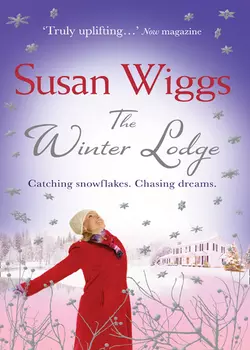

The Winter Lodge

Susan Wiggs

Snow is falling, the fire is roaring – curl up this winter with a Susan WiggsJenny’s lived her whole life in Willow Lake, finding safety and warmth running her little bakery. Until one winter she loses everything in a devastating house fire. Sifting through the ashes she finds a chance for a different life…Whilst touched by the love of the community and surprised by the attention of her gorgeous rescuer, Rourke McKnight, Jenny’s heart is caught by another treasure. An undiscovered family of strangers waiting to make her their own.But in chasing one dream another may slip through Jenny’s fingers. If she stays in Willow Lake long enough for the snow to settle, happiness is waiting to find her. Perfect for fans of Cathy Kelly

Acclaim forNew York Timesbestselling author Susan Wiggs

“this is a beautiful book”

—Bookbag on Just Breathe

“… Unpredictable and refreshing, this is irresistibly good.”

—Closer Hot Pick Book on Just Breathe

“… Truly uplifting …”

—Now Book of the Week

“A human and multi-layered story exploring duty to both country and family”

—Nora Roberts on The Ocean Between Us

“Susan Wiggs paints the details of human relationships with the finesse of a master.”

—Jodi Picoult

“The perfect beach read”

—Debbie Macomber on Summer by the Sea

Also bySusan Wiggs

The Lakeshore Chronicles

SUMMER AT WILLOW LAKE

THE WINTER LODGE

DOCKSIDE

SNOWFALL AT WILLOW LAKE

FIRESIDE

LAKESHORE CHRISTMAS

The Tudor Rose Trilogy

AT THE KING’S COMMAND

THE MAIDEN’S HAND

AT THE QUEEN’S SUMMONS

Contemporary

HOME BEFORE DARK

THE OCEAN BETWEEN US

SUMMER BY THE SEA

TABLE FOR FIVE

LAKESIDE COTTAGE

JUST BREATHE

All available in eBook

TheWinter Lodge

Susan Wiggs

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

In loving memory of my grandparents, Anna and Nicholas Klist.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank the Port Orchard Brain Trust: Kate Breslin, Lois Dyer, Rose Marie Harris, P. J.

Jough-Haan, Susan Plunkett, Sheila Rabe and Krysteen Seelen. Also thanks to the Bainbridge Island Test Kitchen: Anjali Banerjee, Sheila Rabe, Suzanne Selfors and Elsa Watson. As always, thanks to Meg Ruley and Annelise Robey of the Jane Rotrosen Agency, and to Margaret O’Neill Marbury of MIRA Books.

Special thanks to Joan Vassiliadis, Anna Osinski of Warsaw, Poland, Matt Haney, Bainbridge Island Chief of Police, and to Ellen and Mike Loudon of Bainbridge Bakers on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

Kolaches for Beginners

It’s funny how so many bakers are intimidated by yeast. They see it listed as an ingredient in a recipe, and quickly flip the page. There’s no need to fear this version.

This particular dough is quite forgiving. It’s elastic, resilient and will make you feel like a pro. As my grandmother, Helen Majesky, used to say, “In baking, as in life, you know more than you think you know.”

Basic Kolaches

1 tablespoon sugar

2 packets active dry yeast (which is kind of a pain, since yeast is sold in packages of three)

1/2 cup warm water

2 cups milk

6 tablespoons pure unsalted butter

2 teaspoons salt

2 egg yolks, lightly beaten

1/2 cup sugar

6-1/4 cups flour

1-1/2 sticks melted butter

Put yeast in a measuring cup and sprinkle 1 tablespoon sugar over it. Add warm water. How warm? Most cookbooks say 105°-115°F. Experienced cooks can tell by sprinkling a few drops on the inside of the wrist. Beginners should use a thermometer. Too hot, and it’ll kill the active ingredients.

Warm the milk in a small saucepan; add butter and stir until melted. Cool to lukewarm and pour into a big mixing bowl. Add salt and sugar, then pour in beaten egg yolks in a thin stream, whisking briskly to keep eggs from curdling. Then whisk in yeast mixture.

Roll up your sleeves and add flour a cup at a time. When the dough gets too heavy to stir, mix with your hands. You want the dough to be glossy and sticky. Keep adding flour and knead until the dough acquires a sheen. Put dough ball in an oiled mixing bowl, turning it to coat. Cover with a damp tea towel and set in a warm place where the air is very still. In about an hour, the dough should double in size. My grandmother used to push two floured fingertips into the top of the soft mound, and if the dimples made by her fingers remained, she would declare the dough risen. And then, of course, you give it a punch to deflate it. A soft sighing sound, fragrant with yeast, indicates the dough’s surrender.

Pinch off egg-size portions and work these into balls. Place on oiled baking sheets, several inches apart. Let them rise again for 15 minutes and then use your thumb to make a deep dimple in each ball for the fruit filling. The exact filling to use is a source of endless debate among Polish bakers. My grandmother never entered into such a debate. “Do what tastes good” was her motto. A spoonful of raspberry jam, peach pie filling, fig preserves, prune filling or sweet cheese will do.

Create a popsika by mixing 1/2 cup melted butter with a cup of sugar, 1/2 cup flour and a teaspoon cinnamon. Sprinkle the popsika over each kolache. Now place the pans in a warm place—like above the fridge—and allow to double in bulk again, about 45 minutes to an hour. Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 375°F. Bake 20-40 minutes, until golden brown. Pay particular attention to the bottoms, which tend to burn if too close to the heat source.

Take the kolaches out of the oven, brush with melted butter and remove from pans to cool. This recipe makes about three dozen.

My grandmother used to tell me not to worry about how long this whole process takes. Baking is an act of love, and who cares how long love takes?

One

Jenny Majesky pushed away from her writing desk and stretched, massaging an ache in the small of her back. Something—perhaps the profound silence of the empty house—had awakened her at three in the morning, and she hadn’t been able to get back to sleep. She’d worked on her newspaper column for a while, hunched over her laptop in a ratty robe and fuzzy slippers. At the moment, though, she was no better at writing than she was at sleeping.

There was so much she wanted to say, so many stories to put down, but how could she cram the memories and kitchen wisdom of a lifetime into a weekly column?

Then again, she’d always wanted to write more than a column. Much more. The universe, she realized, was taking away all her excuses. She really ought to get started writing that book.

Like any good writer, Jenny procrastinated. Idly, she picked up her grandmother’s wedding band, which had been lying in a small china dish on the desk. She hadn’t quite decided what to do with it, a plain circle of gold that Helen Majesky had worn for fifty years of marriage and another decade of widowhood. When she baked, Gram always slipped the ring into the pocket of her apron. It was a wonder she never lost it. She’d made Jenny promise not to bury her with it, though.

Twirling the ring around the tip of her forefinger, Jenny could picture her grandmother’s hands, strong and firm as they worked a mound of dough, or gentle and light as they caressed her granddaughter’s cheek or checked her forehead for fever.

Jenny slid the ring onto her finger and closed her hand into a fist. She had a wedding ring of her own, given and received with a sense of giddy hope but never worn. It now resided in a bottom drawer she never opened.

It was hard, at this velvet-black hour, not to tally up her losses—her mother, who had walked away when Jenny was small. Then Jenny’s grandfather, and finally, and perhaps most importantly, Gram.

Only a few weeks had passed since she’d laid her grandmother to rest. After the initial flurry of sympathy calls and visits, a lull had settled in, and Jenny felt it in her bones—she was truly alone. Yes, she had caring friends and coworkers who were as dear to her as family. But now the steady presence of her grandmother, who had raised her like a daughter, was gone.

Out of habit, she saved her work on the laptop. Then she wrapped her robe more snugly around her and went to the window, pressing close to the cold glass to look out at the deep winter night. Snow erased all the sharp edges and colors of the landscape. In the middle of the night, Maple Street was entirely deserted, washed in the gray-white glow of a single street lamp in the middle of the block. Jenny had lived here all her life; she’d stood countless times at this very spot, expecting … what? For something to change. To begin.

