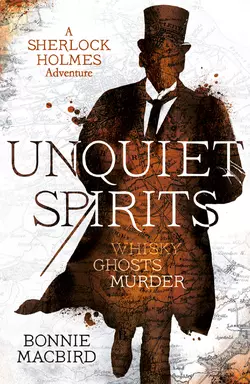

Unquiet Spirits: Whisky, Ghosts, Adventure

Bonnie Macbird

The new novel from the author of Art in the Blood. December 1889. Fresh from debunking a “ghostly” hound in Dartmoor, Sherlock Holmes has returned to London, only to find himself the target of a deadly vendetta.A beautiful client arrives with a tale of ghosts, kidnapping and dynamite on a whisky estate in Scotland, but brother Mycroft trumps all with an urgent assignment in the South of France.On the fabled Riviera, Holmes and Watson encounter treachery, explosions, rival French Detective Jean Vidocq… and a terrible discovery. This propels the duo northward to the snowy highlands. There, in a “haunted” castle and among the copper dinosaurs of a great whisky distillery, they and their young client face mortal danger, and Holmes realizes all three cases have blended into a single, deadly conundrum.In order to solve the mystery, the ultimate rational thinker must confront a ghost from his own past. But Sherlock Holmes does not believe in ghosts…or does he?

Copyright (#ulink_a3ee5e09-1ee7-5d76-99b2-e8a5dcc47034)

This book is a new and original work of fiction featuring Sherlock Holmes, Dr Watson, and other fictional characters that were first introduced to the world in 1887 by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, all of which are now in the public domain. The characters are used by the author solely for the purpose of story-telling and not as trademarks. This book is independently authored and published, and is not sponsored or endorsed by, or associated in any way with, Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd. or any other party claiming trademark rights in any of the characters in the Sherlock Holmes canon.

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Bonnie MacBird 2017

All rights reserved

Drop Cap design © Mark Mázers 2017

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Bonnie MacBird asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008129712

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008201104

Version: 2017-09-22

Dedication (#ulink_0dad9b7c-86f0-57b5-b0be-d863dcd68f48)

For Rosemary and Mac

Contents

Cover (#u1003ae66-0fc8-52cf-ae6b-cbc74b823e87)

Title Page (#u9cfc0692-e286-5fb5-8f1d-d8d83705e339)

Copyright (#ue06594d2-2742-58d5-b128-dd3b8781bae1)

Dedication (#u5384168d-a458-50d9-b6d2-ba494b3f2979)

Preface (#u5aef8e46-1d18-51ed-b8fe-87123e78a712)

PART ONE – A SPIRITED LASS (#ue5f3b7c5-961e-5d22-a6cc-305f5fa1e056)

1. Stillness (#u4ec51616-49e3-5f47-a1be-0b136e5f6d9c)

2. Isla (#ubaa24737-3fe8-5246-851d-6077179d7d3e)

3. Rejection (#u13bfeeeb-6a09-5a1b-b3ba-ed1bfef9104e)

4. Brothers (#u168bf45b-2d6d-5c13-8160-aae9d892fa3d)

5. Nice (#u8feec32b-e7e2-5c9d-8cc9-711761d0f376)

6. Docteur Janvier (#u34f94619-e442-5f92-bcec-0e44984ee103)

PART TWO – GETTING AHEAD (#u99b2ad8b-0919-5486-977e-377e1497c581)

7. Vidocq (#u1e3ce55e-8f9a-5822-bc06-38dcb7c1ce72)

8. Ahead of the Game (#u3f4fea42-5d89-5051-b2d8-a1e4cc533801)

9. The Staff of Death (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Unwelcome Help (#litres_trial_promo)

11. A Fleeting Pleasure (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE – NORTHERN MISTS (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Arthur (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Braedern (#litres_trial_promo)

14. The Highland Magic (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Cameron Coupe (#litres_trial_promo)

16. The Groundsman’s Sons (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Catherine (#litres_trial_promo)

18. Charles (#litres_trial_promo)

19. The Laird’s Sanctum (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Reviewing the Situation (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FOUR – A CHILL DESCENDS (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Dinner (#litres_trial_promo)

22. Ghost! (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Alistair (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Obfuscation (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Where There is Smoke (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FIVE – THE DISTILLATION (#litres_trial_promo)

26. The Whisky Thief (#litres_trial_promo)

27. Divide and Conquer (#litres_trial_promo)

28. Fettes (#litres_trial_promo)

29. Thin Ice (#litres_trial_promo)

30. Romeo and Juliet (#litres_trial_promo)

31. Getting Warmer (#litres_trial_promo)

PART SIX – MATURATION (#litres_trial_promo)

32. The Angel’s Share (#litres_trial_promo)

33. Circles of Hell (#litres_trial_promo)

34. The Missing Man (#litres_trial_promo)

35. You Must Change Your Thoughts (#litres_trial_promo)

36. The Ghost of Atholmere (#litres_trial_promo)

37. Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

38. Golden Bear and Silver Tongue (#litres_trial_promo)

PART SEVEN – THE POUR (#litres_trial_promo)

39. The Lady (#litres_trial_promo)

40. A Wash (#litres_trial_promo)

41. 221B (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_f3b36b0a-2dea-5e15-b75c-e14adecea1e7)

Several years ago, while researching at the Wellcome Library, I chanced upon something extraordinary – an antique handwritten manuscript tied to the back of a yellowed 1880s treatise on cocaine. It was an undiscovered manuscript by Dr John H. Watson, featuring his friend, Sherlock Holmes, published in 2015 as Art in the Blood.

But what happened last year exceeded even this remarkable occurrence. An employee at the British Library whom I shall call Lidia (not her real name) found Art in the Blood in her local bookshop, and upon reading it was struck by the poignancy of Watson’s manuscript surfacing so long after the fact.

It triggered something in her mind and shortly afterwards, I received a phone call in my newly rented flat in Marylebone. This was curious, as our number there is unlisted. She identified herself as ‘someone who works at the British Library’ but would not give her name, and wanted to meet me at Notes, a small café next door to the London Coliseum. She refused to give me any information about the purpose of this meeting, saying only that it would be of great interest to me.

I could not resist the mystery. I showed up early and took comfort in a cappuccino, watching the pouring rain outside. Eventually a woman arrived, dressed as she had told me she would be with a silk gardenia pinned on the lapel of a long, black military-style coat. A pair of very dark sunglasses and a black wig added to her somewhat theatrical demeanour.

She carried a large nylon satchel, zipped at the top. It was heavy, and the sharp outlines of something rectangular were visible within. ‘Lidia’ then sat down, and in deference to her privacy I will not reveal all she told me. But inside her bag was a battered metal container that had come from the British Library’s older location in the Rotunda of the British Museum many years ago. It had somehow been neglected in the transfer to the new building and had languished within a stained cardboard box in a basement corner for some years.

It was an old, beaten up thing made of tin and was stuck shut. She pried it open gently with the help of a nail file.

Certainly you are ahead of me now.

Within that metal box was a treasure trove of notebooks and loose pages in the careful hand of Dr John H. Watson. You can well imagine my shock and joy. Setting my cappuccino safely to the side, I pulled out a thick, loosely tied bundle from the top. It had been alternatively titled ‘The Ghost of Atholmere’, ‘Still Waters’ and ‘The Spirit that Moved Us’ but all of these had been crossed out, leaving the title of Unquiet Spirits.

Like the previous manuscript, this, too, had faded with time, and a number of pages were so smeared from moisture and mildew that I could make out only partial sentences. In bringing this tale to light, I would have to make educated guesses on those pages. I hope then, that the reader will pardon me for any errors.

She left the box in its satchel in my care, wishing me to bring the contents to publication as I had my previous find. As she stood to go, I wanted to thank her. But she held up a black-gloved hand. ‘Consider it a gift to those celebrants of rational thinking, the Sherlock Holmes admirers of the world,’ said she. She never did give me her name, and while I could have ferreted it out in the manner of a certain gentleman, I decided best to let it lie.

I later wondered if she had actually read the entire story that was the first to emerge from that treasured box. But let me not spoil it for you.

And so, courtesy of the mysterious ‘Lidia’, and in memory of the two men I admire most, I turn you over to Dr John Watson for – Unquiet Spirits.

—Bonnie MacBird

London, December 2016

PART ONE (#ulink_48b2c955-8696-5aa2-ba01-e59b6db3de0c)

A SPIRITED LASS (#ulink_48b2c955-8696-5aa2-ba01-e59b6db3de0c)

‘Oh, what a tangled web we weave … when first we practise to deceive’

—Sir Walter Scott

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_bd189caf-4e88-5336-8034-81b6f5f8daa6)

Stillness (#ulink_bd189caf-4e88-5336-8034-81b6f5f8daa6)

s a doctor, I have never believed in ghosts, at least not the visible kind. I will admit I have even mocked those who were taken in by vaporous apparitions impersonating the dead, conjured by ‘mediums’ and designed to titillate the gullible.

