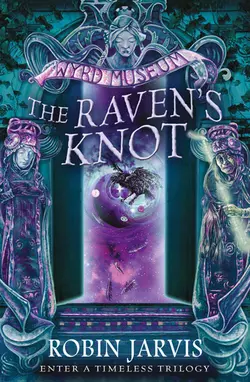

The Raven’s Knot

Robin Jarvis

Timely reissue of the classic fantasy trilogy by Robin Jarvis, following on from the landmark publication of DANCING JAX, his first novel in a decade.In a grimy alley in the East End of London stands the Wyrd Museum, cared for by the strange Webster sisters – the scene of even stranger events.Brought out of the past, elfin-like Edie Dorkins must now help the Websters to protect their age-old secret. For outside the museum’s enchanted walls, a nightmarish army is gathering in the mystical town of Glastonbury, bent on destroying the sisters and their ancient power once and for all…Revisit the chilling, fantastical world of the Wyrd Museum in this sequel to The Woven Path.

THE RAVEN’S KNOT

Robin Jarvis

Dedication

Tales from the Wyrd Museum Trilogy

The Woven Path The Raven’s Knot The Fatal Strand

For Young Adult readers:

Dancing Jax

Contents

Cover (#u75f343ae-6b07-548b-82c1-fca3362763a4)

Title Page (#u1fbe25ac-ec05-565e-99a0-603f59009b8c)

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1 - Out of the Blackout

Chapter 2 - The Chamber of Nirinel

Chapter 3 - Thought and Memory

Chapter 4 - The Lord of the Dance

Chapter 5 - Jam and Pancakes

Chapter 6 - The Crow Doll

Chapter 7 - In the Shadow of the Enemy

Chapter 8 - Aidan

Chapter 9 - Spectres and Aliens

Chapter 10 - Valediction

Chapter 11 - Deceit and Larceny

Chapter 12 - Riding the Night

Chapter 13 - Memory Forgotten

Chapter 14 - Missing the Dawn

Chapter 15 - Drowning in Legends

Chapter 16 - Two Lost Souls

Chapter 17 - Skögul

Chapter 18 - Charred Embers

Chapter 19 - Verdandi

Chapter 20 - The Crimson Weft

Chapter 21 - Hlökk

Chapter 22 - The Tomb of the Hermit

Chapter 23 - The Gathering

Chapter 24 - Within the Frozen Pool

Chapter 25 - Battle of the Thorn

Chapter 26 - Dejected and Downcast

Chapter 27 - The Property of Longinus

Chapter 28 - Blood on the Tor

Epilogue

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue

Five miles outside Glastonbury

2.58 am

Brindled with bitter, biting frost, the plough-churned soil of the Somerset levels was bare and black. Hammered upon winter’s icy forge, the earthen furrows were iron hard – unyielding as the great cold which flooded the moonless dark.

Deep and chill were the silent shadows that filled those expansive fields. As sombre lakes of brooding gloom they appeared, pressing and pushing against the bordering hedgerows. Through those twisted, naked branches the unrelenting hoary darkness spilled and the night was drowned in a black, freezing murk that no glimmer of star could penetrate.

Behind the invisible distant hills, shimmering bleakly upon the rim of the choking night, the pale glare of mankind was weak and dim – the countless faint, orange lights trembling in the frozen air.

In that lonely hour, in the remote realm of the wild empty country, safely concealed by the untame dark, a sound – long banished from the world – disturbed the jet-vaulted heavens. Over unlit fields and solitary farm buildings, the noise of great wings travelled across the sky – free at last of the tethers that had kept them bound for so many ages.

All creatures felt the presence of that awful force which coursed through the knifing cold. Upon the shadow-smothered ground, farm animals grew silent and afraid as the terror passed high above.

Horror and dread spread across the dim landscape which separated Wells and Glastonbury. Owls refused to leave their barns and a fox, cantering leisurely homeward, suddenly flattened itself against the freezing ground when rumour of the unseen nightmare reached its sharp ears.

Dragging its stomach over frost-covered furrows, its brush quivering in fright, the fox darted for cover – tearing in blind panic towards a thicket of hawthorn. It lay there panting feverishly – straining to catch the slightest sound upon the winter airs.

But the unnatural clamour that had so alarmed the fox had already faded and a new, yet more familiar, noise was growing.

Through the night a vehicle came, the faint rumble of its engine a welcome distraction from the fear that had so gripped the fox’s heart and yet it remained crouching beneath the hawthorn until daybreak.

Over the icy road the car swept, the broad beams of its headlights scything through the dark veils in front – snatching brief, stark visions of hedge and ditch as they flashed by.

Inside the vehicle the heater was finally blowing hot air through the vents and the toes of the driver and his passenger were thawing at last. Mellow music issued from the radio, colouring the dark journey home with a languid harmony, reflecting the relaxed and sleepy mood of the car’s occupants.

Resting her head upon her husband’s shoulder, a pretty young woman murmured the few lyrics she remembered of the romantic song and sank a little lower in her seat.

Her voice stopped as she felt him tense and she lifted her head in surprise.

‘Tom,’ she began. ‘What is it?’

A frown had creased the man’s forehead and he hastily switched off the radio.

‘Ssshh!’ he said. ‘Hazel, did you hear that?’

Disconcerted, the woman listened for a moment.

‘Sounds all right to me,’ she answered. ‘Probably something rattling around in the boot.’

‘I’m not talking about the car,’ he said sharply.

‘What then?’

‘Outside.’

Hazel brushed the hair from her eyes and stared at him in astonishment. Her husband was doubled over the steering-wheel, gazing up through the windscreen at the pitch black sky, scanning it fearfully.

‘Tom,’ she ventured.

‘There isn’t anything.’

‘There is!’ he said emphatically. ‘Hazel, it was weird – sort of screaming.’

She shifted on the seat and folded her arms as she began to look out of her window at the dark countryside passing by.

‘What...?’ she began nervously. ‘Like a person? That kind of screaming?’

‘There was more than one,’ came his muddling answer. ‘But it wasn’t quite human – it… it was weird.’

‘Oh, well,’ she breathed with relief, ‘if it wasn’t human...’

The golden glow of Glastonbury’s street-lamps was now clear in the distance, with the majestic outline of the Tor rearing behind them – another ten minutes and she could be in bed.

The car had been steadily picking up speed and now the woman noticed for the first time the beads of perspiration glistening upon her partner’s face.

‘Tom,’ she said. ‘Slow down. There’s black ice all over these roads.’

‘We’ve got to get home, Hazel!’ he told her and the urgency in his voice was startling. ‘We’ve got to get home, and fast! It’s too open here. I don’t like it.’

Before she could respond, something tapped lightly upon the windscreen. It was only a twig but Tom’s reaction to it was surprising.

‘Where’d that come from?’ he demanded, his voice rising with mounting panic.

The woman gaped at him in disbelief. ‘Where d’you think it came from?’ she laughed. ‘It’s a twig! Please, Tom, slow down.’

‘There are no trees on this stretch of road,’ he replied gravely.

Bewildered, Hazel threw her head back. ‘The wind blew it, a bird dropped it – I don’t know! I don’t care – but you’re driving too fast. Listen to me!’

But Tom hardly heard her. All his senses were focused upon the road ahead, yet not one of them prepared him for what happened next.

From the night it tumbled, out of the blind heavens it dropped – hurtling down with ferocious force and by the time he saw it, it was too late.

Into the bright light of the headlamps it fell – a monstrous, massive bough. Raining insanely out of the sky, the mighty limb of ancient oak came plummeting towards them.

With a tremendous, violent crunch of metal, the huge branch slammed into the bonnet of the car and the windscreen shattered into a million tiny cubes.

Screaming, Hazel threw her arms before her face as the vehicle bucked and shuddered beneath the vicious impact, and she braced herself as the tyres skidded upon the icy road.

His face scored by the twigs which had come whipping and flailing in through the splintered window, Tom gripped the wheel tightly and struggled for control as the vehicle shot into a wild, careering spin. But the windscreen was utterly blocked and all he could do was shout to Hazel to hold on.

‘NO!’ the woman yelled, clinging to him frantically as the car flew across the road and burst through the hedgerow. Into a field it thundered, with the branch still wedged upon the bonnet, and over the frozen furrows it charged.

Then, with a lurch, the spin ended and after one final jolt, the terrifying madness was over.

