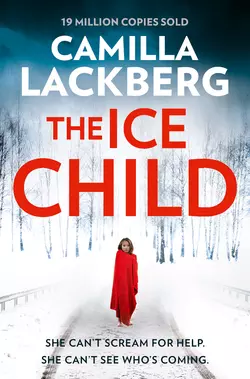

The Ice Child

Camilla Lackberg

No. 1 international bestseller and Swedish crime sensation Camilla Lackberg’s new psychological thriller featuring Detective Patrick Hedstrom and Erica Falck – irresistible for fans of Stieg Larsson and Jo Nesbo.SEE NO EVILIt’s January in the peaceful seaside resort of Fjällbacka. A semi-naked girl wanders through the woods in freezing cold weather. When she finally reaches the road, a car comes out of nowhere. It doesn’t manage to stop.HEAR NO EVILThe victim, a girl who went missing four months ago, has been subjected to unimaginably brutal treatment – and Detective Patrik Hedström suspects this is just the start.SPEAK NO EVILThe police soon discover that three other girls are missing from nearby towns, but there are no fresh leads. And when Patrik’s wife stumbles across a link to an old murder case, the detective is forced to see his investigation in a whole new light.

CAMILLA LACKBERG

The Ice Child

Translated from the Swedish by Tiina Nunnally

Copyright (#ua9747657-8f0b-53cc-a0d5-b26c438c3d67)

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Camilla Lackberg 2014

Published by agreement with Nordin Agency, Sweden

Translation copyright © Tiina Nunnally 2016

Originally published in 2014 by

Bokförlaget Forum, Sweden, as Lejontämjaren

Camilla Lackberg asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover photographs © Richard Boll/Getty Images (girl); Paul Bucknall/Arcangel Images (trees); Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com) (path)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2016 ISBN: 9780007518357

Source ISBN: 9780007518333

Version: 2017-05-09

Dedication (#ua9747657-8f0b-53cc-a0d5-b26c438c3d67)

For Simon

Table of Contents

Cover (#uad97c8cf-8b84-5732-ae5e-48577811da8b)

Title Page (#u14367f6c-7d6d-5ae2-a9fb-71d096e4f35e)

Copyright (#u8462d644-d4e4-51fb-8ef7-6bc5efd26d59)

Dedication (#uf3c43648-dbf5-5388-91b1-04969216f7f0)

Chapter One (#u18d092b7-4283-5b1c-83b3-d1619720092b)

Fjällbacka 1964 (#u8bb5d512-064a-57f1-be16-2a1579728408)

Chapter Two (#u984bb125-8dad-539d-a0ba-42b1b1d41108)

Fjällbacka 1967 (#ua1962454-7aae-51c0-a709-c694bbd1b6a8)

Chapter Three (#u7a70ef52-cf4e-5131-95e8-fc74ef9891cd)

Uddevalla 1967 (#u514eb7b9-2195-5186-958a-97cbc2842ebd)

Chapter Four (#u5938359c-b7ee-52c6-a9c1-d0b262f5cf0d)

Uddevalla 1968 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Uddevalla 1971 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Uddevalla 1972 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Uddevalla 1973 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Uddevalla 1973 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Uddevalla 1974 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Fjällbacka 1975 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Fjällbacka 1975 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fjällbacka 1975 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Hamburgsund 1981 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fjällbacka 1983 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Camilla Lackberg (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ua9747657-8f0b-53cc-a0d5-b26c438c3d67)

The horse could smell the fear even before the girl emerged from the woods. The rider urged the horse on, digging her heels into the animal’s flanks, though it wasn’t really necessary. They were so in tune that her mount sensed her wishes almost before she did.

The muted, rhythmic sound of the horse’s hooves broke the silence. During the night a thin layer of snow had fallen, and the stallion now ploughed new tracks, making the powdery snow spray up around his hooves.

The girl didn’t run. She moved unsteadily, in an irregular pattern with her arms wrapped tightly around her torso.

The rider shouted. A loud cry, and the horse understood that something wasn’t right. The girl didn’t reply, merely staggered onward.

As they approached her, the horse picked up the pace. The strong, rank smell of fear was mixed with something else, something indefinable and so terrifying that he pressed his ears back. He wanted to stop, turn around, and gallop back to the secure confines of his stall. This was not a safe place to be.

The road was between them. Deserted now, with new snow blowing across the asphalt like a silent mist.

The girl continued towards them. Her feet were bare, and the pink of her naked arms and legs contrasted sharply with all the white surrounding her, with the snow-covered spruces forming a white backdrop. They were close now, on either side of the road, and the horse heard the rider shout again. Her voice was so familiar, yet it had a strange ring to it.

Suddenly the girl stopped. She stood in the middle of the road with snow whirling about her feet. There was something odd about her eyes. They were like black holes in her white face.

The car seemed to come out of nowhere. The sound of squealing brakes sliced through the stillness, followed by the thump of a body landing on the ground. The rider yanked so hard on the reins that the bit cut into the stallion’s mouth. He obeyed and stopped abruptly. She was him, and he was her. That was what he’d been taught.

On the ground the girl lay motionless. With those peculiar eyes of hers staring up at the sky.

Erica Falck paused in front of the prison and for the first time studied it closely. On her previous visits she had been so busy thinking about who she was going to meet that she hadn’t given the building or its setting more than a cursory glance. But she would need to give readers a sense of the place when she wrote her book about Laila Kowalski, the woman who had so brutally murdered her husband Vladek many years ago.

She pondered how to convey the atmosphere that pervaded the bunker-like building, how she could capture the air of confinement and hopelessness. The prison was located about a thirty-minute drive from Fjällbacka, in a remote and isolated spot surrounded by fences and barbed wire, though it had none of those towers manned by armed guards that always featured in American films. It had been constructed with only one purpose in mind, and that was to keep people inside.

From the outside the prison looked unoccupied, but she knew the reverse was true. Funding cuts and a tight budget meant that as many people as possible were crowded into every space. No local politician was about to risk losing votes by proposing that money should be invested in a new prison. The county would just have to make do with the present structure.

The cold had begun to seep through Erica’s clothes, so she headed towards the entrance. When she entered the reception area, the guard listlessly glanced at her ID and nodded without raising his eyes. He stood up, and she followed him down a corridor as she thought about how hectic her morning had been. Every morning was a trial these days. To say that the twins had entered an obstinate stage was an understatement. For the life of her she couldn’t recall Maja ever being so difficult when she was two, or at any age. Noel was the worst. He had always been the more energetic one, but Anton was all too happy to follow his lead. If Noel screamed, he screamed too. It was a miracle that her eardrums – and Patrik’s, for that matter – were still intact, given the decibel level at home.

And what a pain it was to get them into their winter clothes. She gave her armpit a discreet sniff. She smelled faintly of sweat. It had taken her so long to wrestle the twins into their clothes so she could take them and Maja to the day-care centre, she hadn’t had time to change. Oh well. She wasn’t exactly going to a social gathering.

The guard’s key ring clanked as he unlocked the door and showed Erica into the visitor’s room. It seemed so old-fashioned that they still made use of keys in this place. But of course it would be easier to get hold of the combination to a coded lock than to steal a key. Maybe it wasn’t so strange that old measures often prevailed over more modern solutions.

Laila was sitting at the only table in the room. Her face was turned towards the window, and the winter sun streaming through the pane formed a halo around her blond hair. The bars on the window made squares of light on the floor, and dust motes floated in the air, revealing that the room hadn’t been cleaned as thoroughly as it should have been.

‘Hi,’ said Erica as she sat down.

She wondered why Laila had agreed to see her again. This was their third meeting, and Erica had made no progress at all. Initially Laila had refused to meet with her, no matter how many imploring letters Erica had sent or how many phone calls she’d made. Then a few months ago Laila had suddenly acquiesced. Perhaps the visits were a welcome break from the monotony of prison life. Erica planned to keep visiting if Laila continued to agree to see her. It had been a long time since she’d felt such a strong urge to tell a story, and she couldn’t do it without Laila’s help.

