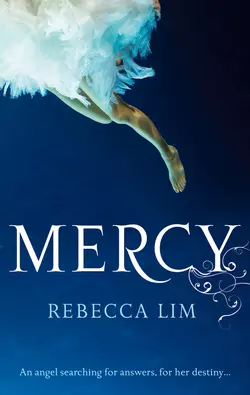

Mercy

Rebecca Lim

An electric combination of angels, mystery and romance, MERCY is the first book in a major paranormal series.There's something very wrong with me. I can't remember who I am or how old I am, or even how I got here. All I know is that when I wake up, I could be any one. It is always this way.There's nothing I can keep with me that will stay. It's made me adaptable.I must always re-establish ties.I must tread carefully or give myself away.I must survive.Mercy doesn't realise it yet, but as she journeys into the darkest places of the human soul, she discovers that she is one of the celestial host exiled with fallen angel, Lucifer. Now she must atone for taking his side. To find her own way back to heaven, Mercy must help a series of humans in crisis and keep the unwary from getting caught up in the games that angels play. Ultimately she must choose between her immortal companion, Lucifer, and a human boy who risks everything for her love.

MERCY

REBECCA LIM

To my husband, Michael Liu, who makes it all possible.

With love always.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u55389a2b-dd97-5ee4-9026-4eba3b13a1d3)

Title Page (#u47ea2a6b-b51c-5e02-81cf-ee488227431c)

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1 (#uf14ace35-235b-5e8b-abfc-ed954e44dd79)

There’s something very wrong with me.

I can’t remember who I am or how old I am, or even how I got here. All I know is that when I wake up, I could be any age and anyone, all over again. It is always this way.

If I get too comfortable, I will wake one morning and everything around me will have shifted overnight. All I knew? I know no longer. And all I had? Vanished in an instant. There’s nothing I can keep with me that will stay. It’s made me adaptable.

I must always re-establish ties.

I must tread carefully or give myself away.

I must survive.

I must keep moving, but I don’t know why.

I am my own worst enemy; that much I’ve figured out.

You know almost as much about me as I do.

I look sixteen. Sometimes I even feel it.

Me? The real me? I’m tall. Though I only have a sense of that.

I’m pale, like milk, but I never get sunburn. Don’t ask me how I know this, seeing as I don’t seem to occupy any physical space at the present time, but I just know.

My hair is brown. Not a nice brown or an ugly one, just brown. It’s weird, but it has no highlights. It’s all the same colour, every single strand straight, even and perfectly the same. It hangs down just past my shoulders and frames my face nicely, which is oval and okay, I suppose. I have a long, straight nose, lips that are neither too thin nor too wide, and perfect eyesight. I can see for miles, through sunshine or moonlight, rain or fog. Oh, and my eyes? They’re brown, too. And I never feel the cold, ever.

When I look in the mirror, I see this face—mine, I have learnt to recognise it, a palimpsest of a face, a ghost’s face—within another’s, a stranger’s. Our reflections co-existing. I am her and she is me, and we, together, inhabit the same body.

How is this possible? I do not know. We are two people with nothing in common, nothing that ties us together, except that I am currently the reason she—whoever she is—can talk and move and laugh, go through the very motions of her life. I am like a grave robber, a body-snatcher, an evil spirit. And she? My zombie alter ego who must do as she is told.

If I think hard about myself, really hard, I get the one word: Mercy. It’s what I’ve taken to calling myself for want of something better. It might even actually be my name, but your guess is as good as mine.

My only real solace? Sleep. In the absence of an explanation for anything, for everything, I live for it and what it can bring.

Though I seem continually reborn, in this fogbound life I still have a kind of compass, a touchstone. He reminds me to call him Luc and appears to me only in my dreams.

His features are more familiar to me than my own. For I have traced them in my head and with my heart, such as it is. And perhaps once—though memory can be a treacherous thing—even with my hands when they were real, made of flesh and bone and blood and not of the insubstantial air.

He has hair of true gold cropped close, with sleek, winged brows of a darker gold, pale eyes, golden skin. He is tall, broad-shouldered, snake-hipped, flawless as only dreams can be. Like a sun god when he walks. Save for his mouth, which can be both cruel and amused. He tells me not to give up, that I must keep searching, find him. That one day it will all make sense. And all this? Will have seemed merely a heartbeat. An inconvenience.

‘I am only a little ahead,’ he laughs as we sway together on a narrow precipice, high above a desert valley floor, the whole sleeping world spread out before us. ‘A little ahead.’

His hand is steady beneath my elbow. If he were not here, I would surely fall, and even in dreams, die. Though my true name always eludes me—like him, it is always just a little ahead—my fear of heights does not. Why this is, again, I do not know.

As always, Luc warns of others looking for me: his erstwhile brothers, eight in number. That if They find me, They will destroy me. And that save for him, They are the most powerful enemies one may have in this world.

‘If They catch you,’ he cautions, ‘They will surely kill you. And that, my love, is no dream.’

He whispers these awful-beautiful things with his familiar half-smile, before light seems to bleed from him for an instant. Then he is gone.

I wake with his warnings in my ears.

I wake now, sitting upright in the back of a bus packed with screaming, gossiping girls in matching school uniforms.

As I look down at the grey and dark red weave of the skirt I am inexplicably wearing, I wonder what disaster I am headed for as I try to figure out who the hell I am supposed to be today.

CHAPTER 2 (#uf14ace35-235b-5e8b-abfc-ed954e44dd79)

‘Carmen? CARRRRRMEN!’

My ears ring with the word, with the operatically rolled Rs, the sonic after-bite.

I lower my head sharply and peer through an unfamiliar fall of black, curly hair. Momentarily disorientated, before I realise suddenly that it is mine.

The racket is emanating from a sharp-faced, pigeon-chested blonde hanging over the seat back diagonally across the aisle from where I am sitting. I press my knees and hands tightly together to stop them from shaking.

So today, I suppose that must be who I am. Carmen. And the thought that I am no longer Lucy, or Susannah, or even the one before, whose name I can no longer remember, but whose life I liked very much and could have kept on comfortably living, makes my world spin, my breathing grow dangerously fast. I can feel the colour draining out of Carmen’s face as I fight for control of her body.

Everything is suddenly too loud, too bright, dialled up by a thousand. Carmen’s heart feels like it will explode in her chest—ours—and if it does, it will be my fault and I will be forced immediately to quit her lifeless body and take residence—like a ghoul, like a vengeful ifrit—in someone else.

Really, I should know what to do by now. You’d think I’ve had enough practice. But it never gets any easier. Not in those fateful first few days and hours, anyway.

I force my breathing to slow, and focus with difficulty. The muscles of Carmen’s neck, her face, refuse to do as they are told. I am drenched in sweat, sure that Carmen’s features are flushed with a strange, hectic blood.

Whoever the blonde is, she can see my clumsiness, the sudden wrongness in Carmen’s expression, her demeanour, because the blonde’s look sharpens, her already shrill voice rises an octave and she shouts,‘What’s wrong with you today, you dopey bitch? Jesus, you’ve been acting really weird. Like, hello? Is anyone in there for, like, the fifteenth time? Don’t you want to know who Jarrod Daniels is doing now?’

And the whole coach falls silent, every head turning our way.

Dopey bitch? With those two words I feel Carmen’s heart kick into even higher gear, almost whining under the strain of my sudden, white-hot anger. I have a temper then; that’s interesting to know.

Inexplicably, my left hand begins to ache dully, and I cradle it inside my right elbow, against my side, as if I have been recently wounded. Carmen’s skin is now so hot that I know for certain that if I allow this to continue, I will kill her. And she is innocent and that cannot happen. It is as if an edict has arisen in me that I am currently powerless to fulfil.

