‘r’s, Amaia inferred that she usually spoke Basque. An old Baztán etxekoandrea, one of a generation of invincible women who had seen a whole century, and who still had the strength to get up every morning, scrape her hair into a bun, cook, and feed the animals; Amaia noticed the powdery traces of the millet the woman had been carrying in the pockets of her black apron, in the old tradition. ‘You do what has to be done.’

As the woman shuffled towards her in her green wellingtons, Amaia resisted the urge to go to her aid, sensing this might embarrass her. Instead she waited until the woman drew level, then extended her hand.

‘Who were you speaking to?’ she said, gesturing towards the open meadow.

‘To the bees.’

Amaia looked at her, puzzled.

Erliak, elriak

Gaur il da etxeko nausiya

Erliak, elriak

Eta bear da elizan argia

(#litres_trial_promo)

Amaia recalled her aunt telling her that in Baztán, when someone died, the mistress of the house would go to where the hives were kept in the meadow and ask the bees to make more wax for the extra candles needed to illuminate the deceased during the wake and funeral. According to her aunt, the incantation would increase the bees’ production three-fold.

Touched by the woman’s gesture, Amaia imagined she could hear her Aunt Engrasi saying, ‘When all else fails, we return to the old traditions.’

‘I’m sorry for your loss,’ she said.

Ignoring Amaia’s hand, the woman embraced her with surprising strength. After releasing her, she lowered her eyes to the ground, wiping her tears away with the pocket of the apron in which she had carried the chicken feed. Amaia – moved by the woman’s dignified courage, which had rekindled the lifelong admiration she’d felt towards that generation – maintained a respectful silence.

‘He didn’t do it,’ the woman said suddenly.

Trained to know when someone was about to unburden themselves, Amaia didn’t reply.

‘No one takes any notice of me because I’m an old woman, but I know who killed our little girl, and it wasn’t that foolish father of hers. All he cares about is cars, motorbikes and showing off. He loves money the way pigs love apples. I should know, I courted men like that in my youth. They would come to pick me up on motorbikes, or in cars, but I wasn’t taken in by all that nonsense. I wanted a real man …’

The old woman’s mind was starting to wander. Amaia steered her back to the present:

‘Do you know who killed her?’

‘Yes, I told them,’ she said, waving a hand towards the house. ‘But no one listens to me because I’m an old woman.’

‘I’m listening to you. Tell me who did this.’

‘It was Inguma – Inguma killed her,’ she declared emphatically.

‘Who is Inguma?’

The old woman’s grief was palpable as she gazed at Amaia.

‘That poor girl! Inguma is the demon that steals children’s souls while they sleep. Inguma slipped through the cracks, sat on her chest and took her soul.’

Amaia opened her mouth, confused, then closed it again, unsure what to say.

‘You think I’m spouting old wives’ tales,’ the woman said accusingly.

‘Not at all …’

‘In the annals of Baztán it says that Inguma awoke once and took away hundreds of children. The doctors called it whooping cough, but it was Inguma who came to rob their breath while they slept.’

Inés Ballarena appeared from around the side of the house.

‘Ama, what are you doing here? I told you I’d fed the chickens this morning.’ She clasped the old lady by the arm, addressing Amaia: ‘You must excuse my mother, she’s very old; what happened has upset her terribly.’

‘Of course,’ murmured Amaia. To her relief, at that moment a call came through on her mobile. She excused herself and moved away to a discreet distance to take the call.

‘Dr San Martín, have you finished already?’ she said, glancing at her watch.

‘Actually, we’ve only just started.’ He cleared his throat. ‘I’ve asked a colleague to help me on this occasion,’ he said, unable to disguise the catch in his voice, ‘but, I thought I’d let you know what we’ve found so far. The victim was suffocated with a soft object, such as a pillow or cushion. You saw the mark above the bridge of the nose; when you conduct your search, keep in mind the measurement I gave you. Forensics are currently examining a few soft, white fibres we found in the folds of the mouth, so that’ll give you some idea of the colour. We also found traces of saliva on her face, mostly belonging to the girl, but there is at least one other donor. It might have been left by a relative kissing her cheek …’

‘When will you be able to tell me more?’

‘In a few hours.’

Amaia ended the call and hurried after the two women. She caught up with them at the front door.

‘Inés, did you bathe your granddaughter before you put her to bed?’