She gave a restless sigh, her breath misting the window. The snow flurries had thickened to flakes, swirling in a blur around the streetlight. Jenny loved the snow; she always had. Staring out at the blanketed landscape, she could easily picture herself as a child, hiking with her grandfather to the sledding hill. She used to literally follow in his footsteps, leaping from one hollowed-out bootprint to the next, pulling the Flexible Flyer on a rope behind her.

Her grandparents had been there for all the moments of her childhood. Now that they were gone, there was no one to hold the memories, to look at her and say, “Remember the time you …”

Her mother had left when Jenny was four, and her father was a virtual stranger she’d met only six months ago. Jenny considered this a blessing in disguise. From what she knew of her biological parents, neither had been as well-equipped to raise a child as Helen and Leo Majesky.

A noise—a thud and then a scratching sound—made her jump, startling her from her thoughts. She cocked her head, listening, then decided it had been thick snow or a row of icicles, falling from the roof. You never knew how quiet a house could be until you were totally alone in it.

Since her grandmother had died, Jenny had been waking up in the middle of the night, her mind full of memories begging to be written down. All of them seemed to emanate, like the smells of baking, from her grandmother’s kitchen. Jenny had kept a diary or journal nearly all her life, and over the past few years, her habit had evolved into a regular column for the Avalon Troubadour, a mingling of recipes, kitchen lore and anecdotes. Since Gram’s passing, Jenny could no longer check a fact with her, or pick her brain about the origin of a certain ingredient or baking technique. Jenny was on her own now, and she was afraid that if she waited too long, she’d forget things.

The thought stirred her into action. She’d been meaning to transcribe her grandmother’s ancient recipes, some of them still in the original Polish, written on brittle, yellowed paper. The recipes were stored in the pantry in a latched tin box that hadn’t been opened in years. Ignoring the fact that it was now three-thirty in the morning, Jenny headed downstairs. When she stepped into the pantry, she was struck by an achingly familiar smell—her grandmother’s spices and the aroma of flour and grain. She stood on tiptoe to reach the old metal box. Sliding it off the shelf, she lost her balance and dropped the thing, its contents exploding at her fuzzy-slippered feet.

She uttered a word she never would have said when Gram was alive, tiptoeing gingerly as she tried not to step on any of the fragile old documents. Now she would need a flashlight, because the dark pantry didn’t have a light. She found a flashlight in a utility drawer but its batteries were dead and there wasn’t another fresh battery in the house. She considered lighting a candle but didn’t want to have a mishap with the one-of-a-kind handwritten recipes. Leaning against the kitchen counter, she rolled her eyes heavenward. “Sorry about that, Gram,” she said.

Her gaze found the smoke detector. Aha, she thought. She dragged a kitchen chair over to it and climbed up, opening the smoke detector, removing its two double-A batteries and fitting them in the flashlight.

She headed back into the pantry, gently picking up the papers, which rustled like dry autumn leaves. She put the loose papers in the box and brought it out to the kitchen. There were old notes and recipes in her grandmother’s native Polish. On the back of a yellowed page with crumbling edges, she spotted a signature in fading, delicate strokes of ink—Helenka Maciejewski—practiced a dozen times in a girlish hand. That was her grandmother’s married name before it had been Anglicized. She must have written it as a young bride.

There were things about her grandparents Jenny would never know. What had it been like for them, as newlyweds barely out of childhood, leaving the only home they knew to start a life half a world away? Were they frightened? Excited? Did they quarrel with each other, cling to each other?

She closed her eyes as a now-familiar onslaught of panic started in her stomach and pushed through her, pressing at her chest. These panic attacks were something brand-new for Jenny, a grim and unexpected development. The first one struck at the hospital as she was moving woodenly through the duties of the next of kin. She’d been signing some form or other when the fingers of her left hand went numb and she dropped the pen to clutch her throat.

“I can’t breathe,” she’d told the clerk. “I think I’m having a heart attack.”

The doctor who treated her, a tired-looking resident from Tonawanda, had been calm and compassionate as he evaluated her and then explained the condition. Not uncommon, the intense attack was a physical response to emotional trauma, the symptoms as real and frightening as they would be for any illness.

Since then, Jenny had become intimately familiar with the symptoms. Practical, levelheaded Jenny Majesky was not supposed to succumb to something as uncontrollable and irrational as a panic attack. She was helpless to stop it now as a singularly unpleasant sensation rose through her, like a parade of spiders climbing up her throat. Her heart seemed to expand in her chest.

She cast a wild look around, wondering where she’d left the bottle of pills the doctor had given her. She hated the pills almost as much as she hated the panic attacks. Why couldn’t she just snap out of it? Why couldn’t she just suck it up and calm herself with a cup of strong coffee and a taste of her grandmother’s apricot-jam kolaches?

That, at least, could be a diversion. Right now, in the middle of the night. One of the few places in Avalon where she could find someone awake at four in the morning was the Sky River Bakery, founded in 1952 by her grandparents. Helen specialized in ko-laches filled with fruit or sweet cheese, and pies that became the stuff of local legend. Her baked goods were in demand from the restaurants and small specialty shops that lined the town square, catering to the well-polished tourists who came up from New York City for Avalon’s cool green summers or blazing fall color.

Now Jenny was the bakery’s sole owner. She dressed hurriedly, layering on fleece long underwear, checked chef pants and a thick wool sweater, tall warm boots, a ski jacket and hat. No way was she driving, not before the snowplow had made its rounds. Besides, getting the car out of the garage would entail shoveling the driveway, something she was heartily sick of doing. The bakery was just six blocks away, on the main square in the center of town. She’d be there in minutes. Maybe the exertion would stave off the panic attack, too.

Just in case, she found her bottle of pills and stuffed it in her pocket.

Grabbing her purse, she walked through frozen silence. The snow had stopped, and the clouds made way for the stars. New snow squeaked beneath her feet as she followed a route she’d walked since she was a tiny girl. She’d grown up in the bakery, surrounded by the heady fragrance of bread and spices, the busy sounds of the mixers and sheeters, timers going off, rolling racks clattering out to the transport bay.

A single light burned over the back entrance. She let herself in, stomping the snow from her boots. Outside the spotless prep area, she took them off and slipped on her baker’s clogs, which were parked on a rack by the door.

“It’s me,” she called, her gaze tracking around the work area. It was immaculate as always, with fifty-pound sacks of freshly milled flour stacked precisely against one wall, honey in 155-gallon drums lying on their sides nearby. Specialty ingredients displayed in clear containers lined the shelves from floor to ceiling—millet, pine nuts, olives, raisins, pecans. The stainless-steel refrigerators, ovens and countertops shimmered under the pendant lights, and the rich scent of yeast and cinnamon filled the air. Three 6 Mafia was blaring from the radio, indicating that Zach was on tonight, and between the beats of the hip-hop music, she could hear the hum of the spiral mixer.

“Yo, Zach,” she called out, craning her neck to find the boy.

He emerged from the mixing area, pushing a rolling cart filled with raw dough. Now a senior in high school, Zach Alger had worked at the bakery for two years. He didn’t seem to mind the early-morning hours, always heading to school with a bag of fresh pastries. He had distinctly Nordic features—pale blue eyes, white-blond hair—and lanky, earnest good looks. “Is anything wrong?” he asked.

“Couldn’t sleep,” she said, feeling a bit sheepish. “Is Laura around?”

“Specialty loaves,” he said, gesturing as he wheeled the tub of dough toward the six-foot-tall proofing cabinet.

Laura Tuttle had worked at the bakery for thirty years, as master baker for twenty-five. She knew the business even better than Jenny did. She claimed to love the early hours, that the schedule was perfectly suited to her circadian clock. “Well, look who’s here,” she said, yet she didn’t glance up as she spoke.

“I had a craving for a kolache.” Jenny swished through the rubber-rimmed swinging doors to the café, where she helped herself to a cup of coffee and a day-old pastry from the case. Then she returned to the prep area, welcoming the familiar taste but feeling no calmer. Out of habit, she grabbed an apron from a hook.

Jenny rarely did the hands-on work; as owner and general manager, she stayed busy in a supervisory and administrative capacity. She had an office upstairs with a view of the town square, and a security monitor gave her a glimpse of the café counter. She spent most days juggling the needs of employees, suppliers, customers and regulatory agencies with a phone glued to her ear and her eyes glued to the computer screen. But sometimes, she reflected, you just had to roll up your sleeves and dive in. There was no sensation quite like plunging one’s hands into a warm mass of silky dough. It felt like something half-alive, squishing through her fingers.

