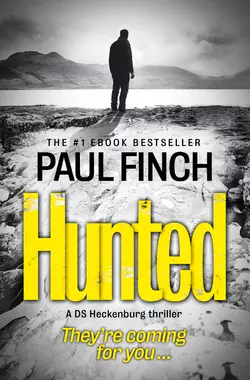

Hunted

Paul Finch

Get hooked on Heck: the maverick detective who knows no boundaries. A grisly whodunit you won’t be able to put down, perfect for fans of Stuart MacBride and TV series ‘Luther’.Heck needs to watch his back. Because someone’s watching him…Across the south of England, a series of bizarre but fatal accidents are taking place. So when a local businessman survives a near-drowning but is found burnt alive in his car just weeks later, DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg is brought in to investigate.Soon it appears that other recent deaths might be linked: two thieves that were bitten to death by poisonous spiders, and a driver impaled through the chest with scaffolding.Accidents do happen but as the body count rises it’s clear that something far more sinister is at play, and it’s coming for Heck too…

Copyright (#uf630308b-9f48-5e3d-84ad-6a1e3811f601)

Published by Avon an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2015

Copyright © Paul Finch 2015

Cover photographs © Arcangel Images / Trevillion Images

Cover design © Andrew Smith 2015

Paul Finch asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007492336

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780007492343

Version: 2017-10-25

Dedication (#uf630308b-9f48-5e3d-84ad-6a1e3811f601)

For my lovely wife, Catherine, whose selfless and unswerving support has been the bedrock on whichI’ve built my career.

Table of Contents

Cover (#uf82b23f7-3512-5b65-8e6f-648c18c4aa1c)

Title Page (#u3d30bde7-55d9-55f2-8541-64f179691264)

Copyright (#u6414abdd-9747-5a3c-b730-c0b057978ae6)

Dedication (#ud289fd7b-2461-5f7e-b49c-6015585c4a2a)

Chapter 1 (#u3d76e201-d0d5-5b73-9c78-58ae802a611c)

Chapter 2 (#u4c965603-7c4a-5df7-b2e6-a1a786221825)

Chapter 3 (#ud47aecf5-ad16-5ee6-9003-bbd33c3c7f54)

Chapter 4 (#u81736a03-fedf-5358-a546-63c247572e08)

Chapter 5 (#u8f75c658-2850-5a8a-b4ec-27d7a640a573)

Chapter 6 (#u4e9dba3f-6881-5097-ae35-7b5d03434808)

Chapter 7 (#u4aad56ec-6ba7-5b96-a876-7741574e1b66)

Chapter 8 (#u5b0c21f3-349b-5555-ac17-ccfb5b7374d6)

Chapter 9 (#uff9e3961-8a97-56c5-84c9-350220d35aa6)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#uf630308b-9f48-5e3d-84ad-6a1e3811f601)

Dazzer and Deggsy didn’t give a shit about anyone. At least, that was the sort of thing they said if they were bragging to mates at parties, or if the coppers caught them and tried to lay a guilt trip on them.

They did what they did. They didn’t go out looking to hurt anyone, but if people got in the way, tough fucking shit. They pinched motors and had a laugh in ’em. That was their thing. And they were gonna keep doing it, because it was the best laugh ever. No one was gonna stop them, and if some geezer ever got pissed off because he’d just seen his pride and joy totalled, so what? Dazzer and Deggsy didn’t give a shit.

Tonight was a particularly good night for it.

All right, it wasn’t perishing cold, which was a shame. Incredible though it seemed to Dazzer and Deggsy, some numbskulls actually came outside, saw a bit of ice and snow and left their motors running for five minutes with the key in the ignition while they went back indoors for a cuppa; all you had to do was jump in the saddle and ride away, whooping. But if nothing else, it was dank and misty, and with it being the tail end of January, it got dark early – so there weren’t too many people around to interfere.

Not that folk tended to interfere with Dazzer and Deggsy.

The former was tall for his age; just under six foot, with a broad build and a neatly layered patch of straw-blond hair in the middle of his scalp, the rest of which was shaved to the bristles. If it hadn’t been for the acne covering his brutish features, you’d have thought him eighteen, nineteen, maybe twenty – instead of sixteen, which was his true age, though of course even a sixteen-year-old might clobber you these days if you had the nerve to look at him the wrong way. The second member of the tag team, Deggsy, though he wasn’t by any means the lesser in terms of villainy, looked more his age. He was shorter and thinner, weasel-faced and the proud owner of an unimpressively wispy moustache. His oily black thatch was usually covered by a grimy old baseball cap, the frontal logo of which had been erased long ago and replaced with letters written in Day-Glo orange highlighter, which read: Fuck off.

There was barely thirty years of experience between them, yet they both affected the arrogant swagger and truculent sneer of guys who believed they knew what was what, and were absolutely confident they were owed whatever they took.

It was around nine o’clock that night when they spied their first and most obvious target: a Volkswagen estate hatchback. A-reg and in poor shape generally: grubby, rusted around the arches, occasional dents in the bodywork; but it ticked all the boxes.

Posh motors were almost impossible to steal these days. All that top-of-the-range stuff was the sole province of professional crims who would make a fortune from ringing it and selling it on. No, if you were simply looking for a fun time, you had to settle for this lower quality merchandise – but that could also be an advantage, because when you went and smacked a bit of rubbish around on the streets, the coppers would tow it away afterwards but would rarely investigate. In addition, this one’s location was good. The old Volkswagen estate was sitting right in the middle of a CCTV black spot that Dazzer and Deggsy had made it their business to know about.

They watched it from a corner, eyes peeled for any sign of movement, but the dim sodium glow of a lone streetlamp illuminated only a rolling beer can and a few scraps of wastepaper flapping in the half-hearted breeze.

Still, they waited. They’d been successful several times on this patch – it was a one-lane access way running between the back doors of a row of old shops and a high brick wall, ending at three concrete bollards. No one was ever around here at night; there were no tenants in the flats above the shops, and even without the January miasma this was a dark, dingy place – but such apparent ease of opportunity only made Dazzer and Deggsy more suspicious than usual. The very fact that motors had been lifted from around here before made the presence of this one seem curious. Did people never learn? Maybe they didn’t. Though maybe there were other factors as well. The row of shops was a bit of an eyesore. Only one or two were occupied during the day, most of the others were To Let, and a couple were even boarded up as if they’d just been abandoned. God bless the Recession.

The lads ventured forth, walking boldly but stealthily, alert to the slightest unnatural sound – but no one called out, no one stepped from a darkened doorway.

The Volkswagen was locked of course, but Deggsy had his screwdriver with him, and in less than five seconds they’d forced the driver’s door open. No alarm sounded, which was just what they’d expected given the ramshackle state of the thing; another advantage of pillaging the less well-off. With rasping titters, they jumped inside, to find that the steering column had been attacked in the past – it was held together by wads of silvery duct tape. A few slashes of Dazzer’s Stanley knife and they were through it. Even in the pitch darkness, their gloved but nimble fingers found the necessary wiring, and the contact was made.

The car rumbled to life. Laughing loudly, they hit the gas.

It was Dazzer’s turn to drive today, and Deggsy’s to ride, though it didn’t make much difference – they were both as crazy as each other when they got behind the wheel. They blistered recklessly along, swerving around bends with tyres screeching, racing through red lights and stop signs. There was no initial response from the other road-using public. Opposing traffic was scant. They pulled a handbrake turn, pivoting sideways through what would ordinarily be a busy junction, the stink of burnt rubber engulfing them, hitting the gas again as they tore out of town along the A246. They had over half a tank of petrol and a very straight road in front of them. Maybe they’d make it all the way to Guildford, where they could pinch another motor to come home in. For the moment though, it was just fun fun fun. They’d probably veer off en route, and cause chaos on a few housing estates they knew, flaying the paint from any expensive jobs that unwise owners had left in plain view.

Some roadworks surged into sight just ahead. Dazzer howled as he gunned the Volkswagen through them, cones catapulting every which way – one struck the bay window of a roadside house, smashing it clean through. They mowed down a ‘keep left’ sign, taking out a set of temporary lights, which hit the deck with a detonation of sparks.

The blacktop continued to roll out ahead; they were doing eighty, ninety, almost a hundred, and were briefly mesmerised by their own fearlessness, their attention completely focused down the borehole of their headlights. When you were in that frame of mind there were almost no limits. It would have taken something quite startling to distract them from their death-defying reverie – and that came approximately seven minutes into this, their last ever journey in a stolen vehicle.

