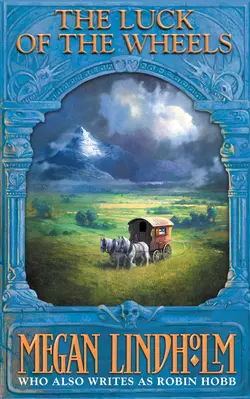

Luck of the Wheels

Megan Lindholm

A reissue of classic backlist titles from the author of the best selling Farseer Trilogy and The Liveship Traders books. LUCK OF THE WHEELS is the fourth and final book in THE WINDSINGERS series, which introduced her popular gypsy characters, Ki and Vandien.Gypsy traders Ki and Vandien should have realised the money was too good to be true. Three georns and a full orn to be paid on arrival – and all they had to do was transport the cargo to Villena! The cargo, however, turned out to be human; a boy called Goat, and his family seemed just a little bit too anxious to be rid of him.The arrangement smelled like trouble. And it was; especially when faced with a few other unexpected problems… like a lovesick stowaway, an army of rebels and road bandits and a magical detour with death itself…

Luck of the Wheels

Book Four of the Windsingers Series

Robin Hobb

Dedication (#ulink_85c2f456-3240-56b3-84df-05521b977bd0)

This book is for James LaFollette

Because every kid deserves the kind of uncle who, when he babysits small nephews, staples them to the wall, or hog-ties them with duct tape and leaves them on the front lawn, or handcuffs larger nephews to the bumpers of cars and abandons them, or offers to teach you how to swim while wearing tire chains or threatens to flush your favorite disgusting army hat down the toilet.

And every kid also deserves the kind of uncle who takes you to the doctor to get the ring you borrowed cut off your finger, or sits by your hospital bed for ten hours on the day you’re facing surgery and comforts you with stories about how humiliated he was when he had to go to the hospital because his cousin shot him in the butt and makes off-the-wall remarks that rattle the nurses, or buys you hordes of books on archaeology and takes you out to look for arrowheads and stone implements, or uses you for a gofer at the gun show, or gives you fencing lessons in the garage on rainy days or brings you a genuine cavalry bugle to blow while your mom is trying to work on the final draft of her book.

And every writer deserves the kind of brother who stays up until midnight choreographing fencing scenes in the kitchen, and proofreads scribbled-on drafts, and tells her when her character is acting like a real wimp and organizes expeditions to Shoreys in Seattle just when the walls are completely closing in on her.

Garf, you’ve been all that and more. We love you.

But I’m still going to nail you for that damn bugle.

Contents

Cover (#uf8396ae1-72f4-583b-b58e-92fc78514e50)

Title Page (#u6665d9ae-e777-56ce-bbbd-ed9b5f597a1c)

Dedication (#udd42e638-c7cc-5b23-bb0a-91588c2ae33d)

One (#u67d6b702-3d19-56d9-8628-0b5c1bf084da)

Two (#u18d29189-62bc-5f00-a959-b61d28baa999)

Three (#u18e1b119-0944-5d2e-acce-8db896a13649)

Four (#u6d250fea-3897-5fb8-ad9c-dae0be79ec37)

Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_0ddf35c6-f8c8-5117-b265-c67841ce8a79)

‘And I’ll tell you another thing,’ the owner of the caravansary went on as she refilled her own glass and then Ki’s. She leaned heavily on the table they shared, shaking a warning finger at Ki so that the tiers of bracelets on her arm rattled against one another. ‘I’d never take a green-eyed man into my bed. Mean, every one of them I ever met. I knew one, eyes green as good jade, and heart cold as the same stone. He’d go out of his way to find a quarrel, and then wasn’t happy until I’d apologized for starting it. Mean as snakes.’

Ki nodded absently to her host’s litany. A soft dry wind blew through the open portals and arched windows of the tavern common room – if common room was what they called it in this part of the world. The wind carried the scent of flowers and dust, and the sounds of foot and cart traffic from the streets outside. The floor of the tavern was raked sand, the walls of worked white stone. Trestle tables were crowded close in the common room, but most of the other tables were deserted at this time of day. Cushions stuffed with straw, their rough fabric faded, were fastened to the long low benches. This far south, not even the taverns looked like taverns. And the wine tasted like swill.

Ki shifted uncomfortably on her cushion, then leaned both elbows on the low table before her. She had wandered in here seeking work. Up north the tavernkeepers had always known who had work for a teamster. But this Trelira only had news of what men were best left unbedded, and the disasters that befell women foolish enough to ignore her warnings. Ki hoped that if she sat and nodded long enough, Trelira might wander onto a more useful topic. She stifled a sigh and wiped sweat from the back of her neck. Damnable heat.

‘Trouble most women have,’ Trelira was going on, ‘is how they look at a man. They look at his face, they look at his clothes. Like buying a horse by how pretty its harness is. What good is that? Prettier a man is, the less you get out of him. I had a man, a few years back, looked like a laughing young god. Sun-bronzed skin, forearms wide enough to balance a pitcher on, black, black hair and eyes as blue and innocent as a kitten’s. Spent all his days in my caravansary, drinking my wine and telling tall stories. And if I asked his help, he’d go into a sulk, and have to be flattered and petted out of it. Fool that I was, I would. Ah, but he was beautiful, with his dark hair and pale eyes, and skin soft as a horse’s muzzle.

‘Then one day a man walked in here, homely as a mud fence and dressed like a farmer. Walked up to me and said, “Your stable door is off its hinges, and every stall in it needs mucking out. For a good dinner and a glass of wine, I’ll take care of it for you.” I tell you, it hit me like a sandslide. Kitten-eyes was out of my tavern less than an hour later, and the other fellow got more than wine and food for his trouble.’

Ki tried to smile appreciatively. ‘Ah, handsome is as handsome does,’ she said blandly. ‘No doubt about it. Now, not to change the subject, but I’ve a freight wagon and …’

‘Not always!’ Trelira blithely ran over Ki’s words. ‘Appearances can be just as important. A man with a dirty beard is bound to be dirty elsewhere … You know what I mean. Bloodshot eyes and a red nose, and he’s going to drink. Nor would I take a man with pale skin. Never met a healthy one yet. Nor one with scars. Working scars on a man’s hands, they aren’t bad. A game leg or bad back might mean he’s just clumsy, or stupid. But scars elsewhere don’t come from being sweet and gentle.’

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ Ki ventured to disagree. She glanced down at her own weathered hands. ‘Anyone who’s lived much is bound to have a few scars. And,’ she added as she smiled to herself, ‘certain scars add character to a man’s appearance.’

‘Don’t kid yourself, girl,’ Trelira advised her with maternal tolerance. ‘I know what you’re thinking. But only silly little girls think a duelling scar means romance. Quarrelsome is more likely. Most times it just means a nasty temper. Look at that one, for instance. You can bet he’s a mean bastard. Don’t stare, now.’

Ki swung her gaze obediently toward the portal. A narrow man, a bit taller than Ki, was framed against the bright daylight. He pushed dark heat-damped curls off his forehead as he squinted around the room. His eyes were darker than one would have expected, even in his deeply tanned face. The easy sureness of his quick movements hinted at ready muscles beneath the loose white shirt. In a land where many wore robes and went barefoot, he wore a wide leather belt and tucked loose trousers into the tops of his kneeboots. He could have been handsome, but for the scar that seamed his face. It began between his eyes and ran down beside his nose past a small, trimmed moustache until it trailed off at his jawline. It was a fine score, nearly invisible against his weathered face but for a pull that tugged at one of his eyes when he smiled, as now. The warmth of that small smile belied the grimness of the scar. He caught Ki’s gaze upon him. The smile widened and he came toward them.

‘Here comes trouble,’ Trelira sighed warningly.

‘Don’t I know it,’ Ki replied wryly. The stranger dropped onto the bench beside her, and picking up her glass, drained it.

‘Vandien.’ Ki made it both a greeting and an introduction. Trelira rose hastily, looking abashed.

‘No offense meant,’ she murmured.

‘None taken,’ Ki replied smoothly, adding in a wicked undertone, ‘You’re absolutely right, anyway.’

Vandien had swallowed the wine and was coughing politely to cover up his shock at its sourness. Ki thumped him on the back pitilessly. ‘Meet Trelira, the owner of this caravansary,’ she invited him when he could breathe again.

‘A lovely place,’ he managed. His smile included her in the compliment. Ki watched with amusement the sudden reappraisal in Trelira’s eyes. With that smile and a story or two, Vandien could scavenge a living anywhere. Ki knew it. A shame, she reflected, that Vandien also knew it.

‘It’s a very dry day out there,’ he added smoothly. ‘Could I trouble you for another glass, and perhaps a bottle of Alys?’

