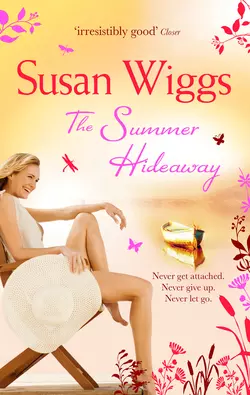

The Summer Hideaway

Susan Wiggs

Retreat to a blissful haven with Susan Wiggs!Private nurse Claire Turner has always lived by the motto, ‘Never get attached’. Fleeing a treacherous past that could catch up with her any day, she finds solace in the anonymity of a big city.Going to a small resort in Avalon, so Claire’s elderly patient can be reconciled with his family, is exactly the kind of thing Claire usually avoids. But meeting her boss’s charming grandson, Ross Bellamy, makes Claire reconsider her life. Maybe here, in the enchantment of Willow Lake, she can find a love that will finally be worth not running away from.Perfect for fans of Cathy Kelly

Praise for the novels of #1 New York Times bestselling author

SUSAN WIGGS

“Wiggs is one of our best observers of stories of the heart… She knows how to capture emotion on virtually every page of every book.”

—Salem Statesman-Journal

“Bestselling author Wiggs’s talent is reflected in her thoroughly believable characters as well as the way she recognizes the importance of family by blood or other ties.”

—Library Journal

“Susan Wiggs writes with bright assurance, humor and compassion.”

—Luanne Rice

FIRESIDE

#1 NewYork Times Bestseller

“Worth a look for the often-hilarious dialogue alone, the latest installment of her beloved Lakeshore Chronicles showcases Wiggs’s justly renowned gifts for storytelling and characterization. A keeper.”

—RT Book Reviews

SNOWFALL AT WILLOW LAKE

A Best Book of 2008—Amazon.com

Reviewer’s Choice finalist—RT Book Reviews

RITA® Award finalist

“Wiggs is at the top of her game here, combining a charming setting with subtly shaded characters and more than a touch of humor.

This is the kind of book a reader doesn’t want to see end but can’t help devouring as quickly as possible.”

—RT Book Reviews

“Wiggs jovially juggles the lives of numerous colliding characters and adds some winter-favorite recipes for a festive touch.”

—Publishers Weekly

DOCKSIDE

“Rich with life lessons, nod-along moments and characters with whom readers can easily relate…

Delightful and wise, Wiggs’s latest shines.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A wonderfully written, beautiful love story with a few sharp edges and a bunch of marvelously imperfect characters, this is one of Wiggs’s finest efforts to date. It’s sure to leave an indelible impression on even the most jaded reader.”

—RT Book Reviews

THE WINTER LODGE

The Best Romance of 2007—Amazon.com

A Best Book of 2007—Publishers Weekly

Reviewer’s Choice finalist—RT Book Reviews

“With the ease of a master, Wiggs introduces complicated, flesh-and-blood characters…[and] sets in motion a refreshingly honest romance.”

—Publishers Weekly [starred review]

“Empathetic protagonists, interesting secondary characters, well-written flashbacks and delicious recipes add depth to this touching, complex romance.”

—Library Journal

“Emotionally intense.”

—Booklist

SUMMER AT WILLOW LAKE

A Best Book of 2006—Amazon.com

“Wiggs’s storytelling is heartwarming…clutter free…[and] should appeal to romance and women’s fiction readers of any age.”

—Publishers Weekly

“How good is perennially popular Wiggs in her new romance? Superb. Wonderfully evoked characters, a spellbinding story line and insights into the human condition will appeal to every reader.”

—Booklist

The Summer Hideaway

The Lakeshore Chronicles

Susan Wiggs

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Acknowledgments

Deepest gratitude to my friends and fellow writers—Anjali Banerjee, Carol Cassella, Sheila Roberts, Suzanne Selfors, Elsa Watson.

Special thanks to the team of experts—Dr. Carol Wiley, Bob Mayer, Robert Dugoni and Andy Watson—for help with researching and brainstorming such disparate topics as helicopters in combat, airborne medical evacuation, brain tumors and legal matters. Any inaccuracies found herein are my own. To my friend Carol Kovac—just talking to you frees the mind.

Thanks to Sherrie Holmes, Joelle Klist, Bree Ogden and Lindsey LeBret for keeping all my ducks in a row. And a very special thank-you to the Jacobi family for their support of P.A.W.S. and for providing inspiration for the fictional pets in this book.

Thanks to Margaret O’Neill Marbury and Adam Wilson of MIRA Books, Meg Ruley and Annelise Robey of the Jane Rotrosen Agency, for invaluable support, advice and input.

Thanks and love to my family—the reason for everything.

Also by SUSAN WIGGS

Contemporary Romances

HOME BEFORE DARK

THE OCEAN BETWEEN US

SUMMER BY THE SEA

TABLE FOR FIVE

LAKESIDE COTTAGE

JUST BREATHE

The Lakeshore Chronicles

SUMMER AT WILLOW LAKE

THE WINTER LODGE

DOCKSIDE

SNOWFALL AT WILLOW LAKE

FIRESIDE

LAKESHORE CHRISTMAS

THE SUMMER HIDEAWAY

Historical Romances

THE LIGHTKEEPER THE DRIFTER

The Tudor Rose Trilogy

AT THE KING’S COMMAND

THE MAIDEN’S HAND

AT THE QUEEN’S SUMMONS

Chicago Fire Trilogy

THE HOSTAGE

THE MISTRESS

THE FIREBRAND

Calhoun Chronicles

THE CHARM SCHOOL

THE HORSEMASTER’S DAUGHTER

HALFWAY TO HEAVEN

ENCHANTED AFTERNOON

A SUMMER AFFAIR

Seeking: Private Duty Nurse (Upstate New York)

PostingID: 146002215 Avoid scams by dealing locally

Reply to godfrey@georgebellamy.com

Senior accomplished gentleman seeks end-of-life nursing care, full-time, days and nights.

Qualifications:

age twenty-five to thirty-five

female (not negotiable)

must have a positive attitude and a sense of adventure

must love children of all ages

must be open to relocation

no emotional baggage

nursing skills and valid state certification a plus

Benefits:

medical, dental, vision, 401(k)

weekly paychecks with direct deposit

Rustic accommodations provided on Willow Lake in the Catskills Wilderness.

Prologue

Korengal Valley, Kunar province, Afghanistan

His breakfast consisted of shoestring potatoes that actually did look and taste like shoestrings, along with reconstituted eggs, staring up at him from a compartmentalized tray in the noisy chow hall. His cup was full of a coffee-like substance, lightened by a whitish powder.

At the end of a two-year tour of duty, Ross Bellamy had a hard time looking at morning chow. He’d reached his limit. Fortunately for him, this was his last day of deployment. It seemed like any other day—tedious, yet tense with the constant and ominous hum of imminent threat. Radio static crackled along with the sound of clacking utensils, so familiar to him by now that he barely heard it. At a comm station, an ops guy for the Dustoff unit was on alert, awaiting the next call for a medical evacuation.

There was always a next call. An air medic crew like Ross’s faced them daily, even hourly.

When the walkie-talkie clipped to his pocket went off, he put aside the mess without a second glance. The call was a signal for the on-duty crew to drop everything—a fork poised to carry a morsel of mystery meat to a mouth. A game of Spades, even if you were winning. A letter to a sweetheart, chopped off in the middle of a sentence that might never be finished. A dream of home in the head of someone dead asleep. A guy in the middle of saying a prayer, or one with only half his face shaved.

The medevac units prided themselves on their reaction time—five or six minutes from call to launch. Men and women burst into action, still chewing food or drying off from the shower as they fell into roles as hard and familiar as their steel-toed boots.

Ross gritted his teeth, wondering what the day had in store for him, and hoping he’d make it through without getting himself killed. He needed this discharge, and he needed it now. Back home, his grandfather was sick—had been sick for a while, and Ross suspected it was a lot more serious than the family let on. It was hard to imagine his grandfather sick. Granddad had always been larger-than-life, from his passion for travel to his trademark belly laugh, the one that could make a whole roomful of people smile. He was more than a grandparent to Ross. Circumstances in his youth had drawn the two of them close in a bond that defined their relationship even now.

On impulse, he grabbed his grandfather’s most recent letter and stuck it into the breast pocket of his flight jacket, next to his heart. The fact that he’d even felt the urge to do so made him feel a gut-twist of worry.

