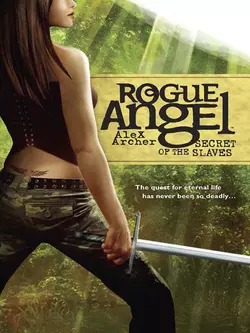

Secret Of The Slaves

Alex Archer

When archaeologist Annja Creed is hired to find the lost city of Promise in Brazil, she is more than intrigued. Legends abound of a magical place where slaves were rumored to have discovered the secret to eternal youth and life.But strangers are not welcome in Promise.Annja soon learns that the residents have gone to extreme lengths to guard their precious secret. Making her way from the steamy port of Belém to the brutal slums of Northeast Brazil, Annja faces unexpected peril, from poisoned arrows to Amazonian anacondas. As she navigates through a land where spirituality collides with the material world, Annja must distinguish between what is real and what is imagined for fear of making a wrong move. Because anyone or anything could be her enemy.And she's getting too close…

Rogue Angel

Secret of The Slaves

Alex Archer

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Epilogue

Prologue

The Upper Amazon Basin

With a growl of its potent diesel engine, the 124-ton bulldozer rumbled into motion across the clearing. Riding outside the enclosed and air-conditioned cab despite the sweltering wet heat, Henrique da Silva felt the power surge through his legs and spine and exulted. Hanging on with one hand and with the Uzi submachine tipped skyward in the other, he felt filled with power, like a conqueror of old. He could even ignore the seismic jiggle the massive engine’s vibration induced in his substantial belly fat, straining against the already sweat-soaked front of his white shirt.

The workers driving the heavy machinery wore coveralls. The heavily armed mercenary force, riding inside and on top of the armored cars that rolled forward flanking him to either side, wore camouflage. But Silva affected dark trousers, shirt and a tie flung rakishly over his shoulder. He was Amazonas State associate secretary for environmental protection. He had an image to project. While some men in his position were only too willing to tart themselves up in rain-forest-pattern battle dress, Silva preferred to distinguish himself from the men he had hired to protect his workers. They too were mere hirelings. He was the man in charge.

Not that that meant he would willingly relinquish his grasp on his submachine gun.

“Your Excellency.” His assistant’s voice crackled with worry as much as static in Silva’s headset. Silva was hardly an excellency. But he seldom reproved his assistant for using the title. He liked its ring. And once they received the returns for the hardwood from the virgin stand of selva on the clearing’s far side—not to mention certain discreet bounties for dealing with native populations that stood in the way of progress— excellency might apply. He knew a number of enterprises where he could rapidly leverage his newfound wealth.

“Excellency, are you sure this is wise? Many men have been lost in this region.” They had landed from a flotilla of riverboats far up the Amazon Basin, distant from anything either man would recognize as civilization.

“Carelessness, Ilyich,” Silva said. “Augmented by silly superstition. Doubtless some earlier parties got themselves ambushed. But we’re not going to be put off by a handful of naked savages, are we?”

“But there are stories—the hidden city of magicians.”

“Fah. You’re a government employee, Ilyich. An educated young man. Not a stupid and ignorant dockhand in Bahia, ready to scuttle off at the first rumor of Indian witchcraft.”

Silva considered himself above all that. The little deer-hide pouch of chicken bones, tobacco and certain other none-too-clearly specified substances he carried inside his watch pocket was merely a memento.

“I’m concerned for our work schedule,” his assistant said. “And costs. Costs, of course.”

“Then let’s not delay. Soares? Are your men in readiness?”

“Yes.” The work-gang boss rode another huge bulldozer. He most closely resembled a brick, in shape, complexion, and consistency. He was a man of medium height with dark reddish brown skin, a curly fuzz of red hair brushed with yellowish white around the fringes of a dome of skull, even slightly reddish murky eyes. The single affirmative was all Silva needed or expected of him—he spoke about as much as a brick. He allowed no nonsense, which recommended him highly for his task, where neither sloppiness nor malingering could be tolerated.

“And you, Colonel Bruckner?” Silva asked.

The security chief was a real German, not a second-or third-generation Brazilian German from down south. He was a veteran of the former East German National People’s Army and a thoroughly work-hardened mercenary—or private military contractor, as he preferred to be called. He was a short man, precise and slim as an ice pick, with a prematurely white buzz cut and coal-black eyebrows over bright blue eyes.

“Yes,” Bruckner replied. “My men champ at the bit. Let’s go kill some savages.” His notion of how to deal with indigenous peoples accorded well with Silva’s.

“Go,” Silva commanded. With a hand on top of the cab, he waved his Uzi in a rough circle in the air. Few actually saw the gesture; they were either sealed into metal boxes or peering intently at the jungle lying ominously in wait. But it made Silva feel like a conqueror.

The vehicles swept forward. The mercenaries mostly rode in their six-wheeled armored cars, the workers clinging to the bulldozers or banging around like loads of papayas in stake-bed trucks. Silva rode a precarious perch just behind the monstrous, hot engine. But as the machine’s treads bit into the black soil and the great blade began to shove down the tall yellow grass in front, he knew it was worth it.

This land was low but only submerged when the rains caused the great river to rise over its ill-defined banks. The path from their river beachhead led across a wide clearing, with its high grass and anomalous black soil. The rich topsoil was called black Indian earth. Found throughout the Brazilian Amazon, it was supposedly a special soil artificially created by the inhabitants. The undersoil of the Amazon Basin was poor, weak and thin. He believed it had to be some kind of unexplained natural phenomenon. Who could believe ignorant savages could create something modern science was unable to duplicate, and so much of it?

The stink of diesel overpowered even the jungle reek of wet and rotting vegetation. The roar of big engines overpowered everything, enclosing Silva in a microcosm of noise and power. A heavy warm wind blew against Silva’s plump face.

Ahead and to the left, a flight of small blue birds rose from the high grass and swirled up chittering in the air, as into an inverted invisible drain. After a reflexive glance at the sudden movement, matched by a sort of interior jerk, Silva ignored them. He was a progressive, a man of the modern world. As far as he was concerned any bit of nature he couldn’t bend to the use of the state—with a bit of profit on the side for him—was just clutter.

The associate secretary assumed the white smoke that puffed into the heavy air ahead was some kind of primitive signal by the savages to alert their friends and relatives to the mechanized doom rolling toward them. Then a fierce crack stabbed his ears right through the engine’s roar.

The hatches of an armored car just four vehicles to his left flew open. An astonishing quantity of black smoke erupted from them. Men scrambled out, shrieking. They burned with flames that were almost invisible in the bright sunlight.

The associate secretary heard Bruckner curse in his earpiece.

“You said these were just Indians, Silva. Where did they get MILANs?”

Silva was still blinking in amazement at the stricken armored car. It had rolled to a stop. Orange flames jetted from the open hatches. Yellow explosions crashed and flashed through them like fireworks as ammunition belts cooked off inside. The vehicles immediately behind it had stopped, more in response to the sudden attack than any obstacle the wreck posed. The word at the end of the German’s sentence made no sense to Silva.

“I hired your men to fight,” Silva replied. “So fight!” As he gave the brusque command machine guns began to snarl from vehicles to either side of his. It made him feel on much firmer ground. He was in charge.

The German had his white-fuzzed head down and was talking into his mike on a different frequency. Over the grumble of engines and the wind-roar of the flames they heard distinct pops from the woods behind them. Having read reports of prior expeditions to this rich virgin district, they were prepared as well as possible. Their 82-mm mortars would clear out any ambushers the machine guns couldn’t deal with.

Beyond Bruckner’s command car, a yellow bulldozer rolled. It was still immense at half the size of the machine Silva rode.

The laborers riding it wore overalls with no shirts beneath, and hard hats. As Silva watched Bruckner give commands he saw a worker simply slip from the dozer and disappear into the grass. A moment later a second followed, and a third.

The bulldozer stopped. The remaining two laborers riding it jumped off and ran. One screamed horribly as the dozer immediately behind, which had swerved to avoid hitting its suddenly stalled mate, sucked a boot into its treads. His leg was twisted off at the thigh.

More pops from overhead, surprisingly flat sounding, drew Silva’s attention upward. He saw dirty gray puffs of smoke unfold against the blue sky overhead. He realized he had not heard the slamming cracks of mortar shells among the trees ahead. Could the savages have somehow exploded the shells in air?

“Impossible!” he exclaimed.