Gingerly, Hazel unfastened her seat belt and reached across to Tom. His hands were still clenched about the wheel and, when she held him, she discovered that he was shaking as much as herself.

Neither one of them spoke, both pairs of eyes were fixed upon the enormous branch that had dropped so unexpectedly and so illogically from above.

‘It might have killed us,’ she whispered, apprehensively reaching out to touch the rough, glassstrewn wood. ‘But where...? Where did it come from?’

Tom made no reply, his heart was pounding in his chest and his eyes widened as he stared upwards.

‘My God...’ he whimpered.

This time Hazel heard it too and her hands clasped tightly about his.

High above them the sky was filled with a terrible yammering, a foul screeching cacophony that grew louder with every awful instant.

‘The engine!’ Hazel cried. ‘Tom, start the engine – quickly!’

Her partner fumbled with the ignition but the car merely coughed pathetically whilst, overhead, the dreadful shrieks mounted steadily.

Down the nightmares swooped, bawling and squawking at the top of their voices – down to where the puny chariot struggled in the frozen mire. They crowed their hideous delight at the prospect which awaited them.

‘Lock the doors!’ Tom cried. ‘Don’t let it inside.’

‘But what is it?’

‘I don’t know!’

Screwing up his face, he tried the key again and the engine turned over.

But it was too late. With a great down-draught and a clamour of high screeching voices, they were caught. There came the beating of gigantic wings and the roof buckled as large dents were punched in the metal beneath the weight of many descending objects.

Then the enormous branch was flicked from the bonnet as easily as if it were a piece of straw. The yammering was deafening now and Hazel’s own voice joined it as she let loose a desperate scream.

Into the car, curving under the roof, there came a great and savage claw which gripped the contorted metal and the vehicle was shaken violently.

A piercing clamour ensued as the vehicle was punctured and talons stronger than steel began to rend and rip. Like a tin of peaches the car was opened, until the two stricken occupants were staring straight up through the torn, jagged rents and knew that their deaths had come.

For a moment, as they were seized and dragged into the upper airs, Tom’s and Hazel’s scream’s equalled the vile, raucous laughter of the foulness which had captured them.

Then the two human voices were silenced and, once the feast was over, the night was disturbed only by a slow, contented flapping as dark, sinister shapes took to the air.

Across the Somerset levels all was peaceful again, except for one remote field just outside Glastonbury, where the engine of an empty, wrecked car chugged erratically and the radio played soft, romantic melodies.

A force dormant for centuries was loose once more – the first of the Twelve were abroad and in the days that were to follow their numbers would increase.

Over the East End of London a bright moon gleamed down upon the many spires of the strange, ugly building known as The Wyrd Museum. But below the sombre structure’s many roofs, its cramped concrete-covered yard was illuminated by a harsher, more livid light.

Bathed in glorious bursts of intense purple flame, the enclosed area flared and flickered. With every spark and pulse, the high brick walls leapt in and out of the shadows and everything within danced with vibrant colour.

Lovingly arranged around a broken drinking-fountain, a new tribute of withered flowers appeared to take on new life once more as the unnatural, shimmering barrage painted them with vivid hues of violet and amethyst.

Yet behind the first floor windows, the source of the lustrous display was already waning as the last traces of a fiery portal guttered and crackled until, finally, the room beyond was left in darkness. Then a child’s voice began to wail and a light was snapped on.

The Separate Collection and everything it had housed were almost completely destroyed. Vicious smouldering scars scored the oak panelling of the walls, blasted and ripped by blistering bolts of energy that had shot from the centre of the whirling gateway.

Yet, from those sizzling wounds, living branches had sprouted and now the room resembled a clearing in a forest, for a canopy of new green leaves sheltered those below from the harsh electric glare of the lights and dappled them in a pleasant verdant shade.

Neil Chapman was drained and weary. His mind was still crowded with images of the past and the frightening events he had witnessed there.

Together with a teddy bear in whose furry form resided the soul of an American airman, he had been sent back to the time of the Second World War to recapture Belial – a demon that had escaped from the museum. This harrowing task they had eventually achieved, but Ted had not returned to the present and the boy didn’t know what had happened to him.

Now, all he wanted to do was leave this peculiar, forbidding room and surround himself with ordinary and familiar objects. To be back in his small bedroom that was covered in football posters and sleep in a comfortable bed was what he craved above anything, and to forget forever the drone of enemy aircraft and the boom of exploding bombs.

His thoughts stirred briefly from the dark time of the Second World War to the present again, as his young brother’s cries pushed out all other considerations and both he and Brian Chapman tried to comfort him.

‘Blood and sand!’ Neil’s father spluttered, unable to wrench his eyes from the bizarre scene around him. ‘What’s been going on? Blood and sand... blood and sand.’

Standing apart from the Chapman family, Miss Ursula Webster, eldest of the three sisters who owned The Wyrd Museum, eyed the destruction with her glittering eyes, the nostrils of her long thin nose twitching as she contained her anger.

Arching her elegant eyebrows, the woman examined the wreckage that surrounded her. All the precious exhibits were strewn over the floor, jettisoned from their splintered display cabinets, and she sucked the air in sharply between her mottled teeth.

‘So many valuable artefacts,’ her clipped, crisp voice declared. ‘It is an outrage to see them unhoused and vandalised in such a fashion.’

Turning, with glass crunching beneath her slippered heel, she clapped her hands for attention and pointed an imperious finger at Neil’s father.

‘Mr Chapman,’ she began. ‘You must begin the restoration of this collection as soon as possible. Such treasures as these must not be left lying around in this disgraceful manner. I charge you to save all you can of them, for you cannot guess their worth. My sisters and I are their custodians for a limited period only, they enjoy such shelter and guardianship as this building can offer and what slight protection our wisdom can afford.’

With a quick, bird-like movement, she turned her head to observe her two wizened sisters who were stooping and fussing over a young girl, then returned her glance to Neil’s father.

‘Mine is a grave responsibility,’ she informed him. ‘See to it that you obey me in this. When you have cleared away the rubble and removed this ridiculous foliage from the walls, throw nothing away. I must inspect everything prior to that, do you understand? We cannot afford to make another mistake.’

Brian Chapman nodded and the elderly woman gave him a curt, dismissive nod before returning to her sisters.

Miss Celandine Webster, with her straw-coloured hair hanging in two great plaits on either side of her over-ripe apple face, was grinning her toothiest smile. At her side Miss Veronica was trilling happily, her normally white-powdered countenance a startling waxy sight, covered as it was by a thick layer of beauty cream.

Edie Dorkins, the small girl brought from the time of the Blitz to the present by the power of the Websters, took little notice of them or the Chapmans. She was staring at a large piece of broken glass propped against the wall and gazing at her reflection. Upon her head the green woollen pixie-hood, a gift from the sisters, sparkled as the light caught the strands of silver tinsel woven into the stitches and she preened herself with haughty vanity.

‘Doesn’t she look heavenly?’ Miss Celandine cooed in delight. ‘And there was I worrying about the size – why it’s perfect! It is, it is!’

Leaning upon her walking cane, Miss Veronica bent forward to touch the woollen hood and sighed dreamily. ‘Now there are four of us. It’s been so long, so very, very long.’

‘Edith!’

Miss Ursula’s commanding voice rapped so sharply that the girl stopped admiring herself and fixed her almond-shaped eyes upon the eldest of the Websters.

Picking her way through the debris, Miss Ursula took the youngster’s grubby hand in her own.

‘I have said that you are to be our daughter, Edith, dear, the offspring which was denied to us and you have accepted. But do you comprehend the nature of the burden you have yoked upon your shoulders?’

An impudent grin curved over the child’s face as she stared up at Miss Ursula. ‘Reckon I do,’ she stated flatly.

The fragment of a smile flitted across the woman’s pinched features but her bony fingers gripped Edie’s hand a little tighter and when she next spoke her voice was edged with scorn.

‘Wild infant of the rambling wastes!’ she cried. ‘Akin to us you may be and many draughts of the sacred water have you drunk, but do not think you know us yet, nor the tale of all our histories.’

But Edie was not cowed by the vehemence of the old woman’s words and, baring her teeth, snapped back. ‘So teach me ’em! Tell me about the sun, the moon an’ the name of everything what grows. What has been – an’ all of whatever will be.’

Miss Ursula loosened her grip and her eyelids fluttered closed as she breathed deeply. ‘Well answered Edith, my dear – tomorrow we shall begin your instruction.’

‘No,’ the girl insisted. ‘Start now!’

