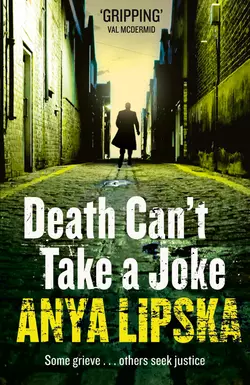

Death Can’t Take a Joke

Anya Lipska

The second Kiszka and Kershaw crime thriller.When masked men brutally stab one of his closest friends to death, Janusz Kiszka – fixer to East London’s Poles – must dig deep into London’s criminal underbelly to track down the killers and deliver justice.Shadowing a beautiful Ukrainian girl he believes could solve the mystery, Kiszka soon finds himself skating dangerously close to her ruthless ‘businessman’ boyfriend. Meanwhile, his old nemesis, rookie police detective Natalie Kershaw is struggling to identify a mystery suicide, a Pole who jumped off the top of Canary Wharf Tower. But all is not what it seems…Sparks fly as Kiszka and Kershaw’s paths cross for a second time, but they must call a truce when their separate investigations call for a journey to Poland’s wintry eastern borders…Lipska was chosen by Val McDermid for the prestigious New Blood Panel at the 2013 Harrogate Crime Festival. Her second in the series promises another intelligent yet gripping detective thriller and a glimpse into the hidden world of London’s Polish community.

Death Can’t Take A Joke

(A KISZKA & KERSHAW MYSTERY)

BY ANYA LIPSKA

Contents

Title Page (#u2cc859c2-269e-5010-b1d2-049cbe8049c9)

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Epilogue

Also by Anya Lipska

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Prologue (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

If I don’t hang on I will die. My fingers are curled into claws. So cold and numb they feel like they’re frozen to the ledge. The blackness comes … recedes again, but leaves only panic and confusion. Is this high, freezing place a mountaintop? I don’t remember climbing it. But then I can’t even recall my name right now above the wind’s howl.

Memories flicker out of the darkness like fragments caught on celluloid, briefly illuminated. A door made of plastic. A man in orange overalls. The insolent swish of something heavy through the air. Ducking – too late.

I try to brace my legs, to keep from falling. But the tremors are so bad, they’re useless. In a blinding surge of rage I vow: Somebody’s going to die for this. Then a great wind screams in my face and tears my fingers from their grip.

And I realise the somebody is me.

One (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

Detective Constable Natalie Kershaw sat on the outdoor terrace of Starbucks in the lee of the Canary Wharf tower, treating herself to an overpriced and underpowered cappuccino. In her chalk stripe trousers and black wool jacket she could have passed for another of the City workers getting their early morning fix of caffeine.

Kershaw was celebrating the last day of her secondment to Docklands nick: the stint in financial crime would look good on her CV, but after three months navigating the murky channels of international money laundering, she was gagging to get back to some proper police work. And not just the routine stuff – the credit card frauds, street robberies and domestic violence that had dominated her career so far. No. In two days’ time she’d finally become what she’d first set her sights on at the age of fourteen – a detective on Murder Squad.

Drinking the last of her coffee, she shivered. Despite the morning sun a chill hung in the air, and a light icing on her car windscreen that morning had signalled the first frost of autumn.

As she stood to go, something drew her gaze towards the glittering bulk of the tower less than twenty metres away.

Suddenly, she ducked: an instinctive reflex. The impression of something dark, flapping, the chequerboard windows of the tower flickering behind it like a reel of film. Then a colossal whump, followed by the sound of imploding glass and plastic. There was a split second of absolute silence before a woman at the next table started screaming, a thin high keening that bounced off the impassive facades of the high-rise office blocks surrounding the café.

Fuck! Kershaw took off running towards the site of the impact – a long dark limo parked nearby that had probably been waiting to pick someone up. There was a metre-wide crater in its roof and the windscreen lay shattered across the bonnet like imitation diamonds. She could hear an inanely cheery jingle still playing on the radio. The car was empty, the guy she presumed to be the driver standing just a few metres away, still holding the fag he’d left the car to smoke. His stricken gaze was fixed on the man-sized dent in the car roof – the spot where his head would have been moments earlier. Kershaw filed it away as a rare case of a cigarette extending someone’s life.

Three or four metres beyond the limo, the falling man lay where he had come to rest, in a slowly spreading lake of his own blood. He’d fallen face down, his overcoat spread either side of him like the unfurled wings of an angel. By some quirk of physics or anatomy, the fall had twisted his head around by almost 180 degrees, so that his half-closed eyes appeared to be gazing up at the wall of glass and concrete, as if calculating how many floors he had fallen.

Two (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

Some eight hours later, Janusz Kiszka strode up the ramp from the tube station to the street, struggling to navigate the ill-mannered torrent of returning rush hour commuters. Did no one in London say ‘excuse me’ any more? he grumbled to himself, before recalling that his father, God rest his soul, used to make pretty much the same complaint – back in eighties Gdansk. A rueful grin crept across his jaw. He’d need to be on guard against turning into a grumpy old man now that he was approaching the wrong end of his forties.

Janusz was out here on the East End’s northern fringe to meet one of his oldest friends, Jim Fulford, for an early evening jar, but he’d just picked up an apologetic message asking if they could delay their rendezvous. Which left him with a conundrum. How the fuck was he supposed to kill a whole hour in Walthamstow?

He stood irresolute at the crossroads on Hoe Street as people flowed around him. One woman in a yellow sari holding a tiny child by the hand stared openly as she passed. Even in this, one of the capital’s motliest neighbourhoods, a man of his height and size wearing a shabby military greatcoat and smoking a cigar was an intriguing sight. Janusz caught a glimpse of one of those brown and white signs indicating a nearby attraction. The William Morris Gallery. Sighing, he threw down his cigar stub. An hour spent looking at Arts and Crafts furniture wasn’t exactly top of his list of things to do but there weren’t too many other options on offer.

Fifty minutes later, he was on his way to the pub where Jim and he had been meeting every couple of weeks for the last twenty years or so. The Rochester stood in a part of Walthamstow where fried chicken takeaways and Asian grocers had given way to the delicatessens and knick-knack shops beloved of the middle class. Estate agents called it the Village to distinguish it from the plebeian multiculturalism of Hoe Street – and to help justify the neighbourhood’s inflated asking prices. It occurred to Janusz that history had come full circle. In the nineteenth century, the area had indeed been a pretty village settled initially by the genteel classes, before the advent of the railway and a building boom brought a surge of humbler folk from London’s slums. He recalled with a grin that in one of Morris’s diaries on display at the museum, the avowed socialist had bemoaned the arrival of the working classes, their mean houses lapping like a mucky tide around his own family’s elegant mansion.

Janusz pushed open the door to the lounge bar of the Rochester – and experienced a sudden jolt of unfamiliarity. He scanned the bar: he was in the right pub alright, but the place had changed beyond recognition. Its patterned carpet and pool table were gone, replaced by bare floorboards, sofas in distressed leather, and tables and chairs that looked like rejects from a charity shop. The walls had been painted a dismal shade of green.

Mother of God, thought Janusz, they’ve turned it into a fucking gastropub.

He felt a surge of rage: sometimes it felt as if everything that had been a comforting fixture in his life for the twenty-five years or more he’d lived in London was doomed to change.

It came as a relief to see a familiar face, at least, behind the bar.

‘Brendan,’ he growled, in not-quite mock fury. ‘What the fuck have you done with our boozer?’

Brendan chuckled but Janusz caught the way his gaze flickered round the bar, as a couple of people looked up, startled by the booming voice.

Janusz looked around, too, but didn’t recognise any of the punters. The only other person at the bar was a young guy in a cardigan frowning into his laptop. His beard, which was carefully coiffed to a point, made him look like he’d just escaped from a Van Dyck painting. And when Janusz checked out his favourite spot by the fireplace, he found it taken by a well-dressed couple chatting softly over food served on what appeared to be kitchen chopping boards.

Lowering his voice, Janusz ordered two bottles of Tyskie. It was one minute to six and Jim was always on time.

‘You’ll be meeting Jimbo then?’ asked Brendan, opening the fridge.

‘Yeah,’ said Janusz. ‘He’s the only guy I know you can order a beer for who’ll turn up while it’s still cold.’

‘Ah, once a Marine always a Marine, as the man himself never tires of saying.’

‘What does he make of his local’s new look then?’ said Janusz, a sly grin creeping across his face. He was picturing the expressions on the new punters’ faces when all eighteen stone of his boisterous crew-cut mate came barrelling in.

Brendan popped the caps off the beers. ‘He’s not what you’d call entirely in sympathy with it,’ he admitted in his Dublin lilt. ‘Especially now he can’t bring that dog of his in any more.’

