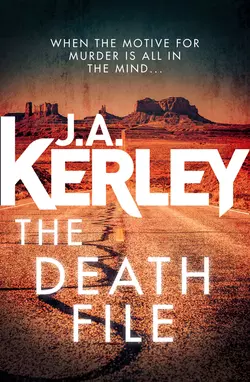

The Death File: A gripping serial killer thriller with a shocking twist

J. A. Kerley

Detective Carson Ryder returns, on the trail of a brutal killer with mysterious motives.Two psychologists are murdered 2000 miles apart – one in Phoenix, Arizona, one in Miami, Florida.Amazingly, both have noted down the name of Carson Ryder – a detective with the Florida Center for Law Enforcement who specializes in catching psychopathic killers.Carson joins forces with troubled Phoenix Detective Tasha Novarro to trace a ruthless killer whose advantages include an uncanny talent for persuasion, an utter lack of remorse, and the horrifying ability to predict their every move. A killer even Carson might not be capable of stopping…

The Death File

J. A. KERLEY

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

KillerReads

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © J. A. Kerley 2017

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com (https://www.shutterstock.com/)

J. A. Kerley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008263751

Version: 2017-09-27

Dedication (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

To Virginia, who loved her beer and baseball…

Table of Contents

Cover (#uf939817c-7b72-5062-a7b7-98dec610e379)

Title Page (#uc39bf07a-dad6-5b6d-b4dc-ac3c15fc5bc4)

Copyright (#u5400f8a4-59b9-5f87-a08d-56abc9a95909)

Dedication (#uab97a0a9-c224-5adf-8b89-75c6b54e3ea7)

Chapter 1 (#ufa41f233-6f08-511a-b382-c829c3a80756)

Chapter 2 (#u7e7f9d8b-9ece-5514-8946-1a20481e47f4)

Chapter 3 (#ud1d735b8-1db5-553c-8cf9-1d37c4b85ee7)

Chapter 4 (#u9a50ca21-b86b-57f1-94a1-6f0a4b35384b)

Chapter 5 (#uce9f6923-0fb3-55d9-aeb0-f7bdae7477f1)

Chapter 6 (#u1f38b2ff-ba0b-5e76-8649-fad56866af98)

Chapter 7 (#u4965caa9-39c3-50e9-8460-04b4d61f1155)

Chapter 8 (#u40c4ad2b-db3f-5c31-bf86-7cf2018b89ce)

Chapter 9 (#u7a5c7d99-de25-5523-a1ba-23688b6551d8)

Chapter 10 (#u3726140e-c28e-592a-b380-14b155010557)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by J. A. Kerley (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

Dr Leslie Meridien watched a vulture appear from the failing glow of a twilight sky to land atop a towering saguaro cactus fifty feet from her second-story window. The predator stared into her brightly lit home office, detecting the motion of Meridien’s hands lifting a glass of Chardonnay and assessing their potential as prey.

After a minute the bird renewed its journey unsated, the black of the vulture consumed by the black of the sky. Meridien sat at her oaken desk dressed in a fifteen-year-old gray college sweatshirt – Harvard, her Alma Mater – and a pair of navy shorts, a workout on the exercise bike just over, her shoulder-length brown hair damp from the shower.

A psychological therapist and counselor, Meridien was transcribing notes from the day’s sessions into her cloud account, currently recalling her last session with Adam Kubiac, ten days back. He’d not shown for today’s scheduled session. Or last week’s.

Meridien wasn’t surprised. Adam had likely dealt with much in the past two weeks, given his father’s sudden death. How had Adam taken the news? With sadness or glee? By weeping or partying? It could have gone either way. The father, Eli Kubiac, was a human mess, misdirected, often clueless in his relationship with his son. A self-made multimillionaire, Eli Kubiac loved being the macho, driven businessman; a man for whom traits such as compassion and sensitivity were suspect, somehow unmanly. And as was often the story in such individuals, Eli Kubiac had a dark side: he’d died on the floor in a motel in Scottsdale, nothing more in the news reports. There was probably a sad story there.

Meridien hoped Adam Kubiac found understanding. And, perhaps against all odds, maturity.

She leaned back and stared into the blank whiteness of her ceiling, a sharp contrast to the dark moods Kubiac often sank into during his private sessions, even carrying his private personal anger into group work, the reason she had removed him from group after several sessions. Adam could be charming and personable – though still emotionally closer to twelve years of age than nearing eighteen – but when his dark moods hit, or his bouts of insecurity-driven megalomania, he was hard to handle, even for Meridien.

Meridien jumped at the sound of a car door slamming. She ran to the front bedroom and looked out the window: a battered blue vehicle at the far side of her drive, the door slamming. But how? Hadn’t she closed the gate at the end of the drive?She watched a rail-thin body leap from the passenger seat.

“I s-see you in the window, Dr Meridien,” yelled a voice from below. “I w-want to talk!”

She blew out a breath and shook her head. Adam Kubiac. He had reverted to the stutter that plagued him when under stress. It had been worse when they started; perhaps the only true headway made.

Meridien walked down the wide stairs and crossed the open-concept great room, its walls of bright wood hung with Native American rugs and paintings, and opened the front door to see the Phoenix-centered desert valley, a 30-mile long plain holding nearly four and a half million people, tens of thousands of lights and looking like a galaxy blazing in the center of the desert.

In the foreground, centering the small porch, was Adam Kubiac. Skinny to the point of gaunt, Kubiac was attractive in a puppyish fashion: large dark eyes, high cheekbones, full lips now framed in a pout. He looked different; the usual battered jeans and black tee now a short brown blazer over a blue work shirt and rolled-cuff black jeans over tan suede kicks. Was that skinny piece of fabric a tie? Meridien couldn’t resolve the fashion with Kubiac: He looked like a kid trick-or-treating as a hipster.

Beside Kubiac stood a petite and gorgeous young woman dressed in a purple jumpsuit, her curling walnut-brown hair in a fluffy ponytail and her searching eyes huge behind outsize round glasses with red frames. She looked in her late teens or early twenties.

“Hello, there,” Meridien said, holding out her hand.

The woman just stared, studying Meridien like cataloging a new species.

“Come inside, then,” Meridien said, putting on false bonhomie. “Why don’t you two have a seat? Would you like—?”

“You knew, d-didn’t you?” Kubiac blurted, his voice thick with sarcasm.

“Knew what, Adam?”

“That my scumbucket male parent fuh-fucked me in his will.”

“Pardon me, Adam? What are you talkin—?”

“I just c-came from the luh-lawyer’s office. You were r-ratting me out all along. Telling the asswipe what I really thought about him. That’s why he did it.”

“Did what, Adam?”

“LEFT ME SHIT!”

Meridien felt her mouth drop open. “What?… How …?”

“HOW? Here’s how … fucking papa dear had $20,000,000. I get $1 when I t-t-turn eighteen. ONE DOLLAR, Meridien … That’s FUCKING IT! The rest goes to a bunch of foundations and charities and WORTHLESS SHIT. I put up with the bastard and his insults and his whores … IT’S M-MY MONEY!”

“Here’s the truth, Adam,” Meridien said, keeping her voice calm. “I never spoke to your father about our sessions. Not a word. I told you about Doctor–Pati…”

“Doctor–patient p-privilege?” Kubiac sneered, his eyes pinpoints of fury. “DON’T LIE TO ME. I KNOW WHAT YOU DID!”

Meridien pointed to the door. “You have to leave, Adam. I’ll be happy to talk to you, but not when you’re angry.”

“WE’RE DONE! I want EVERYTHING BACK!” Kubiac shrieked. “Everything I T-TOLD YOU!” He was flying out of control and making little sense; Meridien had seen it a dozen times before.

“Your records are confidential, Adam. Safe.”

“I WANT MY RECORDS, B-BITCH! GO G-G-GET THEM!”

“I don’t keep records here, Adam. Part of my precautions.”

“I know where you store them,” Kubiac grinned. “I can get them if I want.” He jiggled his fingers in the air as if on a keyboard.

Meridien shook her head. “No way, Adam. The only person who can access your records is me.”

Without a sound the woman crossed the room and tapped the back of Meridien’s head. “They’re still in here, Adam,” she said. “Your records.”

Meridien spun and slapped the hand away.

“Get the hell out of my house.”

The woman pirouetted like a ballerina, striding to the door without a backward glance. When Kubiac followed, Meridien let out a breath. Whatever the reason for the bizarre visit, her visitors were leaving.

