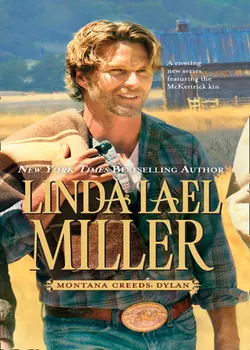

Montana Creeds: Dylan

Linda Lael Miller

Descendants of the legendary McKettrick family, the Creeds are renowned in Stillwater Springs, Montana – for raising hell…Hailed as “rodeo’s bad boy” for his talent at taming bulls and women, Dylan Creed likes life in the fast lane. But when the daughter he rarely sees is abandoned by her mother, Dylan heads home to Stillwater Springs ranch. Somehow the champion bull rider has to turn into a champion father – and fast.Town librarian Kristy Madison is uncharacteristically speechless when Dylan Creed turns up for story time with a toddler in tow. The man who’d left a trail of broken hearts – including her own – is back…and this time Kristy’s determined to tame his wild ways once and for all.Meet the Creed cowboys of Montana: three estranged brothers who come home to find family – and love

Praise for the novels of

LINDA LAEL

MILLER

“As hot as the noontime desert.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Rustler

“Loaded with hot lead, steamy sex and surprising plot twists.”

—Publishers Weekly on A Wanted Man

“Miller’s prose is smart, and her tough Eastwoodian cowboy cuts a sharp, unexpectedly funny figure in a classroom full of rambunctious frontier kids.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Man from Stone Creek

“[Miller] paints a brilliant portrait of the good, the bad and the ugly, the lost and the lonely, and the power of love to bring light into the darkest of souls. This is western romance at its finest.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Man from Stone Creek

“Linda Lael Miller creates vibrant characters and stories I defy you to forget.”

—No.1 New York Times bestselling author Debbie Macomber

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the second of three books about the rowdy McKettrick cousins, the Creeds.

Dylan Creed, seasoned hell-raiser and erstwhile rodeo cowboy, suddenly finds himself the full-time father of a two-year-old daughter. Like his brother, he’s come back to Stillwater Springs, Montana, to face down his demons, but his high school sweetheart, librarian Kristy Madison, shakes him up more than any bull he’s ever ridden in the rodeo! Will he stick around long enough to help Logan make the Creed name mean something again?

I also wanted to write today to tell you about a special group of people with whom I’ve recently become involved. It is The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), specifically their Pets for Life programme.

The Pets for Life programme is one of the best ways to help your local shelter: that is to help keep animals out of shelters in the first place. Something as basic as keeping a collar and tag on your pet all the time, so if he gets out and gets lost, he can be returned home. Being a responsible pet owner. Spaying or neutering your pet. And not giving up when things don’t go perfectly. If your dog digs in the yard, or your cat scratches the furniture, know that these are problems that can be addressed. You can find all the information about these problems—and many other common ones—at www.petsforlife.org. This campaign is focused on keeping pets and their people together for a lifetime.

As many of you know, my own household includes two dogs, two cats and four horses, so this is a cause that is near and dear to my heart. I hope you’ll get involved along with me.

With love,

Also available from

LINDA LAEL

MILLER

The Stone Creek series THE MAN FROM STONE CREEK A WANTED MAN THE RUSTLER

The McKettricks series McKETTRICK’S CHOICE McKETTRICK’S LUCK McKETTRICK’S PRIDE McKETTRICK’S HEART A McKETTRICK CHRISTMAS

The Mojo Sheepshanks series DEADLY GAMBLE DEADLY DECEPTIONS

Don’t miss all the adventures of the Montana Creeds LOGAN DYLAN TYLER

And return to Stone Creek in THE BRIDEGROOM

Montana Creeds: Dylan

Linda Iael Miller

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For Sam and Janet Smith, my dear, funny friends.

Thanks for some of the best advice

I’ve ever received:

Go to Harlequin!

CHAPTER ONE

Las Vegas, Nevada

HE’D KNOWN ALL DAY that something was about to go down, something life-changing and entirely new. The knowledge had prickled in his gut and shivered in the fine hairs on the nape of his neck throughout the marathon poker games played in his favorite seedy, backstreet gambling joint. He’d ignored the subtle mind-buzz as a minor distraction—it didn’t have the usual elements of actual danger. But now, with a wad of folded bills—his winnings—shoved into the shaft of his left boot, Dylan Creed knew he’d better watch it, just the same.

Down in Glitter Gulch, there were crowds of people, security goons hired by the megacasinos to make sure their walking ATMs didn’t get roughed up or rolled, or both, cops and cameras everywhere. Here, behind the Black Rose Cowboy Bar and Card Room, home of the hard-core poker players who scorned glitz, there was one failing streetlight, an overflowing Dumpster, a handful of rusty old cars and, at the periphery of his vision, a rat the size of a raccoon.

While he loved a good fight, being a Creed, born and bred, Dylan was nobody’s fool. A tire iron to the back of the head and being relieved of the day’s take—fifty-odd thousand dollars in cash—was not on his to-do list.

He walked toward his gleaming red extended-cab Ford pickup with his customary confidence, and probably looked like a hapless rube to anybody who might be lurking behind that Dumpster, or one of the other cars or just in the shadows.

Someone was definitely watching him; he could feel it now, a for-sure kind of thing—but it was more annoying than alarming. He’d learned early in his life, though, just by being Jake Creed’s middle son, that the presence of another person, or persons, charged the atmosphere with a crackle of energy.

Just in case, he reached inside his ancient denim jacket, closed his fingers loosely around the handle of the snub-nosed .45 he carried on his frequent gambling junkets. Garth Brooks might have friends in low places like the Black Rose, but he didn’t. Only sore losers, crooks and card sharps hung out in this neighborhood, and Dylan Creed fell into the latter category.

He was within six feet of the truck before he realized there was someone sitting in the passenger seat. He debated whether to draw the .45 or his cell phone in the split second it took to recognize Bonnie.

Bonnie. His two-year-old daughter stood on the seat, grinning at him through the glass.

Dylan sprinted to the driver’s side, scrambled in and lost his hat when the little girl flung herself on him, her arms tight around his neck.

With his elbow, Dylan tapped the lock-button on his armrest.

“Daddy,” Bonnie said. At least, in his mind the kid’s name was Bonnie—Sharlene, her mother, had changed it several times, according to the latest whim.

“Hey, babe,” Dylan said, loosening his grip a little because he was afraid of crushing the munchkin. “Where’s your mom?”

Bonnie drew back to look at him with enormous blue eyes, thick-lashed. Her short blond hair curled in wisps around her ears, and she was wearing beat-up bib overalls, a striped T-shirt and flip-flops for shoes.

I’m only two, her expression seemed to say. How should I know where my mom is?

Dylan turned, keeping one arm around Bonnie, and buzzed down the window. “Sharlene!” he yelled into the dark parking lot.

There was no answer, of course, and he knew by the shift in the vibes he’d been picking up since he stepped through the back door of the Rose that his onetime girlfriend had bailed. Again.

Only this time, she’d left Bonnie behind.

He wanted to swear, even pound the steering wheel once with his fist, but you didn’t do things like that with a kid around. Not if you’d grown up in an alcoholic cement mixer of a home, like he and his brothers, Logan and Tyler, had, jumping at every thump and bump. And there was more to it than that: besides the fact that he didn’t want to scare Bonnie, he felt a strange undercurrent of exhilaration.

He seldom saw his daughter, thanks to Sharlene’s gypsy ways—though she always managed to cash his child-support checks—and being separated from Bonnie, never knowing what was happening to her, ached inside him like a bruise to the soul.

Bonnie settled into his lap, laid her head against his chest, gave a shuddery little sigh. Maybe it was relief, maybe it was resignation.

She’d probably had one hell of a day, given how the night was shaping up.

Dylan propped his chin on top of her head for a moment, his eyes burning and his throat as hot as if he’d tried to swallow a red-ended branding iron. He leaned forward, turned the key in the ignition, shifted gears.

Logan. That was his next thought. He had to get to Logan. His brother was a lawyer, after all. And while Dylan had the money to pay any shyster in the country, and he and Logan were sort of on the outs, he knew there was no one else he could trust with something this important.

Bonnie was his child, as well as Sharlene’s, and by God, she deserved a stable home, decent clothes—the getup she was wearing looked as if it had doubled as a dog bed for a year or two—and at least one responsible parent.

Not that he was all that responsible. He’d been a rodeo bum for years, and now he was a poker bum. He had all the money he’d ever need, thanks to a certain shrewd investment and a spooky tendency to draw a royal flush once in practically every game, and he’d done some high-paying stunt work for the movies, too.

