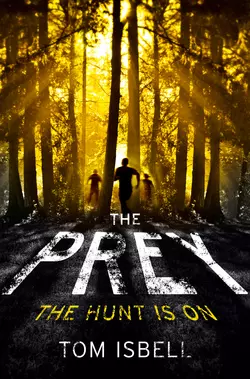

The Prey

Tom Isbell

In the Republic of the True America, it's always hunting season. Riveting action, intense romance, and gripping emotion make this fast-paced adventure a standout debut.After a radiation blast burned most of the Earth to a crisp, the new government established settlement camps for the survivors. At one such camp, Book and the other ‘LTs’ are eager to graduate as part of the Rite.Until they learn the dark truth: ‘LTs’ doesn't stand for lieutenant but for ‘Less Thans’, feared by society and raised to be hunted for sport. Together with the sisters, Hope and Faith, twin girls who've suffered their own haunting fate, they join forces to seek the safety of the fabled New Territory.As Book and Hope lead their quest for freedom, these teens must find the best in themselves to fight the worst in their enemies. But as they are pursued by sadistic hunters, secrets are revealed, allegiances are made, and lives are threatened.

Copyright (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Tom Isbell 2015

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Johnnyhetfield/Getty Images (people); Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com) (trees).

Tom Isbell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007528189

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780007528172

Version: 2015-01-20

Dedication (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

To Pat and Pam,

Sisters

Contents

Cover (#u956a474c-047e-58f9-b396-ea899b2da91c)

Title Page (#u37a8f009-1691-5381-b61f-1e60061c9e2b)

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: Liberty

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part Two: Escape

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Part Three: Prey

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

LIBERTY (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

Wild animals never kill for sport. Man is the only one to whom the torture and death of his fellow creatures is amusing in itself.

—JAMES ANTHONY FROUDE

from Oceana, or, England and Her Colonies

PROLOGUE (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

Blood drips from fingertips, splashing the floor. A mosaic of white hexagons, outlined in black, now splotched with red. Droplets, then a puddle, a pond, a lake.

Blood. Purpling. Coagulating before his eyes.

Darkness presses against the outer reaches of his periphery, narrowing his vision. The world grows dim.

He reaches out a hand against the blood-smeared wall. Fingers squealing on tiles. Tries to call for help but the words get strangled in his throat. He collapses to the floor.

Eyes land on a knife, its razor edge trimmed in red. Blood. His blood.

Darkness closing in. The world reduced to a pinprick. Fatigue washes over him like a summer storm.

My final moments, he realizes. All come down to this.

He does not hear the door swing open, the swift stomping of feet. The ripping of fabric. The improvised tourniquet. Being lifted and carried, swept out the door, leaving behind a world of black and white and red.

1. (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

WE FOUND HIS BODY on a Sunday morning. Three circling buzzards, their black silhouettes etched against a blazing blue sky, clued us in that something might be down there. Down in the gullies where the foothills gave over to desert.

At the very edge of the No Water.

We thought a possum. Perhaps even a wolf. Certainly not a kid fried like an egg, stretched out in the meager shade of a mesquite bush.

He wasn’t dead, but if we hadn’t found him when we did, he would’ve been. Maybe within the hour. Then this story never would’ve happened. There’d be nothing to write about because it all changed that late-spring morning, the day we found him dying of dehydration at the edge of the desert.

He was sandy-haired, about our age, lying spread-eagled on the ground like a giant X. Red ran back to camp to tell the officers, while Flush and I turned him over. The sun had burned his face to a crisp, cracked his lips, swollen his eyes shut. Dried sweat stains marked his black T-shirt and jeans, and, oddly, he was barefoot. Barefoot in the desert! Blisters big as quarters, caked with dirt and blood, dotted the undersides of his feet.

We poured water from our canteens into his mouth. Some of it made it to his throat; the rest dribbled down his neck, carving trails in his dust-covered face.

The camp Humvees came hurtling across the dunes. The boy stirred, his eyes opening into a squint.

“He’s alive!” Flush shouted. Master of the obvious.

He mumbled something neither of us could quite make out. I bent down, stretching my gimp leg out to the side so I could press my ear close to his mouth.

“What was that?” I asked.

I gave him another slurp of water. He tried to speak, the sounds painful to listen to. Like stepping on broken glass, all crunch and scrape.

Red jumped from the Humvee, Major Karsten right behind.

“Th-th-there,” Red said, with his tendency to stutter.

“Stand back,” Karsten said. No one didn’t obey an order from Major Karsten.

Wearing desert camouflage, he marched across the sandy terrain, his boots leaving massive footprints in the earth. He knelt by the boy’s side, picked up his right arm, and examined it. There was a thick burn mark there: a ridge of red scar tissue oozing pus. Karsten inspected it a full twenty seconds before feeling for a pulse. By then, other vehicles had arrived, disgorging brown-shirted soldiers.

“Get him to the infirmary,” Karsten commanded.

The soldiers loaded the boy onto a stretcher and slid him into the Humvee like a pan of dough going into an oven. The vehicle roared back to camp.

“Who found him?”

Major Karsten was looking right at us, his anvil-shaped face skeletal in appearance. The sun cast a deep shadow on the scar that angled from left eyebrow to chin.

“We all did,” Flush said.

“Ever seen him before?”

“No, sir.”

“Did he say anything?”

Flush was about to answer but I beat him to it. “He tried. Nothing came out.”

Karsten’s eyes settled on me. I knew that gaze. Feared that gaze.

“Nothing?” Karsten asked.

“No, sir,” I answered.

His eyes narrowed as though gauging whether I was being truthful or not. “Come see me when you get back, Book. I want a full report. You LTs return to camp,” he said over his shoulder. “That’s enough CC for one day.”

Black smoke belched from the exhaust and the remaining Humvees made doughnuts in the desert before ascending the ridge.

“I saw him first,” Flush said, his pale, round body sinking in the shifting sand as he and Red plodded up the hill ahead of me. “Why didn’t Karsten ask me for a report? Why Book?”

“Do you want to m-meet with Karsten?” Red asked.

“Well, no,” Flush conceded.

“Then shut your p-piehole.”

That’s the way it was—people talking about me as if I wasn’t even there. Sometimes I felt utterly invisible. Like if I turned around and took a suicide walk into the No Water, no one would notice. I guess that’s why I buried myself in books. There was comfort there. Security.

As the heat seeped through the soles of my shoes, a sense of dread settled in my stomach. The prospect of facing Major Karsten was enough to send a wave of nausea through me. Of all the officers in Camp Liberty, he was by far the most feared.

But it was more than that—I had lied. The boy had said something. Words I alone had heard. Words that raised the short hair on the back of my neck.

“You’ve gotta get me out of here,” he said, seconds before the first Humvee pulled up. And then, for good measure, he repeated it once more.

You’ve gotta get me out of here.

2. (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

HOPE BENDS HER EAR to the cave’s entrance, her body tense.

She’s convinced she’s hearing sounds. Not the noises she’s grown accustomed to—scurrying rats, the flap of bats’ wings—but something else entirely. A rustle of leaves? Something … human.

She fears the soldiers are getting close.

“Hope,” her sister whispers.

“Shh.”

“Hope,” Faith says again.

Hope motions her sister to be quiet … and then sees the reason for her distress. Lying on black bedrock, their father’s head lolls listlessly from side to side. Hope leaves the mouth of the cave and hurries to his side. In flickering candlelight, she sees his cheeks are badly sunken, his normally robust face pale as chalk. When she places a hand on his forehead, it’s scalding.

“He’s burning up,” Hope says. She turns and sees the tears welling in her sister’s eyes. Hope points to a small pool farther back in the cave. “Go soak a rag and we’ll place it on his forehead.”

“What rag? We don’t have anything.” Faith’s voice borders on panic.

While it annoys Hope that Faith can’t solve problems on her own, she’s right about this: they don’t have a thing. The last few weeks have been a desperate scramble from one hiding place to another. They’ve been forced to leave nearly all their possessions behind, burying them in remote patches of the wilderness. They’ll have no need of them once they reach the Brown Forest and cross into the new territory.

If they reach the Brown Forest.

Hope rips the bottom off her shirt and hands the filthy wad to Faith. “Here. Now go.”

Faith scuttles to the cavern’s dark recesses.

