A Darker Domain

Val McDermid

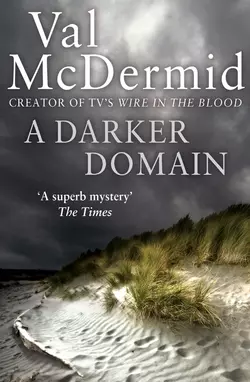

Val McDermid, creator of TV’s Wire in the Blood, mixes fact with fiction, dealing with one of the most important and symbolic moments in recent history.Twenty-five years ago, the daughter of the richest man in Scotland and her baby son were kidnapped and held to ransom. But Catriona Grant ended up dead and little Adam's fate has remained a mystery ever since. When a new clue is discovered in a deserted Tuscan villa – along with grisly evidence of a recent murder – cold case expert DI Karen Pirie is assigned to follow the trail.She's already working a case from the same year. During the Miners' Strike of 1984, pit worker Mick Prentice vanished. He was presumed to have broken ranks and fled south with other 'scabs'… but Karen finds that the reported events of that night don't add up. Where did he really go? And is there a link to the Grant mystery?The truth is stranger – and far darker – than fiction.

VAL McDERMID

A

Darker

Domain

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the memory of Meg and Tom McCall, my maternal grandparents. They showed me love, they taught me about community, and they never forgot the shame of standing in line at a soup kitchen to feed their bairns. Thanks to them, I grew up loving the sea, the woods and the work of Agatha Christie. No small debt.

CONTENTS

Cover (#uede70e9a-f02e-591e-8c0c-fe9eecffba18)

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_3aba105c-76c9-5b96-a462-e6aae968b811)

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes (#ulink_92b685fc-8bf3-5bef-85b5-561cc546cc8f)

Tuesday 19th June 2007; Edinburgh (#ulink_c7a68745-7d3c-516a-9272-80ee179ff951)

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes (#ulink_bce0f6fa-a372-5f37-9162-9ebad0b9281a)

Thursday 21st June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_9c7a70f5-00dd-5019-a5f1-3c04342ff20e)

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes (#ulink_606b32aa-6883-51e3-9342-6156986c9dc7)

Monday 25th June 2007; Edinburgh (#ulink_4ea5e9d0-fbe8-5010-adc0-f8bab35a83c0)

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes (#ulink_83d9c560-a09c-5fc9-bb8d-30fd644acc45)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Edinburgh (#ulink_f5dc4afc-f229-552f-8a83-43e30a878beb)

Monday 18th June 2007; Campora, Tuscany, Italy. (#ulink_dca50873-5424-592a-94d6-da6f41043d6e)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Edinburgh (#ulink_0d0d3d2a-332d-5d03-b798-3dda6b73e25b)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_1002fb2b-4af5-57ae-8696-058fad79dfaf)

Friday 14th December 1984; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_fc0ac21b-50a5-531a-9672-3acc359959b2)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_99e108bd-8eda-56da-9d2a-48b13c3c7b66)

Friday 14th December 1984; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_dd716f13-a167-5311-9aa7-0377e534b6de)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_fdb42784-9952-531f-92b2-47ae914ed88f)

Saturday 15th December 1984; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_76cad499-6858-507b-b17d-b7fb36d65c61)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#ulink_38492be4-08ae-5a09-9e7b-df930891c931)

Glenrothes (#ulink_b039476d-b26b-5503-89aa-e073924d9ce0)

Rotheswell Castle (#ulink_fd1893fd-3f60-5e2b-a9d9-2ae827bfed3c)

Wednesday 13th December 1978; Rotheswell Castle (#ulink_03a9dc27-eeec-5fe9-97c2-ae2bbf19b0fb)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Rotheswell Castle (#ulink_9ea994e6-aec6-581f-9849-cca41ddcf2cd)

Glenrothes (#ulink_993d1285-f204-5f6a-a150-41607419628a)

Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 2nd December 1984; Wemyss Woods (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 28th June 2007; Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 29th June 2007; Nottingham (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 14th December 1984 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 29th June 2007 (#litres_trial_promo)

Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 19th January 1985 (#litres_trial_promo)

Dysart, Fife (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 29th June 2007; Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Nottingham (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 30th November 1984; Dysart (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 29th June 2007; Glenrothes (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 30th June 2007; East Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Newton of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 21st January 1985; Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 30th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 23rd January 1987; Eilean Dearg (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 30th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 30th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 1st July 2007; East Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 2nd July 2007; Glenrothes (#litres_trial_promo)

Campora, Tuscany (#litres_trial_promo)

Peterhead, Scotland (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 21st January 1985; Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 2nd July 2007; Peterhead (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Newton of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 2nd July 2007; Peterhead (#litres_trial_promo)

Campora, Tuscany (#litres_trial_promo)

East Wemyss, Fife (#litres_trial_promo)

Campora, Tuscany (#litres_trial_promo)

Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Boscolata (#litres_trial_promo)

East Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 3rd July 2007; Glenrothes (#litres_trial_promo)

San Gimignano (#litres_trial_promo)

Coaltown of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

San Gimignano (#litres_trial_promo)

Edinburgh (#litres_trial_promo)

Campora (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 4th July 2007; East Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Glenrothes (#litres_trial_promo)

Hoxton, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Dundee (#litres_trial_promo)

Siena (#litres_trial_promo)

Glenrothes (#litres_trial_promo)

Edinburgh Airport to Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 5th July 2007; Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 14th August 1983; Newton of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, 5th July 2007 (#litres_trial_promo)

Glenrothes (#litres_trial_promo)

Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Celadoria, near Greve in Chianti (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 26th April 2007; Villa Totti, Tuscany (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 5th July 2007; Celadoria, near Greve in Chianti (#litres_trial_promo)

Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

Boscolata, Tuscany (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 6th July 2007; Kirkcaldy (#litres_trial_promo)

A1, Firenze-Milano (#litres_trial_promo)

Rotheswell Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 13th July 2007; Glenrothes (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 18th July 2007 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 19th July 2007; Newton of Wemyss (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2008

Copyright © Val McDermid 2008

Val McDermid asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007243297

Ebook edition © SEPTEMBER 2008 ISBN: 9780007287451

Version: 2018-11-05

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Newton of Wemyss

The voice is soft, like the darkness that encloses them. ‘You ready?’

‘As ready as I’ll ever be.’

‘You’ve told her what to do?’ Words tumbling now, tripping over each other, a single stumble of sounds.

‘Don’t worry. She knows what’s what. She’s under no illusions about who’s going to carry the can if this goes wrong.’ Sharp words, sharp tone. ‘She’s not the one I’m worrying about.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Nothing. It means nothing, all right? We’ve no choices. Not here. Not now. We just do what has to be done.’ The words have the hollow ring of bravado. It’s anybody’s guess what they’re hiding. ‘Come on, let’s get it done with.’

This is how it begins.

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

The young woman strode across the foyer, low heels striking a rhythmic tattoo on vinyl flooring dulled by the passage of thousands of feet. She looked like someone on a mission, the civilian clerk thought as she approached his desk. But then, most of them did. The crime prevention and public information posters that lined the walls were invariably wasted on them as they approached, lost in the slipstream of their determination.

She bore down on him, her mouth set in a firm line. Not bad looking, he thought. But like a lot of the women who pitched up here, she wasn’t exactly looking her best. She could have done with a bit more make-up, to make the most of those sparky blue eyes. And something more flattering than jeans and a hoodie. Dave Cruickshank assumed his fixed professional smile. ‘How can I help you?’ he said.

The woman tilted her head back slightly, as if readying herself for defence. ‘I want to report a missing person.’

Dave tried not to show his weary irritation. If it wasn’t neighbours from hell, it was so-called missing persons. This one was too calm for it to be a missing toddler, too young for it to be a runaway teenager. A row with the boyfriend, that’s what it would be. Or a senile granddad on the lam. The usual bloody waste of time. He dragged a pad of forms across the counter, squaring it in front of him and reaching for a pen. He kept the cap on; there was one key question he needed answered before he’d be taking down any details. ‘And how long has this person been missing?’

‘Twenty-two and a half years. Since Friday the fourteenth of December 1984, to be precise.’ Her chin came down and truculence clouded her features. ‘Is that long enough for you to take it seriously?’