They were now out of the town and into the countryside, at which point they clipped a kerbstone at eighty-five. That in itself wasn’t a problem, but Deggsy, who’d just filched his mobile from his jacket pocket to film this latest escapade, was jolted so hard that he dropped it into the footwell.

‘Fuck!’ he squawked, scrabbling around for it. At first he couldn’t seem to locate it – there was quite a bit of junk down there – so he ripped his glove off with his teeth and went groping bare-handed. This time he found the mobile, but when he pulled his hand back he saw that he’d found something else as well.

It was clamped to his exposed wrist. Initially he thought he must have brushed his arm against an old pair of boots, which had smeared him with oil or paint. But no, now he could feel the weight of it and the multiple pinprick sensation where it had apparently gripped him. He still didn’t realise what the thing actually was, not even when he held it close to his face – but then Deggsy had only ever seen scorpions on the telly, so perhaps this was unsurprising. Mind you, even on the telly he’d never seen a scorpion with as pale and shiny a shell as this one had – it glinted like polished leather in the flickering streetlights. It was at least eight inches from nose to tail, that tail now curled to strike, and had a pair of pincers the size of crab claws that were extended upwards in the classic defensive pattern.

It couldn’t be real, he told himself distantly.

Was it a toy? It had to be a toy.

But then it stung him.

At first it shocked rather than hurt; as though a red-hot drawing pin had been driven full-length into his flesh, and into the bone underneath. But that minor pain quickly expanded, filling his suddenly frozen arm with a white fire, which in itself intensified – until Deggsy was screaming hysterically. By the time he’d knocked the eight-legged horror back into the footwell, he was writhing and thrashing in his seat, frothing at the mouth as he struggled to release his suddenly restrictive belt. At first, Dazzer thought his mate was play-acting, though he shouted warnings when Deggsy’s convulsions threatened to interfere with his driving.

And then something alighted on Dazzer’s shoulder.

Despite the wild swerving of the car, it had descended slowly, patiently – on a single silken thread – and when he turned his head to look at it, it tensed, clamping him like a hand. In the flickering hallucinogenic light, he caught brief glimpses of vivid, tiger-stripe colours and clustered demonic eyes peering at him from point-blank range.

The bite it planted on his neck was like a punch from a fist.

Dazzer’s foot jammed the accelerator to the floor as his entire body went into spasms. The actual wound quickly turned numb, but searing pain shot through the rest of him in repeated lightning strokes.

Neither lad noticed as the car mounted an embankment, engine yowling, smoke and tattered grass pouring from its tyres. It smashed through the wooden palings at the top, and then crashed down through shrubs and undergrowth, turning over and over in the process, and landing upside down in a deep-cut country lane.

For quite a few seconds there was almost no sound: the odd groan of twisted metal, steam hissing in spirals from numerous rents in mangled bodywork.

The two concussed shapes inside, while still breathing, were barely alive in any conventional sense: torn, bloodied and battered, locked in contorted paralysis. They were still aware of their surroundings, but unable to resist as various miniature forms, having ridden out the collision in niches and crevices, now re-emerged to scurry over their warm, tortured flesh. Deggsy’s jaw was fixed rigid; he could voice no complaint – neither as a mumble nor a scream – when the pale-shelled scorpion reacquainted itself with him, creeping slowly up his body on its jointed stick-legs and finally settling on his face, where, with great deliberation it seemed, it snared his nose and his left ear in its pincers, arched its tail again – and embedded its stinger deep into his goggling eyeball.

Chapter 2 (#uf630308b-9f48-5e3d-84ad-6a1e3811f601)

Heck raced out of the kebab shop with a half-eaten doner in one hand and a carton of Coke in the other. There was a blaring of horns as Dave Jowitt swung his distinctive maroon Astra out of the far carriageway, pulled a U-turn right through the middle of the bustling evening traffic, and ground to a halt at the kerb. Heck crammed another handful of lamb and bread into his mouth, took a last slurp of Coke, and tossed his rubbish into a nearby bin before leaping into the Astra’s front passenger seat.

‘Grinton putting an arrest team together?’ he asked.

‘As we speak,’ Jowitt said, shoving a load of documentation into Heck’s grasp and hitting the gas. More horns tooted despite the spinning blue beacon on the Astra’s roof. ‘We’re hooking up with them at St Ann’s Central.’

Heck nodded, leafing through the official Nottinghamshire Police paperwork. The text he’d just received from Jowitt had consisted of thirteen words, but they’d been the most important thirteen words anyone had communicated to him for quite some time:

Hucknall murder a fit for Lady Killer

Chief suspect – Jimmy Hood

Whereabouts KNOWN

Heck, or Detective Sergeant Mark Heckenburg, as was his official title in the National Crime Group, felt a tremor of excitement as he flipped the light on and perused the documents. Even now, after seventeen years of investigations, it seemed incredible that a case that had defied all analysis, dragging on doggedly through eight months of mind-numbing frustration, could suddenly have blown itself wide open.

‘Who’s Jimmy Hood?’ he asked.

‘A nightmare on two legs,’ Jowitt replied.

Heck had only known Jowitt for the duration of this enquiry, but they’d made a good connection on first meeting and had maintained it ever since. A local lad by birth, Dave Jowitt was a slick, clean-cut, improbably handsome black guy. At thirty, he was a tad young for DI, but what he might have lacked in experience he more than made up for with his quick wit and sharp eye. After the stress of the last few months of intense investigation, even Jowitt had started to fray around the edges, but tonight he was back on form, collar unbuttoned and tie loose, careering through the chaotic traffic with skill and speed.

‘He lived in Hucknall when he was a kid,’ Jowitt added. ‘But he spent a lot of his time back then locked up.’

‘Not just then either,’ Heck said. ‘According to this, he’s only been out of Roundhall for the last six months.’

‘Yeah, and what does that tell us?’

Heck didn’t need to reply. Roundhall was a low-security prison in the West Midlands. According to these antecedents, Jimmy Hood, now aged in his mid-thirties, had served a year and a half there before being released on licence. However, he’d originally been held at Durham after drawing fourteen years for burglary and rape. As if the details of his original crimes weren’t enough of a match for the case they were currently working, his most recent period spent outside prison put him neatly in the frame for the activities of the so-called ‘Lady Killer’.

‘He’s a bruiser now and he was a bruiser then,’ Jowitt said. ‘Six foot three by the time he was seventeen, and burly with it. Scared the crap out of everyone who knew him. Got arrested once for chucking a kitten into a cement mixer. In another incident, he led some other juveniles in an attack on a building site after the builders had given them grief for pinching tools – both builders got bricked unconscious. One needed his face reconstructing. Hood got sent down for that one.’

Heck noted from the paperwork that Hood, of whom the mugshot portrayed shaggy black hair fringing a broad, bearded face with a badly broken nose – a disturbingly similar visage to the e-fit they’d released a few days ago – had led this particular street gang, which had involved itself in serious crime in Hucknall, from the age of twelve. However, he’d only commenced sexually offending, usually during the course of burglary, when he was in his late teens.

‘So he comes out of jail and immediately picks up where he left off?’ Heck said.

‘Except that this time he murders them,’ Jowitt replied.

Heck didn’t find that much of a leap. Certain types of violent offender had no intention of rehabilitating. They were so set on their life’s work that they regarded prison time – even a prolonged stretch – as a hazard of their chosen vocation. He’d known plenty who’d gone away for a lengthy sentence, and had used it to get fit, mug up on all the latest criminal techniques, and gradually accumulate a head of steam that would erupt with devastating force once they were released. He could easily imagine this scenario applying to Jimmy Hood and, what was more, the evidence seemed to indicate it. All four of the recent murder victims had been elderly women living alone. Most of Hood’s victims when he was a teenager had been elderly women. The cause of death in all the recent cases had been physical battery with a blunt instrument, after rape. As a youth, Hood had bludgeoned his victims after indecently assaulting them.

‘Funny his name wasn’t flagged up when he first ditched his probation officer,’ Heck said.

Jowitt shrugged as he drove. ‘Easy to be wise after the event, pal.’

‘Suppose so.’ Heck recalled numerous occasions in his career when it would have paid to have a crystal ball.

On this occasion, they’d caught their break courtesy of a sharp-eyed civvie.

