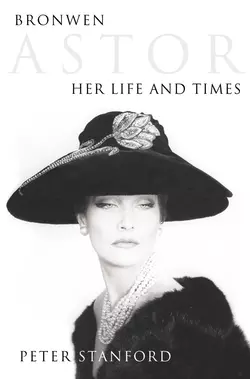

Bronwen Astor: Her Life and Times

Peter Stanford

When Bronwen Pugh married into the celebrated Astor clan in 1960, she seemed to have the world at her feet. She was a media darling, BBC television presenter, the most celebrated model of her generation, and, after her marriage to millionaire Bill Astor, mistress of Cliveden. Three years later her world was turned upside down by the Profumo scandal. Cliveden – with its famous guests, lavish parties and spectacular setting – was alleged to be at the centre of an international web of sexual debauchery and espionage which ultimately brought down Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.Bronwen lost everything in the scandal: husband, home, friends and her good name. Bill Astor was accused of being a louche playboy and an unfaithful husband, Bronwen as little better than Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies, the two escort girls at the centre of the scandal. Bill Astor never recovered, and he died in 1966 of a broken heart.The reversal of fortune for Bronwen Astor was immense, and in charting her private agony behind the public disgrace, Peter Stanford has written a fascinating and moving story of a remarkable and resilient woman.

Bronwen Astor

HER LIFE AND TIMES

Peter Stanford

Dedication (#ulink_726543ec-1a59-59f8-ac7c-e1774e336178)

To Mary Catherine Stanford

1921–1998

whose love and nurturing is behind

everything in my life and whose loss

will always be unbearable

Plan of Cliveden (#ulink_9520bfe3-810f-5b7a-91d4-b1c84b073f30)

The Astrors (#ulink_c0924fec-9a77-5616-9c04-6defab32f7ab)

Contents

Cover (#ucc870cb8-e110-5fa4-9afe-83e905b98af4)

Title Page (#ucd777703-ea4a-55da-9a24-dab68156e0cc)

Dedication (#uff6b1ef9-88b5-546f-9208-55eb72e7dabc)

Plan of Cliveden (#u04b9eea8-e023-5e21-852c-4a5887604b26)

The Astrors (#u382452f2-e236-581f-beca-48770a9cec6e)

Prelude: Cliveden, Berkshire, 1999 (#ueb8b34e0-70ff-5aba-bedf-f4ba7bfeefe8)

Chapter One (#u705c6c91-398a-538b-8502-134eeb123b17)

Chapter Two (#u5cf49763-64b1-54e5-b35c-ebe0582a2c6f)

Chapter Three (#uc28e4415-fde4-5186-a137-da4a5cd2aa5e)

Chapter Four (#ue780bbca-9956-5c92-8be1-983ad79d8ccc)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript: Tuesley Manor, Surrey, 1999 (#litres_trial_promo)

Source Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prelude (#ulink_e9bc7255-1a66-567f-81da-47b122ce076c)

Cliveden, Berkshire, 1999 (#ulink_e9bc7255-1a66-567f-81da-47b122ce076c)

‘Lady Astor’s back.’ In the silence of the main hall at Cliveden, now a hotel, this snippet of understairs gossip hangs for just a second in the air, then disappears before I can catch the intonation. Excited? Nervous? Indifferent? Puzzled? Simply reading the guest list for lunch? Does the cleaner, waitress or under-manager responsible for this sotto-voce broadcast even know which Lady Astor she is talking about?

Cliveden, this most famous – and twice this century notorious – of English stately homes, is today a shrine to its most celebrated inhabitant, Nancy, Lady Astor, the first woman to take her seat in the British Parliament. That was back in 1919, but in the timeless opulence of the wood-panelled hall decades and even centuries merge. In such a self-consciously impressive place, it is hardly a challenge to imagine the redoubtable Nancy sweeping in, all long skirts, fur collars and button boots, barking at her servants in the Virginian drawl that she never lost after almost a lifetime on the British side of the Atlantic, and greeting the houseguests assembled for one of the gatherings of what was mistakenly labelled the ‘Cliveden set’ of Nazi appeasers in the late 1930s.

Yet the Cliveden visitors’ book was far more eclectic than that. In the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s kings, prime ministers, world leaders and Hollywood stars came for the weekend to Cliveden to be entertained by this witty, sharp and unfailingly direct woman. Edward VII, Franklin Roosevelt, George Bernard Shaw, Mahatma Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin all fielded Nancy Astor’s barbs and bouquets over feasts in the ornate French dining room which once graced Madame de Pompadour’s chateau near Paris. Joseph Kennedy, American ambassador to London in the 1930s, brought his brood to stay at Cliveden, linking across decades and thousands of miles one Camelot with another.

As if on cue, Lady Astor arrives. Not Nancy but Bronwen, her successor as mistress of this Palladian mansion which peers down imperiously from its hilltop over the Thames. As she comes through the main doors, she hesitates for a beat before she meets my eyes and walks over to the plush but anonymous hotel settee near the open fire. Later, when more relaxed, she admits that she had stopped in a lay-by near the main entrance to collect her thoughts and pray so that she could walk calmly into her old home. ‘I always used to do it before I lived here and was visiting – as a preparation to face my future mother-in-law.’

Nancy and Bronwen, both Lady Astors, overlapped for less than four years. Bronwen arrived in October 1960 as the third wife of Nancy’s son and heir, Bill. Nancy died in May 1964. Theirs was neither a long-lived nor a close friendship. They could hardly even be described as friends. Bronwen sought to placate her mother-in-law, who was unfailingly critical of everything she did. In her declining years Nancy was not the force she had once been, her wit extinguished and replaced by a certain brutality. Living mainly in London in exile from Cliveden, which she only visited by invitation, she grew bitter and resentful.

Bronwen’s treatment was not unique. Nancy had never been keen on any of her daughters-in-law: she resented them for usurping her place in the lives of her five sons. Strangely, for one whom history acclaims as a female pioneer, she took a perverse delight in making the lives of the women close to her a misery and virtually driving many of them to divorce. And she was particularly cruel to the women Bill, the third Viscount Astor, chose as her successors as chatelaines of Cliveden – though she did once grudgingly admit to her biographer Maurice Collis that Bronwen was ‘the best of the bunch’.

None of the other guests lounging in deep armchairs and sofas scattered around near the carved stone fireplace could have guessed from Bronwen’s demeanour that Cliveden had once been her home. Yet for all her self-effacement in the simple navy blue trouser suit she is wearing, there is an undeniable something about Bronwen Astor. Even in her late sixties, she still turns heads just as surely as she did when, in the 1950s, after a spell as a BB C television presenter, she became the public face of one of the most distinguished Parisian fashion houses.

Bronwen Pugh – her maiden name – was the forerunner of today’s supermodels and in her time was just as much a headline-maker and a household name as Kate Moss, Elle MacPherson and Claudia Schiffer are now. She was muse to Pierre Balmain at the height of his fame. He couldn’t pronounce Bronwen so he called her Bella and told the world that she was one of the most beautiful women he had ever met.

Some faces only last a season. Time and fame take their toll. But Bronwen Astor still has it. ‘It’ is something to do with the combination of her height (just under six foot), her bearing (purposeful, haughty, distant) and a certain freedom from conventional restraints. There is, Balmain believed, a Garboesque quality about her. And then there are her eyes – greeny blue, piercing, wild and Celtic, set in a long, elegant, bony face, framed now by strong, wavy grey hair.

Our preconceptions of models today are of visually stunning but empty-headed women. The gloss was taken off Naomi Campbell’s attempt to write a novel when it was revealed that the text had been put together by a ghost-writer. In that sense, a vast gulf separates contemporary fashion superstars from Bronwen Pugh – or ‘our Bronwen’, as the press dubbed her, turning her into a mascot as potent as the Union Jack or the national football team. ‘Our Bronwen leaves them gasping’, the Daily Herald reported proudly from the Paris fashion shows in 1957.

Being a ‘model girl’, a phrase she prefers to the word model, which in her time carried a tawdry undertone, was never more than a distraction – ‘tremendous fun’, as she invariably puts it. By day she worked with Balmain – or a distinguished procession of designers from Charles Creed to Mary Quant who chart the transition from one fashion epoch to another. But in her spare time she was devouring spiritual and psychological writings like the Russian P. D. Ouspensky’s The Fourth Way (published in 1947), which explored new ways of thinking about consciousness, or the books of the French Jesuit and palaeontologist Teilhard de Chardin, who brought Christianity and science closer together than perhaps any other authority this century.

