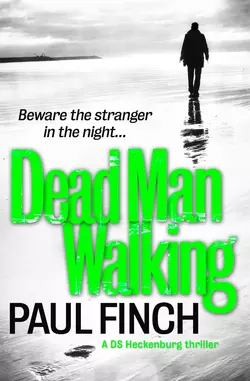

Dead Man Walking

Paul Finch

The fourth unputdownable book in the DS Mark Heckenburg series. A killer thriller for fans of Stuart MacBride and Luther, from the #1 ebook bestseller Paul Finch.His worst nightmare is back…As a brutal winter takes hold of the Lake District, a prolific serial killer stalks the fells. ‘The Stranger’ has returned and for DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg, the signs are all too familiar.Last seen on Dartmoor ten years earlier, The Stranger murdered his victims in vicious, cold-blooded attacks – and when two young women go missing, Heck fears the worst.As The Stranger lays siege to a remote community, Heck watches helplessly as the killer plays his cruel game, picking off his victims one by one. And with no way to get word out of the valley, Heck must play ball…A spine-chilling thriller, from the #1 ebook bestseller. Perfect for fans of Stuart MacBride and James Oswald.

Copyright (#u1fab5290-40ec-584a-937a-13cf9b1484f4)

Published by Avon an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2014

Copyright © Paul Finch 2014

Cover photographs © Shutterstock

Cover design © Andrew Smith 2014

Paul Finch asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007551279

Ebook Edition © July 2013 ISBN: 9780007551286

Version: 2017-11-14

Dedication (#u1fab5290-40ec-584a-937a-13cf9b1484f4)

For my children, Eleanor and Harry, with whom I shared many a chilling tale when they were tots, but whose enthusiasm is as strong now as it ever was

Contents

Cover (#ue777582d-03d9-5d5b-8c0e-5fdde3ffe97c)

Title Page (#u91a87bf6-6e1f-5202-9947-2191eb4ae658)

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue (#u1fab5290-40ec-584a-937a-13cf9b1484f4)

August, 2004

The girl was quite content in her state of semi-undress. The man wasn’t concerned by it either. If anything, he seemed to enjoy the interest she attracted as they drove from pub to pub that sultry August evening.

They commenced their Friday night drive-around in Buckfastleigh, then visited the lively villages of Holne and Poundsgate, before penetrating deeper into Dartmoor’s vast, grassy wilderness, calling at ever more isolated hamlets: Babeny, Dunstone and finally Widecombe-in-the-Moor, where a posse of legendary beer-swilling reprobates had once ridden Uncle Tom Cobley’s grey mare to an early grave.

The girl was first to enter each hostelry, sashaying in through the guffawing hordes, and wiggling comfortably onto the most conspicuous bar stool she could find, while the man took time to find a place in the car park for his sleek, black and silver Porsche. On each occasion, she made an impact. The riot of noise under the low, gnarly roof-beams never actually subsided, but it never needed to. Looking was free.

She wasn’t behaving overtly flirtatiously, but she clearly revelled in the attention she drew. And why not? She had ‘all the tools’, as they say. A tall, willowy blonde, her shapely form showcased to perfection in a green micro mini-dress and strappy green shoes with killer heels. Her golden mane hung past her shoulders in a glossy wave. She had full lips, a pert nose and delicate, feline cheekbones. When she removed her mirrored shades, subtle grey shadow accentuated a pair of startling blue eyes. In each pub she made sure to sit prominently: back arched, boobs thrust forward, smooth tan legs sensually crossed. There was no denying she was playing it up, which was much appreciated by the taproom crowd. For the most part, these were beefy locals, countrymen to the last, but there were also visitors here: car-loads of lusty lads openly cruising for girls and beer; or bluff, gruff oldsters in denims and plaid shirts, down in Devon for the sailing, the fishing, or the moorland walking. They might only be away from their wives for a few days, but they too revealed an eye for the girls; in particular, an eye for this girl. It wasn’t just that she smiled sweetly as they made space for her at the bar, or that she responded with humour to their cheeky quips, but up close it could be seen that she wasn’t a girl after all – she was a woman, in her late twenties, and because of this even more of a taunting presence.

And still the bloke with her seemed oblivious to – or maybe was aroused by – the stir his girlfriend (or perhaps his wife, who knew?) was causing. He was well-dressed – beige Armani slacks, a short-sleeved Yves St Laurent shirt, suede Church’s brogues – and of course, he drove an impressive motor. But he was plumpish, with pale, pudgy features – ‘fucking snail’, as one leery barfly commented to his mate – and a shock of carroty red hair. And he drank only shandies, which made him seem a little soft to have such a tigress on his arm – at least from the locals’ point of view. And yet by the duo’s body language, the man was the more dominant. He stood while she sat. He bought the drinks while she disported her charms, leaning backward against the bar, her exposed cleavage inviting the most brazen stares.

‘Got a right couple, here!’ Harold Hopkinson, portly landlord of The Grouse Beater, said from the side of his mouth. ‘Talk about putting his missus on show.’

‘She’s loving every minute of it,’ Doreen, his foursquare wife, replied.

‘Bit old to be making an exhibition of themselves like that, aren’t they?’

‘Bit old? They’re just the right age. Where do you think they’ll be off to next?’

Harold looked surprised. ‘You don’t mean Halfpenny Reservoir?’

‘Where else?’

‘But surely they know? I mean …’ Harold frowned. ‘Nah, can’t be that. Look, she’s a bonnie girl, and he likes showing the world what he’s got.’

Doreen pulled another pint of Dartmoor IPA. ‘You really believe that?’

Briefly, Harold was lost for words. It all made an unpleasant kind of sense. Halfpenny Reservoir wasn’t Devon’s number one dogging location – it was a long way from anywhere of consequence – but it was well-known locally and it got busy from time to time; at least, it used to get busy before the panic had started. He eyed the fulsome couple again. The woman still perched on her bar stool, sipping a rum and lemonade. Now that he assessed her properly, he saw finger and toenails painted gold, a chain around her left ankle decorated with moons and stars. That was a come-on of sorts, wasn’t it? At least, it was according to some of his favourite websites. Of course, it wouldn’t have been unusual at one time, this. The swinger crowd would occasionally trawl the local boozers en route to Halfpenny Reservoir – somewhat more covertly than this, admittedly, but nonetheless ‘displaying their wares’, as Doreen liked to call it, looking to pick up the passing rough that seemed to be their stock-in-trade.

Things were markedly different now, of course. Or they should be.

‘They must be out-of-towners,’ Harold said. ‘They obviously don’t know.’

‘They’d have to be from another planet not to know,’ Doreen replied tersely.

‘Well … shouldn’t we tell them?’

‘Tell them what?’

‘I don’t know … just advise them it’s a bad idea at the present time.’

She gave him her most withering glance. ‘It should be a bad idea at any time.’

Harold’s wife had a kind of skewed morality when it came to earthy pleasures. She made her living selling alcohol, and yet she had a problem with drunks, refusing to serve anyone she suspected of sampling one too many, and was very quick to issue barring orders if there was ever horseplay in the pub. Likewise, though she consciously employed pretty local girls to work behind her bar, she was strongly antagonistic to ‘tarts and tramps’, as she called them, and was especially hostile to any women she identified as belonging to the swinger crowd who gathered for their midnight revels up at the reservoir – so much so that when ‘the Stranger’ had first come on the scene, targeting lone couples parked up late at night, she’d almost regarded him with approval.

Until the details had emerged, of course.

Because even by the standards of Britain’s most heinous murders, these were real shockers. Harold couldn’t help shuddering as he recalled some of the details he’d read about in the papers. Though no attack had been reported any closer to The Grouse Beater than a picnic area near Sourton on the other side of the moor, twenty miles away as the crow flew, the whole of the county had been put on alert. Harold glanced around the taproom, wondering if the predator might be present at this moment. The pub was full, mainly with men, and not all of the ‘shrinking violet’ variety. Devon was a holiday idyll, especially in summer – it didn’t just attract the New Age crowd and the hippy backpackers, it drew families, honeymooners and the like. But it was a working county too. Even up here on the high moor, the local male populace comprised far more than country squire and Colonel Blimp types in tweeds and gaiters; there were farm-labourers, cattlemen, farriers, hedgers, keepers; occupations which by their nature required hardy outdoor characters. And hadn’t the police issued some kind of statement about their chief suspect being a local man probably engaged in manual labour, someone tough and physically strong enough to overpower healthy young couples? Also, he was someone who knew the back roads, so was able to creep up on his victims unawares, making his getaway afterwards.