Around him he heard explosions, screams, the rippling of machine-gun fire. The bulldozers had all stopped. Even the armored cars had halted, three of them including Bruckner’s out in front of the rest of the mass. The machine cannon in Bruckner’s cupola fired, its sound like the fabric of reality tearing right across.

Silva felt his own machine slow. He pounded on the top of the air-conditioned cab with a palm. “Go! Go, you cowardly piece of shit! Or I’ll have you and your whole worthless family sent to the gold camps!” He did not have to tell the driver a steady stream of humanity flowed into the camps. And almost none returned.

Lights flickered among the trees, still over two hundred yards ahead. Silva had never been under fire before but he couldn’t help recognizing muzzle-flashes. These savages were well-armed. The evil small-arms merchants had much to answer for.

Yet despite the screams and blasts all around he felt no fear. This wasn’t real somehow. He could feel nothing, not even the Amazon heat. He was just barely aware of shock waves drumming against his cheeks. Besides, he was prepared—he was the master of the situation. So the savages had gotten guns from some traitor. He had a preponderance of force. He had Germans, damn it!

“Bruckner,” he shrieked. The German showed no reaction. Though he was barely twenty yards away he couldn’t hear the associate secretary over the head-crushing racket. Silva fumbled with the channel setting on his communicator. “Bruckner, deploy your men! Attack, damn you! They’re nothing but a handful of primitives.”

“Ja,” the German replied. Silva was outraged. He resolved to see to Bruckner when this was done. The man was incompetent, and trying to cover it with impudence in the very belly of battle!

“Soares,” Silva commanded his labor chief, “keep your machines moving forward. If they fear danger, there’s more of it here in the open.” And even more if they fail me! he thought furiously.

There was no response. Just a crackle in the headset.

“Soares!” he shouted in his microphone, as if that would help. “Answer, damn you.”

“He can’t, Excellency.” He heard the voice of Ilyich Chaves, his personal aide. It shook so badly he could barely wring sense from it.

“Why not?” Silva shrieked.

“He’s dead.”

“Dead?”

“An animal,” Ilyich said. “Some horrid beast—it leaped from the grass.”

“Get hold of yourself, imbecile! Speak sense!”

From the right he saw a sudden flicker of yellow—

It emerged from the grass and sprang from the black Indian earth. A great cat, thick bodied, spotted with black rosettes, ears pressed flat to a skull that gleamed like gold in the sunlight. It hit Bruckner in a sort of flying tackle, rocking him back in his seat.

“An onza? ” Silva breathed. “A golden onza? ” It was a jaguar—and more than a jaguar. A huge golden one. An almost mythic beast of the great Amazon woods, seldom seen but always feared.

The German’s gloved fists beat against the great cat’s shoulders as it sank huge yellow fangs into his neck and dragged him out of the hatch onto his back atop the armored vehicle. The beast pounced and raked open Bruckner’s camouflage battle dress and the Kevlar vest beneath as if they were wet tissue paper. Then it began to scoop the guts right out of the mercenary’s living belly, kicking with its monstrous hind legs.

Bruckner’s screams put the thunder of battle to shame.

More motion snapped Silva’s attention away from the nightmare spectacle. His own machine lurched to a final stop.

A young man stood before him, fifteen yards away, clearly visible through a gap in the grass. He was nude, tall and lean and muscled like a god. His long, handsome, high-cheekboned features were impassive. Dark brown dreadlocks cascaded about his broad shoulders.

“Bastard!” Silva shrieked. He clutched the Uzi in both hands and ripped a burst from right to left. It should have stitched the man across his washboard belly. But even as the associate secretary brought his weapon up, the man sidestepped into the high grass and was gone.

Silva sprayed the grass with bullets. The tall stems might shield the naked savage from view, but they wouldn’t keep copper-jacketed lead out of his golden hide. The Uzi’s heavy bolt locked back as the magazine ran dry. Cursing, weeping in frustrated fury, Silva fumbled in his pockets for a backup magazine.

Triumph thrilled through him as his fingers closed around a cold steel bar. “Ha! Ha!” he shouted, pressing the latch and dropping the spent magazine from its well in the Uzi’s pistol grip.

A figure reared up beside him as from the depths of his own nightmares. An anaconda, a huge serpent with mottled brown-and-yellow scales glistened in the hateful sun. Its head was as large as a bull mastiff’s. The eyes were huge and golden and seemed to glow with terrible intelligence.

For a moment it stared straight into Silva’s eyes. He tried to jam the fresh magazine home. Trembling hands could not find the opening. But he could not tear his eyes from that golden gaze.

The serpent opened its mouth. It was like some kind of trap opening. A pink trap, edged with yellow-white.

Silva screamed and tried to swing his otherwise useless Uzi like a club.

The anaconda darted its head forward and crushed Silva’s face with a single grip of its jaws.

1

Pain jabbed the muscle of Annja Creed’s right forearm as she slammed it into the hardwood limb jutting from the trunk-like pole before her.

Good, she thought savagely. She slammed a palm into the slick-polished wood of the trunk itself even as her left forearm blocked into another protrusion.

Faster and faster her hands moved, in and out, over and under the blunt wooden posts stuck in sockets on the central pole. She practiced blocks, traps, strikes with stiffened fingers and fists and palms. A drum-beat rose as muscle and bone met wood with jarring impact.

Annja was a tall, fit woman in her midtwenties. She wore a green sports bra and gray shorts. The humming air conditioner kept her Brooklyn loft cool.

She paused to brush away a vagrant strand of chestnut hair that had worked loose from the bun she had pinned it in. Her scowl deepened.

The stout wooden apparatus rocked to a palm-heel thrust, despite the fact its wide base was weighed down by heavy sandbags. Annja’s sparring partner was a training dummy used as an adjunct to wing chun –style gongfu. She had taken up the study because it was supposed to be highly effective and easy to learn, while giving her another option for nonlethal use of force.

She had plenty of lethal options available. The deadliest was currently invisible to the naked eye. But it was not intangible, not like her rapier-quick intellect or boundless resourcefulness, which she knew could be as deadly as any physical weapons.

She whipped the back of her right hand against a wooden arm. She let the hand flop over it in a trapping move, fired a punch that made the post rock. As she worked into a blinding-fast pattern of blocks and strikes, all oriented toward the centerline of the post, as they would be to the centerline of an opponent’s torso, she found herself worrying about the turn her life had taken.

She thought about the sword—her sword.

She had learned that it had once belonged to Joan of Arc. And that she was the inheritor of the long-ago martyr’s mantle. On a research trip to France she had, seemingly by chance, found the final piece of St. Joan’s sword, broken to pieces by the English captors who burned her. At more or less the same time she had met the man named Roux. He was spry for his gray beard—and even sprier for the fact he claimed Joan had been protégée. He and his apprentice Garin Braden had failed to rescue her from execution. As a result they had been cursed—or blessed—with agelessness.

Roux had spent the half millennium since Joan’s death trying to reassemble the saint’s shattered sword. At first he’d regarded Annja as an interloper and tried to steal the final fragment from her. Yet when she came into the presence of the other pieces, in Roux’s chateau in France, the sword had spontaneously reforged itself at her touch.

It was a bitter pill for a lifelong rationalist to swallow. Especially one who made most of her income as the resident skeptic on the notably credulous cable series Chasing History’s Monsters , on the Knowledge Channel.

Her arms and hands now moved too fast for the eye to follow. The tough, seasoned hardwood creaked and strained to the mounting fury of her blows. Human bone would give way long before that old wood did.

The sword. It had come to dominate her life.

It rested now in its accustomed location—what she thought of as the otherwhere. It was not present in this world, except at her command. To summon it, she had learned, all she needed was to form a hand as if to grasp its hilt, and exert her will. And her hand was filled.

But her life, it seemed, had correspondingly emptied since the sword came into it.

Sweat soaked her hair and flew from her face. Her wrists and knuckles and elbows sounded like machine-gun fire as they struck the muk-jong.

Orphaned at an early age, raised at an orphanage in New Orleans, Annja had always been alone. She was always apart, somehow, different, although she never tried to be. And it didn’t often bother her.

She had never felt as if she couldn’t enjoy companionship. But she didn’t actively seek it. She’d had close friends at college, on digs, among the crew of Chasing History’s Monsters . She had had lovers. But, she had to admit, no truly lasting loves.

And now she figured she never would. At least so long as she bore her illustrious predecessor’s sacred sword.