The contrast between Bronwen’s two worlds could not have been greater – one to do with a skin-deep worship of the body and the creations that cover it, the other probing deep and complex matters concerning the mind and the soul. It made for a curious and ultimately untenable double life. A career in the most material of worlds thrived while her mind was fixed on spiritual concerns. Perhaps that accounted for the distant look that Balmain recognised.

The inter-relation – indeed often competition – between these two elements dominates her life story. She loved her husband in a conventional way but also felt guided towards him by God. At Cliveden she was pulled in opposite directions, acting the chatelaine of a great house but unable for the most part to talk of her inner life even to her husband. Occasionally someone would reveal him- or herself to be on a similar wavelength. Alec Douglas-Home is one name she recalls, but usually she preferred to keep quiet. Only in more recent times has she found fulfilment as a practising psychotherapist and a devout, sacramental, if otherwise unconventional Catholic.

It is not until she settles down next to me on the sofa that Bronwen allows herself a proper look around the Cliveden hall. ‘The tapestries are still the same,’ she says, gesturing with those eyes at three great wall-hangings that face the main entrance. ‘But everything else is different. New.’ She strokes the sofa arm. Her tone is almost casual. Almost. ‘It was all sold, you see. Each of Bill’s brothers got to choose a picture and I took some things for my new home, but everything else was sold.’ Her life with Bill went under the hammer – 2,000 lots snapped up by eager collectors.

On Bill’s premature death in 1966 – from heart failure brought on by the strain of his public disgrace as, allegedly, a player in that landmark of the sixties, the Profumo scandal – the Astor trustees, acting on behalf of Bronwen’s stepson and Bill’s heir, then a minor, decided to relinquish the lease on Cliveden. They handed it back to the National Trust, to which Bill’s father had bequeathed it in 1942. In August 1966 Bronwen Astor and her two daughters, aged four and two, left Cliveden with unseemly haste. In the thirty-three years since, she has only been back inside twice.

When I was a small child I used to have a recurrent nightmare. My parents would move out of our family home and other children would take over the nooks and crannies, hiding holes and secret places in the garden that were properly mine. I would be hiding behind the hawthorn hedge watching them play on my lawn, put their toys in my cupboards, climb the narrow stairs to my playroom, take my cup and saucer out of my special cupboard in the kitchen. They would spot me and ask me to join them. I didn’t know how to respond. I always woke up at that stage.

The dream was never realised, but it took me years to recognise that memories are more than bricks and mortar. For Bronwen Astor, the scale is increased tenfold – she was an adult; this was her marital home where she spent five and a half years with the man who was the love of her life; and Cliveden is considerably grander than my suburban house.

After Bill’s death she had hoped to stay on for at least part of the year, so that her children and her stepson, who had lived with them at Cliveden, could remain together as a family; but she was informed by the trustees that she had to leave. It was a traumatic time. ‘For many years,’ she says, ‘I couldn’t bear to come here, but now it is like looking in on another person’s life.’

Again there is that ability to withdraw to another level of consciousness. I sense she is watching herself disinterestedly as she did on the catwalk as she wanders around the grand entertaining rooms that lead off the hall – rooms where once she played hostess to Bill’s friends from the worlds of politics, international charity work, racing and society. ‘I trod a tightrope,’ she recalls. ‘I tried to live a life among people who came from a different class to me but also to remain who I was. The class system was much stronger then. There was a distaste – always in the background. I was not upper class. My husband’ – and her laugh banishes a darker memory – ‘didn’t like the way I said “round”. He used to try to teach me to say “rauwnd”.’

Her diction, though, is perfect. As a young woman she trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama as a teacher. However much she makes herself sound like Eliza Doolittle, her upbringing was solidly middle class, the privately educated daughter of a Welsh county court judge. Indeed, Lord Longford, an old friend of both Bill and Bronwen Astor, is fond of remarking that, such was her poise when greeting him at Cliveden, his practised eye always took her for the daughter of a duke.

The wool-panelling of the library has been treated, she notices, to make it lighter. She stands close and sniffs it. Amid the formality of a smart hotel it is a curiously relaxed gesture, as if this is still home. Yet one of the smells that she associates with Cliveden has gone.

Outside the window of what was once her drawing room – now the hotel’s dining room – she points out the metal cups set in the balustrade around the terrace that looks out, in Cliveden’s most celebrated view, onto the Thames as it meanders down to London. ‘We used to put an awning up there and eat out in the summer.’

It must, I suggest, have been like living in a huge museum cum art gallery. Even the balustrade had been brought by Bill’s grandfather from the Villa Borghese in Rome. ‘My first impression, I think, was that it was all very cosy. It sounds strange now, but all the rooms lead off the hall and off each other and Bill had a flair for making them, well, cosy.’

Bronwen took on not only Nancy Astor’s tide but her study too. Nancy, a southern belle, had called it her ‘boudoir’. As Bronwen leads the way in, she is halfway through a sentence when she notices a group of hotel guests talking and sipping coffee in there. She pulls up short and turns to leave but one woman calls out in a proprietorial way: ‘Do come back, dear. There’s a wonderful view you should see.’ For a moment Bronwen looks ill at ease. She knows the view only too well. She smiles nervously, as if a fly is about to land on her face. It is the closest she comes to any display of emotion.

Upstairs a footman shows us into her old bedroom – again inherited from her mother-in-law. ‘THE LADY ASTOR ROOM’ the plaque on the door announces. A copy of John Singer Sargent’s portrait of a youthful Nancy on the wall makes plain which Lady Astor is being commemorated. Bronwen Astor, for all the fame that surrounded her when she arrived at Cliveden, does not merit a mention. Her period here, you feel, is regarded as something best forgotten.

Yet on the day of her marriage to Bill a press pack every bit as large and insistent as that which hounded Diana, Princess of Wales, had camped out at the pub that faces the gates of Cliveden in the hope of getting a glimpse of its heart-throb, ‘our Bronwen’, as she married her lord. The previous night, tipped off that a ceremony was in the offing, they had chased her, her mother and father across London in a taxi until the cabbie had somehow given them the slip. It was another of those headline-grabbing matches – supermodel marries one of the richest men in the world, even though he was old enough to be her father.

‘When I arrived here, I didn’t change a thing,’ Bronwen says, walking past the chambermaids, who are making the bed. ‘It was the way Bill wanted it. It was like Rebecca and I was the second Mrs de Winter. I literally didn’t move an ashtray – apart from here and in the boudoir. And even then it was a friend of Bill’s – John Fowler – who helped me.’ She says the name as if I should recognise it. When I stare back blankly, she adds: ‘You know, Colefax and Fowler. Wallpaper.’

I was two when the Profumo scandal that destroyed Bill and Bronwen Astor’s life hit the headlines in July 1963. ‘Steamrollered’ is the word Bill’s younger brother David, celebrated editor and owner of the Observer, uses to describe their experience at the hands of the popular press, society gossips and erstwhile establishment friends. It all began in Cliveden’s swimming pool on a hot weekend in July 1961, when War Secretary Jack Profumo and Soviet official Yevgeny Ivanov frolicked with Christine Keeler, watched by her mentor Stephen Ward. During the Cold War a British minister sharing a girl of ill-repute with a Russian agent had major security implications.

When it leaked out, the sex and spy scandal cost Ward his life, Profumo his career and heralded the end of Harold Macmillan’s government. To the list of victims should also be added Bill and Bronwen Astor. Advised by his lawyers to maintain a dignified silence as allegations of orgies at Cliveden abounded, Bill saw his health was destroyed and he died of a broken heart in March 1966, his reputation in tatters. He is one of the forgotten victims of Profumo. He was labelled a seedy playboy, an adulterer, a coward who abandoned Ward in his hour of need in court, and a fool. He became the symbol, however mistakenly, of a world of lascivious ministers and aristocrats with double standards, who, in the mock-Edwardian Macmillan era, had lectured the public on morals while in private hosting poolside romps and attending sado-masochistic parties.