Miss Ursula studied her, then gave a grim laugh. ‘Come with me!’ she cried. ‘As this is the hour of your joining with us, it is only fitting that you are shown our greatest treasure at once.’

With her gown billowing around her, Miss Ursula strode swiftly from The Separate Collection and Edie Dorkins, her eyes dancing with an excited light, ran after her.

‘Where is Ursula taking our new sister?’ Miss Veronica asked in bewilderment. ‘There’s jam and pancakes upstairs, I prepared them myself. You don’t think they’ll eat them all do you, Celandine? Do you suppose they’ll leave some for me? I love them so dearly.’

Miss Celandine’s nut-brown face crinkled with impatience as she stared after the figures of Miss Ursula and the girl as they disappeared into the darkness of the rooms beyond.

‘You and your pancakes!’ she snorted petulantly. ‘I’m certain little Edith can eat as many as she likes of them – and most welcome she is too...’ Her chirruping voice faded as her rambling mind suddenly realised where the others were going and she threw her hands in the air in an exclamation of joy and wonder.

‘Of course!’ she sang, hopping up and down, her plaits swinging wildly about her head. ‘Ursula will take her there! She will! She will – I know it – I do, I do! Oh, you must hurry, Veronica, or we may be too late.’

And so, bouncing in front of her infirm sister like an absurd rabbit, Miss Celandine scampered from the room and Miss Veronica hobbled after.

Alone with his sons, the dumbfounded Mr Chapman pinched the bridge of his nose and gazed around forlornly.

‘I... I don’t understand,’ he murmured, staring up at the spreading branches overhead. ‘I want to, but I don’t. Neil – what happened here?’

The boy pulled away from him, but he was too exhausted to explain. ‘It’s over now, Dad,’ he mumbled wearily. ‘That’s all that matters. Josh and me are safe. We’re back.’

‘Back from where? Who was that scruffy kid? She looked like some kind of refugee.’

But if Brian Chapman was expecting any answers to his questions he quickly saw that none were forthcoming. Neil’s face was haggard and his eyelids were drooping. Remembering that it was past three in the morning, the caretaker of The Wyrd Museum grunted in resignation and lifted Josh into his arms.

‘I’d best get the pair of you to bed,’ he said. ‘You can tell me in the morning.’

Neil shambled to the doorway but paused before leaving. Casting his drowse-filled eyes over the scattered debris of The Separate Collection, he whispered faintly ‘Goodbye Ted, I’ll miss you.’

Down the stairs Miss Ursula led Edie, down past a great square window through which a shaft of silver moonlight came slanting into the building, illuminating the two rushing figures.

‘Are you ready Edith, my dear?’ the elderly woman asked, her voice trembling with anticipation when they reached the claustrophobic hallway at the foot of the staircase. ‘Are you prepared for what you are about to see?’

The girl nodded briskly and whisked her head from left to right as she looked about her in the dim gloom.

The panelling of the hall was crowded with dingy watercolours. A spindly weeping fig dominated one corner, whilst in another an incomplete suit of armour leaned precariously upon a rusted spear.

‘Here... here we are,’ Miss Ursula murmured, a little out of breath. ‘At the beginning of your new life. The way lies before you, let us unlock the barrier and step down into the distant ages – to a time beyond memory or record.’

Solemnly, she stepped over to one of the panels and rapped her knuckles upon it three times.

‘I used to have to recite a string of ludicrous words in the old days,’ she explained. ‘But eventually a trio of knocks seemed to suffice. This place and I know one another too well to tolerate that variety of nursery rhyme nonsense.’

Striding back to Edie, she turned her to face the far wall then placed her hands upon the young girl’s shoulders and whispered sombrely in her ear. ‘Watch.’

Edie stared at the moonlit panels and waited expectantly as, gradually, she became aware of a faint clicking noise which steadily grew louder behind the wainscoting. Out into the hallway the staccato sound reverberated until it abruptly changed into a grinding whirr and, with an awkward juddering motion, a section of the wall began to shift and slide into a hidden recess.

‘The mechanism is worn and ancient,’ Miss Ursula confessed, eyeing the painfully slow, jarring movements. ‘In the last hundred years I have used it only seldom. Come, you must see what it has revealed.’

Edie darted forward and gazed into the shadowy space that had been concealed behind the panel.

The dusty tatters of old, abandoned cobwebs were strung across it but in a moment she had cleared them away and, with filaments of grimy gossamer still clinging to her fingers, she found herself looking at a low archway set into an ancient wall.

Tilting her head to one side and half closing her eyes, Edie thought it resembled the entrance to an enchanted castle and tenderly ran her hands over the surface of the roughly hewn stone.

‘Here is the oldest part of the museum,’ Miss Ursula’s hushed voice informed her. ‘About this doorway, whilst my sisters and I withered with age – enduring the creeping passage of time, the rest of the building burgeoned and grew. This was the earliest shrine to house the wondrous treasure of the three Fates. We are very near now, very near indeed. What can you sense, Edith? Tell me, does it call to you?’

The girl stood back and studied the wooden door that was framed by the arch. Its stout timbers were black with age and although they were pitted and scarred by generations of long dead woodworm, they were as solid as the stone which surrounded them. Into the now steel-hard grain, iron studs had once been embedded, but most of them had flaked away with the centuries, leaving only sunken craters behind. The hinges, however, were still in place and Edie’s exploring fingertips began to trace the curling fronds of their intricate design, until her hands finally came to rest upon a large, round bronze handle.

At the bottom of the door there was a wide crack where the timbers had shrunk away from the floor and a draught of cold, musty air blew about the child’s stockinged legs – stirring the shreds of web that were still attached to her.

Edie wrinkled her nose when the stale air wafted up to her nostrils, but the sour expression gradually faded from her puckish face and she took a step backwards as the faint, mouldering scent entwined around her.

The smell was not entirely unpleasant, there was a compelling sweetness and poignancy to it, and she was reminded of the roses that had been left to grow tall and wild in the gardens of bombed-out houses – their blooms rotting on the stem.

She had adored the wilderness of the bombsites. In the time of the Blitz, the shattered wasteland had been her realm and of all the fragrances which threaded their way over the rubble, the spectral perfume of spoiling roses had been her favourite.

The tinsel threads woven into her pixie-hood glittered for a moment as the haunting odour captivated her and, watching her reactions, Miss Ursula smiled with approval.

‘Yes,’ she murmured. ‘I see that you do sense it. Nirinel is aware of you, Edith, and is calling. If I needed any further proof that you were indeed one of us, then it has been provided.’

Crossing to the corner where the armour leaned against the panels, she lit an oil lamp which stood upon a small table and returned with it to Edie. Within the fluted glass of the lamp’s shade, the wick burned merrily and its soft radiance shone out over the elderly woman’s gaunt features, divulging the fact that she was just as excited as the child.

Then, with her free hand, Miss Ursula took from a fine chain about her neck a delicate silver key but, before turning it in the lock, she hesitated.

‘Now,’ she uttered gravely, ‘you will learn the secret which my sisters and I have kept and guarded these countless years, the same burdensome years that robbed us of our youth and which harvested their wits.

‘No one except we three have ever set foot beyond this entrance. Prepare yourself, Edith, once you have beheld this wonder there can be no returning. No mortal may gaze upon the secret of the Fates. Your destiny will be bound unto it forever.’

Without taking her silvery blue eyes from the doorway, the girl said simply, ‘Open it.’ Then she held her breath as Miss Ursula grasped the handle and pushed.

There came a rasping crunch of rusted iron as slowly, inch by inch, the ancient door swung inwards.

At once the stale air grew more pungent, yet Edie revelled in it. Holding the lamp aloft, Miss Ursula ducked beneath the low archway.

The darkness beyond dispersed before the gentle flame, revealing a narrow stone passageway which was just tall enough to allow the elderly woman to stand.

‘Have a care, Edith,’ Miss Ursula warned. She lowered her hand so that the light illuminated the ground and showed it to be the topmost step of a steep flight which plunged down into a consumate blackness.

‘This stair is treacherous,’ she continued, her voice echoing faintly as she began to descend. ‘The unnumbered footfalls of my sisters and I have rendered each step murderously smooth. In places they are worn completely and have become a slippery, polished slope.’

Down the plummeting tunnel Miss Ursula went, the cheering flame of the lamp bobbing before her and, keeping her cautious eyes trained upon the floor, Edie Dorkins followed closely behind.

