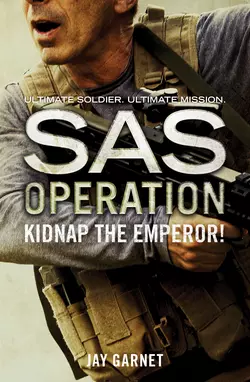

Kidnap the Emperor!

Jay Garnet

Ultimate soldier. Ultimate mission. But can the SAS pull off a daring prison break and escape from Communist-run Ethiopia alive?In 1975, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, recently deposed in a Communist revolution, is declared dead. In the hands of the brutal army officer Mengitsu Haile Mariam, the country has descended into chaos and bloodshed.Then an astonishing truth emerges. The Emperor is being kept alive in prison by Mengitsu, but only until he reveals the location of his billion-pound fortune. The British and American governments will not tolerate a ruthless Communist regime’s acquisition of such wealth: it will destabilize the Middle East and all East Africa.There is only one answer: kidnap the Emperor. Three SAS soldiers ¬are selected for this hazardous mission, which is like nothing the regiment has ever tackled before: to penetrate a remote desert fortress and then to escape through arid highlands with a frail old man in tow. Only extraordinary duplicity will get them in. Only acute tactical expertise and merciless improvisation will get them out. And if anything goes wrong, it will be as if they had never existed.

Kidnap the Emperor!

JAY GARNET

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photograph © Stephen Mulchaey / Arcangel Images

Jay Garnet asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155278

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008155285

Version: 2015-11-10

Contents

Cover (#ub3e7af20-2e14-5cfb-b297-4d6ecafef73b)

Title Page (#u8a155e1e-3d74-50c4-9e4a-9bfc52de5e89)

Copyright (#u9b2a5060-6e6e-5cd3-8b04-04b6854b6d7a)

Prologue (#u0adcb44e-51fa-5d03-aad7-81966024f9e3)

Chapter 1 (#u6a39223e-e398-5ec8-9d34-993c6260a07c)

Chapter 2 (#u9ac2dcbd-c1e7-5a21-b7ec-bb85d6d0ac4e)

Chapter 3 (#u33d39e93-88cd-5647-a926-077de72f209e)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u610b2d2f-3e33-50cc-863d-4659f60235d2)

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

‘Haile Selassie, former Emperor of Ethiopia, who was deposed in a military coup last year, died in his sleep here yesterday aged 83. A statement by Ethiopian radio said he died of an illness after a prostate gland operation two months ago. He was found dead by attendants yesterday.’

The Times, 28 August 1975

April 1976

North and east of Addis Ababa lies one of the hottest places on earth. Known as the Afar or Danakil Depression, after two local tribes, it points like an arrowhead tempered by the desert sun southwards from the Red Sea towards the narrow gash of Africa’s Rift Valley.

For hundreds of square miles the plain is unbroken but for scanty bushes whose images shimmer above the scorched ground. Occasionally here and there a gazelle browses, wandering between meagre thorn bushes across rock or sand streaked with sulphur from the once volcanic crust.

Even in this appalling wilderness, far from the temperate and beautiful highlands more often associated with Ethiopia, there are inhabitants. Most are herders who wander the scattered water-holes. But some make a precarious living trading slabs of salt levered from the desert floor – some five million years ago the depression was a shallow inlet of the Red Sea and its retreat left salty deposits that still cake the desert with blinding white. Camels transport the blocks to highland towns.

Soon after dawn on the morning of 19 April, a caravan of ten camels, groaning under grey slabs of salt done up in protective matting, set off from their camp along unpaved tracks towards the highlands. There were three drovers – two teenagers and their father, a bearded forty-five-year-old whose features seemed parched into premature old age by the desert sun. His name was Berhanu, not that it was known to anyone much beyond his immediate family.

Yet before the week was out it would be known, briefly, to a number of the Marxists who had seized power from the Emperor Haile Selassie eighteen months previously, and most importantly to Lieutenant-Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, then number two in the government but in effect already the country’s implacably ruthless leader. A record of Berhanu’s name may still exist in a Secret Police file in 10 Duke of Harar Street, Addis Ababa, along with a brief description of what Berhanu experienced that day.

The caravan had just rounded a knoll of rock. It was approaching midday. Despite a gusty breeze, the heat was appalling – 120 degrees in the shade. Berhanu, as usual at this time, called a halt, spat dust from his lips, and pointed off the road to a small group of doum-palms that would provide shade. He knew the place well. So did the camels. Nearby there was a dip that would hold brackish water.

With the camels couched, the three sought relief from the heat in the shade of the trees. The two boys dozed. It was then that Berhanu noticed, in the trembling haze two or three hundred yards away, a group of circling vultures. He would not have looked twice except that the object of their attention was still moving.

And it was not an animal.

He stared, in an attempt to make sense of the shifting image, and realized he was looking at a piece of cloth being seized and shaken by the oven-hot gusts. Unwillingly he rose, and approached it. As he came nearer, he saw that the cloth was a cloak, and that the cloak seemed to be concealing a body. It had not been there all that long, for the vultures had not yet begun to feed. They retreated at his approach, awaiting a later chance.

The body was tiny, almost childlike, though the cloth – which he now saw was a cloak of good material – would hardly have been worn by a child.

Berhanu paused nervously. Few people came to this spot. It was up to him to identify the corpse, for he would no doubt have to inform some grieving family of their loss. He walked over to the bundle, squatted down and laid the flapping cloak flat along the body, which was lying on its face. He put a hand on the right shoulder, and rolled the body towards him on to its back.

The sight made Berhanu exhale as if he had been punched in the stomach. His eyes opened wide, in shock, like those of a frightened horse. For the face before him, sunken, emaciated, was that of his Emperor, Haile Selassie, the Power of Trinity, Conquering Lion of Judah, Elect of God, King of Kings of Ethiopia. Berhanu had known little of Ethiopia’s steady collapse into poverty, of the reasons for the growing unrest against the Emperor, of the brutalities of the revolution. To him, Selassie was the country’s father. As a child he had honoured the Emperor’s icon-like image on coins and medals inherited from his ancestors. And eight months previously he had ritually mourned the Emperor’s death.

Berhanu felt panic rising in him. He fell to his knees, partly in adulation before the semi-divine countenance, and partly in a prayer for guidance. He began to keen softly, rocking backwards and forwards. Then abruptly he stopped. Questions formed. The presence of the corpse at this spot seemed miraculous. It must have been preserved, uncorrupted, for the best part of a year, and then somehow, for reasons he could not even guess at, transported here. Preserved where? Was he alone in seeing it? Was there some plot afoot upon which he had stumbled? Should he bury the body? Keep silent or report its presence?

Mere respect dictated that the body, even if divinely incorruptible, should be protected. Then, since others might already know of his presence here, he would show his innocence by making a report. Perhaps there would even be a reward.

Slowly, in the quivering heat, Berhanu gathered rocks and piled them in reverence over the body. Then he walked back, still trembling. He woke his sons, told them what he had seen and done, cursed them for unbelievers until they believed him, and hurried them on their way westwards.

Three days later, he delivered his consignment of salt, which would be sold in the local market for an Ethiopian dollar a slab. He collected his money, and went off with his sons to the local police chief.

The policeman was sceptical, and at first dismissed Berhanu as a madman. Then he became nervous – for peculiar things had been happening in this remote part of Tigré province over the past two years – and made a telephone call to his superiors in Addis.

From there, the bare bones of the report – that deep in the Danakil a local herder named Berhanu had found a corpse resembling the former Emperor – went from department to department. At each stage a bureaucrat decided the report was too wild to be taken seriously; and at each stage the same men decided in turn that they would not be the ones to say so. Within three hours the éminence grise of the revolution, Mengistu Haile Mariam, knew of it. He also knew, for reaons that will become apparent, that the report had to be true.

For the sake of the revolution, both the report and the evidence for its existence had to be eradicated. Mengistu at once issued a rebuke to every department involved, stating the report was clearly a fake, an error that should never have been taken seriously.

Secondly, he ordered the cairn to be visited and the contents destroyed. The following morning, a helicopter containing a senior army officer and two privates flew to the spot. The two privates unloaded a flame-thrower, and incinerated the cairn. The team had specific orders not to look beneath the stones, and never knew the purpose of their strange mission.

