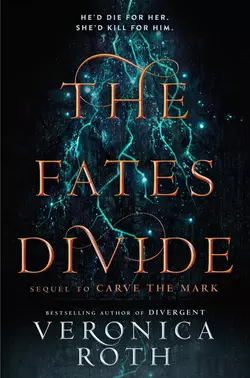

The Fates Divide

Veronica Roth

In the second book of the Carve the Mark duology, globally bestselling Divergent author Veronica Roth reveals how Cyra and Akos fulfill their fates. The Fates Divide is a richly imagined tale of hope and resilience told in four stunning perspectives.The lives of Cyra Noavek and Akos Kereseth are ruled by their fates, spoken by the oracles at their births. The fates, once determined, are inescapable.Akos is in love with Cyra, in spite of his fate: he will die in service to Cyra’s family. And when Cyra’s father, Lazmet Noavek – a soulless tyrant, thought to be dead – reclaims the Shotet throne, Akos believes his end is closer than ever.As Lazmet ignites a barbaric war, Cyra and Akos are desperate to stop him at any cost. For Cyra, that could mean taking the life of the man who may – or may not – be her father. For Akos, it could mean giving his own. In a stunning twist, the two will discover how fate defines their lives in ways most unexpected.

Copyright (#uf3ca19ec-eca2-57fa-abcc-eb37379d90ef)

First published in hardback in the USA by HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. in 2018

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2018

Published in this ebook edition in 2018

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text © 2018 by Veronica Roth

Map © 2017 by Veronica Roth. All rights reserved.

Map illustrated by Virginia Allyn

Typography by Joel Tippie

Jacket art ™ & © 2018 by Veronica Roth

Jacket art by Jeff Huang

Jacket design by Erin Fitzsimmons

Veronica Roth asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008192198

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008192228

Version: 2018-04-09

Dedication (#uf3ca19ec-eca2-57fa-abcc-eb37379d90ef)

To my dad, Frank, my brother, Frankie, and my sister, Candice:

we may not share blood, but I’m so lucky we’re family.

Contents

Cover (#udfa79263-dd7e-54cf-803e-86658aa461be)

Title Page (#ud300c793-4a68-5142-80ba-52af669e79a2)

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue: Eijeh

Part 1

Chapter 1: Cyra (#ue27b7a09-deab-563f-9eeb-594befd7b8d7)

Chapter 2: Cisi (#uaa465c9e-0764-56bf-b2a6-c6d0a48d16c0)

Chapter 3: Cyra (#u1a45e34c-7270-5af3-9cb9-dc8fb9888ddd)

Chapter 4: Akos (#u2484ef74-0520-5433-916a-2099531adb5f)

Chapter 5: Cisi (#u5745b391-dc28-573c-82ec-10c0388fc007)

Chapter 6: Akos (#uad04ac86-e3ea-559f-b289-438cdfe7dc4c)

Chapter 7: Cisi (#u828687f3-ceb0-53c3-affe-3bf0b69d1937)

Chapter 8: Cisi (#u06078a9b-d3b6-5d75-9f44-8045626147d3)

Chapter 9: Cyra (#u113a7ccc-fc5f-5e74-9ad9-66eba1be6092)

Chapter 10: Akos (#ud7e7b29f-36b4-5780-a68b-841719ec0ef2)

Chapter 11: Cyra (#u8da23689-f6db-52cc-84b4-9d5e175591dc)

Chapter 12: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: Eijeh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 2

Chapter 21: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29: Eijeh (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 3

Chapter 31: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 4

Chapter 41: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 5

Chapter 53: Cisi (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55: Akos (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56: Cyra (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: Eijeh

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary

Books by Veronica Roth

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#uf3ca19ec-eca2-57fa-abcc-eb37379d90ef)

“WHY SO AFRAID?” WE ask ourself.

“She is coming to kill us,” we reply.

We were once alarmed by this feeling of being in two bodies at once. We have grown accustomed to it in the cycles since the shift occurred, since both our currentgifts dissolved into this new, strange one. We know how to pretend, now, that we are two people instead of one—though we prefer, when we are alone, to relax into the truth. We are one person in two bodies.

We are not on Urek, as we were the last time we knew our location. We are adrift in space, the bend of the blushing currentstream the only interruption in the blackness.

Only one of our two cells has a window. It is a narrow thing, with a thin mattress in it and a bottle of water. The other cell is a storage room that smells of disinfectant, harsh and acrid. The only light comes from the vents in the door, closed now but not fully sealed against the hallway glow.

We stretch two arms—one shorter and browner, the other long and pale—in unison. The former feels lighter, the latter clumsy and heavy. The drugs have faded from one body but not the other.

One heart pounds, hard, and the other maintains a steady rhythm.

“To kill us,” we say to ourself. “Are we sure?”

“As sure as the fates. She wants us dead.”

“The fates.” There is dissonance here. Just as a person can love and hate something at once, we love and hate the fates, we believe and do not believe in them. “What was the word our mother used—” We have two mothers, two fathers, two sisters. And yet only one brother. “Accept your fate, or bear it, or—”

“‘Suffer the fate,’ she said,” we reply. “‘For all else is delusion.’”

(#uf3ca19ec-eca2-57fa-abcc-eb37379d90ef)

(#ulink_f6700165-2175-5e89-8351-344164e9c772)

LAZMET NOAVEK, MY FATHER and former tyrant of Shotet, had been presumed dead for over ten seasons. We had held a funeral for him on the first sojourn after his passing, sent his old armor into space, because there was no body.

And yet my brother, Ryzek, imprisoned in the belly of this transport ship, had said, Lazmet is still alive.

My mother had called my father “Laz,” sometimes. No one else would have dared but Ylira Noavek. “Laz,” she would say, “let it go.” And he obeyed her, as long as she didn’t command him too often. He respected her, though he respected no one else, not even his own friends.

With her he had some softness, but with everyone else … well.

My brother—who had begun his life soft, and only later hardened into someone who would torture his own sister—had learned to cut out a person’s eye from Lazmet. And how to store it, too, in a preservative, so it wouldn’t rot. Before I truly understood what the jars in the Weapons Hall contained, I had gone there to look at them, on shelves high above my head, glinting in the low light. Green and brown and gray irises, afloat, like fish bobbing to the surface of a tank for food.

My father had never carved a piece of someone with his own hands. Nor had he ordered someone else to do it. He had used his currentgift to control their bodies, to force them to do it to themselves.

Death is not the only punishment you can give a person. You can also give them nightmares.

When Akos Kereseth came to find me, later, it was on the nav deck of the small transport ship that carried us away from my home planet, where my people, the Shotet, now stood on the verge of war with Akos’s home nation of Thuvhe. I sat in the captain’s chair, swiveling back and forth to soothe myself. I meant to tell him what Ryzek had told me, that my father—if he was my father, if Ryzek was even my brother—was alive. Ryzek seemed certain that he and I didn’t actually share blood, that I was not truly a Noavek. That was why, he had said, I hadn’t been able to open the gene lock that kept his rooms secure, why I hadn’t been able to assassinate him the first time I tried.

But I didn’t know how to begin. With the death of my father? With the body we had never found? With the niggling feeling that Ryzek and I were too dissimilar in features to have ever been related?

Akos didn’t seem to want to talk, either. He spread a blanket he had found somewhere in the ship on the ground between the captain’s chair and the wall, and we lay on top of it, side by side, staring out at nothingness. Currentshadows—my lively, painful ability—wrapped around my arms like black string, sending a deep ache all the way down to my fingertips.

I was not afraid of emptiness. It made me feel small. Barely worth a first glance, let alone a second. And there was comfort in that, because so often I worried that I was capable of causing too much damage. At least, if I was small and kept to myself, I wouldn’t do any more harm. I wanted only what was within arm’s reach.

Akos’s index finger hooked around my pinkie. The shadows disappeared as his currentgift countered mine.

Yes, what was within arm’s reach was definitely enough for me.

“Would you … say something in Thuvhesit?” he asked.

I turned my head toward him. He was still looking up at the window, a faint smile curling his lips. Freckles dotted his nose, and one of his eyelids, right near the lash line. I hesitated with my hand just lifted off the blanket, wanting to touch him but also wanting to stay in the wanting for a moment. Then I followed the line of his eyebrow across his face with a fingertip.

“I’m not a pet bird,” I said. “I don’t chirp on command.”