‘Yes, the evening bath relaxed her, it made her sleepy,’ she said, stifling a sob.

Amaia thanked her, then ran up the stairs. ‘We’re looking for something soft and white,’ she said, bursting into the bedroom.

Montes lifted an evidence bag to show her.

‘Snow white,’ he declared, holding aloft the captive bear.

‘How did you …?’

‘From the smell,’ explained Jonan. ‘Then we noticed that the fur looked flattened …’

‘It smells?’ Amaia frowned; a dirty toy seemed incongruous in that room where everything had been carefully thought out down to the last detail.

‘It doesn’t just smell, it stinks,’ said Montes.

6 (#ulink_49b40bd2-4d1f-5b46-bb52-46951cddfd3d)

By the time she left the house, Amaia’s mobile showed three more missed calls from Ros. She’d resisted the temptation to return them, sensing that her sister’s unusual persistence might herald an awkward conversation, which she didn’t want her colleagues to witness. Only once she was in the privacy of her car did she make the call. Ros answered on the first ring, as if she’d been waiting with the phone in her hand.

‘Oh, Amaia, could you come over?’

‘Of course, what’s the matter, Ros?’

‘You’d better come and see for yourself.’

Amaia parked outside Mantecadas Salazar and made her way through the bakery, exchanging greetings with the employees she passed en route to the office at the back. Ros was standing in the doorway with her back to Amaia, blocking her view of the interior.

‘Ros, are you going to tell me what’s going on?’

Ros spun round, ashen-faced. Amaia instantly understood why.

‘Well, well. The cavalry has arrived!’ Flora said by way of greeting.

Concealing her surprise, Amaia approached her eldest sister after giving Ros a peck on the cheek.

‘We weren’t expecting you, Flora. How are you?’

‘As well as anyone could be, under the circumstances …’

Amaia looked at her, puzzled.

‘Our mother met a horrible death a month ago – or am I the only one who cares?’ she said sarcastically.

Amaia flashed a grin at Ros. ‘Of course, Flora, the whole world knows how much more sensitive you are than everyone else,’ she retorted.

Flora responded to the jibe with a grimace, then planted herself behind the desk. Motionless in the doorway, arms hanging by her sides, Ros was the image of helplessness, save for her pursed lips and a glint of repressed rage in her eye.

‘Are you planning to stay long, Flora?’ asked Amaia. ‘I don’t suppose you have much free time with all your TV work.’

Flora adjusted the height of the chair then sat down behind the desk.

‘Yes, I’m extremely busy, but I thought I’d take a few days off,’ she said, rearranging a pile of papers on the desk.

Ros pressed her lips together even more tightly. Observing this, Flora added nonchalantly, ‘Actually, given the way things are, I may decide to stay on.’ She pushed the wastepaper basket towards the desk with her foot then swept up the brightly coloured post-it notes and ballpoint pens with tasselled toppers that clearly belonged to Ros and tossed them in.

‘Great,’ said Amaia. ‘I’m sure Auntie will be delighted to see you when you stop by later. But, Flora, in future, if you want to drop in at the bakery, let Ros know beforehand. She’s a busy woman now that she’s signed a contract with that big French supermarket chain – that deal you were forever chasing, remember? – so she hasn’t time to tidy up the mess you leave behind.’ She leaned over the wastepaper basket to retrieve Ros’s belongings and replace them on the desk.

‘The Martiniés,’ Flora hissed under her breath.

‘Oui,’ replied Amaia with a mischievous grin. She could tell from Flora’s expression that her barb had hit the mark.

‘I set the whole thing up,’ Flora huffed. ‘I did the research, I spent over a year making the necessary contacts.’

‘Yes, but Ros clinched the deal on their first meeting,’ replied Amaia gaily.

Flora stared at Ros, who avoided her gaze, walking over to the coffee machine and setting out some cups.

‘Do you want coffee?’ she said, almost in a whisper.

‘Yes, please,’ replied Amaia, eyes fixed on Flora.

‘No, thanks,’ said Flora. ‘I wouldn’t want to take up any more of your precious time,’ she added, rising from her seat. ‘I just wanted to tell you that I came here to arrange Ama’s funeral service.’

The remark took Amaia by surprise. The notion of a service had never entered her head.

‘But—’ she started to protest.

