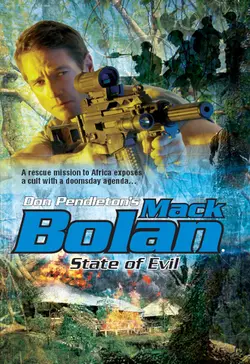

State Of Evil

Don Pendleton

ROAD TO ARMAGEDDONA call from an old friend sends Mack Bolan to the Congo, armed and ready to extract a young man from cultists calling themselves The Process. Led by a fanatical sociopath who believes his ultimate power lies beyond the divine–but also in the hands of an elite security team of Uzi-wielding enforcers– this self-styled prophet's most recent holy act involved removing all traces of a U.S. congressman's humanitarian visit, including the bodies. Making his way through the jungle with his reluctant charge in tow and hunters on his back, Bolan's instincts kick into high gear, quickly turning the rescue mission into a race to stop the detonation of an atomic weapon before the African cult leader's personal Judgment Day leaves no opportunity for second chances….

Bolan had taken on the job for old times’ sake

He was driven by feelings long suppressed if not forgotten, paying an installment on a debt of loyalty he knew would never fully be discharged. In truth, he didn’t want to cut that tie, however tenuous it was.

Sometimes even a scarred and bloodied warrior needed something to remind him of another time. Another life. It might be lost beyond recall, but memories were precious, all the same.

He palmed the GPS device and got his bearings, let the compact gadget point him toward his goal. A stranger waited for him there, not knowing it. Bolan had come to save that stranger from himself, at any cost.

Old ghosts kept pace with Bolan as he struck off through the jungle on a trail invisible to human eyes.

Other titles available in this series:

Killpoint

Vendetta

Stalk Line

Omega Game

Shock Tactic

Showdown

Precision Kill

Jungle Law

Dead Center

Tooth and Claw

Thermal Strike

Day of the Vulture

Flames of Wrath

High Aggression

Code of Bushido

Terror Spin

Judgment in Stone

Rage for Justice

Rebels and Hostiles

Ultimate Game

Blood Feud

Renegade Force

Retribution

Initiation

Cloud of Death

Termination Point

Hellfire Strike

Code of Conflict

Vengeance

Executive Action

Killsport

Conflagration

Storm Front

War Season

Evil Alliance

Scorched Earth

Deception

Destiny’s Hour

Power of the Lance

A Dying Evil

Deep Treachery

War Load

Sworn Enemies

Dark Truth

Breakaway

Blood and Sand

Caged

Sleepers

Strike and Retrieve

Age of War

Line of Control

Breached

Retaliation

Pressure Point

Silent Running

Stolen Arrows

Zero Option

Predator Paradise

Circle of Deception

Devil’s Bargain

False Front

Lethal Tribute

Season of Slaughter

Point of Betrayal

Ballistic Force

Renegade

Survival Reflex

Path to War

Blood Dynasty

Ultimate Stakes

State of Evil

Mack Bolan®

Don Pendleton

There is no arguing with the pretenders to a divine knowledge and to a divine mission. They are possessed of the sin of pride, they have yielded to the perennial temptation.

—Walter Lipmann,

The Public Philosophy

There’ll be no argument with my opponents on this mission. The plan is simple, in and out. God help anyone who stands in my way.

—Mack Bolan

For fighting men and women in harm’s way

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE (#u3d961198-0702-5323-9b55-833122a986e6)

CHAPTER ONE (#uede79647-36d8-5637-a685-052d672072bd)

CHAPTER TWO (#u8411171b-d2ae-5126-862d-29e3ab1070c7)

CHAPTER THREE (#u9917056d-945e-5c47-9ca5-eedeef6433c2)

CHAPTER FOUR (#u1dc7b905-6de2-53c5-9fa3-197b78b80f11)

CHAPTER FIVE (#u9470c545-2b82-51dd-a68e-3ff6568bb534)

CHAPTER SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE

Obike, Republic of Congo

The congressman was sweating, which was no surprise, given the oppressive temperature and humidity. But climate couldn’t explain the tingling chill he felt at the back of his neck.

A sense of being watched.

He turned abruptly in his chair, raising a hand as if to swat a troublesome mosquito, and he caught one of Gaborone’s bodyguards turning away, suddenly anxious to avert his eyes.

It wasn’t paranoia, then.

The goons were watching him.

Lee Rathbun wished he’d never made this trip, but it was too late now for backing out. He was the youngest congressman in California, midway through his second two-year term in Washington and looking for a chance to prove himself. The Congo trip had fit his need, humanitarian and daring all at once, solving a problem, maybe bringing justice to a charlatan while overcoming certain hardships in the process.

Naturally he’d brought a camera crew along to put the show on tape. Why not?

The problem was that he’d been misinformed, somewhere along the line. Ahmadou Gaborone had that Jim Jones/David Koresh air about him, smiling serenely while chaos churned behind his eyes. He spoke sometimes in riddles, other times in parables that could mean anything or nothing. Typically, his voice was soft, almost hypnotic, but when raised to make a point during one of his marathon sermons, it shook the very primal forest that surrounded Obike, the retreat.

Lee Rathbun’s mission was twofold. First, he had promised to inspect Obike and report his findings to constituents whose loved ones had deserted sunny California for the jungle compound where Gaborone was constructing his tentative Eden on Earth. Second, he was supposed to interview the absent kin of those who had besieged his hometown office, seeking help. He would seek out the converts, take a private reading on their health and state of mind, and share his findings with their families.

Simple.

Aside from nailing down some grateful votes, the junket would earn him a page, maybe two, of fresh ink in the Congressional Record, when he filed his report with Congress.

Now he was almost done and it was nearly time to leave, but Rathbun couldn’t shake that creepy feeling that suggested hostile eyes tracking his every move.

One of the guards was moving toward him now, a sullen six-footer whose plaid short-sleeved shirt was unbuttoned, revealing an ebony six-pack that shone as if oiled. His AK-47, Gaborone had explained, was one the group used to protect them against Gaborone’s enemies, those who would harm him for spreading God’s message.

“Say goodbye now,” the guard told Rathbun. “Time to go.”

Rathbun smiled as if trying to win the man’s vote. Behind him, he heard one of the cameramen mutter, “It’s about damned time.”

“Smiles, people, smiles,” Rathbun said to his team. “Remember where we are, and that our host has been extremely generous.”

It was true, to a point. Gaborone had granted them a tour of Obike that revealed austere but functional facilities, the living quarters well tended and almost compulsively tidy. Rathbun’s interviews had also gone without a hitch, at least superficially. Those he sought were all accounted for and pleased to answer questions on their life within the sect.

As for the answers, rehearsed to the point that they all came out nearly verbatim, Rathbun didn’t choose to raise that issue in Obike. Not under the guns of Gaborone’s security force.

Relieved to put the place behind him after three long days and nights, Rathbun rose from his canvas chair and led his people toward the waiting bus.

NICO MBARGA WAITED with the vehicle. His scouts had left an hour earlier, to guard the airstrip and prepare the send-off Master Gaborone had ordered for the visitors. Mbarga wore the smile he deemed appropriate for partings.

The politician approached him, flicking glances at the old converted school bus that would take his people to the airstrip. Parked close behind the bus, a Jeep sat idling with four of Mbarga’s men waiting stoically for his order to roll. They watched Mbarga, not the visitors, because they knew who was their master, once removed.

“Will Mr. Gaborone be joining us?” the politician asked.

“Alas, no,” Mbarga replied. “He has other pressing business, but he wishes you a safe and pleasant journey home. He hopes your visit to Obike was rewarding and your fears are laid to rest.”

The politician frowned. “What fears?”

Mbarga shrugged. “Perhaps that kinfolk of your countrymen have been mistreated here or held against their will.”

The politician blinked. “I saw nothing to indicate that might be true,” he said.

“Good, good. You’re happy to be going home, then. Please take seats aboard the bus, and we shall go to meet your flight.”

Mbarga watched the visitors file past him, all except the politician bearing haversacks and camera equipment. When the last of them had gone aboard, Mbarga followed, nodding to the driver. He sat behind the driver’s seat, sliding his pistol belt around so that the holster with its heavy pistol wouldn’t dig into his hip or thigh.

Mbarga glanced around the bus as it began to move. The visitors—a woman and three men besides the politician—all wore queasy looks, as if their breakfast of plantains and porridge sat uneasily within their stomachs. Mbarga wondered whether any of them had the gift of precognition.

