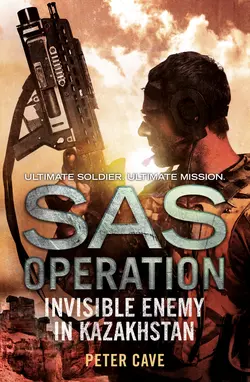

Invisible Enemy in Kazakhstan

Peter Cave

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But will the SAS be able to defeat what awaits them inside a top secret Nazi research facility?In the 1990s, sketchy reports of an accident in a high-security research facility deep within the remote, mountainous region of Kazakhstan filter through to American intelligence. A Russian army team sent in to investigate disappears without trace. The Chinese, terrified that their territory might be threatened by the leak, turn to Britain, an unlikely ally, for help.Only one group of men is capable of discovering the truth behind the underground facility, and the SAS are sent in. In so doing they will have the chance to settle a score which goes back almost half a century but they will also face a new and terrifying enemy – one that will test their endurance, and their equipment, to the limit.

Invisible Enemy in Kazakhstan

PETER CAVE

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover Photographs © Nik Keevil (soldier); Shutterstock.com (textures)

Peter Cave asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155155

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008155162

Version: 2015-11-02

Contents

Cover (#u003bc15e-e71a-5243-8c43-6c59354c6f2e)

Title Page (#u02d5d911-7ce4-5308-a53f-8ab1d5a913f5)

Copyright (#uc80ba62b-b8ca-51bd-81b3-d128a8e4d6d5)

Chapter 1 (#uea564a23-0f29-5e41-bb7a-273d2f5fde66)

Chapter 2 (#u4a371093-4fd7-5733-a38a-bf3cd884ad31)

Chapter 3 (#uf9a9f0ad-f8ec-5a80-815a-22db1b593dc7)

Chapter 4 (#ud6cc7fa5-edc1-555b-9d37-e9ad8947bc9c)

Chapter 5 (#u3f4cadd6-41c7-52ed-a538-9452e56a20bd)

Chapter 6 (#uad424d30-0c86-5fd0-a09a-aa6e2ff68290)

Chapter 7 (#u9467e782-565f-5952-b957-6c0f5482c46f)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#u704970d2-4b81-5c76-838d-5796eadd4af6)

Moscow – March 1945

General Sergei Oropov sucked deeply on a thin, knobbly cheroot of black Balkan tobacco, inhaling the acrid smoke and attempting to savour it. Failing, he sprayed it out from between his clenched teeth, sending it jetting on its way with a convulsive, chesty cough. The faintly blue smoke rose towards the high ceiling of the large, overheated and airless office, blending into a murky pall made thicker by the steam escaping from a leaking radiator. The heating system, along with the ventilation fans, had been faulty for over three months now, and it was still impossible to find labour sufficiently skilled to fix it.

‘Thank God this damned war will soon be over,’ Oropov muttered testily, knowing that it could be merely a matter of weeks before Germany was finally forced to capitulate. Russian troops had almost reached the Oder, the Western Allies had established a firm bridgehead east of the Rhine and troopers of Britain’s already legendary 1 and 2 Squadron SAS ranged throughout Europe, organizing and arming local resistance fighters and carrying out long-range reconnaissance and sabotage attacks as far north as Hamburg and Lübeck.

The remark was not really intended as dialogue, more as a private thought expressed aloud. Nevertheless, Oropov’s companion took it up, seizing on the opportunity for a mild rebuke to be administered, a propaganda point to be gained.

Tovan Leveski’s thin lips parted slightly in a mirthless smile. ‘One does not thank God any more – one thanks Stalin. It was the strength of the Russian bear which crushed the German jackal to death. But of course, comrade, I agree with your sentiments, at least. It will be good to have our brave young men back from the German front – to finish our necessary business in Poland.’

It was Oropov’s turn to smile, but with faintly malicious humour.

‘That too, of course. Although, personally, I was more looking forward to buying some decent Cuban cigars.’

Oropov’s grey eyes twinkled briefly as Leveski twitched, reacting uncomfortably to the obvious jibe. It felt good to score a point over the man, whom Oropov both disliked and distrusted. It was not just the fact that he was, basically, a civilian; it went a lot deeper than that, with potentially more sinister implications.

Leveski represented a new and unknown quantity. The exact nature of his sudden new post was ill-defined, as if deliberately vague. There were mutterings and rumours in the corridors of the Kremlin. No longer obsessed with matters of war, Stalin was stirring politically again. There was talk of new purges to come, of heads rolling and personnel once again disappearing at short notice and in suspicious circumstances. Stalin’s feared secret police, previously concerned with purely internal matters, were now extending their awesome powers. Now the newly formed KGB, with people like Leveski at its head, were moving in to take an active interest in military, European and overseas matters. It impinged directly on Oropov’s authority as head of wartime intelligence, and it was extremely disquieting. It was definitely a time for staying on top, and being clearly seen to be on top. A time to know exactly what was happening all around oneself – and, even more important, who was making it happen and why.

With these thoughts in mind, Oropov decided it was politic to adopt a more conciliatory attitude towards his companion.

‘Speaking of Poland, Tovan Leveski, what news from Warsaw?’

Leveski shrugged, a gesture of vague irritation. ‘Mixed, as ever. Confused and conflicting reports, rumours, snatches of Allied propaganda. The usual wartime rubbish. The very thing my new department was set up to rationalize.’ He broke off to nod deferentially towards Oropov. ‘With your cooperation, of course, comrade.’

‘Of course,’ Oropov said, nodding, his face suddenly more serious. ‘I was merely a soldier, doing a soldier’s job in a time of war. Now we must all work together in the cause of peace, and for the good of the Motherland.’

The brief speech presumed a response. Predictably, Leveski obliged.

‘A toast, comrade?’ he suggested.

‘A toast indeed.’

Oropov slid open a drawer in his desk and drew out a quarter-full bottle of Stolichnaya and two conical, stemless glasses. He handed one to Leveski, filled it, then splashed a generous measure into his own.

‘Rodina,’ Oropov grunted, waving the glass briefly in the air before placing it to his lips and draining the fiery vodka at a single gulp.

‘Rodina’ Leveski responded with suitable fervour in his voice. The word translated simply as The Motherland’, but it carried the patriotic zeal of an entire national anthem to anyone with a drop of Russian blood in their veins. In a society which had largely turned its back on the Church, it was the litany of a new and potent religion.

The time for pleasantries was over, Oropov decided. It was obvious that Leveski had not entered his office on a purely social visit. He returned the bottle of vodka to his desk, smiling up at the man politely. ‘Well, Tovan Leveski, what can I do for you?’

The little man cleared his throat, managing to make the apparently innocent gesture a censure of Oropov’s smoking habit.

‘We are a little concerned about the lack of information currently on file regarding Allied armaments projects.’

Oropov ignored yet another implied rebuke. He raised one shaggy eyebrow the faintest fraction of an inch. ‘We, comrade?’

‘I’, Leveski corrected himself hastily, uncomfortably aware that he had just let something slip, without fully understanding its relevance. Just like General Oropov, he had yet to adjust fully to the scope of his position and powers. ‘I find myself slightly worried about the gaps in our intelligence. I was briefed to acquaint myself fully with current military research, but I find some of your dossiers and files rather sparse, to say the least.’

Oropov made a steeple of his fingers, pressing them gently against his lips. He eyed Leveski stonily. ‘Specifically?’

‘Specifically, this “Manhattan Project”. As a military man, you must surely appreciate the momentous implications of a nuclear fission bomb. Yet we appear to have no idea at all just how advanced the Americans are in its development. Cause for worry, would you not agree, General?’

‘Indeed,’ Oropov agreed. ‘And, equally, a matter for the tightest and most efficient security screen we have ever encountered. The potential power of atomic weaponry is not lost on the Americans, either. Our files represent our finest efforts and the deaths of two top agents. I assume you have followed up on the cross-reference file relating to the German research facility at Telemark?’

Leveski nodded. ‘Of course. Again, a woefully thin report and a disgusting fiasco. The damned Norwegians and the Allies made fools of us. It should have been Russian troops who stormed that laboratory. Then the secret of heavy-water production would be in Soviet hands, not at the bottom of some damned fiord.’

‘Our troops were otherwise engaged at the time,’ Oropov pointed out rather icily. ‘But a tragic loss to Soviet science, I agree. However, I understand our own atomic research facility is now well established.’

