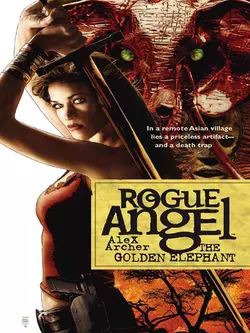

The Golden Elephant

Alex Archer

After risking her life to uncover a Chinese imperial seal, only to have it stolen by a cunning tomb robber, archaeologist Annja Creed feels she has endured one treasure-hunting fiasco too many. But when a mysterious collector offers a reward for a priceless golden elephant, Annja gives in.After all, there are bills to be paid, adventures to be had.The artifact is said to be hidden in a vast and ancient temple complex in the mountainous jungles of Southeast Asia, and Annja must meet with various scholars in order to pinpoint its location. But when each expert she visits is found dead, Annja fears someone else is after the artifact.And her. And she's probably next on the killer's list.

“You aren’t going to leave me to drown!”

The astonishing thought distracted Annja from the floodwaters until they rose above the tops of her waterproofed shoes. Their touch was as cold as the long-dead Emperor’s.

“At least leave me my pack!” Annja shouted, jumping up and swiping ineffectually at the dangling rope-end. She only succeeded in making it swing. She fell back with a considerable splash.

“I’m afraid not,” the woman called. “You have to understand, Ms. Creed. There are two ways to do things—the hard way and the easy way.”

Annja stood for a moment with the water streaming past her ankles. The words were so ridiculous that her mind, already considerably stressed by the moment, simply refused to process them.

Then reality struck her. “Easy?” she screamed. “Not Easy Ngwenya?”

Annja stared. The chill water reached her knees. She stood, utterly overwhelmed by the realization that she had just been victimized by the world’s most notorious tomb robber.

Titles in this series:

Destiny

Solomon’s Jar

The Spider Stone

The Chosen

Forbidden City

The Lost Scrolls

God of Thunder

Secret of the Slaves

Warrior Spirit

Serpent’s Kiss

Provenance

The Soul Stealer

Gabriel’s Horn

The Golden Elephant

Rogue Angel

The Golden Elephant

Alex Archer

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

1

Tomb of the Mad Emperor

“Oops,” Annja Creed said as she felt something give beneath the cleated heel of her Red Wing walking shoe.

The floor of the passageway was caked inches thick in dust. Annja couldn’t see the trigger. She had sensed more than heard something like a twig snapping.

Already in motion, Annja dived for the floor. She heard a grind, a rumble, a rusty creaking. Then with a hefty metallic sound something shot from the stone walls above her.

Catching herself on her hands, Annja looked around by the light of her bulky hand lantern, which lay several feet ahead of her. She spotted three bronze spears spanning the two-yard-wide corridor a yard above the floor. They were meant to impale any unwary intruder. That included her.

Annja shook her head. “Emperor Lu may or may not have been crazy,” she muttered. “But he sure was paranoid.”

The echoes of her words chased each other down the slanting corridor, deep into the earth’s dark recesses.

C AUTIOUSLY A NNJA WIGGLED forward. As her weight came off the hidden floor plate the spears began to retract into the walls. By the time she reached her lantern they had vanished. The stone plates that covered the ports through which the spears had thrust out swung back into place.

Coughing on the dust she had stirred up doing her snake act, Annja sat up and shone her light on the walls. She could see no sign of where the spears had come from. The walls had been painted with some kind of murals, perhaps once quite colorful. They had faded to mere swirls and suggestions of faint color. They worked to camouflage the trap, though.

She shook her head and picked herself up. “Got to move,” she told herself softly as she dusted off the front of her tan shirt and khaki cargo pants. This would be her only shot. With the construction of a giant dam nearby, the floodwaters were rising. By tomorrow they would make the subterranean tunnels unsafe.

With redoubled caution she made her way deeper into the lost emperor’s tomb.

The corridor walls were hewed from a yellow limestone. Tests showed it had been quarried in some hills several miles away. The passageway air was cool and dry. It smelled of stone and earth.

Some indeterminate distance down, as Annja began to feel the weight, not just of years, but of millions of tons of earth pressing upon her, the corridor leveled. It had taken several bends and a couple of doglegs, and had plateaued briefly, as well. Annja wasn’t sure whether the zigs and zags had some ritual significance, were meant to additionally befuddle an interloper or were simply to prevent a cart full of spoil from running all the way back down to the bottom during the digging of the corridor. She suspected it was all of the above.

Far down the hallway, in which she could just stand upright, Annja saw that something was blocking the way. Could that be the door to Lu’s actual tomb? she wondered. Her heart beat quickened. According to the ground-penetrating radar scans, it could be. The last Chinese team to come down here had intended to open the bronze door to the burial chamber proper. She had no idea whether they had or not.

The Beijing University officials who had hired Annja suggested that they felt the last team had indeed made some major discoveries and had then departed by some currently unknown entrance to the great mound before vanishing. There was nothing intrinsically unlikely about that. Such huge structures often had multiple entrances. But she was being asked to play archaeology cop—to find out if the tomb had been plundered and, if possible, to trace the thieves. She was certainly willing enough. Like any real archaeologist she had an unremitting hatred of tomb robbers.

“Of course that assumes a lot of ifs,” Annja said aloud. Her voice, echoing down the chamber, reassured her. Something about the place bothered her.

She flashed her light down the corridor. She thought she saw a hint of green from the obstruction. She knew that was consistent with bronze doors. The copper in the alloy turned green as it oxidized. Otherwise bronze wasn’t prone to corrosion, as iron and steel were.

I wonder if I should have looked more closely for bloodstains around those spear traps, she thought. The two expeditions that had returned had warned about various booby traps.

But she wasn’t here to do forensic work. Time pressed. So did the billions of tons of water that would soon be rushing to engulf the mound.

As she moved forward toward the door she became aware of a strange smell. A bad smell, and all too familiar—the stench of death.

It grew stronger as she approached the door. And then she fell right into another of Emperor Lu’s little surprises.

The floor tipped abruptly beneath her. The right side pivoted up. She dropped straight down.

Without thought she formed her right hand into a fist. Obedient to her call, the hilt of the legendary blade of Joan of Arc filled her hand. Falling, she thrust the sword to her left and drove it eight inches into the pit’s wall.

It was enough. Grabbing the hilt with her left hand, as well, she clung desperately and looked down.

The hint of scent had become a foul cloud that enveloped her. She choked and gagged. The floor trap was hinged longitudinally along the center. The pit was twenty feet long and sank at least twelve feet deep. Bronze spearheads jutted up from the floor like snaggled green teeth.

Entangled and impaled among them, almost directly below her, lay a number of bodies. She couldn’t tell exactly how many; they had become tangled together as they fell onto the spears. The glare of her lantern, which lay tilted fortuitously up and angled in a corner, turned them into something from a nightmare.

One man hung alone to one side, bent backward. His mouth was wide open in a final scream at the spearhead that jutted two feet upward from his belly. The remnants of what looked like a stretcher of sorts, possibly improvised out of backpack-frames, lay beneath him.

At the shadow-clotted base of the pit she could just make out the dome of a skull or the multiple arch of a rib cage protruding from ages of drifted dust. The missing Chinese archaeology team were not the first victims.

She looked up. She had fallen only a couple of yards below the pit’s lip. The sword had entered the wall blade-vertical. It flexed only slightly under her weight. She knew it could break—the English had done it, when they burned its former holder at the stake—but it didn’t seem strained at the moment.

Unwilling to test it any longer than she had to, she swung back and forth experimentally, gaining momentum. Then she launched her legs back and up and let go.

Whatever kind of graceful landing she was hoping for didn’t happen. Her legs and hips flopped up onto the floor. Her head and upper torso swung over empty space—and the waiting bronze spearheads. As her body started to topple forward she got her hands on the rim of the pit and halted herself. Her hair escaped from the clip holding it to hang about her face like a curtain.

With something like revulsion she threw herself backward. She sprawled on her butt and elbows, scraping the latter. Then she just lay like that awhile and breathed deeply.

The sword had vanished into the otherwhere.

One thing her life had taught her since she had come, unwittingly and quite unwillingly, into possession of Joan of Arc’s Sword was to bounce back from the most outlandish occurrences as if they were no more significant or unusual than spilling a cup of coffee.