Detective Sergeant Phil Parhatka watched the end of the video clip then closed the window. ‘I tell you,’ he said, ‘if ever there was a great time to be in cold cases, this is it.’

Detective Inspector Karen Pirie barely raised her eyes from the file she was updating. ‘How?’

‘Stands to reason. We’re in the middle of the war on terror. And I’ve just watched my local MP taking possession of 10 Downing Street with his missus.’ He jumped up and crossed to the mini-fridge perched on top of a filing cabinet. ‘What would you rather be doing? Solving cold cases and getting good publicity for it, or trying to make sure the muzzers dinnae blow a hole in the middle of our patch?’

‘You think Gordon Brown becoming Prime Minister makes Fife a target?’ Karen marked her place in the document with her index finger and gave Phil her full attention. It dawned on her that for too long she’d had her head too far in the past to weigh up present possibilities. ‘They never bothered with Tony Blair’s constituency when he was in charge.’

‘Very true.’ Phil peered into the fridge, deliberating between an Irn Bru and a Vimto. Thirty-four years old and still he couldn’t wean himself off the soft drinks that had been treats in childhood. ‘But these guys call themselves Islamic jihadists and Gordon’s a son of the manse. I wouldn’t want to be in the Chief Constable’s shoes if they decide to make a point by blowing up his dad’s old kirk.’ He chose the Vimto. Karen shuddered.

‘I don’t know how you can drink that stuff,’ she said. ‘Have you never noticed it’s an anagram of vomit?’

Phil took a long pull on his way back to his desk. ‘Puts hairs on your chest,’ he said.

‘Better make it two cans, then.’ There was an edge of envy in Karen’s voice. Phil seemed to live on sugary drinks and saturated fats but he was still as compact and wiry as he’d been when they were rookies together. She just had to look at a fully leaded Coke to feel herself gaining inches. It definitely wasn’t fair.

Phil narrowed his dark eyes and curled his lip in a good-natured sneer. ‘Whatever. The silver lining is that maybe the boss can screw some more money out of the government if he can persuade them there’s an increased threat.’

Karen shook her head, on solid ground now. ‘You think that famous moral compass would let Gordon steer his way towards anything that looked that self-serving?’ As she spoke, she reached for the phone that had just begun to ring. There were other, more junior officers in the big squad room that housed the Cold Case Review Team, but promotion hadn’t altered Karen’s ways. She’d never got out of the habit of answering any phone that rang in her vicinity. ‘CCRT, DI Pirie speaking,’ she said absently, still turning over what Phil had said, wondering if, deep down, he had a hankering to be where the live action was.

‘Dave Cruickshank on the front counter, Inspector. I’ve got somebody here, I think she needs to talk to you.’ Cruickshank sounded unsure of himself. That was unusual enough to grab Karen’s attention.

‘What’s it about?’

‘It’s a missing person,’ he said.

‘Is it one of ours?’

‘No, she wants to report a missing person.’

Karen suppressed an irritated exhalation. Cruickshank really should know better by now. He’d been on the front desk long enough. ‘So she needs to talk to CID, Dave.’

‘Well, yeah. Normally, that would be my first port of call. But see, this is a bit out of the usual run of things. Which is why I thought it would be better to run it past you, see?’

Get to the point. ‘We’re cold cases, Dave. We don’t process fresh inquiries.’ Karen rolled her eyes at Phil, smirking at her obvious frustration.

‘It’s not exactly fresh, Inspector. This guy went missing twenty-two years ago.’

Karen straightened up in her chair. ‘Twenty-two years ago? And they’ve only just got round to reporting it?’

‘That’s right. So does that make it cold, or what?’

Technically, Karen knew Cruickshank should refer the woman to CID. But she’d always been a sucker for anything that made people shake their heads in bemused disbelief. Long shots were what got her juices flowing. Following that instinct had brought her two promotions in three years, leapfrogging peers and making colleagues uneasy. ‘Send her up, Dave. I’ll have a word with her.’

She replaced the phone and pushed back from the desk. ‘Why the fuck would you wait twenty-two years to report a missing person?’ she said, more to herself than to Phil as she raided her desk for a fresh notebook and a pen.

Phil thrust his lips out like an expensive carp. ‘Maybe she’s been out of the country. Maybe she only just came back and found out this person isn’t where she thought they were.’

‘And maybe she needs us so she can get a declaration of death. Money, Phil. What it usually comes down to.’ Karen’s smile was wry. It seemed to hang in the air in her wake as if she were the Cheshire Cat. She bustled out of the squad room and headed for the lifts.

Her practised eye catalogued and classified the woman who emerged from the lift without a shred of diffidence visible. Jeans and fake-athletic hoodie from Gap. This season’s cut and colours. The shoes were leather, clean and free from scuffs, the same colour as the bag that swung from her shoulder over one hip. Her mid-brown hair was well cut in a long bob just starting to get a bit ragged along the edges. Not a doleite, then. Probably not a schemie. A nice, middle-class woman with something on her mind. Mid to late twenties, blue eyes with the pale sparkle of topaz. The barest skim of make-up. Either she wasn’t trying or she already had a husband. The skin round her eyes tightened as she caught Karen’s appraisal.

‘I’m Detective Inspector Pirie,’ she said, cutting through the potential stand-off of two women weighing each other up. ‘Karen Pirie.’ She wondered what the other woman made of her - a wee fat woman crammed into a Marks and Spencer suit, mid-brown hair needing a visit to the hairdresser, might be pretty if you could see the definition of her bones under the flesh. When Karen described herself thus to her mates, they would laugh, tell her she was gorgeous, make out she was suffering from low self-esteem. She didn’t think so. She had a reasonably good opinion of herself. But when she looked in the mirror, she couldn’t deny what she saw. Nice eyes, though. Blue with streaks of hazel. Unusual.

Whether it was what she saw or what she heard, the woman seemed reassured. ‘Thank goodness for that,’ she said. The Fife accent was clear, though the edges had been ground down either by education or absence.

‘I’m sorry?’

The woman smiled, revealing small, regular teeth like a child’s first set. ‘It means you’re taking me seriously. Not fobbing me off with the junior officer who makes the tea.’

‘I don’t let my junior officers waste their time making tea,’ Karen said drily. ‘I just happened to be the one who answered the phone.’ She half-turned, looked back and said, ‘If you’ll come with me?’

Karen led the way down a side corridor to a small room. A long window gave on to the car park and, in the distance, the artificially uniform green of the golf course. Four chairs upholstered in institutional grey tweed were drawn up to a round table, its cheerful cherry wood polished to a dull sheen. The only indicator of its function was the gallery of framed photographs on the wall, all shots of police officers in action. Every time she used this room, Karen wondered why the brass had chosen the sort of photos that generally appeared in the media after something very bad had happened.

The woman looked around her uncertainly as Karen pulled out a chair and gestured for her to sit down. ‘It’s not like this on the telly,’ she said.

‘Not much about Fife Constabulary is,’ Karen said, sitting down so that she was at ninety degrees to the woman rather than directly opposite her. The less confrontational position was usually the most productive for a witness interview.

‘Where’s the tape recorders?’ The woman sat down, not pulling her chair any closer to the table and hugging her bag in her lap.

Karen smiled. ‘You’re confusing a witness interview with a suspect interview. You’re here to report something, not to be questioned about a crime. So you get to sit on a comfy chair and look out the window.’ She flipped open her pad. ‘I believe you’re here to report a missing person?’

‘That’s right. His name’s -’

‘Just a minute. I need you to back up a wee bit. For starters, what’s your name?’

‘Michelle Gibson. That’s my married name. Prentice, that’s my own name. Everybody calls me Misha, though.’

‘Right you are, Misha. I also need your address and phone number.’

Misha rattled out details. ‘That’s my mum’s address. I’m sort of acting on her behalf, if you see what I mean?’

Karen recognized the village, though not the street. Started out as one of the hamlets built by the local laird for his coal miners when the workers were as much his as the mines themselves. Ended up as commuterville for strangers with no links to the place or the past. ‘All the same,’ she said, ‘I need your details too.’

