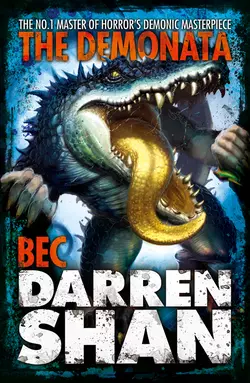

Bec

Bec

Darren Shan

Darren Shan’s Demonata series continues with more shocks, demons and thrilling twists in the chilling Bec.As a baby, Bec fought for her life. As a trainee priestess, she fights to fit in to a tribe that needs her skills but fears her powers. And when the demons come, the fight becomes a war.Bec's magic is weak and untrained, until she meets the druid Drust. Under his leadership, Bec and a small band of warriors embark on a long journey through hostile lands to confront the Demonata at their source.But the final conflict demands a sacrifice too horrific to contemplate…

Scream in the dark on the web at

www.darrenshan.com

For:

Bas, the priestess of Shanville

OBEs (Order of the Bloody Entrails) to:

Emma “Morrigan” Bradshaw

Geraldine “sarsaparilla” Stroud

Mary “Macha” Byrne

Hewn into shape by:

Stella “seanachaidh” Paskins

Fellow questers:

the Christopher McLittle clan

Contents

Beginning

Casualties

Refugees

The Boy

The River

The Stones

The Crannog

Drust

Potential

An Uninvited Guest

Children of the Dark

Family

The Source

The Emigrants

The Geis

Old Creatures

Taming the Wild

The Final Day

The World Beneath

The Sacrifice

Escape

Full Circle

Celtic Terms and Phrases

Other Books by Darren Shan

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

BEGINNING

→ Screams in the dark.

Mother pushes and after a long fight I slip out of her body on to a bed of blood-soaked grass. I cry from the shock of cold air as I take my first breath. Mother laughs weakly, picks me up, holds me tight and feeds me. I drink hungrily, lips fastened to her breast, my tiny hands and feet shivering madly. Rain pelts us, washing blood from my wrinkled, warm skin. Once I’m clean, mother shields me as best she can. She’s weary but she can’t rest. Must move on. Kissing my forehead, she sighs and struggles to her feet. Stumbles through the rain, tripping often and falling, but protecting me always.

→ Banba never believed I could remember my birth. She said it was impossible, even for a powerful priestess or druid. She thought I was imagining it.

But I wasn’t. I remember it perfectly, like everything in my life. Coming into this world roughly, in the wilderness, my mother alone and exhausted. Clinging to her as she pushed on through the rain, over unfamiliar land, singing to me, trying to keep me warm.

My thoughts were a jumble. I experienced the world in bewildering fragments and flashes. But even in my newborn state of confusion I could sense my mother’s desperation. Her fear was infectious, and though I was too young to truly know terror, I felt it in my heart and trembled.

After endless, pain-filled hours, she collapsed at the gate of a ringed, wooden fort — the rath where I live now. She didn’t have the strength to call for help. So she lay there, in the water and mud, holding my head up, smiling at me while I scowled and burped. She kissed me one last time, then clutched me to her breast. I drank greedily until the milk stopped. Then, still hungry, I wailed for more. In the damp, gloomy dawn, Goll heard me and investigated. The old warrior found me struggling feebly, crying in the arms of my cold, stiff, lifeless mother.

“If you remember so much, you must remember what she called you,” Banba often teased me. “Surely she named her little girl.”

But if she did give me a name, she never said it aloud. I don’t know her name either, or why she died alone in such miserable distress, far from home. I can remember everything of my own life but I know nothing of hers, where I came from or who I really am. Those are mysteries I don’t think I’ll ever solve.

→ I often retreat into my early memories, seeking joy in the past, trying to forget the horrors of the present. I go right back to my first day here, Goll carrying me into the rath and joking about the big rat he’d found, the debate over whether I should be left to die outside with my mother or accepted as one of the clan. Banba testing me, telling them I was a child of magic, that she’d rear me to be a priestess. Some of the men were against that, suspicious of me, but Banba said they’d bring a curse down on the rath if they drove me away. In the end she got her way, like she usually did.

Growing up in Banba’s tiny hut. Everybody else in the rath shares living quarters, but a priestess is always given a place of her own. Lying on the warm grass floor. Drinking goat’s milk, which Banba squeezed through a piece of cloth. Staring at a world which was sometimes light, sometimes dark. Hearing sounds when the big people moved their lips, but not sure what the noises meant. Not understanding the words.

Crawling, then walking. Growing in body and mind. Learning more every day, fitting words together to talk, screeching happily when I got them right. Realising I had a name—Bec. It means ‘Little One’. It’s what Goll called me when he first found me. I was proud of the name. It was the only thing I owned, something nobody could ever take from me.

As I grew up, Banba trained me, teaching me the ways of magic. I was a fast learner, since I could remember the words of every spell Banba taught me. Of course, there’s more to magic than spells. A priestess needs to soak up the power of the world around her, to draw strength from the land, the wind, the animals and trees. I wasn’t so good at that. I doubted I’d ever make a really strong priestess, but Banba said I’d improve in time, if I worked hard.

I discovered early on that I’d never fit in. The other children were wary of the priestess’s apprentice. Their mothers warned them not to hurt me, in case I turned their eyes into runny pools or their teeth into tiny squares of mud. I was sad that I couldn’t be one of them. I asked Banba where I came from, if there was a place I could go where I’d be more welcome.

“Priestesses are welcome nowhere,” she answered plainly. “Folk are pleased to have us close, so they can call on us when the crops fail or a woman can’t get round with child. But they never truly trust us. They don’t take us into their confidence unless they have to. Better get used to it, Little One. This is our life.”

The life wasn’t so bad. There was always plenty of food for a priestess, from people eager to win her favour and avoid a nasty curse. And there was respect, and gifts when I made spells work. People wondered how powerful I’d become and what I could do to make the rath stronger. Banba often laughed about that — she said people were always either too suspicious or expected too much.

A few treated me normally, like Goll of the One Eye. Chief of the rath once, now just an ageing warrior. He didn’t care that I was a stranger, from no known background, studying to be a priestess. I was simply a little girl to him. He even spoilt me sometimes, since in a way he felt like my father, as he was the one who found and named me. He often played with me, put me up on his broad shoulders and gave me rides around the rath, grunting like a pig while others laughed or sneered. All the children loved Goll. He was a fierce warrior, who’d killed many men in battle, but he was still a child secretly, in his heart.

Those were the best days. Dreaming of the magic I’d work when I grew up. Harvesting the crops. Herding cattle and sheep. I wasn’t supposed to do ordinary work, but if a child was lazy and I offered to help, they usually let me. Some even became friends over time. They wouldn’t admit it in front of their mothers or fathers, but when nobody was looking they’d talk to me and include me in their games.

Playing… working… learning the ways of magic. Good times. Simple times. Life going on the way it had since the world began, like it was meant to.

Then the demons came.

CASUALTIES

→ A boy’s screams pierce the silence of the night and the village explodes into life. Warriors are already racing towards him by the time I whirl from my watching point near the gate. Torches are flung into the darkness. I see Ninian, a year younger than me, new to the watch… a two-headed demon, pieced together from the bones and flesh of the dead… blood.

Goll is first on the scene. An old-style warrior, he fights naked, with only a small leather shield, a short sword and axe. He hacks at the demon with his axe and buries it deep in one of the monster’s heads. The demon screeches but doesn’t release Ninian. It lashes out at Goll with a fleshless arm and knocks him back, then buries the teeth of its uninjured head in Ninian’s throat. The screams stop with a sickening choking sound.

Conn and three other warriors swarm past Goll and attack the demon. It swings Ninian at them like a club and scythes two of them down. Conn and another keep their feet. Conn jabs one of the monster’s eyes with his spear. The demon squeals like a banshee. The other warrior – Ena – slides in close, grabs the beast’s head and twists, snapping its neck.

If you break a human’s neck, that person will almost surely die. But demons are made of sturdier stuff. Broken necks just annoy most of them.

With one hand the demon grabs the head which Goll shattered with his axe. Rips it off and batters Ena with it. She doesn’t let go. Snaps the neck again, in the opposite direction. It comes loose and she drops it. She pulls a knife from a scabbard strapped to her back and drives it into the rotting bones of the skull. Making a hole, she wrenches the sides apart with her hands, digs in and pulls out a fistful of brains. Grabs a torch and sets fire to the grey goo.

The demon howls and grabs blindly for the burning brains. Conn snatches the other head from its hand. He throws it to the ground and mashes it to a pulp with his axe. The demon shudders, then slumps.

