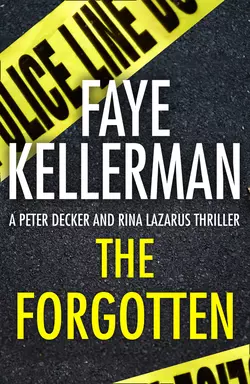

The Forgotten

Faye Kellerman

The thirteenth book in the hugely popular Peter Decker and Rina Lazarus series from New York Times bestselling author Faye KellermanA horrifying crime…Rina Lazarus and her husband, Detective Peter Decker, are appalled when their synagogue is desecrated with swastikas and horrific photos from Nazi concentration camps. Who would strike at the heart of the community in this way?A tormented teenager…An arrest is soon made – 17-year-old Ernesto Golding. Ernesto is a privileged, wealthy kid obsessed with discovering the truth about his Polish grandfather, who moved to Argentina after the collapse of the Nazi regime.A case with devastating consequences…Despite Ernesto’s confession, Decker is unconvinced. And when Ernesto is found brutally murdered at an exclusive camp that caters to troubled kids, the investigation takes a sinister twist. Could this be Decker’s most dangerous case yet?

The Forgotten

Faye Kellerman

Copyright (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in the United States by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, 2001

This ebook edition published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Faye Kellerman 2001

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photography © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

Faye Kellerman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008293604

Version: 2018-12-13

Dedication (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

For Andy, Joanne, and Miriam

In memory of Shira—aleha ha’shalom

Contents

Cover (#u6bd08468-5a71-57c2-ab02-8a44945c0d93)

Title Page (#u4ecdc730-54fd-5fb6-a277-9b193cdb8c71)

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading

About the Author

Faye Kellerman booklist

About the Publisher

1 (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

The call was from the police. Not from Rina’s lieutenant husband, but from the police police. She listened as the man spoke, and when she heard that it had nothing to do with Peter or the children, she felt a “Thank you, God” wave of instant relief. After discovering the reason behind the contact, Rina wasn’t as shocked as she should have been.

The Jewish population of L.A.’s West Valley had been rocked by hate crimes in the past, culminating in that hideous ordeal a couple of years ago when a subspecies of human life had gotten off the public bus and had shot up the Jewish Community Center. The center had been and still was a refuge for all people, offering everything from toddler day camps to dance movements to exercise classes for the elderly. Miraculously, no one had been killed—there. But the monster—who had later in the day committed the atrocious act of murder—had injured several children and had left the entire area with numbing fears that maybe it could happen again. Since then, many of the L.A. Jews took special precautions to safeguard their people and their institutions. Extra locks were put on the doors of the centers and synagogues. Rina’s shul, a small rented storefront, had even gone so far as to padlock the Aron Kodesh—the Holy Ark that housed the sacred Torah scrolls.

The police had phoned Rina because her number was the one left on the shul’s answering machine—for emergencies only. She was the synagogue’s unofficial caretaker—the buck-stops-here person who called the contractors when a pipe burst or when the roof leaked. Because it was a new congregation, its members could only afford a part-time rabbi. The congregants often pitched in by delivering a Shabbos sermon or sponsoring an after-prayer kiddush. People were always more social when food was served. The tiny house of worship had lots of mettle, and that made the dreadful news even harder to digest.

Driving to the destination, Rina was a mass of anxiety and apprehension. Nine in the morning and her stomach was knotted and burning. The police hadn’t described the damage, other than use the word vandalize over and over. From what she could gather, it sounded more like cosmetic mischief than actual constructional harm, but maybe that was wishful thinking.

She passed homes, stores, and strip malls, barely glancing at the scenery. She straightened the black tam perched atop her head, tucking in a few dangling locks of ebony hair. Even under ordinary circumstances, she rarely spent time in front of the mirror. This morning, she had rushed out as soon as she hung up the phone, wearing the most basic of clothing—a black skirt, a white long-sleeved shirt, slip-on shoes, a head covering. At least her blue eyes were clear. There had been no time for her makeup; the cops were going to see the uncensored Rina Decker. The red traffic lights seemed overly long, because she was so antsy to get there.

The shul meant so much to her. It had been the motivating factor behind selling Peter’s old ranch and buying their new house. Because hers was a Sabbath-observant Jewish home, she had wanted a place of worship that was within walking distance—real walking distance, not something two and a half miles away as Peter’s ranch had been. It wasn’t that she minded the walk to her previous shul, Yeshivat Ohavei Torah, and the boys certainly could make the jaunt, but Hannah, at the time, had been five. The new house was perfect for Hannah, a fifteen-minute walk, plus there were plenty of little children for her to play with. Not many older children, but that didn’t matter, since her older sons were nearly grown. Shmueli had left for Israel, and Yonkie, though only in eleventh grade, would probably spend his senior year back east, finishing yeshiva high school while simultaneously attending college. Peter’s daughter, Cindy, was now a veteran cop, having survived a wholly traumatic year. Occasionally, she’d eat Shabbat dinner with them, visiting her little sister—a thrill since Cindy had grown up an only child. Rina was the mother of a genuine blended family, though sometimes it felt more like genuine chaos.

Her heartbeat quickened as she approached the storefront. The tiny house of worship was in a building that also rented space to a real estate office, a dry cleaners, a nail salon, and a take-out Thai café. Upstairs were a travel agency and an attorney who advertised on late-night cable with happy testimonials from former clients. Two black-and-white cruisers had parked askew, taking up most of the space in the minuscule lot, their light bars alternately blinking out red and blue beams. A small crowd had gathered in front of the synagogue, but through them, Rina could see hints of a freshly painted black swastika.

Her heart sank.

She inched her Volvo into the lot and parked adjacent to a cruiser. Before she even got out of the car, a uniform was waving her off. He was a thick block of a man in his thirties. Rina didn’t recognize him, but that didn’t mean anything because she didn’t know most of the uniformed officers in the Devonshire station. Peter had transferred there as a detective, not a patrol cop.

The officer was saying, “You can’t park here, ma’am.”

Rina rolled down the window. “The police called me down. I have the keys to the synagogue.”

The officer waited; she waited.

Rina said, “I’m Rina Decker, Lieutenant Decker’s wife …”

Instant recognition. The uniformed officer nodded by way of an apology, then muttered, “Kids!”

“Then you know who did it?” Rina got out of the car.

The officer’s cheeks took on color. “No, not yet. But we’ll find whoever did this.”

Another cop walked up to her, this one a sergeant by his uniform stripes, with Shearing printed on his nametag. He was stocky with wavy, dishwater-colored hair and a ruddy complexion. Older: mid to late fifties. She had a vague sense of having met him at a picnic or some social gathering. The name Mike came to mind.

He held out his hand. “Mickey Shearing, Mrs. Decker. I’m awfully sorry to bring you down like this.” He led her through the small gathering of onlookers, irritated by the interference. “Everybody … a couple of steps back … Better yet, go home.” Shouting to his men, “Someone rope off the area, now!”

As the lookie-loos thinned, Rina could see the exterior wall—one big swastika, a couple of baby ones on either side. Someone had spray-painted Death to the Inferior, Gutter Races. Angry moisture filled her eyes. “Is the door lock broken?” she asked the sergeant.

“’Fraid so.”

“You’ve been inside?”

“Unfortunately, I have. It’s …” He shook his head. “It’s pretty strong.”

“My parents were concentration-camp survivors. I know this kind of thing.”

He raised his eyebrow. “Watch your step. We don’t want to mess up anything for the detectives.”

“Who’s being brought in?” Rina said. “Who investigates hate crimes?” But she didn’t wait for an answer. As she stepped across the threshold, she felt her muscles tighten, and her jaw clenched so hard it was a wonder that her teeth didn’t crack.

All the walls had been tattooed with one vicious slogan after another, each derogatory, each advocating different ways to exterminate Jews. So many swastikas, it could have been a wallpaper pattern. Eggs and ketchup had been thrown against the plaster, leaving behind vitreous splotches. But the walls weren’t the worst part, minor compared to the holy books that had been torn and shredded and strewn across the floor. And even the sacrilege of the religious tomes and prayer books wasn’t as bad as the horrific photographs of concentration-camp victims that lay atop the ruined Hebrew texts. She averted her eyes but had already seen too much—ghastly black-and-white snapshots depicting individual bodies with tortured faces and gaping mouths. Some were clothed, some nude.