When Keeler’s sidekick, Mandy Rice-Davies, was told in court during Ward’s trial for living off immoral earnings that Lord Astor denied ever having been sexually involved with her, she chirped up: ‘He would, wouldn’t he?’ It earned her immortality and damned him for ever. It has been Bill Astor’s most enduring public legacy, though Rice-Davies’s own detailed account of the assignation soon unravels.

In May 1999 the Independent newspaper, in a profile of one of the ‘accidental heroes of the 20th century’, described Christine Keeler as having been ‘procured for Lord Astor’s Cliveden set’. There was no ‘set’ and Bill Astor was not a man to procure women. Yet the myth is apparently set in stone.

John Profumo redeemed himself by good works among the needy of the East End of London. For Bill Astor, whose philanthropy was on a vast but almost invariably ‘no publicity’ basis and who played a central role in the founding of such inspirational international bodies as the British Refugee Council and the Disasters’ Emergency Committee, there was no such redemption.

Though cleared of any guilt by Lord Denning’s subsequent enquiry into the affair, Bill Astor died feeling himself a social leper. Almost four decades on, it is hard to understand what he and Bronwen were meant to have done wrong, what crime it was that brought such vilification on their heads. The most that can be said about them was that they were too indulgent of Stephen Ward, allowing him to live in a cottage on the Cliveden estate and thereby giving him some kind of respectability. ‘I warned Bill about Stephen,’ Bronwen recalls. ‘From the first time Bill introduced us, I didn’t want him at my dinner table.’ Bill agreed to that but, tragically, did not recognise the deeper unease behind his new wife’s demand and so continued to see Ward elsewhere.

For a man who believed the best of most people, it was a small sin. However, those who had been happy to accept Bill and Bronwen’s lavish hospitality before they heard the rumours of high jinks at Cliveden decided that there was no smoke without fire and shunned them. Bronwen recalls being cut dead at parties and grand gatherings at race tracks, while the writer Maurice Collis, a regular guest at Cliveden, recorded in his diary after a weekend there in 1965: ‘The house was completely empty, the great hall without a soul and nobody coming or going. The silence and emptiness were somehow ominous.’

Unlike most political scandals, the Profumo affair has outlasted the avalanche of headlines, the court case and the ministerial resignations. It has even outlasted most of its principal players. And it lives on in the public imagination as a watershed in the 1960s, the turning point between the stuffy, buttoned-up and sometimes hypocritical post-war world and the more liberated age of the Beatles, the King’s Road and the pill. In 1988 the film Scandal brought the whole business to a younger audience. Visitors to Cliveden today still make for the swimming pool rather than the classical treasures that adorn the house and grounds.

Part of that enduring Profumo myth has been to degrade Bronwen Astor. To the list of victims of the affair should also be added her name, as well as those of Bill Astor’s four children, the youngest just two when her father died.

In the film Bronwen is all pouts and shopping trips funded by Bill, an upmarket version of Keeler. ‘Keeler used to call herself a model,’ Bronwen says, ‘and I think at the time some people, some of our friends even, didn’t know the difference between a model and a model girl. And Stephen [Ward] at the very end, when he was desperate, started telling people that he had introduced Bill to me even though I had never met him until I came to Cliveden.’

It is a slur that still riles Bronwen. In July 1963 Paris Soir published her photograph alongside Keeler’s as one of the women Ward was supposed to have trained to secure rich husbands. Once implanted in the public consciousness that idea has refused to go away, despite the evidence. In Honeytrap, a 1988 best-seller by Anthony Summers weaving a Cold War espionage drama into the Profumo scandal, Bill Astor is described as having been introduced to Bronwen through Ward’s good offices.

After lunch we wander through the grounds. Though it was many years before she could face coming back to the house itself, Bronwen used to return occasionally to see Frank Copcutt, the head gardener who stayed on when first Stanford University and later the hotel took on the lease of Cliveden from the National Trust. And there was her husband’s grave – next to those of his mother, father and grandfather in the Cliveden chapel, an octagonal temple, lavishly decorated with mosaics, set away from the house. ‘I used to come back there regularly on anniversaries, but I don’t feel the need now. Bill’s spirit isn’t there. It’s …’ And she gestures as if to mean everywhere.

‘I think I’d like to be buried in Jerusalem. It’s at the centre.’ Her remark comes out of the blue. Initially I’m not entirely sure what it means but Bronwen Astor, I begin to realise, sometimes moves on a different plane from the rest of us. For one thing she talks unembarrassedly about God in everyday conversation. And then every now and then she throws down a line and you have to seize it. I struggle to take my chance – Jerusalem is more a state of mind than a city. For 5,000 years the Old City has had a legitimate claim to be at the centre of the world. The Islamic Dome of the Rock sits on the spot where Abraham almost sacrificed Isaac, where Muhammad ascended to heaven on a white horse, where the Jews built their Temple, and where Christ died and rose from the dead.

Bronwen has made me think, stretched me. I like that, her capacity to say startling things, her involvement in exploring the frontiers between body, mind and spirit. She is an adventurer who attracts others on to her treks. She has come a long way since her days at Balmain.

After Bill’s death she moved with her two young daughters to a eleventh-century manor house in what feels like a hidden valley outside Godalming. It has not been a conventional widowhood. Free to live her life on her own terms, she converted to Catholicism in 1970 – ‘it was an odd thing for an Astor to do because my mother-in-law hated Catholics’. For four years she ran a charismatic Christian community at her home, open to all comers. Few of her friends and acquaintances had realised that while working as a model or welcoming friends to Cliveden she had been on a secret spiritual journey – ‘most people would look puzzled if you mentioned God’ – so they were horrified to discover that Bronwen had suddenly ‘got God’. They tried to warn her and feared that, in her grief, she was being sucked into what to them had all the signs of a cult.

The community had its crazier moments, she now realises, and its collapse perhaps saved her from further exploitation. Her fellow members had wanted her to give up the remaining trappings of her former life – like the chauffeur or the housekeeper. ‘They meant nothing to me, but I was determined that I was going to bring my girls up as Bill would have wanted, as Astors.’ The spiritual and material once again clashed.

Yet for Bronwen the whole community experience was a great liberation, the first of several subsequent attempts which ultimately gave her life a coherence. After the community was wound down, her spiritual exploration became less public – though she did, in one grand theatrical gesture, hire the Royal Albert Hall in 1983 for a prayer meeting.

Later she trained as a psychotherapist and has achieved a distinction in her chosen field that has attracted eminent academic institutions like the Religious Experience Research Centre at Oxford University. Her appointment as chairman of its support body emphasises how far she has travelled since her days on the Paris catwalk.

Her own spiritual life is now at the heart of each and every day. She prays for half an hour in her private chapel, reads the scriptures and attends communion as often as possible. She is permanently aware of the presence of God, feels close to Him and guided by Him, and she carries with her a spiritual air. She is shy of the word usually employed to describe such people – mystics. In the Christian tradition mystics are the great and the good of the church – John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila, Julian of Norwich. Bronwen is not in their league. In secular terms the word ‘mystic’ carries with it overtones of ‘Mystic Meg’, stargazers and fraudulent eccentrics on Brighton Pier.

If mysticism is stripped of its trappings and seen as something unusual but not unheard of in everyday Christians, the mark of those who have had some direct revelation from God, then she is undeniably a mystic. No priest or religious who has come into contact with her has ever doubted her sincerity.

Yet in spite of these spiritual blessings, that sense of injustice, for herself and for her late husband and his children, has never gone away. With her daughters married, she has finally decided to talk about her own part in the scandal of the century in a final effort to set the record straight.

Our walk round the garden at Cliveden is almost over. The door to the swimming pool hasn’t changed, she remarks as we go through. The pool, however, is smaller than it was on that fateful weekend in July 1961 when Profumo, Ivanov and Keeler met. The reduction is somehow appropriate since the pivotal event of the Profumo scandal was scarcely, for any of the participants, of earth-shattering importance. Only later was it blown out of all proportion as a result, Bronwen now believes, of a complex and profoundly evil conspiracy.

