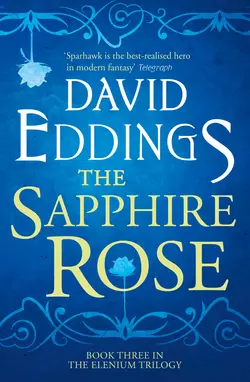

The Sapphire Rose

David Eddings

Book Three of the ELENIUM is fantasy on a truly epic scale, in which the Pandion Knight Sparhawk must finally use the power of the jewel.Sparhawk and his allies have recovered the magical sapphire Bhelliom, giving them the power to wake and cure Queen Ehlana.But while they were away an unholy alliance was brokered between their enemies that threatens the safety of not just Elenia but the entire world.By returning to save the young queen, Sparhawk risks delivering the Bhelliom into the hands of the enemy.As battle looms, Sparhawk’s only hope may be to unleash the jewel’s full power. But no one can predict whether this will save the world or destroy it…

DAVID EDDINGS

The Sapphire Rose

The Elenium

BOOK THREE

Copyright (#ulink_5e28bda5-ae7f-5aaa-96ff-d6805142e119)

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk/)

This edition 1995

Previously published in paperback by Grafton 1992, reprinted once, and by HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1993, reprinted twice

First published in Great Britain by Grafton 1991

Copyright © David Eddings 1991

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015 Cover images © Shutterstock.com

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007127832

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2010 ISBN: 9780007375080

Version 2015-03-20

Contents

Cover (#uef60fc49-7bc3-5447-a766-b57652659621)

Title Page (#ub4203673-09bb-55e1-a1a5-4f180ac547b3)

Copyright (#u1a92c0b3-3f6f-59d7-b8a6-81c14273b49f)

Map (#ue30aa0c6-5ab9-5201-9a2f-8ad79f49564a)

Prologue (#u1f9f5c95-2f87-5a3d-ad2b-f71481ecefee)

Part One: The Basilica (#ua5cf558f-fb09-5a01-b9ab-0cbc2c6d0739)

Chapter 1 (#u525dbd24-7c64-56ff-87f2-fa4bfa1085f3)

Chapter 2 (#ua08d304a-a668-5ef0-ad80-dd506935d9b7)

Chapter 3 (#uda57499e-9be9-5572-b9ed-ee81a9b8980e)

Chapter 4 (#u494df017-3e6a-56fc-92d5-43fb0ce82721)

Chapter 5 (#u95a9d408-3e37-563c-8c70-54bcdf5467ee)

Chapter 6 (#u601569b6-c05c-595a-893a-f4c537c68843)

Chapter 7 (#u19ff264d-f535-56f4-bb97-4977676de6ae)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: The Archprelate (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Zemoch (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Map (#ulink_9b0451e6-76f5-5853-bb66-9d7c9d3df0bb)

Prologue (#ulink_e7b69558-4f80-5d37-9b78-0597cba597bd)

Otha and Azash – Excerpted from A Cursory History of Zemoch. Compiled by the History Department of the University of Borrata.

Following the invasion of the Elenic-speaking peoples from the steppes of central Daresia lying to the east, the Elenes gradually migrated westward to displace the thinly scattered Styrics who inhabited the Eosian continent. The tribes which settled in Zemoch were latecomers, and they were far less advanced than their cousins to the west. Their economy and social organization were simplistic, and their towns rude by comparison with the cities which were springing up in the emerging western kingdoms. The climate of Zemoch, moreover, was at best inhospitable, and life there existed at the subsistence level. The Church found little to attract her attention to so poor and unpleasant a region; and as a result, the rough chapels of Zemoch became largely unpastored and their simple congregations untended. Thus the Zemochs were obliged to take their religious impulses elsewhere. Since there were few Elene priests in the region to enforce the Church ban on consorting with the heathen Styrics, fraternization became common. As the simple Elene peasantry perceived that their Styric neighbours were able to reap significant benefits from the use of the arcane arts, it is perhaps only natural that apostasy became rampant. Whole Elenic villages in Zemoch were converted to Styric pantheism. Temples were openly erected in honour of this or that topical God, and the darker Styric cults flourished. Intermarriage between Elene and Styric became common, and by the end of the first millennium, Zemoch could no longer have been considered in any light to be a true Elenic nation. The centuries and the close contact with the Styrics had even so far corrupted the Elenic language in Zemoch that it was scarcely intelligible to western Elenes.

It was in the eleventh century that a youthful goatherd in the mountain village of Ganda in central Zemoch had a strange and ultimately earth-shaking experience. While searching in the hills for a straying goat, the lad, Otha by name, came across a hidden, vine-covered shrine which had been erected in antiquity by one of the numerous Styric cults. The shrine had been raised to a weathered idol which was at once grotesquely distorted and at the same time oddly compelling. As Otha rested from the rigours of his climb, he heard a hollow voice address him in the Styric tongue. ‘Who art thou, boy?’ the voice inquired.

‘My name is Otha,’ the lad replied haltingly, trying to remember his Styric.

‘And hast thou come to this place to pay obeisance to me, to fall down and worship me?’

‘No,’ Otha answered with uncharacteristic truthfulness. ‘What I’m really doing is trying to find one of my goats.’

There was a long pause. Then the hollow, chilling voice continued. ‘And what must I give thee to wring from thee thine obeisance and thy worship? None of thy kind hath attended my shrine for five thousand years, and I hunger for worship – and for souls.’

Otha was certain at this point that the voice was that of one of his fellow herders playing a prank on him, and he determined to turn the joke around. ‘Oh,’ he said in an offhand manner, ‘I’d like to be the king of the world, to live forever, to have a thousand ripe young girls willing to do whatever I wanted them to do, and a mountain of gold – and, oh yes, I want my goat back.’

‘And wilt thou give me thy soul in exchange for these things?’

Otha considered it. He had been scarcely aware of the fact that he had a soul, and so its loss would hardly inconvenience him. He reasoned, moreover, that if this were not, in fact, some juvenile goatherd prank, and if the offer were serious, failure to deliver even one of his impossible demands would invalidate the contract. ‘Oh, all right,’ he agreed with an indifferent shrug, ‘– but first I’d like to see my goat – just as an indication of good faith.’

‘Turn thee around then, Otha,’ the voice commanded, ‘and behold that which was lost.’

Otha turned, and sure enough, there stood the missing goat, idly chewing on a bush and looking curiously at him. Quickly he tethered her to the bush. At heart, Otha was a moderately vicious lad. He enjoyed inflicting pain on helpless creatures. He was given to cruel practical jokes, to petty theft, and, whenever it was safe, to a form of seduction of lonely shepherdesses that had only directness to commend it. He was avaricious and slovenly, and he had a grossly overestimated opinion of his own cleverness. His mind worked very fast as he tied his goat to the bush. If this obscure Styric divinity could deliver a lost goat upon demand, what else might He be capable of? Otha decided that this might very well be the opportunity of a lifetime. ‘All right,’ he said, feigning simple-mindedness, ‘one prayer – for now – in exchange for the goat. We can talk about souls and empires and wealth and immortality and women later. Show yourself. I’m not going to bow down to empty air. What’s your name, by the way? I’ll need to know that in order to frame a proper prayer.’

‘I am Azash, most powerful of the Elder Gods, and if thou wilt be my servant and lead others to worship me, I will grant thee far more than thou hast asked. I will exalt thee and give thee wealth beyond thine imagining. The fairest of maidens shall be thine. Thou shalt have life unending, and, moreover, power over the spirit world such as no man hath ever had. All I ask in return, Otha, is thy soul and the souls of those others thou wilt bring to me. My need and my loneliness are great, and my rewards unto thee shall be equally great. Look upon my face now, and tremble before me.’

There was a shimmering in the air surrounding the crude idol, and Otha saw the reality of Azash hovering about the roughly-carved image. He shrank in horror before the awful presence which had so suddenly appeared before him and fell to the ground, abasing himself before it. This was going much too far. At heart, Otha was a coward, however, and he was afraid that the most rational response to the materialized Azash – instant flight – might provoke the hideous God into doing nasty things to him, and Otha was extremely solicitous of his own skin.

‘Pray, Otha,’ the idol gloated. ‘Mine ears hunger for thine adoration.’

‘Oh, mighty – um – Azash, wasn’t it? God of Gods and Lord of the World, hear my prayer and receive my humble worship. I am as the dust before thee, and thou towerest above me like the mountain. I worship thee and praise thee and thank thee from the depths of my heart for the return of this miserable goat – which I will beat senseless for straying just as soon as I get her home.’ Trembling, Otha hoped that the prayer might satisfy Azash – or at least distract Him enough to provide him an opportunity for escape.