‘Hi, Erica.’ Laila turned and fixed her unusual blue eyes on her visitor. At their first meeting, Erica had been reminded of those dogs they used to pull sleds. Huskies. Laila had eyes like a Siberian husky.

‘Why do you want to see me if you don’t want to talk about the case?’ asked Erica, getting right to the point. She immediately regretted her choice of words. For Laila, what had happened was not a ‘case’. It was a tragedy and something that still tormented her.

Laila shrugged.

‘I don’t get any other visitors,’ she said, confirming Erica’s suspicions.

Erica opened her bag and took out a folder containing newspaper articles, photos, and notes.

‘Well, I’m not giving up,’ she said, tapping on the folder.

‘I suppose that’s the price I have to pay if I want company,’ said Laila, revealing the unexpected sense of humour that Erica had occasionally glimpsed. She had seen pictures of Laila before it all happened. She hadn’t been conventionally beautiful, but she was attractive in a different and compelling way. Back then her blond hair had been long, and in most of the photos she wore it loose and straight. Now it was cropped short, and cut the same length all over. Not exactly what you would call a hairstyle. Just cut in a way that showed it had been a long time since Laila had cared about her appearance. And why should she? She hadn’t been out in the real world for years. Who would she put on make-up for in here? The nonexistent visitors? The other prisoners? The guards?

‘You look tired today.’ Laila studied Erica’s face. ‘Was it a rough morning?’

‘Rough morning, rough night, and presumably just as rough this afternoon. But that’s the way it is when you have young children.’ Erica sighed heavily and tried to relax. She noticed how tense she was after the stress of the morning.

‘Peter was always so sweet,’ said Laila as a veil lowered over those blue eyes of hers. ‘Not even a trace of stubbornness that I remember.’

‘You told me the first time we met that he was a very quiet child.’

‘Yes. In the beginning we thought there was something wrong with him. He didn’t make a sound until he was three. I wanted to take him to a specialist, but Vladek refused.’ She shivered and her hands abruptly curled into fists as they lay on the table, though she didn’t seem aware of it.

‘What happened when Peter was three?’

‘One day he just started talking. In complete sentences. With a huge vocabulary. He lisped a bit, but otherwise it was as if he had always talked. As if those years of silence had never existed.’

‘And you were never given any explanation?’

‘No. Who would have explained it to us? Vladek didn’t want to ask anyone for help. He always said that strangers shouldn’t get mixed up in family matters.’

‘Why do you think Peter was silent for so long?’

Laila turned to look out of the window, and the sun once again formed a halo around her cropped blond hair. The furrows that the years had etched into her face were mercilessly evident in the light. As if forming a map of all the suffering she had endured.

‘He probably realized it was best to make himself as invisible as possible. Not to draw attention to himself. Peter was a clever boy.’

‘What about Louise? How old was she when she started to talk?’ Erica held her breath. So far Laila had pretended not to hear any of the questions that pertained to her daughter.

It was no different today.

‘Peter loved arranging things. He wanted everything to be nice and orderly. When he was a baby he would stack up blocks in perfect, even towers, and he was always so sad when …’ Laila stopped abruptly.

Erica noticed how Laila had clenched her jaws shut, and she tried to use sheer willpower to coax Laila to go on, to let out what she had so carefully locked up inside. But the moment had passed. The same thing had happened during Erica’s previous visits. Sometimes it felt as though Laila were standing on the edge of an abyss, wishing deep in her heart that she could throw herself into the chasm. As if she wanted to pitch forward but was stopped by stronger forces, which made her once again retreat into the safety of shadows.

It was no accident that Erica was thinking about shadows. The first time they’d met, she had a feeling that Laila was living a shadow existence. A life running parallel to the life she should have had, the life that had vanished into a bottomless pit on that day so many years ago.

‘Do you ever feel like you’re going to lose patience with your sons? That you’re about to cross that invisible boundary?’ Laila sounded genuinely interested, but her voice also had a pleading undertone.

It was not an easy question to answer. All parents have probably felt a moment when they approached that borderline between what is permitted and what isn’t, standing there and silently counting to ten as they think about what they could do to put an end to the commotion and upheaval exploding in their heads. But there was a big difference between acknowledging that feeling and acting on it. So Erica shook her head.

‘I could never do anything to hurt them.’

At first Laila didn’t answer as she continued to stare at Erica with those bright blue eyes of hers. But when the guard knocked on the door to say that visiting time was over, Laila said quietly, her gaze still fixed on Erica:

‘That’s what you think.’

Erica recalled the photographs in the folder and shuddered.

Tyra was grooming Fanta with steady strokes of the brush. She always felt better when she was around the horses. She would have much preferred to be grooming Scirocco, but Molly wouldn’t let anyone else take care of him. It was so unfair. Just because Molly’s parents owned the stable, she was allowed to do anything she wanted.

Tyra loved Scirocco. She had loved him from the first moment she saw him. And the horse had looked at her as if he understood her. It was a wordless form of communication that she’d never experienced with any other animal. Or even with any person. Not with her mother. And not with Lasse. The mere thought of Lasse made her brush Fanta harder, but the big white mare didn’t seem to mind. In fact, she seemed to be enjoying the strokes of the brush, snorting and moving her head up and down as if bowing. For a moment Tyra thought it looked like the mare were inviting her to dance. She smiled and stroked Fanta’s grey muzzle.

‘You’re great too,’ she said, as if the horse had been able to hear her thoughts about Scirocco.

Then she felt a pang of guilt. She looked at her hand on Fanta’s muzzle and realized how trivial her jealousy was.

‘You miss Victoria, don’t you?’ she whispered, leaning her head against the horse’s neck.

Victoria, who had been Fanta’s groom. Victoria, who had been missing for several months. Victoria, who had been – who was – Tyra’s best friend.

‘I miss her too.’ Tyra felt the mare nudging her cheek, but it didn’t comfort her as much as she’d hoped.

She should have been in maths class right now, but on this particular morning she hadn’t felt able to put on a cheerful face and fend off her worry. She had gone over to the school bus stop but instead sought solace in the stable, the only place where she could find any respite. The grown-ups didn’t understand. They saw only their own anxiety, their own sorrow.

Victoria was more than a best friend. She was like a sister. They had been friends from the first day of school and had remained inseparable ever since. There was nothing they hadn’t shared. Or was there? Tyra no longer knew for sure. During those last months before Victoria disappeared, something had changed. It felt like a wall had popped up between them. Tyra hadn’t wanted to nag. She thought that when the time was right, Victoria would tell her what was going on. But time had run out, and Victoria was gone.

‘I’m sure she’ll come back,’ she now told Fanta, but deep inside she had her doubts. Though no one would admit it, they all knew that something bad must have happened. Victoria was not the kind of girl to disappear voluntarily, if such a person existed. She was too content with her life, and she didn’t have an adventurous nature. She preferred to stay home or in the stable; she didn’t even want to go into Strömstad on the weekends. And her family was nothing like Tyra’s. They were super nice, even Victoria’s older brother. He had often given his sister a lift to the stable early in the morning. Tyra used to love visiting their home. She’d felt like one of the family. Sometimes she’d even wished that Victoria’s family was hers. An ordinary, normal family.

Fanta gave her a gentle nudge. A few tears landed on the mare’s muzzle, and Tyra quickly wiped her eyes with her hand.

Suddenly she heard a sound outside the stable. Fanta heard it too. The mare pushed her ears forward and raised her head so swiftly that she rammed into Tyra’s chin. The sharp taste of blood filled the girl’s mouth. She swore, pressed her hand to her lips, and went outside to see what was going on.

When she opened the stable door she was dazzled by the sun, but her eyes quickly adjusted to the light and she saw Valiant coming across the forecourt at full gallop with Marta on his back. Marta pulled up so abruptly that the stallion almost reared. She was shouting something. At first Tyra didn’t understand what she was saying, but Marta kept on yelling. And finally the words made sense:

‘Victoria! We’ve found Victoria!’