Hope takes her father’s hand. It’s rough and callused, more like sandpaper than skin. She studies his left foot, now nearly twice as big as his right. It’s purple and inflamed, with red lines shooting up the calf. All because he stepped on a jutting nail, its tip scarred with rust and radiation. After all they’ve been through, to have it come down to something as simple as a little infection.

Which has grown into a big infection.

She stares at the cave’s entrance, still not sure if she heard something. Drifting clouds obscure what little moon there is.

A voice startles her.

“Go easy … on your sister.” Her father, his words gravelly.

Hope grows suddenly defensive. “I do.”

Her father grunts. “She tries, you know.”

“Yeah, well, sometimes not hard enough.”

He forces a smile, the wrinkles creasing beard stubble. A corner of his black mustache angles up. “Sounds like my words.”

Of course they’re his words. Where else would she have learned them?

His eyes close. Then he whispers, “You’re your father’s daughter. And she’s … her mother’s daughter.”

It’s true, of course—no denying it—and it always strikes Hope as odd that two siblings, born mere minutes apart, can be so utterly different. It’s obvious that she and Faith are twins. Both sport matching black hair, identical brown eyes, the same tea-colored skin. The only physical difference is weight; Faith is perilously thin … and getting more so by the day.

But in all other respects they are wildly different. Faith is shy, introverted, afraid to take chances, while Hope is just the opposite: fearless, athletic, bold to the point of reckless. As far as Hope’s concerned, they may as well have sprung from separate mothers entirely.

Hope remembers the day they raced sticks in the stream behind the house. What were they then, five or six? Although it was obvious Faith would rather have been inside attending to her dolls, she agreed to play, and they ended up shouting with delight, rooting for their tiny twigs tumbling down the mountain creek.

But when the soldiers showed up and the sound of bullets echoed off the surrounding hills, Hope and Faith forgot racing sticks. Forgot how to smile and laugh. The girls’ last memory of that childhood home—and their childhood itself—was their mother lying dead, blood pooling from her forehead onto the warped boards of the front porch.

Hope dragged her sister to a hollow log and there they stayed for two whole days. When their father returned from a hunting trip, the three of them took off, not even daring to return home to bury their mother or pack supplies. They feared the Republic’s soldiers were staking out the house.

That was ten years ago. They’ve been on the run ever since, rifling through abandoned houses, living in trees and caves. They even spent one winter in a grizzly’s den, praying the bear wouldn’t return.

Out of necessity, Hope has grown more tomboyish with each passing day, learning how to start fires, how best to throw a spear. Her only vanity is her hair, which is black and long and silky—resembling her mother’s. A way of honoring her fallen parent.

“One thing,” her father says. “You have a choice to make.”

Hope stares down at him. What’s he talking about? “All we’ve been doing these last ten years is making choices,” she says.

“This one’s different.” His voice is a raspy whisper. “There’s a reason the government’s after us.”

“Yeah, because you didn’t sign the loyalty oath.”

He gives his head a shake. “That’s just part of it.”

What is he about to tell her? And why does she feel a sudden dread?

“Go on,” she says.

“You’re twins.”

Hope sighs in relief. “Gee, I had no idea.”

He continues, “And the government wants twins.”

Hope cocks her head. Where’s her father going with this? Is he delirious with fever or is this for real? “I don’t get it. What’s so special about twins?”

He grimaces. “You have a choice to make. Either stay together … which means you’ll be hunted the rest of your life …”

“Or what?” she dares to ask. She realizes she has ceased to breathe.

“Or separate.”

His words are like a thunderclap. Separate? It’s true, Faith can be irritatingly slow and often holds them up. But separate? The thought has never crossed her mind.

She peers toward the cave’s interior; Faith is wringing water from the rag. Her skeletal silhouette looks ghostlike. Draped around her shoulders is their mother’s pink shawl. It’s tattered and torn, singed from fire.

“Why would we do that?” Hope asks her father. “Faith wouldn’t last a day.”

“If they catch you … neither of you will.”

Hope wants desperately to find out what on earth he’s talking about—but at that moment Faith returns. She places the damp cloth on her father’s forehead. His eyes close and he’s asleep within seconds.

“What was he saying?” Faith asks.

“Nothing,” Hope answers a little too quickly. “Just nonsense. Fever and all.”

Hope crawls back to the cave’s entrance, staring into the dark through a curtain of dripping snowmelt. Her father’s words bounce around her head. Separate from Faith? Abandon her? What an absurd idea.

As the black night presses against her, Hope can only pray it’s a decision she’ll never have to make.

3. (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

I TYPED UP MY report using one of the camp’s bulky typewriters. Although we’d heard of cell phones and computers and something called the internet, all that was fried by the electromagnetic pulse that accompanied the bombs.

Omega, they called that day. The end of the end.

One enormous burst of electromagnetic radiation and everything that was even remotely electronic was fried to a crisp. Computers became the stuff of legend. Most cars were no longer drivable. And although I’d read about them, I’d never seen an airplane in the sky. And figured I never would.

Not that Camp Liberty was without luxuries. Every Friday night we gathered in the mess hall to watch movies, the film projector powered by the camp’s generators. The problem was, only a handful of movies survived, all oldies, and so we saw the same ten films all year, every year. Stagecoach, Shane, To Kill a Mockingbird, that kind of thing.

I stripped the paper from the typewriter’s roller. For obvious reasons, I neglected to mention the boy’s whispered message. I walked the report over to Major Karsten’s office and left it with Sergeant Dekker.

“Slice slice,” he said with a sneer, enjoying the in-joke that—thankfully—only a couple of us understood.

My face burned and I got out of there as fast as I could.

Days passed. Rumors flew. Some claimed the boy in the black T-shirt was a convict on the run. Others said he was no outlaw, merely an LT from an adjoining territory.

What I couldn’t figure out was why he was in the middle of the No Water in the first place, on the outskirts of an orphanage.

That’s what Camp Liberty was, although in official Republic jargon it was called a “resettlement camp.” There were several hundred of us, all guys, most with birth defects brought on by Omega’s radiation. Those toxic clouds remained floating above the earth like Christmas ribbon encircling a present, just waiting for someone to tighten the bow.

Our poor mothers had been doused with so many gamma rays or alpha particles or whatever it was, that they brought us into the world with one too many fingers or one too few or shriveled arms. Or, in my case, one leg shorter than the other. And then they died shortly after giving birth.

It was never clear how it all began. Some say a group of no-goods on the other side of the planet got hold of weapons of the nuclear kind. Others claim our own allies were to blame, attacking countries who then counterattacked. However it started, a dozen nations ended up shooting off nuclear warheads like it was the Fourth of July, until every major city in the world was obliterated. Utterly wiped out.

Of course, since all this took place a good twenty years ago, we had to rely on what the soldiers told us. Which wasn’t always accurate.

It was the other camps I wondered about. They had to be out there, right? There were rumors, of course—grisly tales of torture and atrocities—but who really knew what was true and what was made up.

“John L-183?” A Brown Shirt was standing by my table in the mess hall.

“Yeah?”

“The colonel wants to see you.”

My fork lowered. Whenever Colonel Westbrook asked to see an LT, it usually meant one thing: punishment. Was it the false report? Had the colonel somehow figured out the boy had told me more than I let on?

“Maybe you’re going through the Rite early,” Flush suggested. I shook away the notion. No one graduated until they were seventeen. I still had another year.

“That’ll teach you to read so many books,” Dozer said, snorting. He was a barrel-chested LT who could never be accused of reading books.

The acne-scarred soldier waited for me to get up. Like all the soldiers in camp, he wore a uniform of black jackboots, dark pants, and a brown shirt. That’s why we called them Brown Shirts. We were clever that way.

I left the mess hall feeling like I was headed to my execution. Sunlight blinded me as we crossed the camp’s infield. Above us, the flag atop the pole cracked in the wind like a whip. Snap. Snap.

We approached the headquarters, an ancient, rotting log building that sat in the middle of camp like a festering sore. An older Brown Shirt sat hunched over a sheaf of papers, a sweaty sheen covering his face.

Three straight-backed chairs lined the wall. To my surprise, one of them was occupied. It was the boy from the No Water.

Even though I’d helped save the guy’s life, he didn’t offer a word of thanks. Didn’t even acknowledge my presence.

