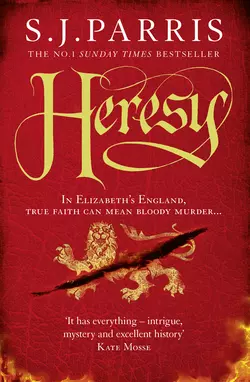

Heresy

S. J. Parris

A vivid and gripping historical thriller set in Elizabethan England introducing Giordano Bruno - philosopher, spy and hero of the stunning new novel SACRILEGE - for all fans of C.J.Sansom and The Name of the Rose.In Elizabeth’s England, true faith can mean bloody murder…Oxford, 1583. A place of learning. And murderous schemes.The country is rife with plots to assassinate Queen Elizabeth and return the realm to the Catholic faith. Giordano Bruno is recruited by the queen’s spymaster and sent undercover to expose a treacherous conspiracy in Oxford – but his own secret mission must remain hidden at all costs.A spy under orders. A coveted throne under threat.When a series of hideous murders ruptures close-knit college life, Bruno is compelled to investigate. And what he finds makes it brutally clear that the Tudor throne itself is at stake…Heretic, maverick, charmer: Giordano Bruno is always on his guard. Never more so than when working for Queen Elizabeth and her spymaster – for this man of letters is now an agent of intrigue and danger.

S. J. PARRIS

Heresy

Copyright (#ulink_9110b8e8-5148-5e32-a046-ca9f184ffc5f)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2010

Copyright © Stephanie Merritt 2010

Stephanie Merritt asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover photographs © Shutterstock

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007317707

Ebook Edition MARCH 2010 © ISBN: 9780007317684

Version: 2017-05-10

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u3b7bf730-36f2-59e0-ab23-3db4fe5deca9)

Copyright (#u73b87430-d043-5cf0-87d3-40102280e045)

Prologue: Monastery of San Domenico Maggiore, Naples 1576 (#uc3752c10-4b27-537c-95ca-662cfa3bce58)

Part One: London, May 1583 (#u033f4383-327a-5cb2-9650-721ec422f791)

Chapter One (#u564ae938-7885-561e-a09b-7674ad394693)

Part Two: Oxford, England, May 1583 (#u0d5ae04b-3ffd-546f-bcc9-7a72961db141)

Chapter Two (#ub63b99af-7c94-51f4-b690-41031177b5b3)

Chapter Three (#u468c7433-4446-5fd9-9a46-2538710547a1)

Chapter Four (#u23b883c4-627e-5ade-bdaa-c76ba93cd138)

Chapter Five (#udd21dec8-6255-5140-ab1d-07c6ddbc5bdb)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: London, July 1583 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise for Heresy (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by S. J. Parris (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_6ae0adf2-e0a9-5273-a9f6-485091f44b75)

Monastery of San Domenico Maggiore, Naples 1576 (#ulink_6ae0adf2-e0a9-5273-a9f6-485091f44b75)

The outer door was thrown open with a crash that resounded along the passage and the floorboards shook with the purposeful marching of several pairs of feet. Inside the small cubicle where I perched on the edge of a wooden bench, taking care not to sit too close to the hole that opened over the cess pit beneath, my little candle flickered in the sudden draught of their entrance, sending wavering shadows growing and shrinking up the stone walls. Allora, I thought, looking up. They have come for me at last.

The footsteps halted outside the cubicle door, to be replaced by the furious hammering of a fist and the abbot’s throaty voice, strained beyond its usual placid tones of diplomacy.

‘Fra Giordano! I order you to come out this instant, with whatever you hold in your hands in plain sight!’

I caught a snigger from one of the monks who accompanied him, swiftly followed by a stern tutting from the abbot, Fra Domenico Vita, and could not help smiling to myself, in spite of the moment. Fra Vita was a man who, in the ordinary course of events, gave the impression that all bodily functions offended him mightily; it would be causing him unprecedented distress to have to apprehend one of his monks in so ignominious a place as this.

‘One moment, Padre, if I may,’ I called, untying my habit to make it look as if I had been using the privy for its proper purpose. I looked at the book in my hand. For a moment I entertained the idea of hiding it somewhere under my habit, but that would be fruitless – I would be searched straight away.

‘Not one moment more, Brother,’ Fra Vita said through the door, a quiet menace creeping into his voice. ‘You have spent more than two hours in the privy tonight, I think that is long enough.’

‘Something I ate, Padre,’ I said, and with deep regret, I threw the book into the hole, producing a noisy coughing fit to cover the splash it made as it fell into the pool of waste below. It had been such a fine edition, too.

I unlatched the door and opened it to see my abbot standing there, his heavy features almost vibrating with pent-up rage, all the more vivid in the gusting light of the torches carried by the four monks who stood behind him, staring at me, appalled and fascinated.

‘Do not move, Fra Giordano,’ Vita said tightly, jabbing a warning finger in my face. ‘It is too late for hiding.’

He strode into the cubicle, his nose wrinkled against the stench, holding up his lamp to check each of the corners in turn. Finding nothing, he turned to the men behind him.

‘Search him,’ he barked.

My brothers looked at one another in consternation, then that wily Tuscan friar Fra Agostino da Montalcino stepped forward, an unpleasant smile on his face. He had never liked me, but his dislike had turned to open animosity after I publicly bested him in an argument about the Arian heresy some months earlier, after which he had gone about whispering that I denied the divinity of Christ. Without a doubt, it was he who had put Fra Vita on my trail.

‘Excuse me, Fra Giordano,’ he mouthed with a sneer, before he began patting me up and down, his hands roaming first around my waist and down each of my thighs.

‘Try not to enjoy yourself too much,’ I muttered.

‘Just obeying my superior,’ he replied. When he had finished groping, he rose to face Fra Vita, clearly disappointed. ‘He has nothing concealed in his habit, Father.’

Fra Vita stepped closer and glared at me for some moments without speaking, his face so near to mine that I could count the bristles on his nose and smell the rank onions on his breath.

‘The sin of our first father was the desire for forbidden knowledge.’ He enunciated each word carefully, running his tongue wetly over his lips. ‘He thought he could become like God. And this is your sin also, Fra Giordano Bruno. You are one of the most gifted young men I have encountered in all my years at San Domenico Maggiore, but your curiosity and your pride in your own cleverness prevent you from using your gifts to the glory of the Church. It is time the Father Inquisitor took the measure of you.’

‘No, Padre, please – I have done nothing—’ I protested as he turned to leave, but just then Montalcino called out from behind me.

‘Fra Vita! Here is something you should see!’

He was shining his torch into the hole of the privy, an expression of malevolent delight spreading over his thin face.

Vita blanched, but leaned in to see what the Tuscan had uncovered. Apparently satisfied, he turned to me.

‘Fra Giordano – return to your cell and do not leave until I send you further instructions. This requires the immediate attention of the Father Inquisitor. Fra Montalcino – retrieve that book. We will know what heresies and necromancy our brother studies in here with a devotion I have never seen him apply to the Holy Scriptures.’

Montalcino looked from the abbot to me in horror. I had been in the privy for so long I had grown used to the stink, but the idea of plunging my hand into the pool beneath the plank made my stomach rise. I beamed at Montalcino.

‘I, my Lord Abbot?’ he asked, his voice rising.

‘You, Brother – and be quick about it.’ Fra Vita pulled his cloak closer around him against the chill night air.

‘I can save you the trouble,’ I said. ‘It is only Erasmus’s Commentaries – no dark magic in there.’

‘The works of Erasmus are on the Inquisition’s Index of Forbidden Books, as you well know, Brother Giordano,’ Vita said grimly. He fixed me again with those emotionless eyes. ‘But we will see for ourselves. You have played us for fools too long. It is time the purity of your faith was tested. Fra Battista!’ he called to another of the monks bearing torches, who leaned in attentively. ‘Send word for the Father Inquisitor.’