‘Thy prayer is adequate, Otha,’ the idol acknowledged, ‘– barely. In time thou wilt become more proficient in thine adoration. Go now thy way, and I will savour this rude prayer of thine. Return again on the morrow, and I will disclose my mind further unto thee.’

As he trudged home with his goat, Otha vowed never to return, but that night he tossed on his rude pallet in the filthy hut where he lived, and his mind was afire with visions of wealth and subservient young women upon whom he could vent his lust. ‘Let’s see where this goes,’ he muttered to himself as the dawn marked the end of the troubled night. ‘If I have to, I can always run away later.’

And that began the discipleship of a simple Zemoch goatherd to the Elder God, Azash, a God whose name Otha’s Styric neighbours would not even utter, so great was their fear of Him. In the centuries which followed, Otha realized how profound was his enslavement. Azash patiently led him through simple worship into the practice of perverted rites and beyond into the realms of spiritual abomination. The formerly ingenuous and only moderately disgusting goatherd became morose and sombre as the dreaded idol fed gluttonously upon his mind and soul. Though he lived a half-dozen lifetimes, his limbs withered, while his paunch and head grew bloated and hairless and pallid-white as a result of his abhorrence of the sun. He grew vastly wealthy, but took no pleasure in his wealth. He had eager concubines by the score, but he was indifferent to their charms. A thousand, thousand wraiths and imps and creatures of ultimate darkness responded to his slightest whim, but he could not even summon sufficient interest to command them. His only joy became the contemplation of pain and death as his minions cruelly wrenched and tore the lives of the weak and helpless from their quivering bodies for his entertainment. In that respect, Otha had not changed.

During the early years of the third millennium, after the slug-like Otha had passed his nine hundredth year, he commanded his infernal underlings to carry the rude shrine of Azash to the city of Zemoch in the northeast highlands. An enormous semblance of the hideous God was constructed to enclose the shrine, and a vast temple erected about it. Beside that temple and connected to it by a labyrinthine series of passageways stood his own palace, gilt with fine, hammered gold and inlaid with pearl and onyx and chalcedony and with its columns surmounted with intricately-carved capitals of ruby and emerald. There he indifferently proclaimed himself Emperor of all Zemoch, a proclamation seconded by the thunderous but somehow mocking voice of Azash booming hollowly from the temple and cheered by multitudes of howling fiends.

There began then a ghastly reign of terror in Zemoch. All opposing cults were ruthlessly extirpated. Sacrifices of the newborn and virgins numbered in the thousands, and Elene and Styric alike were converted by the sword to the worship of Azash. It took perhaps a century for Otha and his henchmen to totally eradicate all traces of decency from his enslaved subjects. Blood-lust and rampant cruelty became common, and the rites performed before the altars and shrines erected to Azash became increasingly degenerate and obscene.

In the twenty-fifth century, Otha deemed that all was in readiness to pursue the ultimate goal of his perverted God, and he massed his human armies and their dark allies upon the western borders of Zemoch. After a brief pause, while he and Azash gathered their strength, Otha struck, sending his forces down onto the plains of Pelosia, Lamorkand and Cammoria. The horror of that invasion cannot be fully described. Simple atrocity was not sufficient to slake the savagery of the Zemoch horde, and the gross cruelties of the inhumans who accompanied the invading army are too hideous to be mentioned. Mountains of human heads were erected, captives were roasted alive and then eaten, and the roads and highways were lined with occupied crosses, gibbets and stakes. The skies grew black with flocks of vultures and ravens and the air reeked with the stench of burned and rotting flesh.

Otha’s armies moved with confidence towards the battlefield, fully believing that their hellish allies could easily overcome any resistance, but they had reckoned without the power of the Knights of the Church. The great battle was joined on the plains of Lamorkand just to the south of Lake Randera. The purely physical struggle was titanic enough, but the supernatural battle on that plain was even more stupendous. Every conceivable form of spirit joined in the fray. Waves of total darkness and sheets of multicoloured light swept the field. Fire and lightning rained from the sky. Whole battalions were swallowed up by the earth or burned to ashes in sudden flame. The shattering crash of thunder rolled perpetually from horizon to horizon, and the ground itself was torn by earthquake and the eruption of searing liquid rock which poured down slopes to engulf advancing legions. For days the armies were locked in dreadful battle upon that bloody field before, step by step, the Zemochs were pushed back. The horrors which Otha hurled into the fray were overmatched one by one by the concerted power of the Church Knights, and for the first time the Zemochs tasted defeat. Their slow, grudging retreat became more rapid, eventually turning into a rout as the demoralized horde broke and ran towards the dubious safety of the border.

The victory of the Elenes was complete, but not without dreadful cost. Fully half of the Militant Knights lay slain upon the battlefield, and the armies of the Elene Kings numbered their dead by the scores of thousands. The victory was theirs, but they were too exhausted and too few to pursue the fleeing Zemochs past the border.

The bloated Otha, his withered limbs no longer even able to bear his weight, was borne on a litter through the labyrinth at Zemoch to the temple, there to face the wrath of Azash. He grovelled before the idol of his God, blubbering and begging for mercy.

And at long last Azash spoke. ‘One last time, Otha,’ the God said in a horribly quiet voice. ‘Once only will I relent. I will possess Bhelliom, and thou wilt obtain it for me and deliver it up to me here, for if thou dost not do this thing, my generosity unto thee shall vanish. If gifts do not encourage thee to bend to my will, perhaps torment will. Go Otha. Find Bhelliom for me and return with it here that I may be unchained and my maleness restored. Shouldst thou fail me, surely wilt thou die, and thy dying shall consume a million, million years.’

Otha fled, and thus, even in the ruins and tatters of his defeat was born his last assault upon the Elene kingdoms of the west, an assault which was to bring the world to the brink of universal disaster.

PART ONE (#ulink_a0570a52-66b2-59d0-b43f-d0afcff29058)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_a4280bf1-4dff-5b6f-85e8-82f9361fdca6)

The waterfall dropped endlessly into the chasm that had claimed Ghwerig, and the echo of its plunge filled the cavern with a deep-toned sound like the after-shimmer of some great bell. Sparhawk knelt at the edge of the abyss with the Bhelliom held tightly in his fist. Thought had been erased, and he could only kneel at the brink of the chasm, his eyes dazzled by the light of the sun-touched column of water falling into the depths from the surface above and his ears full of its sound.

The cave smelled damp. The mist-like spray from the waterfall bedewed the rocks, and the wet stones shimmered in the shifting light of the torrent to mingle with the last fading glimmerings of Aphrael’s incandescent ascension.

Sparhawk slowly lowered his eyes to look at the jewel he held in his fist. Though it appeared delicate, even fragile, he sensed that the Sapphire Rose was all but indestructible. From deep within its azure heart there came a kind of pulsating glow, deep blue at the tips of the petals and darkening down at the gem’s centre to a lambent midnight. Its power made his hand ache, and something deep in his mind shrieked warnings at him as he gazed into its depths. He shuddered and tore his eyes from its seductive glow.

The hard-bitten Pandion Knight looked around, irrationally trying to cling to the fading bits of light lingering in the stones of the Troll-Dwarf’s cave as if the Child-Goddess Aphrael could somehow protect him from the jewel he had laboured so long to gain and which he now strangely feared. There was more to it than that, though. At some level below thought Sparhawk wanted to hold that faint light forever, to keep the spirit if not the person of the tiny, whimsical divinity in his heart.

Sephrenia sighed and slowly rose to her feet. Her face was weary and at the same time exalted. She had struggled hard to reach this damp cave in the mountains of Thalesia, but she had been rewarded with that joyful moment of epiphany when she had looked full into the face of her Goddess. ‘We must leave this place now, dear ones,’ she said sadly.

‘Can’t we stay a few minutes longer?’ Kurik asked her with an uncharacteristic longing in his voice. Of all the men in the world, Kurik was the most prosaic – most of the time.

‘It’s better that we don’t. If we stay too long, we’ll start finding excuses to stay longer. In time, we may not want to leave at all.’ The small, white-robed Styric looked at Bhelliom with revulsion. ‘Please get it out of sight, Sparhawk, and command it to be still. Its presence contaminates us all.’ She shifted the sword the ghost of Sir Gared had delivered to her aboard Captain Sorgi’s ship. She muttered in Styric for a moment and then released the spell that ignited the tip of the sword with a brilliant glow to light their way back to the surface.

Sparhawk tucked the flower gem inside his tunic and bent to pick up the spear of King Aldreas. His chain-mail shirt smelled very foul to him just now, and his skin cringed away from its touch. He wished that he could rid himself of it.

Kurik stooped and lifted the iron-bound stone club the hideously malformed Troll-Dwarf had wielded against them before his fatal plunge into the chasm. He hefted the brutal weapon a couple of times and then indifferently tossed it into the abyss after its owner.

