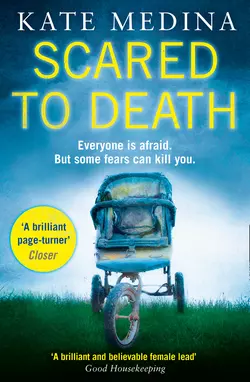

Scared to Death: A gripping crime thriller you won’t be able to put down

Kate Medina

Everyone is afraid. But some fears can kill you.A gripping new thriller featuring a brilliantly complex psychologist, Dr Jessie Flynn, who struggles with a dark past. Perfect for fans of Nicci French and Val McDermid.Sometimes you should be frightened of the dark…A baby is abandoned in the middle of the night. DI Bobby ‘Marilyn’ Simmons suspects the father is planning to take his own life following the violent suicide of his eldest son Danny a year earlier.Meanwhile an investigation begins into the murder of trainee soldier Stephen Foster. Just sixteen years old, he has been stabbed in the neck and left to die in the woods.When psychologist Dr Jessie Flynn sees connections between the deaths of Stephen and Danny, she fears a third traumatized young man faces the same fate…

KATE MEDINA

Scared to Death

Copyright (#uded5e52e-ea5d-5299-b9a9-89810508eba5)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Kate Medina 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Cover photographs © Nikki Smith/Arcangel Images

Kate Medina asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008132323

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008132262

Version: 2018-01-26

Dedication (#uded5e52e-ea5d-5299-b9a9-89810508eba5)

For my mother, Pamela Taylor, with love

The Story of the Three Bears (#uded5e52e-ea5d-5299-b9a9-89810508eba5)

ONCE upon a time there were Three Bears, who lived together in a house of their own in a wood. One of them was a Little, Small, Wee Bear, and one was a Middle-Sized Bear, and the other was a Great, Huge Bear.

Robert Southey, 1774–1843

Table of Contents

Cover (#u392f871c-7a59-58ab-a19f-c49d60e494f7)

Title Page (#ud81328eb-81f0-5ce4-860e-51356879be30)

Copyright (#uc7d5aa0f-63e0-54c7-b207-8dc6383f6f65)

Dedication (#u2420c8ba-453e-5010-a263-9ab8369ab694)

The Story of the Three Bears (#u4943115d-78f4-5df7-a2a4-a121cd30f4ea)

Chapter 1 (#u4705d400-aa4c-5901-b718-d1a8f01f2a08)

Chapter 2 (#u19abbd4e-d173-5e72-bde5-b29eb424be0a)

Chapter 3 (#u9aeb0028-77b3-5e45-8f5d-bc8e9329987e)

Chapter 4 (#udb3d55ce-5b4f-5d97-960e-986997dc4873)

Chapter 5 (#u9d7210e3-d3eb-5e62-9b68-9ea13c4e2b71)

Chapter 6 (#ud68f94dd-9231-5bf3-9f8a-49c8fdaf93dc)

Chapter 7 (#u649863ec-aa29-5fbf-982d-8629ec482cb3)

Chapter 8 (#ufd6e514a-4b08-5015-bc5d-64a4cc3168b2)

Chapter 9 (#u7ce3127e-ecf6-5266-b363-87f852615cb6)

Chapter 10 (#udd6b39b5-93a3-5e46-9fc8-d2c3ee10ab8f)

Chapter 11 (#ue0530fae-3220-5291-9fee-88e942e8ec35)

Chapter 12 (#u83fd10f6-f8e8-5164-9a96-0a236e7c058c)

Chapter 13 (#u97766709-f11d-52b7-8a03-2ed294408c71)

Chapter 14 (#uf209bff8-afdd-577a-af50-6b53ef6d8e3a)

Chapter 15 (#u6c84597b-6fd9-5621-8281-4395bea9fc21)

Chapter 16 (#u966266e6-437c-5696-a3b9-18a2110d9a3d)

Chapter 17 (#u81f2cb84-e6ef-5db0-ac94-3f6842be770f)

Chapter 18 (#u7108c2a2-eaad-5c6f-8bed-a65bdeea2db8)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 70 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 71 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 72 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 73 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 74 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 75 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 76 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 77 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 78 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 79 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 80 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 81 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on for an Exclusive Extract From the New Jessie Flynn Novel: (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Kate Medina (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#uded5e52e-ea5d-5299-b9a9-89810508eba5)

Eleven Years Ago

The eighteen-year-old boy in the smart uniform made his way along the path that skirted the woods bordering the school’s extensive playing fields. He walked quickly, one hand in his pocket, the other holding the handle of the cricket bat that rested over his shoulder, like the umbrella of some city gent. Gene Kelly in Singin’ in the Rain. For the first time in a very long time he felt nimble and light on his feet, as if he could dance. And he felt even lighter in his heart, as though the weight that had saddled him for five long years was finally lifting. Light, but at the same time keyed-up and jittery with anticipation. Thoughts of what was to come drove the corners of his mouth to twitch upwards.

He used to smile all the time when he was younger, but he had almost forgotten how. All the fun in his life, the beauty that he had seen in the world, had been destroyed five years ago. Destroyed once, and then again and again, until he no longer saw joyfulness in anything. He had thought that, in time, his hatred and anger would recede. But instead it had festered and grown black and rabid inside him, the only thing that held any substance or meaning for him.

He had reached the hole in the fence. By the time they moved into the sixth form, boys from the school were routinely slipping through the boundary fence to jog into the local village to buy cigarettes and alcohol, and the rusty nails holding the bottom of the vertical wooden slats had been eased out years before, the slats held in place only at their tops, easy to slide apart. Nye was small for his age and slipped through the gap without leaving splinters or a trace of lichen on his grey woollen trousers or bottle green blazer, or threads of his clothing on the fence.

The hut he reached a few minutes later was small and dilapidated, a corrugated iron roof and weathered plank walls. It used to be a woodman’s shed, Nye had been told, and it still held stacks of dried logs in one corner. Sixth formers were the only ones who used it now, to meet up and smoke; the odd one who’d got lucky with one of the girls from the day school down the road used it for sex.

Nye had detoured here first thing this morning before class to clean it out, slipping on his leather winter gloves to pick up the couple of used condoms and toss them into the woods. Disgusting. He hadn’t worried about his footprints – there would be nothing left of the hut by the time this day was over.

Now, he sprayed a circular trail of lighter fuel around the inside edge of the hut, scattered more on the pile of dry logs and woodchips in the corner, ran a dripping line around the door frame and another around the one small wire-mesh-covered window. Tossing the bottle of lighter fuel on to the stack of logs, he moved quietly into a dark corner of the shed where he would be shielded from immediate view by the door when it opened, and waited. He was patient. He had learned patience the hard way and today his patience would pay off.

Footsteps outside suddenly, footsteps whose pattern, regularity and weight were seared into his brain. Squeezing himself into the corner, Nye held his breath as the rickety wooden door creaked open. The man who stepped into the hut closed the door behind him, pressing it tightly into its frame as Nye knew he would. He stood for a moment, letting his vision adjust to the dimness before he looked around. Nye saw the man’s eyes widen in surprise when he noticed him standing in the shadows, when he saw that it wasn’t the person he had been expecting to meet. His face twisted in anger – an anger Nye knew well.

Swinging the bat in a swift, neat arc as his sports masters had taught him, Nye connected the bat’s flat face, dented from contact with countless cricket balls on the school’s pitches, with the man’s temple. A sickening crunch, wood on bone, and the man dropped to his knees. Blood pulsed from split skin and reddened the side of his face. Nye was tempted to hit him again. Beat him until his head was pulp, but he restrained himself. The first strike had done its job and he wanted the man conscious, wanted him sentient for what was to come.

Dropping the cricket bat on to the floor next to the crumpled man, Nye pulled open the shed door. Stepping into the dusk of the woods outside, he closed it behind him. There was a rusty latch on the gnarled door frame, the padlock long since disappeared. Flipping the latch over the metal loop on the door, he stooped and collected the thick stick he’d tested for size and left there earlier, and jammed it through the loop.

Moving around to the window, too small for the man to fit through – he’d checked that too; he’d checked and double-checked everything – he struck a match and pushed his fingers through the wire. He caught sight of the man’s pale face looking up at him, legs like those of a newborn calf as he tried to struggle to his feet. His eyes were huge and very black in the darkness of the shed. Nye held the man’s gaze, his mouth twisting into a smile. He saw the man’s eyes flick from his face to the lit match in his fingers, recognized that moment where the nugget of hope segued into doubt and then into naked fear. He had experienced that moment himself so many times.

He let the lit match fall from his fingers.