I could have dropped to my knees then and pleaded for clemency, but there would have been no dignity in begging, and Fra Vita was a man who liked the order of due process. If he had determined I should face the Father Inquisitor, perhaps as an example to my brethren, then he would not be swayed from that course until it had been played out in full – and I feared I knew what that meant. I pulled my cowl over my head and followed the abbot and his attendants out, pausing only to cast a last glance at Montalcino as he rolled up the sleeve of his habit and prepared to fish for my lost Erasmus.

‘On the bright side, Brother, you are fortunate,’ I said, with a parting wink. ‘My shit really does smell sweeter than everyone else’s.’

He looked up, his mouth twisted with either bitterness or disgust.

‘See if your wit survives when you have a burning poker in your arsehole, Bruno,’ he said, with a marked lack of Christian charity.

Outside in the cloister, the night air of Naples was crisp and I watched my breath cloud around me, grateful to be out of the confines of the privy. On all sides the vast stone walls of the monastic buildings rose around me, the cloister swallowed up in their shadows. The great façade of the basilica loomed to my left as I walked with leaden steps towards the monks’ dormitory, and I craned my head upwards to see the stars scattered above it. The Church taught, after Aristotle, that the stars were fixed in the eighth sphere beyond the earth, that they were all equidistant and moved together in orbit about the Earth, like the Sun and the six planets in their respective spheres. Then there were those, like the Pole Copernicus, who dared to imagine the universe in a different form, with the Sun at its centre and an Earth that moved on its own orbit. Beyond this, no one had ventured, not even in imagination: no one but me, Giordano Bruno the Nolan, and this secret theory, bolder than anyone had yet dared to formulate, was known to me alone: that the universe had no fixed centre, but was infinite, and each of those stars I now watched pulsating in the velvet blackness above me was its own sun, surrounded by its own innumerable worlds, on which, even now, beings just like me might also be watching the heavens, wondering if anything existed beyond the limits of their knowledge.

One day I would write all this in a book that would be my life’s work, a book that would send such ripples through Christendom as Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium had done, but greater still, a book that would undo all the certainties not only of the Roman Church but of the whole Christian religion. But there was so much more that I needed to understand, too many books I had yet to read, books of astrology and ancient magic, all of which were forbidden by the Dominican order and which I could never obtain from the library at San Domenico Maggiore. I knew that if I were to stand before the Holy Roman Inquisition now, all of this would be pricked out of me with white-hot irons, with the rack or the wheel, until I vomited my hypothesis out half cooked, whereupon they would burn me for heresy. I was twenty-eight years old; I did not want to die just yet. I had no choice but to run.

It was then just after compline; the monks of San Domenico were preparing to retire for the night. Bursting into the cell I shared with Fra Paolo of Rimini, trailing the cold of the night on my hair and habit, I rushed frantically about the tiny room, gathering what few belongings I had into an oilskin bag. Paolo had been lying in contemplation on his straw pallet when I flung the door open; now he propped himself up on one elbow, watching my frenzy with concern. He and I had joined the monastery together as novices at the age of fifteen; now, thirteen years later, he was the only one I thought of as a brother in the true sense.

‘They have sent for the Father Inquisitor,’ I explained, catching my breath. ‘There is no time to lose.’

‘You missed compline again. I told you, Bruno,’ Paolo said, shaking his head. ‘If you spend so many hours in the privy every night, people will grow suspicious. Fra Tomasso has been telling everyone you have some grievous disease of the bowel – I said it would not take long for Montalcino to deduce your true business and alert the abbot.’

‘It was only Erasmus, for Christ’s sake,’ I said, irritated. ‘I must leave tonight, Paolo, before I am questioned. Have you seen my winter cloak?’

Paolo’s face was suddenly grave.

‘Bruno, you know a Dominican may not abandon his order, on pain of excommunication. If you run away, they will take it as a confession, they will put out a warrant for you. You will be condemned as a heretic.’

‘And if I stay I will be condemned as a heretic,’ I said. ‘It will hurt less in absentia.’

‘But where will you go? How will you live?’ My friend looked pained; I stopped my searching and laid my hand on his shoulder.

‘I will travel at night, I will sing and dance or beg for bread if I have to, and when I have put enough distance between myself and Naples, I will teach for a living. I took my Doctor of Theology last year – there are plenty of universities in Italy.’ I tried to sound cheerful, but in truth my heart was pounding and my bowels were turned to water; it was somewhat ironic that I could not now go near the privy.

‘You will never be safe in Italy if the Inquisition name you as a heretic,’ Paolo said sadly. ‘They will not rest until they see you burned.’

‘Then I must get out before they have the chance. Perhaps I will go to France.’

I turned away to look for my cloak. There flashed into my memory, as clear as the day it was first imprinted, the image of a man consumed by fire, his head twisted back in agony as he tried in vain to turn his face from the heat of the flames that tore hungrily at his clothes. It was that human, fruitless gesture that stayed with me in the years afterwards – that movement to protect his face from the fire, though his head was bound to a stake – and since then I had deliberately avoided the spectacle of another burning. I had been twelve years old, and my father, a professional soldier and a man of orthodox and sincere belief, had taken me to Rome to watch a public execution for my edification and instruction. We had secured a good vantage point for ourselves in the Campo dei Fiori towards the back of the jostling crowd, and I had been amazed at how many had gathered to make profit from the event as if it were a bear-baiting or a fair: sellers of pamphlets, mendicant friars, men and women peddling bread and cakes or fried fish from trays around their necks. Neither had I expected the cruelty of the crowd, who mocked the prisoner with insults, spitting and throwing stones at him as he was led silently to the stake, his head bowed. I wondered if his silence were defeat or dignity, but my father explained that an iron spike had been driven through his tongue so that he could not try to convert the spectators by repeating his foul heresies from the pyre.

He was tied to the stake and the faggots piled around him so that he was almost hidden from view. When a torch was held to the wood, there was an almighty crackling and the kindling caught light immediately and burned with a fierce glow. My father had nodded in approval; sometimes, he explained, if the authorities feel merciful, they allow green wood to be used for the pyre, so that the prisoner will often suffocate from the smoke before he truly suffers the sting of the flames. But for the worst kind of heretics – witches, sorcerers, blasphemers, Lutherans, the Benandanti – they would be sure the wood was dry as the slopes of Monte Cicala in summer, so that the heat of the flames would tear at the offender until he screamed out to God with his last breath in true repentance.

I wanted to look away as the flames rushed to devour the man’s face, but my father was planted solidly beside me, his gaze unflinching, as if watching the poor wretch’s agonies were an essential part of his own duty to God, and I did not want to appear less manly or less devout than he. I heard the mangled shrieks that escaped the condemned man’s torn mouth as his eyeballs popped, I heard the hiss and crackle as his skin shrivelled and peeled away and the bloody pulp beneath melted into the flames, I smelled the charred flesh that reminded me horribly of the boar that was always roasted over a pit at street festivals in Nola. Indeed, the cheering and exultation of the crowd when the heretic finally expired was like nothing so much as a saint’s day or public holiday. On the way home I asked my father why the man had had to die so horribly. Had he killed someone? My father told me that he had been a heretic. When I pressed him to explain what a heretic was, he said the man had defied the authority of the pope by denying the existence of Purgatory. So I learned that, in Italy, words and ideas are considered as dangerous as swords and arrows, and that a philosopher or a scientist needs as much courage as a soldier to speak his mind.

Somewhere in the dormitory building I heard a door slam violently.

‘They are coming,’ I whispered frantically to Paolo. ‘Where the devil is my cloak?’

‘Here.’ He handed me his own, pausing a moment to tuck it around my shoulders. ‘And take this.’ He pressed into my hand a small bone-handled dagger in a leather sheath. I looked at him in surprise. ‘It was a gift from my father,’ he whispered. ‘You will have more need of it than I, where you are going. And now, sbrigati. Hurry.’

The narrow window of our cell was just large enough for me to squeeze myself on to the ledge, one leg at a time. We were on the first floor of the building, but about six feet below the window the sloping roof of the lay brothers’ reredorter jutted out enough for me to land on if I judged the fall carefully; from there I could edge my way down a buttress and, assuming I could make it across the garden without being seen, I could climb the outside wall of the monastery and disappear into the streets of Naples under cover of darkness.