Leveski’s lips curled into a sneer. ‘Oh yes, two or three years behind the blasted Allies, at a conservative estimate.’

He hunched his shoulders, as if to subdue a shiver of rage, finally releasing only a faint shrug. ‘However, that is past news. What matters now is the future. Do we have any active personnel inside the Manhattan Project?’

Oropov shook his head. ‘No one with scientific knowledge, I’m afraid. There is a woman – a minor clerical worker – who is able to send us copies of purchasing invoices, interdepartmental memos, that sort of thing. We are able to glean a little theoretical knowledge, but not much else.’

Leveski digested all this information for a while, assimilating it into the dossier in his brain.

‘Have we made any attempts to get to the man Oppenheimer direct?’ he asked finally. ‘Our records suggest that in his postgraduate days, at least, he had certain…sympathies?’

Oropov spread his hands in a gesture of resignation. ‘A fact also realized by the Americans. Oppenheimer is a very important man, and a deeply mistrusted one. His every move is closely monitored. It is impossible to get an agent within shouting distance of him.’

‘So we have nothing? No one? No chance of further information. Is that what you are telling me?’

Oropov was beginning to wilt under the mounting attack. ‘It’s not as bad as that,’ he countered, somewhat lamely.

‘No? Then please tell me how bad it actually is, comrade.’

Leveski knew that he had his man on the run now. There was little point in any further pretence at friendliness.

‘There is one man – in England. Klaus Fuchs. We have him as a sleeper. He is not attached to the Manhattan Project, but his work involves him in a closely related field. In a year or two, perhaps, he may be of great use to us.’

‘A year or two?’ Leveski said dismissively. He rose from his high-backed chair, his mouth twitching angrily with barely repressed frustration. ‘In a year or two, comrade Oropov, Russian science will be left behind like a sick, abandoned animal. Out in the cold, waiting to die.’

There was a slight tremor in Oropov’s voice when he finally spoke again. He was acutely aware that Leveski had only just started to show his claws, and the Kremlin rumours were beginning to assume a chilling reality.

‘What is expected of me, comrade Leveski?’

‘You don’t know? Then I had better spell it out for you,’ Leveski sneered. ‘The demands of this war, and sheer Nazi fervour, have resulted in one of the greatest explosions of science and technology this world has ever known. Those scientific breakthroughs are the key to the future – the richest and most precious spoils of war. At this very minute the Allies are picking their way across Europe like scavengers, snatching up the juiciest morsels. Physicists, rocket experts, engineers, designers, the finest brains of Germany – all falling into capitalist hands. Any day now the Western powers may have the secret of the atomic bomb. In a matter of a few years, the power to deliver it across oceans and continents. In a decade, world domination in their pockets. And if that happens, comrade, we might as well sell our bodies and souls back to the Tsars, because we will have lost everything this great nation has struggled and bled for. Something the Russian people would never forgive, General. And perhaps more important to you, personally, something that I would never forgive.’

The gauntlet was down. Oropov struggled to control a nervous shiver, and failed. His voice was little more than a croak.

‘What do you want me to do, comrade Leveski?’

The man was now regarding him with undisguised contempt. ‘I’m glad that you finally realize how high the stakes are, General. And, no doubt, the penalties for failure. I want a short-term plan. A definite and positive strategy to ensure that Russia snatches some worthwhile prize from this war. Give me a phoenix from the ashes, General – that is all.’

Leveski turned on his heel and moved towards the door. He delivered his parting shot over his shoulder, without turning round. ‘You have forty-eight hours, General. I expect to see a detailed report on my desk by Thursday.’

He closed the door quietly, almost gently behind him. Strangely, this seemed to reinforce the aura of menace he left behind him rather than lessen it.

Alone now, Oropov gave up the uneven struggle to stop his hands from shaking. He delved into his desk, pulled out the vodka bottle and uncorked it with his teeth. Holding the bottle directly to his lips, he gulped down the harsh spirit. It did little to thaw out the icy chill he felt in the pit of his belly.

He stared blankly across his office at the closed door through which Leveski had exited, racking his brain for a single optimistic thought. There was nothing. One realization swamped everything else. War, or at least his kind of war, was coming to an end, and a completely new kind of war was about to begin. With a terrible sense of resignation, he knew that he had little if any part to play in the waging of it.

(#litres_trial_promo)

2 (#u704970d2-4b81-5c76-838d-5796eadd4af6)

Berlin – June 1945

The two jeeps zigzagged through the rubble-strewn streets on the outskirts of what had once been the thriving city of Berlin. Another brilliant innovation from David Stirling, who had created the concept of the SAS in 1941, the small, nippy and versatile American vehicles were ideal for the war-torn terrain. Gutted, smashed and burned-out buildings formed an almost surrealist landscape which could have come straight from the tortured imagination of Hieronymus Bosch.

Corporal Arnold Baker, known affectionately to his comrades as ‘Pig-sticker’, or usually just ‘Piggy’, in tribute to his prowess with a knife, surveyed the dead city from the passenger seat of the leading jeep.

‘Jesus, this was some savage fucking war,’ he said gravely, shaking his head as though he still could not quite believe the evidence of his own eyes.

His driver, Trooper Andy Wellerby, sniffed dismissively. ‘Save your bleeding pity, Corp. When was the last time you saw London? Or Coventry, for that matter.’

‘Yeah.’ Piggy took the point, tearing his eyes away from the desolation and concentrating once more on the road in front of him. ‘What’s that up ahead?’

Wellerby waved his arm over the side of the battered Willys jeep, signalling for the vehicle behind him to slow down. He tapped lightly on the brake and squinted into the distance. Just over a quarter of a mile further up the long, straight road towards Brandenburg, a line of military vehicles sealed it off. Wellerby could make out a line of about a dozen uniformed figures standing guard beside the vehicles. He groaned aloud.

‘Not another bleeding roadblock? Bloody Yanks again, I’ll bet. It’s about time somebody told those bastards that it was us Brits who invented red tape.’

Piggy was also concentrating on the grey-uniformed soldiers. He shook his head slowly. ‘No, they’re not GIs, that’s for sure. Uniform looks all wrong.’

Wellerby let out a slightly nervous giggle. ‘Maybe it’s a bunch of fucking jerries who don’t know the war’s over yet.’

It was meant to be a joke, but one hand was already off the steering wheel and unclipping the soft holster of his Webley .38 dangling from his webbing. At the same time Piggy was checking the drums on the twin Vickers K aircraft machine-guns welded to the top of the jeep’s bonnet. In the utter chaos of postwar Germany, just about anything was possible. All sorts of armed groups were out on the streets, both official and unofficial, from half a dozen nations which had been caught up in the conflict. Quite apart from regular soldiers and covert operations groups, there were resistance fighters with old scores to settle and ordinary citizens with murder in their hearts. Even a shambling line of what appeared to be civilian refugees or released concentration camp prisoners might conceal one or two still dedicated and still fanatical Waffen SS officers who would kill rather than surrender.

‘Damn me. They’re bloody Russkies,’ Piggy blurted out, as he finally recognized the uniforms. He sounded indignant rather than surprised.

‘What the hell are the Russians doing setting up roadblocks?’ Wellerby wanted to know.

Piggy shrugged. ‘Christ knows. Everyone’s getting in on the act. And I thought we had enough problems with the Yanks, the Anzacs and our own bloody mob.’

It was the light-hearted complaint of a fighting soldier increasingly bogged down in the problems of peace. The war might be over, but Berlin was still a battleground of bureaucracy, with checkpoints and roadblocks everywhere and dozens of garrisons of different military groups still waiting for Supreme Allied Command to work out a concerted policy of occupation. For the time being, it was still largely a policy of ‘grab something and hold on to it’. Or just follow the orders one had, and muddle through.

But even so, it did not pay to take chances. The intensive training, both physical and mental, which any potential SAS trooper had to undergo did more than just produce a soldier whose reflexes and abilities were honed to near-perfection. It developed a sixth sense, an instinct for trouble. And Piggy Baker had that instinct now. There was something not quite right about the situation – he could feel it in his bones.

‘Pull up,’ he muttered to Wellerby out of the corner of his mouth. As the jeep stopped, he turned to the second vehicle as it, too, came to a halt some six yards behind.