Thirdly, Mengistu ordered the disappearance of Berhanu and his sons. The police in Tigré had become used to such orders, and asked no questions. The three were found, fed, flattered, transported to a nearby army base with promises of money for their excellent work, and never heard of again. A cousin made enquiries a week later, but was met with bland expressions of sympathy.

The explanation for the presence of the Emperor’s body in the desert in a remote corner of his country eight months after his death had been officially announced might therefore have remained hidden for ever.

There was, as Mengistu himself well knew, a possible risk. One other man knew the truth. But Mengistu had reason to think that he too was dead, a victim of the desert.

The existence of this book proves him wrong.

1 (#u610b2d2f-3e33-50cc-863d-4659f60235d2)

Thursday, 18 March 1976

The airport of Salisbury, Rhodesia, was a meagre affair: two terminals, hangars, a few acres of tarmac. Just about right for a country whose white population was about equal to that of Lewisham in size and sophistication, pondered Michael Rourke, as he waited disconsolately for his connection to Jo’burg.

Still, those who had inherited Cecil Rhodes’s imperial mantle hadn’t done so badly. Across the field stood a flight of four FGA9s, obsolete by years compared with the sophisticated beauties of the USA, Russia, Europe and the Middle East, but quite good enough at present to control the forested borderlands of Mozambique. And on the ground, Rhodesia had good fighting men, white and black, a tough army, more than a match for the guerrillas. But no match for the real enemy, the politicians who were busy cutting the ground from under the whites.

Rourke sank on to his pack, snapped open a tin of lager and sucked at it morosely. He had been in and out of the field for twelve years since first joining the SAS from the Green Jackets: Rhodesia on unofficial loan, for the last two years; before that, Oman; before that, Aden. In between, back to the Green Jackets.

The money here had not been great. But he’d kept fit and active, and indulged his addiction to adrenalin without serious mishap. At thirty-four his 160lb frame was as lean and hard as it had been ten years earlier.

But now he had had enough of this place. He was tired: tired of choppers, tired of the bush. The only bush he was interested in right now belonged to Lucy Seymour, who hid her assets beneath a virginal white coat in a chemist’s down the Mile End Road.

The last little jaunt had decided him.

There had been five of them set down in Mozambique by a South African Alouette III Astazou. His group – an American, another Briton and two white Rhodesians – were landed at dusk in a clearing in Tete, tasked to check out a report that terrorists – ‘ters’, as the Rhodesian authorities sneeringly called them – were establishing a new camp near a village somewhere in the area. Their plan was to make their way by night across ten miles of bush, to be picked up the next morning. Four of them, including the radio operator, were all lightly armed with British Sterling L2A3 sub-machine-guns. One of the Rhodesians carried an L7 light machine-gun in case of real trouble.

Rourke anticipated no action at all. The information was too sparse. Any contact would be pure luck. All they would do, he guessed, was establish that the country along their line of march was clear.

But things hadn’t gone quite as he thought they would. They had moved a mile away from the landing zone and treated themselves to a drink from their flasks, then moved on cautiously. It was slow work, edging through the bush guided between shadow and deeper shadow by starlight alone. Though they could scarcely be heard from more than twenty yards away, their progress seemed to them riotous in the silent air – a cacophony of rustling fatigues, grating packs, the dull chink and rattle of weaponry. To penetrate their cocoon of noise, they stopped every five minutes and listened for sounds borne on the night air. Towards dawn, when they were perhaps a mile from their pick-up point, Rourke ordered a rest among some bushes.

They were eating, with an occasional whispered comment, when Rourke heard footsteps approaching. He peered through the foliage and in the soft light of the coming dawn saw a figure, apparently alone. The figure carried a rifle.

He signalled for two others, the American and the Briton, to position themselves either side of him, and as the black came to within thirty feet of their position he called out: ‘All right. Far enough’. The figure froze.

Rourke didn’t want to shoot. It would make too much noise.

‘Do as we tell you and you won’t be hurt. Put your gun on the ground and back away. Then you’ll be free to go’.

That way, they would be clear long before the guerrilla could fetch help, even if there were others nearby.

Of course, there was no way of telling whether the black had understood or not. They never did know. Unaccountably, the shadowy shape loaded the gun, clicking the bolt into place. It was the suicidal action of a rank amateur.

Without waiting to see whether the weapon was going to be used, the three men, following their training and instinct, opened fire together. Three streams of bullets, perhaps 150 rounds in all, sliced across the figure, which tumbled backwards into the grass.

In the silence that followed, Rourke realized that the victim was not dead. There was a moan.

The noise of the shooting would have carried over a mile in the still air. He paused only for a moment.

‘Wait one,’ he said.

He walked towards the stricken guerrilla. It was a girl. She had been all but severed across the stomach. He caught a glimpse of her face. She was perhaps fifteen or sixteen, a mere messenger, probably with no experience of warfare, little training and no English. He shot her through the head.

He would have been happy to make it his war; he would have been happy to risk his life for a country that wasn’t his; but he was not happy to lose. The place was going to the blacks anyway. So when they offered to extend his contract, when they showed him the telex from Hereford agreeing that he could stay on if he wished, he told them: thanks, but no thanks. There was no point being here any more.

Now he was going home, for a month’s R and R, during which time he fully intended to rediscover a long-forgotten world, the one that lay beneath Lucy’s white coat.

The clock on the Royal Exchange in the heart of the City of London struck twelve. Two hundred yards away, in a quiet courtyard off Lombard Street, equidistant from the Royal Exchange and the Stock Exchange, Sir Charles Cromer stood in his fifth-floor office, staring out of the window. Beyond the end of the courtyard, on the other side of Lombard Street, a new Crédit Lyonnais building, still pristine white, was nearing completion. To right and left of it, and away down other streets, stood financial offices of legendary eminence, bulwarks of international finance defining what was still a medieval maze of narrow streets.

Cromer, wearing a well-tailored three-piece grey suit and his customary Old Etonian tie, was a stocky figure, his bulk still heavily muscled. One of the bulldog breed, he liked to think. He stuck out his lower lip in thought and turned to walk slowly round his office.

As City offices went, it was an unusual place, reflecting the wealth and good taste of his father and grandfather. It also expressed a certain cold simplicity. The floor was of polished wood. To one side of the ornate Victorian marble fireplace were two sofas of button-backed Moroccan leather. They had been made for Cromer’s grandfather a century ago. The sofas faced each other across a rectangular glass table. On the wall, above the table, beneath its own light, was a Modigliani, an early portrait dating from 1908. In the grate stood Cromer’s pride and joy, a Greek jug, a black-figure amphora of the sixth century BC. The fireplace was now its showcase, intricately wired against attempted theft. The vase could be shown off with two spotlights set in the corners of the wall opposite. Cromer’s desk, backing on to the window, was of a superb cherrywood, again inherited from his grandfather.

Cromer walked to the eight-foot double doors that led to the outer office and flicked the switch to spotlight the vase, in preparation for his next appointment. It was causing him some concern. The name of the man, Yufru, was unknown to him. But his nationality was enough to gain him immediate access. He was an Ethiopian, and the appointment had been made by him from the Embassy.

Cromer was used to dealing with Ethiopians. He was, as his father for thirty years had been before him, agent for the financial affairs of the Ethiopian royal family, and was in large measure responsible for the former Emperor’s stupendous wealth. Now that Selassie was dead, Cromer still had regular contact with the family. He had been forced to explain several times to hopeful children, grandchildren, nephews and nieces why it was not possible to release the substantial sums they claimed as their heritage. No will had been made, no instructions received. Funds could only be released against the Emperor’s specific orders. In the event, the bank would of course administer the fortune, but was otherwise powerless to help…

So it wasn’t the nationality that disturbed Cromer. It was the man’s political background. Yufru came from the Embassy and hence, apparently, from the Marxist government that had destroyed Selassie. He guessed, therefore, that Yufru would have instructions to seek access to the Imperial fortune.

It was certainly a fortune worth having, as Cromer had known since childhood, for the connections between Selassie and Cromer’s Bank went back over fifty years.