In the strange manner I sometimes have of taking in too much, too quickly, I register in a split second that there are nineteen other girls present, two teachers—both female, both on the wrong side of old, one with short, iron-grey hair, jangly earrings and a hard face, another with a girly bob and meaty jowls—and a driver who is consumed by the black fear that his wife is about to leave him for another man. It hangs about him like a detectable odour, a familiar on his shoulder, gnawing at his flesh. Is it only me that can see it?

Then the world telescopes, narrows, grows flat, becomes less than the sum of its parts again. Carmen’s heart slows, her breathing evens out. My left hand has ceased to ache and I release it, sit straighter.

Still every eye in the bus is turned on us. Are ‘we’ friends? Who is she to me?

Still struggling to get Carmen’s face under control, I slur, ‘Bad migraine.’

In my last life—well, Lucy’s—I got migraines all the time. For someone like me, who doesn’t feel the cold and never gets sick, not the essential me anyway—it had felt like intermittent war breaking out in my head. As if Lucy’s mind and body kept finding ways to turn on me, determined to finish me off. I don’t miss being Lucy, though I wish her well and hope she’s recovered from my casual trampling upon her life. No doubt, in time, I will forget her, too.

My weak response is enough to satisfy them all, because eyes swing away uninterestedly, the noise level in the bus climbs back up to a jet-engine roar in my ears, and the sharp-faced blonde snaps, ‘That’s soretarded,’ before turning huffily to speak to somebody else and leaving me blessedly alone.

Like a facsimile of a human being, I turn awkwardly to face the window and discern farmland flying by beneath an iron sky, punctuated by dead trees and outbuildings, the occasional chewing cow, ordinary things, the grass by the roadside growing taller and coarser the farther we travel. Red soil gives way to sandy verges, vast stretches of salt plain. I imagine I can smell the sea and wonder where we are. Not Lucy’s domain of smelly high-rises and disgruntled pushers on skateboards. Not Susannah’s toney mansion with the round-the-clock, live-in help and the hypochondriac mother who would never just let her be.

The land is as dry as Carmen’s eczema-covered skin. Without having to think about it too much, I scratch urgently at the rough patch near her right wrist until it begins to bleed steadily onto the cuff of her long-sleeved white shirt.

Some things, I’ve found, the body simply remembers.

We finally pass a sign that says, Welcome to Paradise, Pop. 1503. Beyond it, a hint of dirty grey water, white caps rolling in the distance.

The name causes a little catch in my breathing, though I can’t be certain why. I do not think I have ever been here before, in the way that I can sometimes recall things, impressions really; 16, 32, 48 lives out of context.

Perhaps the town’s misguided civic optimism is something that amuses Carmen. For I get flashes of my girls, my hosts, my vessels, from time to time. They are with me, but quiescent, docile. Maybe they believe they are dreaming and will shortly awaken. Some do occasionally make their way to the surface—like divers who have run out of air, breaking above the waterline clawing and gasping—before simply winking out because the effort is too great to sustain. It makes things only marginally easier that there is not a constant dialogue, a rapprochement, between us. Still, I am very aware that I occupy rented space, so to speak, and it informs everything that I do, everything that I am. I am never relaxed, because I am never wholly comfortable inside a skin that is not mine.

It is so far from it, Paradise, this small, dusty town laid out in a strict grid and set down on the edge of a swampy peninsula, nothing pretty about it,that seems to just peter out into the ocean. The high school we pull into—all low, boxy buildings, cyclone fencing and endlessly painted-over graffiti—sits on the town’s barren outskirts, making no attempt to blend in with the landscape.

The bus shudders to a halt, there is a hiss as the front door releases, and a restive ripple of movement from the people around me, like an animal stirring.

I have not spoken for over an hour, not having trusted myself to form the appropriate words. When someone snaps impatiently for the second time, ‘Carmen Zappacosta’, it is only the blonde girl’s loud, derisive snort that has me raising my head slowly and then my hand. When I let it fall again, it hits my lap with a dull sound, like dead flesh.

I narrow my eyes. It is the teacher with the grey hair and hatchet face speaking. She shakes her head before continuing sourly, ‘House rules are no drinking, no smoking, no sleeping with any member of the host family. Over the years of this little “cultural exchange” program, we’ve had stealing, people going “native”, emergency hospitalisations, immaculate conceptions. Miscreants will be dealt with ruthlessly. And do try to remember why it is that you’re here—as representatives of St Joseph’s Girls’ School. You’re here to sing and that is all. Am I clear, or am I clear?’

The coach is a sea of rolling eyes of every colour as people rise excitedly to get their things. I watch to see what remains and then take it, stumbling after the others as if the bus is a pitching sailboat.

On the way out, I catch the driver’s eyes—like burning holes beneath his meticulous comb-over—and he sees that somehow I know, because he looks away and will not look at me again, even though I stare and stare. Can no one else see it? That misery that envelopes him like a personal fog.

‘Call me when you get over your little episode,’ hisses the frosty blonde over her shoulder as I fall down the stairs behind her under the weight of Carmen’s loaded sports bag, almost landing on my new host father. I register that he is a strong-jawed, dark-haired man of unusual height dressed in khaki pants, a casual shirt and dark blazer. Nice looking. What is the adjective I am looking for? That’s right. Handsome.

I know he is waiting for me because I’m the last girl to get off the bus. All of the other girls are already shrugging off their blazers, letting their hair down,making eyes at their host brothers, sussing out the situation.

‘So this is Paradise!’ I hear the blonde girl exclaim flirtatiously.

If I were to be truly convincing, I should probably be doing the same, but I’m no good at flirting—there’s no sweetness in me—and it is a simple triumph just to stand vaguely upright. I am aware that I am listing slightly and make appropriate, but subtle adjustments to my posture.

The man Carmen has been entrusted to does not notice; he maintains his kind smile, his steady, patient expression. Neither does he notice the indefinable distance between himself and all the other people gathered in the parking lot. Eyes dart his way constantly, there is talk, talk, talk, mouths opening and closing, sly laughter, disapprobation, but he does not see it. Or chooses not to. Instead, he takes Carmen’s bag out of my dead grasp and shoulders it easily.

I follow him numbly, just putting one foot in front of the other; every step I take upon the surface of the world imprinting itself upon my borrowed bones.

CHAPTER 3 (#uf14ace35-235b-5e8b-abfc-ed954e44dd79)

After stowing Carmen’s bag in the trunk of his car, the tall stranger opens the front passenger door and gallantly sees me settled before taking the driver’s seat.

When he puts out his bear-like hand and says kindly, ‘Hello, I’m Stewart Daley,’ I must remind myself to do the same. Not observing the conventions can make you seem like an alien.

‘Uh, hi, uh, Carmen, um, Zappa … costa,’ I mutter awkwardly, searching for the girl’s name in my recently laid-down memory.

If he wonders why I’m having trouble pronouncing my own name, he’s polite enough not to show it.

But the instant my hand meets his, I absorb a sensation like liquid grief, a kind of drowning. It is completely at odds with the man’s friendly exterior and fills the space between us like floodwater surging to meet its level. A wild thing has suddenly been let loose in the car, a wordless horror, screaming for attention, and I cannot help but pull back as if the man is on fire.

Then the car’s mockingly ordinary interior reasserts itself. I clock the leaf-shaped air freshener hanging from the mirror. The slightly smoky tint of the windscreen. The leather bucket seats, faux wood-grain dash, the ragged road map in the passenger side pocket. My breathing evens out, my left hand no longer burns with that strange phantom pain.

Whatever it is, this feeling, this horror, this secret, it lingers about him like a detectable odour, a familiar on his shoulder gnawing at his flesh. I wonder that I didn’t see it before, the man far more adept than the bus driver at hiding the cancer in his soul. It is only discernible through touch. Interesting.

‘I suppose you’ve heard,’ he says, withdrawing his hand quickly. He looks away, blinks twice, before starting the car. ‘This is a place where everyone knows everyone else’s business. They probably worded you up already. Can’t say I blame them. I’d want that for my own kid.’