Sephrenia lifted the glowing sword over her head, and the three of them crossed the gem-littered floor of Ghwerig’s treasure cave towards the entrance of the spiralling gallery that led to the surface.

‘Do you think we’ll ever see her again?’ Kurik asked wistfully as they entered the gallery.

‘Aphrael? It’s hard to say. She’s always been a little unpredictable.’ Sephrenia’s voice was subdued.

They climbed in silence for a time, following the spiral of the gallery steadily to the left. Sparhawk felt a strange emptiness as they climbed. They had been four when they had descended; now they were only three. The Child-Goddess, however, had not been left behind, for they all carried her in their hearts. There was something else bothering him, though. ‘Is there any way we can seal up this cave once we get outside?’ he asked his tutor.

Sephrenia looked at him, her eyes intent. ‘We can if you wish, dear one, but why do you want to?’

‘It’s a little hard to put into words.’

‘We’ve got what we came for, Sparhawk. Why should you care if some swineherd stumbles across the cave now?’

‘I’m not entirely sure.’ He frowned, trying to pinpoint it. ‘If some Thalesian peasant comes in here, he’ll eventually find Ghwerig’s treasure-hoard, won’t he?’

‘If he looks long enough, yes.’

‘And after that it won’t be long before the cave’s swarming with other Thalesians.’

‘Why should that bother you? Do you want Ghwerig’s treasure for yourself?’

‘Hardly. Martel’s the greedy one, not me.’

‘Then why are you so concerned? What does it matter if the Thalesians start wandering around in here?’

‘This is a very special place, Sephrenia.’

‘In what way?’

‘It’s holy,’ he replied shortly. Her probing had begun to irritate him. ‘A Goddess revealed herself to us here. I don’t want the cave profaned by a crowd of drunken, greedy treasure-hunters. I’d feel the same way if someone profaned an Elene Church.’

‘Dear Sparhawk,’ she said, impulsively embracing him. ‘Did it really cost you all that much to admit Aphrael’s divinity?’

‘Your Goddess was very convincing, Sephrenia,’ he replied wryly. ‘She’d have shaken the certainty of the Hierocracy of the Elene Church itself. Can we do it? Seal the cave, I mean?’

She started to say something, then stopped, frowning. ‘Wait here,’ she told them. She leaned Sir Gared’s sword point up against the wall of the gallery and walked back down the passage a little way, and then stopped again at the very edge of the light from the glowing sword-tip where she stood deep in thought. After a time, she returned.

‘I’m going to ask you to do something dangerous, Sparhawk,’ she said gravely. ‘I think you’ll be safe though. The memory of Aphrael is still strong in your mind, and that should protect you.’

‘What do you want me to do?’

‘We’re going to use Bhelliom to seal the cave. There are other ways we could do it, but we have to be sure that the jewel will accept your authority. I think it will, but let’s make certain. You’re going to have to be strong, Sparhawk. Bhelliom won’t want to do what you ask, so you’ll have to compel it.’

‘I’ve dealt with stubborn things before,’ he shrugged.

‘Don’t make light of this, Sparhawk. It’s something far more elemental than anything I’ve ever done before. Let’s move on.’

They continued upward along the spiralling passageway with the muted roar of the waterfall in Ghwerig’s treasure-cave growing fainter and fainter. Then, just as they moved beyond the range of hearing, the sound seemed to change, fragmenting its one endless note into many, becoming a complex chord rather than a single tone – some trick perhaps of the shifting echoes in the cave. With the change of that sound, Sparhawk’s mood also changed. Before, there had been a kind of weary satisfaction at having finally achieved a long-sought goal coupled with the sense of awe at the revelation of the Child-Goddess. Now, however, the dark, musty cave seemed somehow ominous, threatening. Sparhawk felt something he had not felt since early childhood. He was suddenly afraid of the dark. Things seemed to lurk in the shadows beyond the circle of light from the glowing sword-tip, faceless things filled with a cruel malevolence. He nervously looked back over his shoulder. Far back, beyond the light, something seemed to move. It was brief, no more than a flicker of a deeper, more intense darkness. He discovered that when he tried to look directly at it, he could no longer see it, but when he looked off to one side, it was there – vague, unformed and hovering on the very edge of his vision. It filled him with an unnamed dread. ‘Foolishness,’ he muttered, and moved on, eager to reach the light above them.

It was mid-afternoon when they reached the surface, and the sun seemed very bright after the dark cave. Sparhawk drew in a deep breath and reached inside his tunic.

‘Not yet, Sparhawk,’ Sephrenia advised. ‘We want to collapse the ceiling of the cave, but we don’t want to bring that overhanging cliff down on our heads at the same time. We’ll go back down to where the horses are and do it from there.’

‘You’ll have to teach me the spell,’ he said as the three of them crossed the bramble-choked basin in front of the cave mouth.

‘There isn’t any spell. You have the jewel and the rings. All you have to do is give the command. I’ll show you how when we get down.’

They clambered down the rocky ravine to the grassy plateau and their previous night’s encampment. It was nearly sunset when they reached the pair of tents and the picketed horses. Faran laid his ears back and bared his teeth as Sparhawk approached him.

‘What’s your problem?’ Sparhawk asked his evil-tempered warhorse.

‘He senses Bhelliom,’ Sephrenia explained. ‘He doesn’t like it. Stay away from him for a while.’ She looked critically up the gap from which they had just emerged. ‘It’s safe enough here,’ she decided. ‘Take out Bhelliom and hold it in both hands so that the rings are touching it.’

‘Do I have to face the cave?’

‘No. Bhelliom will know what you’re telling it to do. Now, remember the inside of the cave – the look of it, the feel, and even the smell. Then imagine the roof collapsing. The rocks will tumble down and bounce and roll and pile up on top of each other. There’ll be a lot of noise. A great cloud of dust and a strong wind will come rushing out of the cave mouth. The ridge-line above the cave will sag as the roof of the cavern collapses, and there’ll probably be avalanches. Don’t let any of that distract you. Keep the images firmly in your mind.’

‘It’s a bit more complicated than an ordinary spell, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. This is not, strictly speaking, a spell, though. You’ll be unleashing elemental magic. Concentrate, Sparhawk. The more detailed you make the image, the more powerfully Bhelliom will respond. When you’ve got it firmly in your mind, tell the jewel to make it happen.’

‘Do I have to speak to it in Ghwerig’s language?’

‘I’m not sure. Try Elene first. If that doesn’t work, we’ll fall back on Troll.’

Sparhawk remembered the mouth of the cave, the antechamber just inside, and the long, spiralling gallery leading down to Ghwerig’s treasure-cave. ‘Should I bring down the roof on that waterfall as well?’ he asked.

‘I don’t think so. That river might come to the surface again somewhere downstream. If you dam it up, someone might notice that it’s not running any more and start investigating. Besides, that particular cavern is very special, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘Let’s enclose it then and protect it forever.’

Sparhawk pictured the ceiling of the cave collapsing with a huge, grinding roar and a billowing cloud of rock dust. ‘What do I say?’ he asked.

‘Call it “Blue-Rose”. That’s what Ghwerig called it. It might recognize the name.’

‘Blue-Rose,’ Sparhawk said in a tone of command, ‘make the cave fall in.’

The Sapphire Rose went very dark, and angry red flashes appeared deep in its centre.

‘It’s fighting you,’ Sephrenia said. ‘This is the part I warned you about. The cave is the place where it was born, and it doesn’t want to destroy it. Force it, Sparhawk.’

‘Do it, Blue-Rose!’ Sparhawk barked, bending every ounce of his will on the jewel in his hands. Then he felt a surge of incredible power, and the sapphire seemed to throb in his hands. He felt a sudden wild exaltation as he unloosed the might of the stone. It was far beyond mere satisfaction. It verged almost on physical ecstasy.

There was a low, sullen rumbling from deep in the ground, and the earth shuddered. Rocks deep beneath them began to pop and crack as the earthquake shattered layer upon layer of subterranean rock. Far up the ravine, the rock face looming over the mouth of Ghwerig’s cave began to topple outward, then dropped straight down into the weedy basin as its base crumbled out from under it. The sound of the collapsing cliff was very loud even at this distance, and a vast cloud of dust boiled up from the rubble and then drifted off to the northeast as the prevailing wind that raked these mountains swept it away. Then, even as it had in the cave, something flickered at the edge of Sparhawk’s vision – something dark and filled with malevolent curiosity.

‘How do you feel?’ Sephrenia asked, her eyes intent.

‘A little strange,’ he admitted, ‘very strong for some reason.’

‘Keep your mind away from that. Concentrate on Aphrael instead. Don’t even think about Bhelliom until that feeling wears off. Get it out of sight again. Don’t look at it.’