Stepping away from the window, melting a few metres into the woods, Nye stood and watched the glow build inside the hut, listened to the man’s screams, his pleas for help as he himself had pleaded, also in vain, watched and listened until he was sure that the fire had caught a vicious hold. Then he turned and made his way back through the woods, walking quickly, staying off the paths.

It was 13 July, his last day in this godforsaken shithole.

He had waited five long years for this moment.

Thirteen.Unluckyforsome,butnotforme.Notanymore.

2 (#uded5e52e-ea5d-5299-b9a9-89810508eba5)

Twelve Months Ago

He had thought, when the time came, that he would be brave. That he would be able to bear his death with dignity. But his desperation for oxygen was so overwhelming that he would have ripped his own head off for the opportunity to draw breath. He sucked against the tape, but he had done the job well and there were no gaps, no spaces for oxygen to seep through. Wrapping his hands around the metal pipe that was fixed to the tiled wall, digging his nails into the flaking paint, he held on, willing himself to endure the pain, knowing, whatever he felt, that he had no choice now anyway.

Closing his eyes, he tried to draw a picture to mind, a picture of his son, of his face, but the image was lost in the screaming of blood in his ears, the throbbing inside his skull as his brain, his lungs, his whole being ballooned and burst with its frenzied need for oxygen. He felt fingers clawing at his temples. But he had wrapped the gaffer tape tight, layer upon layer of it round and round his head, and his own fingernails, chewed and ragged, couldn’t get purchase.

His lungs were burning and tearing, rupturing with the agony of denied breath.

The room was fading, the feel of his scrabbling fingers numbing. His brain fogged, his limbs were leaden and the pain receded. Danny’s eyes drifted closed and he felt calm, calm and euphoric, just for a moment. Then, nothing.

3 (#uded5e52e-ea5d-5299-b9a9-89810508eba5)

Nobody noticed the pram tucked against the wall inside the entrance to Accident and Emergency at Royal Surrey County Hospital, until the baby inside woke and began to cry. It was another ten minutes before the sound of the crying child registered in the stultified brain of the A & E receptionist who had been working since 11 p.m. the previous night and was now wholly focused on watching the hands of her countertop clock creep towards 7 a.m. and the end of her shift. The ‘zombie shift’, nights were dubbed, both for their obliterating effect on the employee and in reference to the motley stream of patients who shuffled in through the sliding doors. The past eight hours had been the busiest she could remember. Dampness she expected in April, but constant downpours combined with unseasonal heat were a gift to unsavoury bugs. Back-to-back registrations all night, not enough time even to grab a second coffee, and now her nerves, not to mention her temper, were snapping. At fifty-five she was too old for this kind of job, should have taken her sister’s advice and become a PA to a nice lazy managing director in some small business years ago.

She had noticed the pram – she had – she would tell the police when they interviewed her later, but she had assumed that it had been parked there, empty, by one of the parents who had taken their baby into Paediatrics. It had been a reasonable assumption, she insisted to the odd-looking detective inspector, who had made her feel as if she was responsible for mass murder with that cynical rolling of his disconcertingly mismatched eyes. The wait in Paediatric A & E on a busy night was five hours, so it was entirely reasonable that an empty pram could be parked in the entrance for that long. God, at least she didn’t turn up for work looking as if she’d spent the night snorting cocaine, which was more than could be said for him.

Skirting around the desk, she approached the pram, the soles of her Dr Scholl’s sighing as they grasped and released the rain-damp lino. Her stomach knotted tightly as she neared it, recent staff lectures stressing the importance of vigilance in this age of extremism suddenly a deafening alarm bell at the forefront of her mind. But when she peeped inside the pram, she felt ridiculous for that moment of intense apprehension. She breathed out, her heart rate slowing as the tense balloon of air emptied from her lungs.

A baby boy, eighteen months or so he must be, dressed in a white envelope-neck T-shirt and sky-blue corduroy dungarees, was looking up at her, his blue eyes wide open and shiny with tears. Wet tracks cut through the dirt on his cheeks. His mouth gaped, lips a trembling oval, as if he was uncertain whether to smile or cry, four white tombstone teeth visible in the wet pink cavity.

Reaching into the pram, Janet gently scooped him into her arms. Nestling him against her bosom, she felt the chick’s fluff of his hair, smelt the slightly stale, milky smell of him, felt the bulge of his full nappy, straining heavy in her fingers as she slid her hand under his bottom to support his weight. The child gave a sigh and Janet felt his warm body relax into hers.

‘Now who on earth would leave a little chap like you alone for so long?’ she cooed softly. ‘Who on earth?’

How long since she’d held a baby? Years, she realized, with a sharp twinge of sadness. Her youngest nephew fifteen now and already on to his fourth girlfriend in as many months, her own son, nearing thirty, had fled the nest years ago.

She turned back to the reception desk, all efficiency now. ‘Robin, get on the tannoy would you and make an announcement. Some irresponsible fool has left their baby out here and he’s woken up. Probably needs feeding.’ She looked down at the baby. ‘Don’t you worry, sweetheart. We’ll find your mummy and get you fed.’ She tickled his cheek with the tip of her index finger. ‘We will. Yes, we will, gorgeous boy.’ Glancing up, she met Robin’s amused gaze. ‘What? What on earth are you smirking about?’

4 (#ulink_cab8b1ed-4159-5df3-822c-835974e0c551)

Jessie woke with a start and opened her eyes. The room was dark, the air dusty and stale, a room that hadn’t been aired in months. She felt dizzy and nauseous, as if her brain was slopping untethered inside her skull, her tongue a numb wad of cotton filling her mouth. Once again, the man’s voice that had woken her spoke from close by. For a brief moment, caught in that twilight zone between sleep and wakefulness, she had no idea where she was. Which country. Which time zone.

‘Somefolktales–orfairytalesasweliketocallthemnowadays–originatedtohelppeoplepassonsurvivaltipstothenextgeneration.Manyofthestoriesthatwenowtellourchildrenatbedtimewerebasedongruesomerealeventsandwouldhaveservedaswarningstoyoungchildrennottostraytoofarfromtheirparents’protection.’

The radio. Of course. She had left it on when she went to bed last night, used now to being lulled to sleep by noise. The groan of metal flexing on waves, footsteps pacing down corridors, machines humming in distant rooms.

Home. She was home, she realized as cognizance overtook her. Back in England, waking in her own bed for the first time in three months.

‘Overthe yearsthesestorieshavechanged,evolvedtosuitthemodernworld.Eventhoughhumansareasviolentnowadaysastheywerein600BC,wedon’tliketoterrifyourchildreninthesamewaythatourancestorsdid,sowesugar-coatfairytales.Buttheirhorrificoriginsandthemessagesbehindthemaredeadlyserious.’

She had flown into RAF Brize Norton airbase late last night, arrived home at 2 a.m. – 5 a.m. Syrian, Persian Gulf, time – and collapsed into bed, exhausted, jet-lagged, struggling to adjust not only her body clock but her brain from Royal Navy Destroyer to eighteenth-century farmworker’s cottage in the Surrey Hills, a juxtaposition so complete that she had felt as if she was tripping on acid. Washed out from months of shuttling between RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus and the HMS Daring, counselling fighter jet and helicopter pilots flying sorties over ISIS-held territory in Syria and Iraq, working with PsyOps to see how they could win hearts and influence minds in the region. Unused to the impenetrable darkness and graveyard silence of the countryside, she had, for the first time in her life, flipped the radio on, volume turned low, background noise, and fallen asleep to its soft warble.

On the radio, the man’s voice was rising. ‘SnowWhiteandtheSevenDwarvesisbasedonthelifeofasixteenth-centuryBavariannoblewoman,whosebrotherusedsmallchildrentoworkinhiscoppermines.Severelydeformedbecauseofthephysicalhardships,theywerereferredtoasdwarves. ‘WeknowthatLittleRedRidingHoodisaboutviolation,ayounggirlallowingherselftobecharmedbyastranger.ThecontemporaryFrenchidiomforagirlhavinglosthervirginityis“Elleavoitvulecoup”,whichtranslatesliterallyas“Shehasseenthewolf”.’

Reaching an arm out, Jessie jammed her finger on the ‘off’ switch. Silence. Not even birdsong; too early yet for the dawn chorus. Curling on to her side, she closed her eyes and tugged the duvet up around her ears, trying to tilt back into sleep. But she was awake now, her mind a buzz of jetlag-fuelled, pent-up energy. Mayaswellgetupandfacetheday.