There were an awful lot of blokes satisfying those criteria right here, right now.

The more Harold thought about it, the more vulnerable the young couple looked in the midst of this rumbustious crowd. Even if the Stranger wasn’t present, the woman ought not to be displaying herself like that. The man should realise that several of these fellas had already had lots to drink, especially those who were openly ogling; he should know that temptation might get the better of them and that it would be so, so easy just to reach out and place a wandering hand on that smooth, sun-browned thigh. If that happened there might be trouble, swingers or not, and that was the last thing Harold wanted.

‘We have to say something,’ he muttered to Doreen, after they briefly stepped away together into the stock-room.

‘What?’ she sneered. ‘Casually tell them all the local dogging sites are closed? How do you think that’ll go down? They might just be show-offs. Might just have come out for a drink.’

‘But you said …’

‘Just leave it, Harold. We don’t need you making a fool of yourself. Again.’

‘But if they are swingers, and they go up there …?’

‘They’ll be taking a chance. Like they always take chances. Good God, who in their right mind would go looking for sex with strangers in the middle of nowhere?’

‘But darling, if they don’t know …’

‘They’re adults, aren’t they! They should make it their business to know.’

Three minutes later – much to Harold’s relief – ‘the adults’ left, the woman swaying prettily to the pub door, heads again turning to watch, the man digging a packet of cigarettes from his slacks as he idly followed. In some ways it was as if they weren’t actually together; as if the man was just some casual acquaintance rather than a partner, which was a bit confusing. Still, it was someone else’s problem now.

Harold edged to the diamond-paned window overlooking the pub car park.

The duo stood beside the Porsche, the man smoking, the woman leaning on the car with her arms folded, her bag dangling from her shoulder by its strap. They chatted together, in no apparent rush to go anywhere – perhaps they were just a dressy couple out for a few drinks after all? Harold felt a slow sense of relief. Probably a nice couple too, when you got to know them; it was hardly the woman’s fault she was hot as hell.

It was approaching nine o’clock now and the sun was setting, fiery red stripes lying across the encircling moorland. Maybe they were all set to go home? But then, when the man was only halfway through his cigarette, he stubbed it out on the tarmac and placed it in a nearby waste-container. And when they climbed into the Porsche together and drove away, it wasn’t along the B3387 to Bovey Tracey, or even back through the village towards Dunstone and ultimately Buckfastleigh – it was along the unnamed road that ran due northwest from the pub. The next inhabited place it came to was Beardon, some fifteen miles away.

But long before then, it passed Halfpenny Reservoir.

It had been a vintage August day in the West Country, but the heat was finally seeping from the land, the balminess of the evening receding. An indigo dusk layered the hills and valleys of Dartmoor.

By the time they reached the reservoir it would be near enough pitch-black.

The woman checked their rear-view mirror as they drove. Fleetingly, she thought she’d glimpsed headlights behind, but now there was nothing; only the greyness of nightfall. Ahead, the road sped on hypnotically, the vastness of the encircling moor oppressive in its emptiness. Tens of minutes passed, and they didn’t spot a single habitation – neither a cottage, nor another pub – though in truth they were too busy looking for the reservoir turn-off to indulge in any form of sightseeing. Even then, they almost passed it; a narrow, unmade lane, all dry rutted earth in their headlights, branching away between two granite gateposts and arcing off at a slanted angle amongst dense stands of yellow-flowered furze.

They slowed to a halt in the middle of the blacktop.

‘This must be it …?’ the man said. It was more a question than an observation.

The woman nodded.

They ventured left along the rugged route, bouncing and jolting, spiky twigs whispering down the Porsche’s flanks, following a shallow V-shaped valley for several hundred yards before starlit sky broke out ahead; the radiant orb of the moon was suspended there, its reflection shimmering on an expansive body of water lying to their right. Like most of the Dartmoor reservoirs, Halfpenny Lake was manmade, its purpose to supply drinking water to the surrounding lowlands. A row of wrought-iron railings flickered past in the glow of their right-side headlamp as they prowled the shoreline road, and the solid, horizontal silhouette of what looked like a dam blocking off the valley at its farthest end affirmed the mundane purpose of this place.

There were several sheltered parking bays along here, a dump site for used condoms, dog-eared porn mags and pairs of semen-stained knickers – though any such debris now would be old and rotted; there was no one present to add new mementoes.

Apart from the man and the woman.

They parked close to the entrance of the second lot, and there, as per the manual, turned the radio down – it was tuned to an ‘easy listening’ station, so was hardly intrusive in any case – opened all the windows, and climbed into the back seat together. Here, they sat apart – one at either end of the seat, exchanging odd murmurs of anticipation as they waited for their audience.

And so the minutes passed.

The stillness outside was near absolute; a gentle breeze sighing across the heathery moorland tops, groaning amid the tors. The couple’s gaze roved back and forth along the unlit ridges. The only movement came from tufts of bracken rippling against the stars. It was almost eerie how peaceful it was, how tranquil. A classic English summer’s night.

All the more reason why the fierce crackle of electricity jolted them so badly.

Especially the man, who stiffened and fell back against the nearside door.

It happened that fast. He simply froze, his eyes glazed, foam shooting from his rigidly puckered mouth. Then the featureless figure outside who had risen into view from a kneeling posture and reached through the open window with his Taser, now reached through again and opened the door.

All this happened too quickly for the woman to take it in. Almost too quickly.

As the lifeless shape of her beau dropped backward again, this time out onto the gritty tarmac, his head striking it with brutal force, she grappled with her handbag, unsnapping it and fumbling inside. It was a quick, fluid motion – she didn’t waste time squawking in outrage – but their assailant was quicker still. He lunged in through the open nearside door. In the dull green light of the dashboard facia, she caught a fleeting glimpse of heavy-duty leather: a leather coat, leather face-mask, and a leather glove, as – POW! – his clenched fist caught her right in the mouth.

She too slumped backward, head swimming, handbag tipping into the footwell, spilling its contents every which way.

With thoughts fizzled to near-incomprehensibility, the woman probed at her two front teeth with her tongue. They appeared to wobble; at the same time her upper lip stung abominably, whilst her mouth rapidly filled with hot, coppery fluid. She coughed on it, choking.

And then awareness of her situation broke over her – like a dash of iced water.

She was lying on her back, but the intruder was now in the car with her, on the rear seat in fact, already positioned between her indecently spread legs. With one gloved hand, he kept a tight grip on her exposed upper left thigh; it was so high, his thumb was almost in her crotch. With his other hand, he was slowly, purposefully unfastening his coat.

From some distant place, the woman heard a new song on the radio. A rich American voice poured through the nicely central-heated car.

Wondering in the night what were the chances …

A beastly chuckle, hideous and pig-like, snorted from the leather-clad face. Still dazed, the woman strained to see through the greenish, pain-hazed gloom. Frank Sinatra, she recalled. One of her father’s favourites. Old Blue Eyes, The Voice, the Sultan of Swoon …

‘Looks like they’re playing my tune,’ the intruder said, as the final button snapped open and his coat flaps fell apart. If she’d had any doubts before, she had none now.

Strangers in the night …

He hadn’t spoken before. Not a single word – not to her knowledge. But then who would know? The weird sex-murderer who’d begun his crimes by attacking anyone he encountered who was out after dark, but had then begun stalking lovers’ lanes and dogging spots all over Devon and Somerset, had not left a single living witness. All those he’d targeted had been eliminated with precision, ruthlessness, and great, great enjoyment; the men with skulls crushed and/or throats cut, the women sexually mutilated in a ritual that went far beyond everyday sadism. Each one of them, man and woman alike, subjected to one final desecration, when their eyes were stabbed and gouged until they were nothing but jelly.

We were strangers in the night …

‘Definitely my tune.’ He chuckled again, using his left hand to fondle the array of gleaming implements in his customised inner coat lining: the tin-opener, the screwdriver, the mallet, the hacksaw, the razor-edged filleting knife.

The woman could barely move, yet her eyes were now riveted on his eyes: moist baubles framed in leather sockets; and on his mouth, the saliva-coated tongue and broken, stained teeth exposed by a drawn-back zipper. But that voice – it could only have been a whisper in truth, a gloating guttural whisper. But she would remember it as long as she lived.