Now she slipped the apron over her head and joined Laura at a worktable. The specialty breads were done in smaller batches and shaped by hand. Today’s selections would be a traditional Polish bread made with eggs, orange peel and currants, and a savory herb loaf of Laura’s invention. She and Laura worked side by side, weighing portions of dough on a one-pound scale, although both knew the size by feel alone.

Across the room, Jenny could see the refrigerated pie case, filled with her grandmother’s pies. Technically speaking, these were not Helen Majesky’s pies. But the original recipes for the lofty lemon meringue, the glossy three-berry tarts with the lattice tops, the creamy buttermilk chess pie and all the others came from Helen herself, decades ago. Her techniques had been passed on from one master baker to the next, and now, even after her death, she haunted the bakery as gently and sweetly as she had lived.

Jenny felt curiously detached from herself as she braided the dough into fat, rounded loaves. She looked at her white, floury hands and could see her grandmother’s hands, lifting and turning the dough with a patient rhythm that seemed to come from a place Jenny didn’t recognize in herself. The reality of Gram’s passing settled in Jenny’s bones. It had been three weeks, two days and fourteen hours. Jenny hated that she knew, practically down to the precise moment, exactly how long she had been alone.

Laura kept working, setting each oiled loaf in a pan, one by one. She bobbed her head along with the hiphop rhythm coming from the radio. She actually liked Zach’s music, though Jenny suspected Laura didn’t listen too closely to the lyrics.

“You miss her a lot, don’t you, doll?” Laura asked. She was the kind of person who knew things, like a mind reader.

“So much,” Jenny admitted. “And here I thought I was prepared. I don’t know why I feel shell-shocked. I’m not good at this. In fact, I’m terrible at it. Terrible at mourning the dead and at living alone.” She squared her shoulders, tried to shake off the mingling of panic and melancholy. The scary thing was, she couldn’t do it. She had somehow lost control, and even as she felt herself falling apart, she couldn’t do anything to make it stop.

Somewhere outside in the dark, a siren wailed. The noise crescendoed, sounding frantic, like a scream. A couple of dogs howled in response. Automatically, Jenny turned to peer through the double doors to the window of the darkened coffee shop. The town of Avalon, New York, was small enough that the sound of whooping sirens at night attracted notice. In fact, the last time she remembered hearing a siren was when she had called the paramedics.

They had not let her ride with her grandmother. She had driven her car in the wake of the ambulance to Benedictine Hospital in Kingston. Once there, she begged her grandmother to rescind the DNR order she’d signed after her first stroke, but Gram wouldn’t hear of it. So then, with her grandmother’s life force ebbing, there was nothing left for Jenny to do but say goodbye.

She felt a fresh wave of the panic attack trying to push its way to the surface. She stuck with the kneading rhythm her grandmother had taught her, working the dough with steady assuredness. Anyone watching her would see a competent baker, because she knew that on the outside, she appeared no different. The gathering steam inside was invisible.

“I’m going to step out back, grab a breath of fresh air,” she told Laura.

“I just heard sirens. Maybe Loverboy will show up.”

Loverboy was Laura’s nickname for Rourke McKnight, Avalon’s chief of police. He had a reputation that did not go unnoticed in a town this size. Jenny, of course, avoided calling him anything at all. There had been a time when she and Rourke had not been strangers. In fact, they’d known each other with searing intimacy, but that was long ago. They hadn’t willingly exchanged a word in years. Rourke dropped by the bakery for his morning coffee every day, but since Jenny worked in the office upstairs, they never crossed paths. They actually both worked hard at not crossing paths.

Avoiding him required that she memorize his routine. During the week, he kept office hours like any chief of police, but, thanks to a tight municipal budget, he had to make do with substandard pay and a force that was small even by small-town standards. He often took the third watch on weekends, driving patrol like any beat cop. Sometimes he even drove a snowplow for the city. Jenny pretended she didn’t know any of this, pretended to take no interest in the life of Rourke McKnight, and he returned the favor by ignoring her. He had sent flowers to her grandmother’s funeral, though. The message on the card had been typically taciturn: “I’m sorry.” It had accompanied a bouquet the size of a Volkswagen.

As she slipped on her parka and ducked through the back door of the bakery, Jenny felt the now-predictable pattern of the attack. There was the terrible tingling of her scalp, an army of invisible ants marching up her spine and over her head. Her chest tightened and her throat seemed to close. Despite the freezing temperatures, she broke out in a sweat. Then came the eerie pulsations of light, flickering in her peripheral vision.

Stepping into the alleyway behind the bakery, she sucked in air. Then she choked it back out immediately, tasting the acrid burn of Newport cigarettes.

“God, Zach,” she said to the kid leaning against the building. “Those things will kill you.”

“Naw,” he said, flicking his ashes into the Dumpster, “I’ll quit before that happens.”

“Huh.” She cleared her throat. “That’s what they all say.” She hated it when kids smoked. Sure, her grandfather had smoked, rolling his own cigarettes out of Velvet Tobacco. But back in his day, the dangers of the habit were unknown. Nowadays, there was simply no excuse. Grabbing a handful of snow, she tossed it at the cigarette, killing the red ash.

“Hey,” he said.

“You’re a smart boy, Zach. I heard you’re an honor student. So how come you’re so stupid about smoking?”

He shrugged and had the grace to look sheepish. “Ask my dad, I’m stupid about a lot of things. He wants me to spend next year working up at the racetrack in Saratoga to earn my own money for college.”

She knew, by the chintzy tips Matthew Alger left at the bakery’s coffee shop, that Alger—who worked as the city administrator—carried his stinginess into his personal life. Apparently, he applied it to his son’s as well.

Jenny had grown up without a father and had yearned for one more times than she could count. Matthew Alger was proof that the longed-for relationship might sometimes be overrated.

“I’ve heard that quitting smoking saves the average smoker five bucks a day,” she said. She wondered if her voice sounded strange to him, if he could tell she had to force each word past the tightness in her throat.

“Yeah, I’ve heard that, too.” He flicked the damp cigarette into the Dumpster. “Don’t worry,” he said before she could scold him, “I’ll wash my hands before I go back to work.”

He didn’t seem to be in a hurry, though. She wondered if he wanted to talk. “Does your dad want you to work for a year before college?” she asked.

“He wants me working, period. Keeps telling me how he put himself through college with no help from his family, pulled himself up by his bootstraps and all that.” He said it with no admiration.

She wondered about Zach’s mother, who had remarried and moved to Seattle long ago. Zach never talked about her. “What do you want, Zach?” Jenny asked.

He looked startled, as though he hadn’t been asked that in a while. “To go far away to college,” he said. “Live somewhere different.”

Jenny could relate to that. At his age, she’d been certain an exciting life awaited her somewhere far away. She’d never even made it out the door, though. “Then that’s what you should do,” she said emphatically.

He shrugged. “I’ll give it a shot, I guess. I need to get back to work.”

He headed inside. Jenny lingered outside, blowing fake smoke rings with the frozen air. Although the conversation had distracted her briefly, it had done nothing to banish the churning panic. She was alone with the feeling now; it screamed through her like the sirens in the quiet of the night. And like the sirens, the feeling intensified, closing in on her. The ceiling of stars pressed down, an insurmountable weight on her shoulders.

I surrender, she thought and plunged her hand into the pocket of her chef pants, groping for the brown plastic prescription bottle. The pill wasn’t much bigger than a lead BB. She swallowed it without water, knowing it would take effect in a few minutes. It was kind of amazing, she thought, how a tiny pill could quiet the terrified knocking of her heart in her rib cage, and cool the frantic sizzle of her brain.

“Only when you need it,” the doctor had cautioned her. “This medication can be highly addictive, and it has a particularly nasty detox.”

Despite the warning, she already felt calmer as she tucked the bottle away. She smoothed her hand over her pants pocket.

Still thinking about Zach, she scanned the familiar neighborhood, a downtown of vintage brick buildings that housed businesses, shops and restaurants. Years ago, if someone had told Jenny she’d still be in Avalon, working at the bakery, she would have laughed all the way to the train station. She had big plans. She was leaving the small, insular place where she’d grown up. She was headed for the big city, an education, a career.

It probably wasn’t fair to let Zach in on an ugly little secret—life had a way of kicking the support out from under the best-laid plans. At the age of eighteen, Jenny had discovered the terrifying inadequacies of the healthcare system, especially when it came to the self-employed. By twenty-one, she was familiar with the process of declaring personal bankruptcy, and just barely managed to hang on to the house on Maple Street. There was no question of her leaving Gram, widowed and disabled from a massive stroke.

