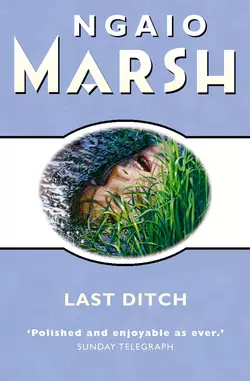

Last Ditch

Last Ditch

Ngaio Marsh

A classic Ngaio Marsh novelYoung Rickie Alleyn had come to the Channel Islands to try to write, but village life was tedious – until he saw the stablehand in the ditch. Dead, it seemed, from an unlucky jump.It might have ended there had Rickie not noticed some strange and puzzling things. But Rickie’s father, Chief Superintendent Roderick Alleyn, had been discreetly summoned to the scene, and when Rickie disappeared, it was the last straw…

NGAIO MARSH

Last Ditch

Copyright (#ulink_695c13d4-96c4-54f7-8fb4-d6b65bd84b53)

HARPER

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1977

Copyright © Ngaio Marsh Ltd 1977

Ngaio Marsh asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of these works.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007328789

EBook Edition © JANUARY 2010 ISBN: 9780007344833

Version: 2014-12-02

Dedication (#ulink_4f511440-b284-5724-bda9-724322edccca)

For the family at Walnut Tree Farm

Contents

Copyright (#u12940b0f-c9d6-59c3-930a-94ece4bb3312)

Title Page (#u66a554fc-04ec-50fb-9170-780fbcac9483)

Dedication (#u995e8931-3e33-5b23-bf26-ac3b0cb54684)

Cast of Characters (#u2364d205-c03d-558b-ae9f-ca1b990182d2)

1 Deep Cove (#ua4330d62-b7d5-5308-98ba-c569f99d8116)

2 Syd Jones’s Pad And Montjoy (#uf8992a0f-758b-50fe-be4f-2ae3824a1ff4)

3 The Gap (#u96a3cf62-d41d-563b-ae7e-98c3bb072407)

4 Intermission (#litres_trial_promo)

5 Intermezzo With Storm (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Morning at the Cove (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Syd’s Pad Again (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Night Watches (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Storm Over (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Cast of Characters (#ulink_bc49b465-7c58-5980-8984-e2821b0fe37d)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_edce5930-3b3c-5da6-8bf9-e80a70f0020d)

Deep Cove (#ulink_edce5930-3b3c-5da6-8bf9-e80a70f0020d)

With all their easy-going behaviour there was, nevertheless, something rarified about the Pharamonds. Or so, on his first encounter with them, did it seem to Ricky Alleyn.

Even before they came into their drawing-room, he had begun to collect this impression of its owners. It was a large, eccentric and attractive room with lemon-coloured walls, polished floor and exquisite, grubby Chinese rugs. The two dominant pictures, facing each other at opposite ends of the room, were of an irritable gentleman in uniform and a lavishly-bosomed impatient lady, brandishing an implacable fan. Elsewhere he saw, with surprise, several unframed sketches, drawing-pinned to the walls, one of them being of a free, if not lewd, character.

He had blinked his way round these incompatibles and had turned to the windows and the vastness of sky and sea beyond them when Jasper Pharamond came quickly in.

‘Ricky Alleyn!’ he stated. ‘How pleasant. We’re all delighted.’

He took Ricky’s hand, gaily tossed it away and waved him into a chair. ‘You’re like both your parents,’ he observed. ‘Clever of you.’

Ricky, feeling inadequate, said his parents sent their best remembrances and had talked a great deal about the voyage they had taken with the Pharamonds as fellow passengers.

‘They were so nice to us,’ Jasper said. ‘You can’t think. VIPs as they were, and all.’

‘They don’t feel much like VIPs.’

‘Which is one of the reasons one likes them, of course. But do tell me, exactly why have you come to the island, and is the lodging Julia found endurable?’

Feeling himself blush, Ricky said he hoped he had come to work through the Long Vacation and his accommodation with a family in the village was just what he had hoped for and that he was very much obliged to Mrs Pharamond for finding it.

‘She adores doing that sort of thing,’ said her husband. ‘But aren’t you over your academic hurdles with all sorts of firsts and glories? Aren’t you a terribly young don?’

Ricky mumbled wildly and Jasper smiled. His small hooked nose dipped and his lip twitched upwards. It was a faunish smile and agreed with his cap of tight curls.

‘I know,’ he said, ‘you’re writing a novel.’

‘I’ve scarcely begun.’

‘And you don’t want to talk about it. How wise you are. Here come the others, or some of them.’

Two persons came in: a young woman and a youth of about thirteen years, whose likeness to Jasper established him as a Pharamond.

‘Julia,’ Jasper said, ‘and Bruno. My wife and my brother.’

Julia was beautiful. She greeted Ricky with great politeness and a ravishing smile, made enquiries about his accommodation and then turned to her husband.

‘Darling,’ she said. ‘A surprise for you. A girl.’

‘What do you mean, Julia? Where?’

‘With the children in the garden. She’s going to have a baby.’

‘Immediately?’

‘Of course not.’ Julia began to laugh. Her whole face broke into laughter. She made a noise like a soda-water syphon and spluttered indistinguishable words. Her husband watched her apprehensively. The boy, Bruno, began to giggle.

‘Who is this girl?’ Jasper asked. And to Ricky: ‘You must excuse Julia. Her life is full of drama.’

Julia addressed herself warmly to Ricky. ‘It’s just that we do seem to get ourselves let in for rather peculiar situations. If Jasper stops interrupting I’ll explain.’

‘I have stopped interrupting,’ Jasper said.

‘Bruno and the children and I,’ Julia explained to Ricky, ‘drove to a place called Leathers to see about hiring horses from the stable people. Harness, they’re called.’

‘Harkness,’ said Jasper.

‘Harkness. Mr and Miss. Uncle and niece. So they weren’t in their office and they weren’t in their stables. We were going to look in the horse-paddock when we heard someone howling. And I mean really howling. Bawling. And being roared back at. In the harness-room, it transpired, with the door shut. Something about Mr Harkness threatening to have somebody called Mungo shot because he’d kicked the sorrel mare. I think perhaps Mungo was a horse. But while we stood helpless it turned into Mr H. calling Miss H. a whore of Babylon. Too awkward. Well, what would you have done?’

Jasper said: ‘Gone away.’

‘Out of tact or fear?’

‘Fear.’

Julia turned enormous eyes on Ricky.

‘So would I,’ he said hurriedly.

‘Well, so might I, too, because of the children, but before I could make up my mind there came the sound of a really hard slap, and a yell, and the tack-room door burst open. Out flew Miss Harness.’

‘Harkness.’

‘Well, anyway, out she flew and bolted past us and round the house and away. And there in the doorway stood Mr Harkness with a strap in his hand, roaring out Old Testament anathemas.’

‘What action did you take?’ asked her husband.

‘I turned into a sort of policewoman and said: “What seems to be the trouble, Mr Harkness?” and he strode away.’

‘And then?’

‘We left. We couldn’t go running after Mr Harkness when he was in that sort of mood.’

‘He might have hit us,’ Bruno pointed out. His voice had the unpredictable intervals of adolescence.

‘Could we get back to the girl in the garden with the children? A sense of impending disaster seems to tell me she is Miss Harkness.’

‘But none other. We came upon her on our way home. She was standing near the edge of the cliffs with a very odd look on her face, so I stopped the car and talked to her and she’s nine weeks gone. My guess is that she won’t tell Mr Harkness who the man is, which is why he set about her with the strap.’

‘Did she tell you who the man is?’

‘Not yet. One musn’t nag, don’t you feel?’ asked Julia, appealing to Ricky. ‘All in good time. Come and meet her. She’s not howling now.’

Before he could reply two more Pharamonds came in: an older man and a young woman, each looking very like Bruno and Jasper. They were introduced as ‘our cousins, Louis and Carlotta’. Ricky supposed them to be brother and sister until Louis put his arms round Carlotta from behind and kissed her neck. He then noticed that she wore a wedding ring.

‘Who,’ she asked Julia, ‘is the girl in the garden with the children? Isn’t she the riding-school girl?’

‘Yes, but I can’t wade through it all again now, darling. We’re going out to meet her, and you can come too.’

‘We have met her already,’ Carlotta said. ‘On that narrow path one could hardly shove by without uttering. We passed the time of day.’

‘Perhaps it would be kinder to bring her indoors.’ Julia announced. ‘Bruno darling, be an angel and ask Miss Harkness to come in.’

Bruno strolled away. Julia called after him: ‘And bring the children, darling, for Ricky to meet.’ She gave Ricky a brilliant smile: ‘You have come in for a tricky luncheon, haven’t you?’ she said.

‘I expect I can manage,’ he replied, and the Pharamonds looked approvingly at him. Julia turned to Carlotta. ‘Would you say you were about the same size?’ she asked.

‘As who?’

‘Darling, as Miss Harkness. Her present size I mean, of course. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.’