“More!” comes a call from near the gate. It’s late — later than demons usually attack. Most of the warriors on the main watch have retired for the night, replaced by children like me. Our eyes and ears are normally sharp. But this close to dawn, most of us are sleepy and sluggish. We’ve been caught off guard. The demons have snuck up. They have the advantage.

Bodies spill out of huts. Hands grab spears, swords, axes, knives. Men and women race to the rampart. Most are naked, even those who normally fight in clothes — no time to get dressed.

Demons pound on the gate and scale the banks of earth outside, tearing at the sharpened wooden poles of the fence, clambering over. The two-headed monster might have been a diversion, sent to distract us. Or else it just had a terrible sense of direction, as many corpse-demons do.

Warriors mount ladders or haul themselves up on to the rampart to tackle the demons. It’s hard to tell how many monsters there are. Definitely five or six. And at least two are real demons — Fomorii.

Conn arrives at the gate, shouting orders. He bellows at those on watch who’ve strayed from their posts. “Stay where you are! Call if clear!”

The trembling children return to their positions and peer into the darkness, waving torches over their heads. In turn they yell, “Clear!” “Clear!” “Clear!” One starts to shout “Cle–”, then screams, “No! Three of them over here!”

“With me!” Goll roars at Ena and the others who fought the first demon. They held back from the battle at the gate, in case of a second attack like this. Goll leads them against the trio of demons. I see fury in his face — he’s not furious with the demons, but with himself. He made a mistake with the first one and let it knock him down. That won’t happen again.

As the warriors engage the demons, I move to the centre of the rath and wait. I don’t normally get involved in fights. I’m too valuable to risk. If the demons break through the barricades, or if an especially powerful Fomorii comes up against us — that’s when I go into action.

To be honest, I doubt I could do much against the stronger Fomorii. Everybody in the rath knows that. But we pretend I’m a great priestess, mistress of all the magics. The lie comforts us and gives us some faint shadow of hope.

The younger children of the rath cluster around me, watching their parents fight to the death against the foul legions of the Otherworld. Their older brothers and sisters are at the foot of the rampart, passing up weapons to the adults, ready to dive into the breach if they fall. But these young ones wouldn’t be of much use.

I hate standing with them. I’d rather be at the rampart. But duty comes at a price. Each of us does what we can do best. My wishes don’t matter. The welfare of the rath and my people comes first. Always.

One of the Fomorii makes it over the fence. Half-human, half-boar. A long jaw. A mix of human teeth and tusks. Demonic yellow eyes. Claws instead of hands. It bellows at the warriors who go up against it, then spits blood at them. The blood hits a woman in the face. She shrieks and topples back off the rampart. Her flesh is bubbling — the demon blood is like fire.

I race to the woman. It’s Scota. We share a hut sometimes (I’m passed around from hut to hut now Banba’s gone). Her usually pale skin is an ugly red colour. Bubbles of flesh burst. The liquid sizzles. Scota screams.

I press my palms to her forehead, ignoring the heat of her flesh and the burning drops of liquid which strike my skin. I mutter the words of a calming spell. Scota sighs and relaxes, eyes closing. I tug a small bag from my belt, open it and pour coarse green grains into the palm of my left hand. Dropping the bag, I spit over the grains and mix them together with a finger, forming a paste. I rub the paste into Scota’s disfigured flesh and it stops dissolving. She’ll be scarred horribly but she’ll live. There are other pastes and lotions I can use to help the wounds heal cleanly. But not now. There are demons to kill first.

I look up. The boar demon has been pierced in several places by the swords and knives of our warriors, but still it fights and spits. I wish I knew where these monsters got their unnatural strength from.

Screams behind me — the children! A spider-shaped Fomorii has crawled out of the hut over the souterrain. The beast must have found the exit hole outside the rath and made its way up the tunnel, then broke through the planks covering the entrance.

Conn hears the screams. He looks for warriors to send to their aid. Before he can roar orders, two brothers hurl themselves into the demon’s path. Ronan and Lorcan, the rath’s red-headed twins, barely sixteen years old. Their younger brother, Erc, was killed several months ago. The twins were always strong fighters, even as young children, but since Erc fell, they’ve fought like men possessed. They love killing demons.

Conn refocuses on the demons at the gate. He doesn’t bother sending other warriors to deal with the spider. He trusts the teenage twins. They might be among the youngest warriors in the rath, but they’re two of the fiercest.

Ronan and Lorcan move in on the spider demon. Now that it’s closer, I see that although it has the body of a large spider, it has a dog’s face and tail. Demons are often a mix of animals. Banba used to say they stole the forms of our animals and ourselves because they didn’t have the imagination to invent bodies of their own.

Ronan, the taller of the pair, with long, curly, flowing hair, has two curved knives. Lorcan, who cuts his hair close and whose ears are pierced with a variety of rings, carries a sword and a small scythe. They’re both skilled at fighting with either the left or right hand. But before they can tackle the dog-spider, it shoots hairs at them. The hairs run all the way along its eight legs and act like tiny arrows when flicked off sharply.

The hairs strike the brothers and cause them to stop and cover their faces with their hands, to protect their eyes. They hiss, partly from the pain, but mostly with frustration. The Fomorii moves forward, barking with evil delight, and the twins are forced back, chopping blindly at it.

I could call Conn for assistance, but I want to handle this on my own. I won’t place myself at risk, but I can help, leaving the warriors free to concentrate on the larger, more troublesome demons.

I hurry to the beehives. We kept them outside the rath before the attacks began, but certain demons have a taste for honey, so we moved them in. The bees are at rest. I reach within a hive and grab a handful of bees, then prise them out, whispering words of magic so they don’t sting me. Walking quickly, I place myself behind Ronan and Lorcan. Taking a firm stance, I thrust my hand out and whisper to the bees again, a command this time. They come to life within my grasp.

“Move!” I snap. Ronan and Lorcan glance back at me, surprised, then step aside. I open my fingers and the bees fly straight at the dog-spider, attacking its eyes, stinging it blind. The Fomorii whines and slaps at its eyes with its legs, losing interest in everything except the stinging bees. Ronan and Lorcan step up, one on either side. Four blades glint in the light of the torches — and four hairy legs go flying into darkness.

The demon collapses, half its legs gone, sight destroyed. Ronan steps on its head, takes aim, then buries a knife deep in its brain. The dog-spider stiffens, whines one last time, then dies. Ronan withdraws his knife and wipes it clean on his long hair. His natural red hair is stained an even darker shade of red from the blood of demons. Lorcan’s stubble is blood-caked too. They never wash.

Ronan looks at me and grins. “Nice work.” Then he runs with Lorcan to where Conn and his companions are attempting to drive the demons back from the fence.

I take stock. Goll’s section is secure — the demons are retreating. The boar-shaped Fomorii has been pushed back over the fence. It’s clinging to the poles, but its fellow demons aren’t supporting it. When Ronan and Lorcan hit, blades turning the air hot, it screams shrilly, then launches itself backwards, defeated. Connla – Conn’s son – fires a spear after the demon. He yells triumphantly — it must have been a hit. Connla picks up another spear. Aims. Then lowers it.

They’re retreating. We’ve survived.

Before anyone has a chance to draw breath, there’s a roar of rage and loss. It comes from near the back of the rath — Amargen, Ninian’s father. He’s cradling the dead boy in his arms. He had five children once. Ninian was the last. The others – and his wife – were all killed by demons.

Conn hurries across the rampart towards Amargen, to offer what words of comfort he can. Before Conn reaches him, Amargen leaps to his feet, eyes mad, and races for the chariot which our prize warriors used when going to fight. It’s been sitting idle for over a year, since the demon attacks began. Conn sees what Amargen intends and leaps from the rampart, roaring, “No!”

Amargen stops, draws his sword and points it at Conn. “I’ll kill anyone who tries to stop me.”

No bluff in the threat. Conn knows he’ll have to fight the crazed warrior to stop him. He sizes up the situation, then decides it’s better to let Amargen go. He shakes his head and turns away. Waves to those near the gate to open it.

Amargen quickly hooks the chariot – a cart really, nothing like the grand, golden chariots favoured by champions in the legends – up to a horse. It’s the last of our horses, a bony, exhausted excuse for an animal. He lashes the horse’s hind quarters with the blunt face of his blade and it takes off at a startled gallop. Racing through the open gate, Amargen chases the demons and roars a challenge. I hear their excited snorts as they stop and turn to face him.

