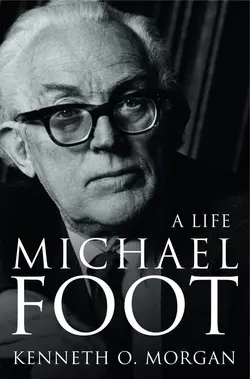

Michael Foot: A Life

Kenneth O. Morgan

The authorised – but not uncritical – life of one of the great parliamentarians and orators of our times, the former Labour Party leader, who was also an eminent man of letters.Michael Foot was a controversial and charismatic figure in British public life, political and literary, for over sixty years.Emerging from a famous west-country Liberal dynasty, he rose as a crusading left-wing journalist in the late 1930s: ‘The Guilty Men’ (his book on the pre-war appeasers of Nazi Germany) is one of the great radical tracts of British history. He was the voice of libertarian socialism in parliament, an international socialist and government minister, and was Labour leader for two-and-a-half years between 1980 and 1983.His political friendships with people like Beaverbrook, Cripps, Aneurin Bevan and Barbara Castle were passionate and profound, but he also had a remarkable and quite different career as a man of letters, with Dean Swift, Tom Paine, Hazlitt, Byron, Wordsworth, Heine, Wells and Silone amongst his heroes. Foot’s two-volume life of Aneurin Bevan is a triumph of political biography.Kenneth Morgan's biography does full justice to both the public and the private side of Michael Foot – no more tellingly than his descriptions of Foot's long and happy marriage to the filmmaker, feminist and writer Jill Craigie.

Kenneth O. Morgan

MICHAEL FOOT

A LIFE

DEDICATION (#uab45db08-0e2b-5479-a9e8-f2ad9dd96fb0)

For Joseph

CONTENTS

COVER (#ubb1abef3-f653-5bb4-ab82-7b7d2667c04d)

TITLE PAGE (#uab9f09de-3a07-5a7f-8c0e-1364cbb46e31)

DEDICATION (#u38604687-5b24-5668-b3cd-992e329cbf51)

PREFACE (#udf4bd50f-39f8-5508-9629-f2531e35bd18)

1 Nonconformist Patrician (1913–1934) (#u2232910b-0873-5ae8-9fb1-2b2747e1ff81)

2 Cripps to Beaverbrook (1934–1940) (#u80ae8a09-23a2-5e35-b0c7-2ff6b5529483)

3 Pursuing Guilty Men (1940–1945) (#u07f4307f-7bb6-58e3-8cbc-8f18a48d8f6c)

4 Loyal Oppositionist (1945–1951) (#uefc669ae-b9f4-506e-a60d-a0a186dee3e5)

5 Bevanite and Tribunite (1951–1960) (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Classic and Romantic (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Towards the Mainstream (1960–1968) (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Union Man (1968–1974) (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Social Contract (1974–1976) (#litres_trial_promo)

10 House and Party Leader (1976–1980) (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Two Kinds of Socialism (1980–1983) (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Into the Nineties (#litres_trial_promo)

ENVOI: Toujours l’Audace (#litres_trial_promo)

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

PRAISE (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

PREFACE (#ulink_1b965bf2-9af2-54e5-a932-b729e9ea1d3a)

Michael Foot has had a very long and colourful life. He was chronicler and participant in central aspects of British twentieth-century history. His first general election found him crusading for Lloyd George’s Liberal Party in 1929. His twentieth and last saw him campaigning for Labour in his old seat, Ebbw Vale/Blaenau Gwent, seventy-six years later. He spans the worlds of Stafford Cripps and Tony Blair. He was a doughty opponent of appeasement in the later 1930s: his book Guilty Men made him famous at the age of twenty-seven. He was vocal in condemning the invasion of Iraq in 2003. He stands, and feels himself to stand, in the great and honourable tradition of dissenting ‘troublemakers’, the heir to Fox and Paine, Hazlitt and Cobbett. He played in his life many parts. As icon of the socialist left, he was custodian and communicator of British socialism. He was the greatest pamphleteer perhaps since John Wilkes, a formidable editor, and author of a glittering biography of his idol, Nye Bevan. He was a scintillating parliamentarian, an inveterate critic and peacemonger as Bevanite, Tribunite and founder member of CND, yet also a belligerent patriot and internationalist from Dunkirk to Dubrovnik. He was a central figure and champion of the unions in the Labour governments of the 1970s, a key player in Old Labour’s last phase. Less happily, he was for almost three tormented years Labour’s leader. Perhaps most important of all, he was a deeply cultured and literate man whose learning was absolutely central to his politics. He was heir to the Edwardian men of letters, the Liberals Morley or Birrell, and politically more innovative than either. Over sixty years he was an inspirational and civilizing force, if a deeply controversial one. His passing will symbolize a world we have lost.

When Michael Foot asked me if I would write a new authorized biography, I was, of course, both excited and honoured. At the same time, I had some doubts. After writing a large biography of one veteran Labour leader, Jim Callaghan, I wondered whether it would be wise to write another, especially on someone so removed from Callaghan’s own wing of the party. Although Callaghan and Foot worked with immense loyalty as colleagues in the Labour government of 1976–79, they were very different as men and as democratic socialists. Someone who worked for them both told me that they were not ‘best buddies’, while Jim Callaghan himself, just before he died in March 2005, showed himself to be a bit wary of my new project. Another point was that, while I had never really been on the right in Labour terms since I first joined the party in 1955, I was not really Old Labour either, despite the stereotypes of amiable journalists who have vainly tried to depict me as its ‘laureate’. On the contrary, I have always been a liberal devolutionist rather than a state centralist (being Welsh may have something to do with that), while on several major issues my views were not those of Michael Foot, notably on CND and on Europe. Although an admirer of Bevan (whose features adorn the sticker on my car window), I was not a Bevanite. And finally, at the start of 2003 I was doing something else, namely writing an academic book on the public memory in twentieth-century Britain. I have always been a historian rather than a biographer; only six of my books have been biographies. I was also an active member of the Lords (dissident Labour), an institution of whose abolition Michael Foot has always been an ardent supporter.

But as soon I began work and began talking to Michael Foot about his career, my doubts immediately dissolved. Having written on Jim Callaghan’s equally fascinating career proved to be a huge stimulus, both in seeing somewhat similar episodes from another perspective, and in finding contrasts and comparisons between two totally different men, each capable of the greatness of spirit to work with someone to whom he was not naturally attuned. The fact that I started from a somewhat different political (and perhaps literary) standpoint from Michael Foot was in itself exciting in trying to examine his principles and his crusades from the outside. Michael himself was typically honourable and honest in recognizing that I came from somewhere else on the Labour continuum, and that in any case I was writing as a detached scholar and lifelong academic. It is characteristic that he has made no effort to read, let alone censor, anything I have written. His view of freedom of expression and interpretation, and the need to pursue them uninhibitedly and audaciously, has been most admirably exemplified in his approach to his own biographer, and I greatly respect that. Even membership of a non-elected House has not, perhaps, been a barrier. And finally, to someone working on the public memory, there is no finer custodian or exemplar of it than Michael Foot, deeply aware, as hardly any contemporary politicians are, of the vital importance of the past – history, legend, memory and myth intertwined – in shaping the present and pointing the way ahead. So writing on Michael Foot has enormously stimulated my earlier interests. As I have moved into my eighth decade, it has given me several new ones: I know far more about Montaigne, Swift or Hazlitt, for example, than I ever did before, and my mind is much the richer for it. In all ways, I have found writing about Michael deeply stimulating. This book has been great fun to write, and it would be nice to think that some readers might find it fun to read. No doubt I shall find out.

There is another personal aspect too. Back in 1981 I received a letter from Jill Craigie, Michael’s wife, in effect suggesting that I might write his life. She invited my wife Jane and me to their house in Pilgrims Lane for a delightful dinner and talk. In fact, for whatever reason, the offer was never actually made – to my relief at that time, as I was then heavily involved with two long books, two small children and a beautiful and dynamic young wife, as well as being a busy Oxford tutor. I was not exactly looking out for ways of filling up my empty hours. I met Jill for the last time in the autumn of 1997 at an event at Congress House, near the British Museum, to celebrate the centenary of Nye Bevan’s birth. She had not been well, and she looked ill and rather sad as she came up to me and (without needing to explain) said quietly that we both knew she should have taken a different decision years earlier. I felt deeply moved, but mumbled something to the effect that I was still very much alive, and that there was still time. Jill died two years later. I would like to think that in writing this book I have been fulfilling a kind of secret bond of trust between us. I well know she would not have agreed with all its contents, but it would have been fun to have been appropriately chastised by this tough, determined but warm, loyal and lovable woman.