“That got the old heart rate going,” she said.

She slowly got to her feet. The trapdoor swung over and began to settle back to the appearance of a normal, innocuous stretch of floor. As it eclipsed the beam of her lost lamp, shining up from the pit like hellfire, she reached up to switch on her headlamp. Its reassuring yellow glow sprang out as the glare was cut off.

It wasn’t very powerful. The darkness seemed to flood around the narrow beam, with a palpable weight and presence. “It’ll be enough,” she muttered. “It has to be.”

Putting her back to the left-hand wall, she edged down the corridor. The dust, which had settled in the past few weeks, hiding the doomed expedition’s footsteps, had been dumped into the pit, except for a certain quantity that still swirled in the air and rasped her lungs like sandpaper. The clean patch of floor, limned by the white light shining from below, made its end obvious.

Cautiously she moved the rest of the way down the corridor toward the green door. No more traps tried to grab her.

As she’d suspected, the door was verdigrised bronze. It had a stylized dragon embossed on it—the ancient symbol of imperial might. She hesitated. She saw no obvious knob or handle.

Reaching into her pocket for a tissue to cover her hand, she pushed on the door. It swung inward creakily. She had to put her weight behind it before it opened fully.

A great wash of cool air swept over her. Surprisingly, it lacked the staleness she would have expected from a tomb sealed for two and a half millennia. Bending low, she stepped inside.

The tomb of Mad Emperor Lu was almost anticlimactic. It was a simple domed space, twenty yards in diameter, rising to ten at the apex, through which a hole about a yard wide opened through smooth-polished stone. Annja wondered if had been intended to allow the emperor’s spirit to depart the burial chamber.

Dust covered the floor, a good four inches deep, so that it swamped Annja’s shoes. In the midst of the dust pond stood a catafalque, four feet high and wide, eight feet long. On it lay an effigy in what appeared to be moldering robes, long cobwebbed and gone the color of the dust that had mounded over it, half obscuring it. A second mound rose suggestively by the feet.

Annja dug her digital camera from her pack. She snapped several photos. The built-in flash would have to do. Feeling time and the approaching floodwaters pressing down, Annja moved forward as cautiously as she could through the dust. Her archaeologist’s reflex was to disturb things as little as possible.

But that wasn’t the reason for her deliberation. Soon all this would be underwater—a great crime against history itself, but one about which she could do nothing. She still sought to do as little damage as possible, in hopes someday the artificial lake might be drained and what the water left of the tomb properly excavated. She was more worried about stirring a cloud of blinding dust.

And more traps.

Uneventfully she reached the foot of the bier. On closer inspection the reclining figure seemed to be a mummy rather than an effigy. Annja presumed it was the man himself, Emperor Lu, his madness tempered by age and desiccation and, of course, being dead. It still gave her a shiver to be in the presence of such a mythic figure.

“This isn’t right,” she said softly. She felt a great sorrow mixed with anger that this corpse, this priceless relic, was soon to be desecrated, and almost certainly to decay to nothing in the waters of a new lake. She thought about trying to carry it out with her.

She sighed and forced herself to let the inevitable happen. She snapped some shots of the old guy, though, from several angles, always being careful where she put her feet, lest the floor swallow her up and dump her down another awful chasm.

But Lu seemed to have no more surprises awaiting intruders upon his celestial nap. Surprisingly little did await the intrepid tomb robber, leaving aside the august but somewhat diminished imperial person. Except, perhaps, that mound by the mummy’s feet.

She finished recording Lu for posterity and knelt by the foot of the bier. The mound was about as wide as a dinner plate and four or five inches high. Gently Annja brushed dust away with her hands.

In a moment she uncovered the artifact—a beautiful circular seal of milky green jade, six inches wide and a good inch thick, engraved with the figure of a sinuous dragon. It was Lu’s imperial seal, beyond doubt. Annju’s heart caught in her throat. Bingo, she thought. Properly displayed in some museum, it would be a worthy relic of Mad Lu’s long-forgotten reign.

Reverently she reached out and touched it. The green stone was smooth as a water-polished pebble. It was hard, yet seemed to have some sort of give, as if it were a living thing and not a carved stone artifact. The workmanship was fully as exquisite as might be expected. Each of the toes on the dragon’s feet was clearly visible, and the characters inscribed around it stood in clear relief. To hold such an object in her hand was itself a reward—reminding her, half-guiltily, how abundantly she would have earned her commission.

A rustle of movement tickled her ear in the stillness of the tomb—a dry creaking, a soft sound as of falling dust. A flicker of motion tugged at her peripheral vision.

She turned. Emperor Lu was sitting up on his bier. The shriveled face with its empty eye sockets looked not just mad, but angry.

Annja gasped.

For a moment she crouched there clutching the jade and staring at its moldering owner like a deer caught in the headlights. And then a great downward geyser of water shot out of the ceiling, drowning the mummy and knocking Annja sprawling.

She was washed toward the bronze door on a torrent of glutinous mud. For a moment the wildly spiraling beam of her headlamp illuminated the mummy. It sat there on its catafalque in the midst of the stream as if taking a shower. The jaw had fallen open, she could clearly see. It was as if Lu laughed at her—enjoying his final joke on the woman who had despoiled his tomb.

Then the water obscured her sight of him. She managed to get onto her feet against the rushing torrent. She scrambled out with the water sloshing around her shins.

Annja realized the corridor was only flat relative to the steep decline she had descended, for it filled with water more slowly than it would have if level. Out of options, she ran for all she was worth. The quick death of tripping some trap, previously discovered or not, and being impaled with ancient spears seemed infinitely preferable to being trapped down here to drown in the dark. The prospect woke a whole host of fears in Annja’s soul, like myriad rats maddened by an ancient plague.

She vaulted the hinged-floor trap, still outlined in thin white lines of light, without hesitation. Her long jump wasn’t quite good enough. The floor pivoted heart-wrenchingly beneath her feet. Adrenaline fueled a second frantic leap that carried her to safety. She raced up the steeper tunnel as the water gurgled at her heels.

It followed her right up the ramp. The place was seriously shipping water. She wondered why the passageway wasn’t fatally flooded already.

That made her run the faster. Her light swung wildly before her.

But even under the direst circumstances Annja never altogether lost her presence of mind. A part of her always kept assessing, evaluating, even in the heat of passion. Or panic.

Since survival in the current situation didn’t require fast thinking so much as fast legwork, she realized why the air in the tomb had not been stale and why dust had settled so deeply on the floor and upon the emperor.

That hole in the ceiling may or may not have been a celestial escape route for Lu’s soul. It certainly was an air shaft. No matter how disposable labor was in his day—and she suspected that it was mighty disposable indeed—Lu had to know his tomb would never get built if the laborers kept dropping dead of asphyxiation the moment they reached the work site. Not to mention the fact that in those days skilled masons and engineers weren’t disposable, and had he treated them that way, his tomb never would’ve been built in the first place.

No doubt an extensive network of ventilation shafts terminated at the tomb mound’s sides at shallow angles. They would have been built with doglegs and baffles to prevent water getting in under normal circumstances. Otherwise the old emperor and his last bier would have been a stalagmite.

That also explained why Annja wasn’t swimming hopelessly upstream right now. One peculiarity— eccentricity was probably the word, considering the creator—of Mad Emperor Lu’s tomb was that it was entered from the top. Annja had made her way gingerly down, and was making her way a good deal less carefully back up a series of winding ramps and passages. The vent shafts were probably entirely discrete from the corridors. Perhaps Lu had contrived a way to flood his subterranean burial chamber from ground water or a buried cistern.

Screaming with friction, spears leaped from the wall to Annja’s left. The green bronze heads crashed the far wall’s stone behind her back. The traps were timed for a party advancing at a deliberate pace. Annja was fleeing.

Up through the tunnels Annja raced. When she dared risk a glance back over her shoulder she saw water surging after her like a monster made of froth. She was gaining, though.

That gave her cold comfort. No way was ground water, much less water stored in a buried cistern, rising this far this fast, she thought. It took serious pressure to drive this mass of water. The valley was clearly flooding a lot quicker than she had been assured it would.

So now she was racing the waters rising outside the mound, as well as those within.