The pair stepped into the night. When the car screeched away, Meridien checked the gate system and saw that everything seemed normal. She must have forgotten to set the …

Wait. The gate, like the alarm system, was computer operated. Adam Kubiac was a computer genius. Meridien hurriedly chain-locked the door, set the deadbolt and paced for twenty minutes thinking about the discordant information swirling in her head. Something was terribly wrong … or not. True, she had actually seen the will leaving Adam one dollar – the father showing it to her, telling her it was a way to force his son into line. “To make Adam behave like an adult,” Elijah Kubiac had said. But he’d also intimated that the will was false, a dummy, a ploy for him to use only as a last resort.

My god … had that been the actual will? Had Eli Kubiac left his only child one solitary dollar? Or …

Jesus, what a quandary. Where to start?

She poured another glass of wine and returned to her office, pen in one hand, phone in the other, dialing a friend she hadn’t seen in far too long.

“Leslie!” Dr Angela Bowers said. “So good to hear from you.”

“I’m not calling you too late, am I, Ange? I just remembered that it’s three hours later in Miami.”

“You’re fine. My first class tomorrow isn’t until eleven so I’m binge-watching old Seinfelds. What’s up?”

“I just had a disturbing contact with a patient. Or former patient, I guess.”

“One of your brilliant young minds?”

“At the age of sixteen he devised a computer algorithm that sped up server traffic by a few nanoseconds. It seems that’s a lot in the computer world. It made him a $100,000. He was about to start his first year at Caltech.”

“Whoa. Not bad.”

“His college career lasted two months. He quit, citing boredom. It’s how we met: a week later his father all but dragged the kid to my office, the father referring to his son as failure and screw-up during the registration process. At one point he slapped the back of his kid’s head.”

“Jesus! The father’s story?”Bowers asked.

“Wealthy, the self-made kind. Made twenty-something million selling cars.”

“No way.”

“He owned five dealerships in LA, one in San Diego, two in Scottsdale. He retired to Scottsdale when the son was twelve. The father was a mess, a heavy drinker who went through a series of women, kept some in a condo in Sedona, bringing others home for drugs and sex while his son was in the house, that type of thing.”

“Not a candidate for father of the year.”

“I actually think the man loved his son – he was, after all, of his flesh – but was horribly misguided and heavy-handed in his efforts to gain control … that’s where things get murky.”

“You said was. Is the father deceased?”

“Two weeks ago,” Meridien sighed. “Something strange happened tonight, Ange. I’d like to run my thoughts by you. And do you still work with that medical ethicist?”

“John Warbley? Sure, his office is one floor down.”

“Could you get his input on this ASAP? I could really use some guidance here …”

The conversation ended minutes later. Meridien typed up the notes from Kubiac’s visit, summarized her conversation with Bowers and dialed her cloud account, inputting her password, surprised by the response on her screen.

Account in use. Please try later.

What did that mean? Rolling her eyes – she’d been sending her files to the account for four years without a hitch – Meridien quit the program, waited six minutes and tried again. The files went through like always. Worn from her day – the last two hours of it at least – Meridien finished her wine, undressed, and went to bed.

* * *

Teet … teet … teet …

It was 3.43 in the morning. Meridien knew because her clock was on the table beside the bed. Something had awakened her, but what?

Teet … teet …

There, a small sound from downstairs. It sounded like the timer on the stove.

Teet …

Somehow she’d set the timer … but how? The last time she’d been near the stove was yesterday morning.

Teet … teet …

Meridien pulled on her robe and followed the sound to the kitchen. She punched the timer off, confused. How had she set it?

A sound at her back. Meridien spun to see a shaven-headed man standing in the doorway, Hispanic, his neck and face coated with tattoos, his eyes as lifeless as chunks of coal. For some reason he wore clear plastic overalls and blue paper booties.

“What are you doing here?” Meridien whispered, her heart trapped in her throat.

The man produced a gleaming knife held in latex-gloved fingers.

“Earning a living, chica. Nothing personal.”

2 (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

The white and blue City of Phoenix PD cruiser blew south on Highway 10 at 80 mph, the flashing lights and piercing siren pushing traffic aside like a dog scattering chickens from a path, until a semi-truck moved aside to reveal an ancient gray van wobbling down the center lane at 30 mph, its roof piled high with a couch, three chairs, a kitchen table and, improbably – or perhaps exactly right – a kitchen sink, all lashed together by clothesline with various lamps and doodads crammed into the mix. The back doors of the van held a large hand-painted picture of Christ.

“JESUS!” deputy investigator Tasha Novarro screamed, cranking the wheel and sending the cruiser into a tire-screeching sideways skid, the rear of the vehicle aiming dead-center at Jesus’s bearded chin until Novarro goosed the gas and yanked the wheel hard right, the cruiser’s tires catching concrete as it straightened out and passed the van on the driver’s side, Novarro’s adrenalin-charged mind photographing the driver: Hispanic, wizened though likely in his forties, a woman beside him in the van, two infants on her lap.

The pair had looked at Novarro with surprise: Qué estás haciendo aquí? – What are you doing here?

Novarro exhaled a breath and stared into the rear-view. A tough life, she thought. Traveling with the crops. Moving north with the harvest, stoop labor, picking beans or grapes or tomatoes or perching on a flimsy ladder to pluck oranges or grapefruit from the tops of trees. Not much had changed since Steinbeck. She shook her head in sadness, sighed and blasted down the exit to Baseline Road, tacking her way south, Phoenix’s South Mountain Park off her left shoulder, the craggy peaks rippling in the morning heat.

Novarro continued through several blocks of small houses with battered vehicles in the drives and angled uphill, passing a small ranch long past its prime, the split-rail fence tumbled, stalls once holding horses now storing a rusted tractor and a faded motorboat.

The road climbed a hundred feet in elevation. The address was in a dozen-home enclave sharing ten acres of north-facing mountainside abutting the park. Novarro pulled through an open wrought-iron gate set in high rock walls to see the kind of home she figured she’d buy someday, that day being the one right after she won the lottery: double-story hacienda-style with adobe walls, a tile roof, and acres of glass, a valley view from the front, the park in the rear. The front yard was landscaped with agaves and barrel cacti, bee brush and bursage, a line of white thorn acacias flanking the south side of the structure. Three City of Phoenix cruisers plus vans from forensics and county medical examiner jammed the circular drive.

A fourth vehicle caught her eye: an SUV from the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office. Novarro heard herself groan.

She passed the ornate wooden door, open, nodding at the pair of forensics techs checking the knob for latents. The room was large and sun-bright and through a side window she saw cops checking for footprints in the sand and pebbles.

“Back here, Tasha.”

Novarro turned to see Agustín Sanches, a tech from the coroner’s department, enter from a room to the rear. Sanches was a friend, late thirties, moderate height, his cooking hobby displayed in a touch of pudge at his belt. His naturally black hair was tinted with just enough red that it could be noted under sunlight. He was one of the very few openly gay people in the department.

“Bad, Augie?” Novarro asked, meaning level of violence.

“Not butchery, but certainly not pleasant.”

Sanches handed her paper booties and she followed him to a marble-tiled solarium off the living area where a woman’s body sprawled on the floor, looking like she was running, upper leg extended, lower one bent back. She wore a threadbare sweatshirt and blue runner’s shorts. The body lay in a dark pool of dried blood, and Novarro gingerly circled it until she discovered the neck cut from ear to ear. Novarro winced: she could see into the windpipe. Drawers had been pulled from cabinets and emptied on the floor, a jewelry box there as well. Flies buzzed throughout the room.

“Dr Leslie Meridien,” Sanches said quietly. “Forty-four, psychologist. Unmarried. This is her home and office.”

Novarro batted away a fly and continued to circle the body, leaning close while jotting in a notepad. She pulled the victim’s sleeve up two inches, frowned, and made another notation.

“Blood’s dry, Augie. No rigor. Got a TOD estimate?”

“I’m a tech, Tash, not my place to—”

“C’mon … give.”

“She’s been dead two days, give or take.”

That made the death on Friday night or Saturday. “How’d she get discovered?”

“It’s cleaning day and the Mexican housekeeper let herself in like always,” a different voice answered. “Felicia Juarez ain’t having a good Monday.”

Novarro looked up to see Sergeant Merle Castle in the doorway, thirty-five, close-cropped brown hair and dark eyes with lashes so thick they could have been ads for Maybelline. Six feet and then some, with iron-pumper biceps crowding the short sleeves of the beige uniform shirt of the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office and ankle-high boots polished to a mirror gloss. Beside him was Burton Claypool, an officer with the Phoenix PD, and buddy of Castle.