The door to an inner office opened and out stepped Colonel Westbrook. He was of medium height with an unimposing face, his dark brown hair styled in a kind of comb-over across his skull. Like all the officers, he wore a dark badge on his left sleeve. It sported the Republic’s symbol: three inverted triangles.

I must’ve seen the colonel a thousand times, but never up close. For the first time I noticed the blackness of his eyes. There was not a bit of color in them at all. My heart was in my throat as I followed him to his office.

There were two others in the room as well. Sergeant Dekker, wearing his customary smirk beneath his oily hair, and Major Karsten, sitting ramrod straight by the window. Perspiration trickled down my side.

Westbrook’s eyes focused on a manila folder opened before him. His finger traced one line of information after another. “You’re John L-183,” he said at last. “The one they call Book, yes?” He said my name as though it was something unpleasant tasting.

“That’s right.”

“Nothing to be ashamed of. We need more scholars. They’re the future of the Republic.” His tracing finger halted, and I knew exactly where he’d gotten to in my life history. Blood rushed to my face.

“Liberty has a new member,” he said, his coal-black eyes boring into me. “We want you to show him around. Any problem with that?”

“Um, no, sir.”

“Get him situated. The sooner he’s one of us, the better for all concerned.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, relieved. This wasn’t a punishment after all.

“And, Book?” Colonel Westbrook leaned in, his fingers splayed on the desk like talons. “See what you can find out. Where’s he from? He’s got no marker and we don’t know much about him. After all, if he’s in need of help we have to know what he’s been through. You can understand that, can’t you?” A pointed reference to my own past.

“Yes, sir,” I said. “But I don’t want to rat on people.”

“It wouldn’t be ratting. It’d be informing.” He smiled grimly. “It’s very simple, Book. You help us, we help you. And who knows? A year from now, when you go through the Rite, we might look into making you an officer.”

Put that way, it didn’t seem so bad. And it was true: I did know a thing or two about secrets. “Okay,” I said.

“It’s settled then. I’ll have Major Karsten check in with you from time to time.”

I looked up at the major. The scar that edged from his eyebrow to his chin seemed to pulse like a living, breathing thing.

I couldn’t get out the door fast enough.

4. (#u08ac49f2-464f-5853-bbc4-8da0dc9e7638)

HOPE KNOWS HE’S DEAD the moment she returns from watch. Faith is tucked into the curve of their father’s body, her tears soaking his shirt.

Hope places her fingers against the crook of his neck. Cold to the touch. No hint of a pulse. It hits her like a punch to the gut.

“Come on,” she says, pulling her sister off.

“We have to bury him,” Faith says, eyes red.

“I know.”

“How’re we going to do that? We don’t have a shovel.”

“We’ll think of something.”

“But what? We can’t leave him like this.”

“I know that …”

Faith is screaming now. “We have to do something! What’re we gonna do?”

Hope slaps her sister hard across the face, regretting it instantly. Faith’s head snaps to one side, the red imprint of Hope’s fingers tattooing her face.

“I’ll take care of it,” Hope says, finding a reason to look away. “We’ll cover him with rocks. That way the animals can’t get him.”

“Is that a proper way to bury someone?” Faith whispers.

“Proper enough. You go take watch. I’ll do this.”

Faith drags herself to the cave’s entrance, running the back of her hand across her runny nose. Hope feels a stab of guilt for the way she treated her. Still, someone has to be the strong one, she tells herself.

The first thing she does is retrieve her father’s few belongings. A knife. A leather belt. Flint from his front pocket. It feels like an invasion, going through his clothes, but she has to do it. Flint means fire. A knife means survival.

There’s something else there, too. A small, gold locket, attached to a thin, tarnished chain. As soon as Hope’s eyes fall on it, she has a distant memory of it dangling from her mother’s neck. And when she undoes the clasp and opens it, she knows what she will see before she sees it.

Two miniature oval photographs. One of her father, one of her mother. From younger days. How innocent they look. And happy. Now encased in a locket’s tomb, facing each other for all eternity. No wonder he carried it with him all these years.

She slips it into her pocket.

The process of dragging rocks is tedious, and she carefully places them atop her father’s body as though—even in death—he can feel the weight. Faith weeps steadily by the cave’s entrance. Hope’s eyes are as dry as sand. There is no time for tears. Her father taught her that.

Live today, tears tomorrow.

Hope has crossed her father’s hands atop his chest when she notices the curled, clenched fingers of his right hand. They are stiff with death and it’s no small struggle to straighten them. More surprising than the effort itself is what she discovers within his gnarled grip.

A small, crumpled slip of paper.

Hope tugs the paper free from her father’s hand. She sees one word written there, scrawled in charcoal.

Separate.

Hope shakes her head and crumples the note back up.

When she finishes the burial mound, both girls gather by the body. They have never been to a funeral before. Or a wedding. Nothing.

In lieu of a prayer, Faith says, “I heard what he told you. About separating.”

Hope tries to hide her surprise. “He was delirious,” she says. “Out of his head with fever. I’m not thinking of it if that’s what you’re asking.”

“I’m not.” Their eyes run up and down the grave of rocks. “But I think we should.”

“You think we should? Separate?”

Faith nods. “If he was right about that twins stuff, it sounds like you’d”—she pauses to correct herself—“we’d have a better chance on our own.”

“Faith, you wouldn’t last a day out there. No offense.”

Faith bristles. “I’m not as helpless as you think.”

“Uh, yes you are.”

Hope can see she’s hurt her feelings. If Hope isn’t slapping her sister with her hand, she’s doing so with her words.

“I’m going to get some food,” she says, impatient and angry all at once.

Faith doesn’t respond.

At the edge of a swampy bog Hope spears half a dozen plump bullfrogs. She brings the meat back to the cave late that afternoon and it cooks up good. They wolf it down without a word. After dinner, they settle on their makeshift beds, still not having spoken since the morning. Hope falls into a deep sleep, dreaming of everything and nothing.

When morning sunlight wakes her, there’s no sign of her sister anywhere.

“Faith,” she calls, first inside the cave, then out. The only answer she gets is birdsong. “Faith!”

Still nothing.

No extra footprints pattern the ground. No sign of wild animals. But Faith’s few possessions are gone. No canteen, no backpack, no shawl.

Hope curses not so silently to herself. She isn’t sure who she is angriest at: Faith, for thinking she can make it on her own, or herself, for basically daring her to go.

Or her father, for bringing up the notion of separating in the first place.

Although Faith’s body is light and her footprints barely dent the ground, Hope will have no problem trailing the flattened grass, the snapped twigs. After ten years of tracking prey at her father’s side, she knows the signs.

Hope finds the trail and determines which way Faith has gone … then promptly goes the other direction. To hell with her sister.

5. (#ulink_7dbd9d28-d49e-539a-8529-133e4f2690f0)

I EXPLAINED THE BASICS: chores in the morning, classes in the afternoon, CC—Camp Cleanup—on the weekends. The boy in the black T-shirt didn’t ask a single question, but I got the feeling nothing escaped his attention.

When we exited the mess hall, I realized I hadn’t introduced myself. “I’m Book,” I said, trying to sound tougher than the name. “Who’re you?”

“L-2084,” he murmured.

Sometime after Omega the government made the decision to label all the boys John. Our last names were what distinguished us: a series of numbers matched with a letter for our camp—L for Camp Liberty, V for Camp Victory, etc. Our “identities” were tattooed on our right arms.

Apparently, all girls were called Jane, but that was only a rumor. We’d never actually seen any for ourselves.

“Not your official name, your nickname,” I said. “Like I’m Book because I read a lot, and there’s Red because he has a red splotch on his face and Twitch because he does and Flush because he doesn’t.”

The boy in the black T-shirt said nothing.

“What’d your friends call you back where you came from?” Then, in an awkward attempt to follow the colonel’s orders, I asked, “Where’d you say that was again?”

“I didn’t,” he growled.

We toured the rest of the camp in silence. Finally, I asked, “What’d you mean in the No Water? About getting out of here?”

“Just what I said,” he answered tersely. As if it didn’t need explaining.

“Why? This is a decent camp. And our grads do really well.”

A small sound escaped Black T-Shirt’s mouth. A grunt? A scoff? But when I turned to look at him, I didn’t get any reaction at all.

