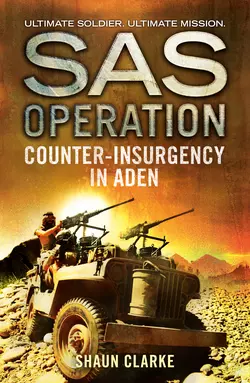

Counter-insurgency in Aden

Shaun Clarke

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But will the SAS be able to rid Yemen of its unstoppable guerrillas?Aden, 1964, and the British are waging two different kinds of war.Inhabitants of northern Yemen’s forbidding mountainous region of Radfan are conducting guerrilla attacks against the British. Armed by the Egyptians and trained by the communist Yemenis, they seem an invincible fighting force.With only one hope of beating them, the British draft in an even more tenacious group of soldiers – the SAS! Their mission: to parachute into enemy territory at night, establish concealed observation posts high in the mountains, and direct air strikes on the rebels moving through the sun-baked passes.At the same time, in an even more dangerous campaign, two- or three-man SAS teams disguised as Arabs must infiltrate the souks and bazaars of the port of Aden in an attempt to ‘neutralise’ leading members of the National Liberation Front. But will their disguise allow them to get close enough to their targets, or get out again alive…?

Counter-insurgency in Aden

SHAUN CLARKE

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover Photographs © www.piciubrothers.altervista.org (http://www.piciubrothers.altervista.org) (main image); Shutterstock.com (textures)

Shaun Clarke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155063

Ebook Edition © November 2015 ISBN: 9780008155070

Version: 2015-10-29

Contents

Cover (#u96d54a7a-b317-5f1d-b43e-821d48d0974f)

Title Page (#uc9f91ced-8e10-5cbb-97d5-7e3ca8a0c8c6)

Copyright (#ud37d9e00-1a48-5513-be97-4be6eac3dfa2)

Prelude (#u4cb10f7a-7bfd-5f57-91d8-826b33472f5d)

Chapter 1 (#u9f27a252-7bf1-53c7-a5e4-98870bceccb4)

Chapter 2 (#u222f3ebc-60cf-5b8f-979e-cdd71c6383d4)

Chapter 3 (#u5e13980e-adbd-500f-af6c-da1f74a97517)

Chapter 4 (#u78d1910e-1218-5210-906c-26357c5fdf77)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prelude (#u4d86fdb7-72f8-53f2-8e0f-8b1600163f65)

The port of Aden is located on a peninsula enclosing the eastern side of Bandar at-Tawahi, Aden’s harbour. It is bounded to the west and north-west by Yemen, to the north by the great desert known as the Rub’ al-Khali, the Empty Quarter, to the east by Oman, and to the south by the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. Though a centre of trade since the days of antiquity, and mentioned in the Bible, the city in 1964 looked less than appealing.

Standing beside his wife, Miriam, on the deck of the P & O liner Himalaya, Norman Blakely, emigrating to Australia from Winchester, where he had taught ancient history at the renowned public school, realized he had known all these facts since his own school days. He certainly recognized the features he had often read about, yet he felt a certain disappointment at what he was seeing, not least the surprising modernity of the place.

Even from this distance, beyond the many rowing boats and motor launches dotted about the mud-coloured waters of the harbour, Aden was no more than an untidy sprawl of white-painted stone tower buildings and warehouses surrounded by an ugly clutter of jibs and cranes, immense oil tanks and huge lights raised high on steel gantries – all hemmed in on two sides by the promontories of Jebel Shamsan (Aden) and Jebel Ihsan (Little Aden). Both of these short necks of bleached volcanic rock thrust out from, and were dominated by, an equally unattractive maritime mountain range that varied from 1000 to 2000 feet and was constantly shadowed by depressing grey clouds.

Rising up the lower slopes of the mountains behind the town, about a mile beyond it, was a roughly triangular maze of low, white-painted buildings, which Norman assumed was the old commercial centre known as the Crater. What he did not know – even though he and the other passengers had received a leaflet gently warning them of the ‘occasional’ dangers of Aden – is that it was the home of the most dangerous anti-British terrorists in that troublesome country.

‘If the town’s as depressing as it looks from here,’ Norman said to Miriam, ‘we’ll take a taxi up to the Crater. It’s almost certainly less commercialized than Aden proper – and hopefully more like the real thing.’

‘That leaflet said not to wander too far from the port area,’ Miriam reminded him.

‘The authorities always exaggerate these situations for their own reasons,’ Norman said with conviction. ‘In this instance, they doubtless want us to remain in the port area because that’s where all the duty-free goods are sold. They just want to make money. Such goods aren’t sold up in the Crater, so that’s where we’ll go.’

Trade in a particular kind of duty-free goods was already taking place in the water below them, where the ‘bum boats’ were packed tightly together by the hull of their ship and stacked high with a colourful collection of souvenirs and other cheap merchandise piled high in wooden crates and cardboard boxes. On offer were ‘hand-tooled’ – in fact, mass-produced – leather purses and wallets; cartons of Senior Service, Players, Woodbine and Camel cigarettes; Zenith 8×30 binoculars, sold in sealed boxes, many of which were fake and did not work; 35mm SLR cameras; transistor radios; counterfeit Rolex wristwatches; and even cartons of Colgate toothpaste. The goods were being sold by shrieking, gesticulating Arabs dressed in a colourful variety of garments, from English shirts and trousers to sarongs and turbans, though all wore thongs about their legs.

The Arabs were bartering by shouting preliminary prices and sending their wares up for inspection in baskets tied to ropes that had been hurled up to the passengers, who had obligingly tied them to the ship’s railing. The individual passenger then either lowered the goods back down in the basket or removed them and deposited the agreed amount of money in their place.

While this noisy, good-natured barter was being conducted between the passengers and the Arab vendors below, other passengers were throwing coins into the water between the bum boats and watching Arab children dive from the jetty for them.

Ignoring these activities, Norman led his wife down the swaying gangplank to embark on the sixty-man transit boat that would take them the short distance to the quay. The latter was guarded by uniformed British soldiers, some in shorts, others in lightweight trousers, some armed with Sten guns or self-loading rifles, others with pistols holstered at their hips.

The sight of the soldiers made Miriam more nervous.

‘Are you sure this is wise?’ she asked Norman.

‘Of course,’ he said resolutely, but with a hint of irritation, for his wife was the anxious type. ‘Can’t let a few tin soldiers bother us. Besides, they’re here for our protection, so you’ve no need to fear.’

‘There’s a war going on here, dear.’

‘Between Yemeni guerrillas and the British army, mostly up in the mountains. Not down here, Miriam.’ He tugged impatiently at her hand. ‘Come on! Let’s explore.’

Walking through the arched entrance of the Aden Port Trust, which was guarded by more British troops, Norman and Miriam stepped into Tawahi Main Road, where they were suddenly assailed by the noise of traffic and a disorientating array of signs in Arabic and English. Stuck on the wall by the entrance was a small blue rubbish bin with a notice saying, in English only: Keep Your Town Clean. Another sign said: Aden Field Force – Forging an Empire. Left of the entrance, lined up against a wire-mesh fence surmounted by three strands of menacing barbed wire which protected the building, was a taxi rank whose drivers, all Arabs wearing a mixture of sarongs, turbans and loose shirts, were soliciting custom from the Himalaya’s emerging passengers. Other Muslims were carrying with one hand trays piled high with bananas, selling steaming rice-based dishes from blue-painted, wheeled barrows, or dispensing water for a price, dishing it out by the ladleful from a well-scrubbed steel bucket.

An enthusiastic armchair traveller on his first real trip away from home, Norman was keen to see the harbour area, which he knew was called Ma’alah. Politely rejecting the services of the beaming, gesturing taxi drivers, he led his wife through the teeming streets. He was instantly struck by the exotic variety of the people – mostly Sunni Muslims, but with a smattering of Saydi Muslims from the northern tribes of northern Yemen, as well as small groups of Europeans, Hindus and Yemeni Jews.

However, the history teacher was slightly put off by the sheer intensity of the noisy throng, with its cripples, blind men, thieves with amputated hands, grimy, shrieking children, armed soldiers, both British and Federation of South Arabia, along with goats, cows and mangy dogs. He was also disillusioned by the forest of English shop signs above the many stores stacked with duty-free goods. Everywhere they looked, Norman and his increasingly agitated wife saw signs advertising Tissot and Rolex wristwatches, Agfa and Kodak film, BP petrol.