The four home-invasion murders they were officially investigating were congregated in the St Ann’s district, east of Nottingham city centre, and an impoverished, densely populated area, which already suffered more than its fair share of crime. The only description they’d had was that of a hulking, bearded man wearing a ragged duffel coat over shabby sports gear, which suggested that he wasn’t able to bathe or change his clothes very often and so was perhaps sleeping rough. However, only yesterday there had been a fifth murder in Hucknall, just north of the city, the details of which closely matched those in St Ann’s. There’d been no description of the perpetrator on this occasion, though earlier today a long-term Hucknall resident – who remembered Jimmy Hood well, along with his crimes – reported seeing him eating chips near the bus station there, not long after the event. He’d been wearing a duffel coat over an old tracksuit, and though he didn’t have a beard, fresh razor cuts suggested that he had recently shaved one off.

‘And he’s been lying low at this Alan Devlin’s pad?’ Heck asked.

‘Part of the time maybe,’ Jowitt said. ‘What do you think?’

‘Well … I wouldn’t have called it “whereabouts known”. But it’s a bloody good start.’

Alan Devlin, who had a long record of criminal activity as a juvenile, when he’d been part of Hood’s gang, now lived in a council flat in St Ann’s. These days he was Hood’s only known associate in central Nottingham, and the proximity of his home address to the recent murders was too big a coincidence to ignore.

‘What do we know about Devlin?’ Heck said. ‘I mean above and beyond what the paperwork says.’

‘Not a player anymore, apparently. His son Wayne’s a bit dodgy.’

‘Dodgy how?’

‘General purpose lowlife. Fighting at football matches, D and D, robbery.’

‘Robbery?’

‘Took some other kid’s bike off him after giving him a kicking. That was a few years ago.’

‘Sounds like the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.’

As part of the National Crime Group, specifically the Serial Crimes Unit, Mark Heckenburg had a remit to work on murder cases across all the police areas of England and Wales. He and the other detectives in SCU (as it was abbreviated) tended to have a consultative investigating role with regard to the pursuit of repeat violent offenders, and would bring specialist knowledge and training to regional forces grappling with large or complex cases. They were usually allocated to said forces in groups of four or five, sometimes more. On this occasion, however, as the Nottinghamshire Police already had access to experienced personnel from the East Midlands Special Operations Unit, Heck had been assigned here on his own.

SCU’s presence wasn’t always welcomed by the regional forces they were assisting, some viewing the attachment of outsiders as a slight on their own abilities – though in certain cases, such as this one, SCU’s advice had been actively sought. Detective Superintendent Gemma Piper, head of SCU, had been personally contacted by Taskforce SIO Detective Chief Superintendent Matt Grinton, who was a keen student of those state-of-the-art investigations she and her team had run in previous years. He hadn’t specifically asked for Heck, but Gemma Piper, having only recently reincorporated Heck into the unit after he’d spent a brief period attached to Cumbria Crime Command, had felt it would be a good way to ease him back in – Nottinghamshire were only looking for one extra body, someone who would bring expertise and experience but who would also be part of the team, rather than a bunch of Scotland Yard men to take over the whole show.

SIO Grinton was a big man with silver hair, a distinguished young/old face, and a penchant for sharp-cut suits, though his most distinctive feature was the patch he wore over his left eye socket, having lost the eye to flying glass during a drive-by shooting fifteen years earlier. He was now holding court under the hard halogen glow of the car park lights at the rear of St Ann’s Central. Uniforms clad in full anti-riot gear and detectives with stab vests under their jackets and coats stood around him in attentive groups.

‘So that’s the state of play,’ Grinton said. ‘We’re moving on this quickly rather than waiting till the crack of dawn tomorrow, firstly because the obbo at Devlin’s address tells us he’s currently home, secondly because if Jimmy Hood is our man there’s been a shorter cooling-off period between each attack, which means that he’s going crazier by the minute. For all we know, he could have done two or three more by tomorrow morning. We’ve got to catch him tonight, and Alan Devlin is the best lead we’ve had thus far. Just remember … for all that he’s a hoodlum from way back, Devlin is a witness, not a suspect. We’re more likely to get his help if we go in as friends.’

There were nods of understanding. Mouths were set firm as it dawned on the Taskforce members just how high the stakes now were. Every man and woman present knew their job, but it was vital that no one made an error.

‘One thing, sir, if you don’t mind,’ Heck spoke up. ‘I strongly recommend that we take anything Alan Devlin tells us with a pinch of salt.’

‘Any particular reason?’ Grinton asked.

Heck waved Devlin’s sheet. ‘He hasn’t been convicted of any crime since he was a juvenile, but he wasn’t shy about getting his hands dirty back in the day – he was Jimmy Hood’s right-hand man when they were terrorising housing estates around Hucknall. Now his son Wayne is halfway to repeating that pattern here in St Ann’s. Try as I may, I can’t view Alan Devlin as an upstanding citizen.’

‘You think he’d cover for a killer?’ Jowitt said doubtfully.

Heck shrugged. ‘I don’t know, sir. Assuming Hood is the killer – and from what we know, I think he probably is – I find it odd that Devlin, who knows him better than anyone, hasn’t already come to the same conclusion and got in touch with us voluntarily.’

‘Maybe he’s scared?’ someone suggested.

Heck tried not to look as sceptical about that as he felt. ‘Hood’s a thug, but he’s in breach of licence conditions that strictly prohibit him from returning to Nottingham. That means he’s keeping his head down and moving from place to place. He’s only got one change of clothes, he’s on his own, he’s cold, damp, and dining on scraps in bus stations. Does he really pose much of a threat to a bloke like Devlin, who’s got form for violence himself, has a grown-up hooligan for a son and, though he’s not officially a player anymore, is probably well respected on his home patch and can call a few faces if he needs help?’

The team pondered, taking this on board.

‘We’ll see what happens,’ Grinton said, zipping his anorak. ‘If Devlin plays it dumb, we’ll let him know that Hood’s mugshot is appearing on the ten o’clock news tonight, and all it’s going to take is a couple of local residents to recognise him as someone they’ve seen hanging around Devlin’s address. The Lady Killer is going down for the rest of this century, ladies and gents. Devlin may still have a rep to think of, but he won’t want a piece of that action. Odds are he’ll start talking.’

They drove to the address in question in five unmarked vehicles; one of them Heck’s maroon Peugeot 308, and one a plain-clothes APC. They did it discreetly and without fanfare. St Ann’s wasn’t an out-of-control neighbourhood, but it wasn’t the sort of place where excessive police activity would go unnoticed, and mobs could form quickly if word got out that ‘one of the boys’ was in trouble. In physical terms, it was a rabbit warren of crumbling council blocks, networked with dingy footways, which at night were a mugger’s paradise. To heighten its atmosphere of menace, a winter gloom had descended, filling the narrow passages with cloying vapour.

Arriving at 41 Lakeside View, they found a boxy, redbrick structure, accessible by a short cement ramp with a rusty wrought-iron railing, and a single corridor running through from one side to the other, to which various apartment doors – 41a, 41b, 41c and 41d – connected.

Heck, Grinton and Jowitt regarded it from a short distance away. Only the arched entry was visible in the evening murk, illuminated at its apex by a single dull lamp; the rest of the building was a gaunt outline. A clutch of detectives and armour-clad uniforms were waiting a few yards behind them, while the troop carrier with its complement of reinforcements was about fifty yards further back, parked in the nearest cul-de-sac. Everyone observed a strict silence.

Grinton finally turned round, keeping his voice low. ‘Okay … listen up. Roberts, Atherton … you’re staying with us. The rest of you … round the other side. Any ground-floor windows, any fire doors, block ’em off. Grab anyone who tries to come out.’

There were nods of understanding as the group, minus two uniforms, shuffled away into the mist. Grinton checked his watch to give them five minutes to get in place, then glanced at Heck and Jowitt and nodded. They detached themselves from the alley mouth, ascended the ramp, and entered the brick passage, which was poorly lit by two faltering bulbs and defaced end to end with obscene, spray-painted slogans. The same graffiti covered three of its four doors. The only one that hadn’t been vandalised was 41c – the home of Alan Devlin.

There was no bell, so Grinton rapped on the door with his fist. Several seconds passed before there was a fumbling on the other side. The door opened as far as its short safety chain would allow. The face beyond was aged in its mid-thirties, but pudgy and pockmarked, one eyebrow bisected by an old scar. It unmistakably belonged to one-time hardman Alan Devlin, though these days he was squat and pot-bellied, with a shaved head. He’d answered the door in a grubby T-shirt and purple Y-fronts, but even through the narrow gap they spotted neck-chains and cheap, tacky rings on nicotine-yellow fingers. He didn’t look hostile so much as puzzled, probably because the first thing he saw was Grinton’s eye patch. He put on a pair of thick-lensed, steel-rimmed glasses, so that he could scrutinise it less myopically.

