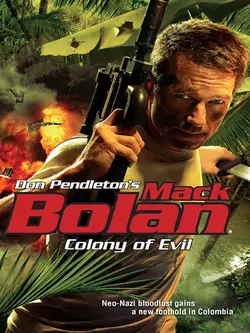

Colony Of Evil

Don Pendleton

Claiming one hundred square miles of mountainous terrain inside Colombia–ideal for the coca crop that supplies its revenue–Colonia Victoria is a sanctuary for humanity's most dedicated fanatics.Organized by one of Hitler's minions still deeply devoted to the eradication of those considered threats to the "master race," this Nazi Neverland is now a deadly global threat. And it's spearheading a new wave of terror–with a little help from drug money, corrupt offi cials and a partnership with Islamic fanatics.Mack Bolan's hunting party includes a Mossad agent and a local guide, as tracking Hans Gunter Dietrich becomes a violent trek deep into the jungle, where Bolan intends to dissolve an unholy alliance in blood.

Each mission held surprises

Few, if any, ran exactly as the plans were drawn—in quiet moments, prior to contact with the enemy. Whether you called it chaos theory or the human element, it all came down to the same thing: variables that could never be anticipated.

Mack Bolan had stayed alive this long because he planned ahead and still retained the flexibility required to change his plans, adapt to any given situation that arose. Some day, he knew, the switch would be too fast for him, his enemy too deadly accurate, and that would be the end.

But hopefully, it wouldn’t be this night.

He understood that there was too much riding on his mission to Colombia, too many lives at risk if he should fail. His own fate was of less concern to Bolan than the job at hand, but he could hardly carry out that job if he was dead.

That wasn’t part of the plan.

Colony of Evil

Mack Bolan

Don Pendleton

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Special thanks and acknowledgment to Mike Newton for his contribution to this work.

At least two-thirds of our miseries spring from human stupidity, human malice and those great motivators and justifiers of malice and stupidity, idealism, dogmatism and proselytizing zeal on behalf of religious or political idols.

—Aldous Huxley,

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow

Fanatics never learn. They never change. Defeat in argument or battle doesn’t faze them. Time has no impact on their beliefs or tactics. When they go too far, the only thing that works is cleansing fire.

—Mack Bolan

To Senator James Webb, for courage under fire in

Vietnam and Washington, D.C.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

EPILOGUE

PROLOGUE

Park Avenue, New York City

The man had proved untouchable; his wife was not. The man—the real target—employed security devices and armed guards, remained inside his consulate whenever possible, and generally lived as if his life was constantly at risk.

In that belief, he was correct.

The trackers had considered sniper rifles, car bombs, even rocket launchers, but they ultimately realized that an assault against the consulate itself would likely guarantee their own deaths, while their target had a good chance of emerging from the blitz unscathed. They found that prospect unacceptable, and so adjusted their approach.

The target’s wife was reasonably pretty, undeniably vivacious, and would not allow herself to be penned up inside drab walls simply because her husband was afraid. She had been hoping, even praying, for the diplomatic posting to New York, and she was not about to waste a moment of her golden opportunity. There were too many stores, boutiques, salons, spas, theaters, cafés—the list was endless, and she meant to try them all before they were recalled to Tel Aviv.

That afternoon she needed jewelry, and she refused to have samples delivered to the consulate. Why suffer a parade of fawning salesmen when she could go out and visit them, have lunch, enjoy herself in the heart of Manhattan?

The trackers watched and waited, mingling with the sidewalk crowd. They were dressed down to fit the setting, pass for tourists, and the woman’s driver didn’t seem to notice them.

Her single bodyguard was first to leave the jeweler’s shop, scanning the street before he beckoned to his charge. The woman followed, carrying a small black satin bag and chatting, distracting her protector when he should have been alert.

The trackers moved together, one drawing a pistol, firing at the bodyguard from point-blank range, then spinning toward the black Mercedes at the curb and bouncing three rounds off its windshield. If the driver chose to save himself, he had to stay inside the car.

The second tracker pulled a clear glass bottle from his pocket, twisted off the cap and hurled its contents at the woman’s startled, screaming face. The tone of her screams changed immediately, from a note of panic to soul-searing agony.

The trackers fled and within heartbeats had been swallowed by the crowd.

Sonora, Mexico

THE BUS HAD BROKEN DOWN again, which meant the tour would be late arriving at the stop in Hermosillo. The hotel was not a problem, and the Mexican tradition of late dining meant they wouldn’t starve, but food was not Eli Dayan’s primary focus.

He was tired of traveling and wondered why he’d let his wife persuade him that a Mexican vacation was a good idea.

The kibbutz where they lived was in a desert, and he’d flown halfway around the world to see more desert through the tinted windows of a bus that suffered some mechanical disruption every day, like clockwork. He was tired of cactus, tired of rural villages that seemed to be constructed out of mud and cast-off refuse, tired of drinking beer because he couldn’t trust the water.

His bowels were grumbling, and he reckoned that he was about to suffer the revenge of Montezuma. It would make the last five days of their grand tour a misery, and something told him that his wife would never forgive him.

The bus was slowing. Mouthing a silent curse, Dayan wondered what the excuse would be this time. A flat tire? Had the lazy driver failed to fill the diesel tank that morning?

“What is this? Why are we stopping?” Hilda, his wife, asked him.

“How should I know?”

“Well, find out!”

“They’ll tell us, if it’s anything important.”

They were stopped now, and he heard the front doors open with a hiss. Two men in military jackets, wearing black ski masks, stood near the driver. Both held rifles Dayan recognized as folding-stock Kalashnikovs.

“What is it! What’s this all about!” Hilda demanded.

“Shut your mouth, woman, before you get us killed!”

On of the gunmen spoke, his accent strange to Dayan’s ears. “Your trip ends here,” he said, smiling behind the horizontal slit that showed his lips. “If you know any prayers, this is the time to call upon your god.”

Miami Beach, Florida

THE DAY HAD STARTED WELL for Ira Margulies. He’d closed the deal on Morrow Island, all two hundred million dollars of it, and his personal commission was a cool three million. His clients on both sides of the transaction were well pleased, and he could almost smell the leather seats in the new Maserati that he planned to buy.

Who said a man of fiftysomething was too old to play with toys?

His brief stop at the strip mall on Dade Boulevard did not involve his business. It was strictly personal. The storefront that he entered, darting from his car at curbside to the swinging door through scalding tropic heat, was one of half a dozen mail drops where he kept post boxes under different names.

Why not? It was entirely legal, and the correspondence he received, while not fit for wife or children to peruse, made his days—and nights—more pleasant. After long days at the office, he enjoyed a little something on the side, and in these days of killer viruses, the safest sex of all was solitary.

He was out again in less than sixty seconds, carrying a package and six envelopes in his left hand. He barely registered the movement on his left, until a man’s voice asked him, “Ira? Is that you?”

Margulies turned, already trying to concoct an explanation, but he did not recognize the speaker. Frowning, he was on the verge of a reply when the stranger produced a pistol, smiled and shot him in the chest.

Already dead before he hit the pavement, Ira Margulies had no thought of embarrassment about the package and the envelopes strewed all around him, soaking up his blood.

CHAPTER ONE

Bogotá, Colombia

Mack Bolan’s Avianca flight was ninety minutes late on touchdown at El Dorado International Airport. It hadn’t been the pilot’s fault, but rather issues of “security” that slowed them. Bolan supposed that meant drugs or terrorism, possibly a mix of both.

For close to thirty years, throughout Colombia, it had been difficult to separate cocaine from politics. The major drug cartels bought politicians, judges, prosecutors, cops, reporters, and killed off the ones who weren’t for sale. They backed right-wing militias that pretended to oppose crime while annihilating socialists and “liberals,” occasionally using mercenary death squads as their front men to attack the government itself.

Colombian police had coined the term narcoterrorism, but they rarely spoke it out loud. To do so invited censure, demotion and transfer, perhaps an untimely death.

Back in the States, Bolan read stories all the time claiming that cocaine trafficking was up or down, strictly suppressed or thriving at an all-time high. He took it all with several hefty grains of salt and got his information from a handful of selected sources he could trust.

The traffic was continuing, and U.S. Customs seized approximately ten percent of the incoming coke on a good day. That figure had been static since the 1980s, with a few small fluctuations. Nothing that had happened in the interim—from cartel wars and Panamanian invasions to the bloody death of Pablo Escobar—had altered the reality of narcopolitics.