“Let’s go, Leroy,” said Nemo, the unit’s crew chief. Then, as he always did, he sang the first few lines of “Get Up Offa That Thang.”

In the convoluted way of the army, Ross had been given the nickname Leroy. It had started when some of the platoon had learned a little—way too little—about his silver-spoon-in-mouth background. The fancy schools, the Ivy League education, the socially prominent family, had all made him fodder for teasing. Nemo had dubbed him Little Lord Fauntleroy. That had been shortened to Leroy, and the name had stuck.

“I’m on it,” Ross said, striding toward the helipad. He and Ranger would be piloting the bird today.

“Good luck with the FNG.”

FNG stood for Fucking New Guy, meaning Ross would have a mission virgin on board. He vowed to be nice. After all, if it weren’t for new guys, Ross would be here forever. According to the order packet he’d received, his forever was about to end. In a matter of days, he’d be stateside again, assuming he didn’t get himself greased today.

The FNG turned out to be a girl, a flight medic named Florence Kennedy, from Newark, New Jersey. She had that baby-faced determination common to newbies, worn as a thin mask over abject, bowel-melting fear.

“What the fuck are you waiting for?” demanded Nemo, striding past her. “Get your ass over to the LZ.”

She seemed frozen, her face pale with resentment. She made no move to follow Nemo.

Ross nailed her with a glare. “Well? What the hell is it?”

“Sir, I…Not fond of the f-word, sir.”

Ross let out a short blast of laughter. “You’re about to fly into a battle zone and you’re worried about that? Soldiers swear. Get used to it. Nobody on earth swears as much as a soldier—and nobody prays as hard. And I don’t know about you, but I see no conflict there. Pretty soon, you won’t, either.”

She looked as though she might cry. He tried to think of something to say to reassure her, but could come up with nothing. When had he stopped knowing how to speak kindly?

When he’d grown too numb to feel anything.

“Let’s go,” he said simply, and strode away without looking back.

The ground crew chief barked out a checklist. Everyone climbed aboard. Armor and helmets would be donned on the chopper to shave off run time.

Ross received the details through his ear piece while he consulted his lap charts. The call was the type they feared most—victims both military and civilian, enemy still in the area. Apache gunships would escort the medical birds because the red crosses on the nose, underbelly and each cargo door of the ship meant nothing to the enemy. The crew couldn’t let that matter; they had to roll fast. When a soldier on the ground was wounded, he needed to hear one key phrase: Dustoff is inbound. For some guy bleeding out in the field, the flying ambulance was his only hope of survival.

Within minutes, they were beating it northward over the evergreen-covered mountains of Kunar province. Flying at full speed across the landscape of craggy peaks, majestic forests and silvery rivers, Ross felt tense and jittery, on edge. The constant din of flight ops, along with strict regulations, kept conversation confined to essential matters only over the headsets. The rush into unknown danger was an everyday ordeal, yet he never got used to it. Last mission, he told himself. This is your last mission. Don’t blow it.

The Korengal Valley was one of the most beautiful places on earth. Also one of the most treacherous. Sometimes the helos encountered surface-to-air missiles, cannonade or tripwires strung between mountain peaks to snag the aircraft. At the moment, the gorgeous landscape erupted with lightning bolts of gunfire and ominous plumes of smoke. Each represented a deadly weapon aimed at the birds.

Ross’s heart had memorized the interval of delay between spotting the flash and taking the hit—one, two, three beats of the heart and something could be taken out.

The gunships broke off to fire on the areas blooming with muzzle flashes. The diversion created a lull so the medical choppers could circle down.

Ross and Ranger, the other pilot, focused on closing the distance between the bird and the other end of the radio call. Despite the information given, they never knew what might be waiting for them. Half of their flights were for evacuating Afghan civilians and security personnel. The country had lousy medical infrastructure, so sometimes a pickup was for patient transport, combat injuries, accidents, even dog bites. Ross’s unit had seen everyone’s horrors and ill luck. But judging by the destination, this was not going to be a simple patient transport to Bagram Air Base. This region was the deadliest of Taliban havens, patrolled on foot and referred to as the Valley of Death.

The chopper neared the pickup point and descended. The tops of the majestic pine trees swayed back and forth, beaten by the wind under the main rotors, offering fleeting glimpses of the terrain. Wedged between the walls of the valley lay a cluster of huts with rooftops of baked earth. He saw scurrying civilians and troops, some fanning out in search of the enemy, others guarding their wounded as they waited for help to arrive.

Muzzle flashes lit the hillsides on both ends of the valley. Ross knew immediately that there was too much small-arms fire below. The gunships were spread too thin.

The risk of drawing enemy fire was huge, and as pilot, he had to make the call. Bail now and protect the crew, or go in for the rescue and save the lives below. As always, it was an agonizing choice, but one made swiftly and followed by steel resolve. No time for a debate.

He took the bird in, hovering as close to the mark as he dared, but couldn’t land. The other pilot shook his head vigorously. The terrain was too rough. They’d have to lower a litter.

The crew chief hung out the cargo bay door, letting the penetrator cable slide through his gloved hand. A Stokes litter was lowered and the first soldier—the one most seriously wounded, was placed in the basket. Ross lifted off, hearing “Breaking ground, sir,” over his headset as the winch began its fast rewind.

The basket was nearly in the bird when Ross spotted a fresh plume of smoke—a rocket launcher. At an altitude of only fifty feet, he had no time to take evasive action. The miniature SAM slammed into the aircraft.

A flash of white lightning whipped through the ship. Everything showered down—shrapnel, gear, chips of paint, and an eerie flurry of dried blood from past sorties, flaking off the cargo area and blowing around. Then a burst of fire raked the chopper, slugs stitching holes in the bird. It bucked and vibrated, throwing off webbing, random bits of aluminum, broken equipment, including a couple of radios, right in the middle of Ross’s first Mayday call to the ops guys at base who were managing the mission. A ruptured fuel line hosed the flight deck.

He felt slugs smacking into his armored chair, the plates in front of his face, the overhead bubble window. Something thumped him in the back, knocking the wind out of him. Don’t die, he told himself. Don’t you fucking die. He stayed alive because if he got himself killed, he ‘d take down everybody with him. It was as good a reason as he knew to keep going.

He had landed a pranged chopper before, but not in these conditions. There was no water to hit. He hoped like hell he could set it down with everybody intact. He couldn’t tell if the crew had reeled the basket in. Couldn’t let himself think about that—a wounded soldier twisting and dangling from the bird.

Ranger tried another radio. The red trail of a smoke grenade bloomed, and then the wind swept it away. Ross spotted a patch of ground just as another hail of fire hit. Decking flew up, pieces glancing off his shoulder, his helmet. The ship whirled as though thrown into a giant blender, completely out of his control. There was no lift, nothing at all. The whistles and whines of the dying ship filled his head.

As the earth raced up to meet them, he found himself focusing on random sights on the ground—a tattered billboard for baby milk, a mangled soccer goal. The chopper roared as it hit, throwing up more steel decking. The jolt slammed through every bone of his body. His back teeth crunched together. A stray rotor slung free, mowing down everything in sight. Ross was in motion even before the thing settled. The reek of JP4 fuel choked him. He flung out a hand, grabbing Ranger’s shoulder, thanking God the other pilot was looking lively.

Nemo was struggling with his monkey strap, the rig used to hold him in the chopper during ops. The straps had tangled, and he was still tethered to a tie-down clamp attached to the ripped-up deck. Ranger went to help him, and the two of them dragged away the wounded guy in the litter, which, thankfully, had been hoisted into the cargo bay before the crash.

“Kennedy!” Ross dropped to his knees beside her. She lay eerily still, on her side. “Hey, Kennedy,” he said, “Move your ass. Move your fucking ass! We need to get out.”

Don’t be dead, he thought. Please don’t be dead. Damn, he hated this. Too many times, he’d turned a soldier over to find him—or her—too far gone, floating in root reflexes.

“Ken—”

“Fuck.” The FNG threw off his hand, hauling herself to her feet while uttering a stream of profanities. Then, just for a second, she focused on Ross. The soft-cheeked newness was already gone from her face, replaced by flinty-eyed determination. “Quit wasting time, Chief,” she said. “Let’s get the fuck out of here.”

The four of them crouched low against the curve of the chopper’s battered hull. Bullet holes riddled the starkly painted red cross and pockmarked the tail boom. The floor was covered with loose AK-47 rounds.