A soldier from the Queen’s Own Highlanders, complete with self-loading rifle (SLR), water bottle and grim, watchful face, stood guard at a street corner by the Aden Store Annexe – the sole agent for Venus watches, proudly displayed in their hundreds in the shop window – under a sign showing the latest 35mm cameras. In another street, the London Store, Geneva Store and New Era Store stood side by side – all flat-fronted concrete buildings with slatted curtains over window-shaped openings devoid of glass – with buckets, ladders and the vendors’ chairs outside and the mandatory soldiers parading up and down. In a third street, the locals were practically jammed elbow to elbow under antique clocks and signs advertising hi-fi systems, televisions and photographic equipment, while the tourists, either seated on chairs or pressed back against the walls by the tide of passers-by, bartered for tax-free goods, oblivious to the armed troops standing watchfully beside them.

As well as blind and crippled beggars, including one who hopped along on his hands and knees like a human spider, the streets were packed with fast-talking Arabs selling phoney Rolex wristwatches and Parker pens. Honking Mercedes, Jaguars and more modest Volkswagen Beetles all had to make their slow progress not only through the teeming mass of humans, but also through the sea of livestock and undernourished dogs.

Towering over the town, the mountains appeared to run right down to the streets, sun-bleached and purplish in the grey light, with water conduits snaking along their rocky slopes.

Stopping by the Miramar Bazaar, Norman wiped sweat from his face, suddenly realized that the heat was appalling, and decided that he had had enough of this place. Apart from its few remaining Oriental features, it was all much too modern and commercialized for his liking.

‘Let’s take a taxi to the Crater,’ he said.

‘It’s called Crater,’ Miriam corrected him pedantically. ‘Not the Crater…And I don’t think we should go up there, dear. It’s supposed to be dangerous.’

‘Oh, tosh!’ Norman said impatiently, eager to see the real Aden. ‘It can’t be any worse than this filthy hole. Besides, you only live once, my love, so let’s take our chances.’

So packed was the street with shops, stalls, animals and, above all, people, that the cars could only inch forward, their frustrated drivers hooting relentlessly. It took Norman some time to find a vacant taxi, but eventually the couple were driven out of town, along the foot of the mountains, to arrive a few minutes later at the foetid rabbit warren of Crater.

Merely glancing out the window at the thronging mass of Arabs in the rubbish-strewn street, wreathed in smoke from the many open fires and pungent food stalls, was enough to put Miriam off. She was disconcerted even more to realize, unlike in the harbour area, there were no British soldiers guarding the streets.

‘Let’s go back, dear,’ she suggested, touching Norman’s arm.

‘Rubbish! We’ll get out and investigate,’ he insisted.

After the customary haggling, Norman paid the driver and started out of the taxi. However, just as he placed his right foot on the ground, a dark-skinned man wearing an Arab robe, or futah, and on his head a shemagh, rushed past him, reaching out with his left hand to roughly push him back into the cab.

Outraged, Norman straightened up and was about to step out again when the same Arab reached under his futah and took out a pistol with a quick, smooth sweep of his right hand. Spreading his legs to steady himself, he took aim at another Arab emerging from the mud-brick house straight ahead. He fired six shots in rapid succession, punching the victim backwards, almost lifting him off the ground and finally bowling him into the dirt.

Even as Miriam screamed in terror and others bawled warnings or shouted out in fear, the assassin turned back to the deeply shocked couple.

‘Sorry about that,’ he said in perfect English, then again pushed Norman back into the taxi and slammed the door in his face. He was disappearing back into the crowd as the driver noisily ground his gears, made a sharp U-turn and roared off the way he had come, the dust churned up by his spinning wheels settling over the dead Arab on the ground.

Shocked beyond words, no longer in love with travelling, Norman trembled in the taxi beside his sobbing wife and kept his head down. Mercifully, the taxi soon screeched to a halt at the archway leading into the Aden Port Trust, where their ship was docked.

‘He was English!’ Norman eventually babbled. ‘That Arab was English!’

Miriam sobbing hysterically in his arms, he hurried up the gangplank, glad to be back aboard the ship and on his way to Australia.

‘He was English!’ he whispered, as they were swallowed up by the welcoming vastness of the Himalaya.

1 (#u4d86fdb7-72f8-53f2-8e0f-8b1600163f65)

The Hercules C-130 transport plane bounced heavily onto the runway of Khormaksar, the RAF base in Aden. Roaring even louder than ever, with its flaps down, it threw the men in the cramped hold together as it trundled shakily along the runway. Having been flown all the way from their base at Bradbury Lines, Hereford, via RAF Lyneham, Wiltshire, the men of D Squadron SAS were glad to have finally arrived. Nevertheless they cursed a good deal as they sorted out their weapons, water bottles, bergen rucksacks, ammunition belts and other kit, which had been thrown together and become entangled during the rough landing.

‘This pilot couldn’t ride a bike,’ Corporal Ken Brooke complained, ‘let alone fly an aeroplane.’

‘They’re pilots because they’re too thick to do anything else,’ Lance-Corporal Les Moody replied.

‘Stop moaning and get ready to disembark,’ Sergeant Jimmy ‘Jimbo’ Ashman told them. ‘That RAF Loadmaster’s already preparing to open the door, so we’ll be on the ground in a minute or two and you can all breathe fresh air again.’

‘Hallelujah!’ Ken exclaimed softly.

In charge of the squadron was the relatively inexperienced, twenty-four-year-old Captain Robert Ellsworth. A recent recruit from the Somerset and Cornwall Light Infantry, the young officer had a healthy respect for the superior experience of the troops who had already served the Regiment well in Malaya and Borneo, particularly his two sergeants, Jimmy Ashman and Richard Parker. The former was an old hand who had started as a youngster with the Regiment when it was first formed in North Africa way back in 1941 under the legendary David Stirling. Jimbo was a tough, fair, generally good-natured NCO who understood his men and knew how to get things done.

Parker, known as Dead-eye Dick, or simply Dead-eye, because of his outstanding marksmanship, was more of a loner, forged like steel in the hell of the Telok Anson swamp in Malaya and, more recently, in what had been an equally nightmarish campaign in Borneo. Apart from being the best shot and probably the most feared and admired soldier in the Regiment, Parker was also valuable in that he had spent his time since Borneo at the Hereford and Army School of Languages, adding a good command of Arabic to his other skills.

Another Borneo hand, Trooper Terry Malkin, who had gone there as a ‘virgin’ but received a Mention in Dispatches for his bravery, was in Aden already, working under cover with one of the renowned ‘Keeni-Meeni’ squads. As a superior signaller Terry would be sorely missed for the first few weeks, though luckily he would be returning to the squadron in a few weeks’ time, when his three-month stint in Aden was over.

Three NCOs who had also been ‘broken in’ in Borneo, though not with the men already mentioned, were among those preparing to disembark from the Hercules: the impetuous Corporal Ken Brooke, the aptly named Lance-Corporal Les Moody and the medical specialist, Lance-Corporal Laurence ‘Larry’ Johnson. All were good, experienced soldiers.

Two recently badged troopers, Ben Riley and Dennis ‘Taff’ Thomas, had been included to make up the required numbers and be trained under the more experienced men. All in all, Captain Ellsworth felt that he was in good company and hoped to prove himself worthy of them when the campaign began.

The moment the Hercules came to a halt, the doors were pushed open and sunlight poured into the gloomy hold. Standing up with a noisy rattling of weapons, the men fell instinctively into two lines and inched forward, past the stacked, strapped-down supply crates, to march in pairs down the ramp to the ground. Once out of the aircraft, they were forced to blink against the fierce sunlight before they could look about them to see, parked neatly along the runway, RAF Hawker Hunter ground-support aircraft, Shackleton bombers, Twin Pioneer transports, and various helicopters, including the Sikorski S-55 Whirlwind, which the squadron had used extensively in Malaya and Borneo, and the ever-reliable Wessex S-58 Mark 1. Bedford three-ton lorries, Saladin armoured cars and jeeps with rear-mounted Bren light machine-guns were either parked near the runway or cruising along the tarmac roads between the corrugated tin hangars and concrete buildings. Beyond the latter could be seen the sun-scorched, volcanic rock mountains that encircled and dominated the distant port of Aden.

The fresh air the men had hoped to breathe after hours in the Hercules was in fact filled with dust. Their throats dried out within seconds, making them choke on the dust when they tried to breathe, and they all broke out in sweat the instant they stepped into the suffocating heat.

‘Jesus!’ Ken hissed. ‘This is worse than Borneo.’