Janusz winced. Jim owned a gym and fitness club off Hoe Street, and although his workout regime and armfuls of tattoos made him look like a member of some neo-Nazi cell, he was in reality the gentlest man Janusz had ever known. He was besotted with his wife Marika – who he’d first laid eyes on at a Polish wedding Janusz had taken him to a decade ago – but it was the way he fussed over his collie dog, Laika, that really gave the lie to his thuggish appearance.

Brendan named the new, eye-watering price for two bottles of beer and Janusz handed over a twenty.

Fifteen minutes later, Janusz sat frowning out of the window into the gathering dusk. Jim was unerringly punctual: he liked to say that in the Marines, being ten seconds late on operations could get your knob shot off. This would be followed by his trademark laugh, which resembled the joyous woof of a large but friendly dog. For all the joking, Janusz knew that Jim’s experiences in the Falklands War had left worse scars than the shiny cicatrice that ran the length of his right arm from knuckles to armpit. Janusz had never once heard him speak of the conflict, but Marika had told him that Jim had been trapped below decks on HMS Coventry after it was struck by an Argentine torpedo.

Jim and Janusz had both been in their twenties when they first met while working on a building site, part of the Docklands development, back in the eighties. At the time, Janusz had his own troubles: he’d recently escaped life under Poland’s communist regime – and a disastrous marriage. Although one hailed from Plaistow and the other from Gdansk, the two men quickly found they shared a black sense of humour and a healthy contempt for faceless authority.

Janusz ran a thoughtful finger down the mist of condensation on Jim’s un-drunk bottle of Tyskie. Thinking about the past always made him melancholic. He pulled out his mobile phone and punched out a message.

Where the fuck are you? it read. It’s your round.

Three (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

As last days at work go, this one had been seriously weird, thought DC Kershaw as she closed down her computer at Canary Wharf nick. It was gone 7 p.m. and she’d only just finished the paperwork on the roof jumper, which would make her late for her own leaving drinks.

That morning, the paramedics had reached the dead guy at the foot of the Canary Wharf tower around ten minutes after he hit the deck. It hadn’t taken them long to confirm the stark staring obvious – that the guy with his head on the wrong way round wasn’t going to make it.

Meanwhile, Kershaw had taken charge of diverting City workers around the scene. They were harmless rubberneckers for the most part, interspersed with the occasional tosser who objected to some five-foot-two-inch blonde girl with a Cockney accent withdrawing his constitutional right to walk where he chose. To be really honest? She liked dealing with these ones the best.

Finally, the promised uniform had arrived from the nick.

‘You took your time,’ she said.

‘Oh, was it urgent?’ he replied, all innocence. ‘I had a croissant on the way.’

She grinned: Nick Ferris was one of the good guys. Recent intake, with none of the ‘who do you think you are, missy?’ undercurrent she still sensed from some of the older uniformed cops.

‘NOT that way, sir,’ Kershaw told a master of the universe wearing a two-grand suit who was attempting a body swerve around her.

‘Have the silly bankers been giving you grief?’ Nick asked under his breath.

‘Nah,’ she said with a sigh of mock-disappointment. ‘I haven’t even had to get my stick out.’

He produced a reel of police tape and they started to cordon off the scene.

‘What’s the story here then?’ Nick nodded towards the body, which the paramedics were in the process of shielding from view with a white pop-up tent. Kershaw shrugged. ‘No idea. Maybe the market turned and he was left holding too many yen.’

In the tower reception, she’d found an upright fit-looking guy in his fifties with prematurely grey hair – unquestionably the head of security – rapping out instructions over his walkie-talkie. She flashed her warrant card and he introduced himself as Dougal Murray before ushering her through the metal security arch and straight into a lift.

‘The highest floor where witnesses saw something go past is the 49th,’ he told her in a no-nonsense Scots accent as they hummed skywards. ‘There’s only one level above that, so I’ve got my team questioning all the companies on 50 to establish whether they have anyone missing.’

‘What about visitors?’ Kershaw asked.

He unfolded a printout. ‘All visitors sign in and out and are issued with a security pass,’ he said. ‘I’ve marked everyone who signed in to visit the 50th floor this morning.’

‘That’s brilliant,’ Kershaw said, eyeing him with admiration. ‘Are you ex-police by any chance?’

‘RMP,’ he said, sticking his chin out.

Military Police. Kershaw grinned. With a bit of luck she’d have the jumper identified and be back at the nick in time for elevenses.

Two hours later, it had begun to dawn on her that she’d be lucky to be back for afternoon tea. Nick the PC had searched the body but found no clues to his identity: no wallet, no Oystercard, nothing. She’d worked through the entire list of 50th floor office workers who’d swiped in that morning and found them all alive and breathing. And then she’d reached the end of the visitors list. That had produced one brief glimmer of hope – a guy who had apparently left after a 7 a.m. meeting but whom the system showed as still present in the building. But when Kershaw called him on his mobile, he’d discovered he was still wearing the pass round his neck. Muppet.

And there was another problem. She and Dougal had made a full tour of the 50th floor and found the windows, which weren’t designed to be opened, sealed and intact. Above that there was only the roof, which was accessible via two flights of concrete stairs in the emergency stairwell. At the top, a push-bar fire door, of the kind you saw in cinemas, gave straight onto the exterior. Green and white letters spelt out the legend: ‘ALARMED DOOR – FIRE EXIT ONLY’.

‘You’ve checked the alarm was working?’ Kershaw asked. Dougal nodded.

‘Since it gives straight onto the roof I’d rather keep it locked,’ he said. ‘But health and safety won’t allow it.’ An arch of his eyebrow had told her what he thought of that.

As Kershaw stepped outside, a cold wind had whipped the hair from her face and stung her eyes.

They traversed the narrow walkway that skirted the building’s iconic pyramid-shaped glass apex, stepping around the steel gantries used to haul window cleaners up and down the 700-foot length of the tower. Halfway along the east side they came to a stop and peered over the edge. At the foot of the yawning cliff of glass, they could see a white dot on the pavement below – the tent covering the body.

Kershaw buttoned her coat to the neck. Up here, the wind, barely noticeable at ground level, had a savage power. ‘I don’t get it,’ she told Dougal, raising her voice above the wind’s roar. ‘There’s no way to get out here without setting off the alarm.’

He shook his head.

She squinted down at the tent far below. ‘Just my luck to get an unidentified suicide on my last day.’

‘You’re on the move then?’

‘Yeah. I’m starting a new job up in Walthamstow. In Murder Squad.’

‘Congratulations.’

‘Thanks. But it looks like I’ll be spending my first few days trying to find out who this guy is.’ She worried at the nail on her little finger.

‘Can you not just leave the case to Docklands police?’ He pronounced it poh-liss.

‘Yeah, I could,’ she said, pulling a sheepish face. ‘But I’ve got this thing. Once I start something I have to finish it.’ From the set of her shoulders, Dougal could tell that the wee girl meant it.

Kershaw’s dad used to tell her that she’d been that way ever since she was little. Not long after her mum died, he’d taken her fishing for the first time up at Walthamstow Reservoir. He said she’d taken to it right away, but the fish weren’t biting that day. One by one the other anglers packed up, and as the sun faded he wanted to call it a day, too. But nine-year-old Natalie wouldn’t leave. He’d tried everything, including the barefaced bribe of a visit to McDonalds. But she just kept saying: Not till I’ve caught a fish. By the time she bagged one – a respectable size tench – her dad was dozing on the bank and the moon had risen, spilling quicksilver across the water.

Descending in the lift with Dougal, Kershaw fell silent, puzzling over the mystery of the falling man. To gain access to the roof he must have disabled the alarm – or got someone to do it for him. But given that he’d fallen at about 9 a.m., when loads of people would have been at their desks, surely somebody must have noticed a strange man prowling around?

‘I’m going to need to interview all your security staff,’ she told Dougal.

He nodded. ‘Including the ones who weren’t on duty?’

‘Especially the ones who weren’t on duty. I think our chum might have got onto the roof during the night, when it was quiet.’

By the time Kershaw had left the tower, dusk had fallen, bringing a penetrating chill to the air. The body and its protective tent had gone and a two-man unit from the local council were using high-pressure hoses to clean blood from the impact site. The wet pavement shone in the reflected glow of a thousand brightly lit offices.

Back at Canary Wharf nick, the uniform skipper on front desk beckoned her over. ‘I’ve got something for you,’ he said. He held out a plastic evidence bag. ‘PC Ferris found this in the gutter. It might have nothing to do with our friend, but he says it was just a few feet from the body.’

A silver coin winked through the polythene: about the same size as a 10p piece, but inset with a bronze roundel depicting a crowned eagle, wings spread wide. Squinting to read the inscription around the edge, one word jumped out at her. Kershaw was no linguist but she knew one thing. Polska meant Poland.