The Apache gunships had broken off and gone into hunter-killer mode, searching out the enemy on the ground, firing at the muzzle flashes on the mountainsides and producing a much-prayed-for lull. The other chopper had escaped and was no doubt sending out distress calls on the unit’s behalf. Pillars of black smoke from mortar rounds rose up everywhere.

With no means of evacuation, the crew had to take cover wherever they could. Heads down, in a hail of debris, they carried the litter toward the nearest house. Through a cloud of dust and smoke, Ross spotted an enemy soldier, hunched and watchful, armed with an AK47, approaching the same house from the opposite direction.

“I got this,” he signaled to Nemo, nudging him.

Unarmed against a hot weapon, Ross knew he had only seconds to act or he’d lose the element of surprise. That was where the army’s training kicked in. Approaching from behind, he stooped low, grabbed the guy by both ankles and yanked back, causing the gunman to fall flat on his face. Even as the air rushed from the surprised victim’s chest, Ross dispatched him quickly—eyes, neck, groin—in that order. The guy never knew what hit him. Within seconds, Ross had bound his wrists with zip ties, confiscated the weapon and dragged the enemy soldier into the house.

There, they found a host of beleaguered U.S. and Afghan soldiers. “Dustoff 91,” Ranger said by way of introduction. “And unfortunately, you’re going to have to wait for another ride.”

The captured soldier groaned and shuddered on the floor.

“Jesus, where’d you learn that move?” one of the U.S. soldiers demanded.

“Unarmed combat—a medevac’s specialty,” said Nemo, giving Ross a hand.

A babble of Pashto and English erupted. “We’re toast,” said a dazed and exhausted soldier. Like his comrades, he looked as if he hadn’t bathed in weeks, and he wore a dog’s flea collar around his middle; life at the outposts was crude as hell. The guy—still round-cheeked with youth, but with haunted eyes—related the action in dull shell-shocked tones. A part of this kid wasn’t even there anymore. When Ross met a soldier in such a state, he often found himself wondering if the missing part would ever be restored.

“Let’s have a look at the wounded,” Kennedy suggested. She seemed desperate to do something, anything. The soldier took her to a row of supine people on the floor—an Afghan teenager holding an iPhone and keening what sounded like a prayer, a guy moaning and clutching his shredded leg, several lying unconscious. Kennedy checked their vitals and looked around, lost. “I need something to write on.”

Ross grabbed a Sharpie marker from her kit. “Right there,” he said, indicating the teenager’s bare chest.

She hesitated, then started to write on the boy’s skin. More gunfire slapped the ground outside. After what seemed like an eternity, but was probably only twenty minutes, another Dustoff unit arrived, lowered a medic on a winch line and then beat away in search of a place to land. Inside the hut, the triage continued, with everyone aiding the medics.

Ross moved past a pair of soldiers who were obviously dead. He felt nothing. He wouldn’t let himself. The nightmares would come later.

“See if you can stop that bleeding,” the new medic said, indicating another victim. “Just hold something on it.”

Ross ripped off a sleeve to staunch a bleeding wound. Only after he’d pressed the fabric into an arm did he see that it was attached to an old guy who was being held by a boy singing softly into the man’s ear. It seemed to calm the wounded guy, Ross observed.

He needed to find the part of him that could still feel. He needed what he saw in the way the boy’s hand caressed the old man’s cheek. Family. It gave life its meaning. When everything was stripped away, family was the only thing that mattered, the only thing that kept a person tethered to the ground. Other than his grandfather, Ross was lacking in that department. He hated feeling so hollow and numb.

Fire from the insurgents subsided. Two more chopper crews arrived with litters, racing across open ground to reach the others. Everyone burst into action, taking advantage of the lull. The wounded were loaded on litters, pulled along on ponchos, carried in straining arms. Those who were ambulatory piled in, creating chaos. The first bird took off, chugging with its burden, then swung like a carnival ride.

Ross was in the second one, the last to board, grasping a cleat for a handhold. The firing started up again, pinging off the skids. The flight passed in a blur of noise and dust and smoke, but finally—thank God, finally—he could see an ops guy mouth the magic words everyone had been waiting—hoping, praying—for: Dustoff is inbound.

They reached the LZ with the last of their fuel, and the ground personnel took over. Ross found somebody in medical to give him some betadine and a couple of bandages. Then he walked out into the compound, the sun beating down on his bare arm where he’d ripped his sleeve off. He was light-headed with the feeling that he’d been to hell and back.

It was barely noon.

Renowned for its swiftness and efficiency, his Dustoff unit had saved a lot of lives. Twenty-five minutes from battlefield to trauma ward was the norm. It was something he’d look back at with pride, but it was time to move on. He was so damn ready to move on.

Guys were milling around the mess tent. Two more air crews were preparing to head out again.

“Hey, Leroy, Christmas came early for you this year,” said Nemo, wolfing down a folded-over piece of pizza from the Pizza Hut tent. “I hear your discharge orders came through.”

Ross nodded. A wave of something—not quite relief—surged through him. It was really happening. At last, he was going home.

“What’re you going to do with yourself once you’re Stateside?” Nemo asked.

Start over, thought Ross. Get it right this time around. “I got big plans,” he said.

“Right,” Nemo said with a chuckle, heading for the showers. “Don’t we all.”

When you were in the middle of something like this, Ross thought, you didn’t plan anything except how not to die in the next few minutes. It was a total mind trip to realize he’d have to think past that now.

He spotted Florence Kennedy hunkered down in the shade, sipping from a canteen and quietly crying.

“Hey, sorry about the way I screamed at you out there,” he said.

She gazed up at him, red eyes swimming. “You saved my ass today.”

“It’s a pretty nice ass.”

“Careful how you talk to me, Chief. That mouth of yours could get you in a world of shit.” She grinned through her tears. “I owe you.”

“Just doing my job, ma’am.”

“Sounds like you’re heading home.”

“Yep.”

She dug in her pocket, took out a card and scribbled an e-mail address on it. “Maybe we’ll keep in touch.”

“Maybe.” It didn’t work that way, but she was too new to know.

He turned the card over to the printed side. “Tyrone Kennedy. The state prosecutor’s office of New Jersey,” he said. “Does this mean I’m in trouble?”

“No. But if you ever get your ass in trouble in New Jersey, try calling my dad. He’s got connections.”

“And yet here you are.” He gestured around the dusty compound. Maybe she was like he’d been—aimless, needing to do something that mattered.

She gave a shrug. “I’m just saying, sir. Anywhere, anytime you need something from me, it’s yours.” She put the cap back on her canteen and headed into the mess, clearly a different person from the newbie he’d met just a few hours before.

He was surprised to see his hand shaking as he tucked the card into his pocket. Other than a few nicks and bruises, he wasn’t wounded, yet everything hurt. His nerve endings had nerve endings. After twenty-three months of numbing himself to all kinds of pain, he was starting to feel everything again.

Chapter One

Ulster County, New York

For a dying man, George Bellamy struck Claire as a fairly cheerful old guy. The dumbest show she’d ever heard was playing on the car radio, a chat hour called “Hootenanny,” and George found it hilarious. He had a distinctive, infectious laugh that seemed to emanate from an invisible center and radiate outward. It started as a soft vibration, then crescendoed to a sound of pure happiness. And it wasn’t just the radio show. George had recently received word that his grandson was coming home from the war in Afghanistan, and that added to his cheerfulness. He anticipated a reunion any day now.

Very soon, she hoped, for both their sakes.

“I can’t wait to see Ross,” said George. “He’s my grandson. He’s just been discharged from the army, and he’s supposed to be on his way back.”

“I’m sure he’ll come to see you straightaway,” she assured him, pretending he had not just told her this an hour ago.

The springtime foliage blurred past in a smear of color—the pale green of leaves unfurling, the yellow trumpets of daffodils, the lavish purples and pinks of roadside wildflowers.

She wondered if he was thinking about the fact that this would be his last springtime. Sometimes her patients’ sadness over such things, the finality of it all, was unbearable. For now, George’s expression was free of pain or stress. Although they’d only just met, she sensed he was going to be one of her more pleasant patients.

In his stylish pressed slacks and golf shirt, he looked like any well-heeled gentleman heading away from the city for a few weeks. Now that he’d ceased all treatment, his hair was coming back in a glossy snow-white. At the moment, his coloring was very good.