Her own memories of the weekend are mundane. ‘It was very hot and we came over from the house on the Saturday night with the guests and found Stephen Ward and some of his friends here. It was nothing. And then on the Sunday, some of the other guests – Ayub Khan, the President of Pakistan, was here and Lord Mountbatten – wanted to go down to the stud and I remember looking in on the pool, seeing Jack and Bill and thinking, “Oh well, they’re all enjoying themselves, that’s fine, I can go.”’

Two years later this ‘weekend took on serious political implications. The papers were alleging that all manner of odd and perverse activities were going on, while the Astors’ friends took care to avoid the pool and Cliveden itself. Teams of photographers in helicopters were flying over the house at all times of the day to try and snatch that visual shot that would prove that Bronwen was running a house of ill-repute. Trapped inside with her child and her ailing husband, she was under siege.

‘You only have to look to see it couldn’t have been true,’ Bronwen says, a note of indignation in her voice as she points to a row of windows overlooking the pool. ‘Taylor the groom and Washington the butler lived there with their families. Nothing could have gone on with them so close.’ Her tone is one of bemusement. After all these years she is still puzzled as to how the whole affair got so out of hand.

We head back to her car. When she lived here, a chauffeur was forever at her beck and call. Guests’ vehicles would be taken off to Cliveden’s own garage, valeted, polished and filled with petrol, ready for the journey back to London. Bill’s fortune and generosity with it meant that Cliveden operated in a style and on a scale that had not been seen in other grand country houses in England since 1939. With his disgrace that life came to an end. Bronwen’s Cliveden was almost the last in the line of the great stately homes.

She is suddenly and unexpectedly overtaken by an air of sadness as she prepares to leave, but I sense it’s not for the house or the lifestyle. After so long, it is not even to do with the unhappy memories attached to the second half of her period here. It is for the things she lost in those years – her husband, her reputation. ‘It seems like another life now,’ she sighs, adding, almost with relief, ‘finally.’ And with that Lady Astor takes her leave.

Chapter One (#ulink_a1e5d505-a011-5d6c-adf1-562898cd1c64)

There is no present in Wales,

And no future;

There is only the past,

Brittle with relics

R. S. Thomas, Welsh Landscape (1955)

Exiles have curious and sometimes contradictory attitudes to their ‘fatherland’. Often the first generation to leave retains a strong emotional bond with all they have abandoned, but for some, depending on the reasons for their departure – adventure, economic necessity, education – return or even nostalgia is out of the question. They develop an antipathy to the past and determine to be assimilated into their new culture and society by virtue of rejecting the old. In succeeding generations, of course, such attitudes can be reversed: children or grandchildren of unsentimental or ambitious exiles may over-compensate for their parents’ or grandparents’ abandonment of the family ‘seat’ with romantic notions about their roots which also offer a means both of rebellion and of self-definition. A place with which their physical connection is tenuous becomes crucial to their psychological and spiritual identity.

Because of the bland image of the plain old English-repressed, over – polite and concerned only with what the neighbours will think – many of those born in England explore family links with Ireland, Wales and scotland in order to appear more exotic. In economic terms, they have, like as not, embraced the values and assumptions of their generally more prosperous English homeland, but in their more rhetorical moods they celebrate their Celtic and Gaelic roots in exiles’ clubs and sporting societies, harking back to something that has been irretrievably lost.

The Pughs fit loosely into this pattern in their attitude to Wales. They were and are proud to be Welsh. They regard it as a defining feature in their make-up. Yet by the time Janet Bronwen Alun Pugh was born in 1930, the family link back to Cardiganshire was wearing distinctly thin. It accounted for just 50 per cent of their bloodline since their mother, Kathleen Goodyear, was solidly English. And even their father Alun – after whom, in a spirit which now seems oddly egotistical, Janet Bronwen Alun, her two elder sisters Eleanor Ann Alun and Gwyneth Mary Alun, and her brother David Goodyear Alun were all named – had been raised in Brighton, studied in Oxford and worked in London.

For the early and middle sections of his career as a barrister Alun Pugh, who had two native Welsh parents, defined himself as Welsh. Since this period coincided with the time of his most influential and hands-on involvement with his children, he passed this self-image on whole and undigested to them and it remains with his two surviving daughters to this day. Only towards the end of his working life, when his increasingly successful career as a judge offered an alternative means of defining himself, did his enthusiasm for all things Welsh mellow.

So when his youngest daughter was seven, Alun Pugh placed her on a stool and invited her to choose between her first two Christian names. Did she want to be called Janet, to the ear more English, though it was in fact chosen to mark a Welsh godmother, or the more unusual, Celtic Bronwen? Given her father’s predilection, her decision was inevitable. ‘I got the impression,’ recalls the family’s nanny, Bella Wells, ‘that Mrs Pugh wasn’t that happy about it, but Mr Pugh was delighted. She was always Bronwen after that.’

Though her formal links with Wales have since childhood been few and far between, Bronwen Pugh in her days at the BBC and later on the Paris catwalks was habitually referred to as the ‘Welsh presenter’, ‘Welsh beauty’ or ‘Welsh model girl’, as if she returned every evening to a mining cottage in the valleys. And outside perceptions reflected both what she had learnt as a child and, more significantly, since the two became inseparable, what she felt in her heart – that her Welsh roots had shaped her personality. ‘It’s made me a bit manic, I think,’ she says. ‘One minute you’re up a mountain and the next you’re in the valley. And romantic. The Welsh are great romantics. We have a tremendous feeling about everything. We’re moody, contemplative and passionate.’

This is, of course, a caricature of the Welsh, a snapshot of a national state of mind that ignores those who are cynical, outgoing and levelheaded; but in the same way that, with our deep-rooted prejudices, we ascribe a love of fair-play and propriety to the English and dourness and attachment to money to the Scottish, it is legitimate to draw the parallel.

Alun Pugh’s parents had both been born in Cardiganshire, two thirds of the way down the west coast of Wales, in the middle years of the nineteenth century. It was and remains a predominantly mountainous, rural, Welsh-speaking area, one of the few strongholds of the language outside the north. It was also very poor. On the eve of the First World War Welsh Outlook, a journal of social progress’, described Cardiganshire as ‘this shockingly backward county’, bottom or near bottom in every measurement of public health in terms of deaths of mothers during childbirth, stuttering, rotten teeth, ear defects, blindness and mental handicaps. A bastion of Nonconformity – in 1887 there were riots in the Tywi Valley against payment of the tithe to the established Anglican Church in Wales – it was also for much of the nineteenth century the victim of an unholy combination of a booming birthrate among poor families and some of the wont excesses of heavy-handed, absentee English landlords. The result was that Cardiganshire became a place from which exiles set off on newly built railways in search of work in the industrial valleys and port towns of South Wales or further afield in England, America and even, from the 1850s onwards, in Y Wladfa Gymreig, the Welsh colony in Patagonia in southern Argentina.

John Williamson Pugh came from the small port of Aberaeron. His family were poor and he left school in his early teens, was apprenticed to a local brewery, then worked on a sailing ship under his uncle, David Jones, and only began to follow the ambitions that led him away from Wales at the age of twenty-two, when he attended teacher training college in Bangor, in the north, becoming a schoolmaster at Ponterwyd in 1875. The classroom was in this era a means of escape from drudgery for many ambitious and bright young men of humble origins, but John Pugh found it too limiting. He aimed even higher and in his late twenties obtained a place to train as a doctor at the London Hospital in Whitechapel, qualifying in 1886 at the age of thirty-four. His first post was at Queen Adelaide Dispensary in Bethnal Green, in the heart of the poverty-stricken East End, but three years later he moved to Brighton, where he joined a prosperous general practice.

Pugh’s wife, Margaret Evans, came from Llanon, another port town, six miles north of Aberaeron. They did not meet in Wales, though their shared background must have attracted them to each other when their friendship blossomed at the London Hospital. Where John Pugh’s upbringing had been characterised by a struggle to get on, Margaret Evans’s was dominated by tragedy. Her family were more prosperous than the Pughs, but her mother died when she was just three and she was brought up, along with her sister Catherine, by her aunt Magdalen and her husband, Daniel Lewis Jones, a general merchant. When Magdalen also died young and her husband remarried, the two girls did not get on with their step-aunt and so packed their bags and headed for London. Catherine’s health soon broke down and she returned to Wales, where she died aged just twenty-one. Margaret stayed on alone, and eventually trained at the London Hospital as a nurse.