I tucked the dagger inside my habit, slung my oilskin pack over one shoulder and climbed to the ledge, pausing astride the window sill to look out. A gibbous moon hung, pale and swollen, over the city, smoky trails of cloud drifting across its face. Outside there was only silence. For a moment I felt suspended between two lives. I had been a monk for thirteen years; when I lifted my left leg through the window and dropped to the roof below I would be turning my back on that life for good. Paolo was right; I would be ex communicated for leaving my order, whatever other charges were levelled at me. He looked up at me, his face full of wordless grief, and reached for my hand. I leaned down to kiss his knuckles when I heard again the emphatic stride of many feet thundering down the passageway outside.

‘Dio sia con te,’ Paolo whispered, as I pulled myself through the small window and twisted my body around so that I was hanging by my fingertips, tearing my habit as I did so. Then, trusting to God and chance, I let go. As I landed clumsily on the roof below, I heard the sound of the little casement closing and hoped Paolo had been in time.

The moonlight was a blessing and a curse; I kept close to the shadows of the wall as I crossed the garden behind the monks’ quarters and, with the help of wild vines, I managed to pull myself over the far wall, the boundary of the monastery, where I dropped to the ground and rolled down a short slope to the road. Immediately I had to throw myself into the shadow of a doorway, trusting to the darkness to cover me, because a rider on a black horse was galloping urgently up the narrow street in the direction of the monastery, his cloak undulating behind him. It was only when I lifted my head, feeling the blood pounding in my throat, and recognised the round brim of his hat as he disappeared up the hill towards the main gate, that I knew the figure who had passed was the local Father Inquisitor, summoned in my honour.

That night I slept in a ditch on the outskirts of Naples when I could walk no further, Paolo’s cloak a poor defence against the frosty night. On the second day, I earned a bed for the night and a half-loaf of bread by working in the stables of a roadside inn; that night, a man attacked me while I slept and I woke with cracked ribs, a bloody nose and no bread, but at least he had used his fists and not a knife, as I soon learned was common among the vagrants and travellers who frequented the inns and taverns on the road to Rome. By the third day, I was learning to be vigilant, and I was more than halfway to Rome. Already I missed the familiar routines of monastic life that had governed my days for so long, and already I was thrilled by the notion of freedom. I no longer had any master except my own imagination. In Rome I would be walking into the lion’s maw, but I liked the boldness of the wager with Providence; either my life would begin again as a free man, or the Inquisition would track me down and feed me to the flames. But I would do everything in my power to ensure it was not the latter – I was not afraid to die for my beliefs, but not until I had determined which beliefs were worth dying for.

PART ONE (#ulink_343c7d02-39b5-5852-87df-29f4f6355e6d)

ONE (#ulink_56e10d3c-8a99-5622-8df4-95d4a34d9004)

On a horse borrowed from the French ambassador to the court of Queen Elizabeth of England, I rode out across London Bridge on the morning of 20th May 1583. The sun was strong already, though it was not yet noon; diamonds of light scattered across the ruffled surface of the wide Thames and a warm breeze lifted my hair away from my face, carrying with it the sewer stinks of the river. My heart swelled with anticipation as I reached the south bank and turned right along the river towards Winchester House, where I would meet the royal party to embark upon our journey to the renowned University of Oxford.

The palace of the bishops of Winchester was built of red brick in the English style around a courtyard, its roof decorated with ornate chimneys over the great hall with its rows of tall perpendicular windows facing the river. In front of this a lawn sloped down to a large wharf and landing place where I now saw, as I approached, a colourful spectacle of people thronging the grass. Snatches of tunes carried through the air as musicians rehearsed, and half of London society appeared to have turned out in its best clothes to watch the pageant in the spring sunshine. By the steps, servants were making ready a grand boat, decked out with rich silk hangings and cushions tapestried in red and gold. At the front were seats for eight oarsmen, and at the back an elaborate embroidered canopy sheltered the seats. Jewel-coloured banners rippled in the light wind, catching the sunlight.

I dismounted, and a servant came to hold the horse while I walked towards the house, eyed suspiciously by various finely dressed gentlemen as we passed. Suddenly I felt a fist land between my shoulder blades, almost knocking me to the ground.

‘Giordano Bruno, you old dog! Have they not burned you yet?’

Recovering my balance, I spun around to see Philip Sidney standing there grinning from ear to ear, his arms wide, legs planted firmly astride, his hair still styled in that peculiar quiff that stuck up at the front like a schoolboy hastened out of bed. Sidney, the aristocratic soldier-poet I had met in Padua as I fled through Italy.

‘They’d have to catch me first, Philip,’ I said, smiling broadly at the sight of him.

‘It’s Sir Philip to you, you churl – I’ve been knighted this year, you know.’

‘Excellent! Does that mean you’ll acquire some manners?’

He threw his arms around me then and thumped me heartily on the back again. Ours was a curious friendship, I reflected, catching my breath and embracing him in return. Our backgrounds could not have been more different – Sidney was born into one of the first families of the English court, as he had never tired of reminding me – but in Padua we had immediately discovered the gift of making one another laugh, a rare and welcome thing in that earnest and often sombre place. Even now, after six years, I felt no awkwardness in his company; straight away we had fallen into our old custom of affectionate baiting.

‘Come, Bruno,’ Sidney said, putting an arm around my shoulders and leading me down the lawn towards the river. ‘By God, it is a fine thing to see you again. This royal visitation to Oxford would have been intolerable without your company. Have you heard of this Polish prince?’

I shook my head. Sidney rolled his eyes.

‘Well, you will meet him soon enough. The Palatine Albert Laski – a Polish dignitary with too much money and too few responsibilities, who consequently spends his time making a nuisance of himself around the courts of Europe. He was supposed to travel from here to Paris, but King Henri of France refuses to allow him into the country, so Her Majesty is stuck with the burden of his entertainment a while longer. Hence this elaborate pageant to get him away from court.’ He waved towards the barge, then glanced around briefly to make sure we were not overheard. ‘I do not blame the French king for refusing his visit, he is a singularly unbearable man. Still, it is quite an achievement – I can think of one or two taverns where I am refused entry, but to be barred from an entire country requires a particular talent for making yourself unwelcome. Which Laski has by the cartload, as you shall see. But you and I shall have a merry time in Oxford none the less – you will amaze the dullards there with your ideas, and I shall look forward to basking in your glory and showing you my old haunts,’ he said, punching me heartily again on the arm. ‘Although, as you know, that is not our whole purpose,’ he added, lowering his voice.

We stood side by side looking out over the river, busy then with little crafts, wherries and small white-sailed boats criss-crossing the shining water in the spring sun, which illuminated the fronts of the handsome brick and timber buildings along the opposite bank, a glorious panorama with the great spire of St Paul’s church towering over the rooftops far to the north. I thought what a magnificent city London was in our age, and how fortunate I was to be here at all, and in such company. I waited for Sidney to elaborate.

‘I have something for you from my future father-in-law, Sir Francis Walsingham,’ he whispered, his eyes still fixed on the river. ‘See what a knighthood gets me, Bruno – a job as your errand boy.’ He drew himself upright and looked about, shielding his eyes with his hand as he peered towards the mooring-place of our craft, before reaching for the oilskin bag he carried and pulling from it a bulging leather purse. ‘Walsingham sent this for you. You may incur certain expenses in the course of your enquiries. Call it an advance against payment.’

Sir Francis Walsingham. Queen Elizabeth’s Principal Secretary of State, the man behind my unlikely presence on this royal visitation to Oxford; even his name made my spine prickle.

We walked a little further off from the body of the crowd gathered to marvel as the barge was decked with flowers for our departure. Beside it, a group of musicians had struck up a dance tune and we watched the crowd milling around them.

‘But now tell me, Bruno – you have not set your sights upon Oxford merely to debate Copernicus before a host of dull-witted academicians,’ Sidney continued, in a low voice. ‘I knew as soon as I heard you had come to England that you must be on the scent of something important.’