The story was an odd one, of considerable interest to historians of City affairs. Cromer’s Bank had become a subsidiary of Rothschild’s, the greatest bank of the day, in 1890. The link between Cromer’s Bank and the Ethiopian royal family was established in 1924, when Ras Tafari, the future Haile Selassie, then Regent and heir to the throne, arrived in London, thus becoming the first Ethiopian ruler to travel abroad since the Queen of Sheba – whom Selassie claimed as his direct ancestor – visited Solomon.

Ras Tafari had several aims. Politically, he intended to drag his medieval country into the twentieth century. But his major concerns were personal and financial. As heir to the throne, he had access to wealth on a scale few can now truly comprehend, and he needed a safer home for it than the Imperial Treasure Houses in Addis Ababa and Axum.

Ethiopia’s output of gold has never been known for sure, but was probably several tens of thousands of ounces annually – in the nineteenth century at least. Ethiopia’s mines, whose very location was a state secret, had for centuries been under direct Imperial control. Traditionally, the Emperor received one-third of the product, but the distinction between the state’s funds and Imperial funds was somewhat academic. When Ras Tafari, resourceful, ambitious, wary of his rival princes, became heir, he inherited a quantity of gold estimated at some ten million ounces. He brought with him to London five million of those ounces – over 100 tons. By 1975 that gold was worth $800 million.

In London, Ras Tafari, who at that time spoke little English, discovered that the world’s most reputable bank, Rothschild’s, had a subsidiary named after a Cromer. By chance, the name meant a good deal to Selassie, for the Earl of Cromer, Evelyn Baring, had been governor general of the Sudan, Ethiopia’s neighbour, in the early years of the century. It was of course pure coincidence, for Cromer the man had no connection with Cromer the title. Nevertheless, it clinched matters. Selassie placed most of his wealth in the hands of Sir Charles Cromer II, who had inherited the bank in 1911.

When Ras Tafari became Emperor in 1930 as Haile Selassie, the hoard was growing at the rate of 100,000 ounces per year. In 1935, when the Italians invaded, gold production ceased. The invasion drove Selassie into exile in Bath. There he chose to live in austerity to underline his role as the plucky victim of Fascist aggression. But he still kept a sharp eye on his deposits.

After his triumphant return, with British help, in 1941, gold production resumed. The British exchange agreements for 1944 and 1945 show that some 8000 ounces per month were exported from Ethiopia. A good deal more left unofficially. One estimate places Ethiopia’s – or Selassie’s – gold exports for 1941–74 at 200,000 ounces per annum.

This hoard was increased in the 1940s by a currency reform that removed from circulation in Ethiopia several million of the local coins, Maria Theresa silver dollars (which in the 1970s were still accepted as legal currency in remote parts of Ethiopia and elsewhere in the Middle East). Most of the coins were transferred abroad and placed in the Emperor’s accounts. In 1975 Maria Theresa dollars had a market value of US$3.75 each.

In the 1950s, on the advice of young Charles Cromer himself, now heir to his aged father, Selassie’s wealth was diversified. Investments were made on Wall Street and in a number of American companies, a policy intensified by Charles Cromer III after he took over in 1955, at the age of thirty-one.

By the mid-1970s Selassie’s total wealth exceeded $2500 million.

Sir Charles knew that the fortune was secure, and that, with Selassie dead, his bank in particular, and those of his colleagues in Switzerland and New York, could continue to profit from the rising value of the gold indefinitely. The new government must know that there was no pressure that could be brought to bear to prise open the Emperor’s coffers.

Why then, the visit?

There came a gentle buzz over the intercom.

Cromer leaned over, flicked a switch and said gently: ‘Yes, Miss Yates?’

‘Mr Yufru is here to see you, Sir Charles.’

‘Excellent, excellent.’ Cromer always took care to ensure that a new visitor, forming his first impressions, heard a tone that was soft, cultured and with just a hint of flattery. ‘Please show Mr Yufru straight in.’

Six miles east of the City, in the suburban sprawl of east London, in one of a terrace of drab, two-up, two-down houses, two men sat at a table in a front room, the curtains drawn.

On the table stood an opened loaf of white sliced bread, some Cheddar, margarine, a jar of pickled onions and four cans of Guinness. One of the men was slim, jaunty, with a fizz of blond, curly hair and steady blue eyes. His name was Peter Halloran. He was wearing jeans, a pair of ancient track shoes and a denim jacket. In the corner stood his rucksack, into which was tucked an anorak. The other man, Frank Ridger, was older, with short, greying, curly hair, a bulbous nose and a hangdog mouth. He wore dungarees over a dirty check shirt.

They had been talking for an hour, since the surreptitious arrival of Halloran, who was now speaking. He dominated the conversation in a bantering Irish brogue, reciting the events of his life – the impatience at the poverty and dullness of village life in County Down, the decision to volunteer, the obsession with fitness, the love of danger, the successful application to join the SAS, anti-terrorist work in Aden in the mid-1960s and Oman (1971–4), and finally the return to Northern Ireland. It was all told with bravado and a surface glitter of which the older man was beginning to tire.

‘Jesus, Frank,’ the young man was saying, ‘the Irish frighten me to death sometimes. I was in Mulligan’s Bar in Dundalk, a quiet corner, me and a pint and a fellow named McHenry. I says to him there’s a job. That’s all I said. No details. I was getting to that, but not a bit of it – he didn’t ask who, or what, or how much, or how do I get away? You know what he said? “When do I get the gun?” That’s all he cared about. He didn’t even care which side – MI5, the Provos, the Officials, the Garda. I liked that.’

‘Well, Peter,’ said Ridger. He spoke slowly. ‘Did you do the job?’

‘We did. You should’ve seen the papers. “IRA seize half a million in bank raid.”’

‘But,’ said Ridger, draining his can, ‘I thought you said you were paid by the Brits?’

‘That’s right,’ said Halloran. He was enjoying playing the older man along, stoking his curiosity.

‘The British paid you to rob a British bank?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Were you back in favour or what?’

‘After what happened in Oman? No way.’

‘What did you do?’

‘There was a girl.’

‘Oh?’

‘How was I to know who she was? I was on my way home for a couple of months’ break. End of a contract. We had to get out or we’d have raped the camels. The lads, Mike Rourke among them, decided on a nice meal at the Sultan’s new hotel, the Al Falajh. She was – what? Nineteen. Old enough. I tell you, Frank – shall I tell you, my son?’

Ridger grinned.

Halloran first saw her in the entrance hall. Lovely place, the Al Falajh. Velvet all over the shop. Like walking into an upmarket strip club. She was saying goodnight to Daddy, a visiting businessman, Halloran assumed. ‘Go on then,’ Rourke had said, seeing the direction of his glance. He slipped into the lift behind her. She was wearing a blouse, short-sleeved and loose, so that as she stood facing away from him, raising her slim arm to push the lift button, he could see that she was wearing a silk bra, and that it was quite unnecessary for her to wear a bra at all. He felt she should know this, and at once appointed himself her fashion adviser.

‘Excuse me, miss, but I believe we have met.’ He paused as she turned, with a half smile, eager to be polite.

He saw a tiny puzzle cloud her brow.

‘Last night,’ he said.

She frowned. ‘I was…’

‘In a fantasy,’ he interrupted. It was corny, but it worked. By then she had been staring at him for seconds, and didn’t know how to cut him. She smiled. Her name was Amanda Price-Whyckham.

‘Eager as sin, she was,’ Halloran went on. A most receptive student, was Amanda P-W. The only thing she knew was la-di-da. Never had a bit of rough, let alone a bit of Irish rough. So when Halloran admired the view as the light poured through the hotel window, and through her skirt, and suggested that simplicity was the thing – perhaps the necklace off, then the stockings, she agreed she looked better and better the less she wore. ‘Until there she was, naked, and willing.’ Halloran finished. ‘My knees and elbows were raw by three in the morning.’

He smiled and took a swig of beer.

‘I don’t know how Daddy found out,’ Halloran continued after a pause. ‘Turned out he was a colonel on a visit for the MoD to see about some arms for the Omanis. You know, the famous Irish sheikhs – the O’Mahoneys?’