If the water outside got too high, the helicopter Annja had hired to bring her here and carry her away when she emerged would simply fly away. She couldn’t much blame the pilot. There’d be nothing to do for her.

Trying hard not to think about the unthinkable, Annja ran harder. A stone trigger gave beneath her feet; another spring trap she hadn’t tripped on her way down thrust its spears from the wall. They missed, too.

From time to time side passages joined the main corridor. In her haste she missed the one that led to the entrance she had come in by, which was not at the mound’s absolute apex. She only realized her error when she came into a hemispherical chamber at what must have been the actual top. A hole in the ceiling let in vague, milky light from an appropriately overcast sky.

Annja stopped, panting. Though she knew it was a bad way to recover she bent over to rest hands on thighs. For the first time she realized she still clutched the imperial seal in a death grip. The expedition wasn’t a total write-off.

Provided I live, she thought.

Forcing herself to straighten and draw deep abdominal breaths, she looked up at the hole. It was small. She guessed she could get through. But only just. She would never pass while she wore her day pack. And she wasn’t going to risk wriggling through with the seal in a cargo pocket. The fit was tight enough it would almost certainly break.

“Darn,” she said. She swung off her pack. Wrapping the seal in a handkerchief, she stuck it in a Ziploc bag she had brought for protecting artifacts. She stowed it carefully in her pack and set off back down the corridor to find the real way out.

She was stopped within a few steps. The water had caught her.

“Oh, dear,” she said faintly as it surged toward her. The valley was flooding fast.

She ran back up to the apex chamber. Cupping her hands around her mouth, she shouted, “Hello? Can you hear me? I need a little help here!”

She did so without much hope. The pilot and copilot would be sitting in the cockpit with both engines running. With the waters rising so fast they had to be ready for a quick getaway. In fact, Annja had no particularly good reason to believe they hadn’t already flown away.

To her surprise she was answered almost at once.

“Hello down there,” a voice called back through the hole. “I’ll lend you a hand.”

Annja stared at the hole for a moment, although she could see nothing but grey cloud. She had no idea who her rescuer was. It sure wasn’t the pilot or the copilot—they weren’t young women with what sounded for all the world like an Oxford accent.

“Um—hello?” Annja called out.

“I’m throwing down a rope,” the young woman said. A pale blue nylon line uncoiled from the ceiling.

“I’ve got a pack,” Annja called up, looking nervously back over her shoulder at the chamber’s entrance. She could hear the slosh of rising water just outside. “It’s got important artifacts in it. Extremely delicate. I’ll have to ask you to pull the pack up first. I can’t fit through the hole while carrying it.”

She expected her unseen benefactor to argue—the primary value of human life and all that. But instead she replied, “Very well. Tie it on and I’ll pull it up straightaway.”

Annja did so. When she called out that it was secure, it rose rapidly toward the ceiling. She frowned, but the woman slowed it down when it neared the top. She extracted it without its synthetic fabric touching the sides of the hole.

“Thanks,” Annja called. “Good job.”

After an anxious moment the rope came through the ceiling again. Except not far enough.

Not nearly far enough. Annja reckoned she could just barely brush it with her fingertips if she jumped as high as she could. She could never get a grip on it.

“Uh, hey,” she called. “I’m afraid it’s not far enough. I need a little more rope here.”

She heard a musical laugh. It made its owner sound about fourteen. “So sorry,” the unseen voice said. “No can do.”

“What do you mean?” Annja almost screamed the words as water burst into the room to eddy around her shoes. “You aren’t going to leave me to drown?”

“Of course not. In a matter of a very few minutes the water will rise enough to float you up to where you can grasp the rope and climb out. A bit damp, perhaps, but none the worse for wear.”

Annja stared. The astonishing words actually distracted her from the floodwaters until they rose above the tops of her waterproofed shoes and sloshed inside them. Their touch was cold as the long-dead emperor’s.

“At least leave me my pack!” Annja shouted, jumping up and swiping ineffectually at the dangling rope. She only succeeded in making it swing. She fell back with a considerable splash.

“I’m afraid not,” the woman called. “You have to understand, Ms. Creed. There’re two ways to do things—the hard way and the easy way.”

Annja stood a moment with the water streaming past her ankles. The words were so ridiculous that her mind, already considerably stressed by the moment, simply refused to process them.

Then reality struck her. “Easy?” she screamed. “Not Easy Ngwenya?”

“The same. Farewell, Annja Creed!”

Annja stared. The chill water reached her knees. She stood, utterly overwhelmed by the realization that she had just been victimized by the world’s most notorious tomb robber.

2

Paris, France

“You’re kidding,” Annja said. “Who doesn’t like the Eiffel Tower?”

“It’s an excrescence,” Roux replied.

“Right,” she said. “So you preferred it when all you had to watch for in the sky was chamber pots being emptied on your head from the upper stories?”

“You moderns. You have lost touch with your natures. Ah, back in those days we appreciated simple pleasures.”

“Not including hygiene.”

Roux regarded her from beneath a critically arched white brow. “You display a most remarkably crabbed attitude for an antiquarian.”

“I study the period,” she said. “I’m fascinated by the period. But I don’t romanticize it. I know way too much about it for that. I wouldn’t want to live in the Renaissance.”

“Bah,” the old man said. But he spoke without heat. “There is something to this progress, I do not deny. But often I miss the old days.”

“And you’ve plenty of old days to miss,” Annja said. Which was, if anything, an understatement. When he spoke about the Renaissance, he did so from actual experience.

Roux was dressed like what he was—an extremely wealthy old man–in an elegantly tailored dove-gray suit and a white straw hat, his white hair and beard considerably more neatly barbered than his ferocious brows.

Annja had set down her cup. She sat with her elbows on the metal mesh tabletop, fingers interlaced and chin propped on the backs of her hands. She wore a sweater with wide horizontal stripes of red, yellow and blue over her well-worn blue jeans. A pair of sunglasses was pushed up onto the front of her hair, which she wore in a ponytail.

Autumn had begun to bite. The leaves on the trees along the Seine were turning yellow around the edges, and the air was tinged with a hint of wood smoke. But Paris café society was of sterner stuff than to be discouraged by a bit of cool in the air. Instead the sidewalks and their attendant cafés seemed additionally thronged by savvy Parisians eager to absorb all the sun’s heat they could before winter settled in.

She found herself falling back onto her current favorite subject. “I’m still miffed at what happened in Ningxia,” she said.

“ You’re miffed? I have had to answer to certain creditors after the shortfall in our accounts. Which was caused by your incompetence, need I remind you?”

“No. And anyway, that’s not true. I got the seal. I had it in my hands.”

“Unfortunately it failed to stay in your hands, dear child.”

“That wasn’t my fault! I trusted her,” Annja said.

“You trusted a strange voice which called down to you through a hole in the ground,” Roux said. “And you style yourself a skeptic, non? ”

Annja sat back. “I was kind of up against it there. I didn’t really have a choice.”

“Did you not? Really? But did you not eventually save yourself by following that vexatious young lady’s suggestion, and waiting until the water floated you high enough so you could climb the rest of the way out?”

“Only to find the witch had flown off in my helicopter. My. Helicopter, ” Annja said.

“Oh, calm down,” the old man said unsympathetically. “She did send a boat for you. Which she paid for herself.”

Annja sat back and tightly folded her arms beneath her breasts. “That just added insult to injury,” she said. The tomb robber had even left her pack. Without the seal. “Whose side are you on, anyway?”

“My own, of course,” Roux said. “Why be mad at me? I only point out things could have gone much worse. You might have seen Miss E. C. Ngwenya’s famous trademark pistols, for example.”

Annja slumped. “True.”

“And it never occurred to you,” Roux said, “simply to wait until the water lifted you high enough to climb out the hole directly, without handing over the object of your entire journey to a mysterious voice emanating from the ceiling?”

Annja blinked at him. “No,” she said slowly. “I didn’t think of that.”

She sighed and crumpled in her metal chair. “I pride myself in being so resourceful,” she said almost wonderingly. “How could it have deserted me like that?”

Roux shrugged. “Well, circumstances did press urgently upon you, one is compelled to admit.”

She shook her head. “But that’s what I rely on to survive in those situations. It’s not the sword. It’s my ability to keep my head and think of things on the spur of the moment!”

“Well, sometimes reason deserts someone like you,” Roux said.