Neither of us spoke as we made our way across camp. As we passed two LTs, one of them knocked into me and I nearly lost my balance. The LT shouted out, “Who’s your boyfriend, Book Worm?”

They laughed. So much for making a good impression on the new guy.

Beneath the arched ceiling of the Quonset hut, a hundred-some bunk beds stretched out in long rows. At the base of each bed was a wooden trunk, storing all our worldly possessions. In my case: books. Dozens of them.

Black T-Shirt stopped, pointing to the very last bunk in the room. “This one taken?” He clambered effortlessly to the top and lay on his back like some Egyptian sarcophagus.

Apparently, the tour was over.

“You don’t get it, do you?” he said.

His words startled me. “Get what?”

“This.” He gestured vaguely to the barracks, the camp itself.

“I get as much as I need to get,” I said, suddenly defensive.

He shook his head. “You have no idea.”

I turned on my heels and stormed out, angry I had ever bothered to help save L-2084’s life in the first place.

I walked to the southwestern edge of camp. Below me lay endless desert; above me a jagged range of mountains. The cemetery itself was soundless. I made my way through a labyrinth of sun-bleached crosses until I found the marker I was searching for.

L-175. Known to us as K2.

A series of eerie images danced through my brain like fireflies.

Giant trees crashing to earth. Startled shouts. A final, haunted expression.

Pounding on a door. Red on white. Blackness darkening the edges of my periphery.

My face grew suddenly clammy. I squeezed my eyes shut and gave my head a violent shake, as if it were that easy to chase away demons.

It didn’t work, of course. Never did.

I opened my eyes to blinding sunlight and reached out a hand to the wooden cross, rubbing my fingertips over its weathered ridges. I tried to speak, but the words got stuck in my throat. Those twin demons, guilt and grief, clamped my mouth shut.

Poor K2.

I noticed a yellow school bus heading up the hill below me, trailing a white plume of choking powder from the gravel road.

I knew who was in it, of course. Orphans. Headed for the nursery, where they’d be raised by surrogates until—one day—they’d become LTs.

There were fewer and fewer buses these days. I didn’t know if that was a good thing or not. All I knew was that I’d go through the Rite and be long gone before these kids could even read or write.

The bus came up the rise. On its fender were three crudely drawn inverted triangles. Inside the vehicle were row after row of boys, some so young they were held in nurses’ arms. Others slightly older, their faces pressed against the window in a mix of fear and wonder. Years from now they wouldn’t be able to recall their mothers or fathers; what they’d remember was the day they arrived at Camp Liberty … and be grateful it wasn’t someplace worse.

I spun around and returned to camp. Gone for the moment was the shame of my past, the guilt I carried, replaced instead with those mysterious words uttered by Black T-Shirt.

You’ve gotta get me out of here.

6. (#ulink_07752a13-c40b-5e5b-bcea-1f46a63e721a)

ORANGE LIGHT FLUTTERS ON Hope’s face. She pulls a gutted rabbit from the spit and eats every last morsel, sucking the bones clean. As she pokes the embers, thoughts of Faith swirl in her head. It’s been nearly a week since they went their separate ways and Hope knows her sister has no flint. Has she been without fire this entire time?

But it was Faith’s decision to go off on her own. Besides, their father said they should make this choice. The thought of him makes her pat her pocket and feel the small gold locket. Also the crumpled bit of paper with that one word: Separate.

No. I can’t think about it.

What she thinks about instead is the boy with the piercing blue eyes. He’d come traipsing through just a few weeks past, looking for a night’s shelter from the rain. Her father allowed it, on the single condition that he stayed at one end of the cave and his two daughters at the other. Hope remembers how she and Faith stared at him long through the night: his sandy hair, the embers’ dull orange light sculpting his face, the rise and fall of his chest as he slept.

He was the first guy her age she’d ever seen, and she often wonders who he was and where he came from. Wonders if she’ll ever see him again. Or if she’s destined to be by herself her entire life.

She tries to sleep, and when she wakes just a few fitful hours later, Hope knows what she has to do. She douses the fire, packs her belongings, and heads out, her route reversed from the day before—she must find her sister.

Faith is ridiculously easy to track. She might as well have left painted arrows on the ground. Did she learn nothing from their father?

Hope suddenly stops. Something has caught her eye.

She retraces her steps. All around her, spring wildflowers poke through the earth: shimmering royal blue, egg-yolk yellow. And a carpet of miniature blossoms, the petals white as snow.

But one is stained with a single dot of red.

Blood. Fresh blood.

Other drops on blades of grass. Faith is bleeding.

Hope takes off in a jog.

Her father’s message echoes in her brain: Separate. What he failed to understand was that she doesn’t have a choice. Faith is her sister—her twin. As different as they are, there’s no separating them.

Late that afternoon, Hope finally spies Faith from a great distance: a solitary figure wading through waist-high weeds. She zigzags back and forth. Is it delirium that pushes her from side to side? Or loss of blood?

Hope has two options: race straight across the valley or hug the tree line and circle around. Her second option will take longer, but it’s obviously safer. A body walking through a barren meadow is just begging for trouble.

Despite her best instincts, Hope chooses the quicker route. Faith is in trouble. She needs Hope now. Hope begins to run, her heart hammering in her ears.

When she finally reaches her, Faith’s words are accusatory. “What’re you doing here?”

Hope is taken aback. “Coming to find you, what do you think?”

“I don’t need to be found. I’m just fine on my own.”

“You’re bleeding …”

Faith clenches her right hand into a fist, but not before Hope sees the thick slice across her palm. “It’s nothing. Knife slipped.”

“Let me see.”

“It’s nothing.”

Hope feels a surge of anger. Here she’s gone to the trouble to find her sister and put her life on the line and Faith wants nothing to do with her.

“Faith, you can’t do this. You won’t make it on your own.”

“I can make it on my own just as well as you,” she says over her shoulder.

“Oh, come on …”

Faith wheels on her twin, nostrils flared. “Why don’t you think I can make it? Because I’m helpless without you? Because he wanted us to separate so you could live and not me?”

“That’s not true and you know it.”

“I heard him, Hope. He was telling you to go your own way. He wanted you to live. Well, guess what? I’m giving him what he wanted.”

Bug bites cover every inch of Faith’s face, and her eyes are nearly swollen shut. But even more painful for Hope is the haunted expression Faith wears. A look of genuine sadness. Hope doesn’t know what to say. What words can possibly ease her sister’s pain?

When Hope is finally about to speak, she’s interrupted by a low rumble. The earth shakes beneath their feet. Their father told them about earthquakes, but they’ve never experienced one. A flash of movement out of the corner of her eye swings her around.

It’s not an earthquake but a thundering of hooves. Horses. Dozens of them, headed straight for the two girls. Atop each of them is a Brown Shirt hoisting a semiautomatic rifle.

It only takes Hope a second to react.

“Run!” she screams at the very top of her lungs.

Hope drags her sister as best she can, tearing through the tall grasses. But there’s no place to hide. Their only hope is to reach the trees and pray the woods are thick enough to keep the horses from following. Then the Brown Shirts will be forced to dismount and lug their heavy weapons.

It’s a long shot, but better than none at all.

The rumble of hooves grows louder. The roar swells like a thunderstorm, hailstones slamming into the ground.

Both girls are sucking wind. Faith’s lungs make harsh, raspy sounds with each inhalation.

“I have … to stop,” she wheezes.

“No!” Hope says.

Faith bends over, clutches her knees. “Go,” she coughs. “I’m done.”

“You’re not done. We can do this.”

The horses are gaining speed. If the sisters leave right now, they stand a chance. But only if they leave this very instant. “Come on!”

Faith shakes her head. “Go,” she says. “It’s what Dad wanted.” She meets Hope’s eyes. “It’s what I want, too.”

Hope looks at her sister. And at the approaching Brown Shirts.

“H and FT,” she says.

Faith doesn’t respond.

“H and FT,” Hope repeats.

It’s their secret code. Has been since they were kids, since that awful day when their mother was shot before their eyes.

H & FT. Hope and Faith Together.

Finally, Faith says it back. “H and FT.”

Hope guides her. In her one hand is Faith’s arm; in the other is her spear. She veers straight for the sun, forcing the Brown Shirts to squint into the sunset. Forcing them to slow down to navigate creek beds and boulders.