We head out of the parking lot in the man’s comfortable family wagon and head at determined right angles through the town, through the main street with its charcoal chicken shops, mini-marts, laundromat, family diners, bars. We don’t speak again until he stops the car outside a white-painted, double-storey, timber family home with prominent gables, a two-car garage, picket fence, bird feeders on the lawn. The place is neat, well maintained, like the man himself.

Unlike its neighbours, the house comes complete with three giant guard dogs, Dobermans, all sleek black-and-tan muscle. Two lie across the footpath to the front door, the other on its back on the lawn, all three languid and deadly. Something about their presence tugs at me, won’t come clear.

‘You’ll want to stay in the car a moment,’ Mr Daley says gently.

He gets out and engages in an elaborate ritual of unlocking a heavy-looking chain and padlock set-up he’s got going on his front gates that would make visiting the Daleys a pretty interesting exercise. When he’s finally swung the gates open, he slips through, whistling for his dogs to follow. But one suddenly lifts its head and breaks rank, then they all do. And without warning, they’re through the gates and circling the car, snarling and spitting. They scratch at the doors, snapping on hind legs, seeking a way in, a way to get to me.

I feel Carmen’s brow furrow, realise I am doing it. Then I remember.

Dogs, more than any other creature, sense me, fear me. Perhaps even see me trapped inside a body that isn’t mine. Where I’ve recalled this from, when, escapes me. All I know is, it’s made Carmen’s time in Paradise a lot more complicated.

‘Come!’ Stewart Daley roars, perplexed when the dogs refuse to obey.

When they continue to ignore him, bent on somehow eating their way through the car door to me, he drags them away by the collar, one by one, and locks them behind a head-high side gate. The dogs continue to howl and froth and claw at the chain-link, barbed-wire-topped fence with their front paws as if they are possessed. It is a scene out of the horror movies Lucy used to live for, as if her own life weren’t horrible enough.

‘I’m sorry,’ Mr Daley says, breathing heavily as he opens my car door. ‘I can’t understand it. I mean, they bark from time to time. But that? Well.’

I shrug Carmen’s thin shoulders—easier than forming words of explanation—and get stiffly out of the car.

When he tries to put a hand on my shoulder to usher me into the house, I cannot stop myself from flinching away. I can almost feel the man’s hurt as he moves ahead, still toting Carmen’s bag.

But I’m grateful for the distance he’s put between us. Several times, like someone in the grip of a dangerous palsy, an incurable illness, I trip over things that aren’t there and I’m glad he doesn’t see it. The walk from the car to the house may as well be measured in light years, aeons. I am perspiring heavily, though the day is overcast and very cool.

His wife suddenly appears at the painted white front door and I stumble to a standstill. It is surprise that does it. Seeing the two of them together like—what is that saying?—chalk and cheese.

‘Carmen?’ she calls out warmly. ‘Welcome, dear, welcome.’

Mrs Daley is an impeccably groomed woman who used to be very beautiful, and still dresses as if she were, with great care and attention to detail. But she has a secret, too, and it is eating away at her soul, has taken up residence in her face, which is all angles, lines, hollows and stretched-tight skin beneath her sleek, dark fall of hair. She wears her grief far less lightly than her husband does, or he is much better at dissembling. Whatever the reason, she looks to me like the walking dead.

I am completely unprepared when she surges out of the house and wraps one of my hands in hers. It is all I can do not to wrench myself away and flee—back past the killer dogs, the unlovely school, the bus driver whose heart has already been removed from him, still beating. There is the sense that I am the only still point in a spinning, screaming world. What resides beneath her skin is a manifold amplification of the horror beneath her husband’s; a charnel-house.

I break contact hastily on the pretence of tying a shoelace and, mercifully, the noise, the shrieking, is cut off. She stands over me silently like an articulated skeleton in cashmere separates and pearl-drop earrings and yet all that is happening beneath the surface of her,behind her eyes. What a pair they make. What kind of place is this? What am I doing here?

‘This way, dear,’ says Mrs Daley calmly as her husband precedes us up the stairs to the bedrooms, Carmen’s bag in hand.

He pushes open a white-painted door to the immediate left of the lushly carpeted staircase. It is clearly a girl’s room, filled with girl’s things—an overflowing jewellery box; posters of heart-throbs interspersed with ponies, whales and sunsets; a vanity unit teeming with glitter stickers and photos of a very pretty blonde girl chilling with a host of friends more numerous than I can take in. Popular, then. There’s a single bed and cushions everywhere, one of which spells out the name Lauren in bright pink letters. Like the house, the room is neat and clean and white, white, white. I wonder where she is, this Lauren.

‘I’m sorry that our son, Ryan, couldn’t be here to greet you,’ Mrs Daley says, shooting a quick look at her husband. Her skeletal hands sketch the air gracefully. ‘We’ve made some space for you in the wardrobe, and you can have the bathroom next door all to yourself. That was—’

Mr Daley half-turns towards the door, says quietly, ‘Louisa …’

His wife smoothly changes tack. ‘It’s entirely free for your use, Carmen. There’s a shower and a bath, hair dryer, toiletries. You’ll find fresh towels in the open shelving unit beside the sink.’

I nod my head. ‘I might use it now, if that’s okay with you, Mrs … Daley, Mr … Daley. It was a very long, uh, trip.’

Little do they know how long. A whole lifetime away, a whole world.

My voice is rusty, hesitant. Accents on all the wrong places, accents where there shouldn’t be any. Not the mellifluous voice of someone who is here to sing, not at all. I watch them warily, waiting for them to spot the one thing in the room that doesn’t belong. But they notice nothing and withdraw gently, still murmuring kind words of welcome.

At least I’m looking forward to waking up here in the mornings. Every time I opened my eyes at Lucy’s, I wanted to be someone else, somewhere else, so desperately that it hurt. So long as I don’t let these people touch me again, maybe things will work out fine.

I finally remember to breathe out.

I wander around the bedroom and bathroom at will and wonder what’s behind the other closed doors on the landing, all of which are painted white and identical.

After my shower, I study myself in the giant wall-to-wall mirror. If her busty, acne-plagued companions on the bus are anything to go by, Carmen is supposed to be nearing the end of high school, right? But she looks about thirteen, with thin shoulders, no curves to speak of, and arms and legs like sticks. Way below average height. Her head of wild, curly hair seems almost too big, too heavy, for her scrawny frame. Carmen’s eczema is really severe, making her naked body look leprous and blotchy. Not a bikini-wearer, then. I can imagine her being a confidante of that bossy blonde on the bus only because she poses no threat to anyone whatsoever. Not in looks or popularity or force of will.

Within the girl’s underwhelming reflection, I discern my own floating there, the ghost-in-the-machine. Somehow weirdly contained, yet wholly separate.

‘Hi, Carmen,’ I say softly. ‘I hope you don’t mind me soul-jacking your life for a while.’

I hear nothing, feel nothing; hope it’s likewise.

Soul-jacking. That’s my own shorthand for whatever this situation is. I mean, like it or not, they’re kind of my hostages and I can make or break them if I choose to. It’s just me at the wheel most of the time. It’s entirely up to me how I play things, however fair that may seem to you, but I try to tread gently. Though in the beginning, when I must have been wild with confusion, rage, pain, pure fear? I am sure I was not so kind.

I’m back in Lauren’s room, wearing only a white towel, when I hear a commotion on the stairs, a heavy, running tread. I hear Mrs Daley shout, ‘Knock before you go in there, Ryan, for heaven’s sake!’ then the door bursts open and I’m face to face with a young god.