Throwing off the duvet, she padded into the bathroom to have a shower, catching her reflection in the huge mirror above the sink that she had erroneously thought it a good idea to install after reading a home décor magazine at the dentist that had waxed lyrical about mirrors opening up small spaces. The harsh electric ceiling lights, another poor idea – same magazine – washed the face looking back at her ghostly grey-white, blue eyes so pale they were nearly translucent, black hair limp and unkempt, a cartoon version of Snow White with a stinking hangover. Jesus,Jessie,onlyyoucouldspendtwelve weeksintheMiddleEastandstillcomebacklookingasifyou’vebeenbleached. Coffee was the answer, and lots of it.

Downstairs, her cottage’s sitting room was show-home spotless, exactly as she had left it: a cream sofa and two matching chairs separated by a reclaimed oak coffee table bare of clutter, fitted white-painted shelves empty of books and ornaments, the sole splash of colour, a vase of fresh daffodils that Ahmose must have left on the coffee table to welcome her home. Herself, by a long way, the messiest thing in the room.

Her gaze found the two framed photographs on the mantelpiece. Looking at Jamie, at his smiley face, all teeth and gums, lips ringed by a smear of chocolate ice cream, she felt the familiar emptiness in her chest, as if under her ribcage was nothing but air. Pushing away thoughts of him, of her past, she padded into the kitchen and made herself a coffee – strong, topped up with lots of full-fat milk, straight from the farm, that Ahmose must have put in her fridge yesterday, along with the bread and butter, lined side by side on the top shelf, an identical space between each item, Ahmose trained now to defer to her extreme sense of order.

She put the kettle back on its stand, straightened the handle flush with the wall, and then deliberately gave it a nudge, knocking it off-kilter. No hiss from the electric suit. No immediate urge to realign it. Not yet. Baby steps, she knew, but progress all the same. Progress she had worked hard, before leaving for her foreign tour, to achieve. Progress that she was determined to maintain, now, coming home.

Unlocking the back door, she stepped out into the garden, glancing up at Ahmose’s bedroom window as she did so. Lights off, curtains closed, still asleep as any sensible person who wasn’t a shift worker or in the Army should be at this pre-dawn hour. Moving slowly across the dark lawn, she inhaled deeply. The air was cool and clean, carrying a faint scent of water on cut grass, the lawn crisp and damp beneath her bare soles. At the bottom of the garden, she settled herself on to the wooden fence and gazed across the farmer’s field. The sunrise was still only a narrow strip of fire on the horizon, the sky above inky blue-black, the somnolent sheep in the field hummocks of barely visible grey, the spring lambs, cleaner, brighter, lying tight against their mothers’ stomachs for warmth.

LittleBoPeephaslosthersheep …

A peaceful pre-dawn, bearing the promise of a beautiful morning.

Home. She was home. Home safe. So why did she still have this odd sensation of emptiness in her chest? Jamie, yes – but something else too. What did she have to worry about? Nothing. She had nothing, or did she?

5 (#ulink_7ba976ce-ca0b-56d4-9d85-c3741665685e)

‘Midnight?’ Detective Inspector Bobby ‘Marilyn’ Simmons snapped. ‘You first noticed the pram at midnight?’ Tugging up his suit jacket sleeve, he tapped his watch with a nicotine-stained index finger. ‘As in midnight eight hours ago?’ His eyes blazed as he looked at the prim, mousy-haired woman in front of him who was clutching a mug of coffee emblazoned with the words Fill with coffee and nobody gets hurt and staring at him as if he was the devil. At least she had the good grace to blush.

‘The baby was asleep.’ She folded her arms defensively across her bust and tipped back on her heels. It was obvious that she was uncomfortable with his proximity, but he was in no mood to take a step back, out of her personal space, and make it easier for her. ‘I thought that the pram was empty.’

Marilyn – a nickname he had acquired on his first day with Surrey and Sussex Major Crimes, the bi-county joint command serious crimes investigation team, thanks to an uncanny resemblance to the ageing American rocker Marilyn Manson – sighed and rubbed a hand over his mismatched eyes. He had a persistent, throbbing headache, which he knew was well-deserved payback for last night’s 2 a.m.’er, knowledge that didn’t make dealing with it any easier. He could murder a cup of that coffee she was clutching. He was also fully aware that he was being an arsehole, could feel disapproval bleeding off Detective Sergeant Sarah Workman standing next to him, her lips pursed, he could tell even without looking. But he wasn’t feeling generous enough to give anyone a break this morning.

The Accident and Emergency waiting room was standing-room only: rows of blue vinyl-upholstered seats, every one of them occupied, a tidal wave of groans, coughs, hawks and the occasional deep-throated retch submerging their conversation. A vending machine was jammed against the wall the other side of the entrance door from the chairs, dispensing fizzy drinks, crisps and chocolate bars to the sick. Thegreatunwashed. The last time he had set foot in a hospital, Southampton General, was four months ago, to collect Dr Jessie Flynn – who he’d worked with on a murder case late last year and fished out of Chichester Harbour, hypothermic and with a gunshot wound to the thigh – and drive her home. That had been a serene experience compared to this one. This A & E department made the rave he’d been at last night feel positively Zen.

‘As you can see, we’re an extremely busy Accident and Emergency department, Detective Inspector,’ the receptionist – Janet, her plastic name badge read – informed him. ‘And occasionally things get missed.’

Marilyn pulled a face. ‘Remind me not to come here when I’m sick. If you can’t spot a bloody baby, you’ve got no chance diagnosing disease.’

‘That day may come sooner than you think.’ Her voice rose in pitch, wobbled. ‘Cancer, I’d say.’

Marilyn raised an eyebrow. ‘Excuse me?’

‘The smell. Smoke. You reek of it.’ She waved a hand in front of her face. ‘You’d be doing yourself, and us, a good turn if you gave up. Now if that’s all, Detective Inspector, I’ll be getting back to work. We are one the best-performing A & E departments in the country with one of the lowest mortality rates and I’d like to do my bit to keep it that way.’ Turning on the sole of one squealing Dr Scholl, she slap-slapped her way down the corridor.

Marilyn glanced at Workman. ‘That went well, Sergeant.’

DS Workman sighed. ‘Shall I get forensics in here, sir?’

‘It’s a baby, Workman, not a corpse. We just need to find the next of kin, pronto.’

‘I’ve been calling the parents. The father left his wallet under the pram. No joy on his home or mobile numbers.’

The air was getting to Marilyn: a stifling smorgasbord of antiseptic, body odour, vomit and the rusty smell of dried blood, all cooked to perfection in the unseasonally warm spring sunlight he could feel cutting through the glass sliding doors behind him. The temperature must be hitting seventy, he thought, despite the best efforts of the air-conditioning unit groaning in the ceiling above him. Although he had chosen to specialize in major crimes, he didn’t have an iron stomach and twenty years of dealing with violent assaults, rapes and murders across Surrey and Sussex, had failed to strengthen it. But, he consoled himself, feeling a pang of guilt at his attitude towards the overworked receptionist, at least he didn’t have to deal with the walking dead who inhabited A & E. The dead he dealt with were certifiably dead, door-nail dead, laid out on metal gurneys, swabbed, wiped down, sexless and personality-less, more akin to shop dummies than recently living, breathing people with hopes and dreams, the single-digit temperatures in the autopsy suite keeping a lid on the most visceral of smells.

‘I’ll be back in a minute, Workman. Keep trying the dad and if we can’t get next of kin by midday, call Children’s Services. We’ll get the kid into a temporary foster home.’

Exiting the hospital building, he crossed the service road, skirting around an ambulance that was disgorging a gargantuan man on a stretcher, the ambulance crew scarlet with strain. Grateful for the fresh air, he leant back against the brick wall and rolled a cigarette. The sky was a relentless clear blue, wispy cotton wool streaks of cirrus lacing it, the sun a hot yellow ball which, even with his dark glasses on, made his one azure eye tear up. Shuffling sideways, he hunkered down in the patch of shade thrown by a bus shelter and lit his roll-up. Back across the service road, patients in hospital gowns crowded next to the A & E doorway, sucking on cigarettes, a few clutching the stem of wheeled metal drip stands, tubes running, via needles, into their bandaged arms. The cloud of smoke partially obscured the sign behind them that read, Strictly a Smoke-Free Zone. Jesus! Janet was right. He needed to give up smoking, drinking, drugs, the works and pronto. Put a stop to the relentless downward slide that was his health before he ended up swelling their ranks in a flapping, backless hospital gown.

DS Workman was crossing the service road towards him. In her beige flats, matching beige shift dress, the hem skimming her solid calves, brown hair cut into a low-maintenance chin-length bob, she could have come straight from the hospital admin department. She looked as diligent and efficient as she was, but her appearance also belied a quiet, cynical sense of humour that ensured their minds connected on a level beyond the mundane, and, anyway, where the hell would he be without her to back him up, dot the i’s, cross the t’s?