Misha’s brows lowered momentarily, then she gave an address in Edinburgh. It meant nothing to Karen, whose knowledge of the social geography of the capital, a mere thirty miles away, was parochially scant. ‘And you want to report a missing person,’ she said.

Misha gave a sharp sniff and nodded. ‘My dad. Mick Prentice. Well, Michael, really, if you want to be precise.’

‘And when did your dad go missing?’ This, thought Karen, was where it would get interesting. If it was ever going to get interesting.

‘Like I told the guy downstairs, twenty-two and a half years ago. Friday 14th December 1984 was the last time we saw him.’ Misha Gibson’s brows drew down in a defiant scowl.

‘It’s kind of a long time to wait to report someone missing,’ Karen said.

Misha sighed and turned her head so she could look out of the window. ‘We didn’t think he was missing. Not as such.’

‘I’m not with you. What do you mean, “not as such”?’

Misha turned back and met Karen’s steady gaze. ‘You sound like you’re from round here.’

Wondering where this was going, Karen said. ‘I grew up in Methil.’

‘Right. So, no disrespect, but you’re old enough to remember what was going on in 1984.’

‘The miners’ strike?’

Misha nodded. Her chin stayed high, her stare defiant. ‘I grew up in Newton of Wemyss. My dad was a miner. Before the strike, he worked down the Lady Charlotte. You’ll mind what folk used to say round here - that nobody was more militant than the Lady Charlotte pitmen. Even so, there was one night in December, nine months into the strike, when half a dozen of them disappeared. Well, I say disappeared, but everybody knew the truth. That they’d gone to Nottingham to join the blacklegs.’ Her face bunched in a tight frown, as if she was struggling with some physical pain. ‘Five of them, nobody was too surprised that they went scabbing. But according to my mum, everybody was stunned that my dad had joined them. Including her.’ She gave Karen a look of pleading. ‘I was too wee to remember. But everybody says he was a union man through and through. The last guy you’d expect to turn blackleg.’ She shook her head. ‘Still, what else was she supposed to think?’

Karen understood only too well what such a defection must have meant to Misha and her mother. In the radical Fife coalfield, sympathy was reserved for those who toughed it out. Mick Prentice’s action would have granted his family instant pariah status. ‘It can’t have been easy for your mum,’ she said.

‘In one sense, it was dead easy,’ Misha said bitterly. ‘As far as she was concerned, that was it. He was dead to her. She wanted nothing more to do with him. He sent money, but she donated it to the hardship fund. Later, when the strike was over, she handed it over to the Miners’ Welfare. I grew up in a house where my father’s name was never spoken.’

Karen felt a lump in her chest, somewhere between sympathy and pity. ‘He never got in touch?’

‘Just the money. Always in used notes. Always with a Nottingham postmark.’

‘Misha, I don’t want to come across like a bitch here, but it doesn’t sound to me like your dad’s a missing person.’ Karen tried to make her voice as gentle as possible.

‘I didn’t think so either. Till I went looking for him. Take it from me, Inspector. He’s not where he’s supposed to be. He never was. And I need him found.’

The naked desperation in Misha’s voice caught Karen by surprise. To her, that was more interesting than Mick Prentice’s whereabouts. ‘How come?’ she said.

Tuesday 19th June 2007; Edinburgh

It had never occurred to Misha Gibson to count the number of times she’d emerged from the Sick Kids’ with a sense of outrage that the world continued on its way in spite of what was happening inside the hospital behind her. She’d never thought to count because she’d never allowed herself to believe it might be for the last time. Ever since the doctors had explained the reason for Luke’s misshapen thumbs and the scatter of café-au-lait spots across his narrow back, she had nailed herself to the conviction that somehow she would help her son dodge the bullet his genes had aimed at his life expectancy. Now it looked as if that conviction had finally been tested to destruction.

Misha stood uncertain for a moment, resenting the sunshine, wanting weather as bleak as her mood. She wasn’t ready to go home yet. She wanted to scream and throw things and an empty flat would tempt her to lose control and do just that. John wouldn’t be home to hold her or to hold her back; he’d known about her meeting with the consultant so of course work would have thrown up something insurmountable that only he could deal with.

Instead of heading up through Marchmont to their sandstone tenement, Misha cut across the busy road to the Meadows, the green lung of the southern city centre where she loved to walk with Luke. Once, when she’d looked at their street on Google Earth, she’d checked out the Meadows too. From space, it looked like a rugby ball fringed with trees, the criss-cross paths like laces holding the ball together. She’d smiled at the thought of her and Luke scrambling over the surface like ants. Today, there were no smiles to console Misha. Today, she had to face the fact that she might never walk here with Luke again.

She shook her head, trying to dislodge the maudlin thoughts. Coffee, that’s what she needed to gather her thoughts and get things into proportion. A brisk walk across the Meadows, then down to George IV Bridge, where every shop front was a bar, a café or a restaurant these days.

Ten minutes later, Misha was tucked into a corner booth, a comforting mug of latte in front of her. It wasn’t the end of the line. It couldn’t be the end of the line. She wouldn’t let it be the end of the line. There had to be some way to give Luke another chance.

She’d known something was wrong from the first moment she’d held him. Even dazed by drugs and drained by labour, she’d known. John had been in denial, refusing to set any store by their son’s low birth weight and those stumpy little thumbs. But fear had clamped its cold certainty on Misha’s heart. Luke was different. The only question in her mind had been how different.

The sole aspect of the situation that felt remotely like luck was that they were living in Edinburgh, a ten-minute walk from the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, an institution that regularly appeared in the ‘miracle’ stories beloved of the tabloids. It didn’t take long for the specialists at the Sick Kids’ to identify the problem. Nor to explain that there would be no miracles here.

Fanconi Anaemia. If you said it fast, it sounded like an Italian tenor or a Tuscan hill town. But the charming musicality of the words disguised their lethal message. Lurking in the DNA of both Luke’s parents were recessive genes that had combined to create a rare condition that would condemn their son to a short and painful life. At some point between the ages of three and twelve, he was almost certain to develop aplastic anaemia, a breakdown of the bone marrow that would ultimately kill him unless a suitable donor could be found. The stark verdict was that without a successful bone marrow transplant, Luke would be lucky to make it into his twenties.

That information had given her a mission. She soon learned that, without siblings, Luke’s best chance of a viable bone marrow transplant would come from a family member - what the doctors called a mismatched related transplant. At first, this had confused Misha. She’d read about bone marrow transplant registers and assumed their best hope was to find a perfect match there. But according to the consultant, a donation from a mismatched family member who shared some of Luke’s genes had a lower risk of complications than a perfect match from a donor who wasn’t part of their extended kith and kin.

Since then, Misha had been wading through the gene pool on both sides of the family, using persuasion, emotional blackmail and even the offer of reward on distant cousins and elderly aunts. It had taken time, since it had been a solo mission. John had walled himself up behind a barrier of unrealistic optimism. There would be a medical breakthrough in stem cell research. Some doctor somewhere would discover a treatment whose success didn’t rely on shared genes. A perfectly matched donor would turn up on a register somewhere. John collected good stories and happy endings. He trawled the internet for cases that had proved the doctors wrong. He came up with medical miracles and apparently inexplicable cures on a weekly basis. And he drew his hope from this. He couldn’t see the point of Misha’s constant pursuit. He knew somehow it would be all right. His capacity for denial was Olympic.

It made her want to kill him.

Instead, she’d continued to clamber through the branches of their family trees in search of the perfect candidate. She’d come to her final dead end only a week or so before today’s terrible judgement. There was only one possibility left. And it was the one possibility she had prayed she wouldn’t have to consider.

Before her thoughts could go any further down that particular path, a shadow fell over her. She looked up, ready to be sharp with whoever wanted to intrude on her. ‘John,’ she said wearily.

‘I thought I’d find you hereabouts. This is the third place I tried,’ he said, sliding into the booth, awkwardly shunting himself round till he was at right angles to her, close enough to touch if either of them had a mind to.

‘I wasn’t ready to face an empty flat.’

‘No, I can see that. What did they have to say?’ His craggy face screwed up in anxiety. Not, she thought, over the consultant’s verdict. He still believed his precious son was somehow invincible. What made John anxious was her reaction.