The tree line grows closer and Hope can make out the dense underbrush. It’s all shrubs and thick tangles of vines. Good for hiding. Living hell for a horse. No way the Brown Shirts can navigate this maze. Hope realizes they’ve caught a break. They should just make it after all.

The first gunshots blast the trees in front of them. Bark explodes. Small birch trees are sliced in half. Faith slows.

“Don’t stop!” Hope yells.

“But they’re shooting at us.”

“And we’ll stop if they hit us!”

They’re a mere twenty yards from the woods when a lead horse circles around and cuts them off. Then another. And another. There’s suddenly no way out.

Still, when a Brown Shirt draws a pistol, Hope reaches back with her spear and sends it flying. It sails through the air, entering the soldier’s chest, the pointy end sticking out his back. A dazed expression paints his face as he tumbles off his horse.

A dozen other Brown Shirts raise their M16s and target them on Hope.

“Don’t shoot!” a voice cries out.

A trailing Humvee comes to a sudden stop and a man waddles forward. He is heavy to the point of obese, with thin, almost invisible lips. Unlike the men on horseback, he doesn’t wear the soldier’s uniform of the Republic, but a black suit with a white shirt and a thin black tie. His most striking feature is the soiled hanky he grips in his hand, which he uses to dab at the corners of his eyes.

“Don’t shoot,” the pudgy man says again, and rifle barrels lower. He appraises the twins with leering eyes. His sausage fingers cup Faith’s chin. “We’ve been looking for you two,” he says in a nasally voice. “Oh yes, we’ve been looking for you for quite some time.”

7. (#ulink_41483520-1b68-5ee3-8048-a908bb24ab54)

THERE WAS A FUNERAL to attend. There were always funerals at Camp Liberty. Another LT had succumbed to the lingering effects of ARS. Acute radiation syndrome. It was a lanky kid named Lodgepole who’d developed a tumor in his neck the size of a softball. Frankly, he was lucky to die when he did.

I didn’t know Lodge well, but had a feeling I would’ve liked him. Which is exactly why I didn’t get to know him. What was the point of making friends if ARS was just going to pick them off?

Another reason why I immersed myself in books.

I read everything I could get my hands on. History, biographies, fiction. If it was on the dusty shelves of our little library, chances were I’d checked it out.

But that wasn’t all. Someone was giving me books as well. It wasn’t uncommon to open my bedside trunk and find some new volume. None of the other LTs got books—just me—and I couldn’t figure out who was doing it.

As for Black T-Shirt, I still hadn’t found out anything about him, other than the fact that he was incredible at everything athletic. Whether it was shooting arrows or kicking soccer balls, he was drop-dead good. Yet another reason he pissed me off.

Now that he wore the camp uniform—jeans, white T-shirt, blue cotton shirt—his old name no longer cut it. So we called him Cat, because he was athletic and mysterious and half the time we didn’t hear him sneak up beside us.

“Lemme ask you a question.” There he was again, standing beside me at the mess hall door. “You’re called LTs, right?”

“That’s right,” I said.

“Why?”

“It’s short for lieutenant. A military abbreviation. ’Cause we’re the future lieutenants of the world.”

“Says who?”

“The camp leaders. Westbrook, Karsten, Dekker, all of ’em.”

Cat shot me a look of disbelief. “Seriously?”

The hair rose at the base of my neck. What was it about this guy that rubbed me the wrong way? “Seriously,” I said.

He tried—not very hard—to stifle a laugh. “So what happens when they leave here? The graduates?”

“You mean after they go through the Rite?”

“Yeah, tell me about the Rite,” he mocked.

“There’s a big ceremony where all the seventeen-year-olds pledge allegiance to the Republic, then they’re bussed to leadership positions elsewhere in the territory. It’s a pretty big deal.”

This time Cat didn’t bother trying to hide his laughter. It was a harsh, mocking laugh, and I couldn’t take it anymore. I brushed past him and stepped outside into the pouring rain. Cat was beside me in a second.

“You don’t have to get all pissy,” he said. “I’m just trying to help.”

“Yeah, well, maybe I don’t need your help.”

“Fine. Your funeral.”

Something about his tone pushed me over the edge. I turned and gave him a shove.

“Who the hell do you think you are?” I demanded.

His expression was blank. Icy rain plastered his hair to his forehead.

“I’ve lived here nearly all my life,” I went on, “but you’re the one who acts like he knows everything. Well, screw you!”

“I don’t know everything …”

“Well, you definitely act that way.”

“… but I know some things. Like you’re crazy to think they call you LT because it’s short for lieutenant.”

“So if you’re so smart, what is it?”

“You really want to know?” His words cut through the rain like a knife. “It’s short for Less Than. Which is exactly what all of you are: a bunch of Less Thans.”

I felt like I’d been sucker punched. I was too stunned to respond.

Cat went on. “When you were a little kid, the Republic decided your fate. They determined where you were going to go, what you were going to be. Soldier, worker, Less Than, whatever.”

“Then how come none of us have ever heard that?” I asked.

“Probably ’cause the Brown Shirts didn’t tell you.”

I struggled to form thoughts. “How do they decide who’s a … Less Than?” Just saying the words made me uncomfortable.

“Handicaps, obesity, skin color, politics, who knows. They don’t announce the criteria, but it’s pretty clear. I mean, look around.”

I thought of the two hundred or so guys in Camp Liberty. Some of it might’ve been true, but that didn’t mean anything. Sure, I had brown skin, and Twitch and June Bug had black. Dozer had a withered arm, Red a splotch on his face, and Four Fingers, well, four fingers on each hand. But all that was just a coincidence. Right?

“Politics?” I asked. “What kid knows anything about politics?”

“Not you, your parents. If they’re dissidents, then you’re branded Less Thans for sure.”

“But why?”

“Because if the normal people want to survive the next Omega, we can’t have a bunch of Less Thans holding us back.”

My head was swimming. Not only was he suggesting we weren’t normal but that we might not even be orphans. “This is an orphanage,” I managed.

“Who said?”

“The Brown Shirts.”

“You don’t think they’d lie, do you?”

My knees felt weak. Was it even remotely possible he was telling the truth? That we’d been ripped from our mothers’ arms and sent here because we were considered “less than normal”? I felt the sudden need to get away.

“What’s the matter?” he called out. “Can’t face facts?”

That did it. I spun around and leaped toward him and we tumbled hard on the rain-soaked ground. My fists began pummeling him. Roundhouses and jabs and uppercuts, one after another, landing first on one side of his face and then the other.

The other LTs made a halfhearted attempt to break us up, but they seemed all too happy to watch. And then I realized: Cat wasn’t fighting back. He was letting me hit him, barely blocking my punches. It made me all the angrier.

“That’s enough,” Cat finally said, and he sent a fist in my direction. I fell to the side.

I pushed myself to a sitting position, blood trickling from my nose. Cat’s one punch had drawn blood; it had taken me a couple dozen to do the same to him.

“You showed him,” said Flush.

But I knew I hadn’t. The LTs drifted off to the barracks.

“Why didn’t you fight back?” I panted.

“I only beat up people if I have reason to. I don’t have a good reason to beat you up.” He sipped a breath. “Yet.”

He pushed himself up until he was sitting in the mud, his face near mine.

“If you’re so smart, let me ask you this,” he said. “What do you know about the men outside camp?”

“You mean the Brown Shirts?”

“I mean the other men.”

I could’ve bluffed my way through an answer, but I was too exhausted for lies. “Nothing,” I conceded.

“I figured as much.” Then he said, “They know about all of you. And if you don’t do something about it, you’ll be dead within the year.”

Although I tried to hide it, my eyes widened. “Prove it,” I said.

“What’re you doing tomorrow afternoon?”

That night I couldn’t stop thinking about what Cat had said, his words jangling around my head like pebbles in a tin can. When I finally fell asleep I dreamed of her again: the woman with long black hair. She existed in some distant memory of mine, but who she was and how I knew her were details forever lost. All I knew was that she’d been appearing in my dreams more and more often until I no longer knew what was memory and what was imagination.

In the dream, we were racing through a field of prairie grass, my child’s hand encompassed in hers. Although she was far older, it was all I could do to keep up with her—two of my short strides matching one of hers.

Behind us came a series of sharp pops, like firecrackers. There were other sounds, too. Shrill whistles. Shouting. Barking dogs.