‘I managed to reach the little boy’s grandmother. She’ll be here in an hour or so.’

‘An hour? Can’t she get here more quickly than that?’

‘She lives in Farnborough and doesn’t have a car.’

‘Can’t she jump in a cab?’

‘I got the sense that taxis were out of her price range, sir.’ Flipping open her notebook, she ploughed on before he could make any more facetious remarks. ‘She said that the baby, Harry, he’s called, lives with his father, her son. She said that he, the father, Malcolm, has been off work for a year with depression.’

Marilyn nodded.

‘She sounded upset, very upset. I tried to reassure her, but she’s convinced that something terrible has happened to him.’

‘Where’s the baby’s mum?’

‘I gather she’s no longer in the picture.’

‘Surname?’

‘Lawson.’

‘Lawson?’ Flicking his roll-up into the gutter, Marilyn looked across and met Workman’s gaze, his forehead creasing in query. ‘Is it a coincidence that his name rings a bell?’

Workman shook her head. ‘Daniel Lawson, sir.’

He racked his brains. Nothing.

‘Danny,’ she prompted. ‘Private Danny Lawson.’

It still took him a moment. PrivateDannyLawson. ‘Oh God, of course.’ Tugging off his sunglasses, Marilyn rubbed a hand across his eyes. Christ, MalcolmLawson.Thatwasallheneeded. He’d had considerably more than he could stomach of the man six months ago.

‘I think we should have a counsellor here when Harry’s grandmother arrives, sir.’

‘With Malcolm Lawson in the picture, I need a bloody counsellor, Workman,’ Marilyn muttered.

With an upwards roll of her eyes that he wasn’t supposed to have noticed, Workman pressed on: ‘Doctor Butter is on annual leave and time is obviously too short to find a counsellor from a neighbouring force.’

Marilyn sighed. Why was he being so obnoxious? No explanation, except for the fact that everything about this hospital was putting him in a bad mood. The detritus of human life washed up on its shores. Something about his own mortality staring him square in the face.

And the baby?

When DS Workman had first telephoned him about a baby abandoned at Royal Surrey County Hospital, he’d acidly asked her if she had a couple of lost puppies he could reunite with their owners or a kitten stuck in a tree he could shin up and rescue. But now, something about this abandoned baby – Harry Lawson – and the history attached to that child’s surname, was giving him a creeping sense of unease.

‘Leave it with me, Sergeant. We do have a tenuous Army connection, so I’ll call Doctor Flynn. I’m sure she’s back from the Middle East this week.’

MalcolmLawson.

He thought he’d well and truly buried that name six months ago. Buried that family. Buried the whole sorry saga. He forced a laugh, full of fake cheer.

‘Those Army types spend ninety per cent of their time sitting around with their thumbs up their arses, so I’m sure Jessie could spare an hour. Find us a nice quiet room where we can chat to Granny.’

6 (#ulink_d071093b-a94a-502a-82d9-09dd0534c160)

The sun was a blinding ball in an unseasonally cloudless, royal-blue sky when Jessie gunned her daffodil-yellow Mini to life, pleasantly surprised that, after so long un-driven, it started first time. She’d popped in to see Ahmose, had been persuaded to stay for a cup of kahwa, strong Egyptian coffee – a terrible idea in retrospect, layered on top of the two cups she’d already downed at home, the time zone change and the jet lag. She felt as if a hive of hyperactive bees had set up residence in her head. Negotiating a slow three-point turn in the narrow lane, she pressed her foot gingerly on the accelerator, the speedo sliding slowly, jerkily – God,haveIforgottenhowtochangegears? – to twenty, no higher. She’d had a near miss with the farmer and his herd of prize milking Friesians last summer while speeding down the lane towards home after a long day at Bradley Court, windows down, James Blunt full volume, and his threats of death and destruction to her prized Mini at the hands of his tractor had been an effective speed limiter ever since.

Fifteen minutes later, she slowed and turned off the public road into Bradley Court Army Rehabilitation Centre. Holding her pass out to the gate guards, she waited, engine idling, while the ornate metal gates were swung open. The last time she had driven along this drive, in the opposite direction, the stately brick-and-stone outline of Bradley Court receding in her rear-view mirror, it had been mid-December, mind-numbingly cold, slushy sleet invading the sweep of manicured lawns like wedding confetti, the trees bleak skeletons puncturing a slate-grey sky. Early April, and the lawn on either side of the quarter-mile drive was littered with red and blue crocuses, the copper beeches that lined the tarmac ribbon unfurling new leaves, hot- yellow daffodils clustered around their bases. Someone had set a table and chairs out on the lawn in front of an open patio door and a group of young men were sitting around it playing cards. Two others on crutches, each with a thigh-high amputation, were making their way along a gravel path towards the lake, both coatless, their shirt sleeves rolled up.

Parking, she made her way up to the first floor where the Defence Psychology Service was located, sticking her head into office doors as she passed, saying her hellos.

‘The nomad returns. Welcome back, Doctor Flynn.’

Gideon Duursema, head of the Defence Psychology Service and Jessie’s boss, half-rose from behind his desk and held out his hand. It felt strange, to Jessie, shaking it. She couldn’t recall ever shaking Gideon’s hand, with the exception of during her job interview and on her first morning at Bradley Court two and a half years ago, when he had formally welcomed her to the department. Gideon must have felt the same sense of oddness, because he dropped her hand suddenly, skirted around his desk and pulled her into a brief, slightly awkward hug.

‘We’ve missed you,’ he muttered, retreating to safety afforded by the physical barrier of his oak desk, lowering himself into his chair. ‘How was the tour?’ he asked, when she had settled herself into the chair opposite.

‘Now I know what living in prison feels like, except that prisoners get better food and their own television set.’

Gideon laughed. ‘Did they chain you up in the bowels of the boat 24/7?’

‘Ship.’ She half-smiled. ‘Ship is the technical naval term. Type 45 Destroyer, if I’m being really pedantic.’

‘Pedantic is good in this job. I like pedantic, but not when it’s directed at me. Type 45 Destroyer. Did they chain you up in the bowels of the destroyer 24/7?’

‘I must have been away from other lunatic psychologists for too long – you’ve lost me completely.’

Holding up a paint brochure, squares of bland off-whites, insipid greys and beiges lined down the page, he squinted at her through one eye.

‘Farrow and Ball colour trends, 2016. Tallow – a perfect match, I’d say. You mustn’t have seen the light of day. Certainly not the light of any Middle Eastern sun, anyway.’

Jessie rolled her eyes. ‘My skin colour is on trend, if nothing else.’ She waved a hand back over her shoulder towards the door. ‘Should we try this again, perhaps? I’ll go out, come back in and you can attempt to avoid the insults. We don’t all have the benefit of a year-round tan.’

Gideon smiled. ‘I’m sorry. I’ve missed you. It’s been dull around here without your chippy attitude to keep me on my toes.’

Originally from Zimbabwe, these days he was almost more English than the English with his tweed jackets, faux Tudor semi-detached on the outskirts of Farnham, Land Rover Discovery, solid middle-class wife and two boys. Jessie had met his sons once, had felt gauche and awkward beside them even though she was five years older than the eldest – both boys a stunning, olive-skinned mix of their black father and English rose mother, both following their father to Oxford.

‘Has Mrs D roped you into doing some DIY?’

‘Sadly, yes, as my pitiful government salary doesn’t run to the eye-watering sums charged by Home Counties building firms.’ Flipping over the brochure, he read in a desiccated monotone: ‘“Is your kitchen looking tired and dated? We can simply resurface your current cabinets in a colour and finish of your choice.”’ He tossed the brochure on the desktop. ‘Various shades of battleship, sorry, destroyer grey are all the rage these days, evidently, though why Fiona can’t continue residing with the browns we have lived with happily for the past twenty years, I have no idea. Never mind the damn kitchen, it’s me who’s tired and dated. Maybe Farrow and Ball can resurface me while they’re at it, two for the price of one.’ Reaching for his bifocals, sliding them on to the bridge of his nose, he fixed Jessie with a searching gaze. ‘Ready to get back to work?’

‘I assume from your tone that my answer needs to be an emphatic “yes”.’

Gideon patted a stack of files on the corner of his desk, ten centimetres high. ‘Preferably accompanied with a beatific smile and boundless energy.’ Sliding a thin cardboard file from the top of the stack, he held it out to her. ‘Here’s your number one. Ryan Jones: sixteen-year-old male trainee, Royal Logistic Corps, Blackdown Barracks. Referred by Blackdown’s commanding officer, Colonel Philip Wallace.’

Jessie flipped open the file. One typed sheet inside. ‘Why was he referred?’

Gideon shrugged. ‘An open-ended “we’re concerned with his mental state”.’