Four (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

At around 8 a.m. the morning after Jim had stood him up at the Rochester, Janusz Kiszka found himself back in Walthamstow, this time on the south side of Hoe Street. Reaching the end of a terrace of two-up two-downs, he spotted what he guessed to be his destination: just outside the ironwork gates of a cemetery, a low redbrick building in the Victorian municipal style. Checking on his phone that he had the right place, he went in and gave his name to the lady on reception.

As he stood waiting, the only thing that cut through the foggy hum that had enveloped his brain since he’d heard the news a couple of hours ago was the smell of the place – a century of dust and old paper mingled with a powerful disinfectant.

He barely acknowledged the uniformed cop awaiting him in the gloomy little anteroom at the end of the corridor. They exchanged a few words, then the cop led the way into a second, larger room. There, drawing back a blue sheet on a hospital-style gurney, he unveiled the face of Jim Fulford.

For a split second, Janusz didn’t recognise him, so alien was this version of his friend. In total repose his face looked … stern, an expression he couldn’t remember ever seeing in the living Jim. But his moment of confusion – and irrational hope – didn’t last. It might not be the friend he’d known for two decades, but there was no denying that this austere waxwork was his body. There was the thumbprint-sized dent in his left temple, souvenir of the time someone accidentally dropped a lump hammer off a scaffold tower. That had been a lifetime ago, on the Broadgate build – and yet Janusz could remember it as though it were yesterday.

A warning shout, Jim going down like a felled oak an arm’s length away, blood streaming from his head. After coming round, he’d claimed he was absolutely fine, and wanted to get back to work. Janusz practically had to wrestle him into a cab, taking him to Whitechapel Hospital, where the medics diagnosed a severe concussion. Even twenty years later Jim was fond of saying, with his friendly bark of a laugh, that Janusz still owed him a monkey – five hundred quid – in lost earnings.

Janusz laid a tentative hand on his dead friend’s chest, still covered by the blue sheet, and found it as cold and unyielding as a sack of flour. He thought of his mother then: her body had at least still felt warm when he’d kissed her goodbye. Was that all life was then – a matter of temperature?

He found himself out on the street again, with no memory of how he’d got there. His thoughts clashed and clattered like balls on a pool table, grief and disbelief battling rage at what had happened. How could it be that Jim had survived a decade working on building sites and an Argentinian torpedo, only to be stabbed to death on his own doorstep, apparently by a couple of junkies? It was nieznosne – unbearable.

People on their way to work averted their eyes as they passed the big man pounding the pavement, his jaw set and eyes narrowed in some blistering inner fury. Mental health case: best avoided, most of them concluded.

Ten minutes later, Janusz turned into Barclay Road, Jim and Marika’s street. As he neared their neat, cream-painted terraced house, he slowed, and saw something that made his insides plummet. The low brick garden wall – a wall that Janusz and Jim had rebuilt with their own hands one hot, beer-fuelled summer’s day – had all but disappeared beneath a drift of cellophane-wrapped bouquets that rustled in the breeze. Two tea lights in red perspex holders on top of the wall completed its transformation into a shrine.

As Janusz watched, a middle-aged woman approached, holding the hand of a little girl. She leaned down to whisper to the child, who, taking an awkward step forward, bent to add a bunch of yellow flowers to the pile.

He paused in the porch to take a couple of deep breaths, determined to master himself. Of course, Marika knew that the man who paramedics had rushed to hospital last night from this address could only be her husband, but as she hadn’t been able to face identifying his body herself, she’d still be inhabiting that hazy hinterland of denial – a zone Janusz had barely left himself.

She opened the front door and searched his face, before sleepwalking into his arms. Holding her to his chest so tightly that her hot tears soaked through to his skin in an instant, he sent a grim-faced nod of greeting over her shoulder to Basia, her sister, who looked on from the kitchen doorway.

Finally, Marika drew her head back and looked up at him. ‘Thank you, Janek, for going to him,’ she said, her voice thick with tears. ‘I will go to see him later, with Basia.’

The three of them sat around the kitchen table nursing un-drunk cups of tea, under the mournful gaze of Laika, who had not raced to greet Janusz today but instead lay silent in her basket, her long black-and-white nose resting on crossed paws.

‘Basia and I, we had gone out to our Pilates class,’ said Marika, ‘and when we came back, about nine o’clock, the police were waiting outside.’ Her voice was husky and almost toneless. ‘They’d … taken him away to the hospital by then, but they say he was already dead.’ Her eyes filled with tears again.

As Basia put an arm around her shoulder, murmuring words of comfort, Janusz realised that Marika was speaking in Polish, which he couldn’t remember her doing since she’d married Jim. Now grief had stripped away the last ten years, throwing her back on her mother tongue.

After a moment, she pulled herself upright and used both hands to sweep the tears from her cheeks – a determined gesture.

‘What did the cops say?’ he asked. ‘Did they question the neighbours straightaway? Right after the … after Jim was found?’

She nodded. ‘Jason who lives two doors down heard a shout when he was putting out the rubbish bags.’ She paused, took a steadying breath. ‘It was starting to get dark, but he saw two men running away, through the garden gate.’

‘Which way were they headed? Hoe Street? Or Lea Bridge Road?’ Janusz was relieved to find himself slipping into private investigator mode.

‘Hoe Street, I think he said.’

‘What did they look like?’

‘They both wore hoodies and balaclavas,’ she said, dropping into English for these unfamiliar words. ‘So all he could say was that one was tall – almost two metres – and slim, the other a little shorter.’

‘Black? White?’

She gave a hopeless shrug. ‘It was dark, and with the faces covered, he couldn’t tell.’

Janusz hesitated. He needed to know exactly how Jim had died but he couldn’t think of a sensitive way to frame the question. From Laika’s basket came a tentative whine of distress.

Marika’s swollen eyes met his and a look of understanding passed between them. ‘The police said …’ her voice had fallen to a croak. ‘They told me he had suffered several deep stab wounds … in his stomach. One severed an artery …’ She tried to go on but then gave up. ‘I’m sorry, Janek,’ she said. ‘Is it okay if I let Basia tell you the rest? I need to lie down.’ She stood unsteadily, her chair grating harshly on the stone floor tiles.

Janusz jumped to his feet and went to her, his shovel-like hands encircling her slender forearms. At his touch, Marika’s eyes filled with fresh tears.

‘You know that he was an only child,’ she said, grief roughening her voice. ‘But he always said he didn’t miss not having a brother – because he had you.’

She winced and Janusz realised that, without meaning to, he had tightened his grip on her arms.

‘You rest, Marika,’ he said, bending to lock his gaze on hers. ‘But there’s something I want you to know. Whatever it takes, I will find the skurwysyny who did this.’

They embraced then, three times on alternate cheeks in the Polish way. He stood watching her walk slowly down the hall, choosing her footing carefully, as though stepping through the debris of her shattered life. Laika rose to follow her, bushy tail down, claws tick-ticking on the wooden floor.

To avoid disturbing Marika – her bedroom lay right above the kitchen – Basia took Janusz into the front room and closed the door.

‘There’s no way he could have been saved,’ she said, eyebrows steepled in sorrow. ‘Marika doesn’t know this, but the police told me those dirty chuje – excuse my language – they practically gutted him. He lost sixty per cent of his blood lying there on the garden path.’

Janusz blinked a few times, trying to dispel an image of his big strong mate lying helpless on the ground, his life ebbing away across the black and white tiles.

‘They wouldn’t let Marika near the house,’ Basia went on. ‘We went to my flat and I only brought her back here once …’ her knuckles flew to her lips ‘… once everything was cleaned up.’ Seeing her stricken face, Janusz remembered something. All those years ago, it had been Basia whom Jim had dated first, if only for a few weeks, before he’d become smitten with her older sister. Janusz had ensured, naturalnie, that Jim got plenty of ribbing down the building site for getting lucky with both sisters, but as far as he could recall, there had been no hard feelings between any of the trio when Jim and Marika became an item.

‘On the phone, you said something about junkies?’

Basia tipped her head. ‘It was something one of the policemen said, that maybe it was a robbery, to get money for narkotyki.’

Janusz frowned. The house was over a mile from the notorious council estates west of Hoe Street, bordering neighbouring Tottenham, that were home to Walthamstow’s drug gangs. Would those scumbags really travel all the way up here to rob a random householder on the doorstep of his modest terraced house? Then he remembered Jim’s text delaying their meeting.

‘Do you know why he was running late for our pint at the Rochester?’

She nodded. ‘Marika asked him to fix a leaking tap in the downstairs cloakroom, so he came back from work early to do it before going out again.’