She was an archaeologist. Her period of concentration was the later Middle Ages and Renaissance Europe. She spoke all the major modern Romance languages, and Latin, and studied any number of archaic forms—and weapons.

She wasn’t sure why she was feeling a sudden gap in her life left by the lack of a lasting relationship. She had her mentor, Roux, and her sometime enemy, Garin. But she didn’t really think those relationships counted. She didn’t want them to.

Great, she thought as she slammed her forearms against the projecting limbs. She recognized the rare feeling she was experiencing.

“I’m lonely!” she said to her empty loft. She slammed an elbow smash into the upright on the last word. It broke free from its base and toppled backward.

“Nice,” she said in disgust. She rubbed her elbow, the pain corresponding to her mood. “Those things cost money.”

She stomped off to the shower.

A NNJA EMERGED from the bathroom wearing a long bathrobe swirled in patterns of green, yellow and blue. Her long hair was wrapped in a towel. She heated a cup of cocoa in the microwave and looked around her loft. While jobs were scarce for a freelance archaeologist, she had lucked into enough supplementary income from her television gig and some publishing deals to afford the space.

With Roux’s assistance she sometimes accepted commissions to do special archaeological assignments around the globe—always consistent with her strict sense of scientific ethics—for employers who wanted them kept discreet. They tended to be a lot more perilous than the usual university dig, and accordingly well compensated. Sometimes only just slightly over the considerable expense such missions tended to incur.

Flopping on her couch in the space left by several piles of manuscripts various contacts had sent her, mostly dealing with her side interest in fringe archaeology, she made the key mistake of clicking on the television.

She was hoping for a distraction. What she got was Kristie Chatham, on location with some kind of cockamamy Knowledge Channel crossover production in England. Annja was all too aware of not having been invited to take part.

“…standing here in front of Stonehenge,” Kristie was saying brightly, “which as we all know was built by the Druids…”

Annja emitted a strangled scream and threw a cushion at the screen. “No, you bimbo,” she shouted. “No, no, no. Stonehenge was built thousands of years before the Druids. Don’t you bother to research anything?” A better question might’ve been, didn’t the Knowledge Channel fact-check anything? But she knew the answer to that one, too.

“I’m here with Reggie Whitcomb of the South England Pagan Federation,” Kristie bubbled on, “who’s going to explain how the Druids levitated the huge cross-pieces, called sarsen stones, into place using their advanced psychic powers.”

Annja grabbed the remote and clicked off the set just as Kristie turned her microphone toward a chinless guy wearing a white robe with a peaked hood that made him look as if he belonged to a middle-school auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan. The skies were black over Salisbury Plain, and the wind cracked like wet sheets whipping on a clothesline. Annja hoped Kristie would get struck by lightning. Or at least soaked to the skin.

Of course that would make Kristie’s sheer white blouse transparent. And Kristie would score another top-viewed video on You Tube. Unlike a lot of its media rivals, the Knowledge Channel never set its legal hounds to pull such videos down—the producers had noticed how ratings spiked for their repeats after one went online.

Annja slammed her remote on top of a stack of printouts on the couch beside her.

“It’s not like I’m Ms. Establishment Science or anything,” she muttered, with her chin down to her clavicle. “It’s just that I don’t open my mind so wide my brain rolls out my mouth.”

Her cell phone rang and she frowned at it in suspicion. If that’s Doug Morrell, his head’s coming right off, she thought.

She picked it up, flipped it open. “Hello.”

“Annja Creed?”

Whomever the voice belonged to, it was not her producer from Chasing History’s Monsters. The voice was like liquid amber poured over gravel—deep, rugged, yet somehow flowing.

Her eyes narrowed. I know that voice, she thought. It sounds so familiar.

“Ms. Creed?” She was certain of the Irish accent.

“Oh. Yeah. Sorry. This is Annja.”

“Ms. Creed, my name is Iain Moran. I’m a musician. You may have heard of me.”

“ Sir Iain Moran?” Annja asked. It couldn’t be.

“The same.” Her mind’s eye could see that famous smile, at once roguish and world-weary.

“Publico? Lead singer for T-34?”

“The very one.”

“Right,” Annja was in no mood for pranks.

“Don’t hang up! Please. I really am Sir Iain Moran.”

“Sure. Multibillionaire rock stars call me every day. If Doug Morrell put you up to this, you’re both way overdue for a good swift kick to the—”

“Please. I’d very much like to consult you on a professional matter, concerning your expertise. Would it help to assuage your doubts if my helicopter collected you on the roof of your flat in fifteen minutes?”

It was original, as pranks go. She had to give her caller that. “You’re on,” Annja said, daring her caller to push this as far as it would go.

Fifteen minutes later she stared openmouthed into the brownish haze of a hot Brooklyn day. Her face and hair were whipped by the downblast as a Bell 429 helicopter descended to the roof.

2

A man with long dark blond hair blowing out behind his craggy face was striding toward the helicopter as its landing gear bumped down into the yellow painted circle of the skyscraper’s helipad. He wore a tan suit with a dark chocolate tie blown back over his shoulder.

Two men stood flanking the doorway the long-haired man had emerged from. Their hands were folded before them and they looked like slabs in black suits. Even from a distance Annja got the impression their musculature was the force-fed beef characteristic of U.S. ground-force soldiers, not the torturously detailed sculpting of weight-room juicers.

The pleasant young Asian woman in a blue-gray business suit who had originally squired Annja aboard the helicopter, and smilingly evaded the questions Annja peppered her with, helped Annja into the heat of the Manhattan summer morning. The man in the pale suit neared. His face split in a smile.

“I’m Sir Iain,” he said, raising his voice to carry over the dying whine of the engine and the slowing blades. “Or Publico, if you prefer.” He took the hand Annja extended in a dry, strong grip.

“It was good of you to accept my invitation on such short notice,” he said. He put fingertips behind Annja’s shoulder and applied gentle pressure. “I’m a huge fan of your work. Your writing, as well as your television career. Please, come with me.”

She found, as he guided her toward the doorway, that she did not resent the physical contact. He was around her height, five-ten maybe five-eleven. His shoulders and chest seemed massive, which seemed unusual for a rock musician; she had them pegged as mostly on the weedy side. But his sense of presence loomed like a skyscraper and warmed like the sun.

There was no mistaking that this really was the famous Publico. There were those blue eyes, pale as the northern Irish sky beneath which he’d grown up. There was the famous craggy profile, looking more like a prizefighter’s than a rock and roller’s, thanks to the nose famously smashed by a British paratrooper’s rifle butt during a Dublin demonstration. The voice, gravelly yet the more compelling for it, was compliments of an Ulster policeman’s baton that nearly crushed his larynx.

Unlike a lot of celebrities, neither Moran nor his two longtime bandmates had any whiff of the poseur about them. They had been there and done that, protesting the English occupation of Northern Ireland, as well as the bloody sectarian violence of both Catholics and Protestants. They’d earned the admiration of the world and the hatred of zealots on all three sides, and had paid their dues in real blood and pain.

The band’s music reflected the socialist activism of its members as well as their fervent Christian convictions—decidedly less popular among their audience, which spanned the age range from preteens to baby boomers. But their sincerity won over even the most irreligious—as did their hard-rocking music.

Annja was intrigued. He seemed wholly aboveboard. Despite the unsolicited contact his manner was correct and friendly. Charisma emanated from him like heat from a forge.

“What exactly did you whisk me here for, Sir Iain?”

He offered a lopsided smile and bobbed his head once. “Fair enough question,” he said. “Permit me to answer with one. How would you like to save the world?”

“That’s not an offer an archaeologist hears very often,” she said. “But I’m afraid I can’t contribute much to any of your causes.”

“It’s not money we want,” he said. “But your courage, your skills—your soul.”

She looked at him and he grinned.

“How would you like to see an authentic cursed tome?” he asked.

She grinned back. “You do know the way to a lady’s heart, sir,” she said. “Lead on.”

“I T’S IMPRESSIVE ,” she said.

With his two shadows drifting along behind—making little more noise than shadows—Moran had squired her down into the skyscraper and to a window he assured her was bulletproof polycarbonate, double paned.

It looked out, and down, on a cold room. In the middle of the sterile white floor, twelve feet below them, stood a large cylinder with what looked like a mirror-polished brass base and a similar cap. The cylinder itself was clear.

“It’s Lexan, as well,” Sir Iain said. “Treated with a special coating inside and out that resists corrosion.”