The land sloped downward to a hollow and we drifted to a stop. She put her hands atop my shoulders and stared at me. Wrinkles etched her face. Crow’s feet danced at the edges of her eyes.

I realized the pops were bullets; I could hear them pinging off the rocks and whistling past my ears. Someone was after us. Someone was trying to kill us.

Even though the woman seemed about to tell me something, I didn’t want to hear it—I didn’t want to be there—so I jolted myself awake, the blackness of the Quonset hut pressing down on me, my breathing fast.

It was another hour before I fell back to sleep, wondering who the woman was and what she was about to say.

8. (#ulink_ad5d5563-f55e-54f2-95e5-2ae4515dbd6f)

HOPE AND FAITH ARE jammed into the back of the Humvee. The convoy makes its way across nonexistent trails until they reach something resembling an actual road.

It’s the first time they’ve ever been in a vehicle. Well, a moving vehicle. They’ve slept in plenty of abandoned ones during their years on the run, but this one is actually in motion. Nothing could prepare them for the sheer speed of it.

The sun sets and an eerie calm settles over the landscape. The Humvee’s twin headlights cut two jagged holes in the darkness.

Hope wonders where they’re being taken. Every so often, the heavyset man swivels his thick head and peers back from the passenger seat. He says nothing.

In the distance, Hope catches a fleeting glimpse of structures. Listing log cabins, tar-paper shacks, old wooden buildings with peeling paint. All surrounded by a ten-foot-high fence, topped with an unending coil of razor wire. Anchoring the four corners are guard towers with Brown Shirts poised behind machine guns.

Hope’s mouth goes dry. After sixteen years, ten of them on the run, she and her sister are about to be imprisoned.

“Camp Freedom,” the obese man says cheerfully. “Your new home.”

The camp’s colossal gates shriek open and the vehicle rolls to a stop. A soldier pulls open the passenger door. There are Brown Shirts everywhere, each wearing the Republic’s distinctive dark badge with three inverted triangles. But it’s the others who draw Hope’s attention.

Girls. Scores of them. All wearing the same coarse, gray dresses that hang limply below their knees. Faded, scuffed boots adorn their feet. Based on their expressions, they seem to regard Hope and Faith as a couple of feral cats.

A tall, stooped man with a tidy mustache and a balding pate emerges from a cinder block building.

“I see you’ve met Dr. Gallingham,” he says. “I’m Colonel Thorason.” He pauses briefly, as if expecting the girls to bow or otherwise show how impressed they are to meet the camp overseer. “Life here is very simple: you abide by the rules or face the consequences. Is that clear?”

Hope and Faith nod.

“In that case—” He interrupts himself when he spies a woman walking their way. She is tall, with straight blond hair and enormously round cheekbones. An ankle-length coat is draped atop her shoulders. Thorason takes a deferential step backward as she approaches.

“Which one threw the spear?” she asks. Her tone is as sharp as the razor wire atop the fence.

“I did,” Hope says.

Hope waits for a reaction. A slap. A punch from a soldier. Something to teach her a lesson. Instead, the woman reaches forward and fondles Hope’s hair, letting the silky strands run between her fingers.

“Such pretty hair,” the woman murmurs. “It’s obvious you take good care of it.” The woman forces a brittle smile and begins to walk away.

“Do what you need to do,” she says over her shoulder to Colonel Thorason. “But that one”—pointing her finger in Hope’s direction—“gets shaved.”

Hope and Faith are taken to a bathhouse, where they’re stripped and showered with a white powder.

“Delousing,” the female guard explains in a flat monotone. She has a square block of a face that seems incapable of smiling. She throws two dresses at them: ill-fitting gray things. A pair of dirty combat boots finishes the ensemble. When the guard turns her back, Hope retrieves her father’s locket from her pants pocket and stuffs it in her boot. That and the scrap of paper.

The woman turns back around, brandishing a large pair of scissors, the blades nicked with rust.

“Don’t move,” she orders, “unless you want this through your eye.”

She snips the scissors twice, then seizes Hope’s hair. Watching her long strands of hair ribbon to the ground, it’s all Hope can do not to cry.

Live today, tears tomorrow.

When the woman finishes, she grabs a broom.

“Here,” she says, thrusting it in Hope’s hand. “Clean up your mess.”

Hope grits her teeth and does as commanded, but not before running a hand over her bald, patchy head. She feels as naked as a plucked bird. But it’s more than that; it’s almost as if—somehow—she’s lost a piece of herself. A piece of her mother.

A male guard with a jutting chin enters. In his hand dangles an odd-looking tool with a pointy end. His gaze lands on Faith.

“Right arm,” he commands.

When Faith doesn’t move, the Brown Shirt sighs noisily and yanks up Faith’s sleeve. He turns on the device, tattooing a number on the outside of her arm. Tears roll down Faith’s cheeks as F-738 is branded into her skin. The guard motions for Hope. She pulls up her sleeve without being told. Her skin prickles as F-739 is engraved.

F-738 and F-739—their new identities.

Photographs are snapped, and then the Brown Shirts usher them back outside to a tar-paper shack. On the front, painted in garish yellow, is a large letter B. A thick chain snakes between the door’s handle and a security bar. The guards open the lock and shove the twins inside.

“You’re in luck.” Jutting Chin smirks. “We have a vacancy.”

Once their eyes adjust to the gloom, Hope and Faith see a series of cots crammed too close together.

And girls. Around twenty or so, all approximately their age. Their expressions are openly hostile.

No one bothers to say anything. “I’m Hope. This is my sister, Faith.” No response. “We’re new.”

“No shit,” someone mutters.

Finally, one of the girls asks, “What happened to your hair?”

Hope runs a hand over her head, still not used to the stubbled absence. “They cut it off.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. Maybe ’cause I killed a Brown Shirt.”

If Hope thinks that will impress the others, she’s wrong. The girls don’t react at all. They just climb into their narrow cots and prepare for sleep.

“Come on,” Hope says to her sister. “Maybe they’ll be more talkative in the morning.” She leads Faith to two empty beds jammed into the corner.

“I meant what I said back there,” Faith says, her first words in hours. “About Dad wanting me to die.”

“No you didn’t,” Hope says.

She cleans her sister’s wound as best she can and helps her get ready for bed. They haven’t slept on anything resembling a mattress in ten years, and Hope can’t get comfortable. Only when she lies on the floor is she able to find a position that’s right.

Stretched out on raw, warped pine, she can’t get her mind off these girls. There’s something odd about them that Hope can’t put her finger on. Something deeply … disturbing.

9. (#ulink_b93a6817-b431-5b01-94dc-67ed95f71ce9)

CAT TOOK TWO OF us: Flush and me.

It was midafternoon when we exited the north side of camp. A couple of Brown Shirts watched us with mild interest; there were no fences at Camp Liberty, and in its twenty-year history, no one had bothered to escape. Where would you go?

After a thirty-minute climb, we veered west, heading up Skeleton Ridge. Finally, we came to a stop, lowered ourselves to the ground, and poked our heads above the ridge. Far below us lay a quiet valley: a meandering stream, dozens of scattered boulders.

“Why are we here again?” Flush asked. He was a few years younger, and not as patient as some of the others.

Cat just gave him a look. You’ll see.

An hour passed. Just when I thought I couldn’t take it anymore, we heard the growl of an engine and watched as a faded red pickup truck rounded a far ridge. It came to a stop and two Brown Shirts emerged from the cab, each sporting rifles.

They made their way to the back of the pickup and unhitched the gate, revealing six LTs. One of the soldiers reached up and grabbed an LT by the back of his shirt and tossed him to the ground. We could hear the muffled thud as his body slammed against the earth.

I couldn’t believe it. Why would a Brown Shirt treat an LT that way? Then the soldier jumped up into the truck and began kicking the boys, yelling at them. Each time a boy tumbled to the ground, the soldiers laughed. I wondered why the LTs didn’t fight back—until I saw their bound wrists.

Cat fished a pair of binoculars out of his pack and handed them to me. I adjusted the focus … and nearly lost my breath.

I recognized the LTs. They were a year older than me and had gone through the Rite the month before. One I knew very well: Cannon. The athlete we all wanted to be. And here he was, wrists lashed together, pleading with the soldiers. One of them sent a boot into his ribs. We heard the crack from a quarter mile away.