The gate closes. A few of the people on the rampart watch silently, sadly, as Amargen fights the demons in the open. Most turn their faces away. Moments later — human screams. A man’s. Terrible, but nothing new. I say a silent prayer for Amargen, then turn my attention to the wounded, hurrying to the rampart to see who needs my help. The fighting’s over. Time for healing. Time for magic. Time for Bec.

REFUGEES

→ No clouds. The clearest day in a long time. Good for healing. I take power from the sun. It flows through me and from my fingers to the wounded. I use medicine, pastes and potions where they’re all that’s needed. Magic on those with more serious injuries — Scota and a few others who were struck by the Fomorii’s fire-blood.

The warriors are tired, their sleep disturbed. They’ll rest later, but most are too edgy to return to their huts straightaway. It takes an hour or two for the battle lust to pass. They’re drinking coirm now and eating bread, discussing the battle and the demons.

I’m fine. I had a full night’s sleep, only coming on watch a short while before the attack. That’s my regular pattern on nights when there isn’t an early assault.

Having tended to the seriously wounded, I wander round the rath, in case I’ve missed anybody. I used to think the ring fort was huge, ten huts contained within the circular wall, plenty of space for everyone. Now it feels as tight as a noose. More huts have been built over the last year, to shelter newcomers from the neighbouring villages in our tuath. Many of those who lived nearby were forced out of their homes and fled here for safety. There are twenty-two huts now, and although the walls of the rath were extended outwards during the spring, we weren’t able to expand by much.

The use of magic has wearied me and left me hungry. I don’t have much power, nothing like what Banba had. The sun helps but it’s not enough. I need food and drink. But not coirm. That would make me dizzy and sick. Milk with honey stirred in it will give me strength.

Goll’s sitting close to the milk pails. He looks downhearted. He’s scratching the skin over his blind right eye. Goll was king of this whole tuath years ago, the most powerful man in the region, with command of all the local forts. There was even talk that he might become king of the province — our land is divided into four great sectors, each ruled by the most powerful of kings. None of our local leaders had ever held command of the province. It was an exciting prospect. Goll had the support of every king in our tuath and many in the neighbouring regions. Then he lost his eye in a fight and had to step down. He’s not bitter. He never talks of what might have been. This was his fate and he accepts it.

But Goll’s in a gloomy mood this morning. He hates making mistakes. Feeling sorry for the old warrior, I sit beside him and ask if he wants some milk.

“No, Little One,” he says with a weak smile.

“It wasn’t your fault,” I tell him. “It was a lucky strike by the Fomorii.”

Goll grunts. That should be the end of it, except Connla is standing nearby, a mug of coirm in his hands, boasting of the demon he hit with his spear. He hears my comment and laughs. “That wasn’t luck! Goll’s a rusty old goat!”

Goll stiffens and glares at Connla. Eighteen years old, unmarried Connla’s one of the handsomest men in the tuath, tall and lean, with carefully braided hair, a moustache, no beard, fashionable tattoos. His cloak is fastened with a beautiful gold pin, and pieces of fine jewellery are stitched into it all over. Unlike most of the men, who wear belted tunics, he favours knee-length trousers. He was the first man in the rath to wear them, although several have followed his lead. His boots are made from the finest leather, laced artistically with horse-hair thongs. He looks more like a king than his father does, and when Conn dies he’ll be one of the favourites to replace him. Most of the young women in the tuath desire him for his looks and prospects. But he’s no great warrior. Everyone knows Connla’s an average fighter. And far from the bravest.

“At least I was there to make a mistake,” Goll growls. “Where were you, Connla — combing your hair perhaps?”

“I was in the thick of the fighting,” Connla insists. “I struck a demon. I think I killed it.”

“Aye,” Goll sneers. “You hit it with a spear. In the back. While it was running away.” He claps slowly. “A most courageous deed.”

Connla hisses. His hand goes for a spear. Goll snatches for his axe.

“Enough!” Conn barks. He’s been keeping an eye on the pair. He always seems to be on hand when Connla’s on the point of getting into trouble. The king steps forward, scowling. “Isn’t it bad enough that we have to fight demons every night, without battling among ourselves too?”

“He questioned my courage,” Connla whines.

“And you called him an old goat,” Conn retorts. “Now shake hands and forget it. We don’t have time for quarrels. Be men, not children.”

Goll sighs and extends a hand. Connla takes it, but his face is twisted and he shakes quickly, then returns to the small group of men who are always huddled close around him. As they leave, he starts to tell them again about the demon he speared and how he’s certain the blow was fatal, boasting of his great skill and courage.

→ Later. The gate of the rath is open. The cows and sheep have been led out to graze. Demons can only come at night, gods be thanked. If they could attack by day as well, we’d never be able to graze our animals or tend our crops.

I go for a walk. I like to get out of the ring fort when my duties allow, stretch my legs, breathe fresh air. I stroll to a small hill beyond the rath, from the top of which I’m able to look all the way across Sionan’s river to the taller hills on the far side. Many of the men have been to those hills, to hunt or fight. I’d love to climb the peaks and see what the world looks like from them. But it’s a journey of many days and nights. No chance of doing that while the demons are attacking. And for all we know, the demons will always be on the attack.

I feel lonely at times like these. Desperate. I wish Banba was here. She was more powerful than me and had the gift of prophecy. She died last winter, killed by a demon. Got too close to the fighting. Struck by a Fomorii with tusks instead of arms. It took her two nights and days to die. I haven’t learnt any new magic since then. I’ve worked on the spells that I know, to keep in shape, but it’s hard without a teacher. I make mistakes. I feel my magic getting weaker, when it should be growing every day.

“Where will it end, Banba?” I mutter, eyes on the distant hills. “Will the demons keep coming until they kill us all? Are they going to take over the world?”

Silence. A breeze stirs the branches of the nearby trees. I study the moving limbs, in case I can read a sign there. But it just seems to be an ordinary wind — not the Otherworldly voice of Banba.

After a while I bid farewell to the hills and return to the rath. There’s work to be done. The world might be going up in flames, but we have to carry on as normal. We can’t let the demons think they’ve got the beating of us. We dare not let them know how close we are to collapse.

→ After a quick meal of bread soaked in milk, I start on my regular chores. Weaving comes first today. I’m a skilled weaver. My small fingers dart like eels across the loom. I’m the fastest in the rath. My work isn’t the best, but it’s not bad.

Next I fetch honey from the hives. The bees were Banba’s. She brought them with her when she settled in the rath many years ago. They’re my responsibility now. I was scared of them when I was younger, but not any more.

Nectan returns from a fishing trip. He slaps two large trout down in front of me and tells me to clean them. Nectan’s a slave, captured abroad when he was a boy. Goll won him in a fight with another clan’s king. He’s as much a part of our rath now as anyone, a free man in all but name.

I enjoy cleaning fish. Some women hate it, because of the smell, but I don’t mind. Also, I like reading their guts for signs and omens, or secrets from my past. I haven’t divined anything from a fish’s insides yet but I live in hope.

The women grind wheat in stone querns, to make bread or porridge. Some work on the roofs of the huts, thatching and mending holes. I’d love to build a hut from scratch, draw a circle on the ground and raise it up level by level. There’s something magical about building. Banba told me that all unnatural things – clothes, huts, weapons – are the result of magic. Without magic, she said, men and woman would be animals, like all the other beasts.

Most of the men are sleeping, but a few are cleaning their blades and still discussing the night’s battle. It was one of our easier nights. The attack was short-lived and the demons were few in number. Some reckon that’s a sign that the Fomorii are dying out and returing to the Otherworld. But they’re dreamers. This war with the demons is a long way from over. I don’t need fish guts to tell me that!

Fiachna is working by himself, straightening crooked swords, fixing new handles to axes, sharpening knives. We’re the only clan in the tuath with a smith of its own. That was Goll’s doing when he was king. Most smiths wander from clan to clan, picking up work where they find it. Goll figured that if we paid a smith to settle, folk from nearby raths, cathairs and crannogs would come to us when their weapons and tools needed repairing, rather than wait for a smith to pass by. He was right. Our rath became an important focal point of the tuath — until the attacks began. The demons put paid to a lot of normal routines. Nobody travels now, unless it’s to flee the Fomorii.

When I get a chance, I walk over to where Fiachna is hammering away at a particularly stubborn blade. I watch him silently, playing with a lock of my short red hair, smiling shyly. I like Fiachna. He’s shorter than most men, and slim, which is odd for a smith. But he’s very skilled. Stronger than he looks. He swings heavy hammers and weapons with ease. If I could marry, I’d like to marry Fiachna. If nothing else, we’re suited in size. Maybe it’s because of the name Goll gave me, or perhaps it’s coincidence, but I’m one of the smallest girls in the rath.