As a private-duty nurse specializing in palliative care for the terminally ill, she met all kinds of people—and their families. Though her focus was the patient, he always came with a whole host of relatives. She hadn’t met any of George’s family yet; his sons and their families lived far away. For the time being, it was just her and George.

He seemed very focused and determined at the moment. And thus far, he reported that he was pain free.

She indicated the notebook he held in his lap, its pages covered with old-fashioned spidery handwriting. “You’ve been busy.”

“I’ve been making a list of things to do. Is that a good idea?” he asked her.

“I think it’s a great idea, George. Everybody keeps a list of things they need to do, but most of us just keep it up here.” She tapped her temple.

“I don’t trust my own head these days,” he admitted, an oblique reference to his condition—glioblastoma multiforme, a heartlessly fatal cancer. “So I’ve taken to writing everything down.” He flipped through the pages of the book. “It’s a long list,” he said, almost apologetically. “We might not get to everything.”

“All we can do is the best we can. I’ll help you,” she said. “That’s what I’m here for.” She scanned the road ahead, unused to rural highways. To a girl from the exhausted midurban places of Jersey and the sooty bustle of Manhattan, the forest-clad hills and rocky ridges of the Ulster County highlands resembled an alien landscape. “It’s not such a bad idea to have too many things to do,” she added. “That way, you’ll never get bored.”

He chuckled. “In that case, we’re in for a busy summer.”

“We’re in for whatever summer you want.”

He sighed, flipping the pages. “I wish I’d thought about these things before I knew I was dying.”

“We’re all dying,” she reminded him.

“And how the devil did I luck into a home health care worker with such a sunny disposition?”

“I bet a sunny disposition would drive you crazy.” Although she and George were new to each other, she had a gift for reading people quickly. For her, it was a key survival skill. Misreading a person had once forced Claire to change every aspect of her life.

George Bellamy struck her as circumspect and wellread. Yet he had an air of loneliness, and he was seeking…something. She hadn’t discovered precisely what it was. She didn’t know a lot about him yet. He was a retired international news correspondent of some renown. He’d spent most of his adult years living in Paris and traveling the globe. Yet now at the end of his life, he wanted to journey to a place far different from the world’s capitals.

Lives came to an end with as much variety as they were lived—some quietly, some with drama and fanfare, some with a sense of closure, and far too many with regrets. They were the slow poison that killed the things that brought a person joy. It was amazing to her to observe the way a generally happy, successful life could be taken apart by a few regrets. She hoped George’s searching journey would be to a place of acceptance.

Those who were uninitiated in her area of care seemed to think that the dying knew the answers to the big questions, that they were wiser or more spiritual or somehow deeper than the living. This, Claire had learned, was a myth. Terminally ill patients came in all stripes—wise, foolish, filled with happiness or despair, logical, loony, fearful…in fact, the dying were very much like the living. They just had a shorter expiration date. And more physical challenges.

The countryside turned even prettier and more bucolic as they wended their way Northwest toward the Catskills Wilderness, a vast preserve of river-fed hills and forests. After a time, they approached their target destination, marked by a rustic sign that read, Welcome To Avalon. A Small Town With A Big Heart.

Her grip tightened almost imperceptibly on the steering wheel. She’d never lived in a small town before. The idea of joining an intimate, close-knit community—even temporarily—made Claire feel exposed and vulnerable. Not that she was paranoid, or—wait, she was. But she had her reasons.

There was no place that ever felt truly safe to her. The early days with her mother, even before all the trouble started, had been fraught with unpredictability and insecurity. Her mother had been a teenage runaway. She wasn’t a bad person, but a bad addict, shot during a drug deal gone wrong on Newark’s South Orange Avenue and leaving behind a quiet ten-year-old daughter.

Her life was transformed by the foster care system. Not many would say that, but in this instance, it was entirely true. Her caseworker, Sherri Burke, made sure she was placed with the best foster families in the system. Experiencing family life for the first time, she inhaled the lessons of life from people who cared. She learned what it was like to be a part of something larger and deeper than herself.

To appreciate the blessings of a family, all she had to do was watch. It was everywhere—in the look in a woman’s eyes when her husband walked through the door. In the touch of a mother’s hand on a child’s feverish brow. In the laughter of sisters, sharing a joke, or the protective stance of a brother, watching out for his siblings. A family was a safety net, cushioning a fall. An invisible shield, softening a blow.

She dared to dream of a better life—a love of her own, a family. Kids. A life filled with all the things that made people smile and feel a cushion of comfort when they were sad or hurting or afraid.

This can be yours was the promise of the system, when it was working as it should.

Then, at the age of seventeen, everything changed. She had witnessed a crime that forced her into hiding—from someone she had once trusted with her life. If that wasn’t a rationale for paranoia, she didn’t know what was.

A small town like this could be a dangerous place, especially for a person with something to hide. Anyone who read Stephen King novels knew that.

If worse came to worst, then she would simply disappear again. She was good at that.

She’d learned long ago that the witness protection programs depicted in the movies were pure fiction. A simple murder was not a federal case, so the federal witness protection program—WITSEC—was not an option for her. This was unfortunate, because the federal program, expertly administered and well-funded by the U.S. marshals, had a track record of effectively protecting witnesses without incident.

State and local programs were a different story. They were invariably underfunded. Taxpayers didn’t relish spending their money on these programs. The majority of informants and witnesses were criminals themselves, trading information for immunity from prosecution. The total innocents, such as Claire had been, were a rarity. Often, witness protection consisted of a one-way bus ticket and a few weeks in a motor court. After that, the witness was on her own. And for a witness like Claire, whose situation was so dangerous she couldn’t even trust the police, sometimes the only ally was luck.

Now the families she had been a part of so briefly seemed like a dream, or a life that had happened to someone else. She used to believe she’d have a family of her own one day, but now that was out of her reach. Yes, she could fall in love, have a relationship, kids, even. But why would she do that? Why would she create something in her life to love, only to expose it to the threat of being found out? So here she was, trapped into an existence on the fringes of other people’s families. She tried so hard to make it work for her, and sometimes it did. Other times, she felt as though she was drifting away, like a leaf on the wind.

“Almost there,” she said to George, noting the distance tracker on the GPS.

“Excellent. The journey is so much shorter than it seemed to me when I was a boy. Back then, everyone took the train.”

George had not explained to her exactly why he had decided to spend his final time in this particular place, nor had he told her why he was making the trip alone. She knew he would reveal it in due course.

People’s end-of-life experiences often involved a journey, and it was usually to a place they were intimately connected with. Sometimes it was where their story began, or where a turning point in life occurred. It might be a search for comfort and safety. Other times it was just the opposite; a place where there was unfinished business to be dealt with. What this sleepy town by Willow Lake was to George Bellamy remained to be seen.

The road followed the contours of a burbling treeshaded stream marked the Schuyler River, its old Dutch spelling as quaint as the covered bridge she could see in the distance. “I can’t believe there’s a covered bridge. I’ve never seen one before, except in pictures.”

“It’s been there for as long as I can remember,” George said, leaning slightly forward.

Claire studied the structure, simple and nostalgic as an old song, with its barn-red paint and wood-shingled roof. She accelerated, curious about the town that seemed to mean so much to her client. This might turn out to be a good assignment for her. It might even be a place that actually felt safe for once.

No sooner had the thought occurred to her than a blue-white flash of light battered the van’s rear-view mirror. A split second later came the warning blip of a siren.

Claire felt a sudden frost come over her. The tips of her fingernails chilled and all the color drained from her face; she could feel the old terror coming on with sudden swiftness. She battled a mad impulse to floor the accelerator and race away in the cumbersome van.

George must have read her mind—or her body language. “A car chase is not on my list,” he said.

“What?” Flushed and sweating, she eased her foot off the accelerator.

“A car chase,” he said, enunciating clearly. “Not on my list. I can die happy without the car chase.”

“I’m totally pulling over,” she said. “Do you see me pulling over?” She hoped he couldn’t detect the tremor in her voice.

“There’s a tremor in your voice,” he said.

“Getting pulled over makes me nervous,” she said. Understatement. Her throat and chest felt tight; her heart was racing. She knew the clinical term for her condition, but it was the layman’s expression she offered George. “Kind of freaks me out.” She stopped on the gravel verge and put the van in Park.

