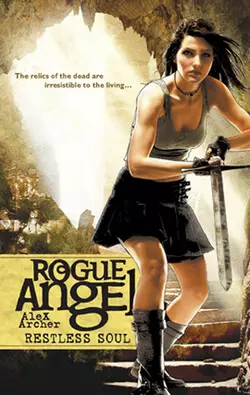

Restless Soul

Alex Archer

In 1966, a group of battle-weary American GIs trekked through the Vietnamese jungle knowing each step could mean facing the enemy's guns. But instead of ambush, they stumbled upon a hidden treasure beyond their wildest dreams. It was a discovery that exacted a terrible cost.A vacation spot picked at random, Thailand is intended to provide relaxation time for globe-trotting archaeologist Annja Creed. Yet the irresistible pull of the country's legendary Spirit Cave lures Annja and her companions deep within a network of underground chambers–nearly to their deaths. The ancient burial sites have slumbered through the ages. Yet no rest is found there–just the voices of the dead. When the dead speak, will they help Annja uncover the perplexing past of a remarkable find or will they call her to join them?

“Annja, come on! Move!”

Annja watched the water. It rose noticeably in the passing of a few heartbeats.

She cursed silently. When she started out that morning, it hadn’t crossed her mind that all the rain would affect her exploration of the caves. She should have considered the possibility. She should have realized there could be flash floods. Being on vacation had made her mind numb.

She glanced at the nearest coffin, then back at the water. The river could conceivably reach the coffins or perhaps completely cover them.

No doubt this chamber had flooded in the past what with the annual rainy season and the monsoons. Perhaps the rising river was the explanation for no bodies…the water had washed them away and left behind only the heavy teak coffins and the most cumbersome pieces of pottery. Maybe the water had even rearranged where the coffins had originally been placed.

She hadn’t imagined the voice. She heard it distinctly now. It hadn’t come from the coffins, though. It was as if it had traveled through the very stone of the cave and seeped into her head. It echoed like a child calling down into a canyon.

Free me…

Restless Soul

Rogue Angel

Alex Archer

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

THE LEGEND

…THE ENGLISH COMMANDER. TOOK JOAN’S SWORD AND RAISED IT HIGH.

The broadsword, plain and unadorned, gleamed in the firelight. He put the tip against the ground and his foot at the center of the blade.

The broadsword shattered, fragments falling into the mud. The crowd surged forward, peasant and soldier, and snatched the shards from the trampled mud. The commander tossed the hilt deep into the crowd.

Smoke almost obscured Joan, but she continued praying till the end, until finally the flames climbed her body and she sagged against the restraints.

Joan of Arc died that fateful day in France, but her legend and sword are reborn….

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Epilogue

Prologue

Vietnam, July 1966

At first, he hadn’t minded the sound of the place.

He was Bronx born and raised, and the constant insect chorus of the Vietnam jungle was an interesting oddity and an almost welcome change from the frequent sirens and ever-present racket of traffic back home.

The birdsong, the swish of the big acacia leaves in the breeze and the occasional chatter of monkeys…it was all a pleasant diversion from orders barked by commanding officers and the grumbles of the men in his rifle company. He even liked the smell.

But that was more months ago than he cared to count.

Now the sounds blurred into a hellish cacophony that he had to pick through to listen for branches snapping, footfalls that weren’t from his men, the metallic click of machine guns and rifles ready to fire. Now the place reeked…of mud and rotting leaves, of things his imagination wasn’t vivid or brave enough to picture, and sometimes of decomposing bodies that neither side had retrieved.

Sergeant Gary Thomsen had learned to hate summer and the jungle. He hated the trails tangled with plants that grabbed at his heavy pack and all his weapons. He hated the sweat running down his face as plentiful as rain. He hated the fear twisting in his gut that someone was hiding around the next tree ready to kill him. He hated everything about Vietnam and the goddamn war that the politicians in the States wouldn’t call a war. A police action—was that the latest term?

He hated the leeches most of all.

He knew that they were clinging to him now. They were somehow always able to find their way up his pants and under his sleeves, into his boots, so they could gorge themselves on his sweet American blood. He’d led his men through brackish ponds and across streams and along a riverbank that morning and well into the afternoon, so there would be leeches on everyone.

He wanted to strip and pull the leeches off, but that would have to wait. There was another three hours or so left of what passed for daylight…the canopy was thick and not much sun was getting through. He had his orders to reach the firebase before dark and regroup with the rest of the platoon.

“Sarge…”

Gary scowled that someone had broken the relative silence. He turned to Private Wallem, a gangly hawk-nosed Texan who was pointing to just north of the trail. A body, mostly bones and scraps of dirty cloth, lay under a big fern.

“It’s one of theirs, Sarge. See? You can tell by the boots. Wonder if we got him or the jungle did? Guess it doesn’t matter. As long as it’s one of theirs and not…”

Gary shut out the rest of Wallem’s words and fixed his eyes on the body, angry with himself that he hadn’t spotted it. Not that it was all that interesting or all that important. But nothing used to get past him.

He’d set himself as point man for the patrol. The squad leader wasn’t supposed to walk point. He was supposed to take the second position. But Gary thought he had the keenest, most experienced eyes, and he wanted to be up front.

There was just too much green. He’d spent too many days in the jungle, and there were all those leeches, attached to his flesh, distracting him.

A good point man should have seen the body and not let anything distract him. What else had he missed? he wondered.

“War is always the same,” Gary thought, quoting President Lyndon Johnson. “It is young men dying in the fullness of their promise. It is trying to kill a man that you do not even know well enough to hate. Therefore, to know war is to know that there is still madness in the world.”

The quote had stayed with him because Gary was sure he was going mad.

Johnson had said the words six months earlier, back in January, shortly before Operation Masher, a large-scale search-and-destroy operation against North Vietnamese troop encampments, began. Johnson had then changed the name to Operation White Wing, which didn’t sound quite so aggressive.

Gary and his men were a part of it, in the Bong Son Plain near the coast. A little more than two hundred American soldiers had died, but almost six times that many North Vietnamese. Gary thought maybe he’d get to go home after it ended, but his sergeant was one of those Americans killed, and he was assigned another tour, promoted to E-5 and given his rifle squad of ten to lead.

The leeches would get some more of his sweet American blood.

“Leave it alone,” he said of the corpse. Sometimes the enemy rigged trip wires and explosives around bodies. “Keep moving,” he ordered.

He checked his compass. West, definitely. They were humping due west on an established trail. It took too much effort to hack straight through the jungle; everything grew too tight.

He’d look at the map again in another few minutes. They were hard to read, the maps. He navigated mostly by gut instinct and the compass.

He heard the steady tromp of the men behind him, the annoying but comforting buzz of insects. The insects rarely quieted. They didn’t seem to mind the presence of soldiers from either side. When they did go quiet, that was when fear seriously twisted in his gut.

God, but he wanted to go home.

A sound like thunder, muted and distant, rumbled. It was a bomb, he knew, from a B-52. The planes carried up to a hundred, dropping them from as high as six miles up. The U.S. regularly bombed North Vietnam and lately had been hitting oil depots around Hanoi and Haiphong.

Gary had read somewhere that Senator Robert F. Kennedy had criticized the president for the bombing, saying the country was heading down “a road from which there is no turning back, a road that leads to catastrophe for all mankind.”

As far as Gary was concerned, there’d been no turning back since the U.S. brought the first planeload of soldiers. He wished they’d bomb the whole damn country into oblivion so he could go home.

There was the thunder of another bomb, coming from even farther away.

Wallem started to speak again, but Gary cut him off with a quick chopping motion of his hand.

Between the sounds of marching and insects buzzing, he’d heard something else, a spitting sound, a sustained whisper that he recognized as machine-gun fire. It wasn’t terribly close, but he prayed it didn’t come closer.

He held his breath and sensed that his men were doing the same, and he gripped the stock of his rifle tighter. He didn’t want to engage any Vietcong, but those were part of his orders—dispatch any VC patrols on the way to the firebase.

The sound came again. Four or five machine guns, he guessed from the bursts. He couldn’t tell which side was doing the shooting. Didn’t matter, did it? The enemy was involved, to be sure.

It suddenly became quiet again…quiet except for the insects.