The pill kicked in, covering the sharp edges of her nerves like a blanket of snow over a jagged landscape. She took in a deep breath and let it out slowly, watching the cloud of mist until it disappeared.

The sky to the north, in the direction of Maple Street, seemed to flicker and glow with unnatural light. She blinked. Probably just the strange aftermath of the panic attack. She should be used to this by now.

Two

When the monitor in Rourke McKnight’s squad car sent out an urgent tone alert and “any unit about clear” for 472 Maple Street, it flash-froze his heart.

That was Jenny’s house.

He had been on the far side of town, but the moment the call came, he grabbed the handheld mike, gave his location and ETA to dispatch and fired the sedan into action. His tires spewing snow and sand, he peeled out, the back end fishtailing on the slippery road. At the same time, he put in a call to the dispatcher. “I’m en route. I’ll let you know when I’m code eleven.” His voice was curiously flat, considering the emotions now roaring through him.

A general page had gone out that the structure—God, Jenny’s house—was on fire and “fully involved.” Besides that, Jenny hadn’t been spotted.

By the time he reached the house on Maple Street, the entire home was wrapped in bright ribbons of flame, with curls of fire leaping out of every window and licking along the eaves.

He parked with one headlamp buried in a snowbank and exited his vehicle, not bothering to close the door behind him, and did a visual scan of the premises. The firefighters, their trucks and equipment, were bathed in flickering orange light. Two pumper hoses attacked the blaze; men struggled to excavate a hydrant from the snow. The scene was surprisingly quiet, not chaotic at all. Yet the wall of flame was impenetrable and unsafe for the firefighters—even fully equipped and clad in bunker gear—to enter.

“Where is she?” Rourke demanded of a firefighter who was relaying messages on a shoulder-mounted radio. “Where the hell is she?”

“Haven’t found the resident,” the guy said, flicking a glance at another emergency vehicle parked in the road—an ambulance, its crew standing ready. “We’re thinking she’s away. Except … her car’s in the garage.”

Rourke strode toward the flaming house, bellowing Jenny’s name. The place burned like a pile of tinder. A window burst, and hot glass rained down on him. Automatically his hand came up to shield his eyes. “Jenny!” he yelled again.

In one instant, all the years of silence fell away and regrets flooded in. As if he could fix anything by avoiding her. I’m an idiot, he thought. And then he bargained with anyone or anything that might be listening. Let her be okay. Please just let her be okay and I’ll keep her safe forever and never ask another thing.

He had to get inside. The front steps were gone. He raced around back, slipping in the snow, righting himself. Someone was shouting at him, but he kept going. The back of the house was in flames, too, but the door was gone, having been hacked through by a firefighter’s ax. More shouting, more guys in bunker gear running at him, waving their arms. Shit, thought Rourke. It was stupid, but it wasn’t the dumbest thing he’d ever done, not by a long shot. Pulling his parka up over his nose and mouth, he went inside.

He’d been in this kitchen many times, yet it resembled a yellow vortex, all but unrecognizable. And there was nothing to breathe. He felt the fire sucking the air out of his lungs. He tried to yell for Jenny but couldn’t make a sound. The linoleum floor bubbled and melted under his feet. The doorway leading to the stairs was a tall rectangle of fire, but he headed toward it anyway.

A strong hand on his shoulder hauled him back. Rourke tried to fight him off, but a second later, something—a railing from upstairs, maybe—came crashing down, raining fire and plaster. The firefighter shoved him out the back door. “What the hell are you doing?” he yelled. “Chief, you need to get back. It’s not safe here.”

Rourke’s throat burned as he gulped in air, then coughed. “No shit. If you won’t send anyone in, I’m going myself.”

The firefighter—a deputy chief Rourke vaguely recognized—planted himself in the way. “I can’t let you do that.”

Fury flashed through him, an unreasoning sting. In one swift movement, Rourke’s arm whipped out, shoving the guy out of the way. “Step aside,” he barked.

The firefighter didn’t say a word, just fell back with his hands raised, eyes darting behind his face shield. “Listen, we’re both on the same side. You saw what it’s like in there. You wouldn’t last thirty seconds. We don’t think the resident’s at home, honest, we don’t. If she was home, she would’ve gotten out.”

Rourke unfurled his fists. Damn. He’d been about to clock the guy. What the hell was he thinking?

He wasn’t thinking, that was the problem. That had always been his problem. He needed to figure out where Jenny was. Possibilities streamed through his mind. Maybe she was at her best friend Nina’s house. But at this time of night? Or maybe Olivia Bellamy’s? No. Though related, the two women weren’t close. Shit, was she dating some guy Rourke didn’t know about?

Then it hit him. Of course. “Damn,” he said, and bolted for the car.

Jenny was still standing outside the bakery, waiting for the dawn, when a blue-white flash lit the sky. The sudden lightning was eerily out of place in the middle of winter. Then she heard the quick yip of a siren and realized it was emergency lights. The vehicle sounded close, as though it was in the next block. Busy night, she thought, heading back into the bakery. She passed through the kitchen, where Zach was wheeling more dough out of the proofer.

She was about to get back to work when she heard an urgent rapping on the front door. “I’ll see who it is,” she called to Laura and Zach, and walked through the café, which at this hour was dimly lit only by the buzzing neon sign of a coffee cup with squiggles of steam rising from it.

The electric blue of a squad car’s emergency overhead lights slashed through the empty café. Hurrying now, Jenny undid the lock. The bell over the front door jangled, and Rourke McKnight strode inside, his long coat swirling on the winter wind.

Avalon’s chief of police looked the part. His square jaw was clean-shaven, his shoulders broad and powerful. Though he was blond and blue-eyed, a crescent-shaped scar on his cheekbone kept him from being too pretty.

“I have a feeling you’re not dropping in for a cup of coffee,” said Jenny. These were probably the first words she’d spoken to him in years.

He gave her a smoldering look, one that made her wonder what it would be like to be his girlfriend, a member of the parade of bimbos who seemed to march through his life with serial regularity. Right, she thought. Why would she want to join a parade of bimbos?

Rourke grabbed her by the upper arms. “Jenny. You’re here.” His voice was rough, urgent.

Okay, so this was interesting. Rourke McKnight, grabbing her, pulling her into his embrace. What on earth had she done to deserve this? Maybe she should have done it long ago.

“I couldn’t sleep,” she said, and glanced at his hands on her. She and Rourke didn’t touch, the two of them. Not since … they didn’t touch.

He seemed to read her thoughts and let her go, jerking his head toward the door. “We’ve got a situation at your house. I’ll give you a lift over there.”

Despite the fuzzy edges of reality imparted by the pill she’d taken, she felt a deep, visceral disturbance. “What kind of situation?”

“Your house is on fire,” Rourke said simply.

Jenny formed her mouth into an O, but no sound came out. What did one say, anyway, when confronted with such a statement?

“Go,” Laura said, thrusting her parka and boots at her. “Call me later.”

The fuzzy edges did not alter as Jenny got into the squad car Rourke drove on the weekends. Even the swirling lights sweeping the area in an ovoid circuit didn’t make her flinch. Yet she was sharp with attention. The wonders of modern chemistry, she thought.

“What happened?” she asked.

“Call came in, a 911 from Mrs. Samuelson.”

Irma Samuelson had lived next door to the Majeskys for years. “It’s impossible,” Jenny said. “I—how could my house be on fire?”

“Seat belt,” he said, and the moment she clicked the buckle, he peeled away from the curb.

“Are you sure there’s no mistake?” she asked. “Maybe it’s someone else’s house.”

“There’s no mistake. I checked. God, I thought—God damn—”

Was his voice shaking? “Oh, no,” she said. “Rourke, you thought I was in the house.”

“It’s a safe assumption at this hour of the morning.”

So that was why he’d grabbed her. It was relief, pure and simple. As they sped toward Maple Street, she became aware of a peculiar smell. “It reeks of smoke in here.”

“You’re welcome to roll down the window if you don’t mind freezing.”

“Where did the smoke smell come—Oh, God. You went into the house, didn’t you?” She could just picture him, pushing past firefighters to battle his way into the burning house. “You went inside to find me.”

He didn’t reply. He didn’t have to. Rourke McKnight was always rescuing people. It was a compulsion with him.

“Did you leave the stove on?” he asked her. “Maybe an appliance …?”