“Little out of your new jurisdiction, Sergeant Castle?” Novarro said. “If I remember correctly, you left the Phoenix PD two months back.”

A smile. “I was on Baseline Road when the call came through, got here five minutes before PPD. It’s all Maricopa County, right?”

“That means you’ll take the case and the paperwork?”

“Funny as always, Tasha.” Castle clapped Claypool on his back. “Plus I wanted to say howdy to my old buddies.”

“Gracias for the assist, Merle, but the City of Phoenix PD is here now.” Novarro shifted her eyes to Claypool. “Where’s Ms Juarez now, Officer?”

Burton Claypool was twenty-seven, medium height, but with a chest and shoulders that seemed to expand an inch a month. He’d started out with a normal physique eighteen months ago, but like several younger male recruits in the South Mountain Precinct, Claypool consciously or subconsciously emulated Castle: his cockiness, his Western swagger, and his physique, not cartoonish, but impressive.

“Juarez got freaked out by the body, Detective,” Claypool said, standing straighter. “I got the name of one of her niños and he came by and got her.”

Niño meant child, a youngster, generally. “How old was the kid? Novarro asked.

Claypool frowned. “I dunno. Thirty or so.”

Another something Claypool had subconsciously or otherwise taken from Castle: an Anglocentric worldview. Novarro saw Sanches study the Claypool-Castle duo, roll his eyes, and return to cataloguing his findings.

“You couldn’t have someone drive the poor woman home, Officer Claypool?”

“She lives in Gilbert, a half hour there and back. We’re short on manpower, Detective.”

She pulled out her notebook and began writing her initial thoughts.

“Want my take?” said a voice at her shoulder: Castle.

“Thanks for stopping by, Merle, but I’ve got it from here.”

A grin. “So when everyone’s gone, we’re back to first names, Tash?”

A waggle-finger wave. “So long, Sergeant Castle. Have a nice day.”

“Some assholes broke in and got surprised by the owner,” Castle said anyway. “It’s a shithole neighborhood. Put a big expensive house on the hillside and every low-life that drives by starts salivating at what’s inside: TVs, computers, jewelry, cash.”

“It’s a mixed neighborhood, Sergeant. Rich, poor, everything in between.”

Castle nodded toward the body. “If that lady lived in Scottsdale she’d be alive right now.”

“You were here first … what was the entry point?”

“No break-in that anyone found yet. A door got left unlocked. People get careless.”

Novarro crossed the room. She’d seen a sign out front advising of a security system, which meant a control panel. Novarro found it in the closet nearest the door. The green power supply light was on.

“Was the system armed when you arrived, Sergeant?”

“Turned off by Sanchez. She has a card key.”

“What else appears missing?”

“There’s an empty space on the vic’s desk where a computer was. Desk drawers open, emptied.”

Novarro pointed across the room. “Yet right there sits a Sony Bravia … what? Fifty-inch flat-screen TV? About a grand, right?”

Castle shrugged. “The perp or perps killed the vic and started bagging up shit, but got spooked by something. A cop siren maybe, heading to some other problem in your, uh …” a hint of grin, “mixed neighborhood.”

“Must have been a real scare, Sergeant Castle,” Novarro said, leaning against the wall and giving Castle an indulgent look. “The doc’s wearing a Movado watch, five-six hundred bills or so. Would have taken two seconds to pop off and pocket.”

Castle jammed his hands into his pant pockets and scanned the ceiling for several seconds. “OK, so fuck my idea. What’s yours, Three-Point?”

The name froze Novarro, but only for a split second. She studied the body on the floor before walking to the sliding glass door and tugging with a gloved finger. “There’s an old Tohono O’odham Indian saying, Merle,” she said. “‘O’nota’y’tanga olemano.’”

Castle rolled his eyes. “Meaning?”

Novarro stared at a black vulture circling against a blue sky. Somehow the bastards always knew.

“I’ll get there when I get there.”

3 (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

The nameplate on my door said, Carson Ryder, Investigative Consultant, Senior Status. The title was an invention of my boss at the Florida Center for Law Enforcement. Being a “consultant” got me out of the stultifying barrage of administrative meetings and other make-work tasks associated with any bureaucracy, even one headed by the bureaucrat-averse Roy McDermott. “Senior status” pretty much allowed me to do whatever I wished, as long as the end result was a better, safer Florida.

On my first day, Roy had said, “I don’t really care what my people do, Carson. All I ask is that it stay within legal bounds and lets me stamp ‘Case Closed’ on a shitload of files.”

So far, I hadn’t let him down.

Outside my twenty-third story window lay the jagged and glittering skyline of Miami, the gemlike turquoise blue of Biscayne Bay in the distance. I was unable to appreciate the beauty, sitting at my desk and filling out reports, grumbling that for all my status bought me, I still had to do paperwork just like a beat cop in Mobile, Alabama, which is how I started.

My phone rang – mobile, not landline – telling me I probably knew the caller, which I did: Vince Delmara, a top homicide detective with the Miami-Dade County PD. We had been friends since my first case for the FCLE, almost three years ago. Vince was old-school, the best aspects at least, believing that experience, hunches, and shoe leather were what solved cases.

And sometimes just plain dumb luck.

“Question, Carson …” Vince said, jumping right in. “You still seeing that shrink in Miami Beach … Dr Angela Bowers?”

I threw my pencil to the desk and leaned back. “What you talking about, Vince?”

“You see a lot of crazy bullshit,” Vince said sotto voce, like sharing a secret. “It’s all right to visit a therapist. Anyway, I ain’t gonna tell no one.”

“Right now, I’m thinking I’m not the one needs a shrink, bud.”

A sigh. “You’re really not seeing a psychologist, are you, Carson?”

“I think I scare them. You got a point here, Vince?”

“I got a problem. You busy, or can you meet up?”

Five minutes later I slipped on a blue linen sport jacket to cover the shoulder rig, dusted eraser rubber from my blue jeans, and headed out, hoping paperwork faeries slipped in to finish my drudgery.

The offices of the Florida Center for Law Enforcement were on floors twenty-two and twenty-three of Miami’s towering downtown Clark Center, the upper location for administrators and top investigators, the lower floor for mid-echelon investigators and support staff. On the way to the elevator I stuck my head into a small office being painted and prepped by a maintenance staffer: dropcloths on half the floor, a ladder, a couple cans of paint.

A painter was crouched in a corner and painting the floor molding.

“The guy who was here …?” I said.

The painter frowned. “He left. Said I was whistling out of tune.”

I continued to a conference room and looked through the glass window to see fellow investigator, Lonnie Canseco, meeting with a pair of forensics accountants from the Tallahassee office. Cold: Not what I was looking for. Onward to a smaller conference room, this one with an FCLE operations manual on the round table, the empty pushed-back chair hung with a purple blazer, size 44 long.

Getting warmer.

I jogged back to the painting-in-progress office, checked for a gray canvas bag beside the desk. Not there, which meant I was warmer still. I took the back staircase to the floor below and pushed through a metal door, entering another door to the rear and smelling sweat and body heat. Angling past a partition I looked across a white-tiled expanse to see the black expanse of Harry Nautilus, pulling on his pants beside a naked white guy.

Hot. I turned to the nude guy, Larry Vincente. “How long was it, Larry?”

Vincente grinned from earlobe to earlobe. “Almost nine.”

I shot a thumbs-up as Vincente shut off the shower nozzle and stepped to a rack to grab a towel. Like most pool investigators Vincente spent about a dozen hours a day working cases and the FCLE’s small gym was a place to grab a quick, stress-reducing workout: a half-dozen strength machines, plus stationary bikes and treadmills. Vincente tried to get in six treadmill miles a day, but today had managed nearly nine – either a slow day or a fast run.

“Let’s boogie, amigo,” I said to Harry, now dressed and cramming sweaty shorts and tee into the gray gym bag. “It’s time to meet Vince Delmara.”

Harry splashed on a palmful of 4711 cologne, light and floral and antithetical to the wet heat of a South Florida summer. “Delmara? The Miami detective who’s afraid of the sun.”

I made a biting gesture. “It’s the vampire in him.”

“Can’t wait.”

Ten minutes later we were racing toward Coral Gables in my moss-green Range Rover Defender. Fully equipped for a safari, it rode hard, ate gas, had a manual transmission prone to sticking, and the AC wasn’t quite up to the Miami heat, but if a case ever took me to the African veldt, I was ready.

“You say this thing belonged to a drug lord?” Harry yelled above the siren as we blew down I-95.

“Confiscated. I found it in the motor pool.”

“When you gonna paint it with a roller?”