Drugs paid too much, across the board, for any government to halt the traffic absolutely. Narcodollars funded terrorism and black ops conducted by sundry intelligence agencies, bankrolled political careers and made retirement comfy for respected statesmen, greased the wheels of international diplomacy and commerce.

The filth was everywhere, and Bolan wasn’t Hercules.

But he could clean one stable at a time.

Or, maybe, burn it down.

His latest mission to Colombia involved cocaine, but only in a roundabout and somewhat convoluted way. His main target was equally malignant, but much older, an abiding evil beaten more than once on bloody battlefields around the world, which still refused to die.

As Evil always did.

In spite of its delays, his flight down from Miami had been pleasant—or at least as pleasant as a flight could be when he was traveling unarmed toward mortal danger, with no clear idea of who might know that he was coming, or of how they might prepare to meet him on arrival.

First, there was the matter of his contact on the ground. The man came recommended by the CIA and DEA, which could spell trouble. Bolan knew those agencies were frequently at odds, despite the “War on Terror” and their separate oaths to operate within the law. One side was pledged to halt narcotics traffic by all legal means; the other frequently played fast and loose in murky realms where drugs were just another form of currency.

The fact that both sides found his contact useful raised a caution flag for Bolan, but it wouldn’t make him drop out of the game. He’d worked with various informers, spooks and double agents in his time, and had outlived the great majority of them.

A few he’d killed himself.

So he would give this one a chance, but keep a sharp eye on him, every step along the way. One false step, and their partnership would be dissolved.

In blood.

Their first stop in the capital would have to be a covert arms merchant, someone who could supply Bolan with the essential tools of his profession. That, he guessed, would be no problem in a nation whose homicide rate topped all the charts. That meant guns in abundance, and Bolan would soon have what he needed.

His bankroll would cover a week of high living, assuming the job took that long and he lived to complete it. The cash was a tax-free donation, furnished that morning by one of Miami’s premier bolita bankers who’d decided, strictly from his heart and the desire to keep it beating, that he wouldn’t miss $250,000 all that much.

Right now, Bolan supposed, the macho gambler’s goons were scouring Dade County and environs for the man who’d dared to rob him, but they wouldn’t find a trace. Bolan had played that game too often to leave tracks his enemies could follow—if, in fact, they had the stones to look him up in Bogotá.

And they would have to hurry, even then, because he didn’t plan on spending much time in the capital. Some shopping, some discreet interrogation, and he would be on his way. His target was not found in Bogotá, in Cali or in Medellín.

That would’ve been too easy.

Bolan couldn’t smell the jungle yet, riding in pressurized and air-conditioned semicomfort, but he’d smelled it many times before. Not only in Colombia, but on five continents where Evil went by different names, wore different faces, always seeking the same ends.

Evil sought power and control, the same things politicians spent their lives pursuing. Which was not to say all politicians were dishonest, prone to wicked compromises in pursuit of private gain. Bolan acknowledged that there might be various exceptions to the rule.

He simply hadn’t met them yet.

And something told him that he wouldn’t find one on this trip.

JORGE GUZMAN WAS SMART enough to check the monitors, but waiting in the crowded airport terminal still made him nervous. El Dorado International’s main terminal sprawled over 581,000 square feet and received more than nine million passengers per year. Toss in the families and friends who came to see them off or to meet them on arrival, thronging shops and restaurants and travel agencies, and visiting the airport was like strolling through a crowded town on market day.

Which made it difficult, if not impossible, for Guzman to detect if anyone was watching him, perhaps waiting to slip a knife between his ribs or to press a silenced, small-caliber pistol tight against his spine before they pulled the trigger.

Guzman had no special reason to believe that anyone would try to kill him here, this evening. He had been cautious in preparing for his new assignment, as he always was, informing no one of the covert jobs that came his way, but he had enemies.

It was inevitable, for a man who led a covert life. Guzman had been a thief and then a smuggler from his youngest days, but for the past eight years he’d also served the cloak-and-dagger lords of Washington, who paid so well for information if it brought results.

Guzman had started small, naming street dealers and some minor smugglers with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, first obtaining their assurance that his name would never be revealed to any native law-enforcement officer or prosecutor under any circumstances. Some of them were honest, to be sure, but Guzman saw them as a critically endangered species, with their numbers dwindling every day.

As time went by and he became more confident, Guzman had traded information on the larger drug cartels. It was a dicey game that guaranteed a slow and screaming death if he was found out by the men he had betrayed. From there, since drugs touched everything of consequence throughout Colombia, it was a relatively short step to cooperating with the Central Intelligence Agency on matters political, sometimes helping the famous Federal Bureau of Investigation find a fugitive from justice in America.

But Guzman’s latest job was something new and different. In the past, he’d kept his eyes and ears open, asked some discreet questions and sold the information he obtained for top dollar. This time, he was supposed to serve as guide and translator, helping a gringo agent carry out his mission, which had not been well explained.

It smelled of danger, and Guzman had nearly told his contacts to find someone else, perhaps a mercenary, but the money they offered had changed his mind. He was a mercenary, after all, in his own way.

Because he was concerned about the greater risks of this particular assignment, Guzman had been doubly careful on his long drive to the airport, glancing at his rearview mirror every quarter mile or so, detouring incessantly to see if anyone stayed with him through his aimless twists and turns.

But no one had.

Still, he was nervous, sweating through his polo shirt, beneath the blazer that he wore for dual reasons. First, it made him look more formal, more respectable, than if he’d shown up in shirtsleeves. Second, it concealed the Brazilian IMBEL 9GC-MD1 semiautomatic pistol wedged beneath his belt, against the small of his back.

The pistol was a copy of the old Colt M1911A1 pistol carried by so many U.S. soldiers through the years, re-chambered for 9 mm Parabellum rounds. The magazine held seventeen, with one more in the chamber. Guzman wore it cocked and locked, prepared to fire when he released the safety with his thumb, instead of wasting precious microseconds when they mattered, pulling back the hammer.

He had a second pistol in his car, beneath the driver’s seat. It was another IMBEL knock-off, this one chambered in the original .45ACP caliber. Guzman had considered carrying both guns into the terminal, but it had seemed excessive and he worried that his trousers might fall down.

A canned voice, sounding terminally bored, announced the long-delayed arrival of the Avianca flight Guzman had been awaiting for the past two hours. Since he did not have a ticket or a boarding pass, he would not be allowed to meet his party at the gate—but then, the pistol he was carrying made it impossible for him to clear security, in any case.

He found a place to watch and wait, between a café and a bookstore, lounging casually against the cool tile of the wall behind him. When the passengers began to straggle past security—ignored because they were arriving, not departing on an aircraft—Guzman studied faces, body types, seeking the man he was supposed to meet.

He had no photograph to guide him; it was too hush-hush for that. Instead he had been given a description of the gringo: six feet tall, around two hundred pounds, dark hair, olive complexion, military bearing. In case that wasn’t good enough, the man would have a folded copy of that morning’s USA Today in his left hand.

He watched a dozen gringos pass the gates, all businessmen of one sort or another. Guzman wondered how many had been aboard the aircraft, and was pondering a way to get that information if his man did not appear, when suddenly he saw an Anglo matching the description, carrying the proper newspaper.

The brief description from his contact had been accurate, but fell short in one respect. It made no mention of the gringo’s air of confidence, said nothing of the chill that his blue eyes imparted when they made contact.

Guzman pushed off the wall and moved to intercept the stranger he’d been waiting for. Above all else, he hoped the gringo would not botch his job, whatever it turned out to be.

Guzman devoutly hoped the stranger would not get him killed.

BOLAN HAD MADE HIS CONTACT at a glance. Unlike the slim Colombian, he had been furnished with a photo of the stranger who would assist him in completion of his task.

He wasn’t looking for a backup shooter when the job got hairy, just a navigator, translator and source of useful information on specific aspects of the local scene. If the informant Jorge Guzman could perform those tasks without jeopardizing Bolan’s mission or his life, they ought to get along just fine.

If not, well, there were many ways to trim deadwood.

The man was coming at him, putting on a smile that didn’t touch his wary eyes. He stuck a hand out, making Bolan switch his carry-on from right to left, crumpling the newspaper that was his recognition sign.