Shearing was staring, too, shaking his head back and forth, while uttering “Oh man, oh man” under his breath. He seemed to have forgotten about her. Rina cleared her throat, partially to break Mickey’s trance, but also to stave back tears. “I suppose I should look around to see if anything valuable is missing.”

Mickey looked at Rina’s face. “Uh, yeah. Sure. Did the place have anything valuable …? I mean, I know the books are valuable, but like flashy valuable things. Like silver ecumenical things … is ‘ecumenical’ the right word?”

“I know what you mean.”

“I’m so sorry, Mrs. Decker.”

The apology was stated with such clear sincerity that it brought down the tears. “No one died, no one got hurt. It helps to get perspective.” Rina wiped her eyes. “Most of our silver and gold objects are locked up in that cabinet … the one with the grates. That’s our Holy Ark.”

“Lucky that you had the grates installed.”

“We did that after the Jewish Community Center shootings.” She walked over to the Aron Kodesh.

Shearing said, “Don’t touch the lock, Mrs. Decker.”

Rina stopped.

He tried out a tired smile. “Fingerprints.”

Rina regarded the lock with her hands behind her back. “Someone tried to break inside. There are fresh scratch marks.”

“Yeah, I noticed. Because you have the lock, they musta figured that’s where you keep all your valuables.”

“They would have been right.” A pause. “You said ‘they.’ More than one?”

“With this much damage, I’d say yeah, but I’m not a detective. I leave that up to pros like your husband.”

Abruptly, she was seized with vertigo and leaned against the grate for support. Mickey was at her side.

“Are you all right, Mrs. Decker?”

Her voice came out a whisper. “Fine.” She straightened up, surveying the room like a contractor. “Most of the damage seems superficial. Nothing a good bucket of soapy water and a paintbrush could take care of. The books, of course, are another story.” Replacing them would put them back at least a thousand dollars, money that they had been saving for a part-time youth director. Like most labors of love, the shul operated on a shoestring budget. A tear leaked down her cheek.

“At least no one tried to burn it down.” She bit her lip. “We have to be positive, right?”

“Absolutely!” Mickey joined in. “You’re a real trooper.”

Again, Rina’s eyes skittered across the floor. Among the photos were Xeroxed ink drawings of Jews sporting exaggerated hooked noses. They probably had been copied out of the old Der Stuermer or the Protocol of the Elders of Zion. Again, she glanced at the grainy photographs. Upon inspection, she realized that the black-and-whites did not look like copies. They looked like genuine snapshots taken by someone who had been there. The thought—someone visually recording dead people—sickened her. Now someone was leaving them around as a frightful reminder or a threat.

Again, her eyes filled with furious tears. She was so angry, so desolate, that she wanted to scream at the world. Instead, she took out her cell phone and paged her husband.

Decker had many thoughts rattling through his brain, most of them having to do with how Rina was coping. Still, there was some space left over for his own feelings. Anger? No. Way beyond anger, and that wasn’t good. Such blinding rage caused people to make mistakes, and Decker couldn’t afford them right now. So instead of mulling over a crime he had yet to see, he looked out the windshield and tried to get distracted by the scenery. By the rows of houses that had once been citrus orchards, by the warehouses and strip malls that lined Devonshire Boulevard. He tried not to think about his stepson in Israel or his other stepson at a Jewish high school. Or Hannah, who was currently in second grade—young and trusting and as innocent as those rows of preschoolers led out of the JCC a couple of years ago after that god-awful shooting.

He realized he was sweating. Though it was the usual overcast May in L.A.—the air cool and a bit moldy—he turned the air conditioner on full blast. Someone had given him the address as a formality, but even if he hadn’t known the locale, the cruisers would have been a tip-off.

He parked his car in a red zone, got out, and told himself to take a deep breath. He’d need to be calm, not to deal with the crime but to deal with Rina. A quartet of uniforms was buzzing around the space like flies. Decker hadn’t taken more than a couple of steps when Mickey Shearing caught him.

“Where is she?” Decker’s voice was a growl.

“Inside the synagogue,” Shearing answered. “You want the details?”

“You have details?”

“I have …” Mickey flipped through his book. “… that the first report came in at eight-thirty in the morning from the guy who operates the dry cleaning. I arrived about ten minutes later, found the door lock broken. I called up the synagogue to find out if there was a rabbi or someone in charge. I got a machine with a phone number on it. Turned out to be your wife.”

“And you didn’t think to call me before you called her?” Decker’s glare was harsh.

“There was just a phone number on it, Lieutenant. I didn’t realize it was your wife until afterward.”

Decker broke eye contact and rubbed his forehead. “S’right. Maybe it’s better coming from you. Anyone been interviewed?”

“We’re making the rounds.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothing. Probably done in the wee hours of the morning.” Shearing slid his toe against the ground. “Probably by kids.”

“Kids as in more than one?”

“A lot of damage. I think so.”

“Tell me about the guy in the dry cleaners.”

“Gregory Blansk. Young kid himself. Uh … nineteen …” He flipped through more pages. “Yeah, nineteen.”

“Any chance he did it and is sticking around to see people admire his handiwork?”

“I think he’s Jewish, sir.”

“You think?”

“Uh … yeah. Here we go. He is Jewish.” Shearing looked up. “He seemed appalled and more than a little frightened. He’s a Russian import himself. Two strikes against him—Jewish and a foreigner. This has to scare him.”

“Currently, Detective Wanda Bontemps from Juvenile is assigned to Hate Crimes. Make sure she interviews him when she comes out. Keep the area clear. I’ll be back.”

Having worked Juvenile for a number of years, Decker was familiar with errant kids and lots of vandalism. He had worked in an area noted for biker bums, white trash, hoodlum Chicanos, and teens who just couldn’t get behind high school. But this? Too damn close to home. He was so distracted by the surroundings, he didn’t even notice Rina until she spoke. It jolted him, and he took a step backward, bumping into her, almost knocking her down.

“I’m sorry.” He grabbed her hand, then clasped her body tightly. “I’m so sorry. Are you okay?”

“I’m …” She shrugged in his arms. Don’t cry! “How long before we can start cleaning this up?”

“Not for a while. I’d like to take photographs and comb the area for prints—”

“I can’t stand to look at this!” Rina pulled away and turned her eyes away from his. “How long?”

“I don’t know, Rina. I’ve got to get the techs out here. It isn’t a murder scene, so it isn’t top priority.”

“Oh. I see. We have to wait until someone gets shot.”

Decker tried to keep his voice even. “I’m as anxious as you are to clean this up, but if we want to do this right, we can’t rush things. After the crews leave, I will personally come over here with mop and broom in hand and scrub away every inch of this abomination. Okay?”

Rina covered her mouth, then blinked back droplets. She whispered back, “Okay.”

“Friends?” Decker smiled.

She smiled back with wet eyes.

Decker’s smile faded as the horror hit him. “Good Lord!” He threw his head back. “This is … awful!”

“They took the kiddush cup, Peter.”

“What?”

“The kiddush cup is gone. We kept it in the cabinet. It was silver plate with turquoise stones and just the type of item that would get stolen because it was accessible and flashy.”

Decker thought a moment. “Kids.”

“That’s what they’re all saying. Why not some evil hate group?”

“Sure, it could be that. One thing I will say on record is it’s probably not a hype. If he wanted something to swap for instant drug money, the crime would have been clean theft.”

“Maybe the cup is hidden underneath all this wreckage.” Rina shrugged. “All I know is the cup isn’t in the cabinet.”

Decker took out his notebook. “Anything else?”

“Fresh scratch marks on the padlock on the Aron—the Holy Ark. They tried to get into it, but weren’t successful.”

“Thank goodness.” He folded his notebook and studied her face. “Are you going to be okay?”

“I’m … all right. I’ll feel better once this is cleaned up. I suppose I should call Mark Gruman.”

Decker sighed. “He and I painted the walls the first time. Looks like we’re going to paint them again.”

Rina whispered, “Once word gets out, I’m sure you’ll have plenty of willing volunteers.”

“Hope so.” Decker stamped his foot. An infantile gesture but he was so damn angry. “Man, I am pi … mad. I’d love to swear except I don’t want to further desecrate the place.”

“What’s the first step in this type of investigation?”

“To check out juveniles with past records of vandalism.”

“Aren’t records of juveniles sealed?”

“Of course. But that doesn’t mean the arresting officers can’t talk. A couple of names would be a good start.”

“How about checking out real hate groups?”