It was Scottish.

The Stranger was a Scotsman.

The key thing now, of course, was to ensure that she did live.

Perhaps he was too busy drawing out that first instrument of torture – the tin-opener, an old-fashioned device with a ghastly hooked blade – to notice her right hand working frantically through the debris littering the footwell.

As he raised the tin-opener to his right shoulder – not to plunge it down as much as to tease her with the terror of it – her fingertips found something she recognised.

He kept her pinned in place with his other hand, a grip so hard in that soft, sensitive spot that it was now agony, as he crooned along to the tune.

They’d first dubbed him ‘the Stranger’ in the West Country press because of the sex-with-strangers scene he’d so viciously crashed. It now seemed even more appropriate. ‘You’re a taunting, godless bitch,’ he added matter-of-factly, still in that notable accent. ‘A whore, an exhibitionist slut, a prick-teasing slag …’

‘And a police officer,’ she said, pointing her snub-nosed Smith & Wesson .38 straight at his face. ‘Move one muscle, you bastard … open that filthy yap of yours one more time, and I’ll put a bullet straight through your fucking skull!’

The expression on his face was priceless. At least it probably would have been, had she been able to see it. As it was, she had to be content with his sudden almost-comical paralysis, the whites of his eyes widening in cartoon fashion around his soulless black pupils, his gammy mouth sagging open between zippered lips.

‘Yeah … that’s right,’ she said, thumbing back the pistol’s hammer. ‘The fun’s over. Now drop that sodding blade.’

Of course, it couldn’t be over in reality, and her heart pounded harder in her chest as this slowly dawned on her. He couldn’t let it end like this – so abruptly, so unexpectedly; or in this fashion: trapped like a rabbit by one of the frail, sexual creatures he so brutally despised. Warily, she transferred the .38 from her right hand to her left, keeping it levelled at him as she lay there. With her empty right hand, she again reached into the footwell. Her radio was down there somewhere, but she was damned if she could find it. All the time, he sat motionless, nailing her with that semi-human gaze, strands of spittle hanging over his leather-covered jaw. And now she saw his mouth slowly closing, those discoloured teeth clamping together in a final, hate-filled grimace. He wasn’t frozen with shock anymore, she realised; he was taut with tension – like a spring set to uncoil.

‘Don’t you do it!’ she warned, but it was too late; he arched down with the tin-opener, intent on ripping her wide apart with its wicked, hooked point.

BANG!

The slug took him in the left side of his upper chest, just beneath the collar bone, flinging him backward out of the car and down onto the tarmac, where he lay silently twisting alongside the prone form of Detective Constable Maxwell.

She found the radio and slammed it to her lips as she threw herself forward through the cordite. ‘All units, this is DC Piper! Converge on Halfpenny Reservoir! Repeat, converge on Halfpenny Reservoir …’

Her words tailed off as a stocky figure rose to its feet outside. For a half-second she tried to kid herself that this was Maxwell, though she knew it couldn’t be. The DC’s head had struck the tarmac with a hell of a whack.

Without a word, the figure swayed around and blundered across the car park.

‘Repeat, this is DC Piper! Decoy unit Alpha. One shot fired. Suspect suffering a chest wound, but on foot and mobile.’

There was a scrabble of static-ridden responses, but even as Piper watched, the lumbering form of the Stranger scrambled over the car park’s low perimeter wall, the dark blot of his outline swiftly ascending through the furze on the other side. He was hurt badly; that was clear – he lurched from side to side, but kept going in a more or less straight line, uphill and away from her.

‘Suspect heading west … away from the reservoir, over open ground,’ she added, clattering onto the tarmac in her tall, strappy shoes. ‘We need an ambulance too.’ She dropped to one knee to check the carotid at the side of Maxwell’s neck. ‘DC Maxwell is severely injured … he’s received a massive shock from some kind of stun-gun and what looks like a head trauma. Currently in a collapsed state, but breathing, and his pulse feels regular. Get that ambulance here, pronto! In the meantime, I’m pursuing the suspect, over.’

She hurried across the car park, but once she was over the wall into the furze, her heels sank like knife-blades in the soft earth. She kicked the shoes off as she ran, flinching as twigs and sharp-edged stones spiked the soles of her feet, and thorns and thistles raked her naked legs. Very briefly, the Stranger appeared above her as a lopsided silhouette on the night sky. But then he was gone again, over the ridge.

‘Get me that back-up now!’ she shouted into her radio.

‘Gemma, you need to hold back,’ came a semi-coherent response. ‘DSU Anderson’s orders! Wait for support units, over!’

‘Negative, that!’ she replied firmly. ‘Not when we’re this close.’

She too crested the ridge. The starlit moor unrolled itself: a sweeping georama of grass and boulders, obscured by patches of low-lying mist but rising distantly to soaring, tor-crowned summits. On lower ground now, but a hundred yards ahead of her at least, a dark blot was struggling onward.

The ground sloped steeply as she gave chase, ploughing downhill through soft, springy vegetation, shouting that he was under arrest; that he should give it up.

Perspectives were all askew, of course, so she wasn’t quite sure where she lost sight of him. Though he wasn’t a vast distance ahead, curtains of mist seemed suddenly to close around him. When she reached that point herself – now hobbling, both feet bruised and bleeding – she found she was on much softer ground, plodding through ankle-deep mud. He ought to have left a recognisable trail, but it was too dark to see and she had no light with which to get down and make a fingertip search.

Further terse orders came crackling over the airwaves.

Again, she ignored them. It occurred to her that maybe the suspect was wearing a vest and therefore not as badly injured as she’d thought. But if that was the case, why had he fled … why not use the advantage to go straight on the attack, ripping and mauling her in the car? No – she’d wounded him; she’d seen the pain in his posture. If nothing else, that meant there’d be blood.

Unless rain came before the forensics teams did.

‘We need the lab-rats up here ASAP!’ she shouted, cutting across the frantic exchanges of her colleagues. ‘At least we’ll have his DNA …’

There was a choked scream from somewhere ahead.

She slowed to a near-halt. Fleetingly, she couldn’t see anything; liquid mist, the colour of purulent milk, drifted on all sides. But had that cry been for real? Was he finally succumbing to his wound? Or was he trying to lure her?

There was another scream, this one accompanied by a strangled gurgling.

She now halted completely.

This was Dartmoor. A National Park. A green and hazy paradise. Picturesque, famous for its pristine flora and fauna. And notorious for its bottomless mires. The third scream dwindled to a series of choked gasps, and now she heard a loud sploshing too, like a heavy body plunging through slime.

‘Update,’ she said into her radio, advancing warily. ‘I’m perhaps three hundred yards west of the reservoir parking area, over the top of the ridge. Suspect appears to be in trouble. I can’t see him, but it’s possible he’s blundered into a mire.’

There was further insistence that she stop and wait for back-up. Again she ignored this, but only advanced five or six yards before she found herself teetering on the brink of an opaque, black/green morass, its mirror-flat surface stretching in all directions as the mist seemed to furl away across it. She strained her eyes, but nothing stirred out there; not so much as a ripple, let alone the distinctive outline of a man fighting to keep his head above the surface.

There was no sound either, which was worrying. Dartmoor’s mires could suck you down with frightful speed. Their bowels were stuffed with sheep and pony carcasses, not to mention the odd missing hiker or two. But all she could identify now were the twisted husks of sunken trees, their branches protruding here and there like rotted dinosaur bones.

Even Detective Constable Gemma Piper, of the Metropolitan Police – wilful, fearless and determined – now realised that caution was the better part of valour. Especially as the mist continued to clear on the strengthening wind, revealing, despite the darkness of night, how truly extensive this mire was. It lay everywhere; not just ahead of her but on both sides as well – as though she’d strayed out onto a narrow headland. It was difficult to imagine that even a local man could have lumbered this way, mortally wounded, blinded by vapour, and had somehow avoided this pitfall. And if nothing else, she now knew their suspect was not a local man – but, by origin at least, from the other end of the country.

As voices sounded behind her, torches spearing across the undulating landscape, she sank slowly and tiredly to her haunches. The delayed shock of what had nearly happened back in the Porsche was seeping through her, leaving her numb. In some ways she felt elated; she’d almost nailed the bastard … but not quite. It was like a no-score draw after a football match. It was a result of sorts, but it was difficult to estimate how much of one.