‘Isn’t the CO a bit high up to be referring trainees?’

Another shrug. ‘From what I know of Philip Wallace, he likes to have his finger in every pie on that base.’

Jessie nodded, taking a moment, eyes grazing down the first page to digest the key details of the referral. Gideon was right – there was little more information than he had just told her. The referral was a triumph of saying nothing in one page of tight black type.

Ryan Thomas Jones

Sixteen and five months

Joined the Army on 2 November last year, the day of his sixteenth birthday

Keen.

Keen or running away from something. In Jessie’s experience, people joined the Army for one of three reasons: patriotism, financial necessity, or to escape. There was a fourth, she privately suspected, though had never voiced: the opportunity to kill people legally. That last one was reserved for the nutters. Which one was Ryan Jones? Probably not the fourth, as Loggies weren’t frontline fighting troops.

Looking up, she met Gideon’s gaze. ‘When is he coming in?’

‘Two p.m.’

‘Oh, OK. So I get the morning to organize my office, drink coffee, chillax. That’s unexpectedly generous of you—’ She broke off, catching his expression. ‘No … I don’t get the morning to chillax. Instead, I get to …’ She let the sentence hang.

‘You get to go to Royal Surrey County Hospital.’

‘And why would I want to do that?’

‘I got a call from Detective Inspector Simmons ten minutes ago. He needs your help.’

‘Since when did we provide psychologists to Surrey and Sussex Major Crimes?’

‘Since DI Simmons asked me nicely. It seems austerity is pinching them as hard as it’s pinching us.’

‘Why does he need a psychologist’s help at the hospital?’

‘He’ll fill you in.’

‘Cryptic.’

‘Not deliberately so. There is an Army connection, he said.’

Jessie’s eyebrows rose in query, but Gideon didn’t provide her with any more information. Stretching his arms above his head, waving one hand vaguely towards the window as he did so, he added, ‘I was in a meeting when Simmons called, so our conversation was brief. You’d better get going. He’s there now, waiting for you at the entrance to A & E, and I have another meeting starting’ – he glanced at his watch – ‘five minutes ago.’ He began searching around under the piles of files, books and papers on his desk, continuing to talk as he did so. ‘Welcome back, Jessie. As I said, I’ve missed you.’ A fleeting, wry smile. ‘And so, as you can see, has my desk. It has felt your absence most keenly. You can’t see my mobile anywhere, can you?’

Ducking down, she retrieved Gideon’s mobile from the floor and handed it to him. ‘Here.’

‘Ah. Thank you.’

‘But that’s it. No more Mrs Doubtfire from me.’ Rising, she tucked Ryan Thomas Jones’s file under her arm. ‘Your desk is going to have to make its own way in the big wide world without my help. Sink or swim. Eat or be eaten.’

Gideon’s eyebrow rose, but he didn’t reply. As she left the room, Jessie glanced back. He was still watching her, the expression on his face conflicted: a part of him hoping that she was right; the other part knowing, from thirty years’ experience as a clinical psychologist, that such deep-seated psychological disorders as hers were far from simple to cure. Jessie hoped that she was right too. She had navigated this morning without so much as a tingle from the electric suit; had navigated her time abroad with only three mild episodes. She’d even managed to leave the house with the kettle handle crooked and an unwashed coffee cup in the sink. Progress. Real progress.

She hoped that settling back into her normal routine would do nothing to disturb the delicate balance of her recovery.

7 (#ulink_9222bb14-8259-551c-9f8c-1d3288f3c034)

Lieutenant Gold was already at the crime scene when Captain Ben Callan, Royal Military Police Special Investigation Branch, parked his red Golf GTI in the car park at Blackdown Barracks. Climbing out of the driver’s seat, he stood – too quickly – swayed and grabbed the top of the door to steady himself. Fuck. He still felt sick and shaky, as if he was coming down off a drinking spree, which he wasn’t. A hangover would, though, provide a plausible excuse for his wrecked physical and mental state. Nothing unexpected in soldiers getting drunk off-duty; it was virtually compulsory.

He’d had some warning of the fit this time: the car in front of him in the fast lane on the A3 starting to jump around as if it was on springs, the central reservation fuzzy, as though his windscreen was suddenly frosted glass. Swerving straight across both lanes, he cut on to the hard shoulder, narrowly missing an elderly couple in an ancient Nissan Micra; the glimpse he’d had of the driver’s whitened face and wide eyes in his rear-view mirror still etched in his mind.

The ground fell away steeply from the hard shoulder into a deep ditch of tangled undergrowth and he slithered down it, making it only halfway before his knees buckled. Falling, rolling, he reached blindly for something to slow his descent, felt reed grass slice through his fingers. His body was writhing, slamming from side to side, legs cycling in the muddy soil and he was freezing cold, shaking uncontrollably, his brain feeling as if it would explode from the pressure inside his skull. Slowly, the fit receded. He lay on the damp ground, sweating and shaking, feeling the muddy ditch water seeping through his clothing, chilling his skin. Pushing himself on to his knees, he reached for the trunk of a sapling, hauled himself to his feet, wincing as the cuts on his fingers met the rough bark. On unsteady legs, he made his way slowly back up the embankment. A Surrey Police patrol car was parked behind his Golf, flashing blue lights washing the uniformed traffic officer standing in front of it neon blue.

‘You do know that it is illegal to stop on the hard shoulder for any reason other than an emergency, don’t you, sir?’

Sir. The policeman’s tone entirely at odds with his words. JustwhatIneedrightnow. Reaching into his back pocket, Callan fished out his military police ID, held it up. The traffic cop studied it, his gaze narrowing.

‘What were you doing, sir?’

Which story was the more convincing? Having a piss? Answering a vital phone call? The truth, not an option. As an epileptic, he shouldn’t hold a driving licence, but if his condition was made public, losing his licence would be the least of his problems. He would lose his job, his livelihood, his future. His tenuous clutch on normality.

‘I was answering a call on my mobile. There’s been a suspicious death at an Army training base near Camberley. I’m on my way there now.’

The policeman’s gaze tracked from Callan’s face to his feet, taking in the sweaty, greyish-pale complexion, the hands jammed in his pockets to stop them from trembling, the mud caked on his white shirt and jeans.

‘If you weren’t an MP, I’d breathalyse you.’

‘I’m not over the limit, Constable.’

‘You don’t look great, sir.’

‘I don’t feel great, but it’s not alcohol. It’s lack of sleep, too much work … You know how it is.’ Callan lifted his shoulders, looking the constable straight in the eye, the lie sliding smoothly off his tongue.

Silence, which Callan had the confidence not to break. He maintained eye contact, an easy smile on his face, posture relaxed, hoping the constable didn’t notice that his legs were shaking.

‘Drive slowly, mate. My shift ends in two hours and I don’t fancy spending it scraping anybody off the central reservation. Even a bloody MP.’

Callan held out his hand; the constable didn’t take it.

‘You’ve had your one favour,’ he muttered. ‘Next time, I throw the book at you.’

Callan stood by his Golf and watched the patrol car pull back into the flow of traffic and accelerate away. Twisting sideways, he retched on the grass. Retched and retched until only his stomach lining remained.

8 (#ulink_1d13c5a6-3499-5f8c-a9bd-8afbb9cb0030)

Squeezing her Mini on to the grass verge, the only spare inch of space available in the hospital car park, ignoring the dirty looks thrown her way by people in huge four-by-fours who were still circling, trying to find a space, Jessie jogged down the stone stairs and across the service road to A & E. Holding her breath as she ducked through the cigarette smoke fogging the entrance, she found Marilyn waiting for her inside. He was propping up the wall by the reception desk, one sole tapping impatiently against the skirting, thumbs skipping across the keys of his mobile. At the sound of her footsteps, he glanced up, his lined face creasing into a smile.

‘Thank you for coming, Jessie.’ A glance towards the packed A & E waiting room. ‘To the asylum.’

‘I won’t say that it’s a pleasure, but Gideon didn’t leave me much choice. For some reason your request shot straight to the top of my day’s admittedly short to-do list.’

‘I must have forgotten to tell you that Gideon and I play golf together every Sunday.’

Her gaze tracked from the black bed-hair to the sallow, ravaged face that made Mick Jagger look a picture of clean living, to those disconcerting eyes hiding the sharp, enquiring mind she’d got to know. He had bowed to pressure from above and replaced his beloved black biker jacket with a black suit which hung from his scarecrow frame, only the suit’s drainpipe trousers hinting that he was anything more than a straight-off-the-production-line policeman.

‘Funnily enough, I don’t see you in checked plus-fours.’

He grinned. ‘Masons?’

‘Ditto.

‘Yacht club?’