Behind the wheel, Trooper Mike ‘Mad Dog’ Mardon looked up with a thoughtful smile on his face. ‘Trouble, boss?’

Piggy shrugged uneasily. ‘I don’t know,’ he admitted. ‘But something smells.’

Mad Dog grinned. ‘Probably just our passenger. The little bastard’s been shitting himself ever since we picked him up.’

Piggy glanced at the small, bespectacled civilian sitting stiffly and uncomfortably in the rear of the vehicle. Stripped of its usual spare jerrycans and other equipment, the jeep was just about capable of carrying two passengers on its fold-down dicky seat. Just as he had throughout the journey, the German looked blankly straight ahead, ignoring Trooper Pat O’Neill, who guarded him with his drawn Webley held across his lap.

‘Pat, I need you up at the front,’ Piggy said. He nodded at the jeep’s own pair of Vickers guns. ‘On the bacon slicer, just in case.’

O’Neill glanced sideways at his prisoner. ‘And what about Florence Nightingale here? Little bastard might decide to do a runner.’

‘Improvise,’ Piggy told him.

‘Right.’ O’Neill cast his eyes quickly around the jeep, finding a length of cord used to lash down fuel cans and fashioning it into a makeshift slip-noose. Dropping it over the German’s neck, he pulled it tight and secured the loose end to the mounting of the spare wheel. Satisfied with his work, he crawled into the passenger seat and primed both the Vickers for action.

Piggy felt a little easier now, but there was just one last little precaution to take. He reached to the floor of the jeep and hefted up his heavy M1 Thompson sub-machine-gun. Slamming a fresh magazine into place, he slipped off the safety-catch and leaned out over the side of the jeep, jamming the weapon into a makeshift holster formed by the elasticated webbing round the spare water cans. The weapon was now concealed on the blind side of the Russian troops, and ready for action if it became necessary.

There was not much more he could do, Piggy thought. He glanced sideways at Wellerby. ‘Right, take us in – nice and slow.’

The two jeeps approached the Russian roadblock at a crawl. Despite Winston Churchill’s eventual conviction that Stalin was one of the good guys after all, there was still a deep-seated mistrust between the two armies.

As Wellerby brought the leading vehicle to a halt, Baker studied the line of twelve Russian soldiers some ten yards in front of him. They stood, stonily, each cradling a PPS-41 sub-machine-gun equipped with an old Thompson-like circular drum magazine. If it had not been for the uniforms, they would have looked exactly like a bunch of desperadoes from a Hollywood gangster film.

There was something about their stance which made Baker feel even more uneasy. In the heady aftermath of victory, most Allied soldiers had tended to let discipline relax, and embrace a general feeling of camaraderie. These Russians looked as though they were fresh out of intensive training and ready to ship out to the front line.

He stood up in the jeep, scanning the line for any sign of an officer. There was none. ‘Who is in charge here? Does anyone speak English?’ he asked in a calm, authoritative tone.

There was no response. The Russian soldiers continued to stare straight through him, virtually unblinking. Several seconds passed in strained silence.

Inside the cab of one of the covered Russian personnel carriers, Tovan Leveski examined the occupants of the two jeeps thoughtfully. He too had been a little confused about their uniforms from a distance, having been briefed to expect a standard British Army patrol. Now, at close hand, he could see that these were no ordinary British soldiers. Clad in dispatch rider’s breeches, motorcycle boots and camouflaged ‘Denison’ smocks, they could have been anything. But it was their headgear which finally gave the clue. The beige berets, sporting the unique winged-dagger badge, clearly identified them as members of that small, élite force which had already started to become almost legendary. Clearly, even four SAS men were not to be taken lightly.

Quietly, Leveski murmured his orders to the eight more armed soldiers concealed in the truck behind him. Satisfied, he opened the passenger door and dropped down to the ground.

Piggy regarded him cautiously. Although the man ostensibly sported the uniform and badging of a full major in the Red Army, he seemed to lack a military bearing. However, the 7.62mm Tokarev TT-33 self-loading pistol in his hand certainly looked official enough.

‘I am in charge of this detachment, Corporal,’ Leveski said in flawless English.

It was a sticky stand-off situation, Piggy thought to himself. Even with the incredibly destructive firepower of the Vickers to hand, he and his men were hopelessly outnumbered – and there was no way of knowing how many other armed troops were inside the vehicles which made up the roadblock. Besides, military bearing or not, the officer still outranked him. For the moment there was nothing to do except play it by ear. They were no longer in a war situation, after all. Apart from the Germans and Italians, everyone was supposed to be on the same side now.

‘Do you mind telling me the purpose of this roadblock?’ Piggy demanded.

Leveski smiled thinly. ‘Certainly. My orders are to monitor all military movement on this road, Corporal. Perhaps you in turn would be so good as to tell me the exact nature and purpose of your convoy.’

Piggy considered the matter for a few seconds, unsure of what to do. His orders had been specific, but were not, as far as he was aware, secret. He could think of no valid reason to withhold information, yet something rankled.

‘With respect, Major, I fail to see what business that is of the Russian Army.’

Leveski shrugged faintly. ‘Your failure to understand is of absolutely no concern to me, Corporal. What does concern me, however, is your apparent lack of respect for a superior officer and your refusal to cooperate.’

Piggy conceded the point, grudgingly and despite the dubious circumstances. ‘All right, Major. I am leading a four-man patrol to escort a German prisoner of war to the railway marshalling yards at Brandenburg. And, since I have a strict schedule to adhere to, I would appreciate it if you would order your men to clear the road so that we can continue.’

‘I’m afraid I can’t do that,’ the Russian said in a flat, emotionless tone. ‘You and your men are in breach of the Geneva Convention, and I cannot allow you to continue.’

Piggy stared at the Russian in disbelief, starting to lose his temper.

‘Since when has it been against the rules of the Convention to transport prisoners of war?’

‘Military prisoners are one thing, Corporal. Civilians are another matter,’ Leveski informed him calmly. ‘You do have a civilian in your custody, do you not? One Klaus Mencken – Dr Mencken?’

‘Doctor?’ Piggy spat out the word, in a mixture of loathing and ridicule. ‘My men and I have come directly from Buchenwald concentration camp, Major. This “doctor” was in charge of horrific, inhuman experiments on Jewish internees there. His speciality, I understand, was removing five-month foetuses from the womb for dissection. The man is a war criminal, Major, and is on his way to an international trial to answer for those crimes against humanity. So don’t quote the Geneva Convention to me.’

The impassioned speech seemed to have had no effect on the Russian, who continued to speak in a calm, emotionless voice. ‘I must insist that you hand Dr Mencken over to me.’

‘By what damned authority?’ snapped Piggy, openly angry now, having had more than a bellyful of the Russians.

‘By the authority of superior strength.’

The new voice came from a few yards away.

Baker’s eyes strayed to his right, where a Russian captain had just jumped down from the back of one of the personnel carriers. The man walked unhurriedly towards the leading jeep, being very careful to stay out of the line of fire of the Vickers.

‘I am Captain Zhann,’ he announced. ‘You and your men are in the direct line of fire of no less than eighteen automatic weapons. Now please, Corporal, I must ask you to move back from that machine-gun and order your men to step calmly out and away from your vehicles. If you do not comply, my men have orders to open fire. You would be cut to ribbons, I can assure you.’

It was a threat that Piggy found easy to believe. Assuming that the remainder of the concealed troops also carried the thirty-five-round PPSh-41 sub-machine-guns which were on display, the Russian captain had the cards fully stacked in his favour. Each individual weapon had an automatic firing rate of 105 rounds a minute, and in a full burst, a cyclic firing rate approaching 900 rounds a minute. And the 7.62mm slugs were real body-rippers. At that range, they would all be dead in the first five seconds. Still, there remained time for at least a token show of defiance.

‘And if I refuse?’ Piggy asked.

Zhann shrugged. ‘Then you and your men will be slaughtered needlessly. A pointless gesture, wouldn’t you say?’

Piggy could only stare at the Russian in disbelief. The whole thing was crazy. It was peacetime, for Chrissake. They had all just fought the most bitter and savage war in human history. It was unthinkable that anyone would want to carry on the killing.

‘You’re bluffing,’ he blurted out at last, suddenly convinced that it was the only explanation. ‘Apart from which, you’d never get away with it.’