Compared to Sharlene, for all his rambling, he was a contender for Parent of the Year.

He didn’t find the note and the shabby duffel bag on the backseat until he got out to South Point, his favorite hotel. Holding a sleepy Bonnie in the curve of one arm while he stood waiting for a valet to take the truck, he read the note.

I’m having some problems, Sharlene had scrawled in her childlike handwriting, slanting so far to the left that it almost lay flat against the lines on the cheap notebook paper, and I can’t take care of Aurora anymore. Aurora, now? Jesus, what next—Oprah? I thought giving her to you would be better than putting her in foster care. I went that route, and it sucked. Don’t try to find me. I’ve got a boyfriend and we’re hitting the road. Sharlene.

Dylan unclamped his back molars, shifted Bonnie’s weight so he could take the ticket from the parking guy and then grab the duffel bag. He’d have his own gear sent over from Madeline’s place, where he usually crashed when he was passing through Vegas. Madeline wouldn’t like it, but he wasn’t about to take his two-year-old daughter there.

South Point was a sprawling, brightly lit hotel. Dylan stayed there whenever he came to the National Finals Rodeo—if Madeline, a flight attendant, was on one of her overseas runs or seeing somebody else at the time—and the establishment was family-friendly.

He and Bonnie were family.

There you had it.

After he’d booked a room with two massive beds, he ordered room-service hamburgers, French fries and milk shakes. While they waited, Bonnie, only half-awake, lay curled on her side on the bed farthest from the door, her right thumb jammed into her mouth, her eyes following every move he made.

“You’re gonna be okay, kiddo,” he told her.

She looked so small, and so vulnerable, lying there in her ragbag clothes. “Daddy,” she said, and yawned broadly before pulling on her thumb again, this time with vigor.

“That’s right,” Dylan answered, turning from the phone to the duffel bag. Inside were more clothes like the ones she was wearing, a kid-size toothbrush with the bristles worn flat and a naked plastic baby doll with Ubangi hair and blue ink marks on its face. “I’m your daddy. And it looks like we’ll be doing some shoppin’ in the morning, you and me.”

There were no pajamas. No socks. No real shoes, for that matter. Just two more pairs of overalls, two more sad-looking T-shirts, the doll and the toothbrush.

Rage simmered midway down Dylan’s gullet. Damn it, what was Sharlene doing with the money he sent to that post office box in Topeka every month? He knew by the way the substantial check always cleared his bank before the ink was dry that her grandmother picked it up for her, the day it came in, and overnighted it to wherever “Sharlie” happened to be.

He had his suspicions, naturally, regarding Sharlene’s spending habits—cocaine, animal-print spandex, tattoos for the fathead boyfriend du jour, if not herself. Bonnie, most likely, had subsisted on fast food and frozen pizza.

Dylan’s jaw tightened to the point of pain; he consciously relaxed it. None of this was Bonnie’s doing. Unlike him, unlike Sharlene, she was innocent, forced to live with the consequences of other people’s mistakes.

Not anymore, he vowed silently.

Much as he would have liked to put all the blame on Sharlene, he knew it wouldn’t be fair. He’d known who—and what—she was when he’d slept with her, nearly three years ago, after a rodeo, in a town he couldn’t even remember the name of now. They’d holed up in a cheap room and had sex for a week, then gone their separate ways. A few clueless months later, Sharlene had tracked him down and told him she was expecting his baby.

And he’d known it was true, long before he’d even laid eyes on Bonnie and seen her resemblance to him, the same way he’d known he wasn’t alone in the parking lot behind the Black Rose.

Listless with fatigue and probably confusion, Bonnie merely nibbled when the room-service food came, and then fell asleep in her overalls. Was she still on formula or something? Should he send a bellman into town for baby bottles and milk?

He sighed, shoved a hand through his tangled hair.

In the morning, he’d take Bonnie to a pediatrician—after buying her some decent clothes so the doc wouldn’t put a call through to Child Protective Services the minute they walked in—for a routine exam and to find out what the hell two-year-olds actually ate.

When he was sure Bonnie was sound asleep, the bedspread tucked around her, he called Madeline. She’d be expecting him, though to her credit, not at an even remotely reasonable hour, since theirs was a sleep-over-when-you’re-passing-through kind of arrangement.

He needed his clothes, and his shaving gear, and his laptop.

“It’s Dylan,” he said, to Madeline’s hello.

“You winnin’, sugar?” She’d cultivated a Southern drawl, but every once in a while, the Minnesota came through, with its faintly Scandinavian lilt.

“I always do,” Dylan murmured, looking at his sleeping child.

“Then we ought to celebrate,” Madeline crooned. “Find us a sexy movie on pay-per-view and—”

“Look, Madeline, I can’t make it over there tonight. Something—er—came up—”

“Where are you?” There was a snap in Madeline’s tone now. She wasn’t possessive—he’d have driven fifty miles out of his way to avoid her if she had been—but she had turned down other offers for the duration of his stay in Vegas, she’d made that abundantly clear, and she clearly wasn’t happy about being stood up.

“I’m at South Point,” he began.

“Damn you,” Madeline said, downright peevish now, “you picked up some—some woman, didn’t you?”

“Not exactly.”

“What do you mean, ‘not exactly’?”

“I’m with my daughter, Madeline,” Dylan said, patient only because he didn’t want to disturb Bonnie. “She’s two years old.”

The croon was back. “Oh, bring her over here! I just love babies.”

Dylan actually considered the offer, for a nanosecond. Then he remembered Madeline’s penchant for impromptu sex, the smell of stale pot smoke that permeated her condo and the bowl of colorfully packaged condoms in the middle of her coffee table.

“Uh—no,” he said. “She’s pretty tired.”

He sensed another huff building up beneath Madeline’s drawl. “Then why did you bother to call at all?” she purred. In a moment, the claws would be out, poised to rip him to bloody shreds.

“I need my stuff,” Dylan admitted, ducking his head a little, the way he had on the playground when he was a kid, in anticipation of a blow. “If you’d just put it all in a cab and send it this way, I’d be obliged.”

“I wouldn’t think of doing that,” Madeline said. “I’ll drop it all off on my way to the club.” Her slight emphasis on the last two words was a clear message—if he was going to be a no-show, far be it from her to sit home alone watching pay-per-view.

“Madeline, you don’t have to—”

“South Point? That’s where you said you are, isn’t it?”

“Yes, but—”

She hung up on him.

Dylan sat down on the edge of his bed, opposite Bonnie’s, and propped his elbows on his thighs. Madeline would want to come straight up to the room, probably to see if he’d lied about the company he was keeping, and he didn’t want her waking Bonnie. But unless he could talk Madeline into sending his things up with a bellman, which didn’t seem likely, he’d have no other choice.

He’d have to leave Bonnie alone to go downstairs, and that wasn’t an option.

Twenty minutes later, the phone rang, causing Bonnie to stir in the depths of some baby-dream, and he pounced on it, whispered, “Hello?”

“I’m downstairs,” Madeline said. “What’s your room number, sweetie?”

Dylan suppressed another sigh. God, he hated being called “sweetie.” “Twelve-forty-two,” he said.

Madeline, a leggy redhead, almost as tall as he was, at six feet, whisked her shapely self to his door with no measurable delay. Looking through the peephole, he saw that she was flanked by a bellman with a loaded cart. Her shiny mouth was tight, and her eyes narrowed slightly.

Reluctantly, Dylan admitted her.

She immediately scanned the room, her gaze landing on Bonnie, while the bellman waited politely to unload some of the stuff from the cart. Dylan handed him a tip and brought in the laptop, his shaving kit and his suitcase himself.

“She is precious!” Madeline enthused, looming over Bonnie’s bed.

“Be quiet,” Dylan said. “She’s had a rough day.” A rough life was more like it. As soon as he got rid of Madeline, he’d bite the bullet and call Logan. They’d made some progress lately, he and his older brother, but the ground could get rocky at any time, and asking big brother for help was going to be hard on his pride.

Madeline put a shh finger to her plump mouth and batted her false eyelashes. Put her in a big Vegas headdress, with feathers and spangles, a skimpy costume, high heels and fishnet stockings, and Bonnie, if she chanced to wake up and see a stranger standing over her, would have nightmares about showgirls until she died of old age.

He took Madeline by the elbow and gave her the bum’s rush toward the door. “Good night, thank you, and what do I owe you for the favor?”

She patted his cheek. “We’ll settle up next time you come through Vegas,” she said. She paused. “The hotel could probably provide a babysitter, then we could—”

“No,” Dylan said flatly.

Blessedly, and none too soon, Madeline left.