I glanced quickly around to be sure no one was within earshot.

‘I have come to find a book,’ I said. ‘One I have sought for some time, and now I believe it was brought to England.’

‘I knew it!’ Sidney grabbed my arm and drew me closer. ‘And what is in this book? Some dark art to unlock the power of the universe? You were dabbling in such things in Padua, as I recall.’

I could not tell whether he was mocking me still, but I decided to trust to what our friendship had been in Italy.

‘What would you say, Philip, if I told you the universe was infinite?’

He looked doubtful.

‘I would say that this goes beyond even the Copernican heresy, and that you should keep your voice down.’

‘Well, this is what I believe,’ I said, quietly. ‘Copernicus told only half the truth. Aristotle’s picture of the cosmos, with the fixed stars and the six planets that orbit the earth – this is pure falsehood. Copernicus replaced the Earth with the Sun as the centre of the cosmos, but I go further – I say there are many suns, many centres – as many as there are stars in the sky. The universe is infinite, and if this is so, why should it not be populated with other earths, other worlds, and other beings like ourselves? I have decided it will be my life’s work to prove this.’

‘How can it be proved?’

‘I will see them,’ I said, looking out over the river, not daring to watch his reaction. ‘I will penetrate the far reaches of the universe, beyond the spheres.’

‘And how exactly will you do this? Will you learn to fly?’ His voice was sceptical now; I could not blame him.

‘By the secret knowledge contained in the lost book of the Egyptian sage Hermes Trismegistus, who first understood these mysteries. If I can trace it, I will learn the secrets necessary to rise up through the spheres by the light of divine understanding and enter the Divine Mind.’

‘Enter the mind of God, Bruno?’

‘No, listen. Since I saw you last I have studied in depth the ancient magic of the Hermetic writings and the Cabala of the Hebrews, and I have begun to understand such things as you would not believe possible.’ I hesitated. ‘If I can learn how to make the ascent Hermes describes, I will glimpse what lies beyond the known cosmos – the universe without end, and the universal soul, of which we are all a part.’

I thought he might laugh then, but instead he looked thoughtful.

‘Sounds like dangerous sorcery to me, Bruno. And what would you prove? That there is no God?’

‘That we are all God,’ I said, quietly. ‘The divinity is in all of us, and in the substance of the universe. With the right knowledge, we can draw down all the powers of the cosmos. When we understand this, we can become equal to God.’

Sidney stared at me in disbelief.

‘Christ’s blood, Bruno! You cannot go about proclaiming yourself equal to God. We may not have the Inquisition here but no Christian church will hear that with equanimity – you will be straight for the fire.’

‘Because the Christian church is corrupt, every faction of it – this is what I want to convey. It is only a poor shadow, a dilution of an ancient truth that existed long before Christ walked the earth. If that were understood, then true reform of religion might be possible. Men might rise above the divisions for which so much blood has been spilled, and is still being spilled, and understand their essential unity.’

Sidney’s face turned grave.

‘I have heard my old tutor Doctor Dee speak in this way. But you must be careful, my friend – he collected many of these manuscripts of ancient magic during the destruction of the monastic libraries, and he is called a necromancer and worse for it, not just by the common people. And he is a native Englishman, and the queen’s own astrologer too. Do not get yourself a reputation as a black magician – you are already suspicious as a Catholic and a foreigner.’ He stepped back and looked at me with curiosity. ‘This book, then – you believe it is to be found in Oxford?’

‘When I was living in Paris, I learned that it was brought out of Florence at the end of the last century and, if my advisor spoke the truth, it was taken by an English collector to one of the great libraries here, where it lies unremarked because no one who has handled it has understood its significance. Many of the Englishmen who travelled in Italy were university men and left their books as bequests, so Oxford is as good a place as any to start looking.’

‘You should start by asking John Dee,’ Sidney said. ‘He has the greatest library in the country.’

I shook my head.

‘If your Doctor Dee had this book, he would know what he held in his hands, and he would have made this revelation known by some means. It is still to be discovered, I am certain.’

‘Well, then. But don’t neglect Walsingham’s business in Oxford.’ He slapped me on the back again. ‘And for Christ’s sake don’t neglect me, Bruno, to go ferreting in libraries – I shall expect some gaiety from you while we are there. It’s bad enough that I must play nursemaid to that flatulent Pole Laski – I’m not planning to spend every evening with a clutch of fusty old theologians, thank you. You and I shall go roistering through the town, leaving the women of Oxford bow-legged in our wake!’

‘I thought you were to marry Walsingham’s daughter?’ I raised an eyebrow, feigning shock.

Sidney rolled his eyes.

‘When the queen deigns to give her consent. In the meantime, I do not consider myself bound by marriage vows. Anyway, what of you, Bruno? Have you been making up for your years in the cloister on your way through Europe?’ He elbowed me meaningfully in the ribs.

I smiled, rubbing my side.

‘Three years ago, in Toulouse, there was a woman. Morgana, the daughter of a Huguenot nobleman. I gave private tuition to her brother in metaphysics, but when her father was not at home she would beg me to stay on and read with her. She was hungry for knowledge – a rare quality in women born to wealth, I have found.’

‘And beautiful?’ Sidney asked, his eyes glittering.

‘Exquisite.’ I bit my lip, remembering Morgana’s blue eyes, the way she would try and coax me to laughter when she thought I grew too melancholy. ‘I courted her in secret, but I think I always knew it was only for a season. Her father wanted her to marry a Huguenot aristocrat, not a fugitive Italian Catholic. Even when I became a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toulouse and finally had the means of supporting myself, he would not consent, and he threatened to use all his influence in the city to destroy my name.’

‘So what happened?’ Sidney asked, intrigued.

‘She begged me to run away with her.’ I sighed. ‘I almost allowed myself to be persuaded, but I knew in my heart that it would not have been the future either of us wanted. So I left one night for Paris, where I ploughed all my energies into my writing and my advancement at court. But I often wonder about the life I turned my back on, and where I might have been now.’ My voice trailed away as I lowered my eyes again, remembering.

‘Then we should not have had you here, my friend. Besides, she’s probably married to some ageing duke by now,’ Sidney said heartily.

‘She would have been,’ I agreed, ‘had she not died. Her father arranged a marriage to one of his friends but she had an accident shortly before the wedding. Drowned. Her brother wrote and told me.’

‘You think it was by her own hand?’ Sidney asked, his eyes dramatically wide.

‘I suppose I will never know.’

I fell silent then, and gazed out across the water.

‘Well, sorry about that,’ Sidney said after a few moments, clapping me on the back in that matter-of-fact way the English have, ‘but still – the women of King Henri’s court must have provided you with plenty of distractions, eh?’

I regarded him for a moment, wondering if the English nobility really did have as little fine feeling as they pretended, or if they had developed this manner as a way of avoiding painful emotion.

‘Oh yes, the women there were beautiful, certainly, and happy enough to offer their attentions at first, but I found them sadly lacking in worthwhile conversation,’ I said, forcing a smile. ‘And they found me sadly lacking in fortune and titles for any serious liaison.’

‘Well, there you are, Bruno – you are destined for disappointment if you seek out women for their conversation.’ Sidney shook his head briefly, as if the idea were absurd. ‘Take my advice – sharpen your wits in the company of men, and look to women only for life’s softer comforts.’

He winked broadly and grinned.

‘Now I must oversee the arrangements or we shall never be on our way, and we are to dine at the palace of Windsor this evening so we need to make good progress. They say there will be a storm tonight. The queen will not be present, naturally,’ he said, noting my raised eyebrows. ‘I’m afraid the responsibility of entertaining the palatine is ours alone, Bruno, until we reach Oxford. Steel yourself and pray to that universal soul of yours for fortitude.’

‘I would not be the one to boast, but my friends do consider me to be something of a poet, Sir Philip,’ the Palatine Laski was saying in his high-pitched voice, which always sounded as if he was voicing a grievance, as our boat approached Hampton Court. ‘I had in mind that if we tire of the disputations at the university’ – here he cast a pointed glance at me – ‘you and I might devote some of our stay in Oxford to reading one another’s poetry and advising on it, as one sonneteer to another, what say you?’