Leveski stepped forward again. ‘I can assure you that Captain Zhann is conducting himself according to my specific orders,’ he muttered chillingly. ‘And what would there be to “get away with”, as you put it? A simple mistake, in the confusion of a postwar city. A tragic accident. The authorities would have no choice but to accept that verdict.’

Piggy’s fingers tightened around the firing mechanism of the Vickers. He moved the twin barrels a fraction of an inch from side to side – mainly to show Leveski that he had control.

‘Aren’t you and your captain forgetting something, Major?’ he pointed out. ‘If it comes to a shoot-out, it’ll be far from one-sided. I can virtually cut your vehicles in half with one of these babies.’

The Russian gave one of his chilling smiles. ‘What I believe the Americans call a Mexican stand-off,’ he observed. ‘However, we would still appear to have the advantage. As you see, I have four covered lorries. Only one of them contains armed troops. Your problem, Corporal, would be in knowing which one to fire on first. You must surely appreciate that you wouldn’t get time for a second guess.’

It was becoming like a game of poker, Piggy thought. But what made the stakes so high? It made no sense at all. Unless, of course, the Russian was bluffing. No stranger to a deck of cards, Piggy decided to call Leveski’s hand.

‘You must understand that my men and I cannot be expected to surrender our weapons,’ he said in a flat, businesslike tone. ‘And I cannot believe that you would push this insanity to its logical conclusion.’

As if understanding his corporal’s reticence to surrender without a fight, Trooper Wellerby spoke up.

‘We ain’t got a choice, have we, Corp? What’s a piece of rubbish like Mencken to us, anyway? If the Russkies want him that bad, you can bet your sweet fucking life they ain’t planning to take him to no birthday party.’

Piggy could not repress a thin smile. In attempting to make light of the situation, Wellerby had hit the nail on the head. He was right: what were the lives of three brave troopers measured against the Butcher of Buchenwald? If only a tenth of the stories about him were true, he deserved not an ounce of human consideration. Whether Mencken died from a British noose or a Russian bullet, it made no difference at all. On the other hand, Piggy knew that he had no moral right to condemn his men to almost certain death. He returned his attention to Leveski.

‘All right, Major,’ he said, ‘in the interests of avoiding conflict, I will allow you to take the prisoner. But I must point out that I regard this as an act of hijacking and I will be reporting it to higher authorities as soon as we reach Brandenburg.’

Leveski allowed the faintest trace of satisfaction to cross his face. ‘Your objections are noted, Corporal.’ He began to walk towards the second jeep. Releasing the hastily made noose, he gestured for Mencken to alight and led the German towards the waiting Russian convoy.

Even now, the Nazi was arrogant. He still felt justified. He had just been obeying orders, he had done no wrong. He glared at Leveski defiantly. ‘I suppose you Russian dogs intend to shoot me. Then do it, and get it over with. I would not expect the luxury of a trial from Bolshevik lackeys.’

Leveski ignored the insults, switching on his chilling smile. ‘Shoot you, Herr Doktor?’ he murmured in a low voice. ‘Oh no. On the contrary, we are going to treat you like a VIP. You are going to Russia to join some of your colleagues. You will soon be working for us, Doctor – doing what you appear to enjoy doing most.’

He took Mencken by the arm, escorting him towards the nearest truck and bundling him up into the cab. Jumping in behind him, Leveski barked instructions to the driver, who fired the vehicle up into life and prepared to move off with a crunch of gears.

As the truck started to move, Leveski stuck his head out of the open window, nodding towards Captain Zhann. ‘You have your orders, Captain,’ he said in a low voice. ‘We cannot afford any survivors to tell the tale.’

Zhann nodded curtly in acknowledgement, but his face was as grim as his heart was heavy. He was a good soldier, a professional soldier. And the job of the soldier was to kill the enemy, not murder what amounted to an ally. But an order was an order, and much as he detested the increasing power and influence of the KGB in military matters, to defy a command was to place his own life on the line.

He glanced at Piggy. It was a mistake which was to cost him his life. For in that fleeting look, Piggy saw something beyond the expression of respect for a fellow soldier. He saw regret, and he saw pity. Even as Zhann’s hand twitched at his side in a prearranged signal, Piggy’s highly tuned senses were already primed. That very special instinct was alerted, and his body tensed to respond.

Ninety-nine soldiers out of 100 would have missed the faint, muted click of a dozen PPSh sub-machine-guns being cocked simultaneously. Piggy did not. More importantly, he pinpointed the exact source of the sound immediately: third lorry, fifteen degrees to his right.

‘Shake out,’ he screamed at the top of his voice. Even as he yelled, the Vickers in his hands was pumping out its devastating 500 rounds a minute – a lethal cocktail of tracer, armour-piercing shells, incendiary and ball. Beside him, Wellerby had already dived over the side of the jeep, retrieved the Thompson and rolled back under the vehicle, from where he began raking the legs of the Russian soldiers who had been standing in line.

Piggy swung the spitting machine-gun along the side of the third lorry from the cab to the tailgate, concentrating his fire at the level where the side panel met the canvas cover. The fabric of the canopy shredded away like mist evaporating in the sunshine, whole sections of it bursting into flame and drifting into the air on its own convection currents. The side panel disintegrated into splinters of wood and metal, finally revealing the inside of the truck like the stage of some monstrous puppet theatre on which life-sized marionettes jerked and twitched in an obscene dance of death.

Caught on the hop, the rest of the Russian troops had reacted with commendable speed. Leaving their unfortunate colleagues who had caught Wellerby’s raking ground-level burst from under the jeep writhing on the ground with shattered legs and kneecaps, those who could still move threw themselves down and rolled for what cover they could find.

The second set of Vickers never had a chance to open up. Pat O’Neill took a chest full of rib-splintering 7.62mm slugs which lifted him out of the jeep and threw him several feet behind it. He was dead before he hit the ground. Seconds later, Mad Dog caught it in the gut and slid lifelessly down in his seat, his head bowed forward like a man in prayer. Beyond the arc of the sub-machine-guns, two surviving Russian soldiers had rolled into a position from which they had a clear line of fire to the underside of the lead jeep. Andy Wellerby did not stand a chance as a deadly cone of fire from the two guns converged on his trapped and prone form.

Piggy had only the satisfaction of seeing Colonel Zhann’s upper torso dissolve into a massive bloody stump before the Russian fire came up over the side of the jeep and caught him in the thighs and groin. He fell sideways, landing half in and half out of the jeep as the clatter of gunfire finally ceased.

Pain swamped his senses, but his eyes were still open and his brain could still register what they saw. Just before the blackness came down, Piggy saw the lorry containing Leveski and Mencken dwindling into the distance.

‘We owe you one, you bastards,’ he grunted from between clenched teeth just before he collapsed into unconsciousness.

Miraculously, Piggy survived. But he was to hobble for the rest of his life on a pair of crutches and one tin leg. Just one year after leaving the military hospital, he joined the Operations Planning and Intelligence Unit at Stirling Lines – ironically enough, nicknamed ‘The Kremlin’ – and had a distinguished career until his retirement in 1986. Throughout his service years, his colleagues would come to know him for one particular conviction, which became almost a catch-phrase.

‘Never trust a fucking Russian,’ Piggy would say. ‘Never trust a fucking Russian.’

3 (#u704970d2-4b81-5c76-838d-5796eadd4af6)

Puerto Gaiba, Bolivia – May 1951

The man who called himself Conrad Weiss watched the two strangers walking along the shabby riverside and knew that the day he had feared and dreaded for six years had finally arrived.

They were coming for him; of that Weiss had absolutely no doubt. The two men were smartly dressed and obviously Europeans – both extreme rarities in a little Bolivian backwater town on the River Paraguay. He assumed that they had been to his house and extracted directions to the boat from his wife. He hoped that they had not tortured or hurt her. Although he had originally taken Conceptua in bigamous marriage purely for reasons of political expediency, Weiss had grown genuinely fond of her and the two olive-skinned sons she had borne him.

The two men strolled unhurriedly towards the luxury motor cruiser, which stood out like a sore thumb among the jumble of dilapidated river fishing craft. Weiss thought, momentarily, of the loaded Luger he kept in his cabin locker, quickly dismissing it. If the men were coming for him they would be trained agents, armed and alert. Besides, even if he did manage to kill them both, others would follow. They knew where he was now.