“Move out.” His voice was so soft the men directly behind him had to strain to hear.

Gary picked up the pace. His legs ached with the punishment of too many miles, but he forced the pain to the back of his mind. Just another hour, two at the outside, to reach the firebase.

Maybe he should call for a five-minute rest, get rid of some of the leeches. Then it would be easier to press on to the base so they could regroup with the others, get rid of more of the leeches, sleep before falling out the next day on some new asinine mission the higher-ups had concocted.

He cut through a particularly tight weave of trees where the trail narrowed, led them through a stretch of marsh and was just about ready to call for that blessed five-minute rest when he spotted something that hadn’t been marked on his map.

“Sarge, what is it?” Private Wallem said. “Sorry!” he added when he realized he’d spoken above a whisper.

Gary glared at Wallem, then turned back to what he’d seen.

Right in front of them was a building of some sort, definitely an old one. The jungle had practically swallowed it. Vines were thick on the columns and what was left of the walls. Most of the stone was stained green, but there were patches of white here and there, and he could see worn symbols that he suspected had once stood out quite prominently.

“Maybe a shrine,” Gary said. The country certainly had enough of them. They were Buddhist, right? They worshipped the smiling fat guy with the bald head, he thought.

Almost half of the building looked intact, and there was an opening midway down the greenish stone. The door, if there had been one, had been eaten away by time and the jungle, and the opening that was left looked like the yawning mouth of a serpent.

They probably had an hour or so left to get to the firebase, if he wasn’t off course. Maybe a little more than that, maybe two at the very outside he was sure.

He knew he shouldn’t take the time to investigate the place, but God, his feet and legs ached from all the walking. And the wide-open stone mouth beckoned.

He edged forward, straight toward the opening, gesturing for Wallem to come behind him. His curiosity tugged him, but it was also his responsibility to make sure no enemy soldiers were hiding inside. Checking would just be following orders.

He held up his fist for his men to stop and wait, then he stepped through the serpent’s mouth. His mouth dropped open.

“Holy spit!” Wallem said when he poked his head inside. He stretched to see over Gary’s shoulder. “Sweet Mary, mother of…”

Gary was so surprised that he didn’t even frown at Wallem for speaking.

Sunlight was shining through a sizable hole in the roof, illuminating gold figurines, several of Buddha with emeralds set in his earlobes and where his belly button would be. There were pieces of ivory, bowls that he figured might have some sort of religious significance because they were so delicate and beautifully painted, jade and coral carvings, and more. It was too much for him to take in.

His gaze flitted from one piece to the next, pausing on a pair of jade koi with intertwined tails before settling on a small Buddha with jewels draped around its neck. The light dimmed, as if the sun was behind a cloud, plunging everything into shadows.

Still, he could see well enough. There was a bird the size of his hand, probably carved from ivory, perched on a shiny black pedestal. It made Gary think of Operation White Wing.

“This is creepy,” Wallem said. He held a covered bowl with dark symbols etched everywhere. He put it down and picked up a fist-size jade turtle. “This is better.”

The treasure didn’t belong there. It didn’t have the mossy green film of the jungle, nor any vines growing on it. And it was polished as if it had just come from a temple or museum. It had to have been put there fairly recently. Maybe by thieves, maybe by monks who, fearing the invading Americans might destroy their precious antiquities, moved them to the middle of nowhere.

Would it hurt to take some of the smaller pieces? There were things that would easily fit in pockets and packs. The jewels draped around the Buddha alone would buy him a Mustang when he got back home. Hell, with that, he could buy a house. Maybe get his mother one, too.

“Sarge?”

Gary didn’t answer. He reached behind his back and eased his pack off, flipped it open and started filling the crannies with pendants and thumb-size jade carvings, taking the small things that looked the most valuable.

There was a ring with a diamond in the shape of a sunflower seed. He’d give it to his girl as an engagement ring when he popped the question after he got back home.

He looped a string of gold beads around his neck. They felt heavy and cold, but they quickly warmed against his skin.

After only a moment’s hesitation, Wallem joined in the looting, snatching the ivory bird first and discovering the wings detached, which made it easier to fit in his pack.

“What about the rest of the men? Should they come in, Sarge? There’s enough for everybody.”

Gary didn’t reply. He was filling his pockets with anything that fit, shoving jade and silver rings on his fingers as he went. His mind raced to figure out how to take one of the golden Buddhas.

He heard muted thunder, and at first thought it was another distant bomb. But it was followed by the patter of rain, some of which found its way inside.

Real thunder. That explained the light slipping away on him. Storms sprang up quickly in Vietnam. The frequent rains were proverbial mixed blessings—they cooled the men off, but they added time to any mission. And worse, the rain smeared all the greens together and made it more difficult to see the enemy.

He muttered a string of soft curses. It would take them longer to reach the firebase now, slogging along a muddy trail through a wet jungle, probably slowed a little bit more by the weight of the treasure. A good weight, he thought. The only good thing about this god-forsaken country was this room full of treasure.

“Get Sanduski and Moore,” Gary said. “Mitchell and Everett and Seger, too, for starters. Those guys go first. Tell ’em all to load up whatever they can. Everybody can take a turn.”

Some part of Gary knew he shouldn’t be doing this, and he knew he’d have a hell of a time trying to get the stuff back home. But he just couldn’t get past all the gold.

“I’ll take it home,” he whispered. “I’ll find a way.” He was nothing if not resourceful.

Besides, his orders never said he couldn’t pick up abandoned treasure. In fact, his orders never mentioned treasure at all.

“This ain’t stealing, Sarge,” Wallem said, as if reading Gary’s mind. “This stuff is just—”

“Lying around,” Gary finished as thunder shook the small building.

“Sanduski and Moore for starters,” he reminded Wallem. They were on their second tour, too, and deserved something for it. Moore, the radio man, had twin boys who’d just turned three. “Then the rest. There’s enough for everybody.”

Wallem managed to stuff the tail-touching koi into his pack after taking out some probably necessary supplies. “We’ll take it all, Sarge. The slope heads just left this unattended. Maybe the owners are dead. It’s all ours and—”

“We can’t take it all. There’s too much,” Gary said sharply as he tried to heft one of the small Buddha statues and discovered it was made of solid gold. “We’ll only get out of here with some of it.”

“A king’s ransom,” Wallem gushed.

Gary heard some of the men talking outside, and then felt a faint vibration through the stones when thunder sounded again.

“Gotta get going,” Gary said. “Gotta get to the firebase. Probably have to clear some ground there tomorrow for a helicopter pad. Gotta get there before dark.”

Wallem called for Moore and Sanduski. “In a few minutes, Sarge. Give us a few more minutes. It’d only be fair for everyone to get something.”

Lightning flashed and thunder followed closely. Then another sound came that Gary didn’t place at first. The rain pelted through the roof and rat-a-tat-tatted on the stone and the golden statues. The light turned gray, but not so dim that the golden statues couldn’t be seen.

Moore gave a whoop and brushed by Gary.

Sanduski stopped in the opening and gaped. “Fort Knox!” He shouted back over his shoulder. “Load up.”

The rest of the group squeezed past Gary.

More than satisfied with his share of the haul, the soldier stepped out into the downpour. He tipped his head back to let the rain wash the sweat off.

His pack felt heavier, and his pockets bulged. He fought the grin that spread across his face and lost, letting out a whoop. He wished he could take one of those Buddhas.

“Grab fast and move out!” Gary called back to his men.

No use looking at his map in this dreary muck. He’d rely on the compass and his gut instinct.

Lightning flashed and the ground rocked again. Above the patter of cleansing rain, the whisper-hiss of machine-gun fire stole his breath. Mud spat up around his feet. Hot fire slammed into his legs.

Gary screamed.

“Wallem!” he managed to call out as he fell. “Company. Moore, get out here. We’ve got—”

1

“Company. Such beautiful company you are, Annja Creed. And I am very much enjoying the pleasures of it.” He stood behind her at the sliding glass door and slid his fingers through her silky chestnut hair.

She leaned against him, happily discovering he hadn’t put on a shirt. At five feet ten inches, Annja was nearly his height.

“And I am so very much enjoying this vacation, Luartaro.”

