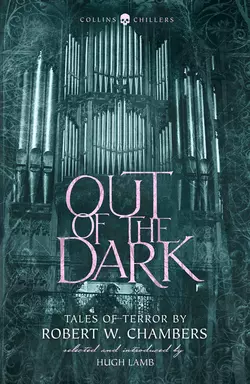

Out of the Dark: Tales of Terror by Robert W. Chambers

Robert W. Chambers

Hugh Lamb

For the first time in one volume, the best stories of one of America’s most popular classic authors of the supernatural.Robert William Chambers’ The King in Yellow (1895) has long been recognised as a landmark work in the field of the macabre, and has been described as the most important work of American supernatural fiction between Poe and the moderns. Despite the book’s success, its author was to return only rarely to the genre during the remainder of a writing career which spanned four decades.When Chambers did return to the supernatural, however, he displayed all the imagination and skill which distinguished The King in Yellow. He created the enigmatic and seemingly omniscient Westrel Keen, the ‘Tracer of Lost Persons’, and chronicled the strange adventures of an eminent naturalist who scours the earth for ‘extinct’ animals – and usually finds them. One of his greatest creations, perhaps, was 1920’s The Slayer of Souls, which features a monstrous conspiracy to take over the world: a conspiracy which can only be stopped by supernatural forces.For the first time in a single volume, Hugh Lamb has selected the best of the author’s supernatural tales, together with an introduction which provides further information about the author who was, in his heyday, called ‘the most popular writer in America’.

Copyright (#u6e753e46-ed42-5e10-a23e-48ba926a85f7)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Collins Chillers edition published 2018

First published in Canada in two volumes by Ash-Tree Press 1998, 1999

Selection, introduction and notes © Hugh Lamb 2018

Cover design by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008265366

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008265373

Version: 2018-09-04

Dedication (#u6e753e46-ed42-5e10-a23e-48ba926a85f7)

This collection of stories by a New York author is dedicated, with great affection, to another writer from that city – my daughter-in-law, Margaret Reyes Dempsey.

Contents

Cover (#u66719167-5630-564d-ae60-a227f6a80040)

Title Page (#u9ac8c185-309c-553b-b7dd-7611e94b50c3)

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

PART ONE: ORIGINS – 1895–1899 (#u8aaf8954-135a-5587-a8e8-fcee6592eb22)

Introduction (#ud484a8c9-687d-5202-95d4-6158ca006691)

The Yellow Sign (#u4c4a3ca9-b50d-5806-afbd-f306b778ce26)

A Pleasant Evening (#ube7387bf-8db7-50f4-910f-13de0c650f8f)

Passeur (#u08c071f7-4f34-5ff6-bae0-37a8964c6566)

In the Court of the Dragon (#u6a941a83-194d-5482-a92d-bca63fadfae5)

The Maker of Moons (#uead35271-eb9b-5cc9-90d7-25e3b90ba0d0)

The Mask (#litres_trial_promo)

The Demoiselle d’Ys (#litres_trial_promo)

The Key to Grief (#litres_trial_promo)

The Messenger (#litres_trial_promo)

PART TWO: DIVERSIONS – 1900–1938 (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#litres_trial_promo)

Out of the Depths (#litres_trial_promo)

Un Peu d’Amour (#litres_trial_promo)

Grey Magic (#litres_trial_promo)

Samaris (#litres_trial_promo)

In Search of the Great Auk (#litres_trial_promo)

The Death of Yarghouz Khan (#litres_trial_promo)

The Sign of Venus (#litres_trial_promo)

The Third Eye (#litres_trial_promo)

The Seal of Solomon (#litres_trial_promo)

The Bridal Pair (#litres_trial_promo)

In Search of the Mammoth (#litres_trial_promo)

Death Trail (#litres_trial_promo)

The Case of Mr Helmer (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also in this series

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PREFACE (#u6e753e46-ed42-5e10-a23e-48ba926a85f7)

Robert William Chambers, in his day one of America’s most popular authors, was born in New York, 26 May 1865, the son of New York lawyer William P. Chambers. The family were of Scottish descent. He had an early interest in art, studying at the Art Students League in New York, and in 1886 he went to Paris where he studied at the Academie Julien for seven years. He was accompanied by Charles Dana Gibson, destined to become one of America’s most celebrated portrait painters, who also illustrated some of Chambers’s books in later life.

When Chambers and Gibson returned to America in 1893, it was Gibson who got the lucky break into an art career. Chambers turned to writing instead. His first book, In the Quarter (1894), was based on his experiences in France. It sold fairly well, enough to encourage him to try his hand at a second book based on his French sojourn. The King in Yellow (1895) turned out to be an instant success and set Chambers on a writing career that lasted forty years. It was also one of the most successful books of the macabre, a genre to which Chambers would return only occasionally during his life.

Out of the Dark contains the best of Chambers’s work in this field, taken from books as far apart in publication as 1895 and 1920. By the time of his death on 16 December 1933, Robert W. Chambers had produced nearly 100 books (88 are listed in the British Library Catalogue in Britain alone). Sadly, only a very few dealt with the macabre.

PART ONE (#ulink_f0acc8f6-7745-5b46-9755-19d4d586b08f)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_4ced8bd6-319e-5620-92f0-a3b9bc1b67ad)

The tradition of the American in Paris – the expatriate enjoying himself in one of Europe’s most appealing cities – goes back way beyond such luminaries as Henry Miller or Ernest Hemingway. So many Americans got to know the place as a result of the First World War that it was quite forgotten that others had been there before, under less trying circumstances.

When Robert Chambers and Charles Dana Gibson went there to study art in 1886, we must hope they had as good a time as Miller (while perhaps not so athletic). They stayed there for seven years, after all. What did come out of it was a book of tales of terror seldom surpassed in the genre, yet in its own way a very unsatisfying work, making the reader wish for more. Which statement just about sums up the writing career of Robert W. Chambers, as far as enthusiasts in this genre are concerned.

Chambers, despite displaying an early, unique talent for tales of terror, returned to them very seldom in later life. He was an astute writer, who knew what sold well, and produced the goods accordingly. Spy novels, adventure stories, society dramas, social comedies – if that’s what the public wanted, then Chambers was happy to oblige.

He was one of the authors featured in ‘How I “Broke into Print”’, an article in the Strand Magazine’s November 1915 edition, and had this to say on his first major success:

My most important ‘break into print’ was with a collection of short stories of a weird and uncanny character, entitled The King in Yellow, which the public seemed to like. So flatteringly was it received, indeed, that it decided me to devote all my time to fiction, and so I have been writing ever since. I cannot say which of my books I prefer, because just as soon as I have finished a story I dislike it. I am continually trying to do something better, so that I presume my ‘best’ book will never be written.

The King in Yellow (1895) is at the same time one of the most enjoyable yet one of the most irritating books in the fantasy catalogue. At its best – as in ‘The Yellow Sign’ – it is genuinely scary, with original ideas seldom equalled. At its worst – as in ‘The Prophets’ Paradise’ (not included here: think yourselves lucky) it is obscure, pompous, and overwritten.

The title refers to a play, rumoured to be so evil that it shatters lives and lays waste souls. We never get to see much of it; in fact, this much-vaunted evil work doesn’t even appear in some of the stories. Where it does, as in ‘The Yellow Sign’ or ‘The Mask’, it adds untold atmosphere. Where it doesn’t, as in ‘The Street of the First Shell’ (again not included), then the book is a distinct let-down. At times, it is hard to see what Chambers is intending with this erratic book. While it is an indispensable part of any self-respecting horror reader’s library, I have to say that it does not live up to its reputation.

And yet, as strange as anything (and at a time when M.R. James was just starting his ghost story career), there comes a line in ‘In the Court of the Dragon’ which could not be more Jamesian:

… I wondered idly … whether something not usually supposed to be at home in a Christian church, might have entered undetected, and taken possession of the west gallery.

‘The Yellow Sign’ is by far and away the most reprinted story from The King in Yellow, and earned the praise of H.P. Lovecraft, among others. It very quickly conjures up an atmosphere of death and decay (count the words in this vein that appear in just the first few paragraphs) and, in the form of the church watchman, one of the genre’s most disturbing figures.

‘In the Court of the Dragon’ and ‘The Demoiselle D’Ys’ are lesser items, though ‘In the Court of the Dragon’ has its own scary church figure. ‘The Mask’ limply trails its fingers in the waters of science fiction, like so many tales from the 1890s. (An odd fact: Chambers mentions Gounod’s ‘Sanctus’ in ‘The Mask’, as a symbol of purity; Werner Herzog used the music over the closing credits of his film Nosferatu in 1979, a most un-pure film.)