My main debt of gratitude is, of course, to Michael Foot himself. Apart from honouring me by asking me to write the book, he was always freely available for formal interviews or offhand chats, always open in making his papers (when they could be unearthed!) available to me, and quite astonishingly kind in giving me some of his own or his father’s books, several of them rare. He is an extraordinarily warm and generous person, a man of unforced, spontaneous learning. Simply to work through his personal edition of Montaigne’s writings, read in Hereford hospital after a serious car crash in late 1963 and covered with his own scholarly pencilled annotations, is in itself an education. Whether at home in his Pilgrims Lane basement rooms or cheerfully installed in an upstairs dining room over the goulash, raspberries and white wine at the Gay Hussar in Greek Street, talking to this ever-young nonagenarian has been nothing less than a joy, and I count myself fortunate indeed. I am also greatly indebted to the quite selfless kindness of Jenny Stringer, who has not only looked after Michael but in many ways looked after me as well during the writing of this book. I am also very grateful to Sheila Noble, who allowed me to look through Michael’s papers in her own possession in Clapham. Kay, Baroness Andrews, was kind in making the initial connections, her interest in the book no doubt shaped by her background as a citizen of Tredegar. I am also grateful to Michael’s many nice housekeepers who gave me so many splendid lunches. I particularly recall lunchtime conversations in Welsh with two of them, observed by Michael with amused tolerance. I have never met the authors of two earlier biographies, Mervyn Jones, and Simon Hoggart and David Leigh, but I would also wish to thank them for valuable information in their books which has helped me, especially on the personal aspects.

I am also hugely indebted, of course, to the kindness of Michael’s friends and colleagues. I have greatly benefited from formal interviews with Ian Aitken, Lord Barnett, Francis Beckett, Tony Benn, Albert Booth, the late Lord Bruce, the late Lord Callaghan, the late Baroness Castle, the late Dick Clements, Roger Dawe, Lord Evans of Parkside, Alan Fox, Vesna Gamulin, Geoffrey Goodman, Brian Gosschalk, Baroness Gould, Lord Hattersley, Lord Healey, Lord Hunt of Tanworth, Jack Jones, Dr Hrvoje Kacic, Sir Gerald Kaufman MP, Lord Kinnock, Jacqui Lait MP, Sir Thomas McCaffrey, Keith McDowall, Lord McNally, Baroness Mallalieu, Nada Maric, the late Lord Merlyn-Rees, Lord Morris of Aberavon, the late Lord Murray of Epping Forest, Sue Nye, the late Lord Orme, Lord Owen, Lord Paul, Sir Michael Quinlan, Caerwyn Roderick, Clive Saville, Lord Steel, Sir Kenneth Stowe, Elizabeth Thomas, Hugh Thomas, Lord Varley, Lord Wedderburn, Baroness Williams of Crosby, Vivian Williams and Sir Robert Worcester.

I am also grateful for valuable information gained from, amongst others, Dr Christopher Allsopp, Lord Anderson of Swansea, Sir Kenneth Barnes, Lord Biffen, Lord Brookman, Dr Alan Budd, Lord Burlison, Lord Carter, Lord Corbett, Sir Patrick Cormack MP, Lord Dubs, Lord Eatwell, Robert Edwards, Dr Hywel Francis MP, John Fraser, Baroness Gale, Jadran Gamulin, Lord Gilmour, Baroness Golding, Dr Andrew Graham, Lord Graham of Edmonton, Peter Hain MP, Lord Hogg, Lord Howe of Aberavon, Lord Irvine, Baroness Jay of Paddington, the late Lord Jay of Battersea, Lord Jones of Deeside, William Keegan, Paul Levy, Lord Lipsey, Lord Mason, Mrs John Powell, Professor Siegbert Prawer, Lord Prior, Lord Rodgers, Lord Sheldon, Dr Elizabeth Shore, Robert Taylor, Baroness Turner of Camden, Dennis Turner and Alan Watkins. I am also indebted to Francis Beckett for audio-visual material.

All academic writers are massively indebted to the philanthropic race of librarians. The staff of the House of Lords Library have been extraordinarily helpful, not least their former chief, David Lewis Jones from Aberaeron – diolch yn fawr iawn i ti am dy caredigrwydd. The librarian of the Reform Club, Simon Blundell, has been eternally helpful. I am also much indebted to the staff of the People’s History Museum, Manchester, where Michael Foot’s formal papers are so admirably housed, especially my old friend Stephen Bird. The helpful staff of the New Bodleian Library in charge of the newspaper stacks; my old friend John Graham Jones of the Political Archive, the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth; Drs Allen Packwood and Andrew Riley at Churchill College, Cambridge; Ms Mari Takayanagi of the House of Lords Record Office; Ms Sally Pagan of Edinburgh University Library; and Ms Rachel Hertz at the Harry Ransom Humanities Center, the University of Texas at Austin, have all been kindness itself, while the library staff of The Queen’s College, Oxford, have served me cheerfully as they have done since 1966. I am truly fortunate in my college, its Provost and Fellows, and all its staff.

I am delighted that the Right Honourable Tony Blair allowed me to publish one of his private letters. I am also very grateful for permission to publish material where trustees own the copyright, notably the Beaverbrook Papers in the House of Lords Record Office; to Baroness Jay for material from the private papers of Lord Callaghan in her possession; and to Sir Patrick Cormack MP for showing me the portrait of Michael Foot in 1 Parliament Street as well as to the artist, Graham Jones, for allowing me to use it in illustrating this book.

For the second time, a manuscript of mine has been read by my old friend Professor David Howell of the University of York. His extraordinary learning and attention to detail have both saved me from many errors and much enriched my knowledge on matters ranging from trade union elections to the goal-scoring exploits of Plymouth Argyle. The Dictionary of Labour Biography is in the best of hands. My MS was also read by my daughter Katherine, and she too was immensely helpful for her insights both as a civil servant and as a young person.

I am also much indebted to Alison and Owain Morgan for generously giving me material on and insights into the career of Isaac Foot, whose life they have published with Michael; Chris Ballinger of Brasenose College, Oxford, for great help with the more recent National Archive records; to my colleague at Queen’s, Nick Owen, for giving me material on Indian politics in the thirties; to Clive Saville for sending me fascinating information on his time with Michael Foot in Whitehall; to my old friend Professor Dai Smith for material on Raymond Williams, whose biography he is writing; to another old friend, Professor Roger Morgan, and to John Allinson for sending much helpful information on Leighton Park School; to an almost lifelong colleague, Professor Wm Roger Louis, for help at the Harry Ransom Center, Austin, Texas; and to Dr Peter Gaunt, Professor John Morrill and Dr Stephen Davies for informing me about the Cromwell Association. I have also benefited from the learning of Dr James Ward and my Lords colleague Ted Rowlands for guidance on Dean Swift. Indeed the companionship of many gifted and humane colleagues in the Lords has been a boon beyond measure, since I have had expert advice from Bhikhu, Lord Parekh, on Indian affairs, from Bill, Lord Wedderburn, on the complexities of labour law, and from Trevor, Lord Smith of Clifton, with shrewd thoughts on many matters from the benches of the Liberal Democrats. Anne-Marie Motard of the University of Montpellier has always been a reassuring force. My literary agent, Bruce Hunter, has been friend and wise adviser as for decades past, and my editor at HarperCollins, Richard Johnson, has made my first experience with that great publishing house quite delightful, as has my wonderful copy-editor, Robert Lacey. Since one of my unfortunate common experiences with Michael Foot is to have been the victim in a serious car crash, in my case in 2004, I would also like to thank Professor David Murray of the Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, Oxford, for restoring me physically (twice).

Most authors owe much to their families. Partly through adversity, ours is closer than most. I am hugely grateful to my two amazing children, David and Katherine, for their love, moral support, knowledge of word processors and unfailing enthusiasm for their obsessive bookish father; to my lovely daughter-in-law Liz, another writer in the making; and to my little grandson Joseph, a free-thinking, free-walking radical to whom this book is dedicated. This is my first big book since 1973 in which my beloved late wife, Jane, played no part. Yet maybe she was present after all. In 1987, at the parliamentary launch party of my book Labour People, one of the politicians dealt with there (very favourably) ignored the publishers’ invitation. He also ignored us in the Commons corridor as we approached the terrace room. By contrast, Michael Foot had replied at once, and made a very warm and witty speech at the event. ‘No surprise there,’ said Jane with finality. ‘Michael Foot is a gentleman.’ As always, she was right.