Dylan showered, shaved, brushed his teeth and headed for bed in his boxer briefs; he hadn’t owned a pair of pajamas since grade school.

But he had Bonnie to think about now. He couldn’t go parading around in front of a two-year-old in his shorts—even if she was asleep.

Fatherhood, he thought, was getting more complicated by the minute. Especially since he didn’t know jack-shit about it—his experience had been limited to a few brief visits with Bonnie whenever Sharlene deigned to light someplace for a month.

He pulled on a pair of jeans and a T-shirt, and then he crashed.

He’d call Logan the next day, he promised himself. Or the next day, or the one after that …

KRISTY MADISON BUSTLED around her big kitchen, opening a can of food for her white Persian cat, Winston, gathering her notes for that night’s book-club meeting at the library, grabbing her cell phone off the counter where she’d been charging it during a quick trip home for supper.

She wished she could stay in tonight, soak in her big claw-foot bathtub and read a book, but the reading group had been her idea, after all. And it had turned out to be a popular one—twenty-six people had signed up.

Privately, Kristy wondered how many of them simply wanted a close-up look at Briana, Logan Creed’s love interest. Before Briana had taken up with Logan, she’d been just another single mother, pulling down a paycheck at the casino on the outskirts of Stillwater Springs, homeschooling her two boys, Josh and Alec, and generally minding her own business.

Kristy bit her lower lip. Thinking of Logan inevitably led to thinking about Dylan, and that was still too painful, even though it had been five years since she’d seen him. He’d been in town recently—the busybodies had made sure she knew—but he hadn’t sought her out, and she’d been half again too proud to chase him down.

Looking at her own reflection in the dark glass of the kitchen window, Kristy saw a slender woman with fashionably mussed, midlength blond hair, blue eyes and good bone structure. But there were shadows under those eyes, her hair needed a trim, and what the hell good did bone structure do a person, anyway? She looked okay in the picture on her driver’s license—that was the extent of the advantage, as far as she’d been able to determine.

Winston, ignoring his food bowl, gave a loud and plaintive meow and slithered across the cuffs of Kristy’s black jeans, leaving a dusting of snow-white hair.

Now, she’d have to lint-roll—again.

Other women carried mints and lipstick in their purses—Kristy had a tape-covered stick.

“I know,” she told Winston gently. “You want to cuddle and watch Animal Planet, but I’ve got to work tonight.”

Winston’s reply was another meow—this time, he’d turned the “pitiful” meter up a few notches.

“You can have an extra mackerel treat when I get home,” Kristy promised. “I won’t be late—nine-thirty at the outside.”

Winston, unappeased, turned and made his way between the various paint cans and wallpaper samples littering the kitchen floor. With a disdainful flip of his bushy white tail, he disappeared into the dining room.

Kristy had been renovating her big Victorian house forever, or so it seemed. She was used to tripping over stuff from Home Depot, and so was Winston, but all of a sudden, it seemed more like a never-ending hassle than the noble restoration effort she’d undertaken as soon as she’d signed the mortgage papers.

“I’m tired of my life,” she told her reflection. “I want a new one.”

“Too bad,” her reflection replied. “You made your bed, and now you have to sleep in it. Alone.”

No husband. No children.

A few more birthdays, a few more cats, and she’d qualify as a crazy old maid. Kids would start saying she was a witch, and avoid her house on Halloween.

Kristy turned away from her window-self, tugged her purse strap onto her shoulder, dropped her cell phone into the bag, along with her notes and a copy of that month’s book-club selection, and headed for the back door.

No matter how blue she might be, the sight of the Stillwater Springs Public Library always lifted her spirits, and this evening was no exception. She loved the squat, redbrick building, with its green shutters and shingled roof. She loved being surrounded by books and readers.

She and a few other people who’d grown up in or around the small western Montana town had fought some hard battles to get the funding to build and stock the library after the old one burned down.

Parking her dark green Blazer in the spot reserved especially for her, Kristy hurried toward the side door, keys jingling. The main part of the library had closed early that night for plumbing repairs in one of the rest-rooms, but the two small meeting rooms would be open—the reading group in one, AA in the other.

She hung her purse on a peg, washed her hands at the sink in the little kitchenette between the meeting rooms and started wrestling with the big coffee urn.

Sheriff Floyd Book was the next to arrive—he carried in a box of books from his personal car and greeted Kristy with a smile and a nod. “I knew if I didn’t get here too quick, you’d make the coffee,” he teased.

Kristy laughed. “Everything in place for your retirement?” she asked, setting out columns of disposable cups, packets of sugar and powdered creamer and the like.

“Everything except me,” Floyd replied, through the open doorway leading to the AA side, already setting out books and pamphlets for that night’s meeting. In Stillwater Springs, nobody was anonymous, but for the sake of what was called The Program, everyone pretended not to notice who came and went from the side entrance to the library on a Tuesday night. “I can’t hardly wait for that special election. Hand my badge over to Jim Huntinghorse or Mike Danvers, and kick the dust of this town off my feet—for a few weeks, anyhow. Dorothy and I are all packed for that cruise to Alaska.”

“Soon,” Kristy soothed good-naturedly. She’d been too busy, until the mention of the woman’s name, to notice that Mrs. Book was nowhere around. “Dorothy isn’t coming to the reading group meeting? She signed up.”

Dorothy Book was confined to a wheelchair, following an automobile accident some years before, and there were people who said she wasn’t right in the head. Kristy had always liked Dorothy—so what if she was a little different?—and she’d been looking forward to having her come to the group’s first meeting.

Floyd shook his head. He’d looked weary lately, worn down to a nubbin, as Kristy’s late mother used to say. Maybe it was the buildup to his retirement, the stresses of his job, and the uncertainty of the special election, but it seemed to Kristy that he was more strained than usual.

“It’s hard for her to get in and out of the car,” the sheriff told Kristy. “And she hates fussing with that wheelchair. I’m hoping the cruise will put some color back in her cheeks and a twinkle in her eyes.”

Kristy stopped fiddling with the coffee things. Floyd Book was the sheriff of a sprawling county—he’d been elected to the office when she was in the second grade and had held it ever since. Until her dad died, just six months after her mother’s passing, Floyd had been a regular visitor out at Madison Ranch. He and Kristy’s father had been best friends, sharing a love of fishing, horseback riding and herding the few cattle Tim Madison had been able to afford to run on that hard-scrabble place.

A pang struck Kristy as she started to ask Floyd, straight out, if something was wrong and if so, what she could do to help. This was a night, it seemed, for painful memories to come up.

“You all right, Kristy?” Floyd asked, crossing the hallway to lay a brawny hand on her shoulder. “You went pale for a second there. I thought you were going to faint.”

“I’m fine,” Kristy lied. She’d been raised as a tough Montana ranch kid, expected to say she was fine whether she was or not.

But the ranch was abandoned now, the barn leaning to one side, the sturdy old house empty. The last time Kristy had forced herself to go out there and stand on the high rise where she used to ride Sugarfoot, her beloved palomino gelding, she’d actually felt her heart break into pieces.

Her parents were both dead, and she had no brothers or sisters, no aunts—now that Great-Aunt Millie had passed away—or uncles, no cousins.

Sugarfoot was gone, too, buried in a horse-size grave in the middle of a copse of trees bordering the Creed ranch. After sixteen years, more than half her life, Kristy still cried when she visited her best friend’s final resting place. People urged her to get another horse—she’d loved riding, and she’d been uncommonly good at it, too—but somehow, she just didn’t have the heart to love something—or someone—that much and risk another loss.

She’d lost so much already.

Her parents, Sugarfoot.

And Dylan Creed.

“Kristy?” the sheriff prompted, peering worriedly into her face now. “Maybe you ought to go home. You might be coming down with something. I could tell the reading-club ladies the meeting’s been postponed.”

Kristy summoned up a smile, straightened her shoulders, looked her father’s old friend straight in the eye. “Nonsense,” she said. “We’ve already postponed it once. I’m just a little tired, that’s all.”

Floyd didn’t seem entirely convinced, but a few of the AA regulars were straggling in, so he finally turned to go and greet them, the way he had every Tuesday night for years—ever since Dorothy’s car accident, and that scandal about him running around with Freida Turlow behind Dorothy’s back. He’d wept, sitting at the kitchen table with Kristy’s dad, out on the ranch, over the pain Dorothy had suffered, not only because of the wreck on an icy road, but because he’d betrayed her with another woman.

It was the first and only time Kristy, watching and listening unnoticed from the hallway, had ever seen a grown man cry.

Her kindly dad had put a hand to Floyd’s shoulder and said, “It’s the drinking, old buddy. That’s what’s messing up your life. You think I don’t know you carry a flask everywhere you go? You’ve got to do something.”