‘What is all this?’ Carlotta demanded in a rising voice. ‘What’s Julia up to?’

‘No good, you may depend upon it,’ Jasper muttered. And to his wife: ‘Have you asked Miss Harkness to stay? Have you dared?’

‘But where else is there for her to go? She can’t return to Mr Harkness and be beaten up. In her condition. Face it.’

‘They are coming,’ said Louis, who was looking out of the windows. ‘I don’t understand any of this. Is she lunching?’

‘And staying, apparently,’ said Carlotta. ‘And Julia wants me to give her my clothes.’

‘Lend, not give, and only something for the night,’ Julia urged. ‘Tomorrow there will be other arrangements.’

Children’s voices sounded in the hall. Bruno opened the door and two little girls rushed noisily in. They were aged about five and seven and wore nothing but denim trousers with crossover straps. They flung themselves upon their mother who greeted them in a voice fraught with emotion.

‘Dar – lings!’ cried Julia, tenderly embracing them.

Then came Miss Harkness.

She was a well-developed girl with a weather-beaten complexion and hands of such a horny nature that Ricky was reminded of hooves. A marked puffiness round the eyes bore evidence to her recent emotional contretemps. She wore jodhpurs and a checked shirt.

Julia introduced her all round. She changed her weight from foot to foot, nodded and sometimes said ‘Uh.’ The Pharamonds all set up a conversational breeze while Jasper produced a drinks-tray. Ricky and Bruno drank beer and the family either sherry or white wine. Miss Harkness in a hoarse voice asked for scotch and downed it in three noisy gulps. Louis Pharamond began to talk to her about horses and Ricky heard him say he had played polo badly in Peru.

How pale they all were, Ricky thought. Really, they looked as if they had been forced, like vegetables, under covers, and had come out severely bleached. Even Julia, a Pharamond only by marriage, was without colour. Hers was a lovely pallor, a dramatic setting for her impertinent eyes and mouth. She was rather like an Aubrey Beardsley lady.

At luncheon, Ricky sat on her right and had Carlotta for his other neighbour. Diagonally opposite, by Jasper and with Louis on her right, sat Miss Harkness with another whisky-and-soda, and opposite her on their father’s left, the little girls, who were called Selina and Julietta. Louis was the darkest and much the most mondain of all the Pharamonds. He wore a thread-like black moustache and a silken jumper and was smoothly groomed. He continued to make one-sided conversation with Miss Harkness, bending his head towards her and laughing in a flirtatious manner into her baleful face. Ricky noticed that Carlotta, who, he gathered, was Louis’s cousin as well as his wife, glanced at him from time to time with amusement.

‘Have you spotted our “Troy”?’ Julia asked Ricky, and pointed to a picture above Jasper’s head. He had, but had been too shy to say so. It was a conversation piece – a man and a woman, seated in the foreground, and behind them a row of wind-blown promenaders, dashingly indicated against a lively sky.

‘Jasper and me,’ Julia said, ‘on board the Oriana. We adore it. Do you paint?’

‘Luckily, I don’t even try.’

‘A policeman, perhaps?’

‘Not even that, I’m afraid. An unnatural son.’

‘Jasper,’ said his wife, ‘is a mathematician and is writing a book about the binomial theorem, but you musn’t say I said so because he doesn’t care to have it known. Selina, darling, one more face like that and out you go before the pudding, which is strawberries and cream.’

Selina, with the aid of her fingers, had dragged down the corners of her mouth, slitted her eyes and leered across the table at Miss Harkness. She let her face snap back into normality, and then lounged in her chair sinking her chin on her chest and rolling her eyes. Her sister, Julietta, was consumed with laughter.

‘Aren’t children awful,’ Julia asked, ‘when they set out to be witty? Yesterday at luncheon Julietta said: “My pud’s made of mud,” and they both laughed themselves sick. Jasper and I were made quite miserable by it.’

‘It won’t last,’ Ricky assured her.

‘It had better not.’ She leant towards him. He caught a whiff of her scent, became startlingly aware of her thick immaculate skin and felt an extraordinary stillness come over him.

‘So far, so good, wouldn’t you say?’ she breathed. ‘I mean – at least she’s not cutting up rough.’

‘She’s eating quite well,’ Ricky muttered.

Julia gave him a look of radiant approval. He was uplifted. ‘Gosh!’ he thought. ‘Oh, gosh, what is all this?’

It was with a sensation of having been launched upon unchartered seas that he took his leave of the Pharamonds and returned to his lodging in the village.

‘That’s an upsetting lady,’ thought Ricky. ‘A very lovely and upsetting lady.’

II

The fishing village of Deep Cove was on the north coast of the island: a knot of cottages clustered round an unremarkable bay. There was a general store and post office, a church and a pub: the Cod-and-Bottle. A van drove over to Montjoy on the south coast with the catch of fish when there was one. Montjoy, the only town on the island, was a tourist resort with three smart hotels. The Cove was eight miles away, but not many Montjoy tourists came to see it because there were no ‘attractions’, and it lay off the main road. Tourists did, however, patronize Leathers, the riding school and horse-hiring establishment run by the Harknesses. This was situated a mile out of Deep Cove and lay between it and the Pharamonds’ house which was called L’Esperance, and had been in the possession of the family, Jasper had told Ricky, since the mid-eighteenth century. It stood high above the cliffs and could be seen for miles around on a clear day.

Ricky had hired a push-bicycle and had left it inside the drive gates. He jolted back down the lane, spun along the main road in grand style with salt air tingling up his nose and turned into the steep descent to the Cove.

Mr and Mrs Ferrant’s stone cottage was on the waterfront; Ricky had an upstairs front bedroom and the use of a suffocating parlour. He preferred to work in his bedroom. He sat at a table in the window, which commanded a view of the harbour, a strip of sand, a jetty and the little fishing fleet when it was at anchor. Seagulls mewed with the devoted persistence of their species in marine radio-drama.

When he came into the passage he heard the thump of Mrs Ferrant’s iron in the kitchen and caught the smell of hot cloth. She came out, a handsome dark woman of about thirty-five with black hair drawn into a knot, black eyes and a full figure. In common with most of the islanders, she showed her Gallic heritage.

‘You’re back, then,’ she said. ‘Do you fancy a cup of tea?’

‘No, thank you very much, Mrs Ferrant. I had an awfully late luncheon.’

‘Up above at L’Esperance?’

‘That’s right.’

‘That would be a great spread, and grandly served?’

There was no defining her style of speech. The choice of words had the positive character almost of the West Country but her accent carried the swallowed r’s of France. ‘They live well up there,’ she said.

‘It was all very nice,’ Ricky murmured. She passed her working-woman’s hand across her mouth. ‘And they would all be there. All the family?’

‘Well, I think so, but I’m not really sure what the whole family consists of.’

‘Mr and Mrs Jasper and the children. Young Bruno, when he’s not at his schooling.’

‘That’s right,’ he agreed. ‘He was there.’

‘Would that be all the company?’

‘No,’ Ricky said, feeling cornered, ‘there were Mr and Mrs Louis Pharamond, too.’

‘Ah,’ she said, after a pause. ‘Them.’

Ricky started to move away but she said: ‘That would be all, then?’

He found her insistence unpleasing.

‘Oh no,’ he said, over his shoulder, ‘there was another visitor,’ and he began to walk down the passage.

‘Who might that have been, then?’ she persisted.

‘A Miss Harkness,’ he said shortly.

‘What was she doing there?’ demanded Mrs Ferrant.

‘She was lunching,’ Ricky said very coldly, and ran upstairs two steps at a time. He heard her slam the kitchen door.

He tried to settle down to work but was unable to do so. The afternoon was a bad time in any case and he’d had two glasses of beer. Julia Pharamond’s magnolia face stooped out of his thoughts and came close to him, talking about a pregnant young woman who might as well have been a horse. Louis Pharamond was making a pass at her and the little half-naked Selina pulled faces at all of them. And there, suddenly, like some bucolic fury was Mrs Ferrant: ‘You’re back, then,’ she mouthed. She’s going to scream, he thought, and before she could do it, woke up.

He rose, shook himself and looked out of the window. The afternoon sun made sequined patterns on the harbour and enriched the colours of boats and the garments of such people as were abroad in the village. Among them, in a group near the jetty, he recognized his landlord, Mr Ferrant.

Mr Ferrant was the local plumber and general handyman. He possessed a good-looking car and a little sailing-boat with an auxiliary engine in which, Ricky gathered, he was wont to putter round the harbour and occasionally venture quite far out to sea, fishing. Altogether the Ferrants seemed to be very comfortably off. He was a big fellow with a lusty, rather sly look about him but handsome enough with his high colour and clustering curls. Ricky thought that he was probably younger than his wife and wondered if she had to keep an eye on him.