Deep into the earth the stairway delved, twisting a spiralling path beneath the foundations of The Wyrd Museum. Occasionally, the stonework was punctuated by large slabs of granite.

At one point a length of copper pipe, encrusted with verdigris, projected across the tunnel and Miss Ursula was compelled to stoop beneath it.

‘So do the roots of the modern world reach down to the past,’ she remarked. ‘Yet, since the well was drained, no water flows from the drinking-fountain above.’

Pressing ever downwards, she did not utter another sound until she paused unexpectedly – causing Edie to bump into her.

‘At this place the outside presses its very closest to that which we keep hidden,’ she said, bringing the lamp close to the wall until the young girl could see that large cracks had appeared in the stones.

‘A few feet beyond this spot lies one of their tunnels. A brash and noisome worm-boring, a filthy conduit to ferry people from one place to another like so many cattle. Perilously near did their excavations come to finding us. Now, when the carriages hurtle through that blind, squalid hole, this stairway shakes as though Woden himself had returned with his armies to do battle one last time.’

Miss Ursula’s voice choked a little when she said this. Edie looked up at her in surprise but the elderly woman recovered quickly.

‘It is most inconvenient,’ her normal clipped tones added. ‘Thus far they have not discovered us, yet a day may come perhaps when these steps are finally unearthed by their over-zealous probing. What hope then for the unhappy world? If man were to know of the terrors which wait to seize control of his domain he would undoubtedly destroy it himself in his madness. That is what we must save them from, Edith. They must never know of us and our guardianship.’

Her doom-laden words hung on the cold air as she turned to proceed.

‘Still,’ she commented dryly, ‘at least at this hour of the night there are no engines to rumble by and impede our progress.’

Further down they travelled, until Edie lost all sense of time and could not begin to measure the distance they had come. Eventually the motion of her descent, joined with the dancing flame, caused her to imagine that she was following a glimmering ember down the throat of a gigantic, slumbering dragon. Down towards its belly she was marching, to bake and broil in the scarlet heats of its rib-encased furnace. A delighted grin split the fey girl’s face.

‘Pay extra heed here,’ Miss Ursula cautioned abruptly, her voice cutting through the child’s imaginings. ‘The steps are about to end.’

As she spoke, the echo altered dramatically, soaring high into a much greater space and Edie found herself standing at the foot of the immense stairway by the mouth of a large, vaulted chamber carved out of solid rock.

Miss Ursula strode inside and Edie saw that the curved walls of the cave were decorated with primitive paintings of figures and animals.

‘Stay by my side, Edith,’ Miss Ursula told her. ‘This is but the first in a series of chambers and catacombs, do not let your inquisitiveness permit you to stray. It might take days before you were found.’

Edie toyed with the exciting notion of wandering around in the complete subterranean darkness but was too anxious to see where she was being led to contemplate the idea for long.

Into a second cavern they went and again the echoes altered, for here great drapes of black cloth hung from the ceiling, soaking up the sound of their footsteps.

‘Gold and silver were those tapestries once,’ Miss Ursula commented, not bothering to glance at them. ‘Very grand we were back then. Several of the chambers were completely gilded from top to bottom, there were shimmering pathways of precious stones and crystal fountains used to fill the air with a sweet tinkling music. There was even a garden down here lit with diamond lanterns and replete with fragrant flowers and fruit trees, in which tame birds sang for our delight.’

The elderly woman pursed her lips contemptuously as she proceeded to guide Edie through the maze of tunnels and caves.

‘However,’ she resumed, ‘the passage of time eventually stripped the pleasure of those decorous diversions from our eyes. Weary of them at last, we allowed the hangings to rot with mould, the jewels we gave back to the earth and the garden was neglected until the bird song ceased. For us there was only one great treasure and we ministered to it daily. Now, Edith, we are here at last.’

They had come to a large gateway which was wrought and hammered from some tarnished yellow metal. Raised in relief across its surface was the stylised image of a great tree nourished by three long roots and Miss Ursula bowed her head respectfully as she reached out her hand to touch it with her fingertips.

‘Behind this barrier is a most hallowed thing,’ she murmured with reverence. ‘Throughout the lonely ages my sisters and I have served it with consummate devotion and now you too shall share the burden. Behold, Edith – the Chamber of Nirinel.’

Swiftly and in silence, the gate opened and suddenly the darkness was banished. A golden, crackling light blazed before them and Edie screwed up her face to shield her eyes from the unexpected, dazzling glare.

Through the entrance Miss Ursula strode, her figure dissolving into the blinding glow until finally the child’s sight adjusted. She stared at the spectacle before her in disbelief and wonder.

The Chamber of Nirinel was far greater than any of the caves they had passed through. Immense and cavernous was its size and Edie stumbled forward to be a part of this awesome vision, in case it was abruptly snatched away from her goggling eyes. Into the light she went, absorbing every detail of the scene before her.

Fixed to the vast, encircling walls a hundred torches burned, casting their splendour over the richly carved rock where, between the graven pillars and sculpted leaf patterns, countless stone faces flickered and glowed. All manner of creatures were depicted there and the untutored Edie Dorkins could only recognise a fraction of them.

Edie gurgled in amusement and hugged herself as the dancing flames made this chiselled bestiary appear to peep down at her with curious stares – even the monstrous serpents seemed to be astonished at her arrival.

‘And why shouldn’t they?’ Miss Ursula’s voice broke in, reading her thoughts. ‘The poor brutes have had an eternity of looking at me.’

Edie laughed, then curtseyed to the silent, stone audience, craning her head back to see just how high the carvings reached up the walls.

It was then that she saw it, the titanic presence which dominated that cathedral-like place. Her mouth fell open at the sight and the giggles died in her throat.

From the moment she had entered the chamber, Edie had been aware of a great shadow which towered over the cavern but not till now did she realise its nature and she froze with shock.

Rising from the bare earthen floor and rearing in a massive arc into the dark heights above, where not even the radiance of so many bright torches could reach, was what appeared to be the trunk of a gigantic tree.

Up into the impenetrable gloom its colossal girth soared, vanishing into the utter blackness of the chamber’s immeasurable height where it straddled the entire length of the cavern before plunging downwards once more, to drive through the furthest wall.

So monumental were its proportions that Edie could only shake her head, yet she noticed that no branches grew from that mighty tree. Only gnarled, knotted bulges protruded from the blighted, blackened bark, like clusters of ulcerous decay, and in places the wood had split to form festering and diseased wounds.

Slowly, Edie rose from her crouching curtsey. That withered giant was the source of the deliciously sickly scent and she took a great lungful before tossing her head and considering the forlorn marvel more closely.

‘What killed it?’ she asked bluntly.

Miss Ursula put her arm about the girl’s shoulders.

‘You are mistaken, Edith,’ she said softly. ‘Nirinel is not dead – not yet. A trickle of sap still oozes deep within the core of its being and, while it does, so there is hope.’

Leaping forward, Edie ran over the mossy soil until the gargantuan arch of putrefying bark loomed far above her. Shouting gleefully, she began to twirl and dance with joy.

‘The tree’s alive,’ her high voice rang within the cavern. ‘It lives, it lives!’

‘Again, I must correct you,’ Miss Ursula told her. ‘This is no tree. It is but the last remaining root of the mother of all forests. We are in the presence of the last vestige of the legendary World Tree – Yggdrasill, which flourished in the dawn of time and from which all things of worth and merit sprang.’

The child ceased her dancing and stared up at the immense, rearing shadow.

‘This is a sacred site,’ Miss Ursula breathed. ‘But come, Edith, I will explain.’

Where the massive root thrust up out of the ground, a circular dais of stone jutted from the floor. Upon this wide ring, which was covered in a growth of dry moss and rotting lichen, the elderly woman sat and patted the space at her side for the girl to join her.

‘I shall not begin at the beginning of things,’ she said. ‘For that time was filled with darkness. My tale commences when Yggdrasill first bloomed and the early rays of the new sun smiled upon its leaves.

‘In that glorious dawn, the World Tree flourished and it was the fairest and most wondrous sight that ever was, or shall ever be. In appearance it was like a tremendous and majestic ash, but many miles was the circumference of its trunk; its three main roots stretched about the globe and its branches seemed to hold heaven aloft. Like a living mountain it rose above the landscape but its great magnitude cast no despairing shade upon the ground below, for Yggdrasill’s foliage shone with an emerald light and in its cradling boughs the first ancestors of mankind were nurtured.’