It seemed best to play innocent, attempt to bluff it out. There was at least a reasonable chance of getting away with it, Weiss reasoned. His false Swiss identity papers were the flawless work of a master forger, and his assumed identity was rock solid. And, even if that failed to impress his investigators, he had distributed vast sums in bribes to corrupt Bolivian officials in high places. That should protect him against an official attempts at extradition. Of course, they might have plans to smuggle him out of South America forcibly. Or simply to kill him where he was. In which case, his six-year run of good luck would have finally run out.

Weiss had developed a philosophical attitude to what had basically been a second life for him. He had been incredibly lucky, and more than a little cunning. When the Allies had liberated Auschwitz, he had managed to slip through the net disguised as one of the Jewish prisoners. Undetected even after six weeks in a temporary transit camp, he had finally managed to buy his ticket to freedom from an American sergeant for a handful of gold nuggets. Whether that sergeant had ever known that those nuggets came from the dental fillings of murdered Jews, Weiss had never known, or cared. He had evaded everybody – even the British SAS units on special duty to round up and arrest known and suspected war criminals. At the time, that was all that had mattered.

For the gold itself, Weiss had cared even less, for it had represented but a small fraction of the fortune in stolen jewelry and valuables he had amassed during his four years in the death camp. It was that fortune which had bought him the identity of Conrad Weiss, a retired Swiss watchmaker, and his passage to Bolivia.

But luck was at best a temporary phenomenon. The two men now mounting the gangplank of his boat both testified to that.

Bluff it out, then. Play the cards you held and hope for the best, Weiss decided. Propping himself up against the stern rail, he tried to look innocently surprised.

The first man aboard had a smile on his face, but his eyes were cold.

‘Herr Weiss?’

The reply was non-committal. ‘Who wants to know?’

‘Ah, you are worried, cautious. As of course you should be,’ Tovan Leveski murmured in good German. His hand dropped slowly and gently towards the front of his well-cut jacket, slipping open the buttons. He studied Weiss’s eyes, following every move.

‘Let me assure you, Herr Weiss, that we mean you no harm. We are not what you probably think we are. For a start, both of us are completely unarmed.’ Leveski pulled his jacket aside carefully, to show that he was not wearing a waist or shoulder holster. He half-turned to his companion, motioning for him to do the same.

Weiss’s surprise was genuine now. ‘Who are you? What is it you want with me?’

‘Just to talk. We have a little proposition to put to you. One that I think you will find extremely fascinating, my dear Doctor.’

The German’s sharply honed survival instinct cut in automatically, despite Leveski’s disarming manner.

‘Doctor? Why do you call me doctor? I was a simple watchmaker in Switzerland until my retirement.’

The cold smile dropped from Leveski’s face. ‘Please do me the courtesy of crediting me with intelligence, Doctor. I have not come all this way to be insulted. You are Dr Franz Steiner. You were in charge of the medical research facility at Auschwitz from 1941 to 1945. Your highly specialized work concerned the grafting and transplantation of amputated limbs in human subjects. You were several years ahead of your time in recognizing the problems of spontaneous rejection – a problem which, I might add, has since been much more widely studied.’

Something told Steiner that, armed or not, Leveski was not a man to antagonize. His bluff had been called, yet no threats had been offered – only a tantalizing reference to his work. Steiner found himself increasingly fascinated.

‘You have overcome the rejection problem? Isolated the antibodies which cause it?’

Leveski shook his head. ‘Not yet, Doctor. But we will – or rather, you will. With our help, of course.’

Steiner suddenly realized that his first question remained unanswered. He repeated it. ‘Who are you? What do you want with me?’

Leveski dipped his hand carefully into the inside pocket of his jacket and drew out his identity card, which he flashed under Steiner’s nose. ‘My name is Tovan Leveski. My companion is Viktor Yaleta. As you see, we are both official representatives of the government of the USSR.’

Leveski saw the look of uncertainty which flickered across the German’s ice-blue eyes. ‘You are surprised, Doctor. You should not be. The fact that we may have been enemies in the past has no relevance to our business here today. It is something which transcends accidents of birth, mere geographical boundaries. We are talking about science, Doctor – pure science. Medical reasearch – the very future of the human race. Does that not interest you?’

Steiner shrugged off the pointless question. ‘Of course. Who could fail to be interested?’

Leveski nodded towards the hatch which led down to the boat’s cabin. ‘Then perhaps we can discuss this in greater comfort?’

Nodding thoughtfully, Steiner turned, leading the two Russians to the short companionway.

‘So, how did you find me?’ Steiner asked, more relaxed now that the danger seemed to have passed, and mellowed by a large glass of local brandy.

Leveski smiled. ‘Find you, Doctor?’ He inclined one shaggy eyebrow. ‘We never lost you. We have known your exact whereabouts since 1946. We simply had no use for your particular talents until now. Your work was well ahead of its time, as you probably realize.’

Steiner sipped at his brandy. ‘And what exactly are you offering me?’

Leveski spread his hands in an expansive gesture. ‘Virtually anything, my dear Doctor. The resources of the finest and most comprehensive research facility in the world. Unlimited funds, an inexhaustible supply of human subjects for experimentation. And, probably most important to you, Doctor, total freedom to conduct biological experiments without any ethical or moral restraints. The chance to play God, in fact.’

Even if Steiner had not already been hooked, this last phrase would have clinched it. His eyes had a dreamy, faraway glaze to them. ‘This research establishment you spoke of. What is its actual purpose?’

‘To push the boundaries of medicine, surgery and biochemistry to their ultimate limits – and then beyond,’ Leveski said grandly. ‘To dream impossible dreams, and then to make those dreams come true. To travel on unknown roads – and to make new maps for others to follow in the future.’

Steiner’s heart surged. It seemed that he had heard such dreams outlined before, not so long ago. But those dreams had gone sour, decried and finally smashed to dust by a world which did not understand. Now, suddenly, it was as if he were being given a second chance.

‘And my colleagues? Who would I be working with?’ he wanted to know.

‘Others like yourself. Scientists who have dared to work in areas avoided by the squeamish and faint-hearted. We scoured Europe for them – the concentration camps, the germ-warfare establishments, the genetic study centres set up by your late Führer in his dream of a pure master race. All supplemented with the cream of our own scientists, of course.’

‘The human subjects? You would use your own people for such experiments?’

Leveski shrugged carelessly. ‘Some. Dissidents, activists, criminals, lunatics – the scum of our society. Polish Jews, prisoners of war, Mongolian peasants – the world is seething with displaced and expendable people, Doctor. As I told you, our supply of subjects is virtually inexhaustible.’

There was only one, comparatively minor question left to ask.

‘What about my wife and sons?’ Steiner wanted to know.

Leveski shook his head firmly. ‘I am afraid that our offer is for you alone, Dr Steiner. You must simply disappear without trace. They would be well provided for, of course. Your own needs would also be well catered for. There will be no shortage of available women where you are going.’

Steiner considered the matter unemotionally. There was just one last point to be cleared up.

‘Suppose I turn down this proposition?’ he asked.

‘Ah.’ Leveski looked apologetic. ‘Unfortunately, you now know too much to be left alive. Perhaps you are aware that at this moment several Israeli assassination teams are highly active throughout South America. We would simply pass on our information about your whereabouts to one of them. It would then be just a matter of time.’

The Russian broke off, to turn to his compatriot. ‘Viktor, why don’t you tell the good doctor how the Israelis’ victims die?’

The other man spoke for the first time, in a deep, guttural voice. His thick lips cracked open in a bestial, malicious grin. ‘Choked to death on their own genitals,’ he grunted, with obvious relish. ‘Hacked off and stuffed down their throats.’

Leveski stared Steiner coldly in the eyes, letting the image sink in. ‘Mind you, they might have something a bit more special for someone who used to perform surgical amputations without anaesthetic,’ he volunteered.

Steiner held the Russian’s gaze, the ghost of a smile playing over his lips. ‘When do we leave?’ he asked.

4 (#u704970d2-4b81-5c76-838d-5796eadd4af6)

London – January 1993

Lieutenant-Colonel Barney Davies glanced around the Foreign Office conference room with a slight sense of surprise. He had not been expecting such a high-powered meeting. Nothing in the message he had received had given any indication that this was to be any more than a briefing session. Now, noting the sheer number of personnel already assembled, and the prominence of some of them, Davies could tell that this was to be no mere briefing. It looked more like a full-blown security conference.