“Señor Cooper?” Guzman said, using Bolan’s current alias.

Bolan accepted the handshake and said, “That’s me. Mr. Guzman?”

“At your disposal. Shall we go retrieve your bags?”

A flex of Bolan’s biceps raised the carry-on. “You’re looking at them,” he replied.

This time, the local’s smile seemed more sincere. “Most excellent,” he said. “This way for Immigration, then, and Customs. Have you any items to declare?”

“I travel light,” Bolan replied.

The Immigration officer asked Bolan how long he was staying in Colombia and where he planned to travel, took his answers at face value and applied the necessary stamps to “Matthew Cooper’s” passport. Customs saw his one small bag and didn’t bother pawing through his socks and shaving gear.

They moved along the busy concourse toward a distant exit, Guzman asking questions. Bolan rejected offers of a meal, a drink, a currency exchange—the latter based upon his knowledge that one U.S. dollar equaled 2,172 Colombian pesos. He would’ve needed several steamer trunks to haul around the local equivalent of $250,000, and all for what?

The people he’d be meeting soon would either deal in dollars, or they wouldn’t deal at all.

Those who refused the bribe, received the bullet—or the bomb, the blade, the strangling garrote. Death came in many forms, but it was always ugly, violent and absolutely final.

“My car is in the visitors’ garage,” Guzman informed him. “This way, if you please.”

Bolan observed his usual precautions as they moved along the concourse, watching for anyone who stared too long or looked away too suddenly, avoiding eye contact. He caught no one observing their reflections in shop windows, kneeling suddenly to tie a loose shoestring or search through pockets for some nonexistent missing item as they passed.

Of course, he didn’t know the players here in Bogotá. Those who had tried to take him out the last time he was here were all long dead.

It would be easier when they got out of town, he thought. The open road made them more difficult to track, and once he reached the forest, started hiking toward his final target, it would be his game, played by his rules.

Or so he hoped, at least.

Each mission held surprises. Few, if any, ran exactly as the plans were drawn in quiet moments, prior to contact with the enemy. Whether you called it Chaos Theory or the human element, it all came down to the same thing: variables that could never be anticipated.

Even psychic powers wouldn’t help, if they existed, since most people in a crisis situation acted without thinking, running off on tangents, never stopping to consider what might happen if they turned left instead of right, sped up or slowed, cried out or bit their tongues.

Bolan had stayed alive this long because he planned ahead and still retained the flexibility required to change his plans, adapt to any given situation that arose. Someday, he knew, the switch would be too fast for him, his enemy too deadly accurate, and that would be the end.

But, hopefully, it wouldn’t be this night.

The sun was setting as they left the airport terminal, but most of the day’s humidity remained to slap him in the face like a wet towel. Bolan followed his contact from the blessed air-conditioning, across a sidewalk and eight lanes of traffic painted on asphalt, to reach the visitors’ garage. Inside, Guzman led him to an elevator, pushed the button, waited for the car and took them up to the fifth level.

“Over here, señor.”

Guzman led Bolan toward a Fiat compact, navy blue, which Bolan guessed was three or four years old. Inside it, Bolan pushed his seat back all the way, to make room for his legs.

“You need certain equipment, yes?” Guzman asked as he slid into the driver’s seat.

“That’s right.”

“Is all arranged,” Guzman replied, and put the car in gear.

“THEY’RE CLEARING THE GARAGE right now,” Horst Krieger said, speaking into his handheld two-way radio. “Be ready when they pass you.”

“Yes, sir!” came the response from Arne Rauschman in the second car. No further conversation was required.

“Get after them!” snapped Krieger to his driver, Juan Pacheco. “Not too close, but keep the car in sight.”

“Sí, señor,” the driver said as he put the Volkswagen sedan in gear and rolled out in pursuit of Krieger’s targets.

Krieger thought it was excessive, sending eight men to deal with the two strangers he had briefly glimpsed as they’d driven past, but he never contested orders from his commander. Such insubordination went against the grain for Krieger, and it was the quickest way that he could think of to get killed.

Besides, he thought as they pursued the Fiat compact, Rauschman’s six-year-old Mercedes falling in behind the Volkswagen, if they faced any opposition from the targets, he could use the native hired muscle as cannon fodder, let them take the brunt of it, while he and Rauschman finished off the enemy.

The Fiat quite predictably took Avenida El Dorado from the airport into Bogotá. It was the city’s broadest, fastest highway, crossing on an east-west axis through the heart of Colombia’s capital.

It was early evening, with traffic at its peak, and Krieger worried that his driver might lose the Fiat through excessive caution.

“Faster!” he demanded “Close that gap! We’re covered by the other traffic here. Stay after them!”

He waited for the standard “Sí, señor,” and frowned when it was not forthcoming. He would have to teach Pacheco some respect, but now was clearly not the time. The Volkswagen surged forward, gaining on the Fiat, while cars that held no interest for Krieger wove in and out of the lanes between them.

Krieger turned in his seat, feeling the bite of his shoulder harness, the gouge of his Walther P-88 digging into his side as he craned for a view of Rauschman’s Mercedes. There it was, three cars back, holding steady.

At least, with a real soldier in each vehicle, the peasants he was forced to use as personnel would not give up and wander off somewhere for a siesta in the middle of the job. Krieger would see to that, and Rauschman could be trusted to control his crew, regardless of their innate failings.

Krieger couldn’t really blame them, after all. The peasants had been born inferior, and there was nothing they could do to change that fact, no matter how hard they might try.

But they could follow orders, to a point. Drive cars. Point guns. Pull triggers. What else were they good for? Why else even let them live?

Horst Krieger would be pleased to kill the two men he was following, although he’d never met them in his life and knew nothing about them. One of them looked Aryan, or possibly Italian, but the race alone meant nothing. There was also attitude, philosophy and politics to be considered.

All those who opposed the sacred cause must die.

Some sooner, as it happened, than the rest.

Speaking across his shoulder, Krieger told the two Colombians seated behind him, “Be ready, on my command.”

He heard the harsh click-clack of automatic weapons being cocked, and felt compelled to add, “Don’t fire until I say, and then be certain of your target.”

“No civilians,” one of them responded. “Sí, señor.”

“I don’t care shit about civilians,” Krieger answered. “But if one of you shoots me, I swear, that I’ll strangle you with your own guts before I die.”

The backseat shooters took him seriously, as they should have. Krieger meant precisely what he said.

Rauschman’s two gunners in the second car would have their weapons primed by now, as well, although the order had to come from Krieger, and he hadn’t found his kill zone yet. It might be best if they could pass the target vehicle on Calle 26, he thought, but then he wondered if it would be wiser to delay and follow them onto a smaller and less-crowded surface street.

Something to think about.

“You’re losing him!” Krieger barked, and the Volkswagen gained speed. Still no response from Juan Pacheco at the wheel.

That bit of insubordination would be more expensive than the driver realized. When they were finished with the job and safely back at headquarters, he had a date with Krieger and a hand-crank generator that was guaranteed to keep him on his toes.

Or writhing on the floor in agony.

The prospect made Horst Krieger smile, though on his finely sculpted face, the simple act of smiling had the aspect of a grimace. No one facing that expression would find any mirth in it, or anything at all to put their minds at ease.

“You see the signal?”

Up ahead, the Fiat’s amber left-turn signal light was flashing, as the driver veered across two lanes of traffic. He did not wait for the cars behind him to slow and make room in their lanes, but simply charged across in front of them, as if the signal would protect him from collisions.

Krieger’s wheelman cursed in Spanish and roared off in pursuit of their intended victims. Angry horns blared after them, but Pacheco paid them no heed.

Krieger considered warning Rauschman, but a backward glance told him that the Mercedes was already changing lanes, accelerating into the pursuit. Rauschman would not presume to pass Krieger’s VW, but neither would he let the marks escape.

“Stay after them!” Krieger snarled. “Your life is forfeit if they get away.”

“WE HAVE A TAIL,” Bolan said, turning to confirm what he’d already seen in his side mirror. Two cars, several lengths behind them, had swerved rapidly to match Guzman’s lane change.

“Maybe coincidence,” Guzman said as his dark eyes flickered back and forth between his rearview mirror and the crowded lanes in front of him.