‘He didn’t say anything about someone coming to the house to see him, before he came to meet me? Maybe that new deputy manager of his?’

The gym was doing so well that Jim had expanded six months earlier, taking on a young local guy to help manage it, although the last time they’d met, Jim had hinted that the new staff member wasn’t proving a great success. I’m not really cut out for bossing people about, he’d confided to Janusz, his usually sunny face downcast.

‘No,’ said Basia. ‘When we left here to go to Pilates, we were all joking around, Jim saying he couldn’t wait to get rid of us so he could sit down and read the paper.’ She lifted a shoulder in the peculiarly expressive way Polish women had. ‘It was just a normal day.’

Janusz gazed out of the bay window that framed the tiny front garden and flower-strewn wall like a tableau. Through the half-closed slats of the blinds a young woman came into view, slowing to a halt in front of the wall. She stooped to lay something, and he saw her lips moving, as though in silent prayer. There was something about her that caught his attention. It wasn’t just that, even half-obscured, she was strikingly beautiful; it was the powerful impression that the sadness on her face and in the slope of her shoulders seemed more profound – more personal – than might be expected from a neighbour or casual acquaintance of the dead man.

‘Basia,’ he growled in an undertone. ‘Do you recognise that girl?’

Basia frowned out through the blinds, shook her head. Outside, the girl bent her head in a respectful gesture, crossed herself twice, and turned to leave.

Driven by some instinct he couldn’t explain, Janusz leapt up from the sofa and, telling Basia that he’d phone to check on Marika later, let himself out of the front door. The girl had nestled a new bouquet among the other offerings, but her expensive-looking hand-tied bunch of cream calla lilies and vivid blue hyacinths stood out from the surrounding cellophane-sheafed blooms. After checking that there was no accompanying note or card, he scanned up and down the street. Empty. Crossing to the other side of the road, he was rewarded by the sight of the girl’s slender figure a hundred metres away, walking towards the centre of Walthamstow.

Gradually, he closed the gap to around fifty metres. By a stroke of luck, a young guy carrying an architect’s portfolio case had emerged from a garden gate ahead of him so that if the girl happened to glance behind she’d be unlikely to spot Janusz. From the glimpses he got he could see that, even allowing for the vertiginous heels, she was tall for a woman, her graceful stride reminiscent of a catwalk model’s.

The girl passed the churchyard that marked the seventeenth-century heart of Walthamstow Village, where the breeze threw a handful of yellow leaves in her wake like confetti, but she didn’t take the tiny passageway that led down to the tube as Janusz had half expected, heading instead for Hoe Street. Once she was enveloped by its pavement throng he was able to get closer, taking in details such as the discreetly expensive look of the bag slung over the girl’s shoulder and the way her dark blonde hair shone like honey in the morning light.

Then a black Land Rover Discovery surged out of the stream of barely moving traffic with a throaty growl and came to a stop, two wheels up on the pavement, ahead of the girl. The driver, a youngish man with a number two crew cut, wearing a black leather jacket, jumped out and went over to her. When she shook her head and carried on, he walked alongside her, talking into her ear. A few seconds later, she tried to break away but he put a staying hand on her upper arm, a gesture at once intimate, yet controlling. She didn’t shake it off, instead slowing to a halt. From the angle of his head it was clear the guy was cajoling her.

Janusz could make out a densely inked tattoo on the back of the guy’s hand, which disappeared beneath the cuffs of his jacket, and emerged above the collar. A snake, he realised – its open jaws spread across his knuckles, the tip of its tail coiling up behind his ear. The girl’s head was bent now, submissive. After a moment or two, she gave an almost imperceptible shrug, and allowed herself to be ushered to the car.

She climbed into the back seat where Janusz glimpsed the outline of another passenger – a man – before the Land Rover slid back into the traffic. He cursed softly: with no black cabs cruising for fares this far east, he had no way of following them. But twenty seconds later, just beyond a Polish sklep where Janusz sometimes bought rye bread flour, the Land Rover threw a sudden left turn that made its tyres shriek.

Janusz doubled his stride towards the turnoff. When he reached the corner it was just as he remembered: the road was a dead-end, and the big black car had pulled up not twenty metres away, its engine murmuring. He stopped, and pulling out his mobile, pretended to be taking a call. Through the rear window of the car, seated next to the girl, he could see a wide-shouldered, bullet-headed man. Judging by his angrily working profile and her bowed head, she was getting a tirade of abuse. Even from this distance the man gave off the unmistakable aura of power and menace. When he appeared to fall silent for a moment, the girl turned and said something. A swift blur of movement and the girl’s head ricocheted off the side window. Janusz clenched his fists: the fucker had hit her! Only a conscious act of self-control stopped him sprinting to the car and dragging the skurwiel out to administer a lesson in the proper treatment of women. A half-second later, the kerbside door flew open and he pushed the girl out onto the pavement. The door slammed, the car performed a screeching U-turn, mounting the opposite pavement in the process, and sped off back to Hoe Street.

Janusz could restrain himself no longer: he jogged over to where the girl half-sat, half-sprawled on the kerb, her long legs folded beneath her like a fawn. She looked up at him, a dazed look in her greenish eyes, before accepting his arm and getting to her feet. Her movements were calm and dignified, but he noticed how badly her hands were shaking as she attempted to button her coat.

He retrieved one of her high-heeled shoes from the gutter and, once he was sure she was steady on her feet, stepped back. The last thing she needed right now was a man crowding her personal space.

‘Can I do anything?’ he asked. ‘I got the number plate – if you wanted to get the police involved, I mean?’

She touched the side of her head – the bastard had clearly hit her where the bruise wouldn’t show – and met his eyes with a look that mixed resignation with wary gratitude.

‘Thank you,’ she said finally, her dry half-smile telling him that the police weren’t really an option. ‘It is kind of you. But really, is not a problem.’ Her voice was attractively husky, with an Eastern European lilt – that much he was sure of – but not entirely Polish. If he had to lay money on it he’d say she hailed from further east, one of the countries bordering Russia, perhaps.

As she dusted the pavement grit from her palms his eyes lingered on her fine, long-boned fingers. Then he remembered why he had followed her in the first place: to find out her connection to Jim and why she would leave a bunch of expensive flowers in his memory. He was tempted for a moment to broach it with her there and then, but some instinct told him that a blunt enquiry would scare her off.

‘Allow me to give you my card, all the same,’ he said, proffering it with a little old-fashioned bow. It gave nothing away beyond his name and number and offered his only hope of future contact with the girl. ‘In case you change your mind – or should ever find yourself in need of assistance.’

She took the card, the wariness in her eyes giving way to a cautious warmth.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘A girl never knows when she might need a little assistance.’ And pocketing it, she turned, as graceful as a ballet dancer, and started to walk away.

‘May I know your name?’ Janusz asked to her departing back.

For a moment he thought she wasn’t going to answer, but then, without breaking step, she threw a single word over her shoulder.

‘Varenka!’

Five (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

Natalie Kershaw woke with a jolt, her heart pounding, convinced she was falling from the top of the Canary Wharf tower. Then the dream was gone, as evanescent as the vapour made by breath in frosty air. Turning over, she threaded an arm across Ben’s warm stomach and dozed, unconsciously synchronising her breathing with his. Ten minutes later, they both surfaced, woken by the muffled roar of a descending plane.

‘Shouldn’t you be getting up, Nat?’ murmured Ben. ‘First day of school and all that?’

Kershaw dug him in the ribs. ‘Don’t start pulling rank on me, just cos we’re in the same nick now.’

‘Am I sensing insubordination, Detective Constable?’ said Ben, putting a hand on her hip and pulling her towards him. ‘I hope this doesn’t mean a return of your well-known issues with the chain of command.’

After a quick mental calculation of how long it would take her to get from Ben’s place to Walthamstow, she added ten minutes to allow for traffic, then reached up to return his lazy kiss.

She and Ben had been together for almost two years now. They’d met while working at Canning Town CID but shortly afterwards their then-sergeant DS ‘Streaky’ Bacon had moved to Walthamstow, and encouraged Ben to apply for a sergeant post there in Divisional CID. Now that Kershaw was joining Streaky’s team on Walthamstow Murder Squad, she and Ben would be working in the same nick again for the first time in ages, although not – luckily – in the same office.

The relationship had had its ups and downs, for sure, but despite her instinctive caution, Kershaw was pretty sure that Ben was a keeper. As a fellow detective, he knew the score, which meant that unlike her previous boyfriend, an estate agent, he never lost the plot if she had to stand him up for dinner or rolled in a bit pissed after drinking with the team. More to the point, he seemed to understand that for her, the Job wasn’t, well, just a job. Okay, so she had, privately, felt somewhat irked when Ben had reached sergeant rank before her, but then he hadn’t been hauled up in front of Professional Standards for ‘flagrant disregard of the rulebook’ like she had.