Jessie rolled her eyes. ‘Shall we get started? I need to be back at Bradley Court by lunchtime. I have work to do. Proper work.’

As they walked side by side down the corridor that cut from A & E to the main hospital, their rubber soles whispering in unison as they gripped and released the lino, Marilyn brought her up to date.

‘We’re not sure how long the baby has been here, but we know that he was left some time before midnight.’

‘Midnight? As in midnight ten hours—’

He held up a hand, cutting her off. ‘Don’t get me started.’

‘He was left by his father?’

‘That’s our working theory. DS Workman and a couple of constables are going through last night’s CCTV footage of the A & E entrance to confirm.’

‘Why would a father abandon his baby?’

‘He abandoned him in a hospital, safe.’

Jessie frowned. ‘A busy A & E department, all sorts coming and going? It’s hardly secure. The fact that the poor kid wasn’t noticed for … what …’ She glanced at her watch, mentally calculating. ‘Seven hours minimum suggests to me that it’s not the first place a caring parent in their right mind would look to deposit their baby for safekeeping.’

‘Right. So the rest of our working theory is that he wasn’t entirely compos mentis at the time.’

Jessie glanced over. ‘Why do you think that?’

They swung left into another corridor, identical to the first. Laying a hand on Jessie’s arm, Marilyn pulled her to a stop outside a door labelled ‘Family Room’. Tilting towards her, he lowered his voice.

‘There’s some history that you need to understand before we meet Granny.’

Jessie caught his tone and raised an eyebrow. ‘And I presume the history is why you wanted me here.’

Marilyn sighed. ‘The history and the story that I suspect may have played itself out last night, and what I fear might be the story going forward.’ He cocked his head towards the family room door. ‘The story that we need to break, as gently as possible, to Granny.’

‘Which is?’

‘The little boy is Harry Lawson. He lives with his father, Malcolm. Malcolm Lawson is also the father of Daniel Lawson.’ He paused. ‘Private Danny Lawson. Ring a bell?’

She shook her head. ‘Should it?’

‘Danny Lawson committed suicide at an Army training base near Camberley a year or so ago. He’d only been in the Army five months. He was sixteen.’

‘I was in Afghanistan with PsyOps around that time. Nothing was on my radar except for that. What happened?’

‘He went AWOL one night while his dorm mates were sleeping. He was found in the showers early the next morning.’

‘And?’

‘And – he had committed suicide.’

‘So you said. How?’

‘The how isn’t important.’

Jessie stared hard at him. ‘If it’s part of the backstory, it is important.’

‘Method isn’t relevant—’

‘Marilyn,’ Jessie cut in.

Marilyn shoved his hands into his pockets and hunched his shoulders. ‘He suffocated himself.’

‘With a pillow?’

‘Tape.’

A shadow crossed Jessie’s face. ‘Tape?’

‘Gaffer tape,’ Marilyn said in a low voice. ‘He wrapped it around his head, covered his mouth and nose with the stuff.’

‘Bloody hell, poor kid,’ she murmured, her eyes sliding from his, finding a crack in the lino at her feet, tracking its rambling progress to the wall, the image that Marilyn’s words had etched into her mind – how desperate sixteen-year-old Danny must have been, to end his life that way – filling her mind with memories. Memories she struggled, at the best of times, to suppress. A little boy hanging by his school tie from a curtain rail, his gorgeous face bloated and purple. This boy, older, but not by so much, making a mask of his face with black gaffer tape. She felt Marilyn’s eyes burning a hole in the top of her skull.

‘He wouldn’t have had unsupervised access to a gun,’ he said.

‘No.’

‘The tape was what he had to hand.’

Biting her lip, Jessie nodded. Gaffer tape – what he had to hand. Aschooltieandacurtainrail–whatJamiehadhadtohand.

‘You OK?’ he asked gently.

Looking up, meeting those odd eyes, she forced a smile, sure that it must look twisted and horrible. ‘What, apart from the dodgy hospital smell and the fact that it’s five hundred degrees centigrade in here? Of course, I’m fine.’

She had formed a friendship of sorts with Marilyn since he had pulled her from the freezing sea in Chichester Harbour four months ago; a comfortable relationship that was characterized by his occasional calls for advice when he felt his own force’s psychologist’s recommendations were way off the mark, the odd cheery email to her whilst she was serving on HMS Daring, emails that had transported her straight back from featureless sea to rolling hills with their description of evenings spent drinking Old Speckled Hen in country pubs, sometimes with Captain Ben Callan. But her own history was something that she didn’t choose to share with anyone besides Ahmose and, once only, in a weak moment, with Callan. She wondered if he knew though, anyway. If Callan had told him. She suspected, from Marilyn’s unease, that he had.

‘So what was Surrey and Sussex Major Crimes’ involvement if Danny Lawson was Army?’ she asked, breaking the laden silence.

‘The Military Police conducted the initial investigation and came to the conclusion that Danny’s death was suicide. But Danny’s dad, Malcolm, refused to accept the verdict. He wrote to his MP, the Defence Secretary, the Armed Forces Minister, even the bloody Prime Minister, anyone and everyone he could think of, calling for the investigation to be reopened by the civvy police. Police without prejudice, I remember he called it. He claimed that the Redcaps were covering up murder. That the Army had so many problems dealing with the Middle East that they didn’t want to admit kids were being murdered on their home turf. I got a call from the Surrey County Coroner telling me that we were to do another investigation.’

‘And?’

Marilyn sighed and shrugged. ‘We reviewed all the evidence and found the same. Suicide.’

‘Cut and dried.’

‘Cut and dried. There was no evidence to suggest murder – and I promise you, I did look for it.’

‘But Malcolm didn’t accept your findings either,’ Jessie murmured.

‘No. No, he didn’t.’ His voice slipped to a monotone. ‘He kept on and on and on. Wrote back to the same cast of politicians, wrote to all the papers, tried to whip up a media storm, but there was nothing there, no story, so none of them bit.’

‘Why was he so determined?’

‘I don’t know. I just remember how mad he was with grief. Grief and anger. I was surprised that he was so damn angry. Grief, I expected, sadness, loss, guilt even, but not anger.’

Jessie was looking at the floor, her arms folded across her chest, defensive body language, she recognized, but too tense to unwrap. ‘Anger is often the go-to emotion that masks others. Sadness, grief, loss – they can all morph into anger, particularly if they’re mixed with frustration or perceived helplessness. It’s hard for family members to accept … suicide.’ She swallowed, eased the word out around the wad that had formed in her throat. ‘Because where there’s suicide, there is a deep, debilitating hopelessness that the victim can’t see a way around. The family often blame themselves because they didn’t notice, or didn’t realize the depth of despair. Guilt, blame, self-recrimination, self-blame – they can eat you up. It’s always easier to look somewhere else to lay that blame.’ She glanced up, met Marilyn’s gaze for a fraction of a second, couldn’t hold it. ‘Children shouldn’t die before their parents,’ she murmured, tracing the meandering crack in the grey lino with the toe of her ballet pump. ‘It flips the law of nature on its head. A parent is programmed to protect their child at all costs, to do anything to keep that child safe, however old the child is.’

A child. A son. Committing suicide.

Jessie had held on to her own grief, dealing with the pain the only way a fourteen-year-old knew: internalizing it, taking the blame for her brother’s suicide squarely on her own shoulders. She had the psychological scars to prove it. Danny Lawson’s father sounded to have done the opposite and looked for someone else to blame. Anyone else to blame. Either way, she knew exactly what he had been going through.

She felt the weight of Marilyn’s hand on her arm. ‘We should go in now, Jessie.’

She nodded. ‘Yes. Yes, of course.’

9 (#ulink_f4c6d7c7-21b3-5c41-a579-59cd6cdb3f42)

Slipping on his Oakley’s, Callan walked slowly, collecting his thoughts with each step following the line of Blackdown’s chain-link, razor-wire-topped boundary fence, towards the thick wooded area where he could see Lieutenant Ed Gold and the scenes of crime boys.

Although he was still two hundred metres away, Callan could see the arrogant rigidity of Gold’s stance, recognize the disproportionate command in the staccato arcs of his gestures, hear each word of his barked orders clear as a bell. Gold was in his element, enjoying the control, even though the scenes of crime technicians were consummate professionals who needed no guidance. Callan would take pleasure in rescuing them, bursting Gold’s bubble.

Callan glanced at his watch. It was a quarter past ten. He was late to the scene, very late. He had received the call notifying him of a suspicious death at Blackdown training base sixty minutes ago, while he’d been sitting in his neurologist’s office, digesting bad news. He only hoped that Gold hadn’t fucked up the crime scene already, though the presence of Sergeant Glyn Morgan, his lead SOCO, a forest ghoul moving silently through the trees in his white overalls, gave him a modicum of confidence that some integrity may have been preserved.