“This is a request, not a command. A humble one,” he said. “Just say my full name, maybe?”

I laughed. “Most of your name is Shotet, remember?”

“Right.” He lunged at my hand with his mouth, snapping his teeth together. It startled a laugh from me. “What was hardest for you to say, when you were first learning?”

“Your city names, what a mouthful,” I said as he let go of one of my hands to catch the other, holding me by pinkie and thumb with all his fingertips. He pressed a kiss to the center of my palm, where the skin was callused from holding currentblades. Strange, that something so simple, given to a hardened part of me, could suffuse me so completely, bringing life to every nerve.

I sighed, acquiescing.

“Fine, I’ll say them. Hessa, Shissa, Osoc,” I said. “There was a chancellor who called Hessa the very heart of Thuvhe. Her surname was Kereseth.”

“The only Kereseth chancellor in Thuvhesit history,” Akos said, bringing my palm to his cheek. I propped myself up on one elbow to lean over him, my hair slipping forward to frame both our faces, long on one side though I was now silverskinned on the other. “I do know that much.”

“For a long time, there were only two fated families on Thuvhe,” I said, “and yet, aside from that one exception, the leadership has only ever been with the Benesits, when the fates have named a chancellor at all. Is that not strange to you?”

“Maybe we aren’t any good at leading.”

“Maybe fate favors you,” I said. “Maybe thrones are curses.”

“Fate doesn’t favor me,” he said gently, so gently I almost didn’t realize what he meant. His fate—the third child of the family Kereseth will die in service to the family Noavek—was to betray his home for my family, in serving us, and to die. How could anyone see that as anything but a hardship?

I shook my head. “I’m sorry, I wasn’t thinking—”

“Cyra,” he said. Then he paused, frowning at me. “Did you just apologize?”

“I do know the words,” I replied, scowling back. “I’m not completely without manners.”

He laughed. “I know the Essanderae word for ‘garbage’; that doesn’t mean I sound right saying it.”

“Fine, I revoke my apology.” I flicked his nose, hard, and when he cringed away, still laughing, I said, “What’s the Essanderae word for ‘garbage’?”

He said it. It sounded like a word reflected in a mirror, said once forward and once backward.

“I’ve found your weakness,” he said. “I just have to taunt you with knowledge you don’t have, and you’re distracted immediately.”

I considered that. “I guess you’re allowed to know one of my weaknesses … considering you have so many to exploit.”

He raised his eyebrows in question, and I attacked him with my fingers, jabbing his left side just under his elbow, his right side just above his hip, the tendon behind his right leg. I had learned these soft places when we were training—places he didn’t protect well enough, or that made him cringe harder than usual when struck—but I teased him now with more gentleness than I had thought myself capable of, drawing from him laughs instead of cringes.

He pulled me on top of him, holding me by the hips. A few of his fingers slipped under the waistband of my pants, and it was a kind of agony I was unfamiliar with, a kind I didn’t mind at all. I braced myself on the blanket, on either side of his head, and lowered myself slowly to kiss him.

We hadn’t kissed more than a few times, and I had never kissed anyone but him, so each time was still a discovery. This time I found the edge of teeth, skimming, and the tip of a tongue; I found the slide of a knee between mine, and the weight of a hand at the back of my neck, urging me closer, further, faster. I didn’t breathe, didn’t want to take the time, and so I ended up gasping against the side of his neck before long, making him laugh.

“I’ll take that as a good sign,” he said.

“Don’t get cocky, Kereseth.”

I couldn’t keep myself from smiling. Lazmet—and whatever questions I had about my parentage—didn’t feel as close to me now. I was safe here, floating on a ship in the middle of nowhere, with Akos Kereseth.

And then: a scream, from somewhere deep in the ship. It sounded like Akos’s sister, Cisi.

(#ulink_4111d0c3-a7ff-50d9-8c91-2f203fa8f805)

I KNOW WHAT IT is to watch your family die. I am Cisi Kereseth, after all.

I watched Dad die on our living room floor. I watched Eijeh and Akos get dragged away by Shotet soldiers. I watched Mom fade like fabric in the sun. There’s not much I don’t understand about loss. I just can’t express it the way other people do. My currentgift keeps me all wrapped up tight.

So I’m a little bit jealous of how Isae Benesit, fated chancellor of Thuvhe and my friend, can let herself grieve. She wears herself out with emotion, and then we fall asleep, shoulder to shoulder, in the galley of the Shotet exile ship.

When I wake up, my back hurts from slumping against the wall for so long. I get up and lean to the left, to the right, while I take note of her.

Isae doesn’t look right, which I guess makes sense, since her twin sister, Ori, died only yesterday, in an arena of Shotet all chanting for her blood.

She doesn’t feel right, either, the texture around her all fuzzy like the way your teeth feel when you haven’t brushed them. Her eyes skip back and forth over the room, dancing across my face and body, and not in a way that would make a person blush. I try to calm her with my currentgift, sending out a smooth feeling, like unrolling a skein of silk thread. It doesn’t seem like it does much good.

My currentgift is an odd thing. I can’t know how she feels, not really, but I can feel it, like it’s a texture in the air. And I can’t control how she feels, either, but I can make suggestions. Sometimes it takes a couple of tries, or a new way of thinking about it. So instead of silk, which had no effect, I try water, heavy, undulating.

It’s a bust. She’s too keyed up. Sometimes, when a person’s feelings are too intense, it’s hard for me to make an impact.

“Cisi, can I trust you?”

It’s a funny word in Thuvhesit, can. It’s can and should and must all squished together, and you can only suss out the true meaning from context. It leads to misunderstandings, sometimes, which is probably why our language is described by off-worlders as “slippery.” That, and off-worlders are lazy.

So when Isae Benesit asks me in my mother tongue if she can trust me, I don’t really know what she means. But regardless, there’s only one answer.

“Of course.”

“I mean it, Cisi,” she says, in that low voice she uses when she’s serious. I like that voice, the way it hums in my head. “There’s something I have to do, and I want you to come with me, but I’m afraid you won’t be—”

“Isae,” I cut her off. “I’m here for you, whatever you need.” I touch her shoulder with gentle fingers. “Okay?”

She nods.

She leads me out of the galley, and I try not to step on any kitchen knives. After she shut herself in here, she ripped all the drawers out, broke everything she could get her hands on. The floor is covered with shreds of fabric and pieces of glass and cracked plastic and unrolled bandages. I guess I don’t blame her.

My currentgift keeps me from doing or saying things that I know will make people uncomfortable. Which means that, after my dad died, I couldn’t cry unless I was alone. I couldn’t say much of anything to my mom for months. So if I’d been able to destroy a kitchen, like Isae did, I probably would have.

I follow Isae out, quiet. We walk past Ori’s body. It has a sheet tucked nicely around it, so it’s just the slopes of her shoulders, the bump of her nose and chin. Just an impression of who she was. Isae stops there, draws a sharp breath. She feels even grittier now than she did before, like grains of sand against my skin. I know I can’t soothe her, but I’m too worried about her not to try.

I send airy feathergrass tufts, and hard, polished wood. I send warm oil and rounded metal. Nothing works. I chafe against her, frustrated. Why can’t I do anything to help her?

I think, for a tick, of asking for help. Akos and Cyra are right there on the nav deck. Mom’s somewhere below. Even Akos and Cyra’s renegade friend, Teka, is right there, stretched out on the bench seats with a sheet of white-blond hair sprawled across behind her. But I can’t call out to any of them. For one thing, I just can’t—can’t knowingly cause distress, thanks to my giftcurse—and for another, instinct tells me it’s better if I can earn Isae’s trust.

Isae leads us down below, where there are two storage rooms and a washroom. Mom’s in the washroom, I can tell by the sound of the recycled water splattering. In one storage room—the one with the window, I made sure of that—is my other brother, Eijeh. It hurt me to see him again, so long after his kidnapping, and so small compared to the pale pillar of Ryzek Noavek next to him. You think when people get older, they’re supposed to get stronger, fatter. Not Eijeh.

The other storage room—the one with all the cleaning supplies—holds Ryzek Noavek. Just knowing he’s that close, the man who ordered my brothers taken and my dad killed, makes me tremble. Isae pauses between the two doors, and it hits me, then, that she’s going in one of those rooms. And I don’t want her to go in Eijeh’s.

I know he’s the one who killed Ori, technically. That is, he was holding the knife that did it. But I know my brother. He could never kill anyone, especially not his best friend from childhood. There has to be some other explanation for what happened. It has to be Ryzek’s fault.