While Chambers borrowed various things from Ambrose Bierce to embellish The King in Yellow, like the names Carcosa and Hastur, he has inspired precious few imitators himself. There may be one: Sidney Levett-Yeats, the British writer, introduces a book written by the devil (in his story ‘The Devil’s Manuscript’ (1899)) which ruins lives when read. It is titled The Yellow Dragon.

As The King in Yellow proved to be a winner, Chambers turned to writing full-time, while still keeping up his artistic habits (though, oddly, he never seems to have illustrated any of his own books, Charles Dana Gibson certainly illustrated some for him). He supplied illustrations for magazines such as Life, Truth, and Vogue, and was photographed for The King in Yellow, palette in hand.

He married Elsa Vaughn Moller in 1898, and they spent their married life at Broadalbin, an 800 acre estate in the Sacandaga Valley, northern New York State. Broadalbin had been in the Chambers family since his grandfather William Chambers first settled there in the mid-1800s. This beautiful country estate in the Adirondacks included a game preserve (where it seems Chambers never shot) and a fishing lake.

Broadalbin House was remodelled by Chambers’s architect brother, William Boughton Chambers, and was crammed with the family’s and Chambers’s collection of books, paintings, and Oriental objets d’art. His collection of butterflies was said to be one of the most complete in America.

Chambers spent most of the year at Broadalbin, travelling into New York to work in an office which he kept secret from his family (so much so that they had trouble finding it when he died). His chauffeur would drop him off and pick him up again at a spot some distance from the office.

Chambers lavished much care and affection on Broadalbin, planting thousands of trees on the estate. When he died, he was buried under one of the oaks.

Not all his time at Broadalbin was contented. He saw 200 acres of the estate vanish under the waters of the Sacandaga Reservoir which now covers much of the valley. He would have been even more desolate at the fate of his carefully planted trees (see Part Two).

Though part of the house at Broadalbin was demolished, the building still stands, now owned by the Catholic Church. It was abandoned (literally overnight, on the death of Chambers’s widow in 1938) for some years, and was vandalised terribly. It is reported that Chambers’s papers were used by intruders and squatters to light fires.

Chambers loved the outdoor life: it shows up in his writing time and again, where his descriptions of nature, scenery and forests are superbly evocative. A keen hunter, shooter and fisher, his characters are so often engaged in these pursuits as to suggest Chambers himself at play. He could apparently call most kinds of birds and was well versed in Indian languages (see ‘The Key to Grief’).

He must have been the most fortunate of authors: successful, rich and surrounded by the life he loved and wrote about. It is easy to see why he was reported to be so popular with his estate workers and neighbours in this period of his life.

To follow up the success of The King in Yellow, Chambers published another book of short stories in 1896, The Maker of Moons.

The title story, included here, is in many ways a practice run at his 1920 novel The Slayer of Souls. As in that book, we have ample helpings of the American secret service (fine men all), Oriental magic, and strange goings-on in the forest. It also shows how Chambers would finally drift away from the fantasy genre, into the world of espionage and adventure. ‘The Maker of Moons’ is nonetheless a superb fantasy, quite unlike anything else around at the time, and holds up well, even now.

From the same book comes ‘A Pleasant Evening’, another indication of the way Chambers would develop. Here, in a fairly traditional theme, he shows the skill that would lead to The Tree of Heaven (in Part Two) – the writing of neat and well crafted supernatural tales, not necessarily meant to frighten.

The next year, Chambers published The Mystery of Choice, a fine set of stories which was a series of vaguely connected tales, set mainly in France, but this time not in Paris. By far and away the most powerful of them was ‘The Messenger’.

This is a long, sometimes rambling story that nevertheless guides the reader along to a most eerie conclusion. The setting – coastal Brittany – has seldom been used to such effect, and the historical tale behind the story’s events has a grotesque ring of truth. This is one of Chambers’s best stories, and its use of the traditional masked figure has never been bettered.

‘Passeur’ from the same book, is a much shorter, traditional ghost story, easily guessed by anyone familiar with the genre. But Chambers is too good to give it all away completely; relish the scenery he depicts in the closing paragraphs.

Sticking out like a sore thumb from the rest of the stories in the book, ‘The Key to Grief’ is set far away from France. Chambers might have borrowed the odd name or two from Bierce for The King in Yellow; here he all but ransacked Bierce’s living-room. This is a shameless reworking of Bierce’s ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’, which still has its own sense of the unknown, and is included here by virtue of its unusual location.

The Mystery of Choice contained a lot of what was to become the cardinal vice of Chambers’s writing as time went by: an awful tendency to be rather soppy, especially in his romantic scenes. This style probably didn’t read too well in the 1890s; nowadays it just grates alarmingly.

After 1900 Chambers moved steadily away from his roots in the fantasy genre, but still – though not often enough – popping back from time to time, as will be seen in Part Two.

Hugh Lamb

Sutton, Surrey

January 2018

THE YELLOW SIGN (#ulink_c22ee24b-1193-5724-9ca2-689c250c4c69)

‘Let the red dawn surmise

What we shall do,

When this blue starlight dies

And all is through.’

I

There are so many things which are impossible to explain! Why should certain chords in music make me think of the brown and golden tints of autumn foliage? Why should the Mass of Sainte Cécile send my thoughts wandering among caverns whose walls blaze with ragged masses of virgin silver? What was it in the roar and turmoil of Broadway at six o’clock that flashed before my eyes the picture of a still Breton forest where sunlight filtered through spring foliage and Sylvia bent, half curiously, half tenderly, over a small green lizard, murmuring: ‘To think that this also is a little ward of God’?

When I first saw the watchman his back was toward me. I looked at him indifferently until he went into the church. I paid no more attention to him than I had to any other man who lounged through Washington Square that morning, and when I shut my window and turned back into my studio I had forgotten him. Late in the afternoon, the day being warm, I raised the window again and leaned out to get a sniff of air. A man was standing in the courtyard of the church, and I noticed him again with as little interest as I had that morning. I looked across the square to where the fountain was playing and then, with my mind filled with vague impressions of trees, asphalt drives, and the moving groups of nursemaids and holiday-makers, I started to walk back to my easel. As I turned, my listless glance included the man below in the churchyard. His face was toward me now, and with a perfectly involuntary movement I bent to see it. At the same moment he raised his head and looked at me. Instantly I thought of a coffin-worm. Whatever it was about the man that repelled me I did not know, but the impression of a plump white grave-worm was so intense and nauseating that I must have shown it in my expression, for he turned his puffy face away with a movement which made me think of a disturbed grub in a chestnut.

I went back to my easel and motioned the model to resume her pose. After working awhile I was satisfied that I was spoiling what I had done as rapidly as possible, and I took up a palette knife and scraped the color out again. The flesh tones were sallow and unhealthy, and I did not understand how I could have painted such sickly color into a study which before that had glowed with healthy tones.

I looked at Tessie. She had not changed, and the clear flush of health dyed her neck and cheeks as I frowned.

‘Is it something I’ve done?’ she said.

‘No – I’ve made a mess of this arm, and for the life of me I can’t see how I came to paint such mud as that into the canvas,’ I replied.

‘Don’t I pose well?’ she insisted.

‘Of course, perfectly.’

‘Then it’s not my fault?’

‘No, it’s my own.’

‘I’m very sorry,’ she said.

I told her she could rest while I applied rag and turpentine to the plague spot on my canvas, and she went off to smoke a cigarette and look over the illustrations in the Courier Français.

I did not know whether it was something in the turpentine or a defect in the canvas, but the more I scrubbed the more that gangrene seemed to spread. I worked like a beaver to get it out, and yet the disease appeared to creep from limb to limb of the study before me. Alarmed I strove to arrest it, but now the color on the breast changed and the whole figure seemed to absorb the infection as a sponge soaks up water. Vigorously I plied palette knife, turpentine, and scraper, thinking all the time what a séance I should hold with Duval who had sold me the canvas; but soon I noticed that it was not the canvas which was defective nor yet the colors of Edward. ‘It must be the turpentine,’ I thought angrily, ‘or else my eyes have become so blurred and confused by the afternoon light that I can’t see straight.’ I called Tessie, the model. She came and leaned over my chair blowing rings of smoke into the air.

‘What have you been doing to it?’ she exclaimed.

‘Nothing,’ I growled, ‘it must be this turpentine!’