Patrik Hedström was sitting at his desk in the Tanumshede police station, enjoying the peace and quiet. He’d come to work early, so he’d missed having to get the kids dressed and take them to the day-care centre. Lately that whole process had become a form of torture, thanks to the twins’ transformation from sweet babies into mini versions of Damien in the film Omen. He couldn’t comprehend how two such tiny people could require so much energy. Nowadays his favourite time with them was when he sat next to their beds in the evening and watched them sleep. At those moments he was able to enjoy the immense, pure love he felt for his sons without any trace of the tremendous frustration he felt when they howled: ‘NO, I WON’T!’

Everything was so much easier with Maja. In fact, sometimes he felt guilty that, with all the attention he and Erica devoted to her little brothers, Maja often ended up neglected. She was so good at keeping herself busy that they simply assumed she was happy. And as young as she was, she seemed to possess a magical ability to calm her brothers down even during their worst outbursts. But it wasn’t fair, and Patrik decided that tonight he and Maja would spend time together, just the two of them, snuggling and reading a story.

At that moment the phone rang. He picked it up distractedly, still thinking about Maja. But the caller quickly grabbed his attention, and he sat up straight in his chair.

‘Could you repeat that?’ He listened. ‘Okay, we’ll be right there.’

He threw on his jacket and shouted into the corridor, ‘Gösta! Mellberg! Martin!’

‘What is it? Where’s the fire?’ grunted Bertil Mellberg, who unexpectedly showed up first. But he was soon followed by Martin Molin, Gösta Flygare, and the station secretary, Annika, who had been at her desk in the reception area, which was the furthest away from Patrik’s office.

‘Somebody found Victoria Hallberg. She was hit by a car near the eastern entrance to Fjällbacka, and she’s been taken by ambulance to Uddevalla. That’s where you and I are headed, Gösta.’

‘Oh, shit,’ said Gösta, and he dashed back to his office to grab his jacket. No one dared venture outdoors without the proper warm clothing this winter, no matter how big an emergency it was.

‘Martin, you and Bertil need to go out to the accident site and talk to the driver,’ Patrik went on. ‘Call the tech team and ask them to meet you there.’

‘You’re in a bossy mood today,’ muttered Mellberg. ‘As the chief of this station, of course I’m the one who should go out to the scene of the accident. The right man in the right place.’

Patrik sighed to himself but didn’t comment. With Gösta in tow, he hurried outside, jumped into one of the two police vehicles and turned on the ignition.

Bloody awful road, he thought as the car skidded into the first curve. He didn’t dare drive as fast as usual. It had started snowing again, and he didn’t want to risk sliding off the road. Impatiently he slammed his fist on the steering wheel. It was only January and, given how long Swedish winters lasted, they could expect at least two more months of this misery.

‘Take it easy,’ said Gösta, clutching the strap hanging from the ceiling. ‘What did they say on the phone?’ He gasped as the car skidded again.

‘Not much. Just that there had been a traffic accident and the girl who’d been struck was Victoria. Unfortunately, it sounds as though she’s in bad shape, and apparently she has other injuries, which have nothing to do with being hit by a car.’

‘What kind of injuries?’

‘I don’t know. We’ll find out when we get there.’

Less than an hour later they arrived at Uddevalla hospital and parked at the front entrance. They hurried to the ER and accosted a doctor named Strandberg, according to his name badge.

‘I’m glad you’re here. The girl is just going into surgery, but it’s not certain she’ll make it. We heard from the police that she has been missing and, in the circumstances, we thought it best if you were the ones to notify her family. I assume you’ve already had a great deal of contact with them. Am I right?’

Gösta nodded. ‘I’ll phone them.’

‘Do you have any information about what happened?’ asked Patrik.

‘Only that she was hit by a car. She has severe internal bleeding, as well as a head injury, though we don’t yet know the extent of that injury. We’ll keep her sedated for a while after the operation in order to minimize any brain damage. If she survives, that is.’

‘We heard that she had suffered some sort of injuries prior to the accident.’

‘Yes,’ said Strandberg, hesitating. ‘We don’t know exactly which injuries are the result of the accident and which occurred previously. But …’ He seemed to be struggling for the right words. ‘Both of her eyes are gone. And her tongue.’

‘Gone?’ Patrik looked at the doctor in disbelief. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Gösta’s equally astonished expression.

‘Yes. Her tongue has been severed, and her eyes have somehow been … removed.’

Gösta covered his mouth with his hand. His face had taken on a slightly greenish tinge.

Patrik swallowed hard. For a moment he wondered whether he was having a nightmare, and hoped he would soon wake up. Then he would be relieved to find it was all a dream and could turn over and go back to sleep. But this was real. Disgustingly real.

‘How long do you think the surgery will take?’

Strandberg shook his head. ‘It’s hard to say. As I mentioned, she has massive internal bleeding. Maybe two or three hours. At the least. You can wait here.’ He gestured towards the large waiting room.

‘I’ll go and ring the family,’ said Gösta, moving away down the corridor.

Patrik didn’t envy him the task. The Hallberg family’s initial joy and relief at hearing that Victoria had been found would swiftly be replaced with the same despair and dread they’d been living with for the past four months.

He sat down on one of the hard chairs. Images of Victoria’s injuries whirled through his mind. But his thoughts were interrupted when a frantic nurse stuck her head in the door and shouted for Strandberg. Patrik hardly had time to react before the doctor dashed from the waiting room. Out in the corridor Patrik could hear Gösta talking on the phone with one of Victoria’s relations. The question was, what news would they hear next?

Ricky tensely studied his mother’s face as she talked on the phone. He strained to read every expression, hear every word. His heart was pounding so hard in his chest that he could hardly breathe. His father sat next to him, and Ricky sensed that his heart was hammering just as hard. It felt like time was standing still, as if it had stopped at that exact moment. All his senses were somehow heightened. Even as he focused his full attention on the phone conversation, he could clearly hear every other sound. He could also feel the wax tablecloth under his clenched fists, the wisp of hair that was tickling the back of his neck under his collar, and the linoleum floor under his feet.

The police had found Victoria. That was the first thing they heard. His mother had recognized the number and grabbed the phone. Ricky and his father had instantly stopped eating their food when they heard her say, ‘What’s happened?’

No courteous greeting, no ‘hello’, no mention of anyone’s name, which was his mother’s usual way of answering the phone. Lately all such things – common courtesies, social rules, what one should or should not do – had ceased to matter. Those sorts of things belonged to their life before Victoria disappeared.

Neighbours and friends had arrived in a steady stream, bringing food and awkwardly offering well-intentioned words. But they never stayed long. Ricky’s parents couldn’t bear all the questions or the kindness, concern, and sympathy in everyone’s eyes. Or the relief, always the same hint of relief that they were not the ones in this situation. Their children were all at home, safe and sound.

‘We’ll leave right now.’

His mother ended the conversation and slowly placed her mobile on the worktop, which was the old-fashioned kind, made of steel. For years she had nagged his father to replace it with something more modern, but he had grumbled that there was no need to replace anything that was clean and in one piece and still fully functional. And his mother had never insisted. She simply brought up the topic on occasion, in the hope that her husband would suddenly change his mind.

Ricky didn’t think his mother cared any longer about what sort of kitchen worktop they had. It was strange how things like that quickly lost all importance. All that mattered was finding Victoria.

‘What did they say?’ asked Ricky’s father. He had stood up, but Ricky was still sitting at the table, staring down at his clenched fists. His mother’s expression told them they wouldn’t want to hear what she had to say.

‘They’ve found her. But she’s seriously injured and in hospital in Uddevalla. Gösta said we need to get there fast. That’s all I know.’

She burst into tears and then sank down as if her legs could no longer support her. Her husband just managed to catch her. He stroked her hair and hushed her, but tears were running down his face too.