Ancient history, she told herself. Today’s a fresh start.

She arrived at the nick a comfortable twelve minutes before the start of her shift. It had been three months since she’d heard she’d got the job, but when she told the receptionist that she was there to start work on Murder Squad, she felt her stomach perform a loop-the-loop.

Climbing the stairs, it hit her that she’d be thirty next year, and only now was her life panning out the way she’d imagined when she left uni. Better late than never, girl, she heard her dad saying. Better late than never. He’d been dead for three years, but so long as she could hear his voice in her head from time to time, it felt like he was still alongside her, somehow. Her mum was a much hazier memory but then Kershaw had been barely nine when she’d died, leaving Dad to bring her up single-handed.

She’d just reached the door marked Murder Squad when her mobile went off: Ben.

‘I was about to tell you, before you went and distracted me this morning, that I got a call from the agents,’ he said. ‘We can move into the new flat end of next week.’

Christ, she thought. That was quick. Over the last few months, Ben had waged a quiet yet dogged campaign for them to move in together, and she’d finally caved in. A couple of weekends ago they’d found the perfect place, a cosy flat in Leytonstone with its own pocket-sized garden.

‘Nat?’

‘Yeah, that’s fine,’ she replied. ‘Should give me plenty of time to box stuff up.’ She hoped her voice didn’t betray the sudden tightening she felt in her chest. Wasn’t this what she wanted? Kershaw told herself. To settle down, share her life with Ben?

‘You sure you’re cool with this?’ he asked. ‘Moving in together, I mean. If it’s too soon for you …’

The note of uncertainty in his voice prompted a rush of guilt. She tried to nail what it was, exactly, that was giving her the heebie jeebies. The prospect of giving up her independence after living on her own for the last two years? Partly, yes, but that wasn’t the whole story. Was it because Ben was sometimes a bit, well, too nice? The thought had barely entered her head before she dismissed it, angry with herself.

‘Of course I’m sure,’ she reassured him. ‘I was just … surprised that we were getting in so quickly.’

After hanging up, she gave herself a stern chat. Too nice?! If you don’t want to end up lying dead and undiscovered in some grimy flat being eaten by your own cats, Natalie Kershaw, you’d better waken your ideas up.

She was pushing open the office door when there came a familiar voice in the corridor behind her.

‘Ah! DC Kershaw!’ It was her old boss Detective Sergeant Bacon. ‘I see you’ve acquired a new hairstyle.’

‘Yes …’ Suddenly self-conscious, her hand flew to her blonde hair, newly styled in an asymmetric cut, one side three inches shorter than the other.

Hitching up the trousers of his ancient suit, he squinted down at her hair.

‘If I was you, I’d go back and ask for a refund,’ he confided. ‘Whoever cut it must’ve been three sheets to the wind.’

‘Yeah, I’ll do that, Sarge,’ she grinned. He’d gained even more weight, and lost a bit more gingery hair from the top of his head, but he was still the same old Streaky.

‘Anyway. Your arrival couldn’t be more timely – we’ve got an old chum of yours in interview room 2.’ Opening a door labelled Remote Monitoring Room, he winked at her. ‘You can watch it all on the telly.’

After Streaky shut the door behind her, and Kershaw took in the hulking figure slouched in a chair on the video feed, she was properly gobsmacked.

What the fuck? The last time she’d laid eyes on Janusz Kiszka had been in Bart’s hospital, after he’d got himself on the wrong end of a vendetta with a Polish drug gang. Since Kershaw’s conduct in that case had earned her a disciplinary hearing, the sight of the big Pole’s craggy mug, today of all days, was about as welcome as a cockroach in the cornflakes.

Hearing Streaky finish reading him the official caution, she forced herself to concentrate.

‘According to the statement you gave my colleague yesterday,’ said Streaky. ‘You’re aware that your friend James Fulford was stabbed to death on his doorstep at around 5.30 p.m. on Monday?’

Fuck! Kiszka was being questioned about a murder?

‘Could you just refresh my memory as to your whereabouts at that time, Mr Kissa-ka?’

Kershaw grinned. Streaky knew perfectly well how to pronounce Kiszka’s surname: he was mangling it deliberately to wind him up.

‘The William Morris Gallery,’ said Kiszka.

‘Go to a lot of galleries, do you?’

He shrugged. ‘I showed the other cop the text Jim sent me. He said he was going to be late for our meeting, so I had time to kill.’

Streaky paused, letting the word dangle in the air.

‘The trouble is, Mr Kiss-aka, I had one of my most experienced officers take your photo down to this … furniture museum – and there wasn’t a single member of staff who remembers you.’

‘It’s the only photo I had to hand,’ he hefted one shoulder. ‘It isn’t a very good likeness.’

Streaky opened the file in front of him and leafed through some papers.

‘Of course, this isn’t the first time you’ve been in a police interview room,’ he went on, fixing his suspect with a deadpan stare. ‘You were questioned in the course of another murder investigation a couple years back: one that involved drugs, shooting, and three dead bodies if memory serves.’

‘I’m a private investigator – it’s an occupation that sometimes requires me to deal with unsavoury characters,’ said Kiszka, staring right back.

‘I’ll bet it does,’ said Streaky, his voice heavy with irony. ‘But you never really explained how someone who claims to make his living chasing bad debts and missing persons ends up in a Polish gangster’s drug factory.’

‘Does your file mention that if I hadn’t been there the body count would have been even higher?’ he growled.

Streaky dropped his gaze. Advantage Kiszka, thought Kershaw.

‘Remind me how it was that you and James Fulford became friendly?’

‘Like I told the other cop, we met on a building site back in the eighties.’

‘And in all that time since then, you say you’ve just been drinking buddies, good mates, right?’

‘Yeah, that’s right,’ he said, pulling a tin out from his pocket.

Kershaw wrinkled her nose, remembering the little stinky cigars he smoked.

‘No smoking in here I’m afraid, Mr Kiss-aka,’ said Streaky, pointing at a sign. ‘So, you’ve never had any involvement in this gym he runs in Walthamstow?’

Kiszka shook his head.

‘No business dealings of any kind with each other? No property deals, for instance?’

‘No, nothing like that.’

Kershaw noticed he’d started tap-tapping his index finger on the cigar tin. A sign of impatience? Or a guilty conscience?

Streaky inserted the tip of his little finger into his ear. After rooting around for a few seconds, he examined the results of his excavation with a thoughtful expression.

‘How old are you, Mr Kiss-aka? Fifty-something?’

‘I’m forty-five,’ he growled.

‘Oh, sorry,’ said Streaky, feigning surprise. ‘Still, lots of people find the old memory banks start to let them down in their forties, don’t they?’

‘My memory is perfectly serviceable,’ he drawled – but Kershaw could tell from the set of his jaw that he was struggling to control his temper. For all his apparent cool and his old-school way of talking, Kiszka could still make the air around him buzz with the possibility of violence.

Streaky took a document from the file in front of him and pushed it across the table.

‘For the benefit of the tape, I have passed the interviewee a copy of the deeds held by the UK Land Registry for Jim’s Gym, Walthamstow, dated the 11th of November 1992.’

Kiszka picked up the document.

‘Would you care to confirm that that is your name on the first page, Mr Kiss-aka?’

As he examined it, the furrows on Kiszka’s face deepened.

‘We all have forgetful moments,’ said Streaky. ‘But I’m finding it hard to believe it slipped your mind that you’re the owner of Jim’s Gym.’

Kershaw gasped. Game to Streaky!

She held her breath as Kiszka opened his mouth to speak, then shut it again. He pushed the document back across the table.

‘I want to call my solicitor.’

Six (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

‘Just give me fifteen minutes with him, Sarge,’ said Kershaw. ‘We spent a lot of time together on that job so I know all his little tics and tells. I might get something useful out of him, even if it’s not admissible.’

Kershaw was perched on the edge of Streaky’s desk as she made her pitch for a chat with Kiszka, now installed in one of the holding cells downstairs. As the new girl on the squad, she was well aware she should be keeping her head down, restricting herself to ‘getting to know you’ chitchat with the other DCs, gathering crucial first day intelligence like where the biros and the digestives were kept – but that might mean her missing the chance to get herself drafted onto the Fulford case.

As Streaky stared into the distance, apparently lost in a daydream, Kershaw waited, knowing that if she pushed him, he’d more than likely blow his top.

‘Copernicus!’ he said finally, slapping the surface of his desk.

‘Sarge?’

‘I’ve been trying to remember the name of Kiszka’s cat,’ he said. ‘You mentioned it once – when you were investigating the murder of that Polish girl he was mixed up in. Stuck in my mind. Not many people name their moggies after Renaissance astronomers.’