“Maybe,” Bolan replied, but he wasn’t buying it. The nearest off-ramp was a mile or more ahead of them. Commuters would already know their exits. Tourists new to Bogotá would have their noses buried in guidebooks or street maps, and the odds that two of them would suddenly change lanes together without need were minuscule.

“You wouldn’t have a gun, by any chance?” Bolan asked. “Just to tide me over, through our little shopping trip.”

“Of course, señor,” his guide replied, and reached beneath his driver’s seat, drawing a pistol from some hidey-hole and handing it to Bolan.

Bolan recognized the IMBEL 45GC-MD1. He checked the chamber, found a round already loaded, pulled the magazine and counted fourteen more.

It could be worse.

Most .45s had straight-line magazines, and thus surrendered five to seven rounds on average to the staggered-box design employed by most 9 mm handguns. IMBEL had contrived a way to keep the old Colt’s knock-down power while increasing its capacity and sacrificing none of the prototype’s rugged endurance.

Bolan wished he might’ve had a good assault rifle instead, or at the very least a few spare magazines, but he was armed, and so felt vastly better than he had a heartbeat earlier.

“Two cars, you think?” Guzman asked.

Bolan looked again, in time to see a third change lanes, some thirty yards behind the second chase car. “Two, at least,” Bolan replied. “There might be three.”

“I took every precaution!” Guzman said defensively. “I swear, I was not followed.”

It was no time to start an argument. “Maybe they knew where you were going,” Bolan replied.

“How? I told no one!”

Grasping at straws, Bolan suggested, “We can check the car for GPS transmitters later. Right now, think of somewhere to take them without risking any bystanders.”

“There’s no such place in Bogotá, señor!”

“Calm down and reconsider. Last time I passed through town, there was a warehouse district, there were parks the decent people stayed away from after dark, commercial areas where everyone punched out at six o’clock.”

“Well…sí. Of course, we have such places.”

“Find one,” Bolan suggested. “And don’t let those chase cars pull alongside while we’re rolling, if you have a choice.”

“Would you prefer a warehouse or—”

“It’s your town,” Bolan cut him off. “I don’t care if you flip a coin. Just do it now.”

His tone spurred Guzman to a choice, although the driver kept it to himself. No matter. Bolan likely wouldn’t recognize street names, much less specific addresses, if Guzman offered him a running commentary all the way.

Bolan wanted results, and he would judge his guide’s choice by the outcome of the firefight that now seemed a certainty.

Headlights behind the Volkswagen sedan showed Bolan four men in the vehicle. He couldn’t see their backlit faces, and would not have recognized them anyway, unless they’d been featured in the photo lineup he’d viewed before leaving Miami. Still, he knew the enemy by sight, by smell, by intuition.

Even if the dark Mercedes and the smaller car behind it, which had changed lanes last, were wholly innocent, Bolan still had four shooters on his tail, almost before he’d scuffed shoe leather on their native soil. That was a poor start to his game, by any standard, and he had to deal with them as soon as possible.

If he could capture one alive, for questioning, so much the better. But he wasn’t counting on that kind of break, and wouldn’t pull his punches when the bloodletting began.

“All right, I know a place,” Guzman announced. “We take the first road on our left, ahead.”

“Suits me,” Bolan replied. “Sooner’s better than later.”

“You think that they will try to kill us?”

“They’re not the welcoming committee,” Bolan said. “Whether they want us dead or spilling everything we know, it doesn’t work for me.”

“There will be shooting, then?”

“I’d say you could bet money on it.”

“Very well.”

Guzman took one hand off the steering wheel, leaned forward and retrieved a pistol from his waistband, at the back. It was another IMBEL, possibly a twin to Bolan’s .45, although he couldn’t tell without a closer look. Guzman already had it cocked and locked. He left the safety on and wedged the gun beneath his right leg and the cushion of the driver’s seat.

“We’re ready now, I think,” he said.

“We’re getting there,” Bolan replied. “We need our place, first.”

“Soon,” Guzman assured him, speaking through a worried look that didn’t show much confidence. “Three miles, I think. If we are still alive.”

CHAPTER TWO

“It’s your ass if they get away!” Horst Krieger snapped at Juan Pacheco.

“Sí, señor.”

“But not too close!”

“Okay.”

It didn’t matter if his orders were confusing. Krieger thought the driver understood their need to keep the target vehicle in sight, without alarming their intended victims and precipitating a high-speed chase through the heart of Bogotá that would attract police.

Another backward glance showed Krieger that his backup car, with Arne Rauschman navigating, had followed them down the off-ramp from Avenida El Dorado. Krieger was surprised to see a third car exiting, as well—or fourth, if he counted his target—but he dismissed the fact as mere coincidence.

Some eight million people lived in Bogotá. Many more commuted to jobs in the city from outlying towns, and Krieger supposed that thousands arrived at the airport each day, for business or pleasure. It was no surprise, no cause for concern, that four cars should exit the city’s main highway at any given point.

“Where are they going?” Krieger asked, and instantly regretted it.

“I couldn’t say, señor,” Pacheco answered.

Was the bastard smirking at him? Krieger felt a sudden urge to smash his driver’s face, but knew such self-indulgence would derail his mission.

He drew the Walther pistol from its holster, holding it loosely in his right hand, stroking the smooth polished slide with his left. A simple action, but he felt some of the pent-up tension draining from him, as if it was transferred to the weapon in his hand.

The better to unleash hell on his enemies, when it was time.

Krieger had not bothered to memorize the streets of Bogotá, but he knew his way around the city. He could name the twenty “localities” of the great city’s Capital District and find them on a map, if need be. He knew all the major landmarks, plus the home addresses of those who mattered in his world. As for the rest, Krieger could read a map or tell his driver where to take him.

But uncertainty displeased him, and whatever happened to displease Horst Krieger also made him angry.

He was angry now.

He couldn’t tell if those he followed knew that he was trailing them, or if the exit off of Calle 26 had been their destination in the first place. And, in either case, he didn’t know where they were going at the moment, whether to a private residence, a restaurant or other public place, perhaps some rendezvous with other enemies, of whom Krieger was unaware.

The latter prospect worried Krieger most. He was prepared to stop and kill his targets anywhere that proved convenient, both in terms of an efficient execution and a clean escape. However, if he led his team into a trap, the eight of them might be outnumbered and outgunned.

Another backward glance showed Rauschman in the second car, holding position a half block behind the Volkswagen. Another car trailed Rauschman’s, hanging back a block or so, but Krieger couldn’t say with any certainty that it was the same car he’d seen departing Avenida El Dorado.

Ahead, his quarry made a left turn, drove two blocks, then turned off to his right. Krieger’s Volkswagen followed, leading the Mercedes-Benz. Unless the bastard at the wheel was drunk or stupid, he had to know by now that he was being followed.

Still, there came no burst of speed, no sudden zigzag steering into alleys or running against the traffic on one-way streets. If the target did know he was marked, he appeared not to care.

“I think he goes to Puenta Aranda, señor,” Pacheco said.

“You think?”

“We’re almost there.”

And Krieger realized that he was right. Ahead, he recognized the fringe of Bogotá’s industrial corridor, where factories produced much of the city’s—and the nation’s—textiles, chemicals, metal products and processed foods.

It was not a residential district, though Krieger supposed people lived there, as everywhere else in the city. There would be squatters, street people and beggars, the scum of the earth. Conversely, Krieger knew that some of the factories operated around the clock, which meant potential witnesses to anything that happened there, regardless of the time.

Too bad it wasn’t Christmas or Easter, the two days each year when the church-enslaved peasants were granted relief. On either of those “holy” days, Krieger could have killed a hundred men in plain sight, with no one the wiser until they returned the next morning.

This night, he would have to take care.

“Move in closer,” he ordered. “They must know we’re here, anyway.”

Palming the two-way radio, he told Rauschman, “Be ready when I move. I’ll choose the spot, then box them in.”

“Yes, sir,” came the laconic answer.

“There!” he told Pacheco, pointing. “Can you overtake them and—”

Without the slightest warning, Krieger’s prey suddenly bolted, tires squealing into a reckless left-hand turn, and sped into the darkened gap between two factories.

“Goddamn it! After them!”

BOLAN WAS BRACED and ready when he saw the opening he wanted, aimed an index finger to the left, and told Guzman, “In there! Hit it!”