‘We need to get going, sweetheart. Put on your jacket, and we’ll leave right away. Ricky, help your mother. I’ll go out and start the car.’

Ricky nodded and went over to his mother. Gently he put his arm around her shoulders and got her to move towards the front hall. There he grabbed her red down coat and helped her to put it on, the way a parent would help a child. One arm in, then the other, and he carefully zipped up the coat.

‘All right,’ he said, placing her boots in front of her. He squatted down and helped her to put them on too. Then he quickly put on his own jacket and opened the door. He could hear that his father had the car running. He was scraping off the windows so frantically that he’d created a cloud of frost, mixed with the vapour from his breath.

‘Bloody winter!’ he cried, scraping so hard that he was probably scratching the windscreen. ‘What a damn, sodding, bloody winter!’

‘Get in the car, Pappa,’ said Ricky. ‘I’ll do that.’ He took the scraper away from his father, after first settling his mother in the back seat. His father complied, offering no resistance. They had always let him believe that he was the one in charge in the family. The three of them – Ricky, his mother, and Victoria – had a secret agreement to allow Markus Hallberg to think that he ruled with an iron fist, even though they knew he was too nice to rule even with one finger. It had always been Helena Hallberg who had ensured that everything was done as it should be done – until Victoria disappeared. She had deflated so swiftly that Ricky sometimes wondered whether his mother had always been this shrivelled and dispirited person who was now sitting on the back seat, staring blankly into space, whether she had ever possessed a sense of purpose. Yet for the first time in months he saw something else in her eyes, a mixture of eagerness and panic prompted by the phone conversation with the police.

Ricky got in behind the wheel. It was strange how a gap in the family was filled, how instinctively he had stepped up to take his mother’s place. As if he possessed a strength he’d never known he had.

Victoria used to tell him that he was like Ferdinand the bull. Lazy and foolishly nice on the outside, but in moments of crisis he would always come through. He’d give her a playful nudge and pretend to be offended, but secretly he was happy to be compared to Ferdinand the bull. Although lately he no longer had time to sit and smell the flowers. He wouldn’t be able to do that again until Victoria came back.

Tears began running down his cheeks and he wiped them off on the sleeve of his jacket. He hadn’t allowed himself to think that she might never come home. If he’d done that, he would have fallen apart.

And now Victoria had been found. Though they didn’t yet know what awaited them at the hospital. He had a feeling they might not want to know.

Helga Persson peered out of the kitchen window. A short while ago she’d seen Marta come riding into the yard at full gallop, but now everything was quiet. She had lived here a long time, and the view was very familiar, even though it had changed a bit over the years. The old barn was still there, but the cowshed, where they’d kept the cows she’d taken care of, had been torn down. In its place was the stable Jonas and Marta had built for their riding school.

She had been happy that her son had decided to settle so close by, that they were neighbours. Their houses stood only a hundred metres apart, and since he ran his veterinary clinic at home, he frequently stopped in to see her. Every visit made her day a little brighter, which was what she needed.

‘Helga! Helgaaaa!’

She closed her eyes as she stood next to the worktop. Einar’s voice filled every nook and cranny of the house, enveloping her and making her clench her fists. But she no longer had the will to flee. He had beat it out of her years ago. Even though he was now helpless and completely dependent on her, she was incapable of leaving him. That wasn’t something she considered any more. Because where would she go?

‘HELGAAAA!’

His voice was the only thing left that still retained its former strength. The illnesses and then the amputation of both legs as a result of neglecting his diabetes had robbed him of his physical strength. But his voice was as commanding as ever. It continued to force her into submission just as effectively as his fists used to do. The memories of all those blows, the cracked ribs and throbbing bruises, were still so vivid that the mere sound of his voice could provoke terror and the fear that this time she might not survive.

She straightened up, took a deep breath, and called out:

‘I’m coming!’

Briskly she climbed the stairs. Einar didn’t like to be kept waiting, he never had, but she didn’t understand why there was always such a hurry. He had nothing else to do but sit and grumble, his complaints ranging from the weather to the government.

‘It’s leaking,’ he said when she came into the room.

She didn’t reply. Simply rolled up her sleeves and went over to him to find out how great the damage might be. She knew he enjoyed this sort of situation. He could no longer use force to hold her captive. Instead he relied on his need for care and attention, which she should have bestowed on the children she’d never had, the ones he had beaten out of her body. Only one had lived, and there were times when she thought it might have been best if that child had also been expelled in a rush of blood between her legs. Yet she didn’t know what she would have done if she hadn’t had him. Jonas was her life, her everything.

Einar was right. The colostomy bag was leaking. And not just a little bit. Half his shirt was soaked through.

‘Why didn’t you get here faster?’ he said. ‘Didn’t you hear me calling? I suppose you had something more important to do.’ He glared at her with his watery eyes.

‘I was in the bathroom. I came as quick as I could,’ she said, unbuttoning his shirt. Carefully she pulled his arms out of the sleeves, not wanting to get even more of his body wet.

‘I’m freezing.’

‘I’ll get you a clean shirt. I just need to wash you off first,’ she said with all the patience she could muster.

‘I’m going to catch pneumonia.’

‘I’ll be fast. I don’t think you’ll catch cold.’

‘Oh, so now you’re a nurse too, huh? I suppose you even know better than the doctors.’

She said nothing. He was just trying to throw her off balance. He liked it best when she cried, when she begged and pleaded with him to stop. Then he was filled with a great sense of calm and satisfaction that made his eyes shine. But today she wasn’t going to give him that pleasure. These days she usually managed to avoid such scenes. Most of her tears had been shed years ago.

Helga went into the bathroom to fill a basin with water. The whole procedure had become routine: fill the basin with water and soap, wet the rag, wipe off his soiled body, put him into a clean shirt. She suspected that Einar purposely made the bag leak. According to his doctor, it was impossible for it to leak so frequently. Yet the bags kept on leaking. And she kept on cleaning up her husband.

‘The water’s too cold.’ Einar flinched as the rag rubbed at his stomach.

‘I’ll make it warmer.’ Helga stood up, went back to the bathroom, put the basin under the tap and turned on the hot water. Then she returned to the bedroom.

‘Ow! It’s scalding! Are you trying to burn me, you bitch?’ Einar shouted so loud that she jumped. But she didn’t say a word, just picked up the basin, carried it out, and filled it with cold water, this time making sure that it was only slightly warmer than body temperature. Then she carried it back to the bedroom. This time he didn’t comment when the rag touched his skin.

‘When is Jonas coming?’ he asked as she wrung out the rag, turning the water brown.

‘I don’t know. He’s working. He went over to the Andersson place. One of their cows is about to calve, but the calf is in the wrong position.’

‘Send him up here when he arrives,’ said Einar, closing his eyes.

‘Okay,’ said Helga quietly, as she wrung out the rag again.

Gösta saw them coming down the hospital corridor. They were hurrying towards him, and he had to fight his impulse to flee in the opposite direction. He knew that what he was about to tell them was written all over his face, and he was right. As soon as Helena met his eye, she fumbled to grab Markus’s arm and then sank to the floor. Her scream echoed through the corridor, silencing all other sounds.

Ricky stood there as if frozen in place. His face white, he had stopped behind his mother while Markus carried on walking. Gösta swallowed hard and went to meet them. But Markus passed him with unseeing eyes, as if he hadn’t seen the same bad news in Gösta’s expression that his wife had seen. He kept on walking along the corridor with no apparent goal in mind.

Gösta didn’t move to stop him. Instead, he went over to Helena and gently lifted her to her feet. Then he put his arms around her. That was not something he usually did. He had let only two people into his life: his wife, and the little girl who had lived with them for a brief time and who now, through the inexplicable workings of fate, had come into his life again. So it didn’t feel particularly natural for him to be standing there, embracing a woman whom he’d known for such a short time. But ever since Victoria disappeared, Helena had rung him every day, alternating between hope and despair, anger and grief, to ask about her daughter. Yet he’d been able to give her only more questions and more worry. And now he had finally extinguished all hope. Holding her in his arms and allowing her to weep on his chest was the least he could do.