‘Er?’

‘Nicolaus Copernicus.’ Streaky enunciated each syllable as though talking to a twelve-year-old. ‘Polish. Established the principle of heliocentrism.’ Peeling the foil back from a half-eaten pack of Rolos, he offered her one. ‘Didn’t they teach you anything at that comprehensive school of yours? Plaistow, wasn’t it?’

‘Poplar actually, Sarge,’ she said, taking one. ‘And I have heard of Copernicus. I’m just not quite sure what it has to do with Kiszka being a suspect.’

‘It tells me, detective, that he’s not your average villain,’ said Streaky, through a mouthful of chocolate. ‘Our Mr Kiszka fancies himself as a bit of an intellectual.’

Kershaw couldn’t disagree with that. Kiszka had always struck her as a man bristling with contradictions. He might have a science degree and the tendency to talk like someone out of a Jane Austen novel, but she knew from experience he wouldn’t hesitate to throw a punch – or break the law – in pursuit of an investigation.

‘So if it was him who shivved his so-called mate – and he’s top of my list at the moment,’ Streaky went on, ‘he might be tempted to play games with us.’

‘And let something slip.’

‘Exactamundo.’

She jumped to her feet. ‘So I can have a chat with him?’

He turned his pale blue gaze on her. ‘I hope you’re not planning any of your old antics,’ he said. ‘Like restaging your famous impression of a one-woman crime-solving machine.’

‘No, Sarge!’ She felt her cheeks redden, aware of her new colleagues earwigging on the conversation. ‘Nothing like that.’

He pointed the half-empty pack of Rolos at her. ‘Don’t make me regret bringing you here.’

‘No, Sarge.’

‘Alright, then,’ he said. ‘Take him a cuppa. And since you’re putting the kettle on, mine’s a builder’s. Three sugars.’

Kershaw found Kiszka pacing up and down his cell wearing a thunderous expression. He looked huge in the tiny space, like Daddy Bear in Goldilocks’ kitchen.

‘I brought you a cup of tea,’ she said brightly.

He glanced at the offering: ‘I don’t drink tea with milk in it,’ he said, and threw himself down on the narrow bunk. He’d shown not a flicker of recognition or surprise on seeing her again.

‘I’ll have it then,’ she said, settling herself at the foot of the bed and taking a sip. Close up he appeared pretty much unchanged – the same caveman good looks, maybe a bit thinner about the face. ‘It must be getting on for two years since I saw you last.’

‘Yeah, and it looks like the cops haven’t got any more intelligent in that time,’ he growled.

She had a sudden vision of their first meeting, a no-holds-barred stand-off which had ended with her – erroneously, as it later turned out – accusing him of murdering a girl, a Polish waitress found dead in a hotel room.

‘Well, you’ve not been exactly helpful so far, have you?’

‘I’ve told them everything I know, twice over! I showed them Jim’s text, his wife has vouched for me – what the fuck else can I do?’ He ran a hand through his dark brown hair, threaded with silver here and there, she noticed. ‘I apologise for the bad language,’ he added after a moment.

Kershaw didn’t say so, but from the point of view of the investigation, the text simply put Kiszka in the right place at the right time for the murder.

‘So why did you clam up when the Sarge showed you that mortgage deed?’

‘No comment.’

She paused. ‘Look, Janusz,’ she said. ‘I’m prepared to believe that you didn’t kill your friend. And from what I know about you, you must be dying to see the scum who did kill him locked up.’

He shot her a look that said locking up wasn’t what he had in mind.

‘And the more time we spend fu… messing around following false trails, the less chance we have of finding the killers.’ Actually, Kiszka was probably more than capable of killing someone in a murderous rage, Kershaw reflected, but the important thing right now was to gain his trust.

Janusz stared at her for a long moment, taking in the little heart-shaped face under the strangely lopsided hair, the steely set of her lips. His determination to find the chuje who had murdered Jim was as strong as ever but he had to admit it couldn’t hurt to have the cops looking for them, too.

‘Anything I say to you is off the record, agreed?’

‘Absolutely.’ This was true: although technically he was still under caution, the CPS took a seriously dim view of unrecorded unofficial chats, so nothing Kiszka told her could be used in court.

‘Because I’m not making any further statements until I talk to my solicitor.’

‘Understood.’

He exhaled. ‘When I first met Jim, he wasn’t in great shape. He’d had a … breakdown, I suppose you’d call it – after fighting for his country.’

‘Yeah, the Sarge mentioned he was a Falklands veteran.’

‘A Royal Marine. He was no coward – they gave him a medal for bravery under fire.’ He frowned at her, making sure she took the point. ‘Anyway, by ‘92, he was just starting to get himself straightened out and he came up with the idea of starting a gymnasium – there wasn’t anything like that in Walthamstow back then. He found a spot he reckoned was perfect for it. A derelict space, under the railway …?’ He sketched a curved structure in mid-air.

‘A railway arch?’

‘Yes, a railway arch.’

‘And you bought it for him?’

He snorted. ‘No! He’d saved up for a deposit while working on the building sites – but he needed a loan to make up the rest and pay for the renovations, the machinery and so on.’

Kershaw paused, remembering that according to the system, Fulford had previous. ‘But no one would lend him the money … because of his criminal record? Assault, wasn’t it?’

‘The guy deserved it,’ said Janusz. ‘It was just after Jim had got out of military hospital – he’d had to have months of skin grafts – when some imbecyl buttonholed him at the bar. Told him that the men who’d fought the Falklands War were “Thatcher’s stooges”.’

Kershaw winced.

‘The guy was lucky to get away with a broken jaw,’ said Janusz. ‘But the law didn’t see it that way.’

Back then, he recalled, no one had heard of PTSD: in fact, the judge who sent Jim down for six months said he was making an example of him because his behaviour had been ‘unfitting for a veteran of Her Majesty’s forces’.

‘So we had to make out the loan was for me. I signed all the paperwork, and the deeds were put in my name.’

‘So why didn’t you tell DS Bacon all this when he asked?’

‘I’d completely forgotten! I haven’t thought about it in twenty years.’

‘Did anyone else know about the arrangement? His wife, for instance?’

‘I don’t know,’ he shrugged. ‘He might have told Marika when they got married, I suppose. He didn’t keep any secrets from her, if that’s what you mean.’

Kershaw’s antennae twitched. At the mention of Jim’s other half, Kiszka seemed suddenly defensive, like he was nursing a guilty conscience. Had he been having an affair with his best mate’s wife?

In truth, the cause of Janusz’s discomfiture lay somewhere else entirely. Remembering the sorrowful look on the face of the girl, Varenka, as she left flowers outside Jim’s house he’d been struck by a sudden thought. Had his mate and the mystery girl been lovers? No way, he told himself, Jim wasn’t the type.

He stood up to indicate their meeting was over, dwarfing Kershaw. ‘It’s been a pleasure to remake your acquaintance,’ he said, bestowing his most charming mittel European smile on her. ‘But now, perhaps you would be good enough to find out whether my solicitor has arrived.’

Back in the office, Kershaw had barely had ten minutes to commit the names of her fellow DCs to memory before Streaky called everyone together for a briefing.

‘As you all know, we’ve pulled in James Fulford’s Polish chum Janusz Kiszka for questioning,’ Streaky told his audience: Kershaw, Ackroyd, three other DCs – two male, one female – and the Crime Scene Examiner. He brandished Kiszka’s arrest mugshot. ‘It turns out that Kiszka was the real owner of the gym Fulford ran. A fact uncovered due to the hard graft of DC Ackroyd who has spent two days wrestling with the jobsworths over at the Land Registry.’

All eyes turned to Adam Ackroyd – sitting next to Kershaw – who blinked rapidly and smiled. She had warmed to him when they were introduced – they were about the same age and had both done criminology at uni. But now she felt a little surge of competitiveness: at Canning Town CID she’d been the one getting the gold stars from Streaky.

‘Mr Kiszka is currently enjoying our hospitality in the guest accommodation downstairs,’ Streaky went on. ‘But we’re a long old way from nailing him for the murder, so let’s go back to basics – what we know and what we can rule out. Adam?’

Ackroyd swivelled in his chair so everyone could hear him. ‘The neighbour at number 159 saw two males in hoodies running from the scene at around 5.45 p.m. One was around six foot, slim build, and the other was an inch or two shorter and with a more muscular build. They were both wearing gloves and balaclavas, so no clue as to ethnicity.’

‘Did the neighbour mention if either of them wore anything green?’ the female DC asked.

‘No, nothing like that,’ said Ackroyd. ‘Mind you, even the B-Street boys wouldn’t be thick enough to wear the bandana while committing a murder.’