‘Alan Devlin?’ the chief superintendent asked.

‘Who the fuck are you?’

Grinton introduced himself, displaying his warrant card. ‘This is Detective Inspector Jowitt and this is Detective Sergeant Heckenburg.’

‘Suppose I’m honoured,’ Devlin grunted, looking anything but.

‘Can we come in?’ Grinton said.

‘What’s it about?’

‘You don’t know?’ Jowitt asked him.

Devlin threw him an ironic glance. ‘Yeah … I just wondered if you did.’

Heck observed the householder with interest. Though clearly irritated that his evening had been disturbed, his relaxed body language suggested that he wasn’t overly concerned. Either Devlin had nothing to hide or he was a competent performer. The latter was easily possible, as he’d had plenty of opportunity to hone such a talent while still a youth.

‘Jimmy Hood,’ Grinton explained. ‘That name ring a bell?’

Devlin continued to regard them indifferently, but for several seconds longer than was perhaps normal. Then he removed the safety chain and opened the door.

Heck glanced at the two uniforms behind them. ‘Wait out here, eh? No sense crowding him in his own pad.’ They nodded and remained in the outer passage, while the three detectives entered a dimly lit hall strewn with litter and cluttered with piles of musty, unwashed clothes. An internal door stood open on a lamp-lit room from which the sound of a television emanated. There was a strong, noxious odour of chips and ketchup.

Devlin faced them square-on, adjusting his bottle-lens specs. ‘Suppose you want to know where he is?’

‘Not only that,’ Grinton said, ‘we want to know where he’s been.’

There was a sudden thunder of feet from overhead – the sound of someone running. Heck tensed by instinct. He spun to face the foot of a dark stairwell – just as a figure exploded down it. But it wasn’t the brutish giant, Jimmy Hood; it was a kid – seventeen at the most with a mop of mouse-brown hair and a thin moustache. He was only clad in shorts, which revealed a lean, muscular torso sporting several lurid tattoos – and he was carrying a baseball bat.

‘What the fucking hell?’ He advanced fiercely, closing down the officers’ space.

‘Easy, lad,’ Devlin said, smiling. ‘Just a few questions, and they’ll be gone.’

‘What fucking questions?’

Jowitt pointed a finger. ‘Put the bat down, sonny.’

‘You gonna make me?’ The youth’s expression was taut, his gaze intense.

‘You want to make this worse for your old fella than it already is?’ Grinton asked calmly.

There was a short, breathless silence. The youth glanced from one to the other, determinedly unimpressed by the phalanx of officialdom, though clearly unused to folk not running when he came at them tooled up. ‘There’s more of these twats outside, Dad. Sneaking around, thinking no one can see ’em.’

His father snorted. ‘All this cos Jimbo breached his parole?’

‘It’s a bit more serious than that, Mr Devlin,’ Jowitt said. ‘So serious that I really don’t think you want to be obstructing us like this.’

‘I’m not obstructing you … I’ve just invited you in.’

Which was quite a smart move, Heck realised.

‘We’ll see.’ Grinton walked towards the living room. ‘Let’s talk.’

Devlin gave a sneering grin and followed. Jowitt went too. Heck turned to Wayne Devlin. ‘Your dad wants to make it look like he’s cooperating, son. Wafting that offensive weapon around isn’t going to help him.’

Scowling, though now looking a little helpless – as if having other men in here chucking their weight about was such a challenge to his masculinity that he knew no adequate way to respond – the lad finally slung the baseball bat against the stair-post, which it struck with a deafening thwack!, before shouldering past Heck into the living room. When Heck got in there, it was no less a bombsite than the hall: magazines were scattered – one lay open on a gynaecological centre-spread; empty beer cans and dirty crockery cluttered the tabletops; overflowing ashtrays teetered on the mantel. The stench of ketchup was enriched by the lingering aroma of stale cigarettes.

‘Let’s cut to the chase,’ Grinton said. ‘Is Hood staying here now?’

‘No,’ Devlin replied, still cool.

He’s very relaxed about this, Heck thought. Unnaturally so.

‘So if I come back here with a search warrant and go through this place with a fine-tooth comb, Mr Devlin, I definitely won’t find him?’ Grinton said.

Devlin shrugged. ‘If you thought you had grounds you’d already have a warrant. But it doesn’t matter. You’ve got my permission to search anyway.’

‘In which case I’m guessing there’s no need, but we might as well look.’ Grinton nodded to Heck, who went back outside and brought the two uniforms in. Their heavy boots thudded on the stair treads as they lumbered to the upper floor.

‘How often has Jimmy Hood stayed here?’ Jowitt asked. ‘I mean recently?’

Devlin shrugged. ‘On and off. Crashed on the couch.’

‘And you didn’t report it?’

‘He’s an old mate trying to get back on his feet. I’m not dobbing him in for that.’

‘When did he last stay?’ Heck asked.

‘Few days ago.’

‘What was he wearing?’

‘What he always wears … trackie bottoms, sweat-top, duffel coat. Poor bastard’s living out of a placky bag.’

The detectives avoided exchanging glances. They’d agreed beforehand that there’d be no disclosure of their real purpose here until Grinton deemed it necessary; if Devlin had known what was happening and had still harboured his old pal, that made him an accessory to these murders – and it would help them build a case against him if he revealed knowledge without being prompted.

‘When do you expect him back?’ Heck asked.

Devlin looked amused by the inanity of such a question (again false, Heck sensed). ‘How do I know? I’m not his fucking keeper. He knows he can come here anytime, but he never wants to outstay his welcome.’

‘Has he got a phone, so you can contact him?’ Jowitt wondered.

‘He hasn’t got anything.’

‘Does he ever come here late at night?’ Grinton said. ‘As in … unusually late.’

‘What sort of bullshit questions are these?’ Wayne Devlin demanded, increasingly agitated by the sounds of violent activity upstairs.

Grinton eyed him. ‘The sort that need straight answers, son … else you and your dad are going to find yourselves deeper in it than whale shit.’ He glanced back at Devlin. ‘So … any late-night calls?’

‘Sometimes,’ Devlin admitted.

‘When?’

‘I don’t keep a fucking diary.’

‘Did he ever look flustered?’ Jowitt asked.

‘When didn’t he? He’s on the lam.’

‘How about bloodstained?’ Grinton said.

At first Devlin seemed puzzled, but now, slowly – very slowly – his face lengthened. ‘You’re not … you’re not talking about this Lady Killer business?’

‘You’ve got to be fucking kidding!’ Wayne Devlin blurted, looking stunned.

‘Interesting thought, Wayne?’ Heck said to him. ‘Is that your bat out there – or Jimmy Hood’s?’

The lad’s mouth dropped open. Suddenly he was less the teen tough-guy and more an alarmed kid. ‘It’s … it’s mine, but that doesn’t mean …’

‘So if we confiscate it for forensic examination and find blood, it’s you we need to come for, not Jimmy?’

‘That won’t work, copper,’ the older Devlin said, though for the first time there was colour in his cheek – it perhaps hadn’t occurred to him that his son might end up carrying the can for something. ‘You’re not scaring us.’

Despite that, the younger Devlin did look scared. ‘You won’t find any blood on it. It’s been under my bed for months. Jimbo never touched it. Dad, tell ’em what they want to fucking know.’

‘Like I said, Jimbo’s only been here a couple of times,’ Devlin drawled. (Still playing it calm, Heck thought.) ‘Never settles down for long.’

‘And it didn’t enter your head that he might be involved in these murders?’ Grinton said.

‘Or are you just in denial?’ Jowitt asked.

‘He was a good mate …’

‘So you are in denial? Can’t see the judge being impressed by that.’

‘It may have occurred to me once or twice,’ Devlin retorted. ‘But you don’t want to believe it of a mate …’

‘Even though he’s done it before?’ Grinton said.

‘Nothing this bad.’

‘Bad enough.’

‘You should get over to his auntie’s!’ Wayne Devlin interjected.

That comment stopped them dead. They gazed at him curiously; he gazed back, flat-eyed, cheeks flaming.

‘What are you talking about?’ Heck asked.

‘He was always ranting about his Auntie Mavis …’

‘Wayne!’ the older Devlin snapped.

‘If Jimbo’s up to something dodgy, Dad, we don’t want any part in it.’