‘What a horrible color it is now,’ she continued. ‘Do you think my flesh resembles green cheese?’

‘No, I don’t,’ I said angrily, ‘did you ever know me to paint like that before?’

‘No, indeed!’

‘Well, then!’

‘It must be the turpentine, or something,’ she admitted.

She slipped on a Japanese robe and walked to the window. I scraped and rubbed until I was tired and finally picked up my brushes and hurled them through the canvas with a forcible expression, the tone alone of which reached Tessie’s ears.

Nevertheless she promptly began: ‘That’s it! Swear and act silly and ruin your brushes! You have been three weeks on that study, and now look! What’s the good of ripping the canvas? What creatures artists are!’

I felt about as much ashamed as I usually did after such an outbreak, and I turned the ruined canvas to the wall. Tessie helped me clean my brushes, and then danced away to dress. From the screen she regaled me with bits of advice concerning whole or partial loss of temper, until, thinking, perhaps, I had been tormented sufficiently, she came out to implore me to button her waist where she could not reach it on the shoulder.

‘Everything went wrong from the time you came back from the window and talked about that horrid-looking man you saw in the churchyard,’ she announced.

‘Yes, he probably bewitched the picture,’ I said yawning. I looked at my watch.

‘It’s after six, I know,’ said Tessie, adjusting her hat before the mirror.

‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘I didn’t mean to keep you so long.’ I leaned out of the window but recoiled with disgust, for the young man with the pasty face stood below in the churchyard. Tessie saw my gesture of disapproval and leaned from the window.

‘Is that the man you don’t like?’ she whispered.

I nodded.

‘I can’t see his face, but he does look fat and soft. Someway or other,’ she continued, turning to look at me, ‘he reminds me of a dream – an awful dream I once had. Or,’ she mused, looking down at her shapely shoes, ‘was it a dream after all?’

‘How should I know?’ I smiled.

Tessie smiled in reply.

‘You were in it,’ she said, ‘so perhaps you might know something about it.’

‘Tessie! Tessie!’ I protested, ‘don’t you dare flatter by saying that you dream about me!’

‘But I did,’ she insisted. ‘Shall I tell you about it?’

‘Go ahead,’ I replied, lighting a cigarette.

Tessie leaned back on the open window-sill and began very seriously.

‘One night last winter I was lying in bed thinking about nothing at all in particular. I had been posing for you and I was tired out, yet it seemed impossible for me to sleep. I heard the bells in the city ring, ten, eleven, and midnight. I must have fallen asleep about midnight because I don’t remember hearing the bells after that. It seemed to me that I had scarcely closed my eyes when I dreamed that something impelled me to go to the window. I rose, and raising the sash leaned out. Twenty-fifth Street was deserted as far as I could see. I began to be afraid; everything outside seemed so – so black and uncomfortable. Then the sound of wheels in the distance came to my ears, and it seemed to me as though that was what I must wait for. Very slowly the wheels approached, and, finally, I could make out a vehicle moving along the street. It came nearer and nearer, and when it passed beneath my window I saw it was a hearse. Then, as I trembled with fear, the driver turned and looked straight at me. When I awoke I was standing by the open window shivering with cold, but the black-plumed hearse and the driver were gone. I dreamed this dream again in March last, and again awoke beside the open window. Last night the dream came again. You remember how it was raining; when I awoke, standing at the open window, my night-dress was soaked.’

‘But where did I come into the dream?’ I asked.

‘You – you were in the coffin; but you were not dead.’

‘In the coffin?’

‘Yes.’

‘How did you know? Could you see me?’

‘No; I only knew you were there.’

‘Had you been eating Welsh rarebits, or lobster salad?’ I began laughing, but the girl interrupted me with a frightened cry.

‘Hello! What’s up?’ I said, as she shrank into the embrasure by the window.

‘The – the man below in the churchyard; he drove the hearse.’

‘Nonsense,’ I said, but Tessie’s eyes were wide with terror. I went to the window and looked out. The man was gone. ‘Come, Tessie,’ I urged, ‘don’t be foolish. You have posed too long; you are nervous.’

‘Do you think I could forget that face?’ she murmured. ‘Three times I saw the hearse pass below my window, and every time the driver turned and looked up at me. Oh, his face was so white and – and soft! It looked dead – it looked as if it had been dead a long time.’

I induced the girl to sit down and swallow a glass of Marsala. Then I sat down beside her, and tried to give her some advice.

‘Look here, Tessie,’ I said, ‘you go to the country for a week or two, and you’ll have no more dreams about hearses. You pose all day, and when night comes your nerves are upset. You can’t keep this up. Then again, instead of going to bed when your day’s work is done, you run off to picnics at Sulzer’s Park, or go to the Eldorado or Coney Island, and when you come down here next morning you are fagged out. There was no real hearse. That was a soft-shell crab dream.’

She smiled faintly.

‘What about the man in the churchyard?’

‘Oh, he’s only an ordinary unhealthy, everyday creature.’

‘As true as my name is Tessie Rearden, I swear to you, Mr Scott, that the face of the man below in the churchyard is the face of the man who drove the hearse!’

‘What of it?’ I said. ‘It’s an honest trade.’

‘Then you think I did see the hearse?’

‘Oh, I said diplomatically, ‘if you really did, it might not be unlikely that the man below drove it. There is nothing in that.’

Tessie rose, unrolled her scented handkerchief and taking a bit of gum from a knot in the hem, placed it in her mouth. Then drawing on her gloves she offered me her hand, with a frank, ‘Good-night, Mr Scott,’ and walked out.

II

The next morning, Thomas, the bellboy, brought me the Herald and a bit of news. The church next door had been sold. I thanked Heaven for it, not that I, being a Catholic, had any repugnance for the congregation next door, but because my nerves were shattered by a blatant exhorter, whose every word echoed through the aisle of the church as if it had been my own rooms, and who insisted on his r’s with a nasal persistence which revolted my every instinct. Then, too, there was a fiend in human shape, an organist, who reeled off some of the grand old hymns with an interpretation of his own, and I longed for the blood of a creature who could play the ‘Doxology’ with an amendment of minor chords which one hears only in a quartet of very young undergraduates. I believe the minister was a good man, but when he bellowed: ‘And the Lorrrd said unto Moses, the Lorrrd is a man of war; the Lorrrd is my name. My wrath shall wax hot and I will kill you with my sworrrd!’ I wondered how many centuries of purgatory it would take to atone for such a sin.

‘Who bought the property?’ I asked Thomas.

‘Nobody that I knows, sir. They do say the gent wot owns this ’ere ’Amilton flats was lookin’ at it. ’E might be a bildin’ more studios.’

I walked to the window. The young man with the unhealthy face stood by the churchyard gate, and at the mere sight of him the same overwhelming repugnance took possession of me.

‘By the way, Thomas,’ I said, ‘who is that fellow down there?’

Thomas sniffed. ‘That there worm, sir? ’E’s night-watchman of the church, sir. ’E maikes me tired-a-sittin’ out all night on them steps and lookin’ at you insultin’ like. I’d a punched ’is ’ed, sir – beg pardon, sir—’

‘Go on, Thomas.’

‘One night a comin’ ’ome with ’Arry, the other English boy, I sees ’im a sittin’ there on them steps. We ’ad Molly and Jen with us, sir, the two girls on the tray service, an’ ’e looks so insultin’ at us that I up and sez: “Wat you looking hat, you fat slug?” – beg pardon, sir, but that’s ’ow I sez, sir. Then ’e don’t say nothin’ and I sez: “Come out and I’ll punch that puddin’ ’ed.” Then I hopens the gate and goes in, but ’e don’t say nothin’, only looks insultin’ like. Then I ’its ’im one, but, ugh! ’is ’ed was that cold and mushy it ud sicken you to touch ’im.’

‘What did he do then?’ I asked, curiously.

‘’Im? Nawthin’.’

‘And you, Thomas?’

The young fellow flushed with embarrassment and smiled uneasily.

‘Mr Scott, sir, I ain’t no coward an’ I can’t make it out at all why I run. I was in the 5th Lawncers, sir, bugler at Tel-el-Kebir, an’ was shot by the wells.’

‘You don’t mean to say you ran away?’

‘Yes, sir; I run.’

‘Why?’

‘That’s just what I want to know, sir. I grabbed Molly an’ run, an’ the rest was as frightened as I.’

‘But what were they frightened at?’

Thomas refused to answer for a while, but now my curiosity was aroused about the repulsive young man below and I pressed him. Three years’ sojourn in America had not only modified Thomas’s cockney dialect but had given him the American’s fear of ridicule.