No, he finally decided, smiling to himself.

If that were true, they wouldn’t be aboard the bus.

Whatever they were thinking, it was now irrelevant.

“SO, WHERE’S THE PLANE?” asked Ellen Friedman, Rathbun’s personal assistant, as she stepped down from the bus.

“Good question.” Rathbun turned to the commander of the escorts and inquired, “Shouldn’t the plane be here by now?”

“Sometimes it’s late,” the bodyguard replied.

“Sometimes?”

“Most times,” the bodyguard amended with a careless shrug.

“We have a flight to catch in Brazzaville,” Rathbun informed him, fudging in an effort to communicate a sense of urgency.

“No problem, sir.”

Turning to scan the airstrip, Rathbun noted that a Jeep had reached the scene ahead of them, bearing four gunmen to the site. With those in the following Jeep and their escort, that left his small party outnumbered.

“Are you expecting trouble here, today?” he asked.

“Always expecting trouble, sir,” the bodyguard replied. “Prophets have many enemies.”

“I see.” Rathbun glanced pointedly at his wristwatch, then saw the gunmen stepping from their vehicles. They didn’t wear their rifles shoulder-slung this time, but carried them as if prepared to fire.

“This stinks,” said Andy Trask, the cameraman. “I don’t like this at all.”

“Relax, will you?” the congressman replied, but he was having trouble suiting words to action. There was something in the way the gunmen watched him now….

“Put down your bags,” their escort said, no longer sounding affable. When Rathbun turned to face him, he discovered that the man had drawn his pistol from its holster.

“What?”

“Put down all bags,” the bodyguard repeated. “Leave them where you stand and line up there.” His final word was punctuated with a gesture from the pistol, indicating open grass beyond the blunt nose of the bus.

“Now wait a minute,” Rathbun said. “What’s going on?”

“I only follow orders,” said the bodyguard.

“And what, exactly, might those orders be?”

“I must protect the master and Obike at all cost.”

“You still aren’t making sense.” Rathbun was striving for a tone of indignation, trying not to whimper. Even here, it was important to save face.

“All threats must be eliminated.”

“Threats? What threats? We’ve spent the past three days among your people, with consent from Mr. Gaborone. Now we’re leaving, as agreed. There’s no threat here.”

“I follow orders,” the bodyguard said again.

Rathbun felt the vicious worm of panic twisting in his gut, gnawing his vitals. It would break him if he faced the others, registered the sudden terror on their faces.

“I don’t understand what’s happening,” he said.

“Step into line. We have orders and a schedule.”

“Just think it through,” Rathbun pleaded. “If Mr. Gaborone is worried about bad publicity, what does he think this will accomplish? You’ll have troops, police, God knows who else, if we don’t get to Brazzaville on time.”

The escort shrugged. “We’re ready for the day of judgment. It will come in its own time.”

It was a sob that broke the last thin shell of Rathbun’s personal composure. Ellen Friedman weeping like a child. Rathbun hardly knew what he was doing when he shouted, “Run!” and drove his right fist hard into their escort’s startled face.

He missed the bastard’s nose but felt the lips mash flat beneath his knuckles, twenty years or more since he had swung a punch that way, at some forgotten enemy from John Wayne Junior High. It staggered his opponent, gave him time to turn and flee.

Too late.

A voice behind him shouted something Rathbun couldn’t understand. He heard the first gunshots when he was still some thirty paces from the trees. Rathbun was the last American to die.

“MY CHILDREN! Harken unto me!”

Ahmadou Gaborone occupied his favorite chair, a throne of woven cane planted atop a dais in the central plaza of Obike. Nearly all of his disciples were assembled on the open ground in front of him, summoned by the clanging of a triangle to hear their lord and master’s words. His bodyguards were shooing stragglers in from here and there, to join the tense, expectant throng.

“My children,” Gaborone repeated, “we have reached a perilous, decisive moment in our history. For three days, enemies have dwelt among us. They conspired with enemies outside to fill the air with lies about Obike and myself. Unchecked, they would have turned the governments of Brazzaville and Washington against us.”

Murmurs from the audience. Quick glances here and there from nervous eyes, as if his people thought the enemies might suddenly appear beside them.

“I have acted as a leader must, to spare his people,” Gaborone continued. “On my order to the guardsmen of Obike, the intruders have been neutralized. They are no more.”

That sent a ripple of surprise through the assembled crowd. Some of his followers were clearly frightened now. The master raised his hands, then stood when the familiar gesture failed to silence them.

“My children! Hear me!” he commanded. “Have no fear of those outside. You know that Judgment Day must come upon us in its own good time. Nothing we do can hasten or delay the hour of atonement. We shall someday face the test against our enemies. Whether tomorrow or ten years from now, I cannot say until the word is given from on high.”

“Master, preserve us!” someone cried out from the audience.

“I shall,” the prophet replied. “Fear no outside force or government. No man can harm us unless God permits it, and He never leaves His faithful children to be slain unless they first fail in their duties owed to Him.”

“What shall we do, Master?” another voice called from his right.

“Stand fast with me,” he answered. “Do God’s bidding as it is revealed to you, through me. With faith in Him, we cannot fail. His grace and power shield us from our worldly enemies and all their schemes. While we are faithful, those who threaten us are vulnerable to God’s holy cleansing fire.”

“Amen!” a handful of his children shouted, others taking up the chant until it seemed to echo from a single giant throat.

“Amen!” he thundered back at them. “Amen!”

Nico Mbarga stood beside the dais, waiting for Gaborone to step down and retreat from his throne. The chanting of “Amen!” continued even after he had left the audience, continued until he was well inside his quarters with Mbarga, just the two of them alone.

“Tell me again, Nico,” he said, “why you are certain that the bodies won’t be found.”

“We burned them, Master, and their ashes have been scattered in the jungle.”

“What of their effects? The camera? The other things?”

“Buried,” Nico assured him. “Buried deep.”

“There will be questions.”

Nico shrugged. “We saw them board the plane and fly away.”

“What of the pilot?”

“He has sisters in Obike. He will land in Brazzaville on schedule. How can he explain the disappearance of his passengers, once they departed from his care?”

“It’s not much of a story, Nico.” Gaborone sometimes enjoyed being the devil’s advocate.

“It is enough, Master,” the bodyguard replied. “We pay the Brazzaville police enough to close their eyes.”

“But what of Washington? Their President wields power, even here. Their dollars buy compliance.”

“You believe they’ll crack the pilot?” Mbarga asked.

“Given time and the incentive, certainly.”

“I’ll see to it myself,” Mbarga said.

“Soon, Nico. Soon.”

“I’ll leave tonight, Master.”

“How many sisters of the pilot share our faith?”

“Three, master.”

“Take one of them with you to the city.”

“Sir?”

“If he should simply die, more questions will be raised. A scandal in the family, however, raises issues the police can swiftly put to rest.”

“A scandal in the family.” Mbarga seemed to understand it now.

“Sadly, not everyone shares our view of morality.”

“No, sir. The woman—”

“Tell her she’s been chosen for a mission in the city. Flatter her, if necessary. Has she any special skills.”

Mbarga shrugged. “I don’t know, Master.”

“Think of something. Use your powers of persuasion, Nico. I’m convinced that you can do it.”

Meaning that he didn’t want the woman dragged aboard a Jeep, kicking and screaming. He didn’t want her spreading stories to her sisters or to anybody else during the short time left before her one-way trip to Brazzaville.

“It shall be done, Master.”

“I never doubted you. And, Nico?”

“Master?”

“Make me proud.”

CHAPTER ONE

Airborne: 14° 2’East, 4°8’South

The aircraft was a Cessna Conquest II, boasting a forty-nine-foot wingspan and twin turboprops with a maximum cruising speed of 290 miles per hour. It had been modified for jumping by removal of the port-side door, which let wind howl throughout the cabin as it cruised around eleven thousand feet.

The air was thin up there, but the aircraft was still below the level where Mack Bolan would’ve needed bottled oxygen to keep from blacking out. His pilot, Jack Grimaldi, didn’t seem to feel the atmospheric change, although he’d worn a leather jacket to deflect the chill.

Twenty minutes out of Brazzaville and they were halfway to the target. Bolan had already checked his gear, but gave it all another look from force of habit, nothing left to chance. He tugged at all the harness straps, tested the quick-release hooks, making sure that he could find the rip cords for the main chute on his back and the smaller emergency pack protruding from his chest. Bolan had packed both parachutes himself, folding the canopies and lines just so, and he was confident that they would function on command.