He reviewed the cluster of faces hovering around the large, oval-shaped table. Nobody seemed prepared to sit down yet; they were all still waiting for the guest of honour to arrive. It had to be pretty high brass, Davies figured to himself, for he recognized at least two Foreign Office ministers, either of whom could quite comfortably head up any meeting up to and perhaps including Cabinet level. He teased his brain, trying to put names to the faces.

He identified Clive Murchison almost immediately. He had had some dealings with the man during the Gulf War, the successful conclusion of which probably had something to do with Murchison’s obvious and rapid climb up the bureaucratic ladder. Tending towards the curt, but irritatingly efficient, Murchison was of the old school, the ‘send a gunboat’ brigade. His presence alone reinforced Davies’s feeling that this meeting was serious stuff.

Naming Murchison’s colleague proved a little trickier. Windley? Windsor? Neither name seemed quite right. It fell into place, eventually. A double-barrelled name. Wynne-Tilsley, that was it. Michael Wynne-Tilsley. Still technically a junior minister but well connected, tipped for higher things. Word was that he had the PM’s ear, or maybe knew a few things he should not. In political circles, Davies reflected, that was the equivalent of a ticket to the front of the queue.

There were half a dozen other people who meant nothing whatsoever to Davies. Whether they were civil servants or civilian advisers, he had no idea, although there was probably the odd man from MI6 or the ‘green slime’ in there somewhere.

There was, however, one more face that he definitely did recognize. Davies’s face broke into a friendly grin as he strolled across to the slightly hunched figure in the electric wheelchair. Reaching down, he gave the man’s shoulder an affectionate squeeze.

‘Well, you old bastard, what are you doing here? Thought you’d retired.’

Piggy Baker looked up, grinning back. ‘I had…have. They dug me up again to bring me in as a special adviser on this one.’ The man extended his hand. ‘Barney, good to see you.’

The two men shook hands warmly. Finally, Davies drew back slightly, appraising his old comrade. He noted that Piggy no longer bothered to wear his artificial leg.

‘So what happened to the pogo stick? Thought they would have rebuilt you as the six billion dollar man by now. All this new technology, prosthetics and stuff.’

Piggy shrugged carelessly. ‘They did offer, a couple of years back. But what the hell? I’m too old to go around all tarted up like Robocop.’ He broke off, nodding down at the wheelchair. ‘These days, I’m happy enough to ponce around in this most of the time.’

Davies nodded, his face suddenly becoming serious. ‘So, what’s all this about? Looks like high-powered stuff.’

Baker’s face was apologetic. ‘Sorry, Barney, but I can’t tell you a thing until the briefing. OSA and all that, you know.’

‘Yes, of course.’ Davies had not really expected much else. He knew all about the Official Secrets Act, and official protocol. He had come up against it himself enough times.

There was a sudden stir of movement in the room. The babble of voices hushed abruptly. Glancing towards the large double doors, Davies was not really surprised to see the Foreign Secretary enter the room. He had not been expecting anyone less.

The Foreign Secretary headed straight for one end of the oval table and sat down. ‘Well, gentlemen, shall we get down to business?’ he said crisply. He glanced across at Wynne-Tilsley as everyone took their chairs. ‘Perhaps you would be so good as to introduce everybody before we begin the briefing.’

Wynne-Tilsley went round the table in an anticlockwise direction. Just as Davies had supposed, most of the personnel were civilian advisers or from the green slime, the Intelligence Corps.

The introductions over, the Foreign Secretary took over once more. ‘Gentlemen, we have a problem,’ he announced flatly. ‘The purpose of this meeting is to determine what we do about it. Let me say at this juncture that it is not so much a question of should we get involved as can we get involved. Which is why I have invited Lieutenant-Colonel Davies, of 22 SAS, here today.’ He paused briefly to nod towards Davies in acknowledgement, before turning to Murchison. ‘Perhaps you would outline the situation for us.’

Murchison rose to his feet, riffling through the sheaf of papers and notes in front of him. He spoke in a clear, confident tone – the voice of a man well used to public speaking and being listened to.

‘Essentially, we’ve been asked by the Chinese to infiltrate former Soviet territory,’ he announced, pausing for a few moments to let the shock sink in. He waited until the brief buzz of startled exclamations and hastily exchanged words were over. ‘Which, as you might gather, gentlemen, makes this a very sticky problem indeed.’ Murchison then turned to face Davies directly. ‘The general feeling was that this is an operation which could only be tackled by the SAS if it could be tackled at all – although the complexities and nature of the specific problem could prove even beyond their capabilities.’

It seemed like a challenge which demanded a response. Davies rose to his feet slowly, addressing the Foreign Secretary directly.

‘You used the word “infiltrate”,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘An ambiguous word at the best of times. Some clarification would be appreciated.’

The Foreign Secretary nodded. ‘I appreciate your concern, Lieutenant-Colonel, and I understand your reserve. Just let me assure you that we are not talking about an invasion force here, nor would we go in with any hostile intent. However, it is possible that your men would encounter hostile forces.’

Not much wiser, Davies sank back into his chair. ‘Perhaps I’d better hear the rest of the briefing,’ he muttered.

Murchison rose to his feet again. ‘I think the background to the problem will be best explained by Captain Baker,’ he said. I know Lieutenant-Colonel Davies is well aware of his colleague’s position, but for the rest of you I had better explain that Captain Baker was for many years with SAS Operations Planning and Intelligence. He has been called here today because he has been close to this particular story for a long time.’

With a curt nod in Piggy’s direction, he yielded the table and sat down again.

‘You’ll excuse me if I don’t stand, gentlemen,’ Piggy began, a wry grin on his face. He paused for a while, marshalling his thoughts. Finally, he took a deep breath and launched into his rehearsed brief.

‘Just after the Second World War, it became apparent that the Russians were gathering together scientists, doctors and medical staff from all over Europe for some sort of secret project,’ he announced. Turning towards Davies, he added a piece of more personal and intimate information. ‘As it happens, I had a personal encounter at the time, and there are three plaques mounted outside the Regimental Chapel at Stirling Lines because of it. So you might say that I have always had a deep and personal interest in the ongoing story.’

So, Davies thought, it was personal – to them both. Family business. An old score that needed settling. But why now? Why the Chinese involvement? He listened intently as his old friend went on, now with a deeper sense of commitment.

‘Suffice it to say that when I moved to OPI I initiated a monitoring operation on this project, which has been kept up to the present day,’ Piggy continued. ‘And although there has been no official liaison with our own Intelligence Corps, I believe that they too have been keeping an eye open, as, indeed, have our American counterparts.’

Davies broke off briefly to cast a questioning glance towards Grieves, the officer from the green slime. The man nodded his head wordlessly, confirming Piggy’s suspicions.

‘We know that the original project was code-named Phoenix by the Russians,’ Piggy went on. ‘Everything suggests that it was never officially embraced by the Soviet government, but placed largely under the control of the KGB, and kept under tight security wraps. For that reason, our intelligence is patchy, to say the least, and we have had to surmise quite a lot of what we were unable to know for fact. What we do know, however, is that in 1947 a secret research facility was set up in a fairly remote and mountainous region of Kazakhstan, fairly close to the Mongolian border. While we still do not know the exact purpose of this original facility, we have always assumed it to be a biological research project of some kind. It is also logical to assume that the underlying concept of this research facility was in military application, although there may have been some spin-offs into mainstream science. It is more than possible, for instance, that the dominance of Soviet and Eastern Bloc athletes during the fifties and sixties was directly due to steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs which were developed in the Kazakhstan facility.’

The Foreign Secretary had been busy making notes. He looked up now, tapping his pen on the table to draw Piggy’s attention.

‘So what you are saying, in effect, is that this project has never actually offered any direct, or perceived, threat to the Western powers, or us in particular? At worst, in fact, it might have cost us a few gold medals in the Olympics?’

Piggy nodded, conceding the point. ‘Up to now, yes. But recent developments have given us cause to think again.’

The Foreign Secretary chewed his bottom lip thoughtfully. ‘And what are these new developments?’