Harry was referring to my former ride back in Mobile, a battered pickup I’d repainted gray with ship paint and a roller. He knew because three years ago he was my partner at the Mobile, Alabama, PD; the man who’d convinced me to join the force when I was living on my mother’s slim inheritance and wondering what to do with a psychology degree gained by interviewing every imprisoned maniac in the South.

We’d been the Harry and Carson Show for over a decade and last year a truly odd quirk of Fate had brought us together again, him on a case from Mobile, me on one in Florida. The cases converged and became one. After we’d closed it, Roy offered Harry a position with the FCLE. Harry finished out his time with the Mobile PD and had made the move just two weeks ago.

“I’m keeping the green,” I said. “It’s such a cheerful color.”

Coral Gables is about six miles from downtown and we made the trip in five minutes. We pulled into the palm-canopied drive, seeing two MDPD cruisers plus a command vehicle, and vans from the ME’s office and scene techs.

“Here we go, Cars,” Harry said. “My first Miami crime scene.”

We strung our IDs around our necks and entered the home, a celebration of pastels: yellows, blues, corals; an uplifting color scheme and très Miami. Vince Delmara, whose spirits didn’t appear lifted, was conversing with a scene tech on the corner, the three-inch bill of Vince’s black fedora projecting past his nose, but not by much. Vince wore a cobalt suit and white shirt, his only concession to color a lavender silk tie. Harry and I went over for introductions.

They shook hands as Vince’s major-league beak probed the air around Harry. “Jeee-sus, something smells great.”

“I shaved and showered before we left HQ,” Harry said.

“You set a high bar,” Vince said. “I try to remember to wash my hands after pissing.”

Vince led us into the house, a flurry of activity, scene techs dusting for latents, vacuuming the carpet, studying doors and windows for signs of entry.

“Who’s the vic?” I asked as we followed Vince to the side of the house. A young tech, Darla Brady, followed with a plastic evidence bag in her hand.

“Bowers, Angela. Psychologist. All we know.”

“Cause?” I asked.

“A slashed throat. She bled out in seconds.” He paused. “It looks like a single cut, Carson. Through the carotid and jugular on both sides. No hesitation.”

A tingle of ice ran down my spine. We saw a lot of knife wounds, most ragged horrors that indicated frenzied slashing. This seemed a professional-style hit: the victim held tight while a razor-sharp blade did its ghastly work. No hesitation, no qualms, nothing but a single and probably practiced move.

We entered the room and I saw a woman in her early fifties, her face a rictus of fear, a dark echo of her final moments. A lake of blood pooled beneath her lifeless body. Harry knelt beside the sprawled form.

“Like Vince said, one deep cut from ear to ear.”

“Take a look at her face, Carson,” Vince asked. “Look familiar?”

“Vince, she’s not my shrink. Or anything else.”

“You’re sure you never saw her before?”

“I wish I wasn’t seeing her now.”

“Bring it, Brady,” Vince said, waggling his fingers in the gimme motion. The tech jogged over with the evidence bag and I saw a 5 x 7 index card inside.

“We found this in the vic’s top-right desk drawer,” Vince said. “On top of everything else there. Position tell you anything?”

“She kept the card within reach. Says it’s probably important.”

“Show the card, Brady.”

The tech held it out to me at eye level. Printed on the card in heavy black marker was my name. After it were three question marks. I held it up to Harry.

CARSON RYDER???

“Why am I not surprised?” he said.

We returned to the department to stare at a copy of the card found in Dr Bowers’s desk drawer. I’d tacked it to a bulletin board in a conference room.

“To me,” I said, “a single question mark suggests a question about an unknown, like ‘Who is this guy?’ Multiple question marks seem to suggest a weighing process, like, ‘Is he the one?’ or ‘Should I contact him?’”

Harry pondered the ceiling. “I’d like to hear you try that one on a witness stand, but I like it. Of course, the woman might have simply had a jones for question marks.”

“We’ll find out soon enough, I expect. Vince will put nails in the killer’s coffin. He’s an ace.”

Harry frowned. “You’re not going to take a case that, uh, has your name written all over it?”

“Doesn’t matter what I want,” I sighed. “I’m excluded.”

“Peripheral involvement,” Harry said, seeing the problem: I was a facet of the case.

I nodded. “No way I could be the lead investigator on the Bowers case.”

Harry stood and went to the window, studying the Miami skyline. “OK, say Vince Delmara led the investigation. If you had thoughts on the case, could you present them to Vince?”

I nodded. “It’d be nuts not to be able to drizzle ideas to Vince. I’m simply restricted from any major role.”

“And you want to follow this thing. From up close?”

“A dead woman I never met had my name in her desk. I’d like to know why.”

He turned from the window. “So what happens if I take the Bowers case as lead? My very first FCLE case. You could follow me around like a little doggie and drizzle all over the place.”

I gave it a half-minute of consideration. “That actually makes sense. And doesn’t break a single rule.”

“Maybe not, Carson. But let’s try it anyway.”

4 (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

Detective Tasha Novarro pulled into the lot of a three-story redbrick building in an industrial park where Phoenix abutted Tempe. Emblazoned across the top story was a chrome-bright sign proclaiming DataSĀF. Beside it was an amoeba shape with squiggly lines running horizontally through it, probably representing a cloud. Novarro had combed through Meridien’s financial records, finding receipts from DataSĀF and figured Meridien, like many concerned with security or just fast and easy data storage, sent her files to a data-storage firm.

There was private security in the lobby and Novarro flashed the brass pass. “Where you headed?” the rent-a-cop asked, an older guy in a uniform the color of a toad.

“I thought I was there,” Novarro said. “DataSĀF. That’s how you say it, right?”

“There’s three divisions: MediFile, BusiniFile and JurisFile.”

“The head office.”

The security guy grinned and lowered his voice. “Actually, it’s all DataSĀF upstairs. It started as three divisions but they’re under the same umbrella these days. I think they think it looks impressive.”

Novarro scanned the open atrium, glass everywhere, five-foot-diameter concrete planters holding small trees. At the far end an immense globe made of hundreds of squiggling rays of multicolored glass hung from the ceiling. Novarro recognized the artist’s work – she had seen it at the Desert Botanical Gardens a few years back – and remembered his name as Dale Chihuly. She figured it was an expensive piece of glassware.

“Helluva big building,” she said. “How many people work here?”

“About thirty.”

Novarro raised an eyebrow. “Must have a lot of empty offices.”

The security guy grinned. “What they got are computer servers, three full floors of the things lined up like black refrigerators with blinking lights. They call it the cloud but it’s made out of machines. It’s spooky.”

Novarro thanked the guy, picked up a visitor pass, and walked to the elevator. Phoenix PD had switched its files to the cloud – calling it “offsite storage” in official parlance – a year back. Whenever Novarro wanted a report or information she sat at her computer and bang! there it was. Sure beat riffling through clunky filing cabinets. Good for you, Cloud, she thought, momentarily wondering if it was cumulus or cirrus.

The elevator arrived and Novarro stood in the lobby of DataSĀF; hues of pinks and grays with a receptionist arena at the far end. A young woman with a severe look and hair sat within the granite-topped semicircle holding a clipboard. She wore a phone headset and was feverishly inputting data into a computer. “There’s a sign-in sheet,” the woman said, not looking up.

“I’m the heat,” Novarro said, holding up the badge. “I need to talk to someone about accessing a client account.”

The woman didn’t blink. “Take a seat and I’ll tell someone you’re out here.”

The chairs were designed to afford hipness before comfort and Novarro found sitting in one of the wobbly rail-and-canvas monstrosities was like trying to stand in a hammock. She leaned against the wall and read DataSĀF’s annual report, the only reading material in the room. It seemed DataSĀF was the largest cloud-based business data storage firm in the Southwest. They were growing at an average of 16 percent a year. They stored about a zillion wiga-diga-gigabytes or something like that. Their motto was “Putting Security Above All.”

Novarro fought the yawn and tossed the report back on a low table.

After ten minutes she returned to the receptionist, who seemed to have moved nothing but her fingers during that time.

“Excuse me,” Novarro said. “I need to—”

“Someone will be out momentarily,” the young woman said, not looking up from her keyboarding. “We’re quite busy here.”

Five more minutes passed. Novarro re-approached the recepti-robot. “Excuse me … could you direct me to the ladies’ room?”

“Down the hall to the left,” the woman said. “But it’s not a ladies’ room. It’s unisex.”

“Wonderful,” Novarro smiled as she turned for the door, “that means I can use my penis if I want.”