Carmen’s heart suddenly skids out of control at the instance of shocked recognition at some subterranean level of me, though I am certain that neither she nor I have ever met him before. Yet he seems so familiar that I almost lift my hands to stroke his face in greeting. And then it hits me—he could be Luc’s real-world brother, possessing the same careless grace, stature, wild beauty. And for a moment I wonder if it is Luc, if he has somehow found a way out of my dreams; an omen made flesh.

Yet everything about the young man towering over me is dark—his hair, his eyes, his expression; all negative to Luc’s golden positive. Like night to day.

No sleeping with any member of your host family.

I suddenly recall the words and it brings a lopsided smile to my face. I mean, it wouldn’t exactly be a chore in this instance. He’s what, six foot five? And built like a line-backing angel.

Just my type then, whispers that evil inner voice. I’ve always loved beautiful things.

‘What the hell are you smiling about?’ Ryan—it must be Ryan—roars.

Carmen’s reaction would probably be to burst into noisy tears. But this is me we’re talking about.

I look him up and down, still smiling, still wearing my towel like it’s haute couture. The need to touch him is almost physical, like thirst, like hunger. But I’m afraid of getting burnt again and there’s a very real possibility of that. There’s a good reason I don’t like being touched, or to touch others. It invites in the … unwanted.

So instead, I plant a fist on each hip and stare up at him out of Carmen’s muddy, green-flecked eyes. ‘I was just thinking,’ I say coolly, ‘about what you’d be like in bed.’

CHAPTER 4 (#uf14ace35-235b-5e8b-abfc-ed954e44dd79)

Ryan rocks back on his heels. ‘I’m going to ignore what you just said and ask what the hell you’re doing here!’ he says after a shocked pause. ‘This bedroom is off-limits.’

‘Ry-an!’ exclaims Mrs Daley, who’s just joined us and overhears the last part.

‘Ry-an,’ repeats his father, who moves to stand in front of me protectively. ‘Carmen is a guest in this house. We’ve talked about it. You know it’s long past time.’

What is he? I wonder, my eyes still fixed on Ryan in fascination. About eighteen? Nineteen?

I don’t bother to engage with any of them because I’m still checking him out and no one can make me rush something I don’t want rushed. I can be stubborn like that. I mean, life’s too short already and I haven’t seen anyone who looks like Ryan Daley in my last three outings, at least. Luc aside—and there’s really no putting Luc to one side—Ryan is quite spectacular.

When I continue to say and do nothing, Ryan turns and snarls in his mother’s face, ‘She’s still alive, you know, alive! What are you doing even letting her come in here? Have you both lost it?’

Then he’s gone, followed swiftly by his father. The door slams twice in rapid succession and the house is quiet.

Mrs Daley sits down shakily on the pristine bed while I quickly shove a tee-shirt from out of Carmen’s sports bag over my head and put some underpants on under the towel before laying it on a chair to dry. Not that I care about the proprieties, but I can see that she does, that they are the only things keeping her from flying into a million pieces. I dig around in the bag a bit more and locate some jeans. They look like something a little boy would wear. I am amazed when they fit perfectly.

‘Stewart says they told you,’ Mrs Daley murmurs softly. ‘About us, I mean. Did they?’

I shake my head. But it’s pretty clear to me that we have a missing girl on our hands and that it was someone’s bright idea to assign me her bedroom. I’m not sure what to make of it, and neither is Carmen’s face, so I blunder into the closet, pretending to look for something, while Mrs Daley clears her throat.

‘We haven’t, ah, hosted anyone since our daughter, Lauren … went away,’ she says, then corrects herself in a tight, funny voice. ‘Was taken.’

I shoot her a quick glance across the room. Her eyes are bright red in her chalky face and I’m afraid of what she’ll do next. Emotion is such a messy thing, apt to splash out and mark you like acid. I look away, refocusing hastily on Carmen’s sports bag, the motley collection of belongings that sits on top. Weird stuff she thought it important to bring—like a frog-shaped key ring and a flat soft toy rabbit, grey and bald in places, that has clearly seen better days. There’s even a sparkly pink diary with a lock and key. Little girl’s things to go with the little boy’s clothes.

When Mrs Daley’s agonised voice grinds into gear again, I begin to unpack in earnest, putting Carmen’s belongings, her religiously themed songbooks, into the spaces allotted for her in Lauren’s closet.

‘We’re trying to … normalise things for the first time in almost two years,’ Mrs Daley whispers to Carmen’s profile. ‘We used to host students all the time. Lauren loved meeting people from your school. She has … had I should say, a lot of Facebook friends from St Joseph’s.’

‘Oh?’ I say. Do I know what a facebook is? It rings no bells with me.

‘Ryan,’ she continues, ‘is having trouble letting go. We’ve almost come to terms with … I mean, you never really stop wondering … if she suffered, what really happened, how we could have prevented it … but we—Stewart and I—don’t think of her as being … present any more, in the sense that you and I are. Though Ryan insists—despite all the evidence to the contrary—that she’s still alive. It’s become something of an obsession with him. He says he can still feel her. He’s …’ She hesitates and looks away. ‘He’s been arrested a couple of times for following “leads” no one else can prove. But it’s impossible. There was a lot of … blood.’

Mrs Daley, eyes welling, is staring at something on the floor between us that I cannot see. I wonder what she used to get the carpets so white again.

‘She must have put up such a fight, my poor baby …’

The woman lets slip a muffled howl through the clenched fingers of one fist and then she is no longer in the bedroom. A door clicks loudly along the hallway. I don’t know why she bothered shutting it because the sound of her weeping rips through the upper storey of the house like a haunting. Habit, I guess, the polite thing.

Only sinew, thread and habit, I decide, is holding Lauren’s mother together. What kind of house is this?

Maybe, I think, I won’t enjoy waking up here in the mornings, after all.

There’s no discernible pattern to the Carmens, the Lucys, the Susannahs that I have been and become. All I know is that they stretch back in an unbroken chain further than I can remember—I can sense them all there, standing one behind the other, jostling for my attention, struggling to tell me something about my condition. If I could push them over like dominoes, perhaps some essential mystery would reveal itself to me; but people are not game pieces, much as I might wish it. And there is nothing of the game about my situation.

When I ‘was’ Lucy, I was a twenty-six-year-old former methadone addict and a single mother with an abusive boyfriend. I think I left her in a better place than where she was when our existences became curiously entwined, but it has all become hazy, like a dream. I think, together, we finally booted the no-hoper de facto wife basher for the last time and got the hell out of town with the under-nourished baby and a swag of barely salvageable items of no intrinsic worth. I still wonder how she’s doing, and if she managed to keep clean, now and forever, amen.

And Susannah? She was finally brave enough—with a little push from yours truly—to get out from under her whining heiress mother’s thumb and accept a place at a college a long, long way from home, but that’s where the story ends. For me, anyway.

I wish them both well.

The other girl? The one whose life I ended up liking but whose name now escapes me? She finally came up with a reason to escape an arranged marriage, change her name, find work in a suburban bookstore and love at her new local—thanks in no small part to me.

I liked that part. Love. It was uncomplicated, sweet. So unlike my own twisted situation. But the details are fraying around the edges and soon she’ll be gone, like all the rest. Doomed to return only in prismatic flashes, if ever.

Carmen looks and acts a lot younger than her three predecessors. Apart from her unfortunate skin condition, she doesn’t appear unhappy or abused in any way. She really does seem to be here just to sing. It’s the family she’s been placed with that has the terrible history. And that’s something that’s got me wondering. Memory is an unreliable thing, but this seems new to me—an unexpected twist, an irregularity, in the unbroken arc of my strange existence to date. It does not feel like anything I have ever encountered before, though I may be wrong. I’m going to have to watch my step.

Once I have the mechanics of someone’s life under my control, the thought always returns—that maybe someone is doing this to me. That I am some kind of cosmic, one-off experiment. Maybe it is the so-called ‘Eight’? But then I wonder, are They even real? Is Luc? Perhaps all this is in the nature of a lesson. But one so obscure I still don’t know what I’m supposed to be learning.