‘Then we must include Bruno in our parley,’ Sidney said, flashing me a conspiratorial grin, ‘for in addition to his learned books, he has written a comic drama in verse for the stage, have you not, Bruno? What was it called?’

‘The Torch-bearers,’ I muttered, and turned back to contemplate the view. I had dedicated the play to Morgana and it was always associated with memories of her.

‘I have not heard of it,’ said the palatine dismissively.

Before our party had even reached Richmond I found myself in complete agreement with my patron, King Henri III of France: the Palatine Laski was unbearable. Fat and red-faced, he had a wholly misplaced regard for his own importance and a great love of the sound of his own voice. For all his fine clothes and airs, he was clearly not well acquainted with the bath-house, and under that warm sun a fierce stink came off him which, mingled with the vapours from the brown Thames at close quarters, was distracting me from what should have been an entertaining journey.

We had launched from the wharf at Winchester House with a great fanfare of trumpets; a boat filled with musicians had been charged to keep pace with us, so that the palatine’s endless monologue was accompanied by the twitterings and chirpings of the flute players to our right. To add to my discomfort, the flowers with which the barge had been so generously bedecked were making me sneeze. I sank back into the silk cushions, trying to concentrate on the rhythmic splashing of the oars as we glided at a stately pace through the city, smaller boats making way on either side while their occupants, recognising the royal barge, respectfully doffed their caps and stared as we passed. For my part, I had almost succeeded in reducing the palatine’s babble to a background drone as I concentrated on the sights, and would have been content to enjoy the gentle green and wooded landscape on the banks as we left the city behind, but Sidney was determined to amuse himself by baiting the Pole and wanted my collaboration.

‘Behold, the great palace of Hampton Court, which once belonged to our queen’s father’s favourite, Cardinal Wolsey,’ he said, gesturing grandly towards the bank as we drew close to the imposing red-brick walls. ‘Not that he enjoyed it for long – such is the caprice of princes. But it seems the queen holds you in great esteem, Laski, to judge by the care she has taken over your visit.’

The palatine simpered unattractively.

‘Well, that is not for me to say, of course, but I think it is well-known by now at the English court that the Palatine Laski is granted the very best of Her Majesty’s hospitality.’

‘And now that she will not have the Duke of Anjou, I wonder whether we her subjects may begin to speculate about an alliance with Poland?’ Sidney went on mischievously.

The palatine pressed the tips of his stubby fingers together as if in prayer and pursed his moist lips, his little piggy eyes shining with self-congratulating pleasure.

‘Such things are not for me to say, but I have noticed in the course of my stay at court that the queen did pay me certain special attentions, shall we say? Naturally she is modest, but I think men of the world such as you and I, Sir Philip, who have not been shut up in a cloister, can always tell when a woman looks at us with a woman’s wants, can we not?’

I snorted with incredulity then, and had to disguise it as a sneezing fit. The minstrels finished yet another insufferably jaunty folk song and turned to a more melancholic tune, allowing me to lapse into reflective silence as the fields and woods slid by and the river became narrower and less noisome. Clouds bunched overhead, mirrored in the stretch of water before us, and the heat began to feel thick in my nostrils; it seemed Sidney had been right about the coming storm.

‘In any case, Sir Philip, I have taken the liberty of composing a sonnet in praise of the queen’s beauty,’ announced the palatine, after a while, ‘and I wonder if I might recite it for you before I deliver it to her delicate ears? I would welcome the advice of a fellow poet.’

‘You had much better ask Bruno,’ Sidney said carelessly, trailing his hand in the water, ‘his countrymen invented the form. Is that not so, Bruno?’

I sent him a murderous look and allowed my thoughts to drift to the horizon as the palatine began his droning recital.

If anyone had predicted, during those days when I begged my way from city to city up the length of the Italian peninsula, snatching teaching jobs when I could find them and living in the roadside inns and cheap lodgings of travellers, players and pedlars when I could not, that I would end up the confidant of kings and courtiers, the world would have thought them insane. But not me – I always believed in my own ability not only to survive but to rise through my own efforts. I valued wit more than the privileges of birth, an enquiring mind and hunger for learning above status or office, and I carried an implacable belief that others would eventually come to see that I was right; this lent me the will to climb obstacles that would have daunted more deferential men. So it was that from itinerant teacher and fugitive heretic, by the age of thirty-five I had risen almost as high as a philosopher might dream: I was a favourite at the court of King Henri III in Paris, his private tutor in the art of memory and a Reader in Philosophy at the great university of the Sorbonne. But France too was riven with religious wars then, like every other place I had passed through during my seven-year exile from Naples, and the Catholic faction in Paris under the Guise family were steadily gaining strength against the Huguenots, so much so that it was rumoured the Inquisition were on their way to France. At the same time, my friendship with the king and the popularity of my lectures had earned me enemies among the learned doctors at the Sorbonne, and sly rumours began to slip through the back streets and into the ears of the courtiers: that my unique memory system was a form of black magic and that I used it to communicate with demons. This I took as my cue to move on, as I had done in Venice, Padua, Genoa, Lyon, Toulouse and Geneva whenever the past threatened to catch up; like many religious fugitives before me, I sought refuge under the more tolerant skies of Elizabeth’s London, where the Holy Office had no jurisdiction, and where I hoped also to find the lost book of the Egyptian high priest Hermes Trismegistus.

The royal barge moored at Windsor late in the afternoon, where we were met by liveried servants and taken to our lodgings at the royal castle to dine and rest for the night before progressing to Oxford early the next day. Our supper was a subdued affair, perhaps partly because the sky had grown very dark by the time we arrived in the state apartments, requiring the candles to be lit early, and a heavy rain had begun to fall; by the time our meal was over the water was coursing down the tall windows of the dining hall in a steady sheet.

‘There will be no boat tomorrow if this continues,’ Sidney observed, as the servants cleared the dishes. ‘We will have to travel the rest of the way by road, if horses can be arranged.’

The palatine looked petulant; he had clearly enjoyed the languor of the barge.

‘I am no horseman,’ he complained, ‘we will need a carriage at the very least. Or we could wait here until the weather clears,’ he suggested in a brighter tone, leaning back in his chair and looking about him covetously at the rich furnishings of the palace dining room.

‘We have no time,’ Sidney replied. ‘Bruno’s great disputation before the whole university is the day after tomorrow and we must give our speaker enough leisure to prepare his devastating arguments, eh, Bruno?’

I turned my attention from the windows to offer him a smile.

‘In fact, I was just about to excuse myself for that very purpose,’ I said.

Sidney’s face fell.

‘Oh – will you not sit up and play cards with us a while?’ he asked, a note of alarm in his voice at the prospect of being left alone with the palatine for the evening.

‘I’m afraid I must lose myself in my books tonight,’ I said, pushing my chair back, ‘or this great disputation, as you call it, will not be worth hearing.’

‘I’ve sat through few that were,’ remarked the palatine. ‘Never mind, Sir Philip, you and I shall make a long night of it. Perhaps we may read to one another? I shall call for more wine.’

Sidney threw me the imploring look of a drowning man as I passed him, but I only winked and closed the door behind me. He was the professional diplomat here, he had been bred to deal with people like this. A great crack of thunder echoed around the roof as I made my way up an ornately painted staircase to my room.

For a long while I did not consult my papers or try to put my thoughts in order, but only lay on my bed, my mind as unsettled as the turbulent sky, which had turned a lurid shade of green as the thunder and lightning grew nearer and more frequent. The rain hammered against the glass and on the tiles of the roof and I wondered at the sense of unease that had edged out the morning’s thrill of anticipation. My future in England, to say nothing of the future of my work, depended greatly on the outcome of this journey to Oxford, yet I was filled with a strange foreboding; in all these rootless years of belonging nowhere, depending on no one but my own instinct for survival, I had learned to listen to the prickling of my moods. When I had intimations of danger, events had usually proved me right. But perhaps it was only that, once again, I was preparing to take on another shape, to become someone I was not.