These two are good, Heck thought. These two are really good.

‘Something you want to tell us, Mr Devlin?’ Grinton asked.

Devlin averted his eyes to the floor, teeth bared. He yanked his glasses off and rubbed them vigorously on his stained vest – as though torn with indecision, as though angry at having been put in this position, but not necessarily angry at the police.

‘Wayne may be right,’ he finally said. ‘Perhaps you should get over there. Her name’s Mavis Cutler. Before you ask, I don’t know much else. She’s not his real auntie. Some old bitch who fostered Jimbo when he was a kid. Seventy-odd now, at least. I don’t know what went on – he never said, but I think she gave him a dog’s life.’

So Hood was attacking his wicked auntie every time he attacked one of these other women, Heck reasoned, remembering his basic forensic psychology. It’s a plausible explanation. Although a tad too plausible, of course.

‘And why do we need to get over there quick?’ Jowitt wondered.

Devlin hung his head properly, his shoulders sagging as if he was suddenly glad to get a weight off them. ‘When … when Jimbo first showed up a few months ago, he said he was back in Nottingham to see her. And when he said “see her”, I didn’t get the feeling it was for a family reunion if you know what I mean.’

‘So why’s it taken him this long?’ Jowitt asked.

‘He couldn’t find her at first. I think he may have gone up to Hucknall yesterday, looking. That’s where they lived when he was a kid.’

Cleverer and cleverer, Heck thought. Devlin’s using real events to make it believable.

‘Someone up there probably told him,’ Devlin added.

‘Told him what?’

‘That she lives in Matlock now. I don’t know where exactly.’

Matlock in Derbyshire. Twenty-five miles away.

‘How do you know all this?’ Grinton sounded suspicious.

Devlin shrugged. ‘He rang me today – from a payphone. Said he was leaving town tonight, and that I probably wouldn’t be seeing him again.’

‘And you still didn’t inform us?’ Jowitt’s voice was thick with disgust.

‘I’m informing you now, aren’t I?’

‘It might be too late, you stupid moron!’ Jowitt dashed out into the hall, calling the two uniforms from upstairs.

‘Look, he never specifically said he was going to do that old bird,’ Devlin protested to Grinton. ‘He might not even be going to Matlock. He might be fleeing the fucking country for all I know! This is just guesswork!’

And you can’t be prosecuted for guessing, Heck thought. You’re a cute one.

‘Don’t do anything stupid, Mr Devlin,’ Grinton said, indicating to Heck that it was time to leave. ‘Like warning Jimmy we’re coming. Any phone we find on Hood with calls traceable back to you are all we’ll need to nick you as an accomplice.’

Out in the entry passage, Jowitt was already shouting into his radio. ‘I don’t care how indisposed they are – get them to check the voters’ rolls and phone directories. Find every woman in Matlock called Mavis bloody Cutler … over and out!’ He turned to Grinton and Heck. ‘We should lock that bastard Devlin up.’

Grinton shook his head, ignoring the door to 41c as it slammed closed behind them. ‘He might end up witnessing for us. Let’s not chuck away what little leverage we’ve currently got.’

‘What if he absconds?’

‘We’ll sit someone on him.’

‘Excuse me, sir,’ Heck said. ‘But I won’t be coming over to Matlock with you.’

Grinton looked surprised. ‘All this groundwork and you don’t want to be in on the pinch?’

Heck shrugged. ‘I’ll be honest, sir: good show Devlin put on in there, but I don’t think Hood has any intention of going to Derbyshire. I reckon we’re being sent on a wild goose chase.’

Jowitt looked puzzled. ‘Why would Devlin do that?’

‘It’s a hunch, sir, but it’s got legs. Despite the serious crimes Jimmy Hood was last convicted for, Alan Devlin let him sleep on his couch. Not once, but several times. This guy is not too picky to associate with sex offenders.’

‘Come on, Heck,’ Jowitt said. ‘Devlin’s in enough hot water as it is – he’s not going to aid and abet a multiple killer as well.’

‘He’s in lukewarm water, sir. Apart from assisting an offender, what else has he admitted to? Even if it turns out he’s sending us the wrong way, he’s covered. It’s all “I’m not sure about this, I’m only guessing that” – there aren’t even grounds to charge him with obstructing an enquiry.’

‘We can’t not act on what he’s told us,’ Grinton argued.

‘I agree, sir. But while you’re off to Matlock, I’m going to chase a few leads of my own. If that’s okay?’

‘No problem … just make sure you log them all.’

While Grinton arranged for a couple of his plain-clothes officers to maintain covert obs on Lakeside View, the rest of them returned to their vehicles and mounted up for a rapid ride over to the next county. Jowitt was back on the blower again, putting Derbyshire Comms in the picture as he jumped into his car. Heck remained on the pavement while he too made a quick call – in his case it was to the DIU at St Ann’s Central. As intelligence offices went, this one was pretty efficient.

‘Heck?’ came the hearty voice of PC Marge Propper, a chunky uniformed lass whose fast, accurate research capabilities had already proved invaluable to the Lady Killer Taskforce.

‘Marge – am I right in thinking that, apart from Alan Devlin, Jimmy Hood has no other known associates in the inner Nottingham area?’

‘Correct.’

‘Okay … I want to try something different. Can you contact Roundhall Prison in Coventry? Find out who’s been visiting Hood this last year and a half. Any regular names that haven’t already cropped up in this enquiry, I’d like to know about them.’

‘Wilco, Heck – might take a few minutes to get a response at this hour.’

‘No worries. Call me back when you can.’

He paused before climbing into his Peugeot. The other mobile units had driven away, leaving a dull, dead silence in their wake. The surrounding buildings were little more than blurred, angular outlines, broken by the odd faint square of window-light, most of which leached into the gloom without making any impression. The passage leading towards Lakeside View was a black rectangle, which bade no one re-enter it.

Heck climbed into his car and switched the engine on.

It was impossible to say whether or not they were on the right track, but it felt right. He still didn’t trust Alan Devlin, but the guy’s partial admissions had revealed that Jimmy Hood had been in this district as well as Hucknall – which put Hood close to all the identified murder scenes and in roughly the right timeframe. Of course, with the knowledge of hindsight, it was all so predictable and sordid. As Heck drove out of the cul-de-sac it struck him that this decayed environment, with its broken glass and graffiti-covered maze of soulless brick alleys, seemed painfully familiar. So many of his cases had brought him to blighted places like this.

His phone rang and he slammed it to his ear. ‘Yeah, Heckenburg!’

‘We could have something here, Heck,’ Marge Propper said. ‘In his last year at Roundhall, Jimmy Hood was visited nine times by a certain Sian Collier.’

‘That name doesn’t ring a bell.’

‘No; she hasn’t been on our radar up to now, though she’s got minor form for possession and shoplifting. She’s white, thirty-two years old and a local by birth. Her last conviction was over five years ago, so she may have cleaned up her act.’

‘Apart from the bit where she gets mixed up with sex killers?’

‘Yeah …’

Heck fiddled with his sat nav. ‘Where does she live?’

‘Mountjoy Height, number eighteen – that’s in Bulwell.’

‘I know it.’

‘Heck, if you’re going over there, you might want to speak to Division first. It’s a lively place.’

‘Thanks for the warning, Marge. But I’m only spying out the land. Anyway, I’ve got my radio.’

The murkiness of the winter night was now to Heck’s advantage – mainly because it meant the roads were empty of traffic, but also because, once he arrived in Bulwell, he was able to cruise its foggy, run-down streets without attracting attention.

When he finally located Mountjoy Height, it was a row of pebble-dashed two-storey maisonettes on raised ground overlooking yet another labyrinthine housing estate. First, he made a drive-by at the front, seeing patches of muddy grass serving as communal front gardens, with wheelie bins dotted across them and rubbish strewn haphazardly. There were only a couple of other vehicles present, but lights were on in most of the maisonette windows. After that, he explored at the rear, working his way down into a lower, winding alley, which ran past several garages. Some of these stood open, some closed. The garage to number eighteen didn’t have a door attached, but was of particular interest because a large, good-looking motorcycle was parked inside it.

Heck glided to a halt and turned his engine off.

He climbed out, listening carefully; somewhere close by voices bickered. They were muffled and indistinct, but it sounded like a couple of adults; he wasn’t initially sure where it was coming from – possibly number eighteen itself, which towered behind the garage in the gloom and was accessible by a narrow flight of steps.