A perplexed receptionist staring at her back, Novarro went left, passing the bathroom and finding the hall opened into a dozen cubicles with tech types perched over keyboards. The décor was stark and soulless: gray walls, white floor, macro photos of color-enhanced computer chips on the wall, artsy in a way that could only appeal to computer geeks.

She saw several young men and women pow-wowing at a long table in a glass-walled meeting room. Standing at the end of the table was a tall and slender man wearing khakis and a pink shirt with wide red suspenders, his sockless feet tucked into what appeared to be suede loafers with running-shoe soles. He appeared in his late thirties, which made him the elder of the tribe. His head was shaved above with a short neat beard below, a contemporary look Novarro thought made men look like their hair had slipped. She pushed open the glass door and leaned into the room.

Mr Shiny-head frowned at her. “Excuse me,” he said, his voice a mix of question and irritation, “but who the hell are you?”

Novarro fully entered the room, beamed, and held up the shield. “I need to talk to someone somewhere about an account with whoever.”

The man blew out a breath, like Novarro had made him forget something important he was about to say.

“Talk to our-our office manager. Turn right and head down to—”

“You’re important, right,” Novarro interrupted.

A raised eyebrow. He still had those. “I’m Kenneth Larkin. The CEO.” He said each letter like it was an individual word.

Novarro kept the smile but did a come-hither with her index finger. “Then you’re just the guy to walk me back and introduce me around.”

Larkin turned to the assembled intelligentsia with rolled eyes and exasperation in his voice. “Excuse me, folks. Back in a minute.”

He led Novarro to an office around the corner, the nameplate reading Candace Klebbin – Director, Administrative Services.A woman at a desk looked up, in her early forties or thereabouts, solid but not overweight, her face handsome in a raw and Western way, with piercing violet eyes, square jaw, high and angular cheekbones. She wore a businesslike dark blue pantsuit, almost masculine in cut.

“Candace can get you started,” Larkin said, spinning back toward the meeting room where Novarro figured there was currently a self-importance deficit.

“I need to look at files belonging to a late client of yours,” Novarro said.

“You have an instrument?” Klebbin asked.

It was one of the few times Novarro had heard a non-legal type refer to a court order as “instrument,” meaning an instrument of the law. She pulled the writ from the inside pocket of her gray jacket. “It’s right here.”

Klebbin gave it a cursory glance. “The legal folks need to take a look. It’s mandat—”

“Pardon my abruptness,” Novarro interrupted. “I know this is an important office, and everyone’s busy boxing up data or whatever, but I’m kind of in a rush and already got chilled in the lobby for a half hour.”

Klebbin absorbed the information and shook her head. “Sometimes they’re so busy being busy nothing gets done. Let me see if I can’t speed things up.” She picked up her desk phone and dialed, cupping her hand over the phone as it rang. “Arthur Lazelle.” She winked. “A law degree from Loyola and I don’t think he’s ever set foot in a courtroo— Hello, Art? It’s Candace. There’s a Phoenix detective in my office with a CO allowing her to access— I know it’s your workout time, Art, but …” She listened and rolled her eyes. “Be that as it may, Arthur, the detective seems a personal friend of Kenneth’s and he said to – OK, see you in a few.”

“Thanks,” Novarro said. “I hope that doesn’t get you in trouble.”

“No problem,” Klebbin smiled. “I don’t expect to be here much longer.”

Three minutes later a wet-haired man in his early thirties bounded into the room. He wore a blue workout suit and a toothy smile. “Sorry, detective,” he said, “we have a corporate gym and I like to get in some CrossFit and take a steam.” The eyes scanned Novarro. “You look like you work out. Got a routine?”

“I like to run the trails at South Mountain Park. I bike some. A little tennis.” Not a trendy or branded workout.

“Sounds, uh, fun,” Lazelle said, suddenly disinterested. “What can I do for you?”

She handed him the writ. “We need to access the records of Dr Leslie Meridien, recently deceased via murder.”

The lawyer read for several seconds. “The writ only covers—”

Novarro nodded. “Names of patients, dates of appointments. No interviews or session files can be viewed. I just need a copy of the aforementioned.”

“No prob,” he said. “Let’s go see Chaz. He’ll pull up everything you need.”

Novarro’s hallway pilgrimage continued around another corner, the nameplate this time saying Charles V. Hinton, Director, Tech Services.

“Knock, knock, buddy,” the lawyer called through the door.

“Busy here,” said the body hunched over the computer, a major-league monitor before him. “Come back later.”

“Got a Phoenix detective with me, bud,” Lazelle said.

“I don’t care if you—”

“She’s a friend of Art’s.”

Chaz Hinton spun to Novarro, the lawyer, and Klebbin, who had followed. The head atop his body seemed too large for the narrow shoulders, the round pink face looking about thirteen, though Novarro thought he might have gone twenty-five. His skin was the color of lard, like he’d been in the sun once in his life and found it distressing. He was wearing an Armani suit with purple sandals.

The lawyer handed Hinton the writ.

“Mostly I need Dr Meridien’s appointment lists,” Novarro said. “Calendars, dates, times, addresses, that kind of thing.”

“I can read,” Hinton said.

He spun in his chair and began ticking on the keyboard. Novarro, Klebbin, and the attorney stepped back. The lawyer turned to Novarro for a bite of schmooze pie. “So you’re a friend of Kenneth’s?” The attorney flashed teeth so pearly white they had to be caps.

“Come on, dammit,” Hinton said, keyboarding away in the background.

Novarro smiled slyly at the attorney. “Ken and I go back a ways.” About ten minutes.

“Come on,” Hinton repeated, more stridently. As if pressure helped, he pounded harder on the keyboard. Novarro wondered if the guy was always this stressy.

“Come on,” Hinton almost screamed. “WORK!”

“Chaz?” the lawyer said, walking to Hinton’s side. “Is something wrong?”

Hinton balled his fists and stared at the screen. ‘IT CAN’T BE,” he said, a fist slamming the desk. “IT CAN’T FUCKING BE!”

The door opened and the CEO strode inside. “What the hell’s going on, Chaz … I’m trying to have a meeting down the—”

“Someone got inside,” Hinton whispered.

Novarro had never seen a human being turn that white that fast.

“No way,” Larkin said, looking like he might tip over.

“Dr Leslie Meridien, client A-4329-09. We’ve stored her data for forty-seven months.” He pulled close a printed page. “The client printout from last week documents 2.5 megs of data in storage. But there’s nothing there.”

“The backups, Chaz,” Candace Klebbin suggested. “It’ll be safe there, right?”

“I JUST CHECKED THE FUCKING BACKUPS, YOU IDIOT!” Hinton railed at Klebbin. “DO YOU THINK I’M STUPID?”

“Chaz …” Larkin rasped. “Talk to me.”

Hinton swallowed like it hurt and turned to his boss. “A-4329-09 is gone, Kenneth … every last byte.”

Larkin put his hands on the edge of the desk and leaned close to the screen, incredulous. “You’ve done the restore protocols?” His voice was trembling.

“There’s nothing to restore. It’s like the data never existed. Even the shell that held them is gone.”

The CEO, lawyer, and tech director stared at the dark screen with open mouths and mute terror.

Novarro shot a glance at Klebbin.

“A good day to update my résumé,” the office administrator said.

5 (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

“Angela didn’t practice any more, Detectives,” Professor John Warbley said to Harry and me, his eyes sad. “She taught.”

We were at the U of Miami. Warbley’s office was three doors down from Angela Bowers’s university digs. Harry had come to root through both Bowers’s office and life, at least as her colleagues knew it. There was, unfortunately, nothing in her office bearing my name or suggesting how it had come to be in her possession. We had already talked to seven colleagues over the course of the day, ending with John Warbley. A fit and trim man in his mid-fifties with graying hair, Warbley had been out of the department all day, but entered as we were leaving.

“Medical ethics?” Harry asked.

“It’s a growing field, given the choices both patients and healthcare professionals face on an increasing basis; end-of-life decisions, the pros and cons of assisted suicide, informed consent and so forth. As a psychologist, Angela was particularly interested in doctor–patient confidentiality and its ramifications.” He swallowed hard and turned away. “Jesus, I can’t believe she’s …”

“We’ll be gone soon enough, Professor Warbley,” Harry said, his big hand on the distraught man’s shoulder. “We need to know a bit more about Dr Bowers.”

“Who would do such a thing?” Warbley said plaintively. “Why?”

“That’s what we’re here to figure out. When did you last speak with Dr Bowers?”

“Yesterday afternoon. She took me to lunch to discuss a topic that, I take it, was a concern to a friend of Angela’s.”