“Of course not,” she snapped. The questions ticked her off because they scared her. Because it was possible she had been careless. She lived alone now, and maybe she was turning strange. Sometimes she couldn’t shake the feeling that she was doomed to live the life of a loner, an outcast with nobody to turn off the coffeemaker if she left it on. She could end up like that old cat lady she and her friends used to make up stories about when they were kids—alone, eccentric, with nothing but a smelly house full of cats for company.

“… zoning out on me, are you?” Rourke’s voice broke in on her thoughts.

“What?” she said, giving herself a mental shake.

“Are you all right?”

“You just said my house is burning down. I don’t think I’m supposed to be all right about this.”

“I mean—”

“I know what you mean. Do I seem anxious to you?”

He flicked a glance at her. “You’re cool, under the circumstances. We’re not there yet, though. Do you know what it means when the fire department says the structure is fully involved?” he asked.

“No, I—” She choked on the rest of the sentence when he turned the corner and she caught a glimpse of her street. Her heart tripped into overdrive. “My God.”

The street was barricaded at both ends and jammed with emergency vehicles, workers and equipment. Amber lights on tripods blazed from the shadows. Neighbors in winter coats thrown over their pajamas were clustered in their front yards or on porches, their heads tilted skyward, their expressions openmouthed with wonder, as though they were watching a Fourth of July fireworks display. Except no one was smiling, oohing or aahing.

Firefighters in full turnout gear surrounded the house, battling flames that lit up the entire two-story height of the building. Rourke stopped the car and they got out. A row of upper-story windows had been blown out as if someone had shot them, one after the other.

Those windows lined the upstairs hallway, which had been hung with family photos—an old-fashioned wedding portrait of her grandparents, a few of Jenny’s mother, Mariska, who was eternally twenty-three and beautiful, frozen at the age she was the year she went away. There was also an abundant, fast-changing array of Jenny’s school portraits through the years.

As a little girl, she used to run up and down the hall, making noise until Gram told her to simmer down. Jenny always loved that expression: simmer down. She would stand with her hands on her head, making a hissing sound, a simmering pot.

She liked to make up stories about the people in the pictures. Her grandparents, who faced the camera lens with the grave stiffness typical of immigrants freshly minted from Ellis Island, became Broadway stars. Her mother, whose large eyes seemed to hold a delicious secret, was a government spy, protecting the world while in hiding in a place so deep underground, she couldn’t even tell her family where she was.

Somebody—a firefighter—was yelling at everyone to get back, to stay a safe distance away. Other firefighters ran up the driveway with a thick, heavy hose on their shoulders. On a raised ladder that unfolded from the engine truck, a guy battled the flaming roof.

“Jenny, thank the Lord,” said Mrs. Samuelson, rushing to greet her. She wore a long camel-hair coat and snow boots she hadn’t bothered to buckle, and she cradled Nutley, her quivering Yorkshire terrier, in her arms. “When I first noticed the fire, I was terrified you were in the house.”

“I was at the bakery,” Jenny explained.

“Mrs. Samuelson, did someone get a statement from you?” Rourke asked.

“Why, yes, but I—”

“Excuse us, ma’am.” Rourke took Jenny’s hand and led her past the fire line to the rear of the engine. An older man was giving orders on a walkie-talkie, and another was rebroadcasting them with a bullhorn.

“Chief, this is Jenny Majesky,” Rourke said. He kept hold of her hand.

“Miss, I’m sorry about your house,” said the chief. “We had an eight-minute response time after the alarm came in, but this one had been going long before we got the call. These older homes—they tend to go fast. We’re doing our best.”

“I … um … thank you, I guess.” She had no idea what to say when her house was going up in smoke.

“Your neighbors said there were no household pets.”

“That’s right.” Just Gram’s African violets and potted herbs in the garden window. Just my whole world, everything I own, Jenny thought. She was shivering in the wintry night despite the layers of warm clothes and the roar of the flames. It was amazing how hard, how uncontrollably, she shook.

Something warm and heavy settled around her shoulders. It took a moment for her to realize it was a first-aid blanket. And Rourke McKnight’s arms. He stood behind her and pulled her against him, her back to his front, his arms encircling her from behind as though to shield her from harm.

With an odd sense of surrender, she leaned against him, as though her own weight was too much for her. She shut her eyes briefly, hiding from the glare and the sting of the smoke. The fire was warm against her face. But the acrid smell nauseated her, made her picture everything in the house feeding the flames. She opened her eyes and watched.

“It’s ruined,” she said, turning her head and looking up at Rourke. “Everything’s gone.”

A guy with a camera, probably someone from the paper, stood in the bed of his truck and aimed his long lens at the scene.

Rourke’s arms tightened around her. “I’m sorry, Jen. I wish I could say you’re wrong.”

“What happens now?”

“An investigation into the cause,” he said. “Insurance claims, inventory.”

“I mean right now. The next twenty minutes. The next hour. Eventually they’ll put the fire out, but then what? Do I go back to the bakery and sleep under my desk?”

He bent his head low. His mouth was next to her ear so she could hear him over the roaring noise, and his body curved protectively over hers. “Don’t worry about that,” he said. “I’ve got you covered.”

She believed him, of course. She had good reason. She’d known Rourke McKnight for more than half her life. Despite their troubled history together, despite the guilt and heartache they’d once caused each other and the great rift that gaped between them, she’d always known she could count on him.

Three

Jenny’s eyes flew open as she was startled from a heavy, exhausted sleep. Her heart was pounding, her lungs starved for air and her mental state confused, to put it mildly. Her mind was filled with a grim dream about a book editor systematically feeding the pages of Jenny’s stories into the bakery’s giant spiral mixer.

She lay flat on her back with her limbs splayed, as though the bed was a raft and she a shipwreck survivor. She stared without comprehension at the ceiling and unfamiliar light fixture. Then, cautiously, she pushed herself up to a sitting position.

She was wearing a gray-and-pinstripe Yankees shirt, so large that it slipped off one shoulder. And a pair of thick cotton athletic socks, also large and floppy. And—she lifted the hem of the shirt to check—plaid men’s boxers.

She was sitting smack in the middle of Rourke McKnight’s bed. His gigantic, California king bed that was covered in shockingly luxurious sheets. She checked the tag of a pillowcase—600 thread count. Who knew? she thought. The man was a sensualist.

There was a light tap on the door, and then he came in without waiting for an invitation. He had a mug of coffee in each hand, the morning paper folded under his arm. He was wearing faded Levi’s and a tight T-shirt stenciled with NYPD. Three scruffy-looking dogs swirled around his legs.

“We made the front page,” he said, setting the coffee mugs on the bedside table. Then he opened the Avalon Troubadour. She didn’t look, not at first. She was still bewildered and trapped in the dream, wondering what had caused her to awaken so quickly. “What time is it?”

“A little after seven. I was trying to be quiet, to let you sleep.”

“I’m surprised I slept at all.”

“I’m not. Hell of a long day yesterday.”

Now, there was an understatement. She had stuck around half the day, watching the firefighters battle the flames to the very last embers. Under heavy, gray winter skies, she had seen her house transformed from a familiar two-story house into a black scar of charred wood, ruined pipes and fixtures, objects burned beyond recognition. The stone fireplace stood amid the rubble, a lone surviving monument. Someone explained to her that after the investigators determined the cause of the fire and the insurance adjustor paid a visit, a salvage company would sift through the ruins, rescuing whatever they could. Then the rubble would be removed and disposed of. She was given a packet of forms to fill out, asking her to estimate the value of the things she’d lost. She hadn’t touched the forms. Didn’t they know her greatest losses were treasures that had no dollar value?

She had simply stood there with Rourke, too overwhelmed to speak or plan anything. She added her shaky signature to some documents. In the late afternoon, Rourke declared that he was taking her home. She hadn’t even had the strength to object. He had fixed her instant chicken soup and saltine crackers, and told her to get some sleep. That, at least, she’d accomplished with ease, collapsing in a heap of exhaustion.

Now he sat down on the side of the bed, his profile illuminated by the weak morning light struggling through translucent white curtains on the window. He hadn’t shaved yet, and golden stubble softened the lines of his jaw. The T-shirt, thin and faded from years of washing, molded to the muscular structure of his chest.

The dogs flopped down in a heap on the floor. And something about this whole situation felt surreal to her. She was in Rourke’s bed. In his room. He was bringing her coffee. Reading the paper with her. What was wrong with this picture?

Ah, yes, she recalled. They hadn’t slept together.