And Floyd had done something. He’d joined AA, gotten sober and, as far as Kristy knew, been a faithful husband to Dorothy from then on.

Kristy left the kitchenette for the reading group’s meeting room, and by some cosmic irony, Freida Turlow was the first to arrive.

An athletic type, attractive in a hardened sort of way, Freida, like Kristy, was a lifelong resident of Stillwater Springs. Except for college, neither one of them had been away from home for any significant length of time.

Kristy was a hometown girl—she’d never wanted to live anywhere else, even after her parents both died during her junior year at the University of Montana. By contrast, Freida, who was at least a decade older, had indeed been Kristy’s babysitter on the rare nights when her mom and dad went out dancing, or to play cards with friends, seemed out of place in Stillwater Springs. She was ambitious and well-educated, and virtually ran the local real estate office. Her brother, Brett, was a classic jerk, sleeping on her couch and famous for stealing money from her every chance he got.

Tonight, her dark chin-length hair pinned up at the back of her head, Freida wore a running suit and sneakers and carried that month’s reading selection under one arm. Like Kristy, Freida had lost her family home—the gingerbread-laced minimansion Kristy now owned—and she was touchy about it. She’d offered to buy back the old house several times, at higher and higher prices, and had gotten progressively more annoyed at every polite refusal.

Kristy understood Freida’s desire to reclaim the venerable Victorian, even sympathized. But that house, except for Winston and her job at the library, which she’d held ever since she got her degree, was all she had.

Where would she go, if she sold it back to Freida?

“News on the real estate front,” Freida told her, with no little satisfaction. “I’ve got an offer on Madison Ranch—or at least, the promise of one.”

Kristy froze. The old place was run-down, but it was big—totaling some thirty thousand acres. Prime pickings for the movie stars and Learjet executive crowd who’d been snatching up properties in Montana over the past couple of decades.

Only the probate tangle had kept it off the market this long.

Technically, the local bank owned Madison Ranch now, though the name had stuck, because there had been Madisons living on that land since that part of the state was settled. They’d foreclosed two months after Kristy’s dad died.

Freida allowed herself a smug little smile.

Then Briana Grant came in. There were rumors that she and Logan Creed were secretly married or would be soon, and sleeping together either way. Briana, a pretty woman who always wore her strawberry-blond hair in a tidy French braid, certainly hadn’t confided the nature of the relationship to Kristy, though the two of them were friendly.

Seeing Freida seated at one of the chairs surrounding the conference table, her book open before her, Briana stopped on the threshold, looked as though she might turn on one heel and bolt.

“Come in,” Kristy urged her, smiling. Inside, though, she was still shaken by Freida’s smug announcement that she had a promising prospect to buy Madison Ranch, and no amount of telling herself it didn’t matter anyway seemed to help.

Briana hesitated, then met Freida’s gaze, lifted her chin a little, and took a place at the table.

“You’ve got your nerve, showing up here, after all the trouble you’ve caused my poor brother,” Freida told her flatly.

Briana flushed, but didn’t give any ground. Sheriff Book had picked Brett Turlow up for questioning a couple of times, after a break-in at Briana’s, but that was all Kristy knew. She wasn’t much for gossip.

“Everybody’s welcome here, Freida,” Kristy said staunchly. While the Stillwater Springs Public Library wasn’t exactly a hotbed of violent controversy, she’d had some experience keeping order. A lot of townspeople used the place as if it were a free day-care center, and once in a while, there was a little dust-up when two voracious readers wanted to check out the only copy of some recent bestseller.

Freida stood, her movements stiff and precise. She grabbed her purse and her book and sniffed, “I don’t know why I stay in this town, with all the riffraff coming in these days.” With that, she swept grandly out.

Tears stood in Briana’s eyes.

Kristy sat down beside her friend, took her hand. “She’s the one with nerve, calling anybody riffraff, with that brother of hers,” she said gently.

Briana sniffled, managed a smile and then a nod. She hugged her library book to her chest like some sort of treasure.

After that, the other members of the book club began trailing in, by chatty twos and threes. Those who wanted to helped themselves to the coffee in the kitchenette, and though they watched Briana with interest, surely speculating about her and Logan Creed, they included her in the discussion.

All in all, Kristy thought, as she locked up an hour later, when both meetings were over, it had been a worthwhile evening, though Winston probably wouldn’t agree.

Back in the Blazer, and alone in the library parking lot, Kristy gripped the wheel with both hands and laid her forehead against her knuckles for a long moment.

She felt strangely on edge, hyperalert, as though something big were about to happen, but big things simply didn’t happen in Stillwater Springs, Montana. Not often, anyway.

She rallied, made herself sit up straight, start the motor, head for home. Winston was waiting, and so was her claw-foot bathtub, along with the page-turner she’d been trying to finish for a week.

Maybe Sheriff Book had been right.

She might be coming down with something.

And maybe that monster-memory she’d been fighting to keep submerged was about to break the surface, finally, and ruin her carefully constructed life.

CHAPTER TWO

FIRST THING IN THE MORNING, after half an hour trying to spoon room-service oatmeal into Bonnie’s tightly closed mouth and finally giving up, Dylan checked out of the hotel and went looking for a Wal-Mart.

Bonnie needed a car seat, and a whole slew of other things.

So he put her into a shopping cart, and the two of them wheeled around. He guessed at her clothes sizes, and she kicked up a fuss when he went to try some shoes on her, but after a brief struggle, he won. In the toy department, he snagged a doll almost as big as Bonnie herself, mounted on a plastic horse no less, but she didn’t show much interest in that, either.

“Toys,” an older woman told him sagely, leaning in to whisper the wisdom, “have to be age-appropriate.”

“Age-appropriate?” Dylan pushed his hat to the back of his head.

The woman tapped the box containing the new doll, sitting tall and straight on her horse. “This is for children five and up. Your little girl can’t be any older than two.”

“She’s small for her age,” Dylan replied automatically, because he didn’t like other people telling him what to do, even when they were right. But once the meddlesome shopper had rounded the bend, he put the doll back on the shelf and rustled up a soft pink unicorn with a gleaming horn and a fluffy mane. According to the tag, it would do.

And Bonnie took to it right away.

After making a few more selections, and paying at the checkout counter, they were good to go. Dylan made a couple of calls from the truck and located a pediatrician on the outskirts of the city.

Jessica Welch, M.D., operated out of an upscale strip mall. She was good-looking, too, with long, gleaming brown hair neatly confined by a silver barrette at her nape. Not that it mattered, but when Dylan met a woman—any woman—he noticed things about her.

“Who do we have here?” Jessica Welch, M.D., asked, chucking Bonnie, who had both arms clamped around Dylan’s neck, under the chin.

Bonnie threw back her head and screamed out one of those ear-piercers that go through a man’s brain like a spike. Ever since Dylan had hauled her into the waiting room, a full forty-five minutes before, she’d been clinging to him. He’d been the only father present, and the looks he’d gotten from the various mothers waiting with quieter, better-behaved kids weren’t the kind he was used to getting from people of the female persuasion.

Dr. Welch was unmoved. Screaming children were not uncommon in her day-to-day life, of course. “This way,” she said.

Dylan and Bonnie followed her down a short corridor and into a small examining room. Bonnie didn’t let up on the shrieking, and she’d added kicking and squirming to the fit; hostilities were escalating.

“I guess she thinks she might get a shot or something,” Dylan said, completely at a loss. By then, Bonnie had knocked his hat off, and she was pulling his hair with both hands.

Dr. Welch simply smiled. “Let’s have a look at you, Miss—?”

“Bonnie,” Dylan said. “Bonnie Creed.”

Bonnie Creed. He liked the sound of that.

The doctor examined the papers on her clipboard. “And you’re her father,” she said. It was rhetorical, a conclusion not a question, but Dylan felt compelled to answer all the same.

“Yes.”

“I would have known by the resemblance,” Dr. Welch said. As it turned out, she had a few tricks up her sleeve. By letting Bonnie listen to Dylan’s heart through a stethoscope, she got the kid to quiet down.

“Any significant health problems?” the doctor asked, finishing up with the routine stuff, like looking into Bonnie’s ears with that little flashlight-type thing and peering down her throat.

“Not that I know of,” Dylan said. “She’s been—er—living with her mother.”

“I see,” Dr. Welch replied solemnly.

“I was hoping you could tell me what to feed her and stuff like that,” Dylan went on. He felt his ears burning. By now, the doctor was probably wondering if she should notify the authorities or something.

“I take it you haven’t been around Bonnie much,” she said thoughtfully.