But it’s not just his size. I like his kind nature and gentle face. He has a short beard – dark-blond, like his hair – which doesn’t hide his smile. Most of the men have beards so thick you can’t see their mouths, so you never know if they’re smiling or frowning.

I often dream of being Fiachna’s wife, bearing his young, fighting demons by his side. But it won’t happen. I’m almost of marrying age – my blood came a couple of years ago, earlier than in most girls – but I can never wed. Magic and marriage don’t mix. Priestesses and druids lose their power if they love.

Sometimes it makes me sad, thinking about not being able to marry. I find myself wishing I could be normal, that the magic would fade from me, leaving me free to wed like other girls my age. But those are selfish thoughts and I try hard to drive them away. My people need my magic. It’s not the strongest in the world and I’m in dire need of a teacher to direct me. But it’s better than having no magician in the rath at all.

Fiachna looks up and catches me staring. He smiles, but not in a teasing way, not like Connla would smirk if he saw me looking at him. “You did well with the bees last night,” Fiachna says in his soft, lilting voice, more like a fairy’s than a human’s.

I feel my face turn red. “It wasn’t much,” I mutter, sticking my big right toe out over the lip of its sandal and stubbing the ground.

“You’re getting stronger,” Fiachna says. “You’ll be a powerful priestess soon.”

We both know that’s a lie but I love him for saying it. I give a big smile, like a baby having its tummy tickled. Then Cera calls me and tells me to give her a hand dyeing wool. “Do you want me to help you with the weapons?” I quickly ask Fiachna, hoping for an excuse to stay with him. “I can bless the blades. Put magic in them. Make them stronger.”

Fiachna shakes his head. “There’s no need. I’m almost finished. I’ll work on farming tools in the afternoon.”

“Oh.” I try not to let my disappointment show. “Well, if you need me, call.”

Fiachna nods. “Thank you, Bec. I will.”

Simple words, but as I dip strands of wool in a vat full of blue dye, they ring inside my skull for ages, making me smile.

→ In the afternoon, while the men are stirring in their sleep and the women are working on the evening meal, a lookout yells a warning. “Figures to the north!”

The rath comes on instant alert. Demons have never attacked this early – there’s at least two hours of daylight left – but we’ve learnt not to take anything for granted. Men are out of their huts and reaching for weapons within seconds. Female warriors throw away their looms, combs, tools and pots, and hurry to the rampart. Those outside the rath are summoned in. They come hastily, anxiously driving the animals ahead of them.

Conn emerges from his hut at the centre of the village, eyes crusty, looking less worried than anyone else. A king should never look scared. He climbs the rampart and strides to the lookout. Stares off into the distance. Connla shouts at him from the ground, “Demons?”

“Doesn’t look like it,” Conn grunts. “Human in shape. But maybe they’re dead.”

The dead often come back to haunt us. The demons get the bodies from dolmens or wedge tombs. They use dark magic to fill the corpses with evil life, sometimes stitching bits from various victims together. We’re not sure why they do it. Maybe some of them can’t make bodies of their own and have to steal the bones of our dead. We’ve gone to all the local tombs that we know of over the last year, burning the corpses. But there are many hidden and forgotten tombs. The demons are always finding new bodies. At times, it seems like there’s more dead than living in the world.

Conn watches for several minutes, more of the clan joining him, shading their eyes with their hands, studying the approaching shapes. I see the more hawk-eyed among them – Ronan, Lorcan, Ena – relax and I know it’s all right. But nobody says anything before Conn. It’s his place to give the all-clear.

Finally, Conn smiles. “Not to worry,” he says. “They’re human. Alive.”

Calm settles over the rath and everyone returns to their normal routine. We’re curious about the strangers but we’ll find out all about them in good time. No point standing around guessing, when there’s work to be done.

→ They arrive half an hour later, ragged and weary from battle and the road. Four men, three women and four children. We know them — the MacCadan. When the demons first attacked, Conn sent an envoy to Cadan and asked if he was open to an alliance. There had been bad blood between us but Conn wanted to make peace, so we could fight the demons together. Cadan refused. He said his people could stand alone. We haven’t heard from them since then.

Cadan’s not among the eleven. The leader’s an old warrior – even older than Goll – who limps awkwardly and trembles pitifully when he’s not on the move. He announces himself at the gate as Tiernan MacCadan and requests entrance. The eleven trudge into the rath and present themselves miserably, heads low.

Conn goes straight to Tiernan and clasps his arms warmly, welcoming him. He asks if they’re hungry or thirsty. Tiernan says they are and Conn gives orders for a feast to be prepared. The women set to the task immediately.

Conn leads our guests to the area in front of his hut and lets them settle. They haven’t brought much – spare clothes, a few weapons, some tools – but it’s plain this is all they have. I know what’s happened, just as Conn and everybody else knows, but nobody says anything. We let Tiernan explain.

The demons overwhelmed them. The end had been coming for a long time but they held out stubbornly, even past the point where they knew it was folly. Their best warriors had fallen to the foul Fomorii, their children had been taken, their animals slain, their crops destroyed.

“Many argued against staying,” Tiernan sighs. “We said it was madness, that we’d perish if we didn’t join forces with our neighbours. But Cadan said we’d lose face if we retreated. He was a proud man, not for bending. But eventually, like all who refuse to bend, he snapped. The Fomorii took him last night, along with three others. This morning, before the sun had risen, we packed our goods and marched here. We hope to fight with you, to offer whatever aid we can, to…”

He trails to a halt. Two of the men are seriously injured and Tiernan’s no chick. One of the women is a warrior but the other two aren’t. And the children are too young to fight. Tiernan’s trying to make it sound like we need them, that they can make a difference. But really they’re just looking for sanctuary. Taking them in would be a mercy, not a merger.

The men of the rath are sitting in a circle around the newcomers. I’m on the outskirts, only allowed this close in case any magical matters arise. I see doubt on the faces of most. We’re already cramped. We’d need to expand the fort again to comfortably hold eleven more people. That’s hard to do when you’re under attack from demons most nights.

Tiernan senses the mood and speaks rapidly. “We could build our own huts. Our women are skilled, the children too. We’d depend on your hospitality for a few weeks but we’d work every hour we can to set up on our own. We wouldn’t be a burden. And when it comes to fighting, we’re stronger than we look. Even the youngest child has drawn blood. We–”

“Easy, friend,” Conn interrupts. “We’re pleased you came to us when there are so many other clans you could have gone to. It’s an honour to receive you. I’m sure you will be of great help.”

Tiernan blinks. He hadn’t expected such a gracious welcome. After the years of feuding, it’s more than he dared hope. Tears well in his eyes but he shakes them away and smiles. “You’re a true king,” he compliments Conn.

“And, I hope, a true friend,” Conn replies, then barks orders for beds to be made for the MacCadan. Some don’t like it – Connla’s face is as dark as a winter cloud – but nobody’s going to argue with our king, certainly not in front of guests. So they obey without question, shifting beds, clothes and goods from one hut to another, bunching up even closer than before, squashing together, making room for the new additions to our demon-tormented clan.

THE BOY

→ Preparations for the feast are at an advanced stage, and the sun is close to setting, when there’s a call from another lookout. “I see someone in the distance running towards us!”

Conn raises an eyebrow at Tiernan. They’ve been talking about their battles with the demons. I’ve sat in close attendance. Our seanachaidh fled not long after the attacks began, so I’ve been charged with keeping the history of the clan. I’m no natural storyteller but I’ve a perfect memory.

“It’s not one of ours,” Tiernan says. “We brought all our living with us.”

“Is it a demon?” Conn shouts at the lookout.

“It doesn’t look like one,” comes the reply. “I think it’s a boy. But the speed at which he’s running… I’m not sure.”

Conn returns to the rampart with Tiernan and a few of our warriors. I slip up behind them. I normally avoid the exposure of the higher ground, but a lone demon in daylight can’t pose much of a threat.

As the figure races closer, we see that it’s a boy, my age or slightly older, running incredibly fast, head bobbing about strangely. He lopes up to the gate, ignoring Conn’s shouts to identify himself, then stops and looks at us dumbly. Dark hair and small eyes. He smiles widely, even though Conn is roaring at him, threatening to stick a spear through his heart if he doesn’t announce his intentions. Then he sits, picks a flower and plays with it.

Conn looks angry but confused. “A simpleton,” he grunts.

“It could be a trap,” Tiernan mutters.

“Demons don’t send humans to lay traps,” Conn disagrees.