The rest of Bolan’s gear included military camouflage fatigues, the tiger-stripe pattern, manufactured in Taiwan and stripped of any labels that could trace them to specific points of origin. His boots were British military surplus, while his helmet bore the painted-over label of a manufacturer whose products were available worldwide.

His weapons had apparently been chosen from a paramilitary grab bag. They included a Steyr AUG assault rifle manufactured in Austria, adopted for use by armies and police forces around the world. The AUG was well known for its rugged construction and top-notch accuracy, its compact bullpup design, factory-standard optical sight and clear plastic magazines that let a shooter size up his load at a glance. Bolan’s sidearm was a Beretta Model 92, its muzzle threaded to accept the sound suppressor he carried in a camo fanny pack. His cutting tool was a Swiss-made survival knife with an eight-inch, razor-sharp blade, its spine serrated to double as a saw at need.

The rest of Bolan’s kit came down to rations and canteens, a cell phone with satellite feed, a compact GPS navigating system and a good old-fashioned compass in case the global positioning satellite gear took a hit at some point. His entrenching tool, flashlight and first-aid kit seemed antiquated by comparison, like items plucked from a museum.

When he was satisfied that nothing had been overlooked or left to chance, Bolan moved forward to the cockpit. Grimaldi glanced back when he was halfway there and raised his voice above the rush of wind to ask, “You sure about this, Sarge?”

“I’m sure,” Bolan replied. He crouched beside the empty second seat, too bulky with his parachutes and pack to make the fit.

“Because if anything goes wrong down there,” Grimaldi said, “you’re in a world of hurt. That’s Africa down there. If you trust the folks at CNN, a lot of it still isn’t all that civilized.”

“Worse than New Jersey?” Bolan asked. “The South Side of Chicago?”

“Very funny.” From his tone, Grimaldi clearly didn’t think so. “All I’m saying is, your sat phone may connect you to the outside world, if it decides to work down there, but even so, it’s still the outside world. You’ve got no backup, no support from anyone official, no supply line.”

“I’ve got you,” Bolan reminded him.

“And I’ll be waiting,” the pilot assured him. “But my point is, even if you call and catch me sitting in the cockpit with my finger on the starter, it’ll be an hour minimum before I’m in position for a pickup. Plus, with the restriction on armed aircraft, I can’t give you anything resembling decent air support.”

“Just be there for the lift. That’s all I ask,” Bolan replied.

Grimaldi shifted gears. “And what about this kid you’re picking up?”

“He’s twenty-two.”

“That’s still a kid to me,” Grimaldi said. “Suppose he doesn’t want to play the game?”

“I’ll make him an offer he can’t refuse,” Bolan said.

Grimaldi frowned. “I mean to say, he’s here by choice. Correct?”

“In theory, anyway,” Bolan said.

“So he’s made his bed. He may not want to leave it.”

“I’ll convince him.”

Bolan didn’t need to check the hypodermic syringes in their high-impact plastic case, secure in a pouch on his web belt, but he raised a hand to cup them anyway. The kid, as Jack called him, would be coming out whether he liked it or not.

Whatever happened after that was up to someone else.

Grimaldi gave it one last try. “Listen,” he said, “I know where this is coming from, but don’t you think—”

“We’re here,” Bolan said, cutting off the last-minute debate. “I’m doing it. That’s all.”

“Okay. You’ve got my cell and pager set on speed-dial, right?”

“Right after Pizza Hut and Girls Gone Wild,” said Bolan.

“Jeez,” Grimaldi said, “I’m dropping a comedian. Who knew?”

“I needed something for my spare time,” Bolan said.

“Uh-huh.” Grimaldi checked his instruments, glanced at his watch, and said, “We’re almost there. You’d better assume the position.”

“Right.” Rising, Bolan briefly placed a hand on his old friend’s shoulder. “Stay frosty,” he said.

“It’s always frosty at this altitude. I’ll see you soon.”

Turning from the cockpit, Bolan made his way back to the open door, halfway along the Cessna’s fuselage.

“WE’VE GOT a quarter mile,” Grimaldi shouted back to Bolan in the Cessna’s open doorway, waiting for the quick thumbs-up.

Whatever was about to happen, it was out of Jack Grimaldi’s hands. He could abort the mission, turn the plane around and violate his old friend’s trust beyond repair, but that option had never seriously crossed his mind.

He was the flyboy; Bolan was the soldier.

He delivered Bolan, and the Executioner delivered where it counted, on the ground.

Grimaldi understood the impetus behind their mission, recognized the urgent strength of loyalty that rose beyond mere friendship to a more exalted level. Still, their small handful of allies was behind them now, and half a world away. The broad Atlantic Ocean separated Bolan and Grimaldi from the support team at Stony Man Farm. Whatever happened on the ground below, Bolan would have to cope with it alone.

And recognizing that, Grimaldi thought, what else was new?

From what Grimaldi knew, Bolan had been a kind of one-man army all his fighting life, from combat sniper service with the Green Berets, through his solo war against the Mafia at home, and in most of the Stony Man missions he’d handled since joining the government team. From boot camp to the present day, Bolan had been unique: a great team player who could nonetheless proceed alone if there was no team left to field.

Most often, in the blood-and-thunder world he occupied, Mack Bolan was the team. Grimaldi simply had the privilege, from time to time, of making sure that Bolan didn’t miss the kickoff.

“Ready!” he shouted in the rush of chilling wind. The drop zone was below them, waiting.

“Ready!” Bolan answered without hesitation.

And when Grimaldi glanced toward the Cessna’s vacant hatch again, he was alone.

THE WIND HIT Bolan like a tidal wave and swept him back along the Cessna’s fuselage, even as he began to fall through space. He plummeted headfirst toward Earth, arms tight against his sides, a hurtling projectile of flesh and bone.

Although he was accelerating by the second, answering the call of gravity, he also felt a lulling sense of peace, deceptive, as if he had been a feather drifting on an errant summer breeze. The jungle canopy below didn’t appear to rush at Bolan, hastening to crush him. Rather, from his vantage point, it seemed to be forever out of reach, a vista seen through plate glass on the far side of a massive room.

Bolan had done enough high altitude, low opening jumps in his time to recognize the illusion for what it was, and to dismiss it from his mind. HALO drops were designed for maximum maneuverability and stealth. The jumper guided himself with pure body language for the first eight thousand feet or so, waiting to pull the rip cord when it counted, minimizing exposure to watchers on the ground.

The jungle helped him there, of course. For spotters to observe his parachute, they’d have to be at treetop level—no mean feat, considering the fact that trees in the Congo jungle below Bolan averaged one hundred feet or more in height. The lofty African mahogany might double that, but climbing giant trees wasn’t child’s play. Unlike most temperate trees grown in the open, giants of the crowded rain forest typically boasted branches only near the top, leaving two-thirds of their trunks entirely bare except for creeping vines and moss or fungus growths.

If Bolan’s parachute became entangled in that lofty canopy, he ran a risk of being killed or crippled in his bid to reach the ground. The first step in his new campaign could also be his last.

Around two thousand feet he pulled the main rip cord. There was a heartbeat’s hesitation, known to every jumper who survives a drop, before the main pack opened and the chute blossomed above him. Bolan’s headlong plummet was arrested as the shroud lines snapped taut, air filling the cells of the sleek pilot chute overhead.

Bolan clutched the risers, using them and the parachute’s slider to guide his descent toward the treetops. This was his most vulnerable time, dipping lower by the moment at a speed most riflemen could easily accommodate. He didn’t think there would be spotters in the treetops, but a hunter in a clearing on the ground might catch a glimpse of Bolan and his parachute, might even have the time to risk a shot before he ran to spread the word.

One clearing in particular preoccupied the jumper’s thoughts.

The drop zone had been chosen based on aerial and satellite reconnaissance, map coordinates for Bolan’s final destination matched against bird’s-eye photographs of the jungle canopy he’d be required to penetrate on D-day. A natural clearing in the forest had been spotted from on high, charted and measured, analyzed for likely risks as far as a computer half a world away could take the problem toward solution. Based on that intelligence, he had been told precisely where and when to leave Grimaldi’s Cessna for his leap of faith.

The dark patch of the clearing lay below him now, and slightly to his left, meaning a hundred yards or so, from Bolan’s altitude. It was a black hole from his viewpoint, while sunlight reflected on the treetops all around that vaguely oval gap amid the foliage. From two thousand feet, it looked like the cup on a putting green. Up close, he guessed, it would resemble an abandoned well or mine shaft yawning to receive him.