However, it was not until three years after John Williamson Pugh arrived in Brighton that the couple married. Their long courtship was a result no doubt of Pugh’s desire to establish himself, but it meant that his bride was already thirty-one when she gave birth to a son, John Alun, on 23 January 1894. He was always known by his second name. It was a difficult birth and the Pughs had no further children.

Despite their new-found prosperity, Dr Pugh never forgot where he had come from and had a reputation for treating those who, in pre-National Health Service days, could not pay. And at home the family spoke Welsh, though Alun’s knowledge of what he came to regard as his native tongue remained inadequate until he settled down to study it as an adult.

The Pughs’ attachment to Wales had its limits, not least in their decision to settle in Brighton and not back in Cardiganshire. They were part nostalgic exiles but part also assimilators, embracing their new world and choosing, when it came to education for young Alun, the very English minor public school Brighton College.

He was both a keen sportsman and a talented student who won a scholarship to read history at Queen’s College, Oxford – not Jesus, bastion of the Welsh. His best friend at both Brighton College and Queen’s was Kenneth Goodyear, the son of a wealthy accountant from Bromley in Kent. As their friendship developed Goodyear introduced young Alun Pugh to his sister Kathleen, a strikingly tall, fair, blue-eyed but shy beauty. They fell in love.

There was some disquiet from T. Edward Goodyear, Kathleen’s father and a man with ambitions to be Lord Mayor of London, about Alun Pugh’s relatively humble forebears, but in spite of such reservations the couple married in Brighton in 1915 when both were twenty-one. Alun Pugh-he was throughout his adult life always referred to by both names, even by junior members of his staff, with the result that the ‘Alun’ and the ‘Pugh’ were linked by an imaginary hyphen – had been admitted to the Inner Temple as a pupil in April the previous year, but the First World War was underway and soon after their marriage, in July 1915, like nearly every young man of his generation, he joined up. He went to Bovington Green Camp at Marlow in Buckinghamshire, close to Cliveden, home of the Astors. He chose the Welsh Guards. Kathleen volunteered as a nurse.

In August 1915 Kenneth Goodyear, who was a conscientious objector, was killed in France behind the lines after serving in Gallipoli as a stretcher-bearer. The effect on his parents was devastating and their attention was ever more focused onto Kathleen, their one surviving child. Second Lieutenant Alun Pugh went out with the Prince of Wales Company of the Welsh Guards to join the British forces in France in February 1916. Seven months later, on 10 September, having already seen many of his colleagues killed in the stalemate of trench warfare, he was badly injured in the knee by a sniper’s bullet at Ginchy during the battle of the Somme. It left him in pain and with a slight limp for the rest of his life, but he owed his survival to his sergeant who, after Alun Pugh had fallen back into the trench, bent double as he carried him on his shoulders to the first aid post. Another officer, wounded at the same time, had been passed back along the trench, but his injured body had appeared above the parapet and was riddled with bullets.

A lengthy convalescence with his young wife and grieving in-laws at Rothesay, their home in Bromley, saw Alun Pugh soon on the mend, but the psychological damage caused by his injury was long-lasting, according to his daughter Bronwen, and affected his whole family: ‘My father felt very fortunate still to be alive, but also guilty too. So many of his friends had been wiped out.’ It gave him – and by association his children – a determination to do what seemed right, to live their lives to the full, regardless of the restrictions of convention, class or social mores.

Today Alun Pugh would have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, but in the aftermath of a world war ex-soldiers simply had to get on with rebuilding their lives. The trenches did, however, remain a painful and sensitive memory for him. While his eldest and most direct daughter Ann questioned him about his experiences, drawing him out on the subject, Bronwen felt inhibited about raising what she saw as a taboo. ‘I’ve always been bad about asking people important questions. I wait to be told. I knew there was something but it went unmentioned. I grew up thinking that the silence meant it had been so terrible that there must have been fighting in the street or something.’

His wartime trauma left Alun Pugh with a profound distrust of anything German. He would not, for instance, have Christmas trees, which he saw as a German custom, imported via Prince Albert. There would be one at the Goodyear house in Kent, where the Pughs spent 25 December, but it was only when Bronwen went to live at Cliveden that, reluctantly, having inherited her father’s prejudice in this as in many things, she had to put up with a tree.

That wartime experience also made Alun and Kathleen Pugh – like many others of their generation-determined in the aftermath of the conflict to re-evaluate the assumptions they had made before its outbreak. They already had one child – David born in 1917 – and Kathleen had lost a baby the previous year. While the couple, following Kenneth’s death, would eventually come into the Good-years’ substantial fortune, there was the question of finding a job and financing a home. Alun Pugh resumed his career in the law and was called to the Bar in June 1918, eventually specialising from chambers in Harcourt Buildings in Inner Temple in workman’s compensation claims.

He found a house in Heathhurst Road in Hampstead, just off the wide-open spaces of the Heath and in the shadow of the house of the poet John Keats – his last London home before he left for Italy and a premature death. Hampstead, then as now, was a favourite place for writers, artists, academics and free-thinkers, though in the 1920s, with its villagey atmosphere, it had acquired little of the smart, expensive image of more recent times.

However, as a place where the normal constraints of the strict class system then prevalent elsewhere did not apply so rigidly, it suited the Pughs. ‘I think my parents decided to live in Hampstead,’ says their daughter Ann, ‘as a gesture of defiance because then it was a rather way out sort of place. Certainly my mother’s parents would have regarded it as an odd choice.’ In that period of post-war optimism, Alun Pugh was searching for an identity that tied together his life before the conflict and his experiences on the battlefield. Increasingly he hit upon Wales as the linking thread, having used his convalescence to brush up on his sketchy knowledge of the Welsh language.

Perhaps the comradeship he had felt in his Welsh Guards battalion, which lost an estimated 5,000 men in France, gave Alun Pugh a sense of belonging to something – the Welsh nation – that had in his parents’ home seemed of little more than sentimental importance. Perhaps also it was a reaction to the death of his father and mother who, having struggled so hard to find prosperity and happiness, died comparatively young within months of each other in 1916 without being able to enjoy the fruit of their efforts. In one sense, though, their deaths may have allowed Alun Pugh to explore roots that had, during their lifetime, been regarded with ambiguity.

It was undeniably a romantic quest. His parents had travelled far – socially, geographically and economically – from Cardiganshire. They had bought their son an English education and his knowledge of Wales was limited to holidays, relatives and family folklore. A public school educated, Oxford graduate had little in common with the relatives who remained in Cardiganshire. Yet Alun Pugh was also a practical man. He did not seek merely to wallow in nostalgia for his parents’ homeland, he wanted to do something of substance that would establish his own bond with it.

In his work as a barrister Alun Pugh developed a reputation for working on Welsh cases, especially those involving coalminers. Bronwen recalls frequent visits to Paddington Station to wave him off on, and greet him from, the train to Cardiff, Swansea and beyond. He sought out the company of other Welsh exiles where he practised in Inner Temple-it had and has a sizeable contingent-and he became a member of the Reform Club, bastion of Welsh Liberalism and favourite haunt of its epitome, David Lloyd George. He was also a pillar of the London Welsh Association.

These were little more than affordable gestures for a man whose career at the Bar was already taking off. At the dawn of the 1920s, however, he saw a more tangible, though risky, chance to make his mark by joining the largely academic and middle-class movement campaigning to protect and preserve the Welsh culture and language by all available means.

The most charismatic figure among Alun Pugh’s new-found friends was Saunders Lewis, like him a son of the Welsh diaspora, born of Welsh parents on Merseyside. Lewis was a visitor to the Pughs’ Hampstead home. Once when he stayed the night, Bronwen gave up her room and moved in with her sister. Her father, she recalls, told her that she should always be proud that Saunders Lewis had slept in her bed. She should ‘never forget’. Among the family’s most treasured possessions was a copy of Lewis’s Braslun 0 Hanes Llenyddiaeth Gymreig – a history of Welsh literature, published in 1932. It had been inscribed by Lewis to his friend Alun Pugh in gratitude for his work on behalf of their people.