Guzman was good behind the wheel. Not NASCAR-good, perhaps, but so far he had followed orders like a pro and handled his machine with total competency. Even on the unexpected left-hand turn, he kept all four tires on the road and lost only a little rubber to acceleration, in the stretch.

Great factories loomed over them on either side, their smoke stacks belching toxic filth into the sky. Bolan had no idea what kind of products either plant produced. It had no relevance to his survival in the next few minutes, so he put it out of mind.

“We’re looking for a place to stand and fight,” he told Guzman. “Some cover and some combat stretch.”

“What is this stretch?”

“I mean some room to move. So we’re not pinned, boxed in.”

“Of course.”

Bolan had leafed through Guzman’s dossier, the one provided by the DEA, but it had said nothing about his fighting ability. He carried guns, but so did many other people who had no idea what it was like to kill a man or even draw a piece in self-defense. He might freeze up, or waste all of his ammunition in the first few seconds, without hitting anyone.

Bolan would have to wait and see.

“There is a slaughterhouse ahead,” Guzman informed him. “On the railroad line. Beside it is a tannery. I think they may be what you’re looking for, señor.”

“Let’s take a look,” Bolan replied. “And call me Matt, since we’re about to get bloody together.”

“Bloody?” Guzman asked.

“Figure of speech.”

“Ah.” Guzman didn’t sound convinced.

Two sets of headlights trailed the Fiat through its final turn. No, make that three. The final car in line was playing catch-up, running just a bit behind.

“Sooner is better,” Bolan told Guzman.

As if in answer to his words, a muzzle-flash erupted from the passenger’s side of the leading chase car. The initial burst was hasty, not well aimed, but Bolan knew they would improve with practice.

“Are they shooting at us?” Guzman asked, sounding surprised.

“Affirmative. We’re running out of time.”

“Hang on!”

With only that as warning, Guzman cranked hard on the Fiat’s wheel and put them through a rubber-squealing left-hand turn. At first, Bolan thought he was taking them into some kind of parking lot, but then he saw lights far ahead and realized it was a narrow access road between the leather plant and yet another factory, much like its neighbor in the darkness, when its lighted windows were the only things that showed.

Somewhere behind him, Bolan thought that he heard the hopeless cries of cattle being herded into slaughter pens. It seemed appropriate, but did nothing to lighten Bolan’s mood.

“We still need—”

Guzman interrupted him without a spoken word, spinning the wheel again, feet busy with the gas pedal, the clutch, the brake. He took them through a long bootlegger’s turn, tires crying out in protest as they whipped through a 180-degree rotation and wound up facing toward their pursuers.

“Is there ‘stretch’ enough?” Guzman asked.

Bolan glanced to either side, saw waste ground stretching off into the night. The hulks of cast-off vehicles and large machines waiting for someone to remove them sat like gargoyles, casting shadows darker than the night itself.

“We’ll find out in a second,” Bolan said. “Give them your brights and find some cover.”

Leaping from the vehicle, Bolan ran to his right and crouched behind a generator easily as tall as he was, eight or ten feet long. Approaching headlights framed the Fiat, glinting off its chrome, but the pursuers would’ve lost Bolan as soon as he was off the pavement.

As for Guzman…

Bolan heard the crack of a 9 mm Parabellum pistol, saw the muzzle-flash from Guzman’s side of the Fiat. Downrange, there came the sound of glass breaking, and one of the onrushing headlights suddenly blacked out.

Not bad, if that was Guzman’s aim, but would he do as well with human targets that returned fire, with intent to kill?

Bolan supposed he’d find out any moment, now, and in the meantime he was moving, looking for a vantage point that would surprise his enemies while still allowing him substantial cover.

He assumed that some of them, at least, had seen him breaking toward their left, his right. He couldn’t help that, but he didn’t have to make it easy for them, either, popping up where they’d expect a frightened man to stand and fight.

Fear was a part of what he felt. No soldier who was sane ever completely lost that feeling when the bullets started flying, but he’d never given in to fear, let it control or paralyze him.

Fear, if properly controlled, made soldiers smart, kept them from being reckless when it did no good. The mastery of fear prevented them from freezing up, permitted them to risk their lives selectively, when it was time to do or die.

Like now.

“HE’S TURNING! Watch it!”

Krieger realized that he was shouting at Pacheco, but the driver didn’t seem to hear or understand him. How could the pathetic creature not see what was happening two hundred yards in front of him?

After its left-hand turn down another dark and narrow access road between two factories, the target vehicle had first accelerated, then spun through a racing turn that left its headlights pointing toward Krieger’s two-car caravan. At first, he thought the crazy bastard was about to charge head-on, but then he realized the other car had stopped. Its headlights blazed to high beams, briefly blinding him, as doors flew open on both sides.

“They’re getting out! Watch—There! And there!

He pointed, but Pacheco and the idiots seated behind him didn’t seem to understand. Pacheco held the wheel steady, but he was slowing as he approached the stationary vehicle they had followed from the airport.

“Christ! Will you be careful?”

Even as he spoke, a shot rang out and Krieger raised an arm to shield his face. The bullet drilled his windshield, clipped the rearview mirror from its post, but missed all four of those who occupied the Volkswagen.

“Get out, damn you!” he snapped at no one in particular, and flung his own door open, using it for cover as he rolled out of the car.

It wasn’t perfect, granted. Anyone who took his time and aimed could probably hit Krieger in the feet or lower legs—even a ricochet could cripple him—but all he needed was a little time to find himself a better vantage point.

He could’ve fired the Walther blindly, made a run for it, but Krieger hated wasting any of the pistol’s sixteen rounds. He had two extra magazines but hadn’t come prepared for any kind of siege and wanted every shot to count.

Both of his riflemen were firing now, short bursts from their CZ2000 Czech assault rifles. They had the carbine version, eighteen inches overall with wire butts folded, each packing a drum magazine with seventy-five 5.56 mm NATO rounds. The little guns resembled sawed-off AK-47s, but in modern times had been retooled to readily accept box magazines from the American M-16 rifle, as well as their own standard loads.

The CZ2000 fired at a cyclic rate of 800 rounds per minute, but Krieger and Rauschman had drilled the mestizos on conserving ammunition, firing aimed and measured bursts in spite of any panic they might feel. So far, it seemed they were remembering their lessons, taking turns as they popped up behind the Volkswagen and stitched holes in the Fiat.

Krieger saw his chance and made his move, sprinting into the midnight darkness of a field directly to his right. He’d seen enough in the periphery of headlights to determine that the field was presently a dumping ground for out-of-date or broken-down equipment. Krieger reckoned he could use the obstacles for cover.

As he crept along through dusty darkness, eardrums echoing to gunfire, Krieger took stock of his advantages. He had eight men, himself included, against two. As far as he could tell, his weapons were superior to those his enemies possessed. He should be able to destroy them without difficulty.

Now, the disadvantages, which every canny soldier had to keep in mind. Krieger was unfamiliar with the battleground, and he could see no better in the darkness than his adversaries could. Night-vision goggles would’ve helped, but how was he to know that they’d be needed?

Another deficit: his men, with one exception—Arne Rauschman—were mestizos, capable of murder but indifferent as soldiers. They obeyed Krieger and his superiors from greed, fear, or a combination of the two. Still, if their nerve broke and their tiny peasant minds were gripped by fear, they might desert him.

Not if I can kill them first, he thought, then focused once again on his hasty Plan B.

Plan A had been to trail the targets, find a place to kill them without drawing any real attention to his team and do the job efficiently. Now that the basic scheme was shot to hell, he needed an alternative that wasn’t based entirely on the prowess of his personnel.

Plan B had Krieger circling around behind his targets, looking for an angle of attack while Rauschman and the six mestizos kept them busy. Now that he considered it, already on the move, it might have been a better scheme with Rauschman circling to the left, a pincers movement, but that hadn’t come to Krieger in his haste.

Besides, he needed someone with the peasants, to make sure they didn’t drop their guns and run away.

More shooting, as he edged around the rusty housing of a bulky cast-off air-conditioner. He marveled at the things some people threw away, while others in the country lived in cardboard shanties or had no roof overhead.

Gripping his pistol in both hands, he was about to edge around the far end of the obstacle when more headlights lit up the scene behind him. Turning, half-expecting the police or some kind of security patrol, Krieger saw a fourth civilian car, convertible, slide to a halt some thirty yards behind Rauschman’s Mercedes.