My friend Sherlock Holmes stood even firmer on the topic. As a man who relied on solid evidence and scientific reasoning, he saw no proof of their existence. And to speak frankly, to a detective, ghosts fulfil no purpose. Without a corporeal perpetrator, justice cannot be served.

But hard on the heels of the diabolical and terrifying affair of ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’ which I recount elsewhere, our disbelief in the supernatural was put to a terrifying test. One might always expect my friend’s rational and scientific approach to triumph, yet some aspects of the strange and weird tale I call Unquiet Spirits defy explanation, and there are pieces of this puzzle that trouble me to this day.

Holmes forbade publication of these events until fifty years after his death, and I believe his reasons were due less to any momentary lapse on the subject of ghosts than they were to the revelation of facts concerning Holmes’s last days at university. Thus I defer to my friend’s wishes, and hope those who are reading this account at some unknown future date will understand and grant us both the benefit of a kindly regard on the actions we took – and did not take – in Scotland, in the winter of 1889.

It had been a year filled with remarkable adventures for us, culminating in the recent terrifying encounter with the Baskervilles and the aforementioned spectral hound. Back in London afterwards, with the great metropolis bustling about us in the noisy pursuit of commerce, progress, science, and industry, the dark occurrences of Dartmoor seemed a distant nightmare.

It was a late afternoon in December, and the coldest winter of recent memory was full upon us. A dense white fog and the promise of snow had settled over the streets of London, the chill penetrating to the bone.

Mary had been called away once again to a friend’s sickbed, and without her wifely comforts, I did not hesitate to return to visit my singular friend in our old haunts at 221B Baker Street, now occupied by him alone.

My overcoat hung dripping in its usual place, and as I stood in our formerly shared quarters awaiting the appearance of Holmes, I thought fondly of my first days in this room. Just prior to first encountering Holmes, I had been in a sorry state. Discharged from the army, alone in London and short of funds, my nerves and health had been shattered by my recent service in Afghanistan. Of that ghastly campaign and its consequences, I have written elsewhere.

The lingering effects of my wartime experiences had been threatening to get the better of me. But my new life with Holmes had sent those demons hurtling back into darkness.

I stood, taking in the familiar sights – the homely clutter, Holmes’s Stradivarius carelessly deposited in a corner, the alphabetised notebooks and files cramming the bookshelves – and found myself wondering about Holmes’s own past. Despite our friendship, he had shared little of his early life with me.

Yet I was certain Holmes had ghosts of his own.

In Paris the previous year the remarkable French artist Lautrec had called my friend ‘a haunted man.’ But then, artists see things that others do not. The rest of us require more time.

A loud, clanking noise drew me from my reverie. Off to one side, on Holmes’s chemistry table, a complex apparatus of tubes and flasks steamed and bubbled, shuddering in some kind of effort. I approached to examine it.

‘Watson! How good of you to stop in!’ exclaimed the familiar voice, and I turned to see the thin figure of my friend bounding into the room in a burst of energy. He clapped me on the back with enthusiasm, drawing me away from the equipment and towards my old chair.

‘Sit, Watson! Give me a moment.’ He moved to the chemistry equipment and tightened a small clamp. The rattling subsided. Gratified by the result, he favoured me with a smile, then dropped into his usual chair opposite mine. Despite his typical pallor, he seemed unusually happy and relaxed, his tousled hair and purple dressing gown giving him a distinctly Bohemian look.

Holmes rooted for his pipe on a cluttered table nearby, stuck it in his mouth and lit it, tossing the match aside. It landed, still smouldering, on a stack of newspapers.

‘Are you well past our ghostly adventure, Watson?’ he asked with a grin. ‘Not still suffering from nightmares?’ A tiny thread of smoke arose from the newspapers.

‘Holmes—’

‘Admit it, Watson, you thought briefly that the Hound was of a supernatural sort, did you not?’ he chided.

‘You know that as a man of science, I do not believe in ghosts.’ I paused. ‘But I do believe in hauntings.’ A wisp of pale smoke rose from the floor next to his chair. ‘Look to your right, Holmes.’

‘Is there a dastardly memory in corporeal form there, Watson, waiting to attack?’

‘No but there is a stack of newspapers about to give you a bit of trouble.’

He turned to look, and in a quick move, snatched up the smouldering papers and flicked them into the grate. He turned to me with a smile. ‘Hauntings? Then you do believe!’

‘You misunderstand me. I am speaking of ghosts from our past, memories that will not let us go.’

‘Come, come, Watson!’

‘Surely you understand. I refer to things not said or left undone, of accidents, violence, deaths, people we might have helped, those we have lost. Vivid images of such things can flash before us, and these unbidden images act upon our nervous systems as though they were real.’

Holmes snorted. ‘Watson, I disagree. We are the masters of our own minds, or can be so with effort.’

‘If only that were true,’ said I, thinking not only of my wartime memories but of Holmes’s own frequent descents into depression.

The clanking from his chemistry table resumed, loudly.

‘What the devil is that?’ I demanded.

He did not answer but instead jumped, gazelle-like, over a stack of books to the chemistry apparatus where he tightened another small clamp. The clatter lessened and he looked up with a smile, before once again sinking back into the chair opposite mine.

‘Holmes, you are leaping about the room as though nothing had happened a year ago. Only last month you were still limping. How on earth did you manage such a full recovery?’

The grievous injuries he had suffered in Lancashire the previous December in the adventure I had named Art in the Blood had plagued him throughout 1889, and even in Dartmoor only weeks earlier. But he had forbidden me to mention his infirmity in my later recounting of the next several cases. Had I described him as ‘limping about with a cane’ (as in fact he was, at least part of the time) his reputation would have clearly suffered.

But now any trace of such an impediment was gone.

He leaned back in his chair, lighting his pipe anew. ‘Work! Work is the best tonic for a man such as myself. And we have been blessed with some pretty little problems of late.’ He flung the match carefully into the fire.

‘Yes, but in the last month?’

‘I employed a certain amount of mind over matter,’ said he. ‘But ultimately, it was physical training. Boxing, my boy, is one of the most strenuous forms of exercise, for the lower as well as upper extremities. Only a dancer uses the legs with more intensity than a boxer.’

‘Perhaps joining the corps de ballet at Covent Garden was out of the question, then?’ I offered, amused at the mental image of Holmes gliding smoothly among dozens of lovely ballerinas.

Holmes laughed as he drew his dressing gown closer around his thin frame. Despite the blaze, a deep chill crept in from outside. A sudden sharp draught from behind the drawn curtains made me shiver. The window must have been left open, and I got up to close it.

‘Do not trouble yourself, Watson,’ said Holmes. ‘It is just a small break in the pane. Leave it.’

Ignoring him, I crumpled a newspaper to stuff into the gap and drawing back the curtain I saw to my surprise – a bullet hole!

‘Good God, Holmes, someone has taken a shot at you!’

‘Or Mrs Hudson.’

‘Ridiculous! What are you doing about it?’

‘The situation is in hand. Look down at the street. It is entirely safe, I assure you. What do you see across and two doorways to the right?’

I pulled back the curtain and peered down into the growing darkness. There, blurred by the snowfall, two doors down and receding, spectre-like into the recesses of an unlit doorway, stood a large, hulking figure.

‘That is a rather dangerous looking fellow,’ I commented.

‘Yes. What can you deduce by looking at him?’

The details were hard to make out. The man was wide and muscular, wrapped up in a long, somewhat frayed black greatcoat, a battered blue cap pulled low over his face. A strong, bare chin protruded, his mouth twisted in what looked like a permanent sneer.

‘Bad sort of fellow, perhaps of the criminal class. His hands are in his pockets, possibly concealing something,’ Here I broke off, moving back from the window. ‘Might he not shoot again?’

‘Ah, Watson. You score on several counts. His name is Butterby. He is indeed carrying a gun, although something more important is concealed. He is dressed to hide the fact that he is a policeman.’

‘A policeman!’

‘Yes, and, in a sense, he is rather “bad”. That is to say, he is among the worst policemen in an unremarkable lot. Even Lestrade thinks him stupid. Imagine.’

I laughed.

‘But he is enough to frighten away my would-be murderer, who is himself a rank amateur. So bravo, Watson, you improve.’

I cleared my throat. ‘A rank amateur, you say? Yet with excellent aim. Who, then?’

‘An old acquaintance with a grudge, but I tell you, the situation is handled,’ he said. Then noticing my worried face, he chuckled. ‘Really, Watson. Your concern is touching, but misplaced. The mere presence of our friend below will end the matter.’