‘I feel like I’m burning up,’ Les groaned. ‘Paying for my sins.’

‘Pay for those and you’ll burn for ever,’ Jimbo told him, breaking away from a conversation with Captain Ellsworth and Sergeant Parker. ‘Now pick up your gear and head for those Bedfords lined up on the edge of the runway. We’ve a long way to go yet.’

‘What?’ the newly fledged trooper Ben Riley asked in shock, practically croaking in the dreadful humidity and wiping sweat from his face.

‘We’ve a long way to go yet,’ Jimbo repeated patiently. ‘Sixty miles to our forward base at Thumier, to be exact. And we’re going in those Bedfords parked over there.’

‘Sixty miles?’ Ben asked, as if he hadn’t heard the sergeant correctly. ‘You mean now?

‘That’s right, Trooper. Now.’

‘Without a break?’

‘Naturally, Trooper.’

‘I think what he means, Sergeant,’ the other recently badged trooper, Taff Thomas, put in timidly, aware that the temperature here could sometimes rise to 150 degrees Fahrenheit, ‘is that a two-week period is normally allowed for acclimatization to this kind of heat.’

Ken and Larry laughed simultaneously.

‘That’s for the bleedin’ greens,’ Les explained, referring to the green-uniformed regular Army. ‘Not for the SAS. We don’t expect two weeks’ paid leave. We just get up and go.’

‘Happy, Troopers?’ Jimbo asked. Both men nodded, keen to do the right thing. ‘Right, then, get up in those Bedfords.’

The men did as they were told and soon four three-tonners were leaving the RAF base. They were guarded front and rear by British Army 6×6-drive Saladin armoured cars, each with a 76mm QF (quick-firing) gun and a Browning .30-inch machine-gun. The convoy trundled along a road that was lined with coconut palms and ran as straight as an arrow through a flat desert plain covered with scattered clumps of aloe and cactus-like euphorbia.

As the Bedfords headed towards the heat-hazed, purplish mountains that broke up the horizon, the coconut palms gradually disappeared and the land became more arid, but with a surprisingly wide variety of trees – acacias, tamarisks, jujube and doum palms – breaking up the desert’s monotony.

Once they were well away from Aden, out on the open plain, the heat became even worse and was made bearable only by the wind created by the lorries. This wind, however, churned up dense clouds of dust that made most of the men choke and, in some cases, vomit over the rattling tailgates.

‘Heave it up over the back,’ Jimbo helpfully instructed Ben as he tried to hold his stomach’s contents in with pursed lips and bulging cheeks. ‘If you do it over the side and that wind blows it back in, over us, you’ll have to lick us clean with your furry tongue. So do it over the rear, lad.’

His cheeks deathly white and still bulging, the trooper nodded and threw himself to the back of the vehicle, hanging over the tailgate and vomiting unrestrainedly into the cloud of dust being churned up by the wheels. He was soon followed by his fellow trooper, Taff Thomas, who picked the exact same spot to empty his tortured stomach, while the more experienced men covered their faces with scarves and either practised deep, even breathing or amused themselves with some traditional bullshit.

‘Don’t worry about it,’ Ken said to Taff as the latter wiped his mucky lips clean with a handkerchief and tried to control his heavy breathing. ‘You’ll feel better after you’ve had a good nosh at Thumier. Great grub they do there. Raw liver, tripe, runny eggs, oysters, octopus, snails that look like snot, green pea soup…’

Taff groaned and went to throw up again over the back of the bouncing, rattling Bedford, into boiling, choking clouds of sand.

‘Bet you’ve never eaten a snail in your life,’ Larry said, more loudly than was strictly necessary. ‘That’s nosh for refined folk.’

‘Refined?’ Ken replied, glancing sideways as Taff continued heaving over the tailgate. ‘What’s so refined about pulling a piece of snot out of a shell and letting it slither down your throat? That’s puke-making – not refined.’

‘Ah, God!’ Ben groaned, then covered his mouth with his soiled handkerchief as he shuddered visibly.

‘Throw up in that,’ Jimbo warned him, ‘and I’ll make you wipe your face with it. Go and join your friend there.’

Shuddering even more violently, Ben dived for the tailgate, hanging over it beside his heaving friend.

‘A little vomit goes a long way,’ Ken said. ‘Across half of this bloody desert, in fact. I never knew those two had it in ’em. It just goes to show.’

Men in the other Bedfords were suffering in the same way, but the column continued across the desert to where the lower slopes of the mountains, covered in lava, with a mixture of limestone and sand, made for an even rougher, slower ride. Here there were no trees, so no protection from the sun, and when the lorries slowed to practically a crawl – which they had to do repeatedly to navigate the rocky terrain – they filled up immediately with swarms of buzzing flies and whining, biting mosquitoes.

‘Shit!’ Les complained, swiping frantically at the frantic insects. ‘I’m being eaten alive here!’

‘Malaria’s next on the list,’ Ken added. ‘That bloody Paludrine’s useless.’

‘Why the hell doesn’t this driver go faster?’ Larry asked as he too swatted uselessly at the attacking insects. ‘At this rate, we might as well get out and walk.’

‘It’s the mountains,’ Ben explained, feeling better for having emptied his stomach and seemingly oblivious to the insects. ‘This road’s running across their lower slopes, which are rocky and full of holes.’

‘How observant!’ Ken exclaimed.

‘A bright lad!’ Les added.

‘Real officer material,’ Larry chimed in. ‘These bleedin’ insects only go for red blood, so his must be blue.’

‘I’m never bothered by insects,’ Ben confirmed. ‘It’s odd, but it’s true.’

‘How’s your stomach?’ Ken asked the trooper.

‘Feeling sick again?’ queried Les.

‘I can still smell his vomit from an hour ago,’ Larry said, ‘and it’s probably what attracted these bloody insects. They’re after his puke.’

Ben and Taff dived simultaneously for the rear of the lorry and started heaving yet again while the others, feeling superior once more, kept swatting at and cursing the insects. This went on until the Bedford bounced down off the slopes and headed across another relatively flat plain of limestone, sandstone and lava fields. They had now been on the Dhala road for two hours, but it seemed longer than that.

Mercifully, after another hour of hellish heat and dust, with the sun even higher in a silvery-white sky, they arrived at the SAS forward base at Thumier, located near the Habilayn airstrip, sixty miles from Aden and just thirty miles from the hostile Yemeni border.

‘We could have been flown here!’ Ben complained.

‘That would have been too easy,’ Ken explained. ‘For us, nothing’s made easy.’

In reality the camp was little more than an uninviting collection of tents pitched in a sandy area surrounded by high, rocky ridges where half a dozen SAS observation posts, hidden from view and swept constantly by dust, recced the landscape for enemy troop movements. There were no guards at the camp entrance because there were no gates; nor was there a perimeter fence. However, the base was surrounded by sandbagged gun emplacements raised an equal distance apart in a loose circular shape and nicknamed ‘hedgehogs’ because they were bristling with 25-pounder guns, 3-inch mortars, and Browning 0.5-inch heavy machine-guns. Though the landscape precluded the use of aeroplanes, a flattened area of desert near one of the hedgehogs was being used as a helicopter landing pad, on which were now parked the camp’s helicopters, including a Sikorski S-55 Whirlwind and a British-built Wessex S-58 Mark 1. The Bedfords of A Squadron were lined up near the helicopters. A line of men, mostly from that squadron, all with tin plates and eating utensils, was inching into the largest tent of all – the mess tent – for their evening meal. A modified 4×4 Willys jeep, with armoured perspex screens and a Browning 0.5-inch heavy machine-gun mounted on the front, was parked outside the second largest tent, which was being used as a combined HQ and briefing room. Other medium-sized tents were being used as the quartermaster’s store, armoury, NAAFI and surgery. A row of smaller tents located near portable showers and boxed-in, roofless chemical latrines were the make-do ‘bashas’, or sleeping quarters. Beyond those tents lay the desert.

‘Home, sweet fucking home,’ Les said in disgust as he clambered out of the Bedford to stand beside his mate Ken and the still shaky troopers, Ben and Taff, in the unrelenting sunlight. ‘Welcome to Purgatory!’

Ken turned to Ben and Taff, both of whom were white as ghosts and wiping sweat from their faces. ‘Feel better, do you?’ he asked.

‘Yes, Corporal,’ they both lied.

‘The vomiting’s always followed by diarrhoea,’ Ken helpfully informed them. ‘You’ll be shitting for days.’