She reached for his hand, wanting contact as much as consolation. ‘It’s time. Six months tops without the transplant.’ Her voice sounded cold even to her. But she couldn’t afford warmth. Warmth would melt her frozen state and this wasn’t the place for an outpouring of grief or love.

John clasped her fingers tight inside his. ‘It’s maybe not too late,’ he said. ‘Maybe they’ll -’

‘Please, John. Not now.’

His shoulders squared inside his suit jacket, his body tensing as he held his dissent close. ‘So,’ he said, an outbreath that was more sigh than anything else. ‘I suppose that means you’re going looking for the bastard?’

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

Karen scratched her head with her pen. Why do I get all thegood ones? ‘Why did you leave it so long to try to trace your father?’

She caught a fleeting expression of irritation round Misha’s mouth and eyes. ‘Because I’d been brought up thinking my father was a selfish blackleg bastard. What he did cast my mother adrift from her own community. It got me bullied in the play park and at school. I didn’t think a man who dumped his family in the shit like that would be bothered about his grandson.’

‘He sent money,’ Karen said.

‘A few quid here, a few quid there. Blood money,’ Misha said. ‘Like I said, my mum wouldn’t touch it. She gave it away. I never saw the benefit of it.’

‘Maybe he tried to make it up to your mum. Parents don’t always tell us the uncomfortable truths.’

Misha shook her head. ‘You don’t know my mum. Even with Luke’s life at stake, she wasn’t comfortable with me trying to track down my dad.’

To Karen, it seemed a thin reason for avoiding a man who might provide the key to a boy’s future. But she knew how deep feelings ran in the old mining communities, so she let it lie. ‘You say he wasn’t where he was supposed to be. What happened when you went looking for him?’

Thursday 21st June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Jenny Prentice pulled a bag of potatoes out of the vegetable rack and set about peeling them, her body bowed over the sink, her back turned to her daughter. Misha’s question hung unanswered between them, reminding them both of the barrier her father’s absence had put between them from the beginning. Misha tried again. ‘I said -’

‘I heard you fine. There’s nothing the matter with my hearing,’ Jenny said. ‘And the answer is, I’ve no bloody idea. How would I know where to start looking for that selfish scabbing sack of shite? We’ve managed fine without him the last twenty-two years. There’s been no cause to go looking for him.’

‘Well, there’s cause now.’ Misha stared at her mother’s rounded shoulders. The weak light that spilled in through the small kitchen window accentuated the silver in her undyed hair. She was barely fifty, but she seemed to have bypassed middle age, heading straight for the vulnerable stoop of the little old lady. It was as if she’d known this attack would arrive one day and had chosen to defend herself by becoming piteous.

‘He’ll not help,’ Jenny scoffed. ‘He showed what he thought of us when he left us to face the music. He was always out for number one.’

‘Maybe so. But I’ve still got to try for Luke’s sake,’ Misha said. ‘Was there never a return address on the envelopes the money came in?’

Jenny cut a peeled potato in half and dropped it in a pan of salted water. ‘No. He couldn’t even be bothered to put a wee letter in the envelope. Just a bundle of dirty notes, that’s all.’

‘What about the guys he went with?’

Jenny cast a quick contemptuous glance at Misha. ‘What about them? They don’t show their faces round here.’

‘But some of them have still got family here or in East Wemyss. Brothers, cousins. They might know something about my dad.’

Jenny shook her head firmly. ‘I’ve never heard tell of him since the day he walked out. Not a whisper, good or bad. The other men he went with, they were no friends of his. The only reason he took a lift with them was he had no money to make his own way south. He’ll have used them like he used us and then he’ll have gone his own sweet way once he got where he wanted to be.’ She dropped another potato in the pan and said without enthusiasm, ‘Are you staying for your dinner?’

‘No, I’ve got things to see to,’ Misha said, impatient at her mother’s refusal to take her quest seriously. ‘There must be somebody he’s kept in touch with. Who would he have talked to? Who would he have told what he was planning?’

Jenny straightened up and put the pan on the old-fashioned gas cooker. Misha and John offered to replace the chipped and battered stove every time they sat down to the production number that was Sunday dinner, but Jenny always refused with the air of frustrating martyrdom she brought to every offer of kindness. ‘You’re out of luck there too.’ She eased herself on to one of the two chairs that flanked the tiny table in the cramped kitchen. ‘He only had one real pal. Andy Kerr. He was a red-hot Commie, was Andy. I tell you, by 1984, there weren’t many still keeping the red flag flying, but Andy was one of them. He’d been a union official well before the strike. Him and your father, they’d been best pals since school.’ Her face softened for a moment and Misha could almost make out the young woman she’d been. ‘They were always up to something, those two.’

‘So where do I find this Andy Kerr?’ Misha sat down opposite her mother, her desire to be gone temporarily abandoned.

Her mother’s face twisted into a wry grimace. ‘Poor soul. If you can find Andy, you’ll be quite the detective.’ She leaned across and patted Misha’s hand. ‘He’s another one of your father’s victims.’

‘How do you mean?’

‘Andy adored your father. He thought the sun shone out of his backside. Poor Andy. The strike put him under terrible pressure. He believed in the strike, he believed in the struggle. But it broke his heart to see the hardship his men were going through. He was on the edge of a nervous breakdown, and the local executive forced him to go on the sick not long before your father shot the craw. Nobody saw him after that. He lived out in the middle of nowhere, so nobody noticed he was away.’ She gave a long, weary sigh. ‘He sent a postcard to your dad from some place up north. But of course, he was blacklegging by then, so he never got it. Later, when Andy came back, he left a note for his sister, saying he couldn’t take any more. Killed himself, the poor soul.’

‘What’s that got to do with my dad?’ Misha demanded.

‘I always thought your dad going scabbing was the straw that broke the camel’s back.’ Jenny’s expression was pious shading into smug. ‘That was what drove Andy over the edge.’

‘You can’t know that.’ Misha pulled away in disgust.

‘I’m not the only one around here that thinks the same thing. If your father had confided in anybody, it would have been Andy. And that would have been one burden too many for that fragile wee soul. He took his own life, knowing that his one real friend had betrayed everything he stood for.’ On that melodramatic note, Jenny got to her feet and lifted a bag of carrots from the vegetable rack. It was clear she had shot her bolt on the subject of Mick Prentice.

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

Karen sneaked a look at her watch. Whatever fine qualities Misha Gibson might possess, brevity was not one of them. ‘So Andy Kerr turned out to be literally a dead end?’

‘My mother thinks so. But apparently they never found his body. Maybe he didn’t kill himself after all.’ Misha said.

‘They don’t always turn up,’ Karen said. ‘Sometimes the sea claims them. Or else the wilderness. There’s still a lot of empty space in this country.’ Resignation took possession of Misha’s face. She was, Karen thought, a woman inclined to believe what she was told. If anyone knew that, it would be her mother. Perhaps things weren’t quite as clear cut as Jenny Prentice wanted her daughter to think.

‘That’s true,’ Misha said. ‘And my mother did say that he left a note. Will the police still have the note?’

Karen shook her head. ‘I doubt it. If we ever had it, it will have been given back to his family.’

‘Would there not have been an inquest? Would they not have needed it for that?’

‘You mean a Fatal Accident Inquiry,’ Karen said. ‘Not without a body, no. If there’s a file at all, it’ll be a missing-person case.’

‘But he’s not missing. His sister had him declared dead. Their parents both died in the Zeebrugge ferry disaster, but apparently their dad had always refused to believe Andy was dead so he hadn’t changed his will to leave the house to the sister. She had to go to court to get Andy pronounced dead so she would inherit. That’s what my mother said, anyway.’ Not a flicker of doubt disturbed Misha’s expression.

Karen made a note, Andy Kerr’s sister, and added a little asterisk to it. ‘So if Andy killed himself, we’re back with scabbing as the only reasonable explanation of your dad’s disappearance. Have you made any attempts to contact the guys he’s supposed to have gone away with?’

Monday 25th June 2007; Edinburgh

Ten past nine on a Monday morning, and already Misha felt exhausted. She should be at the Sick Kids by now, focusing on Luke. Playing with him, reading to him, cajoling therapists into expanding their regimes, discussing treatment plans with medical staff, using all her energy to fill them with her conviction that her son could be saved. And if he could be saved, they all owed it to him to shovel every scrap of therapeutic intervention his way.