Ridger acknowledged the joke with a nod and a lugubrious smile.

‘So Daddy had me out of there. The SAS didn’t want me back, and I’d had enough of regular service. Used up half my salary to buy myself out. So it was back to pulling pints. Until the Brits approached me, unofficial like. Could I help discredit the Provos? Five hundred a month, in cash, for three months to see how it went. That was when my mind turned to banks. It was easy – home ground, see, because we used to plan raids with the regiment. Just plan mind. Now it was for real. I got a taste for it. Next I know, the Garda’s got me on file, and asks my controller in Belfast to have me arrested. He explains it nicely. They couldn’t exactly come clean. So they do the decent thing: put out a warrant for me, but warn me first. Decent! You help your fucking country, and they fuck you.’

‘You could tell.’

‘I wouldn’t survive to tell, Frank. As the bastard captain said, I’m OK if I lie low. In a year, two years, when the heat’s off, I can live again.’

‘I have the afternoon shift,’ said Frank, avoiding his gaze, and standing up. ‘I’ll be back about nine.’

‘We’ll have a few drinks.’

As the door closed, Halloran reached for another can of Guinness. He had no intention of waiting even a week, let alone a year, to live again.

Yufru was clearly at ease in the cold opulence of Sir Charles Cromer’s office. He was slim, with the aquiline good looks of many Ethiopians. He carried a grey cashmere overcoat, which he handed to Miss Yates, and wore a matching grey suit, tailored light-blue shirt and plain dark-blue tie.

Though Cromer never knew his background, Yufru had been living in exile since 1960. At that time he had been a major, a product of the elitist military academy at Harar. He had been one of a group of four officers who had determined to break the monolithic, self-seeking power of the monarchy and attempted to seize power while the Emperor was on a state visit to Brazil. The attempt was a disaster: the rebel officers, themselves arrogant and remote, never established how much support they would have, either within the army or outside it.

In the event, they had none. They took the entire cabinet hostage, shot most of them in an attempt to force the army into co-operation, and when they saw failure staring them in the face, scattered. Two killed themselves. Their corpses were strung up on a gallows in the centre of Addis. A third was captured and hanged. The fourth was Yufru. He drove over the border into Kenya, where he had been wise enough to bank his income, and surfaced a year later in London. Now, after a decade in business, mainly handling African art and supervising the investment of his profits, he had volunteered his services to the revolutionary government, seeking some revenge on the Imperial family and rightly guessing that his experience of the capitalist system might be of use.

He stood and looked round with admiration. Then, as Cromer invited him with a gesture to sit, he began to speak in suave tones that were the consequence of service with the British in 1941–5.

As Cromer knew, Ethiopia was a poor country. He, Yufru, had been lucky, of course, but the time had come for all of them to pull together. They faced the consequences of a terrible famine. The figures quoted in the West were not inaccurate – perhaps half a million would eventually die of starvation. Much, of course, was due to the inhumanity of the Emperor. He was remote, cut off in his palaces. The revolutionary government had attempted to reverse these disasters, but there was a limit imposed by a lack of funds and internal opposition.

‘These are difficult times politically,’ Yufru sighed. He was the ideal apologist for his thuggish masters. Cromer had met the type before – intelligent, educated, smooth, serving themselves by serving the hand that paid them. ‘We have enemies within who will soon be persuaded to see the necessity of change. We have foolish rebels in Eritrea who may seek to dismember our country. Somalia wishes to tear from us the Ogaden, an integral part of our country.

‘All this demands a number of extremely expensive operations. As you are no doubt aware, the Somalis are well equipped with Soviet arms. My government has not as yet found favour with the Soviets. If we are to be secure – and I suggest that it is in the interests of the West that the Horn of Africa remains stable – we need good, modern arms. The only possible source at present is the West. We do not wish to be a debtor nation. We would like to buy.

‘For that, to put matters bluntly, we need hard cash.’

Cromer nodded. He had guessed correctly.

‘The money for such purposes exists. It was stolen by Haile Selassie from our people and removed from the country, as you have good cause to know. I am sure you will respect the fact that the Emperor’s fortune is officially government property and that the people of Ethiopia, the originators of that wealth, should be considered the true heirs of the Emperor. They should receive the benefits of their labours.’

‘Administered, of course, by your government,’ Cromer put in.

‘Of course,’ Yufru replied easily, untouched by the banker’s irony. ‘They are the representatives of the people.’

Cromer was in his element. He knew his ground and he knew it to be rock-solid. He could afford to be magnanimous.

‘Mr Yufru,’ he began after a pause, ‘morally your arguments are impeccable. I understand the fervour with which your government is determined to right historic wrongs…’ – both of them were aware of what the fervour entailed: hundreds of corpses, ‘enemies of the revolution’, stinking on the streets of Addis – ‘and we would naturally be willing to help in any way. But insofar as the Emperor’s personal funds are concerned, there is really nothing we can do. Our instructions are clear and binding…’

‘I too know the instructions,’ Yufru broke in icily. ‘My father was with the Emperor in ’24. That is, in part, why I am here. You must have written instructions, signed by the Emperor, and sealed with the Imperial seal, on notepaper prepared by your bank, itself watermarked, again with the Imperial seal.’

Cromer acknowledged Yufru’s assertion with a slow nod.

‘Indeed, and those arrangements still stand. I have to tell you that the last such communication received by this bank was dated July 1974. Neither I nor my associates have received any further communication. We cannot take any action unilaterally. And, as the world knows, the Emperor is now dead, and it seems that the deposits must be frozen…’ – the banker spread his hands in a gesture of resigned sympathy – ‘in perpetuity.’

There was a long pause. Yufru clearly had something else to say. Cromer waited, still confident.

‘Sir Charles,’ Yufru said, more carefully now, ‘we have much work to do to regularize the Imperial records. The business of fifty years, you understand…It may be that the Emperor has left among his papers further instructions, perhaps written in the course of the revolution itself. And he was alive, you will remember, for a year after the revolution. It is conceivable that other papers relating to his finances will emerge. I take it that there would be no question that your bank and your associated banks would accept such instructions, if properly authenticated?’

The sly little bastard – he’s got something up his sleeve, thought Cromer. It may be…it is conceivable…if, if, if. There was no ‘if’ about it. Something solid lay behind the question.

To gain time he said: ‘I will have to check my own arrangements and those of my colleagues…there is something about outdated instructions which slips my mind. Anyway,’ he hastened on, ‘the instructions have always involved either new deposits or the transfer of funds and the buying of metals or stock. In what way would you have an interest in transmitting such information?’

Yufru replied, evenly: ‘We would like to be correct. We would merely like to be aware of your reactions if such papers were found and if we decided to pursue the matter.’

‘It seems an unlikely contingency, Mr Yufru. The Emperor has, after all, been dead six months.’

‘We are, of course, talking hypothetically, Sir Charles. We simply wish to be prepared.’ He rose, and removed a speck from his jacket. ‘Now, I must leave you to consider my question. May I thank you for your excellent coffee and your advice. Until next time, then.’

Puzzled, Sir Charles showed Yufru to the door. He was not a little apprehensive. There was something afoot. Yufru’s bosses were not noted for their philanthropy. They would have no interest in passing on instructions that might increase the Emperor’s funds.

It made no sense.

But by tonight, it damn well would.

‘No calls, Miss Yates,’ he said abruptly into the intercom. ‘And bring me the correspondence files for Lion…Yes, all of them. The whole damn filing cabinet.’

That evening, Sir Charles sat alone till late. A set of files lay on his desk. Against the wall stood the cabinet of files relating to Selassie. He again reviewed his thoughts on Yufru’s visit. He had to assume that there was something behind it. The only idea that made any sense was that there was some scheme to wrest Selassie’s money from the banks concerned. It couldn’t be done by halves. If they had access – with forged papers, say – then he had to assume that the whole lot was at risk.