Sparhawk tucked the sapphire back inside his tunic.

Kurik looked up the ravine towards the huge pile of rubble now filling the basin which had lain before the mouth of Ghwerig’s cave. ‘That all seems so final,’ he said regretfully.

‘It is,’ Sephrenia told him. ‘The cavern’s safe now. Let’s keep our minds on other things, gentlemen. Don’t dwell on what we’ve just done, or we might be tempted to undo it.’

Kurik squared his heavy shoulders and looked around. ‘I’ll get a fire going,’ he said. He walked back towards the mouth of the ravine to gather firewood while Sparhawk rummaged through the packs for cooking utensils and something suitable for supper. After they had eaten, they sat around the fire, their faces subdued.

‘What was it like, Sparhawk?’ Kurik asked, ‘using Bhelliom, I mean?’ He glanced at Sephrenia. ‘Is it all right to talk about it now?’

‘We’ll see. Go ahead, Sparhawk. Tell him.’

‘It was like nothing else I’ve ever experienced,’ the big knight replied. ‘I suddenly felt as if I were a hundred feet tall and that there was nothing in the world I couldn’t do. I even caught myself looking around for something else to use it for – a mountain to tear down, maybe.’

‘Sparhawk! Stop!’ Sephrenia told him sharply. ‘Bhelliom’s tampering with your thoughts. It’s trying to lure you into using it. Each time you do, its hold on you grows stronger. Think about something else.’

‘Like Aphrael?’ Kurik suggested, ‘or is she dangerous too?’

Sephrenia smiled. ‘Oh yes, very dangerous. She’ll capture your soul even faster than Bhelliom will.’

‘Your warning’s a little late, Sephrenia. I think she already has. I miss her, you know.’

‘You needn’t. She’s still with us.’

He looked around. ‘Where?’

‘In spirit, Kurik.’

‘That’s not exactly the same.’

‘Let’s do something about Bhelliom now,’ she said thoughtfully. ‘Its grip is even more powerful than I’d imagined.’ She rose and went to the small pack that contained her personal belongings. She rummaged around in it and took out a canvas pouch, a large needle and a hank of red yarn. She took up the pouch and began to stitch a crimson design on it, a peculiarly asymmetrical design. Her face was intent in the ruddy firelight, and her lips moved constantly as she worked.

‘It doesn’t match, little mother,’ Sparhawk pointed out. ‘That side’s different from the other.’

‘It’s supposed to be. Please don’t talk to me just now, Sparhawk. I’m trying to concentrate.’ She continued her sewing for a time, then pinned her needle into her sleeve and held the pouch out to the fire. She spoke intently in Styric, and the fire rose and fell, dancing rhythmically to her words. Then the flame suddenly billowed out as if trying to fill the pouch. ‘Now, Sparhawk,’ she said, holding the pouch open. ‘Put Bhelliom in here. Be very firm. It’s probably going to try to fight you again.’

He was puzzled, but he reached inside his tunic, took the stone and tried to put it into the pouch. A screech of protest seemed to fill his ears, and the jewel actually grew hot in his hand. He felt as if he were trying to push the thing through solid rock, and his mind reeled, shrieking to him that what he was trying to do was impossible. He set his teeth together and shoved harder. With an almost audible wail, the Sapphire Rose slipped into the pouch, and Sephrenia pulled the drawstring tight. She tied the ends into an intricate knot then took her needle and wove red yarn through that knot. ‘There,’ she said, biting off the yarn, ‘that should help.’

‘What did you do?’ Kurik asked her.

‘It’s a form of a prayer. Aphrael can’t diminish Bhelliom’s power, but she can confine it so that it can’t influence us or reach out to others. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we can do on short notice. We’ll do something a little more permanent later on. Put it away, Sparhawk. Try to keep your chain-mail between the pouch and your skin. I think that may help. Aphrael once told me that Bhelliom can’t bear the touch of steel.’

‘Aren’t you being a little overcautious, Sephrenia?’ Sparhawk asked her.

‘I don’t know, Sparhawk. I’ve never dealt with anything like Bhelliom before, and I can’t even begin to imagine the limits of its power. I know enough, though, to know that it can corrupt anything – even the Elene God or the Younger Gods of Styricum.’

‘All except Aphrael,’ Kurik corrected.

She shook her head. ‘Even Aphrael was tempted by Bhelliom when she was carrying it up out of that abyss to bring it to us.’

‘Why didn’t she just keep it for herself then?’

‘Love. My Goddess loves us all, and she gave up Bhelliom willingly out of that love. Bhelliom can’t begin to understand love. In the end, that may be our only defence against it.’

Sparhawk’s sleep was troubled that night, and he tossed restlessly on his blankets. Kurik was on watch near the edge of the circle of firelight, and so Sparhawk was left to wrestle with his nightmares alone. He seemed to see the Sapphire Rose hanging in mid-air before his eyes, its deep blue glow seductive. Out of the centre of that glow there came a sound – a song that pulled at his very being. Hovering around him, so close as to almost touch his shoulders, were shadows – more than one, certainly, but less than ten, or so it seemed. The shadows were not seductive. They seemed to be filled with a hatred born from some towering frustration. Beyond the glowing Bhelliom stood the obscenely grotesque mud idol of Azash, the idol he had smashed at Ghasek, the idol which had claimed Bellina’s soul. The idol’s face was moving, twisting hideously into expressions of the most elemental passions – lust and greed and hatred and a towering contempt that seemed born of its certainty of its own absolute power.

Sparhawk struggled in his dream, dragged first this way and then that. Bhelliom pulled at him; Azash pulled at him; and the hateful shadows pulled as well. The power of each was irresistible, and his mind and body seemed almost torn apart by those titanic conflicting forces.

He tried to scream. And then he awoke. He sat up and realized that he was sweating profusely. He swore. He was exhausted, but a sleep filled with nightmares was no cure for that bone-deep weariness. Grimly he lay back down, hoping for an oblivion without dreams.

It began again, however. Once again he wrestled in his sleep with Bhelliom and with Azash and with the hateful shadows lurking behind him.

‘Sparhawk,’ a small, familiar voice said in his ear, ‘don’t let them frighten you. They can’t hurt you, you know. All they can do is try to frighten you.’

‘Why are they doing it?’

‘Because they’re afraid of you.’

‘That doesn’t make sense, Aphrael. I’m only a man.’

Her laughter was like the peal of a small, silver bell. ‘You’re so innocent sometimes, father. You’re not like any other man who’s ever lived. In a rather peculiar way, you’re more powerful than the Gods themselves. Go to sleep now. I won’t let them hurt you.’

He felt a soft kiss on his cheek, and a pair of small arms seemed to embrace his head with a peculiarly maternal tenderness. The terrible images of his nightmare wavered. And then they vanished.

It must have been hours later when Kurik entered the tent and shook him into wakefulness. ‘What time is it?’ Sparhawk asked his squire.

‘About midnight,’ Kurik replied. ‘Take your cloak. It’s chilly out there.’

Sparhawk arose, put on his mail-shirt and tunic and then buckled his sword-belt around his waist. Then he tucked the pouch under the tunic. He picked up his traveller’s cloak. ‘Sleep well,’ he told his friend and left the tent.

The stars were very bright, and a crescent moon had just risen above the jagged line of peaks to the east. Sparhawk walked away from the embers of their fire to allow his eyes to adjust to the darkness. He stood with his breath steaming slightly in the chill mountain air.

The dream still troubled him, though it was fading now. About the only sharp memory he really had of it was the lingering feel of the soft touch of Aphrael’s lips on his cheek. He firmly closed the door of the chamber where he stored his nightmares and thought of other things.

Without the little Goddess and her ability to tamper with time, it was probably going to take them a week to reach the coast, and they were going to have to find a ship to carry them to the Deiran side of the straits of Thalesia. By now King Wargun had undoubtedly alerted every nation in the Elene kingdoms to their escape. They’d have to move carefully to avoid capture, but they nonetheless needed to go into Emsat. They had to retrieve Talen for one thing, and ships are hard to come by on deserted shores.

The night air in these mountains was chill even in summer, and Sparhawk pulled his cloak tighter about his shoulders. His mood was sombre, troubled. The events of this day were the kind that led to long thoughts. Sparhawk’s religious convictions were not really all that profound. His commitment had always been to the Pandion Order rather than to the Elene faith. The Church Knights were largely engaged in making the world safe for other, gentler Elenes to perform those ceremonies the clergy felt were pleasing to God. Sparhawk seldom concerned himself with God. Today, however, he had gone through some rather profoundly spiritual events. Ruefully he admitted to himself that a man with a pragmatic turn of mind is never really prepared for religious experiences of the kind which had been thrust upon him today. Then, almost as if his hand were acting of its own volition, it strayed towards the neck of his tunic. Sparhawk resolutely drew his sword, stabbed its point into the turf and wrapped both hands firmly about its hilt. He pushed his mind away from religion and the supernatural.