KENNETH O. MORGAN

Long Hanborough,

May Day 2006

1 NONCONFORMIST PATRICIAN (1913–1934) (#ulink_645d4388-ba61-5dbf-a6bc-293947bdb611)

On a fine sunny evening on 14 July 2003, the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, hosted a reception in Downing Street. But this was a New Labour event with a difference. It was attended not only by the predictable great and good of the British Labour movement and the associated media, but also by a rich variety of rebels and dissenters, veterans of CND, Tribune and Troops Out, a representative sample of those people that the historian A. J. P. Taylor had christened, in a famous book in 1957, Britain’s ‘troublemakers’. They were there to honour a frail old man of almost ninety, compelled to be seated but full of life and nodding his head in synchronized animation. This was Michael Foot, an almost legendary icon on the Old Left, one-time leader of the Labour Party, long-term oppositionist parliamentarian, editor and essayist, pamphleteer and man of letters, a scourge of Guilty Men in high places ever since he first made his name in that famous wartime tract published just after Dunkirk, sixty-three years earlier. This reception was merely the most spectacular of many events designed to make July 2003 a month of celebration of Michael’s latest landmark. That same week there was to be a massed gathering of his friends at his favourite Gay Hussar restaurant in Greek Street, Soho, at which the eminent journalist Geoffrey Goodman presided and Michael was awarded a shirt of his beloved Plymouth Argyle football team bearing the number 90 on its back. He had, he was told, been formally registered as part of the Argyle squad with the Football League, perhaps to reinforce his team’s left-wing attack. The following week there was another reception in the very epicentre of the establishment, this time the Foreign Office in Carlton Gardens, genially presided over by the Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, Member for Blackburn and successor and protégé of Michael’s old comrade and love, Barbara Castle. He described how Michael had made in the House of Commons in 1981 the finest speech that he, Straw, had ever heard.

But the evening in the Downing Street garden on 14 July, Bastille Day appropriately, was the highlight. It was set, as Foot would have particularly appreciated, in a place steeped in history, where the newly elected Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee had convened his excited ministers in 1945 and Lloyd George’s ‘garden suburb’ of private advisers had once conducted intrigues and manoeuvres from temporary huts set amongst the flowerbeds. People wondered what Tony Blair himself might say about so traditional and committed an Old Labour stalwart. In fact his speech was charming, generous and relaxed. He recalled Michael’s dedication to human rights (though not to socialism), and paid especial tribute to his strong backing of the young Blair’s effort to become candidate for the Sedgefield constituency in 1983 – a reflection no doubt of Foot’s positive response to Blair’s early campaign in the Beaconsfield by-election in 1982, and also perhaps of his determination to ward off the selection of a hard-left Bennite, Les Huckfield. Michael, in response, spoke at much greater length and with less precision, although, to the joy of some present, he did manage an amiable throwaway reference to George Galloway, a far-left socialist shortly to be expelled from the Labour Party for his support for Saddam Hussein. The whole occasion was entirely relaxed and enjoyable, Old and New Labour as one, poachers and gamekeepers drinking in common celebratory cause. Vocal protests from demonstrators outside in Whitehall directed against Downing Street’s later visitor that evening, Israel’s Prime Minister Ariel Sharon (with which many in the garden sympathized), were satisfactorily inaudible. As they left, people commented on how relaxed Tony Blair looked even at a time of pressure during an inquiry by the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee into the origins of the invasion of Iraq four months earlier. This was made especially difficult by the embarrassed evidence from the government scientist, arms expert and apparent whistle-blower, Dr David Kelly. Honouring Michael Foot, himself a vocal critic of the Iraq war, meant for the moment the burying of hatchets all round.

Four days later, the birthday bonhomie disappeared. The body of the tormented David Kelly was discovered in woodland at Southmoor, near his home in southern Oxfordshire. Suicide was suspected. Angry friends accused Tony Blair of indirect complicity. Foot’s birthday party was to prove almost the last happy evening that the Prime Minister would know for many months to come. The shadow of Kelly and the other consequences of the Iraq venture would haunt him right down to the general election of May 2005, which saw Labour’s majority fall by almost a hundred. But whatever these events meant for Tony Blair, they were perhaps not a bad symbol for the career of Michael Foot – loyal acclaim from the party, genial genuflection from the establishment, but an underlying background of conflict, tension and tragedy throughout the near century of which he was chronicler and survivor.

This unique combination of elitism and dissent went right back to Michael Foot’s ancestral roots. His family and forebears shaped his outlook and style more than they do for many public figures. More important, he himself believed that their influence was decisive, and often paid testimony to their historic importance, by word and by pen. It was a background of West Country dissent that dated from the historic conflict between Crown and Parliament under Charles I. Cromwell was very much the people’s Oliver for the tenant farmers and craftsmen of Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. But it was also a tradition of patriotic dissent, of dissent militant. Francis Drake was an earlier hero for the community from which the Foots had sprung, his freebooting illegalities discounted amidst the beguiling beat of Drake’s Drum. In August 1940 Isaac Foot, Michael’s father, was to give a famous broadcast, ‘Drake’s Drum Beats Again’, comparing the little boats at Dunkirk with Drake’s men o’war. Similarly it was Cromwell the warrior whom Michael and all the Foots celebrated – the victor of the battles of Marston Moor, Naseby and Dunbar, the man who supported the execution of his king and conducted a forceful, navy-based foreign and commercial policy – quite as much as the champion of civil and religious liberties. It is not at all surprising that Michael, ‘inveterate peacemonger’, unilateralist and moral disarmer, should also brandish the terrible swift sword of retribution in the Falklands and in Croatia and Bosnia later on. Like the legend of John Brown’s body, his prophetic truth would go marching on.

The Foot dynasty of Devon were robust specimens of West Country self-sufficient artisans. In the main they were village carpenters and wheelwrights, working on the Devon side of the river Tamar which separates that county from Cornwall. On balance, the Foot dynasty were Devonian English, indeed very English, not Brythonic or Cornish Celts. The earliest traced of them is John Foot, who is known to have married Grace Glanvill in the Devon village of Whitchurch, near Tavistock, on 21 October 1703. Then came successively Thomas Foot (born 1716), another Thomas Foot (1744–1823), John Foot (1775–1841) and James Foot (1803–58), all resident in the hinterland of Plymouth, all Methodists subscribing in their quiet way to that city’s tradition of vibrant nonconformity, and with folk memories of Plymouth’s role as a bastion of parliamentarianism, almost republicanism, during the civil wars of the 1640s. Men recalled the siege of Plymouth during those wars, and the citizens’ proud resolve not to be starved by the royalist armies into surrender. There was a permanent monument to it in Freedom Fields, close to the later home of Isaac Foot and his family. The man who really established the Foot tradition and mystique was Michael’s grandfather, the elder Isaac (1843–1927).

(#litres_trial_promo) A carpenter and part-time undertaker by profession, he moved to Plymouth from Horrabridge in north Devon, reportedly with just £5 in his pocket. He built his own house, branched out as a small entrepreneur and as such took a more public role in the civic life of Plymouth. A passionate Methodist and teetotaller, he was anxious to civilize the somewhat turbulent seaport in which he lived, and left as his legacy a Mission Hall in Notte Street, near the city centre, which he himself had financed and built, along with Congress Hall for the Salvation Army. His son, the younger Isaac (1880–1960), began life with clear expectations of a professional career. He qualified as a solicitor, and after a brief period in London was articled to a solicitor back in Plymouth, married a Scots fellow Methodist, Eva Mackintosh, in 1904, set up his own firm of solicitors, Foot and Bowden, in the same year, and moved to live in Lipson Terrace, a comfortable upmarket road in the northern part of the town. It was in this secure bourgeois enclave that the seven children of the Foot dynasty were born.

Isaac Foot, Michael’s father, was the sixth of eight children, of whom five were to live to a considerable age.

(#litres_trial_promo) He was a memorable personality of dominating influence. As its patriarch, he was passionate in his defence of the Foot family. When he wrote to congratulate Michael on a fine maiden speech in Parliament in August 1945, at the same time he condemned Churchill for not appointing his other son Dingle to the Privy Council after his service at the Ministry of Economic Warfare: ‘I shall never forgive him for that. Now the Foot family move to the attack. When folk attack the Foot family, they are biting granite.’