“Isae,” I say. “What are you—”

She touches three fingers to her lips, telling me to hush.

She’s right between the rooms. Deciding something, it seems like, judging by the faint buzz around her. She takes a key from her pocket—she must have lifted it off Teka, when she went out to make sure we were headed to Assembly Headquarters—and sticks it in the lock for Ryzek’s cell. I reach for her hand.

“He’s dangerous,” I say.

“I can handle it,” she replies. And then, softening around the eyes: “I won’t let him hurt you, I promise.”

I let her go. There’s a part of me that’s hungry to see him, to meet the monster at last.

She opens the door, and he’s sitting against the back wall, sleeves rolled up, feet outstretched. He has long, skinny toes, and narrow ankles. I blink at them. Are sadistic dictators supposed to have vulnerable-looking feet?

If Isae’s at all intimidated, she doesn’t let on. She stands with her hands clasped in front of her and her head high.

“My, my,” Ryzek says, running his tongue over his teeth. “Resemblance between twins never fails to shock me. You look just like Orieve Benesit. Except for those scars, of course. How old are they?”

“Two seasons,” Isae says, stiff.

She’s talking to him. She’s talking to Ryzek Noavek, my sworn enemy, kidnapper of her sister, with a long line of kills tattooed on the outside of his arm.

“They will fade still, then,” he says. “A shame. They made a lovely shape.”

“Yes, I’m a work of art,” she says. “The artist was a Shotet fleshworm who had just finished digging around in a pile of garbage.”

I stare at her. I’ve never heard her say something so hateful about the Shotet before. It’s not like her.

“Fleshworm” is what people call the Shotet when they’re reaching for the worst insult. Fleshworms are gray, wriggly things that feed on the living from the inside out. Parasites, all but eradicated by Othyrian medicine.

“Ah.” His smile grows wider, forcing a dimple into his cheek. There’s something about him that sparks in my memory. Maybe something he has in common with Cyra, though they don’t look at all alike, at a glance. “So this grudge you have against my people isn’t merely in your blood.”

“No.” She sinks into a crouch, resting her elbows on her knees. She makes it look graceful and controlled, but I’m worried about her. She’s long and willowy in build, not near as strong as Ryzek, who is big, though thin. One wrong move and he could lunge at her, and what would I do to stop it? Scream?

“You know about scars, I suppose,” she says, nodding to his arm. “Will you mark my sister’s life?”

The inside of his forearm, the softer, paler part, doesn’t have any scars—they start on the outside and work their way around, row by row. He has more than one row.

“Why, have you brought me a knife and some ink?”

Isae purses her lips. The sandpaper feeling she gave off a moment ago turns as jagged as a broken stone. By instinct, I press back against the door and find the handle behind my back.

“Do you always claim kills you didn’t actually carry out?” Isae says. “Because last time I checked, you weren’t the one on that platform with the knife.”

Ryzek’s eyes glint.

“I wonder if you’ve ever actually killed at all, or if all that work is done by others.” Her head tilts. “Others who, unlike you, actually have the stomach for it.”

It’s a Shotet insult. The kind a Thuvhesit wouldn’t even realize was insulting. Ryzek picks up on it, though, eyes boring into hers.

“Miss Kereseth,” he says, without looking at me. “You look so much like the elder of your two brothers.” He glances at me, then, appraising. “Are you not curious what’s become of him?”

I want to answer coolly, like Ryzek is nothing to me. I want to meet his eyes with strength. I want a thousand fantasies of revenge to come suddenly to life like hushflowers at the Blooming.

I open my mouth, but nothing comes out.

Fine, I think, and I let out a peal of my currentgift, like a clap of my hands. I’ve come to understand that not everybody can control their currentgifts the way I can. I just wish I could master the part that keeps me from saying what I want to.

I see how he relaxes when my gift hits him. It has no effect on Isae—none that I can see, anyway—but maybe it will loosen his tongue. And whatever Isae is planning, she seems to need him to talk first.

“My father, the great Lazmet Noavek, taught me that people can be like blades, if you learn to wield them, but your best weapon should still be yourself,” Ryzek says. “I have always taken that to heart. Some of the kills I have commanded have been carried out by others, Chancellor, but rest assured, those deaths are still mine.”

He slumps forward over his knees, clasping his hands between them. He and Isae are just breaths apart.

“I will mark your sister’s life on my arm,” he says. “It will be a fine trophy to add to my collection.”

Ori. I remember which tea she drank in the morning (harva bark, for energy and clarity) and how much she hated the chip in her front tooth. And I hear the chants of the Shotet in my ears: Die, die, die.

“That clarifies things,” Isae says.

She holds her hand out for him to take. He gives her an odd look, and no wonder—what kind of person wants to shake hands with the man who just admitted to ordering her sister’s death? And being proud of it?

“You really are an odd one,” he says. “You must not have loved your sister very much, to offer your hand to me now.”

I see the skin pull taut over the knuckles of her other hand, the one not held out to him. She opens her fist, and inches her fingers toward her boot.

Ryzek takes the hand she offered, then stiffens, eyes widening.

“On the contrary, I loved her more than anyone,” Isae says. She squeezes him, hard, digging in her fingernails. And all the while, her left hand moves toward her boot.

I’m too stunned to realize what’s happening until it’s too late. With her left hand she tugs a knife out of her boot, from where it’s strapped to her leg. With her right, she pulls him forward. Knife and man come together, and she presses, and the sound of his gurgling moan carries me to my living room, to my adolescence, to the blood that I scrubbed from the floorboards as I sobbed.

Ryzek slumps, and bleeds.

I slam my hand down on the door handle and stumble into the hallway. I am wailing, crying, pounding on the walls; no, I’m not, my currentgift won’t let me.

All it allows me to do, in the end, is let out a single, weak scream.

(#ulink_de648c41-1eed-5fb6-a53b-d9d4c692ccc3)

I RAN TOWARD CISI Kereseth’s scream, Akos on my heels, not even bothering with the rungs of the ladder that took me below deck—I just jumped down. I went straight toward Ryzek’s cell, knowing, of course, that he was likely the source of anything that caused screaming on this ship. I saw Cisi braced against the corridor wall, the storage room door across from her open. Behind her, Teka dropped down from the other end of the ship, beckoned here by the same noise. Isae Benesit stood inside Ryzek’s cell, and below her, in a jumble of legs and arms, was my brother.

There was a certain amount of poetry in it, I supposed, that just as Akos had watched his father spill his life on the floor, so I now watched my brother do the same.

It took far longer for him to die than I anticipated. That was intentional, I assumed; Isae Benesit stood over his body the entire time, bloody knife in her fist, eyes blank but watchful. She had wanted to take her time with this moment, her moment of triumph over the one who killed her sister.

Well, one of the ones who killed her sister, because Eijeh, who had held the actual blade, was still in the next room.

Ryzek’s eyes found mine, and almost as if he’d touched me, I was buoyed into a memory. Not one that he was taking from me, but one I had almost hidden from myself.

I was in the passage behind the Weapons Hall, with my eye pressed to the crack in the wall panel. I had gone there to spy on my father’s meeting with a prominent Shotet businessman-turned-slumlord, because I often spied on my father’s meetings when I was bored and curious about the happenings of this house. But this meeting had gone bad, which had never happened before when I peeked in. My father had stretched out a hand, two fingers held aloft, like a Zoldan ascetic about to give a blessing, and the businessman had drawn his own knife, his movements jerky, like he was fighting his own muscles.

He brought the knife to the inside corner of his eye.

“Cyra!” hissed a voice behind me, making me jerk to attention. A young, spotted ryzek slid to his knees beside me. He cradled my face in his hands. I had not realized, before that moment, that I was crying. As the screaming started in the next room, he pressed his palms flat to my ears, and brought my face to his chest.

I struggled, at first, but he was too strong. All I could hear was the pounding of my own heart.

At last he pulled me away, wiped the tears from my cheeks, and said, “What does Mother always say? Those who go looking for pain …”

“Find it every time,” I replied, completing the phrase.

Teka held me by the shoulders, and jostled me a little, saying my name. I looked at her, then, confused.

“What is it?” I said.

“Your currentshadows were …” She shook her head. “Never mind.”