Gösta looked over Helena’s head to meet Ricky’s eye. There was something odd about the boy. For the past few months he had been the family’s mainstay, keeping them going. But now he stood there in front of Gösta, his face white and his eyes empty, looking like the young boy he actually was. And Gösta knew that Ricky had lost for ever the innocence granted only to children, the belief that everything would be okay.

‘Can we see her?’ asked Ricky, his voice husky. Gösta felt Helena stiffen. She pulled away, wiped her tears on the sleeve of her coat and gave him a pleading look.

Gösta fixed his gaze on a distant point. How could he tell them that they wouldn’t want to see Victoria? And why.

Her entire study was cluttered with papers: typed notes, Post-it notes, newspaper articles, and copies of photographs. It looked like total chaos, but Erica thrived in this sort of working environment. When she was writing a book, she wanted to be surrounded by all the information she’d gathered, all her thoughts on the case.

This time, however, it felt as if she might be in over her head. She had accumulated plenty of background details and facts, but it had all been obtained from second-hand sources. The quality of her books and her ability to describe a murder case and answer all the questions readers might have relied on her ability to secure first-hand accounts. Thus far she had always been successful. Sometimes it had been easy to persuade those involved to talk to her. Some had even been eager to talk, happy for the media attention and a moment in the spotlight. But occasionally it had taken time and she’d been forced to cajole the person, explaining why she wanted to dredge up the past and how she intended to tell the story. In the end she had always won out. Until now. She was getting nowhere with Laila. During her visits to the prison she had struggled to get Laila to talk about what happened, but in vain. Laila was happy to talk to her, just not about the murder.

Frustrated, Erica propped her feet up on the desk and let her thoughts wander. Maybe she should ring her sister. Anna had often been a source of good ideas and new angles in the past, but she was not herself these days. She had gone through so much over the past few years, and the misfortunes never seemed to stop. Part of her suffering had been self-imposed of course, yet Erica had no intention of judging her younger sister. She understood why certain things had happened. The question was whether Anna’s husband could understand and forgive her. Erica had to admit that she had her doubts. She had known Dan all her life. When they were teenagers they’d dated for a while, and she knew how stubborn he could be. In this instance, the obstinacy and pride that were such a feature of his personality had proved self-destructive. And the result was that everyone was unhappy. Anna, Dan, the children, even Erica. She wished that her sister would finally have some happiness in her life after the hell she had endured with Lucas, her children’s father.

It was so unfair, the way their lives had turned out so differently. She had a strong and loving marriage, three healthy children, and a writing career that was on the upswing. Anna, on the other hand, had encountered one setback after another, and Erica had no idea how to help her. That had always been her role as the big sister: to protect and support and offer assistance. Anna had been the wild one, with such a zest for life. But all that vitality had been beaten out of her until what remained was only a subdued and lost shell. Erica missed the old Anna.

I’ll phone her tonight, she resolved as she picked up a stack of newspaper articles and began leafing through them. It was gloriously quiet in the house, and she was grateful that her job made it possible for her to work at home. She had never felt any need for co-workers or an office setting. She worked best on her own.

The absurd thing was that she was already longing for the hour when she would leave to fetch Maja and the twins. How was it possible for a parent to have such contradictory emotions about the daily routines? The constant alternating between highs and lows was exhausting. One moment she’d be sticking her hands in her pockets and clenching her fists, the next she’d be hugging and kissing the children so much that they begged to be let go. She knew that Patrik felt the same way.

For some reason thinking about Patrik and the kids led her back to the conversation with Laila. It was so incomprehensible. How could anyone cross that invisible yet clearly demarcated boundary between what was permitted and what was not? Wasn’t the fundamental essence of a human being the ability to restrain his or her most primitive urges and do what was right and socially acceptable? To obey the laws and regulations which made it possible for society to function?

Erica continued glancing through the articles. What she had said to Laila today was true. She would never be capable of doing anything to harm her children. Not even in her darkest hours, when she was suffering from postnatal depression after Maja was born, or caught up in the chaos following the twins’ arrival, or during the many sleepless nights, or when the tantrums seemed to go on for hours, or when the kids repeated the word ‘No!’ as often as they drew breath. She had never come close to doing anything like that. But in the stack of papers resting on her lap, in the pictures lying on her desk, and in her notes, there was proof that the boundary could indeed be crossed.

In Fjällbacka the house in the photographs had become known as the House of Horrors. Not a particularly original name, but definitely appropriate. After the tragedy, no one had wanted to buy the place, and it had gradually fallen into disrepair. Erica reached for a picture of the house as it had looked back then. Nothing hinted at what had gone on inside. It looked like a completely normal house: white with grey trim, standing alone on a hill with a few trees nearby. She wondered what it looked like now, how run-down it must be.

She sat up abruptly and placed the photo back on her desk. Why not drive out there and have a look? While researching her previous books she’d always visited the crime scene, but she hadn’t done that this time. Something had been holding her back. It wasn’t that she’d made a conscious decision not to go out there; more that she had simply stayed away.

It would have to wait until tomorrow though. Right now it was time to go and fetch her little wildcats. Her stomach knotted with a mixture of longing and fatigue.

The cow was struggling valiantly. Jonas was soaked with sweat after spending several hours trying to turn the calf around. The big animal kept resisting, unaware that they were trying to help her.

‘Bella is our best cow,’ said Britt Andersson. She and her husband Otto ran the farm which was only a couple of kilometres from the property owned by Jonas and Marta. It was a small but robust farm, and the cows were their main source of income. Britt was an energetic woman who supplemented the money they made from milk sales to Arla by selling cheese from a little shop on their property. She was looking worried as she stood next to the cow.

‘She’s a good cow, Bella is,’ said Otto, rubbing the back of his head anxiously. This was her fourth calf. The previous three births had all gone fine. But this calf was in the wrong position and refused to come out, and Bella was obviously exhausted.

Jonas wiped the sweat from his brow and prepared to make yet another attempt to turn the calf so it could finally slide out and land in the straw, sticky and wobbly. He was not about to give up, because then both the cow and the calf would die. Gently he stroked Bella’s soft flank. She was taking, short, shallow breaths, and her eyes were open wide.

‘All right now, girl, let’s see if we can get this calf out,’ he said as he again pulled on a pair of long rubber gloves. Slowly but surely he inserted his hand into the narrow canal until he could touch the calf. He needed to get a firm grip on a leg so he could pull on it and turn the calf, but he had to do it cautiously.

‘I’ve got hold of a hoof,’ he said. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Britt and Otto craning their necks to get a better look. ‘Nice and calm now, girl.’

He spoke in a low voice as he began to tug at the leg. Nothing happened. He pulled a little harder but still couldn’t budge the calf.

‘How’s it going? Is it turning?’ asked Otto. He kept scratching his head so often that Jonas thought he would end up with a bald spot.

‘Not yet,’ said Jonas through clenched teeth. Sweat poured off him, and a strand of hair from his blond fringe had fallen in his eyes so he kept having to blink. But right now the only thought in his mind was getting the calf out. Bella’s breathing was getting shallower, and her head kept sinking into the straw, as if she were ready to give up.

‘I’m afraid of breaking something,’ he said, pulling as hard as he dared. And something moved! He pulled a bit harder, holding his breath and hoping not to hear the sound of anything breaking. Suddenly he felt the calf shift position. A few more cautious tugs, and the calf was lying on the ground, feeble but alive. Britt rushed forward and began rubbing the newborn with straw. With firm, loving strokes she wiped off its body and massaged its limbs.

In the meantime Bella lay on her side, motionless. She didn’t react to the birth of the calf, this life that had been growing inside of her for close to nine months. Jonas went over to sit near her head, plucking away a few pieces of straw close to her eye.