Trelira shook her head at the unfamiliar word. ‘This wine is all we offer, this time of year. Tariffs are too high on the rest; no point my buying what my customers can’t afford. But I’ll bring a fresh bottle.’ She departed the table quickly, her bright, loose garments fluttering around her.

‘Not even the water in this town is drinkable,’ he confided to Ki when Trelira was out of earshot. ‘It’s redder than this wine, but not as sour. Leaves more dregs in the cup, though. Did I interrupt something? Smuggling offer, perhaps? That woman looked guilt-stricken when I sat down.’

‘Nothing important. She had just observed that no woman in her right mind would put up with an evil-eyed wretch like you.’

‘I’ll bet,’ he scoffed loftily. A serving boy crept up to set a bottle and glass before him, and scurried off, his bare feet soundless on the soft sand floor. ‘Any luck here?’

‘None. How about you?’

‘Not much better,’ he conceded. ‘I spent the whole morning with some minor official, getting our papers renewed. I told him we had bought our journeying permits at the border already, but he said they were out of date. So we have new papers, with a different seal, for twice as much coin. Made me wish we were back where the Merchant’s Councils ran everything. This Duke everyone speaks of has his officials too scared to take a bribe. And his Brurjan patrollers are everywhere. I never saw so many Brurjans in one place before. Could pave a courtyard with their teeth.’ From inside his shirt he drew a roll of parchment and a flat coin-bag. Ki took them silently. Her face was sour. He shrugged and continued.

‘Then this afternoon, I damn near fell asleep on my feet in the hiring mart. Trouble is that the wagon looks like a peddler’s wagon. Folk ask me what I have to sell, not what I can haul. We did have one query, though. Two sisters came up and asked if we were taking passengers. I gathered that the older girl was running away from home to join her sweetheart. A very uncommon-looking girl she was. Her sister had curling dark hair and blue eyes. But she who wished to run away, she had hair red as a new calf’s hide, and one eye blue and the other green. She …’ He let his words run down in disappointment. Ki was already shaking her head. ‘I know,’ he conceded reluctantly. ‘I had the same visions of outraged kinfolk. I told them we didn’t haul people, and they went away, whispering together. Did hear of one other thing, secondhand. A fellow has twenty chickens he wants to send to his cousin in Dinmaera, about three days from here. A gift of breeding stock to celebrate a wedding.’

‘Damn!’ Ki hissed. ‘Much as I hate hauling livestock, I’d have taken it, if we had the proper wagon for it. But as it is, they’d be inside with us. In this heat.’

‘They’re supposed to be in stout wooden cages.’

‘They’d still stink. And make noises.’

Vandien was taking a cautious sip from his own glass. ‘I left word with the fellow next to me that anyone looking for a wagon and team to hire could find us here. I’m starving. Is the food as bad as the wine?’

‘I haven’t been that brave yet,’ Ki replied distractedly.

‘Shall we order something and find out, or go back to the wagon and fix something ourselves?’

When Ki didn’t reply, Vandien turned to her. She was staring moodily at her wine glass. Her elbow was on the table, her chin propped on her fist. Deft as a cat’s paw, his hand hooked her elbow off the edge of the table, snapping her attention back to him.

‘The wagon,’ she said suddenly, ‘is the whole damn problem. All house and no freight bed. I don’t know why I bought a caravan like that.’

‘I do. It was cheap, and it was there, and we were both in one hell of a hurry to get out of Jojorum. If you wanted a wagon like your old one, with room for freight in the back, you’d have to have it specially built.’

‘Maybe,’ Ki conceded. ‘But that peddler’s wagon hasn’t saved us time or coin. It’s built all wrong; top-heavy and unstable in a river crossing or on a rough road. And where it should be built sturdy, it’s built flimsy. I nearly went right through the door-step yesterday. You know what we should do?’

‘Get a new wagon built?’

‘Yes. Go to the wainwright in Firbanks and get him to …’

‘No.’ Vandien’s denial was absolute. ‘Too many of the people between here and there would remember us too well. And a good number of them are Windsingers that could sing up a killing storm. There’s no going back north for us, Ki.’

‘Just for a short time,’ Ki argued grimly. ‘To get a decent wagon. Look at the thing we’re driving. I can’t even make a living with it. It’s an ugly old peddler’s wagon, not a freight wagon. There’s no space to haul anything. It’s all closed in.’

‘Just like every other Romni wagon I’ve ever seen,’ Vandien cut in smoothly. ‘They seem to cope just fine with their wagons being all living quarters. They don’t worry about how they’re going to pay their expenses. They just travel and live and trust to the luck of the wheels to provide for them. But not you. Sometimes I just don’t understand you. You were raised Romni, but you won’t put your trust in their ways. Think of your old wagon, only half caravan and the rest left open for freight. Some might say due to a lack of faith in the luck of the wheels.’

‘And some might say due to a streak of sanity. I’ve lived by the luck of the wheels, Vandien. You notice they don’t call it the good luck of the wheels. Sometimes it’s very bad. Especially in places like this, where they want a piece of paper sealed and stamped for every breath you take. I’ve seen Romni with a wagon full of children, in the middle of a hostile town, without a bite of food to eat and only the family gold to their names. Gold they’d sooner die for than spend.’

‘And no doubt they all starved to death?’ he asked shrewdly.

‘Well, no,’ she admitted reluctantly. ‘There are ways of getting by. Ways that can get your hand cut off if you’re caught. I’d rather have an open-backed wagon, and a load of freight to haul.’

He tried a new tack. ‘Well, we could pick up a load of trade goods,’ he offered speculatively. ‘You’ve still enough left of Rebeke’s gold to do that. We could get scarves and pans and bells and earrings and lace …’

‘And live in the middle of it all, and open up our home to every customer’s prying eyes. No. I’ve gotten used to the cuddy being private. And I won’t use up the rest of the Windsinger’s gold. It was too hard come by to part with for bells and buttons. No, it’s going to buy me a new, decent wagon, built to my specifications. And that means the wainwright in Firbanks.’

‘It means any wainwright who can build a square corner,’ Vandien contradicted her irritably. He dipped his finger in the wine, idly drew on the tabletop with it. ‘Don’t get so stubborn and set in your ways. Just because he built the last one doesn’t mean he has to build the next one. I don’t think we should go back north. Even if this Duke’s iron hand bothers you. It’s just another set of rules to get used to. We can manage.’

A tired smile broke on Ki’s face. ‘Listen to us. What’s happened to your impulsiveness, that devil-may-care attitude?’

‘A Windsinger scared it right out of me. And you’re a fine one to talk. What’s happened to all your cautions and planning? You’re talking about walking back into the lion’s den.’

Ki refilled both their glasses from Vandien’s bottle. ‘My caution isn’t gone,’ she revealed after a sip. ‘I’m just regaining it. We’ve worked too far south, Vandien. It’s been obvious since we crossed the border into Loveran. I don’t have any contacts here, I don’t understand the coins, I detest the regulations, and I don’t know where the roads go, let alone how safe they are or where the short-cuts are. How can I make a living down here? We’ve been in sunny, dreary Keddi for a week now, with no offer of work. What happens if we don’t get work?’

‘We’d survive.’ He sipped the wine, grimaced.

‘How?’

‘By the luck of the wheels, Ki! Just as all the other Romni survive.’ He paused and looked at her shrewdly. Ki narrowed her eyes warily, but he opened his wide, declaring the innocence of his intentions. ‘Look. Let’s compromise. For a month, let’s live by our wits. Seeing new places, no delivery dates, no pushy customers, no spoiling cargoes. For a month.’

‘In a month, we could starve.’

He gave a snort of disdain. ‘I never starved in all the years before I met you. Lost a bit of weight, learned to be charming to strangers, and not particular about what I ate or where I slept, but I never starved.’

‘We can’t all be stray cats.’

‘No? Let me teach you how.’ He made the offer with his most persuasive smile. His dark eyes, brown half a shade short of black, were inches from her green ones.

‘And at the end of that month?’ Ki asked coolly.

He leaned back with a sigh. ‘If we aren’t successful, then we’ll go back to the wainwright in Firbanks and get a new wagon.’

‘And take up my old trade routes,’ Ki bartered.

Vandien emptied his glass, winced at the taste, and then shook his head. ‘No. The first Windsinger who heard of us would report it to Rebeke. She wouldn’t let us go again.’

‘If we were careful,’ Ki began, leaning forward and speaking quietly but intensely. ‘If we were cautious …’

‘Are you the teamsters for hire?’

Their heads turned in unison. The speaker was an old man. No. With a start, Ki realized that the man standing by their table was only a few years older than she was. It was his eyes that were old, and his voice. He looked as if some task had so wearied him that he had already spent the years of his mind if not his body. Like the child-mystic she and Vandien had seen in Adjutan, who could recite all six thousand of the sacred verses of Krinth. Ancient, weary eyes.