It was almost over now. The time his queen would be compelled to remain confined in the crystal that sustained her life could be measured in days rather than weeks or months. Sparhawk and his friends had trekked all over the Eosian continent to discover the one thing which would cure her, and now that cure lay in the canvas pouch under his tunic. Nothing could stop him now that he had Bhelliom. He could destroy whole armies with the Sapphire Rose if need be. He sternly pulled his mind back from that thought.

His broken face grew bleak. Once his queen was safe, he was going to do some more or less permanent things to Martel, the Primate Annias and anyone who had aided them in their treason. He began to mentally draw up a list of people who had things to answer for. It was a pleasant way to pass the night-time hours, and it kept his mind occupied and out of mischief.

At dusk six days later, they crested a hill and looked down at the smoky torches and candlelit windows of the capital of Thalesia. ‘You’d better wait here,’ Kurik said to Sparhawk and Sephrenia. ‘Wargun’s probably spread descriptions of you through every city in Eosia by now. I’ll go into town and locate Talen. We’ll see what we can find in the way of a ship.’

‘Will you be all right?’ Sephrenia asked. ‘Wargun could have sent out your description as well, you know.’

‘King Wargun’s a nobleman,’ Kurik growled. ‘Nobles pay very little attention to servants.’

‘You’re not a servant,’ Sparhawk objected.

‘That’s how I’m defined, Sparhawk, and that’s how Wargun saw me – when he was sober enough to see anything. I’ll waylay some traveller and steal his clothes. That should get me by in Emsat. Give me some money in case I have to bribe some people.’

‘Elenes,’ Sephrenia sighed as Sparhawk led her back some distance from the road and Kurik rode at a walk on down towards the city. ‘How did I ever get involved with such unscrupulous people?’

The dusk faded slowly, and the tall, resinous fir trees around them turned into looming shadows. Sparhawk tethered Faran, their packhorse and Ch’iel, Sephrenia’s white palfrey. Then he spread his cloak on a mossy bank for her to sit on.

‘What’s troubling you, Sparhawk?’ she asked him.

‘Tired maybe,’ he tried to shrug it off, ‘and there’s always a kind of let-down after you’ve finished something.’

‘There’s more to it than that though, isn’t there?’

He nodded. ‘I wasn’t really prepared for what happened in that cave. It all seemed very immediate and personal somehow.’

She nodded. ‘I’m not trying to be offensive, Sparhawk, but the Elene religion has become institutionalized, and it’s very hard to love an institution. The Gods of Styricum have a much more personal relationship with their devotees.’

‘I think I prefer being an Elene. It’s easier. Personal relationships with Gods are very upsetting.’

‘But don’t you love Aphrael – just a little?’

‘Of course I do. I was a lot more comfortable with her when she was just Flute, but I still love her.’ He made a face. ‘You’re leading me in the direction of heresy, little mother,’ he accused.

‘Not really. For the time being, all Aphrael wants is your love. She hasn’t asked you for your worship – yet.’

‘It’s that “yet” that concerns me. Isn’t this a rather peculiar time and place for a theological discussion, though?’

There was the sound of horses on the road, and the unseen riders reined in not far from where Sparhawk and Sephrenia were concealed. Sparhawk rose quickly, his hand going to his sword-hilt.

‘They have to be around here somewhere,’ a rough voice declared. ‘That was his man who just rode into the city.’

‘I don’t know about you two,’ another voice said, ‘but I’m not really all that eager to find him, myself.’

‘There are three of us,’ the first voice declared pugnaciously.

‘Do you think that would really make any difference to him? He’s a Church Knight. He could probably cut all three of us down without even working up a sweat. We’re not going to be able to spend the money if we’re all dead.’

‘He’s got a point there,’ a third voice agreed. ‘I think the best idea is just to locate him for now. Once we know where he is and which way he’s going, we’ll be able to set up an ambush for him. Church Knight or not, an arrow in his back ought to make him docile. Let’s keep looking. The woman’s riding a white horse. That should make it easier to locate them.’

The horses moved on, and Sparhawk slid his half-drawn sword back into its scabbard.

‘Are they Wargun’s men?’ Sephrenia whispered to Sparhawk.

‘I wouldn’t think so,’ Sparhawk murmured. ‘Wargun’s a little erratic, but he’s not the sort of man who sends out paid assassins. He wants to yell at me and maybe throw me in his dungeon for a while. I don’t think he’s angry enough with me to want to murder me – at least I hope not.’

‘Someone else, then?’

‘Probably.’ Sparhawk frowned. ‘I don’t seem to recall having offended anyone in Thalesia lately, though.’

‘Annias has a long arm, dear one,’ she reminded him.

‘That might be it, little mother. Let’s lie low and keep our ears open until Kurik comes back.’

After about an hour they heard the slow plodding of another horse coming up the rutted road from Emsat. The horse stopped at the top of the hill. ‘Sparhawk?’ The quiet voice was vaguely familiar.

Sparhawk quickly put his hand to his sword hilt, and he and Sephrenia exchanged a quick glance.

‘I know you’re in there somewhere, Sparhawk. It’s me, Tel, so don’t get excited. Your man said you wanted to go into Emsat. Stragen sent me to fetch you.’

‘We’re over here,’ Sparhawk replied. ‘Wait. We’ll be right out.’ He and Sephrenia led their horses to the road to meet the flaxen-haired brigand who had escorted them to the town of Heid on their journey to Ghwerig’s cave. ‘Can you get us into the city?’ Sparhawk asked.

‘Nothing easier,’ Tel shrugged.

‘How do we get past the guards at the gate?’

‘We just ride on through. The gate guards work for Stragen. It makes things a lot simpler. Shall we go?’

Emsat was a northern city, and the steep-pitched roofs of the houses bespoke the heavy snows of winter. The streets were narrow and crooked, and there were only a few people abroad. Sparhawk, however, looked about warily, remembering the three cut-throats on the road outside town.

‘Be kind of careful with Stragen, Sparhawk,’ Tel cautioned as they rode into a seedy district near the waterfront. ‘He’s the bastard son of an earl, and he’s a little touchy about his origins. He likes to have us address him as “Milord”. It’s foolish, but he’s a good leader, so we play his games.’ He pointed down a garbage-littered street. ‘We go this way.’

‘How’s Talen getting along?’

‘He’s settled in now, but he was seriously put out with you when he first got here. He called you some names I’d never even heard before.’

‘I can imagine.’ Sparhawk decided to confide in the brigand. He knew Tel, and he was at least partially sure he could trust him. ‘Some people rode by the place where we were hiding before you came,’ he said. ‘They were looking for us. Were those some of your men?’

‘No,’ Tel replied. ‘I came alone.’

‘I sort of thought you might have. These fellows were talking about shooting me full of arrows. Would Stragen be involved in that sort of thing in any way?’

‘Out of the question, Sparhawk,’ Tel said quite firmly. ‘You and your friends have thieves’ sanctuary. Stragen would never violate that. I’ll talk to Stragen about it. He’ll see to it that these itinerant bowmen stay out of your hair.’ Tel laughed a chilling little laugh. ‘He’ll probably be more upset with them because they’ve gone into business for themselves than because they threaten you, though. Nobody cuts a throat or steals a penny in Emsat without Stragen’s permission. He’s very keen about that.’ The blond brigand led them to a boarded-up warehouse at the far end of the street. They rode around to the back, dismounted and were admitted by a pair of burly cut-throats standing guard at the door.

The interior of the warehouse belied the shabby exterior. It appeared only slightly less opulent than a palace. There were crimson drapes covering the boarded-up windows, deep blue carpets on the creaky floors and tapestries concealing the rough plank walls. A semicircular staircase of polished wood curved up to a second floor, and a crystal chandelier threw soft, glowing candlelight over the entryway.

‘Excuse me for a minute,’ Tel said. He went into a side-chamber and emerged a bit later wearing a cream-coloured doublet and blue hose. He also had a slim rapier at his side.

‘Elegant,’ Sparhawk observed.

‘Another one of Stragen’s foolish ideas,’ Tel snorted. ‘I’m a working man, not a clothes-rack. Let’s go up, and I’ll introduce you to Milord.’

The upper floor was, if anything, even more extravagantly furnished than the one below. It was expensively floored with intricate parquet, and the walls were panelled with highly polished wood. Broad corridors led off towards the back of the house, and chandeliers and standing candelabra filled the spacious hall with golden light. It appeared that some kind of ball was in progress. A quartet of indifferently talented musicians sawed at their instruments in one corner, and gaily-dressed thieves and whores circled the floor in the mincing steps of the latest dance. Although their clothing was elegant, the men were unshaven, and the women had tangled hair and smudged faces. The contrast gave the entire scene an almost nightmarish quality heightened by voices and laughter which were coarse and raucous.