For a moment Annja sat and marinated in her misery. But prolonged self-pity annoyed her. So she sought to externalize her funk. “It’s just losing such an artifact—the only trace of that tomb—to a plunderer like Easy Ngwenya. She just violates everything I stand for as an archaeologist. I’ve always considered her nothing better than a looter.”

She frowned ferociously and jutted her chin. “Now it’s personal.”

Roux set down his cup and leaned forward. “Enough of this. Now, listen. Your secret career is an expensive indulgence—”

“Which I never volunteered for in the first place!” Annja said.

“Details. The fact is, you have been burning money. As I have alluded to, certain creditors grow—insistent.”

Annja frowned thoughtfully. She could see his point. There was no denying her recent adventures had been costly. The rise of digital records and biometric identification hadn’t made official documentation more secure—the opposite, if anything. But full-spectrum false identification was expensive. And Annja relied greatly on fake ID to avoid having her secret career exposed by official nosiness.

She leaned back and crossed her legs. “Has Bank of America been making nasty phone calls?”

“Think less modern in methods of collection, and more Medici.”

“You haven’t been borrowing from Garin again?” Annya asked.

His lips compressed behind his neat beard. “It’s…possible.”

Garin Braden was a fabulously wealthy playboy. He was also Roux’s former protégé and he feared the miraculous reforging of the sword threatened his eternal life.

“I bet you’ve just had a bad streak at the gaming tables,” Annja said accusatorily. “Didn’t you get busted out of that poker tournament in Australia last month?”

“All that aside, we must improve what you Americans charmingly call cash flow.”

She sighed. “Tell me,” she said.

“Somewhere in the mountainous jungles of Southeast Asia there supposedly lies a vast and ancient temple complex. Within it hides a priceless artifact—a golden elephant idol with emerald eyes. I have been approached by a wealthy collector who wants it enough to pay most handsomely.”

“Who?”

“One who treasures anonymity,” Roux said.

“That’s a promising start,” Annja said, not bothering to hide the sarcasm in her voice. “So I take it all this mystery likewise precludes your at least running a credit check?”

“Sadly,” Roux said, “yes.”

He spread his hands in a dismissive gesture. “However, our client—”

“Let’s hold off on this our business until I’m actually signed on, shall we?” Annja said.

“ Our client has offered a handsome preliminary payment, as well as an advance against expenses.”

“The preliminary, at least, needs to be no-strings-attached,” Annja said.

Roux raised his eyebrow again.

“What?” Annja said.

“That would require substantial faith on the client’s part,” Roux said.

“So? Either he-she-it has faith in me, or doesn’t. If they’re not willing to believe in my integrity, then to heck with it. And why come to me, anyway, if that’s the case? If I’m not honest, there’s ten dozen ways I could chisel, from embezzling the expense account to selling to the highest bidder whatever it is this mystery guest wants me to get. There isn’t any guarantee I could give that could protect against that. If I’m a crook, what’s my guarantee worth?”

Roux looked as if he were bursting to respond. She glared him into silence.

“While we’re on the subject,” she said, “there’s not going to be any accounting for expenses incurred. For reasons I really hope you won’t make me explain out loud.”

He sipped his coffee and pulled a gloomy face. “You don’t ask for much, my dear child,” he said, “beyond the sun, the moon and perhaps the stars.”

“Just a star or two,” she said. “Anyway, you’re the one whining the exchequer might be forced to go to bed tonight without any gruel if little Annja doesn’t hie herself off to Southeast Asia and do something certainly arduous, probably dangerous and more than likely illegal. You should be happy to ask for the best no-money-back terms available.”

“I don’t want to scare the client off,” Roux said.

“This strikes me as skirting pretty close to pot-hunting,” Annja said. “The jade-seal affair already came too close.”

“But you’ve done similar things in the past,” Roux said. “And after all, who better to ensure the Golden Elephant is recovered in a…sensitive way rather than ripped from the earth by a tomb-robber?”

He turned his splendid head of silver hair to profile so he could regard her sidelong with slitted eyes. “Or would you prefer to leave the field open to, say, the likes of Her Highness, E. C. Ngwenya?”

“Quit with the psychological manipulation,” she said. But even to her ears her voice sounded less than perfectly confident.

3

London, England

“Tea, Ms. Creed?” asked the bluff and jovial old Englishman with the big pink face, a brush of white hair and a red vest straining slightly over his paunch. With an exquisitely manicured hand he held up a white porcelain teapot with flowers painted on it.

Annja smiled. “Thank you, Sir Sidney.” She started to rise from the floral-upholstered chair. She would term the small round table, the flowered sofa and chairs, the eclectic bric-a-brac in Sir Sidney Hazelton’s parlor as fussy Victorian.

He gestured her to stay seated. He poured the tea with a firm if liver-spotted hand protruding from a stiff white cuff with brisk precision, then brought her the cup with a great air of solicitude.

“Thank you,” she said, accepting.

Sir Sidney reseated himself in his overstuffed chair. He’d offered one like it to Annja, insisting that it was more comfortable than the one she chose. She declined, fearing if she sank into it the thing would devour her. She had to admit that despite his bulk he moved with alacrity, including in and out of the treacherously yielding chair.

“Really, isn’t this notion of lost cities or temples more frightfully romantic than realistic?” he asked. “I mean, what with all these satellites and surveillance aircraft and such today.”

Annja pursed her lips. She had some experience with what could be seen from satellites—and also of things that could not. She chose her words carefully.

“It’s a matter of who pays attention to what image,” she said. She told herself she didn’t need any extra complications. “Not everyone who runs across overhead imaging of, say, a lost temple has the knowledge to recognize what they’re looking at. And many of the most skilled image analysts don’t care. They’re looking for military information, or maybe stray nuclear materials. Not ancient ruins. Although some pretty astonishing ruins have been discovered by overhead photography, just in the last couple of decades.”

“So I gather,” Sir Sidney said. “Well, I must say it does a body good to believe there’s still some mystery left in this old world of ours. Quite bracing, actually.”

She raised a brow. “Aren’t you the expert in lost treasures and fabled ruins?”

He smiled. “My dear, the operative word there is fabled. I am, as you know, a cultural anthropologist. Specifically I am a mythologist. I study the phenomena of myths. Particularly pertaining to myths about lost treasures.”

He grinned. “But there’s very little more exciting than the possibility a myth turns out to be true.”

She had to laugh, both at what he said and his very infectious enthusiasm. “That’s how I feel about it.” Usually, she thought. “And there’s a very definite possibility the trail I’m on might lead to a myth being confirmed.”

He waved grandly. “If I can be of any assistance to a lovely young woman such as yourself—”

He paused to pour more tea and stir in plenty of milk.

“I’ve got to thank you again for sharing your time with me,” Annja said.

“Nonsense, nonsense. The pleasure is mine. I am retired, after all. It’s not as if there are abundant claims upon my time these days. My partner of many years died last year. It was quite sudden.”

“I’m sorry,” Annja said.

“Don’t be,” her host replied. “I’m sure you had nothing to do with it, my dear. I can’t say I’ve grown comfortable with it, or ever shall, I fancy. Doubtless I’ve not that long left in which to do so. On the whole I must say I’m rather glad it happened the way it did. So suddenly and all. It saved him the suffering of a long and possibly agonizing decline—saved us both, really. And at our age it’s not as if our own mortality was a tremendous surprise to us. We’ve seen enough old chums put into the ground to have few illusions on that score.”

Annja smiled.

Sir Sidney leaned forward. “Now,” he said, “suppose you tell me this myth you’re trying to pin like a butterfly to reality’s board.”

After a moment’s pause—she didn’t really like thinking of it that way—Annja did. She shared such scanty information as Roux had provided, plus a few not very helpful details from a file he had subsequently e-mailed her.

Sir Sidney sat listening and nodding. Then he smiled and sat back. “The Golden Elephant,” he said ruminatively. “So you’ve reason to believe it’s real?”

Her heart jumped. “You’ve heard of it?”

“Yes,” he said. “Please don’t get your hopes up quite yet. Just let me think a moment, see what I can recall which might prove of use. Do you mind if I smoke my pipe?”

“No,” Annja said. He produced a pipe from an inner pocket, took up tobacco and various arcane tools from a silver tray on the table next to him.