The unpalatable alternative is that maybe I’m somehow doing this to myself, that I’m some sort of mentally ill freak with a subconscious predilection for self-delusion, impermanence and risk. If that is the case, the real truth—and I pray that it isn’t—there would be nothing left to stop me from topping myself, I swear to God. I almost don’t want to know the answer.

And you need to ask why I call myself ‘Mercy’?

CHAPTER 5 (#uf14ace35-235b-5e8b-abfc-ed954e44dd79)

I have barely closed my eyes when he is with me again. My own personal demon.

But tonight there are to be no perfumed midnight gardens, no bleak rocky outcrops of strange and savage beauty or shifting desert landscapes beneath unbroken moonlight—scenes engineered to enchant and caress the senses; some kind of reward for past injustices meted out. It is just a swirling, buzzing dark with us two at its heart. I sense Luc is angry and I feel a stirring of faintly remembered … fear?

Even so, his golden presence sings through my nerves, makes me feel more alive than any substitute life ever could. I want to touch him as badly as I wanted to touch Ryan Daley, but he holds me apart from him effortlessly, without even moving.

‘Of course I’m real,’ he retorts, as if we are continuing a conversation that started long ago. ‘Do not doubt that. And you know who’s caused this. You’ve never been stupid, so don’t start now. The knowledge is in you despite everything that’s been done to you.’

I know now that I have always been quicktempered, and his words bring forth an answering fury as he continues to hold me away when all I want him to do is wrap me in his arms.

‘You think I don’t know that?’ I spit. ‘That somehow I’ve misplaced my life, my self, somewhere? What more do you expect me to do, the circumstances being what they are?’

I do not like the whining note in my voice. It is unbecoming. I’ve always preferred to think of us as equals, even if he is a longstanding figment of my diseased imagination.

He laughs, the darkness ringing with genuine amusement, and his anger banks, though he moves no closer. He still holds us apart as if he were a being of pure energy.

‘I expect you to do nothing as it concerns your … hosts,’ he smiles, ‘and yet everything to do with finding me. So far, you’ve failed. You’ve got everything the wrong way around.’

I frown. That may be, but how else am I supposed to survive the Lucys, the Susannahs, even the Carmens? Some of their existences are like little hells and yet I am supposed to endure them as they are?

‘But that’s just it,’ I snap, and in the cold dark my left hand aches again with that inexplicable pain. ‘I don’t know how to find me, so I sure as hell don’t know how to find you. And anyway, I’m not even certain you’re worth it any more.’ This last said to wound.

His beautiful mouth curves up in a half-smile. My hand aches harder. I’m lying, of course—he’s the very core, the heart, of my floating world, my floating life—but it still feels good saying it. I was not always this defiant with him and I sense surprise, displeasure, beneath the diverted expression.

‘Do nothing,’ he says again, ‘and in doing so, find me.’

There is a loud crack, like thunder, and I wake alone in Lauren’s pristine bed. The fierce dawn winds blow great sheets of grit through the parched streets and gardens of Paradise like a parody of rain, like the feeling in my borrowed heart.

‘So how was it?’ says the rat-faced blonde from the bus in her hard-as-nails voice.

We’re at the first collective Monday morning choir rehearsal of our fortnight’s‘cultural exchange’ with Paradise High. It’s supposed to culminate in massed, youthful voices belting out Part 1 of Mahler’s Symphony No 8 in E flat major to an appreciative audience of local farmhands, fishermen, small-business owners and parents. I only know this because I spent an hour last night after a tense dinner with the Daleys senior—Ryan’s absence itself a presence—flicking through Carmen’s belongings for clues as to what she was meant to be doing here. The piece is a pretty big ask, given that most of the students seem to be here under some form of duress and a good number of them are likely to be tone deaf. Plus, we seem to have misplaced an entire, uh, symphony orchestra somewhere.

One thing I’m sure of: Mahler is definitely not for sightseers. Carmen’s score is dense with her own handwritten notes and symbols I don’t even recognise. I’d way lost interest in it long before I’d even figured out where the choir’s supposed to come in. Proposed course of action? Just pretend to sing for the next two weeks and hope no one notices. I figure it can’t be too hard to lose yourself in a crowd.

And it is a crowd. It’s eight in the morning and there are more people gathered in the assembly hall than I would have expected. Paradise doesn’t look like it could possess fifty reasonably musical offspring, let alone the roughly two hundred teenagers I see here, checking each other out brazenly. It’s like a meat market, and Carmen’s group is giving as good as it gets. The air is practically sizzling.

‘Are you having another mental attack?’ says Rat-face suspiciously when I don’t answer her right away.

I dart a look at the cover of her score, which bears the name Tiffany Lazer in a cloud of hearts and flowers. It suits her. It’s fluffy and deadly, at the same time.

‘Nope,’ I reply casually. ‘Just scoping for, um … hotties, uh, Tiff.’

It’s the right thing to say because Tiffany relaxes immediately. ‘Speaking of which, so how was it? I hear Ryan Daley looks all male-modelly super-gorgeous but is pretty much a psycho, nut-job disaster waiting to happen. I was soooo jealous at first when I found out who you’d got, but now I’m so glad it’s not me! You’re practically in the middle of an ongoing murder investigation—how twisted is that?’

Silently, I thank Carmen for her diary, which lays out the equal parts longing, equal parts hatred she feels for Tiffany Lazer and her snobby circle of friends. From what I can tell, everything between Carmen and Tiffany is some kind of weird contest for supremacy, though they seem to have nothing in common but the singing thing.

I notice a few of the other St Joseph’s girls hanging off every word Tiffany says, giving me the once-over while they’re doing it. I feel a stab of pity for Carmen—why does she care so much about what the others think?

And they say girls don’t like blood sports. My noncommittal, ‘Oh?’ is a little more antagonistic than I intended.

But Tiffany only hears what she wants to hear, and it’s enough to prompt her to spill her guts about how Ryan Daley is this far away from being locked up in a mental institution for turning vigilante and stalking people he thinks might be responsible for his sister’s abduction.

‘She was taken right out of her bedroom,’ Tiffany says as Paradise High’s music director, a tired-looking little man with wild hair and eyeglasses called Mr Masson, taps the podium microphone with his stubby fingers. People wince at the vicious feedback he triggers but they keep right on talking. Two spots of hectic colour appear on his cheekbones.

‘No signs of forced entry or anything,’ Tiffany continues airily.

Which would explain the invisible force-field that seemed to surround Mr Daley in the car park the other day. To most of the citizens of Paradise, it probably looks like an inside job. It also goes some way to explaining why Louisa Daley resembles a walking corpse and is on the brink of implosion, like a dying sun. Such a corrosive thing, doubt.

‘Lauren was a soprano, just like we are,’ Tiffany adds. ‘Blonde, incredibly bright, beautiful, too. The whole package.’ She looks me up and down as if to say, everything you’re not, baby.

I wonder again why Carmen wants this bitch to like her so badly.

‘Everyone at Paradise High gives Ryan a wide berth,’ Tiffany says as Mr Masson tries and fails to get our attention once again. ‘He’s a weirdo loner with a hair-trigger temper and a gun. People have seen him pull one. They say there was blood everywhere.’

The two statements are complete non sequiturs unless you draw an unsavoury line between them.

Carmen wrinkles her brow, me doing it. ‘So people think Ryan might be in on it, too?’ I say. ‘The father did it? Maybe the son? Both involved. Some weird psycho-sexual thing? Maybe the mother knows something?’

Tiffany nods enthusiastically. ‘Better watch your step. Sleep with one eye open.’

She grins at the girl sitting on her other side as if I’m not right there. Like anyone would want to jump your bones. It’s clear to me what they’re thinking.