I was not convinced and would try again on this subject later. ‘Where is the brandy?’ I said, moving to the sideboard looking for the familiar crystal decanter.

I found the vessel behind a stack of books. It was empty.

‘I am sorry, Watson, there is no brandy to be had,’ said he. ‘The shops are barren except for a few outside my budget. You have heard of the problems with the vineyards in France? I have been studying the subject. But I can offer you this.’

From next to him on a side table, he lifted a beaker of clear liquid. He poured a very small amount into each of two glasses. ‘Try it,’ he said, with a smile.

I took the glass and sniffed. I felt a sudden clearing of my sinus cavities and a burning in the back of my head.

‘Good God, Holmes, this smells lethal!’

‘I assure you it is not. Give it a try. Here, I will drink with you.’ He raised his glass for a toast. ‘Count of three. One. Two—’

On three we both gulped the liquid down. I erupted into such a fit of coughing and tearing of the eyes that I did not notice whether my companion did or not. When it subsided, I looked up to find he had tears streaming down his reddened face and was laughing and coughing in equal measure.

‘What is this stuff?’ I sputtered, wiping myself with a handkerchief.

‘Raw spirits. Distilled pure whisky, but before the ageing which renders it mellow. I diluted it with water, but clearly not enough.’

He held up a small booklet, entitled The Complete Practical Distiller.

‘That was a rather mean trick.’

‘Forgive me, my dear fellow. All in the name of science.’

A sharp pop and a sudden loud hiss emanated from the chemistry table. I glanced back at the complex system of flasks, copper containers and tubing.

Holmes normally employed a small spirit lamp to heat his chemicals, but I now noticed a very bright flame arising from a Bunsen burner which was connected by a length of rubber tubing to the wall. Over this was suspended a small, riveted copper kettle in a strange teardrop shape, one end drooping into a line which proceeded through valves and tubes into various looped and coiled copper configurations, complex and confusing, and—

‘Holmes!’ I cried. ‘That is a miniature still!’

‘Ah, Watson, you improve. Decidedly.’

‘But you have tapped into the gas line! Why? Is that not dangerous?’

‘I needed a higher temperature. And, no, it is not dangerous when you take the precaution of—’

The noise had increased. The entire apparatus began to vibrate. The copper kettle and odd configuration of tubes and beakers rattled and shook. One clamp came loose and clattered off the table to the floor. A tube shook free and several drops of liquid arced into the air.

‘Holmes—!’ I began, but he was up and out of his chair, bounding across the room when a sudden small explosion blew the lid off the copper vessel, broke three glass tubes and an adjacent beaker, and sent a spray of foul smelling liquid up the nearby wall and across a row of books. A flame erupted underneath it.

We shouted simultaneously and in a flash he was upon the equipment, dousing the fire with a large, wet blanket pulled from a bucket he had evidently placed nearby in anticipation of such a possibility. The blanket slid down among the broken pieces. The flame went out and there was silence except for a low sizzle.

The room now reeked of raw alcohol, and a dark, burnt smell. A slow drip fell from the table to the carpet.

Mrs Hudson’s familiar sharp knock sounded at the door. ‘Mr Holmes? Dr Watson?’ she called out. ‘A young lady is here to see you.’

Holmes and I looked at each other like two schoolboys caught smoking. As one, we leapt to tidy the room. Holmes flung a second wet cloth sloppily over the steaming mess in the corner while I used a newspaper to whisk some broken glass and other bits under an adjacent desk.

I threw open the window to let out the hideous odour and in a moment we were back in our chairs, another log tossed onto the fire.

‘Show her in, by all means, Mrs Hudson,’ shouted Holmes.

He picked up his cold pipe and assumed an insouciant air. I was less quick to compose myself and was still sitting on the edge of my chair when the door opened.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_c259135f-7d2e-5d54-94c8-68b773232671)

Isla (#ulink_c259135f-7d2e-5d54-94c8-68b773232671)

rs Isla McLaren of Braedern,’ announced Mrs Hudson.

Into the room stepped a vibrant young woman of about twenty-eight, exquisitely poised, small and delicate in stature. I was struck immediately by her beauty and graceful deportment but equally by the keen intelligence radiating from her regard. She was elegantly clothed in a deep purple travelling costume of rich wool, trimmed with small touches of tartan, gold and lace about the throat.

Her luxurious hair was brown with glints of copper, and her eyes a startling blue-green behind small gold spectacles. She removed these, took in the room, the mess, the smell and the two of us in one penetrating and amused glance. I immediately thought of a barrister assessing an opponent.

‘Oh, my,’ she said, sniffing the air.

A strong, rank odour emanated from the contraption, the newspapers and wet cloth on the chemistry table. This mess continued to hiss and clank intermittently.

I rose quickly to greet her. Holmes remained seated, staring at her in a curious manner.

‘Madam, welcome. Let me close the window. It is so cold,’ I offered, moving towards it.

‘Leave it,’ commanded Holmes, stopping me in my tracks. ‘Do come in, Mrs McLaren, and be seated.’

The lady hesitated and suppressed a cough. ‘Some air is welcome. Well, Mr Holmes, how clearly you have been described in the newspapers. And you must be Dr Watson.’ Her accent carried a hint of the soft lilt of the Highlands, but modified by a fine education. I liked her immediately.

Holmes appraised her coolly. ‘Do sit down, Mrs McLaren, and state your case. And please, be succinct. I am very busy at the moment.’ He waved a hand, indicating the settee before us. I knew for a fact that Holmes had no case at present.

The lady smiled. ‘Yes, I see that you are very busy.’

‘Welcome, madam,’ I repeated, mystified by my friend’s unaccountable rudeness and attempting to mitigate it. ‘We are at your service.’

‘Let me come straight to the point,’ said she, now seated before us. ‘I live in Scotland, in the Highlands to be more precise, at Braedern Castle, residence of Sir Robert McLaren, the laird of Braedern.’

‘McLaren of Braedern. Yes, I know that name,’ said Holmes arising languidly with a slow stretch and then in a sudden movement vaulting over the back of his low chair as if on springs. Arriving at the bookcase, he ran his finger along several volumes of his filed notes, pulled down one and rifled through it.

‘Ah, McLaren. Whisky baron. Member of Parliament. Working at the time of this article to establish business in London. Effectively, it appears. A Tory. Unusual for a Scot. Widower. Late wife very wealthy. And, ah, yes. Go on.’

He returned with the file and draped himself once more in the chair.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘He is my father-in-law.’

‘Obviously. It says here a daughter who did not survive infancy, and three sons.’

‘You are not au courant. Two sons survive. The eldest, Donal, died three years ago, killed during the siege of Khartoum.’

‘You are married to one of the remaining sons. Not Charles, the current eldest, but Alistair, the younger.’

Mrs McLaren smiled. ‘That is correct, Mr Holmes. And how did you deduce this?’

I did not like Holmes’s regard. ‘Madam, how can we help you?’ I said.

But the lady persisted. ‘Mr Holmes?’ she wondered.

‘It is obvious. Your ring. Lady McLaren’s famous amethyst and emerald engagement ring – I have a clipping here on its history – matches your dress perfectly and would surely be on your hand if you had married the elder son. The rest of your jewellery is quite modest. Therefore the younger son.’

The lady put a hand to her small gold brooch from which dangled a charm. Along with a simple wedding band and gold earrings this was the sum total of her jewellery. She smiled.

‘Regarding my jewellery, perhaps I am simply not in the habit of overt display, Mr Holmes. Rather like yourself.’ Her eyes flicked to his dressing gown.

‘Nevertheless?’ Holmes said. She remained silent. Her silence was a tacit acknowledgment. He smiled to himself, then he got up and moved back to the fireplace, making rather a fuss over his pipe. It struck me that she simultaneously disturbed him in some way, and at the same time incited those tendencies which I can only describe as showing off.

‘I have come to London to attend the opera, see my dressmaker, and to do a little Christmas shopping,’ she began. ‘While I was here, I thought—’

‘On second thought, I have heard enough, Mrs McLaren.’

‘Good grief, Holmes! Madam, I beg your forgiveness,’ said I. ‘Please do relate your concerns. We are all ears.’

Before she could answer, Holmes barked out, ‘Your husband either is, or you imagine he is, having an affair. I do not deal in marital squabbles. Kindly close the door behind you.’ He moved sharply away to a bookcase and stood there, his back to her.

She remained seated.

Holmes paused and turned around. ‘Really, madam, I beg you. What would your family think of this visit?’

‘It matters little what my family might think of my visit. I am quite on my own in this matter. Your opinions, while incorrect, are of moderate interest. Do enlighten me as to your train of thought.’