“Lu, please.” He leaned around her and softly kissed her cheek. “How many times do I have to ask you to call me Lu? It’s what my family calls me. And it’s much easier for you to pronounce.”

“Lu.” She blew out the breath she’d been holding, fluttering the hair that hung against her forehead. “Lu. Lu. Lu. This vacation was long overdue.”

He brought a long strand of her hair to his nose and inhaled. “I wish it could go on forever, Annja, this vacation.”

“But we’ve only got another four days,” she said. “Maybe we should leave this bungalow and see a bit of the countryside? We didn’t travel halfway around the world to Thailand to spend all our time in bed.”

“Speak for yourself.” He chuckled.

Annja reveled in his voice, throaty and rich with a sensuous Argentine accent. She waited for him to speak again, but when he didn’t, she edged away and pressed herself against the glass door. It was cool with the rain that had blotted out the July sun. She followed a rivulet with her finger as it slithered down the pane.

The patter was gentle, like his breath on her shoulder, and it made the green of the trees beyond their cabin more intense.

They’d found this resort on the internet, though there were no public internet connections available in the lodge or any of the cabins. Wireless service didn’t exist here. Neither were there television sets, nor telephones, save an old rotary one in the office. With that they had both immediately agreed on the place, as they could keep the world at bay for a while.

Annja had been in South America, filming a segment for Chasing History’s Monsters on the fossils of ancient penguinlike creatures that had been discovered in the mountains. She’d met Luartaro Agustin at one of the dig sites there.

He was charming and smart, and when he’d surprised her by suggesting that they spend some more time together, she’d hesitated only a moment.

She desperately needed time off—from the show, from her life, from everything. So right there in his lavish office, she’d twirled the huge globe that took up most of one corner, closed her eyes and pointed her finger.

Luartaro had come over to see where her finger had landed. Northern Thailand. She’d surprised him by walking over to his immense oak desk and calling the airline to make a reservation. For two.

As she watched the rain, she thought that perhaps Luartaro had fallen in love with her, though he wisely hadn’t said the words.

Would those words frighten her away? Did she love him? Not yet. But perhaps…with time… She’d only known him a handful of days before they’d recklessly packed their bags and flown here. She’d learned through difficult circumstances that life was terribly short, and she decided to take a chance on joy for once.

Could she love him? Perhaps if she let herself. The attraction, physical and otherwise, was strong.

She watched the way the rain distorted his handsome reflection.

He had a rugged face weathered by long days in the sun, a shock of black hair with the faintest hints of silver at the temples, broad shoulders and considerable muscles from years spent digging at sites throughout the mountains and foothills of South America.

He had flashing eyes that she could easily lose herself in. Had lost herself in, she corrected herself. He was intelligent—in addition to being an archaeologist, he taught at a college during the regular academic year, had written three textbooks and was fluent in half a dozen languages. Though, unfortunately, Thai was not one of them. They had a lot in common.

Perhaps she was reading too much into his actions. After all, he knew very little about her, which was a plus, as far as she was concerned.

He didn’t know that danger too often surrounded her and that some mystic force seemed to have chosen her to battle evil.

She hadn’t told him that she was an orphan with little sense of a real connection to people. Nor had she told him—and never intended to—that on a whim she could summon Joan of Arc’s sword from some nether-dimension to fight whatever malignant force had crossed her path.

She had been on a dig in France when she found a piece of the legendary sword. She didn’t know how, but in a heartbeat, magically reformed by her touch, it had appeared in her hand, whole and shining, more than five hundred years after its famous wielder had been put to death by fire. Now the sword was poised just beyond this world, waiting for her call. She sometimes thought of it as waiting in a closet in her mind, though armory might be a better term.

Because of the sword and her risky life, she never allowed herself to become too attached to people. She had Roux and Garin, but they were associated with the sword, Roux claiming they had witnessed Joan’s horrific death and had existed in a kind of decadent limbo in the centuries since.

Luartaro was different. Like so many others, he wasn’t a part of that life. Normally, she would have kept her emotions in check. But there was something special about him. She felt things for him that she hadn’t intended.

And what does he think of me? she wondered. Did he consider her merely a television personality with a flair for archaeology? Or was she just another woman who had quickly succumbed to his boyish grin?

She watched his reflection in the window again. He had moved close enough that he was stroking her hair again, but he, too, was staring out at the rain and the mountains beyond.

The view was the reason she was paying eight hundred baht a night for their cabin, four times what the average room cost. It was more lavishly furnished than most of the other accommodations at the lodge. It even had its own bath and shower. But best of all, it offered an incredible view of the lush countryside.

Beyond the sliding glass doors was the path that led to the swimming hole and another that wound its way to the small restaurant that served only native Thai dishes. The rain was slowly turning those paths into mud slicks.

In the distance, the mountains that ringed the place disappeared into the gloom. “Complicated mountain ranges,” one of the locals had called them on the bus ride to the resort. Misty clouds hung halfway down them, and the rain was blurring the rest.

Mae Hong Son was called the City of Three Mists because no matter the time of year, there were always low-hanging clouds present. “Three” because the mists were different—the forest-fire mist of the summer, the rainy mist in the monsoon season and the dewy mist of their mild winter.

The area had long been considered a “land of exile” because it was largely inaccessible, but tourists had eventually found the place, and buses and rental cars brought them in from larger cities. She and Luartaro had opted for a bus, the seats of which had not been very well padded.

Mae Hong Son claimed a hot spring, small and large crystal clear streams and a magnificent cape—none of which Annja had seen. There was an elaborate Buddhist temple nearby, so the brochures said, and a tribe where the women elongated their necks with a series of rings—the Karen of the Pa Dong.

“I think we should do something touristy,” she said, breaking the silence that had settled comfortably between them. “Maybe we could take an elephant ride or do some mountain biking. The pamphlets—” she pointed at the nightstand “—say they have meditation classes in the mornings, rafting and—”

“If you want to venture outside,” Luartaro interrupted, “why don’t we visit a spirit cave?”

A shiver raced down Annja’s back, and she bit back a No! before it could escape her lips.

She couldn’t explain what brought on the touch of dread, not to herself and not to Luartaro. She could just claim that exploring a cave was too close to her real life as an archaeologist. That wasn’t too far from the truth. She hadn’t planned to let real life interfere with this long-overdue vacation.

She shook her head and turned away from the window. He wrapped his arms around her and held her close; he couldn’t see the sour, conflicted expression on her face.

“I saw a flyer about it in the lobby—a spirit cave,” Luartaro continued. “And I remember it was also mentioned on the internet when we found this place. Ancient coffins carved from trees, burial grounds inside the mountains. There’s such a cave less than a day’s hike from here, and a guide takes you out in the morning. This area is known for its spectacular limestone caverns. There are hundreds of caves in the mountain ranges. It would be a shame not to visit at least one while we’re so close…especially since you want to venture outside.”

She could tell by his voice that the prospect enticed him.

“All right,” she said after a moment. “A spirit cave. First thing tomorrow morning.” Another shiver coursed through her.

“Wonderful! And we’ll manage to make time for an elephant ride or some rafting before we leave,” he added. “And maybe see the long-necked women and that big Buddhist temple. But for the moment, since it’s raining…” He drew her toward the bed.

2

At first glance, Annja couldn’t tell whether the guide was thirty or fifty. His eyes were bright, hinting at youth, but his skin was tanned and leathery from the sun, the wrinkles deep especially at the edges of his eyes. Careworn, she judged his face. His black hair was thin and short, slick with either sweat or oil, and his shoulders hunched slightly.

He smiled broadly and nodded to their little group. “Zakkarat,” he said, holding his index finger to his chest.

He wore khaki pants, frayed and stained green and brown at the ankles as if he’d never bothered to hem them, instead letting the ground and his heels wear the fabric down to a more suitable length. He had a faded polo shirt with an illustration of a gibbon on it, and over that an unbuttoned short-sleeved shirt that was a riot of color—red, blue, green, with birds and flowers. He also wore a cord around his neck with a whistle dangling from it and old black-and-white tennis shoes.

“Zakkarat,” he repeated. “Zakkarat Tak-sin. Your guide to Tham Lod Cave.”