‘We are,’ said Ki. ‘Not any more,’ Vandien chimed at the same instant. The man looked confused. Ki kicked Vandien’s booted ankle under the table.

‘We may be. It depends on the cargo, the distance, the road, and of course, the coin involved. Please, share our table and wine,’ Ki invited him graciously.

Trelira had seen him enter, and was setting an extra glass at the table before he was seated. ‘Brin!’ she greeted him, smiling pleasantly and kissing his cheek. But her eyes darted past his shoulder anxiously. ‘You didn’t bring Gotheris?’

‘No. I left him at home this time, with Channry.’

‘Oh.’ Trelira paused overlong, and Ki wondered what she wasn’t saying. ‘Well. Do you have enough? Something to eat? Well. Good to see you, Brin.’

After each shake of their heads, Trelira had paused, but when at last she could find no excuse to hover by their table, she departed. Ki noticed that almost immediately she was back, raking smooth the sand floor by the next table. Old gossip, Ki thought to herself, and ignored her.

‘I am Brin, as Trelira has let you know,’ the old man began. Vandien had filled his glass for him, but Brin made no move to touch it. ‘Your names are not known to me.’

‘Ki. And my partner, Vandien. You were asking if we were for hire. We are. What cargo?’

‘Well. Not cargo, exactly. Tell me, have you any children?’

Vandien glanced up, startled, but Ki answered succinctly for both of them. ‘No.’

‘Aah. I see. Well, then, that might affect how you might feel about … you see … I have a son. Gotheris. He is come of an age to be put to a useful trade. Years ago, when he was but a tiny child, he showed certain instincts and skills that made my brother, Dellin, most anxious to have him as an apprentice. Dellin is a Jore-healer, you see, a skill that has been long in my family, though not one I chose to follow. So we agreed that when the time came, Gotheris would be apprenticed to him. At that time, Dellin lived in Dinmaera, and we saw him more often. But since then, he has moved to Villena, and so it has been several years since we have seen him.’

Ki and Vandien exchanged puzzled glances. What had all this to do with a freight haul?

‘We’ve had word from him over the years. And I recently sent a message to him that the boy was ready to learn now, and that idleness could only teach him mischief. So he has sent back to me that he is ready to receive the boy at any time.’

‘You want us to take your boy to Villena?’ Vandien guessed.

‘Yes. Exactly. I am willing to pay you three georns now, and at his arrival Dellin would pay you another full orn.’

‘No passengers,’ Vandien said flatly. The cuddy was simply too small a space to share. But Ki raised a hand in a ‘wait a moment’ gesture, and asked quickly, ‘What can you tell me of the roads to Villena this time of year? I won’t pretend that I’m familiar with them.’

Brin looked unshaken by her admission of ignorance. ‘The roads are well marked, but they are caravan roads, soft and sandy, more difficult for a wagon than for men and beasts. There is only one river, low at this time of year, but it has eaten its way deep into the grass plains. The banks of the river are high, steep and rocky. Bridges do not stand in flood time, as has been proven many a time. So all folk go south to the fording place at Rivercross, and then north again to Villena. It is not an easy journey, but the ways are clearly marked, and there are good inns at the towns. It is a journey of, say, ninety kilex, which is …’ Brin paused, converting the distance into time in his mind. He shrugged. ‘Perhaps fourteen days for a wagon, if one takes it at a pleasant pace. There were rumors of thieves and rebels along it last year, but the Duke sent his Brurjan patrols to clean them out. It is a heavily travelled trade route, so the Duke keeps it free of trouble.’

‘If there’s so much traffic between here and Villena,’ Vandien butted in despite Ki’s scowl, ‘why send your boy off with two strangers, instead of with a caravan driver you know, or a trader you’ve done business with?’

‘I …’ The man hesitated, clearly flustered by the question. ‘I saw your wagon. It looked like a comfortable, even pleasant, way to travel. He is my only son, you know. And I would rather he went directly to his uncle, without long stopovers for trading and visiting. The sooner he is with Dellin, the sooner he can begin to learn his trade and become a useful man.’

Vandien rubbed his moustache and lips to cover the twist of his mouth. The man’s reasons did not sound authentic. But Ki was nodding thoughtfully and asking, ‘And how old is Gotheris?’

‘He has seen fourteen harvests,’ the man said, almost reluctantly, but then added brightly, ‘He is large for his years. The Jore blood does that. He will be a good-sized man when fully grown. And he has Jore eyes,’ he added hesitantly, as if they might object to that.

‘I see no problems, then,’ Ki was saying, to Vandien’s total amazement. ‘I’d like to meet the boy, though, before we touch hands on this agreement. Is that acceptable?’

A facial tic twitched Brin’s cheek. ‘Certainly. I will bring him by first thing tomorrow. I will have him bring his things, and I will bring the coins for his passage. That way, as soon as you have agreed, you can be on your way. Acceptable?’

‘I ‘d have to take on supplies first,’ Ki hedged.

‘Then I shan’t bring him by until you are ready. Noon, shall we say? Nothing makes that boy more impatient than waiting. Better not to make him stand about while things are got ready. We shall meet you here at noon, tomorrow. Good evening.’

Vandien frowned after Brin as he vanished through the portal. ‘There’s a strange man. He doesn’t seem to believe we might not take him. And what was his haste? He didn’t even pause to finish his wine.’

‘Given a choice, would you sit here and drink this stuff? Besides, he takes leave of his only son tomorrow. Such a farewell takes time. What’s flustering up your feathers, Van? You questioned him like a jealous lover.’

‘Vandien,’ he corrected her absently, watching the serving boys pull stiff hides across the portals and peg them into place. A dry wind from across the plains rattled sand against the leather. ‘Didn’t he seem awfully anxious to be rid of the boy? I think there’s trouble in this somewhere.’

‘Your tail’s just tweaked because we aren’t going to run off and start a month of vagrancy tomorrow. You think I’m backing out on our agreement, don’t you? Well, I’m not. But why not start the month off with a little coin in hand? Take the boy and drop him off on the way. New places, you said. Well, I’d never heard of Villena until this night. And neither had you, I’ll wager. So why not start from there? Trelira!’ Ki called suddenly across the room. ‘What direction is Villena from here?’

The haste with which the portly caravansary owner trotted to their table betrayed her interest. ‘To the southwest, about fourteen days away. It’s right on the caravan routes. There’s Algona, Tekum, Rivercross, and then Villena. A lot bigger town then Keddi. It was originally a T’cheria settlement, but nowadays there are quite as many Humans there. And a group of Dene have settled at Rivercross. Thinking of going there?’

‘Perhaps. Perhaps not. I was just wondering.’ Vandien played her out on her own curiosity. ‘What are you serving for the evening meal tonight?’

‘I’ve mutton pastries and tubers with onions baked in soft gourds. Barley and bean soup, and a good fresh bake of bread. What takes you to Villena?’

‘Nothing, probably.’ Vandien replied easily, pressing his leg against Ki’s to ask for her silence. ‘Brin wanted us to take his son there, but Ki’s not much for taking passengers. She likes her privacy. Just curiosity made me ask. Neither of us had heard of the place.’

Ki picked up her cue. ‘I’ll have the tubers and onions baked in the gourd, the soup, but no …’

‘Goat? He wants you to take Goat to Villena?’

The avidity of the question trampled over Ki’s attempt to order food.

‘Gotheris was the boy’s name, I thought,’ Vandien ventured.

‘Aye, but he’s been called Goat since he was four or five. He was a spry little fellow then, always gamboling about, so full of energy and mischief. There wasn’t a mother but wished he were her child, when he was small.’ Trelira’s eyes journeyed to some dreaming place and remembered some regret. ‘Why must children change and grow?’ she asked sadly of no one in particular. Then her attention snapped back to Ki, and her eyes went shrewd and businesslike. ‘How much did he offer you for the trip?’

Ki opened her mouth to protest this prying, but Vandien hastily pressed a filled wineglass into her hand. She held her words back behind tight lips.

‘Three georns and a full orn on safe arrival,’ Vandien told her with disarming frankness. His smile made her trustworthy. ‘Have pity on a stranger, Trelira. I can’t even remember how many georns or fiorns in an orn. Given the roads and the distance, would you say that’s a fair price for the trip?’

Trelira took a deep breath for speech, then shut her mouth and gave a quick nod.

Ki took up her part in Vandien’s game. ‘I wonder why he doesn’t wait until he has friends going that way?’ She glanced casually at Trelira.

‘They’d know the … he wouldn’t know anyone. Brin doesn’t know that many folk here. His land is on the edge of the town, alone but for his sheep and his three sons. His wife’s sister was my cousin’s wife,’ she added, speaking softly to herself.

‘Well, we haven’t said we’d take him, yet,’ Vandien admitted casually. But Trelira was no longer listening. She rose and turned, walking slowly back to her kitchen, her head full of her own thoughts. Ki and Vandien exchanged glances.