‘You won’t believe me, Mr Scott, sir?’

‘Yes, I will.’

‘You will lawf at me, sir?’

‘Nonsense!’

He hesitated. ‘Well, sir, it’s Gawd’s truth that when I ’it ’im ’e grabbed me wrists, sir, and when I twisted ’is soft, mushy fist one of ’is fingers come off in me ’and.’

The utter loathing and horror of Thomas’s face must have been reflected in my own for he added:

‘It’s orful, an’ now when I see ’im I just go away. ’E makes me hill.’

When Thomas had gone I went to the window. The man stood beside the church-railing with both hands on the gate, but I hastily retreated to my easel again, sickened and horrified, for I saw that the middle finger of his right hand was missing.

At nine o’clock Tessie appeared and vanished behind the screen with a merry ‘Good morning, Mr Scott’. When she had reappeared and taken her pose upon the model-stand I started a new canvas much to her delight. She remained silent as long as I was on the drawing, but as soon as the scrape of the charcoal ceased and I took up my fixative she began to chatter.

‘Oh, I had such a lovely time last night. We went to Tony Pastor’s.’

‘Who are “we”?’ I demanded.

‘Oh, Maggie, you know, Mr Whyte’s model, and Pinkie McCormack – we call her Pinkie because she’s got that beautiful red hair you artists like so much – and Lizzie Burke.’

I sent a shower of spray from the fixative over the canvas, and said: ‘Well, go on.’

‘We saw Kelly and Baby Barnes the skirt-dancer and – and all the rest. I made a mash.’

‘Then you have gone back on me, Tessie?’

She laughed and shook her head.

‘He’s Lizzie Burke’s brother, Ed. He’s a perfect gen’l’man.’

I felt constrained to give her some parental advice concerning mashing, which she took with a bright smile.

‘Oh, I can take care of a strange mash,’ she said, examining her chewing gum, ‘but Ed is different. Lizzie is my best friend.’

Then she related how Ed had come back from the stocking mill in Lowell, Massachusetts, to find her and Lizzie grown up – and what an accomplished young man he was – and how he thought nothing of squandering half a dollar for ice-cream and oysters to celebrate his entry as clerk into the woollen department of Macy’s. Before she finished I began to paint, and she resumed the pose, smiling and chattering like a sparrow. By noon I had the study fairly well rubbed in and Tessie came to look at it.

‘That’s better,’ she said.

I thought so too, and ate my lunch with a satisfied feeling that all was going well. Tessie spread her lunch on a drawing table opposite me and we drank our claret from the same bottle and lighted our cigarettes from the same match. I was very much attached to Tessie. I had watched her shoot up into a slender but exquisitely formed woman from a frail, awkward child. She had posed for me during the last three years, and among all my models she was my favorite. It would have troubled me very much indeed had she become ‘tough’ or ‘fly’, as the phrase goes, but I never noticed any deterioration of her manner, and felt at heart that she was all right. She and I never discussed morals at all, and I had no intention of doing so, partly because I had none myself, and partly because I knew she would do what she liked in spite of me. Still I did hope she would steer clear of complications, because I wished her well, and then also I had a selfish desire to retain the best model I had. I knew that mashing, as she termed it, had no significance with girls like Tessie, and that such things in America did not resemble in the least the same things in Paris. Yet having lived with my eyes open, I also knew that somebody would take Tessie away some day, in one manner or another, and though I professed to myself that marriage was nonsense, I sincerely hoped that, in this case, there would be a priest at the end of the vista. I am a Catholic. When I listen to high mass, when I sign myself, I feel that everything, including myself, is more cheerful, and when I confess, it does me good. A man who lives as much alone as I do, must confess to somebody. Then, again, Sylvia was Catholic, and it was reason enough for me. But I was speaking of Tessie, which is very different. Tessie also was Catholic and much more devout than I, so, taking it all in all, I had little fear for my pretty model until she should fall in love. But then I knew that fate alone would decide her future for her, and I prayed inwardly that fate would keep her away from men like me and throw into her path nothing but Ed Burkes and Jimmy McCormicks, bless her sweet face!

Tessie sat blowing rings of smoke up to the ceiling and tinkling the ice in her tumbler.

‘Do you know that I also had a dream last night?’ I observed.

‘Not about that man?’ she asked, laughing.

‘Exactly. A dream similar to yours, only much worse.’

It was foolish and thoughtless of me to say this, but you know how little tact the average painter has.

‘I must have fallen asleep about 10 o’clock,’ I continued, ‘and after a while I dreamt that I awoke. So plainly did I hear the midnight bells, the wind in the tree-branches, and the whistle of steamers from the bay, that even now I can scarcely believe I was not awake. I seemed to be lying in a box which had a glass cover. Dimly I saw the street lamps as I passed, for I must tell you, Tessie, the box in which I reclined appeared to lie in a cushioned wagon which jolted me over a stony pavement. After a while I became impatient and tried to move but the box was too narrow. My hands were crossed on my breast so I could not raise them to help myself. I listened and then tried to call. My voice was gone. I could hear the trample of the horses attached to the wagon and even the breathing of the driver. Then another sound broke upon my ears like the raising of a window sash. I managed to turn my head a little, and found I could look, not only through the glass cover of my box, but also through the glass panes in the side of the covered vehicle. I saw houses, empty and silent, with neither light nor life about any of them excepting one. In that house a window was open on the first floor and a figure all in white stood looking down into the street. It was you.’

Tessie had turned her face away from me and leaned on the table with her elbow.

‘I could see your face,’ I resumed, ‘and it seemed to me to be very sorrowful. Then we passed on and turned into a narrow black lane. Presently the horses stopped. I waited and waited, closing my eyes with fear and impatience, but all was silent as the grave. After what seemed to me hours, I began to feel uncomfortable. A sense that somebody was close to me made me unclose my eyes. Then I saw the white face of the hearse-driver looking at me through the coffin lid—’

A sob from Tessie interrupted me. She was trembling like a leaf. I saw I had made an ass of myself and attempted to repair the damage.

‘Why, Tess,’ I said, ‘I only told you this to show you what influence your story might have on another person’s dreams. You don’t suppose I really lay in a coffin, do you? What are you trembling for? Don’t you see that your dream and my unreasonable dislike for that inoffensive watchman of the church simply set my brain working as soon as I fell asleep?’

She laid her head between her arms and sobbed as if her heart would break. What a precious triple donkey I had made of myself! But I was about to break my record. I went over and put my arm about her.

‘Tessie, dear, forgive me,’ I said; ‘I had no business to frighten you with such nonsense. You are too sensible a girl, too good a Catholic to believe in dreams.’

Her hand tightened on mine and her head fell back upon my shoulder, but she still trembled and I petted her and comforted her.

‘Come, Tess, open your eyes and smile.’

Her eyes opened with a slow languid movement and met mine, but their expression was so queer that I hastened to reassure her again.

‘It’s all humbug, Tessie. You surely are not afraid that any harm will come to you because of that?’

‘No,’ she said, but her scarlet lips quivered.

‘Then what’s the matter? Are you afraid?’

‘Yes. Not for myself.’

‘For me, then?’ I demanded gayly.

‘For you,’ she murmured in a voice almost inaudible. ‘I – I care for you.’

At first I started to laugh but when I understood her, a shock passed through me and I sat like one turned to stone. This was the crowning bit of idiocy I had committed. During the moment which elapsed between her reply and my answer I thought of a thousand responses to that innocent confession. I could pass it by with a laugh. I could misunderstand her and reassure her as to my health. I could simply point out that it was impossible she could love me. But my reply was quicker than my thoughts, and I might think and think now when it was too late, for I had kissed her on the mouth.

That evening I took my usual walk in Washington Park, pondering over the occurrences of the day. I was thoroughly committed. There was no back-out now, and I stared the future straight in the face. I was not good, not even scrupulous, but I had no idea of deceiving either myself or Tessie. The one passion of my life lay buried in the sunlit forests of Brittany. Was it buried forever? Hope cried ‘No!’ For three years I had been listening to the voice of Hope, and for three years I had waited for a footstep on my threshold. Had Sylvia forgotten? ‘No!’ cried Hope.

I said that I was not good. That is true, but still I was not exactly a comic opera villain. I had led an easy-going reckless life, taking what invited me of pleasure, deploring and sometimes bitterly regretting consequences. In one thing alone, except my painting, was I serious, and that was something which lay hidden if not lost in the Breton forests.