If he didn’t miss his mark and hang up in the trees.

Bolan was skilled at navigating parachutes. He’d learned the art as a young Green Beret and practiced it sporadically throughout his wars, keeping his skills and reflexes in shape. Still, there were always unexpected twists and turns in any combat mission. Wind might carry him off course, a bird could strike him in the head and render him unconscious, or the guidelines on his chute might snap, leaving him rudderless.

If none of that transpired, he had a chance to hit his mark—and only then would he find out what happened next.

The guide lines didn’t break. No windy gale or suicidal bird disrupted Bolan’s plan. He steered the parachute without a hitch, correcting his descent by slow degrees until the dark mouth of the jungle clearing was directly underneath his feet. Up close it was a black maw, roughly oval, thirty-seven feet, nine inches wide at treetop level.

The dimensions were precise, but Bolan had no clue what might be waiting for him at the bottom of the shaft.

Assuming that he ever got that far.

He marked a bull’s-eye in his mind, steered for it, watching his target instead of the belled chute above him. Bolan pointed his toes, peering between his boots as if they formed a gunsight’s V.

So far, so good.

The treetops rose to meet him much more swiftly now, it seemed, during the final yards of his descent. Gripping the risers firmly, Bolan fought to keep the parachute on course, resisting updrafts from the sun-warmed canopy.

The clearing yawned beneath him. With a hiss of ripstop nylon, Bolan hit his mark. The forest swallowed him alive.

It was a curious sensation, being swallowed by a jungle. First, the sunlight flickered, faded, screened by treetops looming overhead as Bolan cleared the forest canopy. An instant later he felt a drastic change in the humidity and temperature. Though shaded now, Bolan had also lost the morning breeze. It felt like plummeting into a sauna, fully clothed.

Dead air didn’t provide the same support for Bolan’s parachute, either. The pace of his descent accelerated, but he had no room for any kind of meaningful maneuver. What had once gone up was coming down, and he could only brace himself for impact as the ground rose to accept its human sacrifice.

A glance in passing told him that the clearing had to have been created by a lightning strike that shattered one great tree, in much the same way demolition experts drop a skyscraper without inflicting any major damage on its neighbors. Eight feet below him, closing fast, Bolan saw the detritus of the forest giant’s fall. A ragged stump sprouted from mulch and teeming fungus growths, surrounded by remains of charred and rotted wood.

Before he had a chance to think about what might be living, breeding, feeding in the giant compost heap below him, Bolan struck the spongy surface. He had time to veer a yard or two off course, avoid impalement on the sharp-pronged mahogany stump, but that effort cost him balance on the landing and he rolled in filth, smothered in the chute as it descended like a shroud.

Bolan opened the quick-release clasps on his harness and shed it, pulled his knife and slit the parachute, emerging from it like some mutant forest life-form rising from its amniotic sac. At once, he sheathed the blade, unslung his AUG and waited where he stood for any challenge from the jungle murk.

A silent minute passed, then two, and he was satisfied. Keeping his rifle close at hand, Bolan hauled in the flaccid remnants of his chute, and opened his entrenching tool. The mulch beneath his boots was soft and had a mildew stench about it. When he broke the surface crust, it teemed with vermin—ants, worms, beetles Bolan didn’t recognize—but he dug deeper, leaving those he had disturbed to scramble for another path to darkness, out of sight.

He dug until he had a pit of ample size to hold the bundled parachute, his spare, the harness and the helmet he had worn. Filling the hole was faster, but he took the extra time to evenly disperse the surplus mulch he’d excavated from the reeking mound. The next rain, probably sometime that afternoon, would mask whatever signs of digging Bolan left behind. Searchers would have to excavate the spot themselves, to find his gear, and there was no good reason they should even try it if they’d hadn’t seen him drop in from on high.

Digging ditches in ninety-degree heat and ninety-eight-percent humidity drained a strong man’s vigor in a hurry. Bolan was a veteran jungle fighter, long accustomed to the hardships of tropical climates, but every day spent away from the jungle, swaddled in the chill of fans and air conditioners, reduced a subject’s tolerance for enervating heat. His thirty hours in Brazzaville had helped provide a measure of reacclimation, but there was a world of difference between the city—any city—and the bush.

Bolan folded his shovel, stowed it and allowed himself a sip of water from one of his canteens. Ironically, dehydration was a major risk in the midst of a sodden rain forest, where any water he found would be teeming with germs, unfit to drink unless he boiled it first.

And Bolan couldn’t risk a fire.

Not yet.

He might be burning something later, but for now he had to pass unnoticed through the forest en route to his target. Any chance encounters on the way increased the danger to himself and to his mission.

He had taken on the job for old times’ sake, driven by feelings long suppressed if not forgotten, paying an installment on a debt of loyalty he knew would never fully be discharged.

In truth, he didn’t want to cut that tie, however tenuous it was. Sometimes even a scarred and bloodied warrior needed something to remind him of another time. Another life. It might be lost beyond recall, but memories were precious, all the same.

He palmed the GPS device and got his bearings, let the compact gadget point him toward his goal. A stranger waited for him there, not knowing it. Bolan had come to save that stranger from himself, at any cost.

Old ghosts kept pace with Bolan as he struck off through the jungle on a trail invisible to human eyes.

CHAPTER TWO

Cheyenne, Wyoming

Five days before he stepped out of the Cessna into Congo skies, Bolan had followed cowboy footsteps through the streets of what was once a wild and woolly frontier town. He dawdled past gift shops, a bookstore with a lot of history and Western fiction in the windows, glancing at his watch again to verify the time.

Almost.

He didn’t know that much about Wyoming—big-sky country, open range, the Rockies—but it didn’t matter. Dressing like a tourist didn’t make him one. Bolan had business here, and it was causing him a teaspoon’s measure of anxiety.

He was surprised to see a pair of middle-aged civilians pass, both wearing pistols holstered on their hips. No badges visible, and Bolan took a moment to remind himself that this was still the wild frontier, in certain ways.

His own sidearm, the sleek Beretta 93-R with selective fire and twenty Parabellum rounds packing its magazine, was tucked discreetly out of sight beneath a nylon windbreaker. He much preferred the fast-draw armpit rig and had no need to advertise that he was armed.

As long as he could reach the pistol when it mattered.

Bolan had two minutes left to wait, but it was getting on his nerves. That was peculiar in itself, considering that patience was a sniper’s trademark and a trait that kept him breathing, but he wrote it off to special circumstances in the present case. The message from his brother had surprised him and had kept him revved since he received it.

He wasn’t nervous in the classic sense, afraid of what would happen in the next few minutes, worried that he might not find a way to handle it. Bolan had outgrown such emotions as a teenager, had any remnants of them purged by fire as a young man. That didn’t mean he was immune to feelings, though.

Not even close.

He’d driven past the Chinese restaurant first thing, an hour early for the meeting, checking out the street. That part was instinct, watching for a trap. It made no difference that his brother would’ve died before collaborating with an enemy. Betrayal wasn’t even on his mind.

The drive-by was a habit, ingrained for good reason. Johnny would’ve taken care when calling, but that didn’t guarantee their conversation had been secure. What really was, these days? Each day, the NSA’s code breakers intercepted countless e-mails, phone calls, radio transmissions, television programs. Other ears and eyes were also constantly alert. There was a chance, however miniscule, that Johnny had been singled out, his message plucked from the air or off the wires and passed along to someone who would pay to keep the rendezvous.

For one shot at the Executioner.

The drive-by had been wasted, nothing on the street that indicated any kind of trap in place. That didn’t mean the restaurant was clean, simply that Bolan couldn’t spot a snare if one was waiting for him. Call it eighty-five percent relaxed as Bolan turned from the shop window he’d been studying, using the glass to mirror the pedestrians passing behind him, watching both sides of the street. His windbreaker hung open, granting easy access to the pistol if he was mistaken and a trap awaited him within the next block and a half.

The call from Johnny had been short and sweet.

“Val needs to see you, bro,” he’d said. “Can you find time?”

And it was wild, how a three-letter word could reach across the miles and years, clutching his heart in a death grip.

No, that was wrong. Make it a life grip, and it would be closer to the truth.

Val needs to see you, bro. Can you find time?

Hell, yes.

The day seemed warmer as he neared the corner where a left turn was required to reach the restaurant. Bolan could feel a sheen of perspiration on his forehead and beneath his arms. It wasn’t that hot, and the physical reaction made him frown.