“I’m a little bit puzzled by one aspect of this,” Annja admitted as he lit up. His pipe smoke had a sweet but not cloying smell. Annja had never particularly disliked pipe smoke, unlike cigarette smoke. She hoped the interview wasn’t going to go on too long, though. The parlor was stuffy, with windows closed and heat turned up against the damp autumn London chill. In this closeness even the most agreeable smoke could quickly overwhelm her. “I thought Southeast Asia was mostly Buddhist.”

“Quite,” Sir Sidney said, puffing and nodding.

“Not that I know much about Asian mythology. But I’d associate elephants with the Hindu god Ganesha, rather than anything Buddhist.”

He smiled. Blue-white smoke wreathed his big benign pink features. “Ah, but elephants are most significant beasts in all of Asia,” he said, clearly warming to the role. “Not just big and imposing creatures, but economically important.”

“Really?”

“Just so. It needn’t surprise us too much that the elephant occupies a role in Buddhist symbolism. It symbolizes strength of mind. Buddhists envision what they call the Seven Jewels of Royal Power. These basically constitute the attributes of earthly kingship.

“One of these jewels is the Precious Elephant. It represents a calm, majestic mind. Useful trait in a king, although one honored more in the breach than the observance, as it were.”

“If Asian history is anything like that of Renaissance Europe,” Annja said, “that’s probably an understatement.”

He chortled around the stem of his pipe.

They spoke a while longer. Annja enjoyed the old man’s conversation. But she increasingly felt restless. “Are you remembering any more about the myths regarding our fabulous Golden Elephant?” she asked.

He puffed. “It’s said to have emeralds for eyes.” His own pale blue eyes twinkled. His manner suggested a child telling secrets.

She leaned forward, pulse quickening. “That sounds like my elephant.”

“Don’t put it in your vest pocket yet, my dear,” he said. “I’m not yet dredging up much from the murky depths of my poor old brain. But I recall hints of travelers’ tales. Even reports from a certain scientific expedition from early this—in the twentieth century.”

He shook his head. “I find it most disconcerting to refer to the twentieth century as the last century. It may not strike you so, of course.”

She shrugged. “I don’t think about it too much. It does strike me a little odd sometimes that there are people capable of holding intelligible conversations who were born in the twenty-first century.” She laughed. “I guess that means I’m getting old.”

He guffawed. “Not at all, my dear!” he said. “Not by a long shot. I dare say, I don’t think you’ll ever grow old.”

She looked sharply at him.

“I’m sorry,” he said quickly. “I suppose that could be misconstrued, couldn’t it? I didn’t mean you won’t enjoy a long and happy life. What I meant to convey was that however deeply your years accumulate, I anticipate that your outlook will remain youthful. For that matter, I don’t doubt the years will lie less heavily on you than me in any event. By all appearances you keep yourself far better than ever I did.” He patted himself on the paunch.

Annja looked studiously down into her tea and tried hard not to read her future there.

“Ah, but I see I’ve gone and spoiled your mood. Forgive a clumsy old man’s musings. Profuse apologies, dear child.”

“Not needed,” she said. She smiled. It wasn’t forced. She was a thoughtful person, but had no patience for brooding. “Do you have any suggestions how I can track down this expedition you mentioned?”

His big pink face creased thoughtfully. At last he made a fretful noise and shook his head.

“It eludes me for the moment,” he said. “I’ll see what I can dig up. In the meantime I do have a next step to suggest to you.”

“What’s that?”

“Why, visit that great repository of arcane archaeological knowledge, the British Museum, and see what you can turn up.”

She smiled. “I’ll do that. Thank you so much.”

“It’s nothing. Indeed, almost literally—doubtless you’ve thought of the museum already. It’s right down the lane and across the Tottenham Court Road, you know.”

“Yes. Thank you, Sir Sidney. You’ve encouraged me. Really. If nothing else, I know I’m not the only one with fantasies about an emerald-eyed gold elephant.”

She stood. “Don’t get up, please,” she said. “I can let myself out. You’ve got my card—please call me if you think of anything. With your permission I’ll check back with you in a day or so.”

He beamed. “It would be my pleasure.”

On impulse, she went and kissed him on the forehead. Then, collecting her umbrella from the stand by the door—an antique elephant’s foot, she noted with amusement—she walked out of his flat into the rainy street.

4

About midafternoon Annja pushed herself back from the flat-screen monitor. She stretched, trying to do so as unobtrusively as possible. Her upper back felt as if it had big rocks in it.

She had spent a frustrating afternoon in the Paul Hamlyn Library, flipping through catalogs and skimming through semirandom volumes. She caught a whiff from the digitized pages of British Archaeology for fall 1921, which mentioned the Colquhoun Expedition of 1899 to what was then Siam. But when she tracked down the details, including Colquhoun’s journals and his report to the Explorers’ Club, he made nary a mention of gold elephants. With or without emerald eyes.

She shook her head. Certain needs were asserting themselves. Not least among them the need to be up and moving.

Checking her watch, Annja reckoned she had plenty of time for a turn through the Joseph E. Hotung Gallery, which held the Asian collections, before returning to her labors. She’d try the reading room next, and see if her luck improved.

The library jutted out to flank the main museum entrance from Great Russell Street. She emerged into the great court. It was like a time shift and somewhat jarring. The ceiling was high, translucent white, crisscrossed by what she took for a geodesic pattern of brace work, springing from a stout white cylindrical structure that dominated the center of the space. The cylinder housed the new reading room. The sterile style, which put her in mind of a seventies science-fiction movie, contrasted jarringly with the pseudo-Greek porticoed walls and their Dorian-capitaled pilasters.

The court wasn’t crowded. A few sullen gaggles of schoolchildren in drab uniforms; some tourists snapping enthusiastically with digital cameras were watched by security guards more sullen than the children. She was vaguely surprised photography was allowed.

She concentrated on movement, striding purposefully through milky light filtered from the cloudy sky above. She focused on the sensations of her body in motion, on being in the moment.

A sudden flurry of movement tugged at her peripheral vision. A female figure was walking, strutting more, through the room. Annja got the impression of a rounded, muscle-taut form in a dark blue jacket and knee-length skirt. Black hair jutted out in a kinky cloud behind the woman’s head, bound by an amber band.

Annja had never seen the woman in the flesh. But she had seen plenty of pictures on the Internet. Especially in the wake of her recent China adventure.

“Easy Ngwenya,” she said under her breath. She felt anger start to seethe. She turned to follow.

Without looking back, the young African woman continued through the hall, into the next room, which housed Indian artifacts. She moved purposefully. More, Annja thought, she moved almost with challenge. Her head was up, her broad shoulders back. She was shorter by a head than Annja, who nonetheless found herself pressed to keep pace.

Annja felt uncharacteristically unsure how to proceed. Her rival—she tried to think of her as quarry—could not have gotten her famous twin Sphinx autopistols through the Museum metal detectors, if she had even dared bring them into Britain. Although Annja suspected Easy would have smuggled the guns in. Great respect for the law didn’t seem to be one of her major traits.

So that was advantage Annja. No means known to modern science would detect her sword otherwise. Actually using it, with numerous witnesses and scarcely fewer security cameras everywhere, might prove a bit more problematic.

Easy Ngwenya made up Annja’s mind for her by stopping to peer into an exhibit case a few yards ahead of her. I’m practically committed now, anyway, Annja told herself.

The younger woman studied an exquisite jade carving of an elephant in an elaborate headdress, standing with trunk raised to bedangled forehead. Annja felt a jolt. Could she be here for the same reason I am? she thought with something akin to panic.

She dismissed the idea. A collector who came to Annja, even anonymously, would know of her reputation for honesty and integrity, even if she was willing to operate under the radar. Somebody so discerning would hardly recruit a tomb robber as notorious as Ngwenya. Would they? Anyway, elephants weren’t exactly an uncommon motif in Asian art, and Ngwenya might be forgiven a special interest in them, given she was named for one. Also it wasn’t gold.

Annja came up on Easy’s left.

“Annja Creed,” the younger woman said without looking around. Annja realized Easy must have seen her approach in the glass. “What a delightful surprise to encounter you here.”

“A surprise, anyway,” Annja said through gritted teeth, “after the way you marooned me on that tomb mound in the middle of a rising lake.”