It was too late now for me to regret what had occurred during the day. Whatever it had been, pity, a sudden tenderness for sorrow, or the more brutal instinct of gratified vanity, it was all the same now, and unless I wished to bruise an innocent heart my path lay marked before me. The fire and strength, the depth of passion of a love which I had never even suspected, with all my imagined experience in the world, left me no alternative but to respond or send her away. Whether because I am so cowardly about giving pain to others, or whether it was that I have little of the gloomy Puritan in me, I do not know, but I shrank from disclaiming responsibility for that thoughtless kiss, and in fact had no time to do so before the gates of her heart opened and the flood poured forth. Others who habitually do their duty and find a sullen satisfaction in making themselves and everybody else unhappy, might have withstood it. I did not. I dared not. After the storm had abated I did tell her that she might better have loved Ed Burke and worn a plain gold ring, but she would not hear of it, and I thought perhaps that as long as she had decided to love somebody she could not marry, it had better be me. I, at least, could treat her with an intelligent affection, and whenever she became tired of her infatuation she could go none the worse for it. For I was decided on that point although I knew how hard it would be. I remembered the usual termination of Platonic liaisons and thought how disgusted I had been whenever I heard of one. I knew I was undertaking a great deal for so unscrupulous a man as I was, and I dreaded the future, but never for one moment did I doubt that she was safe with me. Had it been anybody but Tessie I should not have bothered my head about scruples. For it did not occur to me to sacrifice Tessie as I would have sacrificed a woman of the world. I looked the future squarely in the face and saw the several probable endings to the affair. She would either tire of the whole thing, or become so unhappy that I should have either to marry her or go away. If I married her we would be unhappy. I with a wife unsuited to me, and she with a husband unsuitable for any woman. For my past life could scarcely entitle me to marry. If I went away she might either fall ill, recover, and marry some Eddie Burke, or she might recklessly or deliberately go and do something foolish. On the other hand if she tired of me, then her whole life would be before her with beautiful vistas of Eddie Burkes and marriage rings and twins and Harlem flats and Heaven knows what. As I strolled along through the trees by the Washington Arch, I decided that she should find a substantial friend in me anyway and the future could take care of itself. Then I went into the house and put on my evening dress, for the little faintly perfumed note on my dresser said, ‘Have a cab at the stage door at eleven’, and the note was signed ‘Edith Carmichel, Metropolitan Theatre’.

I took supper that night, or rather we took supper, Miss Carmichel and I, at Solari’s and the dawn was just beginning to gild the cross on the Memorial Church as I entered Washington Square after leaving Edith at the Brunswick. There was not a soul in the park as I passed among the trees and took the walk which leads from the Garibaldi statue to the Hamilton Apartment House, but as I passed the churchyard I saw a figure sitting on the stone steps. In spite of myself a chill crept over me at the sight of the white puffy face, and I hastened to pass. Then he said something which might have been addressed to me or might merely have been a mutter to himself, but a sudden furious anger flamed up within me that such a creature should address me. For an instant I felt like wheeling about and smashing my stick over his head, but I walked on, and entering the Hamilton went to my apartment. For some time I tossed about the bed trying to get the sound of his voice out of my ears, but could not. It filled my head, that muttering sound, like thick oily smoke from a fat-rendering vat or an odor of noisome decay. And as I lay and tossed about, the voice in my ears seemed more distinct, and I began to understand the words he had muttered. They came to me slowly as if I had forgotten them, and at last I could make some sense out of the sounds. It was this:

‘Have you found the Yellow Sign?’

‘Have you found the Yellow Sign?’

‘Have you found the Yellow Sign?’

I was furious. What did he mean by that? Then with a curse upon him and his I rolled over and went to sleep, but when I awoke later I looked pale and haggard, for I had dreamed the dream of the night before and it troubled me more than I cared to think.

I dressed and went down into my studio. Tessie sat by the window, but as I came in she rose and put both arms around my neck for an innocent kiss. She looked so sweet and dainty that I kissed her again and then sat down before the easel.

‘Hello! Where’s the study I began yesterday?’ I asked.

Tessie looked conscious, but did not answer. I began to hunt among the piles of canvases, saying, ‘Hurry up, Tess, and get ready; we must take advantage of the morning light.’

When at last I gave up the search among the other canvases and turned to look around the room for the missing study I noticed Tessie standing by the screen with her clothes still on.

‘What’s the matter,’ I asked, ‘don’t you feel well?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then hurry.’

‘Do you want me to pose as – as I have always posed?’

Then I understood. Here was a new complication. I had lost, of course, the best nude model I had ever seen. I looked at Tessie. Her face was scarlet. Alas! Alas! We had eaten of the tree of knowledge, and Eden and native innocence were dreams of the past – I mean for her.

I suppose she noticed the disappointment on my face, for she said: ‘I will pose if you wish. The study is behind the screen here where I put it.’

‘No,’ I said, ‘we will begin something new’; and I went into my wardrobe and picked out a Moorish costume which fairly blazed with tinsel. It was a genuine costume, and Tessie retired to the screen with it enchanted. When she came forth again I was astonished. Her long black hair was bound above her forehead with a circlet of turquoises, and the ends curled about her glittering girdle. Her feet were encased in the embroidered pointed slippers and the skirt of her costume, curiously wrought with arabesques in silver, fell to her ankles. The deep metallic blue vest embroidered with silver and the short Mauresque jacket spangled and sewn with turquoises became her wonderfully. She came up to me and held up her face smiling. I slipped my hand into my pocket and drawing out a gold chain with a cross attached, dropped it over her head.

‘It’s yours, Tessie.’

‘Mine?’ she faltered.

‘Yours. Now go and pose.’ Then with a radiant smile she ran behind the screen and presently reappeared with a little box on which was written my name.

‘I had intended to give it to you when I went home tonight,’ she said, ‘but I can’t wait now.’

I opened the box. On the pink cotton inside lay a clasp of black onyx, on which was inlaid a curious symbol or letter in gold. It was neither Arabic nor Chinese, nor as I found afterwards did it belong to any human script.

‘It’s all I had to give you for a keepsake,’ she said, timidly.

I was annoyed, but I told her how much I should prize it, and promised to wear it always. She fastened it on my coat beneath the lapel.

‘How foolish, Tess, to go and buy me such a beautiful thing as this,’ I said.

‘I did not buy it,’ she laughed.

‘Then where did you get it?’

Then she told me how she had found it one day while coming from the Aquarium in the Battery, how she had advertised it and watched the papers, but at last gave up all hopes of finding the owner.

‘That was last winter,’ she said, ‘the very day I had the first horrid dream about the hearse.’

I remembered my dream of the previous night but said nothing, and presently my charcoal was flying over a new canvas; and Tessie stood motionless on the model stand.

III

The day following was a disastrous one for me. While moving a framed canvas from one easel to another my foot slipped on the polished floor and I fell heavily on both wrists. They were so badly sprained that it was useless to attempt to hold a brush, and I was obliged to wander about the studio, glaring at unfinished drawings and sketches until despair seized me and I sat down to smoke and twiddle my thumbs with rage. The rain blew against the windows and rattled on the roof of the church, driving me into a nervous fit with its interminable patter. Tessie sat sewing by the window, and every now and then raised her head and looked at me with such innocent compassion that I began to feel ashamed of my irritation and looked about for something to occupy me. I had read all the papers and all the books in the library, but for the sake of something to do I went to the bookcases and shoved them open with my elbow. I knew every volume by its color and examined them all, passing slowly around the library and whistling to keep up my spirits. I was turning to go into the dining-room when my eye fell upon a book bound in serpent skin, standing in a corner of the top shelf of the last bookcase. I did not remember it and from the floor could not decipher the pale lettering on the back, so I went to the smoking-room and called Tessie. She came in from the studio and climbed up to reach the book.

‘What is it?’ I asked.

‘“The King in Yellow”.’

I was dumbfounded. Who had placed it there? How came it in my rooms? I had long ago decided that I should never open that book, and nothing on earth could have persuaded me to buy it. Fearful lest curiosity might tempt me to open it, I had never even looked at it in book-stores. If I ever had any curiosity to read it, the awful tragedy of young Castaigne, whom I knew, prevented me from exploring its wicked pages. I had always refused to listen to any description of it, and indeed, nobody ever ventured to discuss the second part aloud, so I had absolutely no knowledge of what those leaves might reveal. I stared at the poisonous mottled binding as I would at a snake.