But instead, she was sitting on the floor, back to the wall, knees bent, phone cradled in her lap, notepad at her side. She told herself she was summoning the courage to make a phone call, but she knew in a corner of her mind exhaustion was the real reason for her inactivity.

Other families used the weekends to relax, to recharge their batteries. But not the Gibsons. For a start, fewer staff were on duty at the hospital, so Misha and John felt obliged to pile even more energy than usual into Luke. There was no respite when they came home either. Misha’s acceptance that the last best hope for their son lay in finding her father had simply escalated the conflict between her missionary ardour and John’s passive optimism.

This weekend had been harder going than usual. Having a time limit put on Luke’s life imbued each moment they shared with more value and more poignancy. It was hard to avoid a kind of melodramatic sentimentality. As soon as they’d left the hospital on Saturday Misha had picked up the refrain she’d been delivering since she’d seen her mother. ‘I need to go to Nottingham, John. You know I do.’

He shoved his hands into the pockets of his rain jacket, thrusting his head forward as if he was butting against a high wind. ‘Just phone the guy,’ he said. ‘If he’s got anything to tell you, he’ll tell you on the phone.’

‘Maybe not.’ She took a couple of steps at a trot to keep pace with him. ‘People always tell you more face to face. He could maybe put me on to the other guys that went down with him. They might know something.’

John snorted. ‘And how come your mother can only remember one guy’s name? How come she can’t put you on to the other guys?’

‘I told you. She’s put everything out of her mind about that time. I really had to push her before she came up with Logan Laidlaw’s name.’

‘And you don’t think it’s amazing that the only guy whose name she can remember has no family in the area? No obvious way to track him down?’

Misha pushed her arm through his, partly to make him slow down. ‘But I did track him down, didn’t I? You’re too suspicious.’

‘No, I’m not. Your mother doesn’t understand the power of the internet. She doesn’t know about things like online electoral rolls or 192.com. She thinks if there’s no human being to ask, you’re screwed. She didn’t think she was giving you anything you could use. She doesn’t want you poking about in this, she’s not going to help you.’

‘That makes two of you then.’ Misha pulled her arm free and strode out ahead of him.

John caught up with her on the corner of their street. ‘That’s not fair,’ he said. ‘I just don’t want you getting hurt unnecessarily.’

‘You think watching my boy die and not doing anything that might save him isn’t hurting me?’ Misha felt the heat of anger in her cheeks, knew the hot tears of rage were lurking close to the surface. She turned her face away from him, blinking desperately at the tall sandstone tenements.

‘We’ll find a donor. Or they’ll find a treatment. All this stem cell research, it’s moving really fast.’

‘Not fast enough for Luke,’ Misha said, the familiar sensation of weight in her stomach slowing her steps. ‘John, please. I need to go to Nottingham. I need you to take a couple of days off work, cover for me with Luke.’

‘You don’t need to go. You can talk to the guy on the phone.’

‘It’s not the same. You know that. When you’re dealing with clients, you don’t do it over the phone. Not for anything important. You go out and see them. You want to see the whites of their eyes. All I’m asking is for you to take a couple of days off, to spend time with your son.’

His eyes flashed dangerously and she knew she’d gone too far. John shook his head stubbornly. ‘Just make the phone call, Misha.’

And that was that. Long experience with her husband had taught her that when John took a position he believed was right, going over the same ground only gave him the opportunity to build stronger fortifications. She had no fresh arguments that could challenge his decision. So here she was, sitting on the floor, trying to shape sentences in her head that would persuade Logan Laidlaw to tell her what had happened to her father since he’d walked out on her more than twenty-two years earlier.

Her mother hadn’t given her much to base a strategy on. Laidlaw was a waster, a womanizer, a man who, at thirty, had still acted like a teenager. He’d been married and divorced by twenty-five, building the sour reputation of a man who was too handy with his fists around women. Misha’s picture of her father was patchy and partial, but even with the bias imposed by her mother, Mick Prentice didn’t sound like the sort of man who would have had much time for Logan Laidlaw. Still, hard times made for strange company.

At last, Misha picked up the phone and keyed in the number she’d tracked down via internet searches and directory enquiries. He’d probably be out at work, she thought on the fourth ring. Or asleep.

The sixth ring cut off abruptly. A deep voice grunted an approximate hello.

‘Is that Logan Laidlaw?’ Misha said, working to keep her voice level.

‘I’ve got a kitchen and I don’t want any insurance.’ The Fife accent was still strong, the words bumping into each other with the familiar rise and fall.

‘I’m not trying to sell you anything, Mr Laidlaw. I just want to talk to you.’

‘Aye, right. And I’m the Prime Minister.’

She could sense he was on the point of ending the call. ‘I’m Mick Prentice’s daughter,’ she blurted out, strategy hopelessly holed beneath the waterline. Across the distance, she could hear the liquid wheeze of his breathing. ‘Mick Prentice from Newton of Wemyss,’ she tried.

‘I know where Mick Prentice is from. What I don’t know is what Mick Prentice has to do with me.’

‘Look, I realize the two of you might not see much of each other these days, but I’d really appreciate anything you could tell me. I really need to find him.’ Misha’s own accent slipped a few gears till she was matching his own broad tongue.

A pause. Then, with a baffled note, ‘Why are you talking to me? I haven’t seen Mick Prentice since I left Newton of Wemyss way back in 1984.’

‘OK, but even if you split up as soon as you got to Nottingham, you must have some idea of where he ended up, where he was heading for?’

‘Listen, hen, I don’t have a clue what you’re on about. What do you mean, split up as soon as we got to Nottingham?’ He sounded irritated, what little patience he had evaporating in the heat of her demands.

Misha gulped a deep breath then spoke slowly. ‘I just want to know what happened to my dad after you got to Nottingham. I need to find him.’

‘Are you wrong in the head or something, lassie? I’ve no idea what happened to your dad after I came to Nottingham, and here’s for why. I was in Nottingham and he was in Newton of Wemyss. And even when we were both in the same place, we weren’t what you would call pals.’

The words hit like a splash of cold water. Was there something wrong with Logan Laidlaw’s memory? Was he losing his grip on the past. ‘No, that’s not right,’ she said. ‘He came to Nottingham with you.’

A bark of laughter, then a gravel cough. ‘Somebody’s been winding you up, lassie,’ he wheezed. ‘Trotsky would have crossed a picket line before the Mick Prentice I knew. What makes you think he came to Nottingham?’

‘It’s not just me. Everybody thinks he went to Nottingham with you and the other men.’

‘That’s mental. Why would anybody think that? Do you not know your own family history?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Christ, lassie, your great-grandfather. Your father’s granddad. Do you not know about him?’

Misha had no idea where this was going but at least he hadn’t hung up on her as she’d earlier feared he would. ‘He was dead before I was even born. I don’t know anything about him, except that he was a miner too.’

‘Jackie Prentice,’ Laidlaw said with something approaching relish. ‘He was a strike breaker back in 1926. After it was settled, he had to be moved to a job on the surface. When your life depends on the men in your team, you don’t want to be a scab underground. Not unless everybody else is in the same boat, like with us. Christ knows why Jackie stayed in the village. He had to take the bus to Dysart to get a drink. There wasn’t a bar in any of the Wemyss villages that would serve him. So your dad and your granddad had to work twice as hard as anybody else to be accepted down the pit. No way would Mick Prentice throw that respect away. He’d sooner starve. Aye, and see you starve with him. Wherever you got your info, they don’t know what the hell they’re talking about.’

‘My mother told me. It’s what everybody says in the Newton.’ The impact of his words left her feeling as if all the air had been sucked from her.

‘Well, they’re wrong. Why would anybody think that?’

‘Because the night you went to Nottingham was the last night anyone in the Newton saw him or heard from him. And because my mother occasionally gets money in the post with a Nottingham postmark.’

Laidlaw breathed heavily, a concertina wheeze in her ear. ‘By Christ, that’s wild. Well, sweetheart, I’m sorry to disappoint you. There was five of us left Newton of Wemyss that December night. But your dad wasn’t among us.’