Within an hour, the Devon and Cornwall Police, with assistance from Scotland Yard, had cordoned off this entire stretch of moor, were searching it with dogs, and had even brought heavy machinery in to start dredging the mire and its various connected waterways. At the reservoir car park, the conscious but weakened form of DC Maxwell was loaded into the rear of an ambulance. Gemma Piper meanwhile sat side-saddle in the front seat of a police patrol car, sipping coffee and occasionally wincing as a medic knelt and attended to her bloodied feet and swollen face. At the same time, she briefed Detective Superintendent George Anderson.

The hard-headed young female detective, already impressive to every senior manager who’d encountered her, had just assured herself a glowing future in this most challenging and male-dominated of industries. But of the so-called Stranger, the perpetrator of thirteen loathsome torture-murders – as reported in the Dartmoor Advertiser: ‘These crimes are abhorrent, utterly loathsome!’ – there was no trace.

Nor would there be for some considerable time.

Chapter 1 (#u1fab5290-40ec-584a-937a-13cf9b1484f4)

Present Day

There was no real witchcraft associated with this part of the Lake District. Nor had there ever been, to Heck’s knowledge.

The name ‘Witch Cradle Tarn’ had been applied in times past purely to reflect the small mountain lake’s ominous appearance: a long, narrow, very deep body of water high in the Langdale Pikes, thirteen hundred feet above sea-level to be precise, with sheer, scree-covered cliffs on its eastern shore and mighty, wind-riven fells like Pavey Ark, Harrison Stickle and Great Castle Howe lowering to its north, west and south. It wasn’t an especially scary place in modern times. Located in a hanging valley in a relatively remote spot – official title Cragwood Vale, unofficial title ‘the Cradle’ – it was a fearsome prospect on paper, but when you actually got there, the atmosphere was more holiday than horror. Two cheery Lakeland hamlets, Cragwood Keld and Cragwood Ho, occupied its southern and northern points respectively. For much of the year the whole place teemed with climbers, hikers, fell-runners and anglers seeking the famous Witch Cradle trout, while kayakers and white-water rafters were catered for by the Cragwood Boat Club, based a mile south of Cragwood Keld, near the head of Cragwood Race; a furiously twisting river, which poured downhill through natural gullies and steep culverts before finally joining the more sedately flowing Langdale Beck.

The single pub at the heart of Cragwood Keld only added to this homely feel. A rather austere-looking building at first glance, all grey Westmorland slate on the outside, it was famous for its smoky beams and handsome oak settles, its range of cask ales, its crackling fires in winter and its pretty lakeside beer garden in summer. Its name – The Witch’s Kettle – owed itself entirely to some enterprising landlord of decades past, who hadn’t found The Drovers’ Rest to his taste, and felt the witch business a tad sexier, especially given that most visitors to the Cradle were always awe-stricken by the deep pinewoods hemming its two villages to the lakeshore, and the rubble-clad slopes and immense granite crags soaring overhead. Its inn-sign was a landmark in itself, depicting a rusty old kettle with green herbs protruding from under its lid, sitting on a stone inscribed with pagan runes. It was just possible, visitors supposed, that current landlady, Hazel Carter, might herself be a witch – but if so, she was a far cry from the bent nose and warty lip variety.

At least, that was Heck’s feeling.

He’d only been up here two and a half months, but was already certain that whatever magic Hazel wove, it was unlikely to be the sort he’d resist easily. Not that he was thinking along these lines that late November morning, as he entered The Witch’s Kettle just before eleven, made a beeline for the bar and ordered himself a pint of Buttermere Gold. It was early in the day and there were few customers yet. Only Hazel was on duty. Like Heck, she was in her late thirties, but with rich auburn hair, which she habitually wore very long. She was doe-eyed, soft-lipped, and buxom in shape, a figure enhanced by her daytime ‘uniform’ of t-shirt, cardigan and jeans.

They made close eye-contact but only uttered those words necessary for the transaction. However, as she handed him his pint and his change, the landlady inclined her head slightly to the right. Heck pocketed the cash and sipped his beer, before glancing in that direction. Beyond a low arch lay the pub’s vault, which contained a darts board and a pool table. One person was in there: a young lad, no more than sixteen, with tousled blond hair, wearing a grey sweatshirt, grey canvas trousers and white trainers. He looked once, fleetingly, in Heck’s direction as he worked his way around the pool table, ignoring him thereafter. All the youth had seen, of course, was a man about six feet in height, of average build, with unruly black hair and faint scars on his face, wearing jeans, a sweater and a rumpled anorak. But he’d probably have paid more attention had he known that Heck was actually Detective Sergeant Mark Heckenburg of the Cumbria Constabulary, that he was based very near here, at Cragwood Keld police office, and that he was on duty right at this moment.

To maintain his façade of recreation, Heck found a seat at an empty table, pulled a rolled-up Westmorland Gazette from his back pocket and commenced reading. He checked his watch as he turned the pages, though this was more from habit than necessity. He felt he was following a good lead today, but there was no great pressure on him. Ever since being reassigned from Scotland Yard to Cumbria as part of the Association of Chief Police Officers’ new Anti-Rural Crime Initiative, Heck had been well-placed to work hours of his own choosing and at his own pace. Ultimately of course, he was answerable to South Cumbria Crime Command, and in the first instance to the CID office down at Windermere police station; he was only a sergeant, when all was said and done. But as the only CID officer in the Langdales – the only CID officer in twenty square miles in fact – he was out here on his own as far as many colleagues were concerned: ‘Hey pal, you’re the man on the spot,’ as they’d say. There were advantages to this, without doubt. But it was never a nice feeling that reinforcements were always a good forty minutes away.

Heck’s thoughts were distracted as two other people came down the stairs into the taproom. It was a man and a woman, the former in his mid-thirties, the latter in her mid-twenties, both carrying bulging backpacks. The woman had short, mouse-brown hair, and wore a red cagoule, blue cord trousers and walking boots. The man was tall and thin, with short fair hair. He too wore cord trousers and walking boots, but his blue cagoule was draped over his narrow, t-shirted shoulders. Neither of them looked threatening or in any way unwholesome; in fact they were smiling and chattering brightly. At the foot of the stair, they separated, the man heading to the bar, where he told Hazel he’d like to ‘settle up’. The woman turned into the vault and spoke to the youth, who pocketed his last ball and grabbed up a backpack of his own.

The trio left the pub together, still talking animatedly – a family enjoying their holiday. As the door swung closed behind them, Heck glanced over the top of his newspaper at Hazel, who nodded. Leaping to his feet, he crossed the room to the car park window, and watched as the trio approached a metallic-green Hyundai Accent. He’d been informed by Hazel beforehand that this was the vehicle they’d arrived in two weeks ago, and had already run a check on the Police National Computer, to discover that its registration number – V513 HNV – actually belonged to a black Volvo estate supposedly sold to a scrap merchant in Grimsby nine months earlier. Without a backward glance, they piled into the Hyundai and pulled out of the car park, heading south out of the village.

Heck hurried outside – it was only noon, but it was a grey day and there was already a deep chill. Thanks to the season, the village was quieter than usual. Beyond the pines, the upward-sweeping moors were bare, brown and stubbled with autumn bracken.

Heck climbed into his white Citroën DS4, starting the engine and hitting the heater switch, but resisted the temptation to jump straight onto the suspects’ tail. At this time of year, with traffic more scarce than usual, it would be easy to get spotted. Besides, there was only one way you could enter or leave the Cradle – via the aptly named Cragwood Road, a perilously narrow single-lane which wound downhill over steep, rock-strewn slopes for several hundred feet, sometimes tilting to a gradient of one in three – so it wasn’t like the suspects could turn off anywhere, or even drive away at high speed. Of course, once the trio had descended into Great Langdale, the vast glacial valley at the epicentre of this district, it was another matter. So Heck couldn’t afford to hang back too far.

As such, he gave them a thirty-second start.

It was about three miles from the village to the commencement of the descent, and Heck didn’t see a single soul as he traversed it, nor another car, which was comforting – though it was useful to be able to hide among normal vehicles, an open road was reassuring in the event you might need to chase. As he began his descent, he initially couldn’t see his target, but he refused to panic. The blacktop meandered wildly on its downward route, arcing around perilous bends and through clumps of shadowy pine. But when he finally did sight the Hyundai, it had got further ahead than he’d expected. It was diminutive; no more than a glinting green toy.