‘Don’t touch it, Tessie,’ I said; ‘come down.’

Of course my admonition was enough to arouse her curiosity, and before I could prevent it she took the book and, laughing, danced off into the studio with it. I called to her but she slipped away with a tormenting smile at my helpless hands, and I followed her with some impatience.

‘Tessie!’ I cried, entering the library, ‘listen, I am serious. Put that book away. I do not wish you to open it!’ The library was empty. I went into both drawing-rooms, then into the bedrooms, laundry, kitchen, and finally returned to the library and began a systematic search. She had hidden herself so well that it was half an hour later when I discovered her crouching white and silent by the latticed window in the store-room above. At the first glance I saw she had been punished for her foolishness. ‘The King in Yellow’ lay at her feet, but the book was open at the second part. I looked at Tessie and saw it was too late. She had opened ‘The King in Yellow’. Then I took her by the hand and led her into the studio. She seemed dazed, and when I told her to lie down on the sofa she obeyed me without a word. After a while she closed her eyes and her breathing became regular and deep, but I could not determine whether or not she slept. For a long while I sat silently beside her, but she neither stirred nor spoke, and at last I rose and entering the unused store-room took the book in my least injured hand. It seemed heavy as lead, but I carried it into the studio again, and sitting down on the rug beside the sofa, opened it and read it through from beginning to end.

When, faint with the excess of my emotions, I dropped the volume and leaned wearily back against the sofa, Tessie opened her eyes and looked at me.

We had been speaking for some time in a dull monotonous strain before I realized that we were discussing ‘The King in Yellow’. Oh the sin of writing such words – words which are clear as crystal, limpid and musical as bubbling springs, words which sparkle and glow like the poisoned diamonds of the Medicis! Oh the wickedness, the hopeless damnation of a soul who could fascinate and paralyze human creatures with such words – words understood by the ignorant and wise alike, words which are more precious than jewels, more soothing than music, more awful than death!

We talked on, unmindful of the gathering shadows, and she was begging me to throw away the clasp of black onyx quaintly inlaid with what we now knew to be the Yellow Sign. I shall never know why I refused, though even at this hour, here in my bedroom as I write this confession, I should be glad to know what it was that prevented me from tearing the Yellow Sign from my breast and casting it into the fire. I am sure I wished to do so, and yet Tessie pleaded with me in vain. Night fell and hours dragged on, but still we murmured to each other of the King and the Pallid Mask, and midnight sounded from the misty spires in the fog-wrapped city. We spoke of Hastur and of Cassilda, while outside the fog rolled against the blank window-panes as the cloud waves roll and break on the shores of Hali.

The house was very silent now and not a sound came up from the misty streets. Tessie lay among the cushions, her face a gray blot in the gloom, but her hands were clasped in mine and I knew that she knew and read my thoughts as I read hers, for we had understood the mystery of the Hyades, and the Phantom of Truth was laid. Then as we answered each other, swiftly, silently, thought on thought, the shadows stirred in the gloom about us, and far in the distant streets we heard a sound. Nearer and nearer it came, the dull crunching of wheels, nearer and yet nearer, and now, outside before the door it ceased, and I dragged myself to the window and saw a black-plumed hearse. The gate below opened and shut, and I crept shaking to my door and bolted it, but I knew no bolts, no locks, could keep that creature out who was coming for the Yellow Sign. And now I heard him moving very softly along the hall. Now he was at the door, and the bolts rotted at his touch. Now he had entered. With eyes starting from my head I peered into the darkness, but when he came into the room I did not see him. It was only when I felt him envelop me in his cold soft grasp that I cried out and struggled with deadly fury, but my hands were useless and he tore the onyx clasp from my coat and struck me full in the face. Then, as I fell, I heard Tessie’s soft cry and her spirit fled: and even while falling I longed to follow her, for I knew that the King in Yellow had opened his tattered mantle and there was only God to cry to now.

I could tell more, but I cannot see what help it will be to the world. As for me I am past human help or hope. As I lie here, writing, careless even whether or not I die before I finish, I can see the doctor gathering up his powders and phials with a vague gesture to the good priest beside me, which I understand.

They will be very curious to know the tragedy – they of the outside world who write books and print millions of newspapers, but I shall write no more, and the father confessor will seal my last words with the seal of sanctity when his holy office is done. They of the outside world may send their creatures into wrecked homes and death-smitten firesides, and their newspapers will batten on blood and tears, but with me their spies must halt before the confessional. They know that Tessie is dead and that I am dying. They know how the people in the house, aroused by an infernal scream, rushed into my room and found one living and two dead, but they do not know what I shall tell them now; they do not know that the doctor said as he pointed to a horrible decomposed heap on the floor – the livid corpse of the watchman from the church: ‘I have no theory, no explanation. That man must have been dead for months!’

I think I am dying. I wish the priest would—

A PLEASANT EVENING (#ulink_628800dd-3ab7-5eac-b08b-a95a724b6f28)

‘Et pis, doucett’ment on s’endort

On fait sa carne, on fait sa sorgue,

On ronfle, et, comme un tuyau d’orgue

L’tuyau s’met à ronfler plus fort …’

ARISTIDE BRUANT

I

As I stepped upon the platform of a Broadway cable-car at Forty-second Street, somebody said, ‘Hello, Hilton, Jamison’s looking for you.’

‘Hello, Curtis,’ I replied, ‘what does Jamison want?’

‘He wants to know what you’ve been doing all the week,’ said Curtis, hanging desperately to the railing as the car lurched forward; ‘he says you seem to think that the Manhattan Illustrated Weekly was created for the sole purpose of providing salary and vacations for you.’

‘The shifty old tom-cat!’ I said indignantly, ‘he knows well enough where I’ve been. Vacation! Does he think the State Camp in June is a snap?’

‘Oh,’ said Curtis, ‘you’ve been to Peekskill?’

‘I should say so,’ I replied, my wrath rising as I thought of my assignment.

‘Hot?’ inquired Curtis, dreamily.

‘One hundred and three in the shade,’ I answered. ‘Jamison wanted three full pages and three half pages, all for process work, and a lot of line drawings into the bargain. I could have faked them – I wish I had. I was fool enough to hustle and break my neck to get some honest drawings, and that’s the thanks I get!’

‘Did you have a camera?’

‘No. I will next time – I’ll waste no more conscientious work on Jamison,’ I said sulkily.

‘It doesn’t pay,’ said Curtis. ‘When I have military work assigned to me, I don’t do the dashing sketch-artist act, you bet; I go to my studio, light my pipe, pull out a lot of old Illustrated London News, select several suitable battle scenes by Caton Woodville – and use ’em too.’

The car shot round the neck-breaking curve at Fourteenth Street.

‘Yes,’ continued Curtis, as the car stopped in front of the Morton House for a moment, then plunged forward again amid a furious clanging of gongs, ‘it doesn’t pay to do decent work for the fat-headed men who run the Manhattan Illustrated. They don’t appreciate it.’

‘I think the public does,’ I said, ‘but I’m sure Jamison doesn’t. It would serve him right if I did what most of you fellows do – take a lot of Caton Woodville’s and Thulstrup’s drawings, change the uniforms, “chic” a figure or two, and turn in a drawing labelled “from life”. I’m sick of this sort of thing anyway. Almost every day this week I’ve been chasing myself over that tropical camp, or galloping in the wake of those batteries. I’ve got a full page of the “camp by moonlight”, full pages of “artillery drill” and “light battery in action”, and a dozen smaller drawings that cost me more groans and perspiration than Jamison ever knew in all his lymphatic life!’

‘Jamison’s got wheels,’ said Curtis, ‘—more wheels than there are bicycles in Harlem. He wants you to do a full page by Saturday.’

‘A what?’ I exclaimed, aghast.

‘Yes he does – he was going to send Jim Crawford, but Jim expects to go to California for the winter fair, and you’ve got to do it.’

‘What is it?’ I demanded savagely.

‘The animals in Central Park,’ chuckled Curtis.

I was furious. The animals! Indeed! I’d show Jamison that I was entitled to some consideration! This was Thursday; that gave me a day and a half to finish a full-page drawing for the paper, and, after my work at the State Camp I felt that I was entitled to a little rest. Anyway I objected to the subject. I intended to tell Jamison so – I intended to tell him firmly. However, many of the things that we often intended to tell Jamison were never told. He was a peculiar man, fat-faced, thin-lipped, gentle-voiced, mild-mannered, and soft in his movements as a pussy cat. Just why our firmness should give way when we were actually in his presence, I have never quite been able to determine. He said very little – so did we, although we often entered his presence with other intentions.