The thought seemed petty in the aftermath of what had happened. Gram was dead and her house had burned. Sleeping with Rourke McKnight should not be a priority just now. Still, it didn’t seem quite fair that all she had accomplished in this bed was a bad dream.

“Let’s see.” She reached for the paper, scooting closer to him. This was what lovers did, sat together in bed, sipping coffee and reading the morning paper. Then she spotted the picture. It was a big one, in color, above the fold. “Oh, God. We look …”

Like a couple. She couldn’t escape the thought. The photographer had caught them in what appeared to be a tender embrace, with Rourke’s arms encircling her from behind and his mouth next to her ear as he bent to whisper something. The fire provided dramatic backlighting. You couldn’t tell from looking at the picture that she was shivering so hard her teeth rattled, and that he wasn’t murmuring sweet nothings in her ear, but explaining to her that she was suddenly homeless.

She didn’t say anything, hoping that the romance of the shot was only in her head. She sipped her coffee and scanned the article. “Faulty wiring?” she said. “How do they know it’s faulty wiring?”

“It’s just speculation. We’ll know more after the investigation.”

“And why is this coffee so damn good?” she demanded. “It’s perfect.”

“You got a problem with that?”

“I had no idea you could make coffee like this.” She took another sip, savoring it.

“I’m a man of many talents. Some people just have a gift with coffee,” he added in a fake-serious voice. “They’re known as coffee whisperers.”

“And how do you know I take mine with exactly this much cream?”

“Maybe I’ve made a study of everything about you, from the way you take your coffee, to the number of towels you use when you shower, to your favorite radio station.” He rested his elbows on his knees, cradling the mug in his hands.

“Uh-huh. Good one, McKnight.”

“I thought you’d like it.” He finished his coffee.

She drew up her knees and stretched the oversize shirt down to cover them. “It’s a shallow thing to say, but a good cup of coffee makes even the worst situation less awful.” Closing her eyes, she drank more, savoring it and trying to be in the moment. Given all that had happened, it was the only safe place to be. Here. With Rourke. Safe in his bed.

“What’s funny?” he asked.

She opened her eyes. She hadn’t realized she was laughing. “I always wondered what it would be like to spend the night in your bed.”

“So how was it?”

“Well—” she set her mug on the nightstand “—the sheets don’t match but the thread count is amazing. And they’re clean. Not just-washed clean, but clean like you change your bed more than once in a blue moon. Four pillows and a great-feeling mattress. What’s not to like?”

“Thanks.”

“I’m not sure that was a compliment,” she cautioned him.

“You like my bed, the sheets are clean, the mattress is comfortable. How is that not a compliment?”

“Because I can’t help but wonder what it says about you. Maybe it says you’re a wonderful person who values a good night’s sleep. But maybe it says you’re so accustomed to bringing women home that you pay special attention to your bed.”

“So which is it?”

“I’m not sure. I’ll have to think about it.” She lay back and closed her eyes. There were any number of things she could say, but she decided not to go there. Into the past. To a reminder neither of them could escape, of what they had once been to each other. “I wish I could just stay here for the rest of my life,” she said, forcing lightness into her tone.

“Don’t let me stop you.”

She opened her eyes and propped herself on her elbows. “I just have to ask, and this is a sincere question. Who the hell did I offend? Did I upset some cosmic balance in the universe? Is that why all this shit is happening to me?”

“Probably,” he said.

She threw a pillow at him. “You’re a big help.”

He threw it back. “You want to shower first, or me?”

“Go ahead. I’ll just sit here and finish my coffee and contemplate my fabulous life.” She glanced down at the floor. “What are the dogs’ names?”

“Rufus, Stella and Bob.” He pointed out each one. They were pets he’d rescued, he explained. “The cat’s name is Clarence.”

Rescued. Of course, she thought.

“They’re friendly,” he added.

“So am I.” She scratched Rufus’s ears. He was a thick-coated malamute mix with ice-blue eyes.

“Good to know,” Rourke said. “Help yourself to something to eat. Even if you’re not hungry, you should eat something. It’s going to be another long day.” He went across the hall, and a moment later she heard the radio, followed by the hiss and patter of running water.

Jenny glanced at the clock. Too early to call Nina. Then she remembered Nina was up in Albany at some mayors’ convention. Jenny got up and went to the window, her legs feeling heavy, as if she’d just run a marathon, which was odd, because she hadn’t done anything all day yesterday except stand around in a state of shock and watch her house burn.

Outside, the world looked remarkably unchanged. Her whole life was falling apart, yet the town of Avalon slumbered in peace. The sky was a thick, impenetrable sheet of winter white. Bare trees lined the roadway and the distant mountains wore full mantles of snow. From the window of Rourke’s house, she could see the small town coming to life, a few snow-layered vehicles venturing out after last night’s snowfall. Avalon was a place of old-fashioned, effortless charm. The brick streets and well-kept older buildings of its downtown area were clustered around a municipal park, the snow-covered lawns and playing fields edging up to the banks of the Schuyler River, which tumbled past in a soothing cascade over glistening, ice-coated rocks, leaving beards of icicles in its wake.

This was the sort of town where stressed-out people from the city dreamed of coming to decompress. Some even retired here, buying a rolling acre or two for their golden years. In summer and during the fall leaf season, the country roads, which once held farm trucks and even the occasional horse-drawn buggy, were crowded with German-import SUVs, obnoxious Hummers and midlife-crisis sports cars.

There were still untouched places, where the wilderness was just as deep as it had been hundreds of years before, forests and lakes and rivers hidden among the seemingly endless peaks of the mountains. From the top of Watch Hill—which now bore a cell-phone tower—you could imagine looking down on the forest where Natty Bumppo had hunted in Last of the Mohicans. It always struck Jenny as remarkable that they were only a few hours’ travel from New York City.

Turning away from the window, she surveyed the room. No personal items, no photographs or mementos, no evidence that he had a life or a past or, God forbid, a family. Although she’d known Rourke McKnight since they were kids, a rift spanning several years yawned between them, and she’d never been in his bedroom. He’d never invited her and even if he had, she wouldn’t have come, not under normal circumstances. She and Rourke simply weren’t like that. He was complicated. Their history was more complicated. They were not a match. Not by a long shot.

Because the fact was, Rourke McKnight was an enigma, and not just to Jenny. It was hard to see past the chiseled face and piercing eyes to the man beneath. He had many layers, though she suspected few were able to discover that. He intrigued people, that was for certain. Those who were familiar with state politics knew he was the son of Senator Drayton McKnight, who for the past thirty years had represented one of the wealthiest districts in the state. And people would ask why a man born to such a family, a man who could have any life he chose, had ended up in a tiny Catskills town, working for a living just like anyone else.

Jenny knew she had a part in his decision to settle here, though he would never admit it. She had once been engaged to his best friend, Joey Santini. There had been a time when each of them had dreamed of the charms of small-town life, of friendships that would last a lifetime and loyalties that were never breached. Had they really been that naive?

Neither Rourke nor Jenny talked about what had happened, of course. Each worked hard to buy into the assumption that it was best left in the past, undisturbed.

But of course, neither one of them had forgotten. The peculiar awkward tension, the studied avoidance of each other, were proof of that. Jenny was sure that if she lived to be a hundred, she would never forget. There were very few things she knew for certain, but one of them was this. She would always remember that night with Rourke, but she would never understand him.

The shower turned off, and a few minutes later, he came in with a towel slung low around his hips, his damp hair tumbling over his brow. He was unbelievably good-looking: six-foot-something tall, with broad shoulders and lean hips. He had the kind of face that made women forget their boyfriends’ phone numbers. Jenny’s best friend, Nina Romano, always said he was way too good-looking to be a small-town policeman. With that chiseled jaw, dimpled chin and smoldering blue eyes, and that oh-so-memorable scar high on his right cheekbone, he belonged on billboards advertising high-end liquor or the kind of cars no one could afford. Jenny felt a clutch of pure lust, so sudden and blatant that it drew a laugh from her.

“This is funny?” he asked, spreading his arms, palms out.

“Sorry,” she said, but couldn’t seem to sober up. Her situation was just so completely awful that she had to laugh in order to keep from crying.

“I’ll have you know, this bed has been known to bring women to tears,” he said.