“Did the boat I sent back for you not reach you?” Ngwenya asked. “You must have had an unpleasant swim. Not my intention, I assure you.”

“The boat came,” Annja admitted grudgingly. “That’s not the point. I’m…placing you under citizen’s arrest.”

Ngwenya’s laugh was musical and entirely unconcerned. “Why, whatever for?”

She turned to look up at Annja. Annja was struck by just how young the international adventuress looked. She was in her twenties, having gotten an early start at a life of adventure. Or crime. She looked fifteen.

Annja was also struck by just how pretty Easy was. She had a big rounded forehead, a broad snubbed nose, full lips, a small round chin. That should have been less of a surprise—despite the currently unfashionable fullness of her figure, Ngwenya occasionally did modeling, not always fully dressed. The curves, Annja knew from the pictures she’d seen online, did not come from excess body fat.

“You have committed countless violations of international law regarding traffic in antiquities. As you well know,” Annja said.

The girl batted her eyes at her. Annja wished she wouldn’t. They were huge eyes, the color of dark chocolate, with long lashes. Annja suddenly suspected why she was named “elephant calf.” She had eyes like one.

“You’d already looted the seal from the feet of Mad Emperor Lu,” Ngwenya pointed out. “Congratulations on getting past the booby traps, by the way.”

“I had official permission, if you must know,” Annja said. Whether it was the Museum’s cathedral atmosphere or her own desire to remain as unobtrusive as possible, she kept her voice low. She only hoped she wasn’t hissing like a king snake having a hissy fit. “I had all the proper paperwork.”

Ngwenya laughed loudly. “And so did I! Remarkable how easy such things are to come by for those willing to be generous to underappreciated civil servants. One is tempted to ascribe that to the customary blind Communist lust for money, but honestly, I wonder if it was any different back in dear old mad Lu’s day.”

“It’s not like it was an isolated incident. So come with me,” Annja said.

“You can’t be serious. There are people here. Behave yourself, Ms. Creed.”

“I told you—you’re under citizen’s arrest.”

The young woman laughed again. “Do you think such a legal archaism still has force? This is a country where someone who successfully resists a violent assault is likely to face brisker prosecution and longer jail terms than their attacker. Do you really think they’ll give weight to a citizen’s arrest? Especially by someone who isn’t a citizen? Or were you forgetting that little dust-up of a couple of centuries past? So many of your countrymen seem to have done.”

“When Scotland Yard gets your Interpol file,” Annja said, “they probably won’t be too concerned with the niceties of how you wound up in their custody, then, will they?”

“Oh, this is entirely absurd.” To Annja’s astonishment the young woman turned and walked away. Before Annja could respond, Easy had pushed through into a stairway to the upper level.

Frowning, Annja followed. She expected to find the stairwell empty. But instead of sprinting to the second level and through the door into the Korean exhibit Easy trotted upstairs. Her pace was brisk. But it definitely wasn’t flight.

You cocky little thing, Annja thought.

She caught her up just shy of the upper-floor landing. She grabbed Easy’s right arm from behind. It felt impressively solid. “Not so fast, there.”

Using hips and legs, Easy turned counterclockwise. She effortlessly torqued her arm out of Annja’s grasp. Her left elbow came around to knock Annja’s right arm away as if inadvertently. She thrust a short right spear hand straight for Annja’s solar plexus.

Annja anticipated the attack. Just. She couldn’t do anything about Easy fouling her right hand. But she bent forward slightly, functionally blocking the sensitive nerve junction with the notch of her rib cage while turning slightly to her right. Instead of blasting all the air from her lungs in one involuntary whoosh, the shorter woman’s stiffened fingers jabbed ribs on Annja’s left side.

Annja had no doubts about why they called that strike a spear hand. She felt as if she’d been stabbed for a fact. But that was just pain: she wasn’t incapacitated.

Knowing the omnipresent eyes of the surveillance cameras constrained her Annja straightened, trying at the same time to deliver a short shovel hook upward with her right fist into Ngwenya’s ribs. The woman’s short stature defeated her. The blow bounced off the pot hunter’s left elbow and sent another white spike of pain up Annja’s arm.

Ngwenya frowned at her. “Really, Ms. Creed,” she said primly, “this is most unseemly.”

There was a short flurry of discreet short-range strikes.

After a brief, grunting exchange, barely visible to the high-mounted camera, Easy Ngwenya sidestepped a short punch, reached with her right hand and caught Annja behind the left elbow. She squeezed.

The younger woman was chunkily muscular. Annja had noticed in some of her photographs that she had short, square hands, large for her height. Practical, practiced hands. Even in glamour shots the exiled African princess disdained long nails, even paste-on fakes.

But even her exceptional hand strength couldn’t account for the lightning that shot through Annja’s body.

She could barely even gasp. It wasn’t the pain. There was pain, to be sure; it felt as if a giant spike had been driven up her arm and at the same time right through the middle of her body. The problem was, literally, the shock. It was as if a jolt of electricity had clenched her whole body in a spasm, dropped her to her knees and left her there, lungs empty of breath and unable to draw one. Her vision swam.

“Oh, dear,” Easy’s voice rang, clear with false concern. “Are you quite all right, miss? I’ll go and get help.” She trotted away up the stairs with rapid clacks of her elegant but practical low-heeled shoes.

Annja rocked back and forth. Darkness crowded in around the edges of her vision. What’s wrong with me? she wondered in near panic. It was as if she was suffering a giant whole-body cramp.

An unbreakable one.

But slowly, as if molecule by molecule, oxygen infiltrated back into her lungs and permeated her bloodstream. Slowly the awful muscle spasm began to relax. She slumped.

She was just regaining control of herself when two uniformed guards, a man and a woman in caps with little bills, came pattering down the steps for her.

“Oh, dear, miss,” the man said in a lilting Jamaican accent. “Are you all right?”

She nodded and let them help her to her feet. She didn’t have much choice. She still didn’t have the muscular strength to stand on her own.

“I-I’m fine,” she said. “I get these spells. Epilepsy. Petit mal. Had it since childhood. Really, thank you, it’s passed now.”

The two exchanged a look. “We don’t want you suing us,” said the blond woman.

“No. I’m fine. Did you see which way my friend went?”

“No,” the man said. “She seemed very determined that we help you right away.” He shook his head. “She was quite the little package. It was too bad we had to rush away—”

“Oi!” the woman exclaimed. “That’s so sexist! I’ve half a mind to report you for that.”

“Now, now,” he said, “don’t go flying off here like—”

“Like what? Were you going to make another demanding sexist statement, then?”

“Don’t you mean demeaning? ” the male guard said.

Annja set off at what she hoped was a steady-looking pace, up the stairs to the next level. She made it through the door before she wobbled and had to lean back against it for a moment to gather herself.

The Korean exhibit was nearly empty. It was totally empty of any rogue archaeologist Zulu princesses. Annja drew a deep abdominal breath. It steadied her stomach and cleared her brain. Her vision expanded slowly but steadily. She no longer felt as if she were passing through a tunnel toward a white light.

She managed to walk briskly, with barely a wobble, through a door into a wider hall. Another set of stairs led down. Annja set her jaw.

The stairs descended to the ground level, and then to the north exit. She found herself outside on broad steps with Montague Place in front of her and the colonnaded pseudoclassical facade of the White Wing behind. It was called that not because it was white, but because it was named after the benefactor whose bequest made it possible to build.

The cool air seemed to envelop her. She sucked in a deep breath. The moist draft was so refreshing she scarcely noticed the heavy diesel tang.

A light rain began to tickle Annja’s face. She grunted, stamping one foot. Passersby glanced at her, then walked quickly on.

Calm down! she told herself savagely. This doesn’t always happen. She’s got the better of you twice. That’s not statistically significant.

She walked on as fast as she dared. She didn’t want some kind of behavior-monitoring software routine on the video surveillance to decide she was acting suspiciously. But she wanted to get away from the museum.

For a time she walked at random, lost in thoughts that whirled amid the noise of the city center. She stopped at a little café inside a glass front of some looming office building for a cup of hot tea.

Sitting on an uncomfortable metal chair, she gulped it as quickly as she could without scalding her lips. Outside she was surprised to see that twilight was well along. Gloom just coalesced atom by atom out of the gray that pervaded the cold heart of the city.