It’s been a long time, he admitted. Then, as if to reassure himself, There’s nothing to it. Get a grip.

The nerves were partly Johnny’s fault. He could’ve spelled it out directly, or at least suggested why Val needed him. It had been years since they’d seen each other last, and she had been hospitalized, recuperating from one of those traumas that dogged Bolan’s handful of loved ones and friends. It was his final memory of Val, and he had no idea how well she had recovered from her injuries. What scars remained, inside or out.

At least she wasn’t one of Bolan’s ghosts.

Not yet.

Val needs you.

Why? Presumably she’d tell him to his face.

He cleared the corner, gave the street a final sweep and walked on to the Bamboo Garden, halfway down the block. The door made little chiming sounds as he pushed through it, brought a smiling hostess out to intercept him.

“One for lunch?” she asked.

“I’m meeting someone,” he replied. And as he spoke, he had them spotted. “Over there.”

The hostess bobbed her head. “Please follow me.”

As they moved toward the corner booth, he noted Johnny’s left leg sticking into the aisle, his foot and ankle fattened by a plaster cast. A pair of crutches leaned against the wall beside him.

Val was seated on the inside, next to Johnny on his right. Her raven hair was cut to shoulder length, framing a face with the exotic beauty of her Spanish heritage. Her smile seemed tentative, but what could he expect?

He sat, back to the door, and didn’t even mind. Johnny could watch the street. The hostess handed him a menu and retreated. Bolan knew he was supposed to read it, order food. He simply wasn’t there yet.

“Long time,” Val said. “You’re looking good.”

He wasn’t sure if that was true, but Bolan meant it when he said, “You, too.”

He turned to his brother. “What’s the story on that leg?”

Johnny looked suitably embarrassed. “It’s a classic,” he replied. “Stepped off a ladder, got tangled up and cracked a couple bones.”

“No marathons this season, then.”

“Guess not.”

That much told Bolan part of why Val had reached out for him. Johnny was benched for the duration, and whatever problem had arisen, Bolan guessed it couldn’t wait for him to heal.

“Bad luck,” he said.

“What brings you down from Sheridan?” he asked Val.

Her home was on the far side of the state, near the Montana border, some 330 miles north of Cheyenne. Bolan surmised that Val had picked the meeting place so that she wouldn’t have him on her doorstep.

Just in case.

Trouble had found her in Wyoming once already, and she wouldn’t want a replay. Not if she could help it.

“I thought we could eat first, catch up on old times,” Val said. “Then maybe take a drive and talk about the other when we’re done.”

Where waitresses and busboys couldn’t eavesdrop.

“Sounds all right to me,” said Bolan.

“Good.” Another smile, relieved.

Old times, he thought.

They seemed like bloody yesterday.

VALENTINA QUERENTE had been calling her cat the night Bolan had first seen her, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. On the run and bleeding out from bullet wounds inflicted by a crew of Mafia manhunters, he’d staggered into Val’s life, literally on his last legs, bringing unexpected danger to her doorstep. She had taken Bolan in and nursed him back to health, no questions asked, and in the process her initial sympathy had turned to something deeper, something stronger than she’d ever felt before. Bolan had been startled to discover that he’d felt the same.

The warrior and his lady had spent nearly a month in the eye of the storm, while cops and contract killers turned the city upside down in search of Bolan. Finally, they had decided that he had to be dead, or maybe wise enough to flee the territory for a hopeless life in hiding, parts unknown. His would-be killers left a million-dollar open contract on his head, uncollected, and went back to business as usual.

For some, it was their last mistake.

Bolan had returned from his near-death experience with a vengeance, striking his enemies with shock and awe long before some military PR man had patented the phrase. He left the syndicate’s Massachusetts Family in smoking ruins, but he couldn’t hang around and taste the fruits of victory.

There would be no peace for the Executioner, as he pursued his long and lonely one-man war against the Mafia from coast to coast. No rest from battle and no safety for the ones he loved. Before he left Pittsfield, with no hope of returning, Bolan’s heart and soul were joined to Val’s in every way that counted short of walking down the aisle to say, “I do.” And by that time he’d known that home and family, the picket fence and nine-to-five, had slipped beyond his grasp forever.

There’d be no treaty with the Syndicate, and he could never really win the war he’d started when he executed those responsible for shattering his family. It was a blood feud to the bitter end, and Val hadn’t signed on for that. She would’ve risked it, but he had refused in no uncertain terms.

It had been Val’s idea for her to shelter Bolan’s brother Johnny, at a time when every hit man in the country wanted Bolan’s head. A living relative was leverage, and anyone who harbored him was thus at risk, but on that point she wouldn’t be dissuaded. Bolan might roar off into the flaming sunset and abandon her, but Val knew that he wouldn’t take his brother on that long last ride. She volunteered to make that sacrifice—risk everything she had, future included—to preserve the Bolan line, and thus maintain at least a slender thread of contact with the warrior who had changed her life.

It was a good plan, soundly executed, but the best of human schemes sometimes went wrong. In time, a Boston mobster had divined Val’s secret, kidnapped her and Johnny in a bid to make his prey surrender, trade his life for theirs. Bolan had recognized a no-win situation from the get-go, known his enemy would never let two witnesses escape his clutches. There’d been no room for negotiation as the soldier launched his Boston blitz and damned near tore the town apart. Mobsters and cops alike still talked about the day the Executioner had come to town, but most of those who served the Boston Mafia today had heard the stories secondhand. There weren’t many survivors from the actual event to keep the facts straight as they circulated on the streets.

Before the smoke cleared on that hellfire day, Johnny and Val were safely back in Bolan’s hands. He’d passed them on to Hal Brognola, then chief of the FBI’s organized crime task force. He in turn had assigned FBI agent Jack Gray to handle security for Val and the boy who posed as her son.

And something happened.

Bolan’s first reaction, on hearing from Johnny that Val and Jack were engaged to be married, was a warm rush of relief. Despite the love for her that he would carry to his grave, he felt no jealousy. Bolan had offered Val nothing but loneliness, love on the run and damned little of that. He knew that she deserved the finer things in life, and when she married, when her groom adopted Johnny Bolan and his name was changed to Johnny Gray, Bolan had felt a guilty burden lifted from his shoulders.

Val could live and love without a shadow darkening each moment of her life. Johnny could grow up strong and stable, without hearing schoolyard gibes about his brother on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. And if the end came—when it came—for Bolan, they could mourn him quietly, without fanfare.

They could move on with their lives.

That should’ve been the final chapter, but an echo of the Mob wars had returned to haunt them all, long after Bolan had moved on to other enemies and battlegrounds, with a new face and new identity. A mobster scarred by his encounter with the Executioner, maddened by his pursuit of vengeance, had traced the Grays to their new home in Wyoming, making yet another bid to reach Bolan through those he loved. The hunter missed Johnny, a grown man on his own by then, but he had wounded Jack and kidnapped Valentina, dragging her into a private hell as he reprised the Boston plan of forcing Bolan to reveal himself.

It worked, but not exactly as the lone-wolf stalker planned. He got his face-to-face with Bolan, but he’d found the Executioner too much to handle. Perhaps the old maxim “Be careful what you wish for” echoed through the gunman’s mind before he died.

Or maybe not.

In any case, Val had survived, but at a price. She carried new scars on her psyche, from her brutal treatment at the killer’s hands, and Bolan wasn’t sure if they would ever truly heal. He knew some women bore the strain better than others, and while Valentina ranked among the strongest people he had ever known, nobody was invincible. Some wounds healed on the surface, but could rot the soul.

Bolan had checked with Johnny over time, received his brother’s reassurance that Val had recovered from her ordeal. She was “okay,” “fine,” “getting along” with Jack’s rehab and other tasks she’d chosen for herself.

But now she needed him again.

And Bolan wondered why.

“HOW’S JACK?” he asked as lunch arrived.

“Retired,” Val said. “I guess you knew that, though. He’s doing corporate security and helping me with some of my projects.”

“Which are?”

“I teach a class at community college now and then. Do some counseling on the side. I’ve also established a mentoring program off campus.”

“That must keep you busy,” Bolan said.

“I’m thinking of letting it go.”

He began to ask if that was part of the reason she’d summoned him here, but it didn’t make sense and he kept to his agreement to eat first and ask questions later. The food was a cut above average but nothing to write home about. Bolan ate his meal, drank some coffee and went through the motions when the waitress brought their fortune cookies.

His read, “You will take a journey soon.”