‘Interesting.’ Ki sipped at her wine.

‘Nice mess. Brin says his only son, Trelira says one of three. Brin says he wants the boy comfortable, Trelira says he wouldn’t know anyone else to take him. Whatever smells funny here, she’s got a family tie to it that’s keeping her from gossiping. Suppose he’s a half-wit?’

‘To be apprenticed to a healer?’

‘I could tell you stories about healers that would make you believe it,’ Vandien offered lightly. Then he shrugged, and became serious once again. ‘What else could it be?’

‘Maybe nothing but your imagination. Maybe a boy grown too big for home and small-town life. Don’t sour the deal, friend, before we’ve even seen the boy.’

Food arrived, a double order of everything Trelira had mentioned. Ki frowned as the serving boy set it before them. ‘What’s this?’ she demanded.

The boy stared at her as if she were daft. ‘Food?’ he suggested.

‘We didn’t ask for any yet.’

‘Trelira ordered it for you. Oh, I’m to tell you there’s no charge. To give you good strength for an early start tomorrow.’

Vandien raised a mocking eyebrow at Ki. She only snorted, and pushed her share of the mutton pastries onto his plate. He accepted them. ‘Still not eating meat?’ he asked the soup gravely, smiling behind his moustache.

‘Don’t push me, friend.’ The smell of the pastries was driving her crazy, and her resolve seemed in question. But she’d stick to it, if for no other reason than that he teased her about it. She was breaking her bread over her barley soup when Trelira’s shadow fell across the table again. ‘Goat,’ she began without preamble. ‘He’s family. I’d never speak ill of him. Those that do, don’t know him. That’s all. Actually, I wish him a good journey, with every comfort. So I’ll add two georns of my own to his passage money. And any trader in town will tell you that adds up to a handsome fee for a trip to Villena.’

The two crescent coins clicked onto the table. Ki and Vandien stared at them, unmoving.

‘What if we decide not to take him?’ Vandien asked.

‘You’ll take him,’ she said with decision. ‘One look in his eyes, and no one can refuse the boy. And everyone in town knows that he wants to go away from here.’ Trelira turned on silent feet and was gone.

TWO (#ulink_d919ee5e-0406-5f20-acf5-a3cdff8d0396)

‘The boy looks ordinary enough.’

Vandien leaned out of the cuddy door and let his gaze follow Ki’s. He had just finished storing their provisions in the cupboards and drawers inside the caravan. The two georns had been enough to take on generous supplies, and at Trelira’s urging, they had done so. Vandien was more than a little disgruntled about it. Ki didn’t usually spend advance money until she had decided to take on the job. So much for meeting the boy first. Well, whatever problems came with him, Ki had bought them in advance.

‘Fourteen?’ he observed skeptically.

‘Looks more like sixteen to me. But you never can tell; some boys grow fast,’ Ki replied.

Gotheris walked beside his father, and nearly matched him in height. That put him half a head taller than Ki and the equal of Vandien. His brown hair clung to his head as smoothly as a cap and was cut to one length on the sides and back. In front it touched his eyebrows in a straight line. His eyes were light, though at this distance Vandien could not tell what color they were. His face was long and narrow, with the unfinished look of a boy who is sure of all the answers while still discovering the questions. His young body was lanky, as if growing bones were outracing the meat and muscle that should cloak them. His cream-colored shirt was lavishly embroidered in red and yellow, in gay contrast to the rough brown robe Brin wore. Goat wore loose brown trousers that fluttered around the tops of his sandaled feet. The boy strode empty-handed, but Brin had a large basket buckled to his back and a woven bag in his arms. Vandien frowned at the boy’s laziness, then decided it was none of his business.

‘Well, here we are, all ready to go!’ Brin greeted them. His words rang falsely hearty in Vandien’s ears.

Ki made some noncommital reply, studying the boy. The boy’s eyes were very large, and slightly protruding. So that was what the father had meant by Jore eyes. Up close, they were so pale a green they verged on yellow, and the pupils were not those of a Human. A little crossbreeding, then, somewhere back in the family line. The rest of him seemed Human enough. He had a sweet little pink bow of a mouth, but when he smiled he showed teeth long and narrow and yellow as a goat’s. Goat looked brightly from Ki to Vandien as Brin set his burdens down by the wagon and wiped his sweaty face with a stained kerchief.

‘This is my son, Gotheris. Gotheris, make your respect to the teamster and his wife. Vandien and Ki.’

‘The teamster and her partner. Ki and Vandien.’ Vandien corrected him mellowly.

‘I see. Beg pardon,’ Brin flushed, but Ki ignored the stumble. Gotheris giggled, in a high pitch more like a girlchild’s laugh than that of a youth on the verge of manhood.

‘Well, at least I’ll know from the start who I must-hark to!’ the boy burst out, grinning delightedly from Ki to Vandien. ‘Is this the wagon?’

‘You’ll have to hark to whichever of us speaks,’ Ki said firmly, but the boy had turned from the group and was climbing into the caravan.

‘Please excuse him,’ Brin said hastily, trying to speak smoothly. ‘He’s so excited to finally be on his way, and full of curiosity about you and your caravan. I’m afraid his manners flee before his impulses sometimes. You may find him a bit uncouth, I fear. We have lived an isolated and rural life for so long that Gotheris has none of the graces or sophistication you would find in a city-bred boy. It is unfortunate that boys of that age usually believe themselves the very soul of wit and judgement. With just the two of us, he has grown up speaking his mind rather bluntly to adults, and often gives his opinions before he is asked. But aren’t all boys his age like that? He is a bit coarsely mannered, I’m afraid, but the training and discipline of a healer will soon take off his rough edges.’ Brin’s eyes darted from Ki to Vandien as he sensed their reluctance. He kept nodding at his own words and smiling so earnestly as he explained and excused that finally Ki nodded to make him stop.

‘There’s only the one big bed in here! Do we all sleep together then, tumbled in a pile? I’ll warn you, I’ll ask to be on top!’ The boy was half-hanging out of the caravan door, a wide smile on his mouth. The ribald note in his voice shattered the just-made accord. Before either Ki or Vandien could speak, Brin stepped forward and seized him by the shoulder.

‘Gotheris! Mind your behavior! Do you want these folk to think you witless and rude? Show them some respect, or you’ll never be on your way to Dellin.’

‘Yes, Father,’ Gotheris replied, his manner so suddenly meek and chastened that Vandien felt his disgust abate somewhat.

‘Have you ever been away from home before?’ Ki asked casually.

‘I’m afraid not,’ Brin answered for him. ‘You can see how excited he is; he has wanted to leave Keddi for so long, to see more of the world. I’m afraid he shows himself in a bad light in his excitement.’

‘I’m familiar with the way of boys,’ Ki answered, addressing them both. ‘No one could travel with the Romni and not become accustomed to the antics of children. Even the most disciplined will kick up their heels at the start of a journey. But,’ she added, turning gravely to Gotheris, ‘we must understand things before I touch hands with you on this. If we take Gotheris, he must be willing to obey Vandien and me. I will expect him to help with the camp chores at night, to clean up after himself, and help care for the horses; that means fetching water if needed, helping to unharness at night, that sort of thing. In short, although he will be our passenger, he will have to be a responsible member of the party as well.’

Gotheris’s face had grown more and more indignant with every condition. The words fair burst from him. ‘But my father is paying you to take me!’

‘Hush, Son.’ The man’s big hands flapped at him beseechingly. ‘I am sure you understand that all must cooperate on such a journey. And, Gotheris, think of all the things you’ll learn!’

The boy made no reply, and his eyes dropped to look at the dusty ground. But in the instant before Ki began speaking again, his gaze leaped up to meet Vandien’s in a rebelliously measuring look. Vandien met his look gravely, and the boy looked down, but a half smile rose and lingered on his face. Vandien suppressed a sigh. Soon enough, boy, he promised himself.

‘He must be courteous, not only toward us but to any we meet along the way. And, in such close quarters, I must insist on personal cleanliness, and his awareness of the privacy of others.’ Ki was going on with her list of requirements. Brin was nodding earnestly to all she said, but the boy didn’t appear concerned. First he picked at his yellow teeth, and then squatted down to scratch his ankle vigorously.

‘I’m sure he’ll be no trouble, once he settles into the rhythm of the journey. He knows he has to behave if he is to reach Dellin without delay. He’ll do his best to be useful. Won’t you, Gotheris?’

The squatting boy cocked his head up at his father and gave a quick flash of his teeth. ‘Of course I will, Father. What boy wouldn’t jump at the chance to travel to hot, dusty Villena, there to study his eyes out with his humorless uncle, so he can spend the rest of his years looking at smelly sick folk and birthing squalling babies for screaming women? What else could I possibly want to spend my life doing?’