“But you saw how fast he ran,” Tiernan says. “And he doesn’t look tired. He’s not even sweating. Maybe he’s not human.”

“Bec,” Conn calls, “do you sense anything?”

I close my eyes and focus on the boy. Demons have a different feel to humans. They buzz with the power of their own world. There’s a flicker of that about this child. I start to tell Conn but then something strange happens. I sense a change in the boy. Opening my eyes, I see that the light around him is different. It’s like looking at him through a thick bank of mist. As I squint, I realise the boy is no longer there. Instead, I’m staring at my mother.

There’s no mistaking her. I’ve seen her so many times in my perfect memories. She looks just like she did on the day she gave birth to me — the day she died. Haggard, bone-thin, dark circles under her eyes, stained with blood. But love in her eyes — love for me.

As I stare, numb with wonder – but no fear – my mother turns and points west, keeping her eyes on mine. She says something but her words don’t carry. With a frown, she jabs a long finger towards the west. She starts to say something else but then the mist clears. She shimmers. I blink. And I’m suddenly looking at the boy again, playing with his flower.

“Bec,” Conn is saying, shaking me lightly. “Are you all right?”

I look up, trembling, and think about telling Conn what I saw. Then I decide against it. I’ve never had a vision before. I need time to think about it before I discuss it with anyone. Focusing on the boy, I control my breathing and try to calm my fast heartbeat.

“I th-think he’s hu-human,” I stutter. “But not the same as us. There’s magic in him. Maybe he’s a druid’s apprentice.” That’s a wild guess, but it’s the closest I can get to explaining what’s different about him.

“Does he pose a threat?” Conn asks.

A dangerous question — if I answer wrongly, I’ll be held responsible. I think about playing safe and saying I don’t know, but then the boy pulls a petal from the flower and slowly places it on his outstretched tongue. “No,” I say confidently. “He can’t harm us.”

The gate is opened. Several of us spill out and surround the boy. I’ve been brought along in case he doesn’t speak our language. A priestess is meant to have the gift of tongues. I don’t actually know any other languages but I don’t see the need to admit that, not unless somebody asks me directly — and so far nobody has. I keep hoping he’ll change and become my mother again, but he doesn’t.

The boy is thin and dirty, his hair thick and unwashed, his knee-length tunic caked with mud, no cloak or sandals. His eyes dart left and right, never lingering on any one spot for more than a second. He’s carrying a long knife in a scabbard hanging from his belt but he doesn’t reach for it or show alarm as we gather round him.

“Boy!” Conn barks, nudging the boy’s knee with his foot. No reaction. “Boy! Who are you? What are you doing here?”

The boy doesn’t answer. Conn opens his mouth to shout again, then stops. He looks at me and nods. Licking my lips nervously, I crouch beside the strange child. I watch him play with the flower, noting the movements of his eyes and head. I no longer think he’s a druid’s assistant. Conn was right — he’s a simpleton. But one who’s been blessed in some way by the gods.

“That’s a nice flower,” I murmur.

The boy’s gaze settles on me for an instant and he grins, then thrusts the flower at me. When I take it, he picks another and holds it above his head, squinting at it.

“Can you speak?” I ask. “Do you talk?”

No answer. I’m about to ask again, when he shouts loudly, “Flower!”

I jump at the sound of his voice. So do the men around me. Then we laugh, embarrassed. The boy looks at us, delighted. “Flower!” he shouts again. Then his smile dwindles. “Demons. Killing. Come with.” He leaps to his feet. “Come with! Run fast!”

“Wait,” I shush him. “It’s almost night. We can’t go anywhere. The demons will be on the move soon.”

“Demons!” he cries. “Killing. Come with!” He grabs my hand and hauls me up.

“Wait,” I tell him again, losing my patience. “What’s your name? Where are you from? Why should we trust you?” The boy stares at me blankly. I take a deep breath, then ask slowly, “What’s your name?” No answer. “Where are you from?” Nothing. I turn to Conn and shrug. “He’s simple. He probably escaped from his village and–”

“Come with!” the boy shouts. “Run fast! Demons!”

“Bec’s right,” Connla snorts. “Why would anyone send a fool like this to–”

“Run fast!” the boy gasps before Connla can finish. “Run fast!” he repeats, his face lighting up. He tears away from us, breaks through the ranks of warriors as if they were reeds and races around the rath. Seconds later he’s back, not panting, just smiling. “Run fast,” he says firmly.

“Do you know where you’re from, Run Fast?” Goll asks, giving the boy a name since he can’t provide one himself. “Can you find your way back to your people?”

For a moment the boy gawps at Goll. I don’t think he understands. But then he nods, looks to where the sun is setting and points west. “Pig’s trotters,” he says thoughtfully. For a second I see my mother pointing that same way again, but this is just a memory, not another vision.

Goll faces Conn. “We should bring him in. It’ll be dark soon. We can question him inside, though I doubt we’ll get much more out of him.”

Conn hesitates, judging the possible danger to his people, then clicks his fingers and leaves the boy to his men, returning to the fireside with Tiernan, to discuss this latest turn of events.

→ Run Fast isn’t big but he has the appetite of a boar. He eats more than anyone at the feast but nobody minds. There’s something cheering about the boy. He makes us all feel good, even though he can’t talk properly, except to explode every so often with “Demons!” or “Come with!” or – his favourite – “Run fast!”

As Goll predicted, Run Fast isn’t able to tell us any more about his clan, where he lives or how great their need is. Under normal circumstances he’d be ignored. We’ve enough problems to cope with. But the mood of the rath is lighter than it’s been in a long while. The arrival of the MacCadan has sparked confidence. Even though the eleven are more of a burden than a blessing, they’ve given us hope. If survivors from other clans make their way here, perhaps we can build a great fort and a mighty army, keep the demons out forever. It’s wishful, crazy thinking, but we think it anyway. Banba used to say that the desperate and damned could build a mountain of hope out of a rat’s droppings.

So we grant Run Fast more thought than we would have last night. The men debate his situation, where he’s from, how long it might have taken him to come here, why a fool was sent instead of another.

“His speed is the obvious reason,” Goll says. “Better to send a hare with half a message than a snail with a full one.”

“Or maybe the Fomorii sent him,” Tiernan counters, his bony, wrinkled fingers twitching with suspicion. “They could have conquered his clan, then muddled his senses and sent him to lure others into a trap.”

“You afford them too much respect,” Conn says. “The Fomorii we’ve fought are mindless, dim-witted creatures.”

“Aye,” Tiernan agrees. “So were ours to begin with. But they’ve changed. They’re getting more intelligent. We had a craftily hidden souterrain. One or two would find their way into it by accident every so often, but recently they attacked through it regularly, in time with those at the fence. They were thinking and planning clearly, more like humans in the way they battled.”

Conn massages his chin thoughtfully. Our one great advantage over the demons – besides the fact they can only attack at night – is that we’re smarter than them. But if there are others, brighter than those we’ve encountered…

“I don’t think it’s a trap,” Fiachna says quietly. He doesn’t normally say much, so everyone’s surprised to hear him speak. He’s been sitting next to Run Fast, examining the boy’s knife. “This boy doesn’t have the scent of demons on him. Am I right, Bec?”

I nod immediately, delighted to be publicly noticed by Fiachna. “Not a bit of a scent,” I gush, rather more breathlessly than I meant.

“He’s telling the truth,” Fiachna says. “His people need help. Run Fast was the best they could send. So they sent him, probably in blind hope.”

“What of it?” Connla snorts. I can tell by the way he’s eyeing Run Fast that he doesn’t like him. “We need help too. Our plight’s as serious as theirs. What do they expect us to do — send our men to fight their battles, leaving our women and children at the mercy of the Fomorii?” He spits into the dust.

“He puts it harshly but there’s wisdom in what my son says,” Conn murmurs. “Alliances are one thing, but begging for help like slaves… asking us to go to their aid instead of coming to us…”

“Perhaps they can’t travel,” Goll says. “Many might be wounded or old.”

“In which case they’re not worth saving,” Connla laughs. Those who follow him laugh too — wolves copying the example of their pack leader.

“We should go,” Goll growls. “Or at least send an envoy. If we ignore their pleas, perhaps ours will also be ignored when we seek assistance.”

“Only the weak ask for help,” Connla says stiffly.

Goll smiles tightly and I sense what he’s going to say next — something along the lines of, “Well, it won’t be long before you ask then!”

Luckily Conn senses it too, and before Goll utters an insult which will demand payment in blood, the king says, “Even if we wanted to help, we don’t know where they are, and I don’t trust this empty-headed child to find his way back.”

“If the brehons were here, they could counsel us,” Fiachna says.