Who in hell…?

But Krieger’s mind rebelled at what he saw next.

A young woman, pretty at a glance, leaped from the convertible without resort to doors.

Clutching a pistol in her hand.

BOLAN ALSO OBSERVED the fourth car’s entry to the battle zone and saw its lights go out as someone vaulted from the driver’s seat. He had no clear view of the new arrival, but it seemed to be a single person, no great wave of reinforcements for his enemy.

Whoever they were.

Bolan had his IMBEL autoloader cocked and ready as he circled to his left around the bulky generator. It was shielding him from hostile fire, but it also prevented him from taking any active part in the firefight. To join the battle, he had to put himself at risk.

Same old, same old.

Erratic gunfire—pistol shots, full-auto bursts, a shotgun blast—and he wondered whether Guzman had already fled the scene on foot. Bolan could hardly blame him, if he had, but he still hoped his guide and translator was made of stronger stuff than that.

Leaving the generator’s cover, moving toward what seemed to be an air-conditioner, he glimpsed the fourth car’s driver rising from the murk behind his vehicle and squeezing off to shots in rapid-fire.

Another pistol, aiming…where?

It almost seemed as if the new arrival fired toward the pursuit cars, rather than toward Guzman’s vehicle. Bolan dismissed it as an optical illusion, knowing Guzman had no allies here this night, except Bolan himself.

He started forward, cleared another corner, and immediately saw one of the hostiles standing ten or fifteen feet in front of him. Blond hair, as far as he could tell, and military bearing, minus a defensive crouch.

Take him alive for questioning, Bolan thought, but instantly dismissed the notion as too risky. He had nine guns against himself and Guzman. Playing games with any of his adversaries at the moment was an invitation to disaster.

Bolan raised his IMBEL .45 and shot the stranger in his back, high up between the shoulder blades. It wasn’t “fair” by Hollywood standards, but Bolan wasn’t in a movie and he couldn’t do another take if anything went wrong.

At that range, if the .45 slug stayed intact, he was expecting lethal damage to the spine and heart. If it fragmented, jagged chunks might also pierce the lungs and the aorta.

Either way, it was a kill.

His target dropped facedown into the dust, quivered for something like a second, then lay still. Bolan approached him cautiously, regardless, thankful that the dead man’s comrades couldn’t see him for the bulk of old equipment strewed between them.

Bolan rolled the body over, saw the ragged exit wound and looked no further.

One down, eight to go.

How long before police arrived? He guessed that it was noisy in the factories surrounding him, but someone would be passing by or working near an open window, maybe pacing off the grounds on night patrol. Even in Bogotá, where murders were a dime a dozen, someone would report a pitched battle in progress.

But until the cops showed up, he had a chance to win it and escape.

A sudden escalation in the nearby gunfire startled Bolan. First, he feared the hunters had grown weary of their siege and had decided it was time to rush the Fiat, throwing everything they had into the charge. As Bolan moved to get a clear view of the action, though, he found something entirely different happening.

Two of the hostile shooters—make it three, now—had stopped firing at the Fiat and had turned to face the opposite direction. Bolan checked the access road, saw nothing but the last car to arrive—and then he understood.

The driver of the sleek convertible wasn’t a member of the hunting party: he was something else entirely, and he had been firing at the chase cars, rather than at Guzman.

Why? Who was it?

Bolan couldn’t answer either of those questions in the middle of a gunfight, but he recognized a universal truth.

The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

The strange diversion gave him hope and opportunity.

The Executioner had never wasted either in his life.

JORGE GUZMAN WAS FIGHTING for his life, and he was hopelessly confused. He couldn’t figure out how anyone had tracked him to the airport, but it wouldn’t matter if the gunmen killed him in this filthy place, with rank pollution blotting out the stars above.

He also didn’t understand why a strange woman in a car he didn’t recognize had joined the fight, apparently on his side. It defied all reason, made Guzman question whether he was hallucinating, until one of his opponents stopped a bullet from the woman’s gun and crumpled to the ground.

Don’t think about it! Guzman told himself. Just stay alive!

That was no small task, in itself, with eight men—seven, now—intent on blasting him with automatic weapons, pistols and at least one shotgun. Even in his near panic, Guzman could recognize the sounds of different weapons, picturing what each in turn would do to him if he was hit.

Flesh torn, bones shattered, blood jetting from wounds to drain him dry in minutes flat. Maybe he’d suffer every agonizing second of it, or a bullet to the brain might grant him swift release.

Guzman peeked out, around the Fiat’s left-rear fender, and fired two shots toward the nearest of the enemies who’d pinned him down. He guessed the shots were wasted, since the two men he’d been hoping to deter immediately answered him with rapid fire.

Bastards!

As far as Guzman knew, he hadn’t even wounded one of them, although he’d been the first to fire a shot. God knew it hadn’t helped him, but at least he’d had a fleeting moment when he almost felt courageous, capable of anything.

Now that the grim truth of his situation was apparent, he could only wonder who the woman was, and what had happened to the tall American.

It seemed impossible that Matt Cooper had simply run away and left Guzman to fight alone. He had to have had some strategy, but so far—

Even with the other din, Guzman picked out a gunshot from one side, off in the dark field to his right. Cooper had run in that direction when the Fiat came to rest, not long ago in real-world time, although it felt like hours with the bullets snapping past Guzman.

He wondered if his car would ever run again, after the hits that it had taken and was taking, even now. He doubted it. Cars were such fragile things, despite their bulk and high price tags. A single loose wire ruined everything, and now his little ride was taking bullets like a target in a shooting gallery, most of them through the hood and grille.

Stranded, he thought, then almost laughed out loud.

What did it matter if his car was broken down when Guzman died? Where did he plan on driving, with his brains blown out?

That image made him angry, spurred his need to fight and leave the other bastards bloody, hurting, when he fell at last. Blazing away from cover, Guzman emptied his pistol’s magazine and actually thought he’d seen one of his targets fall before the weapon’s slide locked open on an empty chamber and he fumbled to reload.

He slapped his next-to-last clip into the receiver, knowing that it might as well have been the very last, since he would never have a chance to take the third one from his pocket. Once he rose, exposed himself, and charged the hostile guns, his life span would be timed in nanoseconds.

Still, the Latin concept of machismo said he had to do something, take some action that did not involve hiding and waiting for the enemy to root him out. If he had to die this night, at least it would be as a man and not a cringing worm.

Guzman lunged to his feet, snarling through clenched teeth as he felt the air ripple with bullets zipping past him. One of them would find him soon, but in the meantime he was firing, choosing targets, giving each in turn the double-tap that a policeman friend had taught him at the firing range. Advancing without hope that he would see another sunrise.

And, incredibly, his enemies fell back from Guzman’s wrath, reeling as his rounds sought their flesh and blood. It didn’t quell the hostile fire, but at the very least it spoiled their aim, sent some of the incoming bullets high and wide.

Amazing!

Guzman bellowed at them now, his rage echoing to the sounds of gunfire. He was vaguely conscious of new weapons firing on his left and right, joining their voices to his IMBEL’s hammering reports, and while he knew one of them had to be Cooper’s pistol, one of them the unknown woman’s, Guzman felt as if he had the battlefield all to himself, charging his enemies with more courage than common sense.

The bullet, when it found him, had the impact of a giant mailed fist, slamming viciously into the side of Guzman’s skull. He staggered, felt the earth slip out from underneath his feet, then saw it rush to meet him in a wave of darkness as he fell.

BOLAN SAW GUZMAN DROP but couldn’t help him at the moment. Only finishing their other adversaries would allow him to examine, and perhaps to treat, his contact’s wounds. Meanwhile, he also had to figure out who else had joined the fight, and why a total stranger would risk death to help him.

Nothing made sense yet, in the chaotic moment, and he couldn’t stop to mull it over while five or six gunmen were trying to kill him.

Bolan circled toward the Benz through darkness, ready with the IMBEL .45 for anyone who challenged him. His first clear shot, after the blonde he’d left behind him in the junk-yard, was a short and swarthy shooter with some kind of AK-looking weapon, firing from a fat drum magazine.

The gunner didn’t see him coming, likely never knew what hit him when a single round from Bolan’s autoloader drilled his skull behind the right ear, dropping him as if he was a puppet with its strings cut.