‘Well, thanks for the info,’ I reply coolly, staring down the other girl who looks away uncomfortably. Bet Carmen’s never given her the evil eye before. It feels good doing it. I stare down a few more of the others for good measure and the St Joseph’s sopranos suddenly look everywhere but at me, their eyes scattering like birds.

‘Consider it a community service,’ Tiffany laughs, oblivious to Carmen’s odd steeliness or its weird effect on her posse. Well, she wouldn’t.

‘And can you believe they roped in extra students from Little Falls and Port Marie for this musical “soirée”?’ she adds. ‘It’s still going to sound like shit.’

Mr Masson makes us all jump by abruptly turning on the assembly hall’s ancient sound system loud enough to split our heads open. The vast swell of a massive pipe organ is followed by the sounds of a giant, pre-recorded orchestra and it’s suddenly a mad, page-turning scramble to get to the opening bars of … uh, oh, yes, Hymnus: Veni, creator spiritus. Know it? I’m right with you. The score looks as unfathomable this morning as it did last night. And where did the choir come in again?

I glance sideways at Tiffany and she’s looking straight ahead at Mr Masson, poised to sing. Always ready, always pulled together. Something Carmen wishes she was every minute of her waking life. People want funny things.

I follow Tiffany’s flying finger to the point where her manicured nail leaves off the page and her voice takes over and suddenly, my eyes narrow in shocked recognition. I have seen what I should have seen last night: Part 1 of Mahler’s Symphony No 8 is not in French, or German, or Italian. Languages that casually litter the margins of the score, with which I have little affinity, knowledge or patience.

I should have focused on the title of the opening hymn.

Like the title, the hymn is in Latin. Untranslated Latin.

As the girls of St Joseph’s Chamber Choir begin to blow away the competition with their incredible singing, I realise that I understand every single word they are saying as if it is the language in which I think, in which I dream.

They sing:

Veni, creator spiritusmentes tuorum visita

Come, Creator Spiritvisit the minds of your people

Creator Spirit. The words send a lick of lightning down my spine, the repeating crash of the organ causing little aftershocks in my system.

And the music? It’s like there are seraphim in the room with us. Forget about the hair spray, the injudicious use of mascara, face whitener, concealer, eyeshadow, pout-enhancing lip venom. Shut my eyes and I could be sitting amongst angels. The sound is tearing at my soul. It’s so joyous, so sublime, so incredibly fast, loud, complex. Beautiful. If I’d ever heard this music before in my entire benighted existence, I’m sure I would have remembered it.

The girls of St Joseph’s have long since split into two distinct bodies of voices, two choirs, clear, bright and pure, but, stunned by my new comprehension, I do not open my mouth or attempt to keep up. Neither does most of the room. A few brave souls do their own interesting jazz interpretations of Mahler beneath the main action but these are largely lost in the maelstrom of organ, orchestra and Tiffany, whose voice soars, higher, louder, purer than all of them. Heads are craning to get a look at the source.

‘She’s incredible!’ someone shouts behind me.

I see the music teachers of four schools single out Tiffany approvingly with their eyes as she preens a little and amps up the volume even more.

Poor Carmen. If this is some kind of contest, we are losing it together. I don’t remember how to sing, or even if I can. Silently, I turn the pages with trembling fingers and wonder what else I’ve forgotten about myself.

Mr Masson continues doggedly beating time, while the local girls telegraph clearly that we’re all dead meat and the boys place lively bets among themselves about which of us will get laid the fastest. I shrink down further in my chair and keep turning the pages of my score a microsecond after Tiffany does.

The music changes as I listen intently. I hear bells, flutes, horns, falls of plucked strings. There is a quiet sense of urgency, of building.

‘What’s wrong?’ mouths one of our teachers on the sidelines as Tiffany shoots me a surprised look before glancing sharply down at her own music then back at me.

A shaky tenor seated somewhere in the chilly hall launches into a quavery solo and there is a smattering of laughter, like a reluctant studio audience being warmed up by the second-rate comedy guy. Moments later, Tiffany lifts her bell-like voice in counterpoint and I marvel afresh. When she sings, she sounds the opposite of the way she usually comes across, and that has to be a good thing.

On opposite sides of our row, two St Joseph’s girls frown at me fiercely before hurriedly joining their voices to Tiffany’s. Two more male voices wobble gamely into the fray. Together, they sing:

Imple superna gratia

quae tu creasti pectora.

Fill with grace from on high

the hearts which Thou didst create.

The words fill me with an abrupt sadness I cannot name. It is several pages before I realise that the grey-haired, hatchet-faced teacher from the bus, who is pacing the sidelines and waggling her fists furiously, is trying to catch my eye. People all over the room have begun to notice her jerky, spider-like movements and they crane their necks to look. Chatter begins to build below the surface of the incredible music.

‘Carmen!’ the woman roars suddenly over the backing tape, unable to hold back her fury any longer.

I realise with horror that I have missed some kind of cue, and that it can’t have been the first.

I shake my head at the woman—Miss Fellows, I think her name is—and raise my hands in confusion. She responds like a cartoon character, jumping up and down on the spot and tearing at her short, grey hair so that it stands on end like the quills of some deadly animal.

Mr Masson silences the pre-recorded orchestra. ‘Is there a problem?’ he says with raised eyebrows.

The teachers from the other schools—a grimfaced, white-haired elderly man in a dusty black suit and a lean, handsome young man who doesn’t look old enough to be teaching yet—look my way interestedly. All the St Joseph’s girls are staring at me, too, and talking out of the sides of their mouths. It’s nothing new for Carmen, I suppose. Others in the room point and whisper. There she is, there’s the problem.

I am once more the still point at the centre of a spinning world and Carmen’s face grows hot with sudden blood. I can’t help that. I hate making mistakes.

‘No, no problem,’ Miss Fellows barks. ‘Tiffany, you take Carmen’s part. Rachel, step in for Tiffany. Carmen! Sit this one out for now. Take it from the top of Figure 7.’

Tiffany shoots me a look of immense satisfaction and takes flight after Mr Masson reanimates the orchestra. Frantically reading left to right from Figure 7, I realise belatedly that Tiffany must be one of the soloists.

Shit, I think suddenly. I suppose Carmen must be, too.

The freakin’ lead soloist. When she’s at home.

CHAPTER 6 (#uf14ace35-235b-5e8b-abfc-ed954e44dd79)

I sit there mutely for what feels like forever before the bell rings for first period and students stampede gratefully for the doors. The other St Joseph’s girls are borne away on a wave of male admirers, which has to be something new for most of them. Miss Fellows and the other St Joseph’s teacher, Miss Dustin, steam over in righteous convoy and prevent me from leaving, from even rising out of my chair.

‘Not only did you embarrass yourself,’ spits Miss Fellows without preamble, ‘but you completely ruined it for everyone else! Delia looks to you for cues and what do you do?’

If Miss Fellows suddenly went up in a puffball of sulphurous smoke I’d hardly be surprised, but I’m only listening to her rant with half an ear. Something that Tiffany said before is bothering me and I’m chasing it down the unreliable pathways of Carmen’s brain. Hey, I have to work with what I’ve got.

Miss Dustin puts a steadying hand on Miss Fellows’ arm and cuts her off midstream. I’m seeing classic Good Cop, Bad Cop 101 being played out right here. No prizes for working out who’s who.

‘Is anything … the matter, Carmen?’ Miss Dustin says gravely from under her ridiculous bob. ‘You’ve been quite … out of sorts lately. I can help.’

I have to stifle a burst of laughter that emerges as a fit of unconvincing coughing. From Carmen’s point of view, there’s not a lot that’s going right at the moment, but it would be too hard to explain to Laurel and Hardy here. I shrug, when I probably should be cowering, which just sets Miss Fellows off again.