He assessed the motorbike through the entrance, and despite the darkness was able to identify it as a new model Suzuki GSX; an expensive make for this neck of the woods.

‘DS Heckenburg to Charlie Six,’ he said into his radio. ‘PNC check, please?’

‘DS Heckenburg?’ came the crackly response.

‘Anything on a black Suzuki GSX motorcycle, index Juliet-Zulu-seven-three-Bravo-Foxtrot-Alpha, over?’

‘Stand by.’

Heck moved to the side of the garage and glanced up the steps. The monolithic structure overhead was wreathed in vapour, but lights still burned inside it and the argument raged on; in fact it sounded as if it had intensified. Glass shattered, which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing – it might grant him the right to force entry.

‘DS Heckenburg from PNC?’

‘Go ahead.’

‘Black Suzuki GSX motorcycle, index Juliet-Zulu-seven-three-Bravo-Foxtrot-Alpha, reported stolen from Hucknall late last night, over.’

‘Received, thanks for that. What were the circumstances of the theft, over?’

‘Fairly serious, Sarge. It’s being treated as robbery. A motorcycle courier got a bottle broken over his head outside a newsagent, and then had his helmet stolen as well as his ride. He’s currently in IC. No description of the offender as yet.’

Heck pondered. This sounded more like Jimmy Hood by the minute. On the basis that he was now looking to make an arrest for a serious offence, Heck had the power to enter the garage – which he duly did, finding masses of junk littered in its oily shadows: boxes crammed with bric-a-brac; broken, dirty household appliances; even a pile of chains, several of which were wrapped round an upright steel girder supporting the garage roof.

‘DS Heckenburg … are you saying you’ve found this vehicle, over?’

‘That’s affirmative,’ Heck replied, pulling his gloves on as he mooched around. ‘In an open garage at the rear of eighteen, Mountjoy Height, Bulwell. The suspect, who I believe to be inside the address, is Jimmy Hood. White male, early thirties, six foot three inches and built like a brick shithouse. Hood, who has form for extreme violence, is also a suspect in the Lady Killer murders. So I need backup ASAP. Silent approach, over.’

‘Received Sarge … support units en route. ETA five.’

Heck shoved his radio back into his jacket and worked his way through the garage to a rear door, which swung open at his touch. He followed a paved side path along the base of a steep, muddy slope, eventually joining with the flight of steps leading up to the maisonette. When he ascended, he did so warily. Realistically, all he needed to do now was wait until the cavalry arrived – but then something else happened.

And it was a game-changer.

The shouting and screaming indoors had risen to a crescendo. Household items exploded as they were flung around. This was just about tolerable, given that it probably wasn’t an uncommon occurrence in this neighbourhood. Heck reasoned that he could still wait it out – until he got close to the rear of the building, and heard a baby crying.

Not just crying.

Howling.

Hysterical with pain or fear.

‘DS Heckenburg to Charlie Six, urgent message!’ He dashed up the remaining steps, and took an entry leading to the front of the maisonette. ‘Please expedite that support – I can hear violence inside the property and a child in distress, over!’

He halted under the stoop. Light shafted through the frosted panel in the front door, yet little was visible on the other side – except for brief flurries of indistinct movement. Angry shouts still echoed from within.

Heck zipped his jacket and knocked loudly. ‘Police officer! Can you open up please?’

There was instantaneous silence – apart from the baby, whose sobbing had diminished to a low, feeble keening.

Heck knocked again. ‘This is the police – I need you to open up!’ He glimpsed further hurried motion behind the distorted glass.

When he next struck the door, he led with his shoulder.

It required three heavy buffets to crash the woodwork inwards, splinters flying, bolts and hinges catapulting loose. As the door fell in front of him Heck saw a narrow, wreckage-strewn corridor leading into a small kitchen, where a tall male in a duffel coat was in the process of exiting the property via a back door. Heck charged down the corridor. As he did, a woman emerged from a side room, bruised and tear-stained, hair disorderly, mascara streaking her cheeks. She wore a ragged orange dressing gown and clutched a baby to her breast, its face a livid, blotchy red.

‘What do you want?’ she screeched, blocking Heck’s passage. ‘You can’t barge in here!’

Heck stepped around her. ‘Out the way please, miss!’

‘But he’s not done nothing!’ She grabbed Heck’s collar, her sharp fingernails raking the skin on his neck. ‘Can’t you bastards stop harassing him!’

Heck had to pull hard to extricate himself. ‘Hasn’t he just beaten you up?’

‘That’s cos I didn’t want him to leave …’

‘He’s a bloody nutter, love!’

‘It’s nothing … I don’t mind it.’

‘Others do!’ Heck yanked himself free – to renewed wailing from the woman and child – and continued into the kitchen and out through the back door, emerging onto a toy-strewn patio just as a burly outline loped down the steps towards the garage, only a few yards in front of him. The guy had something in his hand, which Heck at first took for a bag; then he realised that it was a motorbike helmet. ‘Jimmy Hood!’ he shouted, scrambling down the steps in pursuit. ‘Police officer – stay where you are!’

Hood’s response was to leap the remaining three or four steps, pulling the helmet on and battering his way through the garage’s rear door. Heck jumped the last steps as well, sliding and tumbling on the earthen slope, but reaching the garage doorway only seconds behind his quarry. He shouldered it open to find Hood seated on the Suzuki, kicking it to life. Its glaring headlight sprang across the alley. The roars of its engine filled the gutted structure.

‘Don’t be a bloody fool!’ Heck bellowed.

Hood glanced round – just long enough to flip Heck the finger and hit the gas, the Suzuki bucking forward, almost pulling a wheelie it accelerated with such speed.

But the fugitive only made it ten yards, at which point, with a terrific BANG, the bike’s rear wheel was jerked back beneath him. He somersaulted over the handlebars, slamming upside down against another garage door before flopping onto the cobblestones, where he lay twisted and groaning. The bike came to rest a few yards away, chugging loudly, smoke pouring from its shattered exhaust.

‘Bit remiss of you, Jimmy,’ Heck said, emerging into the alley, toeing at the length of chain still pulled taut between the buckled rear wheel and the upright girder inside the garage. ‘Not checking that something hadn’t got mysteriously wrapped round your rear axle.’

Flickering blue lights appeared as local patrol cars turned into view at either end of the alley, slowly wending their way forward. Hood managed to roll over onto his back, but could do nothing except lie there, glaring with glassy, soulless eyes through the aperture where his visor had been smashed away.

Heck dug handcuffs from his back pocket and suspended them in full view. ‘Either way, pal, you don’t have to say anything. But it may harm your defence …’

Chapter 3 (#uf630308b-9f48-5e3d-84ad-6a1e3811f601)

It took a near-death experience to make Harold Lansing realise that he needed to start enjoying life more. Of course, those who didn’t know him would have been startled to learn that he wasn’t leading a very full and pleasurable existence in the first place.

A 45-year-old multi-millionaire bachelor, he was exceptionally handsome – sun-bronzed, with a shock of crisp, grey hair – always fashionably dressed even in casuals, and the owner of two nifty motors, a Bentley Continental V8 and a Hyundai Veloster sport, so it seemed highly unlikely that he wasn’t already one of the most contented men in Britain. He also owned three sumptuous properties: a villa on the Côte d’Azur, where he spent the odd three-day break, a flash apartment in Swiss Cottage, purpose-bought as a crashpad from which to take in the London scene, and his ‘rural retreat’, as he referred to it, though it was actually his regular residence: a palatial, eight-bedroom former farmhouse in the Surrey countryside called Rosewood Grange. With 300 acres of verdant gardens attached, a private tennis court and croquet lawn, its own indoor swimming pool and the near-obligatory complement of priceless artworks and antiques, you’d have expected Rosewood Grange to be the jewel in a party king’s crown, the epicentre of a lavish, playboy lifestyle, where all the best people, including the most glamorous and connected women, came every weekend to get off their face.

Except that it didn’t serve that purpose, and it never really had.

Looks could be deceptive.

Aside from the occasional round of golf and a few restful hours spent angling on the River Mole, Lansing dedicated more energy towards supporting charitable causes than he did his own leisure. In addition, he was a workaholic. He ran several computer companies from his private office in Reigate, and had made the bulk of his money selling software products in the United States and the Far East. He also owned a chain of country inns and hotels aimed at a wealthy clientele. What was more, he liked to stay hands-on with all these interests – not because he didn’t trust his carefully appointed underlings, but more because he couldn’t conceive of a lifestyle spent, to use one of his own phrases, twiddling his thumbs all day.