And what a risk. He let his mind explore that possibility. Two thousand million dollars’ worth of gold from three countries for a start. If he were instructed, as it were by the Emperor himself, to sell every last ounce, it would be a severe blow to the liquidity of his own bank and those of his partners in Zurich and New York. With capital withdrawn, loans would have to be curtailed, profits lost. When and if it became known who was selling, reputations would suffer and rumours spread. Confidence would be lost. Even if there weren’t panic withdrawals, future deposits would be withheld. The effects would echo down the years and along the corridors of financial power, spreading chaos. With that much gold unloaded all at once, the price would tumble. And not only would he fail to realize the true market value, but he would become a pariah within Rothschild’s and in the international banking community. Cromer’s, renowned for its discretion, would be front-page news.

And that was just the gold. There would be the winding-up of a score of companies, the withdrawal of the cash balances, in sterling, Swiss francs and dollars.

Good God, he would be a liability. Eased out.

He poured himself a whisky and returned to his desk, forcing himself to consider the worst. In what circumstances might such a disaster occur?

What if Yufru produced documents bearing the Emperor’s signature, ordering his estate to be handed over to Mengistu’s bunch? With any luck they would be forgeries and easily spotted. On the other hand, they might be genuine, dating from before the Emperor’s death. But that was surely beyond the bounds of possibility. It would belie everything he knew about the man – ruthless, uncompromising, implacably opposed to any diminution of his authority.

But what if they had got at him, with drugs, or torture or solitary confinement? Now that was a possibility. Cromer would gamble his life on it that Selassie had signed nothing to prejudice his personal fortune before he was overthrown. But he might have done afterwards, if forced. He had after all been in confinement for about a year.

Now he had faced the implications, however, he saw that he could forestall the very possibility Yufru had mentioned. He checked one of the files before him again. Yes, no documents signed by the Emperor would be acceptable after such a delay. Anyone receiving written orders more than two weeks old had to check back on the current validity of those orders before acting upon them. The device was a sensible precaution in the days when couriers were less reliable than now, and communications less rapid. The action outlined in that particular clause had never been taken, and the clause never revoked. There it still stood, Cromer’s bastion against hypothetical catastrophe.

Cromer relaxed. But before long he began to feel resentful that he had wasted an evening on such a remote eventuality. He downed his whisky, turned off his lights, strolled over to the lift and descended to the basement, where the Daimler awaited him, his chauffeur dozing gently at the wheel. He was at his London home by midnight.

Friday 19 March

‘So you see, Mr Yufru, how my colleagues and I feel.’

Cromer had summoned Yufru for a further meeting earlier that morning.

‘After such a lapse of time and given the uncertainty of the political situation, we could not be certain that the documents would represent the Emperor’s lasting and final wishes. We would be required to seek additional confirmation, at source, before taking action. And the source, of course, is no longer with us.’

‘I see, Sir Charles. You would not, however, doubt the validity of the Emperor’s signature and seal?’

‘No, indeed. That we can authenticate.’

‘You would merely doubt the validity of his wishes, given the age of the documents?’

‘That is correct.’

‘I see. In that case, I am sure such a problem will never arise.’

Cromer nodded. The whole ridiculous, explosive scheme – if it had ever existed outside his own racing imagination – had been scotched. And apparently with no complications.

To hear Yufru talk, one would think the whole thing was indeed a mere hypothesis. Yufru remained affable, passed some complimentary comments about Cromer’s taste, and left, in relaxed mood.

The banker remained at his desk, deep in thought. He had no immediate appointments before lunch with a broker at 12.30, and he had the nagging feeling that he had missed something. There were surely only two possibilities. Mengistu’s bunch might have forged, or considered forging, documents. Or they might have the genuine article, however obtained. In either case, the date would precede Selassie’s death and they would now know that the date alone would automatically make the orders unacceptable. The fortune would remain for ever out of their reach.

Yufru had failed. Or had he? He didn’t seem like a man who had failed – not angry, or depressed, or fearful at reporting what might be a serious setback to the hopes of his masters. No: it was more as if he had merely ruled out just one course of action.

What other course remained open? What had he, Cromer, said that allowed the Ethiopians any freedom of action? The only positive statement he had made was that the orders, if they followed procedure, would be accepted as genuine documents, even if outdated.

Under what circumstances would the orders be accepted both as genuine and binding? If the date was recent, of course, but then…If the date was recent…in that case the Emperor would have to be…Dear God!

Cromer sat bolt upright, staring, unseeing, across the room. He had experienced what has been called the Eureka effect: a revelation based on the most tenuous evidence, but of such power that the conclusion is undeniable.

The Emperor must still be alive.

Cromer sat horrified at his own realization. He had no real doubts about his conclusion. It was the only theory that made sense out of Yufru’s approach. But he had to be certain that there was nothing to contradict it.

From the cabinet, against the wall, he slid out a file marked ‘Clippings – Death’. There, neatly tabbed into a loose-leaf folder, were a number of reports of Selassie’s death, announced on 28 August 1975 as having occurred the previous day, in his sleep, aged eighty-three.

According to the official government hand-out: ‘The Emperor complained of feeling unwell the previous night (26 August) but a doctor could not be obtained and a servant found him dead the next morning.’

Although he had been kept under close arrest in the compound in the Menelik Palace, there was no suggestion that he had been ailing. True, he had had a prostate operation two months before, but he had recovered well. One English doctor who treated him at that time, a professor from Queen Mary’s Hospital, London, was quoted as saying he had ‘never seen a patient of that age take the operation better’.

There had never been any further details. No family member was allowed to see the body. There was no post-mortem. The burial, supposedly on 29 August, was secret. There was no funeral service. The Emperor had, to all intents and purposes, simply vanished.

Not unnaturally, a number of people, in particular Selassie’s family, found the official account totally unacceptable. It reeked of duplicity. However disruptive the revolution, there were scores of doctors in Addis Ababa. Rumours began to circulate that Selassie had been smothered, murdered to ease the task of the revolution, for all the while he was known to be alive, large sections of the population would continue to regard him, even worship him, as the true ruler of the country. As The Times said when reporting the family’s opinion in June 1976: ‘The Emperor’s sudden death has always caused suspicion, if only because of the complete absence of medical or legal authority for the way he died.’

And so the matter rested. Until now. No wonder there had been no medical or legal authority for the way he died, mused Cromer. But the family had jumped to the wrong conclusion.

‘Sir Charles,’ it was Miss Yates’s voice on the intercom. ‘Will you be lunching with Sir Geoffrey after all?’

‘Ah, Miss Yates, thank you. Yes. Tell him I’m on my way. Be there in ten minutes.’

He stopped at the desk on his way out.

‘What appointments are there this afternoon?’ he asked.

‘You have a meeting with Mr Squires at two o’clock about the Shah’s most recent deposits. And of course the usual gold committee meeting at five.’

The Shah could wait. ‘Cancel Jeremy. I need the early afternoon clear.’

He glanced out of the window. It looked like rain. He took one of the two silk umbrellas from beside Valerie’s desk and left for lunch.

2 (#u610b2d2f-3e33-50cc-863d-4659f60235d2)

Those who had met Sir Charles Cromer over the past twenty years knew him only as a calculating financier, who seemed to live for his bank, seeking a release in his work from a stultifying home life. In point of fact, he was a closet gangster, utterly amoral, and with more than a dash of sadism in him. This aspect of his character had long been suppressed by his intelligence, his social standing and the eminence of the professional role he had inherited.

Only twice in his life had Cromer truly expressed himself. The first time was at school, at Eton. There, as fag and junior, he had borne the crushing humiliations imposed upon him by his seniors, knowing that he too would one day inherit their power. His resilience and forbearance were well rewarded. He became a games player of some eminence, playing scrum-half for the school and for Hereford Schoolboys with a legendary fearlessness. He also became Head of House. In this capacity he had cause, about once a week, to dispense discipline in the sternest public school traditions. Sometimes he would preside, with awful formality, over the ritual humiliation of some unfortunate junior who would be beaten in the prefects’ common room. Meanwhile the prefects themselves read idly, disdainfully refusing to acknowledge the presence of the abhorrent object of Cromer’s displeasure. Sometimes, for a lesser offence, the beating would be administered in his own study. Both occasions gave him joy.

It was at a House beating in his own study that he once allowed his nature to get the better of him. The boy concerned had dared question the validity of his decision. The insolence of the suggestion drove the eighteen-year-old Cromer into a cold and dedicated anger. The beating he then delivered, with the full weight of his body, drew blood beneath the younger boy’s trousers. When examined by a doctor, marks were even found on the victim’s groin, where the cane had whipped around the side of his buttock and hip.