Lewis’s long-term contribution to the nationalist revival was huge, though often in his lifetime he suffered spells of disappointment and marginalisation. ‘The dominance of Lewis,’ writes D. Hywel Davies in his history of Welsh nationalism, ‘from 1926 to 1939 was such that his name and that of the nationalist movement had become almost interchangeable.’ A poet, dramatist, historian and teacher of the Welsh language, he was heavily influenced as a young man by Ireland’s political struggle to break free from Britain and the literary renaissance that ran in parallel. His political ideas – authoritarian and tinged with religion – owed much to the radical conservatism of Charles Maurras’s Action française.

Lewis was the most prominent member of Y Mudiad Cymreig, the Welsh Movement, a society founded in Penarth in January 1924, and the following year, at the National Eisteddfod, threw his lot in with Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru, the National Party of Wales. The aim, Lewis said, was ‘to take away from the Welsh their sense of inferiority … to remove from our beloved country the mark and the shame of conquest’.

Alun Pugh endorsed this manifesto enthusiastically and would often provide legal help to the fledgling party. In 1930, for instance, he sat on a committee of London Welsh with the former Liberal MP John Edwards, which advocated that Plaid should campaign for Wales to be given dominion status within the British empire – treated as if it were equal, free and self-governing like Canada or Australia. Five years later Alun Pugh was again called on to advise whether teachers who took part in the pro-Welsh protests organised by Lewis could face disciplinary action by their employers. There could be, he concluded in July 1935, ‘no martyrdom with safety’. It was a message that was to become increasingly relevant to his own involvement with Plaid.

Those living in Wales able to speak Welsh were in steep decline. Their numbers fell in the decade to 1931 by over 5 per cent, to just 35 per cent of the population. Only 98,000-out of a total population of 2.7 million – used Welsh as their first language at that time. If Plaid successfully but slowly began a reversal in this trend-pressing for the Welsh language to be given more prominence in schools and the new broadcast media – in the political field the party was for many years a failure.

In part this was because it insisted on members breaking all links with existing political parties, including Lloyd George’s Liberals, still dominant in rural Wales, and Labour, now controlling the southern valleys, and with the Westminster Parliament. Hence it had no effective environment in which to operate and gain influence. In part too it was brought about by the extreme political philosophy that Lewis mapped out as Plaid’s president between 1926 and 1939. The Welsh, he argued, echoing other inter-war Utopian schemes like Eric Gill’s distributist guild, had to reject both the capitalism that was destroying the valleys and towns of the south and the socialism offered by the growing Labour Party. Lewis’s own third way-what he called perchentyaeth – dreamt of’distributing property among the mass of the members of the nation’.

The president’s own unpredictable personality also weakened the movement he headed. His decision to become a Catholic in 1932 alienated many in Plaid’s naturally Nonconformist constituency. Yet it was a typically bold Lewis gesture that won Plaid international attention in 1936 and put Alun Pugh’s devotion to the cause to the test. Lewis’s firebomb attack on an RAF training base near Pwllheli on the Lleyn peninsula caused outrage. The ‘bombing school’, as Lewis dubbed it, represented for him British military imperialism in Wales.

For Alun Pugh this was a crucial moment. As a member of the Bar, he could not but deplore breaking the law. Yet as historian Dafydd Glyn Jones has argued, the fire was ‘the first time in five centuries that Wales had struck back at England with a measure of violence … to the Welsh people, who had long ceased to believe that they had it in them, it was a profound shock.’ Such an awakening was what Alun Pugh had been yearning for.

Already before the ‘bombing-school’ episode, the strain between the different elements in Alun Pugh’s life had emerged in his letters to J. E. Jones, a London-based teacher and Plaid’s secretary. ‘The time has come,’ he acknowledged in March 1933, ‘for us to have secret societies to work for Wales – two sorts of societies – one of rich supporters to give advice to us without coming into the open, and the other of more adventurous people willing to destroy English advertisements that are put up by local authorities.’ For all his bravado and implied association with the second group, Alun Pugh’s role was largely confined to the first, as a later letter to Jones in June 1934 testifies when he offers to make a loan to the party.

In the following month he sent some legal advice to Jones but insisted that, if it were used, ‘don’t put my name to it’. In March 1936 he was urging Jones or ‘someone else’ to write a letter to The Times on ‘some other burning issue’, but was obviously unwilling to do so himself. The possibility of compromising his position at the Bar was already exercising his mind. Yet in the same month he told Jones that he was lobbying Lloyd George, through a contact of Kathleen Pugh’s, to give public support to Lewis, who had already embarked on his fire-bombing campaign.

In responding to Lewis’s arrest and trial after the attack on the bombing school, Alun Pugh took a big risk. He gave the defendant legal advice-the case against him and two co-conspirators was transferred from a Welsh court, where the jury could not reach a decision, to the Old Bailey, where the three were sentenced to nine months. ‘Thank you very much,’ wrote J. E. Jones to Alun Pugh in September 1936, ‘for your work in defending the three that burnt the bombing school.’ Alun Pugh clung to the fact that Lewis was advocating violence against public installations, not individuals or private property, but it was a difficult circle to square, his heart ruling his head and potentially posing a threat to his career. His solution was, it seemed, to put different parts of his life into boxes – Wales, the law and, separate from both, his family.

‘As a small child,’ recalls his daughter Ann, ‘I used to be terrified that we would have a knock on the door at three o’clock in the morning and it would be the police coming for my father because he was part of it. There was an attack on a reservoir in the north that supplied Liverpool. The Welsh nationalists were indignant that Welsh water was being piped to England.’

Alun Pugh’s relationship with Lewis underwent further strains with the coming of the Second World War. Lewis’s insistence that it was an English war and nothing to do with the Welsh offended Alun Pugh’s sense of patriotism and ran counter to his own determination to contribute as fully as his injury allowed to the war effort. The detachment of Alun Pugh from active involvement in the Welsh cause gathered pace in the post-war years: his appointment as a judge reduced his freedom for manoeuvre and also crucially provided him with an alternative source for self-definition to his Welsh roots. Yet a link endured through Lewis’s two decades in the wilderness following his defeat by a Welsh-speaking Liberal in a by-election for the only Welsh university seat in 1943, subsequent splits in Plaid about tactics, and on to the great nationalist and Welsh language surge of the 1960s.

However, in the early days there was a strong contrast between Alun Pugh’s middle-class enthusiasm in London and the custom, in many primary schools in the valleys in the 1920s and 1930s, of placing the ‘Welsh knot’ – a rope equivalent of the dunce’s hat – over the head of any child caught speaking Welsh. Practical as many of Alun Pugh’s concerns were for Wales, they were tinged with idealism. He could afford his principles and time off to attend Plaid’s most successful innovation of the period – summer schools. Others, at a time of record unemployment, could not.

The reality of events on the ground is demonstrated by the fate of Ty Newydd (New Cottage), the house in Llanon where Alun Pugh’s mother had grown up with her aunt and uncle. It was bequeathed to him some time after the First World War and later he in turn gave it to Plaid Cymru on condition that it was used only by Welsh-speakers to further the cause. Within a short period of time it was being used, according to Ann, by ‘all and sundry’. The fact that he gave a valuable property to the cause – and not to his family – is evidence, she feels, of the extent to which he could separate his obligations to one or the other in his head and discard the conventional route of leaving such an asset to his children. Yet there were deep ambiguities in Alun Pugh’s attitude: he insisted that a plaque commemorating his son David, who had by that time died, had to be erected in the house before it could be handed over to Plaid.

If he placed each of his responsibilities into separate categories, Alun Pugh never failed to convey the importance of their Welsh roots to his children. ‘We were always very conscious that we were different from most people,’ Bronwen recalls. ‘Primarily it was because we were Welsh, but other things led from that. We were taught to be classless, apart from the class system, and our parents encouraged us to look at things differently. The general atmosphere in our family was not rebellion but revolution. It’s a subtle difference. Outwardly you conform, but all the time you are doing things and thinking things in a different way from others.’ When later she found herself in the class-ridden world of Cliveden, this alternative side of her upbringing gave her the resilience to withstand those who would judge her on the basis of her parents’ income and social standing.

At home Alun Pugh’s conversation over breakfast every morning was always in Welsh. The children became adept at remembering the right word for bread or butter or milk. Sunday worship would often be in the Welsh chapel, though later the Pugh became more solidly and conventionally Church of England. And when it came to schooling, Alun Pugh decided – despite his wife’s reluctance – to send their daughters to boarding school in Wales.