There’s a surprise.

Bolan picked up the check, dismissing Val’s objections, then accepting her reluctant thanks. Reluctance seemed to be the order of the day, in fact. Val had a vaguely worried look about her as they left the Chinese restaurant.

“Are we still driving?” Bolan asked. “My rental’s parked around the corner.”

“Mine’s right here,” Val answered, moving toward a year-old minivan. “I’ll drive.”

Johnny kept pace on crutches, telling Bolan, “I can drive, but Val says no. She’s such a mom sometimes.”

“I heard that,” Val informed him. “If it was supposed to be an insult, you need new material.”

“No insult. I’m just saying—”

“That you’re handi-capable. No argument. Just humor me, all right?”

“Okay.”

Johnny maneuvered into the backseat, while Bolan sat up front with Val. He didn’t mind the shotgun seat. It let him watch one of the minivan’s three mirrors as Val pulled out from the curb. They had no tail, as far as he could see, but he kept watching as she drove.

Habits died hard.

Soldiers who let them slip died harder.

“Do we need to sweep the van for bugs, or can we talk now?” Bolan asked.

Val cut him with a sidelong glance. “I didn’t want to get the restaurant mixed up in this,” she said.

“Mixed up in what?”

“I told you that I do some mentoring, aside from classes.”

“Right.”

“I doubt that you’ve had time to keep up with the trend,” she said. “It sounds like simple tutoring, but there’s a lot more to it. Counseling, sometimes. Guidance toward long-term life decisions if appropriate.”

“Is there some course you take for that, like special training?” Bolan asked.

“I have my counseling credential, plus the teacher’s certificate,” she answered, “but it’s mostly personal experience and observation. Listening as much as talking, maybe more. I don’t come out and tell students they should be lawyers or mechanics. If they have an interest, we address it and discuss the options. If they have problems, we talk about those, too.”

“So, how’s it going?” Bolan asked, sincerely interested.

“I’ve lost one,” Val replied.

“Say what?”

“One of my students.”

“Val—”

“I don’t mean that he’s disappeared,” she hastened to explain. “For that, I would’ve gone to the police.”

“Okay.”

“I know exactly where he is. Well, not exactly, but within a few square miles. And what he’s doing. That’s the problem.”

“Maybe you should start from the beginning.”

“Right. Okay. But promise you won’t think I’m crazy.”

“That’s a safe bet going in,” said Bolan.

“All right, then. His name’s Patrick Quinn. He turned twenty-one last weekend, but I haven’t seen him for three months. It’s thirteen weeks on Friday, if you need to pin it down exactly.”

“Close enough,” he said, and waited for the rest of it.

“He comes from money. Anyway, a lot by how they measure it in Sheridan. His parents raise cattle. They have a few million.”

“Cattle?”

“Dollars,” Johnny answered from the backseat. “Four point five and change.”

“You hacked their bank account?” Bolan asked.

Johnny shook his head. “Bear did it for me.”

Meaning, Aaron Kurtzman, boss of the computer crew at Stony Man Farm, in Virginia.

“So, the Farm’s involved in this?”

“I asked a favor,” Johnny told him. “Strictly unofficial.”

Ah. A backdoor job. But why?

“Still listening,” he told them both.

“Pat’s father wanted him in law school, but he didn’t like the paper chase. Premed was too much science. What he really wanted was a job that let him work for the environment. Something like forestry, the conservation side. It made for stormy holidays at home, to say the least.”

“And he wound up with you,” Bolan said.

“Right. First in a class I taught last year, then counseling after he set his mind on dropping out completely.”

“I guess it didn’t take?”

“We made some headway, working on a new curriculum, before the Process came to town,” Val said.

“You don’t mean that satanic outfit from the sixties, tied in with the Manson family?”

“Wrong Process,” Val corrected him. “At least, I’m pretty sure. This one’s a sect run by an African—Nigerian, I think he is—named Ahmadou Gaborone.”

“Never heard of him,” Bolan admitted.

“He’s spent a lot of time flying below the radar,” Johnny said. “No flamboyant outbursts like Moon or Jim Jones, no public investigations. He’s been sued twice on fraud charges and won both cases.”

“Fraud?”

“The usual,” Val said. “Some youngster donates all of his or her worldly goods to the Process and the parents go ballistic, claiming undue influence, coercion, brainwashing, you name it. Gaborone’s been smart enough, so far, to only bilk legal adults, and they’ve appeared for his side when the cases went to court. All smiles and sunshine, couldn’t be more happy, the usual.”

Bolan shrugged. “Maybe they are,” he said, catching the look Val gave him. “Some folks don’t function well alone. They need a preacher or some other figure of authority directing them, telling them what to think. You see it in the major churches all the time. It’s what your basic televangelists rely on, when they beg for cash.”

“This one is different,” Val informed him. “Gaborone’s not just collecting money, cars, whatever. He’s collecting souls for Judgment Day.”

“You lost me,” Bolan said.

“Recruits—converts, whatever—don’t just pony up whatever’s in their bank accounts. They also leave ‘the world,’ as Gaborone describes it, and move on to follow him. He used to have three communes in the States, in Oregon, Wyoming and upstate New York, but all his people have been called to Africa. The Congo. He’s established a community they call Obike, also known as New Jerusalem.”

“You said the Process had a compound in Wyoming,” Bolan interrupted. “Am I right in guessing that your protégé was part of it?”

“You are,” Val granted. “Now he’s gone. I’m hoping you can bring him back while there’s still time.”

VAL HAD PREPARED for meeting Bolan, talked herself through the emotions that were bound to surface at first sight, considering their history. She’d braced herself, thought she was ready, but the storm of feelings loosed inside her when she saw him in the flesh still took her by surprise. She’d managed eating, barely, and was glad when they were in the minivan, moving, her story starting to unfold. But now, she had begun to wonder if her master plan was such a great idea.

“When you say, ‘bring him back,’” Bolan replied, “you mean…?”

“To us,” she said, too quickly. “Well, of course, I mean his family.”

“Suppose he doesn’t want to come?”

“It’s likely that he won’t, at first,” she said.

“So, it’s a kidnapping you have in mind?”

“If that’s what it takes.”

“I’m not a deprogrammer, Val. I don’t save people from themselves.”

“But Patrick—”

“By your own admission, he’s an adult. Twenty-one, in fact. I don’t know what kind of donation he’s given the Process, but—”

“A few thousand,” she said. Her turn to interrupt. “His parents froze Pat’s trust fund when they found out what was happening with Gaborone.”

“So, has he been declared incompetent to run his own affairs?” Bolan asked.

“Not specifically. His parents have a pending case, but Patrick’s unavailable to testify or be deposed. It’s all in limbo now, with a judicial freeze on his accounts until the court is satisfied he’s not acting under duress.”

“A standoff, basically.”

“So far,” Val said, keeping an eye on traffic as she spoke. “But money’s not my primary concern.”

“I gathered that,” Bolan replied. “So, what’s the problem, really? Do you think he’s been abused? Mistreated? Starved?”

“There’s been no evidence of anything like that,” Johnny remarked. “All members of the Process who’ve been interviewed so far seem happy where they are.”

“In that case,” Bolan said, “I don’t see—”

“Happy messages came out of Jonestown,” Val reminded him, “until the night they drank the poisoned fruit punch. Who knows what people are really thinking, what they’re really feeling in a cult?”

“Not me,” Bolan admitted. “Which explains why I don’t normally go in for kidnapping. Unless you’ve got some evidence—”

“You haven’t heard about the Rathbun party, then?”

Bolan considered it, then shook his head. “It doesn’t ring a bell.”

“Lee Rathbun is—or was—a congressman from Southern California. Orange County, if it matters. Some of his constituents had relatives who’d joined the Process and gone off to live in Africa with Gaborone. Last week, Rathbun and five others flew to Brazzaville and on to Obike. They should’ve been back on Monday, but word is that they’ve disappeared.”

“That’s it? Just gone?”

“It smells,” Johnny said from the backseat. “First, Gaborone and his people swear up and down Rathbun’s party made their charter flight on schedule. When the cops in Brazzaville start checking, they discover that the charter pilot’s killed himself under suspicious circumstances. Killed his sister, too—who, by coincidence, was also in the Process.”

“Why the sister?” Bolan asked.

“Police report they found a note and ‘other evidence’ suggesting incest,” Val said. “They think the sister tried to end it, or the brother couldn’t bear his shame. Theories are flexible, but none of them lead back to Gaborone.”