He was telling some story to the other men in the group. They listened with half-smiles, looking at each other out of the corners of their eyes. When he reached his point they broke into laughter and stamped about, doubled in two, with their hands in their trouser pockets. The group broke up. Mr Ferrant turned towards the house, saw Ricky in the window and gave him the slight, sideways jerk of the head which served as a greeting in the Cove. Ricky lifted his hand in return. He watched his landlord approach the house, heard the front door bang and boots going down the passage.

Ricky thought he would now give himself the pleasure of writing a bread-and-butter letter to Julia Pharamond. He made several shots at it but they all looked either affected or laboured. In the end he wrote:

Dear Mrs Pharamond,

It was so kind of you to have me and I did enjoy myself so very much.

With many thanks,

Ricky.

PS. I do hope your other visitor has settled in nicely.

He decided to go out and post it. He had arrived only last evening in the village and had yet to explore it properly.

There wasn’t a great deal to explore. The main street ran along the front, and steep little cobbled lanes led off it through ranks of cottages, of which the one on the corner, next door to the Ferrants’, turned out to be the local police station. The one shop there was, Mercer’s Drapery and General Suppliers, combined the functions of post office, grocery, hardware, clothing, stationery and toy shops. Outside hung ranks of duffle coats, pea-jackets, oilskins and sweaters, all strung above secretive windows beyond which one could make out further offerings set out in a dark interior. Ricky was filled with an urge to buy. He turned in at the door and sustained a sharp jab below the ribs.

He swung round to find himself face to face with a wild luxuriance of hair, dark spectacles, a floral shirt, beads and fringes.

‘Yow!’ said Ricky, and clapped a hand to his waist. ‘What’s that for?’

A voice behind the hair said something indistinguishable. A gesture was made, indicating a box slung from the shoulder, a box of a kind very familiar to Ricky.

‘I was turning round, wasn’t I,’ the voice mumbled.

‘OK,’ said Ricky. ‘No bones broken. I hope.’

‘Hurr,’ said the voice, laughing dismally.

Its owner lurched past Ricky and slouched off down the street, the paintbox swinging from his shoulder.

‘Very careless, that was,’ said Mr Mercer, the solitary shopman, emerging from the shadows. ‘I don’t care for that type of behaviour. Can I interest you in anything?’

Ricky, though still in pain, could be interested in a dark-blue polo-necked sweater that carried a label ‘Hand-knitted locally. Very special offer’.

‘That looks a good kind of sweater,’ he said.

‘Beautiful piece of work, sir. Mrs Ferrant is in a class by herself.’

‘Mrs Ferrant?’

‘Quite so, sir. You are accommodated there, I believe. The pullover,’ Mr Mercer continued, ‘would be your size, I’m sure. Would you care to try?’

Ricky did try and not only bought the sweater but also a short blue coat of a nautical cut that went very well with it. He decided to wear his purchases.

He walked along the main street, which stopped abruptly at a flight of steps leading down to the strand. At the foot of these steps, with an easel set up before him, a palette on his arm and his paintbox open at his feet, stood the man he had encountered in the shop.

He had his back towards Ricky and was laying swathes of colour across a large canvas. These did not appear to bear any relation to the prospect before him. As Ricky watched, the painter began to superimpose in heavy black outline, a female nude with minuscule legs, a vast rump and no head. Having done this he fell back a step or two, paused, and then made a dart at his canvas and slashed down a giant fowl taking a peck at the nude. Leda, Ricky decided, and, therefore, the swan.

He was vividly reminded of the sketches pinned to the drawing-room wall at L’Esperance. He wondered what his mother, whose work was very far from being academic, would have had to say about this picture. He decided that it lacked integrity.

The painter seemed to think it was completed. He scraped his palette and returned it and his brushes to the box. He then fished out a packet of cigarettes and a matchbox, turned his back to the sea-breeze and saw Ricky.

For a second or two he seemed to lower menacingly, but the growth of facial hair was so luxuriant that it hid all expression. Dark glasses gave him a look of some dubious character on the Côte d’Azur.

Ricky said: ‘Hullo, again. I hope you don’t mind my looking on for a moment.’

There was movement in the beard and whiskers and a dull sound. The painter had opened his matchbox and found it empty.

‘Got a light?’ Ricky thought must have been said.

He descended the steps and offered his lighter. The painter used it and returned to packing up his gear.

‘Do you find,’ Ricky asked, fishing for something to say that wouldn’t be utterly despised, ‘do you find this place stimulating? For painting, I mean.’

‘At least,’ the voice said, ‘it isn’t bloody picturesque. I get power from it. It works for me.’

‘Could I have seen some of your things up at L’Esperance – the Pharamonds’ house?’

He seemed to take another long stare at Ricky and then said: ‘I sold a few things to some woman the other day. Street show in Montjoy. A white sort of woman with black hair. Talked a lot of balls, of course. They always do. But she wasn’t bad, figuratively speaking. Worth the odd grope.’

Ricky suddenly felt inclined to kick him.

‘Oh, well,’ he said. ‘I’ll be moving on.’

‘You staying here?’

‘Yes.’

‘For long?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said, turning away.

The painter seemed to be one of those people whose friendliness increases in inverse ratio to the warmth of its reception.

‘What’s your hurry?’ he asked.

‘I’ve got some work to do,’ Ricky said.

‘Work?’

‘That’s right. Good evening to you.’

‘You write, don’t you?’

‘Try to,’ he said over his shoulder.

The young man raised his voice. ‘That’s what Gil Ferrant makes out, anyway. He reckons you write.’

Ricky walked on without further comment.

On the way back he reflected that it was highly possible every person in the village knew by this time that he lodged with the Ferrants – and tried to write.

So he returned to the cottage and tried.

He had his group of characters. He knew how to involve them, one with the other, but so far he didn’t know where to put them: they hovered, they floated. He found himself moved to introduce among them a woman with a white magnolia face, black hair and eyes and a spluttering laugh.

Mrs Ferrant gave him his evening meal on a tray in the parlour. He asked her about the painter and she replied in an off-hand, slighting manner that he was called Sydney Jones and had a ‘terrible old place up to back of Fisherman’s Steps’.

‘He lives here, then?’ said Ricky.

‘He’s a foreigner,’ she said, dismissing him, ‘but he’s been in the Cove a while.’

‘Do you like his painting?’

‘My Louis can do better.’ Her Louis was a threatening child of about ten.

As she walked out with his tray she said: ‘That’s a queer old sweater you’re wearing.’

‘I think it’s a jolly good one,’ he called after her. He heard her give a little grunt and thought she added something in French.

Visited by a sense of well-being, he lit his pipe and strolled down to the Cod-and-Bottle.

Nobody had ever tried to tart up the Cod-and-Bottle. It was unadulterated pub. In the bar the only decor was a series of faded photographs of local worthies and a map of the island. A heavily-pocked dartboard hung on the wall and there was a shove-ha’penny at the far end of the bar. In an enormous fireplace, a pile of driftwood blazed a good-smelling welcome.

The bar was full of men, tobacco smoke and the fumes of beer. A conglomerate of male voices, with their overtones of local dialect, engulfed Ricky as he walked in. Ferrant was there, his back propped against the bar, one elbow resting on it, his body curved in a classic pose that was sexually explicit, and, Ricky felt, deliberately contrived. When he saw Ricky he raised his pint-pot and gave him that sidelong wag of his head. He had a coterie of friends about him.

The barman who, as Ricky was to learn, was called Bob Maistre, was the landlord of the Cod-and-Bottle. He served Ricky’s pint of bitter with a flourish.

There was an empty chair in the corner and Ricky made his way to it. From here he was able to maintain the sensation of being an onlooker.

A group of dart players finished their game and moved over to the bar, revealing, to Ricky’s unenthusiastic gaze, Sydney Jones, the painter, slumped at a table in a far corner of the room with his drink before him. Ricky looked away quickly, hoping that he had not been spotted.

A group of fresh arrivals came between them: fishermen, by their conversation. Ferrant detached himself from the bar and lounged over to them. There followed a jumble of conversation, most of it incomprehensible. Ricky was to learn that the remnants of a patois that had grown out of a Norman dialect, itself long vanished, could still be heard among the older islanders.

Ferrant left the group and strolled over to Ricky.

‘Evening, Mr Alleyn,’ he said. ‘Getting to know us?’

‘Hoping to, Mr Ferrant,’ Ricky said.

‘Quiet enough for you?’

‘That’s what I like.’

‘Fancy that now, what you like, eh?’

His manner was half bantering, half indifferent. He stayed a minute or so longer, took one or two showy pulls at his beer, said: ‘Enjoy yourself, then,’ turned and came face to face with Mr Sydney Jones.

‘Look what’s come up in my catch,’ he said. He fetched Mr Jones a shattering clap on the back and returned to his friends.

Mr Jones evidently eschewed all conventional civilities. He sat down at the table, extended his legs and seemed to gaze at nothing in particular. A shout of laughter greeted Ferrant’s return to the bar and drowned any observation that, by a movement of his head, Mr Jones would seem to have offered.

‘Sorry,’ Ricky said. ‘I can’t hear you.’