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

Karen stopped at the canteen for a chicken salad sandwich on the way back to her desk. Criminals and witnesses could seldom fool Karen, but when it came to food, she could fool herself seventeen ways before breakfast. The sandwich, for example. Wholegrain bread, a swatch of wilted lettuce, a couple of slices of tomato and cucumber, and it became a health food. Never mind the butter and the mayo. In her head, the calories were cancelled by the benefits. She tucked her notebook under her arm and ripped open the plastic sandwich box as she walked.

Phil Parhatka looked up as she flopped into her chair. Not for the first time, the angle of his head reminded her that he looked like a darker, skinnier version of Matt Damon. There was the same jut of nose and jaw, the straight brows, The Bourne Identity haircut, the expression that could swing from open to guarded in a heartbeat. Just the colouring was different. Phil’s Polish ancestry was responsible for his dark hair, brown eyes and thick pale skin; his personality had contributed the tiny hole in his left earlobe, a piercing that generally accommodated a diamond stud when he was off duty. ‘How was it for you?’ he said.

‘More interesting than I expected,’ she admitted, getting up again to fetch herself a Diet Coke. Between bites and swallows, she gave him a concise précis of Misha Gibson’s story.

‘And she believes what this old geezer in Nottingham told her?’ he said, leaning back in his chair and linking his fingers behind his head.

‘I think she’s the sort of woman who generally believes what people tell her,’ Karen said.

‘She’d make a lousy copper, then. So, I take it you’ll be passing it across to Central Division to get on with?’

Karen took a chunk out of her sandwich and chewed vigorously, the muscles of her jaw and temple bulging and contracting like a stress ball under pressure. She swallowed before she’d finished chewing properly then washed the mouthful down with a swig of Diet Coke. ‘Not sure,’ she said. ‘It’s kind of interesting.’

Phil gave her a wary look. ‘Karen, it’s not a cold case. It’s not ours to play with.’

‘If I pass it over to Central, it’ll wither on the vine. Nobody over there’s going to bother with a case where the trail went cold twenty-two years ago.’ She refused to meet his disapproving eye. ‘You know that as well as I do. And according to Misha Gibson, her kid’s drinking in the last-chance saloon.’

‘That still doesn’t make it a cold case.’

‘Just because it wasn’t opened in 1984 doesn’t mean it’s not cold now.’ Karen waved the remains of her sandwich at the files on her desk. ‘And none of this lot is going anywhere any time soon. Darren Anderson - nothing I can do till the cops in the Canaries get their fingers out and find which bar his ex-girl friend’s working in. Ishbel Mackindoe - waiting for the lab to tell me if they can get any viable DNA from the anonymous letters. Patsy Millar - can’t get any further with that till the Met finish digging up the garden in Haringey and do the forensics.’

‘There’s witnesses in the Patsy Millar case that we could talk to again.’

Karen shrugged. She knew she could pull rank on Phil and shut him up that way, but she needed the ease between them too much. ‘They’ll keep. Or else you can take one of the DCs and give them some on-the-job training.’

‘If you think they need on-the-job training, you should give them this stone-cold missing person case. You’re a DI now, Karen. You’re not supposed to be chasing about on stuff like this.’ He waved a hand towards the two DCs sitting at their computers. ‘That’s for the likes of them. What this is about is that you’re bored.’ Karen tried to protest but Phil carried on regardless. ‘I said when you took this promotion that flying a desk would drive you mental. And now look at you. Sneaking cases out from under the woolly suits at Central. Next thing, you’ll be going off to do your own interviews.’

‘So?’ Karen screwed up the sandwich container with more force than was strictly necessary and tossed it in the bin. ‘It’s good to keep my hand in. And I’ll make sure it’s all above board. I’ll take DC Murray with me.’

‘The Mint?’ The tone in Phil’s voice was incredulous, the look on his face offended. ‘You’d take the Mint over me?’

Karen smiled sweetly. ‘You’re a sergeant now, Phil. A sergeant with ambitions. Staying in the office and keeping my seat warm will help your aspirations become a reality. Besides, the Mint’s not as bad as you make out. He does what he’s told.’

‘So does a collie dog. But a dog would show more initiative.’

‘There’s a kid’s life at stake, Phil. I’ve got more than enough initiative for both of us. This needs to be done right and I’m going to make sure it is.’ She turned to her computer with an air of having finished with the conversation.

Phil opened his mouth to say more, then thought better of it when he saw the repressive glance Karen flashed in his direction. They’d been drawn to each other from the start of their careers, each recognizing nonconformist tendencies in the other. Having come up the ranks together had left the pair of them with a friendship that had survived the challenge of altered status. But he knew there were limits to how far he could push Karen and he had a feeling he’d just butted up against them. ‘I’ll cover for you here, then,’ he said.

‘Works for me,’ Karen said, her fingers flying over the keys. ‘Book me out for tomorrow morning. I’ve a feeling Jenny Prentice might be a wee bit more forthcoming to a pair of polis than she was to her daughter.’

Thursday 28th June 2007; Edinburgh

Learning to wait was one of the lessons in journalism that courses didn’t teach. When Bel Richmond had had a fulltime job on a Sunday paper, she had always maintained that she was paid, not for a forty-hour week, but for the five minutes when she talked her way across a doorstep that nobody else had managed to cross. That left a lot of time for waiting. Waiting for someone to return a call. Waiting for the next stage of the story to break. Waiting for a contact to turn into a source. Bel had done a lot of waiting and, while she’d become skilled at it, she had never learned to love it.

She had to admit she’d passed the time in surroundings that were a lot less salubrious than this. Here, she had the physical comforts of coffee, biscuits and newspapers. And the room she’d been left in commanded the panoramic view that had graced a million shortbread tins. Running the length of Princes Street, it featured a clutch of keynote tourist sights - the castle, the Scott Monument, the National Gallery and Princes Street Gardens. Bel spotted other significant architectural eye candy but she didn’t know enough about the city to identify it. She’d only visited the Scottish capital a few times and conducting this meeting here hadn’t been her choice. She’d wanted it in London, but her reluctance to show her hand in advance had turfed her out of the driving seat and into the role of supplicant.

Unusually for a freelance journalist, she had a temporary research assistant. Jonathan was a journalism student at City University and he’d asked his tutor to assign him to Bel for his work experience assignment. Apparently he liked her style. She’d been mildly gratified by the compliment but delighted at the prospect of having eight weeks free from drudgery. And so it had been Jonathan who had made the first contact with Maclennan Grant Enterprises. The message he’d returned with had been simple. If Ms Richmond was not prepared to state her reason for wanting a meeting with Sir Broderick Maclennan Grant, Sir Broderick was not prepared to meet her. Sir Broderick did not give interviews. Further arm’s-length negotiations had led to this compromise.

And now Bel was, she thought, being put in her place. Being forced to cool her heels in a hotel meeting room. Being made to understand that someone as important as the personal assistant to the chairman and principal shareholder of the country’s twelfth most valuable company had more pressing calls on her time than dancing attendance on some London hack.

She wanted to get up and pace, but she didn’t want to reveal any lack of composure. Giving up the high ground was not something that had ever come naturally to her. Instead she straightened her jacket, made sure her shirt was tucked in properly and picked a stray piece of grit from her emerald suede shoes.

At last, precisely fifteen minutes after the agreed time, the door opened. The women who entered in a flurry of tweed and cashmere resembled a school mistress of indeterminate age but one accustomed to exerting discipline over her pupils. For one crazy moment, Bel nearly jumped to her feet in a Pavlovian response to her own teenage memories of terrorist nuns. But she managed to restrain herself and stood up in a more leisurely manner.

‘Susan Charleson,’ the woman said, extending a hand. ‘Sorry to keep you waiting. As Harold Macmillan once said, “Events, dear boy. Events.”’

Bel decided not to point out that Harold Macmillan had been referring to the job of Prime Minister, not wet nurse to a captain of industry. She took the warm dry fingers in her own. A moment’s sharp grip, then she was released. ‘Annabel Richmond.’