She had opened Pandora’s box. ‘Madam, mine are not opinions, but facts,’ he began in his didactic manner.

‘Go on,’ said she.

‘Holmes!’

‘If you insist. You have recently lost weight. For you, this may be considered beneficial. I observe that your dress has been taken in by a less than professional hand. However, something has changed. You have had your hair elaborately done and now are buying new clothes. The latest fashions are little valued in the Highlands, rather the opposite, and it is too cold for most of them. You are either having an affair here – but not likely as you are wearing your wedding ring – or trying to remake yourself to be more attractive to your husband. The jewellery I have explained. Now please, go away.’

‘You are wrong on several counts, Mr Holmes, but right on two,’ said she. ‘I do wish to make myself as attractive as possible. For women, it is sadly our main, although transient, source of power. Perhaps that may change some day. And yes, Alistair is my husband.’

Holmes sighed. ‘Of course.’

‘However I have not lost weight, this dress has always been too large, and I have fashioned my hair myself. I shall take both errors as compliments.’

Holmes nodded curtly.

‘Why, Mr Holmes, do you have such disdain for women? And what is that smell? Never mind. I wish to get to business. I am here to consult you on a case. I see that you are a bit low on funds, so perhaps you had better hear me out.’

Holmes exhaled sharply. ‘Pray be brief, then, madam. What exactly is puzzling you?’

‘One moment, Mrs McLaren,’ said I. ‘What makes you think Mr Holmes is in need of funds? Surely you are aware of several of our recent cases which have reached the news.’

‘Yes, and I do look forward to your full accounts of them, Dr Watson.’

Just then a sharp noise came from under the wet cloth and it suddenly slid off Holmes’s chemistry table. Holmes leapt to replace the blanket over the crude homemade still but not before the lady had a clear look.

‘An experiment,’ said Holmes sharply. ‘Will you not tell us your problem?’

She appraised him with cool eyes. ‘In a moment, sir. First I will answer Dr Watson. I see clearly that Mr Holmes requires cash. He has recently had his boots resoled instead of buying new. His hair is badly in need of a barber’s attentions. And his waistcoat, trousers, and dressing gown should be laundered, and soon. This does not fit with your description of Mr Holmes. He is either despondent or conserving money. His spirit bottles on the sideboard are empty, and he is rather ridiculously attempting to refill them with homemade spirits. Therefore the latter, most likely.’

‘It is a chemical experiment,’ snapped Holmes. ‘If you require my assistance, please state your case now.’

Isla McLaren reclined in her chair and flashed a small smile at me.

‘There have been a series of strange incidents in and around Braedern Castle,’ said she. ‘I cannot connect them and yet I feel somehow they are linked. I also sense a growing danger. Braedern Castle, as you may know if it appears in your files Mr Holmes, is reputed to be haunted.’

‘Every castle in Scotland is said to be haunted. You Scots are very fond of your ghosts and your faeries.’

‘I did not say that I thought that ghosts were at work. Quite a few of my fellow Scots demonstrate the capacity for rational thought, Mr Holmes. For instance, James Clerk Maxwell, James Watt, Mary Somerville …’

‘Yes, yes, the namesake of your college at Oxford. I see the charm dangling from your brooch, Mrs McLaren.’

Oxford! Isla McLaren grew in stature before my eyes. Somerville College for women was highly regarded, and the young ladies who attended were thought to be among the brightest in the Empire.

‘As I was saying, our small country has contributed a disproportionate number of geniuses in mathematics, medicine and engineering.’

Holmes at last took a seat and faced her, his aspect suddenly altered. ‘I cannot contradict you, Mrs McLaren,’ he said. ‘Forgive me. Let us address your problem.’

Mrs McLaren took a deep breath and regarded my friend for a moment, as if trying to decide something. ‘There have been a series of curious events at Braedern. Perhaps the strangest is this. Not long ago, a young parlour maid disappeared from the estate under unusual circumstances.’

‘Go on,’ said Holmes, as he opened and once again began to flip through the file.

‘Fiona Paisley is her name. She was a very visible member of staff, quite beautiful, with flame red hair nearly to her waist.’

‘Is? Was? Be clear, Mrs McLaren. Where is she now?’

‘Back at work, but—’

‘Continue. An attractive servant disappeared briefly but has returned. What is the mystery?’

‘She did not simply return. She arrived in a basket, bound, drugged, and with her beautiful hair cut off down to the scalp.’

This had at last piqued Holmes’s interest.

‘Start from the beginning. Tell me of the girl, and the dates of these events.’

‘Fiona disappeared last Friday. She returned two days later, three days ago.’

‘Why did you wait to consult me?’

‘Allow me to tell you this in my own way, Mr Holmes.’

Holmes sighed, and waved her to continue.

‘Fiona was flirtatious and forward, quite charming in her way. She had many admirers. Every man in the estate remarked upon her. We thought at first she had run off with someone until the servants appealed to the laird en masse, insisting that she had been kidnapped.’

‘Why?’

‘No one else was missing. She would not have run off alone. And then her shoe was found near the garden behind the kitchen. A search party was sent out, but discovered nothing else.’

‘But she has returned. What was her story? Did she not see her attacker?’

‘No. She could offer no clues.’

Holmes sighed and rose to find another cigarette on the mantle. He lit the cigarette casually. ‘Very well. Every man in the estate noticed her. Might your husband have done so?’

‘“Every” means “every”.’

‘Then you suspect an affair? Perhaps retribution? Is it possible that you or another woman in the house felt threatened by the girl?’

‘Why would I have come to you if I were the perpetrator?’

‘Mrs McLaren, believe me, it has been tried. Let us be frank. There is a certain degree of conceit in your self-presentation.’

‘I would describe it as confidence, not conceit. Will you hear me out, or is your need to put me in my place so much greater than your professional courtesy? Or, perhaps more apropos to you, your curiosity?’

To his credit, my friend received the reprimand with grace. ‘Forgive me. Pray continue, Mrs McLaren. The shoe that was found near the garden. Was there no sign of a struggle, nothing beyond the one object?’

‘None. I made enquiries and undertook a physical search of my own, but her room yielded nothing and the area where the shoe was found was by then so trampled that it was impossible to learn anything.’

‘Do you mean you played at detective work yourself, Mrs McLaren? Would not a call to the police have been in order?’

‘I think not, Mr Holmes. Dr Watson has made clear in his narrative your opinion of most police detective work. Our local constable is derelict in his duty. He is, quite frankly, a drunk. The laird refused to call him in.’

‘Yet I hardly think an untrained amateur such as yourself would be—’

I shot a warning glance at my friend. He was, I felt being unduly harsh. This woman had set something off in him I did not understand.

Isla McLaren was unfazed. ‘It is Fiona’s own story that concerns me. She was frightened beyond words. She was taken at night and there was a heavy mist. She saw nothing.’

‘Yes, well, what then?’

‘She awoke in a cold damp place, on what felt like a stone floor with some straw laid atop, apparently for meagre comfort. She was bound tightly but with padded ropes, and with her eyes covered. She had a terrible headache.’

Holmes had returned to his chair, and was now listening eagerly. ‘Chloroform, then. Easily obtained. Effective, if crude. Next?’

‘Someone who never spoke a word to her stole in and proceeded to cut off her hair with what felt like a very sharp knife. It was done carefully and she had the impression that the person was arranging the locks of hair beside her in some way. Possibly to keep it.’

Holmes exhaled and leaned back. ‘But not harmed otherwise?’

‘Not a bruise upon her. However, for a woman, her hair—’

‘Yes, yes, of course. It does grow back. Who discovered the basket?’

‘The second footman who was leaving to post some letters.’

‘Is that all? Where is the girl now?’

‘At home, but unable to work. She is beside herself. Fiona was superstitious before, and her friends have tried to convince her the kidnapping was the work of something supernatural.’

‘Why on earth?’

‘The attack was so silent. She neither saw nor heard anyone approach.’

Holmes leaned back in his chair and closed his eyes. He did not move for several seconds.

‘Mrs McLaren, tell me more of the girl, her character, her reputation.’

‘Fiona has, or had before her abduction, a sparkling demeanour, flirtatious and flighty. She is no scholar, though canny. She has been unable to learn to read, but enjoys attention and is straightforward about it. I really do not dislike the girl at all, in fact I quite like her. She is, without the slightest effort, a magnet for male attention. I have not bothered to track her own affections or actions, but I wager that there could be any number of men or women who might be jealous of the attention she receives.’

‘You imply much, but can you confirm any specific affairs? A husband’s attraction to a pretty servant would certainly trouble most women, Mrs McLaren. Even you.’