The Pugh children fell into two distinct duos, based on age and emphasised by their names, one pair solidly English, the other ringingly Welsh. David and Ann, thirteen and ten respectively when Bronwen was born, formed one unit, while their new sister and five-year-old Gwyneth were another. In 1926, with the help of Kathleen’s parents, the Pughs had purchased an empty plot of land in Pilgrims Lane two streets away in Hampstead and built a larger house. Number 12 still stands to this day, a suburban version of a gabled country house in Sussex vernacular style, with leaded windows and a formal garden sweeping round the house and down the hill towards the Heath.

Alun and Kathleen Pugh had intended to have no more than three children. Bronwen was not planned. Her parents decided the baby was going to be a boy. They even chose a name – Roderick. Two girls, two boys would have made for a neat symmetry, but there was a more particular reason. David, already away at boarding school, was proving a sickly child, undistinguished in his academic work, poor in exams, unable to participate in sport, underdeveloped physically, mentally and emotionally. At the age of sixteen, Bronwen recalls, he was still insisting that a place be set at the dining table for his imaginary friend, Fern. The contrast with Ann, three years his junior and a robust, practical, natural achiever, could not have been greater. Even if it had not been their original intention, circumstances meant that the Pughs, unusually for the time, made no distinction between their treatment of their son and his sisters. All three girls were encouraged to be independent and to think about careers.

Janet Bronwen Alun was born on 6 June 1930, delivered by caesarean by the family GP in the Catholic hospital of St John and St Elizabeth in London’s St John’s Wood. Her early years were dominated by Frederic Truby King, the New Zealand-born Dr Spock of the 1920s and 30s. Kathleen Pugh followed the methods he advocated in books like The Feeding and Care of Your Baby. Baby Bronwen was on a strict regime of four-hourly feeds, with nothing in between. Picking up the child and cuddling it was not recommended by Truby King in case it encouraged spoiling or over-attachment. ‘A Truby King baby,’ the master wrote of his own methods, ‘has as much fresh air and sunshine as possible. The mother of such a baby is not overworked or worried, simply because she knows that by following the laws of nature, combined with common sense, baby will not do otherwise than thrive.’

Kathleen Pugh was certainly not overworked since the bulk of practical child care fell on the family’s nanny. In spite of their progressive ideas, the Pughs – in line with the middle-class norms of the age – maintained a full complement of domestic help: a maid, a nursery nanny, a cleaner and a part-time gardener. When Bronwen was three, Bella Wells was taken on to look after her, leaving Kathleen Pugh free for most of the day.

Bronwen was not, her sister Ann recalls, a particularly attractive child. ‘She was all eyes, teeth and pigtails. When she was about four, she went off on her bicycle with my mother and when they came back my mother was very upset. Bronwen had had a bad fall. She had managed to pull the muscle at the side of her eye. It left her with a squint which later had to be corrected by surgery, but she still wore glasses.’ There were as yet few signs of her future career on the catwalks. She had to wear a patch over one lens of her glasses to strengthen her eye muscles and later she wore braces to pull her protruding teeth back into line.

She was also, Ann remembers, infuriating. ‘She was always very lively. She’d hide behind the door in the dining room and then when you went in for lunch leap out and say boo! Or else she’d be crawling under the table tickling your feet. She was always on the move, dressing up, play-acting, getting over-excited.’ Bella Wells’s memory is of a very determined three-year-old. ‘On the first day I arrived I took her out in her pram and she just kept saying, “Now can I get out? Now can I get out?” She wanted things her own way.’ One of Bronwen’s greatest delights as a small child was to watch the fire engines going down Hampstead High Street, bells ringing and lights flashing. Her earliest ambition was to be a fireman. It appealed to the theatrical side of her nature. ‘There was the drama of it all, I suppose, and that thing of rescuing people. It must always have been a part of my psyche.’

While Bella Wells was devoted to her charge, mother and daughter had from the start a difficult relationship. Kathleen Pugh’s regret at not having a boy was explicit and was overlaid by personal frustration. She had wanted to find something challenging to do outside the home but Bronwen’s arrival delayed the day when she could seek once again the sense of self-worth that she had enjoyed as a volunteer nurse during the war. She was an intelligent woman: to her husband’s breakfast-table lessons in Welsh she would add her own questions to the children on mental arithmetic. They all learnt early how to keep accounts of how they had spent their pocket money.

Kathleen had finished school at sixteen and, with her staff leaving her with too little to occupy her time in the Hampstead house, she grew bored and occasionally, Ann remembers, impatient with her youngest daughter. Though she had forward-thinking ideas about women’s choices – she had her own car at a time when two vehicles in the family was unusual – Kathleen was by nature a reserved and private person. She mixed with neighbours but had few close friends among them; she found some of the more academic residents of Pilgrims Lane intimidating. She warned her youngest daughter against Dr Donald Winnicott, an eminent child psychiatrist (and the greatest critic of the Truby King method of child-rearing) who lived in the same road, for fear, Bronwen suspects, ‘that he might carry out some strange experiments on us’.

Rather than her reserve throwing her back on her role as a mother, however, it appeared only to exacerbate Kathleen Pugh’s restlessness. Sometimes she could be fun. She taught her youngest daughter to fish – a hobby Bronwen pursues with gusto to this day in the salmon rivers of the Scottish borders. ‘We started off one holiday in Suffolk with a simple piece of string and a weight. You threw it in and waited to see if you caught anything. I must have been six when I caught an eel and I was so pleased.’

Another treat was to raid the dressing-up box with Kathleen or put on a play in the drawing room. Again there was a theatrical element. Their mother was a woman, her daughters recall, who liked, indeed expected, to be entertained by her children; she could grow exasperated if they failed to perform. Yet any frivolous side to her character was strictly rationed. She had an unusual and occasionally cutting sense of humour and for the most part, despite all the Pugh’s progressive ideas, was for Bronwen a rather Victorian figure, distant and dour. She had had a strict Nonconformist upbringing and passed aspects of it on to her children. She would remind them of phrases like ‘the Devil makes work for idle hands’ and circumscribed their lives and her own with peculiar self-denying ordinance like never reading a novel before lunch. Her favourite children’s book was Struwwelpeter, a collection of often brutal, gloomy moral tales about such character as ‘poor Harriet’, who was punished for her wrong-doing by being ‘burnt to a crisp’.

‘My mother was, I now realise, not very child-orientated,’ says Bronwen. ‘I found being with her agony. There was one terrible time when Gwyneth and my father were both away and I had to be with my mother on my own for two weeks. I can only have been six or seven at the time, but once I realised what was happening, I went into a catatonic state. She had to call the doctor. I just sat unable to move for three hours. I was in such a state of shock at the prospect of two weeks on our own. Now it sounds like nothing but then it was a lifetime.’

Siblings experience their parents in different ways and while Bronwen found her mother a cold, distant figure, Ann remembers an entirely separate person with great affection. ‘My mother was not a cuddly sort of person but she was kind and caring.’ Such a divergence of views is not uncommon in brothers and sisters, depending on their temperament and their position in the family. Parents who are strict with their older children, perhaps daunted by the serious business of forming young minds and possibly, at an early stage in their careen, anxious over material matters, become indulgent, relaxed mentors to their younger children, self-confident in then-behaviour and sometimes cushioned by greater financial resources. In Bronwen’s case there was certainly more money around when she was a child and Ann retains the distinct memory that her youngest sister was spoilt and indulged. Yet Bronwen was also aware of a new anxiety in Kathleen Pugh – her desire to break out of the confines of being a stay-at-home parent, which contributed to the temperamental clash between mother and daughter.

Kathleen’s difficult relationship with her youngest and most independent daughter reflected her tense dealings with her own mother, Lizzie Goodyear, who lived on in her Bromley house to the age of ninety-one, surviving her husband by twenty-two years. ‘My mother was scared of my grandmother,’ says Bronwen. ‘I used to be taken to tea when she had to go and visit her mother as a kind of distraction. Out would come the silver and the maid and the cucumber sandwiches-the complete opposite of the way my mother ran our house. So it was wonderful for me but I sensed my mother was terrified.’