I knew what she meant. My currentgift had likely gone haywire, sending sprawling black lines all over me. The currentshadows had changed since Ryzek tried to use me to torture Akos in the cell block beneath the amphitheater. They drifted on top of my skin now, instead of burrowing beneath it like dark veins. But they were still painful, and I could tell this episode had been worse—my vision was blurry, and there were impressions of fingernails in my palms.

Akos was kneeling in my brother’s blood, his fingers on the side of Ryzek’s throat. I watched as his hand fell away, and he slumped, bracing himself on his thighs.

“It’s done,” Akos said, sounding thick, like his throat was coated in milk. “After everything Cyra did to help me—after everything—”

“I won’t apologize,” Isae said, finally looking away from Ryzek. She scanned all our faces—Akos, surrounded by blood; Teka, wide-eyed at my shoulder; me, arms streaked black; Cisi, holding her stomach near the wall. The air was pungent with the smell of sick.

“He murdered my sister,” Isae said. “He was a tyrant and a torturer and a killer. I won’t apologize.”

“It’s not about him. You think I didn’t want him dead?” Akos lurched to his feet. Blood ran down the front of his pants, from knees to ankles. “Of course I did! He took more from me than he did from you!” He was so close to her I wondered if he would lash out, but he made a fitful motion with his hands, and that was all. “I wanted him to fix what he did first, I wanted him to set Eijeh right, I …”

It seemed to hit him all at once. Ryzek was—had been—my brother, but the grief was his. He had persevered, carefully orchestrated every element of his brother’s rescue, only to find himself blocked, again and again, by people more powerful than he was. And now, he had succeeded in getting his brother out of Shotet, but he had not saved him, and all the planning, all the fighting, all the trying … was for nothing.

Akos fell against the nearest wall to hold himself up, closed his eyes, and swallowed a moan.

I found my way out of my trance.

“Go upstairs,” I said to Isae. “Take Cisi with you.”

She looked like she might object, for a moment, but it didn’t last. Instead, she dropped the murder weapon—a simple kitchen knife—right where she stood, and went to Cisi’s side.

“Teka,” I said. “Would you get Akos upstairs, please?”

“Are you—” Teka started, and stopped. “Okay.”

Isae and Cisi, Teka and Akos, they left me there, alone, with my brother’s body. He had died next to a mop and a bottle of disinfectant. How convenient, I thought, and stifled a laugh. Or tried to. But it wouldn’t stay stifled. In moments my knees were weak with laughter, and I fumbled through my hair for the side of my head that was now silverskin, to remind myself how he had sliced and diced me for the entertainment of a crowd, how he had planted pieces of himself inside me, as if I was just a barren field to sow with pain. My entire body carried the scars Ryzek Noavek had given me.

And now, at last, I was free of him.

When I calmed, I set about cleaning up Isae Benesit’s mess.

Ryzek’s body didn’t frighten me, and neither did blood. I dragged him by his legs into the hallway, sweat tickling the back of my neck as I heaved and pulled. He was heavy, in death, as I was sure he had been in life, skeletal though he was. When Akos’s oracle mother, Sifa, appeared to help me, I didn’t say anything to her, just watched as she worked a sheet beneath him so we could wrap him in it. She produced a needle and thread from the storage room, and helped me stitch the makeshift burial sack closed.

Shotet funerals, when they took place on land, involved fire, like most cultures in our varied solar system. But it was a special honor to die in space, on the sojourn. We covered the bodies, all but the head, so the loved ones of whoever was lost could see and accept the person’s death. When Sifa pulled the sheet back, away from Ryzek’s face, I knew she had at least studied our customs.

“I see so many possibilities for how things will unfold,” Sifa said finally, dragging her arm across her forehead to catch some of the sweat. “I didn’t think this one was likely, or I might have warned you.”

“No, you wouldn’t have,” I said, lifting a shoulder. “You only intervene when it suits your purposes. My comfort and ease don’t matter to you.”

“Cyra …”

“I don’t care,” I said. “I hated him. Just … don’t pretend that you care about me.”

“I am not pretending,” she replied.

I had thought, surely, that I might see some of Akos in her. And in her mannerisms, yes, perhaps he was there. Mobile eyebrows and quick, decisive hands. But her face, her light brown skin, her modest stature, they were not his.

I didn’t know how to evaluate her honesty, so I didn’t bother.

“Help me carry him to the trash chute,” I said.

I took the heavy side of his body, his head and shoulders, and she took his feet. It was lucky that the trash chute was only a few feet away, another unexpected convenience. We took it in stages, a few steps at a time. Ryzek’s head lolled around, his eyes open but sightless, but there was nothing I could do about it. I set him down next to the chute, and pressed the button to open the first set of doors, at waist height. It was fortunate that he was so narrow, or his shoulders wouldn’t have fit. Together Sifa and I folded him into the short channel, bending his legs so the inner doors would be able to close. Once they had, I pressed the button again, to open the outer doors and slide the tray in the chute forward to launch his body into space.

“I know the prayer, if you want me to say it,” Sifa said.

I shook my head.

“They said that prayer at my mother’s funeral,” I said. “No.”

“Then let us just acknowledge that he has suffered his fate,” Sifa said. “To fall to the family Benesit. He no longer needs to fear it.”

It was kind enough.

“I’m going to clean myself up,” I said. The blood on my palms was beginning to dry, making them itch.

“Before you do,” Sifa said, “I will warn you of this. Ryzek was not the only person the chancellor blamed for her sister’s death. In fact, she likely began with him because she was saving the more important piece of retribution for later. And she won’t stop there, either. I have seen enough of her to know her nature, and it is not forgiving.”

I blinked at her for a moment before it made sense to me. She was talking about Eijeh, still locked away in the other storage room. And not just Eijeh, but the rest of us—complicit, Isae believed, in Orieve’s death.

“There is an escape pod,” Sifa said. “We can put her in it, and someone from the Assembly will fetch her.”

“Tell Akos to drug her,” I said. “I don’t feel up to a fight right now.”

(#ulink_2e23308a-c227-5118-bbf6-74903e0daab8)

AKOS WADED THROUGH THE cutlery that was all over the galley floor. The water was already heating, and the vial of sedative was ready to dump into the tea, he just had to get some dried herbs into the strainer. The ship bumped along, and he stepped on a fork, flattening the tines with his heel.

He cursed his stupid head, which couldn’t stop telling him that there was still hope for Eijeh. There are so many people across the galaxy, with so many gifts. Somebody will know how to put him right. Truth was, Akos was tired of hanging on to hope. He’d been clawing at it since he first got to Shotet, and now he was ready to let go and just let fate take him where it wanted him to go. To death, and Noaveks, and Shotet.

All he’d promised his dad was that he would get Eijeh home. Maybe here—floating in space—was the best he could do. Maybe that would just have to be enough.

But—

“Shut up,” he said to himself, and he dumped the herbs from the galley cabinet into a strainer. There weren’t any iceflowers, but he’d learned enough about Shotet plants to make a simple calming blend. At this point, though, there was no artistry in it. He was just going through the motions, folding bits of garok root into powdered fenzu shell and squeezing a little nectar on top of it all, for taste. He didn’t even know what to call the plants that made up the nectar—he’d taken to calling the little fragile flowers “mushflowers” while he was at the army training camp outside Voa, because of how easily they fell apart, but he’d never learned the right name for them. They tasted sweet, and that seemed to be their only use.

When the water was hot, he poured it through the strainer. The extract it left behind was a murky brown, perfect for hiding the yellow of the sedative. His mom had told him to drug Isae and he hadn’t even asked why. He didn’t care, as long as it got her out of his sight. He couldn’t quite escape the image of her standing there watching Ryzek Noavek gush blood like it was some kind of show. Isae Benesit may have worn Ori’s face, but she wasn’t anything like her. He couldn’t imagine Ori just standing there and watching someone die, no matter how much she hated them.

Once the extract was brewed and mixed with the drug, he brought it to Cisi, who was sitting alone on the bench just outside the galley.

“You waiting for me?” he said.

“Yeah,” she said. “Mom told me to.”

“Good,” he said. “Will you take this to Isae? It’s just to calm her down.”

Cisi raised an eyebrow at him.

“Don’t drink any of it yourself,” he added.

She reached for it, but instead of taking the mug, she put her hand on his wrist. The look in her eyes changed—sharpened—like it always did when his currentgift dampened her own.

“What’s left of Eijeh?” she asked.

Akos’s whole body clenched up. He didn’t want to think about what was left of Eijeh.