‘I am not most women, Mr Holmes. But I think Fiona’s attractions may be beside the point. I think her desecration is the beginning of a larger threat, as described in the note.’

‘You have a note? Why withhold it? Let me see it!’ Holmes was irritated.

She withdrew a crumpled piece of paper from her handbag. He squinted at it, then thrust it at me. ‘Here, read this, Watson.’

I did so, aloud.

‘The crowning glory sever’d from the rest.

But only hair and n’er a foot nor toe

The victim or her kin ha’e fouled the nest

And ’tis likely best that she should go

If you heed not this warning and persist

In bedding sichan beauties as yon lass

You may lose something which will be more miss’d

And what you feart the most will come to pass

So at your peril gae about your lives

But notice what and whom you haud most dear

And mind your interests, no less your wives

For if unguarded, may soon disappear

You hae been warned and this should not deny

If tragedies befall you, blame not I.

—A true friend to the McLarens’

‘Hmmm’ said Holmes. ‘This ghost is an amateur poet. A schoolboy Shakespearean sonnet, if not a particularly brilliant one. Scots dialect. Paper common in Scotland and all through the north, calligraphic nib on the pen. Letters formed precisely as if copied from a manual, therefore the writer – who is energetic, note the upstrokes – was disguising his or her handwriting, which is only prudent. While this is marginally interesting, Mrs McLaren, I still believe this to be a domestic issue. Look to whoever was ‘bedding’ the lass, and whoever may be discomfited by this.’

Mrs McLaren drew herself up. ‘I consider what happened an act of violence, Mr Holmes. And the note indicates trouble to come. But I sense that you—’

‘Mrs McLaren. I do not take on cases before there is an actual reason. While the events are somewhat unusual, and certainly cruel, I do not share your degree of alarm. Unless of course, you feel personally threatened in some way? Do you?’

‘I do not.’

‘Madam, then this case is not within my purview. It appears to be a common domestic intrigue, although with outré elements. Good day.’

Holmes leaned back in his chair and stubbed out his cigarette. But Isla McLaren was not to be put off so easily. She took a deep breath and pressed on. ‘Mr Holmes, I have come to you for help,’ she said. ‘Braedern is said to be haunted. There have been unexplained deaths. I have a growing sense of unease which I cannot dispel.’

‘Ghosts again! All right, what unexplained deaths?’

‘Ten years ago, the Lady McLaren, mother of the three sons we discussed, went out in a wild, stormy night to supervise the delivery of a foal which proved to be a false alarm. When she tried to return to the castle, she was locked out and could not enter. She froze to death.’

‘Was there an official investigation? Or did you, Mrs McLaren, play detective?’

‘Mr Holmes, you mock me. Obviously this was before my time, and yes, the police investigated. When Lady McLaren died, some of the servants first saw tracks in the snow indicating someone had tried to enter on the ground floor in several places, broke one window, but could not breach the shutters. Her frozen body was found later, and the laird was inconsolable.’

‘No bell was rung? How was it that no one inside was alerted?’ asked Holmes.

‘The bell apparently malfunctioned. I know no more.’

‘A very cold case, and likely an accident. Why bring this up now?’

‘Since that time her spirit is said to haunt the East Tower – a malevolent spirit that causes harm,’ said the lady.

Holmes sighed.

‘What kind of harm, Mrs McLaren?’ I asked.

‘A servant fell down the stairs to his death last year – pushed, it is said, by this ghost. A child, you see, disappeared from that hall years earlier.’

‘Hmmm, that would be … the laird’s only daughter, Anne. Aged two years and nine months,’ murmured Holmes.

‘None of the servants will enter after dark, now, and I fear—’

‘You do not seem the type to believe in ghosts. What precisely do you want of me, Mrs McLaren?’

‘Perhaps you could investigate and prove that there is nothing—’

Holmes waved this thought away. Mrs McLaren steeled herself and changed course. It would be hard to dissuade this woman, and I admired her fortitude, though I wondered at her persistence. The lady was intriguing.

‘Mr Holmes, ours is a complex family. McLaren whisky is renowned but within the family there is dissension over control. Rivalries.’

‘I have heard of your whisky,’ said I, warmly. ‘“McLaren Top” is quite good, I am told.’

‘Yes. Just last year it was adopted as “the whisky of choice” by the Langham Hotel, among others. There is a great deal of money at stake. We could be considered for a Royal Warrant, but plagued as we are by these legends and fears …’

Holmes sighed. He opened his eyes and gazed fixedly upon the lady.

‘A missing girl who is no longer missing. A note in rhyme with the vaguest of threats. Accidental deaths. Ghosts. And now rivalry among brothers. You are scraping an empty barrel, I sense. Madam, there is nothing for me here. Please close the door as you depart.’

But Mrs McLaren was not finished. ‘Mr Holmes, yesterday I found this in the garden shed.’ She reached into her handbag and withdrew a stick of dynamite and a long fuse.

We froze and I heard a sharp intake of air from my friend.

‘Careful with that, Mrs McLaren!’ said Holmes. ‘Hand it to me, please.’

She made no move to do so, but placing it in her lap, instead withdrew a cigarette from her reticule, and before we could stop her, extracted a vesta from a silver case and lit it.

We both shouted and leapt from our chairs, and Holmes managed to snatch the dynamite away. He pulled back from her and stood a moment, holding it stiffly in the air, uncertain, as any step away from her and her lit match would draw him nearer the fire, or nearer the chemistry table which still sizzled quietly under its moist covering.

‘Relax, gentlemen. It is a dummy. I checked. There is no nitroglycerin in this room – unless it is your own.’ The lady smiled sweetly at us.

Holmes glowered at her.

‘You must admit, it captured your attention,’ said she, lighting her cigarette. She inhaled and blew several small circles towards the ceiling, peering upward through them to view my companion with laughing eyes. ‘As it did mine.’

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_16d0438c-af8b-5a08-96e9-a01e7307c543)

Rejection (#ulink_16d0438c-af8b-5a08-96e9-a01e7307c543)

olmes sighed, sniffed, then examined the dynamite stick. Satisfied, he flung it on a side table.

‘Mrs McLaren, you have made your point, albeit more theatrically than necessary. What is so funny, Doctor?’

I shrugged and he continued.

‘Dynamite is the classic tool of the railway builder, the miner, and the anarchist. These appear to be Nobel’s latest type, made in their Scottish factory. What do you think these were doing in this form, wrapped as though filled, and yet not? Dummies, you say. And where exactly did you find them?’

Mrs McLaren smiled. ‘I have no idea. I found these two dummies, and a cache of what I believe were filled sticks in a tool shed in the back of the kitchen garden. And as to your other question, I have only to guess.’

‘Please do not. Guessing is for amateurs. Is there anyone in your family connected to the Scots Separatist movement? To the Russian Revolution? To French anarchists?’ He paused. ‘To the women’s suffrage movement?’

‘You have covered a great deal of territory, Mr Holmes. I myself support women’s right to vote as any clear thinker must. But I am not a radical. As to the rest, I could not be certain. Politics are not the primary subject at our family gatherings.’

‘What is, then?’

‘Money, Mr Holmes. The whisky business. Techniques of distillation, ponies, hunting, local gossip – and ghosts.’

Holmes sighed. ‘Dynamite is used in clearing lands for new buildings, is it not? And has your distillery been recently enlarged? Is there not a logical reason for dynamite to be present for these uses?’

‘Well, yes,’ said the lady. ‘But I wonder about the dummies.’

Silence. Small sounds came from the chemistry table. Holmes’s knee vibrated in impatience.

‘Madam,’ he said after a moment. ‘There are many hints of mystery in your various stories, and yet I am afraid I do not see a case for me. Dr Watson will show you out.’

I will admit my astonishment at this. I thought there was quite enough intrigue presented for several cases! But even more puzzling was Holmes’s rudeness to the lady. While he could on occasion display insensitivity, he was usually the soul of courtesy, especially where women were concerned.

Mrs McLaren stood abruptly and I rose with her. ‘I can find my way out, Dr Watson,’ she said. She then turned to my companion.

‘I am afraid I have wasted your time,’ said the lady. ‘And my own.’

Mrs McLaren took her leave, and as soon as the front door closed behind her downstairs, I could not contain myself. ‘Holmes! Why do you hesitate? There is so much of interest here! And Mrs McLaren—’

‘What? A servant girl has her hair shorn, servants fear ghosts, and some empty dynamite sticks may or may not have been found in a garden shed? By the way, those were not created as dummies. Someone had removed the cordite, for whatever reason. I suspect the lady herself did so, then brought these along to bring out if her other stories failed to get my attention.’

‘Holmes, that is an outrageous notion!’

He shrugged. ‘Do you not think her capable?’