“I can see that.” George calmly drew a monogrammed gold money clip from his pocket. It was filled with neatly folded bills.

“What are you doing?” she demanded, momentarily forgetting her anxiety.

“I suspect he’ll be looking for a bribe. Common practice in third world countries.”

“We’re not in a third world country. I know it might not seem like it, but we’re still in New York.”

The patrol car, black and shiny as a jelly bean, kept its lights running, signaling to all passers-by that a criminal was being apprehended.

“Put that away,” she ordered George.

He did so with a shrug. “I could call my lawyer,” he suggested.

“I’d say that’s premature.” She studied the police car through the van’s side mirror. “What is taking so long?”

“He—or she—is looking up the vehicle records to see if there’s been an alert on it.”

“And why would there be an alert?” she asked. The van had been leased in George’s name with Claire listed as an authorized driver.

Yet something about his expression put her on edge. She glanced from the mirror to her passenger. “George,” she said in a warning voice.

“Let’s just hear the officer out,” he said. “Then you can yell at me.”

The approaching cop, even viewed through the side mirror, stirred a peculiar dread in Claire. The crisp uniform and silvered sunglass lenses, the clean-shaven square jaw and polished boots all made her want to cringe.

“License and registration,” he said. It was not a barked order but a calm imperative.

Her fingers felt bloodless as she handed over her driver’s license. Although it was entirely legitimate, even down to the reflective watermark and the organ donor information on the back, she held her breath as the cop scrutinized it. He wore a badge identifying him as Rayburn Tolley, Avalon PD. George passed her the folder containing the van’s rental documents, and she handed that over, too.

Claire bit the inside of her lip and wished she hadn’t come here. This was a mistake.

“What’s the trouble?” she asked Officer Tolley, dismayed by the nervousness in her voice. No matter how much time had passed, no matter how often she exposed herself to cops, she could never get past her fear of them. Sometimes even a school crossing guard struck terror in her.

He scowled pointedly at her hand, which was trembling. “You tell me.”

“I’m nervous,” she admitted. She had learned over the years to tell the truth whenever possible. It made the lies easier. “Call me crazy, but it makes me nervous when I get pulled over.”

“Ma’am, you were speeding.”

“Was I? Sorry, Officer. I didn’t notice.”

“Where are you headed?” he demanded.

“To a place called Camp Kioga, on Willow Lake,” said George, “and if she was speeding, the fault is mine. I’m impatient, not to mention a distraction.”

Officer Tolley bent slightly and peered across the front seat to the passenger side. “And you are…?”

“Beginning to feel harassed by you.” George sounded righteously indignant.

“You wouldn’t happen to be George Bellamy, would you?” asked Tolley.

“Indeed I am,” George said, “but how did you—”

“In that case, ma’am,” the cop said, returning his attention to Claire, “I need to ask you to step out of the vehicle. Keep your hands where I can see them.”

Her heart seized up. It was a moment she had dreaded since the day she’d realized she was a hunted woman. The beginning of the end. Her mind raced, although she moved like a mechanical wooden doll. Should she submit to him? Make a break for it?

“See here now,” George said. “I would like to know why you’re so preoccupied with us.”

“George, the man’s doing his job,” said Claire, hoping that would mollify the cop. She motioned for him to sit tight and did as she was told, stepping down awkwardly, using the door handle to steady herself.

Tolley didn’t seem put off by George’s question. “There was a call to the station about you and Miss…” He consulted the license, which was still clipped to his board. “Turner. The call was from a family member.” He glanced at a printout the size of a cash register receipt on the clipboard. “Alice Bellamy,” he said.

Claire looked over her shoulder at George, a question in her eyes.

“One of my daughters-in-law,” he said, a note of apology in his voice.

“Sir, your family is extremely worried about you,” said the cop. He stared at Claire. She couldn’t discern his eyes behind the lenses, but could see her own reflection clearly, in twin, convex detail. Medium-length dark hair. Large dark eyes. A plain, she hoped, ordinary, nondescript face. That was always the goal. To blend in. To be forgettable. Forgotten.

She forced herself to keep her chin up, to pretend everything was fine. “Is that a crime around here?” she asked. “To have a worried family?”

“It’s more than worry.” Officer Tolley rested his right hand atop the holster carrying his service revolver. She could see that he’d released the safety strap. “Mr. Bellamy’s family has some serious concerns about you.”

She swallowed hard. The Bellamys were made of money. Maybe the daughter-in-law had ordered a deep and thorough background check. Maybe that check had uncovered some irregularity, something about Claire’s past that didn’t quite add up.

“What kind of concerns?” she asked, dry-mouthed, consumed by terror now.

“Oh, let me guess,” George suggested with a blast of laughter. “My family thinks I’ve been kidnapped.”

Chapter Two

KAIA (Kabul Afghanistan International Airport)

“She did what?” Ross practically shouted into the borrowed mobile phone.

“Sorry, we have a terrible connection,” said his cousin Ivy, speaking to him from her home in Santa Barbara, where it was eleven and a half hours earlier. “She kidnapped Granddad.”

Ross rotated his shoulders, which felt curiously light. For the past two years, he’d been burdened by twenty pounds of individual body armor plates, a Kevlar helmet and vest. Now that he was headed home, the weight was gone. He’d turned in the IBA plates, shedding them like a molting beetle.

Yet according to his cousin, the civilian life had its own kind of perils.

“Kidnapped? ” The loaded word snagged the attention of the others in the waiting room. He waved his hand, a non-verbal signal that all was well, and turned away from the prying eyes.

“You heard me,” Ivy said. “According to my mother, he hired some sketchy home health care worker off of Craigslist, and she kidnapped him and took him to some remote mountain hideaway up in Ulster County.”

“That’s nuts,” he said. “That’s completely nuts.” Or was it? In this part of the world, kidnappings were common. And they rarely had a good outcome.

“What can I say?” Ivy sounded almost apologetic. “It’s my mom at her most dramatic.”

Growing up, first cousins Ross and Ivy had bonded over their drama-queen mothers. A few years younger than Ross, Ivy lived in Santa Barbara, where she created avant garde sculpture and wrote long, angsty e-mails to her cousin overseas.

“And you’re certain Aunt Alice’s overreacting? There’s no chance she might be on to something?”

“There’s always a chance. That’s how my mom operates—within the realm of possibility. She thinks Granddad is losing it. Everybody knows brain tumors make people do crazy things. When can you get to New York?” asked Ivy. “We really need you, Ross. Granddad needs you. You’re the only one he listens to. Where the hell are you, anyway?”

Ross looked around the foreign airport, jammed with soldiers in desert fatigues, trading stories of firefights, suicide bombers, roadside ambushes. Transport here had been his last movement on the ground. He remembered thinking, please don’t let anything happen now. He didn’t want to be one of those depressing items you read about in hometown newspapers—On his last day of deployment, he died in a convoy attack…

He pictured Ivy in her bohemian guest house on the bluffs above Hendry’s Beach. He could hear a Cream album playing in the background. She was probably making coffee in her French press and watching the surfers paddle to the beach-break for an early morning ride.

“I’m on my way,” he said. The homeward-bound soldiers had all been sitting at KAIA for hours. Time dragged at the pace of a glacier. Originally their flight was supposed to leave at 1400, but that had been delayed to 2145. They’d been ordered back to the departure tent and subjected to mandatory lockdown, which meant sitting in an airless tent with nothing to do until it was time to board: 2145 had come and gone, the delay surprising no one.

“Ross?” His cousin’s voice prodded him. “How much longer before you’re home?”

“Working on it,” he said to her. At the moment, he might as well be on a different planet; he felt that far away. “What’s going on with Granddad?”

“Here’s what I know. He’s been in treatment at the Mayo Clinic. I guess they told him then…” She paused, and a sob pulsed through the phone. “They told him it was the worst possible news.”

“Ivy—”

“It’s inoperable. I don’t think even my mother would exaggerate that. He’s going to die, Ross.”

Ross felt sucker-punched by the words. For a few seconds, he couldn’t breathe or see straight. There had to be some mistake. A month ago, Ross had received the usual communiqué from his grandfather. George Bellamy had a curiously old-fashioned style of writing, even with e-mail, starting each message with a proper heading and salutation. He had mentioned the Mayo Clinic—"nothing to worry about.” Ross had failed to read between the lines. He hadn’t let himself go there, even though he knew damn well a guy didn’t go to the Mayo Clinic for a hangnail. He hadn’t let himself think about…sweet Jesus…a terminal prognosis.