(#litres_trial_promo) His outlook and lifestyle were challenging and highly individual. Of all the seven children of this Liberal patriarch it was Michael who was said most to resemble him. Until his nineties Michael would readily turn to his father’s views on politics and literature, on Cromwell or Napoleon, on Swift or Hazlitt or Burke, to bolster his own line of argument. Isaac Foot had been a radical youth, and at the age of eighteen was attracted to H. M. Hyndman’s Marxist party the Social Democratic Federation (SDF),

(#litres_trial_promo) but not for long. He was one of many young professional men stirred by the Liberal landslide victory in the general election of January 1906, when both the two Plymouth seats were captured by Liberals from the Conservatives. In 1907 he was elected a Liberal councillor and rose to become Deputy Mayor in 1920, at hand to take an enthusiastic part in the celebrations of the tercentenary of the sailing from the city of the Mayflower. He was basically an old Liberal, committed to the traditional battles with the bishop, the squire and especially the brewer. He shared to the full the nonconformist crusade for civic equality which made Devon, Cornwall and (to a lesser degree) Somerset more similar to the political outlook of rural Wales than to the rest of southern England. But Isaac responded very positively also to Lloyd George’s social radicalism, his ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909 with its new taxes to pay for social reform, which the Lords rejected, and the successful battle with the Upper House in 1909–11, resulting in the passage of the Parliament Act. Despite the huge Liberal schism created later by the ‘coupon election’ in December 1918, when Lloyd George and his followers continued in coalition with the Unionists (Conservatives), the Welshman remained something of a Foot family talisman from then on. Isaac Foot actually stood for Parliament in January 1910 as Liberal candidate for Totnes, but was heavily defeated by the Conservative. He stood again in December 1910, this time for Bodmin, a seat held by another Liberal the previous January by the slender margin of fifty votes, and was defeated there by an even narrower margin, just forty-one votes. The turnout was 86.6 per cent in this traditionally hard-fought seat, and Foot stayed on as candidate.

During the war he was among those numerous West Country Liberals who took the side of the fallen Asquith after Lloyd George had ousted the Prime Minister in a putsch involving leading Conservatives and press men like Max Aitken (soon to become Lord Beaverbrook) in December 1916. Isaac Foot had in any case been a strong critic on libertarian grounds of the conscription measure passed by the Asquith coalition that May, and defended many conscientious objectors in tribunals during the war. This was not popular, and ensured his heavy defeat in a second contest for Bodmin in the general election of December 1918; he also failed in a by-election in Plymouth in 1919, after which the successful Conservative candidate Nancy, Lady Astor became the first woman MP to take her seat in Parliament. But Isaac hung on, and eventually won Bodmin in a by-election in February 1922 with a strong majority of over three thousand. He held on to the seat in the general elections of 1922 and 1923, lost in 1924 and was returned again to represent the same constituency in 1929 and then in 1931 when (from 3 September) he served in Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government as Minister for the Mines.

Isaac Foot was in every sense a prominent figure in the political and civic life of Plymouth and the West Country. In all he fought Bodmin seven times, and established himself as a powerful politician of charisma and pugnacity. As an orator (and later a broadcaster) he was remarkable, drawing from his lay preaching in Cornish chapels a revivalist style and a vivid vocabulary with which righteously to smite the opposing Philistines. In the 1930s he was to become Vice-President of the Methodist Conference. But for all his devout Methodism and moralism, he showed little compunction in using fair means or foul to make his political points. ‘He fought with the gloves off,’ was his son’s later reflection. He threw himself into electioneering with gusto, taunting the Tories such as the Astor family interest in Plymouth with popular refrains such as ‘Who’s that knocking at my door?’. He was a fund of political and other jokes, and was liable to break into comic songs, sung in a rich Devonian accent.

He showed himself to be equally forceful in following one of his main private interests, the Cromwell Association, of which he was a founder member and which he served as secretary from 1938 and chairman until 1951. Here he would staunchly defend Oliver’s reputation and integrity against all comers. There is reference to Isaac on the monument unveiled in 1939 to mark Cromwell’s great victory at Marston Moor in 1644. Here indeed, as Michael Foot was to describe him, was ‘a Rupert for the Roundheads’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Episcopal opponents were particularly relished. On 20 February 1949, in his seventieth year, Isaac had a ferocious duel in the Observer with the Bishop of London, who had dared to impugn Cromwell’s reputation as a champion of liberty and toleration. Isaac swept the charges contemptuously back in his face. The Bishop’s accusation that Cromwell had condemned prelacy was, however, joyfully endorsed.

(#litres_trial_promo) Isaac flung at him one of Cromwell’s contemporaries, who scorned

You reverend prelates, clothed in sleeve of lawn

Too meek to murmur, and too proud to fawn

Who, still submissive in their Maker’s nod

Adore their Sovereign and respect their God.

In Isaac’s mind, old flames of controversy over tithe, church rate, university tests or Welsh disestablishment still burned fiercely. Cromwell’s reputation went through many vicissitudes over the centuries, from Whigs hailing the champion of parliamentary liberties, to Victorians who saw his Major-Generals as the last refuge of military rule in Britain, on to working-class radicals who revered ‘the People’s Oliver’. For Isaac, Cromwell was simply the great liberator, Milton’s ‘chief of men’, in peace and in war. In 1941 he published with Oxford University Press Cromwell Speaks!, a compendium of militant and patriotic quotations from the great man’s letters and speeches, to help in sustaining the national morale at a time of supreme crisis. His Cromwell Association made a point of honouring their hero’s statue on Cromwell Green in front of the Palace of Westminster, a memorial which had been bitterly attacked by Irish MPs in the 1890s. Isaac Foot was a true believer. He celebrated Cromwell and Milton in the same passionate vein as another Liberal politician, the late-Victorian man of letters Augustine Birrell, did in his 1905 biography of Andrew Marvell. John Gross has written that, for thousands of old Liberals, ‘the seventeenth century was alive with an intensity that now seems hard to credit’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It might have been Isaac – indeed all the Foots down the generations – that he had in mind.

Michael fully inherited this Cromwellian creed, without the roundhead puritanism. Like his elder brother John, he later became a Vice-President of the Cromwell Association, and he gave an eloquent address to it on 2 September 1995, in part a tribute to his father. He had assured the Chairman beforehand (surely quite unnecessarily), ‘My remarks will not be critical in any sense and would not offend members of the Cromwell Association.’ At the age of eighty-two, the ardour of the old believer was quite undimmed. A wreath was laid at Cromwell’s statue (the main theme of Foot’s speech), there were readings from the psalms and the singing of Bunyan’s imperishable hymn, so evocative to a Plymouth pilgrim, ‘He who would true valour see’. As late as September 2005 Michael attended the Cromwell Day service in the chapel of Central Hall, Westminster, and wrote warmly to the Association to convey his pleasure at the event: ‘I trust that several members of our family will be joining the Association soon.’

(#litres_trial_promo) On the other hand, he was sufficiently the disciple of his friend H. N. Brailsford to recognize fully the force behind the progressive egalitarian doctrines of the Levellers as well. Michael drew from his father not simply a cult of Cromwell, the popular tribune who brought blessings like the abolition of the House of Lords or tolerance towards the Jews, but also the need to defend his heroes with the maximum of pugnacity. When he himself entered Parliament, his father encouraged a creed of fortiter in re, not to confine his blows upon opponents to the regions above the belt, but to fight either dirty or clean as circumstances dictated, and Michael duly responded. Isaac Foot remained a keen observer of all his sons’ political progress, but Michael, who advanced from Cromwellian republicanism into a Labour Party of self-proclaimed levellers, was perhaps the most cherished of them all. Isaac would surely have endorsed Michael’s warm commendation in November 2005 of a book by his own former legal adviser, the civil rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson QC. This commemorated John Cooke, who successfully prosecuted the trial of Charles I for treason which led to the King’s execution in 1649. It was an event of which Michael Foot, humanist and opponent of capital punishment, strongly approved.