He slouched across the table and the voice came through.

‘Care to come up to my pad?’ it invited.

There was nothing, at the moment, that Ricky fancied less.

‘That’s very kind of you,’ he said. ‘One of these days I’d like to see some of your work, if I may.’

The voice said, with what seemed to be an imitation of Ricky’s accent, ‘Not “one of these days”. Now.’

‘Oh,’ Ricky said, temporizing, ‘now? Well – ‘

‘You won’t catch anything,’ Mr Jones sneered loudly. ‘If that’s what you’re afraid of.’

‘Oh God!’ Ricky thought. ‘Now he’s insulted. What a bloody bore.’

He said: ‘My dear man, I don’t for a moment suppose anything of the sort.’

Jones emptied his pint-pot and got to his feet.

‘Fair enough,’ he said. ‘We’ll push off, then.’

And without another glance at Ricky he walked out of the bar.

It was dark outside and chilly, with a sea-nip in the air and misty haloes round the few street lamps along the front. The high tide slapped against the sea-wall.

They walked in silence as far as the place where Ricky had seen Mr Jones painting in the afternoon. Here they turned left into deep shadow and began to climb what seemed to be an interminable flight of wet, broken-down steps, between cottages that grew farther apart and finally petered out altogether.

Ricky’s right foot slid under him, he lurched forward and snatched at wet grass on a muddy bank.

‘Too rough for you?’ sneered – or seemed to sneer – Mr Jones.

‘Not a bit of it,’ Ricky jauntily replied.

‘Watch it. I’ll go first.’

They were on some kind of very wet and very rough path. Ricky could only just see his host, outlined against the dim glow of what seemed to be dirty windows.

He was startled by a prodigious snort followed by squelching footsteps close at hand.

‘What the hell’s that?’ Ricky exclaimed.

‘It’s a horse,’ Mr Jones tossed off.

The invisible horse blew down its nostrils.

They arrived at the windows and at a door. Mr Jones gave the door a kick and it ground noisily open. It had a dirty parody of a portière on the inside.

Without an invitation or, indeed, any kind of comment, he went in, leaving Ricky to follow.

He did so, and was astonished to find himself face to face with Miss Harkness.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_d691aed2-f3ce-5b43-816e-5363e554a3f3)

Syd Jones’s Pad and Montjoy (#ulink_d691aed2-f3ce-5b43-816e-5363e554a3f3)

Ricky heard a voice that might have been anybody’s but his saying:

‘Oh, hullo. Good evening. We meet again. Ha-ha.’

She looked at him with contempt. He said to Mr Jones:

‘We met at luncheon up at L’Esperance.’

‘Oh Christ!’ Mr Jones said in a tone of utter disgust. And to Miss Harkness, ‘What the hell were you doing up there?’

‘Nothing,’ she mumbled. ‘I came away.’

‘So I should bloody hope. Had they got some things of mine up there?’

‘Yes.’

He grunted and disappeared through a door at the far end of the room. Ricky attempted a conversation with Miss Harkness but got nowhere with it. She said something inaudible and retired upon a record-player where she made a choice and released a cacophony.

Mr Jones returned. He dropped on to a sort of divan bed covered with what looked like a horse-rug. He seemed to be inexplicably excited.

‘Take a chair,’ he yelled at Ricky.

Ricky took an armchair, misjudging the distance between his person and the seat, which, having lost its springs, thudded heavily on the floor. He landed in a ludicrous position, his knees level with his ears. Mr Jones and Miss Harkness burst into raucous laughter. Ricky painfully joined in – and they immediately stopped.

He stretched out his legs and began to look about him.

As far as he could make out in the restricted lighting provided by two naked and dirty bulbs, he was in the front of a dilapidated cottage whose rooms had been knocked together. The end where he found himself was occupied by a bench bearing a conglomeration of painter’s materials. Canvases were ranged along the walls including a work which seemed to have been inspired by Miss Harkness herself or at least by her breeches, which were represented with unexpected realism.

The rest of the room was occupied by the divan bed, chairs, a filthy sink, a colour television and a stereophonic record-player. A certain creeping smell as of defective drainage was overlaid by the familiar pungency of turpentine, oil and lead.

Ricky began to ask himself a series of unanswerable questions. Why had Miss Harkness decided against L’Esperance? Was Mr Jones the father of her child? How did Mr Jones contrive to support an existence combining extremes of squalor with colour television and a highly sophisticated record-player? How good or how bad was Mr Jones’s painting?

As if in answer to this last conundrum, Mr Jones got up and began to put a succession of canvases on the easel, presumably for Ricky to look at.

This was a familiar procedure for Ricky. For as long as he could remember, young painters fortified by an introduction or propelled by their own hardihood, would bring their works to his mother and prop them up for her astringent consideration. Ricky hoped he had learnt to look at pictures in the right way, but he had never learned to talk easily about them and in his experience the painters themselves, good or bad, were as a rule extremely inarticulate. Perhaps, in this respect, Mr Jones’s formidable silences were merely occupational characteristics.

But what would Troy, Ricky’s mother, have said about the paintings? Mr Jones had skipped through a tidy sequence of styles. As representation retired before abstraction and abstraction yielded to collage and collage to surrealism, Ricky fancied he could hear her crisp dismissal: ‘Not much cop, I’m afraid, poor chap.’

The exhibition and the pop music came to an end and Mr Jones’s high spirits seemed to die with them. In the deafening silence that followed Ricky felt he had to speak. He said: ‘Thank you very much for letting me see them.’

‘Don’t give me that,’ said Mr Jones, yawning hideously. ‘Obviously you haven’t understood what I’m doing.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Stuff it. You smoke?’

‘If you mean what I think you mean, no, I don’t.’

‘I didn’t mean anything.’

‘My mistake,’ Ricky said.

‘You ever take a trip?’

‘No,’

‘Bloody smug, aren’t we?’

‘Think so?’ Ricky said, and not without difficulty struggled to his feet. Miss Harkness was fully extended on the divan bed and was possibly asleep.

Mr Jones said: ‘I suppose you think you know what you like.’

‘Why not? Anyway, that’s a pretty crummy old crack, isn’t it?’

‘Do you ever look at anything that’s not in the pretty peep department?’

‘Such as?’

‘Oh, you wouldn’t know,’ Mr Jones said. ‘Such as Troy. Does the name Troy mean anything to you, by the way?’

‘Look,’ Ricky said, ‘it really is bad luck for you and I can’t answer without making it sound like a pay-off line. But, yes, the name Troy does mean quite a lot to me. She’s – I feel I ought to say “wait for it, wait for it” – she’s my mother.’

Mr Jones’s jaw dropped. This much could be distinguished by a change of direction in his beard. There were, too, involuntary movements of the legs and arms. He picked up a large tube of paint which he appeared to scrutinize closely. Presently he said in a voice which was pitched unnaturally high:

‘I couldn’t be expected to know that, could I?’

‘Indeed, you couldn’t.’

‘As a matter of fact, I’ve really gone through my Troy phase. You won’t agree, of course, but I’m afraid I feel she’s painted herself out.’

‘Are you?’

Mr Jones dropped the tube of paint on the floor.

Ricky picked it up.

‘Jerome et Cie,’ he said. ‘They’re a new firm, aren’t they? I think they sent my Mum some specimens to try. Do you get it direct from France?’

Jones took it from him.

‘I generally use acrylic,’ he said.

‘Well,’ Ricky said, ‘I think I’ll seek my virtuous couch. It was nice of you to ask me in.’

They faced each other as two divergent species in a menagerie might do.

‘Anyway,’ Ricky said, ‘we do both speak English, don’t we?’

‘You reckon?’ said Mr Jones. And after a further silence: ‘Oh Christ, forget the lot and have a beer.’

‘I’ll do that thing,’ said Ricky.

II

To say that after this exchange all went swimmingly at Mr Jones’s pad would not be an accurate account of that evening’s strange entertainment but at least the tone became less acrimonious. Indeed, Mr Jones developed high spirits of a sort and instructed Ricky to call him Syd. He was devoured by curiosity about Ricky’s mother, her approach to her work and – this was a tricky one – whether she took pupils. Ricky found this behavioural change both touching and painful.

Miss Harkness took no part in the conversation but moodily produced bottled beer of which she consumed rather a lot. It emerged that the horse Ricky had shrunk from in the dark was her mount. So, he supposed, she would not spend the night at Syd’s pad, but would ride, darkling, to the stables or – was it possible? – all the way to L’Esperance and the protection, scarcely, it seemed, called for, of the Pharamonds.

By midnight Ricky knew that Syd was a New Zealander by birth, which accounted for certain habits of speech. He had left his native soil at the age of seventeen and had lived in his pad for a year. He did some sort of casual labour at Leathers, the family riding-stables to which Miss Harkness was attached but from which she seemed to have been evicted.

‘He mucks out,’ said Miss Harkness in a solitary burst of conversation and, for no reason that Ricky could divine, gave a hoarse laugh.