Susan Charleson ignored the armchair opposite Bel and headed instead for the table by the window. Wrong-footed, Bel scooped up her bag and the leather portfolio beside it and followed. The women sat down opposite each other and Susan smiled, her teeth like a line of chalky toothpaste between the dark pink lipstick. ‘You wanted to see Sir Broderick,’ she said. No preamble, no small talk about the view. Just straight to the chase. It was a technique Bel had used herself on occasion, but that didn’t mean she enjoyed the tables being turned.

‘That’s right.’

Susan shook her head. ‘Sir Broderick does not speak to the press. I fear you’ve had a wasted journey. I did explain all that to your assistant, but he wouldn’t take no for an answer.’

It was Bel’s turn to produce a smile without warmth. ‘Good for him. I’ve obviously got him well trained. But there seems to be a misunderstanding. I’m not here to beg for an interview. I’m here because I think I have something Sir Broderick will be interested in.’ She lifted the portfolio on to the table and unzipped it. From inside, she took a single A3 sheet of heavyweight paper, face down. It was smeared with dirt and gave off a faint smell, a curious blend of dust, urine and lavender. Bel couldn’t resist a quick teasing look at Susan Charleson. ‘Would you like to see?’ she said, flipping the paper.

Susan took a leather case from the pocket of her skirt and extracted a pair of tortoiseshell glasses. She perched them on her nose, taking her time about it but her eyes never leaving the stark black-and-white images before her. The silence between the women seemed to expand, and Bel felt almost breathless as she waited for a response. ‘Where did you come by this?’ Susan said, her tone as prim as a Latin mistress.

Monday 18th June 2007; Campora, Tuscany, Italy.

At seven in the morning, it was almost possible to believe that the baking heat of the previous ten days might not show up for work. Pearly daylight shimmered through the canopy of oak and chestnut leaves, making visible the motes of dust that spiralled upwards from Bel’s feet. She was moving slowly enough to notice because the unmade track that wound down through the woods was rutted and pitted, the jagged stones scattered over it enough to make any jogger conscious of the fragility of ankles.

Only two more of these cherished early-morning runs before she’d have to head back to the suffocating streets of London. The thought provoked a tiny tug of regret. Bel loved slipping out of the villa while everyone else was still asleep. She could walk barefoot over cool marble floors, pretending she was chatelaine of the whole place, not just another holiday tenant carving off a slice of borrowed Tuscan elegance.

She’d been coming on holiday with the same group of five friends since they’d shared a house in their final year at Durham. That first time, they’d all been cramming for their finals. One set of parents had a cottage in Cornwall that they’d colonized for a week. They’d called it a study break, but in truth, it had been more of a holiday that had refreshed and relaxed them, leaving them better placed to sit exams than if they’d huddled over books and articles. And although they were modern young women not given to superstition, they’d all felt that their week together had somehow been responsible for their good degrees. Since then, they’d gathered together every June for a reunion, committed to pleasure.

Over the years, their drinking had grown more discerning, their eating more epicurean and their conversation more outrageous. The locations had become progressively more luxurious. Lovers were never invited to share the girls’ week. Occasionally, one of their number had a little wobble, claiming pressure of work or family obligations, but they were generally whipped back into line without too much effort.

For Bel, it was a significant component of her life. These women were all successful, all private sources she could count on to smooth her path from time to time. But still, that wasn’t the main reason this holiday was so important to her. Partners had come and gone, but these friends had been constant. In a world where you were measured by your last headline, it felt good to have a bolthole where none of that mattered. Where she was appreciated simply because the group enjoyed themselves more with her than without her. They’d all known each other long enough to forgive each other’s faults, to accept each other’s politics and to say what would be unsayable in any other company. This holiday formed part of the bulwark she constantly shored up against her own insecurities. Besides, it was the only holiday she took these days that was about what she wanted. For the past half dozen years, she’d been bound to her widowed sister Vivianne and her son Harry. The sudden death of Vivianne’s husband from a heart attack had left her stranded emotionally and struggling practically. Bel had barely hesitated before throwing her lot in with her sister and her nephew. On balance it had been a good decision, but even so she still treasured this annual work-free break from a family life she hadn’t expected to be living. Especially now that Harry was teetering on the edge of teenage existential angst. So this year, even more than in the past, the holiday had to be special, to outdo what had gone before.

It was hard to imagine how they could improve on this, she thought as she emerged from the trees and turned into a field of sunflowers preparing to burst into bloom. She speeded up a little as she made her way along the margin, her nose twitching at the aromatic perfume of the greenery. There was nothing she’d change about the villa, no fault she could find with the informal gardens and fruit trees that surrounded the loggia and the pool. The view across the Val d’Elsa was stunning, with Volterra and San Gimignano on the distant skyline.

And there was the added bonus of Grazia’s cooking. When they’d discovered that the ‘local chef’ trumpeted on the website was the wife of the pig farmer down the hill, they’d been wary of taking up the option of having her come to the villa and prepare a typically Tuscan meal. But on the third afternoon, they’d all been too stunned by the heat to be bothered with cooking so they’d summoned Grazia. Her husband Maurizio had delivered her to the villa in a battered Fiat Panda that appeared to be held together with string and faith. He’d also unloaded boxes of food covered in muslin cloths. In fractured English, Grazia had thrown them out of the kitchen and told them to relax with a drink on the loggia.

The meal had been a revelation - nutty salamis and prosciutto from the rare-breed Cinta di Siena pigs Maurizio bred, coupled with fragrant black figs from their own tree; spaghetti with pesto made from tarragon and basil; quails roasted with Maurizio’s vegetables, and long fingers of potatoes flavoured with rosemary and garlic; cheeses from local farms, and finally, a rich cake heavy with limoncello and almonds.

The women never cooked dinner again.

Grazia’s cooking made Bel’s morning runs all the more necessary. As forty approached, she struggled harder to maintain what she thought of as her fighting weight. This morning, her stomach still felt like a tight round ball after the meltingly delicious melanzane alla parmigiana that had provoked her into an excessive second helping. She’d go a little further than usual, she decided. Instead of making a circuit of the sunflower field and climbing back up to their villa, she would take a track that ran from the far corner through the overgrown grounds of a ruined casa colonica she’d noticed from the car. Ever since she’d spotted it on their first morning, she’d indulged a fantasy of buying the ruin and transforming it into the ultimate Tuscan retreat, complete with swimming pool and olive grove. And of course, Grazia on hand to cook. Bel had few qualms about poaching, neither in fantasy nor reality.

But she knew herself well enough to understand it would never be more than a pipe dream. Having a retreat implied a willingness to step away from the world of work that was alien to her. Maybe when she was ready to retire she could contemplate devoting herself to such a restoration project. Except that she recognized that as another daydream. Journalists never really retired. There was always another story on the horizon, another target to pursue. Not to mention the terror of being forgotten. All reasons why past relationships had failed to stay the course, all reasons why the future probably held the same imperfections. Still, it would be fun to take a closer look at the old house, to see just how bad a state it was in. When she’d mentioned it to Grazia, she’d pulled a face and called it rovina. Bel, whose Italian was fluent, had translated it for the others; ‘ruin’. Time to find out whether Grazia was telling the truth or just trying to divert the interest of the rich English women.

The path through the long grass was still surprisingly clear, bare soil packed hard by years of foot traffic. Bel took the opportunity to pick up speed, then slowed as she reached the edge of the gated courtyard in front of the old farmhouse. The gates were dilapidated, hanging drunkenly from hinges that were barely attached to the tall stone posts. A heavy chain and padlock held them fastened. Beyond, the courtyard’s broken paving was demarcated with tufts of creeping thyme, camomile and coarse weeds. Bel shook the gates without much expectation. But that was enough to reveal that the bottom corner of the right-hand gate had parted company completely with its support. It could readily be pulled clear enough to allow an adult through the gap. Bel slipped through and let go. The gate creaked faintly as it settled back into place, returning to apparent closure.

Close up, she could understand Grazia’s description. Anyone taking this project on would be in thrall to the builders for a very long time. The house surrounded the courtyard on three sides, a central wing flanked by a matching pair of arms. There were two storeys, with a loggia running round the whole of the upper floor, doors and windows giving on to it, providing the bedrooms with easy access to fresh air and common space. But the loggia floor sagged, what doors remained were skewed, and the lintels above the windows were cracked and oddly angled. The window panes on both floors were filthy, cracked or missing. But still the solid lines of the attractive vernacular architecture were obvious and the rough stones glowed warm in the morning sun.