Edie gazed up at the vast root, vainly trying to imagine the unbounded size of Yggdrasill.

‘The first civilisation was founded about the eastern side of the World Tree,’ Miss Ursula continued, ‘and Askar was it named. In that early time there was no sickness and its people knew no death. All were content and Askar flourished and thrived.’

Miss Webster’s voice trailed off as she stared into the flames of the torches.

‘Was you there then?’ Edie asked. ‘Is that where you’re from?’

The elderly woman smiled gravely. ‘Yes,’ she murmured. ‘My sisters and I were born in that silvan shade.

‘Yet there were other beings who roamed the globe,’ she continued, shivering slightly. ‘Before the first blossom opened upon Yggdrasill, unclean voices bellowed and resounded in the barren wastes of the ice-locked north.’

Edie grinned and leaned forward, eager to learn more. ‘Was they monsters?’ she demanded. ‘Is that where Belial came crawling out?’

‘No,’ came the patient reply. ‘Belial was much, much later and compared to them his evil deeds are like those of a mischievous schoolboy. Although he will one day pour fire upon the world – they shall come after. They were here before and they will be here at the utmost end.’

Relishing every word, Edie squirmed and rested her dirty chin upon her hands. ‘Who are they then?’ she urged.

‘Spirits of cold and darkness,’ Miss Ursula breathed. ‘Drawn from the freezing waters when the world was formed, who clad themselves in chill flesh as giants terrible to behold. In a desolate, forsaken country where none of the World Tree’s roots had delved, they dwelt. A great gulf and chasm which stretched down to the very marrow of the earth, separated their unhallowed realm from the main continent and over the never-ending darkness they reigned absolutely.’

Miss Ursula paused to gaze up at the huge, decaying root and clicked her tongue with irritation.

‘You and I can only suspect the extent of their fury when the first light burst forth to herald Yggdrasill’s unfurling,’ she said. ‘They had considered themselves to be lords of an echoing darkness and now their dominion was threatened by this unlooked for challenge.’

‘What did they do?’

‘Sought for ways to destroy it,’ Miss Ursula told her. ‘For it was prophesied that as long as there was sap within the smallest leaf of the World Tree, their previous lordship and tyranny would be denied them. So began the building of the ice bridge to span the great chasm. Malice and loathing seethed in their frozen hearts but the people of Askar were unaware of the peril which awaited them...’

‘Oh, Ursula!’ cried another voice suddenly and, with a jolt, Edie turned to see Miss Celandine and Miss Veronica standing by the gate.

Their gaze fixed upon the withered root, the two sisters shambled inside. Then, leaving Miss Veronica to lean upon her stick, Miss Celandine skipped forward – clapping her hands in delight and cooing dreamily.

‘It’s been so long since you let us come down here!’ she declared reproachfully. ‘You are a meanie, Ursula – you know how I adored Nirinel so. Why look how shrivelled it has become. We must anoint it with the water like we used to and make it hale again.’

Anxiously, she trotted over to where Edie and her sister were sitting, then checked herself sharply and gazed at the circular dais in consternation.

‘But, the well!’ she gabbled in a flustered whine. ‘Such neglect. Ursula – what has happened? Why is nothing the same? First the loom was broken and now this!’

Clambering up beside them, she feverishly dragged the dead moss away and Edie saw that the stone platform was embellished with a sumptuously moulded frieze overlaid in tarnished silver and small blue gems. But even as she admired the decoration, Miss Celandine’s knobbly hands pulled away a great swathe of mouldering growth and there in the centre of the dais she uncovered a wide and precipitously deep hole.

Over the brink Miss Celandine popped her head, casting handfuls of the dead lichen down into the darkness – waiting and listening for the resulting splashes. But no sound rose into the cavern and a look of comprehension slowly settled over the woman’s wrinkled face.

‘I... I had forgotten,’ she whispered in a small, crestfallen voice. ‘The waters are gone, aren’t they, Ursula? The well is dry, it is, isn’t it?’

Her sister nodded. ‘The sacred spring dried up many, many years ago,’ she said wearily, as if repeating this information was an hourly ritual. ‘And every last drop of the blessed water was drained fifty years ago in order to vanquish Belial.’

‘Oh, yes,’ Miss Celandine sighed in regret. ‘So we can never heal Nirinel’s wounds. It makes me woefully sad to see it shrunken and spoiled. Oh, how lovely it was when we first arrived, how very, very lovely. Veronica, do you recall? Veronica?’

She whirled about to look at the sister she had left by the gate, then gave a little yelp when she saw the expression on Miss Veronica’s face.

Resting heavily upon her cane, Miss Veronica was staring up at the tremendous root with a ferocious intensity that was alarming to witness. It had been an age since she had last been permitted to venture down here and now the sight of it was stirring up the muddied corners of her vague, rambling mind.

‘I see four white stags ahead of us,’ she uttered huskily, wiping a trembling hand over her brow and smearing the beauty cream which covered it.

‘I don’t want to follow them,’ she wept, edging backwards. ‘Let me return, I must... I... there is something I have to do!’

Lurching against the carved wall, Miss Veronica lifted her cane and waved wildly about her head as if trying to ward something away.

‘Urdr!’ she shrieked, staring at Miss Ursula with mounting panic. ‘Do not force me to go with you. I must go back – I am needed!’

‘Veronica!’ Miss Celandine called, hurrying back to her stricken sister. ‘You have nothing to fear. That time has ended. We are safe – you are safe.’

Her sister’s eyes grew round with terror and she threw her arms before her face. ‘Safe!’ she wailed hysterically. ‘We are old, ancient and haggard, accursed and afflicted from that very hour. Won’t someone save me? The mist is rising. I beseech you – before it is too late. Please, I beg you my sister. Release me! Release me...’

Her cries melted into sobs as she buried her anguished face into Miss Celandine’s outstretched arms.

‘Hush,’ her sister comforted. ‘Come back, Veronica, it’s over now – it is, it is.’ But as she soothed the crumpled, whimpering figure she shot a scornful glance at Miss Ursula.

Still seated upon the edge of the well, Edie Dorkins watched the elderly woman at her side and was astonished to see the extent to which her sister’s outburst had distressed her.

Sitting stiff and as still as one of the stone images which swarmed over the walls, Miss Ursula’s small, piercing eyes glistened with tears and Edie could sense her inner struggle as she battled to control her emotions.

Then, mastering herself at last, Miss Ursula rose and, clenching her fists until they turned a horrible, bleached white, said, ‘Celandine, take Veronica back to the museum. This is no place for her, the... the musty atmosphere is injurious to her. You know that neither of you are allowed down here, I shall lock the doorway behind me next time.’

It appeared to Edie that Miss Celandine was on the verge of retaliating with some choice words of her own, but she must have thought better of it for she turned and helped the weeping Miss Veronica to hobble out through the gateway.

‘It was her,’ Miss Veronica’s blubbering voice sniffed and warbled. ‘She made me do it. I didn’t want to come... I didn’t want any of this.’

Rigid and wintry, Miss Ursula watched them depart.

‘An unhappy family have you joined, Edith,’ she said keeping her voice level, hoping she betrayed nothing of the turmoil which boiled beneath her stern exterior. ‘My two poor sisters are wasting away in mind as well as body. Their lives and mine are bound closely to that of Nirinel – as it fades so, too, do we.’

Edie eyed her shrewdly. ‘And mine?’ she demanded.

‘The young will not perish as swiftly as the aged,’ came the unhelpful reply. ‘I do not foresee what is to come for the loom is damaged and the web was never completed, but I believe you shall be our salvation – in one way or another.’

The child looked down at her feet. Then she asked, ‘What happened to the ice giants? Did they kill the World Tree?’

‘The lords of the ice and dark?’ Miss Ursula paused. ‘The rest of that tale must wait. You have learned much this night, but now I am obliged to go and make certain that Veronica is settled. Let us return to the museum, I too find this environment disturbing. I have recounted all I care to for the time being and you must be patient.’

Edie jumped from the dais and took hold of Miss Ursula’s proffered hand, but the woman’s palm was cold and clammy. The girl knew that Miss Veronica’s words had shaken her more than she dared to admit and she could not help but wonder why.

Far above the subterranean caverns within The Wyrd Museum, all was at peace. Only fine, floating dust moved through the collections, the same invisible clouds of powdery neglect that had flowed from room to room since the day the smaller, original building was founded.

Night crawled by and the museum settled contentedly into the heavy shadows that its own irregular, forbidding bulk created.