It transpired that Syd occasionally visited St Pierre-des-Roches, the nearest port on the Normandy coast to which there was a weekly ferry service.

At a quarter to one Ricky left the pad, took six paces into the night and fell flat on his face in the mud. He could hear Miss Harkness’s horse giving signs of equine consternation.

The village was fast asleep under a starry sky, the sound of the night tide rose and fell uninterrupted by Ricky’s rubber-shod steps on the cobbled front. Somewhere out on the harbour a solitary light bobbed, and he wondered if Mr Ferrant was engaged in his hobby of night fishing. He paused to watch it and realized that it was nearer inshore than he had imagined and coming closer. He could hear the rhythmic dip of oars.

There was an old bench facing the front. Ricky thought he would wait there and join Mr Ferrant, if indeed it was he, when he landed.

The light vanished round the far side of the jetty. Ricky heard the gentle thump of the boat against a pier followed by irregular sounds of oars being stowed and objects shifted. A man with a lantern rose into view and made fast the mooring lines. He carried a pack on his back and began to walk down the jetty. He was too far away to be identified.

Ricky was about to get up and go to meet him when, as if by some illusionist’s trick, there was suddenly a second figure beside the first. Ricky remained where he was, in shadow.

The man with the lantern raised it to the level of his face, and Ricky saw that he was indeed Ferrant, caught in a Rembrandt-like golden effulgence. Ricky kept very still, feeling that to approach them would be an intrusion. They came towards him. Ferrant said something indistinguishable and the other replied in a voice that was not that of the locals: ‘OK, but watch it. Good night.’ They separated. The newcomer walked rapidly away towards the turning that led up to the main road and Ferrant crossed the street to his own house.

Ricky ran lightly and soundlessly after him. He was fitting his key in the lock and had his back turned.

‘Good morning, Mr Ferrant,’ Ricky said.

He spun round with an oath.

‘I’m sorry,’ Ricky stammered, himself jolted by this violent reaction. ‘I didn’t mean to startle you.’

Ferrant said something in French, Ricky thought, and laughed, a little breathlessly.

‘Have you been making a night of it, then?’ he said, ‘Not much chance of that in the Cove.’

‘I’ve been up at Syd Jones’s.’

‘Have you now,’ said Ferrant. ‘Fancy that.’ He pushed the door open and stood back for Ricky to enter.

‘Good night then, Mr Alleyn,’ said Ferrant.

As Ricky entered he heard in the distance the sound of a car starting. It seemed to climb the steep lane out of Deep Cove, and at that moment he realized that the second man on the wharf had been Louis Pharamond.

The house was in darkness. Ricky crept upstairs making very little noise. Just before he shut his bedroom door he heard another door close quite near at hand.

For a time he lay awake listening to the sound of the tide and thinking what a long time it seemed since he arrived in Deep Cove. He drifted into a doze, and found the scarcely-formed persons of the book he hoped to write, taking upon themselves characteristics of the Pharamonds, of Sydney Jones, of Miss Harkness and the Ferrants, so that he scarcely knew which was which.

The next morning was cold and brilliant with a March wind blowing through a clear sky. Mrs Ferrant gave Ricky a grey mullet for his breakfast, the reward, it emerged, of her husband’s night excursion.

By ten o’clock he had settled down to a determined attack on his work.

He wrote in longhand, word after painful word. He wondered why on earth he couldn’t set about this job with something resembling a design. Once or twice he thought possibilities – the ghosts of promise – began to show themselves. There was one character, a woman, who had stepped forward and presented herself to be written about. An appreciable time went by before he realized he was dealing with Julia Pharamond.

It came as quite a surprise to find that he had been writing for two hours. He eased his fingers and filled his pipe. I’m feeling better, he thought.

Something spattered against the window-pane. He looked out and down, and there, with his face turned up, was Jasper Pharamond.

‘Good morning to you,’ Jasper called in his alto voice, ‘are you incommunicado? Is this a liberty?’

‘Of course not. Come up.’

‘Only for a moment.’

He heard Mrs Ferrant go down the passage, the door open and Jasper’s voice on the stairs: ‘It’s all right, thank you, Marie. I’ll find my way.’

Ricky went out to the landing and watched Jasper come upstairs. He pretended to make heavy weather of the ascent, rocking his shoulders from side to side and thumping his feet.

‘Really!’ he panted when he arrived. ‘This is the authentic setting. Attic stairs and the author embattled at the top. You must be sure to eat enough. May I come in?’

He came in, sat on Ricky’s bed with a pleasant air of familiarity, and waved his hand at the table and papers. ‘The signs are propitious,’ he said.

‘The place is propitious,’ Ricky said warmly. ‘And I’m very much obliged to you for finding it. Did you go tramping about the village and climbing interminable stairs?’

‘No, no. Julia plumped for Marie Ferrant.’

‘You knew her already?’

‘She was in service up at L’Esperance before she married. We’re old friends,’ said Jasper lightly.

Ricky thought that might explain Mrs Ferrant’s curiosity.

‘I’ve come with an invitation,’ Jasper said. ‘It’s just that we thought we’d go over to Montjoy to dine and trip a measure on Saturday and we wondered if it would amuse you to come.’

Ricky said: ‘I ought to say no, but I won’t. I’d love to.’

‘We must find somebody nice for you.’

‘It won’t by any chance be Miss Harkness?’

‘My dear!’ exclaimed Jasper excitedly. ‘Apropos the Harkness! Great drama! Well, great drama in a negative sense. She’s gone!’

‘When?’

‘Last night. Before dinner. She prowled down the drive, disappeared and never came back. Bruno wonders if she jumped over the cliff – too awful to contemplate.’

‘You may set your minds at rest,’ said Ricky. ‘She didn’t do that.’ And he told Jasper all about his evening with Syd Jones and Miss Harkness.

‘Well!’ said Jasper. ‘There you are. What a very farouche sort of girl. No doubt the painter is the partner of her shame and the father of her unborn babe. What’s he like? His work, for instance?’

‘You ought to be the best judge of that. You’ve got some of it pinned on your drawing-room walls.’

‘I might have known it!’ Jasper cried dramatically. ‘Another of Julia’s finds! She bought them in the street in Montjoy on Market Day. I can’t wait to tell her,’ Jasper said, rising energetically. ‘What fun! No. We must both tell her.’

‘Where is she?’

‘Down below, in the car. Come and see her, do.’

Ricky couldn’t resist the thought of Julia so near at hand. He followed Jasper down the stairs, his heart thumping as violently as if he had run up them.

It was a dashing sports car and Julia looked dashing and expensive to match it. She was in the driver’s seat, her gloved hands drooping on the wheel with their gauntlets turned back so that her wrists shone delicately. Jasper at once began to tell about Miss Harkness, inviting Ricky to join in. Ricky thought how brilliantly she seemed to listen and how this air of being tuned-in invested all the Pharamonds. He wondered if they lost interest as suddenly as they acquired it.

When he had answered her questions she said briskly: ‘A case, no doubt, of like calling to like. Both of them naturally speechless. No doubt she’s gone into residence at the pad.’

‘I’m not so sure,’ Ricky said. ‘Her horse was there, don’t forget. It seemed to be floundering about in the dark.’

Jasper said, ‘She would hardly leave it like that all night. Perhaps it was only a social call after all.’

‘How very odd,’ Julia said, ‘to think of Miss Harkness in the small hours of the morning, riding through the Cove. I wonder she didn’t wake you up.’

‘She may not have passed by my window.’

‘Well,’ Julia said, ‘I’m beginning all of a sudden to weary of Miss Harkness. It was very boring of her to be so rude, walking out on us like that.’

‘It’d have been a sight more boring if she’d stayed, however,’ Jasper pointed out.

There was a clatter of shoes on the cobblestones and the Ferrant son, Louis, came running by on his way home from school. He slowed up when he saw the car and dragged his feet, staring at it and walking backwards.

‘Hullo, young Louis,’ Ricky said.

He didn’t answer. His sloe eyes looked out of a pale face under a dark thatch of hair. He backed slowly away, turned and suddenly ran off down the street.

‘That’s Master Ferrant, that was,’ said Ricky.

Neither of the Pharamonds seemed to have heard him. For a second or two they looked after the little boy and then Jasper said lightly: ‘Dear me! It seems only the other day that his Mum was a bouncing tweeny or parlourmaid, or whatever it was she bounced at.’

‘Before my time,’ said Julia. ‘She’s a marvellous laundress and still operates for us. Darling, we’re keeping Ricky out here. Who can tell what golden phrase we may have aborted. Super that you can come on Saturday, Ricky.’

‘Pick you up at eightish,’ cried Jasper, bustling into the car. They were off, and Ricky went back to his room.

But not, at first, to work. He seemed to have taken the Pharamonds upstairs, and with them little Louis Ferrant, so that the room was quite crowded with white faces, black hair and brilliant pitch-ball eyes.