‘It’s over now. You were amazing, girl.’

He stroked her smooth black hide and kept on talking, just as he’d done throughout the birth process. At first the cow didn’t respond. Then she wearily raised her head to peer at the calf.

‘You have a beautiful little girl. Look, Bella,’ said Jonas as he continued to pat her. He felt his racing pulse gradually subside. The calf would live, and Bella would too. He stood up and finally pushed the irritating strand of hair out of his eyes as he nodded to Britt and Otto.

‘Looks like a fine calf.’

‘Thank you, Jonas,’ said Britt, coming over to give him a hug.

Otto awkwardly grasped Jonas’s hand in his big fist. ‘Thank you, thank you. Good work,’ he said, pumping Jonas’s hand up and down.

‘Just doing my job,’ said Jonas with a big smile. It was always satisfying when something worked out as it should. He didn’t like it when he wasn’t able to resolve things, either on the job or in his personal life.

Happy with the final results, he took his mobile phone out of his jacket pocket. For a few seconds he stared at the display. Then he dashed for his car.

FJÄLLBACKA 1964 (#ua9747657-8f0b-53cc-a0d5-b26c438c3d67)

The sounds, the smells, the colours. Everything so bedazzling, radiating excitement. Laila was holding her sister’s hand. They were too old for that sort of thing, but instinctively she and Agneta would reach for each other’s hand when anything unusual happened. And a circus in Fjällbacka was undeniably something out of the ordinary.

They had hardly ever been away from the small fishing village. Two day-trips to Göteborg. That was the furthest they’d gone. The circus brought with it the promise of the big wide world.

‘What language are they speaking?’ Agneta whispered, even though they could have shouted without anyone hearing because of the buzz of voices all around them.

‘Aunt Edla said the circus came from Poland,’ she whispered back, squeezing her sister’s sweaty hand.

The summer had consisted of an endless string of sunny days, but this had to be the hottest day so far. Laila had been allowed to take a day off from her job selling sewing accessories. She looked forward to every minute she didn’t have to spend inside that stuffy little shop.

‘Look! An elephant!’ Agneta pointed excitedly at the big grey beast ambling past them, accompanied by a man who looked to be in his thirties. The sisters stopped to watch the elephant, which was so impressively beautiful and so completely out of place in the field outside of Fjällbacka, where the circus was setting up.

‘Come on, let’s go look at the other animals. I heard they have lions and zebras too.’ Agneta tugged at her sister’s hand, and Laila followed, out of breath. She could feel the sweat running down her back and making damp patches on her thin summer dress with the floral pattern.

They ran between the wagons parked around the big tent which was being raised. Strong men in white undershirts were working hard to get everything ready for the next day when Cirkus Gigantus would have its first performance. Many of the locals hadn’t been able to wait until then and had come over to gawp at the spectacle. Now they were staring wide-eyed in wonder, never having seen the like before. Except for the two or three bustling summer months when tourists arrived to spend time on the beach, daily life in Fjällbacka was anything but exciting. One day followed the other with nothing in particular happening. The news that a circus was coming to town for the first time had spread like wildfire.

Agneta kept on tugging at Laila, drawing her over to the wagons where a striped head was sticking out of a hatchway.

‘Oh, look how beautiful it is!’

Laila had to agree. The zebra was so sweet, with his big eyes and long lashes. She had to restrain herself from going over to pet him. She assumed that touching the animals was not allowed, but it was hard to resist.

‘Don’t touch,’ growled a voice in English behind them, making them jump.

Laila turned around. She had never seen such a big man. Tall and muscular, he towered over them. The sun was at his back, so the sisters had to shade their eyes to see anything, and when Laila met his glance, it felt like an electric current surged through her body. She had never experienced such a sensation before. She felt confused and dizzy; her whole face burned. She told herself that it must be the heat.

‘No … We … no touch.’ Laila searched for the right words. Even though she had studied English in school and had learned a good deal from watching American films, she had never needed to actually speak the foreign language.

‘My name is Vladek.’ The man held out a calloused fist, and after a few seconds of hesitation, she responded, watching her own hand disappear in his grasp.

‘Laila. My name is Laila.’ Sweat was now coursing down her back.

He shook her hand as he repeated her name, though he made it sound so different and strange. When her name issued from his lips it sounded almost exotic and not like an ordinary, boring name.

‘This …’ She frantically searched her memory and then ventured: ‘This is my sister.’

She pointed at Agneta, and the big man greeted her as well. Laila was a bit ashamed of her stammered English, but her curiosity won out over her embarrassment.

‘What … what do you do? Here. In the circus.’

His face lit up. ‘Come, I show you!’ He motioned for them to follow and then set off without waiting for them to reply. They had to trot to keep up with him, and Laila felt her blood racing. He strode past the wagons and the circus tent that was still being raised, heading for a wagon that stood apart from the others. It was more like a cage, with iron bars instead of walls. Inside two lions were pacing back and forth.

‘This is what I do. This is my babies, my lions. I am … I am a lion tamer!’

Laila stared at the wild beasts. Inside of her something entirely new began to stir, something frightening but wondrous. And without thinking about what she was doing, she reached for Vladek’s hand.

Chapter Two (#ua9747657-8f0b-53cc-a0d5-b26c438c3d67)

It was early morning at the station. The yellow-painted walls of the kitchen looked grey in the winter haze that hovered over Tanumshede. No one said a word. None of them had slept much, and weariness covered their faces like a mask. The doctors had fought heroically to save Victoria’s life, but without success. At 11.14 yesterday morning, she had been pronounced dead.

Martin had filled everyone’s coffee cup, and Patrik now cast a glance at his colleague. Since his wife’s death, he rarely smiled, and all their attempts to bring back the old Martin had failed. Pia had clearly taken part of Martin with her when she died. The doctors had thought she would live one more year, but things had progressed much faster than anyone anticipated. Only three months after her diagnosis, she was gone, and Martin was left alone with their young daughter. Fucking cancer, thought Patrik as he stood up to begin the briefing.

‘As you know, Victoria Hallberg has died from the injuries she sustained when she was struck by a car. The driver of the vehicle has not been charged with any crime.’

‘That’s right,’ Martin interjected. ‘I spoke with him yesterday. David Jansson. According to him, Victoria suddenly appeared in the road, and he had no time to brake. He tried to veer around her, but the road was slippery and he lost control of the car.’

Patrik nodded. ‘There’s a witness to the accident: Marta Persson. She was out riding when she saw someone come out of the woods and then get hit by a car. She was also the one who called the police and ambulance. And she recognized Victoria. From what I understand, she was suffering from shock yesterday, so we’ll need to talk to her today. Can you handle that, Martin?’

‘Sure. I’ll take care of it.’

‘In addition, we urgently need to make some progress in our investigation of Victoria’s disappearance. That means finding the individual or individuals who kidnapped her and subjected her to such horrific treatment.’

Patrik rubbed his face. The images of Victoria as she lay on the gurney had been etched into his mind. He had driven straight from the hospital to the police station and then spent several hours going through the material they had collected so far. He had studied the interviews they’d conducted with family members, as well as the girl’s classmates and friends at the stable. He was trying to map out Victoria’s inner circle of family and friends and determine what she had been doing in the hours before she disappeared on her way home from the Persson riding school. He had also reviewed the information they had about the other girls who had disappeared over the past two years. Of course the police couldn’t be sure, but it seemed unlikely to be a coincidence that five girls, all about the same age and similar in appearance, had disappeared from a relatively small area. Yesterday Patrik had also sent out new information to the other police districts and asked them to respond in kind if they had anything more to add. It was always possible that something had been overlooked.

‘We’re going to continue to cooperate with the other districts involved and combine efforts as best we can while investigating this case. Victoria is the first of the girls to be found, and maybe this tragic event can at least lead us to the others. And then we can put a stop to the kidnappings. Someone who is capable of the kind of sadistic treatment Victoria was subjected to … well, someone like that can’t be allowed to go free.’