‘Yes, I know, it isn’t official, and we’d all like to believe that somehow she managed to scramble out of the river and is still alive, but the fact is, she probably didn’t,’ she said, staring straight at Amaia. ‘I’ve spoken to the magistrate in Pamplona in charge of the case, and he agrees that it’s a good idea to hold a service.’

‘You called Judge Markina?’

‘Actually, he called me. A charming man, incidentally.’

‘Yes, but …’

‘But, what?’ demanded Flora.

‘Well …’ Amaia swallowed hard, her voice cracking as she spoke: ‘Until we find her body, we can’t be sure she’s dead.’

‘For God’s sake, Amaia! You saw the clothes they dragged out of the river. How could an old, crippled woman have survived that?’

‘I don’t know … In any case, she isn’t officially dead.’

‘I think it’s a good idea,’ Ros broke in.

Amaia looked at her, astonished.

‘Yes, Amaia, I think we should turn the page. Holding a funeral for Ama’s soul will close this chapter once and for all.’

‘I can’t. I don’t believe she’s dead.’

‘For God’s sake, Amaia!’ cried Flora. ‘Where is she, then? Where the hell is she? She couldn’t possibly have escaped into the forest in the dead of night!’ She lowered her voice: ‘They dragged the river, Amaia. Our mother drowned, she’s dead.’

Amaia squeezed her eyes shut.

‘Flora, if you need any help with the arrangements, call me,’ said Ros calmly.

Without replying, Flora picked up her bag and strode to the door.

‘I’ll tell you the time and venue as soon as I’ve arranged everything.’

With Flora gone, the two sisters settled down to drink their coffee. The atmosphere in the office was like the aftermath of an electrical storm, both women waiting for the charged energy in the air to subside and for calm to be restored before speaking.

‘She’s dead, Amaia,’ Ros said at last.

‘I don’t know …’

‘You don’t know, or you haven’t accepted it yet?’

Amaia looked at her.

‘You’ve been running from Rosario all your life, you’ve become accustomed to living with that threat, with the knowledge that she is out there, that she is still out to harm you. But it’s over now, Amaia. It’s over. Ama is finally dead, and – God forgive me for saying so – but I’m not sorry. I know how much she made you suffer, what she almost did to Ibai, but I saw her coat with my own eyes: it was sodden with water. No one could have climbed out of that river alive in the middle of the night. Trust me, Amaia: she’s dead.’

Amaia parked her car opposite Aunt Engrasi’s house and sat for a while, enjoying the golden glow illuminating the windows from inside, as though at its heart a tiny sun or fire were perpetually burning. She gazed up at the overcast sky; night was falling, and although the lights had been on all day, it was only now that they shone in all their glory. She recalled how, as a child, she’d look forward to the occasions when her aunt would ask her to take the rubbish out because it meant she could steal away to the low wall down by the river. She’d sit there, entranced by the sight of the house all lit up, until her aunt began calling for her. Only then would she go inside, her hands and face burning with cold. The sensation of returning home was so intensely pleasurable that she turned it into a custom, a way of drawing out the joy of re-entering the house. She thought of it as a kind of Taoist ritual, one that she’d carried into adulthood, only abandoning the habit when she became a mother. She so longed to see Ibai that no sooner did she reach the door than she would rush inside, eager to touch her son, to kiss him. Tonight, rediscovering this secret, magical game, she reflected on the way she clung, to the point of obsession, to those rituals that had kept her sane through her traumatic childhood. Perhaps it was time for her to leave the past behind.

She climbed out of the car and made her way into the house.Without stopping to take off her coat, she entered the sitting room, where her aunt was clearing up after her game of cards with the Golden Girls. James was holding a book, distractedly, watching Ibai who was in his baby hammock on the sofa. Amaia sat down next to her husband and took his hand in hers.

‘I’m so sorry, things got complicated. I couldn’t get away.’

‘That’s okay,’ he said, without conviction, and leaned over to kiss her.

She slipped out of her coat and draped it over the back of the sofa, then gathered Ibai into her arms.

‘Ama’s been gone all day, and she missed you, did you miss me?’ she whispered, cradling the boy in her arms. He grabbed a strand of her hair, tugging it painfully. ‘I suppose you heard about what happened at the funeral parlour this morning,’ she said, looking up at her aunt.