“I don’t understand,” I mouthed.

“Just watch,” Cat said.

Once all six LTs were on the ground, the pickup driver whipped out a large knife and cut the ties that bound Cannon’s wrists. Cannon rubbed his wrists gratefully.

The soldiers got back in the pickup and drove off.

“What’s going on?” Flush asked. “Is it like a test? Do they have so much time to get back to camp or something?”

Cat barely acknowledged us.

When Cannon untied the other LTs’ ropes, they scrambled to their feet and began to run. In the quiet of the early evening I could nearly hear the whisper of their legs parting grass …

… soon drowned out by the whine of motors. From the same bend where the truck had exited, four ATVs appeared. I’d seen four-wheelers around camp, but these were different. These had been outfitted with metal plates so they resembled some unearthly cross between military machine and triceratops. While the man in the lead wore an orange vest, the others were clad entirely in camo, dressed like it was hunting season.

Which, in a sense, it was.

Slung on their arms were black assault rifles. But somehow different from the M16s the Brown Shirts sported back at camp. Cat read my thoughts.

“M4s,” he explained, “can do everything an M16 can, but with shorter barrels and stocks.”

The Man in Orange stopped, shut his engine down to an idle, and waved a Be my guest gesture. One of the other three took off, exhaust trailing from his ATV. He stopped when he was within a hundred yards of the LTs, whipped up his rifle, and fired. A tendril of smoke plumed from the barrel.

One of the boys stumbled forward, arms flailing. I squeezed the binoculars until my knuckles shone white. But something was missing.

“No blood,” I said, confused.

“Rubber bullets,” Cat explained. “Not meant to kill. Not at first, anyway.”

It was a game: four men with assault rifles versus six LTs with none. Predators vs. prey.

With Cannon supporting his injured friend, the LTs continued running. When they’d covered a good quarter mile, the three men revved their engines and took off. They weren’t letting the LTs go; they were merely giving them a head start. For sport.

Far behind them sat the Man in Orange, arms crossed, observing from a distance. He was their guide. The hunt master.

The men steered the ATVs to the outer rim and corralled the six LTs, shooting wildly. Another boy went sprawling, clutching his face. When he pulled his hands away I saw a slick coating of blood dribbling down his cheek. A bullet got him in the eye.

The ATV whizzed away in search of moving targets. More challenging game.

One Less Than jumped into a stream. He lost his balance and fell face-first into the water with a splash. A four-wheeler followed, coming to a stop directly on top of him. The LT’s arms flailed as he struggled for air, his head below water. The driver laughed.

Two more were brought down in quick succession. Pop! Pop! They lay motionless on the ground.

One of the remaining LTs ran for a scraggly pine, leaping for its outstretched limbs. He swung his legs up over the branch and began to climb.

The men treated him like target practice and riddled him with bullets. When the LT fell, his body sailing through twenty feet of air, he landed hard atop his head. There was no mistaking the sickening sound of his neck snapping in two.

Only two were left: the boy with the missing eye, and Cannon, standing by his side, shielding him from further bullets.

The men seemed intent on prolonging the moment, orbiting the two LTs in ever-closing circles. The heaviest of the group reached into a back compartment and pulled out a jug. They passed it around, each taking deep gulps from whatever homemade brew it contained. Only when the sun settled behind the far ridge did the shooters put away the jug to finish off the LTs.

But when one of them lifted his rifle, Cannon cocked his arm as though making that familiar throw from third to first and gunned a rock forward. It hit the rifleist square in the face. Blood gushed from his nose like a fountain.

While his two companions looked on in a drunken stupor, Cannon raced forward, kicked the wounded man off the ATV, and hopped on himself. He picked up his injured friend, and the two of them went zipping across the pasture, wind sailing through their hair.

When the two other shooters finally understood what was happening, they began to fire wildly. The alcohol made them too unsteady to get off a decent shot.

Cannon and the wounded LT inched closer to the far edge of the valley. They were going to make it. It took everything in my power to refrain from cheering.

I had forgotten about the Man in Orange.

He gave his head a weary shake, and uncrossed his arms. Removing his rifle from its scabbard, he placed Cannon squarely in his sights. From a distance of half a mile he pulled the trigger. Smoke plumed from the barrel; the crack of the rifle shot followed a full second later.

The bullet struck Cannon in the back of the head and both LTs went flying.

By the time the other two men raced forward—now no more than ten yards from their quarry—Cannon had pushed himself to a standing position and round after round landed in his abdomen, his arms, his legs.

He remained standing longer than any human could under such circumstances. He refused to be brought down. Finally, a bullet exploded in his face and he flew backward, landing hard on the ground. This time he did not move.

The Man in Orange joined the others. When he was a couple of feet away, he finished off Cannon and the other LT himself. We could see the bodies quiver with each shot.

The shooters made their way to Cannon’s corpse. One of the men posed with the body as though it were big game he’d brought down on safari. His friend snapped a picture—the camera flash a miniature lightning strike.

When the four ATVs rode out of the valley, their sport completed, they left behind the corpses of six Less Thans, each only a year older than me.

Then the red pickup returned, jostling to a stop when it reached a corpse. The two Brown Shirts went to the body and swung it back and forth until they had enough momentum to fling it into the truck’s bed. Thud! They drove to the next bodies and repeated the process—thud! thud!—their movements weary and nonchalant. As if they’d done this a hundred times.

When all six dead LTs were loaded in the back, the truck bounced back the way it’d come, its red taillights shining like devil’s eyes before disappearing into the darkness.

Just like that the valley returned to its peaceful self.

“Who were they?” Flush demanded as Cat led us back to camp.

“Hunters,” Cat said.

“But why’d they do that?”

“’Cause you’re a bunch of Less Thans.” He said it like it was the most obvious thing in the world. “You’re not only less than normal, you’re less than human.”

“So what’d those LTs do that got them punished?”

Cat stopped. “You’re not listening. You all are prey, and your camp is one big hatchery. Those six LTs did nothing more than have the bad luck to get sent here. Period.”

“A hatchery?” Flush repeated.

“A place where fish are raised, then released into rivers so fishermen have something to catch. You’re just a bunch of Less Thans—being raised to be hunted.”

“So why teach us anything at all?” I asked.

“’Cause otherwise it’d be like shooting fish in a barrel. If it’s too easy, it’s not sport. There’s gotta be some challenge.”

In its own sick way it made a kind of sense.

For the next hour no one spoke. We descended through dense woods, moving as quickly as darkness allowed. Skeleton Ridge was no place to be at night. I don’t think I took a breath until we caught sight of the camp far below, its lights sparkling.

“How do you know all this?” I asked.

“Because I’ve been on the run. I’ve seen people. I’ve talked to them.” His eyes grew suddenly distant. “Before I came here, I stayed with a man and his two daughters. They put me up in their cave. They told me things—like how afraid they were of the Republic and its Brown Shirts. They were running from soldiers. Everyone’s running from soldiers.”

“But that doesn’t—”

“Listen,” he said, his piercing blue eyes cutting through the dark. “All of this is true—the proof is right under your nose. Or under the Brown Shirts’ noses. You rescued me in the desert, I told you about the Hunters. That makes us even. What you do with this is up to you—I don’t give a shit. I’m getting the hell out of here and going to the next territory.”

With that, he turned and scrambled down the mountain.

That night my mind was reeling. I dreamed of her again: the woman with long black hair. We were running through the field of prairie grass, the air so pungent with gunpowder it wrinkled my nose. Behind us came the same awful sounds as before: screams, explosions, the sharp crack of bullets.

Only this time there were others running, too. Cat. My friend K2. Cannon. All running for their lives.

The old woman pulled me low to the ground, and when she opened her mouth to speak, I didn’t force myself awake. This time I let her talk.

“You will lead the way,” she said.

I waited for more.

“I—I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I stammered. “What way? And who on earth will listen to me?”

She smiled briefly and then disappeared, vanishing into the gunpowdery haze.

I woke with a start, my T-shirt clinging to me from perspiration. All around me, LTs slept soundly. I wondered if any were haunted by dreams as I was. Wondered too if I would ever begin to understand mine.

As I tried to get back to sleep, I thought of what Cat had said as we descended the mountain.

Right under the Brown Shirts’ noses.