Granddad’s sign-off was always the same: Keep Calm and Carry On.

And that, in essence, was the way George Bellamy lived. Apparently it was the way he was going to die.

“He finally told my dad,” Ivy was saying. There was still a catch in her voice. “He said he wasn’t going to pursue further treatment.”

“Is he scared?” Ross asked. “Is he in pain?”

“He’s just…Granddad. He claimed he had to go to some little town in the Catskills to see his brother. That was the first I’d heard of any brother. Did you know anything about that?”

“Wait a minute, what? Granddad has a brother?”

The connection crackled ominously, and he missed the first part of her reply. “…anyway, when my mother heard what he was planning, she went, like, totally ballistic.”

Fighting the poor connection and the ambient din of the airport, Ross listened as his cousin filled him in further. Their grandfather had called each of his three sons—Trevor, Gerard and Louis—and he’d calmly informed them of the diagnosis. Then, like a follow-up punch, George had announced his intention to leave his Manhattan penthouse and head for a backwater town upstate to see his brother, some guy named Charles Bellamy. Like Ivy and Ross, most people in the family didn’t even know he had a long-lost brother. How could he have a brother nobody knew about? Was he some guy hidden away in an asylum somewhere, like in the movie Rain Man? Or was he a figment of Granddad’s increasingly unreliable imagination?

“So you are telling me he’s headed upstate with some sketchy woman who is…who, again?” he asked.

“Her name is Claire Turner. Claims to be some kind of nurse or home health worker. My mom—and yours, too, I’m sure—thinks she’s after his money.”

That would always be the first concern of Aunt Alice and of his mother, Ross reflected. Though Bellamys only by marriage, they claimed to love George like a father. And maybe they did, but Ross suspected Alice’s tantrum was less about losing her father-in-law than it was about splitting her inheritance. He also had no doubt his mother felt the same way. But that was a whole other conversation.

“And they called the police to stop her,” Ivy added.

“The police?” Ross shoved a hand through his close-cropped hair. He realized he’d raised his voice again and turned away. “They called the police?” Holy crap. Apparently his mother and aunt had managed to persuade the local authorities that George was with a stranger who meant him harm.

“They didn’t know what else to do,” said Ivy. “Listen, Ross. I’m so worried about Granddad. I’m scared. I don’t want him to suffer. I don’t want him to die. Please come home, Ross. Please—”

“I requested an expedited discharge,” he assured her. So far, the promised out-processing hadn’t given him much of a head start.

His cousin acted as though his homecoming was going to bring about a miraculous cure for their grandfather. Ross already knew miracles weren’t reliable. “When are you flying to New York?” he asked, but by then he was speaking to empty air; the connection had been lost. He shut the mobile phone and brought it over to Manny Shiraz, a fellow chief warrant officer who had lent it to him when Ross’s phone had failed.

“Trouble at home?” Manny asked. It was the kind of question that came up for guys on deployment, again and again.

Ross nodded. “God forbid I should go home and find everything is fine.”

“Welcome to the club, Chief.”

The idyllic homefront was usually a myth, yet everybody in the waiting area was amped up about going back. There were men and women who hadn’t seen their families in a year, some even longer than that. Babies had been born, toddlers had taken their first steps, marriages had crumbled, holidays had passed, loved ones had died, birthdays had been celebrated. Everyone was eager to get back to their lives.

Ross was eager, too—but he didn’t have much of a life. No wife and kids counting the hours to his return. Just his mother, Winifred, a flighty and self-absorbed woman…and Granddad.

George Bellamy had been the touchstone of Ross’s life since the moment a Casualty Assistance Calls Officer had knocked at the door, arriving in person to tell Winifred Bellamy and her son that Pierce Bellamy had been killed during Operation Desert Storm in 1994.

Granddad had flown to New York from Paris on the Concorde, which was still operating in those days. He had traveled faster than the speed of sound to be with Ross. He’d pulled his grandson into his arms, and the two of them had cried together, and Granddad had made a promise that day: I will always be here for you.

They had clung to each other like survivors of a tsunami. Ross’s mother all but disappeared into a whirlwind of panicked grief that culminated in a feverish round of dating. Winifred recovered from her loss quickly and decisively, sealing the deal by remarrying and adopting two stepkids, Donnie and Denise. Ross had been shipped off to school in Switzerland because he had difficulty “accepting” his stepfather and his charming stepbrother and stepsister. The American School in Switzerland offered a comprehensive residential educational program. His mother convinced herself that the venerable institution would do a better job raising her son than she herself ever could.

Ross’s grief had been so raw and painful he couldn’t see straight. Sometimes he wanted to ask her, “In what world is it okay to look at a kid who’d just lost his father and say to him, ‘Boarding school! It’s just the thing for you!’?”

Then again, maybe her instincts had been right. There were students at TASIS who thrived on the experience—a residential school as magical in its way as Hogwarts itself. He hadn’t known it back then, but maybe the long separations and periods of isolation had helped prepare him for deployment.

Being sent an ocean away after losing his dad could have pushed him over the edge, but there was one saving grace in his situation—Granddad. He’d been living and working in Paris and he visited Ross at school in Lugano nearly every single weekend, a lifeline of compassion. Granddad probably didn’t realize it, but he’d saved Ross from drowning. He shut his eyes, picturing his grandfather—impressively tall, with abundant white hair. He’d never seemed old to Ross, though.

On the eve of his deployment, Ross had made a promise to his grandfather. “I’m coming back.”

Granddad had not had the expected reaction. He’d turned his eyes away and said, “That’s what your father told me.” It was a negative thing to say, especially for Granddad. Ross knew the words came from fear that he’d never make it home.

He paced, feeling constrained by the interminable waiting. Waiting was a way of life in the army; he’d known that going in but he’d never grown used to it. When he’d announced his intention to serve his country, Ross had known the news would hit his grandfather hard, bringing back the hammer-blows of shock and relentless grief of losing Pierce. But it was something Ross had to do. He’d tried to talk himself out of it. Ultimately he felt compelled to go, as though to complete his father’s journey.

Ross had started adulthood as a spoiled, self-indulgent, overgrown kid with no strong sense of direction. Things came easily to him—grades, women, friends—perhaps too easily. After college, he’d drifted, unable to find his place. He’d attained a pilot’s license. Seduced too many women. Finally realized he’d better find a vocation that actually meant something. At the age of twenty-eight, he walked into a recruitment office. His age raised eyebrows but they’d given him no trouble; he was licensed to fly several types of aircraft and spoke three languages. The army had given him more of a life than he’d found on his own. Flying a helo was the hardest thing in the world, and for that reason, he loved it. But he couldn’t honestly say it had brought him any closer to his father.

Eventually the first wave of soldiers was taken to the plane. Another hour passed before the bus came back for the rest. Walking onto the transport plane, Ross felt no jubilation; pallets laden with black boxes and duffel bags were still sitting on the tarmac, not yet loaded. This ate up another hour.

A navy LCDR boarded, settling in across from Ross. She flashed him a smile, then pulled out a glossy fashion magazine stuffed with articles about make-up. Ross tried to focus on his copy of Rolling Stone, but his mind kept straying.

About an hour into the flight, the LCDR leaned forward to look out the window, cupping her hands around her eyes. “We’re not in Afghanistan anymore.”

It was too dark to see the ground, but the portal framed a perfect view of the Big Dipper. Ross’s grandfather had taught him about the stars. When Ross was about six or seven, Granddad had taken him boating in Long Island Sound. It had been just the two of them in a sleek catboat. Ross had just earned his Arrow of Light badge in Cub Scouts, and Granddad wanted to celebrate. They had dined on lobster rolls, hot French fries in paper cones and root beer floats from a busy concession stand. Then they’d sailed all evening, until it was nearly dark. “Is that where heaven is?” Ross had asked him, pointing to the sparkling swath of the Milky Way.

And Granddad had reached over, squeezed his hand and said, “Heaven’s right here, my boy. With you.”

There was a stopover in Manas Air Base in Kyrgyzstan, where the air was cool and smelled of grass. During the three-hour wait for bags, he tried calling his grandfather, then Ivy, then his mother, with no luck, so he headed to the chow hall to get something to eat. Although it was the middle of the night, the place was bustling. Ross studied the army’s morale, welfare and recreation posters advertising sightseeing tours, golf excursions and spa services, which sounded as exotic as a glass of French brandy. Before he’d enlisted, everyday luxuries had been commonplace in his life, thanks to his grandfather. Ross was returning hardened by the things he’d seen and done. But at least he was keeping the promise he’d made to his grandfather.