‘With respect, sir, I believe I can best answer that,’ Grieves said, rising to his feet and waving a buff-coloured dossier in one hand. Satisfied that he had the floor, he cleared his throat with a slight cough and carried on. ‘About three months ago, GCHQ monitored what appeared to be some kind of distress signal sent out from the Kazakhstan facility to the old KGB HQ in Moscow. From this, we must deduce two things – A, that some sort of accident or emergency situation had occurred within the complex, and B, the personnel inside are seemingly unaware that the KGB has been virtually broken up and disbanded over the past year or so. This further suggests that they might be completely out of touch with what has been going on inside the Soviet Union and the world at large.’

‘But how can that be?’ the Foreign Secretary wanted to know. ‘Surely they must have regular contact with the outside world – supplies, that sort of thing.’

Grieves shook his head. ‘Not necessarily, sir. Our intelligence has always suggested that the facility was designed to be virtually self-sustaining. As long ago as 1969 an American spy satellite carrying out routine surveillance of the Soviet nuclear weapons testing facility at Semipalatinsk happened to overfly the base and monitor an internal nuclear power source. This suggests that it has its own closed power source, and it is probable that they also have their own hydroponic food-production facility along with a pretty sophisticated recycling system. The very nature of the complex has always been secretive, even autonomous. It is more than likely that it even has its own security system – a private army, in effect.’

‘Just what are we actually talking about here?’ Lieutenant-Colonel Davies interrupted. ‘A scientific research facility or a bloody garrison? Just how big is this damned place, anyway?’

If the Foreign Secretary found Davies’s language at all offensive, he gave no sign. ‘A good question,’ he muttered, glancing questioningly at Grieves.

The Intelligence officer shrugged faintly. ‘Again, inconclusive evidence,’ he said. ‘Satellite observation suggests that much of the complex is built underground, but we don’t know how many subterranean levels there might be. Basically, we have no way of knowing the actual size and personnel strength of the establishment. It might house a few dozen scientists and support staff. Or it could be an autonomous, full-scale community, of several hundred people living in a miniature city. Don’t forget that this place has been established for nearly fifty years now. There’s no guessing how it has developed.’

Grieves fell silent for several seconds. When he spoke again, his face was grim and his tone sombre. ‘Of course, personnel numbers could well be a purely academic point. They may, in fact, all be dead anyway. Which, incidentally, is where the Chinese come in. They’re afraid that some sort of chemical or biological contamination may have escaped from within the complex, and may already have crossed the Mongolian border.’ He paused again, longer this time, to allow the full significance of his words to register.

Finally, Davies attempted a brief recap. ‘So what you’re suggesting is that this place may have been engaged in chemical or bacteriological warfare research, and something nasty might have got loose?’

Grieves nodded. ‘In essence, yes.’

‘Have the Chinese any direct evidence for this?’ Davies asked. ‘Have there been any actual deaths?’

Grieves consulted his notes briefly. ‘It’s difficult to be absolutely sure,’ he replied. ‘You have to understand the unique background and make-up of Kazakhstan itself. It’s vast – almost unbelievably so. You could fit Britain, France, Germany, Spain, Finland and Sweden into it quite comfortably. Yet it only has a total population of some seventeen million – an improbable mix of races and cultures including native Kazakhs, Tartars, Uzbeks and Uigurs along with emigrant Russians, Germans and others. In Stalin’s heyday, Kazakhstan was Gulag territory. When the concentration camps were disbanded, many of the inmates settled in the area. Stalin also used the region as a dumping ground for vast numbers of people he considered “political undesirables” – Volga Germans, Meskhetian Turks, Crimean Tartars and Karachais to name but a few. So we’re talking about millions of square miles still sparsely populated by people of widely differing religions, cultures and languages. And we are also dealing with a particularly remote region, in mountainous terrain not far from Mount Belushka. Because of the nature of this terrain, and the scattered, semi-nomadic distribution of the peasant population, there is no direct communications network. Any information which comes out of the area is essentially rumour, or word-of-mouth reports which might have been passed through several dozen very simple people before reaching the ears of the authorities. However, there are enough reports of dead and missing goatherds, peasant farmers and the like filtering through to give these Chinese fears some credibility.’

‘So why can’t they go in and sort it out for themselves?’ Davies asked. ‘After all, they’re right there on the spot.’

Grieves did not attempt to answer. Instead, he glanced towards the Foreign Secretary.

‘With respect, Lieutenant-Colonel,’ said the latter, addressing Davies directly, ‘you’re looking at this through the eyes of a military man, without taking into account the highly complex and sensitive political issues involved here. This whole region is a territorial minefield. There have been border clashes between the Chinese and Russians for the last three decades, and stability balances on a knife-edge. The Chinese don’t dare to make a serious incursion into Russian territory for fear of sparking off a major incident.’

‘Then it’s up to the Russians to sort it out for themselves, surely?’ Davies suggested.

The Foreign Secretary smiled thinly. ‘Perhaps you’re forgetting that there is virtually no longer any centralized decision-making inside former Soviet territory,’ he pointed out. ‘Every region, every state is in turmoil – fragmented and politically unstable if not actively in the throes of civil war. The Kazakhstan region is no exception. There are perhaps up to half a dozen different guerrilla groups and political and religious factions already fighting for territory virtually on a village by village, valley by valley basis. You only have to look to Georgia, just across the Caspian, to get an idea of what’s going on there.’

Davies nodded thoughtfully. Grieves coughed faintly again, drawing attention back to himself.

‘Actually, to answer Lieutenant-Colonel Davies’s last question, I ought to point out that we believe the Russians did manage to send in at least one military team to investigate,’ he volunteered. ‘Our intelligence suggests that they disappeared without trace, with absolutely no clues as to what happened to them. We have no way of knowing if they even managed to get anywhere near the research facility.’

‘But I still fail to understand how the Chinese reckon to get us involved in all this,’ Davies said, becoming increasingly bogged down in the political intricacy of the entire affair.

The Foreign Secretary treated him to another thin, almost cynical smile. ‘Politics sometimes makes for strange bedfellows,’ he said. ‘The Chinese are desperate for Western acceptance after the Tiananmen Square massacre. They are equally desperate for access to European trade markets, and, rightly or wrongly, they seem to believe that Britain could be holding the top cards in the Euro-deck right now. And, as we are already involved in close association over the Hong Kong business, they feel they have an ace of their own to play.’

Davies started to understand at last. ‘So it’s a threat, basically?’ he said. ‘Unless we play ball with them, they’ll make the Hong Kong negotiations more difficult?’

The Foreign Secretary smiled openly now. ‘I see you’re beginning to get a grasp of modern-day diplomacy,’ he murmured, without obvious sarcasm. He paused to take a slow, deep breath. ‘So, Lieutenant-Colonel Davies, that’s it, in a nutshell. We appear to be stuck with the problem, and the SAS would appear to be our only hope.’

‘To do what, exactly?’ Davies demanded. He was still not quite sure what was actually being asked of him.

The Foreign Secretary stared him directly in the eye. ‘To get in there, monitor the situation and neutralize it if possible. Of course, you understand that we are talking about some of the most difficult and inhospitable terrain in the world, under the most extreme climatic conditions. As I understand it, the difference between daytime and night-time temperatures can be as much as 20°C. Once you’re up into the mountains, you can expect extremes as low as minus thirty – plus fierce and bitter northerly winds straight down from Siberia.’

Davies nodded thoughtfully. ‘Not exactly the Brecon Beacons,’ he muttered. The reference to the SAS testing and training grounds went over the top of the Foreign Secretary’s head.

‘You would, of course, be given the full support of the Intelligence Corps and access to all the relevant files,’ the latter went on. ‘You would be expected to liaise with Captain Baker about the finer points of the operation, including more detailed briefing about the geography of the region. All I require from you at this stage is a gut assessment as to the feasibility of the operation. In short, could your men get a small team of scientists into that complex with a reasonable hope of success?’

The last sentence was a sudden and totally unexpected sting in the tail. Davies jumped to his feet angrily, quite forgetting the company he was in as he banged his fist down on the table. ‘No bloody way,’ he shouted, vehemently.

The Foreign Secretary kept his cool admirably, merely raising one eyebrow quizzically.

‘Come now, Lieutenant-Colonel. I would have thought this was right up your street.’

‘No bloody civilians, no bloody way,’ Davies repeated, virtually ignoring him. ‘The SAS isn’t a babysitting service for a bunch of boffins who probably couldn’t even step over a puddle without getting their feet wet. If we go in at all, we go in alone. And if we need any specialist know-how, we’ll take it in our heads.’