Forward from the crumpled corpse, between the dark Mercedes and the Volkswagen, three shooters bobbed and weaved, rising to fire at Guzman’s Fiat, crouching again for someone else’s turn. Two of them had the same short rifles as the man Bolan had killed a heartbeat earlier; the third carried a sleek pump-action shotgun with extended magazine.

Bolan came in behind them, wasted no time on a warning, caught one of them turning to investigate the sound of his last shot. He drilled that shooter through the left eye, swung a few feet to his left and gave the survivor a double-tap before the target realized that anything was wrong.

The shotgunner was turning, quicker than the others, ratcheting his weapon’s slide-action. Bolan wasn’t sure that he could beat the other man’s reflexes, but it didn’t matter.

From Bolan’s left, a gunshot sounded, and the side of his adversary’s head appeared to vaporize. The dead man standing looked surprised, but if the killing shot had caused him any pain, it didn’t register in his expression. He stood rock-still for a few heartbeats, then folded at the knees and toppled over backward, sprawling on the pavement.

Bolan had already swiveled toward the source of that last shot, the IMBEL automatic following his gaze. The woman who had saved his life—he saw her clearly now, and there could be no question of her femininity—held up an open hand, as if to block his shot, then nodded toward the other gunmen who were still blasting at Guzman’s car.

Split-second life-or-death decisions were a combat soldier’s stock-in-trade. Bolan made his and nodded, turning from the woman who could just as easily have killed him then, returning his whole focus to their common enemy.

Bolan had no idea where she had come from, who she was, or why she’d risk her life to help him in the middle of a firefight, but those questions had to wait. There would be time enough for talk if both of them survived the next few minutes.

Part of Bolan’s mind, condemned to deal with practicalities, wondered if he’d need Guzman to translate his conversation with the woman. And if Guzman died, how in the hell would they communicate?

Focusing once again on here and now, Bolan moved up toward the Volkswagen, with the woman flanking on his left. As far as he could see, two gunmen still remained. One was a short mestizo like most of the others, while the second was a dirty-blond white boy, stamped from the same mold as the one Bolan had left behind him, in the waste ground.

Bolan took the shooter nearest to him, offered no alerts or other chivalrous preliminaries as he found his mark and drilled the rifleman between his shoulder blades. The gunner went down firing, stitching holes across the trunk of the Volkswagen, while his Nordic-looking partner ducked and covered.

Rising from his crouch, the sole survivor caught sight of the woman first, and raised his pistol to confront her. She was faster, snapping off three rounds in rapid fire, stamped a pattern on her target’s chest and slammed him to the ground.

Bolan advanced with caution, made sure that the dead were all they seemed to be, then took another risk and let the woman have a clear shot at his back, while he ran to examine Jorge Guzman’s wounds.

Guzman was grappling back to consciousness as Bolan reached him, tried to raise his pistol, but he didn’t have the strength to stop Bolan from taking it away. Blood bathed the left side of his face and stained the collar of his shirt.

“Wha-What? Am I…Are we…?”

Bolan examined him and said, “You’ve got a nasty graze above your left ear, but the bone’s not showing. Scalp wounds bleed a lot. It doesn’t mean you’re dying.”

“Not…dead?”

“Not even close,” Bolan replied. “You may need stitches, though.”

“Hospital…no…report….”

“I can take care of him,” a new voice said from Bolan’s left. He glanced up at the woman as she nodded toward Guzman. “I’ve stitched up worse than that, believe me.”

Bolan helped Guzman to his shaky feet and held him upright, left hand on the other man’s right arm. It left his gun hand free as he turned toward the woman, saying, “Maybe we should start with names.”

“Of course,” she said. “I’m Gabriella Cohen, and I work for the Mossad. We share, I think, a common goal.”

CHAPTER THREE

Two days earlier, Northern Virginia

The Blue Ridge Mountains looked entirely different from the air than they appeared to earthbound motorists and hikers. Bolan was reminded of that fact each time he flew to Stony Man Farm.

Airborne, he always tried to picture how the area had looked before the first human arrived, despoiling it with axes, saws and plows, road graders and the rest. Sometimes Bolan thought he was close, but then the pristine image always wavered, faded and was gone.

Maybe next time, he thought.

The Hughes 500 helicopter was a four-seater, but Bolan and the pilot had it to themselves.

On any graduated scale of secrecy, the Farm and its activities would rank above “Top Secret,” somewhere off the chart. From day one, Stony Man’s assignment—seeking justice by extraordinary, often extralegal means—had been one of the deepest, darkest secrets of the U.S. government. Beside it, aliens at Roswell and the stealth experiments performed at Nevada’s Area 51 paled into insignificance. Aside from on-site personnel and agents in the field, only a handful of Americans knew Stony Man existed.

Fewer still knew the extent of what it did, had done and might do in the future.

At its birth, the concept had been simple: organize a unit that, when necessary, in the last extremity, would set the U.S. Constitution and established laws aside to deal with urgent threats and/or to punish those whose skill at gliding through the system made them constant threats to civilized society at large.

Some might have called it vigilante justice; others, sheer necessity. In either case, it worked because the operation wasn’t public, wasn’t influenced by politics, and didn’t choose its targets based on race or creed or any factor other than their danger to humanity. Sometimes, Bolan thought it was more like dumping toxic waste.

“Ten minutes,” the pilot said, as if Bolan didn’t know exactly where they were, tracking the course of Skyline Drive, a thousand feet above the treetops. Cars passing below them looked like toys, the scattered hikers more like ants. If any of the hardy souls on foot looked up or waved at Bolan’s chopper, his eyes couldn’t pick them out.

Bolan had been wrapping up a job in Canada when Hal Brognola called and asked him for a meeting at the Farm. Quebec was heating up, with biker gangs running arms across the border from New York. Some of the hardware, swiped from U.S. shipments headed overseas, traveled from Buffalo by ship, on the St. Lawrence River, while the rest was trucked across the border at Fort Covington. Don Vincent Gaglioni, Buffalo’s pale version of The Godfather, procured the guns and pocketed the cash.

It had to stop, but agents of the ATF and FBI were getting nowhere with their separate, often competitive investigations. By the time Bolan was sent to clean it up, they’d lost two veteran informants and an agent who was riding with his top stool pigeon when the turncoat’s car exploded in a parking lot.

Bolan had sunk two of the Gaglioni Family’s cargo ships with limpet mines, shot up a convoy moving overland, then trailed Don Gaglioni to a sit-down with the gang leaders outside Drummondville, Quebec. The meeting had been tense to start with, but they’d never had a chance to settle their dispute. Bolan’s unscheduled intervention, with an Mk 19 full-auto grenade launcher had spoiled the bash for all concerned.

It had been like old times, for just a minute there, but Bolan didn’t set much store in strolls down Memory Lane. Especially when the path was littered with rubble and corpses.

There was enough of that in his future, he knew, without trying to resurrect the Bad Old Days of his one-man war against the Mafia. A little object lesson now and then was fine, but there could be no turning back the clock.

Which brought him to the job at hand—whatever it might be. Brognola hadn’t called him for a birthday party or a house-warming. There would be dirty work ahead, the kind Bolan did best, and he was ready for it.

Which was not to say that he enjoyed it.

In Bolan’s mind, the day a killer started to enjoy his killing trade, the time had come for him to find another line of work. Only a psychopath loved killing, and the best thing anyone could do for such an individual was to put him down before he caused more misery.

Soldiers were trained to kill, the same way surgeons learned to cut and plumbers learned to weld. The difference, of course, was that a warrior mended nothing, built nothing. In battle, warriors killed, albeit sometimes for a cause so great that only blood could sanctify it. Some opponents were impervious to grand diplomacy, or even backroom bribes.

In some cases, only brute force would do.

But those were not the situations to be celebrated, in a sane and stable world. Peace was the goal, the end to which all means were theoretically applied.

Back in the sixties, bumper stickers ridiculed the war in Vietnam by asking whether it was possible to kill for peace. The answer—then, as now—was “Yes.”

Sometimes a soldier had no choice.

And sometimes, he was bound to choose.

“We’re here,” the pilot said as Bolan saw the farmhouse up ahead. Below, a tractor churned across a field, its driver muttering into a two-way radio. There would be other watchers Bolan couldn’t see, tracking the chopper toward the helipad. Fingers on triggers, just in case.