‘That is beside the point! She seems far too intelligent and level-headed to resort to such trickery. Did you not find her story, indeed the lady herself, intriguing?’

‘No, you found her intriguing. I find her—’

‘Utterly fascinating.’

‘—provocative. Really, Watson, you must raise your sights.’

‘Provocative is not a bad beginning for a case, Holmes.’

‘I have decided and that is that. Besides, Mycroft has something for me and I am to meet him in the morning. Would you care to join us? It will most certainly be more interesting than the McLaren imbroglio.’

‘Yes, I will come, Holmes. Though I do not understand this decision. Ah, it is freezing in here now.’

As I moved to close the damaged window, I stole a glance outside. The snow was coming down hard now and the air was growing opaque. But across the way, I saw something that made me stop short.

‘Hullo! Your man is in trouble down there!’

In the deepening shadows, the hulking Butterby was struggling with a tall, well-dressed stranger, who wielded his walking stick like a club. The attacker was clearly at an advantage, and suddenly struck the larger man in the face. Butterby fell back into the shadows.

Holmes bounded to the window, took one glance and ran for the door shouting, ‘Stay here! On no account come down. Do as I say!’

In a moment I saw him dash into the snow sans overcoat and dodge the traffic, across Baker Street to where Butterby had arisen and was now locked in combat with his attacker. From the distance I could only discern a gentleman of about our own age, who was fighting with a particularly vicious energy. Butterby was taking a beating as Holmes ran towards them.

But the attacker sensed his approach, broke free from Butterby and whirling at the last instant aimed a fierce blow at Holmes with his walking stick, striking his shin with a crack I could hear from across the street. Holmes shouted and went down. Two pedestrians nearby fled.

I was down the stairs and into the street without a thought.

By the time I reached the trio, Holmes had regained his footing, and the three were struggling on the slippery pavement, the snow swirling wildly about them. Butterby fell and the attacker turned his attention full on Holmes.

But perceiving my approach and sensing the odds were no longer in his favour, the assailant broke free and started to flee, his camel hair coat billowing behind him. Fate, however, intervened and he suddenly slipped on the icy pavement and fell, striking his head against the base of a lamp post as he went down.

He lay still. We stood gasping, Butterby still splayed on the curb next to us, holding his head.

‘Are you all right, Holmes?’ I shouted over the rising wind.

‘Yes, see to that man, Watson,’ Holmes replied, helping Butterby up.

I turned to the downed attacker. His was a handsome face, chiselled and refined. The eyes remained closed and he was still. I knelt, checking his pulse and his pupils, They were not dilated, a good sign. The wind continued to whip snow around us in a flurry. Holmes and I were without our coats.

‘Get him inside,’ I shouted. Holmes hesitated for only a moment, but then nodded.

With Butterby’s clumsy help, the three of us managed to transport the fellow up to our sitting room, and minutes later, the mysterious attacker was stretched out unconscious on our settee, his hands secured behind him with Butterby’s handcuffs. Holmes grabbed a second pair of cuffs from the mantle and secured his feet to one leg of the settee. I was shivering from my brief exposure to the elements but applied myself to examine the man further. I placed a pillow to raise his head where it had tilted back over the edge of the settee.

My patient was a tall, well-built fellow. His coat was of the finest Savile Row tailoring, now dirtied and torn from the fight. He had suffered a nasty cut on the forehead, and remained unconscious, but his pulse was strong and regular, his breathing normal. I called down to Mrs Hudson for hot water and towels and blotted the wound with a clean handkerchief and some of Holmes’s clear spirits.

A silent and glowering Butterby stood like a plinth in the corner of the room. Melting snow dripped from him, splashing lightly onto the rug. He held a dirty handkerchief to a bleeding cut on his cheek and grimaced. I handed him a clean one. Holmes looked up and, finally noticing him, suggested he fetch Lestrade and be quick about it.

‘Right-o, then,’ Butterby grunted, and lumbered off. Holmes shook his head in annoyance.

Our man on the sofa was struggling to regain consciousness. He groaned and his eyes rolled upwards in their sockets, closed, and opened again. I turned to my friend.

Holmes was pale with exertion and cold, snow still visible on his hair and the shoulders of his dressing gown. He rubbed his shin and grimaced.

‘Are you all right, Holmes?’ I asked again.

‘It is just a bruise. Our man here has been in training since last we met. I underestimated him. What is the damage?’

‘You know him, then?’

‘The damage, Watson?’

‘He will live. I would ask for brandy, but—’

‘Here, give him some of this. My best whisky, though he hardly merits it.’ He handed over a bottle. McLaren Top!

I held the drink to the assailant’s lips, supporting his head. He squinted and took in his surroundings and then suddenly jerked his limbs only to discover his restraints. With a splutter he pulled away from the drink, but clipped it with his chin and several drops spilled over his damaged coat.

He shook his head to focus and suddenly noticed Holmes standing above him. He emitted a deep-throated cry and jolted violently towards me. Struggling against his bonds he began making a series of strange, garbled sounds.

‘Now that is a waste of perfectly good Scotch, St John,’ said Holmes. ‘Not to mention you have further damaged your rather fine coat. I see you have retained your excellent taste in tailoring.’

‘How do you know this man?’ I asked.

‘It is a very long story,’ said my friend, his voice strained.

Another set of unintelligible sounds emerged from the fellow. Turning to stare at him I discovered why. As he continued to make noises, I remarked in horror that the man had lost his tongue! The wound was not recent. There was not a trace of blood, just a dark space where a tongue would rest.

St John glowered.

Holmes turned to me. ‘This is Mr Orville St John. A distinguished member of the St Johns of Northumberland, titled landowners, enormously wealthy from their logging endeavours. We were undergraduates together at Camford. Shall I tell Dr Watson what happened there, St John?’

The man said nothing.

‘I shall presume that was a yes. Mr St John and an equally well-placed friend, both of whom enjoyed great prestige at Camford, took top honors in mathematics and chemistry, until I arrived upon the scene and began to prevail. A prize or two, the favour of a famous professor, and suddenly I was, to them, some kind of nemesis, an object of both envy and derision.’

I noticed St John staring with vehement anger at my friend.

‘They began a campaign to drive me from the University.’ Holmes’s tone was matter of fact, even light, but the tension in his face spoke of more behind the words. ‘He attempted to persuade students and faculty alike that I had harmed his dog, and had blown up a laboratory deliberately. My position was precarious. Not only did I lose the few friends I had – well, not that popularity was ever my goal—’

On the couch, St John snorted.

‘I very much doubt they got the better of you,’ said I.

St John grunted loudly.

‘You would be wrong, Watson. Of course he could speak then. In fact, St John was President of the Union and a champion debater. His nickname was “The Silver Tongue” and he managed by dint of his extraordinary powers of persuasion to turn an entire college and most of the dons against me.’

Holmes paused, remembering. ‘Eventually I was sent down. Although at that point I had lost the will for … other reasons. In any case, Watson, there is my reason for leaving the University, sitting before you in all his glory.’

I was sure that there was much more to this story. St John stared at Holmes, unblinking and cold. Holmes turned to face him, all pretence of humour gone. The hatred between the two was palpable, an electric current travelling through the air.

‘You were very persuasive, St John,’ said he.

I had long wondered about the reason that Holmes had left university without taking his degree. This seemed an incomplete explanation. I pulled him aside, behind St John, where our captive could not see us. I indicated the tongue, with a gesture demanding an explanation. Holmes just shook his head, ‘Later,’ he mouthed.

There was a noise on the stairs and Mrs Hudson showed in Lestrade and two deputies. The wiry little inspector was as usual, full of energy. ‘Mr Holmes!’ he cried.

‘Ah, Lestrade, I see Butterby has succeeded in something at last,’ said Holmes. ‘He has delivered you in a timely fashion. In a moment I would like you to remove this man, Mr Orville St John.’

‘Ah, a gentleman, he appears, but without manners. To gaol then, Mr Holmes? Butterby claims assault and battery. Him as well as you, and the good doctor,’ said Lestrade, with relish.

‘One moment if you please, Inspector.’

Turning to St John, Holmes said the following slowly and carefully. ‘St John, you are now known in these parts and have tried to kill me three times in the last six days.’

Holmes leaned in and removed a revolver from St John’s outer coat pocket. The man inhaled sharply as Holmes opened it, checking the bullets. He handed it to Lestrade. ‘Recently fired, and the calibre and make will match, no doubt, this bullet found in my wall over there.’

He pointed and I discerned a new bullet hole in the wall, just under my picture of General Gordon.

‘Attempted murder, then, as well!’ said the policeman.