The focus of the entire room was a thin man with elaborate curls cascading over his ruffed collar. He was dressed in white satin and the chair upon which he sat near the far end of the room was not quite a throne – but very nearly. His expression was sardonic, and his deep-sunk eyes had about them a look of obscure pain.

Tel stopped at the head of the staircase and talked for a moment with an ancient cutpurse holding a long staff and wearing elegant scarlet livery. The white-haired knave turned, rapped the butt of his staff on the floor and spoke in a booming voice. ‘Milord,’ he declaimed, ‘the Marquis Tel begs leave to present Sir Sparhawk, Knight of the Church and champion of the Queen of Elenia.’

The thin man rose and clapped his hands together sharply. The musicians broke off their sawing. ‘We have important guests, dear friends,’ he said to the dancers. His voice was very deep and quite consciously well modulated. ‘Let us pay our proper respects to the invincible Sir Sparhawk, who, with the might of his hands, defends our holy mother Church. I pray you, Sir Sparhawk, approach that we may greet you and make you welcome.’

‘A pretty speech,’ Sephrenia murmured.

‘It should be,’ Tel muttered back sourly. ‘He probably spent the last hour composing it.’ The flaxen-haired brigand led them through the throng of dancers, who all bowed or curtsied jerkily to them as they passed.

When they reached the man in white satin, Tel bowed. ‘Milord,’ he said, ‘I have the honour to present Sir Sparhawk the Pandion. Sir Sparhawk, Milord Stragen.’

‘The thief,’ Stragen added sardonically. Then he bowed elegantly. ‘You honour my inadequate house, Sir Knight,’ he said.

Sparhawk bowed in reply. ‘It is I who am honoured, Milord.’ He rigorously avoided smiling at the airs of this apparently puffed-up popinjay.

‘And so we meet at last, Sir Knight,’ Stragen said. ‘Your young friend Talen has given us a glowing account of your exploits.’

‘Talen sometimes tends to exaggerate things, Milord.’

‘And the lady is –?’

‘Sephrenia, my tutor in the secrets.’

‘Dear sister,’ Stragen said in a flawless Styric, ‘will you permit me to greet you?’

If Sephrenia were startled by this strange man’s knowledge of her language, she gave no indication of it. She extended her hands, and Stragen kissed her palms. ‘It is surprising, Milord, to meet a civilized man in the midst of a world filled with all these Elene savages,’ she said.

He laughed. ‘Isn’t it amusing, Sparhawk, to discover that even our unblemished Styrics have their little prejudices?’ The blond pseudo-aristocrat looked around the hall. ‘But we’re interrupting the grand ball. My associates do so enjoy these frivolities. Let’s withdraw so that their joy may be unconfined.’ He raised his resonant voice slightly, speaking to the throng of elegant criminals. ‘Dear friends,’ he said to them, ‘pray excuse us. We will go apart for our discussions. We would not for all the world interrupt your enjoyment of this evening.’ He paused, then looked rather pointedly at one ravishing dark-haired girl. ‘I trust that you’ll recall our discussion following the last ball, Countess,’ he said firmly. ‘Although I stand in awe of your ferocious business instincts, the culmination of certain negotiations should take place in private rather than in the centre of the dance-floor. It was very entertaining – even educational – but it did somewhat disrupt the dance.’

‘It’s just a different way of dancing, Stragen,’ she replied in a coarse, nasal voice that sounded much like the squeal of a pig.

‘Ah yes, Countess, but vertical dancing is in vogue just now. The horizontal form hasn’t yet caught on in the more fashionable circles, and we do want to be stylish, don’t we?’ He turned to Tel. ‘Your services this evening have been stupendous, my dear Marquis,’ he said to the blond man. ‘I doubt that I shall ever be able to adequately repay you.’ He languidly lifted a perfumed handkerchief to his nostrils.

‘That I have been able to serve is payment enough, Milord,’ Tel replied with a low bow.

‘Very good, Tel,’ Stragen approved. ‘I may yet bestow an earldom upon you.’ He turned and led Sparhawk and Sephrenia from the ballroom. Once they were in the corridor outside, his manner changed abruptly. The veneer of affectedly bored gentility dropped away, and his eyes became alert, hard. They were the eyes of a very dangerous man. ‘Does our little charade puzzle you, Sparhawk?’ he asked. ‘Maybe you feel that those in our profession should be housed in places like Platime’s cellar in Cimmura or Meland’s loft in Acie?’

‘It’s more commonplace, Milord,’ Sparhawk replied cautiously.

‘We can drop the “Milord”, Sparhawk. It’s an affectation – at least partially. All of this has a more serious purpose than satisfying some obscure personal quirk of mine, though. The gentry has access to far more wealth than the commons, so I train my associates to prey upon the rich and idle rather than the poor and industrious. It’s more profitable in the long run. This current group has a long way to go, though, I’m afraid. Tel’s coming along rather well, but I despair of ever making a lady of the countess. She has the soul of a whore, and that voice –,’ he shuddered.

‘Anyway, I train my people to assume spurious titles and to mouth little civilities to each other in preparation for more serious business. We’re all still thieves, whores and cut-throats, of course, but we deal with a better class of customers.’

They entered a large, well-lit room to find Kurik and Talen sitting together on a large divan. ‘Did you have a pleasant journey, My Lord?’ Talen asked Sparhawk in a voice that had just a slight edge of resentment to it. The boy was dressed in a formal doublet and hose, and for the first time since Sparhawk had met him, his hair was combed. He rose and bowed gracefully to Sephrenia. ‘Little mother,’ he greeted her.

‘I see you’ve been tampering with our wayward boy, Stragen,’ she observed.

‘His Grace had a few rough edges when he first came to us, dear lady,’ the elegant ruffian told her. ‘I took the liberty of polishing him a bit.’

‘His Grace?’ Sparhawk asked curiously.

‘I have certain advantages, Sparhawk,’ Stragen laughed. ‘When nature – or blind chance – bestows a title, she has no way to consider the character of the recipient and to match the eminence to the man. I, on the other hand, can observe the true nature of the person involved and can select the proper adornment of rank. I saw at once that young Talen here is an extraordinary youth, so I bestowed a duchy upon him. Give me three more months, and I could present him at a court.’ He sat down in a large, comfortable chair. ‘Please, friends, find places to sit, and then you can tell me how I can be of further service to you.’

Sparhawk held a chair for Sephrenia and then took a seat not far from their host. ‘What we really need at the moment, neighbour, is a ship to carry us to the north coast of Deira.’

‘That’s what I wanted to discuss with you, Sparhawk. Our excellent young thief here tells me that your ultimate goal is Cimmura, and he also tells me that there may be some unpleasantness awaiting you in the northern kingdoms. Our tipsy monarch is a man much in need of friends, and he bitterly resents defections. As I understand it, he’s presently displeased with you. All manner of unflattering descriptions are being circulated in western Eosia. Wouldn’t it be faster – and safer – to sail directly to Cardos and go on to Cimmura from there?’

Sparhawk considered that. ‘I was thinking of landing on some lonely beach in Deira and going south through the mountains.’

‘That’s a tedious way to travel, Sparhawk, and a very dangerous one for a man on the run. There are lonely beaches on every coast, and I’m sure we can find a suitable one for you near Cardos.’

‘We?’

‘I think I’ll go along. I like you, Sparhawk, even though we’ve only just met. Besides, I need to talk some business with Platime anyway.’ He rose to his feet then. ‘I’ll have a ship waiting in the harbour by dawn. Now I’ll leave you. I’m sure you’re tired and hungry after your journey, and I’d better return to the ball before our over-enthusiastic countess sets up shop in the middle of the ballroom floor again.’ He bowed to Sephrenia. ‘I bid you good night, dear sister,’ he said to her in Styric. ‘Sleep well.’ He nodded to Sparhawk and quietly left the room.

Kurik rose, went to the door and listened. ‘I don’t think that man’s entirely sane, Sparhawk,’ he said in a low voice.

‘Oh, he’s sane enough,’ Talen disagreed. ‘He’s got some strange ideas, but some of them might even work.’ The boy came over to Sparhawk. ‘All right,’ he said, ‘let me see it.’

‘See what?’

‘The Bhelliom. I risked my life several times to help steal it, and then I got disinvited to go along at the last minute. I think I’m at least entitled to take a look at it.’

‘Is it safe?’ Sparhawk asked Sephrenia.

‘I don’t really know, Sparhawk. The rings will control it, though – at least partially. Just a brief look, Talen. It’s very dangerous.’