“Someone who served Ryzek Noavek,” he said, with venom. “Who hated me, and Dad, and probably you and Mom, too.”

“How is that possible?” She frowned. “He can’t hate us just because someone put different memories into his head.”

“You think I know?” Akos all but growled.

“Then, maybe—”

“He held me down while someone tortured me.” Akos shoved the mug into her hands.

Some of the hot tea spilled on both their hands. Cisi jerked away, wiping her knuckles on her pants.

“Did I burn you?” he said, nodding to her hand.

“No,” she said. The softness her currentgift brought to her expression was back. Akos didn’t want tenderness of any kind, so he turned away.

“This won’t hurt her, will it?” Cisi said, tapping a fingernail on the mug so he would hear the ting ting ting.

“No,” he said. “It’s to keep from having to hurt her.”

“Then I’ll give it to her,” Cisi said.

Akos grunted a little. There was some more sedative in his pack, maybe he ought to take it. He’d never been so worn, like a half-finished weaving, light showing between all the threads. It would be easier just to sleep.

Instead of drugging himself to oblivion, though, he just took a dried hushflower petal from his pocket and stuck it between his cheek and his teeth. It wouldn’t knock him out, but it would dull him some. Better than nothing.

Akos was coasting on hushflower an hour later when Cisi came back.

“It’s done,” she said. “She’s out.”

“All right,” he said. “Then let’s get her into the escape pod.”

“I’m going with her,” Cisi said. “If Mom’s right, and we’re headed into war—”

“Mom’s right.”

“Yeah,” Cisi said. “Well, in that case, whoever’s against Isae is against Thuvhe. So I’m going to stick with my chancellor.”

Akos nodded.

“I take it you won’t be,” Cisi said.

“Fated traitor, remember?” he said.

“Akos.” She crouched in front of him. At some point he had sat down on the bench, which was hard and cold and smelled like disinfectant. Cisi rested an arm on his knee. She had tied her hair back, messy, and a chunk of curls had come loose, falling around her face. She was pretty, his sister, her face a shade of cool brown that reminded him of Trellan pottery. A lot like Cyra’s, and Eijeh’s, and Jorek’s. Familiar.

“You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to, just because Mom raised us fate-faithful and obedient to the oracles and all that,” Cisi said. “You’re a Thuvhesit. You should come with me. Leave everyone else to their war, and we’ll go home and wait it out. No one needs us here.”

He’d thought about it. He was as torn now as he’d ever been, and not just because of his fate. When he came out of the daze of the hushflower, he would remember how nice it felt to laugh with Cyra earlier that day, and how warm she was, pressed up against him. And he would remember that as much as he wanted to just be in his house again, walk up the creaky stairs and stoke the burnstones in the courtyard and send flour up into the air as he kneaded the bread, he had to live in the real world. In the real world, Eijeh was broken, Akos spoke Shotet, and his fate was still his fate.

“Suffer the fate,” he said. “For all else is delusion.”

Cisi sighed. “Thought you might say that. Sometimes delusion’s nice, though.”

“Stay safe, okay?” he said, taking her hand. “I hope you know I don’t want to leave you again. It’s pretty much the last thing I want.”

“I know.” She squeezed his thumb. “I still have faith, you know. That one day you’ll come home, and Eijeh will be better, and Mom will stop with the oracle bullshit, and we can cobble together something again.”

“Yeah.” He tried to smile for her. He might have halfway accomplished it.

She helped him get Isae settled in the escape pod, and Teka told her how to send out a distress signal so the pod would be picked up by Assembly “goons,” as Teka called them. Then Cisi kissed their mom good-bye, and wrapped her arms tight around Akos’s middle until her warmth was pushed all the way through him.

“You’re so damn tall,” she said, softly, as she pulled away. “Who told you that you could be so much taller than me?”

“I did it just to spite you,” he replied with a grin.

Then she got in the pod, and closed the doors. And he didn’t know when he would ever see her again.

Teka tripped up to the captain’s chair on the nav deck and pried the cover of the control panel off with a wedge tool she kept on her belt. She did it while whistling.

“What are you doing?” Cyra asked. “Now’s not really the time to take apart our ship.”

“First, this is my ship, not ‘ours,’” Teka said with a roll of her blue eye. “I designed most of the features that have kept us alive so far. Second, do you really still want to go to Assembly Headquarters?”

“No.” Cyra sat in the first officer’s chair, to Teka’s right. “The last time I went there, I overheard the representative from Trella call my mother a piece of filth. She didn’t think I could understand her, even though she was speaking Othyrian.”

“Figures.” Teka made a scoffing sound in the back of her throat as she pulled out a handful of wires from the control panel, then ran her fingers down them like she was petting an animal. She reached under the wires, to a part of the control panel Akos couldn’t see, so far her entire arm disappeared. A projection of coordinates flashed up ahead, glowing right across the currentstream in their sights. The ship’s nose—Akos was sure there was a technical name for it, but he didn’t know it, so he called it a “nose”—drifted so they were moving toward the currentstream instead of away.

“You going to tell us where we’re headed?” Akos said, stepping up to the nav deck. The control panel was lit up in all different colors, with levers and buttons and switches everywhere. If Teka had spread her arms wide, she still wouldn’t have been able to reach all of them from where she sat.

“I guess I can, since we’re all stuck in this together now,” Teka said. She gathered her bright hair on top of her head, and tied it with a thick band she wore around her wrist. Swimming in a technician’s coveralls, with her legs folded up beneath her on the captain’s chair, she looked like a kid playing pretend. “We’re going to the exile colony. Which is on Ogra.”

Ogra. The “shadow planet,” people called it. It was rare to meet an Ogran, let alone fly a ship in sight of Ogra. It was as far from Thuvhe as any planet could be without leaving the safe band of currentstream that encircled the solar system. No amount of surveillance could poke through its dense, dark atmosphere, and it was a wonder they could get any signal from the news feed. They never fed any stories into it, either, so almost no one had ever seen the planet’s surface, even in images.

Cyra’s eyes, of course, lit up at the information. “Ogra? But how do you communicate with them?”

“The easiest way to transmit messages without the government listening in is through people,” Teka said. “That’s why my mom was on board the sojourn ship—to represent the exiles’ interests among the renegades. We were trying to work together. Anyway, the exile colony is a good place for us to regroup, figure out what’s going on back in Voa.”

“I have a guess,” Akos said, crossing his arms. “Chaos.”

“And then more chaos,” Teka said with a sage nod. “With a short break in between. For chaos, of course.”

He couldn’t imagine what Voa looked like now that—the Shotet believed—Ryzek Noavek had been assassinated by his younger sister right in front of them. That was how it had looked, anyway, when Cyra appeared to cut her brother in the arena, waiting for the sleeping elixir she had arranged for him to drink that morning to kick in and knock him flat. The standing army might have taken over, under the leadership of Vakrez Noavek, Ryzek’s older cousin, or those who lived on the outer edges of the city might have taken to the streets to fill the power vacuum. Either way, Akos imagined streets full of broken glass and blood spatter and ripped paper floating in the wind.

Cyra tipped her forehead into her hands. “And Lazmet,” she said.

Teka’s eyebrows popped up. “What?”

“Before Ryzek died …” Cyra gestured vaguely toward the other end of the ship, where Ryzek had met his end. “He told me my father is still alive.”

Cyra didn’t talk about Lazmet much, so all Akos knew was from history class, as a kid, and rumor, not that Thuvhesit rumors about the Shotet had proved to be all that accurate. The Noaveks hadn’t been in power in Shotet before the oracles spoke the fates of the family Noavek for the first time, just two generations ago. When Lazmet’s mother came of age, she had taken the throne by force, using her fate as justification for the coup. And later, when she had been sitting on the throne for at least ten seasons, she had killed off all her siblings so her own children would be guaranteed power. That was the kind of family Lazmet had come from, and he had been, by all accounts, every izit as brutal as his mother.

“Oh, honestly.” Teka groaned. “Is it some kind of rule of the universe that at least one Noavek asshole has to be alive at any given time, or what?”

Cyra swiveled to face her. “What am I, then? Not alive?”

“Not an asshole,” Teka replied. “Bicker with me much more and I’ll change my mind.”

Cyra looked faintly pleased. She wasn’t used to people not considering her just another Noavek, Akos assumed.