“Brehons!” Connla snorts. “Weren’t they the first to flee when the demons arose? Damn the brehons!”

There are mutters of agreement, even from those who don’t normally side with Connla. The law-making brehons deserted us when we most needed them and few are in the mood to forgive and forget.

The men continue debating, the women sitting silently behind them, their children sleeping or playing games. On the rampart the lookouts keep watch for demons.

Goll and Fiachna are of the opinion that we should send a small group with Run Fast to help his clan. “It’s no accident that he arrived on the same day as the MacCadan,” Goll argues. “Yesterday we couldn’t have let anyone go. But our ranks have been bolstered. It’s a sign.”

“Bolstered?” Connla almost shrieks, casting a scornful glance at the four men and three women of the MacCadan.

“Connla!” his father snaps, before the hot-headed warrior disgraces our guests. When he’s sure of his son’s silence, Conn leans forward, sipping coirm, thinking hard. Like any king, he dare not ignore a possible sign from the gods. But he’s not sure this is a sign. And in a situation such as this, there’s only one person he can turn to. “Bec?”

I was expecting his query, so I’m able to keep a calm face. I’ve had time to consider my answer. I believe we’re meant to go with Run Fast. That was what the vision meant. The spirit of my mother was telling me to follow this boy.

“We should help,” I whisper. Connla rolls his eyes but I ignore him. “We’re stronger now, thanks to the MacCadan. We can spare a few of our warriors. I believe Run Fast can find his way back to his people, and I think bad luck would befall us if we refused their plea.”

Conn nods slowly. “But who to send? I don’t want to command anyone to leave. Are there volunteers…?”

“Aye,” Goll says instantly. “Since I argued the case, I have to go.”

“I’ll go too,” Fiachna says quietly.

“You?” Conn frowns. “But you’re not a warrior.”

Fiachna holds up Run Fast’s knife. “This metal is unfamiliar to me. It’s tougher than our own, yet lighter. If I knew the secret of it, I could make better weapons.” He lowers the knife. “I’ll stay if you order it, but I want to go.”

“Very well,” Conn sighs. “But you’ll travel with a guard.” He looks around to choose a warrior to send with the smith. There are many to pick from, but he’s loath to send a husband or father. So it must be one of the younger warriors. As he studies them, his expression changes and a crafty look comes into his eyes. He points to Connla. “My son will protect you.”

Connla gawps at his father. Others are surprised too. This quest is a perilous one. The land is full of demons. The chances of survival are slim. Yet Conn’s telling his own flesh and blood to leave the safety of the rath and serve as guard to a smith. Most can’t see the wisdom of it.

But I can. Conn wants his son to succeed him. But Connla is largely untested in battle and not everyone respects him. If Conn died tonight, there would be several challengers to replace him and Connla might find powerful allies hard to come by. But if he completes this task and returns with a bloodied blade and tales of glory, that would change. This could be the making of him.

And if the quest goes poorly and he dies? Well, that will be the decision of the gods. You can’t fight your destiny.

While Connla blinks stupidly at his father, the teenage twins, Ronan and Lorcan rise. “We’ll go too,” Ronan says, brushing blood-red hair out of his eyes.

“We want to kill more demons,” Lorcan adds, tugging an earring, excited.

Conn growls unhappily. The twins are young but they’re two of our finest warriors. He doesn’t want to let them go but he can’t refuse without insulting them. In the end he nods reluctantly. “Any others?” he asks.

“Me,” a woman of the MacCadan says, taking a step forward. “Orna MacCadan. I’ll represent my clan, to repay you for your hospitality.” Orna is the female warrior I spotted earlier.

Conn smiles. “Our thanks. Now, if that’s all…” He looks for any final volunteers, making it clear by the way he asks that he thinks six is more than adequate.

But one last hand goes up. A tiny hand. Mine.

“I want to go too.”

Conn’s astonished. Everybody is.

“Bec,” Goll says, “this isn’t suitable for a child.”

“I’m not a child,” I retort. “I’m a priestess. Well, an apprentice priestess.”

“It will be dangerous,” Fiachna warns me. “This is a task for warriors.”

“You’re going,” I remind him, “but you’re no warrior.”

“I have to go in case there’s a smith in this village, who can teach me to make better weapons,” he says.

“Maybe I can learn something too,” I reply, then face Conn. “I need to do this. I sense failure if I don’t go. I’m not sure what good I can do – maybe none at all – but I believe I must travel with them.”

Conn shakes his head, troubled. “I can’t allow this. With Banba gone, you’re our only link to the ways of magic. We need you.”

“You need Fiachna too,” I cry, “but you’re letting him go.”

“Fiachna’s a man,” Conn says sternly. “He has the right to choose.”

“So do I,” I growl, then raise my voice and repeat it, with conviction this time. “So do I! We of magic live by our own rules. I was Banba’s charge, not yours. She lived here by choice, as do I — neither of us were of this clan. You had no power over her and you don’t have any over me. Since she’s dead, I’m my own guardian. I answer to a higher voice than any here and that voice tells me to go. If you hold me, it will be against my will and the will of the gods.”

Brave, provocative words, which Conn can’t ignore. Although I’m no more a real priestess than any of the cows in the fields, I’m closer to the ways of magic than anybody else in the rath. Nobody dares cross me on this.

“Very well,” Conn says angrily. “We’ve pledged an ex-king, our smith, two of our best warriors, a guest and my own son to this reckless cause — why not our young priestess too!”

And so, in a bitter, resentful fashion, my fate is decided and I’m dismissed. With a mix of fear and excitement – mostly fear – I trudge back to my hut to enjoy one final night of sheltered sleep, before leaving home in the morning, to face the demons and other dangers of the world beyond.

THE RIVER

→ There are no attacks during the night — an encouraging omen. We depart with the rising of the sun, bidding short farewells to relatives and friends. I want to look back at the huts and walls of the rath as we leave – I might never see them again – but that would be inviting bad luck, so I keep my eyes on the path ahead.

It’s a cloudy day, lots of showers, the coolness of autumn. Summer’s been late fading this year, but I can tell by sniffing the air that it’s finally passed for certain. That could be interpreted as a bad sign – the dying of a season on the day we leave – but I choose to overlook it.

We march east at a steady pace, staying close to Sionan’s river. Our boats were destroyed in a demon attack some months back, so we can’t cross the river here. We have to go east, cross where it’s narrow, then make our way west from there.

The earth is solid underfoot and there are plenty of paths through the trees, so we make good time. Ronan and Lorcan are to the fore of the pack. I’m next, with Orna and Run Fast. He’s eager to move ahead of the rest of us but we hold him back — otherwise he might disappear in the undergrowth like a rabbit. Connla and Fiachna are behind us. Connla’s sulking and hasn’t said a word since we left. Goll brings up the rear.

I brood upon my reasons for leaving the rath as we march, feeling uneasier the more I think about it. Mostly I chose to leave because of the vision of my mother. But there was another reason — fear. The rath seemed to grow smaller every day. I felt so confined, I sometimes found it hard to breathe. I had nightmares where I was trapped, the wall of the fort closing in, ever tighter, squeezing me to death. If our worst fears come true and we fall to the hordes of demons, I don’t want to die caged in.

Is it possible I created the vision to give myself an excuse to leave? I don’t think so. I’m almost certain it was genuine. But the mind can play tricks. What if this is folly, if I’m running away from my fears into worse danger than I would have faced if I’d stayed?

If it wasn’t a trick – if the vision was real – why would the ghost of my mother send me on this deadly quest? She wouldn’t have urged me to risk my life if it wasn’t important. Maybe she wants to help me unravel the secrets of my past. I’ve always longed to know more about my mother, where I came from, who my people were. Perhaps Run Fast can help me find the truth.

If that’s just wishful thinking, and my past is to remain a secret, maybe our rath is destined to fall. My mother’s spirit might have foreseen the destruction of the MacConn and acted to spare me.

Whatever way I look at it, I realise I left for purely selfish reasons. The MacConn need me. I shouldn’t have abandoned them because I was afraid, to hunt down my original people or save myself from an oncoming disaster. I should go back. Fight with them. Use my magic to protect the clan as best I can.

But what if there’s some other reason my mother appeared, if I can somehow help the MacConn by coming on this crazy trek? Banba said we should always follow the guidance of spirits, although we had to be wary, because sometimes they could try to trick us.

Ana help me! So many possibilities — my head is hurting, thinking about them. I should stop and give my brain a rest. Besides, there’s no point worrying now. We’re more than half a day’s march from the rath. We couldn’t return to safety before nightfall. There’s no going back.