‘Yes, the girls told us. It’s a terrible tragedy. I’ve known the family for years, they’re good people. Losing a young baby like that …’ Engrasi broke off to go to Ibai and tenderly stroke his head. ‘I can’t bear to think about it.’

‘No wonder the father went mad with grief. I can’t imagine what I’d do,’ said James.

‘The investigation is ongoing, so I can’t comment – but that isn’t the only reason why I’m late. Clearly, she hasn’t been here, otherwise you’d have told me already.’

James and Engrasi looked at her, puzzled.

‘Flora is here in Elizondo. Ros was in a real state when she called me – apparently, the first thing Flora did was stop off at the bakery, just to wind her up. Then, when I arrived, she announced that she’d come to arrange a funeral service for Rosario.’

Engrasi stopped ferrying glasses back and forth, and looked at Amaia, concerned.

‘Well, I’ve never had much time for Flora, as you know, but I think it’s a great idea,’ said James.

‘How can you say that, James! We don’t even know for sure that she’s dead. To hold a funeral would be utterly absurd!’ exclaimed Engrasi.

‘I disagree. It’s been over a month since the river took Rosario—’

‘We don’t know that,’ Amaia broke in. ‘The fact that her coat was in the water doesn’t mean a thing. She could have thrown it in there to put us off the scent.’

‘To do what? Listen to yourself, Amaia. You’re talking about an old lady, wading across a flooded river in the dark during a storm. You’ve got to admit, that’s highly unlikely.’

Engrasi was standing between the poker table and the kitchen door, lips compressed, listening to them argue.

‘Highly unlikely? You didn’t see her, James. She walked out of that clinic, came to this house, stood where I am now and took our baby boy. She trudged for miles through the woods to get to the cave where she intended to offer him up as a sacrifice. That was no feeble old woman – she was determined and able. I know, I was there.’

‘It’s true, I wasn’t there,’ he replied tersely. ‘But if she’s still alive, where has she been all this time? Why hasn’t she turned up? Scores of people spent hours searching for her, they fished her coat out of the river – she must have drowned, Amaia. The Guardia Civil thinks so, the local police force thinks so, I spoke to Iriarte and he thinks so. Even your friend the magistrate agrees,’ he added pointedly. ‘The river swept her away.’

Ignoring his insinuations, Amaia shook her head and carried on rocking Ibai, who, disturbed by their raised voices, had started to cry.

‘I don’t care. I don’t believe it,’ she muttered.

‘That’s the problem, Amaia,’ snapped James. ‘This is all about you and what you believe. Have you ever stopped to think what your sisters might be feeling? Has it occurred to you that they could be suffering too, that they might need to walk away from this episode once and for all, and that what you believe or don’t believe isn’t the only thing that counts?’

Ros, who had just come in, was standing in the doorway looking alarmed.

‘Everyone knows you’ve suffered a lot, Amaia,’ James went on, ‘but this isn’t just about you. Stop for a moment and think about what other people need. I see nothing wrong with what your sister Flora is trying to do. In fact it might prove beneficial to everyone’s mental health, including mine, which is why I’ll be going to the funeral, and I hope you’ll come with me, this time.’

There was a note of reproach in his voice, and Amaia felt hurt, but above all shocked that James should bring up a subject she thought they’d resolved; it wasn’t like him. By now, Ibai was screaming at the top of his lungs, wriggling in her arms, upset by the tension in her body, her quickened breathing. She held him close, trying to calm him. Without saying a word, she went upstairs, ignoring Ros, who stood motionless in the doorway.

‘Amaia …’ Ros whispered to her sister as she brushed past.

James watched her leave the room then looked uneasily from Ros to Engrasi.

‘James—’ Engrasi started to say.

‘Please don’t, Auntie. Please, I beg you, don’t feed Amaia’s fears, or encourage her doubts. If anyone can help her turn the page, it’s you. I’ve never asked anything of you before, but I’m asking you now – because I’m losing her, I’m losing my wife,’ he said dejectedly, slumping back in his seat.

Amaia kept rocking Ibai until he stopped crying, then she lay down on the bed, placing him beside her so that she could enjoy her son’s bright eyes, his clumsy little hands touching her eyes, nose and mouth until gradually he fell asleep. Just as his mother’s tension had overwhelmed him earlier, she felt infected now by his placid calm.