‘It rushes out before you can stop it,’ Les added. ‘As thin as pea soup. It’s in your pants before you even know you’ve done it. A right fucking mess, it makes.’

‘Christ!’ Ben exclaimed.

‘God Almighty!’ Taff groaned.

‘Keep your religious sentiments to yourselves,’ Jimbo admonished them, materializing out of the shimmering heat haze to study them keenly. ‘Are you two OK?’

‘Yes, Sarge,’ they both answered.

‘You look a bit shaky.’

‘I’m all right, Sarge,’ Ben said.

‘So am I,’ Taff insisted.

‘They don’t have any insides left,’ Ken explained. ‘But apart from that, they’re perfectly normal.’

Jimbo was too distracted to take in the corporal’s little joke. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘So pick up your kit, hump it over to those tents, find yourselves a basha, have a smoko and brew-up, then meet me at the quartermaster’s store in thirty minutes precisely. Get to it.’

When Jimbo had marched away, the weary men humped their 60-pound bergens onto their backs, picked up their personal weapons – either 5.56mm M16 assault rifles, 7.62mm L1A1 SLRs or 7.62mm L42A1 bolt-action sniper rifles – and marched across the dusty clearing to the bashas. Because the two new troopers had been placed in their care, Ken and Les were to share a tent with Ben and Taff.

‘Well, it isn’t exactly the Ritz,’ Ken said, leaning forward to keep his head from scraping the roof of the tent, ‘but I suppose it’ll do.’

‘They wouldn’t let you into the Ritz,’ Les replied, ‘if you had the Queen Mother on your arm. This tent is probably more luxurious than anything you’ve had in your whole life.’

‘Before I joined the Army,’ Ken replied, swatting uselessly at the swarm of flies and mosquitoes at his face, ‘when I was just a lad, I lived in a spacious two-up, two-down that had all the mod cons, including a real toilet in the backyard with a nice bolt and chain.’

‘All right, lads,’ Les said to Ben and Taff, who were both wiping sweat from their faces, swatting at the flies and mosquitoes, and nervously examining the sandy soil beneath the camp-beds for signs of scorpions or snakes, ‘put your bergens down, roll your sleeping bags out on the beds, then let’s go to the QM’s tent for the rest of our kit.’

‘More kit?’ Ben asked in disbelief as he gratefully lowered his heavy bergen to the ground, recalling that it contained a hollow-fill sleeping bag; a waterproof one-man sheet; a portable hexamine stove with blocks of fuel; an aluminium mess tin, mug and utensils; a brew kit, including sachets of tea, powdered milk and sugar; spare radio batteries; water bottles; extra ammunition; matches and flint; an emergency first-aid kit; signal flares; and various survival aids, including compass, pencil torch and batteries, and even surgical blades and butterfly sutures.

‘Dead right,’ Les said with a sly grin. ‘More kit. This is just the beginning, kid. Now lay your sleeping bag out and let’s get out of here.’

Jimbo and Dead-eye were sharing the adjoining tent with the medical specialist, Larry, leaving the fourth bed free for the eventual return of their squadron signaller, Trooper Terry Malkin. After picking a bed, each man unstrapped his bergen, removed his sleeping bag, rolled it out on the bed, then picked up his weapon and left the tent, to gather with the others outside the quartermaster’s store.

‘A pretty basic camp,’ Jimbo said to Dead-eye as they crossed the hot, dusty clearing.

‘It’ll do,’ Dead-eye replied, glancing about him with what seemed like a lack of interest, though in fact his grey gaze missed nothing.

‘Makes no difference to you, does it, Dead-eye? Just another home from home.’

‘That’s right,’ Dead-eye said quietly.

‘What do you think of the new men?’

‘They throw up too easily. But now that they’ve emptied their stomachs, they might be OK.’

‘They’ll be all right with Brooke and Moody?’

‘I reckon so.’

The four men under discussion were already gathered together with the rest of the squadron, waiting to collect the balance of their kit. Already concerned about the weight of his bergen, Ben was relieved to discover that the additional kit consisted only of a mosquito net, insect repellent, extra soap, an aluminium wash-basin, a small battery-operated reading lamp for use in the tent, a pair of ankle-length, rubber-soled desert boots, a DPM (disruptive pattern material) cotton shirt and trousers, and an Arab shemagh to protect the nose, mouth and eyes from the sun, sand and insects.

‘All right,’ Jimbo said when the men, still holding their rifles in one hand, somehow managed to gather the new kit up under their free arm and stood awkwardly in the fading light of the sinking sun, ‘carry that lot back to your tents, leave it on your bashas, then go off to the mess tent for dinner. Report to the HQ tent for your briefing at seven p.m. sharp…Are you deaf? Get going!’

Though dazed from heat and exhaustion, the men hurried back through the mercifully cooling dusk to raise their mosquito nets over the camp-beds. This done, they left their kit under the nets and then made their way gratefully to the mess tent. There they had a replenishing meal of ‘compo’ sausage, mashed potatoes and beans, followed by rice pudding, all washed down with hot tea.

While eating his meal, Les struck up a conversation with Corporal Jamie McBride of A Squadron, who had just returned from one of the OPs located high in the Radfan, the bare, rocky area to the north of Aden.

‘What’s it like up there?’ Les asked.

‘Hot, dusty, wind-blown and fart-boring,’ McBride replied indifferently.

‘Good to get back down, eh?’

‘Right,’ the corporal said.

‘I note we have a NAAFI tent,’ Les said, getting to the subject that concerned him the most. ‘Anything in it?’

‘Beer and cigarettes,’ the weary McBride replied.

‘Anything else?’

‘Blue magazines and films, whores, whips and chains…What do you think?’

‘Just asking, mate. Sorry.’

Realizing that his fellow soldier was under some stress, Les gulped down the last of his hot tea, waved his hand in farewell, then followed the others out of the mess tent.

‘Another fucking briefing,’ he complained to Ken as they crossed the clearing to the big HQ tent. ‘I need it like a hole in the head.’

‘You’ve already got that,’ his mate replied. ‘Between one ear and the other there’s nothing but a great big empty space.’

‘Up yours an’ all,’ said Les wearily.

2 (#u4d86fdb7-72f8-53f2-8e0f-8b1600163f65)

The men were briefed by their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick ‘Paddy’ Callaghan, with whom most of them had recently served in Borneo and who was now on his last tour of duty. Wearing his SAS beret with winged-dagger badge, in DPM trousers, desert boots and a long-sleeved cotton shirt, Callaghan was standing on a crude wooden platform, in the large, open-ended HQ tent, in front of a blackboard covered with a map of Yemen. Seated on wooden chairs on the platform were his second in command, Major Timothy Williamson, and the Squadron Commander, Captain Ellsworth. The members of D Squadron were in four rows of metal chairs in front of Callaghan, their backs turned to the opening of the tent, which, as evening fell, allowed a cooling breeze to blow in.

Outside, a Sikorski S-55 Whirlwind was coming in to land before last light, the noise of Bedfords and jeeps was gradually tapering off, NCOs were bawling their last instructions of the day at their troops and Arab workers, and the 25-pounders in the hedgehogs around the perimeter were firing their practice rounds, as they did every evening.

It was a lot of noise to talk against, but after the usual introductory bullshit between himself and his impatient, frisky squadron of SAS troopers, Lieutenant-Colonel Callaghan knuckled down to the business at hand, only stopping periodically to let some noise from outside fade away.

‘I might as well be blunt with you,’ he began. ‘What we’re fighting for here is a lost cause created by our lords and masters, who are attempting to leave the colony while retaining a presence here at the same time. Most of you men are experienced enough from similar situations to know that this is impossible, but it’s the situation we’ve inherited and we’re stuck with it.’

‘We’re always stuck with it,’ Les said. ‘They ram it to us right up the backside and expect us to live with it.’

‘Who?’ Ben asked, looking puzzled.

‘Politicians,’ the lance-corporal replied. ‘Our lords and masters.’

‘All right, you men,’ Jimbo said in a voice that sounded like a torrent of gravel. ‘Shut up and let Lieutenant-Colonel Callaghan speak.’

‘Sorry, boss,’ Les said.