Heck accelerated, veering dangerously as the road dropped, taking curves with increasingly reckless abandon. He tried his radio, but received only dead-air responses. There was minimal reception in the Cradle, the encompassing cliffs interfering so drastically with signals that most communications from Cragwood Keld nick had to be made via landline. But it would improve as he descended into Langdale. In anticipation of this, he was already tuned to a talk-through channel.

‘Heckenburg to 1416, over?’ he repeated.

He’d descended to six hundred feet before he gleaned a response.

‘1416 receiving. Go ahead, sarge.’ The voice was shrill, with an Irish brogue.

‘Suspects on the move, M-E … heading down Cragwood Road towards the B5343. Where are you, over?’

M-E, or PC 1416 Mary-Ellen O’Rourke, Cragwood Keld nick’s only uniformed officer – she was actually resident there, bunking in the flat above the office – took a second or two to respond. ‘Heading up Little Langdale from Skelwith Bridge, sarge. They still in that green Hyundai, over?’

‘Affirmative. Still showing the dodgy VRM. I’ll give you a shout soon as I know which way they’re headed, over?’

‘Roger that.’

As Heck now descended towards the junction with the B5343, he had a clear vision both west and east along Great Langdale. This was a vastly more expansive valley than Cragwood Vale, its head encircled by some of Cumbria’s most impressive fells; not just the craggy-topped Langdale Pikes, but Great Knott, Crinkle Crags, Bowfell and Long Top – their barren upper reaches ascending to dizzying heights. By contrast, its floor was flat and fertile, and perhaps half a mile across, much of it divided by dry-stone walls and given to cattle grazing. Down its centre, in a west to east direction, flowed Langdale Beck, a broad, rocky river, normally shallow but running deep at present after a spectacularly soggy October and November. A hundred yards ahead meanwhile, at the end of Cragwood Road, the Hyundai passed onto the B5343 without stopping, following the larger route as it swung sharply south, crossing the river by a narrow bridge. Still hoping to avoid detection, Heck dallied at the junction, watching the Hyundai shrink as it ascended the higher ground on the far side.

‘Heckenburg to 1416?’

‘Receiving, sarge … go ahead.’

‘Suspect vehicle heading south along the upper section of the B5343.’ He glanced at his sat-nav. ‘That means they’re coming your way, M-E.’

‘Affirmative, sarge. I’m headed in that direction now. You want me to intercept?’

‘Negative … we haven’t got enough on them yet.’

There was only one patrol vehicle attached permanently to Cragwood Keld police station: the powerful Land Rover Mary-Ellen was currently driving. Decked in vivid yellow-and-turquoise Battenburg, it was purposely designed to be noticeable on these bleak uplands; it even had a special insignia on its roof so air support could home in on it – but that was less useful on occasions like this, with stealth the order of the day.

‘M-E … proceed to Little Langdale village, and park up,’ Heck said. ‘That way, if they reach your position and we still don’t want to pull them, you can get out of sight.’

‘Wilco,’ she replied.

Heck hit the gas as he accelerated onto the B5343 and followed it across the valley bottom, taking the bridge over the beck. The Hyundai was still in sight, but high up now and far away; a green matchbox car. Shortly, it would dwindle from view altogether. Heck floored the pedal, the dry-stone walls enclosing the paddocks falling behind, to be replaced by swathes of tough, tussocky grass, which sloped steeply upward ahead of him. The fleecy white/grey blobs of Herdwick sheep were dotted all over the valley’s eastern sides, several wandering across the road as he accelerated, scattering and bleating in response. Officially, the B5343 no longer bore that title at this point – it was now significantly less than a B-road, but it never rose as high as Cragwood Road, and in fact levelled out at around seven hundred feet. Once again, it banked and swung, though Heck kept his foot down, managing to close the distance between himself and the Hyundai to about four hundred yards.

The ground on the right had now dropped away into a deep, tree-filled ravine, through the middle of which a smaller beck tumbled noisily, draining excess water from Blea Tarn, the next lake on this route, located about five miles ahead. Before that, approaching on the right, there was another pub, The Three Ravens. In appearance, this was more like a Lakeland cottage, low and squat, built from whitewashed stone. Despite its dramatic perch on the very edge of the ravine, a small car park was attached to one side of it, though only one vehicle was visible there at present: a maroon BMW Coupe.

Heck glanced at his watch – it was lunchtime. This was the time of day the bastards usually pounced. His gaze flitted back to the Hyundai, the tail-lights of which glowed red, its indicator flashing as it veered right into The Three Ravens car park, pulling up almost flush against the pub wall.

Heck smiled to himself. They’d sussed this spot out previously, and knew where the outdoor CCTV was unlikely to catch them.

‘Heckenburg to 1416, over?’

The response was semi-audible owing to the higher ground, filtered through noisy static. ‘Go ahead, sarge.’

‘We’re on, M-E. Suspects have called at The Three Ravens pub, overlooking Blea Tarn ghyll. If I’m right, they’re going to hit their next target somewhere between here and the tarn. It’s perfect for them. Five miles of the remotest stretch of road in the Langdales. In fact, I think it’s a must-hit. They won’t want to chance it after that … too many cottages.’

‘Received, sarge. How do you want to play it, over?’

‘Bring your Land Rover up the B5343. Wait on Blea Tarn car park. But tuck yourself out of the way in case they carry on past, over.’

‘Roger, received.’

Heck proceeded past The Three Ravens car park, catching sight of the lad from the Hyundai loitering about, now with his sweatshirt hood drawn up, while the two adults entered the pub, no doubt to size up any potential opposition. Mindful of indoor CCTV, the girl had affected a blonde, shoulder-length wig, while the man had donned a woolly hat with what looked like ginger hair extensions around its rim. Heck could have laughed out loud, except that unsophisticated precautions like these often hugely aided criminals. Though not on this occasion, if he could just get his timings right. Feeling that old tingle of excitement – something in distinct short supply these last two and a half months – he scanned the roadside verges for a lying-up point. A couple of hundred yards further on, he spied a break in the dry-stone wall on his left, a farm track leading through it and dropping out of sight into a hollow. Heck swung through and swerved down the stony lane, only halting among a thicket of alder, where he threw his Citroën into reverse, made a three-point turn and edged back uphill, halting some forty yards short of the gate. Jumping out, he climbed the rest of the track on foot, dropping to a crouch behind the right-hand gatepost and watching the road.

He wasn’t sure how long this thing would take. If his suppositions were correct, the first thing this crew would do was establish whether or not their potential target was likely to be easy: an elderly couple or someone travelling alone would be preferable. Under normal circumstances they’d then ascertain which car in the car park belonged to said party. This was more simply done than the average member of the public might imagine, especially at a time of year when there were fewer cars to choose from. Maps and luggage, for example, would indicate visitors rather than locals; an absence of toys would suggest older travellers, which in its turn might be confirmed by evidence of medication or a choice of music or reading material – it was amazing what you could learn from the books and CDs that routinely littered footwells. In this case of course it would be even easier than usual – there was only one car. After that, it was a straightforward matter of disabling the car in question – previously this had been done by inflicting small punctures on the tyres with an air pistol – and following until it pulled up by the roadside.

A low rumble indicated the approach of a vehicle. Heck squatted lower. A soft-topped Volkswagen Sport roared past, leaves swirling in its wake. It was running smoothly, with no sign that it was suffering any kind of damage.

Heck relaxed again, ruminating for another fifteen minutes, reminding himself that patience and caution weren’t just virtues in this kind of work, they were essential. So much of the success enjoyed by professional criminals was down to the fear they created with their efficiency – the way they came and went like ghosts, the way they knew exactly who to victimise, exactly where to find such easy prey, exactly when to catch it at its most vulnerable. It bewildered and terrified the average man and woman; it was as though the felons possessed supernatural instincts. Yet in reality it owed to little more than thorough preparation and a bit of basic cunning, and in the case of distraction-thieves like this particular crew, a quick glance through the windows of a few parked cars. In some ways, that was impressive – you couldn’t fail to admire someone who was so good at what they did, even something as callous as this – but it didn’t make them the Cosa Nostra.

The radio crackled in his jacket pocket. ‘1416 to DS Heckenburg?’

‘Go ahead, M-E,’ he replied.

‘In position now, sarge.’

‘Stay sharp, over.’

‘Roger that.’