Amaia realised how important the show at the Guggenheim had been for James; she understood why he was disappointed that she hadn’t gone with him. But they’d talked about this. If she had, Ibai would probably be dead. She knew that James understood, but understanding wasn’t the same as accepting. She heaved a sigh, and Ibai sighed too, as though echoing her. Touched, she leaned over to kiss him.

‘My darling boy,’ she whispered, marvelling at his perfect little features, enveloped by a mysterious calm she only experienced when she was with him, bewitching her with his scent of butter and biscuits, relaxing her muscles, drawing her gently into a deep sleep.

She realised she was dreaming, and that her fantasies were inspired by Ibai’s scent. She was at the bakery, long before it became the setting for her nightmares; her father, dressed in his white jacket, was flattening out puff pastry with a steel rolling pin, before it became a weapon. The squares of white dough gave off a creamy, buttery smell. Music drifted through the bakery from a small transistor radio her father kept on the top shelf. She didn’t recognise the song, yet, in her dream, the little girl who was her was mouthing some of the lyrics. She liked to be alone with her father, she liked to watch him work, while she danced about the marble counter, breathing in the odour she now realised was Ibai’s, but which back then came from the butter biscuits. She felt happy – in that way unique to little girls who are the apple of their father’s eye. She had almost forgotten how much he loved her, and remembering, even in a dream, made her feel happy once more. Round and round she spun, performing elegant pirouettes, her feet floating above the ground. But when she turned to smile at him, he had vanished. The kneading table was empty, no light penetrated the high windows. She must hurry, she must go home at once, or else her mother would become suspicious. ‘What are you doing here?’ All at once, the world became very small and dark, curving at the edges, until her dream landscape turned into a tunnel down which she was forced to walk; the short distance between her and the bakery door was transformed into a long, winding passageway at the end of which shone a small, bright light. Afterwards, there was nothing, the benign darkness blinded her, the blood drained from her head. ‘Bleeding doesn’t hurt, bleeding is peaceful and sweet, like turning into oil and trickling away,’ Dupree had told her. ‘And the more you bleed the less you care.’ It’s true, I don’t care, the little girl thought. Amaia felt sad, because little girls shouldn’t accept death, but she also understood, and so, although it pained her, she left her alone. First she heard the panting, the quick gasps of eager anticipation. Then, without opening her eyes, she could sense her mother approaching, slowly, inexorably, hungry for her blood, her breath. Her little girl’s chest that scarcely contained enough oxygen to sustain the thread of consciousness that bound her to life. The presence, like a weight on her abdomen, crushed her lungs, which emptied like a pair of wheezing bellows, letting the air escape through her mouth, as the cruel, ravenous lips, covered her mouth, sucking out her last breath.

James entered the room, closing the door behind him. He sat down beside her on the bed, contemplating her for a moment, experiencing the pleasure of seeing someone who is truly exhausted sleep. He reached for the blanket lying at the foot of the bed, and drew it up to her waist. As he leaned over to kiss her, she opened startled unseeing eyes; when she saw it was him, she instantly relaxed, resting her head back on the pillow.

‘It’s okay, I was dreaming,’ she whispered, repeating the words, which, like an incantation, she had recited practically every night since she was a child. James sat down again. He watched Amaia in silence, until she gave a faint smile, then embraced her.

‘Do you think they might still serve us at that restaurant?’

‘I cancelled; you’re too tired. We’ll go there another time …’

‘How about tomorrow? I have to drive to Pamplona, but I promise I’ll spend the afternoon with you and Ibai. In which case, you have to invite me out to dinner in the evening,’ she added, chuckling.

‘Come downstairs and have something to eat,’ he said.

‘I’m not hungry.’

But James stood up and held out his hand, smiling, and she followed him.

7 (#ulink_15dd5449-7766-5c96-8a5a-51e9f59650a1)

Dr Berasategui had lost none of the composure or authority one might expect from a renowned psychiatrist, and his appearance was as neat and meticulous as ever; when he clasped his hands on the table, Amaia noticed that his nails were manicured. His face remained unsmiling as he greeted her with a polite ‘good morning’ and waited for her to speak.

‘Dr Berasategui, I confess I’m surprised that you agreed to see me. I imagine prison life must be tedious for a man like you.’

‘I don’t know what you mean.’ His reply seemed sincere.