‘So,’ Callaghan continued, ‘a bit of necessary historical background.’ This led to the customary moans and groans, which the officer endured for a moment, before gesturing for silence. ‘I know you don’t like it, but it’s necessary, so please pay attention.’ When they had settled down, he continued: ‘A trade centre since antiquity, Aden came under the control of the Turks in the sixteenth century. We Brits established ourselves here by treaty in 1802, used it as a coaling station on the sea route to India, and made it a crown colony in 1937. Because it is located at the southern entrance to the Red Sea, between Arabia and eastern and north-eastern Africa, its main function has always been as a commercial centre for neighbouring states, as well as a refuelling stop for ships. However, it really gained political and commercial importance after the opening of the Suez canal in 1869 and in the present century as a result of the development of the rich oilfields in Arabia and the Persian Gulf. In 1953 an oil refinery was built at Little Aden, on the west side of the bay. Aden became partially self-governing in 1962 and was incorporated into the Federation of South Arabia, the FSA, in 1963, which is when its troubles began.’

Callaghan stopped to take a breath and ensure that he had the men’s full attention. Though the usual bored expressions were in evidence, they were all bearing with him.

‘Opposition to the British presence here began with the abortive Suez operation of 1956, increased with the emergence of Nasserism via the inflammatory broadcasts of Radio Cairo, and reached its high point with the so-called shotgun marriage of the FSA of 1959–63. This, by the way, linked the formerly feudal sheikdoms lying between Yemen and the coast with the urban area of Aden Colony. Steadily mounting antagonism towards our presence here was in no way eased by the establishment in 1960 of our Middle East Command Headquarters.’

Stopping momentarily to let a recently landed Sikorski whine into silence, Callaghan glanced out through the tent’s opening and saw a troop of heavily armed soldiers of the Parachute Regiment marching towards the airstrip, from where they were to fly by Wessex to the mountains of the Radfan. Having served in Malaya and Borneo, Callaghan had a particular fondness for the jungle, but not the desert. Nevertheless, the sight of that darkening, dust-covered ground guarded by hedgehogs bristling with 25-pounders, mortars and machine-guns brought back fond memories of his earliest days with the Regiment in North Africa in 1941. That war had been something of a schoolboy’s idea of adventure, with its daring raids in Land Rovers and on foot; this war, though also in desert, albeit mountainous, would be considerably less romantic and more vicious.

‘In September 1962,’ the CO continued when silence had returned, ‘the hereditary ruler of Yemen, the Imam, was overthrown in a left-wing, Army-led coup. This coup was consolidated almost immediately with the arrival of Egyptian troops. The new republican government in Yemen then called on its brothers in the occupied south – in other words, Aden and the Federation – to prepare for revolution and join it in the battle against colonialism. What this led to, in fact, was an undeclared war between two colonial powers – Britain against a Soviet-backed Egypt – with the battleground being the barren, mountainous territory lying between the Gulf of Aden and Saudi Arabia.’

‘Is that where we’ll be fighting?’ Ken asked.

‘Most of you in the Radfan; a few in the streets of Aden itself. Aden, however, will be covered in a separate briefing.’

‘Right, boss.’

‘Initial SAS involvement in this affair took place, with discreet official backing from Whitehall, over the next eight years or so, when the royalist guerrilla army of the deposed Imam was aided by the Saudis and strengthened by the addition of a mercenary force composed largely of SAS veterans. Operating out of secret bases in the Aden Federation, they fought two campaigns simultaneously. On the one hand they were engaged in putting down a tribal uprising in the Radfan, adjoining Yemen; on the other, they were faced with their first battle against highly organized urban terrorism in Aden itself.’

‘That’s a good one!’ Ken said. ‘In the mountains of Yemen, a team of SAS veterans becomes part of a guerrilla force. Meanwhile, in Aden, only a few miles south, their SAS mates are suppressing a guerrilla campaign.’

‘We are nothing if not versatile,’ Callaghan replied urbanely.

‘Dead right about that, boss.’

‘May I continue?’

‘Please do, boss.’

‘In July this year Harold Macmillan set 1968 as the year for the Federation’s self-government, promising that independence would be accompanied by a continuing British presence in Aden. In short, we wouldn’t desert the tribal leaders with whom we’d maintained protection treaties since the last century.

‘However, Egyptian, Yemeni and Adeni nationalists are still bringing weapons, land-mines and explosives across the border. At the same time, the border tribesmen, who view guerrilla warfare as a way of life, are being supplied with money and weapons by Yemen. The engaged battle is for control of the ferociously hot Radfan mountains. There is practically no water there, and no roads at all.’

‘But somehow or other,’ Dead-eye noted, ‘the war is engaged there.’

‘Correct. The Emergency was declared in December 1963. Between then and the arrival of A Squadron in April of that year, an attempt to subdue the Radfan was made by a combined force of three Federal Regular Army battalions of Arabs, supported by British tanks, guns and engineers. As anticipated by those who understood the tribal mentality, it failed. True, the FRA battalions did manage to occupy parts of the mountains for a few weeks at a cost of five dead and twelve wounded. Once they withdrew, however – as they had to sooner or later, to go back to the more important task of guarding the frontier – the patient tribesmen returned to their former hill positions and immediately began attacking military traffic on the Dhala Road linking Yemen and Aden – the same road that brought you to this camp.’

‘An unforgettable journey!’ Ken whispered.

‘Diarrhoea and vomit every minute for three hours,’ Les replied. ‘Will we ever forget it?’

‘While they were doing so,’ said Callaghan, having heard neither man, ‘both Cairo and the Yemeni capital of Sana were announcing the FRA’s withdrawal from the Radfan as a humiliating defeat for the imperialists.’

‘In other words, we got what we deserved.’

‘Quite so, Corporal Brooke.’ Though smiling, Callaghan sighed as if weary. ‘Given this calamity, the Federal government…’

‘Composed of…?’ Dead-eye interjected.

‘Tribal rulers and Adeni merchants,’ the CO explained.

‘More A-rabs,’ Ken said. ‘Got you, boss.’

‘The Federal government then asked for more military aid from the British, who, despite their own severe doubts – believing, correctly, that this would simply make matters worse – put together a mixed force of brigade strength, including a squadron each of RAF Hawker Hunter ground-support aircraft, Shackleton bombers, Twin Pioneer transports and roughly a dozen helicopters. Their task was twofold. First, to bring sufficient pressure to bear on the Radfan tribes and prevent the revolt from spreading. Second, to stop the attacks on the Dhala Road. In doing this, they were not to deliberately fire on areas containing women and children; they were not to shell, bomb or attack villages without dropping leaflets warning the inhabitants and telling them to move out. Once the troops came under fire, however, retaliation could include maximum force.’

‘Which gets us back to the SAS,’ Dead-eye said.

‘Yes, Sergeant. Our job is to give back-up to A Squadron in the Radfan. To this end, we’ll start with a twenty-four-hour proving patrol, which will also act as your introduction to the area.’

‘We don’t need an introduction,’ the reckless Corporal Brooke said. ‘Just send us up there.’

‘You need an introduction,’ Callaghan insisted. ‘You’re experienced troopers, I agree, but your experience so far has always been in the jungle – first Malaya, then Borneo. You need experience in desert and jungle navigation and that’s what you’ll get on this proving patrol. We’re talking about pure desert of the kind we haven’t worked in since the Regiment was formed in 1941, which excludes most of those present in this tent. Desert as hot as North Africa, but even more difficult because it’s mountainous. Limestone, sandstone and igneous rocks. Sand and silt. Lava fields and volcanic remains, criss-crossed with deep wadis. The highland plateau, or kawr, has an average height of 6500 feet and peaks rising to 8000 to 9000 feet. The plateau itself is broken up by deep valleys or canyons, as well as the wadis. In short, the terrain is hellishly difficult and presents many challenges.’

‘Any training before we leave?’ Dead-eye asked.

‘Yes. One full day tomorrow. Lay up tonight, kitting out and training tomorrow, then move out at last light the same day. The transport will be 4×4 Bedford three-tonners and Saladin armoured cars equipped with 5.56-inch Bren guns. Enjoy your evening off, gentlemen. That’s it. Class dismissed.’

Not wanting to waste a minute of their free time, the men hurried out of the briefing room and raced each other to the makeshift NAAFI canteen at the other side of the camp, where they enjoyed a lengthy booze-up of ice-cold bottled beer. Few went to bed sober.

3 (#u4d86fdb7-72f8-53f2-8e0f-8b1600163f65)

Rudely awakened at first light by Jimbo, whose roar could split mountains, the men rolled out of their bashas, quickly showered and shaved, then hurried through the surprisingly cold morning air, in darkness streaked with rising sunlight, to eat as much as they could in fifteen minutes and return to their sleeping quarters.