Setting the cup down, she strode out into the early autumn evening. The rain had abated. She headed toward Sir Sidney’s, a dozen or so blocks away. Maybe he’d turned something up.

I T ALWAYS AMAZED A NNJA how many little alcoves and culs-de-sac, surprisingly quiet even in the evening rush, could be stumbled upon in downtown London. Sir Sidney lived on a little half-block street, narrow and lined with trees whose leaves had already turned gray-brown and dead. It was so tiny and insignificant, barely more than a posh alley, it didn’t seem to rate its own spy cameras.

Trotting up the steps to the door of Sir Sidney’s redbrick flat, Annja wondered how his aging knees held up to them. Before she could carry the thought any further, she noticed the white door with the shiny brass knob stood slightly ajar.

She stopped in midstep. Her body seemed to lose twenty quick degrees. Foreboding numbness crept into her cheeks and belly.

“It’s all right,” she said softly. “He’s old. He might be getting absentminded. Just nipped out and forgot to fully close the door—”

Trying not to act like a burglar, she went on up the steps. She knocked quickly. “Sir Sidney?” she called. She was trying to make herself heard if he was within earshot inside without drawing attention to herself from outside.

She did not want to be seen.

Putting a hand in the pocket of her windbreaker, she pushed the door open and stepped quickly inside.

The entrance hallway was dark. As was the sitting room to her right. Nonetheless, the last gloom of day through the door and filtering in through curtained windows showed her the shape of Sir Sidney lying on his back on the floor.

The rich burgundy of the throw rug on which he had fallen had been overtaken by a deeper, spreading stain.

5

Annja knelt briefly at the old man’s side. The skin of his neck was cold. She felt no pulse.

She almost felt relief. If he was still alive with half his head battered in like that—

She shook her head and straightened. She would rather die than persist in such a state. She hoped Sir Sidney had felt the same way.

One way or another, he felt nothing now.

Moving as if through a fog that anesthetized her extremities and emotions, Annja took stock of the sitting room. The gloom was as thick as the cloying combination smell of old age, potpourri and recent death. She didn’t want to turn on a light, though. She wanted to draw no attention to her presence, nor leave any more signs of her presence than she had to.

Than I already have, she thought glumly. Irrationally if unsurprisingly, she regretted the earlier carelessness with which she had handled her teacup and saucer, the careless abandon with which she had handled the objects on display. Could I have left any more fingerprints?

The floor was scattered with toppled furniture. Strewed papers mingled with artifacts. Sir Sidney had welcomed his murderer—or murderers. There was no sign of forced entry. But he had not died easily.

Not far from the body lay a two-foot-high brass statue of Shakyamuni. The screen behind the seated figure was bent. The heavy metal object was smeared with blood. Annja looked away. She had seen too much death in her short life.

An overturned swivel chair drew her attention to the rolltop writing desk. Briskly she moved to it. She had little time. She racked her brain trying to remember if there had been anybody in the short, tree-lined lane who might have seen her enter the flat. Then again, anyone, driven by nosiness, caution or simple boredom, might have been peering out through the curtains to watch a long-legged young woman approach the apartment.

On the desk an old-fashioned spiral-bound notebook lay open. Annja almost smiled. She would have been surprised if the old scholar had kept his notes on a computer. But to her chagrin the first page was blank. Frowning, she started to move on.

Then she turned back and leaned close to study the page in the poor and failing light. With quick precision she tore the page away, folded it neatly and stuck it in her pocket.

She paused by the body. She made herself look down and see what Sir Sidney had suffered. It had been because of her, she knew—the laws of coincidence could be tortured only so far.

“I’m sorry, Sir Sidney,” she said in a husky voice. “I will find whoever did this.”

Already a deep anger had begun to burn toward Easy Ngwenya. Could her presence in the museum that afternoon possibly have been coincidence?

“And I will punish them,” Annja promised. It wasn’t a politically correct thing to say, she knew. Even to a freshly murdered corpse.

But then, there was nothing politically correct about wielding a martyred saint’s sword, either.

She quickly left the flat.

W HEN SHE WAS BACK in her hotel room the sorrow overtook her—suddenly but hardly unexpectedly. She didn’t try to fight it. She knew she must grieve. Otherwise it would distract her; unresolved, it might create a tremor of intent that could prove lethal.

She wept bitterly for a kind and helpful old man she had barely known. And for her own role in bringing death upon his head.

When her eyes and spirit were dry again, she took out the notepaper, ruled in faint blue lines, unfolded it under the lamp on the writing desk and examined it closely. The neat curls and swoops of the old scholar’s precise hand were engraved by the pressure of the pen that had written on the page above it.

Among the tools of the trade she carried with her were a sketch pad and graphite pencil. Extending the soft lead and brushing it across the sheet of paper, Annja was pleased when the writing appeared, white on gray.

She bit her lip. Not what I hoped, she thought. Not at all.

T HE LIGHTS INSIDE THE Channel striped the window next to Annja in the bright and modern Eurostar passenger car. Annja placed her fingertips against the cool glass of the window. It was still streaked on the outside with rain from the storm that had hit London as it moved out, well before it headed into the tunnel beneath the English Channel.

The weather fit her mood.

The notebook page, burned in the hotel room sink to ashes Annja had disposed of crumpled in a napkin in a public trashcan on the street, hadn’t held the key to the mystery of the Golden Elephant as Annja hoped. But Sir Sidney’s memory, and perhaps a little research, had unearthed what could prove to be a clue.

“The Antiquities of Indochina,” Hazelton had written. It appeared to be the title of a book or monograph, since beside it he had written a name—Duquesne.

He had either done a bit of digging on his own or called friends. Without checking his phone records she’d never know. Given her contacts in the cyber-underworld it was possible. But she didn’t want to risk tying herself to the case.

Perhaps he’d simply remembered. In any event, after jotting down a few grocery items he had written “Sorbonne only.” The word only was deeply outlined several times.

It was the only lead she had. But the gentle old scholar’s ungentle murderers also had it.

If Sir Sidney’s murder had been discovered by authorities, it hadn’t made it to the news by the time she boarded the train in the St. Pancras Station—quite close, ironically, both to Sir Sidney’s flat and the British Museum. She’d bought passage under the identity of a Brit headed on holiday on the Continent.

Roux was right, she thought. As usual. This business was expensive. She hoped the commission from this mysterious collector would cover it.

She grimaced then. Nothing would pay for Sir Sidney’s death. No money, anyway. Her resolve to bring retribution on his killer or killers had set like concrete. And she felt, perhaps irrationally, she had a good line on who at least one of them was.

Although she was renowned for going armed, and for proficiency in the use of various weapons—neither of which Annja was inclined to hold against her—cold-blooded murder had never seemed part of Easy Ngwenya’s repertoire. But perhaps greed had caused her to branch out. Annja only wondered how the South African tomb robber could have learned about her quest.

Unless their encounter in the museum—just that day, although it seemed a lifetime ago—was pure coincidence. Oxford educated, Ngwenya kept a house in London. She was known to spend a fair amount of time there. And given she really was a scholar of some repute, it wasn’t at all unlikely she’d find herself in the British Museum on a semiregular basis at least.

But Annja had a hard time buying it.

She made herself put those thoughts aside. You can’t condemn the woman—on no better evidence than you’ve got, no matter how much reason you have to be mad at her, she told herself sternly. For better or worse, from whatever source, you have the role of judge, jury and executioner. You’ve carried it out before. But if you get too self-righteous and indiscriminate, or even just make a mistake—how much better are you than the monsters you’ve set out to slay?

6

“So, you work for an American television program, Ms. Creed?” The curator was a trim, tiny Asian woman with a gray-dusted bun of dark hair piled behind her head and a very conservative gray suit. Annja guessed she must be Vietnamese.

“That’s right, Madame Duval,” she said. “It’s called Chasing History’s Monsters. ”

The woman’s already small mouth almost disappeared in a grimace of disapproval. “I’m employed as—” She started to say “devil’s advocate.” Taking note of the silver crucifix worn in the slightly frilled front of Madame Duval’s extremely pale blue blouse, Annja changed it on the fly. “I’m the voice of reason, on a show which, I’m afraid, sometimes runs to the sensational.”

Did she defrost a degree or two? Annja wondered.