“Definitely, Rina. We’ll work this to the max. Nothing in this geographical area comes to mind. But I remember a group in Foothills—the Ethnic Preservation Society or something like that. It’s been a while. I have to check the records, and to do that properly I need to go back to the office.”

“Go on. Go back. I’ll be okay.” She turned to face him. “Who’s coming down?”

“Wanda Bontemps. She’s from the Hate Crimes Unit. Try not to bite her head off. She had a bad experience with Jews in the past.”

“And this is who they bring down for a Jewish hate crime?”

“She’s black—”

“So she’s a black, and an anti-Semite. That makes it better?”

“She’s not anti-Semitic at all. She’s a good woman who was honest enough to admit her issues to me early on. I’m just … I shouldn’t have even mentioned it.” He looked around and grimaced. “I should learn to keep my mouth shut. I’ll chalk it up to being a little rattled. Wanda’s new and has worked hard to get her gold. It hasn’t been an easy ride for a black forty-year-old woman.”

“I’m sure that’s true,” Rina answered. “Don’t worry about her, Peter. If she just does her job, we’ll get along just fine.”

2 (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

The pictures of the concentration-camp victims had to have come from somewhere. It was possible that they were downloaded from a neo-Nazi on-line site and enhanced to make them look like real photographs. Still, it was equally as likely that they had come from some kind of local organized fascist group. The fringe group that Decker had remembered from his Foothills days had tagged itself the Preservers of Ethnic Integrity. When he had worked Juvenile, it hadn’t been much more than a post-office box and a once-every-six-months meeting in the park. A few quick phone calls told him that the group was still in existence and that it had evolved into something with an address on Roscoe Boulevard. Decker wasn’t sure what they did or what they espoused, but with that kind of a name, the hidden message had to be white supremacy.

He checked his watch, which now read close to eleven. He got up from his desk and went out into the squad room. There were lots of empty spots, signifying that most of Devonshire’s detectives had been called into the field, but luck placed Tom Webster at his desk, and on the phone. The junior homicide detective was blond, blue-eyed, and spoke with a good-ole-boy drawl. If anyone could pose as an Aryan sympathizer, it would be Webster … except for the dress. Neo-Nazis didn’t usually sport designer suits. Today, Tom had donned a navy suit, white shirt, and a maroon mini-print tie—probably Zegna. Not that Decker wore hundred-dollar ties, but he knew the brand because Rina’s father liked Zegna and often gave Sammy and Jake his cast-off cravats.

Webster looked up, and Decker caught his eye, pointing to his office. A minute later, Tom came in and closed the door. His hair had been recently shorn, but several locks still brushed his eyebrows, giving him that “aw shucks” look of a schoolboy.

“Sorry about this morning, Loo.” Webster took a seat across Decker’s desk. “We all heard it was pretty bad.”

“Y’all heard right.” Decker sat at his desk and sifted through his computer until he found what he wanted. Then he pressed the print button. “What’s your schedule like?”

“I was just doing a follow-up on the Gonzalez shooting. Talking to the widow …” He sighed. “The trial’s been delayed again. Perez’s lawyer quit, and they’re assigning him a new PD who is not familiar with the case. Poor Mrs. Gonzalez wants closure and it isn’t going to happen soon.”

“That’s too bad,” Decker stated.

“Yeah, it’s too bad and all too typical,” Webster answered. “I have court at one-thirty. I thought I’d go over my notes.”

“You’re a college grad, Webster. That shouldn’t take you long.” Decker handed him the printout. “I want you to check this out.”

Webster looked at the sheet. “Preservers of Ethnic Integrity? What is all this? A Nazi group?”

“That’s what you’re going to find out.”

“When? Now?”

“Yes.” Decker smiled. “Right now.”

“What am I inquiring about? The temple vandalism?”

“Yes.”

“Am I supposed to be simpatico to the cause?”

“You want information, Tom; do what you need to do. As a matter of fact, take Martinez with you. You’re white, he’s Hispanic. With racists, you can do good cop, bad cop just by using the color of your skin.”

From the synagogue, Bontemps called Decker and told him about the three kids she had hauled in for prior vandalism. All of them had sealed records.

“How about a couple of names?” Decker asked.

Bontemps said, “Jerad Benderhurst—a fifteen-year-old white male. Last I heard, he was living with an aunt in Oklahoma. Jamal Williams—a sixteen-year-old African-American male—picked up not only for vandalism, but also petty theft and drug possession. I think he moved back east.”

“That’s not promising. Anyone else?”

“Carlos Aguillar. I think he’s fourteen, and I think he’s still at Buck’s correction center. Those are the ones I remember for vandalism. If you check with Sherri and Ridel, they might have others.” A pause. “Then again, Lieutenant, you might want to consider the bigger picture when it comes to tagging.”

Decker knew exactly to whom she was referring—a specific group of white, middle-to-upper-class males who were not only testosterone laden, but also terribly bored with life. Recently, after having been caught, the kids had secured their daddies’ highly paid lawyers before they had even been booked. The entire bunch had gotten off, the tagging expunged from the records, and in record time. Most of the kids were enrolled in private schools. For them, even drugs and sex had become too commonplace. Crime was the last vestige of rebellion.

“There was a group of them last year,” Wanda said. “Around twenty of them dressing like homies and trying to act very baaaad. They defaced a lot of property. If I thought about it, I could remember some names.”

“You could also have your ass sued for giving me the names,” Decker said. “As far as the records are concerned, they don’t exist. But I know who you mean.” A glance at the wrist told him it was eleven-twenty. “How’s it going over there?”

“Photographers are almost done. So are the techs. Your wife is waiting with a crew of people—all of them armed with soapy water pails, cleaning solutions, rags, and mops. They are ready to start scrubbing, and they are angry. If the police don’t hurry up, someone’s gonna get impaled on a broomstick.”

“That sounds like Rina’s doing,” Decker stated.

“You want to talk to her? She’s hanging over my shoulder.”

“I am not hanging,” Rina said, off side. “I am waiting.”

Wanda handed her the phone. Rina said, “Detective Bontemps has offered to spend her lunch hour helping us clean.”

“Is that a pointed comment?”

“Well, you might want to take a cue.”

Decker smiled. “I’ll be there as soon as I get off work. I will paint and clean the entire night if necessary. How’s that?”

“Acceptable, although by the time you get here, it may not be necessary.”

“I hear you have quite a gang.”

“Specifically, we’ve got the entire sisterhood here with brooms and buckets. Someone also made an announcement over at the JCC. Six people came down to clean and paint—one guy actually being a professional painter. Wanda, who’s been a doll, actually called up her church and recruited several volunteers. Even the people from the press have offered to help. We’d like to start already.”

“Detective Bontemps told me they’re almost done.”

“It’s just so … ugly, Peter. Every time I look at it, I get sick all over. Everyone feels the same way.”

“Who is down there from the press?”

“L.A. Times, Daily News, there are some TV cameras, but Wanda isn’t letting them in yet.”

“Good for her.”

“Have you narrowed down your suspect list?” Rina asked.

“I’m making a couple of calls. I’ll let you know if I have any luck.” He waited a moment. “I love you, darlin’. I’m glad you have so much support over there.”

“I love you, too. And those mumzerim haven’t heard the last from me. This isn’t going to happen again!”

“I admire your commitment.”

“Nothing to admire. This isn’t a choice, this is an assignment. Have you checked out the pawnshops?”

“What?”

“For the silver kiddush cup. Someone may have tried to pawn it.”

“Actually no, I haven’t checked out the pawnshops.”

“You should do that right away. Before the pawnbroker gets wind of the fact that he has something hot.”

“Anything else, General?”

“Nothing for the moment. Someone’s calling me, Peter. I’ll give you back to Detective Bontemps.”

Wanda said, “She’s quite the organizer.”

“That’s certainly true. Thanks for helping out.”

“It’s the least I could do.”

Decker said, “The taggers you were referring to, Wanda. Most of them went to private school.”

“Some of them did—Foreman Prep … Beckerman’s.”

“That could work in our favor. I’d have a hard time doing search and seizure with kids in public school. But in private school, they are subjected to different rules. Lots of the places have bylaws allowing the administration to open up random lockers to do contraband searches.”

“Why would a private school administrator agree to do that for us, sir?”

“Because it would look bad if they didn’t help us out. Like they were hiding something. Chances are I won’t find much … a secret stash or two.”