‘Patience,’ said Holmes, and turned again to the man restrained before us. ‘I am going to make you an offer for your freedom, St John. If you agree to my terms, I will not press charges. And Lestrade, I ask that you convince Butterby to drop his charges as well. Release this gentleman’s ankles, would you please, Doctor.’ He handed me the keys to his cuffs. ‘And you his hands, Butterby.’

As he was freed from his restraints, St John looked pointedly away, rubbing his wrists. I was unable to read his reaction to these last words. Holmes continued.

‘What is so completely odd, St John, is why now? What has sent you here?’ He leaned forward.

St John turned away again coldly. Holmes sighed. ‘You must let this vendetta go. You know that I am not guilty of that which you accuse me. In your heart of hearts, you know this.’

St John remained inscrutable. I scanned his motionless face but read no sign of the man relenting.

‘Once again, in front of witnesses, can you let this vendetta go? If so, then you walk away a free man. If not, it will be to gaol with you, where I will ensure you stay a very long time.’ Holmes then made several strange gestures in the air with his hands. I recognized the motions as French sign language used by the deaf or mute, but had no clue to the meaning.

St John hesitated, and a torrent of emotions passed over his face as he clearly fought to regain control. He made a brief reply in sign language.

‘Fine then, St John, but consider this. If you do not desist, although I am not a vindictive man, you will leave me no choice. I will investigate your personal business, and create as much difficulty as I can for your family. You will bring trouble down on all you love. Do you agree to let this go once and for all?’

St John closed his eyes for a moment, then opening them, he stared fiercely at my friend, then nodded in assent.

‘I need your word.’

‘Let him say it, Mr Holmes,’ said Lestrade.

Holmes shot a glance at Lestrade. ‘He is mute.’ He turned to glare at St John. The man hesitated, then finally, an affirmative ‘Uh huh’ came from him.

‘That will suffice. Gentlemen. I now formally drop my charges against Mr St John for his attempts on my life. For the time being.’ Turning back to St John he said, ‘Take care that you keep your vow. Do you understand me?’

St John slowly raised his eyes to meet Holmes’s. There was a cold rage, now, in that look. The man was ready to kill Holmes, of that I was sure. And yet my friend seemed eager to let him go.

St John nodded one more time.

‘Escort Mr St John back to the Langham Hotel, please.’

St John started at this.

‘Yes, I know your hotel, and a great deal more,’ Holmes said. Then, to Lestrade, ‘It is a lodging well suited to this gentleman’s means and style. He lives on a grand estate just outside Edinburgh, and he is the respected owner and editor of St John and Wilkins, a major publishing house. He has three small children, a growing business, a loving wife, and a brother in delicate health. He has much to lose.’

St John stood, and as he did, one of Lestrade’s deputies approached and took him by the arm, and they moved to the door. As he stood in the doorframe, St John turned to Holmes and elaborated some complex thought with sign language, ending with an aggressive gesture.

Holmes clearly received the message. He sighed and shook his head.

The men departed, Butterby with them.

Lestrade shook his head. ‘Well, Mr Holmes, I have seen some strange things in these rooms, but that gentleman is surely one of the strangest. I do not have a good feeling about your letting him go like that.’

‘Nor do I, Holmes,’ said I. ‘I think you are making a mistake.’

My friend stood peering into the fire. ‘Gentlemen. I am very tired suddenly and need to rest. If you will excuse me, please. Good evening, Lestrade. Watson, would you be so good as to meet me at the Diogenes Club at 9.30 tomorrow morning.’ He shrugged. ‘Or stay, if you like. Your old room is probably habitable.’

Without a further word, he retired to his bedroom and shut the door. As soon as he did so, I realized that I had meant to have a look at the leg where St John had struck him. But he would not be disturbed now. I turned to Lestrade, who was now staring curiously at the still gurgling chemistry mess in the corner.

‘What on earth is that, if you do not mind my asking?’ he said.

‘I promise you I have not the faintest notion, Inspector.’

‘You must have a very forgiving landlady,’ observed the little man tartly. On cue, the saintly Mrs Hudson appeared with his hat, coat and umbrella.

‘Good evening, Inspector Lestrade,’ I said.

As he left, Mrs Hudson sniffed the foetid air and took in the chemistry disaster. ‘Mr Holmes?’ she enquired.

‘He is resting,’ said I.

‘I shouldn’t wonder,’ she said. ‘I shall bring you both some warm soup. Will you be staying, Doctor?’

‘My room—’

‘It has been made up fresh as Mr Holmes requested.’

I smiled. Had Holmes known that Mary was not home and would not miss me? It should not have surprised me. But meanwhile, the weather had grown increasingly inclement.

‘Thank you, Mrs Hudson. I will stay.’ In truth, I felt uneasy at the recent events. Until I was sure that this St John had been dissuaded from his mission, Holmes might well make use of my help.

Thus I decided to stay the night and accompany my friend in the morning to see his brother, Mycroft Holmes. As it turned out, it was lucky that I did.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_b2dd64a9-9511-55c9-92ba-8ed94d76be66)

Brothers (#ulink_b2dd64a9-9511-55c9-92ba-8ed94d76be66)

n route through snowy Regent Street to Mycroft the following morning, I found myself puzzling over both Holmes’s rejection of Isla McLaren’s case and his handling of the treacherous Orville St John incident. But my friend was in an impatient mood, his black kid-gloved fingers drumming restlessly upon his knee. He refused to be drawn into a discussion of either. I persisted on the St John issue and at last he said, ‘Mr St John will not trouble me again. He is particularly protective of his family and my bluff will suffice. He – why do you look at me that way? Surely, Watson, you cannot imagine that I would forcibly cut a man’s tongue from his head for any reason on earth!’

The thought had in fact occurred to me. ‘Well, not a live one, at any rate. But how did it happen?’

‘It was the act of a madman, a mutual acquaintance, Watson, who has since passed on to meet his Maker.’

‘Strange. But why does this St John think you were responsible? And why attack you now?’

‘Certainly some recent event has served to reanimate his rage. Perhaps a letter. I intend to find out. In any case, it is complicated, and long past. Leave it, I say.’ His tone brooked no argument and I knew it was useless to pursue for the moment. We soon pulled up in front of the Diogenes Club.

‘I shall pay,’ I offered, in an attempt at détente. Perhaps Mrs McLaren had been right and he was in need of cash. I fished in my own pocket.

‘I have it, Watson. You are a bit short of funds yourself.’

It was regrettably true! My practice had suffered recently when a doctor of considerable charm and a decade more experience had hung his brass plate two doors down from my own. But how could he know?

‘What herculean efforts you make to keep track of my personal affairs!’ I exclaimed as we entered the august precincts of the Diogenes. ‘Perhaps better spent elsewhere!’

‘Very little effort at all,’ said he, ‘Watson, you are an open book.’

‘Well, you are wrong about that,’ I insisted.

Soon afterwards were seated in the Stranger’s Room at the Diogenes, awaiting Mycroft Holmes.

The antique globes in their familiar place, the bookshelves filled with leatherbound volumes, the large window onto Pall Mall – all was as it had been before. While the club’s peculiar regulars must have chosen it for its rules of silence, I found the place oppressive.

The Stranger’s Room was the only place in this eccentric institution where one was allowed to speak. Eventually Mycroft Holmes sailed in as a stately battleship through calm waters to sit before us. Mycroft was over six feet tall, and unlike his brother, very wide in girth. He carried a leather dossier in one enormous hand. He smiled in his particular mirthless way, and then he and my friend exchanged the usual pleasantries characteristic of the Holmes brothers, that is to say, none at all.

Coffee was served. The clink of china and silver was hushed in the room.

‘How is England doing?’ asked Holmes finally.

‘We are well,’ said Mycroft. ‘Considering.’

Holmes leaned back in his chair, a twitching knee giving away his impatience. Mycroft eyed his younger brother with a kind of concerned disapproval. ‘But you, Sherlock, must watch your finances. I have mentioned this before.’

‘Mycroft!’ exclaimed Holmes.

‘Little brother, you are an open book.’

I cleared my throat to cover a laugh, and Holmes shot me a look. ‘What is it you want, Mycroft? Trouble in France I hear?’

‘Precipitous. The threat of war. You have heard of the phylloxera epidemic? It is not a virus, but a little parasite, it seems, and it is destroying the vineyards of France. Their wine production is down some seventy-five per cent in recent years. Dead brown vines everywhere. A good, cheap table wine is impossible to come by, and the better brandies, too. An absolute disaster for the French, and keenly felt.’

‘Come now, Mycroft … war?’ said Holmes.

‘There are those highly placed in France who feel the debacle was deliberately engineered. And by Perfidious Albion, no less.’

‘Blaming the epidemic on Britain!’ exclaimed Holmes. ‘Is such a thing possible?’ He smiled. ‘Or is this merely a question of French sour grapes?’