“The topic?” Harry asked.

“My field. A question about medical ethics.”

“It didn’t pertain to Dr Bowers? Not personal?”

“It only affected an old friend and former college roommate, a psychologist in Arizona.”

Two thousand miles away, I thought, not pertinent.

“Did Dr Bowers seem worried about anything, Doctor?” Harry asked. “No boyfriend or significant-other problems?”

A sad head-shake. “Nada. And I’d have been among the first to know. Angela and I were close friends.”

We started to leave, but I had one more question, more for my own edification, since I’d been in tangles where ethics and justice were in conflict and had even lectured on the subject at a couple of symposia.

“What was the ethical question Dr Bowers was asked about?” I said. “In a broad sense.”

“It regarded concerns about doctor–patient confidentiality, among other legalistic permutations. The whole confidentiality topic is fraught with implications; a thorny road.”

“Because psychologists and psychiatrists hear the most intimate aspects of patients’ lives, right?” I said. “Dreams, wishes, fantasies, desires. Even the desire to harm or kill someone.”

He nodded. “For instance, what if, in the course of privileged and confidential conversations, a psychologist comes to suspect someone may – only may – have committed a serious crime? And that this crime may be being perpetrated on one of the psychologist’s patients. There is no proof, only suspicion. To reveal suspicions of this crime to the authorities likely violates doctor–patient privilege. To make matters even more difficult, it’s quite possible there may have been no criminal act whatsoever. Events are proceeding exactly as they are supposed to proceed. What is the psychologist’s legal obligation? Moral obligation? What if they diverge? And who decides what is right?”

“Thorny questions, indeed,” I said, wondering if Warbley was using his conversation with Bowers as the example.

“Consider that there’s also money involved,” Warbley said.

“And suddenly thornier,” I added.

We packaged a few pieces of Bowers’s life for further investigation: a calendar, appointment book and such, then interviewed several of the doctor’s colleagues. We drove to Bowers’s home while mulling the bottom line thus far: Dr Bowers was uniformly respected as a psychologist, an instructor, and a person, selfless in the giving of her time and intellectual prowess to various causes. “Who would harm such a person?” was the one question on every lip.

Bowers had lived in an apartment complex in Wingate, expensive and catering to professionals. The super had a bypass to the electronic locking system. We passed through the living room to her office, stepping delicately around the dried blood on the floor. Her workspace was in muted gray and green tones, indirect lighting, two plush chairs and a long wide couch which made me wonder if she didn’t see the occasional patient.

While I leafed through the deceased’s desk – the one my name had been in – Harry tried the files.

“Locked,” he said. “See anything like keys in the desk, Cars?”

I was going through the top center drawer, the usual pens and pencils and batteries and spare change and paper clips. A small key ring was in back, several small silver keys attached. “Try these,” I said, tossing them over.

“Bingo,” he said, opening the first of three cabinets, pulling the drawer and looking inside. “Six years ago,” he said. “Typewritten transcriptions of therapy sessions, judging by the language. Fits with the time she started working at the U and gave up private practice. I guess she …”

Harry froze, his eyes staring into the cabinet.

“What’s wrong?”

Wordlessly, Harry fished a simple Manila file folder from the drawer and held it up. The subject tab said “Carson Ryder.” He handed it to me, and I found a dozen or so photocopied photos and clippings inside.

“She didn’t just have my name on an index card,” I said, flipping through clipped newspaper reports, “Bowers kept a file on me, cases that made the papers. Check this out.” I held up a photo that had been in the Mobile Press-Register a few years before: Harry and me receiving Officers of the Year awards from the Mayor of Mobile, Alabama.

“Any idea why Bowers kept a file on a detective with the FCLE?” Harry asked.

“Absolutely none,” I said.

He leaned in to scrutinize the photo. “You need a haircut,” he decided. “But I look pretty damn fine.”

We returned to HQ to continue adding to the file on Dr Angela Bowers, riding up in the elevator with my boss, Roy McDermott, the head of the FCLE’s investigative services division and de facto agency head honcho. Roy’s square body was packed into a crisp blue suit, telling me he’d just returned from Tallahassee, where he was a force majeure in securing funds for the agency. Roy knew the names and predilections of every politico in the state down to their favorite foods and sports teams, traveling to the state capitol during budget sessions to give impassioned speeches too convoluted to follow, all with the same bottom line: The FCLE gets results, so keep the funding flowing, folks.

We did, they did, and thus the department – basically a state-sized FBI – was one of the best-funded agencies in the state. We loved Roy for getting us everything we needed, and he loved us back for working our collective asses off.

“Hey, guys,” Roy said, yanking off his tie and jamming it in his suit pocket, the slender end dangling out like fifteen inches of flattened, redstripe snake, “did I read the daily reports right … a murdered psychologist had Carson’s name in her desk?”

“We’re working on finding out why,” I said, not mentioning the latest wrinkle.

Roy raised an eyebrow. “Detective Nautilus is working on finding out why, right?”

“Exactly,” Harry said. “Carson was just along for the ride.”

“If you’re gonna ride at all, Carson, ride in back,” Roy said, patting down the hay-bright cowlick that immediately bounded back in defiance. “And am I correct in my assessment – sent to you last month – that you’re getting a big backlog of vacation time?”

I was never big on vacation unless I had someone to enjoy it with. In the past this was a girlfriend or suitable feminine companionship, but I’d taken up full-time with Vivian Morningstar, whose hospital schedule currently precluded vacation and who would not be overly happy if I ran off with even a temporary vacation companion.

“I, uh – yep, Roy. I’ll vacation, uh … soon.”

“Didn’t you claim a heavy caseload and say you’d take some time off when Nautilus came on board?”

“I, uh may have said …”

“Is this not Nautilus standing beside you, Carson?”

“It seems so,” I admitted. “But Harry’s new and needs—”

Roy turned to Harry. “Can you function without Ryder, Detective Nautilus?”

Harry, blast him, gave it two beats and a grin. “Sometimes better.”

Roy clapped a huge red hand on my shoulder and pulled me close, half hug, half threat. “There you go, Carson, you’re covered, even more when Gershwin gets back next week. Take some time off. Recharge the batteries.” He paused, thought. “Y’know, that’s an order.”

And then the elevator door opened and the whirlwind of Roy McDermott blew out, pulling his pocket recorder as he turned the corner to his office, bellowing, “Memo to self, make sure Ryder starts taking his freaking vacation time!”

“Damn,” Harry said, staring at the corner Roy had vanished around. “He always like that?”

“Not generally,” I said. “Looks like he remembered his Prozac this morning.”

6 (#u22c4cf27-04bb-5477-9432-6626f0504d55)

Jeffrey Cottrell’s desk was shaking so hard one of the drawers rolled open. His nameplate – T. JEFFERSON COTTRELL, ESQ. – tumbled to the blue pile carpet, followed by a ceramic mug loaded with pens and pencils. Cottrell’s eyes were on the closet door across the room, opened wide and mirrored on the inside so he could enjoy the reflection, his jeans down to the tops of his hand-tooled cowboy boots, a woman on the desk with her red dress hiked to her waist, ankles locked around his buttocks.

“Oh yesssss …” the woman hissed as Cottrell’s hands raked her side-drooping breasts.

He shot a glance at his watch. Shit, lost track of time. He increased his rhythm, pushing to the finish, pinching the engorged nipples.

“Easy, Jeffrey,” the woman said. “You’re hurting …”

Cottrell grabbed broad hips and pulled the woman tight as his orgasm arrived in a frenzy of grunts and spasms.

“Urrrr … UHHH.”

And then he was backing away on unsteady legs and reaching for his pants.

“Jesus, Jeffy,” the woman said, pulling down her skirt with one hand and pushing back a stack of disheveled brass-blonde hair with the other. “You’re a crazy man. But fun. Got any more of that Cuervo?”

“You gotta get gone,” Cottrell said, tightening the concho belt around his Levi jeans. “I’m supposed to meet a client.”

“At ten at night?”

“It’s the law biz, hon.” He slapped her ass. “Come on, get moving.”

The woman shot him a dark glance, had a second thought, pecked his cheek with a kiss. “You gonna take me to Casa Adobo this Friday?”

“Yeah, sure. Use the back door, would you?”

A sigh and the woman slung her purse over her shoulder and was gone. Cottrell put the fallen items back on the desktop, pulled on his black sport coat and popped a breath mint, his mouth still tasting of tongue and tequila. He buttoned his pink Oxford shirt in the mirror, slipping the loosened bolo tie to his throat and finger-combing the long silver hair back over his ears. It might start tonight, he thought. Less than three weeks until the reading of the Kubiac will. It might not finish tonight, but it had to start soon.