Something else, too. The stuff about that dad and his daughters. I wondered where they were now—if they’d escaped the soldiers and made it to freedom. Wondered if I’d ever find out.

10. (#ulink_11282363-74b0-55fd-a493-48ffb67433a8)

HOPE NOTICES THE OTHER girls seem oddly subdued. Repressed. Haunted, even.

The only thing that’s clear is that Hope and Faith aren’t the only sisters. In fact, as Hope looks around the mess hall at the hundred or so other girls, it seems as if the vast majority are related.

“What’s with all the twins?” she asks the girl opposite her. She’s tall with red hair and there’s something in how the other girls look at her that makes Hope think she’s in charge.

“You’ll find out,” the girl says.

“You’re not going to tell me?”

The girl’s eyes narrow. “What’s to tell? Everyone’s experience is different.”

Grabbing her tray, the red-haired girl rises and rushes out. She’s followed by another who has identical facial features but is shorter and more fragile-looking. This frailer version of Red Hair hesitates, seems about to say something, then changes her mind. Hope shrugs it off. Another unanswered question.

Roll call follows breakfast. On the grassy infield, the girls line up by barracks in perfect geometries of rows and columns. Colonel Thorason removes a sheet of paper from a binder and calls out a series of Participants. The girls cringe when their numbers are called. Once the announcement is complete, the Participants are met by the pudgy Dr. Gallingham and marched off.

Hope has no idea where they’re being taken. It’s all a nightmarish blur.

She’s assigned to work in the barn; Faith is put on a cleaning crew. Milking cows and shoveling manure reminds Hope of when she used to help her father. Before they were on the run. Back in happier times. The barn is also outside camp, on the other side of the fence, which makes it feel that much closer to freedom.

When she returns to the barracks at the end of her shift, she is met by the same hostile glares.

“Don’t bring that barn stink in here,” one of the girls says. “Latrine’s in back.”

Hope grits her teeth. A number of other girls stand at the metal trough. They grow quiet when Hope enters.

“Can I get in there?” Hope asks, motioning toward the running water.

She’s so focused on scrubbing the dirt from her nails that when she turns around, she’s surprised to see she’s surrounded by a circle of girls, over ten of them.

Hope feels a stab of panic. While her instinct is to run, there’s no possible way she’d make it to the door. Instead, she remembers her father’s advice about not showing fear when facing wild beasts. And what wilder beasts are there than the girls of Barracks B?

Red Hair steps forward.

“Where’d you come from?”

“Out there,” Hope answers, shaking the water from her hands.

“All these years?”

“That’s right.”

“No one could evade the Brown Shirts that long.”

Hope shrugs. “We did.”

Red Hair leans in until their noses are practically touching. Hope doesn’t notice the girl behind her—not until she yanks Hope’s arms back. Hope struggles but it’s no good. The girl who has her arms is one giant slab of muscle.

“You better not be working for the Brown Shirts,” Red Hair says, sending a fist into Hope’s stomach.

Hope’s lungs collapse. Red Hair grabs Hope’s chin and hits her hard across the face. Pain explodes from Hope’s jaw and she crumples to the cold cement floor, tasting the metallic tang of blood.

Through swollen eyes, Hope sees Red Hair bending over her.

“We were just fine until you came along,” she hisses. “And don’t you forget it.”

The girls exit, leaving Hope bruised and bleeding on the latrine floor.

That night at dinner, the other prisoners seem slightly more talkative than before.

But there are two exceptions.

The stub of a girl who grabbed Hope’s arms; her bowl cut of black hair frames a permanently grim expression. And the frail sister of Red Hair. She averts her eyes and doesn’t look at Hope once.

One by one, the girls finish their meager rations and leave the mess hall. When the frail girl walks by, she drops something next to Hope’s plate. A piece of fabric. Hope regards it warily. When she unfolds it, she discovers it’s a head scarf. She fashions it atop her bald head, grateful for the covering.

Back in the barracks, it’s as though Hope and Faith don’t exist. The prisoners go about their routines without the slightest regard for them.

Everyone has climbed into their cots when they hear a loud rattling sound: Brown Shirts stripping the chains from the door. A moment later, a girl appears, haloed by moonlight. Once she’s inside, the door is shut, the chains and locks refastened.

With halting steps she shuffles forward, seemingly unaware of her surroundings. She speaks to no one. Sees no one. She has wet herself and the sharp aroma of urine fills the room.

Red Hair gets up, placing her hands on the girl’s shoulders. “You’re back here now, Diana. We’ll take care of you.”

Diana, a tall, willowy girl with angular features and auburn hair, nods vacantly.

“You’re safe now, Diana.”

“Safe?” Diana echoes.

Her voice is distant, otherworldly.

In the pale moonlight Hope can make out Diana’s eyes. They are glazed and faraway, focused on some remote horizon. It’s like seeing the shell of a person only—a human being without a soul.

Hope shudders.

Too many questions run through her mind.

What’s going on here? she wonders. What kind of world are we in?

Later that night when she uses the latrine she notices a prisoner standing in the back hallway, leaning against the wall as if keeping watch.

Stranger still is the ticking sound she hears as she returns to bed—a metallic clink. As she drifts off to sleep, fingering her father’s locket, she swears she can hear it in her dreams.

Clink. Clink. Clink.

11. (#ulink_a1e77cf2-cad6-578b-8ddc-7d636ae93044)

THE NEXT MORNING CAT was gone.

His bed was made, his trunk empty. There was a good deal of speculation about where he might have gone—abducted by Crazies, recruited by Brown Shirts—but no one could say for sure.

I was out on the field when Sergeant Dekker came marching over.

“The colonel wants to see you,” he said.

“Now?”

“Right now.”

For the second time in a week, I felt my stomach bottom out at the prospect of meeting Colonel Westbrook. With the eyes of every LT—every Less Than—on me, I followed the oily Sergeant Dekker to the headquarters. Instead of being led inside, I was ushered into the back of a Humvee.

“Where am I go—”

“You’ll see,” he answered, cutting me off.

Sweat trickled from my armpits as I sat waiting. Colonel Westbrook and Major Karsten emerged from the headquarters and climbed in the Humvee with me, neither saying a word. We took off. It wasn’t until we’d left Camp Liberty that Westbrook turned around in the passenger seat, his coal-black eyes drilling into me.

“We’re in search of a missing LT,” he said, “and we thought you might be able to help us find him.”

“M-me?” I stammered. “I just met the guy. I don’t know where he is.”

“So you know who I’m talking about.”

“Well, sure, I mean—”

“And that wasn’t you leaving camp with him yesterday afternoon?”

My face burned red, and it was all the answer he needed. The rest of the drive was long and silent.

The roads we followed were gravel and narrow, trailing the foothills of Skeleton Ridge and cutting through dense forests of spruce and pine. All at once we reached a clearing. There before us was a prison.

While it bore a certain similarity to Camp Liberty, there was one glaring difference: the entire site was encircled by a tall barbed wire fence. Guard towers anchored each of the four corners, with Brown Shirts poised behind machine guns.

I wondered who these inmates were who demanded such high security. I could only guess they were the most ruthless of prisoners, the most vile of criminals.

At just that moment the door opened to the tar-paper barracks and out streamed the inmates, all dressed in plain gray dresses and scuffed work boots.

Girls. Dozens and dozens of girls.

The only females I’d ever seen were two-dimensional ones from the movies. To finally see them in the flesh—and my own age, no less—took my breath away. A part of me felt like some ancient explorer encountering tribes from a far-off land.

All around me, girls in drab uniforms marched wearily from one side of camp to the other. But there was something I didn’t understand. How was it these girls—these prisoners—were so highly guarded, while the Less Thans of Camp Liberty could come and go? What had these girls done that made them such dangerous criminals?

Also, there was something about how they moved—something about them—I found oddly disturbing. With downcast eyes and feet shuffling through the dust, they seemed almost … haunted. Like their physical bodies were present but their minds were a thousand miles away.

Colonel Westbrook seemed to read my mind. “So you see, Book,” he said, swiveling in his seat, “there are places in this world worse than Camp Liberty.”

He climbed out of the vehicle.

“Don’t move,” Major Karsten added, fixing me with a skeletal stare.

He and Westbrook disappeared into the headquarters building and I sat in the stifling backseat, trying to make sense of what they had said, of what I was seeing.