The words were unforgivably rude, but the tone was so earnest and sincere that Vandien felt himself at a loss. Was this the blunt speech of a young man who had lived isolated for most of his life? Was it familiar teasing between father and son? Brin more ignored than smiled at the remark.

In the awkward silence that followed, Ki met Vandien’s eyes; he suddenly relaxed. Her look told him all. The boy’s last words had decided her. She wasn’t taking him anywhere. Vandien breathed an inner sigh of relief. Oh, she’d be fractious about having to convert some of the Windsinger’s gold into georns to pay back Trelira’s advance, but that was better than being saddled with that boy. He hadn’t realized how much he’d been dreading the trip until the threat of it was removed. Breaking the news to Brin was Ki’s task. After all, it was her wagon and team; she had the final say on all decisions. Thank the Moon, he added to himself.

He casually wandered over to the horses and began checking their ears for ticks. Two things he didn’t enjoy about these warmer lands they now travelled: the new bugs they encountered, and the spells of watery eyes and running noses that afflicted them both, even in the hottest weather. He wondered idly if they would still follow the caravan route to Villena, even though they had no passenger. He found he hoped so. There would be interesting traffic on the road, and fascinating towns to pass through. Maybe even other Romni. Ki had heard there were tribes this far south, but they had yet to meet any. Even if they met no other Romni, there’d be new towns to explore. Maybe he’d find a leatherworker competent enough to turn out a new sheath for his rapier. His was all but worn through. He thought idly of the sword he had seen yesterday; a peculiar weapon even more flexible than his rapier, but fitted with barbs along the tip. A slapping, ripping weapon, someone had told him. Between a whip and a blade. He’d yet to see one in use. He’d bet on his rapier against one, though. He could imagine such a weapon entangled in an opponent’s clothing, while his rapier could dart in and out swift as the lick of death.

‘Ready to go?’ Ki’s voice was right at his elbow. He turned quickly, hooking her into an impulsive hug, kissing her before she could dodge him. Her skin was dusty against his mouth, but warm. He trapped her against him. ‘Where are we off to?’ he demanded, feeling free as a child.

She worked her elbow up between them and levered herself free. She glanced over her shoulder to where Brin, scandalized, was studying his feet. He didn’t look as disappointed as Vandien had expected him to, and Ki looked more annoyed. ‘Villena, of course. Goat’s putting his things inside the caravan. Oh, he said he doesn’t mind being called Goat; in fact, he prefers it. And the coins are in my pouch. So stop being an ass and let’s get started. Did you check Sigurd’s hoof?’

‘We’re taking the boy?’ Vandien asked in disbelief. His arms dropped away from her.

‘Of course. Well, I nearly backed out of it for a moment there; he has an unruly mouth. But when I asked him if he thought he could do things our way, he changed his attitude at once. He apologized and assured me he’d try his best. I think he embarrassed himself. He’s very anxious to go. I think a lot of that tongue was just showing off for his father, letting him know that he’s a young man now and ready to be off on his own. Boys say the most unfortunate things when they are trying to be clever. You know how they are; they show off their worst manners just when their parents are trying to impress a guest with how well behaved they are. I left him alone with his father to say their goodbyes. Vandien, are you all right?’

‘I was so sure that you weren’t going to do it.’ The bright plans of a moment ago were no more than dancing dust motes now.

‘So was I, for a minute there,’ she conceded, smiling. Her face grew thoughtful. ‘But there’s something about Goat’s face, when you look into it. There’s a man in there, trying to get out. And I suspect he’ll be a pretty good man, once he learns to set childishness aside and deal with people on their own terms.’

‘Oh, Ki.’ He gazed at her reproachfully.

‘Now don’t you get sulky on me!’ She began checking Sigmund’s harness fussily. She spoke over her shoulder, not meeting his eyes. ‘Our deal is still on; I’ll be as irresponsible as you like, right after we drop Goat off. It’s only a fourteen-day trip; you can put up with him for that long. Besides, I don’t think he’ll be that bad, once he’s used to us. Children imitate those around them. If we treat him like a young man, and expect him to behave as one, he will. Every boy has a bit of growing up to do. Goat’s overdue for his, that’s all.’

‘That’s not all he’s overdue for,’ Vandien muttered under his breath. Ki shot him a warning glance.

‘Give him a chance,’ she protested. ‘He’s only a boy.’

Vandien glanced over in time to see Brin clasp his son’s shoulder, then turn and stride hastily away. Goat’s eyes were very wide as he stared after his father, as if Brin’s back were the most amazing thing he had ever seen. Brin lifted a hand to rub quickly at his eyes as he went. A sudden flash of anger ambushed Vandien. ‘When I was his age, if anyone had called me a boy, he would have had to face my blade!’

‘Exactly my point.’ Ki picked it up smoothly. ‘But you grew up, and so will he.’

‘In two weeks you’re going to convert him into a responsible young man, I suppose,’ Vandien observed bitterly.

‘It’s not impossible.’ She blithely refused the quarrel. ‘Look how far I’ve gotten with you, after only a few years. Don’t act so put out; I thought he was the spoiled child,’ Ki added in a more serious tone.

Vandien just looked at her.

‘This trip is only going to be as bad as you make it,’ she observed.

‘That’s right,’ he agreed sourly, and bent to pick up Sigmund’s hoof. Ki began checking Sigurd’s harness. The big greys stood quiet and passive in the sun. Vandien let down the hoof and made a conscious effort to shake off his ill humor. It wasn’t only disappointment. The thought of travelling with Goat filled him with dismay. Vandien couldn’t recall that he had ever been that callow and immature. When he had been as old as Goat, he had been making his own way in the world. He flinched as those early memories touched him. Sleeping in stables and ditches, telling stories by inn fires to earn a bit of bread and a rind of cheese. Being waylaid once and losing everything to the robbers, even his clothing. Stealing garments from a woman washing on a river bank, and being chased by her dogs. Travelling with a group of Dene through Brurjan territory, and being abandoned by them when he slapped a mosquito on his arm and took its life. Such lovely memories, he thought wryly. The ideal shaping for a young man’s early years; no boy should be without such experiences. Maybe he was jealous, he reflected. Jealous of a young man still in the grip of childhood’s innocence and frivolity.

He had been checking the harness straps as he pondered. He paused and leaned against Sigmund’s wide back, watching Ki. She had tied back her long hair, but brown strands of it already dangled around her face. This southern sun had browned her face and arms until her green eyes stood out startlingly. He remembered buying the soft yellow shirt she was wearing tucked into her trousers. The bodice was embroidered with tiny green leaves and pale blue buds. She looked lovely in it. When she wasn’t upset. Lines divided her brows. She took everything so seriously. He cleared his throat and she looked up. He grinned. She stared coolly at him for a moment, then turned her head to hide her answering smile. ‘If you’d told me it made you feel warm and protective, I could have started acting snotty and rude a long time ago,’ he offered, and saw her relax.

‘Dung for brains,’ she observed fondly. ‘Let’s get these wheels turning.’

Ki mounted the high seat at the front of the wagon. Vandien started to follow her up when the door of the cuddy popped open and Gotheris scrambled out onto the seat. He sat down squarely in the middle. ‘I want to drive the team first,’ he announced.

‘Perhaps later,’ Ki suggested. ‘After you’ve watched for a while. It’s not as easy as it looks, especially with all the foot traffic there is in a town.’

‘You said I’d have to help. And my father promised me I’d be learning new things. So I want to drive.’

The whine in his voice grated on Vandien’s nerves.

But he could be tolerant. He’d engage Goat on an adult level. ‘One thing about Ki: she always drives, unless she’s sick, or bored with an arrow-straight flat road. So by the time she lets you take the reins, there’s not much fun to it. With this team, there’s not much challenge anyway. Sigurd and Sigmund pick their own pace and path. So relax and enjoy the ride.’

Goat cocked his head and looked down at Vandien, his eyes shining. ‘Why do you let her say how everything will be? No woman would treat me so. But if the horses are so smart’ – here he rounded on Ki – ‘why can’t I drive the wagon now?’

Ki looked away from the strain on Vandien’s face and spoke directly to Goat. ‘Because it’s not what the team might do that I worry about. It’s the fool that comes dashing out under their noses, or the horseman who thinks he must gallop, and takes the center of the road.’

‘But my father said …’

‘And besides,’ said Vandien, clambering up onto the seat, ‘Ki said no. And I say no. Now move it over so we can get out of here.’

Goat stared up at him, his eyes more yellow than Vandien had yet seen them. ‘For this treatment of me, my father paid good coin,’ Goat commented bitterly, but he edged over on the seat. Ki settled herself and took up the reins. It rankled Vandien that Goat had usurped his seat beside Ki, but he refused to give it a word. He settled beside Goat.

‘Let’s go,’ he suggested softly.