This bond between father and son was illustrated by Isaac’s splendid lecture comparing Oliver Cromwell and Abraham Lincoln given to the Royal Society of Literature in April 1944. Michael Foot’s copy of the published version was inscribed ‘To Michael with love and Cromwellian Salutations from Dad, 23 February 1945’. It seems almost as if Cromwell was a member of the family, a particularly cherished great-uncle. Dingle Foot was to recall that there were twenty to thirty busts or portraits of Oliver in their home. The Cromwellian aspect was obviously well absorbed by Michael. Lincoln, however, he found less appealing, perhaps too conservatively inclined, especially on race questions, and indeed American inspiration generally was less influential on a politician so robustly English. By far the most attractive American for the young Michael was Thomas Jefferson, not so much in his role as an American revolutionary as that of a transatlantic voice for western European enlightenment.

For all his partisanship, Isaac’s cheerful, generous personality won him good friends across a wide spectrum, and indeed these came to include the much-abused Astors themselves. He was always active in the municipal life of Plymouth, and became its Lord Mayor after the end of the war in 1945. He patronized the city’s religious and musical life, and also sporting events in football and cricket: Isaac began a unanimous Foot tradition of supporting Plymouth Argyle FC, based at Home Park and elected to the Football League in 1920. It was a family link that continued from Isaac’s vocal terrace support in the 1920s to Michael’s becoming a club director in the 1980s.

But Isaac’s main influence on his sons and daughters, and especially on Michael, lay not in politics but in books. From his early years he was, as Michael was frequently to describe him, a ‘bibliophilial drunkard’ whose appetite was ‘gargantuan and insatiable’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He had an obsession for rare and other books of all kinds, especially historical, literary and religious. His collecting began when, as a young clerk in London, he spent as much as he could of his fourteen shillings weekly pay in the second-hand bookshops of Charing Cross Road. In his later years every room in his large home at Pencrebar, even (improbably) the laundry room, was crammed full of carefully arranged and notated volumes. He would read for four or five hours every day; he would read as he walked to work, he read in his bath, he would have read in his sleep were it possible. Much of his library was sold off to the University of California, Santa Barbara, for a surprisingly low figure of £50,000 after his death in 1960,

(#litres_trial_promo) less than £1 per book. Other materials went to Berkeley and UC Los Angeles, so sadly the library was dispersed: it had expanded to perhaps sixty thousand books, including no fewer than 240 Bibles, among them priceless octavo and quarto editions of Tyndale’s New Testament of 1536, and many medieval illuminated manuscripts, along with an immense range of antiquarian works by or about Shakespeare, Montaigne (130 volumes), Milton, Swift, Pope, Johnson, Burke, Hazlitt, Wordsworth, Carlyle, Hardy, Conrad and some unexpected intruders onto the old puritan’s shelves, such as the sonnets of Oscar Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. The inventory of UC Santa Barbara library listed three thousand English Civil War tracts, over two thousand volumes on the French Revolutionary period, and over a thousand on the American Civil War, amongst his historical collection. A colossal holding on literature included over three hundred volumes on and by Milton, including first and second editions of Paradise Lost and a first edition of Areopagitica. The religious holdings were equally immense, including titles on and by Luther and Calvin, a hundred contemporary Erasmus imprints, vast collections on Richard Baxter’s Congregationalism, and a Quaker collection of more than two hundred volumes. Isaac Foot also ranged around the classics: one especially priceless book was the 1488 edition of Homer printed in Florence.

Somehow all these volumes were crammed into Pencrebar, though only just. Isaac designated a Bible room and a French Revolution room; when he developed an interest in Abraham Lincoln later in life there was an American Congress room. Many books were extremely rare, yet there was apparently the minimum of security against fire or theft. His home was a shrine to what George Gissing had called ‘the shadow of the valley of books’. So extreme was his mania for collection that A. L. Rowse, a historian at All Souls, Oxford, and no inconsiderable bibliophile himself, claimed that Isaac Foot’s second wife was in tears as one room after another was annexed for his literary stockpiling, supplemented by bookcases to occupy what little room remained. ‘He has the obstinacy of a senile fixation,’ was Rowse’s harsh verdict.

(#litres_trial_promo) But clearly for the young (and middle-aged) Michael his father’s passion for the printed word was breathtakingly exciting, the key to a civilized life. In return, Isaac delighted in Michael’s own emerging skills as a powerful writer of serious literary books. The publication of The Pen and the Sword in 1957, written after Michael had lost his Devonport seat in the 1955 general election, perhaps gave Isaac more pleasure than any other feature of his son’s career. ‘Let the boy be known for his books,’ he lovingly observed.

Isaac’s influence was profound on all his children, but on Michael most of all. Michael’s journey into the Labour Party, a unique adventure for the Foot family, did not threaten their relationship; if anything, it made it stronger. Isaac responded by offering Michael the example of Hazlitt as the supreme inspiration any real radical could ever want. He gave him a passion for language, written and spoken; Michael’s politics were politics of the book. He spelled out for the readers of the Evening Standard (1 June 1964) his philosophy of life, drawn from the critic Logan Pearsall Smith: ‘To read and to act is not achieved by many. And yet to act and not to read is barbarism.’ It was books, as much as the sufferings of his fellow men, that made Michael a socialist and nurtured his unique brilliance as a communicator. More specifically, it was Isaac who directed him to the unique qualities of Swift and Hazlitt, Michael Foot’s prime allies in his assaults on twentieth-century political opponents, his friends in good times and bad. The more measured influence of Montaigne, the cool, sceptical essayist of sixteenth-century France, but also the mentor of Foot’s hero Swift, was another legacy from Isaac when Michael turned to Montaigne’s essays in hospital after a serious car crash in 1963. Another hero was John Milton, not only a matchless poet but in Areopagitica a timeless champion of a free press.

On the other hand, Michael’s growing love of literature was self-nurtured also. Isaac’s literary enthusiasms were mainly pre-Romantic and shaped by a puritan heritage. Michael’s own passionate temperament gave him heroes of a different kind, in particular his beloved Byron, for whose poetry Isaac had no particular regard and which had been fiercely criticized by one of Michael’s own heroes, Hazlitt. Without Isaac’s affection and inspiration, Michael Foot’s career would have been far less distinctive. But it might also have been less dogmatic and he might have been more open to argument from others. Isaac’s literary giants, it seemed, were almost gods, to be treated with near-sanctity. None of them could be lightly impugned. There was also a curious formality, almost a distance, between father and son. When Isaac ran into debt as a result of his solicitor’s business being disrupted during the war when his offices in Plymouth were bombed out, quite apart from his manic book purchasing, Michael, now with a good income from the Evening Standard, loaned him successive sums of money to help him out, ranging from £110 in May 1940 to £875 in March 1941. Each was accompanied by a highly detailed formal IOU drawn up in legalistic terms by Isaac. An IOU of £2,095 up to September 1942 set out both the capital sum and the interest upon it at £4 per annum as a first charge on Isaac’s estate, a strangely formal arrangement perhaps between a father and a son.

(#litres_trial_promo) Having Isaac as a father was both an inspiration and a challenge, but without doubt he contributed most of the components of his son’s passionate but unquestionably bookish socialism.

Michael Foot’s mother, Eva Mackintosh, was also a powerful personality in her way, even if tending to be swamped at home and in spirit by Isaac’s intemperate bibliophilia. Born in 1878 and a year and a half older than Isaac, she was of Scottish and Cornish background, and a strong Methodist like her husband. Indeed, it was on a Wesleyan Guild Methodist outing that Isaac first set eyes on her. With a characteristic Foot blend of impulsiveness and caution, he proposed to her almost immediately and was accepted, but then remained engaged for three years while he built up his solicitor’s practice. They married in 1904, in Callington, a village a few miles north of Plymouth where Eva had latterly lived. It was a long and immensely happy marriage, ended only when Eva unexpectedly died in May 1946, after which Isaac somewhat disconcertingly for the family married a second time. Eva had traditional non-feminist views, which clearly extended to her two daughters, Jennifer and Sally, both of whom had somewhat restricted lives. Her son John’s egalitarian-minded American fiancée evidently found this disturbing when she first visited the Foot household.

Five of Eva’s seven children, including Michael, were given the second name Mackintosh (an allegedly useful asset when brother Dingle stood as Liberal candidate in Dundee). She wrote occasional letters to the local Western Morning News under the thinly-concealed nom de plume of ‘Mother of Seven’. Hugh Foot wrote in his memoirs of how his mother made them all laugh ‘at ourselves and at each other’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Eva was not only happy being a warm and spirited mother, but also gave every encouragement to the professional careers of her talented sons. She was thoroughly at home in a political setting, being herself a robust Liberal, and perhaps more instinctively attracted to radicalism of the Lloyd George type than other members of the family. Michael’s defection to Labour in 1934 was a shock for them all, but Eva appears to have taken the news better than some. When Michael campaigned for Devonport as a Labour candidate in 1945, a meeting was interrupted by the delivery of a large Cornish pasty from his mother, a Methodist’s material peace offering and also a signal that her socialist son was no less favoured than husband Isaac and sons Dingle and John, all Liberal candidates in 1945 (and, unlike Michael, all defeated).