“Whatever the rules of the universe pertaining to Noaveks,” she said, “I don’t know how Lazmet is still alive, just that Ryzek didn’t appear to be lying when he told me. He wasn’t trying to get anything in return, he was just … warning me, maybe.”

Teka snorted. “Because, what, Ryzek loves doing favors?”

“Because he was scared of your dad,” Akos said. When Cyra did talk about Ryzek, she always talked about how afraid he was. What could scare a man like Ryzek more than the man who had made him the way he was? “Right? He’s more terrified than anyone. Or he was, anyway.”

Cyra nodded.

“If Lazmet is alive …” Her eyes fluttered closed. “That needs to be corrected. As soon as possible.”

That needs to be corrected. Like a math problem or a technical error. Akos didn’t know how you could talk about your own dad that way. It rattled him more than it would have if Cyra had seemed scared. She couldn’t even talk about him like he was a person. What had she seen him do, to make her talk about him that way?

“One problem at a time,” Teka said, a little more gently than usual.

Akos cleared his throat. “Yeah, first let’s survive getting through Ogra’s atmosphere. Then we can assassinate the most powerful man in Shotet history.”

Cyra opened her eyes, and laughed.

“Settle in for a long ride,” Teka says. “We’re bound for Ogra.”

(#ulink_024a1fa0-a519-5b83-893a-5e533b242f01)

THE ESCAPE POD IS only just big enough for the two of us pressed together. As it is, my shoulder is still jammed up against the glass wall. I fumble on the little control panel for the switch that activates the distress signal. It’s lit up pink, and it’s one of only three switches in front of me, so it’s not hard to find. I flip it up and hear a high-pitched whistling, which means the signal is transmitting, Teka said. Now all that’s left to do is wait for Isae to wake up, and try not to panic.

Being on a little transport vessel like the one we just left is nerve-wracking enough for a Hessa girl who’s only left the planet a couple times, but the escape pod is another thing. It’s more window than floor, the clear glass curving up over my head and all the way down to my toes. I don’t feel like I’m looking out at space so much as getting swallowed by it. I can’t think about it or I’ll panic.

I hope Isae wakes up soon.

She’s limp on the bench seat next to me, and her body is framed by a blackness so complete, she really does look like the only thing in the entire universe. I’ve known her only a couple years, since Ori disappeared to take care of her after her face got cut with a Shotet knife. She grew up far away from Thuvhe, on a transporter ship that took goods from one end of the galaxy to the other, whatever they could haul.

It was a good thing Ori had been around to force us to talk to each other, in the beginning. I might never have talked to her otherwise. She was intimidating even without the title, tall and slim and beautiful, scars or no scars, and radiating capability like a machine.

I don’t know how long it takes for her eyes to open. She drifts for a while, staring all bleary at what’s in front of us, which is flat nothing in between the far-off wink of stars. Then she blinks at me.

“Cee?” she says. “Where are we?”

“We’re in an escape pod, waiting for the Assembly to come get us,” I say.

“An escape pod?” She frowns. “What did we need to escape from?”

“I think it’s more that they wanted to escape from us,” I say.

“Did you drug me?” She rubs her eyes with a fist, first the left one and then the right. “You gave me that tea.”

“I didn’t know there was anything in it.” I’m a good liar, and I don’t think twice. She wouldn’t accept the truth—that I wanted to get her away from the rest of my family just as much as Akos did. Mom said Isae was going to try to kill Eijeh the same way she did Ryzek, and I wasn’t willing to risk it. I don’t want to lose Eijeh again, no matter how warped he is now. “Mom warned them you might try to hurt Eijeh, too.”

Isae curses. “Oracles! It’s a wonder we even let them have citizenship, with all the loyalty your mother shows her own chancellor.”

I have nothing to say to that. She’s frustrating, but she’s my mother.

I continue, “They put you in the pod, and I told them I was going with you.”

The scars that cross her face stay stiff while her brow furrows. She rubs them, sometimes, when she thinks no one is looking. She says it helps the scar tissue to stretch out, so one day she’ll be able to move those parts of her face again. That’s what the doctor said, anyway. I once asked her why she just let the scars form instead of getting reconstructive surgery on Othyr. It’s not like she didn’t have the resources. She told me she didn’t want to get rid of them, that she liked them.

“Why?” she finally says after a long pause. “They’re your family. Eijeh’s your brother. Why would you come with me?”

Giving an honest answer isn’t as easy as people say. There are so many answers to her question, all of them true. She’s my chancellor, and I’m not going to oppose Thuvhe, like my brother is. I care about her, as a friend, as … whatever else we are to each other. I’m worried about the wild grief I saw in her right before she killed Ryzek Noavek, and she needs help to do what’s right from now on rather than what satisfies her thirst for revenge. The list goes on, and the answer I choose is as much about what I want her to hear as it is about the truth.

“You asked me if you could trust me,” I finally say. “Well, you can. I’m with you, no matter what. Okay?”

“I thought, after what you saw me do …” I think of the knife she used to kill Ryzek dropping to the floor, and push the memory away. “I thought you wouldn’t want to be anywhere near me.”

What she did to Ryzek didn’t disgust me, it worried me. I don’t care that he’s dead, but I do care that she was able to kill him. I don’t try to explain that to her, though.

“He killed Ori,” I say.

“So did your brother,” she whispers. “It was both of them, Cisi. There’s something wrong with Eijeh. I saw it in Ryzek’s head, right before—”

She chokes before she can finish her sentence.

“I know.” I grab her hand and hold on tight. “I know.”

She starts to cry. At first it’s dignified, but then the beast of grief takes over, and she claws at my arms to get away from it, sobbing. But I know, I know as well as anybody that there’s no escape. Grief is absolute.

“I got you,” I say, rubbing circles on her back. “I got you.”

She stops scratching after a while, stops sobbing. Just leans her face into my shoulder.

“What did you do?” she asks, voice muffled by my shirt. “After your dad died, after your brothers …”

“I … I just did things, for a long time. I ate, showered, worked, studied. But I wasn’t really there, or at least, I didn’t feel like I was. But … it was like when feeling comes back to a limb that’s gone numb. It comes back in little prickles, little pieces at a time.”

She lifts her head to look at me.

“I’m sorry I didn’t tell you what I was about to do. I’m sorry I asked you to come see … that,” she says. “I needed a witness, just in case it went wrong, and you were the only one I trusted.”

I sigh, and push her hair behind her ears. “I know.”

“Would you have stopped me, if you knew?”

I purse my lips. The real answer is that I don’t know, but that’s not the one I want to give her, not the one that will make her trust me. And she has to trust me, if I’m going to do any good in the war that’s coming.

“No,” I say. “I know you only do what you have to.”

It was true. But it didn’t mean I wasn’t worried about how simple it had been to her, and the distant look in her eyes as she led me to that storage room, and the perfect hesitation she had shown Ryzek as she waited for just the right moment to stab him.

“They’re not going to take our planet,” she says to me, in a dark whisper. “I won’t let them.”

“Good,” I say.

She takes my hand. We’ve held hands before, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t still send a thrill through me when her skin slides over mine. She is still so capable. Smooth and strong. I want to kiss her, but this isn’t the time, not when there’s still Ryzek’s blood drying under her fingernails.

So I just let the touch of her hand be enough, and we stare out together at nothingness.

(#ulink_cadc027c-f31f-55d8-a2f6-557b96c7692a)

AKOS FUMBLED WITH THE chain around his neck. The ring of Jorek and Ara’s family was a now-familiar weight right in the hollow of his throat. When he wore armor it made an imprint in his skin, like a brand. As if the mark on his arm wasn’t enough to remind him of what he had done to Suzao Kuzar, Jorek’s father and Ara’s violent husband.

He wasn’t sure why he thought of killing Suzao in the arena now, standing outside his brother’s cell. It was time to decide if Eijeh ought to stay drugged—for how long? Until they got to Ogra? After that?—or if, now that Ryzek was dead, it was safe to risk Eijeh wandering around the ship clearheaded. Cyra and Teka had left the decision up to him and his mom.

His mom was right next to him, her head reaching just a few izits higher than his shoulder. Hair loose and messy around her shoulders, curled into knots. Sifa hadn’t been much of anywhere since Ryzek died, holing up in the belly of the ship to whisper the future to herself, barefoot, pacing. Cyra and Teka had been alarmed, but he told them that’s just how oracles were. Or at least, that was how his mother the oracle was. Sometimes sharp as a knife, sometimes half outside her own body, her own time.