The traditions of the school demanded complete stoicism. Even after such a caning, the boy would have been expected to shake hands with his persecutor, then continue life as normal. He might bear the stigmata for weeks, but he would say nothing, nor would anybody else.

This time, however, there was a comeback. The boy’s father was a Jewish textile manufacturer determined to buy the trappings of English culture for his offspring. The boy himself was less certain that he needed them. Cromer’s actions decided him: he telephoned his father, who appeared the following day, pulled his son out of school and obtained a doctor’s report. Copies of the report were passed to the headmaster, the housemaster, Cromer’s parents and his own solicitor. It was only with the greatest skill that a public scandal was averted. Cromer himself, who was amazed to find that he was considered to have done something amiss, was severely reprimanded. It changed his attitude not at all. But it did teach him that, if he wished to indulge in such activities, he would have to cloak them in a veneer of respectability.

The only other time that Cromer was able to let himself go was in Berlin immediately after the war. He had been too young to see any active service. The war was over just as he finished his training. As a newly commissioned second lieutenant, he flew into Tempelhof airport in Berlin in July 1945, the first time the victorious Russians had allowed the Western allies into the former German capital. Berlin was still a charnel house, a wilderness of buildings torn apart, squares and streets littered with rubble, a population half-starved. Cromer rapidly saw that he had been presented with a unique opportunity. The occupying troops were the élite, buying goods, labour and sex with money, cigarettes, food, luxury goods. Marks were worth nothing; sterling and dollars were like gold.

For the first year, when the Germans were still regarded as the enemy and the Russians as friends, Cromer was in his element. He transferred in his own cash and bought for derisory sums anything of value he could lay his hands on. It was amazing that so much had survived the war unscathed – Meissen china, Steinway and Bechstein grand pianos, hallmarked silver, exquisitely embroidered linen, nineteenth-century military paraphernalia by the ton, even a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost. He hired a warehouse near Tempelhof and had it sealed off. For two years, he packed in his treasures. He was by no means the only one to take advantage of the Berliners in this way, though in the scale of his operations he was practically unique.

In early 1948 Cromer, now a captain, was given as administrative assistant a teenage second lieutenant, Richard Collins. For Cromer, this turned out to be a providential appointment. As well as fulfilling his normal duties, organizing patrols and the distribution of food, Collins was soon recruited after hours to supervise the stowing of Cromer’s latest acquisitions. It was not a demanding job – a couple of evenings a week at most – but it was regular, and he was promised a share of the proceeds.

One evening in May, when Collins was closing up for the night, a task he had been taught to do surreptitiously, he heard a crash around the corner. He ran to the side of the building and was in time to see a bottle, flaming at one end, sail through the newly made hole in one of the windows. A Molotov cocktail.

Collins knew it would be caught by the wire-mesh netting inside the window and guessed it would do little damage. Hardly pausing, he sprinted into the rubble-strewn shadows from which the bottle had come, in time to see a slight figure vanishing round the next street corner. Collins was young, fit and well fed, and the teenage fire-bug, weakened by years of malnutrition, had no chance of escape. Collins sprinted up from behind and pushed him hard in the shoulders. The German took off forwards into a heap of rubble, hit it head on and collapsed into the bricks like a sack of potatoes. Collins hauled him over, and found his head dreadfully gashed and his neck broken.

Collins heaved the body across the unlit street and into a bombed building. He then ran back to the warehouse, retrieved the guttering, still unbroken bottle of petrol from the wire grill, stamped out the cloth, poured the contents down a drain, slung the bottle away into the roadside rubble, listened to see if the crash and the noise of running feet would bring a patrol, and then, reassured, went off to find Cromer.

Cromer knew what he owed Collins. He used his own jeep to pick up the body, and by three o’clock in the morning the German had become just another unidentified corpse in a small canal.

There had been some mention of German resentment against profiteering, but this was the first direct evidence Cromer had had of it. He saw that the time had come to stop.

Within a couple of months, Berlin was blockaded by the Russians and the airlift was under way. Planes loaded with food and fuel from the West were landing at Tempelhof every three minutes and taking off again, empty. Except that some were not empty. It took Cromer only two weeks to organize the shipment of his complete stock in twin-engine Dakotas, first to Fassberg, then on to England, to a hangar on a Midlands service aerodrome. A year later, demobbed, Cromer organized two massive auctions that netted him £150,000. In Berlin his outlay had been just £17,000. Not bad for a twenty-four-year-old with no business experience and no more than a small allowance from the business he was destined to take over.

Now Cromer the racketeer was about to resurface.

After lunch Cromer returned temporarily to his hermit-like existence. His staff did not find his behaviour peculiar; there had been crises demanding his personal attention before. He made two telephone calls. The first was to Oswald Kupferbach in Zurich, to an office in the Crédit Suisse, 8 Paradeplatz – one of the few banks in Switzerland which have special telephone and telex lines solely for dealing in gold bullion.

‘Oswald? Wie geht’s dir?…Yes, a long time. We have to meet as soon as possible…I’m afraid so. Something has come up over here. It’s about Lion…Yes, it’s serious, but not over the phone. You have to be here…I can only say that it concerns all our futures very closely…Ideally, this weekend? Sunday evening for Monday morning? That would be perfect…You and Jerry…I’ll have a car for you and a hotel. I’ll telex the details.’

The next call was to New York, to a small bank off Wall Street that had specialities comparable to Cromer’s – though little gold, of course, and more stock-exchange dealings – and a relationship with the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company similar to Cromer’s with Rothschild’s. He spoke to Jerry Lodge.

‘Jerry? Charlie. It’s about Lion…’

The call had a similar pattern to the previous one – prevarication from the other end, further persuasion by Cromer, mention of mutual futures at stake and, finally, a meeting arranged for Monday morning.

In an elegant courtyard of Cotswold-stone farm buildings, some seventy miles north-west of London, Richard Collins raised an arm in a perfunctory farewell to a customer driving off in a Land Rover. A routine morning’s work. One down, twenty-five to go, a job lot from Leyland.

A lot of people envied Dicky Collins. He looked the very epitome of the well-to-do countryman in his tweed jackets, twill trousers, Barbour coats. His Range Rover had a Blaupunkt tape deck, still something of a rarity in the mid-1970s. The farmhouse, with its courtyard and outbuildings, was surrounded by ten acres of woodland and meadow. It was an ideal base for his business, which was mainly selling army-surplus vehicles. In one of the stone barns, converted into a full working garage, there were five Second World War jeeps in various stages of repair, a khaki truck that had last seen action in the Western desert, and several 1930s motorbikes, still with side-cars.

The business turned over quarter of a million. He took £25,000, more than enough in those days. He was forty-eight, fit, successful, unmarried, and bored out of his bloody mind.

For almost ten years he had worked at his bloody Land Rovers and jeeps and trucks, ever since he finished in Aden and Charlie Cromer had given him a £100,000 loan to buy his first 100 vehicles – in exchange for sixty per cent of the equity. Both had judged well. It was a good business, doing the rounds of the War Department auctions. Now things were drying up, prices were rising. Any old jeep you could have got for £100 ten years before now fetched £2000 and up. It was a specialist field, and Collins knew it well. Once he had loved it. The sweet purr of a newly restored engine reminded him of the real thing.

After Aden, he was happy to settle. Hell of a time. Fuzzies fighting for a stump of a country and an oven of a city. Chap needed two gallons of water a day just to stay alive. No point to it all in the end, with Britain pulling out. Not like Borneo – that had been a proper show, all the training put to good use.

Now he was sick of it. Country life could never deliver that sort of kick. Money? It was good, but it would never be enough to excite him. The place was mortgaged to the hilt, the taxman was a sadist, and even if he sold, Charlie Cromer would take most of the profits.