In the small bedroom he shared with Josh, Neil Chapman’s fears were cast aside with the old clothes he had brought from the past and the eleven-year-old boy was steeped in a mercifully dreamless slumber. Beside him, his brother snored softly, while in the room beyond, their father was stretched upon the couch – a half drunk cup of tea teetering upon the padded arm.

Outside the museum, in the grim murk of the sinking, clouded moon, a black shape – darker than the deepest shadow, moved silently through the deserted alleyway, disturbing the nocturnal calm.

Into Well Lane the solitary figure stole, traversing the empty, gloom-filled street before he turned, causing the ample folds of his great black cloak to trail and drag across the pavement.

Swathed and hidden beneath the dank, midnight robe, his face lost under a heavy cowl, the stranger raised his unseen eyes to stare up at the blank windows of the spire-crowned building before him.

From the hood’s profound shade there came a weary and laboured breath as a cloud of grey vapour rose into the winter night.

‘The hour is at hand,’ a faint, mellifluous whisper drifted up with the curling steam. ‘The time of The Cessation is come, for I have returned.’

The voice fell silent as the figure raised its arms and the long sleeves fell back, revealing two pale and wizened hands. In the freezing air the arthritic fingers drew a curious sign and, from the hood, there began a low, restrained chanting.

‘Harken to me!’ droned the murmuring voice. ‘My faithful, devoted ones – know who speaks. Your Master has arisen from His cold, cursed sleep. Awaken and be restored to Him. This is my command – I charge you by your ancient names – Thought and Memory. Listen... listen... listen and yield.’

Steadily, the whisper grew louder, increasing with every word and imbuing each one with a relentless yet compelling power.

‘Let dead flesh pulse,’ the figure hissed, the voice snarling beneath the strain of the charm it uttered. ‘Let eye be bright and cunning rekindle – to obey my bidding once more.’

Up into the shivering ether the strident spell soared, propelled ever higher by the indomitable will of the robed figure below, until the governing words penetrated the windows of The Wyrd Museum and were heard in the desolation of The Separate Collection.

Amongst the jumble of splintered display cabinets and fallen plinths, over the shards of shattered glass and buckled frames, the mighty sonorous chant flowed. Summoning and rousing, invoking and commanding, until there, in the broken darkness – something stirred.

Responding to the supreme authority of that forceful enchantment, a muffled noise began to rustle amid the debris. At first it was a weak, laboured sound – a halting, twitching scrape, like the fitful tearing of old parchment. But, as the minutes crept by, the movements became stronger – nourished by those mysterious, intoning words.

Suddenly, a repulsive, rasping croak disturbed the chill atmosphere and a horrible cawing voice grunted into existence.

In the shadows which lay deep beneath a toppled case, half buried in a gruesome heap of shrunken heads, a black, wasted shape writhed and wriggled with new life.

Brittle, fractured bones fused together whilst mummified, papery sinew renewed itself and hot blood began pumping through branching veins. Within the sunken depths of two rotted sockets a dim light glimmered, as the grey, wafer-thin flesh around them blinked suddenly and a pair of black, bead-like eyes bulged into place.

In the street outside, the cloaked figure was trembling – struggling beneath the almighty strain of maintaining the powerful conjuration. From the unseen lips those commanding words became ever more forceful and desperate – spitting and barking out the summons to call his loyal servants back from death.

Answering the anguished grappling voice, the movements in The Separate Collection grew ever more frantic and wild as the room became filled with shrill, skirling cries accompanied by a feverish, scrabbling clamour.

In the shadows, the shrunken heads were flung aside and sent spinning over the rubble as a winged shape dragged and heaved its way from the darkness.

Emitting a parched croak, the creature yanked and tore itself free, staggering out from under the fallen display case to perch unsteadily upon the splintered wreckage.

In silence it crouched there, enwreathed by the sustaining forces of the incantation as, within its small skull, the crumbled mind was rebuilt and the eyes began to shine with cruelty and cunning.

Bitter was the gleam which danced there – a cold, rancorous hatred and loathing for all of the objects in the room, and its talons dug deep into the length of wood it balanced upon. Soon the rebirth would be complete.

Suddenly, outside the museum, there came a strangled wail and the cloaked figure collapsed upon the pavement. He had not been ready, the effort of invoking and sustaining those mighty forces had drained him and he lay there for some minutes, gasping with exhaustion – the breath rattling from his spent lungs.

Immediately, the link with the creature in The Separate Collection was broken and, giving a startled squawk, it tumbled backwards.

But its lord’s skill and strength had been just enough. The infernal charm was complete and the shape floundered upon its back only for an instant before righting itself. Then, with a flurry of old discarded feathers, it hopped back on to its perch and spread its replenished wings.

Yet no beauteous phoenix was this. The bird which cast its malevolent gaze about the shadows was a stark portrait of misshapen ugliness. Coal black was the vicious beak which speared out from a sleek, flat head, and powerful were its tensed, hunched shoulders. As a feathered gargoyle it appeared and from the restored gullet there came a chillingly hostile call.

Stretching and shaking its pinions, the raven moved from side to side, basking in the vigour of its rejuvenated body, scratching the splintered furniture with its claws and cackling wickedly to itself. The Master had returned to claim it back into His service and the bird was eager to demonstrate its unswerving obedience and fealty.

Fanning out the ebony primary feathers of its wings, the bird flapped them experimentally and rose into the air, cawing with an almost playful joy. It was as if the uncounted years of death and mouldering corruption had only been a dark, deceiving dream, for the bird was as agile and as supple as it had ever been.

Yet the euphoric cries were swiftly curtailed and the creature dropped like a stone as a new, terrible thought flooded that reconstructed brain and its heart became filled with an all-consuming despair.

Leaping across the wreckage, the raven darted from shadow to shadow, hunting and searching, its cracked voice calling morosely. Through the litter of exhibits the bird searched, tearing aside the obstacles in its path as its alarm and dread mounted, until finally it found what it had been seeking.

There, with its head twisted to one side, its shrivelled face covered in shattered pieces of glass, was the moth-eaten body of a second raven.

The reanimated bird stared sorrowfully down at the crumpled corpse and the sharp, guileful gleam faded in its eyes as it tenderly nuzzled its beak against the poorly preserved body.

Mournfully, its yearning, grief-stricken voice called, trying to rouse the stiff, lifeless form – but it was no use. The second raven remained as dead as stone and no amount of plaintive cawing could awaken it.

Engulfed by an overwhelming sense of loss, the bird drew back, shuffling woefully away from the inert dried cadaver, its ugly face dejected and downcast.

Abruptly the raven checked its staggering steps – it was no longer alone. Another presence was nearby, the atmosphere within the room had changed and curious eyes were regarding it intently.

Jerking its head upwards, the bird glowered at the doorway and its beak opened to give vent to an outraged, venomous hiss when it saw a young human child.

Her face was a picture of fascination and not at all astonished or afraid at the emergence of the revivified creature.

Immediately, the raven’s sorrow changed to resentment and it swaggered forward threateningly, pulling its head into its shoulders and spitting with fury.

The girl, however, merely stared back and made a condescending truckling sound as she patted her hands together, beckoning and urging the bird to come closer.

Incensed, the raven gave a loud, piercing shriek and leapt into the air, screeching with rage.

Up it flew until the tips of its wings brushed against the ceiling and with a defiant, shrieking scream it plunged back down.

Edie Dorkins watched in mild amusement as the bird dived straight for her like an arrow from a bow. But the pleasure quickly vanished from her upturned face when she saw the outstretched talons that were already to pluck out her eyes and slash through her skin.

At the last moment, just as the winged shadow fell across her cheek, the girl whisked about and fled from the room.

Yet the raven was not so easily evaded. A murderous lust burned within its invigorated heart, consumed by the need to avenge the death of its companion and break the fast of death by slaking its thirst with her sweet blood.

Into The Egyptian Suite it pursued her, dive-bombing the hapless child, harrying her fleeing form – instilling terror into those tender young limbs.

Through one room after another Edie ran. But wherever she scurried, the raven was always there, beating its wings in her face, pecking her fingers or clawing at the long, blonde hair which had slipped from under the pixie-hood.

Breathlessly, Edie burst on to the landing and began tearing up the stairs, calling for the Websters, but the evil bird had tired of the game and lunged for her.

Into the soft flesh of her stockinged legs it drove the sharp talons. The girl yowled in pain, smacking the creature from her with the back of her hand.