‘A jewel is a jewel,’ Talen shrugged. ‘They’re all dangerous. Anything one man wants, another is likely to try to steal, and that’s the sort of thing that leads to killing. Give me gold every time. It all looks the same, and you can spend it anywhere. Jewels are hard to convert into money, and people usually spend all their time trying to protect them, and that’s really inconvenient. Let’s see it, Sparhawk.’

Sparhawk took out the pouch and picked open the knot. Then he shook the glowing blue rose into the palm of his right hand. Once again a brief flicker darkened the edge of his vision, and a chill passed over him. For some reason the flicker of the shadow brought the memory of the nightmare sharply back, and he could almost feel the hovering presence of those obscurely menacing shapes which had haunted his sleep that night a week ago.

‘God!’ Talen exclaimed. ‘That’s incredible.’ He stared at the jewel for a moment, and then he shuddered. ‘Put it away, Sparhawk. I don’t want to look at it any more.’

Sparhawk slipped Bhelliom back into its pouch.

‘It really ought to be blood-red, though,’ Talen said moodily. ‘Look at all the people who’ve died over it.’ He looked at Sephrenia. ‘Was Flute really a Goddess?’

‘Kurik told you about that, I see. Yes, she was – and is – one of the Younger Gods of Styricum.’

‘I liked her,’ the boy admitted, ‘– when she wasn’t teasing me. But if she’s a God – or Goddess – she could be any age she wanted to be, couldn’t she?’

‘Of course.’

‘Why a child then?’

‘People are more truthful with children.’

‘I’ve never particularly noticed that.’

‘Aphrael’s more lovable than you are, Talen,’ she smiled, ‘and that may be the real reason behind her choice of form. She needs love – all Gods do, even Azash. People tend to pick little girls up and kiss them. Aphrael enjoys being kissed.’

‘Nobody ever kissed me all that much.’

‘That may come in time, Talen – if you behave yourself.’

Chapter 2 (#ulink_58729ad6-11b0-5290-94a6-347ce928ff53)

The weather on the Thalesian Peninsula, like that in every northern kingdom, was never really settled, and it was drizzling rain the following morning as bank after bank of thick, dirty clouds rolled into the straits of Thalesia off the Deiran Sea.

‘A splendid day for a voyage,’ Stragen observed dryly as he and Sparhawk looked through a partially boarded-up window at the rain-wet streets below. ‘I hate rain. I wonder if I could find any career opportunities in Rendor.’

‘I don’t recommend it,’ Sparhawk told him, remembering a sun-blasted street in Jiroch.

‘Our horses are already on board the ship,’ Stragen said. ‘We can leave as soon as Sephrenia and the others are ready.’ He paused. ‘Is that roan horse of yours always so restive in the morning?’ he asked curiously. ‘My men report that he bit three of them on the way to the docks.’

‘I should have warned them. Faran’s not the best-tempered horse in the world.’

‘Why do you keep him?’

‘Because he’s the most dependable horse I’ve ever owned. I’ll put up with a few of his crotchets in exchange for that. Besides, I like him.’

Stragen looked at Sparhawk’s chain-mail shirt. ‘You really don’t have to wear that, you know.’

‘Habit,’ Sparhawk shrugged, ‘and there are a fair number of unfriendly people looking for me at the moment.’

‘It smells awful, you know.’

‘You get used to it.’

‘You seem moody this morning, Sparhawk. Is something wrong?’

‘I’ve been on the road for a long time, and I’ve run into some things I wasn’t really prepared to accept. I’m trying to sort things out in my mind.’

‘Maybe someday when we get to know each other better, you can tell me about it.’ Stragen seemed to think of something. ‘Oh, incidentally, Tel mentioned those three ruffians who were looking for you last night. They aren’t looking any more.’

‘Thank you.’

‘It was a sort of internal matter really, Sparhawk. They violated one of the primary rules when they didn’t check with me before they went looking for you. I can’t really afford to have people setting that kind of precedent. We couldn’t get much out of them, I’m afraid. They were acting on the orders of someone outside Thalesia, though. We were able to get that much from the one who was still breathing. Why don’t we go and see if Sephrenia’s ready?’

There was an elegant coach awaiting them outside the rear door of the warehouse about fifteen minutes later. They entered it, and the driver manoeuvred his matched team around in the narrow alley and out into the street.

When they reached the harbour, the coach rolled out onto a wharf and stopped beside a ship that appeared to be one of the kind normally used for coastal trade. Her half-furled sails were patched and her heavy railings showed signs of having been broken and repaired many times. Her sides were tarred, and she bore no name on her bow.

‘She’s a pirate, isn’t she?’ Kurik asked Stragen as they stepped down from the coach.

‘Yes, as a matter of fact, she is,’ Stragen replied. ‘I own a fair number of vessels in that business, but how did you recognize her?’

‘She’s built for speed, Milord,’ Kurik said. ‘She’s too narrow in the beam for cargo capacity, and the reinforcing around her masts says that she was built to carry a lot of sail. She was designed to run other ships down.’

‘Or to run away from them, Kurik. Pirates live nervous lives. There are all sorts of people in the world who yearn to hang pirates just on general principles.’ Stragen looked around at the drizzly harbour. ‘Let’s go on board,’ he suggested. ‘There’s not much point in standing out here in the rain discussing the finer points of life at sea.’

They went up the gangway, and Stragen led them to their cabins below deck. The sailors slipped their hawsers, and the ship moved out of the rainy harbour at a stately pace. Once they were past the headland and in deep water, however, the crew crowded on more sail, and the questionable vessel heeled over and raced across the straits of Thalesia towards the Deiran coast.

Sparhawk went up on deck about noon and found Stragen leaning on the rail near the bow looking moodily out over the grey, rain-dappled sea. He wore a heavy brown cloak, and his hat-brim dripped water down his back.

‘I thought you didn’t like rain,’ Sparhawk said.

‘It’s humid down in that cabin,’ the brigand replied. ‘I needed some air. I’m glad you came up though, Sparhawk. Pirates aren’t very interesting conversationalists.’

They stood for a time listening to the creaking of rigging and ship’s timbers and to the melancholy sound of rain hissing into the sea.

‘How is it that Kurik knows so much about ships?’ Stragen asked finally.

‘He went to sea for a while when he was young.’

‘That explains it, I guess. I don’t suppose you’d care to talk about what you were doing in Thalesia?’

‘Not really. Church business, you understand.’

Stragen smiled. ‘Ah, yes. Our taciturn holy mother Church,’ he said. ‘Sometimes I think she keeps secrets just for the fun of it.’

‘We sort of have to take it on faith that she knows what she’s doing.’

‘You have to, Sparhawk, because you’re a Church Knight. I haven’t taken any of those vows, so I’m perfectly free to view her with a certain scepticism. I did give some thought to entering the Priesthood when I was younger, though.’

‘You might have done very well. The Priesthood or the army are always interested in the talented younger sons of noblemen.’

‘I rather like that,’ Stragen smiled. ‘“Younger son” has a much nicer sound to it than “bastard”, doesn’t it? It doesn’t really matter to me, though. I don’t need rank or legitimacy to make my way in the world. The Church and I wouldn’t have got along too well, I’m afraid. I don’t have the humility she seems to require, and a congregation reeking of unwashed armpits would have driven me to renounce my vows fairly early on.’ He looked back out at the rainy sea. ‘When you get right down to it, life didn’t leave me too many options. I’m not humble enough for the Church, I’m not obedient enough for the army and I don’t have the bourgeois temperament necessary for trade. I did dabble for a time at court, though, since the government always needs good administrators, legitimate or not, but after I’d beaten out the dull-witted son of a duke for a position we both wanted, he became abusive. I challenged him, of course, and he was foolish enough to show up for our appointment wearing chain-mail and carrying a broadsword. No offence intended, Sparhawk, but chain-mail has a few too many small holes in it to be a good defence against a well-sharpened rapier. My opponent discovered that fairly early on in the discussion. After I’d run him through a few times, he sort of lost interest in the whole business. I left him for dead – which proved to be a pretty good guess – and quietly removed myself from government service. The dullard I’d just skewered turned out to be distantly related to King Wargun, and our drunken monarch has very little in the way of a sense of humour.’

‘I’ve noticed.’

‘How did you manage to get on the wrong side of him?’

Sparhawk shrugged. ‘He wanted me to participate in that war going on down in Arcium, but I had pressing business in Thalesia. How’s that war going, by the way? I’ve been a little out of touch.’

‘About all we’ve had in the way of information are rumours. Some say that the Rendors have been exterminated; others say that Wargun has, and that the Rendors are marching north burning everything that’s the least bit flammable. Whichever rumour you choose to believe depends on your view of the world, I suppose.’ Stragen looked sharply aft.