“It was kind of sudden. Sharlene decided she couldn’t take care of her anymore, and left her with me.” He probably looked and sounded calm, but if Dr. Welch drew her cell phone, he and Bonnie would be out of there in a flash and speeding for the open road. Damn. He should have called Logan. Then he’d have some kind of legal backup at least—

“I’ll need a number where I can contact you, Mr. Creed.”

Dylan gave her his cell number and hoisted a reaching Bonnie off the end of the examining table and back into his arms.

“Two-year-olds,” Dr. Welch went on, with a sudden smile, “usually prefer a semisoft diet—some baby food, not the infant variety. Anything that’s easy to chew.”

“No bottles or anything?” Dylan asked.

“One of those sippy cups, with the lid,” the doctor said. “Bonnie needs a lot of milk, and juice is okay, too, provided you watch the sugar content.”

Dylan figured he ought to have been taking notes. What the devil was a sippy cup, anyhow? And didn’t just about everything have sugar in it?

He kept his questions under his hat, having already made a fool of himself. If the doc didn’t take him for a child abductor, it would be a miracle.

Dr. Welch gave Bonnie a couple of shots—the kid barely noticed—ferreted out a list of healthy foods for children and sent them on their way. Dylan paid the bill, and he and Bonnie left. Until they were fifty miles north of Vegas, he checked the rearview mirror for a squad car every few minutes.

AS IT HAPPENED, Dylan didn’t have to call Logan, because Logan called him—at an inconvenient time, as usual.

Logan was getting married to Briana Grant, that was the gist of it, and there was no talking him out of it, Dylan learned, when he took his brother’s call on his cell phone, seated in a truck-stop restaurant somewhere along the winding road homeward. Bonnie, in the provided high chair, kept flinging strands of spaghetti at him—she was covered in the stuff, and so was he.

And he was losing patience. “Look, Logan, I—” He paused when Bonnie stuck her whole head into her plate and came up looking like some pasta-Medusa. “Stop that, damn it—”

Bonnie merely giggled and preened a little, like all that goopy spaghetti was a wig she was modeling.

“Are you with a woman?” Logan asked.

“I wish,” Dylan said. “I’ve got to hang up now—I said stop it—but I’ll get there when I can. If I don’t show up in time, go ahead without me.”

After that, Dylan barely registered what his brother said.

Logan asked him to get word to Tyler, he remembered that much, and relay the message that he wanted to talk to their younger brother, in person.

As if. Tyler was in pissed-off mode. There would be no getting through to him, and Dylan said so, in so many words.

Then Bonnie started throwing spaghetti again.

This time, she hit the woman in the next booth square in the back of the head.

Dylan ended the phone call, no closer to asking Logan for help than he had been in the first place, scooped up the demon child, tossed the bills to pay for the meal onto the cashier’s counter and fled.

Now, he’d have to find a place to hose the kid down.

He cleaned her up with baby wipes, purchased along with the unicorn, a plastic kid-toilet, the little tennis shoes and the new outfit she’d pretty much ruined.

“Potty,” she said, as they pulled out of the truck stop and onto the highway. “Daddy, potty.”

“There’s no way we’re going back in there,” Dylan said. “We’re probably banned from the place, thanks to you. Eighty-sixed, for all time and eternity.”

“Potty,” Bonnie insisted. Besides Daddy, that seemed to be the only word she knew. He’d sneaked her into at least four different men’s rooms since they’d left South Point that morning. Held her on the seat so she wouldn’t fall in and looked the other way as best he could.

Her lower lip started to wobble. “Potty,” she said pitifully.

“Oh, hell,” Dylan muttered. He pulled the truck over, located the miniature pink toilet, and set it down behind some bushes. Then he unfastened Bonnie from her car seat and carried her, spaghetti stains and all, to the john.

He turned his back.

She must have gotten her pants down on her own, because he heard a cheery little tinkle. When he finally turned around, she was grinning up at him, her hair crusted in spaghetti sauce, and grunting ominously.

Dylan had ridden the meanest bulls on the rodeo circuit, and until he and Cimarron, the bull to end all bulls, met up, he’d never been thrown. He’d held his own in bar brawls and backstreet fights where losing meant getting your head slammed against the curb. Bluffed his way past the toughest poker players at the toughest tables in the toughest towns in America.

But a little girl pooping—now, that was a new one.

“Wipe!” she crowed, upping her known vocabulary to three words.

“Not a chance,” Dylan said. But he got some more baby wipes out of the truck and handed them to her.

She must have used them, because when she came past him, her pants were up and she was pulling the potty-chair behind her. Gnarly as the whole experience had been, Dylan felt a rush of pride. The kid was independent, for a two-year-old. She’d even thought to dump the evidence.

“We need a woman,” he told her, once they were back in the truck and he’d used yet another baby wipe to wash her hands and fastened her into the car seat, which was so complicated it might have been invented by NASA. “Any woman.”

But it wasn’t any woman who came to mind.

It was Kristy Madison.

No way, he told the image.

After that, they drove for hours, and a little past three in the morning, they hit the outskirts of Stillwater Springs, Montana.

Dylan owned a house on the family ranch—Briana and her kids had been living there up until recently, when they’d moved in with Logan, but there had been a break-in and some vandalism, and he didn’t know if Logan had arranged for repairs yet.

So he headed for Cassie’s place.

When they pulled into her driveway, light glowed through the buckskin walls of her famous teepee. Dylan had spent a lot of happy hours in that teepee, with Logan and/or Tyler, pretending to be Indians plotting a raid on a white settlement.

Now, with Bonnie asleep in her car seat and clinging to that naked, inked-up doll like it was her last friend, the pink unicorn spurned, he got out of the truck and headed toward the teepee.

Cassie, a bulky and singularly beautiful woman and the closest thing to a grandmother he’d ever had, sat watching low, flickering flames in the fire pit inside the teepee. It might have been a picturesque scene, if she’d been wearing tribal gear, but double-knit pants, bulging at the seams, neon-green high-top sneakers and a sweatshirt with a picture of Custer on the front, with an arrow through his head, lacked the punch of a fringed leather dress and moccasins.

Custer was a nice touch, though. From his benignly confident expression, the arrow didn’t bother him much.

“Dylan,” Cassie said, looking up. And she didn’t sound surprised.

“I need help,” he told her. No sense beating around the bush with Cassie; she could see right through a person.

She smiled. Nodded. Moved to rise.

He extended a hand to help her up.

Led her to the truck.

She drew in a breath at the sight of Bonnie, still sleeping the sleep of the just. “Yours?” she whispered.

“Mine,” he confirmed and, once again, he felt that same swell of pride.

“Where is her mother?”

“God knows.” Dylan got Bonnie out of the car seat, her head bobbing against his shoulder. “I’m going to petition for full custody, but I need Logan’s help to do that.”

“There are a lot of lawyers in this world,” Cassie pointed out quietly. “Why Logan?”

“Because this could be—well—tricky.”

“Dylan Creed, did you steal that child from her mother?” They’d reached the gate by then, and Cassie led the way up the walk, onto the porch. Jiggled the knob on the door.

Evidently, she couldn’t see through him. Not always, anyway.

“No,” Dylan said. It was late—or early—and he was too wrung out from the long drive and the stress of looking after a two-year-old to go into the story. “Give me a little credit, will you? I’m not a criminal.”

“But you’re looking over your shoulder for some reason,” Cassie whispered, switching on a lamp in the familiar living room of her small, shabby house. She took Bonnie from him, murmured soothingly when the little girl fussed in her sleep.

“I don’t have legal custody,” Dylan answered. “Until I do, I’m keeping a low profile, in case Sharlene changes her mind. I’ll tell you the rest in the morning.”

Cassie stared into his eyes for a long moment, then nodded again. “All right,” she said, making for the spare bedroom. “I’m putting this child to bed. There’s cold chicken in the refrigerator if you’re hungry.”

Grateful, Dylan let himself drop onto the couch, and before he knew it, the sun was up and Bonnie was standing beside him, tugging playfully at his hair.

He grinned, glad to see her. She was wearing one of Cassie’s massive T-shirts, tucked up here and there with safety pins, to make it fit, and she was clean.

God bless Cassie. Despite her obvious misgivings, she’d given Bonnie a much-needed bath, and probably fed her, too.

“Daddy,” Bonnie said angelically, stroking his beard-stubbled cheek with one very small hand.

And if Dylan hadn’t known before that he’d do anything to keep and raise this child—his child—he knew it then.

“DDYLAN’S OUT AT CASSIE’S place,” Kristy’s hairdresser, Mavis Bradley, told her, when she came in for a lunch-hour trim. “I saw his truck parked in her driveway when I came in to work.”