“What specific contraband would you be looking for, sir? Anti-Semitic material?”

“A silver wine cup.”

“Aha. That makes sense.”

“It’s worth a try,” Decker said.

But one not without controversy or consequences. Because in order to appear objective—and the police needed to appear objective—he’d have to search several of the private schools, including Jacob’s Jewish high school. He’d start with that one.

3 (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

What’s the address?” Webster asked.

Martinez gave him the number while taking a big bite out of his turkey, tomato, and mustard sandwich, rye bread crumbs sprinkling his steel-wool mustache. He had been thinking about shaving it off now that it was more gray than black. But his wife told him that after all these years of something draping over his mouth, he probably had no upper lip left. “Any particular reason why Decker is using Homicide Dees for this?”

“Probably because I was in the squadroom.” He looked at his partner’s sandwich. “You carryin’ an extra one, Bertie?”

“Oh, sure.” Martinez pulled a second sandwich out of a paper bag. “You didn’t eat lunch?”

“When did I have time?” He attacked the food, wolfing half down in three bites. “Decker cornered me just as I was hangin’ up on the widow Gonzalez. The loo has a boner for this one.”

“Yeah, it’s personal.”

“It’s personal. It’s also very ugly, especially after the Furrow shooting at the JCC and the murder of the Filipino mail carrier. I think the loo wants to show the world that the police are competent beings.”

“Nothing wrong with us bagging a bunch of punks.” Martinez finished his sandwich and washed it down with a Diet Coke. “You know anything about these jokers?”

“Just what’s on the printout. They’ve been around for a while. A bunch of nutcases.”

Webster slowed in front of a group of businesses dominated by a 99 Cents store advertising things in denomination of—you guessed it—ninety-nine cents. The corner also housed a Payless shoe store, a Vitamins-R-Us, and a Taco Tio whose specialty was the Big Bang Burrito. Cosmology with heartburn: that was certainly food for thought. “I don’t see any Preservers of Ethnic Integrity.”

“The address is a half-number,” Martinez said. “We should try around the side of the building.”

Webster turned the wheel and found a small glass entrance off the 99 Cents store, the door’s visibility blocked by a gathered white curtain. No address, but an intercom box had been set into the plaster. Webster parked, and they both got out. Martinez rang the bell, which turned out to be a buzzer.

The intercom spat back in painful static. “We’re closed for lunch.”

“Police,” Martinez barked. “Open up!”

A pause, then a long buzz. Webster pushed the door, which bumped against the wall before it was fully opened. He pushed himself inside. Martinez had to take a deep breath before entering, barely able to squeeze his belly through the opening. The reception area was as big as a hatchback. There was a scarred bridge table that took up almost the entire floor space and a folding chair. They stood between the wall and the table, staring at a waif of a girl who sat on the other side of the table. Her face was framed between long strands of ash-colored hair. She wore no makeup and had a small, pinched nose that barely supported wire-rim glasses.

“Police?” She stood and looked to her left—at an interior door left ajar. “What’s going on?”

Martinez scanned the decor. Two prints without frames—Grant Wood’s American Gothic and a seascape by Winslow Homer—affixed to the walls by Scotch tape. Atop the table were a phone and piles of different-colored flyers. Absently, he picked up a baby-blue sheet of paper containing an article. The bottom paragraph, printed in italics, identified the writer as an ex-Marine turned psychologist. Martinez would read the text later.

“A synagogue was vandalized earlier today.” Martinez made eye contact with the young woman. “We were wondering what you knew about it.”

Her eyes swished like wipers behind the glasses. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“It’s all over the news,” Webster said.

“I don’t watch the news.”

“You’ve got a radio on. I b’lieve it’s tuned to a news station.”

“That’s not me, that’s Darrell. Why are you here?”

“Because we know what this place is all about,” Martinez said. “We’re just wondering exactly what role you had in the break-in.”

A man suddenly materialized from the partially opened door. He was around six feet and very thin, with coffee-colored frizzy hair and tan eyes. He had a broad nose and wide cheekbones. Martinez wondered how this guy could be an ethnic purist when his physiognomy screamed a mixture of races.

“May I ask who you all are?” he said.

“Police,” Webster said. “We’d like to ask y’all a few questions, if that’s okay.”

“No, it’s not okay,” the man said. “Because no matter what I say, my words will be twisted and distorted. If you have warrants, produce them. If not, you can show yourself to the door.”

“That’s downright unneighborly of you,” Webster said.

The man turned his wrath toward the girl. “How many times do I have to tell you that you don’t let anyone in unless you’re sure of who they are!”

“They said they were the police, Darrell! So what do I do? Just leave them there, knocking?”

“And since when do you believe everything someone says? You know how people are out to get us. Did you even ask for ID?” Darrell turned toward them. “Can I see some ID?”

Webster pulled out his badge. “We’re not interested in your philosophy at the moment, although I reckon we’re not averse to hearing your ideas. Right now, we want to talk about a temple that was vandalized this morning. Y’all know anything about that?”

“Absolutely not!” Darrell insisted. “Why should we?”

“Is there anybody who can vouch for your whereabouts last night or early this morning?” Martinez asked.

“I’ll have to think about it,” Darrell said. “If I knew I was going to be raked over the coals, I would have established an alibi.”

“S’cuse me?” Webster said. “This is being raked over the coals?”

“You barge in—”

“She buzzed us in,” Martinez interrupted. “And you haven’t answered the question. Where were you and what were you doing last night?”

“I was home.” Darrell was smoldering. “In bed. Sleeping.”

“Alone?”

“Yes. Alone. Unless you count my cat. Her name is Shockley.”

“And this morning?” Webster inquired.

“Let’s see. I woke up at eight-thirty … or thereabouts. I don’t want to be held to the exact time.”

“Go on,” Webster pushed.

“I exercised on my treadmill … ate breakfast … read the paper. I got here at around ten-fifty, ten-thirty. Erin was already here.” His eyes moved from the cops’ faces to the pitchfork of the Grant Wood classic. “What exactly do you want?”

“How about your complete names for starters.”

“Darrell Holt.”

Martinez looked at the woman. “You’re next, ma’am.”

“Erin Kershan.”

Holt tapped his foot, then released a storage cell of aggression. “I had nothing to do with the vandalism of a synagogue! That isn’t what this group is all about! We don’t hate! We don’t persecute! And if you were told that, you’ve been misinformed. We do just the opposite of persecute. We encourage ethnic integrity. I applaud Jews who wish to congregate with one another. Jews should be with other Jews. African-Americans should be with African-Americans, Hispanics with Hispanics, and Caucasians with Caucasians—”

“And what exact ethnicity are you?” Webster asked Holt.

“I’m Acadian, if you must know.”

“You don’t sound like any Cajun I ever met,” Webster said.

“The original Acadians came from Canada—Nova Scotia specifically.” Holt gave off a practiced smile. It was condescending and ugly. “I am proud of my heritage, which is why I feel so strong about preserving cultural purity. And it has nothing to do with racism, because as you can see for yourself …” He pointed to his hair and nose. “I have black blood in me.”

“So you admit to being a mutt,” Webster said.

Holt bristled. “I am not talking about bloodlines, I’m talking ethnicity. My ethnicity is Acadian and it is my wish to preserve my ethnic purity. It is our opinion that the mixing of ethnicities has ruined civilization and certainly the individualization and pride of too many cultures. Immigration has turned everything into one big amorphous blob. Look at cuisine! You go out to a French restaurant when you’re in the mood for French food. Or perhaps a Mexican restaurant when you want enchiladas. Or Italian or American or Southern or Tunisian whenever you want the various cuisines. Imagine what it would be like if you mixed up all these nuances, all the flavors. Individually they work; together, they’d make for one horrible stew.”

“We are not beef Stroganoff, sir,” Martinez said. “Food isn’t the issue. Crime is the issue. Vandalism is a crime. What happened today at the synagogue constitutes a hate crime. The vandals will be found, and they will be punished. So if you know something, I suggest you get a load off now. Because if we come back, it’s going to be bad for you.”

“You have us all wrong.” Holt picked up a handful of leaflets and handed them to Martinez. “You’ll probably throw them away. But should you care to enlighten yourself enough to give us a fair shake, you’ll see that what we say makes a lot of sense.”

Erin broke in. “We have all kinds of members.”

“All kinds of ethnicities,” Holt added. “We cater to the disenfranchised.”

“Like who?” Martinez asked.