Boredom, that was Collins’s problem. There was old Molly to do the house. The business ran itself these days, what with Caroline coming in two days a week to keep the VAT man at bay. Stan knew all about a car’s innards and could fix anything over twenty years old as good as new. Collins had other interests, of course, but keeping up with publications on international terrorism and his thrice-weekly clay-pigeon practices hardly compared with jungle warfare for thrills. There were parties, there were girls for the asking, but he wasn’t about to marry again. What had once been a comfortable country nest had become a padded cell.

‘Major,’ Stan called from the garage. ‘Phone.’

Collins nodded. He walked through the garage, edging his way past a skeletal jeep to the phone.

‘Dicky? Charlie Cromer. Got a proposition for you.’

Monday, 22 March

That morning, Sir Charles Cromer, Oswald Kupferbach and Jerry Lodge were together in Cromer’s office. The Swiss and the American sat facing each other on the Moroccan leather sofas beneath the Modigliani. Both had been chosen for their present jobs only after an interview with Cromer, who had judged them right for his needs: astute, experienced, hard. Kupferbach, fifty-two, with rimless glasses, had practised discretion for so long he never seemed to have any emotions at all. Professionally, he didn’t. His one passion was personal: he was an expert in the ecology of mountains above the tree line. Lodge – his grandparents were Poles from the city of Lodz – was quite a contrast: bluff, rotund, reassuring. He found it easy to ensure he was underestimated by rivals.

Between the two on the glass-topped table was newly made coffee and orange juice. Sir Charles was standing, coffee cup in hand, having just outlined the approaches made to him by Yufru.

He concluded by saying: ‘So you see, gentlemen, why we had to meet: I have the strongest possible reasons for believing that the Emperor is not dead. I further believe that unless we move rapidly and in concert, we shall shortly be presented with documents bearing the Emperor’s signature demanding the release of his fortune to the revolutionary government of Mengistu Haile Mariam.

‘This would be a financial blow that we, as individual bankers, should not have to endure. Indeed, the sums in gold alone are so vast that their release would devastate the world’s gold markets. While the short-term implications for our respective economies are not pleasant, the implications for our banks and ourselves as individuals are horrendous.’

The Swiss was thoughtful, the American wide-eyed, caricaturing disbelief.

‘Oh, come on, Charlie,’ he said, ‘that’s got to be the most outrageous proposition I’ve ever heard. What are you on? I mean, my God.’

Kupferbach broke in: ‘No, no, Jerry. It is not so foolish. It fits in. There have been a number of approaches in Zurich for loans. They need the money. But their propositions are unrealistic. The World Bank might consider a loan for fighting the famine, but, of course, it would be administered by World Bank officials. They don’t want that.’

Lodge paused. ‘OK, OK,’ he said at last, ‘let’s follow it through. Suppose the old boy is still alive. Suppose he signs the papers. Don’t you think we could persuade the Ethiopians to leave the gold with us? After all, they have to place it somewhere, don’t they? We arrange a loan for them based on the reserves. They buy their arms and fight their goddam wars, and everyone’s happy. Hey?’

‘It’s possible,’ Cromer said slowly, ‘but it doesn’t look like a safe bet to me. You think Mengistu would pay interest, and if he did, do you think his successors would? Would you invest in a Marxist without any experience of international finance who came to power and preserves power through violence?’

‘I agree. But what do you think would happen if we received these documents and simply ignored them?’ replied Kupferbach.

‘Whadya mean, Ozzie?’ said Lodge. ‘We just don’t do as we’re told? We say we’re not going to hand over the funds? We tell the Ethiopians to go stuff their asses?’

‘In brief, meine Herren yes.’

‘If all this is true,’ said Cromer, ‘that thought must have already crossed their minds. In their position, what would your answer be?’

‘Right,’ Lodge said, jutting his lower jaw and biting his top lip. ‘Jesus, if I was them, I’d make one hell of a storm. Major banks refusing to honour their obligations? Yeah, they could really have a go at us. International Court at The Hague, questions in the UN, pressure on other African countries to make holes in Rothschild and Morgan Guaranty investments in the Third World. We’d come out of it with more than egg on our faces.’

‘Of course,’ added Cromer, ‘to do that, they’d have to reveal that Selassie was still alive. It would make them look pretty damn stupid.’

‘Yes, but they have less to lose.’ It was Kupferbach again, a clear thinker with a coolness that more than matched Cromer’s. ‘Mengistu could write off the previous announcement of the Emperor’s death as a necessity imposed by the revolution. The publicity would be bad for them, but could be catastrophic for us.’

Cromer looked at the two of them in turn.

‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘I have been thinking of nothing else for the last two days. I have rehearsed these arguments many times in my own mind. If the Emperor signs those papers we are lost.’ He paused. ‘We are left with no choice – we have to assume the Emperor is still alive, and we have to get to him before he signs anything.’

Cromer’s two colleagues looked at him expectantly.

‘What the hell are you suggesting?’ said Lodge.

‘We have to do the decent thing. We have to kidnap the Emperor.’

They stared at him.

Lodge shook his head in disbelief and went on shaking it, perhaps at the very suggestion, or perhaps at the impossibility of achieving it.

‘Jerry, Oswald: don’t fight it. It’s the only answer. It’s either that or immediate retirement. I don’t know about you two but I have a very real future in front of me. The Emperor has none. Getting him out, we win all ways. We save him, and we save his fortune – and ours.’

‘You goddam English,’ said Lodge. ‘You think you can still act like you had an Empire. Where I come from, the CIA do that sort of thing, not the goddam bankers…’ He trailed off, still shaking his head.

Kupferbach seemed to be way ahead of him. ‘I see, Charles. You have been doing much preparation for this meeting. May I ask, therefore, why you needed to include us?’

‘For the first step, Oswald, the first step. Getting to Selassie. I think I know how to do it. We still have one card to play. Supposing he is still alive, supposing the Ethiopians make him sign the documents, supposing they are dated for just two days before we receive them, I still do not believe we would have to comply. We could argue that the signature must have been produced under duress, since it is clearly contrary to everything the Emperor has expressed in the past. I think we could make such a refusal stand up in a court of law. Of course, it would not do to let things go on that far. As you say, Oswald, the publicity would be catastrophic. But likewise, they would not get their money.

‘I think we can pre-empt a crisis. We tell them that signature under duress would not be acceptable, quoting UN Human Rights legislation. I also think I could suggest a way around the difficulty: I will propose that the signature be made in the presence either of the bankers concerned or of their duly appointed representatives, in a situation in which the Emperor could be seen – for that particular day, at least – to be in good health and not the object of undue pressure, physical or psychological.

‘That, gentlemen, is how we gain access.’

‘Hold on there a tiny minute,’ broke in Lodge, ‘you’re losing me. You mean this has to be done for real? We have to go and meet the Emperor?’

‘Well, not we necessarily, but yes, there has to be a meeting between our people and the Emperor. And there are, of course, a number of other implications. The Emperor will have to be in a fit state to hold such a meeting. But then, presumably, he has to be in a fit state to sign the documents at all, so it shouldn’t be too much of a problem to produce him in a reasonable state of health.

‘A further implication – and this is where I need you – is that the documents for signature have to be genuine. Only in that way can we guarantee access. We have to see what the Ethiopians want from Selassie, and we have to agree to them in advance. And Selassie will agree.’

‘Yeah?’ said Lodge, sceptically. ‘Tell me why.’

‘One good reason – only with our co-operation can he assure the financial future of his family abroad. I’ve already had the family on my back several times. It is clear that, in a year or two, they will not be able to support themselves in the manner to which they have become accustomed. There are several children and countless grandchildren. All will need financial help, which they will not receive unless Selassie signs what will become, in effect, his last will and testament, one that must also be agreed with the Ethiopian government and ourselves. Everything must be prepared in secret, but as if it was for real.

‘Thereafter, our duty to ourselves is clear: we cannot allow Selassie actually to sign the papers.’

Collins arrived in London early on Monday evening, parked his Range Rover in a garage off Berkeley Square and strolled round to Brown’s hotel in Dover Street. He just had time for a bath, and a whisky and water in his room, when the internal phone went to announce the arrival in reception of Charlie Cromer.

The two dined at the Vendôme, where sole may be had in twenty-four different styles. It took Cromer two courses and most of a very dry Chablis to bring Collins up to date.

‘And now,’ he said over coffee, ‘before I make you any propositions, I want to know how you’re fixed. How’s the business?’