Bronwen’s picture of the house in Pilgrims Lane as one that was lacking in warmth is also qualified by Bella Wells, the nanny. ‘There was no hugging or kissing or anything like that. But then not many people would do that then.’ Much later, in an academic paper she wrote ‘Of Psychological Aspects of Motherhood’, Bronwen reflected obliquely on her own experiences: ‘Assuming the child is wanted from the moment of conception – and many of us are not – and is the right gender – again, many of us are not’, the mother’s love, attitude and behaviour are ‘more fundamental to the child’s early formation than that of the father’.

Her perceptions of the absence of that love from her own mother left a deep scar. ‘I could entertain her – go shopping with her, do the crossword – but she made me feel like a thorough nuisance. I’m still always apologising for being a nuisance. I try to stop now that I know. I had my handwriting analysed recently. “Oh, but you’re still running away from your mother,” the graphologist told me. Even now!’

What love she felt – and therefore returned – was all to do with her father. As she grew up, Bronwen knew from an early age that she did not want to be like her mother. ‘I remember deciding, when I was quite young, that I was going to be more graceful than my mother. She never made the best of herself. She never wore make-up and her hair was cut in an Eton crop like a boy.’

Alun Pugh, by contrast, was his daughter’s hero – indeed the hero of all his daughters. ‘We were all devoted to our father,’ says Ann. ‘I can remember as a girl walking down the High Street in Hampstead with him and saying, “What would you do if the house caught fire? Who would you save?” and being heart-broken when he said, “Your mother, of course.”’ He was, she recollects, a charmer, but part of that charm lay in the fact that he was so seldom at home; his work often took him away and he was unpredictable in his hours. He brought an excitement but also an uncertainty to the home with his eccentricity and sense of adventure. He would have great enthusiasms that were utterly impractical. At one stage he decided it would be fun to keep silk-worms and make their own clothes. So Gwyneth and Bronwen made cocoons out of old newspaper and hung them from the ceiling, but when the worms began to produce silk the little hand-spinner their father had made could not cope with the output. ‘It had closed-in ends, so you couldn’t get anything off it,’ says Bronwen. ‘It was typical of my father, this do-it-yourself-and-have-fun-doing-it mentality, but then never to finish it off. He had lots of imagination and was terrific fun. When he emerged from his study at home, the atmosphere would change at once. But he was totally impractical.’

When he was a student, Alun Pugh had made a jelly in a teapot, thinking it would make an interesting shape, but then he couldn’t get it out. It is a useful symbol for most of his schemes. When he imported hives of bees into the garden, he eventually had to abort the project because his wife grew allergic to their sting, though he did manage to make some mead and plenty of honey.

Like Kathleen, Alun Pugh didn’t go in much for hugging and kissing, but as a substitute he took a keen, almost zealous, interest in his children’s progress, forever pushing them to do better and be the best. When Bronwen was twelve she was taken to see Roy Henderson, then a celebrated voice coach. He said she had a pleasant voice and good pitch, and suggested lessons, but when he made it clear she would never sing solo in the great concert halls of the world, Alun Pugh decided against. ‘You do something to get to the top or you don’t bother at all,’ is how his youngest daughter sums up the prevailing attitude.

Singing had been something Alun Pugh associated with his mother, who reputedly had a beautiful voice and played the harp, with her son accompanying her on the piano. Bronwen was also told that physically she resembled her paternal grandmother and this may have contributed to a special closeness between father and daughter that compensated for the alienation between mother and daughter.

With Ann and David away at school, Bronwen and Gwyneth developed an enduring bond. The two would get up to all sorts of mischief and it was Gwyneth who was Bronwen’s chief source of fun in the house. ‘She was always inventing things,’ Bronwen remembers. ‘Once when she was ill in bed, she spent hours building this elaborate system of pulleys and string so that we could send each other messages from bedroom to bedroom. Or she would devise complicated games where she would be the captain and I would be the boatswain. I was always saying, “Ay, ay, captain,” to her. She was in charge.’

The five-year age-gap with Gwyneth meant that the youngest Pugh sibling often had to while away many hours on her own or with her nanny. There were friends in the neighbourhood and cycle rides around the carefree streets of Hampstead, but going to school just before her fifth birthday came as something of a blessing. St Christopher’s was a Church of England primary on the way down Rosslyn Hill from Hampstead into central London. Though the Pughs retained their links to the Welsh chapel, their ordinary practice of religion had become increasingly Anglican. (When he joined up with the Welsh Guards in 1915, Alun Pugh had claimed to have no religious affiliations at all.)

Bronwen’s reports suggest a model pupil, with hints at future interests. From her earliest days she did well at recitation, and was praised in April 1936 as ‘a useful leader of the class’. She joined a percussion band that same year and the only blot on the landscape was her problems with an unusual addition to the otherwise standard curriculum, Swedish drill, where she ‘sometimes lacks control’. At the end of summer term 1937, aged seven, she was put up two classes – into a group where the average age was fourteen months above hers-on account of her excellent progress. She made the transition effortlessly, save for occasional blips in arithmetic – ‘must try to be more accurate’ – and painting – ‘is inclined to use too pale colours’ (both spring term 1939). By the time of her final report from St Christopher’s, her card was Uttered with ‘very goods’ and adjectives like ‘appreciative’, ‘careful’, ‘neat’ and ‘musical’.

She did not return to the local school that autumn. War had broken out in September and her parents decided to send her early to join her sister Gwyneth at boarding school in Wales. The two older Pugh girls had gone at the age of twelve, but in view of the anticipated threat to London by German bombers and Alun Pugh’s own ambitions to join the war effort, it seemed sensible to pack Bronwen off to the comparative safety of north-west Wales and close up the house in Hampstead. It appeared to Bronwen Astor at the time like an awfully big adventure, but later she came to see 1939 as a pivotal moment in her childhood, the end of an age of innocence and plenty and the start of a period when she was continually without the things and people she needed to sustain her.

At the age of seven Bronwen had been invited by a school friend to a birthday party in Bishops Avenue, a leafy street of very large houses in Hampstead, known today as ‘Millionaires’ Row’. ‘Until then I had thought that our house was big, but this was so much bigger than anything I had seen,’ she recalls. ‘It even had a swimming pool, all the things you were supposed to want. Immediately I felt very uncomfortable there. It seemed so cold and unwelcoming.’

She joined in with a game of hide and seek in the garden but ‘I was suddenly aware that I was standing totally alone. Everyone had disappeared and a voice spoke to me and said, “None of this matters. None of these things. Only love matters.”’ It was, as she now describes it, ‘a flash of understanding, that the beautiful house, the lovely garden were not as important as what I had experienced, love. There was a tension in this family that I had felt. It was not a happy home.’

She did not mention the experience to anyone. ‘I knew it was God because it was said with such authority. My father would say prayers at night and I think he probably had a mystical streak. We would go to church on Sundays, where my mother would enjoy singing the hymns, but it never occurred to me to mention it to either of them. I thought it was something that happened to everyone. I wasn’t frightened, but reassured. It highlighted love for me as the most important thing, as my lodestar.’

Sixty plus years on, without any independent confirmation, it is impossible to verify the details of this incident. However, its broader significance is all too clear. Though she didn’t know it at the time, this was the start of what Bronwen later came to map as her spiritual journey and the first glimpse, however fleeting, of a capacity within her to experience and react to feelings, tensions, fears or pain in a physical way.

Chapter Two (#ulink_63ca0a4b-47f3-5089-b3c6-4d2ca4132baf)

The land of my fathers? My fathers can keep it.

Attributed to Dylan Thomas (1914–1953)

The old Dr Williams’ School building has the look of a neglected North Country nunnery, its wide gables sagging down over grey stone walls blackened with age, its windows positioned high off the ground to shut out the prying eyes of the world. Next to the road out of Dolgellau to Barmouth and the North, it is now part of a local sixth-form college, but a weather-beaten plaque over the main entrance recalls its history. ENDOWED OUT OF THE FUNDS OF THE TRUST FOUNDED IN I716 BY THE REVD DANIEL WILLIAMS DD, ERECTED BY PUBLIC SUBSCRIPTION IN 1878.Williams, a wealthy Welsh Presbyterian minister, had wanted to promote primary education in Wales, but once the state took over such provision in the early 1870s, his trustees had redirected their funds to secondary education and established Dr Williams’ School.