“Read our flyers. Our members write the articles.” He plunked a few from the table. “This one—on the ills of affirmative action—was written by an African-American, Joe Staples. This one is on English as a second language in America, written by an ex-Marine turned psychologist.” He focused in on Martinez. “Mr. Tarpin is just elucidating a well-known point. That in the United States we have only one official language and that language is English. If you read it, you’ll see that he has nothing against Hispanics. Everyone who lives in the U.S. should speak English.” He smiled. “Just like you’re doing right now.”

“I’m glad Mr. …” Martinez looked at the flyer. “Mr. Tarpin would approve of my English skills.”

“Which makes sense, being as Detective Martinez is American,” Webster stated. “Which means, if you’re Canadian, Mr. Holt, Detective Martinez is more of an American than you are. And if you advocate people staying with their own kind, maybe you should go back to Canada.”

Webster was florid with fury, his hands bunched into fists. Martinez, on the other hand, was completely impassive, glancing at Mr. Tarpin’s words on why English was such a wonderful, expressive, and large language. That was certainly true enough. Compared to Spanish’s blooming buds, English was an entire bouquet of flowers because it used words from a variety of other languages. The irony was lost on the author.

Martinez said, “Did you print these flyers yourself?”

“The PEI did. Absolutely.”

“Things were left behind in the synagogue,” Martinez said. “Nazi slogans that were printed on flyers just like these.”

“There’s a Kinko’s about a mile away from here,” Holt retorted. “Why don’t you ask them about it?”

Webster said, “And if we were to download your computer files, we wouldn’t find neo-Nazi groups bookmarked on your favorite places?”

“No, you would not,” Holt said confidently. “But even if you did find anything you deem as offensive, it still proves nothing. I did not vandalize anything!”

“There were also photographs left behind at the temple,” Martinez said. “Horrible pictures of holocaust victims—”

“That’s terrible,” Erin piped up. “That’s not our thing.”

“What is your thing?”

“Erin, I’ll handle this,” Holt said.

She ignored him. “Our thing is keeping ethnic identity pure. Gosh, we do it with animals—purebred this and purebred that. So what’s so wrong about wanting people to stay pure? You call it racism, but like Darrell stated, we are not racists! We are preservationists. We have nothing against Jews as long as they stick with Jews, and stop controlling the stock market—”

“Erin—”

“I’m just saying what Ricky says. He says the Jews control all the computers. Just look at Microsoft!”

“Erin, the head of Microsoft is William Gates III,” Holt said. “Does that sound like a Jewish name?”

“No.”

“That’s because William Gates III is not Jewish. If Ricky told you that, Ricky is full of shit!”

Erin’s mouth formed a soft O.

“Who’s Ricky?” Martinez asked.

“Some jerk …” Holt made a face at Erin. “Why do you bring him up?”

“You said he was your friend. Didn’t you go to Berkeley together?”

Holt rolled his eyes. To the cops, he said, “Ricky Moke is to the right of Hitler. Why don’t you go hassle him?”

“Where can we find him?”

“That’s a good question,” Erin said. “He hides out a lot.”

“Erin, shut up!”

“Don’t yell at me, Darrell. You were the one who gave the cops his last name.”

“Is this Moke a fugitive?”

Erin and Darrell exchanged glances. Holt said, “Moke tells lots of stories. Among them is this tale about his being a wanted fugitive.”

“What is Moke supposedly wanted for?”

“Bombings.”

The cops exchanged glances.

“Bombing what?” Webster asked. “Synagogues?”

Holt shook his head. “Animal laboratories. Not the actual cages, just the data centers. Ricky, by his own admission, is an animal lover.”

4 (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

Torah Academy of West Hills had been molded from an old veterinary clinic. It must have been a thriving practice, and for big animals, because the examination rooms were extra large though still too small for classrooms. So the majority of actual learning took place in prefab trailers that filled the parking lot, save for a few science classes that were held in the animal morgue. The other clinic rooms had been turned into offices for the administration. Decker knew that the school, like everything in this community, was run on hope, volunteers, and the occasional out-of-the-blue donation.

Rabbi Jeremy Culter was in charge of secular studies. He was in his mid-thirties, and considered very modern for an Orthodox rabbi. In addition to being ordained as a rabbi, he had a Ph.D. in education and, most telling, he didn’t have a beard. He was fair complexioned and on the short side—trim with very long and developed arms. His office held a minimal look—a desk, a couple of chairs, and a bookshelf filled with sepharim—Jewish books—as well as books on psychology, sociology, and philosophy. The walls were cedar-paneled and still retained a faint antiseptic odor, along with an occasional waft of urine.

Usually, when Decker visited the school, he wore a yarmulke—a skullcap. But today he was there not as a father but in an official capacity. He didn’t wear a yarmulke when he worked because he often dealt with people who hated him in particular and cops in general, and he didn’t want to give any psycho-felon anti-Semite any more fodder to use against Jews. Still, sitting in front of Culter, he felt exposed without a head covering. If Culter noticed, he didn’t let on.

He said, “I can’t believe you actually think that one of our own boys—your son’s classmates—desecrated a shul and left concentration-camp photos around? Children with grandparents who are survivors!”

Decker looked at him. “How’d you find out about the specifics of the crime?”

“This is a small community. Do I really have to explain this to you?”

“Did my wife call you?”

The rabbi shook his head.

“Must have been one of the members of the bucket brigade.” Decker smiled at him. “I’ve just assigned you the role of my clergyman. Now I have confidentiality. Okay with you?”

Rabbi Culter said, “Go on.”

“This is the deal. We’re calling it a random drug check for the boys. I’m going to use that ruse with all the schools I’m going to. What I’m looking for is evidence of who might have done this. If you and your school cooperate with me, Rabbi, I’ll have muscle when dealing with the other privates.”

Culter nodded. “The law is an objective animal and so are the police.”

“Exactly,” Decker said. “If I searched my own son’s school, then what excuses can the other principals give me?”

“You’re getting resistance?”

“You’re the first school, so I’ll find out. But I can tell you that no swanky private school will freely admit having vandals in their student body. It doesn’t sit well with the parents who pay enormous tuition bills.” He pointed to his chest. “I can attest to that personally.”

“Are you positive that kids did the crime?”

“No, I’m not. The police are checking out a number of leads. I’ve assigned myself the role of school snoop. Lucky me. This isn’t going to give me status with my stepson—invading the privacy of Jacob and his friends. But it’s worth it if I get results. When other principals see a clergyman not attempting to protect his own, what excuse do they have?”

“The parents are not going to be pleased.”

“Rabbi, I want to nail these bastards. I know you do, too.”

Culter lifted his brows. “So I’m supposed to tell everyone that it’s just a random drug check.”

“If you could do that, it would be extremely helpful.”

“What if …” The rabbi folded his hands over his desk. “What if you find something incriminating on your son?”

“Meaning?” Decker kept his face flat.

“I think you know what I mean. Yaakov has given me the impression that you two talk about personal matters.” A very long pause. He rubbed his nose with his index finger. “Perhaps I just spoke out of turn.”

“You mean drugs?”

Culter shrugged.

Decker said, “Jake spoke to me about marijuana use. If it’s more than that, I don’t know about it.”

The rabbi was stoic. “What are you going to do, Lieutenant, if you find anything in his locker?”

It was a legitimate question, and it churned Decker’s stomach. “I’ll decide if and when I have to deal with it. Right now, I’m willing to take a chance. Because I really want these punks behind bars. Please help me out. Help the community out. Not only do we want to find the perpetrators, but we don’t want this to happen again.”

“I agree.”

“So you’ll help me?”

“With reluctance, but yes, I will help you.”

“Thank you, thank you!” Decker stood. “All right. Let’s get this over with.”

“Are you personally going to do the searches?”

“Yep. If it turns out okay, I’ll take the credit. If not, I’ll accept the blame. Where do you want to be during this fiasco?”

“By your side,” Culter said. “You’re not the only one who believes in justice.”

The contraband consisted of a few dirty magazines, as well as several plastic bags of suspicious-looking dried herbs, enough for Decker to act the bad guy and scare a few kids into behaving better. He used fear rather than actual punishment, effective in getting the point across. Yonkie’s locker was literally clean, stacked neatly and free of garbage. The teen’s recent behavior had indicated a change for the good, but Decker couldn’t deny the relief of just one less thing to worry about. As it was, there were going to be repercussions because the kids didn’t understand why Decker—an Orthodox Jewish lieutenant—had singled them out. It played to the boys as the gestapo sending in Jewish capos to persecute their own. Yonkie did have the sense to keep his mouth shut, but his eyes burned with anger and humiliation.