→ Everybody was quiet during the morning’s march, thinking about those we left behind and what lies ahead. We stopped to rest and eat at midday. Ronan and Lorcan caught a couple of rabbits, which we ate raw, along with some berries. After that, as we walked slower on our full stomachs, the talk began, low and leisurely, with Fiachna asking Orna a question about the three-bladed knives she favours.

There were lots more questions for Orna after that. Those from our rath know all there is to know about each other. Orna and Run Fast are the only mysteries in the group, and since Run Fast simply grins and looks away when you ask him anything, that leaves Orna as the focus for our curiosity.

She’s had four husbands, children by three of them. She says she likes men but has never been able to put up with one for more than a couple of years. Goll laughs at that and says the pair of them should marry, since he won’t live much more than a few years.

“I wouldn’t have a lot to leave except memories,” he grins. “But they’d be good memories. I had three wives when I was young and didn’t disappoint any of them!”

“Except when you lost your eye and kingship,” Connla smirks, sending Goll into a foul mood.

“You shouldn’t provoke him like that,” Fiachna whispers harshly.

“He’s an old wreck,” Connla retorts. “My father’s a king and I plan to follow in his footsteps. I’ll speak to the old goat any way I like.”

“We’re not in the rath now,” Fiachna says. “We’re a small, isolated group and we need to rely on each other. Think on — Goll might hold your life in his hands one night soon.”

As Connla scowls and considers that, I ask Orna about her children. Were they among those who arrived yesterday?

“No,” Orna says shortly, gaze set straight, her shaved head glistening in the rain. There are tattoos on both her cheeks – the marks of Nuada, the goddess of war – dark red swirls which suck in the gaze of all who look at them in an almost mesmerising way. “They’re dead. Killed by demons a week ago.”

“Ana protect them,” I mutter automatically.

“Ana keep them dead,” Orna replies tonelessly.

“You didn’t burn the bodies?”

“We couldn’t find them. Demons slipped in through our souterrain and made off with them. They must have been playing in the tunnel. I told them a hundred times never to go down there. But children don’t listen.”

Her eyes are filled with a mixture of sadness and rage. As a warrior, she won’t have allowed herself to mourn. But women can’t make themselves as detached as men. Our hearts are bigger. We feel loss in a way men don’t. Orna has the body and mind of a warrior but her heart is like mine, and I know inside she’s weeping.

→ Ronan and Lorcan spar with Orna in the evening as we cross bogland. She knows a few knife feints which are new to the brothers and they practise until they’ve perfected them. Ronan and Lorcan, in turn, know lots of moves which Orna doesn’t and they teach her a few, promising to reveal more over the coming days.

Once warriors were secretive. They kept their techniques to themselves, always wary of their neighbours, knowing that today’s friend can be tomorrow’s enemy. The Fomorii changed that. Now we share because we have to—warriors, smiths, magicians. The demons have united the various tuatha of this land in a way no king ever has. A shame we can’t join forces and face them on a single battlefield, in fair combat — I’m sure we’d win. But although demons aren’t as clever as humans, they’re sly. They spread out, taking control of paths and routes, limiting the opportunities to travel, dividing prospective allies. We share our arms, learning and experience with others where possible, but I fear we shan’t be able to share enough.

As Ronan and Lorcan spar with Orna, Connla asks Fiachna for advice. He has an idea for a new spear, topped with several sharp fins, and wants Fiachna’s opinion. Fiachna listens politely, then explains why the weapon won’t work. Connla’s disappointed but Fiachna cheers him up by saying if there’s a smith in Run Fast’s village who can make weapons like the boy’s knife, perhaps the two of them can come up with something along the lines of Connla’s design.

I chat to Run Fast, asking him again for his real name, where he’s from, if he has family. But he doesn’t answer. After a while Goll nudges up beside us. “Having trouble, Little One?” he asks.

“He won’t tell me anything,” I huff. “I’m sure he could – if he can tell us his people need help, he must be able to tell us his name – but he won’t!”

“The heads of the touched are hard to fathom,” Goll says, rustling Run Fast’s hair. “My second wife had a brother like this. He couldn’t dress himself, wield a weapon or cook a meal. But he could play the pipes beautifully. In all other ways he was helpless — but set him loose on the pipes and he could play any man into the ground.”

“What happened to him?” I ask.

Goll shrugs. “He went wandering one day and ate poisoned berries.”

“Berries!” Run Fast shouts, rubbing his stomach. He picks up on certain words every so often and repeats them.

“It’s not that long since we last ate,” I tell him. “Wait until dinner.”

“Berries,” Run Fast says again, sadly this time. Then he stamps his right foot several times and looks at me hopefully. “Run fast?”

“No,” I groan. “Not now. You have to stay with us.”

“Run fast,” he sighs, stamping the ground one last time, letting me know that he could race up a storm if I gave him the go-ahead.

Goll laughs. “He’s a lively one. You’ll have your hands full looking after him!”

“I might just push him into Sionan’s river when we cross,” I huff.

“We wouldn’t be able to find his village then,” Goll says.

“I’m not sure we’ll find it anyway,” I grumble. “How do we know he’s leading us the right way? He could have come from a southern tuatha for all we know.”

Goll squints at me with his good eye. “You’re in dark spirits, Little One. Are you tired?”

“No.”

Goll tickles me under the chin until I laugh. “Tired?” he asks again.

“Aye,” I sigh. “I’m not used to all this walking. And you go so quickly! I’ve only got short legs.”

“You should have said.”

“I didn’t want to look like a… a…”

“A child?” Goll smiles. “But you are. And a tiny wee bec of a child at that.”

“Just because I’m small doesn’t mean I can’t keep up!” I fume, quickening my pace. But I’ve not taken five or six steps when Goll wraps a burly arm around my waist and hauls me off the ground. “Hoi!” I cry. “Put me down!”

“Stop struggling,” Goll says and settles me on his shoulders, my legs either side of his head. “We might have need of you later. You’re no good to us fit for nothing but sleep.”

“I’m fit to turn you into a frog if you don’t put me down!” I grunt, but secretly I’m delighted and after struggling playfully for a minute, I settle back and let Goll be my horse for the rest of the afternoon, admiring the view from up high and saving my strength in case I’m called upon to fight demons in the dark.

→ We come to the crossing point of Sionan’s river late in the evening. The river’s narrow here, easy to ford. This is the joining point of two tuatha. A large cashel once stood here, the largest in the province. A couple of wooden roads lead up to and away from the place where the impressive stone fort stood. Many carts used to travel this way and the roads were carefully tended. But the cashel’s a pile of rubble now and the roads are in disrepair. We’d heard the cashel had been overrun by demons but hoped the reports were wrong. This would have been the ideal place to shelter tonight.

“What now?” Connla asks, studying the untidy mound which was once the pride of the province. “Cross the river or camp here?”

“Cross,” Ronan and Lorcan say together.

“There’s no safety here,” Ronan says.

“Where demons attack once, they’ll attack again,” Lorcan agrees.

“And many can’t cross flowing water,” Ronan says. “We’d be safer on the other side.”

Connla nods but looks uneasy. There was never a fort on the opposite side of the river, just some huts where folk of the neighbouring tuath dwelt. They used to greet those who crossed the river and either grant them the freedom of their tuath or turn them back. The huts are still standing but we can’t see any people. They might be hiding or they might all be murdered, demons sheltering inside the huts from the sun.

“Come on,” Goll says, setting me down and taking the lead. “The sun’s setting. Let’s get across and find a hole for the night which we can defend.”

→ There are dugouts tethered to the banks of the river, bobbing up and down. Each holds four people at most. We head for the nearest pair. Ronan and Lorcan team up with Run Fast and me. Goll, Orna, Fiachna and Connla take the other. Lorcan grabs the rope of our dugout and hauls it in. He’s almost pulled the boat up on dry land when I get a warning flash.

“Lorcan! No!” I scream.

He reacts instantly, drops the rope and leaps backwards just in time. A huge demonic eel unleashes itself at him, rising out of the boat like an arrow shot from a bow. Its jaws are impossibly wide, filled with teeth which would be more suited to a bear.

The demon snaps for Lorcan’s head and only misses by a finger’s breadth. It lands hard on the earth and writhes angrily, going for Lorcan’s legs. Ronan steps up beside his brother and stabs at the place where the demon’s eyes should be. But it doesn’t have any. It’s blind, operating by some other form of sense.

Orna jumps on to the demon’s back and hacks at it with her three-bladed knives, one in either hand. The demon bucks and twists desperately, trying to dislodge her, but she rides it like a pony, digging her heels in, face twisted as she screams hatefully, tattoos rippling with fury.