Luartaro reached for Annja’s hand and swung it as if he was a child. He was smiling, too, obviously happy to be off to the spirit cave, as the pamphlet called it. His skin felt warm against hers, and she intertwined her fingers with his and reveled in his boyish attitude.

With them were two other couples, one in their twenties—on an ecohoneymoon, they’d proudly announced. The other was a middle-aged Australian pair who were on their third trip to Thailand.

“Comfortable shoes, all?” Zakkarat looked at everyone’s feet.

“Comfortable shoes, yes,” Luartaro replied. The others nodded in agreement.

“Five, six miles to the cave,” Zakkarat said. “Two hundred baht now, more later for extras. Not much more. This is one of the cheapest trips for tourists.”

Luartaro was quick to pay the guide, whispering to Annja that the pamphlet said there would be a charge to enter the cave and for the raft.

After passing out small water bottles, Zakkarat led the way. He had a quick gait and was nimble, ducking under branches and stepping over ruts, and Annja put him closer to thirty for it. He chattered as he went, pointing first to the tops of the mountains and mentioning the mist. They were unlike other mountains she’d traipsed through, certainly unlike the familiar Rockies and the mountains she and Luartaro had combed through for the ancient penguin remains. These peaks had been weathered away into twisted shapes and odd-looking knobs largely covered by jungle. They were beautiful and ghostlike in the mist.

She regretted not bringing her camera. Luartaro wasn’t taking as many pictures as she would have, or from what she deemed the proper angles. The path Zakkarat took was wide and flat from the traffic of countless tourists. To the sides stretched swaths of dark green moss, still shiny from yesterday’s rain.

Though practically everything was green, there were remarkable variations, Annja noted. Some of the leaves were so pale they appeared bleached bone-white by the sun. Others were a deep green that looked like velvet. Shadows were thick near the ground where the large leaves reminded her of umbrellas. If there were patterns to the colors and light, she couldn’t discern them—everything was a swirl.

Had someone taken a picture of the scenery and turned it into a jigsaw puzzle, it would be one of the most difficult ever to assemble, she thought.

Annja listened intently to hundreds of tiny frogs that chirped like baby birds. After a mile, she spotted a fence far to her left, and a tilled field beyond. On the opposite side the ground rose at a steep angle, and she wondered if there were caves beneath.

A bit farther along, the Australian man drained his water bottle and looked at his watch. “My feet are hurtin’, Jennie,” he said. His wife smiled sympathetically and pointed to a thin river that meandered out of the fields to their left. It widened as they kept walking, eventually paralleling the path, which had started to narrow.

“More than two hundred caves in Pan Mapha in Mae Hong Son alone,” Zakkarat announced. He numbingly rattled off facts about their length in meters and feet with so little inflection that Annja guessed he’d been repeating his speech and leading tours so long that he was bored by it all. “This cave we go to, a most popular spot. Tham Lod Cave does not need climbing equipment. Easy on the feet, yes?”

Good for most of the tourists, Annja thought, wishing for something a little more adventurous and taxing.

The path narrowed to the point they had to walk single file, and Annja noted faded signs tacked on trees written in Thai and English advertising a bird show. They’d obviously been posted years earlier, and she wondered if the show still continued and, if so, what it entailed.

They came to a fork in the trail. Zakkarat pointed to his right and said, “Temple. Tours available there, too.” Through the mist, Annja could barely make out a large stone building with hints of ornate corners. The other course, the one they followed along the river, led to an old wooden gate that hung off its hinges and which they easily stepped through.

The path became rougher, and gnarled tree roots poked through here and there. Zakkarat slowed his pace and jabbed his finger at the largest roots.

“Take care,” he warned. “Take care that you do not trip.” He nodded to another sign advertising a bird show. “Going out with a big group tomorrow night for the birds.”

“So there is a bird show,” Annja mused.

“Ain’t there birds out now?” This came from Jennie, who was looking up into the trees and alternately watching her husband, who was still grumbling about his feet.

Apparently, she’d not noticed the other bird-show signs.

“Ah, there’s a red one with black streaks on its wings.” Jennie pointed. “And there’s another red one. So what’s with the bird show? Are they trained? Parrots?”

The ecotourist wife answered before Zakkarat had a chance. “We’re in the bird group tomorrow night,” she said. “At sunset, all the bats fly out of the cave we’re going to right now and a colony of swifts fly in. Trading places, if you will. There are supposed to be three or four hundred thousand of them. The swifts have adapted to living in the cave and hang on the stalactites like they would tree branches. This is the only place in the world this happens, I’ve heard. We bought some ultra-high-speed film for it. No digital camera for me.” She pointed to the expensive-looking camera around her neck.

“You can come back tomorrow to see the birds if you want, Jennie. I’m not walking back out here again,” the Australian husband announced. “I’m too old for this nonsense. My blisters have blisters. I’m picking our next holiday. A beach somewhere so I can park my bum. Maybe Hawaii? Or Aruba on some package deal?”

The river practically butted up against the path as they made their way. They stopped at a collection of small huts, one of which offered concessions, another of which shaded a dock. It was thirty more baht per person for the bamboo raft ride to the cave.

Luartaro and Annja were the first couple on board.

Zakkarat used a pole to edge the raft away from the bank. “Not deep here,” he said. “But it is wide. Taking this raft is better than wading, yes? Stay dry by taking this raft. The Shan tribe provides the rafts and gets the baht here. That is good.”

He pointed to a woman and child near one of the huts. “Tourism money has cut the Shan’s need for slash-and-burn rice farming. That is very good.”

“Are you a member of the Shan tribe?” Luartaro asked.

“Yes. All the people in my tribe respect the caves and their creatures—the birds, bats, fish and snakes. The tourists who come to see the caves are helping our community.”

The raft floated with the current for several minutes before Zakkarat poled it to a stop against the opposite shore and motioned his passengers to get off.

A young boy collected a few more baht from everyone.

The cave loomed sharply to the right, and Zakkarat took the lead and gestured to a half-dozen crude wooden steps that had been built next to the entrance.

“Follow me, please.”

Annja took the first spot in line and was quickly swallowed by a cavern filled with stalagmites, small sinkholes and vents.

The change in temperature hit her immediately. The air was cool from her knees down, closest to the ground. Above that it remained warm and humid. The light had changed, too, and Annja closed her eyes for a moment. When she opened them, they had adjusted better to the dimness.

She looked up, but couldn’t see the ceiling; it was lost in overlapping shadows dotted with the tips of stalactites.

“Cave elephant,” Zakkarat said, pointing to a formation of rock and limestone that had been fashioned by water dripping across it through the centuries.

Annja could make out the broad shape of it and the outline that could be construed as ears and a trunk.

“Cave dog. Cave monkey.” Zakkarat pointed to other limestone formations that were not quite so easy to make out. “Cave crocodile.”

The ecowife pointed to one that looked like a snake and snapped a picture of it.

Annja shielded her eyes as the woman took another picture and then another, the flash in the darkness almost painful in its sudden brightness.

“So it’s called a spirit cave because of the animal spirits that fill it, right? Spirits in the lime, I guess you could call them,” the ecowife said.

She took several more shots of other formations in rapid succession and of the natural limestone columns that extended twenty meters or more to the ceiling.

“Spirits of dead animals? No.” Zakkarat chuckled. “Some of the local tribes claim that the souls of the human dead live here. That is why it is called a spirit cave. Those tribes, but not the Shan, will not come here. They fear for their lives. Some other tribes, they are not so superstitious. It is these tribes, but not the Shan, that stole most of the artifacts that were here. But there are some pieces, not so good, for you to see. I will show you.”

The group edged deeper into the cave, and bats, hidden by the shadows, started squeaking.

Zakkarat picked up a gas lantern from the floor and lit it. The squeaking grew louder as the light grew brighter. A mud-colored snake slid across the path and toward the wall.

“This is all so beautiful,” Annja said.

“Yes,” Luartaro whispered. “Though not so beautiful as you.” He took a few pictures of her looking at one of the limestone formations, bouncing the flash so it would not be so disturbing.

They both stared at the immense chamber striped with earth colors and shining in the meager light.

No matter how many caves Annja had traipsed through, she never really tired of them and was always amazed by what magnificent formations nature had sculpted.