However, now maybe – just maybe – thanks to a recent accident and a subsequent two-week sojourn in hospital, several days of which he’d spent hooked to a bank of ‘vital signs’ monitors in Intensive Care, he was beginning to readdress things.

As he threw his briefcase into the back of his Bentley that beautiful July morning, he paused briefly to admire the lush, sun-dappled greenery enclosing his home, and to breathe the seductive scents of the English woodland: rosebud, honeysuckle, fresh mint. Quite an improvement on the starch, bleach, and liberally applied antiseptics of the hospital.

Good Lord, it was great to be alive. But how much of a life was he actually living?

Okay, he’d made a kind of resolution while he was in hospital to take more holidays, to travel more regularly and extensively, maybe even to hook up with Monica again. And yet here he was, the first morning of his officially being ‘fit for work’, and he was already heading for the office at seven sharp. It was as though nothing had happened to disrupt his regular-as-clockwork routine. But it wasn’t like it would be difficult to make changes to this; Lansing was the boss after all – the only pressure he ever felt was the pressure he applied to himself. But he would still only get home after eight p.m., and as usual would dine alone on whatever collation Mrs Beetham, his housekeeper, had set out for him – except that no, Mrs Beetham was currently on holiday with Mr Beetham, Lansing’s gardener, so he would actually dine alone on whatever morsel of fast food, most likely a greasy fish and chip supper, he remembered to pick up on the way. His main viewing that night would be the business news, and his bedtime reading the financial press. This was his normal weekday schedule – and he was used to it and satisfied with it. But it was hardly a life in the true sense of the word.

A solitary individual with few real interests outside work, golf and fishing, Lansing had no yearning to ‘go out and do stuff’ as Monica had once tried to persuade him – not long before they broke up, in fact – but the incident on the river had made him realise that unforeseen disaster could be lurking around any corner, and that there were probably quite a few things he had yet to experience that would undoubtedly enrich his time on Earth. The mere memory of the roiling green water thundering in his ears as he was swept over the weir – the weight of it bearing down on top of him, pummelling his body, slamming him again and again on the slimy brickwork at the bottom of the plunge-pool, pinning him deep in that airless, icy void – was enough to set him quaking. How easy to recall the horrific realisation that this was it; that without expectation, anticipation, or even a hint of warning, it was all suddenly, irreversibly over. Everything. The whole show. There would be no goodbyes, no sorting out of affairs, no time to fix the things that needed fixing. This was simply it. His allotted time had run out. Gone. Zip.

Almost in reflex, Lansing stripped off his blue silk tie.

It wasn’t necessarily a rebellion against the regimented world in which he’d so long been immersed. It didn’t mean that he was suddenly casting his sights further afield – looking out for a good time when he’d normally be assessing the markets. But it was a start, he supposed. Monica would certainly be surprised. He’d try and Skype with her later on, and gauge her reaction – and not just to the missing tie, perhaps to an on-the-hoof dinner invitation for whenever she was next in the UK.

Lansing tossed the tie into the back seat of his Bentley as he climbed behind the wheel. With a few deft strokes, he brought the magnificent machine’s six-litre twin-turbocharged engine purring to life. The dulcet strains of Vivaldi filled its leather interior. He eased it down his white gravel drive, increasingly enthused by his new outlook on life, by his determination to have some fun for a change. At the end of the day, why not? The nearby woods were thick with summer leaf, filled with birdcalls. The sun speared through the overhead canopy. When he looked beyond his desk, this world – which had so very nearly been snatched away from him – really was a glorious and invigorating place.

A short distance from the house, he slowed as he approached the drive entrance. The road beyond was only a B road, but it ran in a more or less direct line between Crawley and Dorking, and passed for long, straight stretches through gentle forest and farmland. As such, it was popular with boy racers, even at this early hour – idiots who’d left it too late to set out for work; idiots who were in danger of missing their flights from Gatwick; idiots who were trying to get home before the day began, so they could try to convince their wives or girlfriends that they hadn’t stayed out all night. But even without such a crowd of jackanapeses on the road, the point where Lansing’s drive connected with it was a bad one; right on a blind bend. To compensate, he’d had a large convex mirror fixed on the twisted oak trunk opposite, giving him excellent vantage in both directions for a considerable distance, and right now the way was clear.

As the ‘Spring’ harpsichord kicked in, he thumbed the volume control on the steering column. Lansing loved classical music, but he particularly loved the pastoral pieces, especially while driving through lush countryside on summer mornings. He checked the mirror opposite one final time – the road was still empty in both directions – and casually cruised out between the tall redbrick obelisks that served as his gateposts.

The sound of his collision with the Porsche Carrera was like a volcanic eruption.

When the sports car struck his front nearside it was doing over seventy miles an hour, and it catapulted over the top of him, flipping end over end through the air, turning into a fireball when it hit the road again some forty yards further on, from which point it continued to crash and roll, setting alight every bush and thicket along the verge, before wrapping itself round a hornbeam, which was almost uprooted by the impact.

In comparison to that, Lansing didn’t come off half badly.

His own vehicle, which was also dragged out and flung on its roof along the scorched tarmac, was of course reduced to mangled scrap, but though he was slammed brutally against his belt and airbag, and his legs twisted torturously as the Bentley’s entire chassis was buckled out of shape, he survived.

For what seemed like ages afterwards, he hung upside down, dazed to a near-stupor. The only thought that worked its way through his head was: The mirror … the road was clear, I saw it. He cursed himself as a damn fool for having played the music in his car at such volume that he’d failed to hear the howl of the approaching engine. But that shouldn’t have mattered, because the road was clear. I saw it with my own eyes.

And then another thought occurred to him: about the smell that was rapidly filling his nostrils, and the warm fluid running down his face – which he’d at first assumed was blood. He touched his wet cheek with his fingertips. When he brought them away again, they were shiny and slippery.

Dear God!

The petrol tank had ruptured. Its contents were already seeping in rivulets through the shattered vehicle’s interior. And outside on the road of course, though Lansing’s vision was fogged by pain and shock, pools of flame were burning, some of them in perilous proximity.

Though nauseated and shivering, head banging with concussion, he fought wildly with his seatbelt clip. When it finally came loose, he still didn’t drop, but was held fast by the legs, the agony of which infused his entire lower body.

‘Bloody broken legs,’ he burbled through a mouth seething with saliva.

He could still get out. He had to.

So he wriggled and he writhed, and he grunted aloud, biting down on shrieks of pain as he finally shifted his contorted lower limbs sufficiently to fall like a stone, landing heavily on his shoulders and upper back, but still managing to lurch around and worm his way out through his side window. Even as he slid onto the glass-strewn tarmac, there was movement in the corner of his eye. He spied glistening fuel winding treacherously away towards the burning vegetation on the verge.

Crawling on his elbows, teeth gritted on blinding pain, Lansing dragged himself further and further away. When the car blew behind him, it didn’t go with a BANG as much as a WUMP. He imagined fire ballooning above it in a miniature atom cloud, engulfing the branches overhead. Searing heat washed over him. But heat didn’t hurt you, flame did. And flame didn’t follow.

Realising he was safe, Lansing slumped face down on his folded arms, tears squeezing from eyes already reddened by smoke and fumes. Somewhere nearby he heard the approach of another car, but this one was slowing down. Tyres crunched on a road surface littered with wreckage; an engine groaned to a halt; a handbrake was applied; doors opened; what sounded like two pairs of booted feet clumped on the tarmac. Though it took him a stupefying effort, Lansing rolled over onto his back.

At first, he couldn’t quite make out what he was seeing. When its fuel tank had exploded, the twisted, blazing hulk of his Bentley had righted itself with the force, landing on its wheels again. But more important than this, a heavy vehicle of some sort – green in colour, like a jeep or Land Rover – had parked about ten yards behind it, and two men had climbed out, both dressed in what looked like grey overalls. Instead of coming over to check if Lansing was okay, the first of these two men, the taller one, was standing with hands in pockets, surveying the burning wreck. The other had walked round to the far side of it and, through the flickering orange haze, seemed to be attempting to remove the mirror from the tree trunk.

‘H-hey!’ Lansing stammered. ‘Hey … I’m over here …’

The one with his hands in his pockets casually looked round. Despite the momentous events of that morning, despite the delayed shock that was running through Lansing’s broken body like an icy drug, he was so startled by the face he now beheld, and so horrified at the same time, that he cried out incoherently.