Down the steps the raven cartwheeled, only to rise once more, shrieking with malice as it plummeted down – the powerful beak poised to rip and tear.

Edie squealed and threw up her arms as she leapt up the stairs, but the bird crashed between them and viciously seized hold of her exposed neck.

The girl yelled, but at that moment the raven let out a deafening screech. It thrashed its wings, demented with agony. One of its claws was caught in the stitches of the pixie-hood and the flecks of silver tinsel began to shine, becoming a mesh of harsh, blinding light which blazed and flared in the darkness of the stairway.

Furiously, the creature wrenched and tugged at its foot, for the wool burned and blistered, and a vile, stench-filled smoke crackled up where it scorched the scaly, ensnarled claw.

Edie whirled around, trying to grab the raven and pull it loose, but the bird bit her palm and its lashing feathers whipped the sides of her face. The pain was searing but, however much it battled, the creature could not break free of those stitches for the Fates themselves had woven them.

In a last, despairing attempt, the raven screamed at the top of its shrill voice, closed the beak about its own flesh and snapped it shut.

There was a rending and crunching of bone as the bird twisted and wrenched itself clear, then warm blood spurted on to Edie’s neck.

With crimson drops dribbling from its wound and staining its beak, the bird recoiled, fluttering shakily in the air as it regarded the girl with suspicion and fear. Yet even though it despised her, the creature did not attack again and circled overhead, seething with impotent wrath before flying back into the exhibitions, crowing with rage.

Standing alone upon the stairs, as the glare from her pixie-hood dwindled and perished, Edie pulled the severed talon from the stitches and pouted glumly. Her fey, shifting mind suddenly decided she had enjoyed the raven’s deadly company and wanted to play some more.

An impish grin melted over her grubby face as she decided to follow the bird and chase it from room to room, just as it had done to her. But, even as she began to jump down the steps, there came the faint sound of shattering glass and she knew that the bird had escaped.

From one of the windows in The Separate Collection the raven exploded, canoning out into the cold dregs of night, where it pounded its wings and shot upwards.

Up past the eaves it ascended, soaring over the spires and turrets, letting the chill air-currents stream through its quills as the fragments of broken glass went tinkling down upon the ground far below.

‘Thought,’ a frail, fatigued voice invaded its mind. ‘To me... to me.’

The raven cawed in answer and immediately began to spiral back down. Over the small, bleak yard it flew, fluttering over the empty street – its gleaming eyes fixed upon the hooded figure now standing once more.

‘Come, my old friend,’ the stranger uttered, wearily leaning against the wall as he raised a trembling hand in salutation. ‘Too many ages have passed since you flew before me in battle. It gladdens my heart, my most faithful attendant and counsellor.’

Wincing from the pain of its mutilated and bleeding claw, the raven alighted upon a cloaked shoulder and bobbed its head to greet its ancient Master.

‘Now do I begin to feel whole again,’ the figure sighed. ‘How am I to wreak my revenge without the company and valued assistance of my noble, trusted beloveds?’

The bird croaked softly and brushed its feathery body against the shrouded head.

‘I ought to remonstrate with you for not fleeing that accursed place sooner,’ the voice chided gently. ‘You were rash to assail that child of lesser men, for she has the protection of the royal house. The Spinners of the Wood have favoured her.’

The raven guiltily hung its head but its Lord was chuckling softly.

‘That lesson you have already learned I see. Look at your foot. Is this how you repay the gift of life? To risk it at the first instant, to let spite and hate overcome your wisdom? Such an impulsive deed I might expect from your brother but not of you, Thought. In the past you always considered the consequences of your actions... But where is your brother? Why has he not joined us?’

The unseen eyes within the hood stared up at the broken window of The Separate Collection. ‘I cannot sense him, not now – nor before. Tell me, where is he?’

The raven called Thought rocked miserably to and fro, averting its Master’s questioning glance.

‘Answer me!’ the cloaked figure commanded sternly. ‘The trivial art of speech was my first gift to you both. Have the wasting, dust dry years robbed you of that, or do you merely wish to displease me?’

Blinking its beady eyes, the creature slowly shook its head before opening its black beak. Then, in a hideous, croaking parody of a human voice it spoke.

‘Allfather,’ the raven uttered in a cracked, dirge-like tone. ‘Alas for mine brother, I doth fear the words of Memory shalt forever be stilled. The days of his service unto thee art ended indeed. His dead bones lie yonder still, unable to hear thy summons. The weight of years did ravage him sorely, more so than their corroding action did unto mine own putrid flesh.’

Its Master lifted a wizened hand and caressed the bird tenderly. ‘It is to be expected,’ he murmured sorrowfully. ‘The ages have plundered my strength and my greatness wanes.’

‘Never!’ the raven squawked. ‘Thy cunning and craft endure beyond aught else!’

‘Lift your eyes my slave and look about you. This is not the land you knew. You have been embraced by death many thousands of years. Since you and Memory penetrated the encircling mists at the vanguard of our forces, the world has changed beyond recall.’

‘In truth,’ the bird muttered. ‘Is it indeed so long? Then the battle was lost and the Three victorious.’

‘Can you remember nothing of those final moments?’

Thought closed its eyes. ‘The span of darkness is wide since that time,’ it began haltingly. ‘But hold, I can see the field of combat which lay betwixt us and the woods wherein our enemy did lurk. The day is bright with sword play and the air rings with the music of steel as I ride the wind and view the glorious contest raging below.’

‘What else do you see?’

‘Mine eyes are filled with the glad sight of our conquering forces, the Twelve are with us and no one can withstand their fury. But wait, Memory my brother, he hath hastened toward the wood before the appointed time. I call yet he cannot hear. I fear for him and charge after, yet already he hath gained the trees. To the very edge of that forest I storm, ’til the mist rises and it is too late. I see but briefly the daughters of the royal house of Askar standing beneath the great root and then there is darkness.’

The raven became silent and ruffled its feathers to warm itself.

‘Locked in their custody you have been for all this time,’ the cloaked figure concluded. ‘Yes, the battle was lost and even the Twelve were routed. I, too, was defeated, but the war was not over and still it continues, for I have arisen. Though I am weak and ailing, so too are they. The enchanted wood is no more, the stags are departed and the well is dry.’

Thought cocked its head to one side as its Master continued.

‘There is a chance, but we must be careful. Although the mists no longer shroud the attendants of Nirinel, they have amassed a great store of artefacts within that shrine of theirs. It is the combined power of those treasures which now protects them. If we are to succeed we must draw the loom maidens out, shake the web and when the spiders fall, smite them.’

Upon his robed shoulder, Thought began to hop from side to side. ‘Verily!’ it cried shrilly. ‘Strike the treacherous scourges down and show unto them no mercy. Dearly will they pay for the doom of mine brother. I shalt feast on their eyes and make a nest of their hair. Tell to me how this delicious prospect may be achieved, my Lord – I ache for their downfall.’

‘Many treasures they have acquired over the sprawling centuries,’ the hooded one answered gravely, ‘yet the greatest prize lies without their walls. A marvel so rare and possessed of such surpassing power that it could bring about their ultimate ruin.’

Crowing delightedly, the raven jumped into the air. ‘How is it the witches of the well have been so blind and blundered so?’

‘Oh, they are aware of its existence,’ came the assured reply. ‘Urdr knows, she recognises this thing for what it is and fears it as do I.’

‘Thou art afraid of this treasure?’ Thought cawed in astonishment. ‘How so, my Master?’

‘Much has transpired since you passed into oblivion,’ the figure said darkly. ‘The prize I seek is hidden and cannot be won save by one who has drunk of the sacred water. I must endeavour to compel one of the three sisters to deliver it to me – and in this you are to play an important role. Many leagues from here, where this mighty thing is bestowed, the trap is already set and into it I have poured my failing enchantments.’

The raven landed back upon the shoulder and stared into the darkness beneath the hood.

‘Yes,’ the unseen lips answered. ‘I have laboured long to call them back, my most terrifying and deadliest of servants. Daily their numbers increase and soon they will be Twelve again.’

Cawing softly to itself, Thought shook its wings and glared up at the sky.

‘Once more the old armies shalt ride – inspiring dread and despair into the stoutest of hearts.’

‘And you will lead them,’ the figure instructed. ‘The Twelve are wild creatures of instinct and destruction. They have need of commanding but I must remain here to gather what little strength I can for the final days. I had hoped to despatch both you and your brother to order their movements, yet you shall not go alone. Someone shall go with you.’