Annja felt relaxed in the cave, though she knew from their mannerisms that some of her companions, the Australian husband in particular, were made uneasy by the surroundings. The sense of foreboding she’d had the night before seemed far away.

They walked on, following the bobbing light of Zakkarat’s lantern.

Annja could hear moving water a few minutes before they reached another river, or perhaps a branch of the same one.

Zakkarat indicated another bamboo raft.

“More baht, right?” the Australians said practically in unison. “For the Shan.”

Zakkarat poled them across to the far side of the cave.

“Follow me, please.” He led them up a fairly steep rise to a ledge that overlooked a cavern.

“No rails,” the ecowife noted. “We’ve been to quite a few caves. Not near the safety standards as in Carlsbad Caverns and Mammoth Cave. Or even that Mark Twain one in Missouri. They all had railings.”

Zakkarat’s course took them around a deep sinkhole and to another chamber from which tunnels branched away. Scattered road cones and faded danger signs blocked off a few of the passages, and Annja suspected there was a risk of cave-ins. Another sign, more recent from its bright paint, dangled from a rusty chain. It read Do Not Pass—Low Oxygen.

“See here? Cave painting. Authentic.” Zakkarat pointed to a spot midway up the wall. “One of seven in this cave. But the only one I can show you today. Most paintings are where it is under excavation. Archaeologists from Bangkok found a skeleton under a rock shelf, supposed to be twenty thousand years old. The oldest skeleton found in Northern Thailand. The dig is off-limits, and the skeleton predates the coffins you will see. But this cave painting you can look at. Do not touch, though.”

Annja squinted to make out a faded design. At first glance it looked like a shadow or a smudge. Beneath it, affixed to the stone, was a large black-and-white photograph of what the painting had looked like before tourists had rubbed it away by touching it. The photograph clearly showed a deer, an arrow and the sun overhead.

“There’s writing on the photograph,” Luartaro said. He leaned close and almost touched the picture. “A date. This photograph was taken thirty years ago.”

“Pity that people have to ruin things,” Annja said. “Inadvertent or no, people don’t understand how precious the past is. I wonder what the artist was like. He or she probably painted it with burned bamboo. A lot of bamboo still grows around here.”

“The cave paintings off-limits today are in better condition,” Zakkarat said. “Perhaps it is why they stay off-limits.”

Zakkarat led them up a damp slope, then down, stepping over and through pools of water and past columns that dripped with moisture and glimmered like jewels in the gaslight. They walked down a set of rickety wooden steps, and they reached the river again.

“A beach, I say,” the Australian man grumbled. “That’s where we’re going next. With a book in one hand and a drink in the other. I’ll sit on my bum and soak up the sun. Aruba, I think. Or maybe Jamaica. Rum and cola from a bottomless glass with one of those paper parasols in it.”

Zakkarat pushed the raft into a darkness that his small lamp couldn’t keep at bay. Bats screeched from high overhead and fluttered their wings. The air turned thick with the smell of guano.

“God, the stink. It’s incredible. I can’t believe we paid to smell this stuff.” This came from the ecowife. She doubled over and retched. Her husband hunched over, too, and held his stomach.

“It is the bat droppings,” Luartaro said. “That is what stinks so bad. Thousands of bats. Probably hundreds of thousands. Far more than there were in the other chamber. Amazing. The smell is truly amazing.”

“Amazingly awful,” Annja said. She could tell that even he was affected by the intense smell. She cupped her hand over her nose and mouth and tried not to gag.

Her stomach roiled. She’d been in caves many times before, but none of those had such a large bat population.

Their guide seemed inured to it.

She was grateful when the raft docked and Zakkarat took them up an incline and through a short tunnel that opened into a chamber filled with what looked like coffins.

Though musty and close, the air was considerably better there. No bats were present.

“As I mentioned before, the tribes not afraid of this place stole from it,” Zakkarat said. His voice took on a sad tone. “Stole from this chamber and others. Stole some of our history.”

He turned up the lantern, and the Australians gasped as more details were revealed.

The coffins were hollowed-out teak logs ranging from seven to nine feet long and were relatively well preserved.

“The pamphlet said they date back at least two thousand years,” Luartaro said.

The logs had been intricately carved, and one had deep designs of leaves and vines on it. There were heavy pottery remnants, too, and Zakkarat said the tribes no doubt stole all the good, intact pieces.

Perhaps they’d also stolen the bodies, as Annja couldn’t see a single bone left behind. She shuddered as she stepped close to the largest coffin, as if a cold wind had just whipped across her skin. Her skin prickled, as if tiny red ants were crawling over her.

Were there real spirits here? Were they trying to tell her something? Perhaps they were upset at the presence of tourists who had come to disturb their eternal rest. Maybe they were angry that their remains and relics had been stolen and were seeking justice or retribution. She could provide neither for them.

Sometimes she had an innate sense that something was wrong or that a problem needed addressing. She’d thought it came from inheriting Joan of Arc’s legacy and the sword, but she’d eventually realized it was more than that. Even when she was growing up in the orphanage in Louisiana, she’d had an uncanny knack for knowing when things were amiss or when something untoward was about to happen.

“What?” she mumbled. “What is wrong here?”

“What?” Luartaro touched her shoulder. “I did not catch what you said, Annja.”

“Are there more chambers here with coffins?” Annja directed the question to Zakkarat and hugged herself when she felt the chill intensify. A heartbeat later the odd feeling vanished.

“Not here, in this cave. Not anymore. But there are other spirit caves nearby in this very mountain range,” Zakkarat said. “Many more coffins in them. Soa Hin, Tukta. There is a place called ‘spirit well,’ too, but part of it collapsed and it is not safe. But this cave, Tham Lod, is easiest on the feet and easiest to reach. This is where I take the tourists. It has some of the best limestone formations.”

The Australian man snorted, and Jennie patted his back sympathetically.

“Pi Man Cave, too, has teak coffins,” Zakkarat continued. “Many, many more coffins there. Ping Yah and Bor Krai, too. Not so easy as this to get to. More climbing and squeezing.”

“But you’ve been there,” Annja prompted.

“Yes. Have taken a few people there, to Ping Yah and Bor Krai and Pi Man. But only a few, and that was quite some time ago. There are maps you can buy with directions of how to get there, but I am better than a piece of paper. I am a very good guide.”

“Take us there, please,” Annja said. “To Ping Yah and Pi Man.” The tingling she’d felt moments ago came back stronger and raised goose bumps on her arms.

The cold sensation was almost numbing. She rubbed her arms to keep from shivering. If the answer to her unease was here in this chamber, she couldn’t see it. The answer had to rest elsewhere in the mountains.

“Take me to see more of these coffins,” she said.

Annja felt for the sword at the edge of her mind, seeking its comfort.

“How many baht, Zakkarat?” she pressed. “For you to take me.”

“Us,” Luartaro corrected.

“Take us to Ping Yah and to Pi Man and Tukta and wherever else there are more of these coffins. Places tourists don’t go.” She stood a better chance of investigating without others around.

“You’re crazy,” the Australian man grumbled.

Zakkarat scratched his head. “Not easy going like this place. We would need a little equipment for steep places. Not much, some ropes and pitons, a safety line. Helmets. Maybe a pulley—”

“Do you—”

“Yes, I have some caving equipment. My father and I used to—”

“How much?” Annja knew the price didn’t matter.

“Five hundred baht.”

“Done.”

“Each.”

“Fine.”

“Plus extras, maybe. And I will pack a lunch and water bottles for all of us. No charge for the lunch or water.”

She realized he was testing her to see just how much she’d spend. “When can you take us there?”

“Tomorrow morning,” Zakkarat said. “Very early, we should start. The day I have free. And tomorrow night I take tourists to the bird show. So we have to be back before sunset. We could get in two caves, I think.”

“You’re not taking us to the bird show,” the ecowife said. “Even though I’ve bought the film, I’m tired and God knows I can’t stand this stink.”

Her new husband nodded in agreement.

“The limestone caves that you want to go to…” Zakkarat said, moving close to Annja. “They are off any regular paths, as I said.”

“I understand,” Annja said. “Lu and I are in good shape. Climbing will not be a problem.”

“I can see that you are in good shape.” Zakkarat smiled. “Tomorrow morning very early we will leave. When the sun rises. Very, very early so we have time to see a lot. As the saying goes, I will give you your money’s worth.”