The shorter chap meanwhile was still fiddling with the mirror – not trying to remove it, as Lansing had first thought, but trying to remove something that had been laid over it. Or at least, laid over its glass. Was that a picture? A large, circular picture fitted inside the mirror’s frame?

Good God …

With slow, purposeful steps, the tall one with the face that Lansing couldn’t believe walked across the road towards him.

‘You surely are the luckiest bastard alive, Mr Lansing.’ His voice was muffled, though the words were perfectly clear. ‘But sadly no one’s luck lasts forever.’

‘I’m … I’m hurt,’ Lansing stuttered.

‘I can see that.’

‘Please … get me an ambulance.’

Now the other one came across the road; the one carrying the circular picture he’d torn away from the mirror. His face too brought an astonished croak from Lansing’s throat, but no more so than the picture did – it was a still photograph of this very road, albeit empty, free of oncoming traffic.

‘Look,’ he burbled, ‘this isn’t a game. I’m badly hurt.’

‘Not badly enough, I’m afraid,’ the taller of the two men said. ‘But don’t worry – we can take care of that for you.’

They picked him up, one at either end.

Lansing fought back. Of course he fought back; he knew they weren’t trying to help him. But despite his struggles, they carried him around his vehicle like a sack of meal. At this point he bit one of them; the shorter one, whose latex-covered hand had taken a tight grip on his sweaty, petrol-soaked shirt. He sank his teeth deep, almost through to the knuckle. The assailant yelped and tried to yank his hand free, but Lansing – a dog with a bone, because he knew his life depended on it – wouldn’t let go.

They remained calm, even as they rained blows on his face to try and loosen his clenched teeth. Each impact resounded through Lansing’s skull. His nose went first; then his cheekbones and eye sockets; finally his jaw.

Though his vision was filmed by a sticky crimson caul, he was still aware they were carrying him. The heat of his vehicle washed over him as they halted in front of it.

‘Pleeeaaath,’ he mumbled through his shredded lips. ‘Pleeeaaathe … no …’

‘Think of this as a favour, Mr Lansing,’ the taller one said. ‘You’ve always been a handsome fella. Would you really want to carry on looking the way you do now? Anyway, hypothetical question. A-one, a-two, a-three …’

As they swung him between them his burbled pleas became gurgled wails, which rose to a peak of intensity when they released him and he bounced across the blistered bonnet and clean through the jagged maw of the windscreen into the white-hot furnace beyond.

Even then, it wasn’t over.

Lansing’s clothes burned away in blackened tatters, along with his skin and the thick fatty tissue beneath. Yet he still found sufficient strength to scramble out through an aperture where the driver’s door had once been – to amazed but amused chuckles.

‘This bloke, I’m telling you,’ the taller one said, as they again hefted Lansing by his wrists and ankles, unconcerned at the flambéd flesh coming away in their grasp in slimy layers. As before, they transported his twitching form to the front of the vehicle and launched him across its bonnet, back through its flame-filled windscreen.

Chapter 4 (#uf630308b-9f48-5e3d-84ad-6a1e3811f601)

At Nottingham Crown Court, the presiding judge, Mr Percival Shears, thought long and hard before passing sentence.

‘James Hood,’ he finally said, ‘you have been found guilty of murdering five elderly women in this city. Women of good repute, who were never known to have hurt or offended against any person. Not only that, you murdered them in the most heinous circumstances, forcing entry to their homes and subjecting them to sustained and hideous abuse before ending their lives … and for no apparent purpose other than to gratify your perverted lusts. So grotesque are the details of these crimes that, were this another time and another place, and were it within my power, I would have no hesitation whatsoever in sending you to the gallows.’

There was an amazed hissing and cursing from one end of the public gallery, where a small clutch of Hood’s supporters had installed themselves. For his own part, the prisoner – still a hulking brute, though for once looking presentable in a suit and tie, with his beard trimmed and black hair cut very short – was motionless in the dock, staring directly ahead, making eye contact with nobody.

‘Of course,’ the judge added, ‘thanks to the efforts of men and women vastly more civilised than you, such a course is no longer open to us. Instead, it falls upon me to impose the mandatory life sentence. But in my judgement, to meet the seriousness of this case, I recommend that you never be eligible for parole. Yours is to be a whole-life term. After such dreadful deeds, it is perfectly fitting that you spend the rest of your days under lock and key.’

There was tearful applause from the other end of the gallery, where the relatives of the victims were gathered. Down below, Detective Chief Superintendent Grinton turned to the bench behind and shook hands with DI Jowitt and Heck.

‘Job done,’ he said.

Heck watched as Hood was taken from the dock, glancing neither right nor left as he was escorted down the stairs to the holding cells. This was the last time he would ever be seen in public, but his body language registered no emotion. Like so many of these guys, he’d always probably suspected this was the destiny awaiting him.

Outside in the lobby, the detectives and the prosecution team were mobbed by jostling reporters, flashbulbs glaring, voices shouting excited questions.

‘The full-life tariff is exactly what Jimmy Hood deserves,’ Grinton told a local news anchorwoman. ‘I can’t say it makes me happy to see anyone receive that ultimate sanction, but this is the future he chose for himself. In any case, it won’t bring back Amelia Taft, Donna Broughton, Joan Waddington, Dora Kent or Mandy Burke. Their families are also serving a full-life sentence, and even this result today, satisfying though it is for those involved in the investigation, will be no consolation to them.’

‘Detective Sergeant Heckenburg,’ Heck was asked, ‘as the arresting officer in this case, given that five women still died before you brought Jimmy Hood to justice, do you really feel a celebration is justified?’

‘I don’t think anyone’s celebrating, are they?’ Heck replied. ‘Like Chief Superintendent Grinton said, several lives have been lost. Another life is totally wasted. The whole thing’s a tragedy.’

‘How do you respond to accusations that it was a lucky arrest?’

‘We got one lucky break for sure, and for that we ought to thank a vigilant member of the public. But you have to be on the right track to take advantage of stuff like that. The case still had to be made, and there was a lot of legwork involved. Everyone did their bit.’

‘No one did their bloody bit!’ came a harsh Nottinghamshire voice. ‘That’s the trouble!’

An alley cleared through the throng as Alan and Wayne Devlin, and a handful of similarly shady-looking characters, having descended the stair from the public gallery, now forced their way across the lobby.

‘I hope you’re proud, Heckenburg!’ Devlin shouted, spittle flying from his lips. He and his minions were dressed in suits – Devlin was in his steel-rimmed specs again – yet they made no less menacing a picture. All the hallmarks were there: the tattoos, the facial scars, the cheap jewellery. The one or two women they had with them were blowzy types: overly made-up, chewing gum. ‘You bastards betrayed Jimbo right from the start!’

‘Who are you saying betrayed him, sir?’ a reporter asked.

‘This lot … the authorities.’ Devlin waved a general hand at the detectives. ‘Jimbo never stood a chance. As a kid it was obvious he was off his trolley, but the system kept letting him down. He was in and out of mental wards. Even though he kept telling people he was sick, that he was gonna do someone, they kept letting him go. If he’d been taken care of properly, none of this would have happened. Them poor women would be alive.’

Conscious that cameras and microphones were still on him, Heck merely shrugged. ‘I’m not qualified to comment on any offender’s mental health. All I do is catch them.’

‘He’s bloody lucky you only caught him,’ Devlin retorted. ‘He could have died coming off that bike.’

‘Accidents happen,’ Heck said, sidling towards the entrance doors.

‘You lying shit!’ Devlin and his cohort lurched forward en masse, and suddenly there was pushing and shoving, uniformed officers having to insert themselves into the crowd, hustling the opposing groups apart.

‘And the worst accident of Jimmy Hood’s life was meeting you!’ Heck snarled, briefly losing it, pointing at Devlin’s face. There was further hustling back and forth. ‘You and your mates encouraged him plenty!’

‘Yeah, blame us – the only ones who cared about him! You lying pig!’

‘You should be up for perverting the course of justice,’ Heck replied.

‘You should be up for attempted murder.’

‘If we’d been able to trace that phone call …’

‘What phone call? Eh? What fucking phone call?’

Heck clamped his mouth shut, though the heat had risen in his cheeks until it was boiling. DI Jowitt’s touch on his shoulder prevented him saying something he might totally regret. As Hood’s legal team ushered Devlin and his pals away the bespectacled oaf grinned at Heck in stupid but triumphant fashion, as if merely goading the police was some kind of victory – which it was, of course, for those of a certain mentality.