I had been in London less than a week, staying as a guest of the French ambassador at the request of my patron, King Henri, who had reluctantly agreed to my plea to leave Paris indefinitely, when I received a summons from Sir Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth’s Principal Secretary of State. It was not the kind of invitation one declined, yet the manner of its arrival gave me no clue as to how a statesman of such importance knew of my arrival or what he wanted of me. I rode out the next day to his grand house on the prosperous street of Seething Lane, close by the Tower in the east of the City of London, and was shown through the house by a harried-looking steward into a neat garden, where box trees in geometric patterns gave way to an expanse of wilder grass. Beyond this I saw a cluster of low fruit trees in the full swell of their blossom, a magnificent canopy of white and pink, and among them, gazing up into their twisted branches, stood a tall figure dressed all in black.

At the steward’s nod, I stepped towards the man under the trees, who had turned to face me – or so I believed, for the late afternoon sun was slanting down directly behind him, leaving him silhouetted, a lean black shape against the golden light. I could not gauge his expression, so I paused a few feet away from him and bowed deeply in a manner I hoped was fitting.

‘Giordano Bruno of Nola, at your honour’s service.’

‘Buonasera, Signor Bruno, e benvenuto, benvenuto,’ he said warmly, and strode forward, holding out his right hand to clasp mine in the English style. His Italian was only faintly coloured by the clipped tones of his native tongue, and as he approached I could see his face clearly for the first time. It was a long face, made the more severe by the close-fitting black cap he wore over receding hair. I guessed him to be about fifty years of age, and his eyes were lit with a sharp intelligence that seemed to make plain without words that he would not suffer fools. Yet his face also bore the traces of great weariness; he looked like a man who carried a heavy burden and slept little.

‘A fortnight past, Doctor Bruno, I received a letter from our ambassador in Paris informing me of your arrival in London,’ he began, without preamble. ‘You are well known at the French court. Our ambassador says he cannot commend your religion. What do you think he could mean by that?’

‘Perhaps he refers to the fact that I was once in holy orders, or the fact that I am no longer,’ I said, evenly.

‘Or perhaps he means something else altogether,’ Walsingham said, looking at me carefully. ‘But we will come to that. First tell me – what do you know of me, Filippo Bruno?’

I snapped my head round to stare at him then, wrong-footed – as he had intended I should be. I had abandoned my baptismal name when I entered the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore and taken my monastic name of Giordano, though I had reclaimed it briefly while I was on the run. For Walsingham to address me by it now was clearly a little trick to show me the reach of his knowledge, and he was evidently pleased with its effect. But I recovered myself, and said,

‘I know enough to see that only a fool would attempt to hide anything from a man who has never met me, yet calls me by the name my parents gave me, a name I have not used these twenty years.’

Walsingham smiled.

‘Then you know all that matters at present. And I know that you are no fool. Reckless, perhaps, but not a fool. Now, shall I tell you what else I know about you, Doctor Giordano Bruno of Nola?’

‘Please – as long as I may be permitted to separate for your honour the ignominious truth from the merely scurrilous rumour.’

‘Very well, then.’ He smiled indulgently. ‘You were born in Nola, near Naples, the son of a soldier, and you entered the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore in your teens. You abandoned the order some thirteen years later, and fled through Italy for three years, pursued by the Inquisition on suspicion of heresy. You later taught in Geneva, and in France, before attracting the patronage of King Henri III in Paris. You teach the art of memory, which many consider to be a kind of magic, and you are a passionate supporter of Copernicus’s theory that the Earth rotates around the Sun, though the idea has been declared heretical by Rome and by the Lutherans alike.’

He looked at me for confirmation, and I nodded, bemused.

‘Your honour knows much.’

He smiled.

‘There is no mystery here, Bruno – when you stopped briefly in Padua, you became friends with an English courtier named Philip Sidney, did you not? Well – he is shortly to marry my daughter, Frances.’

‘Your honour could not have found a worthier son-in-law, I am sure. I shall look forward to seeing him,’ I said, and meant it.

Walsingham nodded.

‘As a matter of curiosity – why did you abandon the monastery?’

‘I was caught reading Erasmus in the privy.’

He stared at me for a moment, then threw back his head and guffawed; a deep, rich sound, such as a bear might make if it could laugh.

‘And I had other volumes on the Forbidden Index of the Holy Office. They would have sent me before the Inquisitor, but I escaped. This is why I was excommunicated.’ I folded my hands behind my back as I walked, thinking how strange it seemed to be reliving those days in this green English garden.

He regarded me with an inscrutable expression and then shook his head as if puzzled.

‘You intrigue me greatly, Bruno. You fled Italy pursued by the Roman Inquisition for your suspected heresy, and yet you were also arrested and tried by the Calvinists in Geneva for your beliefs, is it not so?’

I tilted my head, half-assenting.

‘There was something of a misunderstanding in Geneva. I found the Calvinists had only swapped one set of blind dogma for another.’

Again he looked at me with something approaching admiration, and laughed, shaking his head.

‘I have never met another man who has managed to get himself accused of heresy by both the pope and the Calvinists. This is a singular achievement, Doctor Bruno! It makes me ask myself – what is your religion?’

There was an expectant pause while he looked at me encouragingly.

‘Your honour knows that I am no friend of Rome. I assure you that in everything my allegiance is to Her Majesty and I would be glad to offer her any service I may while I remain under her sovereignty.’

‘Yes, yes, Bruno – I thank you, but that is not an answer to my question. I asked what is your religion? In your heart, are you papist or Protestant?’

I hesitated.

‘Your honour has already pointed out that both sides have found me wanting.’

‘Are you saying that you are neither? Are you an atheist, then?’

‘Before I answer that, may I know what the consequences of my answer might be?’

He smiled then. ‘This is not an interrogation, Bruno. I only wish to understand your philosophy. Speak frankly with me, and I will speak frankly with you. This is why we are walking here among the trees, where we will not be overheard.’

‘Then I assure your honour that I am not what is usually meant by the word “atheist”,’ I said, fervently hoping that I was not condemning myself. ‘In France, and here in her embassy, I call myself a Catholic because it is simpler not to make trouble. But in truth, I do not think of myself as Catholic or Protestant – these terms are too narrow. I believe in a greater truth.’

He raised an eyebrow.

‘A greater truth than the Christian faith?’

‘An ancient truth, of which the Christian faith is one later interpretation. A truth which, if it could be properly understood in our clouded age, might enlighten men instead of perpetuating these bloody divisions.’

A pregnant silence fell. The sun was low in the sky now, and in the shade of the trees the air was growing cool. Birdsong became more insistent with the gathering dusk, and Walsingham continued to pace through the grass, the shoulders of his black doublet flecked with white petals of blossom that fluttered from the branches overhead.

‘Faith and politics are now one and the same,’ he went on. ‘Perhaps it was always so, but it seems to have reached new extremes in our troubled century, do you not think? A man’s religion tells me where his political loyalties lie, far more than his place of birth or his language. There are many stout Englishmen in this realm with a greater love for Rome than you have, Bruno, or than they have for their own queen. Yet, in the end, faith is not merely politics. Above all else it is a matter of a man’s private conscience, and how he stands before God. I have done things in God’s name that I must justify before Him at the last judgement.’ He turned and fixed me with an expression of sorrow then. When he spoke again his voice was quiet and expressionless. ‘I have stood by and watched a man’s beating heart ripped from his living body at my command. I have coldly questioned men as their limbs were pulled from their sockets on the rack, and the very noise of that is enough to bring your stomach into your mouth. I have even turned the wheels myself, when the secrets that might spill from a man’s lips as he stretched were too sensitive for the ears of professional torturers. I have seen the human body, made in the likeness of God, forced to the very limits of pain. And I have visited all these horrors and more on my fellow creatures because I believed that by doing so I was preventing greater bloodshed.’