‘You’ve been acting like a flake since we got here, Zappacosta. Tomorrow’s your last chance or Tiffany takes over, and you know where we’re taking this piece, so consider it fair warning! Stuff this up and you’ll never sing a solo with this choir again. It will ruin your chances for performing arts college, and I don’t care how “talented” people think you are …’

She lets that one drift, but the implication is clear enough.

For a moment, I feel a twinge of discomfort, like a pulled muscle. Carmen?

‘Tiffany was always my first choice,’ Miss Fellows says sourly to her colleague knowing full well I am still listening.

‘Her voice doesn’t have the brightness and tone of Carmen’s, Fiona, and you know it,’ Miss Dustin murmurs in reply. ‘Carmen’s not as mature a performer, but you have to admit she’s really outstanding.’

Miss Fellows snorts. ‘If she ever gets going! I shouldn’t have let you talk me into it, Ellen. She didn’t even try to sing. It’s like she’s had a personality bypass since we got here, and she didn’t have that much to begin with …’

There’s that internal twitch again. Don’t worry, Carmen, I think I hate her, too.

The music directors of the other schools file out behind Miss Dustin and Miss Fellows, talking quietly among themselves.

‘Two weeks!’ growls the old man. He shoots me an accusing look over his shoulder, as if the general lack of ability of the combined student bodies of Paradise, Port Marie and Little Falls is somehow my personal fault.

‘Less,’ replies Mr Masson glumly. He doesn’t look at me. I am just one more malfunction in a morning of malfunctions. ‘It’s right on track to be a fiasco this time.’

‘Lauren Daley would have been able to sing that part,’ murmurs the good-looking, young male teacher, who seems to have forgotten that I’m there.

Mr Masson nods. ‘A phenomenon. A once-in-a-lifetime voice. She could have carried them all single-handedly. People would have paid just to hear her sing, never mind the others. There’s not a day goes by that I don’t think of that girl.’

What was it that Tiffany said again? It won’t come clear.

‘Lauren Daley is dead!’ the elderly man exclaims, bringing my attention flying back to them.

All three reach the threshold of the hall. Somehow I can still hear them clearly, as if they are standing just beside me. Are the acoustics that good in here?

‘You don’t know that,’ Mr Masson replies stoutly.

‘Well, if she’s not, she’s as good as,’ the older man mutters as the group turns the corner, leaving me sitting alone in a sea of battered chairs.

What was it that Tiffany said? And it suddenly hits me in that dusty, echoing room. Lauren Daley was a soprano, a standout, a star. Like Tiffany thinks she is; like Carmen is supposed to be. That’s what I was trying to remember all along.

I have to find Ryan Daley. If he hasn’t made the connection already, someone has to tell him.

Maybe I’ve evolved, maybe I used to be some kind of impossible princess back when we first met, but Luc doesn’t know me well enough now if he thinks I’ll just sit around on my borrowed ass and do nothing. If you’ve got a surfeit of time and you need it to fly, you’ve gotta keep busy. Rule numero uno, my friends. Worked out the hard way. Take it from me.

Ryan Daley had a reputation as a troublemaker and I like troublemakers. Always have. Provided they don’t hurt people who don’t deserve to be hurt, I’m all for them.

But Ryan Daley refused to be found all that day. I went from class to class on the fringes of the St Joseph’s crowd, keeping a lookout for six foot five of total knockout, vigilante, gun-toting loner, and all I got was more gossip, conjecture and fantasy.

‘He’s like the Phantom,’ sniggered one of the gangly, amateur tenors who’d attached himself to Tiffany like an adoring limpet. He was good looking in a wet, severe-side-part kind of way, if you didn’t focus on the obvious crater marks on his cheeks from recurrent acne. ‘If it weren’t for the Lauren thing, he’d have been canned ages ago.’

‘She was hot,’ added a towering bass called Tod, who had a footballer’s build now but would some day run to fat. ‘Pity.’

If he’d just come right out and said something tasteless like the world had enough ugly chicks in it without someone making off with one of the good ones, I wouldn’t have been surprised. It was what he meant anyway. Like he’d ever had a chance.

‘There was always something weird about those two,’ sniped a delicate, pretty redhead I recognised from a photo on Lauren’s dresser. Both girls with their arms twined around each other’s necks in a Forever Friends photo frame. ‘It went way deeper than the twin thing. They shoulda looked at him a lot harder than they did.’

‘And you should know, Brenda,’ added the spotty boy. ‘I mean, she’s his ex and everything.’ He licked his lips as he addressed this last remark to us, the interlopers without the necessary backstory.

I zeroed in on Brenda for a second and wondered what Ryan had seen in her. She was pretty, I supposed. In a high-maintenance, high-fashion, don’t-touch-me kind of way.

Tiffany, Delia and Co exchanged satisfied glances as the home crowd bore us towards the school canteen for further updates on the Lauren Daley abduction and subsequent fallout. All day, I listened quietly in my guise as Carmen the stuff-up, Carmen the public disgrace and non-entity, and quietly grew angrier as the day progressed. Who says people don’t speak ill of the dead? Lauren deserved to be found just to shut these phoneys up.

When the home-time bell rang and I prepared to walk back through town to the Daleys’ residence, I was no nearer to finding Ryan than I was his sister.

As I passed faded front-window displays that universally declared Shop here for heavenly savings!—every pun intended—it occurred to me that maybe, just this once, I really was supposed to sit on my hands and do nothing. The problem was nearly two years old, the girl had to be beyond salvation, and better minds than mine had already poured everything they had into it. Surely, the trail had to be cold. Only no one had managed to convince Ryan Daley of that.

I finally spot him crossing his street from the north end—coming from the opposite direction to me—towards his front gates, shouldering a heavy rucksack. He frowns as soon as our eyes meet and stops moving. I wave, which is a stupid, girly thing to do, but I’m no good at acting natural.

We begin converging warily towards each other again. But then the Dobermans start up with their weird howling.

By the time he and I meet up in front of the fence, they’re growling and shaking as if they’ve developed advanced rabies, slobbering and clawing at me through the pickets. Ryan’s timing couldn’t be more perfect. What would I do if he wasn’t here to let me in? Scream for help at the periphery? Just fly over to the front door?

‘Dogs don’t like me,’ I say lamely, by way of a greeting.

‘No kidding!’ Ryan says incredulously, looking at my five feet of nothing and wondering how it’s possible. ‘Just wait here.’

Like his dad did on that first day, he hauls them by force, one by one, behind the side fence and padlocks them in. The dogs don’t let up for a second.

Ryan reshoulders his pack and heads for the front door without a word. Not exactly friendly. But he did call off the hounds from hell.

So I yell out loudly, ‘Hey, I’d like to help you. Find her, I mean.’

And it’s enough to make him look at me, really focus for a second. He frowns again and I just want to take his face in my hands and smooth away the lines that shouldn’t be there. They make him look older, careworn. Boys his age should be making out and getting falling down drunk, right?

‘What makes you think you can help me?’ he says quietly. There is no anger in his voice. Just an old despair.

I don’t blame him for saying it. I mean, I come up to somewhere just past his navel. As Carmen, I look kind of useless, even if I don’t feel it, not on the inside. And all I’m going on is a hunch. Is it worth me feeding his delusion?

I don’t like doing it, but I move closer and steel myself before touching his bare wrist tentatively. I need to know if there’s anything in the rumours before I commit myself. Involvement is usually trouble and, boy, I should know.

It begins as an ache in my left hand, building pressure behind my eyes. Then we flame into contact, but it isn’t as if I’m being immolated exactly, burnt alive, like when his parents laid their hands on me. Ryan’s pain, his grief, is different because he believes Lauren’s still alive somewhere. There’s hope there, and it tempers everything so that I don’t feel as if I’m standing at the heart of someone’s raging funeral pyre. It’s almost bearable. Like a dull ache; a pain present but subsumed.