There’d be trouble at home, but Decker would tolerate it. His strategy had worked. Even before he had cleared out of the yeshiva, Decker had phoned and received an appointment with Headmaster Keats Williams from the exclusive Foreman Prep boys’ school. If the rabbis had agreed to a check, what excuse did the others now have?

Decker was at his car when Yonkie caught up to him. Almost seventeen, the boy had heart-throbbing good looks with piercing ice-blue eyes and coal-black hair. Even in the school’s uniform—white shirt and blue slacks—he was more matinee idol than bumbling teen. The kid was glancing over his shoulder, his body jumping like fat on a griddle.

He said, “This had nothing to do with my former drug use, right?”

“Right.”

“Because you couldn’t have orchestrated all this just to check up on me.”

“Correct.”

“I mean, even you don’t have that kind of power.”

“No, I don’t have that kind of power, and that would be a big abuse of power.”

“Yeah … right. So there had to be another reason.”

Decker could have kissed the boy. “Very good.”

“My friends don’t know that, though. They’re totally wigged. They think you’re pissed at me and taking it out on them.”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“I told them that you’re not from Narcotics. That this is a separate thing. So this whole drug search is probably a screen for something. Does this have anything to do with the shul being vandalized?”

Decker hesitated. “Who told you about that?”

“Dad, it’s all over the school. Everyone knows and is pretty freaked out about it. Now you’re here … You couldn’t think that one of us did it? I can’t believe you’d think that. It’s ludicrous.”

Decker didn’t answer.

“Oh, man!” Yonkie turned away, then faced him again. His face was moist and flushed. “You know, they’re going to talk against you. About how you’re picking on your own people because we’re easy targets. Eema’s going to take a lot of flak. If you had to do this, why did you come personally? To show your bosses that you’re not biased? You should be biased. You should have excused yourself. You should be at Beckerman’s or Foreman Prep. Or do the rich get special privileges?”

Yonkie was a mass of burning indignation, and Decker tried to take it in stride. What had to be done, had to be done. But the words hurt more than he’d like to admit. “I’m not responding to this. You’d better go back to class—”

“It’s not enough that they snicker behind your back,” Yonkie shot out. “You have to make me and Eema and Hannah pariahs as well?”

The barbs cut deep. Such venom from the mouth of a child that he had raised and had taken on as his own. “Jacob, I’m sorry that my position as a cop put you at odds with your friends. But it can’t be helped. I really have to go.”

“Where are you going?” Yonkie demanded to know.

“Not that it’s any of your business, but I’m going to Foreman Prep.”

The boy was quiet, his mind tumbling for something to say. He had reddened with embarrassment. “So you’re like … checking out all the schools?”

Decker offered him a tolerant smile. “I’m checking out everything. The vandalism was vicious. It qualifies as a hate crime that carries extra weight and extra punishments. I’d like to nab the perps. I assume you’d like that, too. That much we can agree upon. Good-bye.”

Jacob blurted out, “Did I just put my foot in my mouth?”

“Don’t worry about it.”

The boy turned his head away but didn’t move. “I used to keep my mouth shut. I never spoke my mind no matter what I was thinking.” He scratched his face. Bits of beard stubble were shadowing his cheek and it irritated him. Jacob used to have a stunning complexion. Porcelain smooth with hints of red at the cheekbones. His skin was still blemish free, but coarser now, like that of a young man. “What the hell happened to me?”

“You had secrets, and were afraid to talk. Now you don’t have secrets. The trade-off is a big mouth. It’s fine, Jake. I’m a tough guy; I can take a little sassing. I’ll see you at home tonight.”

“This whole thing was just a setup.” Jacob was whispering, more to himself than to Decker. “So you could go to the other places and say, ‘I’m checking out everyone, including my own son’s high school.’ Then they wouldn’t have an excuse.” He looked at his stepdad. “Am I right?”

“Shut up and go back to class.”

“I’m really stupid.”

“More like impulsive.”

“That’s true, too.” Instinctively, the kid reached out and hugged him quickly. Then he took off, embarrassed by his sudden display of emotion.

Decker bit his lip and watched him run away. Standing alone, he whispered, “I love you, too.”

5 (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

Driving up to Foreman Prep, Decker was sorely reminded of the difference between parochial private schools and preparatory private schools. The acreage of Foreman was vast and green, shaded by specimen willows and stately sycamores. Behind the layers of arboreal fence were sprawling, Federalist-style, brick buildings. Or probably brick-faced, because architects did not design solid brick structures in earthquake-prone Los Angeles. Whether they were brick or brick-faced, the edifices were impressive and sufficiently ivy-covered to evoke dreams of the eastern universities. Decker didn’t care about the form, but he did care about the content. Foreman Prep had a course catalogue that could rival those of most colleges. Both Decker’s stepsons could have gotten in, but Rina wouldn’t hear of it. Religious education was paramount even if the current yeshiva had minimal grounds and rotating teachers. For her—and for the memory of her late husband—some things were nonnegotiable.

The headmaster, Keats Williams, was a double for Basil Rathbone except for the bald head—a topographic map of veins and bumps pressing against shiny skin. His eyes were hazel green, and his speech held a slight British accent. Affected? Probably. But at least he allowed Decker to present his scheme without sneering. As the headmaster lectured back his response, Decker’s eyes sneaked glances, trying not to widen at the richness of Williams’s office—something that Churchill would have been comfortable in. He wasn’t just a headmaster. Nor was he just a doctor of sociology as indicated by his Ivy League diploma. No, Williams was more. Much more. Williams was a friggin’ CEO.

“We just had an all-school drug check,” the headmaster informed Decker. “We have a zero tolerance for drugs at the school. Drugs, weapons, and explicitly sexual material. Even the swimsuit edition of Sports Illustrated is not to be brought to school, although it isn’t grounds for suspension—the first time. It’s impossible to keep teenage boys from thinking about sex. It’s always there just like a pulse. Still, that doesn’t mean it has to be addressed all the time. We’re out to train progressive minds.”

Decker said, “I heard about that. I’ve also heard that your school offers a very liberal freedom-of-speech policy, including platforms on abortion, legalization of opiates and prostitution, and euthanasia.”

“You’ve heard correctly.”

“You don’t shy away from controversy.”

“Indeed. But I’m sure I don’t have to remind you that these are but some of the issues that have come before our legislative body. We like to keep our students up-to-date … topical if you will. However, controversial issues do not extend to hate crimes, which are odious and against the law. I know you’re using drugs as an entrée to students’ lockers, but if you find any … and I do mean any evidence … that any of our boys are behind this heinous event, I want to know about it immediately. Proper remedies will be taken to assure that this issue will be addressed.”

“Doctor, if I find proof that one of your boys was part of this morning’s vandalism, he will be arrested.”

Williams was silent. It was one thing for him to reprimand and even to punish the students involved. It was quite another for their felonies to be broadcast over airwaves—not the PR that Foreman Prep liked. “Exactly how do you determine proof?”

“It varies.”

“If you should find proof … or perhaps the correct word might be ‘evidence’?”

“‘Evidence’ is fine,” Decker said.

“And if it should be necessary … for you to take appropriate action, is there a way that this can be handled … without a tremendous amount of fanfare?”

“I have no intention of calling up the press.”

“And if the press should call you?”

Decker was silent.

The headmaster placed his hands, fingers fanned out, on his highly polished walnut desktop. “Our boys are minors. If their names are released to the press, there will be problems.”

“Dr. Williams,” Decker chided. “Surely you don’t advocate suppression of the public’s right to know.”

“Innocent until proven guilty,” Williams stated.

Decker smiled. Spoken like a true American with his ass against the wall.

“I’m Dr. Jaime Dahl—special services administrator.”

Decker stuck out his hand. “Thank you for taking the time—”

“I didn’t volunteer for this witch-hunt, it was foisted upon me.” A swish of blond hair. “Let’s get that straight. I don’t approve of any kind of searches. I believe it’s a violation of civil rights.”

His day to get grief. Yet it wasn’t entirely her fault. At Decker’s behest, Dr. Williams hadn’t informed her or anyone else of the true purpose of the search. She’d probably be appalled by hate crimes, though she’d no doubt retort with, “One violation doesn’t excuse another.”