“Eijeh’s not how you remember him,” he said to her. It was a useless warning. She knew it already, for one thing, and for another, she had probably seen him just the way he was now, and a hundred other ways besides.

Still, “I know” was all she said.

Akos tapped the door with his knuckles, then unlocked it with the key Teka had given him and walked in.

Eijeh sat cross-legged on the thin mattress they had thrown into the corner of the cell, an empty tray next to him with the dregs of soup left in a bowl on top of it. When he saw them he scrambled to his feet, hands held out like he might put them in fists and start pummeling. He was wan and red-eyed and shaky.

“What happened?” he said, eyes skirting Akos’s. “W—I felt something. What happened?”

“Ryzek was killed,” Akos replied. “You felt that?”

“Did you do it?” Eijeh asked with a sneer. “Wouldn’t be surprised. You killed Suzao. You killed Kalmev.”

“And Vas,” Akos said. “You’ve got Vas somewhere in that memory stew, don’t you?”

“He was a friend,” Eijeh said.

“He was the man who killed our father,” Akos spat.

Eijeh squinted, and said nothing.

“What about me?” Sifa said, voice flat. “Do you remember me, Eijeh?”

He looked at her like he had only just noticed she was there. “You’re Sifa.” He frowned. “You’re Mom. I don’t—there’s gaps.”

He stepped toward her and said, “Did I love you?”

Akos had never seen Sifa look hurt before, not even when they were younger and told her they hated her because she wouldn’t let them go out with friends, or scolded them for bad scores on tests. He knew she got hurt, because she was a person as well as an oracle, and all people got hurt sometimes. But he wasn’t quite ready for how the look pierced him, when it came, the furrowed brow and downturned mouth.

Did I love you? Akos knew, hearing those words, that he had definitely failed. He hadn’t gotten Eijeh out of Shotet, as he had promised his father before he died. This wasn’t really Eijeh, and what might have restored him was gone, now that Ryzek was dead.

Eijeh was gone. Akos’s throat got tight.

“Only you can know,” Sifa said. “Do you love me now?”

Eijeh twitched, made an aborted hand gesture. “I—maybe.”

“Maybe.” Sifa nodded. “Okay.”

“You knew, didn’t you. That I was the next oracle,” he said. “You knew I would be kidnapped. You didn’t warn me. You didn’t get me ready.”

“There are reasons for that,” she said. “I doubt you would find any of them comforting.”

“Comfort.” Eijeh snorted. “I have no need for comfort.”

He sounded like Ryzek then—that Shotet diction, put into Thuvhesit.

“But you do,” Sifa said. “Everybody does.”

Another snort, but no answer.

“Come here to drug me again, did you?” He nodded to Akos. “That’s what you’re good for, right? You’re a poison-maker. And Cyra’s whore.”

Then Akos’s hands were in fists in Eijeh’s worn shirt, lifting him up, so his toes were just brushing the floor. He was heavy, but not too heavy for Akos, with the energy that burned inside him, energy that had nothing to do with the current.

Akos slammed him into the wall and growled, “Shut. Your. Mouth.”

“Stop, both of you,” Sifa said, her hand on Akos’s shoulder. “Put him down. Now. If you can’t stay calm, you’ll have to leave.”

Akos dropped Eijeh and stepped back. His ears were ringing. He hadn’t meant to do that. Eijeh slid to the floor, and ran his hands over his buzzed head.

“I am not sure what Ryzek Noavek dumping his memories into your skull has to do with being so cruel to your brother,” Sifa said to Eijeh. “Unless it’s just the only way you know how to be, now. But I suggest you learn another way, and quickly, or I will devise a very creative punishment for you, as your mother and your superior, the sitting oracle. Understand?”

Eijeh looked her over for a few ticks, then his chin shifted, up and down, just a little.

“We are going to land in a few days,” Sifa said. “We will keep you locked in here until our descent, at which point we will ensure you are safely strapped in with the rest of us. When we land, you will be my charge. You will do as I say. If you don’t, I will have Akos drug you again. Our situation is too tenuous to risk you wreaking havoc.” She turned to Akos. “How does that plan sound to you?”

“Fine,” he said, teeth gritted.

“Good.” She forced a smile that was completely without feeling. “Would you like anything to read while you’re in here, Eijeh? Something to pass the time?”

“Okay,” Eijeh said with a half shrug.

“I’ll see what I can find.”

She stepped toward him, making Akos tense up in case she needed his help. But Eijeh didn’t stir as she picked up his empty tray, and he didn’t look up at either of them when they left the room. Akos locked it behind him, and checked the handle twice to make sure the lock held. He was breathing fast. That was the Eijeh he remembered from Shotet, the one who walked around with Vas Kuzar like they were born friends instead of born enemies, and the one who held him down while Vas forced Cyra to torture him.

His eyes burned. He shut them.

“Had you seen him that way?” he said. “In visions, I mean.”

“Yes,” Sifa said, quiet.

“Did it help? To know it was coming?”

“It’s not as straightforward as you think,” she said. “I see so many paths, so many versions of people … I’m always surprised to discover which future has come to pass. I am still not sure which Akos I am speaking to, for example. There are many that you could be.”

She lapsed into quiet, and sighed.

“No,” she said, finally. “It didn’t help.”

“I—” He gulped, and opened his eyes, not looking at his mother, but at the wall opposite him. “I’m sorry I couldn’t stop it. I—I failed him.”

“Akos—” She gripped his shoulder, and he let himself feel the warmth and the strength of her hand for a tick.

The cell that had held Ryzek was scrubbed clean, like nothing had ever happened. In some secret part of himself, he wished Eijeh had died, too. It would be easier than this, the constant reminder of how he’d messed it all up, and couldn’t fix it.

“There’s nothing you—”

“Don’t,” he said, more harshly than he meant to. “He’s gone. And now there’s nothing left to do but—bear it.”

He turned, and left her standing there, caught between two sons who weren’t quite the same as they used to be.

They took turns sitting on the nav deck to make sure the ship didn’t steer straight into an asteroid or another spaceship or some other piece of debris. Sifa had the first shift, since Teka was exhausted from reprogramming the ship in the first place, and Cyra had spent the last several hours mopping up her own brother’s blood. Akos cleared the floor of the galley and rolled out a blanket in the corner, near the medical supplies.

Cyra came to join him, her face scrubbed shiny and her hair in a braid over one shoulder. She lay shoulder to shoulder with him, and for a time neither of them said anything at all, just breathed in time together. It reminded him of being in her quarters on the sojourn ship, how he could always hear when she was up because the tossing and turning stopped and all he could hear were her breaths.

“I’m glad he’s dead,” Cyra said.

He turned to face her, propping himself up on one elbow. She had trimmed the hair neatly around the silverskin. He’d gotten used to it now, shining on one side of her head like a mirror. It suited her, really, even if he hated what had happened to her.

Her jaw was set. She started on the straps of the armor that covered her arm, working them back and forth until they were loose. When she shucked it, there was a new cut on her arm, right near her elbow, with a hash through it. He touched it, lightly, with a fingertip.

“You didn’t kill him,” he said to her.

“I know,” she said. “But the chancellor isn’t going to take note of him, and …” She sighed. “I guess I could have gotten some revenge from beyond death, if I had let him go unmarked. Dishonored him by pretending he never existed.”

“But you couldn’t do that,” Akos supplied.

“I couldn’t,” Cyra agreed. “He’s still my brother. His life is still … notable.”

“And you’re upset that you couldn’t punish him.”

“Sort of.”

“Well, if my opinion counts for anything, I don’t think you need to regret showing some mercy,” he said. “I’m just sorry you went to all the trouble of sparing him for me, and then … it didn’t even matter.”

With a heavy sigh, he slumped to the ground again. Just another way that he’d failed.

She laid a hand on him, right over his sternum, right over his heart, with the scarred arm that said so much and so little about her at once.

“I’m not,” she said. “Sorry, I mean.”

“Well.” He covered her hand with one of his own. “I’m not sorry you’ve got Ryzek’s loss marked on your arm, even though I hated him.”

The corners of her mouth twitched up. He was surprised to find that she had chipped off a little piece of his guilt, and he wondered if he’d done the same for her, in his way. They were both people who carried every scrap of everything around, but maybe they could help each other set things down, piece by piece.