On a gleaming chrome pedestal within the cylinder rested a book. It was certainly grand enough—the approximate size and shape of an unabridged dictionary. The cover was thick and cracked from what she could see on the open book. The pages were brown. She could just make out faded, crabbed brown writing on them.

“Nitrogen environment?” she asked.

“Of course.”

She tried not to thrill at that rolling deep baritone.

She turned a raised brow to him. “I’m surprised you’re interested in rare books.”

“You think all rock ’n’ rollers are illiterate, hell-raising dopers?” He shrugged. His shoulders rolled impressively inside his immaculately tailored coat. “I’ve been clean and sober since my well-publicized overdose. I’ve had to find something to do with my time since other than read the Bible.”

I N A ROOM down a flight of stairs he gestured toward a large flat-screen monitor, hung above a modern workstation of stainless steel. Several other computers were set up at other stations. On the big screen two pages were represented many times larger than life. Here the ink looked purplish rather than brown.

“It’s the journal of an eighteenth-century Portuguese Jesuit,” Moran said, “recounting his journey up the far Amazon.”

“A lot of Jesuits made the trip in those days,” Annja said.

“Indeed. I rather suppose they did. Would you care to read it?”

“I generally prefer to read the original document when it’s available,” she said. “The camera so seldom catches everything”

She was a hands-on sort of woman where historical artifacts were concerned. It was a major reason she’d chosen to be an archaeologist as opposed to a historian. She didn’t just want to study history. She wanted to feel history. To see where it had taken place, to hold in her hands implements—or documents—that had changed the world. She wanted to breathe the same air the heroes and heroines of history—unknown and world famous—had breathed when they performed their great deeds. She wanted to be part of history.

And I am, she thought. A lot more literally than I’m comfortable with.

“Not possible, I fear,” he said.

“I understand,” she said, unable to repress a little sigh of frustration. “Obviously it’s in an extremely fragile state to require such extreme preservation measures.”

“You don’t understand, Ms. Creed,” he said. “Everyone who handles this book dies. Horribly.”

She looked aside. A wall-sized window, waist high, opened into the cold room from the reading chamber. The book itself in its high-tech bell jar looked even more impressive closer up.

“I don’t believe in curses, Sir Iain.”

His laugh was short. “There’s nothing paranormal about it,” he said, “or not overtly so. The pages and binding are imbued with a hitherto unknown living organism that is not unlike slime molds. It attacks whoever touches it, both by means of airborne spores and by contact. The effect resembles a cross between flesh-eating bacteria and sarin gas. It isn’t pretty. And it is extremely fast acting. As well as untreatable by any known means.”

“Nice.” She sucked in a sharp breath. The air was cool, smelled vaguely of ozone. “How did you get it back here?”

“Carefully. Very carefully.”

She went to the workstation and sat in the chair. Reading was dead easy. A black wireless mouse controlled a cursor on the screen. She could point to icons around the perimeter of the image. When she ran the cursor over them, text tips popped up.

“Interesting,” she said, frowning slightly in concentration at the huge high-definition screen. “Are these the pages it’s currently open to?”

“Yes,” he said, “although you can page through it. The entire volume has been digitized.”

“I see. Well, it’s open to a very dramatic passage. Our author’s talking about what seems to be the end of his journey, of both the wonders and hazards he encountered—a colossal snake—had to be an anaconda. They’re one of the world’s largest. And, whoa, a golden onza. Hmm.”

“You can read that? That easily?”

“I specialize in archaic Romance languages, Sir Iain.”

“But the handwriting—it’s all just spider tracks to my eyes. Worse than my handwriting, and that’s saying a packet.”

She smiled. “As I guess I hinted earlier, this isn’t the first old Portuguese Jesuit diary I’ve looked at.”

“What’s a ‘golden onza ’?” he asked. “It seemed to strike you as significant.”

“An onza is a jaguar. A golden onza is a particularly impressive specimen. Larger than life, you might say. Legend imbues them, some of them anyway, with incredible intelligence and sometimes outright supernatural powers.”

“Indeed.”

“Okay. Apparently our priest was captured by Indians, blindfolded and taken to something called quilombo dos sonhos, ” Annja said as she continued reading.

She sat back. “ Dos sonhos translates as, ‘of dreams,’” she said. “But what’s a quilombo? ”

He pulled a chair over next to hers and sat, leaning slightly forward, with his elbows on his thighs. “Have you heard of the Maroons, then?”

She turned to face him. “If I recall correctly, that was a name for escaped New World slaves who fought guerrilla campaigns against recapture—sometime with pretty significant success. Toussaint-Louverture ran the French colonial overlords clean out of Haiti. Of course, I suspect they’d be called terrorists today.”

“These quilombos, I’m told, were settlements the Brazilian Maroons formed in the wilds, mostly along the coast,” he said. “Some eventually became republics powerful enough to stand off their erstwhile oppressors for centuries. A few actually maintained their independence until the Brazilian empire became the republic in 1889. Several are still around today as townships.”

He sat back and draped an arm over the back of his chair.

“The most famous of all was the Quilombo dos Palmares in northeastern Brazil. It held out against Dutch attacks, as well as Portuguese, until it was reduced by artillery in 1694.” He frowned. “Curious, really. My researchers inform me they also traded quite frequently with the Dutch and the English, for arms to use against their former masters.”

“Alliances were elastic in those days,” Annja said, drawn irresistibly back to the big screen. “As well as these days, and all other days I’ve ever read about. This quilombo the good Father describes—”

“Father Joaquim,” he said.

“The settlement was a sizable domain including rich farmland—which I thought was actually pretty rare in the Amazon Basin. It surrounded a fabulous city called Promessa—the Promise. There he describes himself as being treated as an honored guest by the inhabitants, whom he says are mostly intermarried Africans—those escaped slaves, I’m guessing, although they seem to have wandered pretty far from the Atlantic Ocean—and Amazonian Indians. He says the people are ‘well-versed in all arts and philosophy.’”

The rock star said nothing. His gaze was so intent she could feel it on her cheek like sunlight. But she was engrossed in the ancient manuscript.

She read through several more virtual pages before surfacing, more to draw a breath than to report. “He speaks of meeting savants whom he claims come from Asia. He might actually know what he was talking about. The Jesuits loved the Orient almost as much as they did South America. He could have spent time in Asia himself. Claims to have witnessed miracles from artificial light to almost instantaneous wound healing and treatment for all manner of disease. And here he writes, ‘Moreover the citizens know not aging, nor die, save by misadventure, or foul murder, or their own choice—wherein, sadly, they flout the Divine Will.’”

She gazed up at the screen a moment more. Then she sighed heavily.

“Okay,” she said, turning around to face her host again. This time there was an edge in her voice as chilly as the air in the room. “So this is a treasure hunt, right?”

The rough-hewed face split in a smile that had thrilled tens of millions of concertgoers—not to mention scores of CEOs and world rulers whom he addressed in his self-assumed capacity of global humanitarian activist.

“Imagine a world,” he said in a low, compelling voice, “in which there’s no disease, no suffering. No death.

“That would be a treasure worth hunting, wouldn’t you say, Ms. Creed?”

3

“With all respect,” Annja said, sipping green tea in a commissary appointed like a five-star restaurant, with dark oak paneling, bronze rails and ferns in place of the more traditional scuffed Formica counters and coffee machines, “Fountain-of-youth yarns have abounded in the Americas since, roughly, forever. As do fanciful accounts from the age of exploration. For that matter, the Jesuits have been known to bend the truth for their own purposes.”

Ignoring his chai latte, Moran nodded encouragingly. “That’s one of the reasons I contacted you,” he said. “You obviously believe in reason, in evidence. You are also willing to keep an open mind.”

“I did wonder,” she said. “I’m not the most famous TV archaeologist on television by a long shot.”

She smiled a bit lopsidedly. “Then again, if it was boobs you were after, you’d have called Kristie Chatham.”

“If you’ll forgive a momentary lapse in political correctness, Ms. Creed,” he said in that voice that had thrilled hundreds of millions, “you’re a beautiful woman. At the same time I’m sure you appreciate a man in my position seldom lacks for attractive female companionship, should that be his intent. For my part I’ve tried to put my wild past behind me. So I also hope you’ll understand that your striking appearance had nothing to do with my interest in engaging your services.”

She set down her cup. Her cheeks felt hot. “Now you’re flattering me.”

“Not a bit of it.”