Annja continued to feel uneasy as she looked around the chamber and studied the coffins. “You don’t mind, Lu? Going to more caves?”

“I would have suggested it if you hadn’t. This is fascinating. And I love caving.” He reached out a hand, but stopped himself just short of touching one of the teak logs. “Too many people have touched these,” he said. “Too many people don’t respect the past.”

“It’s not that,” Annja said. “It’s not a matter of respect, Lu. It’s a matter of ignorance. Too many people just don’t know any better.”

She searched the shadows, thinking she saw movement—a spirit, perhaps—something half glimpsed or maybe just imagined, something that was tugging her or begging her to solve some mystery.

She decided in the end it was just the play of Zakkarat’s light. Still, the troubling cold sensation wouldn’t leave her. What was bothering her? What could possibly—

“Did you hear that, Jennie?” the Australian man said.

“Hear what?” Jennie glanced at the coffins, and then at their guide. “Oh, I heard it. Thunder. The man at the hotel desk mentioned that it might rain today.”

“Rains come unexpected this time of year,” Zakkarat said, frowning. “It is almost our rainy season. Time to leave.” He scratched his head. “Let us hope it doesn’t rain too much. The paths will be muddy and slippery.”

Annja was the last in line this time, taking one final look at the coffins and the shadows and feeling a stronger shiver go down her spine.

Outside, it was pouring.

3

It had rained steadily through the night and was still raining the next morning, though it had turned to a drizzle by the time Annja and Luartaro met their guide outside the lodge.

She’d put her palm-size digital camera and extra batteries in a plastic bag and shoved them in her back pocket for insurance against the weather.

Zakkarat, in the same outfit as the previous day, though with sturdy hiking boots, looked smaller, with his wet clothes hanging on him and hair plastered against the sides of his face. He looked sadder, too, eyes cast down at the puddle between his booted feet, the ball of his right foot twisting in the mud.

“If you do not want to go because of the rain, I understand,” he said. “It rained hard last night, and long. Still going. Maybe going all day. The trail will be sloppy and the river swollen.”

Annja realized his disappointment was in missing out on the thousand baht he would have earned—and wouldn’t have to share with the lodge or tour company.

“I do not have another free day until early next week,” he said. “I can take you then.”

“We’ll be gone in a few days,” Annja said. “Me back to New York.” She paused. “But I don’t mind the rain, Zakkarat. Maybe Lu does, though, and—”

“I like rain fine,” Luartaro said. “When I was a young boy I used to be afraid of storms. But my mother told me that rain is just God washing away some of man’s dirt. Rain makes the world clean again.”

He tipped his face up and grinned to illustrate the point. “And God knows I want these few days to last forever.”

Annja had intended to go to the spirit caves no matter how hard it rained, alone or with a guide. She needed to discover the source of her unease. She’d intellectually accepted that there was a message someone or something was trying to tell her, and she believed that—like it or not—it was her duty to figure out just what that message or warning was and where in the mountains it was coming from.

“Five hundred baht, right?” Luartaro said. “Each? How about six? No. Let’s say seven each because of the rain, and that covers all the extras along the way. Half now.” He placed some bills into Zakkarat’s hand. “The other half when you drop us back here.”

Seven hundred baht was almost what they were paying per night for the cabin, which came to a little more than two hundred U.S. dollars. Giving the tour guide twice that amount for several hours of his time was rather exorbitant, especially for this part of the country. But they had only three days remaining of their vacation, and neither she—nor Luartaro obviously—were hard-pressed for coming up with the amount. And judging from his clothes and worn boots, it looked as if Zakkarat could use the money.

“Seven hundred each.” Zakkarat was quick to nod, his expression visibly brighter. He pointed to an old, rusting Jeep, which had packs and helmets in the back and two coils of rope. He’d come prepared in the event the rain had let up or not deterred them.

“Besides,” Luartaro said as he gallantly waved an arm to let Annja into the front seat. “It’ll be cozy and dry inside the caves.” He climbed in the back.

“You think this is a lot of rain?” Zakkarat made a shrill, forced laugh. “This is nothing compared to our monsoon season. Good for you that the monsoon season is a few weeks away. Because Thailand sits between two oceans, we have either downpours or cool and dry weather. Wet now, but the jungle and the mountains are prettiest.”

Zakkarat drove part of the way, the tires of the Jeep easily churning through mud that was several inches deep in places. The rain both muted and intensified the colors, and the scenery reminded Annja of chalk sidewalk paintings in Brooklyn that ran like impressionist watercolors during spring showers. It was a wonderful blur of green that she found beautiful, and she drew the scents of the flowers and leaves deep into her lungs and held them as long as possible.

“Which cave first?” she asked.

“Ping Yah,” he said. “It is older than Tham Lod, and perhaps has the most to see. It is in the same mountain range, and they are not terribly far apart, but it is harder to get to. Then Bor Krai or Pi Man, as I think I remember how to get there. We’ll have time for at least two. Maybe a third, as it is certain the lodge has canceled my bird-show group tonight. The tourists do not want to walk through all the mud.”

“Pity,” Luartaro said. “That’s too bad about your birding group.” His tone was evidence he did not mean the sympathy.

Annja had heard of Tham Lod Cave even before Luartaro had looked this area up on the internet. But Ping Yah and Bor Krai were new to her.

Although a part of her was excited at the prospect of seeing something that an average tourist never would, she couldn’t shake her worries over the mysterious sensation that niggled at her brain.

“What?” she whispered too softly for the men to hear. “What bothers me?”

She’d been to Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, which one of her companions yesterday had mentioned. It had more than three hundred miles of tunnels, and she’d walked most of them during her many visits.

Three years earlier in California she’d explored a series of caves created in ancient times by volcanoes and earthquakes. And of course she’d been through the Carlsbad Caverns, which was famous because one of its chambers was larger than a dozen football fields.

In France, she’d climbed through the Lascaux Cave that featured paintings that dated back about seventeen thousand years.

Older still, by as much as fifty thousand years some scientists estimated, were the fossils of bears and other creatures found in Poland’s Dragon’s Lair.

On the island of Capri off Italy one summer, she’d journeyed through the Blue Grotto, a four-mile-long cave with breathtaking formations.

Her favorite cave? She thought about it a moment as the Jeep jostled along the road, which was little more than a puddle-dotted path. Perhaps the one in the Austrian Alps, Eisriesenwelt in the Tennengebirge range, one of the world’s largest ice caves. Or maybe the Pierre Saint-Martin Cave that stretched from France to Spain, one of the deepest recorded.

In Australia for a Chasing History’s Monsters special, she’d made a side trip to the Naracoorte Caves, but found them disappointing. The caves were largely a collection of big sinkholes.

Her trip was salvaged when she went to the Waitomo Caves in New Zealand. That had been her favorite, she decided after a few more moments of contemplation, because of the worms.

The same way Zakkarat had poled their group along the river on a bamboo raft in Tham Lod Cave, the New Zealand guide had taken her group in a flatboat into Waitomo.

At various points in their half-hour excursion, the guide had doused the lights. A riot of shimmering stars had appeared overhead. Except they weren’t stars; they were glowworms. Annja had counted herself fortunate that day to have seen something so unique and glorious.

She continued to run the names of caves through her head—ones she’d been to, ones she had no intention of visiting and ones she would like to see while she was still young. She couldn’t recall the name of the cave system in China that was perhaps the longest in the world. That was on her must-see list.

The mental activity was a reasonable distraction to keep the chill away. She’d gotten goose bumps again the minute she’d sat in Zakkarat’s Jeep, and the sensation of ants crawling on her skin had worsened as they’d headed down the road.

It wasn’t the rain and the cool breeze that came with it. The sensation was from something else. Maybe, she wondered, the ill feeling had nothing to do with the limestone caves or the spirits of the dead that had been interred in the teak coffins, but instead about their guide.

Worse, what if her nerves were jangling because of Luartaro? Was either of the men in danger—or dangerous? Would Roux know what was troubling her?

No, it’s the caves, she thought. Maybe not the caves themselves, but something in the mountains.

She realized Luartaro was talking, and she’d missed most of what he’d said—something about the limestone formations they’d seen yesterday.