‘Who Master?’

The figure took a last, despising look at the museum before turning to shamble back along Well Lane.

‘Come,’ he said. ‘There is a great deal to be done and the time is short. There is one nearby who will aid us, although he does not yet know it and will have to be deceived into our service, I believe he will suit the purpose very well. His good must be subverted, we must erode his will and entice him to do our bidding. When the treasure is found it is he who must wield it. Soon the webs of destiny will be destroyed forever and the shrine of Nirinel a smoking ruin.’

With the raven cackling wickedly upon his shoulder, the cloaked stranger shuffled across the street and melted silently into the dim grey shadows of the nearby, derelict houses.

A leaden sky and drenching drizzle heralded the dawn and the thick, slate-coloured clouds that reached across London ensured that the dismal weather was there for the rest of the morning.

It was an uninspiring start to the first day of term after the Christmas break and by the time they splashed to school, the pupils of the local comprehensive were a damp and straggly rabble.

Built just after the war, the buildings were a dreary collection of concrete boxes which, by nine o’clock, were awash with dirty footprints and dripping coats.

For Neil Chapman it was as if he had awakened from a long sleep. That morning was the first time he felt truly free of Miss Ursula Webster’s influence since he and his father and brother had moved into The Wyrd Museum over a week ago. It was a peculiar sensation, that forbidding building, and the manipulating controllers of destiny it contained had fuelled his thoughts from the very first day. Now the real, normal world seemed pale and unimportant by comparison.

The boy shook his head, startled at his own thoughts. Now that everything was as it should be he was finding life a bit dull. At breakfast that morning, Josh had been his usual annoying self and made no mention of what had happened, almost as if he had forgotten the entire episode – either that or he had been made to forget. Then, when Neil tried to explain it to his father, he could see that Brian didn’t believe a word.

Regretfully, Neil realised that it was no use pining for excitement. For him the adventures were over, he had completed his task for the Websters and would now have to get used to living a mundane life again.

Looking around him, he tried to take an interest in his new surroundings, but wasn’t impressed. His old school in Ealing had been much more modern and better equipped, with its own swimming pool and three playing fields, whereas this one had to make do with an all-weather pitch and very little else as far as he could tell.

As for the pupils, they appeared to be a rough looking, slovenly crowd and the uniform which his father had been assured was essential hardly seemed to be adhered to by the majority of them.

Laughing and calling out names, they boisterously jostled their way around the building, scuffling outside classrooms and jeering at each other as they boasted about what they had been given for Christmas.

Waiting at reception, Neil watched them barge by, but hardly anyone bothered to look at the new boy and if they did it was only to snigger and nudge their friends.

‘Chapel did you say?’ came a nasal, unenthusiastic voice. ‘Can’t seem to find you anywhere.’

The boy turned and looked across the desk at the school secretary, a large, middle-aged woman with bleached hair, wearing a turquoise blouse that was one size too small for her ample figure.

‘Chapman,’ he said with mild annoyance, exaggerating his lip movements in case the chunky earrings she wore had made her hard of hearing.

The woman dabbed at the computer with her podgy fingers and without looking up at him said, ‘You’re in Mr Battersby’s form. Room 11a, down the corridor on the right.’

‘Thank you,’ Neil muttered, slinging his bag over one shoulder.

‘They won’t be there now though,’ the secretary added. ‘There’s an assembly this morning. They’ll have gone to the drama centre, across the playground on the left. You’d best get a move on – you’re late.’

Neil didn’t bother to answer that one. He hurried from the main doors and into the rain again. Over a bleak tarmac square he ran to where a low building stood, and hastened inside.

Fortunately, the assembly had not yet begun and Neil slipped in amongst the children still finding their seats.

The drama centre was a modestly sized theatre where school plays, concerts and assemblies were held. It consisted of a stage, complete with curtains and lighting equipment, and tiered rows of seats to accommodate the audience.

Today the atmosphere was rowdy and irreverent. The stale smell of damp clothes and wet hair hung heavily in the air as the congregated pupils settled noisily into their places. The watchful teachers patrolled up and down, keeping their expert eyes upon the troublesome ones. Several of these had pushed their way to the back of the highest row but were already being summoned down again to be divided and placed elsewhere under easy scrutiny.

Neil’s eyes roved about the large room. At the back of the stage there was a backdrop left over from the last school production, depicting the interior of an old country house complete with French windows, and he guessed that it had been a murder mystery.

In front of the scenery was a row of chairs which faced the pupils and already some of the teachers had taken their places upon them. There were two female teachers and three male, but against that painted setting they looked less like members of staff and more like a collection of suspects.

Mentally performing his own detective work, Neil wondered which of them was Mr Battersby. Of the three men sitting there, one was fat and balding, another tall and slightly hunched, but the last one Neil dismissed right away for he was obviously some kind of vicar, dressed in long black vestments.

Suddenly, the level of chatter died down as a small, stern looking woman with short dark hair strode into the room. One of the male teachers who had not yet joined his colleagues raised his hand as though he was directing traffic and at once the children in the theatre stood.

Neil did the same. This was the headteacher, Mrs Stride.

‘Good morning,’ she said, briskly rubbing her hands together.

The children mumbled their replies.

‘I said, “good morning”,’ she repeated, a little more forcefully.

This time the response was louder and Mrs Stride appeared satisfied. Nodding her head, she told them to be seated and the room echoed with the shuffling of over three hundred pairs of feet and the usual chorus of pretended coughs before she could begin.

Only half listening, Neil watched the head pace up and down the stage, but his attention was quickly drawn away from her and directed at the person sitting beside him.

Here was a slight, nervous looking boy with untidy hair and large round spectacles, whose threadbare blazer was covered in badges. With one watchful eye upon the teachers, the boy lifted his bag with his foot, unzipped it and drew out a science fiction magazine which he laid upon his lap and proceeded to read, ignoring everything else around him.

Lowering his eyes, Neil peered at the colourful pages and read the bold type announcing ‘real life’ abductions by strange visitors from outer space.

‘Now,’ Mrs Stride’s voice cut into his musings and Neil returned his gaze to the front of the stage. ‘You all know Reverend Galloway. He came to see you quite a few times last term to talk about the youth club, before it burned down. Well, I haven’t a clue what he’s going to tell us this morning but I’m sure it will be most interesting. He’s even gone all out and put his cassock on for us. Reverend Galloway.’

The head stood aside as the man in the vestments rose from his seat and a distinct groan issued about the theatre.

‘Not the God Squad again,’ complained a dejected voice close by, and Neil looked at the boy at his side who had glanced up from his magazine to contribute this mournful and damning plea.

Neil studied the vicar more closely. Apparently he was a familiar and unpopular guest at these assemblies.

The Reverend Peter Galloway was a boisterous young man with a haystack of floppy auburn hair and a sparse, wispy beard to match. Suddenly, he broke into an enormous, welcoming grin and his large, green eyes bulged forward as if they were about to pop clean out of his head. Then he held open his arms in a great sweeping gesture which embraced the whole audience.

‘I hope you all enjoyed Christmas,’ he said benignly.

The children eyed him warily as though he were trying to sell them something and an agitated murmur rippled throughout the tiered seats.

Peter Galloway looked at the sea of blank faces. The pupils’ expressions were those of bored disinterest but that did not deter him, in fact it spurred him on. For the past seven months, ever since he had left college, he had ministered to the spiritual needs of this difficult area and never once suffered any loss of confidence, whatever the reaction to his exuberant ministries. His soul brimmed with the joy of his unshakable beliefs and he never missed an opportunity to try and share this with others.

In this short time, however, the Reverend had become increasingly aware that the Church was failing to capture the hearts and minds of the younger members of the community, and was grieved to learn of the trouble they got themselves into. If they could only channel all that youthful, restless energy into celebrating the life that God had given to them, as he did, they could enjoy a faith as strong as his own.

This mission to welcome the youngsters into the fold had become a crusade with him. He was passionate about it and tried many different ways to show them that the Church could be fun. There had been concerts of Christian pop music, youth groups, debating societies, sporting events and even sponsored fasts in aid of the Third World. Yet none had been a resounding success, in spite of his finest efforts. The teenagers he saw hanging around in gangs and loitering at street corners never came along to any of them, but it only served to make him even more determined.

Today he had resolved to take a more direct approach with the children and he returned their apathetic stares with a knowing glare of his own.