The truth was that the Manhattan Illustrated Weekly was the best paying, best illustrated paper in America, and we young fellows were not anxious to be cast adrift. Jamison’s knowledge of art was probably as extensive as the knowledge of any ‘Art editor’ in the city. Of course that was saying nothing, but the fact merited careful consideration on our part, and we gave it much consideration.

This time, however, I decided to let Jamison know that drawings are not produced by the yard, and that I was neither a floor-walker nor a hand-me-down. I would stand up for my rights; I’d tell old Jamison a few things to set the wheels under his silk hat spinning, and if he attempted any of his pussy-cat ways on me, I’d give him a few plain facts that would curl what hair he had left.

Glowing with a splendid indignation, I jumped off the car at the City Hall, followed by Curtis, and a few minutes later entered the office of the Manhattan Illustrated News.

‘Mr Jamison would like to see you, sir,’ said one of the compositors as I passed into the long hallway. I threw my drawings on the table and passed a handkerchief over my forehead.

‘Mr Jamison would like to see you, sir,’ said a small freckle-faced boy with a smudge of ink on his nose.

‘I know it,’ I said, and started to remove my gloves.

‘Mr Jamison would like to see you, sir,’ said a lank messenger who was carrying a bundle of proofs to the floor below.

‘The deuce take Jamison,’ I said to myself. I started toward the dark passage that leads to the abode of Jamison, running over in my mind the neat and sarcastic speech which I had been composing during the last ten minutes.

Jamison looked up and nodded softly as I entered the room. I forgot my speech.

‘Mr Hilton,’ he said, ‘we want a full page of the Zoo before it is removed to Bronx Park. Saturday afternoon at three o’clock the drawing must be in the engraver’s hands. Did you have a pleasant week in camp?’

‘It was hot,’ I muttered, furious to find that I could not remember my little speech.

‘The weather,’ said Jamison, with soft courtesy, ‘is oppressive everywhere. Are your drawings in, Mr Hilton?’

‘Yes. It was infernally hot and I worked like the devil—’

‘I suppose you were quite overcome. Is that why you took a two days’ trip to the Catskills? I trust the mountain air restored you – but – was it prudent to go to Cranston’s for the cotillion Tuesday? Dancing in such uncomfortable weather is really unwise. Good-morning, Mr Hilton, remember the engraver should have your drawings on Saturday by three.’

I walked out, half hypnotized, half enraged. Curtis grinned at me as I passed – I could have boxed his ears.

‘Why the mischief should I lose my tongue whenever that old tom-cat purrs!’ I asked myself as I entered the elevator and was shot down to the first floor. ‘I’ll not put up with this sort of thing much longer – how in the name of all that’s foxy did he know that I went to the mountains? I suppose he thinks I’m lazy because I don’t wish to be boiled to death. How did he know about the dance at Cranston’s? Old cat!’

The roar and turmoil of machinery and busy men filled my ears as I crossed the avenue and turned into the City Hall Park.

From the staff on the tower the flag drooped in the warm sunshine with scarcely a breeze to lift its crimson bars. Overhead stretched a splendid cloudless sky, deep, deep blue, thrilling, scintillating in the gemmed rays of the sun.

Pigeons wheeled and circled about the roof of the gray Post Office or dropped out of the blue above to flutter around the fountain in the square.

On the steps of the City Hall the unlovely politician lounged, exploring his heavy underjaw with wooden toothpick, twisting his drooping black moustache, or distributing tobacco juice over marble steps and close-clipped grass.

My eyes wandered from these human vermin to the calm scornful face of Nathan Hale, on his pedestal, and then to the gray-coated Park policeman whose occupation was to keep little children from the cool grass.

A young man with thin hands and blue circles under his eyes was slumbering on a bench by the fountain, and the policeman walked over to him and struck him on the soles of his shoes with a short club.

The young man rose mechanically, stared about, dazed by the sun, shivered, and limped away. I saw him sit down on the steps of the white marble building, and I went over and spoke to him. He neither looked at me, nor did he notice the coin I offered.

‘You’re sick,’ I said, ‘you had better go to the hospital.’

‘Where?’ he asked vacantly. ‘I’ve been, but they wouldn’t receive me.’

He stooped and tied the bit of string that held what remained of his shoe to his foot.

‘You are French,’ I said.

‘Yes.’

‘Have you no friends? Have you been to the French Consul?’

‘The Consul!’ he replied, ‘no, I haven’t been to the French Consul.’

After a moment I said, ‘You speak like a gentleman.’

He rose to his feet and stood very straight, looking me, for the first time, directly in the eyes.

‘Who are you?’ I asked abruptly.

‘An outcast,’ he said, without emotion, and limped off thrusting his hands into his ragged pockets.

‘Huh!’ said the Park policeman who had come up behind me in time to hear my question and the vagabond’s answer; ‘don’t you know who that hobo is? – An’ you a newspaper man!’

‘Who is he, Cusick?’ I demanded, watching the thin shabby figure moving across Broadway toward the river.

‘On the level you don’t know, Mr Hilton?’ repeated Cusick, suspiciously.

‘No, I don’t; I never before laid eyes on him.’

‘Why,’ said the sparrow policeman, ‘that’s “Soger Charlie”; – you remember – that French officer what sold secrets to the Dutch Emperor.’

‘And was to have been shot? I remember now, four years ago – and he escaped – you mean to say that is the man?’

‘Everybody knows it,’ sniffed Cusick, ‘I’d a-thought you newspaper gents would have knowed it first.’

‘What was his name?’ I asked after a moment’s thought.

‘Soger Charlie—’

‘I mean his name at home.’

‘Oh, some French dago name. No Frenchman will speak to him here; sometimes they curse him and kick him. I guess he’s dyin’ by inches.’

I remembered his case now. Two young French cavalry officers were arrested, charged with selling plans of fortifications and other military secrets to the Germans. On the eve of their conviction, one of them, Heaven only knows how, escaped and turned up in New York. The other was duly shot. The affair had made some noise, because both young men were of good families. It was a painful episode, and I had hastened to forget it. Now that it was recalled to my mind, I remembered the newspaper accounts of the case, but I had forgotten the names of the miserable young men.

‘Sold his country,’ observed Cusick, watching a group of children out of the corner of his eyes, ‘—you can’t trust no Frenchman nor dagoes nor Dutchmen either. I guess Yankees are about the only white men.’

I looked at the noble face of Nathan Hale and nodded.

‘Nothin’ sneaky about us, eh, Mr Hilton?’

I thought of Benedict Arnold and looked at my boots.

Then the policeman said, ‘Well, so long, Mr Hilton,’ and went away to frighten a pasty-faced little girl who had climbed upon the railing and was leaning down to sniff the fragrant grass.

‘Cheese it, de cop!’ cried her shrill-voiced friends, and the whole bevy of small ragamuffins scuttled away across the square.

With a feeling of depression I turned and walked toward Broadway, where the long yellow cable-cars swept up and down, and the din of gongs and the deafening rumble of heavy trucks echoed from the marble walls of the Court House to the granite mass of the Post Office.

Throngs of hurrying busy people passed up town and down town, slim sober-faced clerks, trim cold-eyed brokers, here and there a red-necked politician linking arms with some favourite heeler, here and there a City Hall lawyer, sallow-faced and saturnine. Sometimes a fireman, in his severe blue uniform, passed through the crowd, sometimes a blue-coated policeman, mopping his clipped hair, holding his helmet in his white-gloved hand. There were women too, pale-faced shop girls with pretty eyes, tall blonde girls who might be typewriters and might not, and many, many older women whose business in that part of the city no human being could venture to guess, but who hurried up town and down town, all occupied with something that gave to the whole restless throng a common likeness – the expression of one who hastens toward a hopeless goal.

I knew some of those who passed me. There was little Jocelyn of the Mail and Express; there was Hood, who had more money than he wanted and was going to have less than he wanted when he left Wall Street; there was Colonel Tidmouse of the 45th Infantry, N.G.S.N.Y., probably coming from the office of the Army and Navy Journal, and there was Dick Harding who wrote the best stories of New York life that have been printed. People said that his hat no longer fitted – especially people who also wrote stories of New York life and whose hats threatened to fit as long as they lived.

I looked at the statue of Nathan Hale, then at the human stream that flowed around his pedestal.

‘Quand même,’ I muttered and walked into Broadway, signalling to the gripman of an uptown cable-car.