‘Who knows?’ said Mycroft. ‘But, a highly placed gentleman, one Philippe Reynaud is leading the charge. He is Le Sous Secrétaire d’État à l’Agriculture. Reynaud thinks the Scots are behind it. Or at the very least, prolonging it.’

‘The Scots!’ I exclaimed. ‘Why, they have long been allies of the French.’

Mycroft gave me a withering glance.

‘Which Scots? And why particularly?’ asked Holmes, then had a sudden thought. ‘Oh. Whisky, of course.’

‘Three Scottish families are singled out and under suspicion. One may interest you particularly, the McLarens. It is in the report,’ said Mycroft, indicating a dossier which he had tossed on the table between them. The name struck me but Holmes gave nothing away. Mycroft turned to me. ‘Numerous entrepreneurial types including the McLarens, James Buchanan, and others have been laying siege to London clubs and restaurants, aggressively promoting their ‘uisge beatha’ or ‘water of life’ – that is the Scots’ Gaelic term – as the new social drink to be enjoyed in finer society. The fact that spirits, such as brandy, cognac and wine have grown costly and scarce has helped them tremendously.’

‘Oh yes! I particularly like Buchanan’s new Black and White—’ I began.

‘The fortunes of these companies are rising,’ interrupted Mycroft. ‘Not just in London but internationally. The French are talking of trade sanctions, and a couple of militant specimens, including this Reynaud, have pushed for a more aggressive response.’

‘War over drinks?’ I exclaimed. ‘Ludicrous.’

‘It is an entire industry, and war has been declared for less, Watson. The French vineyards are closely tied to French identity,’ said Holmes.

‘Yes, they are quite heated on the subject,’ said Mycroft. ‘Cigarette?’

Holmes took a cigarette from Mycroft’s case and lit it.

Mycroft sighed. ‘These ideas have been gaining purchase, and that is why I have called you in, Sherlock.’

‘What of research?’ asked Holmes. ‘Is there no potential remedy in sight for the scourge?’

‘The leading viticultural researcher is in Montpellier, Dr Paul-Édouard Janvier. He is said to be close to a solution. But, and here is where you come in, dear brother, he has been receiving death threats, and this Reynaud insists they come from Scotland.’

‘What has been done so far?’

‘France has put its “best man” on the case to protect Dr Janvier and discover the source of the threats, but Dr Janvier has taken a dislike to the gentleman in question and I can’t say I blame him. I know the man; he is an irritant, and, based on his past history, I would not put it past him to exacerbate the situation.’

Holmes was smiling at this. ‘France’s “best man” you say? An irritant? This sounds like someone we know.’

‘Yes.’

The brothers exchanged a look of amusement.

‘Who is—wait!’ I suddenly guessed the identity of this this unnamed man. ‘Can it be Jean Vidocq?’ I blurted out. Their silence was confirmation.

The scoundrel! We had had some unfortunate dealings with the famous French detective last year. Vidocq was a dangerous charmer who saw himself as Holmes’s rival. The man had not only attacked me physically but had complicated our case involving a certain French singer and her missing child. This same man claimed to be a descendant of the famous Eugène François Vidocq who founded the Sûreté nearly eighty years ago. But the connection was spurious – the real Vidocq had no known descendants. Despite his questionable character, Jean Vidocq was not without considerable skills, and was frequently consulted by the French government.

‘What exactly do you wish me to do?’ asked Holmes.

‘Three things. First, meet Dr Paul-Édouard Janvier, and let me know the status of his research. How close is he to a cure for the mite? The second is to discover and neutralise whoever is threatening the man and his work – if these threats are indeed genuine.’

‘Why would they not be genuine?’ asked Holmes.

Mycroft shrugged. ‘Attention. Sympathy. Who knows? But if the threats to Dr Janvier are real, and they have been perpetrated by a Briton, then detain that gentleman with the utmost discretion and notify me. The Foreign Office and I shall handle it from there.’

‘And if there is a villain, and he or she is not British?’ asked Holmes.

‘Well, then best to leave it. I shall pass on the information.’

Holmes stopped smiling and sat back in his chair.

‘Protect Britain, that is your only interest? Not this man, or the crisis itself? No, Mycroft,’ he said. ‘I will not undertake this.’

Mycroft seemed not to have heard. ‘And the third task: extricate Jean Vidocq from this situation, the sooner the better. This man Janvier, who is something of a genius, may well be in danger. Vidocq only complicates things and is unlikely to be protecting him.’

Holmes said nothing.

‘As for the three Scottish families I mentioned, at the top of the list are the McLarens. You improve at concealment, Sherlock. I mentioned them before, and you revealed nothing, but in fact, you had a visit from the younger daughter-in-law yesterday. Most convenient.’

Holmes set his coffee cup in its saucer abruptly, ‘Stop having me watched, Mycroft.’

‘You may one day be thankful.’

‘Yet you missed the recent attempts on my life.’

‘Not very effective, was he? Need I say more?’

Holmes said nothing.

‘The McLaren family is or will be en route shortly to the South of France where they winter each year in the vicinity of Nice. This year it is the new Grand Hôtel du Cap Eden Roc in Antibes. Did your client fail to mention this? I wonder why she came to see you? It is a curious coincidence.’

‘She came on another matter. a domestic intrigue. And she is not my client, as I turned down the case.’

‘Dear me! If you are declining cases left and right, how wrong I was to imagine you in straitened circumstances, dear brother.’

Holmes actually turned scarlet at this jab.

‘In any case, you are free to travel,’ Mycroft said.

‘No, Mycroft. Watson, call for our coats, please.’

I stood.

‘Our Monsieur Reynaud fears that an attack on Dr Janvier is imminent. It seems precisely your kind of case, Sherlock. Protect an innocent who advances science.’ Mycroft stubbed out his cigarette and sipped his coffee. He smiled kindly at his brother. I immediately thought of a mongoose.

‘I said no.’ Holmes leaned forward, stubbing his own cigarette into the ashtray in the centre of the table. Without shifting position, and with a dexterity I could scarcely credit, Mycroft suddenly thrust his arm forward and clapped his large hand over Holmes’s long thin one, slamming it into the ashtray and onto the still smouldering cigarette. And there he held it. I could not believe what I was seeing.

His hand unmoving, Mycroft’s voice remained warm and friendly. ‘Consider the plight of this man, Dr Janvier, Sherlock. He is brilliant, a genius with few friends. A naïf in a certain way. But his work is vital, with economic and political repercussions. I assure you, no British official wishes him dead.’

He continued to hold his hand clamped over Holmes’s. My friend indicated nothing, but I could see the sweat beading on his brow. With a sudden move, I took up the coffee pot and poured a small splash of hot coffee on Mycroft’s hand. With a cry he released Holmes and the two sprung back from the table, each cradling an injured hand.

‘So sorry, gentlemen,’ I said. ‘As long as we are discussing saving wine and Western civilization, might we not be a little more civilized ourselves?’ I said.

‘And there is my point, Sherlock. Paul-Édouard Janvier has no Watson. Do this for me, will you not, little brother? You are uniquely suited. England will thank you. I will thank you, and a certain august personage at Windsor will certainly be grateful.’

From his pocket Mycroft now withdrew a large, thick envelope and placed it on the table. ‘You will be needing an advance, of course. Report to me daily on your progress.’

Holmes stared at the envelope in disdain. But he then looked away thoughtfully, and to my surprise, reconsidered.

‘I will do it, Mycroft, for this man Dr Janvier. But not for you,’ said Holmes. He reached down and flicked the envelope back across the table to Mycroft. ‘Keep your advance. Pay me when the case is closed.’

Mycroft smiled and sat down, delicately wiping the coffee from his hand with a white linen napkin. ‘Dr Watson, you have been little challenged of late. Might you break free from the marital bonds to accompany my brother on a trip to the Riviera?’

Little challenged! Had I been watched as well? Holmes glanced my way with a nod of encouragement. ‘This can be arranged,’ said I. ‘My dear Mary has some obligations herself, you see, as she has to—’

‘Capital! The 4.15 from Waterloo, the day after tomorrow,’ said Mycroft. ‘Tickets, and a packet of information will be at Baker Street within the hour. You may change your mind later about the advance, Sherlock. Meanwhile, enjoy the South of France. The sunshine will do you both good.’

He glanced in my direction. ‘But do stay away from the casino, Dr Watson.’

I could feel my cheeks colouring at this comment. ‘I have given up gambling,’ I said.

‘Not at all,’ said both brothers simultaneously.

‘Good day, gentlemen,’ said Mycroft.

I will admit to a curious, if not longing glance at that thick envelope as we departed.