Once by their beds, and already kitted out, they had only to collect their bergens, kit and weapons, then hurry back out into the brightening light and cross the clearing, through a gentle, moaning wind and spiralling clouds of dust, to the column of Bedfords and Saladins in the charge of still sleepy drivers from the Royal Corps of Transport. The RCT drivers drank hot tea from vacuum flasks and smoked while the SAS men, heavily burdened with their bergens and other kit, clambered up into the back of the lorries. Meanwhile, the sun was rising like a pomegranate over the distant Radfan, casting an exotic, blood-red light through the shadows on the lower slopes of the mountains, making them look more mysterious than dangerous.

‘We should be up there in OPs,’ Les complained as they settled into their bench seats in the back of a Bedford. ‘Not wasting our bleedin’ time with a training jaunt.’

‘I don’t think we’re wasting our time,’ Ken replied. ‘I believe the boss. All our practical experience has been in Borneo and that won’t help us here.’

‘I wish I’d been in Borneo,’ Ben said. ‘I bet it was more exotic than this dump.’

‘It was,’ Larry said ironically. ‘Steaming jungle, swamps, raging rivers, snakes, scorpions, lizards, giant spiders, fucking dangerous wild pigs, and head-hunting aboriginals blowing poison darts. Join the SAS and see the world – always travelling first class, of course.’

‘At least here we’ve only got flies and mosquitoes,’ Taff said hopefully, swatting the first of the morning’s insects from his face.

‘Plus desert snakes, scorpions, centipedes, stinging hornets, spiders and Arab guerrillas who give you no quarter. Make the most of it!’

Having silenced the new men and given them something to think about, Les grinned sadistically at Ken, then glanced out of the uncovered truck as the Saladin in the lead roared into life. Taking this as their cue, the RCT drivers in the Bedfords switched on their ignition, one after the other, and revved the engines in neutral to warm them up. When the last had done the same, the rearmost Saladin followed suit and the column was ready to move. The Bedfords and the Saladin acting as ‘Tail-end Charlie’ followed the first armoured car out of the camp, throwing up a column of billowing dust as they headed out into the desert.

The route was through an area scattered with coconut and doum palms, acacias, tall ariatas and tamarisks, the latter looking prettily artificial with their feathery branches. They were, however, few and far between. For the most part, the Bedfords bounced and rattled over parched ground strewn with potholes and stones until, about half an hour later, they arrived at an area bounded by a horseshoe-shaped mountain range. The RCT drivers took the Bedfords up the lower slopes as far as they would go, then stopped to let the men out.

The soldiers were lowering their kit to the ground and clambering down when they saw for the first time that one of the Bedfords had brought up a collection of heavier support weapons, including a 7.62mm GPMG (general-purpose machine-gun), a 7.62mm LMG (light machine-gun) and two 51mm mortars.

‘Looks like we’re in for a pretty long day,’ Les muttered ominously.

‘No argument about that,’ Ken whispered back at him.

When the Bedfords had turned around and headed back the way they had come, Jimbo gathered his men around him. Dead-eye was standing beside him, holding his L42A1 bolt-action sniper rifle and looking as granite-faced as always.

‘The Bedfords,’ Jimbo said, ‘will come back just before last light. Until then we work.’ Pausing to let his words sink in, he waved his hands at the heavy weapons piled up to his left. ‘As you can see, we’ve brought along a nice collection of support weapons. We’re going to hike up to the summit of this hill and take that lot with us. I hope you’re all feeling fit.’ The men moaned and groaned melodramatically, but Jimbo, his crooked lip curling, waved them into silence. ‘For most of you,’ he said, ‘your previous practical experience was in jungle or swamp. A few of us have had experience in the African desert, but even that didn’t involve anything like these mountains. You are here, therefore, to adapt to a terrain of mountainous desert, with all that entails.’

‘What’s that, Sarge?’ Ben asked innocently.

‘Wind and sand. Potentially damaging dips and holes covered by sand, soil or shrubs. Loose gravel and wind-smoothed, slippery rocks. Ferocious heat. All in all, it calls for a wide variety of survival skills of the kind you haven’t so far acquired.’ He cast a quick grin at the impassive Dead-eye, then turned back to the men. ‘And the first lesson,’ he continued, nodding at the summit of the ridge, ‘is to get up there, carrying the support weapons and your own kit.’ Glancing up automatically, the men were not reassured by what they saw. ‘It’s pretty steep,’ Jimbo said. ‘It’s also covered with sharp and loose stones. Be careful you don’t break an ankle or trip and roll down. And watch out for snakes, scorpions and the like. Even when not poisonous, some of them can inflict a nasty bite…So, let’s get to it.’

He jabbed his finger at various groups, telling them which weapons and components they were to carry between them. Corporal Ken Brooke, Lance-Corporal Les Moody, and Troopers Ben Riley and Taff Thomas were assigned as the four-man GPMG team. Lance-Corporal Larry Johnson, already burdened with his extra medical kit, got off scot-free.

‘We picked the wrong specialist training,’ Les complained. ‘Johnson gets off with everything.’

‘It’s not just the fact that I’m our medical specialist,’ Larry replied, beaming smugly. ‘It’s because I have charm and personality. It comes natural, see.’

‘So does farting from your mouth,’ Ken shot back. ‘Come on, Les, let’s hump this thing.’

The four men tossed for it. Ken lost and became number two: the one who had to hump the GPMG onto his shoulders. Sighing, he unlocked the front legs of the 30lb steel tripod, swung them forward into the high-mount position and relocked them. Then, with Les’s assistance, he hauled the tripod up onto his shoulders with the front legs resting on his chest and the rear one trailing backwards over his equally heavy bergen. With the combined weight of the steel tripod, ammunition belts of 7.62mm rounds, and rucksack adding up to 130lb, Ken felt exhausted before he had even started.

‘You look like a bleedin’ elephant,’ Les informed him. ‘I just hope you’re as strong.’

‘Go fuck yourself,’ Ken barked back.

The four-way toss had made Les the gun controller, Ben the observer and Taff the number one, or trigger man. Between them, apart from personal gear, they had to carry two spare barrels weighing 6lb each, a spare return spring, a dial sight, marker pegs, two aiming posts, an aiming lamp, a recoil buffer, a tripod sighting bracket, a spare-parts wallet, and the gun itself.

‘This doesn’t look easy,’ Ben said, glancing nervously up the steep, rocky slope as Les distributed the separate parts of the GPMG.

‘It’s a fucking sight easier than humping that tripod,’ Les informed him, ‘so count yourself lucky.’

‘Move out!’ Jimbo bawled.

The whole squad moved out in single file, spread well apart as they would be on a real patrol, with the men who were carrying the support weapons leaning forward even more than the others. The climb was both backbreaking and dangerous, for each man was forced to navigate the steep slope while looking out for sharp or loose stones that could either break an ankle or roll from under his feet, sending him tumbling back down the mountain. In this, they were helped neither by the sheer intensity of the heat nor the growing swarms of buzzing flies and whining mosquitoes attracted by their copious sweat.

Almost driven mad by the mosquitoes, the men’s attempts to swat them away came as near to unbalancing them as did the loose, rolling stones. More than one man found himself suddenly twisting sideways, dragged down by his own kit or support weapon, after he had swung his hand too violently at his tormentors. Saved by the helping hand of the man coming up behind him, he might then find himself stepping on a loose stone, which would roll like a log beneath him, sending him violently forwards or backwards; or he would start slipping on loose gravel as it slid away underfoot.

By now the breathing of every man was agonized and not helped by the fact that the air was filled with the dust kicked up by their boots or the tumbling stones and sliding gravel. The dust hung around them in clouds, making them choke and cough, and limiting visibility to a dangerous degree, eventually reducing the brightening sunlight to a distant, silvery haze. To make matters worse, each man’s vision was even more blurred when his own stinging sweat ran into his eyes.

The climb of some 1500 feet took them two hellish hours but led eventually to the summit of the ridge. This had different, more exotic trees scattered here and there along its otherwise rocky, parched, relatively flat ground, and overlooked a vast plain of sand, silt and polished lava.

Throwing themselves gratefully to the ground, the men were about to open their water bottles when Jimbo stopped them. ‘No,’ he said. ‘Put those bottles away.’

‘But, Sarge…’ Taff began in disbelief.

‘Shut up and listen to me,’ Jimbo replied. ‘As you’ve all just discovered, the heat in the mountains can wring the last drop of sweat out of you much quicker than you can possibly imagine – no matter how fit you are. If you allow this to happen, you’ll soon be dehydrated, exhausted, and if you don’t get water in time, dead of thirst.’