‘Get up!’ she called to the team, shaking the reins lightly. The greys were ready. They set their shoulders to their collars and the tall yellow wheels of the wagon began to turn. Their heavy, feathered hooves were near silent in the sandy streets. The town of Keddi drifted past them like trees on a riverbank.

‘Is this as fast as they go?’ Goat demanded petulantly.

‘Mmm,’ Ki nodded. ‘But they go all day, and we get there just the same.’

‘Don’t you ever whip them to a gallop?’

‘Never,’ Ki lied, forestalling the conversation. Vandien was scarcely listening. His attention was focused on a street phenomenon. As Ki’s wagon rolled leisurely down the street, all eyes were drawn to it. And as quickly pulled away. All marked Goat’s passage, but no one called a genial farewell, or even a “Good riddance!”’ They ignored him as diligently as they would a scabrous beggar. Not hatred, Vandien decided, nor loathing, nor anything easy to understand. More as if each one felt personally shamed by the boy. Yet that made no sense. Could they have done something to the lad that they all regretted? Some act of intolerance carried too far? Vandien had once passed through a town where a witless girl had been crippled by the idle cruelty of some older boys. She had sat enthroned by the fountain, clad in the softest of raiment, messily eating the delicacies sent anonymously out to her. The focus of the town’s shame and penitence, but still untouchable. This thing with Goat was kin to that somehow. Vandien was sure of it.

‘But they could gallop if they had to?’ Goat pressed.

‘I suppose so,’ Ki replied, her tone already weary. Two more weeks of this, Vandien thought, and sighed.

The black mongrel came from nowhere. One moment the street was quiet, folk trading in the booths and tents of this market strip, all eyes carefully bowed away from Ki’s wagon. The next instant, the little dog darted out of the crowd, yapping wildly at the team. Sigurd flicked his ears back and forth, but calm Sigmund continued to plod along. Why be worried by a beast not much bigger than a hoof, he seemed to say.

Then the dog darted under the very hooves of the team, to nip at Sigurd’s heels. The big animal snorted and danced sideways in his harness. ‘Easy!’ Ki called. ‘Go home, dog!’

The dog paid no mind to Ki, nor to a woman who hastened out from a sweetmeat booth to call, ‘Here, Bits! Stop that at once! What’s got into you? It’s just a horse! Leave off that!’

Around and beneath the horses the feist leaped and snapped, yapping noisily and nipping at the feathers of the huge hooves. Sigurd danced sideways, shouldering his brother, who caught his agitation. The great grey heads tossed, manes flying, fighting their bits. Pedestrians cowered back and mothers snatched up small children as the team seesawed toward the booths. Vandien had never seen the stolid beasts so agitated by such a common occurrence. Nor had he ever seen a dog so intent on its own destruction. Ki stirred the team to a trot, hoping to get out of the dog’s territory, but the feist continued to leap and snap, and the woman to run vainly behind the wagon calling for Bits.

‘I’ll pull them in and maybe she can call it off,’ Ki growled irritatedly. She drew in the reins, but Sigurd fought the restraint, tucking his head to his chest and pulling his teammate on. Vandien was silent as Ki held steady on the reins, baffled by the greys’ strange unruliness.

There was a moment when the dog seemed to be relenting. The trotting woman was almost abreast of them. Then it sprang up suddenly, to sink its teeth into Sigurd’s thick fetlock. The big grey kicked out wildly at this suddenly sharp nuisance. His next surge against the harness spooked Sigmund, and suddenly the team sprang forward. Vandien saw the slip of reins and gripped the seat. The greys had their heads and knew it. Dust rose and the wagon jounced as they broke into a ragged gallop. Vandien heard a yelp and felt a sickening jolt and the dog was no more. Behind them the woman cried out in anguish. The team surged forward as if stung. ‘Hang on!’ he warned Goat, and tried to give Ki as much space as he could. She drew firmly in on the reins, striving for control. Tendons stood out in her wrists, and her fingers were white. Vandien caught a glimpse of her pinched mouth and angry eyes. Then Goat’s face took his attention.

His sweet pink mouth was stretched wide to reveal his yellow teeth in an excited grin. His hands were fastened to the seat, but his eyes were full of excitement. He was not scared. No, he was enjoying this. The last of the huts of Keddi raced past them. Open road loomed ahead, straight and flat.

‘Let them out, Ki!’ Vandien suggested over the creak and rumble of the wagon. ‘Let them run it off!’

She didn’t look at him, but suddenly slacked the reins, and even added a shake to urge the greys on. Their legs stretched, their wide haunches rose and fell rhythmically as they stretched their necks and ran. Sweat began to stain them, soaking the dust on their coats. In the heat of the day they tired soon, and began blowing noisily even before they dropped to a trot, and then a walk. Their ears flicked back and forth, waiting for a sign. Sigmund tossed his big head, and then shook it as if he too were perplexed by his behavior. Silently Ki gathered up the reins, letting the horses feel her will. Control was hers again.

Vandien blew out a sigh of relief and leaned back. ‘What did you make of that?’ he asked Ki idly, casual now that it was over.

‘Damn dog’ was all Ki muttered.

‘Well, it’s dead now!’ Goat exclaimed with immense satisfaction. He turned to Ki, his mouth wet with excitement. ‘These horses can move, when you let them! Why must we plod along like this?’

‘Because we’ll get farther plodding like this all day than by racing the team to exhaustion and having to stop for the afternoon,’ Vandien answered. He leaned around the boy to speak to Ki. ‘Strange dog. Living right by the road like that, and barking at horses: I wonder what got into it.’

Ki shook her head. ‘She probably just got the feist. She’s just lucky it picked a steady team to yap at. Some horses would have been all over that road, people and tents notwithstanding.’

‘It’s always been a nasty dog,’ Gotheris informed them. ‘It even bit me, once, just for trying to pick it up.’

‘Then you knew it?’ Vandien asked idly.

‘Oh, yes. Melui has had Bits for a long time. Her husband gave him to her, just before he got gored by their own bull.’

Vandien turned to Ki, heedless of whether Goat read his eyes or not.

‘Want me to go back, talk to her, explain?’ he offered.

Ki sighed. ‘You’d never catch up with us on foot. And besides, what could you say besides we’re sorry it happened? Maybe she’d just as soon have someone to blame and be angry with.’ Ki rubbed her face with one hand and gave him a woeful smile. ‘What a way to start a journey.’

‘I think it’s begun rather well, myself!’ Goat announced cheerfully. ‘Now that the road’s flat and straight, can I drive? I’d like to take them for a gallop down it.’

Vandien groaned. Ki didn’t reply. Eyes fixed on the horizon, she held the sweating team to their steady plod.

‘Please!’ Goat nagged whiningly.

It was going to be a very long journey.

THREE (#ulink_35f3cfd6-dd05-55e1-ab73-3c00daf97e3a)

Ki yearned for night. She had listened to Goat nagging to drive the team for what seemed a lifetime. When he got no response to his begging, he had tried to reach over and take the reins. She had slapped his hands away with a stern ‘No!’ as if he were a great baby instead of a young man. She had seen Vandien’s tensing, and shot him a glance to warn him that she would handle this herself. But the man’s eyes had a glint of amusement in them. The damn man was enjoying her having to deal with Goat. After a long and sulky silence, Goat had proclaimed that he was bored, that this whole trip was boring, and that he wished his father could have found him some witty companions instead of a couple of mute clods. Ki had not replied. Vandien had merely smiled, a smile that made Ki’s spine cold. Handling Goat on this trip was going to be tricky; even trickier would be preventing Vandien from handling Goat. She wanted to deliver her cargo intact.

Now the sun was on the edge of the wide blue southern sky, the day had cooled to a tolerable level, and in the near distance she could see a grove of spiky trees and a spot of brighter green that meant water. Suddenly she dreaded stopping for the night. She wished she could just go on driving, day and night, until they reached Villena and unloaded the boy.

Ki glanced over at Goat. He was hunkered on the seat between her and Vandien, his bottom lip projecting, his peculiar eyes fixed on the featureless road. It was not the most scenic journey she had ever made. The hard-baked road cut its straight way through a plain dotted with brush and grazing animals. Most of the flocks were white sheep with black faces, but she had seen in the distance one herd of cattle with humped backs and wide-swept horns. The few dwellings they passed were huts of baked brick. Shepherds’ huts, she guessed, and most of them appeared deserted. A lonely land.