As a low chuckle ran round the team, Kershaw felt suddenly in the dark, hit by the realisation that she knew sod-all about her new patch.

Streaky must’ve caught her look. ‘The B-Street gang are the local pond life,’ he said. ‘They were the soldiers for our local drug baron, Turkish bloke by the name of Arslan who recently got sent down for twenty years. The drugs boys raided one of his lock-ups and found 100 kilos of Afghan heroin cunningly disguised as china tea sets.’

‘They still account for most of the area’s drug dealing, street robbery, stabbings and so on,’ the girl added. Sophie. Sophie Edgerton: that was her name, Kershaw suddenly remembered. ‘And they wear green bandanas – it’s, like, their gang colours.’

‘Anyway, we’ve more or less ruled out a random doorstep mugging,’ said Ackroyd. ‘On the other side of Hoe Street, maybe. But it just doesn’t happen in the Village.’

‘And it feels too specific, anyway,’ said Kershaw. Strictly speaking, as a newbie she should really shut up and listen, but she couldn’t help herself.

‘Explain yourself, Natalie,’ said Streaky, although she knew he’d guessed where she was coming from.

‘Well … I don’t know the area,’ she said, ‘but looking at the map, it seems to me if you’re gonna do a quick and dirty mugging, you’d choose a house at the end of a road – so you’re in and out fast? Instead they’ve risked going all the way up this great long road, Barclay Road.’ She shrugged. ‘If you ask me, this was a targeted killing. The perpetrators knew exactly who they were after.’

Streaky grunted his assent. ‘Sophie, what about our mistaken identity theory?’ he asked. ‘Any drug dealers or other known villains living nearby?’

She shook her head: ‘No, Sarge. It’s a nice road, pretty much all owner-occupiers. The worst I could find on the database was a man with a ten-year-old conviction for insurance fraud.’

‘Okay. Let’s go back to Kiszka, who has freely admitted he was on his way to meet Fulford at the time of the murder,’ said Streaky. ‘My working hypothesis is this. There’s a recession on, his private eye business is feeling the squeeze, but the gym – which he officially owns – is going great guns. He decides he wants a piece of it but his pal Fulford doesn’t play ball.’

‘But couldn’t this Kiszka have sold the property out from under Fulford’s feet, if he’d wanted to?’ asked the other DC, the spoddy one whose name Kershaw had already forgotten.

‘Fulford’s an ex-Marine, did time for assault back in the eighties,’ said Streaky. ‘Maybe Kiszka decided that it would be less risky to off him in what looked like a random mugging, so he could take the place over, no questions asked.’

‘Do we know what kind of weapon was used?’ Kershaw asked the Crime Scene Examiner, an older guy called Tony.

‘We’re still waiting for the post-mortem report,’ he said. ‘But Dr King, the pathologist, reckons it was a long blade of some kind. He said the wounds were inflicted with great force – maximum prejudice – was the phrase he used, actually.’

Streaky gave a snort. ‘Nathan King watches too many American crime shows. But it’s true a nasty assault like that will often turn out to be a personal vendetta.’

The Sarge started divvying up who was in charge of what – co-ordinating evidence from CCTV cameras in the area, house-to-house enquiries, and an appeal for witnesses – but Kershaw was only half listening. As she picked at a ragged fingernail – she was on her umpteenth attempt to stop biting her nails – she tried to imagine Kiszka committing such a savage attack. Lashing out at someone in a rage, yes, killing them even, before the red mist cleared, very possibly. But planning and carrying out a cold-blooded execution? She couldn’t quite see it.

She realised that Streaky was winding up the briefing – without giving her any action points.

‘Sorry, Sarge, I know I’m playing catch up here,’ she said. ‘But Kiszka claims he was at some art gallery at the time of the murder? I assume none of the staff saw him there?’

‘Over to DC Cargill,’ said Streaky, indicating a guy in his late fifties, sitting off to the edge of the group. Red-faced and overweight, Cargill wore a brown pinstriped suit so out of date it could be one of Streaky’s cast-offs. Kershaw wondered if he was even aware of the fashion crime he’d committed when he’d twinned it with grey shoes.

As Cargill leafed laboriously through his notebook, Ackroyd bent his head towards Kershaw’s. ‘We call Derek The Olympic Torch,’ he murmured. Seeing Kershaw’s incomprehension he added: ‘He never goes out.’

Kershaw got it. Cargill was the old sweat of the squad, counting the days to retirement and keeping his workload to the absolute minimum.

‘At approximately 1500 hours on Tuesday the 6th of November, I attended the William Morris Gallery in Lloyd Park,’ Cargill intoned, ‘and introduced myself to the female on the front desk. I duly established that she was the manager, name of Mrs Caroline Smalls.’

Kershaw saw a red flush starting to creep up Streaky’s face from his chin, usually a reliable sign that he was about to spit the dummy.

‘I showed her a picture of … Jay-nus … Jah-nuzz …’ After a couple of goes at pronouncing Kiszka’s name, Cargill gave up. ‘… the suspect. I then proceeded to the first floor …’

‘For Christ’s sake, Derek,’ said Streaky, his entire face now a ketchup red. ‘Get to the chuffing point!’

Cargill closed his notebook with some dignity. ‘None of the staff saw him, Skipper.’

Kershaw jumped in. ‘Kiszka did say that the photo he provided was way out of date, Sarge. I just wonder if it’s worth going down there again with his arrest mugshot?’

Streaky didn’t respond. He was still looking daggers at Cargill, who, apparently unconcerned, was now doodling on his copy of the Express.

‘Because if we do charge Kiszka, it could come back to bite our arse in court,’ Kershaw went on. ‘We don’t want his defence saying we didn’t make best efforts to check out his alibi.’

Streaky tore his gaze from Cargill. ‘Good thinking, DC Kershaw. Consider it your first action point.’ He grinned, showing teeth as yellow as old piano keys. ‘Welcome to Murder Squad.’

Seven (#uf1d14aef-50da-52ac-bf55-a90d1115f4ec)

‘So you’re saying the cops charged you with Jim’s murder?’ Oskar said slowly, evidently struggling with the effort of processing this cataclysmic news.

‘No, Oskar! I told you, they don’t have any evidence,’ said Janusz.

Janusz and his oldest mate were heading out to Essex in his battered white Transit van, where Oskar was landscaping the garden of some scrap metal millionaire.

‘My solicitor said that the business with the mortgage deeds is a sideshow,’ Janusz waved a hand. ‘He says unless the cops find something really solid, like … a bloodstained knife in my apartment, they’ve got nothing to justify charging me.’

‘And you haven’t?’ asked Oskar, a worried expression creasing his chubby face.

‘Haven’t what?’

‘Got a bloodstained knife in your apartment?’

‘Of course I fucking haven’t, turniphead!’

‘Calm down, Janek! I’m just trying to … establish the facts.’

‘That doesn’t mean they won’t try to frame me for it, of course,’ he growled. ‘You know what the cops are like.’ Growing up in Soviet-era Poland had instilled in him a visceral distrust of the machinery of state that he’d never quite thrown off.

Seeing a traffic light some fifty metres ahead turn from green to amber, Oskar floored the accelerator. The engine responded with an ear-splitting whinny. A second or two later, realising they wouldn’t make it across the junction in time, Oskar applied the brakes with equal ferocity, hurling both of them against their seat belts.

Janusz lit a cigar to steady his nerves. ‘You need to get that fan belt fixed, kolego.’

‘It just needs some WD40.’ Oskar drummed his fingers on the wheel. ‘You know, I still can’t believe Jim’s dead – God rest his soul.’ The two men crossed themselves. ‘Poor Marika! When is the funeral?’

‘God only knows. She can’t even plan it until they’ve done the post-mortem,’ said Janusz.

Oskar mimed an elaborate shiver. ‘I tell you something, Janek,’ he said. ‘If I die, don’t you let those kanibale loose on me with their scalpels.’ As the light changed to green, he pulled away. ‘And don’t forget what I told you – about putting a charged mobile in my coffin? They’re always burying people who aren’t actually dead.’

Janusz refrained from pointing out that a post-mortem might be the only sure-fire way of avoiding such a fate. He and Oskar had been best mates since they’d met on their first day of national service back in eighties Poland, but he’d learned one thing long ago: trying to have a logical discussion with him was like trying to herd chickens.

‘Remember that time, years back, when Jim took us to see the doggies racing each other at Walthamstow? Oskar chuckled. ‘Kurwa! That was a good night.’

‘I remember,’ Janusz grinned. ‘You got so legless that you kept trying to place a bet on the electric rabbit.’

‘Bullshit! I don’t remember that.’

‘I swear. If Jim hadn’t been watching your back, one of those bookies would have swung for you.’

They fell silent, smiling at their own memories.