Please be okay, Granddad, he thought. Please be like a wounded soldier who gets patched up and sent back out into battle. At the next layover in Baku, Georgia, he had the urge to bolt and travel like a civilian, but he quelled the impulse and bided his time, waiting for the flight to Shannon Airport, in Ireland. He couldn’t allow himself to veer off track, not now.

Because now, it seemed his grandfather was acting crazy, giving up on treatment and haring off after a brother he hadn’t bothered to mention before.

During his deployment, Ross had learned a lot about saving lives—but from shrapnel wounds and traumatic amputations, not brain tumors. There was an image stuck in his head, from that last sortie. He kept thinking about the boy and the wounded old man, trapped in that house, clinging to each other. Everything had been stripped away from those two, yet they’d radiated calm. He’d never found out what became of the two villagers; follow-ups were rare.

He wished he’d checked on them, though.

Chapter Three

“Well, now,” said George, buckling his seat belt. “That was exciting.”

Claire pulled back onto the road, trying to compose herself. “I can do without that kind of excitement.” She drove slowly, with extra caution, as though a thousand eyes were watching her.

George seemed unperturbed by the encounter with the cop. He had politely pointed out that it was a free country, and just because certain family members were worried didn’t mean any laws had been broken.

Officer Tolley had asked a number of questions, but to Claire’s relief, most of them were directed at George. The old man’s no-nonsense replies had won the day. “Young man,” he’d said. “Much as I would enjoy being held captive by an attractive woman, it’s not the case.”

Claire had produced her state license and nursing certificate, trying to appear bland and pleasant, an ordinary woman. She’d had plenty of practice.

The effort must have succeeded because ultimately, the cop could find no reason to detain them. He sent them on their way with a “Have a nice day, folks.”

“Still all right?” she asked George, spying a service station up ahead. “Want to stop here?”

“No, thank you,” he said. “We’re nearly there, eh?”

She indicated the gizmo on the console between them. “According to the GPS, another eleven-point-seven miles.”

“When I was a boy,” said George, “we would take the train from Grand Central to Avalon. From there, we’d board an old rattletrap bus waiting at the station to take us up to Camp Kioga.” He paused. “Sorry about that.”

“About what?”

“Starting a story with ‘when I was a boy.’ I’m afraid you’re going to be hearing that from me a lot.”

“Don’t apologize,” she said. “Everybody’s story starts somewhere.”

“Good point. But to the world at large, my own story is not that interesting.”

“Everyone’s life is interesting,” she pointed out, “in its own way.”

“Kind of you to say,” he agreed. “I’m sure you are no exception. I’m looking forward to getting to know you.”

Claire said nothing. She kept her eyes on the road—a meandering, little-traveled country road leading to the small lakeside hamlet of Avalon.

Which Claire would she show him, this kindly, doomed old man? The star nursing student? The single woman who kept no possessions, who lived her life from job to job? She wondered if he would see through her, recognizing the rootless individual hiding behind the thin veneer of a made-up life. Occasionally one of her patients discerned something just a bit “off” with her.

Which was one reason she worked only with the terminally ill. A grim rationale, but at least she didn’t fool herself about it.

“Trust me,” she said to George, “I’m not that interesting.”

“You most certainly are,” he said. “Your career, for example. I find it a fascinating choice for a young woman. How did you get into this line of work, anyway?”

She had a ready answer. “I’ve always liked taking care of people.”

“But the dying, Claire? That’s got to get you down sometimes, eh?”

“Maybe that’s why my clients are rich old bastards,” she said, keeping her expression deadpan.

“Ha. I deserved that. Still, I’m curious. You’re a lovely, bright young woman. Makes me wonder…”

She didn’t want him to wonder about her. She was a very private person, not as a matter of choice, but as a matter of life and death. She lived a life made up of lies that had no substance, and secrets she could never share. The things that were true about her were the shallow details, cocktail party fare, not that she got invited to cocktail parties. The person she was deep inside stayed hidden, and that was probably for the best. Who would want to know about the endless nights, when her loneliness was so deep and sharp she felt as though she’d been hollowed out? Who would want to know she was so starved for a human touch that sometimes her skin felt as if it were on fire? Who could understand the way she wished to crawl out of her skin and walk away?

Back when she’d gone underground, she had saved her own life. But it wasn’t until much later that she’d realized the cost. It had been simple and exorbitant; she’d given up everything, even her identity.

“Tell you what,” she said, “let’s keep the focus on you.”

“I’ve never been able to resist a woman of mystery,” he declared. “I’ll find out if it kills me. It might just kill me.” His amusement wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. Humor had its uses, even in this situation.

“You have better things to do with your time than pry into my life, George. I’d rather hear about you, anyway. This summer is all about you.”

“And you don’t find that depressing? Hanging around an old man, waiting for him to die?”

“All kidding aside,” she said, “things will go a lot better if you decide to make this summer about your life, not about your death.”

“My family thinks you’re not right for me.”

“I guessed that when they called the police on us. Maybe I’m not right. We’ll see.”

“So far, we’re getting along famously.” He paused. “Aren’t we?”

“You just hired me. We’ve only been together for three days.”

“Yes, but it’s been an intense three days,” he pointed out. “Including this long drive from the city. You can tell a lot about a person on a car trip. You and I are getting along fine.” Another pause. “You’re silent. You don’t agree?”

Claire had a policy of trying to be truthful whenever possible. There were so many lies in other areas of her life, this need not be one of them. “Well,” she said almost apologetically, “there was the singing, back in Poughkeepsie.”

“Everybody sings on car trips,” he said. “It’s the American way.”

“All right. Forget I said anything.”

“Was I really that bad?”

“You were pretty bad, George.”

“Damn.” He flipped through a few pages of his notebook.

“Just keeping it real,” she said.

“Oh, I don’t mind that you hated my singing,” he said. “But you’re making me rethink something on my list. Ah, here it is. I wanted to perform a song for my family.”

“You could still do that.”

“What, so they won’t be sad to see me go?”

“You just need a little backup music for accompaniment, and you’ll be fine.”

“Are you up for it?” he asked.

“No way. I can’t sing. I’ll find someone to help you.”

“I’m going to hold you to that.”

Simple, she thought. All she needed to do was find a karaoke place. And get his family to show up. Okay, maybe not so simple.

“Judging by our encounter with Officer Friendly, your relatives are pretty unhappy with me,” she said. She didn’t much care. As her client, George was her sole concern. Still, it always went better if the family was supportive of the arrangement, because families had a way of complicating things. Sometimes she told herself that the lack of a family was a blessing in disguise. Certainly it was a complication she never had to deal with.

She often imagined about what it was like to have a family, the way a severe diabetic might think about eating a cake with burnt-sugar icing. It was never going to happen, but a girl could fantasize. Sometimes she covertly attended family gatherings—graduation ceremonies, outdoor weddings, even the occasional funeral—just to see what it was like to have a family. She had a fascination with the obituary page of the paper, her attention always drawn to lengthy lists of family members left behind. Which, when she thought about it, was kind of pathetic, but it seemed harmless enough.

“They’re too quick to judge,” he said. “They haven’t even met you yet.”

“Well, you did make all these arrangements rather quickly.”

“If I hadn’t, they would have tried to stop me. They’d say we’re incompatible, that you and I are far too different,” he pointed out.

“Nonsense,” said Claire. “You’re a blueblood, and I’m blue collar—it’s just a color.”

“Exactly,” he said.

“We’re all in the same race,” she added.

“I’m closer to the finish line.”

“I thought we were going to try to keep a positive attitude.”

“Sorry.”

“This is going to go well,” she promised him.

“It’s going to end badly for one of us.”

“Then let’s not focus on the ending.”

There were known psychological and clinical end-of-life stages people went through when facing a devastating diagnosis—shock, rage, denial and so forth. Everyone in her field of work had memorized them. In practice, patients expressed their stages in ways that were as different and individual as people themselves.

Some held despair at bay with denial, or by displaying a smart-alecky attitude about death. George seemed quite happy to be in that phase. His wry sense of humor appealed to her. Of course, he was using humor and sarcasm to keep the darker things at bay—dread and uncertainty, abject fear, regret, despair. In time, those might or might not materialize. It was her job to be there through everything.