Earlier in the day, several caravans had passed them. Most of them were no different from the folk they had seen in Keddi, but she had noticed Vandien perk up with interest as the last line of burdened horses and Humans had passed. The folk of this caravan were subtly different from the other travellers they had seen. The people were tall and swarthy, their narrow bodies and grace reminding Ki of plainsdeer. They were dressed in loose robes of cream or white or grey. Bits of color flashed in their bright scarves that sheltered their heads from the sun, and in the bracelets that clinked on ankles and wrists. Men and women alike wore their hair long and straight, and it was every shade of brown imaginable, but all sun-streaked with gold. Many of them were barefoot. The few small children with them wore brightly colored head scarves and little else. Animals and children were adorned with small silver bells on harnesses or head scarves, so there was a sweet ringing as the caravan passed. Most of their horses plodded listlessly beneath their burdens, but at the end of the entourage came a roan stallion and three tall white mares. A very small girl sat the stallion, her dusty bare heels bouncing against his shoulders, her hair flowing free as the animal’s mane. A tall man walked at her side, but none of the animals were led, or wore a scrap of harness. The little girl grinned as she passed, teeth very white in her dark face, and Ki returned her smile. Vandien lifted a hand in greeting, and the man nodded gravely, but did not speak.

‘I bet they’ve stories to tell. Wonder where they’ll camp?’ Vandien’s dark eyes were bright with curiosity.

‘Company would be nice,’ Ki agreed, privately thinking that Goat might find boys of his own age to run with while she and Vandien made the camp and had a quiet moment or two.

‘Camp near Tamshin?’ Goat asked with disgust. ‘Don’t you know anything of those people? You’re lucky I’m here to warn you. For one thing, they smell terrible, and all are infested with fleas and lice. All their children are thieves, taking anything they can get their dirty little hands on. And it is well known that their women have a disease that they pass to men, and it makes your eyes swell shut and your mouth break out with sores. They’re filth! And it is rumored that they are the ones that supply the rebels with food and information, hoping to bring the Duke down so they may have the run of the land and take the business of honest merchants and traders.’

‘They sound almost as bad as Romni,’ Vandien observed affably.

‘The Duke has ordered his Brurjan troops to keep the Romni well away from his province. So I have never seen one, but I have heard …’

‘I was raised Romni.’ She knew Vandien had been trying to get her to see the humor of the boy’s intolerance, but it had cut too close to the bone. That conversation had died. And the afternoon had stretched on, wide and flat and sandy, the only scenery the scrub brush and grasses drying in the summer heat. A very long day …

At least the boy had been keeping quiet these last few hours. Ki sneaked another look at him. His face looked totally empty, devoid of intelligence. But for that emptiness, the face could have been, well, not handsome, but at least affable. It was only when he opened his mouth to speak, or bared those yellow teeth in his foolish grin, that Ki was repulsed. He reached up to scratch his nose, and suddenly appeared so childish that Ki was ashamed of herself. Goat was very much a child still. If he had been ten instead of fourteen, would she have expected the manners of a man, the restraint of an adult? Here was a boy, on his first journey away from home, travelling with strangers to an uncle he hadn’t seen in years. It was natural that he would be nervous and moody, swinging from sulky to overconfident. His looks were against him too, for if she had seen him in a crowd, she would have guessed his age at sixteen, or even older. Only a boy. Her heart softened toward him.

‘We’ll stop for the night at those trees ahead, Goat. Do you think that greener grass might mean a spring?’

He seemed surprised that she would speak to him, let alone ask him a question. His voice was between snotty and shy. ‘Probably. Those are Gwigi trees. They only grow near water.’

Ki refused to take offense from his tone. ‘Really? That’s good to know. Vandien and I are strangers to this part of the world. Perhaps as we travel together, you can tell us the names of the trees and plants, and what you know of them. Such knowledge is always useful.’

The boy brightened at once. His yellow teeth flashed in a grin. ‘I know all of the trees and plants around here. I can teach you about all of them. Of course, there is a lot to learn, so you probably won’t remember it all. But I’ll try to teach you.’ He paused. ‘But if I’m doing that, I don’t think I should have to help out with the chores every night.’

Ki snorted a laugh. ‘You should be a merchant, not a healer, with your bargaining. Well, I don’t think I will let you out of chores just for telling me the names of a few trees, but this first night you can just watch, instead of helping, until you learn what has to be done every night. Does that sound fair?’ Her voice was tolerant.

‘Well,’ Goat grinned, ‘I still think I shouldn’t have to do any chores. After all, my father did pay you, and I will be teaching you all these important things. I already saved you from camping near the Tamshin.’

‘We’ll see,’ Ki replied briefly, stuggling to keep her mind open toward the boy. He said such unfortunate things. It was as if no one had ever rebuked him for rudeness. Perhaps more honesty was called for. She cleared her throat.

‘Goat, I’m going to be very blunt with you. When you say rude things about the Tamshin, I find it offensive. I have never met with any people where the individuals could be judged by generalities. And I don’t like it when you nag me after I have said no to something, such as the driving earlier today. Do you think you can stop doing those things?’

Goat’s face crumpled in a pout. ‘First you start to be nice and talk to me, then all of a sudden you start saying I’m rude and making all these rules! I wish I had never come with you!’

‘Goat!’ Vandien’s voice cut in over the noise of his protest. ‘Listen. Ki didn’t say you weren’t nice. She said that some of the things you say aren’t nice. And she asked you, rather politely, to stop saying them. Now, you choose. Do you want Ki to speak honestly to you, as she would to an adult, or baby you along like an ill-tempered brat?’

There was a challenge in Vandien’s words. Ki watched Goat’s face flood with anger.

‘Well, I was being honest, too. The Tamshin are thieves; ask anyone. And my father did pay for my trip, and I don’t see why I should have to do all the work. It’s not fair.’

‘Fair or not, it’s how it is. Live with it,’ Vandien advised him shortly.

‘Maybe it seems unfair now,’ Ki said gently. ‘But as we go along, you’ll see how it works. For tonight, you don’t have to do any chores. You can just watch. And tomorrow, you may even find that you want to help.’ Her tone was reasonable.

‘But when I wanted to help today with the driving, you said no. I bet you’re going to give me all the dirty chores.’

Ki had run out of patience. She kept silent. But Vandien turned to Goat and gave him a most peculiar smile. ‘We’ll see,’ he promised.

The light was dimming, the trees loomed large, and with no sign from her the team drew the wagon from the road onto the coarse meadow that bordered it. She pulled them in near the trees. The big animals halted, and the wagon was blessedly still, the swaying halted, the creaking silenced. Ki leaned down to wrap the reins around the brake handle. She put both her hands on the small of her back and arched, taking the ache out of her spine. Vandien rolled his shoulders and started to rise from the plank seat when the boy pushed past him to jump from the wagon and run into the trees.

‘Don’t go too far!’ Ki called after him.

‘Let him run,’ Vandien suggested. ‘He’s been sitting still all day. And I’d just as soon be free of him for a while. He won’t go far. Probably just has to relieve himself.’

‘I hadn’t thought of that,’ Ki admitted. ‘You and I are used to a long day. It would be harder for the boy, especially to ask a stranger to stop the wagon for him. Maybe we should make a point of stopping a few times tomorrow. To eat, and to rest the horses.’

‘Whatever you think.’ Vandien dropped lightly to the ground. He stood stretching and rolling his shoulders. ‘But I don’t think that boy would be embarrassed to say anything.’ He glanced over at Ki. ‘And I don’t think your coaxing and patience will get anywhere with him. He acts like he’s never had to be responsible for his own acts. Sometime during this trip, he’s going to discover consequences.’

‘He’s just a boy, regardless of his size. You’ve realized that as much as I have.’ Ki groaned at her stiffness as she climbed down from the driving seat.

‘He’s a spoiled infant,’ Vandien said agreeably. ‘And I almost think it might be easier to humor him as such for this trip, instead of trying to grow him up along the way. Let his uncle worry about teaching him manners and discipline.’

‘Perhaps,’ Ki conceded as her fingers worked at the heavy harness buckles. On his side of the team, Sigurd gave his habitual kick in Vandien’s direction. Vandien sidestepped with the grace of long habit, and delivered the routine slap to the big horse’s haunch. This ceremony out of the way, the unharnessing proceeded smoothly.

As they led the big horses out of the traces and toward the water, Ki wondered aloud, ‘Where’s Goat gotten to now?’

A loud splashing answered her. She pushed hastily through the thick brush surrounding the spring. The spring was in a hollow, its bank built up by the tall grasses and bushes that throve on its moisture. Goat sat in the middle of the small spring, the water up to his chest. His discarded garments littered the bank. He grinned up at them. ‘Not a very big pool, but big enough to cool off in.’

‘You did get yourself a cool drink before stirring up the mud on the bottom, didn’t you?’ Vandien asked with heavy sarcasm.

‘Of course. It wasn’t very cold, but it was drinkable.’