‘So, Janek. How are you going to track down the skurwysyny who murdered him?’

‘That’s why I wanted to see you,’ said Janusz, tapping some cigar ash out of his window. ‘Walthamstow is more your patch than mine so I thought you could do some sniffing around for me – find out if anyone knows this girl, Varenka, or the chuj who likes to use her as a punchbag.’ He pointed his cigar at his mate ‘But keep it discreet, okay, and don’t mention Jim, obviously.’

‘No problem!’ said Oskar, his expression eager. ‘I’ll start asking around right away. We’ll be like Cagney and Lacey!’

‘Except they were girls, idiota,’ said Janusz. ‘Which reminds me, ladyboy – how is the “landscape gardening” going?’

‘I’m making a mint, Janek,’ Oskar declared, rubbing his fingers together. ‘You should’ve come in with me when I gave you the chance.’

‘So you’re saying these people out in Essex pay you thousands of pounds to muck around with their gardens?’ Janusz made no attempt to keep the incredulity from his voice.

‘Why wouldn’t they? I was in charge of building half the Olympic Park!’ he said, striking his chest.

‘Yeah, but construction isn’t the same thing as landscaping,’ said Janusz. ‘You wouldn’t know a begonia from a bramble patch!’

Oskar waved a dismissive hand. ‘I get all the green stuff down B&Q,’ he said. ‘Anyway, I see my role as creating the architectural framework.’

Janusz grinned. ‘Let me guess. They think they’re getting Monty Don and they end up with paving as far as the eye can see?’

Oskar shrugged. ‘Some people have no vision, Janek. I tell them, once the bushes and shit have grown up a bit, it’ll look fine.’

The unmistakable tones of Homer Simpson singing ‘Spider Pig’ filled the van – Oskar’s latest irritating ringtone.

‘Hello, lady,’ said Oskar into the phone. ‘Yes, I’m on my way to your place right now.’ He used his free hand to change gear, steering the van meanwhile with his knees. ‘I didn’t forget. A classical statue for the water feature.’ Turning to Janusz, Oskar winked. ‘You’re going to love the one I picked out for you. See you soon.’

Throwing the mobile back into the tide of debris washed up on the dashboard, Oskar said: ‘Once I drop this stuff off at Buckhurst Hill, we can head straight back to Walthamstow and start our investigation!’

Things didn’t work out quite so simply. After they parked up on the broad gravel forecourt of a hacienda-style detached house, Janusz stayed in the van while Oskar unloaded and took the stuff round to the back garden. Even from this distance, he was able to ascertain from the pitch of the conversation that the lady of the house wasn’t entirely happy.

After a good ten minutes, he heard Oskar crunching back across the gravel. A moment later he opened the driver’s side door and started to push a large sculpture of some kind up onto the seat, with much huffing and puffing.

‘Give me a hand, Janek!’

‘Can’t you put it in the back?’

‘This is easier.’

‘What the fuck is it meant to be anyway?’ asked Janusz once they’d manhandled the thing up onto the bench seat.

‘What does it look like?!’ Oskar’s tone was incredulous. ‘It’s a moo-eye, obviously.’ Hauling his chunky frame into the front seat, he slammed the van door and threaded the seat belt around their passenger.

Janusz peered at its profile. He could see now that it was a giant head – a clumsy reproduction of one of the monumental Easter Island sculptures, cast in a pale grey resin intended to resemble stone.

‘It’s moai, donkey-brain.’

‘Moo-eye – like I said!’ Oskar started the van. ‘She said she wanted something classical. How is a moo-eye not classical? They’re hundreds of thousands of years old!’ He shook his head. ‘Now she tells me she meant a naked lady.’

As they got closer to Walthamstow the traffic slowed and thickened. The sight of the huge, implacable stone face gazing out through the windscreen of a scruffy Transit van started to draw disbelieving stares from passers-by and appreciative blasts on the horn from fellow motorists.

Oskar lapped up the attention, returning the toots and scattering thumbs-ups left and right, while Janusz sat in silence, one hand spread across his face. The last straw came when Oskar wound down his window to receive a high five from a passing bus driver.

‘Let me out, Oskar,’ he growled. ‘I can walk to the gym from here. And give me a call if you hear anything interesting.’

He found Jim’s Gym open for business and packed with clients squeezing in a lunchtime workout. The faces were all male and for the most part either black, or Asian and bearded. The iron filings smell of sweat and testosterone filled the air like an unsettling background hum. Seeing Janusz, one of the older black guys, a regular called Wayne who sometimes came to the pub, set down the weights he’d been hefting and headed over. Wiping the sweat from his palms onto a towel, he offered his hand.

‘Terrible news about Jim,’ he said, eyes sorrowful, seeking Janusz’s gaze. They shook hands and spoke briefly, before Janusz continued towards the little office at the rear, where he’d sometimes come to pick up Jim on the way to the boozer.

But as he reached for the door handle, he felt himself engulfed by a surge of grief so powerful he had to steady himself against the doorjamb. This had happened more than once since he’d identified Jim’s body, every time it hit him – the dizzying realisation that he would never again see his mate’s face, nor hear that big laugh.

Inside, he was confronted by the sight of the deputy manager, a young black guy called Andre, sprawled in Jim’s chair, behind Jim’s desk, chatting and laughing into a mobile phone. Bad timing. Two strides took Janusz across the room and before the guy could even get to his feet he found the phone slapped out of his hand and across the room.

‘What the fuck, bruv?!’

‘Show some respect,’ said Janusz. ‘Jim’s not even buried yet. And who said you could take his desk?’

Andre jutted his chin out. ‘And who’s you to tell me I can’t, old man?’

A grim smile tugged at the side of Janusz’s mouth. ‘Haven’t you heard? I’m the new owner.’ No need to tell the guy that he’d already instructed his solicitor to transfer ownership of the gym to Marika.

Andre opened his mouth to speak, then shut it again. Seating himself on the desk, facing the kid, Janusz lit a cigar. Smoking in here was probably against the law, but with a murder rap hanging over him he figured he could take the risk. ‘I suppose you’ve had the cops down here already?’

‘Yeah, they was in, asking all this and that,’ said Andre, kissing his teeth.

Janusz suppressed an urgent desire to bitch-slap him. He raised his eyebrows. ‘Ask about me, did they?’

‘Yeah. Like did you and Jim ever have a fight, stuff like that.’ He gave Janusz an assessing look. ‘I told the feds, you might be big but if Jim wanted to he could’ve put you down –’ he mimed a right hook and a left uppercut, ‘– boof boof … no contest.’

‘You’re right about that,’ chuckled Janusz, leaning across him to tap ash into the wastepaper bin. ‘Listen. Since it looks like we’re going to be working together, I need to ask you some stuff.’

‘Sure,’ said Andre, although Janusz saw a guarded look come into his eyes.

‘Did you ever see Jim with a woman, other than his wife, I mean?’

A broad grin spread across Andre’s face, revealing what looked like – but almost certainly wasn’t – a diamond, set in one of his incisors. ‘You tellin’ me Jimbo had a bit of poon on the sly?’

Janusz shrugged, non-committal. It hadn’t escaped his attention that, on hearing the line of questioning, the guy had visibly relaxed. ‘Did he ever mention a girl called Varenka? Tall, blonde, good-looking – speaks with an Eastern European accent? Maybe she’s a member of the gym?’

‘We don’t get too many ladeeez in here,’ said Andre. ‘They might find themselves a bit too popular, if you get what I’m saying.’ He pumped his arms and hips back and forth, miming rough sex, before creasing up at his own joke.

Janusz bent to grind his cigar out on the waste bin, so that Andre couldn’t see the look in his eyes. By the time he’d straightened up, he was smiling. ‘Do me a favour and have a discreet ask around, would you? You know, I’m going to need someone to manage this place once we’ve got the funeral out of the way.’

‘Absolutely. I’ll get straight on it.’ Andre jumped to his feet, doing a passable impression of the young dynamic manager. ‘And don’t worry about things here – I’m all over it.’

Janusz’s gaze swept the office. ‘Where’s Jim’s laptop, by the way?’

Andre’s gaze wavered. ‘No idea, boss. All the gym records get kept on that old piece of junk,’ he used his chin to indicate a scuffed PC in the corner. ‘Like I told the feds, he took his laptop home most nights.’

Janusz knew that Marika had already checked at home and found no sign of it. Had this little punk grabbed the chance to get a free laptop? Or might there be something on the laptop to help solve the puzzle of Jim’s murder, information someone wanted to conceal and had, perhaps, paid good money to get their hands on? Again, Janusz saw Varenka, long legs scissored across the pavement, after she’d been struck by the bullet-headed man. What did she – or her assailant – have to do with Jim?