The family background of the Foots is of quite exceptional importance: the historian John Vincent once called their home, referring to the Hertfordshire seat of the Cecils, ‘a West Country Hatfield’. There were five sons: the eldest Dingle (1905–78), the second Hugh (1907–90), the third John (1909–99), the fourth son and fifth child, Michael (born in 1913), and the youngest son and sixth child, Christopher (1918–84). All went on to have, to varying degrees, fulfilling professional careers. By contrast the daughters, Margaret Elizabeth, known as Sally (1911–65), and Jennifer (1916–2002), had lives that were domestically confined. Jennifer married, but Sally never did. It was a large and lively household, with much family fun and frivolity and a high degree of competitiveness in the playing of games, especially cricket and football, in which Isaac enthusiastically joined. They lived in Lipson Terrace from 1904 until in 1927 they moved to a large white Victorian manor house, Pencrebar, near Callington, some eight miles north of Plymouth, overlooking the Cornish moorland. With its ‘wide sashed windows, large rooms and wide sweeping lawns and shrubberies’, it became a focal point for West Country nonconformist Liberalism and a much-loved family home, as well as a depository for Isaac’s vast library.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was in every sense a close-knit family which made demands of all the children, but enriched them too. They all recalled a cheerful and secure childhood. Hugh noted that ‘we had and needed few outside friends’. The eldest boy, Dingle, with whom Michael had little to do at first because of the eight-year gap between them, immediately showed himself to be talented. He was thought to be the ablest Foot at the time, and Michael later considered him the funniest orator amongst them.

(#litres_trial_promo) As all the Foot boys did, he went to a private secondary school, in his case Bembridge School on the Isle of Wight, where he was taught by a former Liberal MP, J. H. Whitehouse, who was now the school’s headmaster. Dingle went on to Balliol College, Oxford, where he became President of the Liberal Club in 1927 and rose to be President of the Union in 1928, also gaining a second-class honours degree in law. He entered chambers in 1930, becoming a barrister of international distinction, and in 1931 he was elected as Liberal (though pro-government) MP for Dundee, which he represented until 1945. One problem was the physical disability of a tubercular arm. The second son, Hugh, went to Leighton Park, the famous Quaker school near Reading which Michael later attended, and then on to St John’s College, Cambridge, where he showed a notably un-Foot-like enthusiasm for the college rowing club but also became President of the Liberal Club and of the Cambridge Union. There was some fraternal joshing about his alleged relative lack of intellectual sharpness – Michael described him caustically and unfairly in the Evening Standard in 1961 as ‘never considered the brightest of the brood’. But Hugh, like his brothers, ended up with a second-class degree. In fact Michael always had a strong relationship with ‘Mac’, as Hugh came to be known, including a cheerful period as the lodger of Hugh and his wife in the later 1930s. His assessment of his brother concluded: ‘All in all a credit to the family and I can’t say fairer than that, can I?’ With Hugh’s son Paul, the friendship was to be stronger still.

John, the third son and another charming and eloquent Liberal, seemed as talented as any of them. He too went to Bembridge School and Balliol College like Dingle, took a degree in law and also became President of the Liberal Club and the Union, a remarkable dynastic achievement which Michael was soon to extend. He became a solicitor and in due time took over from Isaac as senior partner in the family firm Foot & Bowden. But his political antennae seemed no less acute than those of his two brothers, and he was four times a Liberal candidate, for Basingstoke in 1934 and 1935, and for his father’s old stamping ground of Bodmin in 1945 and 1950. Unexpectedly he failed to win the latter, and ended up as Baron Foot of Buckland Monachorum, though with a radical outlook on social and defence issues very similar to those of his firebrand brother Michael. The two were both Cromwellian enthusiasts, and were very close. Michael would say of John, ‘He was the best speaker of the lot of us.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The two daughters, Jennifer and Sally, as mentioned, were not encouraged to develop their talents, while the youngest son, Christopher, settled down, none too happily, as a local solicitor.

This was the background into which Michael Mackintosh Foot was born on 23 July 1913. It was cradle, crucible and cauldron for him. The tone was set by Isaac. It was distinguished by a passion for both literature and music (the latter less pronounced in Michael’s case until he met Jill Craigie, who introduced him to Mozart), especially Bach’s choral music, and a passionate devotion to the grand old causes of nineteenth-century Liberalism. It was an intimate family whose members kept up warm relations throughout their lives. Michael and his brothers addressed each other in letters or telephone conversations with the words ‘pit and rock’. This private code recalled a famous phrase from the Book of Isaiah: ‘Look unto the rock whence ye are hewn and to the hole of the pit whence ye are digged.’ Hugh thus communicated with Michael while serving at a tense period as Governor of Cyprus in the late 1950s. Life in the Foot family seems to have been inspiring and somewhat pressurizing at the same time, being conducted at a high level of intensity, both political and religious. One newspaper described the household as characterized by ‘bacon for breakfast, Liberalism for lunch and Deuteronomy for dinner’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

One strict rule was abstinence from alcohol until the age of twenty-one, after which the sons would qualify for a small legacy from their grandfather: Michael and John celebrated their release from this thraldom by getting drunk together on a trip to Paris, in pursuit of culture and self-liberation, in 1934. The child Michael, dominated by his three older brothers, Dingle, Hugh and John, was to find a particular kinship with his slightly older sister Sally. A major factor here was that both suffered from severe eczema – a hereditary condition, apparently – and in Michael’s case from growing asthma as well. Outdoor games were to some extent denied him, and he turned naturally to indoor bookish pursuits, where Sally was a natural mentor and guide, with her own unfulfilled artistic and literary talents which later brought friendship, for instance, with Louis MacNeice. Sally introduced Michael to novels and poems which were to stay with him for ever. He would say that she taught him how to read. His lifelong attachment to female relationships, many of a bookish kind, undoubtedly stemmed from his loyal Sally, and his posthumous essay on her, ‘Sally’s Broomstick’, is deeply felt.

(#litres_trial_promo) Her cruel death in the 1960s was a particular blow to him.

It may be that Sally’s presence was a calm refuge in an otherwise hyperactive family. One of the adverse consequences for some of the Foot family was a kind of depressive alcoholism, perhaps a reaction against the dynastic prescription of total abstinence in youth. Dingle ended his career in this sad condition, as did his youngest brother Christopher, whose life ended young, and so too did his sister Sally. Indeed, Sally’s death through apparent drowning may have been more tragic still. Christopher had to give up his solicitor’s work early through some kind of psychological illness. It was Michael, for all his mixed health, who was usually seen as the most stable and normal. So family life was not always as relaxed as when Isaac was telling his stories or Michael was organizing children’s games at parties. Keeping up with the Foots could bring its own pressures.

Every Foot from Isaac onwards showed the influence of family. All shared the unyielding attachment to books, to Cromwell and the West Country, to Plymouth Hoe and Plymouth Argyle. All in important senses remained liberal, or at least libertarian, at heart. Most were political, but with a politics fired in the crucible of Foot family argument, rhetoric and dissent. Nothing showed this continuing tradition more clearly than the sadly posthumous book The Vote by Hugh Foot’s journalist son Paul, long a pillar of the Socialist Worker and a writer of a caustic brilliance equalled only by his cherished uncle Michael.

(#litres_trial_promo) Paul was named after the favourite saint; his brother Oliver derived his name from another cult hero. Paul Foot’s book is on many fronts a debate within the family. It conducts a sporadic, if affectionate, argument with Michael in denouncing his adhesion to a right-wing, disappointingly parliamentary Labour Party. The debate would be continued towards the end of Paul’s life, blighted as it was by illness, on the pavement outside bookshops in the Charing Cross Road, with both bibliophile disputants, uncle and nephew, waving their sticks about to the occasional alarm of passers-by. Paul’s book also engages in a covert dispute with his Aunt Jill, a devotee of the suffragettes, but mainly of the Tory Christabel Pankhurst and her mother Emmeline, whereas Paul Foot (like most socialists) found the social radicalism of Sylvia Pankhurst, the lover of the Labour Party’s founder Keir Hardie, by far the most appealing.