‘Sick bastard,’ muttered Mellberg, causing his dog Ernst to raise his head uneasily. As usual, he’d been sleeping under the table with his head resting on his master’s feet, and he was sensitive to the slightest change in Mellberg’s tone of voice.

‘What can we glean from her injuries?’ Martin leaned forward. ‘Why would the perpetrator do something like that?’

‘If only we knew. I’ve been wondering whether we should bring in a profiler to assist us. So far we don’t have a lot to go on, but maybe there’s a pattern that might prove interesting, a connection that we haven’t seen.’

‘A profiler? You mean one of those psychology guys? A so-called expert who has never had contact with any real criminals? You want someone like that to tell us how to do our job?’ Mellberg shook his head so hard that his comb-over tumbled down over one ear. With a practised hand he pushed it back in place.

‘It’s worth a try,’ said Patrik. He was all too familiar with Mellberg’s resistance to any form of innovation or modern methods when it came to police work. In theory, Bertil Mellberg was chief of the Tanumshede police station, but everyone knew that Patrik was the one who did all the work, and it was thanks to him that any crime ever got solved in their district.

‘Well, it’ll be on your head if the top brass start whining about unnecessary expenses. I wash my hands of the whole business.’ Mellberg leaned back and clasped his hands over his stomach.

‘I’ll find out who’s available,’ said Annika. ‘And maybe we should check with the other districts in case they’ve already gone down this route and forgotten to tell us. We don’t need to duplicate their efforts. That would be a waste of time and resources.’

‘Good idea. Thanks.’ Patrik turned to the whiteboard where he’d already taped up a photograph of Victoria and jotted down the basic facts about her.

From the corridor they could hear the sound of a radio playing pop music. The upbeat melody and lyrics were a sharp contrast to the gloomy mood in the kitchen. The station had a conference room but it was cold and impersonal, so they preferred to hold meetings in the more pleasant surroundings of the kitchen, which also had the advantage of placing them closer to the coffeemaker. They would be drinking many litres of hot coffee before they were done.

Patrik paused to think and stretch his back before doling out the work assignments.

‘Annika, I’d like you to pull together all the materials we have relating to Victoria’s case, along with any information we’ve obtained from the other districts. We’ll need to send as much information as possible to the profiler, when we find one. And please see to it that the file is kept updated with any information we discover from now on.’

‘Of course. I’m taking notes,’ said Annika, who was sitting at the kitchen table with paper and pen. Patrik had tried to get her to start using a laptop or tablet instead, but she refused. And if Annika didn’t want to do something, there was no budging her.

‘Fine. Also, schedule a press conference for four o’clock this afternoon. Otherwise we’ll have the reporters breathing down our necks.’ Out of the corner of his eye, Patrik noticed that Mellberg was smoothing down his hair with a pleased expression. Obviously there would be no keeping him away from the press conference.

‘Gösta, find out from Pedersen when the autopsy report will be ready. We need all the facts ASAP. And please have another talk with the family. See if they’ve thought of something that might be important to the investigation.’

‘We’ve already talked to them so many times. Don’t you think they should be left in peace on a day like this?’ Gösta was looking dejected. He’d had the difficult task of speaking to Victoria’s parents and brother at the hospital, and Patrik could see that the experience had taken its toll on him.

‘Yes, but I’m sure they’re anxious for us to find out who did this. Just be as tactful as you can. We’re going to have to talk to a lot of people that we’ve already interviewed – her family members, friends, and anyone at the stable who may have seen something when she disappeared. Now that Victoria is dead, they might decide to tell us something they previously didn’t want to reveal. For instance, we ought to talk to Tyra Hansson again. She was Victoria’s best friend. Could you do that, Martin?’

Martin murmured his acquiescence.

Mellberg cleared his throat, reminding Patrik that, as usual, he needed to come up with some trivial task for Bertil. Something that would make him feel important without putting him in a position to do any significant damage. Patrik thought for a moment. Sometimes it was wisest to have Mellberg close by so he could keep an eye on him.

‘I talked to Torbjörn last night,’ Patrik went on. ‘And the forensic examination of the crime scene produced no results. It wasn’t an easy job, because it was snowing. They found no trace of where Victoria might have come from. Now they’ve run out of manpower, so I was thinking of summoning volunteers to help by searching a wider area. She might have been held prisoner in some old cabin or summer cottage in the woods. When she reappeared, it wasn’t too far from where she was last seen, so it’s possible she was somewhere in the vicinity the whole time.’

‘That’s what I was thinking too,’ said Martin. ‘Wouldn’t that indicate that the perpetrator is from Fjällbacka?’

‘Perhaps,’ said Patrik. ‘But not necessarily. Not if Victoria’s case is connected to the other disappearances. We haven’t found any clear link between the other towns and Fjällbacka.’

Mellberg again cleared his throat, and Patrik turned to look at him.

‘I thought you could help me with this, Bertil. We’ll go out to the woods, and with a little luck, we may be able to find the place where she was being held.’

‘That sounds good,’ replied Mellberg. ‘But it’s not going to be much fun in this cold.’

Patrik didn’t answer. Right now the weather was the least of his worries.

Anna was listlessly gathering up the laundry. She was unbelievably tired. She had been on sick leave ever since the car accident. By now the physical scars on her body had begun to fade, but emotionally her injuries had not yet healed. She was struggling not only with the grief of losing the baby but also with a hurt for which she alone was to blame.

Feelings of guilt churned inside her like a never-ending nausea. Every night she lay awake, going over and over what had happened and re-examining her motives. But even when she tried to give herself the benefit of the doubt, she still couldn’t work out what had made her sleep with another man. She loved Dan, and yet she had kissed someone else and allowed that man to touch her body.

Was her self-esteem so weak and her need for acknowledgement so great that she had thought another man’s hands and lips would give her something that Dan could not? She didn’t understand it, so how could she expect Dan to understand? He was loyalty and security personified. People said it was impossible to know everything about a person, but she knew that Dan would never even think of being unfaithful to her. He would never have touched another woman. The only thing he wanted was to love her.

After the initial outbursts of anger, the harsh words had been replaced by something much worse: silence. A heavy, suffocating silence. They tiptoed around each other like two wounded animals, while Emma, Adrian, and Dan’s daughters were like hostages in their own home.

Anna’s dreams of running her own home-decorating business had died the moment Dan’s hurt gaze met hers. That was the last time he had looked her in the eye. Now, whenever he was forced to speak to her directly – about something concerning the kids or even something as banal as asking her to pass the salt – he would mumble the words with his eyes lowered. And that made her want to scream. She wanted to shake him, force him to look at her, but she didn’t dare. So she too kept her eyes lowered, not because she felt hurt, but out of shame.

Naturally the children had no idea what was going on. They didn’t understand, but they were suffering from the effects. They went around in silence, trying to pretend that everything was normal. But it had been a long time since Anna had heard any of them laugh.

Her heart was so filled with remorse that she thought it might burst. Anna leaned forward, buried her face in the laundry, and wept.

This was where it all happened. Erica cautiously entered the house, which looked as if it might come crashing down at any moment. Abandoned and neglected, battered by the weather, it had stood here all these years until there was hardly anything left to remind people of the family that had once lived in this place.

Erica ducked under a board hanging down from the ceiling. Pieces of glass crunched under the soles of her winter boots. Not a single windowpane remained intact. The floor and walls bore clear signs of random occupants, with scrawled names and words that meant something only to whoever had written them. Four-letter words and insults, many of them misspelled. Those who chose to spray-paint epithets in empty buildings seldom exhibited any great literary talent. Discarded beer cans lay scattered about, and a condom wrapper had been tossed next to a blanket that was so filthy it made Erica feel sick. Snow had blown inside, piling up in nooks and crannies.