“Well, after a speech that gallant, the least you could do is call me Annja.”

“Done. If you’ll consent to call me Iain,” he said.

“It’s a deal.” She sat back in her chair, picked up her cup and regarded him through a curl of steam rising into the cool air.

“You don’t strike me as the sort to fall for every goofy New Age notion to float past you in a cloud of pot smoke. I presume you have evidence more compelling than a wild diary, even if its pages are protected by a killer mystery fungus. Impress me.”

“I’ll do my best—Annja. In the favelas —the brutal slums—of northeastern Brazil they still speak of the quilombo dos sonhos. Legends still speak, also, of a magical city called Promise, where no one ever dies.”

“Such legends aren’t exactly uncommon worldwide, despite the inroads of science,” Annja said.

“So I thought. Until a hardheaded German business associate of mine, an aggressive atheist and skeptic, began experiencing remarkable dreams. Of a beautiful city, hidden deep in Amazon rain forest, filled with beautiful, ageless people who combined indigenous lore, Asian wisdom and Western science to create a cultural and technological paradise. In these dreams he got flashes of psychic phenomena, of cars that fly without wings or even visible engines.

“Hypnotic regression seemed to substantiate that these were real memories, submerged and now attempting to resurface. I see you look skeptical. I hardly blame you. But when we dug deeper we found recurring spells when my acquaintance dropped out of sight during trips to Brazil. It’s an aggravating thing. He cannot be documented to have ever gone deeper into Amazon than Belém, where the Amazon enters the Atlantic. He merely—vanished.”

An aide appeared, a ponytailed young blond woman in jeans. She handed several manila envelopes to Moran. He thanked her with a smile.

Beckoning to Annja to come closer, he turned and opened one of the folders on the tabletop. “Here are the medical records for my friend,” he said, setting out sheets of paper typed in English with names blacked out. With a forefinger he pushed a color photograph toward her. It showed the bare upper torso, from neck to just above the groin, with a puckered crescent from an appendectomy scar. She was glad the photo cut off where it did.

“Here’s a ‘before’ picture,” Moran said, tapping the image. “And here’s the ‘after.’”

He pushed another photo beside the first. Annja frowned. It showed the same pale, slightly pudgy torso as the first photo, with a distinctive reddish mole at four o’clock from the navel to clinch the identification. But the surgical scar was gone.

“You don’t have to go to the wilds of Brazil to have cosmetic surgery to remove scars,” Annja said.

“You rather make my point, I think,” Publico said with a smile.

Annja shrugged. “I’m intrigued. I’ll admit that much.”

He showed her a frank grin. “So you’re to be a hard sell. Well, I’d expect nothing less of you.”

He braced hands on thighs and stood. “Well, come with me, if you will, and I’ll see if I can sell you.”

“B RAZIL HAS QUITE A HISTORY of widespread and well-documented UFO sightings, you know,” Publico said. “What if some of the Maroons, retreating up the river from encroaching colonists, stumbled upon a crash site?”

They walked along the side of a sunken room Moran referred to as his “command center.” Large plasma monitors hung from the ceiling over rings of workstations where staff wearing Bluetooth earpieces typed rapidly and spoke in earnest murmurs.

Annja chuckled. “I’m not sure that’s the tack to take,” she said. “You know I’m the show’s resident skeptic.”

“Ah, but you have an affinity for the strange, as well.”

She crossed her arms and smiled tightly to hide the little shudder that ran through her. How true that was, she thought.

To divert attention from herself she gestured around them and said, “Where are we, anyway? What’s this building? Yours?”

“In a manner of speaking. It’s the New York headquarters of my eleemosynary network. It belongs to the institute, not to me personally. Although I admit I have freedom of the place.”

“I’m impressed at the word eleemosynary.”

“Not all my degrees are honorary, Ms. Creed. My MBA from Harvard, for example.”

“A Harvard MBA? I thought you were antiestablishment, antiglobalization and all that.”

“Ah, but running a humanitarian operation—actually a global network ranging from relief agencies to activists for a score of worthy causes—is an incredibly demanding task. So I learn the enemy’s skills to use against him, as it were.”

“If you say so.”

He turned to face her. “Annja, I understand your skepticism. But why not go and see for yourself? That’s what the spirit of scientific inquiry is about, isn’t it?”

“Well…yes. And I have to admit you’ve at least given me enough to intrigue me.”

“What do I need to make you passionate? I spoke earlier of saving the world. How about it? You can literally save the world—or many of the people who live on it—by helping track down the secret of conquering death. What else are you doing that’s more exciting? More magnificent?”

“Well. Nothing. Since you put it that way,” Annja said. She felt breathless, overwhelmed, needing to take back a little control of the conversation. “What if there’s nothing to it? I can’t promise results. It will probably turn out to be baseless.”

“Then you’ll do it?”

“I asked you first.”

He laughed aloud. Some of the earnest heads down in the pit turned up to look at him, then back to their business. Annja supposed they were saving the world in the event eternal life didn’t pan out.

“I won’t ask even you to deliver what does not exist,” he said. “But I suspect if I asked the impossible, in just the right way, you’d deliver.”

“Flattery will get you—well, I guess it usually works in the real world, doesn’t it?”

“I never flatter,” he said simply. He took her gently by the arm. “Come and meet your associate.”

“A NNJA , this is Dan Seddon,” Publico said. “He’ll be accompanying you to Brazil.”

They stood in an echoing space beneath what appeared to be the interior of a pyramid of translucent white blocks. A young man stood in the center, next to a slowly rotating statue of dark metal, possibly bronze. The shape suggested a feather sprouting from the floor. He turned with a certain fluid, alert grace at their approach.

When he saw Annja he smiled. She smiled back and held out her hand. He took it and shook it firmly. He didn’t seem the sort to kiss it.

He had a stylish brush of hair, either brown or dark blond, frosted lighter blond. His eyes were a green or hazel, not too different from Annja’s own and alive with curiosity. His face was a tanned narrow wedge with dark brows. His nose had been almost patrician thin and straight, but had been broken at least once and had a bump in the bridge to give it character. His grin had a practiced flash to it.

“Good to meet you, Ms. Creed,” he said, businesslike enough. He wore a lightweight jacket over a white shirt and blue jeans. His shoes were walking shoes, good quality. That scored points with Annja. An experienced field archaeologist who also tramped great distances in the course of her work with Chasing History’s Monsters, she knew the value of good footwear.

“My pleasure, Mr. Seddon,” she said. “So, you’re an archaeologist?”

“No.”

“Anthropologist?”

“No.” His manner was relaxed. Perhaps even a trifle superior.

“Dan is a troubleshooter,” Publico put in as smoothly as his gravelly voice would allow. “He’s been a major activist for years, campaigning against globalization all over the world. Seattle 2000. Italy ’03. Now he specializes in getting things done for me. He’s proved himself a key part of my humanitarian operations.”

Seddon smiled a lazy smile.

Annja frowned. “I’m sure Mr. Seddon has great abilities in his field,” she said. “But I’m not sure what he brings to the table for an archeological expedition.”

“It doesn’t really rise to the level of an expedition yet,” Publico admitted. “I hope it’ll turn into one. In the opening phases, though, it’s likely to entail a combination of intensive historical research and detective work.”

“You’ve got the historical angle nailed,” Seddon said with a grin. “I know you’re good at that. Not like that bimbo Kristie.”

Maybe this guy is okay, Annja thought.

“Mark’s career as a campaigner has involved no small amount of investigative work,” Moran said.

“Digging up dirt on exploiters and polluters,” the young man said. “Also I might just be able to look out for you. I’ve been around some.”

Annja had to press her lips together at the thought of his looking out for her. “I’d certainly appreciate your having my back,” she said, truthfully if not so candidly.

He looked her up and down a little more deliberately than was strictly polite. “That I can do, Ms. Creed,” he said. “That I can do.”

4

“I said, Emo’s for people not optimistic enough to be Goth,” Dan said.

Annja laughed. On the long journey to Brazil from Publico’s Manhattan penthouse her companion had proved consistently entertaining, with a sharp eye and facile wit. Those traits didn’t exactly translate into being of perceptible use in fieldwork, but they did help to pass the time. And there was no doubt that his air of self-assurance, quite untainted by any hint of bragging over his own abilities or achievements, was an encouraging sign.