But the most startling family argument of all for Paul was with his deceased grandfather Isaac, pillar of the Cromwell Association over so many years. Where Cromwell to Isaac (and to Michael too) was the people’s Oliver, champion of liberty, to Paul he was the establishment enemy of the Levellers, who rebutted the dangerous democracy voiced by Rainboro, Lilburne and their friends at Putney in 1647. Paul was indirectly announcing that he was the first Foot to break away from the family shibboleths, that Cromwell was no real hero for the popular, let alone the socialist, cause, and that in the earliest campaign for the vote the puritan establishment was essentially an obstacle. Those political continuities, traced by Liberals over the centuries from Putney to the Parliament Act, were in reality an illusion. Paul Foot’s was an iconoclastic book, but it was notable that it was the family’s boat that had first to be rocked, if not sunk without trace.

His uncle Michael’s early years were comfortable and elitist. The First World War made little direct impact upon him, unlike say the youthful Jim Callaghan down the coast at Portsmouth, whose father served in the navy and fought at Jutland. None of the Foots had any experience of this or any other war. Basically they had disliked every one since 1651. The dominant feature of Michael’s upbringing is the abiding stamp of loyalty to Plymouth itself It symbolized for him Britain’s worldwide mercantile glories, as well of course as embodying an eternal legend of defence against foreign conquest in the great days of Drake. Plymouth, English to its core, was not therefore the natural base for a devotee of European integration. In 1972 Michael spoke strongly in support of his Conservative successor as MP for Devonport, Joan Vickers, in resisting proposals in Peter Walker’s Local Government Bill to merge Plymouth with the surrounding area. There was, declared Foot, a ‘deep lack of affinity between Plymouth and the County of Devon’. In family vein, he went on:

Charles I tried to subdue Plymouth and failed, and Freedom Fields is a monument which bears that out. Charles II tried to subdue the people of Plymouth by establishing a citadel with the guns facing not seawards towards Plymouth sound but inwards, but he, too, failed.

Foot had the joy of representing Devonport in that city for ten years in Parliament, from 1945 to 1955, and hung on as a predictably unsuccessful candidate in 1959, a decision that Aneurin Bevan declared was ‘quixotic’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Well into his nineties, journeys with his friend Peter Jones to see Plymouth Argyle do battle at Home Park were a staple of life. Contact with his private secretary, Roger Dawe, at the Department of Employment in 1974 was greatly eased by the latter’s Devonian and Methodist origins, and his being a fellow Argyle supporter.

During the First World War the Foots moved to Ramsland House in St Cleers, on the edge of the Cornish moors. But Michael always identified intensely with Plymouth, the city which was his boyhood home, where his father was Lord Mayor and where he fell in love with Jill. And to a degree Plymouth identified with him, indeed with all the Foots. David Owen, a future Cabinet colleague and Member for Devonport, grew up there in the fifties under the shadow of the Foots as a dominating dynasty. In the 1970s Michael and Jill, somewhat remarkably, managed to persuade the local authority in Hampstead to rename their road Pilgrims Lane, in tribute to his native city’s most famous exports, and the nickname also of its football team. In later life he would recall happy episodes from his childhood, such as visits to the Palace Theatre. One such recollection became memorable, when in a Commons debate in October 1980 during Labour’s leadership election he spoke of a conjuror who smashed with a hammer a gold watch belonging to a member of the audience, but then forgot the rest of the trick. But it remains open to conjecture how far this was a real Plymouth, or rather an affectionate amalgam of fact, legend and folk memory, specific and selective associations from the Armada to the Blitz, ready for instant political mobilization in argument. Michael Foot’s historical reading and personal background formed a highly usable background. This was true of all his interpretations of past scions of the liberty tree, from the Levellers to the suffragettes, and it applied equally to his vision of a post-modernist Plymouth.

That does not mean, of course, that his childhood memories were necessarily entirely benign. Michael’s schooling was delayed by his severe asthma in 1919, which led him to go to London at the age of six to obtain medical advice. Indeed, his awareness of ill-health and fear of being thought unattractive were important threads in his early years: a robust life into his nineties was not what the doctors might have predicted. His first school in 1919 was a local preparatory school, Plymouth College for Girls, perhaps not a total success for a six-year-old boy. In Recitation, his school report commented, ‘His expression is very good; he should speak out more’ – seldom an injunction needed in later life. Another subject was Needlework – ‘Good, but he works too slowly.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In 1921 he went on to Plymouth College and Mannamead School. Going there was not without its hazards, especially being harassed by local bullies as he made his way across Freedom Fields. In 1923, at the age of ten, he went away to a private boarding school, Forres, in Swanage on the Dorset coast. His brother John was already a pupil there. Michael’s progress was often interrupted by bronchial complaints; nor did the school’s occasional penchant for caning its pupils (including Michael himself for one alleged misdemeanour) appeal to him. But he seems to have developed well, and his headmaster, R. M. Chadwick, wrote enthusiastically when he left Forres in 1927 of the immense contribution he had made, and how his name should be inscribed on the school Honours Board. He was first in his form in every subject from Latin to Scripture, while he had also done well in sport as captain of games – ‘a very good example of all-round keenness’. An earlier report at Christmas 1926 had commended his football skills – ‘Fast and a very good shot at goal. Much more determined than he was last season.’ The headmaster added in his final remarks, ‘We have all grown very fond of him during his time with us and he will leave a big gap. We look forward to making Christopher’s acquaintance next term.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The fourteen-year-old Michael’s next destination was another private school, Leighton Park, the Quaker boarding school near Reading which his older brother Hugh had already attended (as a scholar, unlike Michael). Founded in 1890, Leighton Park was an elitist school in its way, and was sometimes referred to as ‘the Quaker Eton’. Years later A. J. P. Taylor told Lord Beaverbrook, ‘Michael had been educated at Leighton Park, the snob Quaker school, and I at Bootham [York], the non-snob one.’ Beaverbrook gleefully responded (ignoring Taylor’s extremely wealthy cotton-merchant father), ‘You and I are sons of the people. Michael is an aristocrat.’

(#litres_trial_promo) But Leighton Park had much cachet amongst nonconformists in both England and Wales. Its liberal Quaker ethos meant that there was no fagging, no corporal punishment and certainly no cadet corps. Its historian, Kenneth Wright, wrote that it was ‘an unconventional school producing unconventional people who did not fit into predetermined moulds’. It attracted droves of liberal Cadburys from Bourneville and liberal Rowntrees from York, putative pacifists one and all. Michael seems to have found both the teaching and the atmosphere of the school generally congenial. Later on in life he was fiercely to denounce the public schools in the Daily Herald for their atmosphere of snobbery, but clearly Leighton Park escaped this particular contagion. Its school magazine, The Leightonian, gives at that time a cheerful sense of irreverent informality.

At first Michael’s schooling was much interrupted by ill-health. His return for his second term in 1928 was delayed by impetigo and bronchial problems, while his weight was relatively slight. But he soon got into his school subjects with gusto – or at least into those parts of the work which interested him. These clearly did not include a great deal of science. By the spring term of 1928 his science teacher lamented that ‘he has not much aptitude for this subject’ (chemistry). Physics was adjudged to be no better. A year later, science of any kind has disappeared from his schooling, a not untypical instance of the secondary education of the time. By contrast, his mathematics was highly praised for arithmetic, algebra and geometry, with marks in the high eighties in each. But by the end of 1929 that also has vanished from his ken. Michael Foot was never a particularly numerate politician. By contrast, the humanities were going well, especially all kinds of literature, and history, for which he had a fine Welsh teacher. His parents were also pleased to see that he scored 92 per cent in scripture in the summer term of 1928. In the spring term of 1930 his report praised the ‘mastery’ he demonstrated in a paper on the Italian Risorgimento (surely a particularly congenial theme for a romantic young radical), while in European history generally he was thought to be working with ‘considerable intelligence and interest’. The one weakness in his work on humanities subjects appeared to be modern languages. Neither in French nor in German did he distinguish himself French lessons in the spring of 1930 showed that ‘his vocabulary is weak’, and he scored a mere 37 per cent.

(#litres_trial_promo) Surprisingly for a man with such a quick and adaptable mind, this remained a weak point throughout his life. He was never a confident linguist; he gloried in the novels of Stendhal and the poems of Heine, but he read them in translation. But in that he was typical of the political generation of his time. He got his School Certificate with honours in 1930, and his Higher School Certificate a year later.