II

I passed into the Park by the Fifth Avenue and 59th Street gate; I could never bring myself to enter it through the gate that is guarded by the hideous pigmy statue of Thorwaldsen.

The afternoon sun poured into the windows of the New Netherlands Hotel, setting every orange-curtained pane a-glitter, and tipping the wings of the bronze dragons with flame.

Gorgeous masses of flowers blazed in the sunshine from the grey terraces of the Savoy, from the high grilled court of the Vanderbilt palace, and from the balconies of the Plaza opposite.

The white marble façade of the Metropolitan Club was a grateful relief in the universal glare, and I kept my eyes on it until I had crossed the dusty street and entered the shade of the trees.

Before I came to the Zoo I smelled it. Next week it was to be removed to the fresh cool woods and meadows in Bronx Park, far from the stifling air of the city, far from the infernal noise of the Fifth Avenue omnibuses.

A noble stag stared at me from his enclosure among the trees as I passed down the winding asphalt walk. ‘Never mind, old fellow,’ said I, ‘you will be splashing about in the Bronx River next week and cropping maple shoots to your heart’s content.’

On I went, past herds of staring deer, past great lumbering elk, and moose, and long-faced African antelopes, until I came to the dens of the great carnivora.

The tigers sprawled in the sunshine, blinking and licking their paws; the lions slept in the shade or squatted on their haunches, yawning gravely. A slim panther travelled to and fro behind her barred cage, pausing at times to peer wistfully out into the free sunny world. My heart ached for caged wild things, and I walked on, glancing up now and then to encounter the blank stare of a tiger or the mean shifty eyes of some ill-smelling hyena.

Across the meadow I could see the elephants swaying and swinging their great heads, the sober bison solemnly slobbering over their cuds, the sarcastic countenances of camels, the wicked little zebras, and a lot more animals of the camel and llama tribe, all resembling each other, all equally ridiculous, stupid, deadly uninteresting.

Somewhere behind the old arsenal an eagle was screaming, probably a Yankee eagle; I heard the ‘tchug! tchug!’ of a blowing hippopotamus, the squeal of a falcon, and the snarling yap! of quarrelling wolves.

‘A pleasant place for a hot day!’ I pondered bitterly, and I thought some things about Jamison that I shall not insert in this volume. But I lighted a cigarette to deaden the aroma from the hyenas, unclasped my sketching block, sharpened my pencil, and fell to work on a family group of hippopotami.

They may have taken me for a photographer, for they all wore smiles as if ‘welcoming a friend’, and my sketch block presented a series of wide open jaws, behind which shapeless bulky bodies vanished in alarming perspective.

The alligators were easy; they looked to me as though they had not moved since the founding of the Zoo, but I had a bad time with the big bison, who persistently turned his tail to me, looking stolidly around his flank to see how I stood it. So I pretended to be absorbed in the antics of two bear cubs, and the dreary old bison fell into the trap, for I made some good sketches of him and laughed in his face as I closed the book.

There was a bench by the abode of the eagles, and I sat down on it to draw the vultures and condors, motionless as mummies among the piled rocks. Gradually I enlarged the sketch, bringing in the gravel plaza, the steps leading up to Fifth Avenue, the sleepy park policeman in front of the arsenal – and a slim, white-browed girl, dressed in shabby black, who stood silently in the shade of the willow trees.

After a while I found that the sketch, instead of being a study of the eagles, was in reality a composition in which the girl in black occupied the principal point of interest. Unwittingly I had subordinated everything else to her, the brooding vultures, the trees and walks, and the half indicated groups of sun-warmed loungers.

She stood very still, her pallid face bent, her thin white hands loosely clasped before her. ‘Rather dejected reverie,’ I thought, ‘probably she’s out of work.’ Then I caught a glimpse of a sparkling diamond ring on the slender third finger of her left hand.

‘She’ll not starve with such a stone as that about her,’ I said to myself, looking curiously at her dark eyes and sensitive mouth. They were both beautiful, eyes and mouth – beautiful, but touched with pain.

After a while I rose and walked back to make a sketch or two of the lions and tigers. I avoided the monkeys – I can’t stand them, and they never seem funny to me, poor dwarfish, degraded caricatures of all that is ignoble in ourselves.

‘I’ve enough now,’ I thought; ‘I’ll go home and manufacture a full page that will probably please Jamison.’ So I strapped the elastic band around my sketching block, replaced pencil and rubber in my waistcoat pocket, and strolled off toward the Mall to smoke a cigarette in the evening glow before going back to my studio to work until midnight, up to the chin in charcoal gray and Chinese white.

Across the long meadow I could see the roofs of the city faintly looming above the trees. A mist of amethyst, ever deepening, hung low on the horizon, and through it, steeple and dome, roof and tower, and the tall chimneys where thin fillets of smoke curled idly, were transformed into pinnacles of beryl and flaming minarets, swimming in filmy haze. Slowly the enchantment deepened; all that was ugly and shabby and mean had fallen away from the distant city, and now it towered into the evening sky, splendid, gilded, magnificent, purified in the fierce furnace of the setting sun.

The red disk was half hidden now; the tracery of trees, feathery willow and budding birch, darkened against the glow; the fiery rays shot far across the meadow, gilding the dead leaves, staining with soft crimson the dark moist tree trunks around me.

Far across the meadow a shepherd passed in the wake of a huddling flock, his dog at his heels, faint moving blots of gray.

A squirrel sat up on the gravel walk in front of me, ran a few feet, and sat up again, so close that I could see the palpitation of his sleek flanks.

Somewhere in the grass a hidden field insect was rehearsing last summer’s solos; I heard the tap! tap! tat-tat-t-t-tat! of a woodpecker among the branches overhead and the querulous note of a sleepy robin.

The twilight deepened; out of the city the music of bells floated over wood and meadow; faint mellow whistles sounded from the river craft along the north shore, and the distant thunder of a gun announced the close of a June day.

The end of my cigarette began to glimmer with a redder light; shepherd and flock were blotted out in the dusk, and I only knew they were still moving when the sheep bells tinkled faintly.

Then suddenly that strange uneasiness that all have known – that half-awakened sense of having seen it all before, of having been through it all, came over me, and I raised my head and slowly turned.

A figure was seated at my side. My mind was struggling with the instinct to remember. Something so vague and yet so familiar – something that eluded thought yet challenged it, something – God knows what! troubled me. And now, as I looked, without interest, at the dark figure beside me, an apprehension, totally involuntary, an impatience to understand, came upon me, and I sighed and turned restlessly again to the fading west.

I thought I heard my sigh re-echoed – but I scarcely heeded; and in a moment I sighed again, dropping my burned-out cigarette on the gravel beneath my feet.

‘Did you speak to me?’ said some one in a low voice, so close that I swung around rather sharply.

‘No,’ I said after a moment’s silence.

It was a woman. I could not see her face clearly, but I saw on her clasped hands, which lay listlessly in her lap, the sparkle of a great diamond. I knew her at once. It did not need a glance at the shabby dress of black, the white face, a pallid spot in the twilight, to tell me that I had her picture in my sketch-book.

‘Do – do you mind if I speak to you?’ she asked timidly. The hopeless sadness in her voice touched me, and I said, ‘Why, no, of course not. Can I do anything for you?’

‘Yes,’ she said, brightening a little, ‘if you – you only would.’

‘I will if I can,’ said I cheerfully; ‘what is it? Out of ready cash?’

‘No, not that,’ she said, shrinking back.

I begged her pardon, a little surprised, and withdrew my hand from my change pocket.

‘It is only – only that I wish you to take these,’ – she drew a thin packet from her breast – ‘these two letters.’

‘I?’ I asked astonished.

‘Yes, if you will.’

‘But what am I to do with them?’ I demanded.

‘I can’t tell you; I only know that I must give them to you. Will you take them?’

‘Oh, yes, I’ll take them,’ I laughed, ‘am I to read them?’ I added to myself, ‘It’s some clever begging trick.’

‘No,’ she answered slowly, ‘you are not to read them; you are to give them to somebody.’

‘To whom? Anybody?’

‘No, not to anybody. You will know whom to give them to when the time comes.’

‘Then I am to keep them until further instructions?’

‘Your own heart will instruct you,’ she said, in a scarcely audible voice. She held the thin packet toward me, and to humor her I took it. It was wet.

‘The letters fell into the sea,’ she said. ‘There was a photograph which should have gone with them but the salt water washed it blank. Will you care if I ask you something else?’

‘I? Oh, no.’

‘Then give me the picture that you made of me to-day.’