“I could have gone all day without hearing that.” She dabbed at her eyes and then studied him closely. She’d never known a man to have so many contradictions. He looked like a Greek god but seemed to be without vanity. He came from one of the wealthiest families in the state, yet he lived like a working-class man. He pretended not to care about anyone or anything, yet he spent all his time serving the community. He found homes for stray dogs and cats. He took injured birds to the wildlife shelter. If something was wounded or weak, he was there, simple as that. He’d been doing it for years. He had lived many lives, from spoiled Upper East Side preppie to penniless student, to public servant, making choices that were unorthodox for someone of his background.

He kept so much of himself hidden. She suspected it had to do with Joey and what had happened with him, with the three of them.

“… staring at me like that?” Rourke was asking.

She realized she’d been lost in thought, and she gave herself a shake. “Sorry,” she said. “It’s been a long time since we’ve talked. I was thinking about your story.”

He frowned. “My story?”

“Everybody has one. A story. A series of events that brought you to the place you are now.”

The frown eased into a grin. “I like law and order, and I’m good with weapons,” he said. “That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.”

“Even the fact that you joke around to cover up the real story is interesting to me.”

“If that’s interesting, then you ought to be a fiction writer.”

Aha. He pretended he wasn’t interesting. “You’re a good distraction,” she said.

“How’s that?”

“My whole life just went up in smoke, and I’m thinking about you.”

That seemed to make him nervous. “What about me?”

“Well, I just wonder—”

“Don’t,” he cut her off. “Don’t wonder about me or my story.”

How can I not? she thought. It’s our story. And something about the fire had changed things between them. They’d gone from avoiding each other to … this. Whatever “this” turned out to be. Was he drawn to her by his urge to protect, or was there a deeper motivation? Could the fire be a catalyst in making them face up to matters they both avoided? Maybe—at long last—they would talk about what happened.

Not now, Jenny thought. She couldn’t do that now, on top of everything else. For the time being, it was easier to engage in meaningless flirtation, skirting the real issues. Over the years, she’d gotten very good at that.

“I’d better hit the shower,” she said. “Where are my clothes?”

“In the wash, but they’re not dry yet.”

“You washed my clothes.”

“What, you wanted them dry-cleaned?”

She didn’t say anything. She knew that everything reeked of smoke and she ought to be grateful for the favor. Still, it was mind-numbing to realize she had exactly one set of clothes in this world.

He opened the bottom bureau drawer, revealing a fat paper parcel marked with a laundry-service label. “There’s a bunch of stuff in here. You can probably find something to fit. Help yourself.”

Frowning with curiosity, she tore open the parcel and inspected the contents, pulling out each piece and holding it up. There was a baby-doll top, a push-up bra, an array of impossibly tiny women’s underwear. She also found designer jeans and cutoffs, knitted tops with plunging necklines.

She straightened up and faced him. “So what are these, prizes of war? Souvenirs of sex? Things left behind by women who have walked out on you?”

“What?” he asked, but the sheepish look on his face indicated that he knew precisely what. “I had them cleaned.”

“And that makes it all right?”

“Look, I’m not a monk.”

“Clearly not.” She held a thong at arm’s length, between her thumb and forefinger. “Would you wear something like this?”

“Now you’re getting kinky on me.”

“I’m keeping the boxers,” she stated. As she headed to the bathroom, she paused, her face just inches from his bare chest. The damp steam that came off him smelled of Ivory soap. “I’d better get going. Like you said, it’s going to be a long day.”

She stepped into the bathroom. The radio, she discovered, had been set on her favorite station. On the counter were three clean, folded towels—the exact number she preferred to use, in the proper sizes—one bath sheet and two hand towels.

Sure, it was flattering to imagine he was attracted to her. But that was all in the past; he hadn’t said a dozen words to her in years. He had barely noticed her until now. Until she was in her most vulnerable state—grieving, homeless, with nowhere to go and no one to turn to. He didn’t notice her until she needed rescuing. Interesting.

Jenny had to lie back on the bed and suck in her gut in order to get the borrowed jeans zipped over the boxer shorts. According to the designer tag in the waistband, the pants were her size. The jeans had probably belonged to someone named Bambi or Fanny, the sort of girl who enjoyed wearing things that looked as though they had been applied by paintbrush.

The bra was a surprisingly good fit, even though the push-up style was hardly her thing. She pulled on a V-neck sweatshirt, also tight, white with crimson trim and the Harvard seal smack-dab over her left boob. Veritas. It was probably as close as she’d ever get to a Harvard education.

Later she came into the kitchen, her borrowed socks flopping on the linoleum. When Rourke saw her, his face registered something she had never seen before, something that was so quickly gone, she nearly missed it—a sharp, helpless lust. Gosh, she thought, and all it took was dressing like a Victoria’s Secret model.

“Ho Ho?” he said.

“Hey, these clothes came out of your closet,” she said.

He scowled. “No, I mean Ho Ho.” He held out a package of iffy-looking chocolate snack cakes.

She shook her head. “You might be the coffee whisperer, but that—” she indicated the packaged Ho Hos “—is atrocious.”

He was dressed for work now, looking as clean-cut as an Eagle Scout, the youngest chief of police in Ulster County. Ordinarily it took years of experience and clever department politicking to reach chief’s status, but in the town of Avalon, it took no more than a willingness to accept an abnormally small salary. He treated his job seriously, though, and had earned the respect of the community.

She helped herself to a plump orange and sat at the kitchen counter. “You’re working on a Sunday?”

“I always work Sundays.”

She knew that. She just didn’t want to admit it. “What next, Chief?” she asked.

“We go to your house, meet with the fire investigator. If you’re lucky, they’ll make a determination as to the cause of the fire.”

“Lucky.” She dug her thumbnail into the navel of the orange and ripped back the peel. “How come I don’t feel so lucky?”

“Okay, poor choice of words. All I meant was, the sooner the investigation finishes up, the sooner the salvage can start.”

“Salvage. This is all so surreal.” She felt a sudden clutch of anxiety in her gut and remembered something. “You said you washed my clothes?”

“Uh-huh. I just heard the cycle end.”

“Oh, God.” She jumped up and hurried into the tiny laundry area adjacent to the kitchen and flipped open the washer.

“What’s the matter?” he asked, following her.

She yanked out the checked chef pants she’d had on. Plunging her hand into the pocket, she drew out the little brown plastic bottle. The label was still attached, but the bottle was full of cloudy water. She handed it to Rourke.

He took the bottle from her, glanced at the label. “Looks like all the pills dissolved.”

“You now have the most Zenlike, serene washing machine in Avalon.”

“I didn’t know you were on medication.”

“What, you thought I was handling Gram’s death without help?”

“Well, yeah.”

“Why would you think I could do that?”

He set the bottle on the kitchen counter. “You are now. You have been all morning. I don’t see you freaking out.”

She hesitated. Braced her hands on the edge of the counter for support. Then she realized the posture accentuated her boobs in the tight sweatshirt and folded her arms. On a scale of one to ten, the doctor had asked her the night Gram passed away, how anxious did she feel? He told her to ask herself that question before taking a pill so that popping one didn’t become a habit.

“I’m a five,” she said softly, feeling a barely discernible buzz in her circulation, a subtle tension in her muscles. No sweating, no accelerated heartbeat, no hyperventilating.

“I know those aren’t your clothes,” Rourke said, “but I’d say you’re at least a seven.”

“Ha, ha.” She helped herself to another orange. “The doctor said I’m supposed to ask myself how anxious I feel on a scale of one to ten, consciously assessing my need for medication.”

Rourke lifted one eyebrow. “So if you’re a five, does that mean we should make an emergency run to the drugstore?”

“Nope. Not unless I feel like an eight or higher. I’m not sure why I don’t feel more panicked. After everything that’s happened, it’s a wonder I’m not having a nervous breakdown.”

“What, do you want one?”

“Of course not, but it would be normal to fall apart, wouldn’t it?”

“I don’t think there’s any kind of ‘normal’ when it comes to a loss like this. You feel relatively okay now. Let’s leave it at that.”

She sensed something beneath his words. A certain wisdom or knowledge, as though maybe he had some experience in this area.

The morning air felt icy and sweet on her face as she followed him outside. He made sure the dogs had food and water and that the heater in the adjacent garage was on so they could come in out of the cold if they needed to. He closed the gate and then, with a flair of chivalry, he opened the door of the Ford Explorer, marked with a round seal depicting a waterwheel in honor of Avalon’s past as a milltown, and the words Avalon P.D.

Then he came around and got in the driver’s side and started up the car. “Seat belt,” he said. He noticed her looking at him and she wondered if he could tell she was thinking about what an enigma he was to her, the first person to distract her from her grief over Gram. He was being chivalrous because he was chief of police, she reminded herself. He would do the same for anyone.