III

Montjoy might have been on another island from the Cove and in a different sea. Once a predominantly French fishing village, it was now a fashionable place with marinas, a yacht club, surfing, striped umbrellas and, above all, the celebrated Hotel Montjoy itself with its Stardust Ballroom, whose plateglass dome and multiple windows could be seen, airily glowing, from far out to sea. Here, one dined and danced expensively to a famous band, and here, on Saturday night at a window-table sat the Pharamonds, Ricky and a girl called Susie de Waite.

They ate lobster salad and drank champagne. Ricky talked to and danced with Susie de Waite as was expected of him and tried not to look too long and too often at Julia Pharamond.

Julia was in great form, every now and then letting off the spluttering firework of her laughter. He had noticed at luncheon that she had uninhibited table-manners and ate very quickly. Occasionally she sucked her fingers. Once when he had watched her doing this he found Jasper looking at him with amusement.

‘Julia’s eating habits,’ he remarked, ‘are those of a partially-trained marmoset.’

‘Darling,’ said Julia, waggling the sucked fingers at him, ‘I love you better than life itself.’

‘If only,’ Ricky thought, ‘she would look at me like that’ – and immediately she did, causing his unsophisticated heart to bang at his ribs and the blood mount to the roots of his hair.

Ricky considered himself pretty well adjusted to the contemporary scene. But, he thought, every adventure that he had experienced so far had been like a bit of fill-in dialogue leading to the entry of the star. And here, beyond all question, she was.

She waltzed now with her cousin Louis. He was an accomplished dancer and Julia followed him effortlessly. They didn’t talk to each other, Ricky noticed. They just floated together – beautifully.

Ricky decided that he didn’t perhaps quite like Louis pharamond. He was too smooth. And anyway, what had he been up to in the Cove at one o’clock in the morning?

The lights were dimmed to a black-out. From somewhere in the dome, balloons, treated to respond to ultraviolet ray, were released in hundreds and jostled uncannily together, filling the ballroom with luminous bubbles. The band reduced itself to the whispering shish-shish of waves on the beach below. The dancers, scarcely moving, resembled those shadows that seem to bob and pulse behind the screen of an inactive television set.

‘May we?’ Ricky asked Susie de Waite.

He had once heard his mother say that a great deal of his father’s success as an investigating officer stemmed from his gift for getting people to talk about themselves. ‘It’s surprising,’ she had said, ‘how few of them can resist him.’

‘Did you?’ her son asked.

‘Yes,’ Troy said, and after a pause, ‘but not for long.’

So Ricky asked Susie de Waite about herself and it was indeed surprising how readily she responded. It was also surprising how unstimulating he found her self-revelations.

And then, abruptly, the evening was set on fire. They came alongside Julia and Louis and Julia called to Ricky.

‘Ricky, if you don’t dance with me again at once I shall take umbrage.’ And then to Louis. ‘Goodbye, darling. I’m off.’

And she was in Ricky’s arms. The stars in the sky had come reeling down into the ballroom and the sea had got into his eardrums and bliss had taken up its abode in him for the duration of a waltz.

They left at two o’clock in the large car that belonged, it seemed, to the Louis Pharamonds. Louis drove with Susie de Waite next to him and Bruno on her far side. Ricky found himself at the back between Julia and Carlotta, and Jasper was on the tip-up seat facing them.

When they were clear of Montjoy on the straight road to the Cove, Louis asked Susie if she’d like to steer, and on her rapturously accepting, put his arm round her. She took the wheel.

‘Is this all right?’ Carlotta asked at large. ‘Is she safe?’

‘It’s fantastic,’ gabbled Susie. ‘Safe as houses. Promise! Ow! Sorry!

She really is rather an ass of a girl, Ricky thought.

Julia picked up Ricky’s hand and then Carlotta’s. ‘Was it a pleasant party?’ she asked, gently tapping their knuckles together. ‘Have you liked it?’

Ricky said he’d adored it. Julia’s hand was still in his. He wondered whether it would be all right to kiss it under, as it were, her husband’s nose, but felt he lacked the style. She gave his hand a little squeeze, dropped it, leant forward and kissed her husband.

‘Sweetie,’ Julia cried extravagantly, ‘you are such heaven! Do look, Ricky, that’s Leathers up there where Miss Harkness does her stuff. We really must all go riding with her before it’s too late.’

‘What do you mean,’ her husband asked, ‘by your “too late”?’

‘Too late for Miss Harkness, of course. Unless, of course, she does it on purpose, but that would be very silly of her. Too silly for words,’ said Julia severely.

Susie de Waite let out a scream that modulated into a giggle. The car shot across the road and back again.

Carlotta said sharply: ‘Louis, do keep your techniques for another setting.’

Louis gave what Ricky thought of as a bedroom laugh, cuddled Susie up and closed his hand over hers on the wheel.

‘Behave,’ he said. ‘Bad girl.’

They arrived at the lane that descended precipitously into the Cove. Louis took charge, drove pretty rapidly down it and pulled up in front of the Ferrant cottage.

‘Here we are,’ he said. ‘Abode of the dark yet passing-fair Marie. Is she still dark and passing-fair, by the way?’

Nobody answered.

Louis said very loudly: ‘Any progeny? Oh, but of course. I forgot.’

‘Shut up,’ Jasper said, in a tone of voice that Ricky hadn’t heard from him before.

He and Julia and Carlotta together said good night to Ricky, who by this time was outside the car. He shut the door as quietly as he could and stood back. Louis reversed noisily and much too fast. He called out something that sounded like: ‘Give her my love.’ The car shot away in low gear and roared up the lane.

Upstairs on the dark landing Ricky could hear Ferrant snoring prodigiously and pictured him with his red hair and high colour and his mouth wide open. Evidently he had not gone fishing that night.

IV

In her studio in Chelsea, Troy shoved her son’s letter into the pocket of her painting smock and said:

‘He’s fallen for Julia Pharamond.’

‘Has he, now?’ said Alleyn. ‘Does he announce it in so many words?’

‘No, but he manages to drag her into every other sentence of his letter. Take a look.’

Alleyn read his son’s letter with a lifted eyebrow. ‘I see what you mean,’ he said presently.

‘Oh well,’ Troy muttered. ‘It’ll be one girl and then another, I suppose, and then, with any luck, just one and that a nice one. In the meantime, she’s very attractive. Isn’t she?’

‘A change from dirty feet, jeans, and beads in the soup, at least.’

‘She’s beautiful,’ said Troy.

‘He may tire of her heavenly inconsequence.’

‘You think so?’

‘Well, I would. They seem to be taking quite a lot of trouble over him. Kind of them.’

‘He’s a jolly nice young man,’ Troy said firmly.

Alleyn chuckled and read on in silence.

‘Why,’ Troy asked presently, ‘do you suppose they live on that island?’

‘Dodging taxation. They’re clearly a very clannish lot. The other two are there.’

‘The cousins that came on board at Acapulco?’

‘Yes,’ Alleyn said. ‘It was a sort of enclave of cousins.’

‘The Louis’s seem to live with the Jaspers, don’t they?’

‘Looks like it.’ Alleyn turned a page of the letter. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘besotted or not, he seems to be writing quite steadily.’

‘I wonder if his stuff’s any good, Rory? Do you wonder?’

‘Of course I do,’ he said, and went to her.

‘It can be tough going, though, can’t it?’

‘Didn’t you swan through a similar stage?’

‘Now I come to think of it,’ Troy said, squeezing a dollop of flake white on her palette, ‘I did. I wouldn’t tell my parents anything about my young men and I wouldn’t show them anything I painted. I can’t imagine why.’

‘You gave me the full treatment when I first saw you, didn’t you? About your painting?’

‘Did I? No, I didn’t. Shut up,’ said Troy, laughing. She began to paint.

‘That’s the new brand of colour, isn’t it? Jerome et Cie?’ said Alleyn, and picked up a tube.

‘They sent it for free. Hoping I’d talk about it, I suppose. The white and the earth colours are all right but the primaries aren’t too hot. Rather odd, isn’t it, that Rick should mention them?’

‘Rick? Where?’

‘You haven’t got to the bit about his new painting chum and the pregnant equestrienne.’

‘For the love of Mike!’ Alleyn grunted and read on. ‘I must say,’ he said, when he’d finished, ‘he can write, you know, darling. He can indeed.’

Troy put down her palette, flung her arm round him and pushed her head into his shoulder. ‘He’ll do us nicely,’ she said, ‘won’t he? But it was quite a coincidence, wasn’t it? About Jerome et Cie and their paint?’

‘In a way,’ said Alleyn, ‘I suppose it was.’

V

On the morning after the party, Ricky apologized to Mrs Ferrant for the noisy return in the small hours, and although Mr Ferrant’s snores were loud in his memory, said he was afraid he had been disturbed.

‘It’d take more than that to rouse him,’ she said. She never referred to her husband by name. ‘I heard you. Not you but him. Pharamond. The older one.’