A thrill went through Kristy, part dread, part anticipation. She waited it out. If Dylan was in town, he’d soon be gone. That was his pattern. Come in, stomp somebody’s heart to bits under his boot heel and leave again.

“And Cassie was at the store, not an hour later, buying training diapers and toddler’s food in those plastic cartons that cost the earth,” Mavis rattled on, before Kristy could come up with a response. “That’s what Julie Danvers told me, when she came in to have her nails done.”

Kristy took a moment to be glad she’d missed Julie. There was some bad blood between them, at least on Julie’s side, because Kristy had been briefly engaged to her husband, Mike, and he hadn’t taken the breakup well. Now they had two children, a big house and a thriving business, and Mike was a candidate for sheriff. It was a mystery to Kristy why that particular water hadn’t gone under the proverbial bridge.

“Interesting,” Kristy said, because she’d known Mavis since first grade, and she’d just keep prattling on until she got some kind of reaction. Everybody for miles around knew Kristy and Dylan had been passionately in love, once upon a time, and Mavis certainly wouldn’t be the last person eager to tell her Dylan was back.

“Now what would Cassie need with stuff for a little kid unless—”

“Mavis,” Kristy broke in. “I have no idea.”

“Think you’ll see him?”

Kristy actually shrugged. No use pretending she didn’t know who Mavis was asking about. “Maybe around town,” she said, with a nonchalance she certainly didn’t feel. “We’re old news, Dylan and I.”

“So are you and Mike Danvers,” Mavis parried coyly, “but Julie gets her panties in a wad every time he mentions your name. Which, apparently, is quite often.”

Kristy had to be careful how she answered that one. Everything she said would go out over Mavis’s extensive network within five minutes after she’d paid for the haircut and left. “That’s silly. Mike and Julie have been married for a long time. They have two beautiful children and a great life. So Mike mentions my name once in a while? Stillwater Springs is a small town. He probably mentions a lot of people’s names.”

“Well,” Mavis said doggedly, “I’d think you’d at least wonder about why Cassie might buy diapers, and there’s Dylan Creed’s truck parked in front of her house so early in the day that he must have rolled in during the night—”

“I don’t wonder,” Kristy lied, and very pointedly. If Dylan had a child, it would be the height of unfairness on the part of the universe. She was the one who longed for a houseful of kids. Dylan had never wanted to settle down—he’d just pretended he did, for obvious reasons. “What Dylan Creed does—or doesn’t do—is simply none of my concern.”

“Hogwash,” Mavis said. “Your ears are red around the edges.”

“That’s because you’ve been poking me with the scissors at regular intervals. Are we nearly done here? I need to get back to the library.”

Mavis blew out a breath. “The library,” she scoffed. “You were a cheerleader in high school. You were a prom queen. And Miss Rodeo Montana, first runner-up for Miss Rodeo America. Who’d have thought Kristy Madison, of all people, would end up with a spinster-job? It reminds me of that scene in It’s a Wonderful Life, when Donna Reed is this miserable old biddy because George Bailey was never born—”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake, Mavis!” Kristy was ready to leap out of the chair by that point. Tear off the plastic cape and march right out into the street with her hair sectioned off in those stupid little metal clips. “Some of us have moved beyond high school, you know. And what’s so terrible about being a librarian?”

Mavis softened. In the mirror facing the chair, her pointy little face looked sad. “Nothing,” she said quietly.

“I’m sorry,” Kristy said, immediately regretting her outburst. “I didn’t mean to snap at you. It’s just that—”

“It’s just that,” Mavis continued kindly, “when anybody mentions Dylan Creed, you get peevish.”

“Then why mention him?” Kristy asked wearily.

Mavis squeezed her shoulder with one manicured hand. “I didn’t mean any harm. I was just thinking you might be glad Dylan was back. I know you’ve had a hard time, Kristy—losing your folks the way you did, and the ranch and Sugarfoot, practically all at once. I’d like to see you happy again—and you were happy with Dylan, until that blowup the day of his dad’s funeral. So would everybody else in Stillwater Springs—like to see you happy, I mean.”

Kristy fought back tears, not because of the sad memories, but because she was touched. Mavis, in her own clumsy way, did care about her, and so did a lot of other people. “I am happy, Mavis,” she said. “I have my job, my house, my cat—”

“Well, I’ve got a job and a house and four cats,” Mavis argued cheerfully, “but it’s my Bill that makes my heart go pitter-pat.”

“You’re lucky,” Kristy said. And she meant it. Mavis had been married to the same man since the day after her high school graduation and though she and Bill had never had children, it was common knowledge that they were still as deeply in love as ever.

Mavis finished the haircut without mentioning Dylan again, which was a mercy, and Kristy rushed back to the library to grab a sandwich in her tiny office behind the information desk. It was Wednesday, and business was slow enough that her two volunteer helpers, Susan and Peggy, could handle the traffic.

Story hour was coming up at three, though, and it was Kristy’s baby. She still hadn’t chosen a book, and that stressed her a little. She was a detail person, and few details were more important to her than doing her job well.

So she finished her sandwich and went out into the main part of the library, headed for the children’s section. It was always tricky, deciding what story to read, because the kids who gathered in a circle under the mock totem pole in the tiny play area ranged in age from as young as three to as old as twelve. The rowdy ones came, after swimming lessons over at the community pool, still smelling of chlorine and sunshine and always a little soggy around the edges, and the ones with working mothers invariably arrived early.

Harried, Kristy went from book to book, shelf to shelf.

Finally, she fell back on an old standby, one of the Nancy Drew mysteries she’d loved in her own youth. The boys would snicker, and the little ones wouldn’t understand a word, but she knew just listening was part of the magic.

Yes, today, it would be The Secret in the Old Clock.

It would do the girls good to hear about smart, proactive Nancy and her lively sidekicks, George and Bess. And it wouldn’t hurt the boys, either. Call it consciousness raising.

The time passed quickly, since Kristy stayed busy logging in a pile of returned books, and when she looked up from her work, she saw at least a dozen kids gathered in the play area, waiting.

“Showtime,” Susan whispered, smiling. “I’ll finish the returns. And I can stay right up till closing time tonight, too. Jim’s off to Choteau with his bowling league.”

Susan, in her midfifties, was supercompetent. Her staying meant Kristy could leave at five o’clock, instead of nine, like a normal person, and paint at least part of her kitchen before she nuked something for supper and tumbled into bed with Winston to read awhile and then sleep.

“Thanks,” Kristy said, giving her friend a shoulder squeeze.

Carrying The Secret in the Old Clock, she made her way to the play area, took exaggerated bows when the kids clapped and cheered. They always did that, mainly because they liked to make noise in the library, where it was normally forbidden, but Kristy got a kick out of the whole routine anyway.

She settled down on the floor, cross-legged. “Today,” she announced, “Nancy Drew.”

True to form, the boys groaned.

The girls giggled.

The latch-key kids were just happy to see an adult.

Kristy made a production of opening the book. That, too, was part of the show. Always a flourish—kids liked that. Her own mother had made reading—and being read to—so much fun, using a different voice for each character and sometimes even acting out parts of the story.

And when she looked up, ready to begin, her heart jammed itself into the back of her throat and she couldn’t say a single word.

Dylan Creed had appeared out of nowhere. He was sitting, cross-legged like Kristy, at the edge of the crowd, holding positively the cutest little girl Kristy had ever seen within the easy circle of his arms.

Kristy swallowed.

There was no doubt the child was his—the resemblance made Kristy’s breath catch.

Dylan’s blue eyes danced with mischief as he watched her.

She cleared her throat. “Chapter One,” she began.

And then she froze up again.

One of the bigger boys started a chant. “Nan-cy! Nan-cy!”

All the other kids picked it up. Even the angelic being in Dylan’s lap clapped her plump little hands together and tried to join in.

Dylan let out a sudden, piercing whistle.

Silence fell.

The little girl turned and looked up at him curiously.

“The lady,” Dylan said, “is trying to read a story. So you yahoos better settle down and listen.”

Somehow, Kristy managed to get through three chapters of the book, but it was a lackluster performance, for sure. Her gaze kept straying to Dylan and the little girl, and every time that happened, she felt her neck heat up.

At last, mothers started wandering in and collecting their charges. Kristy tried to look busy, but that was hard, given that she was still sitting on the floor with nothing but a book to fiddle with. Worse, her legs had gone to sleep, and she knew if she stood up too suddenly, she’d probably fall on her face.

In front of Dylan Creed.

Why didn’t he just leave, like everybody else?

“Nice job,” he said, and Kristy was startled to realize he was sitting right beside her. The little girl was playing with the large plastic blocks the Friends of the Library had provided for the play area.