It was good he felt this way, he thought. With Eijeh gone, all that he had left to do was meet his fate, and Cyra and his fate were inextricable. He would die for the family Noavek, and she was the last of them. She was a happy inevitability, brilliant and unavoidable.

Acting on impulse, Akos turned and kissed her. She stuck her fingers in one of his belt loops and pulled him tight against her, the way they had been earlier, when they were interrupted. But the door was closed, now, and Teka was fast asleep in some other part of the ship.

They were alone. Finally.

The chemical-floral smell of the ship was replaced with the smell of her, of the herbal shampoo she’d last used in the ship’s shower, and sweat and sendes leaf. He ran potion-stained fingertips down the side of her throat and across the faint curve of her collarbone.

She pushed him over, so she was straddling him, and pinned his hips down for a tick, just to tug his shirt out from under his waistband. Her hands were so warm against him he could hardly breathe. They found the soft give of flesh around his middle, the taut muscle wrapped around his ribs. She undid buttons all the way up to his throat.

He’d thought of this when he helped her take her clothes off before that bath in the renegade safehouse, how it might be to take off their clothes when they weren’t injured and fighting for their lives. He’d imagined something frantic, but she was taking her time, running her fingers over the bumps of his ribs, the tendons on the inside of his wrists as she freed the buttons on his cuffs, the bones that stuck out of his shoulders.

When he tried to touch her back, she pressed him away. That wasn’t how she wanted it just then, it seemed like, and he was happy to give her what she wanted. She was the girl who couldn’t touch people, after all. It sparked something inside him to know that he was the only one she’d done this with—not excitement, but something softer. Tender.

She was his only—and fate said she would be his last.

She pulled back to look at him, and he tugged at the hem of her shirt.

“May I?” he said. She nodded.

He felt suddenly tentative as he started undoing her shirt buttons, from throat to waist. He sat up just enough to kiss the skin he revealed, izit by izit. Soft skin, for someone so strong, soft over hard muscle and bone and steely nerve.

He tipped them over, so he was leaning over her, leaving just enough space between them to feel her warmth without touching her. He stripped his shirt from his shoulders, and kissed her stomach again. He’d run out of shirt to unbutton.

He touched his nose to the inside of her hip and looked up at her.

“Yes?” he said.

“Yes,” she said roughly.

His hands closed over her waistband, and he ran parted lips over the skin he exposed, izit by izit.

(#ulink_1a35b3fe-ab76-55d3-b60f-2038062a3177)

THE ASSEMBLY SHIP IS the size of a small planet, wide and round as a floater but so much bigger it’s downright alarming. It fills the windows of the little patrol ship that picked up our escape pod, made of glass and smooth, pale metal.

“You’ve never seen it before?” Isae asks me.

“Only images,” I say.

Its clear glass panels reflect the currentstream where it burns pink, and emptiness where it doesn’t. Little red lights along the ship’s borders blink on and off like inhales and exhales. Its movements around the sun are so slight it looks still.

“It’s different in images,” I say. “Much less impressive.”

“I spent three seasons here as a child.” Isae’s knuckles skim the glass. “Learning how to be proper. I had that brim accent—they didn’t like that.”

I smile. “You still do, sometimes, when you forget to care. I like it.”

“You like it because the brim accent is so much like your Hessan one.” She pokes her fingertip into my dimple, and I smack it away.

“Come on,” she says. “Time to dock.”

The ship’s captain, a squat little man with sweat dotting his forehead, noses his little ship toward the massive Assembly one—to secure entrance B, I’d heard him say. The letter was painted above the doors, reflective. Two metal panels pull apart under the B, and an enclosed walkway reaches for our ship’s hatch. Hatch and walkway lock together with a hiss. Another crew member seals the connection with the pull of a lever.

We all stand by the hatch doors as they open, making way for Isae to stand at the fore. It’s a skeleton patrol crew that picked us up, meant to cruise around the middle band of the solar system in case someone’s in trouble—or making it. There’s just a captain, a first officer, and two others on board with us, and they don’t talk much. Likely because their Othyrian isn’t strong—they sound like Trellans to me when they do speak.

I skip ahead into the bright tunnel beyond the hatch doors to catch up to Isae. The glass walls are so clean. I feel like I’m floating in nothingness for a tick, but the floor holds firm.

I just make it to Isae’s side when a group of official-looking people in pale gray uniforms greets us. At their sides are nonlethal channeling rods, designed to stun, not kill. The sight is reassuring. This is how things should be—controlled but not dangerous.

The one in front, with a row of medals on his chest, bows to Isae.

“Hello, Chancellor,” he says in crisp Othyrian. “I am Captain Morel. The Assembly Leader has been informed of your arrival, and your quarters have been prepared, as well as those of your … guest.”

Isae smooths her sweater down like that’s going to get the folds out of it.

“Thank you, Captain Morel,” she says, all traces of brim accent gone. “May I introduce Cisi Kereseth, a family friend from the nation-planet of Thuvhe.”

“A pleasure,” Captain Morel says to me.

I let my gift unfold right away. It’s just instinct, at this point. Most people react well when I think of my currentgift as a blanket falling over their shoulders, and Captain Morel is no exception—he relaxes right in front of me, and his smile softens, like he actually means it. I think it works on Isae, too, for the first time in days. She looks a little softer around the eyes.

“Captain Morel,” I say. “Thank you for the welcome.”

“Allow me to escort you to your quarters,” he says. “Thank you for delivering Chancellor Benesit safely here, sir,” he adds to the captain who brought us here.

The man grunts a little, and nods at Isae and me as we turn to go.

Captain Morel’s shoes snap when he walks, and when he turns corners, they slide a little as the balls of his feet twist into the floor. If he’s here, it’s because he was born into a rich family on whatever his home planet is, but doesn’t have the disposition—or the stomach—for actual military service. He’s just right for tasks like these, which require manners and diplomacy and polish.

When the captain delivers me to my room—right next to Isae’s, for convenience—I sigh with relief. After the door shuts behind me, I let my jacket slide off my shoulders and fall to my feet.

The rooms have been set for us, clearly. That’s the only explanation for the field of feathergrass, twitching in the wind, on the far wall. It’s footage of Thuvhe. Right in front of it is a narrow bed with a thick brown blanket tucked around the mattress.

I put a hand on the touch panel near the door, flicking images and text forward until I find the one I want. Wall footage. I scroll until I find one of Hessa in the snow. The top of the hill sparkles red from the domed roof of the temple. I follow the bumps of house roofs all the way to the bottom of the hill, watching weather vanes spin as I do. All the buildings are hidden behind a white haze of snowflakes.

Sometimes I forget how beautiful my home is.

I see just the corner of the fields my dad farmed, and the image cuts off. Somewhere past them is the empty spot where we held Eijeh’s and Akos’s funerals. It wasn’t my idea—Mom was the one who stacked the wood and burnstones, who said the prayer and lit it up. I just stood close by in my kutyah coat, the face shield on so I could cry without anyone seeing.

I hadn’t thought of Eijeh and Akos as lost, truly lost, until then. If Mom was burning the pyres, I thought, that must mean she knew they were dead, in the way only an oracle could know things. But she hadn’t known nearly as much as I thought.

I fall to the bed and stare up at the snow.

Maybe it wasn’t smart to come here, to contend with a chancellor instead of following my own family. I don’t know much about politics or government—I’m Hessa-born, so far out of my realm of knowledge it’s almost funny. But I know Thuvhe. I know people.

And someone needs to look out for Isae before she loses herself in grief.

Isae’s wall just looks like a window to space. Stars all glinting, little pricks of light, and the bend and swell of the currentstream. It reminds me of a fight we had, early on, before I knew her better.

You know nothing about my planet and its people, I said to her then. It was after she had gone public as chancellor. She and Ori had shown up at my apartment at school, and she had been rude to me for being so familiar with her sister. And for some reason, my currentgift had let me be rude back. This is only your first season on its soil.

The broken look she gave me then is a lot like the one she’s giving me now, as I walk into her quarters—twice the size of the ones given to me, but that’s not surprising. She sits on the end of her bed in an undershirt and underwear that’s really just a pair of shorts clinging to her long, skinny legs. It’s more casual than I’ve ever seen her before, and more vulnerable, somehow, like letting me see her right after waking ripped her open somehow.

All my life I have loved this planet, more fervently than my family or my friends or even myself, she had replied back then. you have walked all your seasons on its skin, but I have buried myself deep in its guts, so don’t you dare tell me that I don’t know it.