Gold glanced over, caught sight of Callan and the next order died on his lips.

‘What have we got, Gold?’ Callan asked as he reached him.

‘A dead soldier,’ Gold muttered, his navy-flecked, royal-blue gaze meeting Callan’s insouciantly. A beat later, he added a reluctant ‘sir’ and followed it with a disinclined salute.

Callan returned the salute smartly, though he was more tempted to use his right hand to smack Gold around the head. He knew that it would take all his willpower not to wring the jumped-up little shit’s neck on this case, suspected that Colonel Holden-Hough, Officer Commanding Southern Region, Special Investigation Branch, knew the same, which is why he had been given Gold as his detachment second-in-command in the first place.

‘Who?’ Callan snapped.

‘A trainee, Stephen Foster.’ Gold flipped open his notebook. ‘Aged sixteen.’

‘What was he doing out here?’

‘Guard duty.’

‘Alone?’

Gold shook his head. ‘With a female. Martha Wonsag.’

‘So where the hell was she when he died?’

Gold shrugged. ‘I haven’t got that far yet, sir.’

‘Where is the rest of the guard detachment?’

‘They’re back on normal duties.’ He held up the notebook. ‘I have their names.’

‘What?’ Callan stared at him, incredulous. ‘This is most likely a murder inquiry and the victim’s guard detachment will be top of our list of suspects. Secure a suite of rooms and get the guard rounded up and isolated now. Do not leave them alone for a second, and do not let them talk to each other. I’ll start interviews when I’ve looked at the crime scene.’

His jaw tight with anger, Gold nodded. ‘Right, sir.’

Turning away, feeling the heat of Gold’s fury burning into his back, biting down on his own anger – anger at himself for having been unavailable when the call about a suspicious death came through, at Gold for his incompetence, knowing that a significant part of his anger was fuelled by dislike – Callan climbed into a set of overalls and ducked under the crime scene cordon. Morgan’s SOCOs fell silent as he approached, and he knew what they were thinking. He was famous, or more accurately infamous, in the Special Investigation Branch. Only thirty, eight years in, and he had already taken two bullets whilst on duty. The first a gift from the Taliban eighteen months ago in Afghanistan, still lodged in his brain; the fallout, permanent seizures, manageable at the moment with drugs, his neurologist had told him this morning, but likely to worsen with time. The second, a bullet in the abdomen from a fellow soldier four months ago, in woods not unlike these. He’d only been back on duty for two weeks. He knew that he was well respected in the Branch for being brave and professional, and found it unnerving. How opinions would change if his colleagues found out about his epilepsy and the demons that infested his mind at night. What he was feeling now, walking into this dense, shadowy copse of trees. Déjàvu.

‘Sir.’ Morgan straightened as Callan reached him. At five foot eight the top of his head barely grazed Callan’s shoulder.

‘I’m glad you’re here, Morgan.’

‘I’m glad you’re here, too, Captain.’ A gentle Welsh valleys accent, unmellowed by his decades-long absence from the Rhondda. He was the son of a coal miner, had faced only three life choices: unemployment, life down a pit, or the Army. He had chosen the Army and escape and was a career soldier, experienced and capable, with a degree of cynicism gained over twenty-five years in the Redcaps, that meant he was no longer surprised by any crime that the dark side of human nature could conjure up. ‘My patience was wearing thin with Little Lord Fauntleroy over there.’

With his stocky frame, steel-grey hair and clipped moustache, he reminded Callan of a solid grey pit pony.

‘May I take the liberty of saying that you look like shit, sir,’ Morgan continued. ‘Big night?’

‘Thanks for your honesty, Sergeant. I feel like shit too.’ Scratching a hand through his dirty blond stubble, he stifled a yawn. Branch detectives wore plain clothes most of the time and though he had changed out of his muddy shirt and jeans into a navy-blue suit he kept in the boot of his car for emergencies, he hadn’t been able to do anything about his pasty complexion or his bloodshot eyes.

‘Well, you’re going to need a strong stomach for this one.’

Callan looked where Morgan indicated, taking in the salient details quickly, freeze-framing each segment of the tableau in turn, acclimatizing himself mental snapshot by mental snapshot. In a few moments, he knew that he would have to pick over the scene, the corpse of the kid in forensic detail with Morgan and he wasn’t sure that his mind or his stomach were up to it.

‘He hasn’t been moved?’

Morgan raised an eyebrow.

‘Sorry. Stupid question.’ Callan squatted, taking care not to step too close to avoid contaminating the scene. He could feel his heart beginning to race, took a couple of deep breaths to slow it. The boy was slumped at the foot of a huge oak tree, tilted sideways, like a rag doll that had been propped in place, then slid off centre. His head was lolling on to his chest, dark brown eyes open, staring, and already showing the milky film of death, the tree’s leaves making a dappled jigsaw of his bloodless face. He had been handsome in life, and young – fuck, he was young. He looked like a fresh-faced schoolboy who’d been playing soldiers – youplaydeadnow – except that this victim wasn’t the product of any game. The bloody puncture wound in his throat and the tacky claret bib coating the front of his combat jacket told Callan that this crime scene was all too real.

‘Stab wound to the throat?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Weapon?’

‘A screwdriver.’

‘Where is it?’

‘I’ve bagged it.’

‘Was it still in his throat?’

‘No, it was eight metres away. Here.’ He indicated one of the numbered markers. ‘The tip was dug into the ground, the handle sticking up at forty-five degrees.’

‘Thrown?’

Morgan nodded. ‘Without doubt.’

Shifting closer, Callan studied the stab wound in the boy’s throat.

‘It doesn’t appear to be a vicious blow,’ he heard Morgan say.

‘No.’

There didn’t appear to be any trauma around the wound, no damaged skin or bruising. It was as if the screwdriver had slid in gently, finding the pliable gap between two cartilaginous ridges in the trachea, nothing unduly violent, no loss of control or wild ferocity about this death. Even the expression on the kid’s face showed no fear, merely an odd, chilling sense of calm.

A camera’s flash and Callan straightened, shielding his eyes from the blinding white light. The last thing he needed was another epileptic fit.

‘You OK, sir?’

‘Sure. I just need a coffee and ten hours’ sleep. I’ll leave you to it, Morgan.’

He suddenly wanted out of this wood. There was something about the denseness of the trees, the constant shifting of shadows as the wind moved the branches, and the smell – damp bark and leaf mulch – that catapulted him back to Sandhurst, back to that night in the woods when Major Nicholas Scott, the father of Jessie Flynn’s deeply traumatized four-year-old patient, Sami, had shot him in the back, when he had nearly died for the second time in his life. Jesus,Ben – he took a breath, trying to ease the pressure in his chest – focusonthefuckingcase. Stephen Foster, a sixteen-year-old kid, five months in the Army and already dead. There’d be hell to pay for this one.

10 (#ulink_9939df71-dc7e-5ff7-818b-7cc122768a5d)

The room Jessie and Marilyn entered was small and airless. Scuffed baby-pink walls, a burgundy cotton sofa backed against one wall, two matching chairs facing it, a brightly coloured foam alphabet jigsaw mat laid in the middle of the vinyl floor, each letter fashioned from an animal contorting itself into the appropriate shape – an ape for ‘A’, a beetle for ‘B’, a cat for ‘C’. The air stiflingly hot, even though someone had made an effort to ease the pressure-cooker atmosphere by opening the window as far as its ‘safety-first’ mechanism would allow. A fly, seeking escape, circled by the window, cracking its fragile carapace against the glass with each turn.

A chubby, blond-haired baby boy in a white T-shirt and pale blue dungarees was sitting in the middle of the mat, smacking the handset of a Bob the Builder telephone against its base. An elderly lady – late seventies, Jessie guessed – tiny and reed thin, was perched on the edge of the sofa watching the baby. Her hands, clamped on her knees, were threaded with thick blue veins, her skin diaphanous and liver-spotted with age. She had dressed for a formal occasion in a grey woollen tweed skirt, grey tights and a smart white shirt, the shirt’s short sleeves her only visible concession to the day’s unforeseen heat. Her brown lace-ups were highly polished, but the stitching had unravelled from the inside sole of one, the sole cleaving away from its upper.

Starting at the sound of the door, she looked over, her face lighting briefly with a sentiment that Jessie recognized as hope, half rising to her feet before collapsing back, the light dimming, when she realized that it was no one she knew.

‘Mrs Lawson, I’m Detective Inspector Bobby Simmons and this is my colleague, Doctor Jessica Flynn.’