Was he making fun of her?

Kristy swallowed again. Gulped, was more like it.

“She’s beautiful,” she croaked, inclining her head toward the child.

Dylan nodded. “Her name is Bonnie,” he said.

What do you want? That was what Kristy would have asked if she hadn’t been too chicken, but what tumbled out of her mouth was, “I heard you were passing through.”

Great.

Now he’d think she’d been panting for any Dylan Creed news that might come her way.

“I’m not passing through,” Dylan replied, watching Bonnie with a soft light in his wicked china-blue eyes. “I’m planning to stay on—tear down that old house of mine, now that Briana and her boys don’t need it anymore, and build a new one. I’m going to have a barn, too, and some horses. Maybe even run some cattle with Logan’s herd.”

Why was he telling her all this? Did he think she cared?

Did she care?

No, no, a thousand times no.

Get a grip, she told herself.

Okay, so Bonnie could have been her little girl, as well as Dylan’s, if things had turned out differently. But they hadn’t, and that was that.

She had a house and a job and a perfectly good cat.

An excellent life, damn it.

“That’s nice,” she said, easing her legs out straight and giving them subtle shakes to get the circulation going again so she could stand up and walk away with some degree of dignity. Go about her business. Tell Susan she had a headache and wasn’t staying until five.

But that would be a lie.

It was her heart that ached, not her head.

“How have you been, Kristy?” Dylan asked.

What was this, Be Kind to Former Lovers Week? “Fine,” she said.

One corner of his mouth tilted upward in a sad little grin. “Up until the last time I talked to Logan, I thought you were married to Mike Danvers.”

The name fell between them like a lead weight.

Kristy recovered quickly, but not quickly enough. Something moved in Dylan’s eyes while she was coming up with her response, even though it only took a split second. “It wouldn’t have worked out for Mike and me,” she said.

“Like it didn’t work out for us,” Dylan said, and try though she might, Kristy couldn’t get a bead on his tone.

“We were young,” she heard herself say. “The world was falling apart. Your dad had just been killed in that logging accident, and both my folks—”

“Daddy!” Bonnie whooped suddenly, shrill with joy. “Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!”

She ran at Dylan and he scooped her up in his arms.

“Potty!” Bonnie yelled triumphantly.

Dylan sighed. “Would you mind taking her to the women’s room?” he asked Kristy.

Glad of an excuse to break out of his orbit, if only for a few minutes, and hoping to God her legs had woken up, Kristy got to her feet, took Bonnie by the hand and escorted her to the bathroom.

Because so many of the children who came to the library were small, Kristy was used to that particular duty. But this was Dylan’s little girl. He’d conceived this beautiful moppet with some nameless, faceless woman—not with her.

Damn it. When they’d made love all those times, before the rodeo and death and a lot of other things came between them, they’d always ended up choosing names afterward. They’d call a boy Timothy Jacob, for their fathers. A girl, Maggie Louise, for their mothers …

When she and Bonnie stepped out of the restroom, Dylan was waiting in the corridor, leaning against the wall with that indolent grace that seemed to emanate from his very DNA.

“Thanks,” he said.

“You’re welcome,” she replied.

He hoisted Bonnie up into his arms. “Good to see you again, Kristy,” he said, his voice a little hoarse.

“You, too,” Kristy said. Fortunately, he left before the tears sprang to her eyes.

Thanks.

You’re welcome.

Good to see you again …

You, too.

Kristy ducked back into the women’s restroom, turned on the cold-water faucet and stood splashing her face until the burning stopped. But she still heard the voices, hers and Dylan’s, though this time, they came from the long ago.

When the moon strays off into space, Dylan Creed, and the last star winks out forever, I will still love you.

He’d smiled, and stroked her hair, and kissed her, sending fire skittering along her veins all over again. You read too much, he’d teased. I love that about you. Our kids will have a chance at being smart, with you for a mother.

You’re smart, too, Dylan, she’d protested, meaning it.

Not book-smart, he’d replied. I can’t talk in poetry the way you do.

Does it matter? she’d asked, her heart brimming with tenderness.

Nothing matters but you and me, Kristy.

Nothing matters but you and me.

CHAPTER THREE

DROPPING BY THE LIBRARY had probably been a tactical error, Dylan admitted to himself; it had been a spur-of-the-moment thing, a sudden compulsion to see Kristy again, if only from a distance.

As it happened, though, she’d just rounded up a herd of kids for story-time when he and Bonnie came through the front door, and he’d been drawn into her circle immediately. There might as well have been beating drums and a fire pit, like the one in Cassie’s teepee—the gathering had that same kind of elemental, visceral attraction.

Kristy was still beautiful—five years of living without him to complicate her life had only made her more so. She seemed more centered and serene than before, though it had pleased him to notice that his unexpected presence had thrown her a little.

The only bad part was the hurt he’d glimpsed in her eyes when she’d registered Bonnie’s identity.

He glanced over at his daughter, buckled into her car seat and hugging her inky doll. By rights, the toy should probably be burned, since it had to be germ-central, but he couldn’t bring himself to take it away. Maybe later, when Bonnie was asleep, he’d douse the thing in Lysol or something.

In the meantime, cruising through the shady streets of Stillwater Springs, he was careful to keep to the speed limit. All he needed was Floyd Book or one of his deputies pulling him over and asking for some kind of proof that he hadn’t committed parental kidnapping. He had the note from Sharlene, found in his truck with Bonnie and the duffel bag, but who knew how much weight that would carry?

Logan would, of course. Logan could draw up papers, get everything on the up-and-up.

He headed for the ranch, partly in the vain hope that Logan would be there, and partly because it was home.

“This is where I grew up,” he told Bonnie, as they drove under the newly repaired Stillwater Springs Ranch sign hanging over the main gate.

“No,” Bonnie said cheerfully, chewing on the doll’s punk-rocker hair.

Four words, now. The kid was developing an impressive vocabulary, all right.

The work on the barn was almost finished—new timbers supported it, and the roof had been replaced.

Dylan parked the truck, rolled down his window as one of the workmen came toward him, grinning.

He recognized Dan Phillips, a guy who’d graduated a few years ahead of him, at Stillwater Springs High.

“Logan around?” Dylan asked, though he knew the answer.

Dan shook his head. “Off to Las Vegas to get married.”

“The barn’s looking good,” Dylan said.

Dan stooped for a glimpse at Bonnie. “Didn’t know you were a family man, Dylan,” he commented, with a twinkle.

“I’m full of surprises,” Dylan replied. “You happen to know if Logan arranged to have my house fixed up after that last break-in?”

“Took a crew over there and did it myself. Logan asked me to have Briana’s and the boys’ stuff picked up and moved here, and I did that, too.”

That was something, anyhow, Dylan thought, still unaccountably disappointed that Logan wasn’t home. He and Bonnie could get some groceries and move right in. Cassie had made them welcome, but her place was small and he didn’t want to impose any longer than necessary.

“This must be old home week,” Dan went on, just as Dylan was about to shift gears and drive overland to his place to figure out what he and Bonnie would need besides groceries. “I just saw Tyler. He’s holed up in that old cabin of his, out there by the lake, and he asked me not to tell anybody he’s around. Don’t figure he’d mind your knowing, though.”

Dan figured wrong, but Dylan saw no reason to say so. “I’ll stop by and say howdy,” he answered easily. If I’m lucky, little brother won’t run me off with a shotgun.

“Starting on the house next,” Dan said, with a nod toward the venerable old place. “Putting in some pretty fancy rigging—new master bathroom and a state-of-the-art kitchen to start.”

Dylan grinned. Logan still expected to stay on, settle down, raise a pack of kids with Briana.

He’d believe it when the last of the bunch grew up and got married.

But, then, considering how he felt about his own child, it was possible Logan really had set his mind to “making the Creed name mean something,” as he put it.

“Be seeing you,” Dylan told Dan, because that was what you said, in the boonies, when you wanted to make a polite but speedy exit.

Dan nodded, executed a half salute and went back to work.

Dylan headed for his own place.

“Potty,” Bonnie said solemnly, as they bumped and jostled across the field, going around the orchard and the cemetery.

Sooner or later, he’d have to visit Jake’s grave, but that was way down on the list.

“Hold your horses,” Dylan answered, his tone affable. “We’re almost home.”

“IT’S JUST PLAIN SILLY to get all bent out of shape just because Dylan Creed showed up at story hour with absolutely the most gorgeous child in the universe,” Kristy told Winston, long about sundown as, standing on the top rung of a folding ladder, she swabbed sunshine-yellow paint around the framework of the archway between the kitchen and dining room.