“Too much coincidence,” Johnny declared.

“It’s odd,” Bolan agreed. “I’ll give you that.”

“Just odd?” Val didn’t try to hide the irritation in her tone.

“How were the killings done?” Bolan asked.

“With a panga,” Val replied. “That’s a big—”

“Knife, I know. The pilot stabbed himself?”

“Not quite,” Johnny said. “Seems he put his panga on the kitchen counter, then bent down and ran his throat along the cutting edge until he got the job done. Back and forth. Nearly decapitated.”

“That’s what I call focus and determination.”

“That’s what I call murder,” Val corrected him.

“Assume you’re right, which I agree is probable. Who killed the pilot? Someone from the Process? Why?”

“To silence him,” Val said. “Because he knew that Rathbun’s people didn’t make their flight to Brazzaville on time.”

“How long between their scheduled liftoff and the murder?” Bolan asked.

“Twelve hours, give or take.”

“And how long is the flight from Brazzaville to Gaborone’s community?”

“About two hours,” Johnny said.

“Leaving ten hours for the pilot to contact police and spill the beans about his missing passengers. Why no contact with 911 or the equivalent?”

“We’re guessing the pilot was bribed, threatened, or both,” Val said. “Then Gaborone or someone close to him decided it was still too risky, so they silenced him and staged it in a way that would discredit anything the pilot might’ve said before he died.”

“Okay, it plays,” Bolan agreed. “But it’s a matter for police. There’s nothing to suggest your friend’s involvement with the murders, or that he’s in any kind of danger from—”

“That’s just the point,” Val said. “He is in danger.”

“Oh?”

“The Process is an apocalyptic sect. Gaborone is one of your basic hellfire, end-time preachers, with a twist.”

“Specifically?”

“Lately, he’s started saying that it may not be enough to wait for God to schedule Armageddon. When it’s time, he says, the Lord may need a helping hand to light the fuse.”

“From Africa?”

“It’s what he heard in ‘words of wisdom’ from on high,” Johnny explained.

“I never thought the Congo had much Armageddon potential,” Bolan said.

“Depends on how you mix up the ingredients, I guess,” said Johnny. “In the time since he’s been settled at Obike, Gaborone’s had several unlikely visitors. One party from the Russian mafiya included an ex-colonel with the KGB. Two others were Islamic militants, and there’s a warlord from Sudan whose dropped in twice.”

“You don’t think they were praying for redemption,” Bolan said.

“Not even close.”

“But if we rescue Patrick Quinn, and he agrees to talk, it may all be explained.”

“Maybe,” Johnny agreed.

“Or maybe not,” Bolan counseled. “Even if he turns and gives you everything he knows, the rank and file in cults don’t often know what’s going on behind the scenes with their gurus.”

“It’s still a chance,” Val said. “And Pat deserves his chance to live a normal life.”

“Can you define that for me?” Bolan asked her, smiling.

“You know what I mean.”

“I guess.”

She saw concession in his eyes, knew he was leaning toward agreement, but she couldn’t take a chance on losing him. No matter how it hurt them both, she gave a quick tug on the line, to set the hook.

“So, will you help us, Mack?”

CHAPTER THREE

Five days after he looked into those eyes and said he would help, Bolan was marching through the Congo jungle, guided toward his target by the handheld GPS device. He found it relatively easygoing but still had to watch his step, as much for normal dangers of the rain forest as for a human threat.

Contrary to the view held by most people who have never seen a jungle, great rain forests generally weren’t choked with thick, impenetrable undergrowth. Where giant trees existed, their canopy blotted out the sky and starved most smaller plants of the sunshine they needed to thrive. Ground level, although amply watered by incessant rain, was mostly colonized by ferns and fungus growths that thrived in shade, dwelling in permanent twilight beneath their looming neighbors.

Walking through the jungle, then, was no great challenge except for mud that clung to boots or made the hiker’s feet slide out from under him. Gnarled roots sometimes conspired to trip a passerby, and ancient trees sometimes collapsed when rot and insects undercut their bases, but the jungle’s greatest danger was from predators.

They came in every size and shape, as Bolan realized, from lethal insects and arachnids to leopards and huge crocodiles. He had the bugs covered, at least in theory, with his fatigues. An odorless insect repellent was bonded to the garment fabrics, guaranteed on paper to protect against flies, mosquitoes, ticks and other pests through twenty-five machine washings. As for reptiles and mammals, Bolan simply had to watch his step, check logs and stones before he sat, beware of dangling “vines” that might have fangs and keep his distance from the murky flow of any rivers where he could.

Simple.

Camping wasn’t a problem, since his drop zone was a mere three miles from Bolan’s target. The extraction point was farther west, about five miles, but he could make it well before sundown, if all went according to plan.

And that, as always, was the rub.

Plans had a way of turning fluid once they left the drawing board and found their way into the field. Experience had taught Bolan that almost anything could happen when time came to translate strategy to action. He’d never been struck by lighting, had never watched a meteorite hurtle into the midst of a firefight, but barring divine intervention Bolan thought he’d seen it all.

People were unpredictable in most cases, no matter how you analyzed and scoped them out before an operation started. Fear, anger, excitement—those and any other feeling he could name might motivate a human being to perform some feat of cowardice or daring that was wholly unpredictable. Vehicles failed and weapons jammed. A sudden wind caused smoke to drift and fires to rage out of control. Rain turned a battleground into a swamp and rivers overflowed their banks.

One thing Bolan had learned to count on was the unexpected, in whatever form it might assume.

The jungle climate that surrounded him decreed a range of possibilities. It wouldn’t snow, he realized, unless the planet shifted on its axis—in which case it likely wouldn’t matter what a Congo cult leader was planning, one way or another. He had no reason to suspect that a volcano would erupt and drown the cult compound in molten lava. Sandstorms were unlikely in the middle of a jungle.

He started to watch for traps and sentries when he was a mile east of Obike. Bolan wasn’t sure if Gaborone’s people foraged in the jungle, but he took no chances. If the guru truly thought the Last Days were upon him—or if that was just a scam, and he was double-dealing with some kind of slick black-market action on the side—it was a fair bet that he posted guards. More likely now, if Val and Johnny were correct in their suspicion that the cult had killed a U.S. congressman and members of his entourage.

If Rathbun and his crew weren’t dead, it posed another kind of problem for the Executioner. He’d come prepared to lift one person from the compound, not to rescue seven. Even if he managed to extract that many souls, the chopper rented by Grimaldi wouldn’t seat eight passengers. He couldn’t strap them to the landing struts, and who would Bolan ask to stay behind?

Forget it, Bolan thought. They’re dead by now.

If not…

Then he’d jump off that bridge when he got to it, hoping there was time to scan the water below for hungry crocodiles.

Meanwhile, he had a job to do and it was almost time.

The GPS system led Bolan to Obike with no problem. He could smell the compound’s cooking fires and its latrines before he saw the barracks and guard towers ranged in front of him. And there were sentries, yes indeed, well armed against potential enemies.

Bolan stood watching from the forest shadows, working out a plan to infiltrate the camp to find one man among seven hundred people known to occupy this drab, unlikely New Jerusalem.

After an hour, give or take, the Executioner knew what he had to do.

“GIVE ME THE PEOPLE’S mood, Nico. I need to know what they are thinking, what they’re feeling now.”

Mbarga had expected it. The master often hatched a plan, then put it into motion, only later thinking of the consequences to himself and those around him. That was genius, in a sense—fixation on a goal, a means of solving problems, without letting daily life intrude.

But that could also be a self-destructive kind of genius, doomed to early death.

“I move among them, Master,” he replied. “And as you know, my presence urges them to silence. They work harder and talk less when I am near. We have no listening devices in the camp, so I—”

“Give me your sense of how they’re feeling, Nico. I don’t ask you for confessions of betrayal.”

Nico swallowed hard. Telling the truth was dangerous with Gaborone, but if the master later caught him in a lie that had already blown up in their faces, it could be worse yet.

“Master,” he said at last, “some of the folk are worried. Naturally, they trust your judgment in all things, but still some fear there may be repercussions over the Americans. In these days, when the White House orders bombing raids, invades whole nations without evidence, they fear our actions may yet bring about the Final Days.”

“And they fear that?” Gaborone asked. He seemed confused.

“Some do. Yes, sir.”

“After I’ve told them time and time again they must fear nothing? That the Final Days will simply be our passport into Paradise? Why would they fear a moment’s suffering, compared to that eternal bliss?”