Through designer eyeglasses, she was slinging wicked looks his way. What made it worse was she was a fox—around twenty-five, with lush lips and knockout legs. She was wearing a black business suit and looked more like an actress playing the part of a school administrator. If this were a Hollywood script, they’d be in bed an hour from now. He must have inadvertently smiled, because her eyes grew angrier. She sneered at him. Too bad. He hated being dissed by anyone, let alone a fox.

She spoke in a clipped cadence. “Follow me.”

She led him down a flight of stairs, through a long, wide Berber-carpeted hallway, designated the student locker area. They were waiting for him—rows of adolescent boys standing next to their little bit of privacy, their hands at their sides. Two uniformed guards were watching them. The scene made Decker feel as if he were the aggressor, and that didn’t sit well with him. He stopped. “Is there any specific place I should start?”

“One is as good as the next.” Jaime tapped her toe, her left buttock moving with each rhythmical click of the shoe. “Let’s go from freshmen to seniors. They know what to do. They just went through the routine drill a few weeks ago.”

“They may know the drill, but I don’t.”

Jaime sighed impatiently. “One boy at a time will open his locker, swing the door all the way out, then take two steps back. Then you do your search and seizure. When you’re done, you step away and let the boy close his locker. Give them back a little piece of their stripped dignity.”

“That sounds fine—”

“I’m glad you approve,” Jaime snapped back. “Shall we get on with it?”

“The quicker I’m out of here, the happier I am.”

“I suppose that about sums it up for me, as well.”

“Why are you so unhappy about this, Dr. Dahl? Drug checks are part of standard operation in this school. You had to have known that when you took the job.”

“For the administration to do what’s necessary to maintain standards—that’s one thing. We don’t need the gendarmes telling us how to run our school.”

“Ah—”

“Yes, ah!”

Decker’s smile was wide. He tried to hold it back and that only made her angrier. She stomped over to the first lad—a fourteen-year-old moonfaced kid with a sprig of freckles across the nose—and asked him to open his locker.

He did, following Jaime Dahl’s drill to a tee. Decker was impressed.

Inside were papers, notebooks, pens, a few car magazines, and lots of candy wrappers.

“Thank you,” Decker said, taking a step backward.

The boy closed his locker. Jaime told him that he could go.

The boy left.

One down, about three hundred to go.

The tenth kid had a locker containing two bottles of pills. They looked to be prescription. He asked Jaime about them.

“As long as the medicine is from a doctor, we allow it into the school.”

“Can I pick up the bottles?” he asked her.

“Why are you asking me? You’re in charge.”

He picked up the bottles. “It’s all the same medicine.”

“I have a note,” the kid said anxiously. “You can call my mom.”

Decker looked him over. A stick of a kid: he was shaking. “I’m just wondering why you need sixty pills of any kind at school when the dose is one a day … at night.”

The kid said nothing.

Decker put the bottle back inside his locker. “Something you might want to think about. Someone could get the wrong idea … like you were selling off the excess. Of course, I know that’s not the case. But … it kinda looks bad.”

The kid mumbled a pathetic “Yessir.”

“It’s all right, Harry,” Jaime comforted him. “We can talk about this later.”

“Yes, Dr. Dahl.”

Decker went on to the next one, then the next. Over the course of the next hour, he found lots of bottles that looked suspect. Either they were genuine pharmaceutical containers with pills that didn’t match the prescribed medicine, or they carried counterfeited labels altogether. Since medicine was allowed, Decker left it up to Jaime to discipline. Usually, a stern look from the beautiful doctor was enough to send the boys into paroxysms. Decker felt for the kids, just like he had felt for Jacob after the boy had confessed his drug use. Kids had a way of doing that to him, making him feel bad even when he was just doing his job.

Rooting through the trash of rotting food, old papers, wrappers, and garbage. Not to mention old, wet gym clothes that smelled riper than decayed roadkill. Besides the pills, Decker found more than a fair share of cigarette butts—tobacco and otherwise. He pretended not to notice them. He also came upon packages of condoms—most of them unopened. There were also lots of pinups—mostly female, but there were some studly males as well. All of the posers wore smiles and adequate amounts of clothing. He also found several indiscreet Polaroids that he conveniently overlooked. It didn’t take long before Jaime Dahl became acutely aware of his omissions. It didn’t make her friendlier, but it did make her curious.

She said, “You’re not taking notes.”

“Pardon?”

“I see you’re not making note of any of the material you’re finding.”

“I haven’t found anything significant.”

“What would you consider significant?” The blue eyes narrowed. “You’re obviously not from Narcotics. Why are you here?” Suddenly, she took his arm and pulled him aside, out of earshot of the waiting students. She whispered, “Surely a police lieutenant has better things to do with himself than to hassle young minds in the throes of experimentation for freedom.”

“Surely.”

“You didn’t answer my question.”

It was Decker’s turn to narrow his eyes. It seemed to unnerve her. “If we can’t be buddies, maybe we can try civility?”

“I know your type. Don’t even think about asking me out!”

He stared at her, then laughed. What’s on your mind, honey? He said, “My wife would have a few choice words to say to me if I did.”

Her eyes went to his hand.

Decker said, “Not all married men wear wedding rings.”

“Only the ones who don’t want women to know they’re married.”

“Dr. Dahl, I’ve got a wife, four kids, three stifling private-school tuitions, a choking home mortgage, and car payments on a Volvo station wagon that’s already out of alignment. I’ve got the whole nine yards of suburbia. And I’m still smiling because deep down inside, despite my cynical view of this entire planet that we call Earth, I am a very happy man. Can we move on, please? I have a schedule and I bet you do as well.”

She regarded his face but said nothing. Decker took the silence as an invitation to finish up. He was up to the senior class, and had gone halfway through its roster without finding anything incriminating. He was discouraged by his failure, but encouraged by it as well. Maybe the school was really the best and the brightest.

He was almost done, finishing the last row of lockers. One of them belonged to a good-looking boy of seventeen—around six feet tall and muscular. He wore his brown hair in a buzz cut and had storm-colored eyes—electric and very dark blue. His locker was free of contraband and very neat. No pictures, nothing chemical, nothing out of place. Yet there was something on the kid’s face, a smirk that spoke of privilege. Decker met the kid’s eyes, held them for a moment.

“Let me see your backpack—”

“What?” The boy blinked, then recovered.

“This isn’t the procedure,” Jaime stated.

“I know,” Decker said. He turned to the boy. “Do you object?”

“Yes, I do.” The muscular boy tapped his foot several times. “I object on principle. It’s an invasion of my civil rights.”

Again, Decker met the kid’s eyes. “What’s your name?”

“Do I have to answer that?” the boy asked.

Decker smiled, turned to Jaime Dahl. “What’s his name?”

Putting her in a bind. It was beginning to look like the stud was hiding something. If she didn’t at least minimally cooperate, she’d look like she was hiding something as well. Reluctantly, she said, “Answer the question.”

The boy’s name was Ernesto Golding.

Decker said, “Let me make a deal with you, Ernesto. I’m not interested in drugs, pills, weapons … well, maybe weapons. You have a stash in there, and tell me it’s fish food, I’ll believe you.”

“Then why do you want to look in his backpack?” Jaime asked.

“I have my reasons.” He smiled. “What do you say?”

The boy was silent. Jaime looked at him. “Ernie, it’s up to you.”

“This is clearly police abuse.”

Decker shrugged. “If she won’t make you do it, I don’t have any choice. But you’ll hear from me again, son. Next time I may not be so generous.”

Ernesto stood on his tiptoes, attempting a pugilistic stance. “Are you threatening me?”

“Nah, I never threaten—”

“Sounds like a threat to me.”

“Shall we move on, Dr. Dahl?”

But Jaime didn’t move on. Instead, she said, “Ernie, give him your backpack.”

“What?”

“Do it!”

The boy’s face turned an intense red. He dropped the pack at his feet, the storm in his eyes shooting lightning. Decker picked the knapsack up and immediately gave it to Jaime. “You look through it. I don’t want to be accused of planting anything. Tell me if you see anything unusual.”

“What am I looking for?”

“You’ll know it when you see it.”

What Decker expected to find were obscene photographs of concentration-camp victims. What Jaime Dahl pulled out was a silver kiddush cup.