‘You needn’t pretend with me, Doctor. During the past month I’ve been reading your correspondence, I’ve visited your apartment on several occasions, and, as you know, I’ve had the opportunity to familiarise myself with your culinary taste …’ His lips curled slightly at her last words. ‘For that reason alone, I imagine you find life in here intolerably vulgar and dull. Not to mention what it must mean to be deprived of your favourite pastime.’

‘Don’t underestimate me, Inspector. Adaptability is one of my many talents. Actually, this prison isn’t so different from a reformatory school in Switzerland. That’s an experience which prepares you for anything.’

Amaia studied him in silence for a few seconds, then went on:

‘I have no doubt that you’re clever. Clever, confident and capable; you had to be, to succeed in making those poor wretches perpetrate your crimes for you.’

He smiled openly for the first time.

‘You’re mistaken, Inspector; my intention was never for them to sign my work, but rather to perform it. I see myself as a sort of stage director,’ he explained.

‘Yes, with an ego the size of Pamplona … Which is why, to my mind, something doesn’t add up. Perhaps you can explain: why would a man like you, a man with a powerful, brilliant mind, end up obeying the orders of a senile old woman?’

‘That isn’t what happened.’

‘Isn’t it? I’ve seen the CCTV images from the clinic. You looked quite submissive to me.’

She had used the word ‘submissive’ on purpose, knowing he would see it as the worst sort of insult. Berasategui placed his fingers over his pursed lips as if to prevent himself rising to the bait.

‘So, a mentally ill old woman convinces an eminent psychiatrist from a prestigious clinic, a brilliant – what did you refer to yourself as? – ah yes, stage director, to be her accomplice in a botched escape attempt, which ends in her being swept away by the river, while he’s arrested and imprisoned. You must admit – not exactly your finest moment.’

‘You couldn’t be more mistaken,’ he scoffed. ‘Everything turned out exactly as planned.’

‘Everything?’

‘Except for the surprise of the child’s gender; but I played no part in that. Otherwise I would have known.’

Berasategui appeared to have regained his habitual composure. Amaia smiled.

‘I visited your father yesterday.’

Berasategui filled his lungs then exhaled slowly. Clearly this bothered him.

‘Aren’t you going to ask me about him? Aren’t you interested to know how he is? No, of course you aren’t. He’s just an old man whom you used to locate the mairus in my family’s burial plot.’

Berasategui remained impassive.

‘Some of the bones left in the church were more recent. That oaf Garrido would never have been able to find them; only someone who had contact with Rosario could have known, because she alone had that information. Where are the remains of that body, Dr Berasategui? Where is that grave?’

He cocked his head to one side, adopting a faintly smug expression, as though amused at all this.

It vanished when Amaia continued:

‘Your father was much more talkative than you. He told me you never spent the night with him, he said you went to a hotel, but we’ve checked, and we know that isn’t true. I’m going to tell you what I think. I think you have another house in Baztán, a safe house, a place where you keep the things no one must see, the things you can’t give up. The place where you took my mother that night, where she changed her clothes and no doubt where she returned when she ran off leaving you in the cave.’

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘I’m referring to the fact that Rosario didn’t change at your father’s house, or in your car. The fact that there’s a period of time unaccounted for between you leaving the hospital and stopping off at my aunt’s house. While we were busy rooting around among the souvenirs in your apartment, you stopped off somewhere else. Do you expect me to believe that a man like you wouldn’t have covered such a contingency? Don’t insult my intelligence by pretending to make me believe you acted like a blundering fool …’

This time Berasategui covered his mouth with both hands to stifle the urge to respond.

‘Where’s the house? Where did you take Rosario? She’s alive, isn’t she?’

‘What do you think?’ he blurted unexpectedly.

‘I believe you devised an escape plan, and that she followed it.’

‘I like you, Inspector. You’re an intelligent woman – you have to be, to appreciate other people’s intelligence. And you’re right, there are things I miss in here – for example, holding an interesting conversation with someone who has an IQ above 85,’ he said, gesturing disdainfully towards the guards at the door. ‘And for that reason alone, I’m going to make you a gift.’ He leaned forward to whisper in her ear. Amaia remained calm, although she was surprised when the guards made no effort to restrain him. ‘Listen carefully, Inspector, because this is a message from your mother.’