Bel couldn’t have explained why, but the house drew her closer. It had the raddled charm of a former beauty sufficiently self-assured to let herself go without a fight. Unpruned bougainvillea straggled up the peeling ochre stucco and over the low wall of the loggia. If nobody chose to fall in love with this place soon, it was going to be overwhelmed by vegetation. In a couple of generations, it would be nothing more than an inexplicable mound on the hillside. But for now, it still had the power to bewitch.

She picked her way across the crumbling courtyard, passing cracked terracotta pots lying askew, the herbs they’d contained sprawling and springing free, spicing the air with their fragrances. She pushed against a heavy door made of wooden planks hanging from a single hinge. The wood screeched against an uneven floor of herringbone brick, but it opened wide enough for Bel to enter a large room without squeezing. Her first impression was of grime and neglect. Cobwebs were strung in a maze from wall to wall. The windows were mottled with dirt. A distant scurrying had Bel peering around in panic. She had no fear of news editors, but four-legged rats filled her with revulsion.

As she grew accustomed to the gloom, Bel realized the room wasn’t completely empty. A long table stood against one wall. Opposite was a sagging sofa. Judging by the rest of the place, it should have been rotten and filthy, but the dark red upholstery was still relatively clean. She filed the oddity for further consideration.

Bel hesitated for a moment. None of her friends, she was sure, would be urging her to penetrate deeper into this strange deserted house. But she had built her career on a reputation for fearlessness. Only she knew how often the image had concealed levels of anxiety and uncertainty that had reduced her to throwing up in gutters and strange toilets. Given what she’d faced down in her determination to secure a story, how scary could a deserted ruin be?

A doorway in the far corner led to a cramped hallway with a worn stone staircase climbing up to the loggia. Beyond, she could see another dark and grubby room. She peered in, surprised to see a thin cord strung across one corner from which half a dozen metal coat hangers dangled. A knitted scarf was slung round the neck of one of the hangers. Beneath it, she could see a crumpled pile of camouflage material. It looked like one of the shooting jackets on sale at the van that occupied the lay-by opposite the café on the main Colle Val d’Elsa road. The women had been laughing about it just the other day, wondering when exactly it had become fashionable for Italian men of all ages to look as if they’d just walked in from a tour of duty in the Balkans. Weird, she thought. Bel cautiously climbed the stairs to the loggia, expecting the same sense of long-abandoned habitation.

But as soon as she emerged from the stairwell, she realized she’d stepped into something very different. When she turned to her left and glanced in the first door, she understood this house was not what it seemed. The rancid mustiness of the lower floor was only a faint note here, the air almost as fresh as it was outside. The room had obviously been a bedroom, and fairly recently at that. A mattress lay on the floor, a bedspread flung back casually across the bottom third. It was dusty, but had none of the ingrained grime the lower floor had led Bel to expect. Again, a cord was strung across the corner. There were a dozen empty hangers, but the final three held slightly crumpled shirts. Even from a distance, she could see they were past their best, fade lines across the sleeves and collars.

A pair of tomato crates acted as bedside tables. One held a stump of candle in a saucer. A yellowed copy of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung lay on the floor next to the bed. Bel picked it up, noting that the date was less than four months ago. So that gave her an idea of when this place had been last abandoned. She lifted one of the shirtsleeves and pressed it to her nose. Rosemary and marijuana. Faint but unmistakable.

She went back to the loggia and checked out the other rooms. The pattern was similar. Three more bedrooms containing a handful of leftovers - a couple of T-shirts, paperbacks and magazines in English, Italian and German, half a bottle of wine, the stub of a lipstick, a leather sandal whose sole had parted company with its upper - the sort of things you would leave behind if you were moving out with no thought of who might come after. In one, a bunch of flowers stuck in an olive jar had dried to fragility.

The final room on the west side was the biggest so far. Its windows had been cleaned more recently than any of the others, its shutters renovated and its walls whitewashed. Standing in the middle of the floor was a silk-screen printing frame. Trestle tables set against one wall contained plastic cups stained inside with dried pigments, and brushes stiff with neglect. A scatter of spots and blots marked the floor. Bel was intrigued, her curiosity overcoming any lingering nervousness at being alone in this peculiar place. Whoever had been here must have cleared out in a hurry. Leaving a substantial silk-screen frame behind wasn’t what you would do if your departure was planned.

She backed out of the studio and made her way along the loggia to the wing opposite. She was careful to stay close to the wall, not trusting the undulating brick floor with her weight. She passed the bedroom doors, feeling like a trespasser on the Mary Celeste. A silence unbroken even by bird-song accentuated the impression. The last room before the corner was a bathroom whose nauseating mix of odours still hung in the air. A coil of hosepipe lay on the floor, its tail end disappearing through a hole in the masonry near the window. So they had improvised some sort of running water, though not enough to make the toilet anything less than disgusting. She wrinkled her nose and backed away.

Bel rounded the corner just as the sun cleared the corner of the woods, flooding her in sudden warmth. It made her entry into the final room all the more chilling. Shivering at the dank air, she ventured inside. The shutters were pulled tight, making the interior almost too dim to discern anything. But as her eyes adjusted, she gained a sense of the room. It was the twin of the studio in scale, but its function was quite different. She crossed to the nearest window and struggled with the shutter, finally managing to haul it halfway open. It was enough to confirm her first impression. This had been the heart of the occupation of the casa rovina. A battered old cooking range connected to a gas cylinder stood by a stone sink. The dining table was scarred and stripped to the bare wood, but it was solid and had beautifully carved legs. Seven unmatched chairs sat around it, an eighth overturned a few feet away. A rocking chair and a couple of sofas lined the walls. Odd bits of crockery and cutlery lay scattered around, as if the inhabitants couldn’t be bothered collecting them when they’d left.

As Bel walked back from the window, a rickety table caught her eye. Standing behind the door, it was easy to miss. An untidy scatter of what appeared to be posters lay across it. Fascinated, she moved towards it. Two strides and she stopped short, her sharp gasp echoing in the dusty air.

Before her on the limestone flags was an irregular stain, perhaps three feet by eighteen inches. Rusty brown, its edges were rounded and smooth, as if it had flowed and pooled rather than spilled. It was thick enough to obscure the flags beneath. One section on the farthest edge looked smudged and thinned, as if someone had tried to scrub it clean and soon given up. Bel had covered enough stories of domestic violence and sexual homicide to recognize a serious bloodstain when she saw it.

Startled, she stepped back, head swivelling from side to side, heart thudding so hard she thought it might choke her. What the hell had happened here? She looked around wildly, noticing other dark stains marking the floor beyond the table. Time to get out of here, the sensible part of her mind was screaming. But the devil of curiosity muttered in her ear. There’s been nobody here for months. Look at the dust. They’re long gone. They’re not going to be back any time soon. Whatever happened here was good reason for them to clear out. Check out the posters…

Bel skirted the stain, giving it as wide a berth as she could without touching any of the furniture. All at once, she felt a taint in the air. Knew it was imagination, but still it seemed real. Back to the room, face to the door, she crab-walked to the table and looked down at the posters strewn across it.

The second shock was almost more powerful than the first.

Bel knew she was pushing too hard up the hill, but she couldn’t pace herself. She could feel the sweat from her hand coating the good quality paper of the rolled-up poster. At last the track emerged from the trees and became less treacherous as it approached their holiday villa. The road sloped down almost imperceptibly, but gravity was enough to give her tired legs an extra boost and she was still moving fast when she rounded the corner of the house to find Lisa Martyn stretched out on the shady terrace in a pool chair with Friday’s Guardian for company. Bel felt relief. She needed to talk to someone and, of all her companions, Lisa was least likely to turn her revelations into dinner party gossip. A human rights lawyer whose compassion and feminism seemed as ineluctable as every breath she took, Lisa would understand the potential of the discovery Bel thought she had made. And her right to handle it as she saw fit.

Lisa dragged her eyes away from the newspaper, distracted by the unfamiliar heave of Bel’s breath. ‘My God,’ she said. ‘You look like you’re about to stroke out.’