She gave Ricky a sideways look that he couldn’t fathom. Derisive? Defiant? Sly? Whatever lay behind her manner, it was certainly not that of an ex-domestic cook, however emancipated. She left him with the feeling that the corner of a curtain had been lifted and dropped before he could see what lay beyond it.

During the week he saw nothing of the Pharamonds except in one rather curious incident on the Thursday evening. Feeling the need of a change of scene, he had wheeled his bicycle up the steep lane, pedalled along the road to Montjoy and at a point not far from L’Esperance had left his machine by the wayside and walked towards the cliff-edge.

The evening was brilliant and the Channel, for once, blue with patches of bedazzlement. He sat down with his back to a warm rock at a place where the cliff opened into a ravine through which a rough path led between clumps of wild broom, down to the sea. The air was heady and a salt breeze felt for his lips. A lark sang and Ricky would have liked a girl – any girl – to come up through the broom from the sea with a reckless face and the sun in her eyes.

Instead, Louis Pharamond came up the path. He was below Ricky, who looked at the top of his head. He leant forward, climbing, swinging his arms, his chin down.

Ricky didn’t want to encounter Louis. He shuffled quickly round the rock and lay on his face. He heard Louis pass by on the other side. Ricky waited until the footsteps died away, wondering at his own behaviour.

He was about to get up when he heard a displaced stone roll down the path. The crown of a head and the top of a pair of shoulders appeared below him. Grossly foreshortened though they were, there was no mistaking who they belonged to. Ricky sank down behind his rock and let Miss Harkness, in her turn, pass him by.

He rode back to the cottage.

He was gradually becoming persona grata at the pub. He was given a ‘good evening’ when he came in and warmed up to when, his work having prospered that day, he celebrated by standing drinks all round. Bill Prentice, the fish-truck driver, offered to give him a lift into Montjoy if ever he fancied it. They settled for the coming morning. It was then that Miss Harkness came into the bar alone.

Her entrance was followed by a shuffling of feet and by the exchange of furtive smiles. She ordered a glass of port. Ferrant, leaning back against the bar in his favourite pose, looked her over. He said something that Ricky couldn’t hear and raised a guffaw. She smiled slightly. Ricky realized that with her entrance the atmosphere in the Cod-and-Bottle had become that of the stud. And that not a man there was unaware of it. So this, he thought, is what Miss Harkness is about.

The next morning, very early, Ricky tied his bicycle to the roof of the fish-truck and himself climbed into the front seat.

He was taken aback to find that Syd Jones was to be a fellow-passenger. Here he came, hunched up in a dismal mackintosh, with his paintbox slung over his shoulder, a plastic carrier-bag and a large and superior suitcase which seemed to be unconscionably heavy.

‘Hullo,’ Ricky said. ‘Are you moving into the Hotel Montjoy, with your grand suitcase?’

‘Why the hell would I do that?’

‘All right, all right, let it pass. Sorry.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t fall about at upper-middle-class humour.’

‘My mistake,’ said Ricky. ‘I do better in the evenings.’

‘I haven’t noticed it.’

‘You may be right. Here comes Bill. Where are you going to put your case? On the roof with my upper-middle-class bike?’

‘In front. Shift your feet. Watch it.’

He heaved the case up, obviously with an effort, pushed it along the floor under Ricky’s legs and climbed up. Bill Prentice, redolent of fish, mounted the driver’s seat, Syd nursed his paintbox and Ricky was crammed in between them.

It was a sparkling morning. The truck rattled up the steep lane, they came out into sunshine at the top and banged along the main road to Montjoy. Ricky was in good spirits.

They passed the entry into Leathers with its signboard: ‘Riding Stables. Hacks and Ponies for hire. Qualified Instructors.’ He wondered if Miss Harkness was up and about. He shouted above the engine to Syd: ‘You don’t go there every day, do you?’

‘Definitely bloody not,’ Syd shouted back. It was the first time Ricky had heard him raise his voice.

The road made a blind turn round a dense copse. Bill took it on the wrong side at forty miles an hour.

The windscreen was filled with Miss Harkness on a plunging bay horse, all teeth and eyes and flying hooves. An underbelly and straining girth reared into sight. The brakes shrieked, the truck skidded, the world turned sideways, and the passenger’s door flew open. Syd Jones, his paintbox and his suitcase shot out. The van rocked and sickeningly righted itself on the verge in a cloud of dust. The horse could be seen struggling on the ground and its rider on her feet with the reins still in her hands. The engine had stopped and the air was shattered by imprecations – a three-part disharmony from Bill, Syd and, predominantly, Miss Harkness.

Bill turned off the ignition, dragged his hand-brake on, got out and approached Miss Harkness, who told him with oaths to keep off. Without a pause in her stream of abuse she encouraged her mount to clamber to its feet, checked its impulse to bolt and began gently to examine it; her great horny hand passed with infinite delicacy down its trembling legs and heaving barrel. It was, Ricky saw, a wall-eyed horse.

‘Keep the hell out of it,’ she said softly. ‘You’ll hear about this.’

She led the horse along the far side of the road and past the truck. It snorted and plunged but she calmed it. When they had gone some distance, she mounted. The sound of its hooves, walking, diminished. Bill began to swear again.

Ricky slid out of the truck on the passenger’s side. The paintbox had burst open and its contents were scattered about the grass. The catches on the suitcase had been sprung and the lid had flown back. Ricky saw that it was full of unopened cartons of Jerome et Cie’s paints. Syd Jones squatted on the verge, collecting tubes and fitting them back into their compartments.

Ricky stooped to help him.

‘Cut that out!’ he snarled.

‘Very well, you dear little man,’ Ricky said, with a strong inclination to throw one at his head. He took a step backwards, felt something give under his heel and looked down. He had trodden on a large tube of vermilion and burst the end open. Paint had spurted over his shoe.

‘Oh damn, I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I’m most awfully sorry.’

He reached for the depleted tube. It was snatched from under his hand. Syd, on his knees, the tube in his grasp and his fingers reddened, mouthed at him. What he said was short and unprintable.

‘Look,’ Ricky said. ‘I’ve said I’m sorry. I’ll pay for the paint and if you feel like a fight you’ve only to say so and we’ll shape up and make fools of ourselves here and now. How about it?’

Syd was crouched over his task. He mumbled something that might have been ‘Forget it.’ Ricky, feeling silly, walked round to the other side of the truck. It was being inspected by Bill Prentice with much the same intensity as Miss Harkness had displayed when she examined her horse. The smell of petrol now mingled with the smell of fish.

‘She’s OK,’ Bill said at last and climbed into the driver’s seat. ‘Silly bitch,’ he added, referring to Miss Harkness, and started up the engine.

Syd loomed up on the far side with his suitcase, round which he had buckled his belt. His jeans drooped from his hip-bones as if from a coat-hanger.

‘Hang on a sec,’ Bill shouted.

He engaged his gear and the truck lurched back on the road. Syd waited. Ricky walked round to the passenger’s side. To his astonishment, Syd observed on what sounded like a placatory note: ‘Bike’s OK, then?’

They climbed on board and the journey continued. Bill’s strictures upon Miss Harkness were severe and modified only, Ricky felt, out of consideration for Syd’s supposed feelings. The burden of his plaint was that horse-traffic should be forbidden on the roads.

‘What was she on about?’ he complained. ‘The horse was OK.’

‘It was Mungo,’ Syd offered. ‘She’s crazy about it. Savage brute of a thing.’

‘That so?’

‘Bit me. Kicked the old man. He wants to have it destroyed.’

‘Is it all right with her?’ asked Ricky.

‘So she reckons. It’s an outlaw with everyone else.’

They arrived at the only petrol station between the Cove and Montjoy. Bill pulled into it for fuel and oil and held the attendant rapt with an exhaustive coverage of the incident.

Syd complained in his dull voice: ‘I’ve got a bloody boat to catch, haven’t I?’

Ricky, who was determined not to make advances, looked at his watch and said that there was time in hand.

After an uncomfortable silence Syd said, ‘I’m funny about my painting gear. You know? I can’t do with anyone else handling it. You know? If anyone else scrounges my paint, you know, borrows some, I can’t use that tube again. It’s kind of contaminated. Get what I mean?’

Ricky thought that what he seemed to mean was a load of highfalutin’ balls, but he gave a tolerant grunt and after a moment or two Syd began to talk. Ricky could only suppose that he was trying to make amends. His discourse was obscure but it transpired that he had been given some kind of agency by Jerome et Cie. He was to leave free samples of their paints at certain shops and with a number of well-known painters, in return for which he was given his fare, as much of their products for his own use as he cared to ask for and a small commission on sales. He produced their business card with a note, ‘Introducing Mr Sydney Jones’, written on it. He showed Ricky the list of painters they had given him. Ricky was not altogether surprised to find his mother’s name at the top.

With as ill a grace as could be imagined, he said he supposed Ricky ‘wouldn’t come at putting the arm on her’, which Ricky interpreted as a suggestion that he should give Syd an introduction to his mother.