Let’s get this done, kid …

Cottrell sucked in his gut and threw faux punches at the mirror. Forty-six and I still got it … A bit of roll over the belt, but he’d been busy lately, and the fucking gym was a drag. He had to look into getting a personal trainer, some skank with a hard-body going on. Both of them could get a workout.

Cottrell heard the buzz of the bell in the entry and shot a look at his Rolex, a gift from Ramon Escheverría, a client he’d made good money from in the past, with more undoubtedly coming in the future. El Gila … a scary street name, but Escheverría liked Cottrell, a very good thing.

Eleven on the nose; the kid’s on time at least.

Cottrell went to the door and saw Adam Kubiac, a lithe young woman at his side. His eyes expressed several seconds of visible surprise at seeing Kubiac was accompanied, and he extended a lamp-tanned hand to him. “I haven’t had a chance to call you again, Adam, but I want you to know you have my deepest condolences. Anything I can do to—”

Kubiac swept by with his hands jammed deep in his pockets. “Well, uh … sure,” Cottrell said. “Step back into my office and let’s get comfortable.”

In addition to Cottrell’s desk and chair, the room held a puffy brown leather sofa against a wall and two high-backed chairs facing the desk, also brown leather. “Have a seat, folks,” Cottrell said, gesturing to the chairs. The woman took a chair, sitting and crossing long and slender legs. Kubiac fell into the sofa, arms crossed over his chest. Cottrell leaned back in his swiveling chair and regarded Kubiac with warm sincerity.

“Who’s your friend, Adam?” Cottrell said, smiling politely at the gorgeous young woman while trying to avoid winking.

Kubiac ignored the question, arms tightly crossed as he glared fire at Cottrell.

“I think I know what you’ve come to discuss, Adam. But I have to be perfectly clear that nothing’s going to change.”

“You wrote the fucking thing, bitch,” Kubiac spat. “Hashtag: fuckAdamKubiac.”

Cottrell sighed. “I basically took dictation, Adam. The will reflects your father’s wishes. I probably shouldn’t have showed it to you, but … Hey, I wish I could change things.”

Kubiac’s eyes tightened to slits. “One freakin’ dollar to me. Twenty million to charities and shit? WHAT THE FUCK WAS GOING ON?”

Cottrell tried to shape his face somewhere between empathy and inspirational. “Maybe the will was your old man’s way of saying you’ve already got all you need, Adam: It’s that amazing mind of yours. You can use it to make your own—”

“YOU’RE THE KUBIAC FAMILY LAWYER, RIGHT?” Kubiac screeched. “WHAT ABOUT ME!”

“Adam …” the woman said quietly. “We talked about this.”

“He’s one of them,” Kubiac snarled as if Cottrell wasn’t there. “A Neanderthal.”

“I fought for you, Adam,” Cottrell said. “I told your father: ‘Think what you’re doing, Eli. Don’t punish Adam like this.’ But your father … you know how Eli could get, Adam – like you kid – he was adamant. I figured I could change his mind with just a little time, but, uh, the sad circumstances and …”

“I’M NOT PAYING YOU A CENT, ASSHOLE!”

“Uh, actually, that’s all been taken care of, Adam.”

“What … did you steal a million bucks off the top?”

“Come on, Adam,” Cottrell said, adding irritation to his voice. “Don’t treat me like this. I’ve been on your side from the start. I think you got screwed royally, unfairly … there, I said it.”

Come on, you screwy little bastard. You’re supposed to be so goddamn smart … put it together …

“IT DIDN’T DO A LOT OF GOOD, DID IT?”

The girl left the chair to sit beside Kubiac, her arm around his shoulders as she spoke into his ear so softly that Cottrell could catch nothing.Kubiac stood and pushed the dark mop of hair from his blazing eyes.

“I’ll be outside,” he snapped at the lawyer. “Talk to her from now on.”

“But Adam, you were the one who called me to—”

“Talk to HER!”

Kubiac glared at the lawyer and zipped his forefinger over his lips, Done talking. He strode through the door and slammed it shut. Cottrell winced. Seconds later heard a tapping at his floor-to-ceiling glass window and opened the blinds. Kubiac stood outside, his middle finger aloft in Cottrell’s face.

Cottrell sighed and turned away, conscious of Kubiac’s eyes burning into his back. He could have closed the blinds, but the goofy kid would probably have driven his fucking car through the window. He re-sat in his desk chair and looked at the woman. “How much has Adam told you?”

The lovely woman offered a hint of smile. “Everything. He trusts me.”

Cottrell nodded. “Then you know that when Adam turns eighteen he comes into his father’s legacy.” His eyes lifted to the woman’s eyes and held. “I hope he starts to think about it.”

The woman shot a glance at Kubiac, then returned her eyes to the lawyer. “He thinks about it a lot. I’m sorry if we took up your time, Mr Cottrell. Adam really wanted to come here.”

“He needed to vent. He’s angry.”

“Very.”

“I’m sorry,” Cottrell said, standing and holding out a hand. “But I didn’t get your name, Miss …”

The girl offered her hand over the desk. “Zoe Isbergen,” she said. They glanced toward the window as Kubiac spit against it, thick and viscous.

“And your relationship with Adam, Miss Isbergen?” Cottrell said with a lift of his eyebrow.

A wisp of smile. “Complex.”

7 (#ulink_1fc9d487-2d48-5a31-9a3f-ae029d8feae5)

It was eight minutes past midnight when Tasha Novarro pulled into the Dobbins Point Overlook in South Mountain Park, its sixteen thousand-plus desert acres and jagged peaks making it the largest municipal park in the continental US. The Overlook, far above the desert floor and up a winding grade, was always crowded during park hours, but the park had been closed since seven p.m. No problem for Novarro: South Mountain was under the jurisdiction of the Phoenix Police Department, the cop at the entrance long used to Novarro’s nighttime visits and waving her through the gate.

The Dobbins Point Overlook was Novarro’s own little parcel of Paradise, her sole company the spectral saguaros silhouetted in the light of a gibbous moon. Behind and above her, on the peak, stood a vast array of communications antennae with red lights blinking against the liquid sky.

When Novarro was young, she’d thought the lights themselves formed the communications, a version of the heliographs she’d read about in a book borrowed from the library, the lights flashing semaphoric messages to towers miles away. Only later did she learn that the structures communicated via invisible transmission of short-wave energy called microwaves and the lights were only there to ward off aircraft.

Novarro preferred her earlier interpretation.

She shut off her engine and stepped from the cruiser, looking north across a crucible of light: Phoenix the blazing nexus, Glendale to the west, Mesa to the east, Scottsdale northeast. Headlights shimmered down the geometric maze of streets as a jet dropped from below the moon to land at Sky Harbor International Airport, five miles distant and one of the few airports located in the heart of a major metropolis.

A woman killed, Novarro thought, staring into the vortex of light. She’d spent the last three days interviewing friends, neighbors, and business associates of Leslie Meridien, PhD. A pleasant and outgoing woman, by all reports, no apparent enemies.

No one had an answer, no one understood.

“Leslie was more than a psychologist,” a friend had wept. “She was a force for good.”

The killing had been brutal but efficient. Efficient murders were not the norm, Novarro knew from seven years in uniform and eight months in Homicide. The vast majority of killings were messy affairs, anger- or turf-driven, with slashing blades or emptied bullet clips, ball bats or shotgun blasts, people killed for being in the wrong bed or on the wrong corner.

Meridien’s murder was different. It was dispassionate, ice cold. And all of the victim’s patient files were gone, taken in a manner that baffled high-level computer types.

Merle Castle put it in a box he knew: breaking and entering, probably committed by Hispanics. But a television and watch had been left behind … Overlooked? Not by anyone professional enough to kill so efficiently. It was a wrong note, hell, a wrong chord.

Novarro paced the desolate parking lot for a full hour and came to two conclusions: One, that a highly competent professional had broken into Meridien’s cloud account and erased it, and – given high competence as a standard – two, a similar professionalism was likely employed in Meridien’s murder and what she believed was a staged robbery.

There were fierce and desperate people in the valley who would kill for a week’s worth of heroin, pulling a trigger and running. Move up a level and several thousand dollars bought a backseat strangling and a body dumped in the desert.

This was a higher level still.

Her mind reeling with questions, Novarro returned to her vehicle and descended the mountain, angling down Central Avenue and aiming for her downtown home.