‘Was it?’ Vandien asked drily. He glanced over at Ki, then reached to put Sigurd’s lead into her hands. ‘You explain it to the horses,’ he said. ‘I’m not sure they’d believe me.’ He turned and strode back through the trees to the wagon. Ki was left staring down at Goat. She forced herself to behave calmly. He had not been raised by the Romni. He could know nothing of the fastidious separation of water for drinking from water for bathing. He would know nothing of fetching first the water for the wagon, then watering the horses, and then bathing. Not only had he dirtied all the available water, his nakedness before her was offensive. Ki reminded herself that she was not among the Romni, that in her travels she had learned a tolerance for the strange ways of other folk. She reminded herself that she intended to be patient, but honest, with Goat. Even if it meant explaining these most obvious things.

He grinned at her and kicked his feet, stirring up streamers of mud. Sigurd and Sigmund, thirsty and not fussy, pulled free of her slack grip and went to the water. Their big muzzles dipped, making rings, and then they were sucking in long draughts. Ki wished she shared their indifference.

Goat ignored them. He smiled up at Ki. ‘Why don’t you take your clothes off and come into the water?’ he asked invitingly.

He was such a combination of offensive lewdness and juvenility that Ki couldn’t decide whether to glare or laugh. She set her features firmly in indifference. ‘Get out of there and get dressed. I want to talk to you.’ She spoke in a normal voice.

‘Why can’t we talk in here?’ he pressed. He smiled widely. ‘We don’t even have to talk,’ he added in a confidential tone.

‘If you were a man,’ she said evenly, ‘I’d feel angry. But you’re only an ill-mannered little boy.’ She turned her back on him and strode away, trying to contain the fury that roiled through her.

‘Ki!’ His voice followed her. ‘Wait! Please!’

The change in his tone was so abrupt that she had to turn to it. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said softly, staring at her boots. His shoulders were bowed in toward his hairless chest. When he looked up at her, his eyes were very wide. ‘I do everything wrong, don’t I?’

She didn’t know what to say. The sudden vulnerability after all his boasting was too startling. She couldn’t quite believe it.

‘I just … I want to be like other people. To talk like they do, and be friends.’ The words were tumbling out of him. Ki couldn’t look away. ‘To make jokes and tease. But when I say it, it doesn’t come out funny. No one laughs, everyone gets mad at me. And then I … I’m sorry for what I said just now.’

Ki stood still, thinking. She thought she had a glimpse of the boy’s misunderstanding. ‘I understand. But those kinds of jokes take time. They’re not funny from a stranger.’

‘I’m always the stranger. Strange Goat, with the yellow eyes and teeth.’ Bitterness filled his voice. ‘Vandien already hates me. He won’t change his mind. No one ever gives me a second chance. And I never get it right the first time.’

‘Maybe you don’t give other people a second chance,’ Ki said bluntly. ‘You’ve already decided Vandien won’t like you. Why don’t you change the way you behave? Try being polite and helpful. Maybe by the end of this trip, he’ll forget how you first behaved.’

Goat looked up at her. She didn’t know if his gaze was sly or shy. ‘Do you like me?’

‘I don’t know yet,’ she said coolly. Then, in a kinder voice, she added, ‘Why don’t you get dried off and dressed and come back to camp? Try being likeable and see what happens.’

He looked down at the muddied water and nodded silently. She turned away from him. Let him think for a while. She took the leads from the horses and left them to graze by the spring. They wouldn’t stray; the wagon was all the home they knew. As she pushed through the brush surrounding the spring, she wondered if she should ask Vandien to talk to the boy. Vandien was so good with people, he made friends so effortlessly. Could he understand Goat’s awkwardness? The boy needed a friend, a man who accepted him. His father had seemed a good man, but there were things a boy didn’t learn from his father. She paused a few moments at the edge of the trees to find words, and found herself looking at Vandien.

He knelt on one knee, his back to her, kindling the night’s fire. The quilts were spread on the grass nearby; the kettle waited beside them. As she stepped soundlessly closer, she saw that his dark hair was dense and curly with moisture. He had washed already, yes, and drawn a basin of water for her as well, from the water casks strapped to the side of the wagon. Sparks jumped between his hands; grass smouldered and went out. He muttered what was probably a curse in a language she didn’t know. She stepped closer, put one hand on his shoulder and stooped to kiss the nape of his neck. He almost flinched, but not quite.

‘I knew you were there,’ he said matter-of-factly, striking another shower of sparks. This time the tinder caught and a tiny pale flame leaped up.

‘No, you didn’t,’ she contradicted. She watched over his shoulder as he fed twigs and bits of dry grass to the infant flame. Idly she twined one of his damp curls around her finger. It bared the birthmark on the back of his neck, an odd patch shaped vaguely like spread wings. She traced it with a fingertip. ‘Vandien?’ she began cautiously.

‘Sshh!’ he warned suddenly, but she had already heard it. Hoofbeats; a horse being ridden hard. As one they moved to the end of the wagon, to peer down the road. Goat’s comments on how the Duke felt about Romni had put Ki’s nerves on edge.

A great roan horse with a thick mane and tail galloped heavily toward them. The pale grey of the evening sky and the wide empty plain was behind it; it was the only moving thing on the face of the world. Its hooves were falling clumsily, as if it were too weary for grace, and lather outlined the planes of the animal’s muscles, but for all that it had beauty. Atop it were two girls, their heavy hair spilling black and red and moving with the horse’s stride. Their faces were flushed and bright beneath a haze of road dust. Their loose robes had been hiked up so they could straddle the big roan, and their bare legs and sandaled feet gripped the barrel of his body. Ki watched them come silently, seized by their beauty and vitality.

‘It looks like the two girls from the hiring mart,’ Vandien murmured by her ear. She could hear the smile in his voice. ‘I guess the red-haired one is running off to her sweetheart after all.’

Then: ‘Halloo, the wagon!’ A clear voice rose in the twilight. Vandien stepped out from the wagon and lifted a hand in greeting. The two girls flashed wide grins as they saw him, and then the sweating horse was pulled from the road, and came toward them over the coarse turf. The girl in front pulled in on the reins. The roan tucked his head stubbornly, and then perked his ears to her voice. He halted obediently, but tossed his head as if to show her he obeyed only because he wanted to.

‘Lovely,’ Ki muttered to herself, caught up in his clean lines and proud head.

‘Aren’t they?’ Vandien said as the girls slid from the roan’s back.

She had to nod to that, too. She guessed their ages fell somewhere between fifteen and eighteen years, but could not say which was the older. They were like enough in height and limb to be twins, but there the resemblance ended. The dark-haired girl with the startlingly blue eyes would have been a beauty anywhere, but her beauty would not have been enough to keep anyone’s eyes from her sister. The other girl’s hair gleamed between bright copper and rust. Her mismatched eyes, set wide above a straight nose, met Ki’s frankly; it made what might have been a fault into a flashing attraction. Where her sister was olive, she was pale. Freckles bridged her nose irresistibly. When she smiled, her teeth were very white. She glanced from Ki to her sister, and then to Vandien. ‘I’m so glad we caught up with you!’ she said breathlessly. ‘We didn’t hear you’d left until after noon. If Elyssen hadn’t been able to borrow this horse, I’d never have been able to catch you!’

‘Borrow!’ Elyssen exclaimed. ‘And I’d better have Rud back before morning, or Tomi’s master will have hard words for him.’

‘Ssh!’ the red-haired girl chided her sister, but amusement leaped between them like sparks. They both turned hopeful faces to Vandien. Silence hovered.

‘Come to the fire and tell us why you needed to catch us,’ Vandien suggested. ‘We can offer you a cup of tea after your long ride, if nothing else,’ he added.

Dark was falling rapidly on the open plain. The tiny fire was like a beacon now as Ki and Vandien led the way to it. The girls came behind them, whispering to one another.

‘Did you notice the bundle tied to Rud’s saddle-cloth?’ Ki asked him softly.

Vandien nodded. ‘I told them we couldn’t take passengers.’

‘But then you did!’ It was the red-haired girl, stretching her legs to catch up with them. ‘We heard in Keddi that you were taking Goat to Villena. So we knew you’d changed your mind, and because Tekum’s right on your road …’ Her hand settled on Vandien’s arm, forcing him to meet her hopeful eyes.

‘We don’t take passengers,’ Ki said gently. Going to the fire, she set the kettle of water to simmer.

‘But if you’re taking Goat to Villena, why can’t you take Willow to Tekum?’ Elyssen objected. ‘If he’s a passenger, why can’t she be one? We’ve money to pay for her passage.’

‘Because no angry father is going to come tracking him down. Brin sent Gotheris with us.’ Vandien’s voice was firm, but Ki heard the reluctance that tinged it. Willow’s wide eyes suddenly brightened.

‘But that isn’t how it is! You can ask Elyssen if you don’t believe me. Papa doesn’t mind me marrying Kellich. It’s only that Papa hasn’t much money right now.’

‘Yes, and too much pride to tell Kellich so,’ Elyssen cut in. ‘So when Kellich asked Willow to come away with him, Papa forbade her. Because he couldn’t give her those things that every woman should take with her when she goes with a man.’