Winston, having just devoured his usual feast, groomed one of his forepaws meticulously and offered no comment.

“I mean, it isn’t as if he’s ever had any trouble attracting women,” Kristy went on, wiping a splotch of paint from her nose with the sleeve of the oversize men’s shirt she’d bought at Goodwill for messy jobs.

“Meow,” Winston said, halfheartedly.

“It’s just that it was sort of a shock, that’s all.”

Bored, Winston turned, fluffed out his bushy tail and hied himself to the living room. He liked to curl up on the antique bureau in front of the bay windows and watch the world go by. Slow going, in Stillwater Springs. Hours could pass before a car putted past.

“Typical,” Kristy said to the empty kitchen. “Nobody listens to me.”

In the next instant, somebody rapped at her back door, and Kristy nearly fell off the ladder, she was so startled. What was the matter with her, anyway?

“Come in!” she called, because that was what you did in Stillwater Springs.

When Sheriff Book opened the door and stepped across the threshold, she was surprised, though not enough to take a header to the linoleum.

“You shouldn’t just call out ‘come in’ like that,” Floyd said, taking off his sheriff hat and setting it aside on the counter. “I could have been some drifter, bent on murder and mayhem.” A little grin twitched at the corner of his mouth, softening his otherwise stern expression. “This isn’t the old days, Kristy.”

Kristy set her wet paintbrush in the aluminum tray of sunshine-yellow and climbed down the ladder, smiling. “Coffee?” she asked.

Floyd shook his head, sighed. “Trying to cut down,” he said. “Keeps me awake at night.”

Kristy stood there, waiting for him to get to the reason for his visit.

“You mind sitting down?” the sheriff asked, sounding tired.

Uh-oh, Kristy thought. Here comes the whammy.

Once she was seated at the table, Floyd took a chair across from her. “I guess you know the bank finally untangled that probate mess over the ranch,” he said quietly. “And Freida’s got that movie-star fella all set to buy it.”

Kristy’s throat thickened. She nodded. “She told me it was going up for sale now that all the legal processes are complete.” She was curious as to why Floyd had dropped in to tell her something like that.

“It’s an old ranch,” Floyd went on, his expression downright grim. “A lot happened out there, over the years.”

Kristy felt an uneasy prickle in the pit of her stomach. “Floyd, what are you getting at?”

“I think there might be a body buried on the place,” Floyd said.

Kristy’s mouth dropped open, and her heart stopped, then raced. The monster-memory stirred in the depths of her brain. “A body?”

Floyd sighed. “I could be wrong,” he said, but the expression on his face said he didn’t think so.

“Good God,” Kristy said, too stunned to say anything else and, at the same time, strangely not surprised.

The sheriff looked pained. “There was a man—worked for your daddy one summer when you were just a little thing. Some drifter—I never knew his name for certain. Men like him came and went all the time, stopping to earn a few dollars on some ranch. But one night, late, Tim woke me up with a phone call and said there was bad trouble, and I ought to get out there quick. He didn’t sound like himself—for a moment or two, I thought I was talking to a prowler. Turned out he’d caught this drifter fella sneaking out of the house with some of your mother’s jewelry and what cash they had on hand, which was plenty, because they’d sold some cattle at auction that day. There was a fight, that was all Tim would tell me. That there’d been a fight. I dressed and headed for the ranch, soon as I could. And when I got there, your dad changed his story. Said the drifter had moved on and good riddance to him.”

Dread welled up inside Kristy, but she said, “That must have been the truth, then.” She’d never known her father to lie about anything, however expedient it might be.

But Sheriff Book shook his head again. His eyes seemed to sink deeper into his head, and there were shadows under them. “I took his word for it, because he was my best friend, but there was more to the story, and I knew it. Tim looked worse than he’d sounded on the phone. It was a cold night, but he was sweating, and he had dirt under his nails, and on his clothes, too. You know he always cleaned up before supper, Kristy, and this was well after midnight.”

Kristy couldn’t speak, couldn’t bring herself to ask the obvious question: Did Sheriff Book think her father had killed a man?

“Few days later,” the sheriff went on, clearly forcing out the words, “on a Sunday morning, I came by the ranch for a look around, when I knew you and your folks were at church. And I found what I figured was a freshly dug grave in that copse of trees over near where Tim’s property and the Creed place butt up.”

Kristy felt a surge of relief—he’d seen Sugarfoot’s grave that morning, not that of a human being—but it was gone in a moment. Back then, Sugarfoot had been alive and well.

Floyd reached across the table, squeezed her ice-cold hand. “I asked Tim what was there. He said an old dog had strayed into his barn and died there, and he’d buried the poor critter in the midst of those trees.” He thrust out another sigh. “I was the sheriff. I should have done some digging, both literal and figurative, but I didn’t. I wanted to believe your dad, so I did, but I’ve always wondered, and now that I’m about to retire, I’ve got to know for sure. It isn’t just the coffee that keeps me up at night, it’s certain loose ends.”

Kristy thought she was going to be sick. “You’re going to—to exhume—”

Floyd nodded. “I know Sugarfoot’s buried there, Kristy,” he said gruffly, hardly able to meet her gaze, “and I’ll do my best not to disturb his remains too much. But I’ve got to see, once and for all, if there’s a dog in that grave with him—or a man.”

“You seriously think my father—your best friend—would murder someone and then go to such lengths to hide the body?” Now, Kristy was light-headed. Her heart pounded, and the smell of paint, unnoticed before, brought bile scalding up into the back of her throat.

Don’t remember, whispered a voice in the shadowy recesses of her mind, where migraines and nightmares lurked. Don’t remember.

“I think,” Sheriff Book said quietly, “that there was a fight, and things got out of hand. If Tim did kill that drifter, it was an accident, and nobody will ever convince me otherwise. He’d have been real upset, Tim, I mean, with you and your mother in the house—that would have made the fight one he couldn’t afford to lose. In Tim’s place, I’d have been scared as hell of what that fella might do if I wasn’t up to stopping him.”

Kristy got up, meaning to bolt for the bathroom, then sat down again with a plunk. “But Dad called you,” she muttered. “Would he have done that if he’d killed somebody?”

“He was in a panic, Kristy. He probably called first and thought later.”

“Dad’s gone, and so is Mom. You’re about to retire. Can’t we just let this whole thing … lie?”

“If we can live with knowing what we do. I don’t think I can, not anymore—I’ve got an ulcer to show for it as it is. Can you just go on from here like nothing was ever said, Kristy?”

She bit down on her lower lip. “No,” she said miserably.

If there were human remains buried with Sugarfoot—more likely beneath him—the scandal would rock the whole state of Montana. Tim Madison’s memory, that of a decent, hardworking, honorable man, would be fodder for all sorts of speculation.

How would she handle that?

“Why now?” she asked, closing her eyes briefly in the hope that the room would stop tilting from side to side. “After all this time, Floyd, why now?”

“I told you,” he replied gently. “My retirement. And with that land going up for sale, and some jerk from Hollywood bound on bringing in bulldozers to make room for tennis courts and whatnot—”

Kristy froze. She’d known, of course, that someone would buy Madison Ranch eventually. It was prime real estate. But not once had she considered the possibility that that someone might destroy poor Sugarfoot’s grave.

Tears filled her eyes, and all the old wounds opened at once.

“I’m sorry,” Sheriff Book said.

“When he died,” Kristy murmured, “Sugarfoot, I mean—I wanted to die, too. Crawl right into that grave with him and let them cover me with dirt.”

“You’d just lost your mother then,” Floyd reminded her. “And your dad was already sick. It was a lot for one young girl to bear up under. But you did bear up, Kristy. You kept going, kept living, like you were supposed to.”

A long, difficult silence fell. Kristy broke it with, “You do realize what an uproar this is going to cause, if you find—find something.”

Grimly, Floyd nodded. “Might be I’m wrong. There’s no need to get the community all riled up if there’s really a dog sharing that grave with Sugarfoot. I can keep the whole thing quiet, Kristy, at least for a while. But this is Stillwater Springs, and folks are always flapping their jaws. Word could get out, and that’s why I came over here to talk to you first. So you’d know ahead of time, in case—well, you know.”

Kristy nodded.

The sheriff stood to go. “You going to be all right?” he asked. “I could call somebody, if you want.”

“Call somebody?” Kristy echoed stupidly. Who? Who in the whole wide, upside-down, messed-up world would drop everything and rush over to hold the librarian’s hand?

Dylan, she thought.

“Maybe you oughtn’t to be alone.”

“I’m fine,” Kristy said. Stock answer.

Major lie.

“Lock up behind me,” Floyd said.

Kristy nodded.

But he’d been gone a long time before she even got out of her chair.