‘Something wrong?’ Sparhawk asked him.

‘That ship back there.’ Stragen pointed. ‘She looks like a merchantman, but she’s moving a little too fast.’

‘Another pirate?’

‘I don’t recognize her – and believe me, I’d recognize her if she were in my line of business.’ He peered aft, his face tight. Then he relaxed. ‘She’s veering off now.’ He laughed briefly. ‘Sorry if I seem a little over-suspicious, Sparhawk, but unsuspicious pirates usually end up decorating some wharf-side gallows. Where were we?’

Stragen was asking a few too many questions. It was probably a good time to divert him. ‘You were about to tell me about how you left Wargun’s court and set up one of your own,’ Sparhawk suggested.

‘It took a little while,’ Stragen admitted, ‘but I’m rather uniquely suited for a life of crime. I haven’t been the least bit squeamish since the day I killed my father and my two half-brothers.’

Sparhawk was a bit surprised at that.

‘Killing my father might have been a mistake,’ Stragen admitted. ‘He wasn’t really a bad sort, and he did pay for my education, but I took offence at the way he treated my mother. She was an amiable young woman from a well-placed family who’d been put in my father’s household as the companion of his ailing wife. The usual sort of thing happened, and I was the result. After my disgrace at court, my father decided to distance himself from me, so he sent my mother home to her family. She died not long afterwards. I suppose I could justify my patricide by claiming that she died of a broken heart, but as a matter of fact, she choked to death on a fish bone. Anyway, I paid a short visit to my father’s house, and his title is now vacant. My two half-brothers were stupid enough to join in, and now all three of them share the same tomb. I rather imagine that my father regretted all the money he’d spent on my fencing lessons. The expression on his face while he was dying seemed to indicate that he was regretting something.’ The blond man shrugged. ‘I was younger then. I’d probably do it differently now. There’s not much profit involved in randomly rendering relatives down to dog-meat, is there?’

‘That depends on how you define profit.’

Stragen gave him a quick grin. ‘Anyway, I realized almost as soon as I took to the streets that there’s not that much difference between a baron and a cutpurse or a duchess and a whore. I tried to explain that to my predecessor, but the fool wouldn’t listen to me. He drew his sword on me, and I removed him from office. Then I began training the thieves and whores of Emsat. I’ve adorned them with imaginary titles, purloined finery and a thin crust of good manners to give them a semblance of gentility. Then I turned them loose on the aristocracy. Business is very, very good, and I’m able to repay my former class for a thousand slights and insults.’ He paused. ‘Have you had about enough of this malcontented diatribe yet, Sparhawk? I must say that your courtesy and forbearance are virtually superhuman. I’m tired of being rained on anyway. Why don’t we go below? I’ve got a dozen flagons of Arcian red in my cabin. We can both get a little tipsy and engage in some civilized conversation.’

Sparhawk considered this complex man as he followed him below. Stragen’s motives were clear, of course. His resentment and that towering hunger for revenge were completely understandable. What was unusual was his total lack of self-pity. Sparhawk found that he liked the man. He didn’t trust him, of course. That would have been foolish, but he liked him nonetheless.

‘So do I,’ Talen agreed that evening in their cabin when Sparhawk briefly recounted Stragen’s story and confessed his liking for the man. ‘That’s probably natural, though. Stragen and I have a lot in common.’

‘Are you going to throw that in my teeth again?’ Kurik asked him.

‘I’m not lobbing stones in your direction, father,’ Talen said. ‘Things like that happen, and I’m a lot less sensitive about it than Stragen is.’ He grinned then. ‘I was able to use our similar backgrounds to some advantage while I was in Emsat, though. I think he took a liking to me, and he made me some very interesting offers. He wants me to come to work for him.’

‘You’ve got a promising future ahead of you, Talen,’ Kurik said sourly. ‘You could inherit either Platime’s position or Stragen’s – assuming you don’t get yourself caught and hanged first.’

‘I’m starting to think on a larger scale,’ Talen said grandly. ‘Stragen and I did some speculating about it while I was in Emsat. The thieves’ council is very close to being a government now. About all it really needs to qualify is some single leader – a king maybe, or even an emperor. Wouldn’t it make you proud to be the father of the Emperor of the Thieves, Kurik?’

‘Not particularly.’

‘What do you think, Sparhawk?’ the boy asked, his eyes filled with mischief. ‘Should I go into politics?’

‘I believe we can find something more suitable for you to do, Talen.’

‘Maybe, but would it be as profitable – or as much fun?’

They reached the Elenian coast a league or so to the north of Cardos a week later and disembarked about midday on a lonely beach bordered on its upper end with dark fir trees.

‘The Cardos road?’ Kurik asked Sparhawk as they saddled Faran and Kurik’s gelding.

‘Might I make a suggestion?’ Stragen asked from nearby.

‘Certainly.’

‘King Wargun’s a maudlin man when he’s drunk – which is most of the time. Your defection probably has him blubbering in his beer every night. He offered a sizeable reward for your capture in Thalesia and Deira, and he’s probably circulated the same offer here. Your face is well-known in Elenia, and it’s about seventy leagues from here to Cimmura – a good week of hard travel at least. Do you really want to spend that much time on a well-travelled road under those circumstances? – Particularly in view of the fact that somebody wants to shoot you full of arrows rather than just turn you over to Wargun?’

‘Perhaps not. Can you think of an alternative?’

‘Yes, as a matter of fact, I can. It may take us a day or so longer, but Platime once showed me a different route. It’s a bit rough, but very few people know about it.’

Sparhawk looked at the thin blond man with a certain amount of suspicion. ‘Can I trust you, Stragen?’ he asked bluntly.

Stragen shook his head in resignation. ‘Talen,’ he said, ‘haven’t you ever explained thieves’ sanctuary to him?’

‘I’ve tried, but sometimes Sparhawk has difficulty with moral concepts. It goes like this, Sparhawk. If Stragen lets anything happen to us while we’re under his protection, he’ll have to answer to Platime.’

‘That’s more or less why I came along, actually,’ Stragen admitted. ‘As long as I’m with you, you’re still under my protection. I like you, Sparhawk, and having a Church Knight to intercede with God for me in case I happen to be accidentally hanged couldn’t hurt.’ His sardonic expression returned then. ‘Not only that, watching out for all of you might expiate some of my grosser sins.’

‘Do you really have that many sins, Stragen?’ Sephrenia asked him gently.

‘More than I can remember, dear sister,’ he replied in Styric, ‘and many of them are too foul to be described in your presence.’

Sparhawk looked quickly at Talen, and the boy nodded gravely. ‘Sorry, Stragen,’ he apologized. ‘I misjudged you.’

‘Perfectly all right, old boy.’ Stragen grinned. ‘And perfectly understandable. There are days when I don’t even trust myself.’

‘Where’s this other road to Cimmura?’

Stragen looked around. ‘Why, do you know, I actually believe it starts just up there at the head of this beach. Isn’t that an amazing coincidence?’

‘That was your ship we sailed on?’

‘I’m a part owner, yes.’

‘And you suggested to the captain that this beach might be a good place to drop us off?’

‘I do seem to recall such a conversation, yes.’

‘An amazing coincidence, all right,’ Sparhawk said dryly.

Stragen stopped, looking out to sea. ‘Odd,’ he said, pointing at a passing ship. ‘There’s that same merchantman we saw up in the straits. She’s sailing very light. Otherwise she couldn’t have made such good time.’ He shrugged. ‘Oh well. Let’s go to Cimmura, shall we?’

The ‘alternative route’ they followed was little more than a forest trail that wound up across the range of mountains that lay between the coast and the broad tract of farmland drained by the Cimmura River. Once the track came down out of the mountains, it merged imperceptibly with a series of sunken country lanes meandering through the fields.

Early one morning when they were midway across that farmland, a shabby-looking fellow on a spavined mule cautiously approached their camp. ‘I need to talk with a man named Stragen,’ he called from just out of bow-shot.

‘Come ahead,’ Stragen called back to him.

The man did not bother to dismount. ‘I’m from Platime,’ he identified himself to the Thalesian. ‘He told me to warn you. There were some fellows looking for you on the road from Cardos to Cimmura.’

‘Were?’

‘They couldn’t really identify themselves after we encountered them, and they aren’t looking for anything any more.’

‘Ah.’

‘They were asking questions before we intercepted them, though. They described you and your companions to a number of peasants. I don’t think they wanted to catch up with you just to talk about the weather, Milord.’

‘Were they Elenians?’ Stragen asked intently.

‘A few of them were. The rest seemed to be Thalesian sailors. Someone’s after you and your friends, Stragen, and I think they’ve got killing on their minds. If I were you, I’d get to Cimmura and Platime’s cellar just as quickly as I could.’