Another vehicle was approaching, this time minus the low, steady hum of a healthy engine. Instead, Heck heard a repeating metallic rattle – as if something was broken. He tensed as he lowered himself. Two seconds later, the BMW Coupe from The Three Ravens car park chugged past, its driver as yet unaware he had two slow-punctures on his nearside. Unaware now maybe, though not for long.

Heck tensed again, waiting. The thieves wouldn’t have dashed straight out of the pub in pursuit of the BMW’s occupants – that might have attracted attention – but they wouldn’t want to let them get too far ahead either. And right on cue, only half a minute later, the Hyundai itself came slowly in pursuit.

Heck dashed back to his Citroën, gunned it up the track to the main road and swung left. It was only a matter of distance now. With a single deflating tyre, it was possible an innocent motorist would keep driving, failing to notice, but with two, that was highly unlikely. Around the next bend, the road spooled out clearly for about two hundred yards, at the far end of which Heck saw the BMW wallowing to a halt beneath a twisted ash. The Hyundai prowling after it hadn’t reached that point yet, but was already decelerating.

Heck hit the brakes too, swinging his Citroën hard up onto the nearside verge so that it was out of sight. He jumped out, vaulted over the wall, and scrambled forward along undulating pasture, staying parallel to the road but keeping as low as he could.

This was the ideal spot for an ambush, he realised. Brown Howe was a lowering presence on the left, Pike of Blisco performing the same function on the right. Utter silence lay across the deserted, bracken-clad valley lying between them. The dull grey sky tinged everything with an air of wildness and desolation. No tents were visible, no hikers; there wasn’t even a shepherd or farm-worker in sight.

Heck advanced sixty yards or so, and moved back to the wall, where a belt of fir trees would screen him. The two cars were still visible, the Hyundai parked directly behind the BMW. Four people now stood by the vehicles’ nearside. A dumpy balding man and a thin white-haired woman, both in matching sweaters, had clearly been the occupants of the BMW. But Heck also saw the girl in the blonde wig, and the lean young man in the woolly cap, who even now was stripping off his cagoule, no doubt offering to change one of the BMW’s mangled tyres. Heck could imagine the advice he’d be giving them – mainly because the exact same spiel had been dealt to those others who’d suffered this fate in the Yorkshire Dales and the Peak District.

‘A double blow-out’s a bit of a problem,’ the good samaritan would opine. ‘But if you use the spare to replace the front one, you should be able to get down to the nearest town, where a garage can fix the rear one for you.’

Wise advice, delivered in casual, friendly fashion – and all the while, the third member of the trio, the youth, who the victims wouldn’t even know was present, would be sliding unobtrusively out of the back of the Hyundai’s rear and crawling around to the target vehicle’s offside, from where he could open the passenger door and help himself to whatever jackets, coats, handbags and wallets had been dumped on the back seat. A classic distraction-theft, which even now – as Heck watched – had gone into play. The lad, still in his neutral grey clothing, snaked along the tarmac, passing the Hyundai on all fours.

Heck stayed in the field but ran forward at pace, climbing a low barbed-wire fence, and hissing into his radio. ‘Thieves on, M-E! Thieves on! Move it … fast!’

Mary-Ellen responded in the affirmative, but it was Heck who reached the scene of the crime first, zipping up his anorak as he jumped the wall and emerged on the roadside, coming around the twisted ash before anyone had even noticed.

‘Afternoon all,’ he said, strolling to the rear of the BMW, where the youth, still on hands and knees, but now with a purse, a wallet and an iPad laid on the road surface alongside him, could only gaze up, white-faced. ‘This is illegal, isn’t it?’

The elderly couple regarded Heck in bemusement, an expression that only changed when he scooped down, caught the lad under his armpit and hoisted him into view. At once the younger couple reacted; the girl backing away, wide-eyed, but the bloke turning and sprinting along the road.

He didn’t get far before Mary-Ellen’s Land Rover, blues and twos flickering, spun into view over the next rise, sliding to a side-on halt, blocking the carriageway. The thief fancied his chances when he saw the figure who emerged from it: a Cumbrian police uniform complete with hi-viz doublet, utility belt loaded with the usual appointments, cuffs, baton, PAVA spray and so forth, but with only a young woman inside it – probably younger than he was in fact, no more than twenty-three, and considerably shorter, no more than five foot five. Of course he didn’t know PC Mary-Ellen O’Rourke’s reputation for being a fitness fanatic and pocket battleship. When she crossed the road to intercept him, he tried to barge his way past, only to be taken around the legs with a flying rugby tackle, which brought him down heavily, slamming his face on the tarmac. He lay there groaning, his fake head-piece hanging off, exposing the fair hair underneath. Mary-Ellen knelt cheerfully on his back and applied the handcuffs.

‘Sorry folks,’ Heck said to the astonished elderly couple, as he marched past, driving the other two prisoners by the scruffs of their necks. ‘DS Heckenburg, Cumbrian Constabulary. We’ve been after this lot for a little while.’

‘We’ve not done nothing,’ the girl protested. ‘We were trying to help.’

‘Yeah, by lightening these good people’s load while they were on their holidays,’ Heck replied. ‘Well don’t worry, now you’re going on your holidays. At Her Majesty’s pleasure. You don’t have to say anything, but it may harm your defence if you don’t mention when questioned something you later rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence … in case you were wondering, you’re getting locked up for being a set of thieving little scrotes.’

It was mid-evening when the arresting officers finally returned from Windermere police station, where they’d taken their prisoners for interview and charge. While Mary-Ellen headed to Cragwood Keld nick to sign off and close up for the day, Heck made his first port of call The Witch’s Kettle, not least because on a cold, misty autumn night like this – the chill in the air had turned icy – the warm, ruddy light pouring from its windows was very alluring. Inside, a big fire crackled in the grate, throwing orange phantasms across the olde worlde fittings.

Lucy Cutterby, Hazel’s only barmaid, was alone behind the bar, reading a paperback. ‘Hi, Heck,’ she said, as he approached.

Lucy was nineteen and worked here for bed and board only, because she was actually Hazel’s niece, taking a year out to do some hiking, climbing and sailing and to get in some additional study time before she went to university, where she hoped to take a degree in Sports Science. At present, she looked trim and athletic in grey sweats and white plimsolls, her lush tawny hair worn high. With her blue eyes, pixie nose, and rosebud lips, Lucy had been a welcome addition to the pub’s staff. Hazel assumed she’d attract men to the pub in droves, but on a night like this they’d be lucky to attract anyone. At present only a handful of customers was present: Ted Haveloc, a retired Forestry Commission worker, who now worked on everyone’s gardens; and Burt and Mandy Fillingham, who ran the post office which also doubled as the village corner shop.

Lucy nipped upstairs to get her aunt, who trotted down a few minutes later. ‘And?’ Hazel asked, looking vaguely uneasy.

Heck shrugged off his anorak and pulled up a stool. ‘Couldn’t have done it without you.’

‘You arrested them?’ She looked surprised, but still perhaps a little shaky. Hazel was every inch a local lass – she was well-travelled but had never actually lived outside the Lake District, as her soft Cumbrian accent attested – and the thought of serious crime visiting this peaceful quarter was something she evidently wasn’t getting her head around easily.

‘All three of them,’ Heck confirmed. ‘Caught ’em in the act.’

She served him his usual pint of Buttermere Gold. ‘So what was it all about? Or aren’t you allowed to tell me?’

‘Suppose you’ve a right to know, given the help you’ve provided. Several times in the last fortnight, tourists up here have been waylaid by distraction-thieves. It happened in Borrowdale, near Ullswater and down in Grizedale Forest. The usual form was the visitors stopped for lunch somewhere, but no sooner had they got back on the road than they had to pull over with a couple of flat tyres. A few minutes later, a young bloke and his girlfriend would conveniently stop to assist. Once these two had driven off again, the tourists found valuables missing from their vehicles.’

Hazel looked fascinated, and now maybe a little relieved that the crimes in question weren’t anything more violent. ‘I’ve heard about that on the Continent.’

‘Well … it if works in France and Spain, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t work here. Especially in rural areas. All we knew was that the suspects were driving either a green or blue motor, which might have been a Hyundai. The victims were never totally sure, and we only got rough glimpses of it on car park security footage … on top of that we only ever had partial VRM numbers, and they never seemed to marry up. You won’t be surprised to learn that after we arrested this lot, we found dozens of different plates in the boot, which they changed around regularly.’