He passed a hand across his forehead then, and resumed walking.

‘Our nation is young in the new religion, and there are many in France and Spain who, with the backing of Rome, seek to kill Her Majesty and replace her with that Devil’s bitch, Mary of Scotland.’ He shook his head. ‘I am not a cruel man, Bruno. It gives me no pleasure to inflict suffering, unlike some among my executioners.’ He shuddered, and I believed him. ‘Nor am I the Inquisition – I do not imagine myself responsible for men’s immortal souls. That I leave to those ordained to the task. I do what I do purely to ensure the safety of this realm and the queen’s person. Better to have one priest gutted before the crowds at Tyburn than he should go free to convert twenty, who might in time join others and rise up against her.’

I inclined my head in acknowledgement; he did not seem to expect debate. Beneath the largest and oldest tree in the orchard a circular bench had been constructed to fit around its trunk. Here Walsingham motioned to me to sit beside him.

‘You are a man who knows first-hand the persecutions Rome visits on her enemies. The streets of England would run with blood if Mary of Scotland found her way to the throne. Do you understand me, Bruno? But these conspiracies to put her there are like the heads of the Hydra – we cut off one and ten more grow in its place. We executed that seditious Jesuit Edmund Campion in ’81 and now the missionary priests are sailing for England by their dozens, inspired by his example of martyrdom.’ He shook his head.

‘Your honour’s task is not one I envy.’

‘It is the task God has given me, and I must look for those who will help me in it,’ he said simply. ‘Tell me, Bruno – does the French king provide for you, other than your lodgings at the embassy?’

‘He supports me rather with his good opinion than with his purse,’ I said. ‘I had hoped to supplement my small stipend with some teaching. To that end I planned to visit the famous University of Oxford, to see if they might have some use for me there.’

‘Oxford? Indeed?’ he said, a spark of interest catching in his eyes. ‘Now there is a place mired in the mud of popery. The university authorities make a show of rooting out those who still practice the old faith, but in truth half the senior men there are secret papists. The Earl of Leicester, who is its chancellor, makes endless visitations and orders enquiries, but they scurry away like spiders under stones as soon as he shines a light on them. Then, once our backs are turned, they go on filling the heads of England’s young men with their idolatry – the very young men who will go on to the law and the church, and into public life. Our future government and clergy, no less, being turned secretly to Rome under our very noses. Her Majesty is furious and I have told Leicester it must be addressed with more vigour.’ He pressed his lips together, as if to suggest things would not be so lax if he were in charge. ‘The place has become a sanctuary for those who trade in seditious books, and most of these missionary priests coming out of the French seminaries are Oxford men, you know.’ Then he thought for a moment, and moderated his tone. ‘Yes, you should go to Oxford. In fact, I shall be glad to recommend you if you wish to visit. There is much you might see of interest.’

He paused as if contemplating some idea, then his thoughts appeared to land briskly elsewhere.

‘When you told me you wished to serve Her Majesty in any way she saw fit to use you – was this offer sincere?’

‘I would not make such an offer in jest, your honour.’

‘Her Majesty has money in her treasury for those willing to be employed under my authority, to aid in protecting her person and her realm from her enemies. And she would show her gratitude by other means as well – I know how important patronage and preferment can be to you writers. This would be the greatest service you could perform for her, Bruno – living at the French embassy, you will be privy to a great many clandestine conversations, and anything you hear touching plots against Her Majesty or her government, anything that concerns the Scottish queen and her French conspirators’ – he spread his arms wide – ‘letters you may glimpse, anything that you think may be of interest, no matter how small, would be of great value to us.’

He looked at me then, eyebrows raised in a question.

I hesitated.

‘I am flattered that your honour shows such faith in me—’

‘You have scruples, of course,’ he cut in, impatiently. ‘And I would think the less of any man who did not – I am asking you to present a false face to your hosts, and an honest man should pause before taking on such a role. But remember, Bruno – whenever you feel the wrench between conscience and duty, your care should always be for the greater good. The innocent among them will have nothing to fear.’

‘It is not quite that, your honour.’

‘Then what?’ He looked puzzled. ‘Philip Sidney told me you were so much an enemy of Rome that you would gladly join the fight against those who would bring the Inquisition to these shores.’

‘I am an enemy of Rome, your honour, as I am opposed to all who would tell men what to believe and then execute them when they dare to question the smallest part of it.’

I was silent for a moment while he regarded me through narrowed eyes.

‘We do not punish men for their beliefs here, Bruno. Her Majesty once eloquently declared that she had no desire to make windows into men’s souls, and no more do I. In this country, it is not what a man believes that will lead him to the scaffold, but what he may do in the name of those beliefs.’

‘What he may do, or what he can be proved to have done?’ I asked pointedly.

‘Intent is treason, Bruno,’ he replied impatiently. ‘Propaganda is treason. In these times, even distributing forbidden books is treason, because anyone who does so does it with the intent of converting those into whose hands they place them. And converting the queen’s subjects means seducing their loyalties away from her to the pope, so that if a Catholic force invaded, they would side with the aggressors.’

We sat in silence for a moment, then he placed a hand on my arm.

‘Here in England, a man of progressive ideas such as yours, Bruno, may live and write freely, without fear of punishment. That, I presume, is why you came here. Would you have the Inquisition return to threaten those freedoms?’

‘No, your honour, I would not.’

‘Then you will consent to serve Her Majesty in this way?’

I paused, and wondered how my answer would change my fortunes.

‘I will serve her to the best of my ability,’ I replied.

Walsingham smiled broadly then – I caught the glint of his teeth in the dusk – and clasped my hand between both of his, the skin dry and papery.

‘I am exceedingly glad, Bruno. Her Majesty will reward your loyalty, when it has been proved.’ His eyes shone. Around us the garden was almost in darkness, though a few streaks of gold light still edged the violet banks of cloud behind the trees, and the air had grown chill, the plants releasing sweet scents into the evening breeze. ‘Come, let us go inside. What a poor host I am – you have not even had a drink.’

He rose, with an evident stiffness in his back and hips, and began making his way over the grass.

A servant had lit a series of small lanterns along each side of the path through the knot garden, so that as we approached the house our way was lit by two rows of flickering candles; the effect was charming, and as I took a deep breath of the evening air I felt again an intimation of new possibilities, a future that I could grasp. The long days of travelling through the mountains of northern Italy, staying in filthy roadside inns infested with rats, where I would force myself to keep awake all night with one hand on my dagger for fear of being murdered for the few coins I carried, seemed very far distant; I was entering the intelligence service of the Queen of England. Another of my life’s unexpected turns, but part of the great map of my strange journey through the world, I thought.

Walsingham halted just before the lanterns and leaned towards me.

‘I will arrange for you to meet with my assistant, Thomas Phelippes,’ he said. ‘He organises the logistics – devises ciphers, delivery points for correspondence, that side of business. He is the most skilled man in England for breaking codes. I hardly need to say that you should not breathe a word of our meeting to anyone except Sidney,’ he added, in a low voice.

‘Your honour, I was once a priest – I can lie as well as any man.’

He smiled.

‘I rely upon it. You could not have outwitted the Inquisition for this long without some talent for dissembling.’

So it was that I became part of what I later learned was a vast and complex network of informers that stretched from the colonies of the new world in the west to the land of the Turks in the east, all of us coming home to Walsingham holding out our little offerings of secret knowledge as the dove returned to Noah bearing her olive branch.

A sudden crack of thunder overhead jolted me out of memory, back to the room where I sat pressed up against the rain-slick window of a royal palace, watching a courtyard illuminated by sheets of light. In England I had hoped to live peacefully and write the books that I believed would shake Europe to its foundations, but I was ambitious and that was my curse. To be ambitious when you have neither means nor status leaves you dependent on the patronage of greater men – or, in this case, women. Tomorrow I would see the great university city of Oxford, where I must ferret out two nuggets of gold: the secrets Walsingham wanted from the Oxford Catholics, and the book I now believed to be buried in one of its libraries.