Leighton Park in general seems to have been very good for the teenage Michael Foot academically, and he also flourished in other ways. He was an active member of School House, and in 1930 he became a school prefect. The Leightonian records several of his other activities. He played a role in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance as Sergeant of Police. An old boy of the school wrote that ‘Foot’s performance will go down in the school’s history’: the audience got him to sing one of his songs three times, and ‘in each encore he was even funnier than before’. Despite his asthma and eczema he took his full part in school games, and was commended on his performances as a wing forward in the first rugby XV (‘his dribbling is his best feature’, though his tackling was also sound) and especially at cricket – ‘a good forceful batsman, an excellent cover point fielder and a good bowler who keeps a steady line’. He took six wickets for twenty runs against Bedales, and topped the school bowling averages in 1931, with fifteen wickets at an average of 10.73 apiece.

(#litres_trial_promo) Years later he was to demonstrate his cricketing skills when playing for Tribune against the New Statesman: the latter’s captain and political correspondent, Alan Watkins, came to realize that asking his fast bowlers to be charitable to an amiable old gent was a big mistake. Tennis and rugby fives were other games at which he represented the school. He also began to display talent in the school debating society, which he restarted, and took part as the Liberal candidate in the school mock election on 30 May 1929. He won with fifty-six votes, against thirty-eight for the Conservatives and eleven for Labour – a more substantial majority than he ever gained at Devonport, and one of relatively few Liberal victories that year.

This was a time of much political energy in the Foot household. Their new home in Pencrebar became a significant salon for West Country Liberalism, with Lloyd George himself a visitor. The young Michael Foot was heard to deliver impromptu speeches to garden parties even at the tender age of twelve. Past divisions between Coalition and Asquithian Liberals set aside, the Foot household campaigned en bloc on behalf of Lloyd George’s last crusade in the 1929 election with its famous Orange Book to promote economic recovery, We Can Conquer Unemployment. The Liberals’ eventual tally of seats was a mere fifty-nine, and Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister for the second time, Labour ending up with 289 seats, the largest number in the House. But there was much joy with the return of Isaac again for Bodmin, though with a majority of less than a thousand over Gerald Joseph Harrison, the Conservative who had defeated him in 1924. Isaac took a prominent front-bench role in the new House, and was appointed as a Liberal member of the Round Table conference on India in 1930. Michael’s elder brother Dingle had also made his first attempt on Parliament, but was defeated by a Conservative in Tiverton, despite polling over 42 per cent of the vote. Hugh was now entering the diplomatic service, and would soon embark on a long connection with the Middle East by serving in Palestine. The schoolboy Michael, a vigorous campaigner for Lloyd Georgian Liberalism in 1929 with its multi-coloured cures for economic stagnation, the Green, Yellow and Orange Books, yielded to none of them in the passion of his political commitment. Lloyd George’s battle hymn, ‘God gave the Land to the People’, was a very popular song at Pencrebar. It was always one of Michael’s favourites, next to ‘The Marseillaise’ and ‘The Red Flag’. In The Leightonian (March 1931) he set out his Liberal creed in idealistic terms: ‘The Liberal Party alone had the courage to think out new schemes and the men of vision to put them into effect … It wages a war for liberty, justice and the abolition of poverty.’ The party was no meek middle way, but ‘possesses ideals, unshared alike by Tories who are a little sentimental and Socialists who are a little timid’.

The most distinctive feature of Michael’s political involvement at this time was in the peace movement. This was hardly surprising for a pupil of Liberal background attending a distinctively Quaker school. Leighton Park’s headmaster, Edgar Castle, was a Manchester Guardian reader and a strong supporter of world disarmament. A League of Nations branch flourished at the school, in which Foot was active. He wrote in The Leightonian (March 1931) a sharp critique of scouting as an activity for young people. Its specious militarism and patriotism, and the unquestioned authority of the scoutmaster, were appropriate targets for the seventeen-year-old boy: ‘Scouting must not, hermit-like, shut itself off from the modern world.’ He added one phrase intriguing for the student of his career: ‘We are not meant to play at backwoodsmen all our lives.’

At the age of eighteen, between 7 August and 4 September 1931, in the summer vacation after his last term at Leighton Park, Michael made his most decisive, emphatic gesture yet by taking part in a young people’s peace crusade that took him abroad for the second time (he had had a trip to Holland in May 1931). He went with another boy, L. H. Doncaster, on a John Sherborne bursary which covered all the costs save for £10. They travelled as far as Colmar in Alsace, sleeping rough on ‘a bed of straw in the village schoolroom or a haystack in the cowshed’, though making only limited contact with the other marchers, who were entirely French-and German-speaking. They sang collectively a French song, ‘Nous faisons serment d’alliance’, the words of which were fresh in Michael’s mind seventy-five years later. He paid tribute to their one mobile assistance, a donkey who discharged his duties ‘in a manner which would have put Balaam’s ass to shame’. Michael pressed on to Strasbourg and then to Germany, to the Black Forest. Here, for the first time, he heard the name of Adolf Hitler. It was virtually a holiday, but he enjoyed ‘a pervading sense of self-righteousness’, for all this was done in the cause of peace. The child was father of the Aldermaston marcher. He had enjoyed his schooldays, and his school seemed pleased with its association with him. In the late 1940s the brass plate from his time at Leighton Park was still on display on the door of his old study in School House. In 1990 he spoke at length, wallowing in happy nostalgia, at a school centenary dinner in a private dining room in the Commons. He remained a faithful Old Leightonian to the end.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The decisive change of life for the young radical was to come in 1931, when he followed Dingle and John in becoming an undergraduate at Oxford. This had long been a cherished ambition for Isaac, despite the considerable sums he was obliged to pay for Dingle, Hugh and John at the older universities. Michael at school showed a quick intelligence and literary flair, especially in his history essays. But his teachers’ assessment of his abilities was sufficiently cautious that he was sent forward for entrance examination not to Balliol, the destination of Dingle and John before him, but to the less prestigious Wadham in the same college group, where the competition for places might be less demanding. He took papers in his favoured subjects of Modern History and English, but his greatest good fortune came in his general paper, in which a question asked candidates what proposals should be made by the current Round Table conference in London considering the future governance of India. As noted, Isaac Foot was himself a Liberal member of that conference, with first-hand knowledge of the views of Gandhi and others on India’s future. The night before he sat the paper Michael had had dinner with his father at the National Liberal Club in London, and Isaac had given him a lengthy briefing on future proposals for an Indian federation, along with discourses on the social and economic problems of Indian Untouchables and others. Michael’s examination answer in Oxford the following day was therefore unusually authoritative. His interview with Wadham’s tutors went equally well, especially a discussion with Lord David Cecil, then at the college. Asked by Cecil which historians he particularly admired, Foot naturally shone. His enthusiastic defence of Macaulay’s History of England, reinforced by some additional warm comments on Macaulay’s kinsman George Otto Trevelyan, saw him comfortably home, a college award-holder as an exhibitioner.

(#litres_trial_promo)

So it was to Wadham that he went for the Michaelmas term in October 1931. He stayed for the next three years, the first two years in college, the third in lodgings in the city with his close friend John Cripps. It was a dampish house quite near the river, which did not improve his asthma. Foot’s devotion to his remarkably beautiful college henceforth was unshakeable. Half a century later, in his volume of essays Loyalists and Loners, he hailed it as ‘of all places the greenest and most gracious, the peerless and the most perfect in the whole green glory of Oxford’. Wadham’s virtues were innumerable: it was founded early in the seventeenth century by a woman, Dorothy Wadham, it nurtured the philosophical learning of John Wilkins, the seamanship of Robert Blake, the church-building of Christopher Wren, it spanned almost every aspect of Michael Foot’s intellectual universe. He later became friendly with its formidable future Warden Maurice Bowra, famous for epigrams such as ‘Buggers can’t be choosers.’ Bowra was no socialist, but he shared Foot’s eclectic antiquarianism. On one bizarre occasion in August 1962 he tried to act as a kind of peacemaker between Foot and the Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell when they found themselves, perhaps to their mutual horror, in the same bar in the small Italian town of Portofino, but Gaitskell’s enmity was implacable.

(#litres_trial_promo) No honour pleased Foot more than to be elected an Honorary Fellow of the college in later years. Michael Foot was a supreme Oxford man, but also passionate for the collegiate atmosphere of his college. Dorothy Wadham was so admirable a woman that, in his whimsical view, had she lived centuries later she would have applied for membership of the Labour Party.