‘So this was like their full-time job?’

‘Their career. The way they made their living. Anyway …’ He sipped at his beer. ‘As the crime spree only seemed to start around here two weeks ago, I made a few enquiries with other forces covering tourist spots – and I got several similar reports. A young male and female distraction team targeting motorists out in the sticks. It was always the same pattern. The boy offered to help with the tyre change, while the girl stood around chatting. In no case did the spree last more than two weeks.’

‘They only booked in here for two weeks,’ Hazel said.

‘They never outstay their welcome. The upshot was I canvassed all the hotels and bed and breakfasts.’

‘And that worked?’ She looked sceptical. ‘I mean, even in the off-season there are thousands of young couples who come up to the Lakes.’

‘Yeah, but not so many who’ve got a gooseberry in tow.’

‘I don’t get you.’

‘You may recall … I didn’t ask you if there were any adult couples staying here. I asked if there were any adult trios.’

‘Ohhh.’ Now Hazel looked impressed. ‘Who’s a clever boy?’

‘It struck me there’d have to be a third thief, someone concealed in the Hyundai. He would do the actual stealing while the others put on their show.’

‘And one such trio was staying here,’ she said. ‘And they even drove a Hyundai.’

‘And the rest is history.’ He smiled. ‘Mind you, I’m not saying we didn’t get lucky that they happened to be rooming right here.’

Hazel continued mopping the bar. ‘So long as they’re gone. I mean I hope they haven’t left anything behind … I wouldn’t want them coming back.’

‘I wouldn’t worry about that. Quite a few forces want to talk to them. They’ll be in custody a good while yet.’

Realising he hadn’t paid for his pint, he pushed some money across the bar-top, but she pushed it back. ‘On me. For a job well done. I’ll tell you what … I’d never have had them pegged for criminals. Bit of a curious mix, I suppose … mid-thirties, mid-twenties and a teen, but they didn’t seem rough.’

‘Successful crooks are rarely dumb. You want to infiltrate quiet communities, it doesn’t make any sense to ride in like a bunch of cowboys. Not in this day and age.’

‘Makes you realise how vulnerable we are up here, though.’

‘Nahhh,’ came a brash Irish voice. Mary-Ellen had materialised alongside them, now in a black tracksuit with ‘Metropolitan Police’ stencilled across the back in white. She leapt athletically onto the bar stool next to Heck. She was toothy but pretty, with fierce green eyes and short, spiky black hair. A champion swimmer, fell-walker and rock-climber, she radiated energy and enthusiasm – even now, at the end of a long, tough shift. ‘You’ve got us two, haven’t you?’ she chirped. ‘We’re a match for anyone.’

‘And here’s the other girl of the moment,’ Heck said. ‘Wouldn’t have been able to do it without her, either.’

‘What’ll you have, M-E?’ Hazel asked.

Mary-Ellen gazed at Heck with mock astonishment. ‘You buying, sarge?’

‘I’m buying,’ Hazel said. ‘You two have taken some nasty people off the streets today. Our streets. And with the bad weather due, they could have been stuck around here for God knows how long. Who knows, we could have been murdered in our beds.’

‘Don’t think they were quite that nasty,’ Mary-Ellen replied with her trademark rasping chuckle. ‘But I’ll have a lager, cheers. I’ll tell you what … felt good getting our hands on some proper villains for a change, eh?’

‘Too true,’ Heck said, peeling away from the bar and heading to the Gents. ‘Excuse me, ladies … too sodding true.’

Neither of the women chose to comment on that parting shot.

Mary-Ellen was a newcomer to the Lake District herself, having transferred up only a couple of months ago from the Met, just half a month after Heck in fact. But despite spending her last four years in Britain’s largest urban police force, she had worked exclusively in Richmond-upon-Thames, a well-heeled area with relatively low crime rates, and lacked Heck’s experience of inner-city policing and major investigations. But given that the most serious crimes they tended to have to deal with up here involved low-level drug dealing, thefts from gardens, and the occasional drunken incidents in pubs – she could understand how he might be feeling a little restless. He’d taken to this distraction-thefts enquiry giddily, like a kid in a toy shop, and had almost seemed disappointed they’d closed the suspects down so quickly. Of course, from Hazel’s perspective, the whole thing had been fascinating but also a little unnerving – not just because it had revealed the presence of real criminals, but because it had allowed her a first glimpse of Heck’s edgier, more adversarial character. In the real world, the handsome, homely landlady – newly divorced, thanks to her beer-bloated rat of a husband running off with one of his barmaids two years ago – should be the apple of every single bloke’s eye. The problem was that there weren’t that many single blokes in the Cradle. As such, it was perhaps no surprise Hazel and Heck had gravitated towards each other. But Mary-Ellen couldn’t help wondering how long it could last.

Not that it was very clear to anyone, Heck included, what he and Hazel’s actual relationship was.

Heck himself pondered this as he stood washing his hands in the bathroom. It had occurred by increments, if he was honest. With near-reluctance, as though both parties were trying to avoid being hurt, or perhaps trying to avoid hurting each other. But the mutual attraction had steadily grown: the furtive looks they’d exchanged, the occasional touching of hands, Heck finding himself perched comfortably at the end of the bar where the till and telephone sat, a position of familiarity that wouldn’t normally be reserved for everyday customers. Despite all that, there were some confidences he wasn’t yet prepared to share with Hazel – primarily a concern that he was wasting himself out here in the boondocks. Partly this was through fear. Hazel was so proud of this small, successful business she ran. She adored her tranquil life in Cragwood Keld, this ‘haven in the mountains’ as she called it. The idea of moving anywhere else was hardly likely to appeal to her. In that respect, Heck’s increasing boredom with his current post was a subject he never gave voice to.

‘Will I have to give evidence?’ Hazel asked when he returned to the bar.

Heck pondered. ‘Shouldn’t think so. I mean, there’s nothing they could cross-examine you on. I enquired if you knew anyone matching a certain description. You did and gave me a statement. After that, you had no further involvement. In any case, they’ve already coughed to the distraction-thefts up here in the Lakes, so the chances are that part of the case won’t go to trial.’

‘I may need that from you in writing if I’m not going to worry about it,’ she said, moving away to serve Burt Fillingham.

‘So what do we think?’ Mary-Ellen asked Heck. ‘Good day?’

‘Very good day.’

‘Hazel’s right about the weather. Forecast’s terrible. Freezing fog up here tonight and tomorrow. Maybe even longer. Visibility down to a few feet.’

‘Great. Life’ll be even quieter.’

‘Hey …’ She elbowed him. ‘A few detectives I know’d be glad of that. Catch up on some paperwork.’

‘To catch up on paperwork, M-E, you first have to generate it.’

She regarded him appraisingly. As a rule, Heck didn’t get morose. But he was leaning towards glum at present. ‘Heck, didn’t you volunteer for this Lake District gig?’

‘Yeah … sort of.’ He waved it away. ‘Sorry … quiet is good. Course it is. Means low levels of crime, people sleeping safe in their beds. How can I complain?’

She chugged on her lager. ‘It won’t be cakes and ale. There’ll be accidents. People’ll get lost, get hurt … there’s always some bellend who’ll come up here alone, whatever the weather man says.’

Heck pondered this. It was true – the fells were no place for inexperienced hikers, especially in bad weather. And yet all winter the amateurs would try their hands, necessitating regular and risky turn-outs for the emergency services. If this coming winter turned particularly nasty, the Cradle itself could face problems. With only Cragwood Road connecting it to the outside world, snow, sleet and even heavy rain had the potential to cut them off. The predicted fog would be even more of a nuisance as it might prevent the Mountain Rescue services deploying their helicopter.

‘I think I can safely say,’ Heck concluded, ‘that even I would rather be tucked up warm in bed than dealing with that lot.’

‘I’m sure that’ll be an option,’ Mary-Ellen said, as Hazel came back along the bar.

‘Looks like there won’t be much custom in here for the next few days,’ Hazel commented.

‘Just what we were saying,’ Mary-Ellen said, drinking up. ‘Anyway, I’m off. Thanks for the beer.’

‘Bit early …?’ Heck said.

‘True Detective’s on satellite again tonight. Missed it the first time round.’ She sauntered out of the pub. ‘See you later.’

‘True Detective …?’ Hazel mused. ‘Isn’t that the one where they were after some kind of satanic killer?’

‘Seem to recall it was,’ Heck replied.