“They’re only human, Master,” Mbarga said. “They know pain and loss from personal experience, but none have shared your glimpse of Paradise.”

“They share through me!” Gaborone said, now seeming on the verge of anger. Mbarga knew he had to calm the guru swiftly or his own well-being might be jeopardized.

“They share in words, Master, but it is not the same. You’ve seen the wonders of the other side. Despite your eloquence, unrivaled in the world today, word pictures still fall short of all that you’ve experienced in Heaven.”

“Paradise,” Gaborone said, correcting him.

“Of course, sir. I apologize.”

“How can we calm the people, Nico?”

“They need time, Master. And I will watch them closely.”

“In the matter of our visitors,” Gaborone said, “are they content?”

The delegation had arrived that morning, ferried from the jungle landing strip by Mbarga and his men. No more Americans this time, but men with money in their pockets, anxious to impress the master and do business with him. It was Mbarga’s job to keep them happy in between negotiations, and he took the job seriously.

“Both are resting now, after their midday meal,” Mbarga said. “The South American requested a companion for his bed.”

“He is a pig,” Gaborone said, “but very wealthy.”

“I sent him one of the neophytes. The Irish girl. She’ll see you later, Master, to receive her penance.”

“Ah. A wise choice, Nico. And the other?”

“He asked nothing, Master. I believe he favors young men over girls. The way he looked at some of your parishioners…”

“Enough! There is a limit to my patience.” Gaborone frowned mightily, then added, “If he should insist, choose wisely. Use your own best judgment, Nico.”

“Always, Master.”

“When I speak to them again, tonight, we may—”

The shout came from outside, somewhere across the compound. Nico heard the single word, repeated loudly.

“Fire!”

“What’s that?” asked Gaborone, distractedly.

“A cry of ‘fire,’ Master. I’ll see what—”

“Go! Hurry!” As Nico left the master’s quarters, Gaborone called after him, “And don’t disturb our guests!”

Outside, Mbarga smelled the smoke before he saw it, dark plumes rising from one of the storage sheds. What did they keep in that one? Food. Mbarga wondered if the grain in burlap sacks had grown too hot somehow, inside the shed, or if there’d been some kind of accident to start the fire.

Jaw clenched, Mbarga planned what he would do if it turned out that someone had been smoking, in defiance of the master’s edict.

He joined the flow of people rushing toward the fire, anxious to smother it or just to be a part of the excitement. He was halfway there and shoving rudely past the others when another cry went up, this one arising from the far side of the camp.

“Fire!” someone shouted over there. “Another fire!”

IT WASN’T ANYTHING high tech, but Bolan often put his trust in fire. It ranked among humanity’s best friends and oldest enemies, holding the power to inspire or panic, after all those centuries. A warm fire on the hearth might lead to passion or a good night’s sleep. Flames racing through a household or a village uncontrolled were guaranteed to set off a stampede.

He’d taken time to choose his targets, noting structures here and there around the huddled village that would burn without immediately posing any threat to human life. Storehouses, toolsheds and the like were best. And he was lucky, in that Gaborone’s community hadn’t invested in aluminum or any kind of prefab structures that were fire resistant. They used simple wood, often unpainted, and there seemed to be no fire-retardant chemicals or insulation anywhere.

His first challenge was entering the camp, but Bolan managed it. The watchtowers were manned, but by a careless breed of sentries, more inclined to talk than to scan the tree line for approaching enemies. The guards on foot were spread too thin, and no fence had been raised to help them keep intruders from the village proper. Bolan waited, chose his moment, and crept in when those who should’ve tried to stop him were distracted, feeling lazy in the heat of early afternoon. A light rain shower that had fallen while he circled the perimeter wasn’t refreshing; quite the opposite, in fact.

But luck was with him. As the atmosphere conspired with Bolan to seduce his enemies, so he was shown the young man he had come to find. Bolan carried no photograph of Patrick Quinn. He’d memorized it and returned it to the slim file Val and Johnny had presented to him in Wyoming. He would know Quinn if they met, though, and the straggly wisps of beard his quarry had been cultivating in the past few weeks did little to conceal his face, when Bolan saw him coming out of the latrine.

Quinn had a listless air about him, but that seemed to be the rule for tenants of Obike. He wore what seemed to be the standard uniform for male inhabitants, a pair of faded denim pants with rope pulled through the belt loops, and an off-white cotton shirt. Long sleeves despite the heat, but no one seemed to mind. None of the sleeves he’d seen so far had been rolled up. Perhaps it was another of the guru’s rules.

Quinn had lost weight since he was photographed, and there was no trace of a smile in evidence. Bolan watched as the young man walked from the latrine to one of several barracks buildings on the north side of the compound, went inside and closed the door behind him. Even with the windows open, Bolan guessed it had to have been a sweatbox there, inside.

After determining where Quinn was, Bolan set his fires accordingly. Obike’s honor system helped him, since he found no locks upon the doors, and the midday siesta minimized his contact with the villagers. Bolan met one along the way, about Quinn’s age, unarmed but ready to alert the camp before strong fingers clamped his windpipe shut and Bolan’s fist rocked him to sleep. He bound the young man’s hands with trouser twine and gagged him with the severed tail of his own shirt, then stashed him in a toolshed, propped against a bank of hoes and rakes.

He had gone on from there to set three fires, slow-burners, sited to draw villagers away from Quinn’s barracks and focus their attention elsewhere. The first alarm was shouted moments after Bolan found his hiding place beside the target building, crouched in a convenient shadow.

Those cries of “Fire!” had the desired result. Guards rushed to find out what was happening, while sleepy villagers emerged more slowly from their gender-segregated clapboard dormitories. Bolan watched and waited, heard men stirring just beyond the wall that sheltered him. He couldn’t pick Quinn’s voice out of the babble, but it made no difference.

Leaving his rifle slung, Bolan removed the hypodermic needle from its cushioned case and held it ready in his hand.

NOW WHAT? Patrick Quinn thought. He’d barely fallen back to sleep after his trek to the latrine, and now the sounds of crisis roused him from a troubled dream whose fragments blew away before his mind could catch and hold them.

Someone shouting from a distance. And what were they saying?

“Fire! Fire!”

Quinn bolted upright on his cot, no blankets to restrain him in the stuffy room’s oppressive heat. Around him, others were already on their feet, repeating the alarm in half a dozen languages.

“Hurry!” someone declared.

A new round of warning shouts rose from a different part of the village, bringing a frown to Quinn’s face. Two fires at the same time? Quinn wondered whether it was one of Master Gaborone’s incessant drills. They’d been more frequent lately, since the incident with the American film crew, and failure to perform was bound to mean some sort of punishment.

Quinn started for the door, then hesitated. That was smoke he smelled, no doubt about it. Would the master go that far to make his practice exercise seem real? He wasn’t known for using props, and yet—

When the third cry of “Fire!” rent the air, rising from yet another part of the village, Quinn knew something was wrong. The master’s drills were never that elaborate. He simply sent his guards around to roust the people from their beds or jobs and send then streaming toward the sectors designated as emergency retreats.

A real fire, then—or fires, to be more accurate. When was the last time that had happened? Never, since Quinn first set foot inside the compound.

Sudden fear surprised him, but he had a duty to perform. Each member of the congregation had a role to play, whether at work or in response to situations unforeseen. Quinn reckoned he could be of service to the master and his fellow congregants, if he could just suppress his fear and trust the prophet’s message.

Feeling childish, now that all the others had gone on ahead of him, Quinn rushed the door and made his way outside. He hesitated on the dormitory’s simple wooden steps—all of the buildings in Obike had been raised to keep out snakes and vermin, though Quinn thought the shady crawl spaces beneath had to be like breeding grounds—and scanned the village, seeking out the plumes of rising smoke.

Three fires, spaced well apart, and what could be their cause? Quinn shrugged off the question. That wasn’t his concern. The first job was to douse the fires before they spread and did more damage to the village. Hopefully, no one was injured yet and they would not have lost any vital supplies.

Quinn chose the blur of smoke and frantic action closest to his barracks, on his left, and moved in that direction. He had barely taken two strides past the corner, homing on his destination, when a strong arm clamped around his neck and someone dragged him backward, toward the shadows at the east end of the dormitory.

Quinn resisted, would’ve cried for help if he could speak, but speech and breath alike were suddenly denied him. With his fingernails, he tried to claw the arm that held him fast, but fabric stopped him gouging flesh. He kicked back, barefoot, striking someone’s shin without significant effect.