All her previous patients had been in the city, where it was possible to be an anonymous face in the crowd. This was the first time she had ventured somewhere like this—small and old-fashioned, more like an illustration in a storybook than a real place. It was like coming to a theme park, overrun by trees and beautiful wilderness areas and dotted with picturesque farms and painted houses.

“Avalon,” she said as they passed another welcome sign, this one marked with a contrived-looking heraldic shield. “I wonder if it’s named after a place from Arthurian legend.” She’d gone through a teenage obsession with the topic, using books as a refuge from a frightening and uncertain life. One of her foster mothers, an English professor, had taught her how to live deeply in a story, drawing inspiration from its lessons.

“I imagine that’s what the founders had in mind. Avalon is where Arthur went to die,” George said.

“Not exactly. It’s the island where Excalibur was forged, and where Arthur was taken to recover from his wounds after his last battle.”

“Ah, but did he ever recover?”

She glanced over at him. “Not yet.”

The first thing she did when arriving at a new place was reconnoiter the area. It had become second nature to plan her escape route. The world had been a dangerous place for her since she was a teenager. Avalon was no exception. To most people, a town like this represented an American ideal, with its scrubbed façades and tranquil natural setting. Tree-lined avenues led to the charming center of town, where people strolled along the swept sidewalks, browsing in shop windows.

To Claire, the pretty village looked as forbidding as the edge of a cliff. One false step could be her last. She was already sensing that it was going to be harder to hide here, especially now that she’d been welcomed by the law.

She took note of the train station and main square filled with inviting shops and restaurants, their windows shaded by striped and scalloped awnings. There was a handsome stone building in the middle of a large park—the Avalon Free Library. In the distance was the lake itself, as calm and pristine as a picture on a postcard.

It was late afternoon and the slant of the sun’s rays lengthened the shadows, lending the scene a deep, golden tinge of nostalgia. Old brick buildings, some of them with façades of figured stonework, bore the dates of their founding—1890, 1909, 1913. A community bulletin board announced the opening game of a baseball team called the Hornets, to be celebrated with a pre-game barbecue.

“Are you a baseball fan?” she asked.

“Devotedly. Some of my fondest memories involve going to the Yankee stadium with my father and brother. Saw the Yankees win the World Series over the Phillies there in 1950. Yogi Berra hit an unforgettable homer in that game.” His eyes were glazed by wistful sentiment. “We saw Harry Truman throw out the first pitch of the season one year. He did one with each hand, as I recall. I’ve often fantasized about throwing out the game ball. Never had the chance, though.”

“Put it on your list, George,” she suggested. “You never know.”

They passed a bank and the Church of Christ. There were a couple of clothing boutiques, a sporting goods store and a bookstore called Camelot Books. There was a shop called Zuzu’s Petals, and a grand opening banner hung across the entrance of a new-looking establishment—Yolanda’s Bridal Shoppe. Some of the upper floors of the buildings housed offices—a pediatrician, a dentist, a lawyer, a funeral director.

One-stop shopping, she thought. A person could live and die here without ever leaving.

The idea of spending one’s entire life in a single place was almost completely unfathomable to Claire.

She stopped at a pedestrian crossing and watched a dark-haired boy cross while tossing a baseball from hand to hand. On the corner, a blonde pregnant woman came out of a doctor’s office. The residents of the town resembled people everywhere—young, old, alone, together, all shapes and sizes. It reminded her that folks tended to be the same no matter where she went. They lived their lives, loved each other, fought and laughed and cried, the years adding up to a life. The residents of Avalon were no different. They just did it all in a prettier place.

“Well, George?” she asked. “What do you think? How does it look to you?”

“The town has changed remarkably little since I was last here,” George said. “I wasn’t sure I’d recognize anything.” His hands tightened around the notebook he held in his lap. “I think I want to die in Avalon. Yes, I believe this is where I want it to happen.”

“When was the last time you visited?” she asked, deliberately ignoring his statement for the time being.

“It was August twenty-fourth, 1955,” he said without hesitation. “I left on the 4:40 train. I never dreamed another fifty-five years would pass.”

That long, thought Claire. What would bring him back to a place after so much time?

“Would you mind pulling in here?” George asked. “I need to make a stop at this bakery. It was here when I last visited.”

She berthed the van in a big parking spot marked with a disabled symbol. On good days, George could walk fairly well, and today seemed to be a good day. However, they were in a new place and she didn’t want to push their luck.

The Sky River Bakery and Café had a hand-painted sign proclaiming its establishment in 1952. It was a beautiful spring day, and tables with umbrellas sprouted along the sidewalk in front of the place, shading groups of customers as they enjoyed icy drinks and decadent-looking sweets.

She went around to the passenger side of the van to help him. The key to helping a patient, she’d learned from experience, was to take her cues from him. Respect and dignity were her watchwords.

Though she had a wheelchair available, he opted for his cane, an unpretentious one with a rubber-tipped end. She helped him down and they stood together for a moment, looking around. His somewhat cocky persona slipped a little to reveal a face gone soft with uncertainty.

“George?” she asked.

“Do I look…all right?”

She didn’t smile, but her heart melted a little. Everyone had their insecurities. “I was just thinking you look exceptionally good. In fact, it’s kind of nice to tell you the truth instead of having to pretend.”

“You’d do that? You’d pretend I looked well, even if I didn’t?”

“It’s all a matter of perspective. I’ve told people they look like a million bucks when in fact they look like death on a cracker.”

“And they don’t see through that?”

“People see what they want to see. In your case, there’s no need to lie. You’re quite handsome. The driving cap is a nice touch. Where did you learn to dress like this?”

“My father, Parkhurst Bellamy. He was always quite clear on the way a gentleman should dress, for any occasion—even a bakery visit. He took my brother and me all the way to London for our first bespoke suits at Henry Poole, on Savile Row. I still get my clothing there.”

“Bespoke?”

“Made-to-measure and hand tailored.” He glanced at himself in a shop window. “Do me a favor. If I ever get to the stage where I look like death on a cracker, go ahead and lie to me.”

“It’s a deal.” She hesitated. “So do you expect to see someone you know in the bakery?”

He offered a rueful smile. “After all this time? Not likely. On the other hand, it never hurts to be prepared for the unlikely.” He squared his shoulders and gripped the head of the cane. “Shall we?” He gallantly held the shop door for her.

The bakery smelled so good she practically swooned from the aroma of fresh baked bread, buttery pastries, cookies and fruit pies, and a specialty of the house known as the kolache, which appeared to be a rich, pillowy roll embedded with fruit jam or sweet cheese.

A song by the Indigo Girls drifted from two small speakers. The shop had a funky eclectic decor, with black-and-white checkerboard floors and walls painted a sunny yellow. There was a cat clock with rolling eyes and a pendulum tail, and a hand-lettered menu board. Behind the counter on the wall was a framed dollar bill and various permits and licenses. A side wall featured a number of matted art photographs and articles, including a yellowed newspaper clipping about the bakery’s grand opening nearly sixty years ago.

George seemed like a different person here: gentle and pensive, shedding the impatience he’d shown occasionally on the drive from the city. A small line of patrons were clustered at the main counter. George waited his turn, then ordered indulgently—a cappuccino, a kolache and an iced maple bar. He also ordered a box of bialys and a strawberry pie to go.

She ordered a glass of iced tea sweetened with Stevia.

They took a seat at a side table decorated with a large travel poster depicting a scene at the lake. A guy in a flour-dusted apron and a name tag identifying him as Zach brought their order. He was an unusual-looking young man, his hair so blond it appeared white—naturally, not bleached. Claire had changed her own hair color enough times to know the difference.

“Enjoy,” he said, serving them.

“You didn’t order anything.” George aimed a pointed look at her glass of tea. “How can you come to a place like this and not want to sample at least one thing?”

“Believe me, I want to sample everything,“ she admitted. “I can’t, though. I, um, used to have a pretty bad weight problem. I really have to watch every single thing I put in my mouth.”

“You’re showing remarkable self-denial.”

So much of her life boiled down to that, to self-denial. What she couldn’t tell him was that her diet was not a matter of vanity alone. It was a matter of survival. As a teenager, she had used food as a comfort and a crutch, turning herself into the dateless fat girl. She was the nightmare everyone remembered from high school—overweight, reviled and given over to foster care.