“Why precisely do you seek credentialing to the University of Paris system, Ms. Creed?”

The University of Paris, commonly known as the Sorbonne after the commune’s 750-year-old college, was actually a collection of thirteen autonomous but affiliated universities. Annja stood talking with the assistant curator for the whole system in the highly modernized offices of University I, Panthéon-Sorbonne, one of the four modern universities located in the actual Sorbonne complex itself. If accepted as a legitimate scholarly researcher, she would gain access to collections throughout the system, even those normally closed to the public.

Annja smiled. “Whenever possible I like to combine what I like to call my proper academic pursuits with my work for the show. As an archaeologist I specialize in medieval and Renaissance documents in Romance languages. The predominant language, of course, being French.”

The woman smiled, if tightly. She was definitely warming.

“I have a particular interest in the witch trials of the Renaissance,” Annja said. She knew she gained a certain credibility because she showed she knew when the real bulk of the witch prosecutions took place; most people, including way too many college professors, thought they were a phenomenon of the Middle Ages. Still, the woman stiffened again, ever so slightly.

Annja was hyperattuned to her body language—and keying on that very reaction. “As what you might call the show’s revisionist,” she said, “I am particularly interested in the notion that the church might have had some justification for its actions in the matter. Not their methods, necessarily, but rather the possibility there existed a sort of witch culture that posed a real and deliberate threat to the church. Instead of the whole thing being a sort of mass hysteria, as is mostly assumed these days.”

Everything she said was true in the most legalistic and technical sense. There were such notions; they interested Annja.

Madame Duval smiled. “That appears to me to be a perfectly legitimate course of study,” she said in her own academic French. “If you will come with me, young lady, we will begin the paperwork to provide you the proper credentials.”

“Thank you,” Annja said.

F OUR HOURS LATER A NNJA’S vision was practically swimming. She was accustomed to deciphering fairly arcane writing. The Antiquities of Indochina was printed in a near-microscopic font. Unfortunately, unlike her Internet browsers, Annja’s eyes didn’t come with a handy zoom feature. The early-twentieth-century French itself was no problem; it was just hard to see.

Her heart jumped as she made out the words:

…the 1913 German expedition to Southeast Asia turned up many marvels indeed. Its reports included a fabulous hilltop temple complex, hidden in the reclaiming arms of the jungle, with the breathtaking golden idol of an elephant in its midst.

The passage then went on to talk about rubber production in Hanoi Province, in what was now Vietnam.

“Wait,” Annja said aloud, drawing glares from other researchers in the reading room. She glared back until they dropped their eyes back to tomes and computer screens.

Of course she felt bad about it at once. It’s not their fault, she reminded herself sternly.

Isn’t there more? she wondered.

She returned her attention to the book.

The crisp evening air felt good and smelled of roasting chestnuts. Annja was hungry, walking the summit of Montmartre with her hands jammed in her jacket pockets and her chin sunk into the collar. Over her left shoulder loomed the white domes of the Sacré Coeur Basilica. From somewhere in the middle distance skirled North African music. From nearer at hand came the thud and clank of what she considered mediocre techno music. The days of the Moulin Rouge and other noted, or notorious, cabarets were long gone. The fashionable night spots had long since migrated down across the river to the Left Bank and city center. Nowadays the area was given over to generic discos, artists’ studios and souvenir and antique shops, most of which were closed in the early evening.

Annja had found a fairly deserted section of the windy, narrow streets winding gradually down the hill. That suited her mood.

The one reference to the 1913 German expedition had been it. Not just for the book. For such as she’d been able to check of the University of Paris collection until they booted her out of the reading room at seven-thirty.

The good news was that she now knew stories of a golden elephant statue in a vast lost temple emanated from a German expedition to Southeast Asia in 1913. The bad news was that wasn’t much to go on.

It hadn’t been enough to lead to any more information, at least so far. The various archaeological reviews and journals from the period she had read stayed resolutely mute concerning any such expedition. She would have thought there’d be some mention.

Walking along in air just too warm for her breath to be visible, with fallen dry leaves skittering before her like small frightened mammals, she wondered if chauvinism might have come into play. The Great War, as it was then naively known—and for a few years afterward, until an even greater one happened along—broke out a year or so after the expedition. Indeed, if it set forth in 1913 the expedition might well have still been in progress when the First World War began. And in 1913 the French were still grumpy over the Franco-Prussian War.

So it struck her as possible that mention of German expeditions might’ve been embargoed in French journals. But scientists of the day still would have considered themselves above such political disputes, cataclysmic as they might be. Wars came and went—science endured. So the Germanophobe angle might mean much or little.

I see two main possibilities, Annja told herself as she turned down a quaintly cobbled alley between steel-shuttered storefronts that reminded her of home in Brooklyn. One, that the expedition simply got lost in the shuffle of World War I. It was easy enough to see how that would happen.

And two, she thought, the frown etching itself deeper into her forehead, that it was all just rumor.

That made her bare her teeth in dismay. It was possible. Probable, even. Scientific anthropology and archaeology were rife with such speculations in the wake of Schliemann’s discovery of Troy—or a reasonable facsimile thereof.

So the whole Golden Elephant yarn could just be hyperactive imagination.

“There’s a third possibility,” she said quietly to herself. “Or make it a subset of the first possibility,” she said with a certain deliberateness. “That there was such an expedition—and the only mention of it that still exists anywhere on Earth is the sentence you read in that book today.”

She knew that was an all-too-real likelihood. The priceless ceramic relics Schliemann had sent back to Berlin had been busted in some kind of grotesque drunken Prussian marriage ritual. The Lost Dinosaurs of Egypt had been lost when the Allies bombed the museum where they were stored. Paris had famously been spared the ravages of WWII. But the expedition, of course, was German. That was not so good, from a preservation point of view. The whole country had been handled pretty roughly. And most artifacts went through Berlin—which, between relentless bombing and the Red Army’s European tour, had pretty much been destroyed.

Every last journal or other scrap of writing relating to the 1913 expedition stood a really excellent chance of having been burned up, shelled to fine gray powder.

She sighed again. “Great,” she said. She decided she’d give it at lest one more try in the University of Paris system. If that came up dry—

From behind she heard a masculine voice call out, “There she is!”

7

Annja stopped. She set her mouth. She sensed at least two men behind her. She braced to run. Then from the shadowed brickwork arch of an entry into a small garden courtyard she hadn’t even noticed before, a third man strolled out into the starlight before her.

She’d wandered, eyes wide open, into a classic trap.

Annja scolded herself furiously. Walking around like that and not paying attention to your surroundings! she thought. Doing a perfect impression of a perfect victim. What were you thinking?

Unfortunately, thinking was what she had been doing. In contrast to maintaining situational awareness. It was an unfortunate propensity of hers. And what really annoyed her was that she knew better.

“What have we here?” the man who had appeared in front of her said in nasal, slangy Parisian French. He was a bit shorter than Annja, wearing a knit cap and a long dark cloth coat against the autumn chill.

Annja looked around. The other two men came up on her left and right, winging out to the side. They were positioned to catch her no matter which way she might bolt.

“Careful,” one said in an Algerian accent. “She has long legs, this one. She could run fast.”

She was in a tight spot, she knew. They were very smooth, very tactical, coming on her from three directions, allowing her no options to escape. They radiated hardness, both in attitude and physically. Each one of them would be stronger than she was. Her skill in martial arts, not to mention real fighting experience, gave her an edge on a single man, if he underestimated her. These men almost certainly did. To them she was another American woman, a tourist or student, spoiled, soft and foolish.

Foolish enough to wander dark, deserted city streets with head down and eyes turned inward. A perfect victim, she thought again with a wave of self-disgust.

The first man stopped two yards from her. He seemed aware of the possibility of a long-legged kick.

“Not a good thing for you, missy, being out alone like this,” he said.

“Nice talking to you,” she said. “Now, if you’ll kindly step aside, I’ll be on my way.”

He pulled his head back on his neck like a turtle starting a retreat into its shell and blinked at her with slightly bulbous pale eyes. Then he laughed. “It’s a spirited one we’ve got here.”

“Yeah,” said the third man. “It’s a damned shame.”

“Shut up,” said the Algerian.

Annja’s blood chilled as the men flanking her each grabbed one of her arms.