‘So let us drink our water,’ Les said, shaking his bottle invitingly.

‘No,’ the sergeant replied. ‘Your minimum daily intake of water should be two gallons a day, but on a real operation we won’t be able to resup by chopper because this would give away the position of the OP. For this reason, you’ll have to learn to conserve the water you carry inside your body by minimal movement during the day, replenishing your water bottles each night by sneaking down to the nearest stream.’

‘So we should ensure that the OP site is always near a stream,’ Ben said, ‘and not on top of a high ridge or mountain like this.’

‘Unfortunately, no. It’s because they’re aware of the constant need for water that the rebel tribesmen always check the areas around streams for our presence. Therefore, the site for your OP should be chosen for the view it gives of enemy supply routes, irrespective of its proximity to water. You then go out at night and search far and wide for your water, no matter how difficult or dangerous that task may be.’

‘Sounds like a right pain to me,’ Ken said.

‘It is. I should point out here, to make you feel even worse – but to make you even more careful – that even after dark the exertion of foraging for water can produce a dreadful thirst that can make you consume half of what you collect on the way back. In short, these mountains make the jungles of Borneo seem like sheer luxury. And that’s no exaggeration, believe me.’

‘I believe you,’ Les said, still clutching his water bottle. ‘Can I have a drink now?’

‘No. That water has to last until tonight and you’ve only brought one bottle each.’

‘But we’re all dying of thirst,’ Ken complained.

Jimbo pointed to the trees scattered sparsely along the otherwise parched summit of the ridge. ‘That,’ he said, indicating a tree covered in a plum-like fruit, ‘is the jujube. Its fruit is edible and will also quench your thirst…And those,’ he continued, pointing to the bulbous plants hanging from the branches of a tree that looked like a cactus, ‘are euphorbia. If you pierce them with a knife, or slice the top off, you’ll find they contain a drinkable juice that’s a bit like milk.’

‘So when can we drink our water?’ Taff pleaded.

‘When you’ve put up your bashas, cleaned and checked your weapons, put in a good morning’s firing practice and are eating your scran. Meanwhile, you can eat and drink from those trees.’

‘Bashas?’ Ken glanced down the slopes of the ridge at the barren, sunlit plain below, running out for miles to more distant mountains. ‘What are we putting bashas up for? We’re only here for one day.’

‘They’re to let you rest periodically from the sun and keep you from getting sunstroke. So just make triangular shelters with your poncho sheets. Now get to it.’

The men constructed their triangular shelters by standing two upright sticks with Y-shaped tops about six feet apart, running a length of taut cord between them, draping the poncho sheet over the cord, with one short end, about 18 inches long, facing away from the sun and the other running obliquely all the way to the ground, forming a solid wall. Both sides of the poncho sheet were then made secure by the strings stitched into them and tied to wooden pegs hammered into the soil. Dried grass and bracken were then strewn on the ground inside the ‘tent’ and finally the sleeping bag was rolled out to make a crude but effective mattress.

When the bashas had been constructed, the men were allowed to rest from the sun for fifteen minutes. Though it was still not yet nine a.m. local time, the sun’s heat was already intense.

Once rested, the men were called out to dismantle, clean of dust and sand, oil and reassemble the weapons, a task which, with the dust blowing continuously, was far from easy. Jimbo then made them set the machine-guns up on the ridge and aim at specific targets on the lower slopes of the hill: mostly clumps of parched shrubs and trees. The rest of the morning was spent in extensive practice with the support weapons, first using the tripods, then firing both the heavy GPMG and the LMG from the hip with the aid of a sling.

The GPMG, in particular, had a violent backblast that almost punched some of the men off their feet. But in the end they all managed to hold it and hit their targets when standing. The noise of the machine-guns was shocking in the desert silence and reverberated eerily around the encircling mountains.

Two hours later, when weapons practice was over, the men were again made to dismantle, clean, oil and reassemble the weapons, which were then wrapped in cloth to protect them from the dust and sand. By now labouring beneath an almost overhead sun, the men were soaked in sweat, sunburnt and gasping with thirst, and so were given another ten-minute break, which they spent in their bashas, sipping water and drawing greedily on cigarettes. The break over, they were called out again, this time by the fearsome Sergeant Parker, for training with their personal weapons.

Dead-eye’s instruction included not only the firing of the weapons, at which he was faultless, but the art of concealment on exposed ridges, scrambling up and down the slopes on hands and elbows, rifle held horizontally across the face. The posture adopted for this strongly resembled the ‘leopard crawl’ used for the crossing of the dreaded entrails ditch during ‘Sickener One’ at Bradbury Lines, Hereford. It was less smelly here, but infinitely more dangerous than training in Britain, as the men had to crawl over sharp, burning-hot rocks that could not only cut skin and break bones, but also could be hiding snakes, scorpions or poisonous spiders.

More than one man was heard to cry out and jump up in shock as he came across something hideous on the ground where he was crawling. But he was shouted back down by the relentless Jimbo, who was always watching on the sidelines as Dead-eye led them along the ridge on their bellies.

‘Is that what you’d do if you were under fire?’ Jimbo would bawl. ‘See a spider and jump up like an idiot to get shot to pieces? Get your face back in the dirt, man, and don’t get up again until I tell you!’

While some of the men resented having firing practice when most of them had not only done it all before but had even been blooded in real combat, what they were in fact learning was how to deal with an unfamiliar terrain. Dead-eye also taught them how to time their shots for when the constantly swirling dust and sand had blown away long enough for them to get a clear view of the target. Finally, they were learning to fire accurately into the sunlight by estimating the position of the target by its shadow, rather than by trying to look directly at it. By lunchtime, when they had mastered this new skill, they were thoroughly exhausted and, in many cases, bloody and bruised from the sharp, burning rocks. They were suffering no less from the many bites inflicted by the whining mosquitoes.

‘I look like a bleedin’ leper,’ Ben complained as he rubbed more insect repellent over his badly bitten wrists, hands and face, ‘with all these disgusting mosquito bites.’

‘Not as bad as leeches,’ Les informed him smugly as he sat back, ignoring his mosquito bites, to have a smoko. ‘Those little buggers sucked us dry in Borneo. Left us bloodless.’

‘By the time they finish with us,’ Taff said, ‘you could throw us in a swamp filled with leeches and they’d all die of thirst. I’m fucking bloodless, I tell you!’

In the relative cool of his poncho tent, Ken removed his water bottle from his mouth, licked his lips, then lay back with his hands behind his head and closed his eyes.

‘If you go to sleep you’ll feel like hell when you wake up,’ Larry solemnly warned him.

‘I’m not sleeping,’ Ken replied. ‘I’m just resting my eyes. They get tired from the sunlight.’

‘Getting hotter and brighter every minute,’ Larry said. ‘It’ll soon be like hell out there.’

‘We’ll all get there eventually,’ Les told him, ‘so we’d better get used to it.’

‘Amen to that,’ Ken said.

Immediately after lunch they rolled out of the shade of their bashas to return to the baking oven of the ridge, where, although dazzled by the brilliance of the sky, they took turns to set up, fire and dismantle the 51mm mortar. It weighed a mere 13lb, had no sophisticated sights or firing mechanism, and was essentially just a simple tube with a fixed base plate. Conveniently, it could be carried over the shoulder with its ammunition distributed among the rest of the patrol. The user had only to wedge the base plate into the ground, hold the tube at the correct angle for the estimated range, then drop a bomb into the top of the tube. Though first-shot accuracy was relatively difficult with such a crude weapon, a skilled operator could zero in on a target with a couple of practice shots, then fire up to eight accurate rounds a minute. Most of the men were managing to do this within the first hour, and were gratified to see the explosions tearing up the flat plain below, forming spectacular columns of spiralling smoke, sand and dust.

Even though they had protected their faces with their shemaghs, they were badly burnt by the sun, on the road to dehydration, and very close to complete exhaustion when, in the late afternoon, Jimbo and Dead-eye called a halt to the weapons training and said they would now hike back down the hill to the waiting Bedfords.

Believing they were about to return to the base camp, the men enthusiastically packed up their bashas, humped the support weapons back onto their bruised shoulders, strapped their heavy bergens to their backs, picked up their personal weapons and hiked in single file back down the hill. If anything, this was even more dangerous than the uphill climb, for they were now growing dizzy with exhaustion and were forced to hike in the direction of the sliding gravel and stones, which tended to make the descent dangerously fast. Luckily, they were close to the bottom when the first man, Taff, let out a yelp as the gravel slid under his feet, sending him backwards into the dirt, to roll the rest of the way down in a billowing cloud of dust and sand. He was picking himself up when two others followed the same way, either tripping or sliding on loose gravel, then losing their balance before rolling down the hill. The rest of the group managed to make it down without incident, though by now all of them were utterly exhausted and soaking in sweat.