The Belém riverfront was splashed with noonday sun and alive with people as they strolled along it. It was hot, the humid air like a lead blanket that wrapped about her and weighed her down. The rain that had fallen as they ate a late breakfast at a café near their small but well-appointed hotel had done nothing to alleviate the heat. If anything the extra moisture in the air made it more oppressive.

The floppy straw hat Annja affected helped a little, but she still felt overdressed in sleeveless orange blouse and khaki cargo shorts. She had even forsaken her trusty walking shoes for a pair of flip-flops.

Her companion shook his frosted head. He wore a white polo-style shirt over khaki trousers, a surprisingly conventional upscale-tourist look. When she had called him on it at breakfast he had explained frankly that dressing like a more conventional college-age American, in jeans-and-T-shirt scruff, tended to attract a little too much attention from the local law enforcement.

“If there’s one thing I learned from Genoa,” he had said over a forkful of scrambled eggs and bacon—to Annja’s relief he was no vegetarian—“it’s to pick your battles with the Man carefully.”

Genoa, she had learned, was the antiglobalization protest where police had killed demonstrators, resulting in a scandal that rocked the whole European Union.

“I wish I had a better idea where this shop we’re looking for is,” he said, waving a scrap of paper holding the address of their first contact. “Unfortunately it’s not the sort of place you find in a clean and well-marked spot. Or even on Google Maps.”

Feeling surprisingly rested after what amounted to a protracted nap, Annja was noticing how different Belém looked and felt than Rio de Janeiro, that gaudy metropolis sprawling like a drunken giant along the Atlantic coast far to the south. Tourists didn’t come here as often as they did to Rio, or to São Paulo. It was hot as Dante’s imagination, a degree south of the equator, and hadn’t felt any cooler when they’d arrived at the hotel before sunup.

The esplanade where they walked was wide and bright and clean enough. But they were clearly in a poorer section of the city. Dan stopped and frowned dubiously down a narrow side street. “I’m sure it’s down one of these alleys,” he said. “But I’m afraid we could wander for days looking and not find it.”

“I can’t believe you’re acting like a stereotypical man,” Annja said. “Why not ask for directions?”

He raised both brows at her in an uncharacteristic and utterly amusing look of helplessness. “Because I can’t speak Portuguese?”

“Fair enough. But you know some Spanish, don’t you?”

“Enough to get by. But that’s a different language.”

She laughed. “So native Spanish speakers and Portuguese speakers are always trying to convince me. But if you just listen and try, you’ll find you can make out a whole lot more than you think. Trust me—I did when I first started trying to learn Portuguese after knowing Spanish.”

He set his chin in an expression she took for provisional acceptance. He seemed to cultivate a fashionable sort of perpetual three-day facial fuzz. She had to admit he wore the look well. Perhaps it was the underlying toughness he never alluded to in words, but was to Annja’s practiced eye unmistakable in the wary way he moved. He was always balanced and ready for action. It redeemed him from looking like some orthodontist’s kid from Seattle rebelling against capitalism and the modern world on a five-figure allowance.

Annja spoke to a pair of middle-aged women wearing white blouses and colorful skirts. They seemed surprised to find an American speaking to them in good Brazilian Portuguese, but were as friendly as most Brazilians Annja had encountered, and quickly told her how to find the address.

“Watch yourself,” the taller one suggested. “That’s not the best part of town for a white girl.” It was spoken matter-of-factly.

“I will,” Annja said in response to the warning. “Thanks.”

Annja led Dan away from the river down a relatively wide street.

“How many languages do you speak, anyway?” he asked.

“Several,” she said. “I’m pretty good with the major modern Romance languages. Spanish, of course. Portuguese, Italian, French, Catalan.”

He frowned. “Are you sure it’s a good idea for you to be here?”

She laughed. “One of those nice women warned me, too. But why you? I thought you were used to knocking around the Third World. Emphasis on knocking. ”

“Yeah, I am. And one thing I learned early on—sometimes it knocks back. There’s a lot of resentment at Western colonialism and cultural imperialism. It isn’t all just the wicked Muslims, the way the nutcases back home try to make it. And Brazil is kind of notorious for violence in its poorer areas.”

She noted with approval that he didn’t screw around with euphemisms. While she was no radical—she was pretty determinedly apolitical—Annja found herself more comfortable with the honestly hard core, as opposed to moderates, the mushy centrists, with their political correctness and nervous phrasing. She cared about words and what they meant. They were core to her professional discipline. She had little patience for people who muddied them with soft heads or hearts.

“Favelas,” she said. “Some of the Earth’s most serious slums. You’re thinking more of Rio de Janeiro. And yeah, that’s full-contact poverty. There really are favelas in Rio where the police literally don’t go except in battalion strength, the way they did in one of the worst districts just a couple of years ago.”

“I read about that online,” Dan said.

“I’ve been to Rio,” she said, “and this place has a different feel. For one thing, food’s a lot more readily available than it is in the middle of a huge urban wasteland.”

By chance they had come into a little market square, lined with kiosks offering everything from live chickens in crates to bin after bin of mostly unfamiliar fruits and vegetables to big wheels of cheese. And everywhere fish, of a remarkable range of size and shapes.

“Look around you. The people are mostly smiling, happy,” Annja said.

He shrugged. “Anesthetized to the realities of repression.”

“Dan, that’s not worthy of you,” she said more sharply than she’d intended. “You know nothing about these people.”

A man passed them with a cheerful nod and word of greeting.

“I stand corrected, Ms. Creed. “I confess I’ve been guilty of Western cultural imperialism and assumed superiority. Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa. ”

“You know some Latin,” she said. “That’s a great grounding for Romance languages. And just for the record, I like the wiseass Dan a lot better than the doctrinaire Dan.”

He might just as easily have told her off. They were, after all, contractors on assignment together. But he flashed a devil-may-care grin and said, “Noted. And maybe I do, too.”

They wandered down a line of stalls, listening to the good-natured—mostly—bargaining. Sometimes the African dialects were so prevalent Annja understood little if any better than Dan appeared to.

“Whoa. Those are some ugly fish,” Dan said, waving at a particularly formidable specimen, arrayed with armor and sinister spikes and barbs. “Didn’t I see one of these eating tourists in Mexico on an old episode of Outer Limits on Nickelodeon?”

“It’d have to be a bit bigger and a lot more ambitious than that one looks,” Annja said. “Of course, it is dead.”

“Remind me not to take a dip in the river. Not that it looks that inviting—it’s the color and consistency of pea soup.” He shook his head. “Man spoils everything he touches, doesn’t he?”

“Don’t kid yourself. The crust of old plastic bags and junk is largely man-made. But the river’s color and consistency are all natural, a combination of silt and things exuding into it from the forest all around,” Annja said.

“Huh,” he said, clearly unconvinced. She felt a flash of annoyance. He had a tendency not to see things that clashed with his preconceptions. She tried to let it go.

I have to work with him, she reminded herself. And anyway, for the most part he’s a lot more fun than a lot of partners I’ve had…. She let the thought dangle, unwilling to follow it further.

They pushed on, turning into a narrow street where two-story whitewashed buildings seemed to lean toward each other overhead. They took a right turn into a dank, muddy path that it might have been a compliment to call an alley.

Dan hung back, frowning at Annja. “Uh—” he said.

She stopped and looked sternly at him. “Don’t tell me you’re going all male-chauvinist protective on me.”

He shrugged. “It’s my job to look out for you, Ms. Creed.” She recognized he was in official mode.

“Hasn’t it occurred to you I’ve looked after myself in some pretty rough parts of the world?” And more than that, of course, but she wasn’t sharing that information. With any luck he’d never find out.

“Well—I don’t see a film crew anywhere,” he said. “Not to mention network security staff.”

“You’d be surprised how sparse that is for our show,” she said. “Anyway, look. If it makes you feel better, I happen to have long legs. I know you noticed.”

To his credit his gaze never wavered from hers. “Yeah.”

“So if anything bad happens I can run away real fast. Satisfied?”

He frowned at her a moment. Then his face unclouded and he laughed. “I get the feeling I have to be.”

They stopped at a blue-painted door set into a wall missing some chunks of stucco. He nodded. “After you.”

She pushed her way into darkness.

5

The first thing that hit her, along with the earth-burrow coolness, was the smell. It wasn’t an unpleasant smell, particularly. But it was a complicated one. A skein of smells, a tapestry, woven out of elements familiar, hauntingly reminiscent and outright strange. Some were organic, some chemical and astringent.

“May I help you?” a voice said from the shop’s dim depths.