Zakkarat chattered, too.

She pretended to be distracted by the scenery and pushed their voices to the background.

Her mind touched Joan’s sword—her sword. It waited for her.

But it would have to wait for quite some time, she thought. It had no place in her vacation—especially with Luartaro around. She didn’t want him to see that part of her life. Still, its presence reassured her.

The Jeep slid to the side of the trail, the front bumper coming to rest against an acacia tree as mud flew away from the back tires.

The jolt jarred Annja into alertness.

The trail they’d been bouncing along had suddenly disappeared, as if the jungle had reached out and swallowed it.

“The rest of the way we go on foot,” Zakkarat said. He turned off the engine, pocketed the keys and grinned at Annja. “God is washing away a lot of man’s dirt today.” He eased out of his seat and slogged to the back, fitting the largest pack over one shoulder and a coil of rope over the other. He put on one of the helmets so he would not have to bother carrying it. “Good thing you two wore boots today. And a good thing it does not rain inside the caves. We can dry out quickly inside.”

Luartaro took another pack and the second coil of rope, also putting on a helmet and gallantly leaving Annja the smallest pack to carry.

The rain was coming down harder, thrumming against the hood of the Jeep. It splattered against the big leaves and the mud and her shoulders, then against the helmet she put on. She fell in behind Zakkarat and Luartaro and continued to listen to the rain.

“You walk fast,” Zakkarat said after half a mile or more had passed. “Good thing, that. It leaves more time for the caves and less time in the mud. Most people, the tourists, they don’t walk so fast as you.”

Annja noted that Zakkarat was in good shape, no doubt from walking so many miles daily to take tourists to Tham Lod. She could have easily outpaced him, though; she was in that much better condition.

He told them that the last time he brought a few people this way it had taken nearly two hours to reach the first cave. They managed it in less than one, the mountains looming before them. The rock face they started to climb was slick from the rain.

As Annja worked her fingers into a crack, slid her foot sideways to find a purchase, she grumbled to herself that this was why the typical tourist was not directed this way.

Her foot slipped and she teetered, held in place by just the tips of her fingers and willpower. She fought for balance and slowly righted herself, pressing tight against the cold, wet stone. The rock felt good against Annja’s fingers, and her muscles bunched as she pulled herself up behind Luartaro. The exertion was welcome. Even the thrill of almost falling was welcome. It brought a slight flush to her face and chased away the unnatural cold that had been teasing at her gut.

The first chamber was nearly three hundred feet above the jungle floor, and it was a tight fit to step inside, though from the rock face it had looked to have been larger in earlier years. An earthquake or rock slide had narrowed it.

Luartaro had to shrug off his backpack before he could slip in.

Once past the opening, Zakkarat lit a gas lantern and passed Annja a dented flashlight.

“In case,” he told her. “You should always carry a flashlight in case something happens to the lantern.”

“I have one, too—a flashlight,” Luartaro said, slapping a deep pocket in his khaki pants. “And some extra batteries.” He stroked his chin and the stubble that was growing there. “So tell us about this particular cave. I find all caves fascinating.”

“Fifty years ago,” Zakkarat began, “a United States man came to my country to study plants.” He chuckled and waved his hand to indicate the high, steeplelike chamber they were in.

“Plants, of all things, led to this discovery. The man was studying the Hoabinhiam people who lived in this area in ancient times and who were said to favor the limestone caves. The United States man thought they…” He sucked in his lower lip, searching for the word. “Domesticated! He thought they had farmed, not just gathered, vegetables and fruits, but planted them. And domesticated animals. The Hoabinhiam…”

He paused again, grimacing as he obviously searched for the words to phrase his explanation. “My father taught at the university when I was young. Taught history, and so I know about all of the Hoabinhiam because he taught me, too.”

“My father was also a teacher,” Luartaro said. “Archaeology. I followed in his footsteps, so to speak. He still teaches, guest lecturing mostly at schools and universities in Argentina and Chile.”

“You are an archaeologist?”

Luartaro nodded animatedly to Zakkarat. “For quite a few years. Her, too.” He pointed at Annja. “A famous one. She is on TV. She is the star of Chasing History’s Monsters. Ever see it?”

Zakkarat seemed unimpressed about the television mention. “The United States man,” he continued, “found this very cave. Burma, we are not far from Burma here. Were it not raining you might see a stream outside through that crack on the other side. Burma is past it. Supposedly the stream was a river in ancient times, and the Hoabinhiam hunter-gatherers lived by it…and lived in this cave.”

Still listening to Zakkarat, Annja strolled nearer the closest cave wall. It was covered in drawings of pigs and birds and a trio of images that looked like two-legged lizards. The shifting light from the lamp made it seem as if the figures were moving. Though faded, they were in far better condition than the smudge she saw in Tham Lod Cave.

Zakkarat continued to talk, and she listened closely, about the American fifty years past finding plants—beans, peas, peppers, something like a water chestnut, cucumbers and gourds—all fossilized in this cave.

Annja knew that with a map, she and Luartaro could have likely found this cave with little trouble on their own, but she was glad to have Zakkarat with them, providing information about the ancient-plant discovery.

Zakkarat explained that carbon dating placed all the fossils at roughly 8,000 BC. There had been stone tools, too, which were quickly ensconced in a museum in Bangkok, as well as remains of small animals that suggested the primitive people were not so primitive, after all. They roasted their meat, maybe in containers of green bamboo, a method still used throughout Thailand.

Zakkarat led them into a tight passage with a roof barely six feet high. His voice echoed softly against the stone. “They found pots and pieces of pots, some made with woven cords to make them stronger, some with evidence they were used over a fire. Found lots of tools. My father called them adzes, and they were polished, those tools. You know, the Chinese learned how to polish stones and tools from us, not the other way around.”

He stopped when the passage forked, one route rising steeply, the other passage twisting down at a sharp angle. He took off his helmet, scratched his head and then put the helmet back on. “It has been quite some time since I took people here. I’m not sure—”

“I vote for down,” Luartaro said. “If it’s wrong, we can backtrack and take the other one.”

Annja nodded in agreement. She and Luartaro had discussed last night the possibility of going without a guide, as they were both reasonably good cavers. In the end, they had decided to stick with Zakkarat.

“Down, then,” Zakkarat said, leading the way with Annja right behind him.

The rock was so thick, she could no longer hear the rain, and they were going deeper still. She tried to imagine what living in these caves must have been like centuries upon centuries ago—without such modern conveniences as flashlights and Zakkarat’s gas lantern.

Their course leveled off, then descended again, and the passage became so low they had to crawl. Water covered the floor by several inches.

Annja was struck by the cold air and the stink of patches of guano that floated on it. The floor was alternately squishy and slick with mud, and she struggled to keep her face and shoulders out of the water. Farther, and the air became heavy and saturated with water, the smell of mud hitting her like a wall.

“Underground rivers in these mountains,” Zakkarat said. “Maybe they are rising because God needs to wash away still more dirt.”

The rock floor was sharp in places, evidence that few people came this way, and it bit into Annja’s legs through her now-soggy jeans. Despite it being summer, it was cool in there, and she wished she’d brought a jacket.

“My sister is terribly claustrophobic,” Luartaro said. He was a few feet behind her.

Annja realized she knew actually little about him; she’d never asked about his family. Now she knew his father was a teacher, and he had at least one sibling.

“My sister…she wouldn’t… What is the American expression?” Luartaro continued.

“Be caught dead in here?” Annja suggested.

“Yes, be caught dead. Here, or in any of the other caves I’ve been to. Still, you’d like her, my sister. I hope you get a chance to meet her. Even though she is claustrophobic, you would get along.”

Caught dead. Annja froze. She felt certain that whatever was bothering her had something to do with death.

Free me.

She twisted in the tiny space, looking left, then right, then back over her shoulder. Was someone there?

Zakkarat kept crawling ahead, dragging the lantern with him, the jostling and sloshing of the base of it in the water sending shadows dancing maniacally across the walls and reflecting off the wet stone. He was careful to keep as much of it out of the water as he could; if it got too wet, it would go out. Fortunately, the lantern had a reflector in it, which made its light fairly bright.

Annja felt an icy jab rise up from her knees. Had she heard something, or was her imagination dancing in time with the shadows.