Connla takes aim and hurls a spear at the beast, down its maw of a mouth. The spear sticks deep in its throat. The demon chokes and slams its head downwards, trying to spit out the spear.

Goll darts forward, grabs the shaft of the spear and drives it further into the Fomorii’s throat, twisting savagely. The demon spasms, then weakens. Suddenly the warriors are all over it, hacking away like ants trying to bring down a badger. Fiachna, Run Fast and I watch from nearby.

“Do you think I should help?” Fiachna asks, fingers tapping the head of an axe which hangs from his belt.

“They’re in control,” I tell him.

And, moments later, the battle’s over and the eel demon lies at their feet, covered in the grey blood which previously pumped through its veins, torn to pieces, jaws stretched wide in a final death snarl.

Goll grasps the handle of the spear, yanks it out and hands it to Connla. He laughs and claps the younger warrior on the back. “A master throw!”

Connla smiles sheepishly. “I didn’t mean to hurl it down the beast’s throat,” he says with untypical modesty. “I aimed for the top of its head. But it moved. I got lucky.”

“I’ll always take luck over skill,” Goll says, clapping Connla’s back again. The pair grin at each other like lifelong friends.

“I’ve never fought a water demon before,” Orna grunts, wiping her knives clean on the grass. She dabs at the final few drops of grey blood with her middle finger, then rubs it into the centre spots of her spiral tattoos, one after the other.

“They’re rare,” Ronan says, studying the demon, turning it over on to its back with his foot. “We’re lucky it’s not night or it would have been stronger.”

“Come on,” I mutter, glancing around uneasily. “It’ll be sunset soon. More will be coming.”

That silences everyone. After a quick check to make sure the second dugout is free of demons, we’re in the boats and crossing the river as swiftly as possible, everybody keeping one eye on the water, wary of attack from beneath.

THE STONES

→ Nobody emerges from the huts as we dock. When we’re on dry land, we stare at the huts suspiciously. You’re not supposed to enter a tuath without announcing yourself and being guided by one of your own rank. But times have changed. Many of the old laws no longer apply.

“You in the huts!” Goll bellows, in case anyone’s alive inside.

Silence.

“Should we go see if anybody’s there?” Fiachna asks.

“They’d have answered if there was,” Connla says.

“Unless they’re scared or sheltering underground,” Orna notes.

Ronan points silently at a spot to the left of the huts. My eyes aren’t as sharp as his, so it takes me a few seconds to focus. Then I see it — a small arm, probably a child’s, lying in the dirt.

Goll sighs, draws his sword and moves to the front of the group. “Let’s go,” he says gruffly, and we proceed at a forced, nervous jog.

→ There’s nowhere to shelter, so we don’t stop when the sun sets, but keep going, hoping to outpace any demons which catch our scent. I try to persuade myself that we won’t be noticed. Only a fool travels at night in these troubled times. The Fomorii won’t expect to find anyone out in the open. Maybe they don’t even look any more.

A silly, childish notion. But for an hour it seems as though it might hold true. We don’t sight any demons and hope begins to grow.

But then we hear a howl of inhuman vibrancy far behind us, but not far enough for comfort. We pause and listen as the howl is answered by others. In my mind’s eye I see a group forming, demons and the living dead. They gather around the one who found our trail, sniff the air, lick the earth, quiver with excitement — then lurch forward, to run us down.

“They might be after someone else,” Connla says but his words are hollow. We’ve been discovered.

“Let’s pick up the pace,” Goll says, expression stern.

Run Fast’s head shoots up. “Run fast?” he asks eagerly.

“Aye,” Goll says, then grabs the boy as he starts to shoot off. “Not that fast!”

→ We can hear them, a pack of demons crashing through the woods, snapping off branches, knocking over smaller trees. I’ve never known demons so excited. I guess, when they attack a fort, it’s hard work. It must be frustrating, the scent of prey thick in their nostrils, having to fight their way through, often failing. But out here, in the open, they have only to hunt us down and we’re theirs for the taking. They’re like dogs after a fox.

We’re looking for a place to make a stand, somewhere we can defend. A cave would be perfect. We could squeeze in and fend them off, maybe keep them at bay for the rest of the night, then escape in the morning. But there are no caves, or at least none that we can find.

Goll comes to a halt in a small clearing. Trees have been felled here some time in the last few years. Somebody probably planned to graze animals or build a hut, in the days before the demons came. Goll looks around, assessing.

“Not here,” Connla wheezes, face dark from the strain. “Too exposed.”

“There’s nowhere better,” Goll gasps. He points to a mound of logs covered in moss. “We can start a fire. Fell more trees, stake them in the ground and sharpen the tops. Make it hard for the demons to strike all at once.”

“But…” Connla looks to the others for support, but Ronan, Lorcan and Orna are already drawing their weapons, preparing for battle. Fiachna has his axe out and is studying the trees. They know it’s hopeless, that we’re going to die. But what choice do we have? There’s nothing to do but draw our lines, wait and face those who will most certainly destroy us. Die as warriors, with pride.

I’m thinking about what spells I can use when a small hand slips into mine. I look round. Run Fast is smiling at me. “Run fast?” he whispers.

“Not now,” I sigh.

The boy frowns. “Run fast,” he says more firmly.

I shake my head. “We have to stay and fight. Can you fight? Do you know how to–”

The strange boy’s fingers grab mine tightly and his face hardens. “Run fast!” he hisses, then points with his free hand. “Worm pups!”

I start to snap at him to be quiet. Then pause. There’s a tingling sensation in Run Fast’s fingers. Some sort of magic. I look down. His hand is glowing slightly. The boy looks at it too, then up at me. “Worm pups,” he repeats, softly this time.

“Goll!” I shout. The old warrior glances at me. “We’re leaving.”

“But–”

“Don’t argue!” I move ahead with Run Fast. “We’ll die here. But I think, if we carry on, there’s…” I stop, not sure what might lie beyond, but sensing in my heart that it’s better than this.

Everybody’s looking at me now, torn between hope and suspicion.

“This place isn’t much,” Fiachna says, “but it’s defendable. If we’re caught on the run, we’re finished for sure. Are you certain…?”

“Yes,” I growl. “We have to go. Now. We’re dead if we don’t.”

“But we’ll live if we do?” Connla asks dubiously.

“Perhaps.”

It’s not enough. They don’t trust my instincts. They’re going to stay. I open my mouth to argue afresh, but then Orna lowers her knives and comes to my side. “I’m with the girl.”

“Why?” Goll asks — not a challenge, just curious.

Orna shrugs. “A feeling.”

Lorcan taps a few of his earrings with a knife tip. “I don’t feel like we’ll live if we go, but I’m sure we’ll die if we stay.”

Goll looks around at the others and asks the question with his eyes. They answer with weary glances and resigned shrugs. “So be it,” he says, sheathing his sword. “Bec — lead us.”

We run.

→ Sweat. Terror. The sounds of chasing demons. Almost upon us. A minute, maybe two, and we’ll be forced to stop and fight — stop and die.

The trees are thick around us. Impossible to see far. It’s dark. Too dark. I look up and notice extra branches, scraps of cloth, thatch torn from roofs, all sorts of bits and pieces scattered among the tree tops, linking the upper branches, keeping out the light of the moon and stars.

My stomach sinks. This is a trap! I was wrong. Run Fast was sent to lead us to our doom. And we fell for it. I start to shout a warning, even though it’s far too late. Then…

We burst into the open and come to a surprised halt. There’s a clear circle around us and at the centre — a ring of giant stones. Most are taller than me. Some even tower above the lanky Ronan and Connla. Set in the ground at regular intervals. Ancient, covered in moss and creepers. A place of magic, but magic from a time before ours, the time of the Old Creatures, when this country was the playground of the gods.

The demons are hot on our heels, surging up behind us, their stench foul in the air. “Come on!” Fiachna screams. We fly forward at his call, rushing to the stones, readying ourselves for battle.

We spill past the stones, into the middle of the ring. The stones won’t provide much cover but they’ll make it slightly harder for the demons to get at us and buy us a few seconds. They won’t make a real difference, but you’ve always got to live in hope. Before you die at the hands of a Fomorii.

Lorcan jumps on to a stone which fell on its side many years ago. He waves his sword over his head, screaming a challenge at the demons which are emerging from the cover of the trees. Dozens of twisted, hideous monsters. One has the body of a bear but the head of a hawk. Another looks like a wolf but its inner organs hang from its limbs. Claws, fangs, blood-red eyes. Nightmares everywhere I look.