A beaded curtain rustled. A woman emerged into the front room among close-packed shelves and counters. She was tall, possibly taller than Annja, although the red-and-yellow turban around her head added a few inches. In the gloom it was hard to be sure.

Annja glanced sideways at Dan. “We’d like to talk to the shop owner,” she said.

“That’s me,” the woman said. She seemed to glide forward without moving her feet, doubtless an illusion caused by her long skirts, which brushed the warped boards of the floor. “I am Mafalda. How may I help you?”

As she came close enough to distinguish detail, Annja realized that she was a very beautiful woman, seemingly no older than Annja, with mocha skin and eyes that might have been dark green.

“You’re Americans,” Mafalda said.

Annja smiled.

“What can I do for distinguished visitors from so far away?” Mafalda seemed to be slipping into a familiar role, which Annja guessed was half mystic, half huckster. She probably had one mix for the tourists and another for the locals.

Annja looked openly to Dan. Though never spoken, the arrangement seemed to be that while she was in charge of the scientific and research aspects of the expedition, he spoke for their mutual employer Moran. She wasn’t entirely comfortable with the arrangement, but Sir Iain was paying her very well.

“We understand you might have some information about a hidden city,” Dan said.

“Who told you that?” the proprietor asked. Shrewdly, Annja thought.

“Someone back in the United States,” Dan answered blandly.

Mafalda seemed unimpressed with that response. “Lost-city rumors crawl all over the Amazon like bugs,” she said, unwittingly echoing what Annja had told Sir Iain in his Manhattan headquarters. “They have done so ever since the days of the first explorers. I don’t deal in treasure maps. Perhaps you should seek elsewhere.”

Shooting an exasperated look at Dan, who only shrugged, Annja said, “Perhaps if you’d be so kind as to show us what you do deal in, please, we’d better understand how we might help each other.”

It occurred to Annja that their employer might be playing his cards too close to his well-muscled chest. Unless he simply had no better information to share. But he must have had some reason to send them here.

After favoring Annja with a quick, cool glance of appraisal, Mafalda smiled slightly. “Of course. If the lord and lady will follow me.”

“Lord and lady?” Dan echoed quietly.

Annja sniffled. He cocked his head at her.

“I’m allergic to something in here,” she said.

Mafalda, who had waited coolly for the whispered exchange to end—suggesting some experience with tourists—began her tour. “I serve the practitioner of candomblé. I have here everything needed for the toques, the rituals, whether public or private.”

“What’s candomblé? ” Dan asked as Mafalda led them through narrow aisles with bins of sheaved herbs, colorful feathers and beads.

“It’s a widespread folk religion in Brazil,” Annja said. “It’s basically a combination of Catholicism with West African beliefs.”

“Like voodoo?” Dan asked.

“That’s right,” Annja said, nodding. She dabbed surreptitiously at a droplet that had formed at the end of her nose and sniffled loudly again.

“We believe in a force called axe, ” Mafalda said, leading them into an aisle with a number of tiny effigies that reminded Annja of Mexican Day of the Dead figurines. There were also racks of odd, twisted dried roots and vegetables and sturdy cork-topped jars with not-quite-identifiable things floating in murky greenish fluids.

“Mind the jacaré, ” Mafalda said as an aside.

“Huh?” Dan said. “What’s jacaré? ”

He bumped his head on something hanging from the ceiling. He did a comical double take to find himself looking into the toothy grin of a four-foot stuffed reptile hung from the ceiling.

“One of those,” Annja said. She had found a travel pack of tissues in the large fanny pack she wore, and was in the process of blowing her nose. It made a handy cover for her grin. “An Amazon caiman. There’s a specific species named jacaré, but people around here mostly call all crocodilians that.”

Dan cocked a brow at Mafalda, who wasn’t bothering to hide her own toothy grin. “Decorating with endangered species?”

“We’re more endangered by the jacarés, ” their hostess said promptly. “They eat many Brazilians each year.”

“Is she serious?” Dan asked.

“Oh, yes,” Annja said.

He shrugged, shaking his head.

“You were telling us about axe, ” Annja prompted Mafalda. She had no idea if it had anything to do with their mission—to find some lead, however tenuous, to the mysterious hidden city named Promise—but she was fascinated, personally and professionally, with the local folk religion.

“Oh yes.” The turbaned head nodded. “ Axe is the life force. It permeates all things.”

“So your toques involve evoking this life force?” Annja asked.

The woman led them on toward the front of the cramped store. “Somewhat. Mostly we invoke the orixás. ”

The word was unfamiliar to Annja. “What are they?”

Mafalda flashed a quick smile. “Our gods,” she said, “Olorum is the supreme creator, but he doesn’t pay so much attention to us little people. So we don’t trouble him. The orixás, though, they’re the deities who deal with us humans. So they’re the ones we have to worry about keeping happy.”

“Makes sense,” Dan said.

The tall woman had led them back to the cash register, which was a modern digital model, Annja noted, Beside it stood racks of CDs with colorful covers. Dan picked one up and scrutinized it. “You have a sideline selling Brazilian jazz?” he asked. “These don’t look like New Age meditation CDs.”

“They are for the capoeira, ” Mafalda said.

“The martial art?” Annja asked.

Mafalda laughed. “It’s more than a martial art.”

“What do you mean?”

“Do you know the story of the slaves?” Mafalda asked. Annja felt Dan tense beside her. Her own quick inhalation turned into a sneeze, only half-staged.

“Some,” Annja said cautiously.

“Well, the slaves weren’t happy being slaves. So they practiced to rebel. But the masters would not permit this. So the slaves had to create a way of training that they could practice under the masters’ eye without their suspecting.”

“Hiding in plain sight,” Annja said.

Mafalda nodded, smiling. “Exactly. So they hid their warrior training as a type of dance used in religious rituals.”

“And so in turn capoeira practice got worked into the actual rituals?” Annja asked.

“Perhaps. Today capoeira is all these things—a form of fighting, a dance, candomblé ritual.”

“I see.” Annja skimmed the rack until a cover caught her eye. A very dark, very skinny man was performing a trademark capoeira headstand kick in front of a rank of colorfully dressed dancers shaking what appeared to be feather gourd rattles. “I’ll take this one, please.” It seemed a gracious thing to do, a way to keep open lines of communication with their uninformative informant. Also she was curious.

Mafalda rang up the transaction. She wrapped the CD in fuchsia paper and taped it neatly.

“Some of the slaves did fight back, you know,” she said as she handed the parcel to Annja. “They escaped and fled into the forest. There they fought. Some died, some won their freedom.”

“The Maroons,” Dan said.

“Yes,” Mafalda said. Her manner was suddenly very grave. “The ones about whom you asked—they do not like strangers seeking after them. Capoeira was not the only weapon they created unseen beneath the world’s nose. And their reach is very long.”

6

“Was it just me,” Dan said, sipping strong coffee the next morning at a green metal table at an open-air waterfront café near their hotel, “or did that woman seem scared to tell us about the Maroons?”

“It wasn’t just you,” Annja said. She took a sip of her own coffee. “But she seemed more scared not to.”

“So did we learn anything?” he asked.

“They have a long reach.”

Dan set down his cup, shaking his head. “This is all starting to sound way too Indiana Jones.”

She smiled. “What would you call a quest for a lost city?”

He laughed but shook his head again. “The real world doesn’t work like that.”

“Doesn’t it? I thought terrorizing people to get results was thoroughly modern. Doing it long-distance, even.”

“Touché,” Dan said without mirth. “It just struck me as far-fetched.”

It would have me, not so long ago, Annja thought but did not say.

The café stood near a set of docks servicing riverboats somewhat larger, if not markedly more reputable looking, than the small craft Annja and Dan had seen crowding the river the day before. Dockworkers were swaying cargo off a barge with an old and rickety-looking crane. The stevedores were big men, mostly exceedingly dark and well muscled.

Although it was relatively early in the day and they were both lightly dressed and sat in the shade of an awning, Annja could feel sweat trickling down her back.

“It’s not, really,” she said, sipping her coffee. “Farfetched, I mean. If you think about them just like any other…interest group or faction. A lot of governments go to extremes to protect their secrets.”

“Corporations, too.”

“Sure. Other groups, as well. These people’s ancestors fled to escape slavery and then persecution—attempts to recapture them, reenslave them. That could account for their being a little paranoid.”

“But didn’t Brazil abolish slavery—what? Over a hundred years ago,” Dan said.