They reached the pad and hovered, then began to settle down. Bolan looked through the bubble windscreen at familiar faces on the deck, none of them smiling yet.

It wasn’t home, but it would do.

Until they sent him off to war again.

“GLAD YOU COULD MAKE IT,” Hal Brognola said, while pumping Bolan’s hand. “So, how’s the Great White North?”

“Still there,” Bolan replied as he released his old friend’s hand.

Beside Brognola, Barbara Price surveyed Bolan with cool detachment, civil but entirely business-like. The things they did in private, now and then, might not be absolutely secret from Brognola or the Stony Man team, but Barbara shunned public displays. She was the perfect operations chief: intelligent, professional and absolutely ruthless when she had to be.

“You want some time to chill? Maybe a drink? A walk around the place?” Brognola asked.

“We may as well get to it,” Bolan said.

Clearly relieved, Brognola said, “Okay. Let’s hit the War Room, then.”

Bolan trailed the big Fed and Price into the rambling farmhouse that was Stony Man’s cosmetic centerpiece and active headquarters. From the outside, unless you climbed atop the roof and counted dish antennae, the place looked normal, precisely what a stranger would expect to see on a Virginia farm.

Not that a stranger, trespassing, would ever make it to the house alive.

Inside, it was a very different story, comfort vying with utility of every square inch of the house. It featured living quarters, kitchen, dining room—the usual, in short—but also had communications and computer rooms, though major functions were in the Annex, an arsenal second to none outside of any full-size military base, and other features that the standard home, rural or urban, couldn’t claim.

The basement War Room was a case in point. Accessible by stairs or elevator, it contained a conference table seating twenty, maps and charts for every part of Mother Earth, and audio-visual gear that would do Disney Studios proud.

How many times had Bolan sat inside that room to hear details of a mission that would send him halfway around the world, perhaps to meet his death?

Too many, right.

But it would never be enough, until the predators got wise and left the weaker members of the human herd alone.

Aaron Kurtzman met them on the threshold of the War Room, crunched Bolan’s hand in his fist, then spun his wheel-chair to lead them inside. As Stony Man’s tech master, Kurtzman commonly attended mission briefings and controlled whatever AV elements Brognola’s presentation might require.

Brognola took his usual seat at the head of the table, his back to a large wallscreen. Price sat to the big Fed’s right, Bolan on his left, while Kurtzman chose a spot midway along the table’s left-hand side. A keyboard waited for him on the tabletop, plugged into some concealed receptacle.

“Okay,” Brognola said, “before we start, I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to keep up with the news these past few days.”

“Not much,” Bolan said. “Scraps from radio, while I was driving. Headlines showing from the newspaper dispensers.”

“Fair enough. We’re in the middle of a flap that has the White House nervous, not to mention certain friends abroad. Starting three days ago, on Thursday, we’ve experienced a series of attacks on Jews, here in the States and down in Mexico. It has the White House in an uproar, for assorted reasons, and we’ve got our marching orders.”

Bolan knew the protocol for Stony Man briefings. Brognola went by a script of sorts, and liked to keep his ducks all in a row.

“Who were the victims?” Bolan asked.

The big Fed tipped a nod to Kurtzman and the overheads dimmed just enough to simulate twilight. Behind Brognola’s back, a photo of a smiling couple dressed for formal partying filled up the screen.

“That’s Aderet Venjamin on the left,” Brognola said, without glancing around. “His wife’s Naomi. For the past five years, Venjamin has been assigned to the Israeli consulate in New York City.”

“Someone hit him?” Bolan asked. It was the logical assumption.

“Nope. The wife.”

Bolan’s surprise was indicated by a raised eyebrow.

“On Thursday morning,” Brognola pressed on, “she went out shopping on Park Avenue. One bodyguard, one driver, both ex-military. As she left a jeweler’s, two men on the sidewalk shot the guard, threw nitric acid in her face and fled on foot. No clear description of the perps, no vehicle observed.”

“Survivors?” Bolan asked.

“The lady’s still alive,” Hal said, “if you can call it living. Left eye gone, partially blinded in the right. Skin grafts may help a little, but she’ll never look like that again.” He jerked a thumb in the direction of the screen behind him.

“Anyone claim credit for it?” Bolan asked.

“We’re not sure.”

“Meaning?”

“Two days prior to the attack, the consulate received a note, postmarked Bogotá. It took nine days to be delivered. No one in the postal service can explain exactly why.”

Another nod to Kurtzman, and the happy-couple photo was replaced by a plain sheet of paper. Roughly centered on it was a typed message: “See now, how ugly are the Jews who suck our blood.”

“That’s it?” Bolan asked. “I’d imagine the Israeli consulate gets bags of poison-pen notes every day.”

“You’d win that bet,” Brognola said. “I checked it out. Apparently they average fifteen pounds of hate mail daily, double that around well-known religious holidays.”

“So what sets this apart? The timing or the ‘ugly’ reference?”

“The postmark, actually,” Brognola replied. “But that’s hindsight. Stay with me for a minute, here.”

A nod, another change of photos. Now the carcass of a tour bus filled the screen. Fire damage showed around the frames of shattered windows. Bolan picked out bullet holes along the one side he could see. The bus’s logo, what was left of it, read Tourismo Grand de Sonora.

“This went down about an hour after the Park Avenue attack,” Brognola said. “A busload of Israeli tourists traveling around Sonora, as I’m sure you gathered from the sign. They were en route to Hermosillo, from some kind of mission, when a group of masked men stopped the bus and started shooting. Passersby, they left alone.”

“They wanted witnesses,” Bolan observed.

“Apparently.”

“Survivors on the bus?”

“Not one.”

“You’re linking this to acid on Park Avenue, because…?”

“Of this,” Brognola said, and Kurtzman keyed the next slide. Once again, it showed a common piece of stationery with a one-line message: “Jews suck the lifeblood of nations.”

“So?”

“I couldn’t see it, either,” Brognola replied, “but the Mossad and FBI agree that both notes were prepared on the same manual typewriter. It’s a vintage German model, specifically an Erika Naumann Model 6, last manufactured between 1938 and early 1945.”

“You’re kidding, right?”

“I wish. It just gets worse.”

This time the picture changed without a signal from Brognola. On the screen, a body sprawled in blood and sunshine, with pastel storefronts and palm trees in the background. Bolan couldn’t see the dead man’s face.

Small favors.

“Ira Margulies,” Brognola said. “One of the top fifteen or twenty richest people in Miami Beach. He was a force to reckon with in banking, real estate, what have you—until Friday morning, when a shooter took him down.”

“Where was the note?” asked Bolan.

“Tucked under his left elbow, away from the blood flow,” Brognola said.

And as he spoke, another note filled up the hanging screen. It read, “The Jews are not the people who are blamed for nothing.”

Bolan frowned and asked, “Why does that sound familiar?”

Price fielded that one, telling him, “It’s similar, but not identical, to a note left at one of Jack the Ripper’s London crime scenes back in 1888. The original note misspelled ‘Jews,’ and a couple of other words are slightly different. For plagiarism, it’s a sloppy job.”

“You said, from 1888?”

She nodded, adding, “But it’s quoted in every book and article written about the Ripper since then. How many hundreds are there, all over the world? We think it stuck in someone’s mind. They’re playing games.”

“Same typewriter?”

“Affirmative,” Brognola said.

“But only one note sent by mail,” Bolan observed.

“We think,” Brognola said, “that they were leery of a drop-off at the consulate.”

“One source for all three notes,” Bolan confirmed. “One mind behind the crimes.”

It was the big Fed’s turn to nod. “And on the rare occasions when he mails a note—”

“It comes from Bogotá,” Bolan finished the thought.

“Or somewhere in Colombia, at least. We think the author’s tied in to a Nazi clique established in the country during 1948 or ’49. Are you familiar with a place known as Colonia Victoria?”

“Victory Colony?” Bolan translated with his meager Spanish. “It’s not ringing any bells.”

“No reason why it should, really,” Brognola said. “It gets some bad publicity every ten years or so, but mostly it’s a hush-hush operation. The Colombians don’t like to talk about it, with their public image in the crapper as it is. The German immigrants and their descendants in the colony, well, it’s in their best interest if they don’t get too much ink or TV time.”

“How so?” Bolan asked.