I’m not really certain what I’m looking for, or exactly how this works. I get more images of Lauren, and I’m not sure if they’re things I’ve seen for myself in her bedroom or that exist only inside her twin’s head. But I feel it, too. There’s something of her inside him that isn’t just random memories. It feels fresh, almost recent. It’s uncanny. Faint, like a faded graffiti writer’s tag that refuses to be washed away by the rain. A reaching out. A cry for help. A faint save me.

The Latin comes to me unbidden: salva me.

I see fragments of the things Ryan’s seen or done since Lauren’s disappearance; an avalanche of scenes and faces and pure emotion. A lot of fear. Like today, as he warily combed a deserted complex of buildings on his own, jumping at shadows, testing the ground with an ice pick, when he should have been in class. Layers of long-buried thoughts become clear—memories of fist fights, confrontations, the inside of a jail cell … the inside of a dark basement, with only the sound of someone’s shattered breathing to illuminate the absolute darkness.

I don’t know how long we stand there, but Ryan finally breaks contact, shaking off my light touch angrily. The ghost world fades, replaced by the Daleys’ front yard, the faint tang of salt in the air, the hysterical cries of the dogs. I am no longer deaf, dumb and blind to these things.

‘I don’t need your pity. Or your “help”.’

Ryan’s voice is rough. He tries to open the front door without looking at me again, prepared to shut me and an entire world of sceptics out if necessary. But what I say next draws his shocked gaze.

‘I know where you went today and I think you’re on the wrong track. You should be looking at the house next door. If you’re going to dig, dig there.’

CHAPTER 7 (#uf14ace35-235b-5e8b-abfc-ed954e44dd79)

‘How did you know?’ he demands in a low voice, pulling me through the front door and slamming it behind us roughly.

He’s still gripping the sleeve of the denim jacket I’m wearing when his mother calls from the kitchen, ‘Ryan, is that you, honey? Carmen?’

Neither of us replies, each continuing to stare the other down.

Footsteps come closer and he suddenly explodes into motion, pushing me ahead of him up the stairs. ‘Yeah!’ he shouts finally, from the upstairs landing, steering me away from Lauren’s closed bedroom door towards his, the room on the other side of Lauren’s bathroom.

‘I was worried … the dogs,’ Mrs Daley says below us.

I get a faint glimpse of her standing in a doorway, eyes turned upward trying to see what Ryan’s up to, but he’s a blur of motion. Always running away. Everyone in this house nursing their secrets, their wounds, in isolation.

Ryan yells, ‘Everything’s fine, Mum. I have a paper needs working on. Late with it.’

Then I’m standing in the dimness of his bedroom, heart thudding, close enough to him to smell earth and sweat on his skin.

It’s almost monastic, the room. Just a bed, a chair, a desk, two blank wardrobe doors that tell me nothing about the person that lives here. There’s no … stuff. Sports trophies, magazines, a stereo maybe, posters, smelly sneakers; things I would have expected in a guy’s room. It’s not so much a bedroom as a place to sleep, a kind of blank motel room tricked out in Louisa Daley’s signature spotless monotone shades. Only, there’s a giant picture of Lauren tacked above his bed-head, an impromptu shrine to his missing sister. She’s laughing into the camera, head slightly cocked, looking straight at us.

I move closer to the portrait, study the wide mouth, the dark, lively eyes that are so like Ryan’s. But she’s a fine-boned ash blonde where Ryan’s hair is so dark it could almost be black. Physically, they couldn’t look less like twins.

Maybe that girl was right. Maybe it did go deeper than the twin thing and I should just extricate myself now, say it was all a horrible mistake, sorry for sticking my oar in, what was I thinking? But I don’t. I like a challenge. Recognise it for a truth.

‘She’s beautiful,’ I say.

He lets go of my sleeve, throws down his rucksack, deliberately ignores the comment.

‘How did you know?’ he demands again harshly. ‘About today. Don’t bullshit me, choirgirl.’

‘I saw you,’ I say. He doesn’t need to know that it wasn’t with my eyes. Trust doesn’t need to come into this. ‘You were digging around.’

His gaze slides sideways to his abandoned pack, back to me.

‘Yeah?’ he sneers. ‘You followed me then. Did she put you up to this?’ He rolls his eyes in the direction of the stairs outside. ‘You my new little watchdog now? Got a crush on me, have you? That was quick work. You’ll get over it; plenty have.’ The look on his face is ugly, self-mocking.

I meet his glare steadily. ‘It doesn’t matter how I got there. But the church is too obvious. No one would be able to hide someone who looks like Lauren in the Paradise First Presbyterian Church and get away with it! Especially if she’s some sort of live trophy. Think about how many people go in and out of that place in a week, use the church, the hall, the rec rooms, the outbuildings you were sniffing around today.’

Ryan’s eyes are unfocused for a moment before snapping back to mine.

‘Someone would hear something, see something,’ I say. ‘That place, that room you’re looking for? I don’t think it’s inside the church grounds.’

Ryan is so sunk in thought that he doesn’t realise what I’m saying. I know he isn’t looking for a body, but don’t ask me how it works, this knowledge. He’s looking for some kind of storeroom where a girl is being kept alive. I heard her, too, I almost tell him. She was breathing. It was dark. It has something to do with the fact she can sing like an angel.

‘But I’m getting evangelical music,’ Ryan insists quietly, no longer looking at me. ‘Hymns, snatches of a sermon. It’s got to be the church. It’s the only one in town. Because, funnily enough,’ there is no mirth in his voice, ‘the people of Paradise aren’t huge churchgoers. Contrary to what everyone else says and thinks—even my own parents—Lauren is not dead and she’s close. Close enough that I can sometimes pick up her dreams and her thoughts—the stuff of nightmares, Carmen.’

It’s the first time he’s said my name, and for a minute I’m not sure who he’s talking to. Then I remember who I’m supposed to be, and I shake my head. ‘The manse would be the better bet,’ I say quietly.

He looks at me blindly, his gaze still so inward-focused that he doesn’t ask how it is that I know for sure that the living quarters of the church’s minister are located outside the church grounds. But I saw the place he went to today, if only in illogical fragments. And there was no house there.

‘You know, the preacher’s private residence,’ I go on as his dark eyes finally settle once more on me. ‘It should be close to the church. That’s how it usually works. It’s likely to be less scrutinised, less frequented, but near enough to the church for you to hear the kinds of things you say you’ve heard.’

I don’t elaborate that I’ve heard them, too, through him, through his skin. Voices raised in vigorous Protestant song. An organ. Bible thumping. But the sound was too distant, too faint, not immediate. I perceived snatches of brilliant sunlight, too, falling slantwise down a flight of stairs, blinding when it came. One door. Two. More stairs. The feeling of one room flowing into another. A clock ticking. The sounds of cars leaving a nearby car park in convoy after service, horns tooting. Ordinary things. But then that feeling of terror. With light came misery. The light brought pain and shame and a feeling of wanting to die. I was sure—don’t ask me how—that Lauren found the darkness almost more bearable than the light.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/rebecca-lim-2/mercy/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Rebecca Lim

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An electric combination of angels, mystery and romance, MERCY is the first book in a major paranormal series.There′s something very wrong with me. I can′t remember who I am or how old I am, or even how I got here. All I know is that when I wake up, I could be any one. It is always this way.There′s nothing I can keep with me that will stay. It′s made me adaptable.I must always re-establish ties.I must tread carefully or give myself away.I must survive.Mercy doesn′t realise it yet, but as she journeys into the darkest places of the human soul, she discovers that she is one of the celestial host exiled with fallen angel, Lucifer. Now she must atone for taking his side. To find her own way back to heaven, Mercy must help a series of humans in crisis and keep the unwary from getting caught up in the games that angels play. Ultimately she must choose between her immortal companion, Lucifer, and a human boy who risks everything for her love.