“Something wrong? Something I said?” Luartaro asked.

“No, Lu,” she said. “Nothing’s wrong.” She hurried to catch up to their guide.

The passage twisted sharply and, for several yards, Annja and Luartaro had to crawl on their stomachs, their packs scraping against the ceiling, their faces just above the water. Then the passage rose again, and they were back to crawling on dry stone.

“It cannot be far now.” Zakkarat’s voice bounced off the walls. “I believe we are near. But it has been too long since I’ve been to this cave. Nothing looks familiar.”

“He’s earning his baht,” Luartaro said. A moment later he added, “I’ve a thought, Annja. He’s taking us to see more of these teak coffins, right?”

She nodded, but realized he couldn’t see her.

“But there’s no way those coffins could have fit through this twisting tunnel. So the ancient Thai people couldn’t have brought them down here. We should have taken the other passage. This is my fault. I suggested we take the downward slope.”

“We’re all in this together,” Annja replied.

A few minutes later they were standing in a chamber that stretched at least thirty yards across and at least twice that high. There was a massive crystal flowstone immediately to their right. It ran nearly the height of the chamber and was dotted with delicate calcite and aragonite crystals.

“This cave,” Zakkarat said, “if it is the cave I am thinking of, is known for two different species of blind cave fish. I read about them in one of my father’s magazines. They share the same river, and one of them is scaleless and colorless and uses fins to walk up the banks. I have a picture of one at home.”

He gestured for them to keep moving. The next cavern was not as physically beautiful, but it contained what they had come to see.

One wall was lined with coffins, and another had larger coffins stacked against it. The air was stale, but clean, and there was no evidence that bats had ever frequented the place. It contained a natural chimney that rose on one end, and Annja would have enjoyed climbing it were it not for the coffins.

“You’re right, Lu. There’s no way the coffins were carried along that tunnel we came through,” Annja said. “All of these coffins had to be brought here another way. They’re massive, some of them. And teak is very heavy. Maybe an earthquake changed the passages through the years. Maybe a rock slide. Caves change. Rivers change them, too.”

“Change, yes. But—” Zakkarat held the lantern in front of him. The light casting up and out haloed his puzzled face. “This is not a part of Ping Yah I remember. I’ve seen coffins, but not these. I’ve not been here before. Perhaps this is not Ping Yah at all. Perhaps we should have taken the other way, and went up. Perhaps that was Ping Yah with the blind cave fish. Not this cave.”

He made a tsk-tsking sound, took his helmet off, scratched his head and put the helmet back on. “But you wanted to see coffins, and there are plenty here.”

“Yes, we wanted to see more coffins,” Annja said softly, gritting her teeth as a wave of cold washed over her.

She stepped to the closest coffin. There were intricate carvings on it, some tugging at her memory, as if she’d seen something similar in a book. She reached into her pocket and pulled out her digital camera. The plastic bag had kept it dry. She took several pictures, and then moved to the next coffin.

What is bothering me? she wondered. Something she couldn’t explain had her feeling very unsettled.

Like the coffins from Tham Lod Cave, these held no bodies. Scientists and explorers who had been there before had likely removed them—if there were any to remove. They may even have taken some coffins, too, for it looked as if there were odd gaps between some of them. There were pots inside some of the coffins, probably heavy by the thickness of the clay. They were intact and looked as if they should be in a museum.

“No, maybe this is not Ping Yah at all,” Zakkarat repeated. “I am so sorry. The rain, not coming out here for some time…so sorry. I should have looked at a map and my father’s notes. I have gotten us lost. Nothing here is familiar to me. I will not charge you so much. We can go back and—”

“I’m not sorry,” Luartaro said. “These are magnificent. You did just fine, Zakkarat.” He let out a low, appreciative whistle and retrieved his own digital camera. “In fact, you did very well.”

Annja’s fingers hovered above the teak. She peered inside and used the flashlight to better illuminate a large coffin’s interior. Though there was no trace of a body, there was evidence one had been there. The wood was slightly discolored in the shape of a prone person.

What were these people like? What was their view of life and death? And did they believe in an afterlife? How a society treated its dead often reflected the extent to which they valued life. Annja was certain the primitive people placed great reverence on life—or at least on the lives of the people they had interred in the cave.

“So very sorry,” Zakkarat repeated, shaking his head. He let his pack slip to the ground. “Should have realized this was the wrong way. These coffins would not have fit in the tunnel we crawled through. We barely fit.”

“Maybe an earthquake changed things.” Luartaro voiced what Annja had said earlier. “There have been earthquakes throughout Thailand and all of Asia. Or maybe—”

“Or maybe they brought the coffins in through there.” Zakkarat pointed halfway up the wall, where a wide cleft in the rock looked like the opening to another passage.

Luartaro took a picture of Zakkarat pointing, and then snapped several of Annja and the wall of large teak coffins.

“Let’s hope that’s a passage,” Annja said. She turned away from the coffins and looked back the way they’d come.

Water was spilling into their chamber, meaning the tunnel they’d taken to get there was completely flooded, and the chamber was going to fill next.

“All the rain,” she said, her voice cracking with nervousness. “Yesterday, and today. That underground river is rising quickly. We might soon be dealing with a considerable flood.”

Again she felt for the sword at the edge of her mind. This time its presence offered no comfort. It couldn’t do anything to keep the rising water at bay.

4

“Up! This is flooding!” Luartaro headed toward a section of the chamber wall that looked the most uneven. “Annja, Zakkarat, come on! Move!” Despite his shouts, his voice registered authority rather than panic.

Zakkarat began to chatter nervously in Thai.

It was nothing Annja could decipher, though she felt the fear in his voice. He scrambled toward Luartaro, the light from the lantern he carried bouncing and creating a dizzying effect.

Annja watched the water.

It rose noticeably in the passing of a few heartbeats.

She cursed silently. When she started out that morning, it hadn’t crossed her mind that all the rain would affect her exploration of the caves. She should have considered the possibility. She should have realized there could be flash floods—especially since the cave they visited yesterday had a river running through the middle of it, what the pamphlets called “active.” Being on vacation had made her mind numb.

They should be reasonably safe, she hoped, as the water likely wouldn’t reach the top of the chamber—the roof was so high. Nevertheless, she knew they must look for a way out just to be certain. There was no telling how long the water would remain high and keep them prisoner.

She heard a scuffing sound and turned around.

Luartaro was climbing up the wall toward the dark cleft. The muscles in his back and arms strained and rolled. He glanced back and called to her again.

She looked at the nearest coffin, then back at the water.

The river could conceivably reach the coffins or perhaps completely cover them. Would it damage the ancient teak?

Annja winced at the thought. They should be all right, she decided. No doubt this chamber had flooded in the past, what with the annual rainy season and the monsoons. Perhaps all the rising river was the explanation for no bodies—the water had washed them away and left behind only the heavy teak coffins and the most cumbersome pieces of pottery. Maybe the water had even rearranged where the coffins had been originally placed.

Free me.

She hadn’t imagined the voice. She distinctly heard those two words now. They hadn’t come from the coffins, though. It was as if they’d traveled through the very stone of the cave and seeped into her head. It echoed like a child calling down into a canyon.

Had Luartaro heard it?

“Lu, did you hear—”

“Annja! Now! We have to get out of here!”

The water swirled around the soles of her boots.

Zakkarat continued to babble in Thai, his words laced with anger.

There was another scuffing sound, and a heartbeat later Luartaro’s hand touched Annja’s shoulder. He’d climbed back down to get her.

“Annja, we have to leave. It isn’t safe here, and that tunnel’s flooded. I used to free dive, but not even an Olympic swimmer could hold his breath long enough to get back out that way. Come! The water isn’t going to bother the coffins. No doubt they’ve been flooded before.” He shook her. “Please hurry.”

She focused her thoughts and turned to face him.

The light was low, as Zakkarat had set his lantern inside one of the coffins by the far wall. Luartaro’s face was heavily shadowed, making the angles and planes of it more pronounced and striking.

Did she love him? The question seemed to materialize in her thoughts as mysteriously as the voice did.

His unblinking gaze caught hers.

“The water is—”

“I know,” Annja said. “Rising fast. This might as well be a monsoon.”