Novarro had owned a house in midtown for eight months, making the down payment two days after getting her detective’s shield and the raise accompanying the new badge. The neighborhood was sketchy, but only four blocks from the Roosevelt Historic District, its gentrification effects moving like a slow-motion tsunami toward Novarro’s block.

It was the first home ownership in Tasha Novarro’s family. She’d grown up in a double-wide trailer at the edge of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community between Mesa and Scottsdale, her mother there mostly, her father never. Though it was Novarro, her younger brother, and mother, rarely were there just the three of them in residence; a ragged procession of relatives constantly passing through the house, sometimes for hours, sometimes months. The fragile emotional conditions at the house led Novarro’s Aunt Chyla to proclaim the domicile “a boxed set of thunderstorms.”

Novarro sought refuge in school, her dedication to study leading to a pre-law scholarship at Arizona State University. Her contribution would have been forty-five hundred dollars saved from working nights and weekends at a Ranch Market in northeast Phoenix, but one of her distant cousins – a handsome thirty-year-old charmer needing a place to stay following a forgery stint in prison – boogied off to points unknown after two months, taking her virginity and checkbook and emptying her account before he disappeared.

Left with only grades and ambition she went to the police academy because it was an arm of the law and was free.

And maybe, someday …

Novarro swung around the corner and onto her street, driving to midblock and pulling into her driveway. It was a small house and the windows were grated out of necessity, but she’d spent almost a thousand dollars and dozens of hours landscaping the yard, hard brown dirt and sand when she’d purchased it, beaten down by three large dogs. Now the driveway was bordered with bright flowers, a desert willow embellishing one corner of the boxy structure, a palo verde the other. The backyard held a lime tree that had somehow survived the canine onslaught. It wasn’t much, but everyone said it was the prettiest house on the street.

Novarro was ten steps from her front door when she noticed a centimeter-wide band of light leaking out. Ajar. A sizzle of electricity ran down her spine and she fell into a crouch, slipping her weapon from her rear waistband and creeping to the door. She put her ear to the crack, nothing. Novarro nudged the door open with her foot and peeked past the frame, smelling the sweet scent of marijuana.

“POLICE!” she yelled. “The house is surrounded. Put your hands on your head and walk to the front.”

A sound from somewhere in the rear.

“NOW!” she yelled. “OR YOU’RE DEAD!”

Seconds later a slender Native American male stepped from the hall with his hands atop a head of long black hair in a rubber-banded ponytail. He was boyishly handsome, like a man not fully formed, the face poised between pretty child and handsome adult. He wore a bead-embellished leather jacket over a white tee and blue jeans, a black concho belt around his waist, his feet in red trail runners. He stepped into the living room and pirouetted, stopping with a stumble into the wall and a broad grin aimed at Novarro.

“Jesus, Tash,” he said. “You’re such a drama queen.”

The muzzle dropped. It was Ben, her twenty-one-year-old brother. She’d given him a key months ago, regretted it a week later, but now it was his. If she asked for the key back or changed the lock, she’d be …

An Indian Giver.

Novarro blew out a breath. “I didn’t see your car outside, Ben.”

“A buddy dropped me off. We were out doin’ a li’l partying.”

Novarro heard the slur of pot and alcohol in her brother’s voice and she gave him narrowed eyes. “Your car’s at home, I hope?”

The last time this happened he’d forgotten where he’d parked.

“Fuckin’ bank came an’ got it yesterday, the bast—” He belched into his palm, “—ards.” He looked up. “’S’cuse me.”

Novarro had a mental picture of the repo man hooking up the 2001 Corolla and driving away. Six months back she’d lent – OK, given – Ben the price of the down payment plus two months of installments.

“You got behind on payments,” she sighed.

“The insur’nce was killing me, Tash.”

“Think your driving record has anything to do with it?”

“I, uh, gotta take a whizzer.” As usual when Ben didn’t like the direction of a conversation, he fled.

It was five minutes until the toilet flushed, reminding Novarro of the time the family’s commode had been leaking for a week until a nine-year-old Ben removed the tank top, stared at the mechanism as he flushed several times, then, using a bent bobby pin, fixed the toilet in thirty seconds.

“How are things at your job?” Novarro asked. “They still got you on thermostats?”

“I got tired of tinkering with little shit.” He winked. “So I disappeared in a puff of smoke.”

Novarro felt her heart drop. “Disappeared?”

“I’m the Coyote, Tasha,” Ben grinned crookedly, invoking the mythological, shape-shifting Trickster in many Native American cultures, reckless, self-involved, with a sense of humor both clownish and cruel. “I have the magic in me.”

Novarro shook her head. He’d quit or been fired. Her voice pushed toward anger, but she fought it. “You have too much liquor in you,” she said quietly.

“Me Indian,” Ben said in a cartoon voice, a distorted smile on his face. “Me like-um firewater. It make-um me big happy.”

“Don’t start that crap, Ben. It’s demea—”

“FYA-WATAH!” he whooped, jumping from the couch and beginning a stumbling circular dance, hand patting his mouth. “Owoo-woo-woo … Owoo-woo-woo … Owoo–woo …” He paused as if taken by a sudden thought. “Me need-um a drum track here, Tash,” he slurred, moving his hands up and down like drumming. “You got-um any tom-toms?”

“I got aspirin,” she said. “Coffee.”

Her brother scowled at his choices. “Coyote need-um more firewater.” His hand flashed beneath his jacket and found a pint bottle of red liquid; his favorite grain alcohol into which he’d poured several bags of strawberry Kool-Aid. At 190proof, it was just shy of pure ethanol. Before Novarro could cross the floor it was in his mouth.

“Give me that shit,” she said, grabbing his arm. Ben spun, his hand pushing Novarro away as his lips sucked greedily at the bottle.

“I said give … me … that.” Novarro wrenched the spirits from her brother’s hand and held it beyond his reach as he grabbed wildly at the pint.

“ME NEED-UM FIREWATER!” he railed.

Novarro retreated across the floor. “You need to go to bed.”

He raised an unsteady hand, fingers opening and closing. “Gimme, gimme, Tash. Need-um bad.”

“No fucking way, Ben.”

“IT’S MIIIINE!” he screamed, kicking over an end table and lamp. The action seemed to surprise him and he stared at the fallen furniture.

Novarro’s eyes tightened to pinpoints. “Get out, Benjamin.”

He turned to her. “Hunh?”

“There’s the door,” Novarro said, finger jabbing toward the entrance. “Get out of my house.”

It took several beats for her words to make sense. Her brother tipped forward but caught himself with hands to knees. “You can’t throw me out, Tash,” he said, taking a stutter-step sideways. “Me drunk Indian.”

“Go sleep in the goddamn alley, Geronimo. Or crawl into a trash can.”

“Don’t be mean, Tash,” her brother said in a voice closer to twelve than twenty-one. He bent to retrieve the toppled lamp but momentum carried him to the floor. He tried to push himself up, but his arms buckled and his nose slammed the carpet.

“I’m all fut up,” he wailed, face-down, fingers clawing at the rug like trying to get a grip on a spinning world. “I’M ALL FUT UP!”

“Shhhh, Ben,” Novarro said gently, slipping her hands beneath his shoulders. “Come on, let’s get you to the couch.”

She wrestled her brother to the couch and got a wastebasket from the bathroom. She pulled the area rug several feet from the couch and set the wastebasket beside him as a vomit pail. He’d miss it, of course. He always did.

She sat in the chair across the room and stared at her brother, his eyes rolled back as he neared sleep. Fixing the toilet was just the start, the harbinger of an innate ability with mechanical systems that led to a job in an uncle’s garage at thirteen. His skills flourished in a high school geared to technical pursuits and he’d received a scholarship in mechanical engineering at Arizona State.

He’d dropped out one semester into the program, claiming to be bored, but Novarro suspected Ben had the same problem afflicting so many lower-class kids in college: Fear that he didn’t belong in that world, that he was insufficient, miscast, hearing whispers only spoken in the mind …

How did that one ever get in?

Despite entreaties from his university counselor and two professors – one who took Ben under her wing like a relative – her brother went to work for a company that installed industrial HVAC systems, actually a decent job, his natural abilities impressing higher-ups from day one. But from the moment he’d quit school, the drinking and pot smoking ramped up. He fell in with a loose crew of ambition-free young men content to hang out near the res and do odd jobs, selling loose joints to needy tourists the most profitable.

Three months later the accumulating hangovers and stink of liquor on Ben’s sweat and breath ended with a pronouncement from his supervisor.

“We really like you, kid; you got an incredible gift. But you also got a problem. Get it fixed and we can …”