‘When are you going to pay your calls?’ Ricky asked.

The next day, it seemed. And it turned out that Syd was spending the night with friends who shared a pad in Battersea. Jerome et Cie had expressed the wish that he should modify his personal appearance.

‘Bloody commercial shit,’ he said violently. ‘Make you vomit, wouldn’t it?’

They arrived at the wharves in Montjoy at half past eight. Ricky watched the crates of fish being loaded into the ferry and saw Syd Jones go up the gangplank. He waited until the ferry sailed. Syd had vanished, but at the last moment he re-appeared on deck wearing his awful raincoat and with his paintbox still slung over his shoulder.

Ricky spent a pleasant day in Montjoy and bicycled back to the Cove in the late afternoon.

Rather surprisingly, the Ferrants had a telephone. That evening Ricky put a call through to his parents advising them of the approach of Sydney Jones.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_4047b7c7-b600-54cc-8e83-d5b7b75ced8d)

The Gap (#ulink_4047b7c7-b600-54cc-8e83-d5b7b75ced8d)

‘As far as I can see,’ Alleyn said, ‘he’s landing us with a sort of monster.’

‘He thinks it might amuse us to meet him after all we’ve heard.’

‘It had better,’ Alleyn said mildly.

‘It’s only for a minute or two.’

‘When do you expect him?’

‘Some time in the morning, I imagine.’

‘What’s the betting he stays for luncheon?’

Troy stood before her husband in the attitude that he particularly enjoyed, with her back straight, her hands in the pockets of her painting smock and her chin down rather like a chidden little boy.

‘And what’s the betting,’ he went on, ‘my own true love, that before you can say Flake White, he’s showing you a little something he’s done himself.’

‘That,’ said Troy grandly, ‘would be altogether another pair of boots and I should know how to deal with them. And anyway he told Rick he thinks I’ve painted myself out.’

‘He grows more attractive every second.’

‘It was funny about the way he behaved when Rick trod on his vermilion.’

Alleyn didn’t answer at once. ‘It was, rather,’ he said at last. ‘Considering he gets the stuff free.’

‘Trembling with rage, Rick said, and his beard twitching.’

‘Delicious.’

‘Oh well,’ said Troy, suddenly brisk. ‘We can but see.’

‘That’s the stuff. I must be off.’ He kissed her. ‘Don’t let this Jones fellow make a nuisance of himself,’ he said. ‘As usual, my patient Penny-lope, there’s no telling when I’ll be home. Perhaps for lunch or perhaps I’ll be in Paris. It’s that narcotics case. I’ll get them to telephone. Bless you.’

‘And you,’ said Troy cheerfully.

She was painting a tree in their garden from within the studio. At the heart of her picture was an exquisite little silver birch just starting to burgeon and treated with delicate and detailed realism. But this tree was at the core of its own diffusion a larger and much more stylized version of itself and that, in turn, melted into an abstract of the two trees it enclosed. Alleyn said it was like the unwinding of a difficult case with the abstractions on the outside and the implacable ‘thing itself’ at the hard centre. He had begged her to stop before she went too far.

She hadn’t gone any distance at all when Mr Sydney Jones presented himself.

There was nothing very remarkable, Troy thought, about his appearance. He had a beard, close-cropped, revealing a full, vaguely sensual but indeterminate mouth. His hair was of a medium length and looked clean. He wore a sweater over jeans. Indeed, all that remained of the Syd Jones Ricky had described was his huge silly-sinister pair of black spectacles. He carried a suitcase and a newspaper parcel.

‘Hullo,’ Troy said, offering her hand. ‘You’re Sydney Jones, aren’t you? Ricky rang up and told us you were coming. Do sit down, won’t you?’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ he mumbled, and sniffed loudly. He was sweating.

Troy sat on the arm of a chair. ‘Do you smoke?’ she said. ‘I’m sorry I haven’t got any cigarettes but do if you’d like to.’

He put his suitcase and the newspaper parcel down and lit a cigarette. He then picked up his parcel.

‘I gather it’s about Jerome et Cie’s paints, isn’t it?’ Troy suggested. ‘I’d better say that I wouldn’t want to change to them and I can’t honestly give you a blurb. Anyway I don’t do that sort of thing. Sorry.’ She waited for a response but he said nothing. ‘Rick tells us,’ she said, ‘that you paint.’

With a gesture so abrupt that it made her jump, he thrust his parcel at her. The newspaper fell away and three canvases tied together with string were exposed.

‘Is that,’ Troy said, ‘some of your work?’

He nodded.

‘Do you want me to look at it?’

He muttered.

Made cross by having been startled, Troy said: ‘My dear boy, do for pity’s sake speak out. You make me feel as if I were giving an imitation of a woman talking to herself. Stick them up there where I can see them.’

With unsteady hands he put them up, one by one, changing them when she nodded. The first was the large painting Ricky had decided was an abstraction of Leda and the Swan. The second was a kaleidoscopic arrangement of shapes in hot browns and raucous blues. The third was a landscape, more nearly representational than the others. Rows of perceptible houses with black, staring windows stood above dark water. There was some suggestion of tactile awareness but no real respect, Troy thought, for the medium.

She said: ‘I think I know where we are with this one. Is it St Pierre-des-Roches on the coast of Normandy?’

‘Yar,’ he said.

‘It’s the nearest French port to your island, isn’t it? Do you often go across?’

‘Aw – yar,’ he said, fidgeting. ‘It turns me on. Or did. I’ve worked that vein out, as a matter of fact.’

‘Really,’ said Troy. There was a longish pause. ‘Do you mind putting up the first one again. The Leda.’

He did so. Another silence. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘do you want me to say what I think? Or not?’

‘I don’t mind,’ he mumbled, and yawned extensively.

‘Here goes, then. I find it impossible to say whether I think you’ll develop into a good painter or not. These three things are all derivative. That doesn’t matter while you’re young: if you’ve got something of your own, with great pain and infinite determination you will finally prove it. I don’t think you’ve done that so far. I do get something from the Leda thing – a suggestion that you’ve got a strong sense of rhythm, but it is no more than a suggestion. I don’t think you’re very self-critical.’ She looked hard at him. ‘You don’t fool about with drugs, do you?’ asked Troy.

There was a very long pause before he answered quite loudly, ‘No.’

‘Good. I only asked because your hands are unsteady and your behaviour erratic, and –’ She broke off. ‘Look here,’ she said, ‘you’re not well, are you? Sit down. No, don’t be silly, sit down.’

He did sit down. He was shaking, sweat had started out under the line of his hair and he was the colour of a peeled banana. He gaped and ran a dreadful tongue round his mouth. She fetched him a glass of water. The dark glasses were askew. He put up his trembling hand to them and they fell off, disclosing a pair of pale ineffectual eyes. Gone was the mysterious Mr Jones.

‘I’m all right,’ he said.

‘I don’t think you are.’

‘Party. Last night.’

‘What sort of party?’

‘Aw. A fun thing.’

‘I see.’

‘I’ll be OK.’

Troy made some black coffee and left him to drink it while she returned to her work. The spirit trees began to enclose their absolute inner tree more firmly.

When, at a quarter past one, Alleyn walked into the studio, it was to find his wife at work and an enfeebled young man avidly watching her from an armchair.

‘Oh,’ said Troy, grandly waving her brush and staring fixedly at Alleyn. ‘Hullo, darling. Syd, this is my husband. This is Rick’s friend, Syd Jones, Rory. He’s shown me some of his work and he’s going to stay for luncheon.’

‘Well!’ Alleyn said, shaking hands. ‘This is an unexpected pleasure. How are you?’

II

Three days after Ricky’s jaunt to Montjoy Julia Pharamond rang him up at lunch-time. He had some difficulty in pulling himself together and attending to what she said.

‘You do ride, don’t you?’ she asked.

‘Not at all well.’

‘At least you don’t fall off?’

‘Not very often.’

‘There you are, then. Super. All settled.’

‘What,’ he asked, ‘is settled?’

‘My plan for tomorrow. We get some Harkness hacks and ride to Bon Accord.’

‘I haven’t any riding things.’

‘No problem. Jasper will lend you any amount. I’m ringing you up while he’s out because he’d say I was seducing you away from your book. But I’m not, am I?’

‘Yes,’ said Ricky, ‘you are, and it’s lovely,’ and heard her splutter.

‘Well, anyway,’ she said, ‘it’s all settled. You must leap on your bicyclette and pedal up to L’Esperance for breakfast and then we’ll all sweep up to the stables. Such fun.’

‘Is Miss Harkness coming?’

‘No. How can you ask! Before we knew where we were she’d miscarry.’

‘If horse-exercise was going to make her do that it would have done so already, I fancy,’ said Ricky, and told her about the mishap on the road to Montjoy. Julia was full of exclamations and excitement. ‘How,’ she said, ‘you dared not to ring up and tell us immediately!’

‘I thought you’d said she was beginning to be a bore.’