“In 1880,” Annja said. “It may be,” she continued, setting the cup down and leaning forward over the table, “that Mafalda gave us more information than she intended.”

“What do you mean?”

“I thought a lot about what she told us last night. She was worried, basically, that the Maroons—the Promessans, we might as well call them—might think she talked too much about them.”

“So you’re thinking they’ve got some kind of surveillance on her,” Dan said. “Bugs? Or maybe something astral?” He said the last with a laugh.

“Hey, I’m as hardheaded skeptical about that stuff as you are.” Although I bet I have to work a whole lot harder at it, she thought. “I’m not even sure I go so far as buying electronic eavesdropping, although with snooping gear so incredibly cheap and tiny these days, I guess I shouldn’t dismiss it out of hand.”

“What are you thinking?” He was all business now. In a sense she was pleasantly surprised. While he had been polite and correct the whole time they had been together, she had picked up pretty unequivocal signals he found her attractive. But he also conveyed a certain sense of superciliousness. Not quite disdain. But as if he were the professional here, not she.

Given his background, and current mission brief, she could even understand that, however it irked her. If only he knew how wrong he was. And yet, of course, she couldn’t tell him that the last thing she needed was his protection.

Not that he’d believe her if she tried.

But now he was acting like one pro talking business with another, and that was good. “While it’s not even impossible they could bug Mafalda’s shop long-distance—I mean, all the way from Upper Amazonia—I don’t think that’s the likeliest thing. At least, it’s unlikely to be their only measure,” Annja said.

“Back up a step. You think they could bug the shop all the way from their hidden fortress?” Dan asked.

She shrugged. “Why not? It could be something as prosaic as a satellite phone relay.”

“So you’re not envisioning these people as, like, some kind of lost culture still living in the eighteenth century or whenever?”

“I think that’s King Solomon’s Mines,” she said with a smile. “Not necessarily. Were you? For that matter, is Sir Iain? I thought his whole thing was the possibility they might possess technology far in advance of ours.”

“Well—maybe. But they could possess, say, herbal techniques developed beyond the scope of modern medical science and still have an archaic culture. Or an essentially indigenous one.”

“Maybe. But from what Sir Iain told me, and some research I did afterward, one of the first things the escaped slaves did was start trading with the English and the Dutch for modern weapons.”

“I don’t mean to be racist, but that seems pretty sophisticated for slaves,” Dan said.

“I found out something pretty startling. Not all the slaves were preliterate tribal warriors from the bush. It turns out the Portuguese colonists were so lazy they got tired of administering their plantations and mines and other businesses themselves. So they started kidnapping and enslaving people from places like the ancient African city of Tombouctou. They may even have enslaved their own people from their colonial city of Luanda.”

“Meaning—”

“Meaning they were deliberately capturing and enslaving clerical and middle-management types,” Annja said.

He laughed vigorously. “That’s great,” he said. “Just great. They really were lazy. And so these well-educated urban slaves teamed up with their warrior cousins taken from the tribal lands and created their own high-power civilization.”

“Pretty much. That’s why they were able to stand off their former masters for so long. They were every bit as sophisticated as the Europeans. More, in a way, because of their allying with the Indians early on. They knew the terrain better.”

“A guerrilla resistance,” he said. “I like it.”

“My sense is,” she said, leaning forward onto her elbows with her hands propping her chin, “if this city Sir Iain thinks exists really does, its occupants would be pretty current with modern technology.”

“Or even advanced beyond it.” He arched a brow.

She shrugged. “Your boss seems to think so.”

Dan frowned. “He’s a great man. He’s my friend. You can call him our employer,” he said, emphasizing the our subtly, “but I don’t like the word boss. ”

“Understood,” Annja said.

“So, all right, conceivably these descendants of the long-ago escaped slaves, the Maroons or Promessans, might be able to bug a shop in Belém long-distance. I see that. But you seem to think that’s not what they’re doing.”

“If they really exist,” Annja added.

“Sure.”

She thought a moment, then sighed. “No. I don’t. A key aspect of their early survival was trade. I’d bet they’ve stuck with that as a mainstay of their economy. If for no other reason they’d have agents—factors—in the outside world. Belém is pretty much the gateway to the entire Amazon in one direction and the entire world in the other. And that seems to have been the connection with the German businessman your…Publico told me about. He must have had some kind of commercial relationship with Promessa. What business was he in, do you know?”

“Electronic components of some sort. Controls for computerized machine tools, possibly.”

“Hmm.” She regretted not pressing Moran for further details. The fact was, he had so swept her off her feet during their one and only interview, with the sheer hurricane force of his personality and passion, that she never even thought of it. “Perhaps we can call him or e-mail him. That might be a lead to follow up, too.”

“Maybe,” Dan said. “Publico kind of likes his people to use their own initiative.”

“Well.” Annja wrinkled a corner of her mouth in brief irritation. “Maybe it isn’t necessary. If the Promessans keep agents here for trade, they can just as easily keep them here for other purposes.”

“So their traders are spies.”

She shrugged again. “There’s precedent for that. They may or may not be the same people. We don’t have enough data even to guess.”

“So if we can spot one of these agents we might not need Mafalda’s cooperation.”

“That’s what I’m hoping, anyway,” Annja said.

For a moment they sat, thinking separate thoughts. A young woman came into the open-air café. She was tall, willowy, and—as Annja found distressingly common in Brazil—quite beautiful. She squeezed the water from a nearby beach from her great mane of kinky russet hair. Water stood beaded in droplets on her dark-honey skin, which was amply displayed by the minuscule black thong bikini she wore.

The rest of the café patrons were locals. No one else seemed to take notice of the woman as she strode to an open-air shower to one side of the café, shielded by a sort of glass half booth from splashing any nearby patrons.

Nor did they show any sign of reaction when the young woman dropped a white beach bag with white-and-purple flowers on it to the floor, turned on the water and skinned right out of her bikini.

Annja looked around, trying to keep her cool. Am I really seeing this? The customers continued their conversations or their perusals of the soccer news in the local paper. She glanced back. Yes, there was a stark naked woman showering not twenty feet away from her.

She looked toward Dan. He was looking at her with a studiedly bland expression. “You might as well watch,” she said. “Just don’t stare.”

“Never,” he murmured, and his eyes fairly clicked toward the showering woman.

The young woman finished, toweled herself briskly, then dressed in shorts and a loose white top. She looked up as a small group of young women came into the café, chattering like the tropical birds that clustered in the trees all over town. She greeted them cheerfully and joined them at a table as if nothing unusual had happened.

Dan let the breath slide out of him in a protracted sigh. “Whoo,” he said.

“Whoo indeed,” Annja said. “It’s like a whole different country, huh?”

“Excuse me,” a voice interrupted.

At the quiet, polite feminine query in English both looked up. Two young people stood there, a very petite woman and a very tall man. Both were striking in their beauty and in their exotic appearance. Both wore light-colored, lightweight suits.

“Are you Americans?” the woman asked.

“Are we that obvious?” Dan asked.

The young man shrugged wide shoulders. He exuded immediate and immense likeability. “There are details,” he said in an easy baritone voice. “The way you dress. The way you hold yourselves. Your mannerisms—they’re quicker than ours tend to be, but not so broad, you know?”

“And then,” Annja said with a shrug, “there’s our tendency to gawk at naked women in the café.”

The man laughed aloud. “You were most polite,” he said.

“She probably would have appreciated the attention,” the woman said. “We Brazilians tend to take a lot of trouble over our appearance. Clearly you know that beauty takes hard work.”

“You’ve probably noticed, we don’t have much body modesty hereabouts,” the man said. “But you were wise to be discreet. Brazilians also tend to think that Americans confuse that lack of modesty with promiscuity.”

“They’re probably right,” Dan said, “way too often.”

“Please, sit down,” Annja told the pair. She was not getting threatening vibes from them. And she and Dan were drawing blanks so far. Any kind of friendly local contact was liable to be of some help. At least a straw to clutch at. “I’m Annja Creed. This is Dan Seddon. He’s my business associate.”

Dan cast her a hooded look as the woman pulled out a chair and sat. The man pulled one over from a neighboring table. Annja saw that they both had long hair. The woman’s hung well down the back of her lightweight cream-colored jacket, clear to her rump. The man’s was a comet-tail of milk-chocolate dreadlocks held back by a band at the back of his head, to droop back down past his shoulders.