From beneath her silver hair, the old lady’s dull gaze moved from Marilyn to Jessie and back. She made no move to take Marilyn’s outstretched hand.

‘Have you found Malcolm?’

‘Not yet, Mrs Lawson. We need some details from you to help in our search.’

She nodded, murmured, ‘Of course. Whatever you need.’

While Jessie sat down in one of the chairs opposite the sofa, Marilyn moved to stand by the window, reaching behind him to give it a quick upwards heave to see if it would budge, which it didn’t. Clearing his throat, he glanced down at the notes written in the notebook that DS Workman had thrust into his hand a few moments before Jessie had arrived at the hospital.

‘Malcolm’s car? He drives a dark grey Toyota Corolla, registration number LP 52 YBB? Is that correct?’

Mrs Lawson’s gaze found the ceiling as she tried to summon a picture to mind. ‘The colour is right, yes, and the make. I’m pretty sure that the make is right.’ She paused. ‘The registration number … I’m sorry, but would you repeat it.’

‘LP 52 YBB.’

Her eyes rose again. ‘The 52, yes, but the rest … I’m sorry, but I really can’t remember.’

‘We’ve got this information from the DVLA, so it should be accurate.’

‘The car has a baby seat in the back seat, of course, for Harry. Red and black it is. A red and black baby seat.’

Marilyn made a note. ‘Does Malcolm own or have access to any other vehicles?’

She shook her head.

‘Do you have any idea where he could have gone. Any special places that he likes to go? Friends who he could have gone to visit?’

‘He had a few friends, but he lost touch with them after … after Daniel died. He spends all his time looking after Harry.’

‘Pubs? Clubs?’

‘No.’

‘A girlfriend, perhaps?’

‘No. Really, no.’ Her nose wrinkled. ‘He wouldn’t stay out all night and he wouldn’t leave Harry like that.’

Jessie leaned forward. ‘Where is Harry’s mother, Mrs Lawson?’

‘She’s … she’s in a home, Doc—’ Her voice faltered. ‘Doctor.’

‘Jessie. Please call me Jessie.’

‘She’s in a home.’

‘A home? A hospital?’ Jessie probed. ‘Is she in a psychiatric hospital?’

Breaking eye contact, the old lady gave an almost imperceptible nod, as if she was embarrassed by the information she’d shared.

‘She couldn’t cope when Danny died. She was always fragile and she broke down completely when Danny took his own life.’

‘Where is the home?’ Marilyn asked.

‘It’s … it’s up in Maidenhead somewhere. I remember Maidenhead …’ A pause. ‘I … I can’t remember the name. I’m sorry, I never visited.’

‘Don’t worry, Mrs Lawson,’ Jessie cut in. ‘The police can find out if they need to talk to her.’

‘You won’t get any sense from her.’ The words rushed out. ‘She hasn’t spoken a word of sense since she was admitted six months ago. Malcolm goes to see her, takes Harry along sometimes, but she says nothing to him. Nothing to Harry either.’

‘Thank you, Mrs Lawson. You’ve been very helpful.’ Marilyn cleared his throat again, the sound grating in the claustrophobic space. ‘We are, uh, we’re working on the assumption that Malcolm left Harry here deliberately, because he believed that the hospital was a safe place at that hour of the night, and then went on somewhere else, to a location that we have yet to determine.’

‘To commit suicide?’ Her voice rose and cracked.

Marilyn shuffled his feet awkwardly against the tacky lino, the sound like the squealing of a trapped mouse.

Jessie nodded. ‘It is our working theory at the moment, Mrs Lawson.’

The old lady raised a hand to her mouth, stifling a sob. Jessie’s heart went out to her. She could be sitting facing her own mother: decades older, but with the same raw grief etched on to her face.

‘Something must have happened to him. He wouldn’t have left Harry.’

‘He left Harry in a hospital, Mrs Lawson,’ Jessie said gently. ‘Somewhere safe.’

‘He wouldn’t have left him. Not here. Not anywhere.’ Jamming her eyes shut, she shook her head. ‘And he would never kill himself, not after Danny.’

‘Mrs Lawson, you told DS Workman that Malcolm has suffered from severe depression since Danny’s death,’ Marilyn said. He looked intensely uncomfortable faced with the mixture of defiance and raw grief pulsing from this proud old lady. Jessie wondered if he usually left Workman to deal with families of the bereaved. From his reaction, she concluded that he did, couldn’t blame him.

‘Malcolm believes in God, Detective Inspector. Suicide is a sin in God’s eyes.’

‘Mrs Lawson.’ Jessie waited until the woman’s tear-filled eyes had found hers. ‘Depression is complex and the symptoms vary wildly between people, but it is very often characterized by a debilitating sadness, hopelessness and a total loss of interest in things that the sufferer used to enjoy.’

‘Your own baby?’ Her voice cracked. ‘A loss of interest in your own baby?’

‘A sufferer can feel exhausted – utterly exhausted, mentally and physically, by everything. Little children are tiring enough for someone who is healthy. For someone with depression, having to take care of a young child, however much they love that child, would be incredibly hard, a Mount Everest to climb each and every day. Depression also affects decision-making because the rational brain can’t function properly …’ Jessie paused. ‘And a person suffering from depression can believe that the people they leave behind are better off without them.’

Another sob, quickly stifled. His face wrinkling with concern at the sound, the little boy on the mat looked from his Bob the Builder phone to his grandmother.

‘You’re wrong, Doctor.’

‘Mrs Lawson.’ Moving to sit next to her on the sofa, Jessie laid a hand on her arm. Her skin was papery, chilled, despite the heat in the room. Jessie took a breath, fighting to suppress her own memories. ‘Mrs Lawson.’

‘No. No. You’re wrong.’ Tears were running unchecked down her cheeks. Unclipping her handbag, she fumbled inside and pulled out a crumpled tissue. ‘You’re both wrong. He would never leave Harry, not after Danny. He’s already lost one child, he’d never risk losing another. You need to find him.’ Her voice broke. ‘What are you doing to find him? Why are you sitting here? You need to find Malcolm now.’

11 (#ulink_9e01522b-3033-59b2-9610-607b1d9d7501)

Head down, Jessie walked swiftly down the corridor, forcing herself not to break into a full-on sprint. The heat and that ubiquitous hospital smell of antiseptic struggling to mask an odorous cocktail of bodily fluids felt almost physical, a claustrophobic weight pressing in on her from all sides. And the suit. The electric suit – she’d barely felt it while she’d been abroad – was tightening around her throat, making it hard to breathe.

‘Jessie.’

She took a few more steps, pretending that she hadn’t heard Marilyn’s call. The corner was an arm’s length away. If she swung around it, she could run down the next corridor, cut through A & E and disappear outside before he caught up with her. Escape.

‘Jessie, I know that you can hear me,’ Marilyn called, louder. ‘I don’t do jogging, so wait.’

She stopped, turned slowly to face him.

‘Jesus Christ, I need a drink after that,’ he muttered, catching up with her.

‘It wasn’t the best.’

‘So what do you think?’

Jessie focused on a patch of dried damp on the wall opposite, the result of a historic leak long since repaired but not repainted, avoiding meeting his eyes. ‘I think that you need to find Malcolm Lawson quickly.’

‘Isn’t it likely that he’s already dead?’

‘You can’t make that assumption. He has all sorts of conflicting emotions careering around in his head. Depression, exhaustion, hopelessness sure, but Mrs Lawson is right when she says that he also has a lot of positive emotions, pushing against those negative drivers. He believes in God, and suicide is a sin in the eyes of any Christian church. His older son committed suicide and he was horrified by that. And he has Harry, and for the past year that baby has been the centre of his world—’ She broke off with a shake of her head. ‘Mrs Lawson was adamant that he wouldn’t commit suicide.’

‘And you believe her?’ Marilyn asked gently.

Jessie sighed. ‘No … yes … no. I think that there is a lot of wishing and hoping that’s fuelling her belief. But I also know that suicide won’t be an easy choice for him. You can’t assume that he’s already dead.’

‘So we should be out looking for him?’

‘You should. Now.’

Marilyn tipped back on his heels and blew air out of his nose. ‘It would be a hell of a lot easier if I knew where to start.’

‘There’s no word on his car? If he left Harry here at around midnight, it makes sense to assume that he drove.’

‘It does, but we’ve had no word so far and every squad car in the county has been told to keep an eye out for it.’ Marilyn held out an arm. ‘Shall we get out of here, talk outside? This place is giving me hives.’

They walked towards the exit. Sweat was trickling down Jessie’s spine, pasting her shirt to her back. Marilyn was carrying his suit jacket slung over his shoulder, his lined face gummy with perspiration.

‘Why would Malcolm have decided now?’ he asked.