The Foreign Secretary seemed unperturbed. ‘Yes, Captain Baker more or less warned me that that would be your reaction,’ he observed philosophically. He thought for a few moments. ‘Well, as I can’t order you, we shall have to resort to Plan B. Your men will secure the area and neutralize any obvious threat to an Anglo-Chinese team of scientific experts who will be airlifted in behind you. Can you do that much?’

Davies simmered down. ‘We can have a damned good try,’ he said emphatically. ‘What about insertion into the area?’

‘That’s one of the matters we’re going to have to discuss,’ Piggy put in. ‘But basically you’d probably have to assemble somewhere neutral like Hong Kong. You’d go in as civilians, of course – either as tourists or visiting businessmen. From there you would be contacted by the Chinese and transferred to a military base on the mainland. We would expect the Chinese to put you over the border somewhere just inside Sinkiang Province, probably 100 miles north-east of Tacheng. You would then be facing a foot trek of around 350 miles. It’s going to give you supply problems, but there’s a possibility the Chinks would be willing to risk a brief air incursion into Soviet territory to drop you one advance cache. Certainly no more, since the official Kazakhstan government is extremely well armed with the latest high-tech kit. The republic has even managed to retain nearly fifteen per cent of the former Soviet total nuclear arsenal, much to the Kremlin’s annoyance.’

‘In that sort of mountainous terrain?’ Davies shook his head. ‘No, we’d probably never find it. And if we put it in with a homing beacon there’s every chance someone else would get to it before we did. No, we’d have to go in on a self-sustaining basis. What’s the local wildlife situation?’

Piggy shrugged. ‘Sparse – particularly at this time of year. Probably a few rabbits or even wild deer in the foothills, but not much else. Your best bet would probably be airborne. Carrion crow, the odd golden eagle – probably not much different to turkey if you eat ’em with your eyes shut.’

‘Sorry, but you two gentlemen seem to have lost me,’ the Foreign Secretary put in. ‘I thought we were discussing a military operation, not a gourmet’s picnic’

The politician went up an immediate notch in Davies’s estimation. The man had a sense of humour.

‘It’s a question of weight and distance ratio,’ Davies hastened to explain. ‘With a round trip of 700 miles, my men are going to be limited in the amount of food and supplies they can carry in their bergens. They’re already going to have to be wearing heavy thermal protection gear and, from the sound of it, Noddy suits as well.’

‘Noddy suits?’ the Foreign Secretary queried.

The SAS man smiled. ‘Sorry, sir. I mean nuclear, chemical and biological warfare protection. Cumbersome, uncomfortable, and all additional weight. Quite simply, it’s going to be physically impossible to carry all the gear they will need for an operation of this size and complexity. So we cut non-essential supplies such as food. Troopers are trained to live off the land where necessary.’

‘They could, of course, take in a couple of goats with them,’ Piggy suggested. It was not intended to be a facetious remark, but Davies glared at him all the same.

‘I’m concerned about keeping them alive – not their bloody sex lives,’ he said dismissively. ‘And in that respect, where do we get kitted up, if we’re going in as civvies?’

‘No problem,’ Piggy assured him. ‘We can arrange for anything you ask for to be ready and waiting for you when you arrive at your Chinese base.’

The Foreign Secretary was standing up and gathering his papers together. ‘So I can leave you two to sort out the details?’ he asked, beginning to feel slightly uncomfortable and superfluous. ‘How soon do you think you might be able to come up with a reasonable plan of operations?’

Davies shrugged. ‘Six, seven weeks maybe. There’s a lot of groundwork to be done.’

‘Ah.’ The Foreign Secretary frowned. ‘I’m afraid we don’t have the luxury of that sort of timescale,’ he said. ‘There is another problem.’

‘Which is?’ Davies wanted to know.

Murchison answered for the Foreign Secretary. ‘It’s a question of climate and temperature,’ he explained. ‘If there has been a biological leak, our experts seem to think that the extreme cold might well keep any widespread contagion in check for a while at least. Come the spring, and warmer weather, it could be a different picture altogether. We had been thinking in terms of getting something off the ground in three weeks maximum.’

Davies sucked in a deep breath and blew it out slowly over his bottom lip. It was a tall order, even for the SAS. He looked at the Foreign Secretary with a faint shrug. ‘I’ll see what I can do,’ he said quietly, unwilling to make any firmer promise at that stage.

The Foreign Secretary nodded understandingly. ‘I’m sure you will do everything you can, Lieutenant-Colonel.’ He glanced almost nervously around the table before directing his attention back to Davies. ‘You understand, of course, that if anything goes wrong, this meeting never took place?’

Davies grinned. It was a story he had often heard before. ‘Of course,’ he muttered. ‘They never do, do they?’

The two men exchanged a last brief, knowing glance which established that they were both fully aware of the rules of the game. Then the Foreign Secretary picked up his papers, nodded to his two ministers and led the way out of the conference room.

Left alone, Davies crossed over to Piggy and slapped him on the back. ‘Well, I think you and I need to go and sink a few jars somewhere,’ he suggested.

5 (#u704970d2-4b81-5c76-838d-5796eadd4af6)

‘So, what’s your gut feeling on this one?’ Davies asked Piggy after he had helped install his electric wheelchair in the lift down to the high-security underground car park.

Piggy let out a short, explosive sound halfway between a grunt and a cynical laugh. ‘You know my views on anything to do with the fucking Russians,’ he replied. ‘And I’m not too sure about the bloody Chinks, either. Personally, I’m inclined to the view that every takeaway in London is part of a plot to poison us all with monosodium glutamate.’

Davies grinned. ‘You’re a bloody xenophobe.’

Piggy shook his head, a mock expression of indignation on his face. ‘That’s a vicious rumour put about by those jealous bastards at Stirling Lines. I take my sex straight.’ He paused to flash Davies a rueful grin. ‘At least, I do when Pam hasn’t got a bloody headache these days.’

Davies smiled back. ‘Christ, are you two still at it? You dirty old man.’

‘Lucky old man,’ Piggy corrected him. ‘Actually, I think it’s just the delayed effect of all those hormones I was taking for forty years.’

Davies’s eyes strayed briefy to the wheelchair, and Piggy’s truncated torso. ‘You never had any problems, then?’ he asked, a little awkwardly.

Piggy grinned again. ‘No, the old Spitfire still flies. They may have shot the undercarriage to hell, but there was nothing wrong with the fuselage. The hormone treatment did the rest.’ His face suddenly became serious again, almost sad. ‘No kids, of course – that’s the only part that still hurts.’

Children were a sore point with Davies as well. ‘Count yourself lucky,’ he muttered. ‘Mine hardly ever bother to even talk to me these days. Now they’ve got a new dad and a new baby-sister, I’m just a relic from the past.’

‘You never bothered to remarry, then?’

Davies laughed ironically. ‘Like the old cliché – I married the job,’ he said. ‘And the SAS can be a jealous bitch. Besides, there aren’t that many understanding women like your Pam around these days.’

They had reached the car park level. Piggy looked up into Davies’s eyes as the lift doors hissed open, a wry smile on his face. ‘We’re still doing it, aren’t we?’ he murmured.

‘Doing what?’ Davies didn’t quite understand.

‘The bullshit,’ Piggy said, referring to the casual banter which virtually all SAS men exchanged before operations.

Davies gave no reply. He helped steer the wheelchair through the doors into the underground car park. Instinctively, he began to walk towards his own BMW, suddenly pausing in mid-stride and looking back at Piggy somewhat awkwardly.

‘Look, I’ve only just realized that my car isn’t equipped to take that chariot of yours,’ he muttered in embarrassment.

Piggy smiled easily. ‘No problem, I do have my own transport, you know.’

‘Yes, of course.’ Davies relaxed, feeling a bit better about his near-gaffe. ‘So, where would you like to go for a drink? I’m afraid I’m not really up on London pubs these days.’

Piggy looked at him with a faint look of surprise. ‘Who said anything about a London pub? There’s only one place for a pair of old troopers like us to have a drink – and we both know exactly where that is.’

It was Davies’s turn to look a little bemused. ‘The Paludrine Club?’ he said, referring to the Regiment’s exclusive little watering-hole back at Stirling Lines in Hereford.