PART TWO (#ulink_388d10e9-f50f-52a9-8ac5-aae041c27592)

TWO (#ulink_817d9dd8-4348-5c57-b97b-988efe45c4a6)

We left for Oxford at first light the following morning on horses that Sidney procured from the steward at Windsor, fine mounts with elaborate harnesses of crimson and gold velvet, studded with brass fittings that jingled merrily as we rode, but we were undoubtedly a more solemn party than had set out the day before on the river amid music and gaily coloured pennants. The storm had broken but the rain had set in determinedly, the warmth had evaporated from the air and the sky seemed to sag over us, grey and sullen; it would have been impossible to travel by river without being half-drowned. The palatine was much quieter over breakfast and sat with his fingers pressed to his temples, occasionally emitting a little moan – Sidney whispered to me that this was the penance for a late night and prodigious quantities of port wine – and my mood was much improved accordingly. Sidney was cheerful, as his winnings from the night’s card games had grown steadily in direct proportion to the palatine’s drinking, but the weather had dampened our bright mood and we spent the first part of the journey in silence, broken now and again by Sidney’s observations of the road conditions or the palatine’s unapologetic belches.

To either side, the thick green landscape passed unchanging, bedraggled under the rain, the only sound the muted thud of hooves on the wet turf as Sidney drew his horse alongside mine at the head of the party and allowed the palatine to fall behind, his head drooping to his chest, flanked by the two bodyservants who attended him, their horses carrying the vast panniers containing Laski’s and Sidney’s finery for the visit. I had only one leather bag with a few books and a couple of changes of clothes, which I kept with me, strapped to my own saddle. By the middle of the afternoon we had reached the royal forest of Shotover on the outskirts of Oxford. The road was poorly maintained where it passed through the forest and we had to slow our pace so the horses would not stumble in the puddles and potholes.

‘So, Bruno,’ Sidney said, keeping his voice low, when we were out of earshot of the palatine and his servants, ‘tell me more about this book of yours, that has brought you all the way from Paris.’

‘For the last century it was thought lost,’ I replied softly, ‘but I never believed that, and all through Europe I met book dealers and collectors who whispered rumours and half-remembered stories about its possible whereabouts. But it was not until I was living in Paris that I found real proof that the book could be found.’

In Paris, I told him, among the circle of Italian expatriats that gathered around the fringes of King Henri’s court, I had met an aged Florentine gentleman named Pietro who never tired of boasting to acquaintances that he was the great-great-nephew of the famous book dealer and biographer Vespasiano da Bisticci, maker of books for Cosimo de’ Medici and cataloguer of the Vatican library. This Pietro, knowing of my interest in rare and esoteric works, recounted to me a story passed down to him by his grandfather, Vespasiano’s nephew, who had been an apprentice to his uncle in the manuscript trade during the 1460s, in the last years of Cosimo’s life. Vespasiano had assisted Cosimo in the collection of his magnificent library, making more than two hundred books at his commission and furnishing the copyists with classical texts, so that the book dealer became an intimate associate of the Medici circle, and in particular a friend of Marsilio Ficino, the great humanist philosopher and astrologer whom Cosimo had appointed head of his Florentine Academy and official translator of Plato for the Medici library. As Pietro’s grandfather, who was then the young apprentice, told it, one morning in 1463, the year before Cosimo died, Ficino came to visit Vespasiano at his shop, clearly in a state of some distress, clutching a package. He, Ficino, had already begun work on the Plato manuscripts when he had received word from his patron that he must abandon them and turn his attention as a matter of urgency to the Hermetic writings, which had been brought out of Macedonia some three years earlier by one of the monks Cosimo employed to adventure overseas in search of books from the libraries of Byzantium, but which had yet to be examined. Perhaps Cosimo knew he was dying and wanted to read Hermes more than he wanted to read Plato in the last days of his life, I can only speculate. In any case, the story goes that Ficino told Vespasiano, ashen-faced and trembling, that he had read the fifteen books of the Hermetic manuscript and knew that he could not fulfil his commission. He would translate for Cosimo the first fourteen, but the final manuscript, he said, was too extraordinary, too momentous in its import, to put into the language of men hungry for power, for it revealed the greatest secret of Hermes Trismegistus, the lost wisdom of the Egyptians, a secret that could destroy the authority of the Christian church. This book would teach men nothing less than the secret of knowing the Divine Mind. It would teach men how to become like God.

Ficino had brought this devastating Greek manuscript to the shop with him, carefully wrapped in oilskins; here he handed it over to Vespasiano, exhorting him to keep it safe until such time as they could decide what should be done with it while he, Ficino, would tell Cosimo that the fifteenth book had never been brought out of Byzantium with the original manuscripts. This was the plan, and the remaining books were duly translated; after Cosimo died the following year, Ficino and Vespasiano met to discuss the fate of the fifteenth book. Vespasiano saw the opportunity for profit and favoured selling it to one of the wealthy monastic libraries, where experienced scholars would know how to keep it safe from the eyes of those who might misinterpret or abuse the knowledge it contained; Ficino, on the other hand, had begun to regret his earlier delicacy and wondered whether it might not be better to translate the book after all, bringing its secrets into the light by revealing them first to the eminent thinkers of the Florentine Academy, the better to debate the impact of what was effectively the most blasphemous heretical philosophy ever to be uttered in Italy.

‘So who won?’ Sidney asked, forgetting to keep his voice down, his eyes gleaming through the stream of rainwater dripping from the peak of his cap.

‘Neither,’ I replied bluntly. ‘When they came to take the manuscript from the archive, they made a terrible discovery. The book had been sold by mistake some months before with a bundle of other Greek manuscripts that had been ordered by an English collector.’

‘Who?’ Sidney demanded.

‘I don’t know. Nor did Vespasiano.’ I lowered my eyes and we rode on in contemplative silence.

Here Pietro’s story ended. His grandfather, he said, knew no other details, only that an English collector passing through Florence had taken the manuscript and that Vespasiano was never able to trace it, though he tried through all his contacts in Europe until the end of his long life, in the dying years of the last century. It was little enough to go on, I knew; there had been numerous English collectors of antiquities and rare books travelling through Italy in the past century, and there was no knowing whether the man who had acquired such a book by accident might have sold it on or merely abandoned it to gather dust in some corner of a library, not realising what fortune had dropped into his hands.

‘Then why do you believe it is in Oxford?’ Sidney asked, after a while.

‘Process of elimination. The English collectors travelling through Europe in those years would have been educated men, probably wealthy, and I understand it is the custom of English gentlemen to leave books as a bequest to their universities, since precious few can afford to maintain private collections like your Doctor Dee. If the Hermes book ended up in England, it may well have found its way to Oxford or Cambridge. All I can do is look.’

‘And if you find it …?’ Sidney began, but he was interrupted as his horse suddenly shied sideways with a sharp whinny; two figures had appeared without warning in the middle of the road. We pulled our horses up briskly, the palatine and his servants almost running into the back of us as we looked down at two ragged children, a girl of about ten years old and a smaller boy, barefoot in the mud. The girl’s right cheek was livid with a purple bruise. She held out her small hand, palm upwards, and addressed herself to Sidney in an imploring voice, though her stare was one of pure insolence.

‘Alms, sir, for two poor orphans?’

Sidney shook his head silently, as if in sorrow at the state of the world, but reached at the same time for the purse at his belt and was drawing out a coin for the child when there came a sharp cry from behind us. I wheeled around just in time to see one of the palatine’s servants dragged from his horse by a burly man who had emerged silently, along with two others, from among the shadows of the trees to either side. The palatine gave a little shriek, but gathered his wits remarkably quickly and spurred his horse forwards into a gallop, crashing between Sidney and me and almost trampling the two children, who dived into the undergrowth just in time to watch him disappearing around the bend. I jumped from my horse, pulling Paolo’s knife from my belt as I launched myself at the back of one of the assailants, who was swinging a stout wooden staff at the second servant to knock him out of his saddle. Sidney took a moment to react, then dismounted and drew his sword, making for the men who were now trying to cut the straps holding the packs to the horses.