She mopped the bar-top. ‘Not the kind of thing we get up at Witch Cradle … despite the name.’

‘So I’ve noticed.’

‘These sneaky buggers pinching people’s handbags and wallets are about the toughest we’re used to up here.’

‘Let’s hope it stays that way.’

She gave him a half-smile. ‘Yeah … course you do.’

‘Hey, I may surprise you.’

‘Oh?’

‘I’m adaptable. The quiet life has its attractions.’

‘Such as?’

He shrugged. ‘We’re all adults. It’s not like we can’t find ways to fill these long, uneventful hours.’

Hazel smiled again, saucily, as she pulled Ted Haveloc a pint.

Outside meanwhile, a front of semi-frozen air forged its way across the mountains and valleys of northwest England, sliding under the milder upper air and gradually forming a dense blanket of leprous-grey fog which, in a region already famous for having very few streetlamps, reduced visibility to virtually nothing. The scattered towns and villages were shrouded. Cragwood Keld – a hamlet of only fifteen buildings – was swamped; one house couldn’t see another. And of course it was cold, so terribly cold, with billions of frigid water crystals suspended in the gloom; every twig, every tuft of withered vegetation sprouting feathers of frost. By eleven o’clock, as the last few house-lights winked out and the full blackness of night took hold, the polar silence was ethereal, the stillness unearthly.

Nothing stirred out there.

These were foul conditions, they’d say.

It was a foul night all round.

The foulest really.

Abhorrent.

Loathsome.

Chapter 2 (#u1fab5290-40ec-584a-937a-13cf9b1484f4)

‘We just have to get to lower ground,’ Tara said tiredly. ‘Then we can flag a car down or something.’

‘I agree that’s the obvious solution,’ Jane replied, vexed, ‘but don’t keep saying it over and over, as if it’ll be some kind of doddle and that it’s somehow stupid of us to not have done it already. For the last three hours, the only way to get to lower ground has been over precipices or down vertical drops.’

Tara made no initial response, mainly through guilt.

It had been her idea to finish their week-long camping trip by taking a well-trodden hilltop path from Borrowdale, over High Raise and Great Castle Howe, and down into Great Langdale. On paper it had all looked so straightforward; in fact easier than that, and probably very rewarding. After a difficult week, it had felt as if she was plucking victory from the jaws of defeat. The campsite at Watendlath hadn’t been all they’d hoped for, primarily because it was late November and the tourist season was long over. A few other hardy campers were present – hardier than Tara and Jane, it had to be said – but the site was largely empty, and its facilities operating at a reduced level; the toilets and showers were open, and that was about it. The weather conditions, while not exactly disastrous, were testing; the mornings damp and cold, the afternoons slightly drier but still cold, and the nights, freezing. On top of that, they were not experienced at this sort of thing. Their tent was old and somewhat mouldy; it was also single-skinned, which offered them zero protection against insects and condensation; they’d brought foam mats instead of truckle-beds, and their sleeping bags were old and filled with duck-down, which when it got damp stayed damp – and it had rained several times already that week; boy, had it rained.

None of this had made for a comfortable time. But worse still, they were bored. Neither Tara nor Jane classified themselves as party girls, but they were on their holidays and would have liked a drink now and then. Unfortunately, they’d used up all their spare backpack space on food supplies, and had assumed before arriving there’d be somewhere close by where they could stock up on booze once they’d got here – but there wasn’t and neither had a car, so they couldn’t just drive out. Jane had her iPad, so they could watch movies and listen to music – at least that had been the plan, but the device’s battery had died within a day and Jane had neglected to bring her charger.

As such, Tara’s sudden suggestion that they stop moping around the camp and actually get up into the wilderness – do some real walking, get some proper exercise and fresh air – had seemed like a godsend. It wouldn’t even be that difficult, she’d said, as they pored over a map on the fourth morning. Watendlath to Elter Water was not a great distance. The guidebooks described it as a ‘challenging route’, but they weren’t looking for a stroll in the park. If it took them all day, so much the better – they had nothing but time anyway. Once they reached Elter Water, they could catch a bus to Ambleside, stay overnight in a B&B, and head for home by train.

‘I mean, how difficult can it be to just check the weather forecast?’ Jane grumbled as they trudged doggedly on, their backpacks jolting their aching spines.

‘With what, Jane?’ Tara retorted. ‘The club and bar were closed, so we had no access to a telly. Our phones aren’t getting any signal up here. No one was selling newspapers on the site, and even if there’d been sufficient Wi-Fi for your iPad to be any use, the bloody thing ran out on us …’

‘Alright, alright, for Christ’s sake!’ Jane’s face reddened, and not just from the unaccustomed exertion.

On all sides, meanwhile, the midnight fog hung in impenetrable drapes. At this height and temperature it was like movie fog, a dense, grey mantle that rolled and twisted, obscuring everything. There hadn’t been any sign of this when they’d set off that morning, in broad daylight – it had been clear as a bell. But even if it had still been daylight now, only a few yards of harsh, rocky ground covered with frost-white tussocks would be visible. And of course, it wasn’t daylight; it was dark, which didn’t so much obscure the surrounding landscape as obliterate it. Naturally, they’d neglected to bring a torch. The last few occasions they’d needed light – to try to make sense of a dog-eared map, which was now next to useless anyway, as some time back they’d unconsciously veered off the flinty footway that was their prescribed route – Tara had switched her phone on, using the dull glow of its facia. She was increasingly reluctant to do this now, as she didn’t want to run its power down. It would be typical of their luck if they suddenly entered a better reception area and were able to make an emergency call, only for the battery to die.

The guidebook had predicted the journey would take six hours, meaning they’d finish well before nightfall, but they’d now been struggling along for at least twelve.

‘Look …’ Tara tried a more placating tone. ‘If we can’t find our way down to a road, we should maybe think about pitching the tent. Just camp for the night. Hopefully this fog will have lifted by morning.’

‘Newsflash, Tara … it’s perishing bloody cold!’

‘So we wrap up.’

‘Everything’s wet, you dozy mare! We’ll die from bloody hypothermia.’

Their voices echoed and re-echoed, creating the illusion they were in a chasm rather than on some open hillside. It was more than uncanny.

‘Jane, it can’t be a good idea to just keep ploughing on. We don’t know where we’re going, and this ground seems to be sloping upward.’

‘We can hardly pitch the tent when we can’t see our hands in front of our faces,’ Jane said. ‘Anyway, what if the fog hasn’t gone by tomorrow? We’re up on the fells, remember … not in some nice park a few yards from your mum and dad’s nice little middle-class house.’

‘Alright! You don’t need to be such a bitch about it.’

‘Anyway, what good is sitting tight going to do? No one’ll come looking for us, Tara, because no one fucking knows we’re here. Didn’t it ever enter that air-filled brainbox of yours to tell someone what we were planning? And I don’t mean that bloody campsite owner. I mean someone who might actually care about us, who might actually have been listening when you were talking to them. Like our fucking parents, perhaps! I mean, Jesus, how difficult can it fucking be …?’

‘Alright, I said! Christ’s sake, Jane … I’m in as much danger as you are!’

Jane muttered some incoherent, vaguely foul-mouthed response, and they trod along in silence for a few more minutes, hearing only their own grunted exertions and the hollow thuds of their feet. Fleetingly, oddly, Tara was uncomfortable with the otherwise complete silence. It was a stupid thought, of course. There was no one else up here, but why did she get the sudden feeling their latest outburst, which would likely have been heard for miles and miles on a night like this, might have drawn the attention of someone listening? Even if it had, that ought to be something they’d want – and yet there was a brief queasy sensation in her tummy.

‘Sorry about the airhead thing,’ Jane muttered self-consciously.

‘It’s alright,’ Tara said. ‘Sorry about the bitch.’

Tara Cook and Jane Dawson were able to converse like this, one minute at each other’s throats, the next offering consolation, because they were close enough to be sisters, having grown up together in Wilmslow.

Jane was now a sales assistant at Catwalk, a clothing retailer whose branded products were strictly mid-range, while Tara had a bar job but was also studying for her PhD at Manchester Met. Money was tight for the both of them and, wanting to get away for a bit, it had been Tara’s idea that they visit Cumbria.

‘Let’s just put everything on hold for a few days,’ she’d said enthusiastically. ‘Let’s go camping in the Lakes. We both love it and it will do us a world of good.’