“Are you sure you’re all right?” he asked. “You’re looking at me funny again.”

She felt her face heat and glanced away. She was supposed to be in despair about losing her grandmother and house, yet here she was having impure thoughts about the chief of police. Please don’t let me be that girl, she thought.

“Other than these clothes,” she said, “I’m fine.”

He took a deep breath. “Okay. Let’s focus on today. On right now. We’ll deal with things one by one.”

“I’m all ears. See, I don’t know the drill. No idea what happens after the house burns down.”

“You make a new start,” he said. “That’s what.”

His words took hold of her. For the first time since Gram died, she began to see the situation in a new light. Drowning in grief, she had focused on the fact that she was all alone now. Rourke’s comment caused a paradigm shift. Alone became independent. She had never experienced that before. When her grandfather died, she’d been needed at the bakery. After her grandmother’s stroke, she’d been needed at home. Following her own path had never been an option … until now. But here was something so terrible, she wished she could hide it from herself—she was afraid of independence. She might screw up and it would be all her fault.

Although she’d stood around the previous day and watched her house burn, even feeling warmth from the embers, she felt a fresh wave of shock when she got out of the car. With all the equipment gone, there was nothing but the scaly black skeleton surrounded by a moat of trampled mud, now frozen into hard chunks and ridges.

“What happened to the garage?” she asked.

“A pumper backed into it. It’s a good thing we got your car out yesterday.”

The loss barely registered with her. It seemed minuscule in the face of everything else. She could only shake her head.

“I’m sorry,” he said, patting her shoulder a bit awkwardly. “The fire investigators will be here soon, and you can have a look around.”

She felt an unpleasant chill. “Are you thinking this fire was set deliberately?”

“This is standard. If things don’t add up for the fire investigator, he’ll call for an arson investigation. The insurance adjuster said he’d be here soon. First thing he’ll do is give you a debit card so you can get the basics.”

She nodded, though a shudder went through her. A swath of black-and-yellow tape surrounded the house at the property line.

Seeing the house was like probing a fresh wound. The place was a grotesque mutation of its former self. Against the pale morning sky, it resembled a crude charcoal drawing. The porch, once a white smile of railing across the front of the house, had blackened and blistered into nothing. A couple of tenuous beams leaned crazily out over the yard. There was no front door to speak of. All the remaining windows were shattered.

The plumbing formed a strange, Terminator-like skeleton from which everything else had burned away. In the charred ruins, she could pick out the kitchen—the heart of the house. Her grandparents had been frugal people, but they had splurged on a double-door commercial fridge and a huge double oven. More than five decades ago, Gram had created her first commercial baked goods right in that kitchen.

The upstairs was down now, for the most part, and some of the downstairs was in the basement. Jenny could see straight through to the backyard fence, now a field of snow, including a rippled blanket of white over the garden bed. Throughout Gram’s life, the garden had been her pride and joy. After her grandmother’s stroke, Jenny had worked hard to keep it the way it was, a glorious and artful profusion of flowers and vegetables.

The high-pressure stream from the firefighters’ hoses had criss-crossed the yard in clean, arching swaths. The spray had formed icicles on the back fence and gate, turning the backyard into a sculpture garden.

Heavy boots had tamped down the snow on the perimeter of the property. The entire area smelled of wet charcoal, a harsh and stinging assault on the nostrils.

“I don’t even know where to begin,” she said. “Interesting question, huh? When you lose everything you own in a fire, what’s the first thing you buy?”

“A toothbrush,” he said simply, as if the answer was obvious.

“I’ll make a note of that.”

“There’s a method. The adjuster will hook you up with a salvage company, and they’ll walk you through the process.”

Cars trolled past slowly. She could feel the sting of gawking eyes. People always stared at other people’s troubles and breathed a sigh of relief, grateful it wasn’t them.

Jenny put on protective gear and followed the fire investigator and insurance adjuster up a plank that sloped up to the threshold of the front door in place of the ruined steps. She could pick out the layout of the rooms, could see the filthy remains of familiar furniture and possessions. The whole place had been transformed into alien territory.

She was the alien. She didn’t recognize herself as she tonelessly responded to questions about her routine the night before. She answered questions until her head was about to explode. They ran through all the usual scenarios. She hadn’t fallen asleep smoking in bed. The only sin she’d committed was unintentional and inadvertent. She tried to detach herself, pretend it was someone else explaining that she’d been up late working at her computer. That she’d felt as if she were about to jump out of her skin, so she went to the bakery, knowing someone would be there on the early-morning shift. She answered their questions as truthfully as possible—no, she didn’t recall leaving any appliances on, not the coffeemaker, hair dryer, toaster oven. She had not left a burner on, hadn’t forgotten a burning candle, couldn’t even recall where she kept a supply of kitchen matches. (Under the sink, one of the investigator’s techs informed her.) Her grandmother used to take votive candles to church, lighting row upon row in front of the statue of Saint Casimir, patron of both Poland and of bachelors.

“Oh, no,” she whispered.

“Miss?” the fire investigator prodded her.

“I did it,” she said. “The fire’s my fault. My grandmother had a tin box filled with things from Poland—letters, recipes, articles she’d clipped. The night of the fire, I was … I couldn’t sleep so I was doing some research for my column. I got it out, and—oh, God.” She stopped, feeling sick with guilt.

“And what?” he prompted.

“I used a flashlight that night. Its batteries were dead so I took the ones out of the smoke detector in the kitchen and forgot to put them back. I disabled the smoke alarm.”

Rourke seemed unconcerned. “You wouldn’t be the first to do that.”

“But that means the fire was my fault.”

“A smoke alarm only works when there’s someone to hear it,” Rourke pointed out. “Even if it had been wailing all night, the house would have burned. You weren’t present to hear the alarm, so it didn’t matter.”

Oh, she wanted him to be right. She wanted not to be responsible for destroying the house. “I’ve heard that alarm go off,” she said. “It’s loud enough to wake the neighbors, if it’s working.”

“It’s not your fault, Jen.”

She thought of the tin box filled with irreplaceable documents and writings on onionskin paper. Gone now, forever. She felt as though she’d lost her grandmother all over again. Trying to hold herself together, she studied the fireplace, picturing the Christmases they’d shared in this house. She hadn’t used the fireplace since before her grandmother had died.

Gram used to get so cold, she claimed only a cheery fire in the hearth could warm her. “I used to wrap her up like a ko-lache,” Jenny said, thinking aloud about how she and Gram had giggled as Jenny tucked layer after layer of crocheted afghan around the frail little body. “But she just kept shivering and I couldn’t get her to stop.” Then her face was tucked against Rourke’s shoulder, and it hurt to pull in a breath of air, the effort scraping her lungs.

She felt an awkward pat on the back. Rourke probably hadn’t counted on finding his arms full of female despair this morning. Rumor had it he knew exactly what to do with a woman, but she suspected the rumors applied to sexy, attractive, willing women. That was the only type he ever dated, as far as she could tell. Not that she was keeping track, but it was hard to ignore. More frequently than she cared to admit, she’d spotted him taking some stacked bimbo to the train station to get the early train to the city.

“… go outside,” Rourke was saying in her ear. “We can do this another time.”

“No.” She straightened up, pulled herself together, even forced a brave smile. What sort of person was she, thinking like that under these circumstances? She gave him a gentle slug on the upper arm, which seemed to be made of solid rock. “Excellent shoulder to cry on, Chief.”

He joined her obvious attempt to lighten things up. “To protect and serve. Says so right on my badge.”

She faced the fire investigator, brushing at her cheeks. “Sorry. I guess I needed a breakdown break.”

“I understand, miss. The loss of a home is a major trauma. We advise an evaluation with a counselor as soon as possible.” He handed her a business card. “Dr. Barrett in Kingston comes highly recommended. Main thing is, don’t make any major decisions for a while. Take it slow.”

She slipped the card into her back pocket. It was amazing that she could slip anything into that pocket. The borrowed jeans were constricting her in places she didn’t know she had. The tour continued and somehow she managed to hold it together despite the enormity of her loss. In less than a month, she’d lost Gram, and now the house where she had lived every day of her life.

The official determination had yet to be made, but both the investigator and even the suspicious insurance adjuster seemed to agree that the fire had started in the crawlspace of the attic. Very likely faulty wiring had been the cause. The Sniffer had detected no accelerant and there were no obvious signs of deliberate mischief.