‘Right,’ Dead-eye said. ‘Hump those support weapons back up onto the Bedford, then gather around me and Sergeant Ashman.’

The men did as they were told, then tried to get their breath back while wiping the sweat from their faces and, in some cases, vainly trying to wring their shirts and trousers dry. They were still breathing painfully and scratching their many insect bites when they gathered around the two sergeants.

Any hopes they might have held of heading back to the relative comforts of the base camp were dashed when Jimbo gave them a lecture on desert navigation, much of it based on his World War Two experiences with the Long Range Desert Group. The lecture took an hour and, to the men’s dismay, included a hike of over a mile, fully kitted, out into the blazing-hot desert. This was for the purpose of demonstrating how to measure distance by filling one trouser pocket with small stones and transferring a stone from that pocket to the other after each hundred steps.

‘The average pace,’ Jimbo explained, ‘is 30 inches, so each stone represents approximately 83 yards. So if you lose your compass or, as is just as likely, simply have no geographical features by which to assess distance, you can easily calculate the distance you’re marching or have marched by multiplying the number of stones transferred by eighty-three. That gives the distance in yards.’

Though the exhausted men had been forced to walk all this distance in the burning, blinding sunlight, they had been followed by one of the Bedfords. Fondly imagining that this had come out to take them back, they had their hopes dashed again when some small shovels, a couple of radios and various pieces of wiring were handed down to them by the driver.

Jimbo and Dead-eye, both seemingly oblivious to the heat, then took turns at showing the increasingly shattered men how to scrape shallow lying-up positions, or LUPs, out of the sand and check them for buried scorpions or centipedes. Dead-eye was in charge of this particular lesson and, when he had finished scraping out his own demonstration LUP, he made the exhausted men do the same, kicking the sand back into the scrapes when they failed to do it correctly and making them start all over again. When one of the men collapsed during this exercise, the inscrutable sergeant patiently aroused him by splashing cold water on his face, then made him complete his scrape, which amazingly the man did, swaying groggily in the heat.

A short break was allowed for a limited intake of water, then Jimbo gave them a lesson in special desert signalling, covering Morse code, special codes and call-sign signals; use of the radios and how to clean them of sand; recognition of radio ‘black spots’ caused by the peculiar atmospheric conditions of the mountainous desert; setting up standard and makeshift antennas; and the procedure for calling in artillery fire and air strikes, which would be their main task when in their OPs in the Radfan.

Most of the men were already rigid with exhaustion, dehydration and mild sunstroke when Jimbo took another thirty minutes to show them how to make an improvised compass by variously stroking a sewing needle in one direction against a piece of silk and suspending it in a loop of thread so that it pointed north; by laying the needle on a piece of paper or bark and floating it on water in a cup or mess tin; or by stropping a razor-blade against the palm of the hand and, as with the sewing needle, suspending it from a piece of thread to point north.

Mercifully, the sun was starting to sink when he showed them various methods of purifying and conserving water; then, finally, how to improvise water-filtering systems and crude cookers out of old oil drums and biscuit tins.

‘And that’s it,’ he said, studying their glazed faces with thinly veiled amusement. ‘Your long day in the desert is done. Now it’s back to base camp.’

‘Which you can only do,’ Dead-eye told them, ‘if you manage to leg it back to the Bedfords.’

‘Aw, Jesus!’ Larry said without thinking. ‘Can’t we all pile into that Bedford and let it take us back to the others?’

‘That Bedford is for the equipment only,’ Dead-eye told him. ‘Besides, you men have to get used to the desert, and this last hike is all part of your training. Now get going.’

Relieved, at least, of the heavy support weapons, the men heaved their packed bergens and other kit onto their aching backs, turned to face the sinking sun, and walked in a daze back to the other Bedfords. Two almost collapsed on the way and had to be helped by the others, which slowed them down considerably; but just before last light they all made it and practically fell into the trucks, which bounced and rattled every yard of the half-hour journey back to the camp.

Battered and bruised, covered in insect bites, smeared with sweat-soaked sand and dust, hungry and unbelievably thirsty, they collapsed on their steel beds in the tents and could hardly rouse themselves even to shower, shave and head off to the mess tent. Indeed, most of them were still lying there, almost catatonic, when Jimbo did a round of the tents, bawling repeatedly that those not seen having a decent meal would be RTU’d – returned to their original unit. Though they all cursed the SAS, so great was the shame attaching to this fate that they rolled off their beds, attended to their ablutions, dressed in clean clothes and marched on aching legs to the mess tent to have their scran and hot tea. Somewhat restored, they then made for the NAAFI tent to get drunk on cold beer. Finally, after what seemed like the longest day of their lives, they surrendered to sleep like children.

4 (#u4d86fdb7-72f8-53f2-8e0f-8b1600163f65)

The men began their proving patrol the following evening, loading up the Bedfords just before last light with their individual kit and support weapons. For their personal weapons, old Borneo hands like Ken Brooke and Les Moody still favoured the M16 5.56mm assault rifle, which accepted a bayonet and could fire a variety of grenades although it was not so good in desert conditions because of its poor long-range accuracy and tendency to jam up with sand.

Dead-eye, said to be the best shot in the Regiment, preferred the L42A1 7.62mm bolt-action sniper rifle, which had a telescopic sight, was robust and reliable, and had good stopping power at long range, making it ideal for sniping from high mountain ridges. While some of the other men likewise favoured this weapon, most of them had been issued with the L1A1 SLR, which had a twenty-round box magazine, could be used on single shot or automatic, and was notable for its long-range accuracy.

The support weapons included the 7.62mm GPMG; the L4A4 LMG, which was actually a Bren gun modified to accommodate the 7.62mm round; the 51mm mortar with base plate, its ammunition distributed among the men; and a couple of US M79 grenade-launchers, which could be fired from the shoulder. All of these weapons were hauled up into the back of the Bedfords, then followed in by the men, making for very cramped conditions.

‘Here we go again,’ Larry said, moving his head to avoid the A41 tactical radio set being swung into a more comfortable position on the shoulders of the operator, Lance-Corporal Derek Dickerson. ‘Another luxurious journey on the Orient Express!’

‘It’s nice to have these paid holidays,’ Ben said, twisting sideways to avoid being hit by Larry’s shoulder-slung wooden medical box. ‘It makes me feel so important.’

As the men tried to find comfortable positions on the benches along the sides of the lorries, the sun was sinking low over the distant mountains, casting a blood-red light through the shadows. At the same time, a Sikorski S-55 Whirlwind was roaring into life on the nearby landing pad, whipping up billowing clouds of dust as it prepared to lift off.

‘Where the fuck is he going?’ Les asked in his usual peevish way as he settled into his bench seat in the back of the Bedford.

‘The RAF airstrip at Habilayn,’ answered Ken. ‘It’s only a couple of minutes by chopper from here.’

‘If it’s so close,’ Taff asked, ‘why couldn’t we be flown to the drop zone instead of going by lorry, which will take a lot longer?’

‘And make you throw up,’ Larry chuckled.

‘Ha, ha,’ Taff retorted, now used to their bullshit and also determined never to throw up again.

‘Because the DZ overlooks an Arab village,’ Ken explained, ‘and an insertion by chopper would be seen by every rebel in the area.’

‘Besides,’ Larry added sardonically, ‘an insertion by chopper would be too easy

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/shaun-clarke/counter-insurgency-in-aden/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Shaun Clarke

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But will the SAS be able to rid Yemen of its unstoppable guerrillas?Aden, 1964, and the British are waging two different kinds of war.Inhabitants of northern Yemen’s forbidding mountainous region of Radfan are conducting guerrilla attacks against the British. Armed by the Egyptians and trained by the communist Yemenis, they seem an invincible fighting force.With only one hope of beating them, the British draft in an even more tenacious group of soldiers – the SAS! Their mission: to parachute into enemy territory at night, establish concealed observation posts high in the mountains, and direct air strikes on the rebels moving through the sun-baked passes.At the same time, in an even more dangerous campaign, two- or three-man SAS teams disguised as Arabs must infiltrate the souks and bazaars of the port of Aden in an attempt to ‘neutralise’ leading members of the National Liberation Front. But will their disguise allow them to get close enough to their targets, or get out again alive…?