The whole house gave off an air of misery and loneliness. Erica pulled from her bag the folder of photographs she’d brought along to help her visualize the scene. They showed a different house, a furnished home where people had lived. Yet she couldn’t help shuddering because she thought she could see traces of what had happened in this place. She took a good look around. And then she saw it: dried blood, still visible on the wooden floor. And four marks where the sofa had once stood. Erica again glanced at the photos, trying to orient herself. She was starting to picture the room as it had looked back then. She saw the sofa, the coffee table, the easy chair in the corner, the TV on its stand, the floor lamp to the left of the easy chair. The whole room seemed to materialize before her eyes.

She could also see Vladek’s corpse. His big, muscular body semi-reclining on the sofa. The gaping red gash in his throat, the stab wounds on his torso, his eyes staring up at the ceiling. And the blood gathering in a pool on the floor.

In the photographs the police had taken of Laila after the murder, her eyes looked completely blank. The front of her jumper was soaked with blood, and there were streaks of blood on her face. Her long blond hair hung loose. She looked so young. Nothing like the woman who was now serving a life sentence in prison.

It had been an open-and-shut case. It seemed to have a certain logic to it that everyone simply accepted. Yet Erica had a strong feeling that something wasn’t right, and six months ago she had decided to write a book about the crime. She’d first heard about the case when she was a child, listening to people talk about the murder of Vladek and the family’s terrible secret. The events that took place in the House of Horrors had grown into a legend as the years passed. The house became a place where children could test their mettle, a haunted house they used to scare their friends, where they could show off their bravery and defy their fear of the evil within those walls.

Erica turned away from the family’s old living room. It was time to go upstairs. The chill inside the house was making her joints stiff, so she jumped up and down a few times to get warm before heading for the stairs. She carefully tested each step before proceeding upwards. She hadn’t told anyone that she was coming here, so she didn’t want to crash through a rotting step and end up lying here with her back broken.

The stairs held, but she was equally cautious about deciding to cross the floor on the second level. The floorboards creaked loudly, but they seemed able to bear her weight, so she continued on with greater confidence as she looked about. It was a small house, so there were only three rooms upstairs along with a short hallway. Directly across from the stairway was the larger bedroom that had belonged to Vladek and Laila. The furniture had been removed or stolen, so all that remained were the tattered and dirty curtains. Here too Erica found discarded beer cans. An old mattress indicated that someone had either slept in the empty house or used it for amorous activities far away from watchful parental eyes.

She squinted, trying to visualize the room based on the photographs she’d seen. An orange rug on the floor, a double bed with a pine bedstead and duvet covers with big green flowers. The room screamed the 1970s, and judging by the pictures the police took after the murder, it had been immaculate. Erica was surprised the first time she looked at the photos. Based on what she knew, she had expected to see a home in shambles, dirty and messy and neglected.

She left the parents’ bedroom and entered the next one, which was a little smaller. It had once been Peter’s. Erica found the relevant photo from the file. His room was also nice and tidy, though the bed was unmade. It was traditionally furnished, with blue wallpaper decorated with tiny circus figures. Happy clowns, elephants with plumed headdresses, a seal balancing a red ball on its nose. Lovely wallpaper for a child’s room, and Erica could understand why they had chosen that particular pattern. She raised her eyes from the photograph to study the room. Bits and pieces of the wallpaper were still there, but most of it had flaked off or been covered with graffiti. There was no trace of the thick wall-to-wall carpet except for a few patches of glue on the dirty wooden floor. The bookcase that had held toys and books was gone, as were the two small chairs and the table that were just the right size for a child to sit there and draw pictures. The bed that had stood in the corner to the left of the window was also long gone. Erica shivered. Here too the windowpanes were broken and snow had blown in to whirl across the floor.

She had purposely left the one remaining upstairs room for last. Louise’s bedroom. It was next to Peter’s, and when she took out the photo, she had to steel herself for what she knew she would see. The contrast was so bizarre. While Peter’s room had been so nice, Louise’s room looked like a prison cell, and it had essentially been just that. Erica ran her finger over the big bolt that was still on the door, although it hung loose from several screws. A bolt that had been installed to keep the door securely locked from the outside. To keep the child in.

Erica held up the photo as she stepped inside. She felt the hairs on the back of her neck stand on end. The room had an eerie air about it, but she knew this had to be her imagination. Rooms and houses possessed no memory, no capacity for recalling the past. No doubt it was the knowledge of what had happened in this house that was making her feel so uneasy in Louise’s room.

The room had been virtually empty. The only thing inside was a mattress on the floor. No toys, not even a proper bed. Erica went over to the window. Boards had been nailed across it, and if she hadn’t known better, she would have guessed this had been done after the house was abandoned. She glanced at the photograph. The same boards were evident back then. Here a child had been locked inside her own room. Tragically, that was not the worst thing the police had discovered when they came to the house after being notified of Vladek’s murder. Erica shuddered. It felt as if a cold wind was sweeping over her, but this time it wasn’t because of a broken window. The chill seemed to be coming from the room itself.

She forced herself to stay there a while longer, refusing to succumb to the strange mood. But she couldn’t help breathing a sigh of relief when she emerged into the hall. Cautiously she made her way down the stairs. There was only one more place to see. She went into the kitchen where she found the cupboards empty and gaping, all the doors having been removed. The cooker and fridge were gone, and the mouse droppings in the spaces where they had once stood showed that rodents had been roaming freely, both inside the house and out.

Erica’s fingers trembled as she pressed down the handle on the cellar door to open it, encountering the same strange chill she’d noticed in Louise’s room. She cursed as she peered into the intense darkness, realizing that she hadn’t thought to bring along a torch. She might have to wait until another time to explore the cellar. But she fumbled her hand over the wall and finally located an old-fashioned switch. When she turned the knob, by some miracle, the cellar light came on. It was impossible for a light bulb from the seventies to be still functioning, so someone must have replaced it.

Her heart was pounding as she went down the stairs. She had to duck to avoid cobwebs, and she tried to ignore the creepy feeling on her skin as she imagined spiders slipping under her clothes.

When she reached the cement floor, she took a few deep breaths to calm her nerves. This was just an empty cellar inside an abandoned house. Nothing more. And it did look like an ordinary basement. A few shelves remained, and an old work bench that had belonged to Vladek, but no tools. Next to it stood an empty oil can, and several crumpled old newspapers had been tossed in a corner. Nothing startling to look at. Except for one small detail: the chain, about three metres in length, which had been fastened with screws to the wall.

Erica’s hands shook badly as she searched for the right photograph. The chain was the same as back then, merely rustier. But the shackles were missing. The police had taken them. And in the police report, she’d read that they had been forced to saw them off, because they couldn’t find the key. She squatted down and picked up the chain, weighing it in her hand. It was heavy and solid, clearly sturdy enough to have restrained a much larger person than a thin and undernourished seven-year-old girl. How could anyone do that to a child?

Erica felt a wave of nausea rise to her throat. She was going to have to take a break from visiting Laila. She didn’t know how she could face her again after coming here and seeing with her own eyes these traces of the woman’s wickedness. Photographs were one thing, but as she held the cold, heavy chain in her hands, she had a much clearer idea of what the police must have found on that day in March 1975. She felt the same horror they must have felt when they came down to the cellar and discovered a child chained to the wall.

A rustling in the corner made Erica stand up abruptly. Her pulse again began racing. Then the light went out and she screamed. Panic seized hold of her and she started taking short, shallow breaths. Close to tears, she fumbled her way towards the stairs. Odd little sounds were coming from all directions, and when something brushed against her face, she screamed again. She flailed her arms about until she realized that it was just another cobweb. Feeling sick to her stomach, she threw herself in the direction where the stairs ought to be and then had the breath knocked out of her when she ran right into the railing. The light flickered and then came back on, but she was so filled with terror that she grabbed hold of the railing and dashed up the stairs. She missed one of the steps and hit her shin, but then managed to stumble the rest of the way up to the kitchen.