‘You’ve seen the books, even if you don’t remember them. The profits are there. But there’s a problem with the management.’

‘Fire him.’

‘It’s me, Charlie. It was a joke.’ Cromer shrugged an apology. ‘I’m bored. I’ve been thinking about getting out, taking off somewhere for a year.’

‘Not a woman, is it?’

‘No. I have to keep my nose clean around home – get a reputation for dipping your wick and business can suffer.’

‘So do I take it my call was timely?’

‘Indeed.’

‘Good. You can see what I need: a team of hit men, as our American friends say. We’ll have to work out the details together, but, for a start, we need two more like you, men who like danger, who like a challenge, cool and experienced.’

‘What are you offering in return?’

‘To you? Freedom. I’ll arrange a purchaser for the company and turn any profits over to you. I would imagine you will come out of it with, say, £100,000 in cash. In addition, $100,000 to be deposited in your name in New York and a similar sum to be placed in a numbered account in Switzerland.’

‘That sounds generous.’

‘Fair. I have colleagues who are interested in the successful outcome of this particular operation.’

Collins had decided to take up the offer in any case. ‘Yes. I’m on. I still have a few contacts in the Regiment. I can think of a couple of chaps who may be interested.’

‘There’s another thing,’ said Cromer. ‘You will all have to act the part of bankers. For obvious reasons, I can’t go. Wish I could.’

‘No, you don’t, Charlie. It’s far too risky.’

‘You’ll be handing me a white feather next.’

‘For us, Charlie. Kidnapping an Emperor is quite enough for one job. Spare us looking after you.’

Tuesday, 23 March

Back in the Oxfordshire countryside, Collins had only a few routine matters to attend to. He had to confirm a couple of sales, vet a US Army jeep that would eventually fetch at least £3500, and say ‘yes’ with a willing smile when the village’s up-and-coming young equestrienne, Caroline Sinclair, wanted some poles for a jump. But most of his attention was given to tracking down Halloran and Rourke.

It took several calls and several hours to get to Halloran. He learned of Halloran’s rapid exit from the SAS, and of his re-emergence in Ireland. A contact in Military Intelligence, Belfast, looked up the files. Halloran had blown it: he was never to be used again. For them, Halloran had turned out more dangerous than an unexploded bomb. There had been reprimands for taking him on in the first place. A couple of his Irish contacts were also on file.

‘What’s this for, old boy?’ the voice at the end of the line asked. ‘Nothing too fishy, I hope?’

Collins knew what this meant. ‘Nothing to do with the Specials, the Army, the UDA, the IRA or the SAS. Something far, far away.’

‘Good. In that case, you better move fast. The Yard knows he’s in London. Looks like the Garda tipped them the wink. Could be a bit embarrassing for us if they handle it wrong. Do what you can.’

Collins made three more calls, this time to the Republic – one to a bar in Dundalk and one to each of the contacts on MI’s file. At each number he left a message that an old friend was trying to contact Pete Halloran with an offer of work. He left his number.

At lunch-time, the phone rang. A call-box: the pips cut off as the money went in. A voice heavily muffled through a handkerchief asked for Collins’s identity. Then: ‘It’s about Halloran.’

‘I’ll make it short,’ said Collins. ‘Tell Pete the Yard are on to him and that I may have an offer. Tell him to move quickly.’

‘I’ll let him know.’

The phone clicked off. It could have been Halloran, probably was, but he had to be allowed to handle things his own way.

An hour later, Halloran himself called.

‘Is that you, sir? I had the message. What’s the offer?’

‘Good to hear you, Peter. Nothing definite yet. But I want you to stay out of trouble and be ready for a show. Not here – a long way away. You can come up here as soon as you like. You’ll be quite safe.’

He had assumed Halloran, on the run, tense, perhaps bored with remaining hidden, would jump at it. He did.

‘But what’s this about the Yard?’

‘Just a report that your name has been passed over. Are you sure your tracks are covered? Maybe nothing in it, but just look after yourself, will you? Phone again tomorrow at this time. Perhaps I’ll have more.’

The second set of calls was simpler. From the SAS in Herefordshire to the Selous Scouts in Rhodesia was an easy link. He had no direct contact there, but didn’t need one. He was told Rourke was on his way home. The call also elicited the address of Rourke’s family – a suburban house in Sevenoaks, Kent. Rourke senior was still a working man, a British Rail traffic supervisor. Mrs Rourke answered. Oh yes, Michael was on his way home. Why, he might be in London at that very moment. No, they didn’t know where. He liked his independence, did Michael. They hoped he would be down in the morning, but anyway he was certain to call. How nice of the major. Michael would be pleased to re-establish an old link. No, they didn’t think he had any immediate plans. Yes, she would pass on the message.

Rourke phoned that afternoon within an hour of Halloran. He was still at Heathrow, just arrived from Jo’burg.

‘Can’t tell you yet, Michael,’ said Collins, in response to Rourke’s first question. ‘But it looks like a bit of the old times. Lots of action, one-month contract. Can you be free?’

There was a pause. ‘I’m interested.’

Again, Collins made a provisional arrangement. Rourke would be back in contact later that evening.

Collins’s final call that afternoon, shortly before four o’clock, was to Cromer.

‘Charlie. Just wanted to say the package we were lining up the other day looks good. The other two partners are very interested. We’re ready when you give us the word.’

‘Thanks, Dicky. I have a meeting later which should clarify things. I’ll be in contact tonight.’

3 (#u610b2d2f-3e33-50cc-863d-4659f60235d2)

At five o’clock, with the business of the day cleared from his desk, Cromer prepared himself for Yufru’s arrival. Valerie Yates was briefed to leave when she saw him. Cromer did not want the possibility of any eavesdropping, intentional or otherwise.

He had planned for himself the role he liked best – magnanimous, controlled, polite, manipulative. He did not wish to be overtly aggressive and thus risk forcing Yufru into a corner. If he had guessed correctly, it should be a delicate, but not difficult matter to persuade him that the two of them should be working together.

‘Mr Yufru, Sir Charles,’ came Valerie’s voice over the intercom.

‘Very good, Miss Yates, ask him to come in, and perhaps you could bring in some tea before you go…ah, Mr Yufru, I am sorry to impose upon your precious time. Shall we?’ And he indicated the sofas.

‘It is my pleasure, Sir Charles. Perhaps it is I that owe you an apology. I had no intention of involving you in such an extended intellectual exercise’, said Yufru, as he relaxed back into the ancient polished leather. He crossed his right leg over his left and set the crease of his grey trousers exactly over the kneecap.

‘Your idea interested me,’ Cromer said, ‘so much so that I began to treat it less as an intellectual exercise and more as a practical possibility.’

Yufru’s hands came to rest in his lap. He gave no hint of concern.

Cromer continued: ‘That way, I can be sure that my response will be complete and therefore as helpful as possible. It is because I think I now finally have a realistic answer to your question that I wish to speak to you.’

Valerie knocked at the door and brought in a tray bearing two neat little porcelain cups, teapot, sugar bowl, teaspoons, milk jug and lemon. Yufru was now utterly still, his face expressionless, his attention riveted on Cromer. As Valerie set down the tray on the table between the two men he said smoothly: ‘By all means let us cover all eventualities, Sir Charles.’

Cromer waited until Valerie had closed the door and resumed: ‘In our previous conversation, Mr Yufru, we discussed the possibility of my bank being presented with documents signed by the Emperor several months ago. I said an outdated signature would not be acceptable. I think I should tell you that the date alone would not be our only reason for our refusal to comply with instructions.

‘We are speaking of documents signed by the Emperor after his deposition. It is well known that he was not a free man. We have no reason to think he was badly treated; but equally we must assume, for our client’s sake, that instructions not in his direct interest might have been the product of coercion. In other words, in the circumstances you outlined, we would have a justifiable fear that he might have been forced to append his signature to documents not of his own devising. I fear, therefore, that we could not accept the Emperor’s instructions as both authentic and valid. The date, you see, would be irrelevant if the Emperor was a prisoner at the time of his signature.’

Yufru had begun to breathe a little quicker, the only sign of tension other than his unnatural stillness.