6 (#u0f746847-02e6-5495-8ba5-4f5ec129c6fa)

It stood out, a surface of metal against books and papers. Decker brought his eyes over to the young man’s face. Ernesto Golding was dressed in khakis and a white shirt. Ernesto Golding had intense eyes on a good-looking face, a broad forehead, and weightlifter’s arms. Ernesto Golding didn’t look like a thug. He looked like a macho teen with better things on his mind than killing Jews. Decker took a handkerchief from his pocket and held up the kiddush cup. “Where’d you get this?”

Ernesto folded his arms across his chest, pushing out his bulging biceps with his fists. “It’s a family heirloom.”

“And why are you bringing a family heirloom to school?”

The boy’s face was an odd combination of fear and defiance. “Show-and-tell, sir.”

I’ll bet you’ve been doing lots of show-and-tell, Decker thought. Jaime spoke up. “What’s going on?”

“That’s what I’m trying to figure out,” Decker answered. But his eyes remained on his prey. “The cup has some Hebrew writing on it. See here?” He showed it to Golding. “It’s easy Hebrew. Read it for me.”

“I don’t read Hebrew—”

“I thought you said it was a family heirloom.”

“My family’s origins are Jewish. But that doesn’t mean that I know Hebrew. It’s like assuming every Italian knows Latin.”

Decker was taken aback. “Your family’s Jewish?”

“No, my family is not Jewish. We’re humanists with ancestry in the Jewish race.”

The Jewish race—a Nazi buzz phrase.

“I don’t want to repeat myself,” Jaime stated bluntly, “but what is going on?”

Decker said, “Did you listen to the news this morning, Dr. Dahl?”

“Of course.”

“Then you must know that a local synagogue was broken into and vandalized. I was down there. Most of the damage was ugly, but it can be repaired. The one thing that was reported stolen was a silver benediction cup.”

Jaime looked at Ernesto, then at Decker, who held up the cup. “This family heirloom is inscribed with the words ‘Beit Yosef.’ That’s the name of the vandalized synagogue.”

“It’s a family heirloom,” Ernesto insisted. “We’re doing a family history. A family tree for honors civics. Dr. Dahl is aware of this assignment. Back me up on this one, Doctor.”

“There is a family-tree assignment in honors civics—Dr. Ramparts.”

“Yeah. Third period.” Ernesto rubbed his nose with the back of his hand. “I brought this in specifically to illustrate my family’s past, and to give Dr. Ramparts a more … genuine feel for where I came from. I’m sure there is more than one Beit Yosef in the world.”

The kid was oh so cool. And he probably thought he was pulling it off. Never mind about the beads of sweat that dotted his upper lip. “I’m sure there are, Mr. Golding. Even so, you’re coming with me.”

“I want a lawyer.”

“That can be arranged.”

They took him to Dr. Williams’s office, Decker standing over Ernesto’s shoulder as the kid called his parents—Jill and Carter Golding. Decker could hear outraged voices on the other side of the line. He couldn’t discern much, but he did hear them instruct Ernesto to refrain from talking to anyone. From that point on, things moved quickly.

Mom made it down in six minutes. She was a pixie of a thing with pinched features and thin, light brown hair that was long, straight, and parted in the center. She wore rimless glasses and no makeup. Behind the specs, her eyes were smoldering with anger that only a parent knew how to muster. First, there were a few choice glances thrown in Decker’s direction. The stronger ones were reserved for her son. Decker knew what that was about.

Dad arrived about ten minutes later. He was short and thin. The eyes were dark and most of the face was covered with a neatly trimmed brown beard flecked with silver. He appeared more befuddled than angry. He even shook hands with Decker when introduced. Ernesto didn’t resemble either of his parents, leaving Decker to wonder if the boy had been adopted.

The last part of the equation came in on Dad’s heels. Everett Melrose was an Encino lawyer who had made a name in California Democratic politics. He was well built, well tanned, and had the appropriate amount of sincerity in the eyes and distinction in the curly gray hair. He wore designer suits and dressed with flair. He had a wife, six kids, and was active in his church. He had defended some very big and bad people in his years, and had come out on top. Melrose’s past was squeaky clean as far as Decker knew. Amazing—a lawyer and a politician with nothing to hide. He shook hands all the way around and requested that he speak to his client, the young Ernesto, in private.

His request was granted.

The twenty minutes that followed were protracted and tense.

When they came back into Headmaster Williams’s CEO office, Ernesto looked upset, but Melrose was unreadable. He said, “Can you tell me the basis for this detainment?”

Decker said, “Your client has a stolen cup in his possession—”

“Have we determined that the cup was stolen?” Melrose asked innocently. “My client claims that the cup was an heirloom.”

Decker said, “Counselor, the cup belonged to the synagogue, Beit Yosef, that was vandalized this morning—”

“That’s impossible!” Jill broke in.

“Impossible that the synagogue was vandalized, or impossible that your son could have some involvement in the crime—”

“Don’t answer that!” Melrose interrupted.

“Ernesto, what is going on?” Carter asked.

“I wish I knew, Dad.” Ernesto tapped his toe and made eye contact with the floor.

A good bluff, but not a great one. Decker said, “The cup was taken from Ernesto’s backpack. That’s a fact. Dr. Dahl was there as a witness.”

“Did he give you permission to search his backpack?”

“Absolutely not,” Ernesto stated.

“It’s irrelevant whether or not you gave him permission!” Carter Golding spoke out. “I’d like to know what it’s doing in your possession.”

“So you’re saying it’s not a family heirloom?” Decker remarked.

“Carter, please!” Melrose said. “He’s not saying anything. He’s not the subject of this inquiry. What I’m hearing is that no one was granted permission to check Ernesto’s backpack!”

Dr. Williams came alive. “The school’s bylaws state that faculty can search lockers and personal property of any student at any given time to hunt out contraband or unlawful substances. Mr. Golding is aware of the bylaws. He has signed an honor code, acknowledging such rules with a promise to abide by them. So have Mr. and Mrs. Golding. It is a requirement of attending the school.”

“Lieutenant Decker is not faculty.”

“Dr. Dahl is faculty,” Decker countered. “She was the one who ordered Ernesto to open his knapsack.”

A few seconds of silence before Melrose turned his curious eyes on Jaime Dahl. “If you do routine searches for contraband, I’m assuming you have a list as to what constitutes contraband?”

“Of course.”

“And does it say specifically what items are contraband?”

“Stolen items are contraband,” Williams interjected.

“So a cup is not illegal.”

“The stolen cup is illegal,” Decker said.

“According to you, Lieutenant, a silver cup was reported stolen from a synagogue,” Melrose pointed out. “How do you know for certain that this is the cup in question? There may be hundreds like it.”

“Do you want proof that the cup belongs to the synagogue? That can be arranged. I can probably even dig up the original sales receipt. But I’ll tell you one thing for your own benefit, in case your client wants to change his story. That cup isn’t an heirloom. We bought it a year ago when the synagogue began having regular kiddushes after services.”

“What’s a kiddushes?” Jaime Dahl asked.

“Hors d’oeuvres after the Sabbath prayers. Before you eat, you need to make a benediction using wine. Hence, the silver cup.” Decker just realized that suddenly he was the resident Jewish expert. A position usually reserved for Rina, he felt strange occupying it now.

Melrose said, “You know a lot about this particular synagogue. May I ask if you’re a member?”

“You may ask, and I’ll even answer it, Counselor. Yes, I am a member.”

“So you’re hardly an unbiased party in this investigation.”

“That may be. But that doesn’t negate the fact that I can identify this cup as stolen.”

Melrose bluffed it out. “None of this will hold up in court. It’s an illegal search and seizure done under false pretenses. You told the students that this was a routine contraband check.”

Carter stood up. “Aren’t we missing the main issue? What were you doing with a cup from a vandalized synagogue, Ernesto?”

“It isn’t the right time to talk about this,” Melrose said.

Jill said, “This is all a mistake. Our son would never have anything to do—”

“Are you going to arrest the boy?” Melrose asked. “Yes or no?”

Decker sat back. He addressed his comments to Ernesto. “Mr. Golding, this isn’t going to go away. I am going to find out what happened, and if you’re involved, it’s going to come out. You can be in the catbird seat, or one of your cohorts can bring you down. Take your pick!”

“Ernie, what’s going on?” his mother asked.

“Nothing, Mom,” Ernesto answered. His breathing suddenly became audible. “He’s trying to psych you out. He’s a part of an organization of brutality. Police lie all the time. They’re never to be trusted. How many times have you told me that?”